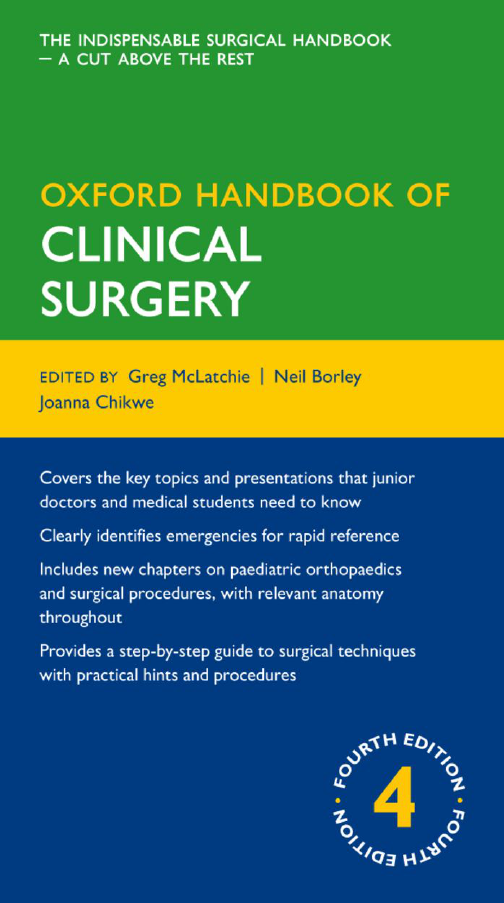

OXFORD MEDICAL PUBLICATIONS

Oxford Handbook of

Clinical Surgery

Published and forthcoming Oxford Handbooks

Oxford Handbook for the Foundation Programme 3e

Oxford Handbook of Acute Medicine 3e

Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia 3e

Oxford Handbook of Applied Dental Sciences

Oxford Handbook of Cardiology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 3e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Dentistry 5e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Haematology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Immunology and Allergy 3e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine – Mini Edition 8e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine 8e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Pathology

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Pharmacy 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Rehabilitation 2e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties 9e

Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery 4e

Oxford Handbook of Complementary Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Critical Care 3e

Oxford Handbook of Dental Patient Care 2e

Oxford Handbook of Dialysis 3e

Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine 4e

Oxford Handbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes 2e

Oxford Handbook of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery

Oxford Handbook of Epidemiology for Clinicians

Oxford Handbook of Expedition and Wilderness Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2e

Oxford Handbook of General Practice 3e

Oxford Handbook of Genetics

Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV and AIDS 2e

Oxford Handbook of Geriatric Medicine

Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology

Oxford Handbook of Key Clinical Evidence

Oxford Handbook of Medical Dermatology

Oxford Handbook of Medical Imaging

Oxford Handbook of Medical Sciences 2e

Oxford Handbook of Medical Statistics

Oxford Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension

Oxford Handbook of Neurology

Oxford Handbook of Nutrition and Dietetics 2e

Oxford Handbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Occupational Health 2e

Oxford Handbook of Oncology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Ophthalmology 2e

Oxford Handbook of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics 2e

Oxford Handbook of Pain Management

Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care 2e

Oxford Handbook of Practical Drug Therapy 2e

Oxford Handbook of Pre-Hospital Care

Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry 3e

Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice 2e

Oxford Handbook of Reproductive Medicine & Family Planning

Oxford Handbook of Respiratory Medicine 2e

Oxford Handbook of Rheumatology 3e

Oxford Handbook of Sport and Exercise Medicine 2e

Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine 3e

Oxford Handbook of Urology 3e

1

Oxford Handbook of

Clinical

Surgery

Fourth edition

Edited by

Greg McLatchie

Consultant Surgeon,

Hartlepool General Hospital,

Hartlepool, UK

Neil Borley

Consultant Colorectal Surgeon,

Cheltenham General Hospital,

Cheltenham, UK

Joanna Chikwe

Associate Professor, Department of Cardiothoracic

Surgery, Mount Sinai Medical Center,

New York, United States

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press, 2013

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published 1990

Second Edition published 2002

Third Edition published 2007

Fourth Edition published 2013

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must

impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 978–0–19–969947–6 (fl exicover: alk.paper)

Printed in China by

C&C Offset Printing Co. Ltd.

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug

dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product

information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product

information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers, and the most recent

codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not

accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text, or for the misuse or

misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages

and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breastfeeding.

v

Preface to the fourth

edition

Sometimes we have to look backward to look forward. Since 1990, sur-

gery has witnessed cataclysmic changes. In our Trust, the fi rst laparoscopic

cholecystectomy was performed in 1992, and has now become the pro-

cedure of choice for most gall bladder disease and many other surgical

operations in the western world. With the expansion of laparoscopic

surgery, we have encountered a whole new range of complications with

an escalation in the demise of general surgery as the result of hyperspe-

cialization. There are many surgical trainees who have scant experience

of open surgery and who have, due to European directives, limited time

exposure to surgical procedures. In fact, most technical training is now

obtained from emergency on call such that a new speciality of emergency

surgery is developing. A recent British Medical Journal (BMJ) article recom-

mended a training programme for surgeons wishing to work in remote

and rural surgery—not only in the Developing World, but in remote and

isolated communities in the United Kingdom! General surgery may largely

have gone, but it should not be forgotten. Most countries in the world do

not have access to these recent innovations and there is still a case in the

developed world for experience in open and general surgery to be incor-

porated in the formal training programmes of junior surgeons.

G. R. McLatchie

Hartlepool, September 2012

vi

Preface to the third

edition

This, the third edition of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Surgery, refl ects

the changes which have occurred in general surgery over the 17 years

since the fi rst edition was published.

Firstly, we have recruited the services of two new editors, a stark con-

trast to the original, which was written by a single author with the assis-

tance of a surgical registrar.

Secondly, each chapter has been written by a specialist consultant or

registrar in the subject and, therefore, presents a modern, state-of-the-art

treatise on each topic.

Again, each condition is covered in the original two-page format with

blank pages for accompanying notes.

I am particularly grateful for the commitment that Jo Chikwe and Neil

Borley have made, and also wish to thank staff at Oxford University Press

for their support and patience. I am also grateful for the contribution and

support given by many colleagues.

G. R. McLatchie

Hartlepool, March 2007

vii

Preface to the fi rst

edition

The idea of this book was fi rst suggested by Mr Gordon McBain, consult-

ant surgeon at the Southern General Hospital, Glasgow. We have received

considerable support from the staff of Oxford University Press, and are

also indebted to Mr J. Rhind and Dr J. Daniel for their contributions and

our surgical teachers, especially Mr J. S. F. Hutchison, Mr M. K. Browne,

Mr J. Neilson, Mr D. Young, Mr A. Young, and the late Mr I. McLennan

whose practical advice and anecdotes pepper the pages….

G. R. McLatchie

S. Parameswaran

1990

viii

Dedications

For Ross, Cameron, Ailidh, Claire, and Calum

GRM

For Alexander, Christopher, and Jennifer

NB

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the support of our colleagues and Oxford University

Press and to Mrs Pamela Lines for her diligent support in the fi nal editing

of the manuscript.

ix

Contents

Detailed contents xi

Contributors xxiii

Symbols and abbreviations xxv

1 Good surgical practice

1

2 Principles of surgery

23

3 Surgical pathology

141

4 Practical procedures

185

5 Head and neck surgery

221

6 Breast and endocrine surgery

239

7 Upper gastrointestinal surgery

271

8 Liver, pancreatic, and biliary surgery

311

9 Abdominal wall

335

10 Urology

353

11 Colorectal surgery

391

12 Paediatric surgery

423

13 Paediatric orthopaedic

457

14 Major trauma

477

15 Orthopaedic surgery

489

16 Plastic surgery

589

17 Cardiothoracic surgery

619

18 Peripheral vascular disease

641

19 Transplantation

675

20 Surgery in tropical diseases

701

21 Common operations

729

22 Eponymous terms and rarities

757

Anatomy and physiology key revision points index 777

Index 779

This page intentionally left blank

xi

Detailed contents

Contributors xxiii

Symbols and abbreviations xxv

1 Good surgical practice 1

Duties of a doctor 2

Communication skills 4

Evidence-based surgery 6

Critical appraisal 10

Audit 12

Consent 14

Death 16

End-of-life issues 18

Clinical governance 20

2 Principles of surgery 23

Terminology in surgery 24

History taking and making notes 26

Common surgical symptoms 28

Examination and investigation of the patient:

Evaluation of breast disease 30

Evaluation of the neck 32

Evaluation of the abdomen 34

Abdominal investigations 36

Evaluation of pelvic disease 38

Evaluation of peripheral vascular disease 40

Evaluation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue disease 42

Surgery at the extremes of age 44

Day case and minimally invasive surgery 46

Preoperative care:

Surgery in pregnancy 48

Surgery and the contraceptive pill 50

Surgery in endocrine disease 52

xii

DETAILED CONTENTS

Surgery and heart disease 54

Surgery and respiratory disease 58

Surgery in renal and hepatic disease 60

Surgery in neurological disease 62

Pre-optimization of the patient:

Fluid optimization 64

Nutrition in surgical patients 66

Enhanced recovery after surgery 68

Perioperative care:

Getting the patient to theatre 70

Prophylaxis—antibiotics and thromboprophylaxis 72

In-theatre preparation 74

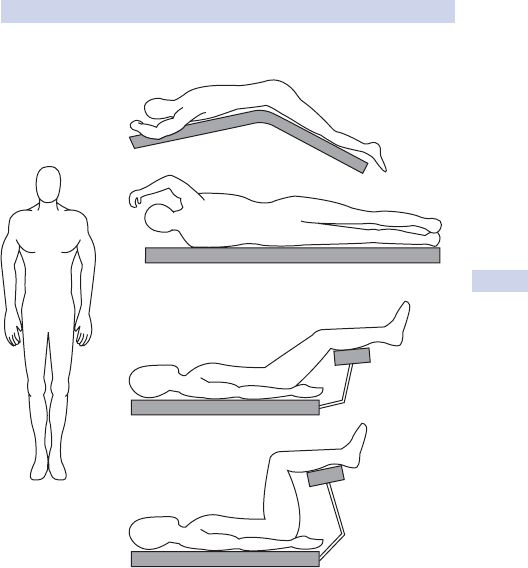

Positioning the patient 76

Sterilization, disinfection, and antisepsis 78

Scrubbing up 79

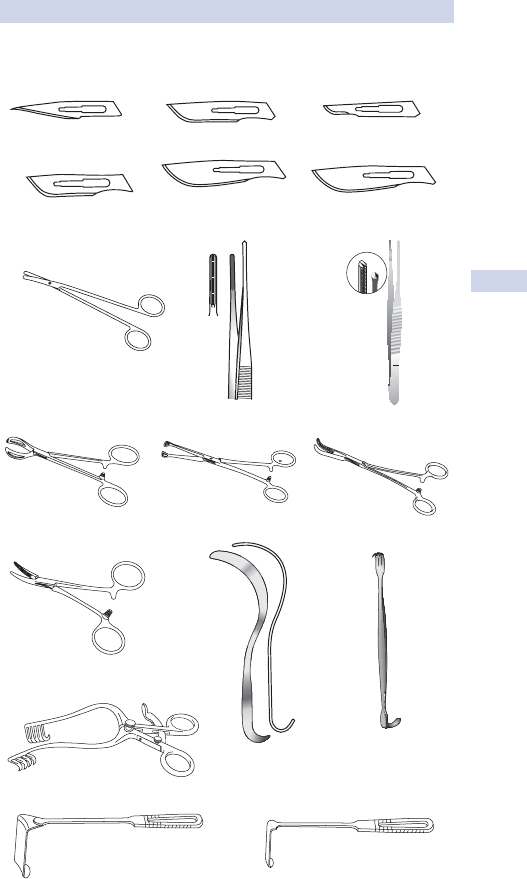

Surgical instruments 80

Incisions and closures 82

Drains 83

Stomas 84

Knots and sutures 86

Post-operative:

Post-operative management 88

Drain management 90

Fluid management 92

Acid–base balance 94

Blood products and procoagulants 96

Transfusion reactions 98

Shock 100

Post-operative haemorrhage 102

Wound emergencies 104

Cardiac complications 106

Respiratory complications 108

Renal complications 110

Urinary complications 112

Gastrointestinal complications 114

Neurological complications 116

Haematological complications 118

Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism 120

Risk scoring 122

xiii

DETAILED CONTENTS

Critical care 124

Commonly used terms in ITU 126

Invasive monitoring 128

Ventilation and respiratory support 130

Circulatory support 132

Renal support 134

Enteral support 136

Sepsis, SIRS, MODS, and ALI 138

3 Surgical pathology 141

Cellular injury 142

Infl ammation 144

Wound healing 146

Ulcers 148

Cysts, sinuses, and fi stulas 150

Atherosclerosis 152

Thromboembolic disease 154

Gangrene and capillary ischaemia 158

Tumours 160

Carcinogenesis 162

Screening 164

Grading and staging 168

Tumour markers 170

Surgical microbiology 172

Surgically important organisms 174

Soft tissue infections 176

Blood-borne viruses and surgery 178

Bleeding and coagulation 180

Anaemia and polycythaemia 182

4 Practical procedures 185

Endotracheal intubation 186

Cardioversion 188

Defi brillation 190

Venepuncture 192

Intravenous cannulation 194

Arterial puncture and lines 196

Insertion of central venous catheter 198

xiv

DETAILED CONTENTS

Chest drain insertion 200

Management of chest drains 202

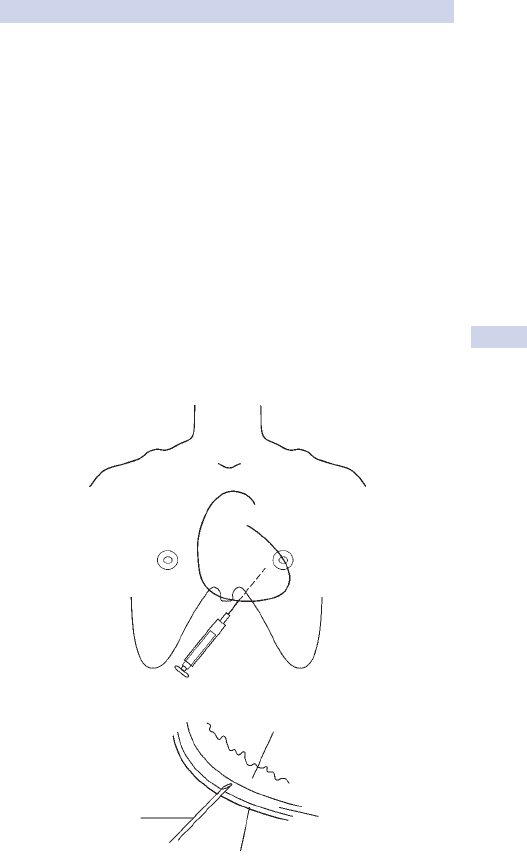

Pericardiocentesis 204

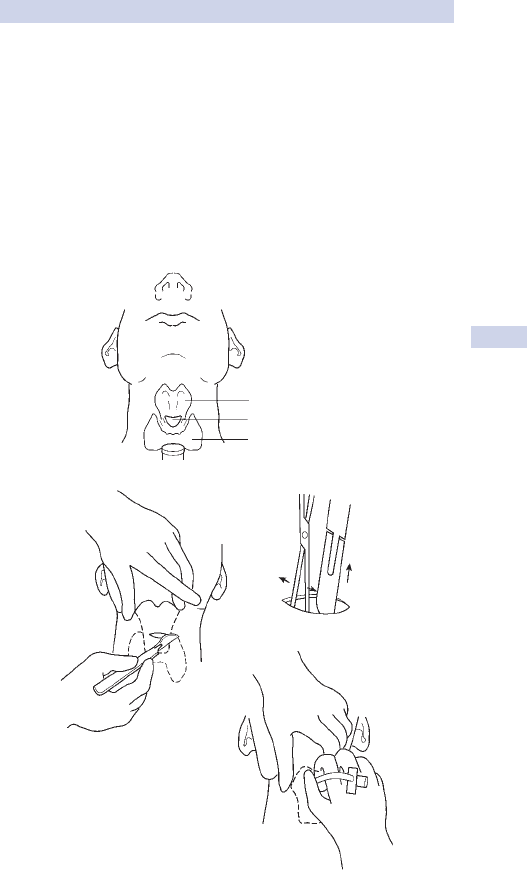

Cricothyroidotomy 206

Nasogastric tube insertion 208

Urethral catheterization 210

Suprapubic catheterization 212

Paracentesis abdominis 214

Rigid sigmoidoscopy 216

Local anaesthesia 218

Intercostal nerve block 220

5 Head and neck surgery 221

Thyroglossal cyst, sinus, and fi stula 222

Branchial cyst, sinus, and fi stula 224

Salivary calculi 226

Acute parotitis 228

Salivary gland tumours 230

Head and neck cancer 232

Facial trauma 234

Neck space infections 236

6 Breast and endocrine surgery 239

Breast cancer 240

Surgical treatment of breast cancer 242

Breast cancer screening 244

Benign breast disease 246

Acute breast pain 248

Goitre 250

Thyrotoxicosis 252

Thyroid tumours—types and features 254

Thyroid tumours—diagnosis and treatment 256

Post-thyroid surgery emergencies 258

Primary hyperparathyroidism 260

Multiple endocrine neoplasia 262

Cushing’s syndrome 264

Conn’s syndrome 266

Phaeochromocytoma 268

xv

DETAILED CONTENTS

7 Upper gastrointestinal surgery 271

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy 272

Oesophageal motility disorders 274

Pharyngeal pouch 276

Hiatus hernia 278

Gastro-oesophageal refl ux disease 280

Oesophageal tumours 282

Peptic ulcer disease 284

Gastric tumours 286

Chronic intestinal ischaemia 288

Surgery for morbid obesity 290

Small bowel tumours 292

Acute haematemesis 294

Acute upper GI perforation 296

Acute appendicitis 298

Acute peritonitis 300

Acute abdominal pain 302

Gynaecological causes of lower abdominal pain 306

Intra-abdominal abscess 308

8 Liver, pancreatic, and biliary surgery 311

Jaundice—causes and diagnosis 312

Jaundice—management 314

Gall bladder stones 316

Common bile duct stones 318

Chronic pancreatitis 320

Portal hypertension 322

Cirrhosis of the liver 324

Pancreatic cancer 326

Cancer of the liver, gall bladder, and biliary tree 328

Acute variceal haemorrhage 330

Acute pancreatitis 332

9 Abdominal wall 335

Abdominal wall hernias 336

Inguinal hernia 338

Femoral hernia 340

Umbilical and epigastric hernias 342

xvi

DETAILED CONTENTS

Incisional hernias 344

Other types of hernia 346

Rectus sheath haematoma 347

Groin disruption 348

Acute groin swelling 350

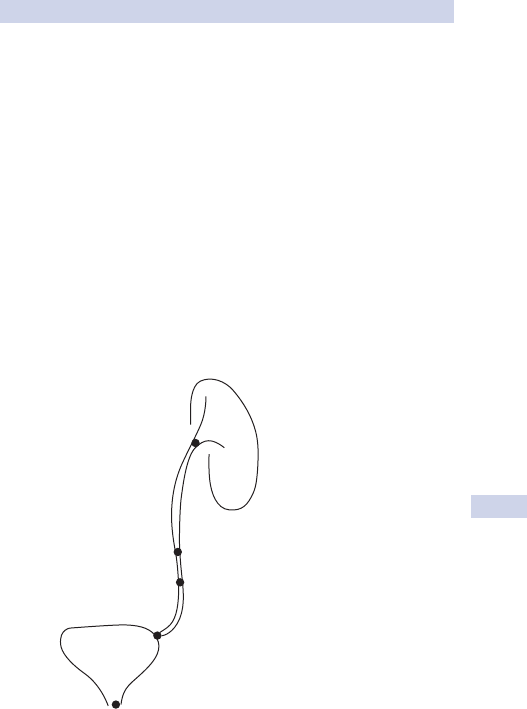

10 Urology 353

Symptoms and signs in urology 354

Investigations of urinary tract disease 356

Urinary tract stones 358

Obstruction of the ureter 360

Benign prostatic hyperplasia 362

Stricture of the urethra 364

Scrotal swellings 366

Disorders of the foreskin 368

Common conditions of the penis 370

Erectile dysfunction 372

Adenocarcinoma of the kidney 374

Transitional cell tumours 376

Adenocarcinoma of the prostate 378

Carcinoma of the penis 380

Testicular tumours 382

Haematuria 384

Acute urinary retention (AUR) 386

Acute testicular pain 388

11 Colorectal surgery 391

Ulcerative colitis 392

Crohn’s disease 394

Other forms of colitis 396

Colorectal polyps 398

Colorectal cancer 400

Restorative pelvic surgery 402

Minimally invasive colorectal surgery 403

Diverticular disease of the colon 404

Rectal prolapse 406

Pilonidal sinus disease 408

Fistula-in-ano 410

Haemorrhoids 412

xvii

DETAILED CONTENTS

Acute anorectal pain 414

Acute rectal bleeding 416

Acute severe colitis 418

Post-operative anastomotic leakage 420

12 Paediatric surgery 423

Principles of managing paediatric surgical cases 424

Acute abdominal emergencies—overview 426

Oesophageal atresia 428

Pyloric stenosis 430

Malrotation and volvulus 432

Intussusception 434

Hirschsprung’s disease 436

Rare causes of intestinal obstruction 438

Abdominal wall defects 440

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) 442

Inguinal hernia and scrotal swellings 444

Other childhood hernias 446

Prepuce (foreskin) and circumcision 448

Undescended testis 450

Solid tumours of childhood 452

Neck swellings 454

13 Paediatric orthopaedic 457

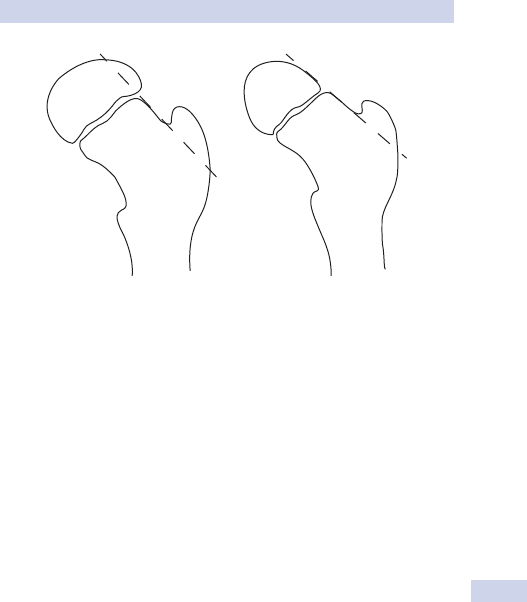

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) 458

Slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE) 460

The limping child 462

The child with a fracture 464

Non-accidental injury (NAI) 466

Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease 468

Motor development 470

Club foot or congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) 471

Flat feet (pes planus) 472

The osteochondritides 474

14 Major trauma 477

Management of major trauma 478

Thoracic injuries 480

xviii

DETAILED CONTENTS

Abdominal trauma 482

Vascular injuries 484

Head injuries 486

15 Orthopaedic surgery 489

Examination of a joint 490

Examination of the limbs and trunk 492

Fracture healing 494

Reduction and fi xation of fractures 498

The skeletal radiograph 502

Injuries of the phalanges and metacarpals 504

Wrist injuries 508

Fractures of the distal radius and ulna 510

Fractures of the radius and ulnar shaft 512

Fractures and dislocations around the elbow in children 514

Fractures of the humeral shaft and elbow in adults 518

Dislocations and fracture dislocations of the elbow 522

Fractures around the shoulder 524

Dislocations of the shoulder region 526

Fractures of the ribs and sternum 530

Fractures of the pelvis 532

Femoral neck fractures 536

Femoral shaft fractures 538

Fractures of the tibial shaft 540

Fractures of the ankle 544

Fractures of the tarsus and foot 546

Injuries and the spinal radiograph 550

Spinal injuries 554

Acute haematogenous osteomyelitis 558

Chronic osteomyelitis 560

Septic arthritis 562

Peripheral nerve injuries 564

Brachial plexus injuries 566

Osteoarthrosis (osteoarthritis) 568

Carpal tunnel syndrome 570

Ganglion 572

Bone tumours 574

Low back pain 578

Paget’s disease (osteitis deformans) 582

The great toe 584

xix

DETAILED CONTENTS

Arthroplasty 586

Useful reading 588

16 Plastic surgery 589

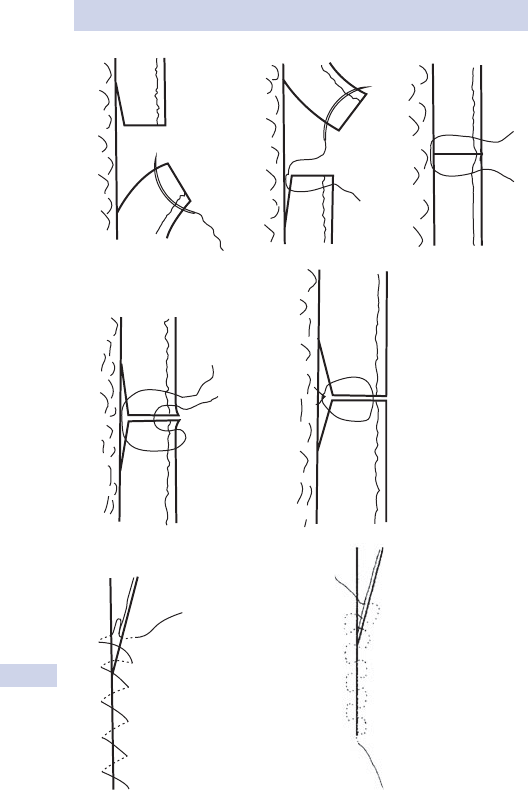

Suturing wounds 590

Skin grafts 594

Surgical fl aps 596

Management of scars 598

Excision of simple cutaneous lesions 600

Skin cancer 602

Burns: assessment 604

Burns: management 606

Soft tissue hand injuries 610

Hand infections 612

Dupuytren’s disease 614

Breast reduction 616

Breast augmentation 617

Breast reconstruction 618

17 Cardiothoracic surgery 619

Basics 620

Principles of cardiac surgery 622

Coronary artery disease 626

Valvular heart disease 628

Cardiothoracic ICU 630

Lung cancer 632

Pleural effusion 634

Pneumothorax 636

Mediastinal disease 638

18 Peripheral vascular disease 641

Acute limb ischaemia 642

Chronic upper limb ischaemia 644

Chronic lower limb ischaemia 647

Intermittent claudication 648

Critical limb ischaemia 650

Aneurysms 652

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm 654

xx

DETAILED CONTENTS

Vascular developmental abnormalities 656

Carotid disease 658

The diabetic foot 660

Amputations 662

Vasospastic disorders 664

Varicose veins 666

Deep venous thrombosis 668

Thrombolysis 670

Complications in vascular surgery 672

19 Transplantation 675

Basic transplant immunology 676

Immunosuppression and rejection 678

Transplant recipients 682

Transplant donors 684

Heart and lung transplantation 690

Kidney transplantation 692

Pancreas and islet transplantation 694

Liver transplantation 696

Small bowel transplantation 698

20 Surgery in tropical diseases 701

Medicine in the tropics 702

Typhoid 704

Amoebiasis and amoebic liver abscess 706

Anaemias in the tropics 708

Malaria 710

Schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) 712

Filariasis 714

Hydatid disease 716

Ascariasis 718

Leishmaniasis 719

Trypanosomiasis 720

Tuberculosis in the tropics 722

Leprosy (‘Hansen’s disease’) 724

Guinea worm infestation 726

Threadworms 727

Mycetoma (madura foot) 728

xxi

DETAILED CONTENTS

21 Common operations 729

Diagnostic laparoscopy 730

Principles of laparotomy 732

Cholecystectomy 734

Appendicectomy 736

Inguinal hernia repair 738

Perforated peptic ulcer repair 740

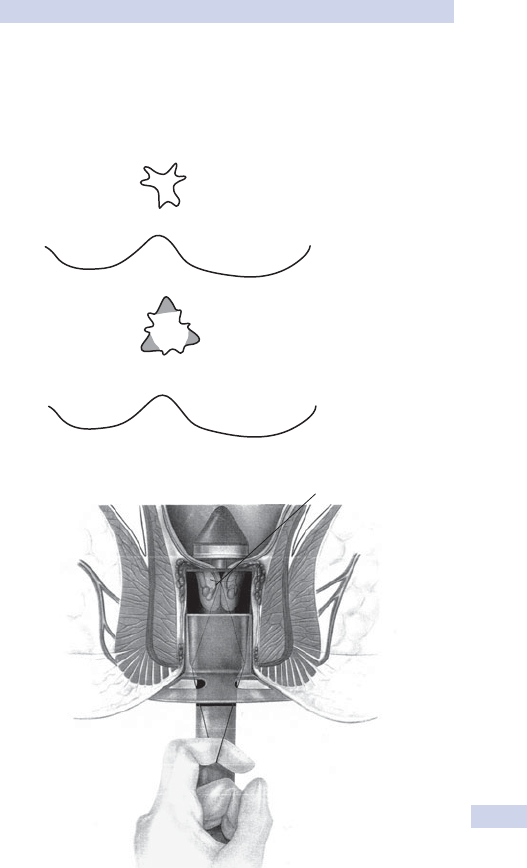

Haemorrhoid surgery 742

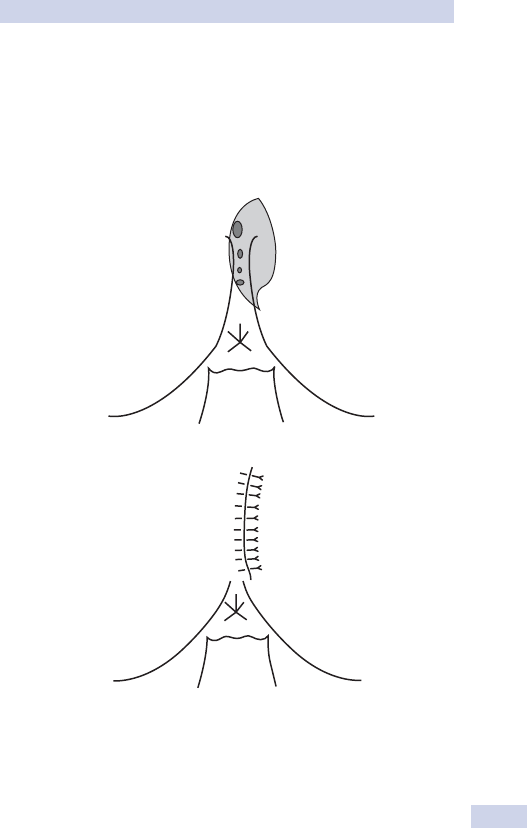

Pilonidal sinus excision (Bascom II) 744

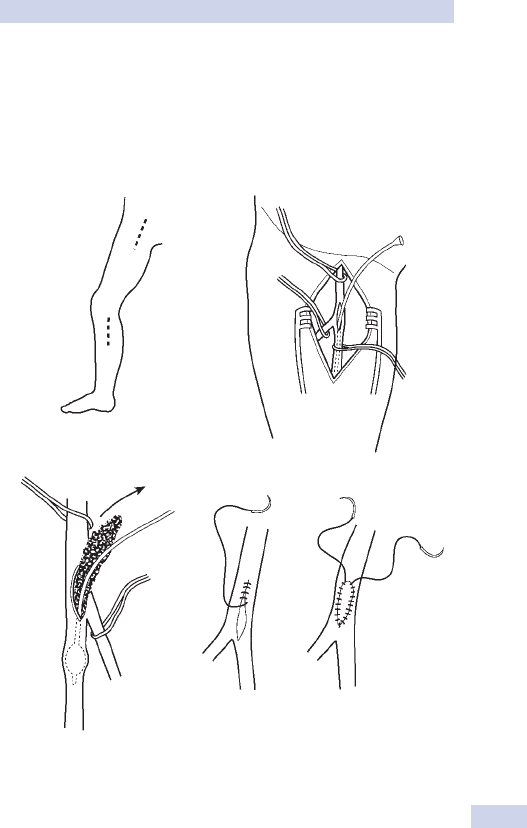

Femoral embolectomy 746

Right hemicolectomy 748

Stoma formation 750

Wide local excision—breast 752

Below knee amputation 754

22 Eponymous terms and rarities 757

Anatomy and physiology key revision points index 777

Index 779

This page intentionally left blank

xxiii

Contributors

Alex Acornley

Consultant Orthopaedic

Surgeon,

Airedale Hospital NHS

Foundation Trust, West

Yorkshire, UK

Anil Agarwal

Consultant General and Colorectal

Surgeon,

North Tees and Hartlepool NHS

Trust, University Hospital of

Hartlepool, UK

Khalid A. Al-Hureibi

Specialist Registrar,

Department of General Surgery,

Lister Hospital, Stevenage, UK

John Asher

Consultant Transplant Surgeon,

Transplant Unit, Western

Infi rmary, Glasgow, UK

David Chadwick

Consultant Urological Surgeon,

The James Cook University

Hospital, Middlesbrough, UK

Lucy Cogswell

Specialist Registrar,

Department of Plastic &

Reconstructive Surgery, John

Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK

J. H. Dark

Consultant Cardiothoracic

Surgeon,

Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon

Tyne, UK

Richard P. Jeavons

Specialist Registrar,

Trauma and Orthopaedics

(Northern Deanery), Department

of Trauma and Orthopaedics,

University Hospital of North Tees,

Stockton, UK

Vijay Kurup

Consultant Breast and Endocrine

Surgeon,

University Hospital of North Tees,

Stockton on Tees, UK

Jamie Lyall

Consultant Head and Neck

Surgeon (Maxillofacial),

Surgical Division, James Cook

University Hospital Trust,

Middlesbrough, Queen Margaret

Hospital, Dunfermline, UK

Alan Middleton

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon,

Department of Hand and Wrist

Surgery, University Hospital of

North Tees, Stockton, UK

Rob Milligan

ST3 General Surgery, Northern

Deanery, UK

Sandrasekeram

Parameswaran

General Surgeon,

Cold Lake Healthcare Centre,

Visiting Surgeon, Canadian forces

base, 4 Wing, Cold Lake, Alberta,

Canada

xxiv

CONTRIBUTORS

Lakshmi Parameswaran

Senior House Offi cer,

Mater Misericordiae University

Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Saumitra Rawat

Consultant Surgeon,

Macclesfi eld District General

Hospital, UK

Andreas Rehm

Consultant Paediatric Orthopaedic

and Trauma Surgeon,

Depatment of Orthopaedic and

Trauma Surgery, Addenbrooke’s

Hospital, Cambridge University

Hospitals NHS Trust, Cambridge,

UK

David Talbot

Consultant Transplant and

Hepatobiliary Surgeon,

Transplant Institute, Freeman

Hospital, Newcastle. Visiting

Professor, University of Sunderland.

Reader, University of Newcastle

upon Tyne, UK

Mark Whyman

Consultant General and Vascular

Surgeon,

Department of Surgery,

Cheltenham General Hospital,

Cheltenham, UK

xxv

Symbols and abbreviations

d decreased

i increased

n normal

l leading to

warning

2 important

3 don’t dawdle

b cross reference

♀ female

♂ male

p primary

s secondary

< less than

> more than

t equal to or greater than

d equal to or less than

% per cent

7 approximately

8 approximately equals to

α alpha

β beta

°C degree Celsius

AAA abdominal aortic aneurysm

ABG arterial blood gas

A&E Accident and Emergency Department

ABPI ankle–brachial pressure index

ACAS Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis Study

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACh acetylcholine

AChE acetylcholinesterase

ACJ acromioclavicular joint

ACL anterior cruciate ligament

ACST Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial

ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone

ADH antidiuretic hormone

ADP adenosine diphosphate

xxvi

AF atrial fi brillation

AFP alpha-fetoprotein

AIDS acquired immunodefi ciency syndrome

AIN anal intraepithelial neoplasia

AKA above-knee amputation

ALI acute lung injury

ALS advanced life support

a.m. ante meridiem

amp ampere

AMPLE allergy/medication/past medical history/last meal/events

of the incident

ANDI abnormalities of normal development and involution

(of breast)

ANF antinuclear factor

APA aldosterone-producing adenoma

APACHE Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation

APC antigen-presenting cell or argon plasma coagulation

APER abdominoperineal resection

APTR activated partial thromboplastin time ratio

APTT activated partial thromboplastin time

AR aortic regurgitation

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

ARR absolute risk reduction or aldosterone/renin ratio

5-ASA 5-aminosalicyclic acid

ASB assisted spontaneous breathing

ATG anti-thymocyte globulin

ATLS advanced trauma life support

ATP adenosine triphosphate

AUR acute urinary retention

AV arteriovenous or atrioventricular

AVM arteriovenous malformation

AVN avascular necrosis

AVS adrenal venous sampling

AXR abdominal X-ray

BCC basal cell carcinoma

BCG Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

BCR B-cell receptor

B-HCG beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin

BiPAP biphasic positive airway pressure

BKA below-knee amputation

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxvii

BMI body mass index

BMJ British Medical Journal

BNF British National Formulary

BP blood pressure

BPH benign prostatic hyperplasia

BS blood sugar

BSA body surface area

BXO balanitis xerotica obliterans

Ca calcium

CABG coronary artery bypass graft

CAD coronary artery disease

CAPD continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

CAVH continuous arteriovenous haemofi ltration

CBP cardiopulmonary bypass

CCF congestive cardiac failure

CD cellular differentiation (molecule)

CDH congenital dysplasia of the hip

CDT Clostridium diffi cile toxin

CEA carcinoembryonic antigen or carotid endarterectomy

CF cystic fi brosis

CFU colony-forming unit

CI confi dence interval

Cl chloride

CLI critical limb ischaemia

cm centimetre

CMI cell-mediated immune (reaction)

CMV cytomegalovirus or controlled mechanical ventilation

CNI calcineurin inhibitor

CNS central nervous system

CNST criminal negligence scheme for Trusts

CO cardiac output

CO

2

carbon dioxide

COAD chronic obstructive airway disease

COC combined oral contraceptive

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CPAP continuous positive airway pressure

CPB cardiopulmonary bypass

C,P,&O cysts, parasites, and ova

CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Cr creatinine

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxviii

CRCa colorectal cancer

CRP C-reactive protein

CSF cerebrospinal fl uid

C-spine cervical spine

CT computerized tomography

CTA CT angiography

CTPA computerized tomography pulmonary angiography

Cu copper

CV central venous

CVA cerebrovascular accident

CVP central venous pressure

CVVH continuous venovenous haemofi ltration

Cx circumfl ex

CXR chest X-ray

2D two-dimensional

3D three-dimensional

DA dopamine

DALM dysplasia-associated lesion or mass

DBD donor after brainstem death

DC direct current

DCD donor after circulatory death

DCIS ductal carcinoma in situ

DDAVP 1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin

DDH developmental dysplasia of the hip

DHS dynamic hip screw

DHT dihydrotestosterone

DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIEP deep inferior epigastric perforator (fl ap)

DIPJ distal interphalangeal joint

dL decilitre

DM diabetes mellitus

DMSA dimercaptosuccinate

DNA deoxyribonucleic acid

DNR do not resuscitate

DOH Department of Health

DP distal phalanx or diastolic pressure

2,3-DPG 2,3-diphosphoglycerate

DPL diagnostic peritoneal lavage

DRUJ distal radioulnar joint

DSA digital subtraction angiography

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxix

DTPA diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid

DVT deep venous thrombosis

EBV Epstein–Barr virus

ECF extracelllular fl uid

ECG electrocardiogram

ECST European Cardiac Surgery Trial

ED erectile dysfunction

e.g. exempli gratia (for example)

ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

EMD electromechanical delay

EMG electromyography

EMR endocospic mucosal resection

EOCP (o)estrogen-containing contraceptive pill

EPL extensor pollicis longus

EPO erythropoietin

ER (o)estrogen receptor

ERAS enhanced recovery after surgery

ERCP endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ES endoscopic sphincterotomy

ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ESWL extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

ET endotracheal tube

EUA examination under anaesthetic

EUS endoscopic ultrasound

EVAR endovascular aneurysm repair

EVLT endovenous laser therapy

FAP familial adenomatous polyposis

FAST focused abdominal sonography for trauma

FBC full blood count

FDP fl exor digitorum profundus

FDS fl exor digitorum superfi cialis

FEV

1 forced expiratory volume in 1 second

FFP fresh frozen plasma

FiO

2 fraction of oxygen in inspired air

FLC fi brolamellar carcinoma

FNAB fi ne needle aspiration biopsy

FNAC fi ne needle aspiration cytology

FPL fl exor pollicis longus

FSH follicle-stimulating hormone

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxx

5-FU 5-fl uorouracil

g gram

G gauge

GA general anaesthetic

GANT gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumour

GCS Glasgow coma scale

GFR glomerular fi ltration rate

GGT gamma glutamyl transferase

GH growth hormone

GI gastrointestinal

GIP gastric inhibitory polypeptide

GIST gastrointestinal stromal tumour

GMC General Medical Council

GORD gastro-oesophageal refl ux

GP general practitioner

GTN glyceryl trinitrate

Gy gray

h hour

HAT hepatic artery thrombosis

Hb haemoglobin

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma

HCG human chorionic gonadotrophin

HCO

3

bicarbonate

HCV hepatitis C virus

HDU high dependency unit

HES hydroxyethyl starch

HGV heavy goods vehicle

HHD handheld Doppler

HIDA hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid

HIT heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

HITT heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis

HIV human immunodefi ciency virus

HLA human leucocyte antigen

HMMA 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymandelic acid

HNPCC hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

H

2

O water

HPV human papilloma virus

HR heart rate

HRT hormone replacement therapy

HSV herpes simplex virus

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxi

5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)

HTLV human T-cell lymphocytotrophic virus

HVA homovanillic acid

IABP intra-aortic balloon pump

IC intermittent claudication

ICA internal carotid artery

ICD intracardiac defi brillator

ICP intracranial pressure

ICU intensive care unit

i.e. id est (that is)

IF intrinsic factor

IGF insulin growth factor

IHD ischaemic heart disease

IM intramuscular

IMA inferior mesenteric artery

IMHS intramedullary hip screw

in inch

INPV intermittent negative pressure ventilation

INR international normalized ratio

IPJ interphalangeal joint

IPPV intermittent positive pressure ventilation

IPSS international prostate symptom score

ITA internal thoracic artery

ITU intensive treatment unit

IU international unit

IV intravenous

IVU intravenous urogram

J joule

JCHST Joint Committee on Higher Surgical Training

JVP jugular venous pressure

K potassium

kcal kilocalorie

KCl potassium chloride

kg kilogram

kPa kilopascal

KUB kidneys/ureters/bladder

L litre

LA local anaesthetic or left atrium/atrial

LAD left anterior descending (artery)

LAP left atrial pressure

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxii

LatexAT latex agglutination test

lb pound

LDH lactate dehydrogenase

LDL low density lipid

LESS laparoscopic and endoscopic single site (surgery)

LFT liver function test

LH luteinizing hormone

LHRH luteinizing hormone releasing hormone

Li lithium

LIF left iliac fossa

LITA left internal thoracic artery

LMS left main stem

LMWH low molecular weight heparin

LOS lower oesophageal sphincter

LSV long saphenous vein

LUQ left upper quadrant

LUTS lower urinary tract symptoms

LV left ventricle

LVEDP left ventricular end-diastolic pressure

LVEDV left ventricular end-diastolic volume

LVF left ventricular failure

m metre

MAG3

99m

Tc-mercaptoacetyltriglycine

MALT mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

MAO monoamine oxidase

MAP mean arterial pressure

MCPJ metacarpophalangeal joint

MCRP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

M,C,&S microscopy, culture, and sensitivity

MCV mean cell volume

MDT multidisciplinary team

MEN multiple endocrine neoplasia

mEq milliequivalent

mg milligram

Mg magnesium

MHC major histocompatibility complex

MHz megahertz

MI myocardial infarction

MIBG meta-iodo-benzyl-guanidine

min minute

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxiii

MIP minimally invasive parathyroidectomy

MIST mechanism of injury/injuries identifi ed/(vital)signs at

scene/treatment administered

mL millilitre

MMF mycophenolate mofetil

mmHg millimetre mercury

mmol millimole

MMR mismatch repair (genes)

MMV mandatory minute ventilation

Mn manganese

MODS multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

mph mile per hour

MR mitral regurgitation

MRA magnetic resonance angiography

MRC Medical Research Council (scale)

MRCP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

ms millisecond

MRSA methicillin (or multiply) resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MSU midstream urine

MTC medullary thyroid carcinoma

mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin

MTP mid-thigh perforator

MTPJ metatarsophalangeal joint

MUA manipulation under anaesthesia

MV mitral valve

Na sodium

NA noradrenaline (norepinephrine)

NaHCO

3

sodium bicarbonate

NAI non-accidental injury

NASCET North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial

NBM nil by mouth

NCEPOD National Confi dential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes

and Death

NEC necrotizing enterocolitis

ng nanogram

NG nasogastric

NGT nasogastric tube

NHS National Health Service

NICE National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxiv

NIPPV non-invasive intermittent positive pressure ventilation

NK natural killer (cell)

NNT number needed to treat

N

2

O nitrous oxide

NSAID non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drug

NSF National Service Framework

NSGCT non-seminomatous germ cell tumour

NSPCC National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

NSTEMI non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

NVB neurovascular bundle

nvCJD new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

NYHA New York Heart Association

O

2

oxygen

OCP oral contraceptive pill

od omne in die (once a day)

OGD oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

OM obtuse marginal

OPT orthopantomogram

ORIF open reduction with internal fi xation

PA pulmonary artery or posterior-anterior

PAC plasma aldosterone concentration

PaCO

2 arterial carbon dioxide tension

PAF platelet-activating factor

PAL primary hyperaldosteronism

PaO

2 arterial oxygen tension

PAP pulmonary artery pressure or placental alkaline phosphatase

PAS patient administration system

PAWP pulmonary artery wedge pressure

PCA patient-controlled analgesia

PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

PCNL percutaneous nephrolithotomy

PCO

2 carbon dioxide tension

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PCV packed cell volume or pressure control ventilation

PDA posterior descending artery

PDGF platelet-derived growth factor

PE pulmonary embolism

PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure

PEFR peak expiratory fl ow rate

PEG percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxv

PEP post-exposure prophylaxis

PET positron emission tomography

PGME Postgraduate medical education

PH portal hypertension

PHPT primary hyperparathyroidism

PICC peripherally inserted central venous catheter

PID pelvic infl ammatory disease

PIPJ proximal interphalangeal joint

PLL posterior longitudinal ligament

PMETB Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board

PMN polymorphonuclear neutrophil

PO orally (per os)

PO

2 oxygen tension

PO

4 phosphate

POSSUM Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the

enumeration of Mortality and morbidity

PPH procedure for prolapse and haemorrhoids

PPI proton pump inhibitor

PPN peripheral parenteral nutrition

PR per rectum

prn pro re rata (as required)

PS pressure support

PSA prostate-specifi c antigen

PSARP posterior sagittal anorectoplasty

PT prothrombin time

PTC percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram

PTE pulmonary thromboembolism

PTEF polytetrafl uoroethylene

PTH parathyroid hormone

PTLD post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder

PTT partial prothrombin time

PUJ pelviureteric junction

PV per vagina

PVD peripheral vascular disease

PVR pulmonary vascular resistance

PVRI pulmonary vascular resistance index

qds quater die sumandus (four times a day)

RA right atrial or rheumatoid arthritis

RAP right atrial pressure

RCA right coronary artery

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

RCT randomized controlled trial

Rh rhesus

rhTSH recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone

RIF right iliac fossa

RLN recurrent laryngeal nerve

RNA ribonucleic acid

RR relative risk or risk ratio

RRR relative risk reduction

RSTL relaxed skin tension line

RTA road traffi c accident

RUQ right upper quadrant

RV right ventricle

s second

SA sinoatrial (node)

SAC specialist advisory committee

SaO

2 arterial oxygen saturation

SBE subacute bacterial endocarditis

SC subcutaneous

SCAT sheep cell agglutination test

SCC squamous cell carcinoma

SCI spinal cord injury

SCM sternocleidomastoid

SD standard deviation

SEMS self-expanding metal stenting

SEPL subfascial endoscopic perforator ligation

SFA superfi cial femoral artery

SFJ saphenofemoral junction

SILS single incision laparoscopic surgery

SIMV synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation

SIRS systemic infl ammatory response syndrome

SL sublingual

SLE systemic lupus erythematosus

SMA superior mesenteric artery

SNP sodium nitroprusside

SPJ saphenopopliteal junction

spp species

STD sodium tetradecyl sulphate

STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

STI sexually transmitted infection

SUFE slipped upper femoral epiphysis

xxxvi

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxvii

SV stroke volume

SVC superior vena cava

SVI stroke volume index

SvO2 percentage oxygen saturation of mixed venous haemoglobin

SVR systemic vascular resistance

SVRI systemic vascular resistance index

SVT supraventricular tachycardia

T

3 triiodothyronine

T

4 thyroxine

TAP transversus abdominis percutaneous

TAPS transabdominal pre-peritoneal surgery

TB tuberculosis

TBSA total body surface area

TCC transitional cell carcinoma

TCR T-cell receptor

TCT transitional cell tumour

tds ter die sumendus (three times a day)

TEDS thromboembolic deterrent stockings

TEMS transanal endoscopic microsurgery

TEPS totally extra-peritoneal surgery

TFCC triangular fi brocartilage complex

TFT thyroid function test

TGF transforming growth factor

THR total hip replacement

TIA transient ischaemic attack

TIBC total iron binding capacity

TIPS transjugular intraparenchymal portosystemic shunt/stent

TKA through-knee amputation

TKR total knee replacement

TLSO thoracolumbar spine orthosis

TMT tarsometatarsal

TNF tumour necrosis factor

TNM tumour nodes metastasis (cancer staging)

tPA tissue plasminogen activator

TPN total parenteral nutrition

TRAM transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (fl ap)

TRUS transrectal ultrasound

H thyroid-stimulating hormone

TT thrombin time or total thyroidectomy

TTE transthoracic echocardiogram

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

xxxviii

TUIP transurethral incision in the prostate

TURP transurethral resection of the prostate

TVF transversalis fascia

U (international) units

UADT upper aerodigestive tract

U&E urea and electrolytes

UC ulcerative colitis

UCL ulnar collateral ligament

UFH unfractionated heparin

UK United Kingdom

UOS upper oesophageal sphincter

USA United States of America

UTI urinary tract infection

UV ultraviolet

V volts

VACTERL vertebral defects/anorectal atresia/cardiac defects/

tracheo-oesophageal fi stula ± (o)esophageal atresia/

renal anomalies/limb defects

VAD ventricular assist device

VATS video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

VF ventricular fi brillation

VHL von Hippel–Lindau (disease)

VIP vasoactive inhibitory polypeptide

VMA vanillylmandelic acid

VQ ventilation/perfusion (scan)

VRE vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus

VT ventricular tachycardia

VTE venous thromboembolism

VWF von Willebrand factor

WCC white cell count

WHO World Health Organization

y year

Symbols and abbreviat

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

2

Duties of a doctor

The General Medical Council (GMC) lists the duties of a doctor in its docu-

ment Good medical practice.

1

The duties can be thought of under three head-

ings (the 3 Cs): competency, communication, correctness (or probity).

Competency

• Keep your professional knowledge and skills up to date.

• Recognize the limits of your professional competence.

Perform an adequate assessment of the patient’s conditions, based •

on the history and symptoms and, if necessary, an examination.

Arrange investigations or treatment where necessary.•

Take suitable and prompt action when necessary.•

Refer the patient to another practitioner when indicated.•

Be willing to consult colleagues.•

Keep clear, accurate, legible, and contemporaneous patient records •

that report relevant clinical fi ndings, decisions made, information

given to patients, and any drugs or other treatment prescribed.

Keep colleagues well informed when sharing the care of patients.•

Provide the necessary care to alleviate pain and distress whether or •

not curative treatment is possible.

Prescribe drugs or treatment, including repeat prescriptions, only •

where you have adequate knowledge of the patient’s health and

medical needs. You must neither give or recommend to patients

any investigation or treatment that you know is not in their best

interests, nor withhold appropriate treatments or referral.

Report adverse drug reactions as required under the relevant •

reporting scheme and cooperate with requests for information

from organizations monitoring the public health.

Take part in regular and systematic medical and clinical audit, •

recording data honestly, and respond to the results of audit to

improve your practice, e.g. by undertaking further training.

Communication

• Treat every patient politely and considerately.

• Respect patients’ dignity and privacy.

• Listen to patients and respect their views.

• Give patients information in a way they can understand.

Correctness (or probity)

• Make the care of your patient your fi rst concern.

• Respect the rights of patients to be involved in decisions.

• Be honest and trustworthy.

• Respect and protect confi dential information.

• Make sure your personal beliefs do not prejudice your patients’ care.

• Act quickly to protect patients from risk if you have good reason to

believe that you or a colleague may not be fi t to practise.

• Avoid abusing your position as a doctor.

• Work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients’ interests.

• In an emergency, wherever it may arise, you must offer anyone at risk

the assistance you could reasonably be expected to provide.

DUTIES OF A DOCTOR

3

Confi dentiality

Patients have a right to expect that information about them will be held

in confi dence by their doctors. Confi dentiality is central to trust between

doctors and patients. Without assurances about confi dentiality, patients

may be reluctant to give doctors the information they need in order to

provide good care. The GMC states that if you are asked to provide infor-

mation about patients, you must:

• Inform patients about the disclosure or check that they have already

received information about it.

• Anonymize data where unidentifi able data will serve the purpose (this

includes your surgical logbook).

• Keep disclosures to the minimum necessary.

• Keep up to date with and observe the requirements of statute and

common law, including data protection legislation.

Daily practice

• When you are responsible for personal information about patients,

you must make sure that it is effectively protected against improper

disclosure at all times (e.g. password-protected electronic fi les).

• Many improper disclosures are unintentional. You should not discuss

patients where you can be overheard or leave patients’ records,

either on paper or on screen, where they can be seen by other

patients, unauthorized health care staff, or the public. You should take

all reasonable steps to ensure your consultations with patients are

private.

• Patients have a right to information about the health care services

available to them presented in a way that is easy to follow and use.

Special circumstances

If in any doubt, contact your medical defence union for advice.

• You must disclose information to satisfy a specifi c statutory

requirement, such as notifi cation of a known or suspected

communicable disease. Inform patients about such disclosures,

wherever that is practicable, but their consent is not required.

• You must also disclose information if ordered to do so by a judge or

presiding offi cer of a court. You should object if attempts are made to

compel you to disclose what appear to you to be irrelevant matters.

• You must not disclose personal information to a third party, such as

a solicitor, police offi cer, or offi cer of a court, without the patient’s

express consent, except when:

The patient is not competent to give consent.•

Reasonable efforts to trace patients are unlikely to be successful.•

The patient has been or may be violent, or obtaining consent •

would undermine the purpose of the disclosure (e.g. disclosures in

relation to crime).

Action must be taken quickly (e.g. in the detection or control of •

outbreaks of some communicable diseases) and there is insuffi cient

time to contact patients.

Reference

1 GMC (2012). Good medical practice. Available at: M http://www.gmcuk.org/guidance/good_

medical_practice.asp

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

4

Communication skills

Communicating with patients and relatives

When

• During admission and before discharge.

• On ward rounds.

• During clinical examinations and procedures.

• When the results of treatments are known and management changes.

• In outpatient clinics.

Where

2 Maintain the patient’s privacy. This is particularly important on an open

ward. Knock on doors and close them after you. Draw the curtains round

the bed. Ask a nurse to accompany you, particularly if you are explain-

ing something complex or breaking bad news. They will have to answer

the patients’ and relatives’ questions when you have left the ward or

clinic room.

How

• Know your facts. Are you giving the right diagnosis to the right

patient? Are you equipped to consent a patient for the surgical

procedure?

• Sit at the same level as the person to whom you are talking, maintain

appropriate eye contact, and introduce yourself.

• Find out what the patient knows and what they are expecting.

• Listen. The patient’s own knowledge, state of mind, and ability to grasp

concepts will dictate both how and how much you explain.

• Tell the truth. Know your facts, be sensitive to what the patient may

not want to know at this stage, and do not lie.

• Avoid jargon. ‘Chronic’ may simply mean ‘longstanding’ to you; to

most patients, it means ‘severe’.

• Avoid vague terms. Try to describe risk quantitatively, ‘a 1 in a

hundred chance’, rather than qualitatively, ‘a small risk’.

• Check that the patient understands. Don’t assume that they do.

• Help the patient to remember. Use information booklets, draw

diagrams, write instructions down.

• Maintain a professional relationship. Never allow your personal likes,

dislikes, and prejudices to hamper your clinical skills.

Breaking bad news

• Is there a relative or friend whom the patient might wish to have with

them, who may be a source of emotional support as well as being

better able to retain information?

• Know what options, if any, are available. If a cancer is inoperable, is

chemotherapy planned? If an operation is cancelled, when is the next

date?

• Do not be afraid to stop to allow the patient time to gather their

thoughts and emotions, and recommence at a later time.

• Do not mistake numbness for calm acceptance and try not to take

anger personally unless the bad news is actually your fault.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

5

Communicating with nurses

• Introduce yourself on arrival to the staff nurse in charge.

• Establish early on which nurses are experienced. The help you get

from them will be different from the questions you get from others.

• In theatre, scrub nurses are not the enemy. Your inexperience is.

• Try to remember all their names as they will remember yours.

• Do ward work effi ciently. Recognize how important it is for the

smooth running of the ward that your ward rounds, note-keeping,

prescriptions, and discharge letters are timely and accurate.

• Let the nurses know when you are going for lunch, teaching, or sleep.

If they can discuss problems now, it will save you being paged later.

• Do an evening ward round to check on problem patients and drug

requirements—your sleep is less likely to be constantly interrupted.

Communication with hospital doctors

• Don’t refer without fi rst asking your consultant or registrar.

• When making requests for clinical consultations, write a concise, but

clear letter in the notes to the appropriate clinician.

• When asked to see a patient, go the same day, write your opinion

in the case notes, stating clearly what you recommend, and always

discuss it with the seniors on your own fi rm.

• If a preoperative patient is complex or has signifi cant comorbidity,

contact the appropriate anaesthetist. They will help you ensure that

the patient is adequately prepared for surgery.

Communication with general practitioners (GPs)

The GP has usually looked after your patient for years and, however

inspired your diagnostic or operating skills, they will be there to sort out

all the complications that are hidden from you once the patient is dis-

charged. They often know your consultant well. So think!

• Telephone the GP in the case of a death of a patient, if you

unexpectedly admit a patient, or to help with a diffi cult discharge.

• Write useful, legible discharge summaries. What would you want

to know if you were going to have to wait 4 weeks for the typed

discharge letter to arrive—at an absolute minimum, the date and name

of the operation, post-operative complications, and plan.

• Keep clinic letters clear and concise.

Radiology and laboratory colleagues

• Know exactly how the investigation will change your management.

• If there is doubt about the correct investigation, telephone for advice.

• Complete request forms correctly and include clinical data. It can make

a big difference, particularly if you have requested the wrong test.

Administration

• Introduce yourself to your consultant’s secretary early, fi nd out how

they like things run, and then run things their way: they will usually

have more than typing input on your reference.

• Produce GMC, defence union, occupational health, holiday, and study

leave paperwork with good grace. They are mostly legal requirements

and being rude won’t change that.

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

6

Evidence-based surgery

Summarizing simple data

This pattern of results is called a normal or Gaussian distribution: the curve

is a symmetrical bell-shaped curve. Height, weight, age, serum sodium,

and blood pressure (BP) are other examples of normally distributed data

(see Table 1.1).

• The mean is the same as the average: add up every result and divide by

the number of results. The average Hb here is 11.1g/dL.

• The standard deviation (SD) is a measure of how spread out the values

are: result – mean = its deviation.

√((sum of deviations

2

/(sample size – 1)) = SD. Here SD = 1.6g/dL.

• With normally distributed data, the mean ± 1 SD includes 68% of

observations; ± 2 SD includes 95%; ± 3 SD includes 99%.

This pattern of results is called a skewed distribution. Post-operative

blood loss (see Table 1.2), length of stay, and survival all show skewed

distributions.

• 2 Don’t use mean and SD to summarize skewed data.

• The mean blood requirement, which is skewed to 8U of blood

because of one outlier (*), is useful for planning budgets.

• The best summary statistic for skewed data is the median (2U of

blood) which is the value exactly halfway through the sample.

• The interquartile range is what the middle 50% of observations were

(1–2U here) and should be used instead of SD when summarizing

skewed data.

Table 1.1 Auditing preoperative Hb in 100 patients

Hb (g/dL) No. of patients Hb (g/dL) No. of patients

7–7.9 1 11–11.9 36

8–8.9 3 12–12.9 9

9–9.9 9 13–13.9 4

10–10.9 37 14–14.9 2

Table 1.2 Auditing post-operative blood transfusions in 100 patients

Units of blood No. of patients Units of blood No. of patients

0 1 45

1 34 5–10 1

2 41 10–20 0

3 17 20–30 1*

* Outlier.

EVIDENCE-BASED SURGERY

7

Tests (see Table 1.3)

Sensitivity (a/(a+c)) A measure of how good the test is at correctly iden-

tifying a positive result (>98% is very sensitive). If a very sensitive test is

negative, it rules the condition out (sign out).

Specifi city (d/(b+d)) A measure of how good the test is at correctly iden-

tifying a negative result (>98% is very sensitive). If a very specifi c test is

negative, it rules the condition in (spin).

Likelihood ratio This is the chance that a person testing positive has the

disease, divided by the chance that a person testing positive doesn’t have

the disease, or sensitivity/(1 – specifi city). A likelihood ratio >10 is large and

represents an almost conclusive increase in the likelihood of disease, <0.1

is an almost conclusive decrease, and 1 signifi es no change.

Treatments and hazards (see Table 1.4)

Absolute risk reduction (ARR) a/(a+b) – c/(c+d) This is the difference in

the event rate between the control and the exposed group. It refl ects the

prevalence of a disease and the potency of a treatment or hazard.

Relative risk or risk ratio (RR) a/(a+b)/c/(c+d) The event rate in the

exposed group divided by the event rate in the control group. Used in

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies. It is not affected

by the prevalence of a disease.

Relative risk reduction (RRR) (a/(a + b) – c/(c + d))/(c/c + d) ARR divided

by the control event rate. It refl ects disease prevalence.

Number needed to treat (NNT) 1/ARR The number of people who must

be treated to prevent one event.

Odds ratio This is the odds of an exposed person having the condition

divided by the odds of the control group having the condition. If the event

is rare, it approximates to relative risk. Odds ratios are less intuitive than

relative risk, but they are used because they are:

• Usually larger.

• Mathematically versatile.

Table 1.4 Risk Assessment

Outcome event No outcome event

Exposure a b

No exposure (control) c d

Table 1.3 Sensitivity

Disease present No disease

Test is positive a b

Test is negative c d

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

8

• Always used in case control studies and appear in meta-analyses of

case control studies.

• The basis of logistic regression analysis.

Statistical signifi cance

• Studies are designed to disprove the null hypothesis that fi ndings are

due to chance.

• The p-value is the probability of a study rejecting the null hypothesis if

it were true (a type I error), i.e. fi nding a difference where none exists.

• Statistical signifi cance is commonly taken as a less than 1 in 20 chance

of this happening, i.e. p <0.05.

• Power is the probability of detecting an association if one exists.

Underpowered trials contain too few patients and may make type

II errors, accepting the null hypothesis when it is false, i.e. fi nding no

difference where one does exist.

• 95% confi dence intervals, derived from the mean and SD, are the range

of results predicted if the study were repeated 95 times.

EVIDENCE-BASED SURGERY

9

Other useful terms

Censored data Essentially incomplete data, usually due to variable lengths

of follow-up. Common in surgical studies because 1) some patients will

have been lost to follow-up and 2) patients will have shorter follow-up

where they had operations more recently in a study.

Actuarial and Kaplan–Meier survival Two methods used to calculate the

percentage of study patients that survive a specifi ed time after an opera-

tion when a study provides censored data.

Survival curves Usually not curves. A linear graph, with percentage sur-

vival (or freedom from a complication) on the x-axis and time on the

y-axis, which drops as each study patient dies (or gets the complication).

If there are thousands of patients in the study, the curve is smooth. If

there are very few, it is possible to see individual deaths/events as steps

in the graph. Ideally, these graphs should have confi dence intervals.

Confi dence intervals These refl ect the precision of the study results.

Narrow confi dence intervals are better than wide ones because the con-

fi dence interval provides a range of values for the percentage survival (or

odds ratio or other proportion) that has a specifi ed probability (usually

95%) of containing the true value for the entire population from which

the study patients were recruited. Always look for confi dence intervals;

they give you a ‘best case and worst case’ snapshot.

Regression analysis Essentially looking back from a group of patients with

a known outcome (e.g. dead/alive) to see whether there were any predic-

tors (e.g. age, recent myocardial infarction (MI)). Univariate analysis looks

at single variables in turn. Multivariate analysis looks at a group of variables

together; it is used to identify independent risk factors for an outcome. For

example, age may be found to be a risk factor for post-operative death

in univariate analysis, but that is because elderly patients are more likely

to have other risk factors for post-operative death (e.g. recent MI). If age

is not found to be an independent risk factor in multivariate analysis, it

suggests that elderly people without other risk factors (e.g. recent MI) are

not at higher risk of post-operative death.

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

10

Critical appraisal

Types of study

Studies appraising treatments can take several forms.

Randomized controlled trial (RCT) Prospective study in which partici-

pants are allocated to control or treatment groups on a random basis.

Gold standard for assessing treatment effi cacy, but time-consuming and

expensive to run.

Cohort study Partly prospective study in which two cohorts of patients

are identifi ed, one of which was exposed to the treatment and one is the

control group. They are followed over time to see the outcome. Cheaper

and quicker than RCT and suitable for looking at prognosis, but prone to

bias or false associations.

Case control study Retrospective study in which patients with the out-

come of interest are identifi ed and paired with patients without the out-

come of interest, and the exposure rates are compared. Cheapest and

quickest way of looking for causation. Bias arises when patients are mis-

classifi ed as cases or controls.

Case series A collection of anecdotes or case reports.

Systematic review Differs from the traditional literature review by apply-

ing explicit, systematic, and reproducible methods to retrieve and appraise

literature to answer a clearly formulated question. Large amounts of data

are summarized and conclusions are more accurate.

Meta-analysis A mathematical synthesis of the results of two or more pri-

mary studies, increasing the statistical signifi cance of positive overall results.

However, it reduces the ability of studies to demonstrate local effects.

Levels of evidence

Studies of treatment/hazard can be arranged in order of decreasing sta-

tistical validity.

• Level 1a. Systematic review of RCTs.

• Level 1b. High quality RCT with narrow confi dence intervals.

• Level 1c. All-or-none case series (either all patients died before

treatment became available, but some now survive or some used to

die, but now with treatment, all survive).

• Level 2a. Systematic review with homogeneity of cohort studies.

• Level 2b. Cohort study or low quality RCT.

• Level 2c. ‘Outcomes’ research.

• Level 3a. Systematic review with homogeneity of case control studies.

• Level 3b. Individual case control study.

• Level 4. Case series and poor quality cohort and case control studies.

• Level 5. Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal or based on

physiology, bench research, or fi rst principles.

How to appraise a paper

Answer these questions systematically. This information should all be

stated explicitly within the manuscript.

CRITICAL APPRAISAL

11

How relevant is the paper?

Does the paper address a clearly focused, important, and answerable clini-

cal question that is relevant to my patients?

How valid are the fi ndings?

• Was the paper published in an independent peer-reviewed journal?

• Does the paper defi ne the condition to be treated, the patients to be

included, the interventions to be compared, and the outcomes to be

examined?

• Was a power calculation performed and is the power adequate?

• Were all clinically relevant outcomes reported?

• Was follow-up adequate?

• Were all patients accounted for at the end of the study?

• Was the appropriate study type selected and was the design

appropriate?

• Were the statistical methods described and were they appropriate?

• Were the sources of error discussed?

Systematic reviews

• Is the clinical question clearly defi ned and an acceptable basis for

including or excluding papers?

• Was the literature search thorough and were other potentially

important sources explored?

• Were trials appropriately included and excluded?

• Was the methodological quality assessed and trials appropriately

weighted?

RCTs

• Were patients properly randomized?

• Were patients treated equally apart from the intervention being

studied?

• Was analysis on an intention-to-treat basis?

• Are confi dence intervals narrow and not overlapping?

Case control studies

• Were patients correctly classifi ed as case or control?

• Were all patients accounted for at the end of the study?

How important are the results?

• Were the results statistically signifi cant?

• Were the results expressed in terms of numbers needed to treat and

are they clinically important?

How applicable are the fi ndings?

• Were the study patients similar to mine?

• Is the treatment feasible within my practice: is information on safety,

tolerability, effi cacy, and price presented?

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

12

Audit

What is audit?

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) defi nes clinical

audit as ‘a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care

and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria

and the implementation of change. Aspects of the structure, processes,

and outcomes of care are selected and systematically evaluated against

explicit criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented . . . and further

monitoring is used to confi rm improvement in health care delivery.’

Why do it?

Clinical audit is currently seen as the most effective way of assessing rou-

tine health care delivery and the basis of improving outcomes.

• All hospital doctors are required to fully participate in clinical audit

(NHS Plan, Department of Health, 2000).

1

• The GMC advises that all doctors ‘must take part in regular and

systematic medical and clinical audit . . . Where necessary, you must

respond to the results of audit to improve your practice’.

How to do it

Audit of outcome or process can be divided into fi ve stages: each stage

needs to be carefully planned to produce a clinically effective audit.

Preparing for audit Choose a topic and defi ne the purpose of the audit.

One option is to identify (by consulting patients and clinicians) a poten-

tial problem that may involve high costs or risks for which there is good

evidence to inform standards and that may be amenable to change. NICE

stresses the importance of identifying skills and resources to carry out

the audit.

Selecting audit criteria Audit can assess process or outcome.

• Defi ne the patients to be included.

• Criteria to assess performance should be derived from the available

evidence, e.g. trials, systematic reviews, society guidelines, or clinician

consensus.

• Benchmarking prevents unrealistically high or low targets.

Measuring performance This is about collecting data. Identify patients or

episodes from several sources (e.g. operating room logbooks and patient

administration system (PAS)) to avoid missing patients because of incom-

plete data. Electronic information systems can improve data collection.

Training dedicated audit personnel can improve the process further.

Making improvements Identify local barriers to change, develop a practi-

cal implementation plan, which should involve several interventions (prac-

tice guidelines, education, and training). Clinical governance programmes

should provide the structure.

Sustaining improvements Repeating the audit to assess improvements is

also called closing the audit loop. Alternatives such as critical incident

review may be effective.

AUDIT

13

Measuring surgical performance

Rationale The Kennedy report on the enquiry into perioperative deaths in

paediatric cardiac surgery at Bristol Royal Infi rmary stated that ‘Patients

must be able to obtain information as to the relative performance of the

Trust . . . and consultant units within the Trust’. The idea that every patient

has the right to expect their surgery to be performed by a surgeon whose

results are not statistically worse than average is widely held.

• League tables ranking cardiothoracic surgeons on the basis of surgeon-

specifi c mortality data have been published by the government.

• Surgeons can be ranked using a number of other outcomes.

• Ranking should incorporate a system that accounts for differences in

case mix, i.e. risk stratifi cation, so that surgeons who operate on sicker

or more complicated patients are not unfairly penalized.

Risk scoring systems Examples include:

• Euroscore and Parsonnet scores for predicting operative mortality in

cardiac surgical patients.

• Apache II scores for intensive care patients.

• POSSUM (Physiologic and Operative Severity Score for the

enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity)—variants exist for vascular

and colorectal surgery.

Presenting results The aim of presenting performance data is to distin-

guish between normal variation between surgeons or institutions and sig-

nifi cant divergence. There are three main ways of doing this:

• Average outcome over a given time frame.

Ranking or league tables of surgical mortality or other •

complications; the data may be crude or risk-stratifi ed (i.e. taking

into account the case mix).

Survival plots which may also be crude or risk-stratifi ed.•

Standardized mortality ratio plots.•

• Volume and outcome control charts.

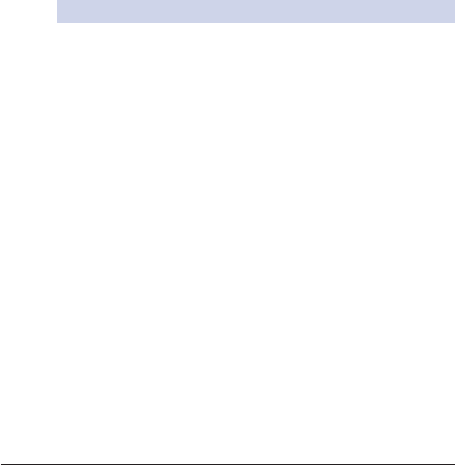

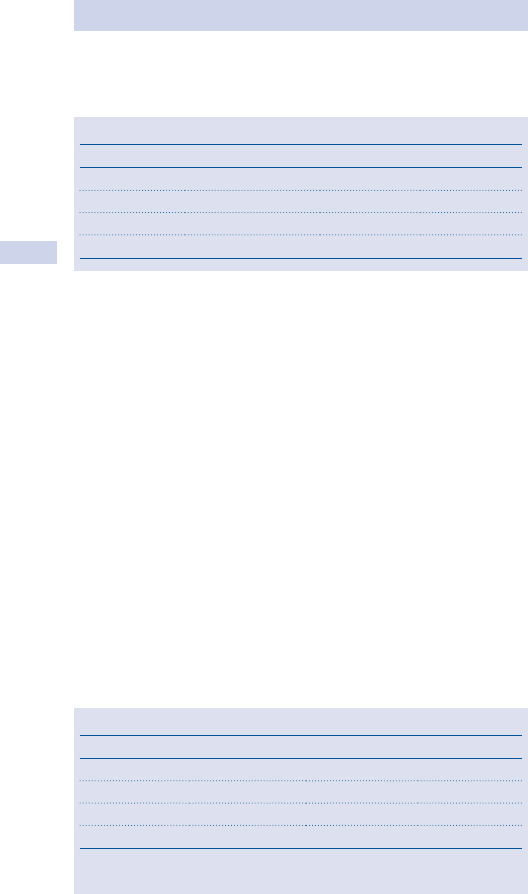

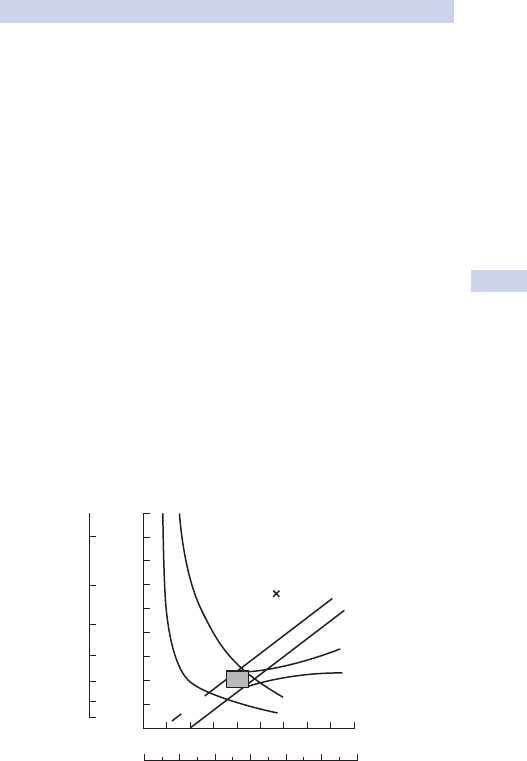

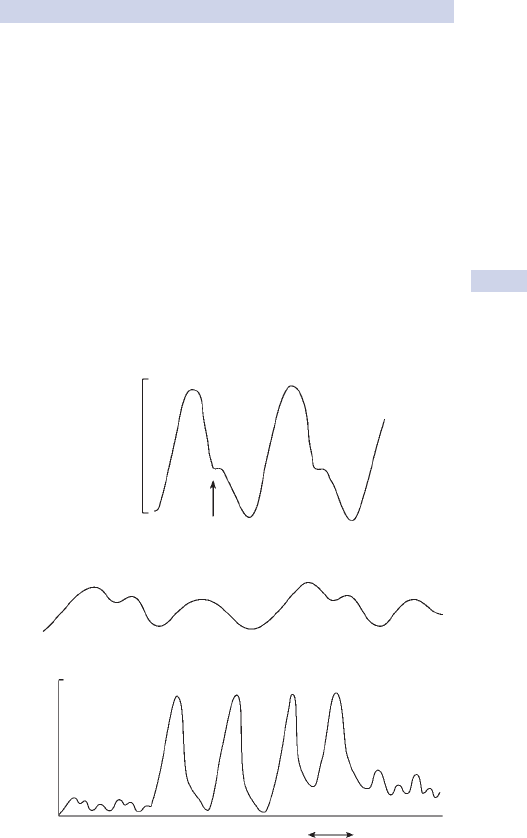

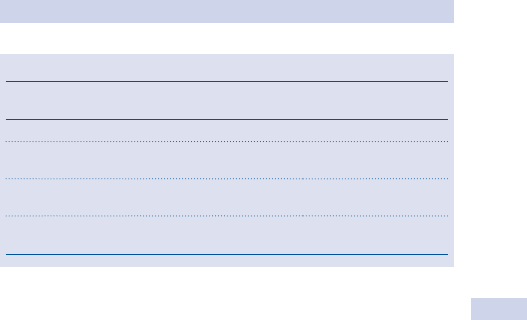

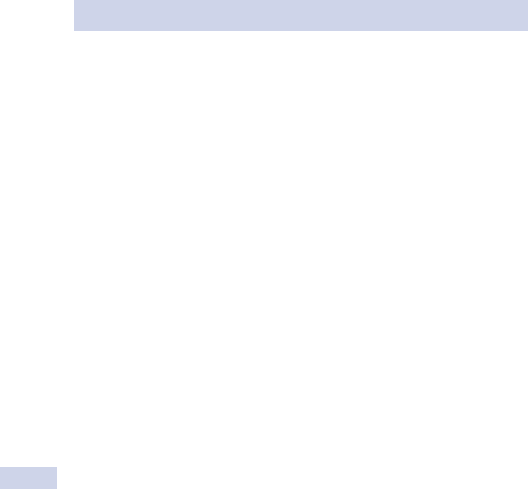

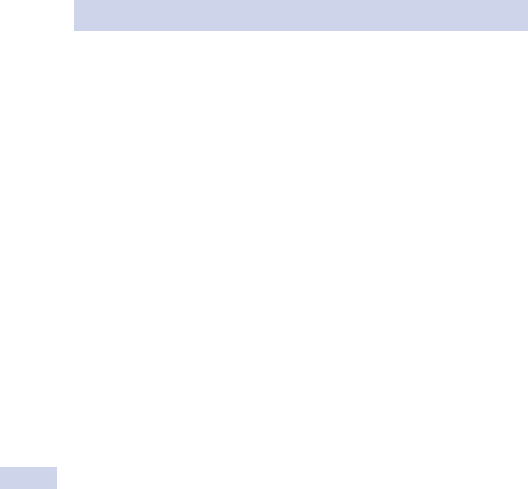

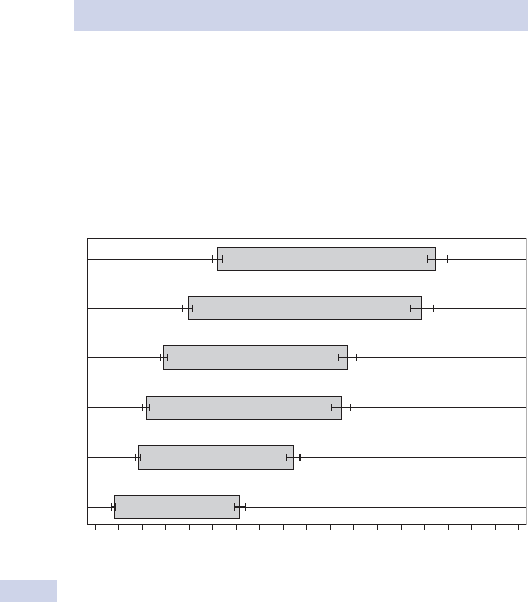

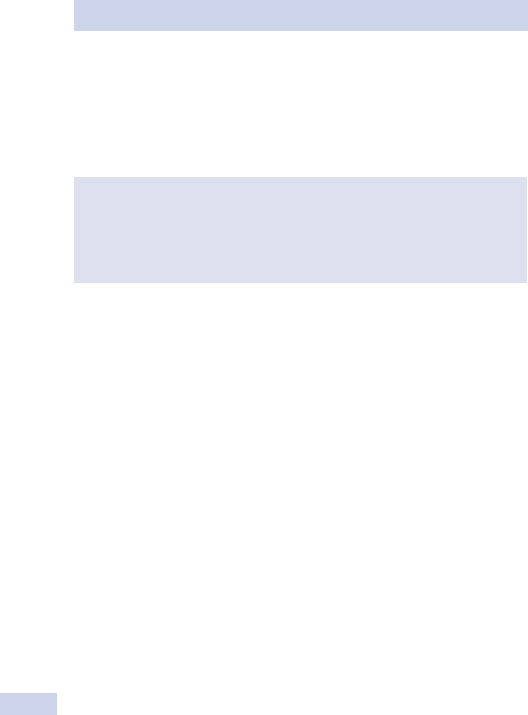

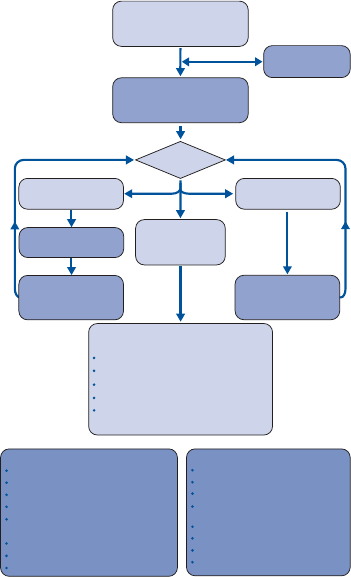

Funnel plots (see Fig. 1.1).•

Spectrum plots.•

• Performance trends over time.

Cumulative summation charts (CUSUM).•

Variable life-adjusted display charts (VLAD), risk-adjusted CUSUM.•

6

Upper 95% Cl Lower 95% Cl

%lanoitaNnoegruS

5

4

3

2

1

0

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

Number of cases

350 400 450 500 550 600

Crude mortality %

Fig. 1.1 Funnel plot of mortality data for 50 cardiac surgeons. The arrow marks

an outlier with mortality outside 95% confi dence intervals (CI).

Reference

1 Department of Health. (2000). The NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. Available at: M

http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/

DH_4002960

CHAPTER 1 Good surgical practice

14

Consent

Legal aspects

Successful surgery depends on a relationship of trust between the patient

and doctor. The patient’s right to autonomy must be respected, even if

their decision results in harm or death. This right is protected by law.

• A doctor performing a procedure on a patient without their consent

can be found guilty of battery.

• A doctor who has failed to give the patient adequate information to

allow them to give informed consent can be found guilty of negligence.

• No adult in the United Kingdom (UK) can legally consent to surgery on

behalf of another adult. It is important to involve relatives, particularly

where patients are unable to consent, but their wishes are not legally

binding and do not form part of the legal consent.

Obtaining consent

The key to good consenting is good communication (see b p. 4). It may

be necessary to use a translator and some Trusts will not accept consent

gained by using patients’ relatives as translators. GMC guidelines state ‘If

you are the doctor providing treatment or undertaking an investigation,

it is your responsibility to discuss it with the patient and obtain consent’.

In practice, this may be done verbally by the consultant or registrar in

clinic, or on a ward round with a house offi cer obtaining written con-

fi rmation later. Consent must be given freely: patients may not be put

under duress by clinicians, employers, police, or others to undergo tests

or treatment. Declare any potential confl icts of interest. The amount of

information should be suffi cient to allow a mentally competent patient

to make an informed decision. It will vary according to the individual, the

nature of the condition, the complexity of treatment, and risks involved. It

is unacceptable to limit the amount of information on the basis that it may

cause distress, but be sympathetic to the patients’ needs. Consent must