PB City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 25

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

Four centuries of decisions made by millions of people have created Balti-

more City. Sometimes, these decisions – local, national, or global in scale

– have challenged the very existence of Baltimore City. At other times, these

decisions have created opportunities for Baltimore to grow, transform, and

thrive.

Within this continual sea of decision making, Baltimoreans have success-

fully steered their City through global turmoil, economic booms and busts,

political and social upheaval, and the extraordinary consequences of techno-

logical change. Throughout Baltimore’s history, its leadership responded to

a number of seemingly insurmountable challenges by reinventing the City

many times: brilliant Baltimoreans have invented and improved upon a vast

range of technologies; shrewd businessmen have seized mercantile advan-

tages; philanthropists have dramatically improved the lives of people within

Baltimore and across the globe; and civic-minded citizens have organized

and re-organized local government and the City’s civic institutions. The next

few pages will chronicle moments in Baltimore’s history when hard, culture-

dening choices had to be made. These choices reveal the tenacity, ingenuity,

and genius of Baltimore and its residents.

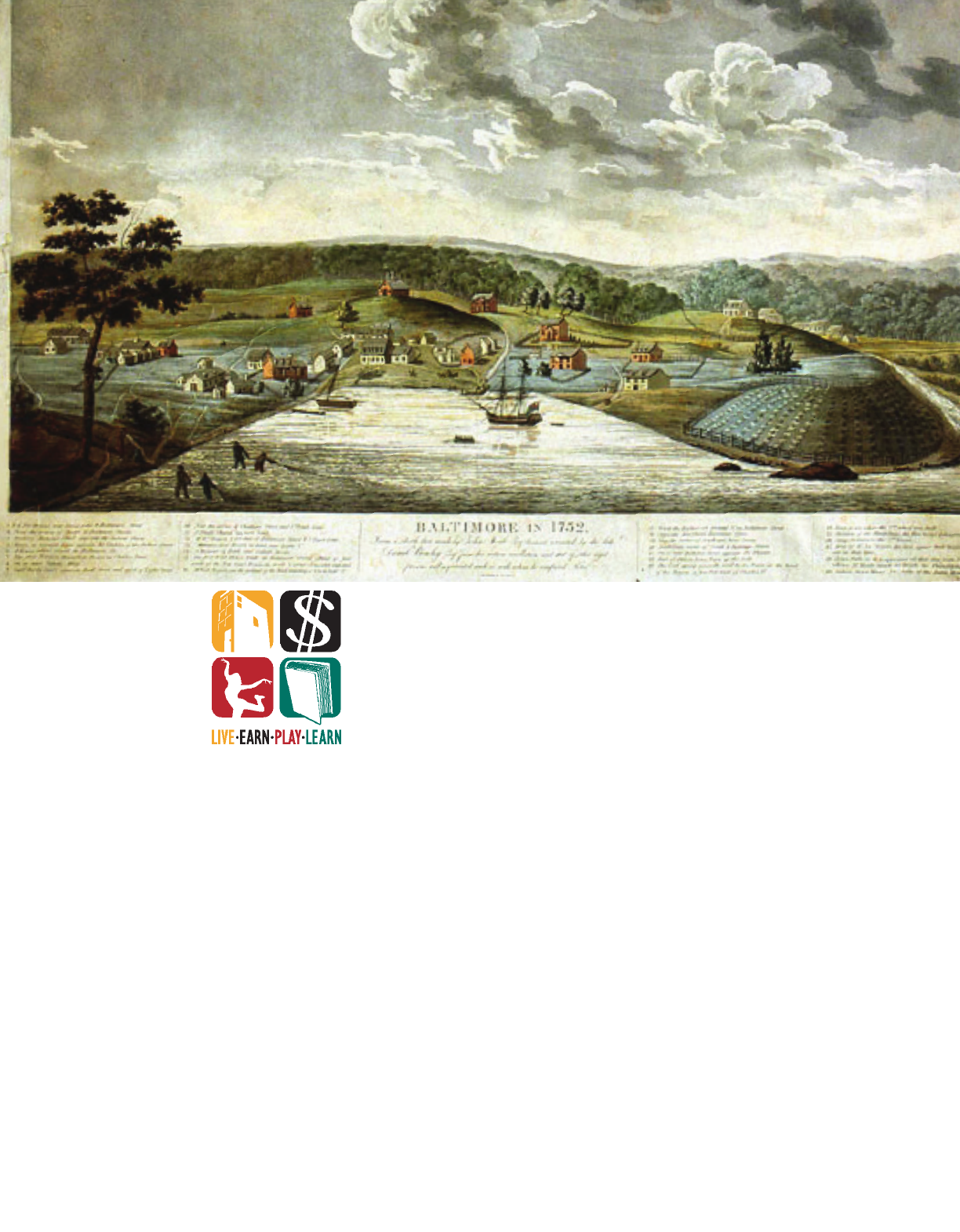

In 1752 John Moale sketched a rough

drawing of Balmore Town as seen

from Federal Hill. In 1817 Edward

Johnson Coale repainted this view,

adding picturesque embellishments.

The History of Baltimore

26 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 27

26 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 27

1729 to 1752 – The Beginning

There was nothing unusual in 1729 when several

wealthy Marylanders pushed through the State Leg-

islature a town charter for Baltimore. Town charters

were issued routinely across the State in those times.

In 1730, Baltimore Town was established with sixty

lots, one-acre each, and located on the north side of

the Inner Basin of the Patapsco River (now the Inner

Harbor). These lots were squeezed in between a shal-

low harbor on the south; the Jones Falls River and

marsh on the east; a bluff and woods on the north; and

large gullies on the west. In 1745, Jonestown, a small

settlement just east of the Jones Falls, was merged

into Baltimore, adding twenty more lots to the town.

By 1752, only twenty-ve buildings had been con-

structed in Baltimore– a rate of approximately one building per year. Shortly

after 1752, the pace changed.

1752 to 1773 – Seizing the Geography

The rise of Baltimore from a sleepy town trading in tobacco to a city rival-

ing Philadelphia, Boston, and New York began when Dr. John Stevenson, a

prominent Baltimore physician and merchant, began shipping our to Ire-

land. The success of this seemingly insignicant venture opened the eyes

of many Baltimoreans to the City’s most extraordinary advantage– a port

nestled alongside a vast wheat growing countryside, signicantly closer to

this rich farm land than Philadelphia.

The town exploded with energy, and Baltimoreans restructured the City’s

economy based on our. Trails heading west were transformed into roads;

our mills were built along the Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, and Patapsco Riv-

er; and merchants built warehouses on thousand-foot long wharves that ex-

tended into the harbor. Soon, the roads from Baltimore extended all the way

to Frederick County and southern Pennsylvania, and Baltimore ships sailed

beyond Ireland to ports in Europe, the Caribbean, and South America.

The City’s widening reach was also apparent in the foreign-born populations

it attracted. In 1756 a group of nine hundred Acadians, French-speaking Cath-

olics from Nova Scotia, made what homes they could in an undeveloped tract

along the waterfront. This pattern would be repeated by numerous groups over

subsequent decades and centuries: entry into Baltimore’s harbor, a scramble

for housing near the centers of commerce, and a dispersion throughout the

city as much as space, means and sometimes stigma would allow. But not all

newcomers started at a disadvantage. During this period, Irish, Scottish and

German families with experience and capital gained from milling in other

parts of the region took advantage of the City’s growth economy.

1773 to 1827 – Improving on the Geography

During the Revolutionary War, Baltimore contributed an essential ingredient

for victory: naval superiority. By the 1770s, Baltimore had built the most ma-

neuverable ships in the world. These ships penetrated British blockades and

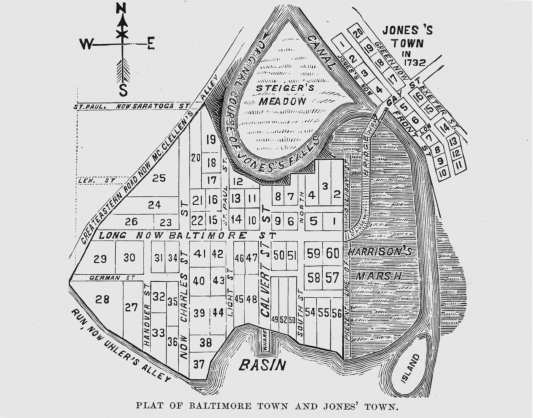

Map showing Balmore and Jonestown

in the mid-18th Century.

26 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 27

26 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 27

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

outran pirates, privateers, and the Royal British Navy. The agility and speed

of these ships allowed Baltimore merchants to continue trading during the

Revolutionary War, which in turn helped to win the war and to propel Balti-

more’s growth from 564 houses in 1774 to 3,000 houses in the mid 1790s.

From the late 1770s through the 1790s, Baltimore was loaded with boom-

town energy. Baltimore’s Town Commissioners implemented a number of

critical public works projects and legislative actions to guide this energy:

Fells Point merged with Baltimore (1773); a Street Commission was cre-

ated to lay-out and pave streets (1782); and a Board of Port Wardens was

created to survey the harbor and dredge a main shipping channel (1783).

Street lighting followed in 1784 along with the establishment of “Marsh

Market,” and the straightening of the Jones Falls. In 1797 Baltimore was

ofcially incorporated as a city, which allowed local ofcials to create and

pass laws. In 1798 George Washington described Baltimore as the “rising-

est town in America” (A.T. Morison, George Washington).

Baltimore City at the beginning of the 19th century overcame many ob-

stacles to growth. The northern shoreline of the Inner Harbor was ex-

tended two blocks south (Water Street marks the original location of the

This engraving of Balmore was

published in Paris and New York around

1834. Since 1752, Federal Hill has been

the vantage point from which to view

Balmore.

28 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 29

28 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 29

shoreline) and devel-

opment expanded in

all directions, usually

following the turnpike

roads that led from

Baltimore’s harbor to

the rural hinterlands.

In 1816, when the

population reached

46,000 residents, Bal-

timore expanded its

boundaries, increas-

ing its size from three

to ten square miles.

Shortly thereafter,

land surveyor Thomas

Poppleton was hired

to map the City and

prepare a plan to con-

trol future street extensions. His plan consisted of a gridiron street pattern

that created a hierarchy of streets: main streets, side streets and small alleys.

This set in motion Baltimore’s basic development pattern of various-sized

rowhouses built on a hierarchical street grid. Catering to several economic

classes, the larger streets held larger houses; the smaller cross streets held

smaller houses; and the alleys held tiny houses for immigrants and laborers.

As Baltimore’s port grew, its trade routes were extended to the Ohio Valley.

In 1806 the Federal Government authorized the building of the National Road

from the Ohio River to Cumberland, Maryland. In turn, Baltimore businessmen

built turnpike roads from Baltimore

to Cumberland, effectively complet-

ing the Maryland portion of the Na-

tional Road. The Road quickly be-

came Baltimore’s economic lifeline

to the fertile lands of the Ohio Val-

ley. By 1827 Baltimore became the

country’s fastest growing city and

the largest our market in the world.

At the same time, other economic

forces were taking hold. Many mills

along Jones Falls were converted

to or built as textile mills. In 1808

the Union Manufacturing Company,

built in the Mount Washington area,

became one of America’s rst tex-

tile mills. Nearly twenty years later,

mills along the Jones Falls were producing over 80% of the cotton duck (sail

cloth) in the country. In addition, 60 our and grist mills, 57 saw mills, 13

spinning and paper mills, 6 foundries, and 3 powder mills were located on

streams near the City, and shipyards, brick kilns, copper and iron works, and

glass factories were built along the shoreline of the harbor.

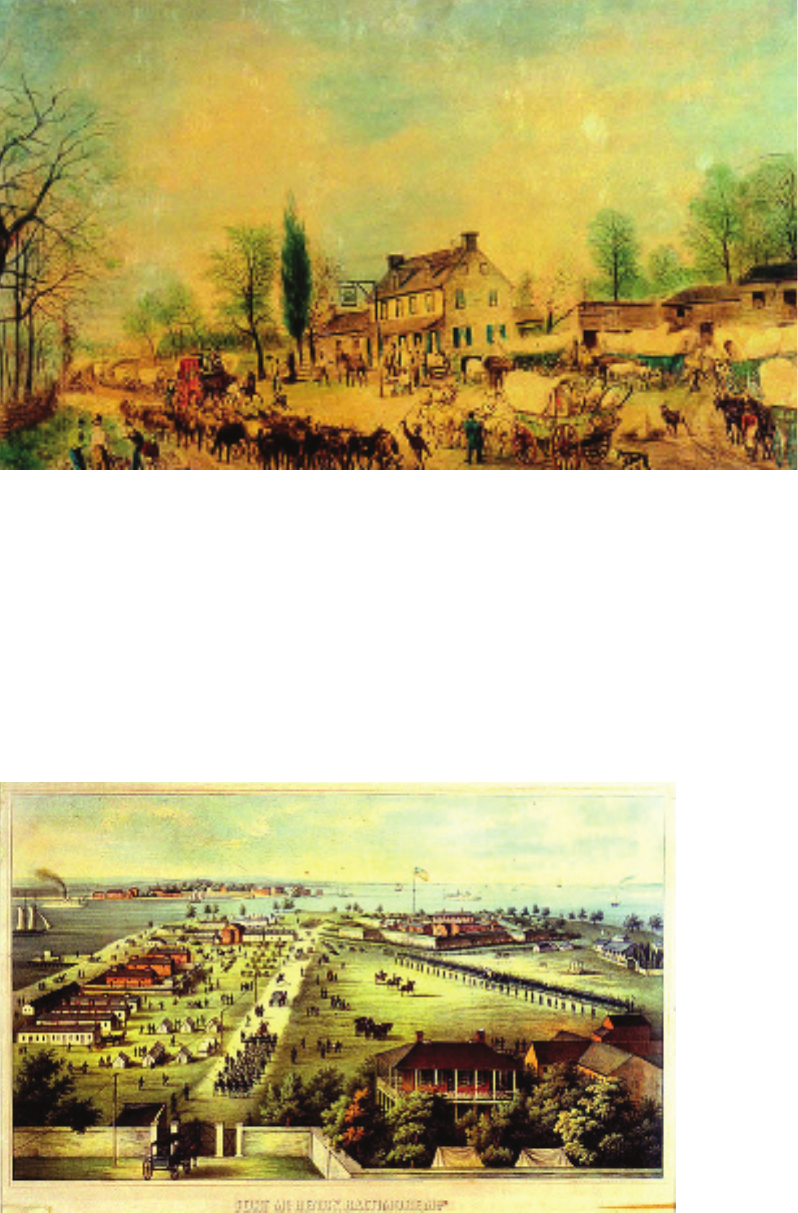

This 1865 view of Fort McHenry was

published by E. Sachse and Company.

Fort McHenry was the military post for

Balmore in the Civil War as well as a

jail for Confederate prisoners.

Fairview Inn was located on the Old

Frederick Road. The inn, known as the

“three mile house,” catered to farmers

bringing wheat, our, and produce to

Balmore. This image was painted by

Thomas Coke Ruckle around 1829.

28 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 29

28 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 29

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

Baltimore also played a key role in

the War of 1812. Privateers, essen-

tially pirates supported by the U.S.

government, played a decisive role

in winning the War. At this time Bal-

timore shipbuilders built the fast-

est, most maneuverable ships in the

world. Known as the “Baltimore

Clipper,” these ships allowed Balti-

more ship captains to wreak havoc on

England’s maritime trade. Captain

W.F. Wise of the Royal Navy said

“In England we cannot build such

vessels as your ‘Baltimore Clippers.’

We have no such models, and even

if we had them they would be of no

service to us, for we could never sail

them as you do.” Of the 2,000 Eng-

lish ships lost during the war, Balti-

more privateers had captured 476 or

almost 25% of them.

The British described Baltimore as ‘a nest of pirates,’ and the City soon be-

came a military target. After the British burned Washington, DC, they sailed

to Baltimore. The City, left to defend itself, looked to Revolutionary War hero

General Samuel Smith to coordinate its defense. Following Smith’s direction,

every able-bodied man toiled for days, building a formidable defense at Hamp-

stead Hill (now Patterson Park) and making preparations at Fort McHenry. A

contemporary of Smith quipped “Washington saved his Country and Smith

saved his City.”

The Battle of Baltimore has been immortalized by not one but two American

treasures. The Battle Monument erected between 1815 and 1825 was the rst

public war memorial in the country and the rst memorial since antiquity to

commemorate the common soldier. It lists every ordinary citizen who died in

the battle. In addition, Francis Scott Key, who was being held prisoner on a

British ship, observed the battle and

recorded the event in a poem, which

he set to the tune of an old drink-

ing song. The Star Spangled Banner

premiered in Baltimore in 1814 and

became our National Anthem in the

early 20th century.

As Baltimore grew in size and popu-

lation, many social and cultural in-

stitutions were founded. As early

as 1773, a theater opened in an old

warehouse near current-day Power

Plant Live. By 1800 there were three

theaters and several theater compa-

nies. In 1797, directly across from

the current-day City Hall, the Balti-

more Dance Club built the New As-

sembly Room featuring a ball room

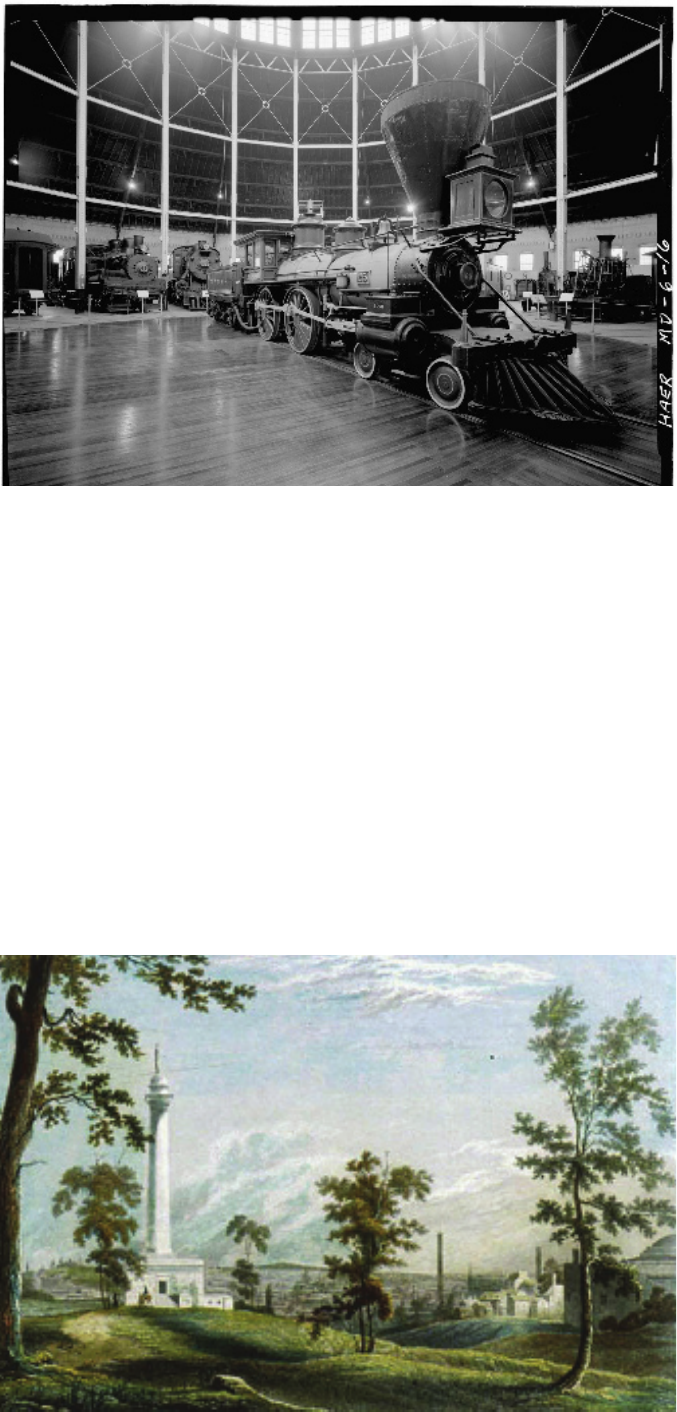

The Washington Monument in 1835 sat

on the grounds of “Howard’s Woods.”

Balmore’s developed area ended a

block south on Charles Street.

In 1829, the Balmore & Ohio (B&O)

Railroad built the Mount Clare Staon.

By 1900 it was a sprawling complex of

32 buildings. This building, the Mount

Clare Passenger Car Shop, built in 1884,

became the B&O Railroad Museum’s

principal building in 1953.

30 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 31

30 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 31

and a subscription library. In 1814, Rembrandt Peale built the rst purpose-

built museum building in the Western Hemisphere and the second in modern

history. The Peale Museum exhibited paintings, sculpture, and the bones of

a mastodon excavated in upstate New York. During the rst half of the 19th

century, Baltimore’s cultural activities grew as literary, science and social clubs

were formed.

The early 19th century was a great time for Baltimore. It seemed to be Amer-

ica’s perennial boom town. It kept growing. It had energy. It was a city full of

merchants of all kinds. Its sailing ships were the fastest, swiftest force on the

world’s oceans. In the 1830 national census, with its population of 80,000, Bal-

timore had become the second largest city in the United States. German settlers

now made up a substantial part of this population (possibly some ten percent

as early as 1796). Substantial numbers of Scotch-Irish moved overland from

Pennsylvania while boatloads of newcomers from Ireland, Scotland and France

were received as well. A number of the new French-speaking arrivals came by

way of the Caribbean from Santo Domingo (present-day Haiti), displaced by a

massive and ultimately successful slave revolt. The blacks among them may

have added as much as 30% to the “colored” population of the town.

1827 to 1850 – The Looming Economic Downturn

In 1825, one boat completed a journey that indirectly shaped Baltimore’s his-

tory for the next 100 years. The packet boat, Seneca Chief, operated by New

York Governor Dewitt Clinton, journeyed from the eastern end of Lake Erie to

New York City, thereby inaugurating the Erie Canal. A year later, 19,000 boats

had transported goods to and from the Midwest and New York. The new freight

rates from Buffalo to New York were $10 per ton by canal, compared to the

cost of $100 per ton by road. The canal became by far the most efcient and

affordable way to transport goods from the Midwest to the Atlantic Ocean.

As trade on the canal began to usurp trade on the National Road, Baltimoreans

foresaw the City’s economic power eroding. Baltimore’s business leaders were

on the verge of panic. They discussed all sorts of wild schemes and alternative

canal locations, but Baltimore’s geography prevented any of these schemes

from becoming reality.

At this point, the luck and stubbornness of Baltimoreans began a course of

events that reinvented the world, even making its arch nemesis, the Erie Canal,

obsolete. Baltimore merchant Philip Evan Thomas while in England became

convinced that England’s “short railroads,” which hauled coal from the mines

to the canals, had long-distance potential. On February 12, 1827, Thomas and

25 other Baltimore merchants met “to take into consideration the best means

of restoring to the City of Baltimore that portion of the western trade which

has lately been diverted from it by the introduction of steam navigation [on the

Mississippi] and by other causes [the Erie Canal].” Four days later, the men

resolved “that immediate application be made to the legislature of Maryland

for an act incorporating a joint stock company, to be named the Baltimore &

Ohio Railway Company.” Twelve days later, the Act of Incorporation for the

company was approved.

Over a year later, on July 4, 1828, with $4,000,000 of capital stock already

raised, Charles Carroll of Carrollton laid the “rst stone” of the B&O Rail-

road. On May 22, 1830, the B&O Railroad began running operations from

Baltimore to Ellicott’s Mills, a distance of 13 1/2 miles. Finally, on December

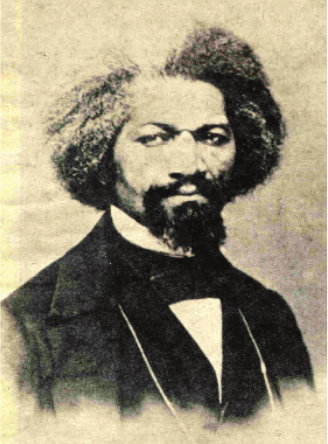

Portrait of Frederick Douglass. Douglass

spent his early years in Balmore

where he learned to read and write.

In the late 1830s, Douglass escaped to

freedom while impersonang a sailor.

30 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 31

30 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 31

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

24, 1852, the last spike was driv-

en in Wheeling, Virginia (now

West Virginia), a distance of 379

miles.

In those few years, Baltimore

citizens had decided how far

apart the rails should be (4 feet

8 1/2 inches), had completely re-

engineered the steam engine, and

in fact had created the world’s

rst long distance railroad, the

world’s rst passenger railroad,

and the world’s rst railroad that

climbed over mountain tops. At

the B&O railroad shops in West

Baltimore, ingenious innovators

perfected passenger and freight

car design, continuously im-

proved the steam locomotive de-

sign, and fabricated bridges for

the growing railroad. Baltimor-

eans unleashed “mighty forces

that were to revolutionize land

transportation, alter the course of trade, make and unmake great cities, and

transform the face of the country” (J. Wallace Brown).

The B&O Railroad shops triggered technological innovation in architecture

and engineering. Wendel Bollman, after working as an engineer for the B&O

Railroad, developed the rst cast-iron bridge system in the country. In 1850,

the Hayward, Bartlett & Company, iron fabricators, moved next to the B&O

Railroad shops and began producing much of the nation’s cast-iron architec-

tural components.

The telegraph became intertwined with the development and success of the

B&O Railroad. In 1844, a telegraph line was completed from Baltimore to

Washington, DC along the B&O Railroad tracks. First the telegraph lines

were buried, but the lines kept failing. Finally, they were strung on poles,

effectively bringing into existence the telephone pole. Later, the railroads and

the telegraph, together, helped to implement standard time zones through-

out the Country. Standard time zones were essential for railroads to safely

schedule their trains, and the telegraph allowed cities across the country to

synchronize their clocks.

The railroad’s rst year of operation coincided with a spike in immigration.

The port’s intake of foreigners doubled in 1830 and again in 1832, from 2,000

to 4,000 to 8,000 per year. Bavarian Jews, for example, settled in Oldtown on

High, Lombard, Exeter and Aisquith streets.

1850 to 1866 – Balmore at Mid-Century

Between 1850 and the Civil War, extraordinary changes spread through Bal-

timore’s landscape. Cast-iron building technology transformed Baltimore’s

downtown. In 1851 the construction of the Sun Iron Building introduced

An 1848 image of the Washington

Monument from Charles and Hamilton

streets. The squares were rst laid out

as simple lawns.

32 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 33

32 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 33

cast-iron architecture to Baltimore and the nation. Its ve-story cast-iron fa-

çade, iron post-and-beam construction, and sculptural detailing were copied

throughout cities worldwide. Back in Baltimore, 18 months after the Sun

Building opened, 22 new downtown buildings incorporated cast iron into

their construction. In 1857 the Baltimore Sun noted, “literally, the City of

yesterday is not the city of today… The dingy edices that for half a century

have stood…are one by one being removed, and in their places new and im-

posing fronts of brown stone or iron present themselves.”

Baltimore was also remarkable during this time for the size and achieve-

ments of its African-American community. In 1820 it was the largest in the

nation. Slave or free, no greater number of blacks could be found anywhere

in the nation. By the time the Civil War erupted, the City contained 26,000

free blacks and approximately 2,000 slaves. Even more remarkable, during

that same period Maryland alone accounted for one out of every ve free

blacks in the country.

African Americans struggled for a piece of Baltimore’s economic activities.

Prior to emancipation, it was common for slaves in the City to rent their skills

and services for wages, part of which went to their masters and part of which

could be used for food, accommodation and amusement. At the same time

racism handicapped free blacks while competing with whites for skilled and

unskilled jobs in the port economy. During times of recession, white working

men sometimes resorted to violence to keep jobs among themselves.

An 1850s-era view of Mount Vernon

Place in relaon with downtown

Balmore.

32 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 33

32 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 33

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

1866 to 1899– Heading Towards Modernity

After the war, the City’s industry gathered momentum. The advent of steam

power in the 1820s released Baltimore’s industry from its stream valleys, and

new larger-scale industries were built close to the harbor. Baltimore’s connec-

tions to the Bay’s shing industry and the fertile farm land around the Chesa-

peake Bay helped to concentrate canning factories around the harbor’s edge.

In fact, by the 1880s, Baltimore had become the world’s largest oyster sup-

plier and America’s leader in canned fruits and vegetables. Complementing

the canning industry was the fertilizer industry. Baltimore became the number

one importer of guano, centuries-old bird droppings scraped off Pacic Coast

islands near South America. Mixed with phosphates, guano became the most

important fertilizer for the farms lining the Chesapeake Bay. By 1880, Balti-

more had 27 fertilizer factories producing 280,000 tons of fertilizer per year.

Baltimore was also becoming a leader in other manufacturing sectors. By the

20th century, the City was a world leader in manufacturing chrome, copper,

and steel products. In 1887, Sparrow’s Point was developed by Pennsylvania

Steel Company. This location brought Cuban iron ore and Western Maryland

coal together, creating a company that helped to shape Baltimore’s economy

for over a hundred years. In addition, Baltimore was America’s ready-made

Immigrants waing to debark at Locust

Point. Close to two million immigrants

arrived in Balmore throughout the

19th and early 20th centuries. (Courtesy

of the Maryland Historical Society,

Balmore, Maryland)

34 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 35

34 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 35

garment manufacturing center and

the world’s largest producer of

umbrellas. Baltimore grew on its

manufacturing strength, and indus-

try expanded along the shorelines

of Faireld, Brooklyn, and Curtis

Bay.

From 1850 to 1900 Baltimore’s

population grew from 169,000 to

508,957. Baltimore’s vibrant and

diverse neighborhoods evolved to

accommodate a constant inux of

immigrants searching for opportu-

nity. More than two million immi-

grants landed rst in Fells Point and

then in Locust Point, making the

City second only to New York as an

immigrant port-of-entry. Most new

arrivals promptly boarded the B&O

Railroad and headed west, but

many stayed in the City to work in

the burgeoning industries or start their own businesses. Irish, German, East-

ern European, Greek and Italian immigrants added their customs, religions

and talents to Baltimore’s colorful tapestry of neighborhoods and industries.

This growth, however, placed great pressure on Baltimore’s physical infra-

structure, and City ofcials responded. To accommodate this growth, Balti-

more expanded its size from ten to thirty square miles in 1888. Prior to this

annexation, the City inuenced the suburban regions through the Baltimore

City Water Works and the development of the horsecar.

In 1853, the Baltimore City government purchased the Baltimore Water Com-

pany. With Baltimore’s water supply clearly a government responsibility,

ambitious plans were implemented. Between 1858 and 1864, the Hampden

Reservoir, Lake Roland and Druid Lake were created. This water system used

the Jones Falls as its source; however, in 1874 the City passed an ordinance to

create another water system with the Gunpowder River as its main source. By

1888, Baltimore had created Loch Raven Reservoir and a seven-mile tunnel

that connected Loch Raven to Lake Montebello.

In addition, horsecar railway companies began laying track along Baltimore

streets in 1859. Many horsecar railway lines followed old turnpike roads,

effectively opening up suburban areas for development. In a matter of years

Baltimore’s neighborhoods and its suburban villages were tied together by

a comprehensive system of horsecar railway lines. In the 1890s, Baltimore

replaced horsecars with the electric streetcar, which opened up even more

suburban areas to development, and by 1900 over 100 suburban villages

surrounded Baltimore.

While horsecars expanded Baltimore’s physical reach, steamships and rail-

roads tied Baltimore to the global economy. The B&O Railroad connected

Baltimore to the West; the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad

connected the City to Philadelphia; and the Maryland and Potomac Railroad

Balmore Harbor image of Locust Point

and Canton around 1860. Images

of Camden Staon (le) and the old

Calvert Street Staon (right) are located

in the upper corners of the picture.

34 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 35

34 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 35

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

connected Baltimore to the South. As early as 1851, Baltimore steamship

companies connected the City to points along the shoreline of the Chesapeake

Bay. In 1869, Baltimore and Bremen businessmen opened the Baltimore

Bremen Line, which began regular runs between Baltimore and Germany.

Samuel Shoemaker, an enterprising Baltimorean, seized the opportunity that

Baltimore’s transportation hub offered. He helped to organize the Adams Ex-

press Company that prided itself on delivering anything, anywhere. This ser-

vice helped to open and settle the West. By the 1880s the company employed

over 50,000 people.

Closer to home, Mayor Swann agreed to allow horsecar companies to lay

track on public streets in exchange for 20% of their gross proceeds to fund a

park system. In 1860 Baltimore created its rst park board and opened Druid

Hill Park. By 1900, the Park board had added eight major parks to Baltimore.

All these parks were incorporated into Baltimore’s major park plan of 1904.

As of 1893, Baltimore had more millionaire philanthropists than any other

city in America; moreover, through the benevolence of four Baltimoreans,

modern philanthropy began. In 1866 the Peabody Institute opened with a mu-

sic school, an art gallery, a lyceum, and a library more comprehensive than

the Library of Congress. Picking up on these themes, Enoch Pratt founded

the City’s library system; William and Henry Walters founded the Walters

Art Gallery; and Johns Hopkins founded Johns Hopkins University and Hos-

pital. During one memorable dinner, John Work Garrett remembers George

Peabody telling Johns Hopkins, “I began to nd out it was pleasanter to give

money away than it was to make it.”

A lithograph of City Hall in 1875 by

A. Hoen Company.

36 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 37

36 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 37

“My library,” Mr. Pratt said, “shall be for all, rich and poor without distinction

of race or color, who, when properly accredited, can take out the books if they

will handle them carefully and return them.” In 1886 with the opening of the

central library and four branch libraries, the Enoch Pratt Free Library became

the rst city-wide library system in the country. The Johns Hopkins Univer-

sity opened in 1876 as America’s rst research-oriented university modeled

after the German university system. The university attracted some of the best

minds of the late 19th century: philosophers Josiah Royce and Charles Sand-

ers Pierce; medical doctor William Osler and chemist Ira Remsen; histori-

ans Frederick Jackson Turner and Herbert Baxter Adams (father of Political

Science); and ambassador Theodore Marburg and future President Woodrow

Wilson.

At the same time, Charles Joseph Bonaparte (future U.S. Attorney Gen-

eral under Theodore Roosevelt), Cardinal Gibbons, Baptist minister Henry

Wharton, Reverend Hiram Vrooman of the New Jerusalem Church, and oth-

ers formed the Baltimore Reform League to reform the election process in

Baltimore. By 1900, the League had managed to signicantly reduce the

level of voting fraud and elect politicians not beholden to Baltimore’s infa-

mous Democratic Machine.

As the 20th century loomed over Baltimore, major economic, physical and

technological changes were taking place. Family-owned businesses began to

give way to corporations. Between 1895 and 1900, Baltimore found itself

fully integrated into the national economy. In 1881 there were 39 corporations

in Baltimore; by 1895 there were over 200 corporations.

During this same period, the City saw the beginnings of a Polish immigra-

tion that began around 1870 and continued until World War I. The rst fami-

lies settled in Fells Point before moving east and northeast of the water. The

City also became home to a small number of Lithuanians eeing assimilation

and service in the Russian army in the 1880s. They settled in East Baltimore

and eventually formed communities along Paca and Saratoga streets. Italians,

eeing drought and poverty, entered Baltimore around the same time. Today’s

Little Italy neighborhood didn’t become Italian until it had seen a succession

of Germans, Irish and Jews.

36 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 37

36 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 37

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

By the turn of the century the wealth and success of many Jewish families

was evident in the size and diversity of the community’s synagogues, some

orthodox, some reform. The wealthier sections of the population were becom-

ing increasingly mobile, able to move northwest out of Oldtown.

African Americans, too, were in need of new and better homes. An inux of

African American rural migrants in the 1870s and 1890s worsened already

crowded conditions in many Baltimore neighborhoods, but discrimination

meant that little to no new housing would be designated for them.

1900 to 1939 – Keeping up with Technology

At the dawn of the 20th century, Baltimore’s population reached over half a

million. Hundreds of passenger trains were funneled through its ve railroad

stations; 13 trust companies controlled large areas of Baltimore manufac-

turing; 21 national banks and 9 local banks controlled Baltimore’s nancial

interests; 13 steamship companies were engaged in coastal trading; and 6

steamship companies connected Baltimore to foreign ports. Technological

progress, economic restructuring, and an increasing population placed great

pressure on Baltimore’s urban fabric.

To confront these immense changes, the Baltimore Municipal Art Society

was formed around 1899 and soon became the voice that directed Baltimore’s

physical development. The society’s initial goals were inspired by the Na-

tional City Beautiful Movement. They commissioned artists to create several

monuments and hired the Olmsted Brothers’ Landscape Architects to create

the 1904 Baltimore City park plan. They advocated successfully for a com-

prehensive sewer system (1914), for annexation (1918), and for a comprehen-

sive zoning ordinance (1923).

Baltimore’s biggest challenge, however, began in 1904. On Sunday, Febru-

ary 7, 1904, Baltimore’s downtown vanished. On that morning, smoke rose

from the basement of a dry goods store on the corner of German (now Red-

wood) and Liberty streets. Shortly before 11:00 a.m., the building exploded,

spreading ames and debris to nearby structures. Driven by a strong wind,

Panoramic view of the destrucon le

by the Great Balmore Fire of 1904.

This view is looking west from near

Balmore and Gay streets.

38 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 39

38 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 39

the blaze moved east and then south. Approximately 30 hours later, remen

from Baltimore and other cities along the East Coast as far away as New York

stopped the blaze at the Jones Falls. The downtown smoldered for weeks. The

re consumed 140 acres, destroyed 1,526 buildings, and burned out 2,500

companies.

Baltimore quickly began rebuilding, and dozens of buildings were being

constructed a year later. Ten years after the re, Baltimore’s downtown was

completely rebuilt. In all, the re made way for several signicant improve-

ments to the downtown: twelve streets were widened, utilities were moved

underground, a plaza was established, and wharves were rebuilt and became

publicly owned. The re also led to stricter re codes for Baltimore and na-

tional standardization of re hydrants and re-hose connectors.

World War I imposed hardships on Baltimore as well as presented economic

opportunities. In 1917, when the U.S. declared war on Germany, Baltimore

swelled with anti-German feelings. German Street was renamed Redwood

Street after Lt. George B. Redwood, Maryland’s rst casualty in the War. The

German-American Bank was renamed the American Bank. Worse, thousands

of German immigrants were classied as enemy aliens, even if they had lived

in Baltimore for years. The War cut off the ow of European immigrants.

Baltimore’s population swelled from 558,485 in 1910 to 733,826 in 1920 as

unemployed rural southerners ocked to Baltimore. Even though the number

of workers increased by a third, labor shortages were still pervasive. This

Memorial Day Parade June 2, 1919.

Here the 808th Infantry, an African

American unit, headed south on

Holliday Street, a half-block from City

Hall.

38 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 39

38 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 39

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

worker-friendly environment helped to bring the eight-hour day to Baltimore,

opened up jobs for women, and provided more skilled jobs for African Ameri-

cans.

In 1918, Baltimore completed a major annexation, instantly enlarging its size

from 30 square miles to almost 90 square miles. In contrast to Baltimore’s

old rowhouse model, the annexed area was developed with bungalows and

other types of suburban-style houses. Street patterns in the annexed area dif-

fered from the older, inner-city area of Baltimore. Alleys disappeared, and

the urban grid softened into irregular and curved patterns. City government

retooled and reorganized in order to thoughtfully develop the annexed area.

The City Plan Committee was appointed in 1918. In addition, Baltimore City

passed the 1923 Zoning Ordinance, and the Board of Municipal and Zoning

Appeals was created. Other bureaucratic reorganization occurred: the Bureau

of Highways was formed (1920s); Bureau of Plans and Survey was created

(1926); and several departments were consolidated into the Department of

Public Works (1926). The Major Street Plan for the annexed area was adopted

in 1923, and from the beginning it was under extreme development pressure.

In an unprecedented effort Baltimore bureaucrats and legislators “adopted a

policy of refusing to extend paving or underground utilities in any street the

location of which had not been approved by the City Plan Committee, and all

sub-division plans were submitted to it.”

In turn, developers adapted to the changes in the bureaucratic approval

process as well as changes in nance, real estate, and building technology.

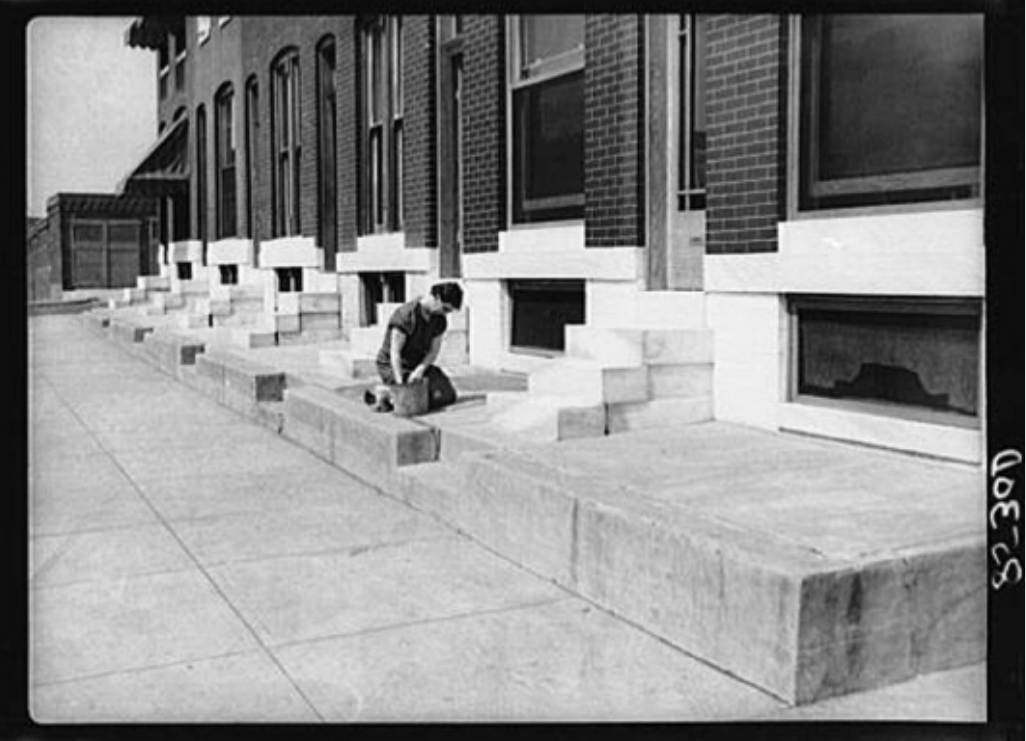

The weekly step-scrubbing ritual, 1938.

Balmore is famous for its ubiquitous

white marble steps lining the streets of

many of its rowhouse neighborhoods.

40 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 41

40 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 41

Developers began to consolidate their development process. They bought

large estates, subdivided them, laid out the roads and underground utilities,

built the houses, set-up building and loan associations (sometimes on site),

and marketed their new neighborhoods. Prior to the 20th century, many of

these steps were done separately. The results were extraordinary: E.J. Gal-

lagher, Ephraim Macht, and Frank Novak built over fty thousand houses in

Baltimore. Other developers, including George R. Morris, Henry Kolbe, and

Kennard and Company, partnered with longtime residents of suburban areas

and formed real estate corporations. The rate of development was extraordi-

nary: in Northeast Baltimore alone between 1900 and 1939 the number of

housing units grew from 279 units to over 14,000 units.

Most African Americans, however, were left out of this suburban expansion.

Three times before World War I the City Council passed ordinances forbid-

ding them from moving into white neighborhoods. Each was overturned, but

unfortunately they represented only the most formal and overt of numerous

racist tactics. With the newest offerings within the expanding housing stock

largely off limits, many blacks bought and rented secondhand. After another

large rural inux in 1900, by 1904, half of the City’s black population had

taken up residence in Old West Baltimore as the area’s German community

branched out further north. Within this single area could be found a rich di-

versity of African American life.

Corporations, more than individuals, reshaped the downtown and surrounding

areas along the shoreline. National corporations built industrial parks, not just

industrial buildings. Western Electric, Standard Oil, and Crown Cork & Seal

each had an industrial complex encompassing more than 125 acres. Standard

Oil also located its regional ofce headquarters on St. Paul Place. Baltimore

found a comfortable position in the new world of national corporations.

By the 1930s, most of our venerable cultural institutions had been created:

the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Walters Art Gallery, the Peale Museum re-

opened as Baltimore’s history museum, Lyric Opera House, and more than a

hundred movie theaters were built throughout Baltimore neighborhoods. Oth-

er institutions were thriving: the Maryland Institute College of Art, Goucher

College, Morgan College (now Morgan State University), Coppin Teachers

College (now Coppin State University), and the University of Maryland at

Baltimore.

By 1931 the Depression hit Baltimore hard. On September 31, 1931, the Bal-

timore Trust Company closed its thirty-two-story skyscraper; by 1933, the

Governor closed all banks to try and prevent mass bank withdrawals. For the

next six years Baltimore spiraled deeper into despair; 29,000 Baltimoreans

were ofcially unemployed in 1934. Federal resources during the latter half

of the 1930s kept Baltimore aoat. Civil engineer Abel Wolman coordinated

the Civil Works Administration (CWA) in Baltimore, which put thousands of

people back to work. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) followed

the CWA, providing work for many more Baltimoreans. But it took another

war to pull Baltimore and the nation out of its doldrums. By 1939, Baltimore

industries began retooling their factories for war.

40 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 41

40 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 41

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

1939 to 1946 – World War II: Balmore Comes Through

Baltimore geared up for World War II in a big way. Even before America’s

entrance into the War, many Baltimore factories were retted to make every-

thing that the war effort required. Dining room table-cover manufacturers

began making the heavy cloth parts for gas masks; automobile makers began

building tanks and jeeps; and the Martin Aircraft Corporation began mak-

ing B-26 and B-29 Superfortress bombers. At the end of World War II, one

Baltimore business, Martin-Marietta, was turning out thousands of airplanes

a year, and at the Curtis Bay and Faireld shipyards an ocean freighter a day

slid into the water.

Migrants from the rural south, looking for work, overwhelmed Baltimore.

Many grand Baltimore houses were cut up into small apartments to house

the population. Rooms in many South Baltimore rowhouses were tted with

multiple beds. Each bed may have slept one man during each 8 hour shift.

1946 to 1968 – Suburbanizaon without End / Charles Center

invented / Historic Preservaon Begins

After World War II, Baltimore City found itself in the middle of tremen-

dous physical and social changes. With the return of soldiers eager to raise

families, suburbanization accelerated and spread past the City limits into the

S.S. Marime Victory Launching,

photograph by A. Aubrey Bodine,

May 1945. (Courtesy of the Maryland

Historical Society, Balmore, Maryland)

42 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 43

42 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 43

surrounding counties. By the 1950s,

7,000 to 8,000 houses a year were

being constructed in the counties

surrounding Baltimore. The popula-

tion within the City boundaries be-

gan a slow, continual decline: the

City lost 10,000 people in the 1950s

and 35,000 in the 1960s. During the

1960s the bulk of the retail activ-

ity in Baltimore’s downtown shop-

ping district and neighborhood main

streets followed their customers and

moved to the suburbs into shopping

centers built around four-leaf-clover

exit ramps of the newly completed

beltway (1962). Industry, too, fol-

lowed their employees. The City’s

old, multi-story brick factories were

vacated as sprawling, new industrial

parks with quick access to the newly

designed highway system were de-

veloped.

The federal government subsidized

much of the development of the suburbs. Federal subsidies, such as new

housing-oriented FHA loans, the 1956 Highway act, and tax incentives for

industrial development, were instrumental in restructuring the City and the

region.

Many Baltimoreans, however, were forced to move. In the City, the rate of

demolition rose from 600 households a year throughout the 1950s to 800 in

the early 1960s. The number reached 2,600 per annum in the late 1960s, as

sites were cleared for expressways, new schools, and public housing projects.

Poor and African American populations were disproportionately affected. At

the same time, blockbusting reached its peak with the population turnover

in Edmondson Village. Over a period of ten years (1955 –1965) most of the

area’s white residents were replaced by African-Americans. In situations such

as this, “investors” could buy low by capitalizing on white residents’ fears of

a worsening neighborhood and sell high to African American families desper-

ate for a chance at homeownership.

A great deal of attention was focused on the City center. Very few new ofce

buildings, large or small, had been built since the Baltimore Trust building in

1929. Baltimore citizens decided to act. In 1958, the Greater Baltimore Com-

mittee, a regional organization of business leaders, in cooperation with City

Government, unveiled a report that called for the transformation of 22 acres

in the heart of downtown Baltimore. To implement the plan, the City created a

public-private corporation known as the Charles Center Management Corpo-

ration. The plan mostly consisted of ofce buildings surrounding three urban

plazas. Underground parking was constructed under each of the plazas and

some of the buildings. While the new buildings were to be unabashedly mod-

ern, four existing ofce buildings were incorporated into the plan. The three

plazas and most of the ofce buildings that surrounded them were linked by

an overhead walkway system that crossed over several busy streets and in-

cluded escalators connecting the elevated walkway to city sidewalks below.

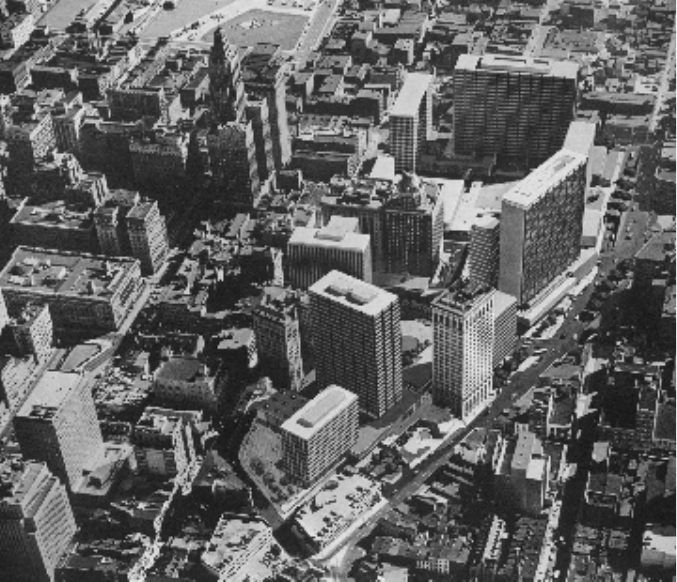

An image from the inial Charles Center

Plan published by the Greater Balmore

Commiee in 1958. A photograph

of the model of Charles Center was

superimposed on an aerial photograph

of downtown, creang an illusion of a

completed project.

42 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 43

42 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 43

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

In addition to the ofce buildings, a hotel, several residential towers, some

ground oor retail establishments, and the Mechanic Theater were incorpo-

rated into the complex. At the time, Fortune Magazine wrote of the Charles

Center Plan, “It looks as if it were designed by people who like the City.”

In 1962, the construction of One Charles Center, located between Center

Plaza and Charles Street, was completed. The 24-story, dark bronze-colored,

metal-and-glass ofce building was designed by Mies van der Rohe, a very

important International Style architect. Fortune Magazine called this building

one of the nation’s “ten buildings that point to the future.” For many years,

the American Heritage Dictionary included a thumbnail illustration of this

building adjacent to the architect’s entry.

The Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation (CHAP) was

created in 1964 to administer design review for the new Mount Vernon local

historic district. Concurrent with the creation of CHAP was the Mount Vernon

Urban Renewal Ordinance, the rst of its kind written to restore, not demolish

the historic mansions that made up the area. Today, Baltimore has more than

50 National Register Historic Districts and 30 Local Historic Districts. Balti-

more has a total of 56,000 structures listed on local and national registers.

1969 to 1999 – Suburbanizaon Connues /

Inner Harbor: A Magical Invenon

In 1956, the Federal Government passed the National Highway Act, which

provided 90% of funding for interstate highway construction. In 1960, the

Planning Commission published a study for the East-West Expressway, which

chronicled eight major proposals to build highways through Baltimore. I-95

would have sliced through Federal Hill and included a bridge to Little Italy.

These proposals would have effectively destroyed all harbor-front neighbor-

hoods as well as pedestrian access to the harbor. Between 1965 and 1967,

the City began condemning property along the proposed highway corridors.

Throughout this process, Baltimoreans organized to oppose the destruction of

the harbor-front neighborhoods. In 1969, Fells Point became a National Reg-

ister historic district, and in 1970 Federal Hill followed suit. Shortly thereafter,

I-95 was rerouted south of Locust Point, and a bridge would span the harbor,

connecting Locust Point to Lazaretto Point. In 1975, the bridge concept was

replaced with the Fort McHenry Tunnel in order to preserve Fort McHenry.

In the 1970s, I-83 was proposed to be built underground in order to preserve

Fells Point, but the idea zzled out as construction costs became prohibitive.

In the end, Baltimore lost over two hundred historic properties and hundreds

of others sat vacant after being condemned for highway construction. It was

the tenacity of Baltimoreans that prevented the highway from obliterating not

only the harbor-front neighborhoods but the Inner Harbor itself.

By 1975, 108 houses in the Otterbein neighborhood had been scheduled for

demolition as part of the Inner Harbor West Urban Renewal Plan. Instead,

these houses were sold to “homesteaders” for one dollar. In turn, homestead-

ers would restore the houses and live in them for at least ve years. 3,000

potential homesteaders visited Otterbein, proving that there was immense de-

mand for downtown living. Homesteading and historic preservation, follow-

ing the Otterbein example, spread to other neighborhoods, including Ridgley’s

Delight, Barre Circle, and Washington Hill. More importantly, however, the

44 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 45

44 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 45

internationally recognized success of homesteading proved that Baltimore

was a place in which people wanted to live. Baltimoreans were beginning to

reinvent their City as a collection of restored and rebuilt neighborhoods.

The roaring success of Charles Center empowered Baltimore ofcials to ex-

pand the reinvention of Downtown. The Charles Center Management Corpo-

ration was renamed the Charles Center Inner Harbor Management Corpora-

tion, and its staff began to work with the Philadelphia consultants, Wallace,

McHarg, Roberts, and Todd to dene the next stage of the Downtown trans-

formation. In 1964, the City and the Consultants came up with a vision: the

harbor should be encircled by a ring of new public spaces all connected to-

gether by a public, waterfront promenade. They envisioned museums, ofce

buildings, hotels, amphitheaters, marinas and piers for visiting ships, parks

and playgrounds, and a new kind of shopping center, the festival market-

place.

Using Federal Urban Renewal funds, the City demolished almost all of the

buildings within the project area and constructed an entirely new infrastruc-

ture of piers, bulkheads, roads, utilities, and parks. A new brick pedestrian

promenade was constructed around the harbor’s edge. The State of Maryland

erected the World Trade Center (1973), a pentagonal concrete-and-glass ofce

building designed by the architect I. M. Pei. One of its columns symbolically

emerges from the water, straddles the promenade, and hovers over the harbor.

The United States Fidelity and Guarantee Company, the City’s largest insur-

ance company, consolidated its downtown ofces and built its new 40-story

headquarters (1970-73), which became the City’s largest ofce building.

During the 1960s, the Inner Harbor looked like a wide open pool of black wa-

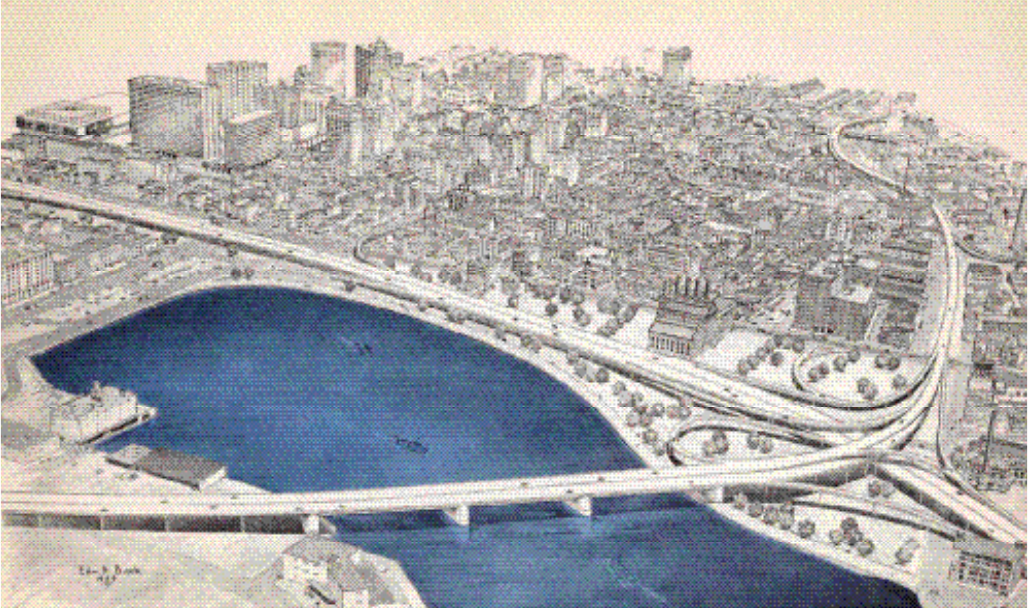

A 1959 rendion of one of several

interstate highway plans that would

have connected I-95 to an East West

Expressway and the Jones Falls

Expressway. Balmoreans fought

for over twenty years to prevent a

highway from destroying their historic

neighborhoods.

44 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 45

44 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 45

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

ter surrounded by a prairie crisscrossed by streets. Those early days are just a

memory now. The Inner Harbor, year by year, was sculpted with a world-class

collection of uses and attractions: the National Aquarium, the Power Plant,

the Gallery, the Hyatt Regency Hotel, the Maryland Science Center, Harbor

Court apartments and hotel, Rash Field, Harbor Place, the USS Constellation,

Scarlet Place, McKeldin Square and Meyerhoff Fountain, and the brand new

Baltimore Visitors Center.

In its rst year, Harborplace (1981) drew more tourists than Disneyland. The

Inner Harbor has become an intricate, exciting people-place that changes all

the time. It is a playground, a front yard, and a main street for the entire City.

It is a place for the City to look at itself and a place for Baltimore to show off

some of its wonders to the outside world.

Perhaps, the Inner Harbor is Baltimore’s most important invention since the

railroad. Elected ofcials, economic developers, and city planners arrive

monthly from all over the world to see and learn from this magical place. It

was invention by meticulous deliberation. The Inner Harbor was put together

brick by brick, building by building, and block by block. The Inner Harbor’s

success can be attributed, in part, to the following features: well-developed

architectural and urban design guidelines; major new attractions every ve

years; attractions for all ages and groups; high quality building materials;

easy access to the water; uniformed policemen and other measures that cre-

ate a feeling of safety; quality events; gardens and owers; and high quality

maintenance.

1999 to the Present: BalMORE THAN EVER

From 1999 to the present, dramatic progress has been made in creating a

safer, cleaner city; a better place for children; and a more attractive place

View of the Inner Harbor today.

46 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 47

46 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 47

for investment. Nevertheless, stubborn urban ills still plague Baltimore.

During the past six years, the City has addressed these challenges in new

and innovative ways.

In 1999, Baltimore was the most violent city in America. Now Baltimore

leads big cities in reducing violence through a three-pronged approach:

more and better drug treatment, youth intervention, and more effective po-

licing. Overall, violent crime is down 40% - to its lowest level since the

1960s.

Baltimore has also been plagued with diseases that fester in poor urban en-

vironments. Throughout the 1990s the City was the most drug addicted city

in America – a fact that dened Baltimore for the rest of America. Today,

we have doubled the number of people able to receive drug treatment from

11,000 to 25,000. Health ofcials now point to Baltimore as having the best

drug treatment system in the nation. In addition, Baltimore was infamous

for the high numbers of deaths caused by sexually transmitted diseases,

tuberculosis, AIDS and lead poisoning. Baltimore has reduced these deaths

dramatically. For example, the City has reduced the number of children

with serious lead poisoning by 45% in just three years. In 2003, the City

achieved the lowest infant mortality rate in its history.

For many years Baltimore public schools have been underperforming and

providing second-rate education. The trend is changing, however, and for

the last ve years, the City has seen real improvement in its educational

system. Our rst and second graders are scoring above the national average

in reading and math for the rst time in 30 years. All grades are improving

faster than the state average on the Maryland School Assessments, and Bal-

timore ranks ahead of cities like New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia

and Los Angeles on state assessment tests. In addition, three of our high

schools are ranked among the State’s top ten, and each year more students

are graduating from our high schools.

Baltimore’s astonishing progress in the last six years is the result of deliber-

ate and comprehensive changes in the City’s bureaucracy. Through the Ci-

tiStat program, Baltimore is moving from a traditional spoils-based system

of local government to a new results-based system of government. CitiStat

is an accountability tool that tracks the activities of City agencies. CitiStat

has won Harvard’s Innovation in Government Award, and Neal Pierce, a

columnist on urban affairs, said that CitiStat “may represent the most sig-

nicant local government innovation of this decade.”

In addition, the City established the 311 system to allow residents to report

non-emergency problems in the city. Residents can now report problems

and track responses to complaints, such as potholes, housing code viola-

tions, and broken lights. For its 311 system, Baltimore is the rst govern-

ment entity to win the Gartner Award for customer relationship manage-

ment.

Cities that are diverse, cities that nurture creativity, cities that are culturally

alive and preserve their history are cities that thrive– because they create a

better quality of life; they create new businesses; they create living neigh-

borhoods; they retain and attract members of a growing creative class.

46 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 47

46 City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan The History of Baltimore 47

INTRODUCTION SUMMARY HISTORY KEY TRENDS LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN IMPLEMENTATION MANAGEMENT FINANCIAL CONCLUSION GLOSSARY APPENDICES

Baltimore is simmering with creativity and entrepreneurs, musicians, artists,

architects, engineers, researchers, and scientists are already moving our lo-

cal economy forward. World-renowned medical research institutions, most

notably Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland, are potent engines

for the future of Baltimore’s economy. Both of the City’s arts districts are

gaining momentum. This year, Entrepreneur Magazine reported that Balti-

more moved from 30th to12th on their list of best cities for entrepreneurs,

and we’re number two in the East.

Qualities embedded in the urban fabric are attracting new residents to Bal-

timore: pedestrian-friendly environments promote less driving; historic

architecture and streetscapes provide tangible connections to the past; res-

taurants, coffee shops, and pubs just a walk away offer social places where

basic human connections are made; and cultural institutions produce char-

acter-dening activities that are enjoyed by all.

Baltimore has been scorched by devastating res, real and gurative, but

from these ashes, Baltimore, once again, is rising. The City’s spirit thrives

on beating the odds and achieving what others thought was unachievable.

Baltimoreans have learned from our past, a past whose buildings, monu-

ments, and diverse cultures still stands strong.

Making bold decisions in times of extraordinary change leads to reinven-

tion. Thus, this is probably Baltimore’s latest reinvention: today’s willing-

ness to change City Government and to tackle the chronic results of pov-

erty. Baltimore’s history also tells us something more: cities never cease to

change, and unknown reinventions will be part of providing our children’s

children with a place to live, earn, play and learn in Baltimore.

View of downtown Balmore and the Inner Harbor at dusk.