European Economic and Social Committee

Civil dialogue and

participatory democracy

in the practice of the

European Union institutions

STUDY

1

Civil Dialogue and Participatory Democracy in the

Practice of the European Union Institutions

This study aims to design a mapping of the existing structures of civil dialogue(s) and to analyse the

situation in order to identify what exists, thereby underlining the patterns and recurring elements. It

intends to fill the present gap in knowledge in the very EU institutions which lack a coherent and

comprehensive view of what has so far been put in place.

This study was carried out by

Johannes W. Pichler

in cooperation with Stephan Hinghofer-Szalkay and Paul Pichler

following a call for tenders launched by the European Economic and Social Committee. The infor-

mation and views set out in this study are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the offi-

cial opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee. The European Economic and Social

Committee does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the European

Economic and Social Committee nor any person acting on the European Economic and Social Com-

mittee’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the contents therein.

2

Abstract

The European Union is at its core a model of transnational governance based inter alia on democracy

and the rule of law. There are two key findings of our survey: On one hand, that civil dialogue is

based on the primary or constitutional law of this Union and addresses the specific challenges of

transnational democracy. On the other hand, that implementation remains a challenge.

Our survey and mapping of its results, legal basis and other relevant data clearly show that the status

quo can still stand considerable improvement, as was stated repeatedly by the EESC. Nonetheless, in

the area of “vertical dialogue” we were able to ascertain significant silver linings: most notably the

openness of DG Agri (ahead of other DGs) and its approach of careful be-legalization of the dia-

logue’s framework. Nonetheless, we find ourselves in agreement with the Ombudsman’s call for a

rigid conflict of interest policy, reviewing and monitoring scheme.

Based on our findings, we present a roadmap towards a single open online tool in order to save mon-

ey, gain broad compliance and ultimately address the ongoing challenge of implementing the re-

quirements of Art 11 paragraph 1 and 2 TEU.

3

Summary

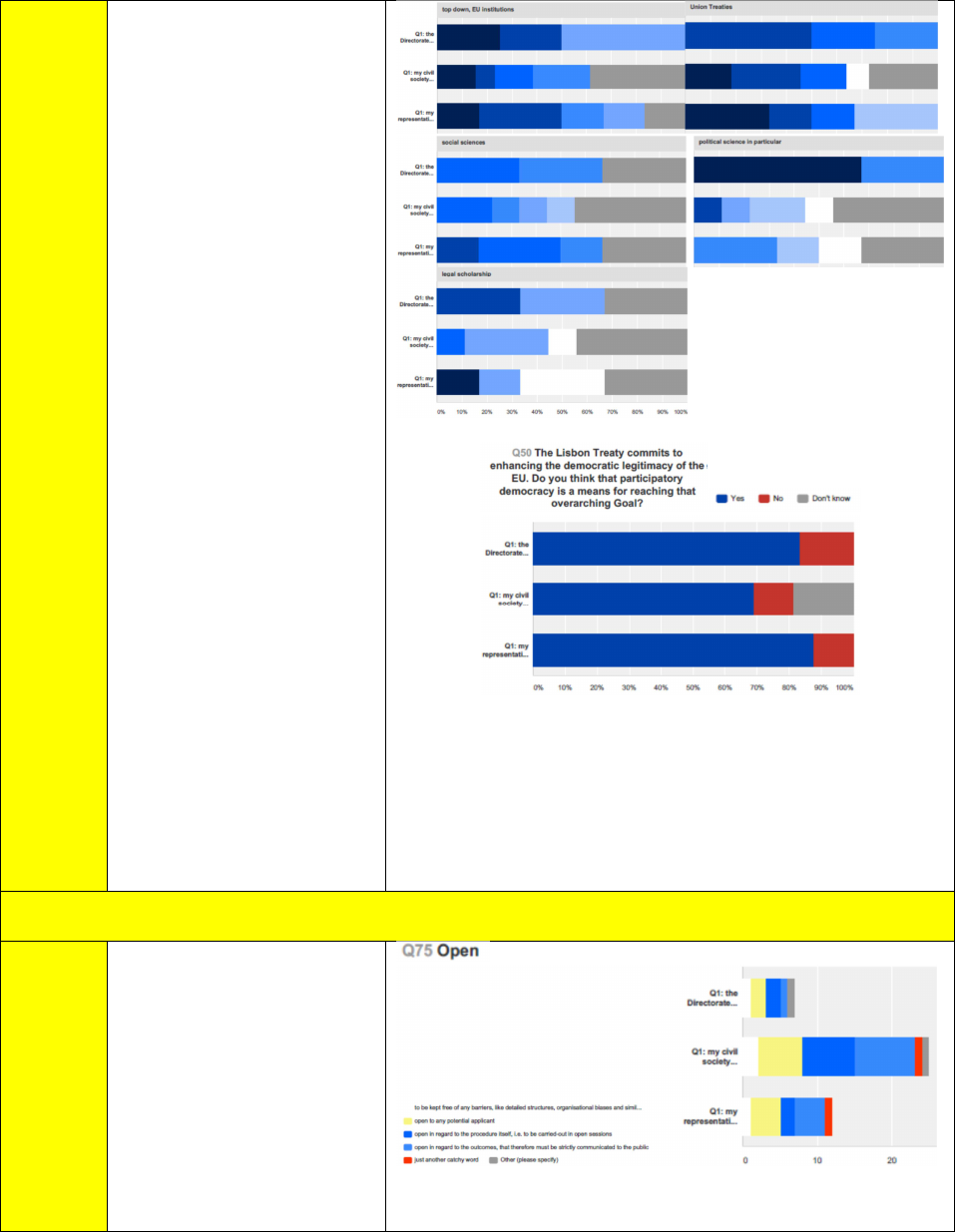

DG Agri in particular has demonstrated that civil dialogue can be a reality. Their openness was re-

flected by their reaction to this survey, for which we are thankful. Fully aware that every DG faces

unique challenges, we still believe this DG can be seen as a role model to emulate. Based on our own

findings in our survey, that cover experiences of CSO´s and RA´s throughout most of the DG´s, we

can gladly report, that we face a fairly positive calculus of those who are actively involved in the ver-

tical civil dialogue under Article 11(2) TEU. This is our prime finding: Civil dialogue has a long way

to go, but considerable progress has been made in key areas. We continue immediately with conclu-

sion based recommendations on how to carry out this enrichment.

1. Our Concept - True Constitutionalism

According to the core criterion of our main task, mapping "what exists" (done quite literally in the

Annex), we have made a commitment on the premise to proceed along certain lines, primarily the Un-

ion Treaties. Only then did we utilize other sources - secondary law and opinions, f. ex. such ones of

the EESC, our own field-survey, qualified statements, literature and scholarship´s expertise, and final-

ly backstage-"rumour" and other findings - as relevant, but of significantly less importance than the

normative prerogatives. We proceeded with the awareness a legal positivist approach can provide,

with a strong sense for the special role of the Unions "holy shrines" and the Lisbon Treaty´s spirit to

constitutionalize Participatory Democracy in favour of "increasing ... the legitimacy of the Union".

This explains our parameters and centres of focus. Unfortunately, our contractual obligations did not

allow us to await the EU Commission’s official reaction to the EU Ombudsman´s ambitious own-

initiative suggestions for the Commission´s further positioning concerning a reform of the civil dia-

logue. We have little doubt though, that this has the potential to truly leverage new and supposedly

long-term foundations for dealing with the civil dialogue.

2. Our Chief Concern - A Gap between the Treaties’ Orders and the Factual Implementation

We respect that there may be good reasons for a certain delay in installing an institution-wide cover-

ing vertical civil dialogue throughout almost all of the institutions (except for the EU Court(s), the Eu-

ropean Council, the ECB ... ), as is ordered under Article 11 (2) Union Treaty and under Article 15 (1)

TFEU, because there is indeed wide leeway for best implementation, because the scholarly expertise

is hardly homogenous, not to say contradictory, and because there are organisational obstacles, hin-

drances and hurdles. But we recommend not be complacent with the state as it is now - and we sub-

stantiate this vague proposal by very concrete and very far reaching recommendations. We believe

4

this to be the logical consequence of bringing the European citizens closer to Europe (as was the in-

augural call of President Juncker) and of constitutional loyalty.

We cannot find any legitimate reason for ignoring the clear order articulated in Article 11(1) Union

Treaty, that the institutions shall, by appropriate means, give citizens (...) the opportunity to make

publicly known and exchange their views ... We did not accept the vindication that lots of general

communication efforts were done as a surrogate implementation of this order, because 11(1) refers

without any doubt to participatory democracy and this has its very own Lisbon concept that does not

match with a concept of blunt information and communication. So we recommend to urgently close

this gap, even aligning with the message on legitimacy contained in President Juncker´s call for

bringing the European citizens closer to Europe.

3. Our Empirical Findings on "What Exists" - Hopeful Voices, Some Mutual Annoyance

Unfortunately some of the institutions and in particular some of the DG´s refused to engage with this

study.. In this, we do not shy away from self-criticism. Scholarly curiosity may have driven us to be

too forward in light of initial silence, a rashness for which we have presented our excuses. Yet the

main reason for the obstacles faced when trying to establish a closer working relationship with the

DGs may have been a pending investigation of the EU Ombudsman going on simultaneously to our

survey. It appears that at least some of the DGs were not entitled to interfere with the pendening offi-

cial response. However, this reluctance has frustrated the offered chance to self-portrait the DG´s true

efforts and achievements. That makes our study somewhat vulnerable to criticism, though the empiri-

cal data gathered stands on its own. On the other hand, the CSOs and RAs demonstrated an encourag-

ing degree of collaboration so that we received a finely nuanced impression, which for that matter was

completed by significant and serious statements of DG officers as individuals, presumably coming

predominantly from the dialogue frontier DG´s Agri and Trade, which we cannot precisely know due

to the strict anonymity of our survey.

The length of our survey also apparently kept some potential contributors from participating. We

nonetheless felt this to be necessary as to escape an overly superficial account. We needed to include

subtle questions in order to get a chance of reading in-between the lines and to cross-relate and dou-

ble-check the validity of responses when putting them into cross-referring light. We have decided in

favour of quality instead of just quantity. Preliminarily imposed open questions have been an extra-

source of fully associatively given hopes and criticisms, which we brought into "speaking out" when

cross-referencing them with the closed questions.

5

Further, we balance that all sources, except for the legal ones, are rather opaque, pluripotent, multi-

evaluable and finally, that the responses of our survey can be biased by professional style and social

desirability. Our recommendations reflect this by reflecting on but not simply applying the survey´s

data. For a condensed picture of the survey’s findings, we invite the reader to browse through the

special part and the "cartography mapping" in the Annex. Thus we come immediately to our conclu-

sions and recommendations.

4. Give Participatory Democracy a Real Chance

This recommendations are addressed to all the institutions. On the background of our proclaimed

premises and the overall evaluation of our findings, we felt obliged to address a dense modus operan-

di, but we are convinced that without an overarching holistic concept any reform must further on re-

produce shortfalls and fail the legitimacy leverage purpose as is the desideration of the Lisbon Treaty.

i. Sensitise for the New Mind-setting by the Treaties

We sense that the practices are still based on an outmoded pre-Lisbon mind-set. We recommend rear-

ranging the dialogue(s) along the philosophy of Committee of Regions´s Multi Level Governance

(MLG) Charter, as are in short: togetherness, partnership, awareness of interdependence, multi-

actorship (...) transparency, sharing best practices (...), open and inclusive policy-making process,

promoting participation and partnership involving relevant public and private stakeholders (...), in-

cluding through appropriate digital tools (...). Employing collaborative democracy and thus Euro-

peanwide multiplication diversifies the dialogue away from Brussels. Civil dialogue issues are a civic

task and the citizens are in their 500 million "out there" and are rather Brussels averse, face it and take

it as a motive to keenly reach-out to them.

We balance the dialogue(s) "unfinished" character and great legitimising potential, which unfortunate-

ly has not yet been brought to its full potential.

ii. Accept the Constitutional Obligation and Take the Responsibility Pro-actively

Respect the spirit of the Treaties and the mission statement of the EU Commission´s President,

corroborate the dialogue culture and do it pro-actively. Copy the ambitious way of DG Agri and

use this as a role model.

6

Bring across the overdue horizontal civil dialogue. This one has even more legitimacy potential than

any other of the participatory instruments under Article 11. Welcome the EESC´s efforts to initiate

this process.

iii. Experiment, Endeavour in Order to Bring Participatory Democracy to its Full Legitimising Poten-

tial

This requires a redirection of the focus from practical considerations to legitimacy leverage desidera-

tion. DG Trade, the second best role model, should become encouraged to keep on going with its crit-

icized way and not to follow suggestions to become more earthed.

In case this "holy legitimacy goal" would not become consented, it could be rethought to put partici-

patory democracy on the delete list for a next convention.

iv. Complete the Fragmentary Composition by Wide Opening of the Eligibility - Even to Single Citi-

zens - And Let a Broader Partnership Principle Break Through

A shift of paradigms towards rigid openness and enhanced transparency, ideally self-controlled by the

dialogue stakeholders themselves, is the prerequisite of any improvement. Consider a two-chamber

model to get the diverse interests into a clearer competition, end-up any "closed shop" possibility and

prevent establishing a new "political" oligarchy. Make societal "seismographs" welcome dialogue

partners.

v. Resolve the Confusion on the Nature of Dialogue - Consultation, Expertise, Communication

Make the dialogue a real dialogue, interactive, of two-way nature, empower it to political bargaining

and protect it against out-watering by intermingling diverse categories, which downgrades the dia-

logue´s constitutional dignity.

vi. Design a Serious Conflict of Interest Policy

Any interest, in the dialogue is acceptable if it is honest and disclosed in full transparency. But rules

should be provided - as has the ombudsman rightly stressed - to detect any conflicts of interest. Oblige

to self-uncover interests and make them competing, also by the suggested two-chamber model; on a

competitive "market" the competitors themselves will be the best regulators.

vii. Clarify the Nature of a Core Dialogue Regime to be developed

7

The Commission´s Communication "Towards a reinforced culture of consultation" of 2002 denies

expressively an over-legalistic approach and favours "culture". We share the underlying assumption

that governance, as we have promoted afore, with its wider inclusion of political actors is a model that

can potentially leverage better and more consensual policy-making than the traditional government

model. Neither should courts substitute political processes. This position is widely backed by the re-

sponses of our survey. Nevertheless, it seems to be indicated under the rule of law principle to make

procedures predictable and resilient, which is apparently the background of the Ombudsman´s legiti-

mate suggestion. Despite the aforementioned leeway for designing the appropriate way of implemen-

tation - whether by hard law or soft law or ethic code or similar – we are in doubt whether a legal re-

gime could really be opted-out in the long run. Article 41 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the

European Union (FRC) indicates that remedial claims cannot be suppressed. We recommend to carry-

out a particular legal analyses on what the bandwidth of a possible legal framework could be. Howev-

er, whichever regime is opted for, it should contain binding standards on admissibility, eligibility and

a selection regime stating who and why is entitled to be dialogue partner, this even despite our rec-

ommendation to open the dialogue to the widest possible range of participants.

viii. Install a Reviewing and Monitoring Scheme

We recommend therefore that this task is best carriedout in cooperation with and as far as possible

along self-evaluation and this should be done on the publicly accessible eTool.

ix. Strengthen the Role of the Dialogue - Turn Partners into Supporters and Public Multipliers

Allow in turn for the admission to partnership your partners to become intermediaries. Use their quali-

fied knowledge for translating and interpreting the DG´s political necessities to the public. And make

them representatives of the public, but make sure that they are really mandated and - as intermediaries

are supposed to do by nature - assure that they are not acting on their own segmentary interest.

x. Install an Online "Eleven-Two-Tool" - Save Time and Money and Gain Broad Compliance

Firstly, without delving too deeply into technical and organisational details, we would like to recall

the benefits of such a tool: Enabling a European wide participation of dialogue partners on the MS

levels and sublevels horizontally as well as vertically. Literally every willing party could make up its

mind on any proposed dialogue issues.

Secondly, and in line with the Ombudsman desideration, such a tool could serve for a more perfect

8

openness. If and when any participant is obliged by rules and "motivated" by social stimulus and un-

der silent group wise internal "supervision" to make herself or himself vitreous, this would be a next

step towards a more perfect transparency.

Thirdly, such a tool could enable a more permanent process which surpasses even the criterion of reg-

ularity and makes any definition by law or courts obsolete, as to what "regular" could imply.

Fourthly, the DGs can require that any proposal should be addressed to the DG preliminarily filtered

by internal co-creation and co-decision making until rather clear positions crystallise. This would en-

able the DG to see which reasoning and majorities support a proposal – in other words, to whom it is

relevant and why.

Fifthly, such a collaborative or cooperative democracy tool discharges the DG´s to be at stake during

the elementary political will-building phase and the finalisation process can therefore be kept fairly

short. Once, when the dialogue partners are trained to deal with e-collaborative democracy, the face-

to-face meetings can be reduced to a short finalisation procedure. This would impact a significant cost

saving effect.

________

If and when the "unfinished" dialogue(s) are fully realized, we predict a great future and we forecast a

significant legitimacy leverage function. We ascertain that the assumptions of the Lisbon Treaty were

right.

Taken all our recommendations together we are convinced that these could comply with the President

of the EU Commission´s inaugural call: ... bringing the European citizens closer to Europe.

9

.

Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................ 2

Summary .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3

I. Fundamentals and Considerations ..................................................................................................................... 12

I. 1 Objectives and Grounds for the Study ........................................................................................................... 12

1. Mandate Description and Scope .................................................................................................................... 31

i. The Mandate - Ascertaining the Status Quo .......................................................................................... 31

ii. The Limits in Law and Democratic Potential ....................................................................................... 32

iii. Introductory Explanations on "What Exists" ..................................................................................... 33

2. The PreLisbon Roots of the Current Legal Regime ................................................................................ 35

3. The Collateral Environment - the Wider Perspective on Participatory Democracy ................ 37

II. Essentials for the Study and for the Questionnaire ............................................................................... 38

1. Taking into Account the Implementer’s Chemistry and Climate ..................................................... 38

i. The Need for Imagination ............................................................................................................................. 39

ii. Where Best to Start with an Evaluation and a Disclosure? ............................................................ 40

2. The Horizontal Civil Dialogue at First and Final Glance ...................................................................... 40

i. Communication‘s a one-way nature ................................................................................................... 40

ii. The PD Orphan - Lack of Trust in Citizen´s Benevolence .......................................................... 41

iii. The EESC´s "My Europe ... Tomorrow!" Project .............................................................................. 42

3. The Vertical Civil Dialogue - The Constitutional Promise and its Perceived Reality ............... 43

i. The Coffey-Deloitte VCD Screening Model - A Solitaire Benchmark Despite Serious

Misconceptions ..................................................................................................................................................... 44

ii. Setting Democracy Values at Market Price ...................................................................................... 44

iii. Identifying the Wrong Rule Maker ...................................................................................................... 44

iv. Legitimacy - A Business Case? .............................................................................................................. 45

v. Working towards the Ultimate Goal: Democracy ......................................................................... 46

vi. The Dialogue is either Legitimacy leveraging – Or else Superfluous .................................... 47

III. The Questionnaire and the Design of the Questionnaire - Methodology ......................................... 48

1. The Overall Design - Primarily Referring to the Open Questions .................................................... 48

i. Methodological Alignment ..................................................................................................................... 48

ii. Highly Homogenious Desiderations and Considerations .......................................................... 48

iii. Hidden Agenda by Open Questioning - And the Worthwhile Outcomes ............................. 49

iv. Tracing Multiple Considerations ......................................................................................................... 50

v. Tracking a Legitimacy Providing Model ........................................................................................... 50

vi. Disentangling Mazy Commingle ........................................................................................................... 52

vii. Constitutional Awareness .................................................................................................................. 53

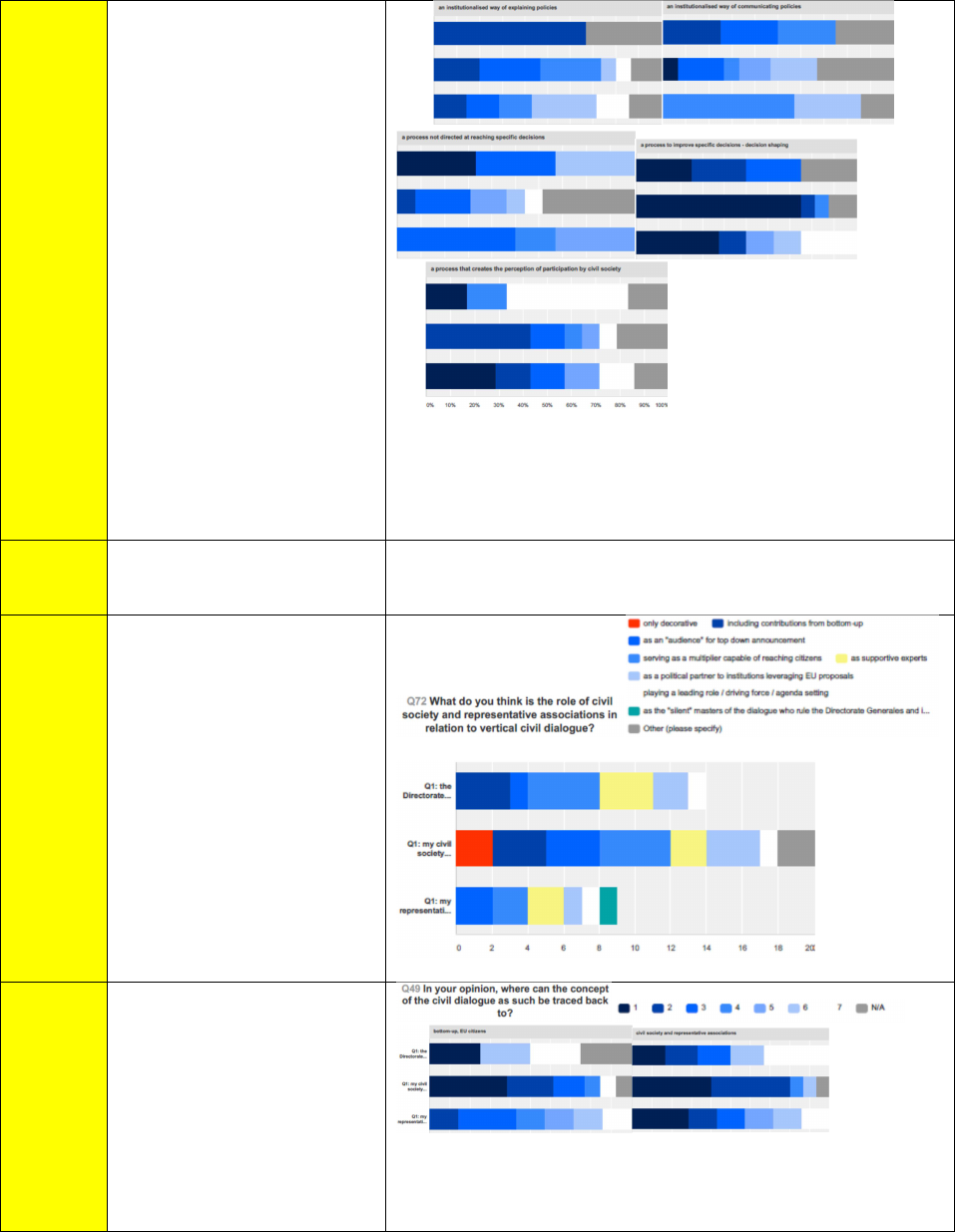

2. The Political Design and its Methodology - Closed Questions ........................................................... 54

i. Adopting a Green Paper Stylus ............................................................................................................. 54

10

ii. Overall Aspects ............................................................................................................................................ 55

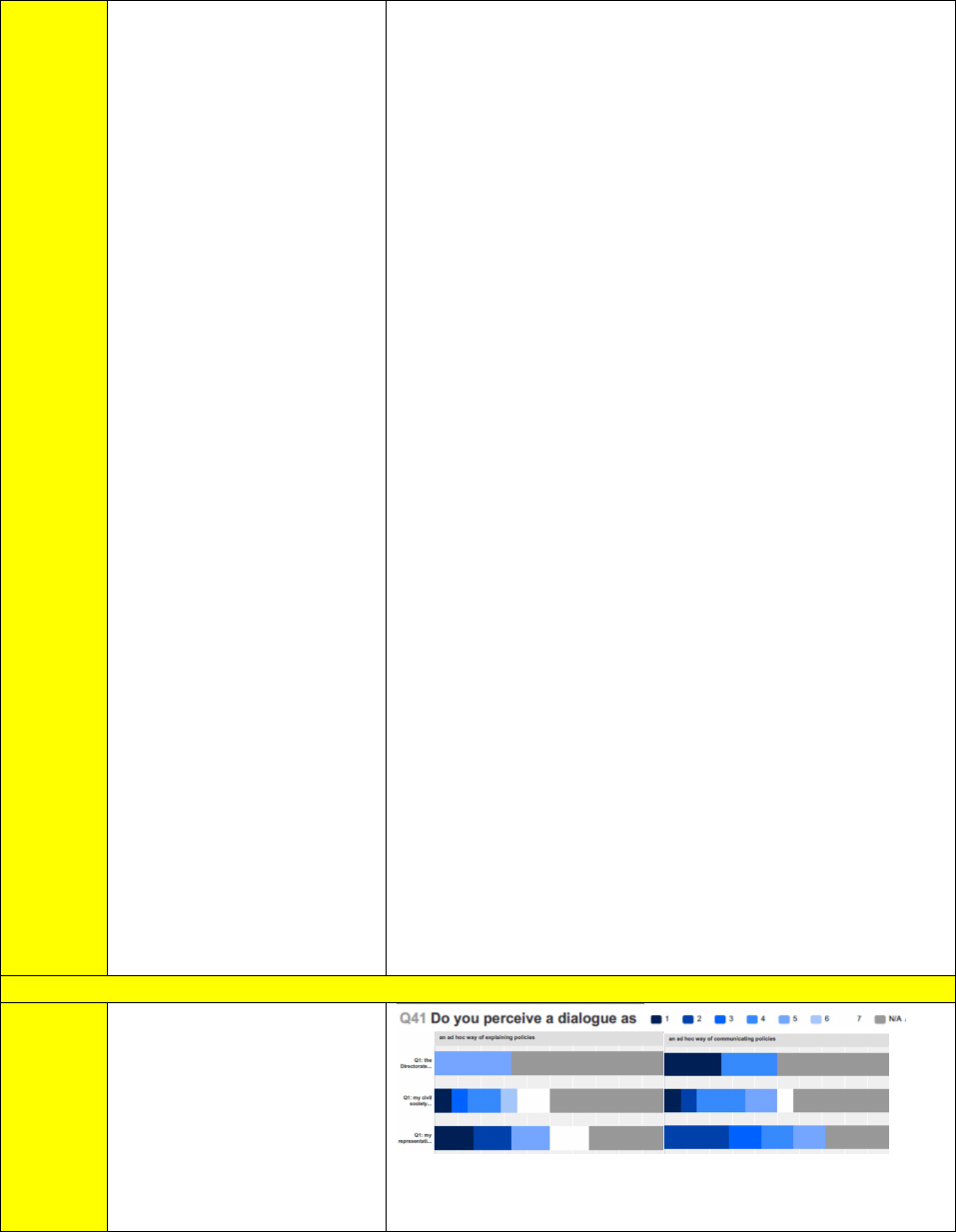

iii. Presumed Benefit as Stimulus for the Use of Dialogue ............................................................... 57

iv. Methodological Implications ................................................................................................................. 58

v. Tracing Perception on Assumed Winners and Losers ................................................................ 58

vi. Dialogue Admittance a One-way Privilege or Source of Associated Duties? ..................... 59

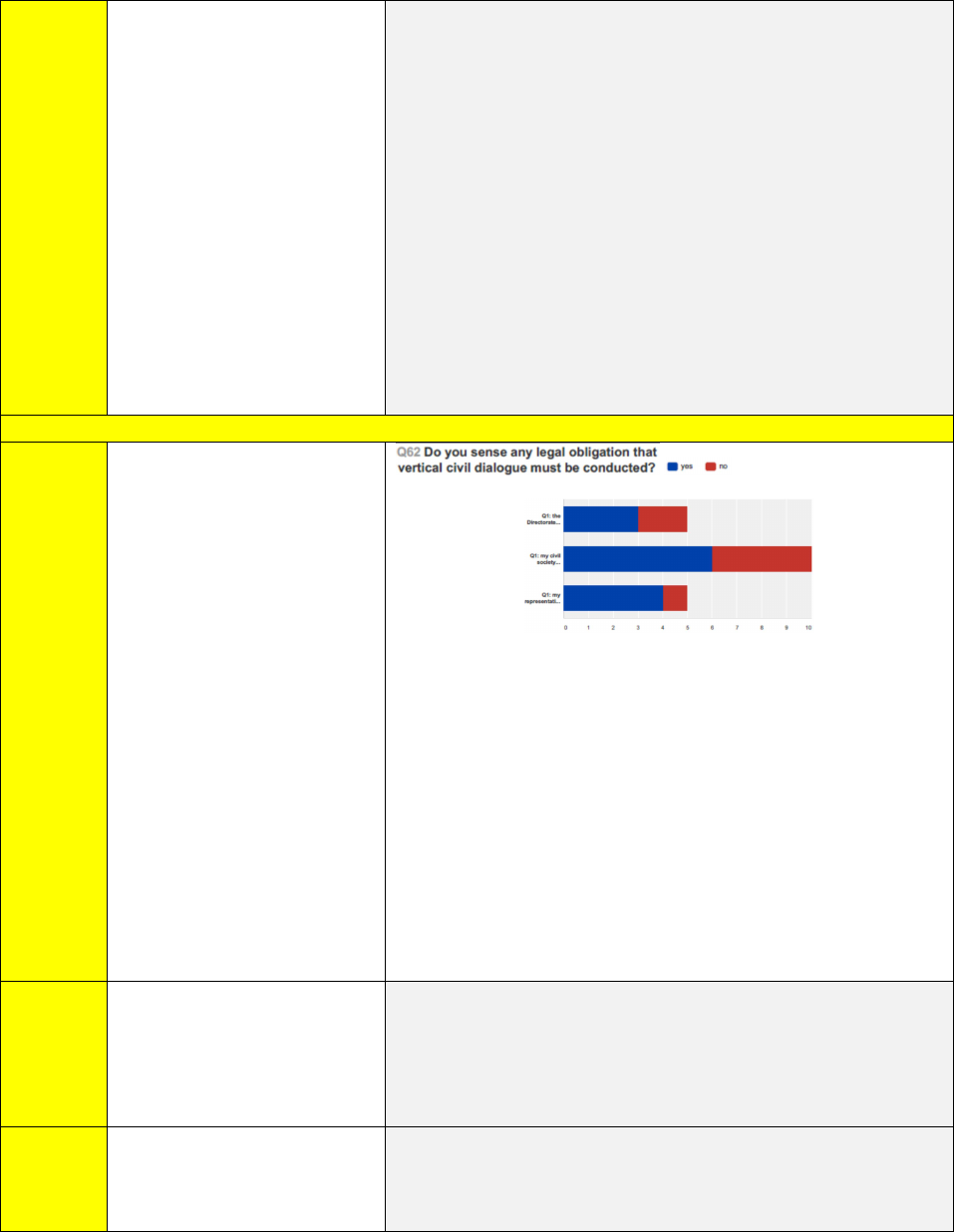

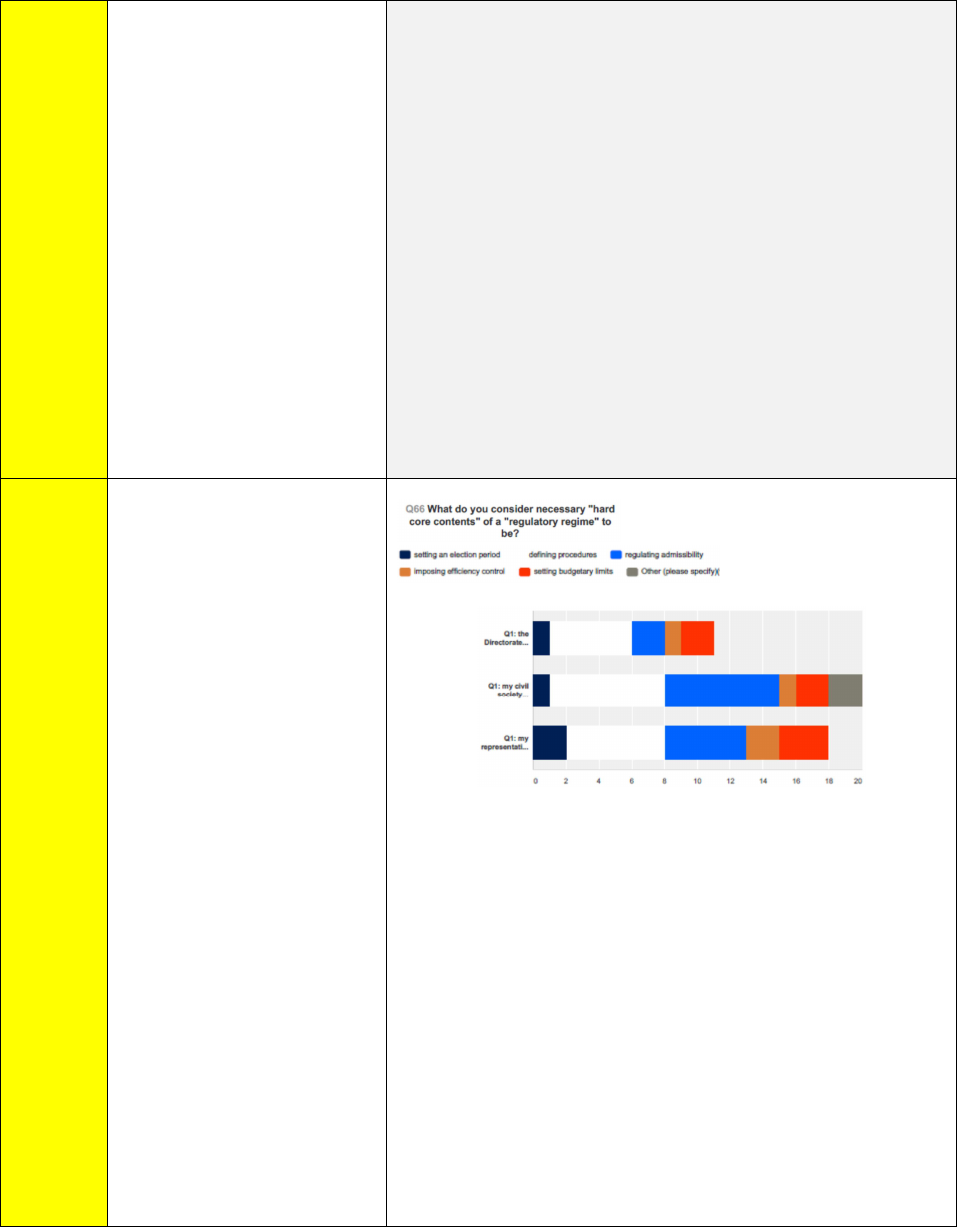

3. The Legal Design of VCD and Methodological Implications - Closed Questions ........................ 59

i. Overall Aspects .................................................................................................................................................. 59

ii. Dialogue a Matter of Law or of Culture? ........................................................................................... 60

iii. Methodological Implications ................................................................................................................. 61

4. The VCD Parameters Concerning the Addressees "Civil Society" and "Representative

Associations" .............................................................................................................................................................. 62

i. Civil Society and Representative Association ................................................................................. 62

ii. Representative Associations AND Civil Society... Pleonasm or Distinction? ..................... 63

iii. Civil Society - Definitial Intricacy and Underlying Suppositions? .......................................... 64

iv. Are Political Parties Civil Society? ....................................................................................................... 65

v. One Body or Two? ...................................................................................................................................... 66

vi. Single Citizens Eligible? ........................................................................................................................... 66

vii. Representative ........................................................................................................................................ 68

viii. Representativity as an Admissibility Criterion ......................................................................... 68

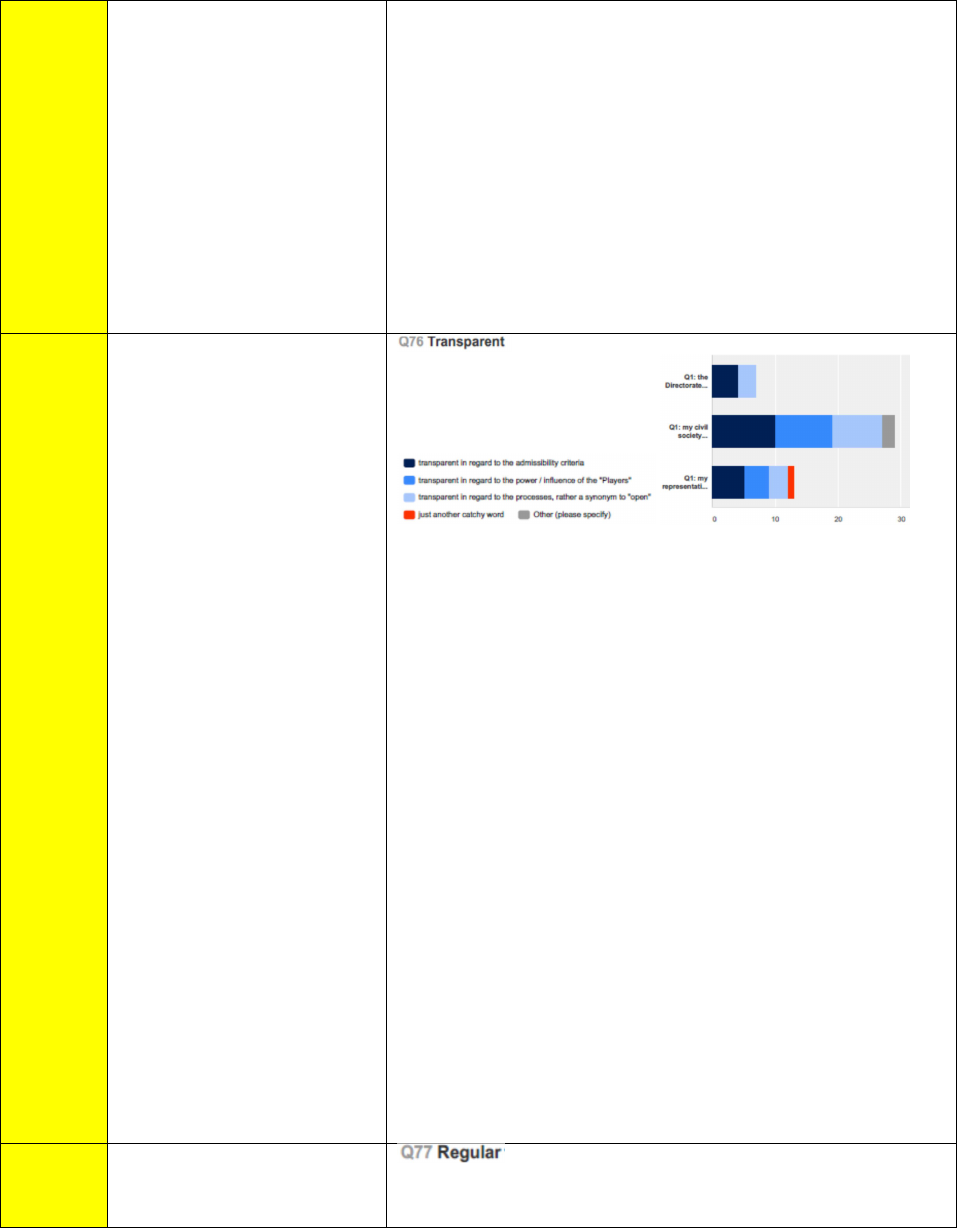

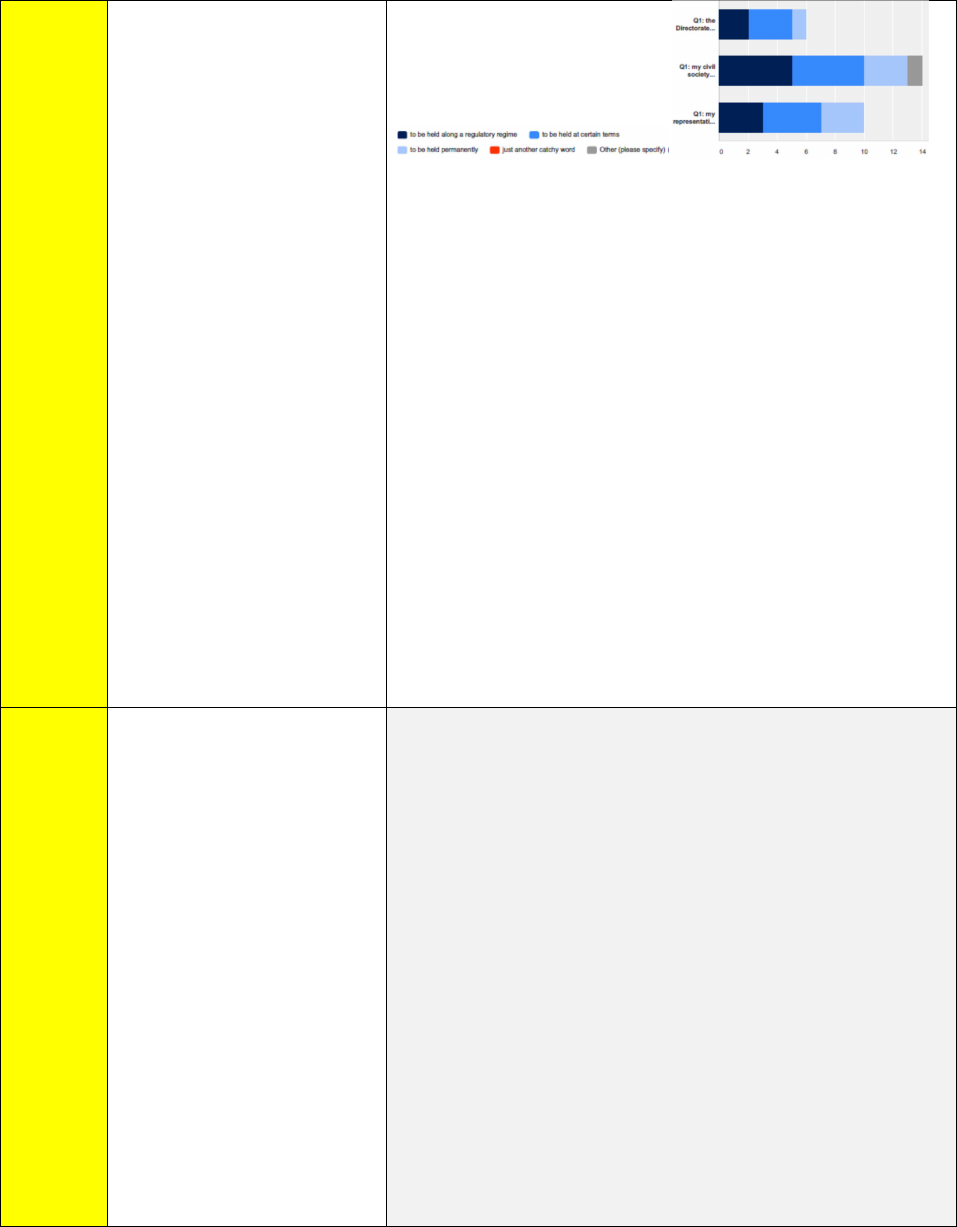

5. The VCD Criteria "Open, Transparent and Regular" ............................................................................. 69

i. An Empty Canonical Trinity? ................................................................................................................. 70

6. Factual Challenges to the VCD - Procedural Aspects, Effectiveness and Relevance ................. 70

i. Procedural Aspects .................................................................................................................................... 70

ii. Dialogue - Intrinsic Value or merely a Tool? ................................................................................... 71

iii. Open to Whom and Why? ....................................................................................................................... 72

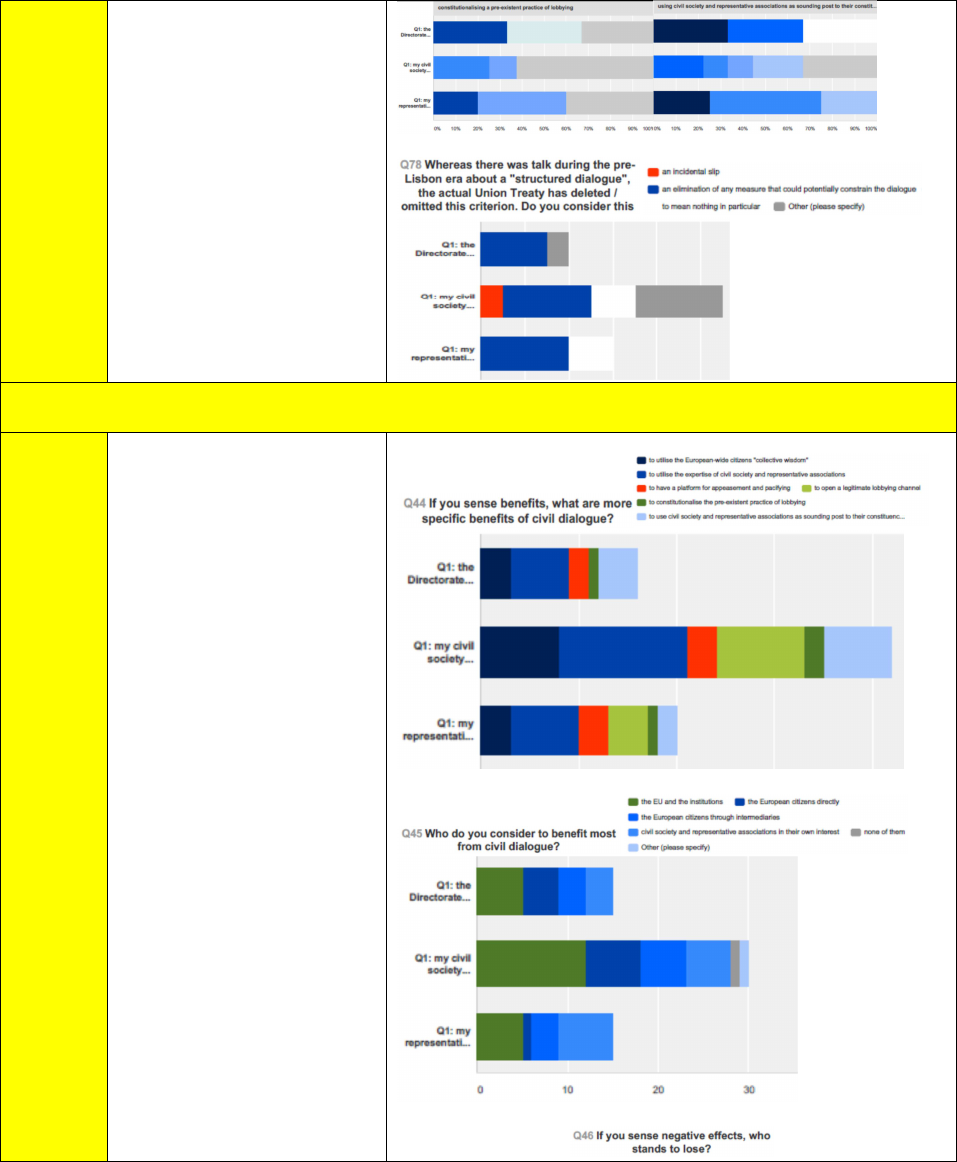

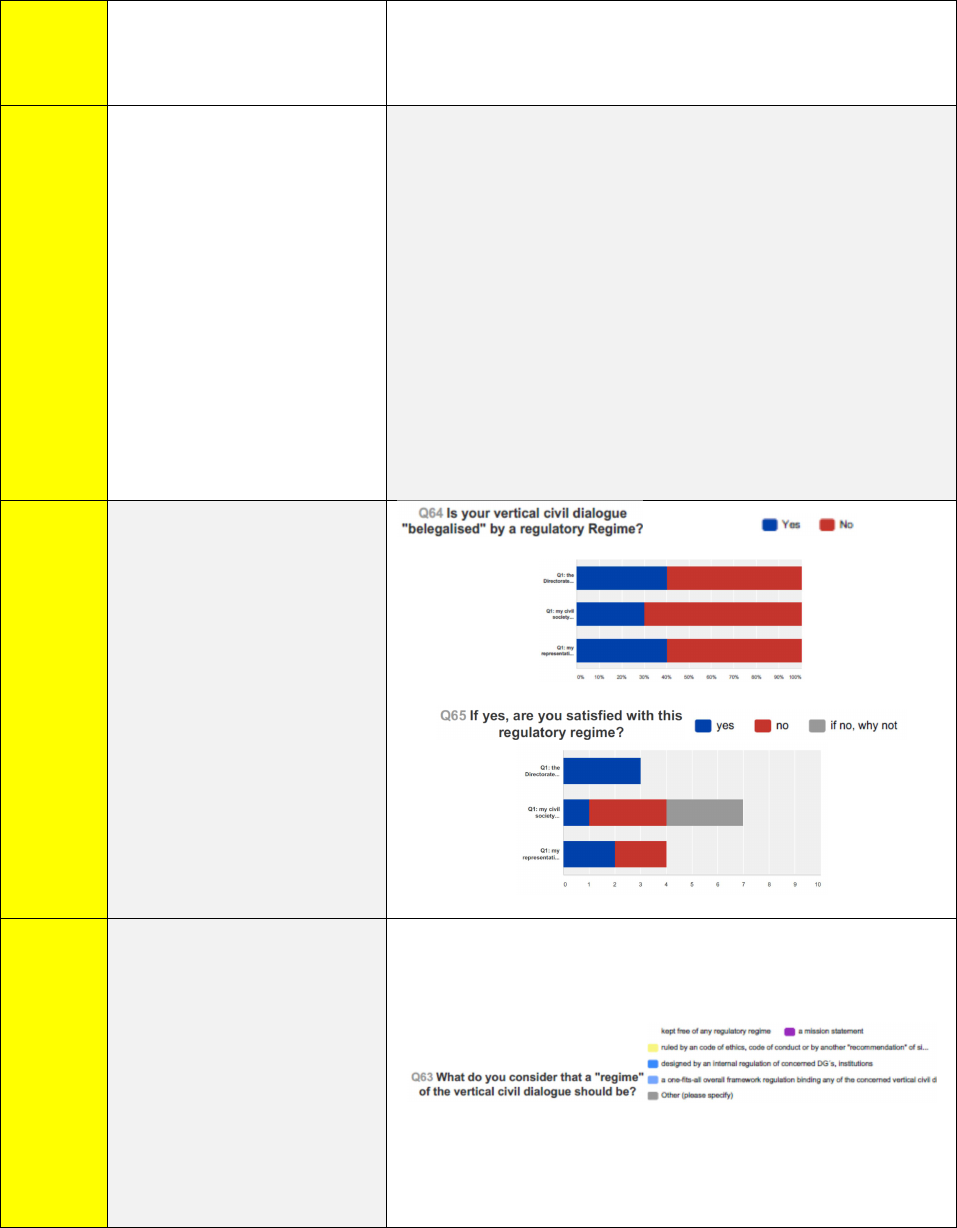

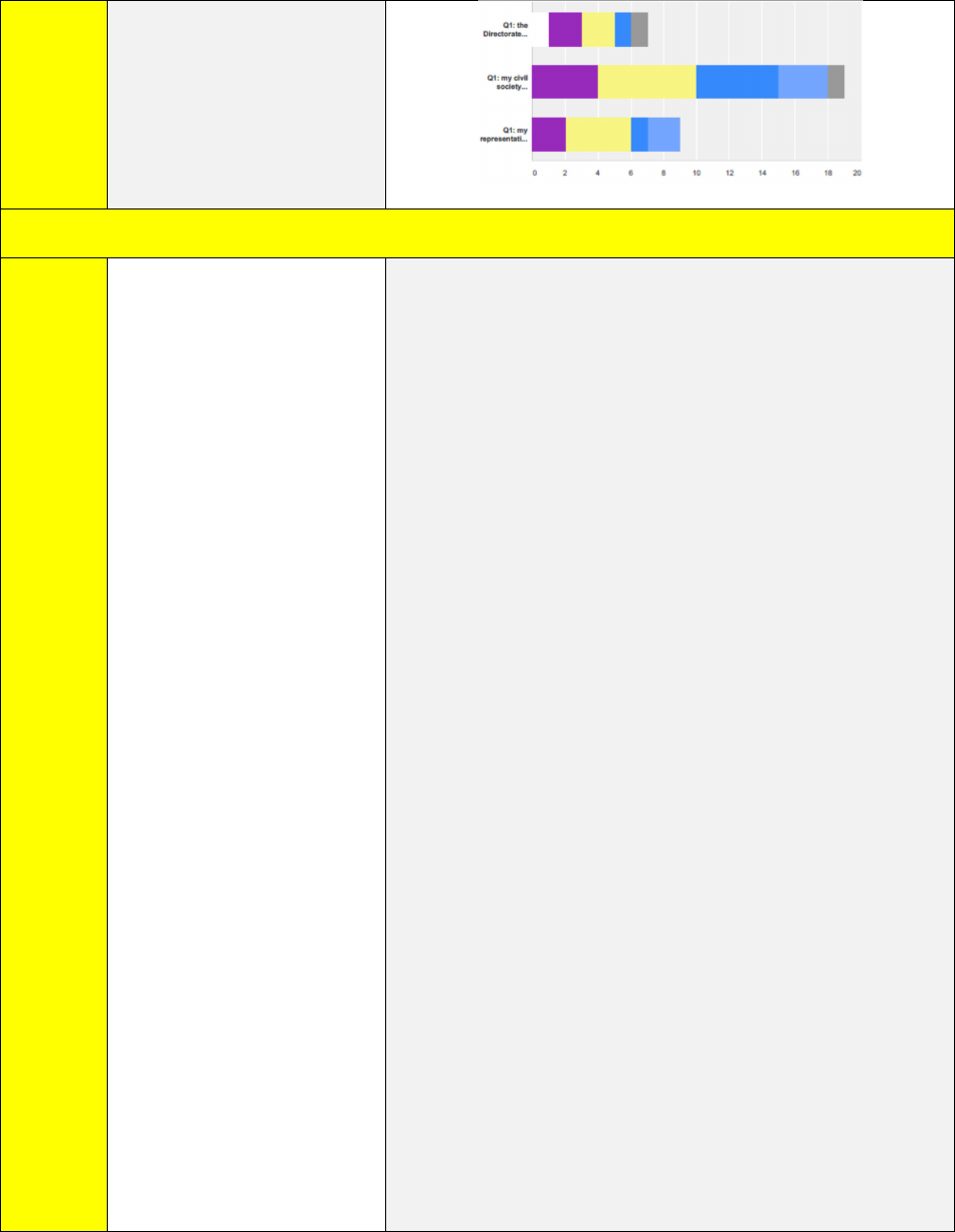

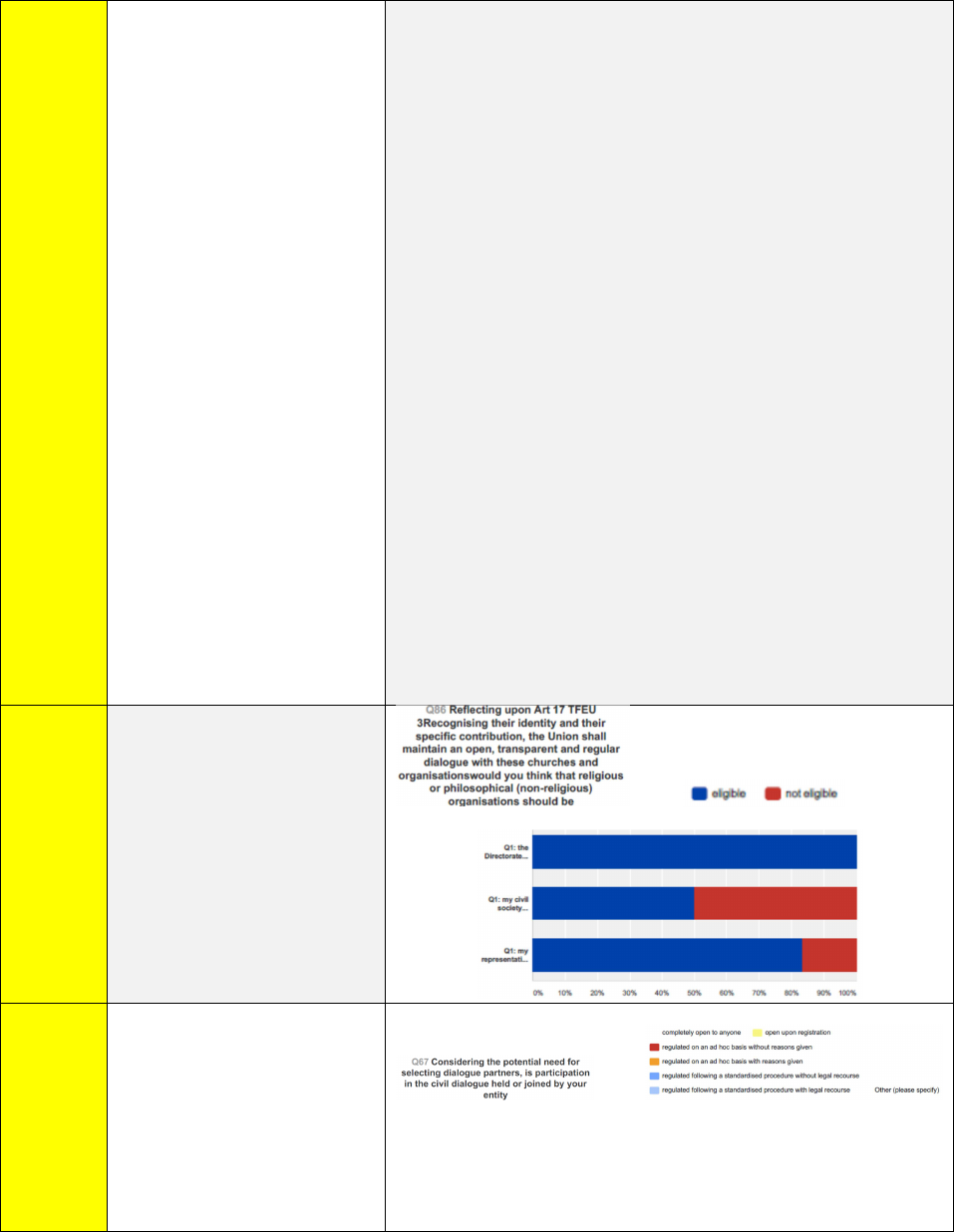

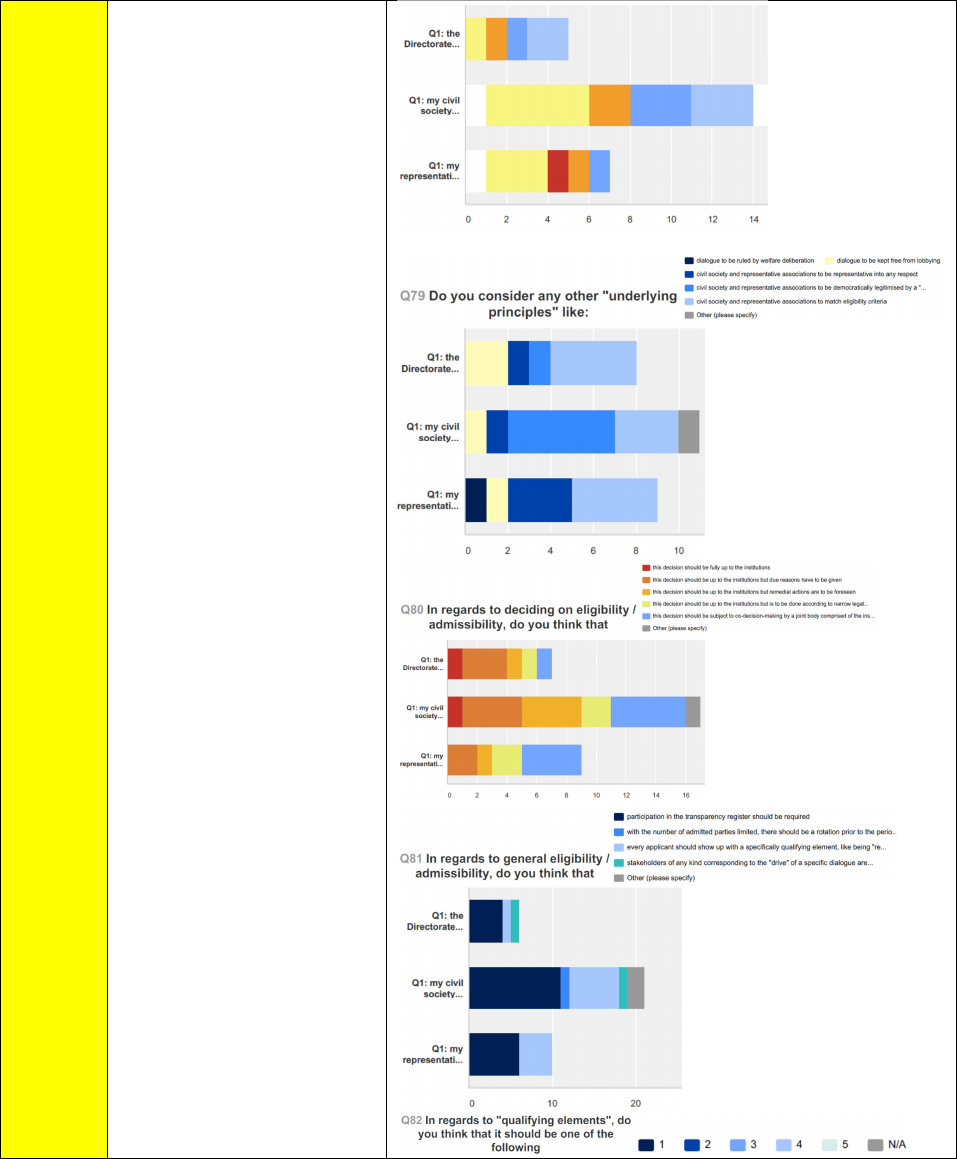

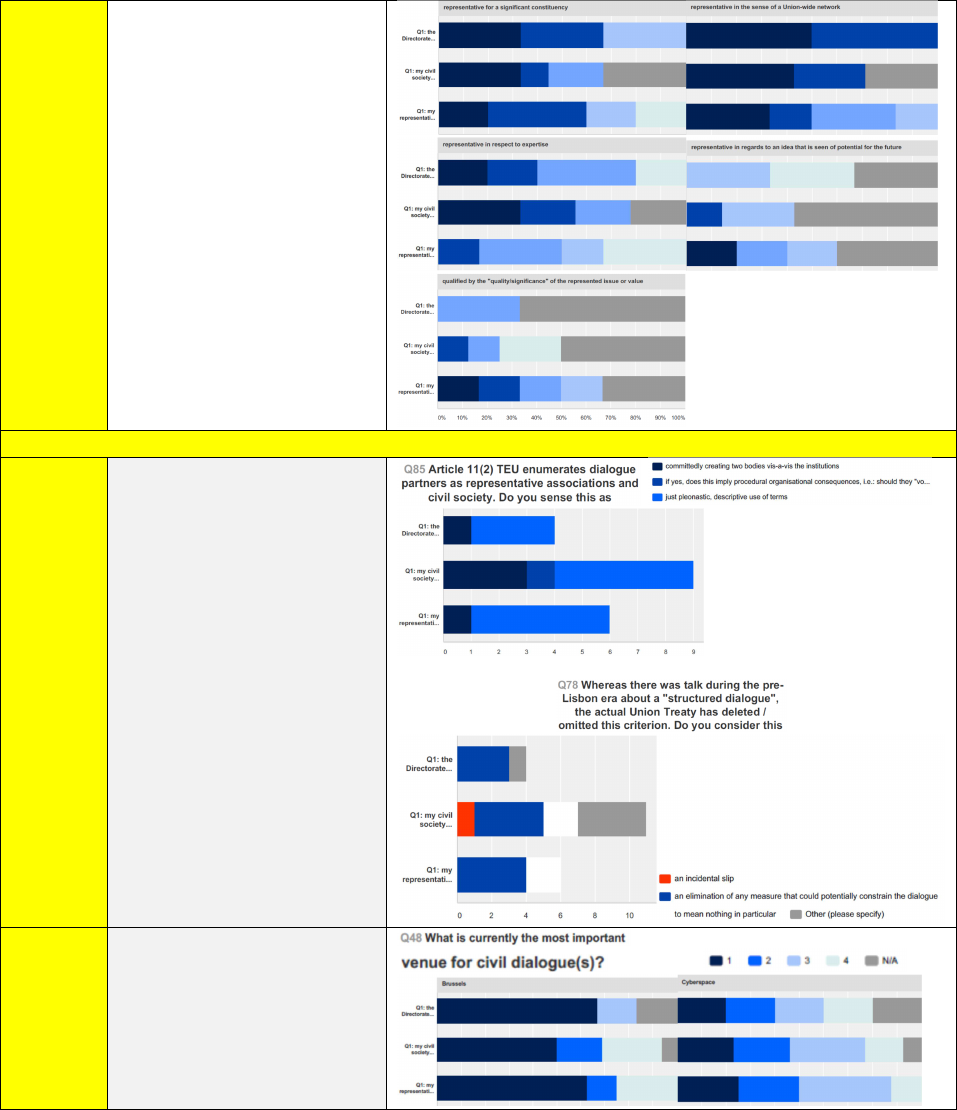

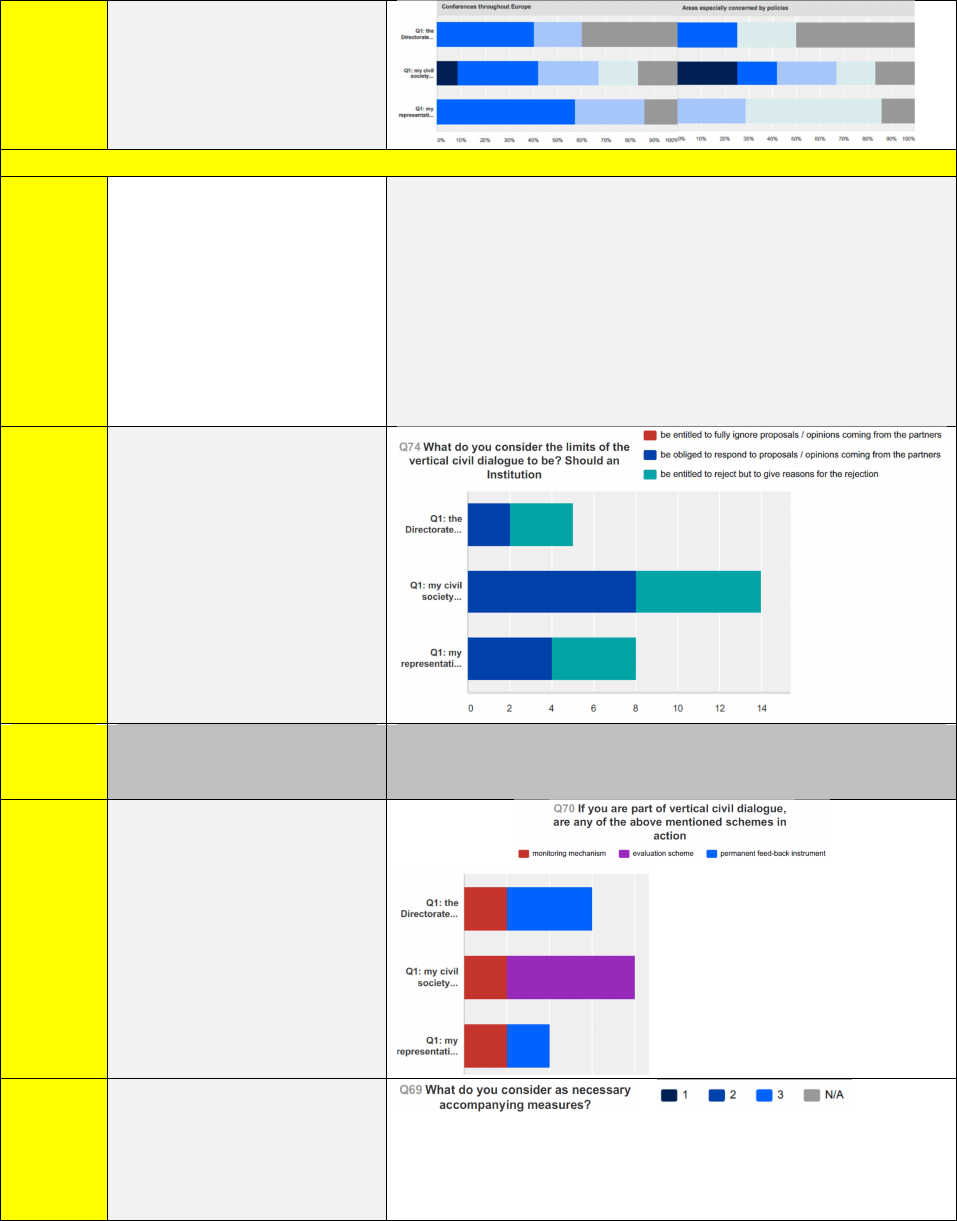

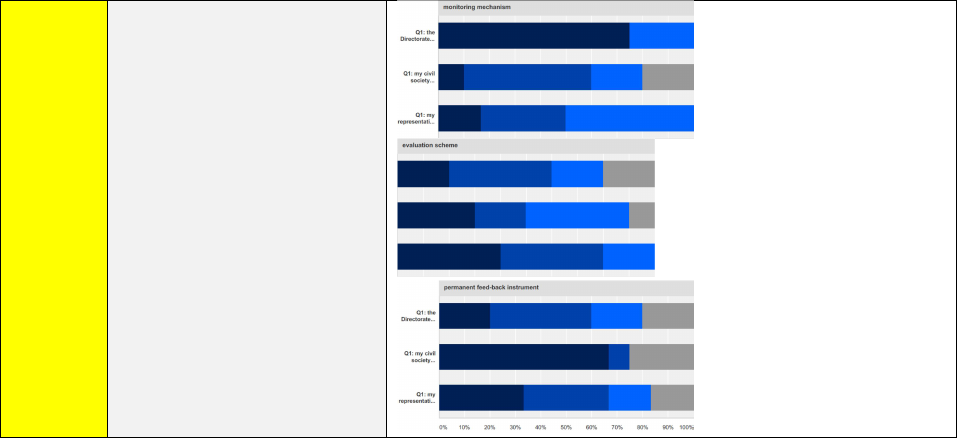

IV. Key Results of the Survey .................................................................................................................................... 73

V. Conclusions and Recommendations: The Unfinished Dialogues .......................................................... 93

1. Premises First - General Objectives .............................................................................................................. 93

i. Adapting to the New Mind-set by the Treaties and a Constitutional Responsibility............ 93

2. Horizontal Civil Dialogue .................................................................................................................................. 95

i. An Orphan in Need of Surrogate Activity? ............................................................................................. 95

ii. Support Surrogate Motherhood from Bottom-up or from the Side "by Appropriate

Means" ...................................................................................................................................................................... 96

3. On the Vertical Civil Dialogue ......................................................................................................................... 96

i. Consensus on the Dialogue’s Necessity - Dissensus on the Status Quo ..................................... 97

ii. Possible Role Models ..................................................................................................................................... 97

iii. Complete the Fragmentary Composition - Where are the Considerations of Average

Citizens? ................................................................................................................................................................... 98

iv. Let a Broader Partnership Principle Break Through ...................................................................... 99

v. Reflecting on the New Wide Opening of the Dialogue(s) ................................................................ 99

vi.Quality Rather than Quantity ................................................................................................................... 100

vii. A Two-chamber Model? ........................................................................................................................... 100

11

viii. Co-designing a Reform Model .............................................................................................................. 101

viii. Resolving the Confusion on the Nature of Dialogue - Consultation, Expertise,

Communication ................................................................................................................................................... 101

ix. Designing a Serious Conflict of Interest Policy - A Case of Transparency in Action ......... 102

x. The Eligibility of Religious and Philosophical and Party-political Organisations .............. 103

xi. Legal frameworks vs. Arbitrariness vs. Culture .............................................................................. 103

xii. A Particular Finding Process is to be Recommended as is a Commission-wide Basic

Regime Model ...................................................................................................................................................... 104

xiii. Standardise an Admissibility, Eligibility and Selection Regime ............................................. 104

xiv. Enhance the Positive Perception of the Performance ................................................................ 105

xv. Consider Reviewing and Monitoring .................................................................................................. 105

xvi. Enrich the Role of the entire Dialogue- Of the Partners, of the Contents, of the Potential

................................................................................................................................................................................... 106

xvii. Install an Online "Eleven-Two-Tool" - Save Time and Money and Gain Broad

Compliance ........................................................................................................................................................... 107

xviii. A Final Remark ......................................................................................................................................... 108

Annexes:

ANNEX I A Mapping

ANNEX II Bibliography

ANNEX III Raw Survey Data

ANNEX IV Legal Scholarship

12

"Last chance Commission", either

we succeed in bringing the European

citizens closer to Europe - or we will fail

Jean Claude Juncker

1

Any bridge needs firm pillars at both ends

and two directions in which to go

Anne-Marie Sigmund

2

Governments – together with socio-economic

and civil society actors – at all levels

have to seize opportunities together

Luc Van den Brande

3

I. Fundamentals and Considerations

I. 1 Objectives and Grounds for the Study

To make the concept of this study lucid requires an intense reflection of its objectives. The foremost

reason for this study is to clarify:

• Firstly, "existing structures" and "what exists". This refers to a mapping of the reality of the

civil dialogue (CD) under participatory democracy (PD) principles, whether and if so, to what extend

these are carried-out (or not carried-out) by the institutions and under which regime.

• Secondly, the task and mandate to analyse the "patterns" requires a very far reaching evalua-

tion of manifold factors as what the rationales are about and whether there is an awareness and a mu-

tual sense of responsibility for overarching aims.

• Thirdly, "recurring elements" can’t refer to anything else but to the normative equipment, and

how it is dealt with. This covers balancing the legal orders for installing and holding civil dialogues

and thus, conclusively and coercingly investigates on the facts behind the opaque perception of the

apparent gap that "exists" between participation law in the books and these laws in action.

• Fourthly, in order to "fill the present knowledge gap" intrinsically, knowledge must firstly be

generated which inevitably includes investigations on all things that in total help build knowledge and

1

Inaugural speech, European Parliament, November 2014

2

Living Europe, Foreword, 2006

3

Van den Brande Report, Consolidating a European Culture of Multilevel Governance and Partnership, 2014

13

• finally, for the mandate to come up with a "conclusion" and "recommendations" requires

making a proposal on how best to overcome this gap. In the light this task, one must inevitably focus

on "what exists" and on "patterns", which implies that there is also to be dealt with even rather silent

and psychological, political, economic interest factors as impacts and biases as well as restraints,

which is a crucial part of "what exist".

"What Exists”: What Is - What Ought to Be- What Appears to Be

To map and to analyse "what exists", is our contracted task. We could contend ourselves not ex-

clusively but primarily to report on the corpus of norms - laws, codes, regulations, recommen-

dations and case law. For lawyers this appears to be the dominant reality

4

, their reality. But this

is only superficial. The law itself tells us just what ought to be

5

. To close the gap between what

ought to be and what is , which is our solemn goal anyway, challenges to go far beyond the sur-

face, the backstage and the considerations, which altogether make "what is". Why are we going

so far into legal sociology and legal philosophy here? This is in order to explain why we won´t

come nearer to "what really is" if we contend ourselves with the normative level and why we

are going after the entire cosmos of the dialogues, because that is what makes "what exists".

As the Union needs not just another document in the style of "wash me but don’t get me wet", we´ll

speak-out very clearly and we will not hesitate to refer to "perceptions" even though this could be-

come discredited as a non-empirical approach. As we know from only one study with serious founda-

tion by in-depth interviews of high-ranking officers of the "apparatus", we will with all respect and

fairness refer to this intensely as we go on and only then additionally report on our own impressions

that could be received over many years. Of course, it is promptly to be confessed right here that such

notions could become rightly blamed as partial and being not more than the subjective observation of

a spectator being biased from his double role as analyst and also having acted in favour of PD.

Despite a large number of documents in favour of participatory democracy, there is an evident wide-

spread distrust in the function of participatory democracy and of the civil dialogue(s) and a certain re-

luctance to implement it proactively. Moreover, there is also some confusion about the definition, role

and function of participatory democracy and civil dialogue. This causes also lurking doubts around

implementation. There are, of course, good arguments for acting dilatorily. Even though we have li-

braries full of scientific interpretations, we are still missing any resilient doctrine on how to close the

aforementioned gap. And the fundamental reasons, why, basically, the gap should be closed are still

hovering in the Cloud of Unknown as the respondents to our survey further prove.

4

Gravers, den juristskapte virkkeligheten, 1982

5

Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739, II,1.1

14

Keeping up with "Constitutionalism": Committed to the Rule of Law

Two eagerly debated problems, one, whether participation can really contribute to make the Union

more democratic and, two, whether the use of participatory democracy and of the civil dialogues can

and will definitely provide legitimacy, neither can nor at all must be resolved by us, because the case

is in fact already closed, Roma locuta causa finita.

The Treaty of Lisbon

6

stands in its preamble determined, when stating one of its "holy" desideration

as: enhancing the democratic legitimacy of the Union. This is a proclamation. This is also an authentic

motive. It is immediately followed by a next Lisbon democracy manifesto on the political priority set-

ting: Title II. Principles of Democracy.

This second proclamation of "Principles", which logically covers also participatory democracy, again,

constitutes the entire underlying concept of participatory democracy of the Treaty on European Un-

ion

7

(TEU) as enshrined in Art 11, in our particular case Art 11(1) and Art 11 (2).

Here is the right moment to come ad fontes and to prominently recall the text of these two dialogues:

Art 11(1): The institutions shall, by appropriate means, give citizens and representative

associations the opportunity to make publicly known and exchange their views in all ar-

eas of Union action.

Art 11(2): The institutions shall maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with

representative associations and civil society.

Core texts, by nature, usually say much on the motives, but lesser on the extent or on the functioning

in reality. Yet the Treaty on the Functioning of the Union

8

(TFEU) does so. Art 15 (1) goes one sig-

nificant step further by conclusively ordering a positive and pro-active mind-setting in the entire Un-

ion´s apparatus: In order to promote good governance and ensure the participation of civil society,

the Union´s institutions, bodies, offices and agencies shall conduct their work as openly as possible.

6

OJ 2007/C 306/01

7

OJ 2012/C 326/01

8

OJ 2012/C 326/01

15

Whatever "openly" means, one thing is for sure when taking this holy shrine of three Treaties into ac-

count: we have and we face a solemn, lucid, "para-constitutional"

9

commitment that both intentions,

ought to be realized by the foreseen instruments: democratizing the Union and consequently a lever-

age of legitimacy. That is reason enough to take the officium nobile to adopt this commitment as our

premises. Premise one: Participatory democracy is a legal term and is only and exclusively addressed

to the instruments and their meaning as exhaustively worded in Art 11 TEU. Premise two: Civil dia-

logue in the context of participatory democracy is another legal term and strictly reserved to the para-

graphs 1 and 2 of Art 11. Consultation as ordered under Art 11 (3) TEU or the citizens initiative under

Art 11(4) are clearly instruments of participatory democracy but not at all to be subsumed as civil dia-

logue(s). For reasons of clarity and not to thin away the Lisbon pledge: whatever other efforts are tak-

en to attract and to engage the European citizenry are welcome voluntary engagements but are neither

mandatory participatory democracy nor civil dialogue. Convincingly, the dialogue under Art 17 (3)

TFEU, is as well a dialogue by legal wording but not participatory democracy in its genuine popular

sense. when Archbishops and Archimandrites meet with the Presidents of the Commission and the EU

Parliament and in separate meetings the Grand Masters and Secretary Generals of secular(ist) organi-

zations. For the sake of completeness of the use of the term "dialogue": The same applies to the politi-

cal dialogue under Art 27 TEU and to the social dialogue under Arts 151ss TFEU. As a result: the

combination of participatory democracy and civil dialogue refers solely to Arts 11 (1) and (2).

Despite hesitant standpoints in EU law commentaries on whether there is a strict implementation ob-

ligation of the civil dialogue(s) - we´ll come back to that in more depth

10

- it appears as unacceptable

to implicitly treat the primary laws like a provisional wishful thinking at anyone’s interpretation dis-

posal - even when the Treaties´ wordings sometimes offer space for interpretation. In such cases the

interpretation of more or less or of so or otherwise is indeed up to the legitimate actors, but not the

decision of whether or not. Implementation omission is neither a legal nothing nor just a peccadillo:

So, finally it would be up to the Courts to render a binding interpretation. If an institution should be

blamed for misperception or infringement we have procedures at stake to take action against that un-

der Art 263 TFEU. There are competent guardians "claimants" for taking action. The order of partici-

patory democracy in the Treaties is not, as sometimes subliminally alleged, an erroneously added or

an injudiciable narrative from just some visionary. It does not stem from souled essayists of the Con-

vention era and of other Pied Pipers, it is the Member States who are giving the orders. Every single

one of the Member States is supposed to have read this document carefully and only then agree con-

clusively on every sentence of this text. Unanimously. Therefore we can talk about potentially twenty-

9

as the approach of right these lines here is a functional one it appears to be at least not counter indicative to refer to the

primary EU law in terms of a "constitution", especially when we summarise that 99% of the core text of the Constitution

Treaty - except for the above mentioned exclusions of deleting "principles" - were published without any significant chang-

es. Of course, a formalist or dogmatist, presumably also a citizen of the UK, would heartily protest against this sloppy prov-

ocation, but we are commited to going on with our functional approach

10

See chapter legal scholarship in Annex 4.

16

eight entitled controllers of the proclivities or disfavours of the institutions and rightly take the Trea-

ties as canon.

Showing loyalty, if not empathy, to one’s own "constitution" is nothing that needs be justified. There-

fore, we appreciate the new German approach of "Verfassungspatriotismus", constitution patriotism,

which means that the cohesion of the Union can be guaranteed by a strong belief in the integrative

power of its constitution. We do not appreciate that this is sometimes put somewhat patronisingly in a

slightly pejorative or smiling light. Indeed, the highflying Lisbon desideration are volitile, maybe ju-

ridifying meta-narratives would also be a heritage from the Constitutional Convention´s enthusiasm.

But what should be wrong with that in a declared "political Union"? There are (albeit long) times for

reasoning, philosophising and, well, also for pettifoggery, but then there are also times when political

and societal activity are necessary - and such times, we guess, are dawning.

The Ombudsman´s (OM) View

This gives leeway for a too subjective evaluation from now on becoming limited. Since January, 27th,

2015 we have a first in-depth analysis with follow-up recommendations which are outstanding and of

highest competence: it is the Ombudsman preliminarily who makes the case in intellectual honesty -

until the Commission either agrees or overrules. These recommendations must be recalled right here

in their entirety because of showing all "risk-zones" and offering solid grounds for the author as well

as for the lector benevole. Nothing could better prove the objectives and grounds of this study.

Just one comment must be added right here to clarify some commingling: it is highly problematic -

and we´ll come back to this in our reflections - to treat consultation and dialogue equally

11

and, then

logically, to analogise the rules. This collides with the concept of the Union Treaty. Unfortunately, the

Ombudsman follows in this respect the observance of the EU Commission, which has not adjusted the

Consultation rules to the Lisbon state. This again refers to our observation that the apparatus, presum-

ably rather unconsciously, still lives with usage of pre-Lisbon patterns. Note: Consultation under par-

agraph 3, Art 11 TEU is also participatory democracy, but is of another nature then the dialogues un-

der paragraphs 1 and 2 Art 11. Whereas the dialogues are clearly construed as an exchange, bargain-

ing and political process, near to the social dialogue, consultation is - despite the practices of hearings

and consulting meetings - by concept in principle a one way instrument. There lies strong proof on

this different concept by the fact, that the order of dialogues is addressed to all of the institutions

whereas the Consultation Procedure exclusively addresses the EU Commission. This makes sense as

the initiation of a law making process is exclusively the competence of the Commission and so far it

11

see Fn 1 of the Ombusman´s Letter to the President, citation next Fn: The Commission may, nevertheless, choose to apply

the measures it adopts in response to this own-initiative inquiry also to such groups.

17

has become its very own of form of collecting objective reasons whereas the political next step, the

political one, allows to respect political aspects, as is the "sovereign" not bound to objective reasons -

or in other words, democracy has its very own objectives and rationales. The sovereign "we, the peo-

ple..." is indeed sovereign. The EU Parliament and the Council have increasingly documented this

"truth" in recent times. The apparent similarity, that the EU Commission gives reasons in both cases,

cannot be understood as sameness. So, even this is not inevitable, the rules can turn out as quite dif-

ferent, respecting the diverse nature of these twofold instruments. If the Union Treaty would have

seen these two elements as the one and the same, it would have expressed this as such, but as it did

not, we can rightly assume that the idea was to open pluralistic channels for providing the institutions

an overview on the bandwidth of perceptions - on equal footing.

A Landmark: OM Inquiry

12

and Position

13

in Brief

After having received feedback from public consultation that the Ombudsman had carried out, she

presented her conclusions as follows:

The main problems identified by stakeholders are (i) the inconsistent categorisation of organisations

that are members of expert groups, (ii) the perceived continued dominance of corporate interests in a

high number of expert groups, (iii) a lack of data on the expert groups register, and (iv) the appoint-

ment of individuals who are closely affiliated with a specific stakeholder group as experts in their

personal capacity, linked to the absence of an effective conflict of interest policy.

This raises concerns on whether it is (i) currently not possible adequately and consistently to review

the composition of specific expert groups because of deficiencies in the framework governing such

groups, as well as in the expert groups register, (ii) that there is no consistent labelling/categorisation

of organisations appointed to expert groups and that the vague category 'association' appears to be

frequently used as a fall-back category. (iii) What is more, the Commission has so far not developed

any general criteria for delimiting different groups of stakeholders. In particular, there are no criteria

for the broader categorization of which groups of stakeholders are deemed to represent economic and

non-economic interests respectively.

The Ombudsman noted, furthermore, that the European Parliament adopted, on 22 October 2014, a

resolution on the general budget of the European Union for the financial year 2015, which envisaged

holding "some appropriations in reserve until the Commission modifies the rules on expert groups and

ensures their full implementation within all DGs". The draft amendment tabled by a group of MEPs,

12

OI/6/2014/NF

13

Letter of the European Ombudsman to the President of the European Commission Jean Claude Juncker, 27 Jan 2015;

http://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/de/cases/correspondence.faces/en/58861/html.bookmark; accessed 21 Feb 2015

18

on which the resolution was based, pointed to what was perceived as a continued failure to ensure a

balanced composition and transparency of expert groups. In light of the contributions received, the

concerns put forward by the European Parliament in the context of the budget procedure, as well as

my own preliminary views as outlined above, I have decided to focus my own-initiative inquiry exclu-

sively on systemic issues which negatively impact on the balanced composition of expert groups and

the transparency of the groups' work.

As positive developments underpinning the Ombudsman´s suggestions for improvements, she evalu-

ated that since December 2013, DG AGRI's civil dialogue groups, a specific type of Commission ex-

pert group, have been governed by a new framework. I consider that this legal framework, the imple-

mentation of which is subject to review in the context of own-initiative inquiry OI/7/2014/NF, presents

clear advantages over the horizontal rules governing Commission expert groups

14

.

Under restraint

15

of a supervening detailed evaluation, which we shall refer to the DG AGRI model as

the benchmark-setting role model. With these statements the Ombudsman came to its own conclu-

sions and recommendations which were to be reflected by the Commission and stated particular sug-

gestions.

A. The (legal) nature of the horizontal rules and achieving a balanced composition:

The Commission should adopt a decision laying down the framework for expert groups. This Com-

mission decision should require the following.

1. A balanced representation of all relevant interests in each expert group.

2. An individual definition of 'balance' to be set out for each individual expert group.

3. A provision containing general criteria for the delimitation of economic and non-economic inter-

ests.

B. Calls for applications:

1. Publish a call for applications for every expert group.

2. Create a single portal for calls for applications to expert groups.

3. Introduce a standard minimum deadline of 6 weeks for all calls for applications.

C. Link to the Transparency Register:

14

see FN 2, Letter of the Ombudsman to the President of the EU Commission; The horizontal rules governing Commission

expert groups are set out in the following Commission Communication: Framework for Commission Expert Groups: Hori-

zontal Rules and Public Register, 10.11.2010 (C(2010) 7649 final, SEC(2010) 1360).

15

see FN 5, Letter of the Ombudsman to the President of the EU Commission

19

1. Use the Transparency Register's categorisation to categorise members in Commission expert

groups.

2. Require registration in the Transparency Register for appointment to expert groups.

3. Systematically check whether registrants sign up to the right section of the Transparency Register.

4. Link each member of an expert group to his/her/its profile in the Transparency Register.

5. See heading D. below for individuals who are not self-employed and who are appointed to expert

groups as individual experts in their personal capacity.

D. Conflict of interest policy for individual experts appointed in their personal capacity:

The Commission should revise its conflict of interest policy and take the following measures.

1. Carefully assess individuals' backgrounds with a view to detecting any actual, potential or appar-

ent conflicts of interest.

2. Ensure that no individual with any actual, potential or apparent conflict of interest will be appoint-

ed to an expert group in his/her personal capacity.

3. Consider, in a situation of conflict of interest, the possibility to appoint an individual as a repre-

sentative of a common interest shared by stakeholders or to appoint his/her organisation of affiliation

to the expert group.

4. Publish a sufficiently detailed CV of each expert appointed in his/her personal capacity on the ex-

pert groups register.

5. Publish a declaration of interests of each expert appointed in his/her personal capacity on the ex-

pert groups register.

(…)

On the basis of the above, the Commission should consider (i) adopting a decision in 2015 laying

down the general framework for expert groups and (ii) reviewing the composition of expert groups

which are active or on hold, once this decision has been adopted.

The EU Commission’s reaction and response times were set out for April, 15th, 2015. Further debates

and a replica are obvious. Supposedly the Commission will not fully disavow its own not so badly

founded position: The EU Commission speaks in its already pre-Lisbon self-imposed Communication

on Rules and Standards

16

clearly about a Reinforced culture of consultation not deriving from any

kind of legislative implementation. Secondly, the EU Commission has ordered itself to be reluctant of

letting things go too far, in order to and based on the rational of efficiency. Setting the rules for Con-

sultation, what again raises valid doubts, such as whether these can be analogously used for the CD,

but in actual practice - the EU Commission has already in the General Rules and Minimum Stand-

16

COM (2002) 704 final

20

ards

17

explicitly stated: A situation must be avoided in which a Commission proposal could be chal-

lenged in the Court on the grounds of alleged lack of consultation of interested parties. Such an over-

legalistic approach would be incompatible with the need for timely delivery of policy, and with expec-

tations of the citizens that the European institutions should deliver on substance rather than concen-

trating on procedures. Note: Efficiency is an "overwhelming" argument and to substitute law by cul-

ture, in the name of lesser regulations, is another highly "convincing" scenery.

However, we will see an impressive discourse, presumably lasting for a while. Although the Om-

budsman has carried out a profound consultation, we do hope to be able to contribute to the discourse

with our approach and with additional empirical enforcement.

Keeping the constitutional tracks anyway

By strongly basing ourselves on the overarching constitutional goals and promises, and severely

committing to not be consumed by open-ended debates nor by non-constitutional level demurs, be

they scientific ones or such based on Realpolitik, we are determined to think about realisation of im-

plementation steps. Still, we are always reconnecting to the normative basement.

This may appear as reference to a positivist method, but we are less pretentious and rather believe that

it is based on a "fundamentalist" pragmatism. Only this strict normative approach augurs realistic and

factual implementation of the "constitutional" desires and orders, in case the responsible politicians

should honestly still consider that, which, of course, can be doubted. The zeitgeist, spirit of the age of

efficiency appears to have surpassed the ranking of democracy. We keep on going on the democracy

primacy premise´s trails anyway. Should the Union not take action and wait until there is an overall,

scientific, administrative, executive and political consensus once on how PD and CD work best, it will

wait until calendas Graecas.

Deeply respecting scholarship, but committed not surrendering to ....

The scientists of very diverse disciplines cultivate a debate on a very sophisticated intellectual level,

regarding our subject. They are going so far to challenge the existence of a civil society or diagnosing

a couple of civil societies and scrutinising, whether there is just one Europe or maybe several Europes

and which of these Europes can be matched with which type of participatory democracy adequate civ-

il society

18

. This approach is problematic. Is there need to rethink Europe from scratch? Intellectual-

ly, this is an amazing, formidable, impressive, awe-inspiring and highly complex and ambitious de-

17

ibid, 6, 10

18

see Kohler-Koch, The Three Worlds of Civil Society - What role for civil society for what kind of Europe?, in: Policy and

Society 28 (2009), 48

21

bate. While reaching out for ever more certainty or even training for uncertainty there is less eager-

ness to intermingle in down-to-earth questions like whether and how a DG should reach-out for a sec-

toral citizen-driven domino-like multilevel-multiactor-multiplier legitimacy leveraging participation

scheme. Of course, this down-to-earth challenge challenges us even more to respect the diverse doc-

trines. For example, it is true, civil society is an ever changing, and, well, sometimes lobbyists in dis-

guise, oscillating, vibrating, ambiguous and finally not strict definable something. But it would be

overdone to negate its presence. If there are multiple faces and functions and weights, then they are to

be put to adequate multiple use, but not to not be used at all. Beate Kohler-Koch

19

has proposed a "ta-

ble" of options, functions and perspectives, that is more than appropriate to serve as a preliminary

guideline for designing a multiple architecture. Dealing with where, how and how far civil society can

be placed in multiple functionalities and responsibilities, it can support the effects as envisaged by the

Treaties. Gautier Busschaert

20

, meanwhile, takes one fairly radical step further and adopts as a prem-

ise that the EU has turned to participatory democracy because representative democracy may be

reaching its limits. So, what now? Can PD and CD be seen as bridge-builder or is this merely a magi-

cal

21

oxymoron? Law is flexible and by modern nature always under construction, so there is no ob-

stacle to optimising this architecture permanently once a more lucid and consented doctrine should

arise. Politology and sociology provide the scholarly ammunition to morally justify the Commission’s

resistance; we´ll come back to that overtone.

... but rather disentangling the complexity

Assuming it will take time until a serious call for "disentangling the debate" becomes a reality our

plead to the institutions is not to merely await this reality. Instead, we advise trust in the assumptions

of the Treaties and to enhance PD and CD. No doubt, a proactive progress could be seen as the Trea-

ties´ desideration payment in advance which maybe pay off. But the engagement and inouts of an ever

more one-sided invited citizenry is no less a payment in advance, which in case of becoming irrele-

vant - this is the "valuta" - would also be seen as a loss. But is there any other option? Bluntly spoken

the Treaties order the Union to exercise on the fields of trial and error. Consequently, legal-political

backers serving as "investment advisers", who inevitably can only free-draw themselves from any

guarantee for success and being exonerated from liability, could be blamed for mere mercenaries.

We could easily, by intellectually fiddling-around, move over to all those scepticisms and pessimisms

and other -isms around the profoundly imposed question, whether the EU could become democratised

19

ibid, 53

20

Participatory Democracy in the European Union : a Civil Perspective, PhD Thesis University of Leicester - School af

Law, 2013

21

Busschaert, 125: The Civil Dialogue : a Magic Cure for the Democratic Ailments of the Community Method?

22

from below

22

, meaning from the man-on-the-street and from civil society. With our own background

it is tempting to scholarly combine all these methodologies for finding a methodology to get things

analysed correctly and to join all those various adept assumptions on democratising democracy. But

we withstand this temptation. As we mentioned before, we made a commitment to share assumptions

though preferably those stated in the Treaties. Because in our norm related approach their dignity is of

the highest obtainable ranking.

So, let us frankly and boldly begin by balancing the widest panorama of the political, philosophical,

scientific and normative order and then come to fact findings and to behavioural imprint challenges

and finally to results and recommendations.

Referring to the Key Actors: EU Commission and the European Economic and Social Committee

As early as 2001, the European Commission, based on its own pre-evaluations explicitly referred to

the European Economic and Social Committee´s (EESC) "Sigmund-Report (I) : The role and contri-

bution of civil society organisations in the building of Europe"

23

and to the EESC´s "Sigmund Report

(II) : The Commission discussion paper "The Commission and non-governmental organisations -

Building a stronger partnership"

24

. Those documents made civil society and participatory democra-

cy a pillar of the Unions´ architecture of democracy. From these days on, the EESC additionally

adopted to its genuine functions

25

a leading role and a factual function as guardian of the issue of par-

ticipatory democracy

26

.

It was then titled the "European Governance - A White Paper"

27

, and announced a fundamental in-

volvement of civil society in the political will building process. Only one year later, this outline was

already surpassed by a new policy approach and another high-ranking mission statement. This was the

Communication of the Commission "Towards a reinforced culture of consultation and dialogue -

General principles and minimum standards for consultation of interested parties by the Commis-

sion"

28

. This next milestone of open governance reinforced the Union´s ambition to obtain European

intermediaries on board of the EU Commission, all in favour of an enhanced democratisation of the

Union´s executive entity, which was previously scolded for being undemocratic for quite some time.

Some years later and as publicly confessed in reaction to the fatal "non" and "nee" in France and

Netherlands to the Constitution Treaty, came a Communication to the Commission, an "Action Plan

22

so recently again Liebert et al (Eds), Democratising the EU from Below?, 2013

23

Rapporteur Sigmund; adopted September, 22, 1999; CES 851/1999 D/GW

24

Rapporteur Sigmund; adopted July, 11, 2000; CES 811/2000 FR/ET

25

OJ 287/ 2001; COM(2001) 421 fin

26

see Brombo, Le Formazioni economico-sociali e l´Unione Europea, in: Theory of Law and State 1/2 (2003), 293ff; Confe-

rence University of Venice Ca’ Foscari, 25 September 2013, Venice...

27

COM (2001) 428 final

28

COM (2002) 704 final

23

to Improve Communicating Europe by the Commission

29

". The document stated in all openness that

the aforementioned rejections had led to the conviction, that the dialogue with the European citizen

has become a Commission priority.

30

The new communication approach was based on three main

principles, namely, (i) listening, (ii) communicating and (iii) connecting with citizens by "going lo-

cal": good communication must meet the local needs of citizens"

31

. A Green Paper on Transparency

32

then spoke of the issue on how to safeguard and to keep "clean" the civil society from disdainful hid-

den lobbyism, and how to disclose particular interests and a follow-up Communication from the

Commission "European Transparency Initiative

33

" what was appointed. Finally, the new Treaty on

European Union

34

in the amended version of the Treaty of Lisbon

35

built the capstone and signalised

that the Union appreciates the participation of the European citizenry and of civil society as a core

strategy to "citizenise" the Union and to "Europeanise" the citizenry. As the Union Treaty remained

fairly imprecise as to what its "constitutional" orders in particular meant concerning the factual im-

plementation, it was again the EESC who pushed for rules that made the invitation to the citizens and

the civil society organisations viable, this time by the "Sigmund Report (III) - The implementation of

the Lisbon Treaty : participatory democracy and the European citizens’ initiative (Art 11) "

36

. So it

was again and again the EESC urging for a more proactive participatory policy of the EU institutions,

as finally documented by the complex "Jahier Report"

37

.

Even when we come back to this issue in more depth, it is worthwhile to acknowledge here that this

invaluable tradition is still in continuity. It was the EESC’s Liaison Group that recently drafted a new

Road Map for the implementation of Arts 11 (1) and 11(2) of the Treaty on European Union. To-

wards better civil dialogue and involvement of citizens for better policy making, then adopted by a

NGO Forum, hosted by the Latvian presidency

38

. The EESC appears to be the "Brussels" motor of

PD and CD. A next generation represented by EESC Member Andris Gobins has taken not only re-

sponsibility but obviously also stakeholder activity to push CSO´s towards organised action.

Participatory Democracy Becoming a Self-runner

29

SEC (2005) 985 final

30

ibid, introductory remarks

31

ibid, summary of the motives

32

COM (2006) 194 final

33

SEC (2007) 360

34

Fn 2

35

Fn 1

36

Rapporteur Anne-Marie Sigmund; CESE 465/2010

37

see CESE 766/2012; 3 October 2012 : Principles, procedures and action for the implementation of Arts 11(1) and 11(2) of

the Lisbon Treaty

38

Riga, 2/3 March 2015.

24

The path from Amsterdam over Nice to Laeken reflected the urgent need for political success with its

solemn confirmation

39

to make the Union more democratic, resulting in a strong debate between pro-

tagonists and antagonists of the direct democracy community on the nature of PD

40

. Even then there

was talk of a European Referendum, which appears to be welcome, just look at proponents like Tony

Blair, Angela Merkel, Wolfgang Schäuble - and Jean-Claude Juncker - but has nothing to do with PD.

One preliminary note right here. Participatory democracy is neither direct democracy nor a revival of

the co-decision concept in any way. Let us part with illusions: the primary goal of representative de-

mocracy is pompously stated in Art 10 (1) TEU. PD is a just accessory and complementary element of

dignity and may be a stepping stone towards direct democracy, which is clearly underrepresented in

the Treaties, but is of another nature and should not be subsumed under "direct". Even when the ECI

comes close, it is just and only agenda setting for further reactions. PD, in particular in form of CD or

CP is not one of the binary instruments which usually end with a yes or no. PD and CD are typical

prerequisites for good governance, as it is a process to find cooperatively and collaboratively solu-

tions, horizontally first, vertically afterwards. Right this is the concept follow up of Art 11, first comes

the internal dialogue amongst the citizens, para 1, then evolve their findings to political bargaining,

para 2, afterwards the results of that process step become aired back to the public for backing or en-

richment or even denial, para 3. PD is based on the inclusion principle and has taken the step from

pure deliberation towards an outcome-related co-design. See instead of all others the doyenne of this

new branche, Beth Noveck

41

. We will also come back to this important bifurcation.

The Committee of the Regions- A New Player Boarding, Decentralising Participatory Democracy

If the institutions would really understand the joint chances and options of a collaborative spirit, it

would definitely induce a change of the mindset. By the way, even when not (over)burdened by the

same far reaching responsibility as indeed is the Commission, the Committee of the Regions has a

better understanding of the challenges for an urgent change of political culture, in order to reach the

citizens, when adopting and solemnly promoting its Multilevel Governance Charter in 2014.

In addition, initially there was no need of prevenient collective shift of mindset. It is, like so often in

39

see Laeken Declaration, 15 th December 2001

40

Also we have for political and communication and simplifications reasons used the categorisation direct democracy, see

Auer / Flauss, Le Référendum Européen (Bruylant 1997); Feld / Kirchgassner, The Role of Direct Democracy in the Euro-

pean Union, in: Blankart / Mueller (Eds), A Constitution for the European Union, 2004); Pernice, Réferendum sur la Consti-

tution pour l'Europe: Conditions, Risques et Implications’ in: Kaddous / Auer (Eds), Les Principes Fondamentaux de la Con-

stitution Européenne, 2006) and: Direct Democracy and the European Union… Is that a Threat or a Promise? (2008) 45

CML Rev 929.

35 See Kohler-Koch, Does Participatory Governance Hold its Promises? in: Kohler-Koch / Larat (Eds), Efficient and Demo-

cratic Governance in the European Union, 2008; Smismans, European Civil Society: Shaped by Discourses and Institutional

Interests, 9 ELJ (2003) 482, 493;

41

Wikigovernment, 2009; Smarter Citizens, Smarter States, 2015

25

history, enough that one key actor acts committedly - which is a statement clearly addressed to the

President of the EU Commission. This MLG concept and recent Charter concept was exclusively de-

veloped and improved by Luc van den Brande, who was President of the COR at the time of the PD

hype. As was, which is reflected in all of the relevant literature, one of the driving forces of PD since

the days of her mandate in the Constitution Convention and then several times as Rapporteur Anne-

Marie Sigmund, who at that time was President of the EESC. All of the afore named put their pro-

posals and documents on right that spirit, as is expressed in the MLG Charter:

togetherness, partnership, awareness of interdependence, multi-actorship, efficiency, subsidiarity,

transparency, sharing best practices (...) developing a transparent, open and inclusive policy-making

process, promoting participation and partnership involving relevant public and private stakeholders

(...), including through appropriate digital tools (...) respecting subsidiarity and proportionality in

policy making and ensuring maximum fundamental rights protection at all levels of governance.

Strengthen institutional capacity building and invest in policy learning amongst all levels of govern-

ance or to create networks between our political bodies and administration.

This is the empathy, that Jeremy Rifkin

42

urges and proclaims a characteristic of advanced and mature

societies.

Critical Scholarly Voices and Rumours

An unprecedented breakthrough of a European Civil Society participation invitation

43

came next, al-

most tuning into an hype in the 2000s. Beate Kohler-Koch

44

may be right when being suspicious that

we are now the heirs of post-hype times. But can we, on the other hand, really pronounce participa-

tory democracy in the EU as such as finally de-mystificated, as recently done so by Beate Kohler-

Koch / Christine Quitkat in their book title

45

? We agree that there are obviously disadvantages on both

sides of the "table". But haven´t we seen only half-hearted implementations and camouflages? Isn´t it

a bit daring to air such an apodictic verdict regarding such a complex issue with no past but maybe a

great future? And, above all: is it really legitimate to disavow the “masters of the Treaties”, who have

signed on to this constitutional concept this early and this fully?

42

Empathic Civilisation, 2009

43

cf. Smismans, European Civil Society. Shaped by Discourses and Institutional Interests, in: European law Journal, 9 (4),

2003, 482 ff

44

Fn 18

45 Die Entzauberung partizipativer Demokratie. Zur Rolle der Zivilgesellschaft bei der Demokratisierung von EU-

Governance (2011).

26

At the backs of our minds, we do share those warnings

46

addressed to the Union’s decision makers not

to neglect either the citizens’ political desires or the implied constitutional call, because, otherwise,

the final political costs would be out of proportion. The main desire of the authors of the (draft) Con-

stitution Treaty was to Europeanize the Europeans

47

and, as already stated above, the subsequent

Treaty also aimed at enhancing the Union’s democratic legitimacy.

48

There is no doubt at all that,

originally, the principle of participatory democracy – as resoundingly trumpeted by the EU Constitu-

tion Treaty

49

– was seen as the most appropriate means for enhancing this legitimacy, introducing a

mechanism in favour of the citizens along the idea of consociationalism

50

and encouraging societal

peace building.

51

Still, there is broad agreement that the citizens must be attracted

52

and affected

53

by

Unions’ issues. But is there still a consensus that Art 11 (2) TEU is the appropriate vehicle to include

the people structurally?

However, key scholarship shows that there is no consensus on whether participation is a boon or

bane

54

and whether it generates legitimacy

55

. However, the breakthrough was achieved and there was

a participatory turn.

56

At least as law in the books would have it. But there is another narrative on air

on the reality of open governance, open participation and open dialogues, which appears to be not so

unlikely. Since the economic crisis the democratisation and in this context the participation desire be-

came overruled by the executive primacy. The Brussels backstage rumour became richer with another

murmur as salvation for dawdling: In times of monetary transfers to Greece and potential imminent

threats to pay for several other risk candidates as symbolised by acronyms such as SSCT and SFT the

people themselves could not care less for democracy. Right or wrong?

46

Cf Craig, The Lisbon Treaty. Law, Politics and Treaty Reform,2011, 77ff; Piris, The Lisbon Treaty. A Legal and Political

Analysis, 2010, in particular 135ff; see also Tiemann/ Treib / Wimmel, Die EU und ihre Bürger, 2011

47

See only Chryssochoou, Civic Competence and Identity in the European Polity, in: Bellamy et al (Eds.), Making European

Citizens. Civic Inclusion in a Transnational Context, 2006, 219ff.

48

See also Lenaerts/ Cambien, The Democratic Legitimacy of the EU after the Treaty of Lisbon, in: Wouters et al (Eds.),

European Constitutionalisation beyond Lisbon, 2009

49

Heading of its Art I-47

50

Cf, still for the post-Lisbon era, Warntjen, Designing Democratic Institutions: Legitimacy and the Reform of Council of

the European Union in the Lisbon Treaty, in: Dosenrode (Ed.), The European Union after Lisbon. Polity, Politics, Poli-

cy,2012, 111ff.

51

See van Leeuwen, Partners in Peace. Discourses and Practices of Civil-Society Peacebuilding, 2009

52

Cf Castiglione, We the Citizens? Representation and Participation in EU Constitutional Politics, in: Bellamy et al (eds.),

Making European Citizens, 75ff.

53

Cf Hilson, EU Citizenship and the Principle of Affectedness, in: Bellamy et al (Eds.), Making European Citizens, 56ff.

54

Pateman, Participation and Democratic Theory,1970; CB Macpherson, The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy (OUP

1977; Barber, Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age, 1984); JD Wolfe, ‘A Defense of Participatory De-

mocracy’ (1985) 47 The Review of Politics 370; Craig, Public Law and Democracy in the United Kingdom and the United

States of America,1990) chaps 10-11; Sintomer, La Démocratie Participative, 2009, 5

55