A

SURVEY

AND

ANALYSIS

OF

TECHNIQUES

USED

IN

ATTRACTING

THE

BLACK

MIDDLE.CLASS

PATIENT

Sydney

Barnwell,

MD,

and

Walter

F.

LaMendola,

PhD

Greenville,

North

Carolina

This

study

presents

a

survey

which

is

based

upon

the

black

physician's

perception

of

the

expectations

of

the

black

middle-class

patient.

This

perception

is

that

the

middle-class

ex-

pectations

are

low;

hence,

satisfaction

is

low,

and

the

result

is

that

prospective

patients

tend

to

utilize

the

services

of

white

physi-

cians.

The

survey

was

designed

to

sample

opinions

of

physicians

attending

the

1983

an-

nual

meeting

of

the

National

Medical

Associ-

ation

in

Chicago,

and

it

determined

the

most

useful

techniques

in

attracting

black

middle-

class

patients.

These

investigators

believe

that

there

is

an

immediate

need

of

a

market-

concept

approach

utilizing

the

results

of

this

study

to

help

the

black

doctor

market

his

serv-

ices

more

effectively.

Such

a

market

concept

approach

is

presented.

Dr.

Barnwell

is

Assistant

Dean

for

Minority

Affairs

and

Dr.

Mendola

is

Associate

Professor,

Division

of

Social

Work,

School

of

Allied

Health

and

Social

Work,

East

Carolina

Uni-

versity.

Requests

for

reprints

should

be

addressed

to

Dr.

Sydney

Barnwell,

1709

Lincoin

Street,

New

Bern,

NC

28560.

Black

doctors

represent

2.6

percent

of

the

na-

tion's

physicians.

They

are

well-organized

and

well-represented

by

the

National

Medical

Associ-

ation.

In

this

changing

practice

environment

where

Diagnosis-Related

Groups

(DRGs),

Pro-

spective

Payment,

and

Preferred

Provider

Organi-

zations

(PPOs)

are

the

order

of

the

day,

the

black

physician

has

to

sharpen

his

competitive

edge

in

order

to

survive.

This

is

made

more

urgent

by

the

increasing

oversupply

of

physicians,

which

will

peak

by

the

end

of

this

decade.

These

pressures

make

it

critical

that

black

practitioners

make

use

of

market

concepts

in

order

to

alter

public

percep-

tion,

increase

the

likelihood

that

prospective

pa-

tients

will

choose

to

use

them,

and

positively

in-

fluence

middle-class

patient

satisfaction.

Four

types

of

independent

variables

relating

to

patient

satisfaction

have

been

studied

by

research-

ers.

These

are

patient

characteristics,

organiza-

tional

characteristics,

doctor-patient

interaction

characteristics,

and

the

physician's

sociodemo-

graphic

characteristics.

This

study

presents

a

sur-

vey

of

the

black

physician's

perception

of

the

expectations

of

the

black

middle-class

patient.

We

propose

a

fifth

type

of

independent

variable,

one

which

states

that

the

racial

characteristics

of

the

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,

1985

379

BLACK

MIDDLE-CLASS

PATIENTS

black

physician

tend

to

influence

negatively

the

black

middle-class

patient's

satisfaction

by

not

meeting

the

latter's

preconceived

expectation

of

quality.

INDEPENDENT

VARIABLES

RELATING

TO

PATIENT

SATISFACTION:

A

REVIEW

OF

THE

LITERATURE

Patient

characteristics

are

usually

discussed

in

terms

of

attitudes-expectations

and

sociodemo-

graphic

factors.

The

more

positive

the

attitude

about

a

given

service,

the

more

satisfied

the

pa-

tient

tends

to

be.I

The

patient's

sociodemographic

characteristics

(including

age,

sex, race,

religion,

education,

occupation,

income,

and

marital

status)

tend

to

be

more

equivocal;

these

do

not

consistent-

ly

affect

satisfaction.1

But

when

the

determinants

of

patient

satisfaction

in

the

sociodemographic

characteristics

of

fee-for-service

solo

practices

are

studied

against

large

prepaid

organized

groups,

there

is

one

consistent

finding,

and

that

is

that

upper-class

patients

are

not

satisfied

with

large

prepaid

organized

groups.2

Organizational

characteristic

determinants

show

that

patient

satisfaction

is

lower

in

large

pre-

paid

organized

groups

than

in

fee-for-service

solo

practices.3

The

doctor-patient

interaction

depends

largely

upon

the

quality

of

such

interaction

affecting

pa-

tient

satisfaction.

Patients

tend

to

be

more

satis-

fied

when

the

physician

is

concerned,

comforting,

and

communicates

openly.4'5

The

sociodemographic

characteristics

of

the

physician

are

very

important

when

patient

expec-

tations

are

studied

vis-a-vis

patient

satisfaction.

Ross

and

his

co-workers

have

shown

that

patients

"halve

expectations

concerning

physicians'

status

characteristics:

that

clients

have

images

not

just

of

what

a

physician

does,

but

of

who

a

physician

is."6

These

authors

have

also

shown

that

images

of

physician

status

characteristics

are

based

on

statistical

norms.

For

example,

patients

expect

doc-

tors to

be

middle-aged,

white

men.

The

mean

is

ac-

cepted

as

the

norm,

and

the

norm

is

equated

with

being

good

and

appropriate.

Thus,

we

expect

that

if

most

physicians

are

white,

middle-aged

men

from

status

backgrounds,

and

of

Protestant

or

Jewish

religions,

then

clients

will

expect

physicians

to

have

these

status

char-

acteristics.

When

these

expectations

are

not

met,

satis-

faction

will

be

low.6

The

review

of

the

literature

indicates

that

a

fifth

type

of

independent

variable-black

physician

in-

teraction

with

the

black

middle-class

patient-has

not

been

examined

as

a

potential

determinant

of

patient

satisfaction.

We

propose

that

the

image

of

the

black

physi-

cian

does

not

fit

the

"great

white

father

image"

as

far

as

the

black

middle-class

patient

is

concerned

and

that

the

physician

does

not

fit

the

norm

which

is

equated

with

the

good

and

the

appropriate.

Therefore,

black

middle-class

patients'

expecta-

tions

are

low

at

the

outset

and

satisfaction

remains

low,

causing

many

black

patients

to

seek

out

white

physicians.7

The

Lloyd

and

Johnson

study7

limits

itself

to

black

medical

alumni

and

compares

re-

sults

of

practicing

patterns

for

graduating

classes

from

1955-1970

and

1973-1975.

According

to

this

study,

the

first

subgroup,

in

their

private

prac-

tices,

takes

care

of

67

percent

black

patients,

while

the

second

subgroup

takes

care

of

77

percent.

When

the

economic

status

of

these

patients

is

studied,

the

results

demonstrate

that

the

tendency

towards

caring

for

patients

from

lower

socio-

economic

backgrounds

predominates,

with

only

6.8

percent

and

6.2

percent

of

the

patients,

re-

spectively,

considered

well-to-do.

NATURE

OF

THE

PROBLEM

Gunnar

Myrdal

identified

the

problem

quite

clearly

in

1944

when

he

wrote

that

"The

Negro

doctor,

in

the

main,

must

depend

on

Negro

pa-

tronage.

And

the

overwhelming

majority

of

both

the

white

and

the

Negro

patients

of

the

Negro

doc-

tor

are

poor.

8

Furthermore,

Myrdal

cited

Carter

G.

Woodson

who

estimated

the

proportion

of

Negro

trade

that

goes

to

the

Negro

doctor

to

be

60

percent.

Wood-

son

went

on

to

say

more

bluntly

that

"the

large

number

of

Negro

leaders

who

after

preaching

race

380

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,1985

BLACK

MIDDLE-CLASS

PATIENTS

patronage

and

even

boasting

of

our

competent

physicians

and

surgeons

as

proof

of

race

progress,

nevertheless

have

employed

white

surgeons

in

undergoing

operations."9

In

1969,

Michel

Richard10

published

a

well-

documented

study

which

examined

the

profes-

sional

experiences

of

98

doctors

practicing

in

New

York

City.

Richard

found

that

many

Negro

pa-

tients

and

Negro

doctors

were

in

unwitting

collu-

sion

to

send

Negro

patients

to

white

doctors.

A

quotation

from

this

work

bears

out

the

point:

Sadly

enough,

it

has

been

observed

that

black

patients

and

Negro

physicians

themselves

have

helped

to

hold

down

the

number

of

specialists.

In

the

past,

at

any

rate,

Negro

patients

preferred

white

specialists

because

they

believe

them

to

be

more

competent,

and

Negro

doctors

often

referred

their

black

patients

to

white

specialists

on

the

assumption

that

they

would

be

reluctant

to

see

such

patients

on

a

continuing

basis,

whereas

the

Negro

spe-

cialist

might

"steal"

them.10

Additionally,

Richard

gave

the

incomes

of

the

doctors,

and

observed

that

although

the

average

Negro

doctor

in

the

sample

received

a

higher

in-

come

than

the

average

American

citizen,

his

in-

come

was

much

smaller

than

that

of

the

average

white

doctor.

10

What

was

true

in

1934

and

1969

is

still

true

to-

day:

the

black

middle-class

has

a

great

tendency

to

gravitate

to

the

white

physician.

Patients

have

expectations

not

just

of

what

a

physician

does

but

of

who

a

physician

is;

these

expectations

influence

satisfaction.

These

problems

resolve

themselves

as

marketplace

problems

and

involve

managing

a

service

or

a

product

so

that

it

can

be

sold

to

cus-

tomers

(patients).

The

customer's

perception

is,

as

much

if

not,

more

important

than

the

actual

qual-

ity

of

the

product.

METHODOLOGY

A

survey

was

designed

to

sample

opinions

of

physicians

attending

the

annual

meeting

of

the

National

Medical

Association,

Chicago,

July

30-

August

4,

1983.

The

survey

was

constructed

in

two

steps.

First,

attendees

at

a

Region

III

meeting

of

the

National

Medical

Association

at

Jackson-

ville,

Florida,

June

23-26,

1983,

were

asked

to

con-

tribute

descriptions

of

techniques

they

used

to

attract

the

black

middle-class

patient.

The

20

re-

spondents

contributed

86

descriptions.

Second,

the

descriptions

were

grouped

by

three

judges

into

25

areas.

The

three

judges

included

a

black

physi-

cian,

a

social

scientist,

and

a

data

analyst.

The

25

areas

were

placed

on

the

survey

form

to

be

rated

by

respondents.

A

copy

of

the

survey

form

is

in-

cluded

as

Table

1.

A

rating

scale

was

constructed

to

assess

the

respondent's

opinion

of

the

item's

utility

in

attracting

black

middle

class

patients.

The

scale

asked

the

respondent

to

rate

the

scale

as

"1

=

Extremely

Useful"

to

"4

=

Not

Very

Use-

ful."

The

respondent

could

have

also

rated

the

item

as

"5

=

Does

not

make

a

difference."

One

hundred

copies

of

the

single

sheet

survey

form

were

distributed

at

the

registration

desk

at

the

Na-

tional

Medical

Association

meeting

in

Chicago.

Respondents

could

have

returned

the

form

at

the

meeting

or

by

mail.

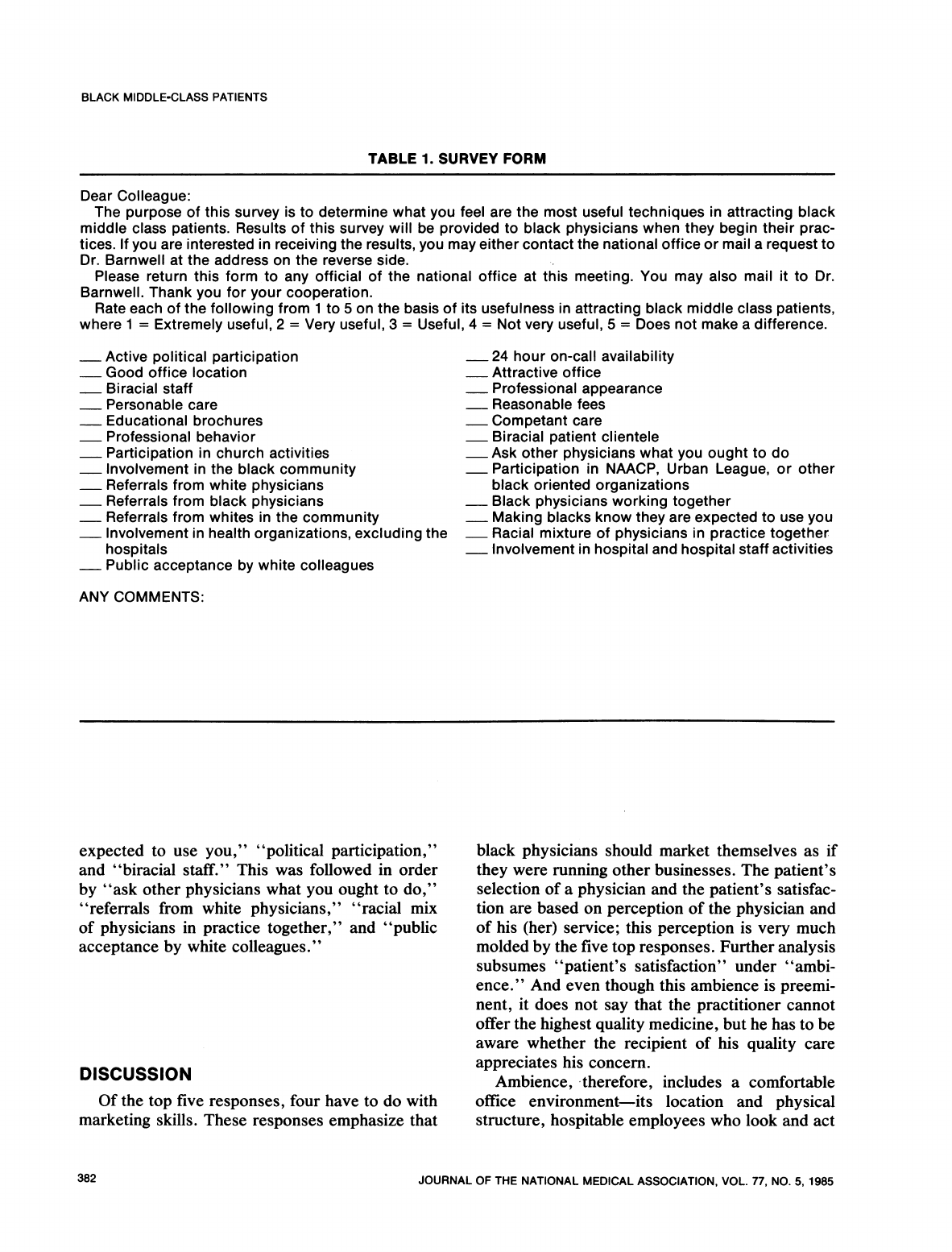

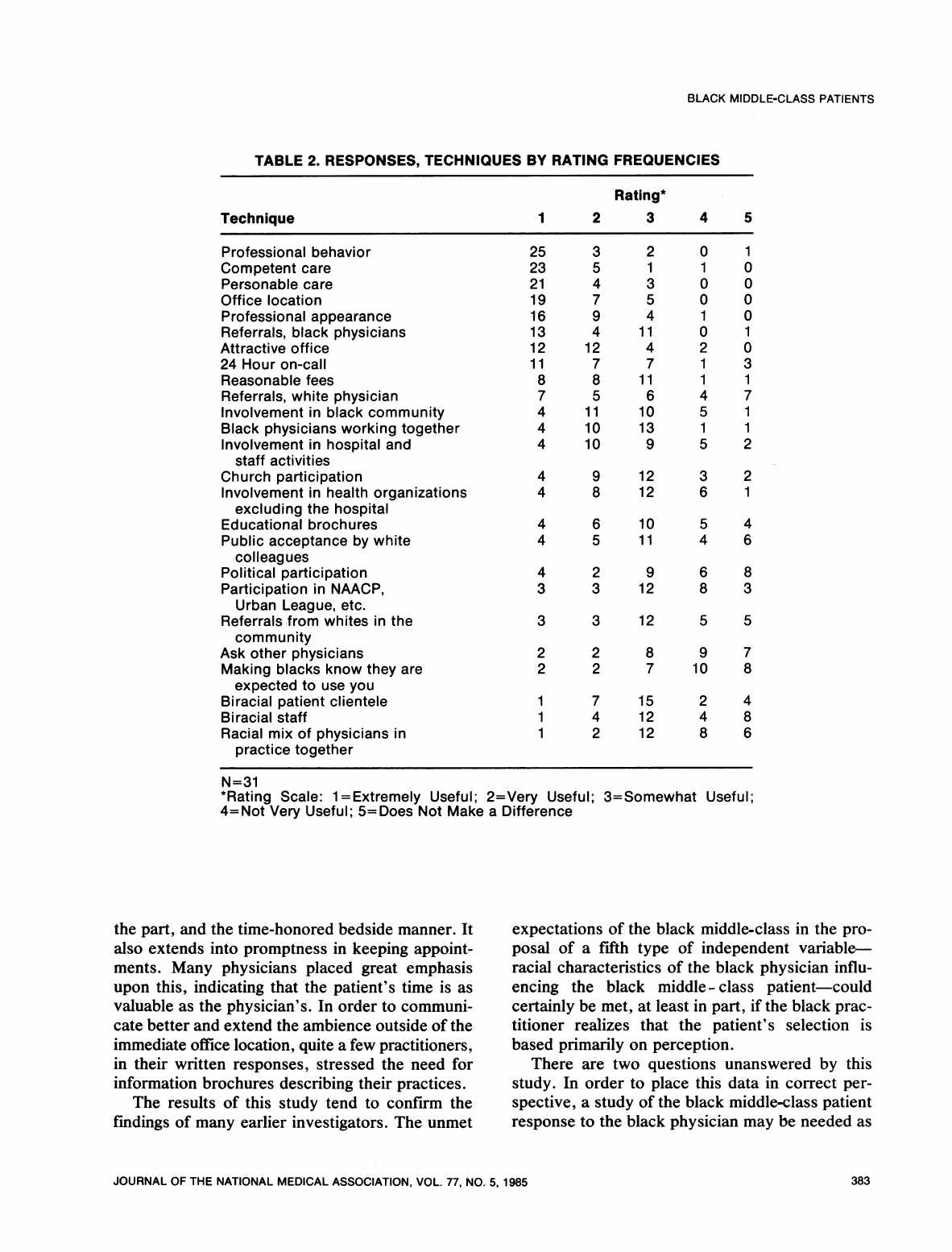

RESULTS

Thirty-one

survey

forms

were

returned.

The

low

rate

of

response

may

be

attributable,

in

part,

to

attitudes

physicians

have

toward

marketing

their

services.

Table

2

presents

the

results,

ranked

by

techniques

rated

as

most

useful.

Professional

behavior

was

judged

most

useful,

followed

by

competent

and

personable

care.

Office

location

and

attractiveness

were

also

judged

to

be

effective

techniques.

Of

all

sources

of

referrals

asked

to

be

rated,

referrals

from

black

physicians

were

judged

to

be

most

effective.

The

technique

judged

least

effective

was

"mak-

ing

blacks

know

they

are

expected

to

see

you."

"Ask

other

physicians

what

you

ought

to

do"

was

next

in

order

of

least

favorable

ratings.

"Partici-

pation

in

the

NAACP,

Urban

League,

or

other

black

oriented

organizations"

and

"racial

mix

of

physicians

in

practice

together"

were

tied

for

the

third

least

useful

rating.

The

techniques

most

often

rated

as

not

making

a

difference

were

"making

blacks

know

they

are

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,

1985

381

BLACK

MIDDLE-CLASS

PATIENTS

TABLE

1.

SURVEY

FORM

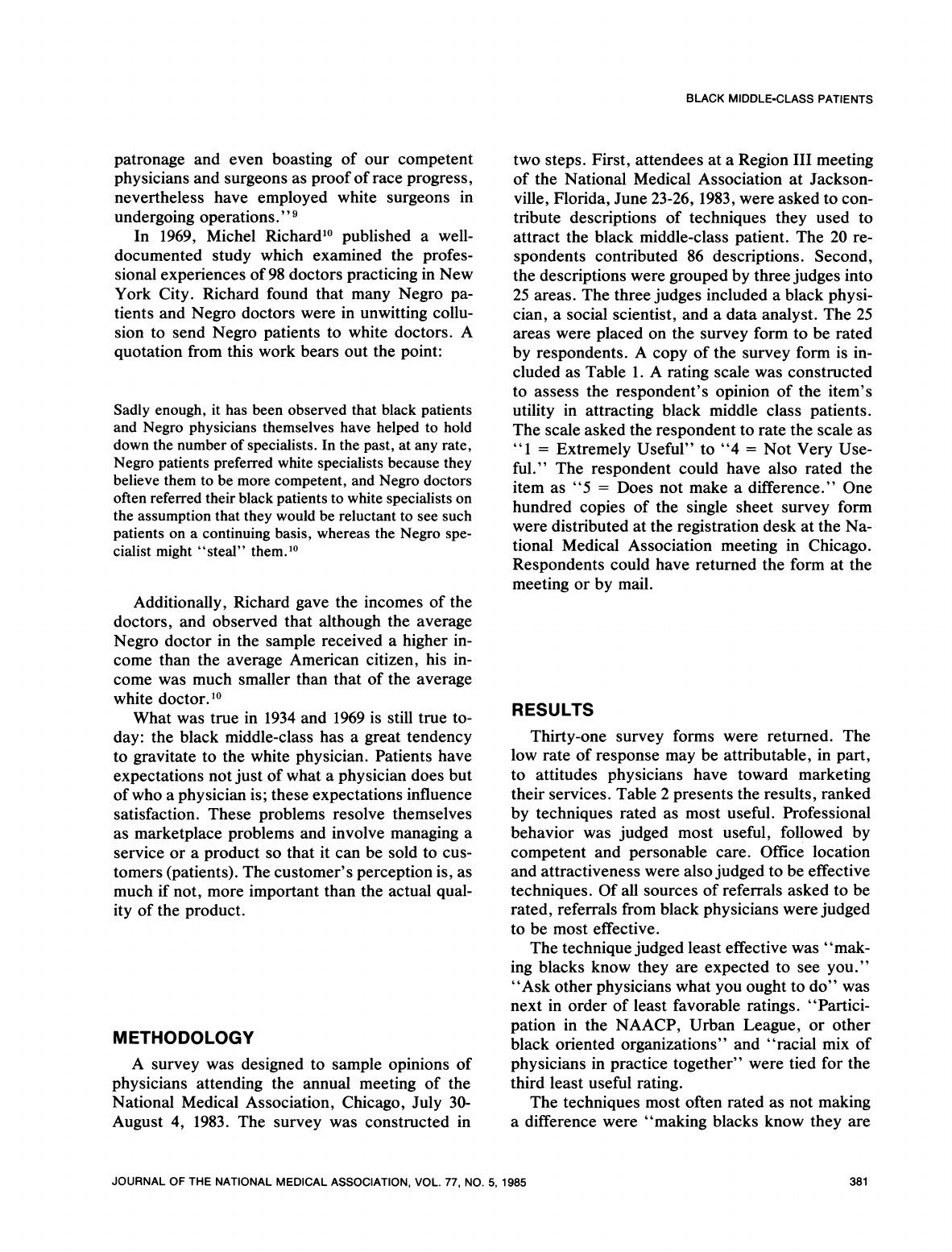

Dear

Colleague:

The

purpose

of

this

survey

is

to

determine

what

you

feel

are

the

most

useful

techniques

in

attracting

black

middle

class

patients.

Results

of

this

survey

will

be

provided

to

black

physicians

when

they

begin

their

prac-

tices.

If

you

are

interested

in

receiving

the

results,

you

may

either

contact

the

national

office

or

mail

a

request

to

Dr.

Barnwell

at

the

address

on

the

reverse

side.

Please

return

this

form

to

any

official

of

the

national

office

at

this

meeting.

You

may

also

mail

it

to

Dr.

Barnwell.

Thank

you

for

your

cooperation.

Rate

each

of

the

following

from

1

to

5

on

the

basis

of

its

usefulness

in

attracting

black

middle

class

patients,

where

1

=

Extremely

useful,

2

=

Very

useful,

3

=

Useful,

4

=

Not

very

useful,

5

=

Does

not

make

a

difference.

Active

political

participation

24

hour

on-call

availability

Good

office

location

Attractive

office

Biracial

staff

Professional

appearance

_

Personable

care

Reasonable

fees

Educational

brochures

Competant

care

Professional

behavior

Biracial

patient

clientele

Participation

in

church

activities

Ask

other physicians

what

you

ought

to

do

Involvement

in

the

black

community

Participation

in

NAACP,

Urban

League,

or

other

Referrals

from

white

physicians

black

oriented

organizations

Referrals

from

black

physicians

Black

physicians

working

together

Referrals

from

whites

in

the

community

Making

blacks

know

they

are

expected

to

use

you

Involvement

in

health

organizations,

excluding

the

Racial

mixture

of

physicians

in

practice

together

hospitals

Involvement

in

hospital

and

hospital

staff

activities

_

Public

acceptance

by

white

colleagues

ANY

COMMENTS:

expected

to

use

you,"

"political

participation,"

and

"biracial

staff."

This

was

followed

in

order

by

"ask

other

physicians

what

you

ought

to

do,"

"referrals

from

white

physicians,"

"racial

mix

of

physicians

in

practice

together,"

and

"public

acceptance

by

white

colleagues."

DISCUSSION

Of

the

top

five

responses,

four

have

to

do

with

marketing

skills.

These

responses

emphasize

that

black

physicians

should

market

themselves

as

if

they

were

running

other

businesses.

The

patient's

selection

of

a

physician

and

the

patient's

satisfac-

tion

are

based

on

perception

of

the

physician

and

of

his

(her)

service;

this

perception

is

very

much

molded

by

the

five

top

responses.

Further

analysis

subsumes

"patient's

satisfaction"

under

"ambi-

ence."

And

even

though

this

ambience

is

preemi-

nent,

it

does

not

say

that

the

practitioner

cannot

offer

the

highest

quality

medicine,

but

he

has

to

be

aware

whether

the

recipient

of

his

quality

care

appreciates

his

concern.

Ambience,

therefore,

includes

a

comfortable

office

environment-its

location

and

physical

structure,

hospitable

employees

who

look

and

act

382

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,

1985

BLACK

MIDDLE-CLASS

PATIENTS

TABLE

2.

RESPONSES,

TECHNIQUES

BY

RATING

FREQUENCIES

Rating*

Technique

1

2

3

4

5

Professional

behavior

25

3

2

0

1

Competent

care

23

5

1

1

0

Personable

care

21

4

3

0

0

Office

location

19

7

5

0 0

Professional

appearance

16

9

4

1

0

Referrals,

black

physicians

13

4

11

0

1

Attractive

office

12

12

4

2

0

24

Hour

on-call

11

7

7

1

3

Reasonable

fees

8

8

11

1

1

Referrals,

white

physician

7

5

6

4 7

Involvement

in

black

community

4

11

10

5

1

Black

physicians

working

together

4

10

13

1

1

Involvement

in

hospital

and

4

10

9

5

2

staff

activities

Church

participation

4

9

12

3

2

Involvement

in

health

organizations

4

8

12

6

1

excluding

the

hospital

Educational

brochures

4

6

10

5

4

Public

acceptance

bywhite

4

5

11

4

6

colleagues

Political

participation

4

2

9

6 8

Participation

in

NAACP,

3

3

12

8

3

Urban

League,

etc.

Referrals

from

whites

in

the

3

3

12

5

5

community

Ask

other

physicians

2 2

8

9

7

Making

blacks

know

they

are

2

2

7

10

8

expected

to

use

you

Biracial

patient

clientele

1

7

15

2

4

Biracial

staff

1

4

12

4

8

Racial

mix

of

physicians

in

1

2

12

8

6

practice

together

N=31

*Rating

Scale:

1=Extremely

Useful;

2=Very

Useful;

3=Somewhat

Useful;

4=Not

Very

Useful;

5=Does

Not

Make

a

Difference

the

part,

and

the

time-honored

bedside

manner.

It

also

extends

into

promptness

in

keeping

appoint-

ments.

Many

physicians

placed

great

emphasis

upon

this,

indicating

that

the

patient's

time

is

as

valuable

as

the

physician's.

In

order

to

communi-

cate

better

and

extend

the

ambience

outside

of

the

immediate

office

location,

quite

a

few

practitioners,

in

their

written

responses,

stressed

the

need

for

information

brochures

describing

their

practices.

The

results

of

this

study

tend

to

confirm

the

findings

of

many

earlier

investigators.

The

unmet

expectations

of

the

black

middle-class

in

the

pro-

posal

of

a

fifth

type

of

independent

variable-

racial

characteristics

of

the

black

physician

influ-

encing

the

black

middle

-

class

patient-could

certainly

be

met,

at

least

in

part,

if

the

black

prac-

titioner

realizes

that

the

patient's

selection

is

based

primarily

on

perception.

There

are

two

questions

unanswered

by

this

study.

In

order

to

place

this

data

in

correct

per-

spective,

a

study

of

the

black

middle-class

patient

response

to

the

black

physician

may

be

needed

as

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,

1985

383

BLACK

MIDDLE-CLASS

PATIENTS

a

corollary.

The

authors

believe

that

this

is

not

necessary

because

the

literature

is

replete

with

studies

of

consumer

responses

and

such

a

study

would

be

a

replication

that

would

yield

little

addi-

tional

information.

A

second

unanswered

question

is

that

raised

by

Carter

G.

Woodson

50

years

ago.

He

wrote

about

the

lack

of

confidence

of

black

people

in

the

com-

petence

of

the

black

physician.

He

observed

that

white

physicians

have

to

talk

to

black

patients

to

make

them

believe

that

doctors

of

their

own

race

are

any

good.9

This

observation

is

not

a

superficial

one

but

one

that

goes

to

the

bone;

when

this

is

combined

with

Reitzes's

assertion

that

black

doc-

tors

often

refer

their

black

patients

to

white

spe-

cialists,

it

goes

even

deeper

to

the

very

marrow

of

the

soul

of

black

people."

The

authors

believe

that

there

is

an

immediate

need

of

a

market

concept

approach

in

the

doctor-

patient

interaction.

This

is

a

"physician-needs"

approach

that

involves

analytic,

diagnostic,

and

prescriptive

techniques

to

help

a

doctor

market

his

service

more

effectively.

The

results

of

this

pres-

ent

study

would

be

valuable

for

this

prescription.

Lenox

has

described

the

effective

use

of

such

an

approach

for

use

in

nonprofit

organizations.'2

A

first

step

is

to

construct

goals,

target

audiences,

identify

needs

and

resources,

and

then

consider

how

congruent

these

are

with

one

another.

A

"'marketing

audit"

provides

a

tool

for

developing

and

controlling

market

activities

by

helping

to

identify

factors

to

be

considered

and

by

putting

them

in

measurable

terms.

Creation

of

a

marketing

program

for

black

physicians

would

include:

a

physician

working

with

a

marketing

firm

to

iden-

tify

the

goals

of

the

practice,

targeting

an

audi-

ence,

and

a

marketing

audit.

The

physician

then

should

be

able

to

proceed

with

a

clear

customer

orientation.

CONCLUSIONS

The

results

of

this

study

make

it

clear

that

black

physicians

understand

the

importance

of

marketing-

based

skills

in

the

development

of

a

successful

practice.

In

order

to

be

competitive,

survive,

and

thrive,

black

physicians

should

consider

the

use

of

marketing

specialists

to

assist

them

in

implement-

ing

specific

marketing

goals.

This

is

especially

true

when

one

reflects

upon

the

public

perception

of

the

black

physician's

competence,

and

the

reluc-

tance,

documented

by

other

investigators,

that

some

black

physicians

display

in

referring

their

patients

to

other

black

practitioners.

The

findings

seem

to

indicate

that

black

doctors

do

not

differ

much

from

their

white

counterparts

in

their

per-

ceptions

of

what

it

takes

to

"sell"

a

practice.

Be-

cause

of

societal

beliefs,

ones

that

are

so

institu-

tionalized

that

even

blacks

accept

them,

black

doctors

face

especially

difficult

marketing

prob-

lems.

Indeed,

these

problems

seem

so

severe

that

they

are

reflected

in

dramatic

wage

differentials

between

black

and

white

practitioners

in

compa-

rable

specialites.

Literature

Cited

1.

Greenley

JR,

Schoenherr

RA.

Organizational

effects

on

client

satisfaction

with

humaneness

of

service.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1981;

22:2-18.

2.

Shortell

S,

Richardson

W,

Lo

Gerfo

J,

et

al.

The

re-

lationship

among

dimensions

of

health

services

in

two

provider

systems:

A

causal

model

approach.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1977;

18:139-159.

3.

Tessler

R,

Mechanic

D.

Consumer

satisfaction

with

prepaid

group

practice:

A

comparative

study.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1975;

16:95-113.

4.

Ben-Sira

Z.

The

function

of

the

professional's

affec-

tive

behavior

in

client

satisfaction:

A

revised

approach

to

social

interaction

theory.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1976;

17:3-11.

5.

Ben-Sira

Z.

Affective

and

instrumental

components

in

the

physician-patient

relationship.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1980;

21:170-180.

6.

Ross

CE,

Mirowsky

J,

Duff

RS.

Physician

status

characteristics

and

client

satisfaction

in

two

types

of

medi-

cal

practice.

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1982;

23:317-329.

7.

Lloyd

SM,

Johnson

DG.

Practice

patterns

of

black

physicians:

Results

of

a

survey

of

Howard

University

Col-

lege

of

Medicine

Alumni.

J

Nat

Med

Assoc

1982;

74:129-

141.

8.

Myrdal

G.

An

American

Dilemma.

New

York:

Harper

and

Row,

1944,

p

323.

9.

Woodson

C.

The

Negro

Professional

Man

and

the

Community.

Washington,

DC:

The

Association

for

the

Study

of

Negro

Life

and

History,

Inc.,

1934,

p

96.

10.

Richard

MP.

The

Negro

Physician:

Babbitt

or

Revo-

lutionary?

J

Health

Soc

Behav

1969;

10:265-274.

11.

Reitzes

D.

Negroes

and

Medicine.

Cambridge:

Har-

vard

University

Press,

1958,

pp

117,

277-278,

347.

12.

Lenox

C.

Marketing

of

community

information

serv-

ices.

The

Information

Community:

An

Alliance

for

Progress

1981;

18:123-135.

384

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION,

VOL.

77,

NO.

5,

1985