ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

PB

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

427

Impact of Scribes on Physician Satisfaction, Patient

Satisfaction, and Charting Efficiency: A Randomized

Controlled Trial

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE Scribes are increasingly being used in clinical practice despite a lack of

high-quality evidence regarding their effects. Our objective was to evaluate the

effect of medical scribes on physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and chart-

ing efciency.

METHODS We conducted a randomized controlled trial in which physicians in an

academic family medicine clinic were randomized to 1 week with a scribe then

1 week without a scribe for the course of 1 year. Scribes drafted all relevant

documentation, which was reviewed by the physician before attestation and sign-

ing. In encounters without a scribe, the physician performed all charting duties.

Our outcomes were physician satisfaction, measured by a 5-item instrument that

included physicians’ perceptions of chart quality and chart accuracy; patient sat-

isfaction, measured by a 6-item instrument; and charting efciency, measured by

time to chart close.

RESULTS Scribes improved all aspects of physician satisfaction, including over-

all satisfaction with clinic (OR = 10.75), having enough face time with patients

(OR = 3.71), time spent charting (OR = 86.09), chart quality (OR = 7.25), and

chart accuracy (OR = 4.61) (all P values <.001). Scribes had no effect on patient

satisfaction. Scribes increased the proportion of charts that were closed within

48 hours (OR =1.18, P = .028).

CONCLUSIONS To our knowledge, we have conducted the rst randomized con-

trolled trial of scribes. We found that scribes produced signicant improvements

in overall physician satisfaction, satisfaction with chart quality and accuracy, and

charting efciency without detracting from patient satisfaction. Scribes appear

to be a promising strategy to improve health care efciency and reduce physi-

cian burnout.

Ann Fam Med 2017;15:427-433. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2122.

INTRODUCTION

E

lectronic health records (EHRs) have radically transformed the

practice of medicine. Driven by federal meaningful use incentives

and penalties,

1,2

more than 95% of US hospitals and 56% of office-

based physicians have adopted EHRs.

3,4

Electronic health records hold

promise to improve patient safety, quality of care, physician efficiency and

performance, patient-physician communication, patient participation, cost

of care, and health outcomes.

5-9

There is also growing evidence, however,

that in their current state, EHRs are associated with decreased physician

productivity and revenue,

10

negative patient-physician interactions and

relationships,

11

and widespread physician dissatisfaction.

12-14

More than one-half of all US physicians experience burnout, with pri-

mary care physicians having one of the highest rates.

15

Among the largest

contributors to burnout is a growing clerical workload.

16-18

For every hour

physicians provide direct face time to patients, 2 more hours are spent on

EHR and desk work.

19

Many physicians leave most charting to the end of

Risha Gidwani, DrPH

1,2

Cathina Nguyen, MPH

3

Alexis Kofoed, MPH

2

Catherine Carragee, BA

2

Tracy Rydel, MD

2

Ian Nelligan, MD, MPH

2

Amelia Sattler, MD

2

Megan Mahoney, MD

2

Steven Lin, MD

2

1

Center for Health Policy and Center for

Primary Care and Outcomes Research,

Stanford University School of Medicine,

Stanford University, Stanford, California

2

Division of Primary Care and Population

Health, Department of Medicine, Stanford

University School of Medicine, Stanford

University, Stanford, California

3

Division of Epidemiology, Department

of Health Research and Policy, Stanford

University School of Medicine, Stanford

University, Stanford, California

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Steven Lin, MD

Suite 405, 211 Quarry Rd

MC 5985

Palo Alto, CA 94304

stevenlin@stanford.edu

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

428

the day, and spend 1 to 2 hours each night working on

the EHR.

19

One strategy to decrease clerical burden is the

use of scribes. Scribes are nonlicensed team members

trained to document patient encounters in real time

under the direct supervision of a physician.

20

Scribes

do not act independently but may assist with chart-

ing, recording laboratory and radiology results, and

supporting physician workflow with EHR data entry.

21

Although the use of scribes as physician extenders in

emergency departments has been reported as early

as the 1970s, it is only recently that the popularity of

scribes has skyrocketed.

22

Scribes are currently being

used in more than 1,000 hospitals and clinics across

44 states.

23

It is estimated that by 2020, there will be

100,000 scribes in the United States, or 1 scribe for

every 9 physicians.

23

Despite the increasing presence of scribes, method-

ologically rigorous studies regarding their impact are

lacking. Two systematic reviews found, using data from

observational studies, that scribes may improve rev-

enue, patient and physician satisfaction, productivity,

efficiency, and the quality of patient-physician interac-

tions.

24,25

There has been no randomized controlled

study of scribes, and few studies have been undertaken

in the primary care setting. Given that most office

visits are to primary care physicians,

26

research in this

setting is particularly warranted.

METHODS

Design

Physicians were randomly assigned to 1 week practic-

ing with a scribe then 1 week without a scribe for the

course of 52 weeks. Randomization at the physician-

week level was chosen instead of randomizing at the

level of patients, as variations in length of patient

appointments posed challenges for proper allocation

of scribes across patients and was too disruptive to

normal clinic flow. We also chose not to randomize

at the physician level, as the small number of physi-

cians included in this study would not properly protect

against imbalance in the scribe and no-scribe groups.

During the week in which a physician was assigned

a scribe, the scribe attended all appointments and

drafted all relevant documentation, including the his-

tory and physical findings, objective examination find-

ings, laboratory and radiology results, assessment and

plan, and patient instructions. The physician reviewed

the note, attested to its accuracy, and signed it before

the chart was closed. During the week in which the

physician was not assigned a scribe, the physician per-

formed all charting duties. The EHR used was the out-

patient version of Epic (Epic Systems Corporation).

The study was conducted from July 2015 to June

2016. Four physicians and 2 scribes participated in

the study, which was undertaken in a family medi-

cine clinic associated with a large academic medical

center in Northern California. All physicians were

board-certified in family medicine and had an aver-

age of 6 years of practice experience. None had prior

experience working with scribes. As part-time clini-

cians, each physician in the study had 4, 4-hour clinic

sessions per week when data were collected. Both

scribes were college graduates who completed an

80-hour training course administered by a commercial

scribe company (Elite Medical Scribes). One scribe

was assigned to 2 physicians in the first 6 months of

the study; in the second 6 months, that scribe was

assigned to the other 2 physicians. This allowed us to

test for any learning effects that may have occurred in

the physician-scribe dyads.

Physician Satisfaction

Physician satisfaction was measured by a self-

administered 5-item questionnaire. Answers were

recorded using a 7-point Likert scale, with a value of

1 indicating strong disagreement (strongly dissatis-

fied) and 7 indicating strong agreement (strongly

satisfied). Physicians were offered 1 questionnaire

after each 4-hour clinic session. For data analyses, we

dichotomized each answer into strongly satisfied vs

non–strongly satisfied (7 vs 1 to 6) because of skewness

in results. In sensitivity analyses, we tested alternate

ways to characterize the outcome by dichotomizing

scores from 1 to 5 and 6 to 7. To investigate the effect

of scribes on aspects of physician satisfaction, each

item was assessed using its own fixed-effects logistic

regression equation with the physician questionnaire

as the unit of analysis and accommodating multiple

observations per physician. We adjusted for whether

the interaction was new so we could test any learning

effects over time within physician-scribe dyads. Specifi-

cally, we investigated whether a physician paired with a

scribe had significantly lower satisfaction scores during

the first quarter than during the second quarter that the

same physician and scribe were paired. We adjusted for

multiple hypothesis testing using the conservative Bon-

ferroni correction, resulting in an α of .01.

27

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was measured using a shortened,

validated, 6-item questionnaire designed for the pri-

mary care setting.

28

Each patient was asked to complete

the questionnaire immediately after the appointment.

To encourage completion, questionnaires were made

anonymous. Answers were recorded using a 7-point

Likert scale, with 1 indicating strong disagreement

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

429

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

428

(strongly dissatisfied) and 7 indicating strong agreement

(strongly satisfied). Each response was dichotomized

into strongly satisfied (7) vs non–strongly satisfied (1 to

6) because of skewness of the distribution. In sensitivity

analyses, we tested alternate ways to characterize the

outcome, specifically dichotomizing scores from 1 to 5

and 6 to 7. We investigated each item separately using

its own fixed-effects logistic regression equation with

the patient questionnaire as the unit of analysis, clus-

tering questionnaires within physician. All tests were

evaluated against a Bonferroni-corrected α of .007.

Charting Efciency

Physician efficiency was measured as the time to chart

close, which is calculated as the time from appointment

start to the physician signing the chart note, which is

marked by timestamps in the EHR. Industry standards

(Medicare documentation guidelines)

29

state that charts

should be completed within 48 hours; therefore, we

dichotomized time to close chart into 48 hours or less

vs more than 48 hours. We ran fixed-effects logistic

regression with chart as the unit of analysis, accommo-

dating clustering of charts within physician.

This study was exempted from formal review by

the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University

School of Medicine.

RESULTS

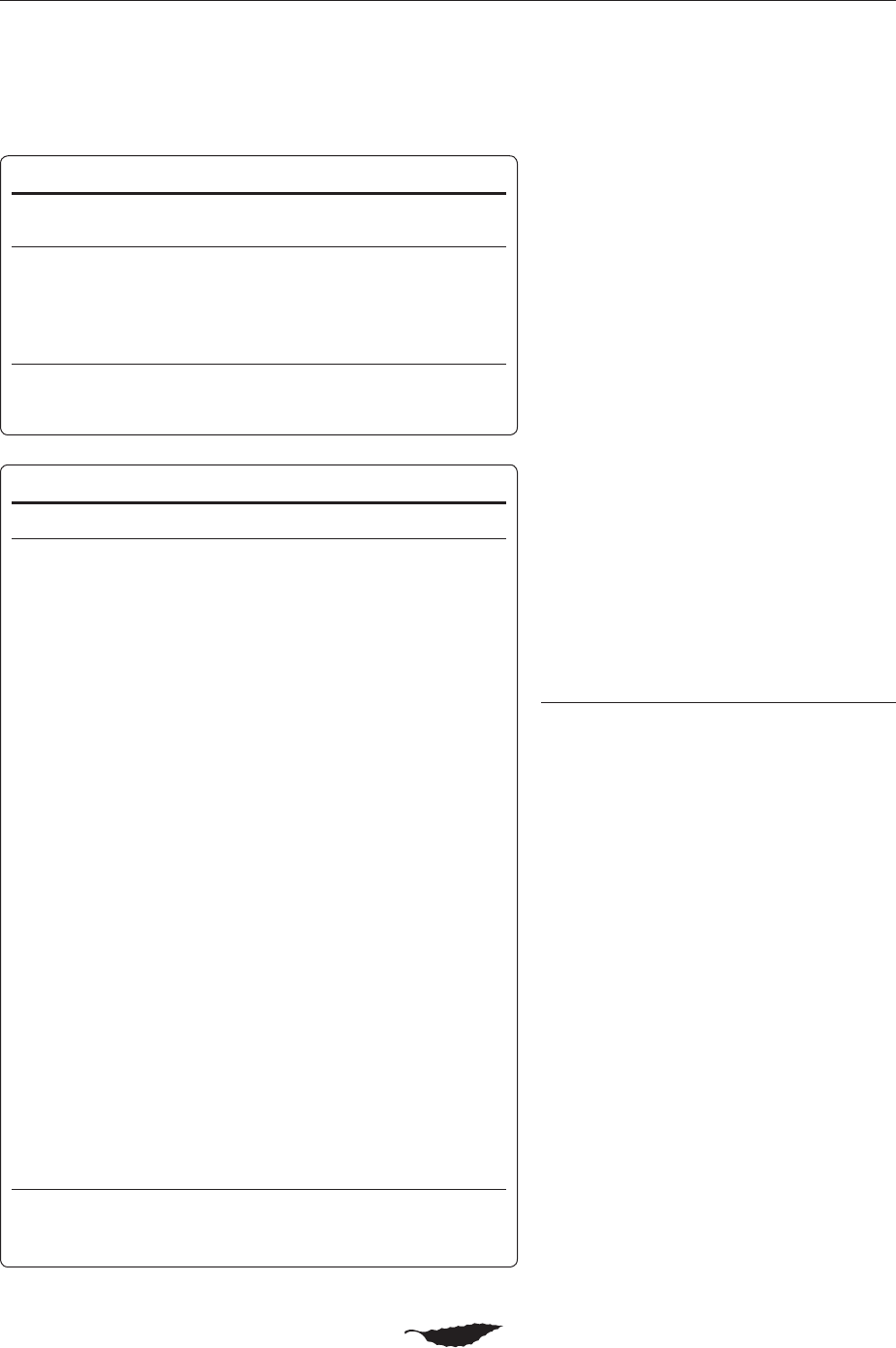

Physician Satisfaction

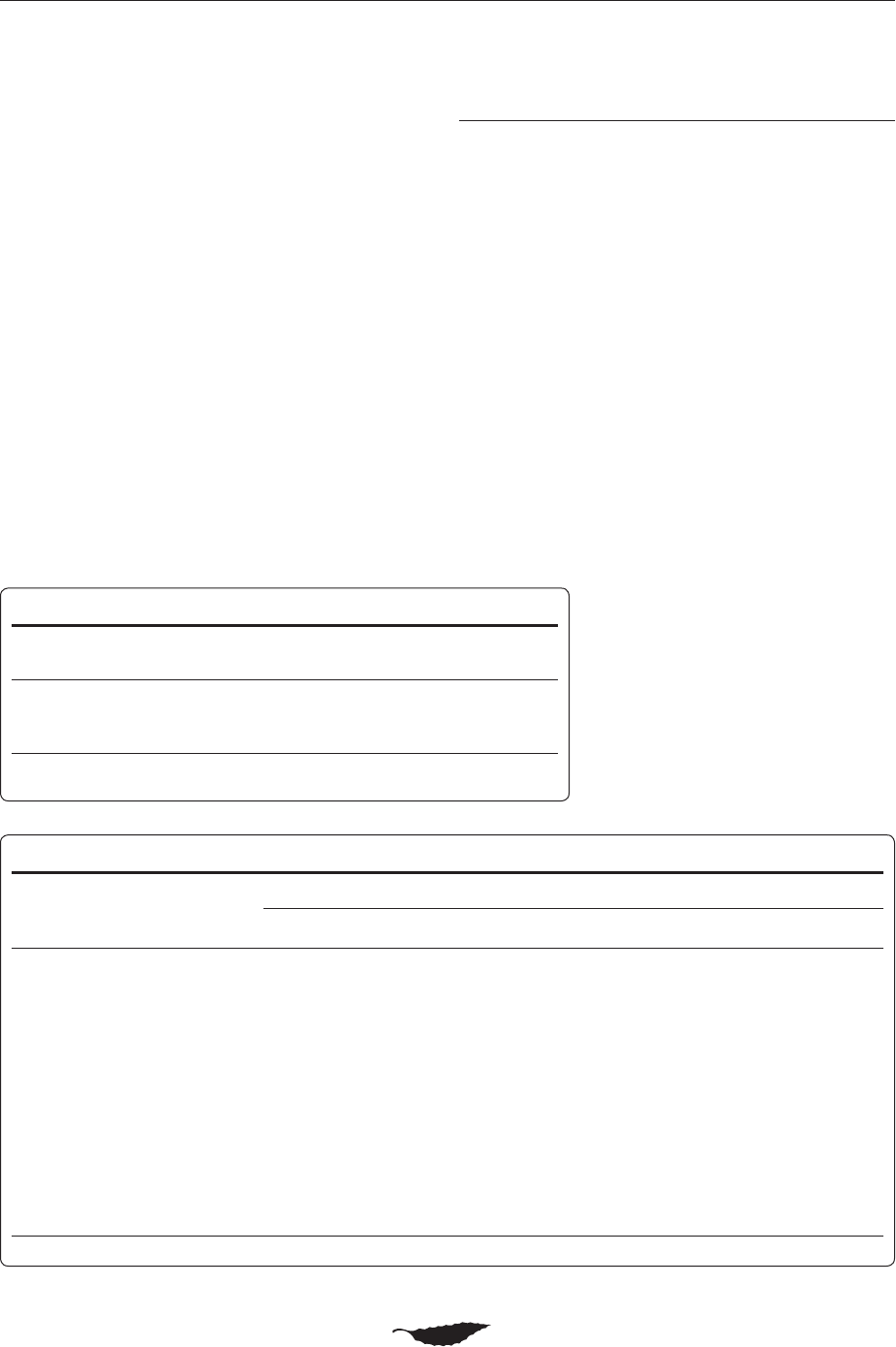

A total of 361 physician satisfaction questionnaires

were completed, for a 73.1% response rate (Table 1).

Physicians were more likely to complete a question-

naire when a scribe was present (53.2%) than when a

scribe was not (46.8%). Scribes produced significantly

higher physician satisfaction in all aspects of care

and charting (Tables 2-4). Physicians who worked

with a scribe had 10.75 the adjusted odds of express-

ing high satisfaction with their clinic that day, 3.71

the adjusted odds of having enough face time with

patients, and 86.09 the adjusted odds of expressing

high satisfaction with the amount of time they spent

charting (all P <.001). Scribes increased physician

satisfaction with the quality and accuracy of their

charts. Physicians reported 7.25 the adjusted odds of

being satisfied with their chart quality when a scribe

was present (P <.001). There was no

difference in satisfaction with quality

when the physician-scribe dyad was

new vs established (P = .451). Physi-

cians reported 4.61 the adjusted odds

of being satisfied with chart accuracy

when a scribe was present (P < .0 01).

Physicians did report being less

satisfied with chart accuracy when

the physician-scribe dyad was new

(adjusted OR = 0.39) vs established,

Table 1. Survey Questionnaire Completion

Characteristic

Scribe

No. (%)

No Scribe

No. (%)

Total

No.

Patient satisfaction questionnaires completed 808 (54.8) 667 (45.2) 1,475

a

Physician satisfaction questionnaires completed 192 (53.2) 169 (46.8) 361

b

Charts analyzed for efciency 1,381 (52.4) 1,255 (47.6) 2,636

a

Of 1,681 questionnaires distributed, 87.7% were returned.

b

Of 494 questionnaires distributed, 73.1% were returned.

Table 2. Physician and Patient Questionnaire Results, Unadjusted

Characteristic

Questionnaire Score

a

1

No. (%)

2

No. (%)

3

No. (%)

4

No. (%)

5

No. (%)

6

No. (%)

7

No. (%)

Physician questionnaire (n = 361)

Overall satisfaction 2 (0.6) 8 (2.2) 16 (4.4) 39 (10.8) 69 (19.1) 122 (33.8) 105 (29.1)

Face time with patients 2 (0.6) 6 (1.7) 16 (4.4) 34 (9.4) 69 (19.1) 90 (24.9) 144 (39.9)

Charting time 8 (2.2) 13 (3.6) 26 (7. 2) 67 (18.6) 66 (18.3) 87 (24.1) 94 (26.0)

Chart quality 3 (0.8) 5 (1.4) 14 (3.9) 27 (7.5) 69 (19.1) 114 ( 31.6) 129 (35.7)

Chart accuracy 2 (0.6) 4 (1.1) 10 (2.8) 36 (10.0) 68 (18.8) 106 (29.4) 135 ( 37.4)

Patient questionnaire (n = 1,475)

Physician explains things to me 8 (0.5) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.1) 2 ( 0.1) 8 (0.5) 84 (5.7) 1,372 (93.0)

Physician listens to me 8 (0.5) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.1) 3 (0.2) 10 (0.7) 67 (4.5) 1,386 (94.0)

Physician cares about me 7 (0.5) 1 (0.1) 0 (0.0) 5 (0.3) 17 (1.2) 72 (4.9) 1,366 (93.1)

Physician encourages me to talk 7 (0.5) 1 (0.1) 1 (01) 5 (0.3) 19 (1.3) 84 (5.7) 1,354 (92.0)

Physician spends enough time with me 7 (0.5) 1 (0.1) 1 (0.1) 6 (0.4) 22 (1.5) 97 (6.6) 1,341 (90.9)

I would recommend this physician 7 (0.5) 1 (0.1) 1 (0.1) 5 (0.3) 10 (0.7) 75 (5.1) 1,375 (93.3)

a

Responses scored on a scale from 1 to 7 where 1 indicates least satisfaction, and 7 indicates most satisfaction.

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

430

but results were not significant using a Bonferroni-

corrected α of .01 (P = .019). There was no difference

in significance of the impact of scribes on physician

survey results when we dichotomized the responses

into 1 to 5 vs 6 to 7.

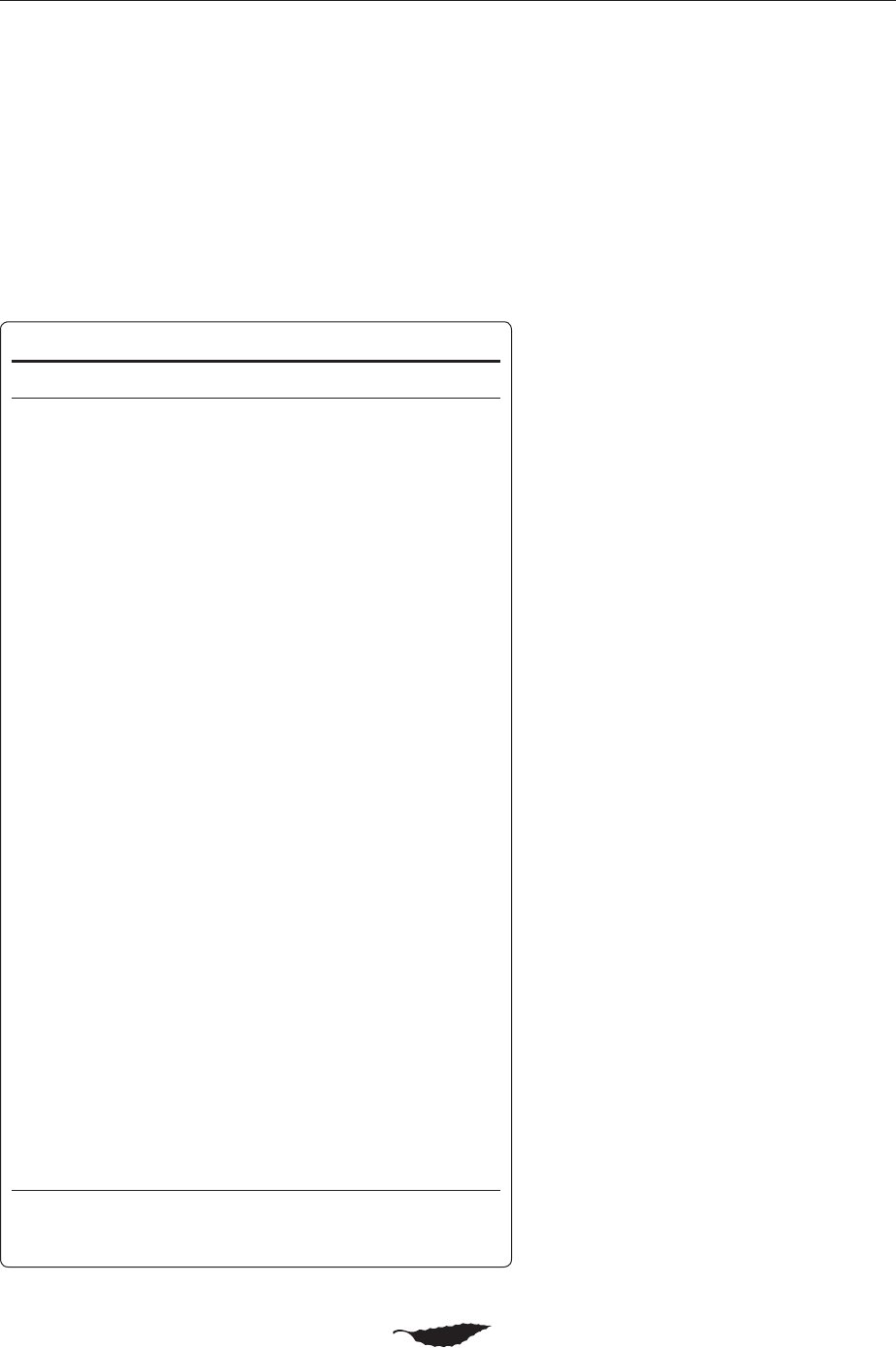

Patient Satisfaction

A total of 1,475 patient satisfaction questionnaires

were completed for an 87.7% response rate (Table 1).

Patients were more likely to complete a questionnaire

when a scribe was present (54.8%) than when a scribe

was not (45.2%). In adjusted analyses, there

were no significant differences in any aspect

of patient satisfaction between physician

visits in which a scribe was or was not pres-

ent (Table 2 and Table 5). Satisfaction across

patient questionnaires, however, was high

with or without a scribe, with more than

91% of patients in either group reporting

being highly satisfied with their care. There

was no difference in significance of the

impact of scribes on patient survey results

when we dichotomized the responses into 1

to 5 vs 6 to 7.

Charting Efciency

Scribes improved time to close chart. In

unadjusted analyses, 28.5% of charts that

were drafted by physicians were closed in 48

hours relative to 32.6% of charts drafted by

scribes. In adjusted analyses, scribed charts

had 1.18 the adjusted odds of being closed

within 48 hours compared with physician-

only charts (P = .028) (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, we have undertaken the

first randomized controlled trial evaluating

the effects of medical scribes. We found

that scribes significantly improved physi-

cian satisfaction across all measured aspects

of patient care and documentation. Scribes

improved physician-perceived chart qual-

ity and chart accuracy, as well as charting

efficiency as measured by the likelihood of

closing a chart within 48 hours.

When working with a scribe, physicians

were much more satisfied with how their

clinic went, the length of time they spent

face-to-face with patients, and the time

they spent charting. These findings suggest

that scribes may have a protective effect on

physicians’ well-being. Implementation of

team documentation is an important com-

ponent of achieving the Quadruple Aim,

30

a

patient-centered approach to care that also

emphasizes improving the work life of physi-

cians. Spending less time on documentation

frees up the physician to pursue direct clini-

Table 3. Physician Satisfaction, Unadjusted Results

Characteristic

Scribe Present

Median Score (IQR)

a

Scribe Not Present

Median Score (IQR)

a

Overall satisfaction 6 (6-7) 5 (4-6)

Face time with patients 6.5 (6-7) 5 (4-7)

Charting time 6 (6-7) 4 (3-5)

Chart quality 6 (6-7) 5 (5-6)

Chart accuracy 6 (6-7) 6 (5-7)

IQR = interquartile range.

a

Responses scored on a scale from 1 to 7 where 1 indicates least satisfaction, and 7 indicates

most satisfaction.

Table 4. Physician Satisfaction, Adjusted Results

Outcome OR 95% CI P Value

Overall satisfaction

Scribe 10.75 5.36-21.58 <.0 01

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.51 0.27-0.96 .038

Physician 2 0.78 0.36-1.71 .539

Physician 3 1.49 0.71-3.12 .288

Physician 4 0.15 0.06-0.41 <.0 01

Face time with patients

Scribe 3.71 1.91-7.21 <.0 01

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.73 0.37-1.46 .375

Physician 2 1.28 0.63-2.60 .498

Physician 3 4.71 2.35-9.44 <.0 01

Physician 4 0.11 0.04-0.31 <.001

Charting time

Scribe 86.09 19.58 -378.41 <.0 01

Physician 1, new interaction

a

1.04 0.56 -1.96 .891

Physician 2 1.75 0.70-4.35 .228

Physician 3 1.31 0.55 -3.16 .542

Physician 4 0.15 0.05-0.46 .001

Chart quality

Scribe 7.25 3.42-15.39 <.0 01

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.75 0.36-1.55 .435

Physician 2 1.34 0.60-3.01 .475

Physician 3 10.18 4.53-22.85 <.0 01

Physician 4 0.13 0.04-0.44 .001

Chart accuracy

Scribe 4.61 2.11-10. 0 6 <.0 01

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.38 0.17-0.85 .018

Physician 2 0.81 0.36 -1.81 .611

Physician 3 15.19 6.9-33.44 <.001

Physician 4 0.09 0.02-0.34 <.001

OR = odds ratio.

Note: Model B.

a

First interaction between scribe and physician.

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

431

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

430

cal care and care coordination, thus enhancing joy of

practice and preventing burnout. In academic centers,

scribes provide faculty physicians more time to teach

medical students and residents.

31

We found that not only were physicians satisfied

with the quality and accuracy of charting done by

scribes, they were more satisfied with scribed charts

than with their own. This finding is consistent with a

study suggesting that scribed notes are of higher qual-

ity than physician-only notes.

32

Patient encounters in

primary care are often highly complex; scribes enable

physicians to capture all the important details in the

note while communicating effectively with the patient

in the room.

During a typical day in the ambulatory setting,

49% of physician time is spent on EHR and desk work,

whereas only 27% is spent face-to-face with patients.

19

Physicians can use EHR shortcuts, such as copy and

paste,

33

but these actions are associated with a risk

of documentation error that can jeopardize patient

safet y.

34,35

In addition, documentation competes with

panel management and EHR inbox completion. It is

estimated that the average primary care physician

receives 76.9 EHR inbox notifications daily, requiring

an investment of approximately 66.8 minutes

per day.

36

Eliminating the burden of writing

notes affords more time for physicians to

attend to the tasks of panel management dur-

ing, not after, their workday.

Our study found no difference in patient

satisfaction between visits with or without

a scribe, perhaps because of ceiling effects;

patients expressed high satisfaction both

during visits with and without a scribe. Nev-

ertheless, we found that the presence of a

scribe did not decrease patient satisfaction.

This finding has been found in other nonran-

domized studies, even in settings as sensitive

as a urology practice.

37

Our study is the first to evaluate charting

efficiency in a randomized controlled man-

ner. We found that scribed charts were more

likely to be closed within 48 hours compared

with charts completed by physicians alone.

Charts that are completed in a timely man-

ner allow patient data to be accessed by

other physicians in the health care system,

which is particularly important to safety and

effective care coordination. Charts com-

pleted in a timely manner may also be more

accurate than those completed multiple days

after the patient’s visit.

This randomized controlled trial was con-

ducted at a single family medicine clinic in an

academic medical center. Although our unit

of analysis was a physicians’ day or patient

encounter, our study’s biggest limitation is

the relatively few physicians and scribes. Our

findings are positive with respect to physi-

cian satisfaction and efficiency, but future

randomized studies should be conducted

with large sample sizes and across multiple

institutions to improve the generalizability

of these findings. The physician satisfaction

instrument we used measured markers related

to joy of practice and was deemed feasible

Table 5. Patient Satisfaction, Adjusted Results

Outcome OR 95% CI P Value

Physician explains things to me

Scribe 0.82 0.48-1.40 .468

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.81 0.48-1.36 .429

Physician 2 0.40 0.22-0.71 .002

Physician 3 1.54 0.72-3.32 .266

Physician 4 0.97 0.50-1.87 .920

Physician listens to me

Scribe 0.88 0.49-1.58 .681

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.75 0.42-1.32 .319

Physician 2 0.64 0.36 -1.11 .113

Physician 3 2.63 1.18-5.87 .018

Physician 4 1.58 0.82-3.04 .717

Physician cares about me

Scribe 1.15 0.67-1.97 .609

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.66 0.38 -1.13 .130

Physician 2 0.39 0.22-0.69 .001

Physician 3 2.19 0.96-5.00 .061

Physician 4 0.79 0.43-1.47 .459

Physician encourages me to talk

Scribe 1.07 0.63-1.80 .808

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.58 0.35-0.97 .037

Physician 2 0.39 0.22-0.68 .001

Physician 3 2.09 0.95-4.60 .068

Physician 4 0.68 0.38-1.23 .202

Physician spends enough time

with me

Scribe 1.12 0.70-1.79 .642

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.92 0.06-1.50 .725

Physician 2 0.53 0.33-0.85 .008

Physician 3 3.20 1.57-6.53 .001

Physician 4 1.55 0.90-2.68 .116

I would recommend this physician

Scribe 1.06 0.60-1.89 .825

Physician 1, new interaction

a

0.59 0.34-1.04 .066

Physician 2 0.34 0.18-0.62 .001

Physician 3 1.79 0.76 - 4.19 .183

Physician 4 0.75 0.38-1.47 .405

OR = odds ratio.

Note: Model B.

a

First interaction between scribe and physician.

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

432

for repeated use, but it was not a validated survey of

joy of practice or burnout. Our findings of improved

efficiency, as measured by time to chart close, would

be strengthened by future work using other objective

approaches, such as time and motion analyses. Our

data show that physicians reported higher satisfaction

with the quality and accuracy of charting when scribes

were present; future work should evaluate chart qual-

ity in an objective way with blinded observers using a

validated instrument. We also found that patient sat-

isfaction was not affected by the presence of a scribe,

but we believe that qualitative work would better elu-

cidate patients’ perceptions of scribes. Other worthy

avenues of research include evaluating team-based care

models using medical assistants or nurses as scribes,

38

the effect of scribes on physician productivity and rev-

enue, as well as cost-benefit analyses, which have been

described by others

39-41

but warrant further research in

the primary care setting.

The challenge of modifying physicians’ practices to

accommodate EHRs without sacrificing quality of care

or quality of physician-patient interactions is not trivial.

Some have suggested that scribes are not an appropriate

solution, arguing that they are no substitute for better

functioning EHRs or may remove some of the pressure

on EHR designers to improve their systems.

23

We ag ree

that scribes are not a replacement for EHR redesign,

but we do consider them an immediate solution that

can be implemented while the more onerous and time-

consuming problem of EHR redesign is also tackled.

We also believe scribes can serve as a complement to a

high-functioning EHR, as the latter will still require the

mundane capture of information that does not require

a physician. By reducing the time that physicians spend

on clerical tasks, scribes serve an important function in

a multidisciplinary health care team.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it

online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/15/5/427.

Key words: medical scribes; electronic health records; work satisfac-

tion; patient satisfaction; efciency; primary care physicians; random-

ized controlled trial

Submitted December 6, 2016; submitted, revised, April 15, 2017;

accepted May 3, 2017.

Funding support: This study was supported by a grant to the senior

author (S.L.) from the Pisacano Leadership Foundation, the philan-

thropic foundation of the American Board of Family Medicine.

Disclaimer: The Foundation had no role in the design of the study; the

collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the decision to

approve publication of the nished manuscript.

Previous presentations: A portion of this manuscript was presented at

the Stareld Summit, April 23-26, 2016, Washington, DC; and the Soci-

ety of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Spring Conference,

April 30-May 4, 2016, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank Sang-ick Chang, MD,

MPH, associate dean for primary care; Tim Engberg, RN, MA, vice

president for primary care; Juno Vega, RN, clinic manager; and Therese

Truong, RN, assistant clinic manager, for their support of the scribe

program.

References

1. Blumenthal D. Wiring the health system—origins and provisions of

a new federal program. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(24): 2323-2329.

2. Blumenthal D. Implementation of the federal health information

technology initiative. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(25): 2426-2431.

3. Ofce of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technol-

ogy. Hospitals Participating in the CMS EHR Incentive Programs,

Health IT Quick-Stat #45. http: //dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/

pages/FIG-Hospitals-EHR-Incentive-Programs.php. Updated Feb

2016. Accessed Nov 1, 2016.

4. Ofce of the National Coordinator for Health Information Tech-

nology. Ofce-based Health Care Professionals Participating

in the CMS EHR Incentive Programs, Health IT Quick-Stat #44.

http: //dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Health-Care-

Professionals-EHR-Incentive-Programs.php. Updated Feb 2016.

Accessed Nov 1, 2016.

5. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Patient Safety and Health

Information Technology. Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer

Systems for Better Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press;

2011.

6. Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, Sykes L, Quan H. The

impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and

outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence.

J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011; 18(6): 732-737.

7. King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, Furukawa MF. Clinical benets of elec-

tronic health record use: national ndings. Health Serv Res. 2014;

49(1 Pt 2): 392-404.

8. Health IT. gov. Benets of electronic health records (EHRs). http: //

www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/benets-electronic-health-

records-ehrs. Updated Jul 2015. Accessed Nov 1, 2016.

9. Slight SP, Berner ES, Galanter W, et al. Meaningful use of electronic

health records: experiences from the eld and future opportunities.

JMIR Med Inform. 2015; 3(3): e30.

10. Fleming NS, Becker ER, Culler SD, et al. The impact of electronic

health records on workow and nancial measures in primary care

practices. Health Serv Res. 2014; 49(1 Pt 2): 405-420.

Table 6. Charting Efciency, Adjusted Results for

Less Than 48 Hours to Close Chart

Variable OR 95% CI P Value

Scribe 1.18 1.02-1.36 .028

Physician 1, new

interaction

a

1.01 0.86 -1.18 .950

Physician 2 6.26 5.04 -7.76 <.001

Physician 3 8.35 6.75-10.33 <.0 01

Physician 4 4.80 3.85-5.99 <.0 01

OR = odds ratio.

Note: Model B.

a

First interaction between scribe and physician.

IMPACT OF SCRIBES

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

433

ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE

✦

WWW.ANNFAMMED.ORG

✦

VOL. 15, NO. 5

✦

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2017

432

11. Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on

patient-doctor communication during consultation: a narrative lit-

erature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009; 15(4): 641-649.

12. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors Affecting Phy-

sician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care,

Health Systems, and Health Policy. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corpora-

tion; 2013.

13. Menachemi N, Collum TH. Benets and drawbacks of electronic

health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2011; 4: 47-55.

14. Boonstra A, Broekhuis M. Barriers to the acceptance of electronic

medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy

and interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010; 10: 231.

15. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and

satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US

working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;

90(12): 1600-1613.

16. Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient

care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med.

2005;3(6):488-493.

17. Gilchrist V, McCord G, Schrop SL, et al. Physician activi-

ties during time out of the examination room. Ann Fam Med.

2005;3(6):494-499.

18. Chen MA, Hollenberg JP, Michelen W, Peterson JC, Casalino LP.

Patient care outside of ofce visits: a primary care physician time

study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011; 26(1): 58-63.

19. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in

ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann

Intern Med. 2016; 165(11): 753-760.

20. Campbell LL, Case D, Crocker JE, et al. Using medical scribes in a

physician practice. J AHIMA. 2012; 83(11): 64-69.

21. Joint Commission. Clarication: Safe use of scribes in clinical set-

tings. Jt Comm Perspect. 2011; 31(6): 4-5.

22. Lin S, Khoo J, Schillinger E. Next big thing: integrating medi-

cal scribes into academic medical centres. BMJ Simulation & Tech

Enhanced Learning. 2016; 2(2): 27-29.

23. Gellert GA, Ramirez R, Webster SL. The rise of the medical scribe

industry: implications for the advancement of electronic health

records. JAMA. 2015; 313(13): 1315-1316.

24. Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care

settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam

Med. 2015; 28(3): 371-381.

25. Heaton HA, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Trotter ER, Erwin PJ, Bellolio

MF. Effect of scribes on patient throughput, revenue, and patient

and provider satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Am J Emerg Med. 2016; 34(10): 2018-2028.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Ambulatory

Medical Care Survey: 2012 State and National Summary Tables.

http: //www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2012_namcs_

web_tables.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed Nov 1, 2016.

27. Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple signicance tests: the Bonferroni

method. BMJ. 1995; 310(6973): 170.

28. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maxwell K, Markham FW, Wender RC, Gonnella

JS. A brief instrument to measure patients’ overall satisfaction with

primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2011; 43(6): 412-417.

29. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims

Processing Manual. Chapter 12 – Physicians/Nonphysician Practi-

tioners. http: //www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/

Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Updated Mar 2016. Accessed

Nov 1, 2016.

30. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care

of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med.

2014;12(6):573-576.

31. Hess JJ, Wallenstein J, Ackerman JD, et al. Scribe impacts on pro-

vider experience, operations, and teaching in an academic emer-

gency medicine practice. West J Emerg Med. 2015; 16(5): 602- 610.

32. Misra-Hebert AD, Amah L, Rabovsky A, et al. Medical scribes: How

do their notes stack up? J Fam Pract. 2016; 65(3): 155 -159.

33. O’Donnell HC, Kaushal R, Barrón Y, Callahan MA, Adelman RD,

Siegler EL. Physicians’ attitudes towards copy and pasting in elec-

tronic note writing. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24(1): 63-68.

34. Siegler EL, Adelman R. Copy and paste: a remediable hazard of

electronic health records. Am J Med. 2009; 122(6): 495-496.

35. Markel A. Copy and paste of electronic health records: a modern

medical illness. Am J Med. 2010; 123(5): e9.

36. Murphy DR, Meyer AN, Russo E, Sittig DF, Wei L, Singh H. The

burden of inbox notications in commercial electronic health

records. JAMA Intern Med. 2016; 176(4): 559-560.

37. Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, Kogan BA. Scribes in an ambulatory

urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010;

184(1): 258-262.

38. Yan C, Rose S, Rothberg MB, Mercer MB, Goodman K, Misra-

Hebert AD. Physician, scribe, and patient perspectives on clinical

scribes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2016; 31(9): 990-995.

39. Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient

interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a pro-

spective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013; 5: 399-406.

40. Bank AJ, Gage RM. Annual impact of scribes on physician produc-

tivity and revenue in a cardiology clinic. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res.

2015; 7: 489 -495.

41. Walker KJ, Dunlop W, Liew D, et al. An economic evaluation of the

costs of training a medical scribe to work in Emergency Medicine.

Emerg Med J. 2016; 33(12): 865-869.