Patient Experience Journal Patient Experience Journal

Volume 7 Issue 3 Article 24

2020

Factors associated with patient rating of physician Factors associated with patient rating of physician

communication effectiveness and satisfaction in musculoskeletal communication effectiveness and satisfaction in musculoskeletal

care care

Amirreza Fatehi

Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Dell Medical School – The University of Texas at Austin

Amanda Gonzalez MD

Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Dell Medical School – The University of Texas at Austin

David Bandell

Department of Surgery and Perioperative care, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin

Joost Kortlever

Department of Surgery and Perioperative care, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin

Léon Rijk

Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Dell Medical School – The University of Texas at Austin

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://pxjournal.org/journal

Part of the Orthopedics Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Fatehi A, Gonzalez A, Bandell D, Kortlever J, Rijk L, Ring D. Factors associated with patient rating of

physician communication effectiveness and satisfaction in musculoskeletal care.

Patient Experience

Journal

. 2020; 7(3):209-222. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1427.

This Research is brought to you for free and open access by Patient Experience Journal. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Patient Experience Journal by an authorized editor of Patient Experience Journal.

Factors associated with patient rating of physician communication effectiveness Factors associated with patient rating of physician communication effectiveness

and satisfaction in musculoskeletal care and satisfaction in musculoskeletal care

Cover Page Footnote Cover Page Footnote

This article is associated with the Policy & Measurement lens of The Beryl Institute Experience

Framework. (http://bit.ly/ExperienceFramework). You can access other resources related to this lens

including additional PXJ articles here: http://bit.ly/PX_PolicyMeasure

Authors Authors

Amirreza Fatehi, Amanda Gonzalez MD, David Bandell, Joost Kortlever, Léon Rijk, and David Ring

This research is available in Patient Experience Journal: https://pxjournal.org/journal/vol7/iss3/24

Patient Experience Journal

Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020, pp. 209-222

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

© The Author(s), 2020. Published in association with The Beryl Institute

Downloaded from www.pxjournal.org 209

Research

Factors associated with patient rating of physician communication

effectiveness and satisfaction in musculoskeletal care

Amirreza Fatehi, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, amir_fatehi@yahoo.com

Amanda Gonzalez, MD, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, amandainezgonzalez@gmail.com

David Bandell, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, d.ba[email protected]

Joost Kortlever, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, joost.kortlever@austin.utexas.edu

Léon Rijk, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, rijk.leon@gmail.com

David Ring, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, [email protected]texas.edu

Abstract

Effective communication is associated with adherence to healthy habits. This study sought factors associated with

communication effectiveness and satisfaction with musculoskeletal specialty care in order to inform efforts to improve

communication effectiveness using measurement, feedback, and coaching. After a new or return upper extremity

specialist visit, 146 adult patients completed a survey recording demographics, measures of catastrophic thinking in

response to nociception, symptoms of depression, and symptoms of anxiety, and they rated communication

effectiveness (5 questions answered on a 4-point Likert scale) and satisfaction with the visit (slider with anchors of 0 and

100). Patients also provided text answers to 4 questions addressing strengths and opportunities for improved

communication. We assessed the association of experience measures (communication and overall satisfaction) with

patient characteristics. Ratings of “clinician listens carefully” were higher in older patients. Higher rating of "clinician

explains in an understandable way" was associated with fewer symptoms of depression. Higher rating of "clinician

showed respect" was associated with fewer symptoms of depression and less catastrophic thinking. Higher rating of

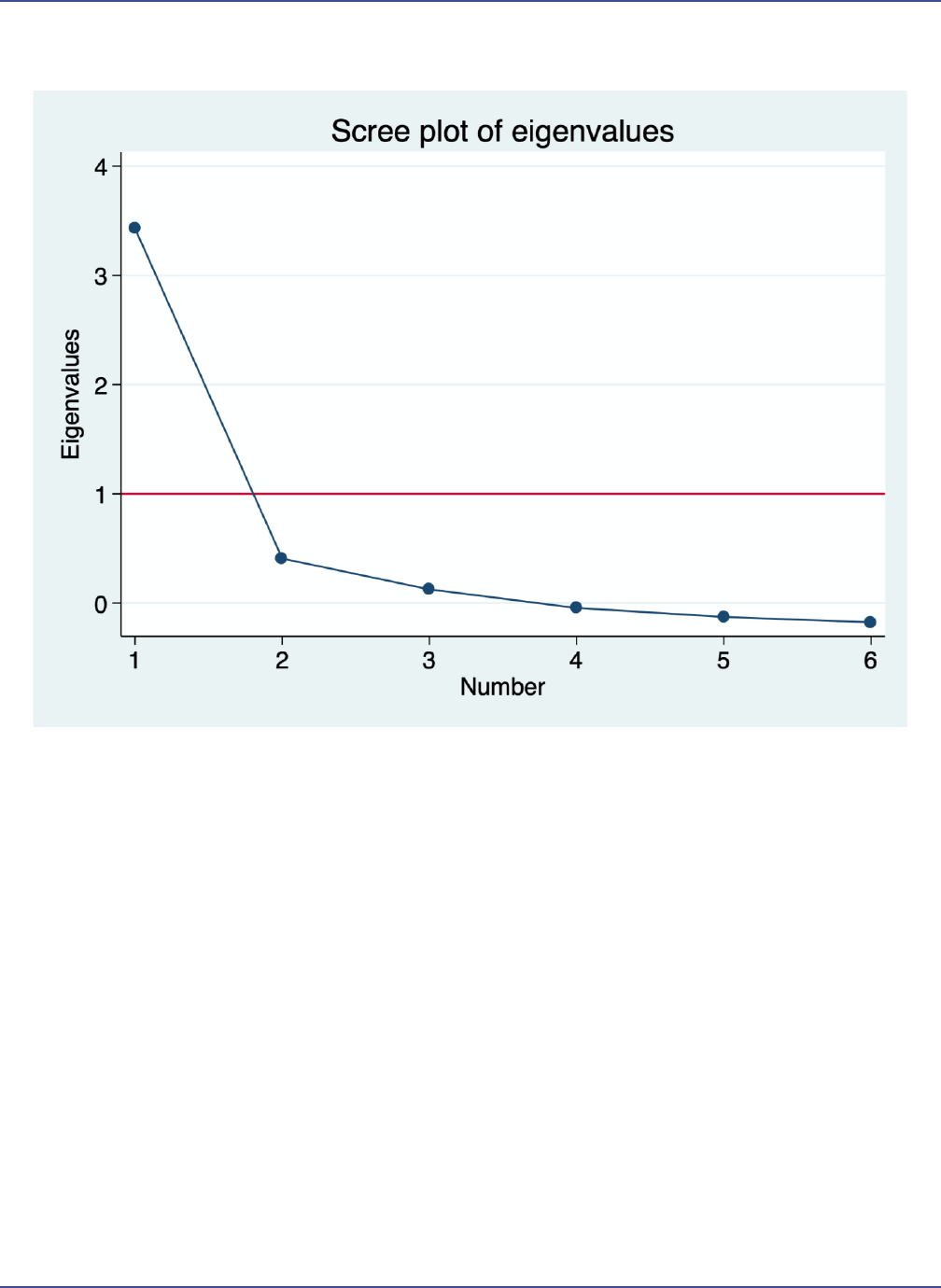

"clinician used models" was associated with older age. Men had higher overall satisfaction scores. In Factor analysis, the

scree plot of eigenvalues showed that the 5 communication questions and the single satisfaction question load onto a

single factor. The finding that age and psychological factors are associated with patient experience – which seems to

reduce statistically to a single underlying construct – emphasizes a potential to attend to mental health in efforts to

improve patient experience.

Keywords

Patient satisfaction, patient experience, patient-physician communication, healthcare, psychosocial, communication

satisfaction, mental health, upper extremity

Introduction

Effective relationships with patients and effective

communication strategies are associated with better

adherence to recommended care, greater agency and self-

efficacy regarding one’s health, and better health.

1,2

Attempts to optimize value in care (improved health for

resources used) can lead to difficult discussions about test

and treatment options that may be a challenge for all

clinicians, even those with highly effective communication

strategies.

3

For instance, not prescribing antibiotics for a

virus or not ordering an MRI for low back pain. Routine

measurement and feedback-tailored strategizing and

training could improve communication effectiveness,

optimizing both value and patient experience.

4

Prior studies found that more highly rated communication

correlates with greater satisfaction, fewer symptoms of

anxiety, and a less negative affect.

5–8

The aim of this study

was to identify factors associated with communication

effectiveness and satisfaction with musculoskeletal care in

order to inform routine measurement of these factors for

quality improvement initiatives. Our primary null

hypothesis is that there are no factors independently

associated with “clinician listens carefully” in

musculoskeletal care. The secondary null hypotheses are:

There are no factors independently associated with patient

rating of “clinician use of models, drawings or information

on a computer or handheld device,” ”clinician explains

things in an understandable way,” “clinician showed

respect of what patient had to say” and “clinician spent

enough time with patient,” and satisfaction with the visit.

We also collected text advice regarding: what the clinician

did well in terms of communication; clinician

communication in comparison to patient expectations;

opportunities to improve clinician patient communication;

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

210 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

and things we can do to improve their satisfaction with

care. As a tertiary (unplanned) inquiry we used factor

analysis to determine if these five communication

questions and the single satisfaction question load onto a

single factor.

Method and Materials

This study was approved by our Institutional Review

Board (IRB). We invited 161 adult patients visiting 6 upper

extremity speciality offices in an urban US city for a new

or return outpatient visit to participate by answering

questions on a web-based HIPAA compatible survey using

REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). A research

assistant invited patients to participate in the study at the

end of their visit. The inclusion criteria were: 1) Age 18

years or greater; and 2) English or Spanish fluency and

literacy. Exclusion criteria was cognitive deficiencies.

After reading a research letter, completing the

questionnaires constituted informed consent. One

hundred and forty-six patients (91%) participated and 15

declined (9%). After the visit, patients completed

questionnaires on an electronic tablet provided by a

research assistant. Subjects completed a demographic

questionnaire including age, gender, race, education level,

work status, marital status, insurance status, visit type and

way of referral.

Subjects also completed several questionnaires. The PCS-

4 (Pain Catastrophizing Scale) is a 4-item measure of

worst-case thinking in response to nociception (the

pathophysiology of actual or potential tissue damage).

Every question is scored on a 5-point Likert scale and the

total scores range from 0 to 16 with zero (no catastrophic

thinking) and 16 (maximum catastrophic thinking). The

PHQ-2 (Patient Health Questionnaire) is a 2-item measure

of symptoms of depression over the past two weeks with a

range of 0 to 6. The GAD-2 (General Anxiety Disorder) is

a 2-item measure of symptoms of anxiety in the past 2

weeks. The total score ranges from 0 to 6.

As our dependent variables, we used the 5 questions

addressing communication effectiveness from the

Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare

Providers and Systems (CG CAHPS) questionnaire, a

standardized tool to measure patient perceptions of care in

an office setting. The following five questions were rated

on the following scale: A. Never, B. Sometimes, C.

Usually, or D. Always and as a convention to include the

top two scores in experience measures,

10–12

all of which

have high ceiling effects, when the measure is

dichotomized, we put always and usually together versus

never/sometimes.

1. How often does the clinician listen carefully?

2. How often does the clinician explain things in an

understandable way?

3. How often did the clinician showed respect for what

the patient had to say?

4. How often did the clinician spend enough time with

the patient?

5. How often does the clinician use of models, drawings,

or information on a computer or handheld device?

As our other dependent variable, we asked patients to rate

their satisfaction with the visit on a slider with anchors of

0 (completely unsatisfied) to 100 (completely satisfied). We

also asked patients four questions and recorded their text

responses:

1. What did the clinician do well in terms of

communication?

2. How did the clinician's communication compare to

your expectations?

3. What opportunities for improved communication did

you identify?

4. In terms of Satisfaction, is there anything we can do to

improve your satisfaction with care?

Statistical Analysis

An a priori power analyses indicated that a sample of 135

subjects would provide 80% statistical power, with alpha

set at 0.05, for a regression with three predictors if one of

the factors would account for 5% or more of the

variability in “clinician listens carefully”, and our complete

model would account for 15% of the overall variability. In

order to account for 5% incomplete responses, we

enrolled 146 patients (Table 1).

Demographics, education, work status, insurance type,

method of referral, new or return visit, PCS-4, PHQ-2,

and GAD-2 were our independent variables, and the five

communication questions and satisfaction scale were

dependent variables. First, a descriptive analysis of the

demographics, PCS-4, PHQ-2, GAD-2, overall satisfaction

and their mean, range and percentages was performed.

Answers for the five communication effectiveness

questions were dichotomized into sometimes/usually

group versus always group and the "use of models"

answers were dichotomized into "yes” versus no" due to

strong ceiling effects. Nobody chose the option “never.”

Associations between nominal with dichotomous variables

were tested using Chi-square and Fisher Exact Tests. The

association between nominal variables and satisfaction

(non-normal continuous) variable was tested by Kruskal-

Wallis test.

We used Mann-Whitney tests to measure the association

between continuous non-normal variables and

dichotomous variables. Spearman ranked correlation

coefficient was used to test correlation between non-

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 211

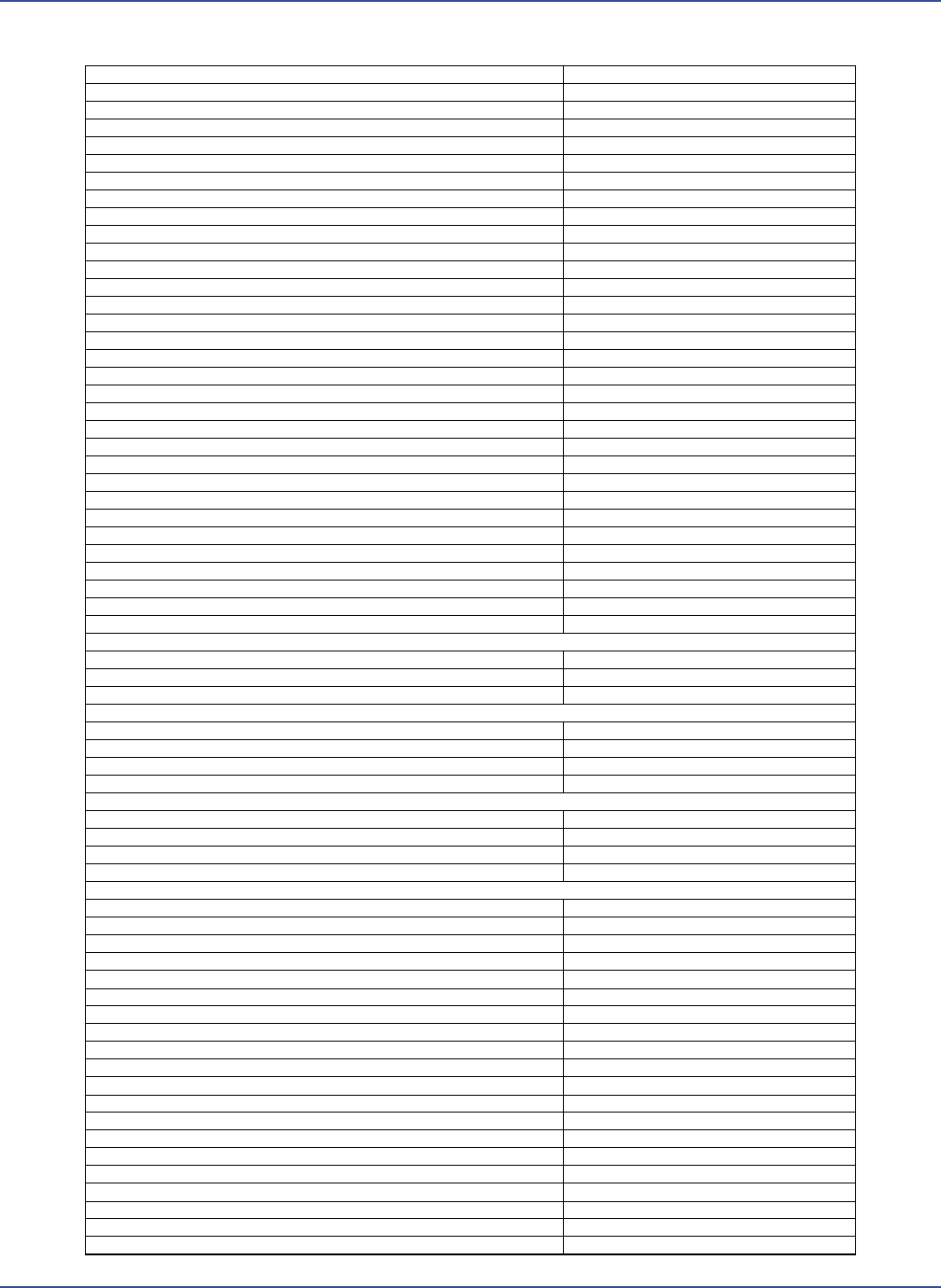

Table 1. Patient and clinical characteristics

Variables

N = 146

Age in years

52 ± 16 (18-86)

Woman

56% (81)

Race/Ethnicity

White

73% (106)

Non White

27% (40)

Marital status

Married

60% (87)

Single

24% (35)

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

16% (24)

Level of education

High school or less

23% (34)

2-year college

23% (34)

4-year college

25% (37)

Post-college degree

28% (41)

Work status

Employed

63% (92)

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

37% (54)

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

67% (98)

Medicare

21% (30)

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

12% (18)

Patient

New

36% (53)

Return

64% (93)

Way of referral

General Practitioner

40% (58)

Own initiative

39% (57)

Other specialist

21% (31)

PHQ-2 total

0 (0-2)

GAD-2 total

0 (0-1)

PCS4-total

3 (1-7)

What did the clinician do well in terms of communication?

Excellent explanation

58% (85)

Excellent communication

25% (36)

Other

17% (25)

How did the clinician's communication compare to your expectations?

Bad

0.7% (1)

Good

20% (28)

Very good

15% (20)

Excellent

64% (87)

What opportunities for improved communication did you identify?

None

87% (127)

Longer visit duration

4% (6)

More explanation

5% (8)

Other

4% (5)

Is there anything we can do to improve your satisfaction with care?

None

87% (127)

Shorter waiting time

4% (5)

Longer visit time

3% (4)

Other

6% (10)

CQ1 (clinician listens carefully)

Sometimes/usually

10% (15)

Always

90% (131)

CQ 2 (clinician explains in an understandable way)

Sometimes/usually

9% (13)

Always

91% (133)

CQ 3 (clinician showed respect)

Usually

8% (11)

Always

92% (135)

CQ 4 (clinician spent enough time)

Sometimes/usually

12% (18)

Always

88% (128)

CQ 5 (providers use of models was helpful)

Yes definitely / somewhat

56% (83)

No/ doctor didn't use models

44% (63)

CQ 6 (rate of satisfaction 0-100)

96 (88-100)

Continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (range) or median (interquartile range [IQR]); Discrete variables as percentage (number). PHQ-2= Patient Health

Questionnaire; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

212 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

normal continuous variables. An alpha level of 0.05 was

used to determine a statistical significance. Variables with

p < 0.1 were included in a multiple logistic regression for

binary dependent variables and linear regression for

continuous variables. We performed a factor analysis to

see if the construct of communication effectiveness and

satisfaction load on a single factor.

Results

In bivariate analysis, ratings of “clinician listens carefully”

were higher with older age, people referred by a general

practitioner, fewer symptoms of depression, and less

catastrophic thinking, and lower among people referred by

another specialist (Table Appendix A.1). Accounting for

potential confounders older age (p=0.02, OR=1.05,

SE=0.02) and referral by another specialist (p=0.048,

OR=0.17 SE=0.15) were retained in the final multivariable

model (Table 2). Because symptoms of depression and

catastrophic thinking were strongly correlated (Spearman

Rho = 0.5, p-value<0.001), we performed a sensitivity

analysis by running the model once with only depression

and again with only pain catastrophizing score and neither

of them were significant. Their influence appears to be

relatively limited.

Higher rating of "clinician explains in an understandable

way" correlates with fewer symptoms of depression in

both bivariate (p value=0.007) and multivariable regression

(p=0.01, OR=0.6 SE=0.19) (Tables Appendix A.2 and 2).

Higher rating of "clinician showed respect" correlates with

fewer symptoms of depression (p=0.007) and lower PCS-4

score (0.009) in bivariate analysis, but in logistic regression

neither factor was significant) (Tables Appendix A.3 and

2).

There were no factors associated with higher rating of

"clinician spent enough time" (Table Appendix A.4).

Higher rating of "clinician used models" was associated

with older age (p=0.026) in bivariate and also multivariable

regression (p=0.04, odds ratio=1.024 SE=0.01) (Tables

Appendix A.5 and 2).

Higher satisfaction was associated with men in bivariate

(p=0.001) and multivariable analysis (p=0.004, SE=1.37,

beta-regression coefficient=4.1) (Table Appendix A.6 and

2).

Table 2. Multivariable logistic and linear regression analysis of factors associated with the dependent variables

Dependent variable

Retained variable

Odds ratio (OR) (95% Confident

interval)

Standard

error

P value

Q 1 (clinician listen

carefully)

Age in years

1.05 (1.0 to 1.1)

0.02

0.02

Way of referral

General Practitioner

Reference value

Own initiative

0.37 (0.07 to 2.0)

0.3

0.26

Other specialist

0.17 (0.03 to 0.98)

0.15

0.048

Q 2 (clinician explains

in an understandable

way)

PHQ-2 total

0.6 (0.4 to 0.9)

0.19

0.01

Insurance status

Private insurance/ military

Reference value

Medicare

>1000

>1000

0.99

Medicaid/No health

insurance/Other

0.8 (0.2 to 3.4)

0.76

0.72

Q 3 (showed respect)

Age in years

1.0 (1.0 to 1.1)

0.02

0.13

PHQ-2 total

0.8 (0.5 to 1.2)

0.24

0.23

PCS4-total

0.9 (0.8 to 1.1)

0.09

0.17

Q 5 (use of models was

helpful)

Age in years

1.01 (1.0 to 1.1)

0.01

0.04

PHQ-2 total

0.8 (0.6 to 1.1)

0.13

0.11

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 213

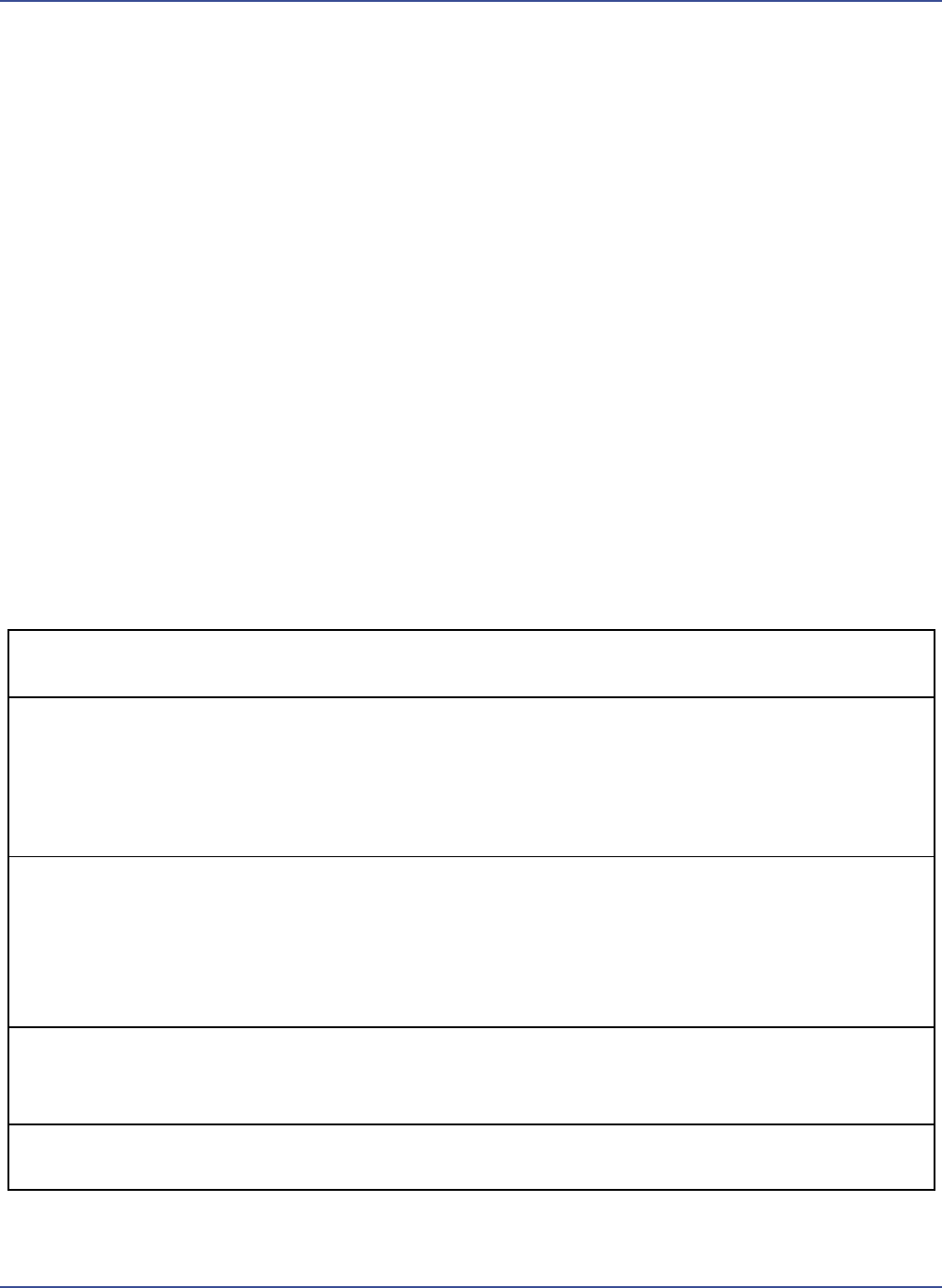

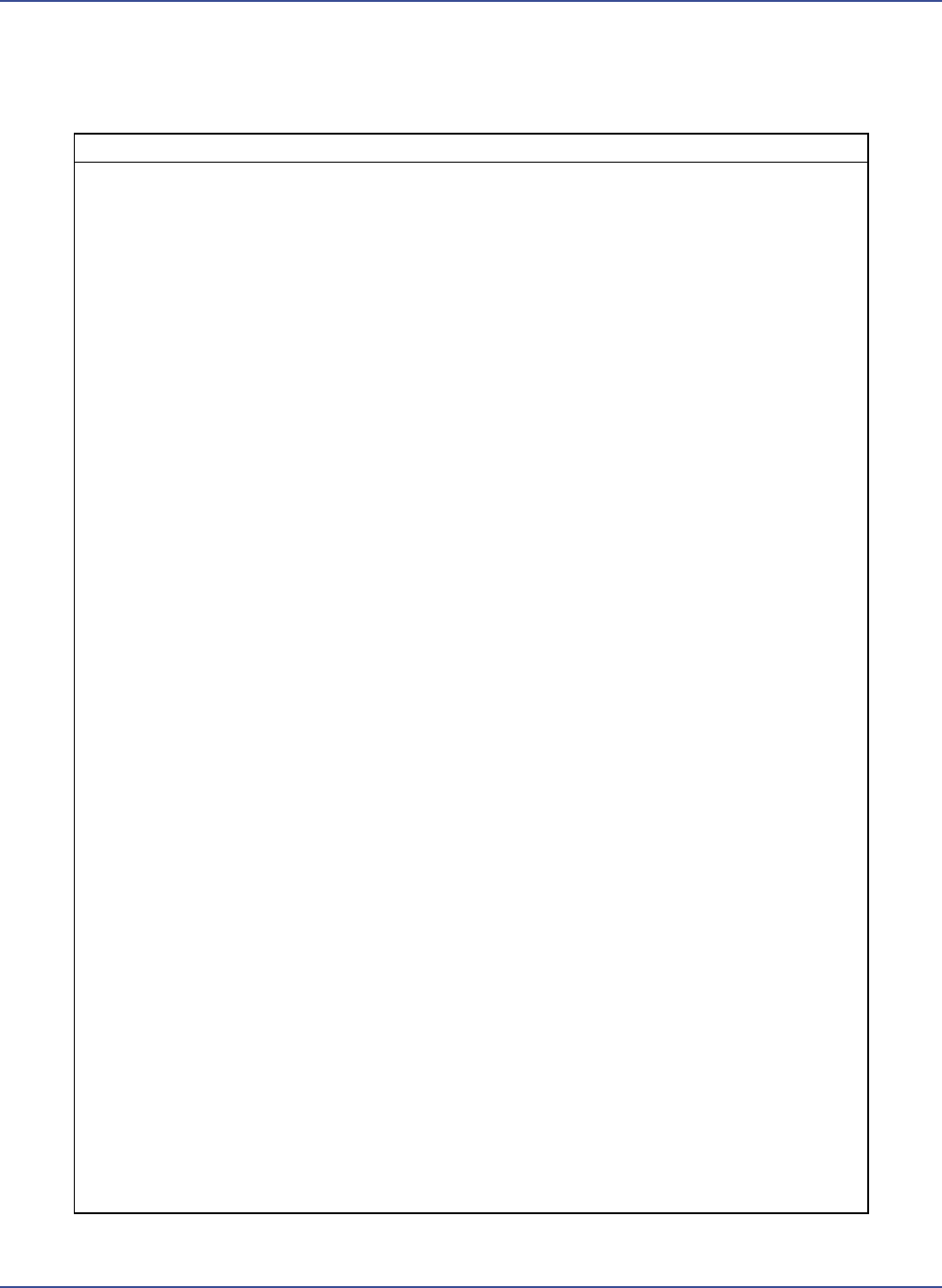

In Factor analysis, the scree plot of eigenvalues shows that

the 5 communication questions and satisfaction question

form one single factor (Figure 1).

Verbatim responses to the question about what the

clinician did well included “good explanation” (54%),

“listened” (9.6%), “clear” (6.8%), and “made me feel

comfortable” (6.2%). Regarding met expectations,

opportunities for improvement, and “how can we

improve”, there were just a few comments such as “slow

down”, “less rushed”, and “written instructions”. One

clearly dissatisfied patient answered all questions indicating

they just wanted a specific test ordered (Table1).

Discussion

Effective communication strategies are associated with

satisfaction, adherence to care and outcomes in prior

studies. A better understanding of the key aspects of

communication that contribute to patient experience could

inform efforts to improve. This study attempted to

discern the personal and illness factors associated with

patient experience of effective communication measured

by the CG-CAHPS questionnaire.

This study can be considered in the context of its

limitations. The small number of people that declined

participation might be part of the small and important

group with less satisfaction, which might influence the

results. The external validity for this study is limited

because we enrolled English-speaking patients with

musculoskeletal illness, visiting male, white orthopedic

surgeons. In our opinion, the findings may generalize to

other types of specialty care. There is evidence that

clinician gender, ethnicity, and specialty and patient

language and race affect satisfaction.

13,14

One might expect

communication effectiveness to increase with return visits

because the patient-clinician relationship is better

established, but we didn’t find such a relationship. Another

limitation was that the order of questionnaire completion

was not randomized. In addition, the total length of

questionnaires, and the similarities of some of the

questions might contribute to survey fatigue that might

have affected the results. There is also a potential for

inflated correlations since all the data was gathered using

Figure 1: The scree plot of eigenvalues for the 5 communication questions and the satisfaction question

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

214 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

REDCap surveys on a tablet (common method variance).

We design our studies to limit this and given the length of

our survey (approximately 7-10 minutes), we think there

was limited fatigue. Prior studies showed no difference

between paper and web-based tablet for most of the

questionnaires we use.

15,16

Given the evidence that people

answer mental health questions differently on tablet-based

surveys,

17,18

we anticipate limited influence of it. As a

survey study, common source bias is possible, but we have

tried to decrease its impact by collecting responses

anonymously.

The observation that age, referral source, symptoms of

depression, and catastrophic thinking correlated with

“clinician listens carefully” in bivariate analysis is

consistent with prior evidence that experience measures

are determined in part by personal factors.

19–23

The

observation that only age and referral by another specialist

were included in the logistic regression analyses is difficult

to interpret. These results are similar to other reports that

show that age correlates with patient ratings of the extent

to which the doctor listened to them.

21

Older age

correlates with higher satisfaction in some

21,24

but not all

studies.

25

The observation that patients referred by other

specialists rated clinicians lower in listening might be due

the complexity of their problem or perhaps due to

frustration with persistent troubling symptoms which

motivated them to see another specialist.

The observation that fewer symptoms of depression were

correlated with higher ratings of “clinician explains in an

understandable way” might reflect the relationship of

concentration and mood. There is also evidence that

greater symptoms of depression are associated with less

alignment of patient and clinician understanding of the

illness, which can make an explanation feel less

understandable. These findings are similar to other studies

that found that symptoms of depression correlated with

“clinician listens carefully”

26

and more satisfaction in

patients with better subjective health

21,27,28

and better

functional status.

24

The observation that symptoms of depression and

catastrophic thinking correlated with “clinician showed

respect” in bivariate analysis is consistent with prior

studies finding a link between cognitive error

(misconception) and feeling less respect.

21,23,26

Neither

factor was retained the logistic regression analyses which is

consistent with prior studies that had difficulty identifying

factors independently and notably correlated with

experience measures.

19,20

Experience measures correlate

highly with one another, but not as strongly with illness

and personal factors.

The observation that age was correlated with “provider

use of models was helpful” suggests that older patients

appreciate the use of models and other educational

measures more than younger patients. In another study,

using models didn’t show any association with perceived

empathy. The duration of the visit was longer when using

a model.

29

The observation that male sex correlated with higher

overall satisfaction seems spurious. The results across

studies are inconsistent and a meta-analysis

22

found no link

between gender and patient experience.

The themes identified in the text responses (good

explanation, listened, clear, and made me feel comfortable,

less rushed, written instructions) reflect a healthy

relationship and effective communication. In the verbatim

questions good explanation was the most significant

satisfactory aspect of communication for patients which

was similar to another cross-sectional study of 1100

patients with diabetes using a qualitative analysis of 180

verbatim comments about doctor-patient interactions

which showed that patients feel that doctors don’t explain

in details had a significant association with satisfaction.

30

The observation that in factor analysis communication

questions and satisfaction scale formed a single factor

suggests that they may be measuring a single underlying

construct. Future studies should plan for the high

intercorrelation of experience measures. One experience

measure should not be used to account for variation in

another. A conceptual distinction between distinct

patients reported experience measures (PREMs) such as

communication effectiveness, perceived empathy, and

satisfaction may prove unhelpful.

31

Instead, it may be

possible to ask just one or two questions that assess the

quality of the patient-clinician relationship that can direct

the improvement efforts of care units to establish better

relationships and improve patient experience.

Conclusion

The observation that symptoms of depression have some

correlation with lower patient ratings of their care

experience directs us to develop strategies to anticipate

and ameliorate this. Training of clinicians to anticipate and

train for the interaction of mental health and physical

symptoms in speciality care has the potential to improve

patient experience. The observation that communication

effectiveness and satisfaction measures load onto a single

factor suggests that they measure a single underlying

construct that—based on other similar studies—we feel

can be conceptualized as “relationship,” reaffirming that

building trust and taking a genuine interesting people are

key aspects of the patient experience.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 215

References

1. Haskard Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician

Communication and Patient Adherence to Treatment:

A Meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826-834.

doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc

2. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-Patient

Communication: A Review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38-

43.

3. Clever SL, Jin L, Levinson W, Meltzer DO. Does

doctor-patient communication affect patient

satisfaction with hospital care? Results of an analysis

with a novel instrumental variable. Health Serv Res.

2008;43(5 Pt 1):1505-1519. doi:10.1111/j.1475-

6773.2008.00849.x

4. Ranjan P, Kumari A, Chakrawarty A. How can

Doctors Improve their Communication Skills? J Clin

Diagn Res JCDR. 2015;9(3):JE01-04.

doi:10.7860/JCDR/2015/12072.5712

5. van Osch M, van Dulmen S, van Vliet L, Bensing J.

Specifying the effects of physician’s communication

on patients’ outcomes: A randomised controlled trial.

Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(8):1482-1489.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.009

6. Locke MC, Wilkerson EC, Mistur RL, Nisar M, Love

WE. 2015 Arte Poster Competition First Place

Winner: Assessing the Correlation Between Patient

Anxiety and Satisfaction for Mohs Surgery. J Drugs

Dermatol JDD. 2015;14(9):1070-1072.

7. Takayama T, Yamazaki Y, Katsumata N. Relationship

between outpatients’ perceptions of physicians’

communication styles and patients’ anxiety levels in a

Japanese oncology setting. Soc Sci Med 1982.

2001;53(10):1335-1350. doi:10.1016/s0277-

9536(00)00413-5

8. Verheul W, Sanders A, Bensing J. The effects of

physicians’ affect-oriented communication style and

raising expectations on analogue patients’ anxiety,

affect and expectancies. Patient Educ Couns.

2010;80(3):300-306. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.017

9. Graugaard PK, Eide H, Finset A. Interaction analysis

of physician-patient communication: the influence of

trait anxiety on communication and outcome. Patient

Educ Couns. 2003;49(2):149-156. doi:10.1016/s0738-

3991(02)00074-5

10. Huizinga MM, Bleich SN, Beach MC, Clark JM,

Cooper LA. Disparity in Physician Perception of

Patients’ Adherence to Medications by Obesity Status.

Obes Silver Spring Md. 2010;18(10):1932-1937.

doi:10.1038/oby.2010.35

11. Abu Al Hamayel N, Brooks J, Wang H, et al. Patient

Satisfaction of Care in the Treatment of Vaso-

Occlusive Crises: A Comparison of Emergency

Department and Infusion Centers in the Escaped

Study. Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):314-314.

doi:10.1182/blood-2018-99-111544

12. AlBahri AF, Arora T, Omar OM, Taheri S. Electronic

Device Use and Academic Performance in

Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1

MeetingAbstract):230-230.

doi:10.1542/peds.141.1_MeetingAbstract.230

13. Renouf T, Alani S, Whalen D, et al. City mouse,

country mouse: a mixed-methods evaluation of

perceived communication barriers between rural

family physicians and urban consultants in

Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. BMJ Open.

2016;6(5):e010153. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-

010153

14. Menendez ME, Loeffler M, Ring D. Patient

Satisfaction in an Outpatient Hand Surgery Office: A

Comparison of English- and Spanish-Speaking

Patients. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24(4):183-189.

doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000074

15. Hohwü L, Lyshol H, Gissler M, Jonsson SH, Petzold

M, Obel C. Web-Based Versus Traditional Paper

Questionnaires: A Mixed-Mode Survey With a Nordic

Perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8).

doi:10.2196/jmir.2595

16. Fanning J, McAuley E. A Comparison of Tablet

Computer and Paper-Based Questionnaires in

Healthy Aging Research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3(3).

doi:10.2196/resprot.3291

17. Guattery JM, Dardas AZ, Kelly M, Chamberlain A,

McAndrew C, Calfee RP. Floor Effect of PROMIS

Depression CAT Associated With Hasty Completion

in Orthopaedic Surgery Patients. Clin Orthop.

2018;476(4):696-703.

doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000076

18. Bernstein DN, Atkinson J, Fear K, et al. Determining

the Generalizability of the PROMIS Depression

Domain’s Floor Effect and Completion Time in

Patients Undergoing Orthopaedic Surgery. Clin

Orthop. 2019;477(10):2215-2225.

doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000000782

19. Epstein AM, Taylor WC, Seage GR. Effects of

patients’ socioeconomic status and physicians’ training

and practice on patient-doctor communication. Am J

Med. 1985;78(1):101-106. doi:10.1016/0002-

9343(85)90469-3

20. White-Means SI, Osmani AR. Racial and Ethnic

Disparities in Patient-Provider Communication With

Breast Cancer Patients: Evidence From 2011 MEPS

and Experiences With Cancer Supplement. Inq J Med

Care Organ Provis Financ. 2017;54:46958017727104.

doi:10.1177/0046958017727104

21. Moore PJ, Sickel AE, Malat J, Williams D, Jackson J,

Adler NE. Psychosocial factors in medical and

psychological treatment avoidance: the role of the

doctor-patient relationship. J Health Psychol.

2004;9(3):421-433. doi:10.1177/1359105304042351

22. Hall JA, Dornan MC. Patient sociodemographic

characteristics as predictors of satisfaction with

medical care: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 1982.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

216 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

1990;30(7):811-818. doi:10.1016/0277-

9536(90)90205-7

23. Fatehi A, Gonzalez A, Ring DC, Queralt M.

Psychosocial Factors Are Associated with Electronic

Portal Registration. Clin Orthop. Published online April

21, 2020. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000001278

24. Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of

patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2001;52(4):609-

620. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7

25. McFarland DC, Johnson Shen M, Holcombe RF.

Predictors of Satisfaction With Doctor and Nurse

Communication: A National Study. Health Commun.

2017;32(10):1217-1224.

doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1215001

26. Vranceanu A-M, Ring D. Factors associated with

patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg. 2011;36(9):1504-

1508. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.06.001

27. Rahmqvist M. Patient satisfaction in relation to age,

health status and other background factors: a model

for comparisons of care units. Int J Qual Health Care J

Int Soc Qual Health Care. 2001;13(5):385-390.

doi:10.1093/intqhc/13.5.385

28. Nguyen Thi PL, Briançon S, Empereur F, Guillemin

F. Factors determining inpatient satisfaction with care.

Soc Sci Med 1982. 2002;54(4):493-504.

doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00045-4

29. Portalatín EL, Carrazana LF, Colon R, Abreu R,

Rivera D, Lojo L. Orthopaedic Surgeon

Communication Skills: Perception of Empathy and

Patient Satisfaction Through the Use of Anatomic

Models. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev.

2018;2(11):e071. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-18-

00071

30. Jalil A, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. Patient

satisfaction with doctor-patient interactions: a mixed

methods study among diabetes mellitus patients in

Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):155.

doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2094-6

31. LaVela SL, Gallan AS. Evaluation and measurement

of patient experience. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(1):28-36.

doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1003

:11.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 217

Appendix

Table A.1. Bivariate analysis of communication satisfaction question 1

Clinician

Q1 (listens carefully)

Sometimes/

usually

Always

p value

Age in years

41 ± 12

53 ± 16

<0.01

Sex

Woman

9

56

Man

6

75

0.27

Race/Ethnicity

White

10

96

Non White

5

35

0.55

Marital status

Married

7

80

Single

5

30

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

3

21

0.44

Level of education

High school or less

1

33

2-year college

2

32

4-year college

5

32

Post-college degree

7

34

0.15

Work status

Employed

10

82

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

5

49

0.76

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

11

87

Medicare

1

29

0.26

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

3

15

Patient

New

6

47

0.75

Return

9

84

Referral

General practitioner

2

56

Own initiative

7

50

0.03

Other specialist

6

25

PHQ-2 total

2 (0-3)

0 (0-1)

0.03

GAD-2 total

0 (0-2)

0 (0-1)

0.65

PCS4-total

5 (3-11)

3 (0-7)

0.04

PHQ-2=Patient Health Questionnaire, GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

218 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

Appendix (cont’d.)

Table A.2. Bivariate analysis of communication satisfaction question 2

Clinician

Q2 (explains in an understandable way)

Sometimes/ usually

Always

p value

Age in years

45 ± 14

52 ± 16

0.12

Sex

Woman

6

59

Man

7

74

0.90

Race/Ethnicity

White

9

97

Non White

4

36

0.75

Marital status

Married

7

80

Single

3

32

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

3

21

0.72

Level of education

High school or less

1

33

2-year college

2

32

4-year college

3

34

Post-college degree

7

34

0.20

Work status

Employed

9

83

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

4

50

0.77

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

10

88

Medicare

0

30

0.07

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

3

15

Patient

New

5

48

Return

8

85

0.86

Referral

General practitioner

5

53

Own initiative

3

54

0.23

Other specialist

5

26

PHQ-2 total

2 (0-3)

0 (0-1)

<0.01

GAD-2 total

0 (0-2)

0 (0-1)

0.42

PCS4-total

4 (2-10)

3 (0-7)

0.27

PHQ-2= Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 219

Appendix A (cont’d.)

Table A.3. Bivariate analysis of communication satisfaction question 3

Clinician

Q 3 (showed respect)

Usually

Always

p value

Age in years

44 ± 13

52 ± 16

0.08

Sex

Woman

6

59

Man

5

76

0.54

Race/Ethnicity

White

9

97

Non White

2

38

0.73

Marital status

Married

6

81

Single

3

32

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

2

22

0.83

Level of education

High school or less

1

33

2-year college

2

32

4-year college

3

34

Post-college degree

5

36

0.56

Work status

Employed

7

85

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

4

50

0.96

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

7

91

Medicare

1

29

0.23

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

3

15

Patient

New

5

48

Return

6

87

0.53

Referral

General practitioner

2

56

Own initiative

4

53

0.10

Other specialist

5

26

PHQ-2 total

2 (0-3)

0 (0-1)

<0.01

GAD-2 total

1 (0-2)

0 (0-1)

0.16

PCS4-total

5 (3-11)

3 (0-7)

<0.01

PHQ-2= Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

220 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

Appendix (cont’d.)

Table A.4. Bivariate analysis of communication satisfaction question 4

Clinician

Q 4 (spent enough time)

Sometimes/ usually

Always

p value

Age in years

48 ± 15

52 ± 16

0.37

Sex

Woman

10

55

Man

8

73

0.32

Race/Ethnicity

White

11

95

Non White

7

33

0.26

Marital status

Married

11

76

Single

5

30

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

2

22

0.83

Level of education

High school or less

2

32

2-year college

2

32

4-year college

5

32

Post-college degree

9

32

0.13

Work status

Employed

12

80

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

6

48

0.80

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

12

86

Medicare

3

27

0.86

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

3

15

Patient

New

8

45

Return

10

83

0.44

Referral

General practitioner

5

53

Own initiative

8

49

0.47

Other specialist

5

26

PHQ-2 total

1 (0-3)

0 (0-2)

0.14

GAD-2 total

0 (0-1)

0 (0-1)

0.51

PCS4-total

4 (3-9)

3 (0-7)

0.23

PHQ-2= Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020 221

Appendix (cont’d.)

Table A.5. Bivariate analysis of communication satisfaction question 5

Clinician

Q 5 (use of models was helpful)

Yes definitely/

somewhat

No/

doctor

didn't use

models

p value

Age in years

49 ± 16

55 ± 14

0.02

Sex

Woman

38

27

Man

45

36

0.74

Race/Ethnicity

White

63

43

Non White

20

20

0.35

Marital status

Married

46

41

Single

21

14

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

16

8

0.44

Level of education

High school or less

20

14

2-year college

20

14

4-year college

19

18

Post-college degree

24

17

0.89

Work status

Employed

54

38

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

29

25

0.61

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

58

40

Medicare

13

17

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

12

6

0.21

Patient

New

31

22

Return

55

38

0.93

Referral

General practitioner

32

26

Own initiative

32

25

Other specialist

19

12

0.85

PHQ-2 total

0 (0-2)

0 (0-1)

0.06

GAD-2 total

0 (0-1)

0 (0-1)

0.58

PCS4-total

4 (3-9)

3 (0-7)

0.38

PHQ-2= Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-2=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PCS-4=Pain Catastrophizing Scale.

Communication effectiveness and satisfaction, Fatehi et al.

222 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3 – 2020

Appendix ((cont’d.)

Table A.6. Bivariate analysis of factors associated with satisfaction scale

Clinician

Q 6 (rate satisfaction 0-100)

p value

Age in years

r= 0.08

0.37

Sex

Woman

93 (87-97)

Man

97 (93-100)

0.001

Race/Ethnicity

White

96 (90-100)

Non White

95 (86-100)

0.38

Marital status

Married

96 (89-100)

Single

96 (87-100)

0.44

Divorced/Separated/Widowed

94 (90-97)

Level of education

High school or less

96 (90-100)

2-year college

96 (92-100)

4-year college

95 (88-100)

Post-college degree

95 (88-100)

0.89

Work status

Employed

96 (87-100)

Other (student, retired, homemaker, unable to work)

96 (92-100)

0.45

Insurance

Private insurance/ military

95 (87-100)

Medicare

96 (92-100)

0.33

Medicaid/No health insurance/Other

97 (92-100)

Patient

New

95 (85-100)

Return

96 (92-100)

0.14

Referral

General practitioner

96 (90-100)

Own initiative

96 (88-100)

0.74

Other specialist

94 (85-100)

PHQ-2 total

r= 0.02

0.85

GAD-2 total

r=0.02

0.80

PCS4-total

r= 0.02

0.79

CQ1 (listens carefully)

r= 0.53

<0.01

CQ 2 (explains in an understandable way)

r= 0.41

<0.01

CQ 3 (showed respect)

r= 0.53

<0.01

CQ 4 (spent enough time)

r= 0.50

<0.01

CQ 5 (use of models was helpful)

r= -0.13

0.10