OCTOBER 2021

A Blueprint for

Enhancing the

Security of the U.S.

Pharmaceutical

Supply Chain

2nd Edition

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

2

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

3

A Blueprint for Enhancing the Security

of the U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

Introduction

Identifying the List of Medicines Most Critical for U.S. Manufacturing

Company-Targeted Incentives Necessary to Secure the U.S.

Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

Broad-Based Incentives Critical to Supporting an Expanded U.S.

Pharmaceutical Economic Footprint

Increasing U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Security Through Global

Coordination

4

6

7

8

10

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

4

A Blueprint for Enhancing the Security of the U.S.

Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

INTRODUCTION

A closely connected, diverse, high-quality and resilient pharmaceutical supply chain based in the United

States and in allied countries is the best means to ensure that U.S. patients and our health care system

have access to a secure and consistent supply of critical medicines. The United States already plays an

important role in this supply chain, with generic companies providing more than 52,000 jobs at nearly

150 facilities, and manufacturing more than 60 billion doses of prescription medicines annually

1

in this

country. This domestic presence, combined with the strength of the industry’s globally diverse supply

chain, allows U.S. patients continued access to the medicines they need, including during the COVID

pandemic.

With strategic support from the U.S. government, the economic footprint of the generic drug industry in

the U.S. can expand even more, leading to increased national security, a stronger, more redundant

supply chain for key pharmaceuticals or their components and an expanded employment base.

The Association for Accessible Medicines and our member companies are ready to partner with U.S.

policymakers to create an environment where even more American jobs play a greater role in ensuring

a resilient U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain.

1 AAM Member Survey and other sources.

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

5

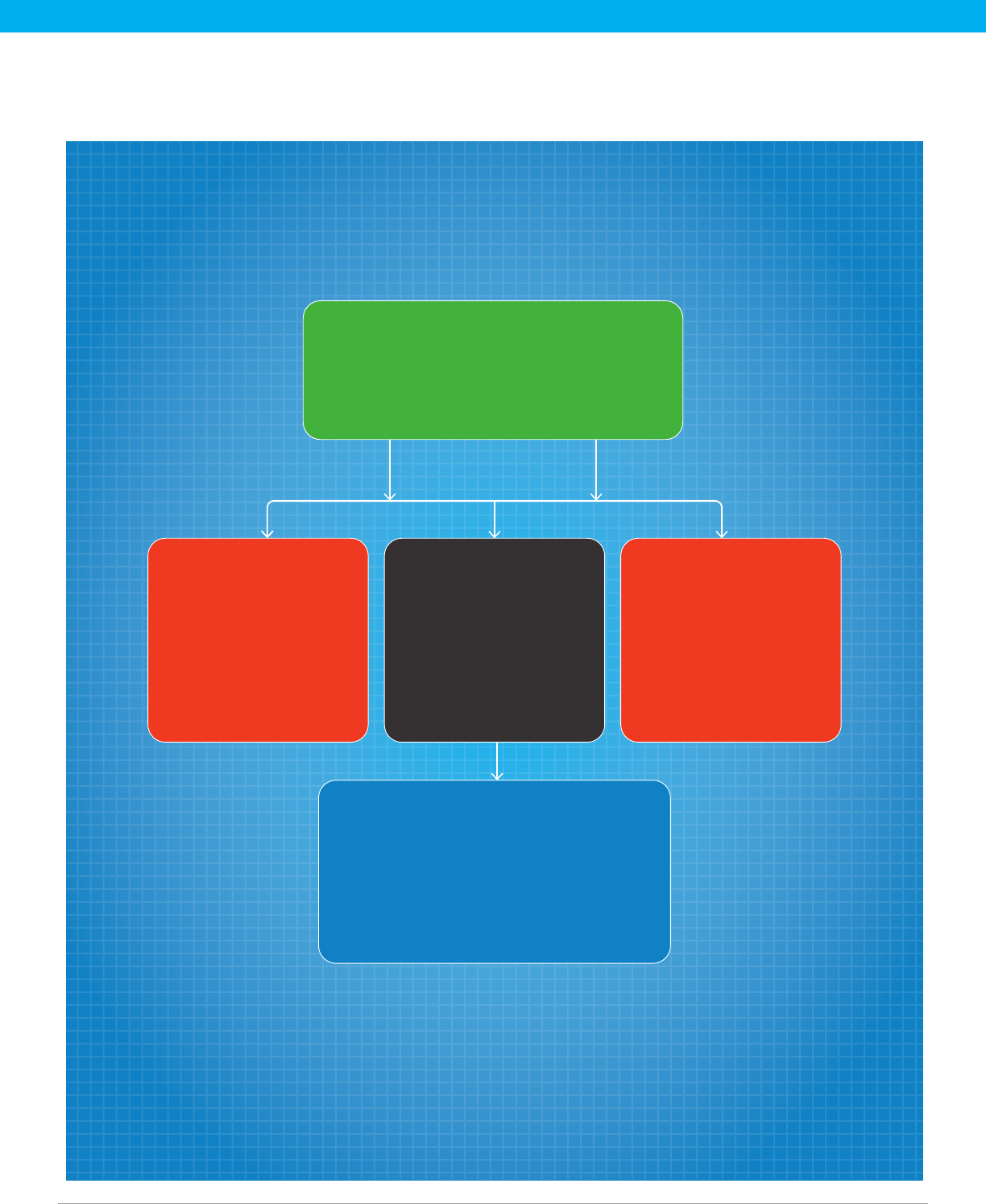

USTR andHHS

launchmultilateraltalks to

promote a cooperative

approachto developing

amanufacturing

basein alliedcountries

HHS engages indirect

discussions with pharma

manufacturersto promote

U.S. manufacturing of

essentialmedicines

FDA strengthens internal

coordination to

ensure expanded

manufacturer engagement

and efficient regulatory

review and approval

Tools to enable viable investments include

grants, tax incentives, loans, guaranteed

price & volume contracts, incentives in the

Medicare and Medicaid programs, and

adoption of regulatory efficiencies

Essential Medicines List:

A list of medicines critical to the U.S. health

care system, updated and shaped by

stakeholder input; reflected in an expanded

Strategic National Stockpile

Expanding HHS’ Ability to Secure the U.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain:

As the United States cannot produce all the medicines needed for its health care system

and its patient population, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

must continue engaging with the pharmaceutical industry to identify specic incentives

necessary to maintain, utilize and attract investments that can cost as much as $1 billion

and take 5-7 years to build.

Key Elements

Proposed Policy Framework

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

6

A. IDENTIFYING THE LIST OF MEDICINES MOST CRITICAL FOR U.S. MANUFACTURING

• List of Essential Medicines. To ensure U.S. government and private sector resources are focused

on the medicines most important to the U.S. health care system at times of urgent need, the

Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), acting through the FDA Commissioner, should

establish and update periodically following stakeholder input a list of essential medicines for the

United States. Essential medicines are defined as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and

finished dosage form, including drugs, biologics and medical countermeasures. The list of essential

medicines should include medicines deemed most critical to the U.S. health care system, vital

during a secretary-designated public health emergency and/or those whose shortage could impact

U.S. national security. In developing the list, the Secretary should consult with the U.S. Food and

Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of

Health (NIH) and other public health agencies, as well as the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of

State. The list shall be subject to a 60-day public comment period.

• Expanding the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) to Include Medicines On the Essential

Medicine List. Ensuring ample supply to the most critical medicines during a national disaster,

pandemic or trade dispute demands the U.S. government secure stockpiles of the medicines on the

List of Essential Medicines, including specific Finished Dosages (FD) and Active Pharmaceutical

Ingredients (API). HHS may take possession of such purchases or may pay manufacturers an

inventory management fee to produce and maintain the specified quantity on behalf of the SNS.

Specific volume and price levels must be negotiated on a company-by-company basis and should

factor in product expirations and inventory management costs. HHS shall engage actively with the

pharmaceutical industry to develop the framework and support necessary to quickly expand the SNS.

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

7

B. COMPANY-TARGETED INCENTIVES NECESSARY TO SECURE THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL

SUPPLY CHAIN

As the U.S. government works to incentivize expanded and new investments by generic manufacturers

in the United States, HHS, the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), the Department of Defense (DoD)

and other government agencies will work closely with individual companies to help secure the U.S.

pharmaceutical manufacturing base for priority medicines, including for specic FD and API. These

incentives include:

• Long-Term Price and Volume Guaranteed Contracts. Guaranteed fixed volume and price

agreements are essential to ensuring the viability of U.S.-based generic manufacturing for essential

medicines and inoculating those investments against low-priced imports of the same medicine.

When engaging with the industry, however, HHS, the VA and the DoD must encourage multiple

suppliers in the market and ensure, whenever possible, that no one company supplies the entire

market (this protects against supply disruptions). HHS should leverage fixed price and volume

guaranteed contracts when expanding the SNS and the VA shall utilize fixed price and volume

guarantees for national contracts to supply the VA and DoD.

• Grants. HHS shall provide grants to support construction, alteration or renovation of facilities for

the U.S.-based manufacture of medicines included on the List of Essential Medicines. Grants

should support pharmaceutical manufacturers relocating production facilities from outside of the

United States back to the United States to cover expenses in moving production and include funds

to offset the cost of building new factories and research centers. Such grants should be provided

only to 1) manufacturers with an approved Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), 2)

manufacturers of an authorized generic, 3) external/contract manufacturers of approved ANDAs or

authorized generics or 4) API manufacturers with a pending or approved Drug Master File. To

support a diverse and reliable supply, such grants must be available to multiple manufacturers of

the same medicine. Grants will be administered by HHS/Biomedical Advanced Research and

Development Authority (BARDA).

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

8

C. BROAD-BASED INCENTIVES CRITICAL TO SUPPORTING AN EXPANDED U.S.

PHARMACEUTICAL ECONOMIC FOOTPRINT

Certain additional measures will be necessary to support the economic viability of a U.S.-based

pharmaceutical for the entirety of the U.S. generic pharmaceutical manufacturing base:

• Tax Incentives. New tax incentives must be adopted that promote U.S. pharmaceutical companies

relocating foreign manufacturing back to the United States, build new greenfield sites, refurbish

already existing manufacturing facilities and/or repurpose existing production lines to focus on

pharmaceuticals that appear on the List of Essential Medicines. Specific tax incentives that will

facilitate the expansion of U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing include:

» A 50% tax credit to offset the costs of manufacturing medications on the priority medicines list

in the United States. The credit is available for as long as the medicine is on the list of priority

medicines and for five years thereafter.

» An increase in the simplified R&D tax credit to 20%

» A tax credit for expenses related to bioequivalence studies via the Research and Development

(R&D) tax credit

» A tax credit for initial and recurring FDA user fees

» A 25% reduction in the tax rate for U.S.-manufactured medicines on the Essential Medicine List

(modeled after the Section 199 tax reduction)

» A 20% tax credit based on wages paid to U.S. workers directly engaged in the production of

essential medicines

» An assurance that grants provided for the establishment of U.S. production of medicines are not

considered taxable income

• Leveraging the Medicare and Medicaid Programs. The Medicare and Medicaid programs

collectively provide health care to more than 136 million beneficiaries. Policymakers can update

these programs to support greater domestic production of essential generic medicines. This can be

accomplished by addressing the long-term viability of domestic manufacturing through the

following three proposals:

» Waive Medicaid rebates for domestically manufactured generic medicines on the FDA’s

Essential Medicines List.

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

9

» Establish a Medicare Star Rating to reward Part D plans that preference domestically

manufactured generic medicines included on the FDA Essential Medicines List.

» Provide bonus payments in Medicare Part B for providers who administer domestically

manufactured generic medicines included on the FDA Essential Medicines List.

• Regulatory Efficiencies. To expedite the approval of a facility and all the products to be produced in

it, the FDA must streamline its regulatory review and approval processes, removing duplicated

actions and reducing the time for approvals across the board. The agency should expand

cooperation with the manufacturer, working collaboratively to evaluate and approve the facility and

the tech transfer processes concurrently, as opposed to waiting until after the facility is built and the

equipment is installed/validated.

To accomplish these goals, the FDA should create an internal, intra-agency working group focused

on helping to expedite reviews and approvals to onshore pharmaceutical manufacturing. This

working group will comprise resources from the Office of Regulatory Affairs; the Office of

Pharmaceutical Quality; the Office of Compliance; reviewers from both chemistry and microbiology

disciplines; and the Office of Generic Drugs. This working group will focus on reviewing for approval

the transfer of production back into either U.S.-approved facilities or newly constructed facilities at

new or existing sites, including those utilizing advanced manufacturing technology. This working

group will grant meetings with the company to discuss the overall transfer plans. For example:

» Inspector(s) and Office of Pharmaceutical Quality staff will make site visit(s) during the

construction or validation phase.

» The mechanism will be similar to a pre-ANDA meeting – that is, a developmental phase

inspection and then a pre-submission inspection.

» Microbiology reviewer(s) will conduct site visits.

» Decouple submission and inspection. Inspections will be completed within 30 days of request

for inspection, regardless of submission.

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

10

D. INCREASING U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN SECURITY THROUGH GLOBAL

COORDINATION

• The International Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Agreement. To promote the benefits of a globally

diverse supply chain, the United States Trade Representative (USTR), working with HHS, should

negotiate a plurilateral agreement with U.S. allies to promote a cooperative approach to securing

the U.S. supply chain, ensuring diversity of supply and responding to global health care challenges

and natural disasters, without resorting to export controls or other barriers that inhibit the trade of

essential medicines or their components (including API). In addition, coordinating the expansion of

pharmaceutical manufacturing with U.S. allies will allow for economies of scale and a coordinated

approach to global pandemics.

Denitions

• “Generic drug” means “any drug that is marketed under an abbreviated new drug

application (ANDA) as well an ‘authorized generic drug.’”

• “Manufacture” has the meaning set forth in the Buy American Act, 41 U.S.C. §§8301-

8305: “completion of an article in the form required for use by the government in the

United States. For drugs this means readied for use as a medicine for human

consumption.”

AAM / A BLUEPRINT FOR ENHANCING THE SECURITY OF THE U.S. PHARMACEUTICAL SUPPLY CHAIN

11

accessiblemeds.org

©2021 Association for Accessible Medicines.