July 2024

ASPE REPORT

1

The Potential Role of The Nonprofit Pharmaceutical

Industry in Addressing Shortages and Increasing Access to

Essential Medicines and Low-Cost Medicines

Oluwarantimi Adetunji, Jon F. Oliver, Sonal Parasrampuria, Grace Singson, Trinidad Beleche

Key Points

o We identified 11 nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that launched between 2000-2022 with mission

statements aimed to enhance access to affordable and essential drugs, or resiliency in the supply chains

of medical products.

o Some of these nonprofit pharmaceutical companies owned for-profit subsidiaries as a strategy to

navigate a complex tax system; the majority did not have any medical products in the domestic

pharmaceutical marketplace, none of them owned their own manufacturing facilities, and their

financial statements suggested these tax-exempt companies were comparable in scale to for-profit

small businesses and start-up companies.

o Two nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that have successfully launched medical products in the

United States used different strategies for commercialization, including using contract manufacturing

organizations for labeling and distribution and entering into a licensing agreement with a for-profit

pharmaceutical company.

o Findings suggest that while nonprofit pharmaceutical companies hold promise in addressing drug

shortages and enhancing access, their capacity and sustainability may be limited due to low production

volumes, uncertainties about funding, and inexperience navigating complex tax, regulatory, and

reimbursement systems.

Introduction

Americans rely on medical products, such as prescription drugs, to prevent or treat acute and chronic diseases.

However, persistent high prices and shortages threaten access to lifesaving therapeutics and pose a risk to the

capacity of America’s health system to effectively mitigate and respond to public health emergencies and

ongoing public health issues.

1,2

These market gaps in the pharmaceutical industry have attracted the adoption

of different business models, such as nonprofit pharmaceutical companies, which are launched with any

specified purpose other than making a profit.

The prevailing business model in the pharmaceutical industry is oriented toward the pursuit of the next

blockbuster drug, defined as a drug with $1 billion or more in annual global sales.

3

For-profit companies may

utilize their profits to reinvest in research and development (R&D) or deliver a high return on investment to

shareholders. However, critics argue that the blockbuster model in the pharmaceutical market incentivizes a

non-innovative culture that results in duplicative and nonproductive ventures targeted to populations where

high revenues are guaranteed.

4

Further, some researchers have indicated that the prioritization of developing

blockbuster drugs contributes to higher prices and unmet public health needs, such as shortages of older

REPORT

JULY 2024

OFFICE OF

SCIENCE & DATA POLICY

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

2

generics and underinvestment in R&D for new antibiotics and drugs for certain rare diseases.

3-6

Researchers

have proposed alternative business models to promote growth in the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector and

address some of the existing market gaps.

7-10

These alternative business models include nonprofit

collaborations with for-profit companies to increase manufacturing and distribution capacity, creation of

nonprofit manufacturing and distribution companies, and partnering with other stakeholders to strengthen

existing capability and expertise (Appendix A).

While the emergence of nonprofit companies to address market failures is not a new phenomenon in non-

pharmaceutical markets,

11

there has been growing interest, including from Congress,

12

in understanding

whether nonprofit pharmaceutical companies could offer solutions to the challenges of drug access and

affordability.

8

Drawing from an environmental scan of the literature and key stakeholder interviews, this

report examines the ways in which nonprofit pharmaceutical companies can address a number of existing

gaps, including their potential role in reducing drug shortages, increasing access to essential medicines, and

providing low-cost alternatives to expensive medications.

Methodology

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy and Evaluation (ASPE) used a qualitative methods approach that

included both an environmental scan and key stakeholder interviews. NORC, under contract with ASPE,

conducted the preliminary searches and key stakeholder interviews.

Defining Nonprofit Pharmaceutical Companies

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies are tax exempt entities that have an established presence in the

pharmaceutical industry, typically pursuing R&D activities and licensing new drugs to for-profit companies. In

this report, we define a nonprofit pharmaceutical company as a tax-exempt entity with a publicly disclosed

goal of pursuing market authorization and commercialization of drugs to deliver low-cost medicines, including

essential drugs and drugs in shortage, and broadening access to medical products. This excludes nonprofit

companies that may invest in drug development to secure licensing agreements with for-profit companies and

nonprofit companies that provide contract services (e.g., contract development manufacturing organizations

(CDMOs)).

Environmental Scan

The environmental scan used a list of primary and secondary search terms to identify peer-reviewed and grey

literature relevant to the topic areas of interest: the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector, low-cost alternatives to

expensive medications, drug shortages, and access to essential medicines. The initial search terms included

keywords such as (“nonprofit pharmaceutical company” OR “nonprofit biopharmaceutical sector”) AND

(“generic drugs” OR “low-cost alternatives”). Appendix B describes the search terms for the preliminary

searches conducted by NORC. The inclusion criteria included materials published in English between 2000 and

January 2023. In addition, ASPE supplemented the preliminary searches conducted by NORC using a

“snowball” approach to identify other relevant information.

Further, we cross-referenced the list of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies generated from the

environmental scan with the IQVIA National Sales Perspective (NSP) dataset to gather market information such

as the number of products and total sales from January 2017 to December 2022. For the identified products

sold by nonprofit pharmaceutical companies in the IQVIA NSP dataset, we compared the sales volume of those

products sold by the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector with the for-profit pharmaceutical sector. We note that

this search resulted in the identification of one nonprofit pharmaceutical company, Civica, which indicates that

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

3

this is the only nonprofit pharmaceutical company marketing products in the United States during the period

of analysis.

Key Stakeholder Interviews

To supplement the environmental scan, NORC facilitated nine (9) interviews with key informants with

expertise in addressing drug shortages, increasing access to essential medicines, or providing low-cost

alternatives to expensive medications. Key informants were affiliated with nonprofit and for-profit

pharmaceutical companies, academic institutions, and hospitals.

Background

Brief History of Nonprofit Companies in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Nonprofit companies are tax-exempt

i

economic entities organized around missions or objectives intended to

further a social cause or provide a public benefit. Nonprofit companies differ from the traditional for-profit

business model, which aims to maximize profit for investors. Nonprofit companies are restricted from

distributing profits to any private shareholder or individual.

13

They leverage their social mission to attract

donations from private entities or funding from public entities to finance the provision of their goods and

services. Many sectors, such as pharmacies, hospitals, hospices, nursing homes, and home health care, are

structured with a mix of nonprofit and for-profit companies. The literature examining non-pharmaceutical

sectors suggests that the co-existence of nonprofit and for-profit companies can promote competition and

increase access to services for consumers.

14-16

However, little is known about the benefits and implications of

these two models in the pharmaceutical industry.

Although the pharmaceutical industry is dominated by for-profit companies, nonprofit companies have a long

history of advancing innovation in this industry.

17-20

The majority of their contributions has been through R&D

activities,

21,22

sponsored by funding from public and private entities. Some independently conduct R&D with

their endowments, royalties, donations, or other funding, while others partner with outside entities leading

these activities. Philanthropic nonprofits

ii

, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and CureDuchenne,

may also fund sponsored targeted R&D projects with nonprofit and for-profit companies.

Typically, nonprofit companies have not pursued commercialization activities, such as obtaining market

authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), manufacturing, and distribution of

pharmaceutical products.

8,17,23

The dominant approach has been for nonprofit companies to license new drugs

from their R&D pipeline to for-profit companies.

8

Some experts have cited that this approach results in

nonprofit companies losing the right to manufacture these drugs exclusively and for-profit companies

launching new drugs with the goal to maximize profits which may result in high prices for consumers. For

example, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF), a philanthropic nonprofit organization, invested $150 million in

a for-profit company to develop ivacaftor, the first drug to address the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis.

24

CFF

then sold the royalty rights to ivacaftor for $3.3 billion to a for-profit company.

25

The list price for ivacaftor

when it was licensed in 2012 was $294,000 per patient per year.

26

In 2019, a new combination product,

Trikafta (elexacaftor/ivacaftor/tezacaftor), was released with an average list price of $322,000 per patient per

year.

27

Similar examples of innovative and expensive drugs that were initially developed or financed by

nonprofit companies and licensed to for-profits for commercialization include voretigene neparvovec for

_______________________

i

In some circumstances, non-profit companies are subject to taxes, such as the unrelated business taxable income (UBTI).

ii

Philanthropic nonprofits may invest in R&D with for-profit pharmaceutical companies.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

4

congenital blindness, tisagenlecleucel for leukemia, and bexarotene for lymphoma.

8,20

While non-exclusive

licenses have been cited as a barrier, it is worth noting that licensors must also weigh factors such as costs or

profitability to determine the terms of the license. For-profit pharmaceutical companies have also used

business strategies such as licensing, mergers, and acquisitions to obtain access to new drugs. Researchers

have reported that the share of revenues coming from innovations sourced outside of for-profit companies has

grown from 25 percent in 2001 to about 50 percent in 2016.

28,29

In this report, we focus on nonprofit companies that are pursuing commercialization activities in the

pharmaceutical industry.

Profile of Nonprofit Pharmaceutical Companies, 2000-2022

Table 1 provides a profile of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that have entered the market between 2000

and 2022 and points to a sector that is largely fragmented. The environmental scan conducted for this report

identified 11 nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that met our definition in the U.S. pharmaceutical market.

Their specific mission statements ranged from providing affordable medications, to enhancing access to

essential medicines or those in shortage. Each mission statement identified product commercialization as one

of its goals. Further, the environmental scan revealed variation with respect to the types and number of

products nonprofit pharmaceutical companies provide—some focus on a specific treatment area with a

handful of products, while others provide dozens of products across multiple therapeutic areas.

The nonprofit pharmaceutical companies also differ in their operations. Some engage in R&D for product

development and commercialization. For example, Medicines360 engaged in R&D and commercialization of its

hormonal intrauterine device (IUD) that is accessible to low-income women in public clinics across the United

States (discussed in more detail in Access to Essential ).

10

In other cases, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies

focus only on commercialization activities, such as manufacturing, distribution, and relabeling. For example,

Drew Quality Group launched in 2014 with the mission to become a supplier of high-quality generic drugs that

were manufactured in the United States.

30

As of March 2023, the environmental scan and key stakeholder

interviewers suggest Drew Quality Group has not yet achieved this objective. Another example is Civica, which

entered the market in 2018 with a focus on relabeling and distribution of generic sterile injectables.

31

While

there is no one-size-fits-all approach, a common theme is the expressed desire to promote the affordability of

drugs and broaden access to pharmaceutical products by engaging in commercialization activities.

All the nonprofit pharmaceutical companies we identified have an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax-exempt

status as either a 501(c)(3) charitable organization

32

or a 501(c)(4)

iii

social welfare organization.

33

Among the

501(c)(3) charitable organizations, some are designated as public charities rather than as private foundations.

iv

By examining all of the nonprofit pharmaceutical companies’ most recent IRS form 990,

34

each reported annual

revenues below $20 million, with the majority reporting annual revenues below $2 million. All of the nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies also reported negative annual net income, indicating expenses exceeded revenues.

In contrast, research suggests that from 2000 to 2018, 35 large for-profit pharmaceutical companies reported

an average annual revenue of $33 billion, and an average net income of $54 billion.

35

While nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies tend to have the revenues or number of employees to be considered small

businesses, the literature and many stakeholders noted that their tax-exempt status does not make them

_______________________

iii

Unlike 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, donations, or contributions to 501(c)(4) social welfare organization are not tax-deductible

on federal tax returns for the entity making the donation.

iv

Private foundations have lower levels of public involvement and scrutiny in their activities than public charities. While public charities

typically receive a greater portion of their funding from public sources, private foundations are typically controlled by small groups of

individuals, such as family members.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

5

eligible for certain types of funding, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Small Business Innovation

Research, the Small Business Administration (SBA) loans, or even bank loans that require some expected level

of revenue.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

6

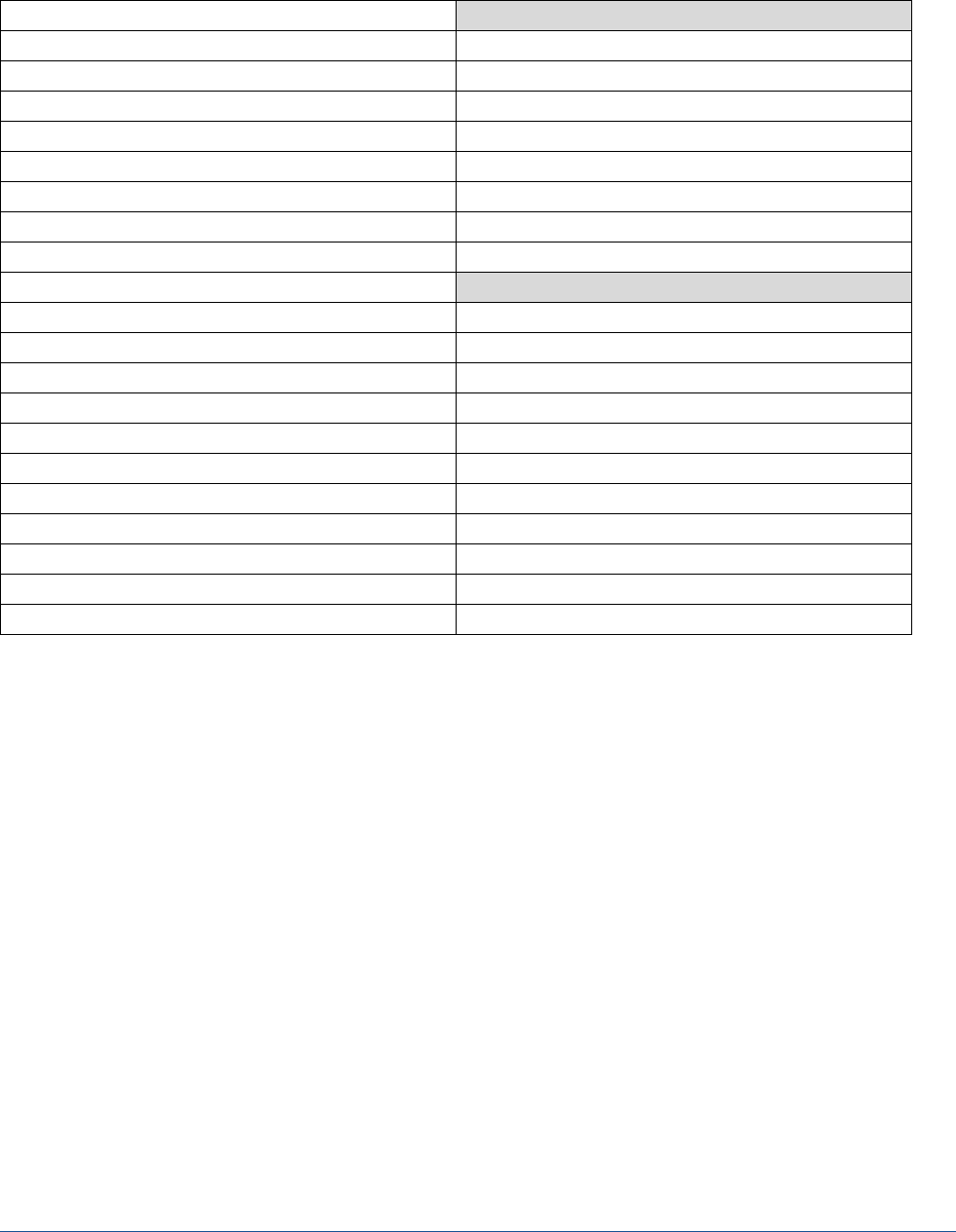

Table 1: Nonprofit Pharmaceutical Companies in the United States, 2000-2022

Name (Year

Founded)

Total

Revenue

(Year)

Mission Statement

Conditions or

Drugs Targeted

Current Drugs in U.S.

Market

Associated Companies

Civica Inc.

(2018)

$16,726,911,

as of 2019

Provide quality generic

medicines that are available and

affordable to everyone.

Various conditions

requiring generic

sterile injectables;

insulin for

diabetes

Civica Rx is involved in

private labeling and

distribution of 60

generic sterile

injectables;

CivicaScript is

distributing

Abiraterone—used to

treat prostate

cancer—and plans to

distribute three low-

priced generic insulin

by 2024.

Civica Rx, CivicaScript and Civica Foundation.

While Civica Rx focuses on generic drugs used in

the hospital setting, CivicaScript, a public benefit

company (PBC)

v

, works with pharmacy benefits

managers (PBMs) and insurers to bring low-cost

generics to outpatient and retail pharmacies.

The Civica Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization

that provides philanthropic support to

manufacture and distribute generic

medications.

Drew Quality

Group (2014)

less than

$50,000, as

of 2021

Improve society’s health by

being a supplier of high-quality

generic drugs, manufactured in

the United States.

Generic drugs

None

N/A

Fair Access

Medicines

(2015)

less than

$50,000, as

of 2021

Identify, develop, and deliver

life-saving medicines to poorly

served patients in the U.S. and

worldwide at the lowest cost

possible.

Insulin for

diabetes

None

N/A

Harm

Reduction

Therapeutics

(2017)

$1,550,000,

as of 2019

Make naloxone more accessible

for everyday people by

combining increased funding,

generating more interest in

public health, and building on

our years of expertise.

Naloxone for

opioid overdose

None. Over-the-

counter naloxone

product approved in

July 2023, with an

expected launch date

in early 2024.

N/A

_______________________

v

Public benefit companies are for-profit entities that maintain profit and public benefit objectives.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

7

Institute for

Pediatric

Innovation

(2006)

$34,443, as

of 2020

Research and develop

innovative products that will

improve the health of children

and support those who provide

care for them.

Pediatric

conditions

None. Mission focus

has evolved to focus

on digital health.

N/A

Medicines360

(2009)

$17,400,453,

as of 2019

Catalyze equitable access to

medicines and devices through

product development, policy

advocacy, and collaboration

with U.S. and global partners.

Contraception,

such as hormonal

IUDs

One branded

hormonal IUD, Liletta,

through Actavis; over

the counter

emergency

contraceptive through

Curae Pharma360.

Medicines360’s subsidiary is Curae Pharma360

Inc. which is a for-profit organization focused on

improving the availability of quality generic

drugs and other medicines that are in short

supply. Medicines360 selected Actavis (formerly

Watson Women’s Health, then Allergan, and

now AbbVie) as its for-profit commercial partner

for a hormonal IUD.

NP2 (2019)

$340,500, as

of 2020

Promote public health by

developing, manufacturing, and

distributing medicines for the

treatment of life-threatening

diseases in underserved

populations.

Generic drugs for

cancer

None

N/A

Odylia (2018)

$60,528, as

of 2020

Accelerate the development of

gene therapies for people with

rare disease, changing the way

treatments are brought from

the lab to the clinic…to bring life

changing treatments to people

with genetic disease regardless

of prevalence or commercial

interest.

Gene therapies

for rare genetic

disorders

None

Odylia has partnered with Cloves Syndrome

Community, SATB2 Gene Foundation, Usher

2020 Foundation, RDH12 Fund for Sight, and

PTC Therapeutics

Institute for

One World

Health | PATH

Drug Solutions

(2000)

$2,972,163,

as of 2018

Develop and deliver lifesaving

medicines to women, children,

and communities around the

globe.

Drugs and

vaccines for

various infectious

diseases,

contraception,

maternal and

child health

An injectable

contraception,

subcutaneous depot

medroxyprogesterone

acetate (DMPA-SC),

through Pfizer.

PATH selected Pfizer as its for-profit commercial

partner for an injectable contraception.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

8

Remedy

Alliance Inc.

(2012)

$95,600, as

of 2021

Ensure harm reduction

programs have sustainable &

equitable access to low-cost

naloxone for distribution in their

communities.

Naloxone for

opioid overdose

Remedy Alliance is

involved in the

distribution of generic

naloxone.

N/A

Tutela

Pharmaceutical

(2020)

Less than

$50,000, as

of 2021

Ensure continued and

affordable access of single-

source medications to patients.

Single-source

medications

subject to

discontinuation or

divestiture by

their

manufacturers.

None. Acquired

license from Astellas

Pharma Inc. for active

ingredient of a

medication previously

tested for COVID-19.

Collaborators include Zensights, Pharmafusion,

Tucker Ellis, LLP, Incubate IP, and Godfrey &

Kahn, SC.

Note: All general information obtained from company websites; financial information was obtained through IRS.gov.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

9

Table 2 presents the number of products, sales, and units sold for the only nonprofit pharmaceutical company,

Civica, identified in IQVIA’s NSP dataset from 2020-2022, as well as the corresponding sales and units sold for

the same products sold by for-profit companies. The data show that Civica sold 350 million units and $256

million in sales for 64 products. We identified 73 for-profit companies, with 20,200 million units sold and

$13,900 million in sales for the same corresponding products, suggesting that sales for the one nonprofit

pharmaceutical company represents about two percent of total sales and volume.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics by Pharmaceutical Sector, United States, 2020-2022

Description

Nonprofit

For-profit

Number of companies

1

73

Number of products

64

64

Total units sold

350.2 million

20,200 million

Total sales

$255.9 million

$13,900 million

Note: A product is defined as a molecule-form-strength combination.

Source: ASPE analysis of IQVIA National Sales Perspective Data.

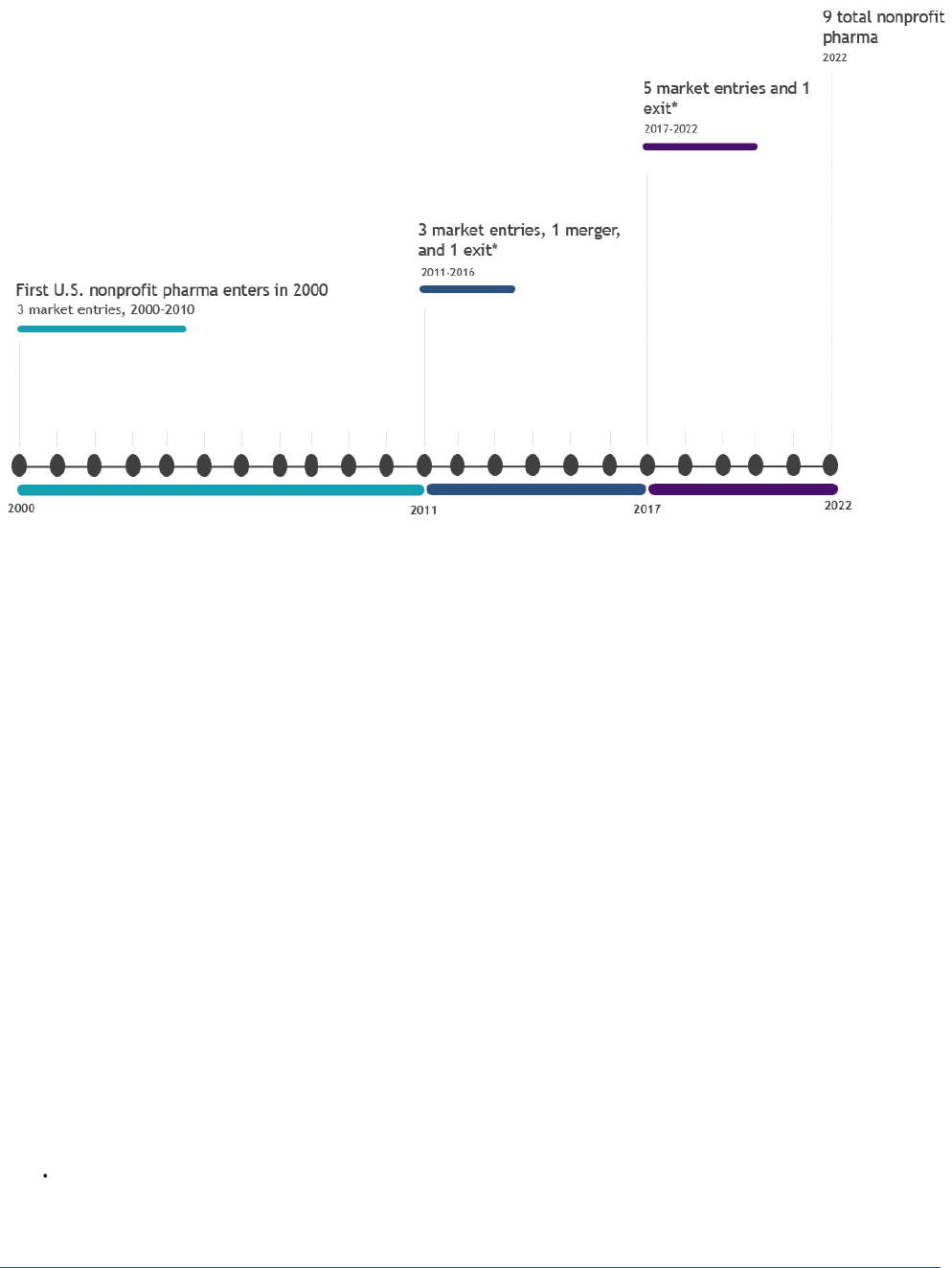

Market Growth

Growth in the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector was slow between 2000 and 2015, with one firm entering the

market every five years, on average. Most of the growth in this sector has occurred in the last five years; on

average, one nonprofit pharmaceutical company entered the market each year during 2017-2021. Out of the

11 identified companies, two are no longer operating as originally envisioned (we consider these market exits),

and one merged with a global nonprofit company in 2011 (Figure 1). As of August 2023, five of the 11

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies had either received FDA marketing authorization or are distributing

medical products in the United States.

The majority of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies were either in the R&D phase of medical product

development or looking to secure start-up capital. As discussed above, most nonprofit pharmaceutical

companies have historically outsourced the manufacturing, packaging, and labeling of their medical products

to contract manufacturers. However, one nonprofit pharmaceutical company, Civica, has exhibited noticeable

growth since its creation in 2018. Civica offers over 60 generic sterile injectable medications to over 1,500

hospitals through Civica Rx.

36

Further, in 2021, Civica created CivicaScript, a PBC, to offer generic drugs used in

the outpatient and retail settings.

37

The Civica Foundation was also established to provide philanthropic

support to manufacture and distribute generics. Civica’s rapid growth has been credited to its ability to

leverage the long-term commitments of its hospital and health system members to secure long-term supply

contracts.

38

These supply contracts have incentivized the reentry of numerous CMOs that had excess capacity

and held many of the Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) for generic drugs that Civica labels and

distributes to its members.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

10

Figure 1: Market Growth Timeline, Nonprofit Pharmaceutical Industry, United States, 2000-2022

*Market exit refers to a shift in mission or operations that no longer covers commercialization activities.

Market Entry Strategies

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies generally begin operations with funding from philanthropic entities or

individuals, including crowdsourcing, that support their mission statement. In contrast, for-profit companies

depend on raising funds through investors who expect a return on their capital. Without the expectation to sell

pharmaceutical products that generate high profit, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have a different risk

tolerance and may be able to provide products with low or negative profit. However, both for-profit and

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies face similar costs, timelines, regulatory oversight when developing and

bringing products to market, and generate revenue from selling drug products and services.

Typically, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies focus on a single product when entering the market. Since they

must demonstrate that its mission is compelling enough to motivate access to philanthropic funding, nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies tend to be organized around addressing intractable market gaps that will improve

social welfare, such as increasing access to medicines at affordable prices, mitigating drug shortages, or

developing new drugs for rare or tropical diseases.

When selecting their target drugs, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies, like their for-profit counterparts,

consider multiple factors, such as the target market size, start-up costs, regulatory requirements, and the

sustainability of their business model. In interviews, stakeholders noted that nonprofit pharmaceutical

companies may prefer to focus on niche drugs such as those with low start-up costs, low margins, or high

volumes. Some niche markets that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have entered are:

Essential drugs or drugs in shortage: Enhancing access to affordable medications, essential or

lifesaving medications, and medications that experience persistent shortages is part of the mission of

many nonprofit pharmaceutical organizations. This mission can also engender trust in the market as

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

11

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies begin to be recognized for filling gaps in market demand and

meeting unmet medical needs.

Generics: By targeting off-patent drugs, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies can focus on products

that are typically associated with low margins, as well as lower start-up, development, and regulatory

costs, and lower litigation risks. These products are generally not attractive to for-profit companies

due to the low margins and intense pressure to keep prices down via competition.

Discontinued drugs: Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies can fill treatment gaps by focusing on

medical products that have been discontinued or abandoned by for-profit companies due to low

volume and profitability. These drugs represent opportunities for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies

to enter the market.

High-volume drugs: By targeting high-volume products like insulin, nonprofit pharmaceutical

companies ensure the market can facilitate competition and business sustainability. Some of these

high-volume drugs have experienced persistently high prices, despite being off patent.

Results

Low-Cost Alternatives to Expensive Drugs

Many life-saving drugs do not have low-cost alternatives, despite being off patent for an extended period of

time. As a result, patients may incur debt or ration their medications, which leads to medication nonadherence

and worse health outcomes.

39

In interviews, stakeholders shared that drug prices are set by for-profit

companies to create shareholder value, which is typically achieved by maximizing profit. In contrast, many

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies promote the affordability of medical products as a goal in their mission

and vision statements. In practice, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies offer a cost-plus model that prices

drugs at the level of margins that ensure their sustainability, adding a fixed percentage to the unit cost of each

product.

Insulin is an example of a drug for which nonprofit pharmaceutical companies want to provide more

alternatives because the global market is currently dominated by three manufacturers.

39,40

Almost a year after

a nonprofit pharmaceutical company announced its two-year plan to enter the insulin market with prices set at

$35 per vial, all three of the for-profit companies cut the out-of-pocket cost to a maximum of $35 per vial.

41-43

However, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies were not the only source of competitive pressure. The decision

by the for-profit companies to lower insulin prices followed announcements by the state of California, in

partnership with a PBC that operates a cost-plus model, to manufacture its own insulin. In addition, the

Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in August 2022, capped out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 per

monthly prescription for Medicare enrollees beginning January 1, 2023.

39,44

The entry of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies into markets with expensive generic drugs, few

manufacturers, and high volume of sales may increase the competitive pressure for all companies to lower

their prices. However, drug pricing is not only a reflection of manufacturer prices that capture the cost of R&D

but also markups by intermediaries, such as PBMs, wholesalers, and pharmacies. Efforts to enhance the

accessibility of affordable medications need to also consider margins that allow companies to recover their

R&D costs. However, drug pricing transparency, particularly around negotiated rebates and discounts, has

been a topic of debate in limiting the public’s understanding of the financial arrangements dictating the profits

of stakeholders in the pharmaceutical marketplace. Stakeholders shared that nonprofit pharmaceutical

companies are attempting to disrupt persistently high prices for expensive medications by adopting

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

12

transparency in their financial arrangements, including disclosing the price and charging the same price for all

members without volume discounts, as one of their core business strategies.

Another strategy that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies adopt to increase competitive pressure is to bring

over-the-counter (OTC) alternatives to expensive prescription drugs to market. OTC drugs are typically sold at

lower prices than drugs that require a prescription or that are administered in hospitals or physician offices. An

example of this is naloxone, a life-saving drug used to reverse an opioid overdose, and whose price hikes

45

attracted the entry of a nonprofit pharmaceutical company, Harm Reduction Therapeutics. Although FDA

encouraged sponsor applications for OTC naloxone products in 2019,

46

no existing for-profit company had

submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) for OTC naloxone until two months after the nonprofit

pharmaceutical company submitted its NDA in late 2022.

47,48

On March 29, 2023, FDA approved the first OTC

naloxone product to a for-profit company, and sales began in the summer 2023.

49

On July 28, 2023, FDA

approved Harm Reduction Therapeutics’ ReVIVE, with sales beginning in early 2024.

50

Challenges

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have limited capacity to offer alternatives for expensive drugs that are

not off-patent or are protected by a market exclusivity. While many contribute to drug discovery and

development, they typically leverage partnerships with for-profit pharmaceutical companies to commercialize

their products, which creates uncertainties on the pricing model that will be used. For example, although

Targretin (bexarotene), a cancer drug, was developed by nonprofit pharmaceutical companies and now has

generic competitors available, it was commercialized in partnership with a for-profit company

22

and is sold for

almost $30,000 for 100 capsules.

51

Relatedly, the business structure of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies

with wholly owned for-profit companies has the potential to undermine their credibility regarding

transparency in drug pricing. One example is CivicaScript, a subsidiary of Civica that was established as a for-

profit PBC, which focuses on generic drugs distributed via retail, mail, and outpatient channels for participating

pharmacies.

38

The low levels of therapeutic concentration and market share of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may not

be sufficient to disrupt drug pricing in the pharmaceutical market for multiple reasons. First, stakeholders we

interviewed noted that prices of nonprofit pharmaceutical company drugs may not be the lowest in the market

at any given time because their prices are designed to create stability in the market and to be the lowest

sustainable price for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies (see Drug Shortages for additional discussion).

Second, like in the for-profit pharmaceutical sector, since list prices for drugs do not reflect markups along the

pharmaceutical supply chain for each distribution channel, it is difficult to quantify the actual savings for

payers and patients when there is a mix in business models. This is especially true for drugs that are

administered in hospitals or physician offices because the reimbursements for those drugs are usually bundled

with the reimbursement for other services.

52

Third, while OTC products tend to be low cost, OTC drugs are not

covered by health insurance, which may limit the savings, number, and types of patients that could benefit

from these drugs.

53

Drug Shortages

According to the FDA,

the majority of drugs in shortage are sterile injectables and older generic drugs with a

median time of 35 years since first approval.

54

Root causes of generic drug shortages are the low profitability

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

13

of generic drugs and the lack of market rewards for generic manufacturers that invest in quality management

maturity; shortages can also occur due to supply chain disruptions or increased demand.

vi

The nonprofit funding model, which does not expect the same high rates of return for investors, suggests that

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may be able to sell drugs, such as generics, that are associated with low

profits. However, just like any organization, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies need to balance their

sustainability and cost goals. Some researchers have proposed the Health Care Utility (HCU)

model,

vii

a novel

governance and financing structure, to address drug shortages and persistent price hikes of generic drugs.

55

The HCU model relies on member

viii

financing to provide products and services at the lowest sustainable price.

Proponents of the HCU model argue that the core tenets of the model address the factors and misaligned

incentives that contribute to drug shortages.

6

The HCU model informed the business structure of Civica Rx,

which provides same-price guarantees with no volume discounts, requires long-term commitments, and

embeds a quality assurance process in its contracts with CMOs.

36,38

This pricing approach includes maintaining

a six-month buffer supply of its products as a mitigation strategy against drug shortages or supply chain

interruptions.

56

Further, Civica Rx limits its volume agreements to 50 percent of each member’s total volume

and establishes contracts with multiple CMOs in North America, Europe, and South Asia to increase the

geographical diversity of its suppliers and mitigate supply chain risks.

36

Challenges

In interviews, some stakeholders shared that the price of products by nonprofit pharmaceutical companies,

like Civica Rx, may not be the cheapest on the market because pricing may account for the cost of investments

in quality management systems to mitigate shortages. Stakeholders shared that the HCU approach to

addressing drug shortages is limited because it provides drugs for its members only. The volume that nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies produce may also be too low to have an impact in the broader market. Further,

since many of the nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may not own the license nor manufacture their own

generic drugs, some function like a group purchasing organization (GPO), and as such, they have no control

over the price that patients ultimately pay.

Some stakeholders have been skeptical about the feasibility of replicating or scaling up models like that of

Civica Rx for multiple reasons. First, long-term contracts may result in members paying higher prices than the

lowest available market price in the short term, although the price would remain unchanged when there is a

shortage. Another risk is the potential to further concentrate bargaining power in one entity and perpetuate

the existing oligopoly in the pharmaceutical industry. Stakeholders shared lessons from the health care

industry, which is dominated by nonprofit health systems, that suggest the nonprofit model may not always

translate to maximizing social welfare. For example, research suggests that nonprofit hospitals are not more

likely to provide charity care or unprofitable services than their for-profit counterparts.

57

Access to Essential Medicines

FDA, in collaboration with other federal agencies, began developing and publishing a list of essential

medicines, medical countermeasures, and critical inputs in 2020 in response to President Trump’s Executive

Order on Ensuring Essential Medicines, Medical Countermeasures, and Critical Inputs are Made in the United

States.

58

FDA’s list of essential medicines identifies those medical products that have the greatest potential

_______________________

vi

Quality management maturity measures the consistency and reliability of business processes to implement and maintain the quality

of products in the marketplace, including early signals to enable actions to prevent drug shortages triggered by quality issues.

vii

Utility is a reference to commonly shared basic goods, such as electricity and gas.

viii

Members are customers of the HCU; for example, health systems are the customers for hospital-based drugs and health insurance

companies are customers for retail drugs. Some call the HCU a “closed-system” model because only members have access to the

products and services.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

14

impact on public health and are most needed by patients for acute and urgent medical conditions. The goal of

the FDA’s essential medicines list is to ensure the American public is protected against outbreaks of emerging

infectious diseases, chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats by ensuring sufficient and reliable,

long-term domestic production of these products.

59

Another list of essential medicines, managed by the World

Health Organization (WHO), identifies medications that may be critical to ensure a nation’s health system can

meet the health care needs of its population. The WHO list of essential medicines prioritizes disease

prevalence, public health relevance, and evidence on efficacy, safety, and comparative cost-effectiveness. For

this report, we examine the role of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies in addressing gaps in the provision of

critical medicines for both chronic and acute health conditions.

60

For purposes of the stakeholder interviews,

essential medicines were broadly defined to include those in the FDA list of essential medicines and others

such as oncology drugs or sterile injectables.

In interviews, stakeholders shared that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies could increase access to essential

medicines by leading R&D for low volume medical products to address unmet health needs, such as rare

diseases, neglected tropical diseases, and antimicrobial resistance. Examples that illustrate the potential for

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies in this area include those that develop new technologies, such as

Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) that is working to develop and commercialize CRISPR gene-editing

therapies to treat sickle cell disease.

61

Further, the environmental scan identified that R&D and

commercialization for new antibiotics to combat antimicrobial resistance is another market gap that may be

appropriate for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies.

62,63

In comparison to brand-name drugs in other

therapeutic areas, new antimicrobials typically have very low volumes and low prices.

64

Strategies to bring critical medical products to market at lower cost include identifying new uses and

indications for approved and off-patent drugs, a strategy known as drug repurposing.

65

Since safety data exists

for approved drugs, it has been estimated that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies can avoid approximately

40 percent of the costs for drug development by repurposing approved drugs.

66

This strategy can be effective

for conditions that have few treatments available, such as rare and neglected diseases. For example, Institute

for One World Health repurposed paromomycin, an off-patent drug that is no longer used as an antibiotic, to

cure visceral leishmaniasis, a neglected, tropical disease.

ix

A closely related strategy focuses on rescuing abandoned compounds for which data demonstrate safety and

efficacy, but which for-profit companies do not complete development and regulatory approval due to

anticipated low profitability. This market gap presents opportunities for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies.

In one example, Tutela Pharmaceutical executed an exclusive license agreement for a compound that was

abandoned by a for-profit company after the completion of phase 1 and 2 clinical trials.

Another market gap of interest to nonprofit pharmaceutical companies is increasing access to drugs to

underserved populations by prioritizing diversity in clinical trials to ensure generalizability of evidence. For

example, Medicines360 sponsored a phase 3 clinical trial for the first hormonal IUD that prioritized diversity in

the enrollment of clinical trial participants. Unlike the hormonal IUD that was already available on the market

at the time, this nonprofit pharmaceutical company generated safety and efficacy evidence for women of all

races, women who had never given birth, overweight or obese women, and women with sexually treated

infections in the United States.

10

The environmental scan identified a study that concluded that patients at a

Title X clinic experienced increased uptake and decreased average payments after the introduction of the

hormonal IUD.

67

This was the only example we identified of a nonprofit pharmaceutical company successfully

_______________________

ix

It is worth noting that NIH’ National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences created a drug repurposes program intended to

facilitate sharing of data and other resources for scientists and others interested in repurposing drugs. See

https://ncats.nih.gov/preclinical/repurpose.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

15

developing and commercializing a branded medical product for the U.S. market. While this nonprofit

pharmaceutical company retained ownership of the NDA, commercialization of the medical product occurred

through a licensing agreement with a for-profit company. In exchange for licensing the intellectual property of

the nonprofit pharmaceutical company, the for-profit pharmaceutical company committed to prioritize

commercializing the hormonal IUD, paid an upfront payment, as well as milestone payments, and continuous

royalties on units sold, which are non-taxable because they are not classified as unrelated business income.

10

Retaining ownership of the license allowed Medicines360 to maintain ownership of the drug and reinvest in

R&D to identify new indications. Stakeholders noted that entry by Medicines360 for an underserved market

spurred additional investment and development of new products by for-profit companies. Other strategies

that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have adopted to launch their products include creating wholly

owned for-profit subsidiaries, partnerships with PBCs, or selling the license to a for-profit pharmaceutical

company. However, as noted above, these types of partnerships or business structures have the potential to

undermine their credibility regarding transparency in drug pricing.

Challenges

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies face challenges with repurposing off-patent drugs and rescuing

abandoned compounds, including difficulty raising capital to conduct expensive phase 3 clinical trials and

aligning with donor priorities.

66

For example, disulfiram, a drug approved as an anti-alcoholism drug, has been

proposed as a candidate to be repurposed to treat many diseases, including various cancers, Alzheimer’s

disease, and COVID-19.

66,68

However, in such circumstances, prioritization of potential new indications to

pursue depends on the interest of donors. While donors to nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may prioritize

public benefits, it is unclear that their priorities will always align with public health needs that maximize social

welfare.

Further, the risk of donor fatigue undermines the long-term sustainability of the nonprofit model. Pull

incentives, wherein the government aims to reward new drug development for underserved markets by

reducing the risk of insufficient future revenue streams through higher reimbursement policies, have been

successfully employed to develop new hospital-based antibiotics. For example, the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services (CMS) have paid new technology add-on payments for novel antibiotics used in the inpatient

setting.

69

However, oftentimes sales revenue from antibiotics cannot sustain a company’s infrastructure costs,

so other investments unrelated to sales revenue would also be necessary to ensure the sustainability of the

nonprofit model for low volume medical products.

64,69

Beyond R&D costs, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies need to raise funds for complex commercialization

activities, such as manufacturing, distribution, reimbursement, and post-marketing commitments. If the

nonprofit tax-exempt status was obtained based on a mission to conduct research, then sales revenue from

commercialized medical products may be subject to business income taxes. Relatedly, stakeholders shared

that commercial activity by nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may attract litigation and jeopardize tax-

exempt status under the IRS “commerciality” doctrine.

x

Stakeholders also noted that FDA has limited

experience working with nonprofit pharmaceutical companies, who may also not be aware of flexibilities

available to them.

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies adopt several strategies to navigate the complex pharmaceutical supply

chains in the United States and retain tax-exempt status. However, some of these strategies may not be

feasible for low-volume products. In one example, stakeholders shared that a nonprofit pharmaceutical

_______________________

x

In its determination that a business entity did not qualify as a 501(c)(3) organization, IRS stated “factors courts have considered in

assessing commerciality are competition with for-profit commercial entities; extent and degree of below cost services provided;

pricing policies; and reasonableness of financial reserves.”

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

16

company regained ownership of a gene-therapy that was licensed to a for-profit company, likely because of

claw back clauses

xi

in the licensing agreement. For several years after gaining the license for the gene therapy,

the for-profit company was unable to meet the comparability

xii

requirement to scale it and terminated related

development activities. While the gene therapy may be available to patients through the compassionate use

program, shareholders stated that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may not have the financial resources

and expertise required to launch phase 3 trials, pay FDA user fees, maintain all of the regulatory requirements

to obtain FDA approval, or meet manufacturing requirements for widespread distribution without a

commercial for-profit partner.

Limitations

This report has several limitations. First, the stakeholder interviews were limited to nine experts, and as such,

the findings from this report may not be generalizable to all stakeholders impacted or involved. For example,

the stakeholder interviews had limited experts from the for-profit pharmaceutical industry. Further, although

the environmental scan aimed to include broad terms, it is possible that our search terms and results did not

capture other key topics or issues. Lastly, given the nascent nature of this sector, there was limited availability

of data to quantitatively examine the role of the nonpharmaceutical companies in increasing the supply of

essential and affordable drugs.

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings from this report suggest that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have the potential to address

drug shortages and enhance access to affordable and essential medicines. However, their sustainability and

effectiveness may be limited due to low production volumes, a complex tax system, ineligibility for small

business funding sources, and to some extent, lack of awareness of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies by

the government and the public at large.

Although this report identified 11 companies in the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector, only one was captured in

a database of drugs sold in the United States during 2020-2022. The data showed that the volume of this

nonprofit pharmaceutical company represented about two percent of the total sales volume for the same

generics sold by for-profit companies. This finding aligns with stakeholder interviews that indicated that

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies currently have limited ability to fill large gaps in the market or create

pressure to bring prices down due to their low production volume.

Second, the lack of profit motive for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies results in a different risk profile and

set of strategies than their for-profit counterparts. Thus, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have the

potential to increase access to essential and affordable medicines. For example, their strategies to repurpose

generics, pick up abandoned products, or bring OTC products to market have partly contributed to pressure on

the industry to increase access to low-cost insulin products and to bring OTC naloxone products to market.

Further, the focus of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies on low volume drugs necessitates the conduct of

R&D or commercialization activities on essential medicines that for-profit companies may not deem

commercially viable.

_______________________

xi

Claw back is a contractual provision that allows an instance of recovering assets or benefits previously given out.

xii

Comparability requirements means demonstrating that phase 2 results are comparable to phase 3 results.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

17

Third, while nonprofit pharmaceutical companies are governed by a different set of tax laws than for-profit

companies, they are subject to the same FDA regulatory requirements and R&D costs to bring products to

market. This has led nonprofit pharmaceutical companies to target products that are low cost to develop and

that have a higher probability of success. In this way, some do not see nonprofit pharmaceutical companies as

disruptors to the industry or a solution to the issues at hand given that many of their activities involve

relabeling approved products and have low sales volume.

Fourth, although nonprofit pharmaceutical companies can leverage their tax-exempt status to seek funding

from diverse sources, the complex tax environment has resulted in a mixed structure of nonprofit and for-

profit companies under the same organization that blur efforts to increase transparency or ensure that drugs

are affordable. Though the majority of nonprofit pharmaceutical companies have operational sizes comparable

with small businesses, their tax-exempt status makes them ineligible for some types of funding from the

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Small Business Innovation Research, the Small Business Administration

(SBA), or even bank loans that require some expected level of revenue. Further, the diverse funding sources

create challenges aligning drug development and commercialization activities of nonprofit pharmaceutical

companies with public health priorities.

The literature and stakeholders have described various approaches to address some of the challenges that

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies face, which can be largely divided into financial and nonfinancial

incentives. Financial incentives include the establishment of a federal program or set of initiatives that could

fund or provide financial support for the development and manufacturing of drugs by nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies at all stages of the product life cycle—from early discovery research activities to

commercialization—as well as for capital investments. Stakeholders have proposed a number of financial

incentives tailored to the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector such as interest-free loans, grants, cooperative

agreements, loans not requiring repayment, and advanced purchasing agreements with the government to

enhance their sustainability. Stakeholders and the literature also cited other existing tools that could be

leveraged to expand eligibility to the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector, including NIH’s Small Business

Innovation Research Grants, the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) 340B Drug Pricing

Program, and advanced purchasing commitments from the Strategic National Stockpile.

In addition to the proposed initiatives discussed above, several Congressional bills have been introduced in

recent years aimed at the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector. This includes Senate Bill 2257, the Expanding

Access to Affordable Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices Act introduced in 2021, which included provisions

for funding and low-interest loans to support nonprofit drug development and required FDA user fee waivers.

Financial initiatives such as the provisions included in this bill could align eligibility with certain criteria such as

manufacturing drugs that are essential, in shortage, or fulfilling a public health need. One example cited by

some stakeholders was Civica’s funding that allowed them to begin construction of a manufacturing facility in

Virginia. This funding was awarded to Phlow Corporation, a U.S. drug manufacturing PBC, by the U.S.

Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) to build manufacturing capacity of essential

medicines in shortage.

70,71

Stakeholders noted that Federal support would increase the financial stability of

nonprofit pharmaceutical companies through funding or purchase agreements that would ensure some level

of volume to be large enough to exert pressure in the industry, increase their sustainability, and also increase

awareness of and trust in the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector. This support could promote market entry,

competition, and expansion in this sector.

Existing literature and stakeholders have also proposed non-financial incentives to encourage growth in the

nonprofit pharmaceutical sector. Specific examples included expediting FDA review of nonprofit applicant

submissions or creating separate regulatory programs for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies. As noted

above, these challenges are not specific to the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector. Past studies focused on the

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

18

for-profit sector have also proposed similar solutions (i.e., reduced FDA timelines, simplification of clinical trial

protocols, increased interactions with FDA, improved predictability of the review process), to reduce the cost

of bringing drugs to market.

72

While FDA already uses existing tools to address drug shortages that involve

prioritizing and expediting review of certain applications and inspections, providing technical assistance and

guidance for small companies,

73

authorizing waivers, reductions, exemptions or refunds of user fees when

certain conditions are met,

74

further research is needed to understand how these existing tools can be

leveraged to address issues that are specific to the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector.

Review of the literature and discussions with stakeholders identified changes to the tax code as a way to lower

the entry barrier for nonprofit companies in the pharmaceutical sector. The policy proposals identified

included creating tax incentives that can facilitate the transfer of patents of abandoned drugs, creating

incentives for for-profit companies to partner with nonprofit pharmaceutical companies, clarifying the tax

code to facilitate activities and funding mechanisms, creating a new tax-exempt designation for nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies that are fulfilling a public health need, classifying drug sales of nonprofit

pharmaceutical companies as non-taxable revenue, and creating protections to uphold the IRS nonprofit

designation. However, stakeholders highlighted the risk of mission drift and oligopoly in the nonprofit

pharmaceutical sector if regulations are not implemented to ensure accountability. Literature and

stakeholders provided lessons learned from the health care industry, which is dominated by nonprofit health

systems, that suggest the nonprofit model may not always maximize social welfare.

To conclude, while the nonprofit pharmaceutical sector holds promise to address drug shortages and enhance

access to affordable and essential medicines, more research is needed to understand the available or potential

tools that can reduce existing barriers and challenges, as well as understand their implications on competition,

drug pricing, and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

19

Appendix A. Alternative Economic Models for Commercialization by Nonprofit

Pharmaceutical Companies

We summarize the alternative economic models that have been proposed in literature to promote market

authorization and commercialization by nonprofit pharmaceutical companies in the marketplace.

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies as a market authorization holder leveraging the

manufacturing and distribution expertise of for-profit companies

Existing literature has proposed that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies could expand their organizational

capacity to pursue market authorization of new products discovered through their R&D pipeline rather than

license or engage in mergers and acquisitions.

8,9,23

In this model, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies would

leverage the expertise of for-profit pharmaceutical companies to maximize efficiency in production and

distribution.

8

For example, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may license new products to multiple for-

profit companies for manufacturing and distribution. Further, the partnership agreements could include

clauses to ensure social welfare outcomes, such as affordability and access for underserved populations, and

balance the need to generate profits and sustainability. Proponents of this model state that this strategy could

ensure that pricing is guided by drug affordability goals.

An important challenge to scale up this strategy is that nonprofit pharmaceutical companies may not have the

expertise or financial resources to navigate clinical development activities, such as phase 3 clinical trials.

Another challenge is ensuring that a nonprofit pharmaceutical company is accountable to its core mission and

will not engage in misaligned actions, such as price-gouging. The participation of major donors and patients,

who have a financial interest in drug affordability and accessibility, on the board of trustees may mitigate this

risk.

6

Medicines360 demonstrated the viability of this concept with the commercialization of its hormonal IUD in the

United States.

10

The product was initially launched with a $82 million grant from a private philanthropic

nonprofit. The total cost, including product liability insurance, of bringing the hormonal IUD to market was

$73.4 million. Medicines360 partnered with Actavis, a for-profit company. However, Medicines360 retained its

rights to market the hormonal IUD at a deeply discounted price to public clinics and hospitals, such as federally

qualified health centers, throughout the United States. Similarly, Medicines360 retained marketing rights to

sell the hormonal IUD in low- and middle-income countries.

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies as a market authorization holder with in-house

manufacturing and distribution expertise

In this model, nonprofit pharmaceutical companies would expand their organizational capacity to manage all

commercialization activities, including manufacturing and distribution.

8,9

An important barrier to adopting this

approach is the high start-up costs for new nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that do not have the ability to

leverage the economies of scale of established for-profit companies. This is a particular problem for low-

volume and new pharmaceutical products. One solution is for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies to modify

this approach by outsourcing actual production to CMOs. Another solution is the potential of selling exclusive

licensing of some products to raise start-up capital for internal commercialization of other products.

8

Proponents state that this strategy could be appropriate for nonprofit pharmaceutical companies that want to

target drugs that are not costly to bring to market such as old generic drugs, which have low profits and

experience frequent shortages.

6

The abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) process to obtain market

authorization for old generic drugs is less expensive because some of the regulatory requirements can be

fulfilled with existing data on efficacy and safety. An ASPE analysis found that the average cost to develop a

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

20

generic drug was $2.4 million ($3.2 million in 2022 dollars) and time required to bring the product to market

was just under five years.

75

One example of a nonprofit pharmaceutical company demonstrating the viability of this model for old generic

drugs is Civica.

38

As of March 2023, Civica Rx is distributing 60 generic sterile injectables to its members in the

United States through its supply contracts with foreign and domestic CMOs. Civica is in the process of

expanding to outpatient and retail pharmacies through CivicaScript. While Civica currently relies on ANDAs of

its CMOs, it plans to obtain its own ANDAs for generic drugs, such as insulin, and is building a manufacturing

facility in Virginia.

36,38

Nonprofit pharmaceutical companies leveraging product development partnerships

Nonprofit Product Development Partnerships (PDPs) is another model that has proven successful for launching

affordable and accessible medical products. PDPs coordinate financial and development efforts for medical

product development, in partnership with for-profits, nonprofits, and public stakeholders. For example, the

Global Alliance for TB Drug Development (TB Alliance) received FDA approval for pretomaid to treat

extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. TB Alliance negotiated license agreements to ensure access in low-

income countries.

76

Nonprofit PDPs have resulted in bringing many medical products to market that address

unmet public health needs in low- and middle-income countries.

77

PATH, a U.S.-based nonprofit, obtained FDA

approval and commercialized depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC), an injectable contraceptive, for

the domestic market through a PDP.

77,78

Similar to the objectives of PDPs, joint academic-industry-government

alliances to foster collaboration are common in the United States.

79

However, they are not formally

incorporated.

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

21

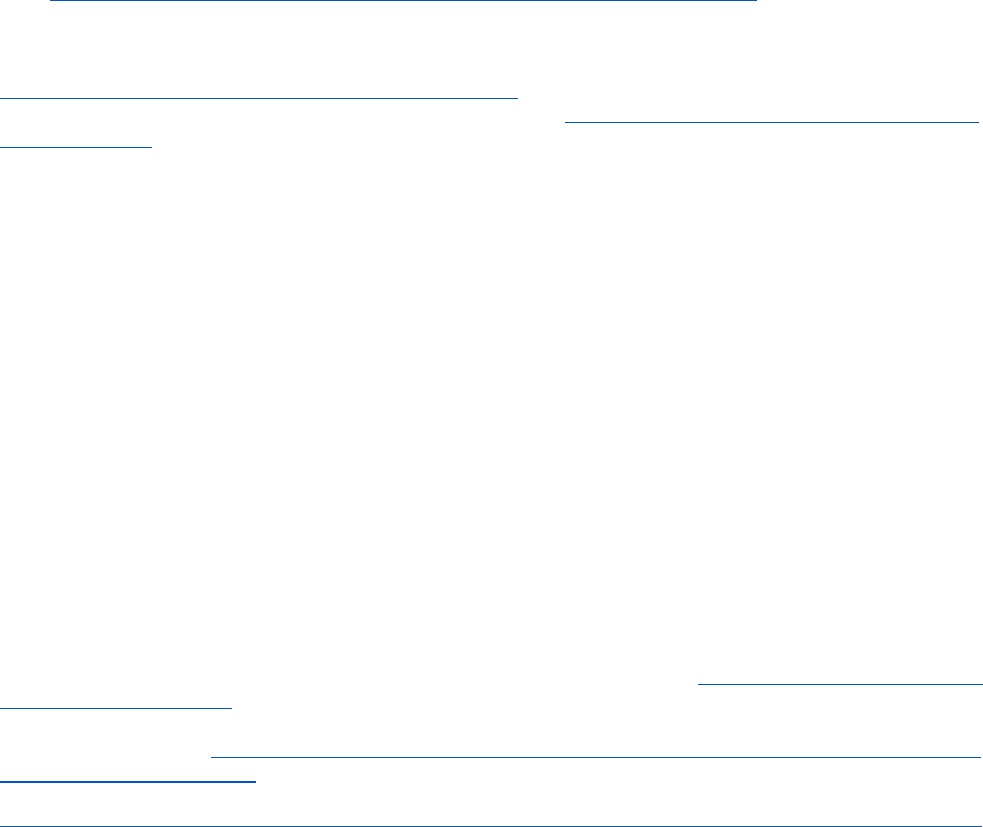

Appendix B. Environmental Scan Search Terms

Primary Search Terms

Secondary Search Terms

Nonprofit pharmaceutical company

Cost/Costly/High Cost

Pharmaceutical Public benefit corporation

Price

Nonprofit pharmaceutical sector

Affordability

Nonprofit pharmaceutical market

Low-cost generic drugs

Nonprofit biopharmaceutical company

Low-cost alternatives

Biopharmaceutical Public benefit corporation

Low-cost substitutes

Nonprofit biopharmaceutical sector

Low-cost biosimilars

Nonprofit biopharmaceutical market

Reimbursement

Biotechnology

Payers

Nongovernmental pharmaceutical company

Access

Charitable organizations

Drug shortage

Tax-exempt organizations

Essential drugs/medications

Life-threatening disease/rare disease

Life-saving medication

Critical drugs

Public health emergency

Orphan drugs

Specific Drugs

• Antibiotics, Antibacterials, Antimicrobials

• Saline

• CNS drugs

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

22

References

1. Bosworth A, Sheingold S, Finegold K, De Lew N, Sommers BD. Price increases for prescription drugs, 2016–2022.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA. 2022;

2. Shore C, Brown L, Hopp WJ, National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Causes and Consequences of Medical

Product Supply Chain Failures. Building Resilience into the Nation's Medical Product Supply Chains. National Academies

Press (US); 2022.

3. Cutler DM. The demise of the blockbuster? N Engl J Med. Mar 29 2007;356(13):1292-3.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp078020

4. Bennani YL. Drug discovery in the next decade: innovation needed ASAP. Drug Discov Today. Sep 2011;16(17-

18):779-92. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2011.06.004

5. Sharp D. Not-for-profit drugs--no longer an oxymoron? Lancet. Oct 23-29 2004;364(9444):1472-4.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17291-7

6. Liljenquist D, Bai G, Anderson GF. Addressing Generic-Drug Market Failures - The Case for Establishing a

Nonprofit Manufacturer. N Engl J Med. May 17 2018;378(20):1857-1859. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1800861

7. Dredge C, Scholtes S. The Health Care Utility Model: A Novel Approach to Doing Business. Catalyst non-issue

content. 2021;2(4)doi:doi:10.1056/CAT.21.0189

8. Jaroslawski S, Toumi M, Auquier P, Dussart C. Non-profit Drug Research and Development at a Crossroads.

Pharm Res. Feb 7 2018;35(3):52. doi:10.1007/s11095-018-2351-3

9. Conti RM, Meltzer DO, Ratain MJ. Nonprofit biomedical companies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Aug 2008;84(2):194-7.

doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.123

10. Medicines360. Nonprofit Pharma, Advancing a New Model for Equitable Access to Medicines. Medicines360;

2023. https://medicines360.org/wp-content/uploads/M360_CaseStudy_FINAL_v4_single.pdf

11. Handy F. Coexistence of nonprofit, for-profit and public sector institutions. Annals of public and cooperative

economics. 1997;68(2):201-223. doi:10.1111/1467-8292.00043

12. Congress.gov. H.R.2617 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617

13. Internal Revenue Service. Exempt Organization Types. 2023. https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/exempt-

organization-types

14. Dalton CM, Bradford WD. Better together: Coexistence of for-profit and nonprofit firms with an application to

the U.S. hospice industry. J Health Econ. Jan 2019;63:1-18. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.10.001

15. Marwell NP, McInerney P-B. The nonprofit/for-profit continuum: Theorizing the dynamics of mixed-form

markets. Nonprofit and voluntary sector quarterly. 2005;34(1):7-28.

16. Rose-Ackerman S. Competition between non-profits and for-profits: entry and growth. Voluntas: International

Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 1990;1(1):13-25.

17. Stevens AJ, Jensen JJ, Wyller K, Kilgore PC, Chatterjee S, Rohrbaugh ML. The role of public-sector research in the

discovery of drugs and vaccines. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(6):535-541.

18. Frye S, Crosby M, Edwards T, Juliano R. US academic drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery.

2011;10(6):409.

19. Kneller R. The importance of new companies for drug discovery: origins of a decade of new drugs. Nature reviews

Drug discovery. 2010;9(11):867-882.

20. Frank GD, Jong L, Collins N, Spack EG. Nonprofit model for drug discovery and development. Drug Development

Research. 2007;68(4):186-196.

21. Chakravarthy R, Cotter K, DiMasi J, Milne CP, Wendel N. Public- and Private-Sector Contributions to the Research

and Development of the Most Transformational Drugs in the Past 25 Years: From Theory to Therapy. Ther Innov Regul Sci.

Nov 2016;50(6):759-768. doi:10.1177/2168479016648730

22. Moos WH, Mirsalis JC. Nonprofit organizations and pharmaceutical research and development. Drug

development research. 2009;70(7):461-471. doi:10.1002/ddr.20326

23. Hale VG, Woo K, Lipton HL. Oxymoron no more: the potential of nonprofit drug companies to deliver on the

promise of medicines for the developing world. Health Affairs. 2005;24(4):1057-1063.

24. Foundation CF. Our Venture Philanthropy Model. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. https://www.cff.org/about-us/our-

venture-philanthropy-model

25. Pollack A. Deal by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Raises Cash and Some Concern. The New York Times; 2014.

Accessed 17 March 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/19/business/for-cystic-fibrosis-foundation-venture-yields-

windfall-in-hope-and-cash.html

July 2024

ASPE REPORT

23

26. Bush A, Simmonds NJ. Hot off the breath: 'I've a cost for'--the 64 million dollar question. Thorax. May

2012;67(5):382-4. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201798

27. Nolen S, Robbins, R. . The Drug Is a ‘Miracle’ but These Families Can’t Get It. The New York Times; 2023. Accessed

17 March 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/07/health/cystic-fibrosis-drug-trikafta.html

28. Bansal R, De Backer, R., Ranade, V. . What’s behind the pharmaceutical sector’s M&A push. McKinsey &

Company; 2018. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/whats-behind-the-

pharmaceutical-sectors-m-and-a-push#/

29. Drug Industry: Profits, Research and Development Spending, and Merger and Acquisition Deals (2017).

30. Weisman R. Nonprofit vows to lower generic drug costs. The Boston Globe; 2015. Accessed 30 March 2023.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2015/12/13/nonprofit-aims-make-affordable-generic-

drugs/u0kd8MHfZmawSzAh0pRnKI/story.html

31. CIVICA. Timeline-2018: Civica is Launched! https://civicarx.org/timeline-2018/

32. Internal Revenue Service. Exemption Requirements - 501(c)(3) Organizations. Internal Revenue Service.

https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/exemption-requirements-501c3-organizations

33. Internal Revenue Service. Social Welfare Organizations. Internal Revenue Service. https://www.irs.gov/charities-

non-profits/other-non-profits/social-welfare-organizations

34. Internal Revenue Service. About Form 990, Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax.

https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-form-990

35. Ledley FD, McCoy SS, Vaughan G, Cleary EG. Profitability of Large Pharmaceutical Companies Compared With

Other Large Public Companies. JAMA. Mar 3 2020;323(9):834-843. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0442

36. CIVICA. Making quality generic and biosimilar medications available at fair prices. CivicaRx.

https://civicarx.org/medications/

37. CivicaScript Announces a New Health Plan Partner, a New President, and a New Drug Manufacturing Partner.

CivicaRx; 2021. https://civicarx.org/civicascript-the-newly-named-civica-initiative/#

38. Dredge C, Scholtes S. The health care utility model: a novel approach to doing business. NEJM Catalyst

Innovations in Care Delivery. 2021;2(4)

39. Report on the Affordability of Insulin (2022).

40. Gaffney A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Prevalence and Correlates of Patient Rationing of Insulin in the

United States: A National Survey. Ann Intern Med. Nov 2022;175(11):1623-1626. doi:10.7326/M22-2477

41. Wingrove P, Bhanvi, S. . Novo Nordisk to slash US insulin prices, following move by Eli Lilly. Reuters; 2023.

https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/novo-nordisk-cut-price-insulin-by-up-75-wsj-2023-03-14/

42. Lovelace B. Sanofi announces insulin price cap after actions by Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. NBC News; 2023.

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/sanofi-insulin-price-cap-rcna75346

43. The Associated Press. Eli Lily Cuts the Price of Insulin, Capping Drug at $35 per month out-of-pocket. The

Associated Press; 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/03/01/1160339792/eli-lilly-insulin-price

44. Sable-Smith BY, Samantha. Eli Lilly slashed insulin prices. This starts a race to the bottom. Fierce Healthcare;

2023. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/finance/eli-lilly-slashed-insulin-prices-starts-race-bottom

45. Rosenberg M, Chai G, Mehta S, Schick A. Trends and economic drivers for United States naloxone pricing, January

2006 to February 2017. Addictive behaviors. 2018;86:86-89.

46. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on unprecedented new efforts to support development

of over-the-counter naloxone to help reduce opioid overdose deaths. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2019.

https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-