SIXTH-GRADE SIGHT-SINGING FOR LOW VISION STUDENTS

A COURSE TO ENHANCE CONFIDENCE AND MUSIC READING ABILITY

By

Jamie Lane Carpenter

Liberty University

A MASTER’S CURRICULUM PROJECT PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF

THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE

OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC EDUCATION

Liberty University

April, 2021

ii

SIXTH-GRADE SIGHT-SINGING FOR LOW VISION STUDENTS

A COURSE TO ENHANCE CONFIDENCE AND MUSIC READING ABILITY

By

Jamie Lane Carpenter

Liberty University

A Curriculum Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Arts in Music Education

Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA

April, 2021

APPROVED BY:

Samantha Miller, D.M.A., Associate Professor of Music

Hanna Byrd D.W.S., Assistant Professor of Worship Studies

iii

ABSTRACT

Students enter the private or public-school system with a wide variety of emotional,

mental, and physical impairments that impact their confidence, self-esteem, and overall path to

their future. One misunderstood and under-represented population of students are those who are

not fully blind but fall under the category of low vision. Since the low vision spectrum is wide,

students must advocate for themselves according to their unique visual condition. While some

students may be nearsighted, others may experience color blindness, tunnel vision, a wide variety

of partial blindness in one or both eyes, and more. If educators are not aware of a student's slight

visual impairment and students are not comfortable advocating for themselves, students could be

missing out on fully exploring their passion and aptitude for music. This study will examine the

existing research on the array of low vision impairments and how to help sixth-grade students

understand and overcome their impairments using tailored techniques to successfully meet their

goals of sight-singing music. A twelve-week curriculum is provided to guide music educators as

they help low vision sixth-grade students meet musical goals despite their visual impairment.

iv

Dedication Page

I dedicate this curriculum project in loving memory of my low vision grandmother, Judy

Lane Alderson and to my parents, sister, and fiancé for being a constant light and support in my

endeavors in face of my own low vision.

v

Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii

Dedication Page ............................................................................................................................. iv

Contents .......................................................................................................................................... v

LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... viii

LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................... x

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1

Definition of Terms............................................................................................................. 6

Sight-Singing Defined ........................................................................................................ 7

Other Definitions ................................................................................................................ 8

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................................... 11

Cognitive Sight-Singing Strategies ................................................................................... 11

The Visual Demands of Reading Music ........................................................................... 12

Low Vision Management and Tools ................................................................................. 13

Music Reading Resources for the Fully Blind .................................................................. 16

Educating Students with Low Vision ............................................................................... 16

Key Components of a Low Vision Curriculum ................................................................ 18

The Social and Emotional Impact of Low Vision ............................................................ 19

vi

CHAPTER III: METHODS .......................................................................................................... 22

Design of Study................................................................................................................. 22

Questions and Hypotheses ................................................................................................ 24

CHAPTER IV: RESEARCH FINDINGS .................................................................................... 26

Section I: Key Components of Low Vision Curriculum .................................................. 26

Section II: Types of Learning Styles ................................................................................ 28

Section III: Unique Pedagogical Techniques .................................................................... 31

CHAPTER V: DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................... 34

Summary of Study ............................................................................................................ 34

Summary of Purpose ......................................................................................................... 34

Summary of Curriculum Development ............................................................................. 35

Summary of Findings and Prior Research ........................................................................ 35

Limitations ........................................................................................................................ 36

Recommendations for Future Study ................................................................................. 37

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 39

APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................. 42

APPENDIX A-Detailed Curriculum................................................................................. 42

Syllabus ............................................................................................................................. 42

Analysis Chart ................................................................................................................... 45

Design Chart ..................................................................................................................... 48

vii

Learning Outcomes According to Bloom’s Taxonomy .................................................... 54

Development Chart ........................................................................................................... 55

Gagne’s Nine Events of Instruction .................................................................................. 59

Implementation Chart ....................................................................................................... 62

Necessary Tasks ................................................................................................................ 64

Evaluation Chart ............................................................................................................... 66

Evaluation and Reflection ................................................................................................. 69

Formative Assessment Description................................................................................... 70

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1……………………………………………………………………………………..……72

Table 2………………………………………………………………………………………..…74

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

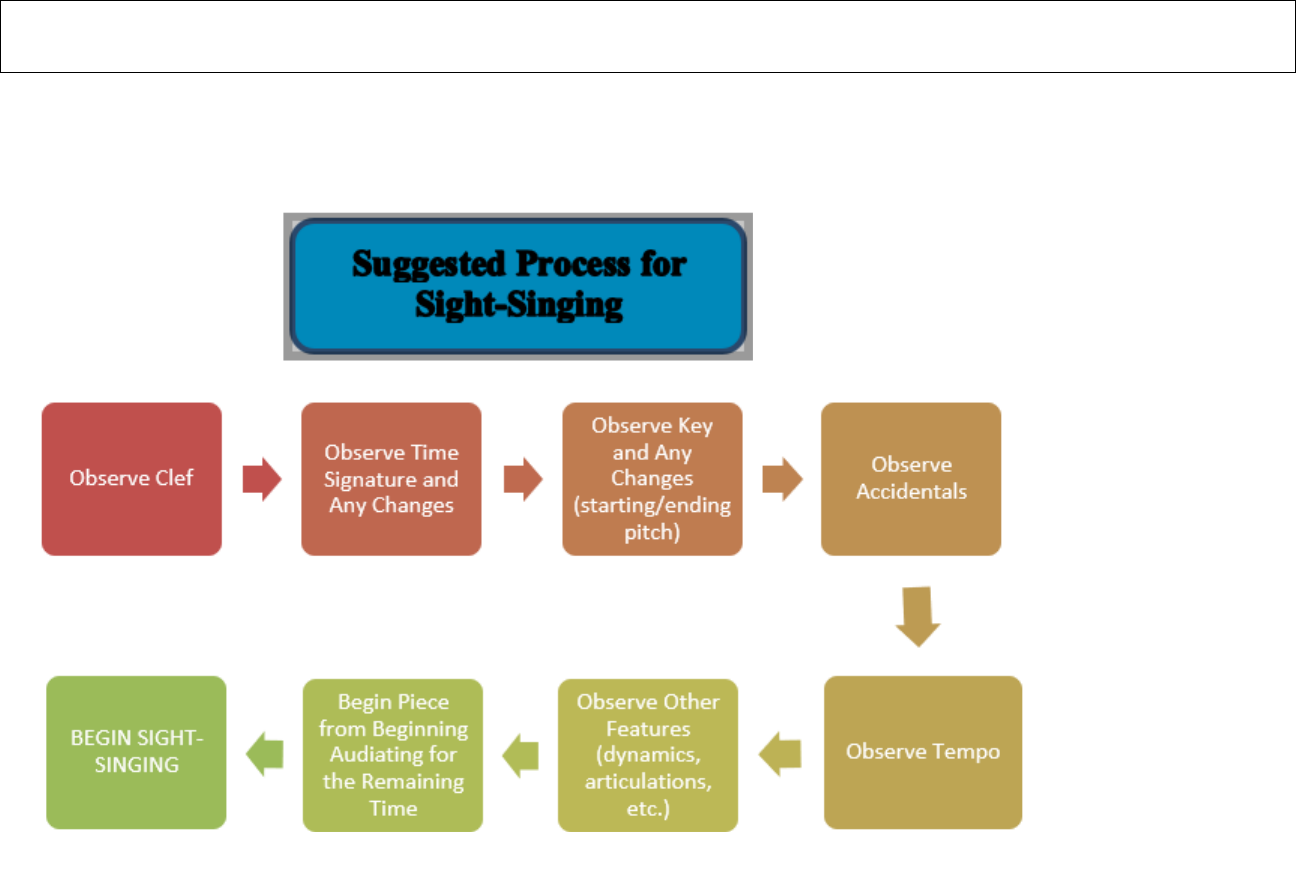

Figure 1………………………………………………………………………………………….56

x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

VI- Visual Impairment

1

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

A number of visually impaired musicians such as Italian opera star Andrea Bocelli or

blues singer and pianist Ray Charles have made names for themselves, perfecting their musical

crafts in the face of adversity. It is a common misconception that musicians like these must have

a natural talent for music because the lack of vision lends to heightened hearing, however, this is

far from true. The article Music Education for the Visually Impaired by Fred Kersten from the

Australian Journal of Music Education states, “A very common myth is that the visually

impaired have innate aptitude for music because of their affliction. This is false as the literature

shows that there are visually impaired that have as many pitch problems and learning difficulties

as the sighted.”

1

Music educators who fall into this pattern of thinking are doing their students a

disservice. Low vision students are more aware of their non-visual senses because they have no

choice, but it does not mean that their visual music reading ability cannot improve through a

structured curriculum.

Students with a Visual Impairment (VI) go through grade school not only learning to

cope with their VI, but trying to meet academic demands, as well as discover who they are and

pursue their interests, one of which could be music. The more educators are aware of what low

vision entails, the more comfortable these students can be in their school and general life

environments. It is considered rare that a student falls under the category of low vision; because

of this, there is little research specific to techniques for enhancing musical success with this

population.

1

Fred Kersten, “Music Education for the Visually Impaired.” (Australian Journal of

Music Education, no. 27 October 1980): 36–38.

2

Background

I have spent my entire life as a legally blind low vision individual witnessing how

different I was from my peers and how I often had to consider things that these peers would not.

As I continue my journey to be the best music educator possible, I wonder what support could

have been in place to enhance the journey of students with low vision. The rarity of low vision

issues like mine brought about confusion and embarrassment because adults in my childhood and

even today simply do not understand my visual impairment. In my particular case, I wear

contacts and appear to be a visual typical person, yet I cannot drive at night, I hold all devices

extremely close to my face, I take pictures of fast food menus and zoom in on them to see better,

I use a flashlight in any dark situation like walking from my vehicle to the front door, and much

more. The progression of technology over the course of my lifetime has enabled me to develop

techniques that I believe other low vision students can benefit from that will be implemented in

this curriculum.

The research conducted identifies the various possible eyesight issues that would

categorize a student as low vision. It can help formalize a music curriculum that is catered to

help these students in a variety of ways. The curriculum in this project is focused on sight-

singing because if one has attained the skills to read music to the best of their ability at sight,

then they will surely be able to confidently read music outside of a sight-singing situation at a

more confident and familiar manner. The concept of sight-singing is strategy based; low vision

students can benefit tremendously from explicit instruction on the various music reading

strategies. The goal of this curriculum is for students to understand their strengths and

weaknesses as well as filter through the strategies that work best regarding their visual

impairment and the ones that do not. One more benefit of focusing this curriculum on sight-

3

singing according to Dee Hansen, author of The Music and Literacy Connection, is that it can

improve literacy outside of music because, “One of the best ways to facilitate reading and

literacy is when students in a music setting sight-read without stopping.”

2

In addition, another goal of this curriculum is to help students emotionally by giving

them opportunities to reflect and problem solve for their specific visual needs with the guidance

of an understanding music educator. Due to the unique nature of visual impairments, students

may often feel isolated from others in their lives, even family members. If a student is passionate

about reading music, their instructor will be someone they can trust to take them through the

process and be sympathetic.

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this research and curriculum is to provide a detailed instruction that

music-educators can follow if they find themselves with one or more sixth-grade students

wanting to improve sight-singing and physical score reading and have a visual impairment other

than full blindness. This program is also intended for the learning-typical visually impaired

student. This curriculum is intended to help learning-typical visually impaired students meet

musical goals and feel more confident under the guidance of a music educator who is sensitive to

their musical needs.

Statement of Problem

There is a lack of awareness and support for visually impaired students to help them

become confident and successful in sight-reading, specifically regarding reading physical copies

of music. Due to the rarity of low vision conditions, there is little research or curriculum

2

Dee Hansen, Elaine Bernstorf, and Gayle M. Stuber, The Music and Literacy

Connection. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014) 53.

4

available to assist students in sight-singing, let alone the subject of music. If a student wants to

audition for a district chorus, state chorus, college ensemble, or community choir, there will

likely be a sight-singing requirement. Depending on the person’s visual impairment, these sight-

singing tasks could possibly be waived, but what about those students that see well enough or

want the satisfaction of completing the required sight-singing with the vision they have?

Whatever the student’s musical goals and desires may be, this curriculum would give them the

ability to reflect on their specific visual impairment in the context of score reading through a

step-by-step process. Another reason for the lack of research could be due to the common myth

that those with low vision or no vision at all must have above average musical skills and

memory. Mary A. Smaligo, author of the article Resources for Helping Blind Music Students

from the Music Educators Journal states that while methods of music reading that involve both

listening and rote can help blind students find success, “…a committed music educator would

not permit him or her to learn music using only recorded materials and rote methods.”

3

However,

the issue is that committed music educators lack the physical resources or training to help their

Visually Impaired (VI) students learn to read written musical notation.

Significance of Study

This study is significant because visual impairments aside from blindness do not receive

much attention in research due to their rarity. This research and curriculum could help support a

music teacher and students that have a passion for engaging in musical activities but lack the

confidence or support. The term sight-singing itself could be enough to make a visually impaired

student feel discouraged about their ability to read music, let alone sight-sing it. Two reasons

3

Mary A. Smaligo. "Resources for Helping Blind Music Students." (Music Educators

Journal 85, 1998) 24.

5

why visual impairments may not receive attention is the fact that students do not feel

comfortable advocating for themselves or because there can be little visual to no visual cue to

show an educator that a student has a visual impairment aside from any medical documentation,

540’s, IEP’s, or tips from other educators at the school. Visually impaired students may not wear

glasses due to financial/family constraints or they may have glasses that look the same as a

student with mild eye-sight issues. Students may also choose not to advocate for themselves in

music courses, or any courses, due to the social environment of school. Asking to sit closer to the

board, holding music closer to the face, being seen with an enlarged copy, having the music

stand closer to the face than others, highlighting or color coding, and more could all put visually

impaired students in an awkward social situation. With a music educator there to work students

through building confidence, students could greatly improve their ability to do what is necessary

for their musical and overall school and life success.

Research Questions and Sub Questions

The primary research question that this curriculum project aims to answer is, what are the

key components of a curriculum that is suitable for low vision pupils?

The following are sub-questions that will be explored:

1. What types of learning styles other than visual can be used to help formalize the

curriculum?

2. What unique pedagogical techniques are used to make a curriculum like this successful?

6

DEFINITION OF TERMS

Low Vision Defined

Low vision is a term used to categorize a wide variety of visual conditions that could be

either hereditary or caused due to onset or accident. People with low vision have difficulty

carrying out everyday tasks and activities such as driving, reading, differentiating colors,

viewing screen technology, and more. These tasks could be difficult at any time of the day for

those with severe low vision, or perhaps only made more difficult in low light or complete

darkness for those with less severe low vision. According to the National Eye Institute the types

of low vision include central vision loss, peripheral vision loss, night blindness, and blurry or

hazy vision.

4

Central and peripheral vision loss are similar in that there is an obstruction of some

of the vision. When one is looking straight ahead (central) or far left or right (peripheral), there is

an obstruction in vision and in order to see they need to shift the eyes or move the head and neck

in different ways than a person with normal vision. The National Eye Institute (NEI) states that

there are many causes of low vision but lists Macular Degeneration, Cataracts, Diabetic

retinopathy, and Glaucoma as the most common causes while also stating that these conditions

are likely found in people of old age.

5

The article Effectiveness of the “living successfully with

low vision” self-management program: Results from a randomized controlled trial in

Singaporeans with low vision from the journal of Patient Education and Counseling defines low

vision as, “vision impairment that is not correctable with spectacles, contact lenses, or surgical

4

NEI. Online Access.

5

Ibid., Online Access.

7

intervention.”

6

This means that with corrective measurements, vision may become improved to

some degree, but not to the point of perfect twenty-twenty eyesight. Macular Degeneration is the

low vision condition I relate to, as my retina was detached. I wear custom contact lenses that

improve my vision enough to function independently in society with mild inconveniences such

as difficulty reading small or distanced writing and a daylight only drivers’ license.

Sight-Singing Defined

Sight-Singing is the act of reading a piece of music one has never seen before at first

sight. This means reading the pitches and rhythms on a five-line staff at the tempo indicated on

the score or the singer’s reasonable tempo choice. Along with communicating the basic notation,

singers are also aiming to think about appropriate phrasing, dynamics, and if possible, emotion.

Singers are given a set amount, often one minute or less, or no time at all to analyze the piece

before beginning to sight-read. They are also encouraged to do their best without stopping to

redo or correct mistakes.

7

Sight-singing is used to enhance music reading competence, audition

for a role in musical theater, chorus, or opera, learn a new piece of music being introduced into

solo or ensemble repertoire, and as a component to school choral festivals. There are instances

when sight-singing can set musicians apart from their peers when auditioning for roles. Sight-

singing is an important skill to learn beyond the purpose of auditions because it is a time saving

6

Ching Siong Tey, Ryan Eyn Kidd Man, Eva K. Fenwick, Ai Tee Aw, Vicki Drury,

Peggy Pei-Chia Chiang, Ecosse L. Lamoureux. Effectiveness of the “living successfully with low

vision” self-management program: Results from a randomized controlled trial in Singaporeans

with low vision, (Patient Education and Counseling, 2019) 1500.

7

Guillaume, Fournier, Maria Teresa Moreno Sala, Francis Dube, and Susan O’Neill.

“Cognitive Strategies in Sight-Singing: The Development of an Inventory for Aural Skills

Pedagogy.” (Psychology of Music 47, no. 2, March 2019) 270-283.

8

tool. The better a person can sight-sing, the quicker they able to understand and internalize

music, which means they will have more time to focus on both musicality and larger amounts of

repertoire. Pamela D. Pike and Rebecca Carter, authors of the article “Employing Cognitive

Chunking Techniques to Enhance Sight-Reading Performance of Undergraduate Group-Piano

Students” from the International Journal of Music Education say, “Sight-reading is a cognitively

complex activity, but components include musical awareness, visual perceptual awareness,

reading comprehension, audiation, musical experiences, motor coordination and problem-solving

skills”

8

Having the skills to sight-sing can help a musician become well-rounded.

Other Definitions

Cataracts: “A cataract is the loss of lens transparency due to opacification of the lens”

9

Chunking: when a sight-reader can quickly identify rhythmic or melodic patterns in a piece of

music while sight-reading. This technique allows the musician to read more notes at once,

making the process of sight-reading easier and leaving time to focus on what is to come.

10

Diabetic Retinopathy: “Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a microvascular (small vessel) disease

affecting the retinal vasculature, leading to progressive retinal damage, which may lead to sight

loss or even blindness.”

11

8

Pamela D.

Pike and Rebecca Carter, “Employing Cognitive Chunking Techniques to

Enhance Sight-Reading Performance of Undergraduate Group-Piano Students.” (International

Journal of Music Education 28, no. 3, 2010). 232.

9

Yu-Chi Liu, Mark Wilkins, Terry Kim, Boris Malyugin, Jodhbir S Mehta, “Cataracts”

(The Lancet, 2017) 600.

10

Pike and Carter, 232.

11

Ramesh R. Sivaraj and Paul M. Dodson, Diabetic Retinopathy: Screening to Treatment

2E (ODL), (Oxford University Press, 2020) ProQuest Ebook Central. 7.

9

Glaucoma: “A disease of the eye, characterized by increased tension of the globe and gradual

impairment or loss of vision. The word was formerly used to denote cataract (New Sydenham

Soc. Lexicon 1885).”

12

Inclusion: this is the notion that any student that may have been excluded from participating in

classes with their typical peers should now be included in those courses for the good of bringing

awareness about disabilities to typical students as well as benefiting the excluded students as

they grow towards adulthood and become a member of functioning society.

13

These students that

should now be included are any student with a disability such as Autistic and ELL students.

Macular Degeneration: “degenerative change involving the macula of the retina; any of various

ophthalmological conditions characterized by this, esp. a form seen with ageing.”

14

Residential School: European styles schools that were responsible for educating specific

populations of students, often with mental or physical disabilities.

15

Retina: “A layer at the back of the eyeball of vertebrates, containing light-sensitive cells (rods

and cones) which trigger nerve impulses that pass via the optic nerve to the brain, where a visual

image is formed; (also) a layer of similar function in the eye of certain invertebrates.

16

The low vision community spans a wide spectrum of eye conditions and each person with

a VI will have slightly different needs, but all VI students may have something in common

12

"glaucoma, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press.

13

Yanoff, 222.

14

"macular degeneration, adj." OED Online. Oxford University Press.

15

Paul M. Ajuwon, and A. O. Oyinlade. "Educational Placement of Children Who are

Blind Or have Low Vision in Residential and Public Schools: A National Study of Parents'

Perspectives." (Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 2008) 325.

16

"retina, n.1" OED Online. Oxford University Press.

10

which is to live a happy life free to explore and succeed to the best of their ability at their

passions, one of which could be music. If music educators could become more informed on how

to assist low vision students, they could be helping students reach new levels of musical success.

11

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW

Students with a VI are just as entitled to the experience of learning to read musical

notation as students with no vision problems. Education is moving in a positive direction in

terms of understanding visual conditions and fostering curriculum and school environments to

include this population, however, there is much to be done. This literature review will look at the

history of education for VI students, the current supports that exist and their practicality, the

demands of sight-reading and strategies, as well as the emotional effects of low vision.

Cognitive Sight-Singing Strategies

Sight-Singing music is a process that takes even the visual-typical person time to master.

Much like when learning to read fluently, there are techniques that singers can practice and

implement to help improve their ability to sight-sing. An article titled Cognitive strategies in

sight-singing: The development of an inventory for aural skills pedagogy in the journal called

Psychology of Music states, “While we recognize sight-singing training as an essential part of

students’ musical development, it remains the nightmare of many college-level music students

and poses one of the greatest pedagogical challenges for their teachers.”

17

These authors were

able to compile a list of seventy-two sight-singing strategies and these strategies were placed into

fourteen categories. Some notable techniques they mentioned that could be particularly helpful to

the low vision community include: compare a pitch with a previously sung pitch, skim music to

identify particularly challenging melodic or rhythm sections, read ahead, use solfege and hand

signs as an anchor, audiate, identify and be aware of one’s own weaknesses and strengths when

sight-singing, do not focus on the fear aspect of sight-singing, work with a partner, and lastly,

17

Fournier, 271.

12

look for common rhythmic and melodic patterns.

18

Whether one has no visual impairment or low

vision, sight-singing is a skill that can be learned with deliberate practice, focus, and time.

Author of the article “The Science of Sight Reading”, Kenneth Saxon states that, “By focusing

on individual techniques, students have the opportunity to make regular, significant process

[sic]”

19

The provided curriculum will guide students into understanding what techniques are

most suitable for them and help them understand a personal process they can repeat each time

they sight-sing.

The Visual Demands of Reading Music

The demands of reading music for people with normal vision can help music educators

understand just how much more difficult it is for the visually impaired. The article “The

challenge of reading music notation for pianists with low vision: An exploratory qualitative

study using a head-mounted display” from the Official Journal of RESNA states that there are

two main ways that vision is used when reading music and describes these as detail vision and

global vision.

20

Detail vision encompasses recognizing if a rhythm is dotted or filled which

therefore changes the length of the rhythm along with determining if a pitch is on a line or space.

Global vision pertains to seeing the bigger picture like reading two staves at once in the case of

pianists, reading ahead, and recognizing overarching patterns and themes. Therefore, the article

18

Ibid., 274-277.

19

Kenneth Saxon. "The Science of Sight Reading." (American Music Teacher 58, no. 6, 2009)

23.

20

Walter Wittich, Bianka Lussier-Dalpe, Catherine Houtekier, Josee Duquette, and

Marie-Chantal Wanet-Defalque. “The Challenge of Reading Music Notation for Pianists with

Low Vision: An Exploratory Qualitative Study Using a Head-Mounted Display.” (Assistive

technology: the official journal of RESNA.) 2019. 1

13

suggests that while reading literature and reading music have similarities, reading music is more

demanding on the eyes and involves more eye movement.

21

Allowing low vision students to

improve their sight-singing through this curriculum may make the overall act of it less strenuous

because they will be more comfortable with the process.

The article continues by saying, “A visual impairment (VI) limits one’s ability to read

musical notation and compromises many aspects of playing a musical instrument; yet, for many

people, music is an essential part of cognitive development.“

22

Due to this, it is essential that

students not be deprived of the ability to learn music to the fullest extent despite having a VI.

The article goes on to explain the gap in research for low vision people, “the challenges inherent

in reading music are not well known, and few means have been identified to help a musician

with a VI read music.”

23

If there are benefits to be gained from VI student’s improving music

reading abilities outside of the improved music skills themselves, then this curriculum is

something that should be considered.

Low Vision Management and Tools

As awareness of low vision conditions has grown throughout the years, some

technological resources have been made available to assist in music reading. One such resource,

Lime Lighter, is a software that imports scanned music then offers the option to magnify the

original size up to 1.5-10x. The Lime Lighter is controlled by a foot pedal that when pressed will

scroll to the next measure.

24

While this technology sounds cutting edge and extremely useful in

21

Ibid., 1.

22

Wittich, 1.

23

Wittich, 1.

24

News. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, (2010) 191.

14

helping the VI learn to sight-read and practice music, there are a few faults that need to be

pointed out. Firstly, it is not conducive to everyday musical situations unless every music

educator is so meticulous in planning that copies of any and all music that will be presented can

be provided to a student, parent, or adult at school to be scanned into the Lime Lighter software

ahead of time. Secondly, this product is not financially affordable for all families. The product

which includes a 17 inch monitor, the pedal, the up-to-date software is high, “The cost for Lime

Lighter is $3,995.”

25

Thirdly, while not as much of an issue today due to the rise in technology

use in public schools, the tablet like device will need to be charged and safely transported and

unlike other mainstream tablets/school technology, if something goes wrong there may not be an

adult that understands how to fix the device promptly. Lastly, depending on the warranty,

replacing this device if it should break is extremely expensive.

According to acquired research, some VI people can benefit from modified written

materials. These modifications can include enlarged photocopying, enlarged paper size, texture

difference, color coding, highlighting, and embossing. It is important to note that not all low

vision conditions are equal and, “For some children with low vision, enlarging print may actually

work to their disadvantage.”

26

A study conducted by George L. Rogers titled Effect of Color-

Coded Notation on Music Achievement of Elementary Instrumental Students from the Journal of

Research in Music Education found that after splitting fifth and sixth-grade beginning musicians

into two groups for twelve weeks in which one read regular notation and the other read color-

coded notation, there were no significant improvements in sight-reading or note naming

25

Ibid., 192.

26

Christine Arter, and al, et. Children with Visual Impairment in Mainstream Settings,

(David Fulton Publishers, 1999), 30.

15

activities.

27

Overall, Roger’s does find that, “…color-coded notation would activate more cell

assemblies and phase sequences than uncolored notation”, and this would aid in retention of

knowledge.

28

He shares, “Some students trained with color-coded materials seemed to depend on

the colors and were not able to read uncolored notation well.”

29

However, for a student to

consistently have access to color-coded music in all sight-reading situations during their primary

and secondary education as well as beyond grade school is impractical and challenging. Roger’s

mentions another form of modified music called shape-notes. This is where each note head

receives a distinct shape rather than each note head being round as with standard notation. The

note shapes are relevant to the tonic, or first scale degree, depending on a songs key signature.

He states that an experiment was conducted in the 1960’s where, “fifth-grade students who were

taught to read music using shape-notes scored significantly higher on sight-reading posttests than

students using standard notation.”

30

Again, while both color-coding and shape-note reading may

have been viable modifications for the typically sighted during these studies where materials

were deliberating prepared, to provide this modification for every musical excerpt and sight-

reading example a VI may encounter throughout their musical endeavors becomes a challenge

due to time, resources, communication, and cost.

27

George L. Rogers. "Effect of Color-Coded Notation on Music Achievement of Elementary

Instrumental Students." (Journal of Research in Music Education,1991): 64.

28

Ibid., 6.

29

Rogers, 72.

30

Rogers, 65.

16

Music Reading Resources for the Fully Blind

Braille, as described by the article Teaching Identity Matching of Braille Characters to

Beginning Braille Readers in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, is a written language

comprised of dots that allows for blind people to navigate the world around them when they pass

their fingers over the risen dots. There are six dots on a diagram and blind readers can understand

the diagram through the amount and order of risen and absent dots.

31

Louis Braille, the languages

inventor, also provided a little-known musical version which similarly uses dots.

32

Braille music

is extremely complex to learn and the process can take many years. It is not a language many

take the time to learn unless their visual impairment is extremely severe. It may be less

challenging and more rewarding for anyone under the low vision category to learn standard

musical notation. A strong curriculum or resources designed to assist low vision students with

this musical task could make music reading even more accessible.

Educating Students with Low Vision

In the 21

st

century there resides a culture of inclusion and this is far from the way

education used to be practiced throughout American History and elsewhere in the world. Of

course, there are still special schools and programs for designated groups of people, but the

public school system in the United States seeks to use inclusion in two ways: to bring awareness

and humility to all typical students and to provide a more social and normal experience to those

who have differences. These differences include students who are English Language Learners

(ELL), Autistic, Physically Disabled, Non-verbal, Emotionally Disabled, Visually Impaired, and

31

J. Saunders Kathryn. “Teaching Identity Matching of Braille Characters to Beginning

Braille Readers.” (Journal of applied behavior analysis. 2017) 279.

32

Smaligo, 23.

17

more. An article in the Journal of Visual Impairment titled Educational Placement of Children

Who Are Blind or Have Low Vision in Residential and Public Schools: A National Study of

Parents’ Perspectives by Paul M Ajuwon and A Olu Oyinlade states, “For more than 175 years,

separate facilities, in either residential schools or day schools, were the main setting for

educating children who are visually impaired…in the United States.”

33

Due to the growing

ideology of inclusion in the mid to late 90’s a huge shift occurred where roughly 83% of students

with a VI were in public schools.

34

While this shift took place in order to improve the quality of

education for students with a VI, Ajuwon and Oyinlade state, “students who are educated solely

within the milieu of public schools can lead sheltered lives.”

35

This is due to the fact that they are

not consistently surrounded by students with similar disabilities that can empathize with their

condition, whereas at a residential school, there are many children with similar disabilities. Now

that schools are becoming more inclusive and instructors are gaining more training on students

with disabilities, this curriculum could begin the next step which is two-fold, making sure

students are receiving inclusive instruction not only in their core curriculum classes like math,

science, and language arts, but also in Physical Education, Art, and Music. Secondly, the

instructors of these courses are given professional development not only for ELL and Autistic

students, but an array of other disabilities no matter how rare such as low vision. Ajuwon and

Oyinlade make some interesting points about residential schools offering more specialized

training and instruction to aid visually impaired students as they grow nearer to adulthood where

they will need to function in society alone, yet they will also gain necessary life skills being

33

Ajuwon and Oyinlade, 325.

34

Ibid., 325.

35

Ajuwon and Oyinlade, 326.

18

around typical peers. If the public schools placed a larger emphasis on educating all staff, as well

as further developing visual impairment departments, the public-school system could be the best

of both worlds. Again, this curriculum could guide a music educator through strengthening VI

student’s music reading skills if they have little knowledge on how to assist this population.

The book, Classroom Teacher's Inclusion Handbook : Practical Methods for Integrating

Students with Special Needs, written by Jerome C. Yanoff states the unfortunate fact that,

“Schools may be reluctant to purchase many of the devices to aid vision because of the high

cost.”

36

Due to situations like this, many low vision students are already learning to do the best

they can, therefore a curriculum designed in this way but with the added reflective elements

along with an understanding instructor could help low vision musicians succeed beyond the

sixth-grade.

Key Components of a Low Vision Curriculum

According to the American Printing House for the Blind’s annual report in 2019, there

were roughly 55,249 children ages 0-21 considered legally blind.

37

This large amount of visually

impaired students only represents those that are registered with APH for the census and may be

excluding many VI students. Of these students, 18,172 are considered “visual readers” meaning

that they do not rely on hearing, braille, or are considered non-readers, but have the ability to

read regular print with a certain degree of difficulty.

38

This is the specific population, however

36

Jerome C. Yanoff. Classroom Teacher's Inclusion Handbook: Practical Methods for

Integrating Students with Special Needs. (Chicago: Arthur Coyle Press, 2006) ProQuest Ebook

Central. 127.

37

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2019.” American Printing House,

nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/aph/app/uploads/2020/04/28130037/Annual-Report-FY2019-

accessible.pdf. 19.

38

Ibid., 19.

19

small, that could benefit from a sight-singing curriculum to boost their music reading confidence.

The research shows that low vision students can have optimal learning success in the classroom

through small practical strategies on behalf of both the teacher and the student. Some things the

music teacher can implement include the way in which they present information to the entire

class. The book Classroom Teacher's Inclusion Handbook : Practical Methods for Integrating

Students with Special Needs suggests, “For greater contrast and readability use an overhead

projector rather than writing on the chalkboard.”

39

Although teachers want to help students sight-

read with little to no modifications, it would be acceptable and beneficial to make materials

intended for the whole class as large as possible up front. To take it one step further, teachers can

ensure that the font on the board or in handouts is, “Roman type standard, serif, or sans serif

types, which are easiest to read.”

40

The Social and Emotional Impact of Low Vision

The article "Vision Impairment and Major Eye Diseases Reduce Vision-Specific

Emotional Well-being in a Chinese Population" from the British Journal of Ophthalmology

shares, “People with vision impairment (VI) may experience emotional reactions like anxieties,

frustration and embarrassment about poor eyesight.”

41

This could not stand more true within

school systems because students are not only trying to meet academic standards with their low

vision, but trying to find a sense of belonging and acceptance among their peers. Engaging in

39

Yanoff, 129.

40

Ibid., 129.

41

Eva K. Fenwick, Peng Guan Ong, Ryan E. K. Man, Charumathi Sabanayagam, Ching-

Yu Cheng, Tien Y. Wong, and Ecosse L. Lamoureux. "Vision Impairment and Major Eye

Diseases Reduce Vision-Specific Emotional Well-being in a Chinese Population." (British

Journal of Ophthalmology, 2017) 686.

20

acts like moving closer to the board (i.e. sitting on the floor or pulling up a chair), asking for a

new seat, putting one’s face closer to papers and electronic devices, or asking questions related

to the inability to see something clearly can cause anxiety and frustration depending on the low

vision student’s personality. Peers may not understand the low vision student’s condition and in

their curiosity and quest for answers may exhibit behaviors such as staring, asking questions, or

asking to try the student’s glasses on if they have them. Encounters like this can be

uncomfortable and to avoid them, the student may make a choice to not help themselves in

situations where they are not able to fully engage. This low vision sight-singing curriculum can

give students confidence to do what is best for their education and aspirations. While there was

little research on the emotional impact of low vision on students, one study found that the impact

on of gradual vision loss on older adults was significant. The 1994 article titled Low Vision: How

to Assess and Treat Its Emotional Impact in the Geriatrics journal states, “Patients may feel a

loss of independence and control, poor self-esteem, and strained social relationships.”

42

When

children are born with low vision such as these older people have acquired, they have a better

chance at a higher quality of life when teachers, friends, and family are aware of the students low

vision condition and can help them find strategies to make daily tasks and passions less tedious

early on. The hope would be that if students are finding successful modifications early in life,

they would be more successful navigating any situation later in life. If a child is interested in

learning to read music, the music could even end up becoming a tool to facilitate the emotional

impact of visual impairment.

42

Leinhaas MAM, and Hedstrom NJ. “Low Vision: How to Assess and Treat Its

Emotional Impact.” Geriatrics 49, no. 5 (May 1994): 53–56. https://search-ebscohost-

com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=107301685&site=ehost-

live&scope=site.

21

When students can learn to read musical notation, it presents cognitive development

benefits and emotional benefits alongside the gained musical skills. Low vision students may

need extra supports such as this curriculum to guide them, but this would be giving children a

chance to discover a passion and perform alongside their visual typical peers, giving them the

skills to continue to pursue music long after they have graduated from high school. This course is

designed in a way to make inclusion easier, to make social situations caused by VI less

challenging, to provide strategies and techniques that can be applied to all music reading

situations, and to reduce the need to purchase expensive assistive technology or consistently take

time to produce modified materials for music courses. In all, this course promotes musical

independence for VI students.

22

CHAPTER III: METHODS

In order to create a unique curriculum centered around supporting the low vision student,

the goal became to not just assist students in becoming independent to find ways to improve their

sight-reading abilities in general, but to also guide them through the emotional and psychological

barriers that present themselves through the process. The curriculum may be a tool for instructors

to track the success of their students through a variety of assignments and sight-singing

experiences. Nilza Nascimento Guimarães states that, “In particular, greater focus should be

placed on examining the need for a core curriculum for students with visual impairments and

establishing practices that can be implemented to promote valuable outcomes in terms of

inclusivity.”

43

This statement showcases the fact that not only is there a gap in music education

curriculum for VI students, but for core academics as well.

Design of Study

Qualitative research was conducted by examining scholarly articles, journals, and books

that pertain to the topics of low vision, music education, curriculum structuring, and more. Since

there was a lack of resources involving a sight-singing curriculum for low vision students at any

age, it was necessary to find research that conducted on the quality and history of education of

low vision students and sight-reading. Research was also conducted regarding the process of

sight-reading for typical students and the impact it has on one’s overall literacy and musical

success.

Considering all of the possible curriculum ideas that could enhance the musicianship of

students that have a VI, sight-singing was decided upon due to the wide variety of musical

43

Nilza Nascimento Guimarães, “Human Anatomy: Teaching–Learning Experience of a

Support Teacher and a Student with Low Vision and Blindness.” (Anatomical sciences

education, 2021), 2.

23

components that are addressed when sight-singing such as rhythm, pattern recognition, reading

ahead, pitch, key signature, time signature, tempo, dynamics, articulation, and expression.

Reading music can already be a challenge so to make sense of one of the most challenging

aspects of music, reading at sight with impaired sight, could instill confidence in students. If they

are able achieve sight-reading improvement through the course, they will be able to read music

more confidently at their own pace too.

This curriculum was designed for sixth-grade students because this is when musical

experiences become more performance and audition based. Joining a chorus or other musical

experience that involves singing such as musical theatre become more common possibilities for

students but also may require a sight-singing component. At the very least students will need

basic music notation reading skills for these opportunities and a sight-singing course can help

them grow their musicianship so they are pro-active and prepared participants. Low vision

students that wish to learn their own music may find they need additional practice time and the

sight-singing curriculum provided will help students understand music reading strategies that

work for them. This course will enhance students’ confidence to pursue any musical goal they

want to achieve.

The course is designed to help students be as successful as possible with the vision they

have so that they can feel and be as independent as possible. Of course, if a student chooses to

use additional supports in their future music endeavors, that is their choice. This curriculum’s

aim is to help students explore and understand what they may be capable of without spending

money on expensive technology and software, spending time color-coding or modifying scores,

or possibly feeling like an outcast due to their noticeable modifications.

24

Questions and Hypotheses

It is hypothesized that this curriculum contains the necessary tools to help low vision

sixth-grade students make great strides in both sight-singing skills as well as having a deeper

understanding of their specific VI. Based on the primary and secondary research questions, the

hypotheses are as follows:

What are the key components of a curriculum that is suitable for low vision pupils?

Students are likely to benefit from components such as presenting content in a way that

students of various learning styles respond well to, the use of a semi-circle seating arrangement,

and lastly, giving students access to the same information in two forms at once such as a handout

or PDF of information displayed on the Smart Board. It is believed that these components will be

low vision students find success because it ensures they have equal and easier access to all

information due to proximity and multiple sources. This may free the students’ minds from

worrying about access to the content and allow them to focus on the content itself.

What types of learning styles other than visual can be used to help formalize the curriculum?

Students are likely to benefit from the combination of group, partner, and one on one

activities as well as reflective assignments throughout the curriculum, helping them gain a well-

balanced experience. It is reasonable to believe this because the wide variety of activities and

ways of presenting content is likely to connect with students of many different learning styles.

25

What unique pedagogical techniques are used to make a curriculum like this successful?

Students are likely to benefit from electronically projected materials as opposed to hand-

written materials as well as clear and concise speaking from the instructor. It is reasonable to

believe this because students may benefit from specific font styles, sizes, and background to text

contrast as opposed to chalk or whiteboard writing. They may benefit from a uniform style of

writing as opposed to personalized handwriting. When teachers are careful about their wording,

tone, and speed, students have a better chance of receiving and retaining information without

having to ask for clarification.

26

CHAPTER IV: RESEARCH FINDINGS

Both the research found, and lack of research available prove that there is an existing gap

in the field of music education for the VI community. The following sections will describe the

research findings and how they pertain to the primary and secondary research questions as well

as how these findings supported the decisions made in the creation of the sixth-grade low vision

sight singing curriculum.

Section I: Key Components of Low Vision Curriculum

For this curriculum to be successful with a VI population, certain criteria must be met.

What are the key components of a curriculum that is suitable for low vision pupils? Firstly, to

make up for what students lack visually, it would be extremely beneficial to present instruction

in various learning styles so that students are able to absorb and process the course content to the

best of their ability. The study, “Assessing Learning Styles Among Students With and Without

Disabilities at a Distance-Learning University” states, “…learning style is considered an inborn

characteristic; that is, although this personal trait is affected by experience and the environment,

it is fairly stable over time.”

44

Secondly, classroom arrangement must be considered. It is hard

for students to learn if basic needs are not met first, and an important basic need of a low vision

student is proximity to information. Students need to be equally arranged in a way that is

conducive to both seeing and hearing the instructor and all presented materials. The format

selected for this course is a seated semi-circle facing the board with the instructor seated in the

center between the board and the students. This allows students to be equally distant from the

44

Tali Heiman. "Assessing Learning Styles among Students with and without Learning

Disabilities at a Distance-Learning University." (Learning Disability Quarterly, 2006), 55.

27

teacher. An article by Rachel Wannarka and Kathy Ruhl found that students, “…asked more

questions in a semi-circle than they did in rows in a pattern that was stable over time.”

45

Since

these students are low vision and may need additional support from the instructor despite all of

the supports in place, proximity will allow students to feel more secure in asking questions and

may become more engaged. Students feeling more open to ask questions and engage will

inadvertently help their peers and possibly make them feel more comfortable to do the same. The

size of a course such as this is suspected to be no more than a handful of students so this

arrangement should be manageable for all teachers implementing this curriculum. One note of

caution provided by the book Children with Visual Impairment in Mainstream Settings, is that,

“It may be that for the child with low vision, their sight is better in one eye than the other.”

46

Due

to this, the instructor may want to ask students which specific seat in the semi-circle arrangement

would suite them best. This text goes on to say that while some low vision learners may be

bothered by sunlight glare, some students with cataracts may actually benefit from sitting near

the sunniest or brightest part of the room.

47

A third key component of low vision curriculum is

the presentation of materials in various mediums at once. The technical paper “Guidelines for

designing text in printed media for people with low vision” published by the University of

Zagreb in Croatia showed success with an 80 year old low vision woman sharing that, “The

45

Rachel Wannarka and Kathy Ruhl. Seating arrangements that promote positive

academic and behavioural outcomes: a review of empirical research. (Support for Learning,

2008), 92.

46

Arter, 20.

47

Ibid., 20.

28

white text (larger than 20 pt) on black background was most suited for her.”

48

If the instructor is

showing rhythm cards or melodic patterns on the board, students should also have a physical

handout or access to a pdf version that students can quickly pull up on their preferred device,

which is a course requirement. Students can acquire an enlarged photocopy from their music

teacher or zoom in on their electronic device until the font is the appropriate size for their

specific visual need. The idea behind presenting the same information in multiple ways is to

lessen the amount of confusion and strengthen student independence.

Section II: Types of Learning Styles

What types of learning styles other than visual can be used to help formalize the

curriculum? Throughout the history of education, one of the most common styles of teaching

has been teachers lecturing while students listen and write notes but not every child learns the

same way whether they are typical or not. Students have different learning styles and instructors

should do their best to vary their teaching to accommodate these. This curriculum will aid

teachers in effectively accomplishing this. The article “Effects of teaching and learning styles on

students’ reflection levels for ubiquitous learning” in the Elsevier journal of Computers and

Education reads, “Learning styles refer to one’s preferences in processing external information

or internal knowledge and experience.”

49

Since students with a VI have trouble seeing, they may

prefer certain learning styles to others due to the fact they do not have to rely solely on vision

48

Maja Brozović, et al. “Guidelines for Designing Text in Printed Media for People with

Low Vision.” (ACTA GRAPHICA Journal for Printing Science and Graphic Communications,

2018), 28

.

49

Hsieh Sheng-Wen, Jang Yu-Ruei, Hwang Gwo-Jen, Chen Nian-Shing. “Effects of teaching

and learning styles on students’” reflection levels for ubiquitous learning, (Computers & Education,

2011), 1195.

29

when they are implemented. The provided curriculum utilizes a variety of learning styles

according to David Kolb’s theory of Experiential Learning and these include reflective

observation, active experimentation, concrete experience, and abstract conceptualization.

50

Since

people tend to lean towards one specific learning style, it is important that all are reflected in the

curriculum so that students have the opportunity to use their strengths since vision is already a

weakness. Here it will be shown how this low vision curriculum addresses all four of these

learning styles to some degree.

The article “Effects of teaching and learning styles on students’ reflection levels for

ubiquitous learning” shares that reflection, “…plays an important role in the learning process

because it increases learning outcomes.”

51

This is why this low vision sight-singing curriculum

includes opportunities for students to look within and examine what the strengths and challenges

of sight-singing are for the individual. Assignments one, three, four, and ten of this curricula are

reflection focused. Sight-Singing Praxis 1 contains a self-reflection, and assignment six is a

partner observation activity which also includes reflective elements.

Experience plays a large role in the music classroom and this sight-singing course is no

different. The notion that experiential learning is effective was made popular by David Kolb. He

describes, “A common usage of the term “experiential learning” defines it as a particular form of

learning from life experience; often contrasted it with lecture and classroom learning.”

52

The

50

David Kolb. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and

Development, Second Edition. (PH Professional Business, 2014), Digital Copy.

51

Sheng-Wen, 1195.

52

David Kolb. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and

Development, Second Edition. (PH Professional Business, 2014), Digital Copy.

30

goal of this course is to prepare students for real life sight-singing experiences therefor students’

sight-sing in the fashion of a real audition more than they sit and listen to lectures. Kolb also

shares, “Knowledge is continuously derived from and tested out in the experiences of the

learner.”

53

This is particularly relevant to the low vision community and those who identify as

concrete experience or active experimentation learners because this population of people are

constantly finding out the best way to accomplish a goal or task to the best of their ability in a

way slightly altered from the techniques of the visual typical.

This curriculum serves as a sort of laboratory where students can become exposed to

various supports and strategies while testing them out through sight-singing experiences to then

make decisions about what works well for their specific visual condition and what does not. This

suits active experimentation learners well because these types of learners are practical, goal

driven, and willing to take calculated risks to achieve their goals.

54

It serves concrete experience

learners well because, “They are often good intuitive decision makers and function well in

unstructured situations.”

55

Students that are considered to be concrete experience or active

experimentation learners may thrive in many tasks throughout the course. In the span of the

twelve-week curriculum students will engage in fifteen sight-singing experiences including one

partner performance, full class performances, solo performances in front of the class, and solo

performances in front of the instructor.

53

Ibid., Digital Copy.

54

Kolb, Digital Copy.

55

Ibid., Digital Copy.

31

Students that identify as abstract conceptualization learners may thrive in this course

because they are, “good at systematic planning, manipulation of abstract symbols, and

quantitative analysis.”

56

Their thinking is more scientific rather than emotional. In many ways

this learning style works well in the context of music reading and sight-reading. It was examined

earlier that sight-reading, while a spontaneous activity, can be accomplished by following a

process and group of strategies tweaked by the specific musician to get the best results for

themselves, thus encompassing systematic planning. It was also noted that one successful

strategy could be the recognition of rhythmic or melodic patterns which falls in line with

manipulation of abstract symbols. These learners will find success with assignments such as

assignment three, sight-singing preparation list activity, where students are to list the order of

steps they take during the one to two-minute period leading up to a sight-singing performance.

Students can think through their progress more carefully and make necessary adjustments if

needed.

Section III: Unique Pedagogical Techniques

What unique pedagogical techniques are used to make a curriculum like this

successful? Teaching a sight-singing course to a presumably small group of low vision students

leaves a lot of room for the instructor to meet specific requests and accommodations depending

on the unique layout and resources at hand for the betterment of everyone’s education. Many

public schools have white erase boards and smart boards, while others may still have chalk

boards or even overhead projector technology. It was mentioned previously that some low vision

students can benefit from enlarged writing, specific font styles, and a stronger color contrast

between the background and writing. It would also offer more consistency to low vision students

56

Kolb., Digital Copy.

32

to see typed language because typing offers each letter to consistently look the same each time it

is typed whereas every person’s hand-writing style can differ even within the same sentence if

not deliberate. For ease of instruction and to ensure the students are focusing more on their

musical skills than second guessing any presented materials, it would be best for instructors to

use a smart board to project typed and enlarged words. This simple instructional delivery change

can help maintain a better class flow and minimize any student feeling uncomfortable about

asking for clarification. To take this a step further, any materials that are to be presented on the

board could also be printed, enlarged, and given to students as handouts. This way students may

hold the images as close to their eyes or at any angle necessary while also referring to the

information covered in class more comfortably outside of class.

The technical paper “Guidelines for designing text in printed media for people with low

vision” states that, “Most of the information published through graphic media is designed for

people with normal eyesight” and continues to share, “There are 285 million people with visual

impairment.”

57

This simple adjustment can help offset the normal printed media standards in

music classrooms. Lastly, students are asked to bring a laptop or tablet device for similar

reasons. Any materials pulled up on a device may be zoomed in on for ease. This gives VI

students three visual ways to access written information, assignments, and even sight-reading

excerpts during the course.

While this next technique should be implemented with any course, music teachers should

speak with a clear, concise, and audible tone while maintaining a reasonable speed as well.

Teacher’s personalities and natural ways of speaking can make their way into the classroom, but

57

Maja Brozović, et al, 25.

33

at times it is important to think more deliberately about how we speak to students so that every

child can understand and there is less time spent on clarifying. For example, if a teacher is

naturally soft spoken or tends to speak quickly, they may consider consciously adjusting when

teaching. The article “Speaking Clearly for the Blind: Acoustic and Articulatory Correlates of

Speaking Conditions in Sighted and Congenitally Blind Speakers” from the journal Plos One

states, “…clear speech provides the listener with audible and visual cues that are used to increase

the overall intelligibility of speech produced by the speaker.”

58

It would also be acceptable for

teachers to err on the side of repetition for students to better absorb information. Alongside

speaking clearly to students, music teachers could also read any information presented in writing

out loud verbatim. Again, this course is intended to show students what they are capable of in

terms of sight-singing music with as little supports as possible aside from enlarged copies and

using a highlighter or writing utensil to make markings, but this does not mean the course and all

materials aside from the sight-singing excerpts is taught without supports. That approach would

take time away from sight-singing goals.

58

Lucie Ménard, Pamela Trudeau-Fisette, Dominique Côté, Christine. “Speaking Clearly

for the Blind: Acoustic and Articulatory Correlates of Speaking Conditions in Sighted and

Congenitally Blind Speakers”, (PLoS ONE (2016), 1.

34

CHAPTER V: DISCUSSION

Summary of Study

This study was created to explore the gap in low vision music curriculum, specifically in

sight-singing for sixth-grade students. Sixth-grade students were chosen as the focus for this

study because this is the point in which sight-reading music for auditions or as part of curriculum

becomes an expected part of ensemble admission and curriculum. Students have the ability to

understand music literacy at a higher level than in previous years combined with the maturing

vocal tone and the notion that just about seven years from this point, these students could

possibly be utilizing these skills for real-world music experiences. Beginning the familiarly of

sight-singing as a low vision student at this age will give students that much more time to make

improvements and add in other important elements that this particular course does not focus on

such as articulation and expressivity. Sight-singing was chosen because all important aspects of

music literacy are encompassed in the act of sight-singing. Students are learning how to bring

together rhythm, melody, tempo, dynamics, and more simultaneously to create music. If students

can gain some confidence in this course, then reading music in a less strict fashion should

become easier and even further build their literacy confidence. Lastly, this course is designed for

only low vision students so that they feel comfortable exploring, reflecting, and experimenting

with the music teacher focusing solely on meeting their needs.

Summary of Purpose

This curriculum is intended to fill a gap in music literacy for low vision sixth-grade

students in public or private schools. Students that have low vision may not excel as much as

they could if their music teacher was aware of their visual impairment and had strategies or

curriculum in place to help them improve. Students with low vision deserve the chance to

35

become proficient music readers like their visual typical peers so that they can engage in the

same musical activities as them. Certain musical activities may require auditions and sight-

reading, with a curriculum to help students identify strategies and understand their own visual

impairment better, they have a higher chance of musical independence helping them follow their

musical passions rather than ruling music reading out altogether.

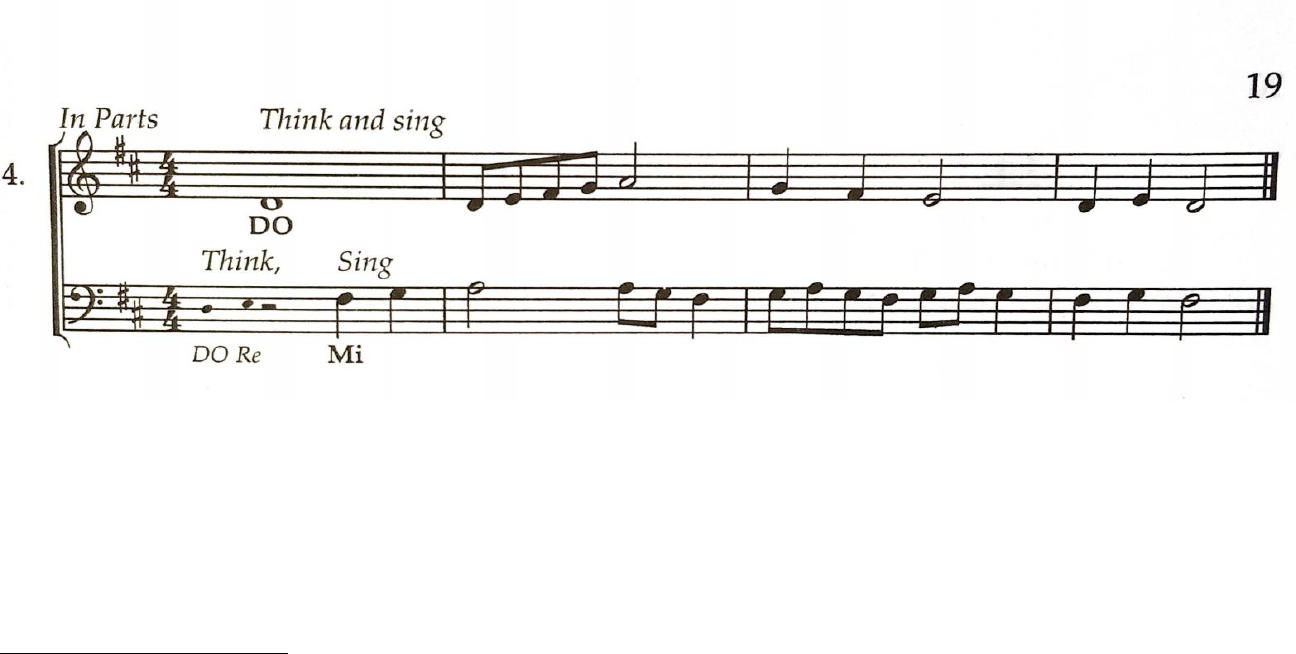

Summary of Curriculum Development

The curriculum provided is a scaffolded approach to sight-singing so that music teachers

with little to no knowledge of VI students can build up their music literacy and guide their

emotional understanding of their disability. Students will be reviewing and strengthening basic

music literacy skills such as understanding rhythm and pitch names as well as solfeggio.

Students will sight-sing pieces that range from four to eight measures with decreasing amounts

of preparation time as the course goes on and they become more familiar with the sight-singing

process and techniques.

Summary of Findings and Prior Research

This research investigated the physical supports and curriculum that already exist to help

both music educators and students reach the common goal of improved sight-reading and music

literacy skills for low vision students. It was found that no curriculum exists to help music

educators improve sight-reading skills in low vision sixth graders. The research conducted found

that there is a lack of curriculum and supports for both low vision students and music teachers to

make improvements in physical score reading and sight-singing. This study explored the

demands of sight-singing and music literacy for visual typical students as well as the music

reading process for the fully blind, but little information was available for the process of low

vision music literacy. It was found that the supports in place for the fully blind would not be

36

conducive to low vision music reading but that sight-singing strategies could be implemented to

help low vision students form a process and comfortability when sight-singing. The research

revealed that the growing popularity of inclusion in public schools is changing the way the

visually impaired learn and function in schools every day.

This study was able to provide research to support the decisions made in the curriculum

and answer the primary and secondary research questions. This study may be one step to help

educate music educators in the instance they find visually impaired, but not fully blind, students

in their music classrooms.

Limitations

The limitations of this curriculum include limited options for students that are low vision,

but more musically advanced. It could be the case that some students find themselves quickly

adapting to the sight-singing process and are ready for more challenging sight-singing pieces

than the course offers. In this case, it can be up to the music instructor’s discretion to find and

implement excerpts appropriate for their specific student population. Seeing as class sizes will

likely be small, it should be doable for teachers to make the necessary adjustments. The same

goes for students who may need easier sight-singing examples than are provided in this

curriculum. Another limitation is that this curriculum is intended as a course for multiple low

vision students in one setting to enhance sight-singing. Perhaps this curriculum could be

expanded with tips for aiding both teachers and students in music literacy during a regularly

scheduled general music, chorus, band, strings, or other school-based music program where the

child functions alongside visual typical peers. This study is also limited by the lack of existing

research on the low vision community as a whole and how the low vision community learns to

read written musical notation. The curriculum is designed as a product of what research could be

37

found in conjunction with the authors existing teaching experience with sight-singing and sixth-

graders as well as the authors personal low vision disability. The author having a bias due to their

own low vision disability, offers this curriculum a unique perspective.

Recommendations for Future Study

It is recommended that future studies observe this curriculum carried out with a group of

low vision sixth-grade students to analyze its effectiveness and make necessary changes to

provide an even stronger curriculum that suites the needs of this specific age group. It is also

recommended that similar curriculum be adjusted to fit students in other grades, perhaps middle

and high school. Creating a level two of this course might also be useful to students that want to

continue to refine their sight-singing skills with their music teacher. A future study may also go

into more detail about the specific eye conditions that cause low vision and how they impact

music literacy. This course has a strong focus on using less visual supports to help students

understand what they’re capable of with little modifications, perhaps a level two course could

help students decide what supports would work best for them during music literacy activities if

they so choose to use them. It has been discovered through this research that there are many

distinctions within the low vision community, so no one support, or modification is a fix all. This

curriculum could also be improved with a list or section detailing the specific definitions of all

types of low vision as well as what sorts of supports benefit each type. For instance, it has