NIST AI 100-1

Artificial Intelligence Risk Management

Framework (AI RMF 1.0)

This publication is available free of charge from:

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.AI.100-1

January 2023

U.S. Department of Commerce

Gina M. Raimondo, Secretary

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Laurie E. Locascio, NIST Director and Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology

Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe

an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommenda-

tion or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that

the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.AI.100-1

Update Schedule and Versions

The Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF) is intended to be a living document.

NIST will review the content and usefulness of the Framework regularly to determine if an update is appro-

priate; a review with formal input from the AI community is expected to take place no later than 2028. The

Framework will employ a two-number versioning system to track and identify major and minor changes. The

first number will represent the generation of the AI RMF and its companion documents (e.g., 1.0) and will

change only with major revisions. Minor revisions will be tracked using “.n” after the generation number

(e.g., 1.1). All changes will be tracked using a Version Control Table which identifies the history, including

version number, date of change, and description of change. NIST plans to update the AI RMF Playbook

frequently. Comments on the AI RMF Playbook may be sent via email to AIframew[email protected] at any time

and will be reviewed and integrated on a semi-annual basis.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 1

Part 1: Foundational Information 4

1 Framing Risk 4

1.1 Understanding and Addressing Risks, Impacts, and Harms 4

1.2 Challenges for AI Risk Management 5

1.2.1 Risk Measurement 5

1.2.2 Risk Tolerance 7

1.2.3 Risk Prioritization 7

1.2.4 Organizational Integration and Management of Risk 8

2 Audience 9

3 AI Risks and Trustworthiness 12

3.1 Valid and Reliable 13

3.2 Safe 14

3.3 Secure and Resilient 15

3.4 Accountable and Transparent 15

3.5 Explainable and Interpretable 16

3.6 Privacy-Enhanced 17

3.7 Fair – with Harmful Bias Managed 17

4 Effectiveness of the AI RMF 19

Part 2: Core and Profiles 20

5 AI RMF Core 20

5.1 Govern 21

5.2 Map 24

5.3 Measure 28

5.4 Manage 31

6 AI RMF Profiles 33

Appendix A: Descriptions of AI Actor Tasks from Figures 2 and 3 35

Appendix B: How AI Risks Differ from Traditional Software Risks 38

Appendix C: AI Risk Management and Human-AI Interaction 40

Appendix D: Attributes of the AI RMF 42

List of Tables

Table 1 Categories and subcategories for the GOVERN function. 22

Table 2 Categories and subcategories for the MAP function. 26

Table 3 Categories and subcategories for the MEASURE function. 29

Table 4 Categories and subcategories for the MANAGE function. 32

i

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

List of Figures

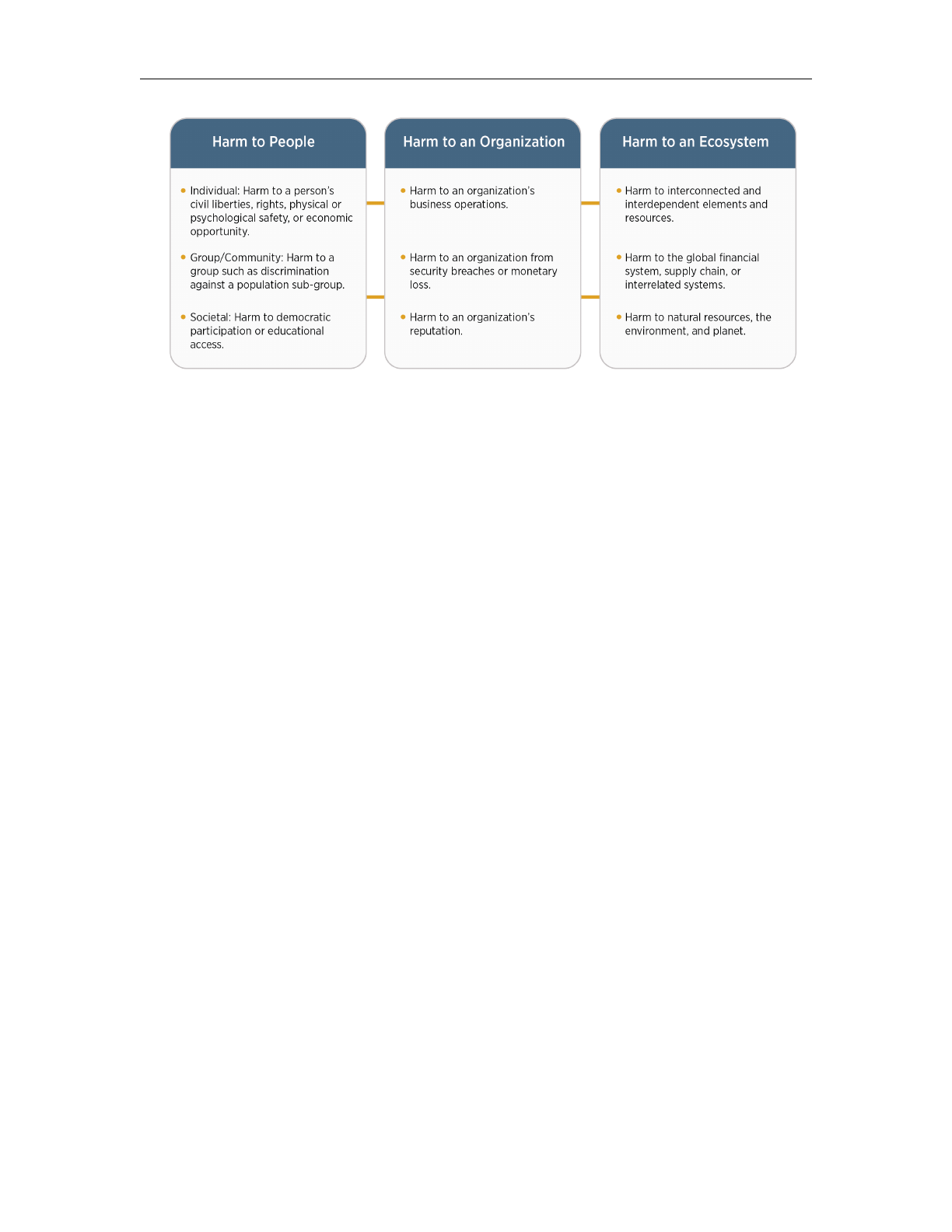

Fig. 1 Examples of potential harms related to AI systems. Trustworthy AI systems

and their responsible use can mitigate negative risks and contribute to bene-

fits for people, organizations, and ecosystems. 5

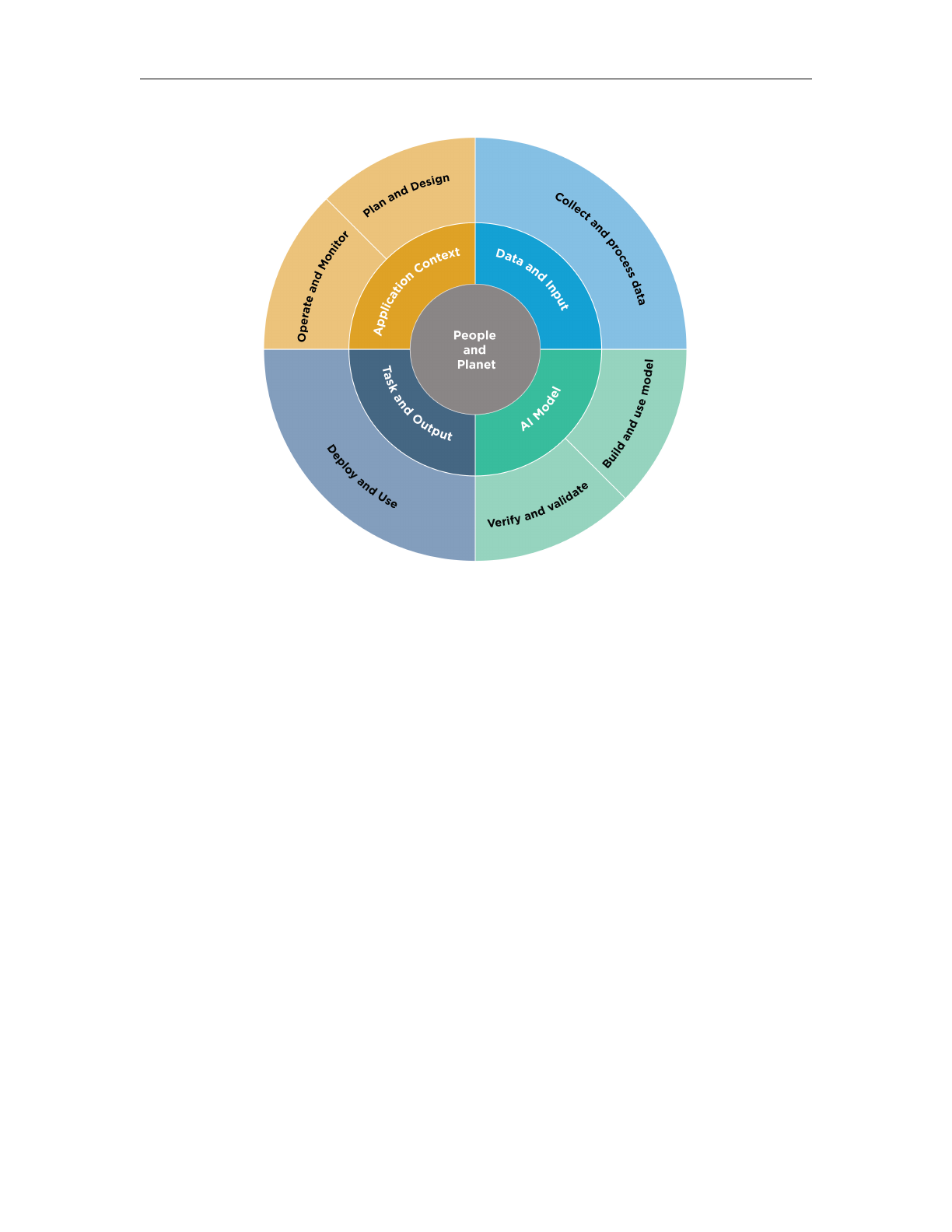

Fig. 2 Lifecycle and Key Dimensions of an AI System. Modified from OECD

(2022) OECD Framework for the Classification of AI systems — OECD

Digital Economy Papers. The two inner circles show AI systems’ key di-

mensions and the outer circle shows AI lifecycle stages. Ideally, risk man-

agement efforts start with the Plan and Design function in the application

context and are performed throughout the AI system lifecycle. See Figure 3

for representative AI actors. 10

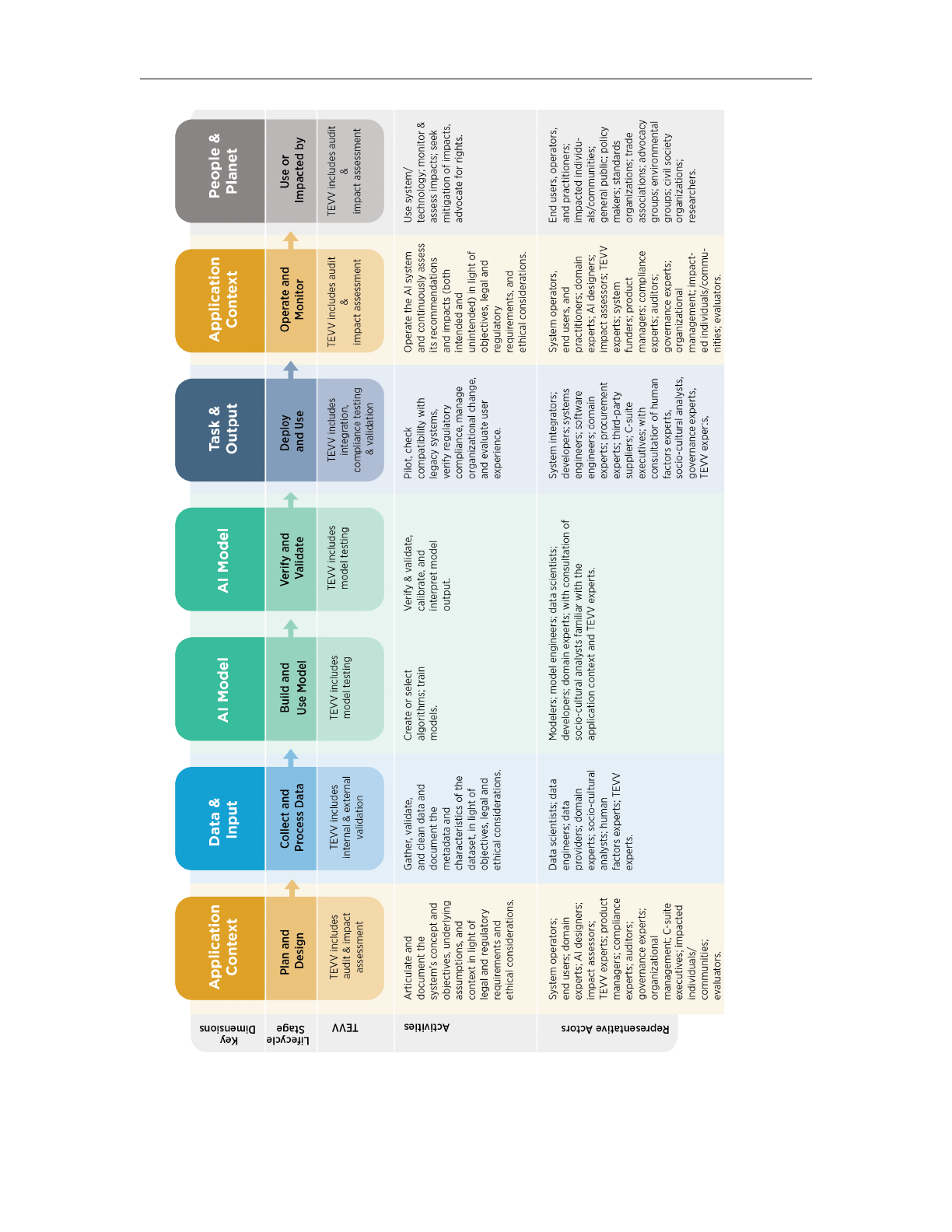

Fig. 3 AI actors across AI lifecycle stages. See Appendix A for detailed descrip-

tions of AI actor tasks, including details about testing, evaluation, verifica-

tion, and validation tasks. Note that AI actors in the AI Model dimension

(Figure 2) are separated as a best practice, with those building and using the

models separated from those verifying and validating the models. 11

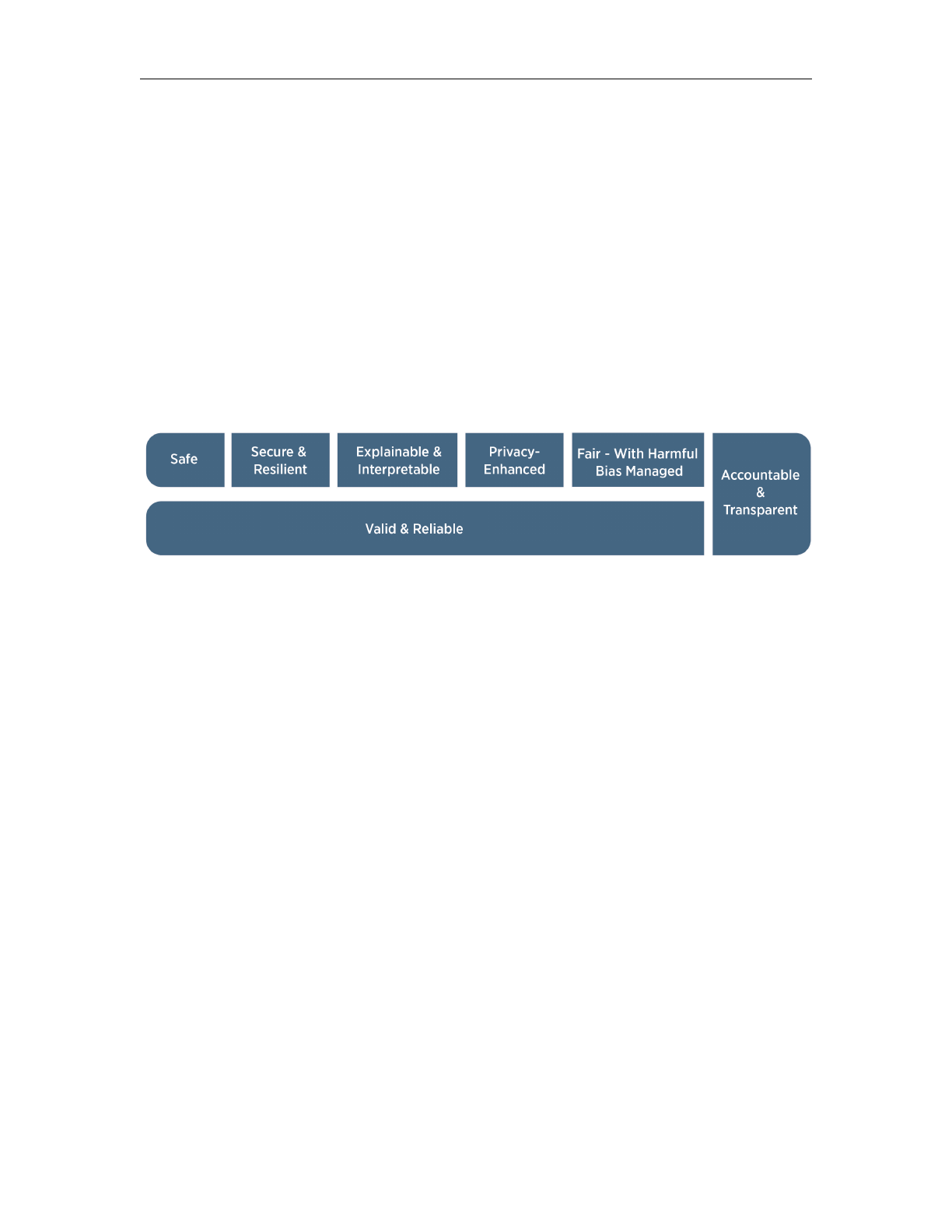

Fig. 4 Characteristics of trustworthy AI systems. Valid & Reliable is a necessary

condition of trustworthiness and is shown as the base for other trustworthi-

ness characteristics. Accountable & Transparent is shown as a vertical box

because it relates to all other characteristics. 12

Fig. 5 Functions organize AI risk management activities at their highest level to

govern, map, measure, and manage AI risks. Governance is designed to be

a cross-cutting function to inform and be infused throughout the other three

functions. 20

Page ii

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have significant potential to transform society and

people’s lives – from commerce and health to transportation and cybersecurity to the envi-

ronment and our planet. AI technologies can drive inclusive economic growth and support

scientific advancements that improve the conditions of our world. AI technologies, how-

ever, also pose risks that can negatively impact individuals, groups, organizations, commu-

nities, society, the environment, and the planet. Like risks for other types of technology, AI

risks can emerge in a variety of ways and can be characterized as long- or short-term, high-

or low-probability, systemic or localized, and high- or low-impact.

The AI RMF refers to an AI system as an engineered or machine-based system that

can, for a given set of objectives, generate outputs such as predictions, recommenda-

tions, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems are designed

to operate with varying levels of autonomy (Adapted from: OECD Recommendation

on AI:2019; ISO/IEC 22989:2022).

While there are myriad standards and best practices to help organizations mitigate the risks

of traditional software or information-based systems, the risks posed by AI systems are in

many ways unique (See Appendix B). AI systems, for example, may be trained on data that

can change over time, sometimes significantly and unexpectedly, affecting system function-

ality and trustworthiness in ways that are hard to understand. AI systems and the contexts

in which they are deployed are frequently complex, making it difficult to detect and respond

to failures when they occur. AI systems are inherently socio-technical in nature, meaning

they are influenced by societal dynamics and human behavior. AI risks – and benefits –

can emerge from the interplay of technical aspects combined with societal factors related

to how a system is used, its interactions with other AI systems, who operates it, and the

social context in which it is deployed.

These risks make AI a uniquely challenging technology to deploy and utilize both for orga-

nizations and within society. Without proper controls, AI systems can amplify, perpetuate,

or exacerbate inequitable or undesirable outcomes for individuals and communities. With

proper controls, AI systems can mitigate and manage inequitable outcomes.

AI risk management is a key component of responsible development and use of AI sys-

tems. Responsible AI practices can help align the decisions about AI system design, de-

velopment, and uses with intended aim and values. Core concepts in responsible AI em-

phasize human centricity, social responsibility, and sustainability. AI risk management can

drive responsible uses and practices by prompting organizations and their internal teams

who design, develop, and deploy AI to think more critically about context and potential

or unexpected negative and positive impacts. Understanding and managing the risks of AI

systems will help to enhance trustworthiness, and in turn, cultivate public trust.

Page 1

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Social responsibility can refer to the organization’s responsibility “for the impacts

of its decisions and activities on society and the environment through transparent

and ethical behavior” (ISO 26000:2010). Sustainability refers to the “state of the

global system, including environmental, social, and economic aspects, in which the

needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations

to meet their own needs” (ISO/IEC TR 24368:2022). Responsible AI is meant to

result in technology that is also equitable and accountable. The expectation is that

organizational practices are carried out in accord with “professional responsibility,”

defined by ISO as an approach that “aims to ensure that professionals who design,

develop, or deploy AI systems and applications or AI-based products or systems,

recognize their unique position to exert influence on people, society, and the future

of AI” (ISO/IEC TR 24368:2022).

As directed by the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Act of 2020 (P.L. 116-283),

the goal of the AI RMF is to offer a resource to the organizations designing, developing,

deploying, or using AI systems to help manage the many risks of AI and promote trustwor-

thy and responsible development and use of AI systems. The Framework is intended to be

voluntary, rights-preserving, non-sector-specific, and use-case agnostic, providing flexibil-

ity to organizations of all sizes and in all sectors and throughout society to implement the

approaches in the Framework.

The Framework is designed to equip organizations and individuals – referred to here as

AI actors – with approaches that increase the trustworthiness of AI systems, and to help

foster the responsible design, development, deployment, and use of AI systems over time.

AI actors are defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) as “those who play an active role in the AI system lifecycle, including organiza-

tions and individuals that deploy or operate AI” [OECD (2019) Artificial Intelligence in

Society—OECD iLibrary] (See Appendix A).

The AI RMF is intended to be practical, to adapt to the AI landscape as AI technologies

continue to develop, and to be operationalized by organizations in varying degrees and

capacities so society can benefit from AI while also being protected from its potential

harms.

The Framework and supporting resources will be updated, expanded, and improved based

on evolving technology, the standards landscape around the world, and AI community ex-

perience and feedback. NIST will continue to align the AI RMF and related guidance with

applicable international standards, guidelines, and practices. As the AI RMF is put into

use, additional lessons will be learned to inform future updates and additional resources.

The Framework is divided into two parts. Part 1 discusses how organizations can frame

the risks related to AI and describes the intended audience. Next, AI risks and trustworthi-

ness are analyzed, outlining the characteristics of trustworthy AI systems, which include

Page 2

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

valid and reliable, safe, secure and resilient, accountable and transparent, explainable and

interpretable, privacy enhanced, and fair with their harmful biases managed.

Part 2 comprises the “Core” of the Framework. It describes four specific functions to help

organizations address the risks of AI systems in practice. These functions – GOVERN,

MAP, MEASURE, and MANAGE – are broken down further into categories and subcate-

gories. While GOVERN applies to all stages of organizations’ AI risk management pro-

cesses and procedures, the MAP, MEASURE, and MANAGE functions can be applied in AI

system-specific contexts and at specific stages of the AI lifecycle.

Additional resources related to the Framework are included in the AI RMF Playbook,

which is available via the NIST AI RMF website:

https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework.

Development of the AI RMF by NIST in collaboration with the private and public sec-

tors is directed and consistent with its broader AI efforts called for by the National AI

Initiative Act of 2020, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence recom-

mendations, and the Plan for Federal Engagement in Developing Technical Standards and

Related Tools. Engagement with the AI community during this Framework’s development

– via responses to a formal Request for Information, three widely attended workshops,

public comments on a concept paper and two drafts of the Framework, discussions at mul-

tiple public forums, and many small group meetings – has informed development of the AI

RMF 1.0 as well as AI research and development and evaluation conducted by NIST and

others. Priority research and additional guidance that will enhance this Framework will be

captured in an associated AI Risk Management Framework Roadmap to which NIST and

the broader community can contribute.

Page 3

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Part 1: Foundational Information

1. Framing Risk

AI risk management offers a path to minimize potential negative impacts of AI systems,

such as threats to civil liberties and rights, while also providing opportunities to maximize

positive impacts. Addressing, documenting, and managing AI risks and potential negative

impacts effectively can lead to more trustworthy AI systems.

1.1 Understanding and Addressing Risks, Impacts, and Harms

In the context of the AI RMF, risk refers to the composite measure of an event’s probability

of occurring and the magnitude or degree of the consequences of the corresponding event.

The impacts, or consequences, of AI systems can be positive, negative, or both and can

result in opportunities or threats (Adapted from: ISO 31000:2018). When considering the

negative impact of a potential event, risk is a function of 1) the negative impact, or magni-

tude of harm, that would arise if the circumstance or event occurs and 2) the likelihood of

occurrence (Adapted from: OMB Circular A-130:2016). Negative impact or harm can be

experienced by individuals, groups, communities, organizations, society, the environment,

and the planet.

“Risk management refers to coordinated activities to direct and control an organiza-

tion with regard to risk” (Source: ISO 31000:2018).

While risk management processes generally address negative impacts, this Framework of-

fers approaches to minimize anticipated negative impacts of AI systems and identify op-

portunities to maximize positive impacts. Effectively managing the risk of potential harms

could lead to more trustworthy AI systems and unleash potential benefits to people (individ-

uals, communities, and society), organizations, and systems/ecosystems. Risk management

can enable AI developers and users to understand impacts and account for the inherent lim-

itations and uncertainties in their models and systems, which in turn can improve overall

system performance and trustworthiness and the likelihood that AI technologies will be

used in ways that are beneficial.

The AI RMF is designed to address new risks as they emerge. This flexibility is particularly

important where impacts are not easily foreseeable and applications are evolving. While

some AI risks and benefits are well-known, it can be challenging to assess negative impacts

and the degree of harms. Figure 1 provides examples of potential harms that can be related

to AI systems.

AI risk management efforts should consider that humans may assume that AI systems work

– and work well – in all settings. For example, whether correct or not, AI systems are

often perceived as being more objective than humans or as offering greater capabilities

than general software.

Page 4

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Fig. 1. Examples of potential harms related to AI systems. Trustworthy AI systems and their

responsible use can mitigate negative risks and contribute to benefits for people, organizations, and

ecosystems.

1.2 Challenges for AI Risk Management

Several challenges are described below. They should be taken into account when managing

risks in pursuit of AI trustworthiness.

1.2.1 Risk Measurement

AI risks or failures that are not well-defined or adequately understood are difficult to mea-

sure quantitatively or qualitatively. The inability to appropriately measure AI risks does not

imply that an AI system necessarily poses either a high or low risk. Some risk measurement

challenges include:

Risks related to third-party software, hardware, and data: Third-party data or systems

can accelerate research and development and facilitate technology transition. They also

may complicate risk measurement. Risk can emerge both from third-party data, software or

hardware itself and how it is used. Risk metrics or methodologies used by the organization

developing the AI system may not align with the risk metrics or methodologies uses by

the organization deploying or operating the system. Also, the organization developing

the AI system may not be transparent about the risk metrics or methodologies it used. Risk

measurement and management can be complicated by how customers use or integrate third-

party data or systems into AI products or services, particularly without sufficient internal

governance structures and technical safeguards. Regardless, all parties and AI actors should

manage risk in the AI systems they develop, deploy, or use as standalone or integrated

components.

Tracking emergent risks: Organizations’ risk management efforts will be enhanced by

identifying and tracking emergent risks and considering techniques for measuring them.

Page 5

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

AI system impact assessment approaches can help AI actors understand potential impacts

or harms within specific contexts.

Availability of reliable metrics: The current lack of consensus on robust and verifiable

measurement methods for risk and trustworthiness, and applicability to different AI use

cases, is an AI risk measurement challenge. Potential pitfalls when seeking to measure

negative risk or harms include the reality that development of metrics is often an institu-

tional endeavor and may inadvertently reflect factors unrelated to the underlying impact. In

addition, measurement approaches can be oversimplified, gamed, lack critical nuance, be-

come relied upon in unexpected ways, or fail to account for differences in affected groups

and contexts.

Approaches for measuring impacts on a population work best if they recognize that contexts

matter, that harms may affect varied groups or sub-groups differently, and that communities

or other sub-groups who may be harmed are not always direct users of a system.

Risk at different stages of the AI lifecycle: Measuring risk at an earlier stage in the AI

lifecycle may yield different results than measuring risk at a later stage; some risks may

be latent at a given point in time and may increase as AI systems adapt and evolve. Fur-

thermore, different AI actors across the AI lifecycle can have different risk perspectives.

For example, an AI developer who makes AI software available, such as pre-trained mod-

els, can have a different risk perspective than an AI actor who is responsible for deploying

that pre-trained model in a specific use case. Such deployers may not recognize that their

particular uses could entail risks which differ from those perceived by the initial developer.

All involved AI actors share responsibilities for designing, developing, and deploying a

trustworthy AI system that is fit for purpose.

Risk in real-world settings: While measuring AI risks in a laboratory or a controlled

environment may yield important insights pre-deployment, these measurements may differ

from risks that emerge in operational, real-world settings.

Inscrutability: Inscrutable AI systems can complicate risk measurement. Inscrutability

can be a result of the opaque nature of AI systems (limited explainability or interpretabil-

ity), lack of transparency or documentation in AI system development or deployment, or

inherent uncertainties in AI systems.

Human baseline: Risk management of AI systems that are intended to augment or replace

human activity, for example decision making, requires some form of baseline metrics for

comparison. This is difficult to systematize since AI systems carry out different tasks – and

perform tasks differently – than humans.

Page 6

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

1.2.2 Risk Tolerance

While the AI RMF can be used to prioritize risk, it does not prescribe risk tolerance. Risk

tolerance refers to the organization’s or AI actor’s (see Appendix A) readiness to bear the

risk in order to achieve its objectives. Risk tolerance can be influenced by legal or regula-

tory requirements (Adapted from: ISO GUIDE 73). Risk tolerance and the level of risk that

is acceptable to organizations or society are highly contextual and application and use-case

specific. Risk tolerances can be influenced by policies and norms established by AI sys-

tem owners, organizations, industries, communities, or policy makers. Risk tolerances are

likely to change over time as AI systems, policies, and norms evolve. Different organiza-

tions may have varied risk tolerances due to their particular organizational priorities and

resource considerations.

Emerging knowledge and methods to better inform harm/cost-benefit tradeoffs will con-

tinue to be developed and debated by businesses, governments, academia, and civil society.

To the extent that challenges for specifying AI risk tolerances remain unresolved, there may

be contexts where a risk management framework is not yet readily applicable for mitigating

negative AI risks.

The Framework is intended to be flexible and to augment existing risk practices

which should align with applicable laws, regulations, and norms. Organizations

should follow existing regulations and guidelines for risk criteria, tolerance, and

response established by organizational, domain, discipline, sector, or professional

requirements. Some sectors or industries may have established definitions of harm or

established documentation, reporting, and disclosure requirements. Within sectors,

risk management may depend on existing guidelines for specific applications and

use case settings. Where established guidelines do not exist, organizations should

define reasonable risk tolerance. Once tolerance is defined, this AI RMF can be used

to manage risks and to document risk management processes.

1.2.3 Risk Prioritization

Attempting to eliminate negative risk entirely can be counterproductive in practice because

not all incidents and failures can be eliminated. Unrealistic expectations about risk may

lead organizations to allocate resources in a manner that makes risk triage inefficient or

impractical or wastes scarce resources. A risk management culture can help organizations

recognize that not all AI risks are the same, and resources can be allocated purposefully.

Actionable risk management efforts lay out clear guidelines for assessing trustworthiness

of each AI system an organization develops or deploys. Policies and resources should be

prioritized based on the assessed risk level and potential impact of an AI system. The extent

to which an AI system may be customized or tailored to the specific context of use by the

AI deployer can be a contributing factor.

Page 7

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

When applying the AI RMF, risks which the organization determines to be highest for the

AI systems within a given context of use call for the most urgent prioritization and most

thorough risk management process. In cases where an AI system presents unacceptable

negative risk levels – such as where significant negative impacts are imminent, severe harms

are actually occurring, or catastrophic risks are present – development and deployment

should cease in a safe manner until risks can be sufficiently managed. If an AI system’s

development, deployment, and use cases are found to be low-risk in a specific context, that

may suggest potentially lower prioritization.

Risk prioritization may differ between AI systems that are designed or deployed to directly

interact with humans as compared to AI systems that are not. Higher initial prioritization

may be called for in settings where the AI system is trained on large datasets comprised of

sensitive or protected data such as personally identifiable information, or where the outputs

of the AI systems have direct or indirect impact on humans. AI systems designed to interact

only with computational systems and trained on non-sensitive datasets (for example, data

collected from the physical environment) may call for lower initial prioritization. Nonethe-

less, regularly assessing and prioritizing risk based on context remains important because

non-human-facing AI systems can have downstream safety or social implications.

Residual risk – defined as risk remaining after risk treatment (Source: ISO GUIDE 73) –

directly impacts end users or affected individuals and communities. Documenting residual

risks will call for the system provider to fully consider the risks of deploying the AI product

and will inform end users about potential negative impacts of interacting with the system.

1.2.4 Organizational Integration and Management of Risk

AI risks should not be considered in isolation. Different AI actors have different responsi-

bilities and awareness depending on their roles in the lifecycle. For example, organizations

developing an AI system often will not have information about how the system may be

used. AI risk management should be integrated and incorporated into broader enterprise

risk management strategies and processes. Treating AI risks along with other critical risks,

such as cybersecurity and privacy, will yield a more integrated outcome and organizational

efficiencies.

The AI RMF may be utilized along with related guidance and frameworks for managing

AI system risks or broader enterprise risks. Some risks related to AI systems are common

across other types of software development and deployment. Examples of overlapping risks

include: privacy concerns related to the use of underlying data to train AI systems; the en-

ergy and environmental implications associated with resource-heavy computing demands;

security concerns related to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the system and

its training and output data; and general security of the underlying software and hardware

for AI systems.

Page 8

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Organizations need to establish and maintain the appropriate accountability mechanisms,

roles and responsibilities, culture, and incentive structures for risk management to be ef-

fective. Use of the AI RMF alone will not lead to these changes or provide the appropriate

incentives. Effective risk management is realized through organizational commitment at

senior levels and may require cultural change within an organization or industry. In addi-

tion, small to medium-sized organizations managing AI risks or implementing the AI RMF

may face different challenges than large organizations, depending on their capabilities and

resources.

2. Audience

Identifying and managing AI risks and potential impacts – both positive and negative – re-

quires a broad set of perspectives and actors across the AI lifecycle. Ideally, AI actors will

represent a diversity of experience, expertise, and backgrounds and comprise demograph-

ically and disciplinarily diverse teams. The AI RMF is intended to be used by AI actors

across the AI lifecycle and dimensions.

The OECD has developed a framework for classifying AI lifecycle activities according to

five key socio-technical dimensions, each with properties relevant for AI policy and gover-

nance, including risk management [OECD (2022) OECD Framework for the Classification

of AI systems — OECD Digital Economy Papers]. Figure 2 shows these dimensions,

slightly modified by NIST for purposes of this framework. The NIST modification high-

lights the importance of test, evaluation, verification, and validation (TEVV) processes

throughout an AI lifecycle and generalizes the operational context of an AI system.

AI dimensions displayed in Figure 2 are the Application Context, Data and Input, AI

Model, and Task and Output. AI actors involved in these dimensions who perform or

manage the design, development, deployment, evaluation, and use of AI systems and drive

AI risk management efforts are the primary AI RMF audience.

Representative AI actors across the lifecycle dimensions are listed in Figure 3 and described

in detail in Appendix A. Within the AI RMF, all AI actors work together to manage risks

and achieve the goals of trustworthy and responsible AI. AI actors with TEVV-specific

expertise are integrated throughout the AI lifecycle and are especially likely to benefit from

the Framework. Performed regularly, TEVV tasks can provide insights relative to technical,

societal, legal, and ethical standards or norms, and can assist with anticipating impacts and

assessing and tracking emergent risks. As a regular process within an AI lifecycle, TEVV

allows for both mid-course remediation and post-hoc risk management.

The People & Planet dimension at the center of Figure 2 represents human rights and the

broader well-being of society and the planet. The AI actors in this dimension comprise

a separate AI RMF audience who informs the primary audience. These AI actors may in-

clude trade associations, standards developing organizations, researchers, advocacy groups,

Page 9

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Fig. 2. Lifecycle and Key Dimensions of an AI System. Modified from OECD (2022) OECD

Framework for the Classification of AI systems — OECD Digital Economy Papers. The two inner

circles show AI systems’ key dimensions and the outer circle shows AI lifecycle stages. Ideally,

risk management efforts start with the Plan and Design function in the application context and are

performed throughout the AI system lifecycle. See Figure 3 for representative AI actors.

environmental groups, civil society organizations, end users, and potentially impacted in-

dividuals and communities. These actors can:

• assist in providing context and understanding potential and actual impacts;

• be a source of formal or quasi-formal norms and guidance for AI risk management;

• designate boundaries for AI operation (technical, societal, legal, and ethical); and

• promote discussion of the tradeoffs needed to balance societal values and priorities

related to civil liberties and rights, equity, the environment and the planet, and the

economy.

Successful risk management depends upon a sense of collective responsibility among AI

actors shown in Figure 3. The AI RMF functions, described in Section 5, require diverse

perspectives, disciplines, professions, and experiences. Diverse teams contribute to more

open sharing of ideas and assumptions about the purposes and functions of technology –

making these implicit aspects more explicit. This broader collective perspective creates

opportunities for surfacing problems and identifying existing and emergent risks.

Page 10

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Fig. 3. AI actors across AI lifecycle stages. See Appendix A for detailed descriptions of AI actor tasks, including details about testing,

evaluation, verification, and validation tasks. Note that AI actors in the AI Model dimension (Figure 2) are separated as a best practice, with

those building and using the models separated from those verifying and validating the models.

Page 11

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

3. AI Risks and Trustworthiness

For AI systems to be trustworthy, they often need to be responsive to a multiplicity of cri-

teria that are of value to interested parties. Approaches which enhance AI trustworthiness

can reduce negative AI risks. This Framework articulates the following characteristics of

trustworthy AI and offers guidance for addressing them. Characteristics of trustworthy AI

systems include: valid and reliable, safe, secure and resilient, accountable and trans-

parent, explainable and interpretable, privacy-enhanced, and fair with harmful bias

managed. Creating trustworthy AI requires balancing each of these characteristics based

on the AI system’s context of use. While all characteristics are socio-technical system at-

tributes, accountability and transparency also relate to the processes and activities internal

to an AI system and its external setting. Neglecting these characteristics can increase the

probability and magnitude of negative consequences.

Fig. 4. Characteristics of trustworthy AI systems. Valid & Reliable is a necessary condition of

trustworthiness and is shown as the base for other trustworthiness characteristics. Accountable &

Transparent is shown as a vertical box because it relates to all other characteristics.

Trustworthiness characteristics (shown in Figure 4) are inextricably tied to social and orga-

nizational behavior, the datasets used by AI systems, selection of AI models and algorithms

and the decisions made by those who build them, and the interactions with the humans who

provide insight from and oversight of such systems. Human judgment should be employed

when deciding on the specific metrics related to AI trustworthiness characteristics and the

precise threshold values for those metrics.

Addressing AI trustworthiness characteristics individually will not ensure AI system trust-

worthiness; tradeoffs are usually involved, rarely do all characteristics apply in every set-

ting, and some will be more or less important in any given situation. Ultimately, trustwor-

thiness is a social concept that ranges across a spectrum and is only as strong as its weakest

characteristics.

When managing AI risks, organizations can face difficult decisions in balancing these char-

acteristics. For example, in certain scenarios tradeoffs may emerge between optimizing for

interpretability and achieving privacy. In other cases, organizations might face a tradeoff

between predictive accuracy and interpretability. Or, under certain conditions such as data

sparsity, privacy-enhancing techniques can result in a loss in accuracy, affecting decisions

Page 12

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

about fairness and other values in certain domains. Dealing with tradeoffs requires tak-

ing into account the decision-making context. These analyses can highlight the existence

and extent of tradeoffs between different measures, but they do not answer questions about

how to navigate the tradeoff. Those depend on the values at play in the relevant context and

should be resolved in a manner that is both transparent and appropriately justifiable.

There are multiple approaches for enhancing contextual awareness in the AI lifecycle. For

example, subject matter experts can assist in the evaluation of TEVV findings and work

with product and deployment teams to align TEVV parameters to requirements and de-

ployment conditions. When properly resourced, increasing the breadth and diversity of

input from interested parties and relevant AI actors throughout the AI lifecycle can en-

hance opportunities for informing contextually sensitive evaluations, and for identifying

AI system benefits and positive impacts. These practices can increase the likelihood that

risks arising in social contexts are managed appropriately.

Understanding and treatment of trustworthiness characteristics depends on an AI actor’s

particular role within the AI lifecycle. For any given AI system, an AI designer or developer

may have a different perception of the characteristics than the deployer.

Trustworthiness characteristics explained in this document influence each other.

Highly secure but unfair systems, accurate but opaque and uninterpretable systems,

and inaccurate but secure, privacy-enhanced, and transparent systems are all unde-

sirable. A comprehensive approach to risk management calls for balancing tradeoffs

among the trustworthiness characteristics. It is the joint responsibility of all AI ac-

tors to determine whether AI technology is an appropriate or necessary tool for a

given context or purpose, and how to use it responsibly. The decision to commission

or deploy an AI system should be based on a contextual assessment of trustworthi-

ness characteristics and the relative risks, impacts, costs, and benefits, and informed

by a broad set of interested parties.

3.1 Valid and Reliable

Validation is the “confirmation, through the provision of objective evidence, that the re-

quirements for a specific intended use or application have been fulfilled” (Source: ISO

9000:2015). Deployment of AI systems which are inaccurate, unreliable, or poorly gener-

alized to data and settings beyond their training creates and increases negative AI risks and

reduces trustworthiness.

Reliability is defined in the same standard as the “ability of an item to perform as required,

without failure, for a given time interval, under given conditions” (Source: ISO/IEC TS

5723:2022). Reliability is a goal for overall correctness of AI system operation under the

conditions of expected use and over a given period of time, including the entire lifetime of

the system.

Page 13

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Accuracy and robustness contribute to the validity and trustworthiness of AI systems, and

can be in tension with one another in AI systems.

Accuracy is defined by ISO/IEC TS 5723:2022 as “closeness of results of observations,

computations, or estimates to the true values or the values accepted as being true.” Mea-

sures of accuracy should consider computational-centric measures (e.g., false positive and

false negative rates), human-AI teaming, and demonstrate external validity (generalizable

beyond the training conditions). Accuracy measurements should always be paired with

clearly defined and realistic test sets – that are representative of conditions of expected use

– and details about test methodology; these should be included in associated documen-

tation. Accuracy measurements may include disaggregation of results for different data

segments.

Robustness or generalizability is defined as the “ability of a system to maintain its level

of performance under a variety of circumstances” (Source: ISO/IEC TS 5723:2022). Ro-

bustness is a goal for appropriate system functionality in a broad set of conditions and

circumstances, including uses of AI systems not initially anticipated. Robustness requires

not only that the system perform exactly as it does under expected uses, but also that it

should perform in ways that minimize potential harms to people if it is operating in an

unexpected setting.

Validity and reliability for deployed AI systems are often assessed by ongoing testing or

monitoring that confirms a system is performing as intended. Measurement of validity,

accuracy, robustness, and reliability contribute to trustworthiness and should take into con-

sideration that certain types of failures can cause greater harm. AI risk management efforts

should prioritize the minimization of potential negative impacts, and may need to include

human intervention in cases where the AI system cannot detect or correct errors.

3.2 Safe

AI systems should “not under defined conditions, lead to a state in which human life,

health, property, or the environment is endangered” (Source: ISO/IEC TS 5723:2022). Safe

operation of AI systems is improved through:

• responsible design, development, and deployment practices;

• clear information to deployers on responsible use of the system;

• responsible decision-making by deployers and end users; and

• explanations and documentation of risks based on empirical evidence of incidents.

Different types of safety risks may require tailored AI risk management approaches based

on context and the severity of potential risks presented. Safety risks that pose a potential

risk of serious injury or death call for the most urgent prioritization and most thorough risk

management process.

Page 14

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Employing safety considerations during the lifecycle and starting as early as possible with

planning and design can prevent failures or conditions that can render a system dangerous.

Other practical approaches for AI safety often relate to rigorous simulation and in-domain

testing, real-time monitoring, and the ability to shut down, modify, or have human inter-

vention into systems that deviate from intended or expected functionality.

AI safety risk management approaches should take cues from efforts and guidelines for

safety in fields such as transportation and healthcare, and align with existing sector- or

application-specific guidelines or standards.

3.3 Secure and Resilient

AI systems, as well as the ecosystems in which they are deployed, may be said to be re-

silient if they can withstand unexpected adverse events or unexpected changes in their envi-

ronment or use – or if they can maintain their functions and structure in the face of internal

and external change and degrade safely and gracefully when this is necessary (Adapted

from: ISO/IEC TS 5723:2022). Common security concerns relate to adversarial examples,

data poisoning, and the exfiltration of models, training data, or other intellectual property

through AI system endpoints. AI systems that can maintain confidentiality, integrity, and

availability through protection mechanisms that prevent unauthorized access and use may

be said to be secure. Guidelines in the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and Risk Manage-

ment Framework are among those which are applicable here.

Security and resilience are related but distinct characteristics. While resilience is the abil-

ity to return to normal function after an unexpected adverse event, security includes re-

silience but also encompasses protocols to avoid, protect against, respond to, or recover

from attacks. Resilience relates to robustness and goes beyond the provenance of the data

to encompass unexpected or adversarial use (or abuse or misuse) of the model or data.

3.4 Accountable and Transparent

Trustworthy AI depends upon accountability. Accountability presupposes transparency.

Transparency reflects the extent to which information about an AI system and its outputs is

available to individuals interacting with such a system – regardless of whether they are even

aware that they are doing so. Meaningful transparency provides access to appropriate levels

of information based on the stage of the AI lifecycle and tailored to the role or knowledge

of AI actors or individuals interacting with or using the AI system. By promoting higher

levels of understanding, transparency increases confidence in the AI system.

This characteristic’s scope spans from design decisions and training data to model train-

ing, the structure of the model, its intended use cases, and how and when deployment,

post-deployment, or end user decisions were made and by whom. Transparency is often

necessary for actionable redress related to AI system outputs that are incorrect or otherwise

lead to negative impacts. Transparency should consider human-AI interaction: for exam-

Page 15

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

ple, how a human operator or user is notified when a potential or actual adverse outcome

caused by an AI system is detected. A transparent system is not necessarily an accurate,

privacy-enhanced, secure, or fair system. However, it is difficult to determine whether an

opaque system possesses such characteristics, and to do so over time as complex systems

evolve.

The role of AI actors should be considered when seeking accountability for the outcomes of

AI systems. The relationship between risk and accountability associated with AI and tech-

nological systems more broadly differs across cultural, legal, sectoral, and societal contexts.

When consequences are severe, such as when life and liberty are at stake, AI developers

and deployers should consider proportionally and proactively adjusting their transparency

and accountability practices. Maintaining organizational practices and governing structures

for harm reduction, like risk management, can help lead to more accountable systems.

Measures to enhance transparency and accountability should also consider the impact of

these efforts on the implementing entity, including the level of necessary resources and the

need to safeguard proprietary information.

Maintaining the provenance of training data and supporting attribution of the AI system’s

decisions to subsets of training data can assist with both transparency and accountability.

Training data may also be subject to copyright and should follow applicable intellectual

property rights laws.

As transparency tools for AI systems and related documentation continue to evolve, devel-

opers of AI systems are encouraged to test different types of transparency tools in cooper-

ation with AI deployers to ensure that AI systems are used as intended.

3.5 Explainable and Interpretable

Explainability refers to a representation of the mechanisms underlying AI systems’ oper-

ation, whereas interpretability refers to the meaning of AI systems’ output in the context

of their designed functional purposes. Together, explainability and interpretability assist

those operating or overseeing an AI system, as well as users of an AI system, to gain

deeper insights into the functionality and trustworthiness of the system, including its out-

puts. The underlying assumption is that perceptions of negative risk stem from a lack of

ability to make sense of, or contextualize, system output appropriately. Explainable and

interpretable AI systems offer information that will help end users understand the purposes

and potential impact of an AI system.

Risk from lack of explainability may be managed by describing how AI systems function,

with descriptions tailored to individual differences such as the user’s role, knowledge, and

skill level. Explainable systems can be debugged and monitored more easily, and they lend

themselves to more thorough documentation, audit, and governance.

Page 16

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Risks to interpretability often can be addressed by communicating a description of why

an AI system made a particular prediction or recommendation. (See “Four Principles of

Explainable Artificial Intelligence” and “Psychological Foundations of Explainability and

Interpretability in Artificial Intelligence” found here.)

Transparency, explainability, and interpretability are distinct characteristics that support

each other. Transparency can answer the question of “what happened” in the system. Ex-

plainability can answer the question of “how” a decision was made in the system. Inter-

pretability can answer the question of “why” a decision was made by the system and its

meaning or context to the user.

3.6 Privacy-Enhanced

Privacy refers generally to the norms and practices that help to safeguard human autonomy,

identity, and dignity. These norms and practices typically address freedom from intrusion,

limiting observation, or individuals’ agency to consent to disclosure or control of facets of

their identities (e.g., body, data, reputation). (See The NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool

for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management.)

Privacy values such as anonymity, confidentiality, and control generally should guide choices

for AI system design, development, and deployment. Privacy-related risks may influence

security, bias, and transparency and come with tradeoffs with these other characteristics.

Like safety and security, specific technical features of an AI system may promote or reduce

privacy. AI systems can also present new risks to privacy by allowing inference to identify

individuals or previously private information about individuals.

Privacy-enhancing technologies (“PETs”) for AI, as well as data minimizing methods such

as de-identification and aggregation for certain model outputs, can support design for

privacy-enhanced AI systems. Under certain conditions such as data sparsity, privacy-

enhancing techniques can result in a loss in accuracy, affecting decisions about fairness

and other values in certain domains.

3.7 Fair – with Harmful Bias Managed

Fairness in AI includes concerns for equality and equity by addressing issues such as harm-

ful bias and discrimination. Standards of fairness can be complex and difficult to define be-

cause perceptions of fairness differ among cultures and may shift depending on application.

Organizations’ risk management efforts will be enhanced by recognizing and considering

these differences. Systems in which harmful biases are mitigated are not necessarily fair.

For example, systems in which predictions are somewhat balanced across demographic

groups may still be inaccessible to individuals with disabilities or affected by the digital

divide or may exacerbate existing disparities or systemic biases.

Page 17

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Bias is broader than demographic balance and data representativeness. NIST has identified

three major categories of AI bias to be considered and managed: systemic, computational

and statistical, and human-cognitive. Each of these can occur in the absence of prejudice,

partiality, or discriminatory intent. Systemic bias can be present in AI datasets, the orga-

nizational norms, practices, and processes across the AI lifecycle, and the broader society

that uses AI systems. Computational and statistical biases can be present in AI datasets

and algorithmic processes, and often stem from systematic errors due to non-representative

samples. Human-cognitive biases relate to how an individual or group perceives AI sys-

tem information to make a decision or fill in missing information, or how humans think

about purposes and functions of an AI system. Human-cognitive biases are omnipresent

in decision-making processes across the AI lifecycle and system use, including the design,

implementation, operation, and maintenance of AI.

Bias exists in many forms and can become ingrained in the automated systems that help

make decisions about our lives. While bias is not always a negative phenomenon, AI sys-

tems can potentially increase the speed and scale of biases and perpetuate and amplify

harms to individuals, groups, communities, organizations, and society. Bias is tightly asso-

ciated with the concepts of transparency as well as fairness in society. (For more informa-

tion about bias, including the three categories, see NIST Special Publication 1270, Towards

a Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in Artificial Intelligence.)

Page 18

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

4. Effectiveness of the AI RMF

Evaluations of AI RMF effectiveness – including ways to measure bottom-line improve-

ments in the trustworthiness of AI systems – will be part of future NIST activities, in

conjunction with the AI community.

Organizations and other users of the Framework are encouraged to periodically evaluate

whether the AI RMF has improved their ability to manage AI risks, including but not lim-

ited to their policies, processes, practices, implementation plans, indicators, measurements,

and expected outcomes. NIST intends to work collaboratively with others to develop met-

rics, methodologies, and goals for evaluating the AI RMF’s effectiveness, and to broadly

share results and supporting information. Framework users are expected to benefit from:

• enhanced processes for governing, mapping, measuring, and managing AI risk, and

clearly documenting outcomes;

• improved awareness of the relationships and tradeoffs among trustworthiness char-

acteristics, socio-technical approaches, and AI risks;

• explicit processes for making go/no-go system commissioning and deployment deci-

sions;

• established policies, processes, practices, and procedures for improving organiza-

tional accountability efforts related to AI system risks;

• enhanced organizational culture which prioritizes the identification and management

of AI system risks and potential impacts to individuals, communities, organizations,

and society;

• better information sharing within and across organizations about risks, decision-

making processes, responsibilities, common pitfalls, TEVV practices, and approaches

for continuous improvement;

• greater contextual knowledge for increased awareness of downstream risks;

• strengthened engagement with interested parties and relevant AI actors; and

• augmented capacity for TEVV of AI systems and associated risks.

Page 19

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Part 2: Core and Profiles

5. AI RMF Core

The AI RMF Core provides outcomes and actions that enable dialogue, understanding, and

activities to manage AI risks and responsibly develop trustworthy AI systems. As illus-

trated in Figure 5, the Core is composed of four functions: GOVERN, MAP, MEASURE,

and MANAGE. Each of these high-level functions is broken down into categories and sub-

categories. Categories and subcategories are subdivided into specific actions and outcomes.

Actions do not constitute a checklist, nor are they necessarily an ordered set of steps.

Fig. 5. Functions organize AI risk management activities at their highest level to govern, map,

measure, and manage AI risks. Governance is designed to be a cross-cutting function to inform

and be infused throughout the other three functions.

Risk management should be continuous, timely, and performed throughout the AI system

lifecycle dimensions. AI RMF Core functions should be carried out in a way that reflects

diverse and multidisciplinary perspectives, potentially including the views of AI actors out-

side the organization. Having a diverse team contributes to more open sharing of ideas and

assumptions about purposes and functions of the technology being designed, developed,

Page 20

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

deployed, or evaluated – which can create opportunities to surface problems and identify

existing and emergent risks.

An online companion resource to the AI RMF, the NIST AI RMF Playbook, is available

to help organizations navigate the AI RMF and achieve its outcomes through suggested

tactical actions they can apply within their own contexts. Like the AI RMF, the Playbook

is voluntary and organizations can utilize the suggestions according to their needs and

interests. Playbook users can create tailored guidance selected from suggested material

for their own use and contribute their suggestions for sharing with the broader community.

Along with the AI RMF, the Playbook is part of the NIST Trustworthy and Responsible AI

Resource Center.

Framework users may apply these functions as best suits their needs for managing

AI risks based on their resources and capabilities. Some organizations may choose

to select from among the categories and subcategories; others may choose and have

the capacity to apply all categories and subcategories. Assuming a governance struc-

ture is in place, functions may be performed in any order across the AI lifecycle as

deemed to add value by a user of the framework. After instituting the outcomes in

GOVERN, most users of the AI RMF would start with the MAP function and con-

tinue to MEASURE or MANAGE. However users integrate the functions, the process

should be iterative, with cross-referencing between functions as necessary. Simi-

larly, there are categories and subcategories with elements that apply to multiple

functions, or that logically should take place before certain subcategory decisions.

5.1 Govern

The GOVERN function:

• cultivates and implements a culture of risk management within organizations design-

ing, developing, deploying, evaluating, or acquiring AI systems;

• outlines processes, documents, and organizational schemes that anticipate, identify,

and manage the risks a system can pose, including to users and others across society

– and procedures to achieve those outcomes;

• incorporates processes to assess potential impacts;

• provides a structure by which AI risk management functions can align with organi-

zational principles, policies, and strategic priorities;

• connects technical aspects of AI system design and development to organizational

values and principles, and enables organizational practices and competencies for the

individuals involved in acquiring, training, deploying, and monitoring such systems;

and

• addresses full product lifecycle and associated processes, including legal and other

issues concerning use of third-party software or hardware systems and data.

Page 21

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

GOVERN is a cross-cutting function that is infused throughout AI risk management and

enables the other functions of the process. Aspects of GOVERN, especially those related to

compliance or evaluation, should be integrated into each of the other functions. Attention

to governance is a continual and intrinsic requirement for effective AI risk management

over an AI system’s lifespan and the organization’s hierarchy.

Strong governance can drive and enhance internal practices and norms to facilitate orga-

nizational risk culture. Governing authorities can determine the overarching policies that

direct an organization’s mission, goals, values, culture, and risk tolerance. Senior leader-

ship sets the tone for risk management within an organization, and with it, organizational

culture. Management aligns the technical aspects of AI risk management to policies and

operations. Documentation can enhance transparency, improve human review processes,

and bolster accountability in AI system teams.

After putting in place the structures, systems, processes, and teams described in the GOV-

ERN function, organizations should benefit from a purpose-driven culture focused on risk

understanding and management. It is incumbent on Framework users to continue to ex-

ecute the GOVERN function as knowledge, cultures, and needs or expectations from AI

actors evolve over time.

Practices related to governing AI risks are described in the NIST AI RMF Playbook. Table

1 lists the GOVERN function’s categories and subcategories.

Table 1: Categories and subcategories for the GOVERN function.

GOVERN 1:

Policies, processes,

procedures, and

practices across the

organization related

to the mapping,

measuring, and

managing of AI

risks are in place,

transparent, and

implemented

effectively.

GOVERN 1.1: Legal and regulatory requirements involving AI

are understood, managed, and documented.

GOVERN 1.2: The characteristics of trustworthy AI are inte-

grated into organizational policies, processes, procedures, and

practices.

GOVERN 1.3: Processes, procedures, and practices are in place

to determine the needed level of risk management activities based

on the organization’s risk tolerance.

GOVERN 1.4: The risk management process and its outcomes are

established through transparent policies, procedures, and other

controls based on organizational risk priorities.

Categories Subcategories

Continued on next page

Page 22

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Table 1: Categories and subcategories for the GOVERN function. (Continued)

GOVERN 1.5: Ongoing monitoring and periodic review of the

risk management process and its outcomes are planned and or-

ganizational roles and responsibilities clearly defined, including

determining the frequency of periodic review.

GOVERN 1.6: Mechanisms are in place to inventory AI systems

and are resourced according to organizational risk priorities.

GOVERN 1.7: Processes and procedures are in place for decom-

missioning and phasing out AI systems safely and in a man-

ner that does not increase risks or decrease the organization’s

trustworthiness.

GOVERN 2:

Accountability

structures are in

place so that the

appropriate teams

and individuals are

empowered,

responsible, and

trained for mapping,

measuring, and

managing AI risks.

GOVERN 2.1: Roles and responsibilities and lines of communi-

cation related to mapping, measuring, and managing AI risks are

documented and are clear to individuals and teams throughout

the organization.

GOVERN 2.2: The organization’s personnel and partners receive

AI risk management training to enable them to perform their du-

ties and responsibilities consistent with related policies, proce-

dures, and agreements.

GOVERN 2.3: Executive leadership of the organization takes re-

sponsibility for decisions about risks associated with AI system

development and deployment.

GOVERN 3:

Workforce diversity,

equity, inclusion,

and accessibility

processes are

prioritized in the

mapping,

measuring, and

managing of AI

risks throughout the

lifecycle.

GOVERN 3.1: Decision-making related to mapping, measuring,

and managing AI risks throughout the lifecycle is informed by a

diverse team (e.g., diversity of demographics, disciplines, expe-

rience, expertise, and backgrounds).

GOVERN 3.2: Policies and procedures are in place to define and

differentiate roles and responsibilities for human-AI configura-

tions and oversight of AI systems.

GOVERN 4:

Organizational

teams are committed

to a culture

GOVERN 4.1: Organizational policies and practices are in place

to foster a critical thinking and safety-first mindset in the design,

development, deployment, and uses of AI systems to minimize

potential negative impacts.

Categories Subcategories

Continued on next page

Page 23

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Table 1: Categories and subcategories for the GOVERN function. (Continued)

that considers and

communicates AI

risk.

GOVERN 4.2: Organizational teams document the risks and po-

tential impacts of the AI technology they design, develop, deploy,

evaluate, and use, and they communicate about the impacts more

broadly.

GOVERN 4.3: Organizational practices are in place to enable AI

testing, identification of incidents, and information sharing.

GOVERN 5:

Processes are in

place for robust

engagement with

relevant AI actors.

GOVERN 5.1: Organizational policies and practices are in place

to collect, consider, prioritize, and integrate feedback from those

external to the team that developed or deployed the AI system

regarding the potential individual and societal impacts related to

AI risks.

GOVERN 5.2: Mechanisms are established to enable the team

that developed or deployed AI systems to regularly incorporate

adjudicated feedback from relevant AI actors into system design

and implementation.

GOVERN 6: Policies

and procedures are

in place to address

AI risks and benefits

arising from

third-party software

and data and other

supply chain issues.

GOVERN 6.1: Policies and procedures are in place that address

AI risks associated with third-party entities, including risks of in-

fringement of a third-party’s intellectual property or other rights.

GOVERN 6.2: Contingency processes are in place to handle

failures or incidents in third-party data or AI systems deemed to

be high-risk.

Categories Subcategories

5.2 Map

The MAP function establishes the context to frame risks related to an AI system. The AI

lifecycle consists of many interdependent activities involving a diverse set of actors (See

Figure 3). In practice, AI actors in charge of one part of the process often do not have full

visibility or control over other parts and their associated contexts. The interdependencies

between these activities, and among the relevant AI actors, can make it difficult to reliably

anticipate impacts of AI systems. For example, early decisions in identifying purposes and

objectives of an AI system can alter its behavior and capabilities, and the dynamics of de-

ployment setting (such as end users or impacted individuals) can shape the impacts of AI

system decisions. As a result, the best intentions within one dimension of the AI lifecycle

can be undermined via interactions with decisions and conditions in other, later activities.

Page 24

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

This complexity and varying levels of visibility can introduce uncertainty into risk man-

agement practices. Anticipating, assessing, and otherwise addressing potential sources of

negative risk can mitigate this uncertainty and enhance the integrity of the decision process.

The information gathered while carrying out the MAP function enables negative risk pre-

vention and informs decisions for processes such as model management, as well as an

initial decision about appropriateness or the need for an AI solution. Outcomes in the

MAP function are the basis for the MEASURE and MANAGE functions. Without contex-

tual knowledge, and awareness of risks within the identified contexts, risk management is

difficult to perform. The MAP function is intended to enhance an organization’s ability to

identify risks and broader contributing factors.

Implementation of this function is enhanced by incorporating perspectives from a diverse

internal team and engagement with those external to the team that developed or deployed

the AI system. Engagement with external collaborators, end users, potentially impacted

communities, and others may vary based on the risk level of a particular AI system, the

makeup of the internal team, and organizational policies. Gathering such broad perspec-

tives can help organizations proactively prevent negative risks and develop more trustwor-

thy AI systems by:

• improving their capacity for understanding contexts;

• checking their assumptions about context of use;

• enabling recognition of when systems are not functional within or out of their in-

tended context;

• identifying positive and beneficial uses of their existing AI systems;

• improving understanding of limitations in AI and ML processes;

• identifying constraints in real-world applications that may lead to negative impacts;

• identifying known and foreseeable negative impacts related to intended use of AI

systems; and

• anticipating risks of the use of AI systems beyond intended use.

After completing the MAP function, Framework users should have sufficient contextual

knowledge about AI system impacts to inform an initial go/no-go decision about whether

to design, develop, or deploy an AI system. If a decision is made to proceed, organizations

should utilize the MEASURE and MANAGE functions along with policies and procedures

put into place in the GOVERN function to assist in AI risk management efforts. It is incum-

bent on Framework users to continue applying the MAP function to AI systems as context,

capabilities, risks, benefits, and potential impacts evolve over time.

Practices related to mapping AI risks are described in the NIST AI RMF Playbook. Table

2 lists the MAP function’s categories and subcategories.

Page 25

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Table 2: Categories and subcategories for the MAP function.

MAP 1: Context is

established and

understood.

MAP 1.1: Intended purposes, potentially beneficial uses, context-

specific laws, norms and expectations, and prospective settings in

which the AI system will be deployed are understood and docu-

mented. Considerations include: the specific set or types of users

along with their expectations; potential positive and negative im-

pacts of system uses to individuals, communities, organizations,

society, and the planet; assumptions and related limitations about

AI system purposes, uses, and risks across the development or

product AI lifecycle; and related TEVV and system metrics.

MAP 1.2: Interdisciplinary AI actors, competencies, skills, and

capacities for establishing context reflect demographic diversity

and broad domain and user experience expertise, and their par-

ticipation is documented. Opportunities for interdisciplinary col-

laboration are prioritized.

MAP 1.3: The organization’s mission and relevant goals for AI

technology are understood and documented.

MAP 1.4: The business value or context of business use has been

clearly defined or – in the case of assessing existing AI systems

– re-evaluated.

MAP 1.5: Organizational risk tolerances are determined and

documented.

MAP 1.6: System requirements (e.g., “the system shall respect

the privacy of its users”) are elicited from and understood by rel-

evant AI actors. Design decisions take socio-technical implica-

tions into account to address AI risks.

MAP 2:

Categorization of

the AI system is

performed.

MAP 2.1: The specific tasks and methods used to implement the

tasks that the AI system will support are defined (e.g., classifiers,

generative models, recommenders).

MAP 2.2: Information about the AI system’s knowledge limits

and how system output may be utilized and overseen by humans

is documented. Documentation provides sufficient information

to assist relevant AI actors when making decisions and taking

subsequent actions.

Categories Subcategories

Continued on next page

Page 26

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Table 2: Categories and subcategories for the MAP function. (Continued)

MAP 2.3: Scientific integrity and TEVV considerations are iden-

tified and documented, including those related to experimental

design, data collection and selection (e.g., availability, repre-

sentativeness, suitability), system trustworthiness, and construct

validation.

MAP 3: AI

capabilities, targeted

usage, goals, and

expected benefits

and costs compared

with appropriate

benchmarks are

understood.

MAP 3.1: Potential benefits of intended AI system functionality

and performance are examined and documented.

MAP 3.2: Potential costs, including non-monetary costs, which

result from expected or realized AI errors or system functionality

and trustworthiness – as connected to organizational risk toler-

ance – are examined and documented.

MAP 3.3: Targeted application scope is specified and docu-

mented based on the system’s capability, established context, and

AI system categorization.

MAP 3.4: Processes for operator and practitioner proficiency

with AI system performance and trustworthiness – and relevant

technical standards and certifications – are defined, assessed, and

documented.

MAP 3.5: Processes for human oversight are defined, assessed,

and documented in accordance with organizational policies from

the GOVERN function.

MAP 4: Risks and

benefits are mapped

for all components

of the AI system

including third-party

software and data.

MAP 4.1: Approaches for mapping AI technology and legal risks

of its components – including the use of third-party data or soft-

ware – are in place, followed, and documented, as are risks of in-

fringement of a third party’s intellectual property or other rights.

MAP 4.2: Internal risk controls for components of the AI sys-

tem, including third-party AI technologies, are identified and

documented.

MAP 5: Impacts to

individuals, groups,

communities,

organizations, and

society are

characterized.

MAP 5.1: Likelihood and magnitude of each identified impact

(both potentially beneficial and harmful) based on expected use,

past uses of AI systems in similar contexts, public incident re-

ports, feedback from those external to the team that developed

or deployed the AI system, or other data are identified and

documented.

Categories Subcategories

Continued on next page

Page 27

NIST AI 100-1 AI RMF 1.0

Table 2: Categories and subcategories for the MAP function. (Continued)

MAP 5.2: Practices and personnel for supporting regular en-

gagement with relevant AI actors and integrating feedback about

positive, negative, and unanticipated impacts are in place and

documented.

Categories Subcategories

5.3 Measure

The MEASURE function employs quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method tools, tech-

niques, and methodologies to analyze, assess, benchmark, and monitor AI risk and related

impacts. It uses knowledge relevant to AI risks identified in the MAP function and informs

the MANAGE function. AI systems should be tested before their deployment and regu-

larly while in operation. AI risk measurements include documenting aspects of systems’

functionality and trustworthiness.

Measuring AI risks includes tracking metrics for trustworthy characteristics, social impact,

and human-AI configurations. Processes developed or adopted in the MEASURE function

should include rigorous software testing and performance assessment methodologies with

associated measures of uncertainty, comparisons to performance benchmarks, and formal-

ized reporting and documentation of results. Processes for independent review can improve

the effectiveness of testing and can mitigate internal biases and potential conflicts of inter-

est.

Where tradeoffs among the trustworthy characteristics arise, measurement provides a trace-

able basis to inform management decisions. Options may include recalibration, impact

mitigation, or removal of the system from design, development, production, or use, as well

as a range of compensating, detective, deterrent, directive, and recovery controls.

After completing the MEASURE function, objective, repeatable, or scalable test, evaluation,

verification, and validation (TEVV) processes including metrics, methods, and methodolo-

gies are in place, followed, and documented. Metrics and measurement methodologies

should adhere to scientific, legal, and ethical norms and be carried out in an open and trans-

parent process. New types of measurement, qualitative and quantitative, may need to be

developed. The degree to which each measurement type provides unique and meaningful

information to the assessment of AI risks should be considered. Framework users will en-

hance their capacity to comprehensively evaluate system trustworthiness, identify and track

existing and emergent risks, and verify efficacy of the metrics. Measurement outcomes will

be utilized in the MANAGE function to assist risk monitoring and response efforts. It is in-