©robertprzybysz/i Stock/Thinkstock

MARCH 2015

The

ORTHODONTIC

workforce

CONTENTS

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 02

©iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Highlights

04 The twenty-first century

orthodontic workforce

Highlights the changes that have

taken place over the past decade and

proles an orthodontic nurse and an

orthodontic therapist.

11 ‘There is a family atmosphere in

our lab’

BDJ Team meets Willette Jean Lati,

a dental technician who works in an

orthodontic laboratory in London.

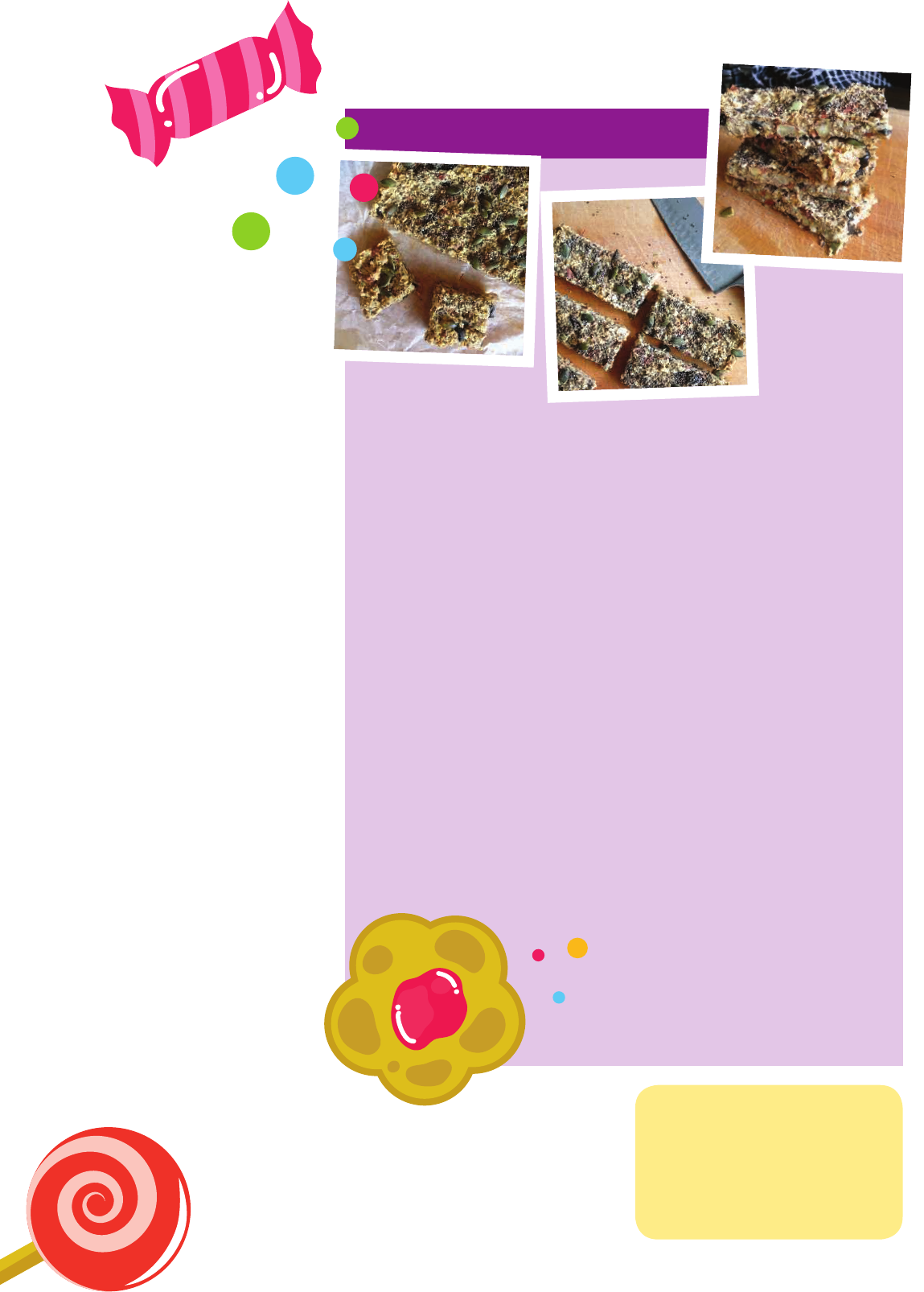

22 Are you addicted to sugar?

Certied health coach and blogger

Laura omas explains how to control

your sugar cravings - and shares a low

sugar apjack recipe.

Regulars

03 News

28 New products

30 BDJ Team verifiable CPD

In this issue

13 Needlestick safety for the whole

dental team

An update on risk management and

the use of sharps.

16 The denture box

How the denture box facilitates

denture hygiene, reduces the chance of

accidental damage, and more.

20 Rules for shared parental leave

Parents of babies due on or aer

5 April 2015 will be able to share

statutory leave.

25 How to dispose of

hazardous waste

Waste segregation and management

in dentistry - with one hour of CPD.

From the Vital archive.

March

2015

04

25

CORE

CPD:

ONE HOUR

www.nature.com/bdjteam

22

NEWS

NEW APP FOR BRITISH DENTAL

CONFERENCE 2015

Delegates at this year’s British Dental

Conference and Exhibition will nd

everything they need at the tip of their ngers

thanks to a new app specially designed for the

event. A rst for 2015, the app is suitable for

both Apple and Android devices and makes

managing your time at the event and getting

around even easier than before. e app is

available to download now via the Apple App

Store or Google Play.

Key features of the new app include:

■

A personal agenda feature allowing

delegates to browse full programme

information and add sessions they would

like to attend to their own personalised

event diary

■

Full speaker bios

■

Venue and exhibition maps

■

Instant event notications

■

Access to special show oers

■

Visitor information from cash machine

locations to car parking

■

Direct access to Twitter and Facebook

allowing users to interact and share views

with other delegates and organisers

■

Notes section that allows you to save and

email notes to yourself.

Linda Stranks, Director of Marketing and

Membership at the British Dental Association

(BDA), said: ‘We have designed this app to

make the event experience as simple and

smooth as possible. Many of our delegates

now carry smartphones so it makes sense

to interact with them and provide show

information directly into their hands. We

want to make the event even more interesting

for visitors and more interactive for

exhibitors.’

is year’s event will take place from 7-9

May at the Manchester Central Convention

Complex with many of the sessions of interest

to the whole team. However, in addition,

there are also a number of sessions which

have been designed with particular team

members in mind.

Dental nurses

One session that’s not to be missed is the

Career Pathways presentation in the Training

Essentials theatre (Friday, 12 noon). In this

special session for dental nurses, BADN

President Fiona Ellwood will look at the

opportunities that are out there for dental

nurses. She will help dental nurses reect

on developing as a specialist practitioner

and consider what a new dental contract

might mean for dental nurses’ future career

pathways.

Dental hygienists and therapists

On Friday morning the BSDHT is hosting a

must-attend Conference Pass session at which

Paul Brocklehurst, Senior Clinical Lecturer/

Honorary Consultant, Dental Public Health

and NIHR Clinician Scientist, University

of Manchester will be looking at

the evidence supporting the

use of dental hygienists and

therapists in primary care.

Another highlight for

dental therapists is the

Paediatric Prevention

presentation in the

Training Essentials

theatre (Saturday,

11 am) in which

Amanda Gallie, Dental

Hygienist and erapist,

and DCP Advisor,

Health Education England

(East Midlands) will look

at systems for developing

a child friendly hygiene and

therapy practice. In total the Training

Essentials theatre oers 19 x 30-minute

sessions based on the BDA’s Training

Essentials portfolio. Topics include dealing

with emergencies, radiation doses in dental

radiography, child and adult safeguarding,

infection control and team working.

Practice managers

and administrators

One highlight that’s not to be missed is the

ADAM team leadership presentation in the

Training Essentials theatre (ursday, 4 pm).

In this special session Association Honorary

Vice President Tracy Stuart will walk through

the steps of building a team rather than a

group of people that turn up to the same

place of work each day. She will help you

understand the many hats you need to wear as

a business owner or manager. She will share

the changes in marketing, what is working

and what isn’t and how you can convert

calls into patients and treatment plans into

solutions the patients wants to pay for without

becoming an aggressive sales person.

Further event highlights include a large

exhibition featuring the live Demonstration

theatre, Speakers’ corner and Innovation

zone, free advice sessions with BDA advisors

and an evening social programme including

networking drinks, a Cuban party night. Up

to 15 hours’ CPD will be on oer with all core

CPD subjects covered.

Conference Passes for dental care

professionals oer great value with a one day

Conference Pass priced at £95 and a full three

day Conference Pass just £155. is gives you

access to all the lectures as well as the shorter

sessions in the Exhibition Hall.

Alternatively, you could attend the event

free of charge by registering for your FREE

Exhibition Pass which gives you access to the

shorter Training Essentials theatre sessions

outlined above as well as the other Exhibition

Hall sessions. Don’t miss out!

Further programme information and

booking details for both Conference

and Exhibition Passes is available at

www.bda.org/conference

Delegates can register online at www.bda.

org/conference or by calling 0870 166 6625.

Please note!

e UK general election will take place on

ursday 7 May 2015. If you are planning to

attend the event on this day and wish to vote

in the election you will need to apply for a

postal vote if you cannot attend your local

polling stations.

Do you have a news story that you would

like included in BDJ Team? Send your press

release or a summary of your story to

the Editor at bdjt[email protected].

©fu rtaev/iStockphoto/Th inkstock

03 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

bdjteam201530

©filiz76/iStockphoto/Thinkstock

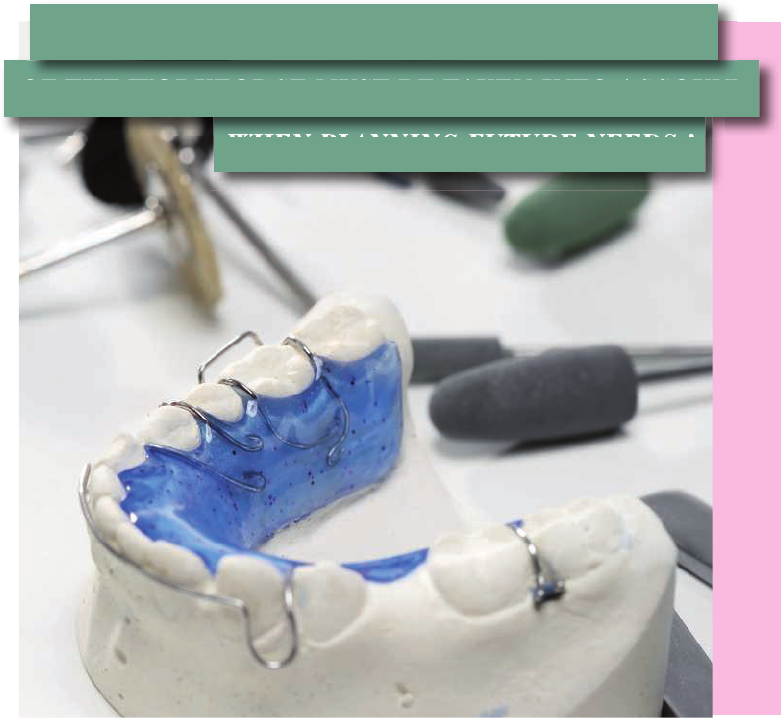

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 04

The twenty-first century

ORTHODONTIC

workforce

Orthodontic workforce planning

Historically, orthodontic workforce planning

has proved dicult. In 1985 Stephens et al.

1

predicted an oversupply of orthodontists

and yet only 13 years later the Task Group

for Orthodontics identied a shortfall and

recommended a target of 480 general dental

service specialist practitioners for the UK.

is wide ranging and perspicacious report

took into account training mechanisms,

European directives and wider drivers from

the Chief Medical and Dental Ocers. At

that time they were mindful of two other

unknowns in planning the workforce, the

inuence of ‘grandfathering’ onto specialist

lists and the potential impact of ‘orthodontic

auxiliaries’ as they were then known.

2

e rst complete survey of the

orthodontic workforce in the UK was carried

out during 2003 and 2004.

3

is survey was

commissioned by the Department of Health

and carried out by the University of Sheeld.

e aim was to assess the existing orthodontic

workforce in relation to current and future

population needs. It was questionnaire-based

and investigated the location of workforce

and the ratio of 12-year-olds per whole time

equivalent orthodontic provider in each

Strategic Health Authority. Type of provider,

case mix and productivity (assessed as

number of cases treated per year) were also

investigated. An orthodontic provider was

considered to be a specialist or non-specialist

who treated more than 30 cases per year.

Of the 1,660 UK orthodontic providers

identied, 919 were General Dental Council

(GDC) registered specialist providers. In the

hospital setting, 243 NHS consultants and

68 university teachers were identied. Fiy-

ve worked in a community setting and 221

were in training. e specialist practitioner

group was the largest group (548) and the

practitioner group (non-specialist providers)

represented 26% of the workforce (432).

At this time, orthodontic therapists did

not exist and attempts were not made to

measure their potential impact on workforce

need. Several scenarios were presented with

the problem of addressing the shortfall in

orthodontists and it was emphasised that the

demand for increased numbers of providers

could be lessened if those patients falling

T. Hodge

1

and N. Parkin

2

highlight the

changes that have taken place

in the orthodontic workforce over

the past decade and review the

roles of various members of the

orthodontic team.

1

Consultant Orthodontist, Leeds

Dental Institute;

2.

Consultant

Orthodontist, Charles Clifford

Dental Hospital, Sheffield

©robertprzybysz/i Stock/Thinkstock

FEATURE

05 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

into low index of treatment need categories

of treatment were not o ered orthodontic

correction. Following this survey, and

the introduction of contracting, for those

patients with a dental health component

(DHC) score of three and below orthodontic

treatment is no longer available on the

NHS. An exception to this rule is those who

fall in the DHC category three where the

aesthetic component scores six or higher. It

was also highlighted in the report that there

was considerable variation in geographic

distribution of providers, similar in fact to the

variation shown in the study by O’Brien and

colleagues.

4

In recent years, probably the most

signi cant change to the orthodontic

workforce has been the introduction of

orthodontic therapists. ere is anecdotal

evidence that this has already impacted on the

employment of some dentists and specialist

orthodontists in the workforce and continues

to impact on the employment of newly

quali ed specialists and clinical assistant

dentists. Future workforce issues will need

to be reassessed by the Centre for Workforce

Intelligence, with input from the British

Orthodontic Society (BOS). Consideration

should be given as to whether potentially

smaller numbers of specialists will be needed

to be trained in the future or whether there

needs to be a reduction in the number of

orthodontic therapist training providers.

In many ways this latter problem should

have been circumvented. e original pilot

study to establish training of orthodontic

therapists, and conducted in Bristol, made

it very clear that a very small number of

centres should be involved. It was recognised

that it was important to fully evaluate the

appropriateness of the training and skills

acquired from the initial courses over time

before further proliferation of programmes

around the UK. At the end of the Bristol pilot

it was suggested that there should initially

be an establishment of one or two auxiliary

training courses in the UK to ensure the

development of a national standard, and

that further courses would then be seeded

from these

THE CURRENT WORKFORCE

Orthodontic nurses

In 2000, a survey was undertaken to

investigate the delegation of orthodontic tasks

and the training of chairside support sta in

Europe.

6

At this stage in the UK the role of the

orthodontic therapist had not been developed.

From the nine tasks investigated, the only

one which was permitted to be undertaken

by a dental nurse in the UK was the taking

of radiographs. is survey highlighted that

UK dental nurses were allowed to work

without quali cations or formal training.

However, currently all dental nurses have to

be registered with the GDC. ose employed,

but not yet quali ed, need to be enrolled

within two years of commencing employment

or waiting to start on a recognised training

programme leading to GDC registration.

In addition, the clinical duties dental

and orthodontic nurses are permitted to

undertake have increased. Many nurses not

only take radiographs but routinely give oral

hygiene instruction, take impressions and

clinical photographs. ese roles, as with all

dental registrants in the team, are laid out in

the GDC Scope of practice documentation.

7

Finally, as well as the Certi cate in Dental

Nursing, the National Examining Board for

Dental Nurses (NEBDN) also run additional

post-quali cation courses leading to

certi cation that many orthodontic nurses

undertake in assisting them perform their

additional clinical roles competently

including the:

■

Certi cate in Orthodontic Nursing

8

■

Certi cate in Oral Health Education

9

■

Certi cate in Dental Radiography.

10

Orthodontic therapists

Orthodontic therapists are a grade of dental

care professional (DCP) introduced in 2007.

e recommendations for the training and

deployment of orthodontic auxiliaries in

the UK were based on the experiences of

the Bristol pilot study,

5

which provided a

foundation for the current training models

being used in Bristol and Leeds. ese were

the rst two training centres to qualify

orthodontic therapists.

11

It was also the

basis for those institutions that subsequently

established programmes (Swansea,

Edinburgh, King’s, Manchester, Preston

and Warwick).

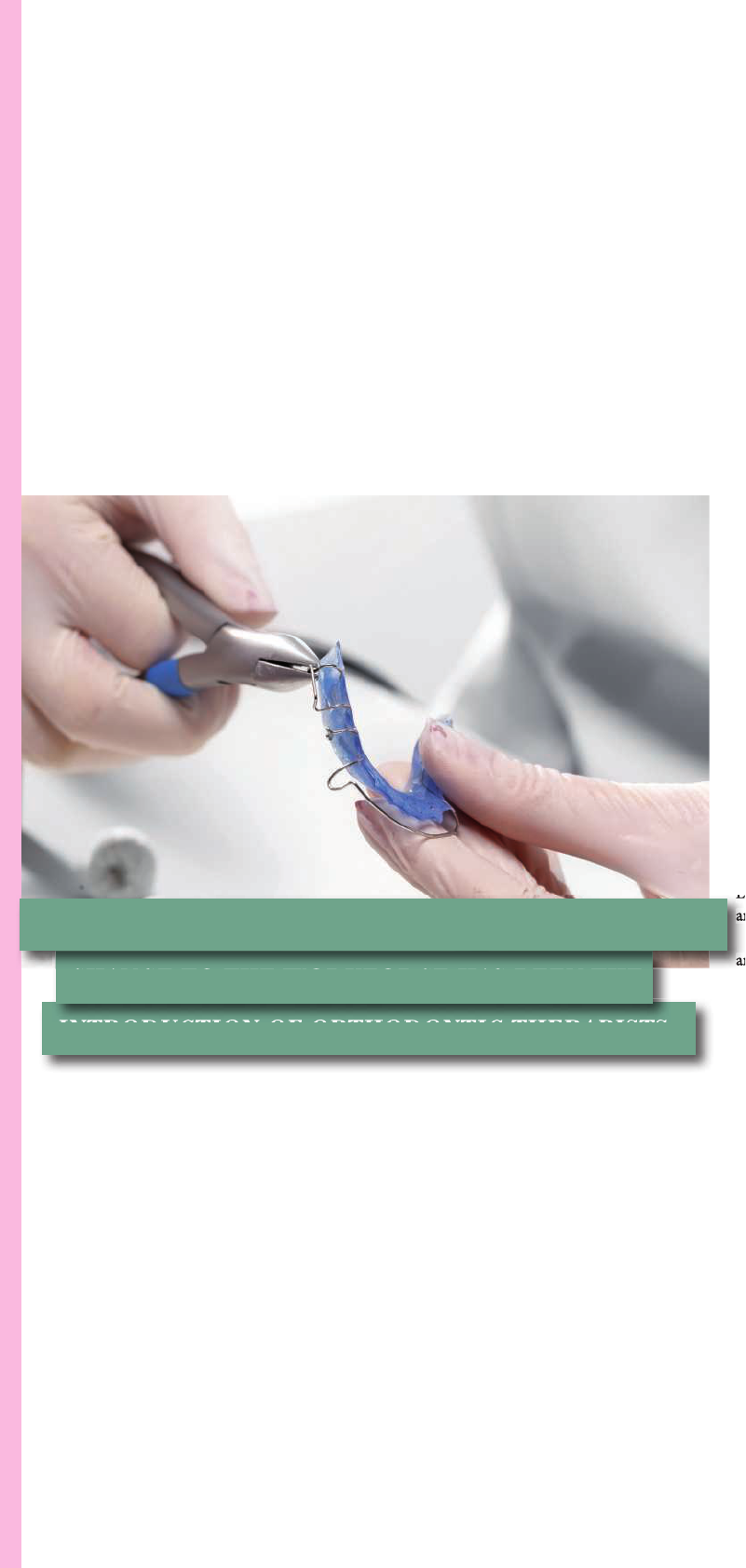

Working under appropriate supervision

12

and following a prescription, orthodontic

therapists are permitted to undertake

numerous reversible orthodontic procedures.

In reality this includes most orthodontic

procedures, such as bonding brackets,

changing archwires, tting functional

appliances and retainers and debonding

appliances.

e exact details of the scope of practice

for orthodontic therapists as laid out by the

GDC

7

are shown in Table 1 and the speci c

capabilities of orthodontic therapists can

be found in the GDC Preparing for practice:

Dental team learning outcomes for registration

document.

13

Since the rst orthodontic therapists

quali ed in 2008, 364 of these personnel are

now registered with the GDC (as of May

2014). is has signi cantly increased the

orthodontic workforce and in many areas

has led to an increase in access to a specialist

led orthodontic service. It is expected that

therapists will have had a bene cial e ect in

reducing geographical inequality of specialist

©robertprzybysz/i Stock/Thinkstock

INTRODUCTION OF ORTHODONTIC THERAPISTS.’

INTRODUCTION OF ORTHODONTIC THERAPISTS.’

CHANGE TO THE WORKFORCE HAS BEEN THE

Edinburgh, King’s, Manchester, Preston

and Warwick).

and following a prescription, orthodontic

CHANGE TO THE WORKFORCE HAS BEEN THE

‘IN RECENT YEARS, PROBABLY THE MOST SIGNIFICANT

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 06

care, although this has still to be conrmed

in the latest BOS survey expected to be

published in the near future.

ere have been possible concerns raised

about the quality of supervision of this

grade of dental registrant.

14

At the outset

many, including a number of educational

providers, were keen that while DCPs could

work independently from a dentist once they

had a treatment plan, due to the nature of

orthodontics where progress and mechanics

were constantly being re-evaluated, an

appropriate reassessment schedule would be

required every visit. erefore an orthodontic

therapist should never be le unsupervised.

15

Others felt this view was over prescriptive

and perhaps such guidelines would be a

disincentive to employing therapists.

16

As a

result, a working party from all the groups

of the BOS convened leading to a set of

guidelines being published on the supervision

of qualied orthodontic therapists by both

the BOS and the Orthodontic National

Group (ONG).

12

Orthodontic technicians

Orthodontic technicians are registered dental

professionals who construct custom-made

orthodontic appliances to a prescription from

a dentist or orthodontist. If they are trained,

competent and indemnied they can:

■

Review cases that come in to the

laboratory to decide how they

should progress

■

Work with the dentist/orthodontist on

treatment planning and appliance design

■

Modify orthodontic appliances according

to a prescription

7

■

Give appropriate patient advice and

carry out shade taking. is may be

especially useful mid-treatment when

constructing temporary pontics to replace

missing units.

17

With additional training, working alongside

an orthodontist, technicians may also

assist in the treatment of patients by taking

impressions, recording facebows and occlusal

registrations, tracing cephalograms and taking

photographs. e skill of an orthodontic

technician in the orthodontic workforce

is probably nowhere more central than in

delivering an orthognathic service where

accuracy, skill and good communication are

crucial for success in treatment outcomes.

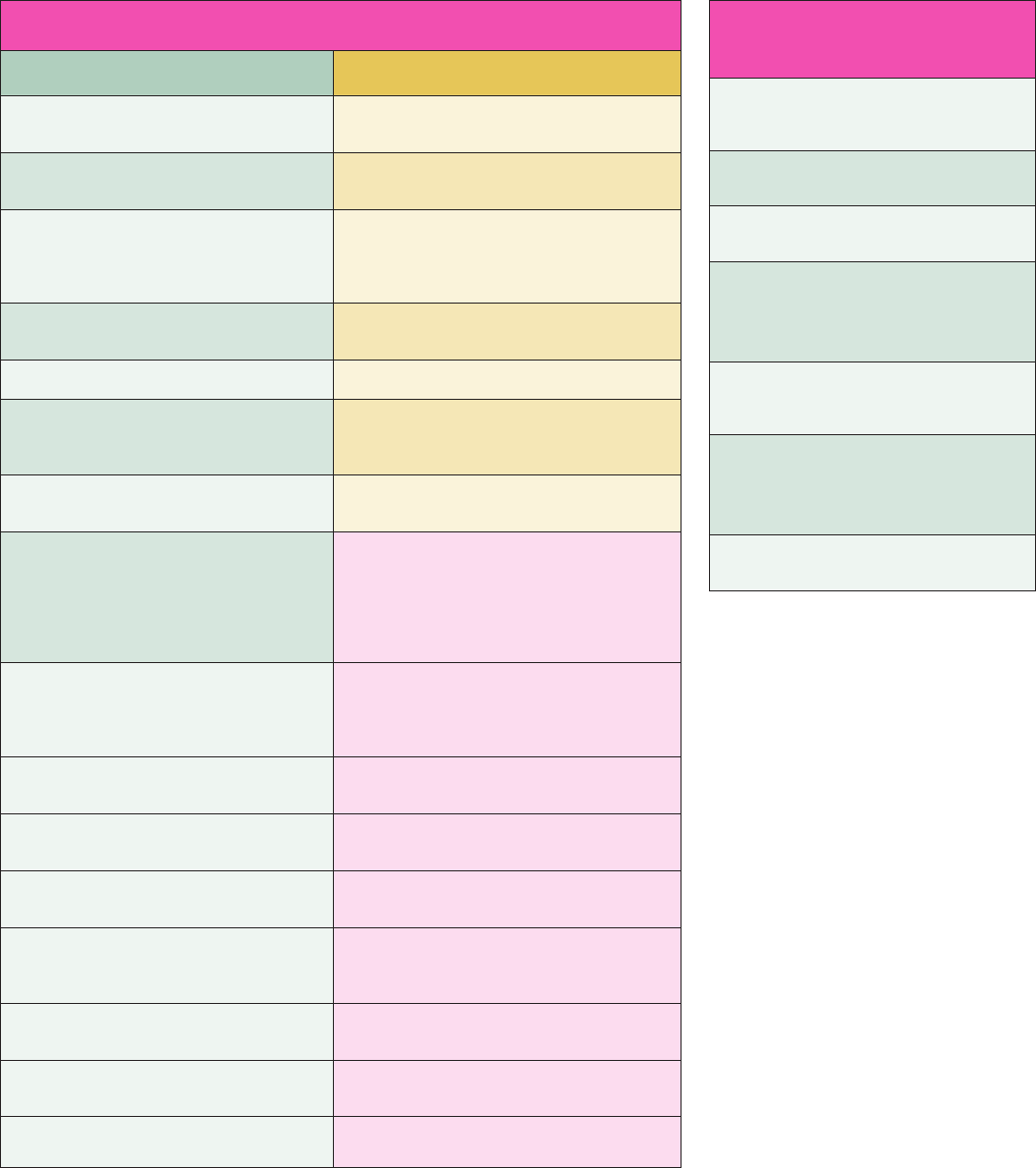

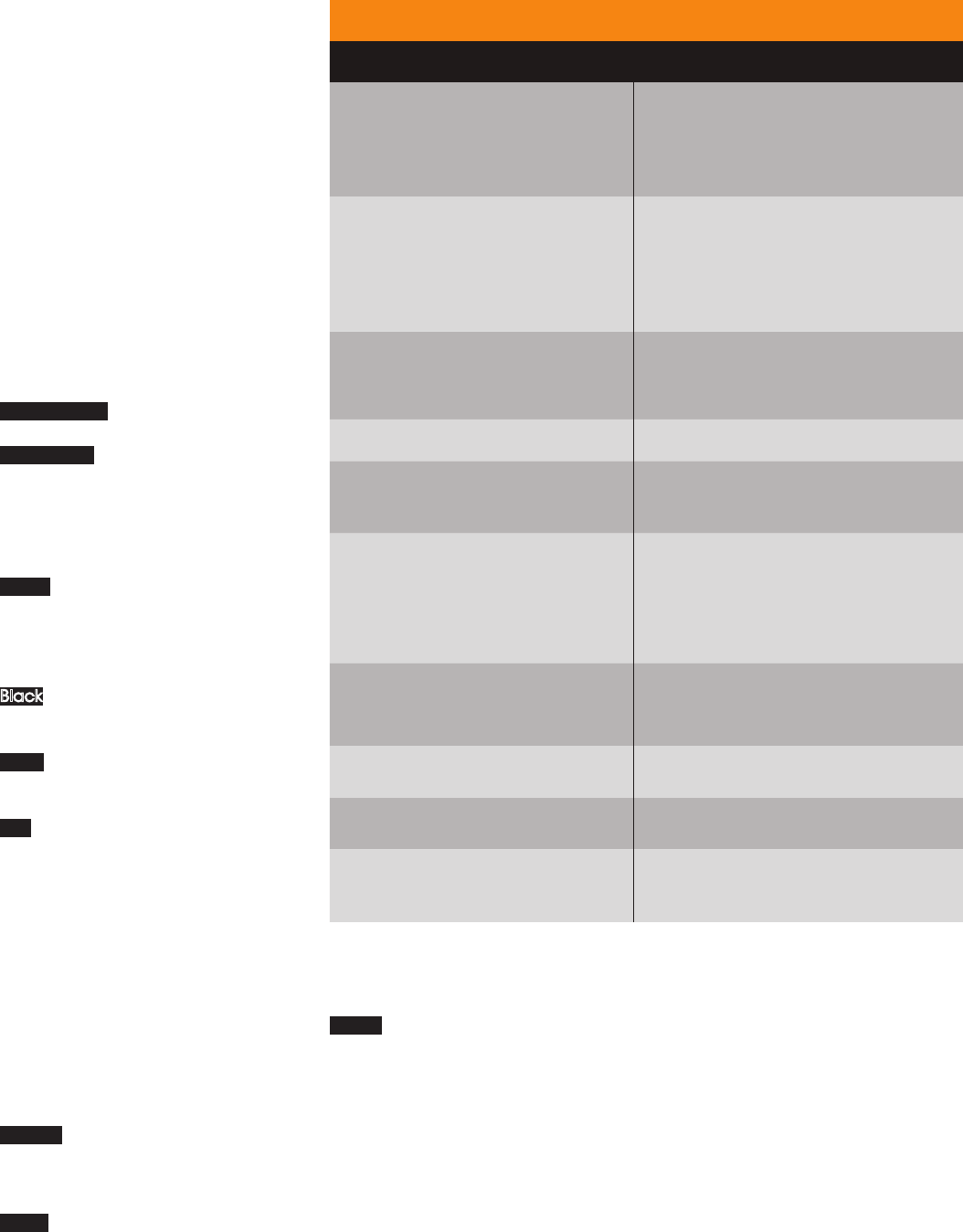

Table 1 Scope of practice of the orthodontic therapist

Orthodontic therapists can: Orthodontic therapists cannot:

Clean and prepare tooth surfaces ready for

orthodontic treatment

Remove sub-gingival deposits

Identify, select, use and maintain appropriate

instruments

Give local analgesia

Insert passive removable orthodontic

Appliances

Insert removable appliances activated or

adjusted by a dentist

Re-cement crowns

Remove fixed appliances, orthodontic adhe-

sives and cement

Place temporary dressings

Identify, select, prepare and place auxiliaries

Place active medications

Take impressions

Pour, cast and trim study models

They do not carry out laboratory work other

than previously listed as that is reserved to dental

technicians and clinical technicians

Make a patients’s orthodontic appliance safe

in the absence of a dentist

Diagnose disease, treatment plan or activate

orthodontic wires - only dentists can do this

Fit orthodontic headgear

Fit orthodontic facebows which have been

adjusted by a dentist

Take occlusal records including orthognathic

facebow readings

Take intra and extra-oral photographs

Additional skills which orthodontic therapists

could develop during their career include:

Place brackets and bands prepare, insert,

adjust and remove arch wire previously

prescribed or, where necessary, activated by a

dentist

Applying fluoride varnish to the prescription of a

dentist

Give advice on appliance care and oral health

instruction

Repairing the acrylic component part of

orthodontic appliances

Fit tooth separators Measuring and recording plaque indices and

gingival indices

Fit bonded retainers Removing sutures after the wound has been

checked by a dentist

Carry out Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need

(IOTN) screening either under the direction of a

dentist or direct to patients

Make appropriate referrals to other healthcare

professionals

Keep full, accurate and contemporaneous

patient records

Give appropriate patient advice

Table 2 GDC learning outcomes

for dentists–management of the

developing and developed dentition

1.13.1 Identify normal and abnormal

facial growth, physical, mental and dental

development and explain their significance

1.13.2 Undertake orthodontic assessment,

including an indication of treatment need

1.13.3 Identify and explain development or

acquired occlusal abnormalities

1.13.4 Identify and explain the principles

of interceptive treatment, including timely

interception and interceptiv orthodontics, and

refer when and where appropriate

1.13.5 Identify and explain when and how

to refer patients for specialist treatment and

apply practice

1.13.6 Recognise and explain to patients the

range of contemporary orthodontic treatment

options, their impact, outcomes, limitations

and risks

1.13.7 Undertake limited orthodontic

appliance emergency procedures

FEATURE

07 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

General dental practitioners and

dentists with enhanced skills

General dental practitioners (GDPs) perform

a key role in the orthodontic workforce acting

as diagnostic gatekeepers. e GDC Preparing

for practice documentation

13

it lists the

learning outcomes for dentists to be registered

with the GDC (Table 2).

Although orthodontics is a very specic

area of expertise, and only those registered

on the specialist list with the GDC can call

themselves a specialist orthodontist, any

registered dentist can carry out orthodontics

as long as they are competent to do so.

Historically, a signicant proportion of

orthodontic treatment has been carried out

by GDPs in the UK. e 2005 report revealed

that 17% of orthodontic providers had no

orthodontic qualication. e report also

highlighted that in some regions, Shropshire,

Staordshire, Trent, North and East Yorkshire

and Lincolnshire, the majority of orthodontic

provision was carried out by non-specialists.

Since 2006 the speciality has seen the end of

fee-for-item payments and the introduction

of the new individualised contracts. While the

majority of these contracts have been made

with specialist orthodontic practitioners,

contracting has occurred among a group of

existing NHS primary care general dentists.

Initially known as dentists with a special

interest in orthodontics,

18

these clinicians are

now known as dentists with enhanced skills

(DES). While not being eligible for specialist

list registration with the GDC these providers

will have gained additional experience

and training in orthodontics and can be

formally recognised by the commissioners

of orthodontic care (known as area teams

since April 2013). A DES is expected to treat

patients within their competence and refer

complex cases to a specialist orthodontist

or local hospital service as part of a local

clinical network. If this clinical network works

eciently and eectively, the likelihood of

population need being met and high quality

of care being maintained will be increased.

Training of DES oen used to take place on

two-year orthodontic clinical assistantship

schemes but now few, if any, of these remain.

Instead, there has been a recent increase in

longitudinal general professional training

(GPT) schemes for foundation dentists with

placements in orthodontic specialist practice

or in hospital departments.

Recently, GDPs have increased their

presence in the orthodontic workforce by

oering short-term orthodontics to adult

patients wanting an improvement in their

anterior smile aesthetics. While this has

caused debate

19

a move away from anterior

alignment using a handpiece to reshape

teeth together with ceramic restorations has

to be welcomed.

20

It should, however, be

appreciated by those practitioners oering

short-term orthodontics that it provides

a relatively limited range of outcomes and

frequently a specialist referral for correction

of a patient’s wider malocclusion may be

indicated.

Specialist practitioners

Specialist practitioners work in primary care

and are registered as specialists with the

GDC. At the time of the introduction of the

specialist lists in the late nineties a number

of people gained entry to this group via

‘grandfathering’. However, entry should now

only be on receipt of orthodontic training

in other EU member states or in the UK by

securing an orthodontic speciality training

registrar post. Entry to these salaried posts

by UK/EU applicants is competitive with

essential criteria for application including the

possession of a dental degree, registration

with the GDC and completion of a period

of dental foundation/vocational training

or GPT demonstrating experience in a

range of dental specialties. Interestingly, the

GDC are currently completing research,

including patient and public, stakeholders’

and registrants’ views on regulation of

the specialties and are asking these three

questions to gather evidence on the way

forward:

21

■

Does regulation of the specialties bring any

benets (potential and/or actual) in terms

of patient and public protection?

■

Is regulation of the specialties

proportionate to the risks to patients in

relation to more complex treatments?

■

Are the specialist lists the appropriate

mechanism for helping patients to make

more informed choices about care not seen

as falling within the remit of the general

dental practitioner?

Many consider that the reason specialist

lists are useful is because specialist training

and dened standards of practice help to

deliver better treatment and improve clinical

outcomes for patients who receive specialist

dental care. In orthodontics the likelihood

that a treatment will benet a patient is

increased if appliance therapy is planned and

carried out by an experienced orthodontist.

22

Orthodontists also spend less time on

treatment and achieve better quality outcomes

than cases treated by general dentists who

have not undergone a specialisation course in

orthodontics.

23

e training programme leading to

specialisation in orthodontics in the UK

is three years full-time (or part-time pro

rata)

24

and involves undertaking a university

postgraduate degree at the Masters

(MSc, MClinDent, MPhil) or Doctorate

(DClinDent, DDS) level and upon successful

completion of the programme, eligibility

to sit the Membership in Orthodontics

examination of the Royal College of Surgeons.

e training programmes are currently

monitored by the Postgraduate Deaneries

and the Specialist Advisory Committee but

with national developments through Health

Education England these arrangements are

likely to change. e workload undertaken by

specialist orthodontic practitioners reects

the comprehensive learning outcomes of

the specialist training programmes which

include being able to diagnose anomalies of

the developing dentition and facial growth,

carrying out a wide range of simple and

complex treatments both interceptive and

comprehensive in nature including multi-

disciplinary management of a variety of

treatments and understanding psychological

aspects relevant to orthodontics.

Community orthodontists

e community orthodontic service is a

long-established part of NHS provision.

In a changing climate of dental provision

over recent years, providing orthodontic

support for Trust-based ‘Personal Dental

Services’ schemes, under the umbrella of the

salaried primary dental care services, has

become increasingly important. Community

orthodontists are specialist-trained providers

who undertake orthodontic treatment for

a range of special care patients who have

limited access to other, appropriate specialist

treatment.

e majority of such patients who are

able to receive orthodontic treatment oen

require close liaison with other health care

professionals for a holistic approach to

management and not infrequently this service

provides a ‘safety net’ in those areas of the

country not well served by specialist practice

or hospital orthodontic providers.

Orthodontic consultants

Consultant orthodontists are those specialists

that have undergone an additional two years

of full-time training (or part-time pro rata),

in many cases sub-specialising for example,

cle lip and palate work, who collectively

can provide any orthodontic service which

the commissioners might require. In

addition eligibility for application to these

posts is subject to satisfactory completion

of the Intercollegiate Speciality Fellowship

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 08

Examination Exam in Orthodontics, FDS

(Orth), although foundation trusts are in a

position to write their own requirements for

appointment to a consultant post. While this

role can be varied, clinical activity is focused

upon the following:

■

Working in conjunction with consultant

oral and maxillofacial surgeons, plastic

surgeons or paediatric surgeons to correct

severe skeletal problems by means of

combined orthodontic and surgical

treatment approaches

■

Liaise with other key specialties to

provide coordinated care for patients

with cle lip and palate, and other

congenital dentofacial anomalies. ere

is also increasing collaboration with ENT

consultants and respiratory medicine to

manage patients with obstructive sleep

apnoea

■

Provide clinical training for undergraduate

dental students, career junior sta , future

specialists and trainee academics and

participate in continuing professional

programmes for all trained providers of

orthodontic care

■

Undertake personal research, innovation

and service evaluation including audit

■

Working with colleagues in primary

care and dental public health as part

of a professional network to manage

orthodontic services locally.

In summary, the role of the consultant

orthodontist is varied but centres on clinical

consultation, the treatment of severe and

multidisciplinary cases, service coordination,

training and research.

DISCUSSION

is article highlights the many varied

personnel involved in the delivery of

orthodontic treatment in the UK and

illustrates how the workforce has evolved in

recent years. From the extension of the role

of the orthodontic nurse, the introduction of

the orthodontic therapist into the team, the

mandatory registration of all DCPs and the

increase in uptake of short-term orthodontic

treatments being o ered in general dental

practice, much has changed over the past

decade.

While we may be clearer now as to who

does what in the orthodontic workforce,

perhaps the next workforce issue that will

arise as a result of these changes is how many

of these varied personnel will be needed to

deliver care and their appropriate training.

e Centre for Workforce Intelligence

published a strategic review in 2013 analysing

the future ‘supply and demand’ of the dental

workforce in England between 2012 and

2040

25

which revealed that there is likely to

be a surplus supply of dentists by as many

as 4,000 by 2040. e mechanisms for the

derivation of these gures is far from clear

and likely to be as hopeless as the information

which led to expansion of undergraduate

numbers in 2006. It is hoped that the report of

the current Workforce Survey Task and Finish

Group of the BOS will form the backbone of

negotiations with the Centre for Workforce

Intelligence, Health Education England

and the Department of Health and will be

instrumental in shaping the future training

of the workforce and delivery of orthodontic

services in England and Wales.

CONCLUSION

ere has been considerable change in the

composition of the orthodontic workforce

over the last decade. It is hoped that the

extension of roles performed by the various

members of the orthodontic team will lead to

increased accessibility of specialist care.

e impact of the change in composition

of the orthodontic workforce, in particular

the addition of orthodontic therapists, must

be taken into account when planning future

manpower needs.

1. Stephens C D, Orton H S, Usiskin L A. Future

manpower requirements for orthodontics

undertaken in the General Dental Service. Br J

Orthod 1985; 12: 168–175.

2. Lumsden K W, Brown D V, Edler R J et al. Task

group for orthodontics. Report. Br J Orthod 1998;

23: 222–240.

3. Robinson P G, Willmot D R, Parkin N A, Hall A C.

Report of the orthodontic workforce survey of the

United Kingdom. She eld: University of She eld,

2005. Online information available at: http://www.

bos.org.uk/Resources/British%20Orthodontic%20

Society/Migrated%20Resources/Documents/

Workforce_survey.pdf (accessed December 2014).

4. O’Brien K, Corkill C. Regional Variations in the

provision of orthodontic treatment by the hospital

services in England and Wales. Br J Orthod 1990;

17: 187–195.

5. Stephens C D, Keith O, Witt P et al. Orthodontic

auxiliaries – a pilot project. Br Dent J 1998; 185:

181–187.

6. Seeholzer H, Adamidis J P, Eaton K A, McDonald

J P, Sieminska-Piekarczyk B. A survey of the

delegation of orthodontic tasks and the training of

chairside support sta in 22 European countries. J

Orthod 2000; 27: 279–282.

7. General Dental Council. Scope of practice. 2013.

Online information available at: http://www.

gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/Publications/

©robertprzybysz/i Stock/Thinkstock

WHEN PLANNING FUTURE NEEDS.’

WHEN PLANNING FUTURE NEEDS.’

OF THE WORKFORCE MUST BE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT

OF THE WORKFORCE MUST BE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT

‘THE IMPACT OF THE CHANGE IN COMPOSITION

FEATURE

09 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

Publications/Scope%20of%20Practice%20

September%202013.pdf (accessed December 2014).

8. National Examining Board for Dental

Nurses. National certi cate examination.

2008. http://www.nebdn.org/documents/

NationalCerti cateProspectus_000.pdf (accessed

December 2014).

9. National Examining Board for Dental Nurses.

Certi cate in oral health education. 2011. http://

www.nebdn.org/documents/OHEProspectus_000.

pdf (accessed December 2014).

10. National Examining Board for Dental Nurses.

Certi cate in dental radiography. 2011. http://www.

nebdn.org/documents/DRPProspectus_001.pdf

(accessed December 2014).

11. Bain S, Lee W, Day C J, Ireland A J, Sandy J R.

Orthodontic therapists – the rst Bristol cohort. Br

Dent J 2009; 207: 227–230.

12. British Orthodontic Society and Orthodontic

National Group. Guidelines on supervision of

quali ed orthodontic therapists. 2012. Online

information available at: http://www.bos.org.

uk/Resources/British%20Orthodontic%20

Society/Author%20Content/Documents/

PDF/Supervision%20of%20orthodontic%20

therapistsBoard%201212.pdf (accessed December

2014).

13. General Dental Council. Preparing for practice.

2011. Online information available at http://www.

gdc-uk.org/newsandpublications/publications/

publications/gdc%20learning%20outcomes.pdf

(accessed December 2014).

14. Hodge T. Orthodontic therapists: a challenge for

the 21st Century. J Orthod 2010; 37: 297–301.

15. Littlewood S, Hodge T, Knox J et al. Supervision of

orthodontic therapists in the UK. J Orthod 2010;

37: 317–318.

16. Day C, Hodge T. Supervision of orthodontic

therapists:

what is all of the confusion about?

Fac Dent J 2011; 2: 192–195.

17. Hodge T M. Clinical pearl:

in-treatment replacement of

missing incisors. J Orthod 2005;

32: 182–184.

18. Department of Health/Faculty of

General Dental Practice (UK).

Guidance for the appointment of dentists with

special interests (DwSIs) in orthodontics. 2006.

Online information available at: http://www.bos.

org.uk/Resources/BOS/Documents/Careers%20

and%20GDP%20documents/dh_4133859.pdf

(accessed December 2014).

19. Maini A, Chate R A C. Short-term orthodontics. Br

Dent J 2014; 216: 386–389.

20. Kelleher M. Porcelain pornography. Faculty Dent J

2011; 2: 134–141.

21. General Dental Council. Reviewing regulation of

the specialties. 2014. Online information available

at http://www.gdc-uk.org/Aboutus/ ecouncil/

Council%20Meeting%20Documents%20

2014/5%20Reviewing%20Regulation%20of%20

the%20Specialties.pdf (accessed December 2014).

22. O’Brien K D, Shaw W C, Roberts C T. e use

of occlusal indices in assessing the provision of

orthodontic treatment by the hospital orthodontic

service of England and Wales. Br J Orthod 1993;

20: 25–35.

23. Marques L S, Freitas Junior Nd, Pereira L J, Ramos-

Jorge M L. Quality of orthodontic treatment

performed by orthodontist and general dentists.

Angle Orthod 2012; 82: 102–106.

24. Joint Committee for Postgraduate Training in

Dentistry Specialty Advisory Committee in

Orthodontics. Guidelines for the UK threeyear

training programmes in orthodontics for specialty

registrars. 2012. Online information available

at: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/jcptd/

higher-specialist-training/documents/

guidelinesfor-the-uk-three-year-training-

programmes-inorthodontics-for-

specialty-registrars-july-2012 (accessed

December 2014).

25. Centre for Workforce Intelligence.

A strategic review of the future dentistry

workforce: informing dental student

intakes. 2013. Online information

available at: http://www.cfwi.org.

uk/publications/a-strategicreview-

of-the-future-dentistry-workforce-

informingdental-student-intakes

(accessed December 2014).

is article was originally

published in the British

Dental Journal as

‘Who does what’ in the

orthodontic workforce

on 16 February 2015 (218:

191-195).

PROFILE - ORTHODONTIC

NURSE

Ruth Mackenzie, 34, is a dental

nurse at Giff nock Orthodontic

Centre in Glasgow. Ruth worked

at a specialist orthodontic

practice from 2002-2006, at

a private general dental practice from

2006-2010, and has been at her current

workplace since 2010. As well as her dental

nurse qualifi cation, Ruth has a certifi cate

in dental radiography, and enjoys

snowboarding, running and travelling.

What first attracted you

to dentistry?

I have always been interested in how

braces can make people’s teeth move. I

had upper and lower xed appliances

myself in the past. I was attracted to

working in orthodontics a er noticing

how much more people would smile

a er having braces tted. My interest

in orthodontics began when I read a

magazine article about clear braces.

I rst started working in an

orthodontic dental practice in 2002.

e general practice that I worked in

later on was far quieter. e sta at the

orthodontic practice were more involved

in the treatment of patients, which I

found very appealing.

We treat a broad mixture of child and

adult patients. It is very satisfying when

patients complete their orthodontic

treatment and are happy with the

outcome - especially with the patients

that were very self-conscious with their

smile before treatment.

Have you undertaken a Certificate

in Orthodontic Nursing?

No but it is something I am interested

in doing and feel I would bene t

from greatly.

Would you recommend working in

an orthodontic practice to other

dental nurses?

Yes, there are many opportunities within

orthodontics and it is very satisfying

to see patients happy with their smile

a er treatment.

Do you have any career plans you

would like to share with us?

I would like to volunteer in a work

placement in a third world country.

©macroart/iStock/Thinkstock

PROFILE - ORTHODONTIC

NURSE

Ruth Mackenzie

nurse at Giff nock Orthodontic

Centre in Glasgow. Ruth worked

at a specialist orthodontic

practice from 2002-2006, at

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 10

PROFILE - ORTHODONTIC THERAPIST

Fiona Carter, 53, is an orthodontic

therapist at Colchester Orthodontic Centre.

Fiona qualifi ed as a dental nurse in

1981 and completed a Certifi cate in Oral

Health Education in 1993, a Certifi cate in

Orthodontic Nursing in 2008, a Diploma in

Orthodontic erapy in 2009, and was PAR

calibrated in 2014 (Peer Assessment Rating

index). Ruth is a member of the Orthodontic

National Group (ONG) and enjoys running,

cycling, yoga and vintage shopping!

What first attracted you to dentistry?

Nursing was my chosen career but when

I le school I was too young to begin the

SRN (state registered nurse) training. I

saw an advertisement for an orthodontic

dental nurse so applied, not realising what it

entailed, and was successful. at was way

back in 1978 and by chance I had found a

profession I really enjoyed.

In 1978 there was no recognised

quali cation for orthodontic nursing so my

orthodontist enrolled me on a local NEBDN

course. I gained experience in general dental

nursing by spending half a day a week

working in various local general dental

practices to successfully gain the National

Certi cate. is con rmed that orthodontics

was the branch of dentistry that I wanted to

continue in.

Fixed appliances were still being made

with stainless steel tape so welding and

soldering attachments was part of the

orthodontic nurse role as was acrylic and

wire repairs to removable appliances,

preforming arch wires and making EOT face

bows which involved learning how to bend

wires, a great skill to have as an orthodontic

therapist (OT). is was together with all

the other duties of running a busy specialist

orthodontic practice.

Following a short break a er the birth

of my two sons I returned to work on a

part time basis in a multi-disciplinary

dental practice working for an orthodontic

specialist. Gaining my Certi cate in Oral

Health Education in 1993 was a great

advantage having a varied patient base and

the help and guidance of GDPs.

As my children got older and more

independent I had the opportunity to work

with the orthodontist I began my career

with in 1978 within the local Primary

Care Trust, treating a variety of complex

orthodontic cases and also dental nursing

in a special care dental department. ere

was a speci c managerial element to

this position as it involved setting up an

orthodontic practice within the community

dental department, sta recruitment,

department management and carrying out

audit, producing the department COSHH

manual, Dental Nurse Policy and Protocol,

following Trust guidelines and liaising with

multidisciplinary departments.

When did you decide to become an

orthodontic therapist?

OTs were being discussed as early as

1978 when I started my career. When the

orthodontic therapy course was introduced

in 2007 I knew that this was what I wanted

to do and that this may be my opportunity!

I applied for an orthodontic nurse position

and I was lucky in nding an orthodontic

specialist who had the con dence in me to

support my application and training and

was prepared to be my training provider.

I studied for the RCS Eng Diploma in

Orthodontic erapy at South Wales

Orthodontic erapy course, based at

Cardi Dental School. It was hard work

but also very exciting with excellent

course tutors.

Was it difficult to get a place?

I considered myself fortunate to be selected

for interview and I was so pleased to

be successful at my rst interview. My

employer/orthodontist also had to be

interviewed as a ‘training provider’.

Was it straightforward finding

employment as an orthodontic

therapist?

Yes because you are trained by the

orthodontic specialist that you work with.

S/he is your ‘trainer’ and a er such a big

investment in time, energy and emotion (not

forgetting nancial investment), successful

OTs tend to stay with their trainers/training

providers.

e transition

from orthodontic

nurse to orthodontic

therapist was very

exciting; however,

it was a change for

the whole practice.

Having a very supportive team made

it easier. Patients had to adjust too but

they were all very understanding and

encouraging. I am con dent working within

my clinical capabilities and I am aware of

my limitations. CPD is an essential and

important part of keeping up to date.

I treat a mixture of both adults and

children but a higher percentage of children.

I work within the limits of the OT GDC

scope of practice and following BOS

guidelines.

At Colchester Orthodontic Centre we

are a small but very happy team of ten:

Gareth Davies, the orthodontic specialist

practitioner; two orthodontic therapists;

four orthodontic nurses; a practice manager;

and two administrative sta .

e most satisfying part of my job is

seeing how delighted the patients are

when treatment is completed and the self-

con dence that this gives them. Not only

because they have a fantastic smile but

because they realise that have they achieved

this through their own hard work. Adult

patients may have missed the opportunity to

undertake orthodontic treatment as a child

and it is rewarding to see the con dence

they gain.

What is the future for OTs?

I think OTs are an asset to an orthodontic

practice and coming from a dental nursing

background OTs are empathetic to the

patient and parents. I think it is an excellent

career path for an orthodontic dental nurse

considering career progression.

bdjteam201531

WHEN TREATMENT IS COMPLETED.’

SEEING HOW DELIGHTED PATIENTS ARE

‘THE MOST SATISFYING PART OF MY JOB IS

Willette Jean Lati is a 26-year-old dental technician

and Clear Aligner Department Assistant Manager

at NimroDental Orthodontic Solutions in London.

FEATURE

Dental destiny

When I was at school, like most people, I was

quite indecisive about what I wanted to do

when I grew up. From a young age till about

secondary school it ranged from wanting to

be a palaeontologist, doctor, vet, chef, scientist

to artist.

I was born in the Philippines but because of

my mum’s work we were relocated to Sydney,

Australia when I was about two-years-old. Aer

ve years, we moved back to the Philippines to

further my education for about six years. We

moved to London in 2002 where I started at

Year 10.

Not doing particularly well during my

A-levels (chemistry, biology, maths and

psychology), I had to look for an alternative

course that catered to my interest in both art

and science. A google search turned me to the

direction of dental technology. So I guess it was

like destiny.

Work experience

To secure a place on a dental technology course

is not very dicult providing you have ve

GCSEs at A*-C (especially in maths, science

and English) and don’t mind getting your hands

dirty. It may be dicult, however, to nd a

dental laboratory to take you on as an apprentice

if you don’t have any prior experience. Work

experience before you start studying is also

recommended as it will give you a better idea of

what sort of business you’re getting yourself into.

I started work experience at NimroDental

in 2007 whilst I was studying my BTEC course

in Dental Technology and have been there

ever since.

I completed a Foundation degree in Dental

Technology in 2009. Both my BTEC and

Foundation Degree courses tried to condense

the principles and practical techniques of all

departments of dental technology (prosthetics,

orthodontics and prosthodontics) in a span of

three years. But I would say that courses focus

more on denture or crown and bridge work.

My class was attended by a majority of girls of

a wide range of dierent ages and backgrounds;

there with only two boys among us. But I

found that other groups or batches were quite

male dominated.

I enjoyed the practical aspect of my

foundation course more than the academic as

I am more of a hands-on sort of learner. It was

interesting to learn and make dierent sorts of

appliances used in dentistry that many would

take for granted. I enjoy being able to build,

recreate, add detail and nish things with my

hands using dierent mediums.

e academic side of my course was a bit

challenging, and also learning to make new

appliances - but practice and persistence does

help to improve and perfect new skills.

In the lab

At NimroDental I make a fair range of

appliances in the lab such as retainers, clear

aligners, removable appliances and Inman

aligners. I have worked my way up from plaster

room technician to assistant manager.

I am currently based on the famous Harley

Street although I wasn’t initially aware of its

reputation until I started working in the lab.

Previously we were located just o Paddington

Street; I used to personally do collections and

drop-os of impressions and appliances in the

Harley Street area and got to meet or see some of

London’s well known dentists and orthodontists.

It was fascinating to learn that a small area has

such a huge reputation of quality of care and

services both from the medical and dental eld.

It was also nice to bump into the odd celebrity

every now and then.

I am currently Assistant Manager of our

Clear Aligner Department headed by Agnieszka

Horton, specialising in the new digital clear

aligner movement system and 3D printed

models. I also attend dental tradeshows to

raise our company’s prole in the dental and

orthodontic industry.

I support my colleague Sophie Cook

11 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

‘ There is a family

atmosphere in our lab’

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 12

(@Nimrodental_SC on Twitter), who is Head

of Marketing, with our social media accounts.

I would like to make special mention of our

mentor Jowita Penkala of Uniqabrand for

teaching us the power of social media marketing

through Twitter and Facebook since November

2014. I have never used Twitter for personal use

but found that it is an amazing tool to connect

to all types of people in the dental industry.

As a lab it is rare for us to be involved with or

to interact with the general public, but we do

try to maintain good relationships with our

clients such as dentists, cosmetic dentists and

orthodontists across the UK and in Europe.

A family atmosphere

Having been at NimroDental for more than

seven years, there is an almost family-like

atmosphere. We are a continuously growing lab

with currently over 30 individuals including the

o ce team.

As a company we enjoy each other’s company

even a er work hours. We organise monthly

work drinks at nearby local pubs or bars.

A few of us have even been travelling around

Europe together.

Regarding my future career ambitions, this

may sound cheesy but they are to be the best at

what I do and to continue to improve and learn

every day, whether it is dental-related or not.

I subscribe to a yearly magazine to regularly

update my CPD hours and try to attend lectures

or nd free CPD websites online to keep my

skills up to date.

I usually nish work around 5 pm but stay

a little longer on busier days. To relax or let o

steam a er work I sometimes go to the gym to

swim or train, do a bit of hot yoga or even just

spend a couple of minutes in the sauna.

To be honest, I haven’t got a clue what I

would have done if I hadn’t become a dental

technician! Wherever the wind had taken me I

suppose. I don’t have a set path and just take any

opportunities that come my way.

If you are good with your hands and have

an interest in science, then I would de nitely

recommend a career in dental technology

to others.

TECHNOLOGY. SO I GUESS IT WAS LIKE DESTINY.’

TECHNOLOGY. SO I GUESS IT WAS LIKE DESTINY.’

TURNED ME TO THE DIRECTION OF DENTAL

TURNED ME TO THE DIRECTION OF DENTAL

ART AND SCIENCE. A GOOGLE SEARCH

ART AND SCIENCE. A GOOGLE SEARCH

THAT CATERED TO MY INTEREST IN BOTH

THAT CATERED TO MY INTEREST IN BOTH

‘...I HAD TO LOOK FOR AN ALTERNATIVE COURSE

What three things can Willette not

live without?

1. My iPhone to connect with people

2. The Internet to connect with

the world

3. Sour candies/sweets because

I have a bit of a sweet (sour) tooth

which is a naughty thing in

my profession!

bdjteam201532

FEATURE

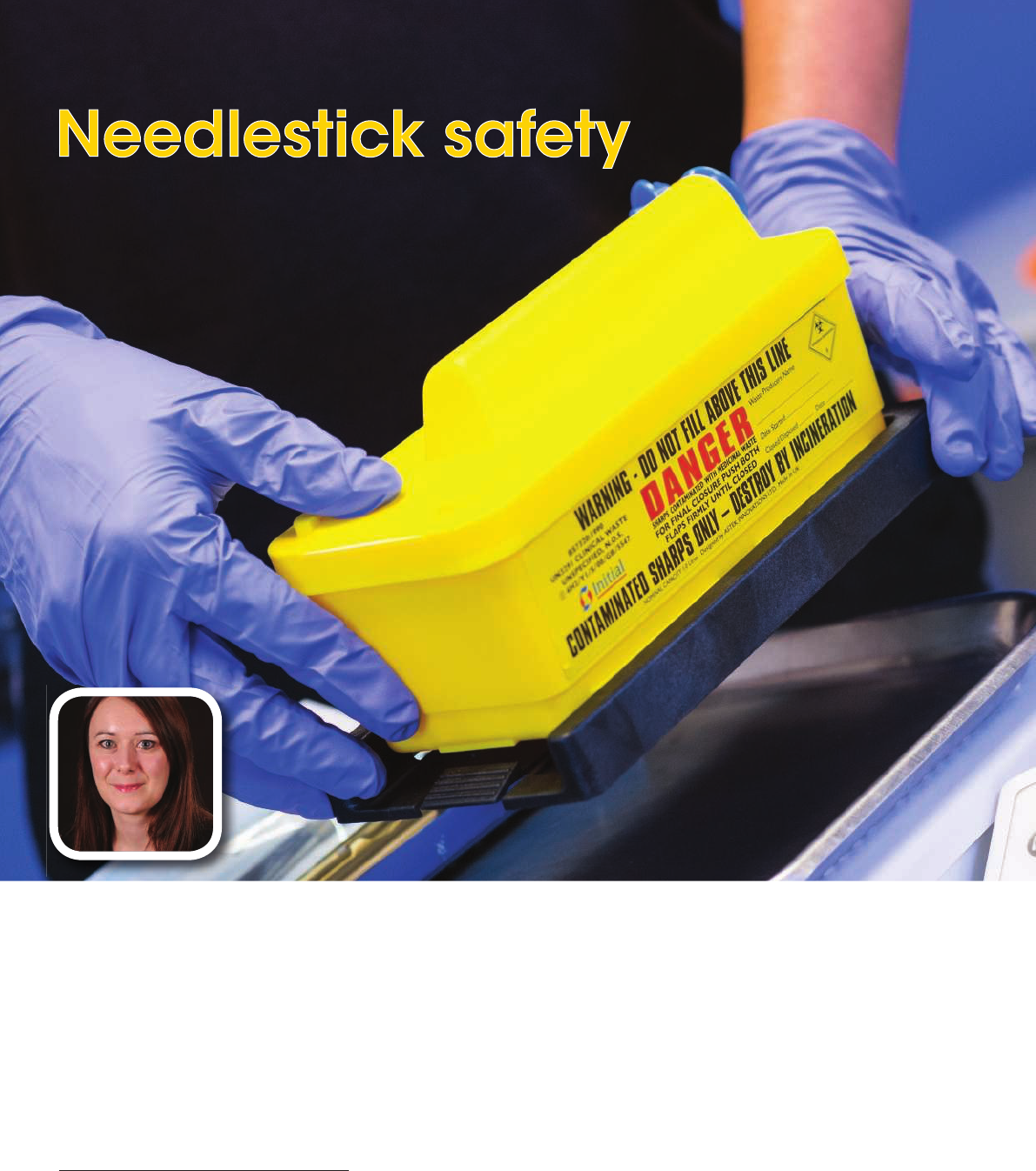

Consider the risk

As part of the dental team, needlestick safety

is something you should be acutely aware of in

your day-to-day role. A survey of 1,216 dental

nurses from the UK and Ireland conducted

in conjunction with the British Association

of Dental Nurses (BADN) in 2014 found that

51.2% of respondents had received a needlestick

injury at some point throughout their career,

with 60% of those saying they’d received more

than one. When you then consider the risk

of infection following a needlestick injury is

estimated to be one in three for Hepatitis B virus

(HBV), one in 30 for Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

and one in 300 for HIV (for healthcare workers

worldwide), it is vital that safety procedures are

put in place in all dental surgeries.

The use of sharps

Following the introduction of e Health &

Safety (Sharps Instruments in Healthcare)

Regulations 2013, all healthcare facilities must

ensure that:

(a) e use of medical sharps at work is avoided

so far as is reasonably practicable

(b) When medical sharps are used at work,

safer sharps are used so far as is reasonably

practicable

(c) Needles that are medical sharps are not

capped a er use at work unless:

i. that act is required to control a risk

identi ed by an assessment undertaken

pursuant to regulation 3 of the

Management of Health and Safety at

Work Regulations 1999 (a)

ii. the risk of injury to employees is

e ectively controlled by the use of

a suitable appliance, tool or other

equipment

(d) In relation to the safe disposal of medical

sharps that are not designed for re-use:

i. there should be written instructions for

employees

ii. clearly marked and secure containers

should be located close to areas where

medical sharps are used at work.

Health and safety law has always placed

general responsibilities on the employer to

provide their sta with a healthy working

environment. However, this legislation now puts

further emphasis on prevention. In reality it

would be di cult, if not impossible, to remove

all sharps from a dental practice, so the next best

thing is to assess the risk correctly, use devices

By Rebecca Allen

1

©Creatas/Thinkstock

1

Rebecca is Category Manager at Initial

Medical (http://www.initial.co.uk/

healthcare-waste/). She has worked

in the healthcare sector for the past

13 years and was a Research Chemist

with Bayer Cropscience prior to joining

Rentokil Initial in 2003. She keeps up to

date on all developments within the

clinical waste management industry

and is an active member of the CIWM,

SMDSA and BDIA.

for the whole

dental team

13 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 14

which limit the risk of injury and dispose of all

sharps in a safe manner.

Top tips for needlestick safety are shown in

Table 1.

Cradle-to-grave rule

It’s important to remember that when it comes

to hazardous and infectious waste such as

syringes and other sharps at a dental practice,

the cradle-to-grave rule applies. e producer

of waste will always be held responsible for the

safe and legal disposal of it, even a er it has been

passed onto the waste carrier collecting it. is is

why it’s important to work with comprehensively

trained sharps waste disposal experts who will

advise on the correct products that comply with

both the UK and EU legislation and safely and

securely dispose of sharps. Health and safety

law is criminal law and healthcare organisations

can be subject to enforcement action if they fail

to comply with the legal requirements. ere

is also always a threat of civil law action if an

employee is injured due to insu cient practices

and technologies being in place.

Staff wellbeing

Everyone has a role to play in the prevention

of sharps injuries, from trainee sta who are

learning the ropes, to practice owners who will

hold legal overall responsibility for the wellbeing

of their sta .

Another quick and simple way to reduce the

risk of needlestick injuries is to use innovative

solutions such as InSafe syringes – a safety

system providing comprehensive protection

for clinical sta from the beginning of the

procedure through to the disposal of the needle.

InSafe’s syringe and sharps box ensure that the

contaminated needle is never exposed except

during the actual injection. It feels and aspirates

just like a traditional syringe so there will be

no interruptions to the dental practice when

introducing the protective system. When the

injection has been administered, the protective

sleeve locks securely into place over the needle,

protecting clinical sta and patients when not

in use. e needle can then be safely disposed

of using a sharps container. Specially developed

sharps disposal bins are designed for such waste

and comply with all EU and UK regulations

and directives, and there are companies

available that provide a dependable and safe

collection service.

BDJ Team promotion

Initial Medical Waste Experts

Initial Medical is an expert in

healthcare waste management,

providing a complete collection,

disposal and recycling service for

hazardous and non-hazardous waste,

such as offensive waste produced

by businesses and organisations

within the UK. The safe management

of healthcare waste is vital to ensure

your activities are not a risk to human

health. Initial Medical’s healthcare

waste services ensure that all of

your waste is stringently handled in

compliance with legislation and in

accordance with Safe Management

of Healthcare Waste best practice

guidelines, providing you with the

peace of mind that you are adhering

to current legislation.

For further information visit

www.initialmedical.co.uk or call

0800 731 0802.

bdjteam201533

Always dispose of used sharps

directly into an approved sharps

container

It is essential that your sharps

are segregated and disposed of

correctly based on their medical

contamination. The lid colour and

label on the container relates to how

the waste should be treated and

disposed of.

Where possible, place the sharps

container at the point of use

This avoids the need to walk anywhere

with a needle, which creates higher

risk of an injury occurring.

Do not re-sheath needles

When the Health & Safety (Sharps

Instruments in Healthcare) Regulations

2013 came into place, the recapping

of needles was banned, so it is

now against regulations to do so.

The purpose of this is to prevent

needlestick injuries from occurring

when removing the needle. You should

use a safer sharps device to remove

needles from your syringe.

Do not leave sharps lying around

Although this may seem obvious,

sharps injuries are still known to occur

as a result of sharps being left lying

around, when other people are not

aware that they are there, so it is

extremely important that they are

disposed of immediately after use.

Report all sharps

injuries immediately

If a sharps injury does occur, you need

to ensure you follow the below steps:

■

Encourage bleeding from

the wound

■

Dry the wound and cover it with a

waterproof dressing

■

Seek urgent medical advice

■

Report the injury and ensure

all details are reported in your

practice’s accident reporting book.

Table 1 Top tips for needlestick safety

WELLBEING OF THEIR STAFF.’

WELLBEING OF THEIR STAFF.’

LEGAL OVERALL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE

LEGAL OVERALL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE

ROPES, TO PRACTICE OWNERS WHO WILL HOLD

TRAINEE STAFF WHO ARE LEARNING THE

PREVENTION OF SHARPS INJURIES, FROM

PREVENTION OF SHARPS INJURIES, FROM

‘EVERYONE HAS A ROLE TO PLAY IN THE

BE PART OF THE LARGEST EVER

CONFERENCE AND EXHIBITION

IN UK DENTISTRY

www.bda.org/conference or call 0870 166 6625

REGISTER TODAY

GAIN UP TO 15 HOURS

OF VERFIABLE CPD

• Widest variety of clinical sessions

• All CORE CPD covered

• Vibrant and FREE to attend Exhibition

GREAT PRICES FOR DCPS

1 day Conference Pass from £95

3 day Conference Pass from £155

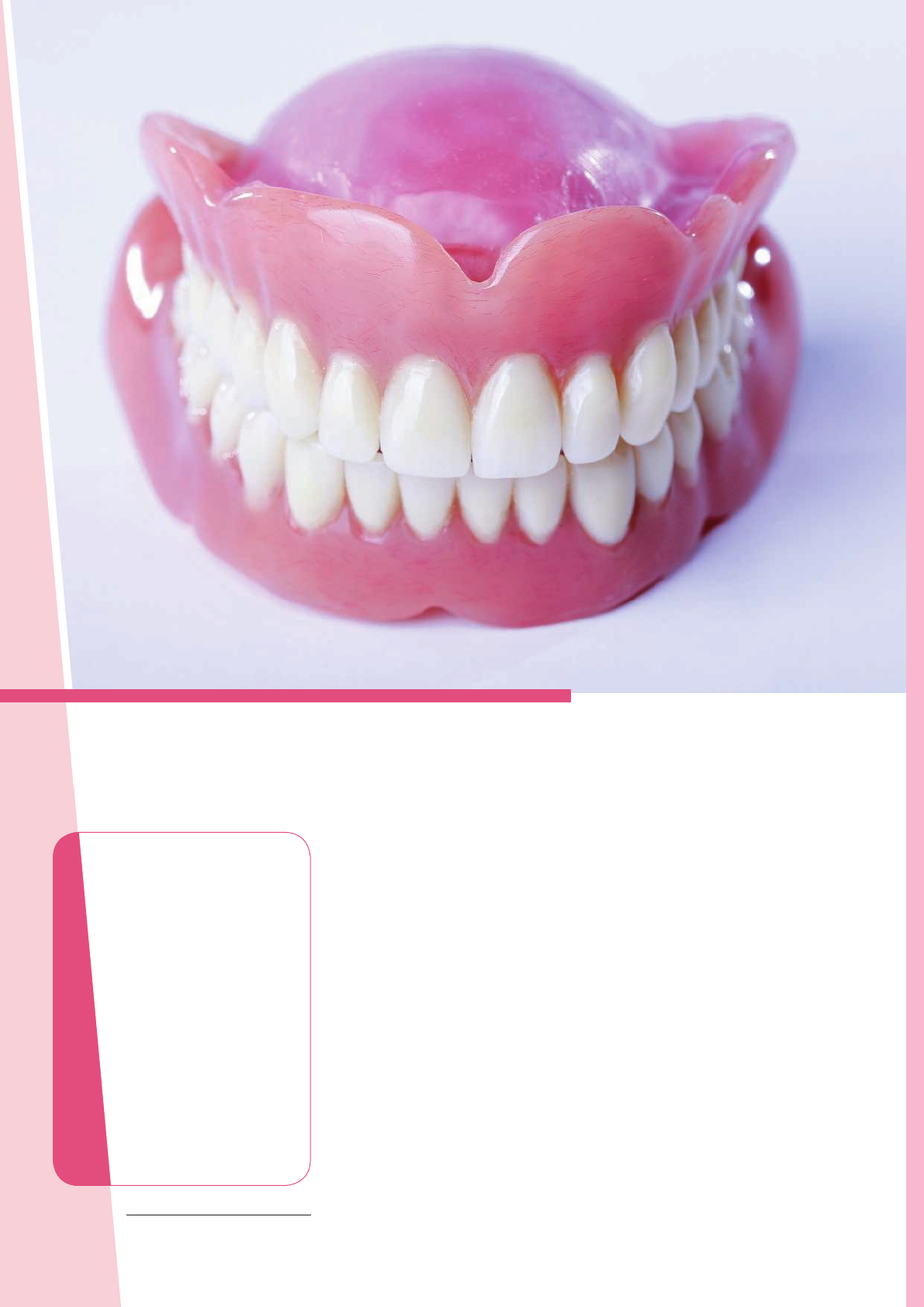

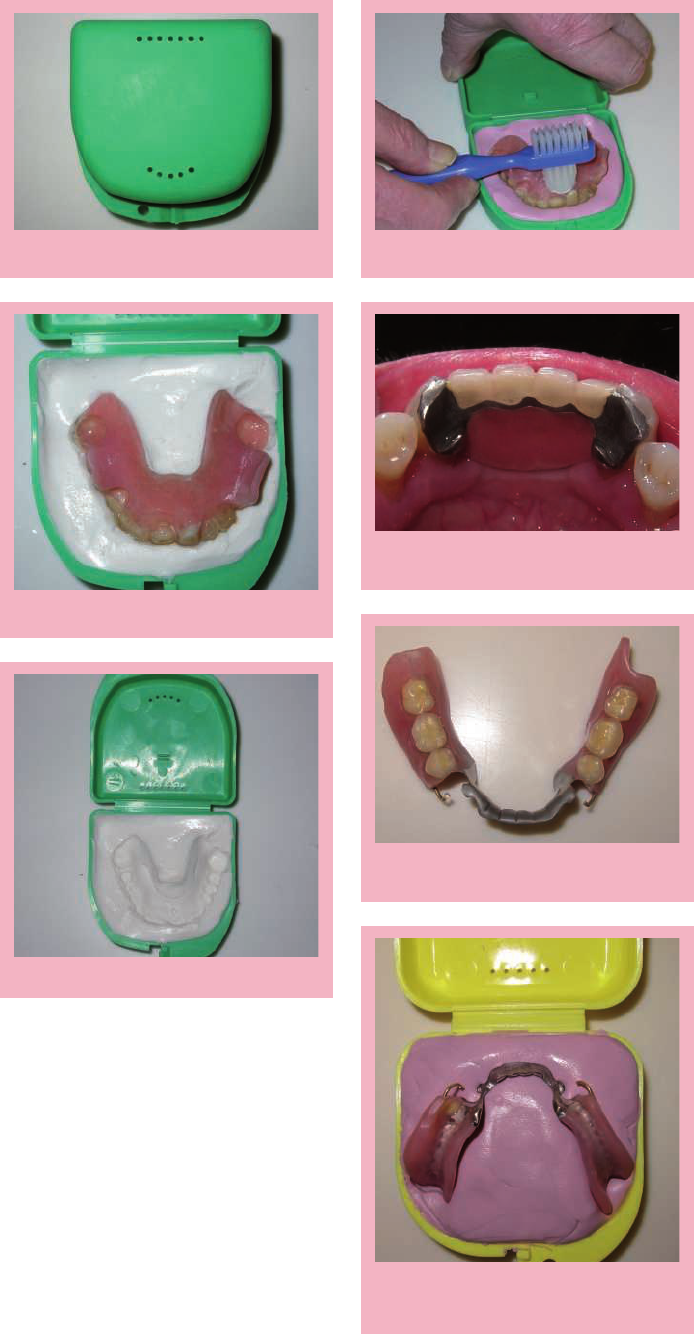

M. J. Faigenblum

1

explains how the denture box facilitates denture

hygiene, reduces the chance of accidental damage and acts as a

means of identification.

1

UCL Eastman Dental Institute

Patients or their carers need

to maintain as low a level of

denture biofilm as possible. This

article notes that the handling

of dentures is unpleasant to

carers and suggests a method

of reducing this contact to a

minimum yet allowing efficient

cleaning by means of brushing.

It also highlights the potential

damage that can occur due

to mishandling or accident.

The denture box acts as a safe

storage unit and its ‘footprint’

allows accurate recovery in an

institution where dentures can

be inadvertently mingled.

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 16

The

denture

box

Edentulous patients

e programme for the 2013 British Dental

Association’s conference contained some

60 lectures, none of which dealt with the

treatment of edentulous patients. is

reects the subject’s relative absence from the

literature and reinforces the perception that

the need for complete dentures is waning.

Nonetheless, as recently as 2009, 6% of the

combined population of England, Wales and

Northern Ireland were edentate and in need

of prostheses.

1

Most of them are ‘elderly’, that

is 75+, and in consequence a proportion are

likely to be in care homes or incapacitated to a

greater or lesser degree.

e York consensus

2

declared that for the

edentulous mandible the minimal standard

of care is the provision of an overdenture

supported by two implants. However, in the

recent update on guidelines for the provision

of such treatment under the NHS,

3

the

authors note ‘…funding for implants on the

NHS is likely to be a precious resource.’ ey

suggest, ‘the decision to provide implants

needs to be balanced against alternative

modes of restoration, their ease of provision,

longevity and outcome rates’.

An alternative mode of restoration is the

provision of optimal dentures, if necessary,

at the hands of an experienced dentist.

is might preclude the need for surgical

intervention and is especially relevant for

patients who are not amenable to surgery.

4

An

added benet is that if correctly designed, the

denture(s) can act as a stent for implants if

they are subsequently required.

A well-made but retentively compromised

complete upper denture can be stabilised

with the judicious use of a dental xative

5

and severe bone resorption of either jaw too

is not necessarily a barrier to a successful

outcome. e eect of a resorbed, mobile

maxillary ridge can be ameliorated by a

careful impression technique.

6

Similarly, in

©Small_World/iStockphoto/Thinkstock

FEATURE

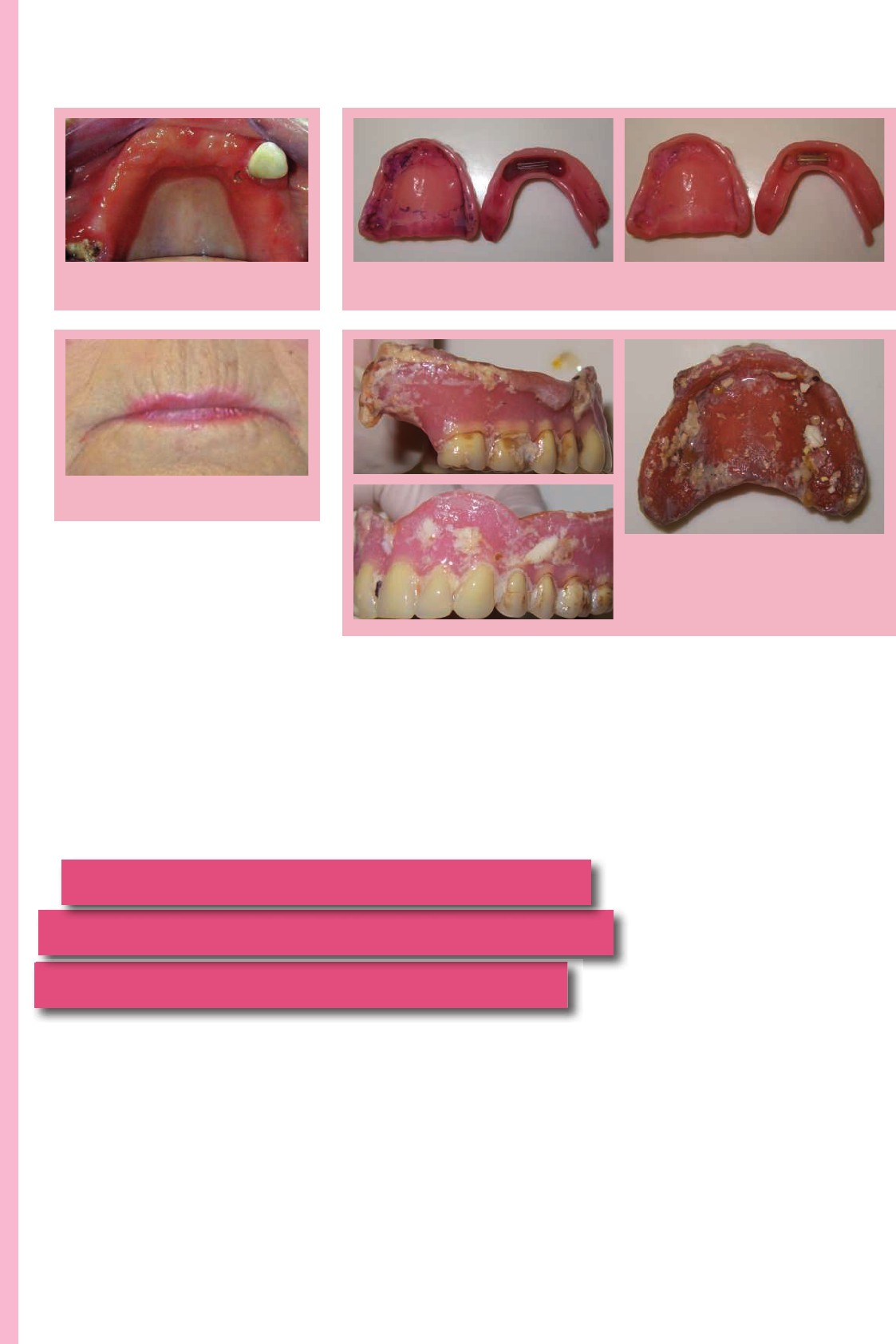

Fig. 2 Angular cheilitis associated with the

stomatitis in Figure 1

Fig. 1 Denture induced stomatitis under an

acrylic partial denture

Fig. 3 Using a plaque disclosing liquid and the result of simple cleaning with a brush and

detergent

Fig. 4 Probable cause for a carer’s

reluctance to handle a denture

FEATURE

17 BDJ Team www.nature.com/BDJTeam

the mandible a skilful technique can provide

a stable denture that can be so -lined if

discomfort cannot be eliminated. e updated

report

3

makes provision under the NHS for

patients who are intolerant to such treatment

and where the implant retained or supported

overdenture

2

would then be treatment of

choice.

e edentate state is most o en the result of

a lack of awareness of the importance of oral

hygiene. It is therefore unlikely that attention

to this will be radically altered when the teeth

are replaced by dentures. Even if this is not

always the case, patients may not be aware of

the potential harm of the denture bio lm.

Denture biofilm

Denture plaque (DP) di ers in its constituents

from the normal dental bio lm.

7

In the

physically healthy individual it can be

aesthetically objectionable with a build-up

of materials found in the mouth that can

produce an unpleasant odour.

8

ey can also

induce mucosal in ammation that is, denture

stomatitis, and a potentially dis guring

angular cheilitis (AC).

9,10

Denture stomatitis (DS) can appear in

di erent forms. Found typically under a

maxillary denture it produces a bright red

imprint of the outline of the denture on

the underlying mucosa (Fig. 1). Due to a

lack of symptoms, its presence is frequently

unnoticed by the patient and by the dental

professional.

Not infrequently, DS is associated with AC

described as a usually bilateral erythematous

ssuring of the corners of the mouth (Fig.

2). e poor appearance that this produces

is exacerbated by deep labial folds that

encourage maceration of the corners of the

mouth with saliva. ese folds are o en

present when the vertical dimension is

signi cantly reduced but is not a cause of the

cheilitis.

11

AC can sometimes be a result of

vitamin and iron de ciency anaemias.

12

Removal of denture plaque is therefore

important. e lm may not be visible but its

presence can be demonstrated to the patient

by the use of a plaque disclosing agent (Fig.

3). e two main denture cleaning methods

of brushing with a non-abrasive paste or

soaking in chemicals have been reviewed.

13

e authors found that there was a lack of

evidence to suggest that one method was

superior to the other. In the author’s opinion

the demonstration of the removal of disclosed

plaque by brushing is preferred to simply

advising chemical soaking. However, without

assistance brushing becomes a problem when

the patient is unable to use one hand, for

example due to injury or a stroke. A possible

solution is suggested below.

e healthy individual can be expected to

respond to oral hygiene advice but this may

not be the case with patients who are seriously

in rm and/or residents in care establishments,

and this can pose a serious problem. It is

now recognised that dental and denture

plaque allow the colonisation of respiratory

pathogens.

14

‘Dentures should be considered

an important reservoir of organisms

which could colonise the pharynx, and the

importance of controlling denture plaque

for the prevention of aspiration pneumonia

cannot be overemphasised.’

15

Where rigorous

oral hygiene procedures have been instituted

a reduction in the rate of pneumonia and

deaths has resulted.

16

Oral care assistance

A Swedish study

17

compared the di erences

in attitude to the maintenance of oral health

PNEUMONIA CANNOT BE OVEREMPHASISED.’

PLAQUE FOR THE PREVENTION OF ASPIRATION

‘THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTROLLING DENTURE

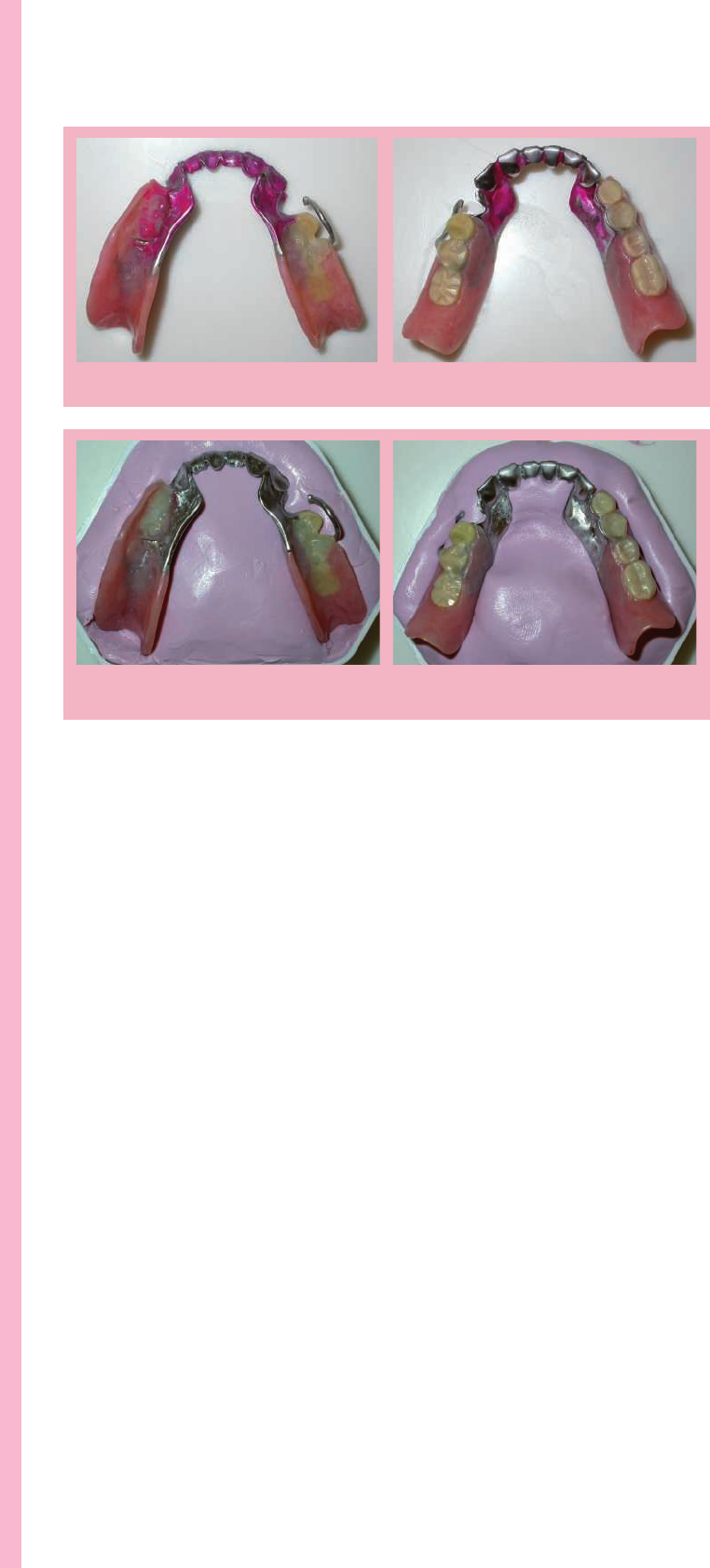

Fig. 6 Denture lightly impressed into the

laboratory putty

Fig. 5 A denture box

Fig. 7 Impression left by the denture

Fig. 9 Resin bonded bridge with

cingulum rests

Fig. 8 The patient is able to steady the box

with his left hand

Fig. 10 Kennedy Class 1 denture with a

cingulum bar major connector

Fig. 11 Kennedy Class 1 denture replaced

into the silicone impression to avoid

accidental damage when cleaning

FEATURE

www.nature.com/BDJTeam BDJ Team 18

in dependant elderly and severely disabled

patients in a group of 398 health workers.

ey were asked regarding a) personal oral

healthcare habits b) experience and attitudes

in assisting oral care and c) willingness to

assist patients/residents with their daily oral

hygiene. is study revealed that oral care

assistance is viewed as more disagreeable than

other nursing activities.

Another study

18

found that nursing sta

considered oral care the most distasteful

aspect of their work (Fig. 4). ey said they

would ‘rather clean up aer bowel movements

or attend to urinary incontinence accidents

than brush a resident’s teeth’.

e denture biolm attached to removable

partial dentures (Fig. 12) will place teeth

at risk, in particular the abutment teeth.

19

Acrylic resin partial dentures, as with

complete dentures, are prone to fracture if

dropped onto a hard surface whereas metal-

based dentures are more resistant to this

danger, but nonetheless can distort aer being

dropped or by mishandling during cleaning.

is is most likely to occur with a mandibular

denture

20

with a lingual or cingulum bar

major connector.

21

As with complete dentures,

cleaning partial dentures may be le to a carer

with the possibility of neglect or damage.

As has been stated, for most individuals the

simplest way to remove the denture biolm

is by mechanical cleaning with a toothbrush

and a non-abrasive paste, at least once a day.

As an adjunct to this, the denture can be

soaked twice a week in 0.1% hypochlorite

solution or chlorhexidine solution for 15-30

minutes.

22

Long-term nocturnal use should be

discouraged.

23

According to Manfredi et al.

22

leaving dentures to soak overnight is counter

to ‘hygienic logic’ because organisms that

inhabit the biolm do not survive prolonged

drying out. ere is no evidence to support

the view that leaving them to dry overnight

will cause warpage of the acrylic.

22

To summarise, both complete and partial

dentures require careful removal of the

denture biolm. However, this may not be

carried out because:

■

e patient is unaware of the need to

do this

■

e patient is unable to physically carry

out the cleaning

■

e carer nds the process unpleasant and

may do this perfunctorily or even avoid it

■

In the process of cleaning, the denture

may be prone to fracture or distortion

if mishandled.

The denture box

is is a simple device to hold the denture in

place during cleaning (Fig. 5). It reduces the

risk of fracture and distortion of a prosthesis.

It will also allow a carer minimal handling of

the denture and allow its storage with reduced

risk of ‘getting lost’. In an institution its

‘footprint’ will make positive discovery of the

owner certain.

One half of an orthodontic retainer or

denture box (or a soap box) is lled with

activated laboratory putty (Fig. 6). e

occlusal surface of the denture is pressed

into the putty suciently deeply to produce

rm retention. e denture can be replaced

in the negative impression and the surface

rigorously cleaned with a brush. Where the

patient has the loss of the use of a hand, the

box can be steadied while brushing or it can

be secured on its base with a suction pad or a

fabric fastener.

e occlusal surface of the denture can be