Rescue Group

Best Practices Guide

This publication Rescue Group Best Practices Guide is intended to provide

general information about rescue best practices The information contained in this

publication is not legal advice and cannot replace the advice of qualified legal

counsel licensed in your state The Humane Society of the United States does not

warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete accurate

or up to date and does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any person

for any loss or damage caused by errors inaccuracies or omissions

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................5

INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................7

SECTION 1 ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

CREATING YOUR MISSION AND VISION ...........................................................................9

INCORPORATING AND APPLYING FOR

501C3 TAXEXEMPT STATUS .....................................................................................9

FORMING YOUR TEAM .....................................................................................................9

Building a Board of Directors ................................................................................................................................. 10

Building Your Staff .................................................................................................................................................... 11

Building a Volunteer Network ................................................................................................................................ 14

OBTAINING INSURANCE .................................................................................................15

CREATING A BUDGET AND BUSINESS PLAN ..................................................................16

FUNDING YOUR ORGANIZATION ...................................................................................16

Types of Funds to Have ........................................................................................................................................... 16

General fund .......................................................................................................................................................... 16

Spay/neuter and general veterinary expenses................................................................................................ 16

Specific medical cases ......................................................................................................................................... 16

Creating a Development Plan ................................................................................................................................. 16

Marketing and branding ...................................................................................................................................... 17

Fundraising ............................................................................................................................................................ 17

Grant writing ......................................................................................................................................................... 17

Cost containment ................................................................................................................................................. 18

IMPLEMENTING A CULTURE OF RESPECT ...................................................................... 18

Engaging in Humane Discourse ............................................................................................................................. 18

Preventing Compassion Fatigue ............................................................................................................................ 18

Customer Service Skills ........................................................................................................................................... 19

SECTION 2 | ANIMAL CARE STANDARDS

THE FIVE FREEDOMS .....................................................................................................21

STANDARDS FOR PRIMARY ENCLOSURES .....................................................................21

CONTENTS

PHYSICAL WELLBEING .................................................................................................. 24

Vaccinations and Parasite Control ........................................................................................................................ 24

Disease Prevention ................................................................................................................................................... 24

Spay/Neuter ................................................................................................................................................................ 25

Microchipping ............................................................................................................................................................ 25

Food ............................................................................................................................................................................. 25

Working with a Veterinarian ................................................................................................................................... 25

MENTAL WELLBEING ....................................................................................................26

Stress .......................................................................................................................................................................... 26

Fear Free .................................................................................................................................................................... 26

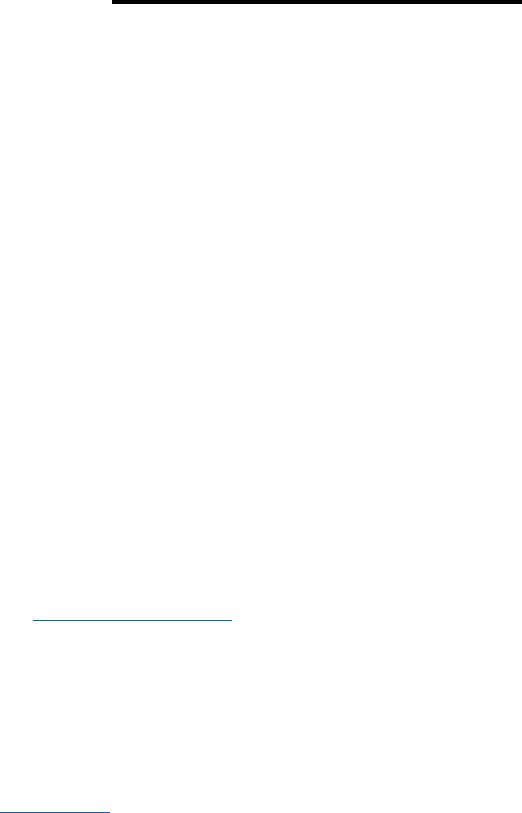

Enrichment ................................................................................................................................................................ 26

Easy automatics .................................................................................................................................................... 26

Win-wins ................................................................................................................................................................ 27

In-cage enrichment .............................................................................................................................................. 27

Out-of-cage enrichment ..................................................................................................................................... 27

Other stress relievers .......................................................................................................................................... 28

Socialization .............................................................................................................................................................. 28

VETERINARY POLICY ...................................................................................................... 29

EUTHANASIA POLICY .....................................................................................................29

SECTION 3 | OPERATIONAL STANDARDS

RECORDKEEPING ..........................................................................................................31

TRANSPARENCY .............................................................................................................31

DETERMINING CAPACITY ............................................................................................... 32

EXCEEDING CAPACITY ...................................................................................................33

ANIMAL INTAKE .............................................................................................................34

Sources of Animals ................................................................................................................................................... 35

Creating a Plan ........................................................................................................................................................... 35

Partner with a Local Shelter ................................................................................................................................... 36

Pet Retention Strategies ......................................................................................................................................... 37

Owner Surrenders .................................................................................................................................................... 38

CONTENTS

Strays ...................................................................................................................................................................... 38

Temporarily Holding an Animal ......................................................................................................................... 38

Use of Boarding Facilities ................................................................................................................................... 39

Transporting Pets ................................................................................................................................................. 39

SHELTERTYPE FACILITIES .............................................................................................39

PROGRESSIVE ADOPTIONS ............................................................................................ 40

Process ................................................................................................................................................................... 40

Setting Your Adopters Up for Success ............................................................................................................ 42

Events and Other Advertising ............................................................................................................................ 42

FOSTER HOMES..............................................................................................................

DISASTER PREPAREDNESS ............................................................................................43

SECTION 4 | COMMUNITY BUILDING

WITH OTHER ANIMAL WELFARE ADVOCATES ...............................................................45

Potential Partners to Increase Lifesaving Efforts .............................................................................................. 45

Building a Transfer Program with Local Shelters ............................................................................................... 45

Building a Transfer Program with Out-of-State Rescues .................................................................................. 46

Building Coalitions .................................................................................................................................................... 46

WITH YOUR SUPPORTERS ............................................................................................

Website ....................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Social Media ............................................................................................................................................................... 48

APPENDIX

(These documents can be found at humanepro.org/rescuebestpractices)

A SAMPLE BUSINESS PLAN

B SAMPLE BUDGET

C SAMPLE EUTHANASIA POLICY

D SAMPLE INTAKE PLAN

E SAMPLE PET RELINQUISHMENT

F SAMPLE TEMPORARY PET RELINQUISHMENT

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 5

The Humane Society of the United States thanks everyone who

provided their wisdom and insights to make this publication as useful

as possible to the rescue community, including PetSmart Charities,

whose grant funding made the original (2015) publication of this

guide possible; Abby Volin, who wrote that original version; and to ev

-

eryone who reviewed it: Todd Cramer, Amber Sitko, Jan Elster, Kaylee

Hawkins, Stacy Smith, Kathy Gilmour, Mandi Wyman, Whitney Horne,

Britney Wallesch, Carie Broecker, Laura Pople and Jme Thomas.

We would also like to acknowledge contributions from current and

former HSUS staff: Betsy McFarland, Inga Fricke, Natalie DiGiacomo,

Sarah Barnett, Hilary Hager, Kathleen Summers, Joyce Friedman,

Lindsay Hamrick, Danielle Bays, Darci Adams, Windi Wodjak, Anne

Marie McPartlin, Dr. Melissa Beyer, Vicki Stevens and Kelly Williams.

Last but not least, we extend our gratitude to all the rescue groups

whose staff and volunteers work so hard to keep pets with their

families whenever it’s possible, and to support homeless pets when

it’s not.

ABOUT THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES

The Humane Society of the United States is the nation’s most effec-

tive animal protection organization. Established in 1954, the HSUS

seeks a humane and sustainable world for all animals—a world that

will also benefit people. The HSUS is America’s mainstream force

against cruelty, abuse and neglect, as well as the most trusted voice

extolling the human-animal bond. The HSUS works to reduce suffer

-

ing and to create meaningful social change by advocating for sensible

public policies, investigating cruelty, enforcing existing laws, sharing

information with the public about animal issues, joining with corpo

-

rations on behalf of animal-friendly policies and conducting hands-on

programs that make ours a more humane world.

Acknowledgements

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 7

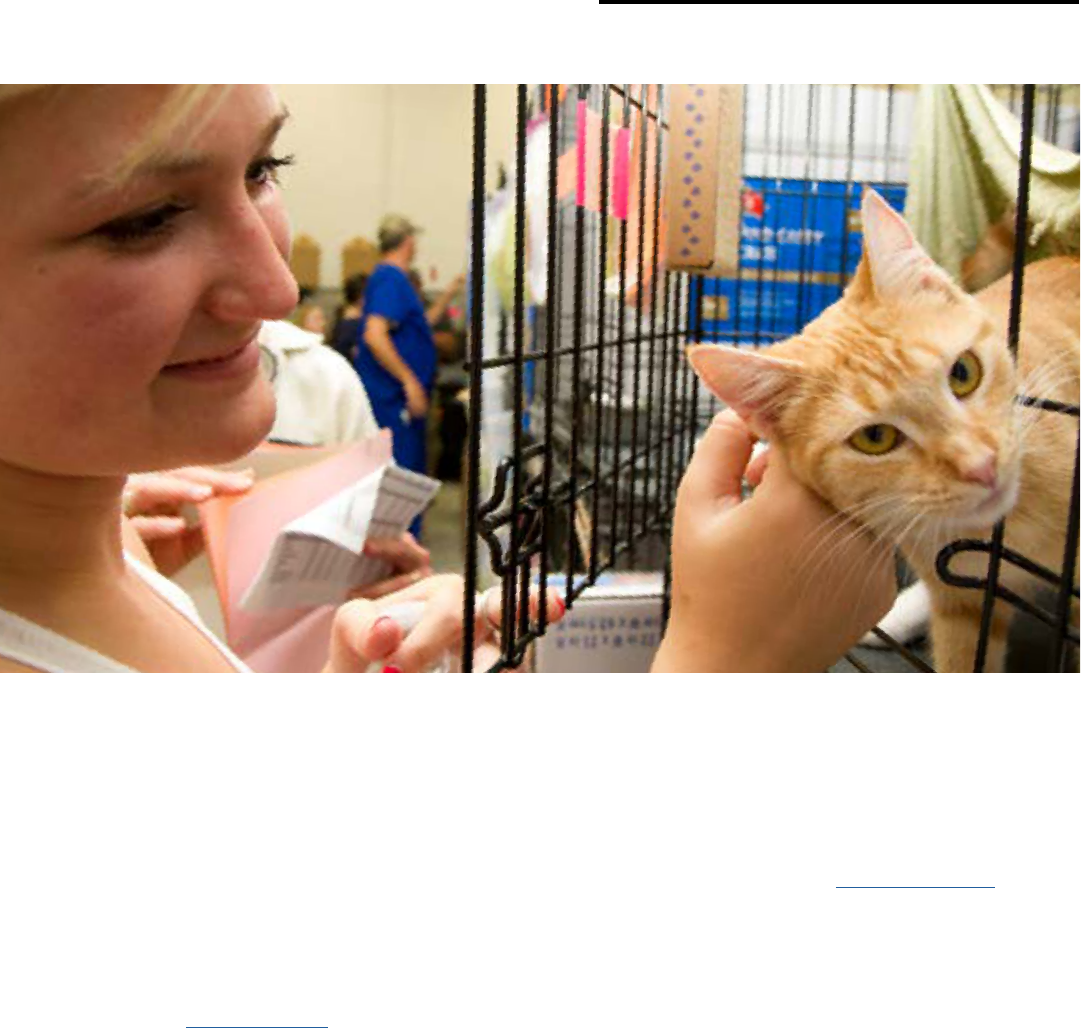

Rescue groups are vital in the world of animal welfare and are

collectively responsible for saving hundreds of thousands of animals

every year. Some shelter animals, such as neonatal kittens or those

with medical or behavioral challenges, may be difficult for shelters

to place into homes. Rescue groups have resources to help these

animals, making the groups' partnerships with shelters invaluable.

They are incredible, lifesaving organizations. But what does it mean

to be a rescue? Does it simply refer to an organization that takes in

homeless animals and finds them homes? Does it mean being part

of an organization with 501(c)(3) nonprofit status? Does it mean

the rescue provides trap-neuter-return services to community cats?

Actually, a rescue can meet all or none of these criteria.

This manual was designed to provide structure and guidance to all

types of rescue groups. It describes best practices for these organi

-

zations and, perhaps more importantly, suggests ways to implement

them to help rescues operate at their maximum potential. This guide

can be used to evaluate the health of established organizations and to

help new groups get off to a successful start.

While there is no one-size-fits-all way to run a rescue group, there are

standards—both from an organizational and an animal care stand

-

point—that all rescue organizations should meet. Above all, rescuers

owe it to the animals in their care to run their rescue operations in

the most professional, collaborative and humane manner possible.

Ultimately, as rescue groups adhere to best practices, they

become more efficient and effective. This allows rescuers not only to

humanely take in and adopt out more animals, but also to build trust

within the community; support pet owners so they can keep their be

-

loved pets, work successfully with local animal welfare advocates; and

help solve the problem of pet homelessness on a community level.

Introduction

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 9

Rescue organizations should be run just like any other business. With

a solid foundation in place, you will have more support to grow

your rescue group, allowing you to bring in more animals and save

more lives.

CREATING YOUR MISSION AND VISION

If you are thinking about starting a new rescue group, define your

mission and vision before you do any other planning. Where is the

greatest need in your community? What do you hope to accomplish,

and why? Conducting a community assessment can assist you in de

-

termining the type of help the animals in your community need.

Typically, forming a rescue group consists of creating an organization

that takes in animals who have been transferred from a shelter, relin

-

quished by their owner or found as a stray; fosters them in a home

environment; and adopts them out.

There are other ways to help. Consider the needs in your community

before deciding what type of rescue group you want to start. If the

market is already saturated with traditional, adoption-based rescues,

you may want to think about creating a prevention-based organiza

-

tion that keeps pets in their homes and stops them from entering the

shelter and rescue system in the first place. Your organization can sit

at the bottom of a broken dam, holding buckets to lessen the deluge

of rushing water, or you can start from the top and plug the holes to

prevent the water from leaking in the first place. Prevention-based

organizations might focus on low-cost spay/ neuter, trap-neuter-re

-

turn for community cats, lost-and-found, behavior assistance, legal

assistance, pet food pantry operation or other valuable programs.

INCORPORATING AND APPLYING FOR 501C3

TAXEXEMPT STATUS

WHY: Incorporating as a business in your state is an easy way to

show the world that your rescue group is a legitimate business ven

-

ture and that you are treating it as such. Further, the corporate for-

mation protects individuals in the organization from legal liability and

debt incurred by the rescue group. More importantly, your organi

-

zation has a significantly better chance of being approved for 501(c)

(3) tax-exempt status if you incorporate. And having that tax-exempt

status is crucial for your organization’s ability to grow. Not only is

the organization exempt from federal income tax, but you can entice

donors with a tax deduction for their contributions and apply for the

many grants that are awarded only to nonprofit organizations. Non-

profits can also apply for a mailing permit that gives them a special

reduced rate for mailings.

HOW: Check your state’s requirements for incorporating a non

-

profit with your state’s corporate filing office (usually called the

department of state, secretary of state or something similar) and

investigate other resources. Contact the state office responsible

for businesses to find out what your state’s specific requirements

are or check out the comprehensive state-specific resources. Many

offices will provide a packet of information on how to incorporate,

along with sample documents. You will also need to draft articles

of incorporation and bylaws in conjunction with incorporating your

organization; these serve as the primary rules governing the manage

-

ment of your corporation. Even if your state does not require bylaws

as a matter of law, it is still a good idea to draft them because they

define your business structure and specify how your organization will

conduct its affairs.

You can find samples for drafting articles of incorporation by search

-

ing for state-specific samples on your state’s government website.

When you are ready to apply for tax-exempt status, all the informa

-

tion you need is on the IRS website. Keep in mind that it can take

many months to obtain 501(c)(3) status, so do not get discouraged.

Moreover, you may want to consult with an attorney or accountant

who specializes in nonprofits, even if it’s just to have them review the

completed application.

Also remember to check whether your state has specific licensing

requirements, if any, for operating a shelter or rescue group. You

can usually find any laws pertaining to animals in your state’s agricul-

ture code.

FORMING YOUR TEAM

Every rescue group needs three layers of support to build a full

team. At the top is the board of directors. These are the members

who oversee the strategic direction, or long-term planning, of an

organization. The next layer consists of staff, including an executive

director, who run the day-to-day operations of the rescue group.

Some rescue organizations are able to pay a few staff members, but

generally these groups rely on volunteers. It is still important to call

these dedicated members “staff” regardless of whether they are

Organizational standards

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 10

paid, because it demonstrates that your organization is run profes-

sionally. Doing so also gives individuals a sense of ownership, respon-

sibility and appreciation for the hours they contribute. The final layer

of your team is the volunteers—people who help out on a regular

basis by supporting the staff. Whether they foster animals, assist at

adoption events, transport animals to veterinary appointments or

participate in countless other activities, volunteers are the lifeblood

of any rescue group.

BUILDING A BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Every organization has a board of directors, which is a body of elect-

ed or appointed members who oversee the activities of the corpora-

tion. Their responsibilities are detailed in the organization’s bylaws,

but typically, members of the board are responsible for governing

the organization, appointing and reviewing the executive director,

approving budgets, approving an organization’s policies and other

similar tasks. Board members have an obligation of allegiance, care

and duty to the organization. For rescue groups, it is important to

recruit people who will help the organization fulfill its mission state

-

ment by providing advice and implementing long-term goals that

will help the organization plan for the future and create the vision of

what it will become.

Board members are not the ones who run the day-to-day aspects

of the rescue group (unless the organization has a “working board,”

where board members double as staff), but instead are involved in

strategic planning. That is, how will the organization get from where

it is today to where it wants to be in a few years? The board of direc

-

tors is a group that advances the organization’s mission by providing

advice, money, time and expertise. A sample strategic plan devised

and implemented by a board of directors may be helpful.

Generally, board members on working boards are expected to be

heavily involved in strategic planning, fundraising and policy decisions

for the organization. When forming your board, think about the type

of people who are going to help fulfill the organization’s mission and

goals: Someone with fundraising abilities? Public relations or market

-

ing savvy? Legal or accounting abilities? Management background?

Political connections? Choosing friends and family to serve on your

board may be necessary at first, but once you become established

you will want to be more strategic in selecting board members. An

independent board is important for your organization’s credibility.

Having family members on the board could be viewed negatively, so

it is an important point to consider.

Check the laws in your state to determine the exact number of

people you need on a board, but at a minimum you will need to have

a president, a secretary and a treasurer. The executive director is not

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 11

normally a board member, but is instead accountable to the board

of directors and also serves as the bridge between the board and

the staff who carry out the day-to-day functions of the organization.

Board members will need to be willing to commit their time and

resources to the organization. You may want to implement term

limits for members of the board or have nonvoting members who

are there exclusively in an advisory role. It is helpful to have a job

description so that prospective members will know what will be

expected of them.

Importantly, the board of directors is responsible for approving new

contracts (such as foster agreements or adoption contracts) and

authorizing certain individuals (usually the executive director, the

board president and the board vice president) to sign documents on

the organization’s behalf. You may also want the board to authorize

specific individuals to sign agreements relevant to their area of ex

-

pertise. For example, the board might allow the adoption coordinator

to sign adoption contracts or authorize the volunteer coordinator to

sign volunteer agreements.

In keeping with good practices and to build a trustworthy organiza

-

tion, it is important for the board to create well-documented polices

that foster transparency. For example, it is essential to have a conflict

of interest policy for the board of directors, a document retention

policy, a code of ethics, a harassment policy, a whistleblower policy

and, if applicable, written compensation practices.

A strong board of directors is vital to the current success and future

development of your rescue group. Pick your board members

thoughtfully!

BUILDING YOUR STAFF

While the board of directors is accountable for the long-term goals

of the organization, the staff is responsible for running the day-to-

day operations of the rescue group. After you have filed the articles

of incorporation and applied to the IRS for tax-exempt status, the

next important task is developing your team. Although the majority

of your staff will be unpaid volunteers with other jobs and obliga

-

tions, it is crucial that all individuals involved are committed to their

positions to ensure that the rescue runs as smoothly as possible.

Do not put someone into a role simply because they offered or be

-

cause you are eager to fill the position. The person’s skills must align

with the post. For example, the outgoing individual who loves meet

-

ing new people but has never balanced a checkbook would better

serve the organization as a volunteer coordinator than the financial

coordinator. Similarly, the individual who does not bat an eyelash

at mounds of paperwork, yet gets easily stressed by demanding

customers, might be a great fit for the records manager but not the

adoption coordinator. Do not be afraid to move people around and

try them in different roles until you have the right fit. Even though

it can be difficult to leave a crucial position empty until you find the

perfect match, in the long run your organization will be much better

off having the right people in place.

Below is a basic template to use in building your rescue group’s staff,

including suggestions for job responsibilities and helpful skills. This

list is not meant to be all inclusive, so use it as a starting point and

tweak it to fit the needs of your organization. And do not be afraid

to split these positions among several people—there is plenty of

work to go around! Just remember that you do not need to fill all

these positions immediately. Start small and continue to build as

your rescue group gains more volunteers. Once your rescue group

is established, it is certainly appropriate to pay staff according to the

laws of your state. Organizations that have paid staff find that it leads

to less turnover and more consistent policies and procedures.

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR This person is the face of your organization

and chosen by the board of directors. In addition to being the rescue

group’s spokesperson, this individual is responsible for the day-to-

day operations of the organization and interacts with the board of di

-

rectors as well as other staff members and volunteers. The executive

director ensures that the organization is operating according to its

mission statement and developing funds and policies for its future.

The individual in this position should have business and media savvy

as well as a considerable amount of patience and tact.

RECORDS MANAGER An obsessively organized and detail-oriented

volunteer should fill this post. This individual should be tech savvy as

she will be dealing with paperwork and animal management soft

-

ware. The records manager will update each animal’s profile with

current location, medical history and outcome, and she’ll update

bios and pictures for the group’s website and other listings. As your

organization grows and the number of animals coming in and out on

a weekly basis increases, this becomes one of the most overwhelm

-

ing jobs. Find a couple of people to share the work or rotate the

responsibilities every few months.

FINANCIAL COORDINATOR Do you know someone who is an

accountant or math whiz? This person might be a good candidate to

keep track of the organization’s finances, both outgoing expenses

and incoming donations. When it comes time to file your 990 tax re

-

turns with the IRS, this person will prepare the information for your

group’s accountant. If someone in your rescue group or community

is an accountant, ask if she will donate her services come tax time. If

you do not have this type of contact, seek help from a professional.

If your rescue group has its 501(c)(3) status, you can inquire about

receiving a reduced rate.

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 12

CORPORATE RELATIONS COORDINATOR You need someone

who can reach out to corporations—such as pet stores or big-box

chains—and other service providers to negotiate prices for food,

veterinary services, transport and other items so your rescue can

minimize expenses.

FACILITY DIRECTOR Are you going to have a brick-and-mortar

facility to house some or all of your animals? Or even a few cages

in a storefront? If so, you will need someone to run each facility.

Ideally, this person will live close to the facility because he will have

to be at the location on a frequent basis, including during emergency

situations. The facility director will create protocols to care for the

animals and ensure their well-being, as well as train, schedule and

supervise volunteers. This position is ideal for someone with com

-

munity outreach experience who can turn a job cleaning cages into

a fun task in which volunteers feel invested. Good people skills are

also a must as this person will be the face of the organization at that

facility. It is critical to have someone on staff who knows how to han

-

dle unvaccinated animals and animals who may have been exposed to

diseases in the community like parvovirus and panleukopenia. They

must also have an in-depth understanding of effective cleaning and

sanitation protocols, and they should be familiar with the Association

of Shelter Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal

Shelters (which outlines best practices for running an animal facility)

and understand how to implement these standards. When setting up

your own facility, be sure to look into local kennel or zoning ordi

-

nances at the outset. Many other issues will have to be considered as

well, such as how to fund the facility and deal with challenges such as

neighbors who may oppose your group’s presence.

FOSTER COORDINATOR This position requires someone with a lot

of patience and good people skills. The foster coordinator needs to

give prospective foster providers a clear list of what the group will

provide and what the foster provider will be responsible for when

caring for animals. Importantly, this person needs to be constant

-

ly accessible via email and phone to respond to foster providers’

questions in a timely manner. Additionally, the foster coordinator

will coordinate returns and find a new foster homes for pets when

necessary. This post might also start a continuing education

program designed to keep foster providers learning and engaged. It

is essential to build good relationships with foster providers to keep

them happy and willing to continue fostering! It is also a good idea

to have this person implement a support network (such as a listserv

or a group on social media) that enables foster providers to connect

with each other.

ADOPTIONS COORDINATOR/COUNSELOR The adoptions coordi

-

nator position is great for someone who has reasonable email access

throughout the day and time to field the many inquiries she is likely

to receive. You want someone who would not feel compelled to use

rigid rules for adoptions but instead would use general guidelines

as set by the board of directors and is comfortable communicat-

ing with potential adopters to support the adoption process. This

is another position that requires considerable tact, sensitivity and

thoughtfulness. This post is a good fit for someone who is a “people

person” and understands that customer service is critical to adop

-

tion success.

ADOPTION EVENT COORDINATOR Who likes to get up early

during the weekend? Grab this person to be the event coordinator

and have him plan and run weekly adoption events. Responsibilities

include showing up every week to set up and break down the event,

having the appropriate paperwork on hand and projecting a warm

and welcoming appearance to all potential adopters and foster pro

-

viders who pass by.

VOLUNTEER COORDINATOR It is a good idea to have a volun

-

teer coordinator on board to manage the various volunteer needs

throughout the organization. This person will take all volunteer

inquiries and direct them to the appropriate staff member, as well

as handle volunteer orientation and training sessions. This person

should be comfortable using social media and other methods to

actively recruit volunteers when needed. Because the volunteer

coordinator is also responsible for troubleshooting volunteer issues

and potentially terminating volunteers who do not work out, choose

someone who is just as comfortable having difficult conversations as

she is engaging and motivating volunteers. It is also important

for the volunteer coordinator to have a general idea of the needs

within each area of the organization so she can create or modify

shifts when there is an imbalance. For example, if one facility has

50 volunteers to fill 14 shifts, but another location has only 10, the

volunteer coordinator can request that some people move to the

second location. Because this person will have contact information

for all volunteers in the group, she will be a good resource when

other immediate needs arise, such as when an animal needs trans

-

port to a new home or to the veterinarian. This is also the go-to

person to coordinate with any outside group, such as a local school

or business, that wants to partner to provide volunteers for a day.

Having a photographer on staff (either a volunteer at your

organization or someone in your community willing to do-

nate time) is key. A good picture can make all the difference

in getting an animal adopted. Watch How to Photograph

Shelter Pets for some great pro tips!

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 13

MEDICAL COORDINATOR This person is responsible for schedul-

ing veterinary appointments and working as a liaison between the

rescue group and any veterinarians the organization works with. It is

confusing and wasteful to allow everyone from the rescue to contact

the veterinarian when an animal has a medical issue. It will make

everyone’s life easier if only one or two people from a rescue group

are allowed to approve veterinarian appointments. Putting approved

veterinarian services in writing and faxing/emailing the authorization

to the veterinarian before an appointment can reduce confusion and

make the experience better for foster providers and veterinarians.

Many veterinarians appreciate the clarity this process provides, and it

can also make it easier to cross-reference invoices with billing state

-

ments down the line. The only caution is that the medical coordina-

tor should have constant access to email and phone, otherwise there

may be problems scheduling and approving emergency appoint

-

ments. Because medical situations can be unexpected and urgent,

it is crucial to identify someone as the backup for this position. The

medical coordinator should have a general knowledge of common

animal health problems so he can readily determine when it is nec

-

essary for an animal to see the veterinarian. This person should also

establish protocols for certain situations. For example, if there is an

emergency and a foster parent takes his foster animal to the veteri

-

narian without getting prior approval from the medical coordinator,

who would be responsible for the bill?

BEHAVIOR AND TRAINING SPECIALIST This person (whether on

staff or not) will assist animals in your rescue with enrichment, train

-

ing and addressing behavior issues, as well as pets and pet owners

struggling with behavior problems at home (as a means of surren

-

der prevention). The individual should have experience in humane

training techniques that use positive reinforcement. It is helpful to

have standard operating procedures already drafted for common be

-

havior issues that could occur with your rescue animals. The person

in this position should work closely with the volunteer, foster and

adoption coordinators to help prevent problems before they start.

Reaching out to local dog training facilities is an option as well; many

trainers will be happy to provide ongoing training for fosters. Check

out Fetching the Perfect Dog Trainer by Katenna Jones for advice on

finding a dog trainer who uses positive reinforcement training meth

-

ods. The HSUS’s Guide to Cat Behavior Counseling and the related

online course are also great resources.

COMMUNICATIONS/MARKETING/PUBLICITY SPECIALIST

Someone with excellent communication skills, social media savvy

and web design experience is perfect for this job. This is also a great

opportunity for someone who enjoys planning fundraising events

or someone who wants to help but is not able to volunteer on a

regular basis. Be careful in your choice—whoever represents you on

social media will be considered the face of your organization. If you

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 14

would not trust the person to give an interview to the media, she is

probably not the best person to manage your organization’s online

presence. You will also want a backup administrator, someone else

who has access to your social media channels, in case you lose the

main volunteer.

GRANT WRITING COORDINATOR Notice the word “coordinator”

on this one. It is not reasonable to expect one person to write all the

grant proposals for your rescue, but it is helpful to have someone

who can search through the resources to find applicable grants and

form a team of people to draft the proposals. The coordinator keeps

track of grant applications in progress, proposal deadlines, proposal

specifications and eventual outcomes.

FUNDRAISING EVENTS COORDINATOR A fundraising team is nec

-

essary to help offset the organization’s expenses. Tasked with leading

your rescue’s fundraising efforts, the individual in this position

should have experience in event planning and should organize several

different types of events throughout the year.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH ORGANIZER

This person will build long-term relationships with community

members as a representative of your rescue group and so must be

personable, engaging and have excellent customer service skills.

Ideally, the candidate originates from the communities being served

and/or is fluent in community language(s). The primary purpose of

this role is to build trusting relationships among stakeholders—pet

owners, your rescue group, veterinary, behavioral and other service

providers, other local animal organizations—to ensure pets in your

community have access to all available resources needed to thrive

with their families. This individual will conduct ongoing outreach to

pet owners in your focus communities, connecting them with spay/

neuter, vaccination and other veterinary/behavior/wellness resources

for their pets when requested by community members. They may

also assist with transporting pets to and from spay/neuter or other

veterinary appointments, and follow up with clients via phone and

home visits as needed to support the family and their pet(s). Further,

this person will assist in planning, organizing, advertising and imple

-

menting community outreach events, as well as collect data neces-

sary for ensuring your program is meeting its objectives and focusing

resources in areas with the highest need.

There are countless other positions your organization can create

to make the rescue group run smoothly. Think about the goals and

needs of your organization and plan accordingly. And remember,

nothing is set in stone—you have the flexibility to adjust positions

and responsibilities to make them work for you. Once you have your

team in place, create an organizational chart so that it is clear to

all staff and volunteers who is in charge of each area within your

rescue group.

BUILDING A VOLUNTEER NETWORK

Volunteers are a crucial part of any rescue group—you cannot run an

organization without them. From taking care of animals to running

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 15

and share a success story along with pictures. Seeing happy pets

in their new homes or learning that 20 animals were adopted in

one weekend is often the most fulfilling part of volunteering for a

rescue group.

As volunteers get more engaged, they may also want to try new

things. Take their offers of help seriously and, if possible, give them

room to try new things that could benefit your group. Sometimes

their suggestions might not be feasible. If this is the case, do not

simply say “no,” but explain the reasoning and offer alternatives. This

increases their buy-in and interest in the group, and it can help retain

those who are truly interested in helping long-term.

For more information, check out the HSUS's resources on

staff/volunteer management.

OBTAINING INSURANCE

Every rescue group should carry insurance to protect the organiza-

tion, its individual board and staff members and its volunteers.

General liability insurance is important to carry; it will cover claims

for bodily injury or property damage to people not associated with

your organization. This ensures that your organization is covered if,

depending on the policy, a customer slips on a wet floor during an

adoption event, a volunteer transporting a pet to her new home has

a car accident and injures the other driver, or a cat bites a potential

adopter. Additionally, you need to purchase workers' compensation

if your organization has paid staff, and possibly property insurance if

your rescue has its own facility. You can also buy insurance to cover

medical costs for volunteers and fosters who are injured while per

-

forming tasks for your organization.

Although forming a corporate entity protects individuals from per

-

sonal liability for any corporate wrongdoing, directors and officers

of a board can still be personally sued for reasons such as misuse of

company funds, fraud, violating the law, gross negligence and neglect

of legal and financial duties. As such, it is a good idea to purchase di

-

rector and officer (often called “D&O”) liability insurance to protect

corporate directors and officers in the event of a lawsuit. This type

adoption events, from transporting animals to creating pet bios and

taking pictures, there are countless opportunities for volunteers to

help your rescue. Having a structured program in place is essential to

recruiting and retaining volunteers. Providing training, guidelines and

support for volunteers will help prevent frequent turnover.

In creating your volunteer program, think about your organization’s

specific needs and the characteristics of your ideal volunteer. Then

ask for just that in your position description. Also think about what

the volunteers are going to get out of the experience. When crafting

a position description, consider elements such as the purpose of the

job, work involved, training required, learning opportunities offered,

commitment needed, level of difficulty involved, skills necessary and

type of environment expected. You should also consider listing the

physical, mental and emotional requirements. At the same time, do

not make your program so rigid and demanding that it discourages

or excludes people who want to volunteer on a somewhat limited

basis. Make room for everyone.

Communication is essential when it comes to running a successful

volunteer program. What are your expectations of volunteers, and

how can they provide feedback to you? Asking for a minimum time

commitment (three months is usually a good length of time) pro

-

vides consistency for everyone involved and gives the volunteer an

out if the experience ends up not being right for them.

It is important to hold an orientation and training session before

you allow volunteers to roll up their sleeves and dig in. Try to hold

orientations and trainings on a regular basis so that you do not lose

someone interested in volunteering because the next orientation is

too far in the future. The orientation should provide an overview of

the organization, details about what is expected of volunteers and

additional information that will help people decide whether or not to

participate. The training session should cover all relevant rules, pol

-

icies and procedures, as well as detailed information people need to

accomplish their specific tasks. Handing out a volunteer manual that

summarizes everything you went over in the orientation and training

is a good practice. You should also create “how-to” guidelines for

every task volunteers are asked to do at your rescue. Even better,

supplement the manual with pictures, and keep it easily accessible.

This will help volunteers and create consistency within the organi

-

zation. The training session is also a good opportunity to collect a

liability waiver from all volunteers (you should also obtain liability

insurance, which is discussed in the next section). If you hold events

at pet stores and other locations that you do not own, make sure you

check for any age requirements before accepting volunteers under

18 years old.

Do not forget to show your volunteers the fruits of their labor. Let

people know on a regular basis which animals have been adopted,

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

It is important to work with trainers and behavior

experts, but they are not always easy to find. The

following resources may be helpful in finding a good

partner for your organization:

apdt.com

m.iaabc.org

ccpdt.org

dacvb.org

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 16

of insurance usually covers legal fees, settlements and other costs.

Sometimes the D&O insurance will also protect a corporation if it is

named as a defendant in a lawsuit.

CREATING A BUDGET AND BUSINESS PLAN

As a tax-exempt organization, you are required to stay in good

standing with the IRS. This means annually filing a 990, 990-EZ or

990-N tax return with the IRS, in addition to fulfilling any local and

state requirements. Engaging in good accounting practices from the

beginning will help you stay organized and focused. An essential step

toward this goal is creating a budget for your organization. Develop

-

ing a budget will require you to thoughtfully estimate costs for the

year for items such as food, veterinary care and insurance, and it will

help you plan fundraising events to support your efforts.

Running a rescue is a legitimate nonprofit endeavor and should be

treated as such to ensure that the organization will be there for the

long haul. Creating a business plan will help you think about building

a sustainable future for your rescue group by outlining your mission,

forecasting budgets, making priorities and setting strategic goals.

You may want to consult a financial adviser to get started on the

right foot. From the beginning, you need to think about where you

want your organization to be in six months, one year and five years

down the road. Think of the business plan as a roadmap to keeping

the organization on track, achieving your goals and fulfilling your

mission. Strategically planning for your rescue group will help ensure

that your organization is around to help animals for many years

to come.

You can find a sample business plan in Appendix A and a sample bud

-

get in Appendix B, available at humanepro.org/rescuebestpractices.

FUNDING YOUR ORGANIZATION

Funding a rescue organization requires some basic business skills in

marketing, fundraising, grant writing and cost containment. Plan to

set aside $5,000 to $10,000 for startup costs for your rescue group.

This should cover startup items such as food, bowls, toys, blankets,

cages, carriers, collars, leashes, litter boxes, litter and veterinary

funds for your first few charges. Even if you run a foster-based orga

-

nization and ask foster providers to cover the daily cost of food, it is

a good idea to have backup items on hand.

Once your organization is established, it is important to have a

reliable and constant source of income. Without a solid plan in place,

your rescue group will not be sustainable.

TYPES OF FUNDS TO HAVE

Good accounting practices require that you keep track of how

donated funds are spent. It is helpful to have several funds to which

people can donate to help you care for the animals.

GENERAL FUND The majority of your donations will fall into this

category, and any funds that are not otherwise earmarked will

go here. You can use this money for anything needed to run your

rescue, such as veterinarian bills, pet food, utility costs, animal

transport and staff salaries. Having a “donate here” button on

your webpage or social media accounts will help with fundraising

for general funds.

SPAY/NEUTER AND GENERAL VETERINARY EXPENSES You

will always need more funding for spay/neuter as well as veteri

-

nary care. Make it easy for people to donate to those causes

by letting them know that you are trying to build funds in

these areas.

SPECIFIC MEDICAL CASES Promoting specific animals with spe

-

cial needs is a great way to pay for unusually expensive cases. Be

careful to ensure that all funds designated for a particular animal

are used for that animal only. All extra funds must be returned

to donors and not used for other animals. Make sure you are

upfront and clear to potential donors about where and how the

funds will be spent so they do not feel misled.

CREATING A DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Do not rely on adoption fees as your sole source of income. Between

spay/neuter, vaccinations and veterinary fees, many times the adop

-

tion fee will not even cover the amount of money you have to spend

on an animal before he can be adopted. While adoption fees are a

way to defray some of these costs, you will need to develop a plan

that brings money into your organization on an ongoing basis.

A rescue group based in Arlington, Virginia, exemplifies how an

organization can diversify its funding base. While some of its

revenue comes from adoption fees, the bulk comes from

donations, fundraising events and partnerships with its for-profit

subsidiary businesses—two pet boutiques and a full-service pet care

company. An organization in Chicago, Illinois, uses the proceeds from

its boarding and training center to fund the nonprofit rescue group.

While these specific models may not be feasible for your organiza

-

tion, the lesson is clear: Diversify your funding base, and do not count

on adoption fees to cover all your costs.

Creating a development plan will provide a path for your organization

to grow and focus on long-term goals. It will also enable you to deter

-

mine which fundraising efforts work and where you should concen-

trate your energy. Importantly, it will help ensure your organization is

there for the long haul.

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 17

MARKETING AND BRANDING Marketing and branding are essen-

tial for highlighting your organization and attracting more donors,

volunteers and adopters. Do not be intimidated; marketing is simply

using strategies and tactics that help you build relationships with

supporters and fulfill your mission. Creating a marketing plan on an

annual basis is an effective tool to help you achieve your goals as it

creates a unified vision for everyone in the organization and guides

decisions about resource allocation.

There are numerous ways to market your organization. Start a

newsletter or fundraising appeal letter (either printed or electronic)

highlighting all the wonderful animals your organization has rescued.

People are more likely to give when they are proactively asked to

donate. There are simple and inexpensive programs available to help

you create a newsletter without the help of a graphic designer. And

remember, people want to hear about the great work your group

does for animals. You are the voice for the animals in your care, so

tell their stories.

Another way to advertise your rescue group is to start a branding

campaign—create a logo and put it on T-shirts, bags and other items

to sell. There are numerous companies that will do this for your orga

-

nization at little or no cost. Once you do create a logo and finalize

your organization’s name, protect your brand by purchasing all web

-

site domains with that name (including both .org and .com suffixes),

apply for a copyright for your name and apply for a trademark for

your logo. You can find information on how to apply on the United

States Patent and Trademark Office’s website. It is possible to fill out

the applications yourself, but you may want to hire an attorney to

ensure it is done properly.

FUNDRAISING Fundraising efforts need to be given the same, if

not more, attention as your efforts to save animals’ lives. In general,

if your organization is unable to raise sufficient funds to pay for its

work, it is unlikely that you will be able to raise those funds at a later

time. More importantly, attempting to raise funds after you have

obligated your rescue group to specific projects is not a sustainable

way to run your organization and makes it unlikely that the group will

last for long.

Fundraising activities are regulated by state law. The majority of

states require nonprofits that solicit donations from within that state

to register with its governing body. Each state has different regis

-

tration requirements, so make sure you have submitted the correct

paperwork and registered in every state where you are soliciting

donations. You may want to consult an attorney familiar with fund

-

raising regulations to ensure full compliance.

Fundraising should not be the responsibility of just one person.

Create a committee charged with developing creative ways to bring

in more funds to your organization, as well as planning and running

fundraising events.

There are a whole host of ways you can fundraise for your organi-

zation: Cultivate donors, establish membership tiers, offer animal

sponsorships, create “in honor of” and “in memoriam” funds, sell

plaques for adoption event cages, post a wish list, develop a planned

giving program, encourage in-kind donations, pursue corporate

sponsorships, send direct mailings, plan fun and creative events—the

list is endless.

When planning an event, consider how many volunteers you will

need, how much time it will take to plan, how you can advertise the

event, how much money you can spend on the event, how much

money you plan to raise from the event and how you can measure

success. Note that it is not always about how much money you

raise—sometimes the exposure you gain is even more valuable.

Many times, all you need to do to secure a donation is ask—so do

not be shy! A rescue group in New York City once reached out to a

cat litter company requesting a donation for the nonprofit organiza

-

tion. The company’s response? It sent 180 eight-pound bags of litter

at no cost.

This brings up another important point: Do not forget about in-kind

donations, which are contributions of goods or services. Many orga

-

nizations prefer to contribute in-kind donations, which can be just as

valuable as cash donations.

Send thank-you emails for every donation, whether cash or in-kind,

and reserve thank-you letters in the mail for larger donations. It is

crucial to include specific information in thank-you notes so that

donors can receive tax deductions for their contributions.

GRANT WRITING This is another area where you should build a

dedicated team. Recruit people who are highly organized, know the

organization well and are good writers. The grant writing process

is not as overwhelming as people often fear, and once your writers

have a couple of proposals under their belt, they will feel more con

-

fident and comfortable with the process. The HSUS has a compre-

hensive list of grants, and Candid, formerly The Foundation Center, is

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Always send a thank-you note to your donors, even if they

only give a small amount. People appreciate the personal

contact, and if you can give an example of how the funds

were used (e.g., picture of a dog toy or cat bed) it helps

cement the connection.

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 18

another great resource to look for more traditional sources of grant

funding. Grant writing is about building relationships, knowing your

organization and simply following directions.

COST CONTAINMENT To be a good steward of your donors' funds,

you need to get the most bang for your buck. There are some well-

known strategies such as buying in bulk, but there are also less

-

er-known ways to save funds for your rescue group. For example, ask

rescue-friendly stores for discounts, contact local grocery stores for

ripped bags of food or dented cans they can no longer use, set up an

Amazon wish list for supplies, check your city and county for surplus

equipment sales, and, if allowed by your state's veterinary medicine

laws, talk to your local hospital about donating infant eye medication

and used medical equipment for use pursuant to your veterinarian’s

instructions. (Note: Make sure this is legal in your state.)

IMPLEMENTING A CULTURE OF RESPECT

While we spend so many resources caring for the animals, we often

forget to care for ourselves as well as the thousands of other people

in the animal welfare community.

The homeless animal issue is a problem bigger than any one orga-

nization can solve. Only through a comprehensive and collaborative

approach will we be able to decrease intake at shelters and rescue

groups (through such initiatives as bolstering spay/neuter and vacci

-

nation clinics, implementing TNR, increasing pet retention and shut-

ting down puppy mills) and find loving homes for adoptable pets (by

conversation-based adoption counseling, expanding foster networks

and increasing transfer rates between shelters and rescue groups).

No single organization can do it alone, and we have a responsibility to

foster a culture of respect within our own organizations and extend

it to others.

ENGAGING IN HUMANE DISCOURSE

In the animal rescue community, we all know there is no one way

to rescue animals. There are more than 10,000 rescue groups in the

U.S. and Canada, and each organization has a different and valid way

of running its program. The animal welfare world has historically

been divisive but, by working together, we will solve the problem of

animal homelessness. We need to recognize that not all communi

-

ties can transform overnight and that it truly takes a village to save

homeless animals.

Humane discourse is not about stifling criticism, nor is it meant to ex

-

cuse unacceptable practices. Instead, it is about finding appropriate

ways to increase dialogue between different organizations and using

suitable outlets for discussing differences. Set aside time in your

next staff meeting to discuss issues of concern instead of posting

your latest frustration on social media outlets or discussing it during

an adoption event. Also think about the impact of the language you

choose. For example, are you rescuing an animal from a shelter

or with a shelter? How can changing that one word impact your

relationships? We all lead by example, and when others see us always

speaking positively and bringing up issues in an appropriate manner,

they will follow suit. Language has an impact. When we tear down

shelters, we risk tearing down shelter animals: Who wants to adopt

from an entity that is considered “bad”? This only serves to create a

greater reliance on limited rescue resources, and it does a disservice

to animals in need.

For more information, check out the HSUS's Humane Discourse

Toolkit and resources on coalition building.

PREVENTING COMPASSION FATIGUE

This work of animal rescue can take an emotional toll. Many of us are

called to do this work because of our love of animals, and it can be

painful to see so many in need. Compassion fatigue is the emotional,

physical, social and spiritual exhaustion that causes a pervasive de

-

cline in our ability and energy to feel and care for others, and it is the

normal consequence of caring. On an individual level, it can manifest

as anger, cynicism, inability to empathize, feeling like what we do is

never enough, guilt or hopelessness, and can lead to

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 19

resistance to change, feeling powerless and apathy. When multi-

ple people in a group are experiencing compassion fatigue, it can

manifest at an organizational level, with high rates of turnover, lack

of flexibility, inability for teams to work together and undermining

the mission of the organization. In order to do our best work for

the animals, we must, as individuals, prioritize our own wellness and

self-care, despite our inclination to run ourselves ragged “for the

animals.” The animals need us at our best, and it’s our obligation to

take care of ourselves first before we assist others.

Learning to recognize the signs of compassion fatigue can help us

to recognize when we might need to step up our self-care, or step

back our levels of engagement. Learning skills to both ameliorate and

manage acute moments of stress as they are happening, as well as

have a healthy relationship with our capacity to help and our bound

-

aries, can help us thrive in the long term in the work. Conversations

about compassion fatigue and self-care, setting boundaries and

managing workloads should be standard in organizations, no matter

the size. Anyone who is struggling should remember that they’re

not alone, that it’s normal, and that help is available—whether by

reaching out to others on their team, taking a break, or accessing

professional mental health support. The success of our movement

depends on each of us being at our best, and we’re in this together;

caring for ourselves and our teams will only allow us to be that much

more effective for the animals we are so committed to helping.

For more information, check out the HSUS's resources on compas

-

sion fatigue.

CUSTOMER SERVICE SKILLS

Good customer service should be the cornerstone of every interac-

tion your organization has with people—whether they are the gener-

al public, potential adopters, volunteers, shelter personnel or animal

control officers. Every person involved with your rescue group is an

ambassador for your organization. Set a good example and ensure

that everyone associated with your rescue treats customers and

potential customers in a welcoming and nonjudgmental way.

Most people are good and treat their animals well. Remember that

many will not have the knowledge that you have, so before thinking

a question such as “Can you ship a dog to me?” is a red flag, con

-

sider that the person may be legitimately unfamiliar with rescue, or

that this is his first pet. Keep in mind that if someone comes to your

organization wanting to adopt, they are already trying to do the right

thing, and you do not want to scare them away by treating them

with suspicion.

Good customer service is essential to the success of your organiza

-

tion as your reputation is priceless and easily destroyed with one bad

encounter. Be accepting of feedback that may not be positive, and

take it as a learning experience. Keep an eye on reviews on Yelp and

other review sites such as Great Nonprofits to see what the general

sentiment is about your organization and your brand. One of the

most frequent complaints from potential adopters is that they did

not receive a response to their inquiry or application. Combat this

by setting organizational standards for responding to questions and

adoption applications so that, for example, all inquiries receive a

reply within 24 hours, and all adoption applications— even if they're

not approved or the animal is not available—receive a response.

Do not miss out on opportunities for an adoption. Make sure your

available pet postings are updated frequently to ensure that all listed

animals are currently available. It can be frustrating for an adopter

to fall in love with a pet online only to find out the pet is not available

after all.

A few practical tips for good customer service: Be prompt with re

-

sponses to inquiries, and use a friendly and warm demeanor; provide

accurate, current and easily accessible information on your organiza

-

tion and the animals in your care; actively listen and be friendly to

the people who approach your rescue group; always remain calm

and professional; and say thank you to the people who work with

your organization.

For more information, check out the HSUS's resources on

Customer Service.

ORGANIZATIONAL STANDARDS

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 20

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 21

Regardless of whether your organization houses animals in foster

homes, an adoption center, boarding kennels or some other type of

facility, or even just temporarily for a trap-neuter-return program,

you must ensure they receive the highest standards of care.

THE FIVE FREEDOMS

While groups can disagree on specifics (e.g., which brand of food

is best, whether harnesses or collars are preferable), there are five

fundamental freedoms to which every animal is entitled:

1. FREEDOM FROM HUNGER AND THIRST All animals need ready

access to fresh water and a diet that allows them to maintain full

health and vigor. This must be specific to the animal. For example, a

puppy, an adult dog, a pregnant cat and a senior cat would all need

different types of food provided on different schedules.

2. FREEDOM FROM DISCOMFORT All animals need an appropriate

living environment, including protection from the elements and a

clean, safe and comfortable resting area. Animals must be provided

with bedding and not sleep on a cold, hard floor. Overcrowding will

increase an animal’s physical discomfort and should be avoided. Do

not forget about temperature and environmental factors, such as

noise levels and access to natural light. And if an animal is outside, he

must have shelter from the elements as well as appropriate food and

water bowls that will not freeze or tip over.

3. FREEDOM FROM PAIN, INJURY OR DISEASE All animals must

be afforded care that prevents illness and injury and that assures

rapid diagnosis and treatment if illness/injury should occur. This

entails vaccinating animals, monitoring animals’ physical health, rap

-

idly treating any injuries and providing appropriate medications for

treatment and pain.

4. FREEDOM TO EXPRESS NORMAL BEHAVIOR All animals need

sufficient space and proper facilities to allow them to move freely

and fully and to engage in the same types of activities as other ani

-

mals of their species. They also need to be able to interact with—or

avoid—others of their own kind as desired. They must be able to

stretch every part of their body (from nose to tail), run, jump and

play at will. Are you overcrowded? Are you housing too many animals

in one room? If so, the animals are probably unable to experience the

fourth freedom.

5. FREEDOM FROM FEAR AND DISTRESS All animals need both a

general environment and handling that allows them to avoid mental

suffering and stress. The mental health of an animal is just as import

-

ant as her physical health. Are you providing sufficient enrichment?

Allowing the animal to hide in a safe space when needed? Ensuring

that there is not too much noise? Are there too many animals in one

room? Remember, psychological stress can quickly transition into

physical illness.

The Five Freedoms were first articulated by England’s Farm Animal

Welfare Council, but they apply to every type of animal in every type

of setting, including shelters, rescues and even private homes. Most

organizations tend to do a good job of providing Freedoms 1, 2 and

3, but 4 and 5, which focus more on an animal’s psychological needs,

tend to be overlooked. It is important to examine your operations

from the perspective of the animals in your care. If each and every

animal is not receiving all Five Freedoms, you must reexamine your

policies and procedures, and you certainly must not take any new

animals into your program until the situation is resolved.

The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Standards of

Care in Animal Shelters—which were developed for “traditional brick

and mortar shelters, sanctuaries and home-based foster or rescue

networks”—are our profession’s most useful tool, largely because

they are premised on the Five Freedoms. The guidelines should be

used as your touch point for answering every question from “Is my

animal housing humane?” to “Is my organization trying to care for

too many animals?” The operating guidelines below are adapted

from the ASV guidelines, and following them is necessary to ensure

the Five Freedoms. Note that these are minimal considerations, not

complete operational plans. We recommend that you read the ASV

document in its entirety and consult your veterinarian to develop

written standards for your organization.

STANDARDS FOR PRIMARY ENCLOSURES

The physical space that will serve as an animal’s primary enclo-

sure—the place where he will eat, sleep and spend the majority of

his time—must be safe, sanitary and of sufficient size to provide a

humane quality of life. IMPORTANT: Cages, crates and carriers that

are intended for travel or short-term, temporary confinement are

unacceptable as primary enclosures; it is also unacceptable to keep

animals on wire or gridded flooring.

Animal care standards

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 22

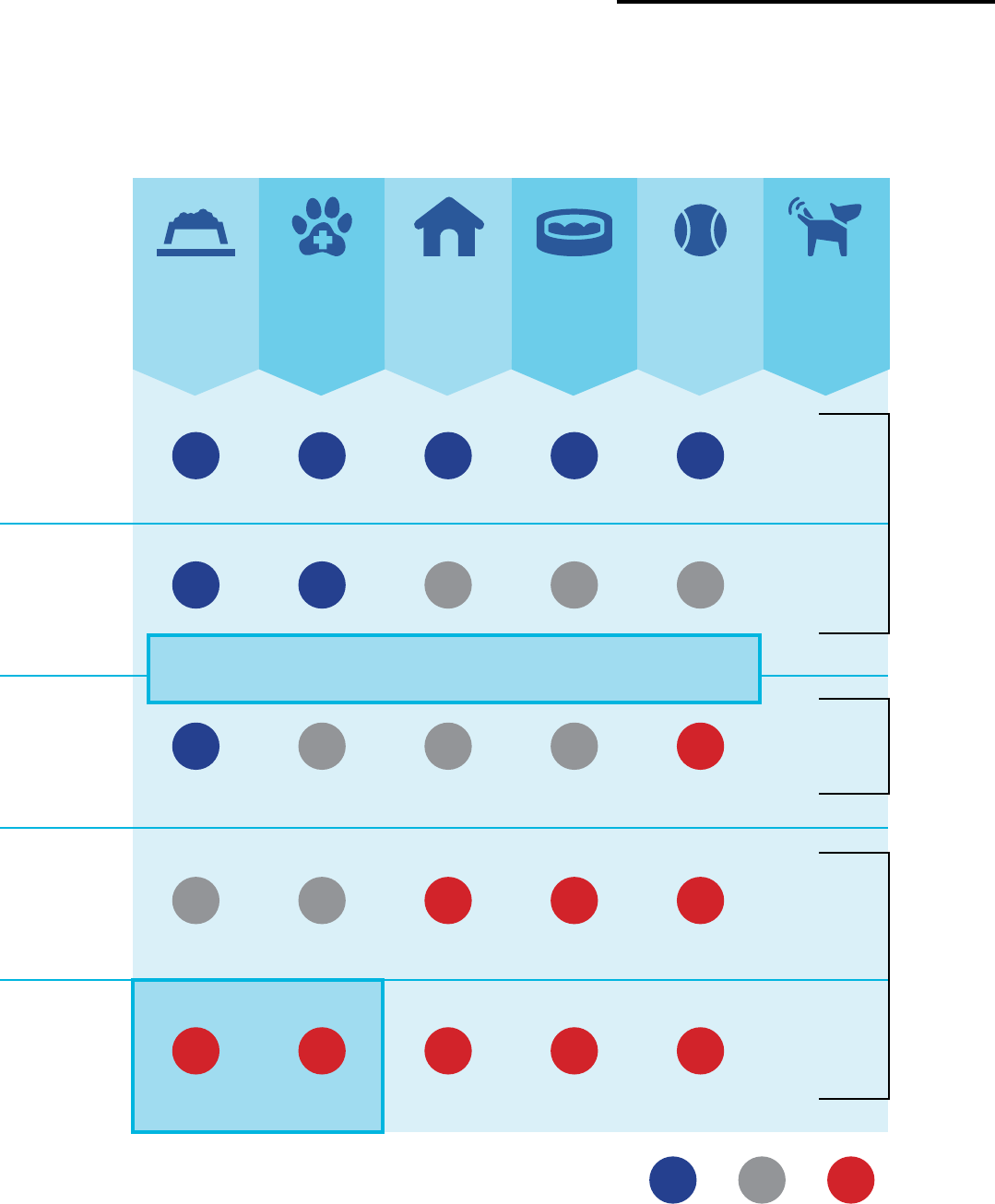

High

Quality

of Life

Always

Competent

caregiving;

welfare

safeguarded,

nurturing

environment

FREEDOM

from

Hunger &

Thirst

FREEDOM

from

Pain, Injury

or Disease

FREEDOM

from

Fear &

Distress

FREEDOM

from

Discomfort

FREEDOM

to Express

Normal

Behavior

HAPPINESS

All Mental

& Physical

Needs

Borderline

caregiving;

animals

at risk

Often

Rarely

Never

Never

Yes +/- No

Good

Quality

of Life

Poor

Quality

of Life

A life not

worth living

Borderline

Quality

of Life

Cruelty typically prosecuted

Minimal caregiving competency

Incompetent

caregiving;

animals

suffer

Five Freedoms for Companion Animals

ANIMAL CARE STANDARDS

ADAPTED FROM A CHART CREATED BY GARY PATRONEK FOR THE FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COUNCIL, 2009.

Rescue Group Best Practices Guide 23

Ensuring that an animal has adequate space can be a challenge, par-

ticularly when several animals are kept in the same room or when an

animal must be confined in a kennel or cage. Regardless of the type of

housing used, every animal must be able to:

Stand up, sit down and lie down comfortably.

Stretch fully from tip of front toes to back toes.

Carry her tail in normal carriage (for cats and certain breeds of

dogs, that means having the tail fully extended).

Engage in normal sleeping, eating/drinking and urinating/defecat

-

ing behaviors (most animals prefer not to eliminate near where

they eat and sleep, so allowing sufficient space to distinguish a

“potty area” is important).

Assume normal posture when sleeping, eating/drinking and

urinating/ defecating.

See out of the enclosure, but also avoid being seen.

With respect to dogs, there are no hard-and-fast rules about ken-

nel dimensions because there is so much variation in size among

breeds—what is essentially a palatial kennel for a Chihuahua can be

cruelly small for a Saint Bernard or Great Dane. Therefore, when

determining the appropriate enclosure for dogs in your care, use

the rules of thumb above as your guide. Does each dog have enough

room to stand up, sit down, turn around and lie down comfortably?

Can the animal establish a potty area sufficiently far away from the