NORTH CAROLINA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE

Office of Archives and History

Department of Cultural Resources

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Burlington, Alamance County, AM2021, Listed 05/02/2016

Nomination by Heather Fearnbach

Photographs by Heather Fearnbach, July 2015

Overall view

Building 16

NPS Form 10-900

OMB No. 10024-0018

(Oct. 1990)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Registration Form

This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box

or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For

functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place

additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all

items.

1. Name of Property

historic name

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

other names/site number

A. M. Johnson Rayon Company, Carolina Rayon Company, Fairchild Engine and

Airplane Corporation, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company

2. Location

street & number

204 Graham-Hopedale Road

N/A not for publication

city or town

Burlington

N/A vicinity

state

North Carolina

code

NC

county

Alamance

code

001

zip code

27217

3. State/Federal Agency Certification

As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination

request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of

Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property

meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally

statewide locally. (See continuation sheet for additional comments.)

Signature of certifying official/Title Date

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources

State or Federal agency and bureau

In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. ( See Continuation sheet

for additional comments.)

Signature of certifying official/Title Date

State or Federal agency and bureau

4. National Park Service Certification

I hereby certify that the property is:

entered in the National Register.

See continuation sheet

Signature of the Keeper

Date of Action

determined eligible for the

National Register.

See continuation sheet

determined not eligible for the

National Register.

removed from the National

Register.

other,(explain:)

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Name of Property

County and State

5. Classification

Ownership of Property

Category of Property

Number of Resources within Property

(Check as many boxes as

apply)

(Check only one box)

(Do not include previously listed resources in count.)

private

building(s)

Contributing

Noncontributing

public-local

district

public-State

site

10 5

buildings

public-Federal

structure

0 0

sites

object

3 0

structures

0 0

objects

13 5

Total

Name of related multiple property listing

Number of Contributing resources previously listed

(Enter “N/A” if property is not part of a multiple property listing.)

in the National Register

N/A

N/A

6. Function or Use

Historic Functions

Current Functions

(Enter categories from instructions)

(Enter categories from instructions)

INDUSTRY: Manufacturing Facility

VACANT: Not in use

INDUSTRY: Industrial Storage

VACANT: Not in use

7. Description

Architectural Classification

Materials

(Enter categories from instructions)

(Enter categories from instructions)

Other: Steel-framed, load-bearing-brick-wall mill

foundation

BRICK

construction

walls

BRICK

Other: Reinforced-concrete construction

CONCRETE

METAL

roof

METAL

RUBBER

other

Narrative Description

(Describe the historic and current condition of the property on one or more continuation sheets.)

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Name of Property

County and State

8. Statement of Significance

Applicable National Register Criteria

Areas of Significance

(Mark “x” in one or more boxes for the criteria qualifying the property

(Enter categories from instructions)

for National Register listing.)

A Property is associated with events that have made

Architecture

a significant contribution to the broad patterns of

Industry

our history.

B Property is associated with the lives of persons

significant in our past.

C Property embodies the distinctive characteristics

of a type, period, or method of construction or

represents the work of a master, or possesses

high artistic values, or represents a significant and

distinguishable entity whose components lack

Period of Significance

individual distinction.

1943-1966

D Property has yielded, or is likely to yield,

information important in prehistory or history.

Criteria Considerations

Significant Dates

(Mark “x” in all the boxes that apply.)

1943, 1951, 1952, 1958, 1959

Property is:

A owned by a religious institution or used for

religious purposes.

Significant Person

B removed from its original location.

(Complete if Criterion B is marked)

N/A

C a birthplace or grave.

Cultural Affiliation

D a cemetery.

N/A

E a reconstructed building, object, or structure.

Architect/Builder

F a commemorative property

Albert Kahn Associated Architects and Engineers, Inc.

Western Electric Company’s Factory Planning and Plant

G less than 50 years of age or achieved significance

Engineering Department

within the past 50 years.

Six Associates, Inc., architects

Narrative Statement of Significance

(Explain the significance of the property on one or more continuation sheets.)

9. Major Bibliographical References

Bibliography

(Cite the books, articles, and other sources used in preparing this form on one or more continuation sheets.)

Previous documentation on file (NPS):

Primary location of additional data:

preliminary determination of individual listing (36

State Historic Preservation Office

CFR 67) has been requested

Other State Agency

previously listed in the National Register

Federal Agency

Previously determined eligible by the National

Local Government

Register

University

designated a National Historic Landmark

Other

recorded by Historic American Buildings Survey

Name of repository: Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

#

May Memorial Library, Burlington

recorded by Historic American Engineering Record

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Name of Property

County and State

10. Geographical Data

Acreage of Property

22.04 acres

See Latitude/Longitude coordinates continuation sheet.

UTM References

(Place additional UTM references on a continuation sheet.)

1

3

Zone

Easting

Northing

Zone

Easting

Northing

2

4

See continuation sheet

Verbal Boundary Description

(Describe the boundaries of the property on a continuation sheet.)

Boundary Justification

(Explain why the boundaries were selected on a continuation sheet.)

11. Form Prepared By

name/title

Heather Fearnbach

organization

Fearnbach History Services, Inc.

date

8/15/2015

street & number

3334 Nottingham Road

telephone

336-765-2661

city or town

Winston-Salem

state

NC

zip code

27104

Additional Documentation

Submit the following items with the completed form:

Continuation Sheets

Maps

A USGS map (7.5 or 15 minute series) indicating the property’s location

A Sketch map for historic districts and properties having large acreage or numerous resources.

Photographs

Representative black and white photographs of the property.

Additional items

(Check with the SHPO or FPO for any additional items.)

Property Owner

(Complete this item at the request of SHPO or FPO.)

name

Donnie Neuenberger, Saucier, Inc.

street & number

5415 Chand Creek Road

telephone

301-440-8136

city or town

Tallassee

state

AL

zip code

36078

Paperwork Reduction Act Statement: This information is being collected for applications to the National Register of Historic Places to nominate

properties for listing or determine eligibility for listing, to list properties, and to amend existing listing. Response to this request is required to obtain

a benefit in accordance with the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended (16 U.S.C. 470 et seq.)

Estimated Burden Statement: Public reporting burden for this form is estimated to average 18.1 hours per response including time for reviewing

instructions, gathering and maintaining data, and completing and reviewing the form. Direct comments regarding this burden estimate or any

aspect of this form to the Chief, Administrative Services Division, National Park Service, P. O. Box 37127, Washington, DC 20013-7127; and the

Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reductions Projects (1024-0018), Washington, DC 20303.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

1

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Section 7. Narrative Description

Setting

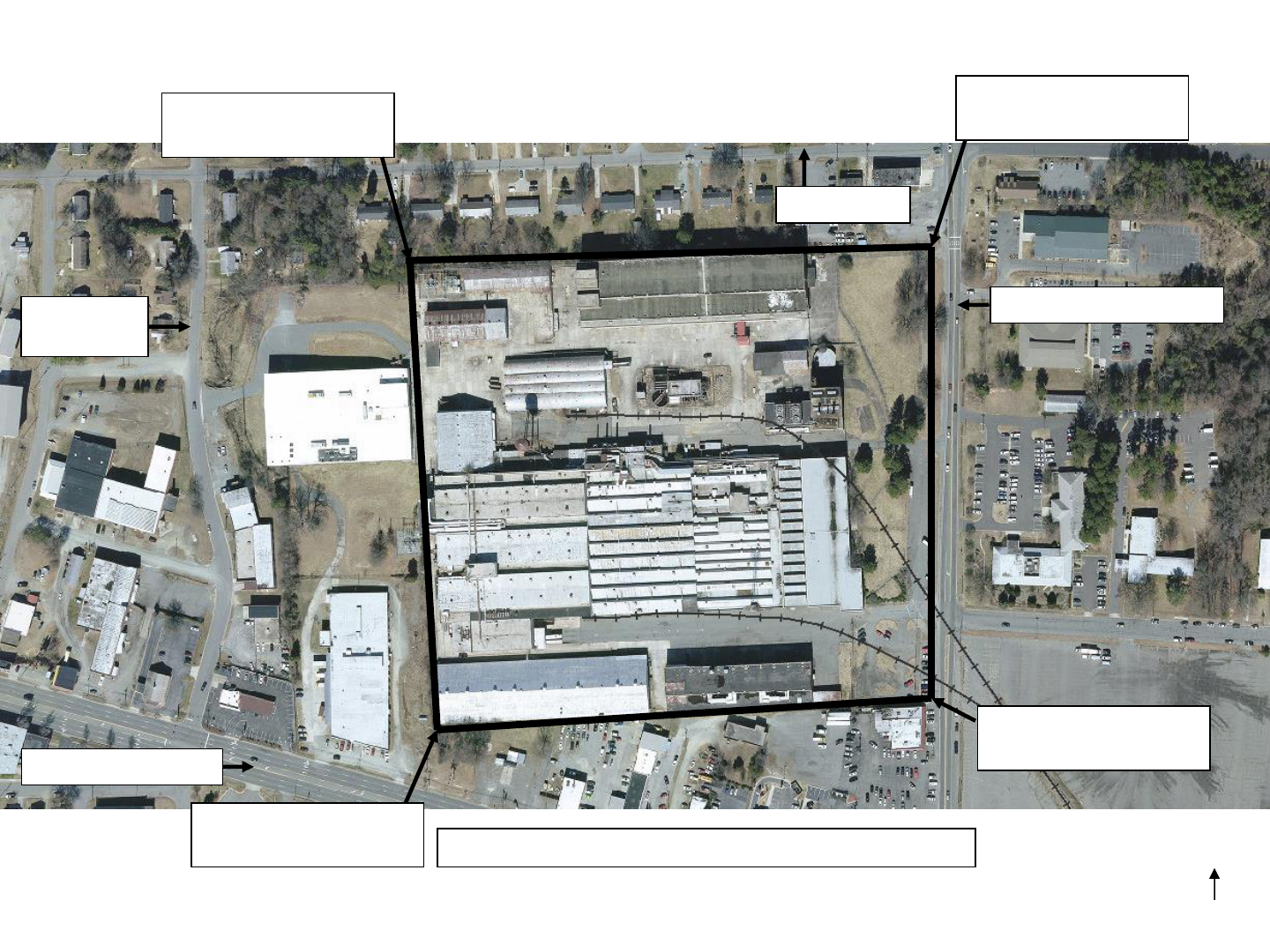

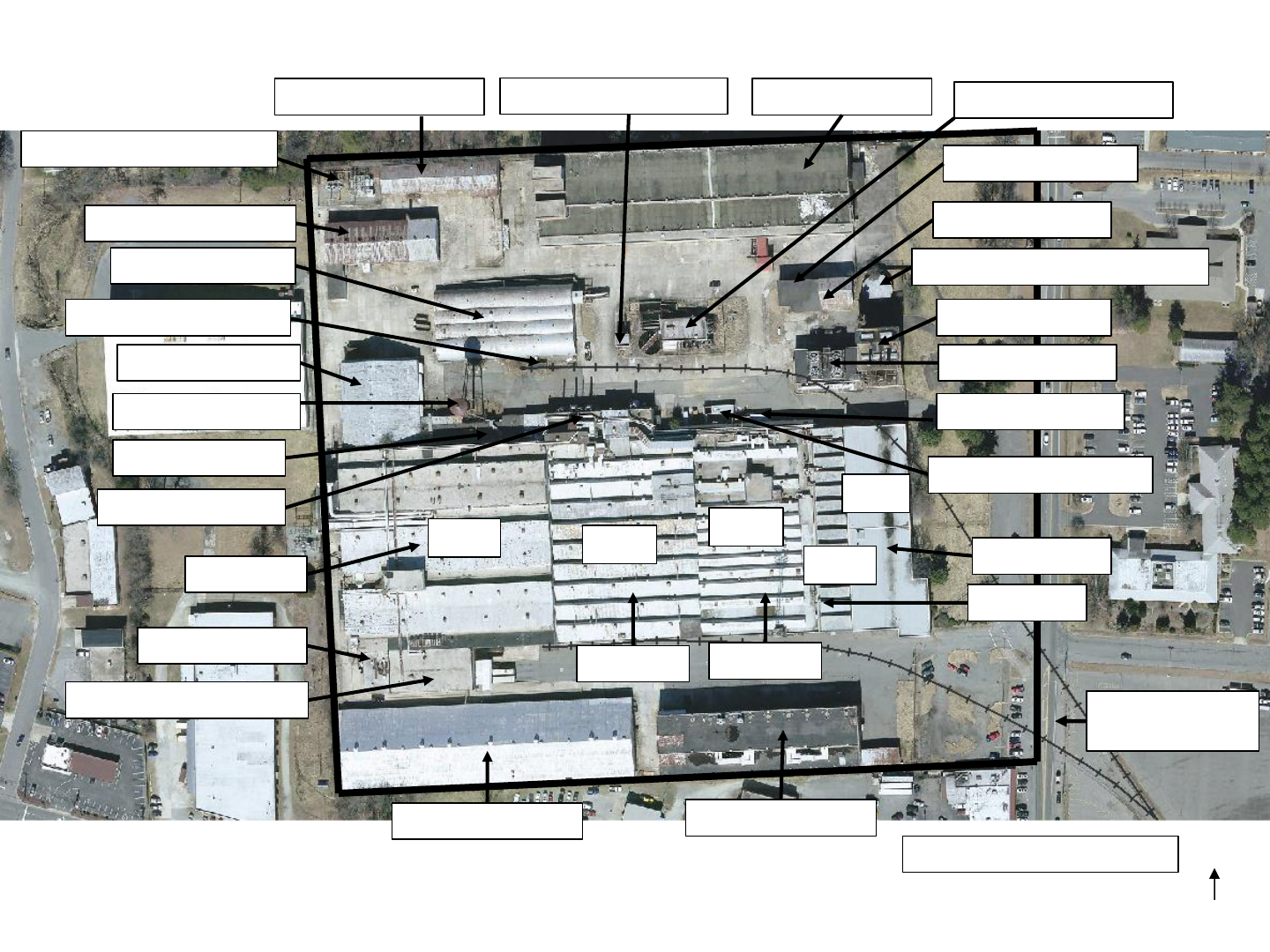

The Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant is located at 204 Graham-Hopedale

Road approximately two miles east of downtown Burlington’s commercial district. The industrial

complex occupies a nearly square, predominately flat, 22.04-acre parcel on the road’s west side. A tall

chain-link fence bounds most of the tract. Within the fence, the site is paved with asphalt and concrete.

Much of the concrete paving was installed in 1959 in order to facilitate radar trailer testing.

The tract’s east section, approximately one-sixth of the parcel adjacent to Graham-Hopedale Road, is

not fenced-in. This linear area contains a grass lawn, deciduous and evergreen trees, and landscaped

beds in its north two-thirds. Foundation plantings line the office (Building 1-A) façade. An asphalt-

paved parking lot occupies the east third of the area between the office and the road. A second asphalt-

paved parking lot fills the parcel’s southeast corner.

The industrial complex encompasses fifteen one- to three-story brick, steel, and concrete buildings

constructed between 1928 and 1978. In order to facilitate the property’s management, Western Electric

assigned each building a number.

1

The largest edifice, which evolved in stages to span most of the

site’s central section, comprises the interconnected brick, steel, and concrete Buildings 1-4, 9-11, 17,

20, and 28. Several relatively small structures are situated between this building and the expansive

three-story brick and concrete Building 16 at the center of the complex’s north end. North of Building

1-A, the power plant (Building 5) and its later addition to the west (Building 18) abut each other. North

of Building 18, Buildings 6 and 19, which served as storage and a garage, are also contiguous. A

tractor shed (Building 21) and the adjacent reservoir are located north of Building 5 and east of

Building 6 in the complex’s northeast quadrant. The site’s primary industrial waste treatment plant

(Buildings 29 and 30) is at the north section’s center. A smaller waste treatment plant (Building 23) is

located to the west, south of Building 12. Four one-story steel-frame structures sheathed with

corrugated-metal panels (Buildings 7, 12, 22, and 31), an electrical substation, and a water tower

occupy the lot’s northwest quandrant. Building 14, a long, one-story, metal-sided warehouse, fills the

complex’s southwest corner. The two-story brick and concrete Building 13 stands to its east.

Two railroad spur lines served the plant, running east-west on the central building’s north and south

sides. Both have been removed.

1

Small wall-mounted interior plaques delineate some building numbers, but a site plan issued by AT&T

Technologies, Inc.’s Plant Engineering Department on October 24, 1989, serves as the most comprehensive primary source

of building numbers.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

2

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Graham-Hopedale Road, flanked in this area by commercial and institutional development, runs north-

south on the tract’s east edge. Immediately south of the Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army

Missile Plant, parcels fronting North Church Street contain predominately mid-twentieth-century

commercial buildings and associated parking lots. To the north, modest mid-twentieth-century

residences, most erected in 1947 to provide housing for Western Electric Company employees, face

Hilton Road.

On the property’s west side, a tall chain-link fence separates several buildings once utilized by Western

Electric from the primary complex. These industrial and commercial buildings are situated on the east

side of North Cobb Avenue. The former Full-Knit Hosiery Mill, constructed in 1938, stands west of

Building 14. Western Electric and AT&T Technologies occupied the structure from around 1960 until

1991, calling it Building 24. The 1938 mill currently houses Good Samaritan Super Thrift Store. The

lot’s grade is lower in elevation than that of the Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile

Plant. The small, rectangular Buildings 25 and 26, both of which have been modified, are northwest of

Building 24. Western Electric also erected two small square structures, one of which was Building 27,

northeast of Building 24. The company constructed the large metal-sheathed building to the north in

1987. The structure now serves as a warehouse. These buildings are not included in the National

Register boundary due to their physical separation from the main complex, ancillary function, and/or

construction after the period of significance.

The inventory list is organized in ascending building number order. As a few of the resources once

encompassed in the complex have been demolished or are located outside the National Register

boundary, the number sequence is not continuous.

Buildings 1-4, 9-11, 17, 20, 28: A. M. Johnson Rayon Mill and Fairchild Engine and Airplane

Corporation and Western Electric Company Additions, 1928, 1930, 1943, 1959, 1970,

Contributing Building

The 1928 rayon mill (Building 2) and later additions to the east and west are physically linked, creating

one building containing approximately 252,000 square feet at ground level. The following description

addresses each section by Western Electric’s numbering system, which begins at the building’s east

end and moves west.

Western Electric Office and Cafeteria Addition (Building 1-A), 1970

Western Electric’s approximately 40,000-square-foot, two-story, flat-roofed office and cafeteria

addition stands on the east side of the 1943 office wing (Building 1). Masons executed the orange brick

walls in running bond capped with cast-stone coping that extends slightly beyond the wall plane. The

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

3

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

projecting block at Building 1-A’s southeast corner features a second story that is cantilevered above

the primary office entrance and supported by square reinforced-concrete columns that are slightly inset

beneath a cast-stone band and matching ceiling panels. Recessed aluminum-frame plate-glass windows

and brick kneewalls enclose the corner block’s southeast first-story room, which has an auxiliary

aluminum-frame double-leaf glazed door on its south wall. To the north, on the east elevation, brick

walls flank the aluminum-frame plate-glass curtain wall from which the primary entrance vestibule

projects. The adjacent open space is paved with concrete. Eight tall, rectangular, second-story window

openings pierce the corner block’s south elevation. West of the corner block, a windowless wall that is

in the same plane as Building 1 contains one single-leaf steel door.

The recessed entrance bay near the east elevation’s center contains two aluminum-frame double-leaf

glazed doors and transoms. In the eight flanking first-story bays, two high, rectangular, tinted-glass

windows span the distance between two tall, narrow, tinted-glass windows, framing sections of brick

wall. The second story is blind.

The same treatment continues on the east bay of Building 1-A’s north elevation. The remainder of the

north wall is windowless. A double-run of below-grade concrete steps with metal-pipe railings leads to

a concrete-paved area outside the double-leaf steel basement door in the east bay. Metal-pipe and wire-

mesh railings top the formed-concrete retaining wall that ameliorates the stairwell’s lower elevation.

To the west, a straight run of concrete steps with metal-pipe railings rises to a single-leaf steel door.

Interior

On Building 1-A’s first floor, a wide, central, east-west corridor separates the south section, which

encompasses offices, from the north section, which contains the expansive cafeteria’s serving and

dining areas. In the south section, the large north room adjacent to the corridor contained central

cubicles. Gypsum-board-sheathed partition walls create four offices at the room’s southeast corner as

well as rooms to the south that flank short north-south and east-west corridors. Many rooms have steel-

frame single-leaf wood doors with glazed upper sections. Dropped aluminum-frame ceilings and

fluorescent lighting panels remain, but acoustical ceiling tiles and vinyl-composition-tile floors have

been removed.

Orange brick sheathes the central corridor walls. To the north, the cafeteria’s square-concrete-

masonry-unit exterior walls are painted, while gypsum board covers some interior walls. In the kitchen

(which occupies Building 1’s north section) and serving line, walls are painted concrete block and

gypsum board and floors are ceramic tile. The accordion partition wall at the cafeteria’s southwest

corner could be closed to create a more private dining venue.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

4

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Stair halls at Building 1-A’a northwest and southwest corners contain steel and concrete steps with

metal-pipe railings that lead to the second story. Identical steps rise from the central corridor’s west

end adjacent to a passenger elevator. Much of the upper floor has an open plan designed to

accommodate office cubicles, although small rooms enclosed with gypsum board and aluminum-frame

curtain walls line the north and east elevations. Several private offices and the conference room within

the projecting corner block at the building’s southeast corner are the sole second-story rooms with

windows.

Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation Office Addition (Building 1), 1943

Only the north and south walls of the one-story, red brick office wing designed by the Detroit

architecture firm Albert Kahn Associated Architects and Engineers, Inc., remain visible from the

exterior. Masons executed the addition in five-to-one common bond. The sawtooth roof monitors

comprise a sloped south face and an almost-vertical north face with bands of tall, multipane, steel-

frame sash.

Historic photographs illustrate that a pent hood sheltered eight windows on the south elevation, all of

which have been enclosed with brick. Western Electric added two entrances: a mid-twentieth-century

double-leaf steel door with a flat-roofed steel canopy, and a late-twentieth-century, double-leaf,

aluminum-frame, glazed door and transom.

Building 1’s east elevation originally featured a long row of windows sheltered by a pent hood as well

as a five-bay-wide and three-bay-deep entrance vestibule at its center. The flat-roofed concrete

structure’s large double-hung windows and double-leaf door and transom were set in slightly recessed

panels beneath a projecting cornice.

2

Western Electric removed the entrance vestibule to facilitate the

1970 construction of Building 1-A. The 1970 addition also entailed the demolition of the north half of

the Building 1’s east wall to allow Building 1’s north section to be renovated to serve as the cafeteria

kitchen.

On the north elevation, which is blind, original and later window and door openings have been

enclosed with brick. The brick wall rises above a painted concrete foundation.

Interior

In Building 1’s north section, the sawtooth roof’s riveted structural-steel trusses are visible. The

building’s narrow width and the double truss system’s strength allowed the architects to dispense with

2

Undated Western Electric photographs in the Raymond Donnell Collection, May Memorial Library, Burlington;

Burlington Chamber of Commerce, “Burlington, North Carolina: An Industrial Summary,” 1952.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

5

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

interior support columns. When the north half of Building 1’s east wall was removed to allow for

connectivity between the kitchen and cafeteria, engineers added supplementary horizontal trusses to

carry the load.

A central east-west corridor bisects Building 1’s north dining room and kitchen and south offices and

infirmary. In the dining room, located immediately north of the corridor, three north-south accordion

partition walls could be opened or closed as needed to create rooms of various sizes. The vinyl-

composition-tile floors have been removed, exposing the poured concrete slab. The ceiling is open to

the sawtooth roof. A short north-south corridor west of the dining room provides access to storage

rooms and the kitchen, where walls are painted concrete block and gypsum board and floors are

ceramic tile.

At the central corridor’s east end, a north-south hall spans the south section’s full length. The south

section’s north half, which functioned as the purchasing office, contains a large room with small

offices lining the north, west, and south walls. The south section’s south half, which housed the

infirmary, has a central north-south corridor flanked by exam rooms and offices. The south section

retains painted gypsum board walls and dropped aluminum-frame ceilings with fluorescent lighting,

but the vinyl-composition-tile floors have been removed.

A. M. Johnson Rayon Mill (Buildings 2-3), 1928, 1930

The one-story 1928 rayon mill (Building 2) is surrounded on three sides by later additions, with only

its seventeen-bay-wide south elevation retaining exterior exposure. The original north wall is intact,

but only visible from the interior as it is spanned by a narrow full-width addition that projects to the

north. Masons executed the brick walls in a distinctive common bond with five courses of stretchers

followed by one course of alternating stretchers and headers. Terra-cotta coping caps the flat parapet.

Decorative corbelling tops tall, wide window and door openings. Paired fifteen-pane steel-frame sash

with operable six-pane lower sections have been painted but are otherwise intact on the north and south

elevations. The concrete window sills are also painted. The door openings in the sixth and twelfth bays

from the east end have been fully enclosed with brick. The fifth bay from the east end contains a

replacement single-leaf steel door with a glazed upper section sheltered by a flat metal canopy. The

remainder of the original opening is filled with brick.

A straight run of steel steps with metal-pipe railings rises above the door to the single-leaf entrance on

the east elevation of the one-story, flat-roofed, windowless, brick control room at the base of the one-

hundred-foot-tall signal tower. Steel lattice columns and Building 2’s south wall support the steel

platform on which the control room rests. Slender riveted-steel members comprise the tower’s frame,

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

6

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

which narrows as it increases in height. The tower transmitted radio signals to portable radar antennae

testing areas on Building 16’s upper and lower roofs.

The eighteen-bay-wide 1930 addition (Building 3) to the west is slightly taller, and thus has larger

window openings. Paired twenty-one-pane steel-frame sash with operable six-pane lower sections

illuminated the interior. The glass has been painted, but peeling paint allows for some light penetration.

In the fourth bay from the east end, a matching two-part, twenty-four-pane, steel-frame transom

surmounts a replacement single-leaf steel door with a glazed upper section. A smaller fourteen-pane

transom tops the double-leaf steel door in the eighth bay from the west end.

Building 20, which housed a chemical plating operation, spans much of Building 3’s north elevation.

East of Building 20, mechanical equipment and loading docks extend along the north wall of Buildings

2 and 3. A few loading docks remain open, but most have been enclosed with metal panels. Pent roofs

project above some of the enclosed docks. Building 28, a metal-sheathed bottled gas storage facility, is

located near the east end of Building 2’s north wall. The mid-twentieth-century brick loading dock

addition that extends from Building 2’s northeast corner has a corrugated-metal roll-up service door as

well as a single-leaf steel door accessed by formed-concrete steps with a metal-pipe railing.

Sawtooth roof monitors comprising a sloped south face and an almost-vertical north face with bands of

tall windows serve the 1928 and 1930 buildings. Riveted structural-steel trusses bear the sawtooth roof

system’s weight. Most of the wood roof decking and multipane steel-frame sash and tempered-glass

panes are intact, but the windows were covered from the outside with metal panels in the 1980s.

Interior

Building 2’s load-bearing brick west exterior wall separates Buildings 2 and 3. The January 1929

Sanborn map indicates that during the rayon mill’s operation Building 2 comprised offices, an ice

plant, and inspection, shredding, grinding, aging, spinning, silk washing, reeling, drying, and caustic

soda rooms. As Building 3 was in the planning phase at the time of the map’s creation, the interior is

depicted as open with the exception of an air conditioning room in its northeast section.

3

In 1946, Western Electric utilized Building 2 as a cabinet shop where employees fitted metal cabinets

with gear for radar trailers. Building 3 functioned as a machine shop with a plating shop at its north

end. The company gradually subdivided portions of Building 2 and 3 with gypsum-board-sheathed

frame partition walls to create laboratories and offices of various sizes. The conference room at

Building 2’s southeast corner features plywood-sheathed wall cases that contain sliding wood boards

3

Sanborn Map Company, “Burlington, North Carolina,” Sheet 9, January 1929.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

7

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

utilized for project tracking purposes. Western Electric also installed dropped aluminum-frame ceilings

and fluorescent lighting panels that remain in some areas. In most spaces, acoustical ceiling tiles and

vinyl-composition-tile floors have been removed and the structural system is exposed.

Round iron posts initially supported the sawtooth roof trusses, sections of which are visible from the

interior. Some iron posts remain, but in many cases steel I-beams have either been added or have

replaced the original posts. The brick exterior walls are painted throughout. On the walls between

Buildings 1, 2, and 3, metal fire doors slide on steel tracks and are held open by weighted pulleys.

Wood-panel, vertical-board, or steel doors hang in some interior doorways. Concrete floors provide a

durable work surface. Fluorescent lights and sprinkler system pipes hang from the ceilings. Rigid metal

ductwork and sizable air handling units remain from the air conditioning systems configured for the

plant in 1963. Surface-mounted metal conduit houses electrical wiring.

Western Electric Addition (Building 20), 1958

The one-and-one-half-story, rectangular Building 20, has a structural-steel frame, stuccoed upper

walls, and brick lower walls with the exception of a wide concrete-block wall that supports a roof

monitor of equal size. Paired fifteen-pane steel-frame sash with operable six-pane lower sections pierce

the monitor’s frame walls. On the north elevation, a straight run of steel steps with metal-pipe railings

rises on the concrete-block bay to the single-leaf steel door that provides exterior access to the

mezzanine. Building 20 included a plating room with a powerful ventilation system that expelled

exhaust into the fiberglass scrubbers with tall circular stacks that are secured to the north wall by metal

braces.

The structural system is completely exposed on the single-room interior, which is open to the monitor

roof and has a concrete slab floor. The walls are painted. Steel I-beams support an equipment

mezzanine with steel-grate floor panels. A frame addition with a slightly lower ceiling height extends

the monitor to the south.

Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation Manufacturing Additions (Building 4), 1943, and

(Building 11), 1943

Detroit architect Albert Kahn’s firm designed Building 4, the expansive two-story steel-frame

structure with brick and concrete walls that extends from the 1930 mill’s west elevation. Two bands of

windows, one just above door transom height and the other a few feet higher, span the south elevation.

Each steel-frame window section contains six large rectangular panes. Beneath the lower band, which

has a concrete sill, masons laid the brick wall in alternating header and stretcher courses. The walls

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

8

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

between the window rows and above the top tier of windows are stuccoed. Gunite panels have been

installed in a reversible manner on the window exteriors. Metal coping caps the flat parapet.

A flat-roofed steel canopy supported by three round steel posts shelters the entrance at Building 4’s

southeast corner. Two aluminum-frame glazed doors flank a central double-leaf door. Insulation panels

cover the sidelights and transom.

Building 9, erected in 1959, and Building 10, an open 1943 structure enclosed in the 1950s, project

from the west section of Building 4’s south elevation. However, the original wall and windows are

intact and visible from inside Building 10. Building 4’s southwest corner remains exposed and a tall,

wide, sliding, steel door encloses the service bay that fills much of the south wall. A double run of steel

steps with metal-pipe railings rises above the service bay to a single-leaf steel door that provides access

to the second story.

Building 4’s north and west elevations are identical to the south elevation in terms of fenestration and

wall composition. However, the west elevation extends above two-story height as the upper section is

stepped to create end walls for three wide roof monitors with vertical north and south faces containing

bands of steel-frame windows. Most glass panes are intact, but the windows have been covered from

the outside with metal siding. Metal-pipe railings mounted on the lower roof parapet adjacent to the

monitors secure the rooftop. Western Electric installed air handling equipment on the roof around

1970.

HVAC equipment lines the west elevation, flanking several single and double-leaf steel doors. A flat-

roofed, corrugated-metal-sheathed, rectangular, 1970s addition projects from the wall at the second-

story level. Rooftop air handlers served a clean room in Building 4. A riveted structural-steel frame

supports the addition.

Building 17, erected in 1952, extends from the west section of Building 4’s north elevation. To the

east, a narrow, one-story, flat-roofed, brick, 1943 structure (Building 11) contains several mechanical

rooms. A one-story, flat-roofed, corrugated-metal-sheathed, circa 1953 loading dock addition extends

from Building 11’s east side.

Interior

Although Building 4’s exterior walls have two tiers of windows, most of the interior was originally one

level open to the roof monitors to allow for ample light and airplane assembly. The structure manifests

characteristics of the standard landplane hangar design developed by Albert Kahn’s firm during World

War II. Steel I-beams, round steel columns, and steel trusses are exposed throughout. An overhead

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

9

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

bridge crane system lifted heavy aircraft components and the building’s poured concrete floor provided

a durable work surface.

Western Electric added painted concrete block and gypsum-board-sheathed partition walls at ground

level and created a steel-frame mezzanine adjacent to the south, west, and north walls to provide

additional offices and laboratories. Plate-glass windows in interior walls illuminate these spaces.

Single-leaf wood and steel doors and roll-up and sliding metal doors secure various rooms. Several sets

of steel steps with metal-pipe railings lead to the mezzanine.

Around 1960, Western Electric added the sprinkler system and dropped aluminum-frame ceilings with

acoustical tiles and fluorescent lighting panels. The acoustical tiles have been removed, as have the

vinyl-composition tiles that covered the concrete floors. Rigid metal ductwork and sizable air handling

units remain from the air conditioning systems configured for the plant in 1963.

At Building 4’s northeast corner, a narrow 1959 entrance bay spans the distance between Building 11,

which extends from the east section of Building 4’s north elevation, and Building 20 on Building 3’s

north elevation. An aluminum-frame clerestory window with large rectangular panes spans the wall

above the double-leaf, steel-frame, glazed door at its center. Square turquoise tile wainscoting sheathes

the walls of the entrance vestibule and a short corridor. Four steps ameliorate the change in grade. The

floor is turquoise terrazzo. Restrooms added in 1959 also have turquoise tile wainscoting.

Two sets of wide concrete stairs with steel treads and metal-pipe railings provide access to the

basement under Building 4’s east third: one at the east wall’s center and one at the building’s southeast

corner. The basement’s south end contains an office-lined corridor with faux-wood-paneled walls on

one side and gypsum-board-sheathed walls on the other. In the large open room in the basement’s

north section, originally a cafeteria, the robust reinforced-concrete mushroom columns that support the

structure are visible. This level also had dropped aluminum-frame ceilings with acoustical tiles and

fluorescent lighting panels and vinyl-composition-tile floors. In the north room and the expansive

restrooms and locker rooms, yellow-glazed rectangular tile covers the walls.

Western Electric Addition (Building 9), 1959

The Army Corps of Engineers erected the windowless, one-and-one-half-story, running-bond red brick

addition south of Building 4 and west of Building 10 to provide additional service bays. The west

elevation contains two corrugated-metal roll-up service doors. Two single-leaf steel doors with glazed

upper sections provide interior access north of the service doors, and a matching door pierces the

structure’s canted southwest corner. The south elevation is blind. A riveted structural-steel frame

supports the building, which is divided into two large rooms on each level.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

10

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation Addition (Building 10), 1943, 1950s

The flat-roofed, five-bay-wide and nine-bay-long, steel and brick Building 10 extends from Building

4’s south elevation. Although the walls rise to a two-story height, the interior is open to the ceiling.

Albert Kahn’s firm designed the original steel-frame structure, erected to accommodate the final stages

of airplane assembly and testing, which had a roof but no walls. In the 1950s, the Army Corps of

Engineers added brick curtain walls and two rows of translucent glass-block rectangular windows on

the east and south elevations, one just above service door height and the other a few feet higher. The

windows have concrete sills. Above the upper windows, corrugated metal siding sheathes the roof

system. The west elevation is blind. Metal coping caps the flat parapet.

A steel post-and-beam shed shelters the three-bay loading dock at Building 10’s southeast corner. The

loading dock’s steel structural system supports the steel-plate decking adjacent to the corrugated-metal

roll-up service doors. The east elevation also contains two single-leaf steel doors with glazed upper

sections near its northeast and southeast corners. Two corrugated-metal roll-up service doors in the

first and fifth bays from the south elevation’s east end provide additional access.

The interior is predominately open to the steel roof trusses and supported a bridge crane system. Steel

steps with a metal-pipe railing lead to an elevated steel mezzanine with a metal-pipe and wire mesh

railing at the building’s southwest corner, called the crow’s nest. Beneath the mezzanine, gypsum-

board-sheathed frame walls enclose a small corner room. A long, narrow, steel mechanical platform,

also at mezzanine level, occupies the northwest corner. Two doors on the west elevation provided

egress to Building 9’s two rooms, but the south opening has been enclosed. A door near the north

elevation’s west end facilitates access to Building 4.

Western Electric Trailer Loading Building (Building 17), 1952, Contributing Building

Building 17 projects north from the west end of Building 4’s north elevation. The proximity was

important to its function, as employees loaded radar trailers with equipment assembled in Building 4.

Corrugated metal panels sheath the one-story structure’s walls and its offset side-gable roof, which is

surmounted by six round ventilators. The roof’s east slope is two bays longer than its west slope. The

building has a poured-concrete foundation. Concrete pavement surrounds the structure, facilitating

access to multiple loading docks.

On the west elevation, two large, rectangular, sashless window openings flank a single-leaf steel door

accessed by concrete steps with a metal-pipe railing. At the wall’s center, a full-height, roll-up,

corrugated-metal service door and a standard-height, double-leaf, metal door provide interior access.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

11

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Four large, rectangular, sashless window openings pierce the wall’s west end above concrete steps that

lead down to the single-leaf steel basement door. A metal-pipe railing surrounds the stairwell.

A full-width, metal-shed-roofed canopy shelters ten loading dock openings on the north elevation.

Although all retain original doors that slide up on tracks mounted to framing posts, seven openings

have been enclosed with plywood. The doors originally comprised four rows of six glass panes, but all

but the second row from the top have been painted or filled with plywood. A flat-metal-roofed

equipment shed with a square steel post-and-beam frame and a concrete floor extends from the north

elevation’s west end. A chain-link fence secures the space.

Concrete steps with a metal-pipe railing rise to the single-leaf steel door at the east elevation’s north

end. At the wall’s center, a metal-shed-roofed canopy surmounts four twenty-four-pane service door

openings. To the south, a higher canopy shelters a tall thirty-pane door accessed by a concrete ramp

with metal-pipe railings.

The riveted structural-steel frame, comprised of slender posts, beams, and closed-gable Pratt trusses, is

exposed on the interior. Batt insulation fills the space between posts. The interior has an open plan and

poured-concrete floors. Fluorescent lights, sprinkler system pipes, and ventilation ductwork have been

dropped from the exposed steel roof system. A concrete ramp leads to the raised concrete platform that

wraps around the north and east elevations adjacent to the loading dock bays. The platform continues

along the south elevation, but has been enclosed with gypsum-board-sheathed frame walls containing a

metal-lined storage vault. Metal panels were also used to create secured second-story offices accessible

from Building 4’s north balcony. An opening in the south wall provides access into Building 4 through

a double-leaf steel door. A sliding corrugated-metal door mounted on the exterior wall further secures

the entrance.

Power Plant (Building 5), 1943, and Chiller Room (Building 18), 1960, Contributing Building

The power plant (Building 5) and the adjacent chiller room (Building 18) stand north of the 1970

office building’s (Building 1-A) north end.

Albert Kahn’s firm prepared plans for the 1943 power plant. The three-bay-wide and three-bay-deep

building has a stepped roof with three flat levels that gradually increase in height from the one-story

south bay to the three-story north bay. Masons executed brick walls in five-to-one common bond

capped with metal coping that extends slightly beyond the wall plane.

On the one-story south section’s south elevation, two high, long, horizontal recessed panels flank a

corrugated-metal roll-up service door. The east elevation contains an identical panel. To the north, the

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

12

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

east elevation of the power plant’s central two-story section featured three tall, narrow, recessed

panels. The three-story north section’s east elevation has always been blind. Its north elevation

contains four tall, narrow, recessed panels and a central double-leaf wood door with glazed upper

sections. The recessed panels may have initially contained windows. However, the brick color and

bond is identical to the surrounding walls and informants familiar with the property beginning in 1950

do not remember windows in this building.

Interior access was not possible. However, according to a 1974 electric power plan drawn by Western

Electric Company’s Factory Planning and Plant Engineering Department, the interior was open with

the exception of a frame-walled workshop at its northwest corner. The building housed three boilers

and a series of air compressors, pumps, tanks, and sprinkler system equipment. The upper levels

originally served as coal storage bunkers. A railroad spur line facilitated coal delivery until the 1959

conversion of the boilers to natural gas.

A tall concrete platform with square posts extends from Building 5’s northwest corner to support an

elevated terra-cotta block ash silo. A steel ladder and walkway allow access to the top of the silo.

The one-story, rectangular, flat-roofed Building 18 projects from Building 5’s west elevation.

Corrugated metal siding sheathes the steel I-beam frame. The north elevation features two tall,

corrugated-metal, roll-up service doors. A single-leaf steel door near the east elevation’s north end

provides interior access. South of the entrance, steel steps with metal-pipe railings rise in two straight

runs with a central landing to the flat roof, where two sizable air-conditioning water towers are located.

Two small square louvered vents pierce the south elevation. Electrical boxes and equipment related to

the power plant’s operation line the south wall.

The open, concrete-floored interior contained four water chillers, all of which have been removed. Six

double-pipe pumps remain near the building’s west wall. Additional equipment occupies the room’s

east end.

Western Electric Storage Building (Building 6), 1943, and Fuel Building/Garage (Building 19),

1958, Two Contributing Buildings

The 1943 storage facility (Building 6) and the adjacent 1950s oil and lubricants storage building and

garage (Building 19) stand north of Buildings 5 and 18 in the complex’s northeast section. The

structures have an east-west alignment.

Building 6, a one-and-one-half-story, side-gable-roofed structure sheathed with corrugated-metal wall

and roof panels, is elevated on a formed-concrete foundation. A one-story, flat-roofed, one-bay-deep

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

13

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

shed extends across the south elevation. A sliding corrugated-metal door with a rectangular six-pane

window in its upper section secures the wide door openings on the shed’s south elevation. Inside the

shed, an identical door is mounted at the entrance to the main block.

Four twenty-five-pane steel-frame windows with central six-pane hoppers pierce the north elevation.

The east elevation contains three matching first-story windows of the same size and two smaller,

similar, gable windows that illuminate the mezzanine.

Steel posts and beams comprise the structural system, which is exposed on the interior. The building

has an open plan and a poured-concrete floor. Steel shelving units with a north-south orientation fill

the first floor and mezzanine. Steel steps with metal-pipe railings and a freight elevator lead to the

mezzanine. Plywood panels mounted on the north railing’s interior provide additional security. The

mezzanine floor consists of steel grates. Wide wood roof decking boards rest on steel trusses.

Building 19 is a two-story, flat-roofed, red-brick structure executed in five-to-one-common bond. A

deep, flat, concrete canopy shelters the elevated concrete loading dock that extends across most of the

south elevation. A sliding metal-clad door is mounted on an interior steel track above the wide central

loading bay. The single-leaf steel door to the east provides access to the upper-level storage room. The

west single-leaf steel door opens into the two-story-tall service bay at the building’s west end.

The north elevation contains a sliding metal-clad door mounted on an interior steel track above the east

workshop’s wide entrance. A central single-leaf steel door also provides access to the workshop. A tall,

corrugated-metal, roll-up service door fills much of the north wall’s west section. A single-leaf steel

door close to the west elevation’s northwest corner also opens into the service bay. The long,

horizontal window opening south of the door contains four twelve-pane steel-frame sash.

The reinforced-concrete and brick structure is exposed on the interior. Both levels have poured-

concrete floors and painted brick walls. In the second story’s single room, tall, deep, steel shelving

units are arranged in east-west rows. The ground-level workshop also has an open plan. In the service

bay, a steel ladder rises on the west wall to a mezzanine with a metal-pipe railing that spans the south

elevation. Fluorescent lights, sprinkler system pipes, and ventilation system ductwork have been

dropped from the ceilings. Round metal electrical conduit is mounted on the walls and ceilings.

Western Electric Paint Shed (Building 7), 1955, 1959, Contributing Building

The one-story, rectangular, side-gable roofed Building 7, which originally functioned as a painting

facility, stands near the complex’s northwest corner. The shed has an east-west orientation with the

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

14

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

primary entrances on the south elevation. Corrugated-metal panels sheath the walls and the roof topped

with eight round ventilators. The building rests on a poured-concrete foundation.

Four large, square, sashless window openings pierce the shed’s south elevation. Two original single-

leaf steel doors and one replacement double-leaf metal door provide interior access. At the building’s

east end, a 1959 addition with concrete-block interior partition walls contains three large spray-

painting bays secured by roll-up corrugated-metal service doors on the east elevation. A single-leaf

door near the north elevation’s east end opens into the north bay. To the west, five window openings

surround a standard-height, double-width door opening and a taller, wider opening secured by

enormous metal doors that slide on tracks mounted above the door opening. A concrete ramp with a

metal-pipe railing leads to the double-leaf metal door at the north elevation’s west end. The west

elevation contains a wide, rectangular, central window opening flanked by two square window

openings.

A single-bay concrete-block 1959 addition with a flat corrugated-metal roof extends from the shed’s

southwest corner. At its north end, a narrow concrete-block platform with a metal-pipe railing provides

elevated workspace. Employees washed radar trailers in this area before moving them to the shed’s

main block, where they were marked prior to being spray-painted and touched up as needed after

painting.

Slender steel columns, beams, and trusses comprise the shed’s structural system, which is mostly

exposed on the interior. The space has an open plan and poured-concrete floors. Gypsum board

sheathes the walls’ lower portions and the areas around doors. Above the finished areas, the batt

insulation that fills the space between posts is visible. Fluorescent lights, sprinkler system pipes, and

central rectangular ventilation ductwork have been dropped from the exposed steel truss roof system.

The storage room at the southwest corner, erected within the past few years, has partial-height frame

walls covered with particle board. On the east elevation, roll-up corrugated-metal service doors

provide access to the three spray-painting bays in the 1959 addition.

Western Electric Storage Building (Building 12), 1952, Contributing Building

Building 12 is located north of Buildings 3 and 4 in the complex’s northwest section. The one-story

rectangular building has an east-west orientation with entrances on the east and west elevations. The

structure served as the primary storage facility for large sections of metals that were cut to size for use

in the machine shop and in the assembly of wire harnesses, circuit boards, and other products. Its

Quonset hut form, developed by private contractors for the U. S. military to be easily expandable,

features four low-arch-roofed, steel-frame sections. The two outer sections are slightly wider as the

roof arc extends all the way to the poured-concrete foundation slab. Corrugated-metal panels sheath

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

15

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

the roof and walls. Round ventilators extend above the roof. Concrete pavement surrounds the

structure, facilitating access.

The north bay of the west elevation contains two square, sashless window openings and a tall double-

leaf service door that currently serves as the primary entrance. Two matching window openings pierce

the west walls of each of the remaining three bays. The south bay originally contained a door identical

to the one in the north bay, but the opening has been enclosed with corrugated-metal panels. Square,

central, louvered vents remain in the wall beneath each roof arch. A metal single-bar guard rail

mounted on a low concrete base wraps around the building’s southwest corner.

The east elevation is similar to the west, although the south bay retains a sliding metal door. The

double-leaf sliding metal door in the north bay is taller and wider, as it served the adjacent loading

dock. An open steel-frame structure with a partial flat metal roof and an overhead crane projects from

the north bay above the loading dock.

Square window openings—ten on the south elevation and nine on the north elevation—provide ample

light. A sliding single-leaf metal door in the fourth bay from the north elevation’s west end allows

interior access. A formed-concrete retaining wall topped with a metal-pipe railing extends along the

north elevation to ameliorate the change in grade, which slopes down to the north and east. A matching

retaining wall borders the north edge of the concrete ramp near the building’s northeast corner.

The structural system is exposed on the open interior. Steel columns mounted on the poured-concrete

floor support the arched steel roof structure. Foam insulation has been sprayed on the roof and exterior

walls. Full-height corrugated-metal panels serve as a two-bay-wide, north-south partition wall near the

northwest corner. Partial-height frame partition walls sheathed with gypsum board as well as thin

sheet-metal on the lower half create a small office adjacent to the north elevation near its east end.

Fluorescent lights and sprinkler system pipes hang from the roof system.

Full-height corrugated-metal panels enclose the building’s southeast corner. The room’s west wall

contains a tall, wide, sliding-metal, south door and a shorter, smaller, sliding-metal door to the north.

The north wall is offset, creating more depth at the room’s east end. Partial-height, gypsum-board-clad,

frame walls enclose a double-leaf entrance vestibule adjacent to the north wall as well as a small room

at the west wall’s south end. Batt insulation has been installed on the southeast room’s ceiling and

south wall.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

16

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

Western Electric Laboratory, Office, Assembly, and Radar Systems Testing Building (Building

13), 1952, Contributing Building

The large, rectangular, brick and reinforced-concrete Building 13 stands at the center of the complex’s

south end, immediately south of Building 2. The structure has an east-west orientation. Engineers

designed the four-bay-wide and eleven-bay-long building’s reinforced-concrete columns, beams, and

floor slabs to support heavy equipment and minimize vibration. The two-level stepped roof increases

in height from the one-and-one-half-story south bay to the two-story north bays. The upper and lower

roofs, served by two freight elevators, served as radar antennae trailer testing areas.

Masons executed the east elevation, which is the most visible from Graham-Hopedale Road, in

running-bond red brick above a painted formed-concrete kneewall. The north two bays are two stories

in height, while the south bay is one-and-one-half stories tall. Near the wall’s south end, a double-leaf

steel door with glazed upper sections provides access to the room at the building’s southeast corner.

The entrance occupies a portion of what was originally one of two large service door openings.

At the east elevation’s center, a single-leaf steel door with glazed upper sections leads to the stair

vestibule. To the north, a flat-roofed metal canopy shelters the primary entrance: a replacement

aluminum-frame double-leaf glazed door and transom. The canopy is a later addition. The sizable,

horizontal, rectangular, window opening north of the entrance was enclosed with metal panels in the

1980s, as were the two second-story windows. Historic photographs illustrate that the original

windows are three-part, steel-frame, multipane sash. Each of the north window sections has eight

panes, while the second-story’s south window sections comprise twelve panes. The large letters

spelling “Western Electric” that were mounted to the wall between the first and second stories have

been removed.

An open three-bay equipment shed supported by square steel posts and beams extends from the east

elevation’s south bay. The concrete retaining wall that spans the shed’s south end includes two sets of

concrete steps. The chain-link fence that surrounds the complex is a few feet south of the retaining

wall.

In each of the north elevation’s eastern nine first-story bays, brick walls originally framed two roll-up

service doors. However, all of the loading dock openings have been enclosed with brick. Four narrow

steel doors with four-pane upper sections and one-double leaf steel door now provide interior access.

Steel steps with metal-pipe railings lead to steel landings at three entrances.

The two first-story bays at the north elevation’s west end and all eleven second-story bays on the north

elevation have concrete-block walls. The westernmost bay is blind at both levels. A pent aluminum

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

17

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

canopy shelters the steel platform that spans the two first-story bays. The second first-story bay from

the west end contains a two-part, sixteen-pane, steel-frame window and a high, short, metal-louvered

vent. Ten second-story bays featured bands of high windows that spanned the top of each bay. All have

been enclosed with metal panels.

The west elevation also has concrete-block walls. One tall original service door remains in the south

one-and-one-half-story bay. The wood-frame door is seven rows tall and eight rows wide. Wood

panels comprise most of the door sections, but the third row from the bottom contains glazed panes.

Roll-up metal grates secure the enormous freight elevators that occupy the west elevation’s two central

bays. Two single-leaf steel doors, one of which is slightly taller than the other, fill the north bay’s

south corner. The second-story’s north bay contains high windows, while the east bay is blind.

The one-and-one-half-story south elevation has high windows at the top of each concrete-block wall.

Near the elevation’s east and west ends, steel steps with metal-pipe railings rise in three straight runs

with central landings to the roof. Metal-pipe railings top the parapet.

Interior

Building 13 contained laboratory, office, and assembly space. The building’s exposed structure—

concrete-block partition walls and reinforced-concrete columns and beams—has been painted on the

interior. Most of the first floor’s west half is one large room. The south two bays are open to the one-

and-one-half-story ceiling height. In this section, steel catwalks provided elevated equipment access.

The north two bays are only one-story tall to allow for a full second story. Fluorescent lights, sprinkler

system pipes, and ductwork hang from the ceiling. Square vinyl-composition tiles originally covered

the concrete floor.

On the west room’s east side, concrete-block partition walls enclose a vault with a heavy steel door and

a mechanical room. In its north section, concrete-block partition walls separate two elevated, narrow

rooms adjacent to the north wall from a series of gypsum-board-sheathed frame partition walls that

enclose office and laboratory space. The elevated area originally served as the loading dock platform.

The northwest room retains electrical equipment. In the west elevation’s two central bays, the south

freight elevator rose to the low roof and the north elevator terminated at the high roof.

A central corridor divides the north two bays in the first floor’s east half. Offices and restrooms flank

the corridor. In the women’s restroom, oversized beige-glazed rectangular tiles sheath the restroom

walls. Most fixtures have been removed. Square peach-colored tiles cover the men’s restroom walls,

while the small square mosaic floor tiles are brown, peach, orange, and pale blue.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

18

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

In the 1980s, AT&T divided the east section’s south bay, once open like the building’s west half, into

two rooms, with the west room being much larger. Both had dropped aluminum-frame ceilings with

acoustical tiles and fluorescent lighting panels, but the acoustical tiles have been removed, as has the

floor covering, which exposed the concrete floors.

Steel stairs with formed-concrete railings topped with metal-pipe handrails provide access to the

second level from the building’s east and west ends. The west stair hall opens into a central east-west

corridor with large rooms on either side. The southwest room contained cubicles. In the southeast

room, cubicles lined the north elevation and gypsum-board partition walls enclose offices adjacent to

the south elevation. Gypsum-board partition walls also create offices flanking a central east-west

corridor in the northeast area.

A small steel passenger elevator and concrete steps near the building’s northeast corner lead to the one-

bay-wide basement under the structure’s north end. Additional steps at the building’s northwest corner

allow basement access from the west. Some equipment remains at the basement’s east and west ends.

Chain-link cages enclose central storage areas.

Western Electric Warehouse (Building 14), 1951, Contributing Building

Building 14 occupies the complex’s southwest corner. Corrugated metal panels sheath its one-story

walls and the side-gable roof, which is pierced by a central row of ventilators at the peak as well as a

later series of ventilators that are lower on each roof slope. The large rectangular building has an east-

west orientation and rests on a poured-concrete foundation. The structural-steel frame is twenty-one

bays long and three bays deep. Concrete pavement surrounds the north and east elevations, facilitating

access to service doors and loading docks. The tall chain-link fence that surrounds the parcel is only a

few feet from the structure’s south and west elevations.

At the east elevation’s center, a tall, wide, service-door opening has been infilled with corrugated-

metal siding and a standard-height, double-leaf steel door. The tall metal doors that slide on tracks

mounted above the original opening height are intact. To the north, a pair of eight-pane steel-frame

sash with central four-pane hoppers and a matching single sash illuminate the interior. The window

openings on the wall’s west end have been covered with plywood. Concrete steps with a metal-pipe

railing lead to the single-leaf steel door at the east elevation’s north end.

The north elevation’s three eastern bays project slightly beneath a shed roof to create a loading dock

with roll-up corrugated-metal doors that are elevated to allow truck access. The fourth bay from the

east end contains a grade-level, roll-up, corrugated-metal service door. Many eight-pane steel-frame

sash with central four-pane hoppers pierce the north elevation. Only a few have been covered with

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

19

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

plywood. A centrally-located single-leaf steel door, an adjacent modern roll-up service door, and a

sliding corrugated-metal service door near the building’s west end provide interior access.

The windows on the west and south elevations have been enclosed with interior insulation panels and

exterior plywood, but it appears that the metal-frame sash are intact. Two single-leaf steel doors near

the south elevation’s east end allow access to the building’s southeast room.

Interior

The riveted structural-steel frame, comprised of slender posts, beams, and closed-gable Pratt trusses, is

exposed on the interior. Batt insulation fills the space between posts. The majority of the interior is

open with poured-concrete floors. Gyspum-board-sheathed frame partition walls have been added to

create four sizable rooms and two small storage and mechanical rooms at the building’s east end, as

well as a series of rooms adjacent to the west wall. Fluorescent lights, sprinkler system pipes, and

ventilation ductwork, and fans hang from the exposed steel truss roof system.

In the northeast corner room, a raised concrete platform extends across the north elevation adjacent to

loading docks where employees received shipments. Gypsum-board-sheathed frame partition walls

with square windows enclose the space. A concrete ramp with a metal pipe and plywood-panel railing

leads to the platform. An open room of approximately equal size is to the west. In that space, the

dropped aluminum-frame ceiling system with acoustical tiles and fluorescent light panels has been

mostly removed.

In the 1980s, AT&T updated the large southeast room with gypsum-board sheathing that covers steel

posts and all walls, thus enclosing exterior windows. Single-leaf doors on the west wall lead to two

small mechanical and storage rooms. Wide openings in the north partition wall provide access to the

northeast rooms. The dropped aluminum-frame ceiling system with acoustical tiles and fluorescent

light panels has been partially removed. The southwest room is identical in finish.

The building’s center is open with the exception of a brick elevated service platform and a concrete

block hydraulic elevator tower in its northeast section. The steel truss roof system and two rows of

steel posts, one near the north wall and one close to the south wall, allow for an expansive interior

space free of structural impediments. The space initially contained two levels of steel warehouse

shelving. The mezzanine floor consisted of steel grates.

Gypsum-board-sheathed frame partition walls enclosed plant maintenance offices and restrooms

flanked by storage rooms adjacent to the west wall. A chain-link fence secures the storage mezzanine

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

20

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

above the offices. Round steel posts supported the mezzanine, which is accessed by a straight run of

steel steeps with metal-pipe railings.

Western Electric Laboratory, Office, Assembly, and Radar Systems Testing Building (Building

16), 1959, Contributing Building

The large, rectangular, brick and reinforced-concrete Building 16 stands at the center of the complex’s

north end. The six-bay-wide and thirty-one-bay-long structure has an east-west orientation, with

entrances on the east, south, and west elevations. Reinforced concrete caps the running-bond brick

walls. In order to accommodate rooftop testing, the building has three levels, with sections becoming

progressively taller and deeper moving north. The one-and-one-half-story south section is one bay

wide, the two-story central section is two bays wide, and the three-story north section is three bays

wide.

The stepped east elevation faces Graham-Hopedale Road. In the south bay’s upper section, a single-

leaf steel door provides access to steel steps with metal railings that rise to the second-story rooftop

testing area. The five south bays are blind. In the north bay, a four-part steel-frame window illuminates

each of the second and third stories.

A tall one-story, flat-roofed, brick entrance bay projects from the east elevation near its center. Deep

eaves shelter a single-leaf steel door with a glazed upper section and the roll-up corrugated-metal door

to the north. A shorter, narrower, flat-roofed, brick room extends from the north bay.

The one-and-one-half-story section’s south elevation has an exposed reinforced-concrete column-and-

beam frame filled with running-bond brick above the first story. Each bay’s upper section also contains

two rectangular metal-louvered vents and a central, wall-mounted, aluminum light fixture. Roll-up

corrugated-metal service doors originally filled the sixteen west and fourteen east bays. However,

Western Electric enclosed most openings with concrete block by 1990, leaving only five original roll-

up doors. In some bays, contractors added single- and double-leaf steel doors to provide interior

access. In the fifteenth bay from the east end, brick sheathes the wall above two original double-leaf

steel doors with glazed upper sections. The east door is wider. A concrete ramp and two-bay loading

dock platform with metal-pipe railings extends from the tenth bay from the east end.

Much of the north elevation is covered with ivy and obscured by other vegetation. A deep concrete cap

protects bands of four-part, steel-frame, second- and third-story windows. Each sash contains three

sections of two horizontal panes. The lower section is an operable hopper. Most windows are intact,

but many have been covered with insulation board from the inside.

NPS Form 10-900-a

OMB Approval No. 1024-0018

(8-86)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

National Register of Historic Places

Continuation Sheet

Section number

7

Page

21

Western Electric Company – Tarheel Army Missile Plant

Alamance County, NC

The west elevation has the same stepped configuration as the east elevation. A flat concrete canopy

projects above the five north bays at the first-story level, sheltering six entrances. A roll-up corrugated-

metal service door fills the north bay. Roll-up metal grates secure three enormous freight elevators.

The third bay from the south end contains a single-leaf steel door and a replacement double-leaf,

glazed, aluminum-frame door. The three-story north section’s north and south bays contain four-part

steel-frame windows, one at each of the second- and third-story levels. The south three bays are blind.

Two square metal-louvered vents pierce the two-story section’s upper wall. Steel steps with metal

railings rise from ground level to a landing outside the single-leaf steel door in the south bay’s upper

section. The stairs then turn and continue to the second-story rooftop testing area.

Two flat-roofed brick and reinforced-concrete freight elevator towers extend above the two-level

rooftop testing area’s west end. The elevators transported radar trailers to the roof. The south elevator