Considerations and Lessons for the

Development and Implementation of

FAST PAYMENT SYSTEMS

Part of the World Bank Fast Payments Toolkit

MAIN REPORT • SEPTEMBER 2021

B | Fast Payment Systems: Preliminary Analysis of Global Developments

© 2021 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

1818 H Street NW

Washington DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000

Internet: www.worldbank.org

This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this

volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent.

The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations,

and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank

concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries.

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

The material in this publication is subject to copyright. Because the World Bank encourages dissemination of their

knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution

is given.

FINANCE, COMPETITIVENESS & INNOVATION GLOBAL PRACTICE

Payment Systems Development Group

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

1. INTRODUCTION 1

2. THE FAST PAYMENTS TOOLKIT 11

3. FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING FAST PAYMENT DEVELOPMENTS 13

4. PAINTING THE BIGGER PICTURE: WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED? 15

4.1 Module A: Structure of a Fast Payment Arrangement 15

4.1.1 Motivation to Introduce Fast Payments 15

4.1.2 Fast Payment Stakeholder Ecosystem and Approach to Setting Up a Fast Payment 18

Arrangement

4.1.3 Funding and Pricing to Participants 23

4.2 Module B: System Specifications and Operating Procedures 25

4.2.1 Infrastructure Development 27

4.2.2 Technical Specifications 32

4.2.3 Network Connectivity 38

4.2.4 Clearing and Settlement 40

4.2.5 Interoperability 43

4.3 Module C: Features of Fast Payment Arrangements 45

4.3.1 Payment Instruments, Payment Types Supported, and Use Cases/Services 45

4.3.2 Overlay Services and Aliases 49

4.3.3 Access Channels 51

4.3.4 User Uptake 56

4.4 Module D: Legal and Regulatory Considerations, Risk Management, 57

and Customer Dispute Resolution

4.4.1 Legal and Regulatory Considerations 57

4.4.2 Risk Management 57

4.4.3 Dispute Resolution and Customer Complaints 61

5. KEY LEARNINGS AND FORWARD OUTLOOK 66

5.1. What’s Next for Fast Payments? 69

ii | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Acknowledgments 72

Appendix B: Glossary, Acronyms, and Abbreviations 76

Appendix C: Primer on Fast Payments 82

Appendix D: Study Methodology 86

Appendix E: Full Jurisdiction List 88

Appendix F: The 25 Jurisdictions Shortlisted for a More Detailed Review 91

Appendix G: Methodology for Selecting the 16 Deep Dives 93

Appendix H: Questionnaire for Primary Research 97

ENDNOTES 103

BOXES

Box 1: Fast Payments versus Other Types of Payment System Arrangements 2

Box 2: Defining Fast Payments 7

Box 3: Ownership of Fast Payment Arrangements 19

Box 4: Messaging Standards for Payments/Financial Transactions 33

Box 5: Customer Authentication in the European Union 35

Box 6: Application Programming Interfaces 37

Box 7: Cross-Border Aspects 44

Box 8: Request to Pay in Fast Payment Arrangements 48

Box 9: Aliases for Fast Payments 50

CHART

Chart 1: Fast Payments Toolkit Illustration 12

FIGURES

Figure 1: Overview of Fast Payments Framework 3

Figure 2: Global Fast Payments Landscape 9

Figure 3: Fast Payment Statistics across Select Jurisdictions (2019) 9

Figure 4: The Fast Payments Toolkit 11

Figure 5: A Project Development Life Cycle for Fast Payments 13

Figure 6: Fast Payments Framework 14

Figure 7: Components of the Different Modules 15

Figure 8: Key Motivators for Introducing Fast Payments 16

Figure 9: Primary Fast Payments Implementation Drivers, as per Survey Findings13 16

Figure 10: Fee Structure in Fast Payment Arrangements for Participants 25

Figure 11: Messaging Standards Adopted 33

Figure 12: Observed Clearing Models 40

Figure 13: Participant Settlement Models Adopted for Fast Payment Arrangements 41

Figure 14: Payment Instruments Supported by Fast Payment Arrangements 46

Figure 15: Transaction and Message Flow for Push and Pull Payments 46

Figure 16: Payment Types 46

Figure 17: Use Cases Supported by Fast Payment Arrangements 47

Figure 18: Access Channels and Their Relevance for Fast Payments 52

Figure 19: Access Channels Supported by Fast Payment Arrangements 53

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | iii

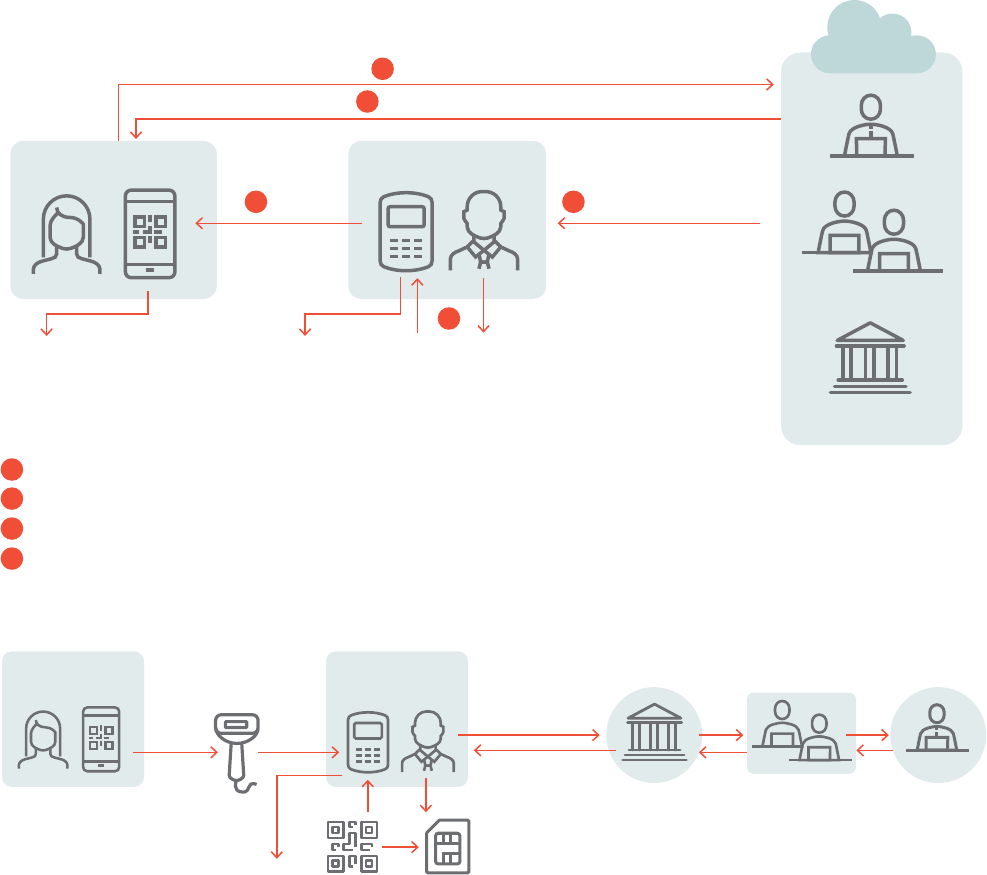

Figure 20: QR Code Payment Process 54

Figure 21: Primary FPS Adoption Drivers as per Survey Findings 55

Figure 22: Benefits and Potential Sources of Fraud Associated with Real-Time Payments 62

Figure 23: Stakeholder Mapping of Key Learnings 67

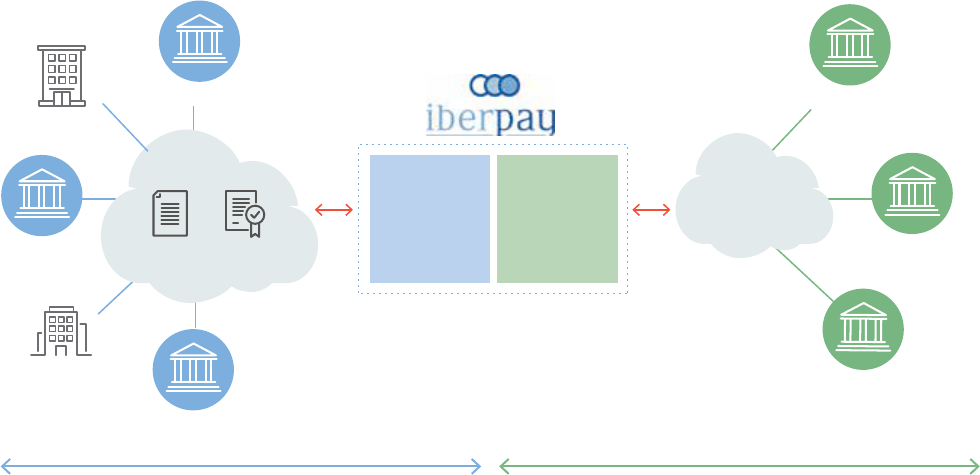

Figure 24: Iberpay’s Integration of a Distributed Ledger with STC Inst. 70

TABLE

Table 1: Key Learnings 4

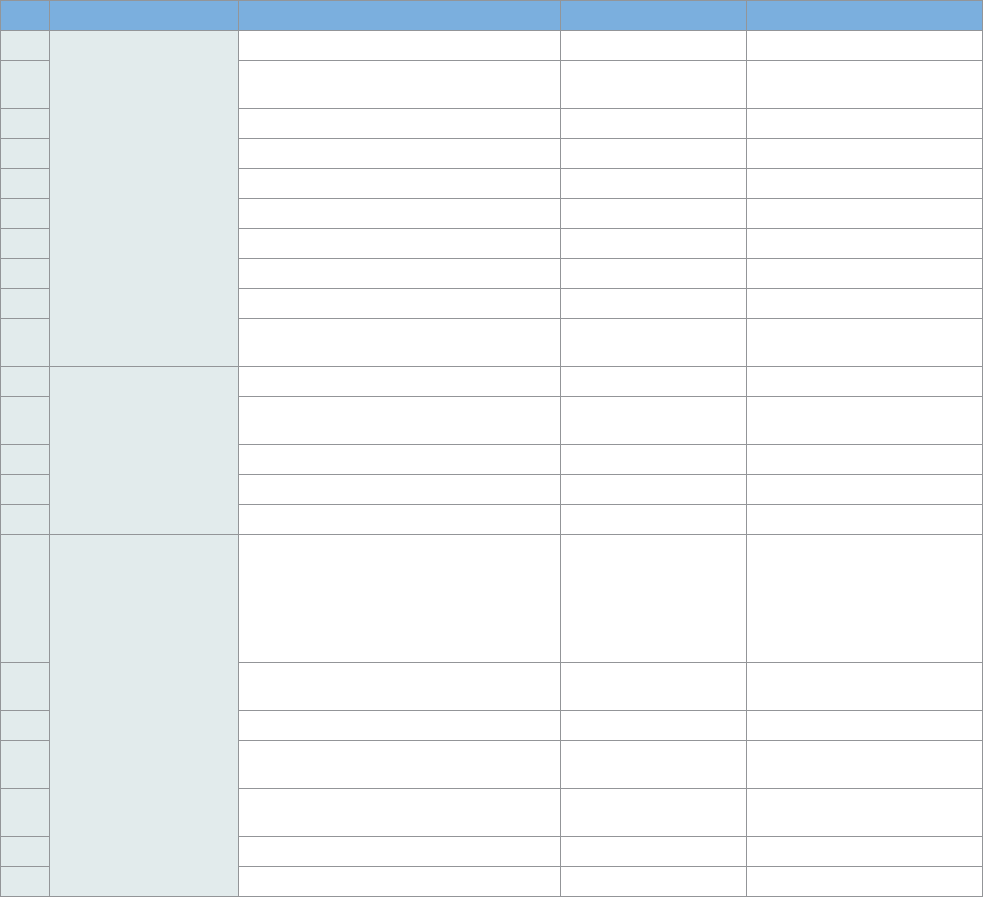

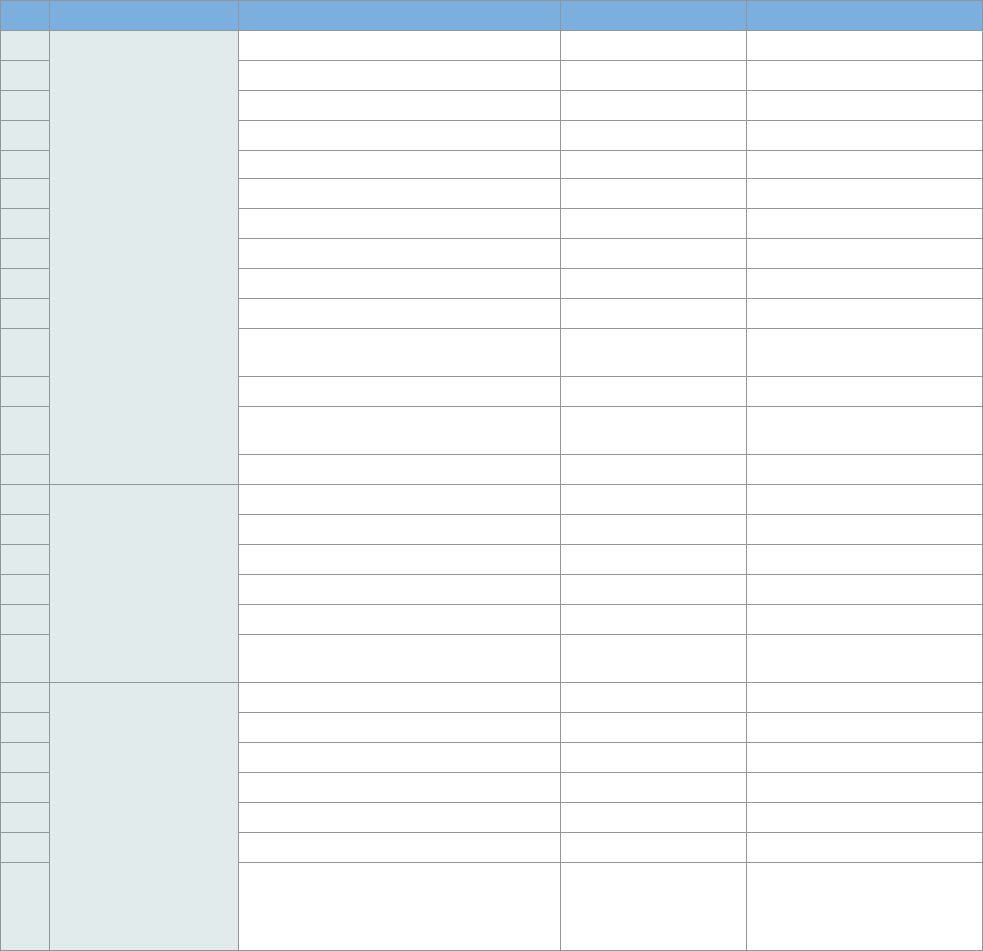

Table 2: Select Findings on Motivation 17

Table 3: Select Findings on Role of Governments and Regulators 17

Table 4: Select Findings on the Division of Roles between Overseer, Operator, and Owners 20

Table 5: Select Findings on Participants in Fast Payment Arrangements and Access Criteria 22

Table 6: Select Findings on Industry Body Collaborations 24

Table 7: Select Findings on the Classification of Fast Payment Arrangements as per 24

Their Systemic Importance

Table 8: Select Findings on Funding 24

Table 9: Select Findings on Fee Structures 26

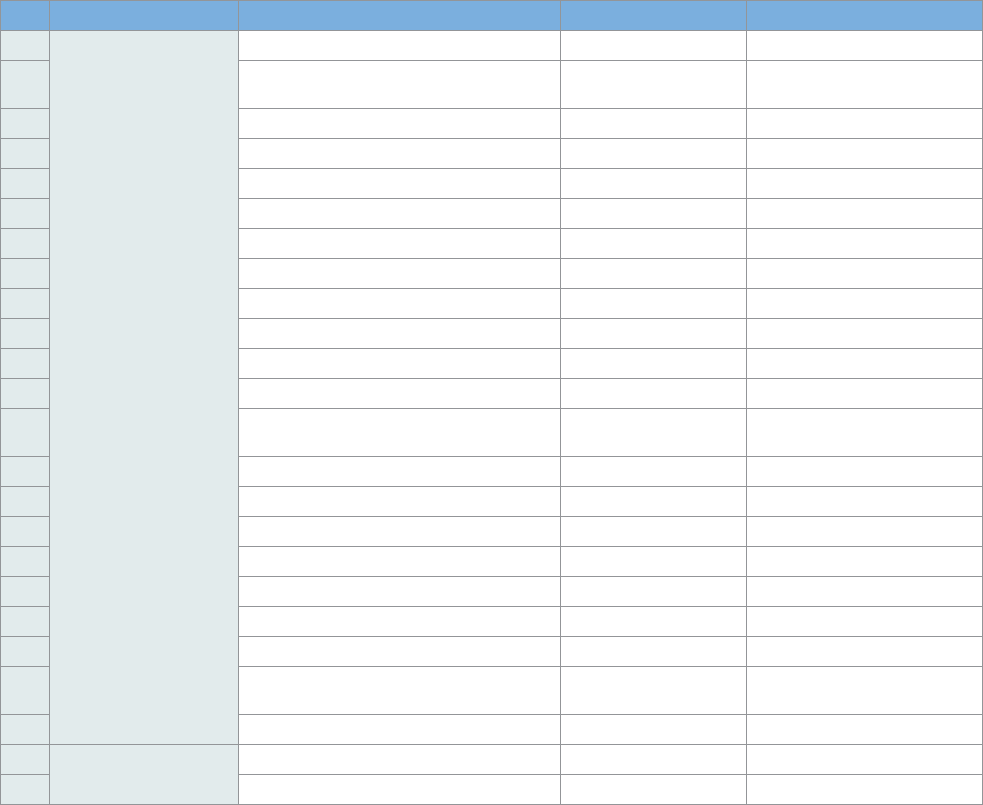

Table 10: Select Findings on New Infrastructure Development versus Existing System Upgrades 28

Table 11: Select Findings on System Development Timelines and Services Available at Launch 29

Table 12: Select Findings on External Vendor versus In-House Development 30

Table 13: Select Findings on Participant Onboarding Process 31

Table 14: Select Findings and Insights into Current Use of Messaging Standards 34

Table 15: Select Findings and Insights into Customer Authentication 36

Table 16: Select Findings and Insights into the Use of APIs in the Context of Fast Payments 38

Table 17: Select Findings on Network Connectivity 39

Table 18: Select Findings on the Clearing and Settlement Models Used for Fast Payments 42

Table 19: Select Findings on Interoperability 43

Table 20: Select Findings and Insights into Request-to-Pay Functionalities and Services 49

Table 21: Select Findings on Overlay Services 50

Table 22: Select Findings on Aliases 52

Table 23: Select Findings on End-User Pricing 56

Table 24: Select Findings on Awareness Initiatives 56

Table 25: Select Findings on Legal and Regulatory Considerations 58

Table 26: Select Findings on Credit and Liquidity Risk 59

Table 27: General Findings on Operational Risk Management 60

Table 28: Select Findings on Cyber Resilience 62

Table 29: Select Findings on Inter-Participant Disputes 63

Table 30: Select Findings on End-Customer Disputes 65

Table 31: Key Learnings from the Application of the Fast Payment Framework 68

EXHIBITS

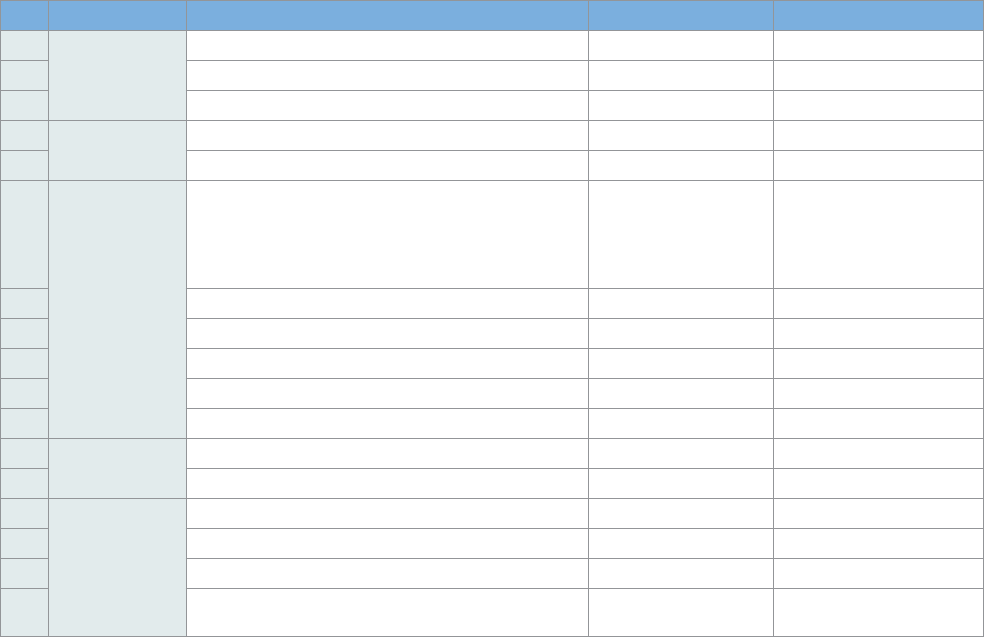

Exhibit A1: External Advisory Experts Group 72

Exhibit A2: Contributors to Interviews and Surveys 73

Exhibit A3: Organizations That Provided Inputs and Perspectives 74

Exhibit B1: Glossary 76

iv | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

Exhibit C1: Emergence of Fast Payment Arrangements over the Years 82

Exhibit C2: Key Characteristics of Fast Payment Arrangements 83

Exhibit D1: Study Approach 87

Exhibit E1: Complete List of Jurisdictions/Systems Studied—Regional Classification 88

Exhibit F1: List of Jurisdictions Shortlisted for Desk Research 91

Exhibit F2: Geographic and Category-wise Distribution of the 25 Shortlisted Jurisdictions 92

Exhibit F3: Key Parameters Studied in the 25 Shortlisted Jurisdictions 92

Exhibit G1: Jurisdictions with Live Fast Payment Implementations Mapped by Region, Country 94

Income Level, and Gross Domestic Product

Exhibit G2: Feature List for Comparison of Jurisdictions 94

Exhibit G3: Feature Comparison across Cluster A 95

Exhibit G4: Feature Comparison across Cluster B 95

Exhibit G5: Feature Comparison across Cluster C 95

Exhibit G6: Feature Comparison across Cluster D 95

Exhibit G7: Final List of 16 Jurisdictions for the Deep Dives 96

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project was led by Holti Banka (Financial Sector Spe-

cialist, World Bank) and Nilima Ramteke (Senior Financial

Sector Specialist, World Bank) under the overall guidance

of Harish Natarajan (Lead Financial Sector Specialist, World

Bank) and Mahesh Uttamchandani (Practice Manager, World

Bank). The team is grateful to Massimo Cirasino (Senior

Consultant, World Bank), Jose Antonio Garcia Luna (Senior

Consultant, World Bank), and Maria Teresa Chimienti (Senior

Financial Sector Specialist, World Bank) for their valuable

inputs and comments. Maimouna Gueye (Senior Financial

Sector Specialist, World Bank), Ivan Daniel Mortimer Schutts

(Senior Operations Officer, International Finance Corpora-

tion), Marco Nicoli (Senior Financial Sector Specialist, World

Bank), and Ryan Rizaldy and Arif Ismail (both of International

Monetary Fund) provided useful comments as peer review-

ers. Ivan Daniel Mortimer Schutts (Senior Operations Offi-

cer, International Finance Corporation) provided not only

peer-review comments but also detailed written inputs for

specific aspects. The team would like to thank the exter-

nal advisory group that was formed to provide insights and

inputs for this project as well as all individuals and institu-

tions that provided written and/or verbal inputs. (A detailed

list can be found in appendix A.) The team would also like to

acknowledge Deloitte for its contributions with research and

analysis, namely Sandeep Sonpatki, Vijay Ramachandran,

Shweta Shetty, Yashna Sureka, Sangeet Deshmukh, Shazada

Allam, Karan Sharma, Pranav Sood, Guneet Chamtrath, and

Maneesh Tiwari. (A Detailed list of contributors can be found

in appendix A.) Editorial assistance was provided by Charles

Hagner, and graphic design was provided by Naylor Design,

Inc. This project would not have been possible without the

generous support of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

For more than two decades, the World Bank has guided and

supported jurisdictions as they develop a safe, reliable, and

efficient National Payments System (NPS). In this context,

the World Bank has been monitoring developments in fast

payments and has undertaken a detailed study of fast pay-

ment implementations across the world. The policy toolkit

provides guidance on the aspects that authorities need to

consider when developing a Fast Payment System (FPS) and

incorporating the same in their NPS reform agenda. The tool-

kit is based on the analysis of multiple FPS implementations

across the world.

The Fast Payments Toolkit consists of the following three

components. Moreover, a dedicated website (https://fast-

payments.worldbank.org) has been created to house the

document, along with the components, and is expected to

be updated periodically to track fast payment implementa-

tions around the world.

1. Considerations and Lessons for the Development and

Implementation of Fast Payment Systems (this report/

guide)

2. Detailed analysis of FPS in a set of representative juris-

dictions

3. Focus notes on specific technical topics deemed highly

relevant for fast payments (see figure 4)

The specific tool that is developed in this guide has been

informed mainly by 16 deep-dive jurisdiction reports. These

16 jurisdictions, while not exhaustive, are quite diverse in

terms of their models/approaches to implementing and

operating their fast payment arrangement.

1

Therefore, the

guide is general enough to be applicable to different coun-

try circumstances.

The guide is being made publicly available along with

the 16 deep-dive reports and 16 specific technical topic

notes. Intermediate desk research on the global landscape

and the exploration of an additional 25 jurisdictions have

also informed the guide.

DEFINITIONS

Fast payments (also referred to as “instant payments,” “real-

time payments,” and “immediate payments”) are payments

where the transmission of the payment message and the

availability of final funds to the payee occur in real time or near

real time, and as near to 24 hours a day, seven days a week

(24/7) as possible. The associated service offered by payment

service providers (PSPs) is referred to as a fast payment ser-

vice, and the underlying scheme and system is referred to as

a fast payment scheme and fast payment system.

FPSs come in various flavors. Some are newly purpose-

built systems; others are part of an existing payment system

and are simply a new scheme (enhancement using the exist-

ing system) or service. Further, some have a number of fea-

2 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

tures, some of which are offered as overlay services. Hence,

to account for these differing implementation options, the

term fast payment arrangements is used in the report.

When referring to a specific system, the term FPS is used.

2

When referring to a specific scheme, the term fast payment

scheme is used. And when referring to a specific service, the

term fast payment service is used.

The features that characterize fast payment arrange-

ment vis-à-vis other types of payment systems are dis-

cussed in box 1.

METHODOLOGY AND KEY CONSIDERATIONS

The analysis presented in this guide has been structured on

the basis of a Fast Payment Framework, created ex profeso

and illustrated in figure 1.

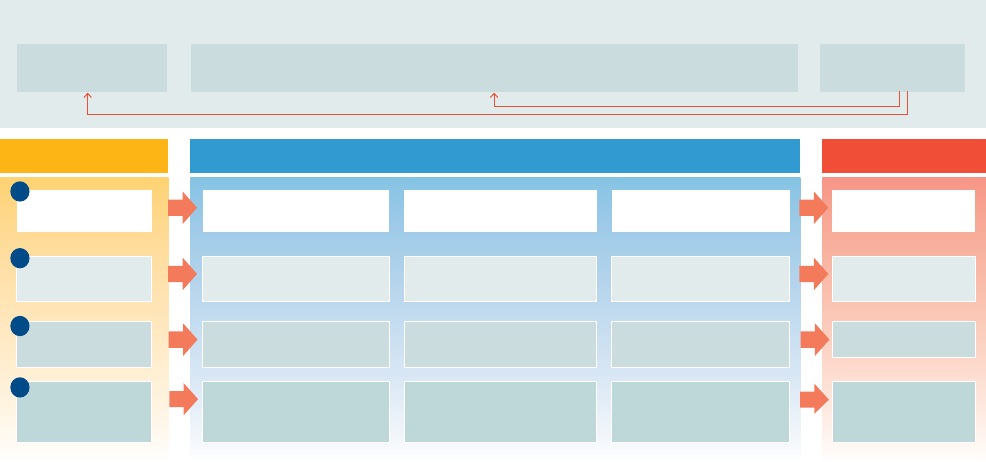

Module A: Three insights are covered in this module: moti-

vation to introduce fast payments; stakeholder ecosystem

and approach to setting up a fast payment arrangement;

and funding and pricing aspects.

Module B: This module focuses on assessing the current

state of technology in aspects such as payment processing

and telecommunications. Five insights are covered in this

module: infrastructure development; technical specifica-

tions; network connectivity; clearing and settlement; and

interoperability.

Module C: This module focuses on assessing customers’

needs, such as speed, payment certainty, simple and con-

venient user experience, pricing, clarity on the timing of

delivery, and integration with bank account/mobile wallet/

e-money, among others. Four specific insights are covered

in this module: payment instruments, payment types sup-

ported, and use cases/services; overlay services and aliases;

access channels; and user uptake.

Module D: This module focuses on some institutional

requirements pertaining to fast payments. Three key insights

are discussed here: legal and regulatory considerations; risk

management; and customer dispute resolution. Some of

these aspects are typically covered under the scheme rules

of a payment system. Scheme rules define the way the sys-

tem will operate and the behavior and interaction of partic-

Conceptually, the characteristic features of fast pay-

ments are real-time availability of funds to the bene-

ficiary and the possibility to make payments 24/7/365

or close enough, regardless of the amount and type of

beneficiary (as long as the latter has an account where

the funds can be credited).

Other payment systems, such as real-time gross set-

tlement (RTGS) systems, already give the possibility to

credit an end user’s account in real time. The material-

ization of this depends largely on the technical inter-

faces developed by RTGS participants between the

system and their internal core banking systems.

In contrast, most RTGS systems are not able to fulfill

the other feature of offering round-the-clock availability

for ordering and executing real-time payments. Indeed,

round-the-clock availability of real-time payments is a

clear differentiator of fast payment arrangements versus

other payment systems.

3

Beyond these core characteristics, the technology

behind many fast payment arrangements supports

the development and launch of multiple, previously

unheard of, value-added functionalities and services

for end users (payers and payees). Those new func-

tionalities promote and facilitate increased uptake and

regular usage of fast payments for multiple purposes.

This is a significant difference between them and

RTGS systems, as most of the latter were built to cater

solely to the needs of banks—and eventually other

participating PSPs.

For operators and overseers/regulators, real-time

availability of funds to beneficiaries and round-the-

clock availability of systems to execute payments also

raise some unique challenges. Robust management of

operational risks, including business continuity, is more

important than ever to ensure ongoing trust in fast

payments. Moreover, possibilities for committing fraud

seem to have expanded, as there is no lag between

when a payment is initiated and when the funds are

transferred to the beneficiary, coupled with settlement

finality offered by most fast payment arrangements.

BOX 1 FAST PAYMENTS VERSUS OTHER TYPES OF PAYMENT SYSTEM ARRANGEMENTS

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | 3

ipants. Scheme rules are defined to minimize risks, maintain

integrity, and provide a common, convenient, secure, reli-

able, and seamless payment experience to customers.

Insights into the various aspects that are highly relevant for

fast payments are mapped to the various modules of the

Fast Payment Framework, and on this basis, key consider-

ations and learnings are drawn.

Overall, the analysis has clearly shown that the key levers

for the adoption and uptake of fast payments have been the

immediate availability of funds, even for small-value trans-

actions, and the catalyst role of central bank in fostering the

development of fast payment systems.

Other crucial elements that have fostered uptake include

the following:

i. Coverage and openness of the fast payment arrange-

ment, including a large variety of use cases, participation

of a wide range of PSPs, and affordable pricing

ii. Convenience and ease of access, including accessibility

through mobile phones, the use of aliases such as mobile

numbers, the use of application programming interfaces

(APIs), and common messaging standards

iii. A robust preexisting market context—namely, penetra-

tion of internet and mobile phones, quality and speed of

other payment options, and overall competitiveness of

the payments market

iv. Awareness-raising and educational campaigns for end

users by public authorities, operators, and participants

LESSONS LEARNED AND FORWARD OUTLOOK

The more detailed key findings and learnings target spe-

cific—often multiple—stakeholders and are organized

across the typical life cycle of a payment infrastructure proj-

ect, as depicted in table 1.

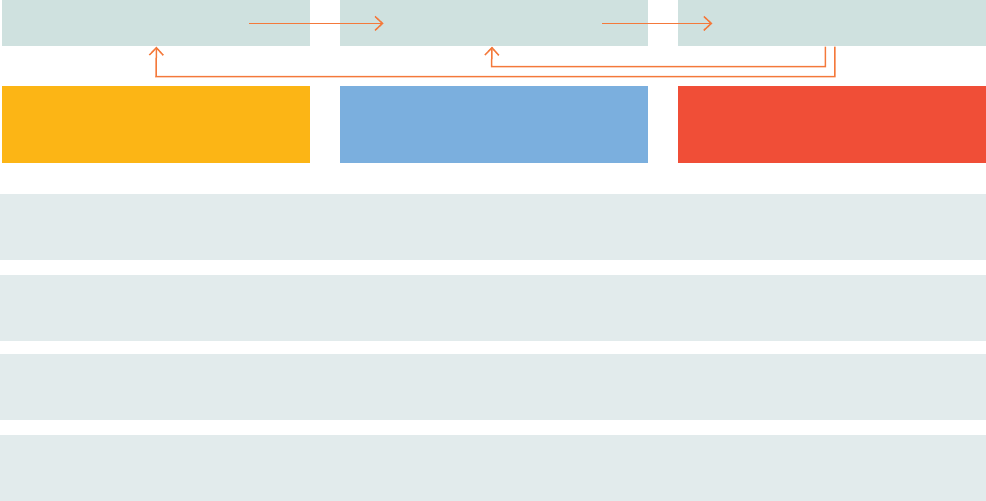

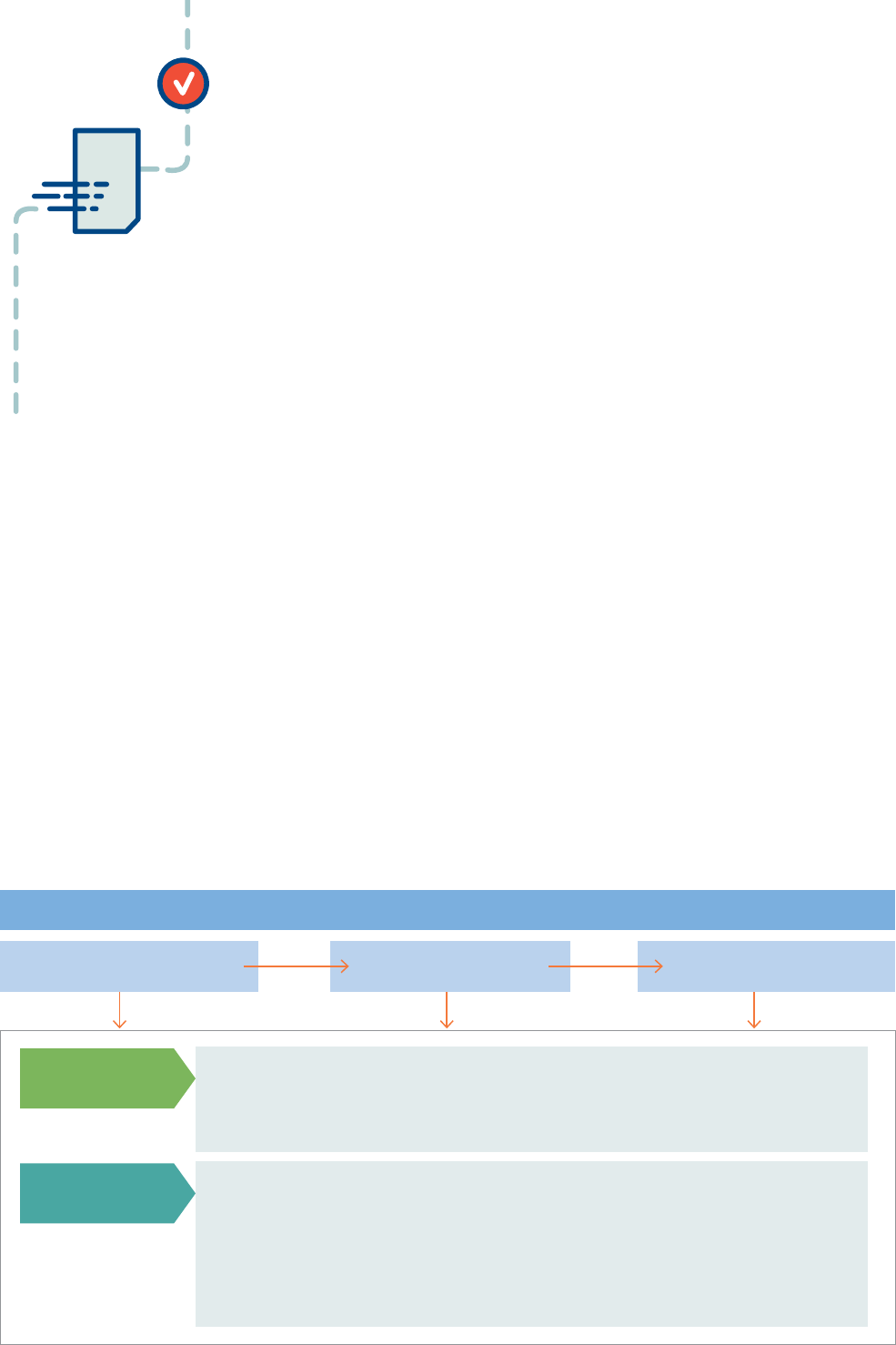

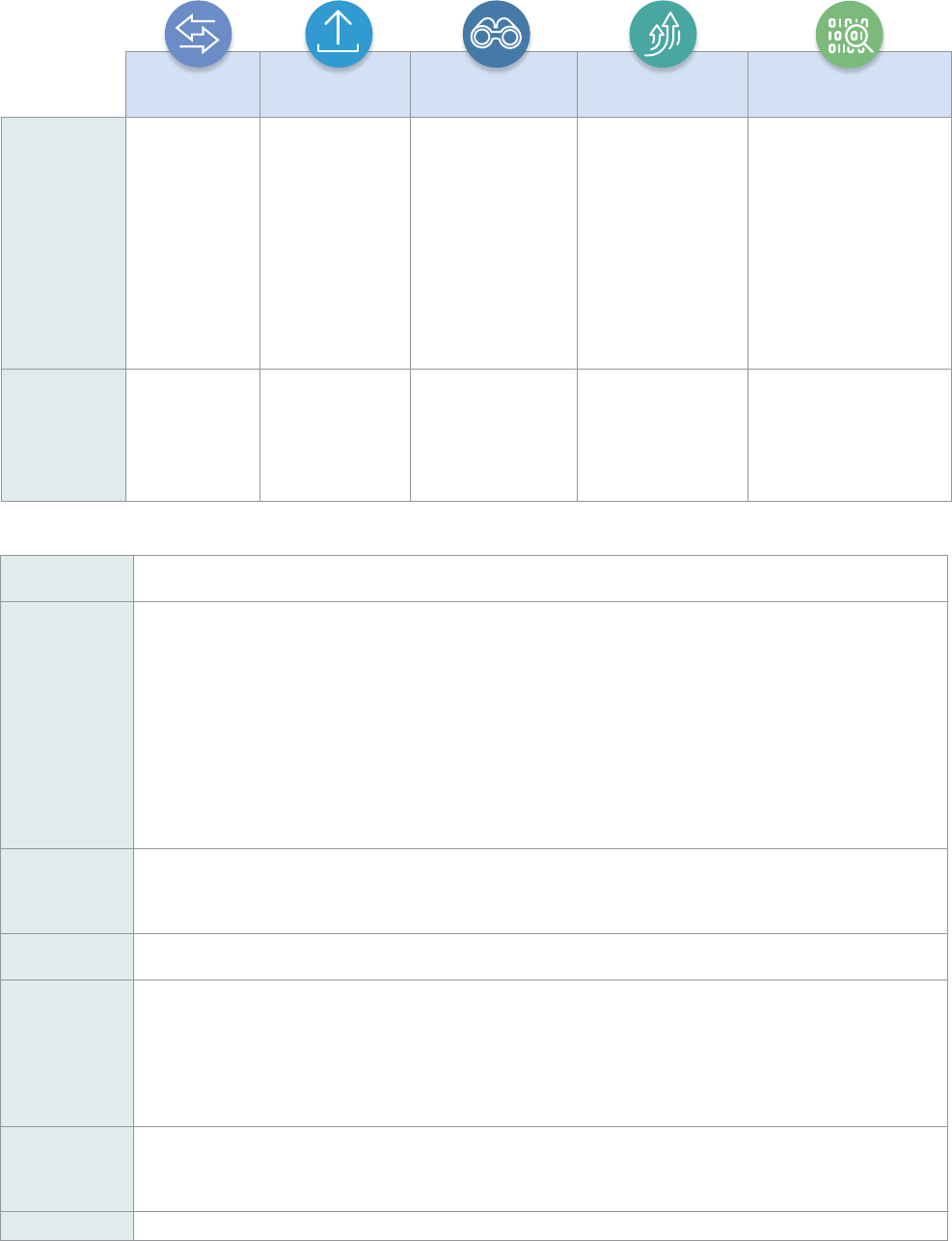

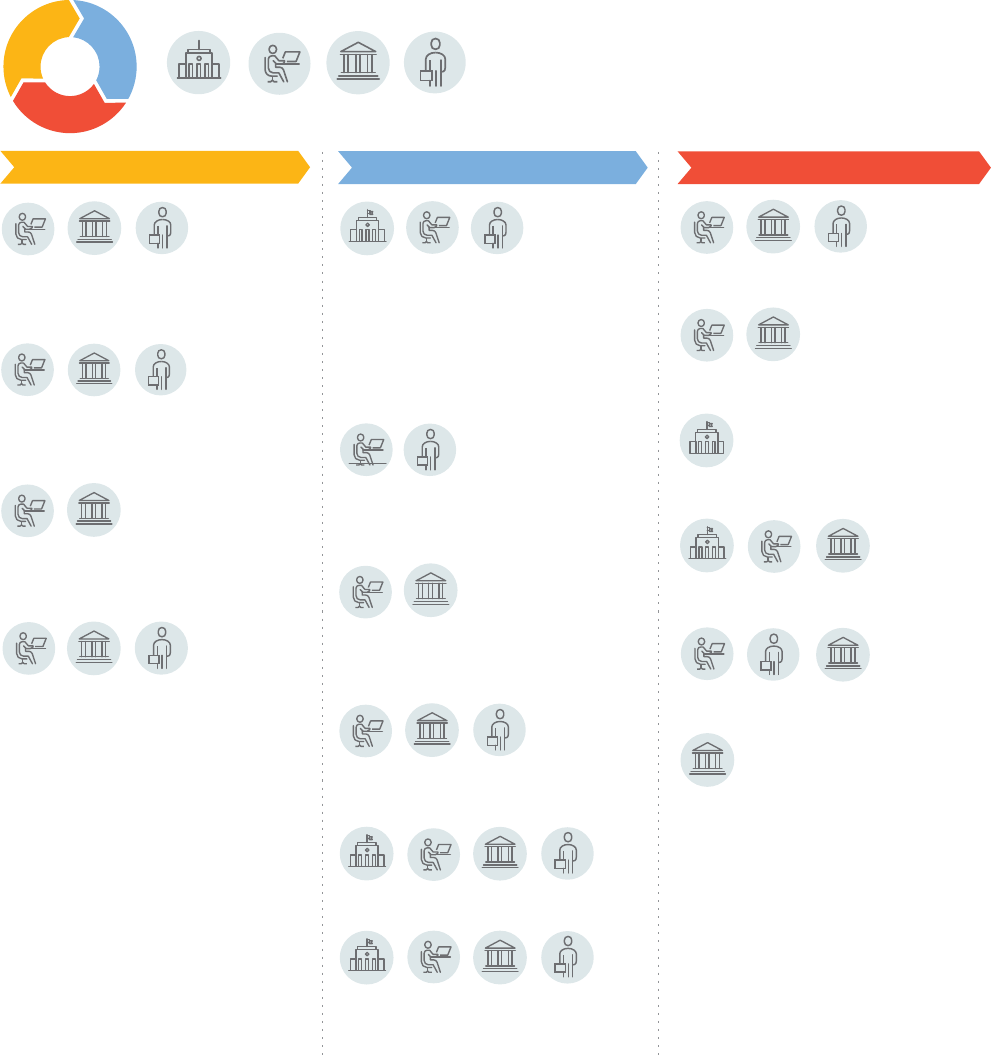

Conceptualize Design & Implement Go-Live & Post Implement

Module A: Structure—Covers an assessment of objectives and developing structural and pricing components in order to drive collaboration and

innovation of the fast payment arrangement

Module C: Features—Covers an assessment of customer requirements and determining payment instruments, payment types, use cases and access

channels with the goal of driving up user uptake

Module B: Specifications—Covers an assessment of technology and designing technical specifications and development components to achieve

interoperability

Module D: Legal and Governance Considerations—Covers an assessment of governance requirements and deciding legal and regulatory frame-

works, risk management practices, and dispute resolution mechanisms in order to enhance safety and security

ASSESS

Get the focus right

DESIGN

Get the concept right

LAUNCH—SCALE

Get the system to thrive

FIGURE 1: Overview of Fast Payments Framework

4 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

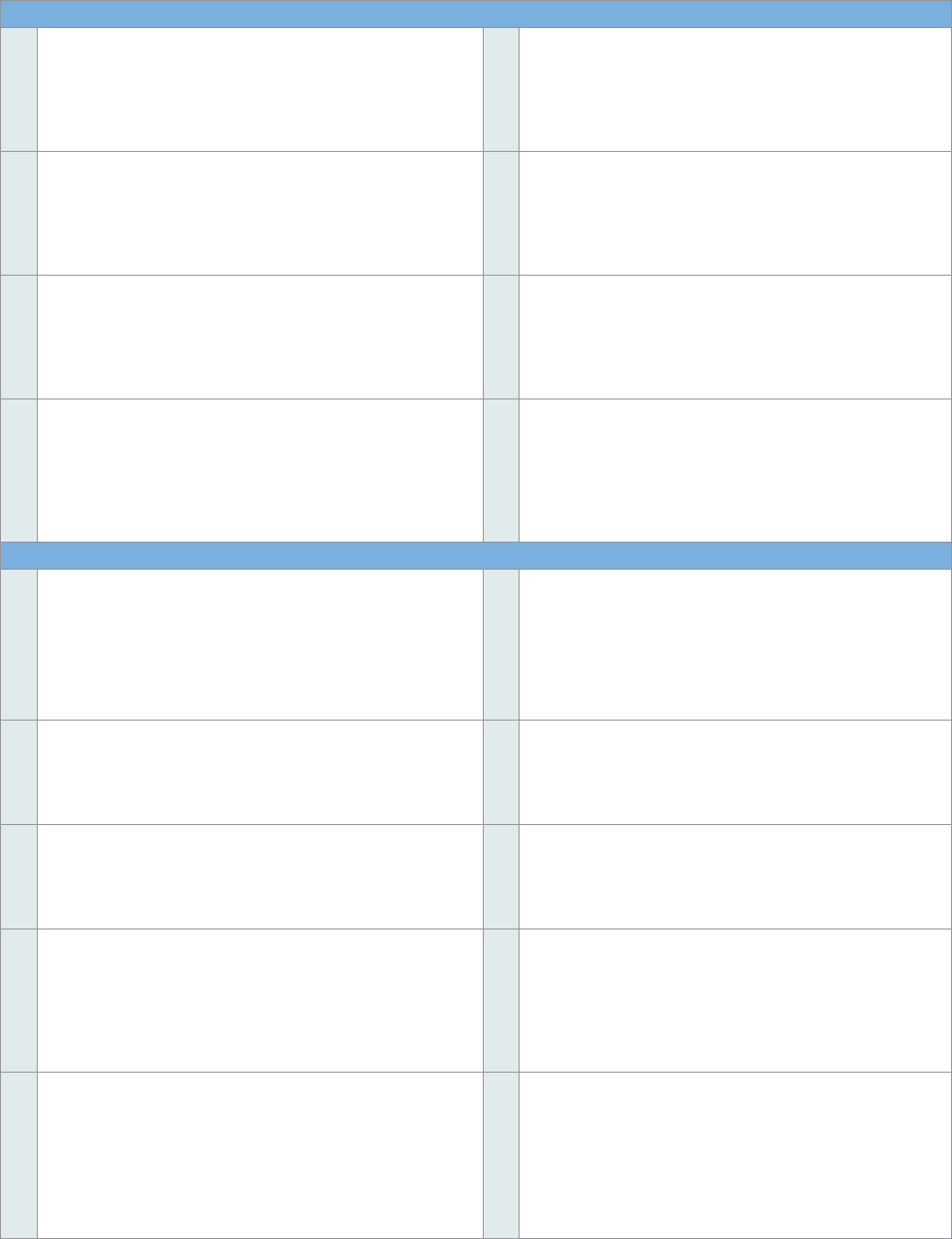

PROJECT CONCEPTUALIZATION STAGE

1

Have clarity on the objective, including motivations/drivers for

developing fast payment services in their jurisdiction.

5 Develop a plan for investing in infrastructure and recovering

cost over a period of time, and avoid focusing on achieving

profitability in the short run. The central bank should

work together with stakeholders to identify the long-term

benefits of the project (direct and indirect) and the broader

long-term interests of the NPS.

2

Obtain knowledge of fast payment arrangements in other

jurisdictions, including the key features of their operating

models and service offerings.

6 Develop a good understanding of the infrastructure

available in the broader ecosystem (for example, phone and

communication network penetration) to determine which

user needs and expectations the fast payment arrangement

will be able to meet at launch and in its early stages of

development.

3

As part of the design, focus on establishing a core platform

and associated services on top of which other stakeholders

can innovate and build further services.

7 Give due regard to the existing payments infrastructure

setup, including such aspects as current familiarity with real-

time payments, instruments available (for example, push

and pull), NPS integration, support of use cases, settlement

models, the accounting practices applicable to payments,

and other banking activities operating 24/7, among others.

4

Underpin the business case with a clear vision of the role

for the fast payment arrangement in terms of use cases and

services it can offer to PSPs and the market in general. This is

critical for developing a credible business plan and garnering

industry support.

8 Study the existing internal infrastructure of banks and other

potential PSPs and assess their ability to achieve immediate

fund transfers with certainty. Jurisdictions could consider

agreeing on minimum criteria for participation up front, in

a way that ensures that at least the major banks and some

other smaller banks and non-bank PSPs can be ready to join

by the predecided “go-live” date.

PROJECT DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION STAGE

9 Assign a top-notch project-management team.

• The relevant stakeholders should also identify personnel

with experience and competency and assign them the

responsibility of project development and implementation.

They should also be made duly accountable for the project.

• Ensure continuity of the people/team assigned to this task

to avoid delays in implementation.

16 Ensure fair, transparent, and risk-based access criteria that

do not preclude membership based on institution type.

This is critical to foster innovation and ongoing competition

in the payment ecosystem, recognizing, though, that

many smaller and mid-sized PSPs may opt for indirect

participation, given the financial and technical requirements

for direct participation.

10 Ensure structured planning and implementation to help

mitigate implementation delays, including those related to

stakeholder onboarding. It is essential to give participants

sufficient time to adapt—that is, for contract negotiation,

internal system development, and implementation.

17 Consider using APIs that have proven most useful for the

connectivity of smaller participants and of other third

parties (for example, entities that provide payment-

initiation services), and to foster standardization of APIs in

the payments market.

11 Going live with a basic service—with limited features—can be

a good strategy to get the ball rolling. The design of the fast

payment arrangement should nevertheless be flexible enough

to accommodate multiple use cases/services based on dynamic

market needs (that is, the “plug and play” approach).

18 Ensure that the pricing scheme(s) for participants promotes

quick participant adoption. The joining fee, fixed fees (if

any), and variable fees should not act as barriers for smaller

players. At the same time, the operator should ensure

sustainability in the medium- to long-term timeframe.

12 Consider user experience as a critical factor that needs to be

kept in mind while designing and developing a fast payment

arrangement. Focus should be placed on providing a seamless

experience across all access channels. The elements that help

enhance the customer experience include the use of aliases

and services provided by third parties (for example, payment

initiation).

19 Ensure that pricing policies for end users foster uptake in

the short term, for which public authorities may encourage

participants to offer fast payments as a low-cost (or even

zero-cost) payment service. However, in the medium term,

this will need to be reconsidered to ensure that participants

have an incentive to introduce additional services and

features.

13 Design and implement a strong governance framework for

the fast payment arrangement. All participants (banks and

non-banks) should be represented and have a say in the

decision-making. The voices of external key parties, such

as fintechs and telcos, also need to be heard and given due

consideration.

20 Give due attention to the type of messaging standard

adopted. The decision to adopt a particular message

standard—proprietary or ISO—should be based on a careful

analysis of the costs and benefits and factor in the need to

facilitate the interoperability of domestic payment systems

and, eventually, to enable cross-border payments. While

other possibilities exist, ISO 20022 is emerging as a leading

messaging standard for fast payments.

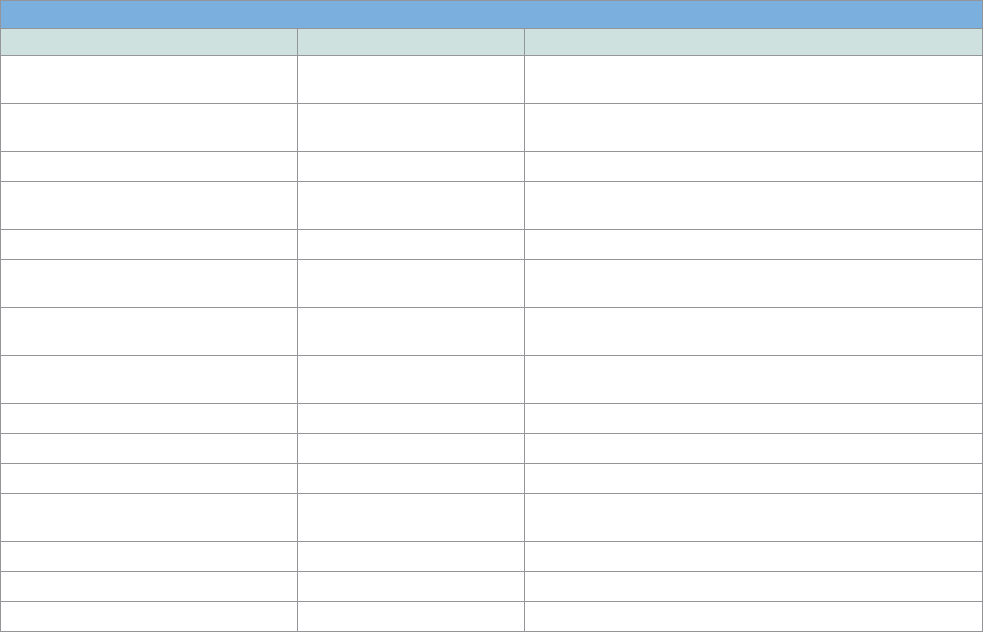

TABLE 1: Key Learnings

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | 5

TABLE 1, continued

Finally, while many jurisdictions have implemented fast pay-

ments, their paths have varied significantly, owing to dif-

ferences in the regulatory environment, support from the

broader ecosystem, consumer preferences, support from

the existing payments and ICT infrastructure, and existing/

competing offerings. Each jurisdiction’s uptake, experi-

ences, and success have also varied. Similarly, the ownership

and operating models have varied, and no particular model

is more likely to succeed or fail.

14 Undertake comprehensive testing before launch (operator

and participants). A fully functional central testing platform

for intra- and inter-participant testing can help identify issues

early in the implementation phase.

21 Establish a clear, documented, effective risk-management

framework to identify, measure, monitor, and manage the

various risks, including those concerning potential criminal

activity (for example, money laundering, the financing of

terrorism, cyberattacks, and data breaches). Participants

should also be mandated by their supervisor to set up

robust internal controls for operational risks.

15 Have a comprehensive rulebook that contains all relevant

rules, parameters, standards, and controls for the operational

efficiency and overall soundness of the fast payment

arrangement. This also promotes a level playing field for

participants.

22 Agree on the settlement model and measures for the

mitigation of settlement risk between operators/manager

and operator/manager and participants. The measures

should be cost efficient. Key decision factors include

whether non-banks will be direct participants (for example,

settling operations on their own behalf) and the specifics

of the local ecosystem (for example, settlement services

provided by the central bank or commercial banks).

PROJECT “GO-LIVE” AND POST-IMPLEMENTATION STAGE

23 Collaborate during post-implementation to ensure that the

fast payment arrangement will be able to reach its maximum

potential over time.

27 Review risk-management frameworks periodically to

mitigate evolving requirements and threats, including cyber.

Technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine

learning can help operators/managers detect failures in

compliance and combat evolving threats.

24 Generate customer awareness in the initial years to

increase registrations and uptake. Customers often require

handholding to familiarize themselves with the new service

and its functionalities.

28 Adapt some of the oversight tools and overall approach

when it comes to fast payments, to ensure that the relevant

systems or underlying arrangements operate safely and

efficiently on an ongoing basis (applicable for regulators/

overseers).

25 Keep the customer registration process simple, to increase

uptake.

29 Leverage payments data to introduce innovative and

customized solutions for end users (for system operators

and system participants) without compromising data-

protection and privacy aspects.

26 Adopt a product road map approach for new use cases/

services and functionalities that shares the vision of the

owner/operator with all participants (and other relevant

stakeholders, such as telcos), ensuring that these stakeholders

will be able to adopt these changes in a timely manner.

30 Evaluate on an ongoing basis whether the system continues

to meet the evolving ecosystem needs; fosters the safety,

efficiency, and reliability of the NPS; and has the right

governance arrangements. Take appropriate actions based

on the evaluation.

6 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

INTRODUCTION

EMERGENCE OF FAST PAYMENTS

For what concerns payment infrastructures, in most juris-

dictions, the National Payments System (NPS) traditionally

comprised a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system for

large-value and time-critical payments; an automated clear-

ing house (ACH) for lower-value payments (for example,

using electronic fund transfer instruments or checks); card

payment processing systems/switches; e-money clearing-

houses (some jurisdictions are merging this with card pay-

ment infrastructure and, in a few cases, with ACH systems);

and mechanisms for cross-border payments.

The global payments industry is nevertheless experienc-

ing a paradigm shift driven by technological innovation, the

changing priorities of central banks and other public author-

ities,

4

changes in economics, demographics, and customer

1

needs for faster, cheaper, and more convenient means of

making payments. As part of this evolution, a new type of

payment service, fast payments, emerged and has been

rapidly gaining track worldwide. Appendix C of this guide

provides details on the main features and evolution of, and

current trends in, fast payments.

Some of the benefits of fast payments derive from their

effect on competition and potential to bolster dynamic

efficiency gains. Immediate access to funds, coupled with

low fees, can reduce what economists refer to as “switching

costs” and make it easier to use multiple accounts. Switch-

ing costs are barriers to changing accounts and can include

those costs that may impede clients from using different

institutions to conducting different types of transactions.

Fees, delays in access to funds, and impediments posed by

user experience or operational constraints may dissuade cli-

The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures

(CPMI) of the Bank for International Settlements defines

fast payments as follows:

“ Fast payments are defined as payments in which the

transmission of the payment message and the avail-

ability of final funds to the payee occur in real time or

near real time and on as near to a 24-hour and 7-day

(24/7) basis as possible.”

For the purposes of this guide, emphasis is placed on

the immediate availability of funds to the beneficiary

of a fast payment transaction—which can be an indi-

vidual, a firm, or a government agency—and that these

transactions can be made during an operational win-

dow during the day that is as large as possible, tending

toward 24/7 availability.

BOX 2 DEFINING FAST PAYMENTS

7

ents from using a different institution for a transaction, even

if they would derive other gains from doing so, such as from

higher interest rates or lower fees.

A reduction in these frictions can also have an impact on

what is referred to as “multihoming.” This relates primarily to

multisided platforms, of which retail payment systems are an

example. Clients may choose to use a single platform (for

example, an account or payment service) or may subscribe

to multiple platforms (multihoming) to interact with differ-

ent users and services or benefit from differential pricing.

An example would be when clients hold an account with

a conventional retail bank as well as an e-commerce pay-

ment service provider (PSP). They may be able to transact

(or have significant advantages) with merchants on Alib-

aba only from their Alipay account; other payment services,

such as for the receipt of salaries or to make interbank

transfers, may require an account at a retail bank.

FPSs can also enhance “platform competition” for retail

payments. Traditionally, alongside cash, card payment net-

works in most countries have dominated retail payments.

With some exceptions, credit transfer systems were not

used to make time-sensitive payments at the point of sale.

FPSs, coupled in particular with the evolution of payment

initiation and merchant services, are changing this. Open

banking arrangements are enabling new independent

providers to offer more choices to both merchants and

consumers, enabling fast payments to compete with card

networks and beginning to focus more competition on val-

ue-added services.

Fast payments have important but ambiguous effects on

multibanking.

5

On the one hand, if FPSs have broad net-

work reach or are accompanied by extensions in interop-

erability, in theory they can diminish the need for clients to

hold multiple payment accounts in which they hold depos-

its. Knowing they can reach many or most other transaction

counterparts quickly, or connect their account via payment

overlay services, they may choose to concentrate their funds

in a primary institution. On the other hand, reductions in

barriers to making transfers between accounts may lead

to an increase in multihoming. Consumers may be able to

choose more readily between different service providers for

different kinds of payments and other financial services in

the knowledge that they can transfer funds between them

instantly at little or no cost. This can shift the focus of com-

petition between financial institutions away from price and

network reach toward other features, such as interest rates

or value-added services.

The pro-competition effects of fast payments may

already be playing a role in some markets. For instance, in

the corporate world, where instant low-cost transfers have

been available for many years, multiple accounts have long

been used to “sweep” balances overnight from different

institutions into a single cash-management institution.

Similarly, in retail markets, while the specific impact of fast

payments is difficult to disentangle from other forces, it

is reasonable to expect that speed and ease of transfers

diminish barriers to picking different services from differ-

ent institutions.

While the specific cause and effect may be difficult to

distinguish, it seems likely that fast payments can have

beneficial impacts on contestability and competition

between services. To achieve this, they should be coupled

with improved access mechanisms (for example, apps), low

fees, and a wide scope of participants or transaction coun-

terparts. The immediacy and ease with which funds can

be transferred between such accounts is likely to enhance

competition between, and uptake of, third-party services

beyond those offered by the institution at which a current

account is held.

Among others, fast payments also play a key role in

the digitization of government payments, either as critical

infrastructure in the end-to-end government’s payments

architecture or by providing incentives for the adoption

of digital payments by the end user. Fast payments have

positive direct and indirect spillovers in the digitization of

government payments when they are leveraged in the gov-

ernment’s payments architecture or when fast payments

are made available to the public on a general basis. One

direct benefit of leveraging fast payments through the gov-

ernment’s payments architecture is real-time collection of

revenue, which allows the government to increase its expen-

diture capacity and efficiency. A similar benefit is perceived

from disbursement of time-sensitive payments, such as

wages, vendor’s payments, and social-protection payments.

For the latter, in most cases, social-protection payments are

directed to vulnerable segments of the population, and for

many recipients, such payments constitute their main source

of income—hence, the relevance of leveraging payments

infrastructure that allows the delivery of financial aid in the

expected time. Furthermore, payments made by the gov-

ernment to address emergency situations are supported

by fast payment schemes, which allow the completion of

urgent transactions in real time and the delivery of financial

aid in a timely manner.

8 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

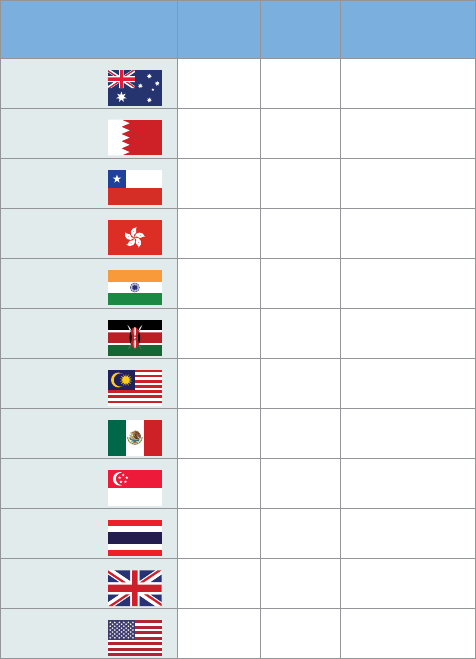

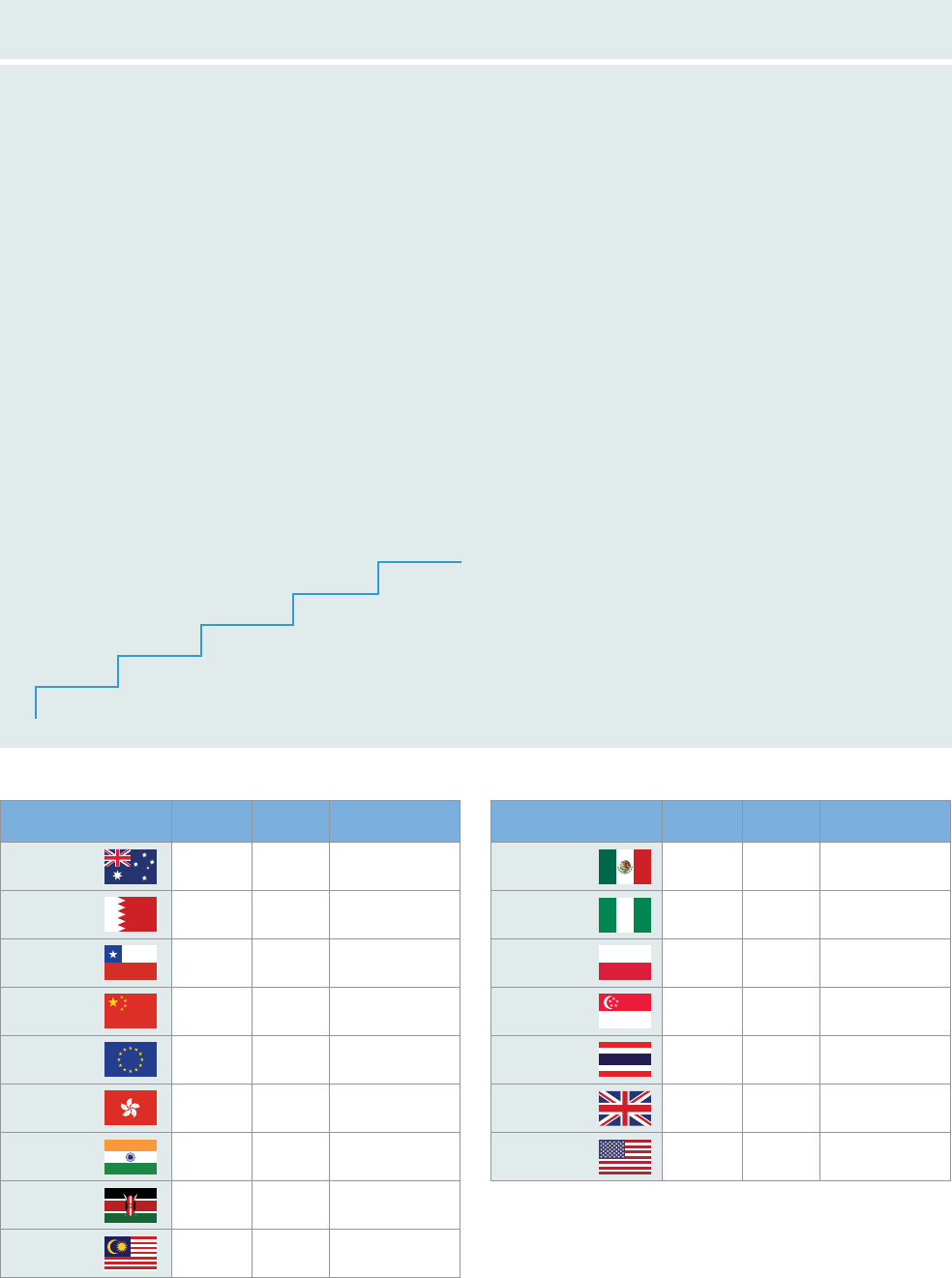

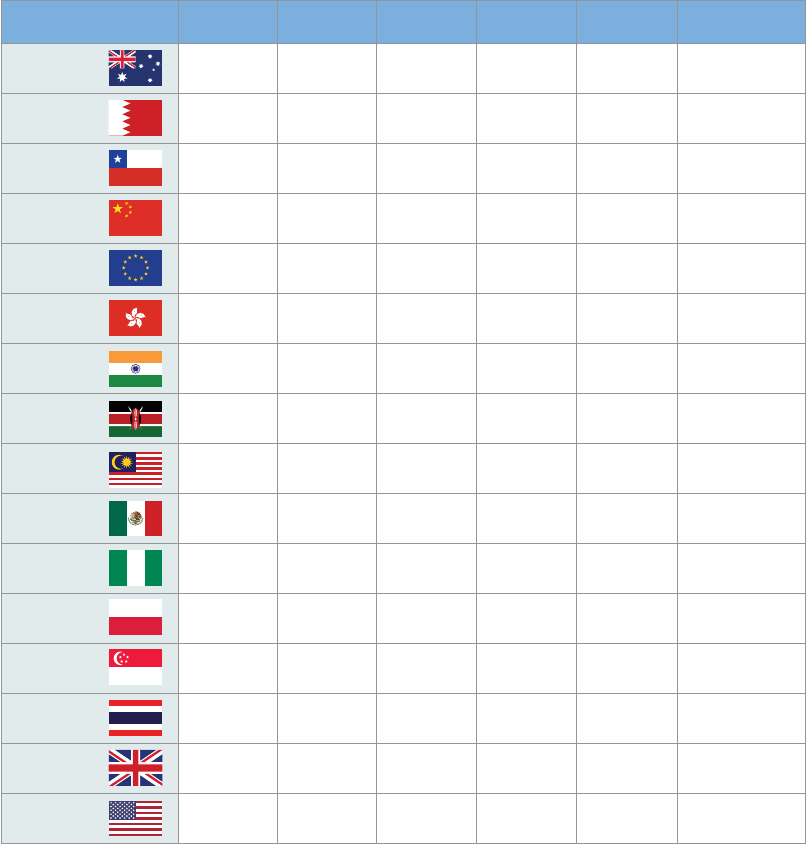

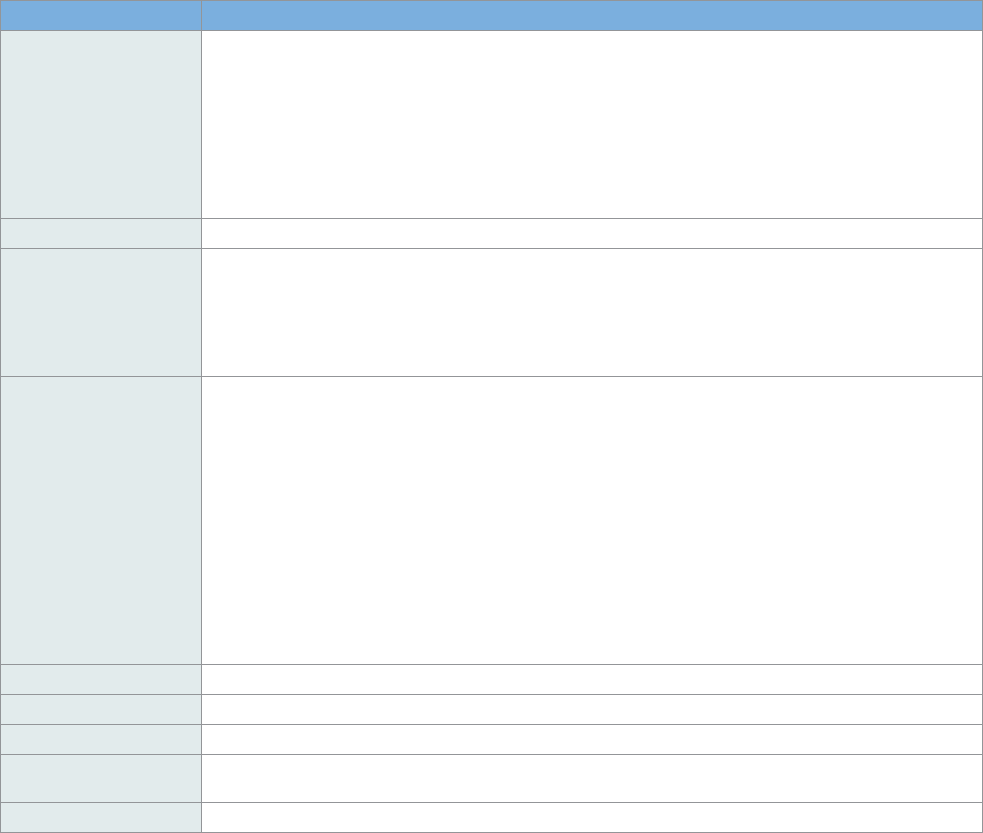

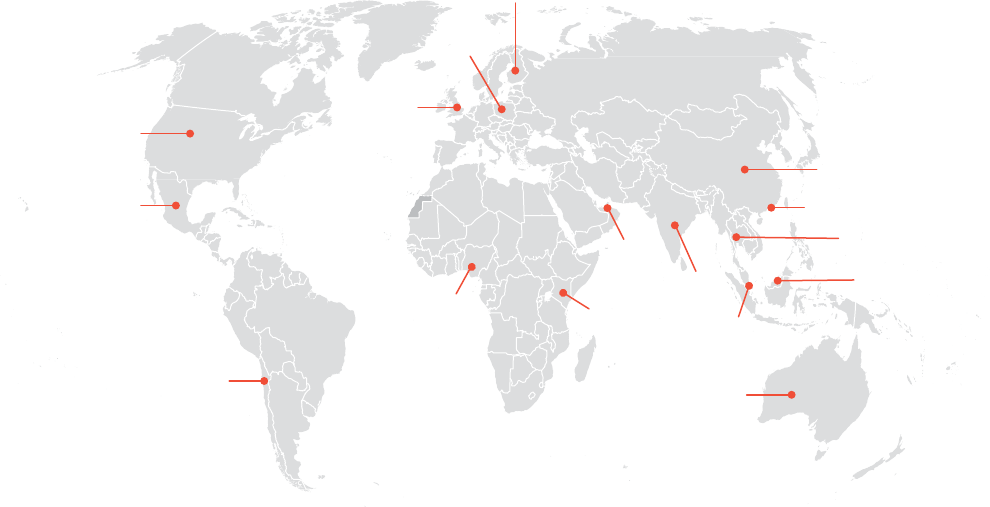

FIGURE 2: Global Fast Payments Landscape

8

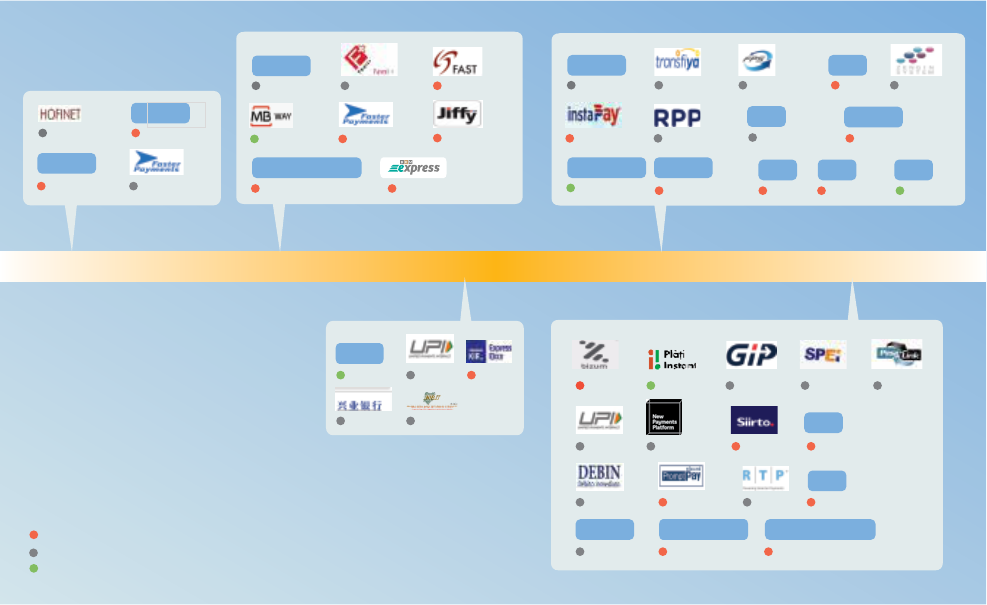

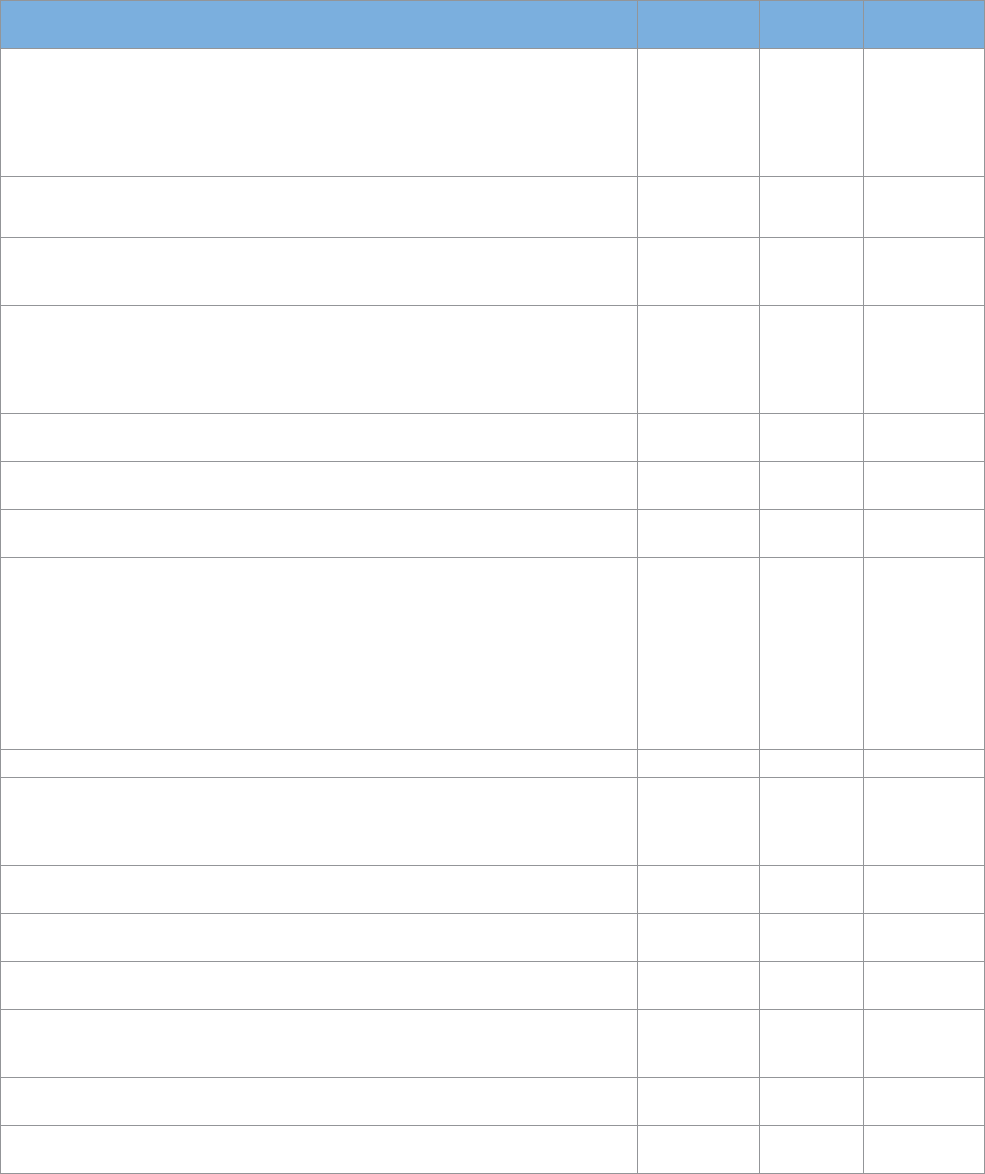

FIGURE 3: Fast Payment Statistics across Select Jurisdictions (2019)

9

JURISDICTION SYSTEM NAME

(YEAR OF LAUNCH)

TRANSACTION VALUE AS

PERCENTAGE OF GDP

TRANSACTION VOLUME

PER CAPITA

Australia NPP (2018) 12% 10.84

Bahrain Fawri+ (2015) 4% 3.84

China IBPS (2010) 112 % 10.02

Hong Kong SAR, China FPS 29% 5.82

India UPI (2016) 15% 9.16

Nigeria NIBSS Instant Payment (2011) 81% 7. 05

Thailand PromptPay (2016) 78% 36.85

UK

FPS (2008) 88% 36.46

Currently, several jurisdictions across the globe have imple-

mented fast payments, and several others have announced

their plans to go live.

6

These are illustrated in figure 2.

7

Many of these implementations have been propelled—if

not directly led—by central banks. The basic principle across

all the jurisdictions remains essentially the same: to provide

a fund transfer facility through which final beneficiaries can

be credited in real time and that is available for making pay-

ments for as many hours as possible each day.

The growth in the contribution of fast payments has

been significant. Figure 3 shows the yearly transaction value

processed via the fast payment arrangement in selected

jurisdiction as well as the number of fast payment transac-

tions per capita.

Live

Under development

Live-Not Full-Fledged

Note: SCT Inst and BCEAO have been considered as a single jurisdiction

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | 9

10 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

ELEMENTS UNDERLYING A FAST PAYMENT

ARRANGEMENT

In practice, fast payment arrangements consist of the follow-

ing components or layers, known to form a payment system:

• The core clearing and settlement infrastructure: Some

fast payment arrangements run existing/incumbent

platforms; in other cases, a brand-new platform has

been created ex profeso for fast payments.

• The operator, which can be a private-sector, public sec-

tor entity, or based on a public-private sector model

• The scheme or rulebook that governs the relationship

between the participants, the operator, and other rele-

vant parties

10

• The overseer (and eventually also the regulator), which

is typically the central bank

• Participating institutions

• End-user solution(s)

• Overlay services

To account for differing implementation options, the term

fast payment arrangements is used throughout this doc-

ument. When referring to a specific system the term FPS

is used.

11

When referring to a specific scheme the term fast

payment scheme is used. And when referring to a specific

service, the term fast payment service is used.

All these elements are described in the following chapters

of this report on the basis of the empirical findings from the

analysis of specific FPSs. (See figure 4.)

THE FAST PAYMENTS TOOLKIT

The development and implementation of a safe, reliable,

and efficient NPS is a crucial component of the World Bank’s

work in the financial sector, given its link to financial inclu-

sion, stability, and economic development. In its unique role

in guiding and supporting jurisdictions as they develop pay-

ments and market infrastructure, the World Bank has under-

taken a study of fast payment implementations across the

world to develop this policy toolkit for fast payment devel-

opment and implementation (hereinafter the Fast Payments

Toolkit or toolkit).

2

The toolkit has been designed to guide jurisdictions and

regions on the likely alternatives and models that could assist

them in their policy and implementation choices when they

embark on their own fast payment implementation journeys.

The guide, the deep-dive reports for 16 jurisdictions, and

the focus notes are being made available as part of the Fast

Payments Toolkit. (See chart 1.)

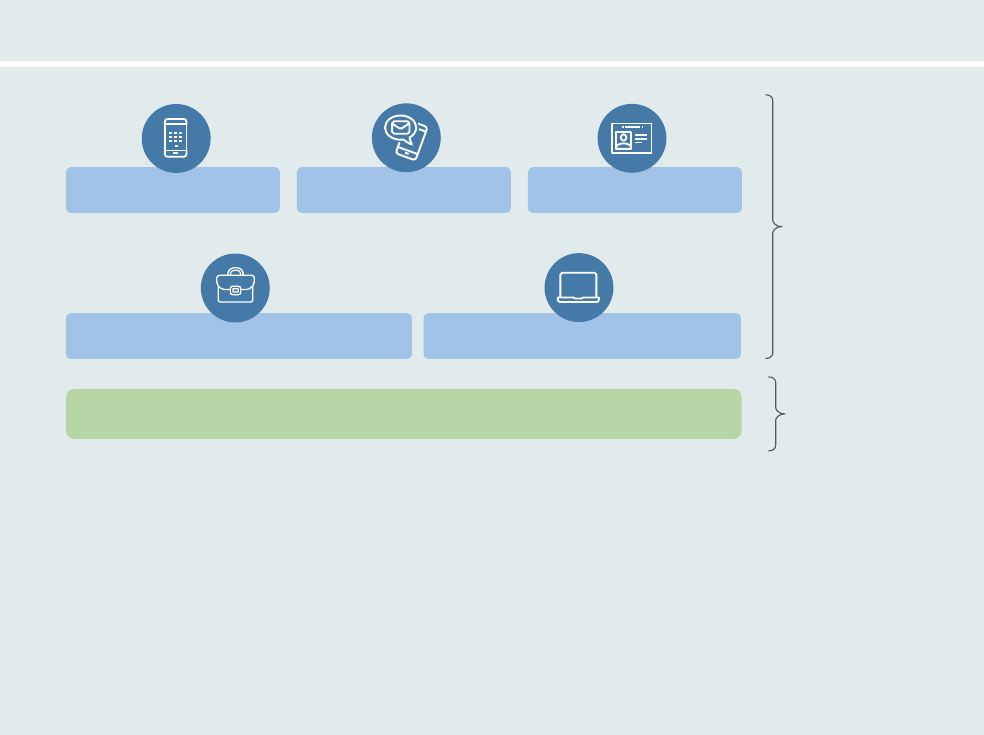

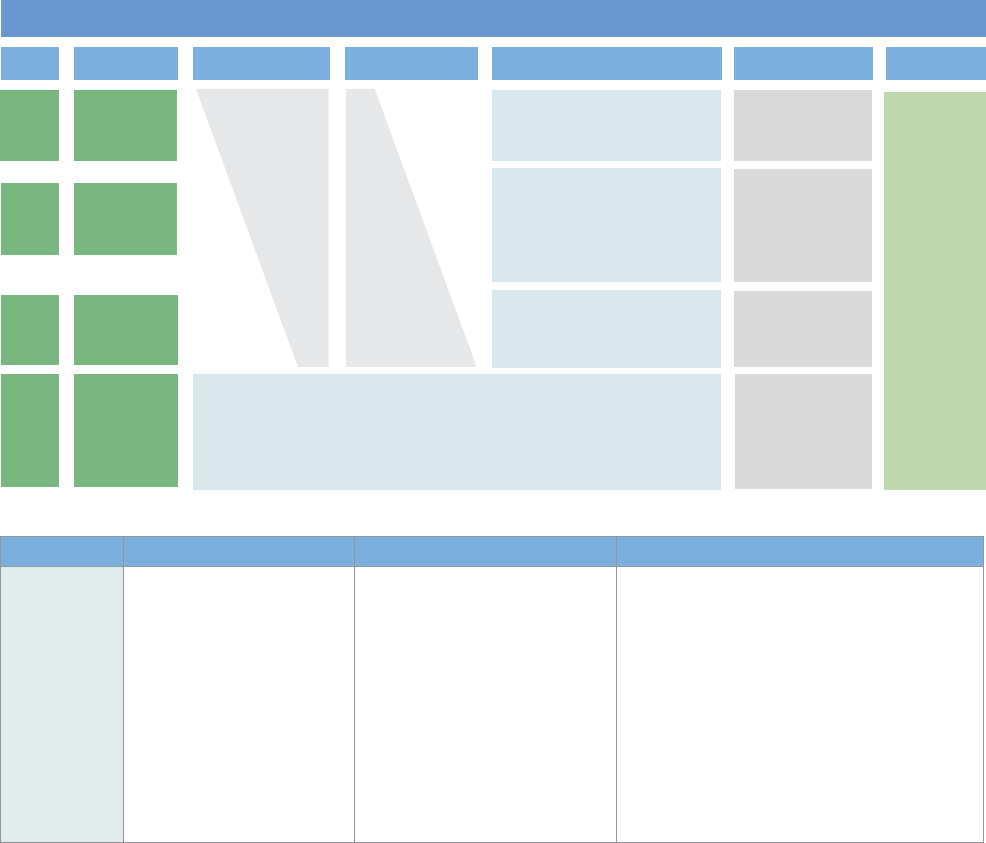

FIGURE 4: The Fast Payments Toolkit

Global landscape of jurisdictions Profiles of 25 jurisdictions*

Deep dive reports for

16 jurisdictions*

1. Framework for fast payments implementation

2. Options / decisions across the course of the implementation journey

3. Key insights from fast payments implementations

4. Key takeaways / recommendations

1. QR codes

2. APIs

3. Customer authentication

4. Messaging standards

5. Consumer protection

6. Dispute handling, reversal,

chargeback and refunds

7. Fraud risks and AML/CFT

8. Pricing structure

9. Proxy identifiers and

database

10. Access aspects

11. Cross-border payments

12. Interoperability aspects

13. Oversight aspects

14. Scheme rules

15. Future of fast payments

16. Infrastructure and

ownership aspects

Main Report

Focus Notes

FAST PAYMENTS TOOLKIT

11

12 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

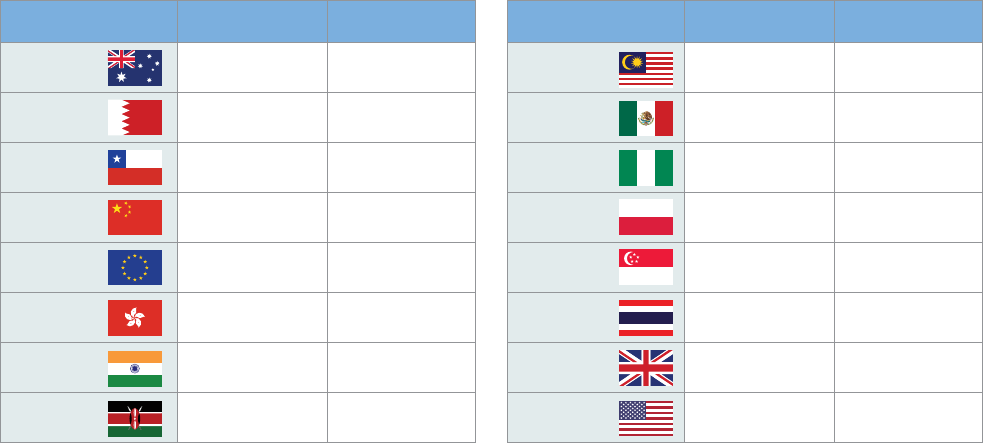

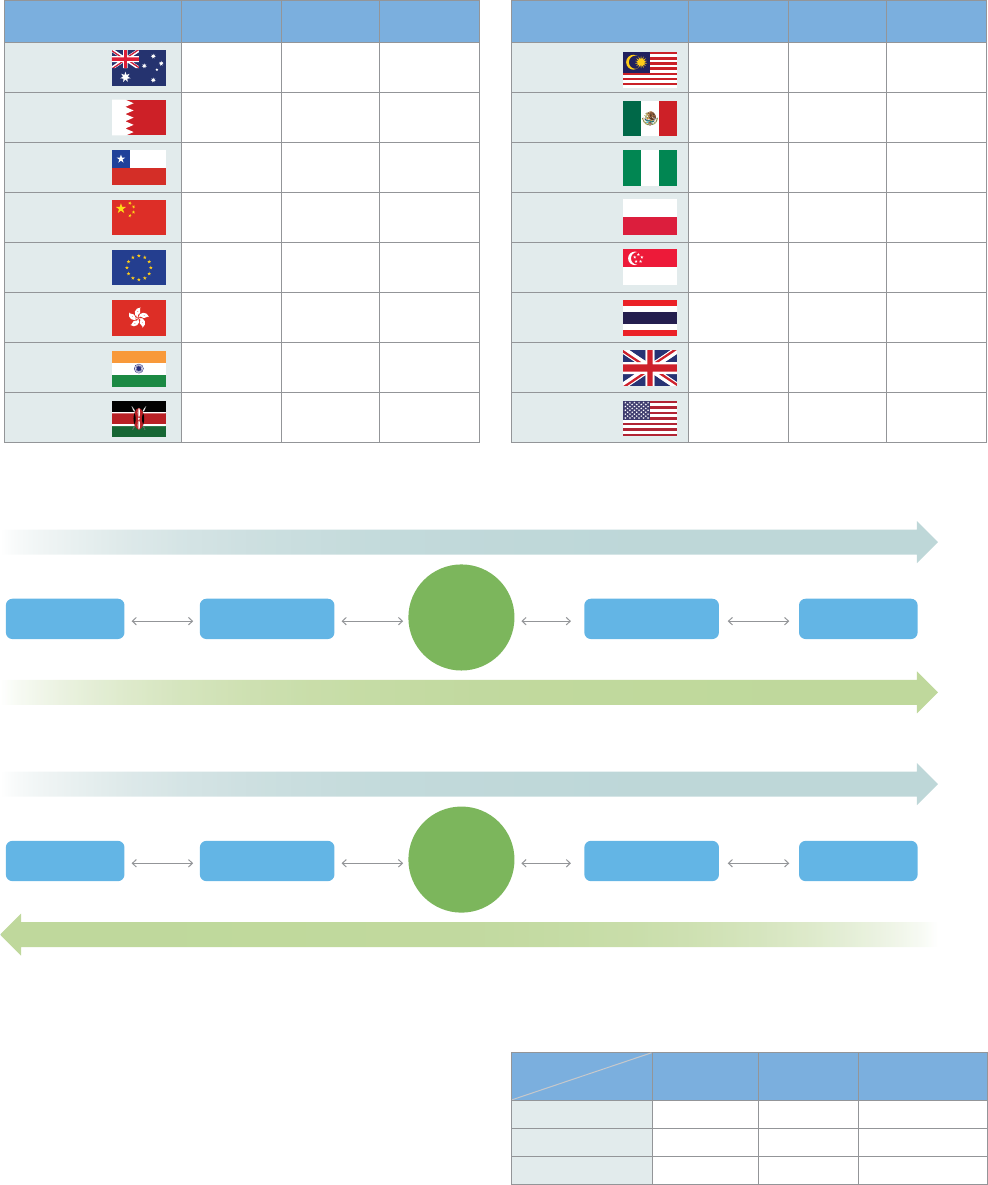

CHART 1: Fast Payments Toolkit Illustration

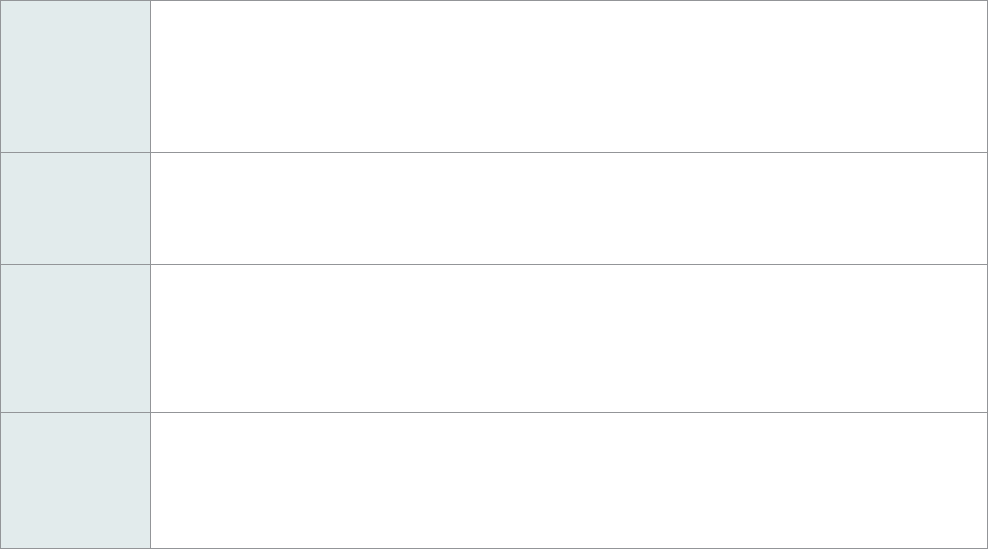

COMPONENT OUTCOME

Global landscape Overview of global FPS landscape, containing information on:

• Fast payments overview

• Customer features

• Technological capabilities

• System participation

16 Deep-dive reports/case

studies

16 in-depth reports:

1. Australia: NPP

2. Bahrain: Fawri+

3. Chile: TEF

4. China: IBPS

5. European Union: SCT Inst

6. Hong Kong SAR, China: Faster Payment

System (FPS)

7. India: UPI and IMPS

8. Kenya: PesaLink

16 Focus technical notes (as

stand-alone notes)

Specific topic notes on topics of

foundational and technical relevance to assist in fast payment implementations.

9. Malaysia: RPP

10. Mexico: SPEI

11. Nigeria: NIP

12. Poland: Express Elixir

13. Singapore: FAST

14. Thailand: PromptPay

15. United Kingdom: Faster Payments

Service (FPS)

16. United States: RTP

FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING

FAST PAYMENT DEVELOPMENTS

As part of this guide, a framework for analyzing fast payment

developments (hereinafter the Fast Payments Framework)

has been created. This framework considers facts and expe-

riences from all jurisdictions studied, but the main inputs

have been extracted from the 16 jurisdictions in which a

deep-dive analysis was performed. These 16 jurisdictions,

while not exhaustive, are quite diverse in terms of their

models/approaches to implementing and operating their

fast payment arrangement. Indeed, the selection of these

16 jurisdictions was not random; rather, the express intent

was to get a diverse mix of countries across various geo-

graphic regions and also adequate coverage across matured

or developed and emerging economies.

12

Therefore, the

proposed framework is considered general enough to be

applicable to different country circumstances.

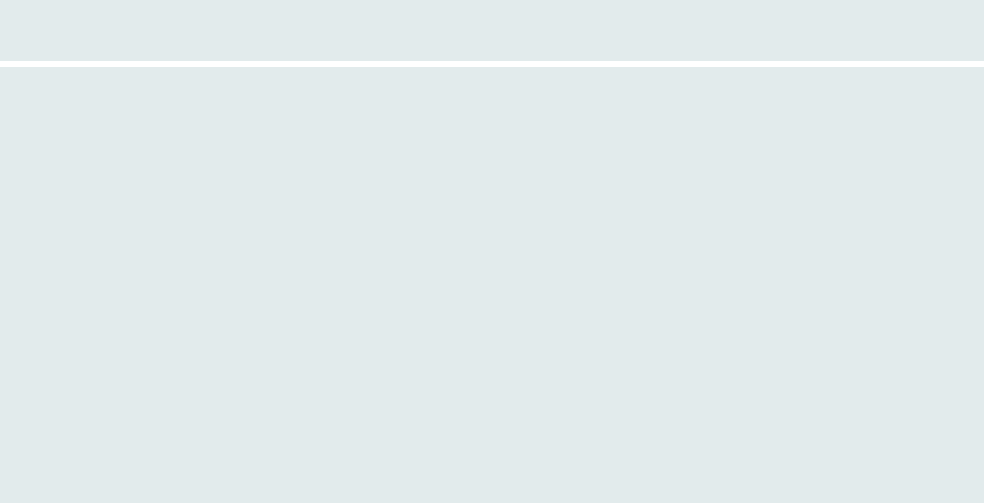

This Fast Payments Framework has two components:

phases, and thematic areas or modules.

In turn, there are three phases: (i) assess; (ii) design; and

(iii) launch and scale. These are aligned to a project devel-

opment life cycle that suits fast payments and is illustrated

in figure 5.

Then there are four broad thematic areas/modules: (a)

the structure of the fast payment arrangements; (b) busi-

ness and technical specifications and operating procedures;

(c) features of the fast payment arrangement; and (d) legal,

regulatory, and governance considerations and risk manage-

ment. These are presented/matched under respective areas

along with additional elements in figure 6.

Figure 6 accordingly collates all these components with

the specific elements that ought to be looked at within each

of the components. The framework is further elaborated

and put into practice in section 4 of this guide.

3

| 13

The main elements underlying each of the three phases

are as follows:

• Assess: A detailed assessment of objectives, technology,

customer requirements, and governance requirements

is critical to set the right precedent. Some jurisdictions

set up independent consultations to arrive at the “best”

concept for their fast payment arrangement. An alterna-

tive is cooperation between the central bank and rele-

vant stakeholders using existing cooperative bodies.

• Design: Key decisions are taken across multiple param-

eters to “get the concept right.” A deep understanding

of design considerations, from the structure of the fast

payment arrangement to pricing and funding, technical

specifications, front-end functionality, risk-management

and dispute-resolution practices, and so on is essential.

FIGURE 5: A Project Development Life Cycle for

Fast Payments

C

o

n

c

e

p

t

u

a

l

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

D

e

s

i

g

n

a

n

d

I

m

p

l

e

n

t

a

i

o

n

G

o

-

l

i

v

e

a

n

d

P

o

s

t

-

I

m

p

l

e

m

e

n

t

a

t

i

o

n

13

14 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

• Launch and Scale: Once an arrangement goes live, the

various stakeholders can start obtaining benefits, either

directly from the new arrangement or indirectly via the

competitive pressures it exerts over other service offer-

ings. Then it is critical to get the new arrangement to

thrive. The launch-and-scale phase is characterized by a

need for continuous improvements and enhancements

to keep up with technological advancements and evolv-

ing consumer needs.

As for the broad thematic areas or modules, these mainly

cover the following aspects:

a. Structure of the fast payment arrangement: Focuses

on the key drivers and objectives for considering the

development of a fast payment project and covers an

assessment of the motivations, proposed arrangements,

stakeholder community, and pricing and funding issues,

among others.

b. System specifications and operating procedures: Cov-

ers an assessment of technology and the determination

of technical specifications and system development

components.

c. Features of the fast payment arrangement: Looks at

customer requirements and determining payment instru-

ments, payment types, uses cases, and access channels

with the goal of driving up user uptake.

d. Legal, regulatory, and governance considerations and

risk management: Covers an assessment of legal and

regulatory aspects and deciding on governance require-

ments, risk-management practices, and other aspects to

enhance safety and security.

The insights obtained from the deep-dive analyses and

interviews with many other institutions are mapped to the

different modules as per the proposed framework. This

approach and the actual insights are analyzed in the next

section of this guide.

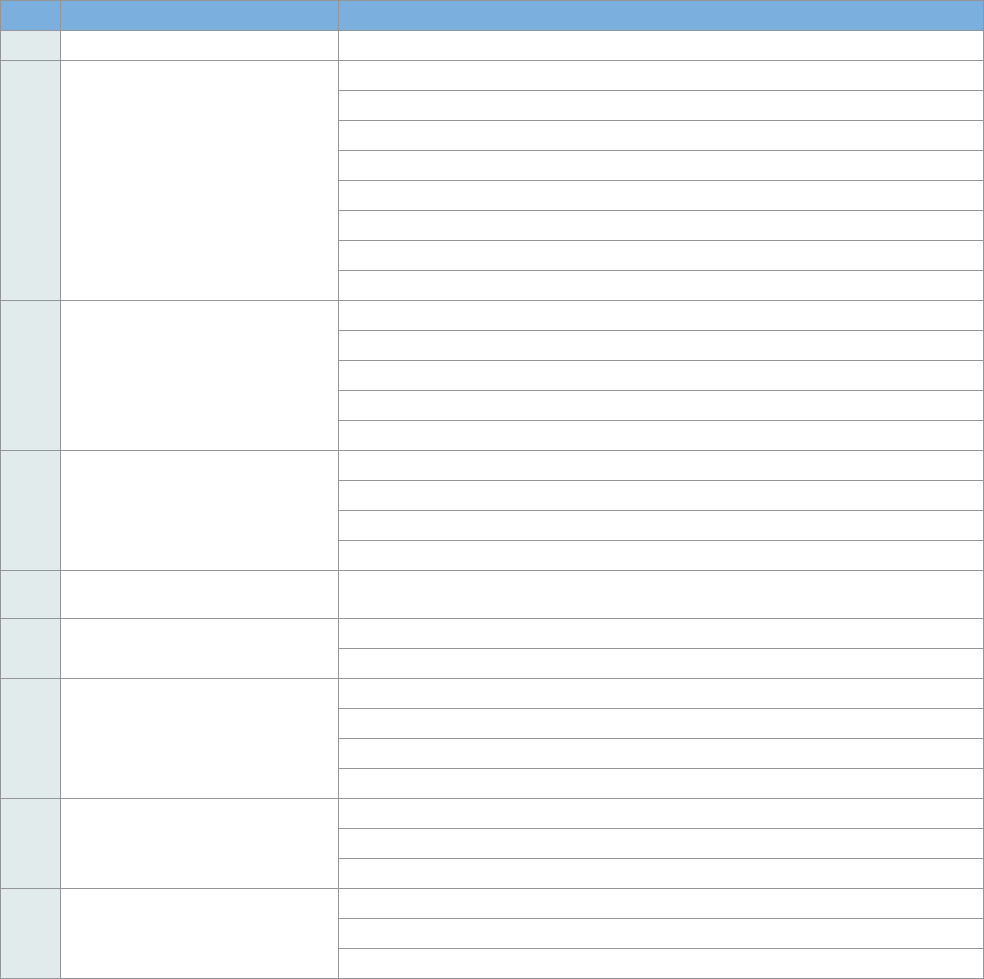

FIGURE 6: Fast Payments Framework

LIFECYCLE—FAST PAYMENTS ARRANGEMENTS

ASSESS DESIGN LAUNCH & SCALE

Objectives

Collaboration &

Innovation

FPS Stakeholders Funding Pricing

Inter-operability

System Development Settlement

Customer

Requirements

User Adoption

Aliases & Overlay

Services

Access Channels

Legal &

Governance

Considerations

Safety & SecurityLegal & Regulatory

Risk Management

Dispute Resolution &

Customer complaints

Conceptualize Design & Implement

D

A

C

B

Go-Live & Post-

Implementation

Current State

Technology

Technical Specifications &

Network Connectivity

Payment Instruments, Types

&

Use Cases / Services

PAINTING THE BIGGER PICTURE:

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED?

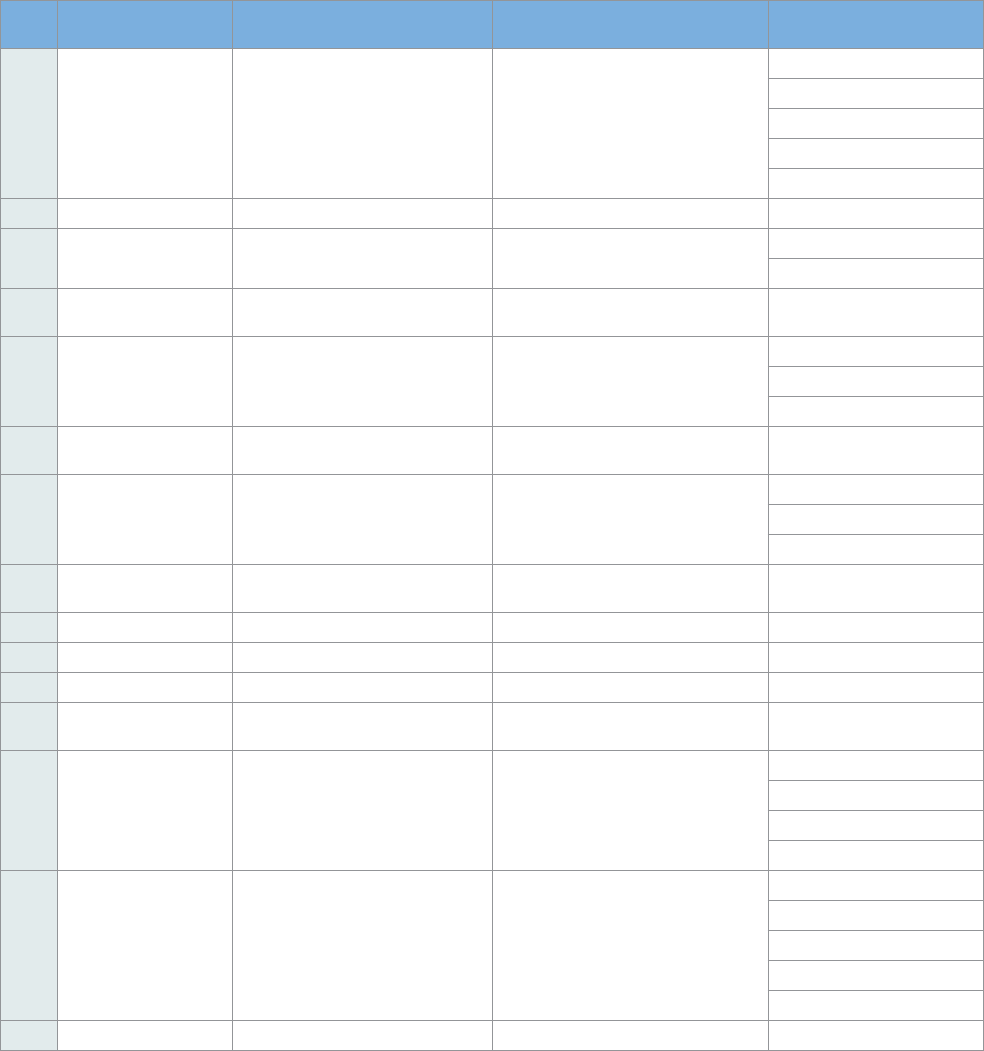

Insights into the various aspects and elements that are

highly relevant for fast payments have been drawn from the

comprehensive analysis of 16 jurisdictions, as well as from

nearly 70 primary interviews and secondary research. These

insights have been analyzed as components under the dif-

ferent modules. (See figure 7.)

These insights are described below, along with juris-

diction-specific inputs and any trends that may have been

identified, to provide the reader with a holistic view of the

decisions/options available.

4.1 MODULE A: STRUCTURE OF A FAST PAYMENT

ARRANGEMENT

The following three insights are covered within this module:

• Motivation to introduce fast payments

• Stakeholder ecosystem and approach to setting up a

fast payment arrangement

• Funding and pricing

4

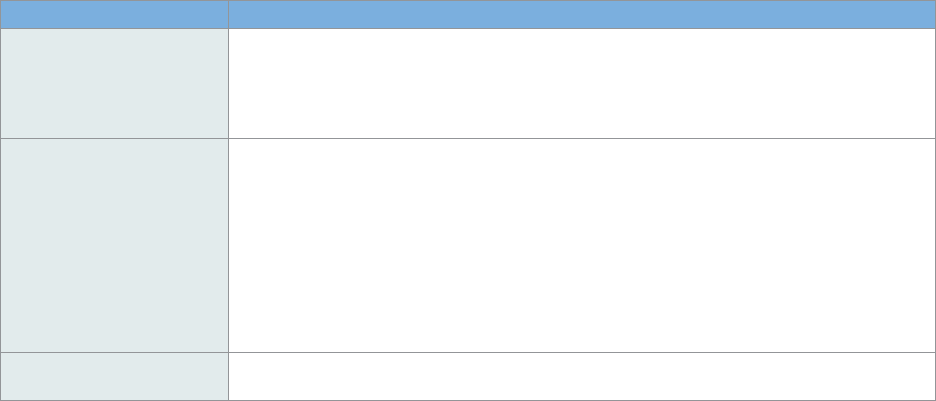

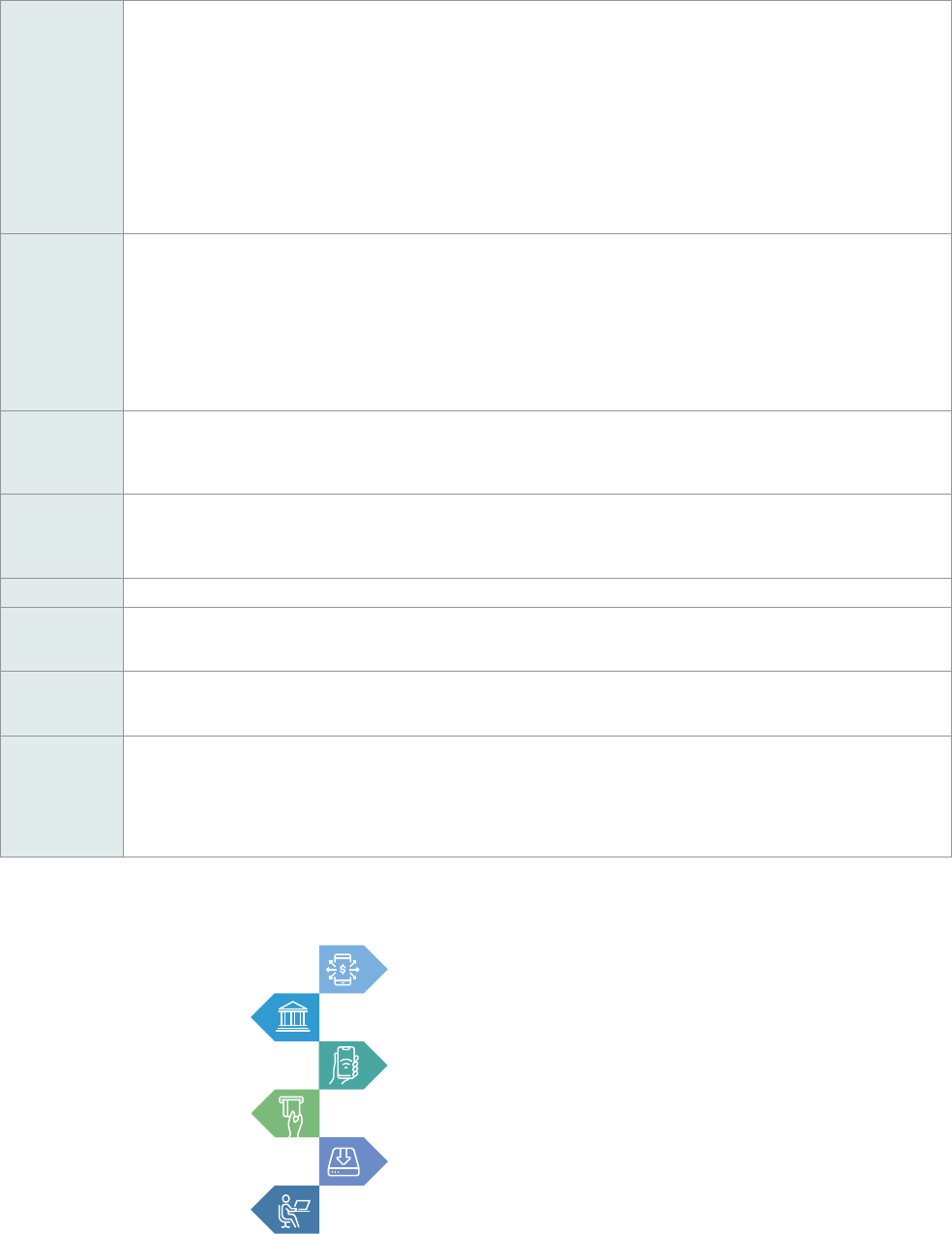

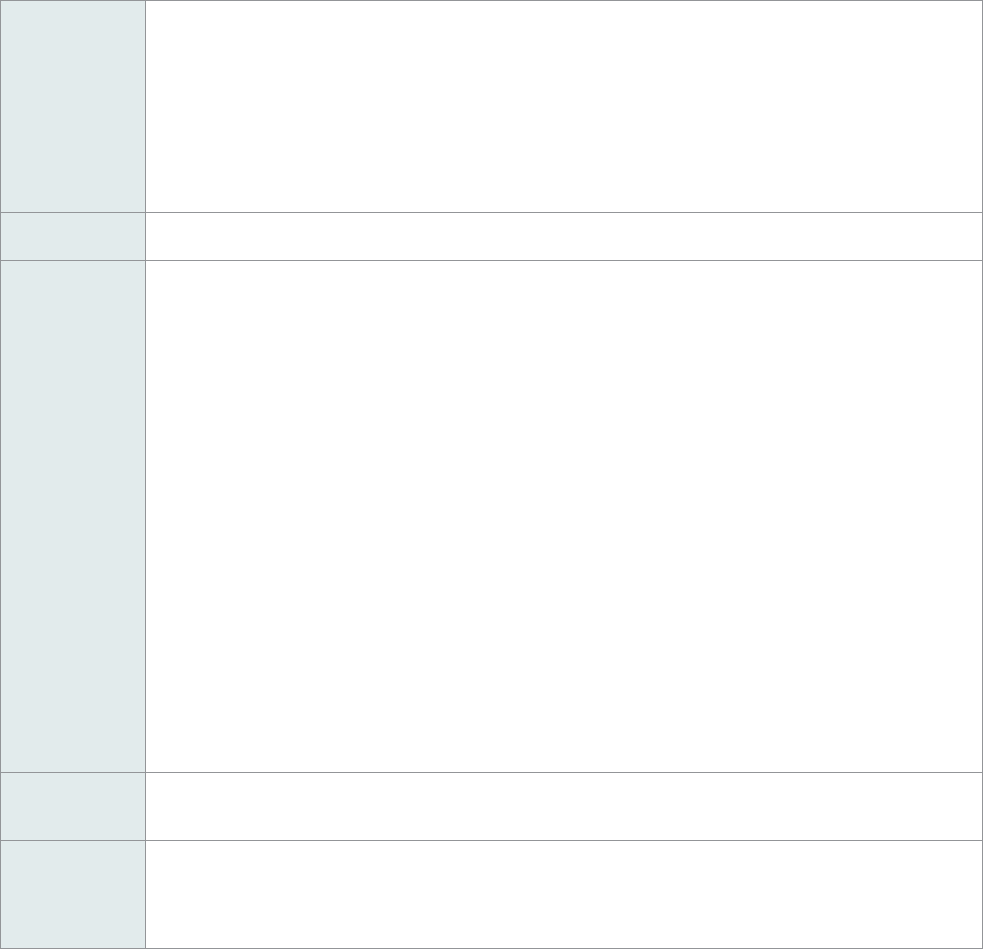

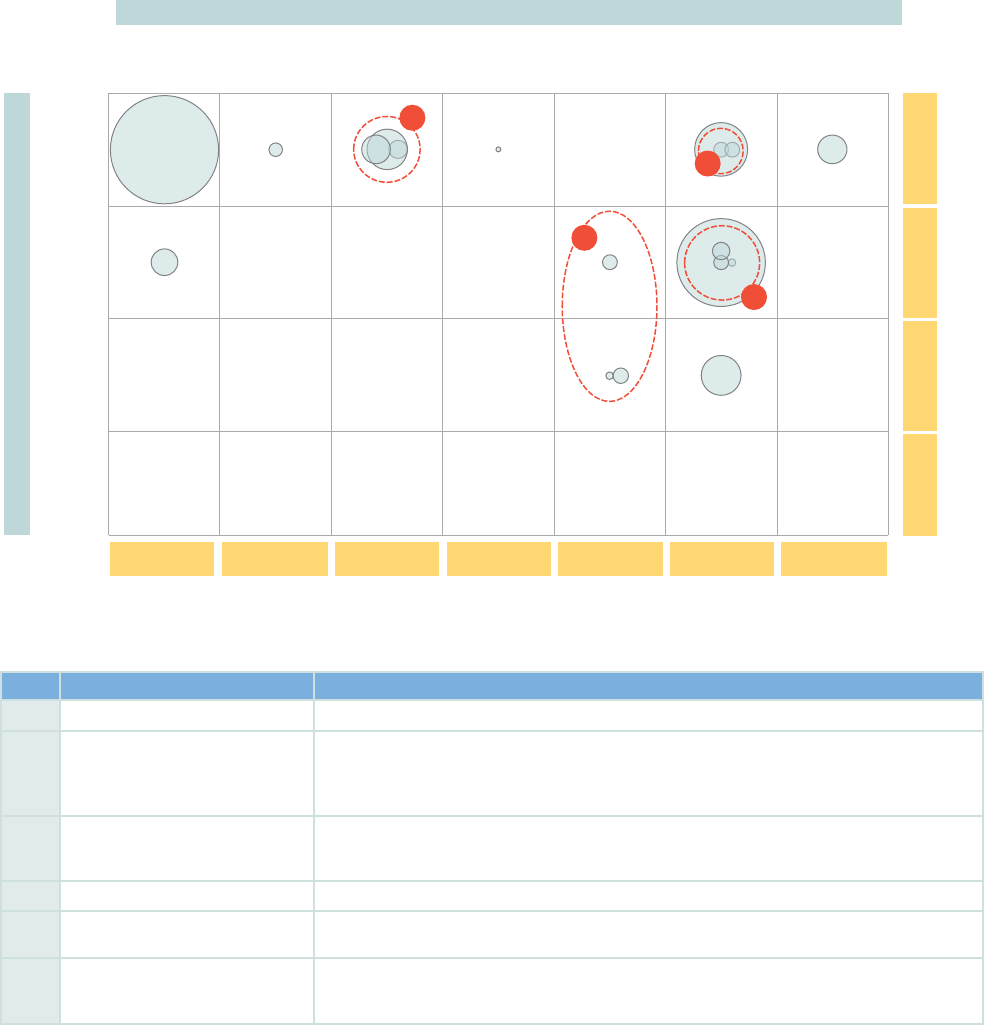

FIGURE 7: Components of the Different Modules

4.1.1 Motivation to Introduce Fast Payments

Jurisdictions across different parts of the world have imple-

mented fast payment arrangement (some have more than

one). The motivation for going for FPS varies across such

themes as financial inclusion, digitization, and driving inno-

vation, among others. (See figure 8.)

The section below details the motivations to introduce

fast payments, covering the findings and insights. These are

presented under following heads: (i) stakeholder-specific

drivers; (ii) public authorities’ initiative/role (for example,

NPS overseers, government agencies, and so on); and (iii)

unique motivators.

i. Stakeholder-Specific Drivers

Perspectives on fast payments differ across stakeholders in

terms of what the drivers of fast payment implementation

are or ought to be.

In general, based on the analysis of 16 jurisdictions, it has

been observed that when the fast payment project is led by

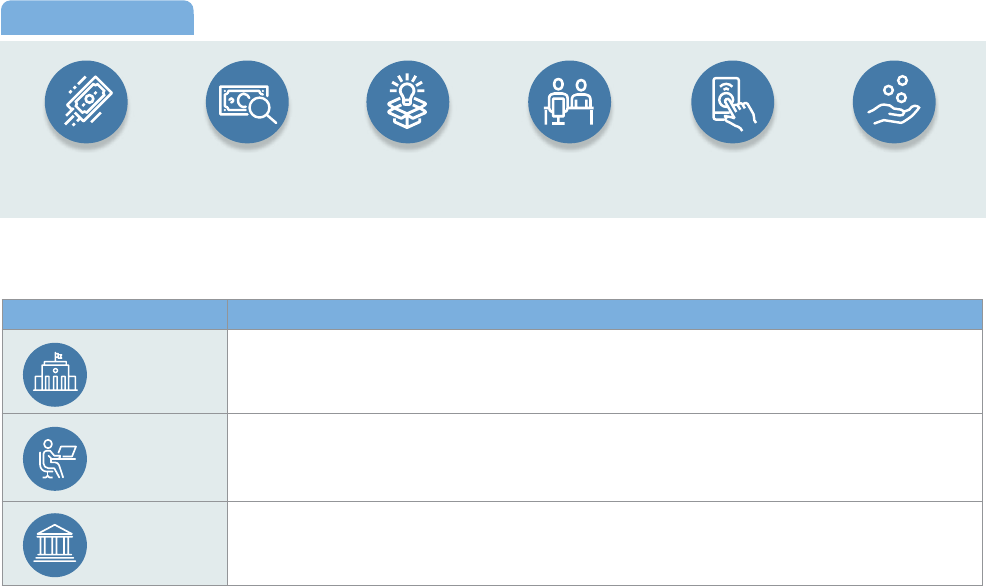

Module A: Structure

1. Motivation to introduce

fast payments

2. Stakeholder ecosystem

and approach to

setting up fast payment

arrangement

3. Funding and pricing

Module B: Specifications

1. Development of fast

payment arrangement

2. Technical specifications

3. Network connectivity

4. Clearing and settlement

5. Interoperability

Module C: Features

1. Payment instruments,

payment types supported

and use cases/services

2. Overlay services and

aliases

3. Access channels

4. User uptake

Module D: Legal &

Governance Considerations

1. Legal and regulatory

considerations

2. Risk management

3. Dispute resolution and

customer complaints

15

16 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

Need for fast

payments

Market/regulator

driven

Enhance customer

experience

Drive

innovation

Digitize

payments

Financial

inclusion

FIGURE 8: Key Motivators for Introducing Fast Payments

the public sector, the agenda is driven by financial inclusion,

payments infrastructure development, and payment digiti-

zation initiatives. (See figure 9.) Central banks have played a

major role in most of these projects.

As can be observed from the jurisdiction-specific anal-

ysis in table 2, financial inclusion has served as a driver in

Bahrain, India, and Mexico. In contrast, when the project is

led by other stakeholders, or when the project is to enhance

the basic infrastructure and functionalities already imple-

mented, some of the drivers differ and/or are expanded—for

example, toward enhancing customer experience and con-

venience to further incentivize customer uptake.

FIGURE 9: Primary Fast Payments Implementation Drivers, as per Survey Findings

13

STAKEHOLDER PRIMARY FPS IMPLEMENTATION DRIVERS

Public

authorities

• Digitization of payments

• Leading innovation in the jurisdiction

• Enhancing consumer experience

Operator

• Market push (recommendation by financial institutions, banking, and payments associations)

• Enhancing consumer experience

• Digitization of payments

• Leading innovation in the jurisdiction

Payment

service

providers

• Better customer experience

• Innovation/newer channels, use cases, and technologies

• Competitor participants’ fast payment offerings

ii. Role of Public Authorities

The majority of surveyed regulators and participants believe

that intervention and promotion of digital payment modes

by the government and/or central bank at a national level

is a critical driver for fast payment implementation.

In all but one of the jurisdictions shown in table 3, the

central bank or other public-sector entities were directly

involved in the discussions that led to the development and

implementation of fast payments. In Thailand, for example,

the government was involved from the conceptualization

stage. In Thailand, as well as in Hong Kong SAR, China, and

Malaysia, fast payments were introduced as part of a larger

program of government measures. In contrast, in Poland, the

development of fast payments was led by a technology and

infrastructure institution of the Polish banking sector. More

generally, it was found that over 75 percent of the jurisdic-

tions included in the deep dives had a push from the central

bank and/or other government agencies acting as a driver

for fast payment implementation.

FPS MOTIVATORS

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | 17

Australia The Payments System Board of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) decided to undertake a “strategic review

of Innovation in the Australian payments system” in May 2010. The purpose was to identify opportunities for

innovation in the Australian payments system. The conclusion of this review included the need for establishing fast

payments. The key strategic objectives laid out by the RBA for the New Payments Platform (NPP) were to receive

low-value payments outside normal banking hours, to send more complete remittance information with payments,

and to address payments in a simple manner.

India The overarching objectives of the Immediate Payment System (IMPS) and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) have

been facilitating financial inclusion and promoting digital payments. IMPS is a multichannel system that can be

accessed using mobile, ATM, internet banking, bank branches, and so on. With the basic infrastructure in place, the

Reserve Bank of India’s focus expanded toward cooperation and collaboration for enhancing customer experience

and convenience. To this end, an interoperable real-time 24/7 mobile-payment system, UPI, was launched in 2016.

14

Mexico The Interbank Electronic Payment System (SPEI) was introduced in the mid-2000s as Banco de México’s new RTGS

system. The objective was to process payments in real time, minimizing credit and liquidity risks. The system was

designed to offer a high level of services to users and participants, including provisions for business continuity

plans, adequate risk management, and legal certainty about a credit on the receipt account. Some years ago, it

was upgraded to offer real-time payments 24/7. To further enhance the user experience, in 2019, Banco de México

launched CoDi, which is a request-to-pay functionality that supports the use of QR codes, near-field communication

(NFC), and messages through the internet for payments.

United States In 2014, the Clearing House (TCH) launched its Future Payments Initiative based on the recommendations from its

supervisory board, which consists of several industry leaders from financial institutions. The aim was to develop

a strategic view of real-time payments based on an extensive study of payment needs in an increasingly digital

economy. TCH worked closely with the Federal Reserve, TCH banks, and industry associations, including the National

Automated Clearing House Association, American Bankers Association, Independent Community Bankers of America,

National Association of Federally Insured Credit Unions, and Credit Union National Association, to identify consumer

and business cases with the greatest need for fast payments that represent the best incremental value for customers.

The Future Payments Initiative considered the experience and lessons from other countries that had already

implemented fast payments. TCH also reviewed ways in which a fast payment arrangement for the United States

could maintain and improve the safety and soundness of existing payment systems.

TABLE 2: Select Findings on Motivation

TABLE 3: Select Findings on Role of Governments and Regulators

Bahrain There was a push from the government to adopt real-time transactions. The Central Bank of Bahrain consulted

with the BENEFIT Company, to provide a real-time payment solution. BENEFIT also handles POS and ATM switch

services in the country.

Hong Kong

SAR, China

With a view to driving innovation and ushering in the era of smart banking in Hong Kong SAR, China, the Hong

Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) in 2017 introduced several major initiatives in the banking sector. One was to

develop the fast payment system FPS and drive innovation by bringing e-wallets on the platform in addition

to banks.

Malaysia The Real-Time Retail Payments Platform (RPP) was created as part of a multiyear program to modernize and

future-proof Malaysia’s payments infrastructure. Pursuant to an industry-wide consultation facilitated by Bank

Negara Malaysia (BNM), PayNet built RPP to meet the emerging and future needs of the economy. In line with

the Interoperable Credit Transfer Framework issued by BNM, RPP was designed to provide fair and open access

to banks and eligible non-bank PSPs, to facilitate interoperability and seamless payments between bank

accounts and e-money accounts.

Poland The introduction of fast payments was market driven. Initially, banks were hesitant to participate in it because

they thought the existing system worked well. In this regard, the RTGS system took four to six hours to process

transactions, which was perceived to be fast enough, and there was no need for immediate payments. Krajowa

Izba Rozliczeniowa (KIR), a technology and infrastructure institution of the Polish banking sector, undertook

extensive research with end users to gauge customer needs and make them aware of the benefits of introducing

fast payments. Thus, KIR built consensus among customers by administering surveys and gauging their

receptiveness toward the initiative and then pitched it to banks. While fast payments were initially viewed as a

premium product, this view has changed over time.

Thailand The National e-Payment Master Plan was created by the government with an objective to have an integrated

digital payment infrastructure. Under this master plan, the PromptPay system was created to facilitate easy, safe,

and convenient fund transfers for all—general public, businesses, and government. Initially, only bulk/batch payment

service was developed in PromptPay, and it was used to transfer government welfare disbursements. This helped

create awareness among the public about the system. In January 2017, the new credit transfer service was enabled

in PromptPay, allowing for real-time person-to-person (P2P) interbank fund transfers.

continued

18 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

iary of the central bank. As shown in table 4, the latter is

the case in China, Hong Kong SAR, China, and Malaysia.

In certain jurisdictions, such as Mexico, the central bank

owns, operates, and oversees SPEI. The operator can also

be a completely independent entity. It is also important to

note that most jurisdictions already have existing retail pay-

ment system operators (for example, for the domestic bulk

payment systems and/or payment card switch). In some

cases, these same entities also operate the fast payment

arrangement. For example, in Thailand, National Interbank

Transaction Management and Exchange (ITMX) was chosen

as PromptPay’s operator, as it already had technical capa-

bilities and was the largest payment system operator in the

country. Overall, there seems to be a slight predominance

of private-sector entities as operators of fast payment

arrangements.

ii. Participants and Access Criteria

Participation of banks and non-bank PSPs of varied cate-

gories is crucial to the success of the fast payment arrange-

ment. Furthermore, to encourage participation by banks

and non-bank PSPs, surveyed overseers and operators

believe that regulatory push/incentives are required in the

initial years following launch. Jurisdictions can have either

only direct participants or a combination of direct and

indirect participants.

Participants in a payment system can be direct or indirect.

In the case of fast payments, direct participants are typically

banks with a direct link to the underlying payment system

infrastructure and having a settlement account at the cen-

tral bank’s settlement system—if settlement occurs in central

bank money. The settlement can take place in commercial

bank money as well. Indirect participants are other financial

institutions or other PSPs using the payment system infra-

structure either directly or via a sponsor primary participant

and leveraging the sponsor’s settlement account with the

central bank for settlement of their transactions. A few fast

payment arrangements allow participation of intermediary

PSPs that receive and transmit transfer of funds on behalf

of other participants. For example, SCT Inst in the European

Union allows intermediary banks to provide services to orig-

United Kingdom In the early 2000s, the Cruickshank Report was published, providing the foundation for the development of fast

payments in the country. The report pointed out the lack of innovation and need to upgrade the existing retail

payment systems. (For example, even if other payment systems, such as BACS, were available, cash was still the

most dominant payment instrument.) This led the government to mandate the Office of Fair Trade to provide

recommendations for innovating the payments landscape in the United Kingdom. The office drafted a report that

was taken to the Payment Systems Task Force, which was charged with developing fast payments to reduce the

payment cycle from three days to a single day. This led to the development of the Faster Payments Service (FPS)

in May 2005.

TABLE 3, continued

4.1.2 Fast Payment Stakeholder Ecosystem and

Approach to Setting Up a Fast Payment

Arrangement

The fast payment ecosystem typically consists of the central

bank (and, in some cases, other regulators), the operator, the

owner(s), participants, third-party providers, and end users

(that is, individuals, merchants, and government agencies).

The following four aspects have emerged as key compo-

nents of this insight and are covered in the sections below:

(i) the division of roles between the overseer, owner, and

operator; (ii) participants and access criteria; (iii) industry

body collaborations; and (iv) the systemic importance of fast

payment arrangements.

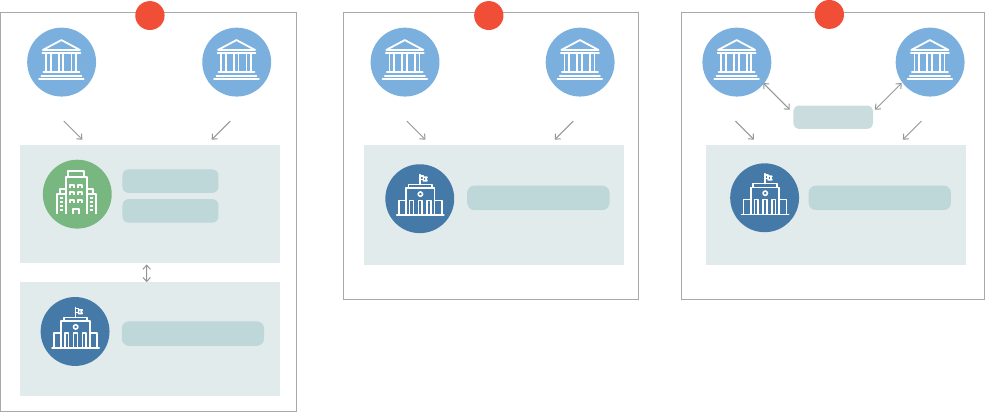

i. Division of Roles between the Overseer, Owner, and

Operator

Central banks typically play a major role as overseers and,

in some cases, also as operators (and owners) of the fast

payment arrangement.

Central banks typically play the role of overseer of payment

systems (and very often the broader NPS). The overseer role

is generally accompanied by a regulatory function. In some

cases, depending on the institutional setting, this regulatory

function may be shared with a different regulatory authority

or performed independently by the latter. A fast payment

arrangement is usually considered a critical national pay-

ment infrastructure. Therefore, the overseer puts in place a

monitoring mechanism to try to ensure that it operates in

a safe and efficient manner. Toward this end, the overseer

requires the operator to have adequate measures in place to

address operational risk, liquidity risks, security, anti-mon-

ey-laundering (AML), and other relevant aspects.

Box 3 provides details on observed ownership alterna-

tives of fast payment arrangements. Additional information

on ownership and funding is provided in section 4.1.3.

The operator or scheme owner is responsible for ensur-

ing compliance with the scheme rulebook, operating pro-

cedures, and official regulations. The operator can be a

separate legal entity owned by participating commercial

banks and, in some cases, by the central bank on its own

or jointly with participants. The operator may be a subsid-

Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems | 19

Both public-sector ownership (most often by the cen-

tral bank) and private-sector ownership of fast payment

arrangements are common, with an overall prevalence

of the latter. In some cases, there is co-ownership of

the central bank with commercial banks or other pri-

vate-sector entities. Moreover, the ownership structure

may change over time, often driven by the needs of

the market, the broader objectives of the owners, and

regulatory requirements. For example, some systems

have moved from public ownership to cooperative

user/membership-based organizations, and in some

cases from there to other corporate arrangements like

privately owned or publicly listed companies.

Central bank ownership of fast payment systems is

often observed in cases where the central bank also

operates some of the traditional key infrastructures for

retail payments, such as the check clearinghouse and/

or the automated clearinghouse for credit transfers and

direct debits. This may be an indication that the central

bank considers this arrangement as a natural continu-

ation of its role as operator of retail payment systems.

Other reasons for central bank ownership can include

trying to ensure universal participation of eligible pay-

ment service providers (PSPs) and/or the notion that

ownership control is critical for truly enhancing financial

inclusion in a particular country context.

Public-sector ownership of retail payments infra-

structure may raise pricing issues which need to be

carefully considered. In some cases, the costs of devel-

oping the infrastructure are absorbed by the central

bank in pursuit of its public policy objectives. In other

cases, the central bank may be subsidizing operational

costs, and therefore pricing of services to participants

may not be reflecting the true costs of operating the

fast payment system. In this regard, if those subsidies

are kept beyond the short-term, central banks ought

to consider the implications for long-term competition

and efficiency.

15

Another aspect that needs to be considered is the

potential conflict of interest that may arise between the

central bank’s role as an operator of the retail payments

infrastructure and its role as an overseer. The central

bank should seek to avoid any impression that it might

use its role as overseer of private sector systems to

support unfairly the operation of its payment systems.

The central bank may therefore make a clear functional

and, if possible, also organizational separation of the

two functions within the central bank’s organizational

chart.

16

Private ownership of fast payment systems also

entails some potential concerns. When these systems

are owned solely by large participant banks closely tied

to the market, they may be less willing to open the sys-

tem and provide access to smaller banks or to non-bank

PSPs. Also, a fast payment system entirely owned by the

private sector is likely to require high upfront invest-

ment and transaction pricing consistent with a target

investment recovery period, usually medium-term. High

per transaction prices may deter participation, espe-

cially of PSPs that cater to low-income customers.

A central bank may intervene to ensure that a for-

profit focus is balanced with a vision that considers the

medium- to longer-term needs and developments of

a market, fosters innovation, makes it possible for all

types of PSPs to join and achieves regular usage by

lower-income users and small and micro enterprises.

Central banks in their role as regulators/overseers

must also make sure that their interventions to ensure

broad participation in the system do not dis-incentiv-

ize future investments by shareholders. In other words,

mandating participation without giving due consider-

ation to the investment and others costs that are borne

by shareholders before they are able to realize or even

clearly foresee a reasonable profit may limit future

investments to grow the business and introduce van-

guard technologies.

More generally, even in circumstances where the pri-

vate sector in a given country appears unable to come

to an agreement to develop a fast payments system and

the central bank decides to intervene to take a more

developmental role (i.e., ownership/operation), the cen-

tral bank should consider this as a starting point and,

from the outset, design the system in a manner that

would enable system participants to innovate and, even-

tually, facilitate the transfer of ownership of and opera-

tional responsibility for the system to the private sector.

Finally, regardless of the ownership model, it is highly

desirable that the owner/operator involve all relevant

BOX 3 OWNERSHIP OF FAST PAYMENT ARRANGEMENTS

continued

20 | Considerations and Lessons for the Development and Implementation of Fast Payment Systems

TABLE 4: Select Findings on the Division of Roles between Overseer, Operator, and Owners

Australia New Payments Platform Australia (NPPA) is the owner and operator of the NPP. The RBA is responsible for the

oversight and regulation of payment systems in the country and empowered to set financial stability standards for

clearing and settlement facilities. Furthermore, the RBA is the operator of the settlement module (that is, the Fast

Settlement Service) that supports the NPP. NPPA was formed by the RBA as a result of an industry collaboration in

response to the “strategic review of Innovation in the Australian payments system.”

Chile Centro de Compensación Automatizado (CCA) is a private ACH and the owner and operator of Transferencias

en Línea (TEF), which is Chile’s fast payments. CCA is owned by three banks: Banco de Chile, Banco Santander,

and Banco de Crédito e Inversiones. These three banks have equal shareholding in CCA. Since June 1, 2019, the

Financial Market Commission (Comisión para el Mercado Financiero, or CMF) has been the lead supervisory entity

of financial markets in Chile and also the supervisor of TEF.

18

China The People’s Bank of China is the owner of the Internet Banking Payment System (IBPS). It is being operated

by China National Clearing Center, which is a public institution fully owned by the People’s Bank of China and

responsible for the operation, maintenance, and management of IBPS.

European Union The European Central Bank is the overseer of the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) Instant Credit Transfer (SCT Inst)

scheme, while the Euro Retail Payments Board fosters the integration of euro retail payments across the European

Union. The European Payments Council (EPC) is the scheme manager and responsible for performing the functions

of management and evolution of the SEPA scheme as defined in the rulebook. PSPs must be connected to at least