Probiotics

BENJAMIN KLIGLER, MD, MPH, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, New York, New York

ANDREAS COHRSSEN, MD,

Beth Israel Residency Program in Urban Family Practice, New York, New York

P

robiotics are live microorganisms

that benefit the health of the host

when administered in adequate

amounts.

1

A large number of

organisms are being used in clinical practice

for a variety of purposes. The most widely

used and thoroughly researched organisms

are Lactobacillus sp. (e.g., L. acidophilus, L.

rhamnosus, L. bulgaricus, L. reuteri, L. casei),

Bifidobacterium sp., and Saccharomyces bou-

lardii, a nonpathogenic yeast.

Pharmacology

Several mechanisms have been proposed to

explain the actions of probiotics. In most

cases, it is likely that more than one mecha-

nism is at work simultaneously. In the pre-

vention and treatment of gastrointestinal

infection, it is likely a combination of direct

competition between pathogenic bacteria

in the gut, and immune modulation and

enhancement. In children with atopic der-

matitis, the mechanism is probably related

to the effect of probiotics on the early devel-

opment of immune tolerance during the

first year of life. Probiotics may help down-

grade the excessive immune responses to

foreign antigens that lead to atopy in some

children.

2

They may also contribute to sys-

temic down-regulation of inflammatory

processes by balancing the generation of

pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, in

addition to reducing the dietary antigen

load by degrading and modifying macro-

molecules in the gut.

3

Probiotics have been

shown to reverse the increased intestinal

permeability characteristic of children with

food allergy, as well as enhance specific

serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) responses

that are often defective in these children.

4

To be most effective, a probiotic species

must be resistant to acid and bile to survive

transit through the upper gastrointestinal

(GI) tract. Most probiotics do not colonize

the lower GI tract in a durable fashion. Even

the most resilient strains generally can be

cultured in stool for only one to two weeks

after ingestion.

3

To maintain colonization,

probiotics must be taken regularly.

Uses and Effectiveness

Most of the identified benefits of probiot-

ics relate to GI conditions, including anti-

biotic-associated diarrhea, acute infectious

diarrhea, and irritable bowel syndrome

(IBS) (Table 1). Some studies indicate a ben-

efit in treating atopic dermatitis in children.

Probiotics are also commonly used for con-

ditions in which firm evidence is lacking,

including vaginal candidiasis, Helicobacter

pylori infection of the stomach, inflamma-

tory bowel disease, and upper respiratory

infections. These uses are not addressed in

this review.

Probiotics are microorganisms with potential health benefits. They

may be used to prevent and treat antibiotic-associated diarrhea and

acute infectious diarrhea. They may also be effective in relieving

symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, and in treating atopic der-

matitis in children. Species commonly used include Lactobacillus sp.,

Bifidobacterium sp., Streptococcus thermophilus, and Saccharomyces

boulardii. Typical dosages vary based on the product, but common

dosages range from 5 to 10 billion colony-forming units per day for

children, and from 10 to 20 billion colony-forming units per day for

adults. Significant adverse effects are rare, and there are no known

interactions with medications. (Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(9):1073-

1078. Copyright © 2008 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

COMPLEMENTARY AND

ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

▲

See related editorial

on page 1026.

Downloaded from the American Family Physician Web site at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright © 2008 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncommercial

use of one individual user of the Web site. All other rights reserved. Contact [email protected] for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

1074 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 78, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2008

ANTIBIOTIC-ASSOCIATED DIARRHEA

A meta-analysis of 19 recent studies showed

that probiotics reduced the risk of devel-

oping antibiotic-associated diarrhea by

52 percent (95% confidence interval [CI],

0.35 to 0.65; P < .001).

5

The benefit was great-

est when the probiotics were started within

72 hours of the onset of antibiotic treatment.

The species that were evaluated included

strains of L. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus, and

S. boulardii. The authors found that the

magnitude of the effect did not differ signifi-

cantly among the strains, although a limited

number of strains were represented.

5

In a second meta-analysis of 25 random-

ized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 2,810),

various probiotics were given to prevent or

treat antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

6

The

relative risk (RR) of developing antibiotic-

associated diarrhea with probiotics was 0.43

(95% CI, 0.31 to 0.58; P < .0001), which

was a significant benefit when compared

with placebo.

6

This analysis also found that

L. rhamnosus, S. boulardii, and mixtures of

two or more probiotic species were equally

effective in preventing antibiotic-associated

diarrhea. The mean daily dosage of the bac-

terial species in these studies was 3 billion

colony-forming units (CFUs), but studies

using more than 10 billion CFUs per day

showed that these dosages were significantly

more effective. The dosages of S. boulardii

were 250 mg or 500 mg per day.

6

The same meta-analysis examined the

prevention and treatment of Clostridium dif-

ficile disease.

6

Six RCTs were analyzed and

revealed a prevention benefit for participants

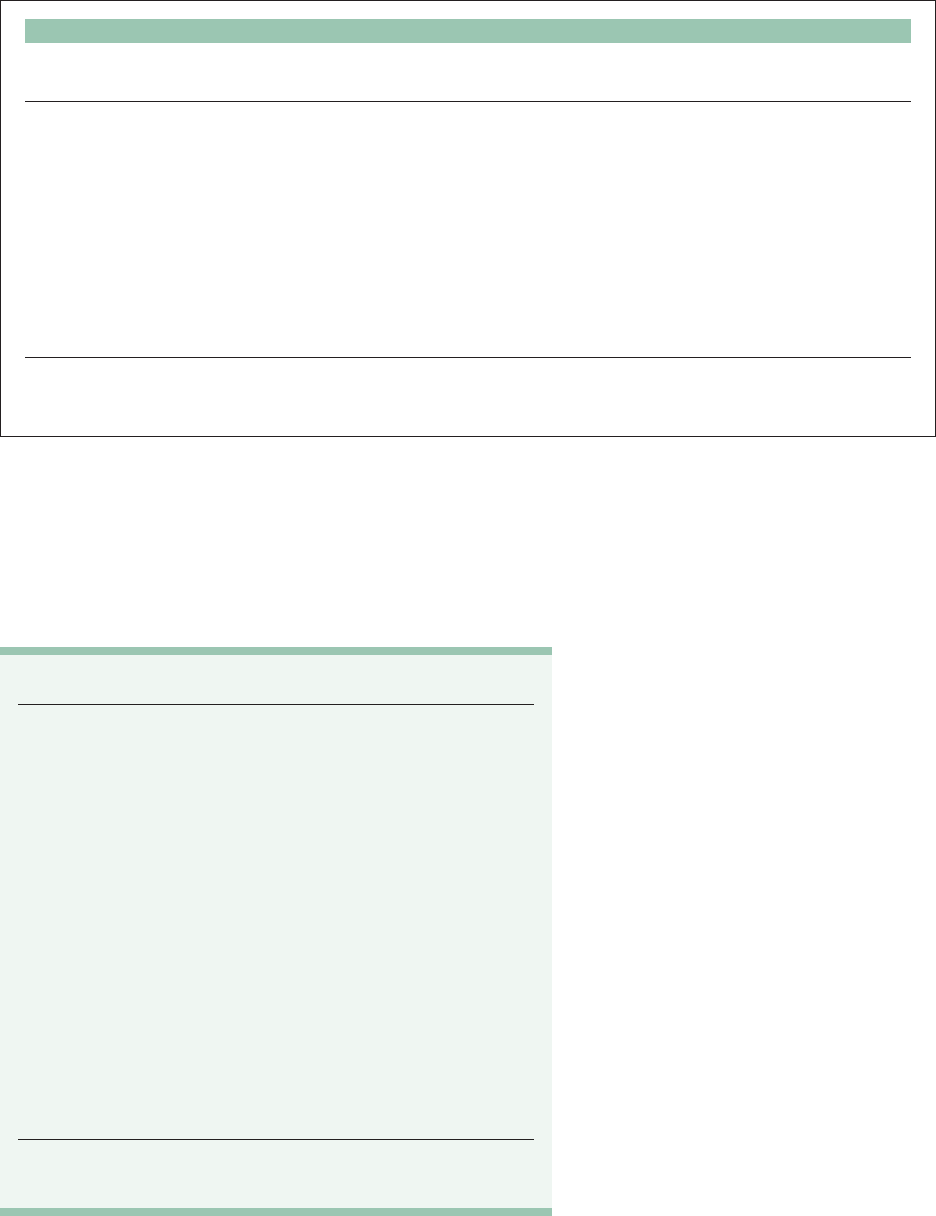

Table 1. Key Points About Probiotics

Effectiveness* Probably effective for antibiotic-associated diarrhea

and infectious diarrhea; possibly effective for

irritable bowel syndrome symptom reduction and

atopic dermatitis for at-risk infants

Adverse effects Common: flatulence, mild abdominal discomfort

Severe/rare: septicemia

Interactions None known

Contraindications Short-gut syndrome (use with caution); severe

immunocompromised condition

Dosage Dosage should match that used in clinical studies

documenting effectiveness: 5 to 10 billion CFUs per

day for children; 10 to 20 billion CFUs per day for

adults

Cost $8 to $22 for a one-month supply

Bottom line Safe and effective for preventing and treating

antibiotic-associated diarrhea and infectious

diarrhea; physicians should consult http://www.

comsumerlab.com or another objective resource for

information about the quality of various brands

CFU = colony-forming unit.

*—Effectiveness depends on probiotic strain and dosage.

SORT: KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Clinical recommendation

Evidence

rating References Comments

Probiotics may reduce the incidence

of antibiotic-related diarrhea.

A 5-7, 9 Most validated products are Saccharomyces

boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

Probiotics may reduce the duration and severity

of all-cause infectious diarrhea.

A 5, 10-12 A large meta-analysis of all-cause infectious

diarrhea included studies with viral

diarrhea and traveler’s diarrhea

Probiotics may reduce the severity of pain

and bloating in patients with irritable bowel

syndrome.

B 17-19 Small trials to date

Probiotics may reduce the incidence of atopic

dermatitis in at-risk infants. There is preliminary

support for treatment of symptoms.

B 20-23, 25-28 —

A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-

oriented evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to http://www.aafp.

org/afpsort.xml.

Probiotics

Probiotics

November 1, 2008

◆

Volume 78, Number 9 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 1075

taking probiotics. The RR of developing

C. difficile disease was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.41 to

0.85; P = .005). Only S. boulardii showed a

reduction in recurrence with treatment.

A meta-analysis of six RCTs (n = 766) that

focused on preventing antibiotic-associated

diarrhea in children found a reduction in

risk from 28.5 to 11.9 percent (RR = 0.44; 95%

CI, 0.25 to 0.77) in those using probiotics.

7

This analysis showed no difference among L.

rhamnosus GG, S. boulardii, and a combina-

tion of Bifidobacterium lactis and Streptococ-

cus thermophilus. However, a recent Cochrane

review found that although a per-protocol

analysis of 10 trials showed a benefit in pre-

vention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea

in children, a more sensitive intention-to-

treat analysis failed to show a benefit.

8

The

authors did find greater effectiveness in the

studies that used dosages of more than 5 bil-

lion CFUs per day than those that used lower

dosages, regardless of the type of probiotic.

Preliminary evidence suggests that pro-

biotics delivered via fermented milk con-

taining L. casei DN-114 001 and the yogurt

starter cultures L. bulgaricus and S. ther-

mophilus may be useful dietary components

that can reduce the risk of antibiotic-

associated diarrhea and C. difficile toxin for-

mation in hospitalized patients.

9

ACUTE INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA

A Cochrane review examined 23 studies

(n = 1,917) that used different types of pro-

biotics to treat acute infectious diarrhea.

10

Definitions of diarrhea and specific out-

comes varied. The reviewers concluded that

probiotics significantly reduced the risk of

diarrhea at three days (RR = 0.66; 95% CI,

0.55 to 0.77; P = .02). The mean duration of

diarrhea was also reduced by 30.48 hours

(95% CI, 18.51 to 42.46 hours; P < .00001).

This analysis included all causes of infectious

diarrhea (e.g., viral diarrhea, traveler’s diar-

rhea). The authors concluded that probiotics

appear to be a useful adjunct to rehydration

therapy in treating acute infectious diarrhea

in adults and children.

A meta-analysis examining S. boulardii

for treatment of acute diarrhea in children

combined data from four RCTs (n = 619).

11

The authors found that S. boulardii sig-

nificantly reduced the duration of diarrhea

when compared with the control group, for

a mean difference of −1.1 days (95% CI,

−1.3 to −0.8). However, a large trial (n =

571) comparing several probiotic prepara-

tions to oral rehydration solution concluded

that L. rhamnosus GG or a combination of

Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, S.

thermophilus, L. acidophilus, and Bifidobac-

terium bifidum was more effective than S.

boulardii or oral rehydration therapy alone

in reducing the duration and severity of

acute diarrhea in children.

12

Another trial examined the prophylac-

tic benefits of probiotics in preventing GI

infections in children.

13

In a double-blind,

placebo-controlled RCT at 14 child care

centers, infants four to 10 months of age

(n = 201) were fed formula supplemented

with L. reuteri SD2112, B. lactis Bb-12, or

no probiotic for 12 weeks. Both probiotic

groups had fewer and shorter episodes of

diarrheal illness, with no change in respira-

tory illness. Effects were more prominent

in the L. reuteri group, which had fewer

absences, clinic visits, and antibiotic pre-

scriptions during the study.

Therapeutic yogurts have also been stud-

ied in the prevention and treatment of

community-acquired diarrhea in chil-

dren.

14,15

Although a benefit is suggested,

more confirmatory studies are indicated.

A meta-analysis of 12 studies (n = 4,709)

found a modest decrease in the risk of trav-

eler’s diarrhea, with an RR of 0.85 (95% CI,

0.79 to 0.91; P < .0001) in patients taking

probiotics.

16

No difference was found among

organisms, including S. boulardii or mixtures

of Lactobacillus sp. and Bifidobacterium sp.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

Although definitive evidence is still lacking,

several studies have found probiotics to be

effective in relieving symptoms of IBS, par-

ticularly abdominal pain and bloating.

17-19

One study found a 20 percent reduction in

symptoms of IBS with Bifidobacterium infan-

tis 35624 at a dose of 1 × 10

8

CFUs compared

with placebo in 362 patients.

17

In another

study, 50 children fulfilling the Rome II

Probiotics

1076 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 78, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2008

criteria for IBS were given L. rhamnosus GG or

placebo for six weeks.

18

L. rhamnosus GG was

not superior to placebo in relieving abdomi-

nal pain, but there was a lower incidence of

perceived abdominal distention (P = .02).

IBS symptoms may also be managed by

adding components to patients’ diets. One

yogurt (Activia), which contains Bifidobacte-

rium animalis DN-173 010, improved health-

related quality of life scores and decreased

bloating symptoms in patients with IBS.

19

ATOPIC DERMATITIS

There may be a role for probiotics as prophy-

laxis in the development of atopic dermati-

tis in high-risk infants. One double-blind,

placebo-controlled RCT (n = 132) of chil-

dren with a strong family history of atopic

disease administered L. rhamnosus GG

(1 × 10

10

CFUs) or placebo to mothers for two

to four weeks prenatally and then to infants

postnatally for six months.

20

The incidence

of diagnosis of eczema by two years of age

was reduced by one half (23 percent in the

probiotic group versus 46 percent in the

placebo group [RR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.32 to

0.84]).

Follow-up visits at four and seven

years of age showed no reduction in asthma,

food allergy, or allergic rhinitis, suggesting

that this intervention will not prevent other

manifestations of atopy.

21,22

A larger study (n = 925) using L. rhamno-

sus GG combined with L. rhamnosus LC705,

Bifidobacterium breve Bb99, Propionibac-

terium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii JS,

and 0.8 g of galacto-oligosaccharides (new-

borns only) showed similar effectiveness for

atopic dermatitis at two years of age.

23

A pla-

cebo-controlled study using L. acidophilus

LAVRI-A1 administered to 231 newborns at

high risk of atopic dermatitis failed to repli-

cate this finding, possibly because of a dif-

ferent strain or dosage.

24

Several small RCTs have shown some

benefit in children with established atopic

dermatitis treated with probiotics.

25-27

In

another study, 56 children six to 18 months

of age with moderate or severe atopic der-

matitis were recruited into a randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

28

The children were given a probiotic (1 × 10

9

Lactobacillus fermentum VRI-033) or an

equivalent volume of placebo twice daily for

eight weeks. A final assessment at 16 weeks

showed a significant reduction in the Sever-

ity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD)

index over time in the probiotic group

(P = .03) but not in the placebo group. Sig-

nificantly more children receiving probiotics

(92 percent) had a SCORAD index that was

better than baseline at week 16, compared

with the placebo group (63 percent; P = .01).

However, other interventions to improve

allergic symptoms have not been successful.

Contraindications, Adverse Effects,

and Interactions

There are no absolute contraindications to

probiotics comprised of Lactobacillus sp.,

Bifidobacterium sp., S. thermophilus, or

S. boulardii. There are typically few or no

adverse effects; flatulence or mild abdominal

discomfort, usually self-limited, are reported

occasionally. There have been reports of

pathologic infection, including bactere-

mia with probiotic species following oral

administration. These are rare, occurring in

severely ill or immunocompromised hosts,

or in children with short-gut syndrome. It is

prudent to avoid probiotics in these patients,

or to be aware of the risk of sepsis. A recent

systematic review examined the safety of L.

rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium sp. and

concluded that the risk of sepsis is low, with

no cases reported in any prospective clinical

trial.

29

There are no reports of sepsis or other

pathologic colonization in healthy patients.

There are also no known interactions with

medications or other supplements.

Dosages

A wide range of dosages for Lactobacillus sp.

and other probiotics have been studied in

clinical trials, ranging from 100 million to

1.8 trillion CFUs per day, with larger dos-

ages used to reduce the risk of pouchitis

relapse. Most studies examined dosages in

the range of 1 to 20 billion CFUs per day,

although exact dosages for specific indica-

tions varied within this range. Generally,

higher dosages of probiotics (i.e., more than

5 billion CFUs per day in children and more

Probiotics

November 1, 2008

◆

Volume 78, Number 9 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 1077

than 10 billion CFUs per day in adults) were

associated with a more significant study

outcome. There is no evidence that higher

dosages are unsafe; however, they may be

more expensive and unnecessary. The dos-

ages of S. boulardii in most studies range

between 250 mg and 500 mg per day.

Probiotics are generally sold as capsules,

powder, tablets, liquid, or are incorporated

into food. The specific number of CFUs

contained in a given dose or serving of food

can vary between brands. Patients should be

advised to read product labels carefully to

make sure they are getting the proper dose.

A recent study analyzed a range of

brands of probiotics and found that of the

19 brands examined, five did not contain

the number of live microorganisms stated

on the label.

30

Because some labels are

unreliable, physicians should recommend

specific brands known to be of reasonable

quality or encourage patients to research

brands before purchasing a specific product

(Table 2). Guidance on probiotics can be

found at http://www.usprobiotics.org and

at the National Center for Complementary

and Alternative Medicine’s Web site, http://

nccam.nih.gov/health/probiotics/.

For patients who dislike taking pills

or powder, therapeutic yogurt prepara-

tions may be preferred option. Traditional

yogurts likely do not contain sufficient

concentrations of probiotics to deliver the

type of CFU doses studied in the clinical

trials. Therapeutic fermented dairy prod-

ucts such as Danactive, which contains

10 billion CFUs of L. casei DN-114 001 per

serving, and Activia, which contains about

5 to 10 billion CFUs of B. animalis DN-173 010

per 4-oz. container, are currently available.

Yo-Plus and Stonyfield yogurts contain

well-studied probiotic strains B. lactis Bb-12

and L. reuteri ATCC 55730, respectively, but

at undisclosed levels. Danimals, a drink-

able yogurt marketed for children, contains

1 billion live L. rhamnosus GG. More studies

are warranted on many food sources of pro-

biotics to provide confidence in effective-

ness and dose recommendations.

The Authors

BENJAMIN KLIGLER, MD, MPH, is associate professor of

family medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine

of Yeshiva University in New York, NY. He received his

medical degree from Boston (Mass.) University School of

Medicine and completed a residency in family medicine at

Montefiore Medical Center in New York, NY.

ANDREAS COHRSSEN, MD, is program director of the Beth

Israel Residency Program in Urban Family Practice in New

York, NY. He received his medical degree from the Johann

Wolfgang Goethe—Universität Frankfurt (Germany), and

completed a residency in family medicine at Lutheran

Medical Center in New York, NY.

Address correspondence to Benjamin Kligler, MD,

MPH, Continuum Center for Health and Healing, 245

Fifth Ave., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10016 (e-mail:

bkligler@chpnet.org). Reprints are not available from

the authors.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

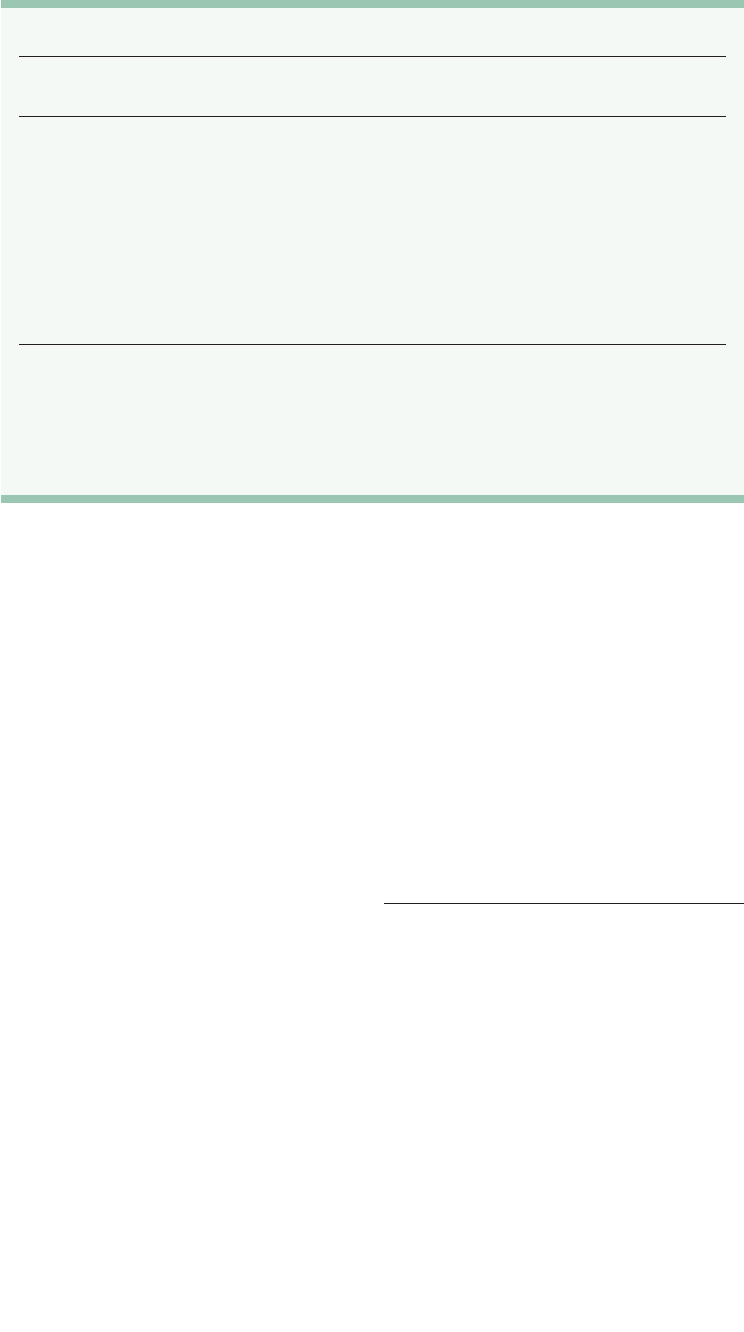

Table 2. Probiotic Strains and Preparations

Probiotic strain

Recommended

daily dosage Preparations*

Lactobacillus

rhamnosus GG

10 billion CFUs Capsules (Culturelle)

Therapeutic yogurts and fermented milks

Lactobacillus sp./

Bifidobacterium sp.†

100 million to

35 billion CFUs,

depending on

preparation

Capsules (Align, Primadophilus)

Powder (Primal Defense)

Capsules or powder (Fem-Dophilus, Jarro-Dophilus)

Therapeutic yogurts and fermented milks (Activia,

Danactive, Yo-Plus)

Saccharomyces

boulardii

250 mg to 500 mg Capsules (Florastor)

CFU = colony-forming unit.

*— This is not a complete list of commercially available preparations.

†—Most commercial brands contain a mixture of strains that may include Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. rhamnosus,

Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum, and others. Exact combinations of strains

vary among brands.

Information from references 30 and 31.

Probiotics

1078 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 78, Number 9

◆

November 1, 2008

REFERENCES

1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

and the World Health Organization. Health and nutri-

tional properties of probiotics in food including powder

milk with live lactic acid bacteria. Cordoba, Argentina;

2001. http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/fs_

management/en/probiotics.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2008.

2. Prescott SL, Dunstan JA, Hale J, et al. Clinical effects

of probiotics are associated with increased interferon-

gamma responses in very young children with atopic

dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(12):1557-1564.

3. Doron S, Snydman DR, Gorbach SL. Lactobacillus GG:

bacteriology and clinical applications. Gastroenterol

Clin North Am. 2005;34(3):483-498.

4. Rosenfeldt V, Benfeldt E, Valerius NH, Paerregaard A,

Michaelsen KF. Effect of probiotics on gastrointestinal

symptoms and small intestinal permeability in children

with atopic dermatitis. J Pediatr. 2004;145(5):612-616.

5. Sazawal S, Hiremath G, Dhingra U, Malik P, Deb S, Black

RE. Efficacy of probiotics in prevention of acute diar-

rhoea: a meta-analysis of masked, randomised, placebo-

controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(6):374-382.

6. McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the

prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the

treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastro-

enterol. 2006;101(4):812-822.

7. Szajewska H, Ruszczy ´nski M, Radzikowski A. Probiot-

ics in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in

children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled tri-

als. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):367-372.

8. Johnston BC, Supina AL, Ospina M, Vohra S. Probiot-

ics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated

diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):

CD004827.

9. Hickson M, D’Souza AL, Muthu N, et al. Use of probiotic

Lactobacillus preparation to prevent diarrhoea associ-

ated with antibiotics: randomised double blind placebo

controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7610):80.

10. Allen SJ, Okoko B, Martinez E, Gregorio G, Dans LF.

Probiotics for treating infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane

Database of Syst Rev. 2004;(2)CD003048.

11. Szajewska H, Skórka A, Dylag M. Meta-analysis: Sac-

charomyces boulardii for treating acute diarrhoea in

children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(3):257-264.

12. Canani RB, Cirillo P, Terrin G, et al. Probiotics for

treatment of acute diarrhoea in children: randomised

clinical trial of five different preparations. BMJ.

2007;335(7615):340.

13. Weizman Z, Asli G, Alsheikh A. Effect of a probiotic for-

mula on infections in child care centers: comparison of

two probiotic agents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):5-9.

14. Pedone CA, Arnaud CC, Postaire ER, Bouley CF, Reinert P.

Multicentric study of the effect of milk fermented by

Lactobacillus casei on the incidence of diarrhoea. Int J

Clin Pract. 2000;54(9):568-571.

15. Pedone CA, Bernabeu AO, Postaire ER, Bouley CF,

Reinert P. The effect of supplementation with milk fer-

mented by Lactobacillus casei (strain DN-114 001) on

acute diarrhoea in children attending day care centres.

Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53(3):179-184.

16. McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the

prevention of traveler’s diarrhea. Travel Med Infect Dis.

2007;5(2):97-105.

17. Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an

encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624

in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastro-

enterol. 2006;101(7):1581-1590.

18. Bausserman M, Michail S. The use of

Lactobacillus GG in

irritable bowel syndrome in children: a double-blind ran-

domized control trial. J Pediatr. 2005;147(2):197-201.

19. Guyonnet D. Chassany O, Ducrotte P, et al. Effect of a

fermented milk containing Bifidobacterium animalis DN-

173 010 on the health-related quality of life and symp-

toms in irritable bowel syndrome in adults in primary

care: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, controlled

trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(3):475-486.

20. Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Arvilommi H, Kero P, Koski

-

nen P, Isolauri E. Probiotics in primary prevention of

atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial.

Lancet. 2001;357(9262):1076-1079.

21. Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, Arvilommi H, Iso

-

lauri E. Probiotics and prevention of atopic disease:

4-year follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled

trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9372):1869-1871.

22. Kalliomäki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, Isolauri E. Probiotics

during the first 7 years of life: a cumulative risk reduc-

tion of eczema in a randomized, placebo-controlled

trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):1019-1021.

23. Kukkonen K, Savilahti E, Haahtela T, et al. Probiotics

and prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharides in the preven-

tion of allergic diseases: a randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;

119(1):192-198.

24. Taylor AL, Dunstan JA, Prescott SL. Probiotic supplemen

-

tation for the first 6 months of life fails to reduce the risk

of atopic dermatitis and increases the risk of allergen sen-

sitization in high-risk children: a randomized controlled

trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(1):184-191.

25. Viljanen M, Savilahti E, Haahtela T, et al. Probiotics in

the treatment of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome in

infants: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Allergy.

2005;60(4):494-500.

26. Sistek D, Kelly R, Wickens K, Stanley T, Fitzharris P,

Crane J. Is the effect of probiotics on atopic dermatitis

confined to food sensitized children? Clin Exp Allergy.

2006;36(5):629-633.

27. Passeron T, Lacour JP, Fontas E, Ortonne JP. Prebiot

-

ics and synbiotics: two promising approaches for the

treatment of atopic dermatitis in children above 2 years.

Allergy. 2006;61(4):431-437.

28. Weston S, Halbert A, Richmond P, Prescott SL. Effects

of probiotics on atopic dermatitis: a randomised con-

trolled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(9):892-897.

29. Hammerman C, Bin-Nun A. Safety of probiot

-

ics: comparison of two popular strains. BMJ.

2006;333(7576):1006-1008.

30. ConsumerLab.com product review: probiotic supple

-

ments (including Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifido-

bacterium, and others. http://www.consumerlab.

com/results/probiotics.asp. Accessed July 2, 2008.

31. Usprobiotics.org. http://www.usprobiotics.org. Accessed

October 8, 2008.