February 24, 2012

Creating Effective Cloud

Computing Contracts for

the Federal Government

Best Practices for Acquiring IT as a Service

A joint publication of the

In coordination with the

Federal Cloud

Compliance Committee

[ i ]

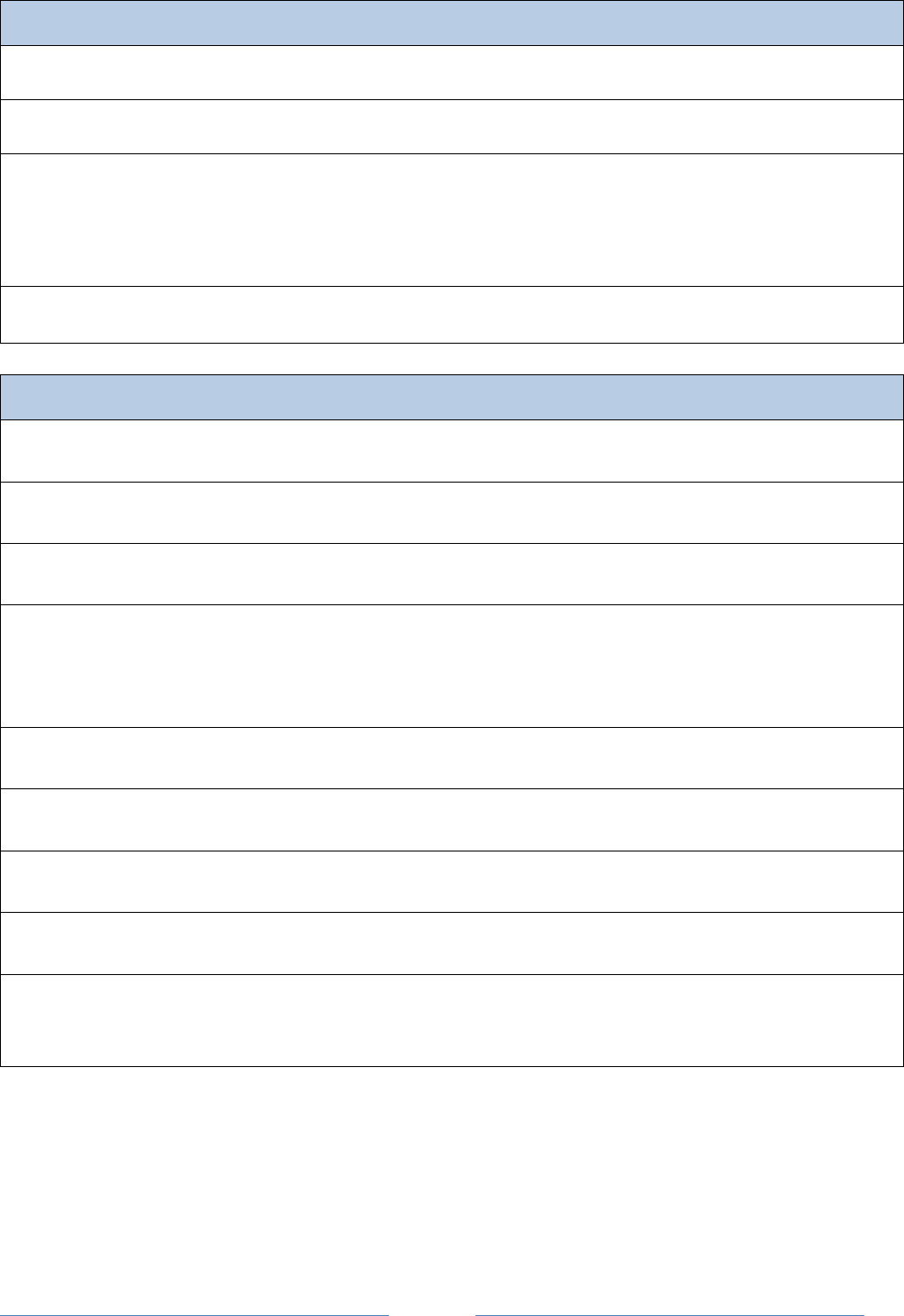

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3

Selecting a Cloud Service ......................................................................................................................... 5

Infrastructure, Platform, or Software-as-a-Service .............................................................................. 5

Private, Public, Community, or Hybrid Deployment Models ................................................................ 5

CSP and End-User Agreements ................................................................................................................ 6

Terms of Service Agreements ............................................................................................................... 6

Non-Disclosure Agreements ................................................................................................................. 7

Service Level Agreements ........................................................................................................................ 7

Terms and Definitions ........................................................................................................................... 7

Measuring SLA Performance ................................................................................................................. 8

SLA Enforcement Mechanisms ............................................................................................................. 8

CSP, Agency, and Integrator Roles and Responsibilities ......................................................................... 8

Contracting with Integrators ................................................................................................................. 9

Clearly Defined Roles and Responsibilities ........................................................................................... 9

Standards .................................................................................................................................................. 9

Reference Architecture ....................................................................................................................... 10

Agency Roles in the Use of Cloud Computing Standards .................................................................... 11

Internet Protocol v6 ............................................................................................................................ 11

Security ................................................................................................................................................... 11

FedRAMP ............................................................................................................................................. 12

Clear Security Authorization Requirements ....................................................................................... 12

Continuous Monitoring ....................................................................................................................... 13

Incident Response ............................................................................................................................... 14

Key Escrow .......................................................................................................................................... 15

Forensics ............................................................................................................................................. 15

Two-Factor Authentication using HSPD-12 ......................................................................................... 15

Audit .................................................................................................................................................... 16

Privacy..................................................................................................................................................... 16

Compliance with the Privacy Act of 1974 and Related PII Requirements .......................................... 17

Privacy Impact Assessments (PIA)....................................................................................................... 19

[ ii ]

Privacy Training ................................................................................................................................... 20

Data Location ...................................................................................................................................... 21

Breach Response ................................................................................................................................. 22

E-Discovery ............................................................................................................................................. 23

Information Management in the Cloud .............................................................................................. 25

Locating Relevant Documents ............................................................................................................ 25

Preservation of Data in the Cloud ....................................................................................................... 26

Moving Documents through the E-Discovery Process ........................................................................ 27

Potential Cost Avoidance by Incorporating E-Discovery Tools into the Cloud ................................... 28

FOIA Access ............................................................................................................................................. 28

Conducting a Reasonable Search to Meet FOIA Obligations .............................................................. 29

Processing ESI Pursuant to FOIA ......................................................................................................... 30

Tracking and Reporting Pursuant to FOIA ........................................................................................... 30

Federal Recordkeeping .......................................................................................................................... 30

Proactive Records Planning ................................................................................................................. 31

Timely and Actual Destruction of Records Required by Record Schedules ........................................ 32

Permanent Records ............................................................................................................................. 33

Transition of Records to New CSPs ..................................................................................................... 33

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 34

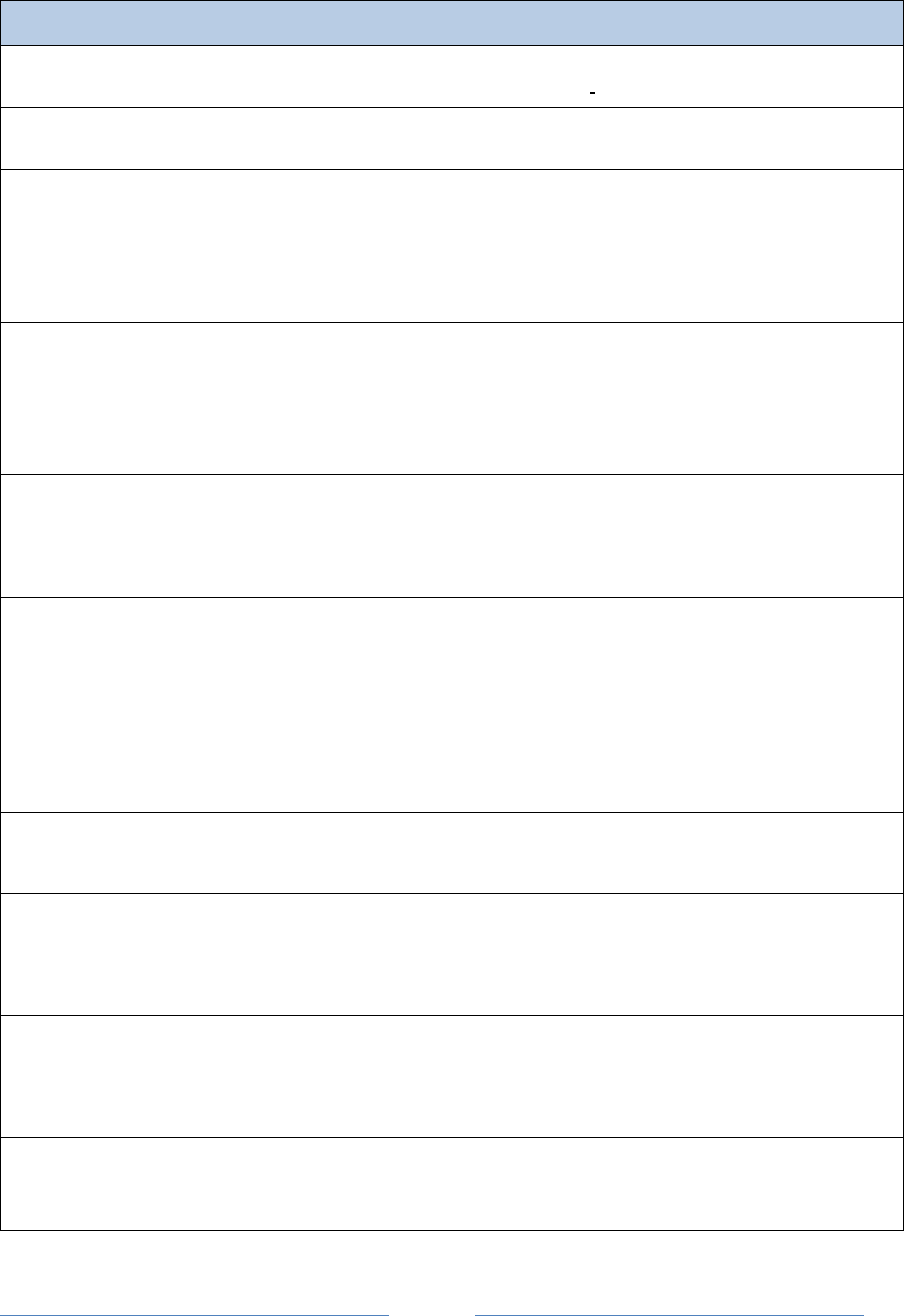

Suggested Procurement Preparation Questions: ...................................................................................... 35

General Questions .............................................................................................................................. 35

Service Level Agreement ..................................................................................................................... 37

CSP and End User Agreements ........................................................................................................... 37

E-Discovery Questions ........................................................................................................................ 37

Cybersecurity Questions ..................................................................................................................... 39

Privacy Questions ................................................................................................................................ 39

FOIA Questions ................................................................................................................................... 40

Recordkeeping Questions ................................................................................................................... 41

[ 1 ]

Executive Summary

The US Federal Government spends approximately $80 billion dollars on Information

Technology (IT) annually

1

. However, a significant portion of this spending goes towards

maintaining aging and duplicative infrastructure. Instead of highly efficient IT assets enabling

agencies to deliver mission services, much of this spending is characterized by low asset

utilization, long lead times to acquire new services, and fragmented demand. To compound this

problem, Federal agencies are being asked to do more with less while maintaining a high level

of service to the American public.

Cloud computing presents the Federal Government with an opportunity to transform its IT

portfolio by giving agencies the ability to purchase a broad range of IT services in a utility- based

model. This allows agencies to refocus their efforts on IT operational expenditures and only pay

for IT services consumed instead of buying IT with a focus on capacity. Procuring IT services in a

cloud computing model can help the Federal Government to increase operational efficiencies,

resource utilization, and innovation across its IT portfolio, delivering a higher return on our

investments to the American taxpayer.

In order to leverage the power of cloud computing across the Federal Government’s IT

portfolio, the Administration established a “Cloud First” policy in the 25 Point Implementation

Plan to Reform Federal Information Technology published in December of 2010

2

. Under this

policy, Federal agencies are required to “default to cloud-based solutions whenever a secure,

reliable, cost-effective cloud option exists.”

Subsequent to the publication of the 25 Point Plan, the Administration published the Federal

Cloud Computing Strategy in February of 2011

3

. This document represented the first step in

providing guidance to Federal agencies on successfully implementing the “Cloud First” policy

and catalyzing more rapid adoption of cloud computing services across the Federal IT

landscape.

Additionally, in December of 2011, the Federal Chief Information Officer released a new policy,

Security Authorization of Information Systems in Cloud Computing Environments, detailing the

new Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP). FedRAMP provides

Federal agencies with a unified way to secure cloud computing services through the use of a

standardized baseline set of security controls for authorizing cloud systems. This standard

approach to securing cloud computing systems works in concert with the elements detailed in

this paper to create a solid foundation of transparent standards and processes the government

should use when buying cloud computing systems.

1

http://www.itdashboard.gov.

2

http://www.cio.gov/documents/25-Point-Implementation-Plan-to-Reform-Federal%20IT.pdf.

3

http://www.cio.gov/documents/Federal-Cloud-Computing-Strategy.pdf.

[ 2 ]

The adoption of cloud computing across the Federal IT portfolio represents a dramatic shift in

the way Federal agencies buy IT – a shift from periodic capital expenditures to lower cost and

predictable operating expenditures. With this shift comes a learning curve within government

regarding the effective procurement of cloud-based services. Simultaneously, this move has

created a burgeoning market in which private industry can provide these cloud-based services

to the Federal Government.

This paper is the next step in providing Federal agencies more specific guidance in effectively

implementing the “Cloud First” policy and moving forward with the “Federal Cloud Computing

Strategy” by focusing on ways to more effectively procure cloud services within existing

regulations and laws. Since the Federal Government holds the position as the single largest

purchaser in this new market, Federal agencies have a unique opportunity to shape the way

that cloud computing services are purchased and consumed.

The design, procurement, and use of cloud computing services involve unique and different

equities within a Federal agency. Proactive planning with all necessary agency stakeholders

(e.g. chief information officers (CIO), general counsels, privacy officers, records managers, e-

discovery counsel, Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) officers, and procurement staff), is

essential when evaluating and procuring cloud computing services.

In developing this paper, we reached out to working groups under the Office of Management

and Budget, Federal CIO Council (Information Security and Identity Management Committee

(ISIMC), Cloud Computing Executive Steering Committee, etc.), procurement specialists who

have issued Federal cloud computing services implementations, and other related experts (IT

security, privacy, general counsel’s office, etc.) both internal and external to the Federal

Government

4

. This paper brings together these collective inputs to highlight unique contracting

requirements related to cloud computing contracts that will allow Federal agencies to

effectively and safely procure cloud services for agency consumption

5

.

By highlighting the areas in which cloud computing presents unique requirements compared to

the traditional IT contracts, this paper will help to continue the forward momentum the Federal

Government has made in adopting cloud computing. By understanding these unique

requirements and following the proposed recommendations, agencies can implement cloud

computing contracts that deliver better outcomes for the American people at a lower cost.

4

We would like to express our appreciation to Scott Renda, Matthew Goodrich, Allison Stanton, Jonathan

Cantor, Jodi Cramer, and the Federal Cloud Compliance Committee for their tremendous efforts in helping to

develop this paper.

5

This paper is not intended to be the definitive source for guidance on cloud services contracts for Federal

agencies. Instead it is meant to be guidance developed from the best practices across government and

industry for agencies to use when entering the procurement process.

[ 3 ]

Introduction

As a result of the Administration’s goal to accelerate the adoption of cloud computing, Federal

agencies are increasingly migrating systems of growing importance to the cloud. As agencies

embrace this “Cloud First” policy, there are lessons to be learned and best practices to be

shared from early adopters.

The most consistent lessons learned from the early adopters show that the Federal

Government needs to buy, view, and think about IT differently. Cloud computing presents a

paradigm shift that is larger than IT, and while there are technology changes with cloud

services, the more substantive issues that need to be addressed lie in the business and

contracting models applicable to cloud services. This new paradigm requires agencies to re-

think not only the way they acquire IT services in the context of deployment, but also how the

IT services they consume provide mission and support functions on a shared basis. Federal

agencies should begin to design and/or select solutions that allow for purchasing based on

consumption in the shared model that cloud-based architectures provide.

Cloud computing allows consumers to buy IT in a new, consumption-based model. Given the

dynamic nature of taxpayer needs, the traditional method of acquiring IT has become less

effective in ensuring the Federal Government effectively covers all of its requirements. By

moving from purchasing IT in a way that requires capital expenditures and overhead, and

instead purchasing IT “on-demand” as an agency consumes services, unique requirements have

arisen that Federal agencies need to address when contracting with cloud service providers

(CSPs).

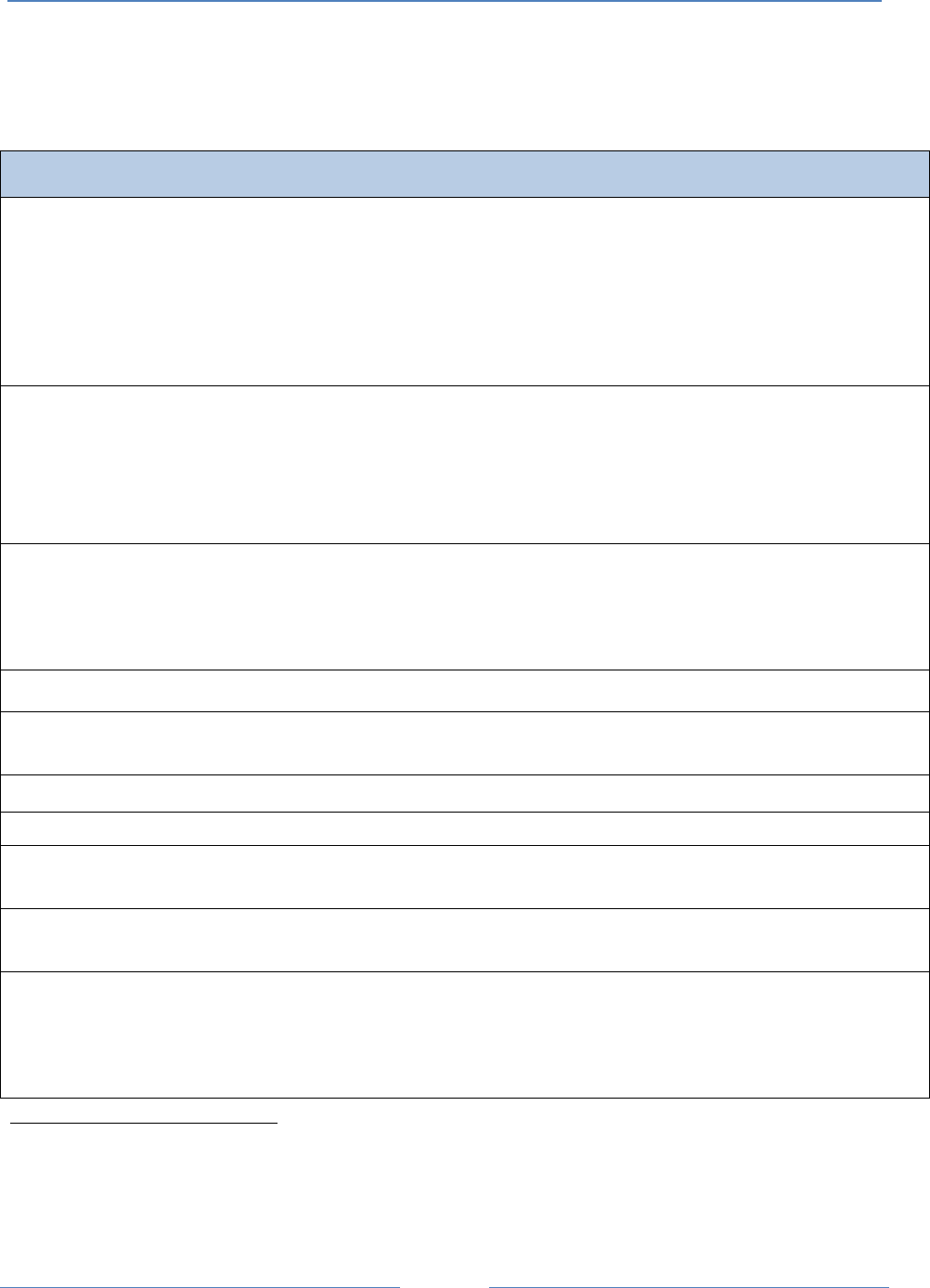

At this point in time, the following ten areas require improved collaboration and alignment

during the contract formation process by agency program, CIO, general counsel, privacy and

procurement offices when acquiring cloud computing services:

6

Selecting a Cloud Service: Choosing the appropriate cloud service and deployment

model is the critical first step in procuring cloud services;

CSP and End-User Agreements: Terms of Service and all CSP/customer required

agreements need to be integrated fully into cloud contracts;

Service Level Agreements (SLAs): SLAs need to define performance with clear terms and

definitions, demonstrate how performance is being measured, and what enforcement

mechanisms are in place to ensure SLAs are met;

6

Federal agencies must ensure cloud environments are compliant with all existing laws and regulations when

they move IT services to the cloud. This paper focuses on a number of requirements that require a special

analysis when acquiring cloud services. The paper does not address other procurement and acquisition

requirements, such as but not limited to compliance with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 or

confidential statistical information (as protected by the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical

Efficiency Act of 2002 or similar statutes that protect the confidentiality of information collected solely for

statistical purposes under a pledge of confidentiality).

[ 4 ]

CSP, Agency, and Integrator Roles and Responsibilities: Careful delineation between

the responsibilities and relationships among the Federal agency, integrators, and the

CSP are needed in order to effectively manage cloud services;

Standards: The use of the NIST cloud reference architecture as well as agency

involvement in standards are necessary for cloud procurements;

Security: Agencies must clearly detail the requirements for CSPs to maintain the security

and integrity of data existing in a cloud environment;

Privacy: If cloud services host “privacy data,” agencies must adequately identify

potential privacy risks and responsibilities and address these needs in the contract;

E-Discovery: Federal agencies must ensure that all data stored in a CSP environment is

available for legal discovery by allowing all data to be located, preserved, collected,

processed, reviewed, and produced;

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA): Federal agencies must ensure that all data stored in

a CSP environment is available for appropriate handling under the FOIA; and

E-Records: Agencies must ensure CSP’s understand and assist Federal agencies in

compliance with the Federal Records Act (FRA) and obligations under this law.

These ten unique areas of focus are not an exhaustive list of unique issues with cloud

computing. Through government working groups under the OMB, the Federal CIO Council,

reviews of existing cloud contracts, reviewing industry and academia papers and studies, and

speaking with procurement and legal experts across the Federal Government, these ten areas

were identified as requiring the most attention at this time. By addressing these unique areas

to cloud computing in addition to traditional contracting best practices and bringing the

relevant stakeholders together proactively, Federal agencies will be able to more effectively

procure and manage IT as a service.

[ 5 ]

Selecting a Cloud Service

The primary driver behind purchasing any new IT service is to effectively meet a commodity,

support, or mission requirement that the agency has. Part of the analysis of that need or

problem is determining the appropriate solution. When the solution involves technology, the

Administration’s “Cloud First” and “Shared First” policies dictate that an agency must default to

using a cloud computing solution if a safe and secure one exists. However, choosing the cloud is

only the first step in this analysis. It is also critical for Federal agencies to decide which cloud

service and deployment model best meets their needs.

Infrastructure, Platform, or Software-as-a-Service

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has defined three cloud computing

service models: Infrastructure as a Service, Platform as a Service, and Software as a Service

7

.

These service models can be summarized as:

Infrastructure: the provision of processing, storage, networking and other fundamental

computing resources;

Platform: the deployment of applications created using programming languages,

libraries, services, and tools supported by a cloud provider; and

Software: the use of applications running on a cloud infrastructure environment.

Each service model offers unique functionality depending on the class of user, with control of

the environment decreasing as you move from Infrastructure to Platform to Software.

Infrastructure is most suitable for users like network administrators as agencies can place

unique platforms and software on the infrastructure being consumed. Platform is most suitable

for users like server or system administrators in development and deployment activities.

Software is most appropriate for end users since all functionalities are usually offered out of the

box. Understanding the degree of functionality and what users in an agency will consume the

services is critical for Federal agencies in determining the appropriate cloud service to procure.

Private, Public, Community, or Hybrid Deployment Models

NIST has also defined four deployment models for cloud services: Private, Public, Community,

and Hybrid

8

. These service deployments can be summarized as:

Private: For use by a single organization;

Public: For use by general public;

Community: For use by a specific community of organizations with a shared purpose;

and

Hybrid: A composition of two or more cloud infrastructures (public, private,

community).

These deployment models determine the number of consumers (multi-tenancy), and the nature

of other consumers’ data that may be present in a cloud environment. A public cloud does not

7

See NIST Special Publication 800-145.

8

Id.

[ 6 ]

allow a consumer to know or control who the other consumers of a cloud service provider’s

environment are. However, a private cloud can allow for ultimate control in selecting who has

access to a cloud environment. Community clouds and Hybrid clouds allow for a mixed degree

of control and knowledge of other consumers. Additionally, the cost for cloud services typically

increases as the control over other consumers and knowledge of these consumers increases.

When consuming cloud services, it is important for Federal agencies to understand what type of

government data they will be placing in the environment, and select the deployment type that

corresponds to the appropriate level of control and data sensitivity.

To choose a cloud service that will properly meet a unique need, it is vital to first determine the

proper level of service and deployment. Federal agencies should endeavor to understand not

only what functionality they will receive when using a cloud service, but also how the

deployment model a cloud service utilizes will affect the environment in which government

data is placed.

CSP and End-User Agreements

CSPs enforce common acceptable use standards across all users to effectively maintain how a

consumer uses a CSP environment. Thus, use of a CSP environment usually requires Federal

agency end-users to sign Terms of Service Agreements (TOS). Additionally, Federal agencies can

also require CSPs to sign Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) to enforce acceptable CSP

personnel behavior when dealing with Federal data. TOS and NDAs need to be fully

contemplated and agreed upon by both CSPs and Federal agencies to ensure that all parties

fully understand the breadth and scope of their duties when using cloud services. These

agreements are new to many IT contracts because of the nature of the interaction of end-users

with CSP environments – both due to Federal agency access to cloud services through CSP

interfaces and CSP personnel access and control of Federal data.

Terms of Service Agreements

Federal agencies need to know if a CSP requires an end-user to agree to TOS in order to use the

CSP’s services prior to signing a contract. TOS restrict the ways Federal agency consumers can

use CSP environments. They include provisions that detail how end-users may use the services,

responsibilities of the CSP, and how the CSP will deal with customer data. Provisions within a

TOS may contradict unique aspects of Federal law that apply only to agencies as well as the

terms of the contract between a Federal agency and a CSP. Given that, Federal agencies are

advised to work with CSPs to understand what they require in order for Federal agency end-

users to access a CSP environment and at the same time ensure that any TOS document

incorporated into the contract is acceptable to the Federal agency. If the TOS are not directly

within the contract but referenced within the contract, the TOS should be negotiated and

agreed upon prior to contract award.

Additionally, TOS sometimes include provisions relating to CSP responsibilities, controlling law,

indemnification and other issues that are more appropriate for the terms and conditions of the

[ 7 ]

contract. If these provisions are included within service agreements, they should be clearly

defined. Furthermore, any agreements must address time requirements that a CSP will need to

follow to comply with Federal agency rules and regulations

9

. Any contract provisions regarding

controlling law, jurisdiction, and indemnification arising out of a Federal agency’s use of a CSP

environment must align with Federal statutes, policies, and regulations; and compliance should

be defined before a contract award. This may be done through a separate document or be

included in the actual contract.

Non-Disclosure Agreements

Federal agencies often require CSP personnel to sign NDAs when dealing with Federal data.

These are usually requested by Federal agencies in order to ensure that CSP personnel protect

non-public information that is procurement-sensitive, or affects pre-decisional policy, physical

security, etc. Federal agencies will need to consider the requirements and enforceability of

NDAs with CSP personnel. The acceptable behavior prescribed by NDAs requires Federal agency

oversight, including examining the NDAs’ requirements in the rules of behavior and monitoring

of end-users activities in the cloud environment. Federal agencies should ensure that they do

not overlook such provisions when creating NDAs. CSP and end-user agreements such as TOS

and NDAs are important to both Federal agencies and CSPs in order to clearly define the

acceptable behavior by end-users and CSP personnel when using cloud services. These

agreements should be fully contemplated by both CSPs and Federal agencies prior to cloud

services being procured. All such agreements should be incorporated, either by full text or by

reference, into the CSP contract in order to avoid the usually costly and time-consuming

process of negotiating these agreements after the enactment of a cloud computing contract.

Service Level Agreements

Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are agreements under the umbrella of the overall cloud

computing contract between a CSP and a Federal agency. SLAs define acceptable service levels

to be provided by the CSP to its customers in measurable terms. The ability of a CSP to perform

at acceptable levels is consistent among SLAs, but the definition, measurement and

enforcement of this performance varies widely among CSPs. Federal agencies should ensure

that CSP performance is clearly specified in all SLAs, and that all such agreements are fully

incorporated, either by full text or by reference, into the CSP contract.

Terms and Definitions

SLAs are necessary between a CSP and customer to contractually agree upon the acceptable

service levels expected from a CSP. SLAs across CSPs have many common terms, but definitions

and performance metrics can vary widely among vendors. For instance, CSPs can differ in their

definition of uptime (one measure of reliability) by stating uptime is not met only when services

are unavailable for periods exceeding one hour. To further complicate this, many CSPs define

9

This includes statutory requirements and associated deadlines, such as those found under FISMA and FOIA,

and applicable regulatory structures, such as those governing Inspector General (IG) investigations and

audits.

[ 8 ]

availability (another measure of reliability sometimes used within the definition of uptime) in a

way that may exclude CSP planned service outages. Federal agencies need to fully understand

any ambiguities in the definitions of cloud computing terms in order to know what levels of

service they can expect from a CSP.

Measuring SLA Performance

When Federal agencies place Federal data in a CSP environment, they are inherently giving up

control over certain aspects of the services that they consume. As a best practice, SLAs should

clearly define how performance is guaranteed (such as response time resolution/mitigation

time, availability, etc.) and require CSPs to monitor their service levels, provide timely

notification of a failure to meet the SLAs, and evidence that problems have been resolved or

mitigated. SLA performance clauses should be consistent with the performance clauses within

the contract. Agencies should enforce this by requiring in the reporting clauses of the SLA and

the contract that CSPs submit reports or provide a dashboard where Federal agencies can

continuously verify that service levels are being met. Without this provision, a Federal agency

may not be able to measure CSP performance.

SLA Enforcement Mechanisms

Most standard SLAs provided by CSPs do not include provisions for penalties if an SLA is not

met. The consequence to a customer if an SLA is not met can be catastrophic (unavailability

during peak demand, for example). However, without a penalty for CSPs in the SLA, CSPs may

not have sufficient incentives to meet the agreed-upon service levels. In order to incentivize

CSPs to meet the contract terms, there should be a credible consequence (for example, a

monetary or service credit) so that a failure to meet the agreed to terms creates an undesired

business outcome for the CSP in addition to the customer.

With many of the high profile cases of cloud service provider failures relating to provisions

covered by SLAs, as a best practice, Federal agencies need SLAs that provide value and can be

enforced when a service level is not met. SLAs with clearly defined terms and definitions,

performance metrics measured and guaranteed by CSPs, and enforcement mechanisms for

meeting service levels, will provide value to Federal agencies and incentives for CSPs to meet

the agreed upon terms.

CSP, Agency, and Integrator Roles and Responsibilities

Many Federal agencies procure cloud services through integrators

10

. In these cases, integrators

can provide a level of expertise within CSP environments which Federal agencies may not have,

thus making a Federal agency’s transition to cloud services easier. Integrators may also provide

a full range of services from technical support to help desk support that CSPs might not provide.

When deciding to use an integrator, the Federal agency may procure services directly from a

CSP and separately with an integrator, or it may procure cloud services through an integrator,

10

For ease of discussion, “integrators” is being used as an umbrella term to include service providers such as

system integrators, resellers, etc.

[ 9 ]

as the prime contractor and the CSP as subcontractor. Whichever method the Federal agency

decides to use, the addition of an integrator to a cloud computing implementation creates

contractual relationships with at least three unique parties, and the roles and responsibilities

for all parties need to be clearly defined.

Contracting with Integrators

Integrators can be contracted independently of CSPs or can act as an intermediary with CSPs.

This flexibility allows Federal agencies to choose the most effective method for contracting with

integrators to help implement their cloud computing solutions. As a best practice, Federal

agencies need to consider the technical abilities and overall service offerings of integrators and

how these elements impact the overall pricing of an integrator’s proposed services.

Additionally, if a Federal agency contracts with an integrator acting as an intermediary, the

Federal agency must consider how this affects the Federal agency’s continued use of a CSP

environment when the contract with an integrator ends.

Clearly Defined Roles and Responsibilities

Whether an agency contracts with an integrator independently or uses one as an intermediary,

roles and responsibilities need to be clearly defined. Scenarios that need to be clearly defined

within a cloud computing solution that incorporate an integrator include: how a Federal agency

interacts with a CSP to manage the CSP environment, what access an integrator has to Federal

data within a CSP environment, and what actions an integrator may take on behalf of a Federal

agency. Failure to address the roles and responsibilities of each party can hinder the end-user’s

ability to fully realize the benefits of cloud computing. For instance, if initiating a new instance

of a virtual machine requires a Federal agency to interact with an integrator, then this

interaction breaks the on-demand essential characteristic of cloud computing.

The introduction of integrators to cloud computing solutions can be a critical element of

success for many Federal agencies. However, the introduction of an additional party to a cloud

computing contract requires Federal agencies to fully consider the most effective method of

contracting with an integrator and clearly define the roles and responsibilities among CSPs,

Federal agencies, and integrators.

Standards

When Federal agencies procure cloud solutions, U.S. laws and associated policy require the use

of international, voluntary consensus standards except where inconsistent with law or

otherwise impractical

11

. Standards Developing Organizations (SDOs) are continuing to develop

conceptual models, reference architectures, and standards to facilitate communication, data

exchange, and security for cloud computing applications. Standards are already available in

support of many of the functions and requirements for cloud computing. While many of these

11

Trade Agreements Act of 1979, as amended (TAA), the National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act

(NTTAA), and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-119 Revised: Federal Participation in

the Development and Use of Voluntary Consensus Standards and in Conformity Assessment Activities.

[ 10 ]

standards were developed in support of pre-cloud computing technologies, such as those

designed for web services and the Internet, they also support the functions and requirements

of cloud computing. Other standards are now being developed in specific support of cloud

computing functions and requirements, such as virtualization.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) publishes guidance and standards for

agencies to follow when procuring cloud and other technologies, as well as roadmaps for

agencies to understand the development of standards for future use. These publications

address, for example, security, interoperability, and portability

12

. NIST Special Publication 500-

291, NIST Cloud Computing Roadmap, presents these standards in the context of the NIST

Cloud Computing Reference Architecture using the NIST taxonomy in NIST Special Publication

500-292, NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture.

When procuring cloud solutions, it is important for Federal agencies to understand:

1. How vendor solutions and agency roles map to the NIST Reference Architecture; and

2. The role of Federal agencies in the use of cloud computing standards.

Reference Architecture

Understanding the roles and responsibilities among all actors deploying a cloud solution is

critical to successful implementations. The NIST Reference Architecture describes five major

actors with their roles and responsibilities using the newly developed Cloud Computing

Taxonomy. The five major participating actors are: (1) Cloud Consumer; (2) Cloud Provider; (3)

Cloud Broker; (4) Cloud Auditor; and (5) Cloud Carrier

13

.

These core actors have key roles in the realm of cloud computing. For example, an agency or

department normally functions as a Cloud Consumer that acquires and uses cloud products and

services. The purveyor of products and services is the Cloud Provider

14

. A Cloud Broker may act

as the intermediate between Cloud Consumer and Cloud Provider to help Consumers through

the complexity of cloud service offerings and may also offer value-added cloud services. A

Cloud Auditor provides a valuable function for the government by conducting the independent

performance and security monitoring of cloud services. A Cloud Carrier is an organization who

has the responsibility of transferring the data, akin to the power distributor for the electric grid.

In order to fully delineate the roles and responsibilities of all parties in a cloud computing

contract, Federal agencies should align all actors with NIST Reference Architecture.

12

Special Publication 500-291, NIST Cloud Computing Standards Roadmap, lists relevant standards for

security (see Table 5), interoperability (see Table 6), and portability (see Table 7).

13

For more information relating to the definitions and roles and responsibilities of the five major actors

described above, please reference NIST Special Publication 500-292, NIST Cloud Computing Reference

Architecture.

14

Because of the possible service offerings (Software, Platform or Infrastructure) allowed for by the Cloud

Provider, the level of responsibilities related to some aspects of the scope of control, security, and

configuration need to be re-evaluated when procuring cloud services.

[ 11 ]

Agency Roles in the Use of Cloud Computing Standards

There are several means by which agencies can ensure the availability of technically sound and

timely standards to support their missions.

1. Standards specification: In accordance with Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

Circular A-119, Federal Participation in the Development and Use of Voluntary

Consensus Standards and in Conformity Assessment Activities, agencies should specify

relevant voluntary consensus standards in their procurements. The NIST Standards.gov

website includes a useful list of questions that agencies should consider before selecting

standards for agency use

15

.

2. Standards requirements: Federal agencies should contribute clear and comprehensive

mission requirements to help support the definition of performance-based cloud

computing standards by the private sector

16

.

Federal agencies should request that cloud service providers categorize their services using the

NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture. This can be accomplished by the vendor’s

“mapping” of services to the reference architecture, and presenting this “mapping” along with

the vendor’s customized marketing and technical information. The reference architecture

mapping provides a common and consistent frame of reference to compare vendor offerings

when evaluating and procuring cloud services.

Internet Protocol v6

In support of IPv6, the Civilian Agency Acquisition Council and the Defense Acquisition

Regulations Council issued a final rule in December 2009 amending the Federal Acquisition

Regulation (FAR) to require all new information technology acquisitions using Internet Protocol

(IP) to include IPv6 requirements expressed using the USGv6 Profile and to require vendors to

document their compliance with those requirements through the USGv6 Testing Program.

Accordingly, agencies shall institute processes to include language in solicitations and contracts,

where applicable.

17

Security

Placing agency data on an information system involves risk, so it is critical for Federal agencies

to ensure that the IT environment in which they are storing and accessing data is secure. As

such, all IT systems used by Federal agencies must meet the requirements of the Federal

Information Security and Management Act (FISMA) and related agency-specific policies. FISMA

requires that all systems undergo a formal security authorization which details the

15

See: http://standards.gov/egov-analysis-private-sector-standards.cfm.

16

Agencies should participate in the cloud computing standards development process. Agency support for

concurrent development of conformity and interoperability assessment schemes will help to accelerate the

development and use of technically sound cloud computing standards and standards-based products,

processes, and services.

17

For a summary of the relevant FAR amendments, refer to http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/pdf/E9-

28931.pdf. To review these amendments in their full context, refer to

https://www.acquisition.gov/far/index.html.

[ 12 ]

implementation and continuous monitoring of security controls CSPs must maintain. After the

CSP’s environment has gone through a security authorization, a Federal agency must review the

risks posed by placing Federal data in that system, and if this risk level is acceptable, the agency

may grant an authority to operate (ATO).

FedRAMP

On December 8, 2011, OMB released a policy memo addressing the security authorization

process for cloud computing services. Specifically, this memo requires all Federal agencies to

use the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) when procuring and

subsequently authorizing cloud computing solutions. Specifically, each agency must:

1. Use FedRAMP when authorizing cloud services;

2. Use the FedRAMP process and security requirements as a baseline for authorizing cloud

services;

3. Require CSPs to comply with FedRAMP security requirements;

4. Establish a continuous monitoring program for cloud services;

5. Ensure that maintenance of FedRAMP security authorization requirements is addressed

contractually;

6. Require that CSPs route their traffic through a Trusted Internet Connection (TIC); and

7. Provide an annual list of all systems that do not meet FedRAMP requirements to OMB.

FedRAMP will assist agencies to acquire, authorize and consume cloud services by adequately

addressing security from a baseline perspective. FedRAMP will allow Federal agencies to

coordinate assessment and authorization activities from the first step in authorizing cloud

services to the ongoing assessment of the risk posture of a cloud service provider’s

environment. However, FISMA requires that Federal agencies authorize and accept the risk for

placing Federal data in an IT system. Consistent with existing law, agencies will maintain this

responsibility within FedRAMP. However, FedRAMP will standardize and streamline the

processes agencies use to accomplish assessment and authorization activities, saving time and

money.

When Federal agencies consider implementing a cloud computing solution, there are seven key

security areas they need to address: clear security authorization requirements, continuous

monitoring, incident response, key escrow, forensics, two-factor authentication with HSPD-12,

and auditing.

Clear Security Authorization Requirements

Because of the variability in risk postures amongst different CSP environments and differing

agency mission and needs, the determination of the appropriate levels of security vary across

Federal agencies and across CSP environments. Federal agencies must evaluate the type of

[ 13 ]

Federal data they will be placing into a CSP environment and categorize their security needs

accordingly

18

.

Based on the level of security that a Federal agency determines a CSP environment must meet,

the agency then must determine which security controls a CSP will implement within the cloud

environment based on NIST Special Publication 800-53 (as revised) and agency-specific policies.

Within this framework, Federal agencies need to explicitly state not only the security impact

level of the system (i.e., the CSP environment must meet FISMA high, moderate, or low impact

level), but agencies must also specify the security controls associated with the impact level the

CSP must meet.

In order for Federal agencies to adequately provide clear security authorization requirements,

they must:

Analyze the type of Federal data to be placed in the cloud and categorize the data

according to Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 199 and 200; and

Include contractual provisions with CSPs that specify not only what security impact level

a CSP environment must meet, but also what specific security controls must be

implemented to ensure a CSP environment meets the security needs of the agency.

Continuous Monitoring

19

After Federal agencies complete a security authorization of a system based on clear and

defined security authorization requirements detailing the security controls a CSP must

implement on their system, Federal agencies must continue to ensure a CSP environment

maintains an acceptable level of risk. In order to do this, Federal agencies should work with

CSPs to implement a continuous monitoring program

20

. Continuous monitoring programs are

designed to ensure that the level of security through a CSP’s initial security authorization is

maintained while Federal data resides within a CSP’s environment.

Continuous monitoring programs must be developed in accordance with the NIST Publication

800-137 framework and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) guidance, detailed

contractually, and must at a minimum address updates to the authorization based on any

significant changes to a CSP environment, address new FISMA requirements, and provide

updates to control implementations on a basis frequent enough to make on-going risk based

decisions. By implementing an effective continuous monitoring program, Federal agencies

ensure they have the proper view into a CSP environment. This allows Federal agencies to

provide for the ongoing security and continued use of a CSP environment at an acceptable level

of risk.

18

Agencies should refer to NIST FIPS 199 and 200 when categorizing the security level of the information

systems they use to store Federal data.

19

See NIST Publication 800-137 and NIST Special Publication 800-53.

20

See DHS’ National Cyber Security Division memo: “FY 2011 Chief Information Officer Federal Information

Security Management Act Reporting Metrics.”

[ 14 ]

In order to effectively implement a continuous monitoring program, Federal agencies should:

Fully understand the risks associated with a CSP environment when granting an ATO for

use with Federal data;

Work with CSPs to develop and implement a continuous monitoring program to ensure

the level of security provided during the initial security authorization is maintained while

Federal data resides within the CSP environment;

Ensure that CSPs update their continuous monitoring program (and possibly security

authorization) whenever significant changes occur to a CSP environment;

Ensure that CSPs address all FISMA requirements as they are updated; and

Ensure the CSP’s continuous monitoring program is designed in accordance with the

NIST framework and DHS guidance and provides updates with a frequency sufficient to

make ongoing risk-based decisions on whether to continue to place Federal data in a

CSP environment.

Incident Response

Incident response refers to activities addressing breaches of systems, leaks/spillage of data, and

unauthorized access to data. Federal agencies need to work with CSPs to ensure CSPs employ

satisfactory incident response plans and have clear procedures regarding how the CSP responds

to incidents as specified in Federal agencies’ Computer Security Incident Handling guides.

Federal agencies must ensure that contracts with CSPs include CSP liability for data security. A

Federal agency’s ability to effectively monitor for incidents and threats requires working with

CSPs to ensure compliance with all data security standards, laws, initiatives, and policies

including FISMA, the Trusted Internet Connection (TIC) Initiative, ISO 27001, NIST standards,

and agency specific policies. By doing this, Federal agencies will be able to adhere to DHS U.S.

Computer Emergency Readiness Team (U.S. CERT) guidance on incident response and threat

notifications and work with the U.S. CERT to stay aware of changes in risk postures to CSP

environments.

Generally, CSPs take ownership of their environment but not the data placed in their

environment. As a best practice, cloud contracts should not permit a CSP to deny responsibility

if there is a data breach within its environment. Federal agencies should make explicit in cloud

computing contracts that CSPs indemnify Federal agencies if a breach should occur and the CSP

should be required to provide adequate capital and/or insurance to support their indemnity. In

instances where expected standards are not met, then the CSP must be required to assume the

liability if an incident occurs directly related to the lack of compliance. In all instances, it is vital

for Federal agencies to practice vigilant oversight.

When incidents do occur, CSPs should be held accountable for incident responsiveness to

security breaches and for maintaining the level of security required by the government. Federal

agencies should work with CSPs to define an acceptable time period for the CSP to mitigate and

re-secure the system.

[ 15 ]

At a minimum, Federal agencies should ensure when implementing an incident response policy

that:

They contractually ensure CSPs comply with the Federal agency’s Computer Security

Incident Handling guides; and

CSPs must be accountable for incident responsiveness, including providing specific time

frames for restoration of secure services in the event of an incident.

Key Escrow

Key escrow (also known as a fair cryptosystem or key management) is an arrangement in which

the keys needed to decrypt encrypted data are held in escrow so that, under certain

circumstances, an authorized third-party may gain access to those keys. Procedural and

regulatory regimes in environments where the Federal agencies own the systems storing and

transporting encrypted data are fairly well settled. These regimes, however, become

increasingly complex when inserted into a cloud environment.

Federal agencies should carefully evaluate CSP solutions to understand completely how a CSP

fully does key management to include how the key’s encrypted data are escrowed and what

terms and conditions of escrow apply to accessing encrypted data.

Forensics

When Federal agencies use a CSP environment, the agency should ensure that a CSP only

makes changes to the environment on pre-agreed upon terms and conditions; or as required by

the Federal agency to defend against an actual or potential incident. Federal agencies should

require CSPs to allow forensic investigations for both criminal and non-criminal purposes, and

these investigations should be able to be conducted without affecting data integrity and

without interference from the CSP. In addition, CSPs should only be allowed to make changes to

the cloud environment under specific standard operating procedures agreed to by the CSP and

Federal agency in the contract. As a best practice, cloud systems should include the Federal

banner language so that users are aware that the site is monitored and could be subject to

forensic investigations.

To ensure that Federal agencies are able to properly do forensics in a CSP environment, they

should:

Determine who will conduct forensics on a CSP environment;

Ensure appropriate forensic tools can reach all devices based on an approved timetable;

and

Ensure CSPs only install forensic or software with the permission of the Federal agency.

Two-Factor Authentication using HSPD-12

When Federal agencies use cloud services where authentication, encryption, and digital

signatures services are provided, they are required to use two-factor authentication based on

[ 16 ]

standard technologies

21

through the use of Personal Identity Verification (PIV) cards. The PIV

cards must be compliant with Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 (HSPD-12) which

mandates a Federal standard for secure and reliable forms of identification.

Two-factor authentication to gain access to a CSP environment using HSPD-12 provides various

benefits that add heightened security to agency use of cloud services. These benefits include

(but are not limited to):

Digital signature, encryption, and archiving of data;

High trust in identity credentials;

High confidence in an asserted identity when logging onto government networks from

remote locations; and

Use of a single authentication token for access to CSP environments.

When two-factor authentication is needed for cloud services, agencies are advised to include

contract language requiring CSPs to use HSPD-12 compliant PIV cards. Such language would

supplement the existing FAR requirements related to using the PIV card for contractor access.

Audit

FISMA requires Federal agencies to preserve audit logs

22

. Federal agencies must work with CSPs

to ensure audit logs of a CSP environment are preserved with the same standards as is required

by Federal agencies. Federal agencies must outline which CSP personnel have access to audit

logs prior to placing Federal data in the CSP environment. All CSP personnel who have access to

the audit logs must have the proper clearances as required by the Federal agency.

Some key considerations for Federal agencies to focus on when ensuring that CSPs maintain

audit logs to meet FISMA requirements:

All audit/transaction files should be made available to authorized personnel in read only

mode;

Audit transaction records should never be modified or deleted;

Access to online audit logs should be strictly controlled. Only authorized users may be

allowed to access audit transaction files; and

Audit/transaction records should be backed up and stored safely off site per agency

direction.

Privacy

23

Federal agencies have a duty to recognize and consider the privacy rights of individuals as well

as identify and address potential privacy risks and responsibilities that result from any data they

place in a cloud computing environment. Federal agencies and employees can be subject to

both criminal and civil penalties for misuse and erroneous disclosures of data that contains

21

Such as Security Assertion Markup Language 2.0 (SAML 2.0).

22

See NIST Special Publication 800-53.

23

The agency’s Chief Privacy Officer, Senior Agency Official for Privacy, or other privacy staff will be a

valuable resource in conducting this analysis.

[ 17 ]

protected information, even when this data is in a CSP environment. Personal information, and

specifically Personally Identifiable Information (PII), can relate to information about Federal

agency employees, other internal users, and a broad array of individual members of the public

and can be found in email, agency reports, memos, or even web pages

24

. Federal agencies

should consult their legal counsel and privacy offices to obtain advice and guidance on

particular laws and regulations when data they place in a CSP environment will contain PII.

Five areas identified as key factors for Agencies to consider when PII is or could be a part of the

data moved to the cloud environment are: compliance with the Privacy Act of 1974 and related

PII requirements, privacy impact assessments (PIAs), privacy training, data location, and how a

CSP responds to a breach. How a CSP addresses privacy concerns within their environment may

impact the overall price and technical structure for a proposed solution, so Federal agencies are

advised to gather privacy requirements as early as possible in order to fully understand how a

CSP will enable an agency to maintain its duty to protect PII.

Compliance with the Privacy Act of 1974 and Related PII Requirements

The first step a Federal agency must take when outsourcing any information system, including

cloud computing solutions, is to determine if the Privacy Act of 1974 (“The Privacy Act”), as

amended,

25

applies to the data that will be stored or processed. The Privacy Act establishes a

wide range of privacy protection for covered Federal records in which information about an

individual is retrieved by name or other personal identifier

26

. Subsection (m) of the Act makes

the Act applicable to any systems of records

27

operated by a government contractor, including

a CSP that operates a system of records containing such data

28

. CSPs and Federal agencies

should be mindful that there are both civil and criminal implications whenever the Federal

agency or the contractor knowingly and willfully acts or fails to act as described in the Act

29

. If a

system operated by a CSP is covered by the Privacy Act, Federal agencies must ensure that CSPs

understand the applicable requirements, and that contracting officers include the specific

clauses required by the FAR in the solicitations and contracts for such cloud services

30

.

24

Under OMB guidance, PII is broadly defined as “information which can be used to distinguish or trace an

individual’s identity, such as their name, social security number, biometric records, etc. alone or when

combined with other personal or identifying information which is linked or linkable to a specific individual,

such as date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, etc.” Available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/fy2007/m07-16.pdf.

25

5 U.S.C. § 552a.

26

Id. at § 552a(a)(4)-(5).

27

Id. at § 552a(a)(5).

28

5 U.S.C. § 552a(m)(1). For guidance concerning this provision, see OMB Guidelines, 40 Fed. Reg. 28,948,

28,951, 28,975-76, (July 9, 1975), available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/omb/inforeg/implementation_guidelines.pdf.

29

When a CSP is determined to be a subsection (m) contractor, the records being handled by the CSP must

not only comply with the Privacy Act’s requirements, but the CSP will also be subject to the criminal penalties

provision of the Act.

30

See FAR Subpart 24-1, Protection of Individual Privacy; FAR 52.224-1 – 52.224-2 (2010).

[ 18 ]

When the Privacy Act applies to data Federal agencies will place in a CSP environment, the

following are some key actions to consider:

Determine the extent to which the Privacy Act will apply to data about individuals that

will be maintained by the CSP solution, i.e., will any of that data be retrieved by name or

other personal identifier?

31

;

Ensure that, before the system is operated, the Federal agency has published or

amended the applicable system of records notice(s) (SORN(s)) that covers the records in

the Federal Register, and that the SORN includes all necessary routine uses,

32

including a

routine use that will permit disclosure of the records to the CSP for maintenance,

storage, or any other CSP-provided service or use;

Consider how the Federal agency and/or the CSP will provide individuals with the right

to access and/or amend their records within a CSP environment, under the time frames

legally specified in the Privacy Act

33

;

Determine how the Federal agency and/or the CSP will provide individuals with the

required statement of authority, purpose, etc., in a CSP environment, if the CSP solution

will be used to collect information from individuals;

Ensure the CSP can either meet or is contractually obligated to assist the Agency in

meeting all other requirements of the Privacy Act (e.g. maintenance requirements,

protecting against unauthorized disclosure, developing and maintaining an accounting

of disclosures from any Privacy Act system operated by the CSP); and

Ensure that the contract or other appropriate documentation clearly defines agency and

CSP roles and responsibilities, including responsibilities in the event of any request for

disclosure, subpoena, or other judicial process seeking access to records subject to the

Privacy Act.

Furthermore, Federal agencies and CSPs must exercise care whenever they are handling any

type of PII on behalf of a Federal agency, regardless of Privacy Act coverage

34

. PII includes all

information about an individual and because that information may be used in unanticipated

ways leading to harm and embarrassment, PII must be appropriately protected. Handling

sensitive PII requires the agency and CSP to take even greater care because of the increased risk

of harm to an individual if the sensitive PII is compromised. Sensitive PII may generally be

thought of as PII, which if lost, compromised, or disclosed without authorization, could result in

31

It is possible that moving data to a CSP will provide the Agency with a new or different method of

organizing and retrieving records that will change whether the Privacy Act applies. For example, prior to

moving data to the CSP, the agency may have retrieved records sequentially, and will instead under the CSP

solution retrieve them by name or other identifier that would trigger the Privacy Act.

32

5 U.S.C. § 552a(a)(7) states “the term ‘routine use’ means, with respect to the disclosure of a record, the use

of such record for a purpose which is compatible for the purpose it was collected.”

33

5 U.S.C. § 552a(d), (f).

34

The Privacy Act requires Federal agencies and contractors to have adequate safeguards and procedures for

any systems of records subject to that Act. 5 U.S.C. § 552a(e)(10). This requirement is consistent with the

requirement in FISMA that Agencies have system security plans for all Federal information systems, as

discussed elsewhere in this document.

[ 19 ]

substantial harm, embarrassment, inconvenience, or unfairness to an individual. Further, the

context and combination in which PII is used or located may also determine whether PII may be

deemed sensitive, such as a list of employee names with poor performance ratings or a list of

individuals with sub-standard credit ratings. Federal agencies and CSPs must, as appropriate,

contractually document how sensitive PII will be secured by a CSP. Aspects of that agreement

should discuss the following key areas:

Federal agencies must assess all categories of PII they might place in a CSP

environment;

35

Collection of sensitive PII must be authorized by Federal agencies;

Federal agencies should limit, to the maximum extent possible, the collection of

sensitive PII;

Federal agency and CSP copying or proliferating of sensitive PII should be restricted to

the maximum extent possible; and

How a CSP ensures the constant security of sensitive PII should be clearly defined.

Privacy Impact Assessments (PIA)

The PIA process helps ensure that Federal agencies evaluate and consider how they will

mitigate privacy risks, and comply with applicable privacy laws and regulations governing an

individual’s privacy, to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability of an individual’s

personal information at every stage of development and operation. Section 208 of the E-

Government Act of 2002

36

requires PIAs when an agency proposes “new uses of an existing IT

system, including application of new technologies [that] significantly change how information in

identifiable form is managed in the system.”

37

Typically, Federal agencies conduct a PIA during

the security authorization process for IT systems before operating a new system and update as

required by FISMA. A PIA must be made publicly available, usually on the agency’s web site.

When a Federal agency places any data in an information system, and in particular a cloud

computing environment, the agency must complete a privacy threshold analysis and, if

warranted, a PIA. Because CSPs may have different approaches for backup, disaster recovery,

disposal, authentication, access control, and server locations, Federal agencies must fully

35

This should include an assessment of whether the records contain any category of PII with unique statutory

or regulatory protection in addition to the Privacy Act, such as, but not limited to, those records like protected

health information (PHI) under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule

(45 C.F.R. Parts 160 and 164 (2010)), tax information protected by the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. §

6103, et seq.) certain educational records protected by the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C.

§ 1232g), and Census records (13 U.S.C. § 9). Obligations under these authorities may limit the options

available for cloud deployments.

36

PIAs are required under section 208 of the E-Government Act of 2002. See Public Law 107-347, codified at

44 U.S.C. § 101, et seq.

37

See OMB Memorandum M-03-22, OMB Guidance for Implementing the Privacy Provisions of the E-

Government Act of 2002 (Sept. 26, 2003), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/memoranda_m03-

22/. This requirement also applies to any electronic information collection activity (e.g. online form,

questionnaire, or survey to ten or more persons) subject to OMB review and clearance under the Paperwork

Reduction Act.

[ 20 ]

understand a CSP environment and any third party tools used to develop them in order to

properly conduct a PIA. Some of the normal PIA considerations to include are:

What information will be collected and put into the CSP environment;

Why the information is being collected;

Intended use of the information;

With whom the information might be shared (either by the Federal agency or CSP);

Whether individuals will be notified that their information will be maintained in a CSP

environment and what opportunities individuals have to decline to provide information

that will be maintained in a CSP environment;

What ability individuals have to consent to particular uses of the information, and how

individuals can grant consent;

How the Federal agency and CSP will secure information in the cloud; and

Whether the Federal agency is creating a system of records under the Privacy Act (see

above).

In addition, a cloud computing PIA should focus specific attention on:

The physical location of the data maintained by the CSP;

The retention policies that apply to the data maintained in a CSP environment;

The mechanism by which a Federal agency maintains control over Federal data (e.g. by

contractual provisions, non-disclosure agreements) that is maintained by CSPs; and

The means by which the CSP will terminate storage and delete data at the end of the

contract or project lifecycle.

Privacy Training

When Federal agencies place PII in cloud computing environments, they still maintain the duty

to protect the data as if the data was stored on internal government environments

38

. Federal

agencies must ensure that CSPs are aware of the criteria the agency uses to identify certain

data elements as PII, as well as the controls, safeguards, and training the agency expects the

CSP to maintain, on its behalf, over the collection, use, retention, and disposal of PII.

If a Federal agency places PII in a CSP environment, Federal agencies must provide information

privacy training and awareness to CSP personnel in accordance with FISMA, the Privacy Act, and

existing policy

39

. This includes general awareness and job-specific training for those who work

with PII. FISMA does not make a distinction between CSP personnel and Federal agency

employees who work with Federal data. As noted above, the Privacy Act, which also requires

training, extends to contractors operating systems of records about individuals. In addition

under FISMA, Federal agencies must prepare and make available to CSP personnel a training

module, electronic or hardcopy, addressing the criteria the agency uses for determining how

38

See, e.g. 5 U.S.C. § 552a(m).

39

44 U.S.C. § 3541, et seq.

[ 21 ]

data is classified as PII or sensitive PII

40

. Further, the training must include information on

Federal privacy laws, regulations, policies, and penalties for inappropriate access and

disclosure. Pertinent CSP personnel must be required to acknowledge their completion of the

training module at the inception of the agreement, and on a periodic (typically annually) basis

thereafter. The overarching objective is for anyone who has access to Federal data to

understand their role in identifying and safeguarding personal information.

Key considerations for training include:

Negotiating and allocating responsibility and costs of training (i.e. whether the Agency

and/or the CSP will administer it and who will pay for it);

Which CSP personnel shall be required to have training;

What training shall be required, depending on the category of personnel to be trained;

How often training shall be conducted (e.g. annually, quarterly, upon assignment to or

employment under the contract); and

What testing or other verification of training must be required.

Data Location

Many CSP environments involve the storage of data across multiple facilities, often across the

globe. Where Federal data resides changes a Federal agency’s applicable legal rights,

expectations, and privileges based on the laws of the country where the data is located. Federal

agencies need to first consider the type of data they plan to place in a cloud environment, and

then the laws and policies of the country where the cloud providers’ servers are located in

order to fully understand who may have access to this data, as well as what ability a Federal

agency has to retrieve privacy data as required by Federal law.

Almost every country has different standards and laws for handling personal information that

CSPs must meet if they maintain facilities within their borders. Some countries allow persons

with rights of access to personal information that may not directly align with the legal

framework in the United States

41

. Other countries may permit law enforcement to request

more data from cloud providers than within the United States. It may not be clear how the

privacy laws and protections apply in these situations. In any situation where a CSP

environment goes outside of U.S. territories, there is a potential for conflict of law; and Federal

40

See OMB Memorandum M-10-15, FY 2010 Reporting Instructions for the Federal Information Security

Management Act and Agency Privacy Management (Apr. 21, 2010), available at:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/memoranda_2010/m10-15.pdf.

41

See generally Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the

protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such

data, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31995L0046:EN:HTML.

See also The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (Canada), available at

http://www.priv.gc.ca/leg_c/leg_c_p_e.cfm.

[ 22 ]

agencies must take sufficient time to proactively consult with legal counsel about the possible

ramifications

42

.

Under the Privacy Act, Federal agencies must be able to inform individuals, in the applicable

SORN, where their data is being maintained, which can be complicated in a CSP environment

43

.

The storage of Privacy Act records in non-U.S. facilities potentially subject to foreign law could

also potentially affect the CSP’s ability to secure such records adequately from access by

unauthorized individuals, or to make such records readily available to the Agency or the

individuals who have a right to review or amend their records under the Act

44

. The location of

this data may also alter the privacy risks, and how the Agency describes and mitigates those

risks in its PIA,

45

what privacy training the agency would provide, and how the agency and/or

CSP will respond to breach incidents

46

.

Before signing a cloud computing contract, a Federal agency should take care to understand the

CSP environment and where Federal data might reside. Some key things to consider include:

Ensure the contract clearly defines the specific requirements for data in motion and

data at rest (including the location of data servers and redundant servers);

Fully incorporate the security controls as articulated in NIST Guidance in the agreement

and understand how CSPs will implement those controls;

47

and

Contractually define a procedure for what CSPs must do in the event of any request for

disclosure, subpoena, or other judicial process from outside the United States seeking

access to agency data.

Breach Response

When placing Federal data that contains PII in a CSP environment, Federal agencies need to be

aware of issues related to data loss incidents or breaches that are specific to the CSP

environment. Federal agencies have longstanding specific requirements related to reporting

and responding to incidents of possible or confirmed exposure of PII, no matter how a Federal

42

In addition, other Federal agencies may have negotiated arrangements on behalf of the United States with

other countries or international organizations such as the EU or the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation

(APEC) that may help resolve some of these difficult issues. For example, the Department of Commerce,

International Trade Administration has negotiated Safe Harbor agreements with the European Union and