1

Contents

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2

Undergraduate Premedical Curriculum ......................................................................... 2

Coursework in the Social Sciences and the MCAT

Biochemistry

Science Electives

General Program Information

Curriculum Planning ........................................................................................................ 4

Transfer Credit

A Note to Students in the Joint Program with List College

A Note to Students in the Dual and Joint Degree Programs with Sciences Po,

Trinity College, and CityU

A Note to International Students

Further Program Planning Tips

An Alternative Route to Medical School

Healthcare Experience ..................................................................................................... 10

Volunteering in the Emergency Room

Clinical Research

Wet Lab Research

Medical Volunteering Abroad

Shadowing

A Note on the Application Process ............................................................................... 12

Letters of Recommendation ........................................................................................... 12

Faculty Recommendations

Other Recommendations

Requesting Recommendations

Waivers

Premedical Committee Letter: Eligibility Requirements ............................................ 15

The Premedical Community at GS ................................................................................ 17

Workshops and Information Sessions .......................................................................... 17

Premedical Communications .......................................................................................... 17

Some Advice about Advising .......................................................................................... 17

Accessing Academic Help ............................................................................................... 19

Study Guidelines ............................................................................................................... 20

Undergraduate Premedical Frequently Asked Questions........................................... 22

Premedical Curriculum Worksheet ................................................................................ 24

2

Introduction

This handbook is designed for School of General Studies undergraduate students (including those

enrolled in joint- and dual-degree programs) considering premedical studies in preparation to apply

to medical, dental, or veterinary school or education in another health profession. Please note that

we generally refer throughout this handbook to “premedical” and “medical school” because the vast

majority of our students interested in a health profession do plan to enter a medical school program.

Much of what we say here, however, applies to significant (albeit varying) degrees to those preparing

to pursue educations to become dentists and veterinarians, and much of it also pertains to the

planning and preparation of future physician assistants, physical therapists, podiatrists, and nurses,

among other allied health professions. We recommend this handbook be used as a complement to

individualized advising from the staff of the GS Premedical Office.

Undergraduate Premedical Curriculum

Medical schools in the United States require students to complete a fairly standard course of study

before applying for admission. The Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) is designed on the

assumption that students sitting for the examination have completed this preparation. Therefore,

you must carefully plan your curriculum to ensure that you complete the proper science coursework

for your application.

Columbia offers you a strong advantage in completing this coursework. Medical schools view

Columbia students as strong applicants because they recognize how thoroughly our students are

prepared in the sciences. This is especially true of biology. Medical schools highly value the fact that

Columbia students are taught the most contemporary topics in molecular and cellular biology and

study with faculty actively engaged in research. As a group, Columbia students score more than four

points higher than the national average on the MCAT. And Columbia alumni currently in medical

school frequently remark how much better prepared they are for the rigor of the medical school

curriculum because of how biology is taught here.

The medical school admissions process has always been competitive, and with each passing year

seems to become more so. For this reason, it is extremely important for premedical students to

receive a rigorous grounding in the premedical sciences and earn excellent grades and MCAT scores.

It is impossible, of course, to detail every contingency here, but what follows gives you a good deal

of crucial information about the curriculum.

To be considered for admission to medical school, students must complete certain undergraduate

courses in the arts and sciences. There are some slight variations in these requirements from medical

school to medical school and from state to state. To prepare students as fully as possible, and to

assure that they will be in a position to apply to the greatest range of schools, the GS Premedical

Committee prescribes the following premedical curriculum for students seeking its support of their

medical school applications:

• One year of college English.

• One year of Mathematics, including one semester of Calculus and one semester of Statistics.

• One year of General Physics, including laboratory.

3

• One year of General Chemistry, including laboratory.

• One year of Organic Chemistry, including laboratory.

• One year of Biology, including laboratory, and with an emphasis on molecular and cellular

biology.

The worksheet at the end of this handbook indicates the bulletin numbers of these courses at

Columbia.

Coursework in the Social Sciences and the MCAT

The Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), the standardized admission test taken by applicants

to American medical schools, includes a section devoted to the psychological, social, and biological

foundations of behavior. (For more information, please consult the Association of American

Medical Colleges (AAMC) website.) The GS Premedical Committee does not require premeds to

take psychology and sociology since coursework in these subjects is not generally required by the

medical schools themselves. We do, however, recommend that students who have not yet taken a

college-level introductory psychology course plan to take The Science of Psychology (PSYCH

UN1001), the course at Columbia providing the most comprehensive introduction to pertinent

topics on the MCAT. While we certainly encourage GS premeds to take sociology courses, there is

no one course that we recommend. Furthermore, the MCAT puts greater emphasis on psychology

than on sociology (in a proportion of roughly 80 percent to 20 percent). Many premeds may find

they can learn the key sociology concepts through self-study.

Biochemistry

A number of medical schools require a semester of biochemistry and others will likely add it as a

requirement in the future. Although Contemporary Biology I (BIOL UN2005/2401), the first

semester of Columbia’s introductory biology sequence, covers many of the foundational concepts of

biochemistry (and therefore is sufficient preparation for the MCAT),

1

we cannot guarantee that all

medical schools will accept this in fulfillment of a biochemistry course prerequisite, and therefore

recommend that GS premeds take a biochemistry course (it does not necessarily have to be taken

before applying).

Science Electives

For some students, our premedical curriculum represents only the minimum program to be

completed. In consultation with advisors, premed students may consider taking additional

coursework in biology and biochemistry. Biochemistry is a course all premeds should consider

taking because a number of medical (as well as dental and veterinary) schools require it (see above).

While medical schools value a student’s background in the humanities and social sciences, and do

not necessarily encourage premedical students to major in the sciences, most students in medical

school either completed science majors or took additional coursework in the sciences. One reason

GS premed students are successful in gaining admission to medical school is their willingness to

continue their preparation beyond the minimum requirements.

1

Please note, the introductory biology course sequence at Barnard does not cover biochemistry in any detail. Students

who elect to take biology at Barnard should consider taking a semester of biochemistry before taking the MCAT.

4

General Program Information

Take all premedical courses for letter grades. No premedical course in which a P is earned satisfies a

requirement.

2

We recommend that premeds take all math and science courses, including electives,

for letter grades.

Advanced Placement (AP) work will not fulfill the premedical requirements, even if your previous

college or Columbia has awarded you credit for such work. Most medical schools expect you to

complete letter-graded university courses, and this remains an eligibility requirement for committee

support. High school work, however advanced, cannot be equated with college courses. If you are

eligible for advanced placement in calculus, you can satisfy the premedical requirement of a semester

of calculus with Calculus II (MATH UN1102) or III (MATH UN1201) or Honors Math (MATH

UN1207), depending on your AP score. If you are eligible for advanced credit in statistics, you will

still need to take a statistics course (unless you plan to take two semesters of calculus). If you are

eligible for advanced standing credit in biology, you should still plan to take Columbia’s introductory

biology sequence (BIOL UN2005-2006 and 2401), unless an advisor in the Department of

Biological Sciences approves a different course of study. If you are eligible for advanced placement

in chemistry, you will still need to complete at least four semesters of chemistry at Columbia to be

eligible for committee support (one of those semesters can be biochemistry). Please see the section

on AP Credit on the General Studies website under “Academic Policies.”

Required courses are offered at various times of the day, and frequently in the evening. For course

descriptions, please see the Columbia University School of General Studies website. Many of the

courses have course websites as well. These should be consulted before you register to assess the

demands of the courses in both difficulty and time.

Placement tests in mathematics and chemistry are optional. Students who are not sure which math

or chemistry class to begin with are strongly encouraged to take the appropriate diagnostic

placement exam to determine the best placement. You are, of course, welcome to consult your

advisor if you have any questions about this. If you prefer to begin with Preparation for College

Chemistry and/or Precalculus, there is no need to take placement tests.

Pre-Chemistry, the course you must take if you are not ready for General Chemistry I, is offered in

the summer and fall. Students pay for two points of tuition, but the course carries no degree credit.

There is no placement test for physics; however, students who have had no significant prior

exposure to physics may wish to consider taking Basic Physics to prepare for the required course

sequence. Basic Physics is offered in the summer only. Again, students pay for two points of tuition,

but the course carries no degree credit.

Please be reassured that that many GS students who began their premedical studies with these

preparatory courses have gone on to gain admission to medical school.

Curriculum Planning

To plan your course of premedical studies at Columbia, you have several important resources. Your

first resource is your undergraduate advisor in the Dean of Students Office, who will guide you in

your course selection to ensure that you meet all of your degree requirements. Secondly, your GS

premedical advisor will work with you and your advisor to plan your course of premedical study and

to guide you through the application process. Students in the Joint Program with List College are

2

Students who took courses in the spring 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, may have received pass-fail grades by

mandate of the school they attended. This may be an exception to the normal requirement of letter grades.

5

also urged to consult with their JTS advisor about how best to fit the premedical requirements into

the curriculum requirements of the Joint Program.

Once you have decided to begin pursuing the premedical or prehealth course of studies, you should

notify your undergraduate advisor who will help you to identify your premed advisor and to

schedule an appointment with them. It is advisable to meet with a premed advisor before confirming

any schedule involving required premed courses. Your premedical advisor will arrange for you to

receive the weekly premedical e-mail newsletter and will review your academic records, including

courses taken outside Columbia, to determine which premedical requirements, if any, you may have

already satisfied. To facilitate your program planning, the premedical advisor can communicate his

or her findings by means of the Premedical Course Clearance Form.

Thoughtful program planning is crucial, especially in the early stages of the premedical curriculum

when you are learning how to study science, getting used to taking courses graded on a curve, and

refining your time management skills.

When you are nearing completion of the required courses and are readying to take the MCAT exam,

perhaps as early as the spring of your junior year, you will begin to work closely with your

premedical advisor who will guide you in preparing your medical school applications. Keep an eye

open for notices in the premedical newsletter about mandatory general advising meetings to attend,

and next steps to take and when to take them.

Note: Medical schools do not require you to major in science. You should select a major of interest to you as you are

more likely to do well in it. Admissions committees look for academic diversity when admitting a class in order to bring

together a variety of opinions and perspectives.

Medical schools expect that the basic premedical science courses be completed during regular terms

of enrollment since the accelerated schedule of summer courses often results in a less thorough

academic preparation. Please plan your program accordingly. Of the four basic premedical sciences,

your grades in biology and organic chemistry will be weighted the most heavily. General Physics II

and General Chemistry II are the only science lecture courses that students are routinely allowed to

complete during Columbia’s summer session in the specially designed 12-week course format. It is

also acceptable to take math, psychology, and the lab courses for Physics II, General Chemistry,

Organic Chemistry, and Biology in the summer.

Doubling up: Although it is not a requirement, we strongly recommend that premeds who are not

science majors take at least two science lecture courses concurrently in at least two semesters. By

doubling up on science lecture courses and earning strong grades you will provide admissions

committees with a powerful demonstration of your capacity to manage the academic demands of

medical school.

The medical school admissions calendar reflects the fact that the vast majority of medical school

applicants are applying as they near the end of a “traditional” college career. Undergraduates

typically sit for the MCAT in the spring or early summer of their junior year and complete their

medical school applications, including secondary applications, that summer. During their senior year,

students make themselves available for medical school interviews. Some schools will make their

decisions in the fall, but most students are notified in the spring for admission to medical school for

the fall following their college graduation.

This is an idealized timetable, and it may be difficult (unwise, even) for General Studies

undergraduate students to adhere to it. Many undergraduates have a “gap” during their application

6

year (applying as seniors, rather than as juniors). This provides students with the opportunity to gain

experience in medical research, if desired.

Transfer Credit

Some students matriculate at the School of General Studies having already completed premedical

coursework at another institution. The Premedical Committee routinely reviews such coursework

and, at its discretion, may accept some or all of it in satisfaction of premedical requirements. A

number of considerations enter into the review of such coursework: Where were the courses taken?

How long ago were they taken? What grades were earned in them? Will they count toward your

major at Columbia? Will they prepare you to take upper level courses at Columbia? To enjoy the

support of the Premedical Committee when you apply to medical school, you must complete at least

fifteen points of premedical study at Columbia (excluding English, psychology, and all preparatory

coursework). (See Premedical Committee Letter: Eligibility Requirements for more on the eligibility

requirements for support.)

If you earned strong grades in the entire premedical curriculum prior to matriculation at Columbia,

you will (with rare exceptions) need to take introductory biology at Columbia and then complete at

least another nine points of upper-level lecture courses in order to have the committee’s support.

Typically, a student in this situation would do so by majoring in biology or biochemistry. This

approach is more likely to be successful the more there is consistency between the grades earned

before Columbia and those earned at Columbia.

A Note to Students in the Joint Program with List College

Completion of the premedical curriculum poses special challenges for undergraduates in the Joint

Program with List College for several reasons. First, these students are working to complete two

degrees concurrently, toward which end they must complete two majors, as well as other general

degree requirements. Secondly, they are less likely than their GS peers to matriculate having

completed any of the premedical requirements. In addition, there is work involved in completing the

application to the Premedical Committee, preparing for the MCAT, and applying to medical school.

Completing the premedical requirements on top of the requirements for the two degrees, though

difficult, can be done successfully, but it requires careful program planning, consultation with

advisors, and use of the Academic Resource Center and other forms of academic support whenever

appropriate. Joint Program students will need to consult their JTS dean, in addition to their GS

advisor and premed advisor, regarding how to reasonably schedule JTS, GS, and premedical

requirements. The availability of spring/summer course sequences in General Physics and General

Chemistry may offer greater flexibility in planning their programs. In some cases, it may be advisable

to allow themselves additional semesters so that they can excel in their work.

A Note to Students in the Dual and Joint Programs with Sciences Po, Trinity College, and

City U

Students in the dual and joint degree programs with Sciences Po, Trinity College, and CityU face

some special challenges in completing premedical studies at GS. In particular, they won’t be able to

use any science coursework completed abroad to satisfy the requirements of the premedical

curriculum. Consequently, it may not be feasible to complete all degree and premedical requirements

within a two-year period. Students with a strong commitment to becoming physicians should inquire

to arrange for additional time in which to complete their requirements. We recommend that such

students inform their advisors of their aspiration for medicine, dentistry, or veterinary medicine as

early as possible to allow time for thoughtful planning. Those joint and dual degree students who are

international students should also read the following note.

7

A Note to International Students

International students who must maintain an F1 Visa are required to register for a full-time course

load of at least 12 points. This full-time status must be maintained in each semester of enrollment.

International students are also advised that most U.S. medical schools give preference in admissions

to applicants from their own states or regions. It is therefore very difficult for an international

student to gain admission to a U.S. medical school, unless he or she becomes a U.S. citizen or

permanent resident. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, a total of 53,030

applicants sought admission to medical school for the entering class of 2020 and a total of 22,239

matriculated (nearly 42% of applicants). Of these matriculants, only 131 were neither U.S. citizens

nor permanent residents.

This number reflects several circumstances. For example, many public institutions may limit

admission to state residents, and private institutions may require international applicants to pay the

entire cost of their medical education up front (or place the funds in escrow). We therefore

encourage every international student pursuing a course of study in premedicine at the School of

General Studies to consider seeking permanent residence and eventually citizenship to improve their

chances of admission to an American medical college. In any case, we urge you to be as informed as

possible about the application process, admissions constraints, and alternative routes to medical

school.

Further Program Planning Tips

General

• Do not feel that you must adhere to an artificial or self-imposed timeline to complete the

required courses. You should take the courses when you are academically ready for them. Many

GS graduates currently in medical school started with Pre-Calculus and/or Pre-Chemistry.

Calculus

• You cannot begin Physics unless you have taken Calculus or are taking it as a co-requisite. If you

have never taken Calculus or Physics before, it may be a good idea to complete Calculus before

you start Physics.

• If you are not in Calculus while taking the first semester of the General Chemistry sequence, you

should be enrolled in it by the time you take the second semester of the course.

General Chemistry

• You cannot take Organic Chemistry or Biology at Columbia until you have successfully

completed General Chemistry.

• Columbia offers General Chemistry I and II during the summer. Each is just six weeks long. We

strongly advise against taking these courses in this summer session format. If you are thinking of

taking either or both of them, you should discuss this with your prehealth advisor.

8

• General Chemistry I is offered in both the fall and spring semesters. If you take General

Chemistry I in the spring, you should take the 12-week summer session General Chemistry II.

• The one-semester, 3-credit General Chemistry Lab course can be take alongside the second

semester of the General Chemistry lecture course sequence or afterward. (It is offered during

summer session in both a six-week and a twelve-week format—either is acceptable.)

Physics

• Physics I is offered in both the fall and spring semesters. If you take Physics I in the spring, you

should take the 12-week summer session Physics II.

• Columbia offers Physics I and II during the summer. Each is just six weeks long. We strongly

advise against taking these courses in this summer session format. If you are thinking of taking

either or both of them, you should discuss this with your prehealth advisor.

• If you are new to Calculus and Physics, we recommend that you complete the former before

taking the latter.

• Physics labs ought to be taken concurrently with physics.

Biology

• Columbia’s Biology I is offered only in the fall semester and its Biology II course is offered only

in the spring semester.

3

• The one-semester, 3-credit Contemporary Biology Lab course can be take alongside either

semester of Contemporary Biology. It is also sometimes offered during summer session.

• EEEB majors may take Environmental Biology I (EEEB UN2001) to satisfy the first half of the

biology sequence; they should plan to take BIOL UN2006 or UN2402 to complete the

sequence. A semester of biochemistry is also recommended.

Organic chemistry

• Columbia does not offer Organic Chem I in the spring and does not offer Organic Chem II in

the fall.

4

• Columbia does offer Organic Chem I and II during the first and second six-week summer

sessions respectively. Each is just six weeks long. We strongly advise against taking these courses

in this condensed summer session format. If you are thinking of taking either or both of them,

you should discuss this with your prehealth advisor.

3

But see below concerning Barnard College course offerings.

4

But see below concerning Barnard College course offerings.

9

• Organic chemistry lab is offered during the summer as a single course taught in a six-week

format. If you completed organic chemistry during the prior academic year and still need to take

the lab, it is acceptable to take the lab in the summer.

Barnard College courses

• Barnard College courses in biology and organic chemistry are compatible with committee

support; however, access to these courses may be limited. Premeds who choose to take biology

at Barnard are advised to take a separate biochemistry course to prepare for the MCAT.

• GS premeds should not take general chemistry at Barnard, since the curriculum for that course is

incompatible with Columbia’s other premedical requirements.

• The contents of Barnard College’s two-semester course sequences in biology and organic

chemistry begin in the spring and end in the fall.

• Barnard College courses in biology and organic chemistry may not count toward the majors in

Columbia’s Departments of Chemistry and Biological Sciences. Students planning to major in

the sciences should plan to complete all their premedical prerequisites at Columbia.

Summer session courses

• We recommend that only the following science lecture courses be taken in the summer: the 12-

week versions of General Chemistry II and Physics II. Any exceptions to this must be approved

by your premedical advisor.

• Generally speaking, any of the labs may be taken in the summer, although physics lab courses

are normally taken alongside the corresponding physics lecture courses.

• Space in summer lab sections for biology and organic chemistry may be limited.

• Summer lab courses may be taken in either the 6-week or (where available) the 12-week format.

G.P.A.

• Please be advised that, in general, successful applicants to medical school present an overall

cumulative grade point average that is at least 3.5 and a science cumulative average that is at least

3.3. Preferably, both should be higher. According to the Association of American Medical

Colleges, the mean science grade point average of a 2021 medical school matriculant was 3.68;

the mean cumulative grade point average was 3.75.

Course workloads

• Use the course look-up tool to research course workloads before registration. Many students

who decide to drop a course, typically a lab, lament that they did not realize in advance how

much work was involved. All of the premedical courses have websites; please consult them

carefully before meeting with your advisor.

10

An Alternative Route to Medical School

The FlexMed Program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is an option some GS

undergraduates may wish to explore. This is an early assurance program to which interested students

apply by October 1 of their sophomore year. It is intended to encourage undergraduates to pursue

study in areas of interest to them without the medical school application process casting its long

shadow over their undergraduate years. If accepted into this program, the premed goes on to

complete an abridged form of the premedical curriculum, but also takes courses in medical ethics,

health policy, public health, and translational medicine. If you are interested in this program, we

recommend you discuss this with your premedical advisor early on. Be advised, however, that

admission to this program is highly competitive. For more information, visit the FlexMed page.

Healthcare Experience

Strong grades in science courses are not enough to make one a competitive applicant to medical

school. Medical schools are also interested in what students do to help others and to learn about the

day-to-day workings of medicine. Many institutions deem actual medically-related experience

imperative; some see it as one of many ways to demonstrate a caring attitude, good interpersonal

skills, and sincere motivation for a career in medicine. For information on specific schools’

requirements, students should visit their websites or contact their admissions offices. Generally,

volunteer work is definitely a plus and even more so if it involves patient contact. All medical

schools agree that it is critically important that applicants know what they are getting into, and have

tested their aptitude for a career in medicine before they apply. Health care work, usually as a

volunteer, helps to address these concerns. Many students also find that service as a volunteer helps

them keep their ultimate goal in sight while their attention is focused on the immediate demands of

the premedical curriculum. All premedical students at GS are required to have significant health care

experience that runs over an extended period of time, since medical schools will look for evidence of

your preparedness to maintain a commitment. To be eligible for committee support, you will need

to complete at least 120 hours of service in an appropriate volunteer or paid clinical health care

capacity. Upon completion of your service, or at least by the time you are about to apply to medical

school, you should have your supervisor or the hospital’s volunteer coordinator verify the sum total

of your hours of work. The Premedical Office has a form available for this purpose; however, a brief

statement on the hospital’s letterhead stationery is also acceptable.

Volunteering in the Emergency Room

Often, the most readily available opportunity is to serve as a volunteer in a hospital emergency

room. Most hospitals look for a commitment of three or four hours (but sometimes more) each

week. All students should begin volunteering as early as possible in their programs of study; a

sudden flurry of hours in your final semester may appear insincere. Volunteering in the private

practice of a family member will look equally suspect, if it represents the majority of your

experience. Please consult The Postbac News (a twice-weekly listserv for GS prehealth students) and

the Postbac Premed Program website for a list of local hospitals and the contact information for

their volunteer offices. Listings are also available for prevets and predents. You are encouraged to

seek your premed advisor’s opinion of any health care work opportunity you have been offered.

Clinical Research

It is certainly possible to find opportunities beyond the emergency room setting. Be sure to consult

the weekly Postbac Premed News & Announcements newsletter, which frequently contains notices

of such openings. Most commonly, students find clinical research volunteer positions, whether in an

11

emergency room or elsewhere in the hospital, where they help physicians conduct research by

recruiting eligible patients for research studies.

Wet Lab Research

Opportunities in basic science medical research (wet lab) are more limited. Wet lab research is

valued highly by the most competitive medical schools, which, not surprisingly, are often those with

large research enterprises located within major medical centers. Admissions Deans at some top-tier

schools report that applicants are more competitive if they have completed wet lab research by the

time they file their applications. Please be aware, however, that many premeds matriculate at medical

schools without wet lab experience.

Undergraduates majoring in the sciences can frequently get some exposure to research in advanced

courses in their majors, through summer research fellowships, or as volunteer research assistants.

With so many medical schools in New York City, many opportunities are available, although it may

require some effort to find them. The Premedical Office will post many available openings in the

Postbac Premed News & Announcements newsletter. Because of their positive experiences with GS

premeds in the past, many researchers post their openings exclusively through the GS Premedical

Office. Another good source are the human resources web pages at major medical centers where

they may be listed as “technician” or “laboratory technician” positions. Leads from fellow students

may be especially fruitful. Because of the nature of research work, students are usually asked to

commit ten to twelve hours each week as a volunteer research assistant for one year, and sometimes

longer. An added benefit of volunteering as a research assistant is that it sometimes leads to full-time

paid employment as a research assistant during the application year.

Wet lab experience is something we recommend that every premed consider; however, we do not

recommend you undertake such work, unless you are positively interested in, or very curious about,

it. Admission to medical school does not depend upon working in a wet lab.

Medical Volunteering Abroad

Many GS premeds are eager to volunteer in health care settings outside of the United States, where

access to medical care may be extremely limited and avidly sought. We are all for helping others in

need wherever in the world they may be. Be advised, however, that such work does not necessarily

make an applicant to medical, dental, or veterinary school more competitive. There are several

reasons admissions committees may be inclined to regard such work with diffidence; these include:

the excessive cost of participating, which makes it prohibitive for many capable students, and the

generally short duration of such volunteer commitments (one or two weeks is typical). Also, medical

schools often feel they can make a better assessment of an applicant’s commitment to the difficult

profession of medicine on the basis of work undertaken in unglamorous settings in the United States

rather than work done in an exotic locale. Postbac Premed students who wish to do service abroad

should regard it as a supplement to the clinical and research work they complete domestically.

Students who pursue opportunities abroad should ensure that the tasks they assume are

commensurate with their experience and training and the work is conducted under the supervision

of a health care professional. Students should be advised that the School of General Studies has not

vetted or endorsed any of the programs listed on our website under Clinical and Research

Opportunities; they therefore must investigate any program before joining it.

Students who arrange work abroad during their enrollment at GS should notify their advisor

beforehand and register with International SOS, an emergency services insurance program that

provides worldwide assistance in the event of an emergency.

12

Prior to volunteering abroad, students are also encouraged to review the AAMC reference

Guidelines for Premedical and Medical Students Providing Patient Care During Clinical Experiences

Abroad. Predents should review Guidelines for Predental Students Providing Patient Care During

Clinical Experiences Abroad. The information in these documents is general enough in nature that

prevets and allied health pre-professionals are also encouraged to consult them.

Shadowing

Many students are interested in shadowing physicians, and we think it’s a great thing to do. Students

who shadow often have opportunities to observe interactions and procedures that volunteers may

not see. Some medical schools may even expect viable applicants to have done some shadowing.

Even so, the majority of your work ought to be in a service-oriented role.

5

Part of the purpose of

volunteering is to enable you to show your commitment to service. As an admissions dean put it

during a medical school admissions panel held at Columbia several years ago, “shadowing is for you;

volunteering is for others.”

Note: Please be advised that jobs and volunteer positions in healthcare posted on the website and

sent via the premed mailing list have not been screened by anyone at the School of General Studies.

The posting of a position does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation by the School of

General Studies. Investigate all opportunities before committing.

A Note on the Application Process

A key function of the premedical advising program at the School of General Studies is to guide and

support GS premeds through the complex and lengthy application process. Generally speaking, in

the fall semester before applying to medical school over the following summer, premeds should

attend a group advising session devoted to the application process. Thereafter they should become

acquainted with the documents on the Postbac Program website describing the essays and other

materials prehealth students must upload to their Prehealth Portfolios and with the timeline for

submission of the portfolio and the common application, and for the taking of the standardized

admissions test (MCAT, DAT, GRE).

Premedical advisors want to do more than explain what applicants must do. They want to help you

understand why the things you are required to do matter and provide some guidance in how to

finesse them. Moreover, because the writing of the essays for your portfolio is such an important

part of your preparation to apply, the premedical advisors want to encourage undergraduates to

speak with them, if any questions arise as they are writing them. While grades in science courses and

standardized test scores are an important part of a premed’s application, the bulk of it is a written

account of the applicant’s life experiences and motivations for a career in medicine. Understanding

why such information weighs so heavily in the thinking of admissions committees will help you

write the essays with greater confidence. It is also our hope that if you begin working on these essays

early on, your reflections on yourself and your life experiences to date will help to vivify your current

experiences.

While we won’t provide an extended discussion of the application process here, it does seem useful

to address the subject of letters of recommendation, since this is something many students may want

to begin thinking about long before they enter the application phase.

5

In distinguishing between volunteering and shadowing, we are well aware that many volunteer positions include a

significant amount of shadowing. This is perfectly acceptable and need not be debited from your hours. We recommend

that you be less concerned with whether the Premedical Committee will audit your health care experience (we won’t)

than whether that experience makes you as compelling an applicant as you can be.

13

Letters of Recommendation

Medical schools will attach great weight to the recommendations submitted in support of your

candidacy for admission. There are three principal kinds of recommendations: faculty

recommendations, recommendations from employers or from volunteer activities, especially (though

not exclusively) those related to medicine and health care, and the recommendation of the

Premedical Committee (discussed separately below). Admissions committees are interested in letters

only from people under whom you have studied or worked. With rare exceptions, character

references or letters from family physicians and the like are not appropriate.

Note to Prevets: The process for compiling letters of recommendation is very different from that

described here. It is recommended that you consult with your preveterinary advisor regarding this

matter before proceeding to request letters.

Faculty Recommendations

The medical school admissions process seeks to determine whether you possess the academic ability

to succeed in medical school. For this reason, substantial weight is placed on the recommendations

of your instructors. Most medical schools expect several references from science faculty; some ask

that these be distributed across the premedical science curriculum.

Request three letters of recommendation from Columbia science faculty. While we require two such letters to

complete the Committee Letter, it is advantageous for the committee to have letters to choose from.

Also, requesting an additional letter or two may ensure you have back up, in case one of your

referees falls behind. Request letters from science faculty immediately upon the completion of each

course. Requesting letters of recommendation at the last minute will reflect poorly on you,

needlessly inconvenience your referees, and possibly delay your medical school application. Be

advised, however, that some faculty may prefer to wait until you are entering the application process

before submitting a letter for your file. As in other aspects of the application process, be flexible in

your expectations.

Some faculty members have specific requirements about letters. For example, they may not write for

you if you take the course in the summer, or they may want you to submit a resume. Identify these

requirements early so you can meet them.

Request at least one letter of recommendation from a faculty member not in the sciences, preferably

from your major.

Request any letters from former faculty at your previous college early in the process. Any letter that

is received will be held in your file until you apply.

Other Recommendations

Request at least one letter of recommendation from someone who has supervised your service as a

volunteer (whether in a clinical or research setting).

Request a letter of recommendation from each of your previous employers in the field of medicine

or health care.

If you have substantial work experience outside of the field of medicine or health care, request

letters of recommendation from your employers, past and present.

14

If you have competed in organized sports or were active in one of the performing arts, you should

consider requesting a letter from a former coach, teacher, director, or conductor.

If you intend to apply to MD/PhD programs, you should have letters of recommendation from

each of the scientists under whom you have conducted research.

Requesting Recommendations

Begin to seek recommendations as early as possible. Failure to request letters of recommendation in a timely

fashion is one of the greatest causes of delay in students’ applications. When requesting letters from

former employers and from instructors at previous schools, be sure to let them know what and how

well you have done at Columbia to demonstrate the seriousness with which you are pursuing your

premedical preparation.

It is important that your referees mention in their letters that they are writing specifically in support of

your candidacy for admission to medical school. Medical schools want to know that when a letter was

composed the writer knew exactly for what purpose his or her support was being solicited. That

said, you should tell your referees that they are not expected to comment upon your potential either

for medical study or for professional success as a physician. It is sufficient for them to say simply

what work you did for them and how well you did it, and that it is on that basis that they are

recommending you for admission. Of course, if your referees are able to add further information

based on their personal knowledge of you and their knowledge of medicine, admissions committees

will be happy to have it.

Make sure your referees understand that they should address their letters generically “To the

Admissions Committee,” rather than to an advisor or a specific medical school. Be especially clear

on this point with referees outside Columbia, who sometimes confuse the fact that you are a

premedical student here with the idea that you may be applying to Columbia University’s medical

school (or, even, to Columbia’s Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program!). Letters of recommendation

addressed to the Columbia School of Medicine will be returned to your referee for correction—a

time-consuming process with an uncertain outcome.

If you have a dossier of recommendation letters at another institution you should have it forwarded to the GS

Premedical Office. If the letters in your dossier were not originally written for medical school

applications, you should ask your referees to write new letters specifically mentioning that they are

recommending you for medical school.

In general, you should request letters from those who know you well. Obviously it would be best if

each of your faculty referees knew you personally; but medical schools also recognize the reality of

large lecture classes. Therefore, the expectation is that letters from science faculty will speak to the

rigor of the course and your rank in the class. For example, an ideal letter from an undergraduate

instructor would come from someone from whom you took more than one course, or under whom

you completed a substantive research project or thesis. Many times in large lectures it will be difficult

to get to know the instructor, even if you seek additional help with the course material during office

hours. In addition to expanding on the course requirements and the meaning of the grade, faculty

will add personal observations when they can, sometimes relying on input from teaching assistants.

In any case, the decision of whether to provide a reference, and with what enthusiasm, is exclusively

the referee’s prerogative. If you have not been in contact with instructors from your previous

schools, you can refresh their memories with a letter, a resume, a photo, a copy of a paper

completed for their class and, if feasible, a personal visit.

15

Inform your referees that recommendations should be typed on the referee’s institutional letterhead,

signed, and dated. Institutional letterhead and a signature help to authenticate the letter.

Make sure to send along a recommendation waiver form (see below).

Letters can be transmitted to the GS Premedical Office in several ways:

• A scanned copy of the signed and dated letter, accompanied by the waiver form, may be e-

mailed to gs-letters@columbia.edu.

• The letter and waiver form may be mailed to the GS Premedical Office (the mailing address

is on the waiver form). Some Columbia faculty members prefer to hand-deliver it, and that is

also acceptable. Please provide referees with stamped envelopes preaddressed to our office

to facilitate the mailing of their letters to us.

• Once you have established your Prehealth Portfolio, you will be able to make entries for

referees. When you do so, the system will send each referee an e-mail with a unique link at

which to upload their letter. We encourage you to use this system; however, it is advisable to

communicate with your referees about your desire for their letters before entering them into

your portfolio. You will be able to track online the arrival of those letters submitted directly

to your portfolio.

N.B. You must not function as the courier for your letters. We will discard any letters received from

you, whether by hand, US Mail, or e-mail.

Thank-yous: We encourage you to send your referees a brief note to thank them for writing on your

behalf. Referees will also be delighted to learn where you plan to matriculate. Please consider letting

them know.

Waivers

The Federal Family Education Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, as amended (the “Buckley

amendment”), provides students with the right of access to educational records. In the case of

recommendations, the law provides that students, if they choose, may waive that right. You should

determine for yourself whether your interests will be best served by recommendations that are

accessible to you. Confidential recommendations will be written and submitted by faculty and others

with the explicit understanding that they will be read only by the Premedical Committee and medical

school admissions committees. The presumption is that letters to which you have waived your right

of access are more candid assessments of your ability and potential as a medical student. For this

reason, if you do not trust that a reference will be satisfactory, you would probably do better not to

request it, rather than to retain your right to review it.

Whether you choose to waive your right of access or not, your decision must apply consistently to

all your letters. Your decision to waive or not to waive your right of access also extends to your

Premedical Committee Letter. In other words, you cannot waive access to individual letters of

recommendation, but retain it for the Committee Letter, or vice versa. Furthermore, when you

waive your right of access to your letters, you also waive your right to know which letters the

Premedical Committee chooses to attach to your Committee Letter.

Every recommendation you request should be accompanied by a statement of its status as a confidential or non-

confidential evaluation. These waivers forms are available in the waiting area outside the Premedical

Office and on the Postbac Program website (gs.columbia.edu/content/applying-medical-school).

You should supply one to each of your referees when you request their support. (However, if you

16

are arranging for letters to be submitted online, the waiver statement will be incorporated into the

system-generated e-mail sent to your referees.)

Premedical Committee Letter: Eligibility Requirements

Most medical schools expect applicants to have the support of the Premedical Committee of the

institution at which they completed their premedical requirements. At the School of General Studies,

the Premedical Committee, comprising the four premedical advisors, provides its support in the

form of a “Committee Letter.” To be eligible for a Premedical Committee Letter, you must meet the

following conditions:

• Completion of the premedical curriculum, including one year of English; at least 15 points of

premedical science coursework should be completed while enrolled at GS

• All of the premedical courses must be completed by the summer of the application year

• You must be in good academic standing. (N.B. For the purpose of eligibility, GS students

placed on Conditional Disciplinary Probation are ineligible for support notwithstanding their

good disciplinary standing because they have been found responsible for prohibited

behavior.)

• To satisfy a course requirement, you must earn a grade of at least C

• Completion of a minimum of two semesters at GS

• Documented completion of at least 120 hours of appropriate work (volunteer or paid) in a

health care setting providing opportunity to interact with patients.

• You must have the written support of two Columbia faculty members, or instructors, from

the premedical sciences and mathematics departments. Toward this end, we urge you to

request at least three such letters of recommendation

• Timely completion and submission of the online prehealth portfolio (in effect, your

application for committee support), along with all the other materials required by the

committee (letters of recommendations, certification of volunteer work, a copy of your

submitted common application, etc.)

• An interview with a member of the Premedical Committee (Portfolio Review)

GS does not provide Committee Letters for students who, having begun studies at Columbia,

subsequently complete required premedical coursework elsewhere. If you defer application to

medical school beyond your last semester at GS, the Committee will provide a letter of support only

if you apply within three years of graduation under the following conditions:

• You have completed most of your premed requirements within two years prior to graduation

• You have met the eligibility requirements for a letter

• You meet the internal deadlines for a committee letter

17

If you do postpone application to medical school after completing your undergraduate degree, you

are advised to keep active in a health-related field and remain in touch with your GS prehealth

advisor.

Reapplication: If your application is unsuccessful, you will retain your eligibility for committee support

for four years after the first application cycle in which you become eligible for it. Reapplicants are

required to submit additional materials to the Premedical Committee by the published deadlines.

This includes a brief supplement to your portfolio, verification of additional hours of health care

work, additional letters of recommendation, and a copy of the submitted common application for

the new application cycle. Please see the Postbac Premed website for details or consult with your

premed advisor.

The Premedical Community at GS

In addition to the undergraduate premeds, the School of General Studies is home to some four

hundred Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program students who take the same premedical courses as

their undergraduate peers through a non-degree program. These students give shape and energy to

the premedical community at GS and are represented by their own student organization, the Postbac

Premed Student Council (PPSC). While you, as an undergraduate, are not eligible to run for office in

the PPSC, you will receive invitations to all kinds of events the PPSC sponsors throughout the year.

We urge you to attend as many as appeal to you. The social events give you a chance to meet other

premedical students who, like you, are facing the challenges of completing premedical preparation

while leading independent lives. Events such as the Medical School Fair Deans’ Panel give you a

chance to hear from medical school admissions deans, while the MCAT Panel, the Application Year

Panel, and similar events allow you to learn about aspects of the premedical experience from the

perspective of current and former students who are further along in the process.

Workshops and Information Sessions

Throughout the academic year, the GS Premedical Office offers workshops and information

sessions to augment students’ classroom experience and the support they receive from their

premedical advisor. Workshops and information sessions are held on a variety of topics including

application preparation, personal statement writing, interviewing skills, and glide year planning.

Dates and additional information on these workshops and information sessions may be found in the

weekly Postbac Premed News & Announcements newsletter and on the Postbac Premed calendar.

Premedical Communications

As a premedical student, you will be added to the premedical e-mailing list, which will provide:

• Crucial information about deadlines, medical school visits, changes in the medical school

admissions process and events of interest to premeds

• Notices of group advising meetings, panels on the MCAT, workshops on interviewing, etc.

• Postings of clinical and research opportunities, both paid and volunteer, to help you acquire

direct experience of medicine and patient care.

18

The primary vehicle for this information is the weekly Premed Weekly newsletter. We urge you to

read it regularly. We also recommend you look at the Postbac website; please do not be put off by

the term “Postbac”: much of the information applies to undergraduates also.

Some Advice about Advising

The premedical path is a difficult one to follow; however, if you are sincerely interested in a career in

medicine, we encourage you to pursue it. Every premed comes to the task with different experiences

and different strengths. It is good to know what yours are. We encourage you to go on the

assumption—one that we make—that you can do it. From there it is all (well, perhaps not quite all)

a matter of strategy, planning, hard work, and the exercise of good sense. This is where your advisor

can be helpful. We encourage you to speak with your advisor to discuss a workable plan of action.

We also ask you to consider carefully your advisor’s advice.

19

Accessing Academic Help

Prepared by the Postbac Premed Council (PPSC)

Welcome to the Premedical Program at Columbia. There are many resources available for guidance

and assistance in your class work and we urge you to use them.

Peers

You are each other’s best resource. Do not feel shy about approaching your classmates for help, to

form a study group, or just to ask advice. Everybody has different academic strengths and

weaknesses, so it’s a good idea to pool your knowledge—everyone learns more that way. If you have

no academic weaknesses (lucky you), it’s still to your benefit to help others. The best way to test

your knowledge is to teach someone else. Your peers are also your best source for information

about course requirements, professors’ teaching styles, and scheduling.

Professors and Teaching Assistants (TAs)

Professors and TAs have office hours to answer questions or clarify material. Some people feel more

comfortable approaching TAs, while some like speaking with professors. Both are useful sources of

information. TAs and professors are generally very accommodating; if you can’t meet them during

office hours (due to work, etc.), call or email them for an appointment. TAs will also hold recitation

(an hour-long review of lecture material and homework) at least weekly, and it is a mandatory part of

most courses. For many students, this is an extremely useful supplement to attending lecture.

Departmental Help Rooms

The physics, math, and statistics departments have free help rooms. The hours vary, but your

professors will announce them at the beginning of the semester. They are staffed by graduate

students who are willing to answer all your questions.

Academic Resource Center (ARC)

The Academic Resource Center offers free academic support in all premedical subjects, including

tutor-led study groups, a weekly premed work room, and traditional tutoring appointments. These

resources are designed to help students at all levels of mastery: whether you’re struggling with an

entire subject or trying to turn an A to an A+, the ARC can help!

In addition to tutoring services, the ARC also offers support consultations on study skills, test taking

strategies, time management, critical reading skills, optimizing your study group, and more. Services

are constantly evolving based on student needs and requests—so if there’s something you’d like to

see that isn’t offered, your input is always welcome.

Paid Tutors

You can find a paid tutor in two ways. First, look around for advertisements on campus.

Alternatively, department offices will provide you with a list of graduate students who tutor for a

fee. The tutors from the biology, chemistry, and math departments have departmental approval.

Many tutors offer group rates.

20

Study Guidelines

By Professor Deborah Mowshowitz

[Professor Deborah Mowshowitz has written the following guidelines for Columbia’s biology class. We believe they can

be applied to any course.]

1. Come to class. In some courses all you have to do is read the book, but that is not the case here.

There is too much stuff in the book, and the lecture will key you in to what is important and

what isn’t; it will also provide a framework to stuff all the facts into. If you have to miss a class,

get the notes from a fellow student. Get the phone number of at least one other student now, so

that you’ll have someone to call if necessary.

2. Take notes. Everything that really matters will be discussed in the class; the book is really just for

back up (this may not make sense, but this is how we do it). There are many styles of taking

notes—some people prefer to get all down word-for-word and some people prefer to just write

down the critical points. Either way is fine, but be sure you get the point (if you are

concentrating on transcribing every word) and be sure you understand the necessary details (if

you are concentrating on the point). Taping is permitted, but the transcribing of tapes is very

time consuming and we don’t recommend it. You are probably better off forming a study group

and going over notes together to fill in the holes. We do not give out notes because we believe

you learn more from taking your own.

3. Form a study group or partnership. Don’t try to do it alone. (If you are too shy to ask anyone, we will

help you find a partner.) Study groups are generally good because they help you go over the

material (see above), give you an opportunity to practice explaining your answers (see below),

and provide moral support.

4. Do the problems. Seriously and carefully. This is probably the most important thing. All the other

advice is just to get you in shape to do this. Do the unstarred problems first and leave the starred

ones for later (to test yourself). Go over the unstarred problems until you feel confident with the

material; go over them more than once if necessary, but don’t do the starred ones until you

understand the others. Once you feel on top of the material, do the starred ones as if it were a

test—write out the answers and write out the explanations of how you got your answers.

5. Make pictures, diagrams, summary charts, concept maps, etc. The ones in the book (and the ones we

hand out in class) may be good, but for best results, you should make your own. Don’t copy

over your notes or outline the book word-for-word; digest each section of the notes or text first

and write your own, private, condensed version (in whatever form you prefer—use diagrams,

charts, etc.).

6. Keep up. The current material is always based on what came before, so once you get behind it is

very difficult to catch up.

7. Read one of the texts before class if the material is new to you. It is very hard to follow the lecture if every

word and concept is unfamiliar. It probably does not pay to spend too much time on the text(s),

as explained above in point 2, but some people learn better from books than they do from

lectures.

21

8. Ask questions. If you don’t understand something, ask. That is what the TAs are here for and that

is how the lecturer finds out if he or she is going at the right pace. Don’t wait for the class

bigmouth to speak up—do it yourself. Don’t be afraid of looking stupid—looking dumb before

the exam is a lot smarter than looking dumb afterwards. To get the most out of recitations and

office hours, go through the problems and/or notes first and come prepared with a list of

questions. The more effort you put into asking questions, the more you will get out of the

answers.

9. Master the vocabulary. The stress in this course may be on using the vocabulary, but you won’t get

anywhere until you learn it first. So try to master all the new terms as fast as possible. Be

especially careful about words that seem similar, but mean different (often related) things (such

as peptide/protein, chromosome/chromatic, gene/allele, etc.). Once you get the vocabulary

down pat, you will find it much easier to follow the lectures and do the problems.

10. A word or two about grades. The two most common complaints about grades heard in this class are

“the exam grade doesn’t reflect my knowledge of the material” and “my grade doesn’t reflect the

amount of time and effort I put into this course.” Sometimes these complaints are justified, but

often they mean the student does not understand what is expected of him or her, or is

concentrating on (and spending too much time on) the wrong things. In this course you have to

know how to use the material, not just repeat it. If you think your performance on the exam

does not reflect your knowledge, it often means you have memorized the facts but have not

practiced enough at selecting the right ones and applying them to whatever problem is presented

to you.

22

Undergraduate Premedical Frequently Asked Questions

How does GS come to recognize that I’m premed?

Once you realize you are premed, predent, or otherwise “prehealth,” be sure to tell your advisor and

ask that you be linked (through the GS Student Success Portal) with your premed advisor. You will

then be able to schedule an appointment with your prehealth advisor. In anticipation of your

appointment, your prehealth advisor will review transcripts of coursework you completed before

Columbia (where applicable) to determine whether any requirements have been satisfied. With your

permission, your premed advisor will also arrange to have you added to the weekly premed listserv

(The Premed Weekly). We encourage you to meet periodically with your premed advisor to discuss

your premed academic track, academic preparation, health care experiences, and medical school

applications.

Who does the premed advising?

GS has an excellent premed advising staff which also advises non-degree students in the

Postbaccalaureate Premedical Program, the oldest and largest of its kind in the U.S. All

premed/prehealth students at GS are assigned a premed advisor from the GS Premedical Office

Your premed advisor will work with you on the specific order and combination of courses to be

taken to fulfill the premed requirements, guide you through the process of applying to professional

schools, and, for students who qualify, provide written support in the form of a committee letter.

Can I substitute previous coursework at other schools or other courses at Columbia or

Barnard for any of the premedical requirements?

Students are expected to fulfill the specified premedical course requirements at Columbia. Any

substitution or equivalent coursework to be used, whether taken at Columbia or elsewhere, must be

officially approved in writing by your GS premedical advisor.

What if I have completed some of these required courses elsewhere?

Premeds must complete at least fifteen points of required premedical coursework at Columbia. It is

also recommended that they double up on their science lecture courses over the course of two

semesters. Students who have completed some of these basic courses prior to matriculation at GS

may be advised by the Premedical Committee to take advanced level science courses in order to

fulfill eligibility requirements for a committee letter as well as to be more competitive applicants for

medical school. These decisions are made on a case-by-case basis.

What summer session courses can be taken to satisfy premedical requirements?

We recommend that GS premeds take only the following summer session courses in satisfaction of

the premed requirements prior: the 12-week General Chemistry II course (CHEM S1404); the 12-

week General Physics II course (PHYS S1202); general chemistry laboratory; organic chemistry

laboratory; biology laboratory; and courses taken in fulfillment of the math-related requirement. It is

also acceptable to take the Science of Psychology (PSYC S1001), a course recommended to premeds

who will eventually take the MCAT. If you are thinking of taking the physics or chemistry lecture

courses offered in Columbia’s Summer Session in a six-week format, you should discuss with your

advisor the pros and cons of doing so.

What if the premed courses are included in the requirements for my major?

Students who satisfactorily complete the premedical requirements are eligible for committee support

even if some of the premed courses satisfy major requirements.

23

Can premedical courses count toward the fulfillment of the GS core requirements?

Yes, required premedical courses may be counted toward fulfillment of the GS science core

requirement.

If I did hospital volunteer work before matriculating at GS, must I continue to volunteer?

You are required to complete at least 120 hours of health care work while enrolled at GS, volunteer

or paid. Even if you have prior experience, there is always more to learn about medicine, and New

York City, with its many health care facilities, is a great place to do so. By continuing to volunteer,

you will demonstrate to medical schools the extent of your knowledge about, and your enthusiasm

for, medicine.

What if I am interested in veterinary or dental medicine or other healthcare professions?

The basic premedical curriculum will prepare most students who are interested in going on to other

kinds of health care professional programs. Students interested in other health care professions, such

as veterinary medicine, should consult with their premedical advisor about additional, particular, or

substitutional prerequisites for admission to other professional programs.

Additional Questions?

Please consult with your GS premed advisor.

24

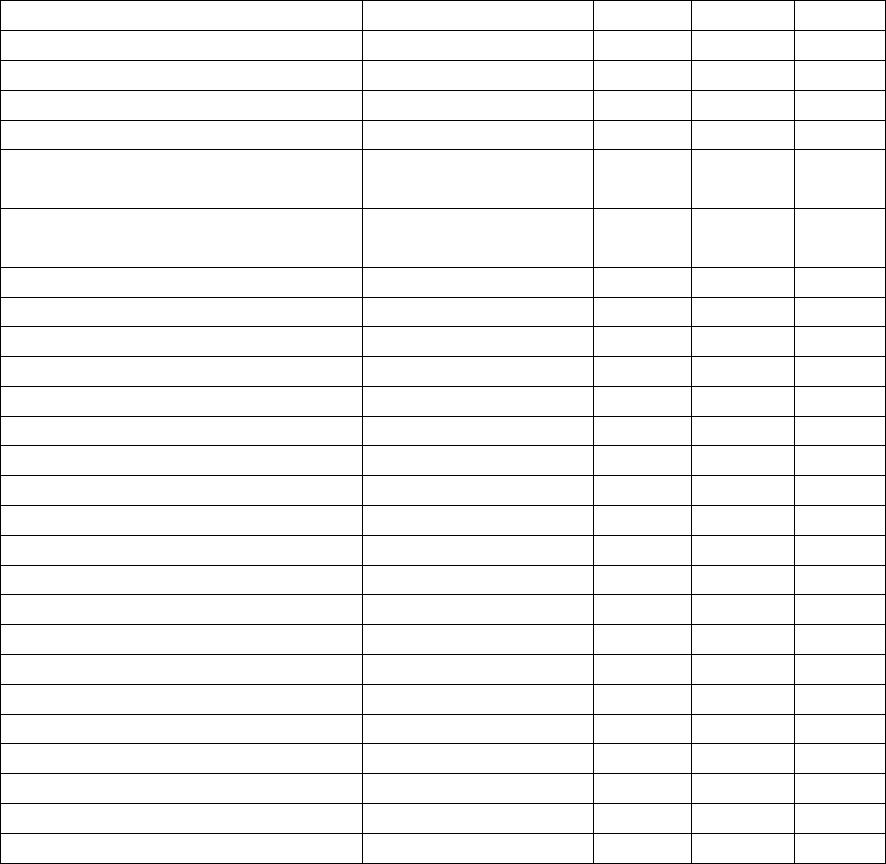

Premedical Curriculum Worksheet

Course

Course Number

Points

Semester

Grade

English (University Writing)

ENGL GS1010

3

Literature (in English)

ENGL 3000-level or higher

3 or 4

Pre-Calculus*

MATH UN1003

3

Calculus I

MATH UN1101

3

Statistics or Calculus II

STAT UN1101 or

MATH UN1102

3

Introductory Psychology**

PSYC UN1001 or

equivalent

3

Pre-Chemistry*

CHEM UN0001

0

General Chemistry I

CHEM UN1403

4

General Chemistry I Recitation

variously numbered

0

General Chemistry II

CHEM UN1404

4

General Chemistry II Recitation

variously numbered

0

General Chemistry Lab

CHEM UN1500***

3

Basic Physics*

PHYS UN0001

0

Physics I Lecture

PHYS UN1201

3

Physics I Lab

PHYS UN1291

1

Physics II Lecture

PHYS UN1202

3

Physics II Lab

PHYS UN1292

1

Intro Biology/Contemporary Biology I

◊♣

BIOL UN2005 or UN2401

3 or 4

Intro Biology/Contemporary Biology II

◊

BIOL UN2006 or UN2402

3 or 4

Contemporary Biology Lab

◊

BIOL UN2501

3

Organic Chemistry I

◊

CHEM UN2443

4

Organic Chemistry I Recitation

variously numbered

0

Organic Chemistry II

◊

CHEM UN2444

4

Organic Chemistry II Recitation

variously numbered

0

Organic Chemistry Lab I

◊

CHEM UN2493

§

1.5

Organic Chemistry Lab II

◊

CHEM UN2494

§

1.5

* This is a prerequisite for a required course, but not itself a requirement for medical school. Neither Preparation for

College Chemistry nor Basic Physics may be taken toward the degree.

** This course is not required for premedical study, but it is recommended as preparation for the MCAT.

*** The lab course is accompanied by a zero-credit lab lecture (UN1501).

§

The lab course is accompanied by a zero-credit lab lecture (UN2495, UN2496).

◊

The biology and organic chemistry requirements may be satisfied with Barnard College coursework (subject to

availability of space in the course); however, premeds who choose to take biology at Barnard are advised to take a

separate biochemistry course to prepare for the MCAT. They are also advised that they should not take the Barnard

College courses, if they plan to major in one of the sciences.

♣

Students who plan to major in ecology, evolution, and environmental biology may take Environmental Biology I:

Elements to Organisms (EEEB UN2001) in place of BIOL UN2005/UN2401; they should take BIOL

UN2006/UN2401 for the second semester of biology and are also advised to take a separate biochemistry course to

prepare for the MCAT.