The ERA-NET promoting European research on biodiversity

STAKEHOLDER

ENGAGEMENT

Handbook

BiodivERsA

© BiodivERsA, Paris, 2014

BiodivERsA2 (2010-2014), ERA-Net funded under the

EU’s 7th Framework Programme for Research.

BiodivERsA is the network of national funding organisations

promoting pan-European research that oers innovative

opportunities for the conservation and sustainable manage-

ment of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

For further information on the ERA-NET BiodivERsA2,

please contact:

Coordinator

Xavier Le Roux

BiodivERsA Secretariat

Executive Manager: Frédéric Lemaître

frederic.lemaitr[email protected]

Fondation pour la Recherche sur la Biodiversité

195, rue St Jacques

75005 Paris

France

Tel: +33 (0)1 80 05 89 37

Fax: +33 (0)1 80 05 89 59

www.biodiversa.org

Acknowledgements:

BiodivERsA would like to thank everyone who contributed to the development of this Handbook.

The main authors were Emma Durham, Helen Baker, Matt Smith, Elizabeth Moore and Vicky Morgan of the Joint

Nature Conservation Committee UK (JNCC).

Xavier Le Roux, Frédéric Lemaître, Claire Freour and Claire Blery of the Fondation pour la Recherche sur la Biodiver-

sité (FRB, France), Hilde Eggermont of the Belgian Biodiversity Platform/ BELSPO (Belgium) and Henrik Lange of the

Swedish Research Council FORMAS (Sweden) provided contributions and support.

The Partners in BiodivERsA2 contributed information on national practices.

Additional material and review was provided by Ros Bryce (Perth College, University of the Highlands and Islands, UK),

Mark Reed (Birmingham City University, UK) and Anna Everly (Project Maya).

Representatives from 21 of the BiodivERsA research projects, along with Peter Bridgewater and Richard Ferris (JNCC,

UK), Marie Vandewalle (Biodiversity Knowledge), Juliette Young (SPIRAL), Cathy Jolibert (University of Barcelona,

Spain), Mark Reed (Birmingham City University, UK) and Anna Evely (Project Maya), made important contributions at

a workshop in April 2013.

The Handbook was copy edited by Neil Ellis (JNCC, UK) and the design and layout completed by Angélique Berhault

(Belgian Biodiversity Platform/ BELSPO, Belgium).

BiodivERsA is also grateful to all those who kindly contributed to the development of the Handbook through response

to the public consultation process.

This publication should be cited as:

Durham E., Baker H., Smith M., Moore E. & Morgan V. (2014). The BiodivERsA Stakeholder Engagement Hand-

book. BiodivERsA, Paris (108 pp).

For further information on this report, contact:

Helen Baker ([email protected].uk) or Matt Smith ([email protected].uk)

© BiodivERsA, Paris, 2014

BiodivERsA2 (2010-2014), ERA-Net funded under the

EU’s 7th Framework Programme for Research.

BiodivERsA Stakeholder Engagement Handbook

Best practice guidelines for stakeholder engagement

in research projects

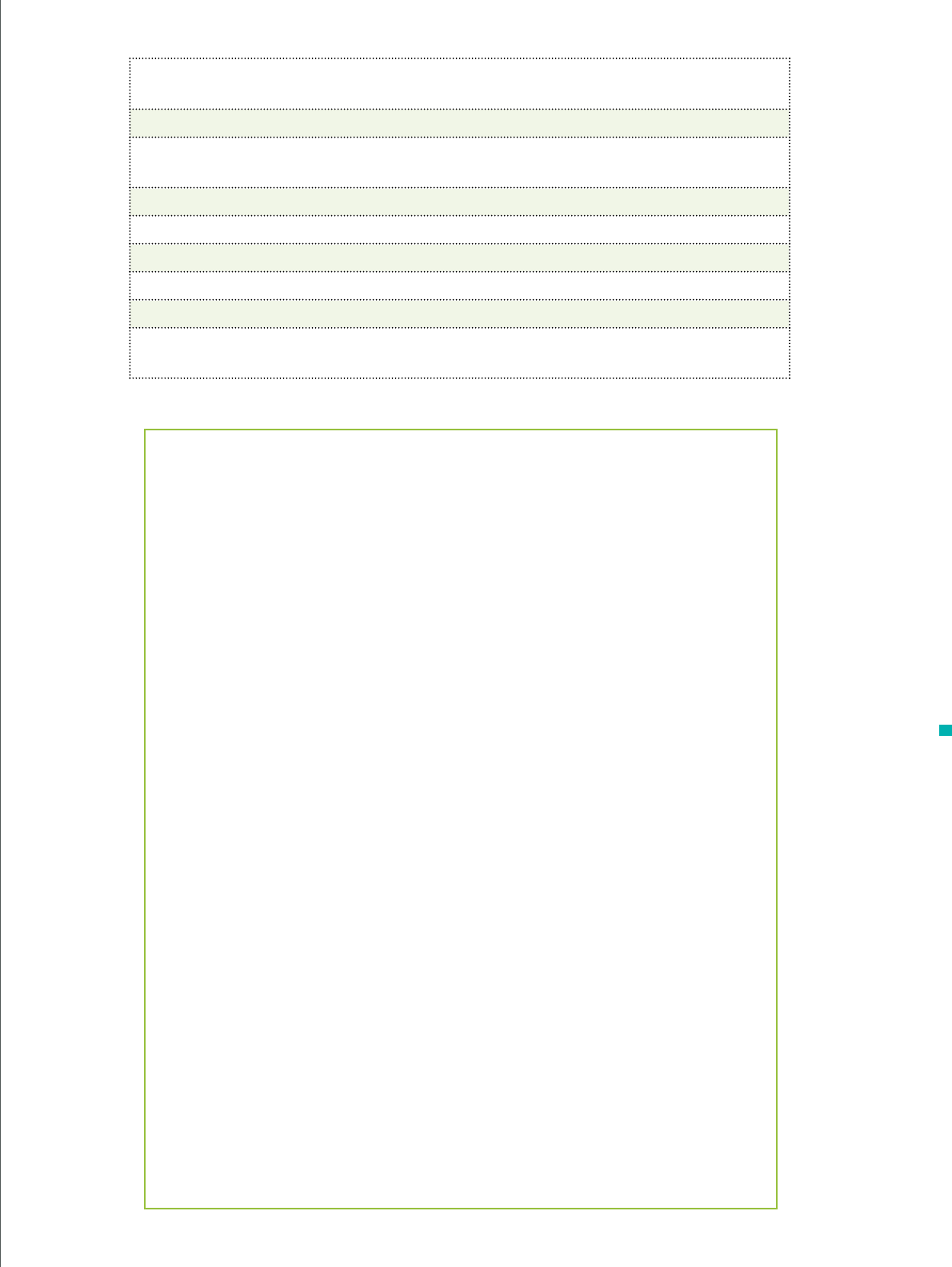

Contents

Foreword: why does BiodivERsA promote stakeholder engagement in research projects? ................. 1

Part 1 ...................................................................................................................................................... 3

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3

Background ............................................................................................................................................ 3

How does the Handbook work?............................................................................................................. 4

What do we mean by engagement? ...................................................................................................... 5

What is a stakeholder? ........................................................................................................................... 5

Why is stakeholder engagement benecial? .......................................................................................... 5

Challenges and limits to engagement .................................................................................................... 9

Key points to consider for eective stakeholder engagement ............................................................. 13

How BiodivERsA can help in stakeholder engagement ....................................................................... 15

General information and advice ........................................................................................................... 15

Information from other researchers and projects ................................................................................. 15

References ........................................................................................................................................... 16

Part 2 .................................................................................................................................................... 20

Why engage with stakeholders ............................................................................................................ 20

Scope and context ............................................................................................................................... 21

References ........................................................................................................................................... 25

Part 3 .................................................................................................................................................... 28

How to identify stakeholders ................................................................................................................ 28

Stage 1: Who are your stakeholders? .................................................................................................. 28

Stage 2: Assess, analyse and prioritise stakeholders .......................................................................... 33

Stage 3: Understand your stakeholders ............................................................................................... 39

Summary of the three stages of stakeholder identication .................................................................. 42

References ........................................................................................................................................... 43

Part 4 .................................................................................................................................................... 46

When to engage with stakeholders ...................................................................................................... 46

Mapping stakeholder roles to dierent stages of the project lifecycle................................................. 47

References ........................................................................................................................................... 50

Part 5 .................................................................................................................................................... 51

Methods for engagement ..................................................................................................................... 51

Types of engagement method .............................................................................................................. 51

Practical methods notes ...................................................................................................................... 56

Engagement skills ................................................................................................................................ 56

Matching methods to levels of engagement ........................................................................................ 57

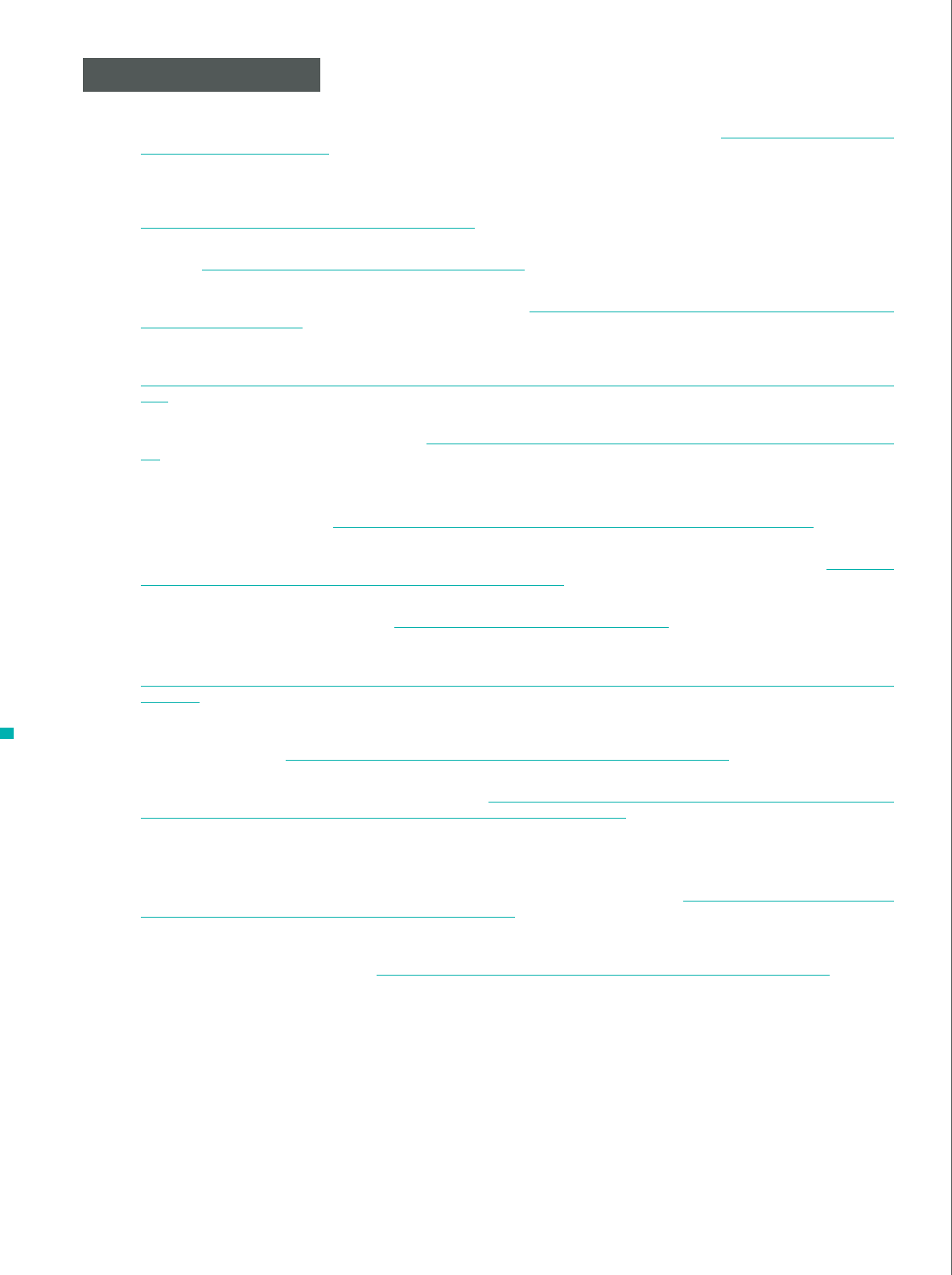

n CONTENTS-

FOREWORD: Why does BiodivERsA promote stakeholder engagement in research projects? 6

PART 1: INTRODUCTION 8

Background 10

How does the handbook work? 11

What do we mean by engagement? 11

What is a stakeholder? 12

Why is stakeholder engagement benecial? 12

Challenges and limits to engagement 15

Key points to consider for eective stakeholder engagement 19

How BiodivERsA can help in stakeholder engagement 21

General information and advice 21

Information from other researchers and projects 21

References 22

PART 2: WHY ENGAGE WITH STAKEHOLDERS 24

Why engage with stakeholders 26

Scope and context 28

References 32

PART 3: HOW TO IDENTIFY STAKEHOLDERS 34

How to identify stakeholders 36

Stage 1: Who are your stakeholders? 36

Stage 2: Assess, analyse and prioritise 40

Stage 3: Understand your stakeholders 46

Summary of the three stages of stakeholder identication 49

References 51

PART 4: WHEN TO ENGAGE WITH STAKEHOLDERS 52

When to engage with stakeholders 54

Mapping stakeholder roles to dierent stages of the project lifecycle 55

References 59

PART 5: METHODS FOR ENGAGEMENT 60

Methods for engagement 62

Types of engagement method 62

Practical methods notes 67

Engagement skills 67

Matching methods to levels of engagement 68

References 69

PART 6: PLANNING THE DETAIL OF THE ENGAGEMENT 70

Planning the detail of the engagement 72

The engagement planning table 73

Practicalities, feasibility and implementation 75

The engagement table: share, adapt and update 76

References 77

PART 7: MANAGING STAKEHOLDER CONFLICT 78

Managing stakeholder conict 80

Conicts with and between stakeholders: types and causes 80

Stakeholder perspectives on conict 81

Analysing conict 83

Conict management tools 85

Constructing a conict timeline 85

References 89

PART 8: MONITORING AND EVALUATING THE ENGAGEMENT 90

Monitoring and evaluating the engagement 92

Benets of evaluation 93

What to evaluate? 93

When to evaluate? 93

Stages of evaluation 94

Stage 1: From the outset 94

Stage 2: Throughout the process – on-going evaluation 94

Stage 3: Final evaluation 95

Evaluating the process 95

Evaluating the outcomes 96

References 97

APPENDIX 1: Approach used to develop case studies to demonstrate the dierent stages 100

in stakeholder engagement in biodiversity research

Aims 100

Methods 100

COPYRIGHTS 104

ANNEXES: available online at http://www.biodiversa.org/577

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

6

n FOREWORD-

WHY DOES BIODIVERSA PROMOTE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT IN RESEARCH PROJECTS?

BiodivERsA is the network of national funding agen-

cies in Europe that aims to build a dynamic plat-

form for encouraging excellent and policy-relevant

biodiversity research at a pan-European scale.

Between 2008 and 2014, it launched ve major

calls for proposals on prioritised topics that corre-

spond to the most pressing strategic issues that

biodiversity and ecosystem services currently face.

BiodivERsA aims to launch annual calls in future.

BiodivERsA partners recognise that research on biodi-

versity and associated ecosystem services is not only

an environmental issue, but as much an economic,

political, food-security and energy-security one. Being

a cross-cutting subject, biodiversity research needs to

promote interdisciplinarity, integrate a range of actors,

reach academic excellence, and have a clear soci-

etal impact. Biodiversity scientists have already been

involved in the provision of knowledge to stakehold-

ers, including policy makers, adopting new ways of

disseminating and explaining their ndings. Still, for

researchers it is not always clear how to eectively

engage with stakeholders as exemplied by a recent

statement from the principal investigator of one of the

BiodivERsA-funded projects: “A key point for me is

understanding who are the key persons to be involved

in research and what is the best way of communicating

research results while having an impact; which is the

lever we need to activate in order to make our results

be used and change the course for the foreseeable

future”.

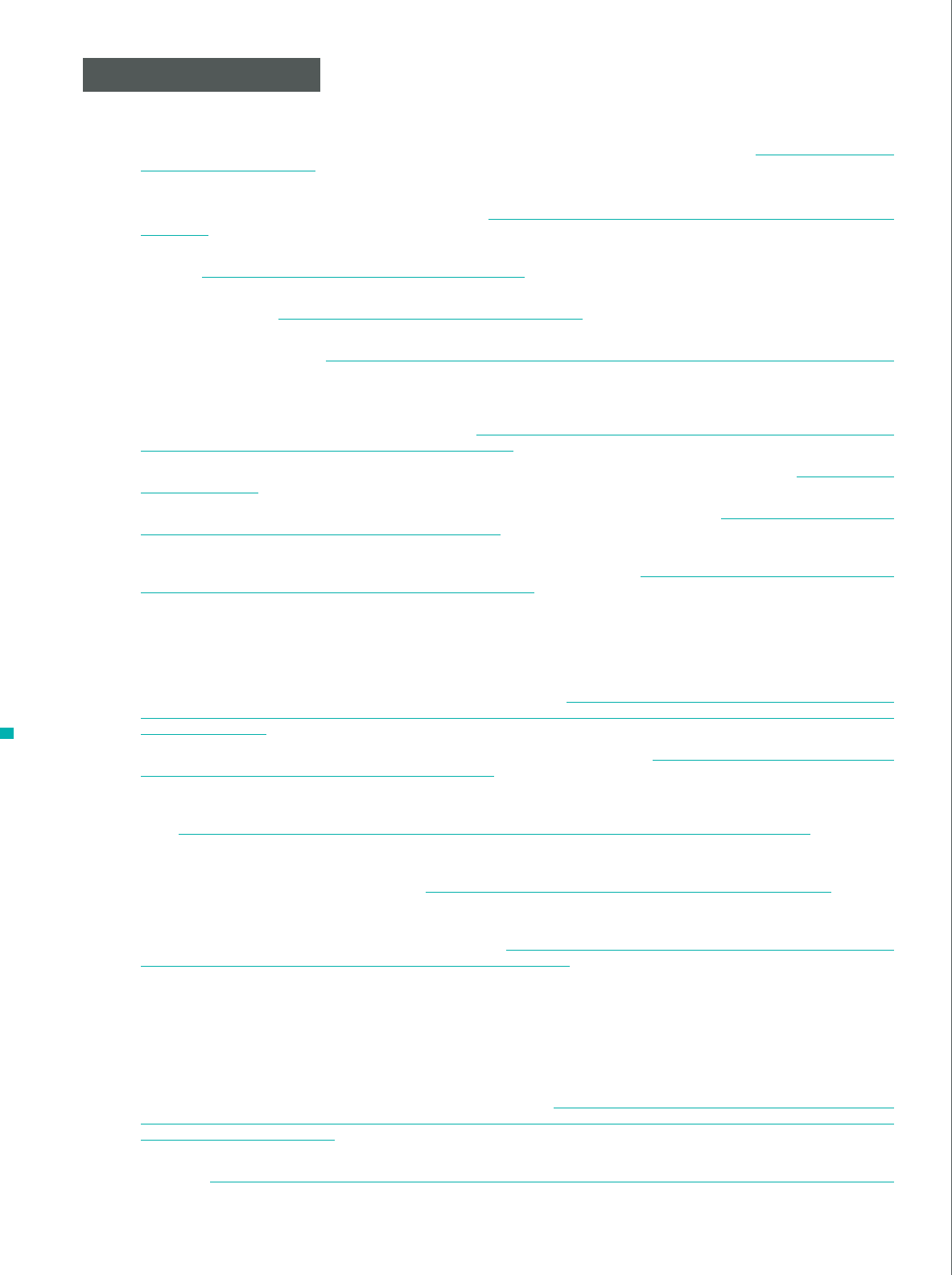

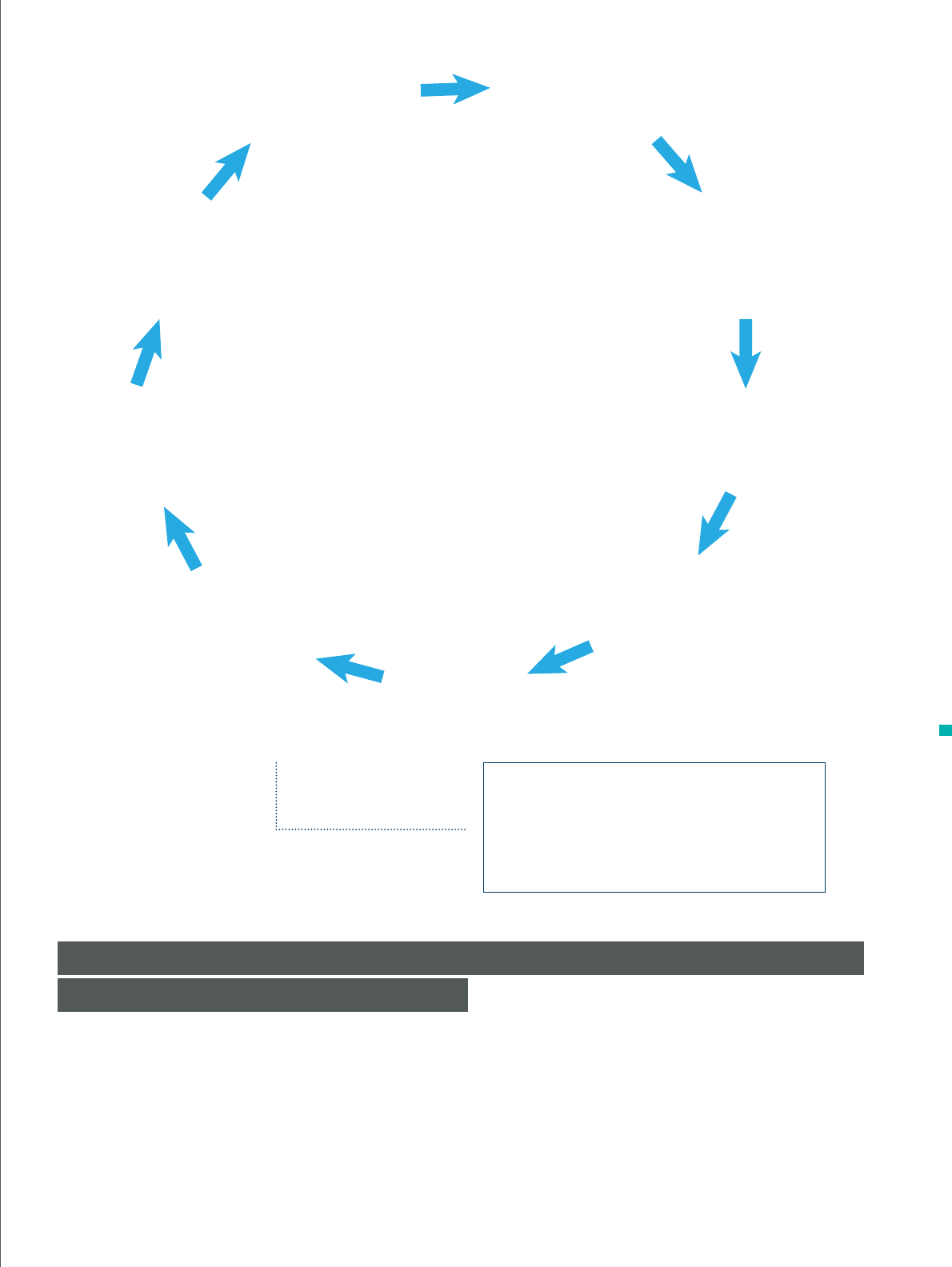

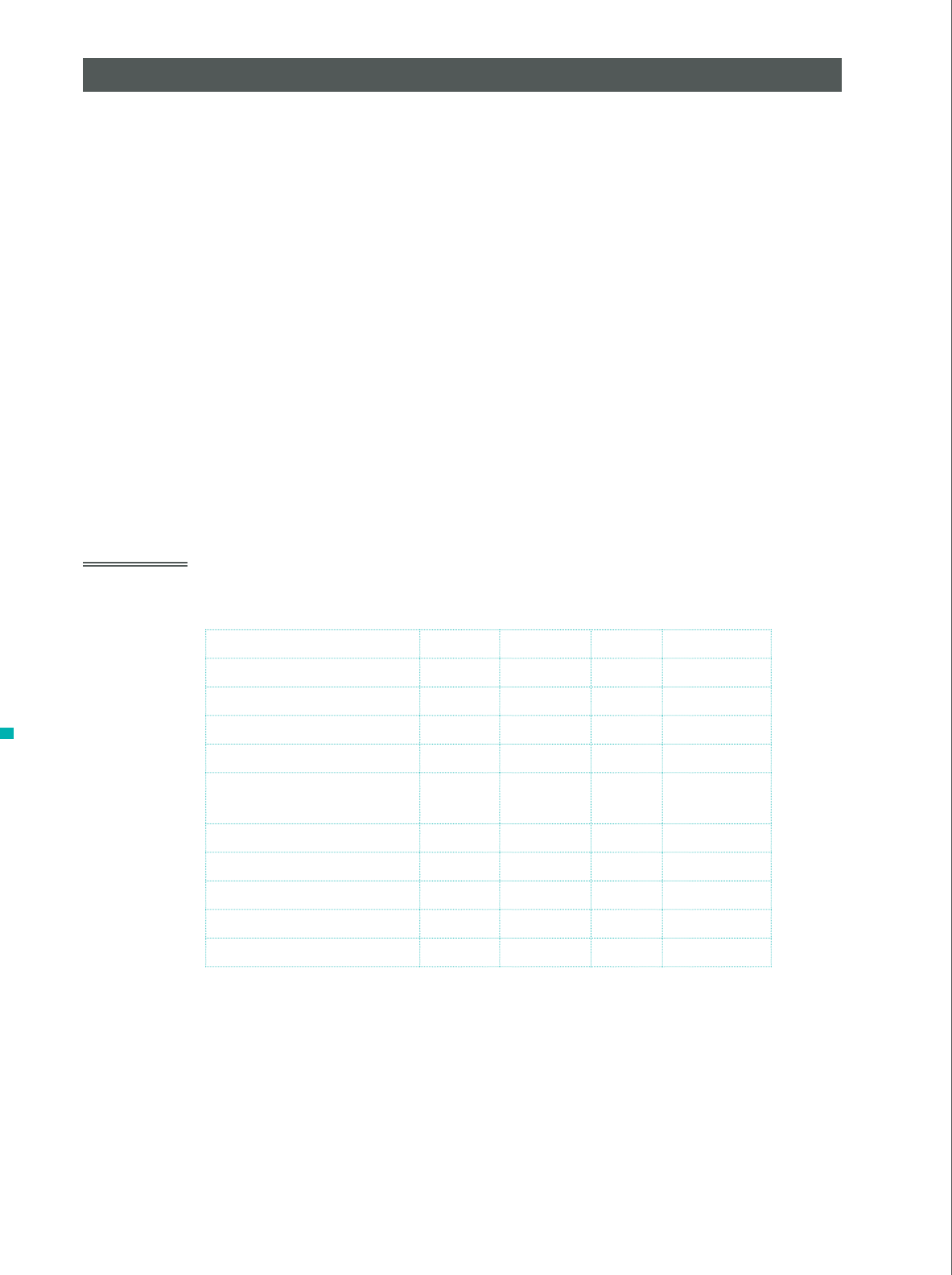

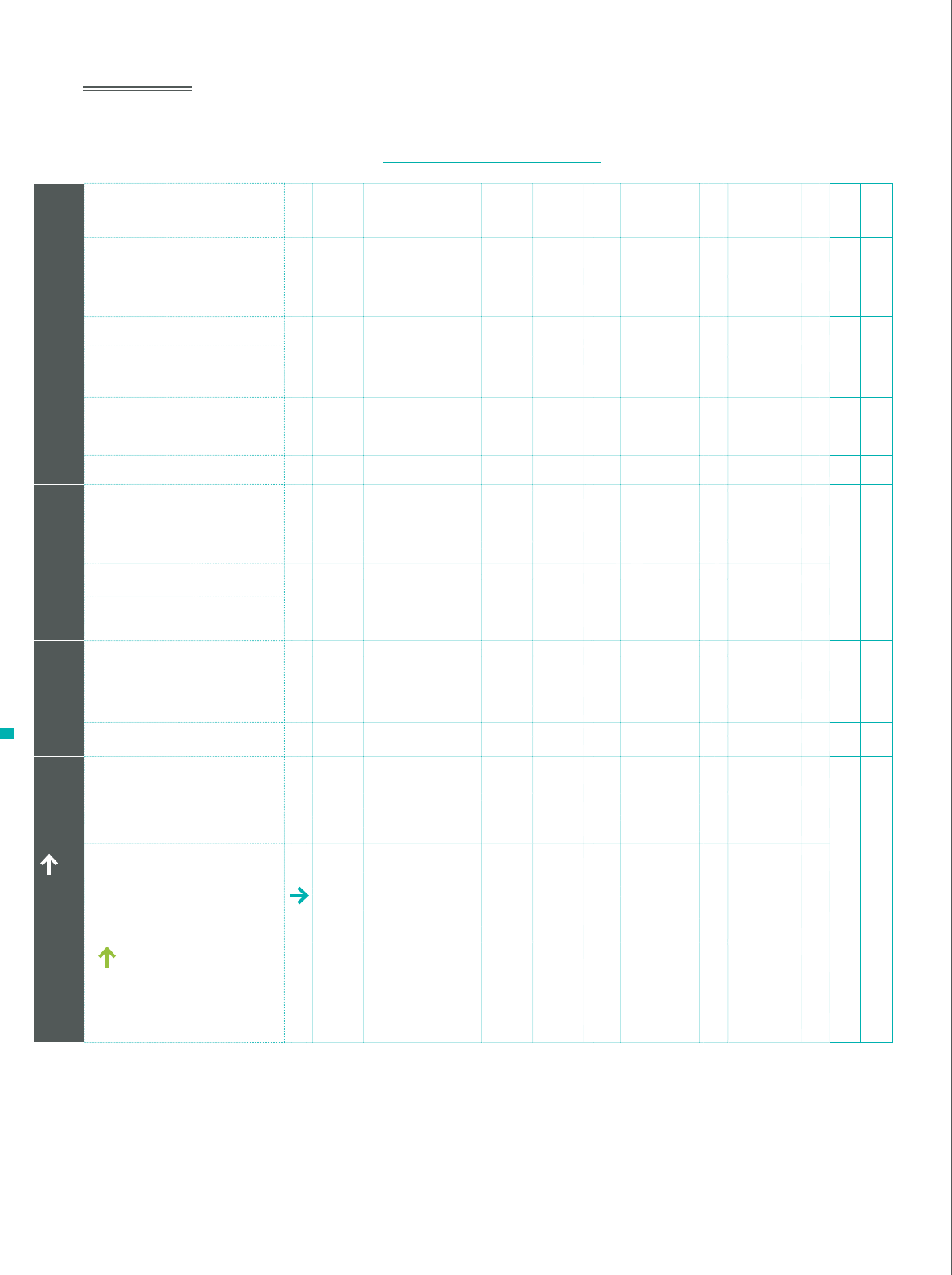

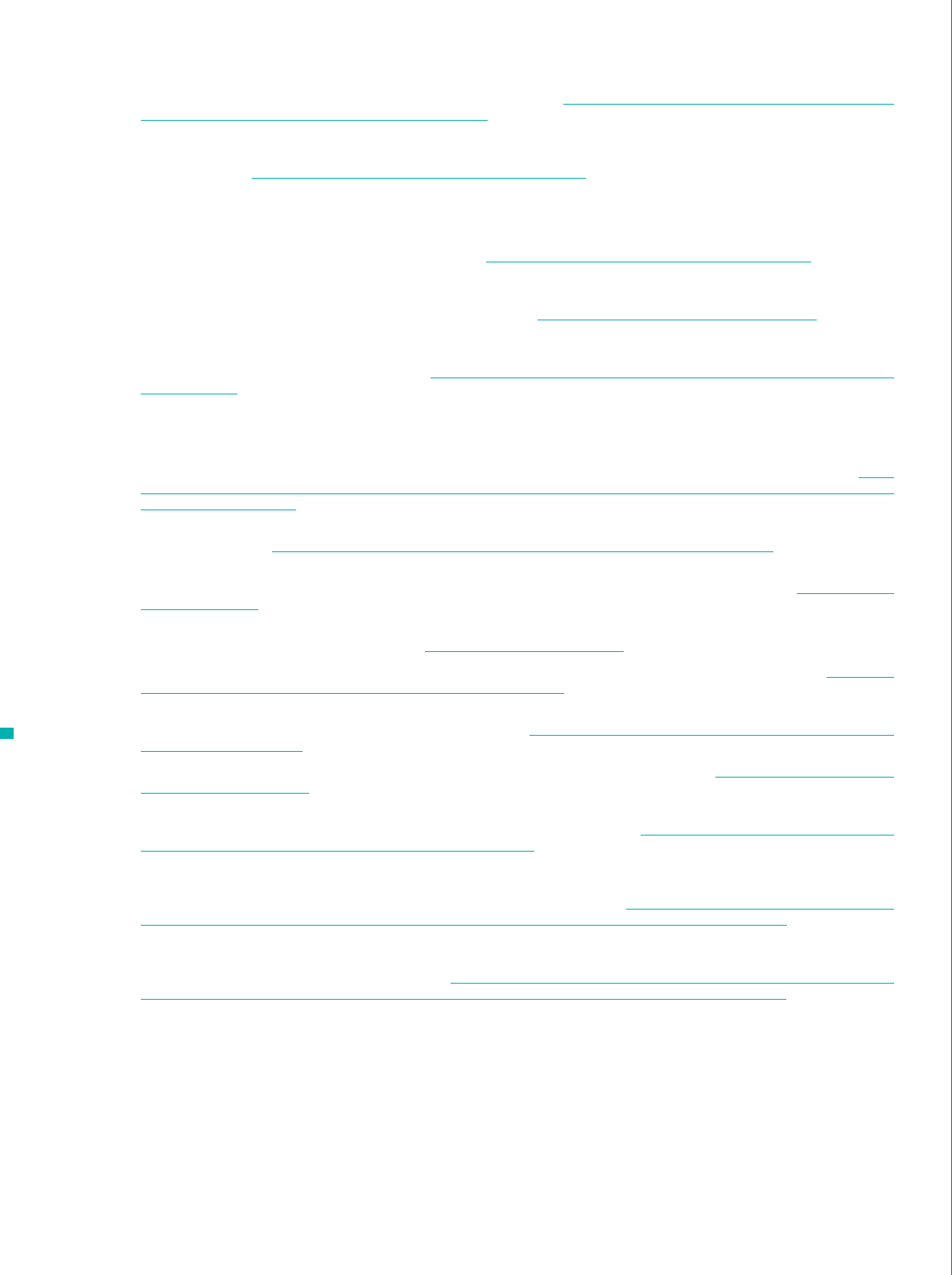

In this context, BiodivERsA is promoting science-

society and science-policy interfacing along the whole

research process, from inception onwards (Figure F1).

BiodivERsA recognizes that it is particularly challeng-

ing for researchers to ensure academic excellence

and societal impact at the same time. In particular,

it appears that biodiversity scientists (probably as

scientists from many other domains) are very strong in

developing and using scientic frameworks and meth-

odologies, but often lack such clear frameworks and

methodologies when engaging with stakeholders. A

selection of frameworks and methodologies designed

to ensure a balanced representation of relevant stake-

holders in research activities are available, but are

often not applied in biodiversity research.

In this context, BiodivERsA has developed this best

practice handbook on stakeholder engagement

in research projects, providing practical guidance

to researchers to better plan and engage with non-

academic stakeholders, including policy makers. The

development of this handbook has been led by the

Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), one

of the UK partners in BiodivERsA and an established

authority in the eld of stakeholder engagement prac-

tices. The objective of this BiodivERsA handbook is

not to provide a detailed and prescriptive methodol-

ogy; the handbook provides a framework and selec-

tion of tools so that each research consortium can

determine which types of stakeholder engagement are

the most protable for their research project.

Making the engagement process more inclusive and

enhancing the legitimacy and societal relevance of

scientic research is considered a crucial aspect of

BiodivERsA’s activities to reinforce the European

research community in the eld for reaching excel-

lence in terms of both academic outputs and societal

relevance. We hope this handbook will further pave the

way to knowledge provision and illuminate solutions

for better protecting, managing and using biodiversity

to tackle key environmental and societal challenges at

the European level.

Xavier Le Roux

FRB, BiodivERsA coordinator and CEO

Hilde Eggermont

BELSPO, BiodivERsA WP5 leader

Helen Baker

JNCC, leader of the Task for stakeholder

engagement in BiodivERsA

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

7

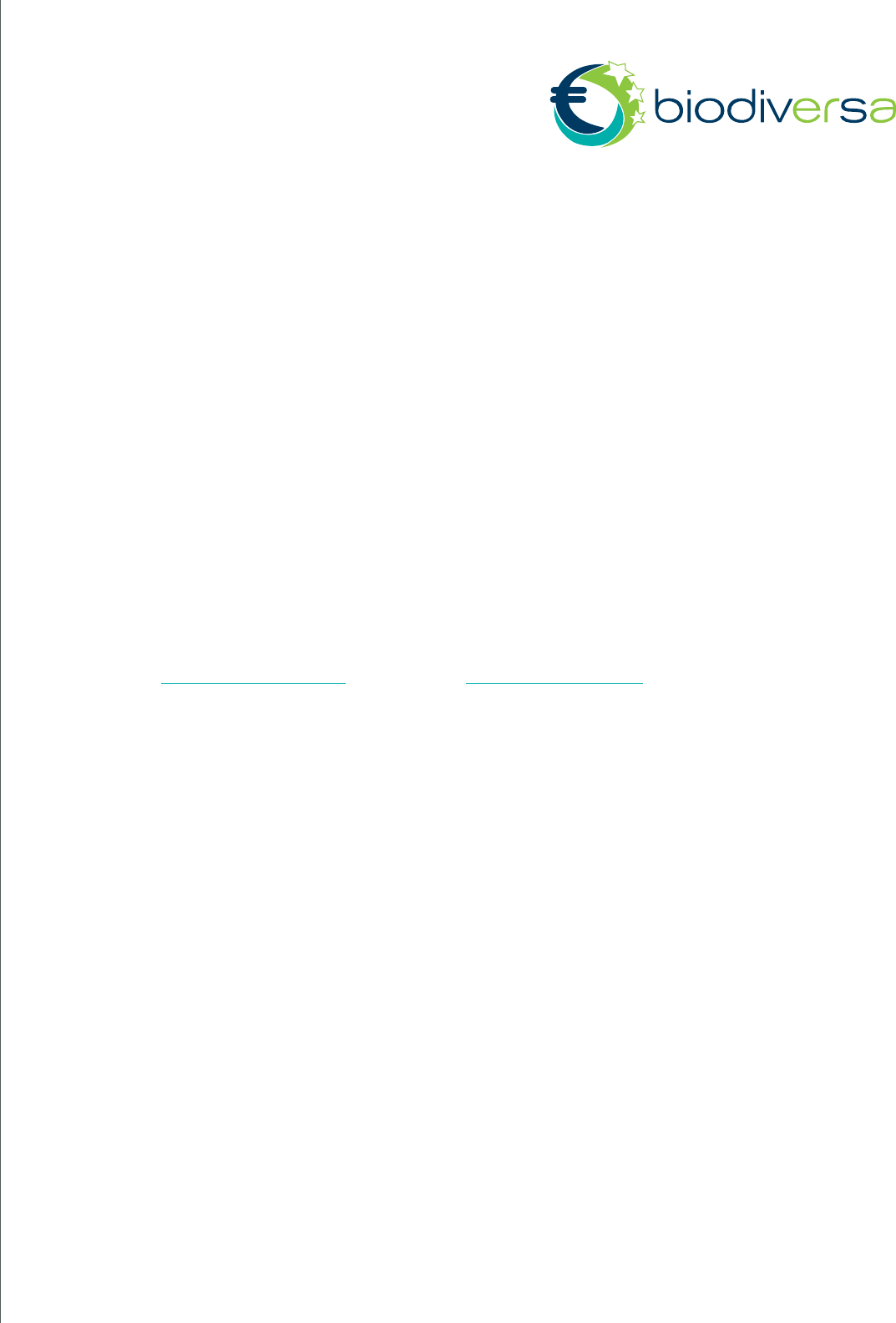

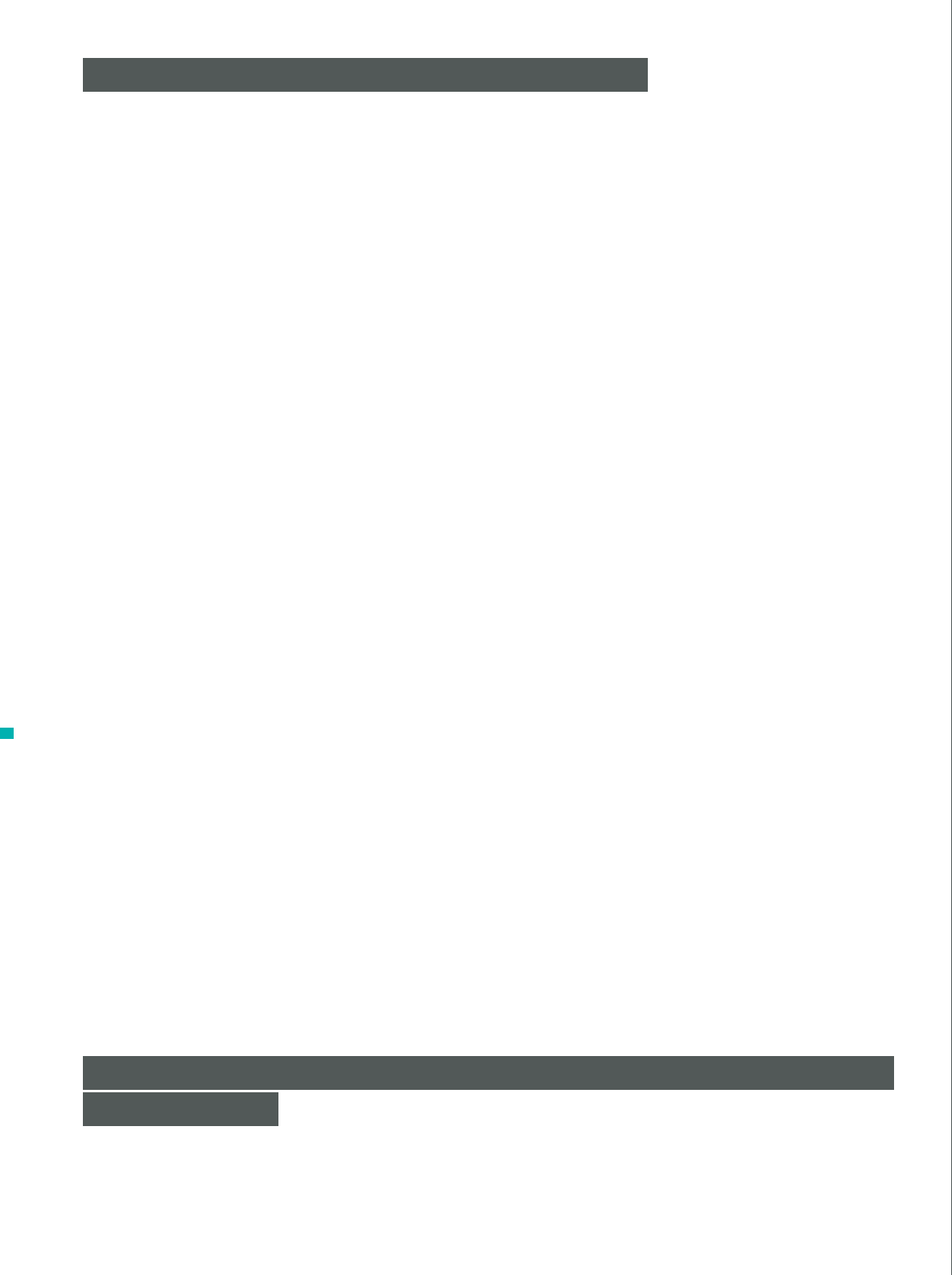

CO-PRODUCTION

O

-PRODUCTIO

N

C

O

CO-DESIGN

DISSEMINATION OF RESULTS AND PROMOTION

OF FUNDED PROJECT IMPACT

Results dissemination to stakeholders and policy

makers

-By the project leaders themselves

-By BiodivERsA through specific materials

(e.g. policy briefs)

Evaluation of funded project outcomes and impacts

Assessments of both academic excellence &

societal impact

Survey & monitoring of funded projects

Societal impacts assessment by the

stakeholder advisory board

Transdisciplinarity

stakeholder

engagement

Identification of topics for joint calls

& programmes alignment

Use of specific evaluation criteria (policy relevance; societal

impact; stakeholder engagement)

Establishment of a common roadmap

Priorities and topics depend on societal

challenges

Mapping

Involvement of funding agencies and ministries +

stakeholder & scientific advisory boards

Stakeholder involvement

Academic involvement

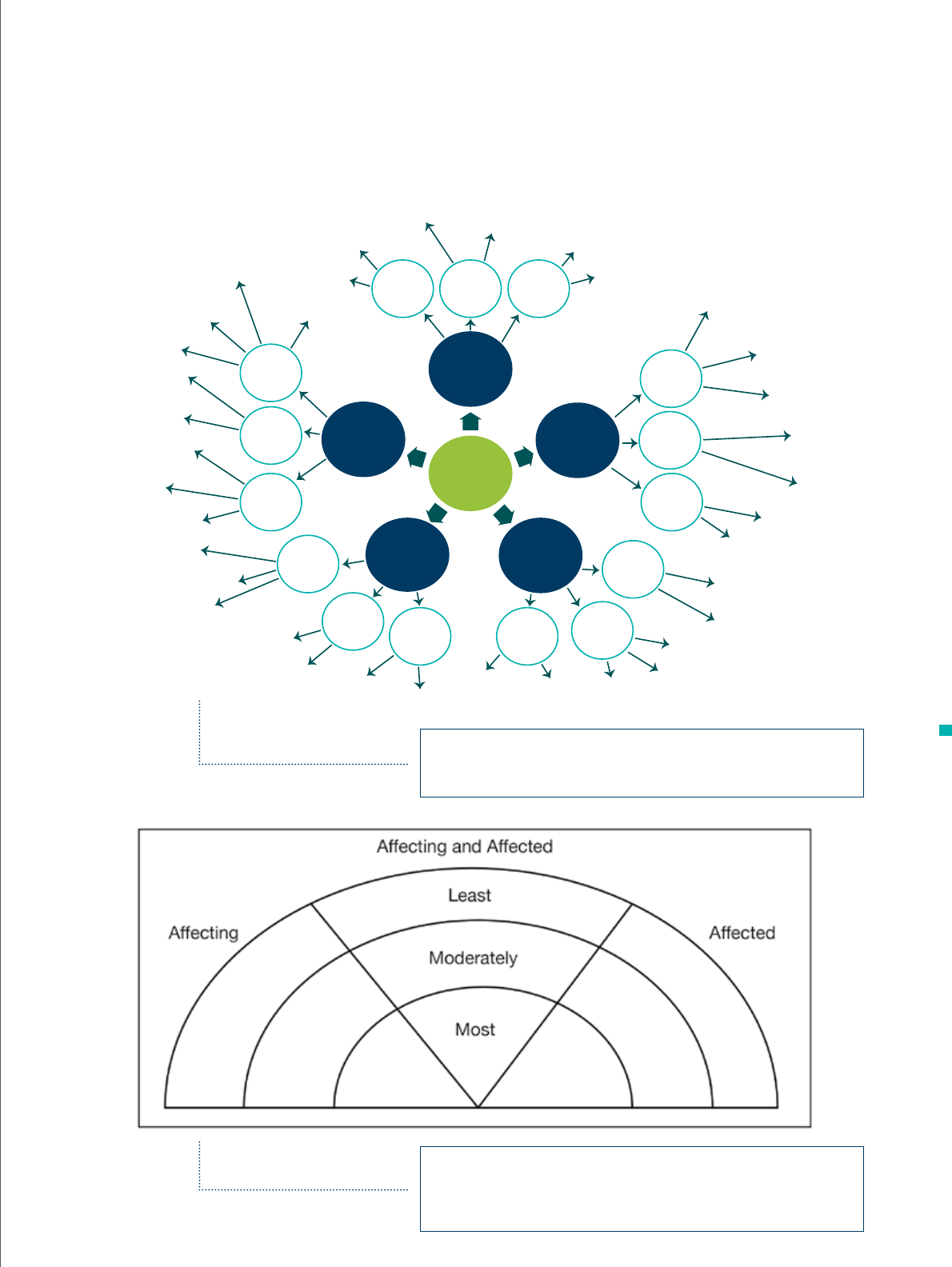

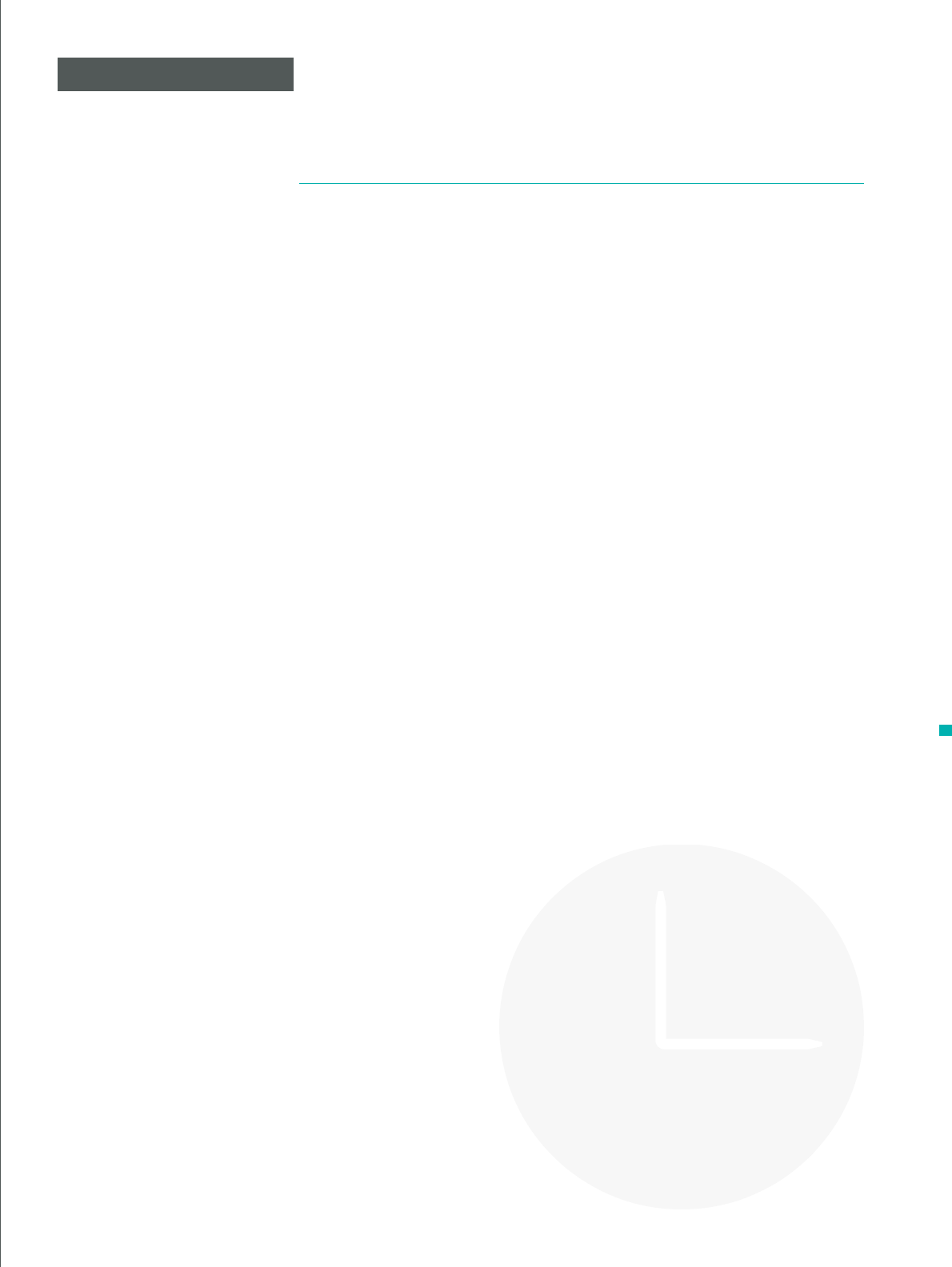

Figure F1. Approach and methodology used to engage

stakeholders and promote the science-policy and

science-society dialogue in BiodivERsA throughout

the research (development) process. While academic

excellence is a major criterion for evaluating research

to be supported in BiodivERsA, innovative approaches

are used (from co-design of programmes to promotion

of research results) to increase the societal impact of

the funded research.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

8

› Background

› How does the Handbook work?

› What do we mean by engagement?

› What is a stakeholder?

› Why is stakeholder engagement benecial?

› Challenges and limits to engagement

› Key points to consider for eective stakeholder engagement

› How BiodivERsA can help in stakeholder engagement

›› Case studies

Benets of stakeholder engagement

Barriers to successful engagement: Science to policy

Allow time for scoping and pilot studies

What will the outputs of the stakeholder engagement process be?

Introduction

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

9

Part 1

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

10

n BACKGROUND-

The BiodivERsA Stakeholder Engagement Handbook

has been created for researchers planning and carry-

ing out research projects on biodiversity and ecosys-

tem services, and may be a useful resource for the

wider environmental science community. It is designed

to assist research teams identify relevant stakeholders

to engage with in order to enhance the impact of their

work, and select appropriate methods of stakeholder

engagement. It may also be useful for those evaluating

applications to BiodivERsA research calls as context

for the specic approaches taken by research teams.

Biodiversity and ecosystems research can have wide

ranging applications and benets; it is a cross-cutting

subject, which has economic, social and political

impacts. Thus, to be eective and comprehensive

biodiversity research needs to take a trans-disciplin-

ary approach and to involve a wide range of dierent

researchers and scientists from dierent disciplines

1

,

from ecologists to social scientists and economists,

as well as other stakeholders, from engineers to policy

makers, land-owners, businesses, NGOs, the media,

and the general public. A trans-disciplinary approach

has its own complications; those involved may well

have dierent ways of approaching and undertaking

the research, as well as diering views on the desired

aims and outcomes of the research. The ndings

from research need to be communicated eectively

2

and acted upon, in order to bring about a change in

attitudes and behaviour which ultimately may deliver

better outcomes for biodiversity and society. However,

the complex nature of biodiversity issues means that

agreement on concepts and solutions from such a

diverse range of stakeholders is rarely straightforward,

and can be dicult to achieve.

BiodivERsA is a pan-European biodiversity research

funding mechanism that generates new knowledge

for the conservation and sustainable management

of biodiversity. It follows that the main users of this

research, and therefore critical stakeholder groups,

include:

✶ policy makers

✶ research funders

✶ non-governmental organisations

✶ natural resource managers (practitioners),

including businesses and industry.

However, policy and managerial decisions can also

aect the public and so it may be important to consider

a wider range of stakeholders in the research process.

Several previous studies have assessed stakeholder

engagement in biodiversity research

3-5

, including

approaches to social learning

6

, and some guidance

is available, for example the SPIRAL Handbook on

science-policy interfacing

2

, the UK programme ‘Living

With Environmental Change’ knowledge-exchange

guidelines

7

. These studies demonstrate that no single

approach to stakeholder engagement can be applied

to all projects and generally that the engagement

carried out is considered to be ‘too little, too late’.

Additionally, existing literature outlines the importance

of managing the expectations of both the researchers

and the stakeholders – not only regarding desirable

outcomes of a project that result from the engagement

activities, but also what stakeholders can realistically

expect to achieve and/or receive from engaging with a

project

8,9

. The existing literature provides a clear set of

generally agreed engagement rules, which this Hand-

book follows.

In determining the approach to take, previous stud-

ies demonstrate that it is important to consider, at a

minimum

10

:

✴ the aims and objectives of the engagement

✴ the expectations of the stakeholders regard-

ing the outcomes of the engagement

✴ the available resources (in particular time

and money).

The Handbook aims to address these requirements,

by providing a clear, simple guidance, which considers

‘why’, ‘who’, ‘when’ and ‘how’ to engage, as well as

guidance on planning engagement activities, manag-

ing conict and monitoring outcomes.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

11

n HOW DOES THE HANDBOOK WORK?-

The Handbook is designed to provide advice to

researchers on how to plan or manage the way that

they engage with stakeholders. Exactly which stake-

holders are engaged, how many there are, and the

most successful methods of engagement, will depend

on the type of research.

The Handbook covers topics such as: identifying the

benets of engagement; identifying appropriate stake-

holders; when and how to work with stakeholders to

inform the scope of research and share knowledge;

and choosing the best techniques for engagement.

It provides guidance on planning, carrying out, and

following-up on stakeholder engagement. The Hand-

book should not be viewed as prescriptive; it provides

suggestions to help users ensure that they:

✶ account for all factors necessary for

conducting eective engagement,

✶ consider what tools are available for engag-

ing stakeholders, and

✶ communicate decisions and outcomes

(within the project team, with funders, and

with stakeholders).

The Handbook demonstrates that there is a wide

range of stakeholder engagement methods and tools

available, each with their own advantages and limita-

tions

10

. Additionally, it describes how dierent stake-

holders are likely to make diering contributions and

require dierent levels of communication at each key

stage of a project

11

. Not all stakeholders will need to

be engaged all of the time, or in the same way so the

degree of engagement is likely to vary throughout the

project

12, 13

.

The Handbook comprises seven main sections:

✶ Dening the outcomes desired from the

engagement (why)

✶ Identifying the stakeholders to be involved

(who), including assessing, analysing, prior-

itising and understanding their motivations

✶ Identifying the best times to engage with

stakeholders (when)

✶ Choosing the best methods for engagement

(how), including information on the most

frequently used approaches

✶ Planning the detail of the engagement

✶ Dealing with conict in stakeholder engage-

ment

✶ Reviewing and assessing the process to

demonstrate achievements and to identify

lessons learned for informing future engage-

ment exercises.

Whilst each of these sections can be used sepa-

rately, they can also be used in sequence to ensure

a comprehensive and well-designed engagement

process is developed. Case studies and templates,

along with references for further reading, are provided.

n WHAT DO WE MEAN BY ENGAGEMENT?-

Engagement means the active involvement and

participation of others in some aspect of a research

project. Dierent levels of stakeholder engagement

can be identied, depending on the ultimate aims

of engagement activities and the project. Within the

Handbook, four levels of engagement have been

dened for simplicity. At the highest level, fully active

engagement is undertaken, where stakeholders are

eectively partners with the research team, driving the

research direction, and/or contributing resources and

perspective (dened as ‘collaboration’). At the lowest

level, communication with more-passive stakeholders

might be designed to simply share information about

the project or deliver the outcomes to those whom it

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

12

may aect (dened as ‘inform’). Informing is typically a

one-way ow of information, but is included as a form

of engagement because it still requires the research

team to communicate in a way that suits the stake-

holder. The middle levels of engagement are designed

to meet the needs of stakeholders who are ‘consulted’

(e.g. they are asked for opinions or information); and

those with whom ‘involvement’ occurs (e.g. they are

more fully engaged, and may also provide resources

or data).

Individual projects may, and often do, engage stake-

holders at more than one level. Most research proj-

ects require at least the rst level of engagement (i.e.

‘inform’), but dierent levels are likely to be appropri-

ate for dierent projects and situations. Many projects

will include a mix of all four levels of engagement.

n WHAT IS A STAKEHOLDER?-

The Handbook uses the following denition of stakeholder

14

:

❝ A stakeholder is any person or group

who inuences or is inuenced by the research ❞

This broad, inclusive denition covers anyone, or any

group, directly or indirectly aected by a project, as

well as those who may have interests in a project and/

or the ability to inuence its outcome, either positively

or negatively. A stakeholder does not have to be a

direct user of, or directly aected by, project outcomes

to be inuenced by them.

It should be noted that there is a distinction between

those undertaking or participating in research in a

project, either other academics or non-academics as

subjects of study, and those who are not. The scope

of this Handbook is focussed on engaging with those

individuals or groups who are not undertaking the

research as part of a research team or are not them-

selves the subject of research. In other words, it is not

a handbook of research methods in social science.

Stakeholders are often broadly grouped, for example

‘policy-makers’ might be identied as an important

stakeholder group for a project, but there is likely to

be much variation in the interests and motivations of

dierent stakeholders in a grouping. Such variation

might be aected by factors such as the geographical

scale at which they make decisions or operate, and

resource availability. For this reason, it is important to

recognise that not all stakeholders in one broad group

are likely to have the same interests and motivations,

and so the engagement levels may vary for dierent

individuals or organisations in a group.

n WHY IS STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT BENEFICIAL?-

There are a number of reasons for undertaking stake-

holder engagement within research. These include:

promoting links between science and society; gain-

ing access to additional information or resources, and

improving the relevance or utility of the research to

users and beneciaries (see Table 1.1 for a summary).

For example, by engaging with stakeholders, the

research outcomes can become tailored more eec-

tively to local contexts, increasing the likelihood that

outcomes are adopted and applied, and leading to

benecial impacts for all

15-17

.

Additionally, engagement can lead to learning and

empowerment. By engaging with researchers, stake-

holders can learn and assist in the generation of

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

13

new knowledge (e.g. social learning

6

; knowledge

exchange

7

), and may be empowered to become

involved in future research

15,18,19

.

Furthermore, by considering local knowledge in the

research process, it becomes possible to anticipate

and improve unexpected negative outcomes before

they occur

20-23

. Well managed engagement can also

facilitate learning and trust between participants

17,24

,

and help mediate conicts

25

.

Establishing the reason(s) for engagement is a criti-

cal rst step to take before any engagement is under-

taken. Existing literature suggests that the benets of

engagement can far outweigh the risks, including those

risks posed by lack of engagement

26

. If well planned,

and adequately resourced, successful engagement

can enrich research and deliver better knowledge, and

thus better outcomes for biodiversity and society.

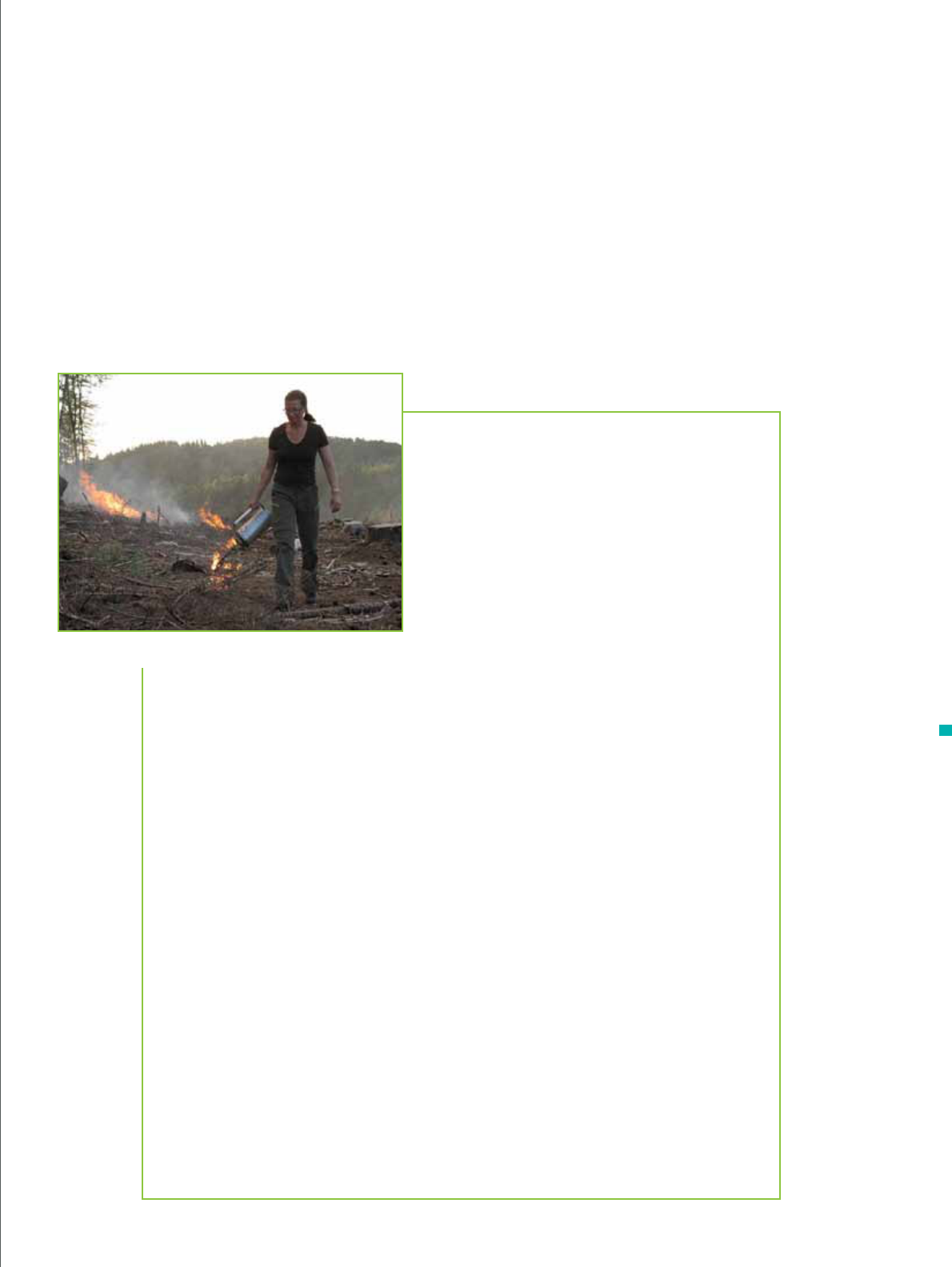

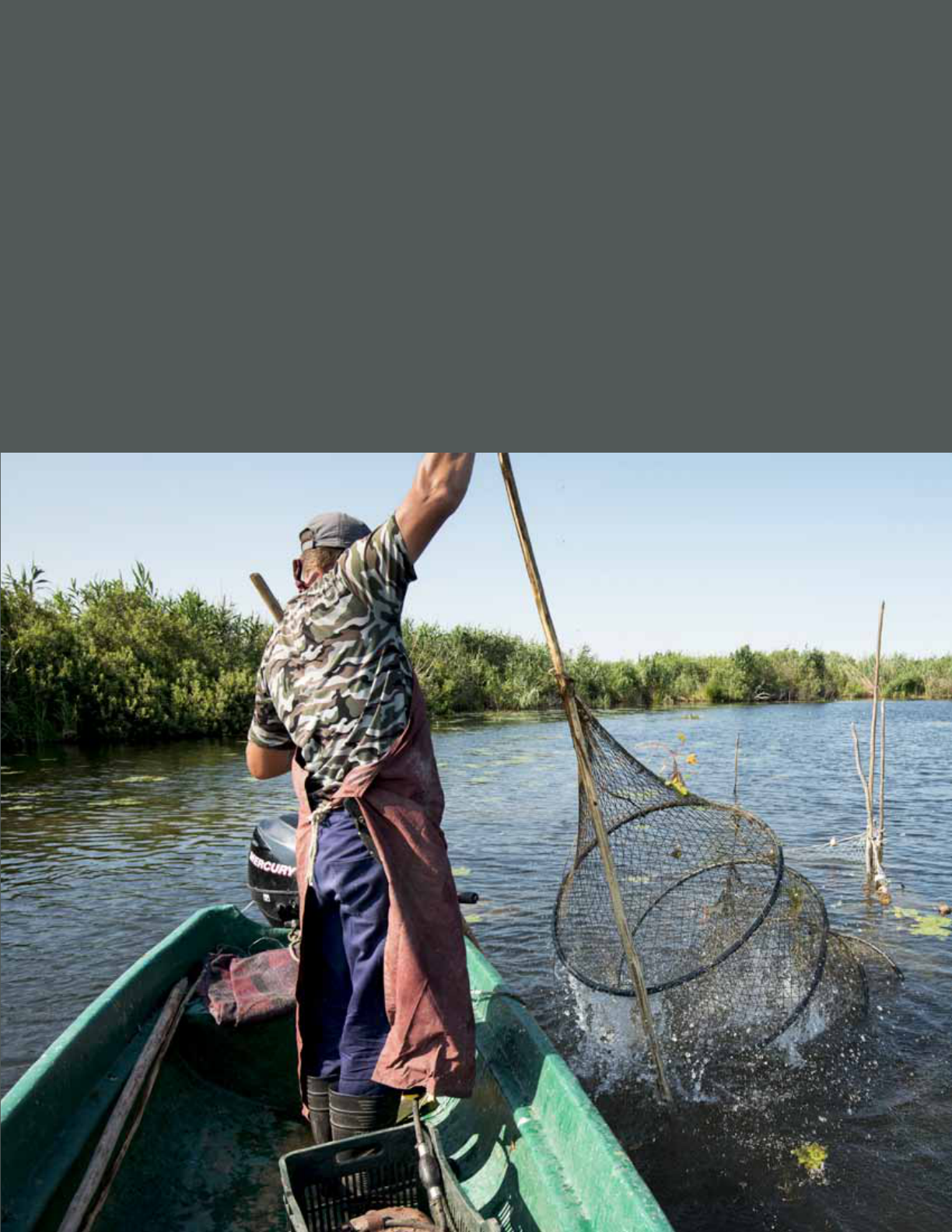

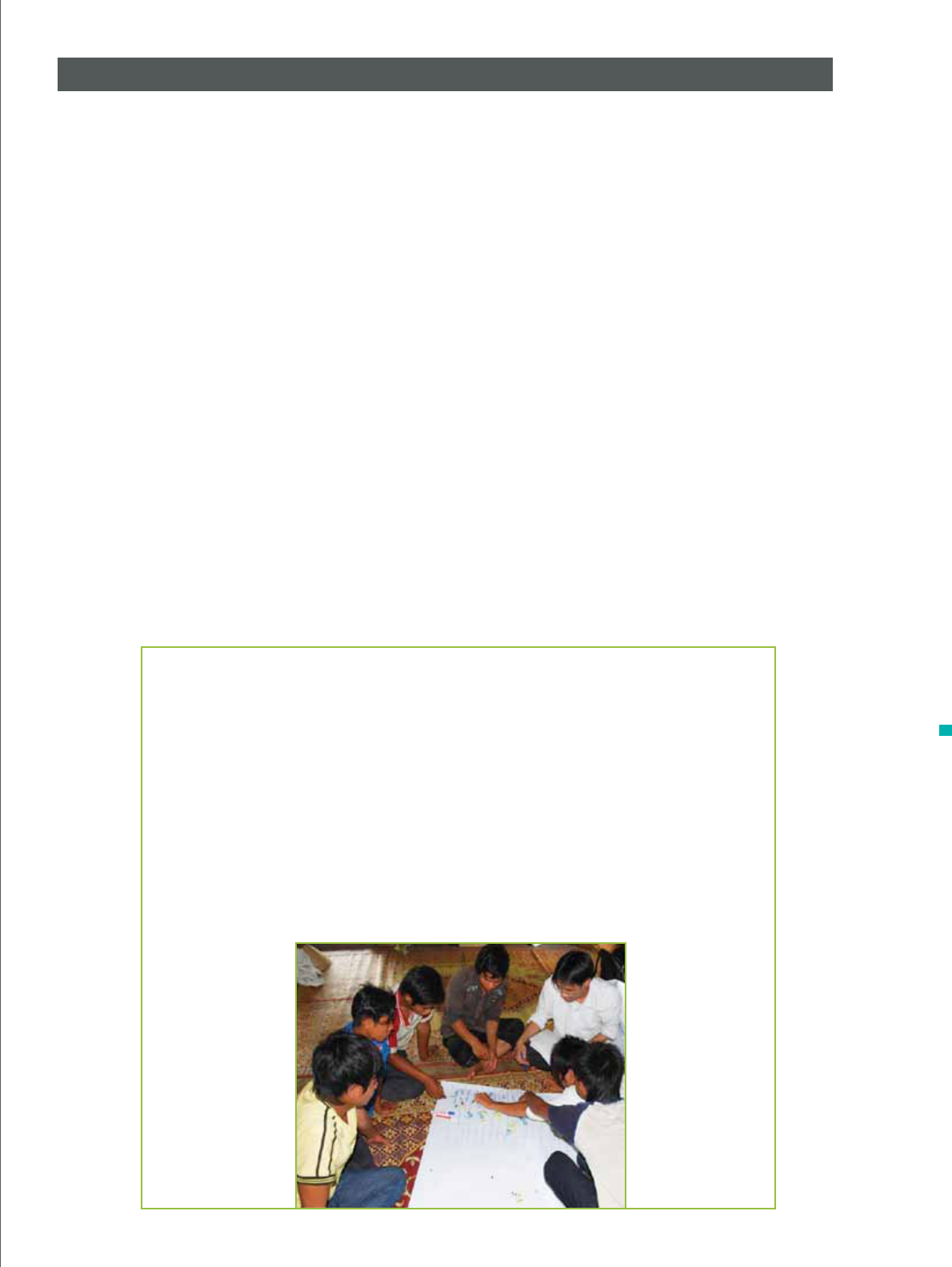

0 CASE STUDY

BENEFITS OF STAKE-

HOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Experiences from the BiodivERsA FIREMAN

project (see Appendix 1) illustrate well a range

of benets that stakeholder participation can

bring. This project investigated the role of re

management in maintaining biodiversity in

dierent European ecosystems and involved a

high level of stakeholder participation to inform re-vegetation models under climate

change scenarios. The following benets were described by a researcher from FIRE-

MAN:

✴ Researchers developed a deep understanding of practical re manage-

ment issues by participating in stakeholder workshops across Europe

where they discussed re management directly with land managers from

dierent countries. This informed the development of complex ecosystem

models.

✴ Discussions with stakeholders diused conict between stakeholder groups

with diering perspectives on re management, resulting in constructive

dialogue.

✴ Sharing experiences in re management across borders: International

meetings and a conference were held which brought together stakeholders

from dierent European countries to discuss re management research.

The opportunities for managers to discuss re management with others

in contrasting ecosystems and in dierent countries were perceived

to be extremely insightful and valuable for informing their own practice.

One stakeholder reported that insights gained from their participation in

international events had been integrated into practical forestry training

programmes in Spain.

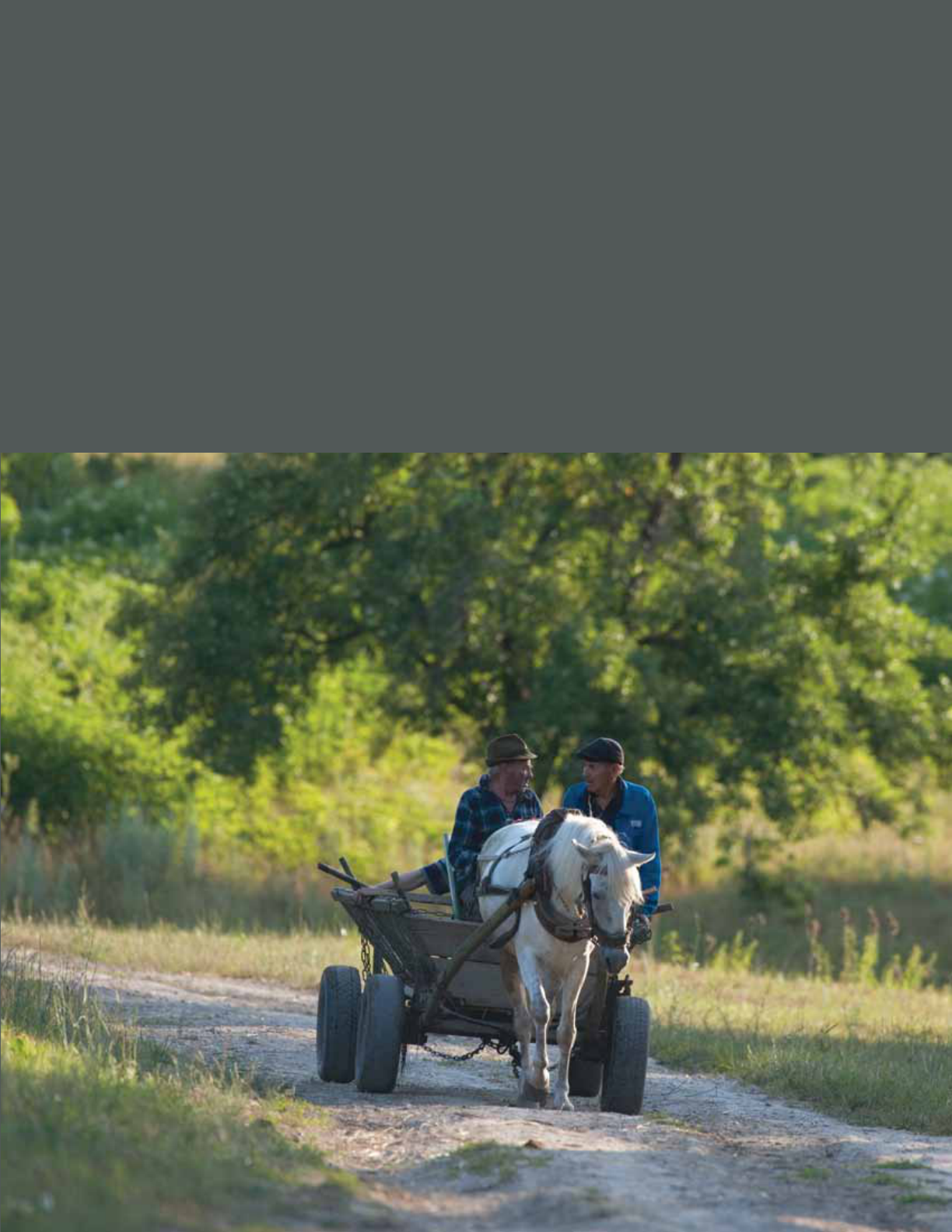

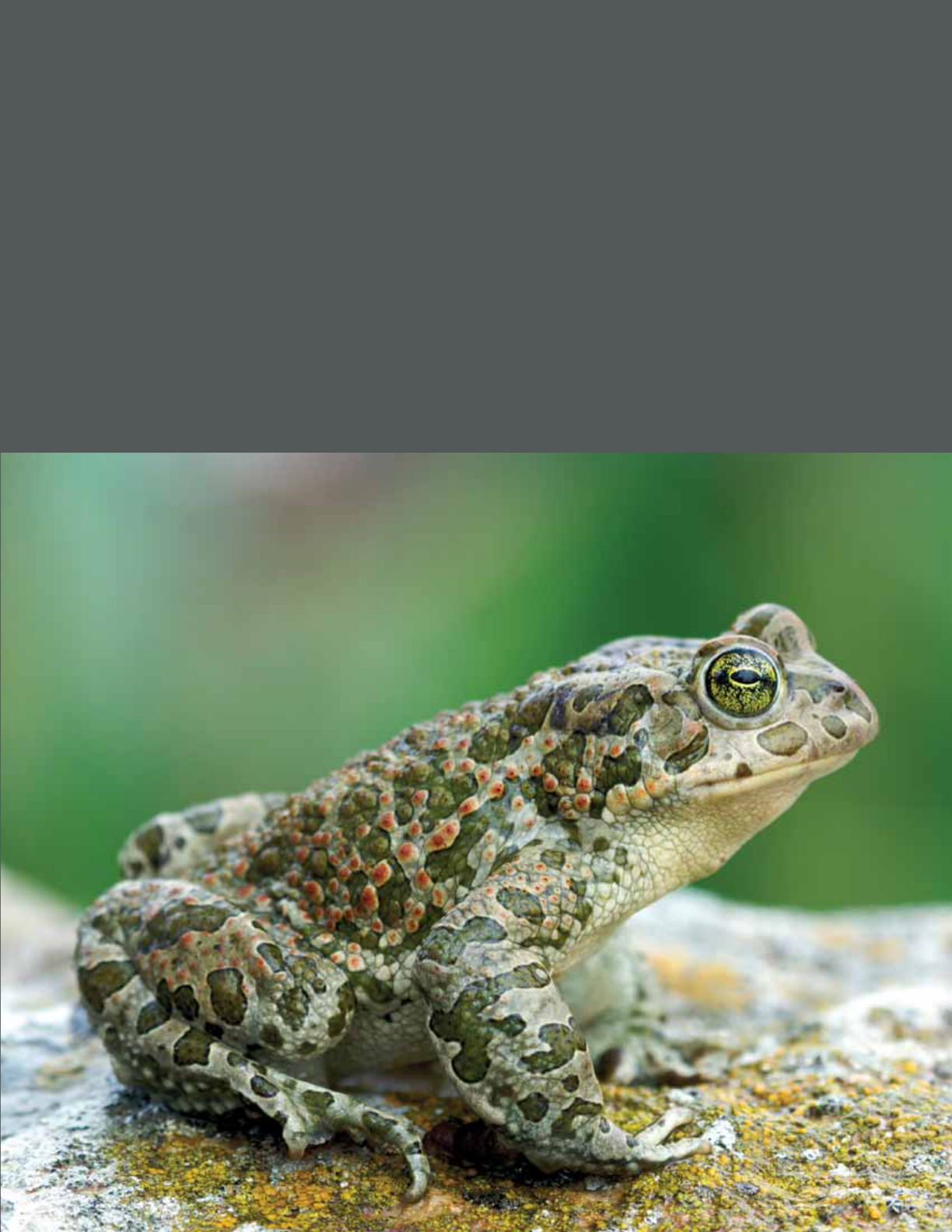

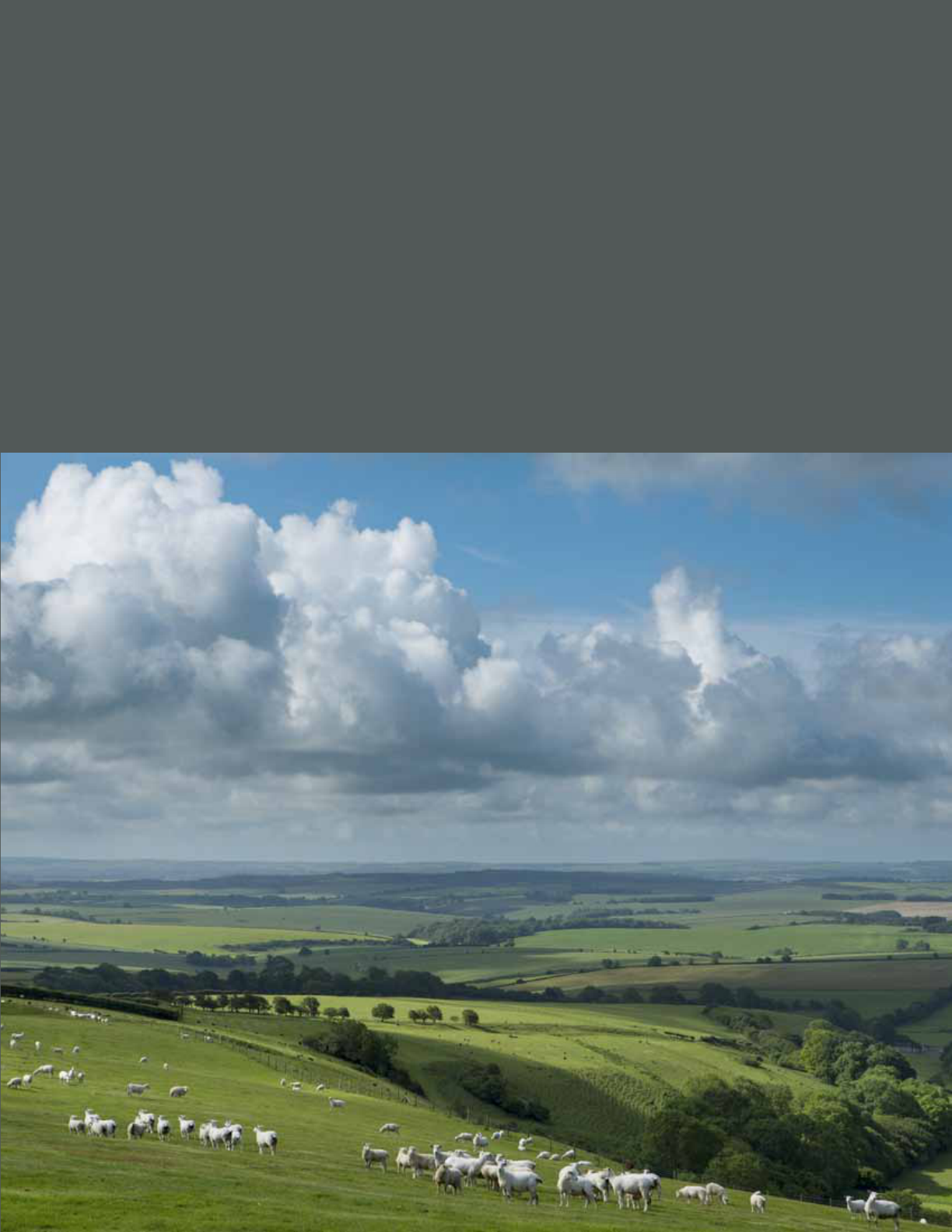

Fire management on a European heatland ecosystem, as part of the

FIREMAN project.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

14

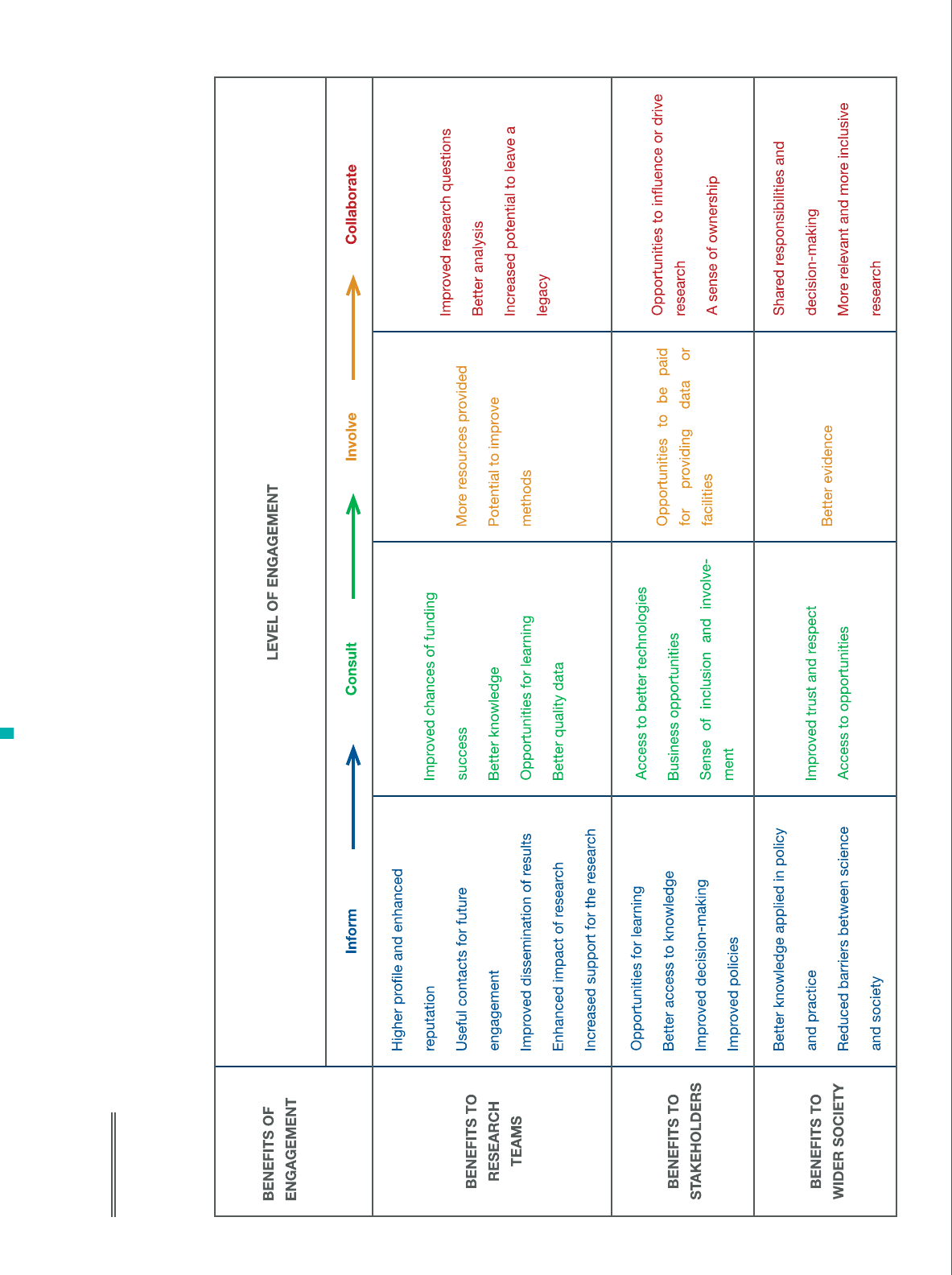

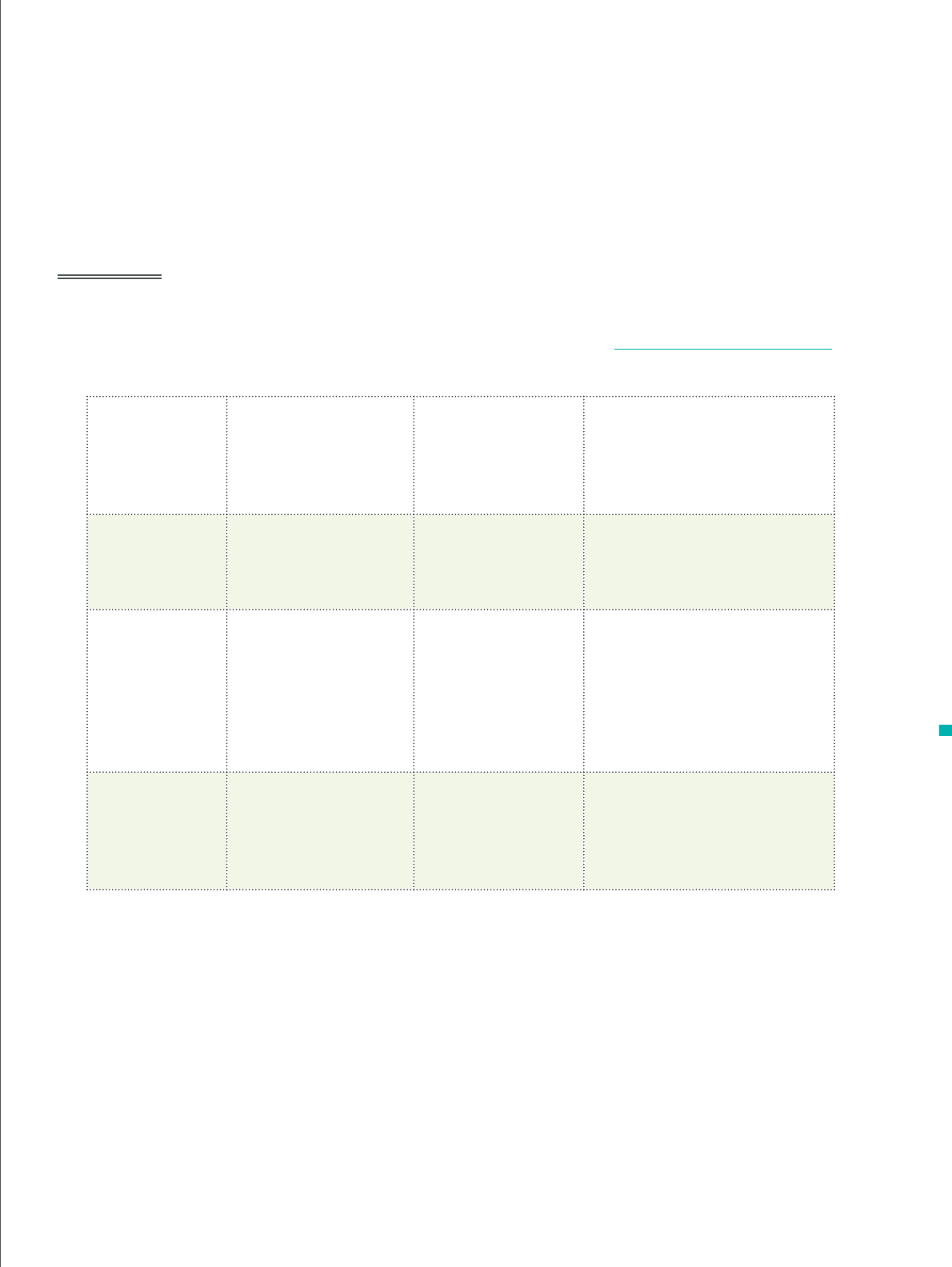

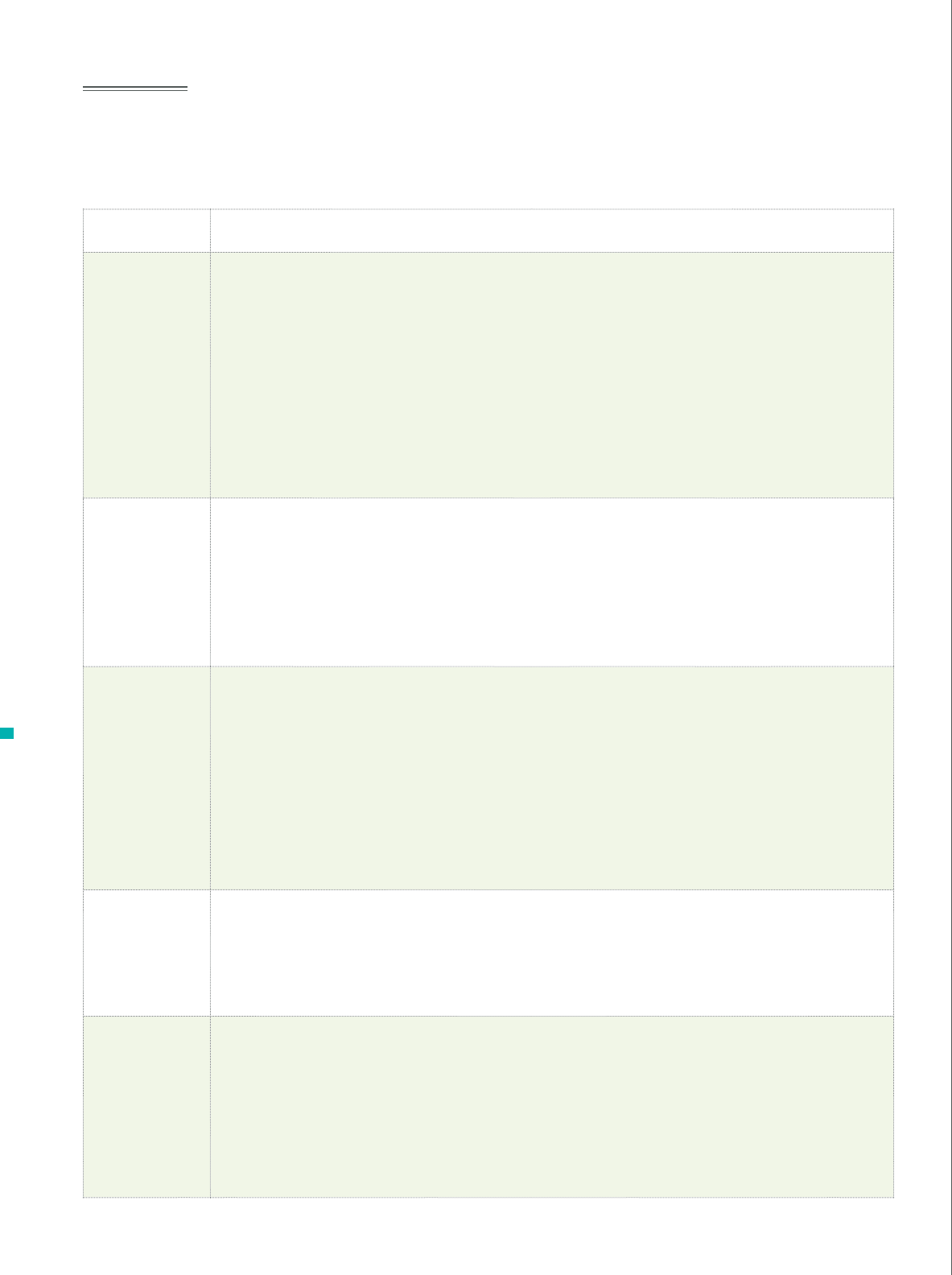

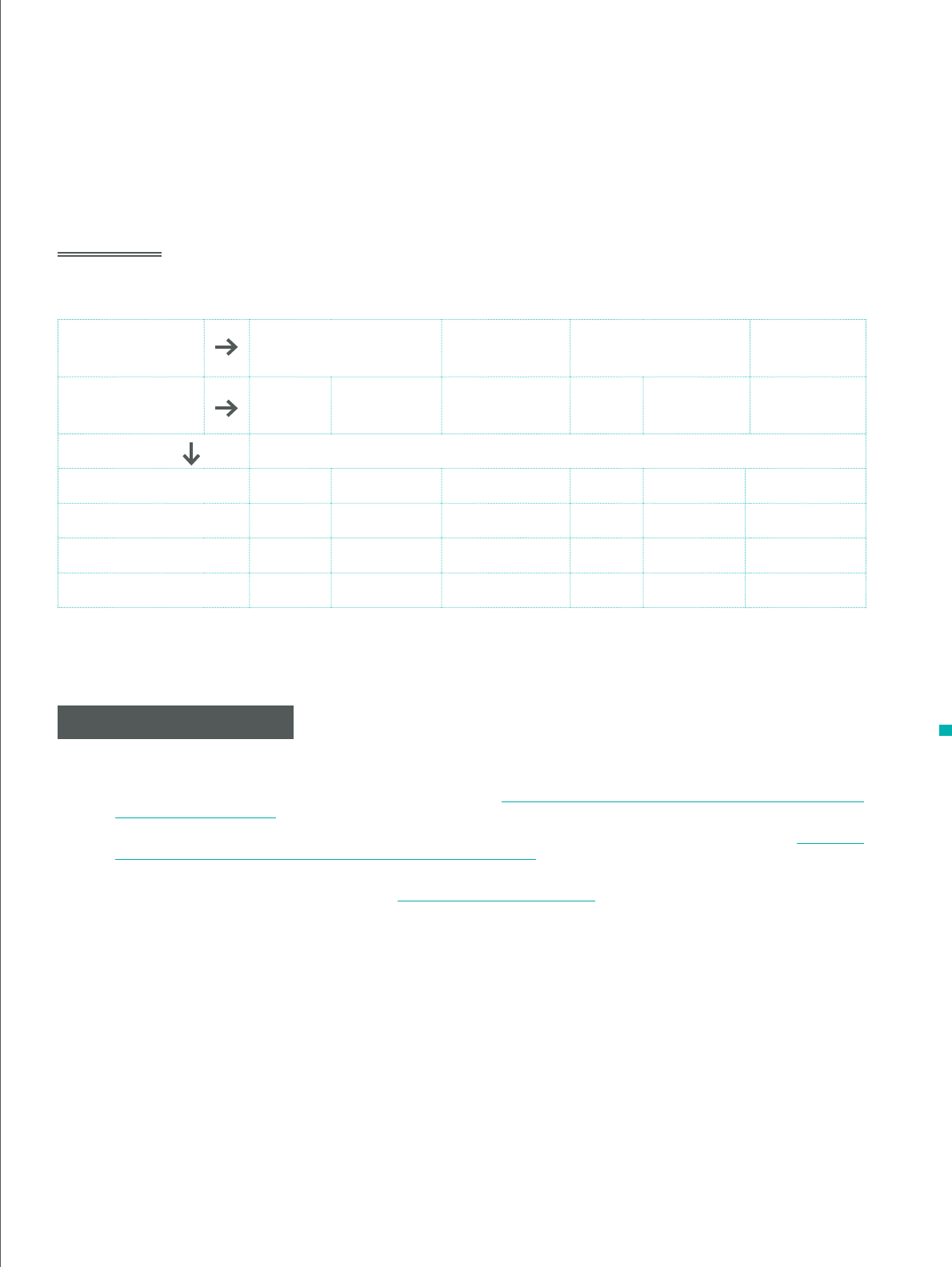

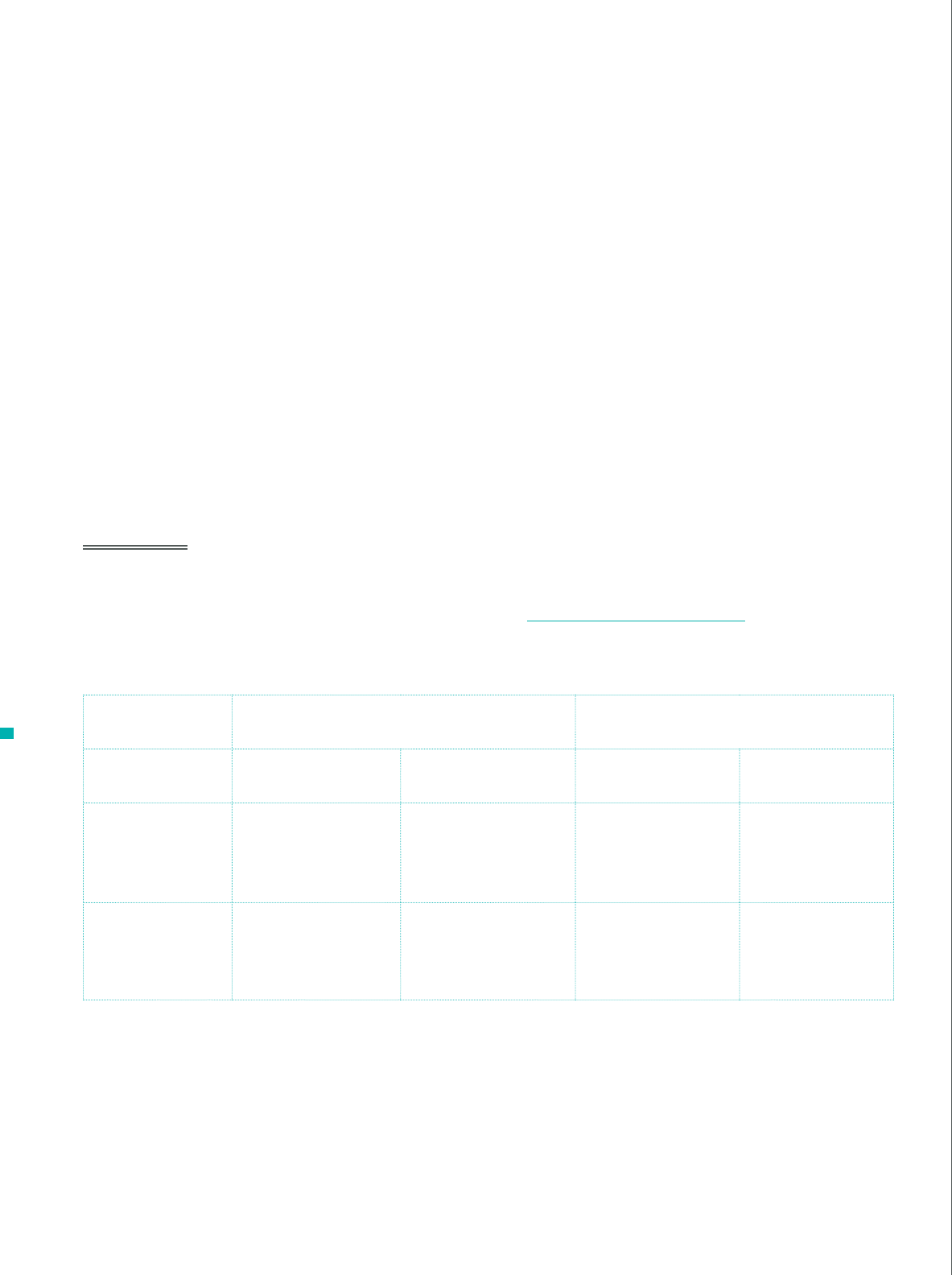

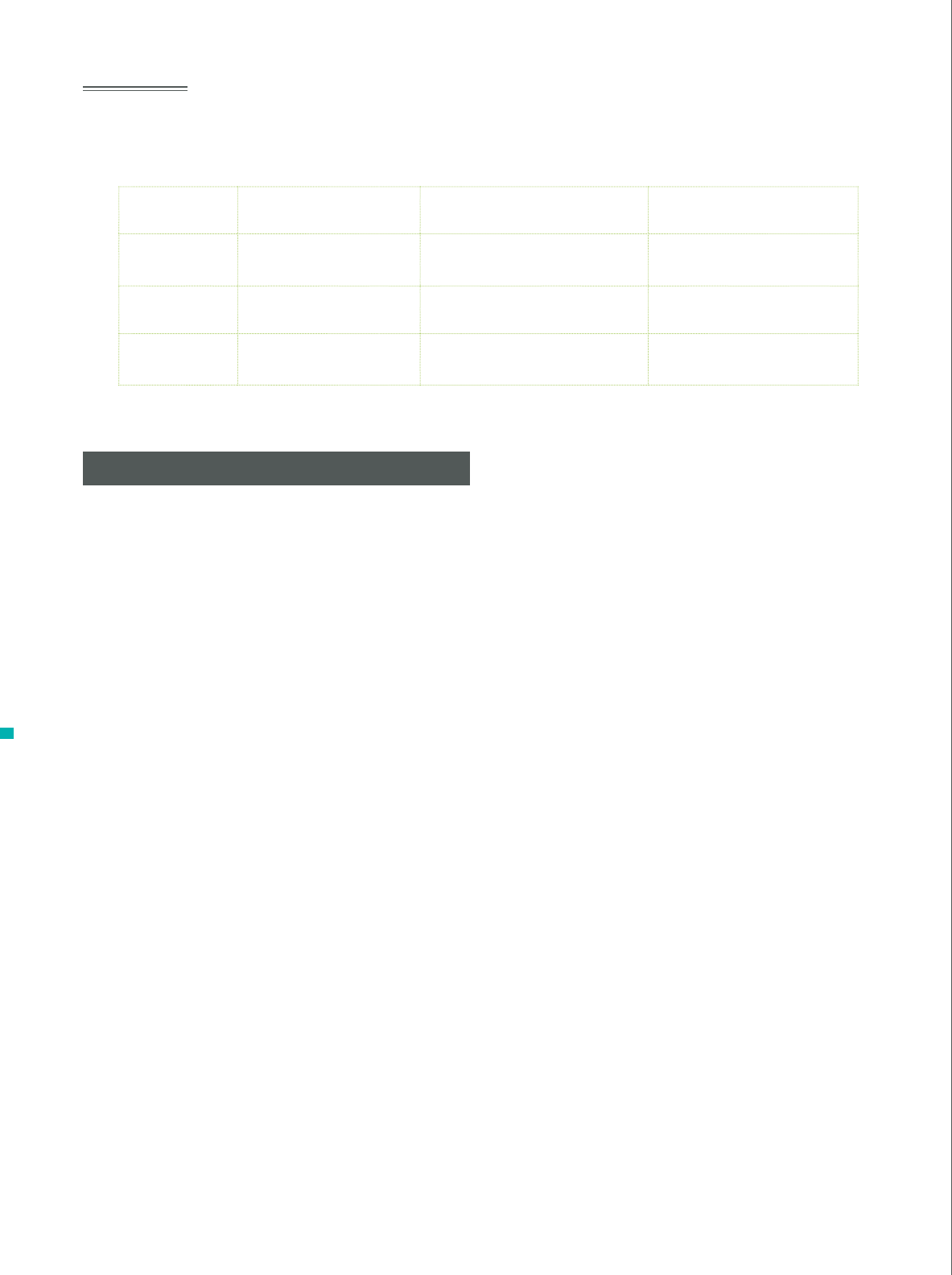

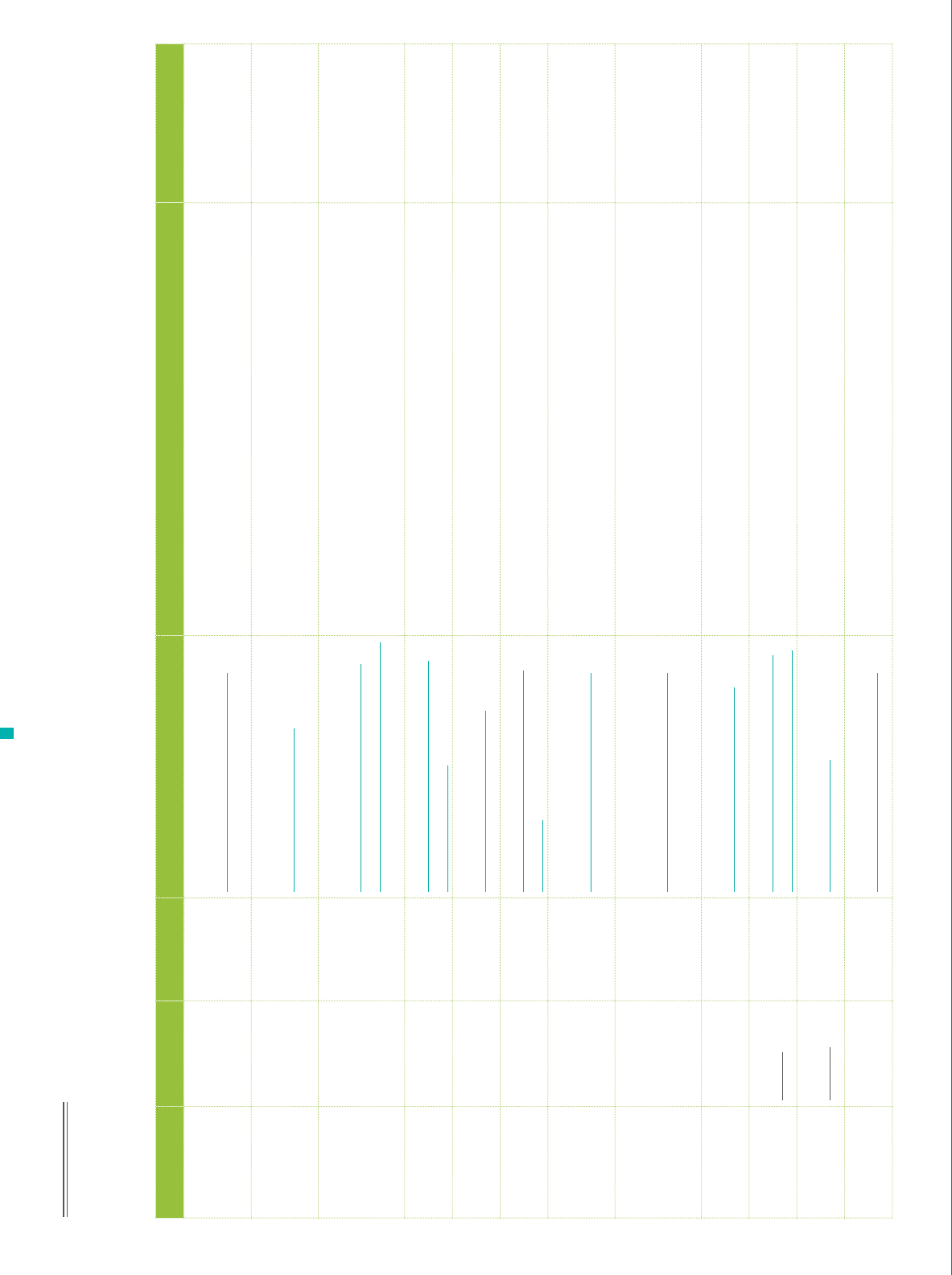

Table 1.1

Summary of potential benets from stakeholder engagement in research on biodiversity and ecosystem services based on the four levels of engagement

presented in the Handbook (see Part 3 for a full description of the levels of engagement). Note that benets identied for lower levels of engagement are also

appropriate for all higher levels (i.e. the benets identied for the ‘inform’ level of engagement also apply to ‘consult’, ‘involve’, and ‘collaborate’).

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

15

n CHALLENGES AND LIMITS TO ENGAGEMENT-

Although there is strong evidence that eective

engagement can bring many benets to the research

process, it is important to approach engagement criti-

cally, and be aware of some of the challenges and limi-

tations that may be faced. For example, engagement

increases the costs to both the research project and

the stakeholders in the short term, and might make the

undertaking of the project more complicated; whereas

the useful outcomes can be longer term or seem

intangible and remote. Some scientists may see the

involvement of stakeholders as a constraint instead of

an opportunity

27

, and some stakeholders may lack the

time to engage, or experience ‘stakeholder fatigue’,

that is they begin to feel overloaded with engage-

ment activities, which negatively aects willingness to

participate and lessens the quality of their input.

In addition, unbalanced engagement can lead to

perverse or poor decisions if it inadvertently reinforces

existing privileges, or where group dynamics discour-

age minority perspectives from being expressed

11

.

Ethical considerations include intellectual property

rights (IPR), which need to be discussed and agreed

to ensure stakeholders are clear about the implica-

tions of their involvement, especially if they are data

suppliers.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

16

n Stakeholder engagement – making it CREDIBLE, RELEVANT AND LEGITIMATE

For research to be considered valid and valuable, it has been recognised that it should be under-

taken with credibility, relevance and legitimacy (sometimes referred to as ‘CRELE’)

28,29,2,30

.

These three factors can be strengthened by appropriate engagement with stakeholders

31

.

However, the same principles can be applied to the stakeholder engagement undertaken

within that research – to give it more validity and impact it should incorporate the characteris-

tics of credibility, relevance and legitimacy.

CREDIBILITY is the perceived quality and validity of the stakeholder engagement process

and the people involved with the engagement

30

. To improve credibility, a stakeholder engage-

ment process should have clear objectives, use the most appropriate people and methods, but

avoid exclusion of those with opposing views, and be transparent; the view that others have

of the process is also important. Some continuity of those involved in stakeholder engage-

ment exercises is also considered important to ensure that knowledge and skills are built upon,

and to maintain relationships and build trust.

RELEVANCE refers to the usefulness of the engagement process and its outcomes – how closely

it relates to stakeholders and researchers needs, and how responsive the process is to chang-

ing needs

31

. Adopting understandable language for dierent stakeholder groups; ensuring the

timing of the engagement, and particularly the outcomes of the engagement, is appropriate; and

being adaptable to changing circumstances can all enhance relevance. Relevance can also be

improved through identication of key stakeholders in the planning stages of the process, and

ensuring eective engagement and communication with them throughout. Relevance is key to

motivating participation and ultimately having a real impact.

LEGITIMACY is the perceived fairness and balance of the stakeholder engagement process, and is

particularly important in cases where conict may occur. A clearly stated, appropriate and agreed stake-

holder engagement process, along with appropriate methods, can help manage conict and dissent,

and therefore enhance legitimacy

30

. In addition, stakeholders need to feel satised that their interests

have been taken into account appropriately. The inclusion of a balanced group of multiple stakehold-

ers can improve legitimacy, although care must be taken to ensure this legitimacy is not threatened if

some of the stakeholders are viewed to be inappropriate by others in the group

28

. Employing unbiased

facilitators to help run engagement activities can also help.

Getting the CRELE balance

Building these three factors into the stakeholder engagement process takes time, eort

and resources, and it may not always be possible to enhance all aspects of CRELE. For

example, making a link with policy makers may improve the relevance of the engage-

ment process and its desired outcomes for some stakeholders, but may be perceived by

others as aecting the legitimacy of the process

28

.

The most appropriate approach will be dependent on the individual project, and the desired

outcomes of the engagement. However, early engagement is likely to make the engage-

ment process more credible and relevant; and nding the right mix of participants and ensur-

ing no groups have been excluded will enhance legitimacy and credibility.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

17

There are examples of research projects in which

stakeholder engagement failed to deliver intended

outcomes, or led to unanticipated negative conse-

quences, but benets were still accrued.

In certain circumstances stakeholder engagement can

occur in a situation of conict, which must be handled

carefully and sensitively. Many scientists are unused

to working in situations where conicts between

individuals and goals are present, and may prefer to

avoid it. However, in some areas of biodiversity study,

conict is to be expected and should be planned for in

a positive, constructive way. Guidance on dealing with

conict is included in Part 7 of the Handbook.

The majority of barriers to engagement can be over-

come with eective design and good facilitation

17

.

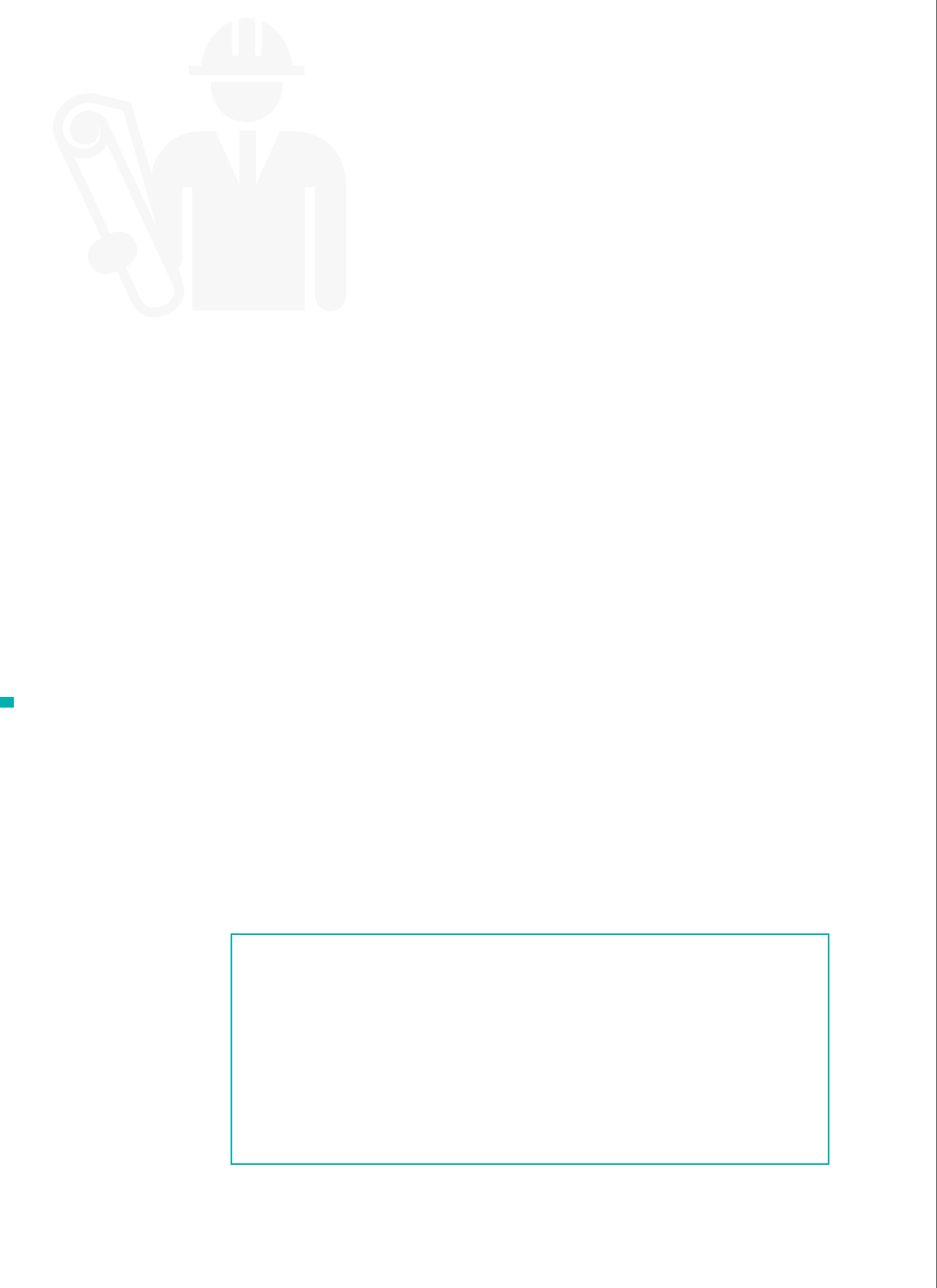

Table 1.2 provides an overview of key challenges and

limitations associated with stakeholder engagement,

with a brief list of ways these could be avoided or

overcome.

0 CASE STUDY

BARRIERS TO SUCCESSFUL ENGAGEMENT:

SCIENCE TO POLICY

A researcher in the BiodivERsA INVALUABLE project (Integrating valuations, markets

and policies for Biodiversity and Ecosystem services; see Appendix 1) highlighted a

common issue facing collaborations between researchers and policy makers. Policy

makers tend to work on far shorter time-scales than researchers and require quick

answers from researchers as policy develops. They look for quick solutions with

a high level of certainty to aid decision-making. However, results emerging from

research can be complex, uncertain and highly dependent on context, and often

require renement through further research projects on a longer time-scale. It is

therefore important that expectations of policy makers are taken into account and

are carefully managed from the beginning of a project, through explicit discussions of

what policy makers require and expect from the engagement and research process.

Researchers can then steer the research towards outcomes more relevant to policy

where possible, or negotiate compromises with the stakeholders to ensure benets

for all parties. For example, it may be possible for the research team to provide

literature-based assessments of present-day evidence to inform policy early in the

research cycle, before empirical data has been collected. Members of the policy

community often do not have access to this literature or the skills to critically evalu-

ate it. Therefore making initial literature reviews available in this way can be a way to

provide useful outputs early, although it may be a signicant investment for research-

ers.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

18

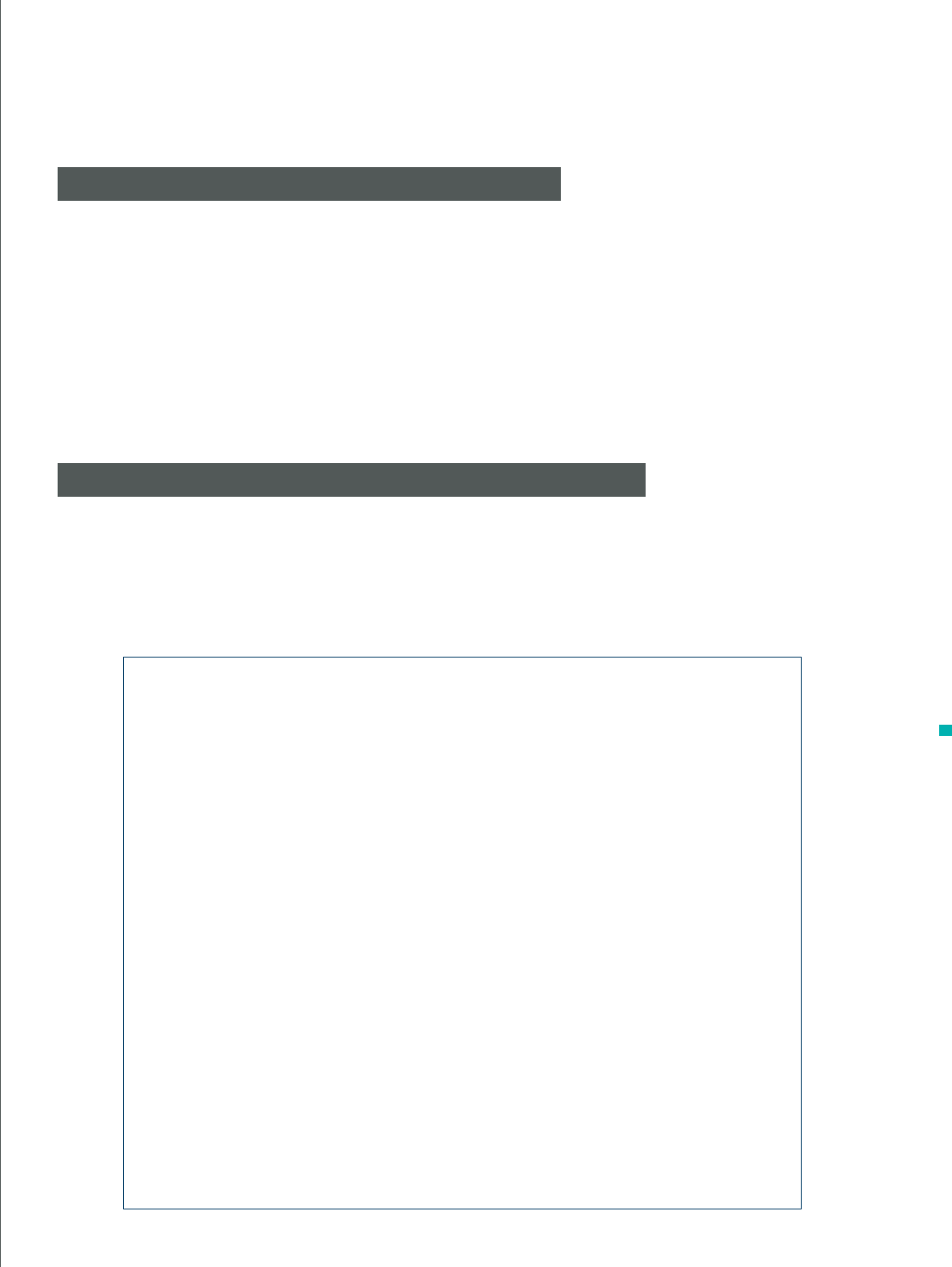

Table 1.2

Ways of overcoming some of the challenges and limitations to stakeholder engagement

CHALLENGES AND LIMITATIONS WAYS TO AVOID OR OVERCOME

(covered in more details in dierent parts of the Handbook)

STAKEHOLDER FATIGUE

32-34

: may occur

where many stakeholder engagement initia-

tives have taken place in the past, especially

in circumstances where they did not lead to

tangible outcomes for stakeholders. This may

result in limited engagement with research.

Where possible, avoid working with communities suering

from stakeholder fatigue. Where this is not possible, ensure

there will be tangible benets for stakeholders from engaging

with your research, and work with opinion leaders (who you

may identify using stakeholder analysis) to persuade others

that it is important to engage with the project.

BIASED REPRESENTATION OF STAKE-

HOLDERS OR KEY STAKEHOLDERS MISS-

ING

35-37

: this may lead to questions being

raised over the legitimacy of outcomes by

some stakeholders.

Conduct a systematic stakeholder analysis to identify and

prioritise those who should be engaged. Consider who might

have most inuence, but do not neglect those stakeholders

with signicant interest in your research, who may be power-

less or marginalised.

POWER IMBALANCES WITHIN STAKE-

HOLDER ENGAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

16,17

:

may lead to dominance by particular individu-

als and agendas, at the expense of others,

whose ideas are not heard, making them feel

marginalised, and potentially leading to or

exacerbating conict.

Carefully design stakeholder engagement activities with a

professional facilitator, considering: parallel activities for

groups in conict or with signicant dierences in power; and

facilitation methods that enable all participants to provide

and comment on ideas (possibly anonymously). If there is no

facilitation budget, undertake basic facilitation training for a

member of the research team.

SHORT-TERM ENGAGEMENT

7

: stakeholder

engagement often lasts only for the dura-

tion of funded projects, making it dicult to

achieve impacts and deliver benets expected

by stakeholders.

Identify local organisations that might have a long-term pres-

ence in your study area and plan the legacy of your research

with them from the outset, giving them sucient ownership

of the research to continue investing in outcomes long after

the research has ended. Find ways to fund ongoing engage-

ment, even if very limited, to maintain relationships, and lay

foundations for future research that could be funded.

UNREALISTICALLY HIGH EXPECTATIONS

7,16

: engagement can sometimes create unre-

alistically high expectations among stake-

holders who engage early in the research

process, and discover their suggestions are

not compatible with the scope of the research

or are not funded.

Manage expectations carefully from the outset. If engaging

with stakeholders during project development, make it clear

if funding is uncertain; make sure you are engaging with those

who have a strong interest in your research; identify which

ideas the project team may be able to work with immediately,

and update stakeholders as soon as possible with research

plans to show which of their ideas have been integrated and

why it was not possible to integrate all ideas.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

19

n KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER FOR EFFECTIVE-

WHY?

✴ Have clear aims for stakeholder engagement in your project, and set these aims from the outset.

✴ Identify the benets for stakeholders who engage with you.

✴ Determine and understand the motivations of stakeholders to be involved in the research process.

HOW?

✴ Every engagement process is dierent and needs to be properly funded and managed by those with under-

standing (and ideally training) in stakeholder engagement.

✴ Adapt the process to suit the needs of both the researchers and stakeholders alike.

✴ Plan your engagement and make sure you engage early in the research process (as early as possible); include

scoping studies where appropriate.

✴ Think about the timing of your research and its outputs, and consider whether it can inform any relevant external

or policy processes.

WHO?

✴ Systematically identify those who are likely to hold an interest in the research, including those who have power

to inuence the uptake of the research ndings.

✴ Be inclusive – do not exclude groups that are dicult to reach and ensure balanced participation of all relevant

demographic groups.

WAYS TO SUCCESSFUL ENGAGEMENT

✴ Engage in dialogue with stakeholders as equals and value their knowledge.

✴ Give stakeholders the opportunity to help plan their own engagement.

✴ Remember that not all stakeholders will have the same role or desire to be involved; not every stakeholder needs

to be involved all of the time.

✴ Where it is considered appropriate give stakeholders power to inuence the course of the research project;

embed them where suitable in the project team (e.g. via stakeholder advisory panels).

✴ Use ‘knowledge brokers’ (who are connected to, and trusted by, dierent stakeholder groups) and experts in

stakeholder engagement (including professional facilitators or science advocates) if project teams do not have

the expertise or experience.

✴ Address ethical issues, including intellectual property rights (IPR).

✴ Manage expectations by being clear on what can or cannot change.

✴ Be prepared to be exible and adaptable, tailoring research activities and communication of ndings (e.g. policy

processes or topical issues) as required

✴ Ensure communications can be easily understood by all stakeholders – do not use complex or technical language

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT-

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

20

unless this is asked for by the stakeholder.

✴ Tailor engagement to the practical and cultural needs of stakeholders, bringing the project to where they are, at

times of the day and year that are suitable for them; where deemed appropriate, consider selecting or splitting

groups according to gender or age.

✴ Do not forget to provide feedback to stakeholders as soon as possible/in a timely manner.

BEYOND THE PROJECT’S LIFE

✴ Think about the long-term impacts of the project, and the potential legacy.

✴ Assess the success of engagement throughout the research process, share good practice with peers, reect on

whether certain approaches need to be adapted, and assess the implications of any future practice.

0 CASE STUDY

ALLOW TIME FOR SCOPING AND

PILOT STUDIES

Good planning is fundamental to the success of stakeholder engagement activities

and maintaining the positive perceptions of the engagement experience for stake-

holders. Researchers of the BiodivERsA FORCE project (see Appendix 1) committed

considerable resources to scoping activities within focal Caribbean communities that

depend on the health of coral reefs for their livelihoods, before beginning stakeholder

engagement. The subsequent stakeholder activities were perceived to be successful

and this is partly attributable to the investment in the scoping work. The following

measures were taken:

Avoiding potential stakeholder fatigue: stakeholders were informed of proj-

ect aims and asked if similar research had been conducted to avoid replication.

Rening methodologies: a pilot project was run in one area to ensure

approaches and questions were well received and understood by stakeholders.

Raising awareness: community meetings were widely publicised using yers

and spreading the word verbally to ensure that the communities were well informed

of the aims of the research project.

Developing local contacts: researchers recruited local assistants who had a

good knowledge of the local communities and local issues to assist with stakeholder

engagement. Researchers who are viewed as ‘outsiders’ from another country may

be viewed with distrust; developing relationships with local contacts who are known

and trusted can be a good way of overcoming this.

Some of the details of local case studies (e.g. study sites) were jointly decided with

stakeholders to ensure the research was of interest and relevant to them.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

21

n HOW BIODIVERSA CAN HELP IN

n GENERAL INFORMATION AND ADVICE

Establishing best-practice approaches to engagement

may require consultation with others who have been

involved in similar processes. The BiodivERsA Secre-

tariat may be able to help research teams by provid-

ing information on how existing research projects have

approached stakeholder engagement, contact details

of stakeholder engagement experts from these proj-

ects, and information from other EU projects that may

be relevant (e.g. the SPIRAL project handbook and

briengs on engaging policy makers

2,38

). Key infor-

mation for applicants is posted on the BiodivERsA

website [www.biodiversa.org]. In addition, information

on professional media specialists might also be avail-

able.

n INFORMATION FROM OTHER RESEARCHERS AND PROJECTS

The BiodivERsA Database [http://www.biodiversa.

org/database] provides a comprehensive ‘map’ of

the current state of biodiversity research in Europe

in order to improve the identication of existing gaps

and future needs for new research programmes,

new facilities, as well as to detect potential barriers

for successful cooperation. It includes information

on research projects on biodiversity that are funded

through national programmes and details of research

institutes and other organisations (including stake-

holders) involved, and researchers leading the proj-

ects. The database can help research teams to iden-

tify potential resources and network opportunities to

further develop their research. In particular, it can help

applicants nding relevant stakeholders to approach

for a particular research project.

0 CASE STUDY

WHAT WILL THE OUTPUTS OF THE

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PROCESS BE?

Deciding on the required outputs of the stakeholder process is an important part of

the planning stage and allows researchers to manage the expectations of stakehold-

ers. It may be that outputs are decided before stakeholders are involved or there

may be exibility to decide on this in partnership with stakeholders based on their

needs. In the BiodivERsA Ecocycles project, stakeholder members of the national

consultative forum were asked in the rst meeting at the beginning of the project

what they wanted to gain from their participation. They expressed a wish to work

towards a specic output that would be useful in informing the management of

rodent outbreaks in the future and it was agreed that an adaptive management proto-

col would be co-developed during the project. This clear goal maintained the interest

of stakeholders throughout the process.

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT-

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

22

n REFERENCES-

1 NEßHOVER, C., TIMAEUS, J., WITTMER, H., KREIG, A., GEAMANA, N., van den HOVE, S., YOUNG, J. and WATT, A. 2013. Improv-

ing the Science-Policy Interface of Biodiversity Research Projects. GAIA, 22(2): 99–103. Available from: http://ipbes.net/images/

GAIA_2_2013_Nesshoever.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2014].

2 YOUNG, J.C., WATT, A.D. VAN DEN HOVE, S. and SPIRAL project team. 2013a. Eective Interfaces between Science, Policy and

Society: the SPIRAL Project Handbook. Available from: http://www.spiral-project.eu/sites/default/les/The-SPIRAL-handbook-

website.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2014].

3 EDIT. 2007. Stakeholder Engagement in Biodiversity and Environmental Projects – component 4.1.2BIS. Project Report, 37 pp. Avail-

able from: http://www.e-taxonomy.eu/les/StakeholderReport1.pdf [Accessed 6 June 2014].

4 POMEROY, R. and DOUVERE, F. 2008. The engagement of stakeholders in the marine spatial planning process. Marine Policy, 32,

816–22. Available from: http://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/149479.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2014].

5 JOLIBERT, C. 2011. Stakeholder Engagement in EU Research: Bringing Science to Bear on Biodiversity Governance. Conference

ESEE, 18 pp. Available from: http://www.esee2011.org/registration/fullpapers/esee2011_c3e403_1_1304967722_4161_2164.pdf

[Accessed 6 June 2014].

6 SHAW, A. and KRISTJANSON, P. 2013. Catalysing Learning for Development and Climate Change. An exploration of social learn-

ing and social dierentiation in CGIAR. CCAFS Working Paper no. 43. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture

and Food Security (CCAFS), Copenhagen. Available from: http://ccafs.cgiar.org/publications/catalysing-learning-development-and-

climate-change-exploration-social-learning-and#.U5G26_ldWYQ [Accessed 12 March 2014].

7 LIVING WITH ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE (LWEC). 2012. LWEC Knowledge Exchange Guidelines. Available from: http://www.lwec.

org.uk/ke-guidelines [Accessed 29 November 2013].

8 ACCOUNTABILITY. 2008. AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard 2011. 52 pp. Available from: http://www.accountability.org/

images/content/3/6/362/AA1000SES%202010%20PRINT.PDF [Accessed 5 December 2013].

9 GARDNER, J., DOWD, A.-M., MASON, C. and ASHWORTH, P. 2009. A Framework for Stakeholder Engagement on Climate Adapta-

tion. CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper, No. 3, 32 pp. Available from: http://csiro.au/~/Media/CSIROau/Flagships/

Climate%20Adaptation/CAF_WorkingPaper03_pdf%20Standard.pdf [Accessed 6 December 2013].

10 ANDERBERG, S. 2010. Stakeholder Involvement and Dialogue in LUsTT. Brieng Paper, 19 pp.

11 ERBOUT, N., DE COCK, L., DE BOEVER, M. and LAUWERS, L. 2010. Best Practice for Stakeholder Involvement at National Level for

Research Prioritisation. Institute for Agricultural and Fisheries Research, ILVO, Belgium, 35 pp.

12 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION (IFC). 2007. Stakeholder Engagement: A Good Practice Handbook for Companies Doing

Business in Emerging Markets. IFC, Washington. 201 pp. Available from: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content

/ifc_external_corporate_site/ifc+sustainability/publications/publications_handbook_stakeholderengagement__

wci__1319577185063 [Accessed 6 June 2014].

13 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH. 2008. Stakeholder Engagement. 7 pp. Available from: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/54409298/

Stakeholder-Engagement-Guidelines-University-of-Edinburgh [Accessed 30 April 2012].

14 CARNEY, S., WHITMARSH, L., NICHOLSON-COLE, S. and SHACKLEY, S. 2009. A Dynamic Typology of Stakeholder Engagement

within Climate Change Research, Tyndall Working Paper, 128. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, Norwich, 47 pp. Available

from: http://www.tyndall.ac.uk/content/dynamic-typology-stakeholder-engagement-within-climate-change-research [Accessed 5

December 2013].

15 MARTIN, A. and SHERINGTON, J, 1997. Participatory research methods: implementation, eectiveness and institutional context.

Agricultural Systems, 55, 195–216. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308521X97000073 [Accessed

11 April 2014].

16 REED, M.S. 2008. Stakeholder Participation for Environmental Management: A Literature Review. SRI Papers, No. 8, Sustainability

Research Institute, University of Leeds, 25 pp. Available from: http://sustainable-learning.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Stake-

holder-participation-for-environmental-management-a-literature-review.pdf [Accessed 9 June 2014].

17 DE VENTE, J., REED, M.S., STRINGER, L.C., VALENTE, L.C., VALENTE, S., NEWIG, J. (in press). How does the context and design

of participatory decision-making processes aect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands.

Journal of Environmental Management.

18 MACNAUGHTEN, P. and JACOBS, M. 1997. Public identication with sustainable development – investigating cultural barriers to

participation. Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions, 7, 5–24.

19 WALLERSTEIN, N. 1999. Power between the evaluator and the community: research relationships within New Mexico’s healthier

communities. Social Science and Medicine, 49, 39–53. Available from: http://www.researchgate.net/prole/Nina_Wallerstein/publi-

cation/12884336_Power_between_evaluator_and_community_research_relationships_within_New_Mexico’s_healthier_communi-

ties/le/9c960533b581515f36.pdf [Accessed 9 June 2014].

20 FISCHER, F. 2000. Citizens, Experts and the Environment. The Politics of Local Knowledge. Duke University Press, London. Avail-

able from: http://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Citizens_Experts_and_the_Environment.html?id=rUEFMenCPH0C&redir_esc=y

[Accessed 9 June 2014].

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

23

-

21 KOONTZ, T.M. and THOMAS, C.W. 2006. What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collab-

orative management? Public Administration Review, 66, 111–121. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-

6210.2006.00671.x/abstract [Access 11 April 2014].

22 NEWIG, J. 2007. Does public participation in environmental decisions lead to improved environmental quality? Towards an analytical

framework. Communication, Cooperation, Participation. Research and Practice for a Sustainable Future, 1, 51–71. Available from:

http://195.37.26.249/ijsc/docs/artikel/01/03_Forschung_Newig_nal.pdf [Access 11 April 2014].

23 NEWIG, J. and FRITSCH, O. 2009. Environmental governance: participatory, multi-level – and eective? Environmental Policy and

Governance, 19, 197–214. Available from: http://econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/44744/1/604559410.pdf [Access 11 April 2014].

24 STRINGER, L.C., PRELL, C., REED, M.S., HUBACEK, K., FRASER, E.D.G. and DOUGILL, A.J. 2006. Unpacking ‘participation’ in

the adaptive management of socio-ecological systems: a critical review. Ecology and Society, 11, 39. Available from: http://www.

ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art39/ [Accessed 9 June 2014].

25 REED, M. and SIDOLI, J. 2014. Alternative approaches to managing conservation conicts: from top-down to bottom-up. In: J.

Young and S. Redpath (Eds). Conicts in Conservation: Strategies for Coping with a Changing World, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

26 AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT (DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND CITIZENSHIP). 2008. Stakeholder Engagement: Practitio-

ner Handbook. National Communications Branch of the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Belconnen, Australia, 37 pp.

Available from: http://www.immi.gov.au/about/stakeholder-engagement/_pdf/stakeholder-engagement-practitioner-handbook.pdf

[Accessed 5 December 2013].

27 MORGAN, V.M., MOORE, E.A., DURHAM, E.L. and BAKER, H. 2012. BiodivERsA task 2.1. Analysis of Stakeholder Engagement

Approaches: Towards Best Practice Guidelines. Unpublished BiodivERsA report. Available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/pdf/

WP2%20milestone%207%20report%20with%20coversheet.pdf [Access 11 April 2014].

28 CASH, D., CLARK, W., ALCOCK, F., DICKSON, N., ECKLEY, N. and JAGER, J. 2002. Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries:

Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making. Available from: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=372280

[Accessed 9 June 2014].

29 CASH, D.W., CLARK, W.C., ALCOCK, F., DICKSON, N.M., ECKLEY, N., GUSTON D.H., JAGER, J. and MITCHELL, R. 2003. Knowl-

edge systems for sustainable development. PNAS, 100 (14): 8086-8091. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/content/100/14/8086.

full.pdf [Accessed 9 June 2014].

30 YOUNG, J.C., WATT, A.D. van den HOVE, S. and the SPIRAL project team. 2013b. The SPIRAL synthesis report: A resource book on

science-policy interfaces. Available from: http://www.spiral-project.eu/content/documents [Accessed 11 April 2014].

31 UNEP and IOC-UNESCO. 2009. An Assessment of Assessments, Findings of the Group of Experts. Start-up Phase of a Regular

Process for Global Reporting and Assessment of the State of the Marine Environment Including Socio-economic Aspects. Available

at: http://www.un.org/Depts/los/global_reporting/regular_process_background.pdf [Accessed 9 June 2014].

32 HANDLEY, J.F., GRIFFITHS, E.J., HILL, S.L. and HOWE, J.M. 1998. Land restoration using an ecologically informed and participative

approach. In: H.R. Fox, H.M. Moore and A.D. McIntosh (Eds), Land Reclamation: Achieving Sustainable Benets. Balkema, Rotter-

dam.

33 WONDOLLECK, J. and YAFFEE, S.L. 2000. Making Collaboration Work: Lessons from Innovation in Natural Resource Management.

Island Press, Washington DC.

34 BURTON, P., GOODLAD, R., CROFT, J., ABBOTT, J., HASTINGS, A., MACDONALD, G. and SLATER, T. 2004. What Works

in Community Involvement in Area-Based Initiatives? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Home Oce Online Report 53/04.

Research Development and Statistics Directorate, Home Oce, London. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.

uk/20110218135832/http:/rds.homeoce.gov.uk/rds/pdfs04/rdsolr5304.pdf [Accessed 24 March 2014].

35 GRIMBLE, R. and CHAN, M.-K. 1995. Stakeholder analysis for natural resource management in developing countries. Natural

Resources Forum, 19(2), 113–114.

36 PRELL, C., HUBACEK, K. and REED, M., 2009. Stakeholder analysis and social network analy-

sis in natural resource management. Society and Natural Resources, 22, 501–518. Available from:

http://sustainable-learning.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Stakeholder-Analysis-and-Social-Network-Analysis-in-Natural-

Resource-Management.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2014].

37 REED, M.S., GRAVES, A., DANDY, N., POSTHUMUS, H., HUBACEK, K., MORRIS, J., PRELL, C., QUINN, C.H. and STRINGER, L.C.

2009. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental

Management, 90, 1933–1949. Available from: http://sustainable-learning.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Who%E2%80%99s-in-

and-why-A-typology-of-stakeholder-analysis-methods-for-natural-resource-management.pdf [Accessed 9 June 2014].

38 SARKKI, S., NIEMELÄ J. and TINCH, R. 2012. Summary Report on Assessment Criteria for Science-Policy Interfaces. SPIRAL inter-

facing biodiversity and policy. Unpublished report, SPIRAL, April 2012.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

24

› Scope and context

›› Case studies

Identifying reasons to engage stakeholders

Reasons to engage stakeholders: European Beech

Forest for the Future (BeFoFu)

Why engage with

stakeholders

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

25

Part 2

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

26

n WHY ENGAGE WITH STAKEHOLDERS-

❝ Dene why you wish to undertake stakeholder engagement

and what outcomes you wish to achieve. Begin outlining the

scope of the engagement and its context at the outset of the

project and continuously develop it. ❞

The rst, and perhaps the most critical, step in the

stakeholder engagement process is to identify why the

engagement activity is necessary, what outcomes are

aimed for, and the scope and context of the engage-

ment

1

. No stakeholder engagement strategy can be

devised without considering the reasons for engage-

ment, and what is being sought from the process

1-8

.

This initial step is dened as the ‘preliminary’ or ‘scop-

ing’ phase because the scope and extent of engage-

ment is dened at this point

4,9

.

Depending on the level of engagement sought, there

may be more, or less, engagement with stakehold-

ers to identify the scope and context of engagement.

In projects that are mainly operating in ‘inform’ and

‘consult’ modes (Table 1.1), this information may be

made available to potential stakeholders, in an appro-

priate format. The information provided needs to be

clear about the aims of engagement and how it will

help the project meet the needs of stakeholders, so

they can make an informed choice about whether or

not they want to become involved with the research.

For projects engaging predominantly in the ‘involve’

and ‘collaborate’ modes, it is important to engage

stakeholders in this initial scoping phase of the work.

Engaging stakeholders as early as possible in the

research programme can increase the likelihood that

research meets the needs and priorities of stakehold-

ers, who are in consequence more likely to feel owner-

ship of research outcomes

10,11

. Potentially, researchers

may need to negotiate the goals of the research with

stakeholders, perhaps identifying new stakeholders if

goals change. The negotiating may be done as part

of a stakeholder analysis; for example Dougill et al.

12

and Prell et al.

13

used an initial stakeholder analysis

to identify key informants for scoping interviews in

which they discussed and expanded the scope of the

research, before revisiting their stakeholder analysis to

include those with a stake in the revised scope of the

research.

It is essential to have a denite purpose for stake-

holder engagement that should be used to drive the

desired activities, outcomes and outputs. Outputs

are the tangible products needed to achieve desired

outcomes, such as reports, websites, newsletters,

or data. For example, if the reasons for engaging

stakeholders are primarily about pragmatic issues

(concerned with facts or actual occurrences rather

than testing scientic theories), there is likely to be

a stronger focus on outcomes of the process (e.g.

increased abundance of a particular species). On

the other hand, if the purpose is primarily normative

(seeking to establish a norm, setting a standard/den-

ing methods of good practice), then there may be a

stronger focus on the benets of the process itself

(e.g. increased learning and trust, and reduced levels

of conict).

A well-crafted purpose for engagement will be

focused, clearly dened, easily understood, with clear

aims and objectives

4,9

. Some reasons for undertaking

stakeholder engagement, and desired outcomes, are

provided in Table 2.1

4,7,9,14,15

:

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

27

Table 2.1

Reasons for stakeholder engagement

✴ Raise awareness of the research project.

✴ Gain trust and improve working relationships, form new partnerships, create new networks,

galvanize external support, and provide a clearer understanding of the benets of the research.

✴ Encourage a sense of ‘ownership’ of the project by those likely to benet, be aected by, or inter-

ested in, research outcomes.

✴ Provide people with an opportunity for personal development through engagement activities.

✴ Explore issues, share ideas and best practice, generate ideas and identify and raise better aware-

ness of emerging issues.

✴ Co-design projects with stakeholders that may assist with producing a clearer denition of desired

outcomes. Taking a broad spectrum of ideas and thoughts on board enables the adoption of a

more holistic approach to addressing potential problems, limitations or conicts.

✴ Aid the development of a transparent decision-making process and ensure policy decisions can

be based upon stakeholder views and enable decision-makers to consider societal ‘wants’ and

‘needs’. This can help reduce conict and overcome barriers between science, policy makers

and society.

✴ Involve stakeholders to make it easier to obtain endorsement of, or agreement on, resulting deci-

sions from parties likely to either use or be aected by the results of the research.

✴ Gain access to resources or to obtain information data.

✴ Create new (or improved) communication channels, identify eective dissemination avenues and

improve clarication of ‘common’ language.

✴ Provide equal rights and open access to scientic knowledge (‘democratizing science’).

✴ Enable researchers to identify cross-cutting issues and ascertain where research may be applied

to other areas. It also improves the relevance, value and depth of the research and broadens the

knowledge base, identies knowledge gaps, addresses information needs and creates opportu-

nities to link research more directly to policy and practice.

✴ Leads to improved risk management.

Identifying and clarifying desired outcomes is an

important part of the planning process and helps to

ensure that the focus on achieving aims as the proj-

ect progresses is maintained

4

. In the early stages of

a project, it is benecial to consider the reasons for

conducting engagement activities and the desired

outcomes, aims and outputs. This information can

also be of use in the nal ‘review’ phase of the proj-

ect when it will be necessary to assess whether the

desired outcomes have been achieved. The success

criteria of the project can be dened from the original

objectives dened during initial scoping activities.

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

28

n SCOPE AND CONTEXT-

In addition to establishing the purpose of the engage-

ment, and its desired outcomes, it is also important to

determine the scope and extent of the engagement

and its context. The ‘scope’ of stakeholder engage-

ment determines where the boundaries of engagement

lie and assist in dening achievable outcomes from

engagement activities. The scope considers what the

objectives can realistically achieve, what impact it may

have, and whether it will contribute anything to the

project aims. If the proposed engagement presents

no benet to the project then stakeholder engage-

ment is likely not appropriate or necessary

16

. Scoping

exercises help identify stakeholders who might wish

to become involved and ascertain whether adequate

resources are available to carry out engagement

4

. The

costs, both in terms of time and resources, of stake-

holder engagement to both the project and the stake-

holder should not be underestimated at the scoping

stage

2,5

. Furthermore, risks associated with undertak-

ing engagement need to be assessed and taken into

consideration to ensure that they are managed eec-

tively.

The extent of the engagement may, to some degree,

be driven by resource and time availability. Consider-

ing the potential cost and time requirement of engag-

ing early on in project lifecycle will ensure sucient

funds can be made available to enable engagement

activities to be comprehensive, t-for-purpose, and

benecial to all parties involved.

The scoping phase needs to consider the context

of the engagement - the background to the subject

being addressed by the engagement process. Every

research project is unique and is shaped by the issues

under consideration, the people involved, the pre-

history of the work, and relevant wider decision-making

processes, amongst other factors. These issues may

aect what can, and cannot, be done within the

engagement process and are likely to dictate which

activities it will be appropriate to adopt. Understanding

the context also helps to ensure that the engagement

process builds upon previous experience and incor-

porates lessons learnt, rather than simply duplicating

previous eorts. Dening context also makes certain

that the engagement is of relevance to the potential

stakeholders

5

.

Important points to consider when dening the scope of stakeholder engagement activities:

What can the engagement realistically achieve in the time available? What are the limitations and

how can these be clearly set?

How are stakeholders to be involved - are they to be kept informed throughout the project lifecycle

(see Figure 4.1), asked for their opinions, or involved fully in the decision making process? What

impact will this have on the scope of planned activities?

What types of information will need to be gathered (quantitative versus qualitative) and how will this

be collected and over what timescale?

What additional resources might be required to facilitate eective engagement (sta training, exter-

nal contractors, and trans-disciplinary collaboration)? What will be the cost of engaging (both nan-

cial and other resources [e.g. sta time, cost of external contractors, and cost of training for sta])?

What are the potential risks associated with stakeholder engagement activities at a particular scale?

How are these best addressed?

How are the outcomes of the engagement going to be implemented? How and when will the

outcomes be communicated back to the stakeholders?

How will the success of the engagement be measured?

biodiversa stakeholder engagement handbook

29

Important points when considering the background and context for engagement

activities:

What similar projects have been undertaken previously?

How successful were the projects and what were the key elements in achieving or failing

the objectives?

What stakeholders, or stakeholder groups, have been engaged in the past?

What is the historical context to the project?

What wider decision-making processes that may aect the project need to be considered?

Do existing networks exist, and, if so, how can these be utilised?

What is the relationship status with stakeholders or potential stakeholders?

Are there any relevant activities, events or communication channels that could be used to

engage with stakeholders?

0 CASE STUDIES

IDENTIFYING REASONS TO ENGAGE STAKE-

HOLDERS

The objectives of stakeholder engagement for a number of the case study projects

(see Appendix 1 for details) is briey summarised below in relation to the level of

engagement sought by the researchers:

✴ Inform and consult: One of the objectives of the BiodivERsA INVALUABLE project

was to inform policy makers about the use of market based instruments (MBIs) for

the management of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Researchers engaged

with stakeholders to produce policy-relevant documents to advise how MBIs

could be better used to meet biodiversity conservation objectives.

✴ Involve: The FP7 MOTIVE project researchers involved stakeholders in a variety

of ways to integrate experience and knowledge from forestry management into

adaptive models to analyse the impacts of climate- and land-use-change on Euro-

pean forests. The FP7 FORCE project worked with communities in four Caribbean

countries to gather data on the factors inuencing the health of coral reefs and their

relationship with community livelihoods to inform management of reefs and more-

sustainable resource use. Findings were widely disseminated to communities and

national stakeholders. In the FP5 BIOSCENE project, stakeholders with diering

perspectives were involved with the development of a sustainability appraisal of

scenarios for agriculture in mountain regions of Europe. Stakeholders were also

involved in the development of scenarios to inform the design of re management

models in the BiodivERsA FIREMAN project. Participation was encouraged though

international meetings and practical demonstration events. In the FP7 BESAFE

project, researchers are working with stakeholders in biodiversity conservation

to gather information on the eectiveness of arguments used for advocating the

protection of biodiversity at dierent scales of governance and in dierent contexts

through case study projects. Early ndings have been widely disseminated via

policy briefs and a stakeholder panel has agreed to co-development of a web tool

that will make ndings accessible and relevant to policy makers and stakeholders

lobbying for biodiversity protection. The framework for the BESAFE

project shown in Figure 1 shows how central stakeholders are in achieving the proj-

ect goals.

✴ Collaborate: The FP7 HighARCS project worked with local communities and key