PLANNING AND

EVALUATING

THE SOCIETAL

IMPACTS OF

CLIMATE CHANGE

RESEARCH

PROJECTS:

A guidebook for

natural and physical

scientists looking to

make a difference

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword 3

Authors 3

Acknowledgements 3

Introduction 4

Part 1. Introducing Societal Impacts 4

Why consider the societal impacts of research? 4

What are Societal Impacts? 6

Long-term vs. short-term change 6

Five categories of societal impacts 6

How do researchers generate social impacts? 8

Who are societal partners? 10

Contribution or Attribution? 11

Part 2. Using Logic Models to Document Research Impacts 13

Societal Impacts Framework for Project Planning and Design 13

Societal Impacts Framework for Impact

Assessment and Project Reflection 20

Documenting Impacts – Worksheets and Case Studies 26

Part 3. Additional Context and Information 34

Appendix A: Exploring Societal Impacts Categories 34

Process as an Indicator of Impacts 35

Impacts in Context 35

Summary 36

Appendix B: Socially Engaged Research 37

Appendix C: Challenges of Impacts Assessment 40

Knowledge Generation and Information Use 40

Methodological Barriers 40

Appendix D: Concerns about Societal Impacts Evaluation 42

References 43

3

FOREWORD

As scientists, we aim to generate new knowledge and insights about the world around

us. We often measure the impacts of our research by how many times our colleagues

reference our work, an indicator that our research has contributed something new

and important to our field of study. But how does our research contribute to solving

the complex societal and environmental challenges facing our communities and our

planet? The goal of this guidebook is to illuminate the path toward greater societal

impact, with a particular focus on this work within the natural and physical sciences.

We were inspired to create this guidebook after spending a collective 20+ years

working in programs dedicated to moving climate science into action. We have seen

firsthand how challenging and rewarding the work is. We’ve also seen that this

applied, engaged work often goes unrecognized and unrewarded in academia. Projects

and programs struggle with the expectation of connecting science with decision

making because the skills necessary for this work aren’t taught as part of standard

academic training.

While this guidebook cannot close all of the gaps between climate science and

decision making, we hope it provides our community of impact-driven climate

scientists with new perspectives and tools. The guidebook offers tested and proven

approaches for planning projects that optimize engagement with societal partners, for

identifying new ways of impacting the world beyond academia, and for developing the

skills to assess and communicate these impacts to multiple audiences including the

general public, colleagues, and elected leaders.

We would like to thank our colleagues in the Climate Assessment for the Southwest

(CLIMAS), the Southwest Climate Adaptation Science Center (SW CASC), the Northwest

Climate Adaptation Science Center (NW CASC), and the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences

and Assessments (GLISA) for inspiring this work and for their contributions to making

our communities and environments healthier and stronger, even as we face the

challenge of climate change.

Sincerely,

Alison Meadow

Gigi Owen

4

Suggested citation: Meadow, Alison M. and Gigi Owen (2021) Planning and

Evaluating the Societal Impacts of Climate Change Research Project: A guidebook for

natural and physical scientists looking to make a difference.

5

AUTHORS

Alison M. Meadow, Ph.D.

Associate Research Professor – University of Arizona; Arizona Institutes

for Resilience

Alison Meadow has a background in environmental anthropology and urban

planning. Her research focuses on the process of linking scientists with

decision makers to improve the usability of climate science, with a particular

emphasis on evaluating the outcomes of such research partnerships.

Gigi Owen, Ph.D.

Research Scientist, University of Arizona, Arizona Institutes for Resilience;

Climate Assessment for the Southwest (CLIMAS)

As a qualitative social scientist with a background in geography and political

ecology, Gigi’s research interests center on the interactions between humans

and their environments. Her current research portfolio includes building

equitable and resilient local food systems, assessing climate adaptation

strategies, and evaluating how interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research

supports a thriving Southwest region.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank The Center for Advancing Research Impacts in Society

(ARIS) for the opportunity to participate in the 2020 Fellows Program; our

colleagues in the 2020 ARIS fellows cohort; the Arizona Institutes for Resilience

at the University of Arizona; and Molly Hunter, Michelle Higgins, Connie

Woodhouse, Sarah Olsen, Natasha Wingerter, Julie Risien, and Peter Ruggiero

who reviewed and helped us refine, strengthen, and improve this guidebook.

This document was developed as part of the Advancing Research Impacts in

Society (ARIS) Center Fellows Program supported through a grant from the NSF

(#1810732). The findings and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do

not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

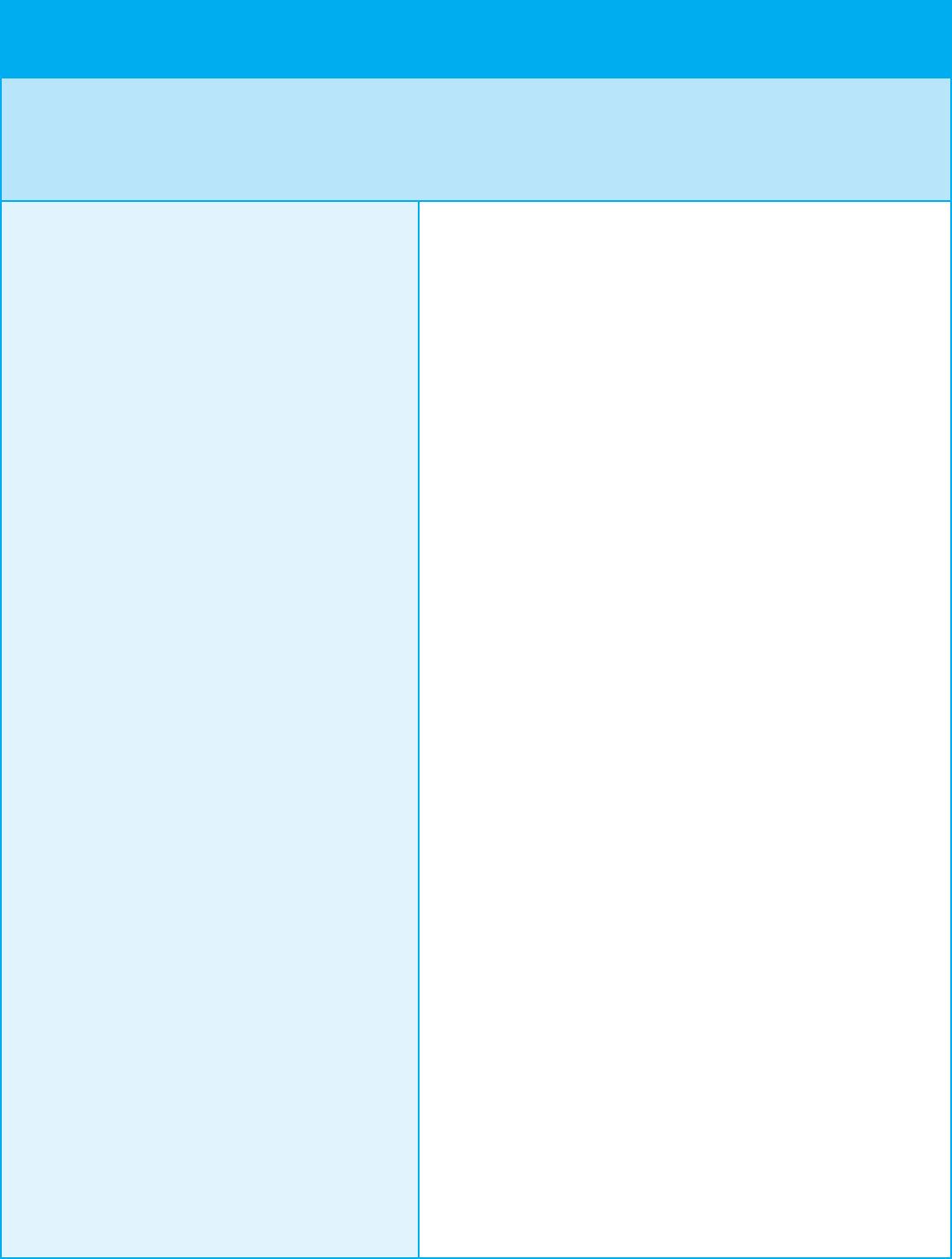

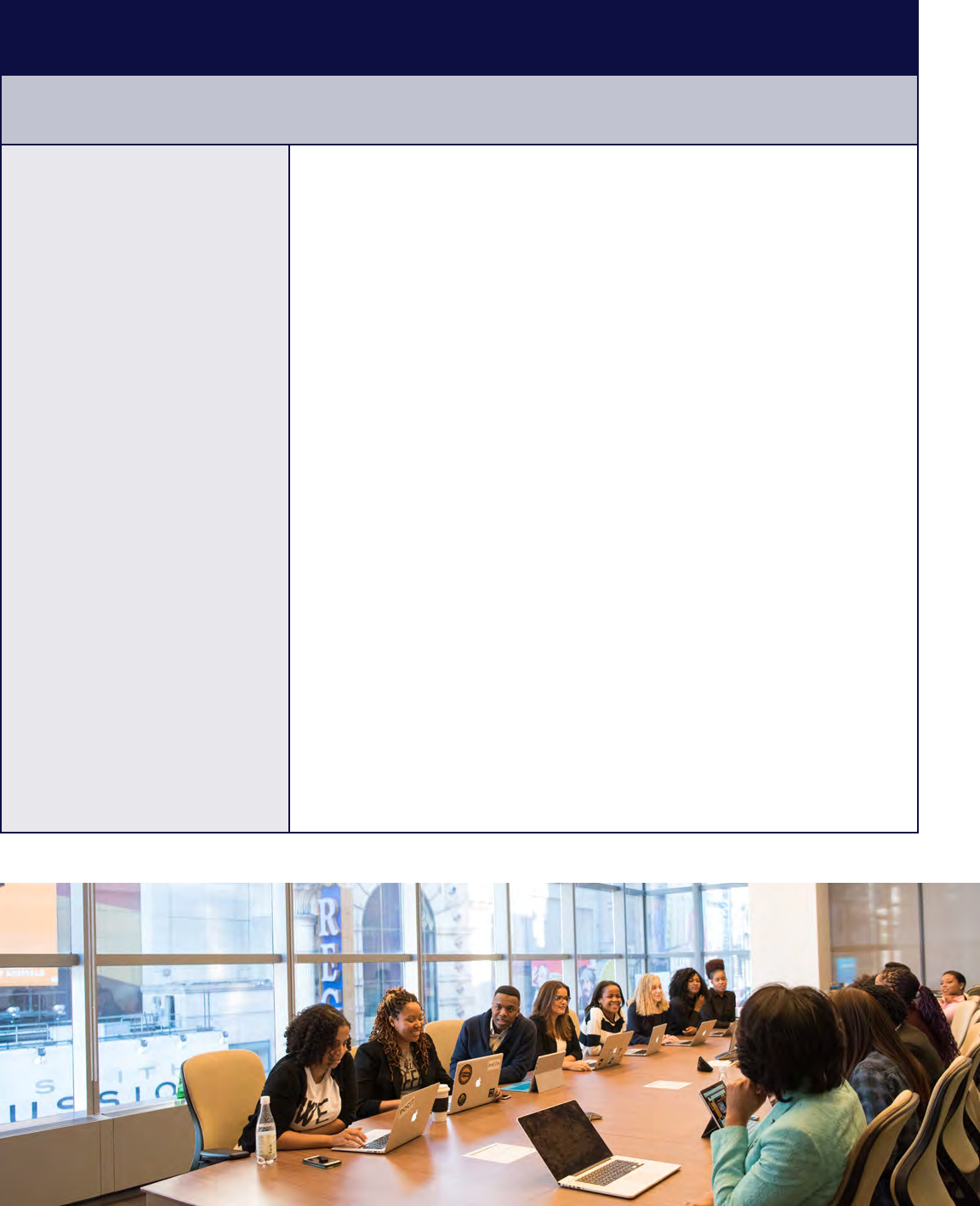

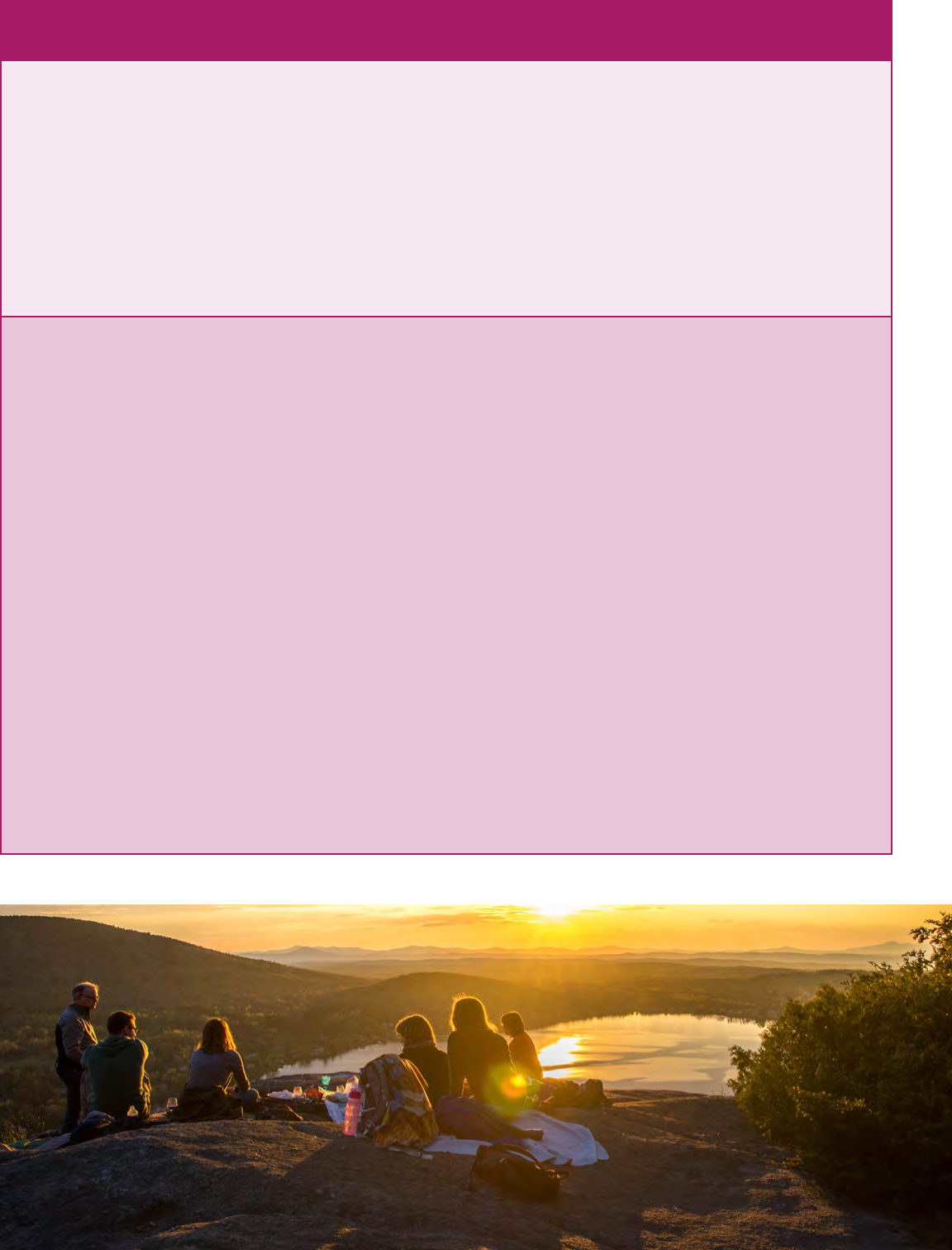

photography throughout courtesy of Unsplash

6

7

As scientists, we aim to generate new knowledge and insights about the

world around us. We often measure the impacts of our research by how many

times our colleagues reference our work – an indicator that our research has

contributed something new and important to our field of study. Considering

the challenges facing our society and environment, this type of impact is no

longer enough. Many researchers are seeking ways to have greater and more

direct impacts on communities and our environment by helping solve complex

challenges such as climate change.

But how can we structure our research to contribute directly to solving the

complex social and environmental challenges facing our communities and our

planet? This guidebook offers techniques to help researchers plan to increase

their impacts beyond academia as well as document and evaluate those impacts.

In order to identify and describe the impacts that may be generated by research,

we use a set of five impact types that range from creation of new connections

between researchers and partners in broader society to tangible, beneficial

changes in social and/or ecological systems (i.e. socio-ecological systems).

Collectively, we refer to this range of impacts as societal impacts.

The framework we present is applicable to all types of academic research.

However, we specifically tailored this guidebook for physical and natural

scientists working in the field of climate change. Global society is in a moment

where swift and intentional action is needed, but it seems difficult to know

which actions will be most effective and for whom. The environmental and

societal challenges associated with climate change are diverse and complex.

It is necessary to understand how climate research can most effectively guide

climate action, where it has been most successful doing so, and reveal the types

of action that are currently missing.

This guidebook is formatted into three main parts. In the first part we provide

background information about the societal impacts of research. In the second

part, we present a framework for planning for and assessing the societal

impacts of research, including worksheets and case studies. The third part

contains a series of appendices that provide additional context for the

information in this guidebook.

INTRODUCTION

8

Why consider the societal impacts of research?

1 See for example NSF Dear Colleague Letter 21-059, A Broader Impacts Framework for Proposals Submitted to NSF's Social, Behavioral, and Economic Sciences

Directorate.

The harmful social and environmental impacts associated

with global warming and climate change present urgent

and complex challenges for humankind. These challenges

have encouraged natural and physical scientists to

make their research more responsive to communities,

resource managers, and policy makers. Many researchers

choose the profession because they see possibilities for

generating new knowledge to benefit the environment and

society. However, academic researchers are not always

supported by their institutions or departments to engage

with societal partners, produce research outputs for public

audiences, or conduct applied research.

Funders and universities are starting to pay more

attention to the ways that academic research generates

positive impacts for society – in economic terms and

far beyond. In much of Europe, the United Kingdom, and

Australia, universities are required to report on their

societal impacts as part of the requirements to receive

federal research funding. In the U.S., the National Science

Foundation (NSF) includes broader impacts criteria in its

funding calls, which require applicants to describe their

plans to achieve impacts beyond the production of high-

quality research. For example, applicants may develop

activities that connect their fundamental research efforts

to empowering people and improving their quality of life.

1

Other federal funding programs also expect researchers to

engage with decision makers in the course of producing

“actionable” or “usable” knowledge. The Department of

the Interior’s Climate Adaptation Science Center network

is one example; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration’s long-running Regional Integrated Science

and Assessment program is another. Both programs

award 5-year grants to academic institutions that can

demonstrate skill and experience in producing science

about climate variability and change that can be directly

linked with resource management and policy making.

Crafting a societal impacts plan and an evidence-based

assessment of project impacts can improve your chances

of receiving funds from agencies that prioritize societal

and broader impacts.

PART 1.

Introducing Societal Impacts

9

Larger issues of trust and accountability are also in play

in considering societal impacts. Academic researchers can

help build relationships of trust between universities and

their surrounding communities through public engagement

and problem-solving at a local scale. The Association

of Public and Land Grant Universities’ recent report,

Public Impact Research: Engaged Universities Making

the Difference, makes the case that using public impact

research along with fundamental research, “communicates

powerfully to the public the value of university research

and could help restore public trust in our institutions.”

Researchers contribute to their university’s trust-building

work through effective engagement and by documenting

impacts in local, regional, or international communities.

2 Abel, Steve, and Rod Williams. 2019. The Guide: documenting, evaluating and recognizing engaged scholarship.: Purdue University, Office of Engagement.

3 See for example:

Alvesson, Mats, Yiannis Gabriel, and Roland Paulsen. 2017. Return to meaning: A social science with something to say: Oxford University Press.

Foster, Kevin Michael. 2010. Taking a stand: Community-engaged scholarship on the tenure track. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 3 (2):20.

Hicks, Diana, Paul Wouters, Ludo Waltman, Sarah De Rijcke, and Ismael Rafols. 2015. Bibliometrics: the Leiden Manifesto for research metrics. Nature News 520

(7548):429.

4 See Appendix D for more information regarding concerns about the role of societal impacts in academic performance reviews.

At the scale of individual researchers, societal impacts

have not often been included in academic assessments for

promotion and tenure. This trend, however, is changing.

For example, Purdue University now includes promotion

and tenure criteria that is specific to engaged scholarship.

2

Other efforts have been made to broaden academic

performance metrics beyond the restrictive focus on

publications, citations, and grants and include measures of

societal relevance and impact.

3

A well-crafted and well-

supported statement on the societal impacts of research

can be integrated into performance review and promotion

packets as an example of outreach and service.

4

10

What are Societal Impacts?

Societal impacts are the ways that research, and the process of conducting research, influences the world

beyond the academic realm.

While often in the climate and environmental sciences, we aspire to long-term and large-scale impacts like

measurable risk reduction or changes in ecosystem health, these kinds of impacts take substantial time to

develop and are dependent on a wide range of variables, such as the ability of societal partners to enact

new policies or practices. For example, a forest may not be demonstrably more resilient to fire in the span

of 2-3 years—the length of a typical research grant. Likewise, a city may not know if it is more resilient to

storm surges until the next time a large storm hits. However, there are a range of nearer-term impacts that

occur along a pathway to long-term and large-scale impact that can tell us about the ways in which our

research is helping to make beneficial changes.

In this guidebook, we present five categories of societal impacts. However, we focus on four that are more

likely to manifest on short- to medium-term timescales. We can observe and document these impacts and

use them as indicators of the likelihood of future socio-environmental impacts. Throughout this guidebook,

you will see most of our discussion involves the first four categories, but we will occasionally reference the

fifth (socio-environmental impacts) as part of the larger context of impacts evaluation.

11

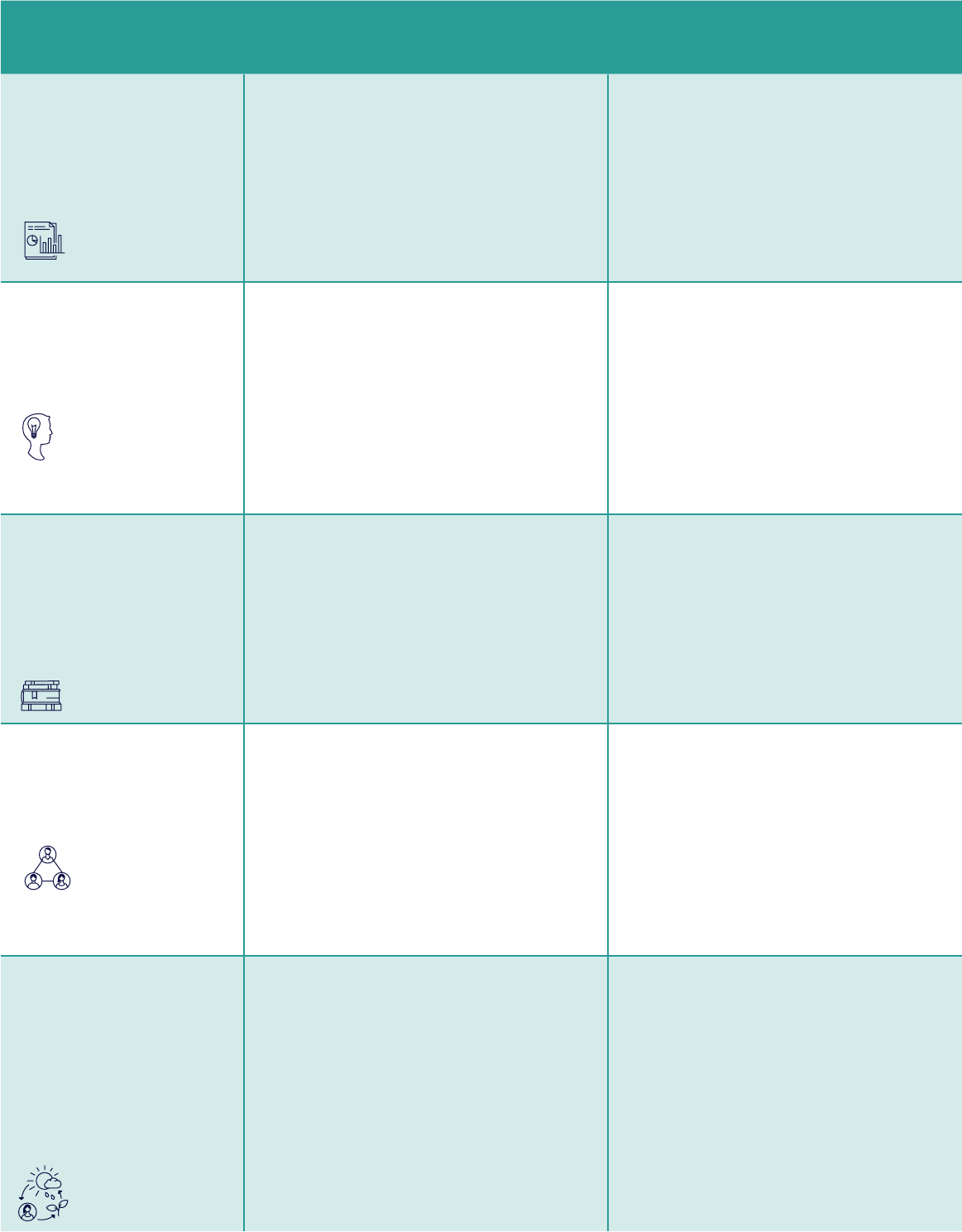

FIVE CATEGORIES OF SOCIETAL IMPACTS

Instrumental applications

your research led to tangible changes to plans, decisions,

practices, or policies

Conceptual impacts

your research contributed to changes in people’s knowledge

about or awareness of an issue

Capacity building impacts

your research contributed to enhancing the skills, expertise, or

resources of an organization or group of people

Connectivity impacts

your research led to new or strengthened relationships,

partnerships, or networks that endure after the project ends

Socio-environmental impacts

changes to social and/or ecological systems, such as

improvements in health and well-being or in ecosystem

structure and function, that result from actions taken because

of your research.

Societal impact

categories

Example in practice #1 Example in practice #2

Instrumental

impacts

Changes to plans, decisions,

practices, or policies

“We worked with the staff of the local wildlife

management agency throughout this research.

When it came time for them to update their

species management plan, they cited our report

and journal article in the plan. They also asked

both myself (PI) and my Co-I to review their

plan to ensure that the research findings were

explained accurately.”

“The state Department of Transportation used

our research findings regarding drought and

the sources and patterns of dust storms,

which have caused numerous highway

casualties, to apply for federal funds to improve

highway signs, warnings, and road markings.

Funding was approved; new infrastructure was

installed in 2017.”

Conceptual impacts

Changes in people’s knowledge

about or awareness of an issue

“Health professionals who participated in this

project reported that they understood the

science behind regional temperature projections

much better than when the project started.

Two of these professionals took the initiative

to present the findings of our research to an

internal group in their health center, in order to

explain the research methods and findings to

their colleagues.”

“Results from our paleoclimate project,

conducted with a federal agency, provided

new insight into how temperatures impact

streamflow and drought in the Colorado River

basin. During subsequent meetings, water

managers explicitly discussed how they could

apply this insight into new techniques for

water management.”

Capacity building

impacts

Enhancing the skills, expertise,

or resources of an organization

or group of people

“Three graduate students, from backgrounds

often under-represented in STEM fields,

participated in this project. They gained data

collection, analysis, and project management

skills, participated in the writing of four

academic papers, and all three were accepted

into post-doctoral climate research programs.”

“We provided municipal planners with data

about flooding impacts on their city. We worked

with them in several workshops and phone

calls to ensure the data were clearly presented

and addressed the planning needs of the

city. Our partners have said they already feel

more confident and capable when discussing

flooding with city residents.”

Connectivity impacts

New or strengthened

relationships

“A group of city planners met for the first time

at a workshop we held as part of our project.

After the workshop, this group began meeting

regularly to collaborate on a funding proposal

for their city. They continue to invite me [the

researcher] to attend their meetings, and I do on

a regular basis.”

“In 2015, utility employees identified several

climate and environmental risks that could

impact their operations. Our research

team provided them with tailored data and

analyses to address their concerns. A year

later, utility employees contacted us again to

propose collaborating to develop scenarios for

carbon reduction. has turned into an ongoing

new project.”

Socio-environmental

impacts

Changes to social or ecological

systems, such as improved

health and well-being

or ecosystem structure

and function

“Our research team modeled the likelihood of

future heatwaves in our region. After working

with us on the research project, the City revised

its extreme heat response protocols. We now

have 10 years of data on heat-related deaths

in the city which show a significant decline,

despite the fact that we’ve had more and hotter

heatwaves during this same 10-year period.”

“We worked with local residents to develop a

reforestation plan, using findings from previous

research. The residents got funding from the

City for the project and they planted over 200

trees. Over the last three years, residents

noticed that several bird and mammal species

had repopulated the area. The reforestation

plan is bringing back biodiversity to the region.”

13

Societal impact

categories

Example in practice #1 Example in practice #2

Instrumental

impacts

Changes to plans, decisions,

practices, or policies

“We worked with the staff of the local wildlife

management agency throughout this research.

When it came time for them to update their

species management plan, they cited our report

and journal article in the plan. They also asked

both myself (PI) and my Co-I to review their

plan to ensure that the research findings were

explained accurately.”

“The state Department of Transportation used

our research findings regarding drought and

the sources and patterns of dust storms,

which have caused numerous highway

casualties, to apply for federal funds to improve

highway signs, warnings, and road markings.

Funding was approved; new infrastructure was

installed in 2017.”

Conceptual impacts

Changes in people’s knowledge

about or awareness of an issue

“Health professionals who participated in this

project reported that they understood the

science behind regional temperature projections

much better than when the project started.

Two of these professionals took the initiative

to present the findings of our research to an

internal group in their health center, in order to

explain the research methods and findings to

their colleagues.”

“Results from our paleoclimate project,

conducted with a federal agency, provided

new insight into how temperatures impact

streamflow and drought in the Colorado River

basin. During subsequent meetings, water

managers explicitly discussed how they could

apply this insight into new techniques for

water management.”

Capacity building

impacts

Enhancing the skills, expertise,

or resources of an organization

or group of people

“Three graduate students, from backgrounds

often under-represented in STEM fields,

participated in this project. They gained data

collection, analysis, and project management

skills, participated in the writing of four

academic papers, and all three were accepted

into post-doctoral climate research programs.”

“We provided municipal planners with data

about flooding impacts on their city. We worked

with them in several workshops and phone

calls to ensure the data were clearly presented

and addressed the planning needs of the

city. Our partners have said they already feel

more confident and capable when discussing

flooding with city residents.”

Connectivity impacts

New or strengthened

relationships

“A group of city planners met for the first time

at a workshop we held as part of our project.

After the workshop, this group began meeting

regularly to collaborate on a funding proposal

for their city. They continue to invite me [the

researcher] to attend their meetings, and I do on

a regular basis.”

“In 2015, utility employees identified several

climate and environmental risks that could

impact their operations. Our research

team provided them with tailored data and

analyses to address their concerns. A year

later, utility employees contacted us again to

propose collaborating to develop scenarios for

carbon reduction. has turned into an ongoing

new project.”

Socio-environmental

impacts

Changes to social or ecological

systems, such as improved

health and well-being

or ecosystem structure

and function

“Our research team modeled the likelihood of

future heatwaves in our region. After working

with us on the research project, the City revised

its extreme heat response protocols. We now

have 10 years of data on heat-related deaths

in the city which show a significant decline,

despite the fact that we’ve had more and hotter

heatwaves during this same 10-year period.”

“We worked with local residents to develop a

reforestation plan, using findings from previous

research. The residents got funding from the

City for the project and they planted over 200

trees. Over the last three years, residents

noticed that several bird and mammal species

had repopulated the area. The reforestation

plan is bringing back biodiversity to the region.”

These categories do not represent all possible

types of societal impacts.

5

However, they provide

a foundation for exploring the societal impacts

of climate-related research. If your research

generates impacts that do not fit in one of these

five categories, you can still use the framework

presented in this guidebook to identify and

document your research impact and insert your

own impact categories as appropriate.

6

Impact categories are not hierarchical – one is not

more important than another. They all represent

meaningful results from the process of conducting

research. Impacts may interact within and across

categories and will often amplify each other.

For example, a network established to connect

researchers and policymakers may improve

relationships and trust among network members.

Within the network, policymakers feel free to ask

key questions, consider new data, and ultimately

become sufficiently confident in the research to

include it in a new environmental policy. All the

impact categories can contribute to beneficial

socio-environmental changes. They are worth

tracking to understand the changes that have

already occurred; they also indicate the likelihood

that more changes are coming.

5 Other frameworks can be found in:

Pedersen, David Budtz, Jonas Følsgaard Grønvad, and Rolf

Hvidtfeldt. 2020. Methods for mapping the impact of social sciences

and humanities—A literature review. Research Evaluation 29 (1):4-21.

Reed, Mark S. 2018. The Research Impact Handbook. 2nd ed: Fast

Track Impact.

Edwards, David M, and Laura R Meagher. 2020. A framework to

evaluate the impacts of research on policy and practice: A forestry

pilot study. Forest Policy and Economics. 114: 101975.

6 See Appendix A for further discussion about categories of

societal impacts.

14

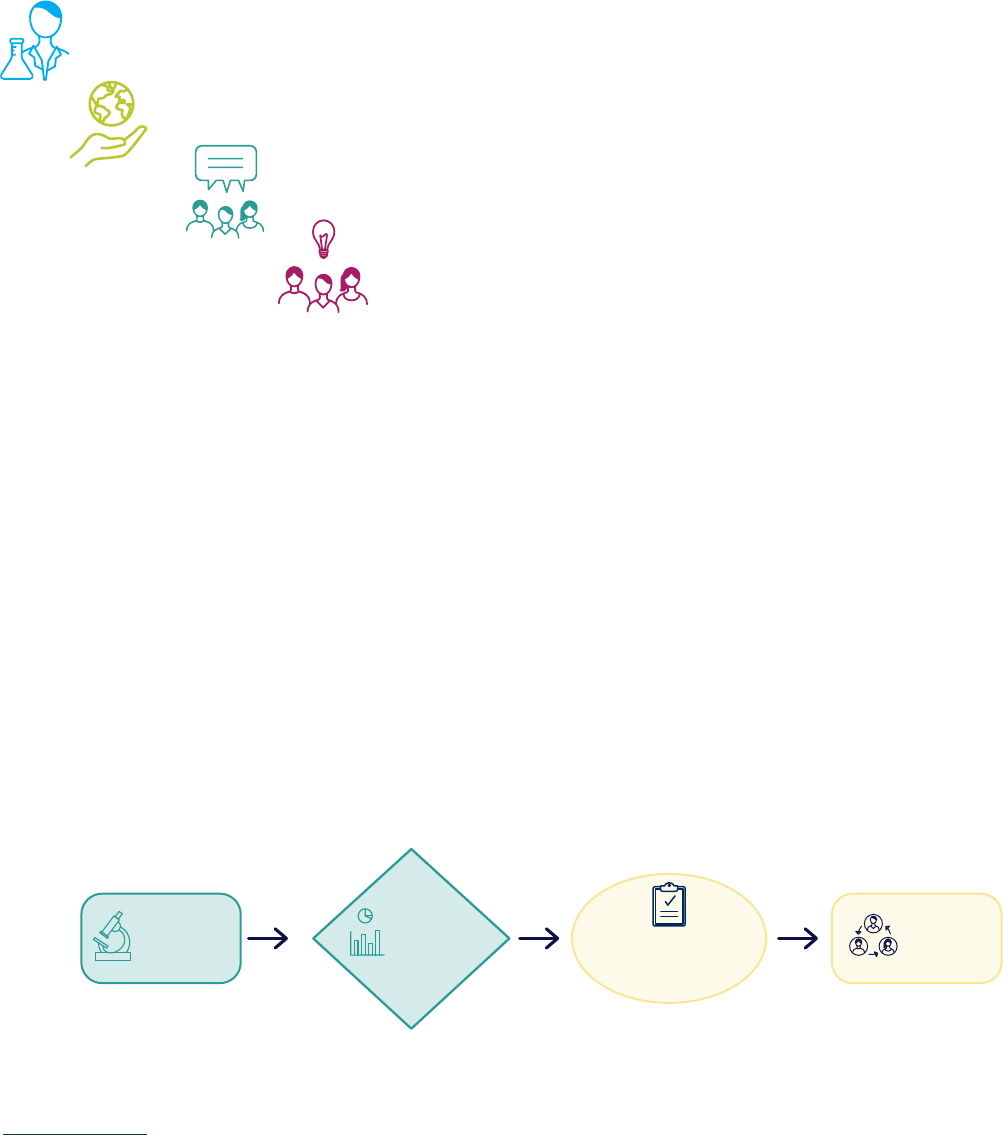

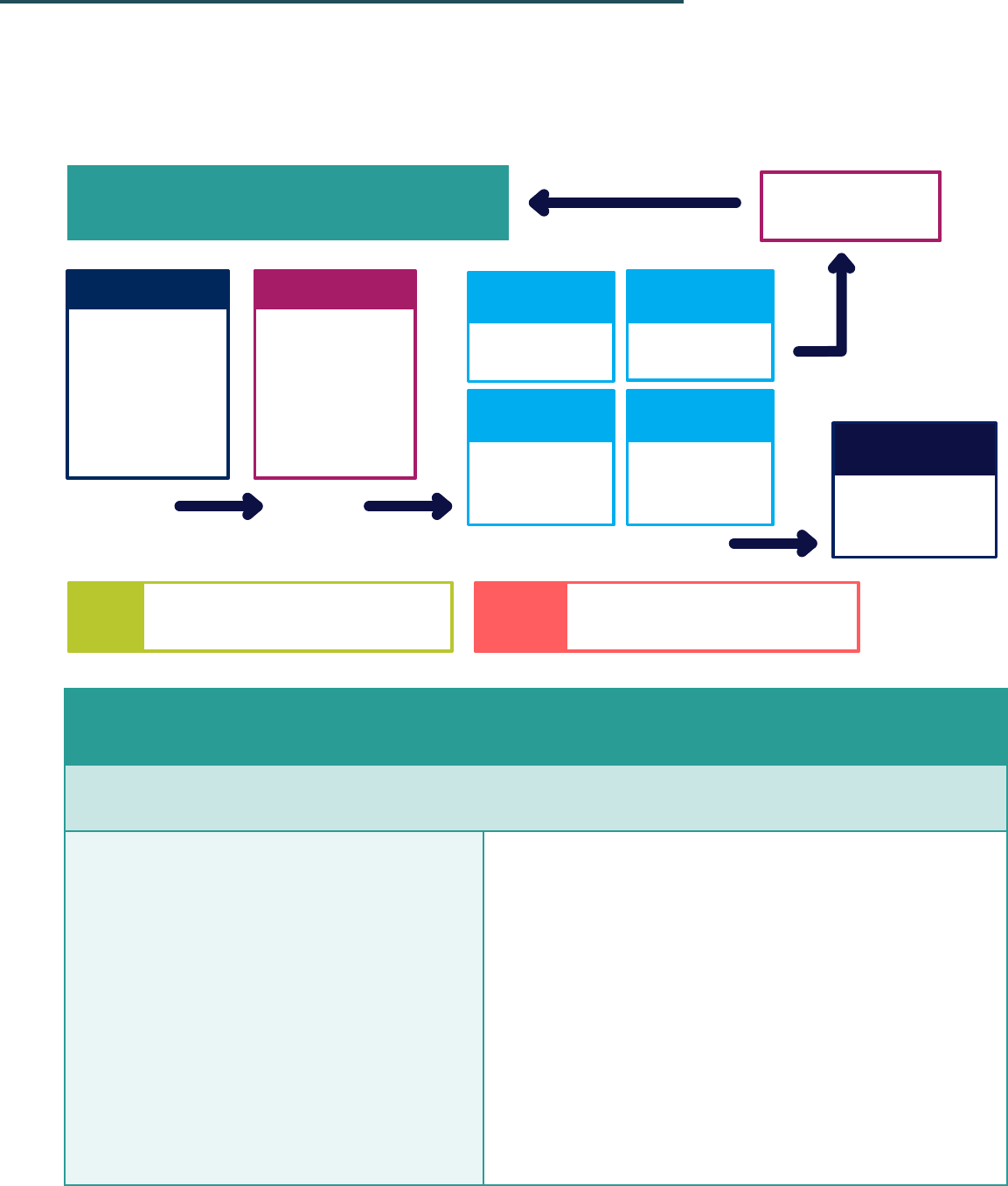

How do researchers generate societal impacts?

There are several pathways that connect research to societal impacts. Often, they

flow through the following steps:

#1. You do robust, credible, and relevant research.

#2. That research connects to society.

#3. Societal partners use that research.

#4. That research changes something in the world.

It is in Step #2 — how research connects to society – that a number of different

pathways toward generating societal impacts open up. We introduce a few of these

pathways below.

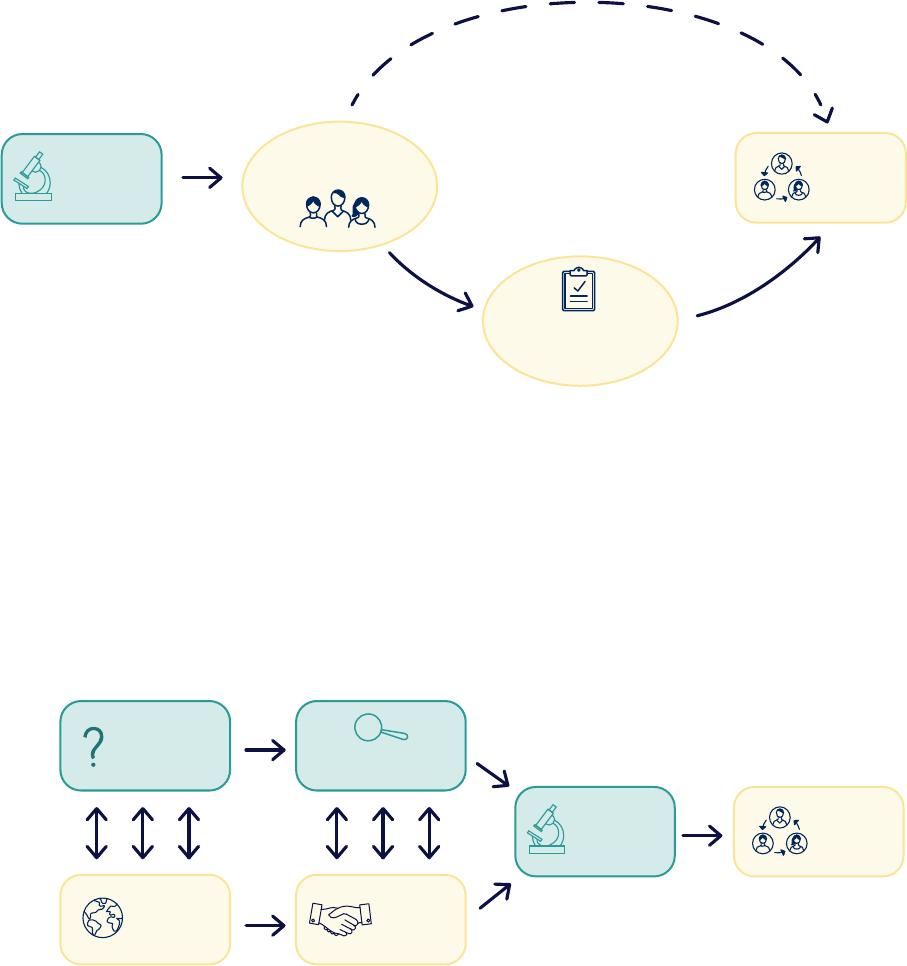

Indirect Connections between Research and Research Users

One pathway involves indirect connections between researchers and research users. Perhaps someone comes across

your research findings in a book, journal article, or report and uses it to address their needs. They might cite these

research findings in a management or policy document. Along the indirect pathway, the researcher and the person

using research findings never interact in person. Indirect pathways are sometimes referred to as a “classical pipeline” or

“loading dock” model.

7

7 Read more about the “classical pipeline” pathway in: Muhonen, Reetta, Paul Benneworth, and Julia Olmos-Peñuela. 2020. From productive interactions to impact

pathways: Understanding the key dimensions in developing SSH research societal impact. Research Evaluation 29 (1):34-47.

Read more about the “loading-dock” model in: Cash, D. W., J. C. Borck, and A. G. Patt. 2006. Countering the loading-dock approach to linking science and decision

making - Comparative analysis of El Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) forecasting systems. Science, Technology and Human Values 31 (4):465-494.

RESEARCH

RESEARCH

OUTPUT

POLICY MAKER OR

PRACTITIONER

SOCIETAL

IMPACT

Adapted from Muhonen et al. 2020

15

Connecting through Public Engagement

A second pathway involves public engagement activities like giving talks to the general public or having your research

appear in news media, social media, or popular media like podcasts. In this case, members of the public may choose to

use your findings in their lives and the information might be conveyed from the general public into a policy or practice

use, such as if citizens advocate for a particular governmental action.

Direct Engagement Between Researchers and Societal Partners

A third pathway involves direct engagement between researchers and societal partners over the course of a project.

These partners might include natural resource managers, policy makers, or those responsible for managing the impacts

of climate change within their community, city, region, or country.

PUBLIC

AUDIENCE

SOCIETAL

IMPACT

RESEARCH

POLICY MAKER OR

PRACTITIONER

Adapted from Muhonen et al. 2020

SOCIETAL

IMPACT

RESEARCH

SOCIETAL

PARTNERS

RESEARCHERS

RESEARCH

QUESTION

SOCIETAL

NEED

Adapted from Muhonen et al. 2020

16

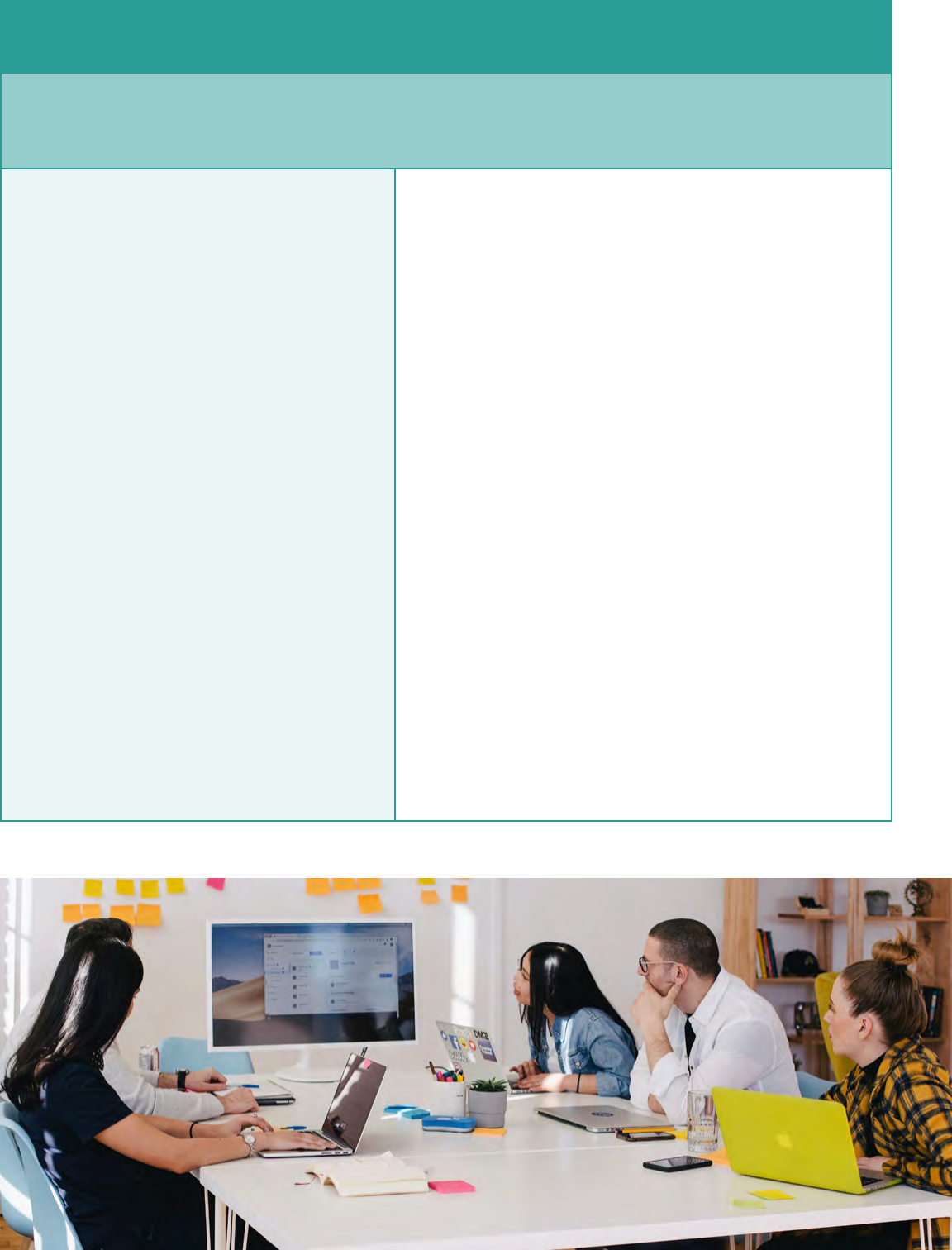

This guidebook focuses mostly on this third pathway – direct interaction between researchers and societal partners

throughout the research process. This pathway stems from decades of evolution in socially-engaged research practices,

which are more consistently effective in generating research that is useful to and used by society.

8

This approach

might involve interactive activities such as: researchers and societal partners jointly developing research questions and

project design, conducting fieldwork together, collectively analyzing data, and producing co-authored outputs, such as

papers or reports.

Who are societal partners?

In this guidebook, we use the term “societal partners,” or

“partners” for short, to refer to people who are engaged

in a research project but live or work outside of the

formal, academic research enterprise. Other common

terms for this group of people include practitioners,

decision makers, stakeholders, and community partners.

Our use of the term societal partners indicates that the

people engaged in the research process, and those who

are affected by the research, are active participants

in the research effort—not passive recipients of the

research outcomes.

Although engaged research approaches are the most effective

in moving research into use, these approaches come with some

challenges. They tend to be more time and resource intensive, which

imposes some “costs” on participants in terms of their own time,

energy, and resources. This is true for both researchers – who also

need to devote time and energy to their academic impacts – and

for societal partners – who also need to devote time and energy to

their own work and life responsibilities. Often, societal partners are

asked to participate in multiple research efforts due to their unique

perspectives or experiences. It is important to be aware of partner

burn-out

9

and researcher stress.

10

Some of these additional “costs”

can be mitigated through careful project planning and ensuring

adequate research funding and time.

8 See Appendix B for more information on socially-engaged research practices.

9 Young, Nathan, Steven J Cooke, Scott G Hinch, Celeste DiGiovanni, Marianne Corriveau, Samuel Fortin, Vivian M Nguyen, and Ann-Magnhild Solås. 2020. “Consulted

to death”: Personal stress as a major barrier to environmental co-management. Journal of environmental management 254:109820.

10 Cvitanovic, Christopher, Mark Howden, RM Colvin, Albert Norström, Alison M Meadow, and PFE Addison. 2019. Maximising the benefits of participatory climate

adaptation research by understanding and managing the associated challenges and risks. Environmental Science & Policy 94:20-31.

17

Contribution or Attribution?

Although it can be tempting to try to connect a research effort to a new policy or to an environmental change,

generating societal impacts from research is rarely a straight line. It is not always (quite rarely, really) possible to

attribute a change in policy, practice, or in the socio-ecological system directly to one particular research finding or

project. Multiple factors influence whether research is used and what impact it has for the intended users. Perhaps your

partners realize they need to build more internal capacity before being able to move forward with a new plan. Or, as is

often the case, the organization’s decision-making framework may require evidence from multiple sources before feeling

confident in taking action. Sometimes, a perfectly planned and executed project does not result in anticipated changes

due to factors outside of your control, such as budgetary constraints or changes in leadership.

Although it is not always possible to attribute specific impacts to individual projects, it does not mean that a project

has not been successful. More often, research has been a contributing factor – or one of several factors – in creating

change. While a singular research project or finding is not typically the sole factor in generating an impact, we can still

illustrate how and in what ways it contributed to the impact. Contributing to change is a positive outcome and should be

reported as such.

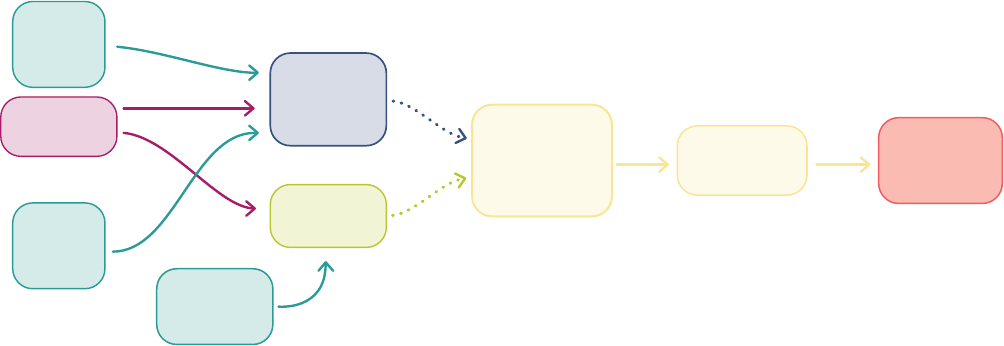

In a contribution model, like the one below, you might see that your research was one part of the process of making

changes in practice that ultimately contributed to improved environmental conditions.

Practitioners

work to make

changes in their

organizations

Sufficient

amount of

evidence

accumulated

Necessary new

skills acquired

Other

research

efforts

Other

research

efforts

Your

research

Improved

societal and

environmental

conditions

New

Management

practice in use

Professional

development

opportunity

How Research Contributes to Societal Impacts

18

First, your research might be one of several projects examining the phenomenon in question. A management agency is

likely to require several sources of evidence before it is willing to consider a change in practice. Therefore, having your

research as part of that evidence is crucial to the process. Second, a change in practice may require agency staff to

develop new skills. The agency may seek that training from another source and that source becomes another contributor

to the impact. When the new evidence and training is combined, the agency may be more able and willing to make the

change in practice. However, work still must take place within the agency to craft new policy language, move it through

internal decision channels, and secure appropriate funding – all of which require significant effort and know-how on the

part of agency personnel. In this example, that change in practice eventually leads to improved environmental outcomes.

The conceptual model below illustrates how one research project is part of a larger system that supports a change in

practice and, ultimately, a change in environmental conditions. While your research project may not be solely responsible

for changes in practice, policy, or socio-environmental conditions, using a contribution model like this one helps

demonstrate how your work has contributed to those greater impacts.

11

11 See Appendix C for more information about the challenges of documenting societal impacts.

19

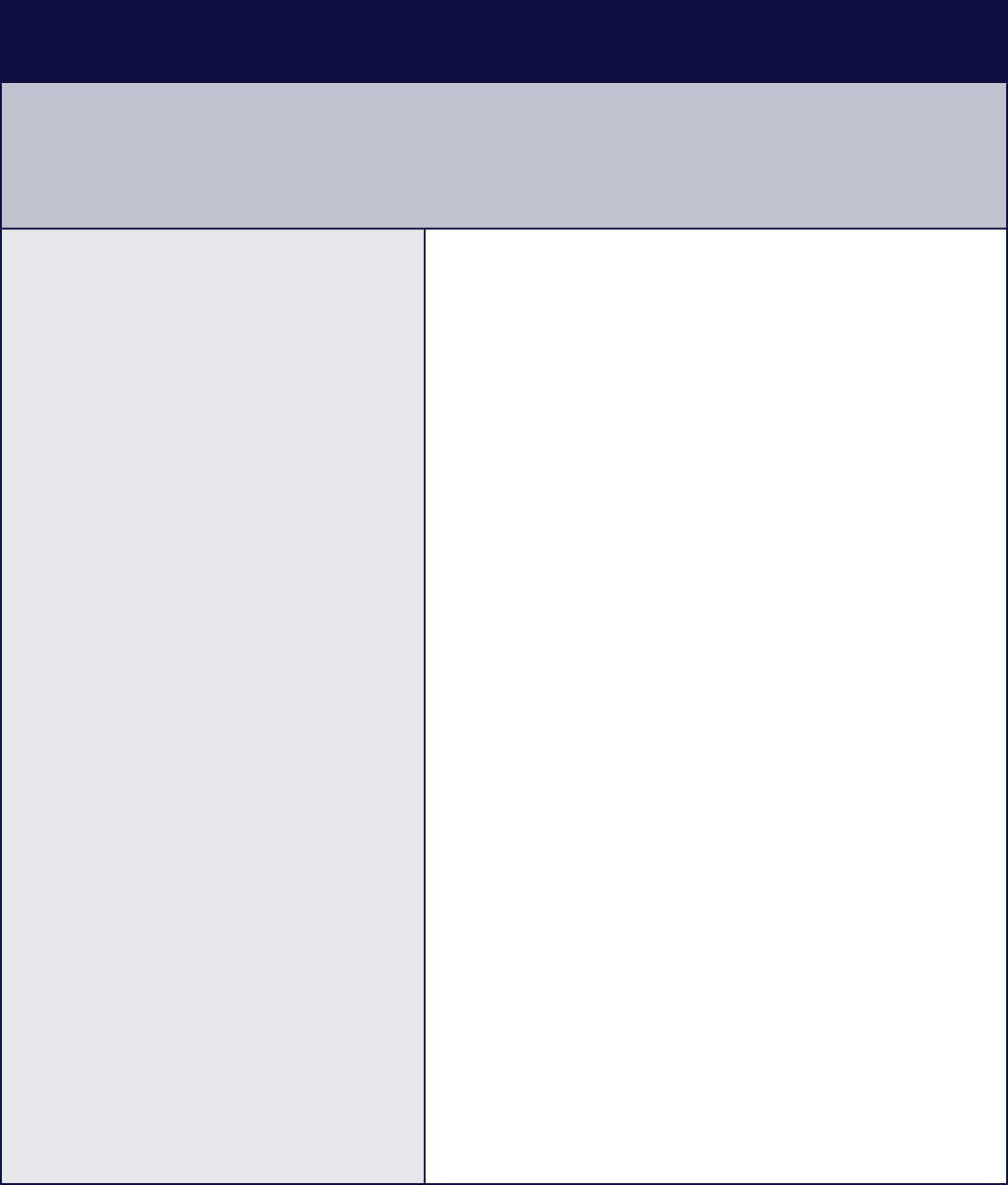

The process for identifying and documenting research

impacts presented in this guidebook is built on an

outcome-oriented logic model framework.

12

Logic models

have similar basic components, but do not always look

the same. They can be adjusted to apply to projects and

programs in multiple ways. Logic models are not rigid;

they are flexible tools that can be used in a variety of

ways. A general way to understand logic models is that

they offer a comprehensive explanation of how and why

a desired change is expected to happen in a particular

context. This framework invites researchers to make

explicit connections between project resources, activities,

outputs, and how these lead to specific

impacts or changes.

12 See W.K. Kellogg Foundation http://www.wkkf.org/knowledgecenter/resources/2006/02/WK-Kellogg-Foundation-Logic-Model-Development-Guide.aspx

In this section, we present two applications of the logic

model framework. The first variation is meant to guide

researchers who are in the planning and design stages

of a project. The second variation is geared toward

researchers who are in the middle or final stages of a

project and want to document impacts that have already

occurred. To illustrate how this framework functions, we

will work through both variations separately and apply

them to a case study example about coastal flooding and

sea level rise.

PART 2.

Societal Impacts Planning

and Assessment Frameworks

2.1 Framework for Project Planning and Design

Generating societal impacts requires re-thinking the way research projects are designed. For example, the degree

to which societal partners are involved (or not) at various steps of the research process will determine the types of

impact.

13

Used during research planning, design, and proposal writing stages, the following logic model framework

encourages researchers to think through and explicitly connect what they anticipate doing and producing during their

project, to the societal impacts they anticipate achieving at the end of their project.

13 Shirk, Jennifer L, Heidi L Ballard, Candie C Wilderman, Tina Phillips, Andrea Wiggins, Rebecca Jordan, Ellen McCallie, Matthew Minarchek, Bruce V Lewenstein, and

Marianne E Krasny. 2012. Public participation in scientific research: a framework for deliberate design. Ecology and society 17 (2).

20

ACTIONS/ACTIVITIES

OUTPUTS

How will you

address the issue?

• Methods for

engagement

with partners

• Project activities

INPUTS

What are the

interests of both the

researchers and

societal partners?

What resources

and expertise are

necessary for

this project?

What tangible

products do you

expect to produce?

• Reports

• Papers

• Circula

•Databases

SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

Changes to social or ecological

systems over time

For whom,

will things change

CONCEPTUAL

IMPACTS

INSTRUMENTAL

IMPACTS

CONNECTIVITY

IMPACTS

CAPACITY BUILDING

IMPACTS

Gain new knowledge

or awareness

Direct applications

of research

Establish or

strengthen

partnerships

Gain or improve

skills or expertise

What societal problem do you aim

to address in your research?

PROBLEM STATEMENT

What societal problem do you aim to address in your research?

Write out the specific societal or

environmental issue that your research

addresses. It should speak to the broader

issue that your research will inform. Most

likely, it will be different from your actual

research questions or objectives. In your

statement, include who is affected by this

issue.

Floodsville Project Problem Statement:

A tropical storm caused major flooding in a neighborhood of

the City of Floodsville. Ocean water breached the existing

coastal wall, leading the city’s planners and emergency

managers to question whether they had the most accurate

projections for sea level rise. They need to up-to-date sea

level rise information so they can make better informed

policies and decisions for the future of the city.

21

INPUTS

• What resources are available or necessary to conduct your research?

• What are the interests of both the researchers and the research partners?

Describe the inputs that you have available or

that you will need to conduct your research.

Your inputs will vary depending on the type

of project you are conducting. Fundamental

resources include time and funding. Consider

the human resources needed to carry out your

research, including skills, types of knowledge,

and expertise. Describe the members of your

research team (including yourself) and the

expertise, knowledge, and skills each person

offers to the project. If you do not already have a

research team established, write down the types

of members you will seek out. Once your team is

established, each member should think through

their individual motivations for participating

in the research. What kinds of societal impact

goals motivate each research team member?

How will they contribute toward those impacts?

The financial and human resources available

and the motivations of the research team will

drive the research design, as well as the project’s

activities, outputs, and impacts.

Floodsville Project Inputs:

Human resources needed:

• Climatologist with skill in climate modeling, experience

with sea level rise

• GIS specialist to map model projections

• Floodsville City official with knowledge about

city policies and the climate adaptation plan and

connections to city planners and emergency managers

• Neighborhood Association representative where

flooding occurred

• Social scientist to gather qualitative data about

residents’ experiences

Physical resources needed:

• Funding for climate modeler, GIS specialist, social

scientist, neighborhood association representative

• Time from city officials who participate in the project

• Time from community members who participate

in the project

Motivations, objectives, and interests of the

research team:

• Climatologist: to apply their modeling knowledge to a

specific societal issue

• GIS specialist: to fulfill their contract, but wants to help

solve the City’s issue

• City official: to ensure safety for the future of the City

• Community member: to ensure safety for

neighborhood residents

• Social scientist: to engage with local community

members and help inform a better adaptation plan

22

ACTIVITIES

• What activities will you do to address the broader societal issue?

• Do your proposed project activities incorporate the project inputs and the interests of your

research team?

In the activities section, focus on the

infrastructure of your project, which may

include things such as: a calendar timeline

of your proposed activities; the research

methods you will use; a description about

how you and your research team plan to

interact and communicate throughout the

project; or describing the responsibilities of

each member of the research team.

Floodsville Project Activities:

This two-year project will include two main

components of research:

1. Risk assessment: analyzing current climate models

for sea level rise for the region around Floodsville. The

climatologist will run the model analyses and produce

downscaled climate projections. She will coordinate with

the GIS specialist to construct risk maps for the region

based on these analyses.

2. Qualitative analysis of people’s experiences with the

flood and future plans to deal with flood risk. The

social scientist will coordinate with the community

representative and the Floodsville city official to develop

protocol for focus groups with the neighborhood

association and with city planners and emergency

managers. Three focus groups will occur with the

neighborhood association and three will occur with the

city planners and emergency managers in the first year.

The entire research team will meet monthly throughout the

project to discuss updates and coordinate next steps. Between

regular meetings, team members will communicate via email

and phone as necessary.

At the end of the project, the research team will present

findings and recommendations for the city’s adaptation plan to

city officials, planners, and emergency managers. We will also

present our findings at a neighborhood association meeting.

23

OUTPUTS

• What do you plan to produce through your research?

In this section, write out the tangible research

outputs that you and your team plan to produce

over the course of your project. These outputs

may include several different types of products,

such as: data analyses and models; public

outreach materials; white papers and peer-

reviewed articles; teaching curricula or training

materials; reports tailored to specific audiences;

websites; or fact sheets. As you outline this

section, think about when you want these

outputs to be completed, keeping in mind that

some of them may fall outside of your anticipated

timeline.

Floodsville Project Outputs:

1. Climate model analysis

(Completed in 6 months)

2. Risk map of Floodsville region

(Completed by end of Year 1)

3. Policy recommendations for City’s Adaptation Plan

regarding sea level rise

(Completed in 18 months)

4. Fact sheet report for neighborhood where flooding

occurred (printed and available on City website;

completed by end of Year 2)

5. Peer-reviewed paper submitted

(completed 1 year after end of project)

24

IMPACTS

• What do you expect to change as a result of your activities, your interactions with the public and your

research partners, and your outputs?

• For whom will things change or who will change because of your research?

In this section, think through the types of

impacts you anticipate having through your

research project. Your impacts section does

not need to be comprehensive, but it should

contain a list of attainable goals. As we know,

research projects often do not proceed as

intended. Not all research projects will yield

outcomes in all categories. Achieving one

impact may depend on accomplishments

in other impact categories. At the end of

a project, you may also discover several

unanticipated impacts.

We suggest starting with the first four of the

five categories of impact we introduced earlier

in this guidebook, which include:

• Conceptual impacts – new knowledge or

awareness gained

• Connectivity impacts – partnerships

established or strengthened

• Capacity building impacts – skills or

expertise strengthened or acquired

• Instrumental impacts – direct

applications of research

As you work through your anticipated impacts,

define who your societal partners are, such as:

resource management agency representatives,

policy makers or government officials,

community members, industry professionals,

students, or members of the general public. As

part of this section, you might also consider

the demographics of the people who will be

impacted by your research. Will your research

impact the audiences that you aim to reach?

Floodsville Project Impacts:

Conceptual impacts

• City officials, planners and emergency managers have a

better understanding of future flood risk and sea level rise;

they also understand the experiences of the residents

whose neighborhood was flooded

• Neighborhood residents have increased awareness about

why the recent flooding happened and the future impacts

they might face

• Researchers have a better understanding of the city

planning processes and experiences of flooding in the city

Capacity building impacts

• City residents feel better equipped to prepare for

future flood risk

• City officials feel equipped to discuss climate projections

and make decisions to address future flood risk

Connectivity impacts

• Connect city officials with neighborhood residents

• Increase connections between emergency planners and

city managers – currently there is little communication

between these agencies.

Instrumental impacts

• Inform Floodsville’s new multi-hazard mitigation plan

regarding flood

• Inform emergency management policies to deal with

future flood risk

Socio-ecological impacts (long-term aspirations)

• As sea-level rise occurs, Floodsville does not experience

any further flooding

• Floodsville saves significant amounts of money by

implementing actions from their hazard mitigation plan

25

PLANS TO COLLECT EVIDENCE OF CHANGE

• How will you know that your research changed things for people?

Your research design should incorporate plans

to systematically collect pieces of evidence that

corroborate the impacts of your research. Some

research projects will require external evaluation,

which can generate high quality data from formal

surveys, interviews, and even randomized control

trials. However, societal impacts evidence can

also be collected by research team members

and societal partners. These sources of evidence

might include: feedback from partners in the

form of emails, letters, or conversations you are

able to document; reference to your work in a

management/policy document; or feedback from

the general public.

Floodsville Project Evidence of Change:

• Citations in Floodsville’s Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan

• Emails and discussions with City officials, planners, and

emergency managers and with neighborhood residents

• Solicit feedback via survey at final project meetings

with City officials, planners, and emergency managers

and with neighborhood residents

REVIEW YOUR PLAN

Once you have completed outlining each piece

of your project framework, review your plan to

see if each step logically flows into the next

step. Make sure your inputs relate to your project

activities; that activities relate to outputs; that

your outputs relate to your anticipated impacts;

and that impacts address the original interests

and motivations of the research team. Write a

quick summary about how your impacts address

the societal problem you are trying to inform with

your research.

Floodsville Project Design Review:

This project will provide up-to-date projections for sea

level rise in the region around the City of Floodsville.

By working with city officials, planners, and emergency

managers, as well as gathering evidence with

neighborhood residents, our project will provide insight

into how people cope with flood-related disasters

and will help them prepare for, and hopefully prevent,

future flood risk.

26

2.2

Societal Impacts Framework for Impact

Assessment and Project Reflection

What societal problem did you aim

to address in your research?

ACTIONS/ACTIVITIES

OUTPUTS

INPUTS CONTEXT

CONCEPTUAL

IMPACTS

INSTRUMENTAL

IMPACTS

CONNECTIVITY

IMPACTS

CAPACITY BUILDING

IMPACTS

SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL

IMPACTS

How did you try to

address it?

• Methods for

engagement

with partners

• Project activities

What resources, skills,

and existing relationships enabled

you to conduct your research?

What social, environmental, and

political factors facilitated or

inhibitied your research?

What tangible

products did

you produce?

• Reports

• Papers

• Circula

•Databases

New knowledge or

awareness gained

Direct applications

of research

Partnerships

established or

strengthened

Skills, expertise

strengthened or

acquired

Changes to social or

ecological systems

over time

For whom,

did things change

PROBLEM STATEMENT

• What societal problem did you aim to address in your research?

Summarize the specific societal or

environmental issue that you addressed in

your research in one or two sentences. It will

likely be different from your actual research

questions or objectives. In your statement,

include who was affected by this issue.

Floodsville Project Problem Statement:

A tropical storm caused major flooding in a neighborhood of

the City of Floodsville. Ocean water breached the existing

coastal wall, leading the city’s planners and emergency

managers to question whether they had the most accurate

projections for sea level rise. They wanted to up-to-date sea

level rise information so they could make better informed

policies and decisions for the future of the city.

27

ACTIVITIES

• What actions did you take to address the broader societal issue?

In this section, state your

research methods briefly.

Then provide a description

of how you interacted or

communicated with societal

partners through your research.

Floodsville Project Activities:

• Downscaled climate and sea level rise projections to the scale of

Floodsville and the surrounding region.

• Attended 4 meetings with city planners and emergency managers during

the winter and spring of 2017. We presented our research (using maps) at

each meeting and engaged in discussions with decision makers about the

research process as well as implications of our findings.

• City officials called us regularly throughout their planning process to

confirm their understanding of the research (March – November 2017).

• Attended two community association meetings focused on the flood event

and community plans for flood relief (summer 2017). Answered questions

about projections of future flood events linked to sea level rise.

• Conducted two focus groups with community members (one with 10

participants and one with 8), one focus group with city planners (5

participants), and one with emergency managers (8 participants). All

occurred in spring and summer 2017. These focus groups helped us

understand the scale of analysis that was most helpful to all three groups,

how to present the data, and made us more aware of questions and

concerns of the community members.

• Provided city officials and community members with detailed maps

and summaries of our analysis during a presentation with each group

(December 2017).

28

OUTPUTS

• What did you produce through your research?

Briefly describe your research

findings. Then write out the tangible

research outputs you produced.

If you anticipate producing more

outputs (such as a peer-reviewed

article) note that here as well.

Your outputs could take many

forms, such as: data analyses and

models; public outreach materials;

white papers and peer-reviewed

articles; teaching curricula or

training materials; reports tailored

to specific audiences; websites; or

fact sheets.

Floodsville Project Outputs:

Findings: We found that the City’s current sea wall was not high

enough for the current sea levels or future levels. We provided

estimates to inform the height of a new wall.

Products:

• Downscaled climate projections for the Greater Floodsville region.

• Maps of projected sea level rise in the region – maps comply with

FEMA data standards for easy use in planning documents.

• Presentations summarizing research findings provided to

city planners.

• Two-page factsheet, aimed at community audience, summarizing the

research and addressing questions and concerns raised by community

members at meetings.

• A peer-reviewed publication has been submitted.

IMPACTS

• What changed as a result of your activities, your interactions with the public and your research

partners, and your outputs?

• For whom did things change or who changed because of your research?

In this section, identify what your project activities and outputs did for your societal partners. Think through

how your activities led to certain outputs, and how your activities and outputs contributed to change. In

reviewing your original research design, did you have the type of impacts you anticipated? Did you have any

unanticipated impacts?

Begin your description of impacts with one of the impact categories we introduced above: conceptual impacts –

new knowledge or awareness, connectivity impacts – partnerships established or strengthened, capacity building

impacts – skills or expertise strengthened or acquired, and instrumental impacts – direct applications of research.

Identify for whom things changed because of your research. This list may include resource management agency

representatives, policy makers or government officials, community members, industry professionals, students, or

members of the general public. You might also consider the demographics of the people who were impacted by

your research. Did your research impact the audiences that you aimed to reach?

29

IMPACTS CONTINUED

Floodsville Project Impacts:

Conceptual impacts:

• Our research team received emails from city council about their increased understanding about the risks of sea

level rise.

• Community members asked increasingly in-depth questions about the impacts that they might face, and used

this to think about new ways they would prepare for floods

People impacted: Floodsville community members from a neighborhood that had historically been underfunded

for infrastructure improvements by the Floodsville city government; Floodsville city councilmembers.

Capacity building impacts:

• A city council member used our Powerpoint presentation files to give a presentation to another city that was

recently flooded.

• Floodsville City Government gave staff members time to learn GIS skills from our research team in our lab

facilities, which helped them to be able to map the projections. This was a new skill set for the staff.

People impacted: Floodsville city government staff members.

Connectivity impacts:

• We built new relationships with city planners and community members.

• Our existing relationships with emergency managers were strengthened.

• The city planners invited us to do a new project about implementing green infrastructure.

• Our research team continues to get requests from the city for presentations.

People impacted: Floodsville community members; Floodsville city planners and emergency managers; members

of the project research team.

Instrumental impacts

• The new projection maps were used in the city’s new multi-hazard mitigation plan.

• The city’s multi-hazard mitigation plan was accepted by FEMA.

People impacted: Floodsville city government officials.

Long-term socio-ecological impacts (assessed using long-term evaluation process)

• 25 years later, sea level rise of 1 meter occurred, but flooding of the town was avoided

• Floodsville saved $5 billion USD by implementing actions from their hazard mitigation plan

30

EVIDENCE OF CHANGE

• How do you know that your research changed things for people?

Here, you can cite evidence that shows how

your research was used or how things changed

because of your research. Some examples of

evidence include:

Feedback from your partners

• Formal (letters of recommendation or

partnership)

• Informal (email or phone calls)

Reference to your work in a management/

policy document

• Citation to support statements

• Research findings forming the basis of

policy document

• Citation in management reports or publications

Feedback from the general public

• Audience surveys

• Emails or other engagement from public

• Media interviews/reference to your work

Formal evaluation of your work

• Randomized control trials

• Pre-post tests

• Surveys/interviews of partners

Floodsville Project Evidence of Change:

• City of Floodsville Multi-hazard Mitigation Plan. 2018.

Floodsville Department of Emergency Management.

• City of Floodsville Long-Range Infrastructure Plan. 2018.

Floodsville Department of Planning.

• Documents available online at:

floodsvillestoppedflooding.gov

• Emails from community members

and government employees

• Qualitative data from a survey distributed to city

employees and community members

31

PROJECT REFLECTION AND REVIEW

• What resources and factors enabled this project and your research impacts?

• What components of the research were effective and which ones were not as effective?

Once you have completed outlining your

research impacts, you may want to reflect on

the parts of your project that were effective

and those that were not effective. Write down

some of the resources you had available

that enabled your research. Think about the

environmental, social, and political factors

that helped or hindered your research. Some

examples include:

• Process oriented factors – the way the

problem was framed; project management;

the way findings were disseminated; outputs

matched partner needs

• Inputs – key skill sets, funding, and

resources of the research team

• External factors – the political, economic, or

social context supported, or did not support,

action or change

Floodsville Project Review:

Overall, our project turned out to be effective. After the flood,

the City looked back at their hazard mitigation plan regarding

flooding and decided to update it. They want to keep in touch

about future updates to sea level rise projections. Residents

in the neighborhood that experienced flooding feel prepared

to deal with future risk and have more trust in the city’s

multi-hazard mitigation plan to reduce their future risk.

Some of the inputs that helped enable our project include:

• The knowledge and capacity on our research team to

provide projections

• Funding for research and engagement with partners

• Existing relationships between researchers an Floodsville

City Emergency Managers

Some of the context that enabled our project include:

• A flood event happened which galvanized

action in the city

• Community members were motivated to address the issue

• The city made it a priority to update their hazard plans

32

2.3

Documenting Impacts –

Worksheets and Case Studies

PROJECT TITLE:

Societal or Environmental Issue:

What societal problem do you aim to address in your research?

• Summarize your problem statement in 1 – 2 sentences

• Different from your research questions and research objective

• Address who is affected by this societal problem

Inputs

What resources are available or necessary to conduct your research?

What are the interests and motivations of each member of your research team?

• Describe the resources that you have available or will need to conduct your research

• Define your research team, and the skills, types of knowledge, and expertise each member offers to the project

• Identify the societal impact goals that motivate each research team member to be part of the research project

This section contains worksheets filled with guidance and additional case study examples to help you plan and

document your own research impacts. The first set of worksheets pertain to the Societal Impacts Framework for

Project Planning and Design. The second set of worksheets are based on the Societal Impacts Framework for Impact

Assessment and Project Reflection.

Societal Impacts Worksheet for Project Planning and

Design Guidance Document

Click here to download your own worksheet template for project

planning and design in Google Drive.

33

PROJECT CONTINUED:

Anticipated Activities

What actions will you take to address the societal issue?

• State your research methods

• Outline roles and responsibilities for each member of the research team

• Describe how the research team will engage and communicate with one another during the project

• Outline the activities that will take place throughout the project

Anticipated Outputs

What do you plan to produce through your research?

• Observations and data

• Tangible research outputs might include:

• Public Outreach Materials

• Models/Datasets

• Reports for Partners

• Fact Sheets

• Websites

• Peer-reviewed articles

• Curricula

• Others

Anticipated Impacts

What do you expect to change as a result of your activities, your interactions with partners, and your project

outputs?

• Conceptual outcomes - new knowledge or awareness gained

• Connectivity outcomes - partnerships established or strengthened

• Capacity Building outcomes - skills, expertise strengthened or acquired

• Instrumental outcomes - direct applications of research

For whom do you expect things will change?

Evidence of Impact

How will you know that things have changed?

• Describe your plan to collect, document evidence of change. Some examples include:

• Feedback from your partners

• Reference to your work in management or policy documents

• Feedback from the general public

• Formal evaluation of your work

34

PROJECT TITLE:

The Influence of Temperature and Soil Moisture on Colorado River Water Resources

Societal or Environmental Issue:

The U.S. Southwest is an arid region and is becoming hotter and drier due to climate change. Climate model-based

temperature projections indicate Colorado River streamflow reductions of 20 percent by 2050 and 35 percent by

2100. Approximately 40 million people in the western U.S. and northwestern Mexico rely on Colorado River water for

domestic, industrial, and agricultural uses.

This project aims to better understand how temperature has influenced Colorado River water resources. Water

resource managers who work in the Colorado River Basin will use this information to inform resource management

plans and operations, which has implications for people, cities, and ecosystems across the Southwest.

Inputs

To develop the proposal, we have engaged with a group of Colorado River basin water managers who have

assisted in directing research questions and ensuring the project is relevant to resource management. This group

of water managers will form an advisory board to guide the analysis and generation of research products through

interaction with the science team. The members of the advisory board have long-standing relationships with

members of the science team from previous research engagements. They are interested in using the research

findings for their own purposes, and are informing the project design, but are not interested in collecting or

analyzing data.

The science team will be collecting and analyzing the data and communicating findings to the advisory board. The

science team is an interdisciplinary group with expertise in climatology, paleoclimatology, hydrologic modeling, and

climate projection analysis, with extensive experience working with resource managers. The members of the team

want to apply their expertise to address water management issues in the Southwest. One member of the team

will be using part of this research for her dissertation.

This project has funding for 2 years.

Anticipated Activities

• Engagement activities include:

• quarterly meetings with the advisory board

• email and phone calls between science team and advisory board members as needed

• a final project workshop with water resource managers

The science team will meet monthly to discuss project updates and will communicate as needed

by phone and email.

Societal Impacts Worksheet for Project Planning and Design

Case Study Example

35

The Influence of Temperature and Soil Moisture on Colorado River Water Resources

Anticipated Outputs

• Analysis of instrumental data

• Analysis of tree-ring chronologies

• Soil moisture model

• Project website, kept up to date as research is completed

• Quarterly reports to advisory board

• Presentations to academic audiences

• Workshop with water resource managers

• Final report for water resource managers

• Academic publication

Anticipated Impacts

• Inform decision making and planning for water management and conservation measures, by providing

information about the roles seasonal precipitation, temperature, and antecedent moisture conditions

• Raise awareness of possible impacts of warming temperatures on drought and expected runoff

now and in the future

• Increase awareness about how to use tree-ring data for future planning, recognizing t that the past

is not an analog for the future

• Increase awareness about the climate connections between winter precipitation and fall and spring

temperatures in the Colorado River Basin

Evidence of Impact

• Annual interviews with members of the advisory board about the research process and how they have used

or plan to use project findings

• Interviews with members of the science team about the research process, research findings, and

implications of their findings

• Feedback from workshop participants via online survey

• Evidence from emails and feedback from advisory board about use of information

36

PROJECT TITLE:

Summary Statement of Impacts

Return to this section after you have completed the rest of the worksheet.

Summary of the Research

What societal problem did you aim to address in your research?

• Summarize this problem statement in 1 – 2 sentences

• This is likely to be different from your research questions and your research objective

• Be sure to address who is affected by this societal problem

Project Engagement Activities

What actions did you take to address this issue?

• State your methods briefly to give a sense of the kind of research you did

• Provide a description of your approach to societal engagement

Research Outputs

What did you produce through your research?

• BRIEFLY describe your research findings

• Tangible research outputs:

• Public Outreach Materials

• Models/Datasets

• Reports for Partners

• Fact Sheets

• Websites

• Peer-reviewed articles

• Others

Societal Impacts Worksheet for Project

Reflection and Impact Assessment

Guidance Document

Click here to download your own worksheet template

for project planning and design in Google Drive.

37

PROJECT CONTINUED:

Details of Impacts

What changed as a result of your activities, your interactions with partners, and your outputs?

• Conceptual Impacts - new knowledge or awareness gained

• Connectivity Impacts - partnerships established or strengthened

• Capacity Building Impacts - skills, expertise strengthened or acquired

• Instrumental Impacts - direct applications of research

For whom did things change?

Evidence of impact

Examples of evidence of change

• Feedback from your partners

• Formal (letters of recommendation or partnership)

• Informal (email or phone calls)

• Reference to your work in a management/policy document

• Citation to support statements

• Research findings forming the basis of policy document

• Citation in management reports or publications

• Feedback from the general public

• Audience surveys

• Emails or other engagement from public

• Media interviews/reference to your work

• Formal evaluation of your work

• Randomized control trials

• Pre-post tests

• Surveys/interviews of partners

38

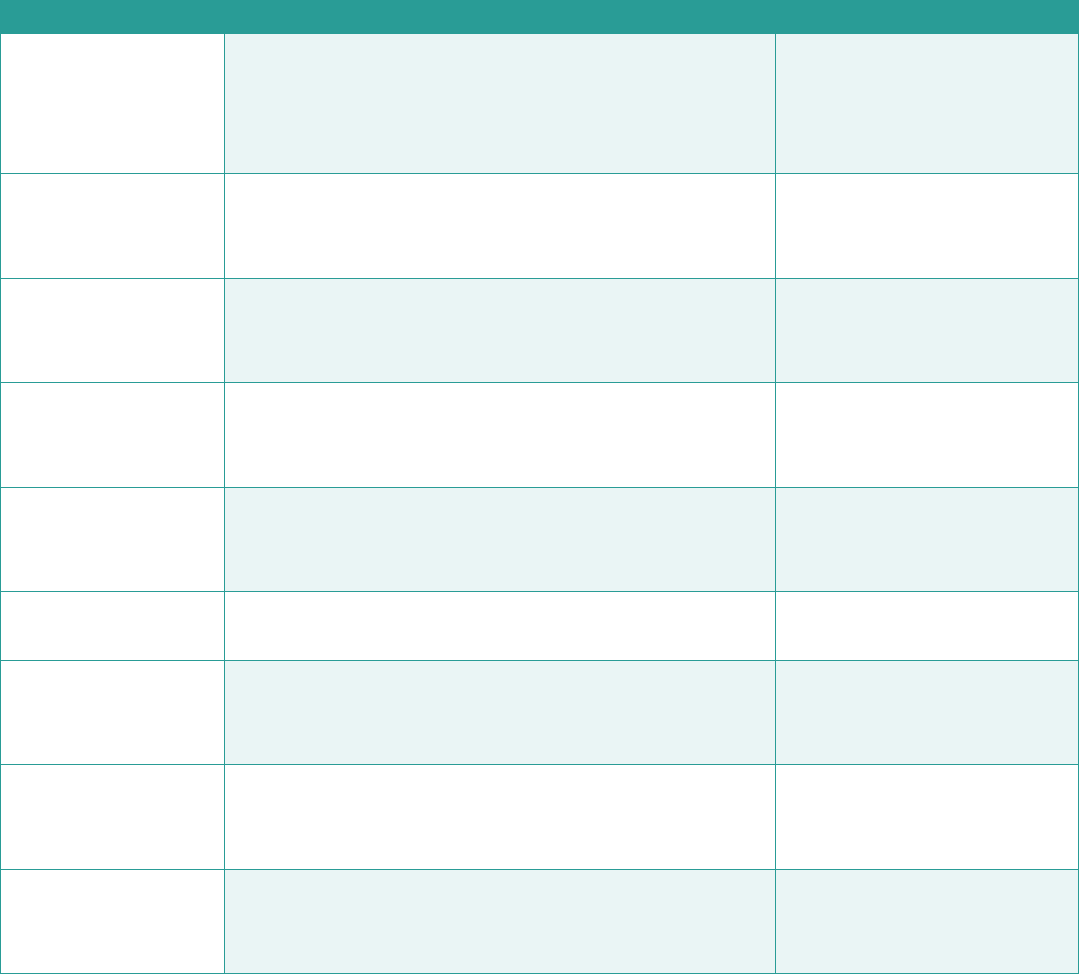

PROJECT TITLE:

Climate Change and Regional Fish Management

Summary Statement of Impacts

We worked closely a coalition of natural resource managers to identify the cumulative impacts of climate change,

habitat degradation, and invasive species on an important fish species in this region. Based on this research,

the coalition was able to prioritize funding for management of this species. In addition, a federal resource

management agency used the findings to inform its decision to build a physical barrier to protect the key species

from an invasive competitor.

Summary of the Research

This project used a novel modeling approach to develop multi-species climate change vulnerability assessments,

which offer the ability to relatively rank and prioritize populations of multiple sympatric species. We concluded

that climatic drivers, which are damaging the species’ habitat, as well as introduction of an invasive species are

contributing to the loss of the focal species in the region.

Project Engagement Activities

The lead researcher worked closely with the coalition group. The coalition’s mission is to support the management

of ecologically significant species in this region through building awareness and sharing best practices between

and among federal and state natural resource management agencies in the region. The researcher attended

coalitions meetings approximately 3 times each year during the project (2016 – 2018) and co-convened a workshop

with the coalition (Summer 2018) where they elicited feedback from other regional resource managers about early

project findings.

The researcher and the coalition leaders communicated regularly by phone and email, at least every month. The

coalition team members remarked on how often the researcher attended their general meetings.

Research Ouputs

• Several scientific papers analyzing the extent to which the focal species is affected by invasive fish species in

the region and the rate of habitat degradation expected due to climate change.

• Maps of currently stressed and fragmented habitat areas.

• Maps of areas likely to become more stressed in the future due to climate change impacts.

• Maps of presence of focal species and invasive species.

• All maps were integrated into an existing decision support tool used regularly by

resource managers in the region.

Societal Impacts Worksheet

Case Study Example Document

39

Climate Change and Regional Fish Management continued

Details of the Impacts

• The management coalition used our research findings as part of its decision to prioritize funding for

management of the focal species. They reallocated available resources to their efforts to restore habitat

in the region.

• A federal agency used the findings to inform its decision to build a physical barrier at one key location (identified

through our work) to protect the focal species from its invasive competitor.

Sources that corroborate the Impacts

• Regional Aquatic Species Management Coalition Strategic Plan 2018 – 2023.

• Federal Agency Species Management Plan 2019.

• Environmental Impact Statement regarding placement of physical barrier at No Invasives Creek. 2018.

40

Appendix A: Exploring Societal

Impacts Categories

A number of different impact categories have been

developed for use in different contexts. Many people

use a common core of impact types but refine or add

new categories to better suit a particular use. There are

good reasons to rely on a common typology, such as the

ability to compare and contrast projects, programs, and

organizations, and to provide consistency over time to

measure progress in achieving impact goals. However,