Reed, M.S., Duncan, S., Manners, P., Pound, D., Armitage, L., Frewer, L., Thorley, C.

and Frost, B. (2018) ‘A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement

with research’. Research for All, 2 (1): 143–162. DOI 10.1854 6/RFA.02.1.13.

* Corresponding author – email: mark.r[email protected] ©Copyright 2018 Reed, Duncan, Manners, Pound, Armitage, Frewer,

Thorley and Frost. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

A common standard for the evaluation of public

engagement with research

Mark S. Reed* – Newcastle University, UK

Sophie Duncan – National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, UK

Paul Manners – National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, UK

Diana Pound – Dialogue Matters, UK

Lucy Armitage – Dialogue Matters, UK

Lynn Frewer – Newcastle University, UK

Charlotte Thorley – Queen Mary University of London, UK

Bryony Frost – Queen Mary University of London, UK

Abstract

Despite growing interest in public engagement with research, there are many

challenges to evaluating engagement. Evaluation ndings are rarely shared or

lead to demonstrable improvements in engagement practice. This has led to calls

for a common ‘evaluation standard’ to provide tools and guidance for evaluating

public engagement and driving good practice. This paper proposes just such

a standard. A conceptual framework summarizes the three main ways in which

evaluation can provide judgements about, and enhance the effectiveness of,

public engagement with research. A methodological framework is then proposed

to operationalize the conceptual framework. The standard is developed via a

literature review, semi-structured interviews at Queen Mary University of London

and an online survey. It is tested and rened in situ in a large public engagement

event and applied post hoc to a range of public engagement impact case studies

from the Research Excellence Framework. The goal is to standardize good practice

in the evaluation of public engagement, rather than to use standard evaluation

methods and indicators, given concerns from interviewees and the literature

about the validity of using standard methods or indicators to cover such a wide

range of engagement methods, designs, purposes and contexts. Adoption of the

proposed standard by funders of public engagement activities could promote

more widespread, high-quality evaluation, and facilitate longitudinal studies to

draw our lessons for the funding and practice of public engagement across the

higher education sector.

Keywords: responsible research and innovation; public participation; public

understanding of science; co-production; monitoring and evaluation

144 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Key messages

●

A common ‘evaluation standard’ is proposed to provide tools and guidance

for evaluating public engagement with research, to promote good practice

and enable comparison between projects with different methods in different

engagement contexts, and to monitor changes in the effectiveness of

engagement across time and space.

●

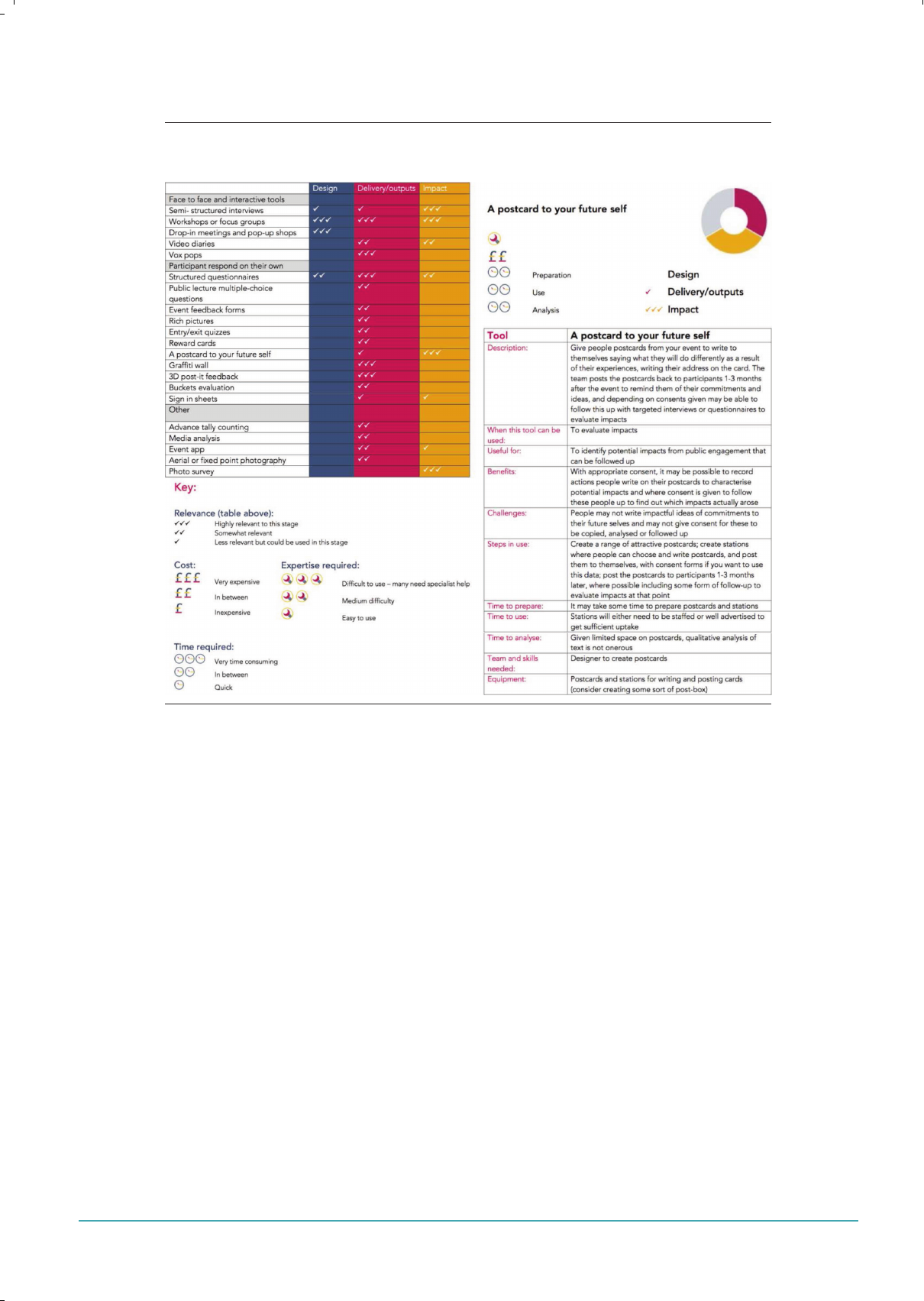

Tools have been developed (and classied by cost, time and expertise required)

to evaluate the: (1) design of public engagement activities for a given purpose

and context; (2) delivery and outputs of public engagement; and (3) long-term

impacts of public engagement with research.

●

Systematic application of the proposed standard may enable better evaluation

of long-term impacts from public engagement under the Research Excellence

Framework, for example showing how engagement contributes to learning,

behaviour change and capacity building.

Introduction

Interest in public engagement with research has never been higher. The Higher

Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) dened public engagement with

research as:

Specialists in higher education listening to, developing their understanding

of, and interacting with non-specialists. The ‘public’ includes individuals

and groups who do not currently have a formal relationship with an HEI

[higher education institution] through teaching, research or knowledge

transfer.

(HEFCE, 2006: 1)

It has been proposed that public engagement is a means of ‘ensuring that science

contributes to the common good’ (Wilsdon and Willis, 2004: 1) and restoring public

trust in science (Wynne, 2006). A major driver for this in the UK is the Research

Excellence Framework (REF), which evaluates the social and economic benets of

excellent research in the UK. Similar systems are being considered in other countries

that have signicant public investment in research (for example, Australia and Germany

are currently considering introducing impact into their national research evaluation

exercises, Excellence for Research in Australia and Forschungsrating; Reed, 2016). The

European Commission (2015) identies public engagement as one of the six ‘keys’ for

responsible research and innovation, and is considering ways of better evaluating the

impact of its research in the successor to Horizon 2020.

However, there are many challenges to the evaluation of public engagement.

As many public engagement activities are unplanned, there is often limited budget,

stafng or evaluation expertise available. Even when the resources are available to

evaluate public engagement, it may be difcult to motivate researchers to evaluate

their engagement practice (Rowe and Frewer, 2005; Burchell, 2015). Often, this is due to

resource constraints and a lack of structured techniques for identifying relevant publics

and other end users (Emery et al., 2015). Pathways from public engagement to impact

can be complex, non-linear and indirect (ESRC, 2009; ESRC, 2011; Molas-Gallart et al.,

2000). In addition, issues of time lags and attribution plague the evaluation of impacts

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 145

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

arising from public engagement, given the complex range of factors that may delay or

inuence impacts (Morris et al., 2011; Fazey et al., 2013; Fazey et al., 2014).

We dene the evaluation of public engagement with research as a process

that collects, analyses and reports data (via quantitative or qualitative means) on

the effectiveness of public engagement programmes and activities in terms of their

design (in relation to their context and purpose), delivery and immediate outputs, and

the benecial impacts that arise for participants and wider society, and subsequently

improves the effectiveness of future engagement and/or enables timely, reliable

and credible judgements to be made about the effectiveness of engagement (after

Stufebeam, 1968; Stufebeam, 2001; Patton, 1987). There is a normative assumption

within this denition that public engagement should produce benets for the economy

or society, and that evaluation should therefore assess the subjective worth or value of

engagement to different publics and stakeholders (Hart et al., 2009).

There are a large number of toolkits and resources available to guide the evaluation

of engagement projects (NCCPE, 2017a). Useful work has also been done to develop

indicators to allow institutions to evaluate and audit their engagement at a macro-

level (Hart et al., 2009; Neresini and Bucchi, 2011; Vargiu, 2014; European Commission,

2015). Despite this, there are claims that evaluation of public engagement tends to

be done rather poorly (not just in higher education, but in most sectors) (Bultitude,

2014), and that evaluation ndings are rarely shared widely or lead to demonstrable

changes in engagement practice (Davies and Heath, 2013). As a result, there are now

calls for the establishment of a common ‘evaluation standard’ to provide tools and

guidance for evaluating public engagement in order to promote good practice and

enable comparison between projects (Smithies, 2011; Neresini and Bucchi, 2011;

Bultitude, 2014). This paper is a rst step towards developing such a standard, which

can subsequently be applied to compare the efcacy of different methodological

approaches in different engagement contexts, and to monitor changes in the

effectiveness of public engagement across time and space.

The aim of the paper is to propose a linked conceptual and methodological

framework that can be used as a common evaluation standard for public engagement

projects across a wide range of possible contexts and purposes. The conceptual

framework summarizes the three main ways in which evaluation can provide judgements

about, and enhance the effectiveness of, public engagement. A methodological

framework is then proposed to operationalize the conceptual framework. The

development of the standard is informed by literature review, an online survey and semi-

structured interviews in Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), who commissioned

the development of a ‘public engagement evaluation toolkit’ to inform their work,

which could be used across the higher education sector. The standard is then tested

and rened in situ in a large public engagement event hosted by QMUL and post

hoc to a range of public engagement impact case studies from the 2014 Research

Excellence Framework.

Background

As greater emphasis is placed on public engagement with research, it is increasingly

important to be able to evaluate what works. An important starting point is to

understand the reasons why both researchers and publics wish to engage with each

other. It is not possible to evaluate ‘what works’ without rst understanding what is

being sought through public engagement.

146 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

A study of the views of scientists and publics about engagement in the context

of stem cell research identied three types of public engagement: education, dialogue

and participation in policymaking (Parry et al., 2012). The Department for Business,

Innovation and Skills (BIS, 2010) reframed these in their ‘public engagement triangle’

as transmitting, receiving and collaborating. Although widely used, these typologies of

engagement have limited theoretical basis. However, a new typology of engagement

published by Reed et al. (2017), argues that types of engagement can in theory be

distinguished by their mode and agency, leading to combinations of top-down and

bottom-up approaches for informing, consulting and collaborating with publics in

more or less co-productive ways (in line with NCCPE, 2017b):

• Informing, inspiring, and/or educating the public. Making research more

accessible, for example:

dissemination: making research ndings available and accessible to publics

inspiration and learning: where researchers share their research to inspire

curiosity and learning

training and education: where research is used to help build capacity of

individuals and groups in terms of knowledge, skills or other capacities

incentives: engagement with publics to incentivize public acceptance of

research.

• Consulting and actively listening to the public’s views, concerns and insights,

for example:

interaction: bringing researchers and research users together to learn from

each other

consultation: using focus groups, advisory groups or other mechanisms to

elicit insight and intelligence.

• Collaborating and working in partnership with the public to solve problems

together, drawing on each other’s expertise, for example:

deliberation and dialogue: working ‘upstream’ of new research or policy to

ensure that the direction of travel is informed by the public

doing research together: producing, synthesizing or interpreting research

ndings with publics, for example citizen science and collaborative research

facilitation: action research, where researchers enable the public to facilitate

desired change

enhancing knowledge: where research ndings are informed by multiple

perspectives and so are more robust and relevant

informing policy and practice: involving the public to ensure their insights,

expertise and aspirations inuence the evidence base for policy and practice.

Each of these three broad reasons for engaging publics is valid, and may be appropriate

depending on the context and purpose for which engagement is conducted. Contrary

to normative arguments that collaborative approaches should always be preferred

(see Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of participation), we adopt the approach taken by the

NCCPE and Reed et al. (2017), which takes a non-judgemental stance on engagement,

proposing that the type of engagement is matched to the context and purpose of

engagement, embracing communicative approaches where these are suited to the

context and purpose of engagement.

These different motivations for engaging with publics often lead to different

types of impacts. Impacts occur when public engagement gives rise to tangible

benets for people (such as enhanced well-being or educational attainment), and are

typically difcult to evidence. Research Councils UK denes research impact as ‘the

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 147

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy’

(HEFCE, 2016: n.p.). Public engagement may give rise to a range of impacts, including

(after Hooper-Greenhill et al., 2003; Davies et al., 2005; Nutley et al., 2007; Belore and

Bennett, 2010; Morrin et al., 2011; Meagher, 2013; Facer and Enright, 2016):

1. instrumental impacts (for example, nancial revenues from widespread public

adoption of a new technology or policy change resulting from public pressure)

2. capacity-building impacts (for example, new skills)

3. attitudinal impacts (for example, a change in public attitudes towards issues that

have been researched)

4. conceptual impacts (for example, new understanding and awareness of issues

related to research)

5. enduring connectivity impacts (for example, follow-on interactions and lasting

relationships, such as future attendance at engagement events or opportunities

for researchers and members of the policy community to work more closely with

publics).

The ESRC (2009; 2011) emphasized the critical role of process design versus contexts in

determining the impacts arising from public engagement. This was explored empirically

by de Vente and colleagues (2016) and theoretically by Reed and others (2017), to

identify design principles that could increase the likelihood that public engagement

processes lead to impacts. These studies emphasize the importance of evaluating

the design of public engagement processes. If design is evaluated a priori, or early

in a public engagement project (that is, formative evaluation), it may be possible to

adapt the design of engagement to better address contextual factors and increase the

likelihood of impacts arising from the work.

Sciencewise (2015) took this a step further, differentiating between the design,

context and delivery of public engagement as key determinants of impact. They

argued that a well-designed process that is well suited to its context may still fail

to achieve impacts if poorly delivered. As such, it is vital to evaluate the delivery of

public engagements and the immediate outcomes that arise from effective delivery, in

addition to evaluating the eventual impacts of engagement. In addition to evaluating

the design of engagement, evaluating the pathway to impact in this way can further aid

the adaptation of engagement processes to ensure they achieve impacts (Reed, 2016).

Building on this, it is possible to propose a series of principles to underpin

the evaluation of public engagement (adapted from Pearce et al. (2007) and

Sciencewise (2015)):

• Start early: evaluate engagement throughout the design and delivery of

the project.

• Be clear: on purpose, scope, approach, levels of engagement in, and limits of,

the evaluation.

• Use evaluation methodologies that are rigorous and t for purpose.

• Seek understanding and learning, rather than apportioning blame or evaluating

merely to satisfy funder requirements.

• Facilitate ows of knowledge, information and benets between researchers

and publics.

• Build trust: partnerships deepen and develop through extended reciprocity and

improved access.

• Respect condentiality: protecting the sensitivity of data collected, and avoiding

personal or reputational harm.

148 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

• Avoid conicts of interest: including privileged access to information not being

used for future competitive advantage.

• Be proportionate: using sufcient resources to probe in sufcient depth to meet

evaluation objectives.

• Be transparent: the evaluation should be explained to participants and

stakeholders, and evaluation ndings published.

• Be practical: evaluation data sought can be collected, assessed and reported

within timescale and budget.

• Make it useful: evaluation ndings should be reported in accessible language

and in a form that is useful for learning and to provide evidence of impacts, what

works, and lessons for the future.

• Be credible: use evaluation frameworks and methods that deliver intended

outcomes.

In certain circumstances, in particular summative evaluations (that provide judgements

of engagement and impact) for reporting to funders in large projects, it may also be

important for the evaluation to be independent (from commissioners, funders, delivery

team and participants). However, the focus of this paper is to create a standard that may

be used by both researchers who wish to evaluate their own practice and independent

evaluators.

A range of evaluation methodologies have been developed to enact these

principles. Warburton (2008) and Sciencewise (2015) describe a methodological

framework for evaluating public engagement that describes the purpose for which

engagement is being used, the scope and design of the engagement process, the

people who are engaged and the context in which engagement takes place. They

suggest that there should be three stages in any evaluation of public engagement:

baseline assessment, interim assessment of design and delivery, and nal assessment

of the overall project and its impact.

Logic models (such as logical framework analysis or ‘logframes’; Gasper,

2000) and ‘theory of change’ (Quinn and Cameron, 1988) are more widely applied

in international development settings, but they may also be used to evaluate public

engagement.Each of these approaches requires a clear understanding of the desired

or planned change, ‘long-term outcomes’ or goals that are sought from engagement.

Bothapproaches then help teams to identify the steps that are needed to reach these

goals (including the identication of specic inputs and activities), and help them to

articulate and interrogate the assumptions that lie behind each of these steps in a

change process. Each approach also species milestones and indicators that can be

used to monitor progress towards impacts.

Contribution analysis takes a logic model approach (Morton, 2015). It attempts

to address issues of attribution in evaluation by assembling evidence to validate the

logic model, including an examination of alternative explanations of impact. First, a

pathway to impact is mapped, then assumptions and risks are identied for each stage

of the pathway and impact indicators are identied. Using these indicators, evidence

is collected for each part of the pathway and a ‘contribution story’ is written. In doing

this, contribution analysis attempts to build a credible case about what difference is

being made as a result of public engagement.

Similarly, outcome mapping (Earl et al., 2001) considers how public engagement

might directly inuence the behaviour of individuals, groups and organizations, known

as ‘boundary partners’, recognizing the many factors that are outside the control of

the project. Outcome mapping therefore seeks to understand the contribution made

by a project to impact, rather than claiming denitive attribution. Desired changes in

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 149

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

boundary partners are rst identied, strategies for supporting change are developed

and a monitoring system to track changes is used to evaluate engagement.

Realist evaluation (Pawson et al., 2005) asks what works for whom in what

circumstances and in what respects, and how, using a mixed methods approach,

drawing on quantitative, qualitative, comparative and narrative evidence, as well as

grey literature and the insights of programme staff. The ‘adjudicator’ then evaluates to

what extent the data collected can be used to build or prove a theory of change or a

pattern of outcomes.

The ‘most signicant change’ technique (Davies and Dart, 2005) is a qualitative

and participatory evaluation method that uses stories of change to assess the impact

of public engagement. Rather than measuring indicators, stories are sought about

specic changes that have occurred as a result of engagement, and these stories are

then compared and analysed through multi-stakeholder discussion to decide which

changes are most credible and important.

Finally, it is worth sounding a cautionary note that many of the theories,

assumptions and methods discussed above align closely with the historic ‘public

understanding of science’ movement. There is limited evidence that this movement

increased public acceptance or trust in controversial research applications (such as

genetically modied foods), but it has been credited with opening research activities

up to public scrutiny.

Methods

A literature review, drawing upon peer-reviewed and grey literature, summarized in the

previous section, led to the development of an initial evaluation framework. Arising

from this review were several key principles:

• A reective approach to evaluation that builds it into project planning and

delivery is essential – it should not be left until the end.

• It is helpful to guide people through a set of prompts to encourage them to

make explicit their assumptions about change – and to encourage them to

revisit these.

• It helps to differentiate between inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts as

part of this.

• A ‘logical framework’ approach is particularly helpful in structuring the key

questions/considerations people need to engage with to design and execute

quality evaluation.

QMUL co-authors commissioned the research underpinning this article, and helped

to identify likely users of a toolkit, who could help scope and shape its development.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author with ve QMUL staff

(who are not co-authors on this paper). A purposive sample was selective based on

experience of public engagement, representing a range of disciplines and roles

(professional services, events management, ethics, physics and geography) and levels

of seniority (from PhD student to pro-vice-chancellor). Interview topics included:

discussion of their role and experience of public participation, elements needed in a

public engagement evaluation toolkit, and examples of good practice. Based on these

examples, respondents were asked to identify generalizable good practice principles.

Interviews with QMUL staff were supplemented with an online survey completed by

ten further respondents from other UK universities, who self-identied themselves as

potential users of the toolkit via social media. They were asked a range of questions

150 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

under each of the topics used in the semi-structured interviews, including: the most

valuable resources they drew upon to inform their evaluation of public engagement,

methods and approaches for evaluating public engagement, key challenges for

evaluating public engagement (that the toolkit could address); they were also asked to

identify indicators of successful public engagement.

A thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and open survey questions

was used to rene the conceptual framework and scope the specication of a

public engagement evaluation toolkit. The structure of the toolkit was based on the

conceptual framework, and its purpose and functionality was based on feedback from

the semi-structured interviews.

The toolkit was then trialled at a major UK public engagement festival (the

Festival of Communities, organized by QMUL from 21 May to 4 June 2016 in Tower

Hamlets, London). Evaluation data collected at the festival ranged from qualitative

survey responses and social media commentary to visitor counts and demographics,

and was analysed using qualitative (thematic and content analysis) and quantitative

(descriptive statistics) techniques.

To test its wider applicability, the framework was applied retrospectively to

QMUL’s Research Excellence Framework (REF) impact case studies from 2014, focusing

on those that involved public engagement, and sourced from the HEFCE impact

case study database. Application of the framework to these case studies aimed to

explore how the use of the toolkit could both improve the design of the engagement

processes, and better evidence if and how impacts had been achieved.

Feedback from QMUL festival organizers who trialled the toolkit, and insights

from its application to REF case studies, was used to further rene the toolkit. The

resulting toolkit was then reviewed by public engagement specialists and potential

users from drama, physics and geography at QMUL, and further rened in response to

their feedback.

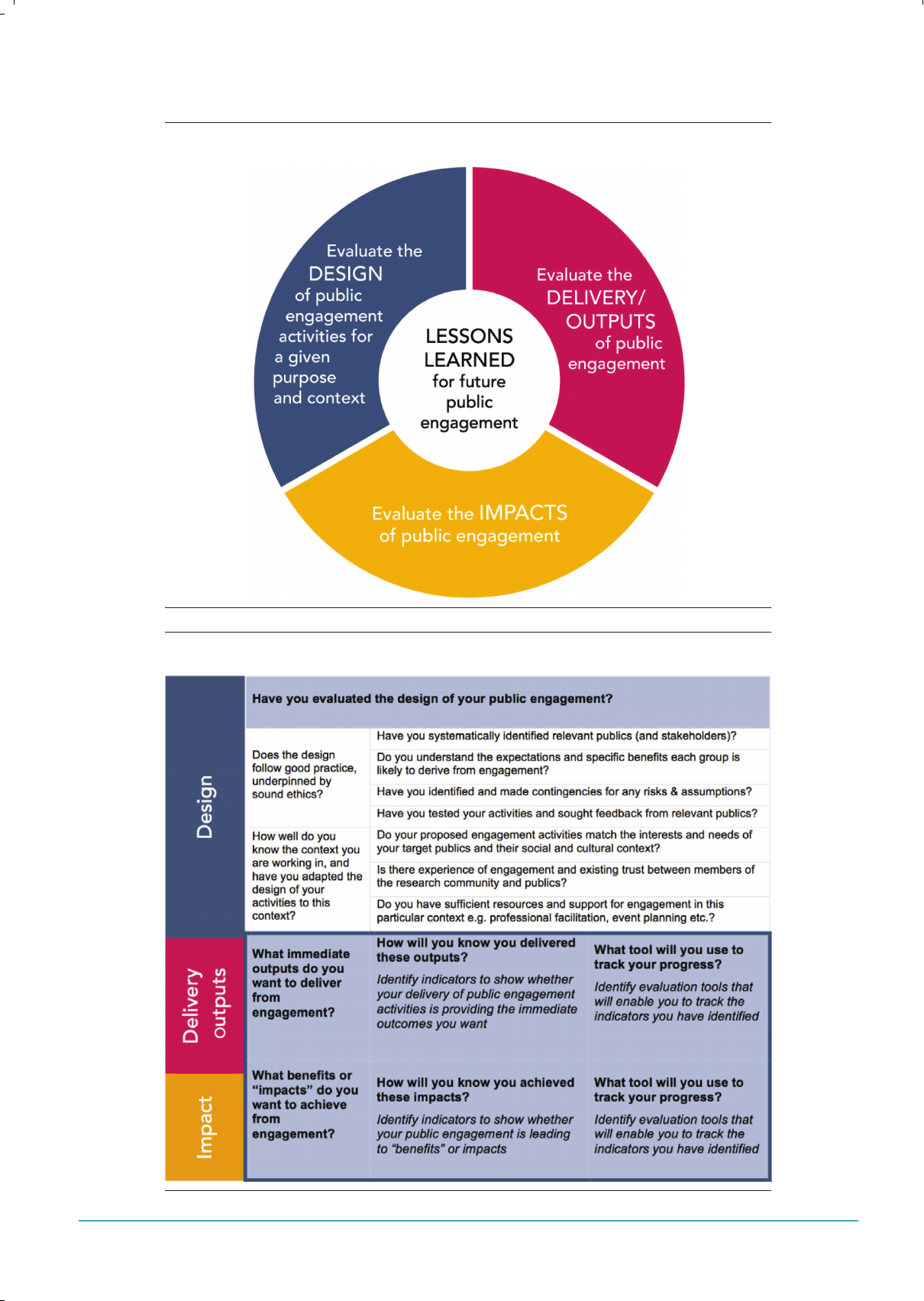

A framework for evaluating public engagement

This section describes a linked conceptual and methodological framework for the

evaluation of public engagement, as it was developed through this research. The

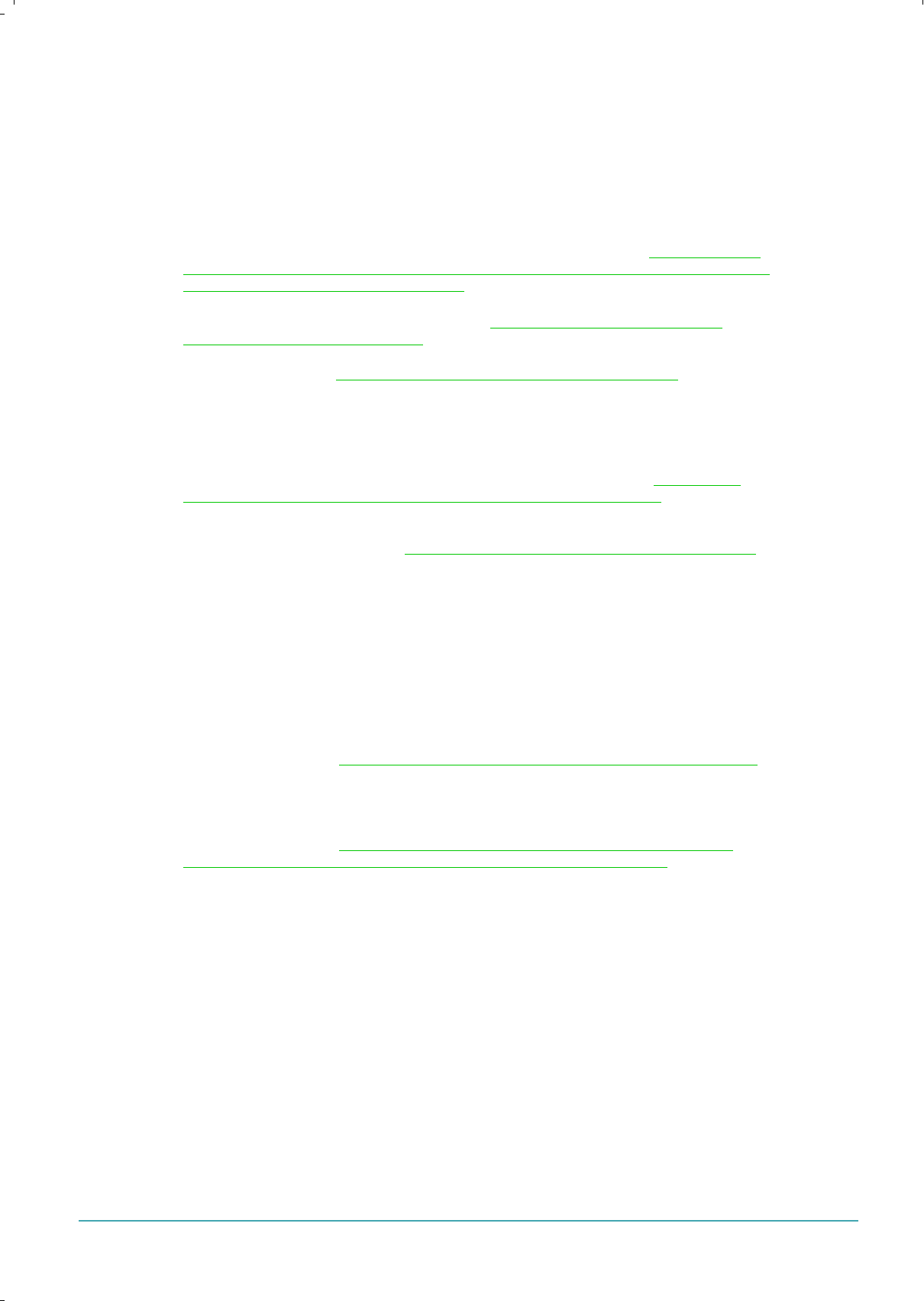

conceptual framework summarizes the three main ways in which evaluation can

provide judgements about, and enhance the effectiveness of, public engagement (see

Figure 1):

1. Evaluate the design of public engagement activities for a given purpose and

context: to what extent is/was the design of the public engagement process and

activities appropriate for the context and purpose of engagement?

2. Evaluate the delivery and immediate outputs of public engagement: to what extent

do/did the delivery of the public engagement process and activities represent

good practice and lead to the intended outputs?

3. Evaluate the impacts of engagement: to what extent do/did engagement activities

lead to planned (or other) benets for target publics and researchers?

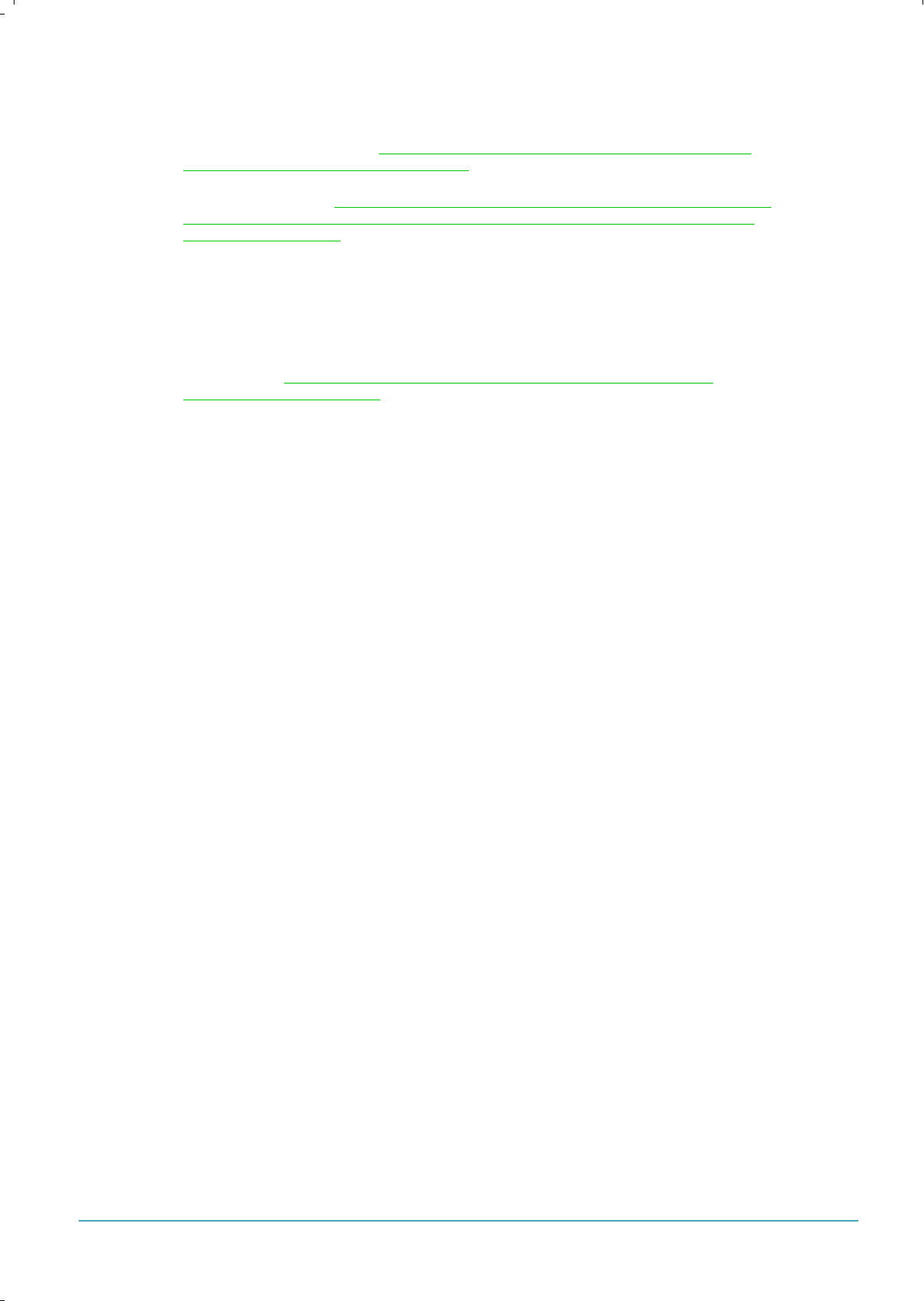

This is then operationalized via a methodological framework, based on a logic model

approach (see Figure 2), as described below.

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 151

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Figure 1: Three ways to evaluate public engagement

Figure 2: Public engagement evaluation planning template

152 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Evaluate the design of public engagement activities

Many of the most common mistakes in public engagement can easily be avoided if

formative evaluation of the design is done at an early stage. It is important to evaluate

the design of planned public engagement against good practice principles, and check

if activities are appropriate to the context and likely to meet intended goals.

As shown in the case study that follows in the next section, using the evaluation

planning template in Figure 2, it is possible to evaluate the design of planned public

engagement:

1. Does the design follow good practice, underpinned by sound ethics and avoid

known issues that commonly lead to failure?

2. Is the design appropriate and relevant for the context in which it is taking place,

including the needs, priorities and expectations of those who take part?

Are any of these factors likely to present challenges for the planned approach to

public engagement? If the evaluation of design is done prior to engagement, it may

be possible to improve the design before delivering the project.

Evaluate the delivery and immediate outputs of public engagement

Public engagement is often assessed in terms of the number and range of people taking

part. However, it is just as important to know about the quality of the engagement:

good delivery of public engagement results in all sorts of positive outputs, and poor-

quality engagement can achieve little, and in some cases make things worse.

Using the evaluation planning template in Figure 2, it is possible to identify

specic outputs that researchers and/or publics would expect to see as a result of

engagement (for example, new learning and awareness, or changes in behaviour).

Then indicators can be identied that would show progress towards these outputs. It

is useful to systematically identify outputs, and associated indicators and tools linked

to each planned engagement activity.

In contrast to most logic models, the proposed standard moves from design to

delivery and outputs, and then impacts (missing outcomes). This was done in response

to feedback from users unfamiliar with evaluation methods, who found it difcult to

understand the difference between outputs, outcomes and impacts. As a result, we

do not provide an academic discussion of the differences between these terms here,

to avoid further confusion given the conceptual overlaps that exist between them.

Instead, we provide explanatory examples of outputs in the case study below, and

accept that this term can be used loosely in practice, without compromising the rigour

of the evaluation.

Evaluate the impacts of engagement

The third way that we are proposing to evaluate public engagement is to focus on the

impacts of engagement. If the goal is to report benets arising from public engagement,

it will be necessary to consider the sorts of impacts that might be expected as a result

of the engagement. Depending on how indirect and long term these impacts are, it

will typically be necessary to include evaluation activities sometime after the original

project is completed (where resources permit). These activities can build on any initial

evaluation to capture longer-term impacts. Although many researchers tend to look

primarily for instrumental impacts, the previous section of this paper has shown other

types of impacts that may arise from public engagement with research.

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 153

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Once impact goals have been identied, it is possible to use the evaluation

planning template in Figure 2 to assign indicators to track progress towards each of

these impacts, using relevant tools.

Collect, analyse and report evaluation data

With an evaluation plan in place, it is now possible to start collecting and analysing

data for each of the selected indicators, using the tools chosen from a menu in the

toolkit. There are almost always opportunities to learn from the experience of doing

public engagement, and an effective evaluation will provide lessons that can enhance

future practice. Larger, longer-term projects can consider how they can improve their

practice using the evaluation planning template in Figure 2. This uses a trafc light

system to colour code each indicator to show if it is ‘on track’ (green), ‘improving’

(amber) or ‘not on track’ (red). The tool has space to record reasons for these

assessments, and what can be done to improve the public engagement approach, or

address unexpected challenges. To enable this, the trafc light system is adapted from

a project management tool, and combined with the three logic model components

(evaluate the design, evaluate the delivery and immediate outcomes, and evaluate the

impacts of engagement) covered in Figure 2.

Results

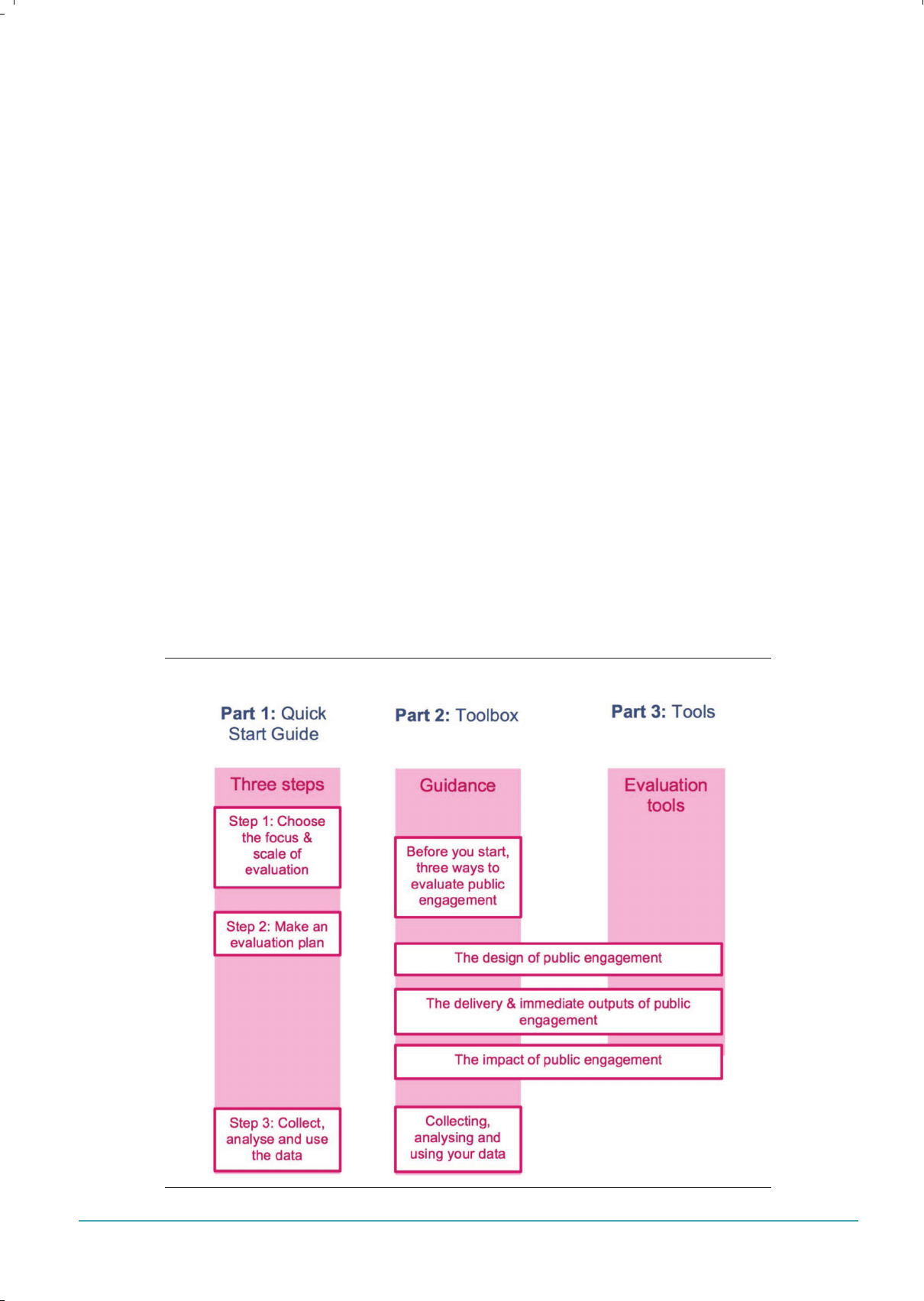

Figure 3 shows the structure and contents of the toolkit that was developed. Figure

4 shows the menu of tools, an example tool and the key to interpret symbols used in

the tool.

Figure 3: Structure and content of the public engagement evaluation toolkit

154 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Figure 4: Menu of tools, an example tool and the key to interpret symbols used

in the tool

Interview ndings

Thematic analysis of data from interviews with QMUL staff showed that those

interviewed perceived formative feedback from evaluation to be more important than

summative feedback, although it was recognized that both would be necessary in the

toolkit that would be developed for them. The perceived importance of formative

feedback was in recognition of its value in enhancing engagement practice during the

engagement process. An emphasis was placed on kinaesthetic evaluation techniques,

for example involving participants placing counters in buckets, sticking shapes on walls

or Post-it notes on 3D shapes to evaluate public engagement activities. Consistent

with concerns raised by the Wellcome Trust (Burchell, 2015), there was a desire for

evaluation techniques that could be used simply and quickly by researchers: ‘pick

up and play’, as one interviewee put it. With this in mind, it was suggested by one

interviewee that it should be possible for non-academic support staff to be able to use

the evaluation toolkit on behalf of researchers. While there was support for a common

evaluation standard that could enable comparison between projects, interviewees also

emphasized the need to be able to select goals, indicators and tools for a wide variety

of purposes and contexts: ‘tools not rules’, as one interviewee put it. For this reason, the

evaluation planning template in Figure 2 was made as open and exible as possible, so

that users can identify unique goals for projects, with appropriate indicators tailored to

measure progress towards those goals. The toolkit does, however, provide suggestions

of methodological tools that can be used to collect data for a range of indicators, and

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 155

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

so monitor progress towards goals. Interviewees wanted to see a mixture of tools that

could provide quantitative and qualitative data. The toolkit is designed to make it easy

to select relevant tools, using an index of tools and/or a graphical key at the start of

each tool. Both the index and graphical key show users which part of the engagement

process the tool is most suited to (for example, evaluating the design of engagement

versus evaluating impact), and the time, expertise and resources likely to be required

in its use.

In situ case study application

Interview ndings were combined with insights from the literature review to create

a draft public engagement evaluation toolkit, which was trialled at a major public

engagement event, the QMUL Festival of Communities, in Tower Hamlets, London.

As part of this, a range of tools were trialled from the toolkit, from each of the three

major sections: evaluating the design of engagement, its delivery and immediate

outputs, and its impact. This was a collaboration between QMUL and local community

organizations aimed at enabling cohesion between different local communities and

fostering long-term relationships between these communities and the university:

• Evaluate the design of public engagement activities: Before running its rst

Festival of Communities in 2016, QMUL evaluated the design of the event using

a focus group with community leaders and academics. Participants discussed

the goals of the festival, target publics, risks and assumptions associated with

planned activities, and whether or not these activities were likely to achieve the

goals of the festival for each of the target publics. Community leaders provided

valuable feedback about contextual factors that may limit the success of the

festival, such as language barriers and objections to noise from surrounding

communities. Where plans were already in place to adapt the design of the

festival to this context, these were communicated to participants (for example,

coordinating the location and timing of noisy activities with the local mosque)

and, where necessary, the design of activities was adapted (for example,

recruiting student volunteers with relevant language skills to assist stallholders).

• Evaluate the delivery and immediate outputs of public engagement: In

QMUL’s Festival of Communities, two evaluation tools were used to assess

progress towards the immediate goal of having engaged a wide range of publics

(many for the rst time). These tools were designed to collect data that could

indicate the balance of participants from different communities, ages, genders

and backgrounds, and the proportion who were engaging with research for the

rst time. Face-to-face surveys were carried out by student volunteers with a

random sample of participants during family ‘fun days’, and questionnaires were

administered at a selection of other festival events. During fun days, participants

received reward cards and could collect stickers (different colours for different

activities) for doing something new, with completed cards being entered in a

prize draw.

• Evaluate the impacts of engagement: The impact goals of the QMUL

Festival of Communities included an increased acceptance of different cultures

within local communities, and to generate long-term relationships between

the university and local communities. Indicators of success for these impacts

included evidence of more positive attitudes towards different cultures and the

university from among community members, and increased engagement with

QMUL (for example, via future events) after the festival. The tools that were used

156 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

to measure progress towards these goals via these indicators were the collation

of comments on social and other media linked to the festival, and a follow-up

survey (pertaining to this and other impacts) with those who signed up for email

updates at the festival and those commenting on the festival via social media.

Attendance at future events will also be monitored, with questions in future

evaluation forms asking about previous engagement with QMUL, including

specic reference to the festival.

• Collect, analyse and report evaluation data: Data collection at the QMUL

Festival of Communities was done by an evaluation team supported by student

volunteers for fun days, and by QMUL event organizers throughout the rest of

the festival. Across the festival, sampling was used to collect data efciently

while representing the widest possible range of public engagement activities.

For example, ve stalls were selected at the fun day to represent the main types

of activities on offer, and visitor counts were conducted in 15-minute periods

spread out across the day, including visual assessments of diversity criteria (for

example, gender and broad age categories). Examples of data analysis from

the QMUL Festival of Communities include content analysis of social media

comments linked to the festival, and quantitative (descriptive statistics) and

qualitative (thematic analysis) analysis of data from questionnaires. Evaluation

ndings are being used to communicate outputs and impacts from the festival to

stakeholders and to shape future festival designs. Formative feedback from the

evaluation has been supplemented via interviews with members of the organizing

team, and used to formulate specic recommendations for improvements that

can be made for future events.

Post-hoc application to other case studies

Finally, the revised toolkit was tested post hoc on a wider range of public engagement

programmes and activities, described in the QMUL REF impact case studies. The

purpose of this step was to test the wider applicability of the evaluation standard, and

test its applicability as a post-hoc tool, not to provide guidance on how to evaluate

public engagement in REF. Of the 77 case studies submitted, 43 referenced keywords

associated with public engagement (as detailed in NCCPE, 2016).

Analysis of these ‘public engagement’-relevant case studies provided insights

into the types of impact claimed through public engagement, which predominantly

focused on enriching public discourse and understanding – often through media

appearances. While there were several case studies where public engagement

played the key role in achieving impact, many included public engagement alongside

substantial policy engagement and/or engagement with practitioners. The public

was primarily referred to as ‘one group’, with few attempts to dene their target

publics. The evidence provided for impact included detailed lists of the number of

outlets, with the size of audience also featuring in many of the case studies. Evidence

was also provided through expert testimonial, and in a few cases through audience

feedback. This is reected in the analysis of the REF case studies completed by the

NCCPE (2016) that illustrated the role of public engagement in creating impacts

relevant to the REF.

The case studies are specically framed around the criteria for the UK’s Research

Excellence Framework (signicance and reach of impacts arising from excellent

research, which were used as criteria in 2014 and will be used again in 2021), and

do not typically provide details about how they evaluated engagement. However, we

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 157

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

can make some assumptions about the evaluation approach based on the evidence

provided in the case study. Retrospectively applying the toolkit principles to these case

studies suggests that evaluation could be strengthened to develop more effective

approaches to public engagement, including more clearly dened aims and a better

understanding of audiences/participants. In addition, the toolkit would enable more

convincing evidence of impact to be assessed, by creating baseline data to assess

progress over time, by better understanding the nature of those participating in the

engagement activities, and by providing approaches to enable researchers to explore

the nature of any change on those engaged.

The analysis of the case studies, albeit limited by the nature of the REF case

studies, suggests that the toolkit can provide a useful framework for evaluating public

engagement, improving engagement practice and evidencing impact (including for

the REF).

Discussion

In its initial form, those who used the draft toolkit in situ found the resulting evaluation

plan too detailed and difcult to follow. In response to this feedback, backed up by

calls from interviewees, all the sections of the evaluation plan that could be completed

by users were removed except for the template in Figure 2, and a cut-down version

of this table was provided in an initial ‘quick-start guide’, providing users with quick

access to basic evaluation planning over two pages.

This feedback, evidence from interviews and literature, and the analysis of the

REF case studies suggests that the quality of engagement practice and the rigour of

impact assessment could be greatly enhanced by investing in evaluation training and

capacity building.

Additionally, the review of the REF case studies identies some particular

challenges arising from the types of engagement currently being practised in higher

education, reinforcing the ndings of the NCCPE’s review of the whole REF case study

sample (NCCPE, 2016). There is a need to evidence more effectively how engagement

through the media actually inspires learning, behaviour change or capacity building.

Most case studies assume that appearing in the media is an impact in itself, and

therefore do not gather further evaluative data showing how ideas from the research

inuenced public discourse. Conceptual impacts were the most common type of

impacts claimed in public engagement-related case studies in REF 2014. However, in

future, consideration could be given to the broader range of impact types that may be

achieved through public engagement.

The process of developing a public engagement evaluation standard has

reinforced a number of messages that have arisen repeatedly in the literature:

• Clarity about the purpose(s) of your planned evaluation is essential (for example,

to inform more effective design or execution of engagement activities, to nd

out what happened as a consequence). The REF case studies illustrated a need

for a more effective approach to evaluation for engagement activities, which

would improve the effectiveness of the activities, and evidence what change has

happened as a result.

• It helps to think ‘systemically’: projects always exist within a wider context. Being

clear about that context and how your project contributes to a wider system is

important in making robust judgements about its effectiveness.

• Usually you are making a ‘contribution’, rather than achieving the impact through

your intervention alone. Several of the REF case studies analysed evidenced

158 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

impact where the direct link between the research and the impact was not clear.

In several of these case studies, it would be interesting to see a wider context

for the impact claimed, with a recognition that this may be a contribution to the

desired change, rather than the only factor in achieving the impact.

• Evaluating public engagement is particularly challenging because its impacts are

often subtle (on understanding, attitudes or values); these are hard to measure

and they change over time, and it is often challenging to isolate the contribution

made by the activity being evaluated. Very few of the REF case studies made any

attempt to evidence long-term impacts arising from public engagement.

• Different disciplinary and practice areas have rather different philosophical,

epistemological and practical frameworks guiding their practice (often implicitly).

These need to be acknowledged – while some fundamental principles cut

across all disciplines, it is important to develop different approaches and ways of

describing evaluation that are ‘tuned in’ to people’s professional contexts and

mindsets. The review of the REF case studies revealed signicant differences

in how researchers in the different panels chose to describe and rationalize

their engagement activities, with those in the sciences usually seeking to raise

public awareness of their research through the media, and those in the arts and

humanities more often working in partnership to weave their public engagement

activity into a more integrated approach to inuencing cultural policy and

practice.

Conclusion

This paper has developed a set of common standards for the evaluation of public

engagement with research, consisting of three ways of evaluating engagement

linked to a logic model. The goal is to provide a framework that explains what should

be considered when evaluating public engagement with research, rather than to

use standard evaluation methods and indicators, given concerns from users and the

literature about the validity of using standard methods or indicators to cover such a

wide range of engagement methods, designs, purposes and contexts. The adoption

of such a standard by funders of public engagement activities could promote more

widespread evaluation of public engagement. In this way, it may be possible to

create an evaluation data repository that could facilitate longitudinal studies and

enable lessons to be drawn for the funding and practice of public engagement

across the sector.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England’s

Higher Education Innovation Fund and the Wellcome Trust’s Institutional Strategic

Support Fund, awarded to Queen Mary University of London. Thanks to Peter McOwan,

Vice Principal (Public Engagement and Student Enterprise) at QMUL who led the

commissioning of this research. Thanks to Gene Rowe for constructive feedback on an

earlier draft of this paper. The project was delivered in partnership with the NCCPE.

Figure design by Anna Sutherland.

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 159

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Notes on the contributors

Mark S. Reed is a transdisciplinary researcher specializing in social innovation, research

impact and stakeholder participation in agri-food systems. He is Professor of Social

Innovation at Newcastle University, and a Visiting Professor at the University of Leeds

and Birmingham City University. He has written more than 130 publications, which have

been cited more than 10,000 times, and does research impact training through his

spin-out company, Fast Track Impact.

Sophie Duncan is Deputy Director of the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public

Engagement. She has over 20 years’ experience of public engagement, including

leading engagement campaigns for the BBC, managing national programmes for

Science Year, and curating exhibitions for the Science Museum, London. Sophie is

committed to the development of high-quality engagement, and the strategic use of

evaluation to improve and evidence practice. She is co-editor of Research for All.

Paul Manners is Associate Professor in Public Engagement at UWE Bristol and director

of the UK’s National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE).Before

founding the NCCPE, Paul trained as a secondary English teacher and, after teaching

for ve years, joined the BBC, where his credits include the long-running BBC2 series

Rough Science and a variety of national learning campaigns.

Diana Pound is a participation expert and founding director of Dialogue Matters.

She has two decades’ experience designing and facilitating environmental dialogue

in research or resource management, at local to international levels and in over 25

countries. She researches good practice, advises governments, UN conventions and

other organizations, has trained about 2,000 people in good practice and won the

2015 CIEEM Best Practice award.

Lucy Armitage is a senior facilitator and trainer for Dialogue Matters. She has

facilitated dialogue in research and resource management contexts, including in

tense and difcult situations. On behalf of Dialogue Matters she is a trainer for the

British Council’s internationally esteemed Researcher Connect course, and has trained

researchers in the UK, China and Brazil.

Lynn Frewer is Professor of Food and Society in the School of Natural and Environmental

Sciences at Newcastle University in the UK. Previously Lynn was Professor of Food

Safety and Consumer Behaviour at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. Lynn

has worked at the Institute of Food Research (Norwich and Reading), the Institute of

Psychiatry in London and the University of Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea. She has

interests in transdisciplinary research focused on food security.

Charlotte Thorley is a freelance public engagement specialist and researcher based

in Brussels. From 2012–16 she established the nationally recognized Centre for Public

Engagement at Queen Mary University of London, as well as undertaking her doctoral

research exploring the role of the scientist in engagement activities.She is Honorary

Senior Research Associate at the UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

Bryony Frost has spent several years working in science communication and public

engagement. After studying for a physics degree and an MSc in science communication

at Imperial College London, Bryony has worked at Queen Mary University of London in

several roles, including as an outreach ofcer and in the Centre for Public Engagement,

where she worked on support and advice, training and evaluation.

160 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

References

Arnstein, S.R. (1969) ‘A ladder of citizen participation’. Journal of the American Institute of Planners,

35 (4), 216–24.

Belore, E. and Bennett, O. (2010) ‘Beyond the “toolkit approach”: Arts impact evaluation research

and the realities of cultural policy‐making’. Journal for Cultural Research, 14 (2), 121–42.

BIS (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) (2010) The Public Engagement Triangle

(Science for All – Public Engagement Conversational Tool Version 6). Online. http://webarchive.

nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121205091100/http:/scienceandsociety.bis.gov.uk/all/les/2010/10/pe-

conversational-tool-nal-251010.pdf (accessed 4 October 2017).

Bultitude, K. (2014) ‘Science festivals: Do they succeed in reaching beyond the “already engaged”?’

Journal of Science Communication, 13 (4). Online. https://jcom.sissa.it/sites/default/les/

documents/JCOM_1304_2014_C01.pdf (accessed 2 November 2017).

Burchell, K. (2015) Factors Affecting Public Engagement by Researchers.London: Policy

Studies Institute. Online. https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/les/wtp060036.pdf (accessed

2 November 2017).

Davies, H., Nutley, S. and Walter, I. (2005) ‘Assessing the impact of social science research:

Conceptual, methodological and practical issues’. Background discussion paper for the ESRC

Symposium on Assessing Non-Academic Impact of Research, London, 12–13 May 2005.

Davies, M. and Heath, C. (2013) Evaluating Evaluation: Increasing the impact of summative

evaluation in museums and galleries. London: King’s College London. Online. http://visitors.

org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2004/01/EvaluatingEvaluation_November2013.pdf (accessed

4 October 2017).

Davies, R. and Dart, J. (2005) The “Most Signicant Change” (MSC) Technique: A guide to its use.

London: CARE International. Online. www.kepa./tiedostot/most-signicant-change-guide.pdf

(accessed 4 October 2017).

De Vente, J., Reed, M.S., Stringer, L.C., Valente, S. and Newig, J. (2016) ‘How does the context

and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from

sustainable land management in global drylands’. Ecology and Society, 21 (2). Online. www.

ecologyandsociety.org/vol21/iss2/art24/ (accessed 2 November 2017).

Earl, S., Carden, F. and Smutylo, T. (2001) Outcome Mapping: Building learning and reection into

development programs. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

Emery, S.B., Mulder, H.A.J. and Frewer, L.J. (2015) ‘Maximizing the policy impacts of public

engagement: A European study’. Science, Technology, and Human Values, 40 (3), 421–44.

ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) (2009) Taking Stock: A summary of ESRC’s work

to evaluate the impact of research on policy and practice. Swindon: Economic and Social

Research Council. Online. www.esrc.ac.uk/les/research/evaluation-and-impact/taking-stock-a-

summary-of-esrc-s-work-to-evaluate-the-impact-of-research-on-policy-and-practice (accessed

4 October 2017).

ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council) (2011) Branching Out: New directions in

impact evaluation from the ESRC’s Evaluation Committee. Swindon: Economic and Social

Research Council. Online. www.esrc.ac.uk/les/research/evaluation-and-impact/branching-

out-new-directions-in-impact-evaluation-from-the-esrc-s-evaluation-committee/ (accessed

4 October 2017).

European Commission (2015) Indicators for Promoting and Monitoring Responsible Research and

Innovation: Report from the Expert Group on Policy Indicators for Responsible Research and

Innovation. Brussels: European Commission.

Facer, K. and Enright, B. (2016) Creating Living Knowledge: The Connected Communities

Programme, community–university relationships and the participatory turn in the production of

knowledge. Bristol: AHRC Connected Communities Programme.

Fazey, I., Bunse, L., Msika, J., Pinke, M., Preedy, K., Evely, A.C., Lambert, E., Hastings, E., Morris, S.

and Reed M.S. (2014) ‘Evaluating knowledge exchange in interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder

research’. Global Environmental Change, 25, 204–20.

Fazey, I., Evely, A.C., Reed, M.S., Stringer, L.C., Kruijsen, J., White, P.C.L., Newsham, A., Jin, L.,

Cortazzi, M., Phillipson, J., Blackstock, K., Entwistle, N., Sheate, W., Armstrong, F., Blackmore,

C., Fazey, J., Ingram, J., Gregson, J., Lowe, P., Morton, S. and Trevitt, C. (2013) ‘Knowledge

exchange: A review and research agenda for environmental management’. Environmental

Conservation, 40 (1), 19–36.

Gasper, D. (2000) ‘Evaluating the “logical framework approach” towards learning-oriented

development evaluation’.Public Administration and Development,20 (1),17–28.

A common standard for the evaluation of public engagement with research 161

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Hart, A., Northmore, S. and Gerhardt, C. (2009) Auditing, Benchmarking and Evaluating Public

Engagement. Bristol: National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement.

HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England) (2006) Beacons for Public Engagement:

Invitation to apply for funds. Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England. Online.

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100202100434/http:/www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/

hefce/2006/06_49/06_49.pdf (accessed 4 October 2017).

HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England) (2016) ‘REF impact: Policy guide’. Online.

www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/REFimpact/ (accessed 4 October 2017).

Hooper-Greenhill, E., Dodd, J., Moussouri, T., Jones, C., Pickford, C., Herman, C., Morrison, M.,

Vincent, J. and Toon, R. (2003) Measuring the Outcomes and Impact of Learning in Museums,

Archives and Libraries. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries. Online. https://

www2.le.ac.uk/departments/museumstudies/rcmg/projects/lirp-1-2/LIRP%20end%20of%20

project%20paper.pdf/view (accessed 4 October 2017).

Meagher, L.R. (2013) Research Impact on Practice: Case study analysis. Swindon: Economic and

Social Research Council. Online. www.esrc.ac.uk/les/research/evaluation-and-impact/research-

impact-on-practice (accessed 4 October 2017).

Molas-Gallart, J., Tang, P. and Morrow, S. (2000) ‘Assessing the non-academic impact of grant-

funded socio-economic research: Results from a pilot study’. Research Evaluation, 9 (3), 171–82.

Morrin, M., Johnson, S., Heron, L. and Roberts, E. (2011) Conceptual Impact of ESRC Research:

Case study of UK child poverty policy. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council.

Morris, Z.S., Wooding, S. and Grant, J. (2011) ‘The answer is 17 years, what is the question:

Understanding time lags in translational research’. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine,

104 (12), 510–20.

Morton, S. (2015) ‘Progressing research impact assessment: A “contributions” approach’. Research

Evaluation 24 (4), 405–19.

NCCPE (National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement) (2016) Reviewing the REF impact

case studies and templates: The role of public engagement with research.

NCCPE (National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement) (2017a) ‘Evaluating public

engagement’. Online. www.publicengagement.ac.uk/plan-it/evaluating-public-engagement

(accessed 4 October 2017).

NCCPE (National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement) (2017b) ‘Why engage? Deciding

the purpose of your engagement’. Online. www.publicengagement.ac.uk/plan-it/why-engage

(accessed 4 October 2017).

Neresini, F. and Bucchi, M. (2011) ‘Which indicators for the new public engagement activities?

An exploratory study of European research institutions’. Public Understanding of Science,

20 (1), 64–79.

Nutley, S.M., Walter, I. and Davies, H.T.O. (2007) Using Evidence: How research can inform public

services. Bristol: Policy Press.

Parry, S., Faulkner, W., Cunningham-Burley, S. and Marks, N.J. (2012) ‘Heterogeneous agendas

around public engagement in stem cell research: The case for maintaining plasticity’. Science

and Technology Studies, 25 (2), 61–80.

Patton, M.Q. (1987) Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G. and Walshe, K. (2005) ‘Realist review: A new method of

systematic review designed for complex policy interventions’. Journal of Health Services

Research and Policy, 10 (Supplement 1), 21–34.

Pearce, J., Pearson, M. and Cameron, S. (2007) The Ivory Tower and Beyond: Bradford University at

the heart of its communities: Bradford University’s REAP approach to measuring its community

engagement. Bradford: University of Bradford.

Quinn, R.E. and Cameron, K.S. (eds) (1988) Paradox and Transformation: Toward a theory of change

in organization and management. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Reed, M.S. (2016) The Research Impact Handbook. Huntly: Fast Track Impact.

Reed, M.S., Vella, S., Sidoli del Ceno, J., Neumann, R.K., de Vente, J., Challies, E., Frewer, L. and van

Delden, H. (2017) ‘A theory of participation: What makes stakeholder and public participation in

environmental management work?’ Restoration Ecology.

Rowe, G. and Frewer, L.J. (2005) ‘A typology of public engagement mechanisms’. Science,

Technology, and Human Values, 30 (2), 251–90.

Rowe, G., Horlick-Jones, T., Walls, J. and Pidgeon, N. (2005) ‘Difculties in evaluating public

engagement initiatives: Reections on an evaluation of the UK “GM Nation?” public debate

about transgenic crops’. Public Understanding of Science, 14 (4), 331–52.

162 Mark S. Reed et al.

Research for All 2 (1) 2018

Sciencewise (2015) Evaluating Sciencewise Public Dialogue Projects (SWP07). Harwell: Sciencewise

Expert Resource Centre. Online. www.sciencewise-erc.org.uk/cms/assets/Uploads/Evaluation-

docs/SWP07-Evaluating-projects-22April15.pdf (accessed 4 October 2017).

Smithies, R. (2011) A Review of Research and Literature on Museums and Libraries. London: Arts

Council England. Online. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160204121949/http://www.

artscouncil.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/browse-advice-and-guidance/museums-and-libraries-

research-review (accessed 4 October 2017).

Stufebeam, D.L. (1968) Evaluation as Enlightenment for Decision-Making. Columbus: Ohio State

University Evaluation Center.

Stufebeam, D.L. (2001) Evaluation Models (New Directions for Evaluation 89). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Vargiu, A. (2014) ‘Indicators for the evaluation of public engagement of higher education

institutions’. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5 (3), 562–84.

Warburton, D. (2008) Deliberative Public Engagement: Nine principles. London: National Consumer

Council. Online. www.involve.org.uk//wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Deliberative-public-

engagement-nine-principles.pdf (accessed 4 October 2017).

Wilsdon, J. and Willis, R. (2004)See-through Science: Why public engagement needs to move

upstream. London: Demos.

Wynne, B. (2006) ‘Public engagement as a means of restoring public trust in science: Hitting the

notes, but missing the music?’ Community Genetics, 9 (3), 211–20.