Radiological Habits Survey

Rosyth 2015

Public Report

Report Date: October 2016

1

Radiological Habits Survey: Rosyth 2015

Authors and Contributors:

A. Tyler, A. Watterson, I. Dale, L. Evans, A. Varley, V. Peredo-Alverez, D. Copplestone, S.

Bradley, B. Shaw, P. Smith, M. Clarke, P. Bartie and P. Hunter

Occupational and Environmental Health

Environmental Radioactivity Laboratory

&

1

Contents

Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5

List of abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 9

Units ..................................................................................................................................... 9

1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 10

1.1 Regulatory Context ............................................................................................... 10

1.2 Definition of the Representative Person................................................................ 10

1.3 Dose Limits and Constraints ................................................................................. 11

1.4 Survey Aim ........................................................................................................... 11

2 Rosyth Survey Area..................................................................................................... 13

2.1 Rosyth Site Location and History.......................................................................... 13

2.1.1 Current Activity .............................................................................................. 13

2.1.2 Changes since 2010...................................................................................... 15

2.2 Estimated Activity Concentrations from Licensed Discharges from Rosyth........... 16

2.3 Survey Area.......................................................................................................... 17

2.4 Land Cover Data................................................................................................... 19

2.5 Soil Data............................................................................................................... 20

2.6 Crop Production.................................................................................................... 20

3 Methods....................................................................................................................... 23

3.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 23

3.2 Postal Survey........................................................................................................ 23

3.3 Radiometric Surveys............................................................................................. 26

3.3.1 In Situ Dosimetry ........................................................................................... 26

3.3.2 Beta Dosimetry.............................................................................................. 27

3.3.3 Sampling........................................................................................................ 27

3.3 GPS Tracking ....................................................................................................... 27

3.4 Conduct of the Survey .......................................................................................... 27

3.5 Meetings, Informal Contacts and Focus Groups ................................................... 28

3.6 Data Conversion................................................................................................... 29

3.7 Data Rounding and Grouping ............................................................................... 29

3.8 Qualitative and Quantitative Observation.............................................................. 31

3.9 Dose Assessment Tool......................................................................................... 31

4 Survey Site Introduction............................................................................................... 33

4.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 33

4.2 Survey Area Descriptions...................................................................................... 33

4.3 Site Descriptions for the Firth of Forth Northern Shore.......................................... 33

2

4.3.1 Kincardine...................................................................................................... 33

4.3.2 Culross .......................................................................................................... 34

4.3.3 Preston Island, Torry Bay and Crombie Point ................................................ 35

4.3.4 Charlestown................................................................................................... 37

4.3.5 Limekilns........................................................................................................ 38

4.3.6 Rosyth ........................................................................................................... 39

4.3.7 North Queensferry ......................................................................................... 40

4.3.8 Inverkeithing .................................................................................................. 41

4.3.9 St David’s Harbour and Dalgety Bay.............................................................. 42

4.3.10 Aberdour........................................................................................................ 44

4.3.11 Silversands.................................................................................................... 45

4.3.12 Burntisland..................................................................................................... 46

4.3.13 Kinghorn Harbour Beach and Pettycur........................................................... 48

4.4 Site Descriptions for the Firth of Forth Southern Shore......................................... 50

4.4.1 Bo’ness.......................................................................................................... 50

4.4.2 Carriden......................................................................................................... 51

4.4.3 Blackness ...................................................................................................... 52

4.4.4 Society Point.................................................................................................. 53

4.4.5 Port Edgar and South Queensferry................................................................ 54

4.4.6 Hound Point................................................................................................... 55

4.4.7 Cramond........................................................................................................ 56

4.4.8 Granton.......................................................................................................... 57

4.4.9 Newhaven...................................................................................................... 58

5 Aquatic Radiation Pathways ........................................................................................ 59

5.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 59

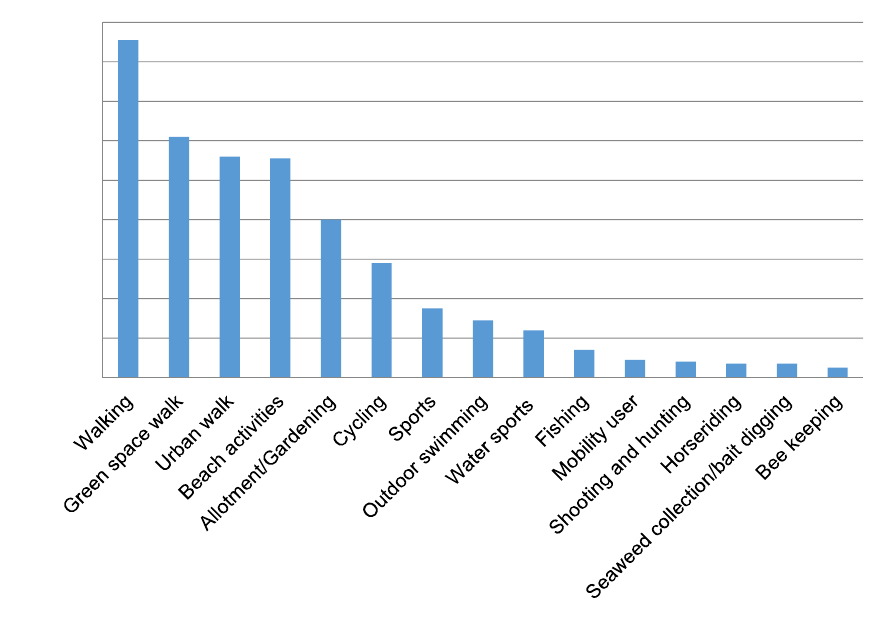

5.2 Postal Survey Results........................................................................................... 59

5.2.1 Internal exposure........................................................................................... 61

5.2.2 External Exposure ......................................................................................... 62

5.3 Commercial fisheries ............................................................................................ 63

5.4 Seafood operations............................................................................................... 63

5.5 Fishing and Angling .............................................................................................. 64

5.6 Wildfowling ........................................................................................................... 64

5.7 Pleasure Craft using the Firth of Forth .................................................................. 65

5.8 Other Pathways .................................................................................................... 66

5.8.1 Wild Swimmers.............................................................................................. 66

5.8.2 Rowing........................................................................................................... 67

5.8.3 Professional Dog Walkers.............................................................................. 67

3

5.8.4 Ramblers ....................................................................................................... 67

5.8.5 Animals Grazing ............................................................................................ 67

5.8.6 Bridge Building............................................................................................... 68

5.9 Internal Exposure.................................................................................................. 68

5.9.1 Adults’ Consumption Rates............................................................................ 68

5.9.2 Children and Infant Consumption Rates......................................................... 70

5.10 External Exposure................................................................................................. 71

6 Terrestrial Radiation Pathways .................................................................................... 74

6.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 74

6.2 Postal Survey Results........................................................................................... 74

6.2.1 Internal Exposure.......................................................................................... 74

6.2.2 Outdoor Activities........................................................................................... 77

6.3 GPS Survey Results ............................................................................................. 77

6.4 Private Food Production........................................................................................ 77

6.4.1 Allotments and Community Gardens.............................................................. 77

6.4.2 Use of Seaweed as a soil conditioner ............................................................ 79

6.5 Other Pathways .................................................................................................... 80

6.5.1 Production of Honey ...................................................................................... 80

6.6 Internal Exposure.................................................................................................. 81

6.6.1 Internal Exposure Adult Consumption Rate ................................................... 81

6.6.2 Children and Infant’s Consumption Rates...................................................... 83

7 Direct Radiation Exposure ........................................................................................... 84

7.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 84

7.2 Mobile Gamma Spectrometry Survey.................................................................... 84

7.2.1 Survey Area................................................................................................... 84

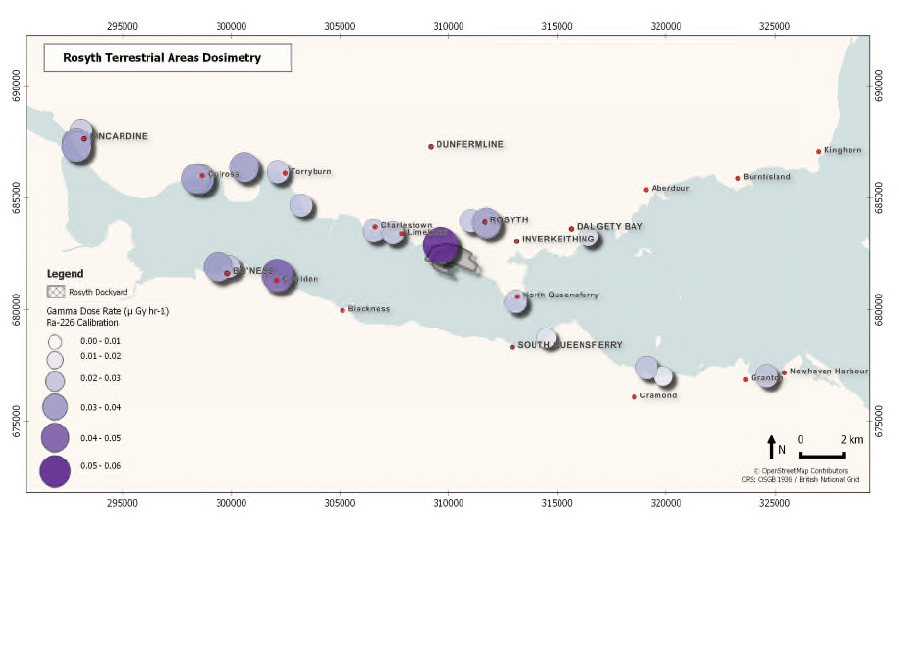

7.3 In-Situ Gamma Dosimetry..................................................................................... 85

7.3.1 Terrestrial Areas ............................................................................................ 85

7.3.2 Intertidal areas............................................................................................... 87

7.4 In-Situ Beta Dosimetry.......................................................................................... 89

7.5 Sample Analyses.................................................................................................. 89

7.6 Occupancy levels.................................................................................................. 90

7.6.1 Occupancy data for the survey area .............................................................. 90

7.6.2 Occupancy rates within 1km of BRS (inside/outside work or home)............... 91

8 Doses to the Representative Person............................................................................ 93

8.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 93

8.2 Aquatic Radiation Pathways ................................................................................. 93

8.2.1 Internal exposure ................................................................................................ 93

4

8.2.2 External exposure.......................................................................................... 93

8.3 Terrestrial radiation pathways............................................................................... 94

8.3.1 Internal exposure........................................................................................... 94

8.3.2 External exposure.......................................................................................... 94

8.4 Overall combined radiation exposure......................................................................... 95

8.4.1 Total exposure (excluding direction shine on site).......................................... 95

8.4.2 With direct shine including from onsite sources.............................................. 95

9 Comparisons with the previous survey......................................................................... 97

9.1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 97

9.2 Aquatic Survey...................................................................................................... 97

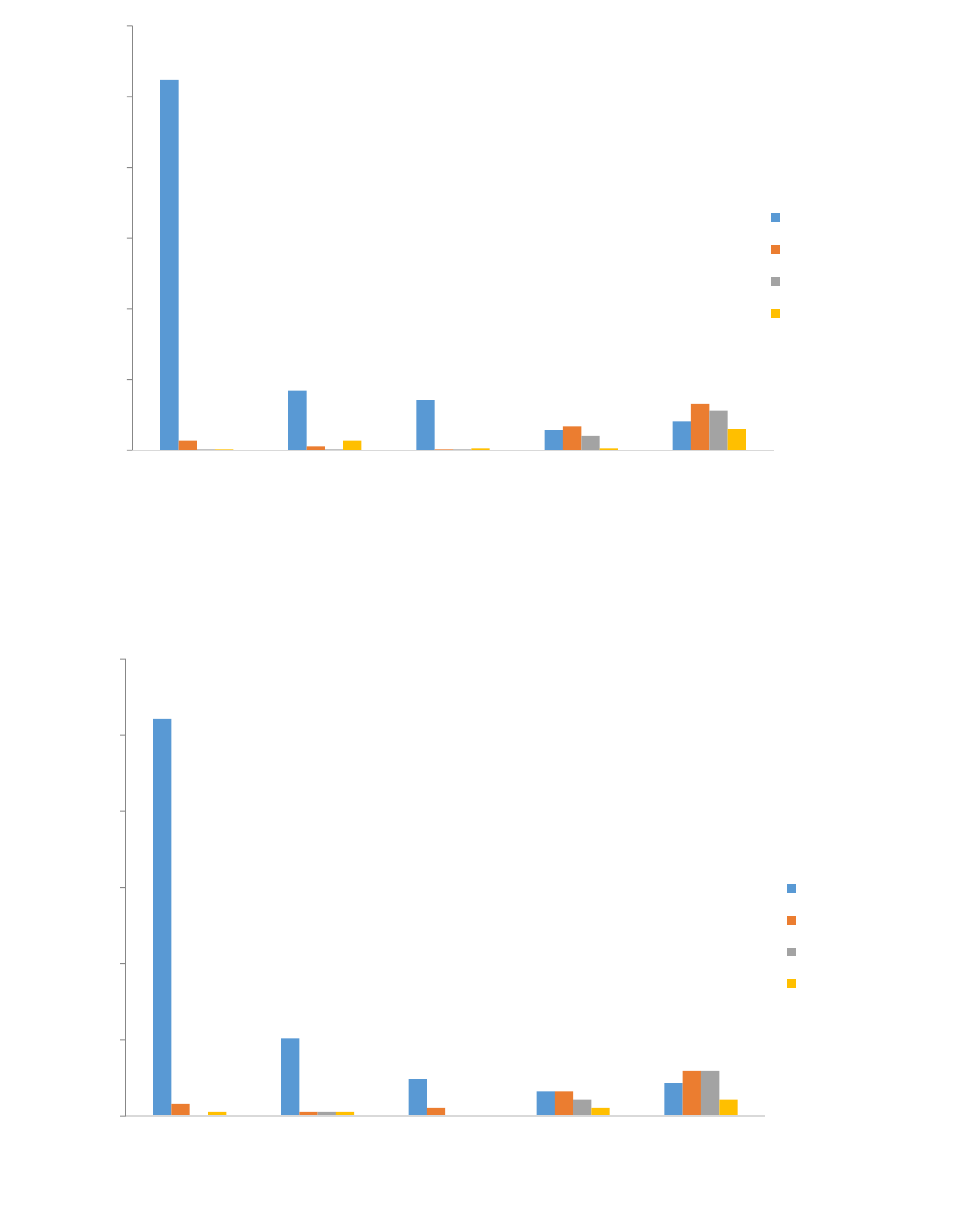

9.2.1 Postal Survey: Internal Exposure................................................................... 97

9.2.2 Postal Survey: External Exposure.................................................................. 97

9.2.3 Face-to-Face: Adult Consumption Rates - Internal Exposure......................... 97

9.2.4 Face-to-Face: Children and Infants’ Consumption Rates - Internal Exposure 98

9.2.5 Face-to-Face: Adults Intertidal Occupancy - External Exposure .................... 99

9.2.6 Face-to-face: Children and Infants Intertidal Occupancy - External Exposure

100

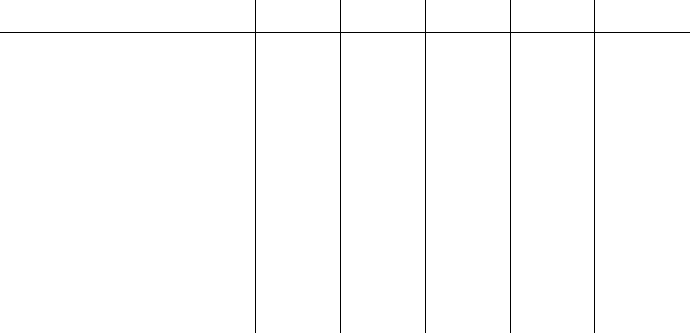

9.3 Terrestrial Survey................................................................................................ 101

9.3.1 Postal Survey: Internal Exposure................................................................. 101

9.3.2 Postal Survey: External Exposure................................................................ 101

9.3.3 Face-to-Face: Adult Consumption Rates - Internal Exposure....................... 101

9.3.4 Face-to-Face: Children and Infants Consumption Rates - Internal Exposure102

9.4 Direct Radiation Survey........................................................................................... 103

10 Recommendations and Suggestions for Monitoring Programme Changes................... 104

10.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 104

10.2 Conclusions and Recommendations ............................................................... 104

References ....................................................................................................................... 106

5

Summary

This report presents the results of the 2015 survey to determine the habits and consumption

patterns of people living and undertaking recreational activities in the vicinity of the Babcock

Rosyth Site (BRS). The site is authorised to discharge gaseous radioactive waste in addition

to the discharge of liquid radioactive waste through an outfall into the Firth of Forth. Sources

of direct radiation are also found at this site.

The survey targeted three areas that were likely to be affected by discharges from the site,

defined as;

The aquatic survey area; covering the Firth of Forth from Kincardine Bridge in the

west to Kinghorn in the east

The terrestrial survey area; extending 5 km from the centre of the Active Waste

Accumulation Facility

The direct radiation survey area; extending 1 km from the centre of the Active Waste

Accumulation Facility

During the survey, a number of potential exposure pathways were investigated through

postal and face-to-face surveys; the consumption of foods produced within the terrestrial

survey area; occupancy of terrestrial areas and within the direct radiation survey area;

consumption of aquatic food from within the aquatic survey area; occupancy of aquatic and

intertidal areas; handling of equipment used within the aquatic survey area.

Interviews with members of the public were carried out over a period of 14 days and data for

528 individuals are presented and discussed. Those high-rate individuals are identified using

established methods comprising a ‘cut-off’ to define the high-rate group and 97.5

th

percentiles for dose assessment analysis.

The aquatic survey area

Two commercial fishing boats within the survey area fished for brown and velvet crabs and

also lobster.

Fish, crustaceans, molluscs and wildfowl were all consumed by adults. The mean

consumption rates for adult high-rate groups for each of these food groups were:

109 kg y

-1

for fish (bass, cod, mackerel, salmon)

31 kg y

-1

for crustaceans (common lobster)

16 kg y

-1

for molluscs (mussel)

26 kg y

-1

for wildfowl (sourced out with survey area)

6

One child was found to consume 1 kg y

-1

of fish and one infant was found to consume 7.8 kg

y

-1

of fish and 15.6 kg y

-1

of molluscs.

No consumption of marine plants or algae was identified.

Aquatic activities included sea angling, freshwater angling, boat maintenance, being on a

dive boat, canoeing, commercial fishing, commute via boat, diving, jet skiing, paddling,

rowing, safety boat duties, sailing, sports fishing, sub-aqua diving, swimming, power boating,

water skiing, and working on a boat and the Forth Road Bridge.

Intertidal activities included bait digging, beachcombing, boat maintenance, collecting

mussels, razor clams, seaweed or winkles, crabbing, handling creels, dog walking, fixing

moorings, horse riding, paddling, playing, research/educational purposes, rock pooling and

wildfowling. The activities found for adults involving the handling or maintenance of

equipment included boats and boating equipment, clothes and overalls, diving gear, fishing

gear, swimming gear.

The mean rates for the adult high-rate group for occupancy within the aquatic survey area

were:

2664 h y

-1

for intertidal activities

106 h y

-1

for activities in the water

2969 h y

-1

activities on the water

1460 h y

-1

handling equipment

A total of 37 in-situ gamma dose rate measurements were made over intertidal surfaces.

Also, beta dosimetry of skin dose was measured over objects and clothing immersed within

the Firth of Forth.

The terrestrial survey area

The mean consumption rates for the high-rate groups for terrestrial foods were:

68.3 kg y

-1

green vegetables

38.7 kg y

-1

root vegetables

46 kg y

-1

potatoes

38.7 kg y

-1

domestic fruit

20.8 kg y

-1

beef

10.6 kg y

-1

poultry

7

No consumption of locally produced milk, eggs, game, sheep meat, wild fruit or honey was

identified. A total of 46 gamma dose rate measurements were taken in terrestrial

environments.

The direct radiation survey area

The highest occupancy rates in the direct radiation area were as follows:

5110 h y

-1

for the total occupancy rate (for a resident)

3650 h y

-1

for the indoor occupancy rate (for a resident)

1460 h y

-1

for the outdoor occupancy rate (for a resident)

A significant portion of the direct radiation survey area was surveyed by car-borne gamma

spectrometry.

Comparisons with previous surveys

The results of the 2015 Rosyth habits survey were compared with the last habits survey

carried out at Rosyth in 2010.

In the aquatic survey area, the overall mean consumption rate for the adult high-rate group

for fish, crustaceans, molluscs and wildfowl increased in 2015 compared to 2010. The main

species of fish consumed by adults were mackerel and cod in 2010 compared with

mackerel, salmon and cod in 2015. The main crustaceans consumed by adults in 2010 were

brown crab and common lobster, this remained the same in 2015. In 2010 the only molluscs

consumed by adults were winkles compared with mussels in 2015.

The only fish species consumed by children was mackerel (self-caught in the Forth) in 2015

and fish consumed by infants were cod and salmon. The same infant also consumed

mussels in 2015.

The handling of aquatic equipment was found to be lower in 2015 compared to 2010 and

activities included boat maintenance, handling clothes and overalls, diving gear, fishing gear

and outdoor swimming gear.

Consumption rates increased in the 2015 survey in the vegetables (green) food group in

comparison to the 2010 survey. Consumption rates decreased in the 2015 survey in the

following food groups: vegetables (root), vegetables (potatoes), fruit (domestic), meat (beef)

and meat (poultry) in comparison to the 2010 survey. Eggs, rabbit/hare and wild fungi were

not identified in 2010 or 2015. Locally produced milk, pig meat or fresh water fish were not

identified as being consumed in 2010 compared to one person identified in 2015 who

consumed fresh water brown trout from within the survey area.

8

In 2015 the total occupancy, highest indoor occupancy and highest outdoor occupancy

decreased from 2010.

Suggestions for changes to the monitoring programme

The following suggestions for changes to the current environmental monitoring programme

are provided for consideration;

Gamma dose rates should be reported as terrestrial gamma dose rates.

Include mussels within routine monitoring especially from North Queensferry

Harbour.

9

List of abbreviations

AWAF- Active Waste Accumulation Facility

BRS - Babcock Rosyth Site

BSS - Basic Safety Standards

CEFAS – Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture

DCC - Dose conversion coefficient

FCYC - Forth Corinthians Yacht Club

GPS - Global positioning system

HP laundry – Health Physics Laundry

HSE - Health and Safety Executive

ICRP - International Commission on Radiological Protection

ILW – Intermediate Level Waste

MoD - Ministry of Defence

NDAWG – National Dose Assessment Working Group

ONR - Office for Nuclear Regulation

QE - Queen Elizabeth

RIFE - Radioactivity in Food and the Environment

RSA - Radioactive Substances Act 1993

SCAPE - Scottish Coastal Archaeology and the Problem of Erosion

SEPA - Scottish Environment Protection Agency

SMoGSS – Mobile Gamma Spectrometry System

Units

Bq - becquerel g - gram

Gy - gray h

-1

- per hour

kg

-1

- per kilogram l

-1

- per litre

µSv - microsievert mSv - millisievert

y

-1

- per year MBq - mega becquerel

10

1 Introduction

1.1 Regulatory Context

The Babcock Rosyth Site (BRS) holds an extant authorisation under the Radioactive

Substances Act 1993 (RSA ’93) to dispose of radioactive waste. The impact of these

disposals needs to be monitored under the requirements of Article 35 of the Basic Safety

Standards (BSS) 96/29 Euratom and to ensure that the doses to the representative person

are within the 1 mSv whole body dose limit and 50 mSv skin dose limit. There are three

primary pathways that may result in the exposure of the public: discharges to the aquatic

environment; discharges to the atmosphere; and direct exposure from the site. Thus,

members of the public may be exposed directly from radiation shine from the licensed site or

through inhalation, and/or indirectly due to exposure to contaminated materials, primarily

foodstuffs (Smith and Jones, 2003). It is also recognised that enhanced doses from external

exposure due to regulated discharges and the consumption of locally sourced foods may

occur as a result of contemporary and historical discharges being concentrated through

natural processes leading to environments with elevated concentrations of anthropogenic

and technological enhanced radioactivity (Dale et al., 2008; Tyler et al., 2013; Tyler et al.,

2009; Tyler et al., 2006). It is the responsibility of the Scottish Environment Protection

Agency (SEPA) to regulate the discharges from site ensuring the public is appropriately

protected. Exposure to direct shine from nuclear, radiation or waste facilities from the

nuclear licensed site at Rosyth is the responsibility of the Office for Nuclear Regulation

(ONR) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) where any direct exposure impacts on

facility workers.

1.2 Definition of the Representative Person

The optimal approach for assessing doses to the public is through a combination of site

specific habit data (to determine occupancy and local food consumption rates) and an

environmental monitoring programme (to determine ambient dose rates and concentrations

in foodstuffs). The actual dose received by an individual is dependent upon age, size, sex

and metabolism in addition to the various interactions they may have with sources of

exposure. Thus, the accepted approach is to identify and consider these sources of

variability in appropriate groups. The concept of the representative person was introduced

by ICRP (2006) and recommended to replace the previously used concept of the critical

group in 2007 (ICRP, 2007). The representative person is the individual that represents the

more highly exposed members of the public and is typically defined by a cut-off, for example

the top 97.5 % of the dose distribution within one or more routes of exposure. Within this

11

concept, if the dose received by the representative person(s) can be demonstrated to be

within the accepted dose limits and constraints, then the general public are considered to be

protected.

1.3 Dose Limits and Constraints

The system of dose limitation recommended by the International Commission on

Radiological Protection (ICRP, 2007) and subsequently by the Radioactive Substances

Basic Safety Standards (BSS) requires that dose equivalents received by individuals shall

not exceed the limits set out in Article 13 of the Council Directive 96/29/Euratom (CEC,

1996).

The retrospective maximum permissible dose limits are set out as 1 mSv y

-1

. For

prospective assessments, the maximum permissible doses or constraints used by SEPA

are:

(i) 0.3 mSv y

-1

for any single source of radioactivity, and

(ii) 0.5 mSv y

-1

for a single site from which radioactive discharges are made.

It is also accepted by the UK Government that it should be possible to operate existing

nuclear facilities without exceeding the 0.3 mSv y

-1

constraint (Hunt et al., 1982; Leonard et

al., 1982; Sherlock et al., 2006). It is therefore incumbent upon SEPA to ensure that these

dose limits are not exceeded for all authorised discharges of ionising radiation to the

environment.

1.4 Survey Aim

The aim of the survey is to collect data to allow a bespoke assessment to be made,

identifying the representative individual(s) in combination with data from SEPA’s routine

environmental monitoring programme. The survey may identify any habits which the routine

programme does not currently adequately cover and may also recommend removal of

monitoring that is no longer required. The survey does this by:

(i) Collecting data on a range of habits/activities by the general public across Rosyth

and surrounding areas that might lead to exposure to radioactivity or radiation from

any combination of licensed liquid or gaseous discharges, or direct radiation from on-

site activities at Rosyth.

12

(ii) Collecting information on consumption of food grown or produced (including wild &

free foods) in the survey area and determining an annual rate of consumption for

each individual surveyed and household members of all ages.

(iii) Identify the amounts of radioactivity, radiation and subsequent doses to individual

members of the general public as a result of the disposals or operations of the

nuclear site.

This report presents the findings for the 2015 habits survey of the BRS on the Firth of Forth.

The previous survey was undertaken during the period 26

th

July and 3

rd

August 2010

(Romney et al., 2013) and comparisons are made in Chapter 9.

As SEPA is bound by the Data Protection Act, information which may allow the identification

of specific individuals is not presented in this report.

13

2 Rosyth Survey Area

2.1 Rosyth Site Location and History

The BRS is located on the north bank of the River Forth in Fife, 3 km west of the Forth Road

Bridge and some 50 km from the mouth of the Firth of Forth. It is sited on reclaimed land,

with reclamation completed in 1916. From 1916 the Site was known as HM Dockyard Rosyth

and activities conducted there included refitting and maintaining warships.

The Royal Dockyard and HM Naval Base Rosyth were co-located until 1996 when the Naval

Base closed and operational ships were withdrawn.

In February 1997, MoD sold the Rosyth Dockyard Site to Babcock International Group plc.

The BRS, a wholly owned subsidiary of Babcock International Group Marine Division, holds

a Nuclear Site Licence from ONR and a RSA 93 Authorisation from SEPA to dispose of

Radioactive Waste from the Authorised Premises. The BRS was set up in 1997 to be

responsible for the decommissioning of the Authorised Premises and the management of

radioactive waste that has arisen from the re-fitting and the dismantling of nuclear

submarines berthed on the Authorised premises.

Historically, refitting or de-equipping nuclear submarines has been the prime nuclear

activities carried out at the BRS. However, these activities ended in 2003.

2.1.1 Current Activity

Since 2003, until now, the prime nuclear activities being carried out have been the safe

management of legacy radioactive wastes from submarine refitting operations such as

radioactively contaminated ion exchange resins, and the management of radioactive wastes

from site decommissioning works. The MoD contracts the BRS to carry out these activities

with the Ministry of Defence as the radioactive waste owner performing an assurance

function.

The Queen Elizabeth (QE) Class aircraft carriers are currently being assembled at the BRS.

The site also includes the Rosyth Business Park with a range of buildings used by

commercial companies and educational organisations.

Radioactive waste at Rosyth primarily takes the form of solid waste with an associated liquid

waste discharge. Some parts of the Authorised Premises are also licensed by ONR under

the Nuclear Installations Act 1965 (as amended). Currently, this includes Dry Dock Number

14

2 and Dry Dock Number 3 and the Active Waste Accumulation Facility (AWAF). The ONR is

currently assessing an application from the BRS to delicense the Dock 3 area of the site.

Disposal of radioactive waste from the AWAF is regulated by SEPA under the current BRS

RSA93 Authorisation. Other parts of the site are not subject to licensing under the Nuclear

Installations Act 1965, but disposals of radioactive waste from those parts of the site are

regulated by SEPA under the current RSA 93 Authorisation granted to the BRS.

The BRS is authorised by SEPA under RSA 93 to dispose of solid, aqueous and gaseous

radioactive wastes arising from site decommissioning operations and the management of

legacy radioactive wastes from former submarine refitting operations at the BRS. The BRS

was the first nuclear site operator to have a SEPA multi-media authorisation which was first

granted in 2004 and the conditions and limitations were substantially amended in the notice

of variation, VN01, issued by SEPA to the BRS in 2008. The site is authorised to discharge

cobalt-60 (

60

Co), tritium (

3

H) liquid radioactive waste and other beta-emitting radionuclides

(at an annual limit of 300 MBq) through an outfall into the Firth of Forth. Carbon-14 (

14

C) and

3

H gaseous radioactive waste, and beta associated with particulate (with an annual limit of

0.1 MBq), are authorised to discharge to the atmosphere. Whilst there is a potential for

atmospheric discharge, none has been detected and filters are installed to prevent

particulate atmospheric discharges. Radiographic material testing is undertaken on site

which can lead to locally elevated direct radiation exposure during the duration of a test,

however the effect on the public from the use of such sources within the site and the

resultant shine outwith the site is controlled by the ONR and the Health and Safety Executive

(HSE).

The main facilities which deal with the radioactivity and radioactive waste at Rosyth are:

(i) The AWAF with resin catch tank storage, ventilation plant, ILW Storage pits, Drum

store, compaction and shredding and non-compactable low level waste storage

area. This facility currently stores the radium-226 (

226

Ra) particles from Dalgety

Bay.

(ii) The Radiochemistry Laboratory that produces solid waste, in the form of soft

waste (papers, gloves) and smaller amounts of non-compactable waste such as

glassware, and liquid waste that is treated and discharged into the River Forth

from the Low Active Effluent Discharge Line at high tide.

(iii) The effluent from the Health Physics (HP) laundry flows into an underground

detention tank located outside the HP laundry. The contents are mixed and

15

sampled and analysed for radioactive content prior to discharge via the Low Active

Effluent Discharge Line.

(iv) The High Intensity Calibration Centre.

On site, the dockyard has approximately 2,300 core employees, supplemented with around

4,000 additional agency/subcontract workers. Core employees are deployed across a variety

of projects covering Marine, Nuclear, Oil & Gas and Renewables. The additional workers

predominantly support the construction of the two new Aircraft Carriers – HMS Queen

Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales.

There is a cycle to work scheme at the BRS but little evidence for cycling identified. The site

is also served by bus, which travels through the site and there is also a bus scheme,

associated with a Park and Ride from the M90 Motorway.

New housing developments have taken place in the area along Admiralty Road.

Rosyth port has a waterfront and land adjacent to it capable of accommodating a diverse

range of energy, renewables, tourism and financial and business services. Since the last

survey in 2010, the Lexmark factory on Admiralty Road has closed and has recently re-

opened as a fish factory (Meridian Salmon Group). The Fife Coastal Path was extended to

start in Kincardine in 2011 and runs along the coast of the survey area. This is a change

from the previous survey in 2010 with a possible increase of people walking the full length.

2.1.2 Changes since 2010

In 2014, the Office for Nuclear Regulation granted its consent for a project to decommission

and dismantle seven out-of-service nuclear submarines, following an application by the

licensee, the BRS. The application was made under the Nuclear Reactors (Environmental

Impact for Decommissioning Regulations 1999). Submarine dismantling is not planned to

commence until at least 2016 but before starting, the BRS will need a new RSA 93

Authorisation granted by SEPA to allow disposals of low-level radioactive waste arising from

submarine dismantling operations. SEPA is currently determining an application from the

BRS for such a new RSA 93 Authorisation.

A staged approach will be applied to submarine dismantling until MoD announces its

decision where to locate an interim store for the Intermediate Level Waste (ILW) produced

from submarine dismantling operations at the BRS. During Stage 1 dismantling (Initial

Dismantling), only Low Level Waste will be removed from the submarines at the BRS, after

which they will return to storage afloat. When planning permission for the interim ILW store is

16

granted, Stage 2 dismantling will commence, (expected to begin 2020) during which ILW

and any remaining radioactive waste will be removed. The interim ILW store will be used to

store items such as the reactor pressure vessels removed from the submarines.

During decommissioning of the submarines these pressure vessels will be temporarily stored

in the AWAF. Final disposal is likely to be by deep geological disposal at an undetermined

site.

In October 2014, Fife Council produced a development plan which included a proposal for a

biomass plant together with a bypass for Rosyth. The plan identified the wider area around

Rosyth, Inverkeithing and Dalgety Bay up to the Forth Bridgehead as attractive for business,

tourism and residential investment. The plan identified Rosyth port as a strategic

employment and economic activity location and the preferred location for additional freight

capacity and noted possibilities for further development in Rosyth Europark 1, 2 and 3.

In 2015, the Forth (Rail) Bridge was awarded World Heritage site status and a large visitor

centre is now proposed in North Queensferry to cater for those wishing to visit the World

Heritage site.

2.2 Estimated Activity Concentrations from Licensed Discharges from

Rosyth.

Actual licensed discharges of

3

H (5.91E+07 Bq y

-1

) and

60

Co (1.48E+06 Bq y

-1

) from the BRS

reported in 2013 were used to calculate aquatic activity concentrations in water using the

DORIS model within PC CREAM (Public Health England, 2008). Assuming a continuous

release, activity concentrations were modelled in unfiltered seawater, fish, seaweed,

crustaceans and molluscs, with outputs at 1, 5, 50, 500, 10,000 and 100,000,000 years. For

all element dependent parameters (sediment distribution coefficients, KD and deep water),

local compartment details (depth, coastline length, volumetric exchange rate, suspended

sediment load, sedimentation rate, sediment density and diffusion rate) and regional model

information (volume, depth, suspended sediment load, sedimentation rate, sediment density,

diffusion rate) the default values of Rosyth on PC CREAM were used.

Activity concentration values reported at 50 years for aquatic activities were 1.5E-8 Bq l

-1

for

3

H and 4.2E-7 Bq l

-1

for

60

Co. Activity concentrations in fish (

60

Co 1.28E-04 Bq kg

-1

and

3

H

1.49E-08 Bq kg

-1

), crustaceans (

3

H 1.49E-08 Bq kg

-1

and

60

Co 1.40E-03 Bq kg

-1

) and

molluscs (

3

H 1.49E-04 Bq kg

-1

and

60

Co 6.97E-04 Bq kg

-1

).

17

Atmospheric activity concentrations were also modelled using the Plume model in PC

CREAM. As no actual discharges occurred, the authorised limits in 2014 for the BRS were

modelled with PC CREAM. These included

14

C (5.00E+8 Bq y

-1

) and

3

H (2.00E+08 Bq y

-1

).

DORIS was set to calculate activity concentrations released at three different stack heights

(10, 15 and 20 metres) and at a distance of 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 and 5,000 metres. As

the default deposition velocity settings for

14

C and

3

H in PC CREAM have a value of zero, no

activity concentration was reported by our model. PC CREAM was exclusively used to model

activity concentrations and not to calculate doses.

Where present, the modelled activity concentrations were used in the dose assessment tool

to calculate doses through internal pathways such as ingestion of water, fish, crustaceans

and molluscs, and external pathways for aquatic and intertidal activities. These are reported

in Section 3.9. However, it should be noted that in reality if

3

H discharge did occur some

washout would occur resulting in deposition

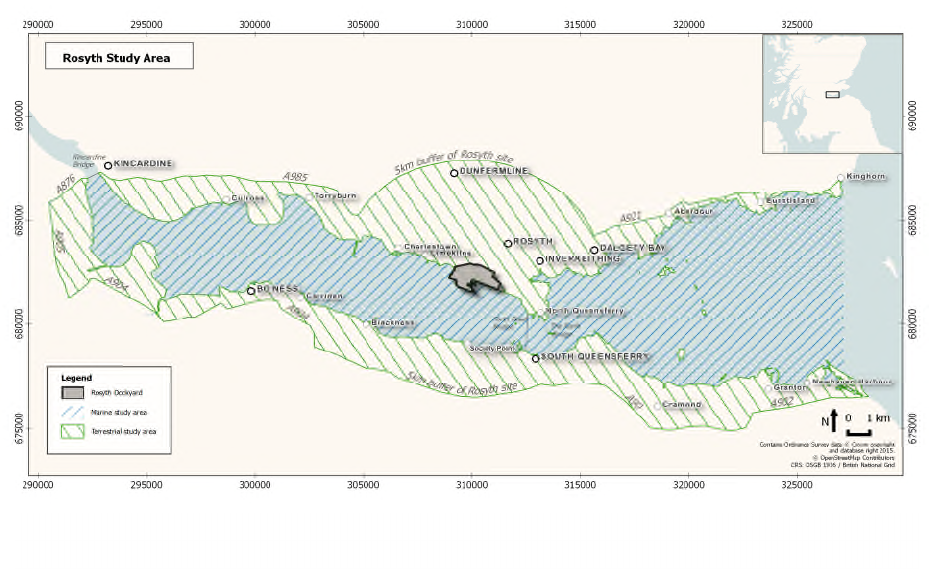

2.3 Survey Area

Despite the very low radionuclide concentrations modelled by PC CREAM (Public Health

England, 2008) within the Firth of Forth, to remain consistent with previous Rosyth Habits

surveys, the 2015 survey area was defined by three main factors:

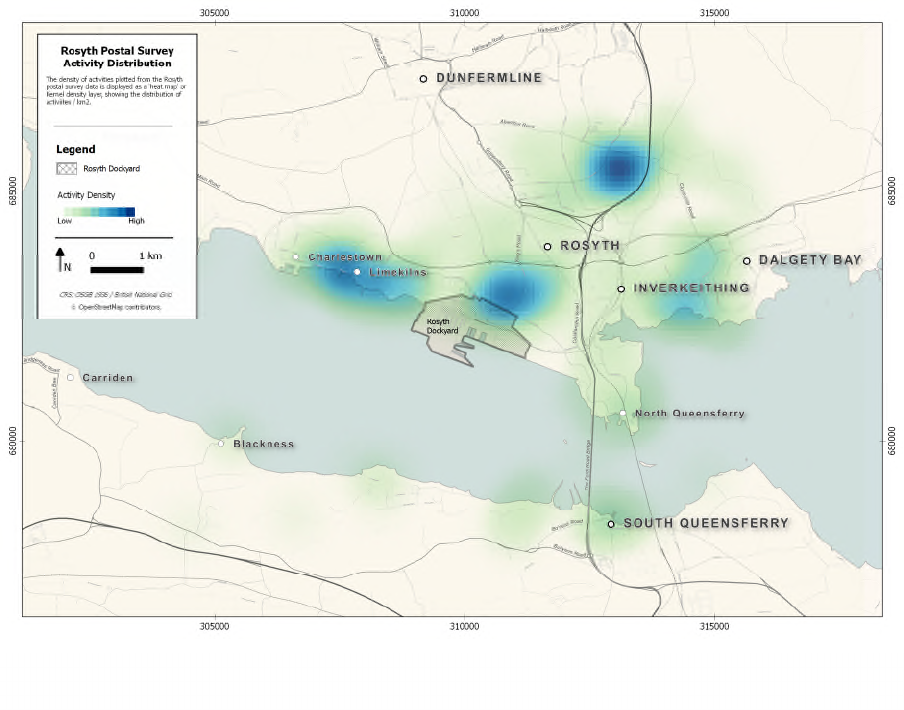

Figure 2.1

The Rosyth survey area covering the Firth of Forth from Kincardine to

Kinghorn on the northern shore and from Bo’ness to Newhaven on the southern shore.

18

(i) to cover all potential pathways of exposure,

(ii) to extend beyond the 2010 survey area to reflect the survey areas covered by

Babcock International and encompass more of the locally caught fish,

(iii) to cover the same areas used in previous habits surveys conducted in the Rosyth

area for direct comparison and identify any changes since the last survey.

Since there are no current gaseous releases from the site (RIFE 20), the main pathway of

public exposure from the BRS is the aquatic pathway from discharges of

60

Co and

3

H into

the Firth of Forth. The survey area for the marine pathway covered the Firth of Forth and its

intertidal areas from Kincardine Bridge in the west to Kinghorn in the east on the northern

shore of the estuary, and from Bo’ness in the west to Newhaven in the east on the south

shore (Figure 2.1).

To address potential atmospheric discharges of

14

C and

3

H the survey area was defined as a

5km radius from the Active Waste Accumulation Facility (AWAF). Any possible atmospheric

releases are likely to have minimal impact on the terrestrial survey area. The direct radiation

survey area was represented by the immediate public areas around the AWAF inside the

BRS and up to 1 km around its boundaries. Outside the 5 km area used to model

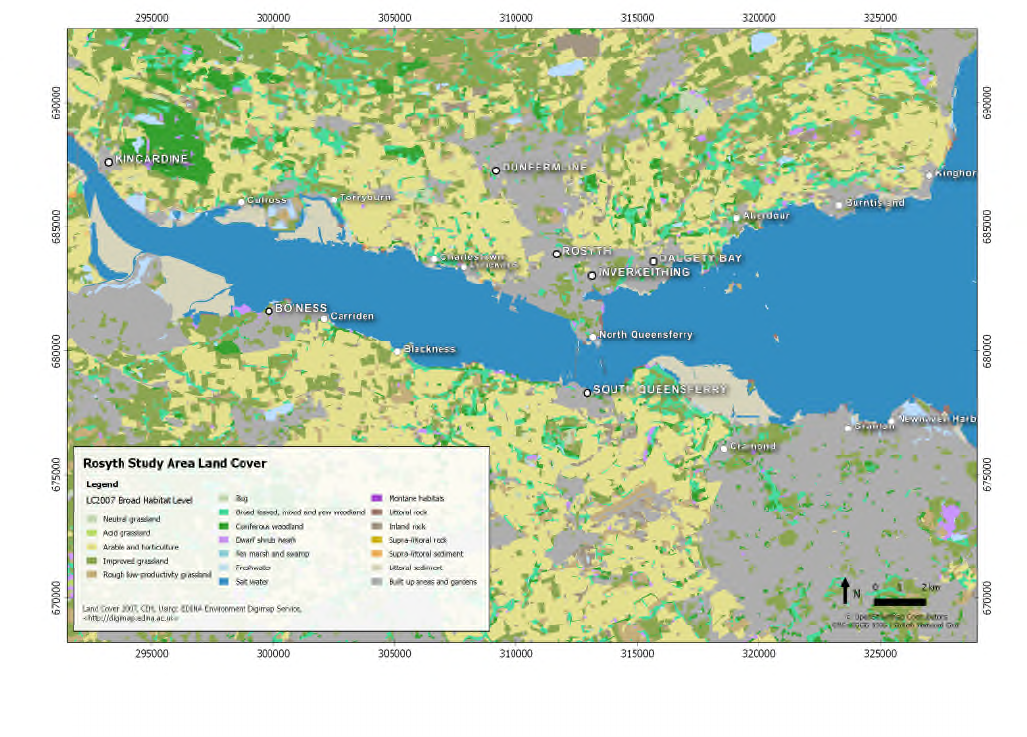

Figure 2.2 Land cover data for the Rosyth, Firth of Forth area (EDINA online 2007).

19

atmospheric discharges, the terrestrial survey area was bounded by the coastal roads on the

northern and southern shorelines (Figure 2.1).

2.4 Land Cover Data

The land cover data for the survey area is shown in Figure 2.2 (EDINA online 2007) and

shows that the area is dominated by built up areas and gardens and arable and horticultural

land capable of producing moderate to good crop yields and moderate grassland is the third

most dominant land cover type outside the aquatic environment. This is summarised in

Table 2.1, which provides a summary of the land cover types within the 1 km, 3 km and 5 km

areas surrounding the BRS.

Table 2.1 shows the increasing importance of arable and horticultural land within increasing

buffer size around the site increasing from 14% in the 1 km zone to 25.5 % in the 5 km zone,

largely at the expense of built up areas and gardens.

Table 2.1 Area of land cover in hectare with buffer zones surrounding the BRS

Land Cover 2007 Broad Habitats

Within

1 km

(hectares)

Within

3 km

(hectares)

Within

5 km

(hectares)

Arable and Horticulture 164 84 2,827

Broad Leaved, Mixed and Yew Woodland 14.8 160 509

Built up Areas and Gardens 335 1,058 2,218

Coniferous Woodland 4.38 73.3 278

Dwarf Shrub Heath 0.00 26.1 48.7

Freshwater 0.00 10.7 20.4

Improved Grassland 81.8 318 756

Inland Rock 12.67 21.6 96.9

Littoral Rock 0.00 13.3 20.6

Littoral Sediment 16.4 47.6 95.7

Neutral Grassland 0.00 2.14 66.1

Rough Low-Productivity Grassland 0.83 43.5 175

Salt Water 518 2,254 3,986

Supra-littoral Sediment 2.81 2.81 5.29

Grand Total 1,151 4,871 11102

20

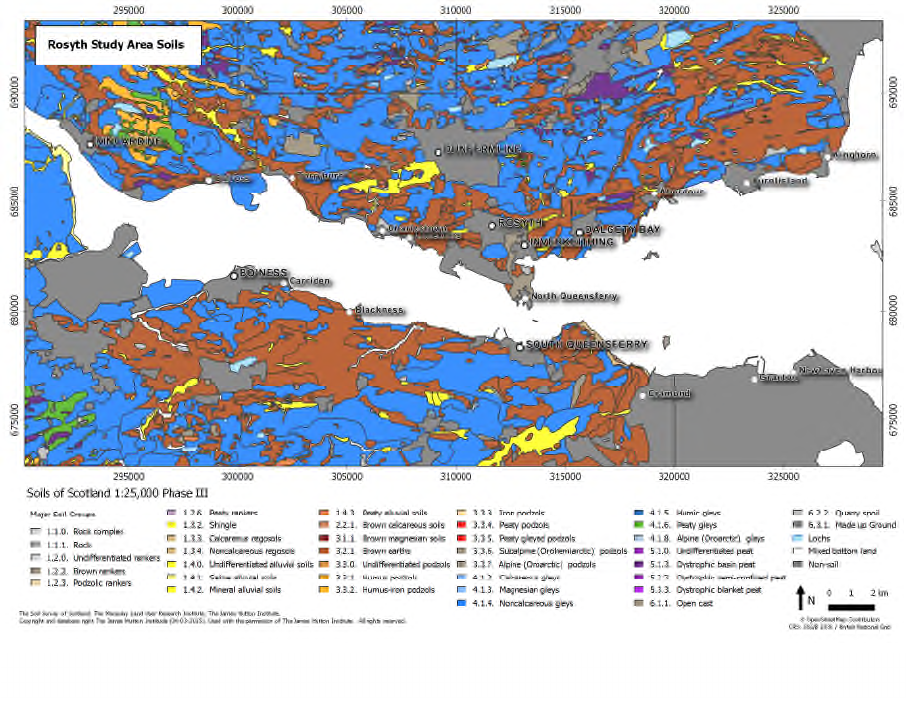

2.5 Soil Data

The soil data for the study area surrounding the BRS is presented in Figure 2.3 and

reproduced from data provided by the Macaulay Land Use Research Institute. The soils are

dominated by brown earths and non-calcareous gleys with minor amounts of alluvial soils

and peaty gleys and podsols towards the west of the study area.

2.6 Crop Production

Figure 2.3

Soil types surrounding the BRS (Macaulay Land Use Research Institute)

21

Whilst Rosyth itself is largely urban, the survey area either side of the Firth of Forth has a

significant amount of agriculture land. The Scottish Agricultural Census data for the parishes

(defined by postcodes as used by the Scottish Government) surrounding the BRS has been

summarised in Table 2.2. The data were kindly supplied by the Environment and Forestry

Directorate of the Scottish Government, including Dalgety, Dunfermline, Inverkeithing on the

north side of the Firth of Forth, and Abercorn and Dalmeny to the south. A total of 13,489

hectares of land are available for production in these parishes. Cereal production is

dominated by wheat and barley production for crops, and Table 2.2 summarises the number

of holdings, the area under production for crops and the estimated yield.

In addition, potatoes, peas, beans and other vegetables are produced in these parishes. Soft

fruit and orchard fruit are also grown. Table 2.3 summarises the remaining use of the

agricultural land usage in the parishes surrounding Rosyth.

Table 2.2 Summary of commercial crop production in the Rosyth area (2014),

summarised from the Scottish Agricultural Census

Crops and Fallow

Land

Number of

Holdings

Area

(hectares)

Estimated

Yield (tonnes)

Wheat 24 1,175 11,363

Winter Barley 16 680 5,648

Spring Barley 23 904 5,566

Total Barley 27 1,584 10,327

Oats, Triticale and

Mixed Grain

10 156 1,090

Rape for Oilseed and

Linseed

12 597 2,519

All Other Crops 14 48

Fallow Land < 5

Years

26 242

Fallow Land > 5

Years

9 23

Total Crops, Fallow

and Set-side

43 3,980

22

Table 2.3 Summary of other agricultural land in the Rosyth area (2014), summarised from

the Scottish Agricultural Census

Grazing and other Holdings Hectares

Grass under 5 years old 34 356

Grass 5 years and older 104 2,758

Rough grazing 41 2,969

Total grass and rough grazing 129 6,083

Utilised agricultural area

(crops, grass and grazing land)

139 10,062

Woodland 41 2,898

Other land 60 479

Total 152 13,439

23

3 Methods

3.1 Introduction

To provide consistency and traceability to previous Habit surveys, the methods employed

and described in this chapter are largely based on the approach outlined in Leonard et al.

(1982), Green et al. (2001) and National Dose Assessment Working Group (NDAWG)

(2013). The previous habit survey in 2010 provided a useful frame of reference for

undertaking this survey of the BRS site. Chapter 2 described the desktop study undertaken

to characterise and define the Habits Survey, including:

(i) a review of site activities

(ii) the modelling of the atmospheric and marine discharges from the site to define the

survey area boundary

(iii) an assessment of the land cover and agricultural activity

The 2015 Habits Survey of Rosyth covers activities and food consumption. Following

discussion with SEPA, the survey introduces the following new methods to try and capture a

full range of relevant habits, validate methods and characterise the radiological environment:

(i) an initial postal survey to help target the subsequent face-to-face survey

(ii) a mobile radiometric survey to characterise the heterogeneity of radiation in the

environment surrounding the Rosyth site

(iii) GPS tracking on a number of volunteers to better understand the time spent by

individuals as they interact with the environment (although due to the limited number

of individuals tracked and resultant specific personal data obtained the results are not

directly reported in this report)

(iv) Information and focus groups during and after the face-to-face surveys to validate the

data and findings

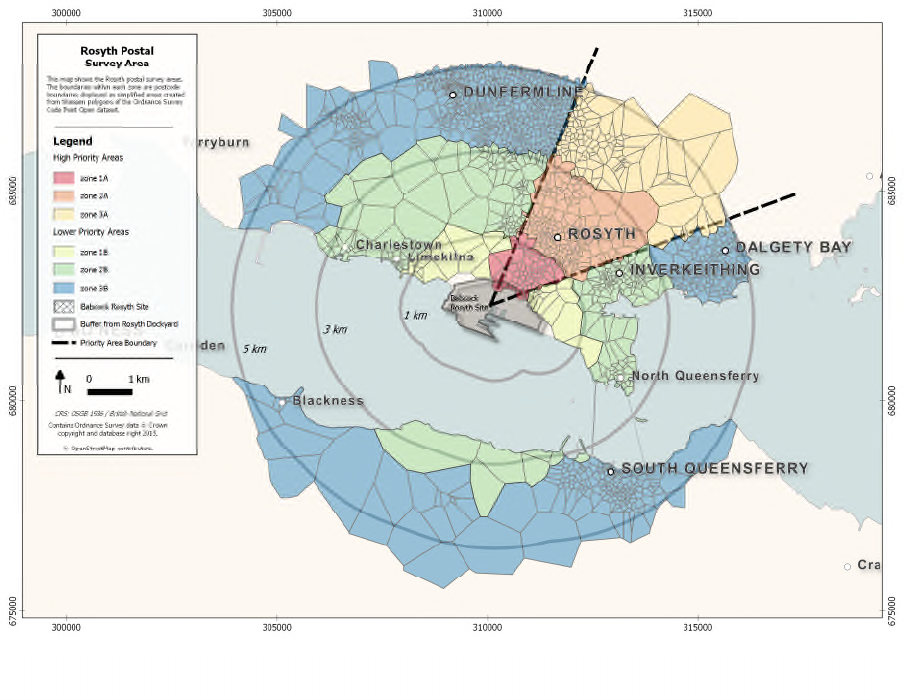

3.2 Postal Survey

To obtain a provisional independent assessment of the activity and food consumption habits

of the local community living within the study area through the survey, a postal questionnaire

for households was designed, piloted, and after ethical approval, distributed to 1000

households selected using stratified random sampling methods, based on the areas defined

in Figure 3.1. The survey included a map for identifying the range of activities undertaken by

household members. The sample included populations living in the following geographical

areas (see Figure 3.1):

24

(i) Within 1 km from the site boundary (zone 1B)

(ii) Between 1 km and 3 km from the site (zone 2B)

(iii) Between 3 km and 5 km from the site (zone 3B)

(iv) Zones 1-3 repeated within the plume area. This was governed by the prevailing wind

direction (zones 1A to 3A)

Postcodes for all the geographical areas described above, and shown in Figure 3.1, were

generated. The electoral register was grouped according to the zones shown in Figure 3.1.

Contact details of people living within these postcode areas were randomly selected to

provide a demographic cross-section of individuals. An assessment was made of the

deposition areas from the plume using the prevailing wind direction. Under the area of the

potential plume, 50% of the surveys were posted to people living north west of the BRS.

Considering the weighting factor under the plume, the number of surveys were equally

divided on each zone, with zones 1 to 3 under the plume receiving 167 surveys each and

Zones 1, 2 and 3 outside of the plume receiving 167, 166 and 166 respectively. Sampling

and surveying at different distances from the site enabled the relationship between distance

and habits to be explored and provided a means of producing additional potentially useful

Figure 3.1

The postal survey zones for the Rosyth area centred from the site boundary

25

data. The postal survey produced an independent data set from a broader cross section of

the population living in the area again potentially providing the means to identify new or

missed habits that might provide useful focus to target some of the face-to-face surveys or

information groups.

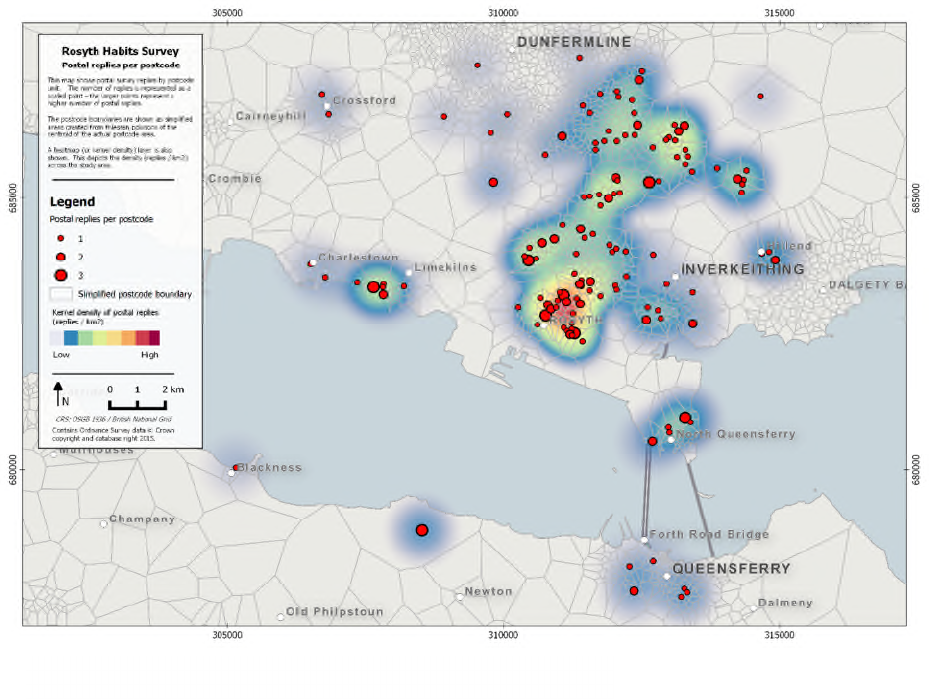

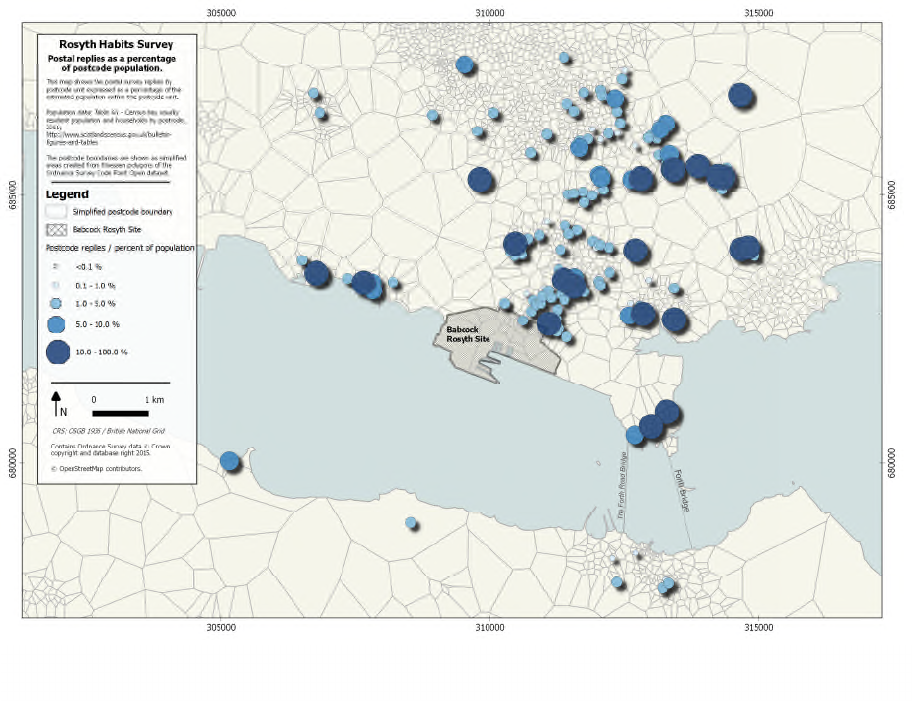

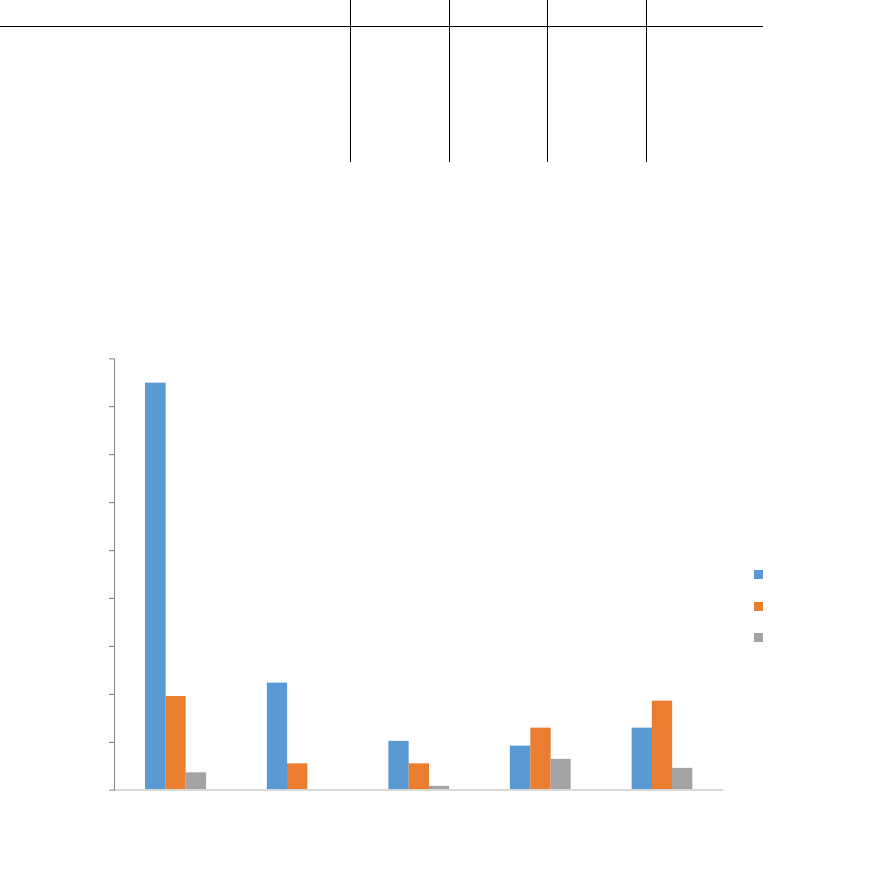

The survey and information was mailed out and a reminder was sent out after 2 weeks to

people who had not returned the survey. The distribution of the questionnaire responses, by

postcode, is shown in Figure 3.2. The percentage response received per head of estimated

population in each postcode area is presented in Figure 3.3. It is important to note that

postcodes with very small populations can result in 100 % response when surveys are

returned.

The postal survey helped refine and revise the face-to-face survey tools and identify the

optimal areas to target the face-to-face surveys. It also provided information on sites for the

collection of observation data and indicated at what times the areas might be busy and

supplied additional information and contacts with regard to both individuals and a wider

range of activities that might merit further investigation in the later survey work.

Figure 3.2

Postal Survey Responses for the Rosyth Area

26

3.3 Radiometric Surveys

The radiometric surveys comprised a carborne gamma spectrometry survey, in-situ air-

kerma dosimetry and beta skin dosimetry. The carborne survey work is described in

Appendix A.

3.3.1 In Situ Dosimetry

The ERL has ISO 17025:2005 accredited procedures for the deployment and recording of

gamma dose rate in air (air kerma), using ISO 17025:2005 accredited (UKAS) accredited

calibrations for two Thermo Radeye instruments. Measurements were undertaken at all

locations where occupancy or location was likely to lead to higher exposure to radioactivity

or radiations as a result of site activities. These included areas that may have elevated

radionuclide concentrations where fine sediment is known to accumulate (e.g. salt marshes

and mudflats). The effective dose from terrestrial gamma radiation was calculated and

reported in μSv h

-1

. Further details of the in-situ methodology can be found in Appendix B.

Figure 3.3.

Showing the percentage response per size of local population (local

population from postcode headcounts 2011)

27

3.3.2 Beta Dosimetry

A ruggedized Thermo BP19RD /Electra instrument was deployed to assess the Beta

dosimetry of skin dose [H’(0.07)]. The BP19RD provided a wide area monitor instrument

(100 cm

2

) and used to monitor items that were used in the Firth of Forth and potentially

exposed to the higher radioactivity concentrations, i.e. close to licensed discharge points.

Items monitored included: wetsuits, waterproof clothing, fishing tackle and nets. Further

details of the Beta skin dosimetry can be found in Appendix C.

3.3.3 Sampling

Where unusual foodstuffs or areas of possible contamination were identified and not

included within the SEPA’s monitoring programme, samples were collected and analysed by

gamma spectrometry in accordance with ISO17025 protocols.

3.3 GPS Tracking

A number of methods of tracking user location were investigated, from using Google

Location histories in mobile phones to custom mobile application development. However, to

ensure consistency in data a wearable GPS tracking device was considered the most

suitable device for the Rosyth Habits Survey. Further details of the system deployed are

described in Appendix D.

3.4 Conduct of the Survey

Preparatory work undertaken before the fieldwork survey entailed discussions with SEPA,

meetings and telephone calls with the BRS staff, on site visits and exploratory observations

around the survey area prior to the commencement of the survey itself. The approach to the

face-to-face surveys is described in more detail in Appendix E. Past survey reports were

reviewed and web-based searches were conducted to ensure as many relevant groups were

identified and captured along with a range of maps to planning for the survey. A large

directory of key groups involved in activities, occupancy and food production and sale in the

area was compiled and used (see Chapter 5 for additional detail) to contact key groups and

individuals in the locality. This included sailing, yachting, motor powered sailing, wild

swimming, rowing, walking, cycling and running groups, social clubs, youth groups and

playgroups within and outwith the area where necessary because some of their members

used the area for recreation and other activities.

28

The team also approached both the Fife local authority, a number of community councils in

the area and employers such as those involved in the construction of the new Forth Bridge.

Some focus groups and informal meetings were arranged prior to the surveys and also

during and after the surveys to gain additional information and fill in any critical gaps that

might emerge in the face-to-face interviews

The nature and timing of the fieldwork survey was discussed with SEPA prior to the start of

the work. The fieldwork was conducted primarily between 29

th

June 2015 and 12

th

July 2015.

A number of follow-up visits were also undertaken in the area.

The survey team that conducted the face-to-face interviews, observations and

measurements totalled 9 people all of whom had received appropriate training and several

had experience from conducting previous surveys. The team were provided with site specific

field manuals developed for the survey.

From the preliminary survey visits and planning, the team of 9 were able to cover multiple

sites at multiple times over the survey period. They interviewed those engaged in a wide

range of activities, some living in close proximity to the BRS and some who consumed local

produce from land or sea. Adults with children and infants were included. Those surveyed

included wild swimmers, kayakers, rowers, yachts people, boat repairers, bridge builders,

emergency workers, café owners, postal staff, community gardeners, allotment keepers,

walkers, professional dog walkers, runners, cyclists and people fishing.

3.5 Meetings, Informal Contacts and Focus Groups

In the 2015 survey, a variety of data were gathered by a variety of approaches. This included

holding a range of meetings with relevant parties and individuals as well as a ‘standard’ face-

to-face interview schedule. The multi-methods approach provided a means to ‘triangulate’

(verify) the data acquired through the different approaches: for example to check occupancy

and activity data against the ‘snapshot’ observations recorded over a limited number of days

in one season acquired from the individual face-to-face interviews. The meetings also

provided some additional information about local produce grown by householders, allotment

owners, horticulturalists and farmers and consumption of particular types of local food such

as honey and game. The information gathered also facilitated some snowballing of the

survey because the individual meetings and focus groups provided additional contacts to

follow-up on. These groups were approached prior to, during and after the face-to-face

interviews by telephone and email.

29

Additionally, prior to and during the survey a directory of local groups, bodies and

organisations relevant to the survey was compiled. The directory proved an invaluable

resource through the survey period both for contacting groups and for use as a checklist

against which responses and non-responses from potentially important groups with regard to

activity, occupancy, exposure and local food consumption could be recorded. For future

surveys, the directory will provide a useful starting point and a means of monitoring any

changes in group/business or other activity in the area. The directory development required

extensive web searches, follow-up telephone calls and use of earlier contacts across

organisations and businesses.

Focus groups and various related informal meetings were also held with groups such as

rowing clubs, community councils, community groups and centres, social clubs, youth

groups and other local organisations and business groups. The information gathered helped

to ensure the face-to-face interviews were relevant, relatively comprehensive and covered all

the key topics necessary. The meetings also supplemented information from the postal

survey and the face-to-face interviews and provided an opportunity to probe in more detail

information or address omissions relating to the face-to-face surveys. Information gleaned

for example related to type of activity or food consumption. This included provision of

information on new developments and location of activities and increase in activities.

3.6 Data Conversion

During the face-to-face interviews data on food consumption were recorded in units provided

by respondents (e.g. pounds, grams, and ounces) and later converted into kilograms per

year. In some cases, respondents were unable to estimate food consumption in kilograms

per year and instead gave the number of plants grown or the length and number of rows,

these data were converted into consumption rates using conversion weights where possible

e.g. one broccoli plant typically yields 700g (Garden Forum Horticulture, 2009; Hessayon,

2014) so that all consumption figures were reported in kilograms per year.

3.7 Data Rounding and Grouping

All data collected from the face-to-face and postal surveys were reported to two significant

figures. For the food consumption data the total annual consumption (kg) of different food

types were calculated by multiplying the quantity (kg) and frequency (times per year). The

food items were placed into groups with similar attributes (Table 3.1) these groups are

similar to those used in previous reports but focussed on the most common food items.

Respondents were given the option to add any additional food items in ‘Other’ food category.

30

Table 3.1 Food Groups used in the Habits Survey

Food

G

roup

Example of

F

oods within this

G

roup

Green Vegetables asparagus, broccoli, brussel sprouts, cabbage, calabrese,

cauliflower, chard, courgettes, herbs, kale, lettuce, marrow, spinach,

broad bean, french bean, pea, kohi rabi, pepper, runner bean,

sweetcorn

Root Vegetables beetroot, carrot, celery, fennel, garlic, jerusalem artichoke, leek,

onion, parsnip, radish, shallot, spring onion, swede, turnip

Potato potato

Domestic Fruit apple, blackberry, blackcurrant, blueberries, cucumber, gooseberry,

grape, pear, plum, raspberry, redcurrant, strawberry, tayberry,

tomato

Milk milk, yoghurt, cheese

Cattle Meat beef, buffalo

Pig Meat pork

Sheep Meat lamb, mutton

Poultry chicken, turkey, goose

Eggs hens’ eggs

Wild/Free Foods apple, blackberry, garlic, elderflower, cherries, meddlers,

mushrooms, raspberry, sloe berries

Honey honey

Game pheasant, wild venison

Fish bass, cod, mackerel, pollock, salmon

Crustaceans brown crab, common lobster

Molluscs winkle, mussels

Wild fowl mallard, pink-footed goose, teal, wigeon

The time respondents spent carrying out activities was calculated by multiplying frequency

(occasions per year) and duration (hours) taking into account seasonality where appropriate.

In addition to food consumption a ‘liquid’ category was also added and respondents who

carried out aquatic activities that could result in the inadvertent ingestion of water, e.g.

outdoor swimming/sailing, were identified to account for this pathway.

31

The age groupings used in this report are based on International Commission of

Radiological Protection (ICRP) recommendations and are listed below in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 ICRP age groups used in the dose assessment

Name of age group Age range

Group 1 0-5 year old

Group 2 6-15 year old

Group 3

16 year old and over

3.8 Qualitative and Quantitative Observation

Whilst undertaking the face-to-face surveys, observational data were acquired on obvious

changes to each location such as new build housing, along with information on site usage

and numbers of individuals undertaking specific habits. Observations were acquired over a

specified time period, e.g. 20 minutes, and on-shore and offshore (including intertidal)

activities were noted. The number of individuals, their gender and their approximate age

group undertaking each activity were also noted or estimated where large numbers were

observed, e.g. beach activities. Some individuals were approached where possible and

subsequent face-to-face surveys were conducted. Contact with individuals during face-to-

face interviews frequently allowed the accuracy of observations to be checked and

sometimes to be expanded: for example dog walkers might also engage in beachcombing

and sailing at other times. Along with noting the weather conditions at the time of survey, this

approach provided a basis for making a comparison of habits at different times and within

and outwith the period of the local school holidays.

3.9 Dose Assessment Tool

The Habits Dose Assessment Spreadsheet Tool collates the data from the face-to-face

survey in Rosyth and then used the consumption rates and habits data to calculate the

retrospective dose to each interviewed member of the public, covering the total exposure

from all pathways. It should be noted that only the consumption of locally produced food has

been included in the retrospective dose assessment. Dose assessment was carried out

following the guidance in NDAWG and ICRP for the Representative Person.

Activity concentration values came from modelling Rosyth discharges for 2013 using the

default settings in PC CREAM 08 (PHE, 2008) and measurements of samples collected in

the field. Dose coefficients for different age groups are described by ICRP (2012). As

32

described in Section 3.7, data for the 2015 Rosyth Habits Survey were collected in three age

groups (Table 3.2). The dose conversion coefficients (DCCs) for each age group were taken

from ICRP: Group 1 - infants; Group 2 - 10 year olds; and Group 3 - adults.

The tool analyses four general exposure pathways:

(i) Internal terrestrial, which includes the consumption of locally produced meat, fruit and

vegetables;

(ii) External terrestrial, which determines the external doses from exposure to radiation

present in the terrestrial environment as a result of deposition from atmospheric

discharges and direct exposure through shine from on-site activities with radioactive

materials;

(iii) Internal aquatic, which includes ingestion of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and

inadvertent consumption of seawater. A proxy for inadvertent drinking of water was

calculated by multiplying the time spent on aquatic activities by the known average of

water ingested in such activities as described in Leonard et al. (2014), McBride

(2012) and Stone et al. (2008); and

(iv) External aquatic, which estimates the dose from external exposure through aquatic

activities, e.g. from radionuclides present in the aquatic environment (in water and

sediments in saltmarshes or intertidal areas).

The direct exposure to shine in publically accessible areas to on-site activities was included

in the analysis using in-situ measurements.

The representative person was calculated independently for the total exposure and then by

each exposure pathway. To identify the representative person, the 97.5 percentile rate cut

off method was applied (see Chapter 1). The representative person was calculated

separately for external terrestrial and external marine exposure, internal terrestrial and

internal marine consumption related exposure. The combined calculated total integrated all

routes of exposure. In cases when the representative person (i.e. between the 93 and 97.5

percentile) was not found by the survey, the tool calculated a hypothetical representative

person. The report therefore details both the hypothetical representative person and the

most exposed person(s) found for that pathway during the survey.

33

4 Survey Site Introduction

4.1 Introduction

The survey locations were established from the analysis presented in Chapter 2 and to

provide consistency with the previous Rosyth Habits Survey undertaken in 2010. The sites

were visited throughout the survey period and selected where possible to be revisited before

and during the local school holiday period. Offshore and onshore observations were

undertaken at each site. Each site was visited for varying lengths of time according to the

survey schedule, site activity and proximity to the BRS.

4.2 Survey Area Descriptions

The terrestrial/aquatic survey area (shown in Figure 2.1) covered a stretch of the Firth of

Forth and its intertidal areas - the northern shore stretched from Kincardine to Kinghorn and

the southern shore stretched from Bo’ness to Newhaven. The survey site was extended to

accommodate areas outwith the concentrated survey area from the BRS. Preliminary visits

showed little commercial or hobby fishing. The survey is reported from west to east starting

on the northern shore with the most western area visited being Kincardine. The southern

shore is also reported from west to east with the most western area visited being Bo’ness.

Many sites reported the presence of mudflats and bait diggers which would be expected

given the estuary’s SSSI designation and classification under the NATURA 2000 regulations.

On the northern shore the entire survey reported the extensive use of the Fife Coastal Path

which runs along the coast of the survey area. This was extended to start in Kincardine in

2011 therefore a change from the previous survey in 2010 with a possible increase of people

walking the full length. The region is well served by the East Coast Railway from

Inverkeithing to Dundee.

For both the northern shoreline and southern shoreline, the observation descriptions are

described in survey locations starting from the west to east.

4.3 Site Descriptions for the Firth of Forth Northern Shore

4.3.1 Kincardine

The most western point on the northern shore of the survey area was Kincardine (Figure

4.1). Observations were made at this site but no face-to-face interviews were undertaken.

The area observed was by the shore with the coastal path running alongside and scrub

woodland behind to the north. The Fife Coastal Path was extended to Kincardine with the

34

development of the new Kincardine Bridge in 2011 and now connects Kincardine to Culross

without the need for extensive use of the road network. The coastal path moves away from

the coast as it passes the Longannet coal fired power station before returning to the coast at

Culross. No onshore habits were observed other than the occasional walker. Offshore there

were three boats moored, one fishing boat and five paddleboats to the west of the

Kincardine Bridge.

Figure 4.1 View to the south towards Kincardine Bridge from Kincardine

4.3.2 Culross

Culross is a popular tourist area with a number of attractions. On the sea front (Figure 4.2)

access to the beach and jetty is available to foot traffic via the level crossing with the stone

railway embankment forming the sea wall. The railway line from Inverkeithing lies between

the shore and Culross itself. There are two large car parks both east and west to the main

35

village area. There was a range of onshore activities which included dog walking, walking,

cycling, jogging, tourists, families’ with children playing at the park, children playing football

in the green park space and people walking along the beach and beach combing. Tourists

from outwith the survey area made up the majority of people with numbers visiting the area

approximately in excess of 20, 60 and 100 per day when visited during the survey period.

The onshore activities noted were all during the local school holiday period, no activities

were noted outwith (Appendix H). Two sailing boats and a rowing boat were moored offshore

and at some distance offshore a commercial ship, a leisure boat and a sail boat were

observed during the survey period. The lower shore substrate was that of mud and stone. A

disused jetty was also noted.

Figure 4.2 View to the East along the coast at Culross from Culross

4.3.3 Preston Island, Torry Bay and Crombie Point

Torry Bay is a small village overlooking the Firth of Forth and to the west is Preston Island

which forms a promontory between Culross and Torry Bay. A children’s playground area is

situated directly behind the shore separated only by the coastal path (Figure 4.3). A new

36

housing development overlooks the bay with building plots for sale. A public car parking area

is situated by Torry Burn.

During the survey period this site reported relatively low occupancy with three dog walkers,

one cyclist, one walker and two families playing in the playground by the shore observed

when visited during the survey period. No children or families were playing in the playground

outwith the local school holidays (Appendix H). As would be expected from villages close to

Edinburgh a steady stream of commuting traffic was noted. On the south side of the Forth

one boat was observed with two people on it and two boats were moored. The shore area at

low tide reveals a large area of mud and large boulders. Torry Bay forms part of the

designated nature reserve which has areas of salt marsh formed from artificial lagoons built

from ash from the Longannet Power Station. The reserve forms part of the larger area

between Longannet Point and Crombie Point and has an intertidal substrate of mud flats.

This area is home to overwintering birds. Torry Bay is an area where wildfowling is permitted

but no wildfowlers were identified during the survey period.

Figure 4.3 View towards the east at Torry Bay from Torry Bay

Eastwards from Torry Bay there is access to the shore at Crombie Point. Although the area

is largely woodland there are around ten residential houses looking south over the Firth of

37

Forth with cycle paths and agricultural land noted in the surrounding area. The beach area

was mainly sand and mud and the people observed included five dog walkers, one walker,

one person jogging and several people paddling. There were in excess of 60 people playing

on the beach noted during the local school holiday period in contrast to solely dog walkers,

cyclists and walkers outwith the school holiday period. Access eastwards along the shore is

prevented by the MoD base, RNAD Crombie, with the Fife Coastal Path re-joining the coast

at Charlestown.

4.3.4 Charlestown

Along the coastline eastwards, between Charlestown to Limekilns, there were several small

bays made up of sand, mud and pebbles. Rocky outcrops were also noted. There is a small

harbour in Charlestown (Figure 4.4) with over 30 boats and three sail boats moored within

the harbour. No activities offshore with boats were noted either outwith or during the local

school holiday period (Appendix H). At the time of survey he was working on his boat and

continued to spend a large amount of time there. The boats moored were all observed to sit

on the mud substrate when the tide went out. Onshore beside the harbour one person was

observed undertaking boat maintenance. Other onshore activities consisted of dog walking,

walking and people working in their gardens in the nearby residential area. During the school

holiday period several children were observed playing and walkers and dog walker numbers

increased from four outwith the holiday period to 10 within the holiday period.

38

Figure 4.4 Charlestown Harbour

4.3.5 Limekilns

Limekilns is a small coastal town with several shops, pubs and restaurant/bistro. There is a