Review of the Summer 2023

Microsoft Exchange Online

Intrusion

March 20, 2024

Cyber Safety Review Board

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................................. i

Message from the Chair and Deputy Chair ......................................................................................................................... ii

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ iii

1 Facts........................................................................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 1

1.2 Intrusion Details ................................................................................................................................................... 3

1.3 Incident Management .......................................................................................................................................... 9

1.4 Public Reporting ................................................................................................................................................. 14

2 Findings and Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 17

2.1 Cloud Service Providers ..................................................................................................................................... 17

2.2 U.S. Government ................................................................................................................................................ 23

Appendix A: Review Participants – External Parties ......................................................................................................... 25

Related Briefings ............................................................................................................................................................. 25

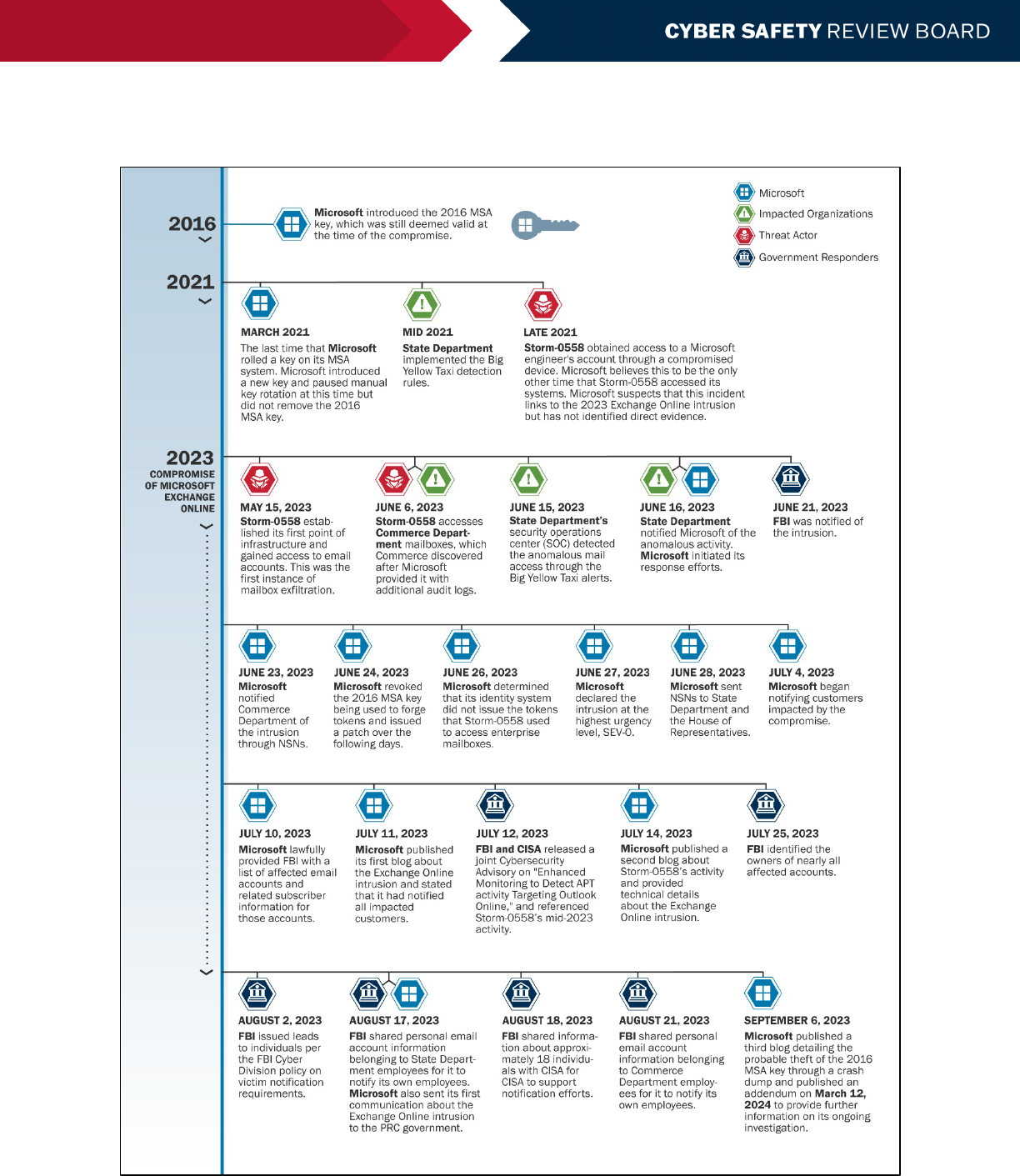

Appendix B: Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion Timeline ............................................................................................. 26

Appendix C: Review Participants – CSRB Members ......................................................................................................... 27

Appendix D: Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 28

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

ii

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND DEPUTY CHAIR

It is not an exaggeration to say that cloud computing has become an indispensable resource to this nation, and indeed,

much of the world. Numerous companies, government agencies, and even some entire countries rely on this

infrastructure to run their critical operations, such as providing essential services to customers and citizens. Driven by

productivity, efficiency, and cost benefits, adoption of these services has skyrocketed over the past decade, and, in

some cases, they have become as indispensable as electricity. As a result, cloud service providers (CSPs) have become

custodians of nearly unimaginable amounts of data. Everything from Americans’ personal information to

communications of U.S. diplomats and other senior government officials, as well as commercial trade secrets and

intellectual property, now resides in the geographically-distributed data centers that comprise what the world now calls

the “cloud.”

The cloud creates enormous efficiencies and benefits but, precisely because of its ubiquity, it is now a high-value target

for a broad range of adversaries, including nation-state threat actors. An attacker that can compromise a CSP can

quickly position itself to compromise the data or networks of that CSP’s customers. In effect, the CSPs have become

one of our most important critical infrastructure industries. As a result, these companies must invest in and prioritize

security consistent with this “new normal,” for the protection of their customers and our most critical economic and

security interests.

When a hacking group associated with the government of the People’s Republic of China, known as Storm-0558,

compromised Microsoft’s cloud environment last year, it struck the espionage equivalent of gold. The threat actors

accessed the official email accounts of many of the most senior U.S. government officials managing our country’s

relationship with the People’s Republic of China.

As is its mandate, the Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB, or the Board) conducted deep fact-finding around this

incident. The Board concludes that this intrusion should never have happened. Storm-0558 was able to succeed

because of a cascade of security failures at Microsoft, as outlined in this report. Today, the Board issues

recommendations to Microsoft to ensure this critical company, which sits at the center of the technology ecosystem, is

prioritizing security for the benefit of its more than one billion customers. In the course of its review, the Board spoke

with a range of large CSPs to assess the state of their security practices, and—as is also its mandate—the Board today

issues recommendations to all CSPs for establishing specific security controls for identity and authentication in the

cloud. All technology companies must prioritize security in the design and development of their products. The entire

industry must come together to dramatically improve the identity and access infrastructure that safeguards the

information CSPs are entrusted to maintain. Global security relies upon it.

We, and all the members of CSRB, are grateful for Microsoft’s full cooperation in this review. The company provided

extensive oral and written submissions since November 2023, and we believe answered all of our questions to the best

of its ability. We also received full cooperation from U.S. intelligence, law enforcement, and cyber defense agencies.

As we complete our third review since the Board’s establishment in 2022, we are gratified more broadly to observe the

track record of cooperation that CSRB has developed with industry, security researchers, the academic community, and

foreign government agencies. We are more confident than ever in the Board’s role as a truly public-private institution

that conducts authoritative fact-finding and issues actionable recommendations in the wake of major cyber incidents.

We are grateful to Alejandro Mayorkas, Secretary of Homeland Security, and to Jen Easterly, Director of the

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, for their continued belief in and support of this Board, including by

charging us with consequential mandates like this review of the Microsoft Exchange Online incident.

We offer our thanks to the 20 organizations and individual experts who offered their experience and expertise to allow

us to conduct this comprehensive review. Finally, we express deep appreciation to our colleagues on the Board for their

continued commitment to our charge, and to the determined and gifted staff who helped the Board discharge its task

and bring this important review to conclusion.

Robert Silvers Dmitri Alperovitch

Chair Deputy Chair

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In May and June 2023, a threat actor compromised the Microsoft Exchange Online mailboxes of 22 organizations and

over 500 individuals around the world. The actor—known as Storm-0558 and assessed to be affiliated with the People’s

Republic of China in pursuit of espionage objectives—accessed the accounts using authentication tokens that were

signed by a key Microsoft had created in 2016. This intrusion compromised senior United States government

representatives working on national security matters, including the email accounts of Commerce Secretary Gina

Raimondo, United States Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China R. Nicholas Burns, and Congressman Don

Bacon.

Signing keys, used for secure authentication into remote systems, are the cryptographic equivalent of crown jewels for

any cloud service provider. As occurred in the course of this incident, an adversary in possession of a valid signing key

can grant itself permission to access any information or systems within that key’s domain. A single key’s reach can be

enormous, and in this case the stolen key had extraordinary power. In fact, when combined with another flaw in

Microsoft’s authentication system, the key permitted Storm-0558 to gain full access to essentially any Exchange Online

account anywhere in the world. As of the date of this report, Microsoft does not know how or when Storm-0558

obtained the signing key.

This was not the first intrusion perpetrated by Storm-0558, nor is it the first time Storm-0558 displayed interest in

compromising cloud providers or stealing authentication keys. Industry links Storm-0558 to the 2009 Operation Aurora

campaign that targeted over two dozen companies, including Google, and the 2011 RSA SecurID incident, in which the

actor stole secret keys used to generate authentication codes for SecurID tokens, which were used by tens of millions

of users at that time. Indeed, security researchers have tracked Storm-0558’s activities for over 20 years.

On August 11, 2023, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas announced that the Cyber Safety Review

Board (CSRB, or the Board) would “assess the recent Microsoft Exchange Online intrusion . . . and conduct a broader

review of issues relating to cloud-based identity and authentication infrastructure affecting applicable cloud service

providers and their customers.”

The Board conducted extensive fact-finding into the Microsoft intrusion, interviewing 20 organizations to gather

relevant information (see Appendix A). Microsoft fully cooperated with the Board and provided extensive in-person and

virtual briefings, as well as written submissions. The Board also interviewed an array of leading cloud service providers

to gain insight into prevailing industry practices for security controls and governance around authentication and identity

in the cloud.

The Board finds that this intrusion was preventable and should never have occurred. The Board also concludes that

Microsoft’s security culture was inadequate and requires an overhaul, particularly in light of the company’s centrality in

the technology ecosystem and the level of trust customers place in the company to protect their data and operations.

The Board reaches this conclusion based on:

1. the cascade of Microsoft’s avoidable errors that allowed this intrusion to succeed;

2. Microsoft’s failure to detect the compromise of its cryptographic crown jewels on its own, relying instead on a

customer to reach out to identify anomalies the customer had observed;

3. the Board’s assessment of security practices at other cloud service providers, which maintained security

controls that Microsoft did not;

4. Microsoft’s failure to detect a compromise of an employee's laptop from a recently acquired company prior to

allowing it to connect to Microsoft’s corporate network in 2021;

5. Microsoft’s decision not to correct, in a timely manner, its inaccurate public statements about this incident,

including a corporate statement that Microsoft believed it had determined the likely root cause of the intrusion

when in fact, it still has not; even though Microsoft acknowledged to the Board in November 2023 that its

September 6, 2023 blog post about the root cause was inaccurate, it did not update that post until March 12,

2024, as the Board was concluding its review and only after the Board’s repeated questioning about

Microsoft’s plans to issue a correction;

6. the Board's observation of a separate incident, disclosed by Microsoft in January 2024, the investigation of

which was not in the purview of the Board’s review, which revealed a compromise that allowed a different

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

iv

nation-state actor to access highly-sensitive Microsoft corporate email accounts, source code repositories, and

internal systems; and

7. how Microsoft’s ubiquitous and critical products, which underpin essential services that support national

security, the foundations of our economy, and public health and safety, require the company to demonstrate

the highest standards of security, accountability, and transparency.

Throughout this review, the Board identified a series of Microsoft operational and strategic decisions that collectively

point to a corporate culture that deprioritized both enterprise security investments and rigorous risk management.

To drive the rapid cultural change that is needed within Microsoft, the Board believes that Microsoft’s customers would

benefit from its CEO and Board of Directors directly focusing on the company’s security culture and developing and

sharing publicly a plan with specific timelines to make fundamental, security-focused reforms across the company and

its full suite of products. The Board recommends that Microsoft’s CEO hold senior officers accountable for delivery

against this plan. In the meantime, Microsoft leadership should consider directing internal Microsoft teams to

deprioritize feature developments across the company’s cloud infrastructure and product suite until substantial security

improvements have been made in order to preclude competition for resources. In all instances, security risks should be

fully and appropriately assessed and addressed before new features are deployed.

Based on the lessons learned from its review and its fact-finding into prevailing security practices across the cloud

services industry, the Board, in addition to the recommendations it makes to the President of the United States and

Secretary of Homeland Security, also developed a series of broader recommendations for the community focused on

improving the security of cloud identity and authentication across the government agencies responsible for driving

better cybersecurity, cloud service providers, and their customers.

•

Cloud Service Provider Cybersecurity Practices: Cloud service providers should implement modern control

mechanisms and baseline practices, informed by a rigorous threat model, across their digital identity and

credential systems to substantially reduce the risk of system-level compromise.

• Audit Logging Norms: Cloud service providers should adopt a minimum standard for default audit logging in

cloud services to enable the detection, prevention, and investigation of intrusions as a baseline and routine

service offering without additional charge.

• Digital Identity Standards and Guidance: Cloud service providers should implement emerging digital identity

standards to secure cloud services against prevailing threat vectors. Relevant standards bodies should refine,

update, and incorporate these standards to address digital identity risks commonly exploited in the modern

threat landscape.

• Cloud Service Provider Transparency: Cloud service providers should adopt incident and vulnerability

disclosure practices to maximize transparency across and between their customers, stakeholders, and the

United States government, even in the absence of a regulatory obligation to report.

• Victim Notification Processes: Cloud service providers should develop more effective victim notification and

support mechanisms to drive information-sharing efforts and amplify pertinent information for investigating,

remediating, and recovering from cybersecurity incidents.

• Security Standards and Compliance Frameworks: The United States government should update the Federal

Risk Authorization Management Program and supporting frameworks and establish a process for conducting

discretionary special reviews of the program’s authorized Cloud Service Offerings following especially high-

impact situations. The National Institute of Standards and Technology should also incorporate feedback about

observed threats and incidents related to cloud provider security.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

1

1 FACTS

1.1 OVERVIEW

In May 2023, a threat actor known as Storm-0558

1

compromised the Microsoft Exchange Online mailboxes of a broad

range of victims in the United States (U.S.), the United Kingdom (U.K.), and elsewhere. Storm-0558, assessed by

multiple sources to pursue espionage objectives and maintain ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

2, 3

accessed email accounts in the U.S. Department of State (State Department, or State), U.S. Department of Commerce

(Commerce Department, or Commerce), and U.S. House of Representatives.

4

This included the official and personal

mailboxes of U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo; Congressman Don Bacon; U.S. Ambassador to the PRC, R.

Nicholas Burns; Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Daniel Kritenbrink;

5

and additional

individuals across 22 organizations.

6

These senior officials have substantial responsibilities for many aspects of the

U.S. government’s bilateral relationship with the PRC. Storm-0558 had access to some of these cloud-based mailboxes

for at least six weeks,

7, 8

and during this time, the threat actor downloaded approximately 60,000 emails from State

Department alone.

9

State Department was the first victim to discover the intrusion when, on June 15, 2023, State’s security operations

center (SOC) detected anomalies in access to its mail systems.

10

The next day, State observed multiple security alerts

from a custom rule it had created, known internally as “Big Yellow Taxi,”

11

that analyzes data from a log known as

MailItemsAccessed, which tracks access to Microsoft Exchange Online mailboxes. State was able to access the

MailItemsAccessed log to set up these particular Big Yellow Taxi alerts because it had purchased Microsoft’s

government agency-focused G5 license that includes enhanced logging capabilities through a product called Microsoft

Purview Audit (Premium).

12

The MailItemsAccessed log was not accessible without that “premium” service.

13

Though the alerts showed activity that could have been considered normal—and, indeed, State had seen false positive

Big Yellow Taxi detections in the past—State investigated these incidents and ultimately determined that the alert

indicated malicious activity. State triaged the alert as a moderate-level event and, on Friday, June 16, 2023, its security

team contacted Microsoft.

14, 15

Microsoft opened and conducted an investigation of its own, and over the next 10 days,

ultimately confirmed that Storm-0558 had gained entry to certain user emails through State’s Outlook Web Access

(OWA). Concurrently, Microsoft expanded its investigation to identify the 21 additional impacted organizations and 503

related users impacted by the attack and worked to identify and notify impacted U.S. government agencies.

16

Microsoft initially assumed that Storm-0558 had gained access to State Department accounts through traditional

threat vectors, such as compromised devices or stolen credentials. However, on June 26, 2023, Microsoft discovered

that the threat actor had used OWA to access emails directly using tokens that authenticated Storm-0558 as valid

1

Microsoft uses its internal naming taxonomy to label threat actors based on several characteristics including country of origin,

infrastructure, and objectives. Source: Lambert, John; Microsoft, “Microsoft shifts to a new threat actor naming taxonomy,” April 18, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/04/18/microsoft-shifts-to-a-new-threat-actor-naming-taxonomy/

2

Anonymized.

3

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

4

Anonymized.

5

Schappert, Stefanie; CyberNews, “Another US Congressman reveals emails hacked by China,” November 15, 2023,

https://cybernews.com/news/us-congressman-emails-hacked-china-microsoft/

6

Anonymized.

7

Anonymized.

8

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

9

State Department, “Department Press Briefing – September 28, 2023,” September 28, 2023,

https://www.state.gov/briefings/department-press-briefing-september-28-2023/

10

Anonymized.

11

Sakellariadis, John and Miller, Maggie; Politico, “All thanks to ‘Big Yellow Taxi’: How State discovered Chinese hackers reading its emails,”

September 15, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/09/15/digital-tripwire-helped-state-uncover-chinese-hack-00115973

12

State Department, Board Meeting.

13

Microsoft, “Compare Office 365 Government Plans: Microsoft 365,” https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-

365/enterprise/government-plans-and-pricing

14

Anonymized.

15

State Department, Board Meeting.

16

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

2

users. Such tokens should only come from Microsoft’s identity system, yet these had not. Moreover, tokens used by the

threat actor had been digitally signed with a Microsoft Services Account (MSA)

17

cryptographic key that Microsoft had

issued in 2016. This particular MSA key should only have been able to sign tokens that worked in consumer OWA, not

Enterprise Exchange Online. Finally, this 2016 MSA key was originally intended to be retired in March 2021, but its

removal was delayed due to unforeseen challenges associated with hardening the consumer key systems.

18

This was

the moment that Microsoft realized it had major, overlapping problems: first, someone was using a Microsoft signing

key to issue their own tokens; second, the 2016 MSA key in question was no longer supposed to be signing new

tokens; and third, someone was using these consumer key-signed tokens to gain access to enterprise email accounts.

According to Microsoft, this discovery triggered an all-hands-on-deck investigation by Microsoft that ran overnight from

June 26 into June 27, 2023, focusing on the 2016 MSA key that had issued the token as well as the access token

itself. By the end of the day, Microsoft had high confidence that the threat actor had forged a token using a stolen

consumer signing key. Microsoft then escalated this intrusion internally, assigning it the highest urgency level and

coordinating its investigation across multiple company teams. As a result, Microsoft developed 46 hypotheses to

investigate, including some scenarios as wide-ranging as the adversary possessing a theoretical quantum computing

capability to break public-key cryptography or an insider who stole the key during its creation. Microsoft then assigned

teams for each hypothesis to try to: prove how the theft occurred; prove it could no longer occur in the same way now;

and to prove Microsoft would detect it if it happened today. Nine months after the discovery of the intrusion, Microsoft

says that its investigation into these hypotheses remains ongoing.

19

Microsoft began notifying potentially impacted organizations and individuals on or about June 19 and July 4, 2023,

respectively.

20, 21

As detailed below, this effort had varying degrees of success. Ultimately, Microsoft determined that

Storm-0558 used an acquired MSA consumer token signing key to forge tokens to access Microsoft Exchange Online

accounts for 22 enterprise organizations, as well as 503 related personal

22

accounts, worldwide.

23

Of the 503

personal accounts reported by Microsoft, at least 391 were in the U.S. and included those of former government

officials,

24

while others were linked to Western European, Asia-Pacific (APAC), Latin American, and Middle Eastern

countries and associated victim organizations.

25, 26, 27

Microsoft found no sign of an intrusion into its identity system and, as of the conclusion of this review, has not been

able to determine how Storm-0558 had obtained the 2016 MSA key; it did find a flaw in the token validation logic used

by Exchange Online that could allow a consumer key to access enterprise Exchange accounts if those Exchange

accounts were not coded to reject a consumer key. By June 27, 2023, Microsoft believed it had identified the technique

used to access victim accounts and rapidly cleared related caching data in various downstream Microsoft systems to

invalidate all credentials derived from the stolen key. Microsoft believed that this mitigation was effective, as it almost

immediately observed Storm-0558 begin to use phishing to try to gain access to the email boxes it had previously

compromised.

28

However, by the conclusion of this review, Microsoft was still unable to demonstrate to the Board that

it knew how Storm-0558 had obtained the 2016 MSA key.

17

Consumer accounts are validated by MSA consumer signing keys, and Azure AD accounts are validated through Azure AD enterprise

signing keys. As these keys are from separate providers, and managed in separate systems, they should not be able to validate for the other

system. Source: SecureTeam, “Microsoft Key Used for Unauthorised Email Access,” July 27, 2023,

https://secureteam.co.uk/2023/07/27/microsoft-key-used-for-unauthorised-email-access/

18

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

19

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

20

Anonymized.

21

Anonymized.

22

The term “personal” in this context means an individual account. “A Microsoft [personal] account is the name given to the identity service

that provides authentication and authorization to Microsoft's consumer services. You use a personal Microsoft account to connect to

Microsoft apps, services, and devices.” Source: Microsoft, “What’s the difference between a Microsoft account and a Microsoft 365 work or

school account?” October 10, 2023, https://support.microsoft.com/en-au/office/what-s-the-difference-between-a-microsoft-account-and-a-

microsoft-365-work-or-school-account-72f10e1e-cab8-4950-a8da-7c45339575b0

23

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

24

Anonymized.

25

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

26

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

27

Microsoft, Response to Board Request for Information.

28

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

3

1.2 INTRUSION DETAILS

1.2.1 TIMELINE

The Board finds that the intrusion began in May 2023 and known adversaries’ techniques were remediated by the end

of June 2023. A high-level timeline follows, and a more complete chronology is included in Appendix B.

May-June 15, 2023: Initial Intrusion, Before Discovery

Storm-0558 compromised Microsoft Exchange Online mailboxes of certain victims in the U.S., the U.K., and elsewhere

between May and the first half of June.

29, 30

However, the Board heard that Microsoft’s window of compromise may

have started earlier than May 15, as it had published, based on standard 30-day log retention practices.

31

June 15-19, 2023: Department of State Detects the Intrusion

State first detected anomalous activity on June 15, notified Microsoft on June 16, and, with support from Microsoft,

investigated and analyzed the data over the course of the holiday weekend. By June 19, State determined that a threat

actor had accessed six State email accounts, including those of personnel supporting the Secretary of State’s

upcoming trip to Beijing. State discovered that the threat actor accessed six other accounts between June 21 and June

24, and later discovered the compromise of one other account through the analysis of a seized virtual private server

(VPS).

32

June 16-26, 2023: The Investigation Broadens; Department of Commerce is Identified as a Victim

State reached out to Microsoft, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI).

33, 34

CISA already had personnel at State conducting proactive threat hunting who began collecting

data for analysis;

35

FBI shared details about the threat actor, its targets and exploitation vectors, and other indicators

of compromise.

36, 37

After outreach from State, on June 16, Microsoft conducted an initial investigation, which

assumed that Storm-0558 had gained entry to user emails through State’s OWA.

38

On June 19, Microsoft notified an organization in the U.K. that it was a victim; Microsoft later identified other victim

organizations in the U.K.

39

On June 23, Microsoft notified Commerce Department that it, too, was a victim.

40

On or

about June 26, Microsoft determined that Storm-0558 was using the stolen 2016 MSA key to issue tokens that allowed

it to access both consumer and enterprise accounts.

41

June 24, 2023: Closing the Attack Vector

On June 24, Microsoft invalidated the stolen key the threat actor was using.

42, 43

Microsoft believed that this action

ended Storm-0558’s access to the email accounts, as it almost immediately observed Storm-0558 attempt phishing

and other methods to regain access to the email boxes it had previously compromised.

44

July 4, 2023 and Beyond: Continue Victim Notification and Remediation

Microsoft began victim notification during its initial investigation, and this continued for weeks. Because of the nature

of the intrusion, only Microsoft was able to identify most of the victims. It worked with the U.S. government to provide

29

Anonymized.

30

Anonymized.

31

Anonymized.

32

State Department, Board Meeting.

33

FBI, Response to Board Request for Information.

34

State Department, Board Meeting.

35

Anonymized.

36

State Department, Board Meeting.

37

FBI, Board Meeting.

38

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

39

Anonymized.

40

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

41

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

42

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

43

Anonymized.

44

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

4

victim information, and federal agencies undertook separate efforts to notify impacted individuals.

45, 46

These different

efforts had varying degrees of success. Microsoft also took additional steps to ensure that the 2016 MSA key was

replaced and that previously issued tokens would not work on any impacted individual customers’ environments.

47

1.2.2 THREAT ACTOR PROFILE

Storm-0558 has been active since approximately the year 2000.

48

Microsoft described Storm-0558 as “a China-based

threat actor with activities and methods consistent with espionage objectives. While we have discovered some minimal

overlaps with other Chinese groups such as Violet Typhoon (ZIRCONIUM, APT31), we maintain high confidence that

Storm-0558 operates as its own distinct group.” Microsoft historically observed the group primarily targeting U.S. and

European diplomatic, economic, and legislative governing bodies; media companies, think tanks, and

telecommunications and equipment services providers; and individuals connected to Taiwan and Uyghur geopolitical

interests.

49

Microsoft assesses that the Microsoft Exchange Online intrusion was a targeted information-collection

operation aimed at fulfilling the PRC’s intelligence needs.

50

Microsoft has developed insights into Storm-0558’s activity clusters, ways in which its operational network overlaps

with Microsoft’s environment, and its affiliates and partnerships.

51

FBI and CISA assess that this latest campaign by

Storm-0558 was also consistent with that of a nation-state threat actor with a high level of sophistication,

52

particularly

with its knowledge of identity and access management (IAM) systems.

53

Following disclosure of the Storm-0558 breach, Google’s Threat Analysis Group was able to link at least one entity tied

to this threat actor to the group responsible for the 2009 compromise of Google and dozens of other private companies

in a campaign known as Operation Aurora,

54, 55

as well as the RSA SecurID incident.

56, 57

The threat group believed to

have been behind the Operation Aurora campaign has been known to compromise cloud identity systems, steal source

code, and engage in token-forging activities to gain access to targeted individuals’ email accounts.

58, 59

Particularly,

this threat group sought to understand the location of account login source code and the specific engineers involved in

its development, ways in which organizations deploy account login systems to their production environment, and where

and how organizations manage their cryptographic keys for account login cookies. In the wake of these attacks,

investigators assessed that this threat group’s tooling and reconnaissance activities suggest that it is well resourced,

technically adept, and deeply knowledgeable of many authentication techniques and applications.

60

45

Anonymized.

46

Anonymized.

47

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

48

Anonymized.

49

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

50

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

51

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

52

FBI, Board Meeting.

53

CISA, Board Meeting.

54

Google, Board Meeting.

55

Operation Aurora was a series of cyberattacks from China that targeted U.S. private sector companies in 2010, compromising the

networks of Yahoo, Adobe, Dow Chemical, Morgan Stanley, Google, and more than two dozen other companies to steal their trade secrets.

Google was the only company that confirmed it was a victim and publicly attributed the incident to China. The incident is viewed as a

milestone in the recent history of cyber operations because it raised the profile of cyber operations as a tool for industrial espionage. Source:

Council on Foreign Relations, “Operation Aurora,” January 2010, https://www.cfr.org/cyber-operations/operation-aurora

56

The 2011 RSA SecureID intrusion resulted in the compromise of sensitive information relating to its two-factor SecurID authentication

system. Source: Schwartz, Mathew; Dark Reading, “RSA Pins SecurID Attacks On Nation State,” October 12, 2011,

https://www.darkreading.com/cyberattacks-data-breaches/rsa-pins-securid-attacks-on-nation-state

57

Anonymized.

58

O’Gorman, Gavin and McDonald, Geoff; Symantec, “The Elderwood Project,” September 6, 2012,

https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs6410/2012fa/slides/Symantec_ElderwoodProject_2012.pdf

59

Google specifically described the attack as a highly sophisticated and targeted attack on their corporate infrastructure that resulted in

theft of intellectual property and access to targeted Gmail accounts. Source: Google Official Blog, “A new approach to China,” January 12,

2010, https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2010/01/new-approach-to-china.html

60

Google, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

5

1.2.3 2023 COMPROMISE OF MICROSOFT EXCHANGE ONLINE

1.2.3.1 Storm-0558’s Possession of the 2016 MSA Key

Microsoft learned that, in 2021, Storm-0558 had accessed a variety of documents stored in SharePoint and assessed

that the threat actor was specifically looking for information on Azure service management and identity-related

information.

61

Despite Microsoft’s pursuit of the 46 key-theft hypotheses,

62

the Board assesses that Microsoft does not

know how Storm-0558 obtained the 2016 MSA key. Microsoft stated in a September 6, 2023 blog post that the most

probable way Storm-0558 had obtained the key was from a crash dump

63

to which it had access during the 2021

compromise of Microsoft’s systems. However, Microsoft had only theorized that such a scenario was technically

feasible in the 2016 timeframe. While Microsoft updated this blog on March 12, 2024 to correct its assessment of

these theories,

64

it has not determined that this is how Storm-0558 obtained the key.

65

The Board further determines that Microsoft has no evidence or logs showing the stolen key’s presence in or exfiltration

from a crash dump. During the Board’s interview with Microsoft in November 2023, Microsoft said that soon after

publication, it realized that the statements in the September 6 blog were inaccurate: Microsoft had found no evidence

of a crash dump containing the 2016 MSA key material.

66

While Microsoft’s latest update about this incident

acknowledges that it did not find a crash dump containing the impacted 2016 MSA key material,

67

the possibility that

the threat actor had accessed other keys and sensitive data, in addition to the 2016 MSA key, also remains

unresolved,

68

adding to the Board’s concern about the full consequences of the incident and remaining uncertainty.

In its November 2023 interview, Microsoft also told the Board that it was debating when to issue a new or updated blog

based on the progress of its investigation but had not made any decisions.

69

In a written response to the Board on

March 5, 2024, Microsoft maintained that it “intends to publish an update to the blog in the near future.”

70

Over six

months after its publication of the September 6 blog, and four months after acknowledging to the Board that the blog

was inaccurate, Microsoft publicly corrected its mistaken assertions in an addendum, based on its “latest

knowledge.”

71

1.2.3.2 How Storm-0558 Used the 2016 MSA Key

Storm-0558 established its first identified component of external hosting infrastructure to execute the Exchange Online

intrusion and gained access to email accounts on May 15, 2023.

72

After State notified Microsoft about the intrusion on

June 16, 2023, Microsoft reviewed logs pertaining to the event, from the month of May, and identified that the first

instance of malicious activity took place days after Storm-0558 had established its infrastructure. Microsoft also said

that Storm-0558 had, in the past, used more sophisticated covert networks, but Microsoft believes that a previous

disruption of the threat actor’s infrastructure forced it to use a less sophisticated infrastructure for this intrusion that

was more readily identifiable once discovered.

73

In this instance, Storm-0558 occasionally used infrastructure located

geographically near its targets, likely to try to blend in with legitimate activity.

74, 75

61

Microsoft, Response to Board Request for Information.

62

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

63

A system crash (also known as a "bug check" or a "Stop error") occurs when Windows cannot run correctly. The dump file that is produced

from this event is called a system crash dump. Source: Microsoft Learn, “Generate a kernel or complete crash dump,” September 2, 2022,

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/troubleshoot/windows-client/performance/generate-a-kernel-or-complete-crash-dump

64

MSRC; Microsoft, “Results of Major Technical Investigations for Storm-0558 Key Acquisition,” September 6, 2023 (updated March 12,

2024), https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/09/results-of-major-technical-investigations-for-storm-0558-key-acquisition/

65

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

66

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

67

MSRC; Microsoft, “Results of Major Technical Investigations for Storm-0558 Key Acquisition,” September 6, 2023 (updated March 12,

2024), https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/09/results-of-major-technical-investigations-for-storm-0558-key-acquisition/

68

Anonymized.

69

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

70

Microsoft, Response to Board Request for Information.

71

MSRC; Microsoft, “Results of Major Technical Investigations for Storm-0558 Key Acquisition,” September 6, 2023 (updated March 12,

2024), https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/09/results-of-major-technical-investigations-for-storm-0558-key-acquisition/

72

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

73

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

74

Anonymized.

75

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

6

Microsoft designed its consumer MSA identity infrastructure more than 20 years ago. Later, it introduced an enterprise

Entra infrastructure, previously known as Azure Active Directory (AD). Initially, the consumer MSA system had no

process for automated signing key rotation or deactivation and utilized a manual process instead. Over time, Microsoft

automated the key rotation process in the enterprise system with the intent for the consumer MSA system to follow and

use the same technology, but it had not done so in the consumer MSA system before the intrusion. Microsoft continued

to rotate consumer MSA keys infrequently and manually until it stopped the rotation entirely in 2021 following a major

cloud outage linked to the manual rotation process. While Microsoft had paused manual key rotation, it neither had,

nor created, an automated alerting system to notify the appropriate Microsoft teams about the age of active signing

keys in the consumer MSA service.

76

Thus, possession of the 2016 MSA key—dated though it was—enabled the threat actor to forge authentication tokens

that allowed it to access email systems. This access should have been limited to consumer email systems,

77

but due to

a previously unknown flaw that allowed tokens to access enterprise email accounts, Storm-0558 was able to get into

systems such as those at State and Commerce. The flaw was caused by Microsoft’s efforts to address customer

requests for a common OpenID Connect (OIDC) endpoint service that listed active signing keys for both enterprise and

consumer identity systems.

78

However, Microsoft had not adequately updated the software development kits (SDKs),

which Microsoft and its partners both used, to differentiate between the consumer MSA and the enterprise signing keys

within the common endpoint. As a result, this allowed successful authentication to the Entra system for certain

applications, such as mail, regardless of which key was used.

79

Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, the stolen 2016 MSA key in combination with the flaw in the token validation system

permitted the threat actor to gain full access to essentially any Exchange Online account.

80, 81

Cloud Service Vulnerabilities

Cloud service providers (CSPs) do not always register and publicly disclose common vulnerabilities and exposures

(CVEs) in their cloud infrastructure when mitigating those vulnerabilities does not require customer action.

82

This

lack of disclosure, which is counter to accepted norms for cybersecurity more generally, makes it difficult for CSP

customers to understand the risks posed by their reliance on potentially vulnerable cloud infrastructure.

83

Microsoft does not know when Storm-0558 discovered that consumer signing keys (including the one it had stolen)

could forge tokens that worked on both OWA consumer and enterprise Exchange Online. Microsoft speculates that the

threat actor could have discovered this capability through trial and error. It assessed that during this incident, the actor

was researching Microsoft technologies and used this knowledge to pivot and circumvent Microsoft’s security

measures within test cloud tenants.

84

76

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

77

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

78

OpenID providers like the Microsoft identity platform provide an OpenID Provider Configuration Document at a publicly accessible endpoint

containing the provider's OIDC endpoints, supported claims, and other metadata. Client applications can use the metadata to discover the

URLs to use for authentication and the authentication service's public signing keys. Source: Microsoft; “OpenID Connect on the Microsoft

identity platform,” October 23, 2023, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/v2-protocols-oidc

79

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

80

Anonymized.

81

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

82

Anonymized.

83

Anonymized.

84

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

7

Figure 1: Storm-0558 Token Abuse with Stolen 2016 MSA Key

1.2.4 2021 COMPROMISE OF MICROSOFT CORPORATE NETWORK BY STORM-0558

Microsoft told the Board that Storm-0558 had compromised Microsoft’s corporate network via an engineer’s account,

which occurred between April and August 2021. Microsoft believes, although it has produced no specific evidence to

such effect, that this 2021 intrusion was likely connected to the 2023 Exchange Online compromise because it is the

only other known Storm-0558 intrusion of Microsoft’s network in recorded memory. During this 2021 incident,

Microsoft believes that Storm-0558 gained access to sensitive authentication and identity data.

85

As announced on March 26, 2020 and completed on April 23, 2020, Microsoft acquired a company called Affirmed

Networks

86

that worked in 5G technology and advanced networking. Microsoft believes that prior to the acquisition,

Storm-0558 targeted an engineer and compromised their device due to their experience in 5G technology and

advanced networking. After the acquisition, Microsoft supplied corporate credentials to the acquired engineer that

allowed access to Microsoft’s corporate environment with the compromised device. Leveraging this access, Storm-

0558 captured an authentication token, then replayed the token to authenticate as the Microsoft employee on

Microsoft’s corporate network.

87, 88

85

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

86

Khalidi, Yousef; Microsoft, “Microsoft announces agreement to acquire Affirmed Networks to deliver new opportunities for a global 5G

ecosystem,” March 26, 2020, https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2020/03/26/microsoft-announces-agreement-to-acquire-affirmed-

networks-to-deliver-new-opportunities-for-a-global-5g-ecosystem/

87

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

88

Anonymized.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

8

While Storm-0558 exhibited an advanced understanding of Microsoft’s network and demonstrated a particular interest

in information associated with identity and engineering, Microsoft does not have direct evidence linking the two

incidents. Microsoft’s insider threat investigation also did not find evidence to indicate that a malicious insider was a

part of the 2023 intrusion. Through its ongoing investigations, Microsoft said it believes that alternative initial access

vectors, such as an insider threat, remain unlikely.

89

Still, the 2021 compromise of Microsoft’s corporate network highlights gaps within the company’s mergers and

acquisitions (M&A) security compromise assessment and remediation process. Microsoft told the Board that, where

applicable and based on the risk profile associated with the acquisition and the terms of the agreement, Microsoft

deploys telemetry and threat intelligence tools to assess whether an acquisition has been compromised, and

remediation can occur pre- or post-closing. Microsoft and the acquisition target formalize a security incident response

process to coordinate security incidents until close. Following the acquisition, Microsoft’s internal audit team may

conduct security audits of an acquisition leveraging findings from due diligence security assessments to inform the

scope of these assessments.

90

1.2.5 INCIDENT IMPACT

The Microsoft Exchange Online intrusion was significant: Storm-0558’s combined possession of the 2016 MSA key and

its ability to access enterprise Exchange accounts allowed the threat actor to access any Microsoft Exchange Online

account. Although Microsoft expressed confidence resulting both from extensive log analysis and direct actor tracking

that this intrusion only impacted Microsoft Exchange Online, the stolen key also could have been used by the threat

actor to access other Microsoft cloud applications had it chosen to do so. These include both Microsoft and third-party

applications reliant on Microsoft’s identity provider (IDP) that were either intentionally (due to supporting consumer

accounts) or unintentionally (due to using client libraries or bespoke code that failed to properly validate authentication

tokens) trusting tokens signed by the stolen key.

91, 92, 93

Microsoft believes that Storm-0558 itself limited the scope of

this intrusion, as it appeared to be selective in its targeting, balancing its information-gathering objectives with

probabilities of detection.

94

The Board believes that the actor also prioritized high-value and time-sensitive collection

missions.

Yet while the number of victims was relatively low given the breadth of the access available to the actor, they were

widespread: Storm-0558 accessed the email accounts of 22 enterprise organizations,

95

including government

agencies and three think tanks.

96

This intrusion also impacted the personal accounts of individuals likely associated

with these organizations.

97

The non-U.S. victims included four foreign government entities, three private sector

organizations, and four educational entities.

98

Impacted U.K. Accounts

Storm-0558 compromised several U.K. organizations’ email accounts and exfiltrated an unknown number of emails.

Initially, Microsoft reported three affected accounts to the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC),

99

but further

investigation by Microsoft revealed additional victims. This discovery underscores both the evolving nature of this

incident’s impact assessment and the delayed victim identification.

100

The Board has not learned why these U.K.

individuals were chosen over others.

89

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

90

Microsoft, Response to Board Request for Information.

91

Anonymized.

92

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

93

Anonymized.

94

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

95

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

96

Anonymized.

97

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

98

Anonymized.

99

NCSC, the U.K.’s version of FBI Cyber Division, supports the most critical organizations in the U.K., the wider public sector, industry,

subject matter experts, and the general public. Source: NCSC, “What we do,” https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/section/about-ncsc/what-we-do

100

NCSC, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

9

Microsoft knew the identity of all of the individuals whom Storm-0558 targeted, many of whom were linked to entities

associated with Western European, APAC, Latin American, and Middle Eastern countries.

101, 102

Of these accounts, the

intrusion impacted at least 391 personal email accounts in the U.S,

103

including some Hotmail accounts belonging to

current and former employees of an affected government organization.

104

The threat actor compromised the official and personal mailboxes of many senior U.S. government officials, some of

which likely contained information about the U.S.’s diplomatic and economic policies toward the PRC. The timing of the

intrusion, just before Secretary Blinken’s trip to Beijing in 2023, combined with the seniority of the officials targeted,

highlights a potential partial rationale for such intrusions.

105

1.3 INCIDENT MANAGEMENT

1.3.1 HOW STATE DEPARTMENT DISCOVERED THE INTRUSION

State Department was the first entity to detect the intrusion when on June 16, 2023, a State SOC analyst observed

multiple alerts from the “Big Yellow Taxi” custom alert rule. Detecting an intrusion like this is difficult; State Department

found Storm-0558 because it had purchased enhanced logging through the G5 licenses,

106

which few, if any, victims

had similarly acquired.

107

As standard practice, State’s SOC uses that enhanced logging to build custom alerts like “Big

Yellow Taxi” in response to an evolving threat environment.

108

Just purchasing the additional logging alone would not

have been enough; in fact, the Board heard that few organizations analyzed the voluminous MailItemsAccessed log in

detail, and such in-depth analysis would be difficult for smaller organizations.

State, however, used the data to build custom detection rules to enable it to identify anomalous access to mailboxes

such as the activity undertaken in this intrusion. State Department’s SOC designed custom alerting capabilities based

on three years of experience dealing with anomalous access to mailboxes. In particular, State curated log events like

the MailItemsAccessed data to enumerate all applications accessing mailboxes within its infrastructure, and to trigger

alerts for any anomalous events.

109

It also designed a rule to detect deviations in mailbox activity by comparing

baseline interactions of applications with Exchange Online.

110

These rules provided detailed information about

application IDs touching mailboxes, specific application details, and context about particular mailboxes involved,

thereby enhancing State’s ability to pinpoint potential issues quickly.

111

1.3.2 INVESTIGATION AND ANALYSIS

1.3.2.1 Microsoft’s Investigation

After receiving State Department’s report on June 16, 2023, Microsoft began an initial investigation using its normal

processes, which involved Microsoft’s Detection and Response Team (DART). Microsoft attributed the intrusion to

Storm-0558 after identifying infrastructure associated with the threat actor. This investigation continued until June 26,

2023. At the time, Microsoft determined the impact was larger in scope and may have involved the compromise of

Microsoft’s systems. Specifically, Microsoft discovered the threat actor was able to access emails directly using forged

tokens signed with a consumer token signing key that was supposed to have been inactive. Once it identified and

revoked the stolen 2016 MSA key, Microsoft was able to use the key to inform its hunting efforts: since the key was

inactive at this point, the Microsoft identity system was not using it to sign any tokens. Thus, all signing instances using

this key constituted nefarious activity. This insight helped Microsoft determine that its identity system had not issued

the invalid tokens and identify threat actor activities with high confidence,

112

meaning the threat actors had an MSA

101

MSRC; Microsoft, “Microsoft mitigates China-based threat actor Storm-0558 targeting of customer email,” July 11, 2023,

https://msrc.microsoft.com/blog/2023/07/microsoft-mitigates-china-based-threat-actor-storm-0558-targeting-of-customer-email/

102

Microsoft, Response to Board Request for Information.

103

Anonymized.

104

Anonymized.

105

Anonymized.

106

State Department, Board Meeting.

107

Anonymized.

108

State Department, Board Meeting.

109

State Department, Board Meeting.

110

Anonymized.

111

State Department, Board Meeting.

112

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

10

key that could be used to issue working—though fraudulently issued—tokens that could grant application access to

mailboxes within the enterprise environment.

113

In response, on June 26, 2023, Microsoft launched an overnight investigation focusing on the key and token and

assessed with high confidence that the threat actor had forged a token using a consumer MSA key that should have

been inactive. Upon confirming that Storm-0558 had forged the token, Microsoft began converging individual

processes into its Software and Services Incident Response Plan (SSIRP), which has different urgency levels based on

multiple criteria, including the number of impacted customers. On June 27, 2023, Microsoft assigned this intrusion a

SEV-0 rating, the highest urgency level. This meant that the incident required robust communication, visibility, and

coordination across Microsoft and up to its most senior leadership, including its Board of Directors.

114

Microsoft’s incident response plan leverages several specialty teams that coordinate response for large and small

incidents. While some incidents are local, like a good faith researcher reporting a vulnerability that can be repaired

without needing cross-team coordination, in this case Microsoft leveraged its standardized global security response

processes, allowing it to coordinate across multiple teams and establish separate workstreams for containment,

customer impact, incident notifications, and investigating the key’s exfiltration. For the last workstream, it assembled

team members from DART, the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC), and various security teams to hypothesize

potential egress points for the key. This collaborative effort generated the three sub-workstreams dedicated to

investigating Microsoft’s 46 hypotheses.

115

After reexamining the 2021 compromise of the engineer and analyzing what Storm-0558 could have accessed using

the stolen credentials at that time, Microsoft determined that it needed to expand its investigation to scan for the

presence of the 2016 MSA key across its network. Microsoft told the Board that it continues to engage in this work.

Additionally, after Microsoft put protections in place to prevent future token generation by invalidating the key, it saw

the actor experiment and unsuccessfully attempt to generate new tokens.

116, 117

Storm-0558’s use of the invalid key to

sign authentication requests allowed Microsoft’s teams to determine the scope of the threat actor’s access.

118

Microsoft found no evidence of a breach in the perimeter of the signing system. During the investigation, Microsoft

examined the threat actor’s targeting methods, and looked for evidence of a compromise or the introduction of an

external device into the corporate network as possible attack vectors. The investigation uncovered what Microsoft

believes is the precise number of targeted individuals, and enabled Microsoft’s acquisition of the malware that Storm-

0558 used to sign tokens for accessing OWA. This discovery was pivotal in focusing the search across Microsoft’s logs

for any additional threat activity. Microsoft has not yet determined how Storm-0558 obtained the 2016 MSA key and

says that it is continuing to investigate.

119

1.3.2.2 Investigations by Victim Organizations

Victims found it difficult to investigate these intrusions after initial detection because Microsoft could not, or in some

cases did not, provide victim organizations with holistic visibility into all necessary data. Although Microsoft activated

enhanced logging for identified victims who did not have the appropriate license, Microsoft could not give historical logs

to customers unless they already had the premium licenses at the time of the intrusion. Thus, customers could capture

data from the time that Microsoft enabled additional logging capabilities but were unable to view past intrusion activity.

State’s SOC had limited visibility into the activity but, based on the particular email accounts that the threat actor

accessed, quickly determined that the targeted individuals were supporting the Secretary’s upcoming trip to Beijing.

This approach significantly aided State in refining its analysis of the activity. Later joined in its response by the National

Security Agency (NSA), CISA, and Microsoft, State confirmed the intrusion into the mailboxes on June 19, 2023. It then

began a comprehensive investigation to understand what was happening and what the actor had exfiltrated. On June

21, 2023, after issuing a legal process to the U.S.-based VPS provider that hosted the attacker’s infrastructure, the

government obtained a disk image from the provider that contained valuable insights into the threat actor’s intrusion

113

Anonymized.

114

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

115

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

116

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

117

Anonymized.

118

Microsoft Threat Intelligence; Microsoft, “Analysis of Storm-0558 techniques for unauthorized email access,” July 14, 2023,

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/07/14/analysis-of-storm-0558-techniques-for-unauthorized-email-access/

119

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

11

attempts and follow-on activity. That same day, the FBI was notified of the intrusion and received this information. In

parallel with CISA, FBI conducted an independent analysis on the disk image and made its findings available to the

broader group.

120

Microsoft first notified Commerce’s Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) about the intrusion into the Commerce

Department’s systems on June 23, 2023, one week after State Department’s discovery. According to Microsoft’s initial

reports, Storm-0558 accessed and exfiltrated data from Commerce on June 21, 2023.

121, 122

However, later audit logs

provided by Microsoft showed Storm-0558 had initially accessed Commerce data on June 6, 2023.

123

Commerce Department’s Enterprise SOC (ESOC) team immediately contacted CISA for assistance, marking the

beginning of the entity’s efforts to understand the intrusion.

124

It then asked Microsoft to share relevant logs, and

Microsoft provided some data and activated G5 logging. However, Commerce could not view past activity as these logs

only captured data from the time that Microsoft enabled the advanced logging. Microsoft told Commerce that it had

derived some of its information about the incident from additional logging capabilities available to internal Microsoft

teams for monitoring threat actor behavior.

125, 126

Commerce Department asked Microsoft to share these logs so that it

could do its own assessment of the incident, including any potential impact to other subordinate bureaus’ systems.

Microsoft shared certain portions of Commerce’s impacted unified audit logs and provided Internet Protocol (IP)

addresses that the organization could use to search across its network. This incomplete dataset impacted Commerce

Department’s ability to do a complete assessment of the incident.

127

Commerce Department collected all affected user devices, temporarily suspended impacted mailbox usage, and

deployed signatures at its ESOC to monitor for and detect related activity. Commerce also shared all signatures with

subordinate Bureaus to deploy. To monitor for follow-on threat activity and identify impact beyond initial reporting,

Commerce activated G5 logging, but as discussed, it could not analyze historical telemetry for malicious activity

because Microsoft could only provide these logs and data going forward—it had not collected and did not possess the

data for earlier activity because Commerce did not have the G5 licenses then.

128

1.3.2.3 Investigations by Government Incident Responders

On June 21, 2023, State Department notified the FBI Washington Field Office’s Cyber Task Force that a threat actor

had accessed official State mailboxes between June 13 and June 20, 2023. FBI told the Board that Microsoft was

critically important to its ability to understand the nature of the compromise, who the targets were, and how the threat

actor had exploited the vulnerability. Microsoft also helped FBI in continuing to develop proof of high-level attribution to

Storm-0558 and voluntarily provided indicators of compromise (IoCs) for further investigation.

129

CISA was a central point for information sharing related to detection, mitigation, and remediation across and between

federal agencies, and with private sector partners and victims. It also shared guidance to agencies for how to detect

this intrusion, specifically to examine their logs, to the extent that they had access to the G5 service level, for

unexpected MailItemsAccessed events with irregular application IDs.

130

At the time of the intrusion, CISA was already

providing State Department with proactive threat hunting services as part of a routine, by-request engagement. CISA

shifted to incident response following State’s detection of Storm-0558 activity and analyzed the pattern of threat

activity. CISA also collected data and surveyed observations from other stakeholder organizations to search for

compromises beyond State.

131

CISA tried to recreate Storm-0558’s activity but could not replicate the forged token as it did not possess the necessary

stolen MSA key. Without the 2016 MSA key, CISA could only emulate the incident in a limited way and had to rely on its

knowledge of Exchange Online and logs from State Department to conduct its investigation. Leveraging tokens it

120

State Department, Board Meeting.

121

Anonymized.

122

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

123

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

124

Commerce Department, Response to Board Request for Information.

125

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

126

Anonymized.

127

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

128

Commerce Department, Board Meeting.

129

FBI, Board Meeting.

130

Anonymized.

131

CISA, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

12

generated in OWA, similar to those used by Storm-0558, CISA conducted a test to emulate the application programming

interface (API) used by the threat actor to exfiltrate email. Subsequent forensics on the threat actor’s tooling validated

that CISA’s emulation accurately reflected Storm-0558’s activities other than the initial token forgery. As a result of this

emulation work, CISA assessed that the threat actor could not avoid generating the MailItemsAccessed log data during

the intrusion, which meant that it could detect similar future activity if it had the relevant logs.

132

CISA also worked with international partners; the NCSC engaged CISA during the first week of its investigation after

realizing the breadth of the intrusion. The NCSC told the Board that the conversations were useful as the NCSC and

CISA shared information on intrusion impacts and each organization’s respective engagement with Microsoft.

133

While Microsoft has longstanding relationships with CISA, in this instance, Microsoft delayed reaching out to CISA until

it could confirm additional details of the intrusion. Microsoft did not know the root cause of the intrusion for some time

and was reluctant to share data with CISA and others until it had more certainty. CISA reached out to Microsoft to share

its investigative efforts, at which point Microsoft confirmed that it had observed CISA’s replication of the intrusion using

a test commercial tenant. As a result of this outreach, Microsoft further engaged with CISA and provided detailed

briefings, disclosing how it had uncovered Storm-0558’s presence within its network and providing details on the

nature and methodology of the threat actor. During these discussions, Microsoft provided some of the intrusion’s

technical details and gave CISA limited access to its forensics about the threat actor’s infrastructure.

134

International Partners: NCSC

The U.K. victims did not have enhanced logging capabilities, which inhibited the NCSC’s ability to verify Microsoft’s

claims of earlier threat activity. During its response, the NCSC had to balance disabling the compromised

environment with leaving it operational so it could further analyze the intrusion and ensure that Storm-0558 could

not regain access if the NCSC’s mitigations failed to close the underlying vulnerability.

135

Based on Microsoft’s initial advice, the NCSC suspected the threat actor was likely stealing tokens from endpoints,

particularly iOS devices. This led the NCSC to gather as many devices as possible from victims over the first two days

of its investigation. However, this theory proved fruitless, highlighting the difficulty that organizations faced in

determining the intrusion’s attack vector. By the second week of the NCSC’s investigation, Microsoft had revoked the

key and the NCSC’s focus shifted from stopping malicious activity to identifying exfiltrated data. Finally, by mid-July,

the NCSC turned its attention to examining potentially compromised corporate accounts.

136

1.3.3 VICTIM COORDINATION AND NOTIFICATION

Victim coordination was complicated for this incident as it involved multiple U.S. government agencies, foreign

governments, senior government officials, private sector organizations, and private individuals. While both Microsoft

and government agencies undertook separate efforts to notify victims, Microsoft had legal and contractual limitations

on what victim information it could share with the government, absent victim consent.

137

FBI worked with Microsoft to obtain the U.S. victim information, and on July 10, 2023, Microsoft lawfully provided FBI

with a list of affected email accounts and related subscriber information for those accounts. FBI engaged directly with

almost every victim with an affected personal account. For compromised enterprise accounts, FBI worked with system

owners, who in turn informed individuals whose accounts were part of the intrusion.

138

By July 25, 2023, FBI had identified the owners of nearly all affected accounts and had begun issuing leads to notify

government officials deemed to have the most sensitive information, in line with FBI Cyber Division policy on victim

notification requirements. FBI learned that some victims were unaware that a threat actor had accessed their emails.

Microsoft informed FBI that it had notified customers through several methods, including short message service (SMS)

132

CISA, Board Meeting.

133

NCSC, Board Meeting.

134

CISA, Board Meeting.

135

NCSC, Board Meeting.

136

NCSC, Board Meeting.

137

Microsoft, Board Meeting.

138

FBI, Board Meeting.

Review of the Summer 2023 Microsoft Exchange Online Intrusion

13

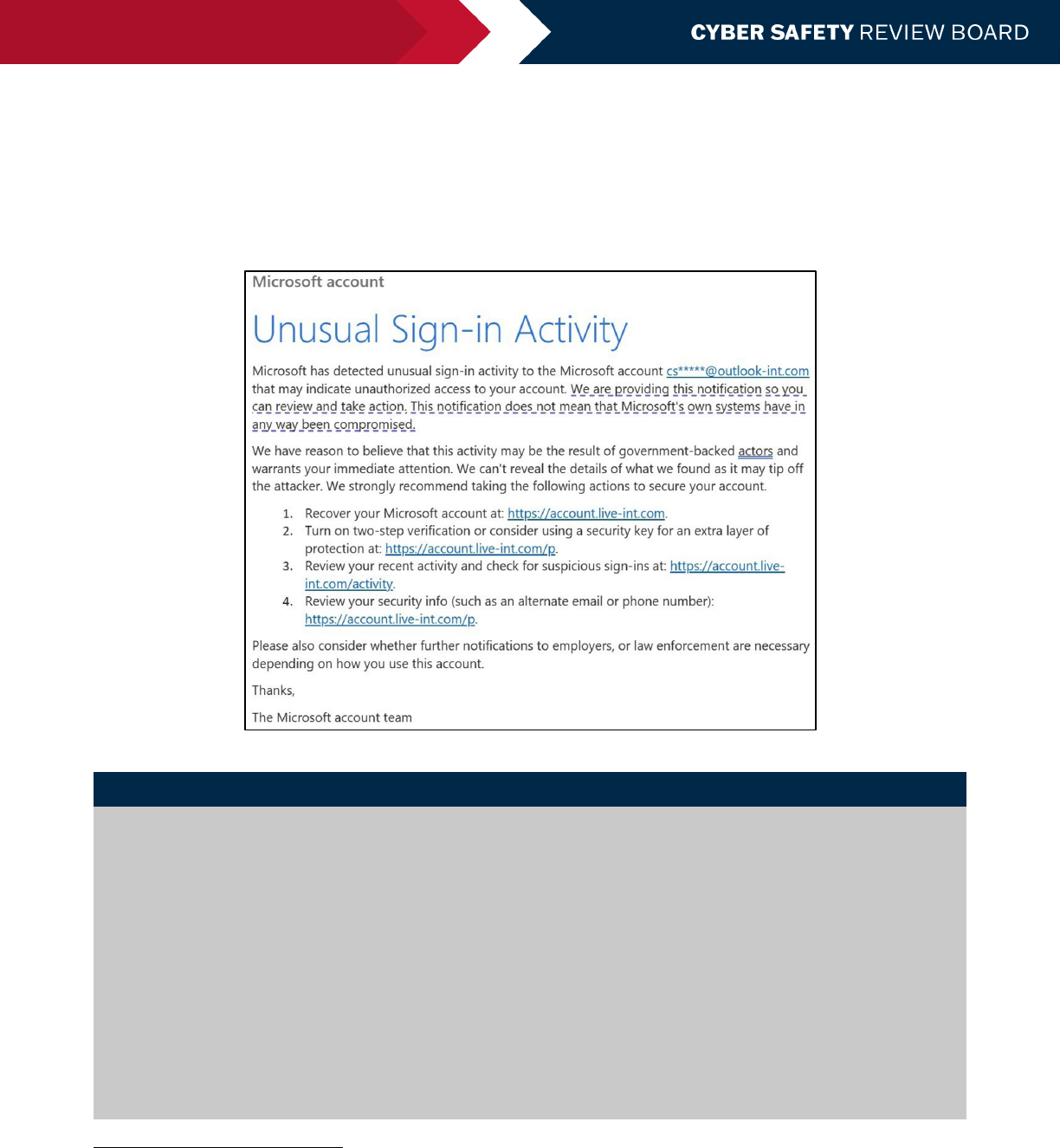

text messages, nation-state notifications (NSNs),

139

emails sent to recovery accounts (see Figure 2), and pop-up

messages via an authenticator application, but some victims told FBI that they viewed these notifications as possible

spam and disregarded them. As a result, FBI changed its stance and notified every identified account owner through

coordination with FBI field offices, Department of Justice (DoJ), CISA, State, and Commerce. FBI provided each victim

with a joint Cybersecurity Advisory previously published by FBI and CISA on July 12, 2023, as well as a copy of

Microsoft’s blog outlining analysis of Storm-0558 activity and cyber hygiene best practices.

140

Figure 2: Microsoft Victim Notification Email

Case Study: Congressman Don Bacon

Congressman Don Bacon is a Member of the House of Representatives and currently serves on the House Armed

Services Committee, including its Strategic Forces and Tactical Air and Land Forces subcommittees. Congressman

Bacon is also a member of the House Taiwan Caucus.

141

As a prominent congressional voice on national security

matters, Congressman Bacon is a high-value target for adversarial intelligence-gathering objectives. Microsoft’s first

noticed outreach to Congressman Bacon about the intrusion was an email prompting him to change his password,

sent a month before FBI contacted him. Congressman Bacon thought the password change email looked strange

and was potentially fraudulent, so he changed his password directly rather than using the link provided in the

notification instructions. He later learned from FBI that his personal email had been compromised. FBI assured him

that his devices were secure and that he had done nothing wrong; rather, the intrusion originated from a

compromise affecting Microsoft. Microsoft did not advise Congressman Bacon to take any action to protect his

account beyond the one email recommending a password change. At some point after the initial password change

email, Microsoft sent another that provided details about the intrusion, including that Microsoft believed it had been

synchronized with Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit, June 16 to June 21, 2023, and Commerce Secretary Gina

Raimondo’s visit, August 27 to August 30, 2023, to China.

142

139

Whenever an organization or individual account holder is targeted or compromised by observed nation-state activities, Microsoft delivers

an NSN directly to that customer to give them the information they need to investigate the activity. Source: Lambert, John; Microsoft,