THE CREDIT DEFAULT SWAP MARKET

Report

THE BOARD

OF THE

I

NTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF SECURITIES COMMISSIONS

FR05/12

JUNE 2012

ii

Copies of publications are available from:

The International Organization of Securities Commissions website www.iosco.org

© International Organization of Securities Commissions 2012. All rights reserved. Brief

excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated.

iii

Contents

Chapter

Page

Executive Summary

1

1

Introduction

2

2

Basic Functioning of Credit Default Swap contracts and market size

3

2.1 Basic functioning of CDS contracts

3

2.2 Size of the CDS market

4

3

Features of the CDS market

11

3.1 Contract standards

11

3.2 Market structure

18

3.3 Counterparty risk and collateralization

24

3.4 CDS prices and bond spreads

27

3.5 CDS role under Basel III

30

4

The impact of CDS on the bond market

31

4.1 CDS impact on credit spreads and creditor incentives

31

4.2 CDS impact on the secondary market of underlying bonds

32

4.3 CDS role in the price discovery process

34

5

Conclusion

36

Appendix A -- References

39

Appendix B – Composition of the SCRR sub-group

44

1

Executive summary

The market for credit default swaps (“CDS”) is going through rapid change. Over the last

several years, CDS contracts have become more standardized, and electronic processing and

central clearing of trades have increased. Large amounts of CDS data have become publicly

available, and abundant research has been conducted to assess the role that CDSs play in

global financial markets.

This report discusses those recent changes and current trends in the CDS markets, and

provides information from recent literature about the trading, pricing and clearing of CDS.

The report is meant to inform the ongoing regulatory debate and highlight some key policy

issues. However, policy recommendations are left for other reports.

In summary, the amount of CDS trading has continued to increase even after the onset of the

financial crisis while standardization and risk management practices have significantly

expanded. Trade compression has reduced CDS contracts by tens of trillions dollars. A non-

negligible amount of CDS trades are currently being cleared by several central counterparties

(CCP) around the world and the number of cleared CDS contracts is expanding.

Because of its highly concentrated and interconnected nature, and given the evidence of

possible under-collateralization of CDS positions, one of the main sources of risk in the CDS

market is counterparty risk generated by the default of large protection sellers. The use of

central counterparties has been seen as a way of mitigating counterparty risk and preventing

default contagion.

Though the amount of public information on CDS has increased over the recent years, the

CDS market is still quite opaque. Regulators would benefit from better access to information

on trade and position data, which is necessary for financial stability supervision, for

improving the assessment of counterparty risk by CCP and for the detection of market abuse.

As for transparency towards market participants (disclosure of pre- and post-trade

information), results from theoretical research and empirical work on the OTC bond market

in the US for the time being suggest that greater transparency may reduce information

asymmetries and transaction costs, but it may also discourage dealers from providing

liquidity. IOSCO will continue to examine these issues in order to provide a sound basis for

possible future policy proposals on how to best improve the functioning of the CDS markets.

Available research shows that CDS have an important role in the price discovery process on

credit risk and that the inception of CDS trading has a negative impact on the cost of funding

for entities of lower credit quality. To date, there is no conclusive evidence on whether

taking short positions on credit risk through naked CDS is harmful for distressed firms or

high-yield sovereign bonds. IOSCO will continue to monitor market developments on this

issue, however, going forward.

2

1) Introduction

This report has been prepared by IOSCO to respond to a mandate given by the G20 to assess

the functioning of the CDS market and the role of CDS in price formation of underlying

assets. The report is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly describes the basic structure and

payoff of CDS contracts and reports market statistics, discussing their informative role in

terms of evaluating counterparty risk and credit risk reallocation performed by CDS. The size

of the CDS market is compared to that of the underlying bond market, in order to evaluate

whether the relative market activity in CDS has changed over the recent years.

Section 3 illustrates a series of operational features that characterize the functioning and

regulation of the CDS market. The Section 3.1 describes the evolution of the self-regulatory

framework, which over the last 3 years has led to strong contract standardization and to the

emergence of centralized procedure to liquidate contracts in case of credit events.

Section 3.2 then illustrates the available evidence on the structure of the market, with specific

reference to trade transparency and interaction between different types of market participants

(dealers and end-users), presenting some statistics on trade frequency and trade size that

indicate differences between the CDS market and other markets with strong retail

participation.

Next, Section 3.3 discusses counterparty risk and collateralization practices in CDS market,

highlighting some important differences from other OTC derivatives, and then illustrates the

role of central counterparties in the CDS market.

Sections 3.4 and 3.5 are dedicated to the arbitrage between CDS and bonds and to the role of

CDS under Basel III regulation. As for the first point, it is shown why arbitrage should make

CDS spreads equal bond spreads, then highlighting frictions and market imperfections that

explain why in practice such equivalence is often violated. As for the second point, the

discussion focuses on the role of CDS under Basel III in order to measure capital charges

related to counterparty risk.

Section 4 reviews the main academic literature related to the impact of CDS on bond and

credit markets.

The first part of the Section discusses the issue of whether CDS can reduce credit spreads or

enable firms to issue more debt and whether CDS can make bankruptcies more likely than

restructurings.

The second part of the Section reviews the academic research on the impact of the CDS

market on the liquidity and orderly functioning of the underlying bond market.

Finally, the last part of the Section analyzes the evidence and the academic debate on the role

of CDS in the price discovery process.

Section 5 concludes and summarizes the main issues of more relevance from a policy

perspective.

3

2) Basic functioning of Credit Default Swap (CDS) contracts and market size

2.1 Basic functioning of CDS contracts

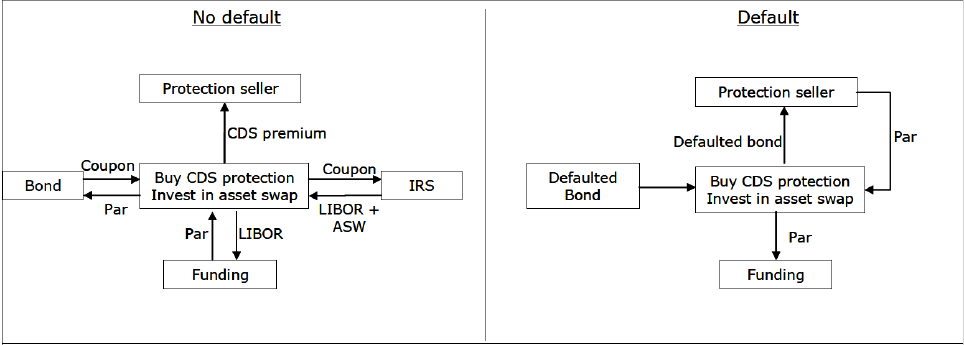

Credit Default Swaps (CDS) are a bilateral OTC contracts that transfer a credit exposure on a

specific (“reference”) entity across market participants. In very general terms, the buyer of a

CDS makes periodic payments in exchange for a positive payoff when a credit event is

deemed to have occurred

1

. These contracts are linked to either a specific reference entity

(“single name CDS”) or a portfolio of reference entities (“index” or “basket” CDS).

Selling protection through a CDS contract replicates a leveraged long position in bonds of the

underlying reference entity

2

, exposing protection sellers to risks similar to those of a creditor.

Buying protection through CDS replicates instead a short position on bonds of the underlying

reference entity (with proceeds reinvested at the riskless rate)

3

.

Buyers of protection through a CDS contract can hedge a credit exposure on the underlying

reference entity or effectively take a short position on credit risk. This is the case when the

CDS buyer has no credit exposure on the reference entity (so called “naked” CDS position)

or has an exposure lower than the value of the CDS contract (so called “over-insured”

position).

While it is possible for a protection buyer to replicate the economic payoff of a CDS contract

by shorting bonds of the underlying reference entity and reinvesting the proceeds at the

riskless rate, CDS may be an attractive alternative to short selling because of their ability to

eliminate the risk associated with rolling over short positions.

When a credit event occurs, the contract is terminated. In this case, if “physical delivery” is

the specified settlement method, the CDS seller must pay to the buyer the nominal contract

value and the CDS buyer must deliver bonds of the reference entity (of a pre-specified type).

Alternatively, if “cash settlement” is the agreed settlement method, the seller must pay to the

buyer the difference between the notional contract value and the market value of the bonds.

1

As it will be better explained further on, the International Swap and Derivatives Association (ISDA) has

developed a standard legal documentation format for CDS contracts (see next §3.1) that includes a list

of credit-event situations (which go from bankruptcy to debt restructuring). Though contract

counterparties are free to amend the ISDA definitions, the vast majority of CDS trades are covered by

the standard ISDA documentation.

2

More specifically, selling protection through CDS is similar to a leveraged long position in a floating

rate note (FRN) of the reference entity. The intuition for such equivalence is that, similar to FRN, CDS

prices reflect changes in credit risk, while are insensitive to changes in the yield curve. Since, as it will

be shown further on (§3.4), CDS prices should equal bond spreads (ignoring counterparty risk and other

market frictions), the periodic payment received by a CDS seller should be equivalent to the spread

over Libor (or Euribor) that the reference entity would pay if it were to issue a FRN (this spread is

usually referred to as the “asset swap spread”, i.e. the spread over Libor at which a fixed coupon of the

reference entity is swapped for a floating coupon). On the other hand, a pay-off in which one receives

the spread on a FRN can be replicated by buying the FRN using Libor/Euribor financing; hence, the

CDS premium should equal the pay-off of a leveraged FRN long position, which is in turn equivalent to

the asset swap spread (see Duffie 1999 for the initial formalization of these arguments, and De Wit

2006 for a simple illustration of the details of the CDS-FRN or CDS-asset swap spread equivalence).

3

Following the same argument of note 2, paying the CDS price should be equivalent to paying the FRN

spread, which in turn can be replicated by shorting the FRN and investing the proceeds at Libor/Euribor

rate.

4

For index or basket CDS a credit event on one of the component reference entities will not

cause the contract to be terminated and the buyer of protection will receive a compensation

proportional to the weight of the reference entity on the index (see next §3.1 for more

details).

There are a number of ways to “terminate” or change the economic exposure associated with

a CDS contract other than those related to the occurrence of a credit event. The first is

referred to as “novation”, which entails the replacement of one of the two original

counterparties to the contract with a new one. A novation is executed by identifying a market

participant that is willing to assume the obligations of one of the original counterparties at

prevailing market prices. There are however two quite different kinds of novation: the first is

the one in which a new party replaces one of the parties of the original trade and the second

in which both parties give up the trade to a central counterparty (so called “CCP novation” –

see next §3.3), though in this latter case there is no change or termination in the economic

exposure for the original counterparties. Other changes may be related to early termination

clauses

4

or to contract terminations due to “compression” mechanisms designed to cancel

redundant contracts due to offsetting positions. For example, if the same counterparties have

entered into offsetting positions on contracts with the same economic terms, a compression

trade cancels these contracts and creates a new contract with the same net exposure as the

original contracts. It is also possible to terminate a position by entering into a transaction of

opposite sign (“offsetting transaction”) with other market participants. The difference

between an offsetting transaction and a novation is that in the first case the original contract is

not cancelled and remains a legal obligation

5

. Though offsetting transactions are the most

common way to terminate the economic exposure related to the reference entity underlying

the CDS contract, they create a network of exposures that results in increased counterparty

risk.

2.2 Size of the CDS market

Quantifying the trading activity and the economic exposure of market participants in the CDS

market is quite difficult. Data on new trades will underestimate actual transaction activity

because, as noted above, novation and termination provide alternative ways to modify the

exposure to the underlying reference entities and may contribute to price formation. Because

of the mentioned importance of offsetting transactions, data on outstanding contracts (gross

notional value) may largely overstate the economic exposure towards the underlying

reference entities. The sum of the net positions of the net buyer of protection (net notional

value) gives instead a better estimate of the net exposure because it represents the aggregate

payments that would be made in the event of the default of a reference entity

6

(assuming the

market value of defaulting bonds is equal to zero

7

).

4

Early termination may occur in case one of the counterparties defaults (see §3.4 for a full discussion of

the contractual arrangements in such situation).

5 This is not the case when a central counterparty (CCP) interposes itself between the original

counterparties to each contract (through the mentioned novation process). In this case, traders’

positions are offset multilaterally and each trader ends up with a bilateral balance against the CCP.

6 This is technically correct only if operators adhere to a contractual multilateral offsetting mechanism of

the positions should a credit event occur. This type of service is supplied for example in the US by the

Depository and Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC).

5

Hence, the gross notional value of outstanding contracts gives an indication of the size of the

CDS market in terms of counterparty risk, while the net notional value is a measure of the

size of the market in terms of credit risk reallocation.

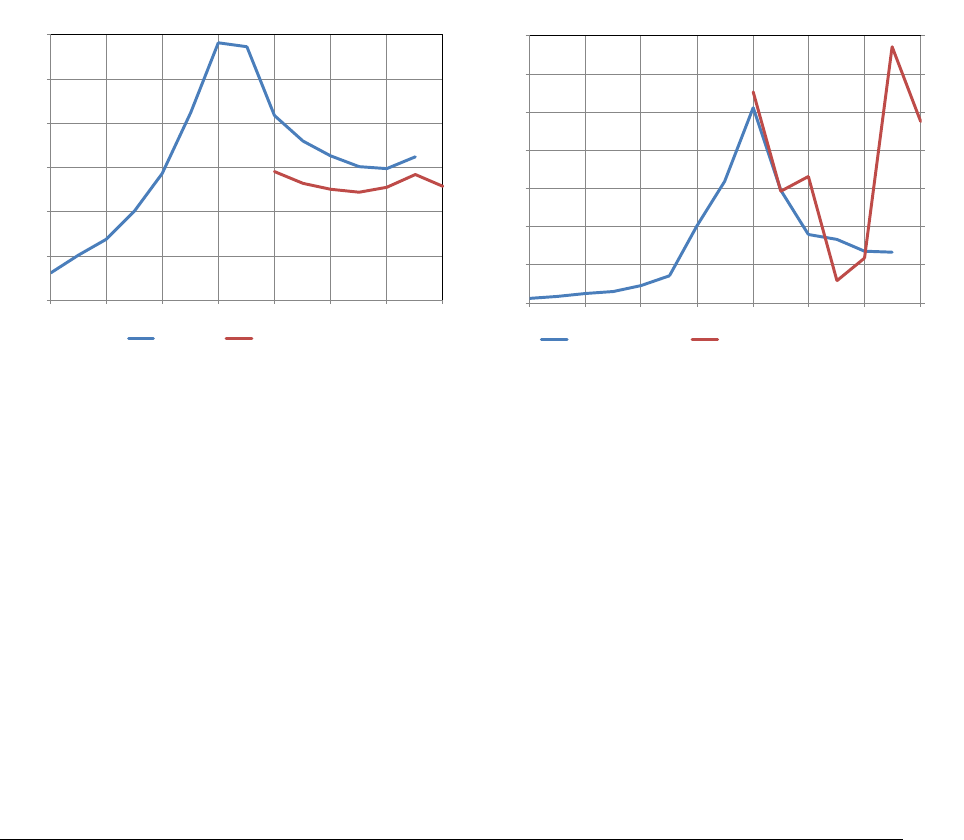

At the end of 2011, the gross notional value of outstanding CDS contracts amounted to

approximately 26,000 billion US dollars (Figure 1), which has a corresponding net notional

value of approximately 2,700 billion US dollars (roughly 10% of the gross notional value).

Single name CDS account for approximately 60% of the overall market in terms of gross

notional, while the remaining share is represented by index and basket CDS and by so called

“tranche” CDS that are structured to take exposures on specific segments of an index loss

distribution (Figure 2) .

Figure 1 – Size of the CDS market

(semi-annual data in bln of US$ for outstanding contracts at the end of period)

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

Dec-04

Dec-05

Dec-06

Dec-07

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

Gross notional

BIS da ta

DTCC data

2,200

2,300

2,400

2,500

2,600

2,700

2,800

2,900

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

Dec-04

Dec-05

Dec-06

Dec-07

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

Net notional and gross market value

Gross market value

Net Notional (right- hand scale)

Source: Calculation on Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation

(DTCC) data. BIS collects open positions of leading global dealers through central banks of 11 reporting

countries (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United

Kingdom and United States). All BIS published figures are adjusted for double-counting of positions between

reporting institutions. DTCC provides information on CDS contracts registered in the DTCC’s Trade

Information Warehouse. “Net notional” with respect to any single reference entity is the sum of the net

protection bought by net buyers (or equivalently net protection sold by net sellers). The “gross market value” is

the sum of the absolute values of all open contracts with both positive and negative replacement values

evaluated at market prices prevailing on the reporting date.

7 The market value is usually greater than zero as it considers an estimate of the recovery rate. The

payment value in the event of default would therefore amount to: net notional value x (1- recovery

rate).

6

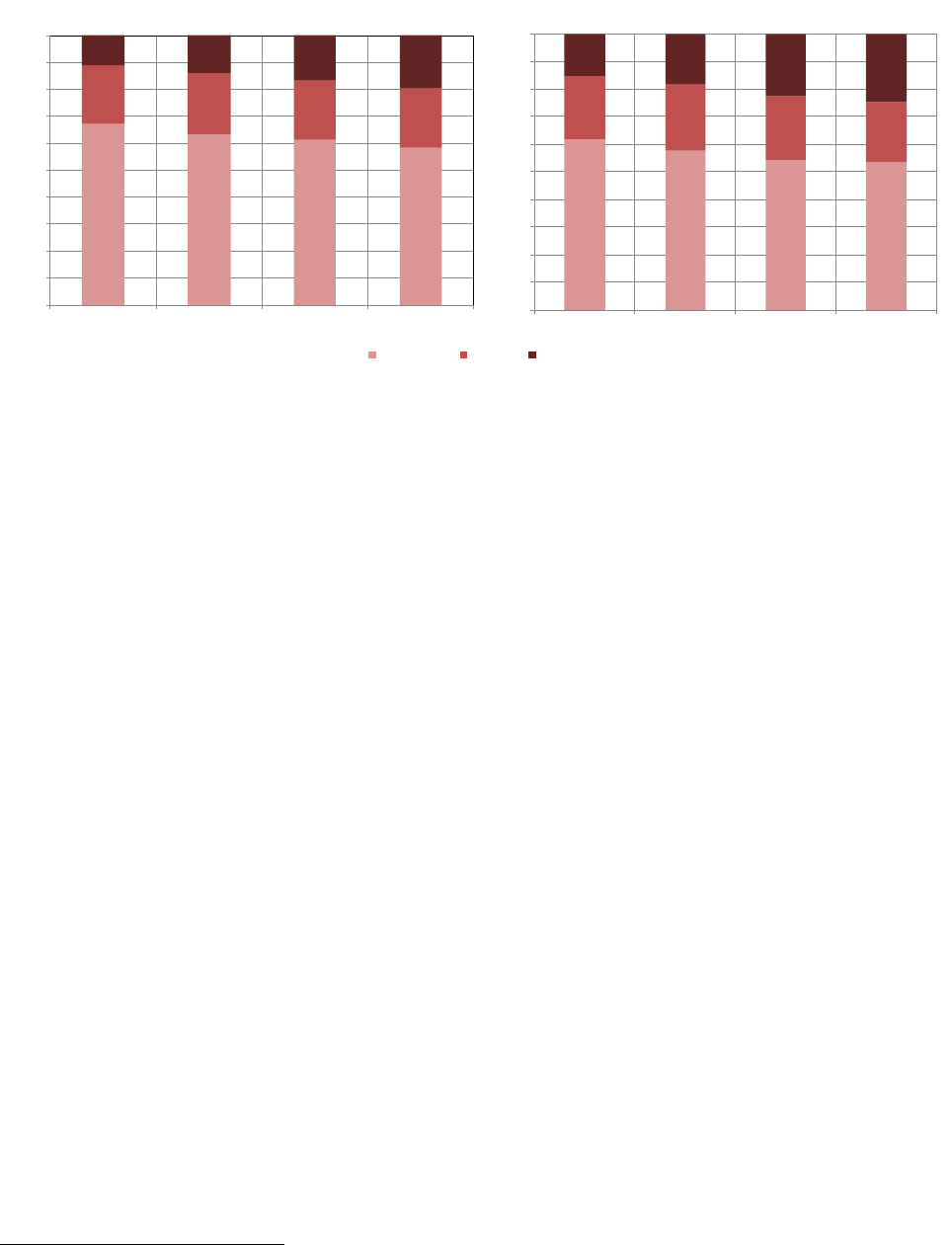

Figure 2 – CDS gross notional by instrument type

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Dec

- 08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

DTCC

Single Name CDS

Index CDS

Tranche CDS

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Dec

-04

Dec-05

Dec

-06

Dec-07

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Jun-11

BIS

Single na m e CDS

Mu lti n am e CDS

Source: Calculation on Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation

(DTCC) data.

According to different data sources, it can be estimated that roughly 60% of the outstanding

contracts (in terms of gross notional) are concluded between dealers (i.e. financial institutions

that post regularly indicative buy and sell quotes – see next §3.2), while the remaining share

is represented by contracts between a dealer and a non-dealer – mostly financial - institutions

(banks, institutional investors, central counterparties and hedge funds) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – CDS gross notional amount outstanding by counterparty categories

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

DTCC

between dealers

between dealers and non dealers

between non dealers

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Jun-2010

Dec-2010

Jun-2011

BIS

between dealers

between dealer and other financial institutions

between dealer and CCP

between dealer and hedge fund

between dealer and non financial insitutions

Source: Calculation on Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation

(DTCC) data.

Since offsetting transactions increase outstanding contracts without changing the overall

economic exposure to the underlying reference entities, the industry has increasingly

developed the recourse to the mentioned compression mechanism to eliminate legally

redundant (or nearly redundant) contracts. The strong growth of compression practices has

been made possible by parallel industry initiatives to standardize CDS contracts (in terms of

maturity and coupon size; see next §3.1 for a full discussion) and has resulted in a great

reduction in the gross notional value of outstanding CDS positions.

7

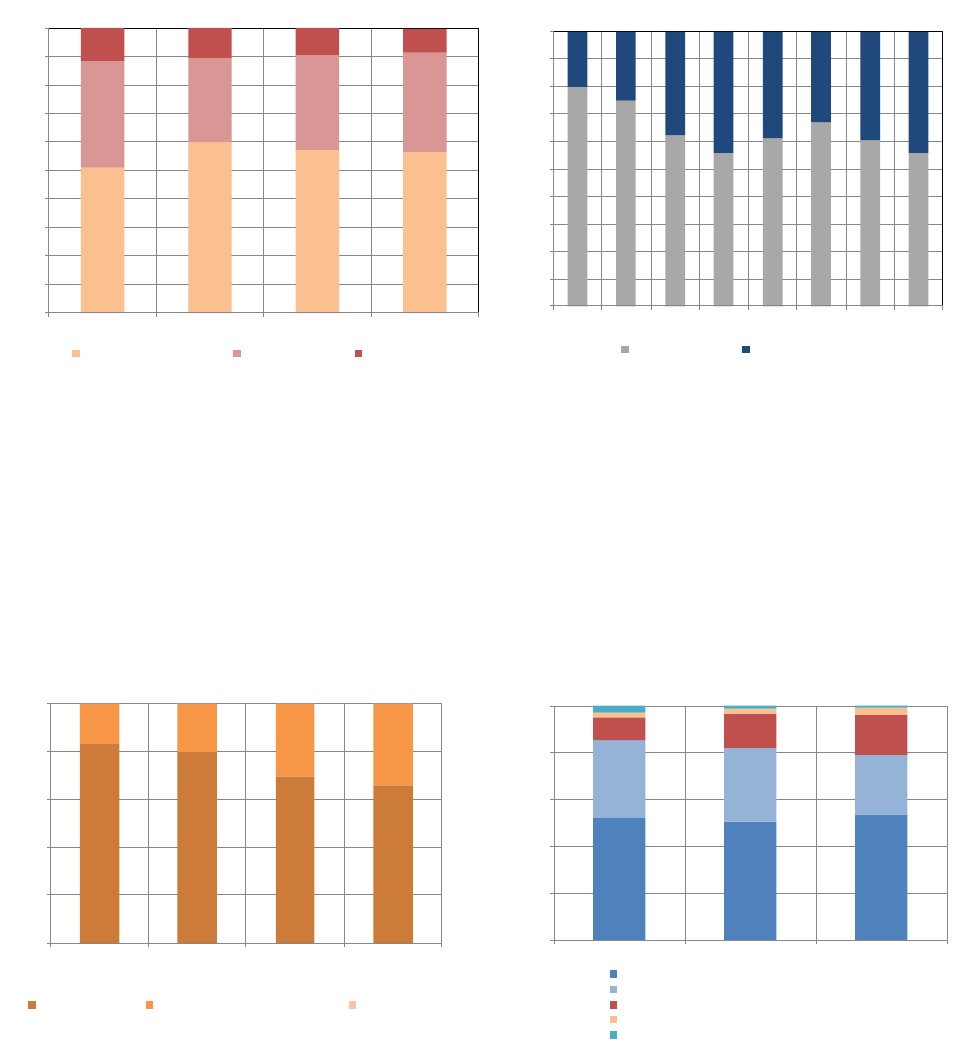

In fact, according to Vause (2010) the gross notional value of the CDS contracts has more

than halved since the peak of 2007 (when it reached almost 60,000 billion US dollars)

because of the great development of compression mechanisms, while CDS trading has

continued to grow even after 2007. Data from TriOptima, one of the main providers of

compression services, confirm the relevance of CDS compression, which peaked in 2008

(Figure 4).

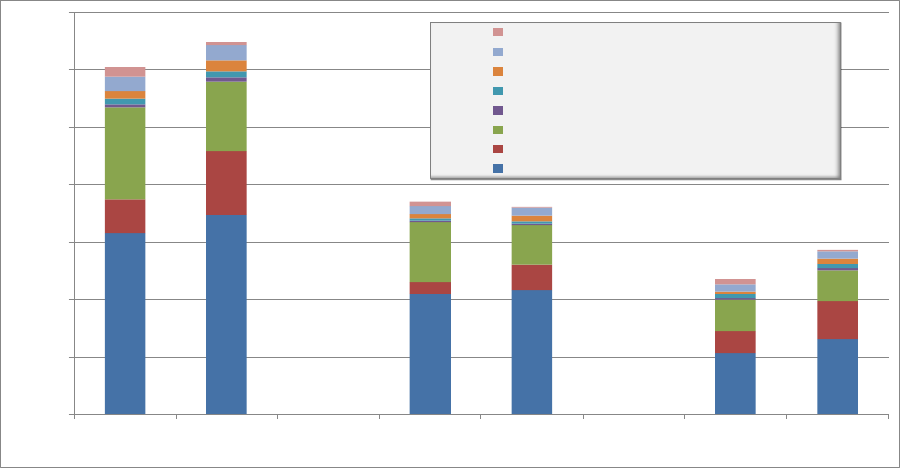

Figure 5 shows the break-down of the total gross and net notional CDS exposure between

sovereign and private (financial and non- financial) entities. The share of CDS on sovereign

entities has grown steadily since 2008, from around 15% to almost 25% of total net notional

value. At the end of 2011, slightly more than 50% of the net notional value of outstanding

CDS had non-financial reference entities as underlying, while CDS on financial entities

accounted for roughly 20%. Thus, the notional CDS exposure to private entities is

approximately four times the notional CDS exposure to sovereign entities.

8

Figure 4 - Example of CDS compression and value of CDS terminated

Compression example

Notional value of CDS terminated by TriOptima (US$

trillion)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Source: Bank for International Settlement and TriOptima.

8 The greater weight of CDS on private issuers as compared with that of the CDS on sovereign issuers

partly reflects the different dimension of the market of government bonds as compared to that of

corporate bonds. The data from the Bank of International Settlements for advanced countries and the

main emerging countries show that in September 2010 the value of government bonds amounted to

approximately 38,000 billion US dollars, as compared to approximately 10,000 billion US dollars for

bonds of non-financial issuers and 41,000 billion dollars for bonds of financial issuers (including

securitisations and structured securities, such as collateralized debt obligation, collateralized bond

obligation, etc.). Bonds of private issuers therefore amounted to approximately 51,000 billion dollars,

compared to the 38,000 billion dollars of government bonds. On the other hand, as mentioned in the

text, the notional value of CDS on private issuers is four times that of the CDS on sovereign issuers.

This difference may reflect the fact that the hedging needs through CDS are more relevant for

corporate issuers than for sovereign issuers.

Identifies the situation where A has sold to B

a protection in notional amount equal to 2.

The differently

colored

arrows identify

different reference entities.

1

A

B

C

A

B

2

2

Before compression

1

A

B

C

2

After compression

2

2

2

3

8

Figure 5 – CDS gross and net notional by sector of the reference entities

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

Gross notional amount

non financial

financial

sovereign

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Dec-08

Dec-09

Dec-10

Dec-11

Net notional amount

Source: Calculation on BIS and Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) data.

Figure 6 reports evidence on the size of the CDS market relative to the underlying debt for

listed banks and for the top 100 reference entities by CDS gross notional value reported by

the DTCC. Underlying debt is calculated as the sum of short- and long-term debt from end-

of-year balance sheet data (as reported in the Worldscope database). Figure 6 also reports

evidence on the size of the CDS market relative to public debt for sovereign issuers in the top

1,000 reference entities (approximately 50 issuers).

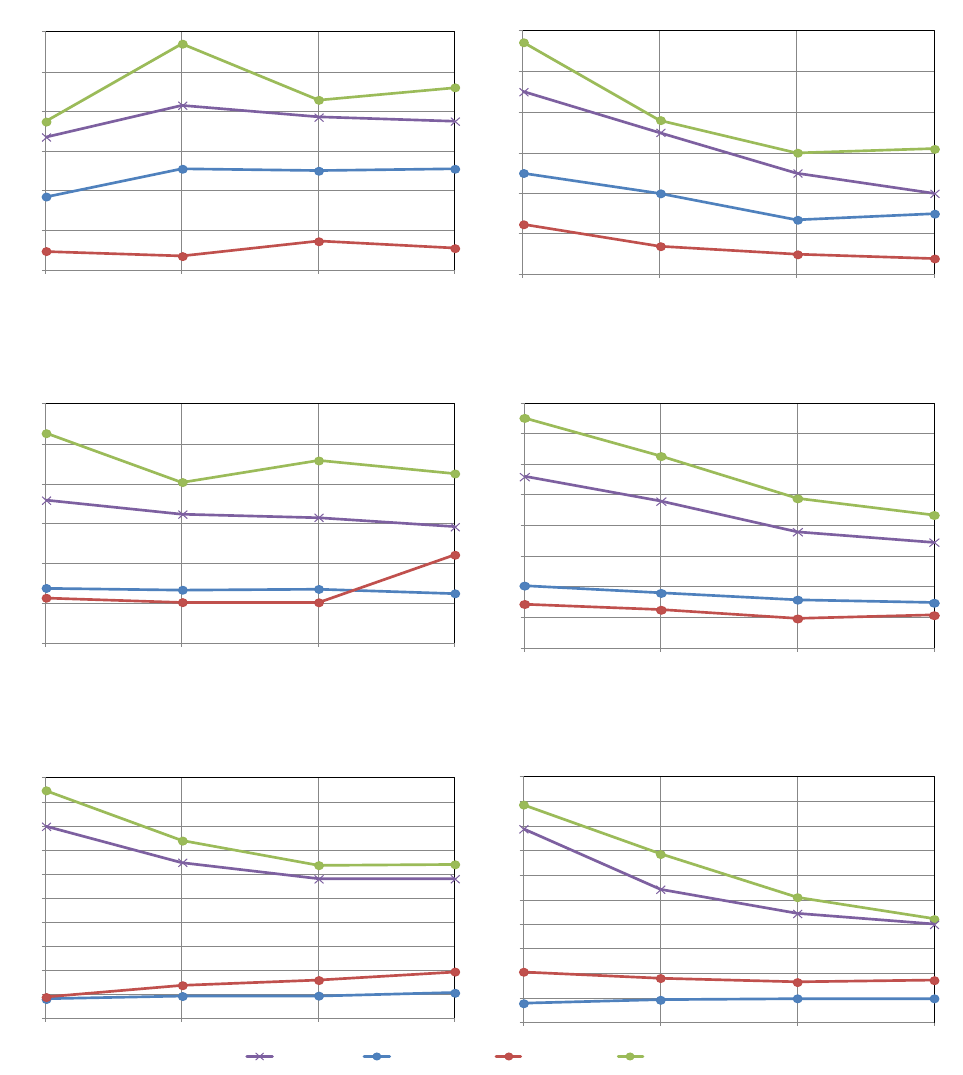

Figure 6 shows that, in terms of gross notional, bank CDS have remained quite stable relative

to the underlying debt over the period 2008-2011 (the weighted mean of gross notional to

underlying debt has remained close to around 9%

9

), while it has decreased in terms of net

notional (the weighted mean of net notional to underlying debt has decreased from around

0.9% to 0.7%). Similar evidence emerges for corporates (the weighted mean of the ratio of

gross notional to underlying debt has remained stable at values higher than 100%, while the

weighted mean of the ratio of net notional to underlying debt has decreased from 10% to

around 7%), but the ratio of gross/net notional to underlying debt is more than 10 times

higher than for banks. At the end of 2011, for three quarters of the corporate firms in our

sample the CDS gross notional largely exceed outstanding debt. Moreover, smaller corporate

firms (in terms of issued debt) tend to have a higher CDS net notional relative to underlying

debt (since the simple mean is much higher than the weighted mean) and it is more so than

for banks.

Hence, for private issuers the size of the CDS markets relative to underlying debt has

remained relatively stable in terms of gross notional over the last four years, while it has

significantly reduced in terms of net notional. Moreover, the use of CDS is proportionally

higher for smaller firms and is much more intense in the corporate sector than in the banking

sector. This last evidence may be due to different factors. First, the average credit quality of

the corporate firms in our sample may be lower than that of banks and this may explain a

9

The weighted mean of the ratio of gross/net notional to underlying debt is equal to the ratio of total

gross/net notional to total underlying debt.

9

higher use of CDS for hedging purposes; second, irrespective of the credit quality, some

banks may be perceived as too-big-to-fail and this reduces the incentive to use CDS.

For sovereign entities the weighted mean of gross/net notional to underlying debt has

remained rather stable (respectively, at approximately 5% and 0.5%) and close to values

similar to those observed for banking sector. There is however more dispersion in the

distribution of both ratios compared to banks. The weighted mean is constantly below the 25

th

percentile because countries such UK, US and Germany have a large public debt but a very

small CDS gross/net notional, and below the simple mean because smaller countries tend to

have a higher ratio of CDS gross/net notional to public debt.

Finally, Figure 7 confirms the evidence on the relative stability of the size of the CDS market

for euro area sovereigns, contrary to the suggestions that the debt crisis may have increased

the demand of CDS for hedging purposes. In fact, though for some peripheral euro area

sovereigns the ratio of gross notional to public debt has actually increased since the inception

the crisis, the ratio of net notional to public debt has remained stable or actually decreased for

countries more exposed to the crisis such as Ireland, Portugal and Greece.

10

Figure 6 – Size of the CDS market relative to the underlying debt

(percentage values)

Banks

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

2008 2009 2010 2011

Gross notional value / debt

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

2008 2009 2010

2011

Net notional value /debt

Non financial

firms

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

2008 2009 2010 2011

Gross notional value /debt

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2008 2009

2010

2011

Net notional value /debt

Sovereign

entities

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2008 2009 2010 2011

Gross notional value /debt

Simple mean

Weighted mean

25 percentile

75 percentile

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

2008 2009 2010 2011

Net notional value /debt

Source: Calculations on DTCC, Datastream-Worldscope and IMF data. Banks are all listed banks included in

the top 1,000 reference entities by CDS gross notional at the end of each year (50 in 2011, 49 in 2010, 46 in

2009, 45 in 2008); non financial firms are the first 100 non financial listed firms in the top 1,000 reference

entities by CDS gross notional; sovereign entities are all sovereigns included in the top 1,000 reference entities

by CDS gross notional (55 in 2011, 53 in 2010, 52 in 2009, 47 in 2008). For banks and non financial firms debt

11

is the sum of short and long term debt from balance sheet data in the Datastream-Worldscope database (codes

03051 and 03251); for sovereigns debt is the government consolidated gross debt computed by the IMF.

Figure 7 – Size of the CDS market relative to public debt for selected euro area

countries

(weekly data; from 31/10/2008 to 31/12/2011)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Oct-08

Apr-09

Oct-09

Apr-10

Oct-10

Apr-11

Oct-11

%

CDS gross notional amount on government debt

Ita ly

France

Spain

Germany

Greece

Portugal

Ireland

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Oct-08

Apr-09

Oct-09

Apr-10

Oct-10

Apr-11

Oct-11

%

CDS net notional amount on government debt

Source: Calculation on DTCC, Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters data.

3) Features of the CDS market

3.1 Contract standards

The growth of the CDS market has been fostered by the development of a solid self-

regulatory environment, promoted by the initiatives of the International Swap and Derivative

Association (ISDA)

10

such as contract standardisation, aimed at facilitating back office and

contract management operations, and reducing legal disputes.

In 1992 ISDA developed a Master Agreement together with related documentation applying

to any OTC derivatives trades, including CDS, to ensure the enforceability of netting and

collateral provisions. The Master Agreement was then revised in 2002. With specific regards

to CDS contracts, ISDA defined a format for trade confirmation (Master Confirmation

Agreement on Credit Default Swaps) and a standardized legal documentation predefining

various optional variables and information such as: i) reference entity (underlying in form of

a legal entity, indices or sovereign), ii) nominal value, iii) maturity date (agreed tenor or by

credit event), iv) agreed premium/coupon, v) credit event trigger (and related reference

obligation) and vi) contract liquidation procedure in case of a credit event. In particular, the

codification of credit events and the definition of the liquidation process have helped to

reduce the risk of potential legal disputes (see further on for more details on this point).

Compliance with the Master Agreement allows counterparties to: a) define the net amount to

be transferred following the aggregation of all credit and debt positions with regards to a

10 ISDA is a private international association founded in 1985 to improve the industry’s operational

infrastructure in derivative trading and its members are represented by more than 800 market

participants, including dealers, institutional investors, non financial and law firms.

12

single counterparty; b) close all positions in case of default of one counterparty through a

single payment ("close-out netting").

As a result of the growing importance of CDS and of the increasing demand for contract

standardization to facilitate compression mechanisms and the development of central

counterparties (CCP – see §3.3), in 2009 ISDA developed a new Master Confirmation

Agreement (so called “Big Bang Protocol”), to which more than 2,000 market participants

(including banks, hedge funds and institutional investors) voluntarily adhered. The Big Bang

Protocol introduced two main changes. First, it established Determination Committees

allowed to takes binding decisions on whether a credit event occurs, replacing the previous

bilateral negotiation. Second, it made auction the default option to set the price of distressed

bonds in order to liquidate CDS contracts in case of credit events (see the discussion further

on), whereas previously it needed to be agreed to upon the occurrence of a credit event, and

made the use of such auction mechanism binding for those parties that signed to the Protocol.

The ISDA also introduced strong contract standardization, in terms of expiry dates and

premiums, which has allowed the growth of CCP and compressions. CDS premiums were set

at 100 or 500 basis points for US contracts and at 25, 100, 500 or 1000 basis points for

European single name CDS. Hence, protection sellers or buyers may be required an upfront

payment to compensate for the difference between the market price and the standardized

premium set by the protocol.

In light of different regional practices and legal definitions, in 2009 ISDA also developed

several “Standard CDS Contract Specifications” (for instance, a “Standard European CDS

Contract Specification” and a “Standard North American CDS Contract Specification”).

In order to clarify open issues in the Big Bang protocol relative to the absence of a common

definition of Chapter 11 for European firms and to the qualification of restructuring events,

ISDA introduced in July 2009 the so called “Small Bang” protocol. This Supplement to the

Master Agreement extends the auction hardwiring provisions of the Big Bang Protocol to

restructuring credit events.

Specific contractual arrangements and market conventions apply to CDS contracts on a

basket of reference entities or securities, so called index and tranche CDS.

The main provider of indices used as underlying in the CDS market is Markit, which

developed two main index families using the most liquid single-name CDS. The “CDX”

family of indices has North American and Emerging Markets reference entities as

constituencies, while the “iTraxx” family has European and Asian reference entities. Both

CDX and iTraxx index families provide several sub-indices for various industries or regions

and for different maturities. The most heavily traded indices are the CDY.NA.IG on US

investment grade firms and the CDY.NA.HY on US high-yield firms. CDY.NA.IG is

composed of 125 investment grade entities domiciled in North America, each with an equal

weighting of 0.8%.

Index CDS have different design and trading rules compared to single name CDS.

Every March and September the composition of the basket of a certain index CDS is

redefined (rolled) according to certain rules (e.g. minimum amount of debt securities

outstanding and liquidity of the CDS of the single reference entities). Each of these “roll”

results in a new series of the relevant index. For instance “iTraxx Series 17” was launched on

March 20, 2012, with a maturity of June 20, 2017 for the 5 year contract. Although the latest

13

roll is the most frequently traded, the older roll will be updated until final maturity of the

series.

Definition of Credit Events

Though counterparties in a CDS trade are free to agree on whatever definition of credit

events that trigger contract liquidation, the vast majority of CDS trades use the ISDA

definitions of credit event. ISDA has in fact codified the following situations as credit

events

11

: 1) bankruptcy; 2) obligation acceleration (i.e. a situation where the relevant

obligation becomes due and payable as a result of a default by the reference entity before the

time when such obligation would otherwise have been due and payable); 3) obligation default

(i.e. a situation where the relevant obligation becomes capable of being declared due and

payable as a result of a default by the reference entity before the time when such obligation

would otherwise have been capable of being so declared); 4) failure to pay (i.e. a failure of

the reference entity to make, when and where due, any payments under one or more

obligations); 5) repudiation/moratorium (i.e. a situation where the reference entity or a

governmental authority disaffirms, disclaims or otherwise challenges the validity of the

relevant obligation); 6) restructurings binding for all creditors, i.e. excluding those agreed

voluntarily by creditors (covers events as a result of which the terms, as agreed by the

reference entity or governmental authority and the holders of the relevant obligation,

governing the relevant obligation have become less favourable to the holders than they would

otherwise have been). For instance, this could result from a reduction of the coupon or

amount of principal (haircut), deferral of payments of interest or principal (maturity

extension), subordination of the obligation and change of the currency. However, in order to

avoid any doubts, counterparties have to agree on the applicable restructuring definition.

Restructuring clauses are not common in the North American CDS contract specification,

since in North America corporate restructuring automatically triggers a “chapter 11”

bankruptcy event. By contrast, European firms may restructure their debt without necessarily

entering into a formal bankruptcy procedure (so called out-of-court restructuring).

Consequently, the “Standard European CDS Contract Specification” refers to restructuring as

a specific credit trigger event. However, different restructuring clauses exist. The original

“unmodified” version of restructuring, allows the protection buyer to deliver bonds of any

maturity in case of any forms of restructuring occurs. The “modified restructuring” (MR)

clause limits deliverable obligations to bonds with maturity of less than 30 months after

restructuring and was a common practise in North America until 2009. The “Modified

Modified Restructuring” clause (MMR) is a modified version of the MR clause that resulted

from the criticism that MR was too strict with respect to deliverable obligations. Under the

MMR clause, which is more popular in Europe, deliverable obligations can be maturing in up

to 60 months after a restructuring.

As noted above, voluntary restructurings are not considered credit events Hence, an important

criterion in order to have a restructuring event is that the restructuring has to be binding for

all holders of the restructured debt. For bonds with a “collective action clause” (CAC) or a

loans with a qualified majority voting clause of 75%, changes in the terms of the bonds or

loans become binding to all creditors if 75% of them agree on the restructuring. This means

11

See, however, the original ISDA “Credit Derivatives Definitions” for a more comprehensive and legally

accurate description of the following six definitions of credit events.

14

that the new terms are binding to all creditors, irrespective of whether they did not vote or

voted against the restructuring.

Credit event decisions and contract liquidation

As previously mentioned, the Determinations Committee (DC), introduced in 2009 by the

ISDA Big Bang Protocol and consisting of market participants and legal experts

12

, decides on

whether a certain situation can be qualified as a credit event. The decision process starts with

a request by one or more market participants, based on publicly available information, to

review a certain situation relative to a reference obligation or entity in order evaluate if it falls

within the definition of credit events under the ISDA protocol. The DC decides first to start a

determination process for the reference obligation and second whether a credit event is

actually triggered or not. The decision of the DC is binding to all parties that have signed to

the ISDA protocol, irrespective of the nature of the reference entity or obligation (corporate

or sovereign). With supermajority voting (12/15 of the members) the DC can decide that a

credit event has occurred without asking for an external legal review.

A “Successor Event” occurs in the case a reference entity enters in a merger, acquisition or a

spin-off and hence a new obligor(s) of the previously existing debt has to be defined. In this

situation the DC defines the successor entity as reference entity for the CDS contracts.

In case of a credit event, there can be different contract liquidation procedures. Until 2005,

CDS contracts were mostly physically settled, in the sense that the protection seller bought

the distressed loan or bond (the “deliverable obligation”) from the protection buyer at par. In

this case, the protection seller, as the new owner of the defaulted asset, realizes the recovery

rate and can gain or lose from subsequent changes in the market price of distressed securities.

Physical settlement was acceptable as long as CDS were mainly used for hedging, so that the

value of CDS did not normally exceed that of the underlying reference entity. With the

growth of the CDS market, cases of CDS notional value exceeding the value of the

underlying bond became more frequent and in such situations, in case of a credit event, the

buyers of protection, who might not have the underlying bonds to deliver in order to comply

to physical settlement, had to buy them on the secondary market creating the potential for an

artificial price pressure (short squeeze). In order to avoid short squeezes, cash settlement

became an option and the payment to protection buyers could be determined as the difference

between the nominal and the market value of the reference obligation. In contrast to physical

settlement, the protection buyer keeps the exposure to the distressed bond for price changes

subsequent to the contract liquidation.

One main drawback of such cash settlement arrangement is that obtaining quotes for

distressed securities is often quite difficult, since liquidity dries up rapidly in case of credit

events. For these reasons and in order to increase the transparency of the settlement process,

ISDA protocol has introduced the mentioned centralized auction as a default procedure to

define the reference price for cash settlement. From mid-2009 auction settlement became the

standard settlement mechanism for CDS contracts.

The auction is based on a two-stage procedure. The first step identifies an indicative price,

the “initial market mid-point” (IMM), and the net open interest (NOI) for the defaulted

12

Members of the several regional Determination Committees are published by ISDA:

http://www.isda.org/dc/dc_info.asp

15

bonds. The IMM provides a first indication of final price, while the NOI indicates the size

and direction of the open interest. The second step gives the definitive (final) price to be used

for the settlement of CDS contracts. With majority voting, the DC sets the auction terms

(auction date, initial and subsequent bidding periods, inside market quotation amount,

maximum inside market bid-offer spread and minimum number of valid inside market

submissions).

In the first stage of the auction dealers supply two-way market quotes on the basis of a pre-

defined maximum spread and with a pre-defined quotation size associated with it. Additional

inputs are the “Physical Settlement Requests”. These are the requests to buy or sell

bonds/loans (at the final price), which when combined with the cash settlement of their CDS

trade adds up to be equivalent to physical settlement.

In the second stage, the NOI from the first stage of the auction process is cleared, in order to

determine the definitive (final) price for cash settlement, through a standard uniform price

auction in which dealers and investors can submit limit orders with the relative quantity.

In case of a credit event of a reference entity that is a constituent of an index CDS, contracts

on such index CDS is settled via participation in the credit event auction and the result of the

auction is reflected on a pro rata basis according to the weight of the reference entity on the

index. The notional amount of the CDS index contracts will be reduced by the weight of the

defaulted entity on the index itself so that there is no replacement or creation of a new index

series, though in the following roll a new index series will be defined.

The Greek case

In general, the described procedure to ascertain a credit event and to liquidate CDS contracts

applies to private as well to sovereign entities. However, the restructuring of sovereign debt

may differ in some aspects from that of corporate debt.

In the case of the Greek sovereign debt crisis, for example, the initial hypothesis on a debt

restructuring had raised questions on whether it could be considered a credit event because

the Greek Government and the EU Commission were looking for a voluntary debt

restructuring arrangement.

The Greek case highlighted that, in order to have a credit event under ISDA rules, it is crucial

to determine whether the restructuring is voluntary or mandatory. As noted above, a

voluntary debt restructuring agreement does not trigger a credit event, since it only binds

those investors that agree to the restructuring.

Greece first tried to come to a voluntary debt restructuring agreement and on March 1, 2012,

the ISDA Determination Committee for EMEA area stated that a voluntary haircut agreement

could not be considered a credit event. However, since it turned out that the voluntary

restructuring could not result in the expected debt reduction, the Greek authorities took the

unilateral decision to retroactively introduce collective action clauses (CAC) for bonds issued

under the domestic Greek law. Though the introduction of CAC is not per se a credit event, it

has had the effect to bind all bondholders to a debt swap restructuring implying a significant

haircut and for this reason, on 9 March 2012, the ISDA Determinations Committee decided

that a “Restructuring Credit Event” occurred relative to the Greek debt. Consequently, on 19

March an auction was held according to the previously described procedures.

16

The voluntary exchange of the outstanding Greek debt for new debt (under the so called

“Private Sector Involvement” program) that became binding for all bondholders implied

losses for 53.5% of the nominal value. Investors received 31.5% of the original face value of

their bonds in newly- issued bonds with 30 years maturity, 15% in bonds issued by the

European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) with 2 years maturity and a “GDP Warrant” that

may increase coupons by 1% after 2015 depending on the GDP growth rate.

The deliverable bonds for CDS settlements were the newly-issued bonds with 30 years

maturity and the price of these bonds in the auction held on 19 March was set at 21.5%

(recovery rate). The settlement of the CDS contracts resulted in net payment by protection

sellers of 2.89 billion US dollars, against a gross amount of outstanding CDS of around 80

billion US dollars. The large difference between gross and net exposures, also highlighted in

Figure 7, was due to the high incidence of offsetting positions. However, since most of the

exposures were collateralized the impact of the CDS settlement in terms of liquidity risk has

been limited.

BOX 1: The Greek debt restructuring

On 27

th

of February 2012, ISDA received a query about whether the voluntary acceptance by

some private banks of a haircut on their holdings of Greek debt could be defined as a credit

event. On the 1

st

of March, ISDA issued a note clarifying that, according to the facts recorded

until that date, this event could not be considered as a default event.

13

Following a similar

query posed a few days later, ISDA announced on the 9

th

of March that the triggering of the

collective action clauses in domestic-law bonds was a “Restructuring” credit event for the

CDS contracts on Greek debt.

The agreement on the voluntary exchange of Greek debt for new debt, as reflected in the

Private Sector Involvement (PSI) agreement, implied that the private investors in Greek

bonds would accept losses of 53.5% of the notional value of their bonds. In exchange for this,

the investors would receive 31.5% of the original face value of their bonds in 30-year Greek

bonds, 15% in 2-year bonds issued by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and a

“GDP Warrant” that could increase the payments of the bonds’ coupons by 1% after 2015

depending on the GDP rate of growth.

In the execution of the CDS contracts, the restructuring payments were set using the newly-

issued Greek bond with a 30-year maturity. The price of this last bond, and hence the

recovery rate, was settled in an auction held on March 19

th

. As a result, the recovery rate was

set at 21.5%, which was close to some market estimations made before the auction.

According to DTCC, the settlement of the auction resulted in net cash flows of $2.89 billion,

against a gross amount outstanding of Greek CDS of around 80 billions of dollars. The

difference between the gross and the net exposures was due to the fact that investors closed

13

In the case of Greece, the 15 institution which had the right to vote for the evaluation of the credit event

included 10 dealers, who were selected according to their volume of transaction in the CDS market, and

5 non-dealer institutions, that were selected randomly from a pool of buyers of protection.

17

many of their positions by offsetting their contracts which increases the total gross notional

amount outstanding. The above amount of net exposures is nevertheless consistent with some

sellers of protection having an exposure larger than $2.89 bn.

Due to the fact that these exposures would be partially compensated by the recovery rate of

the underlying and that many of these contracts were collateralized the total payment at the

time of the credit event would have been much lower. Specifically, the recovery rate was set

at 21.5% and, on average, 70% of the exposition of the derivatives was collateralized, with an

average level of collateralization above 90% for the CDS transactions, according to ISDA.

Thus, according to these figures, a high proportion of the total $2.89 bn could have been paid

shortly after the declaration of the credit event.

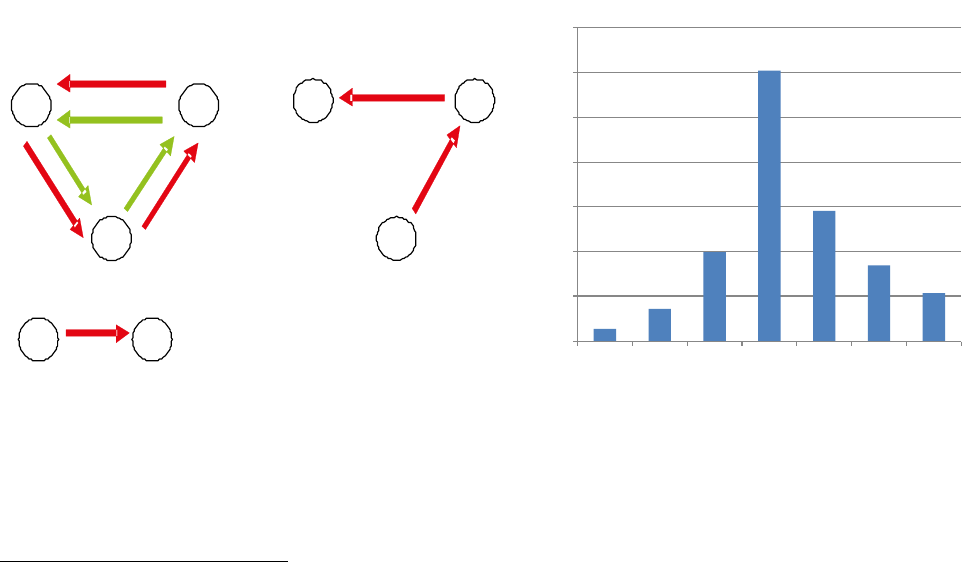

A central question at that time was whether this credit event would lead to a large flow of

payments to the buyers of protection and whether this could have any material effect on the

financial system at large, due to the high degree of concentration in this market, and

especially with regard to the European banks by virtue of their direct and indirect expositions.

In spite of this, however, the impact of the credit event was remarkably low, with no visible

effect on the indicators of financial soundness of those institutions more exposed to CDS on

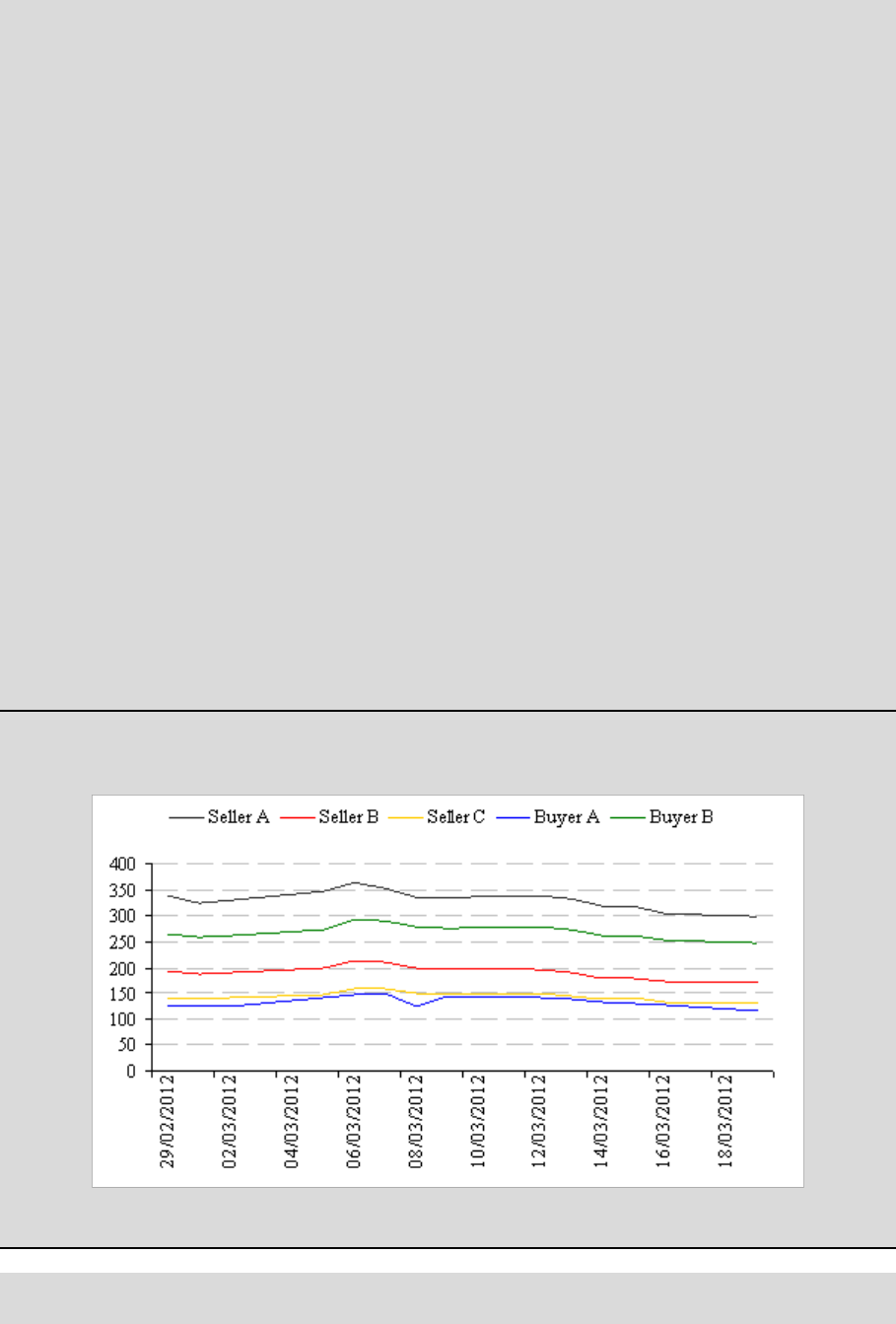

Greek debt. For instance, the next figure shows that the announcement of the credit event by

ISDA did not have a significant effect on the CDS premium of five European banks, three of

which were the main European bank-sellers of protection on Greek debt and two of them the

European bank-buyers at that time according to the data made available by the European

Banking Authority. As it can be directly inferred from that figure, the CDS premiums for

these five financial institutions did not react significantly around the referred date.

CDS premiums for the main European-bank net protection sellers and buyers of CDS on the Greek

debt (in basis points)

Source: EBA and CMA

18

It turned out that the initial fears of a systemic impact of the Greek credit event, related to a

possibly high concentration of the exposures on few protection sellers, were overstated. The

impact of the Greek credit event has been smaller than that of the Lehman Brothers default in

September 2008. In fact, the exposure on Greece was lower (and probably more

collateralized) than that on Lehman Brothers and the recovery rate was higher (21.5%

compared with 9% for Lehman Brothers bonds).

In sum, the CDS market has worked in an orderly way after the credit event of Greece,

although this episode also brought to the forefront several doubts on the future of this market,

especially, in case there is a default of another sovereign with a larger volume of CDS

contracts. In particular, the Greek event has reinforced the need for supervisors to have a

thorough understanding and transparency of exposure across institutions. This aspect was

partially overcame thanks to the EBA reporting of detailed disclosures on banks’ exposures

to sovereign CDS which could have helped avoid the emergence of weakly-founded concerns

about the fragility of some key players in the CDS market. Still, after this credit event several

technical issues remain related to the deliverable bonds, the definition of credit events and the

setting recovery rate that deserve further attention, for their potentially implications in the

well-functioning of CDS markets, as pointed out recently by Duffie and Thukral (2012).

3.2 Market structure

The CDS market, similarly to other OTC derivatives market, is characterised by two types of

transactions.

The first type of transaction, which represents the majority of trades, originates by end-user

and transaction agents who trade with dealers operating as market-makers. The typical

transacting agent is a registered investment advisor that serves as a “buy-side” intermediary

on behalf of end-users that transact infrequently but desire beneficial ownership. The dealer

side is largely dominated by the so called G14 dealers

14

, who are the largest derivatives

dealers worldwide and hold roughly 90% of the CDS notional amount. Some studies tried to

assess the degree of concentration in the CDS dealer market, finding that there is a low or

moderate degree of concentration based on several measures.

15

Buy-side market players are represented mainly by institutional investors and other non-

dealer financial institutions (very few, if any, retail investors are involved in the CDS

market). The interaction between end-users, possibly intermediated through transacting

agents, and dealers, as in other OTC markets, takes place through bilateral contacts, based on

indicative and unbinding quotes posted on major data providers.

The second type of transaction is represented by inter-dealer trades to manage or hedge

transactions with buy-side clients or the dealers’ inventories. These trades are usually

intermediated by so called “inter-dealer brokers”. These intermediaries do not take any

14 Goldman Sachs, HSBC, J.P. Morgan, Morgan Stanley, Royal Bank of Scotland, Société Générale, UBS

and Wachovia Bank.. Nomura joined the group in August 2011 and Crédit Agricole is expected to join

in 2012.

15 See for example ISDA (2010a).

19

proprietary positions, but only match dealer orders, guaranteeing counterparty anonymity

until the transaction is concluded. Inter-dealer brokerage systems have gradually evolved

from traditional voice brokerage mechanisms into electronic trading platforms. Such

platforms provide automatic order execution and allow dealers to observe and transact

anonymous quotes posted by other dealers

16

.

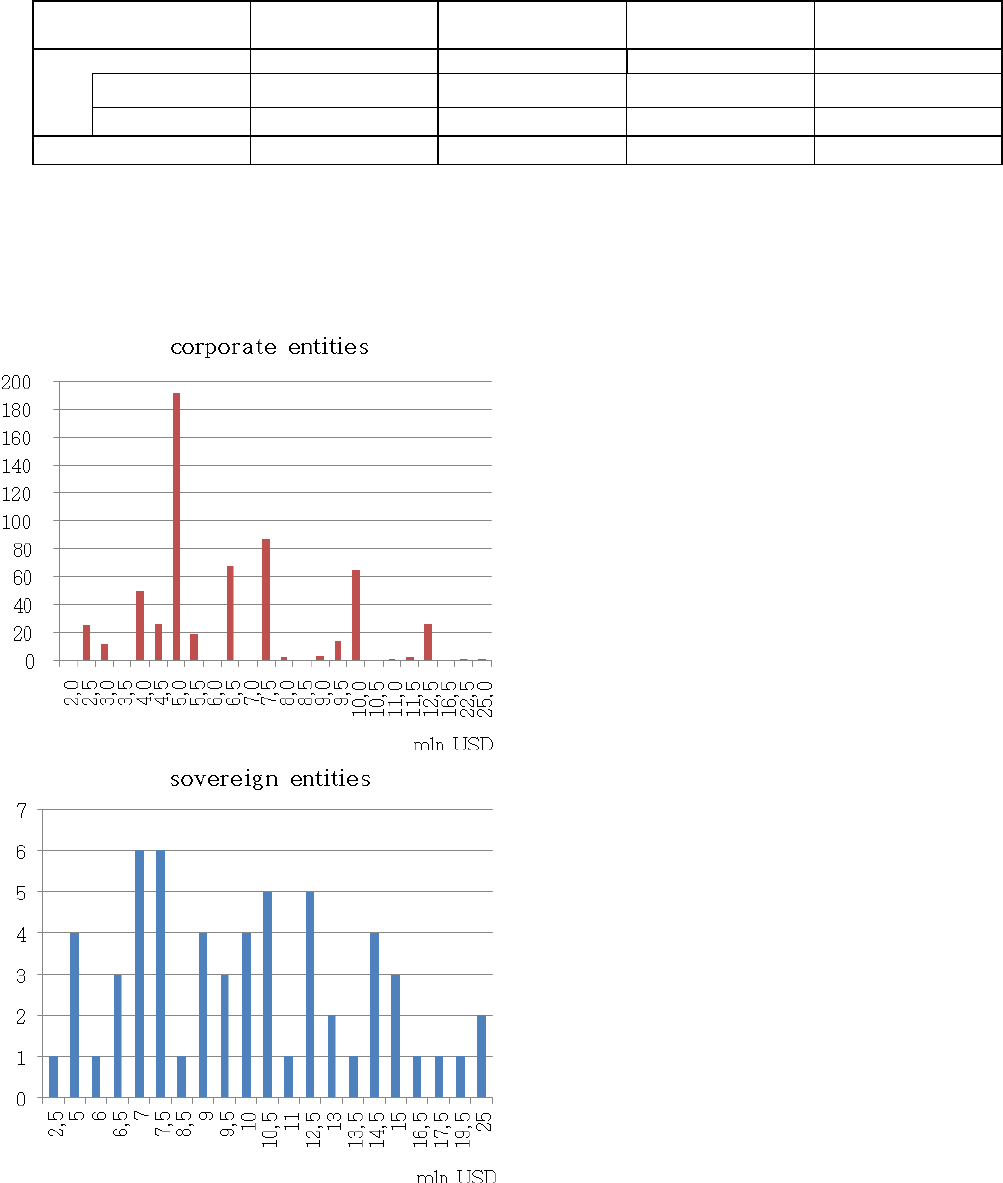

The CDS market is characterized by a relatively low trade frequency and large average trade

size compared to the bond market. Table 1 gives summary statistics for the average daily

number of trades for CDS on the top 1,000 single-name reference entities and for index CDS

from the DTCC database. Single-name CDS trade on average 5 times per day, with CDS on

sovereigns trading more frequently than corporate CDS. Trade frequency increased for both

corporate and sovereign entities in the past two years, but the sovereign sector showed a

stronger increase. The index CDS are traded much more frequently than single-name CDS

(each index series trades on average 20 times per day, compared to roughly 5 times per day

for single-name CDS).

The most frequent notional trade size for single-name CDS is 5 million US dollars for

corporate and 7.1 million for sovereign entities. For index CDS the modal trade size is 25

million US dollars but the frequency distribution of trade size is skewed to the right (Figure

8). The average notional trade size for index CDS is much larger than for single-name CDS

(55.5 against 6.6 million US dollars – Table 2).This is driven by some large outliers, namely

CDX.NA.IG and “iTRAXX Europe” indices, which increase the average notional trade size.

Similar statistics of low trade frequency and high average trade size in the CDS market are

also reported by Chen et al. (2011) and Amadei et al. (2011) among others.

Table 1 - Trade frequency in the CDS market

June - Sep 2011

June 2009 - March 2010

Number of reference

entities

Average n. of

trades per day per

reference entity

Number of reference

entities

Average n. of trades

per day per reference

entity

Top 1000 single-name

1000

4.9

996

4.3

Corporate

934

4.3

934

4.1

Sovereign

66

13.5

62

8.0

June – Sep 2011

March – Sep 2010

Index CDS

137

20.2

117

15.7

Source: Calculation on DTCC data.

16 See Avellaneda and Cont (2010).

20

Table 2 - Trade size in the CDS market

number of reference

entities

mean trade size

(mln. US $)

median trade size

(mln. US $)

modal trade size

(mln. US $)

Top 1000 single-name

898

6.6

6.3

5.0

Corporate

839

6.4 5.8 5.0

Sovereign

59

10.5

10.0

7.1

Index CDS

86

55.5

45.0

25.0

Source: Calculation on DTCC data. Data from June to September 2011. Average trade size is calculated

dividing average daily traded notional amount by the average daily number of trades using the publicly available

DTCC data, Entities with average numbers of daily trades equal to zero are excluded causing a divergence from

the total number of reference entities in Table 1.

Figure 8 - Frequency distribution of CDS trades

21

Source: Calculation on DTCC data. Data from June to September 2011.

After the global financial crisis, financial regulators and some experts called for greater

transparency in the OTC derivatives markets, on concerns that the opaque nature of these

markets had exacerbated the crisis.

17

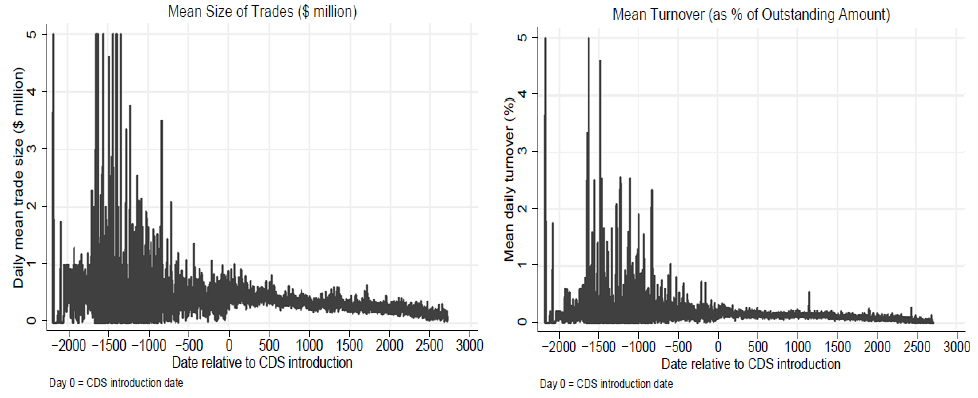

Transparency in this context may refer to the

information available on the issuers’ terms of sale (pre-transparency), to prices and volumes

of transactions carried out in the market (post-transparency) or to the available information

on the positions held by each dealer, an issue which is of special relevance for the

identification and assessment of potential aggregate risks. In all these cases, there is a rather

general consensus around the fact that in all these dimensions, the level of transparency is

still suboptimal.

There is a large amount of research on transparency in regulated stock, bond and exchange-

traded derivatives markets with large retail involvement, but these markets are different from

the CDS market, as previously illustrated, and direct research evidence from the CDS market

is limited. A number of recent analyses have stressed some benefits that the establishment of

transparency regimes in these markets might be expected to bring. Such benefits can be

broken down into those accruing mainly to the supervisory authorities and those which would

benefit market participants (see e.g. Stulz 2010). SLWGFR (2009) argues that increased

transparency about the terms of market transactions would, in general, increase the quality of

the market for these contracts, in terms of lower costs, including through greater competition

between intermediaries, and higher liquidity. Litan (2010) expresses similar views, arguing

that enhanced pre- and post-transparency would bring more efficiency to these markets,

enriching the information content of the prices and reducing the bid-ask spreads.

Avellaneda and Cont (2010), leveraging on the literature more specific to the OTC markets

(in particular on the introduction of the post-trade transparency on the OTC corporate bond

market in the US through the so called TRACE system), argue that the cost of increased

transparency may accrue to large dealers, while end-users may benefit from reduced

17

See e.g. the G20 Leaders’ declarations following the summits held in Pittsburgh (September, 2009) and

Toronto (June, 2010) and the FSB report “Implementing OTC Derivatives Markets Reforms” (October,

2010). For an early academic contribution on this issue, see e.g. the Squam Lake Working Group on

Financial Regulation, SLWGFR (2009).

22

execution costs. In fact, reviewing the empirical evidence on the introduction of the TRACE

system, Bessembinder and Maxwell (2008) conclude that there is evidence that increased

transparency is associated with a substantial decline in investors’ trading costs and that this

result is consistent with the theoretical argument that in an opaque market dealers may be

able to extract rents from uninformed customers and profit from reduced competition (as, for

example, in the models of Pagano and Roell 1996 and Madhavan 1995).

More generally, the evidence from the economic literature on whether increased transparency

may reduce bid-ask spreads and execution costs is not conclusive. For example, Goldstein et

al. (2007) and Bessembinder et al. (2006) find evidence of reduced execution costs after the

introduction of TRACE post-trading transparency, while Madhavan (1996) and Madhavan et

al. (2005) find evidence that transparency increases execution costs. The literature based on

experimental studies points to contrasting results as well: for example, Flood et al. (1999)

find that bid-ask spreads are higher in opaque markets but just at the openings of the trading

day, while Bloomfield and O’Hara (1999) find opposite results that disclosure increase

opening bid-ask spreads.

Moreover, Avellaneda and Cont (2010) argue that the TRACE experience is not directly

applicable to the CDS market because the corporate bond market is composed of many more

participants, including retail clients, and information was much more dispersed prior to the

introduction of the TRACE system. By contrast, the CDS market is an institutional market,

much more concentrated on a small network of dealers: search costs should be lower and

dissemination of pre-trade information through bilateral exchanges may be quite effective. It

may be also important to distinguish CDS indices from single name CDS.

Nevertheless, some have warned on the potential losses for some market participants

steaming from more transparency. For instance, Avellaneda and Cont (2010) conclude that

the main beneficiaries from higher transparency standards would be the less informed

participants together with those who carry out small volume transactions (due to the

reduction of transaction costs). However, they contend that increased transparency

requirements could erode the benefits obtained by CDS dealers.

18

The possibility that dealers’ positions are known by other market participants may expose

dealers to predatory trading, i.e. if the market knows that a dealer has a large position to

hedge or unwind, other market participants will trade in the same direction to anticipate the

expected price movement. In their theoretical model Brunnermeier and Pedersen (2005) show

that predatory trading is more likely and intense the more the market is illiquid and the more

dealers’ activity is concentrated on few players. Given that the CDS market shares most of

the mentioned characteristics, the downside of post-trade transparency in terms of

discouraging dealers’ activity may be significant, unless the disclosure is sufficiently delayed.

As regards the information available for supervisors, there seems to be a general consent on

the idea that the notion regulatory transparency should extend to granular transaction and

position data. For instance, Acharya et al. (2009) argue that transparency may help improve

the correct assessment of counterparty risk, thus, leading to greater efficiency in the

determination and use of the margins required in contracts. The implicit argument is that, by

improving information about the positions and risks of each participant, the bilateral margins

could be calculated in such a way as to be better aligned with each particular risk. Kiff et al.

18

Litan (2010) analyses the potential conflicts of interest between the several market participants and

identifies some possible elements of resistance to pro-transparency reforms on the part of some major

CDS dealers.

23

(2009) emphasize the idea that the fears of systemic risk in CDS markets could abate if super-

visors and participants had access to more detailed information about the reference entities of

the different contracts and the counterparties. Stultz (2010) also notes that trade reporting

could also help in identifying market manipulation in the form of insider trading.

Several initiatives were taken by regulators and the industry at national and international

levels to mitigate the risks in the OTC markets, including requiring the central clearing of

standardized OTC derivative products (see next §3.3) and dissemination of additional

information on the markets.

The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporate (DTCC), for example, started to publish CDS

data in November 2008 from its Trade Information Warehouse on a weekly basis. The greater

use of electronic platforms in the inter-dealer segment of CDS market also enables to provide

some degree of pre-trade transparency. Market participants also have access to real time non-

binding quotes posted by dealers and information on intraday prices available from data

providers like Markit.

The Committee of European Securities Regulators (CESR – which has since become the

European Securities and Markets Authority) examined the possibility to extend MiFID

transparency requirements to non-equity financial instruments in a consultation paper

published in May 2010. CESR, based on the comments received, recommended certain post-

trade transparency requirements for the OTC markets in accordance with the size (net value)

of transactions (the smaller the size of transactions, the higher the level of transparency

required). However, while recognizing a need for harmonization across jurisdictions, CESR

did not propose at that stage to introduce mandatory pre-trade transparency requirements

given that the market microstructure and the degree of liquidity varied widely across different

OTC products.

Though the amount of public information on CDS has increased over the recent years, the

CDS market still retains a high degree of opacity because post-trade transparency is scarce

and pre-trade transparency is limited to part of the inter-dealer market (see e.g Litan 2010).

Summing up, available research on the impact of transparency on execution costs and on the

incentives to provide liquidity does not provide conclusive results. However, some policy-

oriented papers insist on the benefits of introducing more transparency both toward market

participants (market disclosure) and towards supervisors (reporting).

As for market disclosure (basically pre- and post-trade transparency), SLWGFR (2009)

concludes that more transparency about the terms of market transactions may increase market

quality and bring lower costs, higher liquidity and greater competition between

intermediaries, and Litan (2010) argues that enhanced pre- and post-trade transparency would

bring more efficiency, enriching the information content of prices and reducing bid-ask

spreads.

As for reporting, there seems to be a general consensus that regulators should have access to

granular information on trade and position data. Benefits from reporting are highlighted by,

for example, Acharya et al. (2009), who note that reporting may help improve the assessment

of counterparty risk by CCP, and Stultz (2010), who argues that trade reporting helps in the

detection of market manipulation and insider trading.

24

3.3 Counterparty risk and collateralization

While CDS buyers reduce credit exposure to a reference entity, they also take on

counterparty risk because of the exposure to the protection seller. One of the main concerns

regarding the functioning of the CDS market is related to the counterparty risk generated by

the default of large protection sellers. This may happen by a failure to meet payments

obligations following a credit event or inability to post collateral following a downgrade of

the credit rating of dealer itself. If the protection seller defaults, the CDS positions would be

replaced at unfavorable market prices. Because of the highly concentrated and interconnected

nature of the CDS market, this may create systemic risk. The bailout of AIG, a major CDS

dealer, and the bankruptcy of another important CDS dealer like Lehman Brothers in 2008

illustrate the importance of counterparty risk in the risk management of CDS.

One distinctive feature of CDS compared to other OTC derivatives is the price discontinuity

before default that is often referred to as the “jump to default”. The market value of a CDS

position (i.e. its replacement cost) prior to a credit event occurs can be a small fraction of the

notional, but the actual exposure upon default may represent a large fraction of the notional.

This implies that the protection seller could suddenly owe large amounts that it may not pay.

This jump-to-default risk complicates the risk management of CDS and may result in under-

collateralization or underestimation of variation margins because of the complex modeling

required (Pirrong 2011).

Indeed, in order to mitigate counterparty risk in OTC contracts, market participants may post

collateral, which is intended to absorb first losses in case of default of the counterparty. Initial

margins may be required on initiation of the contract. In practice, due to the jump-to-default

risk, initial margins in bilateral CDS contracts can reach 10–30 percent of the notional

amount, while they are normally much lower for other OTC derivatives. Furthermore, margin

levels are regularly adjusted through margin calls, which can reach large amounts in case of a

sudden deterioration of the creditworthiness of the reference entity or of the financial

situation of one of the counterparties.

Although collateral is not systematically required in CDS transactions, collateralization

agreements have been increasing in recent years. The ISDA (2010b) margin survey reports

that 93 percent of the flow of all new credit derivatives trades executed in 2009 became

subject to collateral arrangements. ISDA stock data indicate that about 70 percent of OTC

derivatives net credit exposure was collateralized, though for the European market the

ECB/Banking Supervisory Committee survey

19

estimates that only 44 percent of net

exposures are collateralized.

Different studies estimate that the magnitude of under-collateralisation for the overall OTC

derivatives markets can be substantial. Cecchetti et al. (2009) estimate the under-

collateralization at end-2008 at about 1 trillion of US dollars, taking the difference between

the gross credit exposure (estimated at 5 trillion US dollars on the basis of BIS statistics) and

the amount of collateral used (estimated at 4 trillion US dollars on the basis of the ISDA

margin survey). With specific reference to the CDS market, Singh (2010) infers the degree of

19

See ECB (2009).

25

under-collateralization from an estimate of the collateral cost of moving CDS to central

clearing, arriving at figures ranging from 40 to 80 billion US dollars.

Under-collateralization in OTC derivative markets may be due to the fact that collateral

arrangements depend not only on the creditworthiness, but also on the type of the

counterparty. For example, sovereigns, central banks, AAA insurers, Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac and other similar clients sometimes do not post collateral. Dealers only post collateral

with each other for their net exposures. Furthermore, collateral received may be

rehypothecated, i.e. re-used by the recipient as collateral for a different transaction.

According to the ISDA (2010b) margin survey, 44 percent of all respondents and 93 percent

of large dealers on derivative markets report rehypothecating collateral. Survey respondents

as a whole report rehypothecating 33 percent of collateral received while the large dealers

report rehypothecating 82 percent of collateral received.

The default of a protection seller may create default contagion. In this respect, network

models provide a useful tool to analyse the impact of credit derivatives on systemic risk. In

particular, Cont (2009) shows that the magnitude of financial contagion depends on some

properties of the network structure other than on the exposure of its largest participants.

Central clearing

As a result of the financial crisis, and particularly after the AIG bailout, the use of central

counterparties (CCP) has been seen as a way of mitigating counterparty risk in CDS contracts

and preventing default contagion.

In fact, CCP, acting as a buyer to every seller and a seller to every buyer of protection, isolate

counterparties from the default of each other and the consequent reduction of bilateral

interconnectedness between financial institutions mitigates contagion risk in the financial

system. In the event of default by a clearing member, CCP may use different pool of

resources to absorb losses, such as margin calls, guaranty funds (to which clearing members

may contribute according to the riskiness of their positions) and its own capital. These

different layers of protection are designed to limit the risk of contagion by immunizing each

member from the default of others. Moreover, centralized clearing makes it possible to

establish harmonized requirements for monitoring and managing counterparty risk and may

improve risk management practices by market participants, thereby increasing the confidence