University of Mississippi University of Mississippi

eGrove eGrove

Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School

2016

Framing Ole Miss Coverage In Mississippi Newspapers Framing Ole Miss Coverage In Mississippi Newspapers

Christina Steube

University of Mississippi

Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd

Part of the Journalism Studies Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Steube, Christina, "Framing Ole Miss Coverage In Mississippi Newspapers" (2016).

Electronic Theses and

Dissertations

. 647.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/647

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

FRAMING OLE MISS COVERAGE IN MISSISSIPPI NEWSPAPERS

A Thesis

presented in partial fulfillment of requirements

for the degree of Master of Arts

in the Meek School of Journalism and New Media

by

CHRISTINA M. STEUBE

August, 2016

!

!

ii!

Copyright Christina M. Steube 2016

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

!

!

!

ii!

ABSTRACT

The University of Mississippi, a public institution also known as Ole Miss, is naturally of

public interest and consequently is the subject of constant, and sometimes controversial, media

coverage. Through the last few years, Ole Miss Athletics has garnered much of that media

attention due to its recent successes. However, coverage at Ole Miss, independent of its athletic

programs, gets media coverage in a much different way.

Sometimes that coverage will involve academic achievements, large financial donations

and campus changes. However, other types of coverage, especially over the last four years, have

been controversial, dealing with student conduct issues and race-related incidents.

The purpose of this study is to explore the types of coverage of Ole Miss that exist in

Mississippi newspapers and to determine if the majority of news coverage is negative. An

internal perception is that Ole Miss is subject to much more negative than positive coverage.

However, a content analysis of 402 newspaper articles from Mississippi newspapers revealed

that Ole Miss tended not to receive undue amounts of coverage that reflected negatively on the

university. In fact, quite the opposite relationship emerged.

The results of this study show journalists tend to frame Ole Miss is a positive light. From

the sample of 402 articles, 293 (73%) dealt with non-controversial, positive topics such as

research and accomplishment recognition.

!

!

iii!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………ii

LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………..........iv

LIST OF FIGURES ………………………..…………………………………..v

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND…………….…………………………..….…..1

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW…………………………………….…5

HYPOTHESES………………………………………………………………..23

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY…………………………………………….26

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS…………………………………….……………….32

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION…………………………………………………42

REFERENCES………………………………………………………………..50

APPENDIX……………………………………………………………………58

VITA…………………………………………………………………………..63

!

!

iv!

LIST OF TABLES

1. Descriptive Statistics…………………………………………………………32

!

!

v!

LIST OF FIGURES

1. WREG Story ……………………………………..

2. The Clarion-Ledger Article………………………………………

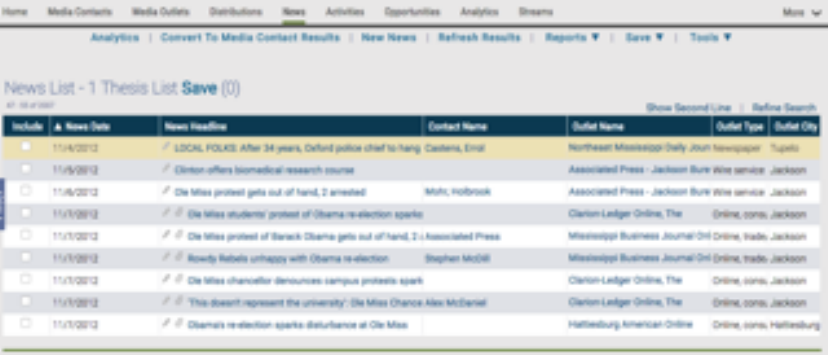

3. Vocus Listing Screen……………………………………………….

4. Vocus Article Listing……………………………………………

!

!

1!

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND

The University of Mississippi, past and present, has been associated with racial tension.

These racial incidents involve issues on campus that create a discussion about race relations at

the university and often include a call for change or response from students, faculty, staff, alumni

and community members.

The university has a storied past. During the Civil War, enrolled students left the

university to join the confederate army. In 1962, a riot occurred on campus as the first African-

American, James Meredith, enrolled, requiring then-President John F. Kennedy to send the

National Guard to the Oxford campus. As a result of this history, as well as the fact that it is the

flagship and largest public institution in the state, Ole Miss is also the subject of constant media

coverage. Although the reminders of the racial history of Ole Miss have always been present, the

last four years have resulted in more turmoil on the university campus. In October 2012, Ole

Miss was celebrating the 50

th

anniversary of Meredith enrolling in the university. Less than one

month later, Barack Obama was reelected as President of the United States. Just before midnight

after results were announced, students gathered, both in support of Obama and in protest. The

incident, first reported by students on social media, began as arguments on two sides of the

political spectrum. However, the disagreements became racially charged, bringing the word

“riot” to the forefront on social media and some media reports, on both state and national levels

(Banahan & Melear, 2013). A study conducted by an internal incident review committee

concluded erroneous reports of a riot and

!

!

2!

gunfire as well as inaccurate descriptions of events and racially charged comments began on

Twitter (2013). Much of that information was re-tweeted by the dozens and picked up by student

media. The IRC found that the majority of the 400 of students present were observers, but their

passive presence resulted in difficulties with crowd control and negative coverage (2013). The

university was also quick to condemn these actions, releasing a statement and holding a

candlelight vigil the following day. When this report was released two months after the incident,

the only report of violence witnessed by students occurred when a young woman slapped a

young man in the face. But the damage to Ole Miss was already done, and this incident was yet

another black eye to the reputation of the university.

In 2014, Ole Miss was subject to state wide and national scrutiny once again. On

February 15, three students and fraternity members placed a noose around the statue of James

Meredith, located behind the Lyceum, along with an old Georgia state flag, which includes a

Confederate emblem. Those actions were condemned by the university, and the case was turned

over from University Police to the Federal Bureau of Investigations. Two of the men have been

charged and sentenced. As the legal process in this case continues, so does the news coverage,

bringing constant reminders of the association of racial incidents to Ole Miss.

According to former University Communications Chief Communications Officer Tom

Eppes (personal communication, April 18, 2016), positive stories about donations, university

improvements and student achievements garner some coverage throughout the state. However,

negative events such as student misconduct stories and any instances involving race are subject

to much more coverage, often resulting in national news organizations making their way to the

campus. This coverage has negatively affected the brand of the university even though several

on-campus organizations are working towards racial reconciliation and equality, such as the

!

!

3!

William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation and the Center for Inclusion and Cross

Cultural Engagement. Eppes also said that constant association with racial incidents is cyclical,

meaning these incidents continue to happen on campus because prospective out-of-state students

feel the university is a “haven for racist activity,” (Eppes, 2016). He added that when reporters

cover racial incidents at the university, they also tend to cover other student misconduct stories

with more scrutiny as well, once again causing more coverage that reflects negatively on Ole

Miss. Of prospective students in Mississippi surveyed by telephone, 75 percent indicated they

were likely to apply to Mississippi State University, while 65 percent likely to apply to the

University of Mississippi (Ivanova, 2013). Of the other universities mentioned in the study,

University of Southern Mississippi, University of South Alabama and the University of

Alabama, the University of Mississippi is the only one in which participants mentioned the

atmosphere was “not good, racist, prejudiced or snobby” (2013).

Most recently, the university has taken proactive measures concerned race. In October

2015, Ole Miss removed the Mississippi flag from campus, which bears the Confederate emblem

in the upper left corner, at the request of the Associated Student Body, Faculty Senate, Graduate

and Staff Councils. It became the fourth university in the state to do so, following three

historically black institutions. In March 2016, Chancellor Jeffrey Vitter has worked with campus

and historical organizations to provide historical context to the Confederate symbols and names

still present on campus. Both issues were covered by newspapers across the state.

This thesis will explore the relationship between type of incident and the way it is

covered to see if incidents of race are covered only negatively, for example, while other

newsworthy events are covered positively. The comparison will determine if Ole Miss gets any

!

!

4!

positive coverage of racial progress, or if the history of the university has forever tarnished the

way it is presented in news stories across the state.

!

!

5!

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Throughout the research process of analyzing how stories involving race-related incidents

about Ole Miss are framed by Mississippi newspaper reporters, communication theories of media

framing, agenda-setting and gatekeeping appear.

Framing

Media framing is the concept that news media take a certain issue and focus attention on

certain events within that issue when presenting it as content, thereby placing those events within

a specific field of meaning (McQuail, 2010). Attitude or opinion the media consumer derives

from a news story is not because of what is being reported, but how it is reported and presented

(Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011). In this study of newspaper articles, how the reader interprets

information depends on how that information is contextualized (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011).

Schuefele distinguishes two types of frames: media frames and individual frames (Qin, 2015).

Media frames serve as interpretive packages that give context and meaning to an issue, while

individual frames are internal structures in the mind of the reader that give meaning and

understanding to a whirlwind of events (Qin, 2015).

In a psychology study conducted by Jerome Bruner and Leigh Minturn in the 1950s, a

symbol was shown to participants that could either be interpreted as the letter “B” with a slightly

detached line or the number “13” (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011). When subjects were shown

numbers prior to the symbol, they interpreted it as the number 13. When they were shown letters,

!

!

6!

they interpreted it as the letter “B” (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011). This study sums up how

different presentations of the same information can cause a different reaction. Scheufele

describes media framing as an equivalent to how a gallery owner would display a painting

(2011). Potential customers would view a painting in a large, gold-plated frame much differently

than if the same painting was shown in a plain, aluminum frame (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011).

Media frames are patterns of interpretation expressed by the journalist producing the

piece (Bruggeman, 2014). Framing goes beyond news bias, as it is not merely a slant in

coverage, but the journalist deciding what issue is to be reported to the public. According to

Bruggeman, frame-building by journalists has not been deeply explored. However, it is

essentially unavoidable for reporters, because the way a newspaper story is framed is based on

the sources the journalist speaks to about an issue. Sources of information for the story frame

their messages, and media users interpret the information they receive (Bruggeman, 2014).

Journalists use frames as a way to quickly put together and simplify a story for their readers. For

the purposes of this research, the focus will be on the frame the journalists create in their news

stories, which includes the sources cited and past negative occurrences mentioned in the story.

Both would create a journalistic frame around the information presented.

News framing falls under the applicability model (Scheufele &Tewksbury, 2007). This

means the way an issue is understood by readers and applies the information is based on the way

that issue is characterized in media reporting (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). The focus of

framing, as opposed to agenda-setting, is on the construction of the message. This is not to say

that news framing is unethical. News becomes relevant when it is placed in the context of

society. Journalists do not always put a “spin” on a story to deceive the reader (Scheufele &

!

!

7!

Tewksbury, 2007). Instead, framing allows reporters to break down a complex issue, like stem

cell research, so that the layperson can understand the story. Framing effects are more likely to

occur when the reader pays close attention to a story, rather than skimming the news report

(Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007).

Frames of Accountability

Media framing also involves the journalists’ responsibility and accountability. Four

frames of media accountability have been identified (Dennis, 1989). The first is the frame of law

and regulation. This frame involves public policy, and the goal is to keep healthy relationships

by reducing harm to private and public interests (Dennis, 1989). In the market frame, the

interests of media organizations and producers, as well as clients and audiences, are balanced.

The frame of public responsibility involves the society’s needs being directly expressed and the

media fulfilling a civic duty of building a relationship between media and society. According to

Dennis, multinational control of media and media concentration undermine this framing model.

The final frame is that of professional responsibility. It involves the ethical development of

journalists who are held to a standard and is perhaps the most common media frame. This frame

scope encourages self-improvement and self-control (Dennis, 1989).

Overall, the ideal goal of media framing when using one of the four frames of

accountability is to achieve complete objectivity when reporting the story, because the news

frame is a reflection of everyday reality. However, some believe that true objectivity cannot be

achieved when a frame exists (Scheufele, 1999).

Framing is not a new concept and has been used in propaganda for centuries. Many

associate propaganda with World War I and World War II because of its prominent role in those

!

!

8!

conflicts, but according to the American Historical Association (2013), it can be traced back to

ancient Greece. Today, stories are framed in many ways, defining the tone of the story as more

than just positive or negative. This adds more angles and dimension to the content.

In a study conducted to determine public attitudes of embryonic stem cell research,

researchers found that people use news frames to form opinions about scientific issues of which

they have no extensive knowledge (Ho, Brossard, & Scheufele, 2008). Coverage of stem cell

research includes terms such as “scientific progress” and “discoveries,” framing the issue

positively. However, results of the study indicated that opinion often formed based on current

predispositions and ideologies of an individual (2008). The stem cell study showed that

individuals who were more religious still thought negatively about the research, even though it

garnered positive coverage, whereas individuals who were moderately religious were more

susceptible to a positive news frame (2008).

The Involved Journalist

In the 1930s, theories were developed about the role of journalists and how they should

be detached from their work. However, since the practice of journalism requires collaboration

with sources and editors, complete detachment is difficult (Hellmueller & Mellado, 2015).

Research has shown the way journalists’ view their roles in their profession influences the way

they report the news. This means journalistic roles influence journalism practice (2015). Because

journalists are citizens of the societies they cover, they are subject to internal pressures to meet

demands and keep relationships with sources, all of which are factors that influence how they

frame a story.

!

!

9!

For example, a research study conducted in Philadelphia for the Society for Nutrition and

Behavior examined news coverage of obesity, specifically dealing with sugar-sweetened

beverages, by gathering news articles published between October 2010 and March 2011. During

this time, a health campaign was launched in January that focused on reducing consumption of

sweetened beverages (Jeong, 2014). The study concluded the news media framed stories of

obesity on the individual level before and after the campaign launched. In the weeks after the

campaign, the media began to add focus and framing to the systemic level, including beverage

companies. This study showed two points: 1) local media feed off of societal events when

presenting stories and 2) public health officials consider the public support garnered from a news

story when developing a policy or campaign (Jeong, 2014).

Media and Public Policy

The way coverage of race issues is framed can determine whether or not media users

support public policies associated with the issue (Gandy, Kopp, Hands, 1997). Although

background and social circumstances play a vital role in public opinion, media also have a large

influence (Gandy, 1997). Coverage of racial differences in the present-day can be a result of

racial hostility, as evident from recent coverage of the Mississippi state flag debate and the

Confederate symbols that tie-in with the issue. When issues involving race are framed for media

coverage, even small details can influence users. However, now that social media have become

more prevalent, controversial topics have become popular with readers and therefore garner

more coverage.

When it comes to sensitive topics, readers are more interested in stories that are framed

negatively (Trussler & Soroka, 2014). Because media act as a watchdog of government, they

!

!

10!

have been historically referred to as the fourth estate since the 1950s and have acted as such

since the eighteenth century (Schultz, 1998). As a result, journalists often have a very critical and

cynical view of government entities. Because the University of Mississippi is a publicly funded

institution, journalists often present it from a critical perspective. The fourth estate concept

originated mainly for checks and balances on political figures and issues, but some of the

concepts apply to controversial topics as well (Hutchison, Schiano, & Whitten-Woodring, 2016).

For instance, the study explains that negative frames come from creating news that prioritizes

new and exciting information (Trussler & Soroka, 2014). Because this information is churned

out much faster than policy news, it can result in a negatively-toned frame. Surveys indicate that

media users do not necessarily prefer negative frames; however, the political climate of the issue

at hand influences the tone (2014). Support for one side or the other of a controversial issue may

result in action, giving the media consumer an incentive to pay attention (2014). According to

Zaller, (1999) the media consumer is engaged with conflict and bored with consensus. Therefore,

when media highlight disagreements and controversies, they often gain readers.

A study in 2012 explored the framing theory involving coverage of race as it relates to

school shootings (Park, Holody & Zhang, 2012). The way Park et al. studied race vastly differs

from the purposes of this study, but it does provide interesting insight in the way attributes are

mentioned in a news story when they are not really relevant (2012). This study investigates how

newspapers in the United States racialized the shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007. There are

several mentions that the shooter is Asian in prominent news coverage, though his race is not

relevant to crime or mental illness (2012). In comparison, the shooter in the Columbine incident

did not have their race reported prominently. Park et a. added that strong empirical evidence

!

!

11!

shows that Americans have the false perception that immigrants are more prone to criminal

behavior (2012).

An example of these types of attributes framing the story from a university perspective

has occurred recently. For example, in March 2015, WREG television in Memphis reported a

story, shown in Figure 1, and posted it to their website title “Update: Graphic video shows Ole

Miss student biting the head off a hamster” (Rufener, 2015).

Figure 1.

WREG Story

While that information is true, the incident shown in the video did not even take place in

the state of Mississippi, let alone the Oxford campus and the fact that the person in the video is a

student is not really relevant to the horrific action in the video, yet it was mentioned prominently.

On the contrary, a story reported by The Clarion-Ledger newspaper in Jackson reports a story on

their website, shown in Figure 2, in August 2015 titled “Two Mississippians arrested for trying

to join ISIS” (Apel, 2015).

!

!

12!

Figure 2.

The Clarion-Ledger Article

The two subjects of the story were both Mississippi State students – once a recent

graduate and another a sophomore. However, that information is not revealed until the fourth

paragraph of the story. While these are two completely different media in two different locations,

they are still examples of how constructing the presentation of factual information in a certain

way leads to opinions and associations by the reader.

Pushing some attributes to the foreground while burying others in a story is a primary

way a frame can affect a reader (Lechler & de Vreese, 2012). In coverage of the 2011 Egyptian

revolution, a study concludes that both CNN and Fox News described the revolution in news

coverage in a way that affects U.S. citizens (Guzman, 2016). The event received more coverage

by American news organizations than any other international story from 2007 to 2011 (Guzman,

2016). To justify international coverage, American journalists often explain the relevance of a

topic to the U.S. audience, including how they will be affected. According to the study, this

!

!

13!

resulted in residents of Egypt and the surrounding region to be either portrayed as a friend or

enemy to the United States, which cause frame political opinion of the viewer (Guzman, 2016).

In addition, a public perception of media bias can influence the way readers participate in

politics (Ho, et al., 2011). For example, that state of Mississippi and the Ole Miss campus have

received news coverage about the state flag issue within the last year. In fact, that coverage has

been pretty heavy, with many news outlets features multiple stories on the issue, as it is a

controversial one. In some cases, readers who want to keep the state flag have commented about

the “liberal media” leaving out the “historical facts” of the flag to promote a political agenda. On

the opposing side, residents who want the flag changed comment in and on these stories about

wanting to put the issue on the ballot. This is directly influencing the political process and call to

action.

History Creating Controversy

Because of the university’s tumultuous racial past, newspaper reporters in Mississippi are

likely to frame stories covering race incidents in a manner that they would not if the university

had not had such a negative history regarding race (Eppes, 2016). That history traces back to the

Civil War, when university students left school to fight for the Confederacy. It also includes the

conflict over the enrollment of James Meredith, the first African-American student at the

university. That controversy resulted in a riot and death on the campus. More recently, the

protest of the presidential results on election night in 2012 and the hanging of a noose on the

James Meredith statue in 2014, have resulted in the history of Ole Miss being mentioned, even

though the university has actively worked to create an inclusive environment and ease racial

tensions. Based on the previous coverage of Ole Miss during race-related incidents, the

!

!

14!

researcher predicts these incidents at Ole Miss are mentioned in stories in which the initial

subject is not a race-related incident involving the university.

Frame Sending

Media framing also can occur from the source of information. Framing is when a

journalist frames coverage based on personal interpretations of the information at hand. Frame

sending differs from a journalists’ interpretation and refers to the journalist sending out the

message of their source in their coverage (Bruggeman, 2014). However, this does not mean that

quoting a source is frame sending. In fact, a minimal amount of frame sending will occur in any

journalistic practice, as reporters tend to shorten statements and interviews before publication. In

doing so, a journalist is framing by personally determining what information is more important

within the issue at hand and what should be presented to the media users. Both frame-setting and

frame sending are ways that journalists shape news content (2014).

Framing can also occur in the photography process. If a controversial photo accompanies

a story, it will likely be viewed more times than a simple graphic or photo of a noncontroversial

nature. Tighter shots to show emotion or the person involved are preferred in the news gathering

process to wide shots, especially in controversial issues.

Ethical Responsibilities

Journalists reporting in a specific region have interests in that region. They want stories

to appeal to readers in an area. Because of the proximity of the story to the community in which

the journalist covers, the researcher predicts journalists in the southern portion of the state, or in

areas with other prominent universities, will report more negative stories about Ole Miss than

!

!

15!

journalists in the northern portion of the state near Ole Miss. Geographical proximity can

determine newsworthiness and also set the frame of the story (Curtis, 2012).

Other news values can influence the frame of the story as well. The timeliness of the

story, for example, if the event is breaking news, can influence accuracy and thoroughness of the

story as well as tone, depending on the facts the journalist has currently gathered (Curtis, 2012).

Impact involves the number of people the incident in the story will effect. Prominence deals with

how high-profile the subject of the story is (2014). For example, if it involves a public figure or a

well known institution, it is more likely to be covered by journalists. Any story involving

conflict, meaning anything that causes public outrage or disagreement, is likely deemed for

interesting, therefore published (2014). The more bizarre a story is, the more likely it is to be

published, and in the age of new media, go viral. Lastly, currency determines newsworthiness as

well. This means stories of public interest such as the Casey Anthony trial, publication of the last

Harry Potter book, and the ongoing gun control debate are stories that are not necessarily

impactful to a large group or happening near someone, but they are still a matter of public

interest (2014). All of these values not only determine how the story is framed, but determine

newsworthiness as well.

News reporters also are subject to commercial pressures. Although journalism is

considered by many to be a public service, it is still a business seeking profit (Kim, Carvalho, &

Davis, 2010). The “if it bleeds it leads” mentality in news is still evident today, as coverage of

controversy, crime and violence tend to get more audience readership and engagement than

positive stories. In a content analysis of the Occupy Wall Street movement, Xu found that in

USA Today and New York Times articles, news coverage highlighted violent behavior and violent

potential behavior of a few protestors, rather than the actions of the majority of peaceful

!

!

16!

protestors or the movement as a whole (Xu, 2013). The coverage also focused on negative

aspects of the protest, such as disruption to transportation or residents of the neighborhood, and

attributes such as age, appearance and eccentric apparel, which he said trivializes the issue

(2013).

Gatekeeping

The other theory in question is gatekeeping, which works in conjunction with the framing

theory. In framing, the theory is based on how the story is presented, which is primarily the role

of the reporter or author. However, gatekeeping falls under the purview of the editor or producer,

who determines newsworthiness and placement of the story.

The communications theory of gatekeeping goes hand-in-hand with the theory of

framing. Gatekeeping practices are a main portion of the editing process. It involves deciding

which stories need to be covered, assigning those stories, and determining what final copy gets

published – all of which are an editor’s judgment calls. This concept was applied in the 1950s

after a wire editor determined what content would appear in the newspaper, and it has since been

used to describe how journalists and editors select the news they cover and publish (McElroy,

2013). In new media, gatekeeping also refers to monitoring online comments within news

articles and on social media websites to maintain civility and remove profane or vulgar language

or derogatory insults (McElroy, 2013).

The essence of gatekeeping is deciding what stories are relevant enough to be produced

for public consumption (Roberts, 2005). The producers and editors are the gatekeepers of news,

and they control what happens throughout the news process.

!

!

17!

Positive stories about Ole Miss are covered, but University Communications CCO Tom

Eppes (personal communication, April, 18, 2016) said the intensity of coverage for negative

stories published about Ole Miss is greater than a positive story. The researcher predicts the

sample of content articles will illustrate this belief.

Eppes (personal communication, April 18, 2016) also noted that many negative events,

incidents and problems that occur on the Ole Miss campus happen on other college campuses as

well, some to an even larger degree. He said the constant negative coverage of Ole Miss is likely

due to the aggressiveness of the daily student newspaper on campus, The Daily Mississippian.

Eppes (2016) said because of the hard work and attention to detail of the award-winning student

journalists at the university, stories are told that would otherwise go unnoticed at other

universities. Because this paper is a daily newspaper, it is part of the Mississippi Press

Association and other state newspapers either publish or further investigate the content originally

reported by the student newspaper.

The news process begins with the raw material, which is turned into a story and then

edited to become a finished product. That means content travels from the news gatherers to the

news processors. However, McNelly (1959) argued that the focus should be primarily on the

news gatherers, because stories that are not reported on will never reach the level of processing.

Those gatekeepers also can be responsible for assigning content to be gathered, which brings

them into a deeper level of the process. In addition, gatekeepers also are responsible for final

headlines as well as fine-tuning the content. As a result, a particular frame of news content can

occur. Because editors are the decision-makers when it comes to headline, story placement and

photos accompanying a story, the researcher predicts that controversial stories about Ole Miss

!

!

18!

have a negative tone in the headlines, are placed on a more prominent page in the newspaper and

have more photos to accompany the story than a noncontroversial story about Ole Miss.

Finally, from a perspective of assigning stories to reporters, gatekeeping questions the

newsworthiness of a topic, and factual information as well. It is an editor’s responsibility to

determine which stories add value to public conversation and knowledge, and it is the

responsibility of the journalist to keep false information from spreading to a mass audience.

The idea of gatekeeping expands throughout media to include literary publishers and

editorial and production work in both print and television (McQuail, 2010). Gatekeeping in

media has strengths and weaknesses. Because of editorial gatekeeping, newsworthy and factual

stories are sought for coverage and publication. However, because this is a subjective process,

this also can result in a weakness of the concept, allowing lesser or non-newsworthy stories to be

published while others deserving of publication may be deemed unimportant and not published.

A selection criterion leads to some news stories being presented, while others are left out. This

results in news managers influencing decisions about what is available for public consumption

(McQuail, 2010). In the current age of new media and instant access to information, the original

concept of gatekeeping has completely changed. Before search engines, the main form of

information came from information editors who decided to present on nightly newscasts or in

newspapers (McQuail, 2010). Now, a simple search term offers media users a variety of options

to receive their information, opening the gates to the flow of information on any specific topic.

Social media have changed the gatekeeping practice through citizen journalists and user

generated content. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Periscope and blogs allow anyone to post and

share information to engage an audience. This increases the amount of information from a story

that is available and offers different and unique angles of coverage (Ali, 2013). This strongly

!

!

19!

differs from how journalists associated with traditional media choose content. However, media

organizations still monitor these citizen journalists’ claims and stories, choosing which

information to further investigate and creating their own content. It is not uncommon to see news

stories of events or instances that first occurred on social media.

Traditional media mainly view user-generated content primarily as entertainment news.

However, these social technologies also have influenced the way major events are covered (Ali,

2013). For example, social media revealed information about three major conflicts in the western

world, including the uprising in Iran in 2009 after the victory of Ahmadinejad, the overthrow of

Mubarak and the overthrow of Gaddafi’s regime (Ali, 2013). In the case of Ahmadinejad,

citizens began documenting the way protestors were struggling on social media, getting this

information out in a society where traditional media would otherwise not have known about this

type of event. Twitter was heavily used during this time, and the story eventually reached the

Washington Post and Newsweek. Traditional media, acting as gatekeepers, further investigated

these stories from social media.

At the University of Mississippi, after the 2012 presidential election results were

reported, a student protest was described as a “riot” on social media. Prominent media outlets

picked up the content from social sites as the event was happening, acting as gatekeepers.

Agenda-setting

The idea behind both the theories of media framing and gatekeeping is agenda-setting.

The concept of agenda-setting essentially was developed to convey that news media tell the

public what the main issues are, which leads the public to perceive that those are the main issues

when it comes to current events (McCombs & Shaw, 1993). Research shows that the public

!

!

20!

attaches significance to the issues to which media give priority. According to theorists, three

different agendas exist: media priorities, public priorities and policy priorities (McQuail, 2010).

Although the ideas behind agenda-setting vary, exploring the possibilities has opened the door to

understanding different media effects on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors. Those media

effects include the bandwagon effect, the spiral of silence, the diffusion of news and media

gatekeeping (McQuail, 2010). In essence, agenda-setting is the hypothesis that media sources

give more or less attention to certain issues based on public pressure, world events or an

interested group of people (2010). These media choices affect public opinion, but the effects are

short lived, according to research.

Pingree (2013) suggests that news editors select stories based on what it believes is

important. That selection directly influences agenda-setting, allowing journalists to prioritize

social problems for an audience (2013). This introduces a bias, as media are telling society what

is important. Research on the topic of agenda-setting concludes that exposure to news stories

affects perceptions of social problems (2013). Agenda-setting in media is more of a process of

making a news issue more accessible in the minds of media consumers. The gap in this research,

however, is finding out how media consumers should prioritize issues without being prompted

and what role media play in that process (2013). If a journalist writes with an agenda in mind

about Ole Miss, for example, they can intentionally omit certain important facts to create a

perception. From that, the researcher predicts there is a relationship between the information

omitted in controversial stories about Ole Miss and live events happening. For the journalists,

this may be due to pressure to get a story written quickly. It may also be based on media framing.

!

!

21!

Other external factors can influence frame. Societal norms, organizational pressures,

pressure from interest groups and the way a journalist gets their information can all have an

effect on the frame of a news story (Kim, Carvalho, & Davis, 2010).

If a journalist fails to distinguish between students enrolled at the university and outside

protestors with no ties to Ole Miss in events of racial tension and protests, the public perception

will be that Ole Miss students are the primary participants in these actions. If the story is

distributed more broadly, it can lead to the public believing Ole Miss harbors racist attitudes.

Agenda-setting is based on memory models and the idea that people process information

for making decisions based on information that is most salient (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007).

This differs from the applicability model and is known as the accessibility effect (2007).

However, the two models do work together and have joint influence, so they are not

mutually exclusive. For instance, an applicable frame is more likely to be activated when it is

more salient (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). In essence, the salience of an issue refers to how

often it is covered and the prominence of that coverage (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011). The

simplified version of the idea states that readers are more likely to feel an issue is important if it

is covered daily and featured on the front page of the newspaper or website. Salience of

attributes within an issue can influence frame as well. In the study of race in media coverage of

school shootings, news reports frequently mentioned the race of the shooter, even in reports

published well after the event when it was no longer newsworthy or relevant (Park, Holody, &

Zhang, 2012).

Studies have shown accessibility can have a significant impact. Researchers from the

Harvard Business School determined that scandals on college campuses – such as hazing, sexual

assault or other crimes – can directly hurt colleges by causing a decline in applicants (Luca,

!

!

22!

Rooney, & Smith, 2016). The study showed that if a scandal on a college campus was covered

once by The New York Times, the university experienced a five percent drop in applicants. A

scandal covered in-depth in a newspaper, referenced as longer than a two-page article in this

study, led to a 10 percent drop (Luca, Rooney, & Smith, 2016). The upside of this for

universities is the media coverage serves as a watchdog of the campus, and incidents of scandal

are less likely to happen the following year (2016). Ole Miss, not included in this study, seems to

be an exception to this. Several incidents that can be defined as “scandalous” (i.e. Meredith

noose incident, election night incident) have occurred on campus the last four years, yet the

enrollment continues to grow to the highest it has ever been in school history.

BP: A Study in Strategic Framing

In 2012, a study was conducted to analyze the strategic framing of the BP Deepwater

Horizon oil spill of 2010 in the Gulf of Mexico. While most studies of framing focus on the

journalistic aspect, this was incorporates public relations in a crisis, which is relevant to this

study, as these controversial racial incidents at Ole Miss have resulted in crises from a PR

standpoint. Incidents of crisis threaten an organization’s goals and reputation (Schultz, et al.,

2012). The BP oil spill led to a large amount of media coverage. In this study of associative

frames, the researchers consider the message and how the message is presented, but also the

actors in the messages, which include BP, political actors, protestors, and issues, like the cause,

consequence and solution of the spill (Schultz, et al., 2012). Schultz discovered through a content

analysis that, in some cases, the agenda of a press release in somewhat present in news coverage

(2012). For example, BP focused more on the spill and solutions and little to the cause. This

tended to be reflected in coverage, meaning solutions and the spill itself were reported more than

!

!

23!

the cause, or absence thereof when the company was still investigating (2012). The result of

coverage focuses little on causes and placing more attention on the actors, such as BP and

President Barack Obama, essentially allowed BP to frame this devastating crisis in such a way

that they avoided responsibility, at least from the news media. This strategic framing allowed BP

to maintain control of its image to more of a degree than the company would have been able to if

the cause was consistently questioned (Schultz, et al., 2012).

Hypotheses

These theories allow several hypotheses to be presented regarding the University of

Mississippi and the coverage it receives.

H1: More than half of the news stories about Ole Miss that are not race-related will

mention racial incidents in the past.

The researcher creates this prediction based on association. Since the general public often

associates the university with racial incidents, the majority of newspaper stories likely mention a

racial incident at Ole Miss when the main topic of the story is about another subject.

H2: University response will be referenced in stories that are race-related or controversial

incidents more often than when compared with non-controversial incidents. In the BP study, the

company avoids responsibility by focusing on a solution. However, when it comes to Ole Miss,

reporters want immediate responses as to what is being implemented from a university

standpoint to solve this problem. From this, the researcher predicts journalists cite the university

response in their story, even if it is listed as “no comment.”

H3: Negative stories will have photos that contain tighter, close-up shots more than wider

shots.

!

!

24!

Because tighter shots focus on one person or convey more emotion, the researcher

predicts tighter shots are used more often in negative stories to inflict an emotional response

from the reader

H4: The region of the state where the paper is located also has an influence on tone of the

story. Reporters in the northern region of the state are likely to cover Ole Miss more favorably

than newspaper reporters in Jackson (central region) or along the coastal region.

H5: More controversial stories about Ole Miss are published in Mississippi newspapers

than positive, non-controversial stories.

Eppes said in his experience leading communications, Ole Miss gets more negative

coverage than positive coverage (2016).

H6: More than half of controversial articles mention The Daily Mississippian as an

original source of the story.

Eppes said the negative coverage state-wide and nationally was a result of the aggressive

daily student newspaper on campus, which most other universities do not have. The Daily

Mississippian is regarded as a professional publication, as stories and photos are picked up by

other media organizations with some frequency.

H7: Stories about racial issues on the Ole Miss campus will have more than one photo.

Negative stories draw more attention, engagement and opinion from readers. Therefore,

newspapers are likely to provide more photos with these types of stories to keep the audience

engaged.

H8: Most articles dealing with controversial events will not distinguish between outside

protestors and university students.

!

!

25!

When reporters and editors are unclear about the information presented, it leads the

public to believe students are behaving in a particular way as representatives of the university,

rather than those unaffiliated with Ole Miss.

!

!

!

26!

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

For the purpose of this study, the information sought is how Ole Miss is presented in

Mississippi newspapers and why that news coverage is organized and presented the way that it

is. The most effective way to gather this information is through a content analysis of newspaper

coverage in Mississippi.

Method

To properly analyze content based on this subject, the researcher examined newspaper

articles over the last four years that covered race-related incidents as well as non-race news

issues at the University of Mississippi. The choice of this date range was not accidental. In

October 2012, the university celebrated the enrollment of James Meredith 50 years prior. Shortly

after on November 6, 2012, following the re-election of President Barack Obama, an incident

involving student protests led to heated arguments involving racial slurs and sparked racial

tension among students. In February 2014, three fraternity members placed a noose around the

statue of James Meredith. In October 2015, rallies and protests were held on campus regarding

the state flag of Mississippi. In March 2016, the university began placing discussing the

placement of plaques near existing Confederate symbols on campus. Interspersed with these

racial incidents during this time period were also controversial topics, including the non-renewal

of the employment contract for Chancellor Dan Jones in March 2015 as well as numerous

incidents of student misconduct.

!

!

27!

These articles came from both daily and weekly publications throughout the state of

Mississippi. The sample frame from which the articles were chosen is the Cision, formally

known as Vocus, public relations software database (2016).

The content within the articles that was analyzed included the headline, accompanying

photo, tone of the story and topic covered, as well as numerous other variables. A full list of

variables can be found on the code sheet (Appendix A). The code sheet was used as a guideline

to record the variety of data in the articles into a numerical form so the information can be

analyzed in a statistical software program.

Procedure

The procedure for content analysis began by searching within Cision from the date range

October 1, 2012, to May 31, 2016, with the terms “Ole Miss” and “University of Mississippi,”

which yielded 11,843 results (2016). By excluding mentions of athletics, duplicate wire stories

and stories that only mention the university as part of a biography, but not in an anecdotal

context, the results were narrowed to 2,007 articles, seen below in Figure 3, and organized

primarily in order of date.

Figure 3.

Vocus Listing Screen

!

!

28!

Using systematic sampling, the researcher chose every fifth article from the sample

frame. One issue encountered when choosing the sample was that some older articles were

unable to found in their entirety. When this happened, the next available article was chosen. For

example, if number 100 could not be found, 101 to 104 were searched until a news article was

found. However, while using systematic sampling, some articles labeled to be from, for example,

The Oxford Eagle, resulted in the publication of a verbatim press release from the University

Public Relations Department. A university press release was completely unrecognizable, as seen

in Figure 4, until the text for the story was searched for using Google.

Figure 4.

Vocus Article List

These were left in the sample to measure the percentage of this occurrence and what type

of story in which this happened. This method resulted in a final sample of 401 articles. The news

articles were not readily available from the Cision system. Therefore, the researcher performed

internet searches for each article in order to find the story. In some instances, searching the title,

author and newspaper title did this. In other cases, a Google search of the abstract text of the

story, listed near the bottom of Figure 3, produced the story result.

!

!

29!

Prior to coding, the primary researcher conducted a training session with an additional

coder to ensure the definitions of the criteria were clear and a discussion was held to determine

the definition of tone or slant of the story and headline. In many cases, the tone or slant was

neutral and provided only facts. Though the tone was neutral, the story or headline could still

have reflected negatively on the Ole Miss. This led to the creation of an additional column to

include a variable that describes how the tone or slant reflects on the university.

The headlines were analyzed for positive, neutral or negative tone, terminology,

publication, and how they mention the university and reflection on the university (Appendix A).

The body of the articles is reviewed for tone, sources quoted or paraphrased, mentions of racial

incidents and which incident was identified. The photos that accompanied the articles are

analyzed as well. Questions to be asked in reviewing the photos included: how many people are

shown in the photo? Was it a tight or a wide shot? Does the photo contain symbols? and Does

the photo match the headline and body of the story (Appendix A)? In testing three variables of

headline tone, story tone, and reflection of the story on Ole Miss for inter-coder reliability

between the primary researcher and additional coder, Krippendorf’s alpha was .89, .65 and .83,

respectively.

Defining Criteria

In coding each portion of the news story, there are clear operational definitions for the

criteria. For publication type, newspaper is defined as a traditional publication printed daily or

weekly in the state of Mississippi. Wire is defined as a story originating, for these purposes, from

the Associated Press and printed in a Mississippi newspaper. A University Relations publication

!

!

30!

is defined as a news release distributed from the public relations department and appears in its

original form in a Mississippi newspaper.

A news story is one that is defined as a breaking news article or a first or second day

story of an event or announcement, while a follow-up story is one that continues coverage of an

ongoing event. An op-ed piece is an editorial, usually written by an editor or an executive board

of a publication offering a commentary on a subject. Finally, a feature or analysis is a story not

written in inverted-pyramid style that adds an in-depth commentary on an ongoing story or

profiles an individual or event.

The state of Mississippi can be broken into five regions when determining location of a

publication: the Gulf Coast, which includes Harrison, Hancock and Jackson counties; Southern

Mississippi which extends north of the Coast to Jackson and includes McComb and Natchez;

Central Mississippi, which includes Jackson and extends east to Meridian and North to

Columbus and the surrounding areas; Mississippi Delta in the western portion of Mississippi

which encompasses the areas of Clarksdale and Cleveland and extends south to Vicksburg; and

North Mississippi, which is the area above Winona that extends east to Tupelo and north to

Corinth.

To determine sources cited in an article, university administration is defined as senior

leadership, such as chancellor, vice-chancellors and department directors. Mississippi legislators

are categorized as the governor and his staff, state and U.S. House and Senate members as well

as city leaders, including mayors, city councils and boards of aldermen. University faculty and

staff includes department deans, professors and any staff employee at Ole Miss. Athletics staff

members include the athletics director, coaches and sports information directors. Mississippi

!

!

31!

residents and non-Mississippi residents are defined as community members not affiliated with

the university.

If the information was not applicable to a story, the criteria were left blank. For example,

it would be erroneous to answer that the noose incident was not mentioned if it had not happened

yet; therefore for all stories published prior to February 15, 2014, that information would not be

applicable. The same thought process went behind the question “were protestors sourced in the

story.” If the story did not involve a mention of a protest, this question was not applicable.

All coded information was added to the statistical data analysis software program JMP

(Version 12).

!

!

32!

CHAPTER 4

RESULTS

Several findings emerged . Of the 402 articles, the majority of news articles, 294 (73%),

were from newspaper publications. However, 78 (19%) stories were published in Mississippi

newspapers, yet originated from a wire service. The remaining 30 (8%) of stories published in a

Mississippi newspaper were verbatim news releases distributed by the University Relations

Department at Ole Miss. Through the Vocus system, Memphis news media was manually added,

and the original search results lists included stories from the WMC-TV website. However, due to

an unknown error, articles from The Commerical Appeal did not appear in the search results list

and therefore could not be sampled.

A large majority of the coverage throughout the last four years, understandably, came

from The Daily Mississippian. The on-campus publication was responsible for 92 (23%) stories

in the sample. The Associated Press produced 79 (20%) of those stories, followed by The

Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal with 56 (14%) stories, The Clarion-Ledger with 48 (12%)

stories, The Oxford Eagle with 43 (11%) stories, and the Mississippi Business Journal with 20

(5%) stories. The remainder of the sample included stories from the Chickasaw Journal, the

Clinton News, The Commercial Dispatch, The Daily Corinthian, The Greenwood

Commonwealth, The Hattiesburg American, Jackson Free Press, Mississippi Press, Mississippi

Today, Natchez Democrat, New Albany Gazette, Oxford Citizen, Sun Herald, The Local Voice,

The Neshoba Democrat, the Webster Progress Times and the Winston County Journal, all

making up the remaining 64 (15%) stories in the sample.

!

!

33!

News stories dominated the sample chosen at 238 (59%) stories. Feature stories

accounted for 90 (22%) stories in the sample and follow-up news accounted for 32 (9%)

stories, while 42 (10%) stories were editorial articles. Additionally, about 259 (64%) stories in

the sample included a photo or graphic of some kind, while 143 (36%) did not. No story in the

sample included a map of any kind.

Racial incidents made up a minority percentage of mentions in stories analyzed. The

1962 integration of James Meredith was mentioned 34 (8%) times. The removal of the school

mascot was mentioned 9 times (2%). Of the 393 stories in the sample written on or following

the election night incident on November 6, 2012, 10 (3%) mentioned the incident and 383

(97%) did not. Of the 295 samples articles written after a noose was placed on the James

Meredith statue on February 15, 2014, only 21 (7%) mentioned the incident and 274 (93%) did

not. Of the 95 articles in the sample published on or after the date of the student rally and KKK

counter protest involving the state flag on October 16, 2015, 5 (5%) mentioned the rally and 90

(95%) did not. Of the 95 articles written following the vote by the Associated Student Body

October 20, 2015 and Faculty Senate October 22, 2015 to remove the state flag from campus,

11 (12%) mentioned the vote and 84 (88%) did not. Finally, of the 80 stories in the sample

written after October 26, 2015 when the state flag was removed from campus, only 9 (11%)

mentioned the action, while 71 (89%) did not

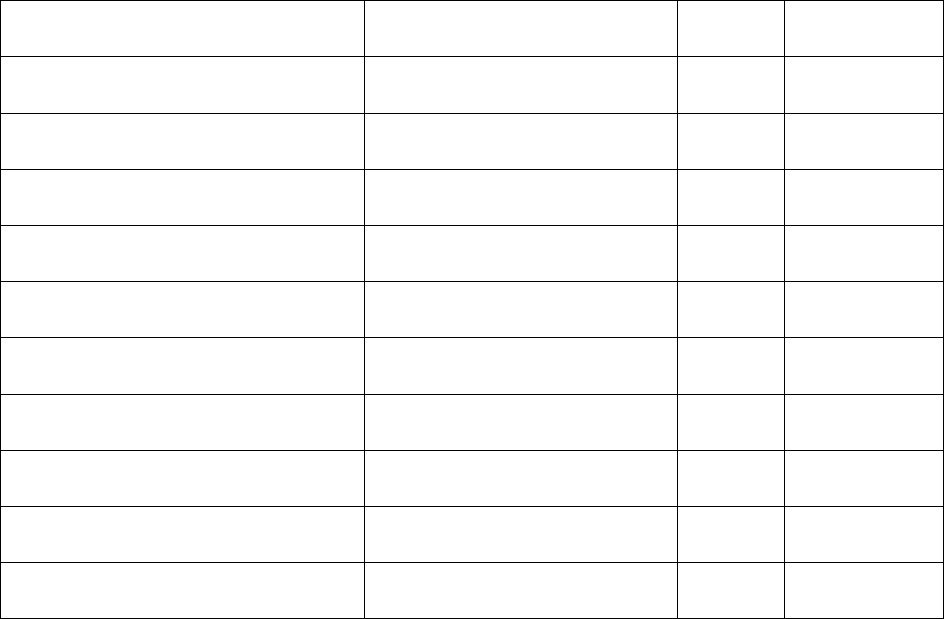

Other descriptive statistics can be found in more detail on the following page in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

Variable

Level

N

%

Publication Type

Newspaper

294

73

!

!

34!

Wire

78

19

University Relations

30

8

Topic of Story

Racial Incident/State Flag

49

12

Student Misconduct

12

3

Professor/Staff/Alum

Recognition

52

13

Student Recognition

21

5

Research

25

6

Construction/Parking

29

7

Chancellor Job

48

12

Tuition

7

2

Donation/Funding

19

5

Education

58

14

Other

49

12

Events

23

6

UMMC

10

3

Type of Story

News

238

59

Editorial

42

10

Feature

90

22

Follow-up Story

32

9

!

!

35!

Location of Publication

North Mississippi

237

59

Mississippi Delta

1

.3

Central Mississippi

156

39

Southern Mississippi

3

.7

Gulf Coast

5

1

“UM” in Headline

Yes

254

63

No

148

37

Racial Incident in Headline

Yes

44

11

No

358

89

Photo or Graphic With Story

Yes

259

64

No

143

36

Of Stories with Photo, Type

Tight Shot

33

15

Medium Shot

126

56

Wide Shot

21

9

Head Shot of Source

30

13

Head Shot of Author

17

7

Tone of Headline

Positive

106

26

Negative

38

10

!

!

36!

Neutral

255

63

Mixed

3

<1

Reflection of Headline on UM

Positive

165

41

Negative

61

15

Neutral

163

41

Mixed

13

3

First Paragraph Mentions Racial

Incident

Yes

46

11

No

356

89

1962 Integration Mentioned

Yes

34

8

No

368

92

Removal of Mascot Mentioned

Yes

9

2

No

393

98

Election Night Incident

Mentioned

Yes

10

3

No

383

97

!

!

37!

Noose Incident Mentioned

Yes

21

7

No

274

93

Flag Rally/KKK Protest

Mentioned

Yes

5

5

No

90

95

ASB/Faculty Senate Vote

Mentioned

Yes

11

12

No

84

88

State Flag Removal Mention

Yes

9

11

No

71

89

Sources Mentioned

University Administration

137

34

Mississippi Legislators

27

7

University Faculty and Staff

112

28

University Alumni

39

10

University Police

8

2

Athletics Staff

7

2

University Spokesperson

33

8

Students

92

23

Anonymous Sources

4

1

!

!

38!

Other Sources

163

41

Tone of the Story

Positive

218

54

Negative

50

12

Neutral

107

27

Mixed

27

7

Reflection of Story on UM

Positive

244

61

Negative

63

15

Neutral

52

13

Mixed

43

11

Through the JMP data analysis software, the hypotheses concerning news framing of

Ole Miss were tested.

H1: More than half of the news stories about Ole Miss that are not race-related will

mention racial incidents in the past. Word did not find any entries for your table of

contents.

Of 353 articles that did not deal with race, only 16 (4%) of them mentioned a race-

related incident. χ

2

(1) = 161.3, p < .001. More than half of news stories about Ole Miss that

were not race-related also did not mention racial incidents in the past, likely because journalists

chose not to frame these stories by included irrelevant facts a majority of the time. This

hypothesis was not supported.

!

!

39!

H2: University response will be referenced in stories that are race-related, such as

coverage of the student tying the noose on the Meredith statue, or controversial incidents, such

as the job status of former Chancellor Dan Jones, more often than when compared with non-

controversial incidents.

In the sample, 229 news stories mentioned a response from either university

administration, faculty or spokesperson by way of quotation or paraphrased comment. Only 55

(14 %) of those were controversial and 174 (43%) were non-controversial, χ

2

(1) = 2.57, p < .11.

This result is likely due to the fact that gathering sources and responses for a positive or non-

controversial news story is a much quicker and easier process than if the topic is controversial,

as sources need time to gather their response before speaking to media. This hypothesis was not

supported.

H3: Stories that negatively reflect on the university will have photos that contain

tighter, close-up shots more than wider shots.

From the sample, 63 stories had a negative reflection on the university, but 39 (62%) of

those stories contained photos. Of the 39 stories, 34 (87%) contained a medium shot or tight

shot, including head-shots of sources and authors. Only 5 (13%) stories contained a wide shot.

The relationship was significant, χ

2

(1) = 24.19, p < .001, and this hypothesis is supported.

H4: The region of the state where the paper is located also has an influence on tone of

the story. Reporters in the northern region of the state are likely to cover Ole Miss more

favorably than newspaper reporters in Jackson (central region) or along the coastal region.

News stories from North Mississippi newspapers comprised 59% of the total sample.

From this region, there were 163 positive stories (69%), 27 neutral stories (11%), 26 mixed

reflection stories (11%) and 21 negative stories (9%). In the Delta region of the state, only one

!

!

40!

story was published from this sample, and it was positive (100%). Central Mississippi, which

includes Jackson and larger publications such as The Clarion-Ledger and The Associated Press,

resulted in a total of 156 stories from the sample. Positive stories accounted for 48% (75), while

26% (41) were negative, 15% (23) neutral and 11% (17) mixed. In Southern Mississippi, only

three stories were published and 2 (66%) were positive and 1 (33%) was negative. Five stories

were published on the Gulf Coast, 3 (60%) positive, 1 (20%) negative and 1 (20%) neutral. The

North Mississippi has the largest sample size and the largest positive reflection of coverage on

the university, χ

2

(12) = 29.89, p < .4304. Therefore, this hypothesis is not supported. It is

important to also note that Krippendorf’s Alpha for this variable was .65, so results are suspect.

H5: More controversial stories about Ole Miss are published in Mississippi newspapers

than positive, non-controversial stories.

Of the 402 stories analyzed, 109 (27%) dealt with controversial incidents including

race, the firing of former Chancellor Dan Jones and student misconduct and 293 (73%) dealt

with non-controversial topics such as research, professor and student recognition and

donations.

Based on this sample, Mississippi newspapers publish substantially more non-

controversial stories than controversial stories, χ

2

(1) = 87.4, p < .001. This surprising result is

likely due to readers sharing negative stories more often on social media and discussing them,

creating the appearance that more negative coverage exists. This hypothesis was not supported.

H6: More than half of controversial articles mention The Daily Mississippian as an

original source of the story.

!

!

41!

Of 109 controversial articles (27% of the sample), 26 stories (24%) either referenced

The Daily Mississippian or originated from the publication, meaning 83 (76%) did not

reference the student newspapers, χ

2

(1) = 31.34, p < .001.

Controversial stories tended not to reference The Daily Mississippian as an original

source. This is likely due to the fact that, because the entire coverage area of the student

publication is the university campus, a majority of stories written by them are positive. This

hypothesis was not supported.

H7: Stories about controversial issues on the Ole Miss campus will have photos, while

noncontroversial stories will not.

In the sample, 58 (14 %) stories were either the topic of a race-related incident or

mentioned race. Of those stories, 55 % included photos. However, 28 (48%) of the stories

included only one photo, two stories included two photos, one story had six accompanying

photos and one story had seven photos. A possible error in this data could have resulted in the

way the articles were retrieved through Internet searches. By searching in Google for older

articles, the format was sometimes compromised. There’s a possibility more photos or graphics

could have accompanied the photo, but were no longer available at the time of research.

Nonetheless, with a result of χ

2

(8) = 8.66, p < .371, there is no relationship and this hypothesis was

not supported.

H8: Most articles dealing with controversial events will not distinguish between outside

protestors and university students.

This variable was only applicable in two stories of the 402 where confusion between,

unaffiliated protestors or organizations and students were mentioned. In both instances (100%),

!

!

42!

the reporter made a clear distinction between outside protestors and students. For example, in a

story published in The Clarion-Ledger, this paragraph offers a clear distinction:

“Nonstudents identifying themselves with the International Keystone Knights — a Ku

Klux Klan affiliate — and the League of the South staged a counter rally, which led to heated

exchanges involving profanity between the two groups, NAACP members and other

students.This hypothesis is not supported” (Swayze, 2015).

CHAPTER 5

DISCUSSION

The idea for this study formed due to the internal perceptions the administration, staff,

alumni and students have regarding media coverage of University of Mississippi. However, this

study and its hypothesis revealed that notion is untrue, at least in the examination of newspapers

articles from October 2012 to May 2016. Negative or controversial coverage may be more

salient, but, from an overall standpoint, the coverage of Ole Miss is framed more positively than

negatively.

Theories

This study does not negate the fact that journalistic framing occurs in race-related stories

or any other stories involving Ole Miss. In fact, very few stories analyzed were neutral (16%) in

frame and the majority included either a positive, negative or mixed tone, meaning there was a

journalistic frame in one direction or other. The information reported and the manner in which is

!

!

43!

it presented likely has an impact on the reflection of the university and public perception.

Previous studies have shown an individual can interpret the same piece of information differently

solely by the way it is presented (Scheufele & Iyengar, 2011). Though it cannot be determined

from this study the manner in which a media consumer interpreted the information, we do know

that this frames serve as a packaging method for reporters to provide context and meaning for a

layperson, especially when a complex issue or event is involved (Qin, 2015).

Although racial incidents or mentions did not dominate the topics of coverage involving

Ole Miss, it did account for 14% of the sample. According to Trussler and Soroka (2014),

readers are more interested in controversial topics. While that information cannot be directly

determined by this study, it is still interesting to not that media coverage reflects society, but

society also reflects media coverage. And, as noted, when the media feature conflict in stories,

readers are often gained (Zaller, 1999).

One of the more interesting theories that did appear in the results of this study is the one

of salience as it relates to the agenda-setting portion of framing. While the study revealed that

education was the most covered topic by Mississippi newspaper reporters (58 stories, 14%), the

single most covered incident was that involving the firing of Chancellor Dan Jones. The majority

of stories were published in March and April 2015, but the ongoing saga made of 12% of the

sample with 48 stories. In previous studies, accessibility of a story or topic can have a significant

impact on changes (Luca, Rooney, & Smith, 2016). The heavy coverage of this topic resulted in

mostly positive reflections on Ole Miss, but overwhelming negative reflections on the governing

!

!

44!

board of Mississippi colleges and universities, the Institutions of Higher Learning. The more

salient the story, the more likely the public is to promote action. In this case, constant coverage

and the publishing of editorials could possibly have resulted in the rallies calling for the renewal

of his contract as well the decision of the IHL to offer Jones an extension, which he ultimately

declined. As stated in previous studies, the salience of a story can affect public perception and

value of the topic by the reader (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007).

This model of accessibility and magnitude of coverage ties into gatekeeping as well, as it

is the final call of the editor to decide how often a story of a certain topic is published. For

example, 49 stories (12%) from the sample were published in Mississippi newspapers that had a

topic of a racial incident at the university. The editors decides how many times those incidents

are covered and how many follow-up stories are published about a topic by assigning the story to

the reporter. Similarly, 48 stories (12%) were published about the chancellor controversy within

a span of just a few months. If editors feel a topic is of more importance to the reader, they are

likely to assign more stories involving that topic to a reporter. As stated earlier, salience of a

story can result in a different interpretation by the reader (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007).

Therefore, framing, frame-sending the concept of salience in agenda-setting and gatekeeping are

all theories closely related and not mutually exclusive.

While frame-sending is not the result in merely quoting a source (Bruggeman, 2014),

several journalists did use several of the same sources and similar remarks from this sample of

articles. Because frame sending is defined by sending out the intended message of the source in

coverage, one can conclude from this study that news publications did participate in frame-

sending when verbatim news releases from the university were printed in their publication or

website. This implies that, while uncommon, frame-sending does occur. In this study, frame-

!

!

45!

sending tends to occur when the story involves a positive reflection of Ole Miss, such as an

achievement.

In a time where news is gathered and reported and reported instantly by both

professionals and citizen journalists, the former definition of “news values” have become

blurred. What would have previously been deemed uninteresting or unimportant two decades ago

now has the potential to “go viral” on social media, and a small local story can easily spread to

tens of thousands of media consumers. The seven traditional news values journalists learn when

studying their trade include timeliness, impact, conflict, currency, human interest, prominence

and proximity (Curtis, 2014). In this study, news content seemed to be framed mostly based on

traditional news values. For example, coverage of the chancellor job story involved several

elements, including timeliness, impact, conflict and prominence. However, because of the of the

magnitude of coverage of this ongoing topic, one can conclude electronic media allows a story to

be framed by salience that it remains timely and impactful, as there is no limit on space or

recurring stories when it comes to posting on a publication’s website or social media page,

whereas when only a print publication existed, space was limited.

Because controversy falls under the news value of conflict, it was surprising to find the

majority of news coverage by Mississippi newspapers of Ole Miss involved non-controversial

topics. Based on the information in this study, journalists tended to frame the university in a