University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School

University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository

Articles Faculty Scholarship

2020

Expungement of Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study Expungement of Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study

J.J. Prescott

University of Michigan Law School

Sonja B. Starr

University of Michigan Law School

Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2165

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles

Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Law and Society

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Prescott, J.J. "Expungement of Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study." Sonja B. Starr, co-author.

Harv.

L. Rev

. 133, no. 8 (2020): 2460-555.

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law

School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of

University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact

mlaw[email protected].

2460

VOLUME 133 JUNE 2020 NUMBER 8

©

2020

by The Harvard Law Review Association

ARTICLE

EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

J.J. Prescott & Sonja B. Starr

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 2461

I. E

XPUNGEMENT

P

OLICIES

AND

R

ELATED

R

ESEARCH

................................................ 2468

A. The Economic and Legal Aftermath of a Criminal Conviction ................................ 2468

B. Sealing of Criminal Records: The Legal and Policy Landscape .............................. 2472

C. Research Questions and Existing Empirical Research on Expungement ............... 2476

D. Our Empirical Setting and Data ................................................................................. 2480

II. T

HE

U

PTAKE

G

AP

: W

HO

S

EEKS

AND

R

ECEIVES

E

XPUNGEMENTS

?...................... 2486

A. Estimating Uptake Rates............................................................................................... 2488

B. Who Receives Expungements? ..................................................................................... 2493

C. What Explains the Uptake Gap? .................................................................................. 2501

1. Lack of Information .................................................................................................. 2502

2. Administrative Hassle and Time Constraints ........................................................ 2502

3. Fees and Costs ............................................................................................................ 2504

4. Distrust and Fear of the Criminal Justice System ............................................... 2504

5. Lack of Access to Counsel ......................................................................................... 2505

6. Insufficient Motivation to Pursue Expungement .................................................. 2506

III. R

ECIDIVISM

O

UTCOMES

................................................................................................... 2510

A. Recidivism Among Expungement Recipients ............................................................. 2511

B. Interpretation and Implications ................................................................................... 2518

IV. E

MPLOYMENT

O

UTCOMES

............................................................................................... 2523

A. Employment and Wage Trajectories for Expungement Recipients ........................... 2524

B. Interpretation: Expungement Effect, Motivation, or Mean Regression? ................ 2533

V. O

THER

O

BJECTIONS

TO

E

XPUNGEMENT

L

AWS

.......................................................... 2543

A. General Deterrence......................................................................................................... 2544

B. Statistical Discrimination or Stereotyping................................................................. 2548

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................................. 2550

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2461

EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

J.J. Prescott and Sonja B. Starr

∗

Laws permitting the expungement of criminal convictions are a key component of modern

criminal justice reform efforts and have been the subject of a recent upsurge in legislative

activity. This debate has been almost entirely devoid of evidence about the laws’ effects, in part

because the necessary data (such as sealed records themselves) have been unavailable. We were

able to obtain access to de-identified data that overcome that problem, and we use it to carry

out a comprehensive statewide study of expungement recipients and comparable nonrecipients

in Michigan. We offer three key sets of empirical findings. First, among those legally eligible

for expungement, just

6

.

5

% obtain it within five years of eligibility. Drawing on patterns in

our data as well as interviews with expungement lawyers, we point to reasons for this serious

“uptake gap.” Second, those who do obtain expungement have extremely low subsequent crime

rates, comparing favorably to the general population — a finding that defuses a common public-

safety objection to expungement laws. Third, those who obtain expungement experience a

sharp upturn in their wage and employment trajectories; on average, within one year, wages go

up by over

22

% versus the pre-expungement trajectory, an effect mostly driven by unemployed

people finding jobs and minimally employed people finding steadier or higher-paying work.

INTRODUCTION

oday, somewhere between 19 and 24 million Americans have felony

conviction records,

1

and an unknown — but presumably much

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

∗

Henry King Ransom Professor of Law and Henry M. Butzel Professor of Law, respectively,

and Co-Directors of the Empirical Legal Studies Center, University of Michigan Law School. The

authors gratefully acknowledge the generous financial support of the National Science Foundation

(Award No. SES 1023737) and the assistance of several Michigan state agencies in obtaining data:

the State Police; the Workforce Development Agency; the Unemployment Insurance Agency; the

Department of Technology, Management and Budget; and the State Court Administrative Office.

We are also grateful to Miriam Aukerman, Jeff Morenoff, and David Harding for early advising, to

conference and workshop participants at the NBER Summer Institute, Harvard Law School, the

University of Michigan, the Center for American Progress, and the Michigan District Judges

Association for helpful feedback, to colleagues at Michigan and elsewhere for fruitful discussions,

and to all the experts whose interviews and emails are cited herein for sharing their insights. We

are indebted to Margaret Love and David Schlussel for their advice and support on this project,

and we thank the many research assistants who contributed during the project’s ten-year history,

including Patrick Balke, Grady Bridges, Gabriella D’Agostini, David Do, Haley Dutch, Jonathan

Edelman, Nathaniel Givens, Seth Kingery, Rami Krispin, Elena Malik, German Marquez Alcala,

Charlotte McEwen, Chris Pryby, Chelsea Rinnig, Zehra Siddiqui, and especially Simmon Kim for

his extensive efforts.

1

See The Economic Impacts of the

2020

Census and Business Uses of Federal Data: Hear-

ing Before the J. Econ. Comm., 116th Cong. 12 (2019) (statement of Nicholas Eberstadt, Henry

Wendt Chair in Political Economy, American Enterprise Institute); Sarah K.S. Shannon et al.,

The Growth, Scope, and Spatial Distribution of People with Felony Records in the United

States,

1948

–

2010

, 54 D

EMOGRAPHY

1795, 1806 (2017). When arrests are added, 75 million

Americans — a third of adults — have criminal records. See FBI, N

OVEMBER

2018 N

EXT

T

2462 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

larger — number have misdemeanor conviction records.

2

In recent

years, policymakers, civil rights advocates, and scholars have paid in-

creasing attention to the substantial barriers to employment,

3

housing,

4

and social integration

5

that these records can pose, not to mention the

hundreds of collateral legal consequences that typically flow from crim-

inal convictions, such as restrictions on public-benefits eligibility and

occupational licensing.

6

Taken together, these hurdles have been de-

scribed as amounting to a “new civil death,”

7

and on a collective scale,

this phenomenon magnifies racial disparities in employment and other

outcomes due to disparities in the distribution of criminal records. For

all these reasons, a core part of this century’s emergent criminal justice

reform movement has been a search for effective policy levers to miti-

gate the reentry barriers faced by people with criminal records. This

effort is picking up steam in virtually every corner of the country, with two-

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

G

ENERATION

I

DENTIFICATION

(NGI) S

YSTEM

F

ACT

S

HEET

1 (2018), https://www.fbi.gov/file-

repository/ngi-monthly-fact-sheet/view [https://perma.cc/5KQJ-UBL5].

2

No studies currently document the total number of Americans with misdemeanor convictions.

However, statistics collected between 2008 and 2016 indicate that misdemeanors routinely make up

over 70% of a state’s criminal caseload. Megan Stevenson & Sandra Mayson, The Scale of Misde-

meanor Justice, 98 B.U.

L. R

EV

. 731, 746 n.81 (2018).

3

See, e.g., N

AN

A

STONE

, M

ICHAEL

K

ATZ

& J

ULIA

G

ELATT

, U

RBAN

I

NST

., I

NNOVATIONS

IN

NYC H

EALTH

& H

UMAN

S

ERVICES

P

OLICY

: Y

OUNG

M

EN

’

S

I

NITIATIVE

6 (2014),

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/32651/413057-Innovations-in-NYC-Health-

and-Human-Services-Policy-Young-s-Men-s-Initiative.PDF [https://perma.cc/V954-Y23W]; Fact

Sheet: President Obama Announces New Actions to Promote Rehabilitation and Reintegration for

the Formerly-Incarcerated, O

BAMA

W

HITE

H

OUSE

A

RCHIVES

(Nov. 2, 2015),

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/11/02/fact-sheet-president-obama-

announces-new-actions-promote-rehabilitation [https://perma.cc/F89L-69K4].

4

See, e.g., A

NNE

M

ORRISON

P

IEHL

, H

AMILTON

P

ROJECT

, P

UTTING

T

IME

L

IMITS

ON

THE

P

UNITIVENESS

OF

THE

C

RIMINAL

J

USTICE

S

YSTEM

9 (2016), https://www.

hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/reducing_punitiveness_piehl_policymemo.pdf [https://perma.cc/

XQ5P-DWKF];

M

ARIE

C

LAIRE

T

RAN

-L

EUNG

, S

ARGENT

S

HRIVER

N

AT

’

L

C

TR

.

ON

P

OVERTY

L

AW

, W

HEN

D

ISCRETION

M

EANS

D

ENIAL

: A N

ATIONAL

P

ERSPECTIVE

ON

C

RIMINAL

R

ECORDS

B

ARRIERS

TO

F

EDERALLY

S

UBSIDIZED

H

OUSING

1 (2015), https://www.

povertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/WDMD-final.pdf [https://perma.cc/GV7K-GSEV].

5

See, e.g., Amy L. Solomon, In Search of a Job: Criminal Records as Barriers to Employment, NIJ

J., June 2012, at 42, 44, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/238488.pdf [https://perma.cc/2T6Y-TK9F];

Letter from Eric H. Holder, Jr., U.S. Attorney Gen., to State Attorneys Gen. (Apr. 18, 2011) (available

at https://web.archive.org/web/20120227180437/http://www.nationalreentryresourcecenter.org/

documents/0000/1088/Reentry_Council_AG_Letter.pdf).

6

See M

ARGARET

C

OLGATE

L

OVE

ET

AL

., C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

OF

C

RIMINAL

C

ONVICTIONS

: L

AW

, P

OLICY

AND

P

RACTICE

§§ 1:12, 2:8, 2:75, 6:16 (2018); see also Gabriel J.

Chin, The New Civil Death: Rethinking Punishment in the Era of Mass Conviction, 160 U.

P

A

. L.

R

EV

. 1789, 1811–14 (2012); Alexandra Natapoff, Misdemeanor Decriminalization, 68 V

AND

. L.

R

EV

. 1055, 1089–94 (2015). See generally National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Con-

viction, CSG

J

UST

. C

TR

.

, https://niccc.csgjusticecenter.org [https://perma.cc/N79E-5PFN] [herein-

after CSG Inventory].

7

Chin, supra note 6, at 1790; see also J

AMES

B. J

ACOBS

, T

HE

E

TERNAL

C

RIMINAL

R

ECORD

4 (2015) (observing that criminal records are “for life” and “there is no statute of limitations”).

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2463

thirds of U.S. states adopting one or more such policies in 2018,

8

and forty-

three states, the federal government, and the District of Columbia passing

an “extraordinary 153 laws” aimed at this problem in 2019.

9

Perhaps the policy levers with the greatest theoretical potential to

improve reentry outcomes are laws that allow criminal conviction rec-

ords to be wholly expunged or, at least, sealed from public view. We

will refer to such laws collectively as “expungement laws,” and this pro-

cess as “expungement,” although such shorthand elides some differ-

ences.

10

Expungement offers the possibility of sweeping aside a wide

range of legal and socioeconomic consequences at once; these laws typ-

ically authorize individuals to apply for jobs, housing, schools, and ben-

efits as though their convictions did not exist.

Today, a substantial majority of U.S. states provide some form of

expungement procedure for otherwise-valid adult convictions.

11

Many

states have recently adopted, or are presently considering, new expunge-

ment laws or expansions to existing ones.

12

For example, New Mexico,

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

8

A major report by the Collateral Consequences Resource Center documents the “extraordi-

nary number of laws passed [by thirty-two states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin

Islands] in 2018 aimed at reducing barriers to successful reintegration for individuals with a crimi-

nal record,” calling it the “most productive legislative year since a wave of ‘fair chance’ reforms

began in 2013.” Press Release, Collateral Consequences Resource Center, New Report on 2018 Fair

Chance and Expungement Reforms (Updated)

(Jan. 10, 2019), https://ccresourcecenter.

org/2019/01/10/press-release-new-report-on-2018-fair-chance-and-expungement-reforms/#more-18004

[https://perma.cc/4AGU-6CH5]; see also

M

ARGARET

L

OVE

& D

AV ID

S

CHLUSSEL

, C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

R

ES

.

C

TR

., R

EDUCING

B

ARRIERS

TO

R

EINTEGRATION

: F

AIR

C

HANCE

AND

E

XPUNGEMENT

R

EFORMS

IN

2018, at 2–3 (2019), https://ccresourcecenter.org/wp-content/

uploads/2019/01/Fair-chance-and-expungement-reforms-in-2018-CCRC-Jan-2019.pdf

[https://perma.cc/9QA5-9PMM].

9

M

ARGARET

L

OVE

& D

AVI D

S

CHLUSSEL

, C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

R

ES

.

C

TR

.,

P

ATHWAYS

TO

R

EINTEGRATION

: C

RIMINAL

R

ECORD

R

EFORMS

IN

2019, at 1–2 (2020),

http://ccresourcecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Pathways-to-Reintegration_Criminal-

Record-Reforms-in-2019.pdf [https://perma.cc/35MG-734Y].

10

The details vary by jurisdiction, and many advocates use various terms such as “expungement,”

“sealing,” and “set-aside” interchangeably. Typically, a true “expungement” legally eliminates the record

from the state’s perspective. “Sealing” maintains the record for some limited state purposes (for exam-

ple, law enforcement investigations of future crimes) but insulates it from public view.

11

Two useful online resources contain periodically updated collections of these laws; at our last

check, we found slightly different information at the two sites, but both include close to forty states

with some form of expungement law for valid, nonpardoned, and nonvacated adult criminal con-

victions. See

50

-State Comparison: Expungement, Sealing & Other Record Relief, C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

R

ESOURCE

C

TR

., https://ccresourcecenter.org/state-restoration-profiles/50-state-

comparisonjudicial-expungement-sealing-and-set-aside [https://perma.cc/JA4B-2HUD] [hereinafter

CCRC State Survey]; States,

C

LEAN

S

LATE

C

LEARINGHOUSE

, https://cleanslateclearinghouse.

org/compare-states [https://perma.cc/94VU-UPRD].

12

For example, in 2018 alone, twenty states passed twenty-nine bills expanding expungement

eligibility. L

OVE

& S

CHLUSSEL

, supra note 8, at 2. In 2019, there was still further activity, with “31

states and D.C. enact[ing] no fewer than 67 bills creating, expanding, or streamlining record relief,” and

twenty states “authoriz[ing] diversion programs that produce non-conviction dispositions newly eligible

for record-clearing under existing law.” L

OVE

& S

CHLUSSEL

, supra note 9, at 10. Fifteen of these

states took “incremental” steps, and five made more dramatic eligibility-enhancing changes. Id. at

2464 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

for the first time, passed a law in 2019 to make a petition-based expunge-

ment process available,

13

and it is not alone.

14

In 2018, Pennsylvania be-

came the first state to adopt a sweeping program of automatic expunge-

ment of adult criminal convictions — specifically, nonviolent

misdemeanors after ten crime-free years.

15

In 2019, Utah, New Jersey,

and California also enacted automatic expungement laws,

16

which are

more ambitious in some ways. For example, Utah has only a five-year

waiting period in some instances,

17

and California’s recent legislation

has even shorter waiting periods (none in some cases) and encompasses

minor felonies as well as misdemeanors, although the law only operates

prospectively.

18

The New Jersey law extends automatic expungement

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

10–17. We note that many of the new or amended laws have features that roughly parallel the

Michigan law we study, and therefore, our work can be useful in predicting the likely consequences

of these reforms.

13

Danny W. Jarrett et al., New Mexico Adopts Ban-the-Box, Expungement Laws,

J

ACKSON

L

EWIS

(Apr. 22, 2019), https://www.jacksonlewis.com/publication/new-mexico-adopts-

ban-box-expungement-laws [https://perma.cc/96SE-ABY9]. The expungement law went into effect

on January 1, 2020. Id.

14

See L

OVE

& S

CHLUSSEL

, supra note 9, at 14 (“New Mexico, North Dakota, Delaware, West

Virginia, and Colorado made particularly dramatic changes to their petition-based systems to ex-

tend eligibility for relief to a range of non-conviction and conviction records. None of the first four

states had previously authorized relief for felony-level offenses, and Colorado had authorized seal-

ing only for drug convictions. The comprehensive schemes enacted by North Dakota and New

Mexico are noteworthy as the first laws in those states to authorize sealing of adult criminal records.

Both states extend relief to most felonies, but they also require the applicant to pay a filing fee and

make the case for relief at a court hearing. (North Dakota courts may dispense with the hearing if

the prosecutor agrees.)”).

15

Faith Karimi, Pennsylvania Is Sealing

30

Million Criminal Records as Part of Clean Slate

Law, CNN (June 28, 2019, 4:46 AM), https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/28/us/pennsylvania-clean-slate-

law-trnd/index.html [https://perma.cc/5XVN-RFFE]. Felonies, as well as violent and certain other

serious misdemeanors, are ineligible for automatic expungement. 18 P

A

. C

ONS

. S

TAT

. § 9122.3(a),

(b) (2019). But such offenses are still potentially eligible for expungement by petition. Id. § 9122.3(c).

16

Jessica Miller, Utah Lawmakers Pass the “Clean Slate” Bill to Automatically Clear the Criminal

Records of People Who Earn an Expungement, S

ALT

L

AKE

T

RIB

., (Mar. 16, 2019)

https://www.sltrib.com/news/2019/03/14/utah-lawmakers-pass-clean [https://perma.cc/HVV7-VFE6];

Press Release, State of N.J., Governor Murphy Signs Major Criminal Justice Reform Legislation (Dec.

18, 2019), https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562019/approved/20191218a.shtml [https://

perma.cc/V5YE-RK8F]; CCRC Staff, California Becomes Third State to Adopt “Clean Slate” Record

Relief, C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

R

ESOURCE

C

TR

. (Oct. 10, 2019), http://ccresourcecenter.

org/2019/10/10/california-becomes-third-state-to-adopt-clean-slate-record-relief

[https://perma.cc/8U5C-XSRJ].

17

U

TAH

C

ODE

A

NN

. § 77-40-102(5)(a)(iii)(A) (LexisNexis 2020). The waiting periods are six

years for more serious misdemeanors and seven years for certain drug crimes. Id. §§ 77-40-

102(5)(a)(iii)(B)–(C).

18

C

AL

. P

ENAL

C

ODE

§ 1203.425(a)(2)(E) (West 2020) (stating that automatic relief is available

only for convictions “on or after January 1, 2021,” and only for misdemeanors, infractions, and

offenses resulting in a sentence of probation). For all crimes resulting in probation sentences (even

felonies), relief is automatic after completing probation, with no further waiting period. Id.

§ 1203.425(a)(2)(E)(i). Automatic expungement is also available for all misdemeanors, even those

resulting in jail time; in that case the waiting period is one year. Id. § 1203.425(a)(2)(E)(ii).

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2465

to some felonies as well as misdemeanors, without limits as to the num-

ber of convictions expunged, after a ten-year period with no subsequent

convictions.

19

Other states may soon follow suit.

20

More typically, ex-

pungement laws require individuals to go through a judicial process to

apply for relief, usually giving judges the discretion to deny the petition.

Many states have stringent eligibility requirements as to crime type or

severity or the number of convictions on the individual’s record, and

many have waiting periods.

21

Despite the considerable legislative ferment and the excitement that

surrounds these “Clean Slate” initiatives in the civil rights and criminal

justice reform worlds, what has been missing from the debate is hard

evidence about the effects and true potential of conviction expungement

laws. Empirical studies in this area have been difficult to carry out.

Expunged criminal records are, obviously, not typically available to

study — and other relevant outcome data, such as wage information or

employment status, are also protected by privacy laws. While there are

many persuasive theoretical reasons to believe that expungement laws

will have large and important effects across many domains,

22

the dearth

of empirical evidence is a significant hindrance to reform and experi-

mentation. It leaves policymakers almost entirely in the dark.

In this Article, we present the results of an unprecedented statewide

study that overcomes existing limitations on research on expungement and

seeks to fill various policy-relevant gaps in our empirical knowledge. Pur-

suant to a data-sharing agreement with the State of Michigan, we were

able to obtain complete, de-identified criminal records from the

Michigan State Police (MSP) on all individuals who had received convic-

tion expungements (known as “set-asides” in Michigan) as of March 2014,

as well as full criminal history records for much larger comparison groups

of individuals with convictions that were not expunged. In addition, the

state matched these criminal histories with detailed wage and employment

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

19

Criminal History Record Information — Expungement, 2019 N.J. Sess. Laws Serv. 11–12

(West) (to be codified at N.J.

S

TAT

. A

NN

. § 2C:52–5.3). In the immediate term, this relief is petition

based, but a task force has been directed to develop an automated process. Id. at 12–14 (to be

codified at N.J.

S

TAT

. A

NN

. § 2C:52–5.4).

20

See, e.g., Expungement Bill Package Passes House with Overwhelming Bi-partisan Support, M

ICH

.

H

OUSE

D

EMOCRATS

(Nov. 22, 2019), https://housedems.com/article/expungement-bill-

package-passes-house-overwhelming-bi-partisan-support [https://perma.cc/2PWU-2ZVL]; Kelan Lyons,

Winfield to Swap Out Lamont’s Clean Slate Bill with a Broader Measure, CT

M

IRROR

(Feb. 26, 2020),

https://ctmirror.org/2020/02/26/winfield-to-swap-out-lamonts-clean-slate-bill-for-a-broader-measure

[https://perma.cc/2AX2-BMWZ].

21

See sources cited supra note 11; see also infra section I.B, pp. 2472–76 (describing this legal

landscape in more detail).

22

See, e.g., Brian M. Murray, Unstitching Scarlet Letters?: Prosecutorial Discretion and Ex-

pungement, 86 F

ORDHAM

L. R

EV

. 2821, 2824–26 (2018); Amy Myrick, Facing Your Criminal Rec-

ord: Expungement and the Collateral Problem of Wrongfully Represented Self, 47

L

AW

& S

OC

’

Y

R

EV

. 73, 74 (2013).

2466 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

data for the same individuals from the state’s unemployment insurance

program, sharing these data with us as well.

Michigan is an ideal setting in which to study expungement laws: it

is a large, diverse state with criminal justice challenges typical of the

United States today. Moreover, the version of Michigan’s expungement

law we study has many of the common features of a petition-based

record-clearing law, and it applies to a diverse set of records (e.g., vio-

lent/nonviolent, misdemeanor/felony), carries a fairly short waiting pe-

riod, has relatively straightforward eligibility rules, and went untouched

for more than two decades, allowing us to study results over time.

We use our unique data to investigate a number of interrelated em-

pirical questions, which can be grouped into three main areas of inquiry.

First, we examine the critical question of the “uptake rate”: the rate at

which those who are legally eligible for expungements actually receive

them.

23

We find that Michigan’s expungement uptake rate is discour-

agingly low; our best estimate is that only 6.5% of all eligible individuals

receive an expungement within five years of the date at which they first

qualify for one.

24

To better understand the uptake process, we examine

the characteristics of expungement recipients and their offenses and as-

sess whether some characteristics are predictive of uptake by eligible

individuals. We then use these data, plus interviews with Michigan ex-

pungement lawyers and advocates for people with criminal records, to

inform a discussion of why people might not apply for expungements

despite their potential benefits.

Second, we investigate expungement recipients’ subsequent criminal

offending.

25

We find very low rates of recidivism: just 7.1% of all expunge-

ment recipients are rearrested within five years of receiving their expunge-

ment (and only 2.6% are rearrested for violent offenses), while reconvic-

tion rates are even lower: 4.2% for any crime and only 0.6% for a violent

crime. Indeed, expungement recipients’ recidivism rates compare favor-

ably with those of the Michigan population as a whole.

26

We do not

claim that these low rates are necessarily because of expungements, al-

though there are several channels by which expungement receipt could

potentially contribute to lower recidivism risk. Another likely explana-

tion is that people who have limited criminal records and have gone at

least five years since their last conviction are simply very low risk to

begin with. This finding is consistent with the broader empirical liter-

ature on patterns of desistance from crime. Whatever the cause, the low

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

23

See infra Part II, pp. 2486–2510.

24

Although our data do not identify unsuccessful applicants, it is clear from follow-up inquiries with

the Michigan State Police that the low uptake rate can be primarily attributed to individuals’ failure to

apply, rather than to denials of applications by judges. See infra section II.C.6, pp. 2506–210.

25

See infra Part III, pp. 2510–23.

26

See infra p. 2514.

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2467

recidivism rates we observe help to defuse an otherwise potentially con-

vincing policy argument against expungement laws: that the public (in-

cluding employers and landlords) has a safety interest in knowing about

the prior records of those with whom they interact.

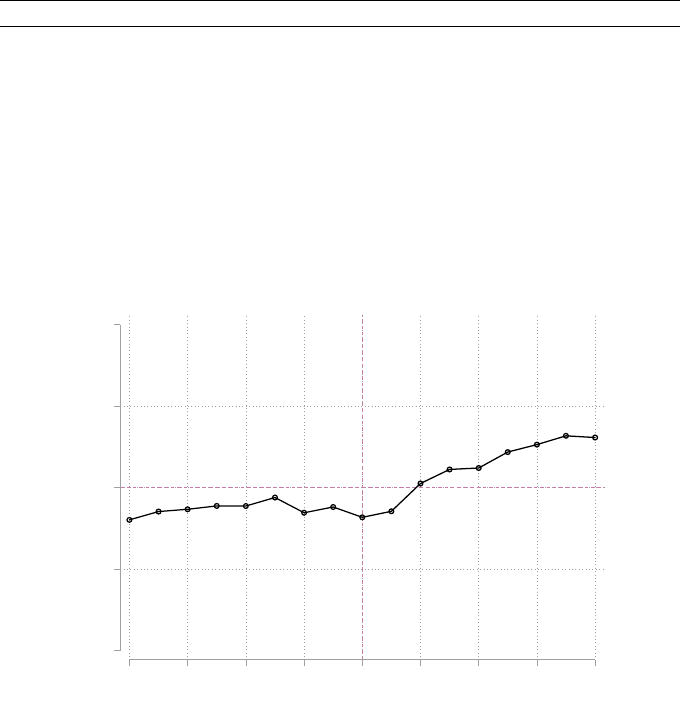

Third, we examine the employment consequences of criminal record

expungement.

27

After accounting for an individual’s prior employment

and wage history, as well as broader changes in the economy, we find

that expungement recipients experience considerable gains shortly after

receipt. Within one year, on average, an individual’s odds of being em-

ployed (earning any wages at all) increase by a factor of 1.13; their odds

of earning at least $100/week (a slightly more demanding employment

measure) increase by a factor of 1.23; and their reported quarterly wages

increase by a factor of 1.23 (and are sustained in subsequent years).

These results suggest that those with expunged records gain access to

more and better-paying jobs. To be sure, one has to be cautious about

drawing causal inferences here; it is very possible that some of the gains

come about because people choose to seek expungement at a time that

they are especially motivated to seek improvements in their economic

situation. Nonetheless, our data and other supporting evidence give us

some confidence that at least a large fraction of the improvement that

we observe stems from the clean record itself.

We provide background on expungement laws, existing relevant em-

pirical research, and our research setting (including our data and their

limitations) in Part I. We then present the three major components of

our work — our analyses of expungement uptake, the recidivism rates

among expungement recipients, and the relationship between expunge-

ment and subsequent employment outcomes — in Parts II, III, and IV,

respectively. In Part V, we respond to two potential objections to ex-

pungement, which might, if accurate, influence the policy takeaways of

our empirical results. In the Conclusion, we address policy implications

and consider future research possibilities.

Our findings tell a good news/bad news story: when expungement is

not automatic (and takes time, effort, and even money to apply), only a

very small share of the people eligible for relief actually apply for and

receive an expungement — but those who do experience clear improve-

ments in economic outcomes and pose little public-safety risk. Taken

together, these conclusions have a clear policy upshot: they support the

expansion of expungement availability, an easing of the procedural hur-

dles associated with seeking expungement, and, in particular, the emerg-

ing movement to make expungement occur automatically after a period

of time, rather than after an application process.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

27

See infra Part IV, pp. 2523–43.

2468 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

I.

E

XPUNGEMENT

P

OLICIES

AND

R

ELATED

R

ESEARCH

Several large bodies of scholarly research, as well as active policy

debates and commentary, inform and motivate our study. In section I.A,

we describe the many hurdles people with public criminal records face;

paring back these hurdles is the core policy motivation for expungement

laws and efforts to expand them. In section I.B, we add some further

detail to the Introduction’s description of the current legal and policy

landscape surrounding expungement. In section I.C, we discuss the very

limited empirical research that exists on expungement and identify the

key unanswered empirical questions that we seek to address. In section

I.D, we turn to our specific empirical setting, describing Michigan’s ex-

pungement law and the data that we use in our study.

A. The Economic and Legal Aftermath of a Criminal Conviction

The consequences of criminal convictions do not end when people

convicted of crimes complete their formal sentences. For many individ-

uals, punishments such as probation, fines, and even incarceration may

be dwarfed in importance by what comes next: exclusion from employ-

ment, obstacles to social integration, and a vast array of collateral legal

consequences that often last a lifetime.

28

A growing body of academic

research documents the scope, ubiquity, and size of these hurdles.

29

First, people with criminal records face serious employment barri-

ers — indeed, these barriers may exceed those facing any other disad-

vantaged group.

30

While many aspects of these individuals’ back-

grounds, as well as the interruptions to work and education experienced

by those who are incarcerated, may put them at greater risk of unem-

ployment than the general population,

31

the criminal record itself also

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

28

See Sarah B. Berson, Beyond the Sentence — Understanding Collateral Consequences, NIJ

J., Sept. 2013, at 25, 25 https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/241927.pdf [https://perma.cc/C2FM-

8GF3]; CSG Inventory, supra note 6; see also L

OVE

ET

AL

., supra note 6, §§ 1:11–1:12, 2:44.

29

See, e.g., P

EW

C

HARITABLE

T

RS

., C

OLLATERAL

C

OSTS

: I

NCARCERATION

’

S

E

FFECT

ON

E

CONOMIC

M

OBILITY

(2010), https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_

assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.pdf [https://perma.cc/B7XB-MCEN]; Anastasia Christman &

Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, Research Supports Fair Chance Policies, N

AT

’

L

E

MP

. L. P

ROJECT

(Aug. 1, 2016), https://www.nelp.org/publication/research-supports-fair-chance-policies [https://

perma.cc/V7GG-YQNT].

30

See Harry J. Holzer et al., Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Ra-

cial Hiring Practices of Employers, 49 J.L.

& E

CON

. 451, 471 (2006); Devah Pager, The Mark of a

Criminal Record, 108 A

M

. J. S

OC

. 937, 960 (2003).

31

D

EBBIE

M

UKAMAL

, U.S. D

EP

’

T

OF

L

ABOR

, F

ROM

H

ARD

T

IME

TO

F

ULL

T

IME

:

S

TRATEGIES

TO

H

ELP

M

OVE

E

X

-O

FFENDERS

FROM

W

ELFARE

TO

W

ORK

,

Part

III.B (2001),

https://hirenetwork.org/sites/default/files/From%20Hard%20Time%20to%20Full%20Time.pdf

[https://perma.cc/2XM8-H8KT]; A

MY

L. S

OLOMON

ET

AL

., U

RBAN

I

NST

., F

ROM

P

RISON

TO

W

ORK

: T

HE

E

MPLOYMENT

D

IMENSIONS

OF

P

RISONER

R

EENTRY

8–11 (2004),

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/58126/411097-From-Prison-to-Work.PDF

[https://perma.cc/6W2R-CFQS]; J

EREMY

T

RAVIS

ET

AL

., U

RBAN

I

NST

., F

ROM

P

RISON

TO

H

OME

:

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2469

seems to directly harm employment prospects.

32

Many employers report

that they take steps to avoid hiring individuals with records.

33

Their

motivations for doing so vary. A report prepared for the Department of

Labor has found that many employers are driven by “bias and stigma.”

34

Some believe that individuals with records cannot be trusted.

35

Others

fear a negligent-hiring lawsuit if an employee hired with a criminal rec-

ord commits a crime while on the job.

36

Experimental results confirm employers’ reluctance to hire individ-

uals with records. Devah Pager had matched pairs of testers, differing

only in criminal history, apply for a range of employment positions.

37

She found that applicants without records received more than twice as

many callbacks.

38

More recently, Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr sent

around 15,000 fictitious job applications paired by race to entry-level

jobs mainly in the restaurant and retail industries.

39

They found that

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

T

HE

D

IMENSIONS

AND

C

ONSEQUENCES

OF

P

RISONER

R

EENTRY

31–33 (2001), http://re-

search.urban.org/UploadedPDF/from_prison_to_home.pdf [https://perma.cc/K2Z6-RYGR].

32

C

HERRIE

B

UCKNOR

& A

LAN

B

ARBER

, C

TR

.

FOR

E

CON

. & P

OLICY

R

ESEARCH

, T

HE

P

RICE

W

E

P

AY

: E

CONOMIC

C

OSTS

OF

B

ARRIERS

TO

E

MPLOYMENT

FOR

F

ORMER

P

RISONERS

AND

P

EOPLE

C

ONVICTED

OF

F

ELONIES

10–13 (2016), http://cepr.net/images/

stories/reports/employment-prisoners-felonies-2016-06.pdf?v=5 [https://perma.cc/M58K-E5FE];

S

COTT

H. D

ECKER

ET

AL

., C

RIMINAL

S

TIGMA

, R

ACE

, G

ENDER

,

AND

E

MPLOYMENT

: A

N

E

XPANDED

A

SSESSMENT

OF

THE

C

ONSEQUENCES

OF

I

MPRISONMENT

FOR

E

MPLOYMENT

56 (2014), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/244756.pdf [https://perma.cc/M82H-3DHQ].

In a small study of expungement seekers in Chicago, “participants reported attempts to use face-to-

face contact with potential employers and landlords to convince them that, despite their criminal

records, they were trustworthy and dependable. However, participants with both extensive and

minor criminal record histories indicated that these attempts were ineffective.” Simone Ispa-Landa

& Charles E. Loeffler, Indefinite Punishment and the Criminal Record: Stigma Reports Among

Expungement-Seekers in Illinois, 54 C

RIMINOLOGY

387, 401 (2016) (internal citations omitted).

33

M

ICHELLE

N

ATIVIDAD

R

ODRIGUEZ

& M

AURICE

E

MSELLEM

, N

AT

’

L

E

MP

’

T

L

AW

P

ROJECT

, 65 M

ILLION

“N

EED

N

OT

A

PPLY

”: T

HE

C

ASE

FOR

R

EFORMING

C

RIMINAL

B

ACKGROUND

C

HECKS

FOR

E

MPLOYMENT

1 (2011), https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/

uploads/2015/03/65_Million_Need_Not_Apply.pdf [https://perma.cc/8YS6-F2SR]; Holzer et al.,

supra note 30, at 455; Sarah Esther Lageson et al., Legal Ambiguity in Managerial Assessments of

Criminal Records, 40 L

AW

& S

OC

. I

NQUIRY

175, 191 (2015).

34

M

UKAMAL

, supra note 31, at III.B.

35

See Harry J. Holzer, Collateral Costs: Effects of Incarceration on Employment and Earnings

Among Young Workers, in D

O

P

RISONS

M

AKE

U

S

S

AFER

? T

HE

B

ENEFITS

AND

C

OSTS

OF

THE

P

RISON

B

OOM

239, 248 (Steven Raphael & Michael A. Stoll eds., 2009).

36

L

OVE

ET

AL

., supra note 6, §§ 6:18–6:29; see also M

UKAMAL

, supra note 31, at IV.A.2; S

OC

’

Y

FOR

H

UMAN

R

ES

. M

GMT

. & C

HARLES

K

OCH

I

NST

., W

ORKERS

WITH

C

RIMINAL

R

ECORDS

5

(2018), https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/pages/second-

chances.aspx [https://perma.cc/JDQ8-T9ME]; Holzer, supra note 35, at 243.

37

Pager, supra note 30, at 946–48.

38

See id. at 958 fig.6.

39

Amanda Agan & Sonja Starr, Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A

Field Experiment, 133 Q.J.

E

CON

. 191, 192, 198 (2018) [hereinafter Agan & Starr, Ban the Box];

Amanda Agan & Sonja Starr, The Effect of Criminal Records on Access to Employment, 107 A

M

.

E

CON

. R

EV

. 560, 560–61 (2017).

2470 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

when employers asked about criminal history, the applicants without rec-

ords received 63% more callbacks, even though the records in question

were relatively minor.

40

Many employers, influenced by the national “Ban

the Box” movement and resulting law changes, have removed questions

about criminal history from initial job applications — but these employers

typically still conduct background checks before finalizing a hire.

41

A sur-

vey in 2012 reported that 87% of randomly sampled employers performed

criminal background checks on at least some employees; 69% performed

background checks on all employees.

42

This represented an expansion

from an earlier era, driven by the availability of easier and less costly

internet-based searches.

43

Almost all states place court records on the

internet,

44

and private companies, such as Westlaw and LexisNexis, also

market criminal history databases.

45

In addition to these employment consequences, criminal convictions

bring with them a wide range of other “collateral” legal consequences —

that is, consequences that are not part of the sentence but a function of

a wide array of civil laws. Licensing restrictions categorically exclude

previously convicted individuals from hundreds of professions.

46

These

individuals are often prohibited from receiving various social services,

including welfare and health benefits, public housing, and food

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

40

Agan & Starr, Ban the Box, supra note 39, at 195, 200.

41

See id. at 193 n.3. The slogan refers to the fact that such questions are often set apart in a

box on the application form.

42

See S

OC

’

Y

FOR

H

UMAN

R

ES

. M

GMT

., SHRM S

URVEY

F

INDINGS

: B

ACKGROUND

C

HECKING

— T

HE

U

SE

OF

C

RIMINAL

B

ACKGROUND

C

HECKS

IN

H

IRING

D

ECISIONS

(2012),

https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Pages/

criminalbackgroundcheck.aspx [https://perma.cc/3EQU-KBQL].

43

See J

ACOBS

, supra note 7, at 5; L

OVE

ET

AL

., supra note 6, § 5:2; Jeffrey Selbin et al.,

Unmarked? Criminal Record Clearing and Employment Outcomes, 108 J.

C

RIM

. L. &

C

RIMINOLOGY

1, 9 (2018).

44

See Privacy/Public Access to Court Records: State Links, N

AT

’

L

C

TR

.

FOR

S

T

. C

TS

.,

https://www.ncsc.org/topics/access-and-fairness/privacy-public-access-to-court-records/state-links

[https://perma.cc/V2HP-3J6M].

45

See Ben Geiger, Comment, The Case for Treating Ex-offenders as a Suspect Class, 94 C

ALIF

.

L. R

EV

. 1191, 1198–99 (2006).

46

See C

HIDI

U

MEZ

& R

EBECCA

P

IRIUS

, N

AT

’

L

C

ONFERENCE

OF

S

TATE

L

EGISLATURES

,

B

ARRIERS

TO

W

ORK

: I

MPROVING

E

MPLOYMENT

IN

L

ICENSED

O

CCUPATIONS

FOR

I

NDIVIDUALS

WITH

C

RIMINAL

R

ECORDS

3 (2018), http://www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/

Labor/Licensing/criminalRecords_v06_web.pdf [https://perma.cc/6GKS-GJUF]; Alec C. Ewald,

Collateral Consequences and the Perils of Categorical Ambiguity, in L

AW

AS

P

UNISHMENT

/L

AW

AS

R

EGULATION

77, 87–88 (Austin Sarat et al. eds., 2011); Policy Changes Needed to Unlock

Employment and Entrepreneurial Opportunity for

100

Million Americans with Criminal Records,

Kauffman Research Shows, B

USINESS

W

IRE

(Nov. 29, 2016, 8:00 AM), https://www.businesswire.com/

news/home/20161129005528/en/Policy-Needed-Unlock-Employment-Entrepreneurial-Opportunity-

100 [https://perma.cc/UA6K-VEEG]; Shoshana Weissmann & Nila Bala, Opinion, Criminal Justice,

Occupational Licensing Reforms Can Go Hand in Hand, T

HE

H

ILL

(Apr. 15, 2018, 4:30 PM),

https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/383262-criminal-justice-occupational-licensing-reforms-can-

go-hand-in-hand [https://perma.cc/R7SU-ZMWZ].

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2471

stamps.

47

Whole families can be evicted from public housing on the

basis of one member’s convictions.

48

Exclusion from housing renders

individuals with records homeless at high rates — for instance, in 1997,

the California Department of Corrections estimated that 10% of its pa-

rolees were homeless.

49

The specifics of these exclusions vary from state

to state, although some are encouraged or required by federal law.

50

They also vary based on crime type.

51

Because so many Americans have conviction records, these conse-

quences have a large aggregate impact. Repercussions include spillover

effects on family members never convicted of any crime; the Center for

American Progress estimates that almost half of U.S. children have a

parent with some form of criminal record (including arrests).

52

In addi-

tion, because criminal records are not equally distributed across the popu-

lation,

53

the effects of these collateral consequences are disproportionately

concentrated by race, gender, and poverty status, especially affecting black

men.

54

This concentration of criminal records may therefore be a signifi-

cant contributor to racial disparities in employment and other socioeco-

nomic outcomes.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

47

See S

TANDARDS

FOR

C

RIMINAL

J

USTICE

ch. 19, introductory cmt. (A

M

. B

AR

A

SS

’

N

3

d ed.

2004

)

; P

AUL

S

AMUELS

& D

EBBIE

M

UKAMAL

, L

EGAL

A

CTION

C

TR

., A

FTER

P

RISON

:

R

OADBLOCKS

TO

R

EENTRY

12–13, 16 (2004), http://www.november.org/resources/LACReportCard.

pdf [https://perma.cc/FGV5-39ZZ]; Jeremy Travis, Invisible Punishment: An Instrument of Social

Exclusion, in I

NVISIBLE

P

UNISHMENT

: T

HE

C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

OF

M

ASS

I

MPRISONMENT

15, 23–25 (Marc Mauer & Meda Chesney-Lind eds., 2002); Geiger, supra note 45,

at 1204–06.

48

Jenny Roberts, Why Misdemeanors Matter: Defining Effective Advocacy in the Lower Crim-

inal Courts, 45 U.C.

D

AVI S

L. R

EV

. 277, 299 (2011).

49

C

AL

. S

TATE

D

EP

’

T

OF

C

ORR

., P

REVENTING

P

AROLEE

F

AILURE

P

ROGRAM

: A

N

E

VA LUAT IO N

2 (1997), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/180542NCJRS.pdf

[https://perma.cc/JX2E-V3BZ].

50

See M

UKAMAL

, supra note 31, at III.A.1; Gwen Rubinstein & Debbie Mukamal, Welfare and

Housing — Denial of Benefits to Drug Offenders, in I

NVISIBLE

P

UNISHMENT

, supra note 47, at

37, 41–42; Geiger, supra note 45, at 1204.

51

See SAMUELS & MUKAMAL, supra note 47, at 16.

52

Rebecca Vallas et al., Removing Barriers to Opportunity for Parents with Criminal Records

and Their Children, C

TR

.

FOR

A

M

. P

ROGRESS

(Dec. 10, 2015, 12:01 AM), https://www.

americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2015/12/10/126902/removing-barriers-to-opportunity-

for-parents-with-criminal-records-and-their-children [https://perma.cc/KU9B-YUH7].

53

See E. A

NN

C

ARSON

, U.S. D

EP

’

T

OF

J

USTICE

, P

RISONERS

IN

2016, at 10 (2018),

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf [https://perma.cc/68J8-QFQT] (showing imprison-

ment rates in 2016 at 1609, 857, and 274 per 100,000 U.S. residents for black, Hispanic, and white

adults, respectively); Robert Brame et al., Demographic Patterns of Cumulative Arrest Prevalence

by Ages

18

and

23

, 60 C

RIME

& D

ELINQ

. 471, 476 (2014) (finding about half of black men have

been arrested by age twenty-three compared to 38% of white men).

54

See P

EW

C

HARITABLE

T

RS

., supra note 29, at 27; Andi Mullin, Banning the Box in

Minnesota — and Across the United States!, C

OMMUNITY

C

ATALYST

(Dec. 2, 2013),

https://www.communitycatalyst.org/blog/banning-the-box-in-minnesota-and-across-the-united-

states [https://perma.cc/69C6-TBU2].

2472 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

B. Sealing of Criminal Records: The Legal and Policy Landscape

More than two-thirds of states have adopted statutes that permit

adult criminal convictions to be sealed, set aside, or expunged.

55

These

laws generally require state agencies to ignore the affected individual’s

criminal record for most purposes other than law enforcement, thereby

lifting any statutory barriers to public employment, licensing, and ben-

efits. The laws also give an individual expungement recipient the legal

right to respond “no” when an employer or landlord asks if the applicant

has a criminal record.

56

In most states (including Michigan), sealed con-

victions remain available for law enforcement purposes, and for sen-

tencing in the event of a subsequent crime.

57

The specific eligibility requirements for criminal record expunge-

ment vary widely across jurisdictions. For example, some states’ laws

exclude certain classes of crimes, such as violent felonies.

58

Waiting pe-

riods also vary: In some states, at least for some categories of crime,

individuals can apply for expungement immediately after completing

their sentence (although evidence of rehabilitation must generally be

shown, which can be harder if little time has passed).

59

Other states, by

contrast, have minimum waiting periods ranging from one to twenty

years.

60

In some states (including Michigan), it is illegal for an employer

to discriminate on the basis of an expunged conviction if the employer

becomes aware of it.

61

The Collateral Consequences Resource Center

and the Clean Slate Clearinghouse provide comprehensive state-by-state

information on expungement laws.

62

Beyond adult conviction records, most states have other expunge-

ment policies covering at least some other types of criminal records, such

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

55

See supra note 11 and accompanying text; see also Ispa-Landa & Loeffler, supra note 32, at 392.

56

Adult Criminal Record FAQs, P

APILLON

F

OUND

., http://www.papillonfoundation.org/

information/expungement-faqs#Adult_Criminal_Record [https://perma.cc/SA3T-GWF6].

57

See, e.g., M

ICH

. C

OURTS

, N

ONPUBLIC

AND

L

IMITED

-A

CCESS

C

OURT

R

ECORDS

(2020),

https://courts.michigan.gov/administration/scao/resources/documents/standards/cf_chart.pdf [https://

perma.cc/9SVE-MJR5] (cataloging different kinds of court records and the access restrictions imposed

on those records “by statute, court order, or court rule,” id. at i, as of January 2020).

58

E.g., N.C. G

EN

. S

TAT

. § 15A-145.5 (2019); O

KLA

. S

TAT

. tit. 22, § 18(A)(11) (2020).

59

See, e.g., A

RIZ

. R

EV

. S

TAT

. A

NN

. § 13-907 (2020); C

AL

. P

ENAL

C

ODE

§§ 1203.4, 1203.4a

(West 2020).

60

See CCRC State Survey, supra note 11.

61

See, e.g., C

AL

. L

AB

. C

ODE

§ 432.7(a)(1) (West 2020) (prohibiting employment discrimination);

see also C

AL

. G

OV

’

T

C

ODE

§ 12952 (West 2020) (prohibiting disclosure in its new enactment). In

Michigan, to use or divulge information about an expunged conviction is a misdemeanor. M

ICH

.

C

OMP

. L

AWS

A

NN

. § 780.623(5) (West 2020) (“Except as provided in subsection (2), a person, other

than the applicant . . . , who knows or should have known that a conviction was set aside under

this section and who divulges, uses, or publishes information concerning a conviction set aside un-

der this section is guilty of a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for not more than 90 days

or a fine of not more than $500.00, or both.”).

62

See sources cited supra note 11.

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2473

as juvenile records, nonconviction records, or convictions that have been

overturned or are subject to successful collateral attack.

63

Many also

have deferred-adjudication programs available for certain defendants

(for example, first-time drug crime defendants or youthful defendants),

in which no conviction is ever entered if the defendant completes certain

requirements.

64

These laws raise related empirical and policy questions,

and discussions about them might well be able to draw on our findings.

But we focus here on state laws that expunge otherwise-valid adult con-

victions that have become final; these policies have been expanding in

scope in recent years and are the subject of active political debates in

many states. Although supported by the American Bar Association,

65

and by advocacy groups such as the National Employment Law Project,

the Center for American Progress, and Community Legal Services,

66

they have also met with considerable political opposition, principally

from employers, who want access to information that they consider rel-

evant to hiring decisions.

67

The most recent wave of efforts to expand and improve expungement

laws — often referred to by advocates as the “Clean Slate” movement —

has focused to a large degree on the potential for automatic expungement

of certain criminal records after a certain period of time.

68

The ground-

breaking success in this area was the adoption of Pennsylvania’s Clean

Slate Act, which extends court-ordered criminal record sealing to encom-

pass a broader set of offenses and creates an automatic computerized pro-

cess for sealing certain eligible convictions: minor nonviolent misdemean-

ors after ten years without a subsequent conviction.

69

The Clean Slate

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

63

See id.

64

See id. (describing deferred-adjudication programs).

65

See S

TANDARDS

FOR

C

RIMINAL

J

USTICE

§ 19-2.5 (A

M

. B

AR

A

SS

’

N

3

d ed.

2004

)

; A

M

.

B

AR

A

SS

’

N

, R

EPORT

TO

THE

H

OUSE

OF

D

ELEGATES

, R

ESOLUTION

109B, at 1 (2019),

https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/house_of_delegates/resolutions/

2019-midyear/2019-midyear-109b.pdf [https://perma.cc/SJ5R-2ZV8].

66

See Press Release, Ctr. for Am. Progress, Removing Barriers to Economic Opportunity for

Americans with Criminal Records Is Focus of New Multistate Initiative by CAP, NELP, and CLS

(Sept. 12, 2017), https://www.americanprogress.org/press/release/2017/09/12/437592/release-removing-

barriers-economic-opportunity-americans-criminal-records-focus-new-multistate-initiative-cap-nelp-

cls [https://perma.cc/E73W-W8BK].

67

See, e.g., Alison Knezevich, New State Laws to Help Marylanders Clear Arrest Records, B

ALT

.

S

UN

(Sept. 26, 2015, 11:02 PM), https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/bs-md-expungement-

changes-20150926-story.html [https://perma.cc/R3X3-4YFD]; Nancy Reardon, Activists Want Law

to Seal Criminal Records Sooner, P

ATRIOT

L

EDGER

(July 28, 2009, 9:11 PM), https://www.

patriotledger.com/x836550449/Activists-want-law-to-seal-criminal-records-sooner

[https://perma.cc/B5R6-W3MN].

68

See C

LEAN

S

LATE

, https://cleanslateinitiative.org [https://perma.cc/S3FF-JPGA].

69

See Act of June 28, 2018, No. 402, 2018 Pa. Laws No. 56; Press Release, Governor Tom Wolf

of Pa., Governor Wolf: “My Clean Slate” Program Introduced to Help Navigate New Law (Jan. 2,

2019), https://www.governor.pa.gov/governor-wolf-my-clean-slate-program-introduced-to-help-

navigate-new-law [https://perma.cc/ENF7-UDRE]; Frequently Asked Questions About Clean Slate,

2474 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

Bill received nearly unanimous legislative endorsement and was sup-

ported by an overwhelming majority of Pennsylvania residents.

70

Pennsylvania’s club became larger in 2019, when Utah, New Jersey,

and California enacted automatic expungement laws,

71

and similar reform

efforts are now underway in several other states,

72

including Michigan.

73

These newer laws have all been broader than Pennsylvania’s pioneering

statute along some dimensions. Of these laws, California’s is the most

ambitious, although (unlike the others) it does not apply retrospec-

tively.

74

The California law applies to all misdemeanors and to some

felonies resulting in probation,

75

and it imposes no lengthy waiting pe-

riod — indeed, none beyond sentence completion in some cases.

76

Utah’s

law, like Pennsylvania’s, is limited to nonviolent misdemeanors, but its

waiting periods for most crimes are only five to seven years depending

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

C

OMMUNITY

L

EGAL

S

ERVS

. P

HILA

. (June 26, 2018), https://clsphila.org/learn-about-issues/

frequently-asked-questions-about-clean-slate [https://perma.cc/3PY5-U3CM].

70

See J.D. Prose, Pennsylvania Becomes First State with “Clean Slate” Law for Nonviolent

Criminal Records, T

HE

T

IMES

(June 28, 2018, 5:00 PM), https://www.timesonline.com/

news/20180628/pennsylvania-becomes-first-state-with-clean-slate-law-for-nonviolent-criminal-rec-

ords [https://perma.cc/2EVM-B5RE].

71

See C

AL

. P

ENAL

C

ODE

§ 1203.425(a)(2)(E) (West 2020); N.J. S

TAT

. A

NN

. § 2C:52-5.4 (West

2020); U

TAH

C

ODE

A

NN

. § 77-40-102 (LexisNexis 2020).

72

See, e.g., David Brand, A Criminal Justice Reform Would Give Thousands a Clean Slate — If

Only They Would Apply, B

ROOKLYN

D

AILY

E

AGLE

(Nov. 25, 2019), https://brooklyneagle.com/

articles/2019/11/25/a-criminal-justice-reform-would-give-thousands-a-clean-slate-if-only-they-

would-apply [https://perma.cc/34H3-NDKR]; Gemma Gaudette, Bipartisan Proposal Would Give

Some Former Idaho Inmates a “Clean Slate,” B

OISE

S

T

. P

UB

. R

ADIO

(Jan. 29, 2020),

https://www.boisestatepublicradio.org/post/bipartisan-proposal-would-give-some-former-idaho-

inmates-clean-slate#stream/0 [https://perma.cc/L6E3-8WXZ]; Asti Jackson & Phil Kent, A Criminal

Record Should Not Be a Lifetime Sentence; That’s Why We Need the Clean Slate Law, H

ARTFORD

C

OURANT

(Mar. 15, 2020, 6:00 AM), https://www.courant.com/opinion/op-ed/hc-op-jackson-kent-

clean-slate-0315-20200315-7bohb5by5nfmpkrbh6fngml4fy-story.html [https://perma.cc/9WZY-

Z3GH]. There is also activity at the federal level. Nila Bala & Rebecca Vallas, Opinion, State

Momentum in Criminal Record Sealing Fuels Federal Clean Slate Bill, T

HE

H

ILL

(Mar. 2, 2020,

2:00 PM), https://thehill.com/opinion/criminal-justice/485477-state-momentum-in-criminal-record-

sealing-fuels-federal-clean-slate-bill [https://perma.cc/W5MN-T2GB]; Press Release, Ctr. for Am.

Progress, supra note 66.

73

See, e.g., Riley Beggin, Michigan Eyes Reform to Costly, Confusing System of Expunging Crimi-

nal Records, B

RIDGE

M

AG

. (Nov. 4, 2019), https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-government/

michigan-eyes-reform-costly-confusing-system-expunging-criminal-records [https://perma.cc/4D83-

CZXU]; Miriam Francisco, New Bill Would Automate Process of Criminal Record Expungement

for Certain Convictions, D

ETROIT

M

ETRO

T

IMES

(Sept. 20, 2019, 3:24 PM), https://www.me-

trotimes.com/news-hits/archives/2019/09/20/new-bill-would-automate-process-of-criminal-record-

expungement-for-certain-convictions [https://perma.cc/AC4M-DTGF].

74

C

AL

. P

ENAL

C

ODE

§ 1203.425(a)(2)(E) (noting that the automatic conviction relief only ap-

plies to “conviction[s] [that] occurred on or after January 1, 2021”).

75

Id.

76

Id. (indicating that otherwise-qualifying individuals who receive probation become eligible

for such relief immediately after successfully completing probation while those with misdemeanor

or infraction convictions become eligible immediately after completing their sentence, so long as a

year has elapsed since the conviction’s date of judgment).

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2475

on the crime class.

77

New Jersey’s automatic expungement law has a

ten-year waiting period, but it allows some more serious crimes to be

automatically expunged; it delegates to a task force the development of

the process.

78

In addition, proposed federal legislation would require

automatic expungement one year after completing a sentence for mari-

juana offenses and certain other minor drug offenses.

79

Many states and local jurisdictions have also adopted other laws de-

signed to reduce barriers to employment of people with criminal records.

The most important category (along with expungement laws) are Ban-

the-Box laws and policies, which typically bar employers from asking

about records on initial job application forms and in initial interviews.

80

Thirty-five states (and the District of Columbia) and over 150 cities and

counties have passed Ban-the-Box laws governing public employers,

and a further thirteen states and eighteen cities and counties now extend

them to private employers.

81

In terms of the number of people affected,

Ban-the-Box laws are far more sweeping than typical expungement laws

because they apply to all criminal records and contain no eligibility re-

quirements. However, expungement, for those who do obtain it, offers

potentially far more significant relief from the consequences of criminal

convictions, cutting across different domains of life and, in effect, legally

erasing the conviction in question. In contrast, Ban-the-Box laws pri-

marily affect employer practices, and only change the timing of employ-

ers’ receipt of record-related information; they can still refuse to hire an

applicant after completing a background check.

82

Still, Clean Slate ad-

vocates typically see the two types of reforms as complementary, and

many advocacy organizations have pushed for both.

83

Some states have also adopted laws that substantially restrict employ-

ers’ use of criminal record information — for example, requiring that they

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

77

U

TAH

C

ODE

A

NN

. § 77-40-105(2–3) (LexisNexis 2020).

78

N.J. S

TAT

. A

NN

. § 2C:52-5.4 (West 2020).

79

Clean Slate Act of 2019, H.R. 2348, 116th Cong.

80

See L

INDA

E

VA NS

, A

LL

OF

U

S

OR

N

ONE

, B

AN

THE

B

OX

IN

E

MPLOYMENT

: A

G

RASSROOTS

H

ISTORY

8 (2016), http://www.prisonerswithchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/

2016/10/BTB-Employment-History-Report-2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/6P9Z-AP38]. The Ban-the-

Box campaign was initiated in 2004 by All of Us or None, a national civil rights movement, to

eliminate the box on employment forms (as well as other applications) that asks whether an appli-

cant has ever been convicted of a felony. See id. at 10.

81

B

ETH

A

VERY

, N

AT

’

L

E

MP

’

T

L

AW

P

ROJECT

, B

AN

THE

B

OX

1 (2019),

https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Ban-the-Box-Fair-Chance-State-and-Local-Guide-

July-2019.pdf [https://perma.cc/33QT-FEZK].

82

See Agan & Starr, Ban the Box, supra note 39, at 193.

83

See, e.g., Angela Hanks, Ban the Box and Beyond, C

TR

.

FOR

A

M

. P

ROGRESS

(July 27, 2017,

9:03 AM), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2017/07/27/436756/ban-box-

beyond [https://perma.cc/5T7V-58NU].

2476 HARVARD LAW REVIEW [Vol. 133:2460

only rely on information that is job relevant.

84

These laws essentially rep-

licate guidance long given by the federal Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC), which holds that overly sweeping bans on employ-

ees with records can amount to disparate impact racial or national origin

discrimination.

85

Unfortunately, courts have been reluctant to enforce

these restrictions.

86

Many employers throughout the country continue

to implement blanket exclusions of individuals with records, notwith-

standing EEOC’s guidance

87

— which, in any event, the Fifth Circuit

recently ruled is not enforceable.

88

These practices, and the difficulty of

eliminating them through other legal mechanisms, are among the moti-

vations for expungement laws.

C. Research Questions and Existing Empirical

Research on Expungement

There has been very little empirical research on any of the many

questions surrounding expungement laws, despite the clear importance

of these inquiries to policymakers and the lives of millions of Americans.

In truth, most of these questions really cannot be answered effectively

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

84

See A

VERY

, supra note 81, at 1–2.

85

See U.S. E

QUAL

E

MP

’T O

PPORTUNITY

C

OMM

’

N

, N

O

. 915.002, E

NFORCEMENT

G

UIDANCE

: C

ONSIDERATION

OF

A

RREST

AND

C

ONVICTION

R

ECORDS

IN

E

MP

LOYMEN

T

D

ECISIONS

U

NDER

T

ITLE

VII

OF

THE

C

IVIL

R

IGHTS

A

CT

OF

1964 (2012),

https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/arrest_conviction.cfm [https://perma.cc/UK3G-DAAH].

86

See Dallan F. Flake, When Any Sentence Is a Life Sentence: Employment Discrimination

Against Ex-offenders, 93 W

ASH

. U. L. R

EV

. 45, 80 (2015) (“[T]he EEOC has yet to prevail in

court . . . .”); see also Benjamin Levin, Criminal Employment Law, 39 C

ARDOZO

L. R

EV

. 2265,

2303 (2018); Geiger, supra note 45, at 1203 (indicating that at least early versions of state laws were

“severely underutilized”); id. at 1199 (“[R]egulations [may be] especially difficult to enforce since, in

order for an applicant to know that a rejection was based on the use of prohibited criminal history

information, either the applicant would have to sue and obtain subpoena power to see the job

application information or the employer would have to freely admit the illegal basis for rejecting

the applicant.”).

87

See R

ODRIGUEZ

& E

MSELLEM

, supra note 33, at 3; U.S. C

OMM

’

N

ON

C

IVIL

R

IGHTS

,

C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

: T

HE

C

ROSSROADS

OF

P

UNISHMENT

, R

EDEMPTION

,

AND

THE

E

FFECTS

ON

C

OMMUNITIES

134 (2019), https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2019/06-13-Collateral-

Consequences.pdf [https://perma.cc/WX86-2BMM] (“Employment is difficult to access for those

individuals with a criminal conviction as many employers choose to use a blanket ban on hiring

any person with a prior criminal conviction regardless of the offense committed by the person.”);

Miriam J. Aukerman, The Somewhat Suspect Class: Towards a Constitutional Framework for

Evaluating Occupational Restrictions Affecting People with Criminal Records, 7 J.L.

& S

OC

’

Y

18,

26 (2005); Mark Jones et al., Challenges Facing Released Prisoners and People with Criminal Rec-

ords: A Focus Group Approach, 2 C

ORR

ECTIONS: P

OL

’

Y

P

RAC

. & R

ES

.

91, 97–98 (2017); see also

M

UKAMAL

, supra note 31, at III.B.

88

See Texas v. EEOC, 933 F.3d 433, 451 (5th Cir. 2019); CCRC Staff, Appeals Court Invalidates

EEOC Criminal Record Guidance, C

OLLATERAL

C

ONSEQUENCES

R

ESOURCE

C

TR

. (Aug. 7, 2019),

http://ccresourcecenter.org/2019/08/07/appeals-court-invalidates-eeoc-criminal-record-guidance

[https://perma.cc/9PT6-245J]; Alonzo Martinez, Fifth Circuit to EEOC — Don’t Mess with Texas,

F

ORBES

(Aug. 13, 2019, 4:57 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/alonzomartinez/2019//13/fifth-circuit-

to-eeoc-dont-mess-with-texas/#4e17c8f6c897 [https://perma.cc/5GMY-Z9Y7].

2020] EXPUNGEMENT OF CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 2477

absent comprehensive access to individual-level data on people whose

records have been expunged, and because those records are generally

unavailable, research has been stymied. Fortunately, by taking ad-

vantage of our unusual data access, we are able to examine several key

questions that have long remained unanswered.

First, there is essentially no research on the question of “uptake” in