National Registry of Exonerations

A project of the University of California Irvine • Newkirk Center for Science & Society,

the University of Michigan Law School, and Michigan State University College of Law

Race and Wrongful

Convictions in the

United States

2022

Samuel R. Gross, Senior Editor, srgross@umich.edu

Maurice Possley, Senior Researcher

Ken Otterbourg, Researcher

Klara Stephens, Research Fellow

Jessica Weinstock Paredes, Research Fellow

Barbara O’Brien, Editor

NATIONAL REGISTRY OF EXONERATIONS

SEPTEMBER 2022

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page ii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Race and Wrongful Convictions

in the United States 2022

Preface

This Report is about the role of race in the conviction of innocent people. We discuss cases that

are listed in the National Registry of Exonerations, an ongoing online archive that includes all

known exonerations in the United States since 1989, 3,248 as of this writing. The Report

describes racial patterns in the first 3,200 individual exonerations in the Registry, those posted

by August 8, 2022. Information about individual exonerations we discuss may be found by

searching for the exonerees by name on the Registry website. Other data are readily available on

that site, or by request.

The Registry’s first report on race and wrongful convictions, which was made possible by a

generous grant from the Proteus Fund, was released in 2017. The current Report covers a great

deal more ground than we did five years ago. It includes many more details, more extensive and

better data throughout, and several parts are entirely new.

The number of exonerations we consider has grown by almost 70% since 2017, 3,200 compared

to 1,900, which makes the patterns we detect more reliable as well as more current. In the

intervening five years we also completed a thorough study of Government Misconduct and

Convicting the Innocent; as a result, our discussion of misconduct by police and prosecutors in

this Report is more detailed and informative.

This is the first Report by the Registry that includes extensive discussion of changes over time.

That required patience. Many, probably most, of the important changes are in the investigations

and prosecutions that produce false convictions—but we don’t begin to learn about them until

the convicted defendants are exonerated, on average 11.6 years later. We’re now able to describe

and analyze changes that occurred in the twenty-first century. For example, many innocent

Black men used to be convicted of rape after they were misidentified by the white victims, but

DNA pre-trial testing has now reduced that problem to a fraction of what it once was.

Finally, we know far more about false drug crime convictions than we did five years ago. We

have two-and-a-half-times as many exonerations (554 vs. 221), including 259 drug crime

exonerees, overwhelmingly Black people, who were framed by police. And we have additional

data on thousands of defendants—again, primarily Black people—who were wrongfully

convicted of drug crimes by systematic practices of misconduct by police officers.

Samuel R. Gross

Maurice J. Possley

Ken Otterbourg

Klara Huber Stephens

Jessica Weinstock Paredes

Barbara O’Brien

September 23, 2022

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page iii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Executive Summary

I. Introduction

• Black people are 13.6% of the American population but 53% of the 3,200 exonerations

listed in the National Registry of Exonerations. Judging from exonerations, innocent

Black Americans are seven times more likely than white Americans to be falsely

convicted of serious crimes.

• We see this racial disparity, in varying degrees, for all major crime categories except

white collar crime. This report examines racial disparities in the three types of crime

that produce the largest numbers of exonerations: murder, sexual assault, and drug

crimes.

• For both murder and sexual assault, there are preliminary investigative issues that

increase the number of innocent Black suspects: for murder, the high homicide rate in

the Black community; for rape, the difficulty of cross-racial eyewitness identification.

For both crimes, misconduct, discrimination and racism amplify these initial racial

discrepancies.

• For drug crimes, the preliminary sorting that increases the number of convictions of

innocent Black suspects is racial profiling. In addition, the Registry lists 17 “Group

Exonerations” including 2,975 additional wrongfully convicted defendants, many of

whom were deliberately framed and convicted of fabricated drug crimes in large-scale

police scandals. The overwhelming majority are Black.

II. Murder

• Innocent Black people are about seven-and-a-half times more likely to be convicted of

murder than innocent white people. That applies equally to those who are sentenced

to death and those who are not.

• A major cause of this disparity is the high homicide rate in the Black community, a

tragedy that kills many Black people and sends many others to prison. Like the

families of those who are killed, innocent defendants who are falsely convicted are

victims who are deeply harmed by murders committed by others.

• In addition, Black people who are convicted of murder are about 80% more likely to

be innocent than other convicted murderers.

• Part of that disparity is tied to the race of the victims. About 13% of murders by Black

people have white victims, but twice as many—26% of innocent Black murder

exonerees— were convicted of killing white people.

• The convictions that led to murder exonerations with Black defendants were almost

50% more likely to include misconduct by police officers than those with white

defendants.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page iv • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

• In addition, on average Black murder exonerees spent three years longer in prison

before release than white murder exonerees.

• The number of murder exonerations has been increasing, and many of the recent

exonerees are Black murder defendants who spent decades in prison. Most of these

long-serving Black murder defendants were exonerated by a handful of big-city

prosecutorial conviction integrity units (CIUs). More are likely on the way.

• Many of the convictions of Black murder exonerees were influenced by racial

discrimination, from unconscious bias and institutional discrimination to explicit

racism.

• Most innocent defendants who are convicted of crimes are not exonerated. Judging

from the rate of false conviction among death sentences, at least several thousand

defendants have been falsely convicted of murder in America in the past 40 years.

Judging from the exonerations that have occurred, more than half of them were Black.

III. Sexual Assault

• Innocent Black people are almost eight times more likely than white people to be

falsely convicted of rape. A prisoner serving time for sexual assault is more than three

times more likely to be innocent if he is Black than if he is white.

• The major cause of this huge racial disparity is the high danger of misidentification of

Black suspects by white victims of violent crimes.

• Assaults on white women by Black men are a small minority of all sexual assaults in

the United States, but nearly half of sexual assaults with eyewitness misidentifications

that led to exoneration.

• Eyewitness misidentifications do not completely explain the racial disparity in rape

exonerations. Some of the misidentifications were obtained by deliberately tainted

identification procedures, and Black men are also overrepresented in rape

exonerations without misidentifications.

• A substantial number of the convictions that led to rape exonerations of Black

defendants were marred by implicit biases, racially tainted official misconduct and, in

some cases, explicit racism.

• Black sexual assault exonerees received much longer prison sentences than white

sexual assault exonerees, and spent, on average, more than four years longer in prison

before exoneration.

• Exonerations of misidentified rape defendants are much less common than they used

to be. There have been only two from rape convictions in the last 12 years. That’s

because DNA testing is now routinely used to determine the identity of rapists before

trial. This technology has prevented convictions of hundreds or thousands of innocent

rape suspects, mostly Black men who were accused of raping white women.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page v • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

IV. Drug Crimes

• Sixty-nine percent of drug crime exonerees are Black and 16% are white. That means

that innocent Black people are 19 times more likely to be convicted of drug crimes

than innocent whites—a much larger disparity than we see for murder and rape—

despite the fact that white and Black Americans use illegal drugs at similar rates.

• Because drug crimes are almost never reported to police, the police choose who to

pursue for drug offenses—and they choose to stop, search and arrest Black people

several times more often than whites. That’s racial profiling. One of its deplorable

consequences is drug crime convictions of innocent Black defendants.

• Most false drug crime convictions involve comparatively low level charges and

sentences that rarely attract the effort necessary to obtain exonerations. Almost all the

erroneous drug convictions we know about are in a single cluster in Harris County,

Texas (Houston), where a unique practice of testing alleged drugs after defendants

pled guilty led to 157 exonerations; 62% of the exonerees are Black in a county with

20% Black residents.

• These convictions are errors—mostly caused by defective field drug tests—but most

are not innocent errors. Most Black exonerees were stopped and searched—and

subjected to the risk of these errors—because of their race.

• We also know of dozens of groups of innocent defendants who were deliberately

framed by police officers who planted drugs on them. Almost all are Black people or

other racial or ethnic minorities. So far, we list 259 individual exonerees who were

convicted of these fabricated drug crimes, primarily in three group exonerations; 87%

of them are Black.

• There are many more such cases in dozens of groups across the country. These

numbers will rise as we are able to add them to our lists.

• It’s no mystery why these outrageous programs of framing innocent drug defendants

target Black people. Guilty or innocent, drug law enforcement always focuses

disproportionately on Black people. Of the many costs that the war on drugs inflicts

on the Black community, the practice of deliberately charging innocent defendants

with fabricated crimes may be the most shameful.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page vi • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Race and Wrongful Convictions in the United States 2022

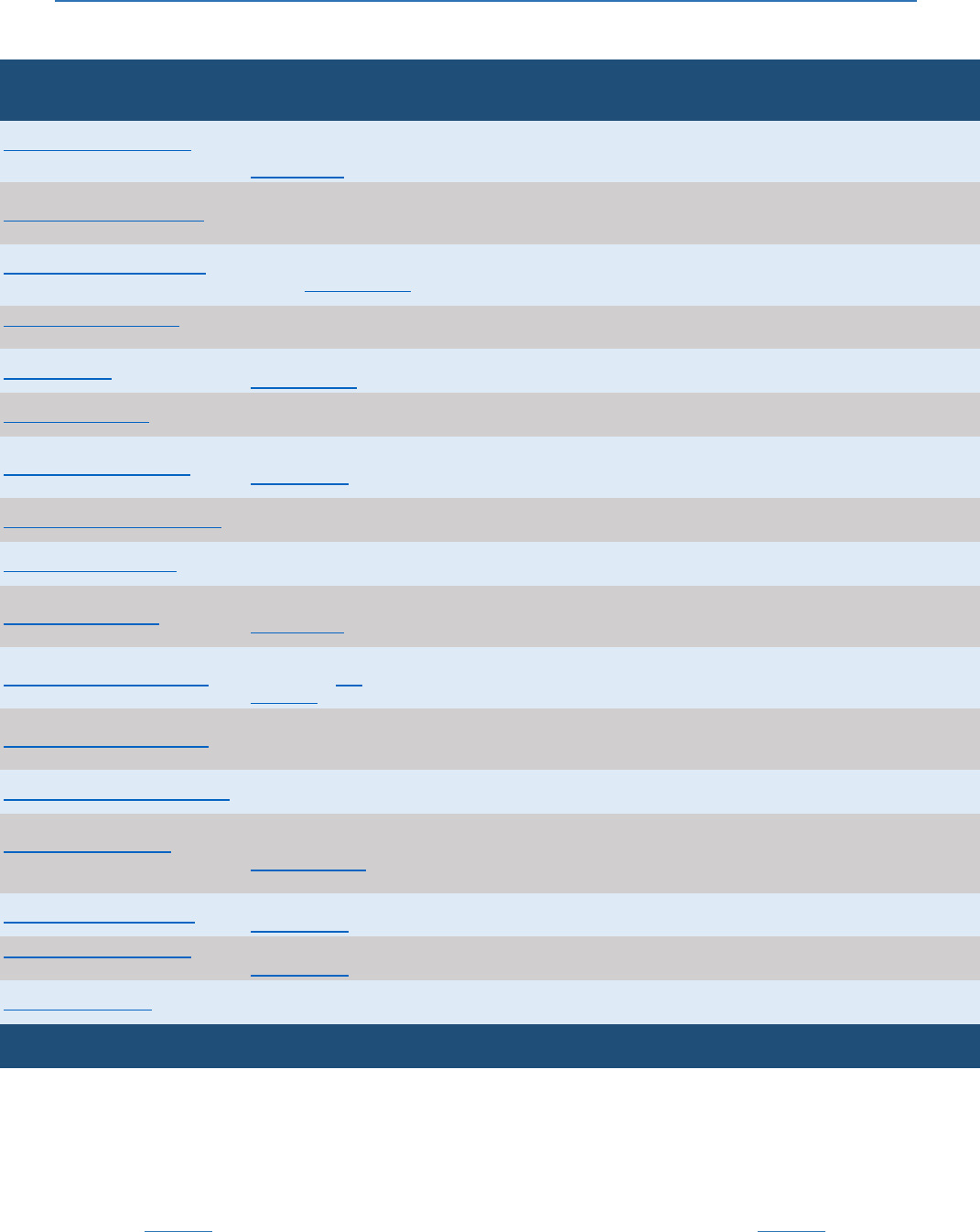

Table of Contents

I.

I. Introduction ............................................................................. 1

II. Murder .................................................................................... 3

1. Racial patterns in murders and exonerations .................................................... 3

2. Additional racial disparities in murder exonerations ........................................ 4

a) Race of victim ...................................................................................................................... 4

b) Misconduct and delay ......................................................................................................... 6

c) Changes over time ............................................................................................................... 9

d) Intentional and structural discrimination ......................................................................... 15

3. The net effect ...................................................................................................... 17

III. Sexual Assault ........................................................................ 18

1. Race and false conviction for rape ..................................................................... 18

2. Eyewitness misidentification ............................................................................. 19

3. Misconduct and discrimination ........................................................................ 20

a) Tainted identifications ...................................................................................................... 20

b) Rape exonerations without eyewitness misidentifications ............................................... 21

c) Racism and discrimination ............................................................................................... 22

4. Sentencing and time in prison before exoneration .......................................... 23

5. Changes over time ............................................................................................. 24

IV. Drug Crimes ........................................................................... 27

1. The structure of drug crime enforcement ..........................................................27

2. Race and drug crime prosecutions ................................................................... 28

3. Innocent drug crime defendants ....................................................................... 29

4. Clusters of drug crime exonerations ................................................................. 30

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page vii • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

a) Error: post-guilty plea drug testing exonerations in Harris County ................................. 31

b) Misconduct: Group Exonerations ...................................................................................... 31

c) Patterns over time ............................................................................................................. 32

5. Mistaken convictions discovered after guilty pleas in Harris County, Texas .. 33

6. Fabricated Drug Crimes in Group Exonerations .............................................. 36

a) The nature and number of group exonerations ................................................................ 36

b) Group exonerations and the individual Registry .............................................................. 40

c) The impact of the police misconduct ................................................................................ 42

d) Why do these scandals happen? ....................................................................................... 43

V. Conclusion ............................................................................ 45

VI. Appendix ............................................................................... 46

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 1 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

I. Introduction

Race is central to every aspect of criminal justice in the United States. The conviction of

innocent defendants is no exception. Thousands of exonerations across dozens of years

demonstrate that Black people are far more likely than white people to be convicted of crimes

they did not commit.

As of August 8, 2022, the National Registry of Exonerations listed 3,200 defendants who were

convicted of crimes in the United States and later exonerated because they were innocent;

1

53%

of them were Black, nearly four times their proportion of the population, which is now about

13.6%.

2

Judging from exonerations, innocent Black Americans are seven times more likely than

white Americans to be falsely convicted of crimes.

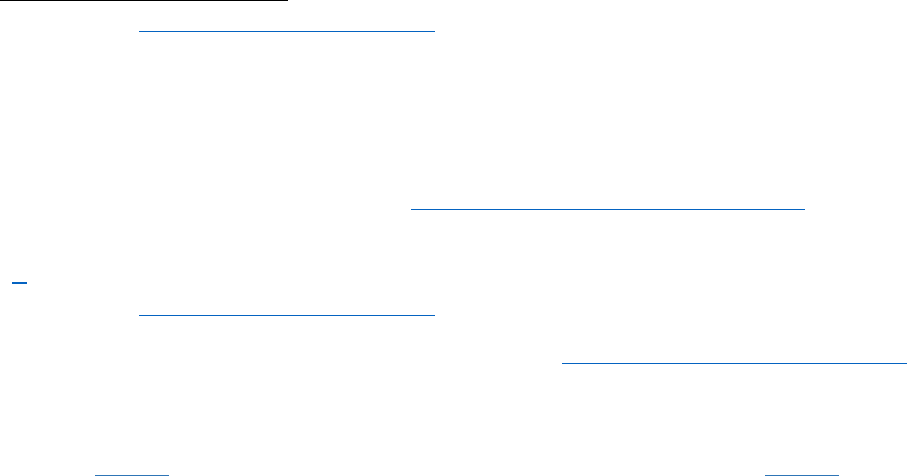

Black people are over-represented to a greater or lesser extent among exonerations for all major

crime categories listed in the Registry, except white collar crimes. See Table 1.

3

Table 1: Exonerations by Race of Defendant and Type of Crime

(N=3,200)

White

Black

Hispanic

Other

Total

Murder

(1,167)

32%

55%

12%

2%

100%

Sexual Assault

(350)

33%

59%

7%

1%

100%

Child Sex Abuse

(310)

60%

28%

10%

2%

100%

Robbery (151) 19% 64% 15% 2% 100%

Other Violent Crimes (342) 42% 39% 13% 6% 100%

Drug Crimes (554) 16% 69% 14% 1% 100%

White Collar (77) 79% 10% 3% 8% 100%

Other Non-Violent Crimes

(249)

28%

52%

16%

5%

100%

All Crimes (3,200)

33%

53%

12%

2%

100%

1

All National Registry data reported in this paper are as of August 8, 2022, when the Registry listed 3,200 individual

exonerations. Information about any individual exonerations we discuss may be found by searching for the exonerees

by name on the Registry web site.

2

United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts, 2021.

3

As used in Table 1, on the Registry, and throughout this report, the categories “white” and “Black” do not include

individuals who identify themselves as Hispanic or Latino. We do not discuss false convictions and exonerations of

Hispanic or Latino defendants (except in a few places); the same applies to Asian and Indigenous defendants, and to

all other defendants who are grouped together in Table 1 in the column labeled “Other.” To study them separately we

would need national criminal justice statistics on reported crimes, arrests, convictions and imprisonment, and the

studies that are available use inconsistent standards for tabulating those racial and ethnic categories, suffer from high

rates of missing data, or fail to address the issue entirely.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 2 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Nearly 3,000 additional defendants who were wrongfully convicted of crimes in 17 large-scale

police misconduct scandals were cleared in “Group Exonerations;” the great majority of those

defendants were also Black. Judging from the cases we know, a large majority of all innocent

people who are convicted of crimes in the United States are Black.

What explains this stark racial disparity? We examine this question by looking at exonerations

for murder, sexual assault and drug crimes, the three types of crime that produce the largest

numbers of exonerations. What we see—as so often in considering the role of race in America—is

complex and disturbing, familiar yet often ignored.

There is no one explanation for the heavy concentration of Black defendants among those

convicted of crimes they did not commit. The causes we have identified run from inevitable

consequences of patterns in crime and punishment to deliberate acts of racism, with many steps

in between. They differ sharply from one type of crime to another.

A major cause of the high number of Black murder exonerations is the high murder rate in the

Black community—a tragedy that kills many Black people and sends many others to prison.

Exonerated defendants go to prison, but not because they deserve to; they, like those who are

killed, are innocent victims of crimes committed by others. But homicide rates alone do not

explain the high number of Black people who were falsely convicted of murder or the length of

time they spent in prison before release. Misconduct and discrimination also played major roles.

Most innocent Black defendants who were exonerated for sexual assault had been convicted of

raping white women (128/207). The leading cause of these false convictions was mistaken

eyewitness identifications (101/128)—a notoriously error-prone process when white Americans

are asked to identify Black strangers. As with murder exonerations, however, the leading cause

is far from the only one. We see clear evidence of racial bias, ranging from unconscious bias to

explicit racism. And, as with murder if not more so, Black sexual assault exonerees spent more

time in prison than their white counterparts.

Prosecutions for drug offenses are very different from murder and rape cases. A murder or rape

investigation is initiated when a violent crime is reported to the police. Drug transactions and

drug possession have no immediate victims and are almost never reported. Instead, police have

essentially unlimited discretion to choose how and where to enforce drug laws—and against

whom, which opens the door to pervasive discrimination.

We see the effects in two settings. Because of racial profiling, Black people are more likely to be

stopped, searched, arrested and prosecuted in routine drug possession cases; as a result, they

are also more likely to be convicted by factual mistakes. Many false drug convictions, however,

are not mistakes. Black people are also the main targets in a shocking series of scandals in which

police officers systematically framed innocent defendants for drug crimes that never occurred.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 3 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

II. Murder

About half of those who are parties to homicide in the United States—those who kill and

those who are killed—are Black, seven times the rate for the remainder of the

population. One of the predictable consequences of this national calamity is that a

comparably high proportion of innocent defendants who are convicted of murder are

also Black.

The high homicide rate in the Black community accounts for most of the

overrepresentation of Black people among murder exonerees—but not all. Black

murder defendants are not only more numerous than whites, they are also more likely

to be innocent, especially if the victims were white. Many of the investigations and

prosecutions that lead to convicting innocent Black murder suspects are marked by

racial discrimination, including explicit racism.

Black murder exonerees are more likely than white murder exonerees to be the victims

of misconduct by police officers, and they spend more time in prison before

exoneration. We don’t yet know the extent of these differences. The number of murder

exonerations has been increasing in recent years, and many of the exonerations that

are being added are for murder defendants—overwhelmingly Black—who remained in

prison since they were convicted 25 to 40 years ago, or longer. Most of these recent

exonerations of innocent Black murder defendants who spent decades in prison are the

work of a handful of big-city prosecutorial conviction integrity units—and more, it

seems, are on the way.

1. Racial patterns in murders and exonerations

Fifty-five percent of all defendants exonerated for murder are Black people (628/1,167), who

make up 13.6% of the population of the United States.

4

For the population at large, that’s about

seven-and-a-half times the rate for whites, who comprise 59.3% of the population

5

but only 32%

of murder exonerations. Much of this racial disparity can be traced to a comparable disparity in

murder convictions. Black people are more than seven times more likely to be imprisoned for

4

United States Census Bureau, QuickFacts, 2021

5

Id.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 4 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

murder than white people,

6

and more than six times as likely to be killed in a homicide.

7

Murder

in America is overwhelmingly intra-racial: 84% of white murder victims and 93% of Black

murder victims are killed by members of their own race.

8

This high murder rate means that Black people are far more likely than white people to be

investigated, arrested and convicted of murder. Mostly, those who are investigated and

convicted are guilty. But innocent Black people also face a much higher risk of being suspected

of murder, and of being investigated, arrested and sometimes convicted despite their innocence.

Innocent Black murder suspects, especially those who are falsely convicted—like the families of

those who are killed—are additional victims of murders committed by others. Those who have

been exonerated spent on average almost 16 years in prison before they were released. Many

more have not been exonerated at all; more often than not, they will die in prison.

Innocent Black people are about equally overrepresented among murder exonerees who were

sentenced to death, 56% (74/134); those sentenced to life imprisonment, with or without the

possibility of parole, 55% (294/535); and those sentenced to imprisonment for terms shorter

than life, 54% (270/497). However, innocent Black defendants who escaped sentences of death

or life imprisonment received sentences that averaged 35 years, compared to 28 years for white

murder exonerees who were sent to prison for terms less than life.

2. Additional racial disparities in murder exonerations

Differences in homicide rates may explain most of the enormous racial disparity in exoneration

rates for murder, but not all. Forty percent of defendants imprisoned for murder are Black,

9

compared to 55% of murder exonerations. Unless some unknown and improbable process gives

innocent Black prisoners a big advantage in obtaining exonerations, that means that Black

people who are convicted of murder are about 80% more likely to be innocent than other

convicted murderers.

a) Race of victim

About 38% of murder victims in the United States are white.

10

The proportion of murder

exonerees of all races who were convicted of killing white victims is somewhat higher, 46%

6

E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2020 – Statistical Tables, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice; Tables 15

&18, pp. 29, 33. The numbers of prisoners reported in this study by the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics are

estimates of the prison population on a particular date, in this case December 31, 2019. So are most of the general

statistics we discuss on arrest, conviction and imprisonment. The murder exonerations to which we compare these

numbers are based on convictions that occurred over decades, from the 1960s through 2016—almost all since

1980—and the proportions of crimes and convictions by race have varied over that period. As a result, throughout

this report, all rates and comparisons we discuss that depend on general criminal justice statistics are estimates or

illustrations.

7

Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice. Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008. (November

2011): p. 3, Table 1. The rates of homicide victimization by race reported in this study are for all Black and white

victims, including those who identify as Hispanic or Latino, or other racial categories.

8

Id. p. 13; Sherman, Amy. An updated look at statistics on black-on-black murders. PolitiFact Florida. (May 2015).

9

E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2020 – Statistical Tables, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice; p.30,

Table 5.

10

The only national statistics on the race of murder victims come from the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Reports.

These data have three limitations: (i) They are incomplete. (ii) They combine murder and non-negligent

manslaughter. (iii) They do not identify Hispanic or Latino victims, so their racial categories—“white” and “black”—are

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 5 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

(537/1,167).

11

The concentration of murder defendants who were convicted of killing white

victims is considerably greater among exonerees who were sentenced to death, 66% (89/134).

Many studies in at least 15 states have shown that defendants who are charged with killing white

victims, regardless of their own race, are more likely to be sentenced to death than those

charged with killing Black victims.

12

Since 1976, 75% of executions in the United States were for

murders of white victims.

13

The disparities we see in our data suggest that innocent defendants

who are charged with killing white victims are more likely to be sentenced to death, and

sometimes no doubt executed, than those charged with killing Black victims.

There are also sentencing disparities among murder exonerees who avoided death sentences.

More than half of non-capital murder exonerees were sentenced to life imprisonment,

14

or to life

without the possibility of parole (535/1,033), and the rest were sentenced to prison for terms

shorter than life. Fifty-eight percent of non-capital murder exonerees who were convicted of

killing white victims were sentenced to life imprisonment (262/448), compared to 46% of those

who were convicted of killing Black victims (206/444).

In other words, judging from exonerations, the pattern of harsh sentencing for murder

convictions with white victims and lighter sentencing for those with Black victims is not

restricted to death sentences. If they avoid the death penalty, innocent murder defendants in

white-victim cases are also more likely to be sentenced to life in prison than those charged with

killing Black victims.

The race-of-victim disparity in murder exonerations also interacts with the race-of-defendant

disparity. Only about 13% of murders by Black people have white victims,

15

but 26% of innocent

Black murder exonerees were convicted of killing white people (168/638). This is a considerable

disparity; it could explain most or all of the difference in murder exonerations by race beyond

general homicide rates.

Part of the explanation for the high number of Black murder exonerees who were convicted of

killing white victims may be the perils of cross-racial eyewitness identification. We discuss that

not limited, as ours are, to non-Hispanic white and Black victims. The estimate in the text is the average percent of

“white” victims reported by the FBI from 2001 through 2010, multiplied by 0.79 to correct for the 21% of “whites” who

were identified as Hispanic or Latino in the 2010 census. U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts - United States.

11

We classify a murder exoneration as a “white victim” case if it included at least one murder victim who was white.

Eighteen cases in the Registry with multiple murder victims had both at least one white victim and at least one Black

victim each. They are coded as white victim cases.

12

For reviews of the literature on this issue, see Grosso, Catherine M., Barbara O’Brien, Abijah Taylor, and George

Woodworth. “Race Discrimination and the Death Penalty: An Empirical and Legal Overview.” America's Experiment

with Capital Punishment 525 (James R. Acker, Robert M. Bohm, & Charles S. Lanier, eds., 3d ed. 2014); O’Brien,

Barbara, Catherine M. Grosso, George Woodworth, and Abijah Taylor. “Untangling the Role of Race in Capital

Charging and Sentencing in North Carolina, 1990-2009.” 94 N.C. L. Rev. 1997 (2016).

13

Death Penalty Information Center. Race of Victims Since1976.

14

This category also includes any sentence of 99 years in prison or longer.

15

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2014 – Crime in the United States. The estimate in the text is the proportion of

“White” victims for “Black or African American” offenders, multiplied by 0.79 to correct for the 12% of “whites” who

were identified as Hispanic or Latino in the 2010 census. See supra, note 10.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 6 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

issue in more detail in the next section, on sexual assault exonerations, where it looms larger.

16

Beyond that, it is no news that inter-racial violence by Black people is punished more harshly

than intra-racial violence. It would not be surprising to learn that it is also pursued with greater

ferocity and less accuracy.

b) Misconduct and delay

Two racial differences in murder exonerations might help explain the disproportionate number

of murder exonerations with Black defendants.

Misconduct: Official misconduct is more common in murder convictions that lead to

exonerations of Black defendants than in those with white defendants.

Delay: Exonerations of Black murder defendants take longer than exonerations of white

murder defendants.

Misconduct. Seventy-two percent of the murder prosecutions that led to exoneration included

official misconduct that we know about (845/1,167). We have identified many different types of

misconduct. The most common is concealing exculpatory evidence—often called “Brady

violations” after the landmark 1963 Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland

17

—which occurred

in 63% of the cases (736/1,167). The next most common type is witness tampering—everything

from misleading a witness at a lineup, to threatening a witness, to suborning perjury—which

occurred in 35% of murder exoneration cases (416/1,167); followed by perjury by a state official,

which happened in 20% of the cases (230/1,167).

The rate of official misconduct is considerably higher among murder exonerations with Black

defendants than those with white defendants, 78% (500/638) compared to 64% (236/369). The

overall rate of misconduct is a bit higher in capital cases—up from 73% to 78% (105/134)—but

the difference by race is similar: 85% (63/74) of Black exonerees who were sentenced to death

were victims of official misconduct, compared to 70% (32/46) of white death-row exonerees.

Most of these differences by race are due to misconduct by police officers. The rate of

misconduct by prosecutors is about the same for all murder exonerations regardless of race,

48% for Black defendants (308/638) and 45% for whites (167/369). (There is a slightly larger

difference in prosecutorial misconduct among capital exonerations, 65% for Black defendants

(48/74) and 59% of whites (27/46).) On the other hand, there is a substantial difference in the

rate of misconduct by police: 58% for Black murder exonerees (370/638) compared to 38% for

whites (142/369).

The high rate of misconduct by police in murder cases with Black defendants is reflected in the

nature of the misconduct that occurs. Eighty-four percent of perjury by government officials is

committed by police officers.

18

It happened in 21% of murder exonerations with Black

defendants (136/638) and 14% of those with white defendants (51/369).

16

Only 35% of murder exonerations of Black defendants convicted of killing white victims included eyewitness

misidentifications (58/164), compared to 78% of sexual assault exonerations of Black men who were convicted of

sexual assaults on white women (101/130).

17

Brady v. Maryland, 73 U.S. 83 (1963).

18

Samuel Gross, et al., Government Misconduct and Convicting the Innocent, National Registry of Exonerations

(2020) at p. 96.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 7 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Witness tampering is also committed primarily by police officers.

19

It happened in 42% of

murder exonerations with Black defendants (271/638) but only 25% of those with white

defendants (91/369). In 17% of Black defendant murder exonerations the witness tampering

included violence or threats to the witness (106/638), compared to 7% for white defendant cases

(24/369). For example:

Kendrick Scott and Justly Johnson were arrested and charged with murder

within hours after Lisa Kindred was shot and killed in Detroit on May 9, 1999,

and convicted in 2000. Antonio Burnette and Raymond Jackson had been

arrested hours earlier as part of the same investigation, and they told the police—

and later testified in court—that Scott and Johnson told them that they had

committed the murder.

Scott and Johnson were exonerated in 2018 after the victim’s son—who

witnessed the killing at close range when he was eight, but was never questioned

by anyone before trial—testified that he was certain that neither Scott nor

Johnson was the gunman. In addition, Burnette testified that the police

“whooped” him during his interrogation and that he was afraid he would be

charged with the murder himself if he did not say what they wanted to hear, and a

cousin of Jackson’s testified that before he died in 2008, Jackson told her that he

had lied because he was afraid of the police and the prosecution.

Tainted identification procedures

are a particularly dangerous form of misconduct. They

occurred in 10% of murder exonerations, that we know (112/1,167): 5% of cases with white

defendants (18/369), and more than twice as often—12%—of those with Black defendants

(75/638). Their purpose, often successful, is to produce false evidence that an eyewitness to the

crime identified the defendant based on their memory of what they saw. These are cases in

which police (and, rarely, prosecutors) tell witnesses, in one form or another, who to identify in

a lineup or other identification procedure. Sometimes they use visual cues:

In 1985, Nathson Fields, a member of the El Rukn street gang in Chicago, was

misidentified by members of a rival gang as one of two men who gunned down

two of their comrades the previous year. Fields was the only person in the lineup

wearing short sleeves, which showed an El Rukn tattoo on his forearm. He was

exonerated in 2009.

And sometimes they use threats:

A year after Charles Wilhite was convicted of murder in Springfield,

Massachusetts in 2010, the critical eyewitness testified that a detective repeatedly

threatened to charge him as an accessory to the murder if he didn’t identify

Wilhite—who was acquitted at a retrial in 2013.

Police used threats in 52% of tainted identification procedures that produced false identification

of Black murder exonerees (39/75), compared to 11% of those that produced false identifications

of white exonerees (2/18).

19

Id. at p.35

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 8 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

We only know about misconduct that is reported in documents we can obtain. Official

misconduct in criminal cases is under-reported because, by its very nature, most misconduct is

deliberately concealed—and much if not most remains hidden.

20

That means that wrongful

murder convictions are also more likely to include undiscovered misconduct when the

defendant is Black: in exonerations for which some misconduct already is known, in those with

no known misconduct, and among false murder convictions that have not resulted in

exoneration.

Delay. Black murder exonerees spend longer before release than white murder exonerees, about

16 years on average compared to about 13, whether or not they were sentenced to death. Three

additional years in prison is a severe penalty. For reference, the average total time spent in

prison for drug crime exonerees is about one year; excluding those who served no time because

they got probation, it’s still under two years. This longer pipeline to exoneration also means that,

at any given time, a larger proportion of Black murder defendants who will eventually be

exonerated are still in prison.

Murder exonerations with known misconduct do take longer than those without, 17.7 years to

12.2 years, on average. The higher rate of misconduct in cases with Black exonerees may cause

some of the longer average time they wait to be exonerated, perhaps because the authorities

resist exoneration more strenuously in cases with government misconduct. The longer time to

exoneration for Black exonerees may also contribute to the higher rate of known misconduct

because it provides a better opportunity for misconduct that occurred to be discovered. In any

event, differences in time to exoneration by race persist even after controlling for government

misconduct. Among murder exonerations with official misconduct, the average time to

exoneration is 19.1 years for Black exonerees and 16.6 years for white exonerees; among murder

exonerations without misconduct, it’s 13.3 years for Black exonerees and 11.3 for whites.

It seems that innocent Black people who are convicted of murder are at a disadvantage not only

because their convictions were more likely to have been influenced by official misconduct, but

also simply because of their race.

Consider this case:

In 1984, 19-year-old Henry McCollum and his 15-year-old half-brother, Leon

Brown, were sentenced to death for the rape and murder of 11-year-old Sabrina

Buie in Robeson County, North Carolina. McCollum and Brown were from New

20

In some contexts, the fact that we can only report on misconduct that has been uncovered can lead to reporting

biases. For example, the rate of observed misconduct in death penalty exonerations is almost twice the rate for

sexual assault exonerations, 78% vs. 41%. That may be due to a higher rate of misconduct in capital murder

investigations and prosecutions, at least among cases that end in exoneration; it may also be due, at least in part, to

a higher rate of uncovering whatever misconduct occurred in post-conviction investigations in capital cases. Death

sentences are re-examined more thoroughly than other crimes, and the trials that produce them are heavily litigated

in successive reviews. As a result, we are more likely to know if misconduct was committed in capital cases. By

contrast, many rape exonerations are based entirely on DNA tests that clear the innocent defendant but provide no

information about any chicanery that may have led to the false conviction—which can create a false impression that

no misconduct occurred. Because of the danger of biases such as this, we are generally cautious in making

generalizations about patterns of misconduct from the data in the Registry. That danger does not apply to the

comparisons we make here. We can think of no plausible reason why official misconduct leading to a murder

conviction of an innocent person is more likely to come to light if the defendant is Black than if he is white. The racial

disparities we see seem to be caused by real differences in the rates of official misconduct in murder cases, mostly

by police officers.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 9 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Jersey; they were visiting relatives in North Carolina. Both were intellectually

disabled, and both falsely confessed under pressure from police. No physical

evidence connected them to the crime.

In 2010, after decades of unsuccessful efforts to prove their innocence through

the courts, the North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission agreed to

investigate the case. It determined that DNA from a cigarette butt found at the

scene of the crime came from Roscoe Artis, a proven serial murderer and rapist

who was himself sentenced to death for raping and killing an 18-year-old woman

in the same county about a month after McCollum and Brown had confessed.

Artis had been a suspect in the Sabrina Buie rape-murder. In 1984, the police had

asked the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigations to compare the

fingerprints found on beer cans at the crime to those of Artis—but they hid that

request from the defense. The authorities also concealed the fact that a witness

who testified at trial that McCollum and Brown had admitted to the murder, had

not only previously denied knowing anything about the case, but had taken a lie

detector test that confirmed his denial.

McCollum and Brown were exonerated in 2014, after nearly 31 years in prison.

They were pardoned by the Governor of North Carolina in 2015 and received

$750,000 each in compensation from the state. Even so, after their release the

prosecutor who sent them to death row told The New York Times: “No question

about it, absolutely they are guilty.”

Certainly there was misconduct that contributed to the conviction of McCollum and Brown, and

that may have contributed to the decades of resistance to reopening the case. Did it also matter

that the defendants were Black—as well as strangers to the community and intellectually

disabled? Did their race contribute to authorities’ unjustified and apparently unexamined

confidence in their guilt even as evidence of innocence mounted? That would fit the data we see

across cases.

McCollum and Brown are two of 75 innocent death-row defendants who spent 30 years or

longer in prison before they were exonerated, 67% of whom are Black (50/75).

The racial pattern is similar for all murder exonerees, regardless of sentence. Of the 181

exonerees who spent 25 years or longer in prison before release, 68% are Black; among the ten

who lost 40 or more years to prison, it’s 80%.

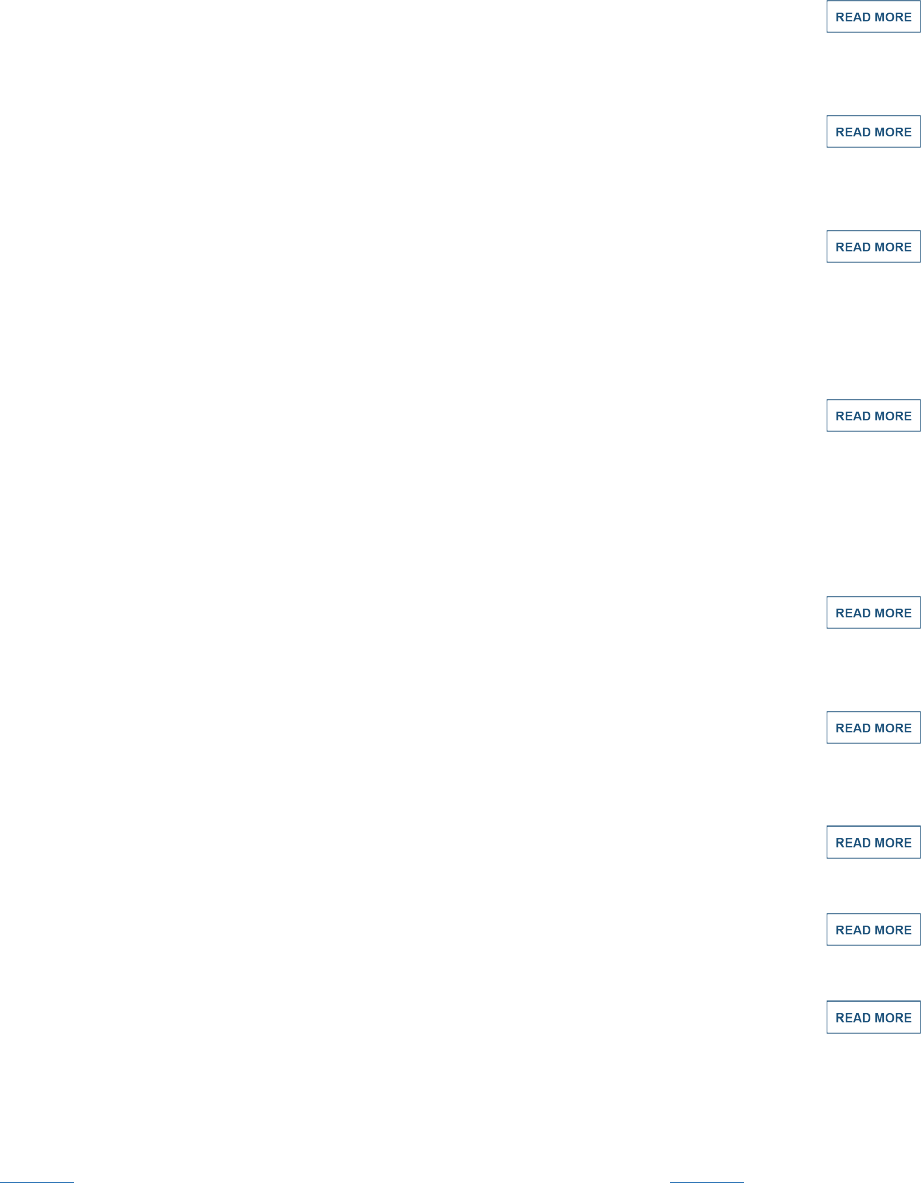

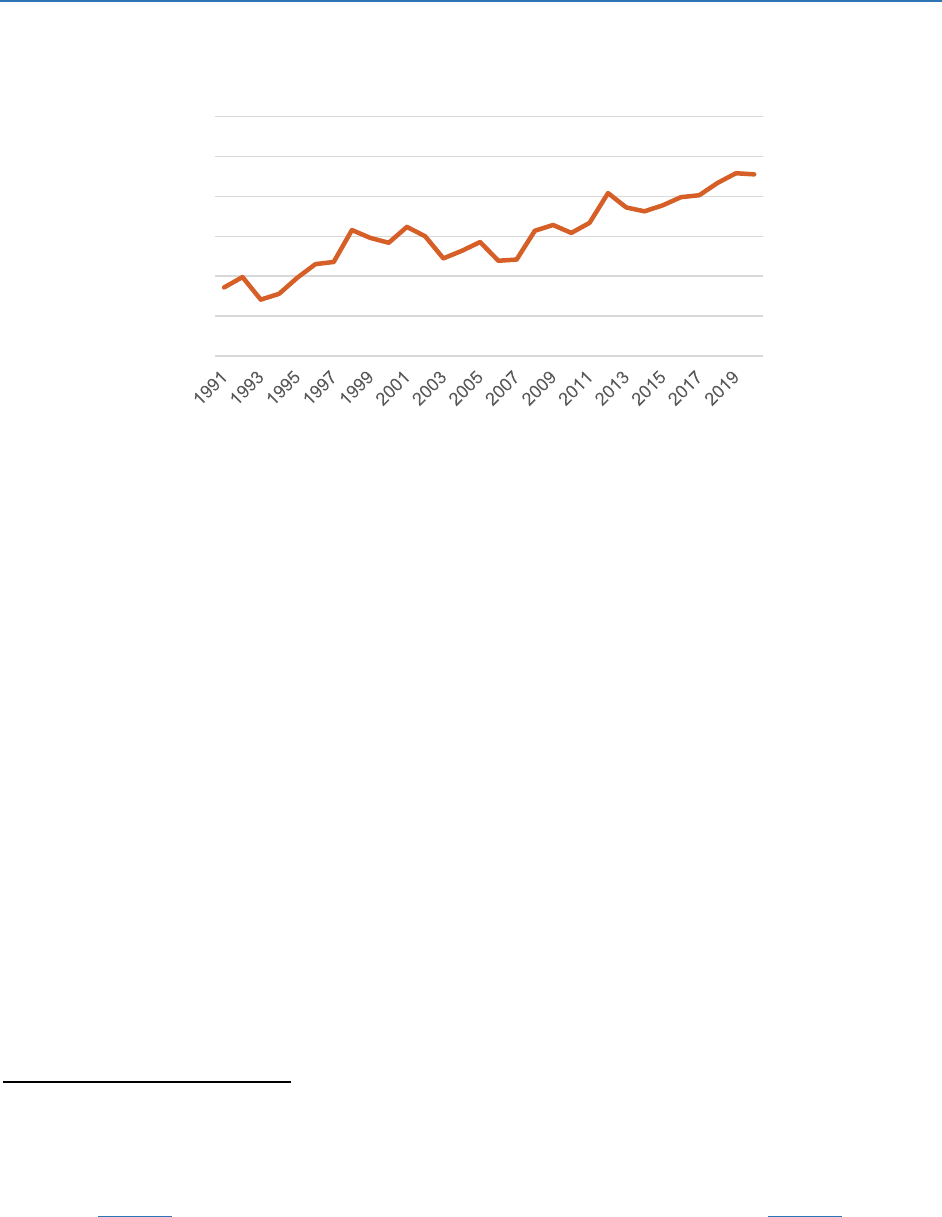

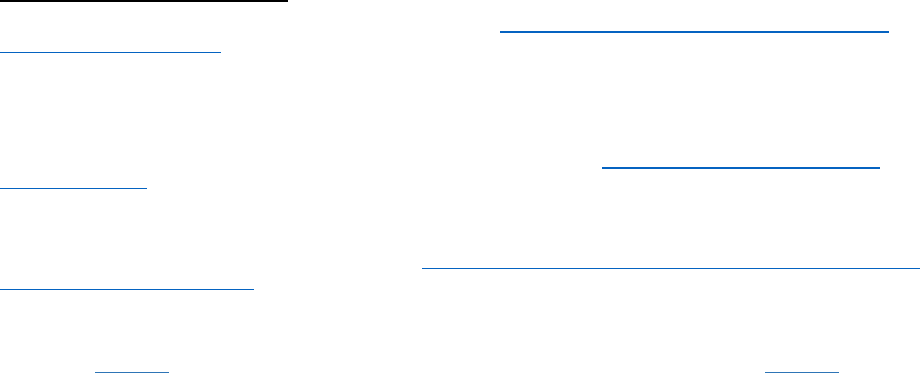

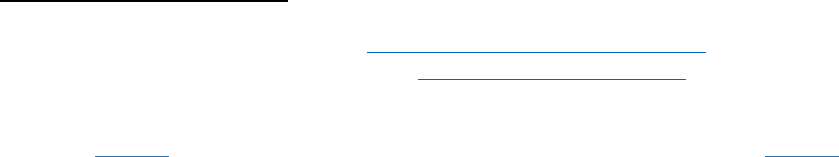

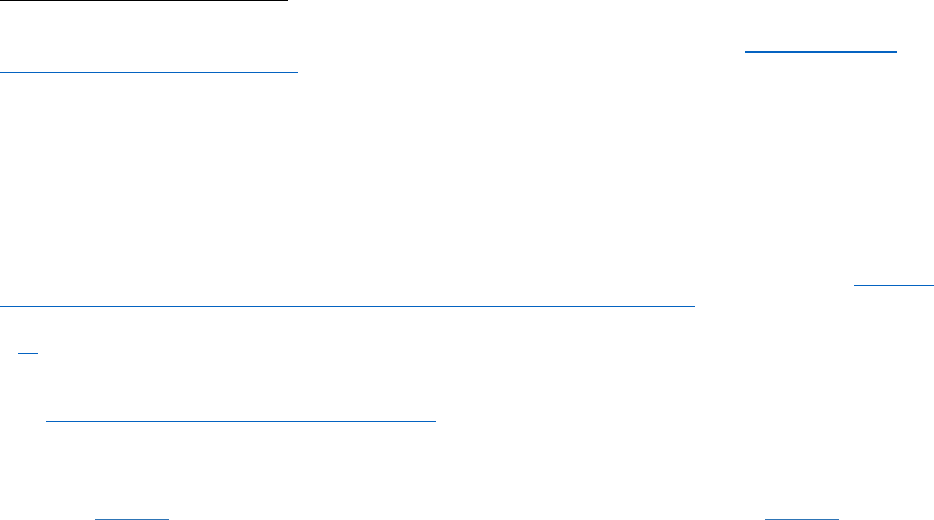

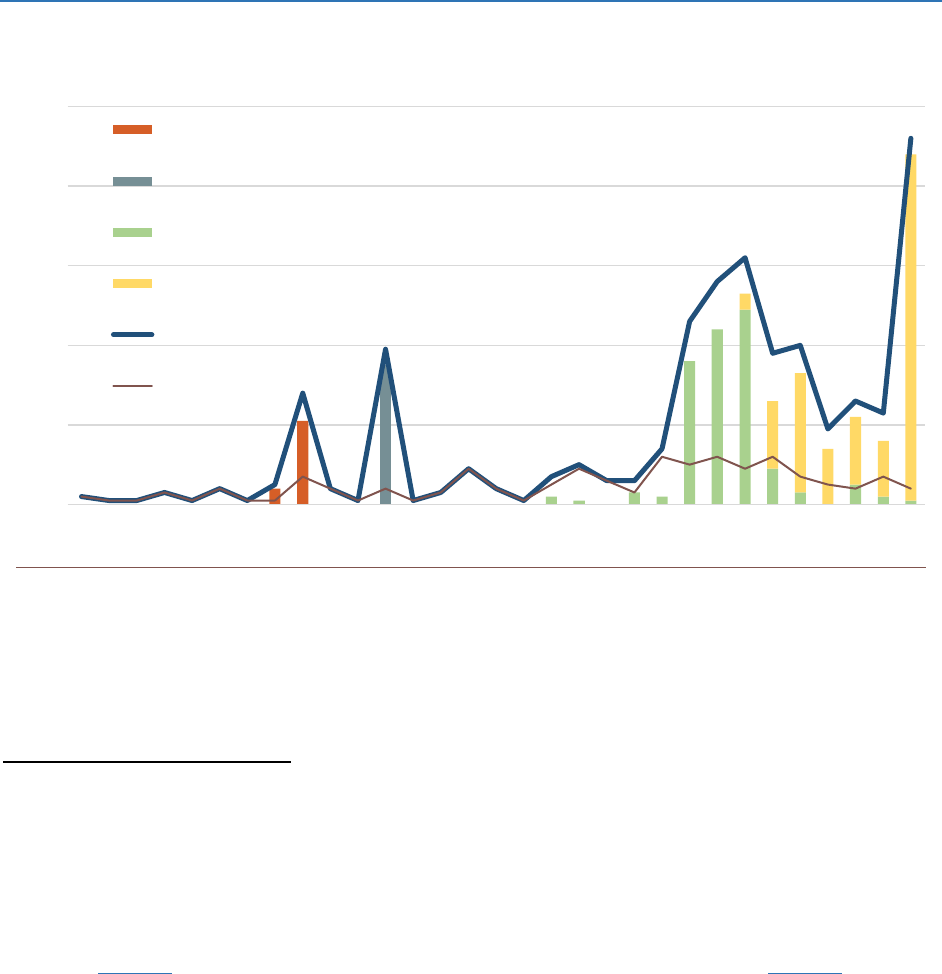

c) Changes over time

We can date an exoneration in at least two ways. The conventional one is by the date the

exoneration itself occurred, the occasion on which the defendant was finally cleared. This

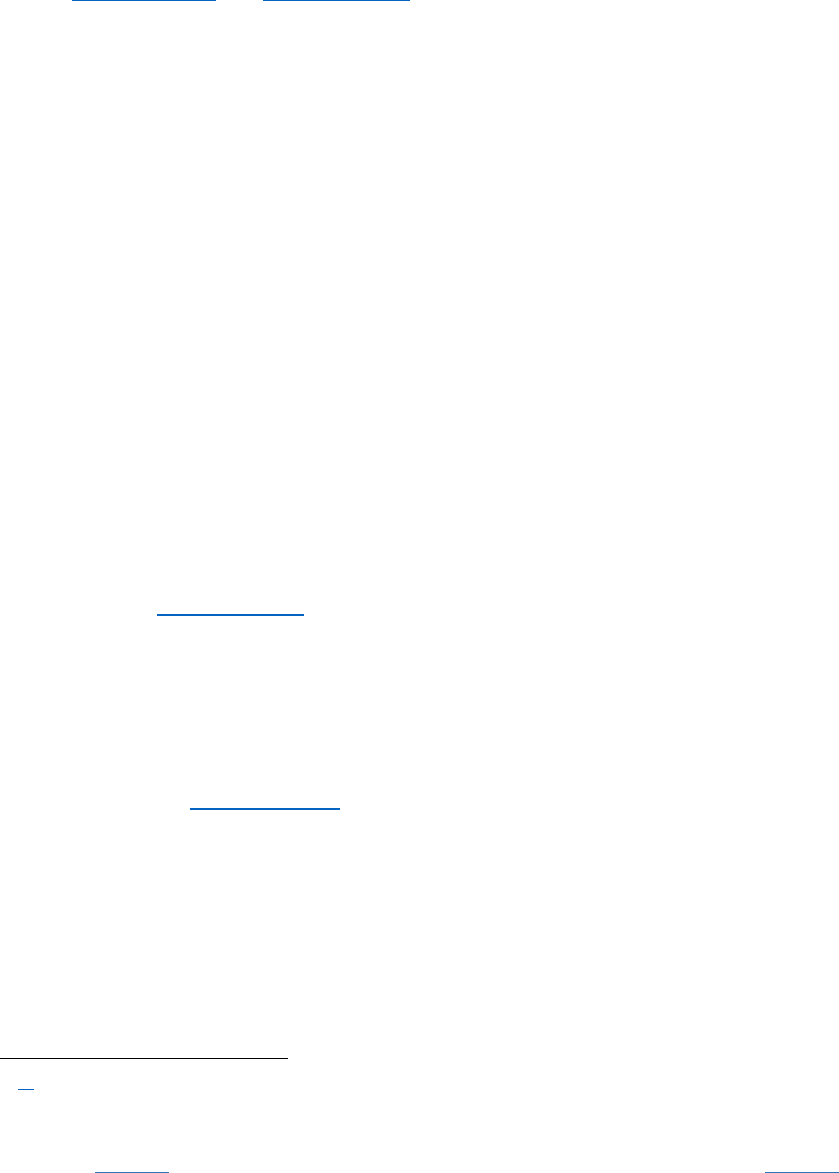

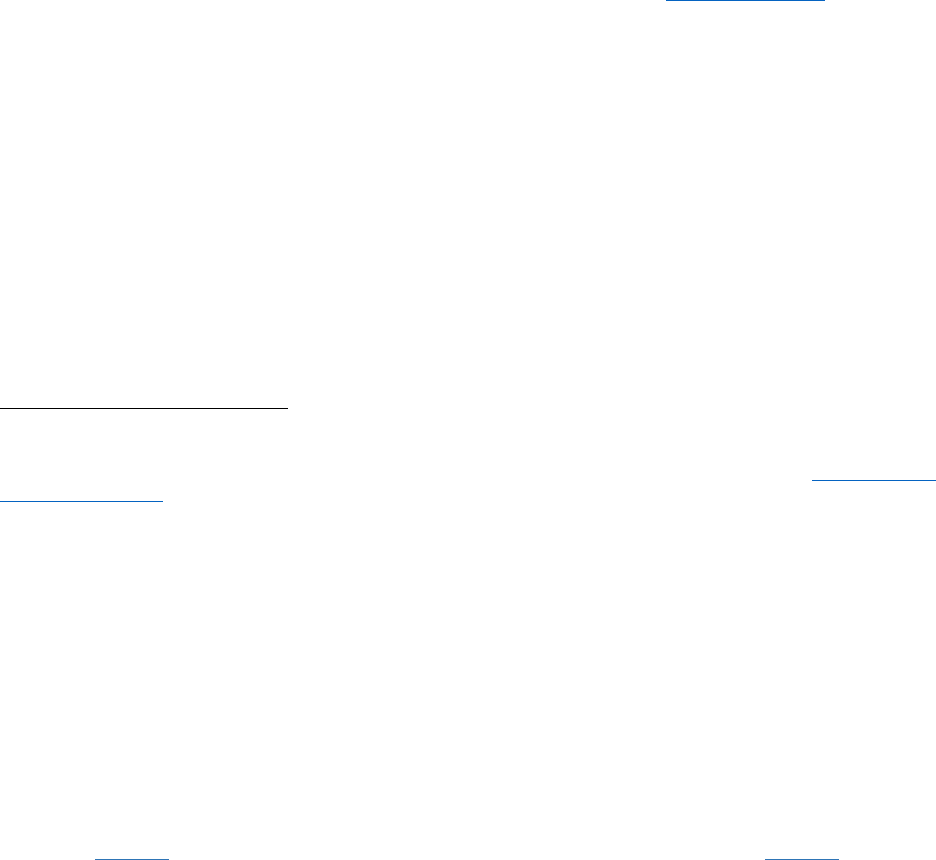

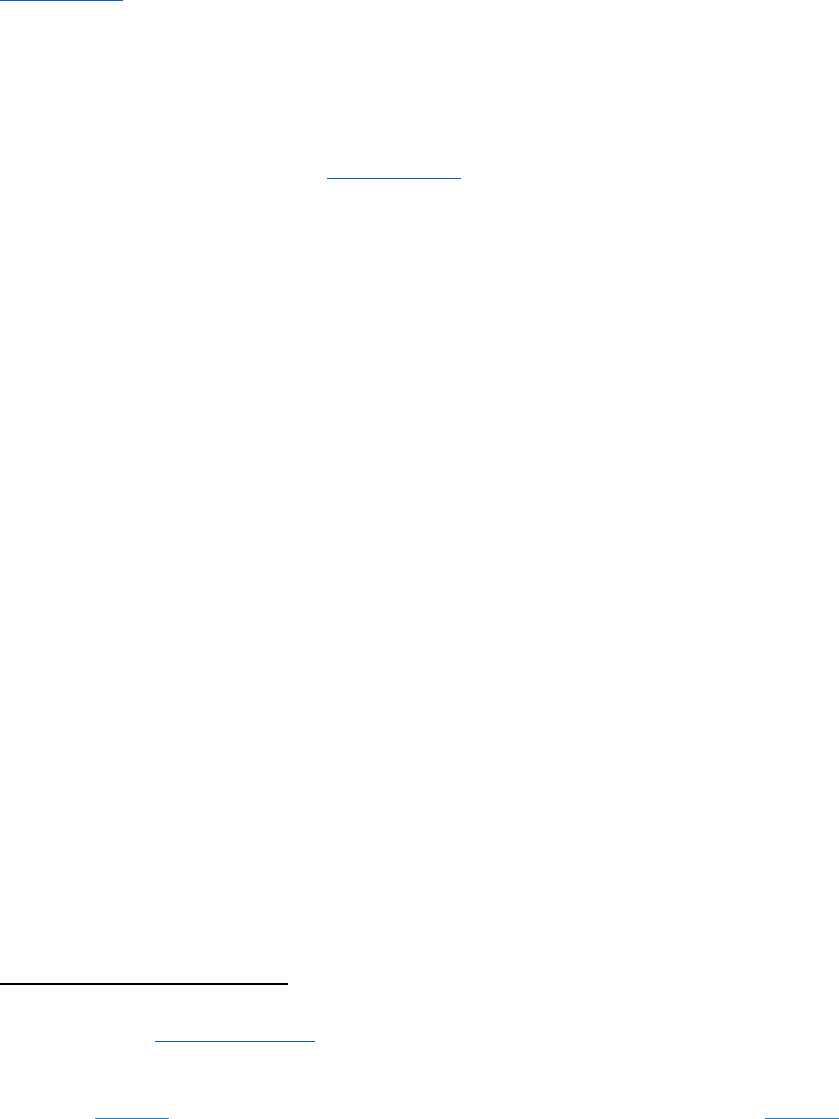

sorting describes that timing of the process of exonerating innocent defendants. Figure 1, for

example, shows that the annual number of murder exonerations has been growing pretty

steadily since 1989.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 10 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

Figure 1: Number of Murder Exonerations by Year of Exoneration

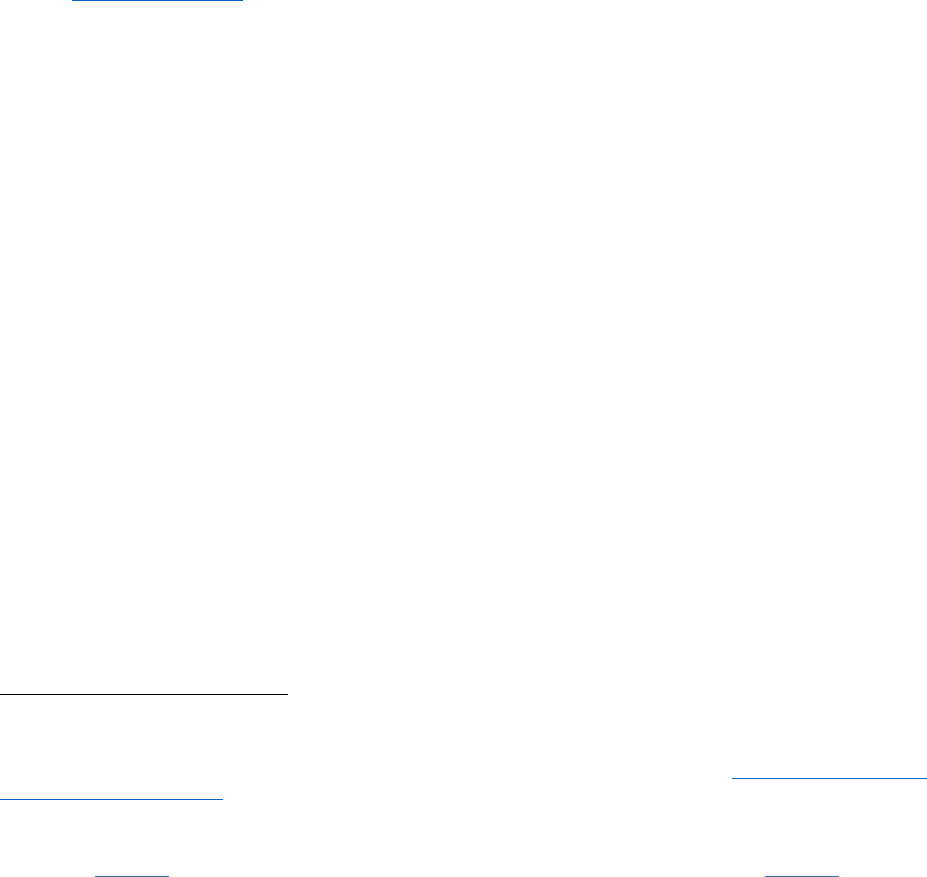

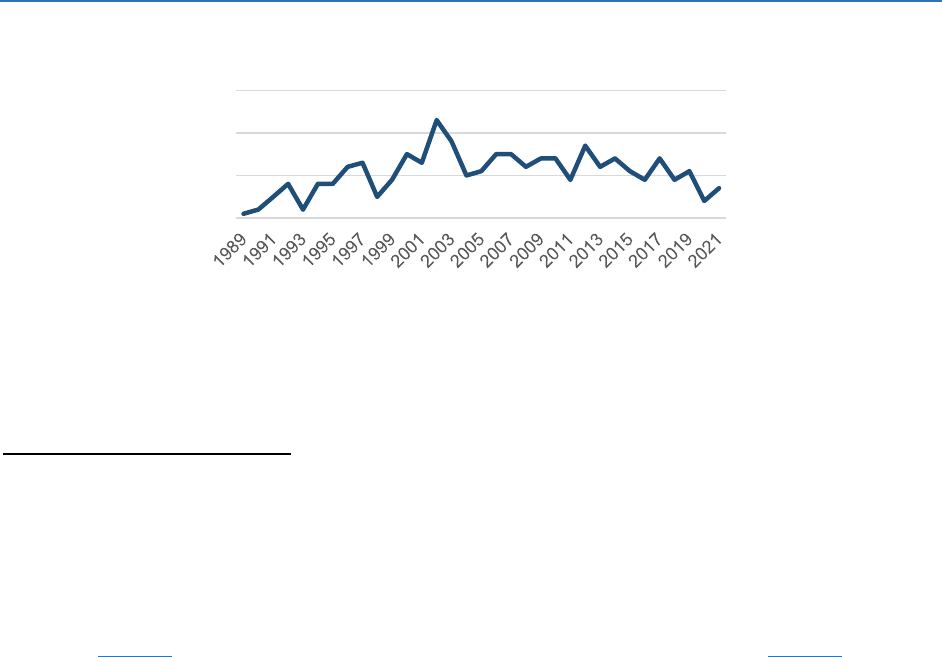

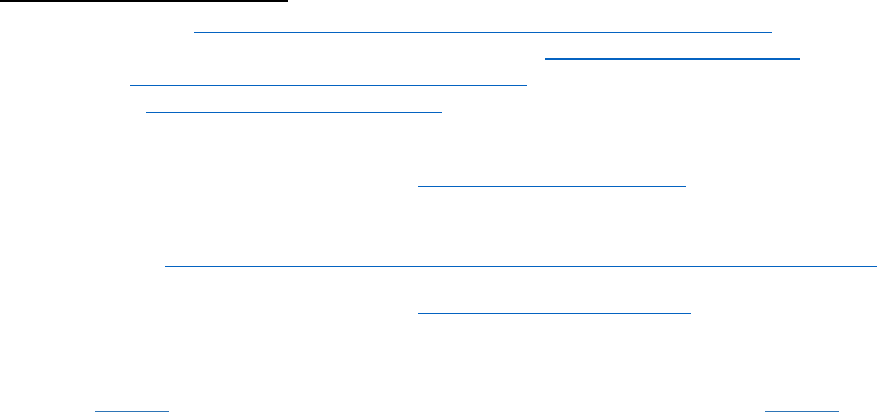

In order to study the process that led to an innocent defendant’s conviction, however, we need

to focus on the period leading up to that event, and classify exonerations by date of conviction.

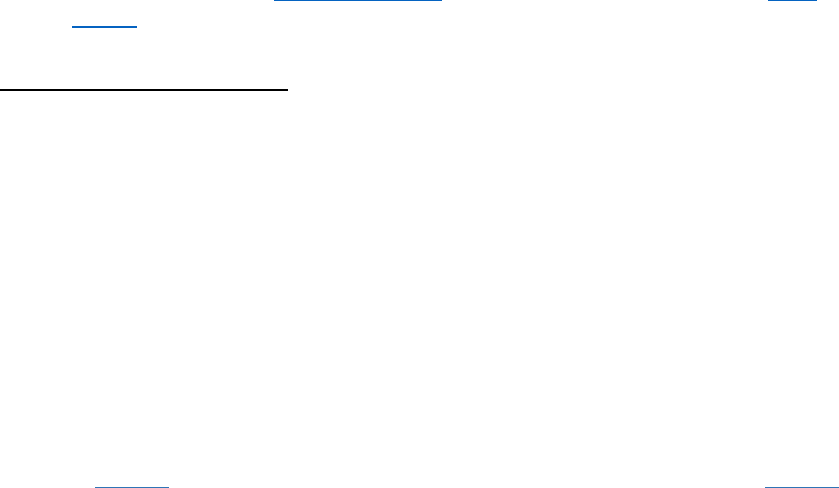

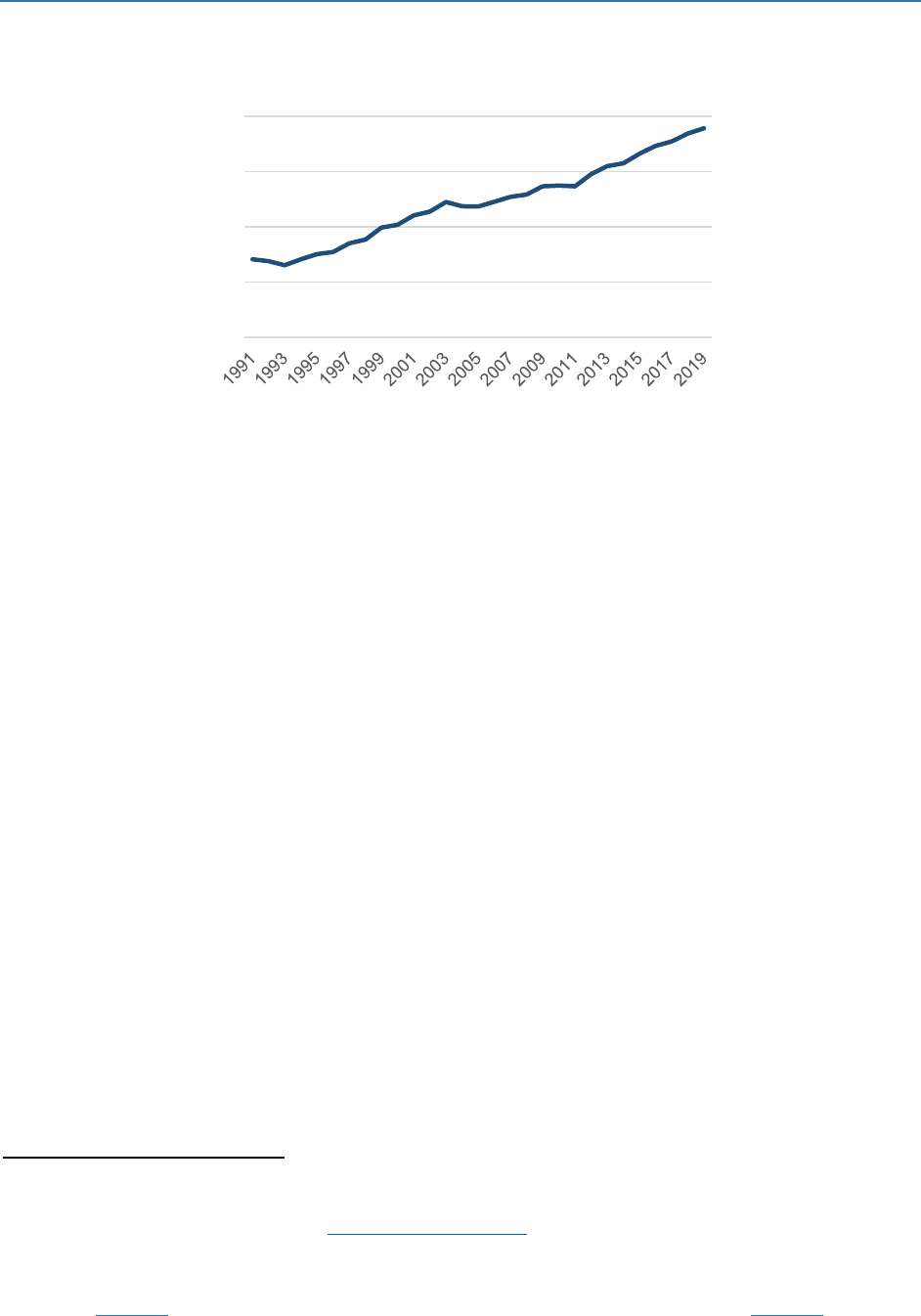

Figure 2 displays the number of murder exonerations by the year in which the exonerees were

convicted. It shows that dates of conviction are more spread out than dates of exoneration; they

range from 1956 to 2019, and rise to a sharp peak from 1992 to 1998.

Figure 2: Number of Murder Exonerations by Year of Conviction

A major reason for the drop off in exonerations for convictions after the mid-1990s is the time

lag from conviction to exoneration, which averages 16.2 years for murder exonerations. As a

result, many exonerations that will eventually happen for murder convictions after 1995 have

not yet occurred, including some in cases that are already more than 25 years after conviction.

It’s likely, however, that even when all those murder exonerations are recorded, there will be a

peak for convictions in the mid-1990s because the all-time high-water mark in the number of

murders in the United States lasted from 1990 to 1994, with convictions trailing by one to a few

years.

21

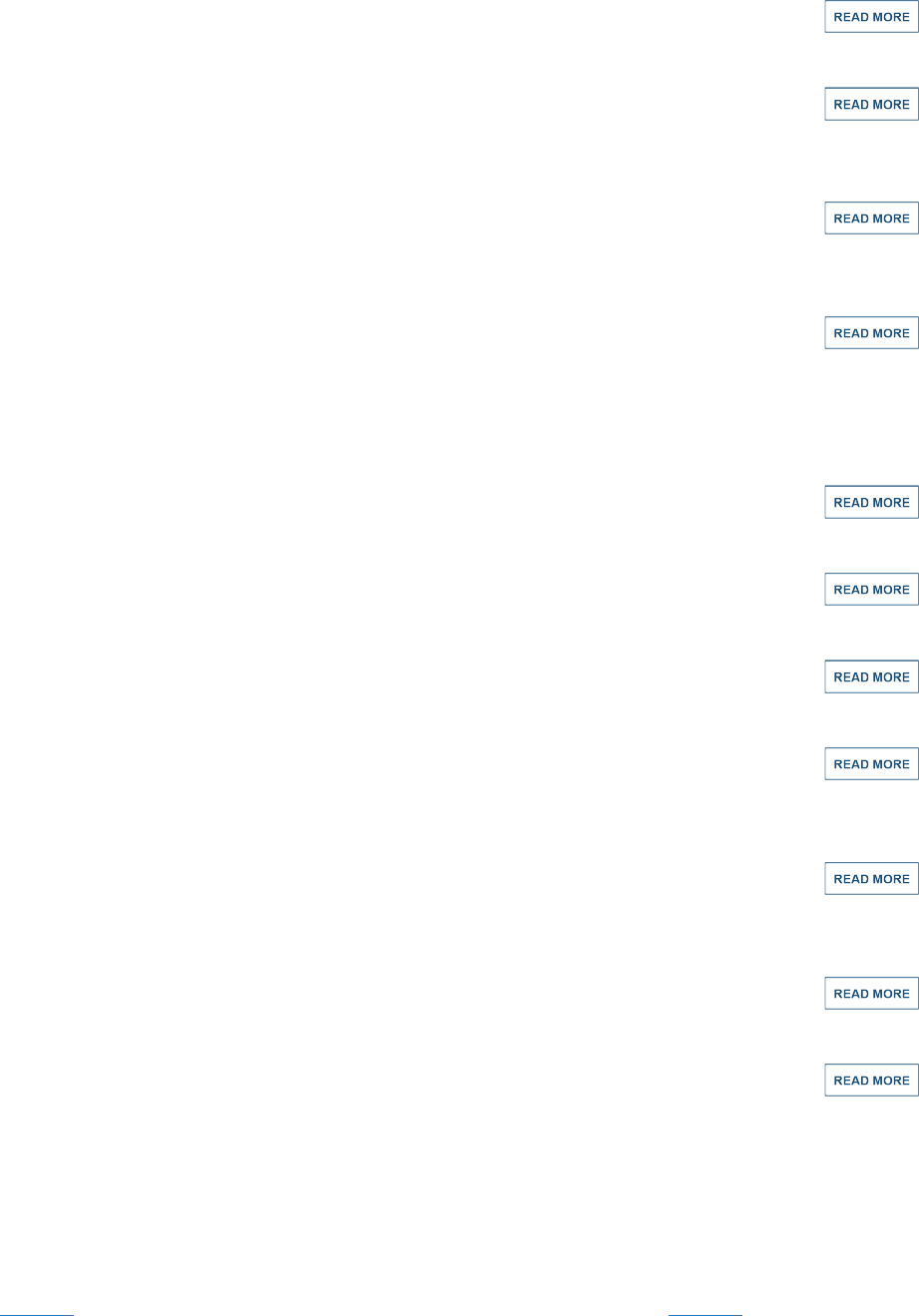

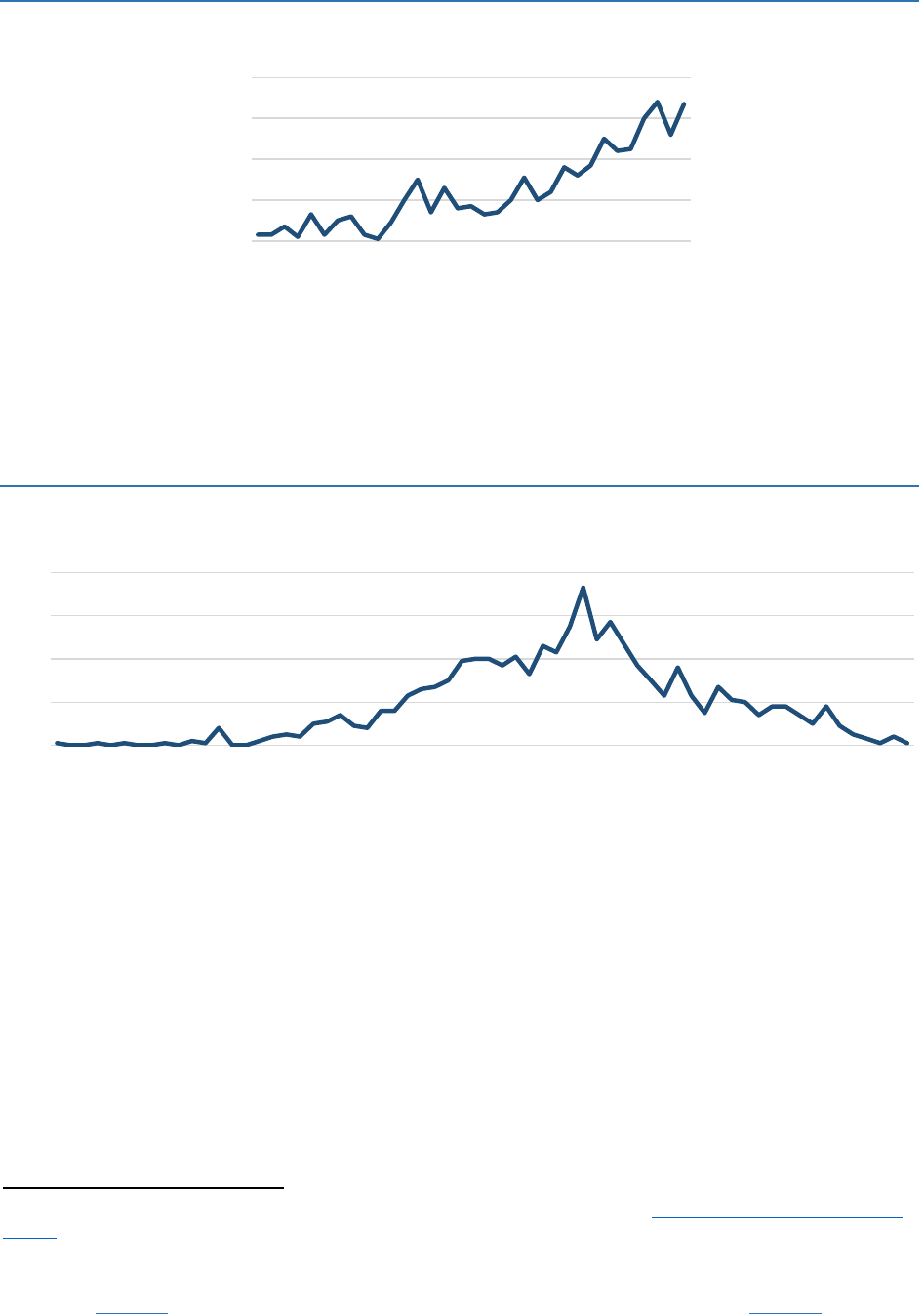

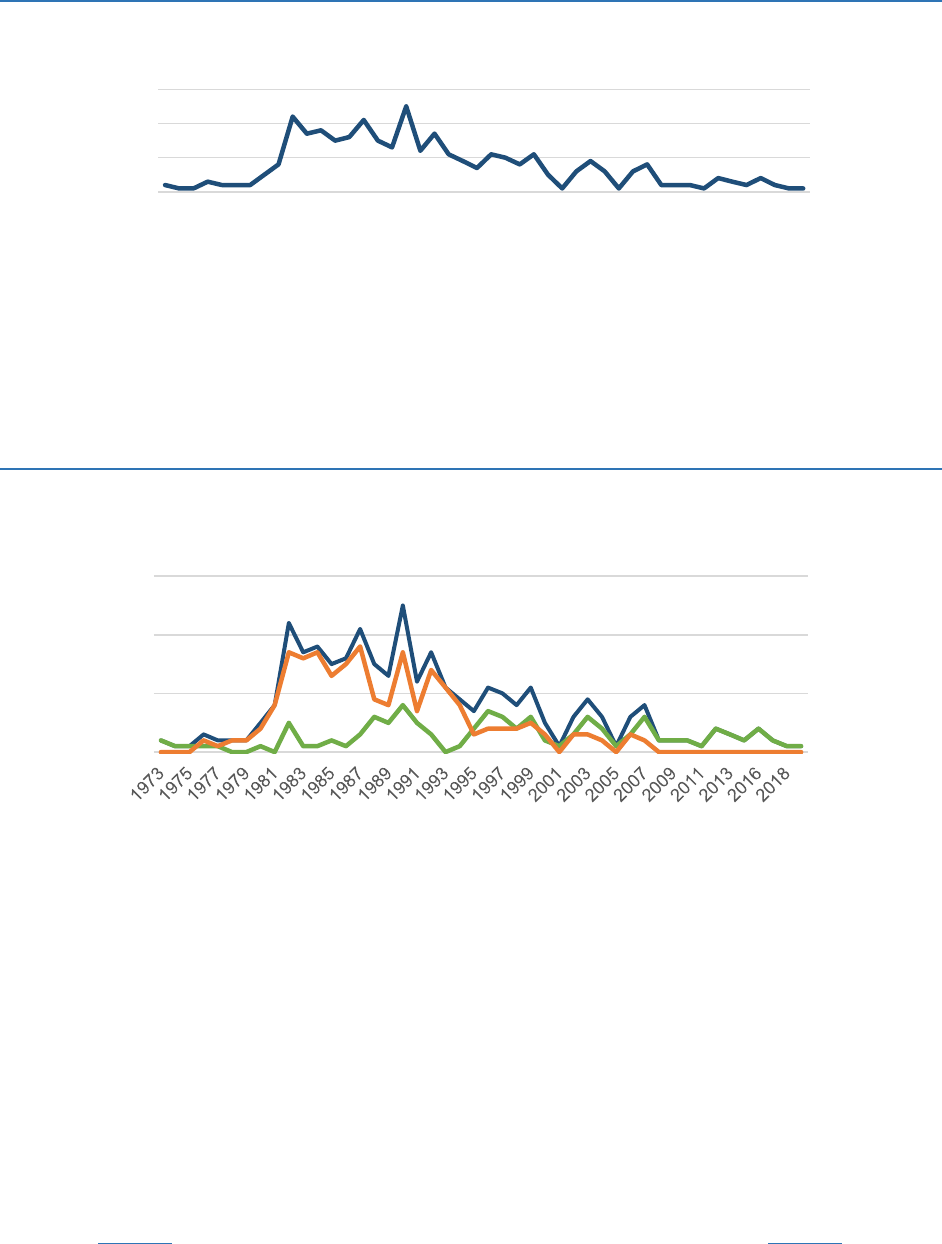

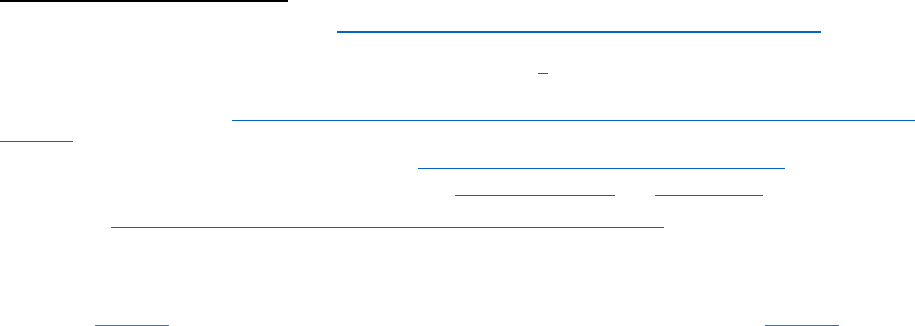

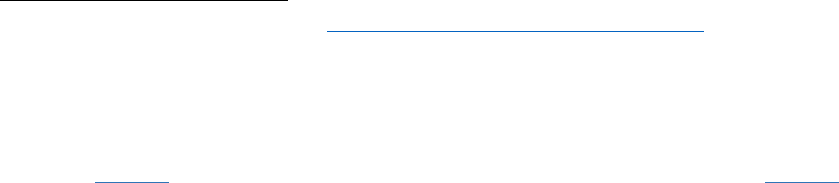

If we separate out homicide exonerations by race of defendant, we see more Black murder

exonerees than white for all but a handful of years of conviction, despite the fact the Black

people are a small minority of the population. This disparity is concentrated—and accounts for

21

For a useful compilation of FBI crime statistics by year, see The Disaster Center, Unites States Crime Rates 1960

– 2019.

10

30

50

70

90

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

2021

0

20

40

60

80

1956

1958

1960

1962

1964

1966

1968

1970

1972

1974

1976

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 11 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

the largest number of cases—in the period from 1992 through 2000, the years for which the

number of all murder exonerations is highest. See Figure 3.

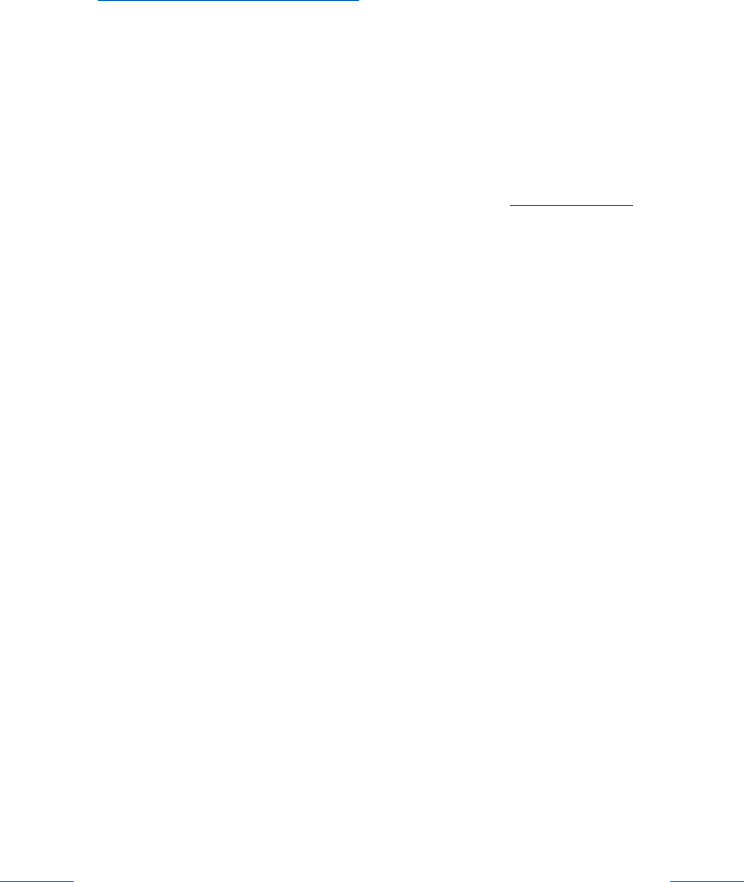

Figure 3: Number of Murder Exonerations by Year of Conviction and Race of Defendant

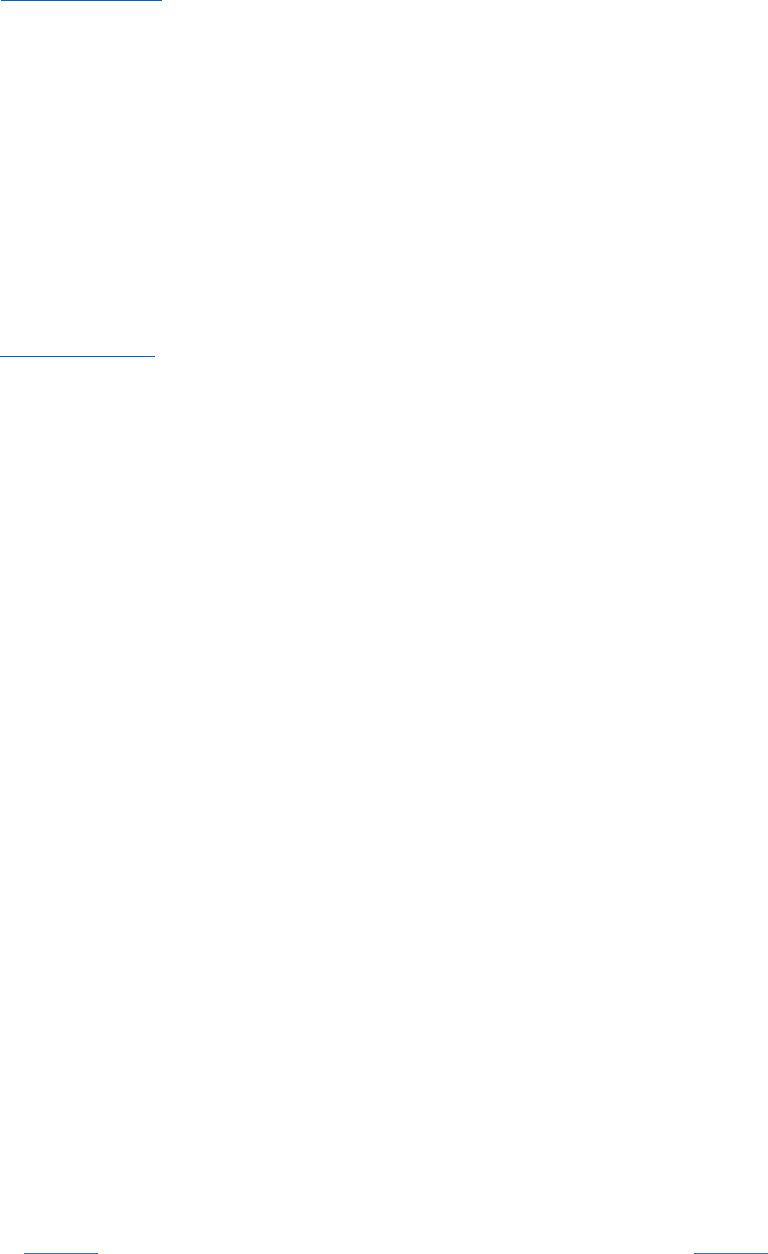

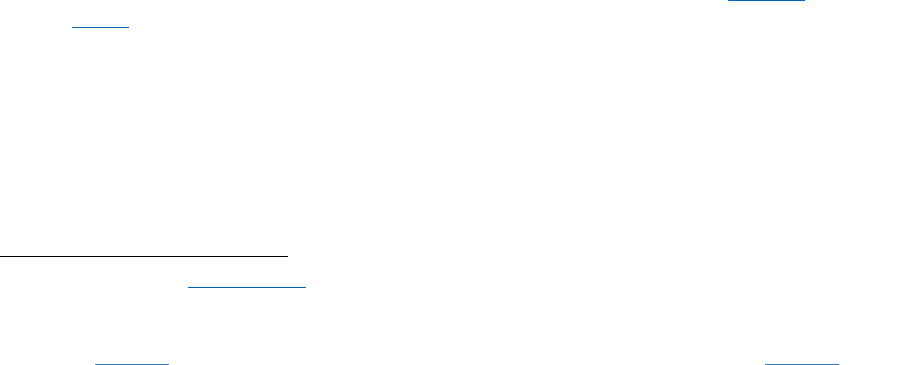

Figure 4 displays a running 5-year average of the percent of murder exonerations with Black

exonerees. By year of conviction, this proportion has remained fairly stable since 1980, ranging

back and forth from 45% to 61%, between three-and-a-half and four-and-a-half times the

proportion of Black people in the population.

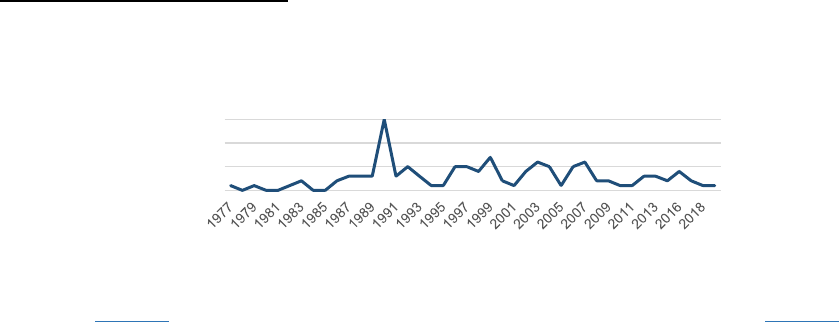

Figure 4: Percent of Murder Exonerations with Black Defendants by Year of Conviction

(Five-Year Moving Average)

22

22

For each year, the value of the “Five-Year Moving Average” in Figure 4 is the average of the values for that year,

the two years before and the two years after.

0

20

40

60

80

1956

1958

1960

1962

1964

1966

1968

1970

1972

1974

1976

1978

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

All

Black

White

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 12 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

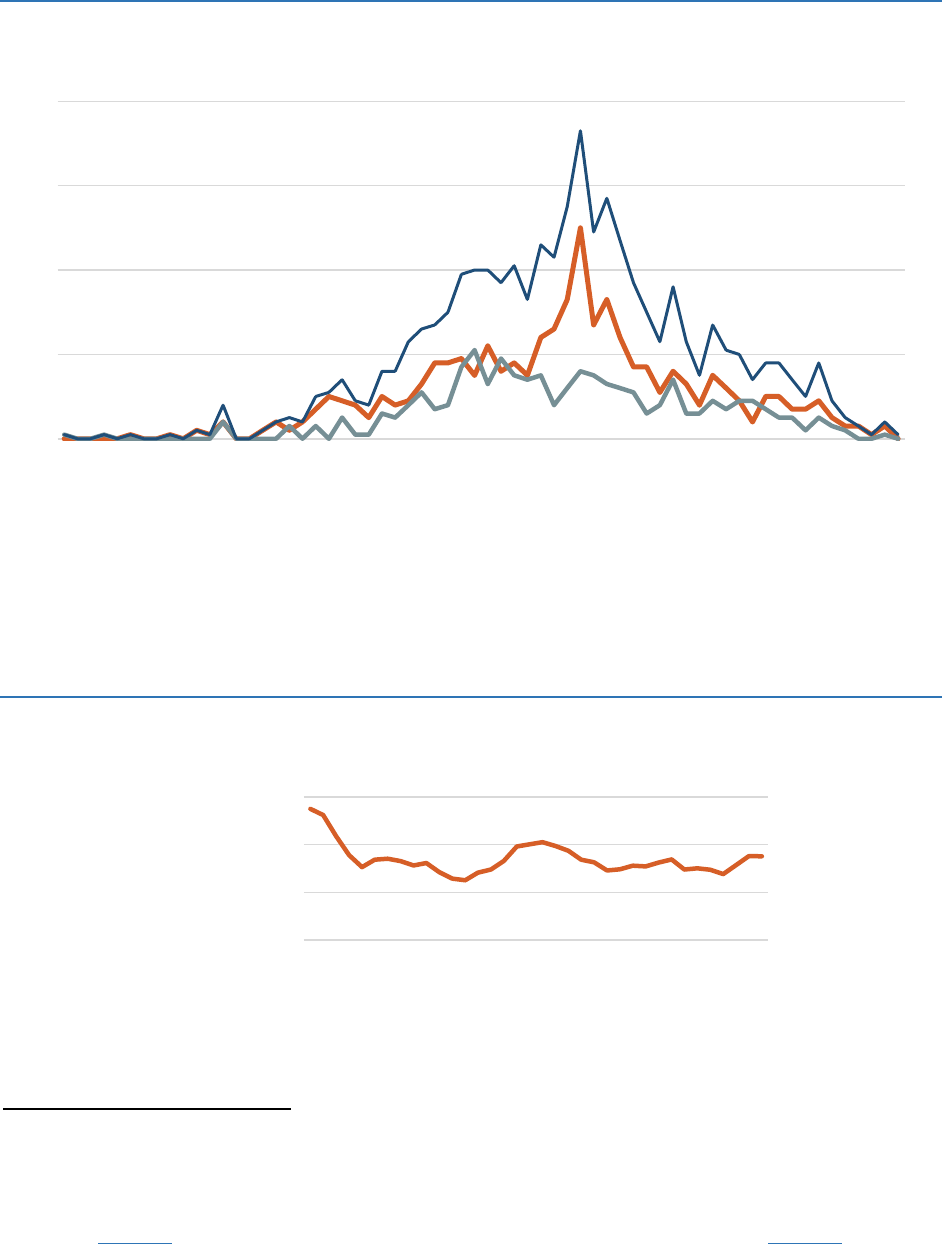

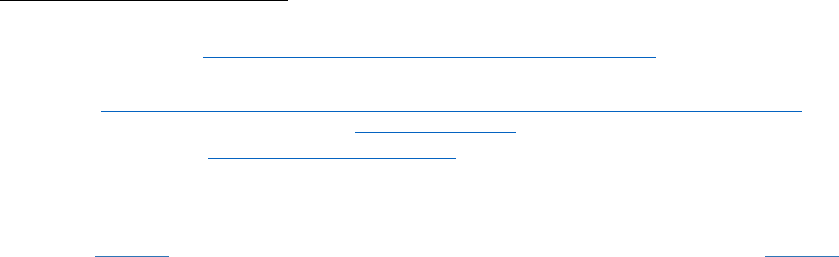

On the other hand, there has been a large and reasonably steady increase in the proportion of

Black murder exonerees by year of exoneration, from 37% in 1991 to 66% in 2020, as we see in

Figure 5.

Figure 5: Percent of Murder Exonerations with Black Defendants by Year of Exoneration

(Five-Year Moving Average)

23

Why has there been a sharp increase in the percentage of Black murder exonerees by year of

exoneration since 1991 (Figure 5), while the percentage of Black murder exonerees by year of

conviction remained roughly steady (Figure 4)? The answer turns on two other patterns. First,

as we saw in the previous section, Black murder exonerees spend on average three years longer

in prison before exoneration than white murder exonerees. Second, as we see in Figure 6, the

average time spent in prison for all murder exonerees nearly tripled over the same period, from

less than 7 years for those cleared in 1991 to 19 years for those exonerated in 2019.

23

For each year, the value of the “Five-Year Moving Average” in Figure 5 is the average of the values for that year,

the two years before and the two years after.

20.0

30.0

40.0

50.0

60.0

70.0

80.0

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 13 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

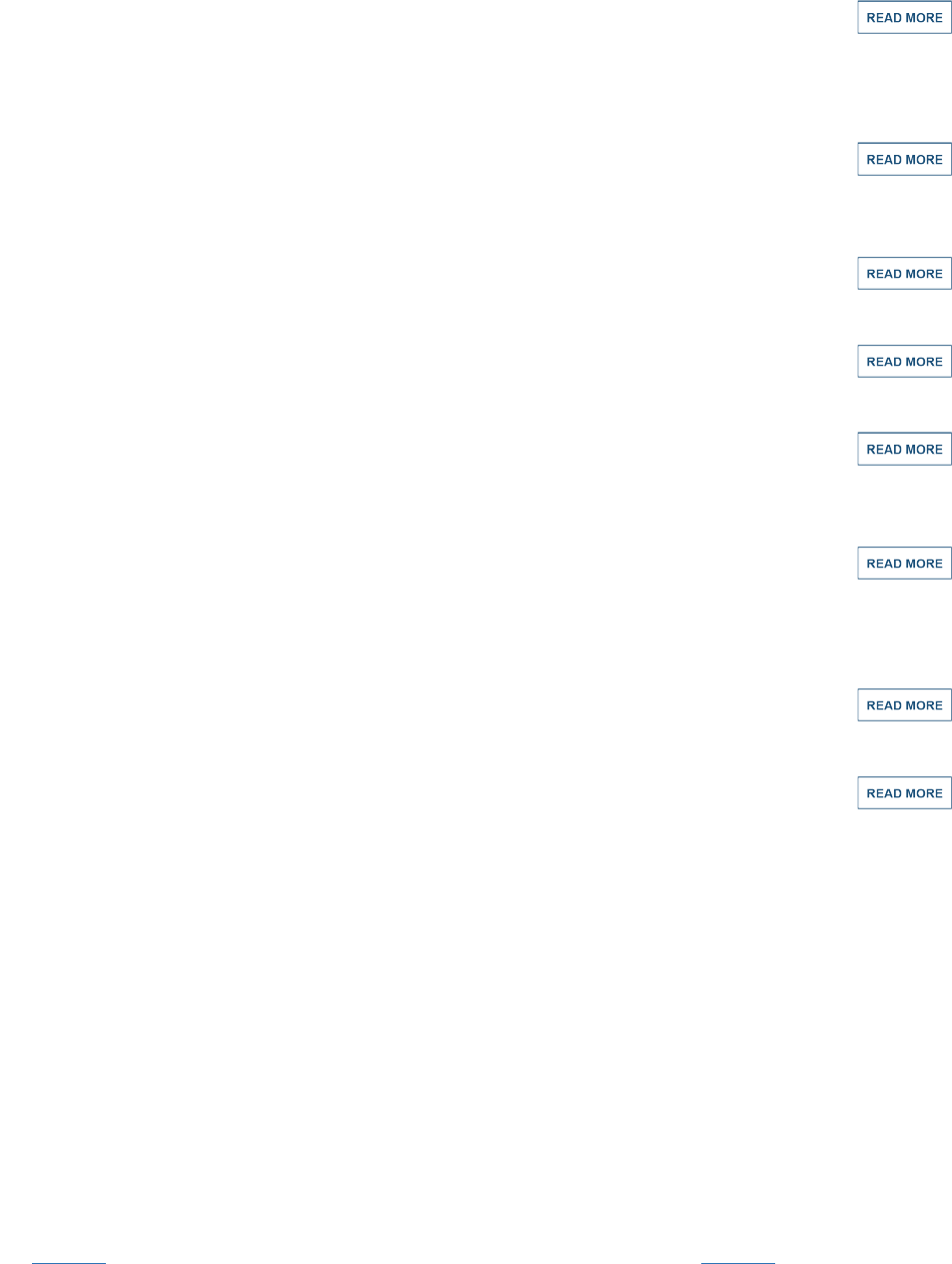

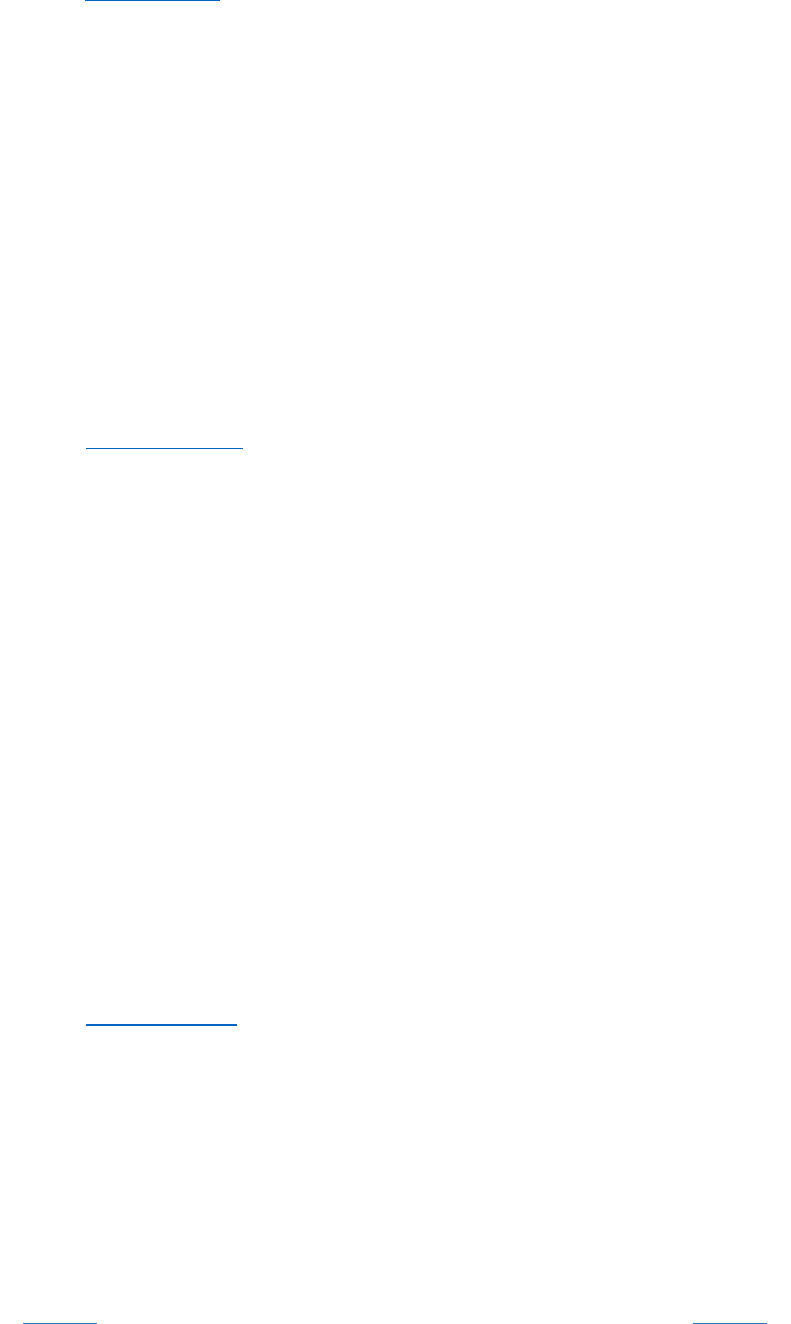

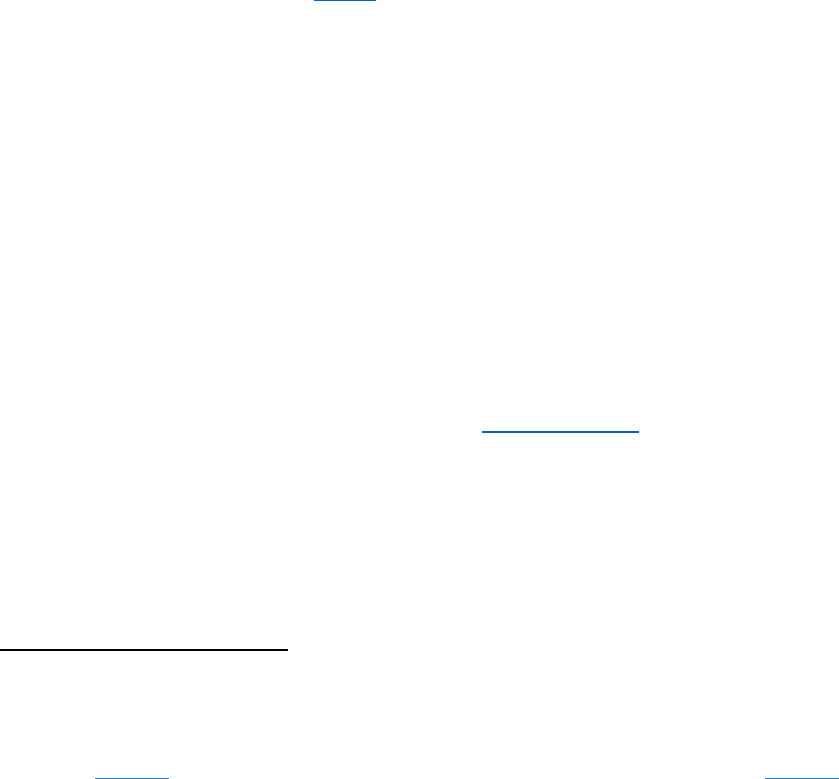

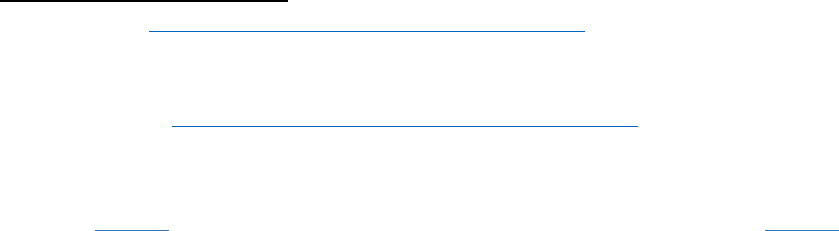

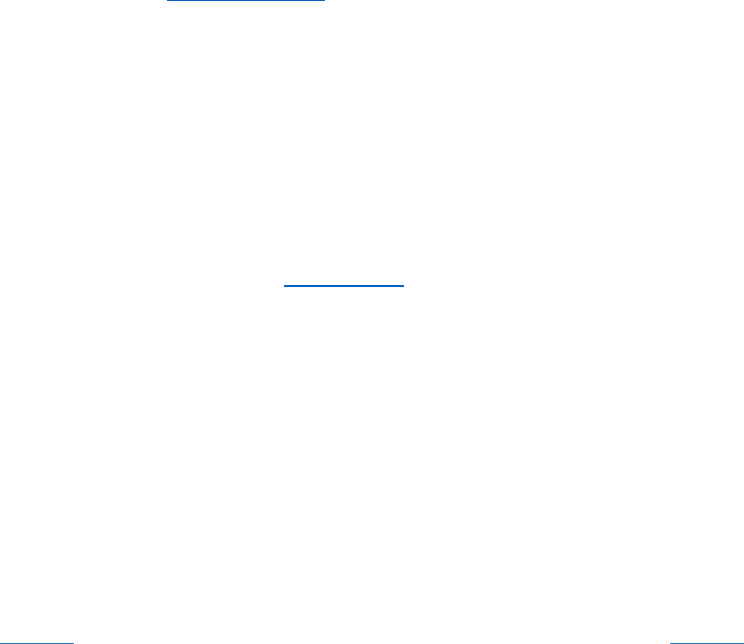

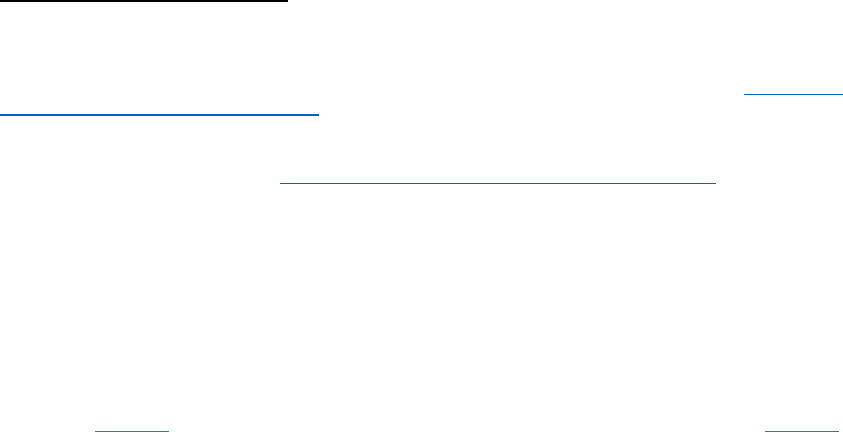

Figure 6: Years in Prison before Murder Exonerations by Year of Exoneration (Five-Year

Moving Average)

24

The rate of exonerating innocent murder defendants has picked up steam in spurts since 1989,

rising from about 16 a year through 1993, to 69 murder exonerations a year for the most recent

five-year period. See Figure 1. Along the way, it seems that many of those who worked on these

exonerations—innocence organizations, defense attorneys, prosecutors, judges—began to focus

attention on innocent murder defendants who remained in prison and had been there the

longest.

This process would have occurred at different times in different offices, courts and counties. In

many, probably most, it will happen—if ever—in years to come. But whenever it happens, in

most large American counties, the great majority of the innocent murder defendants who are

identified will be Black prisoners who’ve been ignored for 10, 20, 30 years, or longer. As they are

exonerated, the proportion of Black murder exonerees will rise—as will the average time from

conviction to exoneration. How could it be otherwise? Innocent Black defendants are not only

more likely to be convicted of murder than innocent white defendants, they also receive harsher

sentences and were less likely to be exonerated in early years after conviction.

Many of the innocent Black murder defendants who spent decades in prison were exonerated by

Conviction Integrity Units (CIUs), divisions of prosecutorial offices whose mission is to prevent,

identify, and correct false convictions.

25

The first CIU was founded in 2002 and did little. As of

2007, there were two CIUs in the country; they had been involved in three exonerations. And

then the numbers began to climb exponentially—literally—doubling every few years. By the end

of 2012 there were 9 CIUs across the country; in 2015 there were 24; in 2018, 44; at the end of

2021, 93.

The number of CIU exonerations has followed a similar pattern. From 2008 through 2013, there

were 42 CIU exonerations, an average of 7 a year. In 2014 alone there were 51 CIU exonerations.

24

For each year, the value of the “Five-Year Moving Average” in Figure 6 is the average of the values for that year,

the two years before and the two years after.

25

The National Registry of Exonerations, Conviction Integrity Units.

0.0

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 14 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

From 2015 through 2021, there were 441 CIU exonerations, an average of 63 a year, 37% of all

exonerations in that period (441/1,200).

Since the beginning of 2014, when CIU exonerations became common, CIUs have been involved

in about a third of all murder exonerations (170/538). Sixty-three percent of all murder

exonerees in this period are Black (337/538), compared to 52% for the eight years from 2006

through 2013 (141/270)—in line with the upward trend we see in Figure 5. But only 54% of non-

CIU murder exonerations since 2014 had Black defendants (199/368), compared to 81% of CIU

murder exonerations (138/170). In other words, almost all of the increase in the proportion of

Black murder exonerees in the last eight years is due to the extraordinary concentration of Black

exonerees in CIU murder exonerations. The CIU murder exonerees in this period spent more

time in prison before exoneration, about 21 years on average, compared to 17 for non-CIU

murder exonerees.

Have CIUs been addressing a backlog of innocent Black murder defendants from decades past?

Some clearly have. For example:

In 1988, Curtis Crosland, a 23 year-old Black man, was convicted of murder in

Philadelphia for shooting a grocery store owner during a robbery. He was

sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Crosland’s conviction

was based primarily on evidence that a witness, who refused to testify at trial, had

testified at a preliminary hearing that he heard Crosland admit that he shot the

store owner. That conviction was reversed on appeal, but Crosland was convicted

again in 1991 based on similar evidence, except that at the second trial the main

witness did testify and explicitly recanted his earlier testimony at the preliminary

hearing.

Over the next 29 years, Crosland and various attorneys working with him

petitioned state and federal courts many times to reopen his case. Along the way,

they obtained statements from three witnesses who had not testified at trial—one

who was in the store and two who were at a window across the street —who did

not see Crosland but did identify other men who were at the scene with guns. All

of those petitions were rejected.

In 2018, Larry Krasner took office as District Attorney of Philadelphia. In his

election campaign, he promised to invigorate the county’s Conviction Integrity

Unit, which until then had participated in three exonerations over a period of

four years. In 2020, a much more active Philadelphia CIU agreed to review the

Crosland case. They found a trove of previously concealed evidence, including

documents that show that the main witness against Crosland had lied about that

case and other matters on many occasions; and that a man who had been seen at

the robbery by the witnesses who were found by Crosland’s post-conviction

attorneys had also been identified to the police as the shooter repeatedly, in the

initial investigation in 1988.

In late May 2021, in a proceeding in federal court, the Philadelphia District

Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit agreed that Crosland’s conviction should be

vacated because the trial prosecutors “violated Crosland’s right to due process by

not disclosing this evidence to him prior to trial, resulting in his wrongful

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 15 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

conviction.” In June 2021, charges were dismissed, and Crosland was released

after 33 years in prison.

Curtis Crosland is the twenty-second of 25 CIU murder exonerees in Philadelphia since 2014

26

—

92% of whom are Black. That number is highly unusual. Most CIUs have had no exonerations at

all so far (53/94), including at least nine units that opened five years ago or longer; many others

have been involved in only one or two exonerations.

27

The 138 Black CIU murder exonerees since 2014 are spread across 26 different CIUs, but not

evenly. Almost four-fifths (108/138)—including a third of all Black murder exonerees in the

United States in this period—come from CIUs in eight counties, all in large East Coast or

Midwestern cities: Philadelphia (23), Brooklyn (19), Detroit (19), Chicago (17), Baltimore (13),

Boston (7), Queens (6) and the Bronx (4).

28

There’s no reason to think this trend will slow down

in those cities, and as more CIUs become active the pace may accelerate.

In sum: We know how many exonerated murder defendants are Black—55%—but we don’t know

the percentage of Black people among all falsely convicted murder defendants. We also know

that Black murder exonerees spend longer in prison before exoneration than whites, which

means that when the rate of exonerations is rising, as it has been since 1989, innocent Black

defendants may be underrepresented among those who have been exonerated. Since the

beginning of 2014, the number of murder exonerees who spent 20, 30 or even 40 years in prison

has grown, and the proportion of murder exonerees who are Black has increased substantially. A

handful of big-city CIUs are responsible for most of that increase. Without them, 56% of murder

exonerees since the beginning of 2014 would have been Black; with them, it’s 64%.

d) Intentional and structural discrimination

In some cases, it’s easy to spot racism in the investigations or the prosecutions that led to the

false murder convictions we study:

In 1980, a Texas Ranger investigating the rape-murder of a high school student

described what was coming to the two custodians who found the body, Clarence

Brandley and a white colleague. He said, “One of you is going to have to hang for

this” and, turning to Brandley, added, “Since you’re the nigger, you’re elected.”

Brandley was sentenced to death in 1981 and exonerated in 1990.

In 1987, in Monroeville, Alabama, police framed Walter McMillian for the

murder of a clerk at a dry cleaner’s. McMillian, a 46-year old Black man, had

numerous alibi witnesses, all Black: he was at a fish fry at the time of the killing.

But he also had a white girlfriend, which was reason enough for the police to

target him. McMillian was sentenced to death in 1988 and exonerated in 1993.

More often, discrimination is less overt:

In 2014, Glenn Ford was exonerated after 30 years on death row in Louisiana. He

was released because over the decades after his conviction, his lawyers discovered

26

All but one were obtained after Larry Krasner became the District Attorney in 2018.

27

The National Registry of Exonerations, Conviction Integrity Units.

28

The counties are: Baltimore City, Maryland; Bronx, New York; Cook (Chicago), Illinois; Kings (Brooklyn), New

York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Queens, New York; Suffolk (Boston), Massachusetts; Wayne (Detroit), Michigan.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 16 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

several facts that undermined the state’s case: trial testimony by the state’s expert

witnesses was false or misleading; police officers lied to the jury about what Ford

said to them; hidden police reports included tips from informants that implicated

two other suspects, but not Ford; and one of those two suspects admitted that he

was the actual killer.

In 2015, A.M. “Marty” Stroud III, the former trial prosecutor who put Ford on

death row in 1984, published a remarkable apology: “Glenn Ford was an innocent

man. He was released from the hell hole he had endured for the last three

decades.”

29

Stroud takes painful personal responsibility for the tragedy, but not because of

deliberate misconduct. He was inattentive: “My fault was that I was too passive. I

did not consider the rumors about the involvement of parties other than Mr. Ford

to be credible…. Had I been more inquisitive, perhaps the evidence would have

come to light years ago.”

Stroud describes how he played by rules that gave him an unfair advantage over

an innocent man: “I did not question the unfairness of Mr. Ford having

appointed counsel who had never tried a criminal jury case much less a capital

one.” Even more troubling: “The jury was all white, Mr. Ford was African-

American. Potential African-American jurors were struck with little thought

about potential discrimination because at that time a claim of racial

discrimination in the selection of jurors could not be successful….”

30

Stroud is unsparingly self-critical, but he does not describe himself as racist: “In

1984, I was 33 years old. I was arrogant, judgmental, narcissistic and very full of

myself. I was not as interested in justice as I was in winning.” He believed Ford

was guilty and did not question that belief. The same is probably true of the

police officers who concealed information about the real killers, the judge who

presided over the selection of an all-white jury, and the jury itself, which

sentenced Ford to death.

Some police and prosecutors may habitually assume that any Black murder suspect they deal

with is a killer. That’s false, of course, and it’s a form of racial profiling. If they are white, they

may mistrust claims of innocence by Black defendants and alibi evidence from Black witnesses

because Black people are unfamiliar to them and seem less trustworthy than those who are more

similar to themselves.

All of us—including judges and jurors as well as lawyers and police—are subject to unconscious

racial biases—and all of us are prone to go along with accepted practices. Routine, institutional

discrimination is more common than intentional racism, and probably harder to detect and

29

Stroud III, A.M. “Marty”. Lead Prosecutor Apologizes for Role in Sending Man to Death Row. Shreveport Times.

March 2015.

30

Ford was convicted two years before the landmark case of Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986), in which the

Supreme Court for the first time created a procedure for challenging the use of peremptory challenges to create all-

white criminal trial juries.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 17 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

correct. Perhaps that is one reason why Clarence Brandley, the target of explicit racism, was

exonerated nine years after he was convicted, while Glenn Ford had to wait 30 years.

Would Glenn Ford have been convicted and sentenced to death if he had not been a Black man

charged with killing a white victim? There’s no way to know. Hundreds of white defendants have

also been falsely convicted of murder, and most of their cases included serious official

misconduct. But we do know that innocent Black murder defendants as a group are at a

disadvantage because of their race, and that sometimes it costs them their freedom, and most or

all of their remaining years.

3. The net effect

We don’t know the number of false criminal convictions, for murder or any other crime. Most by

far remain hidden—false convictions far outnumber exonerations—and we have too little

information to estimate that hidden figure.

31

Except in one context: death sentences.

Death sentences have a far higher rate of exoneration than other criminal convictions, and we

have far more detailed data on them than any other category of criminal sentences. A study

published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences made use of these unique

characteristics to calculate “a conservative estimate of the proportion of false convictions among

death sentences in the United States”—4.1%.

32

As the study is careful to point out, this estimate is for death sentences only. It cannot be applied

to all crimes, or even to all murders. Still, it’s a starting point; it suggests that the rate of

miscarriages of justice for murders in general is somewhere in the general vicinity of the rate for

capital murders.

Assume for a moment that the proportion of innocent defendants among all murder convictions

is half the rate for death sentences, 2%. That would mean there would be about 3,300 innocent

defendants among the estimated 165,000 inmates who are in American prisons for murder

convictions,

33

plus thousands more among the comparable number of defendants who were

convicted of murder in the past 40 years but are not now in prison because they were released or

have died.

In short, it’s likely that at least several thousand defendants have been falsely convicted of

murder in the time period covered by the Registry, and—judging from the exonerations we have

seen—more than half of them were Black.

31

Gross, Samuel R. What We Think, What We Know, and What We Think We Know About False Convictions. Ohio

State J. of Crim Law, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Spring 2017), at pp. 765-67.

32

Gross, Samuel R., O’Brien, Barbara, Hu, Chen and Kennedy, Edward. Rate of False Conviction of Criminal

Defendants Who Are Sentenced to Death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 111, No. 20 (May

20, 2014); pp. 7230-7235.

33

As of the end of 2019. E. A. Carson, Prisoners in 2020 - Statistical Tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t

of Justice (December 2021). Calculated from Tables 15 and 18, pp. 29, 33.

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 18 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

III. Sexual Assault

Nearly 60% of rape exonerations involve Black people, who are the defendants in less

than a quarter of rape convictions. The majority of rape exonerees were misidentified

by victims who had been raped by strangers. Two thirds of those misidentified rape

defendants were Black men, most of whom were misidentified by white victims.

Cross-racial eyewitness identification is a notoriously risky process. It appears

to be the leading cause of rape convictions of innocent Black men in the United

States. But it’s not the only factor. Some of the misidentifications were obtained

by deliberately tainted identification procedures, and Black men are also

overrepresented in the minority of rape exonerations without

misidentifications. In addition, Black rape exonerees received longer sentences

than whites, and spent several more years in prison before release.

This country has a horrific history of racism in addressing accusations of inter-

racial rape against Black men. The persistence of that racism is easy to spot in

some rape exonerations. In others, no doubt, it’s hidden beneath the surface.

Most rape exonerations are based on post-conviction DNA evidence that proves

that the exoneree was not the rapist. Such exonerations became increasingly

uncommon as DNA testing became widely available to determine the identity of

rapists before trial. There have been no DNA rape exonerations for convictions

after 2007: DNA testing has greatly reduced false convictions based on

mistakes about the identity of rapists. This is a major achievement. It has

prevented the conviction of hundreds if not thousands of innocent rape suspects,

mostly Black men who were accused of raping white women.

1. Race and false conviction for rape

Fifty-nine percent of sexual assault exonerees are Black, four-and-a-half times the proportion in

the population; 33% are white. That suggests that innocent Black people are almost eight times

more likely than white people to be falsely convicted of rape. Unlike murder, these numbers are

way out of line with the racial composition of sexual assault convictions. As of the end of 2019,

21% of those serving time in state prisons for sexual assault were Black, 39% were white, and

25% Hispanic.

34

Judging from known erroneous convictions, a prisoner serving time for sexual

assault is more than three times more likely to be innocent if he is Black than if he is white.

34

Id. (the remaining 15% were Indigenous People; Asians, and Pacific Islanders; and persons of two or more races).

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 19 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

2. Eyewitness misidentification

The leading cause of false sexual assault convictions is eyewitness misidentification of

defendants who are strangers to the victims.

Ninety-eight percent of sexual assault exonerations have female victims. Strangers commit only

about a quarter of rapes in the United States,

35

but they account for 69% of the false rape

convictions that result in exoneration (243/350).

In 75% of sexual assault exonerations, the identity of the man who committed the rape was the

central issue at trial (263/350); 87% of those cases were rapes by strangers (228/263), and 89%

included mistaken eyewitness identifications (233/263). In the remaining 25% of sexual assault

exonerations the assault never happened (87/350). Instead, the supposed victim lied about a

consensual sexual encounter or fabricated an attack from scratch. None of these “no-crime”

exonerations involved mistaken eyewitness identifications; in 83% the complainant knew the

innocent defendant (72/87).

There were eyewitness misidentifications in 67% of all sexual assault exonerations (233/350),

including 84% of the cases in which the defendants were strangers to the victims (205/243). The

rate of eyewitness errors is much higher for innocent Black defendants—74% (154/207)—than

for white defendants, 53% (61/116).

In 44% of all sexual assault exonerations with eyewitness misidentifications, Black men were

convicted of raping white women,

36

a racial combination that appears in less than 11% of sexual

assaults in the United States.

37

According to surveys of crime victims, about 70% of white sexual

assault victims were attacked by white men and only about 13% by Black men.

38

But 52% of

sexual assault exonerees with white female victims are Black (129/49), and 43% are white

(106/249)—which suggests that Black defendants convicted of raping white women are more

than six times more likely to be innocent than white men convicted of raping women of their

own race.

There are many possible explanations for this disturbing pattern, but the simplest is probably

the most powerful: the perils of cross-racial identification. One of the oldest and most consistent

findings of systematic studies of eyewitness identification is that white Americans are much

more likely to mistake one Black person for another than to mistakenly identify members of

their own race.

39

35

See, e.g., Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Criminal Victimization in the United States, 2008,

Statistical Tables, Table 27.

36

To be precise, this ratio is the number of sexual assault exonerations with mistaken eyewitness identification, and

with Black defendants and white victims, divided by the number of all sexual assault exonerations with mistaken

eyewitness identification in cases in which the races of the defendants and all the victims are known (101/229).

37

Black offenders accounted for an average of approximately 11% of all rapes and sexual assaults of white victims

from 1996 through 2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice. Criminal Victimization in the United

States, 1996-2008 (based on the National Criminal Victimization Survey; the statistic fluctuates because for each

year it is usually extrapolated from a sample of ten or fewer survey responses).

38

Id.

39

See Meissner, Christian A. and John C. Brigham. “Thirty Years of Investigating the Own-Race Bias in Memory for

Faces: A Meta-Analytic Review.” 7 Psychol., Pub. Pol’y & L. 3 (2001).

Race and Wrongful Convictions

Page 20 • National Registry of Exonerations • September 2022

The problem of cross-racial identification in rape prosecutions in America is asymmetrical. It

poses a greater risk of misidentification for Black sexual assault defendants than for white

defendants, for two reasons. First, a lower proportion of sexual assaults by white perpetrators

are cross-racial. Most sexual assault victims are friends, family members or acquaintances of the

attackers, who are likely to be of the same race—and if the victim is a stranger, she is likely to be

white regardless of the race of the attacker simply because whites are the great majority of the

population. Second, in experimental studies, white subjects show stronger “own race bias” than

Black subjects—they tend to be worse at identifying members of other races. This is not

surprising. As members of the majority group, many white Americans have little contact with

Black people, but almost all Black people have regular dealings with white people.

40

3. Misconduct and discrimination

a) Tainted identifications

Eyewitness misidentifications do not occur in a vacuum. Some are the products of misconduct

and racial bias.

Marvin Anderson was suspected of rape in Virginia because the real rapist told

his victim that he “had a white girl,” and Anderson was the only Black man

known to the local police who lived with a white woman. Anderson had no

criminal record, so an officer showed his color employment identification photo

to the victim together with half a dozen black-and white mug shots of other men,

and asked her to pick the perpetrator. Naturally, she chose Anderson, who spent

15 years in prison before he was exonerated by DNA.

Anderson’s false conviction was the product of a tainted identification, a dangerous form of

misconduct in which police, directly or (as in this case) indirectly, tell an eyewitness who to pick

in a formal identification procedure.

Tainted identifications occurred in 10% of the investigations of defendants who were convicted

of rape and later exonerated (35/350). That’s about the same rate we saw for murder

exonerations (112/1,167), but the process was quite different.

In murder cases, about 40% of tainted identification threats were used to induce the witnesses

to identify the defendants—usually threats of arrest or prosecution (44/112). Predictably, that