Western Kentucky University

TopSCHOLAR®

Masters ;eses & Specialist Projects Graduate School

Spring 2017

Inexhaustible Magic: Folklore as World Building in

Harry Po!er

Samantha G. Castleman

Western Kentucky University, castlemansamantha@gmail.com

Follow this and additional works at: h<p://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses

Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Social

and Cultural Anthropology Commons

;is ;esis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters ;eses & Specialist Projects by

an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact t[email protected].

Recommended Citation

Castleman, Samantha G., "Inexhaustible Magic: Folklore as World Building in Harry Po<er" (2017). Masters eses & Specialist

Projects. Paper 1973.

h<p://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1973

INEXHAUSTIBLE MAGIC:

FOLKLORE AS WORLD BUILDING IN HARRY POTTER

A Thesis

Presented to

The Faculty of the Department of Folk Studies and Anthropology

Western Kentucky University

Bowling Green, Kentucky

In Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Arts

By

Samantha G. Castleman

May 2017

Kate Horigan

iii

Acknowledgments

Many thanks in this project are owed to my committee, Drs. Timothy Evans, Erika Brady

and Kate Horigan who were incredibly supportive and enthusiastic about this research. I

appreciate each and every one of the challenges these individuals presented to me

throughout the process and am grateful for their input. My appreciation goes out to the

entire Folk Studies department at Western Kentucky University, both faculty and

students, as the curiosity and enthusiasm of these individuals inspired me every day in

this process, making it truly a rewarding experience. Specific thanks also to Kristen

Clark, who not only withstood my midnight text messages about wanting to research

folklore in Harry Potter and encouraged me to pursue this idea, but also supplied all of

the research I could ever need on fantasy literature and secondary world building. Thank

you all!

iv

Contents

I. Introduction: “Hogwarts will always be here to welcome you home.” ........................................ 1

II. “Liberties with folklore”: Cultural Expression in the Potter Series .......................................... 18

III. “I should not have told yer that”: Narrative Constructions of the Potterverse ......................... 42

IV. “The last enemy to be conquered is Death”: the Deathly Hallows as Cultural Texts .............. 65

V. Conclusion: “Of course it’s happening inside your head, but why on earth should that mean

that it’s not real?” ........................................................................................................................... 83

Bibliography .................................................................................................................................. 98

iv

Samantha G. Castleman May 2017 101 pages

Directed by: Timothy Evans, Erika Brady, Kate Horigan

Department of Folk Studies and Anthropology Western Kentucky University

The practice of secondary world building, the creation of a fantasy realm with its own

unique laws and systems has long been a tradition within the genre of fantasy writing. In

many notable cases, such as those publications by J.R.R. Tolkien and H.P. Lovecraft,

folklore exhibited in the world of the reader has been specifically used not only to

construct these fantasy realms, but to add depth and believability to their presentation.

The universe of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series demonstrates this same practice of

folklore-as-world-building, yet her construction does much more than just create a

fantasy realm. By using both folklore which predates her writing as well as created

elements which while unique to her secondary world specifically reflect the world of the

reader, Rowling is able to create a fantasy realm which is highly political, complex and

multivocal, yet still accessible to young readers through its familiarity. Specifically

through her use of cryptids, belief representation, and folk narratives both invented and

recontextualized, Rowling is able to juxtapose her fantasy universe to the real-world of

the reader, in effect inventing a believable secondary world but also demonstrating to

young readers the ways in which her writing should be interpreted.

INEXHAUSTIBLE MAGIC:

FOLKLORE AS WORLD BUILDING IN HARRY POTTER

I. Introduction: “Hogwarts will always be here to welcome you

home.”

The realm of folkloristics is one which encompasses everything from the study of

material culture to the examination of ritual activity. Within such a large scope of

application, the study of folklore both in and as literature has long claimed a prominent

stance within the field, tracing its relevance to the very birth of American folkloristics

and the early focus by anthropologists on folk narratives as mirrors of culture. As

folkloristic research grew inclusive of other forms of cultural expression, creating the

vast field we know today, discussions of interdisciplinary thought became intrinsic to the

field of folklore. This practice once again illustrated the strong correlation between

folkloristic study and literary criticism, arguing for the examination of folklore’s

inclusion within literary works.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series which first came into public recognition with

the release of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 1997, has experienced a

growth in the examination of the folklore present therein. Rowling’s use of folklore is

intentional, as she stated in an Edinburgh "cub reporter" press conference, "I love

freakish names and I have always been interested in folklore and I think it was a logical

thing for me to end up writing even though it came so suddenly" (ITV 2005). This love of

folk material, including everything from Greek mythological references to homeopathic

remedies and belief systems, certainly found its way into Rowling’s writing, and in many

cases became the very tool by which the author constructed the world in which her novels

are set. Through the use of cultural materials ranging from expressions of belief to folk

narratives, Rowling creates a fantasy universe which mirrors and seems to symbolize in

2

its parallels the world of the reader. This secondary realm, while complex and unique, is

familiar and accessible to the audience due particularly to the use of recognizable

folkloristic elements.

Studies examining similar uses of folklore in literature have a long history within

the field of folkloristics. Folklore in Literature: A Symposium, published by the Journal

of American Folklore in 1957, includes works by Daniel G. Hoffman and Carvel Collins

among others, on the use of folklore interpretation in literary criticism, specifically the

varied uses to which cultural elements are called upon to enact within literature; among

these being to add verisimilitude or symbolic meaning within writing. Collins’ short

entry, “Folklore and Literary Criticism” argues that folklorists must both establish and

critically examine “texts,” meaning both literary publications and the folkloristic

references which these may include, in order to gain an understanding of the use of such

traditional elements within literature. (Collins 1957:10). Collins asserts that while critics

examining the presence of folklore in literary works have contributed a great deal to the

study of folklore use in literature, the field has yet more to offer such criticism and that

still more research must be done before the relationship between folklore and literature is

fully understood (9). Examinations of contemporary literature such as the Potter series

effectively serve as a continuation of the interdisciplinary study of folklore in literature.

By continuing to question the relationship between the two fields and their productions,

researchers are not only able to ask deeper and more meaningful questions, but to

examine the ways in which this relationship and its interpretations have evolved over

time.

3

Hoffman’s final entry to the symposium, “Folklore in Literature: Notes Toward a

Theory of Interpretation,” takes Collins’ understanding of the use of the folkloric in

literature a step further, pointing out not only the use of individual motifs and folklore

structures within literary works, but also arguing the circular relationship which exists

between the “folk and the sophisticate,” as both to some extent inform and influence the

other (Hoffman 1957:18). In his examination of the uses of folkloristic references within

literature, Hoffman defines three categorizations for the use of folklore in literary works:

to provide verisimilitude, to be “unified and elaborated” by authors, or to provide a

structure of symbolism. Hoffman, by way of conclusion, argues that critics must take into

account both the function of a traditional element within its native habitat and the

qualities such inclusions contribute to their respective literary works to truly understand

the importance of such references within literature (20).

While this early symposium on the interaction of folklore and literature was

groundbreaking in its discussion of the relationship between folklore theory and literary

criticism, it was Alan Dundes’ 1965 article, “The Study of Folklore in Literature and

Culture: Identification and Interpretation” which clearly established an analytical method

for such research. Dundes asserts that the investigation of the use of folklore in literature

involves a two-step process. First, the critic of folklore in literary work must identify the

folkloric elements being used, however, Dundes also argues:

too many studies of folklore in literature consist of little

more than reading novels for the motifs or the proverbs,

and no attempt is made to evaluate how an author has used

folkloristic elements and more specifically, how these

folklore elements function in the particular literary work as

a whole (Dundes 1965:136).

4

It is this evaluation and interpretation which Dundes argues must be the second step in

analyzing the use of folklore in literature (136). In order for the importance of folkloristic

reference in literature to be understood, examinations should question the change of

context of folkloric elements from the original location to the literary work, and the ways

in which such alterations allow understanding of the phenomenon itself to prosper.

Roger Abrahams’ article, “Folklore and Literature as Performance,” published

seven years later, shows the growth in folkloristic understanding of literary inclusion as it

complicates the binary approach to folklore in literature. Rather than supporting a

simplistic two-step process to interpretation, Abrahams argues that performance,

particularly as it applies to folklore and literature, depends on performer-audience

coordination, thereby affecting the scholarly interpretation of the identified folkloristic

material within literature (Abrahams 1972:76). Abrahams is careful to point out, “one

does not understand the effect of a Faulkner novel by being able to point to the traditions

which he drew upon in his stories: rather, one understands because there is something

within such a work which has excited the reader into investing some of his own energy

into the reading of the work” (84). It is this investment of self which Abrahams believes

to be the purpose of folklore in literature; to influence readers to thoroughly connect to

the product at hand. Rowling’s use of the folkloric in the construction of her fantasy

universe demonstrates this very exercise. The recontextualization of traditional materials

within her series serves to build a world relatively similar to the world of the reader.

These similarities connect young readers to the fantasy world by making the realm more

familiar and accessible, and therefore easier with which to connect. Young readers invest

themselves into the world of Harry Potter because they recognize it.

5

This focus on performative interpretations of folklore in literature and the

relationship between meaning and context continues in Cristina Bacchilega’s “Folklore

and Literature” (Bacchilega 2012:451). Folklore in literature, Bacchilega argues, should

be envisioned on a continuum rather than as a strict binary dichotomy. The focus of this

approach would rely upon the varieties of interpretation offered by including traditional

elements in literature through recognizing both genres and functions within their local

systems as well as their literary context. This new direction of study stands in sharp

contrast to the earlier focus on the importance of finding the origin of folkloristic

materials (451). As the world of Harry Potter draws heavily both from folklore and

fantasy literary sources, the relationship between these two realms in Rowling’s writing

clearly does not exhibit a dichotomous structure. Elements of Rowling’s created world

instead lie in a variety of locations along Bacchilega’s continuum.

To further illustrate the idea of a continuum, Bacchilega’s discussion of folklore

and literature turns towards theories of intertextuality, generally referencing theory

argued by Julia Kristeva and claiming the concept to be “not the dialogue of fixed

meanings or texts with one another: it is an intersection of several speech acts and

discourses [...] whereby meanings emerge in the process of how something is told and

valued, where, to whom, and in relation to which other utterances” (Bacchilega

2012:453). Maria Jesus Martinez Alfaro, author of “Intertextuality: Origins and

Development of the Concept,” ultimately describes intertextuality as a “network of

relations” within each text and between the product itself and the individual parts which

constitute it (Alfaro 1996:281). Alfaro claims this is “everything, be it explicit or latent,

that relates one text to others” (280), yet only as far as it is perceived by the audience

6

(281), once again echoing the importance of audience participation argued by Roger

Abrahams. Specifically in terms of literary works, authors are able to build thoroughly

intertextual fantasy universes referencing both sources which were combined in its

creation as well as aspects of its own being, thereby creating a network of backdrop and

meaning. While based obviously within the world of the audience, these created

universes are something clearly separate and unique.

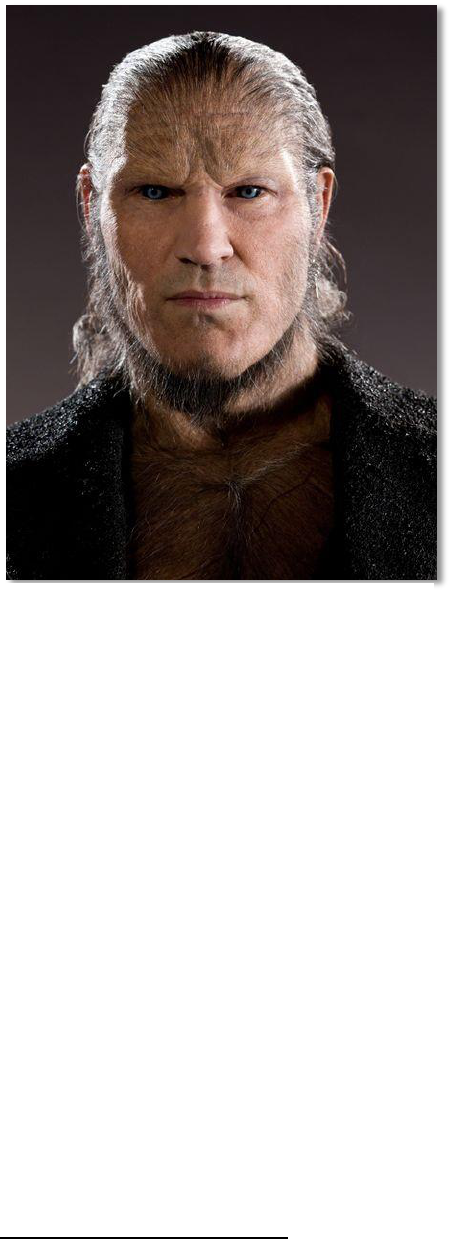

When applied to Harry Potter, this idea of intertextuality works in multiple ways.

Rowling’s writing and creation of setting, characters, and backstory incorporates a

number of differing folkloristic references, ranging from historical legends regarding

Nichols Flamel to emic and etic misunderstandings of art. The intermingling of these

sources does exhibit intertextuality, however it is not merely the appropriation of these

sources, but rather their influence upon each other within various productions created by

Rowling which thoroughly shows the use of folklore within the series to be intertextual.

A number of Rowling’s folkloric references appear not only in the original Potter series,

but also in additional publications within this universe, such as Fantastic Beasts and

Where to Find Them and The Tales of Beedle the Bard. The use of these folkloristic

sources in multiple productions demonstrates the ways in which these references

influence each other within the series as well as actively build Rowling’s fantasy

universe.

While Bacchilega points out the “dynamic” boundary between systems of

communication and their respective purposes (Bacchilega 2012:452), she is also careful

to describe genre as “not structures or forms, but frameworks of orientation which are

dynamic, often hybrid, and emergent so that linking a text with a genre inevitably effects

7

an ‘intertextual gap’” (453). What is identified as “folklore” or as “literature” is located

contextually within textual production and cultural history (457) and tends to have

“porous boundaries” which alter with context (455). With the idea of contextual genre

distinction in mind, defining what is considered “folklore” and what is acknowledged as

“fact” within the realm of Rowling’s created literary universe could potentially shine a

light on authorial choices in structure, thematic distinction and world building as both are

used to construct a believable fantasy world.

The focus on the importance of context is the predominant argument behind Frank

de Caro and Rosan Augusta Jordan’s book, Re-Situating Folklore, in which the authors

present examples of folklore which has been “de-situated” from its natural context, and

“re-situated” within the literary realm (de Caro 2004:6). It is this recontextualization, de

Caro and Jordan argue, which allows literary authors to create structure, plot, or symbolic

meaning from borrowed folkloristic elements (7). De Caro, unlike his predecessors,

however, presents the idea of world building within the fictional realm through the use of

folklore:

Folklore can also be used to suggest remoteness of place or

time, or it can even be revised in the construction of

alternate fantasy or science fiction worlds. For instance,

J.R.R. Tolkien creates for his fantasy world an array of

what are supposed to be orally transmitted songs which

pass on the stories of past deeds and events. Though these

songs constitute a made-up folklore and though the context

in which they exist is purely a fantasy one, they partly serve

to give an impression of their world as a place very much

like what we may imagine a more ancient time in our real

world to have been like [...]. The fantasy world thus

acquires a patina of antiquity which makes it seem more

real, though also more distant (16-17).

8

This idea of folklore-as-world building is one which Sullivan thoroughly

examines in his article, “Folklore and Fantastic Literature,” using J.R.R. Tolkien’s

terminology “secondary world,” described as a realm harboring its own laws in which the

mind of the reader can enter and find believable in his essay “On Fairy Stories” (Tolkien

1947:12). Earlier criticism of fantasy works by Tolkien further defines the concept as

“the illusion of historical truth and perspective […] which is largely a product of art”

(Tolkien 1991 [1936]:16). Sullivan argues that “fantasy and science fiction authors use

traditional materials, from individual motifs to entire folk narratives, to allow their

readers to recognize, in elemental and perhaps subconscious ways, the reality and cultural

depth of the impossible worlds these authors have created” (Sullivan 2001:279). To

Sullivan, the use of folklore in world building practiced by authors such as Rowling adds

depth and believability to the secondary worlds of the fantasy genre. Authors of these

genres, Sullivan points out, are required to create a world which “makes sense in and of

itself” (280). This closed realm must then become the secondary world, in contrast to the

primary world of the reader, despite what traditional materials it may borrow in its

creation.

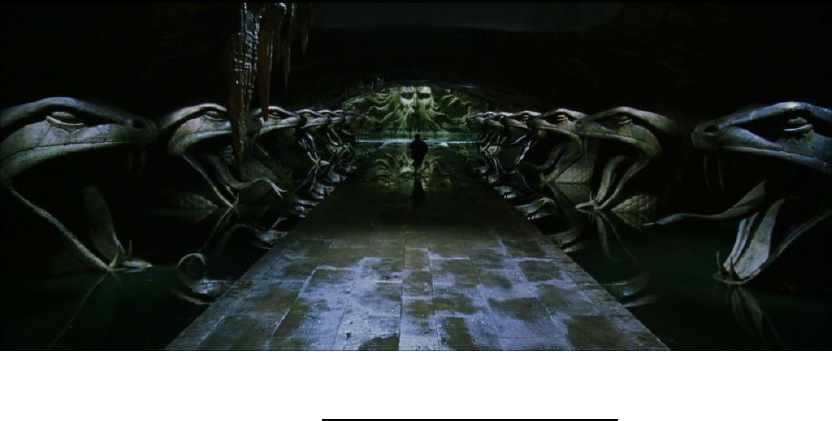

In Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, the secondary world can easily be identified

as Middle Earth and the locations and landscapes therein. Rowling’s secondary world,

however, is more complex as the Harry Potter series is intentionally set in a world

identifiable to the real-world of the reader. Rowling’s secondary world is a universe in

which a secret culture and identity exists inside of a world very much like our own. The

hidden wizarding world, however, also alludes to a number of subgroups within itself,

such as Death Eaters, the Order of the Phoenix, individual Houses within Hogwarts, and

9

Deathly Hallows believers. Rowling’s secondary world, then, harbors the wizarding

world and all of its specific subgroups as well as the Muggle, or nonmagical, world

which is meant to reflect the world of the reader.

This created universe has come to be known in online forums and social media as

the Potterverse, specifically referencing the “universe” of Harry Potter, and this is the

term by which I will refer to Rowling’s secondary world. While the Potterverse first only

contained the original seven novels, its construction has grown immensely as the series

has progressed. Today, the Potterverse includes not only the original series but all

additional publications such as The Tales of Beedle the Bard, eight movies based off the

original series, illustrated special editions of the original series, a theme park, any fan

fiction written on the series, the popular practice of Harry Potter character cosplay, two

parody musicals produced by the University of Michigan, among a variety of other

parody productions, and a number of both sanctioned and unsanctioned websites for

Harry Potter fans, including the Pottermore website established by Rowling herself in

which fans can be sorted into their own Houses, be awarded their own wands, and

discover their individual patronuses. The 2016 releases of Harry Potter and the Cursed

Child, an eighth installment in the Harry Potter narrative which took the form of a play,

and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, the first of a new five-part movie series,

demonstrate the vastness and continued growth of the Potterverse.

As Sullivan’s article argues, the borrowing of “traditional material” in world-

building leads to the creation of folklore-like materials unique to each specific secondary

world, citing authors who “have used traditional, recognizable sayings with which the

reader would be familiar to set up for later sayings indigenous to the secondary world in

10

which they are heard” (282). To Sullivan, such practices become the primary purposes of

folklore use in literature: “to give verisimilitude and local color” and “to serve as ‘models

for production of folklore-like materials’” (282).

Brian Attebery’s Stories about Stories, also focuses on the importance of

secondary world building in fantasy literature; however, he takes the inclusion of

folkloristic elements beyond Sullivan’s focus on verisimilitude to argue the importance of

the symbolism of the elements of these worlds (Attebery 2013:4). Attebery writes,

“fantasy is fundamentally playful--which does not mean that it is not serious” (2), arguing

that while literal interpretations of fantasy works can result in conflict for the reader

(162), the “nonfactuality” of fantasy literature offers the freedom of symbolic truth

without pressuring the reader to take a stance regarding what the interpretation of that

truth may be (4). While these symbolic meanings must be indirect (164), the range of

reaction to these materials, a point also stressed by Bacchilega, shows their variability to

be a direct result of their vagueness as well as marker of their importance (8). These

symbolic interpretations allow the reader to make personal and individual judgments

without the influences of others and can demonstrate great variability from person to

person.

Rowling’s use of folklore in secondary world building is not a new phenomenon,

instead directly reflecting similar choices made by a number of well-renowned fantasy

authors. Timothy Evans’ article, “A Last Defense against the Dark: Folklore, Horror, and

the Uses of Tradition in the Works of H.P. Lovecraft,” investigates the particular ways

the writer of horror tales (a subset of fantasy, as described in A Short History of Fantasy

by Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James) creates authenticity in fiction through the use

11

of both borrowed and created folklore material. Evans clearly states, “Lovecraft used

actual folklore in his fiction, though he often transformed it” (Evans 2005:116).

Evans’ purpose is not merely to point out the recontextualization of preexisting

folklore, but rather to demonstrate the ways in which such materials authenticated forms

unique to Lovecraft’s secondary world and therefore strengthened the world itself. He

claims “Lovecraft was quite critical of those who simply used or valued folklore in

literature for its own sake, without reworking it. He advocated using ‘folk myths’ to

create ‘new artificial myths.’” Evans argues it was Lovecraft’s use of the structures and

devices of the folkloric, along with invented scholarly sources which intertextually

referenced both other inventions by Lovecraft and established folkloric elements backing

up his claims, which gave his fiction “authenticity” and made the created elements within

“seem” like folklore (119).

This focus on the intertextuality of invented and preexisting folkloric materials is

a topic Evans revisits in “Folklore, Intertextuality, and the Folkloresque in the Works of

Neil Gaiman,” published in Michael Dylan Foster and Jeffrey A. Tolbert’s 2016

publication, The Folkloresque, a term defined by the authors as “popular culture’s own

(emic) perception and performance of folklore. That is, it refers to creative, often

commercial products or texts (e.g. films, graphic novels, video games) that give the

impression to the consumer (viewer, reader, listener, player) that they derive directly

from existing folkloric traditions” (Foster 2016:5). Foster and Tolbert complicate the idea

of the folkloresque by focusing not on whether a material is genuine, but rather why it

succeeds (8). Oftentimes, the authors argue, popular culture success can be linked to an

attachment to folklore material (14), to the power, much like that called upon in

12

secondary world building, “to connect to something beyond the product itself” (3). It is

this “connection,” that Attebery claims adds symbolism and imbues meaning, which is

demonstrated in Rowling’s own folkloresque world building.

While a fairly new area of study in folkloristic research, examples of the use of

the folkloresque can be found throughout the history of sf/fantasy genres. Merely a small

sampling of this practice includes ballads and riddle use by J.R.R. Tolkien, local and

supernatural legends both alluded to and specifically created in the works of H.P.

Lovecraft, C.S. Lewis’ use of biblical allegory and the prevalence of creatures from

classical mythology within his Chronicles of Narnia series, and the vast array of folk

elements within the publications of Neil Gaiman, encompassing everything from

foodways to culturally specific belief systems.

1

Much like in the works of Lovecraft and Gaiman, folkloresque inventions are

pervasive within the Harry Potter series. While Rowling does include a number of

folkloristic references attributed to the world of the reader, Rowling herself has stated,

"I’ve used bits of what people used to believe worked magically just to add a certain

flavor, but I’ve always twisted them to suit my own ends. I mean, I’ve taken liberties

with folklore to suit my plot” (Harry Potter and Me 2001). It seems that, like Lovecraft,

Rowling rarely explicitly presents unaltered folkloristic material, but rather uses these

elements to build her own Potterverse folklore. Examples of Rowling’s

1

The Hobbit, the prequel to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series, includes a number of traditional Old

English riddles as a contest of wits between Bilbo Baggins and Gollum. One such example presented is

“Alive without breath,/As cold as death:/ Never thirsty, ever drinking,/ All in mail never clinking.”

Lovecraft’s “The Shunned House” is based directly on a legendary haunted House in Providence, Rhode

Island, and the use of biblical allegory is evident in the sacrifice of Aslan the lion in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion,

the Witch and the Wardrobe. Neil Gaiman’s American Gods includes not only mythological references to

deities such as Odin and Loki, but also discussions regarding the differences between Johnny Appleseed

and Paul Bunyan, and a focus on foodways most clearly exemplified in the numerous references to pasties.

13

recontextualization of traditional materials, such as her folkloresque reimagining and

presentation of cryptid beings and ritual enactment fill chapter two of this work. The

overhauling of preexisting folk narratives, the folkloresque invention of a unique

Potterverse legend, and the combination of “old” form to “new” content in Potterverse

children’s tales are examined in depth in chapter three.

The investigation of intertextuality and the folkloresque within J.K. Rowling’s

Harry Potter series is a topic which has attracted growing interest in recent years. Carlea

Holl-Jensen and Jeffrey A. Tolbert’s article, “‘New-Minted from the Brothers Grimm’:

Folklore’s Purpose and the Folkloresque in The Tales of Beedle the Bard,” included in

The Folkloresque, examines the portrayal of Potterverse-specific folk materials:

specifically the Beedle the Bard fairy tales referenced in Harry Potter and the Deathly

Hallows and then published as a separate compendium after the series’ conclusion. Holl-

Jensen and Tolbert present a discussion touching on the two main ways the authors

understand the use of fairy tales within the Potter series. The first of these uses, they

argue, is to “enrich a world of fiction through intertextual references” (Holl-Jenson

2016:165); as they claim, “It is clear that Rowling imagines the wizarding and Muggle

(or nonmagical) worlds as parallel cultures with parallel bodies of folklore” (168).

This argument relates directly to the one which Sullivan presents in “Folklore and

Fantastic Literature.” It is the borrowing of traditional materials, such as the structure and

motifs of fairy tales described in Holl-Jenson and Tolbert’s article, which Sullivan points

out “allow[s] readers to recognize, in elemental and perhaps unconscious ways, the

reality and cultural depth of the impossible worlds these authors have created” (Sullivan

2001:279). As Sullivan argues, it is the borrowing of folkloristic material, such as fairy

14

tale structures, which leads to the creation of unique secondary world materials, such as

the content of the Beedle the Bard tales themselves, adding, as Sullivan claims,

“verisimilitude and local color” to the Potterverse (282).

This practice of world building is investigated one step further by Holl-Jensen and

Tolbert, who claim understanding of such folkloric references can only be reached by

analyzing “the work as a whole, its reception by its audience, and other factors external to

the folkloric material itself” (167). Such analysis, according to the authors, reveals

assumptions on the part of the author about the nature of specific folkloric material, such

as its origin, function and relevance to modern society. The revelation of these

assumptions becomes the second primary purpose of fairy tales within Rowling’s writing

as “metafolklore and metafictional uses of folkloric material” which “provide direct

insight into what people think about folklore” (171). By mimicking the form of European

marchen, Rowling is able to juxtapose cultural values of her own universe with those of a

different culture, specifically the Potterverse (169). This second argument of their study,

then, falls directly in line with Attebery’s discussion on symbolic interpretations of the

fantasy genre. The juxtaposition of real-world morals and values offered through

Rowling’s presentation of Potterverse culture supplies the reader with the exact “indirect”

symbolic interpretation Attebery claims allows the audience to experience truth without

the threat of harm or the demand to choose sides.

“New-Minted from the Brothers Grimm” is by no means the only work of

scholarship to have been completed on the use of folkloric materials in the Harry Potter

series. “The Wisdom of Wizards—and Muggles and Squibs: Proverb Use in the World of

Harry Potter,” by Heather Hass, investigates the practice of proverb usage within

15

Rowling’s series. Haas claims that similar to fantasy authors before her like J.R.R

Tolkien, “Rowling also uses a number of ‘proverbial comparisons’ and ‘proverbial

similes’ [...]—including several that seem clearly to be unique to the wizarding world”

(Haas 2011:34). Some of these materials presumably unique to the Potterverse are

classified as anti-proverbs, defined by Wolfgang Meider as “parodied, twisted, or

fractured proverbs that reveal humorous or satirical speech play with traditional

proverbial wisdom” (as quoted in Haas: 37). To Haas, the issue becomes identifying the

distinctions between anti-proverbs and true-proverbs within their own fantasy context.

Taking a structural look into folkloric elements of the Harry Potter series, Joel B.

Hunter presents a Proppian analysis of the Potter series, first examining each book

individually, then the series as a whole (Hunter 2013:7) in order to discover if “the

aesthetic satisfaction with any particular book in the series positively correlates to that

book’s fairy tale structure as enumerated in Propp’s system of thirty-one functions of a

folktale’s dramatis personae” (2). Hunter’s analysis makes no assertions that Rowling

intentionally followed a Proppian morphology in her writing, but he does argue that

“Rowling followed unconsciously the ‘cultural script’ of folktales in writing the

Hogwarts saga” (3).

While a considerable body of work exists examining the possible psychological

and societal influences the Harry Potter series may exhibit for readers, this type of study

removes the focus from intertextual and folkloresque interpretations in favor of reader

response and functionalist theories. While works such as Jordana Hall’s “Embracing the

Abject Other: The Carnival Imagery of Harry Potter,” “Deconstructing the Grand

Narrative in Harry Potter: Inclusion/Exclusion and the Discriminatory Policies in Fiction

16

and Practice” by Luisa Grijalva Maza and “Harry Potter and the Functions of Popular

Culture,” written by Dustin Kidd, prove enlightening reads, these nonetheless fall short in

relevance to discussions on Rowling’s intertextual world building.

My research investigates the ways in which J.K. Rowling adheres to the fantasy

tradition of folkloresque world building within the universe established in her seven-part

Harry Potter series and the potential such construction has to offer symbolic

interpretations of the writing. This line of investigation includes the original seven books

of the Potter series, as well as additional publications set within the Potterverse such as

the textbook Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Tales of Beedle the Bard.

Chapter two of this work identifies folkloristic references and the ways in which these

have been altered within the Potter series specifically in the realm of ritual enactment,

belief representation, and cryptozoology. Chapter three examines the ways in which

Rowling uses legend tales from the world of the reader combined with folkloresque

created narratives to build her fantasy world and enhance both the depth of social

structures and values of this realm and its believability due to similarities between the

primary and secondary worlds. Chapter four serves as a specific example of this complex

folkloresque world building in reference to the Beedle the Bard narrative, “The Tale of

the Three Brothers,” and the Deathly Hallows legend which accompanies the fairy tale

within the Potterverse.

The conclusion identifies the ways in which Potterverse folklore reflects

materials, beliefs and practices visible within the realm of the reader's reality and the

symbolic functions to which this practice can be applied within Rowling’s secondary

world. This conclusion presents briefly the idea of Potterverse interpretations to

17

demonstrate real-word applicability, at least as far as making symbolic interpretation

more accessible for young and under-developed readers and presents possible ideas for

further research into the use of folklore within the Harry Potter series.

Like those authors who preceded her, Rowling calls on a number of existing

traditional materials, from mythical creatures to proverb usage. While these folkloric

elements, specifically traditional narratives, reference both each other as well as the

original contexts from which they were drawn, Rowling also manages to establish such

references as a springboard for her own folkloristic creations within her fictional world, a

practice exhibited most notably in her presentation of oral lore and traditional narratives.

The use of folk narratives, both invented and preexisting, and the reflection of real-world

belief negotiation within the series creates a believable and substantial secondary world

which effectively mirrors our own.

18

II. “Liberties with folklore”: Cultural Expression in the Potter

Series

J.K. Rowling’s fascination with folklore and its influences within her writing is a

topic often discussed in author interviews and press conferences. During a 1999 radio

broadcast Rowling even claimed, “I would say - a rough proportion - about a third of the

stuff that crops up is stuff that people genuinely used to believe in Britain. Two thirds of

it, though, is my invention” (Rehm 1999), thereby admitting that while a large amount of

the beliefs and practices witnessed within the series do hold some footing in history and

existing folkloric systems, somewhat more of the cultural expression within the series is

actually completely unique to Rowling’s Potterverse. Rather than simply presenting

folklore which predates the conception of her Potter series, Rowling creates and adds

elements of the folkloresque to these materials in a way which both compliments and

strengthens the believability of the Potterverse through its similarity to and reliance on

the reader’s primary world.

Comments such as these by the author clearly illustrate Rowling’s intent to

recontextualize folklore, and deny the possibility of such folkloristic references being

merely coincidence. The author’s use of folklore is no accident. She herself stated in the

same radio interview, “I do do a certain amount of research, and folklore is quite

important in the books, so where I'm mentioning a creature or a spell that people used to

believe genuinely worked […] then I will find out exactly what the words were, and I

will find out exactly what the characteristics of that creature or ghost was supposed to be”

(Rehm 1999). While the idea that folklore is something which “used to” be believed

marginalizes those materials as merely survivals of the past, Rowling’s attention to detail

19

when describing such traditional elements rather creates a world in which these materials

are alive and well in the modern age.

References to “ghosts,” “creatures,” and “spells” demonstrate another aspect of

Rowling’s use of folklore. Rather than enlisting one singular motif, custom or material,

Potterverse folklore is variable, including a range of cultural expression as eclectic and

diverse as such materials are understood to be within any given culture in the world of the

reader. The Harry Potter series demonstrates a great amount of customary folklore of

Rowling’s own invention, specifically in the realm of ritual; a variety of belief

representations which correlate directly to preexisting folk beliefs; and a wealth of

creatures and beings which, while common in modern fantasy literature, can also find

their roots in cryptozoology and folklore. Although many of these traditional

representations within the series are common among fantasy writing as well, Rowling’s

own admitted focus on folklore argues the importance of these elements as traditional

expressions while simultaneously aligning to a folkloresque tradition of world building

practiced by the fantasy writing community. By calling upon both existing folklore and

her own folkloresque inventions to build her fantasy universe, Rowling fulfills a generic

tradition practiced by such notable writers as J.R.R. Tolkien, H.P. Lovecraft and Neil

Gaiman. These folkloristic elements both borrowed and created by Rowling construct a

world which is complex and multivocal but easily accessible to young readers in the way

in which it mirrors reality. The similarities between the two realms create a sense of

familiarity and safety which welcomes the audience and allows for investment and

understanding of the Potterverse to occur.

Rituals in Harry Potter

20

The use of ritual, while prominent within the series, is so ingrained within the

development of plot and action that its importance as cultural expression is easy to

overlook. A number of transitionary scenes take place in which some form of secular

ritual unique to the wizarding world occurs.

2

While rituals, specifically those involved in

English boarding school membership, have appeared in a number of literary works from

Jane Eyre to The Portrait of An Artist as a Young Man, this does not diminish the

folkloristic undertones and origins of these practices, but rather strengthens the validity of

such customs both within the realm of the reader’s reality and the secondary world which

the author is working to create. These instances within the Potter series, while

folkloresque creations invented by Rowling, begin to structure the passage of time as well

as the growth of ability and maturity for the students of Hogwarts in a way which is

comparable both to boarding school rituals in other works of literature and to coming of

age rituals within the world of the audience.

The first of these occurs early in the Potter series when Harry receives his letter

of acceptance from Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (Rowling 1997:34).

Although the importance of the letter is obvious from the continued attempts at delivery

despite alterations to Harry’s location, the amount of envelopes and the various ways in

which these find their way inside the home of Harry’s guardians (his aunt and uncle, the

Dursleys), and Mr. Dursley’s frantic avoidance and escape from the materials until

ultimately the letter is hand delivered by the physically imposing Rubeus Hagrid, the

2

Rituals in the Harry Potter series are able to be identified as secular rather than sacred due to the lack of

religious connotation or meaning attributed to such customs. The rituals discussed in this section do

represent coming of age and rite-of-passage rituals, yet these practices reference not religiosity but the

physical and mental growth and maturity experienced by childhood development, specifically as it is

acknowledged through school traditions such as standardized testing.

21

importance of this occurrence as a cultural phenomenon is not fully explored until the last

installment of the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

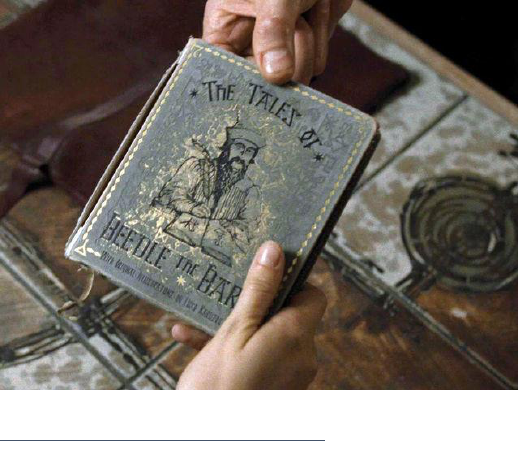

The introductory textbook Living Folklore, by Martha Sims and Martine

Stephens, presents a concise explanation of what may be referred to as ritual: “rituals are

habitual actions, but they are more purposeful than customs; rituals are frequently highly

organized and controlled,

often meant to indicate or

announce membership in a

group” (Sims and Stephens

2011:99). While Harry’s

own beleaguered acceptance

process does exhibit some

modicum of organization

and control by an unknown

third party and the letter itself

announces Harry's acceptance at the proper age into the wizarding community, it is not

until Harry’s exploration of Snape’s memory after his death that the audience begins to

understand how truly important this ritual is within the Potterverse.

3

Harry’s own experience with his acceptance to the wizarding school is tempered

by more pressing epiphanies within the first novel. Harry, only ten years old when he

3

Harry’s attempted coming of age initiation through the Hogwarts letter includes painfully correct

addresses on envelopes referencing Harry’s exact sleeping arrangements, the ever-increasing amount and

locations of owls as Mr. Dursley continuously forbids Harry from reading his own mail, and the appearance

of the letters inside of a dozen eggs. These acts show intelligence and manipulation by someone holding a

high level of authority and power. Therefore, while the individual in command of the event is not

physically present, organization and control are still detectable.

Figure 2.1: Harry’s acceptance letter. Source: Harry Potter and the

Sorcerer’s Stone film: 2001.

22

receives his letter, not only learns that he is a wizard just like both of his parents, but also

the actual circumstances surrounding the tragic death of Mr. and Mrs. Potter.

4

This

information would be shocking to any individual, let alone a young child whose entire

understanding of the world has just been challenged. Snape’s flashback in Deathly

Hallows, however, presents the ritual of Hogwarts acceptance without such strings.

Snape’s memory presents to Harry the boy’s own mother’s acceptance into the wizarding

world through Snape’s point of view. While Snape is a pure-blood wizard and has grown

up knowing of Hogwarts and what acceptance into the school means, Harry’s mother

Lilly, is a child of a non-magical family. As Harry travels through Professor Snape’s

memory learning the truth about a man he thus far thought of as only pure evil, he is

presented a scene in which young Severus Snape is educating Lily on the rules attached

to admission to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry:

“…and the Ministry can punish you if you do magic

outside school, you get letters.”

“But I have done magic outside school!”

“We’re all right. We haven’t got wands yet. They let you

off when you’re a kid and you can’t help it. But once

you’re eleven,” he nodded importantly, “and they start

training you, then you’ve got to go careful” (Rowling

2007:666).

Even more telling regarding the importance of this ritual in identifying group

membership among wizards, as Snape’s memory progresses Harry is given a look into

the conflict which arises between family members who gain acceptance into the

wizarding world and those who do not. Young Lily complains that her older sister,

4

Although this research makes no effort to examine the eight Harry Potter movies, images in chapters two,

three and four meant to help contextualize the analysis and the series itself are screen captures taken

directly from the films. There are noticeable differences between the book and movie productions, yet these

images are taken from scenes which align closely to Rowling’s original writing and description of incidents

and situations.

23

Petunia, who is non-magical like their parents, tells her that Snape is lying about the

magical school. Later, a rift between the two sisters grows when it is revealed that

Petunia wrote her own letter to the headmaster of Hogwarts School asking to be allowed

to attend classes. As the conversation turns heated, Petunia, previously depicted as

loving, if not overbearing, towards her younger sister, refers to Lily and Snape as

“freaks” and, quite literally, turns her back on her sister (670). It is assumed that this

moment was a turning point in the sisters’ relationship, as the Petunia of Harry’s time is

distrustful and hateful towards the wizarding community and refuses to speak of the

Potters and their abilities, while the Petunia of Snape’s memory demonstrates almost

motherly tendencies towards her younger sister.

While this scene is important within the narrative in order to demonstrate both the

origins of the Dursley’s hate for the wizarding community and Snape’s true character,

folkloristic readings suggests more complex emic and etic interpretations of the initiation

ritual specifically linked to the coming-of-age which is attached to the letter of

acceptance within the Potterverse. While the Hogwarts letter itself serves as the first step

in a lengthy initiation process to join the wizarding community, it is one which is time

specific, as letters are only delivered to children who exhibit magical ability and are

about to turn eleven—if a child doesn’t receive the letter around their eleventh birthday,

they never will. This focus on age marks the ritual not only as an initiation but also a

coming of age in the ways which this initiation effects the magical use of the child. As

Snape informs Lilly, once a wizarding child begins study at Hogwarts it is understood

that he or she has the ability to exhibit control over his or her power and is no longer

allowed to perform magic without restraint as he or she was as a young child.

24

Snape, the insider among wizarding society, must inform Lily, the outsider, of the

rules and expectations attached to group membership in order for Lily to fully

comprehend the importance of her initiation into the community. Harry, like his parents

and Snape before him, experiences a rite of passage in which he crosses from a normal

human boy to a student of wizardry at a well-known school, but he too, as a circumstance

of being raised by the Dursleys, must be informed of group expectations. Whereas

occurrences such as his hair growing back and a python being set loose during his visit to

the zoo would have remained odd but unimportant without his initiation into this other

society, these events take on new meaning once Harry’s true character is revealed. As a

side effect of the Hogwarts letter, Harry more fully understands the events which have

occurred around him all his life, but he, along with the rest of the new Hogwarts students,

now must control his magic, as he is thought of as being old enough to do so. Hogwarts

membership comes not only with community membership, but group rules which must be

policed. Folkloristic readings of this ritual demonstrate not only the importance of the

acceptance letter as a marker of group membership, but the distinctions and issues which

arise between those who become a part of this society and those who do not. While the

story of Lilly and Petunia within the Potter series merely serves to explain the older

woman’s animosity towards her own family, folkloristic interpretations reveal issues of

group dynamics and politics between those who are members and those who are not.

The Hogwarts acceptance letter proves to be only the first in a series of rite-of-

passage rituals present within the Harry Potter series. Similar to standardized tests such

as end of grade and end of course examinations common in Western education, tests such

as the Ordinary Wizarding Level (O.W.L.’s) and the Nastily Exhausting Wizarding Test

25

(N.E.W.T.) are both examples of rites of passage. In order to undergo the exam,

Hogwarts students are separated from the rest of the student body, given the exam, and

only allowed to return to the main population upon completion. While the N.E.W.T.

exam is taken at the end of a student’s seventh year and must be passed in order to

transition into the wizarding community as an adult and fully competent wizard, the

O.W.L. examination is given the end of the fifth year at Hogwarts, understood as the last

of the “underclassmen” years. Hogwarts students are given subject tests on classes

required of first through fifth year students, and based off their scores are given

placement in higher level classes and allowed to choose courses as sixth and seventh year

students which will specifically prepare each individual for the occupation of his or her

choosing. Highly secular, these rites of passage must be undertaken at particular degrees

within the Hogwarts schooling process and students are only able to move forward in

their education as these rites are successfully completed. The Sorting Hat ceremony—

closely illustrated in Sorcerer’s Stone and revisited in Goblet of Fire—is, however, the

best representation of a high-context initiation ritual present in the series.

At a glance, the Sorting Hat ceremony is fairly simplistic. First year Hogwarts

students are separated from the rest of the student body as a “patched and frayed and

extremely dirty” wizard’s hat is brought before the assembly (Rowling 1997:117). This

hat then sings a song telling of the creation of Hogwarts School and the characteristics

attributed to each House. Then, Deputy Headmistress Minerva McGonagall calls forth

each student who then dons the old hat, has his or her respective House announced, and

then finally joins the Hogwarts student body by sitting at the assigned House table (119).

This ceremony, then, clearly demonstrates the tripartite structure of a high-context ritual,

26

identified by Arnold van Gennep as the preliminal phase, in which those undergoing the

ritual are separated from those witnessing, the liminal phase during which the transition

in status occurs, and the postliminal phase in which the individual is reincorporated into

society at large (van Gennep 1960:13).

Much like rituals themselves, Rowling’s writing of the Sorting Hat Ceremony

focuses on the liminal space Harry experiences once placing the wise Hat on his head.

During the opening of the ceremony Harry feels ill at ease. He is unsure what task will be

asked of him, wondering if he will be expected to pull a rabbit from the Hat (117). While

Harry understands he is no longer a Muggle, or non-magical person, he also fears the

Sorting Hat will announce his invitation to the school as a mistake and send him back to

the Dursley’s. Once the time comes for Harry to be sorted, it is ultimately he who decides

to proceed with the ritual, another component of liminal space. As the Hat ponders the

boy’s “plenty of courage,” “not a bad mind,” “talent” and “thirst to prove himself,” Harry

“grip[s] the edges of the stool and [thinks], Not Slytherin, not Slytherin” (121). This

request not only demonstrates the boy’s belief in the magical realm and desire to enter

into this new society, but also specifically locates where he envisions his role among this

Figure 2.2: Harry undergoing the Sorting Ceremony as an initiation into Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and

Wizardry. Source: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Film: 2001.

27

group to be; not with the Slytherins who are known for ambition, cunning, and a tradition

of turning out dark wizards, but the Gryffindors who are envisioned as the brave

protectors of the wizarding world. Harry’s choice propels him forward, ending both his

liminal space and his ritual enactment, and he is allowed to join his Housemates. Harry’s

initiation is complete.

Representations of Belief

One of the most notable forms of cultural expression within the Potter series

comes in the form of belief. While the belief in magic itself clearly differentiates the

wizarding and Muggle worlds from one another, this dichotomous representation is only

the beginning. Within this framework of belief acceptance and negation, Rowling builds

an intricate discussion of the plausibility of Hogwarts students’ beliefs—practices which

mirror belief systems within the primary world as well.

Herbology, a class Harry is enrolled in from the time he begins studying at

Hogwarts, is a course dedicated to identifying and caring for plants which either

themselves are magical or may be used for magical purposes after harvesting. It is here

that Harry learns about the human-shaped Mandrake root during his second year,

described as “a powerful restorative […] used to return people who have been

transfigured or cursed to their original state” (Rowling 1998:92). The mandrake root is no

newcomer to literary writings. Juliet, upon waking in the tomb to find her lover’s dead

body references the “shrieks like mandrakes torn out of the earth” (Romeo and Juliet; Act

4, Scene 3) also described by Rowling. John Donne’s “Song,” commonly known as “Go

and Catch a Falling Star,” metaphorically links women, alluded to as lacking virtue and

trustworthiness, to the deadliness of the mandrake’s legendary cry (Donne 1633; line 2),

28

and while no reference to the legendry power of the mandrake is made, even Genesis

30:14-16 equates mandrake roots to the deceptiveness and sexual promiscuity of women

when Leah uses the root to pay for a night with Jacob.

With such a lengthy history in literature, the magical use of the mandrake root is

not unheard of in folklore. Rowling’s explanation of the plant’s “restorative powers” is,

however, not an ability commonly attributed to the mandrake, although the plant is often

confused for ginseng, which is also shaped like a human child.

5

It is clear despite this

alteration that Rowling is aware of mandrake lore, as the author’s focus on the “cry of the

mandrake,” described by Harry as “bawling at the top of [its] lungs” (93) is a common

motif in folk narrative (F992.1). This presentation of homeopathic remedy and belief

within the Potterverse mirrors the reliance upon the belief of the individual in use

exhibited within the primary world of

the reader.

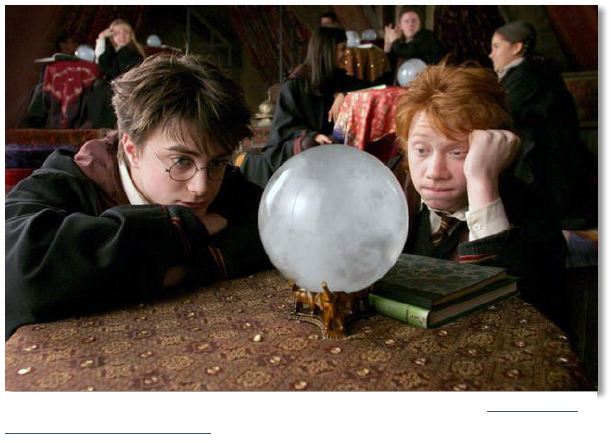

Discussions of belief become

more prominent in Harry’s third year

of study when he, Ron and Hermione

begin studying Divination, a class

instructed by an almost ethereal seer.

6

It is here that the trio begin to attempt

palmistry, analyzing tea leaves, and

5

Motifs commonly attributed to the mandrake include growth from the blood of a person hanged on the

gallows (A26115.5), use as a magic forecaster (D1311.13.1), to show the location of treasure (D1314.7.1),

to gain invulnerability (D1344.10), to protect against evil spirits (D1385.2.6), and to conceive (T511.2.1).

6

Later in the series it is revealed Professor Trelawny has a grandmother named Cassandra who also

possessed the gift of sight, obviously a reference to the Greek legend of Cassandra who was cursed with

sight by the god Apollo for denying his advances and was believed to be insane despite correctly foretelling

the fall of Troy (Buxton 2004:100).

Figure 2.3: A Gryffindor student after pulling a Mandrake. Notice the

earmuffs to protect from the Mandrake’s cry. Source: Harry Potter nd the

Chamber of Secrets. Film: 2002.

29

reading magic balls. Although these practices are presented by Professor Trelawney as

actual skills rather than belief practices, it is important to note that none of these activities

go unquestioned within the series.

Hermione Granger, Harry’s Muggle-born best friend and often identified

“brightest witch of her age” (Rowling 1999:346) has an especially difficult time

accepting the practices being instructed in Trelawney’s course. Ultimately, after yet

another prediction of Harry’s painful and tragic impending death, Hermione loses her

patience and exclaims “Oh, for goodness’ sake! […] Not that ridiculous Grim again”

(Rowling 1999:298). Then, after being told that her mind is “hopelessly mundane,” she

does something completely out of character and walks out of the class never to return

(299). While Hermione is consistently the student to question the validity of the

Divination lessons, others, namely Lavender Brown and Padma Patil exhibit a strong

belief in such practices. After Hermione’s dramatic exit from the classroom, Rowling

writes:

“Ooooo” said Lavender suddenly, making everyone start.

“Oooooo, Professor Trelawney, I’ve just remembered! You

saw her leaving, didn’t you? Didn’t you, Professor?

‘Around Easter, one of our number will leave us forever!’

You said it ages go, Professor!” (299).

While the wording of Trelawney’s prediction and her habit of predicting deadly

accidents seem far more dramatic than a student merely dropping a class, Lavender’s

unwavering belief in the Professor overlooks such discrepancies and aligns the woman’s

prediction to the actual events which have just occurred. Interestingly enough, while

Rowling does make the point to demonstrate both extremes regarding this argument on

belief, in interviews the author has clearly stated which opinion she would side with. The

30

Harry Potter and the

Chamber of Secrets

DVD hosts among its

special features an

interview with J.K.

Rowling and

screenwriter Steve

Kloves. When

discussing their favorite

characters to write Rowling states, “if you need to tell your readers something just put it

in [Hermione]. There are only two characters that you can put it convincingly into their

dialogue. One is Hermione, the other is Dumbledore” (Harry Potter and the Chamber of

Secrets DVD interview with Steve Kloves and J.K. Rowling 2003). Rowling, it seems,

who characterizes Hermione as stunningly academically intelligent with a zeal for

learning, and Dumbledore as the wise and philosophical elder, uses these two characters

to serve as her own voice within the series, delivering thematic and moralistic statements

and thoughtful inquiries through each of their individual dialogues, though the two

characters never interact themselves.

The reliance on Dumbledore is important in that it complicates the discussion of

belief as the series progresses. The Hogwarts Headmaster, described by Professor

Trelawney as being “ill-disposed towards Divination” (Rowling 2005:544), admits to

Harry that originally he had thought the seer a fraud until she unwittingly made a

prophesy foretelling the downfall of Lord Voldemort (Rowling 2003:840). Whatever the

Figure 2.4: Harry and Ron attempting to read magic balls. Source: Harry Potter

and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Film: 2004.

31

Headmaster’s feelings towards Divination, this event convinced him of Trelawney’s

worth, giving her a position among the Hogwarts faculty, defending her when the

maniacal Professor Umbridge, a transplant from the Ministry of Magic determined to

“reform” Hogwarts education, attempted to kick her out of the institution, keeping her

identity as the woman who prophesied the Dark Lord’s demise safe not only from

Voldemort’s army of Death Eaters, but also from Trelawny herself who has no memory

of the prophecy, and ultimately raising a young Harry Potter to act as savior for the entire

world as her prophesy foretold.

As Rowling has claimed Dumbledore “speaks for” her in a number of interviews,

the Chamber of Secrets DVD interview being one of them, this simultaneous acceptance

and reliance on prophesy in the midst of rejecting other belief patterns such as crystal ball

and tea leaf readings complicates the views on belief present in the series. Rather than

offering a blanket acceptance or denial of the efficacy such folkloristic belief practices,

Rowling and the characters through which she speaks are able to distinguish one belief

pattern from another and choose what they each do and do not feel comfortable accepting

within their own realities. While each of the belief practices presented within the series

do exist within the primary world as well, it is the negotiation of belief which strengths

the complexity and reliability of the Potterverse, as such discussions must occur among

practitioners in the real world. Seldom do individuals within the primary world present

universal belief patterns either accepting or denying the multitude of belief systems

presented within a community. Rather, individuals are selective regarding their personal

belief practices, a habit mirrored within the Potterverse in a way which adds depth and

believability to its use of folkloristic material.

32

Fantastic Beasts and Magical Beings

Though the Potterverse is inhabited by a number of creatures such as Dementors,

Threstals and Blast-Ended Skrewts which are unique to Rowling’s fantasy universe, most

of the creatures referenced within the series seem not to be new inventions, but rather

notable beings which exhibit lengthy histories in both folklore and fantasy literature.

Characters such as elves, goblins, trolls and giants, all of which have roots in folklore and

are similarly common in fantasy literature, are beings which are awarded—to varying

degrees—status as intelligent beings within Potterverse society. These individuals,

however, experience little development or exploration of character or status within the

series. By contrast, centaurs and werewolves, both creations of folklore with lively

fantasy performances, are used in Rowling’s writing as tools with which to explore social

issues such as racism and medical stigma.

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them is the textbook Harry and his friends

are assigned for their first year of Care of Magical Creatures, a class taught by the lovable

half-giant Rubeus Hagrid in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Published by

Scholastic Books in aid of the Comic Relief charity organization in 2001, this

supplementary Potterverse work fulfills the fantasy genre tradition of folkloresque

materials similar to Lovecraft’s History of the Necronomicon and blog posts and

referential materials created by Neil Gaiman, both which have been examined by

Timothy Evans for folkloresque content and world-building strategies (2005;2016). Much

like these notable fantasy writers and their folkloresque fantasy world creations,

Rowling’s supplementary textbook offers intertextual descriptions which reference both

the Potterverse and the existing folkloristic systems from which many of Rowling’s

33

cryptid beings are drawn in a way which adds depth to their believability and sense of

reality.

Comparison of this supplementary publication to the Potter series serves as a

useful tool when examining the perceptions of magical “beasts” within Rowling’s

universe. While the book itself lists concise descriptions and backgrounds of a number of

creatures which supposedly dwell within the Potterverse, the publication also harbors

intertextual commentary by Harry and his friends regarding their personal experiences

and views on the beasts included therein. Comparing the Fantastic Beasts textbook

description of such beings and the trio’s comments within to representations of such

figures within the series as well as to what is available in terms of folkloristic description

of these beings allows for an investigation of the ways in which the Potterverse relates to

preexisting folklore, and the specific ways such recontextualized materials serve to build

Rowling’s Potterverse.

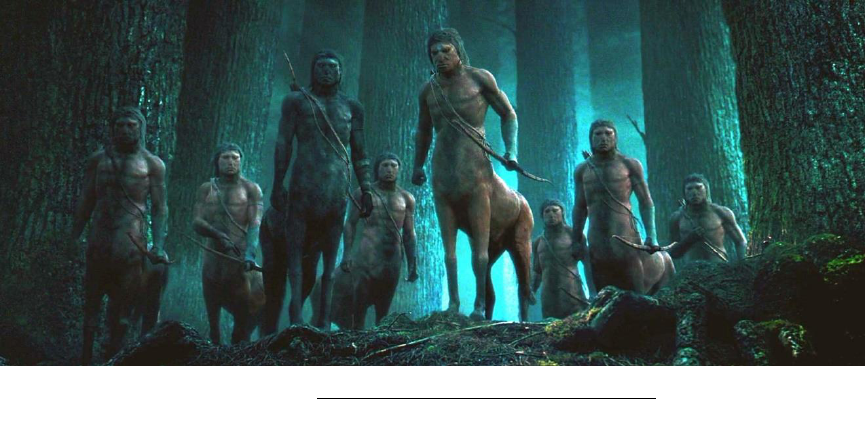

Centaurs are described in Fantastic Beasts as having “a human head, torso and

arms joined to a horse’s body which may be any of several colours” (Scamander

2001:11) and a danger classification of four out of five “X,” reflecting the need for

specialist knowledge in interaction, although it is noted that such classification is

awarded “not because it is unduly aggressive, but because it should be treated with great

respect” (footnote, pg. 11).

7

These beings, it is noted, are intelligent and are only

classified as a “beast” per the species’ own request to the Ministry of Magic, but are

7

Although written by Rowling, Fantastic Bests and Where to Find Them was published under the name

“Newt Scamander,” the author of the text as identified within the Potter series. Scamander, a former

student at Hogwarts, is also the main character in the 2016 film release of Fantastic Beasts, which

chronicles his adventures in America during the 1920’s.

34

generally considered to be another race of magical beings, alongside elves and goblins,

rather than merely a creature.

Centaurs begin playing a complicated role in the Potter series towards the

conclusion of Rowling’s first book. When serving his detention sentence assisting Hagrid

in the Forbidden Forest after being caught out of bed past curfew, Harry is saved from a

malevolent hooded figure by a centaur with “white-blond hair and a palomino body”

(Rowling 1997:256). This being, later identified as Firenze, is the third centaur Harry has

met that evening, and although his first encounter with the centaur Ronan was amicable

enough, involving dubious astrological commentary (253), Firenze’s willingness to allow

Harry to ride upon his back sparks controversy amongst the centaur herd who have a

history of experiencing prejudice at the hands of the wizards and so have adopted a

stance of distance from the affairs of man.

Relations between the herd and those humans who visit the forest never fully

recover from this ordeal. Ultimately, Firenze is banished from the herd for agreeing to

join the Hogwarts staff as the astrology professor as this is seen to be teaching sacred

knowledge to the humans, and the centaurs begin arming themselves and issuing threats

Figure 2.5: The centaur herd. Source: Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Film: 2007.

35

to any outsiders who venture into the Forest (Rowling 2003:698). This disintegration of

the human/centaur relationship influences Hermione to lead an unsuspecting Professor

Umbridge, known for her hatred of any beings considered “sub” or “partially” human,

into the heart of the centaur’s land, where the professor’s ego and prejudice enrage the

herd, instigating a riot: “Over the plunging, many-colored back and heads of the centaurs

Harry saw Umbridge being borne away through the trees by Bane, still screaming

nonstop; her voice grew fainter and fainter until they could no longer hear it over the

trampling of hooves surrounding them” (756). Although Rowling offers no explanation

of what Umbridge experiences at the hands of the centaurs, later it is noted:

Since she had returned to the castle she had not, as far as

any of them knew, uttered a single word. Nobody really

knew what was wrong with her either. Her usually neat

mousy hair was very untidy and there were bits of twig and

leaf in it, but otherwise she seemed to be perfectly

unscathed.

“Madam Pomfrey says she’s just in shock,” whispered Hermione.

“Sulking, more like,” said Ginny.

“Yeah, she shows signs of life if you do this,” said Ron,

and with his tongue he made soft clip-clopping noises.

Umbridge sat bolt upright, looking wildly around (849).

These descriptions and encounters with the centaur herd allow Rowling

throughout the series to create a dynamic representation of not only a mythological

creature, but also the society to which it would belong and the relationship this being

could potentially have with humans. Despite keeping the “semi-equine, semi-human

form” known to the species, Rowling’s centaurs exhibit an overhaul of character. Richard

Buxton’s The Complete World of Greek Mythology identifies centaurs as “wild, unruly

and unpredictable” with “a crude animality which often exploded into violence” (Buxton

2004:117). Buxton’s descriptions of the species, both during the labors of Hercules and

36

the wedding of Hippodameia involve a “drastic weakness for wine” unseen in Rowling’s

interpretation of the creatures, just as the characterization of “wild” and “unruly” falls

short of identifying those centaurs which inhabit the Forbidden Forest which forms the

borders of the Hogwarts grounds.

Greek stories of centaurs, in full actualization of the “wild” character type, often

depict the beings in the act of attempted rape. The centaur Nessus is caught trying to rape

Hercules’ wife Deianeira, and Hippodameia is subjected to similar treatment at her own

wedding (129). While Rowling herself has never commented on this aspect of centaur-

lore or what actually happened to Professor Umbridge after her kidnapping, Jacopo della

Quercia, writer for cracked.com, an online article database covering popular culture

topics ranging from how to interpret the latest hit movies, to celebrity death reports, to

recent political commentary, questions the innocence of the event and those involved.

Quercia points out that Umbridge’s final appearance in Order of the Phoenix depicts her

“suffering from some kind of major trauma that didn't involve any damage to the visible

parts of her body,” hinting towards the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder which often

accompanies sexual assault (Quercia 2011). Quercia continues, arguing Hermione’s

forethought in the act, pointing out that if any of the characters in the Potterverse were to

be familiar with traditional centaur-lore, it would be Hermione, “the character whose

main purpose in the plot is to know absolutely everything.”

While Rowling herself has made no comments on this accusation, it is hard to

completely deny such a possibility. Rowling, the author who drops subtle Greek

mythological references in family names and spell phrasing, would surely have been

aware of the rape narratives told regarding centaurs, yet such a topic as inter-species

37

sexual assault would not be deemed appropriate for children and young readers. By

simply not informing the reader explicitly of Umbridge’s fate at the hands of the centaur

herd, Rowling allows those who are aware of the beings’ traditional characterization to

fill in the blanks, while those unfamiliar with such tales are able to overlook this

possibility.

This use of existing folk characters adds depth to both Potterverse social systems

and to the individual characterizations of those involved in the ordeal. If Hermione did

intend such harm to come to Umbridge, this fact casts her character in a drastically darker

light. No longer merely a victim searching for a means of escape, Hermione herself

becomes an arbiter of violence, and Harry, in following through and not questioning

Hermione’s actions, becomes complicit in her misdeeds. Similarly, an acknowledgement

of traditional centaur lore introduces the possibility of rape and sexual assault into a

series for young readers, whereas merely hinting at tradition centaur narratives only

suggests such an act within Rowling’s writing. While the threat of sexual violence is one

which is new to the series in Order of the Phoenix, the series’ fifth installment, it is

revisited in later in the series suggesting such interpretations of Umbridge’s kidnapping

to not be far off-base, a topic I will return to shortly.

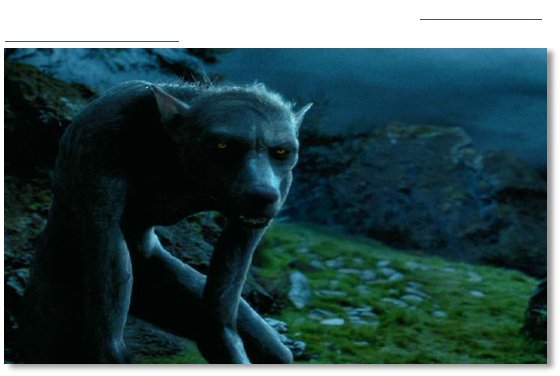

A far less controversial creature representation within the Potterverse is that of the

werewolf. Described in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them as an “otherwise sane

and normal wizard or Muggle” who “transforms into a murderous beast” at the full moon,

the werewolf is designated the highest danger rating, yet Harry’s handwritten

commentary notes they “aren’t that bad” (Scamander 2001:83). This notation is clearly a

reference to Harry’s fondness for one of only two werewolves included in the Potter

38

series, Remus Lupin, a one-time professor of Defense Against the Dark Arts and close

friend to Harry’s deceased parents and godfather. Lupin, introduced in Prisoner of

Azkaban, not only teaches Harry how to combat the effects of the Dementors by eating