B oard of G overnors of the F ederal R eserve S ystem

Uncertain Terms:

What Small Business Borrowers

Find When Browsing Online

Lender Websites

This and other Federal Reserve Board reports

and publications are available online at

www.federalreserve.gov/publications/default.htm.

To order copies of Federal Reserve Board publications

offered in print, see the Board’s Publication Order Form

(www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/orderform.pdf)

or contact:

Publications Fulfillment

Mail Stop N-127

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Washington, DC 20551

(ph) 202-452-3245

(fax) 202-728-5886

(e-mail) [email protected]

B oard of G overnors of the F ederal R eserve S ystem

Uncertain Terms:

What Small Business Borrowers

Find When Browsing Online

Lender Websites

December 2019

Barbara J. Lipman

Manager, Policy Analysis Unit, Division of Consumer & Community Affairs

Federal Reserve Board

Ann Marie Wiersch

Senior Policy Analyst, Community Development

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Special thanks to Scott Colgate and PJ Tabit from the Federal Reserve Board for their considerable

assistance with the technical aspects of the website review, including the assessment of visitor

tracking tools.

The authors wish to thank the following colleagues for their thoughtful comments, managerial support,

and guidance: Angelyque Campbell and Alejandra Lopez-Fernandini from the Federal Reserve Board

and Lisa Nelson from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. The authors also appreciate research

assistance provided by Lucas Misera and Logan Herman, former interns at the Federal Reserve Bank

of Cleveland. Finally, thanks are due to Madelyn Marchessault, Susan Stawick, Pamela Wilson,

and Anita Bennett from the Federal Reserve Board for the valuable assistance they provided to this

publication.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not

necessarily those of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System or the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Mention or display of a trademark, proprietary product, or firm

in the report does not constitute an endorsement or criticism by

the Federal Reserve System and does not imply approval to the

exclusion of other suitable products or firms.

Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................... 1

Overview of Small Business Online Lending ......................................... 3

About the Study ............................................................. 5

Themes and Observations from Online Lender Website Analysis ......................... 11

Comparing Online Lender Websites to those of Banks and Payments Processors ............ 21

Tracking Website Visitors ....................................................... 23

Implications and Policy Questions ................................................. 25

1

Executive Summary

This report discusses findings of a study conducted by the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal

Reserve Bank of Cleveland to assess the information presented to prospective borrowers on small

business online lender websites. The Federal Reserve has an ongoing interest in small businesses

and their access to the credit they need to succeed and grow. Without adequate credit, they may

underperform, slowing economic growth and employment. As the small business credit market

evolves, prompting discussion about borrower protections, the experiences of small business

owners are an important consideration.

Nonbank online lenders are becoming more mainstream alternative providers of financing to small

businesses. These nonbank lenders offer small-dollar credit products including cash advances,

lines of credit, and various types of loans, typically under $100,000. Borrowers can apply in minutes

and receive funds in days or even hours, expedience made possible with data-driven technologies.

The industry’s growing reach has the potential to expand access to credit for small firms, but also

raises concerns about product costs and features, and the manner in which these are disclosed to

prospective borrowers.

This study considers the information that is important to prospective borrowers and the availability

of such information on lender websites for the purposes of understanding and comparing product

costs and features. The study includes a systematic analysis of the content on online lender

websites, such as, where and how credit products’ costs and other details are disclosed, how

much product information is made available before website visitors are asked to supply the owner’s

personal or business information, and the extent to which visitors are tracked.

Key Findings of the Study

Online lenders varied significantly in the amount of information provided, especially on costs.

Lenders that offer term loan products were likely to show costs as an annual rate, while others

convey costs using terminology that may be unfamiliar to prospective borrowers. Still others,

particularly those that offer merchant cash advances, provide no information at all.

Among lenders that provide cost details, their websites varied in the presentation of information.

Lenders commonly present lowest-available rates. Ranges or average rates, if shown, are most

often found in footnotes, fine print, or frequently asked questions (FAQs).

On a number of the websites examined for this study, prospective borrowers must provide the

lender with personal and business information in order to obtain details about products’ costs

and terms. Lenders’ policies permit any user-provided data to be used by the lender and other

third parties to contact business owners, often leading to bothersome sales calls.

Online lenders make frequent use of trackers to monitor visitors on their websites. So, even when

visitors do not share identifying information with the lender, embedded trackers may collect this

information, as well as data on how visitors navigate the lender’s website and other sites they visit.

2

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Several implications arise from these findings, and addressing these issues is all the more important

as online lending becomes more mainstream. For one, the lack of standardization in product

descriptions across lenders’ websites was identified in previous focus group research to be a source

of confusion for small business owners. Focus group participants reported challenges understanding

product terms and making product comparisons, suggesting that standardized disclosures could

support more informed borrowing decisions. Moreover, in cases where lenders do not provide up-

front pricing details, businesses incur a “cost” when sharing their information to request a quote

or start an application. In addition to exposing their business to a potentially burdensome number

of phone calls and a flurry of marketing content, some lenders may run credit checks early in the

process, even if the business owner is just shopping rates. Furthermore, businesses could be

subjecting their data to use by lenders and other third parties.

Finally, the data collected from trackers may be matched with data from external sources to develop

profiles of small businesses that shop for credit online. Small business advocates have voiced

concerns that data collected surreptitiously through trackers may be matched with data from third-

party sources to identify individual business owners. It is unclear whether these data are used to

underwrite and price offers of credit.

3

Overview of Small Business Online Lending

Online lenders are nonbank credit providers that serve small business borrowers using data-driven

processes and technology. These lenders are increasingly becoming mainstream providers of

financing to small businesses.

1

According to the Federal Reserve’s Small Business Credit Survey

(SBCS), an annual survey of small businesses, credit seekers are increasingly turning to online

lenders. Over the past three years, the share of applicants that reported they applied at an online

lender increased from 19 percent in 2016 to 24 percent in 2017, and to 32 percent in 2018.

2

Customers of online lenders apply, are processed, underwritten, receive funds, and are serviced

largely—though not entirely—online. While the structure and features of the credit products vary

significantly, they generally fall into one of two categories:

Loans and lines of credit: Some loans are term loans with fixed rates, multi-year terms, and

fixed monthly payments. Other products have a less traditional structure, with fixed fees or total

repayment amounts, and requiring weekly or daily payments. Equivalent annual percentage rates

(APRs) typically range from 10 percent to 80 percent, and funds are often repaid in six to 18

months.

Merchant cash advances (MCAs): MCAs entail the sale of future receivables for a set dollar

amount, repaid with a set percentage of the business’s daily sales receipts. For example,

$50,000 in capital is provided in exchange for $65,000 in future receipts, repaid with automatic

draws of 10 percent of daily credit card sales. Depending on the speed of repayment, equivalent

APRs may exceed 80 percent or even rise to triple digits. MCAs are generally repaid in three to

18 months.

Lenders themselves vary in their business models, as some lend their own funds while others

connect borrowers with investors. Note that for purposes of this report, lenders utilizing any of these

business models and offering these types of products are referred to as “online lenders.” Though

some online lenders specialize in specific types of financial products, it is clear from Federal Reserve

focus group studies that small business owners view these companies collectively as lenders, and

their various products as loans. Payments processors are also active in lending, as they offer loans

to the merchants that process payments through their online platforms, but for this analysis are

considered separately.

Lenders assert that they are broadening access to credit, reaching borrowers underserved by

traditional lenders. SBCS data suggest that smaller, newer, and minority-owned firms are more likely

1

Because online lenders have no requirements to report lending volumes, there are no reliable figures on industry growth;

however, top small business lenders that publish statistics have indicated steady increases in lending.

2

The Small Business Credit Survey is an annual survey of employer and non-employer small firms administered by the 12

Federal Reserve Banks; see https://www.newyorkfed.org/smallbusiness/small-business-credit-survey-2018.

4

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

to apply to online lenders.

3

In addition, the data suggest medium- and high-credit-risk applicants

have had greater success obtaining credit at online lenders than at traditional banks (approval rates

of 76 percent versus 34 percent at large banks and 47 percent at small banks).

4

Applicants that chose to seek financing at online lenders reported the most important factors in their

choices were the speed at which they expected lenders to approve and/or fund their application,

and their perceptions that they had a better chance of being approved at an online lender.

While more applicants are successfully funded at online lenders, the SBCS indicates satisfaction

levels with online lenders are far lower than with traditional lenders (net satisfaction of 33 percent

at online lenders versus 73 percent at small banks and 55 percent at large banks).

5

In 2018, 63

percent of online lender applicants reported challenges working with their lender, with more than half

saying they experienced high interest rates and almost a third reporting concerns with unfavorable

repayment terms.

Also, it is important to note that the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) rules that apply to consumer loan and

credit products generally do not apply to business credit, so in practice, lenders have more flexibility

in their disclosures of product costs and features.

6

And indeed, as discussed in the next section,

qualitative studies suggest that small business owners struggle to understand the wide range of

products offered by online lenders and the unfamiliar terminology that some lenders use in their

product descriptions.

3

Ann Marie Wiersch, Barbara J. Lipman, and Brett Barkley, Click, Submit: New Insights on Online Lender Applicants

from the Small Business Credit Survey, (Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland special report, October 2016), https://www.

clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/special-reports/sr-20161012-click-submit.aspx. As of this writing, an

updated version of this report is forthcoming. See also, Mark E. Schweitzer and Brett Barkley, “Is ‘Fintech’ Good for Small

Business Borrowers? Impacts on Firm Growth and Customer Satisfaction,” Working Paper 17-01 (Federal Reserve Bank

of Cleveland, February 2017), https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/working-papers/2017-

working-papers/wp-1701-is-fintech-good-for-small-business-borrowers.aspx.

4

Federal Reserve System, 2019 Report on Employer Firms: Small Business Credit Survey, https://www.fedsmallbusiness.

org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-employer-firms-report.pdf. Approval rate is the share of firms approved

for at least some credit.

5

In the SBCS, net satisfaction is the share of firms satisfied minus the share of firms dissatisfied.

6

The Truth in Lending Act is implemented through Regulation Z. Regulation Z does impose certain substantive protections

applicable to credit card holders, including where the card is issued for business use. Alternative small business lenders,

however, do not typically issue credit cards.

5

About the Study

This study builds on prior work, including two rounds of focus group studies conducted by the

Federal Reserve (see box 1) and quantitative findings from the SBCS.

7

The participants in these

focus group studies—more than 80 small business owners—completed a “virtual shopping” exercise

and compared mock products based on real online product offerings. These studies found that

small business owners struggle to understand many of the products offered by online lenders and

the unfamiliar terminology that some lenders use in their product descriptions.

8

Box 1. Background on Focus Groups Studies

Online focus groups with more than 80 business owners

Two rounds of focus groups: 2014–2015 and 2017

Participants were the business owner or financial decisionmaker

Participants’ small businesses:

— Less than $2 million in revenue, fewer than 20 employees

— In business at least two years

— Included a variety of industries from across the United States

— Had applied for credit in the prior 12 months (2017 focus group only)

Topics:

— Process for seeking short-term credit

— Impressions of websites when virtually “shopping”

— Evaluations of mock credit products and recommendations

Key findings:

— Participants found the websites appealing, but many noted information they sought was not readily accessible

— They strongly disliked that information they considered important appeared in fine print or footnotes

— Terminology used to describe the products was unfamiliar to some

— They reported that aspects of the product descriptions were confusing or lacking sufficient detail

— They found it challenging to identify interest rates or estimate costs

— They made (sometimes mistaken) assumptions about the products based on past experiences with traditional

bank loans

This present study considers the information that is important to prospective borrowers and the

availability of such information on lender websites for the purposes of understanding and comparing

7

See Barbara J. Lipman and Ann Marie Wiersch, Alternative Lending Through the Eyes of “Mom & Pop” Small Business

Owners: Findings from Online Focus Groups (Cleveland, OH: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2015), https://www.

clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/special-reports/sr-20150825-alternative-lending-through-the-eyes-

of-mom-and-pop-small-business-owners.aspx; and Barbara J. Lipman and Ann Marie Wiersch, Browsing to Borrow:

“Mom & Pop” Small Business Perspectives on Online Lenders (Washington: Federal Reserve Board, 2018), https://www.

federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2018-small-business-lending.pdf.

8

It is important to note that focus groups are designed to gather insights, not to measure incidence. Findings are not

necessarily reflective of a wider population of small businesses.

6

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

product costs and features. The study includes a systematic analysis of the content on online lender

websites, including:

where and how credit products’ interest rates, fees, repayment and prepayment terms, and other

features are disclosed;

how much product information is made available before website visitors are asked to supply the

owner’s personal or business information; and

the extent to which data on visitors are collected, either passively through trackers or actively

through inquiry forms.

This work was inspired by two previous efforts, one by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the

other from the Financial Conduct Authority, the United Kingdom’s consumer protection agency.

9

Both studies examined how information was displayed on the websites of consumer online lenders,

identifying the number of clicks needed to obtain certain product information and the font displaying

that information. The FTC study also looked at the extent to which site visitors are tracked. These

two studies focused on consumer lenders, while the study presented in this report focuses on small

business credit providers.

Among the caveats to note, the scope of this study includes only the content and features of select

lender websites. Therefore, the findings should not be considered representative of all websites in

the industry. Importantly, the websites covered in the study largely overlap, but differ somewhat from

those that the participants chose to view in the focus group studies. Note that the study does not

explore what information lenders communicate directly to individual small business owners that seek

credit. Finally, the study does not address provisions of formal offers of credit or loan agreements,

and makes no attempt to assess whether the product terms described on lenders’ websites match

the terms in actual loan agreements.

Methodology

The authors considered several factors in developing the list of 10 online lending companies included

in the study. The list was compiled so as to include established lenders that report significant small

business credit activity. In addition, the authors considered which lenders small business owners

would encounter when conducting internet searches for small business lenders. To this end, the

authors consulted numerous lists of the industry’s largest lenders and conducted multiple keyword

searches, identifying those lenders that appeared earliest in the search results. Finally, the authors

attempted to ensure that a cross-section of lenders—based on business models and products

offered—were included. Note that the list is not representative of the composition of the industry,

which is highly fragmented and includes a significant number of small lenders, MCA providers, and

broker websites.

9

This study builds on earlier work by the Federal Trade Commission, “A Survey of 15 Marketplace Lenders’ Online

Presence,” June 2016, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_events/944193/a_survey_of_15_marketplace_

lenders_online_presence.pdf and the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, Payday Lending Market Investigation, “Review of

the Websites of Payday Lenders and Lead Generators,” appendix 6.4, February 2015, https://assets.publishing.service.

gov.uk/media/54ebb75940f0b670f4000026/Appendices_glossary.pdf.

7

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Separate from the 10 online lenders, the study reviewed the websites of two payments processors

that extend loans to their merchant customers. These companies were considered separately

because offers of credit products are made to existing customers, based on information that the

company already has. Many of the considerations in the study, therefore, do not apply. Finally, for

comparison purposes only, the authors identified five commercial banks that offer online applications

for small business loans, and reviewed the presentation of product information on those websites.

The study itself involved a systematic review of the content on lenders’ websites, ways in which

their products are described, and the processes through which lenders collect information from

prospective small business borrowers. The authors reviewed 15 different aspects of the content,

documenting in standard forms the language used and where and how the information is displayed.

The specific variables reviewed are described in the following section. In addition, the study utilized

a Chrome browser extension to identify and quantify the number and types of third-party trackers

employed by the websites.

As noted earlier, this study is intended to capture the information that prospective borrowers

encounter when researching and comparing credit products. Therefore, throughout the report, the

content described is not associated with the names of specific lenders.

10

Although the information

shown is publicly available, company names have been anonymized as this analysis is intended

to describe typical practices in the marketplace rather than to single out practices of individual

companies.

Considerations for the Study

To ascertain which aspects of product descriptions should be considered in the study, the authors

consulted various sources.

Focus group studies: The participants in the two rounds of focus groups (outlined in box 1)

described the information they were looking for when they completed a virtual shopping exercise.

Participants identified the following details as being important to them as they searched for

information on online lenders and the funding products these lenders offer:

application process and information required by the lender for the application

approval requirements/qualifications

interest rates, fees, and other charges

repayment terms (frequency, length of term, method of repayment)

maximum available loan amounts

10

Online lenders considered in this study include BFS Capital, CAN Capital, Credibly, Fundation, Funding Circle, Kabbage,

Lending Club, National Funding, OnDeck, and Rapid Finance. Payments processors include PayPal Working Capital and

Square Capital. Commercial banks include Bank of America, Live Oak Bank, TD Bank, US Bank, and Wells Fargo. The

order in which the companies are listed here does not correspond to the identifiers used in subsequent sections of this

report.

8

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

time to approve application and speed of funding

trust cues (customer reviews, Better Business Bureau ratings, etc.)

Truth in Lending Act: While, as noted earlier, TILA rules generally do not apply to business credit,

the requirements provide a frame of reference for disclosure of credit products. Additionally, because

the business owners using online lenders tend to be smaller “mom & pops,” they are very consumer-

like in their approach to financing.

11

Most have limited financial expertise and, more often than not,

do not have a dedicated chief financial officer on staff.

Although not intended for small business credit, TILA provides useful guidelines for the advertising of

consumer credit products, including what’s shown on websites. The requirements ensure the costs

of various credit products are comparable since financing charges must be shown as an APR. The

guidelines also help to ensure important details—like repayment terms and fees—are described

clearly, so consumers are not misled by statements in advertising.

FTC dot.com guidance: The website analysis considers not only what is presented, but how it’s

presented. The FTC’s dot.com guidance says disclosures should

12

be truthful; not misleading or unfair,

use understandable language,

be readily noticeable to consumers and not require scrolling,

use the same font size as other text,

be located near advertising claims they qualify, and

not relegate necessary information to “terms of use.”

Taking the focus group findings, the TILA rules, and the FTC guidance into account, the authors

developed a framework for a systematic review of the description and display of 15 items (see box 2).

11

See Small Business Credit Survey, 2019 Report on Employer Firms, Data Appendix, Employer Firms by Revenue, https://

www.fedsmallbusiness.org/survey.

12

Federal Trade Commission, .com Disclosures: How to Make Effective Disclosures in Digital Advertising (March 2013),

https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/press-releases/ftc-staff-revises-online-advertising-disclosure-guidelines/

130312dotcomdisclosures.pdf.

9

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Box 2. Elements Included in Systematic Website Review

Lenders’ appeal to prospective customers

— Main marketing pitch

— Trust cues, such as customer reviews, Better Business Bureau ratings, etc.

Application process

— Approval requirements and borrower qualifications

— Information required to initiate an application

— Application form and identification of product

— Impact of an inquiry on credit score

— Speed of approval and funding

Products, rates, fees, and features

— Level of detail in product descriptions

— Terminology used to describe interest rates and additional costs and fees

— Repayment terms

— Prepayment savings or penalties

— Maximum loan amounts

This review tracked language used on websites, the level of detail provided, and the position and

appearance of text for key information.

11

Themes and Observations from Online

Lender Website Analysis

Online Lenders Seek to Engender Trust

While online lenders have grown and become more mainstream, the industry is still relatively new

and faces challenges in attracting customers. One contributor to those challenges is the unfavorable

views of the industry held by some prospective borrowers.

During the focus group studies, small business participants were asked for their initial impressions

of “online lenders.” Some participants had positive perceptions. They thought of these lenders

as being faster, more efficient, and more willing to work with small business borrowers. Some

thought that, since they have less overhead, online lenders would be more affordable. However,

a larger share of participants had negative impressions, associating online lenders with high costs

and interest rates. Some of their responses indicated a lack of trust in online lenders, while others

mentioned unwanted calls, mail, and email.

Online lenders have positioned themselves as trusted alternative providers of small business credit,

advertising their faster, more convenient processes and their product options for firms with low credit

scores. The content on the lenders’ websites reflects their awareness of borrowers’ perceptions of

the industry. Indeed, focus group participants reported having more positive impressions of online

lenders after visiting some of the lender websites during the virtual shopping exercise.

The headings, taglines, and other prominent text on lenders’ websites convey their focus on speed

and simplicity (“Get a quote in minutes,” “minimal paperwork”), while also highlighting their flexibility

and willingness to work with small businesses with less-than-perfect credit (“High approvals,” “All

credit scores are considered”).

Some focus group participants were impressed with sites that offer comparison charts, but a review

of these charts suggests many lack specific content. Lenders give themselves check marks for fast

funding, easy process, and flexible approval criteria, shown side-by-side with unfavorable marks (Xs

or blanks) they attribute to nonspecific competitors (“banks” or “other lenders”). In most cases, these

charts simply reiterate companies’ sales propositions, while relaying minimal details about product

features or costs that would be useful to a prospective borrower who is comparison-shopping.

This analysis finds that online lenders seek to engender the trust of businesses visiting their

websites. This was most evident in the display of badges and logos of various business

intermediaries—such as the Better Business Bureau, Trust Pilot, and similar organizations. Mentions

of their companies in the media also were often featured on the pages, as well as ratings and

endorsements from outside organizations. Five of the 10 lenders also referenced a relationship with

an FDIC-insured bank. This strategy does appear to reassure some visitors:

12

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

“I’m not sure why I trust them, but I do. Maybe because they

state they are BBB accredited.”

“I appreciated how they address concerns about their

credibility up front with their BBB and TrustPilot rating.”

While reviews, ratings, and testimonials were valued by some focus group participants, a scan

of online lenders’ reviews and ratings revealed very little specific information about products;

however, these are the details that are important to borrowers, based on responses from focus

group participants. Most reviews were positive, but limited to customers’ early interactions with

their lenders. The majority either commented on positive experiences with sales representatives,

simple applications, or quick turnaround; they offered little insight on the products themselves or

experiences with the lenders after receipt of funding.

Inquiries Lead to Collection of Prospective Borrowers’ Data

All of the online lenders’ websites prominently feature links and buttons prompting visitors to “apply

now” or “get a quote.” These links connect visitors to pages on the websites with online forms to

input their personal and business information. These forms typically serve as an initial inquiry with a

lender, either requesting pricing information or initiating an online application. They collect contact

information from prospective borrowers, and in many cases, financial details—including annual

revenues, credit scores, and account balances. In at least one case, the lender requests that the

applicant grant access to the business’s Quickbooks account to expedite the application process.

Table 1. Select details on application processes from online lender websites

Online lender

Common application

form for all products

Initial inquiry impact

on credit score*

Consent to use of

contact information

Company A Not applicable, only one

product offered

Soft pull: “won’t affect your credit

score”

By clicking “continue” on

lenders “get a quote” form,

user gives consent

Company B Common application; fine

print on application form

notes user is not applying

for a specific product

Soft pull: “will not impact your personal

credit score”

By clicking “continue” on

application form, user gives

consent

Company C Common application; all

“get quote” links for all

products lead to same

form, same URL

Soft pull: “no credit impact to get a

quote”

By clicking “continue” on

“get my quote” form, user

gives consent

13

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Company D Not applicable, only one

product offered via online

application

Credit check: FAQs specify that credit

report is pulled for business owner

By clicking “get started”

on application form, user

consents to privacy policy

(includes permission to

contact)

Company E Common application;

all “apply now” links

lead to same form/URL,

regardless of page or

product

Soft pull: “no impact on credit score” Website’s terms of use

specifies that user expressly

consents to be contacted

Company F Common application;

“get started” links on all

product pages lead to

same form/URL

Soft pull: prequalification “does not

negatively impact your credit score”

Prequalification form

includes authorization to

contact

Company G Not applicable, only one

product offered

Soft pull: “won’t impact your credit

score”

Website’s terms of use

specifies that user expressly

consents to be contacted

Company H Common application;

all “apply now” links

lead to same form/URL,

regardless of page or

product

Not specified; terms and conditions

authorizes company and affiliates to

request credit report

By clicking “get started”

on application form,

user consents to terms

and conditions (includes

permission to contact)

Company I Common application for

two products, though

application link appears

only in the menu and not

with product descriptions

Not specified; privacy policy specifies

that the company may obtain credit

reports

Website’s privacy policy

specifies that users consent

to be contacted

Company J Common application for

two types of loans and

MCAs; “apply now” links

on both product pages

lead to same form/URL

Credit check; “personal credit check is

part of the approval process”

User must check box

indicating agreement with

privacy policy; permission to

contact also described in a

footnote on application form

Note: Although all information shown is publicly available, company names have been anonymized, as this analysis is intended to describe

typical practices in the marketplace rather than to single out practices of individual companies.

* A “soft pull,” also known as a soft inquiry, is a credit check performed by a lender to pre-qualify a prospective borrower. Unlike hard credit

inquiries, soft pulls do not appear on customers’ credit reports and do not affect their credit scores.

Source: Authors’ analysis of company websites, as of August, 2019.

A majority of the companies utilize a common application, that is, a single form for all products. For

example, the “apply now” link shown with a lender’s business loan description, and the “apply now”

link shown with their MCA description both lead to the same URL and application form. In such a

case, a prospective borrower may complete an application seeking a business loan. The concern is

that this may be a potential source of confusion for borrowers who think they may be applying for

one product, but are offered another product with different terms than what they were seeking.

Once a user completes a lender’s application or inquiry form, the lender begins steps to verify

the creditworthiness of the user and to establish terms of any credit offer that may be extended.

14

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Several companies advertise that their initial credit check will not affect the user’s credit score, often

specifying that only a “soft pull” is done upon receipt of the application or inquiry. Other companies

state, typically in Terms of Use or FAQ pages, that a credit check is part of the application process,

without reference to a soft pull.

Lack of Information Prompts Solicitation

Lenders vary significantly in the level of upfront information they provided to prospective borrowers.

On some sites, product descriptions feature little or no information about the actual products, but

instead focus on the ease of applying and qualifying for funding, the speed at which applications

are approved, and the array of uses for loan proceeds. Details that were important to focus group

participants—rates, fees, and repayment information—were absent from several of the websites. In

some cases, details like loan terms were found on Terms and Conditions pages or in FAQs. Note

that the lack of detail described here is typical of lenders that cater to higher-risk borrowers and

those that offer MCAs.

As noted earlier, on the websites of several online lenders included in this study, visitors must enter

their personal and business information in order to obtain information about the lenders’ products.

Some focus group participants that encountered such sites during the virtual shopping exercise

were frustrated by the lack of information:

“All these sites are a lot of clicking around and not getting

very far without providing information I’m not ready to

provide. I don’t want to be solicited for the rest of my life just

because I was looking for some information.”

“I hoped to see rates, terms and what I qualified for. [The

site] wouldn’t provide any information without an email or

contact info.”

“I couldn’t get info unless I signed in. I wanted to know how

much interest, and if I paid back quickly, was there lower

interest.”

Several participants cited concerns about lenders’ requests for information about their businesses

in online forms and the prospect of receiving solicitations as a result of providing this information.

Indeed, the lenders themselves are somewhat transparent about their intent to use the information

collected to make contact with the business. As shown in table 1, all of the companies include

some provision for users to grant permission to the lenders and lenders’ affiliates to contact them

using any information the lender collects. On some sites, the consent is described explicitly on the

15

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

application form; on others, consent is implicitly given, as described in the sites’ privacy policy or

terms of use pages. The consent provisions cover purposes that include communications regarding

applications and loans, but also marketing and sales of additional products.

More than three-quarters of the focus group participants reported receiving some type of contact

from online lenders in the past, either in the form of email, mail, phone calls, or offers. These

contacts, particularly the phone calls, were bothersome to the participants:

“I get these calls and emails almost every day. The worst

part is they almost never take ‘no’ for an answer.”

“I received 20+ calls a week after I secured a loan with [an

online lender].”

“I get calls twice a week and emails all the time. You just

want to shut it off and not be bothered by it.”

Online Lender Websites Vary in Cost Information Provided

Some sites provide more details about the features of their financing products than others.

13

However, even on websites with more information, specific details about repayment, fees, and other

items important to focus group participants were sometimes missing or not readily displayed. For

example, one lender featured in prominent bold print the “as low as” rate for a loan product, but in

a footnote, disclosed a far higher average rate for the product. A few lenders relied on footnotes to

convey key details about products, especially costs (see table 2).

13

This analysis covers companies’ business loans, merchant cash advances, and lines of credit. Certain specialized products

offered by some lenders, such as equipment leases and industry-specific loans, are not included.

16

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Table 2. Select details from online lender websites

Online lender

Location of cost

information

Product cost description* Additional fees

Company A On home page in box,

details in footnotes

Business loans: rates described as

a Total Annualized Rate; fixed rates

ranging from 5.99% to 29.99%

Origination fee: 1.99% to

8.99% of loan amount

Company B On home page in plain

text, details on product

pages in feature text and

in footnotes

Term loans: costs shown as simple

interest starting at 9% for short-term

loans and Annual Interest Rate (AIR)

starting at 9.99% for long-term loans

(both rates exclude fees).

Lines of credit (LOCs): costs shown

as Annual Percentage Rate (APR)

(starting at 13.99%, weighted average

is 32.6%)

Origination fee: up to 4%

of loan amount; monthly

maintenance fees on LOC

Company C Not provided Loans and lines of credit: no rates

or product costs are described

MCAs: factor rates usually between

1.14 and 1.48

No information

Company D On Rates and Terms page

in feature text, details in

footnotes

Loans: costs are described as a

monthly fee determined by the fee

rate, which ranges from 1.5% to 10%

Third-party partners may

charge up to an additional

1.5% per month

Company E Not provided Loans and MCAs: No rates or

product costs are described on the

website

3% origination fee (loans),

$395 admin fee (MCAs)

Company F On product page in plain

text

Working capital loans and MCAs:

factor rates as low as 1.15

Business expansion loans: interest

rates starting at 9.99% (not an APR)

Set-up or underwriting fee:

2.5% of loan total; Admin fee

up to $50/month

Company G On home page in feature

text, details in tables on

Rates and Fees page

Loans: costs shown as fixed annual

interest rate, ranging from 4.99% to

26.99%

Origination fee: 0.99% to

6.99%; late payment fee: 5%

of missed payment

Company H Not provided Loans and MCAs: No rates or

product costs are described on the site

No information

Company I Not provided Loans and MCAs: No rates or

product costs are described on the site

No information

Company J Not provided Loans and MCAs: No rates or

product costs are described on the site

No information

Note: Although all information shown is publicly available, company names have been anonymized, as this analysis is intended to describe

typical practices in the marketplace rather than to single out practices of individual companies.

* A factor rate is a rate used to calculate a borrowing fee, often expressed as a percentage of the borrowed amount and typically shown in

decimal form.

Source: Authors’ analysis of company websites, as of August, 2019.

17

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

The placement of product cost information on lenders’ websites varies from lender to lender. In

some cases, cost information—typically the lowest-available rate—is conspicuously displayed in an

upfront manner that would be highly visible to a user visiting the website. A few lenders prominently

advertise their costs in “feature” text, that is, in font that is larger than other text on the page, often in

bold or in an accent color. Lenders also may display the information as part of graphic features like

tables and boxes. By contrast, other lenders provide cost information in a way that is less visible to

users of the websites—for example, in plain text or in footnotes at the bottom of a page.

Focus group participants had mixed reactions to footnotes. Many were frustrated by fine print,

and said they thought lenders were trying to conceal information. Conversely, other participants

appreciated the additional information provided in the footnotes, after being unable to successfully

locate such details on some of the websites they encountered during their shopping exercise.

“Any company hiding things in fine print and buried in

paperwork should not be trusted.”

“Fine print [has] what I want to see. They’re being more

upfront and aboveboard about the reality of their loans.”

In some cases, footnotes and fine print contain information on fees that companies typically charge

for their products, aside from interest charges. These fees are most often for product origination,

but others include administrative fees, account maintenance fees on credit lines, or fees charged by

partners. Fees may be disclosed as a range of rates, flat monthly or one-time charges, or charges

“up to” a set percentage. Some lenders do not describe any fees on their websites.

The website analysis found significant variation in the terminology used to explain products’ costs.

As shown in table 2, two lenders provide costs in the form of an annual rate that excludes fees; a

third describes costs in APR terms for only one product, their line of credit. Several lenders describe

costs for at least one of their products using nontraditional terminology, such as a “factor rate,”

“fee rate,” or “simple interest.” Four lenders provide no rates or costs for any of their products. For

traditional term loans, product descriptions tend to be somewhat detailed, while descriptions for

MCAs include little or no information about the actual costs and repayment terms.

The variation in the product cost descriptions was confusing to focus group participants. They found

it challenging to determine products’ actual costs and to compare products when descriptions used

unfamiliar or varying terminology.

18

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

“It is difficult [to compare when] they are using different

models and different terminology.”

“They don’t like to use the word ‘interest,’ and they dress it

up in other ways to conceal the real cost of the loan.”

“I don’t know what a ‘factor rate’ is.”

“Full disclosure, like on credit cards or mortgages… is what

is necessary. They need to state the actual APR.”

Participants noted that the varying product descriptions provided no common basis for cost

comparisons, and several suggested that APR would be helpful for that purpose. In fact, determining

the equivalent APR on some products may be challenging, given the non-standard terminology and

structure of products offered by online lenders. Table 3 presents APR-equivalents for a common

scenario in which $50,000 is repaid in six months according to the terms and rates promoted on the

lenders’ sites.

Table 3. Estimated APRs for select online products

Rate advertised on website Product details Estimated APR equivalent

1.15 factor rate • Total repayment amount $59,000 Approximately 70% APR

• Fees: 2.5% set-up fee; $50/month

administrative fee

• Term: none (assume repaid in six

months)

• Daily payments (assume steady

payments five days/week)

4% fee rate • Total repayment amount $56,500 Approximately 45% APR

• Fee rate: 4% (months 1–2), 1.25%

(months 3–6)

• Fees: none

• Monthly payments

• Term: six-month term

9% simple interest • Total repayment amount $54,500 Approximately 46% APR

• Fees: 3% origination fee

• Weekly payments

• Term: six-month term

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on product descriptions on company websites.

19

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

The non-standard terminology also proved challenging for focus group participants trying to

compare online offerings with traditional credit products. For example, when asked to compare

a sample short-term loan product with a 9 percent “simple interest” rate to a credit card with a

21.9 percent interest rate, most participants incorrectly guessed the short-term loan to be less

expensive.

14

For another sample product—a $50,000 MCA with a factor rate of 1.2 and total

repayment of $60,000—focus group participants were asked for their guesses of an interest rate, if

the funds were repaid in one year. Interestingly, although all participants were presented with exactly

the same information about the product, they responded with a wide range of estimates, from 10

percent to over 50 percent.

15

Payment Arrangements Are a Source of Confusion

All companies described the frequency of required payments for their products, ranging from daily

to monthly payments. Fixed payments were most common for term loans. Payments on MCAs are

typically variable, as the payment amount usually fluctuates with sales volume. A few companies

provided no information on the payment structure for one or more products offered.

As shown in table 4, companies provide limited details on the impact of prepayment. A few note that

by prepaying, the customer incurs savings on interest (as they would with a traditional loan). Other

companies advertise that some borrowers may qualify for prepayment discounts on their remaining

financing charges. Still others provided no details regarding charges or savings associated with early

repayment.

Table 4. Select details on product repayment from online lender websites

Online lender Payment amount and frequency Term length (loans only) Prepayment

Company A Fixed monthly payments 1–5 years Interest savings

Company B Fixed daily or weekly payments 3–36 months “Potential interest

reductions”

Company C Loans: fixed daily, weekly, or monthly

payments

MCA: variable daily or weekly

payments based on sales volume

LOC: daily or weekly payment (fixed

vs. variable not specified)

3–60 months Not specified

14

See Lipman and Wiersch, Browsing to Borrow, 18 (sample Product B). According to the product description, Product B

has a 3 percent origination fee and requires weekly payments.

15

See Lipman and Wiersch, Browsing to Borrow, 18 (sample Product C). Note that although interest owed on this product is

20 percent of the principal value, the effective rate, assuming daily payments and steady sales, would be on the order of 40

percent.

20

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Company D Monthly payments in set amounts

established at loan origination

6–18 months Savings on monthly fees

implied

Company E Loans: fixed daily payments

MCA: variable daily payments based

on sales volume

6–18 months Discount available on loans

repaid within 90 days of

origination

Company F Loans: fixed daily or weekly payments

MCA: variable daily payments based

on sales volume

6–24 months Not specified

Company G Fixed monthly payments 6 months to 5 years Interest savings

Company H Loans: daily or weekly payments (fixed

vs. variable not specified)

MCA: variable daily payments based

on percentage of sales

4–24 months Discount available on loans

repaid within 100 days of

origination

Company I Loans: biweekly payments (fixed vs.

variable not specified)

LOC: fixed monthly payments

Up to 4 years Interest savings

Company J Loans: fixed daily or weekly payments

MCA: variable daily payments based

on percentage of sales

Up to 18 months Not specified

Note: Although all information shown is publicly available, company names have been anonymized, as this analysis is intended to describe

typical practices in the marketplace rather than to single out practices of individual companies. MCA is a merchant cash advance and LOC is

a line of credit.

Source: Authors’ analysis of company websites, as of August, 2019.

Early repayment on products with fixed payback amounts was particularly confusing for focus

group participants. Using the same sample MCA described above—an advance of $50,000 with

a repayment amount of $60,000 paid back with a small percentage of daily credit card sales—

participants were asked the impact of higher-than-expected sales on the repayment of the advance.

While most participants correctly noted that repayment would occur more quickly, their expectations

regarding the effect on their interest rate were varied:

“I would definitely plan to [pay] the loan back much sooner

and have a lesser repayment amount.”

“The stronger [your] sales the faster you could pay off the

loan which would in effect lower the interest rate.”

Importantly, some participants, accustomed to traditional consumer products, expected that their

interest or financing charges would be reduced by repaying quickly. In fact, faster repayment would

increase the effective interest rate and would not reduce the $60,000 amount owed.

21

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Comparing Online Lender Websites to

those of Banks and Payments Processors

To provide a frame of reference for the findings from the analysis of online lenders’ websites,

the authors conducted similar systematic reviews of two other groups of lenders: (1) payments

processors that provide small business credit, and (2) commercial banks that offer their own small

business credit products online.

Payments processors: This study looked at the two major payments processors that offer credit

to their small business customers. Though these companies are among the largest online lenders,

they are excluded from the set of online lenders analyzed in this study for several reasons. First,

these companies lend exclusively to their existing customers by making customized offers to their

merchants based on the data they already collect on sales processed through the platforms (sales

data as well as inflows and outflows to and from the merchants’ accounts). Therefore, key elements

of the website analysis undertaken for this study are not relevant, as the companies already have

their customers’ data. Furthermore, these lenders communicate product information to their

customers through the credit offers themselves; therefore, the content on the websites serves a less

critical role in informing the prospective borrower.

That said, issues around the comparability of products are relevant for the payments processors, as

would-be borrowers may have a need to compare offers of credit from these companies to products

available at other online lenders, or to other options such as credit cards.

The payments processors, like many other online lenders, use non-standard cost structure and

product terminology. In some ways, their products are hybrids of MCAs and loans. Like an MCA, the

products feature a fixed repayment amount, and further, the credit is repaid through swipes of daily

sales receipts, so payment amounts vary with sales volume. However, like a term loan, these lenders

require loans to be fully repaid in a set number of months, regardless of sales activity. The lenders

may require periodic supplemental payments if sales are slow.

Focus group participants were shown a sample product like that offered by one of the payments

processors. For the sample loan, the borrower chooses a “repayment percentage,” that is, the

portion of their daily sales devoted to repayment, and borrowing costs are set accordingly.

16

The

terminology and the corresponding change in cost were confusing to many focus group participants.

Some appeared to equate the repayment percentage with an interest rate.

16

Lipman and Wiersch, Browsing to Borrow, 16 (Product A).

22

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

“It doesn’t make sense that if the fee is 30%, the

[repayment] amount is lower.”

“What are the monthly installments?”

“The interest rates are not published so you have to

calculate yourself.”

“I feel like they are trying to hide the true cost of the loan.

Just tell me the % interest.”

“I’m not interested in paying that high of fees. The minute I

saw 30% I was turned off.”

Commercial Banks: Again for comparison purposes, this study considered the manner in which

credit products’ costs and features are communicated on bank websites. For a suitable comparison,

the five banks identified for the study offer small business credit and an online application process.

Their online products are loans and lines of credit, generally unsecured, and typically up to

$100,000.

17

In their advertising, these banks placed far less emphasis than online lenders on easy credit, and

as a general rule, the minimum qualifications described were more stringent. In addition, the banks

downplayed their speed of funding and processing times. The two banks that do reference funding

times specify a week to 10 days.

As with online lenders, the analysis finds considerable variation across the bank sites in the level

of detail provided. Three of the five banks provided cost information for their credit products; two

provided none. Among the three that did give more thorough product information, the products

tended to be traditional term loans with fixed monthly payments, and were described using familiar

terminology. Costs were described using an annual interest rate, such as prime plus a fixed percent.

Similar to online lenders, the banks featured their “as low as” rates, and some cost details were

conveyed in footnotes and FAQs.

17

Websites were reviewed in August, 2019. One institution offers secured loans and lines of credit only, and one offers

unsecured loans up to $250,000.

23

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Tracking Website Visitors

As stated in the introduction, a goal of this study was determining the extent to which online lender

website visitors are tracked. In addition to the collection of customer data through the use of forms,

described earlier, lenders have robust tools for tracking and identifying customers. Some of these are

generally imperceptible to customers, though a few of the small business focus group participants

expressed concerns about their privacy during the virtual shopping exercise and in their prior

experiences:

“I was wondering if my IP address was being tracked

because I was getting solicitations through my email while

researching.”

“I just feel violated because I never applied for any loans.

It’s a scary feeling wondering how these people get your

information.”

Companies use “trackers” to collect data on prospective customers. When installed on a lender’s

website, trackers collect identifying information about website visitors and attempt to match them

to known businesses or owners, using data from a variety of sources including Facebook, Amazon,

Twitter, LinkedIn, and other common web platforms.

18

The profiles may contain information like

company name, address, and internet activity, as well as more sensitive data including financial

information and owner demographics. So, even when visitors do not share identifying information

with the lender, embedded trackers may collect this information, as well as data on how visitors

navigate the lender’s website and other sites they visit. Such details can then be shared with data

aggregators to build a more complete profile.

The analysis of trackers on lender websites utilized Ghostery, an open source browser extension,

to measure the extent to which visitors are tracked on websites using embedded trackers. The

Ghostery tool analyzes every network request (e.g., clicks) generated on a specific web page and

then matches the outgoing URL patterns against a database of known trackers to determine which

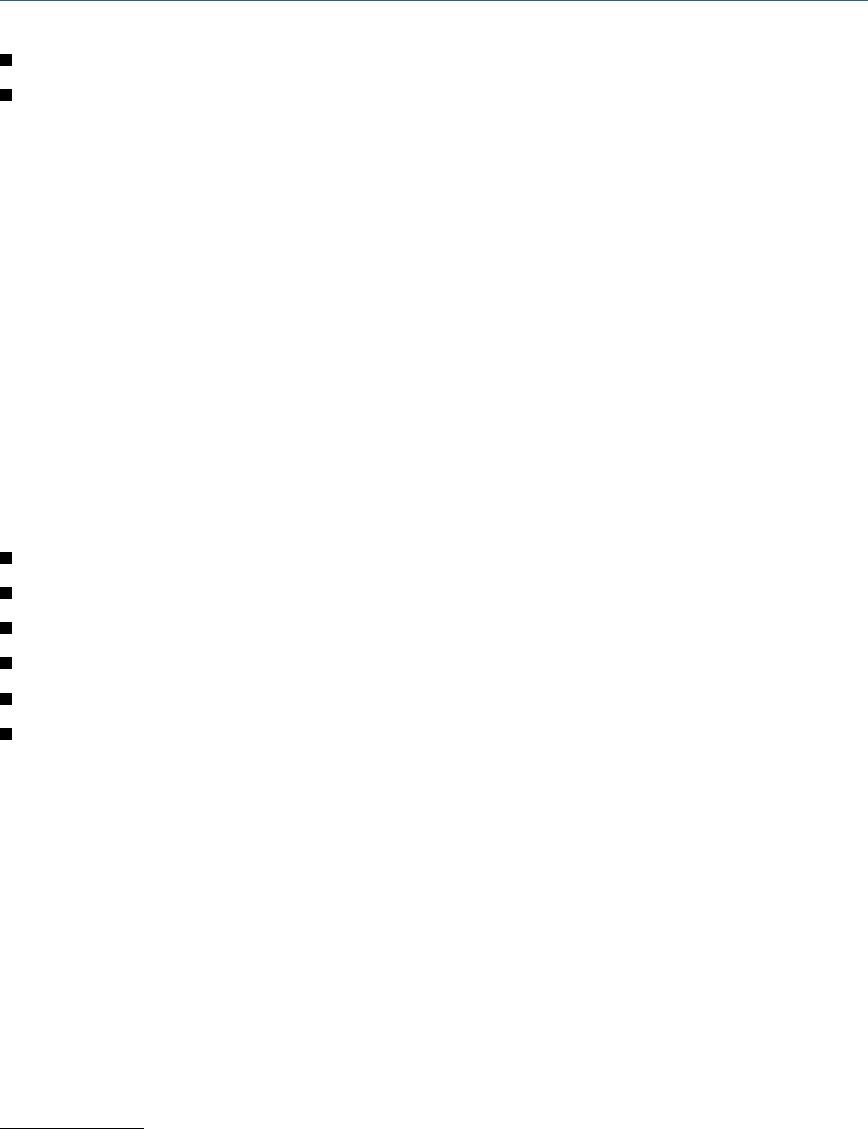

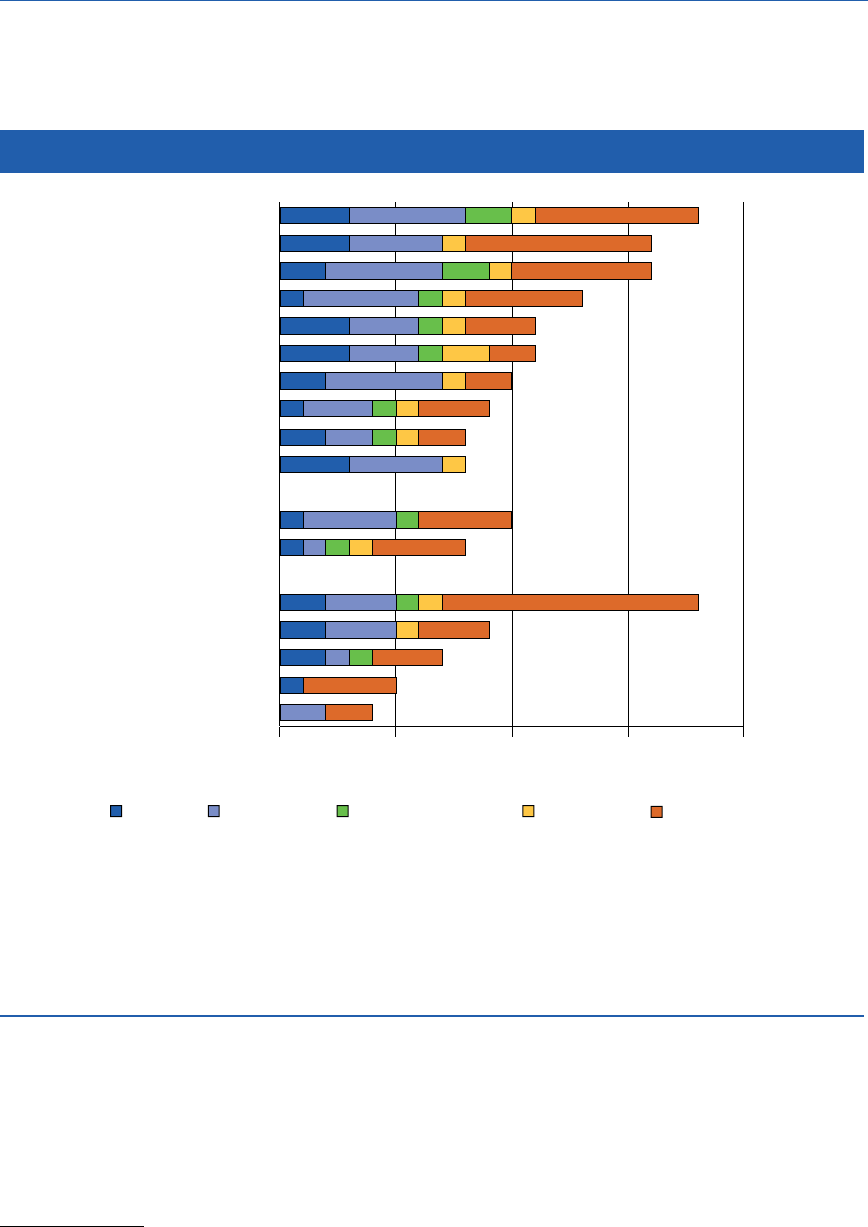

trackers are present on the website (see figure 1).

19

The analysis finds that third-party trackers are

commonly used by both online lenders and banks, though the online lenders were more likely than

18

See, for example, Wolfie Christl, Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life: How Companies Collect, Combine, Analyze,

Trade, and Use Personal Data on Billions (Vienna: Cracked Labs, June 2017), https://monoskop.org/images/b/ba/Cracked_

Labs_Corporate_Surveillance_in_Everyday_Life_2017.pdf. See also, Katharine Kemp, “Getting Data Right,” Center for

Financial Inclusion at Accion (blog), September 27, 2018, https://www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/getting-data-right.

19

The analysis does not include websites’ use of so-called “zero day trackers,” which are designed to be undetectable.

24

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

the banks included in this study to have trackers in greater numbers. Each of the 10 online lender

websites used at least eight trackers, and most used several in each category.

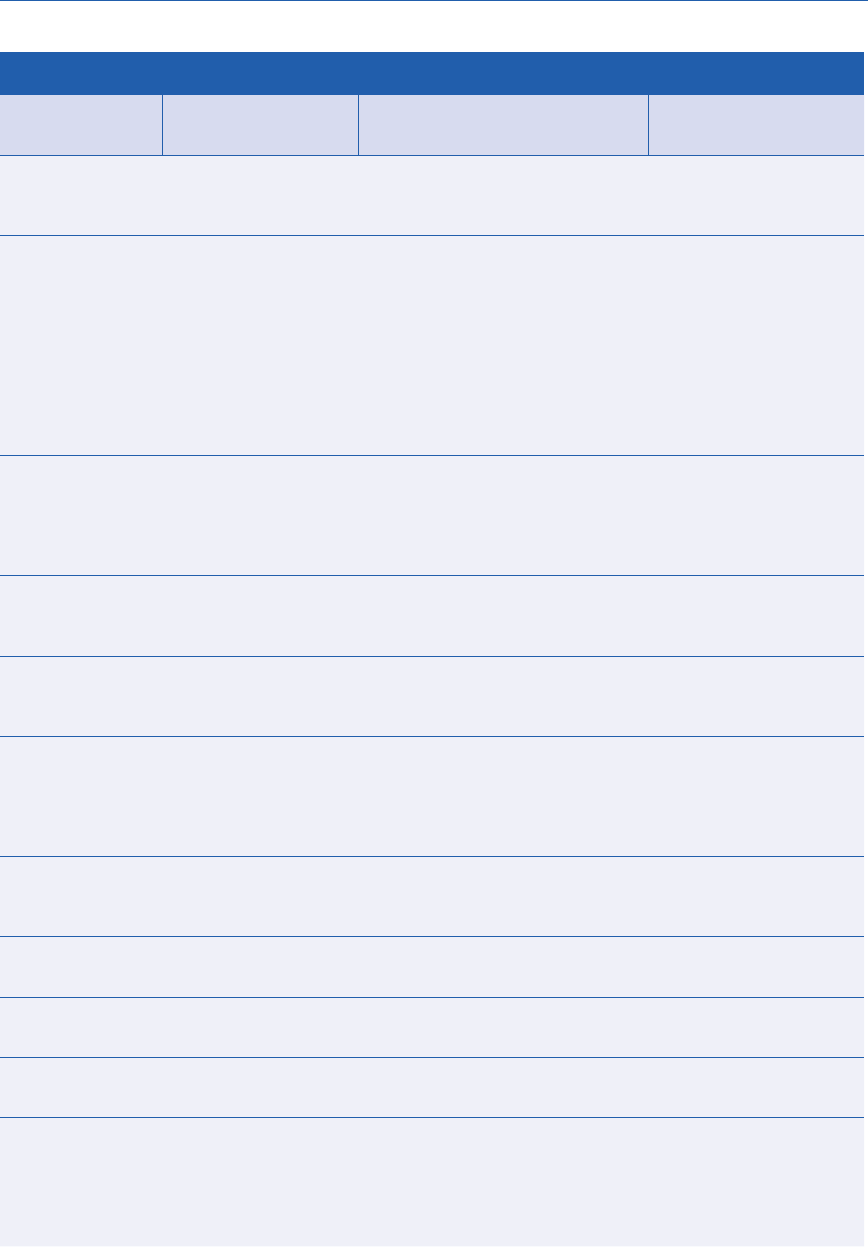

Figure 1. Use of trackers on select online lender and bank websites.

Company 1

Company 2

Company 3

Company 4

Company 5

Company 6

Company 7

Company 8

Company 9

Company 10

Payments Processor 1

Payments Processor 2

Bank 1

Bank 2

Bank 3

Bank 4

Bank 5

0 5 10 15 20

Number of trackers

Essential

Site analytics

Customer interaction

Social media

Advertising

Note: Key identifies bars in order from left to right. Company names have been anonymized; the order in which they are listed here does not

correspond with the order in tables 1, 2, and 4, or with the order in footnote 10.

Essential includes tag managers, privacy notices, and technologies that are critical to the functionality of a website.

Site analytics

collects and analyzes data related to site usage and performance.

Customer interaction includes chat, email messaging, customer support, and other interaction tools.

Social media integrates features related to social media sites.

Advertising provides advertising or advertising-related services such as data collection, behavioral analysis, or retargeting.

Source: Federal Reserve Board analysis, as of September, 2019

Lenders use trackers much the way other companies do—to collect as much information as

possible about each visitor in order to customize visitors’ experiences and reach them through

targeted advertising. However, privacy experts as well as small business advocates have suggested

that data collected through trackers may be used along with the other alternative data (such as cash

flow, invoicing, and shipping information) that online lenders employ in their algorithms to underwrite

and price offers of credit.

20

20

See Christl, Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life, 53. Also see FinRegLab, The Use of Cash-Flow Data in Underwriting

Credit (September 2019), https://finreglab.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/FinRegLab-Small-Business-Spotlight-Report.pdf.

25

Implications and Policy Questions

As discussed earlier in the analysis of product descriptions on companies’ websites, the online

lenders varied significantly in the amount of information provided, especially on costs. Lenders that

offer term loan products were likely to show costs as an annual rate, while others use nontraditional

terminology to convey costs. Still others, particularly those that offer MCAs, provide no information at

all. That said, virtually all the sites focus on the ease of applying and qualifying for funding, the speed

at which applications are approved, and the array of uses for loan proceeds.

The study also found that, in many cases, prospective borrowers must furnish information about

themselves and their businesses in order to obtain details about product costs and terms. This

information, as well as other data collected on website visitors through the use of trackers, may be

used to build profiles of small businesses.

These practices, coupled with relatively low satisfaction rates shown in the SBCS, raise

concerns that some borrowers may be opting for credit products that are not well-suited for their

businesses—even in some cases, putting their businesses at risk.

21

Merits of Standardized Disclosures

The debate about small business borrower protections and product disclosures has accelerated

recently with California enacting truth in lending legislation applicable to small business online

lenders—an action being considered by other states.

22

At the national level, legislators, regulators,

and policy advisory groups continue discussions about whether and how to address concerns in

small business lending.

23

Also, some in the online lending industry itself continue their efforts to promote standardization of

disclosures. In 2016, several lenders in coordination with a nonprofit organization, launched the

SMART Box disclosure initiative, aimed at developing a format for voluntary disclosures in loan

documents that would present total cost of the loan, APR, and other repayment terms. The effort

21

Record of Meeting, Community Advisory Council and the Board of Governors (October 5, 2018), 7, https://www.

federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/files/cac-20181005.pdf: “The Council notes a growing trend among small business owners

getting into trouble with expensive online small business loans, such as merchant cash advances (MCA). Oftentimes, the

pricing and structure of these loans [are] deliberately obscured, and small business owners take on debt burdens and fees

that they are not able to sustain.”

22

California SB-1235, “Commercial Financing Disclosures,” was signed into law on September 30, 2018. As of this writing, it

has not yet been implemented as the California Department of Business Oversight is adopting regulations. The New York

and New Jersey legislatures are considering similar bills.

23

See, for example, U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Small Business, “Financing through Fintech: Online

Lending’s Role in Improving Small Business Capital Access,” hearing held October 26, 2017, https://www.govinfo.gov/

content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg27255/html/CHRG-115hhrg27255.htm. See also, the Bipartisan Policy Commission report

Main Street Matters: Ideas for Improving Small Business Financing (August 2018), https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/

main-street-matters-ideas-for-improving-small-business-financing/.

26

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

is voluntary and, as of this writing, an updated version of the SMART Box is being considered.

24

It

is the case, though, that the required inclusion of APR for products is a point of contention in the

industry.

Some lenders argue APR should not apply to small business products with variable payments and

no fixed term, such as MCAs. However, small business advocates suggest that APR is important

for cost comparisons with other products, including consumer products like credit cards and home

equity lines of credit that are often used to finance small businesses. Furthermore, APR is a familiar

metric. Prospective borrowers generally are aware from their experiences with consumer products

what constitutes a high APR.

It seems apparent that clearer descriptions of products and, in particular, their costs would position

small business owners to make better borrowing decisions. That said, research suggests that

borrowing decisions are not always driven by costs. For example, while among the focus group

participants, “best price” was the most commonly mentioned top factor in their choice of lender,

“quick and easy loan application process,” “a lender I know and trust,” and “likelihood application will

be approved” were primary considerations for others. Similarly, the SBCS finds that several factors—

including the likelihood of approval and speed of the decision and funding—are more important than

cost for online lender applicants in their choice of a financing source. Therefore, clearer information—

in the form of standardized disclosures—will not necessarily alter the decisions of some small

business borrowers about whether and where to obtain financing.

Even so, the clear disclosure of product costs and terms could help many of these business owners

make informed decisions about the amounts they borrow, cash flow management, early repayment,

and repeat borrowing. Focus group participants reacted favorably to a sample disclosure box

with total cost of capital, the term, payment frequency, APR, average payment amount, and basic

information about prepayment.

25

Their comments indicated that such information, presented clearly

and in a standard format, would be very useful for product comparisons. A majority of participants

commented that APR was among its most helpful details. The repayment amount, frequency of

payments, and prepayment penalties were also cited as important.

When small business borrowers receive disclosures may be nearly as important as what is disclosed.

Nearly all focus group participants said they would want clear upfront information to help them make

borrowing decisions, stating they would want the level of detail that is provided in the disclosure

as early as possible in the process. Many remarked that presenting the product rate and terms at

loan closing is too late, as they have already invested time in the application process, shared their

financial data with the lender, and may have already committed the expected loan proceeds.

24

Two of the lenders included in the website analysis are SMART Box adopters and both present sample SMART Boxes on

their websites, showing rates that are nearly the lowest offered by these lenders. According to their websites, one lender

provides the SMART Box at the time credit is offered; the other includes it with the loan agreement. For more information on

the SMART Box Model Disclosure Initiative, visit http://innovativelending.org/smart-box/.

25

Lipman and Wiersch, Browsing to Borrow, 22.

27

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

To this end, much as technology has introduced efficiencies and increased the speed of lending,

technology-based solutions may be leveraged to inform borrowers early in the process. For example,

one focus group participant suggested lenders make interactive tools available on their websites that

would enable small business owners to input their information (e.g., credit scores, monthly sales,

years in business) to see—upfront—the average interest rates and terms for a business like theirs.

In sum, greater transparency and early disclosure would enable business owners to determine

which lenders offer products with rates and terms they would find acceptable, and would encourage

prospective borrowers to explore additional financing options and make informed comparisons.

Privacy Concerns and Business Owners’ Data

This study considers the level of information about products and their costs that small business

owners can access without providing the lender with information about themselves or their

businesses. Indeed, there is a “cost” to the business incurred by sharing their information to request

a quote or start an application. In addition to exposing their business to a potentially burdensome

number of phone calls and a flurry of marketing content, some lenders run credit checks early in the

process, even if the business owner is just shopping rates. A few of the focus group participants

voiced concerns about this practice and the potential impact on their credit scores. Furthermore,

while many of the participants in the most recent focus group study appeared resigned to the

potential for data breaches with any financial services provider, some were particularly concerned

about the security of their information with online lenders. As a practical matter, providing personal

and business information to numerous lenders simply for the purpose of comparison shopping is

certainly not ideal from the standpoint of preserving a prospective borrower’s privacy. Such concerns

may limit a prospective borrower’s willingness to explore all their options.

The analysis in this report on the use of website trackers by small business lenders only scratches

the surface on issues regarding privacy and use of data collected. Though the use of trackers is

widespread in many industries, there are unique issues associated with the use of data by lenders.

Little is known about online lenders’ underwriting algorithms and the data they employ. Small

business advocates have voiced concerns that data collected surreptitiously through trackers may

be matched with data from third-party sources to identify individual business owners. It is unclear

whether these data are used to underwrite and price offers of credit.

26

However, this potential use

of alternative data raises questions about how such practices could amplify—or perhaps mitigate—

concerns about fair lending.

Questions for Future Research and Analysis

The lack of data on small business lending remains a critical issue that hampers the ability of

lenders and policymakers to make informed decisions about lending and policy. Nonbank lending

is a particular blind spot, as comprehensive data for the online lending industry are not available.

27

26

See Christl, Corporate Surveillance in Everyday Life, 53.

27

Section 1071 of the Dodd Frank Act amended the Equal Credit Opportunity Act to require that lenders gather information

on credit applications made by small businesses, and women- or minority-owned businesses. As of this writing, this

requirement has not yet been implemented by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

28

Uncertain Terms: What Small Business Borrowers Find When Browsing Online Lender Websites

Policymakers would benefit greatly from data on outcomes for small business credit applicants

and borrowers to strengthen understanding of the impact of being denied credit, and how firms

fare after securing credit—either from traditional or alternative lenders. Such insight would benefit

organizations that serve small businesses and the business owners themselves, as they make

borrowing decisions.

For online lenders, specifically, greater insight is needed on the information disclosed to prospective

borrowers throughout the entire application process, that is, beyond the shopping phase. As

small business applicants receive actual offers of credit from online lenders, are they given clear

information that is sufficient to support decisionmaking? Furthermore, are the credit agreements,

presented to business owners at closing, explicit about costs and terms? Do borrowers have a

clear understanding of their obligations and any possible penalties?