Dental and Skeletal Maturity

The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012 309

A

ccurate evaluation of patient’s growth is important

in many fields of dentistry. The practitioner placing

implants needs to know that skeletal growth is com-

plete.

1,2

The orthodontist benefits from assessing the amount

of skeletal growth already completed in planning orthopedic

treatment.

3

Surgeons likewise assess growth before planning

surgeries involving growing structures.

4

Hand-wrist radi-

ographs are accepted as the standard for skeletal growth

evaluation, but require additional time and exposure of the

patient to additional radiation.

5

For this reason, investigators

have searched for additional ways to assess growth with

commonly taken radiographs, such as periapical, panoramic

and cephalometric radiographs.

3

Dental formation has long been employed as a method to

assess chronological age and skeletal development.

6

Erup-

tion of the dentition was investigated but it is influenced by

systemic and local factors whereas root development is not.

7

Children and adolescents have multiple teeth to evaluate

development, as most of the teeth are still forming. About

the age of 14, most of the teeth cease development at the

apex except third molars.

8

The third molars are the last to

begin development and finish development, and are thus of

interest in evaluating the growth of mid to late teens.

9

This

paper reviews articles using dental development to assess

skeletal growth from routine dental radiographs.

PubMed was searched for the following keywords: skele-

tal maturity, skeletal growth, cervical vertebra maturity,

hand-wrist radiographs, dental maturity, tooth development,

dental staging, dental radiographic stage assessment, dental

mineralization, third molar development, and orthopan-

togram. In addition, hand searches from the references of

relevant studies were performed. All studies were gathered

and reviewed for similarities and differences.

&.)"*+)"' )(!*

There are three main radiographic means to determine

skeletal development: hand-wrist radiographs; cephalomet-

ric radiographs; and panoramic or periapical radiographs.

Skeletal evaluation of the hand can be evaluated by observ-

ing changes in the epiphysis in different joints of the hand,

fusion of plates, and the presence of the sesamoid bone.

Generally, the proximal, middle and distal phalanx of the

third finger, middle phalanx of the fifth finger, sesamoid

bone and the radius are analyzed. Skeletal maturity indices

(SMI) from 1–11 have been described by Fishman (Table

I).

10-12

These stages are useful in determining remaining

growth potential. These 11 stages are divided into four cate-

gories including ephiphyseal widening (SMI 1-3), ossifica-

tion of the sesamoid of the thumb (SMI 4), capping of the

third and fifth finger epiphyses over their diaphyses (SMI

5–7), and finally fusion the third finger epiphyses and

'))$+"'&'&+$+,)"+/."+!#$+$+,)"+/)'%

"' )(!"****%&+-".

John M. Morris * / Jae Hyun Park **

There have been many attempts to correlate dental development with skeletal growth. The relationship is

generally considered to be moderate at best. However, there is evidence that hand-wrist radiographic inter-

pretation of remaining growth can be augmented by taking into account the developing dentition. In addi-

tion, the practicality of evaluating routine dental radiographs and avoiding additional radiation is advan-

tageous. To this point, no system has been described to match apical development by Demirjian’s stages

and compare it to skeletal development and remaining growth. This study reviewed articles pertinent to the

relationship between developing teeth and skeletal maturity and remaining growth, and a system is proposed

to give practitioners an additional assessment for growth and development.

Keywords: dental maturity, skeletal maturity, cervical vertebrae maturity, mandibular third molar

J Clin Pediatr Dent 36(3): 309–314, 2012

* John M. Morris, DDS, DHSc, Private practice, Gilbert, AZ, Former

Postgradaute Orthodontic Resident, Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral

Health, A.T. Still University, Mesa, AZ.

** Jae Hyun Park, DDS, MSD, MS, PhD, Associate Professor and Chair,

Postgraduate Orthodontic Program, Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral

Health, A.T. still University, Mesa, AZ and International Scholar, the

Graduate School of Dentistry, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea.

Send all correspondence to Dr. Jae Hyun Park, Postgraduate Orthodontic

Program, Arizona School of Dentistry & Oral Health, A.T. Still University,

5835 East Still Circle, Mesa, AZ 85206.

Tel: 480.248.8165,

Fax: 480.248.8180

E-mail: [email protected]

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022

Dental and Skeletal Maturity

tion of hand-wrist films.

23

In contrast, Sidlauskas et al

24

reported a close correlation between hand-wrist films and

m

andibular and maxillary growth. Growth may be difficult

to determine from hand-wrist radiographs during final

stages, such as determining whether an orthognathic patient

is ready for surgery.

25

Thus, additional information that can

be easily acquired should be considered in evaluating

r

emaining growth.

26

+)$(!$'%+)")"' )(!*

)-"$-)+)$%+,)+"'&

Lateral cephalograms show the cervical vertebrae, and

their morphologic changes in size and shape as an individual

grows. These changes are divided into 6 major stages

(Figure 1 and Table I). The vertebrae increase vertically and

horizontally during the stages, and the concavities become

more pronounced as growth occurs.

27

The cervical vertebral

maturation (CVM) stage 1 is correlated with initial of

growth (85-100% remaining); stage 2 with acceleration of

growth (65-85% remaining); stage 3 with transition of

growth (25-65%); stage 4 with deceleration of growth

(10–25%); stage 5 with maturation of growth (5-10%); and

stage 6 with completion of growth (0%).

13

Some have ques-

tioned the reproducibility of staging cervical vertebra, and

intra- and inter-observer consistency is questioned.

28

This

technique has been modified by Bacetti et al

2

9

to include 5

stages on the basis that it is difficult to differentiate between

cervical stage (CS) 1 and 2.

29

Reproducibility of this modi-

fied CVM technique is reportedly as high as 98.6%. With the

use of thyroid collars, CVM1 was revised to include only the

310 The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012

diaphysis and radius (SMI 8–11). The clinician can quickly

gauge the remaining growth by first viewing whether the

a

dductor sesamoid bone of the thumb is present. If it is not,

then the epiphyses of the third and fifth finger can be viewed

for widening at select points, and the appropriate stage deter-

mined. If the sesamoid bone is present the third and fifth fin-

ger can be viewed for capping. If there is no capping, then

t

he individual is in the ossification stage. The capping stages

can be determined from the select points of the third and

fifth finger. If the sesamoid is present and capping is com-

pleted, the third finger and radius can be viewed for

fusion.

1

1,12

The peak growth spurt of an individual is between

stages 5–6.

13,14

Accuracy of hand-wrist predictions is greater right

around the peak growth spurt and when different time points

are viewed, which may require repeated radiographic expo-

sure.

15

In addition, single ossification events are not as accu-

rate as bone staging.

16

Hand-wrist radiographs are not difficult to assess or

acquire. However, to decrease radiographic exposure to

patients and when other indications may be utilized for

rough estimates, hand-wrist films may not be practical.

17

Many orthodontists can get adequate estimations of growth

from patient questionnaires, observed growth changes in

patients, and cervical vertebral changes on lateral cephalo-

grams.

Hand-wrist films and the developmental patterns from

the bones are regarded as the standard for evaluating growth.

In original publications, hand-wrist coordinated growth to

statural height, and this has been validated by other stud-

ies.

1

8,19

It is reported, though, that the correlation between

hand-wrist and remaining statural growth is around r = 0.7,

and predicting growth of the face is even lower r = 0.52.

17

Another study measured mandibular growth in three groups

of individuals during acceleration, peak and decelerating

phases of puberty (determined from hand-wrist radiographs)

and found that there were no statistical differences between

the groups.

20

There was, however, an acceleration of

mandibular growth during the peak growth spurt. The

mandibular growth has also been shown to be different in

early or late maturers, and in molar classifications (Class I,

II and III).

21,22

In addition, ethnic variations can introduce

variability in growth patterns, complicating the interpreta-

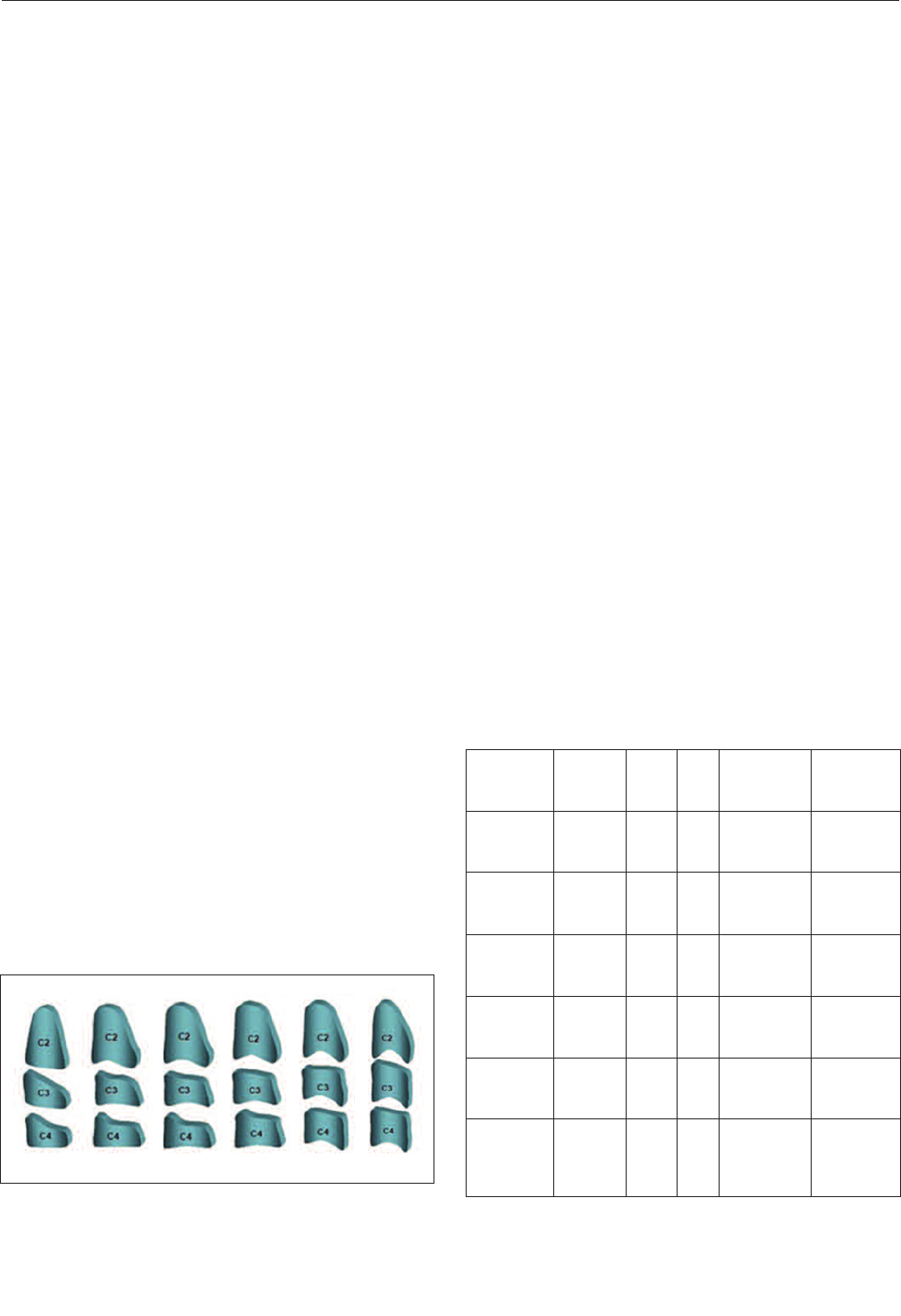

Figure 1. Cervical Maturation Stages. Remaining growth can be

assessed from the morphology of the vertebrae 2-4. As growth

occurs, the vertebrae bodies grow more vertically than horizontally,

and deeper concavities are observed on the lower borders.

CS1 CS2 CS3 CS4 CS5 CS6

Remaining

Pubertal

Growth

Velocity

of

Growth

SMI CS

Dental

Stage

G-H

Mandibular

Third Molar

85%-100% Slow 1-2 1 1st molars

and central

incisors

No bud, or

radiolucent

bud

65%-85% Moderate 3-4 2 1st molars

and central

incisors

Radiolucent

bud

25%-65% Peak 5-6 3 Mandibular

canines

Crown

formation

beginning

10%-25% Moderate 7-8 4 2nd

premolars

Crown

calcification

complete

5%-10% Slow 9-10 5 2nd molars Root

formation

beginning

0% Slow 11 6 All teeth

complete

except third

molars

Root

formation

1/3 to 2/3

SMI, skeletal maturity index according to Fishman;

10

CS, cervical

stage according to Hassel and Farman;

13

Demirjian dental stages

modified by Krailissari et al.

53

Table I. Relationships between skeletal and dental maturity and

their association with growth

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022

Dental and Skeletal Maturity

The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012 311

2–4th vertebrae, as the 5-6th were no longer imaged.

13

Despite criticisms, CVM stages are consistently correlated

w

ith skeletal maturity indicators in the hand.

30-32

Gu and McNamara

3

3

measured mandibular growth

and cervical maturation. They determined that peak

mandibular growth occurs between CS2 and CS3. Average

intervals between stages were 16-17 months, except CS5-

C

S6, which was 12 months. Bacetti et al

29

a

lso investigated

CVM and determined peak mandibular growth and found

peak growth between cervical vertebral maturation stage

(CVMS) II and CVMS III (CS3-CS4). Postpubertal cranio-

facial growth prediction from CVM is modestly effective.

3

4

The cervical vertebrae as maturational indicators offer

several advantages and disadvantages. There is reduced radi-

ation exposure, and cephalograms are routinely taken in an

orthodontic office. Proper interpretation of the stages of

CVM can be problematic, as illustrated in a study where

clinicians trained in CVM interpretation only agreed with

themselves 62% of the time on repeated analysis.

28

The same

study showed an improvement when there are two longitu-

dinal radiographs to review. However, the clinician should

be aware of any and all indicators of growth when treatment

planning, as each individual has their own pattern of growth.

&')%"')()"("$)"' )(!*

&+$-$'(%&+

As the teeth develop, the roots undergo similar morpho-

logical stages. These stages have been described by several

authors, and compared to other growth indicators, such as

hand-wrist radiographs and cervical vertebrae. Some com-

mon morphological categories were reviewed.

3

5-39

Among

these, Olze et al

40

reported that Demirjian et al

36

offers the

most reproducible assessment of mandibular third molar

development and is thus employed frequently in staging the

third molar development. Furthermore, Dhanjal et al

41

reported intra-observer agreement was highest using Demir-

jian’s method. The development stages described by Demir-

jian are described in Table II.

Teeth vary in development.

42

This can be due to ethnicity,

sexual differences and on an individual basis. Some develop

early dentally and late skeletally, or vice versa.

43

Dental

maturity is generally accepted in the literature to be variable

and the relationship to skeletal development is reported as

moderate.

15,44-46

While some authors have reported high

correlations between skeletal growth and dental develop-

ment,

7,47-49

others findings have demonstrated low correla-

tions.

50

There is no denying that observing the developing denti-

tion is the quickest and most accessible test for maturity that

is available without additional exposure. For this reason,

several studies have suggested using routine radiographs for

a first estimate or adjunct, and if more detailed information

is needed about growth, additional sources can be

utilized.

3,5,15,51

The mandibular canine is of interest because just before

its apex calcifies it is correlated to other events of

puberty.

43–45,48

This can be useful for an indicator of an

impending growth spurt. The first molar and central incisor

is finishing development at the root apex during cervical

vertebral stage (CVS) 1 and 2, just before or at the beginning

of pubertal growth.

7

By the end of growth, all teeth except

third molars are likely to be finished or near finished in api-

cal development.

52

The mandibular second premolar has shown a high cor-

relation with skeletal markers of the hand, substantiated by

several investigators.

51-53

Basaran et al

7

demonstrated that the

second premolar was nearing completion of apex formation

at the CS4.

Mandibular third molars are useful especially in deter-

mining the remaining growth of a patient over the age of 14,

and offer a unique perspective because their development

lasts an extended period of time.

52,54

Also, in determining

remaining skeletal growth of an orthodontic patient, the

third molar is the only remaining tooth to undergo develop-

ment during final growth.

54

The correlation between mandibular third molar develop-

ment and skeletal development was investigated in several

studies, and some showed a strong relationship between

third molar development and skeletal maturity.

47-49,54,55

In con-

trast, some studies have reported poor relationships.

50,55

Third

molars vary in development by ethnicity and sex, and this

should be considered when evaluating their develop-

ment.

5,7,53,56

Relationships between skeletal, cervical, and

dental maturity associated with growth are summarized in

Table I.

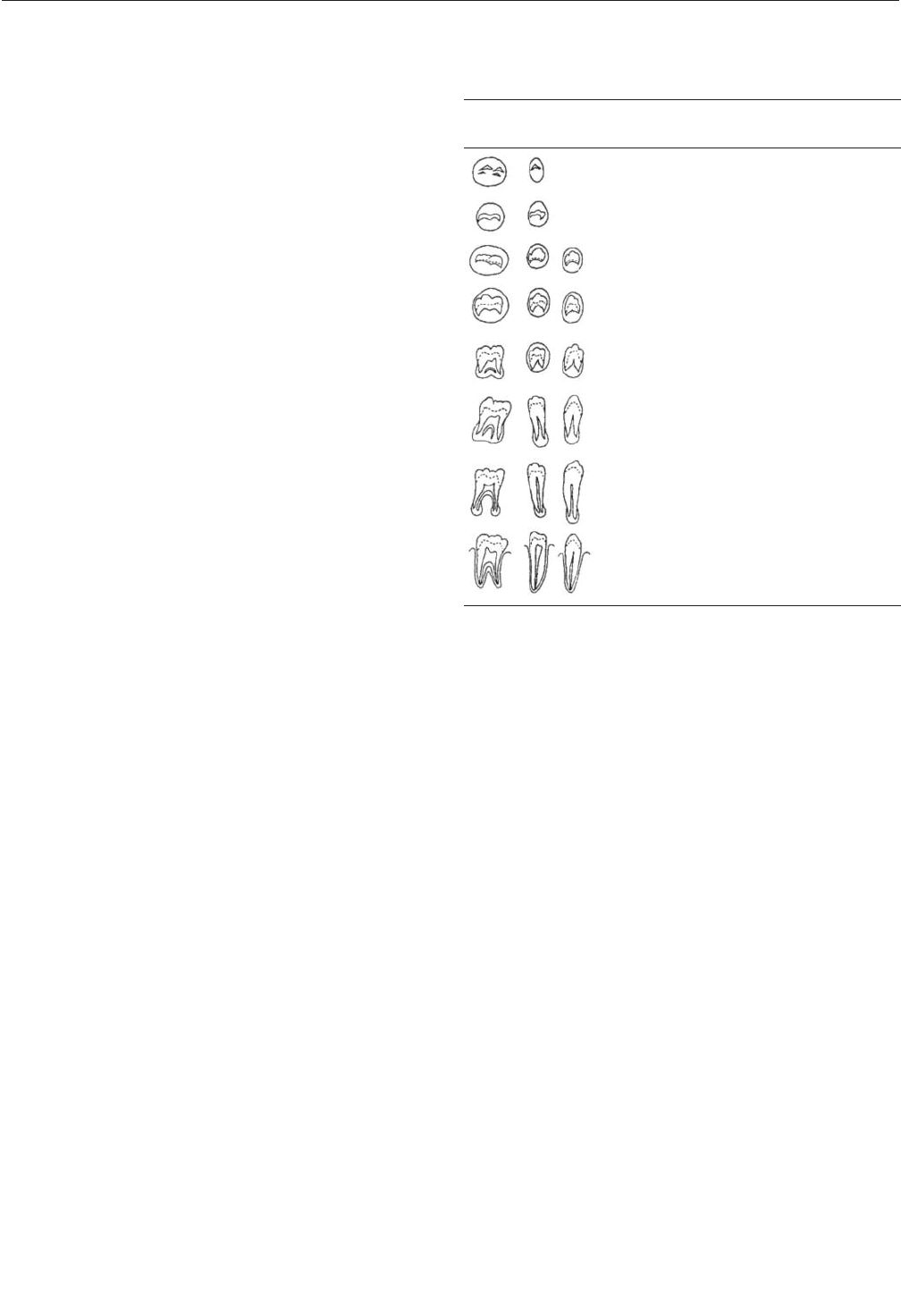

Molar Premolar

Canine

Stage Morphologic Characteristics

A

Calcification of single occlusal

points without fusion

B Fusion of mineralization points

C

Enamel formation completed at the

occlusal surface, dentin formation

started

D

Crown formation complete to the

CEJ, root formation commenced

E

Root length less than crown height,

bifurcation commenced calcification

F

Root length equal or greater than

crown height, roots have distinct

form

G

The walls of the root canal are paral-

lel, apical end open

H

The root apex is completely closed,

periodontal ligaments are uniform

throughout

Table II. Stages of tooth development by Demirjian et al

3

6

modi-

fied by Krailassiri et al

53

(Used with permission from The

Angle Orthodontist)

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022

Dental and Skeletal Maturity

Dental development is variable. Similar to height measure-

m

ents, the current number or category may not be as impor-

tant as the change. Thus, evaluating the dentition over a

period of time may indicate an individual pattern. If an indi-

vidual is clearly an early dental developer, the teeth finish-

ing apical development may differ from those listed in the

c

hart. This is one of the difficulties of assessing growth – it

may be different for each patient, and skeletal growth can be

different than growth of the dentition or face. All helpful

information should be considered when evaluating growth.

25

Developing tooth apices have been correlated with

stature and menarche.

57

Stature is correlated with skeletal

development.

58

In fact, serial height measurements are a

good way to estimate growth patterns, with a reported high

correlation to height change and skeletal development.

59

In

females, menarche does not always happen before peak

height velocity, though it is a fairly good indicator of accel-

erating growth.

60

It does not appear to be strongly correlated

with dental development. In males, prepubertal to male

voice change can be used with other factors as an indicator

for pubertal growth spurt.

61

Insulin-like growth factor 1

(IGF-1) has also shown promise for use in assessing

growth.

62

Planning orthopedic treatment for orthodontics is impor-

tant. McNamara et al

6

3

reported that in patients treated with

the Frankel appliance, greater increase of mandibular length

was observed during ages closer to puberty. Pancherz and

Hagg

64,65

reported greater effects of Herbst appliance therapy

during peak growth periods. Malmgren et al

66

reported sim-

ilar findings with an activator and high pull headgear. Treat-

ing just before and during the time of peak growth allows for

more skeletal than dental change.

53

It is generally accepted that orthognathic surgery must be

planned to occur after growth has been completed according

to a survey of orthodontists.

67

Often cleft palate patients

undergo surgical intervention during growth, and decreased

postsurgical development of the maxilla has been docu-

mented.

68

This decreased growth and the potential for

changes deviant from the final surgical position can be

avoided by assessing growth and timing treatment when it is

complete.

69

It may be difficult to determine final stages of

growth from hand-wrist. For this reason, it is recommended

that other indicators of growth such as serial cephalometric

radiographs and vertical height changes be viewed, espe-

cially for Class III patients with condylar hyperplasia.

25

Likewise, implant placement requires careful timing. The

ideal treatment for missing teeth may involve either substi-

tution or single tooth implant placement.

70

Timing and treat-

ment is best determined by an interdisciplinary team and

outcomes are improved through a team approach.

71,72

In the

case of a growing patient, space must be managed carefully

for the final implant, which should only be placed when a

patient’s growth is completed. It is recommended that

implants be placed after vertical growth is complete, which

is in the second decade of life.

73

Nevertheless, mature adults

m

ay exhibit vertical growth similar to adolescents and verti-

cal steps due to growth have been observed.

7

4

In some cases,

such as ectodermal dysplasia, implant placement in a grow-

ing patient may be appropriate.

75

Thus, growth determination

is vital to various interdisciplinary treatment planning.

Environmental factors may influence the development of

teeth, but generally root formation is not affected by malnu-

trition, or other processes that interfere with growth.

7

6

Care

should be taken when the patient has any endocrine disor-

ders, or conditions that may cause delayed development of

the dentition. In categorizing dental formation, multiple

stages of development used for dental maturity assessment

and the method of evaluating skeletal maturity introduce

variability.

41

Although Demirjian et al

36

offers good intra-

observer agreement, developing crowns of molars may be

angled so that differing crown stages is not very practical. In

addition, in classification systems the more stages the

greater chance for error.

56

In an effort to increase accuracy,

more stages have been added, but this may make classifying

the stages more difficult.

41,77

Different radiographic techniques may introduce vari-

ables. Accurate radiographs are important in assessing both

the skeletal and dental development structures. It is interest-

ing to note that a study using periapical radiographs of the

third molars had a higher correlation than other studies using

panoramic radiographs.

76

Some advantages are seen with

improved imaging techniques like digital panoramic radi-

ographs.

78

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) imag-

ing systems may further assist assessment of morphological

changes of developing teeth.

Each person has their own individual growth pattern, and

they do not necessarily follow the averages. Skeletal growth

of the long bones of the body does not always correlate

strongly to facial skeletal growth, which should be consid-

ered when treatment planning.

Hand-wrist examination is the gold standard for evaluating

remaining growth, yet it clearly can be augmented with addi-

tional information such as dental development. Cervical ver-

tebrae morphology can also be evaluated for remaining

growth as it correlates strongly with skeletal maturity indi-

cators. The relationship between dental maturity and skele-

tal maturity is reported to be strong, yet should not be the

only evaluation done in assessing growth when more

detailed information is required. There is some promise for

using the dentition as a rough estimator and an adjunct in

evaluating patients for skeletal growth and development. In

addition, in some situations it may obviate the need for addi-

tional exposure for hand-wrist radiographs.

312 The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022

Dental and Skeletal Maturity

The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012 313

1. Sharma AB, Vargervik K. Using implants for the growing child. J Calif

Dent Assoc, 34: 719–724, 2006.

2. Carmichael RP, Sándor GKB. Dental implants, growth of the jaws, and

determination of skeletal maturity. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin

North Am, 16: 1–9, 2008.

3. Sahin Sağlam AM, Gazilerli U. The relationship between dental and

skeletal maturity. J Orofac Orthop, 63: 454–462, 2002.

4. McIntyre GT. Treatment planning in Class III malocclusion. Dent

Update, 31: 13–20, 2004.

5. Uysal T, Sari Z, Ramoglu SI, Basciftci FA. Relationships between den-

tal and skeletal maturity in Turkish subjects. Angle Orthod, 74:

657–664, 2004.

6. Demisch A, Wartmann P. Calcification of the mandibular third molar

and its relation to skeletal and chronological age in children. Child Dev,

27: 459–473, 1956.

7. Başaran G, Ozer T, Hamamci N. Cervical vertebral and dental maturity

in Turkish subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 131: 447.e13–20,

2007.

8. Prieto JL, Barbería E, Ortega R, Magaña C. Evaluation of chronologi-

cal age based on third molar development in the Spanish population. Int

J Legal Med, 119: 349–354, 2005.

9. Lewis JM, Senn DR. Dental age estimation utilizing third molar devel-

opment: A review of principles, methods, and population studies used

in the United States. Forensic Sci Int, 201: 79–83, 2010.

10. Fishman LS. Radiographic evaluation of skeletal maturation. A clini-

cally oriented method based on hand-wrist films. Angle Orthod, 52:

88–112, 1982.

11. Fishman LS. Chronological versus skeletal age, an evaluation of cran-

iofacial growth. Angle Orthod, 49: 181–189, 1979.

12. Fishman LS. Maturational patterns and prediction during adolescence.

Angle Orthod, 57: 178–193, 1987.

13. Hassel B, Farman AG. Skeletal maturation evaluation using cervical

vertebrae. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 107: 58–66, 1995.

14. Kamal M, Goyal S. Comparative evaluation of hand wrist radiographs

with cervical vertebrae for skeletal maturation in 10-12 years old chil-

dren. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent, 24: 127–135, 2006.

15. Flores-Mir C, Nebbe B, Major PW. Use of skeletal maturation based on

hand-wrist radiographic analysis as a predictor of facial growth: a sys-

tematic review. Angle Orthod, 74: 118–124, 2004.

16. Hunter CJ. The correlation of facial growth with body height and skele-

tal maturation at adolescence. Angle Orthod, 36: 44–54, 1966.

17. Verma D, Peltomäki T, Jäger A. Reliability of growth prediction with

hand-wrist radiographs. Eur J Orthod, 31: 438–442, 2009.

18. van Rijn RR, Lequin MH, Robben SG, Hop WC, van Kuijk C. Is the

Greulich and Pyle atlas still valid for Dutch Caucasian children today?

Pediatr Radiol, 31: 748–752, 2001.

19. Thodberg HH, Neuhof J, Ranke MB, Jenni OG, Martin DD. Validation

of bone age methods by their ability to predict adult height. Horm Res

Paediatr, 74: 15–22, 2010.

20. Gomes AS, Lima EM. Mandibular growth during adolescence. Angle

Orthod, 76: 786–790, 2006.

21. Silveira AM, Fishman LS, Subtelny JD, Kassebaum DK. Facial growth

during adolescence in early, average and late maturers. Angle Orthod,

62: 185–190, 1992.

22. Alexander AEZ, McNamara JA, Franchi L, Baccetti T. Semilongitudi-

nal cephalometric study of craniofacial growth in untreated Class III

malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 135: 700–701, 2009.

23. Mora S, Boechat MI, Pietka E, Huang HK, Gilsanz V. Skeletal age

determinations in children of European and African descent: applica-

bility of the Greulich and Pyle standards. Pediatr Res, 50: 624–628,

2001.

24. Sidlauskas A, Zilinskaite L, Svalkauskiene V. Mandibular pubertal

growth spurt prediction. Part one: Method based on the hand-wrist radi-

ographs. Stomatologija, 7: 16–20, 2005.

25. Wolford LM, Karras SC, Mehra P. Considerations for orthognathic

surgery during growth, part 2: maxillary deformities. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop, 119: 102–105, 2001.

26. Sato K, Mito T, Mitani H. An accurate method of predicting mandibu-

lar growth potential based on bone maturity. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop, 120: 286–293, 2001.

27. Mourelle R, Barbería E, Gallardo N, Lucavechi T. Correlation between

dental maturation and bone growth markers in paediatric patients. Eur

J Paediatr Dent, 9: 23–29, 2008.

28. Gabriel DB, Southard KA, Qian F, et al. Cervical vertebrae maturation

method: poor reproducibility. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 136:

478–480, 2009.

29. Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA. An improved version of the cer-

vical vertebral maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of

mandibular growth. Angle Orthod, 72: 316–323, 2002.

30. Gandini P, Mancini M, Andreani F. A comparison of hand-wrist bone

and cervical vertebral analyses in measuring skeletal maturation. Angle

Orthod, 76: 984–989, 2006.

31. San Román P, Palma JC, Oteo MD, Nevado E. Skeletal maturation

determined by cervical vertebrae development. Eur J Orthod, 24:

303–311, 2002.

32. Lai EH, Liu J, Chang JZ, et al. Radiographic assessment of skeletal

maturation stages for orthodontic patients: hand-wrist bones or cervical

vertebrae? J Formos Med Assoc, 107: 316–325, 2008.

33. Gu Y, McNamara JA. Mandibular growth changes and cervical verte-

bral maturation. a cephalometric implant study. Angle Orthod, 77:

947–953, 2007.

34. Fudalej P, Bollen A. Effectiveness of the cervical vertebral maturation

method to predict postpeak circumpubertal growth of craniofacial

structures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 137: 59–65, 2010.

35. Gleiser I, Hunt EE. The permanent mandibular first molar: its calcifi-

cation, eruption and decay. Am J Phys Anthropol, 13: 253–283, 1955.

36. Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age

assessment. Hum Biol, 45: 211–227, 1973.

37. Gustafson G, Koch G. Age estimation up to 16 years of age based on

dental development. Odontol Revy, 25: 297–306, 1974.

38. Harris MJ, Nortjé CJ. The mesial root of the third mandibular molar. A

possible indicator of age. J Forensic Odontostomatol, 2: 39–43, 1984.

39. Kullman L, Johanson G, Akesson L. Root development of the lower

third molar and its relation to chronological age. Swed Dent J, 16:

161–167, 1992.

40. Olze A, Bilang D, Schmidt S, et al. Validation of common classifica-

tion systems for assessing the mineralization of third molars. Int J

Legal Med, 119: 22–26, 2005.

41. Dhanjal KS, Bhardwaj MK, Liversidge HM. Reproducibility of radi-

ographic stage assessment of third molars. Forensic Sci Int, 159 Suppl

1: S74–77, 2006.

42. Lewis AB. Comparisons between dental and skeletal ages. Angle

Orthod, 61: 87–92, 1991.

43. Nadler GL. Earlier dental maturation: fact or fiction? Angle Orthod, 68:

535–538, 1998.

44. Chertkow S. Tooth mineralization as an indicator of the pubertal

growth spurt. Am J Orthod, 77: 79–91, 1980.

45. Coutinho S, Buschang PH, Miranda F. Relationships between

mandibular canine calcification stages and skeletal maturity. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 104: 262–268, 1993.

46. So LL. Skeletal maturation of the hand and wrist and its correlation

with dental development. Aust Orthod J, 15: 1–9, 1997.

47. Engström C, Engström H, Sagne S. Lower third molar development in

relation to skeletal maturity and chronological age. Angle Orthod, 53:

97–106, 1983.

48. Sierra AM. Assessment of dental and skeletal maturity. A new

approach. Angle Orthod, 57: 194–208, 1987.

49. Lauterstein AM. A cross-sectional study in dental development and

skeletal age. J Am Dent Assoc, 62: 161–167, 1961.

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022

Dental and Skeletal Maturity

50. Demirjian A, Buschang PH, Tanguay R, Patterson DK. Interrelation-

ships among measures of somatic, skeletal, dental, and sexual maturity.

Am J Orthod, 88: 433–438, 1985.

51. Rózylo-Kalinowska I, Kolasa-Raczka A, Kalinowski P. Relationship

between dental age according to Demirjian and cervical vertebrae

maturity in Polish children. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20558591

accessed August 15th, 2010.

52. Sisman Y, Uysal T, Yagmur F, Ramoglu SI. Third-molar development

in relation to chronologic age in Turkish children and young adults.

Angle Orthod, 77: 1040–1045, 2007.

53. Krailassiri S, Anuwongnukroh N, Dechkunakorn S. Relationships

between dental calcification stages and skeletal maturity indicators in

Thai individuals. Angle Orthod, 72: 155–166, 2002.

54. Cho S, Hwang C. Skeletal maturation evaluation using mandibular

third molar development in adolescents. Korean J Orthod, 39: 120,

2009.

55. Steel GH. The relation between dental maturation and physiological

maturity. Dent Pract Dent Rec, 16: 23–34, 1965.

56. Bai Y, Mao J, Zhu S, Wei W. Third-molar development in relation to

chronologic age in young adults of central China. J Huazhong Univ Sci

Technol Med Sci, 28: 487–490, 2008.

57. So LL. Correlation of sexual maturation with stature and body weight

& dental maturation in southern Chinese girls. Aust Orthod J,

14:18–20, 1995.

58. Moore RN. Principles of dentofacial orthopedics. Semin Orthod, 3:

212–221, 1997.

59. Moore RN, Moyer BA, DuBois LM. Skeletal maturation and craniofa-

cial growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 98: 33–40, 1990.

60. Hägg U, Taranger J. Maturation indicators and the pubertal growth

spurt. Am J Orthod, 82: 299–309, 1982.

61. Kucukkeles N, Acar A, Biren S, Arun T. Comparisons between cervi-

cal vertebrae and hand-wrist maturation for the assessment of skeletal

maturity. J Clin Pediatr Dent, 24: 47–52, 1999.

62. Masoud MI, Masoud I, Kent RL, et al. Relationship between blood-

spot insulin-like growth factor 1 levels and hand-wrist assessment of

skeletal maturity. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 136: 59–64, 2009.

63. McNamara JA, Bookstein FL, Shaughnessy TG. Skeletal and dental

changes following functional regulator therapy on Class II patients. Am

J Orthod, 88: 91–110, 1985.

64. Hägg U, Pancherz H. Dentofacial orthopaedics in relation to chrono-

logical age, growth period and skeletal development. An analysis of 72

male patients with Class II division 1 malocclusion treated with the

Herbst appliance. Eur J Orthod, 10: 169–176, 1988.

65. Pancherz H, Hägg U. Dentofacial orthopedics in relation to somatic

maturation. An analysis of 70 consecutive cases treated with the Herbst

appliance. Am J Orthod, 88: 273–287, 1985.

66. Malmgren O, Omblus J, Hägg U, Pancherz H. Treatment with an ortho-

pedic appliance system in relation to treatment intensity and growth

periods. A study of initial effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 91:

143–151, 1987.

67. Weaver N, Glover K, Major P, Varnhagen C, Grace M. Age limitation

on provision of orthopedic therapy and orthognathic surgery. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 113: 156–164, 1998.

68. Wolford LM, Cassano DS, Cottrell DA, et al. Orthognathic surgery in

the young cleft patient: preliminary study on subsequent facial growth.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 66: 2524–2536, 2008.

69. Bailey LJ, White RP, Proffit WR, Turvey TA. Segmental LeFort I

osteotomy for management of transverse maxillary deficiency. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg, 55: 728–731, 1997.

70. Kokich VG, Spear FM. Guidelines for managing the orthodontic-

restorative patient. Semin Orthod, 3: 3–20, 1997.

71. Richardson G, Russell KA. Congenitally missing maxillary lateral

incisors and orthodontic treatment considerations for the single-tooth

implant. J Can Dent Assoc, 67: 25–28, 2001.

72. Lewis BRK, Gahan MJ, Hodge TM, Moore D. The orthodontic-restora-

tive interface: 2. Compensating for variations in tooth number and

shape. Dent Update, 37: 138–140, 142–144, 146–148, 2010.

73. Fudalej P, Kokich VG, Leroux B. Determining the cessation of vertical

growth of the craniofacial structures to facilitate placement of single-

tooth implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, 131(4 Suppl):

S59–67, 2007.

74. Bernard JP, Schatz JP, Christou P, Belser U, Kiliaridis S. Long-term

vertical changes of the anterior maxillary teeth adjacent to single

implants in young and mature adults. A retrospective study. J Clin Peri-

odontol, 31: 1024–1028, 2004.

75. Sharma AB, Vargervik K. Using implants for the growing child. J Calif

Dent Assoc, 34: 719–724, 2006.

76. Bhat VJ, Kamath GP. Age estimation from root development of

mandibular third molars in comparison with skeletal age of wrist joint.

Am J Forensic Med Pathol, 28: 238–241, 2007.

77. Moorrees CF, Fanning EA, Hunt EE. Age variation of formation stages

for ten permanent teeth. J Dent Res, 42: 1490–1502, 1963.

78. Introna F, Santoro V, De Donno A, Belviso M. Morphologic analysis of

third-molar maturity by digital orthopantomographic assessment. Am J

Forensic Med Pathol, 29: 55–61, 2008.

314 The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry Volume 36, Number 3/2012

Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/jcpd/article-pdf/36/3/309/2192962/jcpd_36_3_l403471880013622.pdf by Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College & Hospital user on 25 June 2022