Shaker Dining Table

Form meets function in this classic design

b y C h r i s t i a n b e C k s v o o r t

F I N E W O O D W O R K I N G

72

Photos, except where noted: Tom Begnal; this page: Michael Pekovich

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

T

his table is based on a piece built at the Shaker commu-

nity in Hancock, Mass. (It’s now in the collection of the

Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Mass.) The original, made

from cherry, is almost 11 ft. long, with a third trestle to support the

center. Such a length made good sense for communal dining, but

it’s not practical for most homes today. My version has only two

trestles, and I typically make the top either 8 ft. or 9 ft. long.

A trestle table has appeal for a few reasons. For one, it can be

“knocked down” without fuss. Remove the top from the base parts

and the stretcher from the trestles, and you can move the table

through doors and up or down stairs. Unlike most tables, which

have aprons around the perimeter to stiffen the structure, trestle

tables have a single center stretcher. This gives more vertical leg-

room. On the other hand, most trestle tables have flat feet, which

tend to get in the way of the feet of diners sitting at either end.

This Shaker design solves that inconvenience by replacing the flat

feet with arched feet. This simple change not only makes the piece

more ergonomic, but also gives it an especially graceful look.

Most lathes will handle these posts

I make the posts first, using 16/4 stock. If this size isn’t readily

available, consider face-gluing two pieces of 8/4 stock from the

same board. Using the same board means the grain and color of

the pieces will be close and the glue joint less visible.

Mill the stock to about 3

5

⁄8 in. sq. and crosscut it to 24

1

⁄2 in. long.

Then mount it in a lathe and turn it to 3

1

⁄2 in. dia. At a point 6 in.

from the top and 4 in. from the bottom, use a parting tool and

calipers to establish the 2

3

⁄8-in. diameter of the center section.

Continue using the parting tool to make a series of 2

3

⁄8-in.-dia.

cuts between the end cuts. With these cuts serving as a depth

guide, use a gouge to reduce the entire center section to 2

3

⁄8 in.

Coves and beads.

Each end of the mid-

section terminates

in a cove and bead.

Mark the

7

⁄8-in. width

of the detail by lightly

touching a pencil point

against the spinning

post. Cut the cove with

a roundnose chisel or

small gouge, then the

bead with a diamond-

point or skew chisel.

The posts are simple turnings

Turn the blank. Becksvoort turns a 3

5

⁄8-in.-sq. blank to 3½ in. dia., then makes a series of

2

3

⁄8-in.-dia. parting cuts along the midsection, checking the diameter with calipers. After that,

with the parting cuts serving as guides, he reduces the entire midsection to 2

3

⁄8 in. dia.

2

3

⁄8 in.

dia.

3½ in.

dia.

1

⁄16 in.

1

⁄16 in.

¼ in.

½ in.

1

⁄16 in.

73

www.finewoodworking.com

S E P T E M B E R / O C T O B E R 2 0 0 7

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

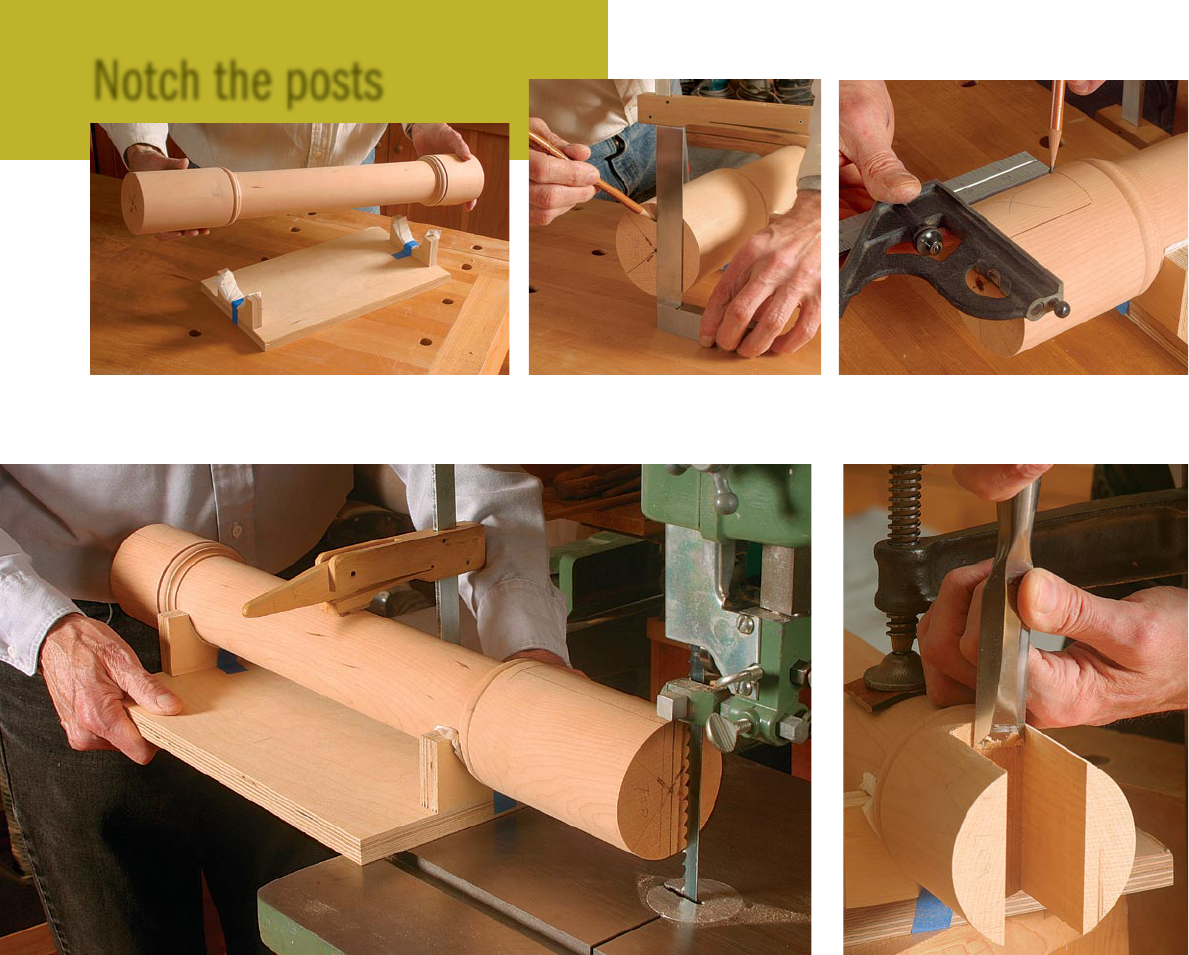

Notch the posts

dia. At each end of the center section, turn a small cove and a

bead with a small flat at each end of it (see drawing, p. 73). If your

turning skills are rusty, practice first on a shorter blank.

Jig simplifies post joinery

Once both posts are turned and sanded, they need to be notched

for the braces, feet, and stretchers. To hold them for layout and

machining, I clamp the posts to a shopmade cradle that consists

of a couple of U-shaped saddles screwed to a rectangular piece of

plywood. A narrow piece of paper towel in each saddle, held in

place with masking tape, helps prevent scratches on the posts.

Place the cradle on a bench (with the clamp between the opened

jaws of the vise so the cradle can rest flat). Use a square to lay out

the width and length of the notch on each end of the post. To lay

out a notch, first use a square to mark a vertical line through the

center of the turning. Using that centerline as a reference, mark

the width of the notch. Finally, mark the depth of the notch. The

notches can be cut by hand with a deep backsaw; but a bandsaw

does as good a job in less time. With the post clamped in the

cradle, carefully saw between the lines to the bottom of the notch.

Then, nibble out the bottom of the notch with the blade. As you

switch from one end to another, you’ll need to reposition the

clamp so that it doesn’t bump into the saw table as you cut.

Rout a shallow groove for the stretcher—There’s one more

machine cut to make on each post—a groove,

1

⁄4 in. deep by 1 in.

wide by 5 in. long, that will accept the end of the stretcher. You

can cut the groove with a chisel, but it’s easier on a router table.

Again, I use the cradle to support the post. A clamp gets in the

way on the router table, so I made a wooden yoke that serves as

a clamp. With the yoke screwed to the base of the cradle, the post

stays securely in place. Before tightening the yoke, make sure the

cheeks of the slot are parallel with the router-table surface.

Install a 1-in.-dia. straight bit in the router, and raise the bit to

make a

1

⁄4-in.-deep cut in the post. Adjust the router-table fence

so that when the cradle slides against it, the bit is centered on

the post. Also, clamp a stop block to the fence to stop the cradle

Build a cradle. Two saddles screwed to a base, ¾ in.

thick by 8 in. wide by 12½ in. long, create a cradle for the

post that simplifies a number of construction steps.

Lay out the location of the notches. With the cradle on a flat surface, use a square to

mark a vertical centerline on each end of the post (left). Measure and mark the width of

the notch, then use a square to scribe the notch depth (right).

Cut the two notches. With the post securely clamped in the cradle, use a bandsaw to

cut the notch on each end, following your layout lines by eye.

Hand work. Smooth the ends of the notches

and the cheeks with a sharp chisel.

F I N E W O O D W O R K I N G

74

Drawings: Bob La Pointe

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

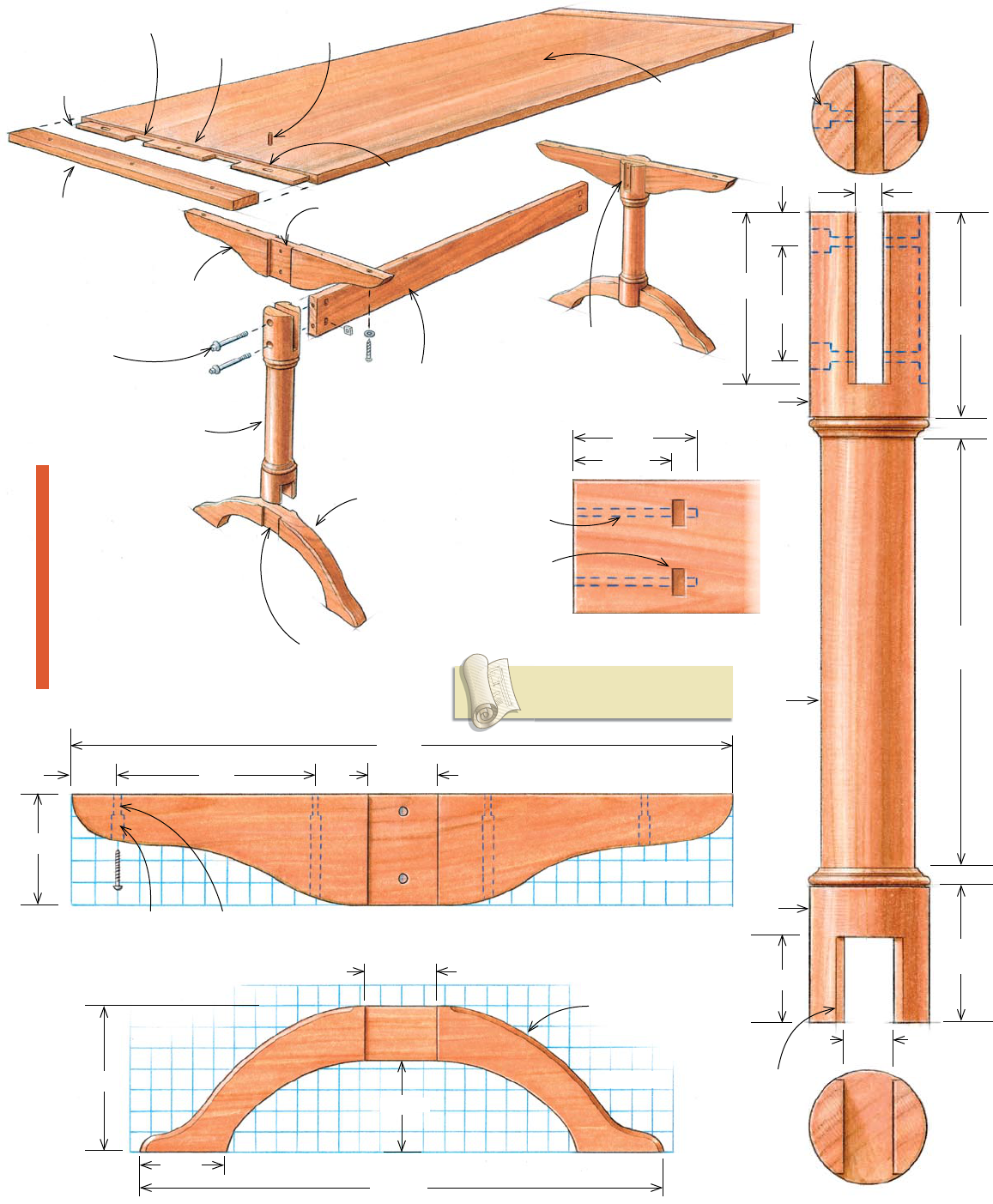

Post, 3½ in. dia.

by 24½ in. long

Brace, 1¼ in.

thick by 5 in. wide

by 30 in. long

Foot, 2 in. thick

by 7 in. wide by

25 in. long

Stretcher, 1 in.

thick by 5 in. wide

by 57½ in. long

Top, 1 in. thick by

36 in. wide by 94 in.

long (includes tenons

at each end)

Breadboard end,

1 in. thick by 3 in.

wide by 36 in. long

Bed bolt,

3

⁄8 in. dia.

by 6 in. long

End holes are

elongated.

Tenon,

3

⁄8 in.

thick by 2 in.

long

Stub tenon,

1

⁄4 in. long

Notch, ¼ in. deep

by 2

7

⁄8 in. wide

Notch, ¼ in. deep

by 3¼ in. wide

6 in.

7

⁄8 in.

12¾ in.

4 in.

5 in.

2½ in.

1 in.

3¼ in.

7

⁄8 in.

Flats,

1

⁄4 in. wide

¾ in.

1½ in.

25 in.

30 in.

5 in.

7 in.

4½ in.

45º chamfer

(top edge only)

7

⁄8-in.-dia.

counterbored

hole

Shank hole is

slotted to allow

wood movement.

2 in. 9 in. 3¼ in.

2

7

⁄8 in.

1-in.-dia. by

5

⁄8-in.-

deep counterbore

BRACE

POST

T R E S T L E

TA B L E

Lightly sand all

exposed corners

(except for the

foot chamfers) to

a

1

⁄8-in. radius. For

maximum strength,

use straight-grained,

defect-free wood for

the feet.

Peg,

3

⁄8 in. dia.

by 1 in. long

Add glue to

center tenon

only.

Stopped groove

for stretcher, ¼ in.

deep by 1 in. wide

by 5 in. long

STRETCHER END

Mortise for

square nut,

7

⁄8 in. deep

by

3

⁄8 in. wide

by 1 in. long

3½ in.

2½ in.

Bolt hole,

3

⁄8 in. dia.

Full-size plans for this table and

other projects are available at

FineWoodworking.com/PlanStore.

4 in.

FOOT

2

3

⁄8 in.

dia.

3½ in. dia.

3½ in.

dia.

S E P T E M B E R / O C T O B E R 2 0 0 7

75

www.finewoodworking.com

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

when the groove is 5 in. long. Hold the cradle firmly against the

fence as you slide it forward to feed the post in the bit.

The router bit leaves rounded corners at the end of each groove.

Use a chisel to cut them square.

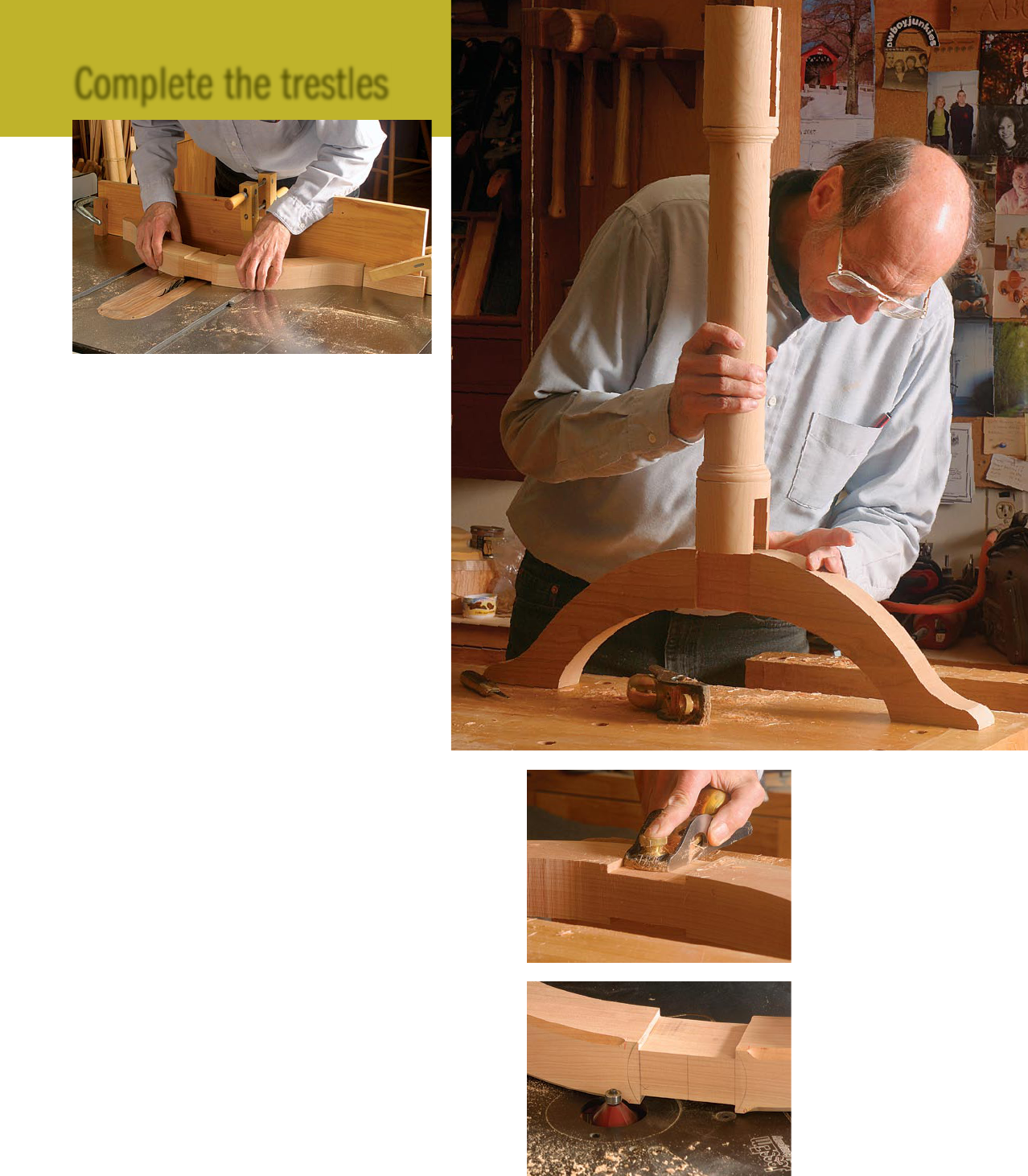

Fit the other parts to the posts

Templates for the brace and feet can be found on p. 75, but you’ll

need to enlarge them to full size. I’m not fussy about pattern stock;

light cardboard or poster paper works just fine.

Use the patterns and a pencil to transfer the profiles to the

stock. Cut the parts on the bandsaw, staying just outside the lines.

Next, lay out and mark the location of the dadoes in the braces

and feet. These mate with the deep notches in the posts. They

can be cut by hand, with a router, or with a dado blade on the

tablesaw. To save time, I use the dado blade set for the widest

possible cut.

To support the braces and feet during the dado cuts, clamp a

long fence to the miter gauge. The fence should extend at least

15 in. on either side of the dado blade. Add a pair of stop blocks

to ensure that the shoulders of the dadoes align perfectly on both

sides of the joint. When setting the depth of cut, I leave the areas

between the dadoes a bit thick. That way, I can trim them with a

rabbet plane for a perfect final fit.

With the dadoes cut, I smooth concave edges of the braces and

feet using a spindle sander, and convex edges using a stationary

disk sander. Smooth the curved edges further by hand-sanding.

Now use the router table and a chamfer bit to rout a

1

⁄4-in.

chamfer along the top edges of the feet. Stop each chamfer at a

point

1

⁄2 in. from the dadoes.

Notch the posts (continued)

Cut small shoulders.

Cut a flat on each side

of the notches to en-

sure gap-free contact

between the post and

the brace and foot.

First, lay out each flat

with a pencil and ruler

(right), then make a ver-

tical cut with a chisel to

establish the end point.

Finally, make horizontal

cuts with the chisel to

pare the stock to the

layout line (below).

Cut the groove for the stretcher. With a U-

shaped yoke screwed to the cradle serving as a

clamp, use a router table to cut a stopped groove

in the top end of the post (top). Square the round-

ed end left by the router bit with a chisel (right).

F I N E W O O D W O R K I N G

76

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

To fit a joint, first make a knife cut at the shoulders

of the dado to sever the wood fibers before trimming

the dadoes with a rabbet plane. When the joint begins

to engage, I mark the leading edges of the slots with a

pencil, which shows me exactly where the joint is still

tight. A few more strokes with the rabbet plane and the

joint should fit snugly.

Once all braces and feet are fitted to their respective

posts, the parts can be glued and clamped to create a

trestle. A pair of clamps, each spanning from brace to

foot, is all that’s needed. After that, at one end of the

trestle, measure the distance from the top edge of the

brace to the bottom edge of the foot. Do the same at

the other end. The measurement should be the same. If

they differ, adjust the pressure on the two clamps until

the measurements agree. Once dry, sand the bottom of

the post and the underside of the arched foot until flush.

When making the stretcher, I start with slightly thicker stock.

Then I make light passes with a thickness planer until the stretcher

fits snugly in the groove routed in the top of the post.

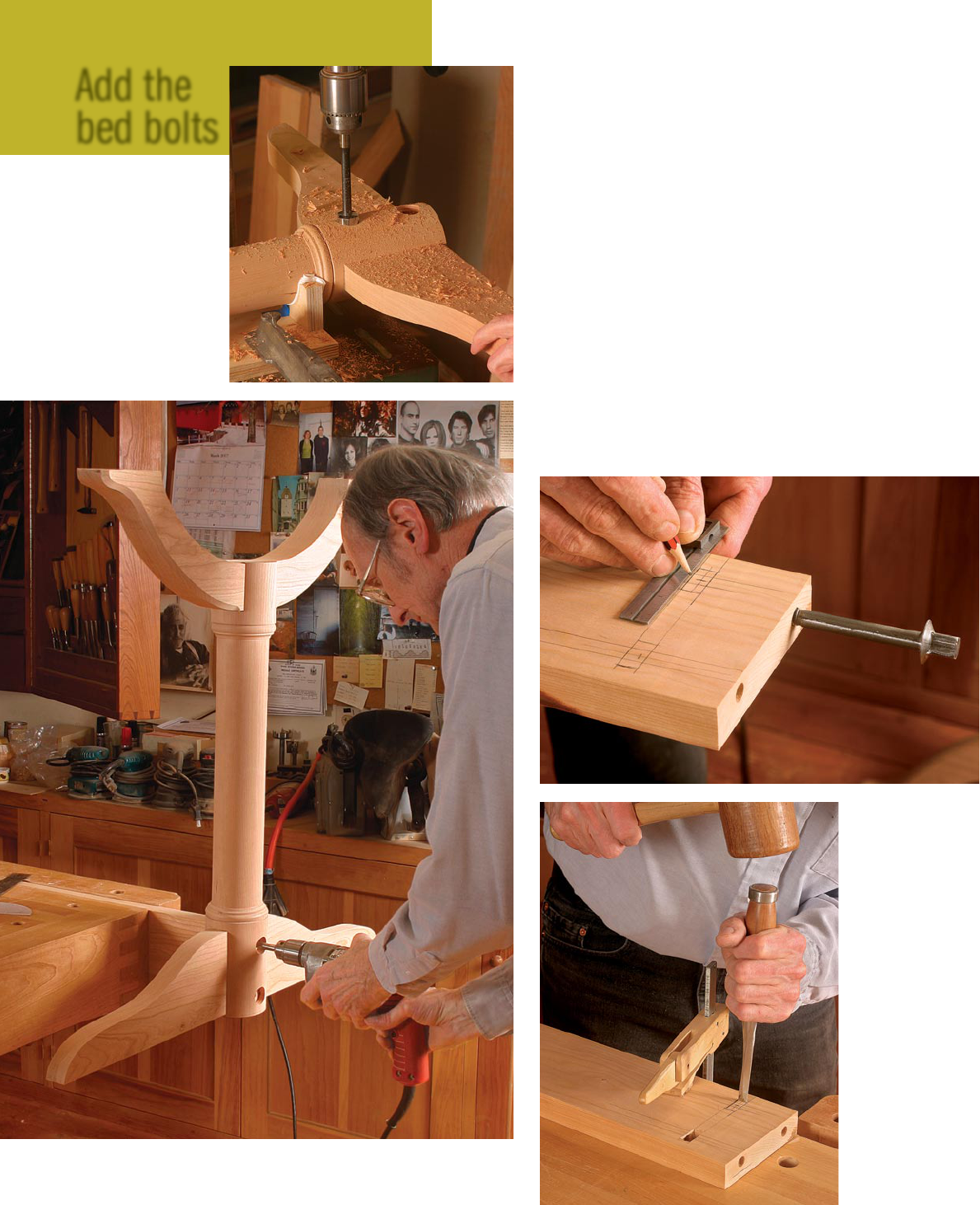

How to install bed bolts

Each trestle attaches to an end of the stretcher with a pair of

3

⁄

8

-in.

by 6-in. bed bolts and nuts (available from Horton Brasses; www.

horton-brasses.com). Each bolt extends through a post and brace

and into the end of the stretcher. The end of the bolt threads

through a nut mortised into the stretcher. When the bolt and

nut are tightened, the stretcher and trestle are pulled together to

produce a rock-solid joint.

The bed-bolt work starts at the drill press. Once again, the cradle

comes in handy. Use the yoke to secure the trestle to the cradle,

with the stretcher groove facing down. Make sure the sides of the

brace and trestle are parallel to the worksurface. If the parts tilt,

the holes won’t be square.

Measuring from the top end of the post, mark the hole centers

at 1 in. and 4

1

⁄4 in. Position the cradle so that a 1-in. Forstner bit

is centered on the upper hole. Clamp the cradle to the drill press,

Complete the trestles

Dado the legs and braces. Cut a wide dado on each side of

the brace and foot (above). Use the tablesaw miter gauge with

a long auxiliary fence to support the parts during the cuts. A

pair of stop blocks helps ensure that the ends of the dadoes

end up perfectly aligned on both sides of the parts.

Dry-fit the parts. Check

the fit of the posts to

each dado (above). If too

tight, use a rabbet plane

(left) to trim the sides or

bottom of the dado.

Rout chamfers. A cham-

fer bit in a router table is

used to chamfer the top

edges of the feet. Stop

the cut ½ in. short of the

dado.

S E P T E M B E R / O C T O B E R 2 0 0 7

77

www.finewoodworking.com

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

and then bore a

5

⁄8-in.-deep hole to accept the head of the bed

bolt. Replace the Forstner bit with a

3

⁄8-in.-dia. brad-point bit and

bore a hole completely through the post and brace. Repeat the

process for the remaining holes.

Next, clamp the stretcher in a vise and temporarily mount one

of the trestles. Transfer the

3

⁄8-in.-dia. bit from the drill press

to a portable drill. Using the holes in the trestle as guides, drill

matching holes in the end of the stretcher. Remove the trestle and

continue drilling until the hole is at least 3

1

⁄2 in. deep, measured

from the end of the stretcher.

Portable drills rarely produce a hole perfectly square to the

stretcher ends. So, to make sure the mortise for the nut is properly

located, I use a bed bolt as a guide. Allow a good portion of the

bolt to extend from the hole. Then place a long ruler so it’s cen-

tered along the length of the exposed bolt. Use a pencil to extend

the centerline along the face of the stretcher. With the centerline

showing the location of the bolt hole, measure 2

1

⁄2 in. from the

end of the stretcher, and lay out the location of the mortise for

the nut. A few minutes’ work with a chisel yields a mortise just

Add the

bed bolts

Start by drilling. With

a trestle clamped in

the cradle, and the

cradle clamped to the

drill-press table, use a

1-in.-dia. Forstner bit to

drill a

5

⁄8-in.-deep hole

(right). Then, remove the

Forstner bit and use a

3

⁄8-in.-dia. brad-point bit

to drill a hole complete-

ly through the post.

Drill holes in the ends of the stretcher. Add a trestle to the stretcher

temporarily, then use a

3

⁄8-in.-dia. brad-point bit to extend the bed-bolt

hole slightly into the end of the stretcher. After that, remove the trestle

and drill deeper to complete the hole.

Lay out the

location of the

bed-bolt nuts.

With a bed bolt in a

stretcher hole serv-

ing as a guide (in

case the hole isn’t

drilled perfectly

square), mark the

location of the bed-

bolt nut (above). Cut

the mortises for the

nuts (left) just deep

enough to allow the

bolt to thread into

the nut.

F I N E W O O D W O R K I N G

78

Photos, facing page: Michael Pekovich

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.

big enough to accept the nut. You’ll know the alignment is OK

if you can slip the bolt into the hole and thread it into the nut. I

use a special bed-bolt wrench (available from Horton Brasses; a

12-point socket also works) to turn and tighten the bolts.

With the holes drilled and all the mortises cut, you can mount

the trestles to the stretcher.

Build the top and breadboard ends

I make the tabletop by edge-gluing 1-in.-thick stock, using three

or four well-matched boards across the 36-in. width.

Breadboards are applied to either end. The original table, made

from

7

⁄8-in.-thick stock, had a

1

⁄4-in.-thick by

1

⁄2-in.-long tongue

cut fully across each end of the top and pinned to allow for wood

movement. The tongue fit into a corresponding groove cut across

the entire length of the breadboard end. I make my tenons lon-

ger for added strength (see “Keeping Tabletops Flat,” FWW #183,

pp. 32-37, for more detailed instructions).

The top is attached with screws driven through counterbored

holes in the braces and stretcher. To allow the top to expand and

contract in width due to seasonal changes in humidity, be sure

to elongate the shank holes in the braces.

For a finish, I use an oil-and-varnish mix (equal parts of each),

applying three coats to all the table surfaces, including the top

and bottom of the top and breadboard ends. For added durability,

the top then gets two more coats. •

Contributing editor Christian Becksvoort builds furniture in New Gloucester,

Maine.

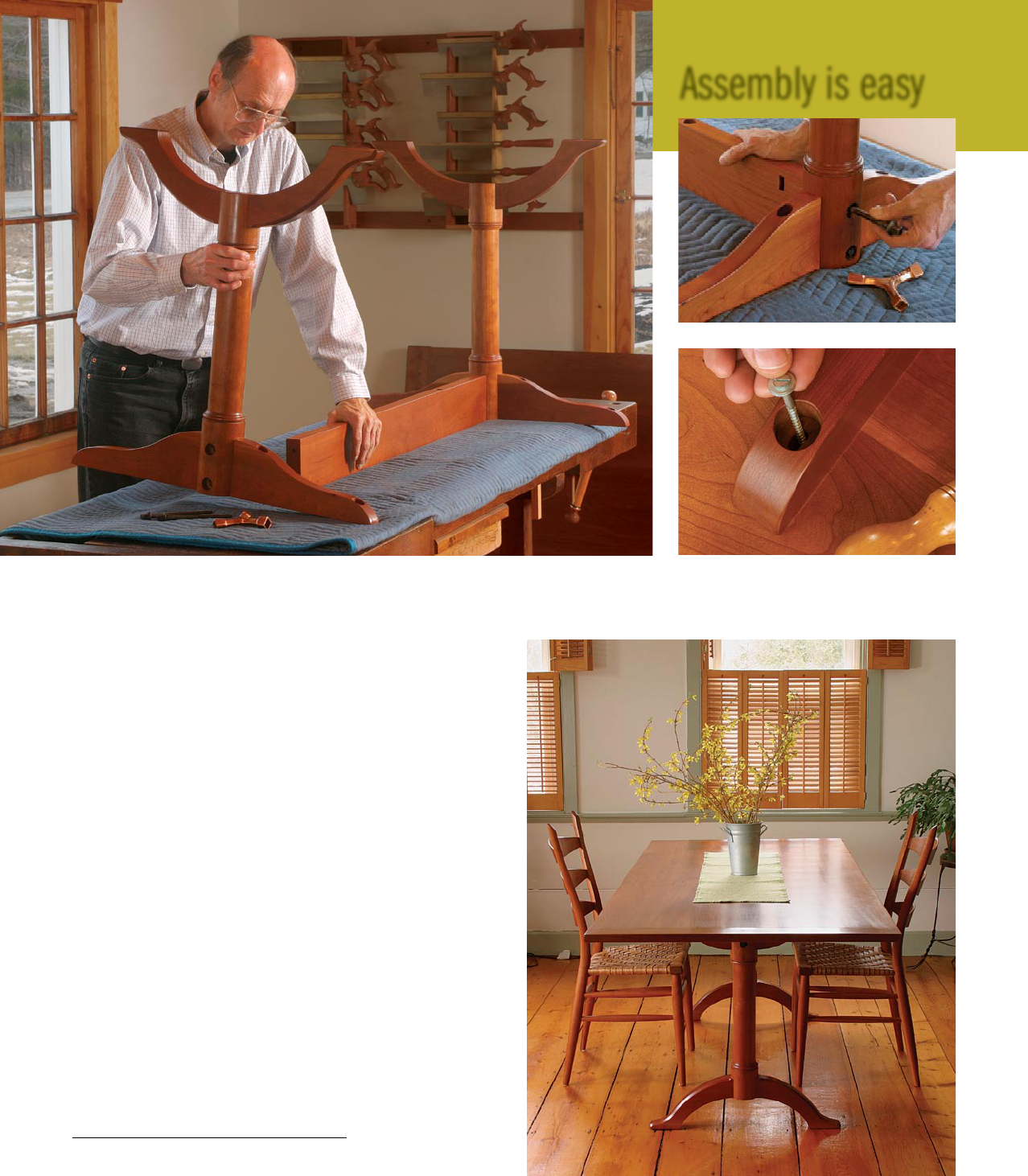

Assembly is easy

Put it together. After all the parts have been sanded and finished, it’s finally time to put the table

together. With the table parts upside down, slide the ends of the stretcher into the post grooves and

slip the bed-bolt nuts into the mortises in the stretcher. Then, insert the bolts (top right).

Attach the top. A screw and washer go into

each counterbored hole in the braces. The slot-

ted shank hole allows wood movement.

S E P T E M B E R / O C T O B E R 2 0 0 7

79

www.finewoodworking.com

COPYRIGHT 2007 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted.