The sequential acquisition of L2 Spanish gender marking: Assignment and agreement

Irma Alarcón

INTRODUCTION

In Spanish, all nouns, whether their referent is animate or inanimate, are assigned

either masculine or feminine gender. For animate nouns, gender is related to the idea of

sex, and is thus considered natural or inherent gender. For example: padre (father) is

masculine, and madre (mother) is feminine. When nouns, particularly inanimate ones, do

not have natural gender, their gender assignment is strictly grammatical. The noun espejo

(mirror) is masculine, which simply means the articles and adjectives it takes are

masculine, as in un espejo redondo (a round mirror).

Nouns having natural gender can be classified as follows: nouns expressing

gender with two different lexical items, such as hombre (man) and mujer (woman); nouns

in which the masculine form ends in “-o” and the feminine form ends in “-a”, such as hijo

(son) and hija (daughter); nouns with the feminine form ending in an “-a” but the

masculine form ending in “zero”, such as profesora (female professor) and profesor

(male professor); and, finally, nouns having one invariant form for both masculine and

feminine, such as joven (young person) in which the article or adjective shows whether

the referent is male or female, such as in el/la joven (the young man/the young woman).

Nouns bearing grammatical gender can also be classified as: nouns that end in

“-o” for masculine and “-a” for feminine, such as el almuerzo (lunch), and la lengua

(language); nouns that are either masculine or feminine depending on the modifying

words they take, since there is nothing in the surface form or the meaning that serves as a

clue for determining their gender, as in la identidad (the identity), and un examen largo

(a long exam); nouns that end in “-o” but are feminine, and nouns that end in “-a” but are

masculine, such as la mano (the hand), and el día (the day); ambiguous nouns that can be

either masculine and feminine, such as el lente (the lens), and la lente (the lens); and

finally, nouns that have one form, but change their meaning when used as masculine or

feminine, such as el capital (the money), and la capital (the capital).

In Spanish, the noun determines the gender of the accompanying elements in the

phrase (Roa, 1993, p. 44). Thus, identifying the gender of nouns, i.e., gender assignment,

is fundamental for acquiring the Spanish gender system. The Spanish system requires that

the marking of a noun be reflected overtly by the other components of the noun phrase or

clause. This is done by providing appropriate elements that match the gender of the noun,

i.e., gender agreement. Consequently, learners of Spanish need to acquire both gender

assignment and gender agreement in their interlanguage systems to be able to

communicate efficiently in the target language.

PREVIOUS STUDIES

Andersen (1984) examined both inherent and grammatical gender in oral

production. In a case study of a non-instructed English-speaking learner of Spanish, he

interviewed a twelve-year-old boy for an hour. His findings revealed that his subject

marked inherent gender “overtly, clearly, and consistently, but that he disregards totally

all other gender marking” (p. 80). His subject produced correctly marked nouns 95 times

in a sample of 100 nouns, for example, hermano (brother) and papel (paper). However,

2

Anthony, the subject, did not show article-noun agreement, using only un and la with no

marking for gender or number, such as in un nena y un nene (a girl and a boy), and la …

esposas y la esposos (the … wives and the husbands). Furthermore, he used only the

masculine unmarked form for quantifiers, determiners and adjectives. His subject also

displayed the influence of English in certain contexts, including the possessive

constructions Brian amigo (Brian’s friend) and él mamá (his mother). According to the

author, “transfer applies in these cases precisely because it leads to a semantically

‘reasonable’ and economical system” (p. 89), which was the kind of system his subject

had: a very simplified Spanish system. In addition, Andersen considered whether the

restricted system of gender his subject possessed was a liability, either for learning

Spanish, or for communicating with native speakers. His findings showed that Anthony

did have problems in both learning and communicating in his L2.

In a study of first-year Spanish learners, Finnemann (1992) reported the noun

phrase agreement behavior displayed by three university freshmen during a period of six

months. His data consisted of nine semi-guided conversation sessions taped in two-to-

three week intervals. His results showed that “learners operate with default values in the

acquisition of both number and gender agreement; each subject showed a preference for

singular and masculine forms of modifiers” (p. 134). In addition, Finnemann found that

number agreement improved far more quickly for all subjects than gender agreement.

Gender agreement was found to be influenced by the properties of the referent: “all

subjects showed a high rate of agreement with ‘self’ and with human female referents.

On the other hand, nouns with ambiguous human reference ... were frequently treated as

unmarked masculine” (p. 134). Furthermore, Finnemann claimed that “the individual’s

propensity to use the ‘marked’ form may be a revealing feature of the learner’s basic

cognitive acquisition strategy” (p. 134): meaning-oriented learners tend to use the

unmarked forms, while form-oriented learners make more use of the marked forms (pp.

133-134).

In a different study, Fernández-García (1999) examined gender agreement in the

noun phrase by intermediate second language learners of Spanish. The purpose was to

determine “whether there would be any identifiable patterns in the gender agreement

behavior of learners at this stage of acquisition of the language” (p. 6). The participants

were seven native English-speaking university juniors, and the data were taken from one-

hour tape-recorded interviews. Nouns and modifiers in a noun phrase were codified for

errors in gender agreement. Nouns were categorized as gender marked, non-gender

marked, or deceptively marked, and for the presence or absence of semantically marked

gender. In addition, Fernández-García included (in)definite articles and adjectives as

modifiers. Results revealed that most subjects performed better in masculine contexts.

Furthermore, masculine forms were especially overused with indefinite articles and

adjectives. Fernández-García also found that her subjects were more accurate with

articles than adjectives, leading her to conclude that gender agreement with the article is

acquired earlier than with the adjective. Rates of accuracy for -o/-a nouns were found to

be higher than for non-overtly marked nouns. Also, the subjects performed better with

nouns that were inherently marked for gender. Finally, according to Fernández-García,

“the gender of the referent may play a role in gender agreement in adult second language

acquisition” (p. 13).

3

An analysis of native Spanish children acquiring gender is offered in an

experimental study done by Pérez-Pereira (1991). The purpose of his study was to

“determine the relative importance of intralinguistic and extralinguistic clues, as

evidenced by the ability of Spanish children to recognize the gender of a noun upon

hearing it in a particular frame, and consequently, to establish the agreement of other

variable elements accompanying it” (p. 571). In order to test these different clues in

children aged 4-11, Pérez-Pereira used colored pictures of imaginary beings showing

either natural or mixed gender, and bearing invented names with masculine, feminine,

and unmarked endings. His experiment was designed to use different combinations of

clues with twenty-two invented nouns. His results strongly reveal that children “rely on

intralinguistic rather than extralinguistic information to recognize the gender of a noun

and to establish gender agreement” (p. 588).

Hardison (1992) investigated the acquisition of grammatical gender in French to

study the development of formal accuracy of L2 learners in assigning gender. She also

examined the strategies learners use when establishing agreement. Her subjects were

college students taking non-required French courses. The tasks involved selecting the

appropriate article according to the gender of the noun they heard. Then they were asked

to circle a number, on a scale from 1 to 4, representing the confidence with which each

gender decision was made. Finally, they were asked to describe the strategies they used to

assign gender. Her findings showed that “L2 learners utilize gender-noun ending

correspondences in the language learning environment to formulate rules of association

based on the most salient member of each phonetic ending category” (p. 304). Thus, the

category [ad] was correctly associated with feminine gender, including promenade (walk)

and limonade (lemon soda). The results of the study also demonstrated that “learners are

processing cues indicative of gender and utilizing strategies similar to those used by

native speakers” (p. 304), such as focusing on the noun ending, recalling previous

experience with more familiar nouns, and using the article that “sounds best.”

Research done on the acquisition of gender in Spanish and other languages has

focused either on the analysis of errors learners make in gender agreement (Andersen,

1984; Finnemann, 1992; Fernández-García, 1999) or on the clues and strategies learners

use to identify the gender of a noun (Pérez-Pereira, 1991; Hardison, 1992). However,

none of these studies has considered developmental acquisition of Spanish gender

marking. This paper examines the acquisition of Spanish gender marking, including both

gender assignment and gender agreement, by English-speaking learners of Spanish at

four different levels: first-, second-, third-, and fourth-semester university Spanish. The

purpose is to see how the length of exposure to Spanish affects the acquisition of Spanish

gender marking.

PRESENT STUDY

The following research questions guided the study:

1) Does length of exposure affect acquisition of Spanish gender marking?

2) Is natural gender acquired before grammatical gender?

3) When do learners acquire deceptively and non-overtly marked nouns?

4) Do learners tend to overuse the unmarked masculine forms?

5) What is the relationship between the acquisition of gender assignment and gender

agreement?

4

METHOD

Subjects

The 69 English-speaking learners of Spanish who participated in this study were

enrolled in four different levels of Spanish courses at Indiana University: first-, second-,

third-, and fourth-semester (S100, S150, S200, and S250, respectively). The distribution

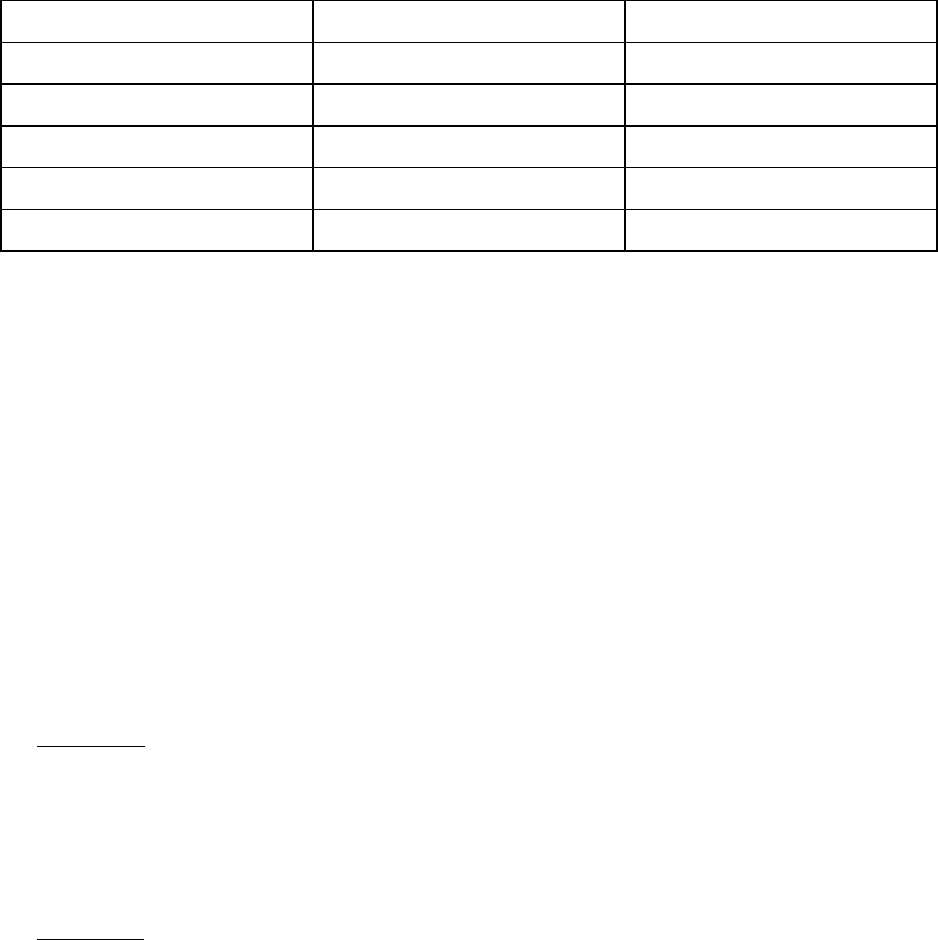

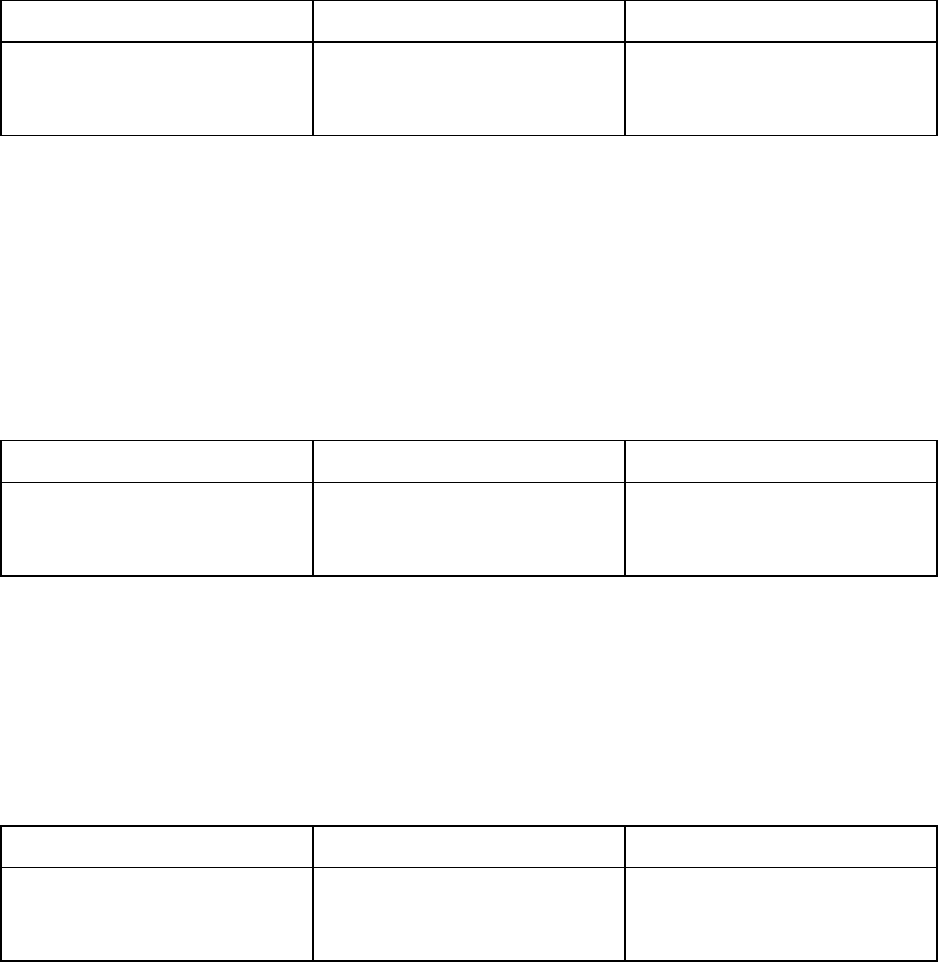

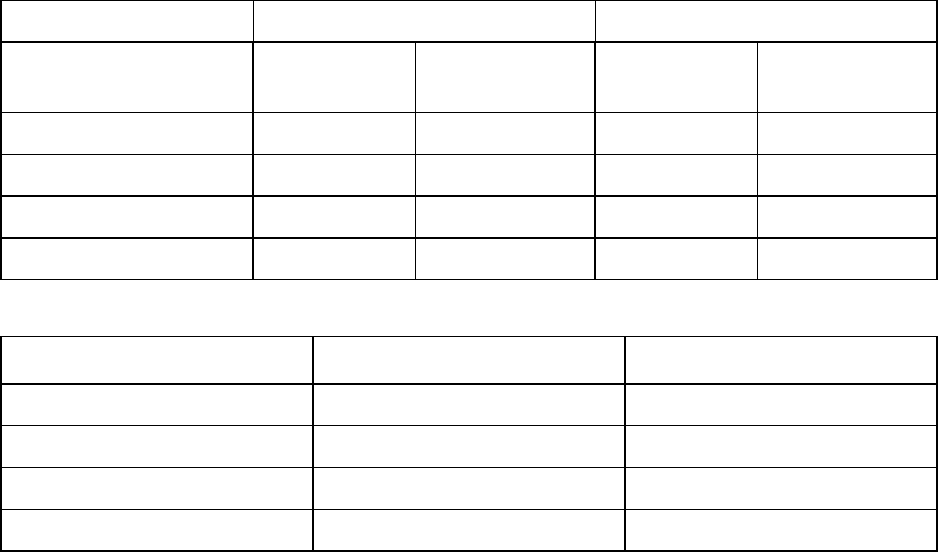

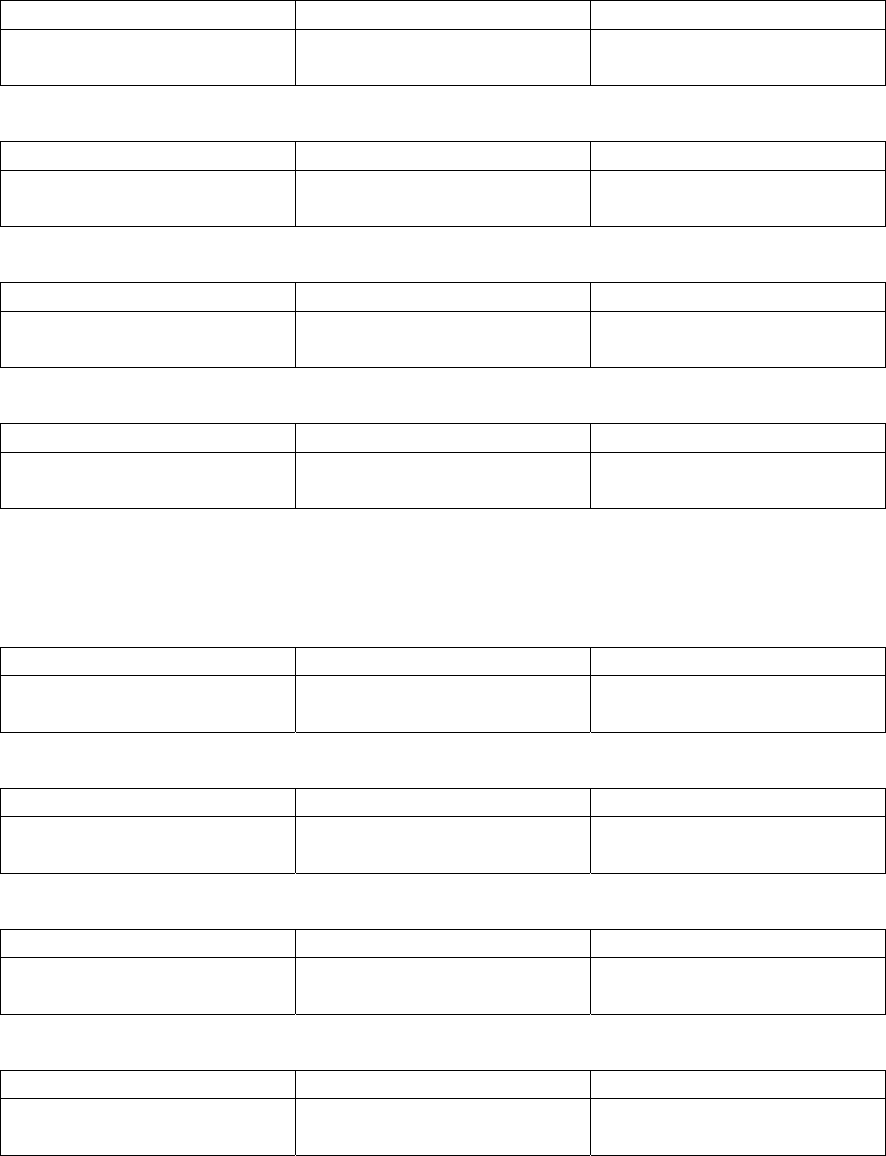

of the subjects by level is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Subjects’ distribution according to number and sex

Spanish Level Number of subjects Female / Male subjects

S100 15 6 F / 9 M

S150 20 9 F / 11 M

S200 17 12 F / 5 M

S250 17 11 F / 6 M

Total 69 38 F / 31 M

The subjects’ linguistic learning experience in Spanish is fairly homogeneous,

since it is restricted to Spanish as a foreign language, and since 97% of the participants in

this study (67/69) had never studied in a Spanish speaking country. More important, most

of the subjects in the higher-level courses had previously taken the lower-level classes,

although a few of the subjects had tested out of some of the earlier courses. (See

Appendix A for details.)

Materials and procedures

Data collection consisted of a two-part written test in which the subjects were first

asked to indicate whether each given noun from a list of 24 nouns was masculine or

feminine by writing the appropriate definite article - el, la, los, las - in front of the word

(gender assignment). The second part briefly described 12 situations, and asked the

subjects to write an appropriate adjective according to the context (gender agreement).

See examples A and B for a sample of questions from parts I and II, respectively. The

complete test is included in Appendix B.

Example A

Part I. Write el, la, los or las next to the corresponding word. If you don’t know,

write “?”

1) _______ productos (products-masculine)

2) _______ día (day-masculine)

3) _______ nariz (nose-feminine)

Example B

Part II. Write an appropriate adjective according to the situation.

1) Mi compañera tiene 5 exámenes mañana. Está muy ________________.

(My classmate has 5 exams tomorrow. (She) is very ________________ ).

5

2) Carlos prefiere chicas con manos _________________.

(Carlos prefers women with hands _________________ ).

3) Einstein creó la Teoría de la Relatividad. Fue un hombre _________________.

(Einstein created the Theory of Relativity. (He) was a man _________________ ).

The nouns included in the test were taken from the two textbooks learners were

using in their college classes. These nouns were categorized as (1) Natural gender nouns

that were either a) overtly marked (-o/-a endings): el caballo and la vecina, b) non-

overtly marked (any other vowel or consonant endings): el presidente and las mujeres, or

c) zero/-a alternation: el adivinador and la escultora; or (2) Grammatical gender nouns

that were either a) overtly marked: el almuerzo and la lengua, b) non-overtly marked: el

examen and la nariz, or c) deceptively marked: el idioma and la mano.

1

Noun categories and subcategories were equally distributed on the test, including

feminine and masculine nouns, with singular and plural forms. The distribution of the

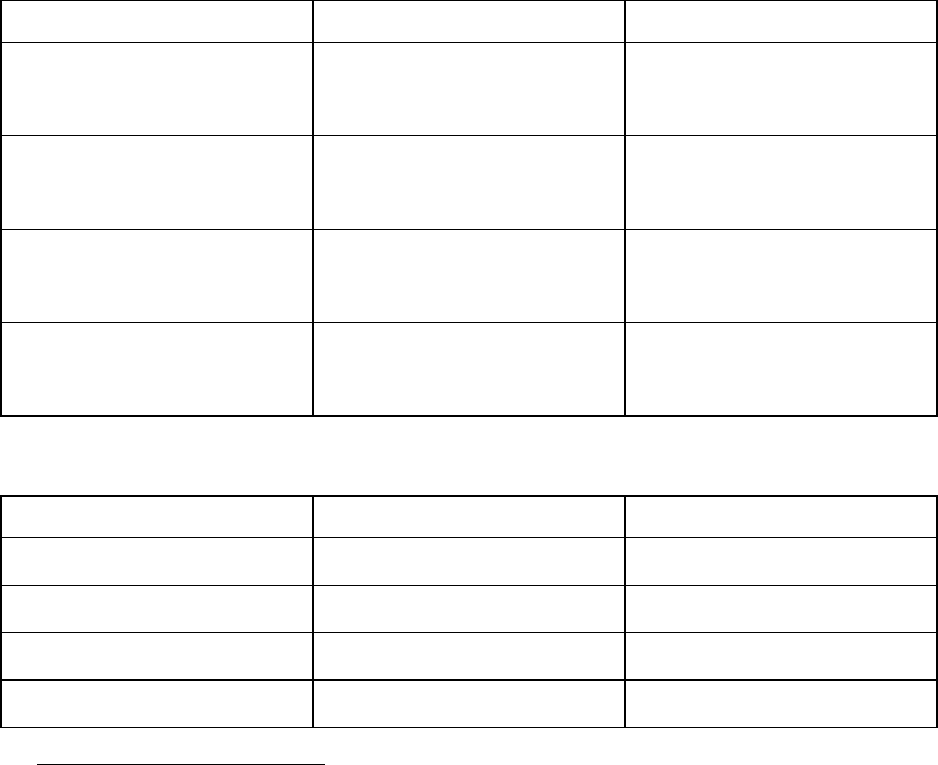

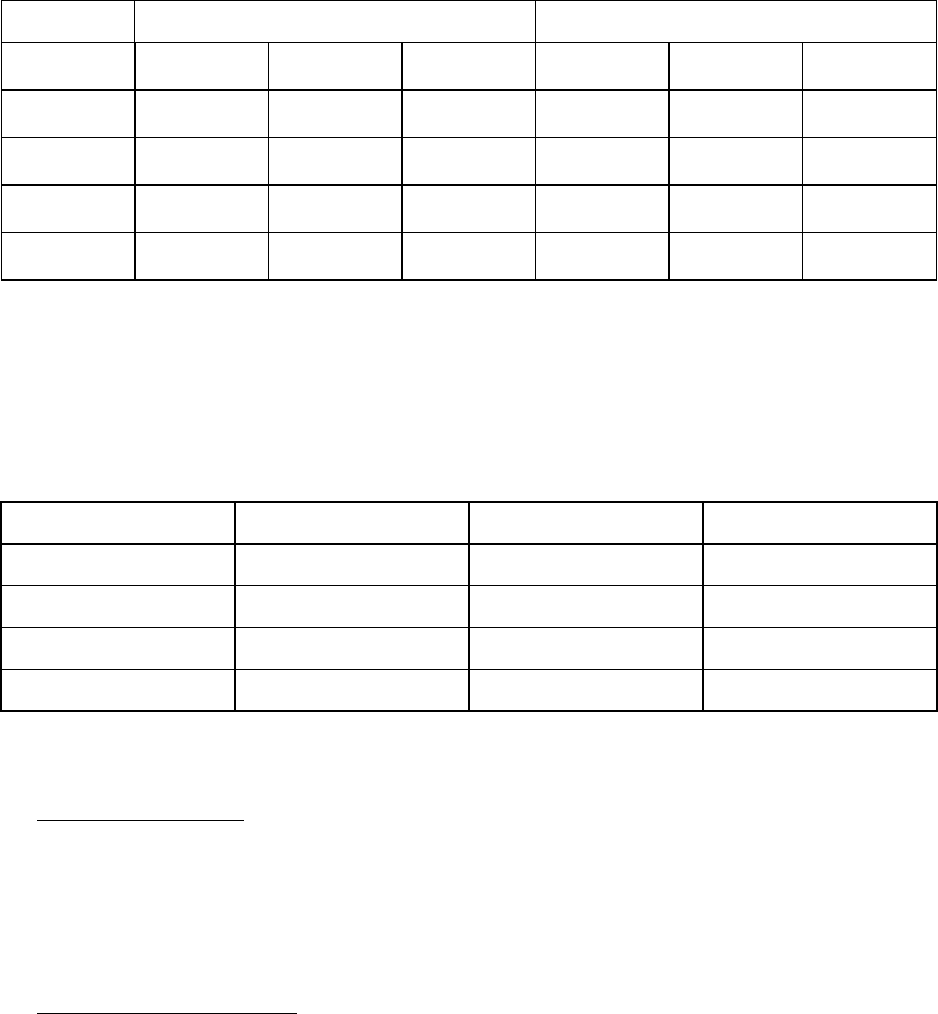

nouns in each of these categories and subcategories is given in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2: Noun categories and subcategories for gender assignment (part I)

Noun subcategories Natural gender Grammatical gender

Overtly marked (-o/-a ending) caballo, horse (m/s)

camarera, waitress (f/s)

arquitectos, male architects (m/p)

vecinas, female neighbors (f/p)

almuerzo, lunch (m/s)

lengua, language (f/s)

productos, products (m/p)

tiendas, stores (f/p)

Non-overtly marked (-e/-C ending)* presidente, male president (m/s)

gente, people (f/s)

tigres, tigers (m/p)

mujeres, women (f/p)

examen, exam (m/s)

nariz, nose (f/s)

menús, menus (m/p)

identidades, identities (f/p)

Zero/-a alternation adivinador, male psychic (m/s)

escultora, sculptoress (f/s)

profesores, male teachers (m/p)

directoras, female directors (f/p)

-----------------------

Deceptively marked ----------------------- día, day (m/s)

mano, hand (f/s)

emblema, seal (m/s)

idioma, language (m/s)

*-C = consonant

Table 3: Noun categories and subcategories for gender agreement (part II)

Noun subcategories Natural gender Grammatical gender

Overtly marked (-o/-a ending) primo, male cousin (m/s)

compañera, female classmate (f/s)

pelo, hair (m/s)

ropa, clothes (f/s)

Non-overtly marked (-e/-C ending) hombre, man (m/s)

mujeres, women (f/p)

chiste, joke (m/s)

habitación, bedroom (f/s)

Zero/-a alternation pintor, male painter (m/s)

diseñadora, female designer (f/s)

--------------------------------

Deceptively marked -------------------------------- programas, programs (m/p)

manos, hands (f/p)

1

English glosses for these nouns are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

6

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Gender assignment

A. Natural gender assignment: individual word scores

The majority of S100 subjects (over 90%) assigned correct gender to all overtly

marked nouns, for example caballo (horse) and camarera (waitress). This was not the

case with non-overtly marked nouns, in which only presidente (president) was assigned

correct gender by all subjects (100%). The nouns gente (people) and tigres (tigers)

received low accurate gender marking rates of 27% and 47%, respectively. The word

mujeres (women) was assigned correct gender by half of the subjects (53%). Two zero/-a

alternation nouns, escultora (sculptress) and profesores (teachers-masculine), showed

correct gender assignment by over 90% of the subjects. The word adivinador (psychic-

masculine) was assigned correct masculine gender by 87% of the subjects, and directoras

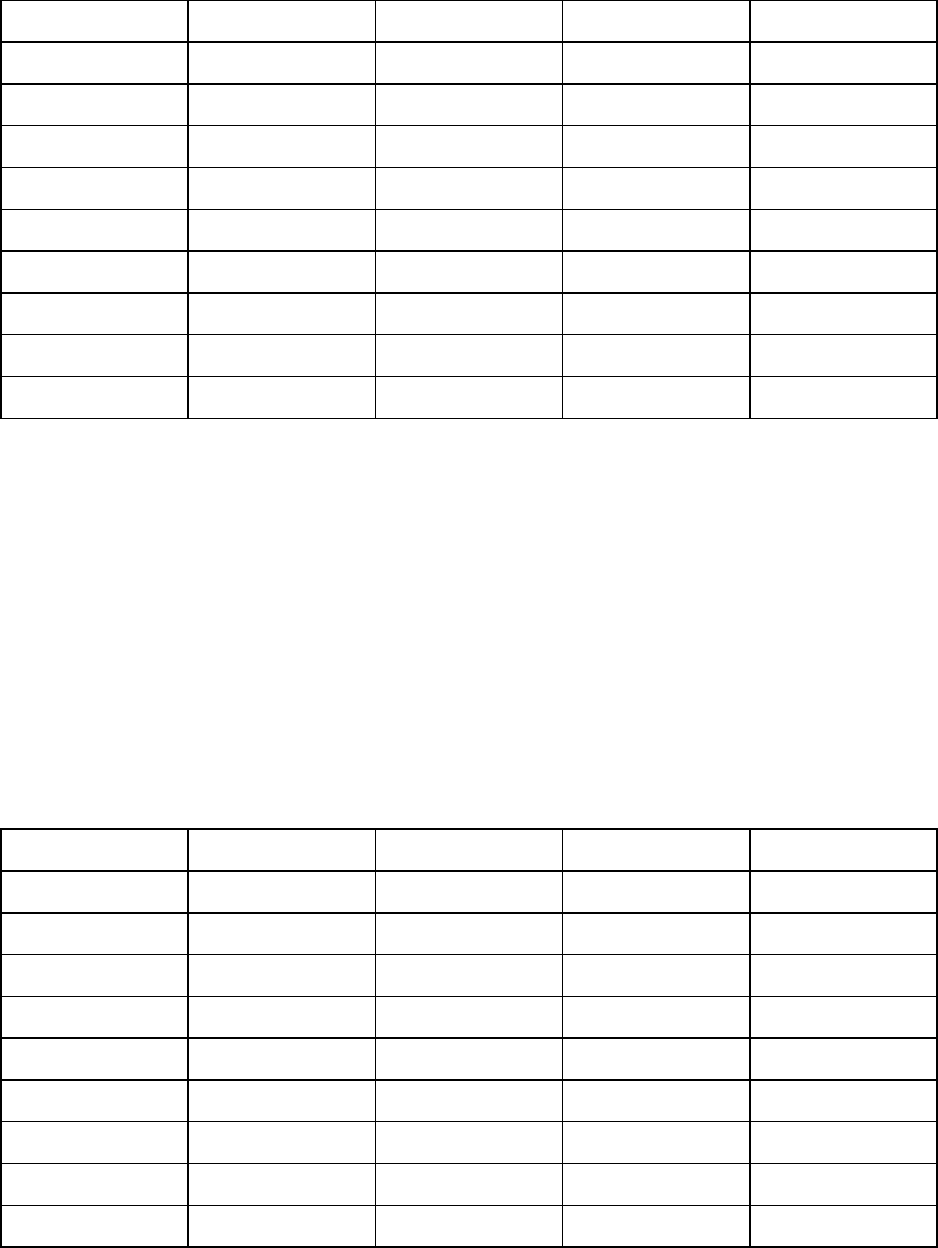

(directors-feminine) by 67% of them. Table 4 summarizes this data.

Table 4: S100 subjects’ natural gender assignment

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

caballo: 15/15 - 100 %

camarera: 14/15 - 93 %

arquitectos: 15/15 - 100 %

vecinas: 14/15 - 93 %

presidente: 15/15 - 100 %

gente: 4/15 - 27 %

tigres: 7/15 - 47 %

mujeres: 8/15 - 53 %

adivinador: 13/15 - 87 %

escultora: 14/15 - 93 %

profesores: 14/15 - 93 %

directoras: 10/15 - 67 %

S150 subjects were similarly proficient concerning overtly marked nouns: most of

the subjects assigned gender correctly to these nouns. The non-overtly marked noun

presidente was assigned correct gender by 100% of the subjects. Half of the subjects

(10/20) identified both mujeres, and gente as feminine; and tigres was assigned correct

gender by 80% of the subjects. Moreover, all nouns showing zero-/a alternation were

assigned correct gender by over 90% of the subjects. See Table 5.

Table 5: S150 subjects’ natural gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

caballo: 20/20 - 100 %

camarera: 20/20 - 100 %

arquitectos: 19/20 - 95 %

vecinas: 20/20 - 100 %

presidente: 20/20 - 100 %

gente: 10/20 - 50 %

tigres: 16/20 - 80 %

mujeres: 10/20 - 50 %

adivinador: 18/20 - 90 %

escultora: 20/20 - 100 %

profesores: 18/20 - 90 %

directoras: 18/20 - 90 %

All S200 subjects assigned correct gender to all -o/-a ending nouns. Two non-

overtly marked nouns, presidente and tigres, were assigned correct gender by over 90%

of the subjects. The word gente shows a low accurate rate for gender assignment (41%),

higher than S100 (27%), but lower than S150 (50%). However, mujeres was assigned

correct gender by 76% of the subjects, a higher rate than the previous levels. Three zero/

-a alternation nouns were assigned correct gender by 100% of the subjects, escultora,

profesores and directoras. The noun adivinador was assigned correct gender by only

76% of the subjects, lower than the two previous levels. Table 6 shows this information.

7

Table 6: S200 subjects’ natural gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

caballo: 17/17 - 100 %

camarera: 17/17 - 100 %

arquitectos: 17/17 - 100 %

vecinas: 17/17 - 100 %

presidente: 17/17 - 100 %

gente: 7/17 - 41 %

tigres: 16/17 - 94 %

mujeres: 13/17 - 76 %

adivinador: 13/17 - 76 %

escultora: 17/17 - 100 %

profesores: 17/17 - 100 %

directoras: 17/17 - 100 %

Almost all of the S250 subjects assigned correct gender to -o/-a ending nouns. As

seen in the other levels, the rate of accuracy for the non-overtly marked noun presidente

was also 100%. In addition, the noun mujeres was also assigned correct gender by 100%

of the subjects. The word gente was assigned correct feminine gender by 88% of the

S250 subjects, double the S200 rate (41%). 82% of the subjects identified tigres as a

masculine plural noun. Finally, S250 subjects behaved exactly as S200 subjects in zero/-a

alternation nouns. Table 7 displays this data.

Table 7: S250 subjects’ natural gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

caballo: 17/17 - 100 %

camarera: 16/17 - 94 %

arquitectos: 17/17 - 100 %

vecinas: 17/17 - 100 %

presidente: 17/17 - 100 %

gente: 15/17 - 88 %

tigres: 14/17 - 82 %

mujeres: 17/17 - 100 %

adivinador: 13/17 - 76 %

escultora: 17/17 - 100 %

profesores: 17/17 - 100 %

directoras: 17/17 - 100 %

B. Grammatical gender assignment: individual word scores

Three out of four overtly marked nouns were identified correctly by over 90% of

S100 subjects; the noun almuerzo (lunch) was assigned gender correctly by 80% of the

subjects. Percentages of correct gender assignment for non-overtly marked nouns ranged

from 27% for identidades (identities) to 73% for menús (menus). Rates for correct gender

assignment for all deceptively marked nouns fall below 30%, with the nouns mano

(hand), emblema (symbol), and idioma (language) having only13% correct gender

assignment each. This is shown in Table 8.

Table 8: S100 subjects’ grammatical gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked deceptively marked

almuerzo: 12/15 - 80 %

lengua: 14/15 - 93 %

productos: 15/15 - 100 %

tiendas: 15/15 - 100 %

examen: 10/15 - 67 %

nariz: 6/15 - 40 %

menús: 11/15 - 73 %

identidades: 4/15 - 27 %

día: 4/15 - 27 %

mano: 2/15 - 13 %

emblema: 2/15 - 13 %

idioma: 2/15 - 13 %

S150 subjects performed similarly to S100 subjects when assigning correct gender

to overtly marked nouns: most subjects (over 85%) were accurate. Non-overtly marked

nouns show a wider range of correct gender assignment, from 20% for identidades to

90% correct gender assignment for examen. The deceptively marked noun emblema was

not identified as masculine by any subject (0%). The noun mano was assigned feminine

gender by only 5% of the subjects. These rates are lower than those of S100 for the same

two nouns. But higher rates than S100 are found for día (70%) and idioma (20%). Table

9 displays this data.

8

Table 9: S150 subjects’ grammatical gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked deceptively marked

almuerzo: 17/20 - 85 %

lengua: 17/20 - 85 %

productos: 20/20 - 100 %

tiendas: 20/20 - 100 %

examen: 18/20 - 90 %

nariz: 11/20 - 55 %

menús: 18/20 - 90 %

identidades: 4/20 - 20 %

día: 14/20 - 70 %

mano: 1/20 - 5 %

emblema: 0/20 - 0 %

idioma: 4/20 - 20 %

S200 subjects also performed better when assigning gender to -o/-a ending nouns,

with over 90% correct gender assignment, than to the other categories. The non-overtly

marked noun identidades had a lower rate than for S100 (27%) or S150 (20%), only 12%

correct gender assignment. In the same category, though, examen was assigned correct

gender by 100% of the subjects. The word nariz was identified as feminine by 47% of the

subjects, and menús was assigned correct masculine gender by 94%. The rates for correct

gender assignment of deceptively marked nouns ranged from 65% for día to 5% for

emblema. This information is summarized in Table 10.

Table 10: S200 subjects’ grammatical gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked deceptively marked

almuerzo: 17/17 - 100 %

lengua: 16/17 - 94 %

productos: 17/17 - 100 %

tiendas: 17/17 - 100 %

examen: 17/17 - 100 %

nariz: 8/17 - 47 %

menús: 16/17 - 94 %

identidades: 2/17 - 12 %

día: 11/17 - 65 %

mano: 4/17 - 24 %

emblema: 1/17 - 5 %

idioma: 6/17 - 35 %

Most S250 subjects assigned gender correctly to overtly marked nouns. For non-

overtly marked nouns, though, their success was higher compared to S200 subjects in

some cases, such as nariz (59%) and identidades (35%), but lower for nouns such as

examen and menús (both 88%). As Table 11 shows, more S250 subjects identified the

correct gender of deceptively marked nouns than at any previous level, día (94%), mano

(35%), emblema (24%), and idioma (41%), although the latter three rates are low.

Table 11: S250 subjects’ grammatical gender assignment

-o/-a ending Non-overtly marked deceptively marked

almuerzo: 17/17 - 100 %

lengua: 15/17 - 88 %

productos: 17/17 - 100 %

tiendas: 16/17 - 94 %

examen: 15/17 - 88 %

nariz: 10/17 - 59 %

menús: 15/17 - 88 %

identidades: 6/17 - 35 %

día: 16/17 - 94 %

mano: 6/17 - 35 %

emblema: 4/17 - 24 %

idioma: 7/17 - 41 %

C. Natural and grammatical gender assignment: group scores

Combining the results of the individual nouns in each subcategory reveals that

subjects at each level assign gender correctly to -o/-a ending nouns in over 90% of the

cases, for both natural and grammatical gender nouns. Non-overtly marked natural nouns

show strong development, which extends from 57% (S100) to 93% (S250) of correct

gender assignment by the subjects’ fourth semester. Non-overtly marked grammatical

nouns display weak development, with correct gender assignment reaching only 68% for

the fourth semester subjects. Zero/-a alternation nouns show high rates of correct gender

assignment, which increases in the first three levels, and stabilizes in S250. Deceptively

9

marked nouns also exhibit substantial development, but reach only 49% correct gender

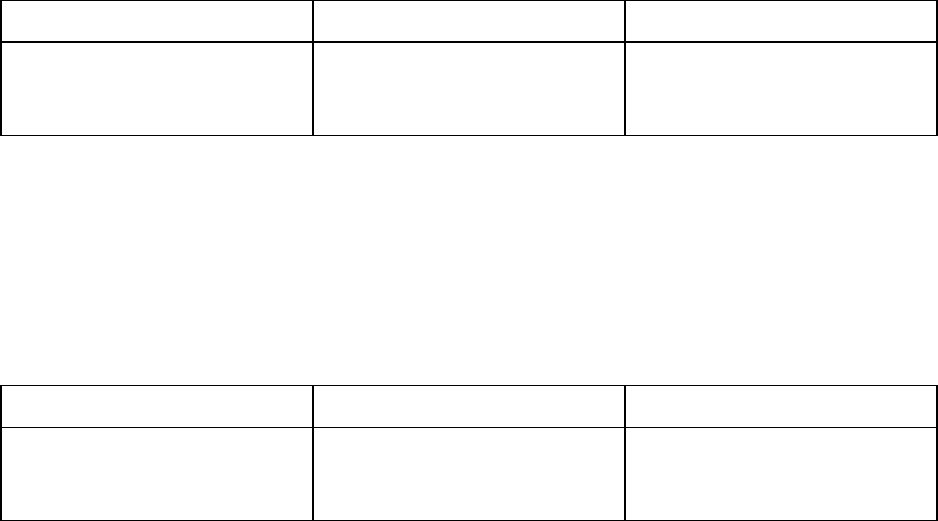

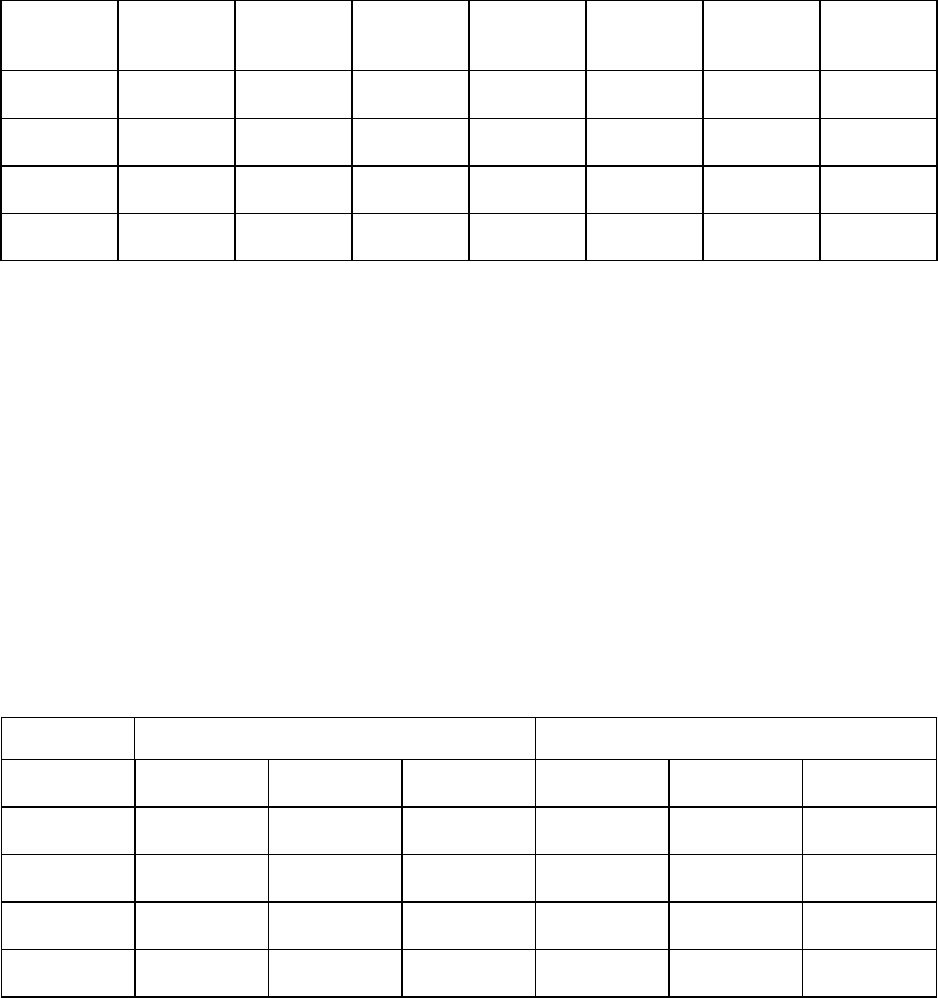

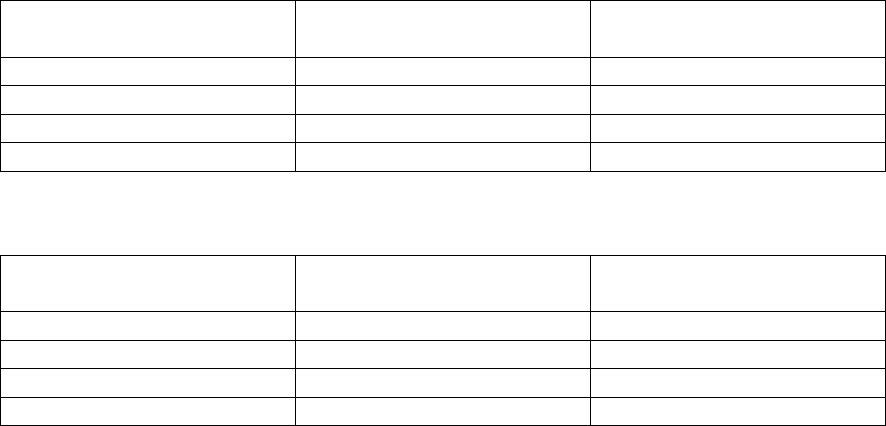

assignment by the S250 subjects. This is indicated in Table 12.

Table 12: Group scores for gender assignment according to noun subcategories

NATURAL GENDER GRAMMATICAL GENDER

SPANISH

LEVEL

-o/-a ending non-overtly

marked

zero/-a

alternation

-o/-a ending non-overtly

marked

deceptively

marked

S100

(15x24=360)

97 % (58/60) 57 % (34/60) 85 % (51/60) 93 % (56/60) 52 % (31/60) 17 % (10/60)

S150

(20x24=480)

99 % (79/80) 71 % (57/80) 93 % (74/80) 93 % (74/80) 64 % (51/80) 24 % (19/80)

S200

(17x24=408)

100% (68/68) 78 % (53/68) 94 % (64/68) 99 % (67/68) 63 % (43/68) 32 % (22/68)

S250

(17x24=408)

99 % (67/68) 93 % (63/68) 94 % (64/68) 96 % (65/68) 68 % (46/68) 49 % (33/68)

These results show that gender assignment improves at each level and that, at all

levels, gender is correctly assigned more frequently to natural than to grammatical gender

nouns. By the fourth semester, gender is correctly assigned to the former at a 95% rate,

but to the latter at a rate of only 71%. This information, and the figures combining the

two categories, is provided in Table 13.

Table 13: Scores for gender assignment according to natural and grammatical nouns

LEVEL NATURAL GRAMMATICAL TOTAL

S100 (15x24=360) 79 % (143/180) 54 % (97/180) 67 % (240/360)

S150 (20x24=480) 88 % (210/240) 60 % (144/240) 74 % (354/480)

S200 (17x24=408) 91 % (185/204) 65 % (132/204) 78 % (317/408)

S250 (17x24=408) 95 % (194/204) 71 % (144/204) 83 % (338/408)

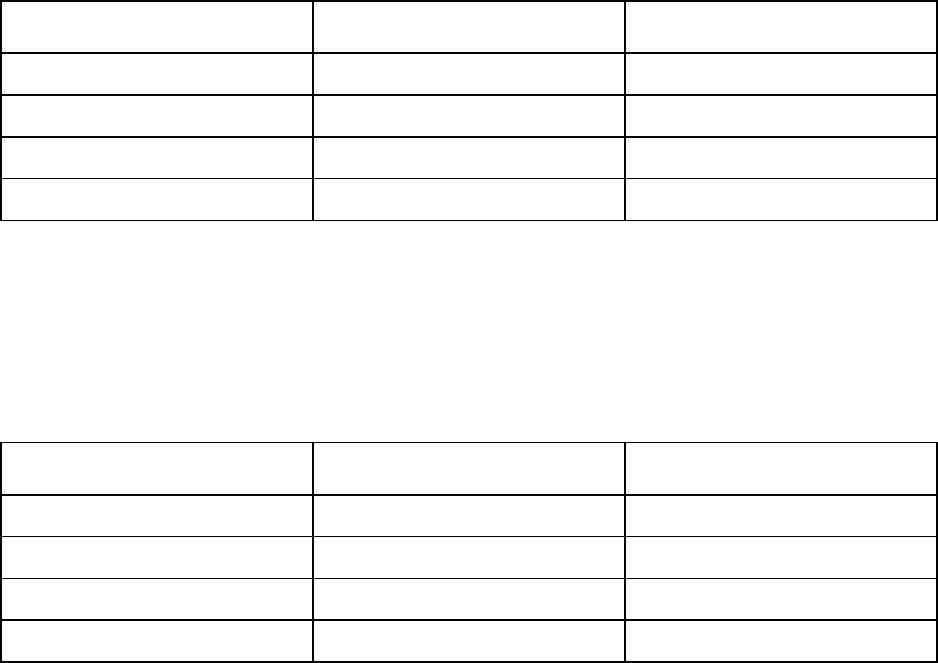

D. Gender assignment: preferred gender in cases of incorrect gender assignment

Natural gender nouns

When S100 subjects do not assign natural gender correctly, 72% of the time they

assign masculine gender to feminine nouns (26/36). A similar situation is observed at the

S150 and S200 levels, in which subjects tend to overuse the masculine forms with

feminine referents at a rate of 70% (21/30) and 78% (14/18), respectively. In contrast,

S250 subjects show a tendency to overuse feminine gender forms with masculine nouns

at a rate of 70% (7/10).

Grammatical gender nouns

At all levels, rates for grammatical gender nouns reveal no striking preference for

either masculine or feminine forms. Nonetheless, S100 subjects show the lowest

preference for masculine forms with feminine referents, 41% (34/82). S150 subjects

reflect no preference, since they use both masculine and feminine forms in the same

proportion (50%). Both S200 and S250 subjects show the same behavior, with 54% of

their incorrect responses assigning masculine forms to feminine nouns. See Table 14.

10

Table 14: Preferred gender forms according to natural and grammatical gender nouns

NATURAL GENDER GRAMMATICAL GENDER

SUBJECTS Femenine nouns

assigned

masculine gender

Masculine nouns

assigned

femenine gender

Femenine nouns

assigned

masculine gender

Masculine nouns

assigned

fememine gender

S100 (15 subjects) 72 % (26/36) 28 % (10/36) 41 % (34/82) 59 % (48/82)

S150 (20 subjects) 70 % (21/30) 30 % (9/30) 50 % (47/94) 50 % (47/94)

S200 (17 subjects) 78 % (14/18) 22 % (4/18) 54 % (38/71) 46 % (33/71)

S250 (17 subjects) 30 % (3/10) 70 % (7/10) 54 % (32/59) 46 % (27/59)

Gender agreement

A. Gender agreement: what learners produce

This section of the test showed a variety of responses. Subjects provided forms

showing three types of agreement: 1) target-like agreement (TA), implying a completely

native-like agreement in meaning and form, such as diseñadora famosa, pelo negro, and

manos pequeñas; 2) grammatical agreement (GA), which refers to agreement where the

adjectival form is native-like, but the meaning is not, such as in primo contento (happy

cousin) for a context requiring enojado (angry), mujeres contentas (happy women)

instead of cansadas (tired), and pelo bajos (small hair), for corto (short); and 3) invented

word agreement (IA), consisting of an invented word reflecting correct agreement, as in

ropa expensitiva for ropa cara, primo alegro for primo alegre, and ropa confortadora for

ropa cómoda. Subjects also provided forms ending in -e or consonant that do not reveal

gender: pintor brillante, hombre inteligente, and manos grandes. In addition, subjects

produced forms without showing agreement, such as compañera tenso, mujeres

agobiado, and pintor moderna. Subjects also responded with different appropriate

answers, including adverbs or adverbial phrases, for example chiste-más, programas-de

la television, and diseñadora-en Los Angeles. Some of the subjects’ responses were

nonsensical, as in ropa-en el restaurante, hombre-realidad, and primo-muchos amigos.

Finally, some subjects opted for omitting a response.

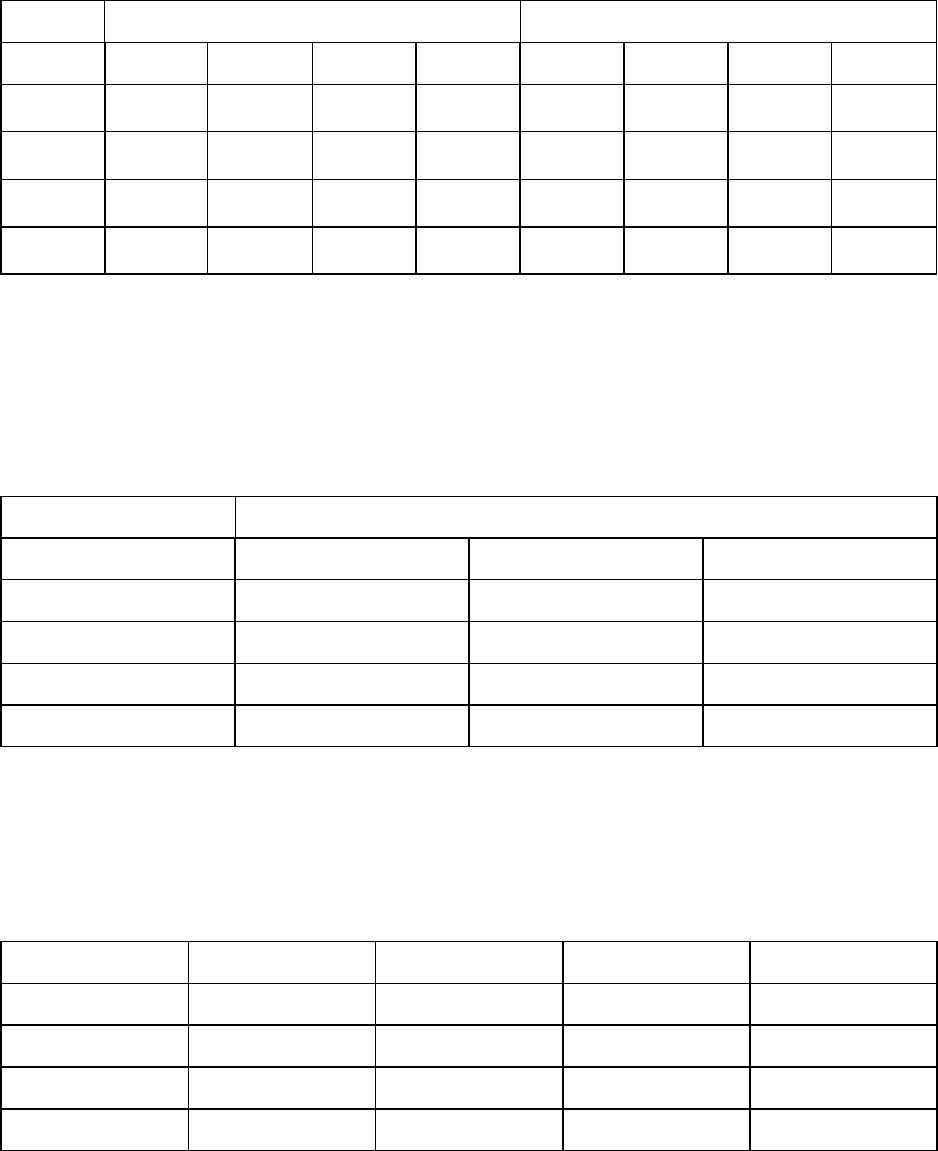

Table 15 shows the distribution of subjects’ responses by level. (For the

percentages of subjects showing agreement for each individual noun, see Appendix C.)

Rates for agreement (TA, GA, IA) are not very high, but they show steady improvement

as level increases. The percentage of -e/-C ending nouns also increases by level, but these

forms do not reveal gender agreement. Non-agreement forms remain stable along all four

levels. The percentage of appropriate answers without an adjective is very low, and

decreases at the S250 level. The percentage of nonsensical responses also decreases, from

22% (S100) to 8% (S250). Also, the percentage of omitted responses diminishes by the

subjects’ fourth semester: S100 subjects do not respond in 35% (64/180) of the cases, and

S250 subjects omit responses in only 7% (15/204).

11

Table 15: Distribution of subjects’ responses by Spanish level

LEVEL Agreement

(TA, GA,

IA)*

Non-

revealing

Non-

agreement

Different

appropriate

response

Response

without any

sense

No

response

TOTAL

S100 18 %

(32/180)

12 %

(22/180)

11 %

(20/180)

2 %

(3/180)

22 %

(39/180)

35 %

(64/180)

100 %

(180/180)

S150 26 %

(63/240)

19 %

(46/240)

15 %

(35/240)

3 %

(8/240)

25 %

(59/240)

12 %

(29/240)

100 %

(240/240)

S200 39 %

(79/204)

20 %

(41/204)

17 %

(36/204)

2 %

(4/204)

12 %

(24/204)

10 %

(20/204)

100 %

(204/204)

S250 47 %

(96/204)

21 %

(42/204)

16 %

(33/204)

1 %

(2/204)

8 %

(16/204)

7 %

(15/204)

100 %

(204/204)

* TA = target-like agreement; GA = grammatical agreement; IA = invented word agreement

B. Gender agreement: group scores according to noun categories and subcategories

Considering only forms that show agreement (TA, GA, IA), distribution by noun

categories/subcategories reveals improvement at all levels, and for almost every noun

subcategory. (The two exceptions are non-overtly marked natural nouns for S250 and

non-overtly marked grammatical nouns for S200.). However, agreement rates for natural

gender nouns, in general, are lower than the rates for grammatical gender nouns. Thus, by

the subjects’ fourth semester, correct agreement rates for overtly marked natural nouns

(47%) are much lower than for overtly marked grammatical noun (82%); the rates for

non-overtly marked natural nouns (38%) are also lower than for their grammatical

counterparts (41%), though very close. Finally, zero/-a alternation nouns show only 26%

agreement, and deceptively marked nouns show 47% agreement. These results are

displayed in Table 16.

Table 16: Gender agreement according to noun categories

NATURAL GENDER GRAMMATICAL GENDER

LEVEL -o/-a ending non-overtly

marked

zero/-a

alternation

-o/-a ending non-overtly

marked

deceptively

marked

S100

(15x12=180)

7 % (2/30) 17 % (5/30) 13 % (4/30) 37 % (11/30) 13 % (4/30) 20 % (6/30)

S150

(20x12=240)

32 % (13/40) 18 % (7/40) 20 % (8/40) 42 % (17/40) 23 % (9/40) 23 % (9/40)

S200

(17x12=204)

41 % (14/34) 38 % (13/34) 32 % (11/34) 70 % (24/34) 18 % (6/34) 32 % (11/34)

S250

(17x12=204)

47 % (16/34) 38 % 13/34) 26 % (9/34) 82 % (28/34) 41 % (14/34) 47 % (16/34)

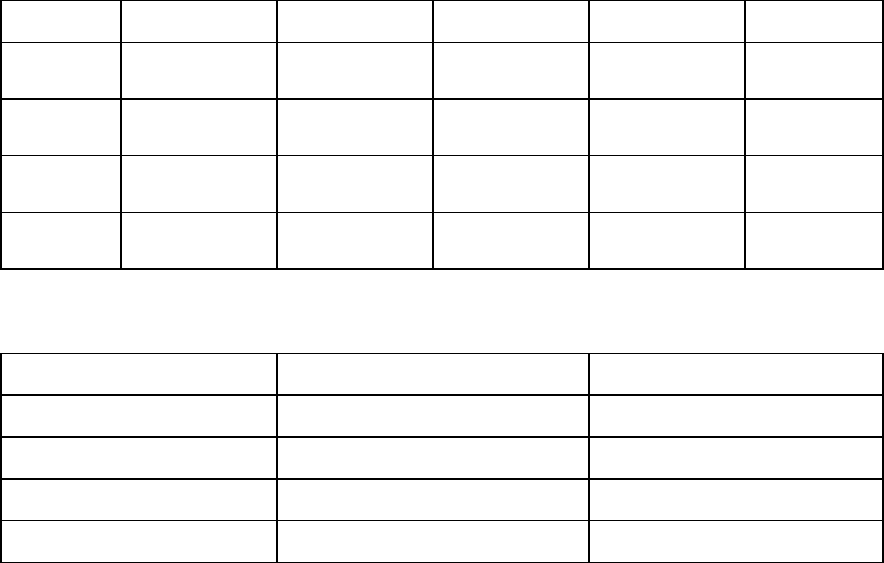

C. Gender agreement: distribution of agreement according to type and level

The distribution of the different types of agreement, TA, GA, and IA, is given in

Table 17. There is clear improvement in the use of target-like forms (TA) with natural

gender nouns. For grammatical gender nouns, target-like rates are higher and more

consistent, moving from 90% in S100 to 97% at the S250 level. The rate of grammatical

agreement (GA) in natural nouns decreases as level increases, from 64% in S100 to 21%

in S250. But GA with grammatical gender nouns is strikingly low compared with that of

12

natural gender nouns, with a rate of 5% in S100 decreasing to 0% in S250. Rates for

invented word agreement (IA) in both natural and grammatical nouns are fairly low, and

completely absent with natural gender nouns by the subjects’ fourth semester.

Table 17: Distribution of the different types of agreement

NATURAL GENDER GRAMMATICAL GENDER

LEVEL TA GA IA TOTAL TA GA IA TOTAL

S100 36 %

(4/11)

64 %

(7/11)

0 %

(0/11)

100 %

(11/11)

90 %

(19/21)

5 %

(1/21)

5 %

(1/21)

100 %

(21/21)

S150 64 %

(18/28)

32 %

(9/28)

4 %

(1/28)

100 %

(28/28)

86 %

(30/35)

6 %

(2/35)

8 %

(3/35)

100 %

(35/35)

S200 74 %

(28/38)

24 %

(9/38)

2 %

(1/38)

100 %

(38/38)

93 %

(38/41)

5 %

(2/41)

2 %

(1/41)

100 %

(41/41)

S250 79 %

(30/38)

21 %

(8/38)

0 %

(0/38)

100 %

(38/38)

97 %

(56/58)

0 %

(0/58)

3 %

(2/58)

100 %

(58/58)

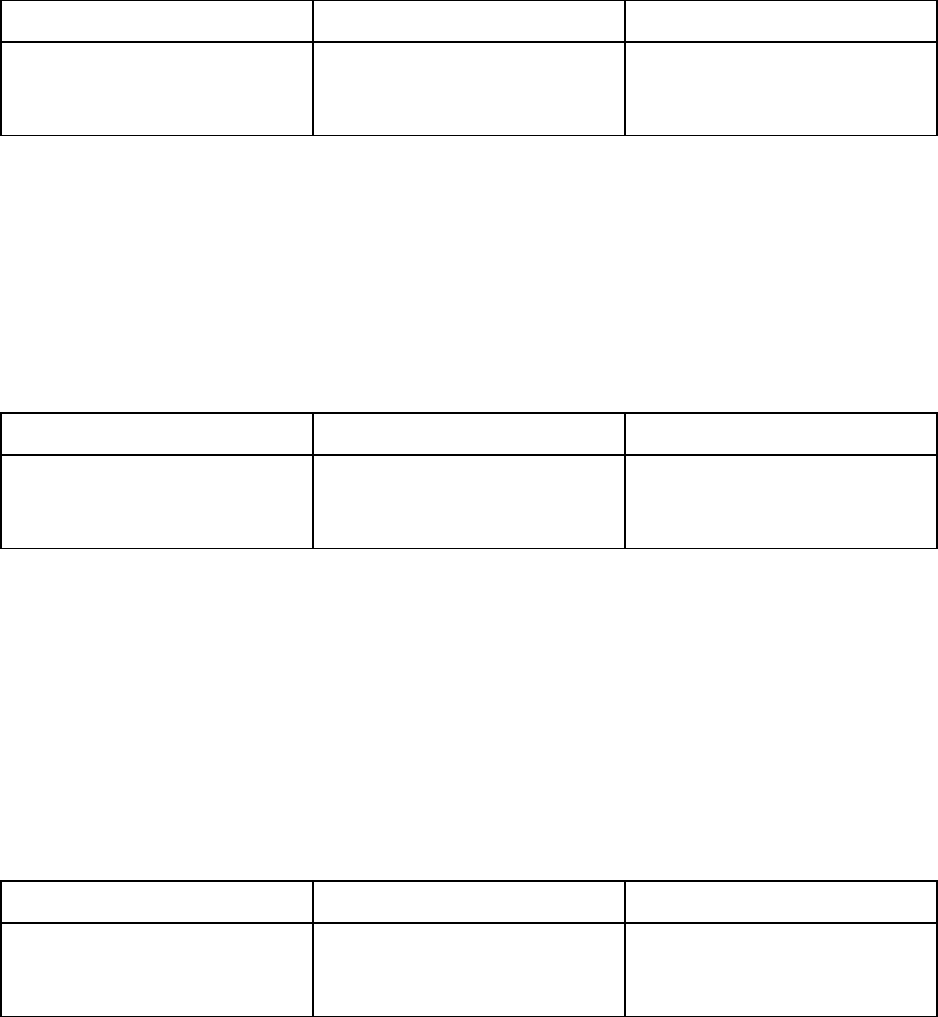

D. Gender agreement: overall gender agreement scores

Results for gender agreement demonstrate development at all levels with both

natural and grammatical gender nouns. Nevertheless, as Table 18 displays, rates for

agreement with natural gender nouns are lower than those for grammatical gender nouns,

at all levels.

Table 18: Gender agreement: group scores according to natural and grammatical nouns

GENDER AGREEMENT

LEVEL NATURAL GRAMMATICAL TOTAL

S100 (15x12 = 180) 12 % (11/90) 23 % (21/90) 18 % (32/180)

S150 (20x12 = 240) 23 % (28/120) 29 % (35/120) 26 % (63/240)

S200 (17x12 = 204) 37 % (38/102) 40 % (41/102) 39 % (79/204)

S250 (17x12 = 204) 37 % (38/102) 57 % (58/102) 47 % (96/204)

Although S250 subjects exhibit 37% agreement for natural gender nouns, thus

showing no improvement over the S200 subjects, this can be accounted for by the high

production (50%) of non-revealing forms (-e/-C ending words) the S250 subjects

produced. See Table 19.

Table 19: Non-revealing forms with natural gender nouns

LEVEL -o/-a ending Non-overtly marked zero/-a ending Total

S100 (n=15) 17 % (5/30) 20 % (6/30) 13 % (4/30) 17 % (15/90)

S150 (n=20) 18 % (7/40) 38 % (15/40) 18 % (7/40) 24 % (29/120)

S200 (n=17) 24 % (8/34) 35 % (12/34) 15 % (5/34) 25 % (25/102)

S250 (n=17) 21 % (7/34) 50 % (17/34) 18 % (6/34) 30 % (30/102)

13

E. Gender agreement: preferred gender forms with incorrect gender agreement

With natural gender nouns, subjects at all levels tend to use more masculine

adjectives with feminine referents than feminine adjectives with masculine referents.

Subjects clearly prefer masculine over feminine forms when providing an adjective that

does not agree with the referent. Table 20 reveals the same pattern with grammatical

gender nouns. The results for natural and grammatical gender nouns are combined in

Table 21, further clarifying the substantial tendency to use more masculine adjectives

with feminine nouns than feminine adjectives with masculine nouns.

Table 20: Preferred gender forms according to natural and grammatical gender nouns

NATURAL GENDER GRAMMATICAL GENDER

SUBJECTS Feminine nouns

with masculine

adjectives

Masculine nouns

with feminine

adjectives

Feminine nouns

with masculine

adjectives

Masculine nouns

with feminine

Adjectives

S100 (15 subjects) 67 % (4/6) 33 % (2/6) 57 % (8/14) 43 % (6/14)

S150 (20 subjects) 79 % (11/14) 21 % (3/14) 71 % (15/21) 29 % (6/21)

S200 (17 subjects) 80% (8/10) 20 % (2/10) 73 % (19/26) 27 % (7/26)

S250 (17 subjects) 70 % (7/10) 30 % (3/10) 78 % (18/23) 22 % (5/23)

Table 21: Preferred gender forms with incorrect gender agreement

SUBJECTS Feminine nouns with non-agreeing

masculine adjectives

Masculine nouns with non-agreeing

feminine adjectives

S100 (15 subjects) 60 % (12/20) 40 % (8/20)

S150 (20 subjects) 74 % (26/35) 26 % (9/35)

S200 (17 subjects) 75 % (27/36) 25 % (9/36)

S250 (17 subjects) 76 % (25/33) 24 % (8/33)

F. Gender agreement: deceptively marked nouns

Deceptively marked nouns, such as programas and manos, have been analyzed

separately because, though they are not transparent for gender as are overtly marked

forms, they mislead learners by bearing the opposite gender of what the overt markings

usually suggest. Deceptive nouns ending in -a are masculine (idioma, for example), and

those ending in -o are feminine (such as mano).

Table 22 shows how subjects responded to the noun programas. Rates for correct

agreement are low, but there is steady improvement. The majority of S100 subjects tend

to provide a non-agreeing adjective (33%), and target-like agreement is shown by 13% of

the subjects (2/15). S150 subjects’ responses were mainly divided into forms showing

agreement (30%), non-agreement (25%), and nonsensical responses (25%). S200 subjects

split essentially into target-like agreement (47%) and non-agreement (35%). Finally,

S250 subjects’ responses fall into three categories: target-like agreement, non-agreement,

and nonsensical responses. These subjects show the highest TA rate (59%), and the

lowest non-agreement rate (23%).

14

Table 22: Deceptively marked masculine noun: programas

CODING S100 S150 S200 S250

Agreement (TA) 13 % (2/15) 25 % (5/20) 47 % (8/17) 59 % (10/17)

Agreement (GA) 0 % 5 % (1/20) 0 % 0 %

Agreement (IA) 0 % 0 % 0 % 0 %

Non-agreement 33 % (5/15) 25 % (5/20) 35 % (6/17) 23 % (4/17)

Not revealing 13 % (2/15) 15 % (3/20) 12 % (2/17) 0 %

Different answer 13 % (2/15) 5 % (1/20) 0 % 0 %

Nonsensical 13 % (2/15) 25 % (5/20) 6 % (1/17) 18 % (3/17)

No response 13 % (2/15) 0 % 0 % 0 %

TOTAL 100 %* (15/15) 100 % (20/20) 100 % (17/17) 100 % (17/17)

* The above percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding error.

Results for gender agreement with the noun manos, when compared to

programas, show higher rates for non-agreement responses at all levels except S100.

S100 subjects had the highest rate of omission for this word (20%). In addition, the same

percentage of S100 subjects (27%) provided forms with agreement (TA and GA) and

non-agreement. 40% of S150 subjects’ responses show non-agreement forms, and only

15% show agreement (TA); moreover, 35% of the subjects gave nonsensical responses.

Compared to S150, S200 subjects show similar results for agreement and non-agreement

responses: 18% agreement and 41% non-agreement. However, the number of nonsensical

responses is much lower, only 6%. S250 subjects display the highest rate of TA forms,

35%, but the percentage of non-agreement forms is the same as S200, 41%. See Table 23

for a display of these data.

Table 23: Deceptively marked feminine noun: manos

CODING S100 S150 S200 S250

Agreement (TA) 20 % (3/15) 15 % (3/20) 18 % (3/17) 35 % (6/17)

Agreement (GA) 7 % (1/15) 0 % 0 % 0 %

Agreement (IA) 0 % 0 % 0 % 0 %

Non-agreement 27 % (4/15) 40 % (8/20) 41 % (7/17) 41 % (7/17)

Not revealing 13 % (2/15) 5 % (1/20) 23 % (4/17) 12 % (2/17)

Different answer 0 % 0 % 6 % (1/17) 0 %

Non-sensical 13 % (2/15) 35 % (7/20) 6 % (1/17) 6 % (1/17)

No response 20 % (3/15) 5 % (1/20) 6 % (1/17) 6 % (1/17)

TOTAL 100 % (15/15) 100 % (20/20) 100 % (17/17) 100 % (17/17)

15

Relation between gender assignment and agreement

The relationship between gender assignment and gender agreement can be

established by comparing results obtained for particular nouns, such as mujeres and

mano/s, on both sections of the test. (See Appendix D for an analysis of other words.)

For mujeres, 53% of S100 subjects assigned correct gender, but only 13 % of

them provided correct agreement with an adjective. The same tendency is observed in

S150, in which 50% of the subjects assigned correct gender, but only 30% of them

showed correct gender agreement. S200 subjects also show a higher rate for gender

assignment, 76%, and a lower rate for gender agreement, 41%. Finally, 100% of S250

subjects assigned correct gender to mujeres, while only 65% of them provided

appropriate agreeing adjectives. Table 24 summarizes these results.

Table 24: Gender assignment and gender agreement: mujeres

LEVEL Gender assignment:

las mujeres

Gender agreement:

... mujeres cansadas ...

S100 53 % (8/15) 13 % (2/15)

S150 50 % (10/20) 30 % (6/20)

S200 76 % (13/17) 41 % (7/17)

S250 100 % (17/17) 65 % (11/17)

Table 25 demonstrates that the relation between gender assignment and gender

agreement for mano/s is erratic. At the S100 and S150 levels, subjects were two to three

times more likely to provide correct agreement than correct gender assignment. At the

two higher levels, though, the correct assignment rate was higher (S200) or equal to

(S250) the rate for correct agreement.

Table 25: Gender assignment and gender agreement: mano/s

LEVEL Gender assignment:

la mano

Gender agreement:

... manos pequeñas ...

S100 13 % (2/15) 27 % (4/15)

S150 5 % (1/20) 15 % (3/20)

S200 24 % (4/17) 18 % (3/17)

S250 35 % (6/17) 35 % (6/17)

16

DISCUSSION

Gender assignment

Results support the hypothesis that acquisition of Spanish gender assignment is

positively correlated with length of exposure to the input. Subjects in their fourth

semester of college Spanish show higher rates of correct gender assignment, for both

natural and grammatical gender nouns, than the less advanced learners. Nonetheless, only

gender assignment of natural gender nouns has been acquired by the subjects’ fourth

semester (95% correct gender assignment). At that time, grammatical gender assignment

is still developing in the subjects’ interlanguage (71% correct gender assignment). These

results confirm the notion that “semantics [inherent gender] seems to help second

language learners to make correct gender assignments” (Fernández-García, 1999, p. 13).

These findings are also consistent with those of other studies. In Andersen (1984), the

subject performed better with inherent gender nouns than lexical (grammatical) gender

nouns: “Anthony marks inherent semantic gender overtly and clearly...” (p. 86).

Of all the grammatical gender nouns, nariz and identidades (not overtly marked),

and mano and emblema (deceptively marked), were the most problematic at all levels.

Why these words? Three of them had been introduced early in S100, and identidades was

encountered in S200. Input frequency is a factor. Nariz is infrequently used, since

students tend to refer to other features when describing faces; emblema is an uncommon

word, generally restricted to references to symbols; identidades was only encountered in

an S200 lesson on cultural identity. The noun mano is frequently used, but is a feminine

noun with a deceptively masculine ending. The most common deceptively marked nouns

are almost always masculine.

Results concerning the tendency of subjects to assign either masculine gender to

feminine nouns or feminine gender to masculine nouns reveal no preference. This

behavior is observed at all levels. These results contradict findings in other studies, in

which the masculine/unmarked form shows higher rates of preference than the

feminine/marked form (cf. Andersen, 1984; Finnemann, 1992; Fernández-García, 1999).

Gender agreement

In addition to agreement and non-agreement forms, such as compañera tensa and

habitación sucio, respectively, results in the gender agreement section of the test exhibit

four types of unpredicted responses: non-revealing forms (primo popular); responses that

are correct but are not adjectives (ropa-regularmente); nonsensical forms (manos-

extrovertidad); and omissions. At all levels, however, agreement rates are higher

compared to those for other types of responses. Moreover, agreement rates improved

substantially from level to level, reflecting incremental development as exposure to the

language increased.

Natural and grammatical gender agreement results reveal gender agreement is still

developing in the subjects’ interlanguage. Although development is evident at all levels

in both natural and grammatical gender agreement, these rates are still too low (37% for

natural and 57% for grammatical gender nouns) to claim that Spanish gender agreement

has been acquired by the learners’ fourth semester.

The natural gender nouns receiving the lowest rates of correct agreement were

hombre, compañera, and diseñadora. For hombre, this is explained by the high rate of

non-revealing adjectives produced by the learners for this specific noun. Why both

17

compañera and diseñadora show low rates of correct agreement is harder to understand.

Both forms are overtly marked nouns, and gender assignment rates are high for -o/-a

ending nouns. A possible explanation is that subjects do identify the referent nouns as

feminine, but consider marking the adjectives as feminine unnecessary and, therefore, use

the default masculine form of the adjective. This explanation reflects the claim that “a

linguistic feature is more likely to be omitted when it is redundant to the meaning being

conveyed, more likely to be produced when it transmits necessary information”

(Littlewood, 1981, p. 151 quoted in Young, 1993, p. 77).

The grammatical gender nouns that show the lowest rates of accuracy are

habitación, programas, and manos. The first noun is non-overtly marked for gender, but

it is frequently encountered, and learners have reported using the “-ción” ending as a clue

for feminine gender assignment (Alarcón, 2000). Thus, it is difficult to explain the low

agreement accuracy rate found at all levels. The nouns programas and manos are

deceptively marked. The former is masculine, and the latter is feminine, so it is not

surprising that learners will incorrectly provide adjectives modifying these particular

nouns. Nevertheless, by providing non-agreement forms, learners show they are

following interlanguage rules of gender agreement. As Fernández-García (1999)

commented: “... errors with nouns deceptively marked for gender also evidenced

subjects’ tendency to relate these endings to a particular gender” (p. 13).

Results concerning the preference for either masculine or feminine forms show a

substantial propensity for the unmarked masculine form: subjects tend to use more

masculine adjectives modifying feminine nouns than feminine adjectives with masculine

nouns. This finding is manifested at all levels, and is consistent with results of other

studies. Andersen’s (1984) subject showed exclusive use of masculine forms for all

determiners, quantifiers, and adjectives. Finnemann (1992) found that subjects displayed

a preference for singular and masculine forms of modifiers. Subjects in Fernández-

García’s (1999) study “performed better in masculine contexts” (p. 9).

Relation between gender assignment and agreement

When contrasting the results obtained by mujeres and manos in both gender

assignment and gender agreement, it was found that gender assignment definitely

precedes gender agreement. Subjects who had assigned gender correctly to a particular

noun were unable to provide correct gender agreement for the same noun. This implies

that if the learner has acquired gender agreement, then s/he has also acquired gender

assignment.

CONCLUSION

Results demonstrate that length of exposure to the input does help learners to

acquire gender marking, since there is evidence of incremental development from level to

level. Natural gender assignment is acquired before grammatical gender assignment.

Although neither natural nor grammatical gender agreement has been acquired by the end

of the fourth semester of university instruction, the latter shows higher rates of

agreement. In addition, non-overtly and deceptively marked grammatical nouns are not

acquired after two years of college Spanish. Furthermore, learners tend to overuse the

masculine forms only in gender agreement, not in gender assignment. Finally, and

18

contrary to what was predicted, it was found that learners who correctly assign gender to

particular nouns do not necessarily exhibit correct gender agreement. However, learners

who show correct gender agreement do show correct gender assignment.

Further research is required to replicate these findings. The two-part test design

proved to be an efficient instrument for eliciting quick responses on both gender

assignment and agreement. (The test took between 5 to10 minutes). However, high rates

of no response in part II may indicate subjects were not familiar with the vocabulary

(even though the test nouns had been taken from their textbooks). Consequently, a screen

word selection would be a necessary first step for deciding which words ought to be

included on a revised instrument. This could be done, for example, by asking subjects to

provide the English equivalents of given Spanish nouns, and including on the test only

words with which a majority of the subjects were familiar. Another refinement of the

instrument would be to use the selected words on both parts of the test. (On the

instrument used in the present paper, only two words, mujeres and manos, appeared in

both Parts I and II). This would allow for more accurately determining the relationship

between assignment and agreement. A third step would be to incorporate an oral

component that would also consider the gender acquisition of the selected words. This

could be carried out through a semi-guided interview in which the researcher would use

the selected nouns without giving clues of their gender when asking questions such as:

Cuando tu compañera tiene muchos exámenes ¿cómo está? (When your classmate has

lots of exams, how is (she)?). This three-part test could be given to Spanish learners at

different levels in three separate sessions. The purpose of this new research project would

be to continue investigating the sequential acquisition of Spanish gender marking by

English-speaking university learners.

2

2

I am grateful to my colleagues Scott Lamanna, Paul Malovrh, and Gregory Newall for their helpful

comments on an earlier version of this paper.

19

REFERENCES

Alarcón, I. (2000). The sequential acquisition of Spanish gender marking. Unpublished

manuscript, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Andersen, R.W. (1984). What’s gender good for, anyway? In R. Andersen (Ed.),

Second languages: A cross-linguistic perspective, (pp.77-100). Rowley, MA:

Newbury House.

Fernández-García, M. (1999). Patterns of gender agreement in the speech of second

language learners. In J. Gutiérrez-Rexach & F. Martínez-Gil (Eds.), Advances in

Hispanic linguistics: Papers from the 2nd Hispanic linguistics symposium (pp.

3-15). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Finnemann, M.D. (1992). Learning agreement in the noun phrase: The strategies of three

first-year Spanish students. IRAL, 30(2), 121-136.

Hardison, D.M. (1992). Acquisition of grammatical gender in French: L2 learner

accuracy and strategies. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 48(2), 292-

306.

Littlewood, W.T. (1981). Language variation and language acquisition theory. Applied

Linguistics, 2, 150-158 (cited by Young, 1993).

Pérez-Pereira, M. (1991). The acquisition of gender: What Spanish children tell us.

Journal of Child Language, 18(3), 571-590.

Roa, A. (1993). Gramática castellana. Santiago: Editorial Salesiana.

Young, R. (1993). Functional constraints on variation in interlanguage morphology.

Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 76-95.

20

APPENDIX A: SUBJECTS’ INFORMATION

SPANISH CLASSES SUBJECTS HAVE TAKEN AT INDIANA UNIVERSITY

LEVEL S100 S150 S105 S200 S250

S100

(n=15)

100%

(15/15)

S150

(n=20)

80 %

(16/20)

100 %

(20/20)

S200

(n=17)

----------- ----------- 70 %

(12/17)

100 %

(17/17)

S250

(n=17)

12 %

(2/17)

18 %

(3/17)

47 %

(8/17)

94 %

(16/17)

100 %

(17/17)

SUBJECTS WHO HAVE STUDIED IN A SPANISH SPEAKING COUNTRY

LEVEL NO YES

S100 100 % (15/15) ---

S150 100 % (20/20) ---

S200 100 % (17/17) ---

S250 88 % (15/17) 12 % (2/17)

21

APPENDIX B: TEST

Please circle the appropriate information:

1) Sex: M or F

2) I’ve taken S100, S105, S150, S200, S250 at IU (including the class you are taking

right now)

3) I have studied in a Spanish speaking country: Yes or No

*** Please answer the questions quickly, going with your first impressions ***

PART I

. Write el, la, los or las next to the corresponding word. If you don’t know,

write “?”

1) ______ productos 9) _______ menús 17) _______ mujeres

2) ______ día 10) _______ vecinas 18) _______ profesores

3) ______ nariz 11) _______ presidente 19) _______ almuerzo

4) ______ arquitectos 12) _______ adivinador 20) _______ identidades

5) ______ tigres 13) _______ tiendas 21) _______ idioma

6) ______ escultora 14) _______ mano 22) _______ gente

7) ______ lengua 15) _______ examen 23) _______ directoras

8) ______ emblema 16) _______ camarera 24) _______ caballo

PART II

. Write an appropriate adjective according to the situation.

1) Mi compañera tiene 5 exámenes mañana. Está muy _____________________

2) Carlos prefiere chicas con manos _____________________

3) Einstein creó la Teoría de la Relatividad. Fue un hombre ____________________

4) Carmen prefiere los hombres con pelo _____________________

5) Estudió en Paris. Hoy trabaja en Hollywood y es diseñadora ___________________

6) En la fiesta, Eduardo dijo un chiste ____________________

7) Los amigos de mi primo olvidaron su cumpleaños. Mi primo está ________________

8) Me gusta comprar ropa __________________

9) Después de correr 7 millas, muchas mujeres se sienten ____________________

10) “Seinfeld” y “Friends” son programas _______________________

11) Me encanta mi habitación en Teter porque es ______________________

12) “Guernica” es una pintura de Picasso. Este pintor era ______________________

22

APPENDIX C: GENDER AGREEMENT (Distribution of scores for individual words)

NATURAL GENDER NOUNS

S100 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

primo: 2/15 - 13 %

compañera: 0/15 – 0 %

hombre: 3/15 - 20 %

mujeres: 2/15 - 13 %

pintor: 2/15 - 13 %

diseñadora: 2/15 - 13 %

S150 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

primo: 6/20 - 30 %

compañera: 7/20 - 35 %

hombre: 1/20 - 5 %

mujeres: 6/20 - 30 %

pintor: 4/20 - 20 %

diseñadora: 4/20 - 20 %

S200 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

primo: 6/17 - 35 %

compañera: 8/17 - 47 %

hombre: 6/17 - 35 %

mujeres: 7/17 - 41 %

pintor: 9/17 - 53 %

diseñadora: 2/17 - 12 %

S250 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked zero/-a alternation

primo: 6/17 - 35 %

compañera: 10/17 - 59 %

hombre: 2/17 - 12 %

mujeres: 11/17 - 65 %

pintor: 5/17 - 29 %

diseñadora: 4/17 - 24 %

GRAMMATICAL GENDER NOUNS

S100 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked deceptively marked

pelo: 8/15 - 53 %

ropa: 3/15 - 20 %

chiste: 3/15 - 20 %

habitación: 1/15 - 7%

programas: 2/15 - 13 %

manos: 4/15 - 27 %

S150 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked deceptively marked

pelo: 15/20 - 75 %

ropa: 2/20 - 10 %

chiste: 7/20 - 35 %

habitación: 2/20 - 10 %

programas: 6/20 - 30 %

manos: 3/20 - 15 %

S200 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked deceptively marked

pelo: 14/17 - 82 %

ropa: 10/17 - 59 %

chiste: 5/17 - 29 %

habitación: 1/17 - 6 %

programas: 8/17 - 47 %

manos: 3/17 - 18 %

S250 subjects who show agreement (TA, GA, IA)

-o/-a ending non-overtly marked deceptively marked

pelo: 17/17 - 100 %

ropa: 11/17 - 65 %

chiste: 12/17 - 71 %

habitación: 2/17 - 12 %

programas: 10/17 - 59 %

manos: 6/17 - 35 %

23

APPENDIX D: RELATION BETWEEN GENDER ASSIGNMENT AND

AGREEMENT

Zero/-a alternation nouns: adivinador and pintor

LEVEL Gender assignment:

el adivinador

Gender agreement:

pintor creativo

S100 87 % (13/15) 13 % (2/15)

S150 90 % (18/20) 20 % (4/20)

S200 76 % (13/17) 53 % (9/17)

S250 76 % (13/17) 29 % (5/17)

Overtly marked nouns: camarera and compañera

LEVEL Gender assignment:

la camarera

Gender agreement:

compañera preocupada

S100 93 % (14/15) 0 % (0/15)

S150 100 % (20/20) 35 % (7/20)

S200 100 % (17/17) 47 % (8/17)

S250 94 % (16/17) 59 % (10/17)