Linguistic Portfolios Linguistic Portfolios

Volume 9 Article 5

2020

Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the

Composition of Hispanic L2 Learners of English Composition of Hispanic L2 Learners of English

Claudia Membreno

St. Cloud State University

Diana Lowry

St. Cloud State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling

Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Membreno, Claudia and Lowry, Diana (2020) "Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the

Composition of Hispanic L2 Learners of English,"

Linguistic Portfolios

: Vol. 9 , Article 5.

Available at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Linguistic Portfolios by an authorized editor of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

49

ADJECTIVAL COMPLEMENTS AND RESOLUTION RULE ERRORS IN THE

COMPOSITION OF HISPANIC L2 LEARNERS OF ENGLISH

CLAUDIA MEMBRENO AND DIANA LOWRY

ABSTRACT

1

The syntactic distribution of adjectives in Spanish and in English is different but share some

commonalities. Besides the syntactic distribution, Spanish adjectives differ from English adjectives

in that they usually carry out the morphological information of gender and always agree in number

with the noun they refer to. The purpose of this paper is twofold: 1) to shed light onto similarities

and differences between syntactic distribution patterns of Spanish and English adjectives and 2)

to differentiate the morphological transformations that Spanish adjectives undergo in order to

agree in number and gender with their referent. Spanish is one of the top three non-English

languages spoken in Minnesota as well as in the rest of the country. It is our intent that the

information provided in this analysis inform pedagogical practices for teaching Spanish-speaking

learners of English.

1.0 Introduction

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in the fall of 2015,

approximately 4.9 million K-12 students in the United States were English language learners. More

than three-quarters, or 77.7% of ELL students were Hispanic (de Brey, et al., 2019, p. iv). In fact,

Spanish is the second most common language used in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau,

2018). It will, therefore, be helpful for teachers to be aware of those aspects of Spanish that may

interfere with their students’ learning of English. One such topic is the use of adjectives. Adjectives

exist in all languages, and they function the same way—to describe nouns and pronouns. However,

“their form, their number, and their frequency vary greatly from language to language” (Koffi,

2015, p. 231). This paper aims to provide a comparison of the syntactic distribution of adjectives

between Spanish and English, to analyze Spanish adjectives resolution rules, and to investigate if

there is transfer of those rules to the learner’s L2 English.

2.0 Syntactic Analysis

Spanish and English are Indo-European languages; however, Spanish is a Romance

language, while English is from the Germanic branch. Due to this fact, syntactic differences occur.

According to Sleeman and Perridon (2011), the Romance languages may have a pre- or post-

nominal adjective, modifying the head noun. On the other hand, the Germanic languages are more

restricted, as adjectives are normally in the prenominal position (p. 11). Consequently, the

common position of English adjectives is preceding the noun, whereas Spanish allows the

adjective’s alternate position after the noun. In addition, Bello (1891) notes that Spanish adjectives

agree in gender and in number with the nouns they modify, resulting in morphological inflections

(p.12). Hence, these structural differences can be problematic for the Spanish L2 learner of

English.

1

Authorship Responsibilities: Author 1 and Author 2 share equally the rights, privileges, and responsibilities of this

publication.

1

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

50

2.1 General Position of Adjectives in Noun Phrases

One of the Greek translations of adjective, “the one lying near the noun,” (Koffi, 2015, p.

231) is indicative of one of the sources of possible confusion for Spanish L2 learners of English;

the adjective may appear before or after the noun. Therefore, the English Phrase Structure Rule is

NP® (Det) (Adj) N, and the Spanish noun phrase structure is NP ® (Det) (Adj) N ( Adj). The

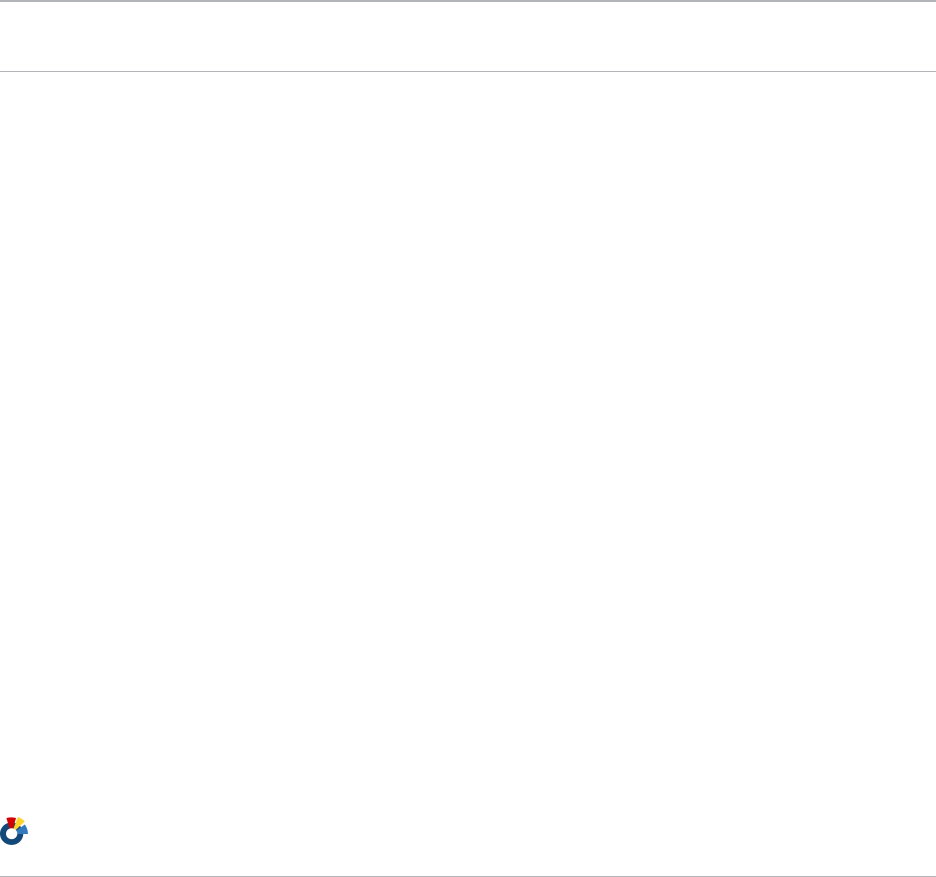

following tree diagrams show the basic differences between Spanish and English noun phrases:

English Noun Phrase Spanish Equivalent

As shown in the NPs in each diagram, the adjective comes before the noun in English and after

the noun in Spanish. It is important to note, though, that Spanish allows adjectives to also appear

before the head noun. Let us consider the following examples:

(1) English NP Spanish equivalent

(2) English NP Spanish equivalent

Diagrams (1) and (2) present NP structures that obey the syntactic patterns of the phrase of each

language. However, the semantics of the Spanish adjective shifts when the adjective precedes the

head noun. Sleeman and Perrion (2011) state that there has been great debate to answer what

2

Linguistic Portfolios, Vol. 9 [2020], Art. 5

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

51

establishes the adjective position/order NP ® N + Adj or NP ® Adj + N in Romance languages.

One explanation suggests that in French, for example, adjectives placed after the noun reflect

objective properties. Adjectives placed before the noun, in contrast, include evaluative or

emotional properties toward the noun (p. 11). “A poor man” in English and “Un hombre pobre”

in Spanish are indicative of a man who does not have much money. Both descriptions are objective.

However, in Spanish, when the adjective is moved before the noun, as in “Un pobre hombre,” the

meaning of the phrase is changed to a more subjective description: “A poor man” (whom is worthy

of my pity). “An old friend” in English and “Un viejo amigo” both express the idea of having a

friend for a number of years. In contrast, moving the Spanish adjective after the noun, “Un amigo

viejo,” means a friend who is old, or advanced in age.

2.2 Adjective Position as Subject Complements

When the adjective is functioning as a subject complement, the NP structure rules are

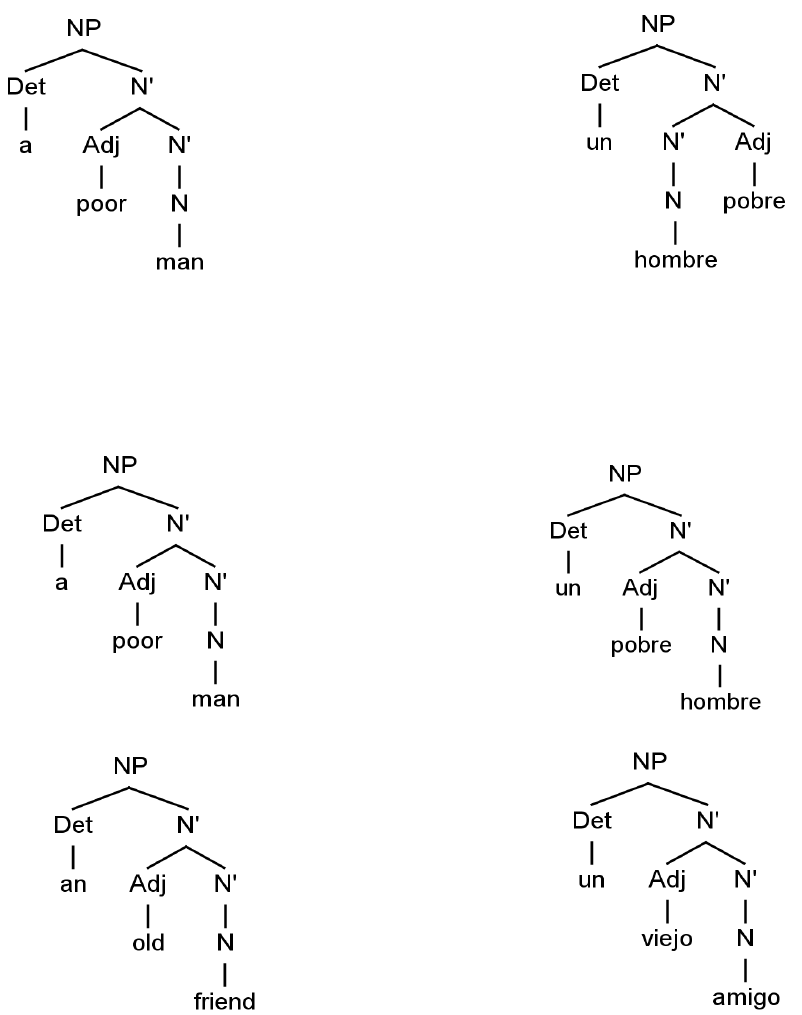

common to both languages as shown in the following tree diagrams:

English sentence Spanish Equivalent

Both diagrams show that the position of the adjective in English and in Spanish is after the verb

when it is functioning as a subject complement. As mentioned previously, it is acknowledged that

Spanish adjectives require agreement with the head noun they modify in gender and number; the

morpheme {-s} marks the number for determiners, nouns, and adjectives. In contrast, in English,

even when the noun is plural, the adjective does not take a plural marker. We see this in the

following examples:

English sentence Spanish Equivalent

3

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

52

In English, the adjective “new” modifies “shoes” which is in the plural form, but the adjective

does not have any plural marker. Let us contrast this with the adjective “nuevos” and the noun

“zapatos.” Because the noun “zapatos” is in plural, the adjective must agree with it in number.

Therefore, the adjective “nuevos” is also in plural.

3.0 Resolution Rules

According to Koffi (2015) “a number and person agreement system known as resolution

rules has been found to be universal” (p. 427). Givon (1970) introduced the term, which explains

the rules of agreement between number, gender, and person (as cited in Cotner, 2018, p. 136). “By

age three, Spanish-speaking children acquire the gender agreement rules in Spanish and, once

acquired, they produce agreement with near 100% accuracy, like adult native speakers” (Montrul

& Potowski, 2007, p. 306). Considering this, it is hypothesized that Spanish speakers may

misapply the resolution rules from Spanish into their English compositions by making plural nouns

to agree with adjectives. To test this hypothesis, we will consider sentences written by Spanish

learners of English. We focus mostly on sentences in which the adjective functions as a subject

complement.

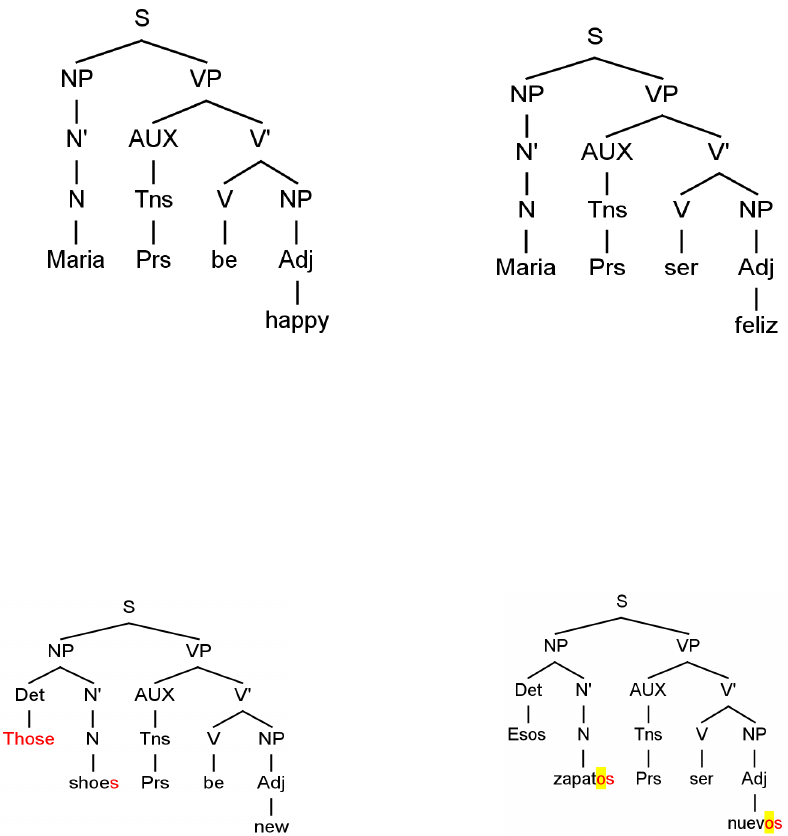

3.1 Resolution Rules: Agreement of number and gender of Spanish adjectives

According to Montrul and Potowski (2007), “gender agreement in languages like Spanish

is a syntactic feature-checking operation handled by the syntax” (p. 306). Gender is an inherent

feature of nouns, whereas adjectives and articles’ gender is determined by the head noun with

which they appear. The masculine gender is usually marked in nouns by the inflectional ending

{-o} (perro/dog), and the feminine gender is usually marked with the morpheme {-a} (perra/dog).

However, such correspondence differs at times, and therefore, some masculine Spanish nouns end

with {-a} (clima/weather; idioma/language; problema/problem; mapa/map), and some feminine

nouns end with {-o} (mano/hand). Moreover, some Spanish nouns have no obvious gender

marking (leche/milk; nariz/nose). Let us consider the following examples:

1. La gata blanca y el gato negro…

The/fem cat/fem white/fem and the/ masc cat/masc black/masc

2. El gato blanco y la gata negra…

The/masc cat/masc white/masc and the/ fem cat/fem black/fem

3. La niña está feliz.

The/fem girl/fem is happy/fem

4. El niño está feliz.

The/masc boy/masc is happy/masc

5. La mano es pequeña.

The/fem hand/fem is small/fem

6. El mapa es pequeño.

The/masc map/masc is small/masc

4

Linguistic Portfolios, Vol. 9 [2020], Art. 5

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

53

Noun phrases 1 and 2 provide examples of a singular feminine noun with the inflectional

ending /a/ as in “gata” and a singular masculine noun with the inflectional ending /-o/, as in

“gato.” As it can be seen in both examples, the inflectional ending of the adjectives corresponds

to the inflectional ending of the head noun, and the definite article also agrees in gender with the

noun. It is “el” for masculine singular nouns, and “la” for feminine singular nouns. Sentences 3

and 4 provide an example of an adjective such as “feliz” (happy) that does not take a gender

marking. Included in this category are adjectives such as “paciente” (patient), “triste” (sad),

“inteligente” (intelligent), “facil” (easy), etc. Sentences 5 and 6 illustrate a feminine noun with

the inflectional ending /o/ “mano” and a masculine noun with the inflectional ending /a/ “mapa.”

Even if an adjective modifies a feminine noun that ends with /o/ such as “mano,” the adjective

still takes an /a/ ending, as in the phrase “mano pequeña,” (small hand). Similarly, when a

masculine noun ends in /a/ as is the case of “mapa,” the adjective still takes /o/ as in “mapa

pequeño” (small map). For plural number agreement, the marker is in most cases the morpheme

/s/ but changes to /es/ in some cases, as shown in the examples below:

Las manzanas rojas Los zapatos rojos

The Pl apple Pl red Pl The Pl shoe Pl red Pl

Los zapatos azules… Los estudiantes felices…

We see that the plus definite article for masculine nouns is “los,” as in the phrases “los zapatos,”

and “los estudiantes.” If the definite article is feminine, then we see “las” as in “las manzanas”

(the apples). The adjectives “rojo” agrees with noun in gender and number. Since “manzanas”

(apples) is feminine, the plural adjective would be “rojas.” The same goes for plural masculine

nouns such as “zapatos.” The modifying adjective becomes “rojos.”

The Pl shoe Pl blue Pl The Pl student Pl happy Pl

Now, adjectives such as “azul” and “feliz” that end in a consonant make their plural in /es/. This

explains why we have “Los zapatos azules” or “Los estudiantes felices.”

5

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

54

3.2 Is there transfer of resolution rules from the L1 to the L2?

One of the greatest challenges for Spanish speakers of English is mastering the agreement

system. Koffi (2015) notes that “ESL/EFL teachers can expect negative transfer in the person and

number agreement system from their students, especially where agreement is not controlled by the

same hierarchy patterns” (p. 427). We collected and analyzed data from 41 Salvadoran English

learners; all were college monolingual Spanish speakers, enrolled in a Basic English class.

2

They

were given 14 sentences in Spanish to translate into English. The adjectives in all 14 sentences

functioned as subject complements following the copular verb “be”. Each student received a score

based on transfer occurrence from L1 to L2 for both, gender and number, and a general score for

resolution rules transfer. The general average for resolution rules transfer was 10.8% and the

standard deviation was 12.6. Individual transfer scores of gender and number differed greatly from

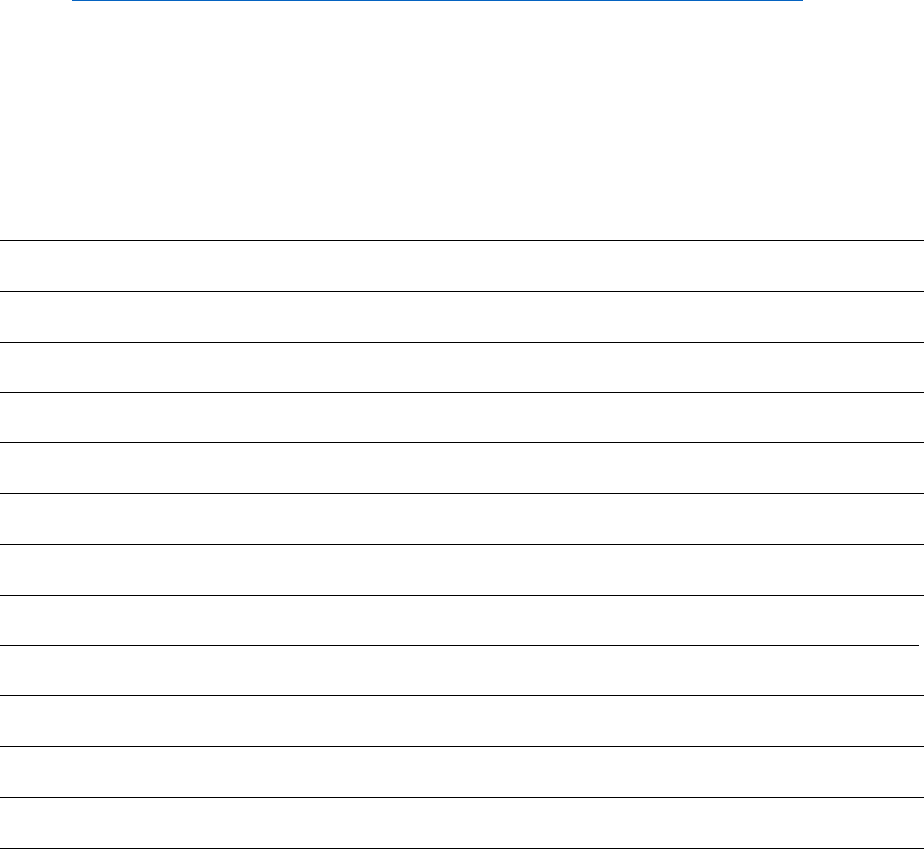

these results. As it can be noted in Table 1, none of the participants transferred gender agreement

rules from L1 to L2. Nevertheless, scores for transfer of number agreement rules reached up to

79% at the individual level. The average for number agreement rule transfer was 16% and the

standard deviation was 17.7 (see Appendix B). The following are sample sentences taken from the

students’ translations:

1. Mis amigos son diferentes

My friends are differents.

2. Estos zapatos son nuevos

These shoes are news.

3. Los dos hombres son ignorantes

The two men are ignorants.

4. Los ninos estan cansados

The boys are tired.

5. Mis amigos son honestos

My friends are honest.

These examples demonstrate that gender agreement transfer was not present in the

students’ translations. It is noteworthy that in examples 1-3 resolution rules for number agreement

were applied to the adjectives, yet they were not applied to adjectives in examples 4 and 5. We can

only speculate as to why there is transfer in some sentences but not in others. We opine that

perhaps some English words such as ‘tired’ and ‘honest’ are familiar to most L1 learners.

“Ignorant” and “Intelligent” do not appear in the first two thousand high frequency word lists.

Instead, they are found in the Academic Word List (AWL). The question of familiarity with the

words themselves is a valid issue. We also speculate that gender resolution was not transferred

because of the morphological structure of English adjectives. They are not easily amenable to the

Spanish inflectional suffixes /a/ or /o/. We further speculate that /s/ was added to the adjective

“new” and “ignorant” because it performs the same function in the morphology of both

languages. Even though the percentage of resolution rules transfer is small, and the transfer

behavior is inconsistent, no one can deny that it happens.

2

We are grateful to colleagues in El Salvador who made the data available to us for analysis.

6

Linguistic Portfolios, Vol. 9 [2020], Art. 5

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

55

Table 1 provides additional examples for the transfer of number agreement on adjectives.

Table 1: Transfer behavior for number agreement

Students were given 14 Spanish adjectives, but their word choices for the translation varied

for some. A total of 19 different adjectives appeared in the translations. Transfer of the number

marking occurred in 80% of the translations (14 pluralized adjectives out of a total of 19). The

data offers some insights on number resolution transfer. In the case of the adjectives “different,”

“absent,” “important,” “intelligent,” and “ignorant,” we see that they end in /-nt/. If students

transfer the /s/ to the end of these words to satisfy the plural requirement of the head nouns,

phonologically, the sounds of “differents,” “absents,” “importants,” “intelligents,” and

“ignorants,” ,the derived adjectives, sound correct. They sound just like the nominal form of the

adjectives, namely: “difference,” “absence,” “importance,” “intelligence,” and “ignorance.”

This may explain why students pluralized these adjectives. They draw from their L1 knowledge

of gender agreement between adjectives and their nouns. The vowel at the end of ‘new’ and

‘pretty’ may also explain why students added a plural /s/ to them in English. Many adjectives in

Spanish end in vowel sounds: /a/ for feminine and /o/ for masculine. Perhaps the presence of a

vowel sound at the end of English adjectives such as ‘new’ and ‘pretty’ facilitates inflectional

plural transfer from Spanish to English. Finally, because of coda cluster simplification, some

learners produce the word ‘honest’ as “*honess.” Thus, adding another /s/ is redundant. This

explains why none of the learners made a mistake. Now, let’s assume that some of the learners

did not delete the final /t/ in the coda. If it is kept, then the resulting spelling would be “*honests.”

The students may have avoided this spelling because the coda cluster /sts/ does not exist in Spanish.

4.0 Pedagogical Implications

The previous analyses have shed some light on the morphosyntactic differences and

similarities between Spanish adjectives and English adjectives. In so doing, we draw teachers’

attention to possible challenges that Spanish learners may face when using adjectives in English.

Erroneous though these transfers may be, they are not unmotivated. They occur for a variety of

reasons. As we have seen throughout this paper, some of the reasons are morphosyntactic, others

N0

Spanish

English

Transfer

occurrences

Transfer

Percentage

Translation

1.

diferentes

different

25 times

61.0%

differents

2.

nuevos

new

15 times

36.6%

News

3.

ignorantes

ignorant

11 times

26.8%

Ignorants

4.

importantes

important

8 times

19.5%

importants

5.

bonitas

pretty/

beautiful/cute

7 times

17.1%

4 pretties; 1 pretyes/ 2

beautifuls

(cute 0 times)

6.

ausentes

absent

6 times

14.6%

Absents

7.

iguales

equal

6 times

14.6%

Equals

8.

inteligentes

inteligent/ smart

6 times

14.6%

5 intelligents/ 1 smarts

9.

viejas

old

3 times

7.3%

Olds

10.

pequenos

small/short/little

2 times

4.9%

shorts/ smalls (little 0

times)

11.

baratos

cheap

2 times

4.9%

Cheaps

12.

caros

expensive

2 times

4.9%

expensives

13.

cansados

tired

0 times

0.0%

14.

honestos

honest

0 times

0.0%

7

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

56

appear to be phonological. Adjectives ending in /nt/ and those ending in a vowel are more likely

to undergo number resolution rules than those that end in coda clusters that do not exist in Spanish.

Our findings suggest that if teachers are aware of these factors, they can provide explicit

instructions to help their students avoid these negative transfers. Teachers can also highlight the

differences between number and gender resolution rules between Spanish and English. Telling

Spanish learners that English adjectives do not agree in number and gender with the head noun is

a good starting point.

5.0 Conclusion

Since acquiring a second language is a difficult undertaking, teachers must consider aspects

of the native languages of their students. For Spanish speakers, adjectives used as subject

complements is challenging because of some similarities but also important phonological and

resolution rules between their L1 and English. This issue has not been widely written about in

the L2 composition literature. However, our data and findings indicate that these mistakes are

found in learners’ compositions. The reasons behind these negative transfers are still not fully

understood because there are inconsistent behaviors among learners. This issue should be

investigated further. An in-depth phonological analysis may shed some light as to why the transfer

occurs in some cases but not in others.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Claudia Membreno is a graduate student in the MA TESL/Applied Linguistics program. She has

spent most of her life in El Salvador. She earned a BA degree in English from Universidad

Tecnológica de El Salvador (UTEC). She has taught English as a Foreign Language for seven

years at the elementary level in El Salvador. In addition, she has taught advanced English courses

at the college level, including English Phonology and English Grammar. She can be reached at:

Diana Lowry is a graduate student in the TESL/Applied Linguistics program. She has spent most

of her life in Missouri. She earned a BSE in English and an MA in English from Truman State

University in Kirksville, Missouri. She also has an MA in counseling from Stephen College in

Colombia, Missouri. She has taught English Language Arts for grades 7 through 12 and English

composition at the college level for twenty-two years. She can be reached at:

Recommendation: This paper was recommended for publication by Professor Ettien Koffi, PhD,

Linguistics Department, Saint Cloud State University, Saint Cloud, MN. The paper originated

from his Pedagogical Grammar class. We are grateful to him for additional comments and editorial

help.

References

Andres Bello, D. (1981). Gramatica de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos.

Roger & Chernoviz (Ed.). Paris.

Cotner, J. (2018) Number resolution rules agreement in Arabic writers L2 English compositions.

Linguistic Portfolios, 7, 132-151. Retrieved from

http://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol7/iss1/9

de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A.,

Branstetter, C., and Wang, X. (2019). Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic

Groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National

8

Linguistic Portfolios, Vol. 9 [2020], Art. 5

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

57

Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/

Koffi, E. (2015). Applied English syntax (2nd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing

Company

Montrul, S. & Potowski, K. (2007) Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish-

English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism, 11, 301-328.

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Retrieved from

https://factfinder.census.gov/rest/dnldController/deliver?_ts=573837187878

Sleeman, P. & Perridon, H. (Eds.). (2011) The Noun Phrase in Romance and Germanic

Structure, Variation, and Change. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Rojo, G. (1975). Sobre la coordinacion de adjetivos en la frase nominal y cuestiones conexas.

Verba, 2, 193-224

Appendix A

Questionnaire: ¿Cómo dirías en inglés?

Mis amigos son diferentes.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Estos zapatos son nuevos.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Mis amigas están ausentes (absent).

____________________________________________________________________________________

Las clases son importantes.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Esas casas son viejas.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Los niños son pequeños.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Las dos niñas son iguales (equal).

____________________________________________________________________________________

Los zapatos son baratos.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Los carros son caros.

.___________________________________________________________________________________

Los niños están cansados.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Mis hermanos son inteligentes.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Las mujeres son bonitas.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Mis amigos son honestos.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Los Dos hombres son ignorantes.

____________________________________________________________________________________

9

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

58

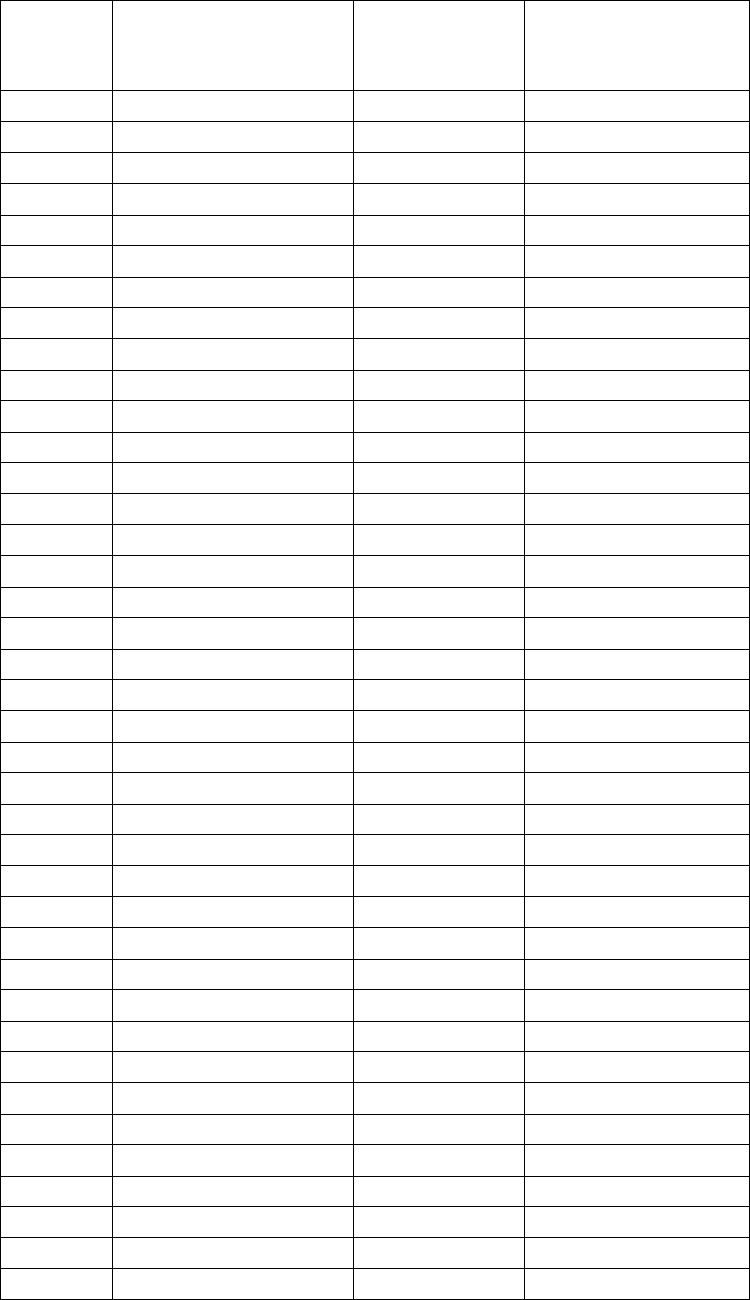

Appendix B

Student

Resolution Rules

Transfer Score

Gender

Transfer Score

Number Transfer

Score

1

23%

0

36%

2

9%

0

14%

3

0%

0

0%

4

5%

0

7%

5

18%

0

29%

6

18%

0

29%

7

32%

0

50%

8

23%

0

36%

9

32%

0

50%

10

14%

0

21%

11

0%

0

0%

12

9%

0

14%

13

14%

0

21%

14

0%

0

0%

15

23%

0

36%

16

0%

0

0%

17

9%

0

14%

18

0%

0

0%

19

9%

0

14%

20

0%

0

0%

21

0%

0

0%

22

14%

0

21%

23

0%

0

0%

24

0%

0

0%

25

5%

0

7%

26

5%

0

7%

27

14%

0

21%

28

0%

0

0%

29

0%

0

0%

30

5%

0

7%

31

64%

0

79%

32

5%

0

7%

33

9%

0

14%

34

9%

0

14%

35

18%

0

29%

36

27%

0

43%

37

0%

0

0%

38

14%

0

21%

39

5%

0

7%

10

Linguistic Portfolios, Vol. 9 [2020], Art. 5

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/5

Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 |

59

40

5%

0

7%

41

5%

0

7%

Average

10.8%

16.0%

Standard

Deviation

12.6

17.7

Table 2: Resolution rules transfer from L1 to L2 scores

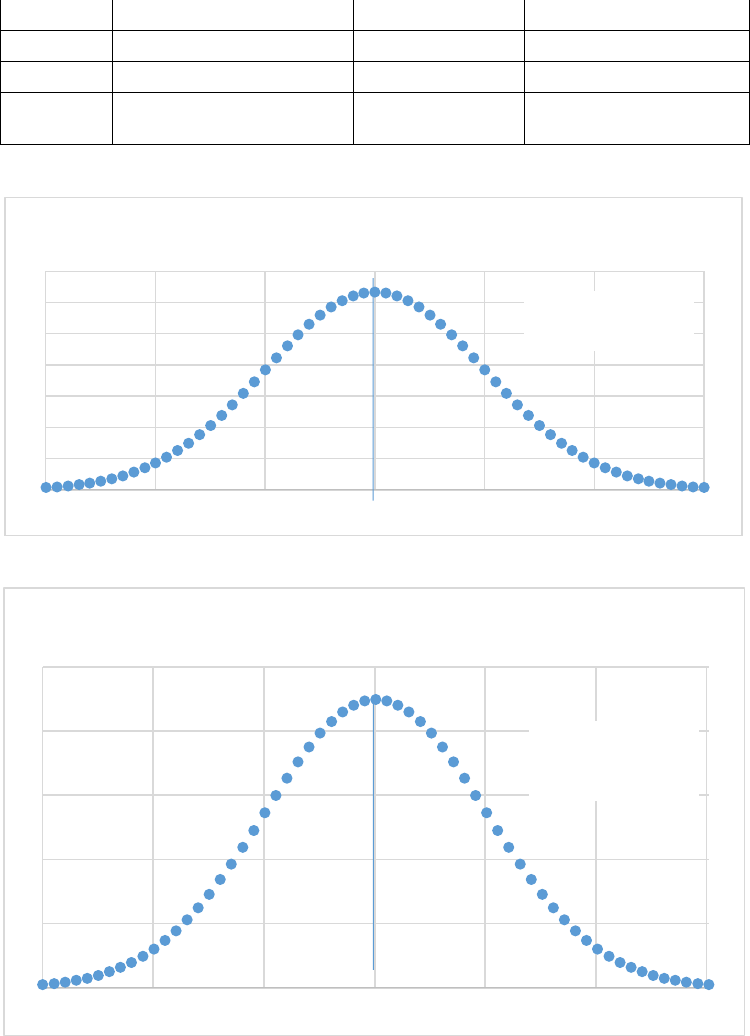

Diagram 1: Scores distribution of resolution rules (gender and number)

Diagram 2: Score distribution of transfer of number resolution rules

-27.0 -14.4 -1.8 10.8 23.4 36.0 48.6

Resolution Rules Transfer

Average 10.8%

SD: 12.6

-37.1 -19.4 -1.7 16.0 33.7 51.4 69.1

Number Transfer

Average 16.0%

SD: 17.7

11

Membreno and Lowry: Adjectival Complements and Resolution Rule Errors in the Composit

Published by theRepository at St. Cloud State, 2020