GUIDE TO LEADING POLIcIEs, PRAcTIcEs

& REsOURcEs:

sUPPORTING THE EMPLOYMENT OF VETERANs

& MILITARY FAMILIEs

Prepared by:

Institute for Veterans and Military Families, Syracuse University

The Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University (IVMF) is pleased to

offer this “Guide to Leading Policies, Practices & Resources: Supporting the Employment of

Veterans and Military Families.”

In light of ongoing and planned reductions in the size of the U.S. military, issues related

to the employment situation of those who have served in uniform have been a salient

public policy concern. As a result, politicians and policy-makers have espoused the im-

portant role that America’s employers can play by supporting private sector initiatives

focused on creating careers for military veterans and their families. These calls to action

have been warmly received by the employer community. That said, many employers

have voiced an ongoing concern related to the shortage of shared and public resources

positioned to facilitate the implementation of state-of-the-art human resource practices

and processes supporting veteran employment initiatives.

This publication represents a response to calls for such a shared resource, and is the

result of the collaborative effort of the IVMF, and more than 30 private sector employ-

ers, plus many more whose activities are reected in the report. These leading rms and

organizations agreed to share with the community of employers lessons learned and

innovations with regard to recruitment, assimilation, retention, and advancement of

veterans in the workforce.

It is our hope that this publication serves to empower America’s employers, large and

small, to adopt a strategic and sustainable approach to the advancement of veterans in

the civilian workforce. We are convinced that by doing so, both America’s veterans and

America’s employers will benet.

Respectfully,

J. Michael Haynie, Ph.D.

Executive Director and Founder

Institute for Veterans and Military Families

Syracuse University

From the

Executive

Director

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the Institute for Veterans and Military Families would like to thank

the following employers for their participation and support of this effort:

In addition, rms participating in the 100,000 Jobs Mission have also shared practices with

the consortium of employers, and have graciously permitted the IVMF to learn from them

and share these practices with the community of employers. Other companies have shared

publicly with veterans’ organizations, military services, and others, through their veteran-

specic websites and recruiting efforts, social media, and more. Many of those efforts are

reected in this report.

We greatly appreciate the collaboration with, and support provided by, the Center

for a New American Security (CNAS), with whom we co-hosted the Military Veteran

Employment Leading Practices Summit aboard the USS Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum

on Nov. 30, 2011. We wish to acknowledge Mirza Tihic, Rosalinda Maury, Jaime Winne

Alvarez, Ellie Komanecky, and James Schmeling for their tireless effort conducting

research for this publication. Finally, a special thanks goes to the staff of the USS Intrepid

for hosting our best practices summit.

Accenture

AstraZeneca

AT&T

BAE

Bank of America

Burton Blatt Institute

CINTAS Corporation

Citigroup

Deutsche Bank

Ernst & Young

General Electric

Google

Health Net

Humana

JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Merck

PepsiCo

PLC Global Solutions

Prudential

TriWest

U.S. Chamber of

Commerce

U.S. Department of Labor

U.S. Small Business

Administration

Walmart

WILL Interactive

Contents

Part I 1

Executive Summary

Introduction

Setting the Context:

▶ Veterans and Employment

▶ Labor Market Trends Impacting Veterans Employment

▶ Projected Job Creation Impacting Veteran

Employment

▶ Public Policy and Public Sector Initiatives Impacting

Veteran Employment

▶ Noteworthy Law and Regulation Impacting Veterans

Employment

▶ Summary

Employer Challenge: Articulating a Business Case

for Veterans’ Employment

Employer Challenge: Certification, Licensure, and

Experience

Employer Challenge: Skills Transferability, Supply,

and Demand

Employer Challenge: Culture, Leadership

Champions, and Veterans’ Employment

Employer Challenge: Tracking Veterans in the

Workforce

Employer Challenge: Deployment Issues and

Challenges

Employer Challenge: Attrition and Turnover of

Veterans

Part II 30

1

2

3

4

5

7

6

Leading Practices: Veteran Recruiting and

Onboarding

Leading Practices: Training & Professional

Development

Leading Practices: Assimilation and Employee

Assistance

Leading Practices: Leveraging Financial and

Non-Financial Resources

Teaming and Developing Small Business Partners

Summary

Part III 54

1

2

3

4

5

6

Part IV 100

Checklist for Employers: Veteran Recruiting and

Onboarding

Checklist for Employers: Training and Certification

Checklist for Employers: Assimilation and Employee

Assistance

Checklist for Employers: Philanthropy

Select Initiatives Supporting Veterans’ Employment

Unemployment Rate of Veterans Within Each State,

2003-2011

Summary of State-Specific License, Certification,

& Training/Education Initiatives

Appendices 130

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Citations 148

Summary 128

Part IV 100

In Support of the Employer: Issue Paper Library

Issue Paper: Demographic Variables That Affect

Unemployment

▶ Veteran Employment

▶ Geography

▶ Gender, Age, and Race

▶ Disability

▶ Family Support

▶ Education Attainment

Issue Paper: Health and Wellness

▶ Access to Healthcare

▶ Benefits

▶ Disability

1

B

A

Part I

I do not believe we can repair

the basic fabric of society until

people who are willing to work

have work. Work organizes life.

It gives structure and discipline

to life.

— Bill Clinton

“

”

Our military veterans have conferred a

great gift to all Americans through their

service. Importantly, thanks to the rigor-

ous and excellent training that our service

members receive while on active duty,

our veterans are well positioned to offer

America’s employers a great gift as well.

Our nation’s employers have, in essence,

been handed a workforce of men and

women who are highly trained and, in

some cases, uniquely skilled. These are

individuals who are creative, focused on

the mission, can motivate a team, identify

and solve problems, and deliver outcomes

that will contribute positively to the bottom

line. Further, military veterans are well

positioned to meet the demand for a skilled

workforce and through their service have

demonstrated the ability to function in

dynamic environments. In fact, in today’s

fast-paced American workplace, it’s hard to

imagine what’s not appealing about a job

candidate who really means it when he or

she checks “yes” next to the box that says,

“Works well under pressure.”

All this said, data published by the U.S.

Department of Labor (DOL) over the past

four years consistently suggests that the

employment situation of recent veterans

compares unfavorably to non-veterans.

This raises the question, what explains this

disparity, and how can it be addressed in a

way that benets veterans, communities,

and the nation’s employers?

One explanation is likely a lack of un-

derstanding among employers as to the

underlying business case for hiring military

veterans. Another contributing factor is

likely a lack of understanding among hiring

managers and human resources person-

nel as to the most efcient and effective

approaches to recruit, acclimate, develop,

and otherwise cultivate a robust veteran

workforce. This publication is designed to

address these issues, and more. Specically,

this guide has been designed to provide

employers both context and insight into the

idiosyncratic issues and challenges impact-

ing the employment situation of veterans,

and to open the door to leveraging public

sector programs, private sector initiatives,

and leading practices of civilian employers

in a way that supports the adoption of a

strategic and efcient approach to hiring

military veterans.

Executive Summary

Since 2001, more than 2.8 million military personnel have made

the transition from military to civilian life. Another one million ser-

vice members will make this transition over the next five years. For

a great majority of the men and women that have or will make this

transition, their most pressing concern is employment.

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 1

The “Guide to Leading Policies, Practices &

Resources: Supporting the Employment of

Veterans and Military Families” was devel-

oped from an employer-centric perspective,

and is designed to offer a broad but focused

view of the issues, challenges, and oppor-

tunities represented by the employment of

military veterans. Specically, the publica-

tion accomplishes the following:

▶ offers context for the employment

challenges facing veterans, and also

for the employer-centric barriers and

facilitators related to employment

of veterans;

▶ combines academic research grounded

in human resources and organizational

behavior, with the practical

experiences of employers, to highlight

leading practices in the employment of

veterans and military family members;

and

▶ details resources situated in both the

public and private sector positioned to

support employer efforts to cultivate

and nurture a strategic approach to

veteran employment.

Put simply, the goal of this publication is to

leverage state-of-the-art research and prac-

tice to increase employment opportunities

for veterans. This publication was designed

to accomplish this goal in two ways.

Part I

2 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

What This Guide Does

First, the guide details a series of practice

and policy issues identied by research

and through our work with the employer

community, as impacting veteran employ-

ment initiatives. These include:

▶ A Research-Informed Business Case

Supporting Veteran Employment

▶ Implications of Corporate Culture on

Veteran Employment Initiatives

▶ Implications of Leadership Champion-

ing of Veteran Employment Initiatives

▶ Overview of Human Resource

Programs and Processes Impacting

Veteran Employment

▶ Navigating Tension Between External

Pressures and Internal Realities

▶ The Imperative of Tracking Veterans

in the Workforce

Also included throughout this guide are

discussions, descriptions, and case studies

illustrating leading corporate practices im-

pacting veteran employment that address:

▶ Recruiting and Onboarding

▶ Assimilation and Socialization

▶ Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)

▶ Training and Certication Issues

▶ Leveraging Financial and

Non-Financial Resources

▶ Leveraging Supplier Programs

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 3

Further, the guide offers materials and

resources, in the form of concise issue

briefs and checklists, positioned to provide

additional context and background related

to veteran employment, and resources that

can be leveraged by employers to support

internal employment initiatives. These

resources address topic areas that include:

▶ Veteran Employment

▶ Geography

▶ Gender, Age, and Race

▶ Disability

▶ Family Support

▶ Education Attainment

▶ Access to Healthcare

▶ Benets

▶ Disability

The guide has been issued as a printed version, an e-book, and a PDF. Importantly, many of

the issue briefs and related content described above are complemented by web-based and/

or video materials that may be accessed directly from the digital version of the publication.

What’s Next?

At a time when so many industry lead-

ers compare the business landscape to

a battleeld, this effort is positioned to

empower the nation’s employers to act on

the advantages of hiring someone who has

boots on the ground experience managing

the uncertainty and chaos characteristic of

the contemporary business environment.

As such, this publication is a means to

realizing that important end.

However, we recognize that the publica-

tion of this guide is only a rst step toward

creating the culture change necessary to

foster an environment where both veter-

ans and employers are fully empowered.

Moving forward, it is our hope and goal to

build from this document a robust and dy-

namic set of employer-focused resources,

which can be shared among those rms

pursuing veteran-focused employment

initiatives.

As these resources are developed

and become available, they can be

accessed through the IVMF web portal,

http://vets.syr.edu. In the end, this

collaborative effort will benet our

veterans, our nation’s employers, and

ultimately, all Americans.

4 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Part I

In periods where there is no

leadership, society stands still.

Progress occurs when

courageous, skillful leaders

seize the opportunity to change

things for the better.

— Harry S. Truman

“

”

Introduction

In 2011, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that 21.6 million

living Americans have served the nation in uniform. Of this population of

military veterans participating in the labor market, just under one million (8.3%)

were unemployed at any given time throughout the past year. Historically, this

employment situation compares favorably to the non-veteran population; that

is, across the entire population of veterans participating in the labor market (all

eras of service/age groups); there has not been a significant difference in the

unemployment rate between veterans and non-veterans. However, this favorable

comparison has not held true as it relates to the contemporary generation of

military veterans.

Specifically, Gulf War Era II veterans (post-9/11)

have experienced disproportionally higher

unemployment rates compared to other veteran and

non-veteran demographic segments throughout the

period from 2008 to 2011. The disparity in the

employment situation that exists between Gulf War

Era II veterans and 1) non-veterans, and 2) veterans

representing prior periods of military service,

represents an important public and private sector

concern for the following reasons:

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 5

Employment as a Bridge to

Civilian Life:

After a decade at war, large numbers of

veterans, many who have served multiple

combat deployments, will be making the

transition to civilian life over the next ve

years. Employment represents an impor-

tant means through which to mitigate the

uncertainty and culture-change associated

with this transition. Not only does gain-

ful and meaningful employment serve to

provide economic stability throughout the

transition period, but it also serves the

purpose of creating a social support struc-

ture, important during the discontinuous

life change represented by separating from

military service. This bridge is important to

both the veteran, and those connected to

the veteran, including those communities.

Employment as an Antecedent to

Well-Being:

Research highlights that gainful and

meaningful employment is positively

correlated to enhanced physical and psy-

chological well-being. Alternatively, the

inability of transitioning military mem-

bers to secure gainful and meaningful

employment after leaving service has been

strongly linked to the myriad of dysfunc-

tional and declining health and wellness

outcomes. Those experiencing declining

health and wellness outcomes will likely

enter the Social Security benet system,

with its concomitant expenditure of re-

sources, and will likely access Department

of Veterans Affairs (VA) disability com-

pensation at higher rates than employed

veterans. Because these are poverty-level

supports, this situation will likely contrib-

ute to even further deterioration in health

and wellness outcomes.

Employment as an Agent of

Socialization:

The military is an institution that relies on

strong socialization processes to effectively

link an individual’s identity with that of

the organization, an imperative given the

military mission and the extreme demands

placed on members of the armed forces.

However, one of the most signicant is-

sues facing transitioning service members

with regard to effective reintegration into

civilian society is the need to nd and

cultivate organizational attachments that

replace the sense of belonging conferred

previously through their attachment to the

military organization. Gainful and mean-

ingful employment represents an opportu-

nity to create and cultivate new organiza-

tional attachments, positioned to facilitate

effective socialization into a non-military

culture. (Universities and colleges may also

play similar roles, but that is outside the

scope of this publication.)

While the importance of gainful and

meaningful employment for those tran-

sitioning from military to civilian life is

somewhat intuitive, it is also important to

note the opportunity inherent in this area

for the nation’s employers, particularly in

a time of declining support for workforce

training and education at all levels in the

civilian sector. That opportunity is based

on leveraging the unique skills, training,

and experiences conferred to veterans as

a consequence of their military service, in

order to advance the competitiveness of

American businesses. Unfortunately, to

date the business case for hiring veterans

has been largely informed in the public

domain by non-specic clichés about lead-

ership and mission focus.

▶ ▶

▶

Part I

leadership ability and the strong sense of

mission that comes from military service

are characteristics that are highly valued

in a competitive business environment.

However, by themselves these generaliza-

tions have not been enough to empower

U.S. employers in their hiring efforts to

fully benet from the knowledge, train-

ing, values, and experiences represented by

those who have served in the military.

Importantly, the business case validating

the organizational value of a veteran is

supported by academic research in a way

that is both more robust and more complex

than leadership and mission focus alone.

Specically, academic research from the

elds of business, psychology, sociology,

and decision making strongly links charac-

teristics that are generally representative of

military veterans to enhanced performance

and organizational advantage in the con-

text of a competitive and dynamic business

environment. In other words, the academic

research supports a robust, specic, and

compelling business case for hiring in-

dividuals with military background and

experience.

This business case focusing on positive at-

tributes of veterans is detailed later in this

publication. However, it is important here

to highlight that the community of military

veterans represents for the nation’s employ-

ers a robust pool of talent positioned to

confer competitive advantage to those rms

committed and willing to invest in cultivat-

ing a veteran-focused hiring initiative. This

talent represents investment of signicant

training and educational resources,

including those specic to the military, e.g.,

the service academies with their science,

technology, engineering and mathematics

education; robust human resource leader-

ship and management training at every

level of supervisory responsibility; special-

ized technical and skills-based training;

investment in civilian post-secondary

education through assignments in pursuit

of degrees or tuition reimbursement; and,

through defense-industry specic educa-

tional institutions, such as the Defense Lan-

guage Institute’s foreign language training,

the National Intelligence University, the

National Defense University, and various

other contracted and government-operated

education programs. It is this context that

represents the aim of this publication; that

is, to both inform in theory and empower

through practice the nation’s employers, in

a way that leverages the skills and experi-

ences of those who have served in the mili-

tary for the benet of both the employer

and the veteran.

In what follows we rst provide context for

the employment challenges facing veter-

ans, and then highlight public and private

sector policies and initiatives positioned

to address those challenges. Next, we

move to actionable practice, illustrating

employment-focused initiatives and prac-

tices identied through collaboration with

the private sector, in a way that opens the

door to replication and continuous innova-

tion by others working to advance veteran

employment initiatives. Finally, we offer a

series of issue-based discussions designed to

provide supporting resources, context, and

education related to policy, programs, and

research that can be leveraged by employ-

ers to inform practice in the area of veteran

employment.

6 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

To be clear:

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 7

Veterans and Employment

As previously cited, recent veterans are

unemployed at higher rates as compared to

their non-veteran peers, and this disparity

is most signicant in the cases of female,

Hispanic, and younger veterans. A review of

existing data, policy, and academic research

—considered in the context of extensive

interviews with both veterans and employers

—suggests several possible explanations for

this situation:

Skills Transfer:

The applicability of vocational skills and

abilities learned in the military to a civilian

work context is not always intuitive to both

the veteran and the employer. Further, the

transferability of skills learned in the mili-

tary varies as to marketability in the civilian

labor market. Robust understanding of the

education and skills, and their transferability

whether direct or indirect, of military veterans

will enhance demand for veterans by business

and industry.

Knowledge Gap:

Gaps in knowledge about the civilian employ-

ment sector among young veterans–or by

career military service members who have

never participated in the civilian labor mar-

ket–appear to represent a signicant barrier

to employment. Further, gaps in employer

understanding of veterans as prospective em-

ployees are pervasive, based on research and

employer interviews conducted for this guide,

as are misconceptions related to the civil-

ian employment implications of continuing

service obligations, and a high rate of volun-

teerism characteristic of many veterans.

Setting the Context

This section is designed to provide an overview of the issues and

challenges that impact the employment situation of veterans. This

information is provided as a means to educate civilian employers

and provide context for public and private sector initiatives related

to veteran employment.

a.

▶

▶

▶

▶

Stigma:

Stigmas related to mental health issues that

have been generalized to the veteran com-

munity appear to play a meaningful role in

the unemployment situation of veterans.

In a similar way, the increased number of

returning veterans with unmet healthcare

needs attributable to a variety of factors

also represents a barrier to employment.

These include mental-health care, which

may need to be addressed prior to veterans

actively seeking employment, or potentially

through accommodations and employee

assistance programs during employment.

Media portrayals of veterans with post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including

those by uninformed media pundits, were

specically cited by employers in the con-

text of this research, and negatively impact

employer willingness to consider veteran

employees.

Preparation for Employment:

Many of our youngest veterans are leaving

rst-term enlistments, and are often tran-

sitioning from active service directly from

combat deployments. There are several

apparent correlations to the high unem-

ployment rate representative of this group.

Specically, they may not be actively seek-

ing employment, they may not be ready for

employment, or employers may perceive

that they are not ready for employment.

Further, the availability of unemployment

compensation appears to impact some

veterans with regard to the ‘urgency’ of

their employment search, as might need for

health care, and time for reunication with

family and friends.

b.

Geography:

The tendency among veterans to return

to their home-of-record (residence upon

entering the military) after leaving military

service, and importantly, the fact that many

transitioning service members appear to be

making the decision about where to relocate

before beginning the job-search process, is

reported by employers as impacting veteran-

focused hiring initiatives. This tendency im-

pacts employment for several reasons. Data

suggests that rural Americans enter service

at higher rates than urban Americans, in

part due to lack of access to jobs and educa-

tion. According to a study conducted by

the Pew Research Group, 44% of those who

have served in uniform since 2001 were

from rural America.

1

Those who return to

rural areas tend to experience challenges re-

lated to availability of suitable employment

at adequate wage levels, among other issues.

Particularly, enlisted service members do

8 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Part I

not adequately consider availability of

employment opportunities when deciding

to return home. Recruiting efforts targeted

to transitioning service members may not

reach them during their transition, while

they focus on a return home rather than a

career opportunity.

Based on available data, interviews, and

historical context, the factors noted above

are most commonly cited by both veterans

and employers as factors impacting the

employment situation of veterans. While

certainly this listing is not all-inclusive,

it does serve to provide context for the

employment challenges facing both stake-

holder groups.

In the same way that the factors cited

above impact the supply side of the em-

ployment situation of veterans, it is also

important to consider trends in the labor

market as they relate to industry demand

for work roles that represent likely employ-

ment opportunities for veterans. These

trends are detailed in the next section.

Labor Market Trends Impacting

Veterans Employment

In 2011,

2

the labor force participation rate

for Gulf War Era I veterans was 83.8%, and

this population experienced an unemploy-

ment rate of 7.0%. The labor market par-

ticipation rate for Gulf War Era II veterans

was roughly equivalent to the Gulf War Era

I veterans, at 81.2% through 2011. How-

ever, Gulf War Era II veterans experienced

unemployment at a rate of 12.1%. These

gures compare to a labor force participa-

tion rate of 67.1% for non-veterans in 2011,

and an average unemployment rate for the

non-veteran population of 8.7%. This data

suggests that on average, veterans partici-

pate in the labor force at higher rates than

non-veterans–demonstrating a willingness

▶

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 9

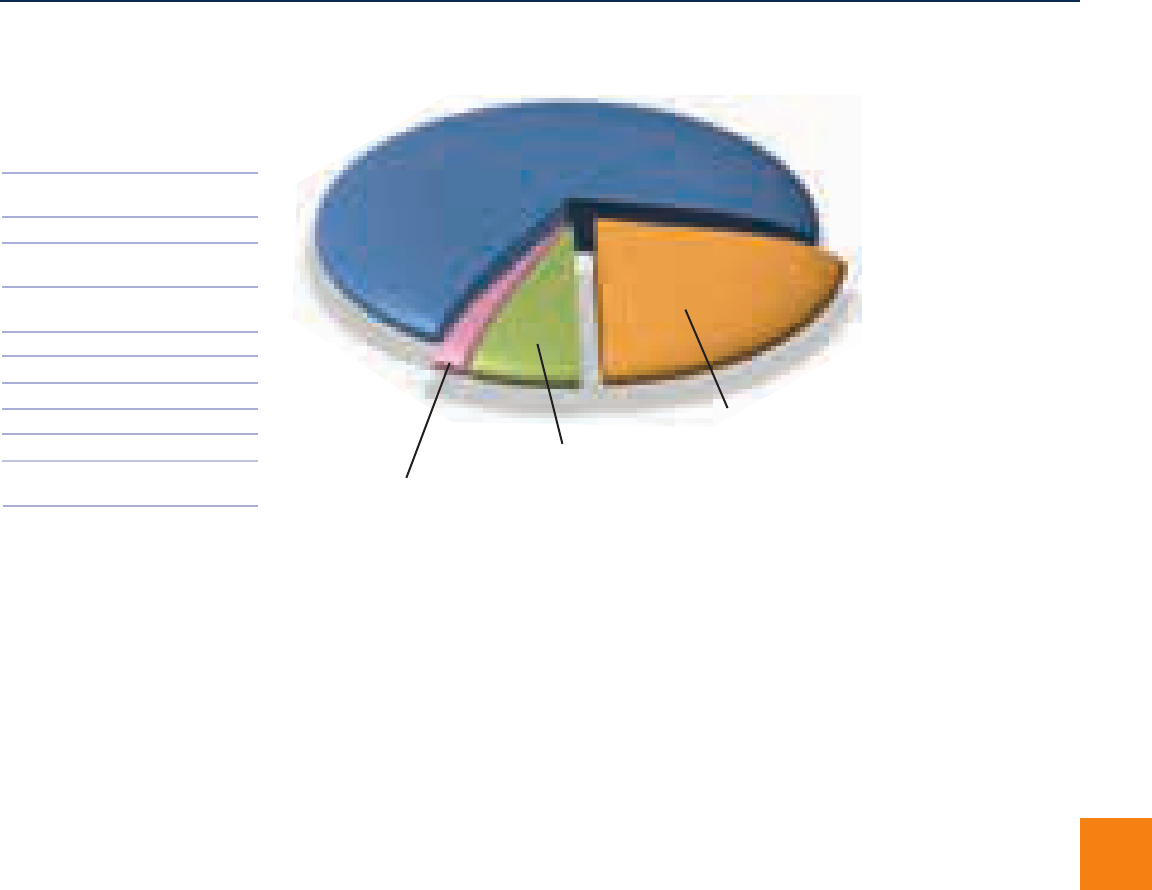

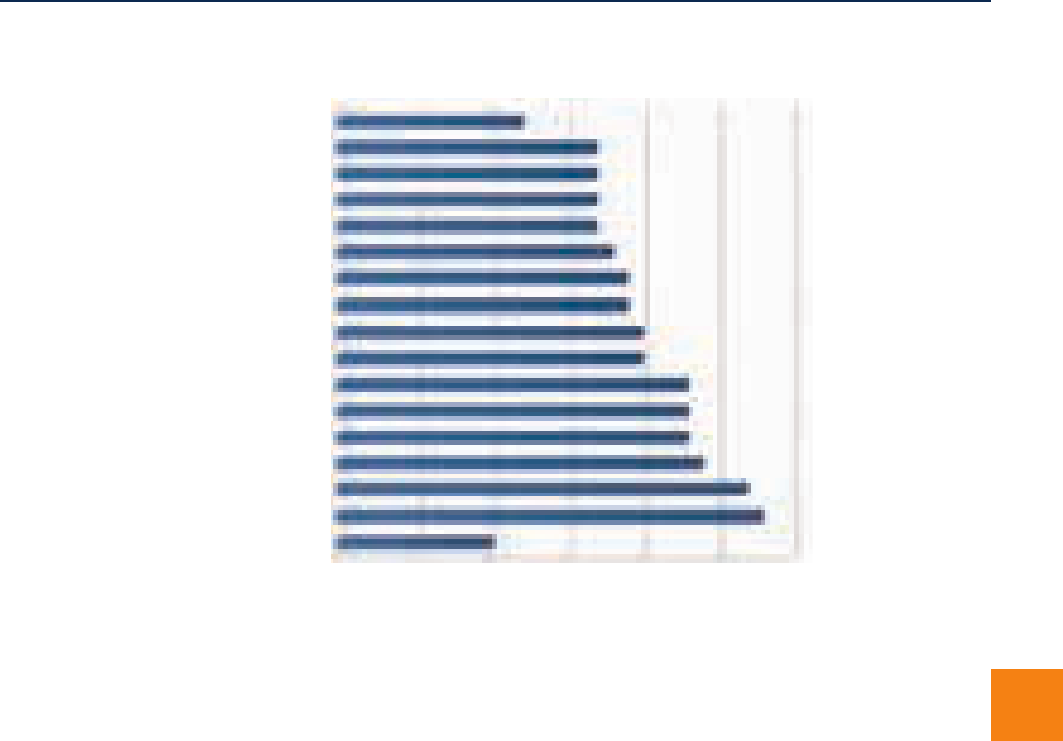

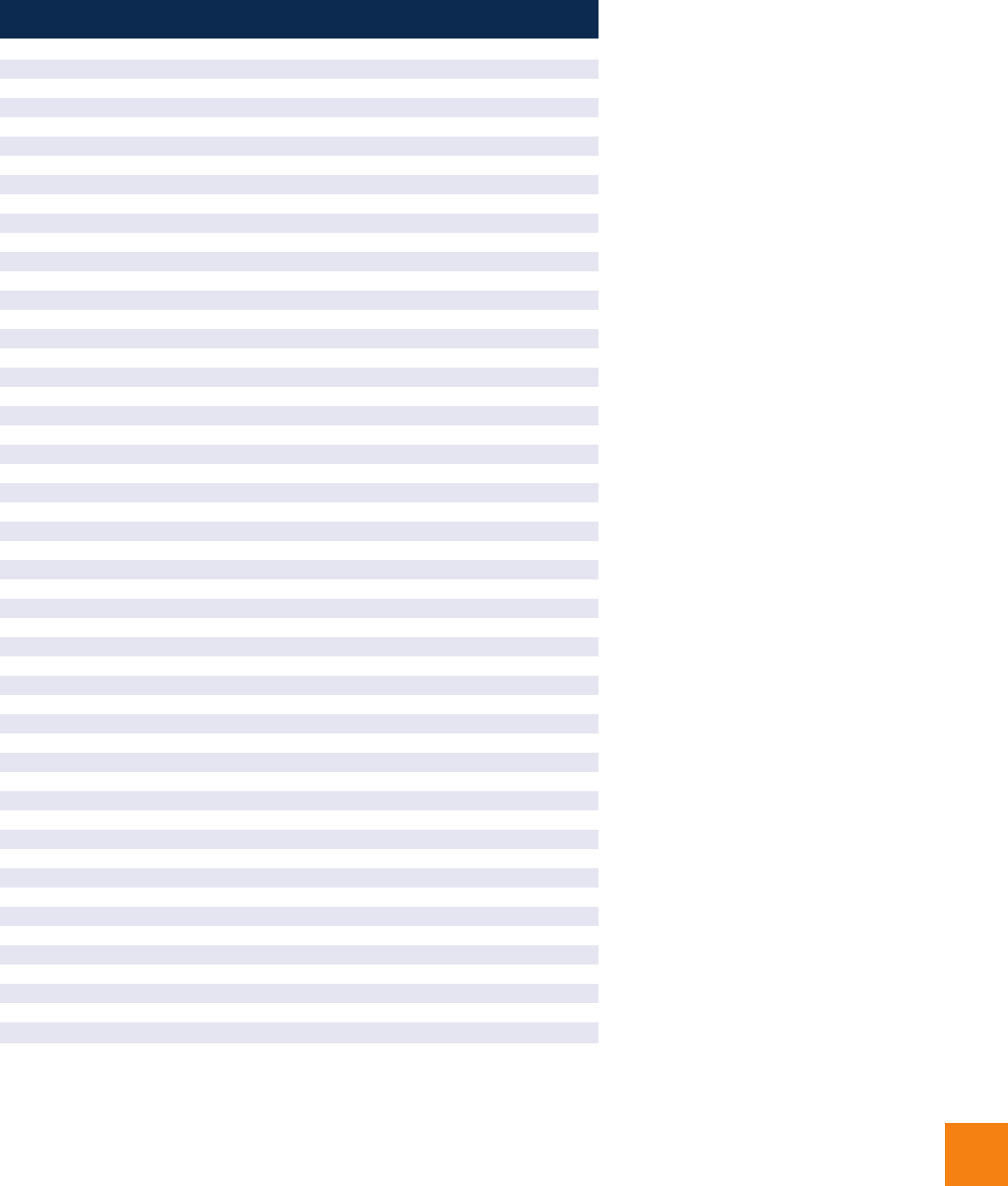

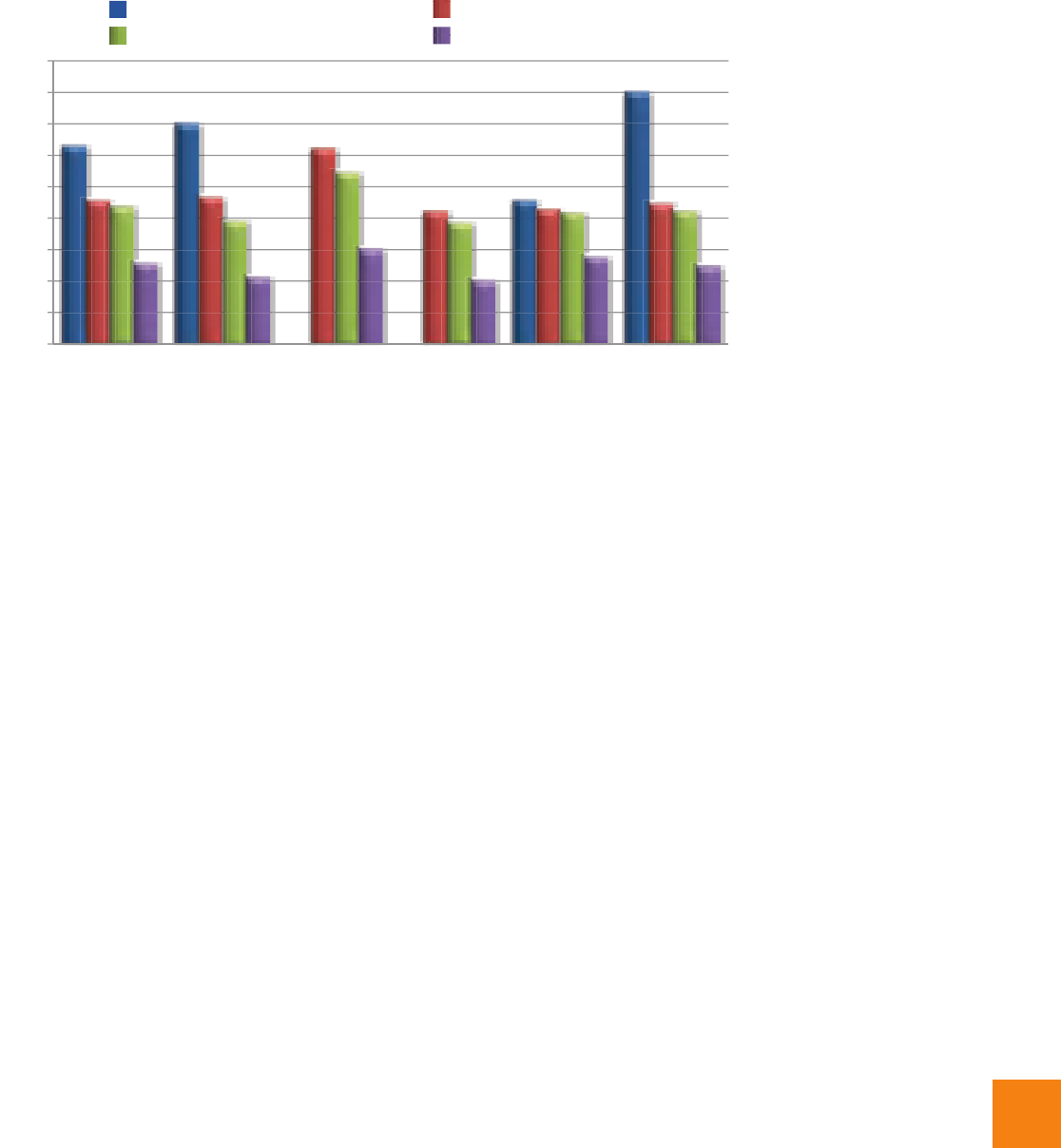

FIGURE 1: DISTRIBUTION OF EMPLOYED BY VETERAN BY INDUSTRY, 2011

PRIVATE INDUSTRY:

Manufacturing 13.00%

Professional and

business services 10.10%

Retail trade 8.20%

Education and

health services 8.20%

Transpor tation and

utilities 7.10%

Construction 5.20%

Financial activities 4.60%

Leisure and hospitality 4.00%

Wholesale trade 2.80%

Information 2.40%

Mining, quarrying, and

oil and gas extraction 0.90%

Other services 3.10%

PRIVATE INDUSTRY: 69%

PRIVATE INDUSTRY: 69%

AGRICULTURE

AND RELATED

INDUSTRIES

GOVERNMENT

SELF-EMPLOYED

WORKERS,

UNINCORPORATED

2%

2%

7%

7%

22%

22%

to work and to be economically engaged.

That said, unemployment rates for Gulf War

Era I veterans are more favorable than for

Gulf War Era II.

With regard to the channels through which

veterans engage the labor market, the 2011

Employment Situation of Veterans report

prepared by the DOL indicates that 69.5%

of all employed veterans work in private,

nonagricultural industries. An additional

21.7% were employed by federal, state

and local governments, and 6.8% were self-

employed.

3

Figure 1 presents an overview of veteran employment by sector

in the private, nonagricultural industries. Specifically, the top

five industries employing veterans in 2011 were: manufacturing

(13.0%), professional and business services (10.1%), education

and health services (8.2%), retail trade (8.2%), and transportation

and utilities (7.1%).

10 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

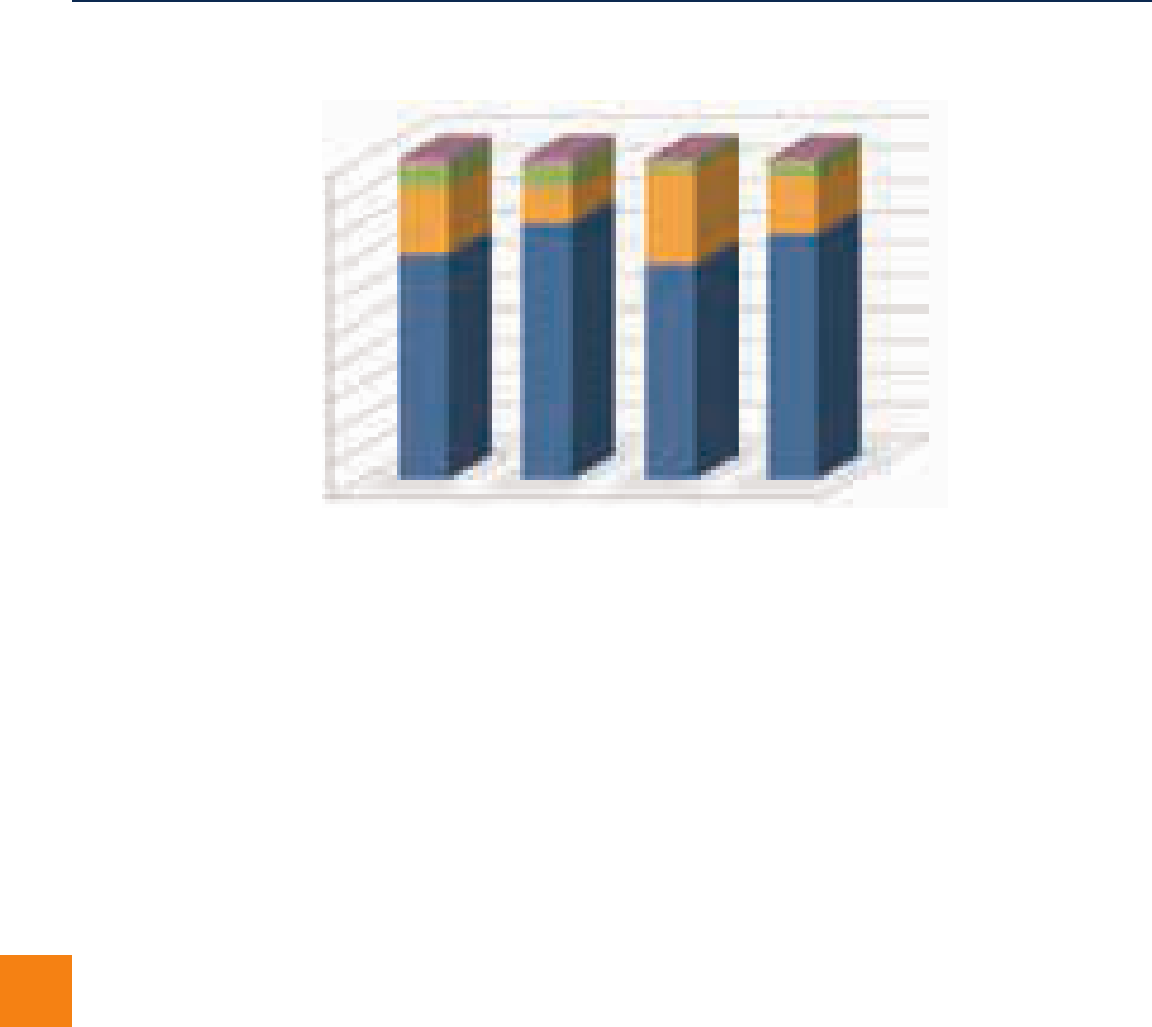

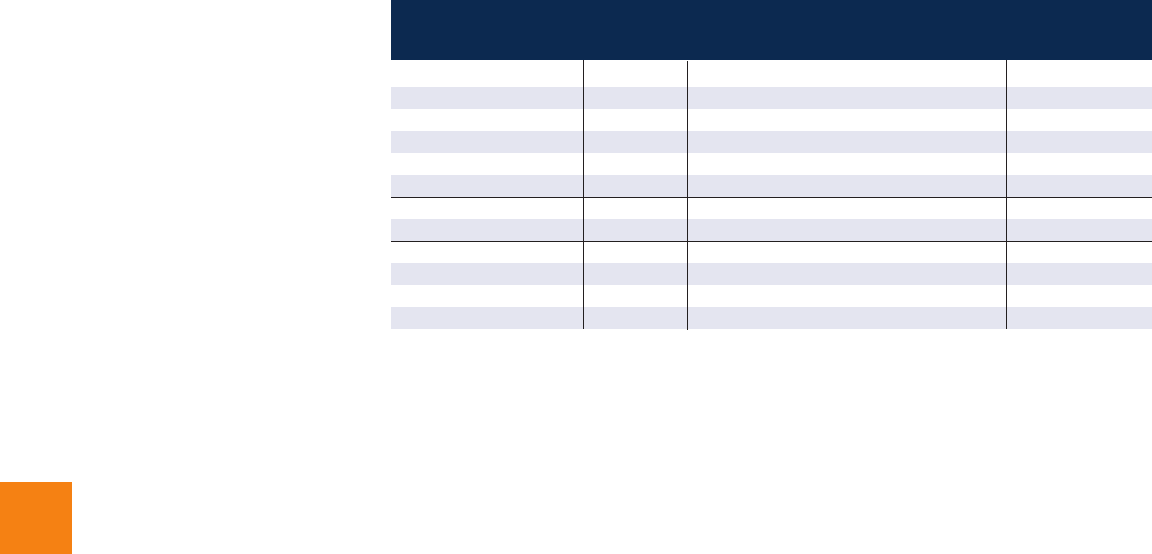

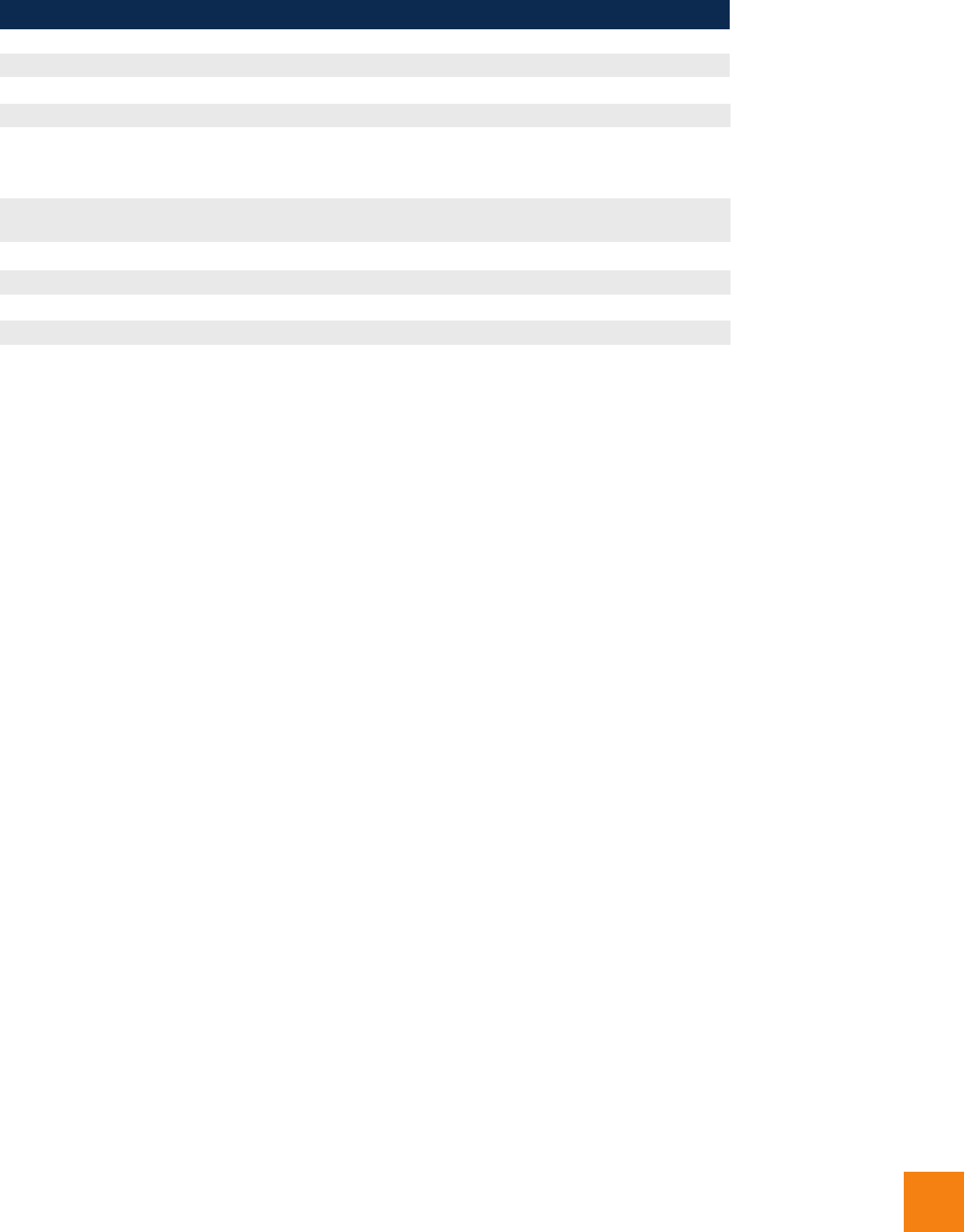

FIGURE 2:

DISTRIBUTION OF EMPLOYED BY VETERAN STATUS, GENDER, AND INDUSTRY, 2011

Agriculture and

Related Industries

Self-Employed

Workers,

Unicorporated

Government

Private Industries

MALE FEMALE

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Veterans Non-veterans Veterans Non-veterans

70%

70%

67%

67%

76%

76%

80%

80%

21%

21%

29%

29%

11%

11%

18%

18%

7%

7%

7%

7%

3%

3%

5%

5%

1%

1%

1%

1%

2%

2%

2%

2%

Further, Figure 2 presents an overview

of the nation’s employment situation by

sector, as a function of veteran status and

gender.

4

These rates are unadjusted annual

averages for 2011 and represent the popula-

tion of individuals ages 18 and over.

In summary, this data suggests that vet-

erans are more likely to be employed by

government as compared to non-veterans,

but the overwhelming majority of veterans

are employed in private-sector, nonagricul-

tural industries. The same amount of male

veterans are self-employed (7%) compared

to male non-veterans (7%), while the

self-employment rate for female veterans

(3%) is slightly less, as compared to non-

veterans (5%).

Part I

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 11

c.

FIGURE 2:

DISTRIBUTION OF EMPLOYED BY VETERAN STATUS, GENDER, AND INDUSTRY, 2011

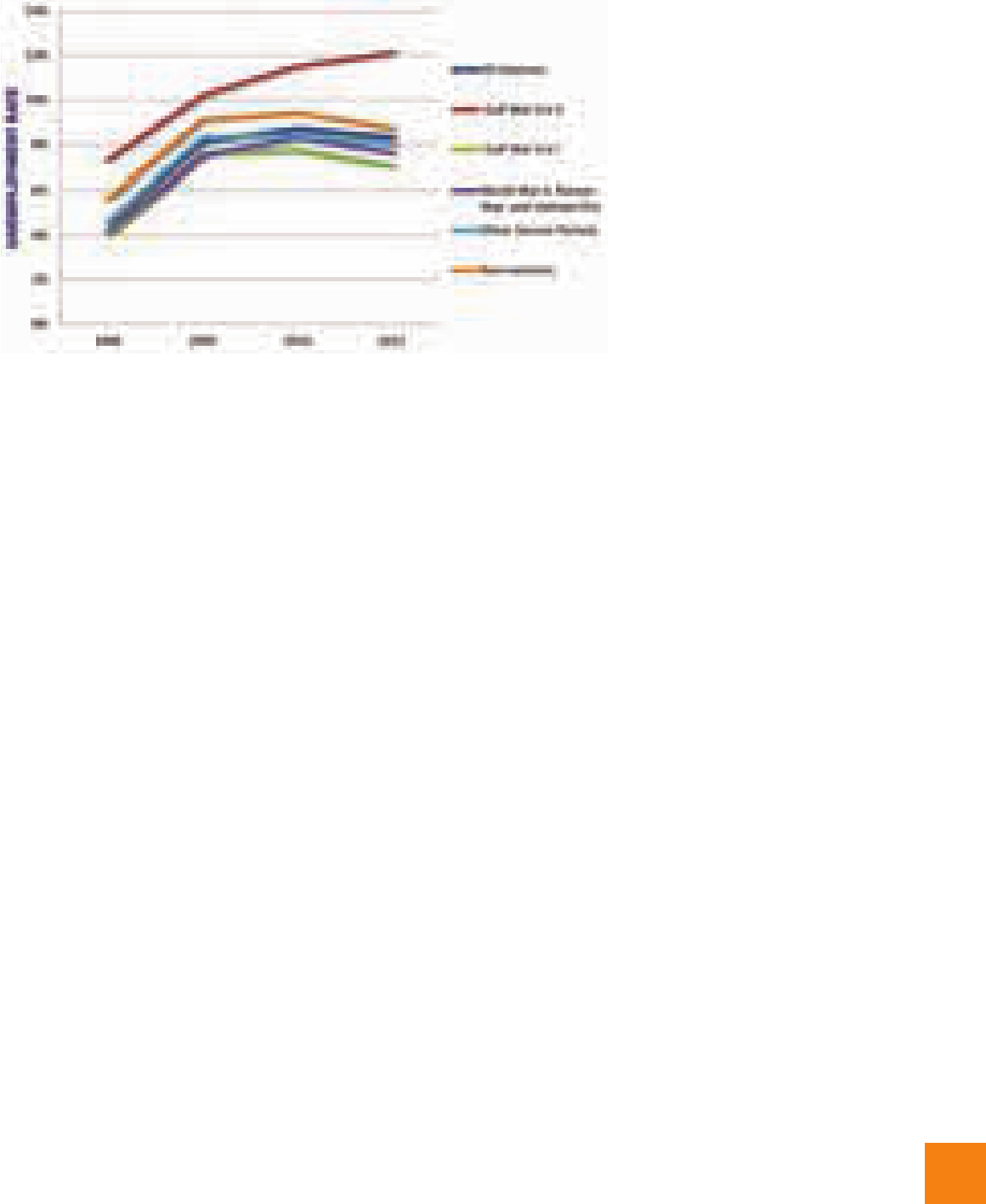

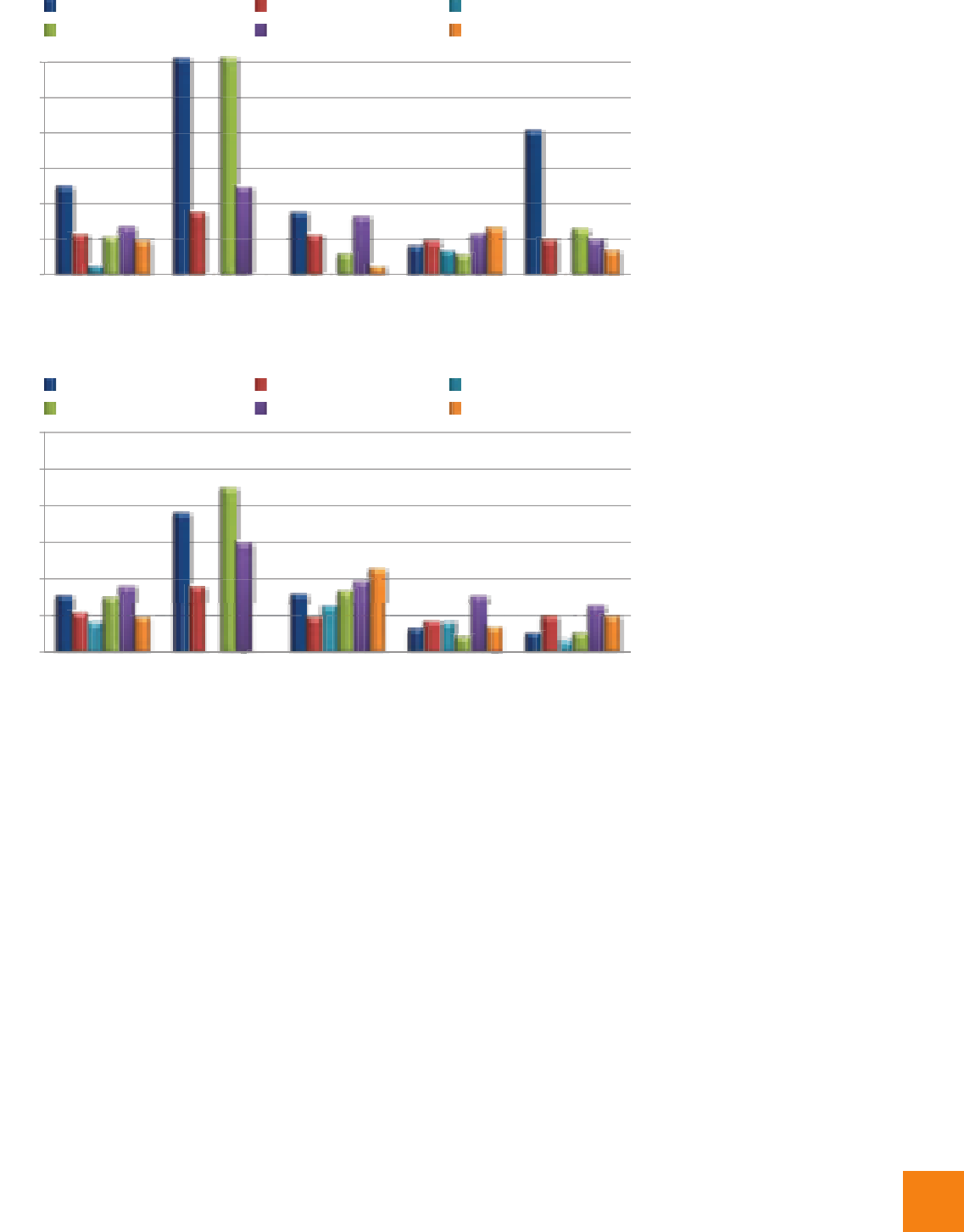

FIGURE 3: GROWTH PROJECTIONS, MEDIAN ANNUAL PAY (5-8 years of experience), 2008-2018

6

Business Development Manager

Project Manager, Construction

Intelligence Analyst

FBI Agent

Program Manager, IT

Technical Writer

Fireman

Helicopter Pilot

Systems Analyst

Information Technology (IT) Consultant

Network Administrator, IT

Network Engineer, IT

Systems Engineer (Computer Networking/IT)

Management Consultant

Field Service Engineer, Medical Equipment

HVAC Service Technician

All Veteran Jobs

$72,200

$66,000

$69,500

$77,600

$91,000

$53,400

$41,900

$58,600

$70,500

$74,000

$50,000

$62,500

$67,300

$87,000

$62,400

$42,000

$52,900

BLS GROWTH PROJECTIONS

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30%

Projected Job Creation

Impacting Veteran Employment

Data suggests that veterans have realized

success nding employment in industry

sectors projected to grow over the next

decade. A recent study by the PayScale

Research Center identied sixteen of the

most frequent work roles held by veter-

ans in the private sector, all of which are

jobs that, according to the DOL, represent

growing industry sectors. Further, these

are work roles where the BLS suggests vet-

erans are over-represented (as compared

to non-veterans). Figure 3 depicts the jobs

that are lled by veterans at a higher

percentage, as compared to non-veterans,

and also illustrates the median annual

pay of those vocations (with 5-8 years of

experience).

5

One reason cited by PayScale as explaining

why veterans are over-represented in these

work roles relates to the skills that military

training confers; PayScale’s study identied

that veterans are more likely (as compared

to non-veterans) to hold technological skills

in areas such as computer networking, com-

puter security, electronic troubleshooting,

Microsoft SQL Server experience, informa-

tion security risk management, and infor-

mation security policies and procedures.

Additional research by PayScale identied

the top 15 employers of veterans, high-

lighting rms that employ veterans as an

explicit consequence of the specic skills

and competencies that veterans bring to the

workforce; that is, PayScale included only

employers–and positions at those employ-

ers–which had direct connections to the

military service experience of the veterans,

e.g., a cafeteria worker at a defense contrac-

tor was not counted, while a technician or

an engineer was counted. Among these em-

ployers were Booz Allen Hamilton, Boeing,

SAIC, and Lockheed Martin.

7

12 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Part I

hire future reservists and guard members

when the burdens of service fall to those

components, and when deployments may

be more frequent than previously contem-

plated. Such issues may be likely to deter

future service by current members as well

as future generations. This may be par-

ticularly true if service is viewed as having

a negative impact on future life-course,

including employment for veterans. Fur-

ther, nancial instability caused by lack of

employment likely contributes to family

destabilization, increasing these impacts.

The Cost of Unemployment and

Related Public Benefit Programs:

Unemployment benets are costly and

time limited. Disability benets are both

costly and potentially ongoing for an

indenite period of time. Other public

benets which often accompany disability

benets, such as food stamps and hous-

ing vouchers, are also potentially life-long

entitlements. Some benets are means-

tested, and are therefore less likely to

result in situations where the individual is

gainfully employed. Usage rates of public

benet programs may be mitigated by

employment; the accompanying wellness

resulting from gainful employment and

history suggests that effective and expe-

dited paths to reemployment (or educa-

tion) may prevent reliance on disability

and other public benets throughout one’s

lifetime.

Public Policy and Public Sector

Initiatives Impacting Veteran

Employment

Public policy impacting veteran employ-

ment is complex and multifaceted, leading

to public-sector initiatives that range from

those that incur direct to indirect nancial

costs (including costs either to address or

to ignore the employment issue), implicate

national economic competitiveness, and

those positioned to leverage the training

and experience afforded to veterans as a

consequence of taxpayer dollars. Public-

sector initiatives also invoke the unem-

ployment situation of veterans as a national

security concern, given the imperative

of elding an all-volunteer military. In

general, the scope of policy and regulatory

efforts impacting veteran employment can

be categorized as being motivated by one

(or more) of the following:

National Obligation to Veterans:

The need for veterans to be supported and

successful in their post-service employ-

ment pursuits is critical in order to main-

tain an all-volunteer force. Lengthy and

frequent deployments impact family mem-

bers, particularly children, in ways which

we may not yet understand, and for which

there may not yet be adequate support and

response. Employers may be unwilling to

d.

▶

▶

have signicant work experience, ranging

from a few years to more than 20 years

of service, which, when appropriately

matched to private sector jobs, may impact

the economic competitiveness of U.S. busi-

nesses and industries.

Leveraging Public-Sector

Investments in Human Capital:

Related to the above argument, the U.S.

has invested in both accession and train-

ing for each military member. Accession

costs in FY 2010 were $22,898 per member

of the Army, and included funding for

educational loan repayment and the Army

College Fund. Costs for training averaged

$73,000 for those with advanced individ-

ual training (AIT) at a second duty station,

or $54,000 for those who attended AIT at

the original training location.

10

This cost is

signicantly higher than the 10-year aver-

age cost reported by GAO for FY94 through

FY03, of $6,400 per selected Army occupa-

tion. Other service averages for the same

10-year period were $18,000 for the Navy

and $7,400 for the Air Force, both reported

as training cost averages for members

separated under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

11

A more recent report by GAO reported

training and recruitment costs per service

member ranging from $19,382 to $90,813

per person, with reported costs included

varying by each service.

12

Networks, trust,

experience and other factors beyond

training also are relevant components of

human capital.

▶

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 13

Health and Wellness Implications:

Unemployment leads to poor health out-

comes and as previously noted, potentially

increased higher use of the public benets

system in the best cases. Unemployment is

correlated with increasing rates of home-

lessness, severe mental health impacts,

substance abuse and alcoholism, and even

suicide in the worst cases. Employment

is known to positively impact health and

wellness, and may potentially prevent

poor health outcomes leading to increased

public expenditure or poor life outcomes

for veterans. Unemployment and lack

of access to health benets may further

exacerbate physical and mental-health

illnesses.

Enabling National

Competitiveness:

Public education and training expen-

ditures are decreasing in times of scal

restraint, and there is a strong case to be

made that leveraging the unique skills

and education represented by veterans

will enhance national competitiveness.

Veterans are already a select group, with

7 in 10 Americans ineligible for military

service due to education, criminal re-

cords, substance or alcohol use, and other

factors. “Over 97% of all entering service

members have a high school diploma

and above (not including the GED), com-

pared to a rate of only 81% for the general

population (excluding the GED/alternative

credential),”

8

compared to a rate of only

70.5% for the general population. As of

2011, 27.20% of veterans had earned a

bachelor’s degree or higher and 34.19% of

veterans had some college or an associate’s

degree. Over 82% of ofcers had either a

bachelor’s degree (45.0%) or an advanced

degree (37.7%), compared to only 29.9% of

the U.S. population age 25 and over with

at least a bachelor’s degree.

9

Veterans also

In what follows we briefly expand on each motivation above,

so as to concurrently highlight noteworthy public and private

sector actions positioned to address veteran employment

issues and aims.

▶

▶

14 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

National Obligation to Veterans

Highly visible public White House engage-

ment through First Lady Michelle Obama

and Dr. Jill Biden leading the Joining Forces

initiative raises awareness of veteran and

family issues. This effort emphasizes and

relies on volunteerism, such as Give an

Hour and other volunteer-based not-for-

prot organizations.

Examples of intergovernmental collabora-

tion include the recently released report

from the DOD and Department of the

Treasury calling on state governments

to streamline licensure and certication

requirements for military spouses moving

from one state to another. Licensure and

evaluation activities are similarly called

for to enable veterans and their family

members to obtain licensure when mov-

ing into a state in their post-service lives.

There are current and proposed activi-

ties in many states related to this activity

detailed later in this report, and there may

be opportunities for transfer of learning,

and for businesses with activity in multiple

states to encourage new models. This will

require evaluation of military experience

and training, collaboration between states

and DOD, as well as the various service

branches, and between the states in order

to evaluate and appropriately credit expe-

rience, education, training, licensure, and

certications across oversight boundaries.

Such evaluation might also benet from

experience garnered by the American

Council on Education (ACE), through its

articulated evaluations of experience,

training and education in the military, and

its relevance to certication and licensure

education and experience requirements.

The nation’s obligation to those who have

served is also reected in widespread

welcome home celebrations for deployed

service members, yellow ribbon cam-

paigns, clarity of the VA’s exemption from

sequestration in budget cuts, engagement

of the DOL with the private sector through

the Secretary of Labor’s Advisory Com-

mittee on Veterans’ Employment, Train-

ing and Employer Outreach (ACVETEO),

Governor Cuomo’s New York State Council

on Returning Veterans, JPMorgan Chase’

(JPMC) 100,000 Jobs Mission consortium

of employers, the U.S. Chamber of Com-

merce’s Hiring Our Heroes campaign, pub-

lic/private partnerships such as Employer

Support of the Guard and Reserves (ESGR),

and many others. Such efforts highlight

that novel times call for innovative part-

nerships to fully engage the actors with the

necessary experience to address compre-

hensive issues.

There are a variety of policy initiatives

that are intended to address obligation to

veterans for service by addressing employ-

ment issues directly. These include pro-

tecting employment rights, prohibiting

discrimination, implementing afrmative

employment action, providing incentives

and credits, and providing support for vet-

eran employment through peer supports,

encouragement, recognition and other ac-

tivities. Some address veterans’ unemploy-

Part I

Examples of the public sector’s expression of obligation to

veterans include public/private partnerships such as the

White House’s Joining Forces initiative, focused messaging, and

explicit employment partnerships.

13

Expression of the obligation

to veterans also includes intergovernmental collaboration.

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 15

ment directly, e.g., the Veterans’ Preference

Act of 1944, as amended, and now codied

in Title 5, United States Code, the Veterans’

Employment Opportunities Act; the VOW

to Hire Heroes Tax Credit; the Uniformed

Services Employment and Reemployment

Rights Act (USERRA); Vietnam-Era Veteran

Employment Readjustment Assistance Act

(VEVERAA); state unemployment compen-

sation systems; a new Veterans’ Job Corp

initiative; and others.

Indirectly, the GI Bill, the Post-9/11 GI

Bill, and the Yellow Ribbon GI Bill impact

employment by providing vocational and

post-secondary education funding which

allows veterans, and with the Post-9/11

GI Bill their dependents, to prepare for

careers. The Americans with Disabilities

Act (ADA) provides for accommodations

for those with disabilities incurred in

military service. And the Family and

Medical Leave Act (FMLA), in addition to

its provisions for typical occurrences in

civilian life, specically covers leave rights

when military members are deployed and

when caregivers of military members incur

injuries which impact veteran and family

member employment.

Title 38 U.S.C Section 43, USERRA, pro-

hibits discrimination in employment or

adverse employment actions against service

members and veterans. Specically, “An

employer must not deny initial employ-

ment, reemployment, retention in em-

ployment, promotion, or any benet of

employment to an individual on the basis

of his or her membership, application

for membership, performance of service,

application for service, or obligation for

service in the uniformed services.”

14

It

also provides reemployment rights for

those who are deployed from their civilian

jobs. USERRA also includes requirements

for reasonable accommodations, includ-

ing obligations to assist veterans in their

reemployment to become qualied for

jobs through training or through retrain-

ing. This obligation applies regardless of

wheter or not the disability is connected

to a veteran’s service. USERRA’s disability

denition is less stringent than the ADA’s,

and it applies to all employers unlike the

ADA which applies only to employers

with 15 or more employees. VEVRAA also

requires non-discrimination in employ-

ment for veterans for federal contractors

(and not just to Vietnam-era veterans) with

contracts that meet certain thresholds

(generally greater than $100,000/year)

and which don’t fall in certain exceptions

(e.g., out of country, and for certain state

or local governments). Some states, such

as Washington, provide for preferences in

hiring veterans under state law, and some

states, e.g., California, provide signicantly

more protections related to disability, and

therefore veterans with disabilities, than

the ADA.

16 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

The Cost of Unemployment

Compensation & Public

Benefits

Unemployment compensation is available

to veterans for up to 99 weeks through the

Unemployment Compensation for Ex-Ser-

vicemembers (UCX) program, Emergency

Unemployment Compensation (EUC08),

and the Extended Benet (EB). Benets

are repaid to the states by the military

branches as no withholding exists for

unemployment compensation from ser-

vice member paychecks. States, however,

determine the benet programs available,

benet amounts, number of weeks of

benets available, as well as the eligibility

for benets.

15

“For FY 2010, approximately $1,571 mil-

lion in unemployment benets (UCX,

EUC08, EB, and the since expired $25 fed-

eral additional compensation benet) were

distributed to former military personnel.”

16

Purely from an employment outcome per-

spective, it may be better to direct the UCX

benets to other employment or training

programs. From a public policy perspec-

tive, and to the extent that unemployment

benets support health, mental health,

nancial

stability, and perhaps needed time

out of the labor force, UCX may serve mul-

tiple purposes other than income support.

Unemployment benets for veterans range

from a low of $235 per week to as high as

$862 per week, or approximately $12,200

to nearly $45,000 annually (depending on

the state in which the claim is led). This is

equivalent to minimum wage at 34 hours

per week on the low end of the scale, and

signicantly less than earnings in service.

However, it may be equivalent or nearly

so to those jobs available in some rural

areas with little available employment. By

comparison, a junior enlisted service mem-

ber at the grade of E-4 with over 3 years

of service earns base pay of about $22,600

annually, with housing and meals provided

or housing and food allowances paid as ad-

ditional income. Those veterans from 18 to

24 years of age who separate are most likely

junior enlisted members. While calcula-

tions of comparative wages are beyond the

scope of this guide, understanding relative

compensation of junior enlisted members,

employment opportunities and wages

immediately available to them, and the

unemployment benets available to them

for up to 99 weeks may partially explain

delays in seeking employment. This may

be particularly true in comparison to jobs

readily available in certain geographic

locations post-service.

Public policy may also encourage delays

in seeking employment or structuring the

job search to maximize benet eligibility.

For example, it is possible in some states

to seek unemployment compensation and

then to begin workforce development sys-

tem-funded training, particularly for high

demand industries. This allows receipt of

unemployment benets, tuition payments

for education and training lasting up to

two years, and no concurrent obligation

to seek work during the training. At the

end of the training, often provided at a

community college and bearing degree

Part I

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 17

credit, the veteran may transition off of

unemployment, into a four-year degree

program, and only then begin using GI Bill

benets with their accompanying living

stipend. Thus, while formally counted as

unemployed and seeking work during the

rst two years, the veteran is actually in

training with signicant income.

Many employees turn over in their rst or

second jobs during their rst one to two

years post-service at higher rates than in

later years or later jobs–likely due to poor

t between the veteran’s employment

or life goals and the jobs they are able

to nd in the current economy, in their

geographic area, or due simply to taking

short-term positions for income or benets

without regard to long term t. However,

most veterans remain in jobs they begin

more than one year post-service–likely

as they have found a better t, but also

potentially because they have been able to

address other life issues which they were

unable to address while still in service,

e.g., relationship renewal with family

members post-deployment, transitioning

into civilian healthcare systems, moving to

a permanent home or geographic location,

or other factors.

Because the challenges in veteran unem-

ployment are complex and multifaceted

and not yet fully understood through

research, the public policy context for veter-

ans’ and dependents’ employment must

include not only employment policy but

also directly related policy, e.g., transporta-

tion, healthcare, disability, mental health,

education, community reintegration, rural/

urban distinctions and more. Policy impact-

ing veterans is managed through a diverse

stakeholder group, including the VA, DOL,

DOD, and others. Indirectly, policies related

to housing, homelessness, Social Security,

Medicaid, Medicare, private healthcare,

transportation, and other areas impact

veterans and their families. Fully address-

ing the complex challenges may require

public/private partnerships in policy, and

the support of local communities, non-

governmental organizations (NGOs), and

veteran service organizations (VSOs) in tran-

sitioning veterans back into civilian life.

18 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Implications for Employment

and Well-being

Ultimately, employment is a key to eco-

nomic, social and psychological well-

being, community reintegration, family

nancial stability, and more. Therefore,

employment practices, collaboration with

businesses and industries, and more are

critically important to the post-service life

course of veterans leaving service. Public

policy that supports integrated services,

one-stop information gathering, referral

and access to services, and other initiatives

to streamline reintegration into civilian

society will play an important role. Com-

munities, including the civilian popula-

tion, civic organizations, businesses and

industries, healthcare, educational insti-

tutions, public ofcials, and others have

signicant roles to play in the reintegra-

tion of veterans.

A review of relevant research illustrates

strong associations between poor health

outcomes and unemployment, with over

40 articles related to the topic.

17

One study

explored the relationship between unem-

ployment and mental health, and found

the most signicant predictor of mental

health during unemployment was engage-

ment in activity and perception of being

occupied.

18

Another recent study discussed

the interactions between gender, fam-

ily role, and social class, and found that

“The nancial strain of unemployment

can cause poor mental health, and stud-

ies have reported the benecial effects

of unemployment compensation in such

contexts. However, unemployment can

also be associated with poor mental health

as a result of the absence of nonnancial

benets provided by one’s job, such as

social status, self-esteem, physical and

mental activity, and use of one’s skills.”

19

The study found that unemployment

impacted the mental health of women less

than men, in part due to family care re-

sponsibility, which kept them engaged in

activity. Additionally, the study found that

receiving benets during unemployment

was correlated with better mental health

outcomes. Voluntary or involuntary job

loss, particularly followed by periods of

unemployment, also negatively impacts

health. Among health conditions which

are linked to job loss were hypertension,

heart disease, and arthritis.

20

Additional

negative health outcomes attributed to

unemployment included depression, sub-

stance abuse, and even suicide.

21

However, there are mitigating measures,

including benets, access to healthcare,

community engagement, productive use of

time, family responsibilities and more. A re-

cent study found: “The unemployed receiv-

ing unemployment compensation or ben-

ets from other entitlement programs did

not report signicantly higher depression

Part I

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 19

relative to the employed.”

22

Finally, people

who have impaired health will also have

longer periods of unemployment,

23

making

access to health care a critical component

of unemployment policy. There are many

similar studies focused on the relationship

between health and employment.

During periods of unemployment, it may

be particularly important to mental health

for the community to remain engaged

with veterans, specically with veteran

men or others who are not productively

engaged. Education and training programs

may have a signicant role to play, as

may faith-based organizations, volunteer

service opportunities, and others which

impact their self-perception. Community

coalitions can and should address the

needs of veterans with a wide range of

services, activities, and opportunities for

productive engagement in order to reduce

negative mental health impacts, which

might in turn otherwise prolong periods

of unemployment. Additional support for

these activities comes from hiring man-

agers who report that they would like to

see unemployed job applicants who have

been engaged in training or education,

temporary or contract work, or volunteer-

ing.

24

These activities all support health

outcomes and have additional networking

effects, improved skills, and civilian reinte-

gration components.

Additional concerns may include access

to health care during periods of transition

or unemployment. Those family mem-

bers who previously had health access to

military service providers may no longer

have such access. Regardless of access,

with a transition likely comes nding and

engaging with a new healthcare provider,

even with immediate employment. When

mental health is also involved, it may be

both more difcult to nd a provider, and

to gain access to appointments. During

transitions from military to VA healthcare,

there may be delays in accessing care or

in transferring records. Stigma may also

play a role, both in forming a new patient/

provider relationship and trusting the

provider with mental health information,

and in evaluating the risk of disclosure of

a mental health diagnosis while seeking

employment. Many veterans have shared

anecdotally that they fear disclosure of a

mental health diagnosis to healthcare pro-

viders because they believe employers will

have access to such records, as supervisors

and commanders were perceived to during

military service.

Another public policy component related

to health and wellness outcomes for

veterans is scally motivated and relates

to the impact of unemployment on state

Medicaid budgets. During heightened un-

employment more people turn to Medicaid

and to State Children’s Health Insurance

Programs (SCHIP), so states will often cut

access to programs and services, including

healthcare through Medicaid and SCHIP,

and post-secondary education,

25

causing

unemployed veterans to have less access

to programs and services. This may in turn

create further calls on public benets and

budget implications.

Ultimately, employment is a key to economic, social and psychological

well-being, community reintegration, family financial stability, and more.

20 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Enabling National

Competitiveness

In addition to legislated and executive

policies, concerns over national competi-

tiveness have motivated calls to action by

political and governmental players with

regard to participation of the private sector

and of the community in addressing the

employment needs of military veterans.

It is clear that the government is asking

the private sector to take a role in hiring,

e.g., VA Secretary Eric Shinseki engaging

with the International Franchise Associa-

tion (IFA) and its members, which have

pledged 75,000 hires of veterans and their

spouses by 2014. Other examples are the

100,000 Jobs Mission initiated by JPMC

and partners, President Obama’s call for

private industry to hire 100,000 veterans,

and others. Each is making progress; for

example, the 100,000 Jobs Mission, at less

than 12 months old, has reported that

their 50 (and growing) member companies

collectively hired 12,179 veterans through

March 31, 2012. Even more important

is that the coalition has begun sharing

practices, tracking methods, and other

resources with each other and with other

interested employers, which may positive-

ly impact future veteran employment.

However, private sector initiatives have

not yet been sufcient, and with over 1

million veterans returning to the civilian

sector over the next ve years, more will

need to be understood.

To date, the business case for hiring a

veteran has been largely informed in the

public domain by non-specic clichés

about leadership and mission focus. While

leadership ability and the strong sense of

mission that comes from military service

are characteristics that are highly valued

in a competitive business environment,

alone these generalizations are not enough

to empower U.S. employers to move be-

yond art to science, and in doing so gain

competitive advantage and fully benet

from the knowledge, training, and expe-

riences represented by those who have

served in the military.

Importantly, the business case validating

the organizational value of a veteran is

supported by academic research in a way

that is both more robust and more complex

than leadership and mission focus alone.

Specically, academic research from the

elds of business, psychology, sociology,

and decision-making strongly links charac-

teristics that are generally representative of

military veterans to enhanced performance

and organizational advantage in the con-

text of a competitive and dynamic business

environment. In other words, the academic

research supports a robust, specic, and

compelling business case for hiring individ-

uals with military background and experi-

ence. This competitive advantage must be

communicated to business and industry,

and demonstrated through the contri-

butions of veterans to high-performing

organizations. However, until that message

is compellingly communicated and widely

adopted, public/private and public initia-

tives will remain important in the direct

employment context.

Part I

22 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Part I

Leveraging Investments in

Human Capital

Investment in human capital has slipped in

the United States, from education in K-12 to

state funding of college education. The mil-

itary, however, has continued to invest in

training and education, and is selective in

recruiting enlisted military members who

have completed high school and score well

enough on the ASVAB military entrance

exam. For the ofcer corps, the military

recruits those who have already attended

college, participated in ROTC, or have been

educated in the service academies prior to

commissioning.

Recent analysis by PayScale demonstrates

understanding of the human capital

represented by veterans by companies

such as Booz Allen, saying “Veterans are

exceptional individuals who have served

our country, upheld the highest ethical

standards, and strive to do important work

that makes a difference. Because of these

qualities, veterans embody many of Booz

Allen’s core values and they thrive within

our culture.”

26

They follow on with discus-

sion of military skill to civilian market

opportunities with clients that included

DOD, Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps

and Homeland Security. The relationships

and familiarity of veterans with these

organizations has immediate, cognizable

value. SAIC, another rm that has exten-

sive government relationships cites similar

values and skillsets. With SAIC’s workforce

consisting of 25% veterans, and 22% of

last year’s new hires, the value they place

on the human capital acquired through

military service is clear. PayScale’s analysis

shows that the top four industries hiring

veterans for their specic skills include

“weapons and security, aerospace,

government agencies and information

technology.” Industry jobs include technical

jobs and engineering, as well as government

processes, which are learned through mili-

tary service. Perhaps most important in con-

sideration of human capital are networks.

Military veterans are strongly aligned to

each other, and are a source of recruitment,

networking between rms and agencies,

and are interested in supporting other veter-

ans and their families in employment.

Research demonstrates that high road

companies, those that are high perform-

ing and knowledge-based, often invest in

human capital. They understand the value

of providing training and education to their

workforce, and continue to provide them

as means to reach a competitive advantage.

Common traits of these companies, which

are similar to military service, include

“selection of employees with technical,

problem-solving, and collaborative skills;

signicant investment in training and

development; commitment to building

trust and relying on employees to solve

problems, coordinate operations, and drive

innovation.”

27

Veterans are likely to value

and understand companies that will contin-

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 23

ue patterns of education and training they

experienced while in the military —that is,

companies that train for next assignments,

provide mentoring, and are committed to

their employees and enabling them to be

productive. However, research also notes

that while private business and industry

may expend between $70 and $100 billion

to train their executives or pay for tuition

for higher education, they do not spend

similarly for employees in technical jobs,

for manufacturing, or for service. Those

jobs may provide an excellent t since

many veterans have the skills and experi-

ence for these midlevel jobs, provided by

military experience, training and education

which allow immediate t when properly

translated. Additional research on high-

performance workplaces, which should be

similar to high-performing military work-

places, demonstrates signicant benets for

both employee and rm, including “ef-

ciency outcomes such as worker productiv-

ity and equipment reliability; on quality

outcomes such as manufacturing quality,

customer service, and patient mortality;

on nancial performance and protability;

and on a broad array of other performance

outcomes.”

28

Expectations for training,

mentoring, supervision with feedback and

similar activities may also assist with accul-

turation to the new civilian employer.

Many companies are beginning to tap

another component of human capital–the

networks of their military veteran employ-

ees. Once veterans are employed, and nd

ts, they may be the best representatives to

other highly qualied veterans, and may

have the best access to veteran networks.

Tools may include professional networks

like LinkedIn and BranchOut, military-spe-

cic networks for those who have served,

and social networks such as Facebook,

Twitter, and Google Plus where many

veterans maintain close ties to other mili-

tary members and veterans with whom

they have served. Additionally, veterans

who attend college may be members of stu-

dent veteran clubs or chapters of Student

Veterans of American (SVA) and may be

familiar with other vets in priority recruit-

ment colleges and universities. Given the

opportunity to surround themselves with

high-performing colleagues, they may assist

in recruitment, and may help to form rela-

tionships with other agencies or businesses

where their former colleagues have roles.

With a critical mass for employee resource

groups, they may also assist with retention.

These networks expand beyond recruit-

ment and retention, as well. Networks

of veterans across companies may create

opportunities for cross-company collabo-

ration or formation of new partnerships.

Veterans may also have familiarity with

process and subject matter in government,

in the service branches, and with activities

in other countries. The networks of others

with subject matter and process knowledge

that a veteran may tap into bring business

value to organizations that understand and

capitalize on the networks.

One less intuitive nding related to hu-

man capital relates to health and wellness,

with one author noting, “Military service

also occurs at an age when service mem-

bers are forming lifelong habits that will

affect their health in the future.”

29

Health

also includes drug-free status, which may

be even more likely for Guard and Reserve

members with continuing service obliga-

tions who are subject to random drug tests

with signicant consequences. This sug-

gests, from an employer perspective, that

the health behaviors exhibited by veterans

may be reected in reduced health care

costs and lost work days.

24 INSTITUTE FOR VETERANS AND MILITARY FAMILIES

Part I

Noteworthy Law and

Regulation Impacting

Veterans Employment

Equal Opportunity

USERRA protects the job rights of past and

present members of the uniformed ser-

vices, applicants to the uniformed services,

and those who voluntarily or involuntarily

leave employment positions to undertake

military service or certain types of service

in the National Disaster Medical System.

By providing for the prompt reemploy-

ment of such persons upon their comple-

tion of such service, USERRA is intended

to minimize the disruption to the lives of

service members, as well as to their em-

ployers, their fellow employees, and their

communities. Title 38 U.S.C Section 43 of

the act prohibits discrimination in em-

ployment or adverse employment actions

against service members and veterans.

Congress designated that the federal gov-

ernment should be a model employer in

demonstrating the provisions of this chap-

ter. Most importantly, the Supreme Court’s

interpretation of the legislation includes

a mandate for its liberal construction for

the benet of service members, indicating

that no practice of employers or agree-

ments between employers and unions can

cut down the service adjustment benets

which Congress has secured for veterans

under the act.

30

Companies like Allied Barton Security

Services, Verizon Communications, United

Research Services Corporation, and Gen-

eral Electric (GE) all indicate that they

have a company policy to comply with the

intent of USERRA. Additionally, a new bill

(H.R. 3670)

31

proposed on December 14,

2011, would require the Transportation

Security Administration (TSA) to comply

with USERRA. In short, employers in both

the public and private sectors have com-

mitted to honoring the provisions of the

act, and many more companies continu-

ally join the list of its supporters. While

USERRA provides protections for veterans,

the burden of proof of discrimination

rests with the veteran. The DOL enforces

USERRA and provides ombudspersons to

engage with employers to assist in resolv-

ing complaints prior to either litigation or

enforcement actions, but voluntary sup-

port, and particularly public statements of

support, such as engaging with ESGR, may

prove more advantageous than enforced

support.

Though not a military-specic law, the

ADA of 1990 affects veterans who have

sustained physical or mental disabili-

ties related to their service, by protect-

ing against discrimination based on the

presence of disabilities and mandating

that employers make appropriate and

reasonable accommodations for employ-

ees with disabilities.

32

The ADA denes

accommodation as any enabling change to

a work environment that allows a quali-

ed person with a disability to apply for

or perform a job, as well as any alteration

that ensures equal employment rights and

privileges for employees with disabilities.

Corporations complying with this law will

afford veteran employees with disabilities

an equal foundation on which to apply

and further their skills and talents. USER-

RA contains disability accommodation

requirements that go beyond the ADA as

The policy motivated initiatives and collaboration identified in

the prior section have, in some cases, been codified into law

and regulation impacting the employment situation of veterans.

In what follows, such law and regulation is detailed relevant to

its real and perceived impact on employers.

e.

GUIDE TO LEADING POLICIES, PRACTICES & RESOURCES 25

well, requiring afrmative steps to bring

an employee to the level of being qualied