Peralta 23

Robert L. Peralta

Alcohol Use and the Fear of Weight Gain

in College: Reconciling Two Social Norms

1

Recent research reports a link between diet-related behavior and alcohol abuse among women,

but fails to explain this relationship. In the present study, a grounded theory approach is used

to explore the link between diet-related behavior, body image, and alcohol use among a

sample of college students. In the feminist tradition of “giving voice,” 78 college students

participated in semi-structured, face-to-face interviews to generate insight into the socio-

cultural practice of diet behavior and its association with alcohol use. Four specific categories

of diet-related behaviors in the context of alcohol use emerged. Students reported altering

their eating and drinking patterns, self-induced purging, or exercising to stave off unwanted

weight gain believed to be caused by alcohol use. These categories are useful for understand-

ing the alcohol-use and diet-related behavior associations reported in previous studies. Re-

sults suggest drinking behavior among some college students is perhaps mutually influenced

by socio-cultural pressures to conform both to body-image norms and to drinking norms.

Interventions to reduce college alcohol use and the social consequences that accompany such

behavior may need to take into account these social and psychological factors.

Introduction

Many studies have identified risk factors associated with problematic al-

cohol use for women (see Wilsnack and Wilsnack 1997). Diet-related behavior

has, for example, been identified as an important risk factor for alcohol-related

problems among clinical samples of women (Kozyk et al. 1998; Krahn et al.

1992, 1996; Cooley and Toray 2001). To my knowledge, no studies have at-

tempted to explain why diet-related behavior is predictive of alcohol use or

abuse among women, or if this association exists for men. Exploring the diet/

drinking association among college students is important for college health

professionals, alcohol prevention researchers, and educators given the increas-

ing prevalence and incidence of diet-related behaviors among both women and

Dr. Robert L. Peralta is an assistant professor at the University of Akron, Department of Sociology. His

research focuses on how social structural and cultural features of communities affect individual behavior.

In his research he addresses the roles of race, gender, and sexuality in alcohol use and alcohol-related

interpersonal violence.

24 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

men (Hoyt and Kogan 2001; Luciano 2002) and the stability of problematic

drinking behaviors among students despite college-based intervention efforts

designed to reduce abusive drinking on campus (Wechsler et al. 1998).

Background: Gender, Body Image, Diet-Related Behavior, and Alcohol Use

While men in college continue to drink more alcohol more often com-

pared to women, self-reported drinking rates among college women remain

high (Wechsler et al. 2002). Theories of gender construction have been pro-

posed to explain these gender differences (West 2001). Capraro (2000) argues

men drink “to be men” on campus or to construct and reinforce existing nor-

mative assumptions about manhood and male behavior. McCreary et al. (1999)

and others (West 2001; Cruz and Peralta 2001; Tomsen 1997) have indicated

male alcohol use and alcohol problems often are associated with pressures to

adhere to hegemonic masculinity standards (see Messerschmidt 1993; Connell

1995).

2

Indeed, alcohol use appears to be among the repertoire of behaviors

men rely upon to construct masculinity (see Messerschmidt 1993; West 2001).

Historically, similar problems with alcohol at the level experienced by

men largely have been absent for women (Wilsnack and Wilsnack 1996). Re-

searchers suggest that different societal expectations for female behavior serve

as protective factors and thus explain these gender differences (McCreary 1999).

While empirical evidence suggests drinking is largely of the “male domain,” in

general (Wilsnack and Wilsnack 1996) how gender roles influence alcohol use

among male and female college students is not well researched.

3

The recent proliferation of research on college alcohol use has overlooked

the important association between alcohol use and diet-related behavior. Alco-

hol abuse has been found to be associated with severe and less severe forms of

diet-related behavior. This area of research has theoretical promise for explain-

ing gender differences by highlighting differing socio-culturally-based reasons

why men and women use substances such as alcohol. The possible impact

these reasons have on how substance use is expressed by men and women is

also of interest.

Severe and less severe disordered eating patterns in clinical subgroups

reportedly have a fairly high comorbidity rate with alcohol abuse (Bulik et al.

1992; Striegel-Moore and Huydic 1993; Bulik 1987), especially eating disor-

ders that involve bulimia (Lacey and Moureli 1986; Strasser et al. 1992). In one

study, 225 college freshman women were asked questions on eating behavior

and alcohol use; seven months later 104 of the same women were reassessed.

Participants who reported greater use of alcohol during their freshman year,

Peralta 25

and who were more likely to report signs of alcohol use and abuse, also tended

to show worsening symptoms of eating pathologies (Cooley and Tamina 2001).

In another study using a sample of college students, Cooley and Toray

(2001) reported heavier alcohol use to be associated with worsening scores on

bulimia. Krahn et al. (1992) similarly reported a positive association for col-

lege-aged women between alcohol use and dieting severity. In sum, research

suggests as dieting severity increases, intensity and frequency of alcohol use

also increases. Researchers have concluded diet-related behavior and certain

alcohol- and drug-use behavior both appear to be culturally supported for ado-

lescent women (Krahn et al. 1992).

Historically, overweight men in the United States have been tolerated rela-

tive to overweight women. Furthermore, research suggests women in U.S. so-

ciety are more likely to be dissatisfied with their own bodies than are men

(Thompson et al. 1998; Grogan 1999). Dieting is so pronounced among girls in

the United States that at any given point in time, between one-half and two-

thirds of adolescent girls may be dieting (Huon and Brown 1986). The most

recent literature on body satisfaction indicates women continue to be more

dissatisfied with their bodies than men (McCreary and Sasse 2000). As a result,

women are more likely than men to use dieting and other weight-reduction

methods such as fasting and laxative abuse to help acquire a socially desirable

body shape. Laxative abuse, extreme dieting regimens (e.g., fasting), and self-

induced regurgitation are among the most extreme behaviors reported by women

to achieve a desired body shape (Grogan 1999). The pressures to achieve so-

cially approved bodies among women in college may be at odds with similar

pressures to engage in social alcohol use. The conflict exists because of the

belief that alcoholic beverages are high in calories. These opposing factors

create a social context where adaptation is required to meet two expectations of

alcohol use and socially acceptable appearance.

We know women are more likely than men to struggle with body-image

concerns. We also know associations between dieting behavior, eating disor-

ders, and alcohol use have been reported specifically for women. What we do

not know is how the social process of drinking in college and the meanings

attached to alcohol and its use are associated with diet-related behaviors. Prior

studies of student drinking often fail to ask open-ended questions about drink-

ing behavior and have thus been ill-equipped to address social-contextual ques-

tions about student alcohol use. Because prior reliance upon survey methodol-

ogy restricted students’ answers to limited and imposed choices, respondents

have not been able to inform investigators about their alcohol-related experi-

ences with meaningful depth. The social pressures and expectations college

26 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

students face have gone undetected in the absence of exploratory and in-depth

analyses.

Few studies have employed qualitative techniques to understand the socio-

contextual mechanisms associated with drinking among college students (West

2001). This research addresses these limitations directly by giving voice to

students and employing the exploratory technique of grounded theory. This

study does not define dieting and other weight management behaviors as “clini-

cal eating disorders.” Instead, I incorporated college students’ beliefs as ex-

pressed by their narratives to record, document, and chronicle their experi-

ences and views about dieting and physical appearance in relation to student

drinking experiences. Narratives capture contextual nuances and reveal the

meaning of college drinking in a way prevalence studies cannot.

4

Method

Participants

Respondents were a self-selected purposive sample of 78 undergraduate

students at a medium-sized state university in the mid-Atlantic region. Data

were collected between 1997 and 2001. College class ranking ranged from

freshmen to senior status. Students lived both on and off campus. Of the sample,

71% were White (N=55) and 26% (N=20) were Black. Two respondents were

of Hispanic origin and one respondent self-described as Asian. Fifty-three per-

cent (N=41) were male; 47% were female (N=37). Seventy-two percent (N=56)

self-identified as heterosexual, 22% (N=17) self-identified as homosexual, and

the remaining 6% (N=5) self-identified as bisexual. The mean (+/- SD) age was

20 years old +/- 2.75. Thirty-two percent (N=24) reported being freshmen at

the time of the interview, 15% were sophomores (N=11), 22% were juniors

(N=18), and 31% were seniors (N=25). Fifteen percent (N=11) of the sample

were members of a fraternity or sorority. Pseudonyms are used to protect the

informants’ identity.

Instrument

A semi-structured, open-ended interview guide consisting of 12 main ques-

tions was developed and pilot-tested by the primary author to study alcohol use

among college students. Many questions were presented in projective form to

reduce the response effect on threatening questions (see Sudman and Bradburn

1982). Demographic questions were asked in addition to questions about drinking

Peralta 27

quantity and frequency, attitudes toward drinking, reasons for drinking, expec-

tations of alcohol use, and consequences of drinking. The questionnaire instru-

ment included: “What do you think of the idea of getting drunk?”; “What have

been your experiences with alcohol use on this campus?”; “Do you (or do you

know anyone who) diets because of their drinking?”; and “Are you concerned

with the caloric content of alcohol?” Respondents were asked if they perceived

gender differences for each question.

Analysis

The purpose of this study was to explore issues related to drinking behav-

iors on a college campus. Grounded theory is the appropriate analytical tech-

nique for such a study. This technique allows respondents to inform the devel-

opment of both theory and relevant hypotheses for testing in future research

(see Lincoln and Guba 1985). All interviews were transcribed and coded by the

author and three trained research assistants. An initial content analysis was con-

ducted to identify patterns. After the initial analysis, a more thorough examina-

tion of the transcripts was conducted to identify emergent themes. Concepts

were developed and grouped, based upon the frequency of similar articulations

to substantiate emergent themes.

Once concepts were identified, inter-rater reliability was used to verify

consistency in coding and interpretation. After each transcript was coded inde-

pendently, the author and assistants met to identify coding and interpretation

discrepancies. Assistants included a sociology professor trained in qualitative

methods, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology with expertise in qualitative analysis,

and an undergraduate majoring in sociology. Discrepancies involving specific

concepts and themes were discussed and resolved through group consensus.

The emergent themes produced through this study included: social space (Black,

White, homosexual, and heterosexual space); coercion and power; gender con-

struction; social control; and diet-related behavior.

Procedure

This research was a part of a larger study on the drinking behaviors of

college students. A qualitative research design was used to document partici-

pants’ experiences with alcohol at a single mid-sized university in the mid-

Atlantic region of the United States. Students responded to class announce-

ments in sociology and criminology courses and to 10 posted notices placed in

campus areas frequented by students. Racial and sexual minority students were

purposely over-sampled to give voice to those who have been traditionally

28 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

excluded from research. Difficulty recruiting minority participants (African-

American and gay and lesbian students) prompted the use of $10 stipends to

encourage their participation.

The University Office of Human Research granted ethical approval for

the project. Interpersonal, in-depth interviews of 78 participants lasted from 45

minutes to one hour each and were conducted in private university offices.

Informed consent was given for participation and all respondents were assured

confidentiality. The interviews were conducted by the author (N=64; 82%) who

was a 27-year-old male at the time the interviewing began, and a trained 28-

year-old female research assistant (N=14; 18%).

Findings

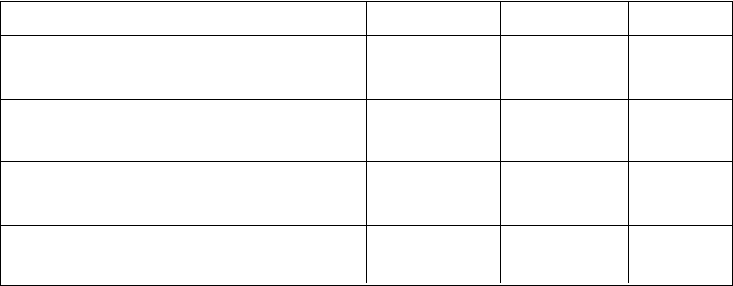

This section presents the findings from the interviews conducted with both

men and women at the university. Table 1 presents a summary of the results by

gender. Percentages pertain to the number of students who engaged in the stated

behavior. Student descriptions of their behavioral processes associated with

conforming to both body image and drinking norms produced four major themes:

(1) altering eating patterns through skipping meals and/or eating less than usual

during a meal to reduce the total number of calories consumed; (2) adopting

altered drinking preferences (drinking less) or choosing alcoholic beverages

assumed to contain less calories such as “lite” beer to reduce the total number

of calories consumed; (3) exercising before and/or after a drinking event to

eliminate the body of calories already ingested; and (4) self-induced purging to

rid the body of calories already ingested.

Nearly 18% of the sample (17.9%) altered their eating patterns. A similar

number altered their drinking preferences in the context of alcohol use. Only

5.1% and 3.8% of the entire sample used exercise or self-induced purging to

eliminate ingested alcohol-calories. Women were at least twice as likely to re-

port engaging in any of the four diet-behaviors in comparison to men [See

Table 1].

The amount of drinking reported in this study is not as high as that re-

ported in studies using nationally representative samples.

5

Of the college women

in the present study, 9% reported drinking an average of four or more drinks in

a row when they did drink. Of the college men, 15% reported drinking five or

more drinks in a row when they did drink.

6

Students in the present study sug-

gest this type of drinking behavior is not necessarily due to a preference for the

taste of alcohol over other beverages. In fact, many students reported not en-

joying the “taste” of alcohol; other social and psychological reasons were used

Peralta 29

to explain drinking and heavy forms of drinking. A number of students did,

however, discuss “drinking to get drunk.” Concerns with body image emerged

as a reason indirectly related to the “drinking-to-get-drunk” phenomenon, as

illustrated by the following quote. Below, Jan’s account of why she chooses to

“drink to get drunk”:

I used to not drink beer because it’s fattening and I’ve had troubles with eating so it’s just like fat is

bad, so I don’t drink beer a lot. I don’t understand the concept of drinking socially. I like to drink to

get drunk. I mean that is the reason, the sole reason, I am drinking. You know, I mean it tastes

disgusting. I don’t like drinking at all. I don’t think I ever will like it, I don’t see a purpose of doing

it socially.

Jan reports that it does not make sense for her to drink in moderation. Jan

defined “drinking socially” as having a glass of wine with a meal. Dinking

socially, i.e., in moderation, does not achieve the intended purpose of drinking,

which is believed to be intoxication. If Jan is going to drink, she reports it is

necessary to become intoxicated, else she would acquire “empty calories” with-

out having felt the euphoria associated with heavy drinking. Jan suggests reaching

the goal of intoxication and hence euphoria counterbalances the ingestion of

empty calories. These sentiments were not uncommon and were expressed in

the narratives that support each of the four themes described in detail below.

Students’ direct experiences with these behaviors are presented first. Students’

knowledge of friends and acquaintances (responses to projective questions)

are presented following accounts of personal involvement with said behaviors

for each of the four emergent themes.

Table 1

Percent of Students Who Reported Engaging in Dieting-Related Behaviors in Relation to

Alcohol Use by Gender (n=78)

Women Men Total

Altered Eating Patterns 29.7% 7.3% 17.9%

(11) (3) (14)

Altered Drinking Preferences 27% 9.8% 17.9%

(10) (4) (14)

Exercising 10.8% 0 5.1%

(4) (0) (4)

Purging 5.4% 2.4% 3.8%

(2) (1) (3)

30 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

Altering Eating Patterns

Dieting is a strategy regularly used for weight maintenance (Huon and

Brown 1986), yet prior research has not identified alcohol use specifically as a

reason to diet. This study reveals how some men and women report dieting in

response to alcohol use. Of the entire sample, 18% reported altering their eat-

ing patterns in response to alcohol use. More women in the present study (29.7%)

report relying upon limiting food consumption as a solution to the problem of

ingesting “high-calorie” or “empty-calorie”

alcohol compared to men (7.3%).

7

Some students noted eating less than usual in order to drink as much as

desired without having to worry about gaining weight, while other students

skipped meals altogether before a planned night of drinking. Skipping meals

was a particularly attractive option, for two reasons. One, students reasoned it

took less alcohol to get drunk, which translated into fewer calories ingested;

second, food calories acquired through dinner, for example, were entirely

avoided. The following narratives illuminate these socio-cultural practices.

Kim: We used to not eat dinner before we would go out and drink. We usually drink lite beer, and

maybe if we want to get drunk more quickly we will not eat that day. It sounds really unhealthy and

it does become a factor [in staying healthy]. I don’t like to think I drink a ton but I don’t want to gain

weight from drinking.

Kim reported not eating dinner before a “party” night along with her friends

in order to avoid the problem of ingesting too many calories. Her account was

similar to others. The pressure to participate in alcohol-related social activities

and the pressure to maintain or achieve a desired body shape informed Kim’s

decision to exchange her dinner plans for a night of “partying.” Tara reported

similar experiences when answering a question about alcohol’s caloric content:

“I worry about that [alcohol use and eating]. During school we wouldn’t eat the

entire day and then we would go and drink.”

Men similarly expressed types of diet-related behavior discussed above.

Take James, for example. A male student who aspired to work in law enforce-

ment, he mirrored the activities and reasoning of his female counterparts docu-

mented above:

James: Yeah, I work out. It has to do with what I want to do, [which is] law enforcement. It’s my

career and I like to be in good shape. I don’t want to be fat. I’m not a muscle head, you know, I don’t

use steroids to stay ripped. But in summertime, especially in summertime, I think about the calories

in alcohol and avoid eating and drinking too much as [often] as I can.

Consider the following statement by Jack, a male undergraduate majoring

in engineering, regarding his anxiety over the caloric content of alcohol:

Peralta 31

Jack: I’m a light eater anyway, but you have to understand that a beer has a minimum of 100 calories

and I’m guessing that is for a lite beer. You put down 15 in a night and that’s a day’s meal for a lot of

people, so I try to avoid drinking and eating at the same time as much as possible.

Both men and women discussed their friends’ and classmates’ attempts to

maintain or conform to appropriate body shape norms through diet-related be-

havior in the context of pressure to use alcohol. Some women and men on

“party nights” avoided excess calories by not consuming as much food, which

in turn freed them to indulge in heavy alcohol use. With little to no food calo-

ries consumed on a night of planned drinking, students reported enjoying the

added benefit of requiring less alcohol to become intoxicated. Consider Mary’s

words in relation to this theme: “I think people do skip meals because they can

get drunk quicker and because they will consume fewer calories.” Similarly,

Julia said, “I know some of my friends would skip meals but they didn’t verbal-

ize it [skipping meals] as much.” Finally, another female voice provided further

insight into what is known about the use of dieting behavior in relation to alco-

hol use. Christine used the term “lightweight” in relation to her experiences

with college women, alcohol use, and diet-related behavior:

Christine: [Many] women here [at the university] will [call themselves] “lightweights” because a lot

of them don’t eat. Women will feel the effects of alcohol because they are not eating!

Many students discussed this issue with fellow students in their dorm rooms.

Jenny’s words exemplify how these social behaviors are communicated and

discussed among women:

Jenny: We used to talk about it actually, probably freshman year. We used to compare how many

calories were in something compared to beer. That didn’t last long, but I do know people who, if they

were gonna go out and drink, would cut back on their food calories for the day so that they could

make up for them [with alcohol].

Some students described their friends as “anorexic” when discussing the

question of alcohol use and dieting behavior. Take Stacy’s account:

My anorexic friend goes through extremes as far as cutting back a little bit. She just wouldn’t eat all

day. Sometimes we would say something to her and maybe she would have a piece of bread or

something. There was [always] an excuse to drink but never [one] to eat.

Samantha further illuminated this theme in talking about her friend’s be-

havior:

A female friend of mine would skip meals before going out and partying, she was really anorexic but

she also used to drink a lot.

32 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

These two examples are suggestive of the presence of eating disorders

among college females. Unfortunately, there is no way of verifying whether or

not any respondents or the friends they speak of are or have been clinically

diagnosed with eating disorders. In the next section, the negotiation of drinking

and body-image norms are further explored in the context of altered drinking

patterns.

Altered Drinking Preferences

Drinking habits are a part of college culture and are routinely controlled

by many factors, including socio-cultural control agents (Peralta, 2005). Al-

tered drinking preferences emerged as a theme because the fear of weight gain

informed the question of choice of alcohol type (regular beer versus lite beer)

and how much alcohol was to be used per sitting (quantity). Of the sample,

18% discussed altering their drinking patterns in response to the fear of weight

gain. Primarily women (27%) reported altering their drinking patterns in their

attempt to negotiate drinking pressures with pressures to conform to body shape.

Nearly 10% of men acknowledged engaging in this behavior.

In terms of quantity, students reported the fear of weight gain as altering

their drinking behavior in an unexpected direction. At first glance, one would

think heavy drinking would be avoided due specifically to the caloric content

of alcohol, especially for those men and women concerned with body image.

But for some men and women the exact opposite was the case. As one female

student plainly said, “If you are going to drink, you better get drunk,” because

“it makes no sense to drink alcohol if you don’t get some kind of buzz.” Spe-

cifically, it makes “no sense” to drink for the pleasure of having a single drink

or having a glass of wine with a meal because of the unnecessary consumption

of empty calories and the dreaded possibility of weight gain.

Women were more likely than men to self-report favoring lite beers, shots,

or mixed drinks. Men were more likely to avoid lite beers or other “feminine”

drinks, while a minority of men did seek out these lower-calorie alcoholic bev-

erages. Women preferred lite beer, shots, and mixed drinks because of the per-

ceived lower caloric content of these drinks. Men self-reported favoring beer,

especially heavier or dark beers, unless they themselves took steps to adhere to

body image norms.

While most men did not alter their drinking preferences due to body image

concerns, some did. The following two accounts specifically demonstrate how men

sometimes altered their drinking preferences due to body image concerns. Greg

discussed his diet, which involved choosing between certain types of alcohol

8

:

Peralta 33

Greg: “Recently I have been watching [my weight]. I’ve started this diet where I need to drink all lite

beer. I’m not crazy about it, but you know. The guys call me “Coors Lite”, [or] “Girls Lite.”

Finally, Adam below discusses why he chooses “hard” liquor over beer:

Adam: Yes, I think about it [calories in alcohol]. I guess that’s the advantage of drinking hard liquor.

It’s not as hard on the appearance of your body. I’m sure hard liquor is worse for you internally

[Adam is referring here to alcohol-related health consequences] but I still do it to avoid the calories.

The calorie-percent-to-alcohol ratio of mixed drinks and lite beers com-

pared to regular beer or other types of drinks was actively sought out by those

concerned enough about body image to alter their drinking patterns. Take Meg’s

account as an example of how choice of alcohol is influenced by body image

concerns for acquaintances and friends of respondents: “One of my best friends

went on a diet and she stopped drinking beer altogether while she was on that

diet.” Another student named Amy mentioned how she would frequently “over-

hear” people in her dorm discuss their concerns over the caloric-content of

alcohol. Choosing lighter drinks was thought to compensate for the threat of

weight gain posed by partying.

Tamara: I remember one time I asked for a Sam Adams and this girl was like, “How can you drink

that? It has so many calories!” Girls definitely care about what they drink and it affects me. We don’t

want to gain weight.

Comparatively, most men interviewed did not report being concerned about

alcohol’s caloric content enough to alter their own alcohol use. Some men,

however, reported knowing of women’s concerns with the caloric content

of alcohol. Mike’s statement is an example of how some men discuss

women’s concerns over the “fattening” aspects of alcohol use. He reported,

“The girls always complain about the amount of calories in alcohol. I’ve never

really thought about it.” Mike constructed the concern as primarily a “woman’s

issue.”

Many men recount examples of their female acquaintances engaging in

specific drinking styles. Mitch, for example, said, “I know girls who will drink

only shots or they will drink like mixed drinks that are sugar free [due to

caloric content of other types of alcoholic beverages].” Tyler observed,

“Women will drink a lite beer and will drink less because they don’t want to

get fat.” Justin further noted, “The girls who worry about how they look,

they’re usually the ones who drink more; they’re the ones who worry about

their self image.”

Women, too, had their stereotypes of female drinking behavior.

34 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

Meg: If women are that concerned about calories, which they are, I don’t think they should be

drinking beer at all, because the food is going to be better for you than beer, and if you’re that worried

about your shape you should not drink beer.

Some students reported altering drinking habits is a way for them to curb

their intake of calories, whether it be through limiting their intake of alcohol or

by choosing one form of alcohol over another (e.g., beer versus hard liquor, or

regular beer versus lite beer). Engaging in these behaviors helps women and

men avoid the stigmatized status of being “overweight” (Schur 1984) while

complying with the normative culture of college alcohol use.

Exercise and Self Induced-Purging

Reliance upon exercise and self-induced purging were the third and fourth

sets of behaviors associated with college students’ alcohol use. Of the sample,

5% reported engaging in these behaviors as a result of alcohol use. The use of

exercise as a strategy to maintain an ideal weight or to lose weight has been

well established in the research literature (Thompson and Chad 2002; O’Dea

and Abraham 2002). Excessive exercise and self-induced purging after meals

are understood as symptomatic of eating disorders (Thompson and Chad 2002;

O’Dea and Abraham 2002) and alcohol problems among clinical samples of

women (Bulic 1987).

What follows is an analysis of college student narratives pertaining to

these two diet-related behaviors as they are utilized in relation to alcohol use.

Only 10.8% of these women reported regularly exercising before or after a

night of drinking to “burn the alcohol calories off.” Use of exercise was the

only diet behavior men did not report using to stave off unwanted weight gain

due to alcohol use. Patty’s account illustrates how women use exercise in rela-

tion to their alcohol use:

Patty: I exercise a lot before and after drinking because of the calories. I got pretty skinny and I

thought I looked great. But I have to keep an eye on it [the drinking and exercise to maintain my

weight]”.

Perhaps the most disturbing theme to emerge was the reliance upon self-

induced purging as a way to negate superfluous alcohol-calories. Two women

and one male student reported purging purposefully after a night of drinking.

While this behavior is not meant to be indicative of existing eating disorders for

students in this study, students did discuss this behavior in relation to their own

existing eating disorders. Sarah, for example, explicitly refers to herself as

“anorexic”:

Peralta 35

Sarah: It’s different for me because I exercise all the time and a lot of times I won’t eat. So that affects

me. Because I’m anorexic, it’s a disease I will have forever. That’s one of the reasons I get so drunk

when I drink. After I drink, I make myself throw up.

While this was one of the least self-reported behaviors, many students

reported knowing someone who did engage in self-purging due to the fear of

gaining weight from alcohol calories. A female student recalled how her friend

would “throw up” after drinking:

I know women who are concerned with the calories. A friend of mine throws up after she drinks,

especially after she realized a Corona has 600 calories per bottle! I used to be concerned with my

body, but now I am comfortable with it. When I was dieting, I would only drink hard alcohol and not

beer because hard alcohol has empty calories whereas beer just goes straight to your thighs. Every-

one thinks this; if you are at all concerned about your body, this is what you do.

Kim was asked if she knew anyone who made conscious decisions about

what type of alcohol they were going to drink:

Kim: Girls will sometimes not eat as much because then it takes less to get drunk which means you

absorb fewer calories…and if you don’t eat a lot, then maybe you can throw up. Some girls like to

because then they think they are getting rid of [the calories].

Jessica described the intertwined aspects of exercise and self-induced purg-

ing in relation to alcohol use:

Jessica: I have a friend who likes to make herself throw up when she’s been drinking and we try to

talk her out of it because it’s not healthy to do, and sometimes we will all exercise a lot at the

beginning of the week if we know we are going to be drinking a lot later in the week.

While the majority of students did not describe themselves as engaging in

purging and exercise directly, these same students did report knowing of some-

one who exercised to burn off alcohol calories. Students suggested I should

visit the school gym on Thursday or Friday early evenings (“party nights”) or

on Sundays (“recovery days”) to witness the “packed” gym. Students felt the

gym was packed with students who were ridding their bodies of unwanted

calories obtained from weekend drinking activities. Ben and Angie provided

narratives illustrative of this behavior among students other than themselves:

Ben: Girls are concerned with the amount of calories in alcohol ... like last night we did shots, like

four or five apiece, and the one girl who doesn’t work out didn’t say anything about the calories but

the other girl who works out was complaining about the calories and how she had worked out really

hard that day and so she ended up burning off those calories that she drank in the shots ... and so that

it ‘evened it out’ for her, she said. She wasn’t complaining about it as much as she was stating how

she was going to go work out again in order to burn more off ... she mentioned her workout that day

[needed to] equalize her drinking.

36 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

Angie’s narrative similarly illustrates the use of this diet-related behavior

to negotiate the problem of weight gain caused by the social pressure to drink

among friends, classmates, and college acquaintances.

Angie: I know people that exercise to make up for heavy nights of drinking. Some friends actually

during the day when they know they are going to go out that night will say, “Oh, we better get our

exercise in right now so we will burn calories by the time tonight comes.” This [exercising] also

happens the day before [planned drinking events].

While the behaviors described in this section were the least self-reported

among students interviewed, many students knew of other students who en-

gaged in these specific diet-related behaviors. The socio-cultural pressure to

remain or become thin or fit, couched in a culture of alcohol use, appears to

produce adaptations in students’ behavior that range from modifying eating

and drinking practices to using exercise and self-induced purging to rid the

body of excess calories.

Women and men alike reported feeling pressure from their peers to drink.

This social context represents a component of what students referred to as the

“college drinking culture.” Students felt this “drinking culture” was a signifi-

cant aspect of their college experience. While not all students reported drinking

to the point of intoxication, many students did imply that drinking implicitly

meant heavy drinking.

9

Similar to drinking pressures, both male and female students reported feel-

ing pressure to maintain or construct an “ideal” body type. In the present study,

40% of students reported concern about the calories in alcohol. To be success-

ful at meeting the demands of drinking and staying thin, students admitted to

engaging in more extreme forms of dieting activity to reconcile the two com-

peting pressures of drinking and maintaining an appropriate body shape. Im-

plications for these self-reported behaviors are discussed below.

Discussion

This study explores why diet-related behaviors might be associated with

alcohol use. A relationship between alcohol use and diet-related behavior was

evident from interviews, and therefore corroborates existing research (see Kozyk,

Touyz, and Beumont 1998; Krahn et al. 1992, 1996; Cooley and Toray 2001).

Student narratives reveal how the cultural pressures to use alcohol are inter-

twined with similar cultural pressures to conform to beauty standards. Emer-

gent themes suggest drinking behavior and efforts to comply with dominant

standards of “health” (perhaps a code word used for beauty) intertwine, rein-

Peralta 37

force, and inform one another in a body-image conscious society. These find-

ings call attention to the importance of socio-cultural pressures to conform to

perceived body-image and drinking standards and their effect on drinking be-

havior among college students.

Women in college, like men, use alcohol in part to be accepted by peers

(Wechsler et al. 2002). Historically, women have had to meet strict beauty norms

compared to men (Schur 1986). Men, however, are increasingly exposed to

rigid standards of beauty (Luciano 2001). Thus, both women and men are likely

to feel social pressure to reconcile drinking norms with the desire for a socially

acceptable body shape. While in college, cultural pressures to drink, as well as

cultural pressures to conform to body image norms, may be playing a role in

shaping drinking behaviors.

Empirical evidence for a relationship between diet-related behaviors and

drinking behaviors rooted in a socio-cultural landscape of conflicting norms

and expectations emerged from this study. What is more, this relationship was

found for both college men and women, suggesting men also are susceptible to

the interrelationship between alcohol-use norms and pressures to conform to

beauty norms. Data presented here suggest a number of women and men in the

present sample express sufficient anxiety over caloric content of alcohol to

engage in diet-related behaviors of varying severity. These behaviors appear to

be adopted specifically to avoid the possibility of alcohol-related weight gain.

Moreover, students who did not admit to engaging in these reported diet-re-

lated behaviors did mention that they were aware of friends and acquaintances

who engaged in these behaviors for similar reasons. The four specific emergent

themes identified here were: (1) altered eating patterns; (2) altered drinking

preferences; (3) use of exercise; and (4) self-induced purging. These themes

highlight how diet-related behaviors can be associated with the use of alcohol.

The first two themes can be understood as changes in consumption be-

haviors resulting from a concern for calories. Some students reported alcohol

and eating cannot fit harmoniously into their daily lives. Of the interviewed

students, 18% were categorized as students who were conscious of food and

alcohol calories and tended to eat less or skip meals altogether before or after a

night of drinking. Eighteen percent of students were found to be conscious of

the caloric content of alcohol and thus active in limiting their alcohol use or

altering the type(s) of alcohol consumed. These behaviors are reportedly being

used to enable students to conform to perceived drinking standards and to beauty

norms.

The last two themes can be understood as behaviors designed to eliminate

alcohol calories already absorbed by the body. Five percent of students re-

38 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

ported negotiating the drinking and weight gain problem through exercise. These

diet-related behaviors comprised the third theme emerging from the present

study. Finally, nearly 4% of the sample reported using self-induced purging as

a strategy to negotiate the alcohol-diet dilemma and purging behaviors do not

require students to curb their eating or drinking like the first two descriptive

categories. These behaviors allowed students to continue eating and drinking

what they desired despite competing body image norms which may have

blocked others from doing so. Concerns with body image were dealt with through

exercise or purging in the time before or after drinking events. These behaviors

can thus be understood as behaviors used to rid the body of excess calories

acquired through alcohol use.

These data have implications for university student policies. College health

professionals, college administrators, and researchers alike should consider diet-

related behaviors among men and especially among women as potential risk

factors for alcohol abuse. When considering prevention efforts, college coun-

selors, coaches, and health professionals should note body image concerns

may be associated with alcohol use. Moreover, students presenting with alco-

hol abuse problems may need to be screened for eating disorders. Finally, risks

associated with under-eating or fasting before a night of partying may need to

be included in educational presentations, pamphlets, and other alcohol-related

material distributed to college students.

It is important to note the strengths and weaknesses of this study. Con-

ducting qualitative research on college drinking is a valuable yet underutilized

technique. This methodology allows for students to discuss at length what al-

cohol use means to them and what the social processes involved in drinking

entail. The open-ended questioning technique and grounded theory approach

used here generated data rooted directly in the experiences of students. Use of

these techniques grants students the opportunity to effectively contribute to the

development of empirically rooted theories about gender, diet-related behav-

iors, drinking and alcohol among students. The question of diet-related behav-

iors was not considered at the outset of the study. Pilot interviews with students

revealed the importance and relevance of body-image consciousness and diet

behavior to the use of alcohol. In keeping with qualitative methodology, themes

concerning diet behavior in relation to alcohol use emerged on their own.

Two limitations of the present study are addressed here. First, because this

was an exploratory study designed to develop theoretical constructs and to

explore the meaning of alcohol use for college students and the social context

of college alcohol use, purposive and non-probability sampling was use. Dif-

ferent experiences may be found at universities with differing populations and

Peralta 39

locations. Our understanding of the relationship between alcohol use and diet

behavior would benefit from replicating this study at other universities. Adopt-

ing representative samples would provide generalizable and more conclusive

data about the association between drinking behaviors and diet-related behav-

ior. Second, this research cannot identify the cause-and-effect relationship be-

tween dieting behavior and drinking. Did the drinking or the diet behavior

emerge first, or did they develop simultaneously? Longitudinal work may re-

veal important patterns relevant to the etiology of drinking and dieting behav-

ior.

As with many studies, this research produced more questions than an-

swers. Drinking behaviors among female college students are especially im-

portant to understand given women’s particular risk for physical and sexual

victimization associated with alcohol use (Vicary et al. 1995; Harrington et al.

1994; Wechsler et al. 1998; Synovitz and Byrne 1998) as well as school-related

and other health-related problems unique to women. Moreover, the drinking

styles reported here (such as drinking “on an empty stomach”) may place stu-

dents, especially women, at risk for various forms of victimization and may in

turn partly explain why women who use alcohol are at elevated risk for specific

alcohol-related problems such as sexual assault, date rape, and rape (Vicary et

al. 1995; Harrington et al. 1994; Wechsler et al. 1998; Synovitz and Byrne

1998; Bachman and Peralta 2001).

Two research questions in particular emerge from this study: (1) Are women

and men who engage in the types of diet-related behavior described above at

increased risk for interpersonal violence while in college given their suscepti-

bility to higher levels of intoxication compared to those who do not diet? and

(2) What is the prevalence of these behaviors in relation to alcohol use in the

general population? While use of exercise and purging behaviors was less com-

mon for this sample compared to the first two categories of diet-related behav-

ior, it is important to determine the prevalence and incidence of these behaviors

for college students and people in general given the corresponding increased

risk for alcohol-related and health-related consequences (e.g., bulimia and an-

orexia).

Finally, one of the goals behind examining the drinking experiences of

students was to gain an understanding of student’s general experiences with

alcohol, particularly the positive and negative consequences of alcohol use.

Although there is a growing body of knowledge about the prevalence and con-

sequences of alcohol use among students (Wechsler et al. 2001), it remains

unclear how the social context of the college environment influences alcohol

use for students. What meaning does alcohol hold for these men and women,

40 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

and more importantly, what are the social processes involved in the use of

alcohol? Are alcohol use and associated concerns with body image of concern

to college students of color, and if so, how? Answers to these questions can

inform the literature on alcohol use, college health, and larger sociological ques-

tions of gender and race simultaneously.

Notes

1. I would like to thank professors Cynthia Robbins, Margaret Andersen, and Ronet Bachman for

their support and guidance on all aspects of this research. I am indebted to the insight and suggestions

made on drafts of this paper from J. M. Cruz, Ph.D., and P. Guerino. To Tricia Wachtendorf and Erin

Gladding, thank you for all your assistance in the collection and analysis of data. For the careful and

critical thought put into an earlier draft of this paper, I would like to acknowledge the anonymous

reviewers at Gender Issues. And finally, I am grateful to the students who shared with me their views

and experiences with alcohol use.

2. Alcohol problems include health problems, alcohol-related violence, problems with addiction,

and other social problems stemming from the abuse or dependence on alcohol.

3. What is more, the narrowing gender gap in substance use has not been adequately explained.

This is in part due to a lack of systematic research on the question of gender construction in substance

abuse research (Johnson et al. 2001). Socio-cultural questions related to gender issues such as “dread of

weight gain” may explain some of the lower rates of drinking we have seen and continue to see among

college women.

4. It is important to note the question of race in this research. Future manuscripts will document

systematically the racial differences emerging from the present study and their sociological implications

for alcohol abuse, race relations between and among students, and differing social constructs of beauty.

The majority of Black women interviewed (N=20) reported very little if any alcohol use. Further, Black

women did not report engaging in any dieting-related behavior associated with alcohol whatsoever.

These important racial differences speak to cultural differences as well as to the racialized space of the

college campus where the study took place (see Peralta, 2005). Thus, the data presented in this paper

speak to the experiences of White college student participants.

5. This may be due to the sampling technique employed and/or the face-to-face interview aspect

of the present study, which differs from research designs used by large, national probability samples.

6. The prevalence of “binge” drinking reported here is far below the national figures reported in

the literature. Wechsler et al. (2001) report over 40% of college students engage in risky and heavy

drinking behavior. The lower rates reported here may be an artifact of the sample. It is unknown whether

students who engage in heavier drinking practices engage in more diet-related behaviors.

7. “High-calorie” and “empty-calorie” were terms used by students to describe alcoholic bever-

ages.

8. Greg’s reference to “Girls Lite” refers to the gendered nature of alcoholic beverages. “Lite

beer” connotes a female beverage because women are expected to be more concerned with body image

than are men. Despite the fact that Greg admits to drinking lite beer, his narrative suggests men who

drink lite beers are a contradiction in terms, as men are not supposed to consume beverages meant for

women and are hence susceptible to ridicule.

9. Four or more drinks for women, five or more for men has been defined as “binge” drinking for

students in the college student alcohol use literature (see Wechsler et al. 2001).

References

Bachman, R., and R. L. Peralta. “The Relationship Between Alcohol and Violence in an Adolescent

Population: Does Gender Matter?” Deviant Behavior 23, no.1 (2002): 1-19.

Bradstock, K., M. R. Forman, N. J. Binkin, E. M. Gentry, G. C. Hoegelin, D.F. Wiliamson, and F.I.

Peralta 41

Throbridge. “Alcohol Use and Health Behavior Lifestyles Among U.S. Women: The Behavior Risk

Factor Surveys.” Addictive Behavior 13, no. 2: 61-71. 1988.

Bulik, C. M. “Drug and Alcohol Abuse by Bulimic Women and Their Families.” American Journal of

Psychiatry 144 (1987): 1604-06.

Bulik, C. M., P. F. Sullivan, and L. H. Epstein. “Drug Use in Women with Anorexia and Bulimia

Nervosa.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 11 (1992): 213-25.

Capraro, R. L. “Why College Men Drink: Alcohol, Adventure, and the Paradox of Masculinity.”

Journal of American College Health 48, no. 6 (2000): 307-16.

Connell, R. W. Masculinities. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Cooley, E., and T. Toray. “Disordered Eating in College Freshman Women: A Prospective Study.”

Journal of American College Health 49, no. 5 (2001): 229-35.

Cooley, E., and T. Toray. “Body Image and Personality Predictors of Eating Disorder Symptoms During

the College Years.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 30 (2001): 28-36.

Cruz, J. M., and R. L. Peralta. “Family Violence and Substance Use: The Perceived Effects of Substance

Use Within Gay Male Relationships.” Violence and Victims 16, no. 2 (2001): 161-72.

Grogan, S. Understanding Body Image in Men, Women, and Children. London: Routlege, 1999.

Harrington, N. T., and H. Leienberg. “Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Victim Behav-

iors Immediately Preceding Sexual Aggression by an Acquaintance.” Violence and Victims 9, no. 4

(1994): 315-24.

Hoyt, W. D., and L. R. Kogan. “Satisfaction With Body Image and Peer Relationships for Males and

Females in a College Environment.” Sex Roles 45 (2001): 199-215.

Huon, G. F., and L. Brown. “Attitude Correlates of Weight Control Among Secondary School Boys and

Girls.” Journal of Adolescent Health Care 7 (1986): 178-82.

Johnston, L. D., P. M. O’Malley, and J. G. Bachman. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on

Drug Use: 1975-2000. Vol. 2: College Students and Young Adults Ages 19-40. NIH Publication 01-

4925. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2001.

Keeling, R. P. “Social Norms Research in College Health.” Journal of American College Health 49, no.

2 (2000): 53-56.

Kozyk, J. C., S. W. Touyz, and P. J. Beumont. “Is There a Relationship Between Bulimia Nervosa and

Hazardous Alcohol Use?” International Journal of Eating Disorders 24 (1998): 95-99.

Krahn, D., C. Kurth, M. Demitrack, and A. Drewnowski. “The Relationship of Dieting Severity and

Bulimic Behaviors to Alcohol and Other Drug Use in Young Women.” Journal of Substance Abuse

4 (1992): 341-53

Krahn, D., D. Piper, M. King, C. Kurth, and D. Moberg. “Dieting in Sixth Grade Predicts Alcohol Use

in Ninth Grade.” Journal of Substance Abuse 8, no. 3 (1996): 293-301.

Lacet, J. H., and E. Moureli. “Bulimic Alcoholics: Some Features of a Clinical Subgroup.” British

Journal of Addiction 81 (1986): 389-93.

Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry. London: Sage, 1994.

Luciano, L. Looking Good: Male Body Image in Modern America. New York: Hill and Wang,

2002.

McCreary, D. R., M.D. Newcomb, and S. W. Sadava. “The Male Role, Alcohol Use, and Alcohol

Problems: A Structural Modeling Examination in Adult Women and Men.” Journal of Counseling

Psychology 46 (1999):109-124.

McCreary, D. R., and D. K. Sasse. “An Exploration of the Drive for Masculinity in Adolescent Boys

and Girls.” Journal of American College Health 48, no. 6 (2000): 297-304.

Messerschmidt, J. W. Masculinities and Crime: Critique and Re-Conceptualization of Theory. Mary-

land: Rowman and Littlefield, 1993.

O’Dea, J. A., and S. Abraham. “Eating and Exercise Disorders in Young College Men.” Journal of

American College Health 50, no. 6 (2002): 273-78.

Peralta, R. L. “Race and the Culture of College Drinking: An Analysis of White Privilege on Campus.”

In Cocktails and Dreams: An Interpretive Perspective on Drug Use. Edited by W. Palacios. Princeton,

NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2005.

Robbins, C. A., and S. S. Martin. “Gender, Styles of Drinking, and Drinking Problems.” Journal of

Health and Social Behavior 34 (1993): 302-21.

42 Gender Issues / Fall 2002

Rubin, H. J., and I. S. Rubin. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage, 1995.

Schur, E. M. Labeling Women Deviant: Gender, Stigma, and Social Control. New York: McGraw Hill,

1984.

Strasser, T. J., K. M. Pike, and B. T. Walsh. “The Impact of Prior Substance Abuse on Treatment

Outcome For Bulimia Nervosa.” Addictive Behavior 17 (1992): 387-95.

Striegel-Moore, R., and E. S. Huydic. “Problem Drinking and Symptoms of Disordered Eating in

Female High School Students.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 14 (1993): 417-25.

Sudman, S., and N. M. Bradburn. Asking Questions: A Practical Guide to Questionnaire Design. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1982.

Synovitz, L. B., and T. J. Byrne. “Antecedents of Sexual Victimization: Factors Discriminating Victims

From Non-Victims.” Journal of American College Health, 46 (1998): 151-58.

Thompson, J. K., and G. D. Levy. “Effects of Potential Partners’ Costume and Physical Attractiveness

on Sexuality and Partner Selection.” The Journal of Psychology, 124 (1998): 371-89.

Thompson, A. M., and K. E. Chad. “The Relationship of Social Physique Anxiety to Risk for Developing

an Eating Disorder in Young Females.” The Journal of Adolescent Health, 31 no. 2 (2002): 183-89.

Tomsen, S. “A Top Night: Social Protest, Masculinity, and the Culture of Drinking Violence.” British

Journal of Criminology 37 (1997): 90-97.

Vicary, J. R., L. R, Klingaman, and W. L. Harkass. “Risk Factors Associated with Date Rape and Sexual

Assault of Adolescent Girls.” Journal of Adolescence 183 (1995): 289-306.

Wechsler, H., A. Davenport, G. W. Dowdall, B. Moeykens, and S. Castillo. “Health and Behavioral

Consequences of Binge Drinking in College: A National Survey of Students At 140 Campuses.”

Journal of the American Medical Association 21 (1994):1672-77.

Wechsler, H., B. Moeykens, A. Davenport, S. Castillo, and J. Hansen. “The Adverse Impact of Heavy

Episodic Drinkers On Other College Students.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56 (1995): 628-34.

Wechsler, H., T. Nelson, and E. Weiztman. “From Knowledge To Action: How Harvard’s College

Alcohol Study Can Help Your Campus Design a Campaign Against Student Alcohol Abuse.”

Change 32, no. 1 (1996): 38-43.

Wechsler, H., G. W. Dowdall, G. Maenner, J. Gledhill-Hoyt, and H. Lee. “Changes in Binge Drinking

and Related Problems Among American College Students Between 1993 and 1997: Results From

the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study.” Journal of American College Health

47 (1998): 57-68.

Wechsler, H., K. Kelly, E. R. Weitzman, J. P. San Giovanni, and M. Seibring. “What Colleges Are

Doing About Student Binge Drinking.” Journal of American College Health 48, no. 5 (2000): 219-

27.

Wechsler, H., J. E. Lee, M. Kuo, M. Seibring, T. F. Nelson, and H. Lee. “Trends in College Binge

Drinking During a Period of Increased Prevention Efforts: Findings From Four Harvard School of

Public Health College Alcohol Surveys: 1993-2001.” Journal of American College Health 50, no. 5

(2002): 203-17.

West, C., and D. H. Zimmerman. “Doing Gender.” Gender and Society 1 (1987): 125-51.

West, C., and S. Fernsermaker. “Power, Inequality, and the Accomplishment of Gender: An

Ethnomethodological View”. In Theory on Gender/Feminism on Theory (pp. 151-74). Edited by P.

England. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1993.

West, L. A. “Negotiating Masculinities in American Drinking Subcultures.” Journal of Men’s Studies 9

(2001): 371-92.

Wilsnack, R. W. and S. C. Wilsnack. Gender and Alcohol: Individual and Social Perspectives. New

Brunswick, NJ: Alcohol Research Documentation, 1997.