NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

Carol Rees Parrish, MS, RDN, Series Editor

32 PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders

and Gastrointestinal Disorders

Theresa Hedrick, MS, RDN, LD

Registered Dietitian Nutritionist, Oregon

Nutrition Counseling, LLC, Corvallis, OR

Eating Disorders (EDs) have a direct physiological effect on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and

microbiota, which can lead to GI dysfunction. Additionally, there is a higher prevalence of EDs among

individuals with disorders affecting the GI tract compared to those without GI disorders. Several

simple screening tools exist to help clinicians identify EDs and should be utilized before prescribing a

restrictive diet. If an ED is detected, connections to an ED-specialized registered dietitian nutritionist

and mental health provider should be facilitated. This article reviews the connection between eating

disorders and GI disorders as well as provides ways to identify and manage EDs in the GI population.

Theresa Hedrick

INTRODUCTION

I

deally, eating is a exible behavior that balances

internal needs (e.g., hunger and satiety cues,

food preferences, nourishment needs, etc.)

with external constraints (e.g., food availability,

personal schedule, acceptable social behavior, etc.).

It is generally a neutral to positive experience to the

person eating. Thoughts about desired foods and

meal planning are a part of daily life, but do not take

up a disproportionate amount of time relative to

other tasks. Disordered eating involves food-related

behaviors that have a negative physiological and/or

psychological impact, yet do not meet the criteria

for an eating disorder diagnosis. Examples include

rigid self-imposed rules around food, feelings of

anxiety, guilt or shame associated with eating,

frequent dieting, a preoccupation with food, a loss

of control around food, and restricting intake to

compensate for eating “bad” foods. The severity of

these behaviors exists along a continuum, and some

of these behaviors are socially acceptable despite

not being supportive of health. An eating disorder

(ED) is a specic severity of disordered eating

that meets the criteria outlined in the American

Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022 33

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

There is some evidence that gut microbiota

could have a role in the initiation and progression

of anorexia nervosa (AN) by acting on the gut-

brain axis to distort hunger and satiety cues,

alter brain function, and disrupt gut barrier

function.

18

Restricted food intake in AN may

contribute to dysbiosis by lowering microbial

diversity, decreasing butyrate-producing bacteria,

and increasing mucin-degrading bacteria.

12,18,20

Additional research is needed to further elucidate

the bidirectional relationship between AN and the

microbiota, examine the role of and effects on the

microbiota in other EDs, and investigate potential

microbiota-targeted interventions.

EDs can cause GI dysfunction as a direct

physiologic result of restricting food intake,

purging, or weight loss.

3,5,21

As the body is denied

essential nutrients, GI motility is slowed, and GI

hormone release is altered.

3,19

Esophageal motility

is usually unaffected in AN, but patients can have

dysphagia, heartburn, and regurgitation.

2,3,19,21

Delayed gastric emptying is common in AN and

bulimia nervosa (BN), as are complaints of early

satiety, postprandial fullness, epigastric discomfort,

bloating, and nausea.

2,3,19,21

There have been reports

of gastric bezoars and need for gastric dilation in

AN.

2,21

Gallstones have been reported in those with

signicant weight loss.

3

Lack of food intake can

cause a reduction in the absorptive surface area of the

small intestine,

3,21

altered nutrient and ion transport,

and increased permeability to macromolecules.

18

Delayed gut transit time is common in AN and

BN.

2,19,21

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA)

syndrome in AN has also been reported due to loss

of the mesenteric fat pad between the abdominal

aorta and the SMA.

2,3,19,21

Constipation is common

in AN and BN for a variety of reasons including

smooth muscle atrophy, electrolyte abnormalities,

delayed intestinal transit, sick euthyroid syndrome,

and pelvic oor dysfunction.

2,3,19,21

Hepatic injury

and noninammatory brotic injury to the pancreas

are possible due to malnutrition from AN.

2,21

All of

these symptoms will improve with refeeding.

2,3,5

Specic to BN where purging is done by

vomiting, it is common for individuals to experience

heartburn, spontaneous vomiting, regurgitation,

chest pain, dysphagia, and nocturnal aspiration

when lying supine due to weakening of the lower

esophageal sphincter.

2,3,19,21

Mallory-Weiss tears

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth

Edition (DSM-5).

1

The consequences of EDs can affect any body

system, with impacts on the gastrointestinal (GI)

tract being particularly prevalent.

2,3

Postprandial

fullness and abdominal distention are the most

common GI complaints among individuals with

EDs, followed by bloating, early satiety, abdominal

pain, nausea, constipation, heartburn, and gastritis.

3

EDs can occur before, during or after the onset of

GI symptoms.

4

Individuals with GI disorders are more likely

to display disordered eating than healthy controls;

5

those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in

particular are more likely to engage in disordered

eating behaviors (missed meals, irregular mealtimes,

not eating when hungry, vomiting after eating)

than healthy controls.

7-9

Dietary restriction to

manage GI symptoms may be an expected adaptive

response in some patients given that up to 90% of

individuals with IBS attribute their GI symptoms

to certain foods.

10

It may also be a maladaptive

coping mechanism in others as the severity and

duration of IBS have been positively correlated

with the number of ED symptoms/characteristics

self-reported on a standardized questionnaire.

11

EDs have one of the highest mortality rates

of any psychiatric illness.

3,12

There are numerous

adverse physiological consequences of EDs;

psychological comorbidities such as self-harm and

suicide are common. Therefore, it is important to

consider EDs when managing GI patients. This

article reviews reasons GI conditions and EDs

overlap, as well as how to identify EDs in the GI

patient and intervene for those individuals.

Why Eating Disorders and GI Disorders Overlap

EDs may exacerbate pre-existing GI disorders.

There is evidence of an increased prevalence

of EDs compared to the general population in

individuals with conditions such as celiac disease,

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and postural orthostatic

tachycardia syndrome.

13-15

Associations have also

been seen between EDs and both food allergies

and inammatory bowel disease.

16,17

Once an ED

has developed, it can be difcult to discern which

symptoms are due to the concurrent disease state

versus the ED.

34 PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

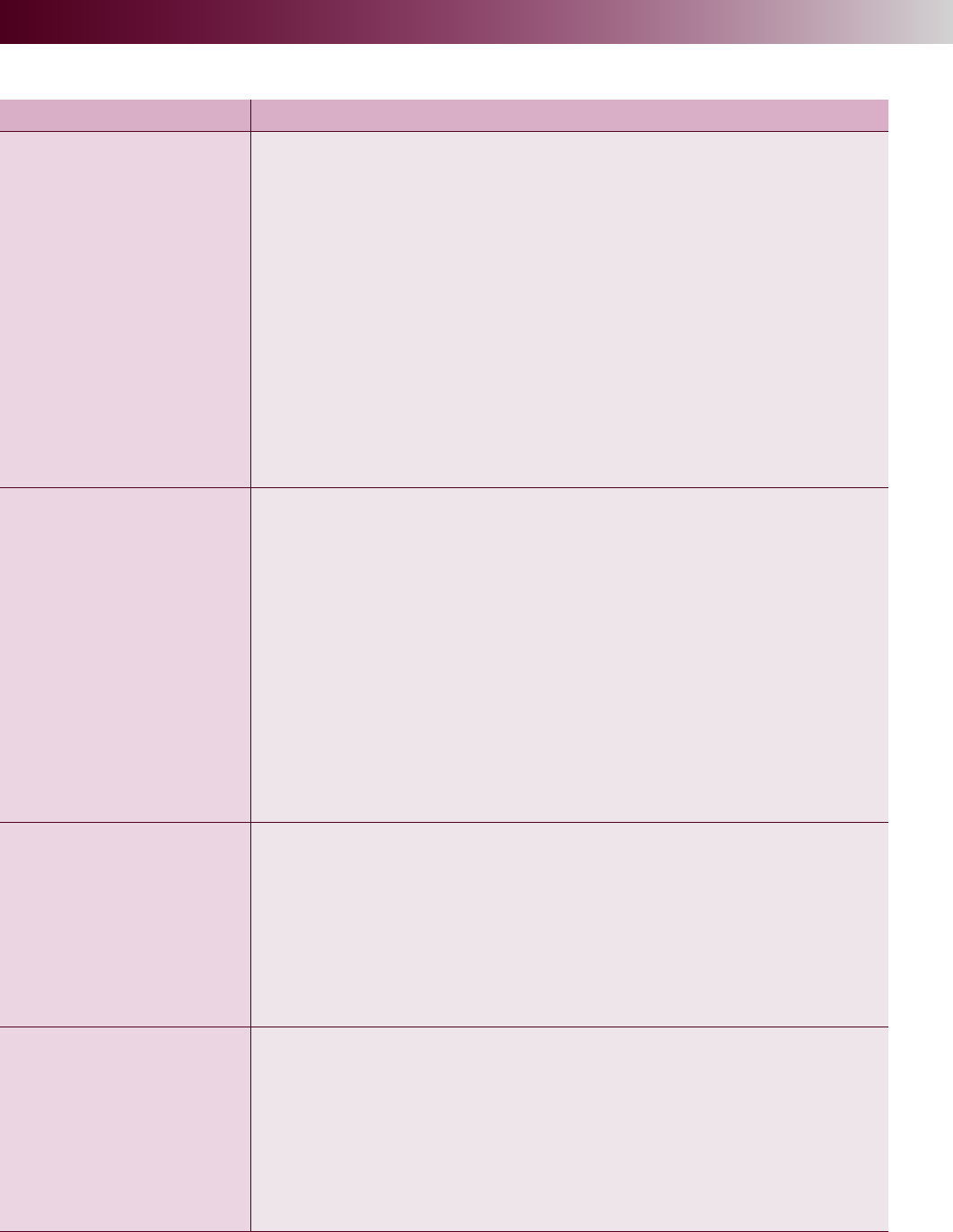

Table 1. GI Symptoms Associated with Eating Disorders

2,3,5,19,21,22

Eating Disorder Possible GI Symptoms

Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

·Dysphagia

·Heartburn

·Regurgitation

·Delayed gastric emptying

·Early satiety

·Postprandial fullness

·Epigastric discomfort

·Bloating

·Nausea

·Gastric bezoars

·Gallstones

·Delayed gut transit time

·Superior mesenteric artery syndrome

·Constipation

·Hepatic injury

·Pancreatic noninflammatory fibrotic injury

Bulimia Nervosa (BN)

·Delayed gastric emptying

·Early satiety

·Postprandial fullness

·Epigastric discomfort

·Bloating

·Nausea

·Heartburn

·Spontaneous vomiting

·Regurgitation

·Dysphagia

·Nocturnal choking when supine

·Mallory-Weiss tears

·Delayed gut transit time

·Constipation

·Rebound constipation & fluid retention with cessation of laxative abuse

Binge Eating Disorder

(BED)

·Heartburn

·Regurgitation

·Dysphagia

·Bloating

·Diarrhea

·Fecal urgency

·Fecal incontinence

·Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

·Altered perception of satiety

Avoidant Restrictive Food

Intake Disorder (ARFID)

·Loss of appetite

·Dysphagia

·Esophagitis

·GERD

·Gastroparesis

·Gastritis

·Abdominal pain

·Nausea

·Constipation

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022 35

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

may occur

21

and individuals with BN may be at

risk for Barrett’s esophagus from frequent exposure

of esophageal mucosa to acidic emesis.

3,5

When laxatives are used to purge in BN, it

is common to see electrolyte abnormalities,

dizziness, and dehydration.

3,19,21

Individuals can

also experience rebound constipation and uid

retention (cathartic colon syndrome) if laxatives

are stopped.

3,19,21

In binge eating disorder (BED), binge

behavior can lower esophageal sphincter pressure,

exacerbating heartburn and regurgitation, while

the acid reux can potentially lead to dysphagia.

19

Other possible impacts of BED on the GI system

include bloating, diarrhea, fecal urgency, fecal

incontinence, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,

and altered perception of satiety.

2,5,19,21

The most common GI complaints in those

with ARFID are nausea, constipation, loss of

appetite, and abdominal pain.

22

Dysphagia,

esophagitis, gastroesophageal reux disease

(GERD), gastroparesis, and gastritis have also been

reported.

22

See Table 1 for a list of GI symptoms

associated with each type of ED.

Recovery from an ED can also trigger GI

issues. When an individual increases their

energy intake after restricting food intake, it can

take weeks to months for their slowed motility

to return to normal depending on how quickly

the individual’s nutritional status and weight

are restored.

3,5

Because they are trying to eat an

increased amount with a slowed transit time,

they can experience early satiety, postprandial

fullness, abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating, and

distention. These symptoms are disconcerting to

the individual experiencing them. However, if they

continue to consume enough to meet their energy

needs despite the increase in GI symptoms, motility

will normalize, and symptoms will resolve. This

generally happens within a month of eating enough

to fully meet energy needs.

3

If the individual is

eating more than they used to, but is still in a

relative energy decit, this phase can be drawn out.

Screening for Eating Disorders

There are two validated screening tools to help

identify EDs for use in the primary and specialist

care settings: the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary

Care (ESP) and the Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food

(SCOFF) (Table 2).

23

These are not diagnostic;

rather, they indicate whether further investigation

is warranted. In general, 0-1 abnormal answers rule

out an ED. Two or more abnormal answers should

prompt a more complex assessment. In addition to

the screening tool questions, asking a patient to,

“Tell me about your relationship with food,” may

be helpful. If further information is needed, asking

hypothetical questions to the effect of, “Would

you be willing to eat more food if it resolved

(continued on page 43)

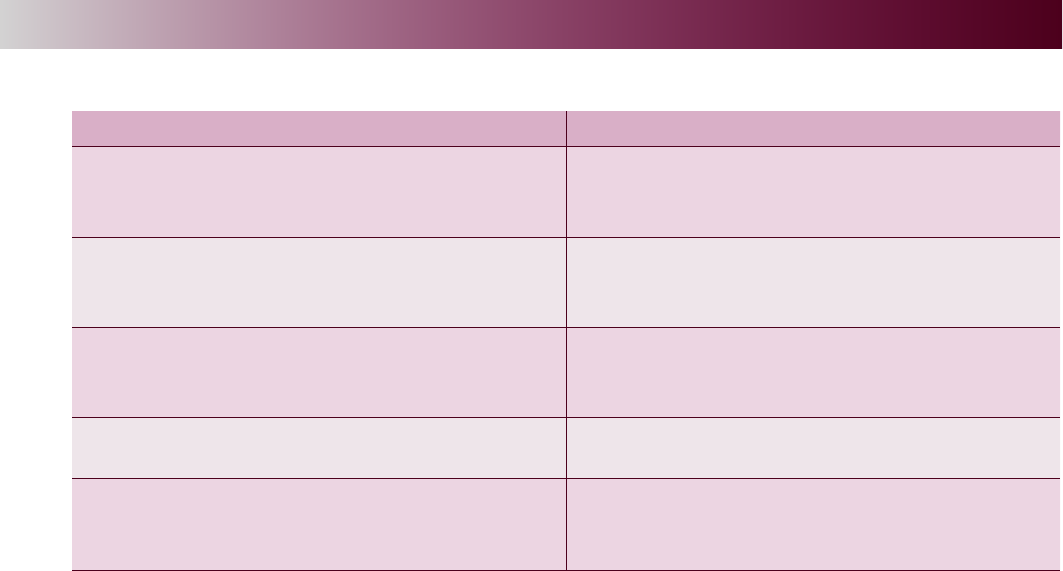

Table 2. Eating Disorder Screening Questions

23

ESP (Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care) SCOFF (Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food)

• Are you satisfied with your eating

patterns? (A “no” to this question is

considered an abnormal response).

• Do you make yourself Sick because you

feel uncomfortably full?

• Do you ever eat in secret?

(A “yes” to this and all other questions

is considered an abnormal response).

• Do you worry you have lost Control over

how much you eat?

• Does your weight affect the way you

feel about yourself?

• Have you recently lost more than One

stone (14 lb or 7.7 kg) in a three-month

period?

• Have any members of your family suffered

with an eating disorder?

• Do you believe yourself to be Fat when

others say you are thin?

• Do you currently suffer with, or have you

ever suffered in the past with an eating

disorder?

• Would you say that Food dominates your

life?

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022 43

your GI symptoms?” or “Would you be willing

to gain weight if it resolved your GI symptoms?”

might also provide insight. Responses that express

rigidity, anxiety, shame, fear of judgement around

food, or an intense fear of weight gain may indicate

an ED. When determining if ED behaviors like

vomiting or laxative abuse are present, ask direct,

specic questions. Examples of these include,

“How often do you make yourself vomit?” and

“How often do you use laxatives when you are

not constipated?” Individuals with EDs may not

volunteer information about these behaviors.

Food-related fear and avoidance in individuals

with food intolerance are not always pathological.

However, if a patient is not distressed by multiple

dietary restrictions that would seem burdensome to

others, it may be a red ag. For example, restricting

dairy, wheat, and corn would eliminate many of the

foods Americans eat regularly and make it difcult

to consume an adequate balanced diet without a

tremendous amount of preplanning. If a patient

presented restricting those items, but did not feel

bothered by the inconvenience or limited choices,

it would be a red ag for an ED.

If a patient following a restrictive diet is

reluctant to reintroduce foods to their diet, it may

represent anxiety about the consequences of food

reintroduction or it may be a red ag for an eating

disorder. To elucidate, inquire about how restricting

is serving them. For a patient afraid of how the food

reintroduction may impact their quality of life or

activities of daily living, there may be a way to

work together and/or with a registered dietitian

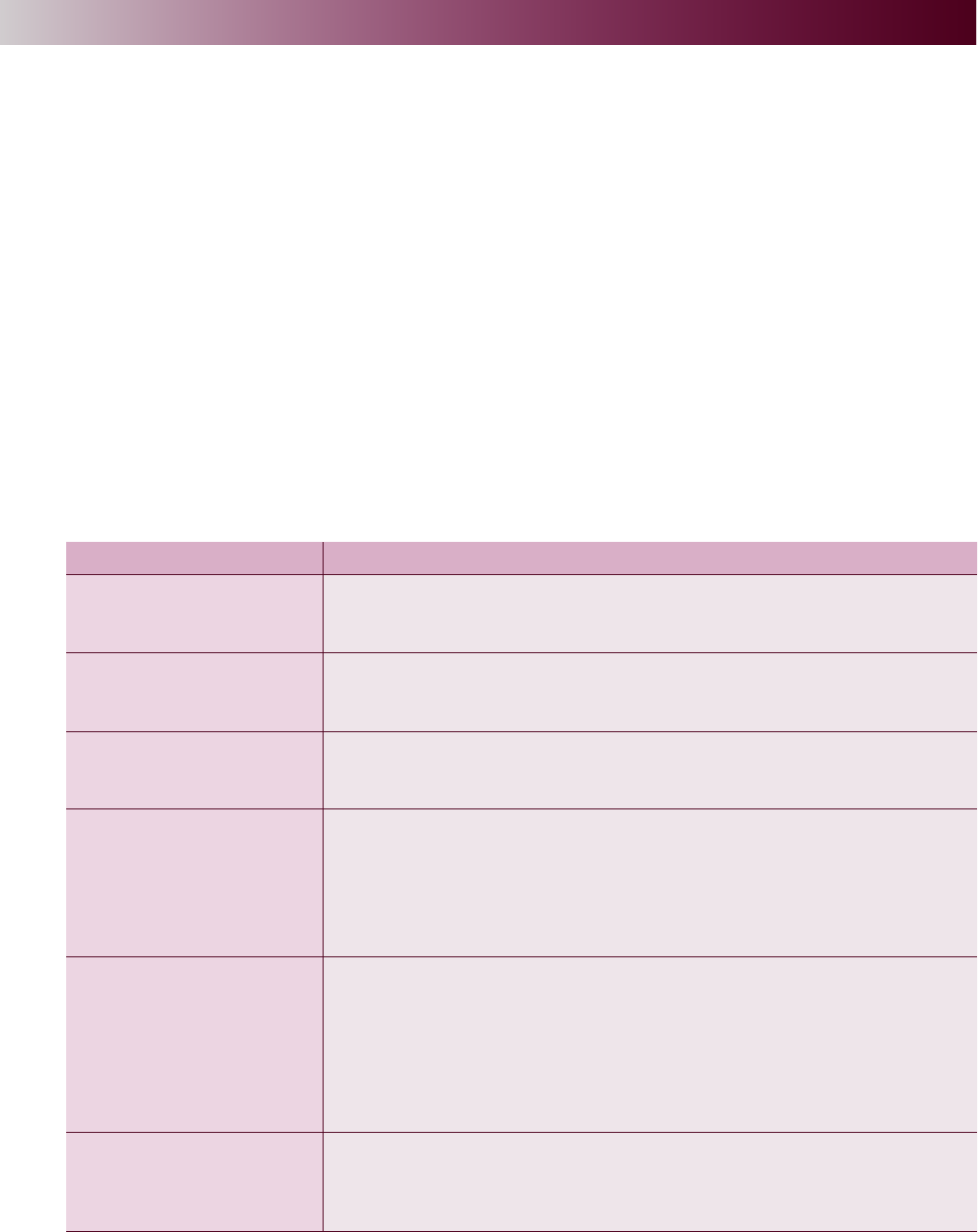

Table 3. Summary of Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

1,30

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Criteria

Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

·Restricted energy intake

·Intense fear of gaining weight

·Disturbance in the way weight/shape experienced

Bulimia Nervosa (BN)

·Episodes of binge eating

·Compensatory behavior to offset food intake

·Disturbance in the way weight/shape experienced

Binge Eating Disorder

(BED)

·Episodes of binge eating

·Marked distress about binge

·No compensatory behaviors

Avoidant Restrictive Food

Intake Disorder (ARFID)

Eating/feeding disturbance associated with ≥1 of the following:

·Significant weight loss (or failure to gain height or weight as expected in

children)

·Significant nutritional deficiency

·Dependence on enteral feeding or oral supplements

·Marked interference with psychosocial functioning

Other Specified Feeding or

Eating Disorders (OSFED)

(Previously Eating

Disorder Not Otherwise

Specified)

Behaviors do not meet the strict diagnostic criteria for one of

the other eating disorders, but are still significant including:

·Atypical Anorexia Nervosa

·Bulimia Nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration

·Binge Eating Disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration

·Purging Disorder

·Night Eating Syndrome

Orthorexia*

·Pathological preoccupation with healthy eating

·Emotional consequences from non-adherence to self-imposed nutrition

rules

·Psychosocial impairment

*Not a separate diagnosis per the DSM-5. Considered an OSFED diagnosis.

(continued from page 35)

44 PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM–5).

1

EDs do not always fall neatly into categories.

For example, purging by vomiting does not

necessarily indicate bulimia nervosa; a diagnosis

of anorexia nervosa – binge/purge subtype might

be more tting. Being in a larger body does not

indicate binge eating disorder (BED); one could

have atypical AN. BN and BED are characterized

by objective binges, but individuals with AN may

report subjective binges.

What Clinicians Should Know

About Eating Disorders

The initiation of a weight loss diet can lead to the

development of an ED.

27

There is a lack of research

as to whether restrictive diets could precipitate a

similar progression, but a greater adherence to a

low-FODMAP diet has been associated with ED

behavior.

26

EDs do not have “a look.” Many individuals

with EDs fall within a normal BMI range.

5

Any ED

behaviors disclosed to a healthcare provider should

be taken seriously. Having ED behaviors dismissed

by a healthcare provider because the patient does

not appear thin enough may reinforce the ED and

delay treatment.

Individuals do not choose to have EDs.

28

There

is a strong genetic component to EDs inuenced

by hormonal, developmental, and environmental

pressures to initiate the illness.

28,29

Individuals

can choose to recover, but it is often not an easy

decision to come to or pursue for a multitude of

reasons such as resources, life circumstances,

ineffectiveness of prior treatment, and a lack of

availability of appropriate programs.

The duration of EDs is protracted, relapses are

common, and many individuals with EDs never

achieve recovery. If ED behaviors are lessened

but not fully resolved, the remaining ED behaviors

can continue to cause GI symptoms for the reasons

discussed earlier.

Individuals with EDs may knowingly or

unknowingly be looking for a physiological cause

of their symptoms. Both dismissing and repeatedly

evaluating GI complaints can have adverse effects

on ED recovery.

3

Ambivalence towards treatment is common in

EDs. The individual may recognize that their eating

nutritionist to empower them to partially or fully

liberalize their diet while mitigating the risks. For

example, if a patient is worried that reintroducing

a food could cause diarrhea while at work, the food

reintroduction trial could be done on the weekends

and/or the concerns could be offset with the use of

a medication or supplement. Or, if abdominal pain

is a primary complaint, implementing a medication

that lowers visceral hypersensitivity prior to

reintroducing foods might be helpful. Feeling

strongly about the need to keep the diet limited

without being able to give clear concrete reasons

as to why, or having an excessive fear of mild GI

consequences, may be suggestive of an ED.

Alternatively, reluctance to add foods back to

the diet may indicate an ED that is capitalizing on

a medically or socially acceptable reason to restrict

food. Making statements about being “healthy”

and adopting vegetarian or vegan diets are some

ways that people with EDs begin restricting in

socially acceptable ways.

24,25

A registered dietitian

nutritionist can conduct an in-depth assessment of

nutrition status and food-related behaviors when

a physician’s practice setting does not allow time

for detailed determination.

It is important to screen for ED risk before

further restricting an individual’s diet. It is generally

not recommended to initiate an elimination diet in a

patient with an ED or a history of an ED. However,

there may be instances where it is appropriate to

guide a patient through a modied version of a

necessary diet, while emphasizing the non-food

interventions like psychoeducation, medications or

supplements (motility agents, prebiotics, probiotics,

herbal supplements, etc.), toilet positioning and

routine, hypnotherapy, psychotherapy, etc. This

is best done under the supervision of a registered

dietitian experienced in eating disorders. Continued

screening for EDs is prudent given the association

between restrictive diets and ED behaviors.

26

Prevention of EDs is more effective than treatment.

Diagnosing Eating Disorders

Table 3 shows a synopsis of the diagnostic criteria

for anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa

(BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant

restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), other

specied feeding or eating disorders (OSFED), and

orthorexia. Full diagnostic criteria can be found in

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022 45

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

patterns are causing issues, but the ED-related

thoughts will minimize the size, scope, and impact

of those issues. For these reasons, the clinician may

need to provide psychoeducation on the connection

between food intake and the function of the GI tract

more than once. Due to minimization, individuals

with EDs may have difculty following through on

scheduling recommended appointments with ED-

specialized providers. Assisting them in making

the appointments can be helpful.

The best chances of ED recovery are when

intervention is early and aggressive. The optimal

treatment of an ED involves the individual

concurrently seeing a registered dietitian

nutritionist, mental health provider, and physician,

all who specialize in treating EDs.

CONCLUSION

In summary, EDs have direct physiological effect

on the GI tract and microbiota. Several screening

tools exist to help clinicians detect EDs and should

be used prior to prescribing a restrictive diet. If an

ED is suspected, refer the patient to a registered

dietitian nutritionist and a mental health provider

who specialize in EDs and coordinate care. Several

ED professional groups have provider directories

to assist in locating nearby ED specialists (see

Table 4).

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and Eating

Disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual

of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric

Association Publishing, Arlington, Virginia. 2013.

2. Hetterich L, Mack I, Giel KE, et al. An update on

gastrointestinal disturbances in eating disorders. Mol

Cell Endocrinol. 2019;497:110318.

3. Mehler PS. Gastrointestinal Complications. In: Mehler

PS, Andersen AE ed. Eating Disorders, 3rd Edition.

Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

2017;126-142.

4. Salvioli B, Pellicciari A, Iero L, et al. Audit of digestive

complaints and psychopathological traits in patients

with eating disorders: A prospective study. Dig Liver

Dis. 2013;45(8):639-644.

5. McGowan A, Harer KN. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

and Eating Disorders: A Burgeoning Concern

in Gastrointestinal Clinics. Gastroenterol Clin North

Am. 2021;50(3):595-610.

6. Satherley R, Howard R, Higgs S. Disordered eating

practices in gastrointestinal disorders. Appetite.

2015;84:240-250.

practicalgastro.com

Visit our Website:

PRACTICALPRACTICAL

GASTROENTEROLOGYGASTROENTEROLOGY

Table 4. Resources for Clinicians

Websites

National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA): nationaleatingdisorders.org

The Academy for Eating Disorders (AED): aedweb.org

International Association of Eating Disorder Professionals (IAEDP): iaedp.com

Books

Eating Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide to Medical Care and Complications

4th Edition 2022; edited by Mehler and Andersen

Winning the War Within: Nutrition Therapy for Clients with Eating Disorders

3rd Edition 2020 by Myers ES, Caperton-Kilburn C. Helm Publishing, Inc.

Nutrition Counseling in the Treatment of Eating Disorders

2nd Edition 2013 by Herrin and Larkin

46 PRACTICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY • AUGUST 2022

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #224

7. Bavani NG, Hajhashemy Z, Saneei P, et al. The

relationship between meal regularity with Irritable

Bowel Syndrome (IBS) in adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022.

8. Okami Y, Kato T, Nin G, et al. Lifestyle and

psychological factors related to irritable bowel

syndrome in nursing and medical school students. J

Gastroenterol. 2011;46(12):1403-10.

9. Reed-Knight B, Squires M, Chitkara DK, et al.

Adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome report

increased eating-associated symptoms, changes in

dietary composition, and altered eating behaviors:

a pilot comparison study to healthy adolescents.

Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(12):1915-1920.

10. Hayes P, Corish C, O’Mahony E, et al. A dietary survey

of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr

Diet. 2014;27(Suppl 2):36-47.

11. Kayar Y, Agin M, Dertli R, et al. Eating disorders in

patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 2020;43(10):607-613.

12. Voderholzer U, Haas V, Correll CU, et al. Medical

management of eating disorders: an update. Curr Opin

Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):542-553.

13. Nikniaz Z, Beheshti S, Farhangi MA, et al. A systematic

review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and odds of

eating disorders in patients with celiac disease and

vice-versa. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(9):1563-1574.

14. Baeza-Velasco C, Lorente S, Tasa-Vinyals E, et

al. Gastrointestinal and eating problems in women

with Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Eat Weight Disord.

2021;26:2645–2656.

15. Benjamin J, Sim L, Owens MT, et al. Postural

Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Disordered

Eating: Clarifying the Overlap. J Dev Behav Pediatr.

2021;42(4):291-298.

16. Jafri S, Frykas TL, Bingemann T, et al. Food Allergy,

Eating Disorders and Body Image. J Affect Disord.

2021;6.

17. Ilzarbe L, Fabrega M, Quintero R, et al. Inammatory

Bowel Disease and Eating Disorders: A systematized

review of comorbidity. J Psychosom Res. 2017;102:47-

53.

18. Lam YY, Maguire S, Palacios T, et al. Are the Gut

Bacteria Telling Us to Eat or Not to Eat? Reviewing

the Role of Gut Microbiota in the Etiology,

Disease Progression and Treatment of Eating

Disorders. Nutrients. 2017;9(6):602.

19. Santonicola A, Gagliardi M, Pier Luca Guarino M,

et al. Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Diseases.

Nutrients. 2019;11(12):3038.

20. Di Lodovico L, Mondot S, Doré J, et al. Anorexia

nervosa and gut microbiota: A systematic review

and quantitative synthesis of pooled microbiological

data. ProgNeuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

2021;106.

21. Bern EM, Woods ER, Rodriguez L. Gastrointestinal

Manifestations of Eating Disorders. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(5):e77-e85.

22. Cooper M, Collison AO, Collica SC, et al.

Gastrointestinal symptomatology, diagnosis, and

treatment history in patients with underweight

avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia

nervosa: Impact on weight restoration in a meal-

based behavioral treatment program. Int J Eat Disord.

2021;54(6):1055–1062.

23. Cotton MA, Ball C, Robinson P: Four Simple Questions

Can Help Screen for Eating Disorders. J Gen Intern

Med. 2003;18(1):53–56.

24. Sergentanis TN, Chelmi M-E, Liampas A, et al.

Vegetarian Diets and Eating Disorders in Adolescents

and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Children.

2021;8(1):12.

25. Zickgraf HF, Hazzard VM, O’Connor SM, et

al. Examining vegetarianism, weight motivations,

and eating disorder psychopathology among college

students. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53:1506-1514.

26. Mari, A, Hosadurg D, Martin L, et al. Adherence with

a low-FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: are

eating disorders the missing link? Eur J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 2019;31(2):178-182.

27. Memon AN, Gowda AS, Rallabhandi B, et al. Have

Our Attempts to Curb Obesity Done More Harm Than

Good?. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10275.

28. Steiger H, Booij L. Eating Disorders, Heredity and

Environmental Activation: Getting Epigenetic Concepts

into Practice. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1332.

29. Frank GKW, Shott ME, DeGuzman MC. The

Neurobiology of Eating Disorders. Child Adolesc

Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28(4):629-640.

30. Bartel SJ, Sherry SB, Farthing GR, et al. Classication

of Orthorexia Nervosa: Further evidence for placement

within the eating disorders spectrum. Eat Beha. 2020;38.

EP IGENETIC SIT

P

N M X C V P H

INUL IN

MOTILITY

T

SET N N S C M

HEED

CELIAC AGE

E

U CUE U

LURE PRE GROWTH

I

E D O I A E

AUTO IMMUNE

DR

IP

L C U A D B E A

CHART BEAUMONT

F N TAX F P I

SCHLAFEN

AFFE

CT

I E LEA P E N I

PINT

D FIBRO

SIS

12345 67

8

91011

12 13

14 15 16 17 18

19

20 21 22 23 24

25 26

27 28 29

30

31 32

33

34 35 36 37

38 39

40 41

Answers to this month’s crossword puzzle: