RANCHERS’ AGRICULTURAL

LEASING HANDBOOK:

Grazing, Hunting, and Livestock Leases

RANCHERS’ AGRICULTURAL

LEASING HANDBOOK:

Grazing, Hunting, and Livestock Leases

Tiffany Dowell lashmeT

shannon ferrell

rusTy rumley

Paul GoerinGer

Acknowledgements

e authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Ms. Cari Rincker,

owner of Rincker Law, PLLC in New York, New York, Mr. Jim Bradbury, owner

of James D. Bradbury, PLLC, in Austin, Mr. James Decker, partner at Shahan

Guevara Decker Arnott in Stamford, TX, Mr. Trace Blair, partner at Wiginton

Rumley Dunn & Blair in San Antonio, Mr. Austin Voyles, Potter County

Agricultural Extension Agent, and Fred Hall, Tarrant County Agricultural

Extension Agent who provided innumerable insights to the subject matter of this

handbook and reviewed its contents.

Disclaimer

is handbook is for educational purposes only, does not create an attorney-

client relationship, and is not a substitute for competent legal advice by an

attorney licensed in your state. e checklists and forms are provided only as

general guidance and are certainly not exhaustive. On the other hand, many

of the suggested terms may be unnecessary in all circumstances. e authors

strongly suggest that all parties consult with their own attorney when entering

into a lease agreement.

Funding

Funding for the development of these materials was provided by the USDA

National Institute of Food and Agriculture through the Southern Risk

Management Education Center, Agreement Number: 21665-05.

Author Credit

Authorship credit is as follows: Tiany Dowell Lashmet (Chapters 1, 2, 4, 5, 6,

and 7), Shannon Ferrell (Chapters 2, 3, and 4), Rusty Rumley (Chapters 8 and 9),

and Paul Goeringer (Chapters 10 and 11).

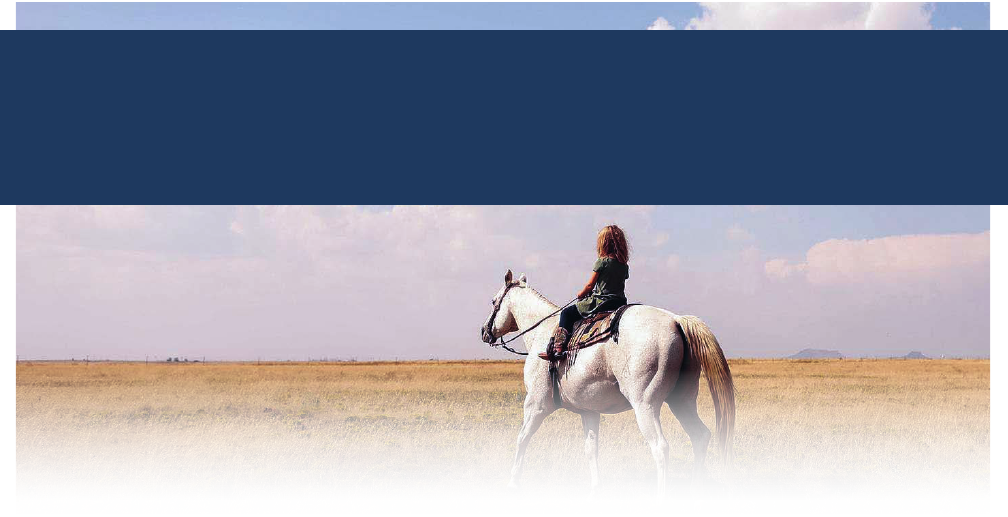

Photo Credit

Cover photo courtesy of Paige Wallace Photography, taken at Perez Cattle

Company, Nara Visa, New Mexico.

Intro photos for Chapters 1, 4, and 7 courtesy of Britt Fisk.

Contents

CHAPTER 1: Why Lease Land or Livestock?........................................1

A. Benefits of Leasing to the Lessor . ..........................................1

B. Benefits of Leasing to the Lessee .......................................... 2

CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary? ................................3

A. The Importance of Written Agreements................................... 3

B. The “Four Corners Rule”................................................... 4

C. Continuation of Lease after Sale of Property?.............................. 5

D. Ending the lease .......................................................... 7

E. Attorney Review of Written Leases ........................................ 9

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for your Lease....................................11

A. Cash Rental Agreements versus Share Rental Agreements ................11

B. Setting a Cash Rental Amount ........................................... 14

C. Setting Shares under a Share Rental Agreement..........................20

D. Pasture Lease Rates ......................................................25

E. Conclusions .............................................................28

CHAPTER 4: When can a Landowner/Lessee

be Liable for Injuries to a Third Party? .........................................29

A. Common Legal Claims ..................................................29

B. General Landowner Liability .............................................30

C. Attractive Nuisance Doctrine ............................................33

D. Landowner Liability During Lease Term .................................34

E. Recreational Use Statutes ................................................35

F. Agritourism Statutes .....................................................38

G. Farm Animal Liability Acts...............................................42

CHAPTER 5: Drafting a Valid Liability Waiver ..................................49

A. Texas Law ...............................................................49

B. Oklahoma Law .......................................................... 51

C. Conclusions .............................................................52

CHAPTER 6: Grazing Lease Checklist.............................................53

CHAPTER 7: Sample Grazing Lease ...............................................59

CHAPTER 8: Hunting Lease Checklist ............................................63

CHAPTER 9: Sample Hunting Lease ..............................................69

CHAPTER 10: Livestock Lease Checklist ..........................................73

CHAPTER 11: Sample Bull Lease ...................................................77

Appendix I (TX, OK, & AR Recreational Use Statutes)............................ 81

Appendix II (TX, OK, & AR Agritourism Statutes) ................................ 91

Appendix III (TX, OK, & AR Farm Animal Liability Acts)........................99

CHAPTER 1: Why Lease Land or Livestock? | 1

CHAPTER 1:

Why Lease Land or Livestock?

Whether a person owns land or is seeking to nd land to rent, leasing property for

grazing or hunting leases can be benecial for both parties. Similarly, both the owner

and lessee of livestock benet from lease agreements as well. According to one article,

“Leasing land can benet almost any farmer in any situation.”

1

A. Benefits of Leasing to the Lessor

For a landowner (“lessor”), leasing property can serve many purposes. First, the

payments made by the tenant (“lessee”) for a grazing lease serve as an added

source of income. is may allow a landowner to expand his or her operation

and make land payments using lease income. For example, if a family purchases

land subject to a mortgage and then leases the land to a third party for at least

the amount of the mortgage payment, the family would be able to use that lease

income to build equity in their own land. Second, a grazing lease arrangement

may allow the lessor to ensure care for the property by another, thereby avoiding

some expenses and physical eort otherwise required of the landowner. is is a

particularly desirable situation for older landowners who may no longer be able

to care for the land as they were before.

Another issue that may make leasing land desirable for a landowner involves

the special use valuation for agricultural or open space land with regard to ad

valorem taxes. Most states oer an alternative method of calculating property

taxes due on agricultural land. Rather than basing the taxes owed on the fair

market value of the land—which may be greatly in excess of the potential

agricultural income that can be derived from the property—the property taxes

are calculated based on the potential agricultural productivity value that could

be generated with prudent agricultural practices on the land. is can make

a signicant dierence in the amount of property taxes due by a landowner.

1

See Meg Grzeskiewicz, Building your farm business on leased pasture, On Pasture (May 20, 2013).

2 | CHAPTER 1: Why Lease Land or Livestock?

2

See Dan Nosowitz, USDA vows to help young farmers, but will it be enough?, Modern Farmer (Nov. 13, 2015).

3

Id.

One h-generation ranch in Texas recently reported that without the ag use

valuation method, their taxes would have been 10 times higher, making the taxes

more than the income generated from the land. If a landowner is not in a position

to satisfy the requirements for agricultural valuation, a lease may allow the

landowner to retain the benets of the special tax valuation method. Landowners

should be careful to understand the rules in their states and in their particular

appraisal district in order to ensure they are compliant with the requirements

needed to receive the special use valuation.

ird, with regard to hunting leases, a landowner can supplement his or her

income, while still farming or ranching the land the remainder of the year.

Oentimes, a landowner can run cattle or grow crops while still making a

sizable income from lease payments during prime hunting seasons. Additionally,

allowing hunters to harvest animals that may be competing with livestock for

forage can also be benecial.

Fourth, leasing livestock can be benecial for the livestock owner by allowing the

owner to retain ownership rights in the animal while generating an additional

income and seeing how the animal might produce. For example, if a cattle

rancher has a young bull, he might consider leasing the bull to a neighbor and

seeing how the calves turn out before using the bull on his own herd.

B. Benefits of Leasing to the Lessee

For a tenant, a grazing lease can provide the ability to start or grow a livestock

operation without the high capital investment needed to purchase his or her own

land. For new farmers, the extensive costs involved with getting into the industry

pose a signicant problem. As a result, statistics show that the average age of the

American farmer has risen to 58. is means that for every six farmers over the

age of 65, there is only one under the age of 35. Leasing land may be a key option

in reversing this trend by allowing younger farmers to enter into agricultural

production. Further, leased land allows the lessee to avoid having a large down

payment oen required to qualify for a mortgage to purchase land, and to avoid

paying interest or property taxes on land.

Similarly, leasing livestock can oer cost-saving benets as well. While a producer

may desire to improve the quality of herd or implement new genetics, the costs of

purchasing new livestock—particularly breeding stock—may make doing so seem

unfeasible. By leasing a breeding animal (particularly a male), a producer may

be able to obtain the new genetics at a fraction of the cost that purchasing the

animal outright would require.

Lessees and lessors alike should carefully consider the benets and obligations

oered by grazing, hunting, and livestock leases.

CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary? | 3

CHAPTER 2:

Why is a Written Lease Necessary?

Lease agreements are governed by state law. Leases are simply one type of contract,

and the principles of contract law apply. ere are several applicable legal provisions

that are important for parties negotiating a lease agreement to consider.

A. The Importance of Written Agreements

e agriculture industry is perhaps that most reliant on the handshake deal.

For decades, producers have made deals with their friends, neighbors, and other

ranchers to lease land. Although in a perfect world, a person’s handshake might

be good enough to memorialize a lease agreement, this is simply not true in the

real world.

e most important step a party to an agricultural lease can take it to put the

lease terms in writing. Here are a number of reasons why.

■

Written leases protect relationships. Oentimes, ranchers say, “I cannot ask

for a written lease; he will think that I do not trust him!” Distrust is simply

not a valid reason to obtain written lease agreements. On the contrary, written

lease agreements can actually help ensure trust and understanding between

the parties and protect the relationship between them. Leases do not have to

be one-sided but can be draed to carefully protect both parties’ interests and

investments.

■

Written leases ensure details are well thought through. When two people

verbally agree to a lease agreement, there are oentimes important details

that just did not come up and were not thought through by the parties.

When a person undertakes to put the details of an agreement on paper, many

additional thoughts, details, and issues arise. Having a written lease agreement

assists not only in memorializing the parties’ agreement but also in helping the

parties come up with the topics on which such agreement is needed.

4 | CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary?

■

Written leases protect in the event the unexpected happens. Sometimes,

life throws curveballs out of the blue. Written leases can help provide stability

in the event one of these curveballs aects a lease agreement. For example,

assume a cattle rancher leased land from his friend for the past 20 years on

an oral lease agreement without incident. Now assume the friend died, and

the land is inherited by his nephew from New York City, who has never seen

a cow, never set foot on a ranch, and has no idea what is common in a grazing

lease arrangement. e new landlord could make the tenant’s life miserable

if there were no written lease in place for the tenant to rely on to protect his

rights.

■

Some written leases must be in writing to be enforceable. A legal doctrine

known as the Statute of Frauds—which exists in some form in all 50 states—

requires that certain contracts be in writing in order to be enforceable.

Although the details of the Statute of Frauds dier by state, most states require

that at least some agricultural leases be in writing and signed by the person

against whom enforcement is sought. For example, in many states, leases

lasting at least one year must be in writing in order to be legally enforceable.

us, if a person entered into a 5-year oral grazing lease, he or she would not

be able to successfully sue for breach of contract because, pursuant to the

Statute of Frauds, the lease would not be a valid contract.

1

e specic details of the Statute of Frauds dier by State. Here is more specic

information:

• Texas: 3 Texas Business & Commerce Code Chapter 26 requires that

“a lease of real estate for a term longer than one year” be written and

signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought in order to be

enforceable.

• Oklahoma: 15 Oklahoma Code Section 15136.4 requires “an agreement

for the leasing for a longer period than one year” be written.

• Arkansas: Arkansas Code Annotated Section 4-59-101(a)(5) applies to

“any lease of lands, tenements, or hereditaments for a longer term than

one year.”

B. The “Four Corners Rule”

Another important legal principle related to lease agreements is the “Four

Corners Rule,” which deals with how courts analyze lease agreements in the

event of a dispute. e rule, applicable in most states, provides that when

analyzing a breach of contract case, a court will begin with the “four corners of

the document.” In other words, the court will begin by reading the language of

the contract.

If the contractual language is unambiguous—meaning that the language

itself clearly answers the question at hand—the court will not consider any

evidence beyond the lease language in making its decision. In this instance, the

information contained in the four corners of the lease agreement will govern.

1

ere are other legal remedies based in equity that may still be available in this situation, even if a breach of

contract claim is not an option.

CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary? | 5

If, on the other hand, the lease is silent or ambiguous on the pertinent issue, the

court could then consider other—what is called extrinsic—evidence. Examples

of extrinsic evidence include oral statements made by the parties, testimony

regarding what is common in the industry, and evidence showing the past course

of dealing by the parties.

e lesson to be taken from the Four Corners Rule is that it is absolutely critical that

every detail and every promise involved in a lease agreement be included in writing.

A party who relies on an oral statement or an industry custom could nd herself

without the ability to bring that evidence before a judge or jury based on this rule.

C. Continuation of Lease after Sale of Property?

Suppose a person has leased land for grazing for years from a landowner. en,

one day without warning, the landowner decides to sell the property to someone

the cattle rancher does not know. An important question will immediately arise:

Does the lease continue aer the property is sold? As with most legal questions,

the answer depends on the facts.

■

Texas

ere is surprisingly little Texas case law on this issue. ere does, however,

appear to be fairly settled rules that govern this situation.

First, if the lease agreement itself between the landlord and tenant addresses

the issue, the term will be enforced as written. For example, if a lease states

that the landlord shall have the right to terminate the lease if the property is

sold, then the landowner has that right. It is highly recommended that the

parties consider whether continuation of the lease (or perhaps the right to

continue the lease if desired) will occur aer the property is sold and include

this type of provision in the lease agreement. Having an express agreement

upfront about what will happen if the property is sold is the best option for all

involved.

What about a scenario where the lease is silent as to what happens if the

property is sold during the term? en the common law applies, and the

question becomes whether the new purchaser of the land was on “notice” that

the lease agreement was in place. If the new purchaser had notice, the sale

of the property does not terminate the agreement, and the new purchaser

basically steps into the shoes of the prior owner until the lease is concluded.

How, then, can notice occur?

• Record notice: A lessee can accomplish record notice by ling a

memorandum of lease or a copy of the lease agreement in the deed

records at the courthouse in the county where the property is located.

e ling would then come up in a title search and would inform

potential buyers of the lease’s existence. In this situation, even if the new

purchaser never conducted a title search and found the document, the

fact that it was led in the records would be sucient to constitute notice

and allow the lease to continue.

6 | CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary?

• Actual notice: Actual notice occurs when the purchaser is informed

of the existence of a lease. Oen, the seller, a realtor, or the tenant

could contact the potential buyer and inform him or her that the lease

agreement exists. Of course, it is always best for a tenant to do this in

writing in order to have proof that actual notice occurred.

• Constructive notice: e most dicult type of notice to prove is

constructive notice, which requires the existence of the lease to be open

and obvious to an ordinary person. For example, assume a farmer is

purchasing farmland in Texas that was owned by a woman in New York

City. Also assume that grain harvest is currently happening and the eld

is full of tractors, combines, grain carts, and semi-trucks. ese are the

types of facts that could put the new purchaser on notice that a lease

exists. However, whether a judge or jury would nd that constructive

notice existed would be determined on a case-by-case basis.

One additional issue that may arise if termination occurs during the middle

of the term involves which party has the right to harvest and sell any growing

crops. is issue is governed by the "doctrine of emblements,” which is

discussed in detail in Section D below.

■

Oklahoma

In Oklahoma, case law provides that a landowner selling land subject to a

lease is selling the landowner’s right to receive the property back to him- or

herself aer the expiration of the lease (his or her “reversionary interest”).

e general assumption of Oklahoma law is that anyone who purchases land

takes that land subject to the leases on the property at the time the purchaser

takes title to the property.

2

A land purchaser that attempts to cancel an

otherwise valid lease on the property he or she purchased may be liable to the

tenant for damages.

3

e assumption that a purchaser takes the land subject to the leases on it can

be changed by the language of the lease; for example, if the lease says that the

sale of the land terminated the lease, the lease will be enforced.

4

As with Texas, one of the most important tools in Oklahoma for protecting

landlords and tenants is the recording of the lease in the county land records.

Recording the lease is construed by the courts as providing notice to the

entire world—including any prospective purchasers of the land—that the

lease is in place.

If a lease is terminated either by sale of the property with a lease that provides

the sale terminates the lease, or if the lease is terminated for any other reason

that is not caused by the tenant (for example, termination for failure to

pay rents would be a termination caused by the tenant, but the failure of a

landlord to renew a periodic lease would not be a termination caused by the

2

See Sevy v. Stewart, 122 P. 544 (Okla. 1912).

3

See Scheer v. Cihak, 142 P. 1007 (Okla. 1914).

4

Cf. Scheer v. Cihak, 142 P. 1007 (Okla. 1914).

CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary? | 7

tenant), the tenant is entitled to either re-enter the property to harvest any

crops growing at the time of the termination or to have the crops harvested

and turned over to them.

5

D. Ending the lease

Another important issue to consider is how and when the lease may end. Again,

dierent rules apply depending on the state in which the property is located.

■

Texas

First, it is important to note that Texas law respects the parties’ rights to enter

into contractual agreements. Because of this, if the lease agreement addresses

the issue of termination and notice required, the court will respect that

agreement. For example, if the lease states a specic end date, such as “this

lease shall run from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016,” then the lease

will terminate based upon its own terms without any additional notice being

required. Similarly, if the lease provides that it lasts “from January 1, 2016

to December 31, 2016, but shall automatically renew unless written notice

is given by either party 60 days prior to the end of the lease term,” the court

would follow this agreement as well, and notice would be required to be given

in writing 60 days before the end of the term.

If, on the other hand, a lease is silent with regard to notice, Texas law will

imply requirements with regard to what notice is required to cancel the lease.

e Texas Property Code provides that if the rent-paying period of a lease

is at least one month, then at least one month notice must be given.

6

If the

rent-paying period is less than one month, the lease terminates at the later

of the day notice is given or the day following the expiration of the period

beginning on which day the notice is given.

7

With agricultural leases—particularly those involving crops such as hay or

other row crops—an issue arises with regard to a tenant’s rights if the lease is

terminated while crops are growing in the eld. As with nearly all potential

issues, the best approach for the parties is to address this issue in the lease

agreement themselves, as set forth the rights and responsibilities should this

arise. If the lease is silent as to the tenant’s rights in this situation, Texas law

provides that this issue is governed by the “doctrine of emblements.”

is doctrine provides that a former tenant has the right to re-enter the

leased property to cultivate, harvest, and remove crops that were planted

prior to the termination of the tenancy. In order for this doctrine to apply,

the following elements must be proven: (1) the tenancy was for an uncertain

duration; (2) the termination was due to an act of God or by an act of the

landlord and the termination was no fault of the tenant and was done without

his previous knowledge; and (3) the crop was planted by the tenant during his

right of occupancy.

5

See Moore v. Coughlin, 128 P. 257 (Okla. 1912), Bristow v. Carriger, 103 P. 596 (1909).

6

Tex. Property Code § 91.001(b).

7

Tex. Property Code § 91.001(c).

8 | CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary?

• Uncertain duration: In order for the doctrine of emblements to apply,

the lease at issue must be for an uncertain duration. Many times, parties

have unwritten leases or leases that have continued for years without

certain termination dates. ese leases would fall under the doctrine.

Further, a lease for a set period of time, but which could end based on

certain circumstances prior to the conclusion of the set time period is

considered to be a lease of uncertain duration for which the doctrine

can apply. For example, a lease for 5 years that provided that should the

property be sold during that time, the lease would terminate, was found

to meet this requirement.

8

Additionally, if the parties to a lease for a

certain duration agreed to allow a crop to be planted with knowledge

or agreement that harvest would occur aer the lease terminated, the

tenant may still have a right to the growing crops. Generally, however, a

lease for a specic duration of time, such as a lease that will terminate on

a certain date, would not be within the doctrine.

• Termination due to act of God or landlord and not the fault or with

knowledge of the tenant: Not surprisingly, the doctrine does not apply to

situations where the tenant is at fault for the termination. For example, if

a tenant is evicted from the property for failure to pay rent, he or she is

not entitled to harvest the crops that were planted during the lease.

• Crop planted during right of occupancy: In order for the doctrine

to apply, the crop must have been planted during the time that the

tenant was permitted access to the property. For example, if a landlord

terminated a lease in March, but the tenant trespassed and planted crops

in April, the tenant would have no right to harvest those crops. Similarly,

if the tenant knows that a landlord claims possession to the property or

that a lawsuit regarding the title of the property is pending at the time he

or she plants the crop, the doctrine oers the tenant no protection.

■

Oklahoma

In Oklahoma, a lease may provide for an end date within the lease itself.

For example, if the lease says, “this lease shall run from January 1, 2016 to

December 31, 2016,” then the lease ends on its own terms, and no additional

notice is required by either the landlord or tenant to end the lease on that

date. However, many leases may be “periodic” leases, meaning those leases

automatically renew on a regular basis unless either the tenant or the

landlord provides notice to the other party that they wish to end the lease at

the date of the next renewal. In Oklahoma, such notices must be provided in

writing, and have to be provided with the following advance times prior to

the renewal date:

• If the lease period is year-to-year, three-months’ notice.

• If the lease period is from 1to 3 months, 1-months’ notice.

• If the lease period is less than one month, one period’s notice.

8

Dinwiddie v. Jordan, 228 S.W. 126 (Tex. Ct. App. 1921).

CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary? | 9

For example, if a lease period runs from January 1 to December 31, three

months of notice means the written notice must be provided on or before

September 30.

One factor that can arise in agricultural leases is setting renewal dates (and

the corresponding notice dates) in the middle of a crop’s growth cycle. For

example, many leases have periods running from January 1 to December 31.

A notice that the lease will not be renewed could be provided as late as

September 30th, but crops such as winter wheat would already be planted by

that date. Oklahoma cases suggest that a tenant on a periodic lease who had

planted a crop without knowing the lease would not be renewed would be

allowed to re-enter the land to harvest the crop. However, the most prudent

course for both landlord and tenant is to set renewal periods and notice dates

so that both landlord and tenant can know the status of the next year’s lease

with plenty of time to make planting and other production decisions.

E. Attorney Review of Written Leases

As with all written contracts, it is extremely important to hire an attorney to

review any lease agreement before signing. Although this handbook will provide

checklists and sample lease language, it is by no means a substitute for qualied

legal counsel from an attorney licensed in your jurisdiction. Without question,

having an attorney review a lease is an additional up-front expense. It is, however,

well worth that expense if it can save a legal dispute down the road. Additionally,

because most attorneys bill by the hour, using the resources in this handbook to

prepare a dra lease agreement for an attorney to review, rather than having the

attorney start from scratch, will likely save time and, therefore, money.

How, then, does a person go about nding a knowledgeable attorney to review a

grazing, hunting, or livestock lease agreement? ere are a number of resources

available to assist people in nding attorneys well-versed in agricultural law.

First, the authors of this textbook have numerous connections with agricultural

attorneys across the country and would be happy to assist with locating attorneys

in specic states. Second, the American Agricultural Law Association is the

national membership organization for agricultural attorneys. e executive

director maintains a list of members in all 50 states. ird, attorneys must

register with the State Bar Association in all states in which they are licensed to

practice. Generally, these registrations include seeking information about areas

of practice for attorneys, which may help a person to determine which attorneys

practice agricultural law.

In trying to determine which attorney to hire, the following factors may be useful

in selecting the right representation for an agricultural lease.

• Can you have an intelligent conversation with the attorney?

Unfortunately, not all attorneys are easy to communicate with. In order

for you to obtain the best representation, it is essential that you can easily

communicate with your attorney. You need to be able to understand your

attorney, and your attorney needs to listen carefully and understand you.

ere will need to be an open dialogue between you and your attorney,

10 | CHAPTER 2: Why is a Written Lease Necessary?

and the conversation will likely, at some point, include dicult or

uncomfortable issues. Ensuring that you can communicate well with your

attorney is a key rst step in evaluating who to hire.

• Does he or she promptly return emails and phone calls? e biggest

complaint against attorneys with state bar associations is failure to keep a

client informed of the status of the case with the prompt return of emails

or phone calls. Now, it is important to be realistic in this expectation, as

your attorney has other cases and clients to tend to as well. A good rule

of thumb is that an attorney should respond to you in some way within

24 to 48 hours of you contacting them. is may be a returned phone call

or email discussing the issues you wish to raise, or it may just be a short

email letting you know that he or she is in court but setting a time to talk

in the future. is is something that can be determined by vising with

other clients of the attorney, and by making a phone call or two to the

attorney early on in the process to see how he or she responds.

• Does he or she have experience with the specic legal issue you are

dealing with? One misconception a lot of people have about attorneys is

that in law school, we learned the law, all of it. Sometimes, people expect

an attorney to be able to answer any question from agricultural leases

to DWIs, divorce to patent law. e truth is, it is nearly impossible for

an attorney to be procient in every area of the law! It is important that

you nd an attorney who is capable of handling your specic legal issue.

For example, it may well be that a general practitioner can easily help

you prepare an estate plan, dra a will, and litigate a breach of contract

dispute. If, however, you end up in a complex water law case before

the United States Supreme Court, you may need to bring in another

attorney to assist you. During the initial consultation, be sure you ask

the attorney about his or her experience with your specic legal issue.

• Does the attorney know the dierence between a cow and a bull?

ose of us involved in agriculture may take for granted that everyone

understands farming and ranching. If you have a legal issue for which

a background in agriculture is important, you may want to consider

seeking an attorney who has that type of background. is is not to say

that only attorneys who own cattle are worth hiring, but it is something

to consider depending on your specic legal issue.

• Is the fee structure clear to you? Everyone knows that attorneys are

expensive. ere is no real way to sugar coat that. It is important for

you to understand the fee structure that a prospective attorney will

be using. Oentimes, attorneys bill a set fee per hour worked. Other

times, attorneys may quote a at rate to handle one project (i.e., a will).

Still other times, an attorney might take a case on a contingency basis,

meaning you do not pay upfront, but will share some portion of the

eventual recovery with the attorney. Make sure you understand the

approach that will be taken for your case and ask questions like who

pays for fees such as copying or legal research database charges, how

oen billing statements will be coming in the mail, and exactly how a

contingency fee will be calculated.

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 11

CHAPTER 3:

Setting Payments for your Lease

Note: is chapter is adapted from “Fixed and Flexible Cash Rental Arrangements

for your Farm,” North Central Farm Management Extension Committee Publication

NCFMEC-01, “Crop Share Rental Arrangements for Your Farm,” North Central Farm

Management Extension Committee Publication NCFMEC-02, and “Pasture Rental

Agreements for your Farm,” North Central Farm Management Extension Committee

Publication NCFMEC-03.

As you will see in this handbook, numerous considerations go into writing a lease

agreement for your agricultural land. Chapter 2 emphasized the importance of

a written lease and the fact that the process of negotiating the lease can help the

landowner and tenant think through a number of issues. at process can prevent a

lot of problems before they even occur. Similarly, a thorough discussion of how rents

will be paid encourages the parties to think not only about the economics of their

arrangement but also about how both parties will cooperate in the management of the

property.

A. Cash Rental Agreements versus Share Rental

Agreements

Traditionally, rental agreements fell into two categories: a “cash rent”

arrangement in which the tenant paid a specic dollar amount in rent or a

“share rent” arrangement in which the tenant gave the landlord a share of the

crop produced from the land (usually with the landlord and tenant sharing in

the input costs for growing the crop). Recent years have seen the development

of many varieties of these two basic arrangements. Before committing to either

category of arrangements, though, both landlords and tenants need to consider

the potential advantages and disadvantages of each arrangement.

12 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

1. Cash Rental Agreements

Cash rental arrangements are generally considered the most straightforward

rental arrangements since the tenant makes a pre-determined lease payment

on a regular basis, and the landlord provides little or no input into the

management decisions for the land during the period of the lease. Even in

a cash rental agreement, though, there are a number of considerations to

ponder for both landlord and tenant.

a. Advantages of Cash Renting for Landlords

Perhaps the most easily identied advantage of cash rental agreements for

landlords is their simplicity. As mentioned above, the landlord does not

have to involve him- or herself in production or marketing decisions. is

can be an important advantage for a landlord with little or no experience

in operating agricultural land (note, though, that this does not mean the

landlord should be uninterested in the management of the property and

just wait on the “mailbox money” to come in). Fixed cash rental payments

also shi virtually all of the price, cost, and production risk of the crop to

the tenant, leaving the landlord only with the nancial risk of the tenant’s

ability to pay. Landlords relying on lease payments to support them in

retirement may nd this an important benet. Further, income under

xed cash rental arrangements is not considered self-employment income

(and thus is not subject to self-employment tax) and does not reduce Social

Security benets if the landlord is retired.

b. Disadvantages of Cash Renting for Landlords

Although cash rental agreements can be simple, determining a rental

rate can be dicult, as discussed below. Further, once that rate is set,

psychological factors may make it dicult to change the rate even though

several market forces may suggest a change is needed. e transfer of risk

to the tenant means the tenant not only bears “downside” risk (the risk

that input costs might increase, commodity prices might decrease, or that

production may be low) but that they get all the advantages of “upside”

risk (input costs decrease, commodity prices increase, or production

increases). ere may also be fewer alternatives for tax management

compared to a share lease (the reason for this is discussed below with

share rental agreements). Finally, there are some incentives for tenants to

“mine” the land’s nutrients—especially under a short-term lease—since

the tenant’s prots under a xed cash lease come from increasing yields

while minimizing costs such as fertilizer or soil amendments. However,

longer term leases and well-written leases can signicantly reduce these

risks.

c. Advantages of Cash Renting for Tenants

Tenants in a cash rental agreement have signicant freedom in their

management decisions since there is little or no requirement for

management input from the landlord. e pre-determined nature of the

rental payment makes the cost of operation xed, which provides more

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 13

stability in projecting costs for the year(s) ahead. Since they bear the

majority of risks in production, the tenant can reap all the “upside” risk in

crop production if prices and/or production conditions are favorable.

d. Disadvantages of Cash Renting for Tenants

Bearing virtually all of the risk in a cash rental arrangement, the tenant

may have diculty making rental payments if economic conditions have

been dicult. Psychologically, even if conditions have been dicult for a

number of several consecutive years, landlords may not adjust rental rates

downward. Finally, the tenant faces the cash-ow issues of bearing all

costs of crop inputs (compared to a share arrangement where the landlord

participates in the purchase of crop inputs).

2. Share Rental Agreements

In a share rental agreement, the landlord and the tenant are both actively

involved in the production of the crop. Both parties participate in the

management decisions and the costs of growing and marketing the crop. e

rent paid is a proportion of the crop produced, which can be paid either by

turning over part of the physical commodity itself or paying the landlord that

proportion of the revenue from the sale of the crop by the tenant.

a. Advantages of Share Renting for Landlords

Share rental agreements naturally result in the sharing of risk between the

landlord and tenant. As a result, the benets of a “good year” are shared

by both parties. is enables the landlord to capture some of the “upside

risk” involved in production. If the landlord is an experienced producer,

they can use that experience to aid the tenant in management decisions,

which hopefully increase the returns to the landlord. Since the landlord

is actively involved in the agricultural operation of the land, they can use

that participation to build Social Security base since their income from

the rent is subject to self-employment tax, and the landlord can also take

advantage of Internal Revenue Code Section 179 depreciation on capital

investments made in the agricultural operation.

b. Disadvantages of Share Renting for Landlords

e risk of a “bad year” means the landlord’s returns are subject to the

same variability as those of the tenant. is can mean share leases may

provide too much risk for landlords depending on rents for their primary

source of income. Depending on the nature of the landlord’s involvement,

the income from the lease may also reduce the amount of Social Security

benets for which the landowner is eligible if he or she is retired. e

amount of involvement required for a share lease agreement may also

make these agreements unsuitable for landlords without signicant

experience in operating a farm or ranch.

14 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

c. Advantages of Share Renting for Tenants

Perhaps the two greatest advantages of a share rental agreement for

tenants is the reduction in operating capital requirements and the sharing

of risk with the landlord. Since the landlord and tenant both share in

the operating costs of the land, the tenant is not required to nance the

entire cost of those inputs as he or she would be under a xed cash rental

agreement. Similarly, the cost of rent is reduced (in cash equivalent terms)

in “bad” years. e ability to tap into the expertise of the landlord through

shared management decisions can be another important advantage,

particularly for beginning producers.

d. Disadvantages of Share Renting for Tenants

e risk-sharing features of a share rental agreement mean the tenant

has less ability to capture “upside” risk since that upside must be shared

with the landlord. Determining and delivering shares also involves more

work on the part of the tenant since he or she may have to make multiple

deliveries of product to multiple locations. Finally, the management input

of the landlord may conict with the desired decisions of the tenant.

B. Setting a Cash Rental Amount

Although cash rents are quite simple once established, establishing that amount

can be one of the most complicated and contentious pieces of negotiating a rental

agreement. Determining the rental rate depends not only on the local land market,

but on the land itself and the parties as well. Markets matter, and all other things

being equal, an active local market for land will drive rental rates upward just

as relatively little demand for agricultural land will drive rental rates down. e

characteristics of the land itself, including its soils, drainage, size, shape, location,

and facilities drive values, as do the production history of the tenant and the lease

provisions desired by the parties. All of these factors combine in dierent ways to

create several dierent approaches to establishing a cash-rent value.

1. Cash-Rent Market Approach

e cash-rent market approach is the standard against which all other

methods are measured; if another method yields a rental rate signicantly

above or below the market rate, there should be signicant justication

for that dierence. is is probably the approach coming rst to mind for

landowners and tenants and may sound like the most straightforward—

simply ask around for rates paid for similar land.

However, that simplicity can be deceptive for two primary reasons. First, it

can be dicult to get objective information about rental rates. Rates may be

subject to exaggerations or from transactions that are not the result of arms-

length transactions between unrelated parties. e quality of information

obtained is thus very important. A good place to start are lease surveys

conducted by your state Extension service or the National Agricultural

Statistics Service (USDA-NASS), but also remember that these surveys

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 15

generally present averages of values and may not be specic to your very local

area. at leads to the second reason market data can be deceptive—it reects

values paid for land other than the land actually in question. Numerous

adjustments have to be made from market rates to reect the unique traits of

the land at hand.

Despite these challenges, the cash-rent market approach should be the

starting point of any rental rate calculation. Start with the best data available,

and think carefully about any adjustments that need to be made from the

prevailing rates to take into account the positive or negative production

characteristics of the land to be leased.

a. Landowner’s Ownership Cost Approach

e landowner ownership cost approach does just what its name implies—

calculates the cost of ownership to the landlord—and uses that cost

to determine a base for the rental amount. Put another way, the rental

amount should at least exceed the ownership cost of the land and provide

a measure of prot to the landowner while also providing the tenant the

opportunity to make a prot.

e rst piece of information needed for this approach is the fair-market

price of the land (valued for agricultural use, and not for some other use

such as residential development). Second, an “interest charge” (meaning

the “opportunity cost” of owning the land—in other words, if the land

was sold and placed into an investment with similar risk, what rate of

return would it yield?) must be calculated. is is oen done by using

the “rent to value” ratio reported by USDA-NASS for various regions in

the United States. Together, the price and interest rate provide an annual

charge for the land itself. Next, the real estate taxes paid on the land

by the landowner are incorporated as an ownership cost. Finally, land

improvement costs such as treatments for soil pH, building or maintaining

conservation structures, etc. are included. Adding these costs together on

an annual basis provides a starting point for the landowner’s asking price

in rents.

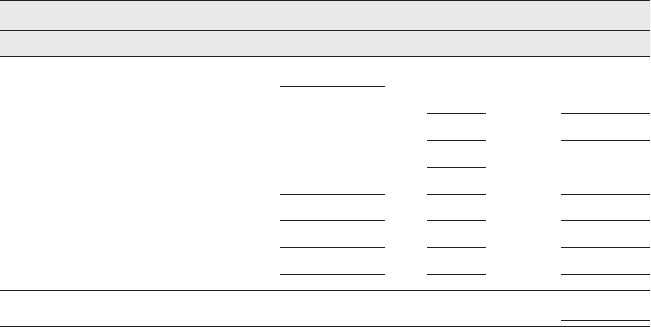

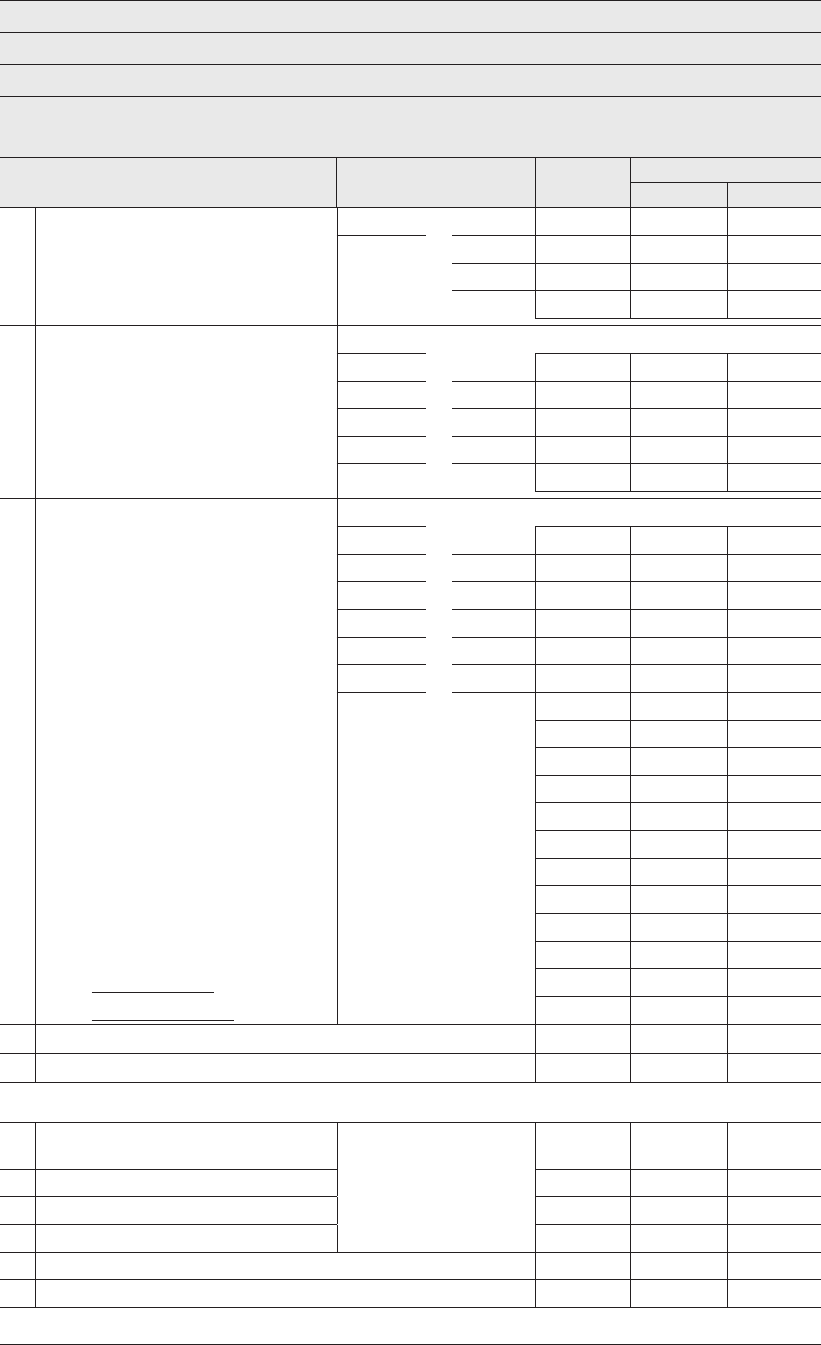

Figure 3-1: Example of Landowner’s Ownership Costs Calculation (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Crops Grown: Corn, soybeans, wheat Acres: 150

Item Per Acre Value Rate Annual Charge

Land

$

4,000

×

Interest

×

4

% $

160

Real Estate Tax

×

0.5

% $

20

Land Improvements

Tiling

$

500

×

5

% $

25

Surface drainage

$ × % $

Conservation practices

$ × % $

Liming

$ × % $

Total Cost

$

205

16 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

b. Landowner’s Adjusted Net-Share Rent Approach

is approach works to calculate the cash-rent equivalent of a share lease.

e general assumption is that a cash rent should be slightly less than a

share lease amount since, under a cash lease, the tenant bears almost all the

risk. To calculate a cash rent under an adjusted net-share rent approach, the

landlord and tenant must rst determine the prevailing shares for the crop

in question—these shares vary signicantly from crop to crop and region

to region, and frequently occur as 1/3–2/3 shares, 1/2–1/2 shares, or 40–60

percent shares. Next, historical data for the yields of the land in question and

for input and product costs should be gathered to determine what the average

share rent would have been for the property. Finally, and adjustment should

probably be made to reect the additional risk that the tenant will take under

a cash rental approach. e following provides an example of how rent can be

calculated under this approach.

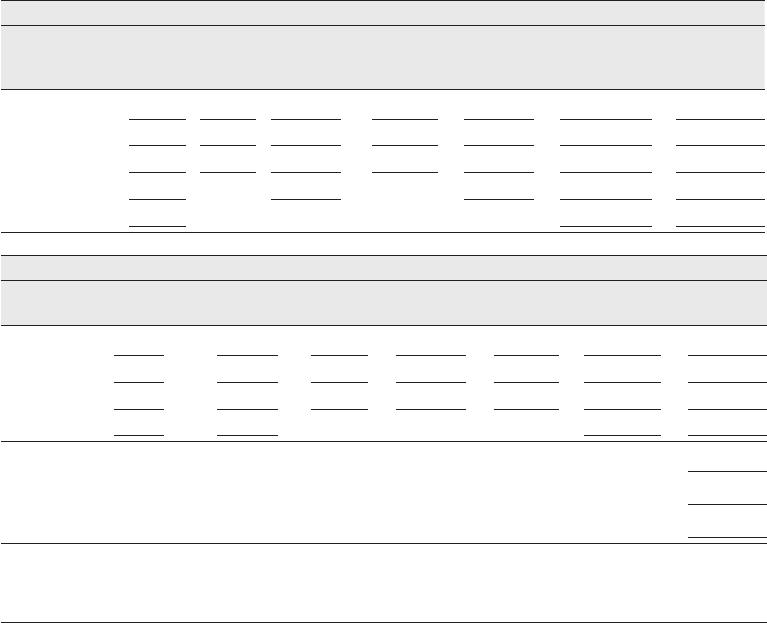

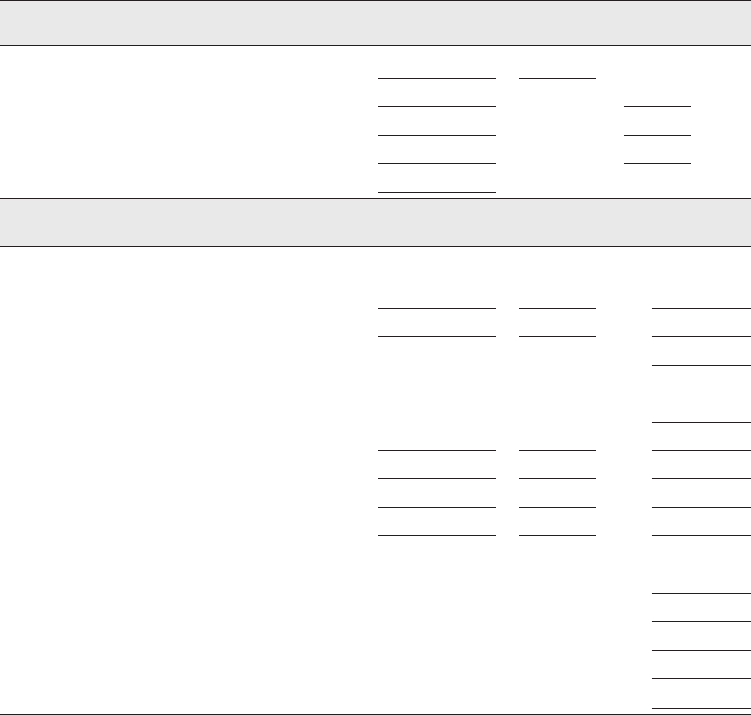

Figure 3-2: Example of Landowner’s Adjusted Net-Share Rent Approach (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Landowner's Share of Gross Crop Value

Crops Acres

Yield

per

Acre

2

Percent

of Crop

Tons or

Bushels Price

3

Total

Value

Per Acre

Value

Corn

5 10 50

%

65

$

4.50

$

28,68

$

Soybeans

40 50 50

%

1000

$

11.00

$

11,000

$

Wheat

5 65 50

%

118

$

6.00

$

6,825

$

Other Income

4

% $ $ $

Totals (A)

150

$

46,512

$

10.08

Landowner's Share of Shared Expenses

Crops

Landowner

Share Seed

3

Fert. &

Lime

3

Pesticides

Harvest/

Drying

3

Total

Cost Cost/Acre

Corn

50

% $

,5

$

4,125

$

1,12

$

1,688

$

10,500

$

Soybeans

50

% $

1,160

$

20

$

400

$

500

$

2,80

$

Wheat

50

% $

560

$

1,12

$

228

$

48

$

2,58

$

Totals (B)

% $ $ $

16,018

$

106.

Landowner's Crop Rent (A–B)

$

20.2

Less risk shifted to operator

5

$

15.50

Net landownder's share rent per acre

$

1 8.

1

If whole farm leased on a cash-rent basis, list all crops grown, income and shared expenses from each crop

2

Use average yields, allowing for both good and bad years. Incorporate trend in yields

3

Use current prices and costs

4

USDA payments, crop stover, etc.

5

Example risk value is 5% of total crop receipts. This number will vary depending on the production risk in your area.

c. Operator’s Net Return to Land Approach

e operator’s net return to land approach is something of a counterpoint

to the landowner’s ownership cost approach in that it is a calculation of

what the tenant (or operator) can aord to pay given the productivity of the

land. is approach takes into account the productivity of the land and the

costs of inputs, xed costs, and returns to labor and management. Per-acre

costs are deducted from per-acre returns to determine how much rent can

be paid at a break-even level given the assumptions made. An example is

provided in Figure 3-3 on the next page.

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 17

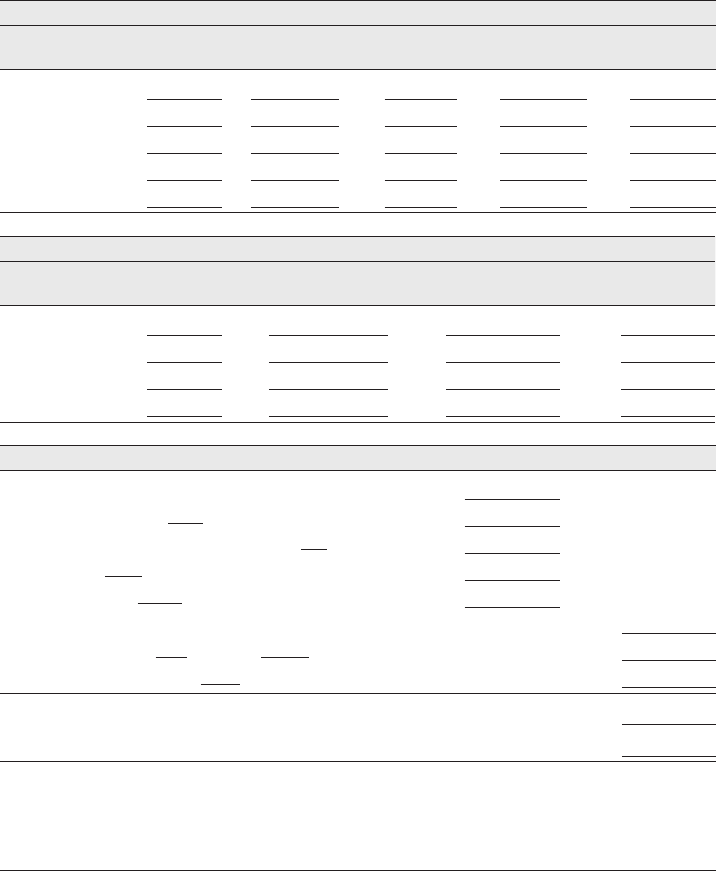

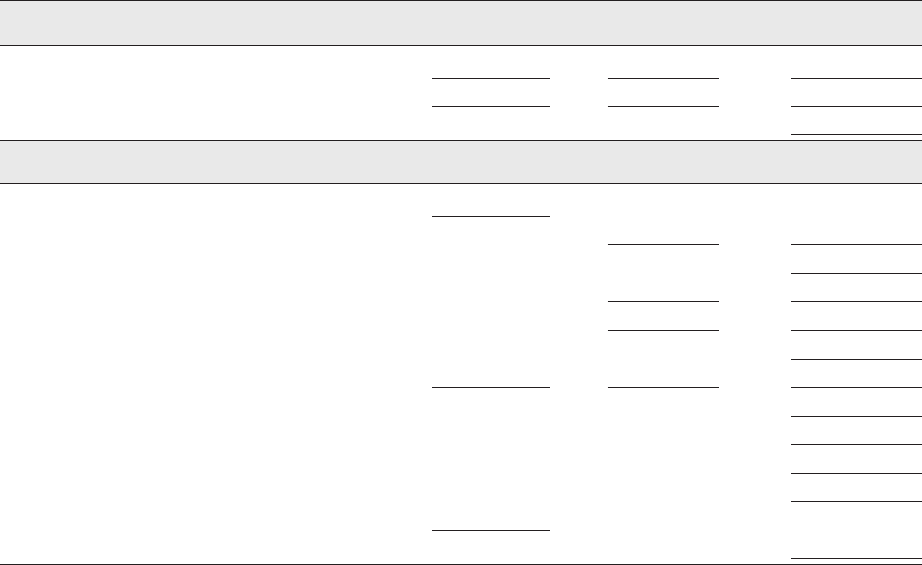

Figure 3-3: Example of Operator’s Net Return to Land Approach (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Gross Value of Crops Produced

Crops Acres

Yield

per Acre

2

Price

3

Total Value

Per Acre

Value

Corn

5 10

$

4.50

$

5 ,5

$

Soybeans

40 50

$

11.00

$

22,000

$

Wheat

5 65

$

6.00

$

1,650

$

Other Income

4

$ $ $

Totals (A)

$

,025

$

620.1

Total Variable Costs

3

Crops Acres

Variable Costs

per Acre

2

Total Variable

Costs

Per Acre

Value

Corn

5

$

40

$

25,500

$

Soybeans

40

$

10

$

,60 0

$

Wheat

5

$

180

$

6,00

$

Totals (B)

150

$ $

,400

$

262.6

Total Fixed Costs, Labor, and Management

3

Crop machinery: machinery value per acre

$

500.00

Depreciation for 10 years

$

50.00

Interest on average investment at 6 percent

$

0.00

Taxes at %

$

Insurance at .25 %

$

1.25

(C) Total machinery xed costs

$

81.25

(D) Labor charge5 ( 2.0 hrs/ac @ $13 /hr)

$

26.00

(E) Management charge ( 5.0 % of total crop values)

$

1.01

(F) Total production costs (B+C+D+E)

$

40 0.

(G) Amount that can be paid for rent per acre (A–F)

$

21.24

1

If whole farm leased on a cash-rent basis, list all crops grown, income from each crop, and variable expenses for each

crop.

2

Use average yields, allowing for both good and bad years. Incorporate trend in yields.

3

Use current prices and costs. Variable costs include fuel, oil, repairs, fertilizer, herbicide, insecticide, interest on

operating costs, custom hire, drying, insurance, and miscellaneous costs.

4

USDA payments, crop stover, etc.

5

Labor expense or charge may be included in variable expenses.

d. Percent of Land Value Approach

Perhaps the most straightforward of all the cash rental approaches

discussed here, the percent of land value approach simply consists of

calculating the “opportunity cost” of the land. In other words, if the

landowner sold the land and invested the proceeds in a similar investment

(in the case of land, a long-term investment with similar risks), what

would that investment yield on an annual basis? For agricultural land, the

best way of calculating an opportunity cost is the rent-to-value ratio (the

average ratio in a region of agricultural land’s rent to the total value of the

land). e per-acre value of the land in question is then multiplied by the

“opportunity cost” interest rate—in this example, the rent-to-value ratio—

to determine the desired per-acre rent. Note, though, that this approach

may not reect the market realities in the area, and that rent-to-value ratios

may be slow to change over time and thus may be further o in years where

there have been signicant changes in returns to agricultural land.

18 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

Figure 3-4: Example of Percent of Land Value Approach (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Crops Grown: Corn, soybeans, wheat Acres: 150

Item Per Acre Value Rate Annual Charge

Land

$

4,000

×

Typical Rent to Value

×

5

%

Total Cost or Desired Return

$

200

e. Percent of Gross Revenue Approach

Another angle of attack to determine a rental amount would be to calculate

the percent of gross revenues a landowner would be entitled to under a share

rental agreement. is requires collection of data on the average production

of the land in question, historical commodity prices, and the percentage

of gross income received by landowners under share leases in the region.

Note that there is an important distinction to be made in determining the

landlord’s percentages under this method—the percentages used should

be from leases in which the tenant pays all of the input costs for the leased

land since the landlord will be paying no input costs under this method. An

example of this calculation is provided in Figure 3-5 below.

Figure 3-5: Example of Percent of Gross Revenue Approach (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Crop

Expected

Yield

Expected

Price

Expected

Gross

Revenue

Rent as %

of Gross

Revenue

Cash Rental

Rate

Corn

10 bu.

$

4.50

$

65

% $

252.45

Soybeans

50 bu.

$

11.00

$

550 40

% $

220.00

Wheat

65 bu. 6.00

$

0 45

% $

15.55

Weighted Average:

Based on Corn: 5 acres, soybeans: 40 acres, wheat: 5 acres $ 225.85

f. Dollars per Bushel of Production Approach

A method that can take into account the specic productivity of a piece of

land is the dollars per bushel of production approach. With this approach,

historical rents and crop production records in the area are reviewed to

determine how much rent has been paid per bushel of production. Once

this has been calculated, the landowner and tenant have two options:

they can use the historical average productivity of the specic parcel and

this per-bushel amount to set rent in advance, or they can make the rent

variable based on the actual production of the land that year (though it

should be noted that making the rent variable aects a number of factors

in the advantages and disadvantages of the lease, as well as potentially

impacting the tax implications of the lease).

Figure 3-6: Example of Dollars per Bushel of Production

Approach (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Crops Grown: Corn Acres: 150

Item

Average

Yield

1

Price per

Bushel

2

Annual

Charge

Corn 10

×

$

1.20

$

204

1

Certain states have a productivity rating that may be used

2

Based on a percent of observed historical rents

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 19

g. Fixed Bushel Rent Approach

e xed bushel rent approach is something of a variation on the dollars

per bushel of production approach in that the xed bushel rent approach

uses the historical average production of the land and an agreed price to

calculate a rental rate. It also relies on information from share rental rates

in the region to determine what share of production would be paid to the

landlord (assuming the landlord pays no other expenses other than land).

Assuming that a dollar-per-bushel amount is xed at the time the lease is

entered, the lease is considered to have a xed cash rent, but if that number

is exible, the lease is considered a variable rent, with all that implies.

Figure 3-7: Example of Fixed Bushel Rent (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Crops Grown: Corn Acres: 150

Item

Bushel

Rent

1

Price per

Bushel

2

Annual

Charge

Land

56 bu.

×

$

4.50

$

252

1

Based on historic rent as a percent of revenue. Based on an equitable

crop share percentage (landowner paying no expenses except land) with a

discount for production risk.

h. Flexibility in Cash Leases

A common theme throughout this discussion has been the allocation of risk

to the tenant under almost all cash rent forms. In some cases, tenants may

be willing to accept that risk allocation, but may want some protection if

either input or product prices get so far away from averages that cash rent

payments become extremely dicult. By the same token, landlords may

want to take advantage of some “upside risk” when times are exceptionally

good. us, both parties may want to introduce some exibility into the

lease by providing for a baseline rate of cash rent that is adjusted by some

formula based on either input costs, product prices, the productivity of the

land, or even some combination of all elements. A number of these methods

are discussed in the NCFMEC publications referenced at the end of this

chapter. To keep this discussion relatively brief, any adjustments need to

have very clear triggers and calculations that can be objectively determined

by both parties. For example, if one variable is the price of a commodity,

the lease should be very clear about both when that price is determined

(for example, at a set date, when harvest is commenced, when harvest

is completed, etc.) and how that price is determined (by local elevator

cash price, by USDA market report, by nearby futures contract price,

etc.). Consider also that it may be inequitable for only one party to have

the benet of exibility—a tenant may be uncomfortable signing a lease

wherein the landlord gets the advantage of upside risk, but the tenant bears

all downside risk. Further, the more variable a lease becomes, the more

potential tax implications are triggered, and the more the lease looks like a

share lease. At some tipping point, a share lease may be more desirable.

i.

Combining the Methods to Calculate a Fair Cash Rent

is discussion examined a number of methods used to calculate a cash

rent amount. Which method is the right one? e answer might be one,

20 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

more, or all of them. Neither landlord nor tenant may have the time or

resources to pull together the information needed to calculate a rental rate

under all the methods but calculating two or more methods might help

both parties get some dierent perspectives on what a fair rental amount

could be. Additionally, calculating the rent under dierent methods

can trigger some important insights—if all of the methods used arrive

at roughly similar amounts, it is a strong suggestion that a rent amount

in that range is fair to the parties. If one or more methods are sharply

dierent, there may be cause to examine why those dierences arise, as

they may indicate something about the market or the land that justies a

dierent lease rate.

Figure 3-8: Comparison of Calculation Methods (Source: NCFMEC-01)

Example Farm Your Farm

Cash Rent Market Approach

$ 200.00 $

Landowner's cost or desired return (Worksheet 1)

$ 205.00 $

Landowner's Adjusted Net-share Rent (Worksheet 2)

$ 1 8. $

Operator's Net Return to Land (Worksheet 3)

$ 21.24 $

Percent of Land Value (Worksheet 4)

$ 200.00 $

Percent of Gross Revenue (Worksheet 5)

$ 225.85 $

Dollar per Bushel (Worksheet 6)

$ 204.00 $

Fixed Bushel Rent (Worksheet 7)

$ 252.00 $

Discussing the calculation methods can not only help landlord and tenant

arrive at a mutually-agreeable rental rate but can also help them discuss the

risk factors faced by both, which can lead to a better rental agreement itself.

2. Setting Shares under a Share Rental Agreement

At a fundamental level, share leases focus on sharing both the costs operating

the agricultural land and the prots from its production. is means both

upside and downside risk are shared by the parties as well. But how does one

set the appropriate shares to be paid and received by the landlord and tenant?

e North Central Farm Management Extension Committee has proposed

ve principles to help set shares:

1. Variable expenses that increase yields should be share in the same

percentage as the crop is shared. e principles of agricultural economics

demonstrate that using this principle will make sure the incentives for

both the landlord and the tenant will guide them to use the most ecient

levels of inputs. Conversely, not following this principle will create

incentives for one party to use too much of an input to capture more

revenue while shiing costs to the other party.

2. Share arrangements should be adjusted to reect the eect new

technologies have on relative costs contributed by both parties. New

technologies can cause substitutions of inputs, which can shi the

economics of the lease arrangement. For example, when a farm is shiing

from conventional tillage to a low- or no-till system, chemical weed

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 21

control may be used as a substitute for mechanical weed control through

cultivation. So, should the cost of chemical weed control be paid by the

landlord, the tenant, or shared? Another example is seed (such as corn

seed) that is frequently bundled with other inputs such as herbicide,

insecticide, and perhaps even fertility products. If the seed product aects

the need for other inputs, who should pay for the seed? e answers to

these questions depend on the nature of the substitution.

• If the input is a yield-increasing input, the landowner and operator

should share the costs in the same proportion as the crop is shared,

as discussed in principle 1.

• If the input is a true substitution, the party responsible for the item

substituted in the original lease should pay for the input.

• If the input is both yield-increasing and a substitute, the lease needs

to address this situation aer a discussion of how the cost should be

shared by the parties.

3. e landlord and tenant should share total returns in the same

proportion as they contribute resources. is principle sounds simple but

may be the most complex to implement. e parties have to discuss and

determine the value of what each is “bringing to the table,” so to speak. e

landlord is contributing the production asset, land, and the tenant is likely

contributing the majority of operating labor and machinery expenses.

Both contribute management and bear risk. In many cases, the operator’s

primary costs (labor and machinery) are largely the same, whether dealing

with high-quality or low-quality land, but other input costs may vary

considerably. For this reason, shares on high-quality land and/or crops with

high variable input costs tend to be more equal, whereas shares on lower-

quality land and/or crops with low variable input costs tend to place larger

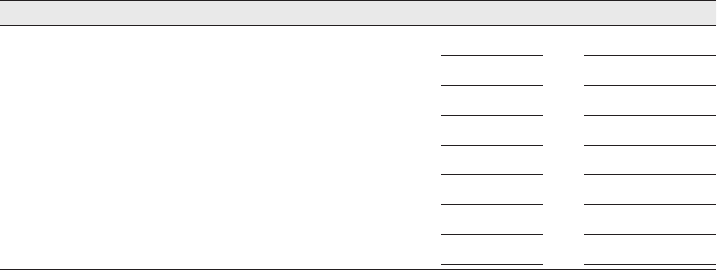

share values with the tenant, as illustrated below.

Yield, bu/ac

Most productive land

Land Quality/Value

Least productive land

1/2 Landowner

YIELD

1/3 Landowner

1/4 Landowner

2/3 Operator

3/4 Operator1/2 Operator

Operating cost, $/ac

60

55

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Figure 3-9: Eect of Land Quality and Farm Costs on Crop-Share Rental Arrangements

(Source: NCFMEC-02)

22 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

4.

Tenants should be compensated at the termination of the lease for the

undepreciated balance of long-term investments they have made. In some

cases, the parties may need to invest in inputs whose lives could extend

beyond the life of the lease, such as perennial seeds (alfalfa, for example),

pH amendments to the soil such as lime, and tiling or other soil drainage. A

tenant will likely be unwilling to share in those costs if they are not assured of

having access to the land for the entirety of the inputs’ productive life. us, it

may be wise to include lease language that guarantees the tenant will receive

back the undepreciated share of their investment if their lease is terminated

before the end of the investment’s life.

5

. Good, open, honest communication should be maintained between the

landowner and tenant. Communication is vital in any productive lease

arrangement, but it is even more important in a share leasing arrangement

since the parties must share in many of the decisions made in the course of

agricultural operations on the leased land. Frequent communication between

the parties can do much to provide transparency and to make both parties feel

that their concerns have been acknowledged and understood by the other.

Subject to these two principles, the rst step in determining what shares would be

equitable for the leasing arrangement is to form a thorough crop budget for the

land in question. e items in the budget will do a great deal to show the value

to be contributed by each party, which in turn will help determine the equitable

balance of shares for the lease.

■

Land: e land in question should be valued at its fair market value in

agricultural use; non-agricultural uses (such as residential development or

recreational uses) should be ignored since they are not relevant to the crop

enterprise for the purposes of the budget.

■

Interest on land: As discussed above, the usual value placed on land interest

(“opportunity cost”) for the purposes of lease budgeting is the rent-to-value

ratio for the area. One way of determining a land cost for the purposes of the

crop budget is to multiply the land value by the rent-to-value ratio.

■

Cash rent on land: Cash rent on land can also be a valid measure for the value

of the land contributed to the lease. Here, cash rent represents the cost that

would be incurred if the parties had to lease the land on a cash basis.

■

Real estate taxes: Real estate taxes can be a carrying cost of land, but be careful

not to include this value twice, since it is likely imputed to the values for cash

rental rates or on interest on land.

■

Land development: e average cost per year for lime, conservation practices,

and other improvements are another land cost. Use caution with these costs

to avoid double-counting just as with real estate taxes, though, as they too are

oen included in cash rental rates.

■

Crop machinery: e machinery charges should be the average value of a good

line of machinery needed to farm the land in question, which is not necessarily

the same as the value of new machinery.

■

Depreciation: Use a market rate of depreciation for machinery (oen 8 to 12

percent of the average value annually), not a tax-based depreciation rate tax rates

are oen far higher and will result in an over-charge of the machinery cost.

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 23

■

Machinery repairs, taxes, and insurance: Research data suggests annual

repairs average between 5 to 8 percent of the machinery’s original value. Taxes

and insurance costs can be obtained from actual costs in farm records.

■

Machinery interest: e prevailing local interest rate for machinery loans (or

operating capital loans) can be used to determine the opportunity cost for

machinery).

■

Custom rates: Rates for activities that the parties intend to hire out, such

as fertilizer application or harvesting, can be entered using bids from local

providers.

■

Irrigation equipment, depreciation, repairs, taxes, insurance, and interest:

ese costs for irrigation systems can be determined and calculated in much

the same fashion as machinery costs, as discussed above.

■

Labor: Labor may be contributed solely by the tenant or may be joint between

the tenant and landlord. However, the contribution of signicant labor by

the landlord can make the share lease look much more like a joint venture

or partnership, and that may not be the desired legal outcome of the parties.

When valuing labor, use prevailing wage rates for comparable agricultural

labor in the area. Note that the value contributed by the management skills of

the tenant may make them far more valuable than the average farm laborer in

the area, but that value is captured separately.

■

Management: e management contributions of the landlord and tenant can

vary signicantly depending on their operational experience. In most cases,

management charges may simply be a function of the bargaining power of the

parties. ere are a number of ways this can be valued, but two possible rules of

thumb are:

• One rule is that management should be valued at 1 to 2.5 percent of the

average capital managed in the business, measured as the market value of

the land, machinery, and irrigation equipment. is rule is probably more

stable since it will not uctuate as much as the next rule on a year-to-year

basis.

• Another guide can be the management fees charged by professional farm

managers. ese managers commonly charge between 5 to 10 percent of

adjusted gross receipts.

Once these costs have been compiled and a budget for the production of the crop

has been estimated, the parties can use one of two methods to determine the

appropriate shares for the landlord and tenant.

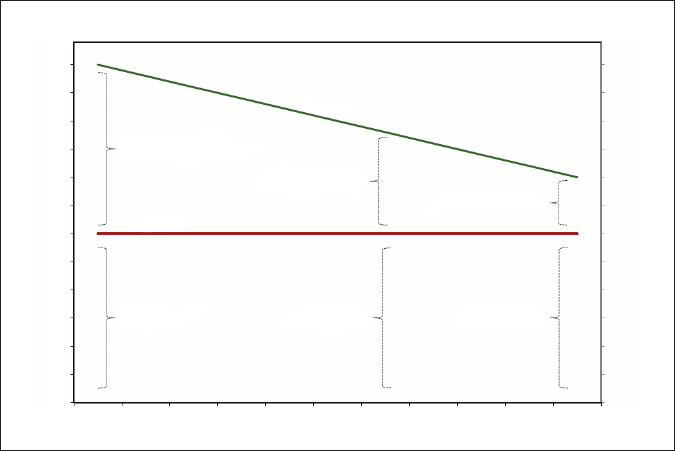

3. The Contribution Approach

In the contribution approach, the percentage of overall costs contributed by

each party are calculated, as well as those costs that are shared by some pre-

determined proportion. e remaining costs—which should be the “yield-

increasing inputs” as discussed above—and the income should be shared in

the same proportions. Consider the following example using a corn-soybean

rotation:

24 | CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease

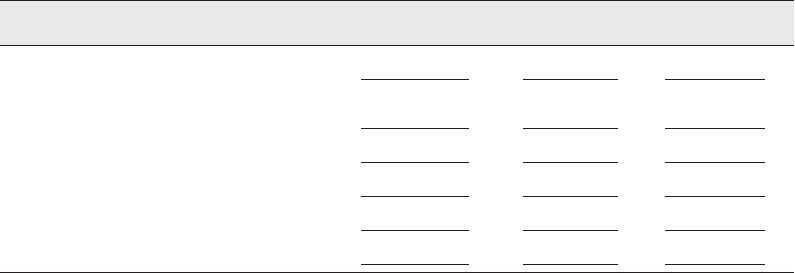

Figure 3-10: Example Crop Budget Worksheet (Source: NCFMEC-02)

Crop(s): Corn and soybeans

Acres: Approximately 156 llable acres

Farm: NE 1/4 of Brown Place

Comment: Average costs/acre for c-sb rotaon (share ferlizer, chemicals, and

crop insurance)

Line Value

a

Annual

Rate

Annual

cost

a

Contributor cost

a

Landlord Tenant

1. Land

b

$0

×

4.00% $0.00

1a. Real-estate tax

×

0.50% $0.00

1b. Land maintenance

×

0.00% $0.00

1c. Cash rent (in lieu of lines 1-1c)

$225.00 $225.00

2. Crop machinery

$250

2a. Depreciation

×

9.00% $22.50 $22.50

2b. Interest

×

. 0 0 % $1. 50 $1.50

2c. Repairs

×

6.00% $15.00 $15.00

2d. Taxes and insurance

×

0.50% $1.25 $1.25

2e. Custom rates (in lieu of lines 2a-2d)

3. Irrigation equipment

$0

×

3a. Depreciation

×

5.00% $0.00

3b. Interest

×

. 0 0 % $0.00

3c. Repairs

×

1.00% $0.00

3d. Taxes and insurance

×

0.50% $0.00

4. Labor (hours and $/hour)

2.00

×

$15.00 $0.00 $0.00

5. Management

$5,000

×

1.00% $50.00 $20.00 $0.00

6. Seed

Enter charges

only for non-yield

increasing items

(those inputs not shared in

the same percentage as

the crop).

$5.00 $5.00

7. Fertilizer

8. Herbicides

9. Insecticides/fungicides

10. Crop insurance

11. Fuel and oil

$18.00 $18.00

12. Irrigation pumping expense

13. Custom machinery hire

14. Drying

15. Hauling

16.

Other miscellaneous

$10.00 $2.50 $.50

17.

Other

18. TOTAL SPECIFIED COSTS (lines 1 through 17)

$464.25 $24.50 $216.5

19. Percent of Specied Costs (percent of total costs to each party)

100.0% 5.% 46.%

Adjustments to Reach Desired Share

20.

Cash transfer beeen pares to

achieve desired split

Add items previously

shared or include a cash

transfer between parties

to obtain desired shares.

$0.00 –$15.50 $15.50

21.

22.

23.

24. ADJUSTED TOTAL (lines 19 + lines 20 through 23)

$464.25 $22.00 $22.25

25.

Percent Crop Share Desired (percent of total costs to each party)

100.0% 50.0% 50.0%

a

Value and annual coat can either be total for farm/eld or average per acre.

b

Land contribution should be either land value × interest rate or cash rent

CHAPTER 3: Setting Payments for Your Lease | 25

In the example, the costs contributed by the landlord equal $247.50 per acre

or 53.3 percent of the total costs, and the costs contributed by the tenant

are $216.75 or 46.7 percent of the total costs. Note also that the worksheet