U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Coordinating Council

on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

A primary purpose of the juvenile justice system is to hold juvenile

offenders accountable for delinquent acts while providing treatment,

rehabilitative services, and programs designed to prevent future involve-

ment in law-violating behavior. Established in 1899 in Chicago, IL, in

response to the harsh treatment children received in the criminal justice

system, the first juvenile court recognized the developmental differences

between children and adults and espoused a rehabilitative ideal. However,

since the passage of revised death penalty statutes in the last quarter of

the 20th century, and during recent periods of increased violent crime, a

shift in the juvenile justice system toward stronger policies and punish-

ments has occurred.This shift includes the waiver or transfer of more

juvenile offenders to criminal court than in the past. Increasing numbers

of capital offenders, including youth who committed capital offenses prior

to their 18th birthdays, are now subject to “absolute” sentences, including

the death penalty and life in prison without parole.

Currently, 38 States authorize the death penalty; 23 of these permit the

execution of offenders who committed capital offenses prior to their

18th birthdays.

1

However, the laws governing application of the death

penalty in those 23 States vary, and the variation is not necessarily tied to

rates of juvenile crime. Since 1973, when the death penalty was reinstat-

ed, 17 men have been executed for crimes they committed as juveniles

(see table 1), and 74 people in the United States currently sit on death

row for crimes they committed as juveniles (Streib, 2000).

2

Debate about the use of the death penalty for juveniles has grown more

intense in light of calls for the harsher punishment of serious and violent

Juveniles and the

Death Penalty

Lynn Cothern

From the

Administrator

The appropriateness of the death

penalty for juveniles is the subject of

intense debate despite Supreme

Court decisions upholding its use.

Although nearly half the States

allow those who commit capital

crimes as 16- and 17-year-olds to

be sentenced to death, some ques-

tion whether this is compatible with

the principles on which our juvenile

justice system was established.

This Bulletin examines the history

of capital punishment and Supreme

Court decisions related to its use

with juveniles. It also includes pro-

files of those sentenced to death for

crimes committed as juveniles and

notes the international movement

toward abolishing this sanction.

I hope that this Bulletin enhances

our understanding of the issues

involved in applying the death penal-

ty to juveniles so that we may focus

our energy and resources on

effective and humane responses

to juvenile crime and violence.

John J.Wilson

Acting Administrator

John J. Wilson, Acting Administrator November 2000

juvenile offenders, changing

perceptions of public safety, and

international challenges to the

death penalty’s legality. Proponents

see its use as a deterrent against

similar crimes, an appropriate sanc-

tion for the commission of certain

serious crimes, and a way to main-

tain public safety. Opponents

believe it fails as a deterrent and is

inherently cruel and point to the

risk of wrongful conviction.The

constitutionality of the juvenile

death penalty has been the subject

of intense national debate in the

last decade. Several Supreme Court

decisions and high-profile cases

have led to increased public inter-

est and closer examination of the

issues by academics, legislators, and

policymakers.

This Bulletin examines the status

of capital punishment in the sen-

tencing of individuals who commit

crimes as juveniles.

3

It examines

the history of the death penalty,

including the juvenile death penal-

ty; provides a profile of those cur-

rently on death row; notes State-

by-State differences in sentencing

options; and reviews the use of the

death penalty in an international

context.

History of the Death

Penalty

A

pproximately 20,000 people

have been legally executed

in the United States in the

past 350 years (Streib, 2000). Exe-

cutions declined through the

1950’s and 1960’s and ceased after

1967, pending definitive Supreme

Court decisions.This hiatus ended

only after States altered their laws

in response to the Supreme Court

decision in Furman v. Georgia,

4

a

contribution to acceptable goals

of punishment.

In Furman, the Supreme Court

ruled that the death penalty was

arbitrarily and capriciously applied

under existing law based on the

unlimited discretion accorded to

sentencing authorities in capital

trials. As a result, more than 600

death sentences for prisoners then

on death row were vacated.

In response, States began to revise

their statutes in 1973 to modify the

discretion given to sentencing

authorities, and some States again

began sentencing adult offenders

to death. By 1975, 33 States had

introduced revised death penalty

statutes.These statutes went

untested until Gregg v. Georgia,

5

a

case in which the Supreme Court

found, in a 7–2 decision, that the

5–4 decision that the death penalty,

as imposed under existing law, con-

stituted cruel and unusual punish-

ment in violation of the 8th and

14th amendments of the U.S. Con-

stitution.To decide eighth amend-

ment cases, the Supreme Court

uses an analytical framework that

includes three criteria. A punish-

ment is cruel and unusual if:

●

It is a punishment originally

understood by the framers of

the Constitution to be cruel

and unusual.

●

There is a societal consensus

that the punishment offends

civilized standards of human

decency.

●

It is (1) grossly disproportionate

to the severity of the crime

or (2) makes no measurable

2

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

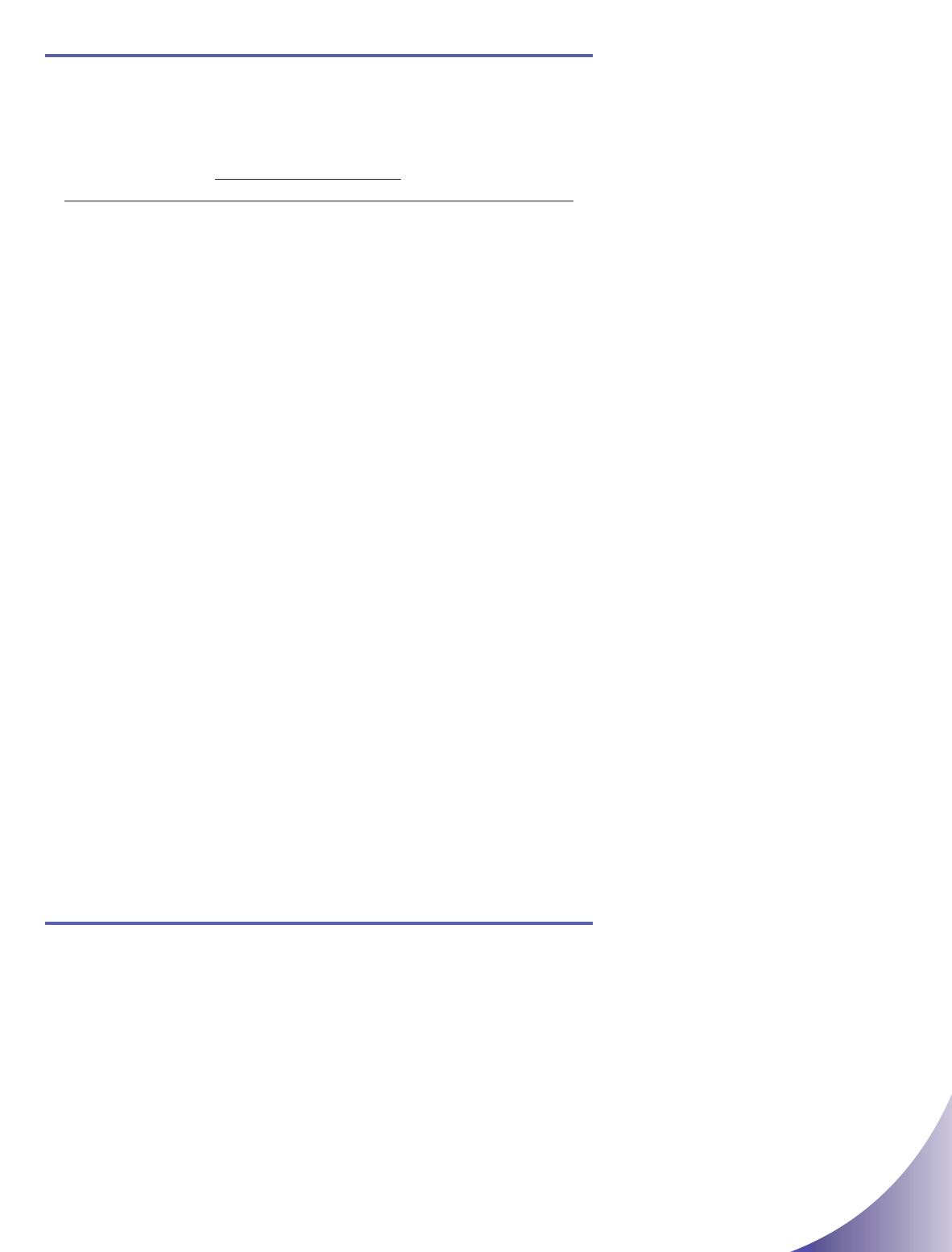

Table 1. Executions of Juvenile Offenders,

January 1, 1973, through June 30, 2000

Date of Place of Age at Age at

Name Execution Execution Race Crime Execution

Charles Rumbaugh 9/11/1985 Texas White 17 28

J.Terry Roach 1/10/1986 S. Carolina White 17 25

Jay Pinkerton 5/15/1986 Texas White 17 24

Dalton Prejean 5/18/1990 Louisiana Black 17 30

Johnny Garrett 2/11/1992 Texas White 17 28

Curtis Harris 7/1/1993 Texas Black 17 31

Frederick Lashley 7/28/1993 Missouri Black 17 29

Ruben Cantu 8/24/1993 Texas Latino 17 26

Chris Burger 12/7/1993 Georgia White 17 33

Joseph John Cannon 4/22/1998 Texas White 17 38

Robert A. Carter 5/18/1998 Texas Black 17 34

Dwayne A.Wright 10/14/1998 Virginia Black 17 26

Sean R. Sellars 2/4/1999 Oklahoma White 16 29

Christopher Thomas 1/10/2000 Virginia White 17 26

Steve E. Roach 1/19/2000 Virginia White 17 23

Glen C. McGinnis 1/25/2000 Texas Black 17 27

Gary L. Graham 6/22/2000 Texas Black 17 36

Source: Streib, 2000.

death penalty did not per se violate

the eighth amendment.The Gregg

decision allowed States to establish

the death penalty under guidelines

that eliminated the arbitrariness

of sentencing in capital cases.The

following safeguards were developed

to make sentencing more equitable:

●

In death penalty cases, the

determination of guilt or inno-

cence must be decided sep-

arately from hearings in which

sentences of life imprisonment

or death are decided.

●

The court must consider aggra-

vating and mitigating circum-

stances in relation to both the

crime and the offender.

●

The death sentence must be

subject to review by the highest

State court of appeals to ensure

that the penalty is in proportion

to the gravity of the offense and

is imposed even-handedly under

State law.

By 1995, 38 States and the Federal

Government had enacted statutes

authorizing the death penalty for

certain forms of murder.

History of the Juvenile

Death Penalty

T

homas Graunger, the first

juvenile known to be exe-

cuted in America, was tried

and found guilty of bestiality in

1642 in Plymouth Colony, MA

(Hale, 1997). Since that execution,

361 individuals have been executed

for crimes committed when they

were juveniles (Streib, 2000).

The Supreme Court decided its

first juvenile case—Kent v. United

States,

6

in which it limited the wai-

November 2000

3

based on the defendant’s age

(Eddings was 16 at the time he

murdered a highway patrol officer).

Without ruling on the constitu-

tionality of the juvenile death

penalty, the Court vacated the

juvenile’s death sentence on the

grounds that the trial court had

failed to consider additional miti-

gating circumstances. Eddings was

important, however, because the

Court held that the chronological

age of a minor is a relevant mitigat-

ing factor that must be considered

at sentencing. Justice Powell, in

writing for the majority, stated:

[Y]outh is more than a chrono-

logical fact. It is a time of life

when a person may be the

most susceptible to influence

and psychological damage. Our

history is replete with laws and

judicial recognition that minors,

especially in their earlier years,

generally are less mature and

responsible than adults.

8

The Supreme Court rejected five

requests between 1983 and 1986

to consider the constitutionality of

imposing the death penalty upon a

juvenile (Jackson, 1996). It was not

until 1987, in Thompson v. Okla-

homa,

9

that the Supreme Court

agreed to consider this specific

issue. The 5–3 decision vacated the

defendant’s death sentence (at the

age of 15,Thompson had partici-

pated in the murder of his former

brother-in-law). However, only four

justices agreed that the execution

of a 15-year-old would be cruel

and unusual punishment under all

circumstances (per se). Applying

the standard eighth amendment

analysis, Justices Stevens, Brennan,

Marshall, and Blackmun opined that

the execution would constitute

ver discretion of juvenile courts—

in 1966. Initially, juvenile courts had

enjoyed broad discretion in decid-

ing when to waive cases to crimi-

nal court. However, waiver de-

cisions were not consistent across

States, and legislatures began to

reform the process by standardiz-

ing judicial decisionmaking. Kent

held that juveniles were entitled to

a hearing, representation by coun-

sel, access to information upon

which the waiver decision was

based, and a statement of reasons

justifying the waiver decision.The

court also laid out a number of

factors that the juvenile court

judge must consider in making the

waiver decision (Evans, 1992),

including:

●

The seriousness and type of

offense and the manner in

which it was committed.

●

The sophistication and maturity

of the juvenile as determined by

consideration of his or her

homelife, environmental situation,

emotional attitude, and pattern

of living.

●

The juvenile’s record and history.

●

The prospects for protecting

the public and rehabilitating the

juvenile.

Juveniles were thus guaranteed cer-

tain rights, but they still potentially

faced the same punishments, includ-

ing capital punishment, as adults in

the criminal justice system.

In the 1980’s, the Supreme Court

was repeatedly asked to rule on

whether the execution of a juve-

nile offender was permissible

under the Constitution. Eddings v.

Oklahoma

7

was the first case the

Supreme Court agreed to hear

4

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

cruel and unusual punishment

because it was inconsistent with

standards of decency and failed to

contribute to the two social goals

of the death penalty—retribution

and deterrence. Justice O’Connor

concurred, but pointed out that

Oklahoma’s death penalty statute

set no minimum age at which the

death penalty could be imposed.

Sentencing a 15-year-old under

this type of statute violated the

standard for special care and delib-

eration required in capital cases.

The outcome of the decision was

that a State’s execution of a juve-

nile who had committed a capital

offense prior to age 16 violated

Thompson unless the State had a

minimum age limit in its death

penalty statute (Jackson, 1996).

The next year, in Stanford v.

Kentucky

10

and Wilkins v. Missouri,

11

the Supreme Court expressly held,

in a 5–4 decision, that the eighth

amendment does not prohibit the

death penalty for crimes commit-

ted at age 16 or 17. In both cases,

the Supreme Court upheld the

death penalty sentence.While the

Thompson plurality used the three-

part analysis (see page 2) to deter-

mine if sentencing a juvenile off-

ender to the death penalty

constituted cruel and unusual

punishment, the Stanford plurality

did not.The Stanford plurality

rejected the third part of the test,

namely, that the punishment is dis-

proportionate to the severity of

the crime and makes no measura-

ble contribution to the deterrence

of crime.

In Stanford, the Court considered

the evolving standards of decency

in society as reflected in historical,

judicial, and legislative precedents;

current legislation; juries’ and pros-

ecutors’ views; and public, profes-

sional, and international opinions.

The Court based its determination

of evolving standards of decency

on legislative authorization of the

punishment.The dissenting judges

argued that the record of State

and Federal legislation protecting

juveniles because of their inherent

immaturity was not relevant in

constituting a national consensus.

The justices also found that public

opinion polls and professional

associations were an “uncertain

foundation” on which to base con-

stitutional law. In the end, the

Court found that capital punish-

ment of juveniles ages 16 or 17

did not offend societal standards

of decency.

Profile of Youth

Affected

S

ince the series of Supreme

Court decisions upholding

the use of the death penalty

for juveniles, juvenile offenders have

received the sentence of death fair-

ly consistently, at least during the

past 20 years. Since 1973, 196 juve-

nile death sentences have been

imposed.This accounts for less than

3 percent of the almost 6,900 total

U.S. death sentences. Approximately

two-thirds of these have been

imposed on 17-year-olds and nearly

one-third on 15- and 16-year-olds

(see table 2).

The rate of juvenile death sentenc-

ing was initially somewhat erratic,

fluctuating in the years following

Furman v. Georgia (1972), but be-

came more consistent in the mid-

1980’s. The rate dropped some-

what in the late 1980’s, possibly

because of cases pending before

the Supreme Court (Streib, 2000).

In the 1990’s, however, the annual

rate returned to a consistent 2–3

percent of all sentences, despite

the dramatic increase in juvenile

arrests for murder that occurred

between 1985 and 1995.

Of the 196 juvenile death sen-

tences imposed since 1973, 74 (or

38 percent) remain in force and

105 (54 percent) have been

reversed. Of the 17 executions

that have occurred since 1973, 4

took place this year. Many juveniles

are well into adulthood by the

time they face execution.The

length of time on death row has

ranged from 6 to 20 years (Streib,

2000).

As of June 2000, 74 adults, ranging

in age from 18 to 41 years old,

remain on death row for crimes

committed as juveniles:

●

All 74 offenders are male.

●

Seventy-three percent commit-

ted their crimes at age 17.

●

Sixty-three percent are

minorities.

●

They are on death row in 16

different States.

●

They have been on death row

for periods ranging from a few

months to more than 21 years.

Of their victims, 80 percent were

adults, 64 percent were white, and

53 percent were female.Texas,

with 24 offenders on death row

who committed their crimes as

juveniles, holds 34 percent of the

national total of such offenders

(Streib, 2000).

Little information exists to charac-

terize juvenile capital offenders

beyond bare demographics.

November 2000

5

Although the 1976 Gregg decision

established that the court must

consider mitigating circumstances,

capital offenders are often repre-

sented by public defenders or

other appointed counsel who often

do not have the time or resources

to adequately investigate mitigating

factors such as psychiatric history,

family issues, and mental capacity.

Thus, a complete profile of capital

offenders is difficult to obtain,

because detailed information

about them is seldom available.

The few researchers who have

examined this information have

added to the profile of juveniles

sentenced to the death penalty.

In the mid-1980’s, Lewis and

colleagues (1988) conducted diag-

nostic evaluations of 14 (40 per-

cent) of the 37 juvenile offenders

on death row in the United States.

12

Through these comprehensive

assessments, Lewis and colleagues

found that all 14 had sustained

head injuries as children. Nine had

major neuropsychological dis-

orders, 7 had had psychotic disor-

ders since early childhood, and 7

had serious psychiatric distur-

bances. Seven were psychotic at

the time of evaluation or had been

diagnosed in early childhood. Only

two had IQ scores above 90 (100

is considered average). Only three

had average reading abilities, and

another three had learned to read

on death row. Twelve reported

having been brutally abused physi-

cally, sexually, or both, and five

reported having been sodomized

by relatives.

Many of these factors, however,

had not been placed in evidence at

the time of trial or sentencing and

had not been used to establish

mitigating circumstances:

The time and expertise re-

quired to document the nec-

essary clinical information

were not available. Further-

more, the attorneys’ alliances

were often divided between

the juveniles and their families.

[O]n several occasions, attor-

neys who chose to make use

of our evaluations requested

that we conceal or minimize

parental physical and sexual

abuse to spare the family....

Brain damage, paranoid

ideation, physical abuse, and

sexual abuse, all relevant to

issues of mitigation, were

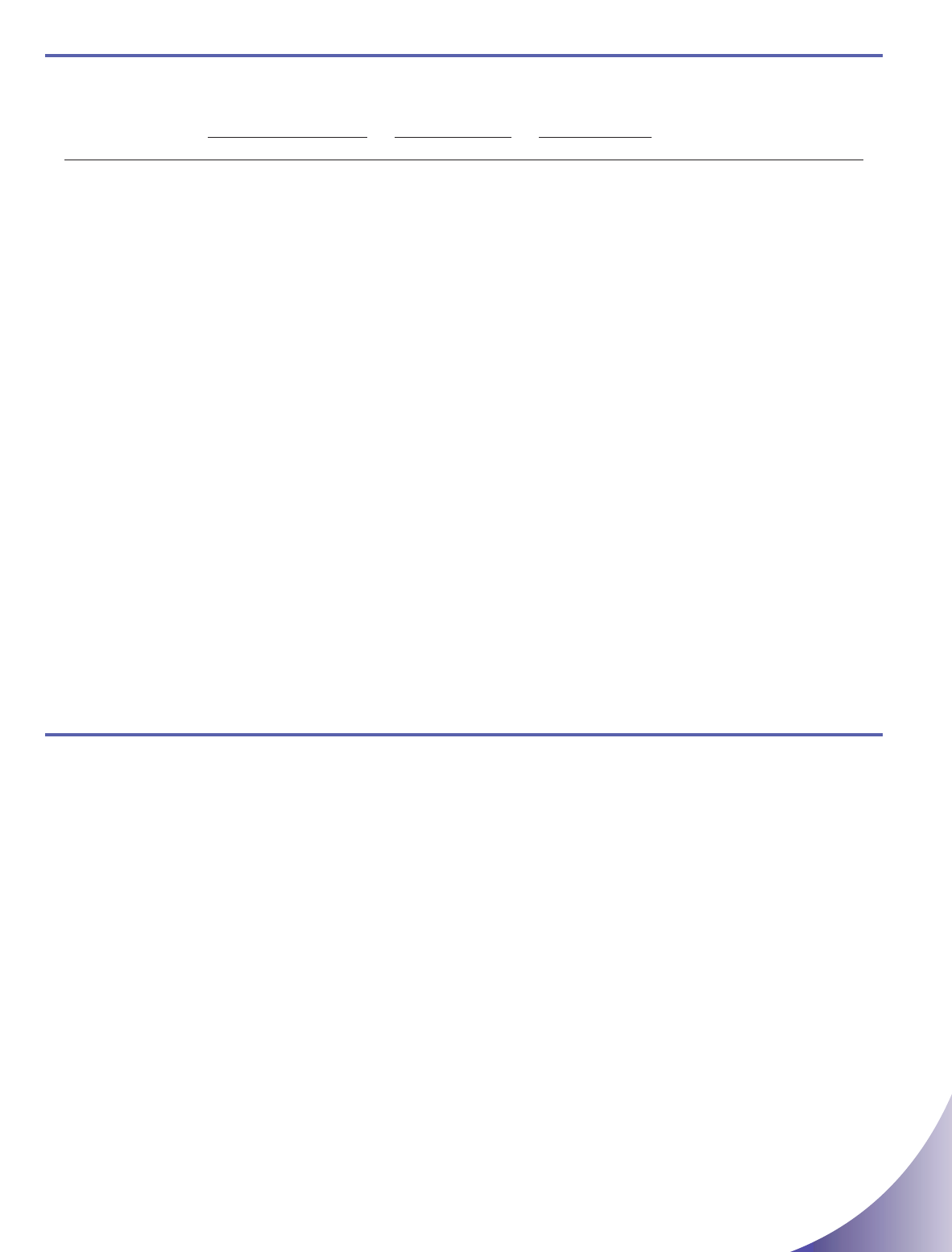

Table 2. Death Sentences Imposed for Crimes

Committed as Juveniles, 1973–2000

Juvenile Death

Sentences

Percentage of Juvenile

Total Death

(Age at Crime)

Sentences as Portion

Year Sentences* 15 16 17 Total of Total Sentences

1973 42 0 0 0 0 0.0%

1974 149 1 0 2 3 2.0

1975 298 1 5 4 10 3.4

1976 233 0 0 3 3 1.3

1977 137 1 3 8 12 8.8

1978 187 0 1 6 7 3.7

1979 152 0 1 3 4 2.6

1980 174 2 0 3 5 2.9

1981 229 0 2 6 8 3.5

1982 268 0 1 13 14 5.2

1983 254 0 4 3 7 2.8

1984 283 3 0 3 6 2.1

1985 268 1 1 4 6 2.2

1986 299 1 3 5 9 3.0

1987 289 1 0 1 2 0.7

1988 291 0 0 5 5 1.7

1989 263 0 0 1 1 0.4

1990 252 1 3 4 8 3.2

1991 264 1 0 4 5 1.9

1992 289 0 1 5 6 2.1

1993 291 0 1 5 6 2.1

1994 321 0 4 13 17 5.3

1995 322 0 2 9 11 3.4

1996 317 0 4 6 10 3.2

1997 274 0 4 4 8 2.9

1998 285 0 4 7 11 3.9

1999 300

†

0 3 6 9 3.0

2000 150

†

0 0 3 3 2.0

Total 6,881

†

13 47 136 196 2.8

Note: Adapted from Streib, 2000.

* Data for this column were taken from Snell, 1999.

†

Estimates as of June 2000.

either overlooked or deliber-

ately concealed (Lewis et al.,

1988:588).

In most cases, Lewis and colleagues

found that the inmates and their

families did not want to acknowl-

edge past abuse or mental illness.

Only 5 of the 14 inmates under-

went any pretrial psychiatric evalua-

tion, and the research team found

these evaluations to be both in-

complete and inaccurate. In many

instances, the defendants were rep-

resented by public defenders or

court-appointed attorneys who

were insufficiently prepared for

trial.

13

Amnesty International found simi-

lar results. In 9 of 23 juvenile

cases it examined, lawyers

handling later appeals identified

mitigating evidence that had not

been presented at the trial or

sentencing hearing (Amnesty

International, 1991). A case in

point is Dwayne Allan Wright,

who was executed October 14,

1998, in Virginia’s Greensville

Correctional Center for a crime

he committed at age 17.

14

The

court nominated a clinical

psychologist, whom the defense

accepted, only to find out later

that the psychologist was the

author of a study that concluded

that mental illness and environ-

ment are not mitigating factors in

the commission of crimes and

that “criminals act because they

develop an ability to ‘get away

with’ their crimes and ‘live rather

well’ as a result” (Amnesty Inter-

national, 1998:30).

The research of Robinson and

Stephens (1992) corroborated

that of Lewis and colleagues.

Robinson and Stephens applied

(see table 3). Since 1973, Alabama,

Florida, and Texas have used the

penalty more than other jurisdic-

tions. Of the juveniles sentenced

to the death penalty, all 21 His-

panic offenders were sentenced

in Arizona, Florida, Nevada, and

Texas.Ten of the eleven cases in

Louisiana involved African Ameri-

can offenders, and all Oklahoma

offenders were white. There were

four cases of female offenders, one

each in Alabama, Georgia, Indiana,

and Mississippi. The 13 youngest

offenders, who were age 15 at the

time of their crimes, came from

10 different States (Streib, 2000).

The States have responded differ-

ently to the requirement imposed

by Thompson (see pages 3–4).The

Supreme Court of Louisiana held

that Thompson prevents 15-year-

old offenders from being executed

in that State (State v. Stone

15

and

Dugar v. State

16

).The same is true

for Alabama (Flowers v. State

17

),

Florida (Allen v. State

18

), and Indiana

(Cooper v. State

19

).The Florida

Supreme Court ruled that the

Florida Constitution also prohibits

the death penalty for 16-year-olds

(Brennan v. State

20

) (Streib, 2000).

Currently, 38 States and the Federal

Government have statutes authoriz-

ing the death penalty for certain

forms of murder. In 16 of those

jurisdictions (40 percent), offenders

must at a minimum be age 18 at the

time of the crime to be eligible for

that punishment (see table 4). Five

jurisdictions (13 percent) have a

minimum age of 17. Nineteen juris-

dictions (47 percent) use age 16 as

the minimum age. In 7 of these

jurisdictions, age 16 is expressed in

the statute; in the other 12, age 16

has been established by court ruling

(American Bar Association, 2000).

5 descriptive categories to 91

juveniles who had been sentenced

to death between 1973 and 1991.

The categories were based on

mitigating circumstances that had

been established by the evidence

and were in addition to “youth”—

a mitigating factor established in

Eddings v. Oklahoma. Robinson

found that:

●

Almost half of those sentenced

had troubled family histories

and social backgrounds and

problems such as physical

abuse, unstable childhood

environments, and illiteracy.

●

Twenty-nine suffered psycho-

logical disturbances (e.g., pro-

found depression, paranoia,

self-mutilation).

●

Just under one-third exhibited

mental disability evidenced by

low or borderline IQ scores.

●

More than half were indigent.

●

Eighteen were involved in inten-

sive substance abuse before the

crime.

Juveniles sentenced to death share

varying combinations of these miti-

gating circumstances, in addition to

their youthful age. In 61 of the 91

cases (67 percent), one or more

factors in addition to “youth” was

present.

State-by-State

Differences in

Sentencing Options

T

wenty-two States—more

than half of the 38 jurisdic-

tions authorizing the death

penalty—have imposed the death

penalty on offenders who commit-

ted capital offenses before age 18

6

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

November 2000

7

Significant State legislative activity

concerning the death penalty

occurred in 1999.

21

Both Nebraska

and Illinois mandated a compre-

hensive evaluation of the death

penalty. Although the Governor

of Nebraska vetoed a proposed

moratorium on executions, legisla-

tion was enacted that called for a

comprehensive study to determine

whether the death penalty is

applied fairly. The Governor of

Illinois ordered an evaluation after

13 death row inmates in the past

few years were found not guilty

when their cases were reexamined.

Legislatures in Connecticut,

legislation that barred the imposi-

tion of the death penalty on

offenders who were under age 18

at the time they committed capital

offenses. Similar bills were intro-

duced in Indiana, Pennsylvania,

South Carolina, South Dakota, and

Texas. Bills that called for the

expansion of the death penalty to

juvenile offenders ages 16 and 17

were rejected in several States,

including California (American Bar

Association, 2000).

Maryland, Missouri, Montana, North

Carolina, and Pennsylvania saw

the introduction—but not the

passage—of legislation calling for

moratoriums on the death penalty

or authorizing studies of its use. In

1999, 12 of the 38 States that cur-

rently have the death penalty saw

the introduction of bills to abolish

it—8 more States than in the previ-

ous year (American Bar Associ-

ation, 2000).

In 1999, many States also were

involved in reassessing their use of

the death penalty for juveniles.

Montana’s legislature approved

Table 3. State-by-State Breakdown of Juvenile Death Sentences, 1973–2000

Total Total

Race of Offender Sex of Offender Age at Crime

Juvenile Juvenile

Rank State Black Latino White M F 15 16 17 Sentences Offenders

1 TX 23 16 10 49 0 0 0 49 49 48

2 FL 8 1 21 30 0 3 9 18 30 25

3 AL 11 0 10 20 1 1 9 11 21 20

4 MS 6 0 6 11 1 0 5 7 12 11

5LA100111025411 11

6GA 406 91 109 10 7

7NC 502 70 106 7 6

7OK 007 70 133 7 6

7SC 304 70 034 7 7

8 OH* 5 0 1 6 0 0 1 5 6 6

8PA 501 60 123 6 6

9AZ 032 50 022 5 5

9VA 302 50 023 5 5

10 MO 2 0 2 4 0 0 2 2 4 4

11 IN 2 0 1 2 1 1 0 2 3 3

11 KY 1 0 2 3 0 1 0 2 3 3

11 MD* 2 0 1 3 0 0 0 3 3 2

12 AR 2 0 0 2 0 1 1 0 2 2

12 NV 1 1 0 2 0 0 2 0 2 2

13 NE* 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

13 NJ* 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1

13 WA* 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1

Total 95 21 80 192 4 13 47 135 196 182

Note: Adapted from Streib, 2000.

* State statute no longer allows the death penalty for offenders who commit capital offenses before age 18 (American Bar Association, 2000).

International

Context

W

ith increasing globaliza-

tion and a developing

world economy, it is

difficult not to look beyond the

borders of the United States to

the practices of other nations. In

deciding Stanford, for example, the

Supreme Court considered the

international context in determin-

ing evolving standards of decency.

International law has expressly

determined that the death penalty,

specifically, the death penalty and

life imprisonment without possibil-

ity of release for crimes commit-

ted while a juvenile, is a human

rights issue (see pages 10–12 for

a discussion of life imprisonment

without possibility of release

(parole)). According to Amnesty

International, since the adoption

of the Declaration of Human

Rights 50 years ago, more than

half of the world’s countries have

abolished the use of the death

penalty (Amnesty International,

1998). Table 5 lists the document-

ed executions of offenders in

other countries who were under

age 18 at the time of execution for

the period 1985–95. However, the

extent of the international use of

the death penalty for juveniles is

largely unknown. If age at the time

of crime had been used, rather

than age at execution, the numbers

would be greater. Undocumented

cases would also increase the

global number.

The United States has not adopted

several international bans on the

juvenile death penalty. Introduced

on March 23, 1976, the United

Nations’ (U.N.’s) International

Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR) states that the

“sentence of death shall not be

imposed for crimes committed by

persons below eighteen years of

age” (article 6(5)).The United

States signed the ICCPR in

October 1977, although the

Supreme Court had recently, in

Gregg v. Georgia, permitted States

to resume use of the death penal-

ty. At the time of signing, the

Federal Government expressly

reserved the right to impose the

death penalty for crimes commit-

ted while under age 18. Eleven

countries objected to the United

States’ reservation and, in 1995,

the U.N.’s Human Rights Com-

mittee, which monitors compliance

with the ICCPR, asked the United

States to withdraw the reservation

(Amnesty International, 1998). In

1998, the United States was again

asked to withdraw its reservation,

this time by the U.N. Special Rap-

porteur on extrajudicial, summary,

or arbitrary executions, but the

United States declined to do so.

Article 37(a) of the U.N. Conven-

tion on the Rights of the Child

(CRC) states that “neither capital

punishment nor life imprisonment

without possibility of release shall

8

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Table 4. Status of the Death Penalty, by American

Jurisdiction

Death Penalty, Death Penalty,

Minimum Age 18 Death Penalty, Minimum Age 16

(Total = 15 States Minimum Age 17 (Total = 18 States

and Federal (civilian)) (Total = 5 States) and Federal (military))

California* Florida

†

Alabama*

Colorado* Georgia* Arizona

‡

Connecticut* New Hampshire* Arkansas

‡

Illinois* N. Carolina* Delaware

‡

Kansas* Texas* Idaho

‡

Maryland* Indiana*

Montana* Kentucky*

Nebraska* Louisiana

‡

New Jersey* Mississippi

‡

New Mexico* Missouri*

New York* Nevada*

Ohio* Oklahoma

‡

Oregon* Pennsylvania

‡

Tennessee* S. Carolina

‡

Washington* S. Dakota

‡

Federal* (civilian) Utah

‡

Virginia

‡

Wyoming*

Federal* (military)

Sources: Streib, 2000. Data on States with a minimum age of 16 were taken from American Bar

Association, 2000.

* Express minimum age in statute.

†

Minimum age required by Florida Constitution per Florida Supreme Court in Brennan v. State,

754 So. 2d 1 (Fla. 1999).

‡

Minimum age required by the Constitution per the Supreme Court in Thompson v. Oklahoma,

487 U.S. 815 (1988).

November 2000

9

be imposed for offences commit-

ted by persons below eighteen

years of age.”

22

China, which has

long upheld the death penalty and

historically executed more people

annually than any country in the

world, changed its laws in 1997 to

conform to article 37(a) of the

CRC. President Clinton signed the

CRC in 1995 with a reservation to

article 37(a).The Senate has not

yet ratified the CRC. Of 154 U.N.

members, the United States and

Somalia are the only 2 countries

that have not yet ratified the CRC.

Sentencing and

Program Options

A

lthough researchers have

begun to analyze and evalu-

ate the effects of program-

ming on serious, violent, and

chronic juvenile offenders, few pro-

grams target juvenile capital offen-

ders per se. A literature search of

the National Criminal Justice

Reference Service (NCJRS) data-

base reveals scant research on

programs for juvenile capital of-

fenders. One effective program is

Texas’ Capital Offender Program,

which originated in 1988 at the

Giddings State Home and School.

This structured, intensive, 16-week

program helps small groups of

juvenile capital offenders gain

access to their emotions through

role-playing. The goal of this empa-

thy training program is to address

offenders’ emotional detachment

and inability to accept responsibili-

ty for their crimes. Each parti-

cipant is required to reenact the

crime committed, first as the per-

petrator and then as the victim,

in addition to other scenes from

their lives (Matthews, 1995).

A qualitative evaluation found

the program to be effective.The

youth unanimously believed that

the program gave them insight into

their own and others’ feelings.

A quantitative study would yield

more information about the long-

term effectiveness of this program.

The development of sentencing

and program options for juvenile

capital offenders is difficult in light

of the lack of knowledge about this

small population. With greater

attention paid to assessing juvenile

capital offenders, correctional facili-

ties could more effectively provide

programs that address offenders’

needs. An additional difficulty is the

difference in how the courts han-

dle juvenile capital offenders. Some

young offenders are kept in juvenile

court, while others are transferred

to criminal court.These offenders

face a variety of sentencing pat-

terns, depending primarily on State

law, the local and national political

climate, and the skills of defense

counsel.

A review of individual juvenile and

adult death penalty cases often

reveals years of trauma and depri-

vation prior to the commission of

capital offenses. Public investment

in early intervention programs for

children at risk of abuse, academic

support for low-functioning stu-

dents, and positive involvement

with caring adults will go a long

way toward eliminating violent

crimes, including capital offenses

and the resulting sentences that

drain the Nation’s resources—

both human and financial.

In recent years, various innovative

and effective interventions have

been developed to prevent juve-

nile delinquency. Minimizing risk

factors and maximizing protective

factors throughout the develop-

mental cycle from birth through

adolescence can give all youth a

better chance to lead productive,

crime-free lives. Early intervention

programs and services for ju-

veniles engaged in high-risk and

minor delinquent behaviors are

significantly reducing the number

of juveniles penetrating the juve-

nile and criminal justice systems.

Many interventions geared toward

Table 5. Documented Executions of Juvenile

Offenders in Foreign Countries, 1985–1995

Age at Date of

Country Name of Offender Execution Execution

Bangladesh Mohammed Sleim 17 February 27, 1986

Iran Kazem Shirafkan 17 1990

Three unnamed males 16, 17, 17 September 29, 1992

Iraq Five Kurdish males 15–17 November–December 1987

Eight Kurdish males 14–17 December 30–31, 1987

Nigeria Matthew Anu 18 February 26, 1989

Pakistan One male 17 November 15, 1992

Saudi Arabia Sadeq Mal-Allah 17 September 2, 1992

Yemen Nasser Munir Nasser 13 July 21, 1993

al’Kirbi

Source: Streib, 1999.

10

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Life in Prison Without Possibility of Release

The justice system’s recent shift toward stronger

punishment policies has been marked not only by

increased use of the death penalty but by increases

in the number of offenders—including juveniles who

committed offenses prior to their 18th birthdays—

being sentenced to life in prison without the possi-

bility of parole.

Only Washington, DC, Indiana, and Oregon ex-

pressly prohibit courts from imposing life without

parole on offenders younger than age 16 at the time

of their offense (Logan, 1998). A few States effec-

tively disallow a sentence of life without parole for

such offenders by setting a minimum age for waiver

or establishing sentencing limitations. Several States

fail to indicate whether life without parole can be

imposed on those younger than age 16, and some

States do not use the sentence at all.

The overwhelming majority of American juris-

dictions, however, allow life without parole for

offenders younger than age 16. Some even make it

mandatory for defendants convicted of certain

offenses in criminal court. In Washington State,

offenders as young as age 8 can be sentenced to

life.

1

In Vermont, 10-year-olds can face the sentence.

2

Assessing the Constitutionality of Life

in Prison Without Parole: Supreme

Court Standards

The eighth amendment to the U.S. Constitution

prohibits punishment that is cruel and unusual. The

Supreme Court has interpreted this prohibition to

mean that punishment must be proportional to the

crime for which it is imposed.

3

Proportionality analysis in cases involving life with-

out parole has been far less clear than in cases

involving the death penalty. Beginning in the 1980’s,

the Supreme Court decided several cases focusing

on the constitutionality of life sentences. In the first

of these, Rummel v. Estelle,

4

the Court upheld the

constitutionality of a mandatory life sentence (with

the possibility of parole) imposed under a Texas

recidivist law. Holding that the State legislature knew

best how to punish recidivists, the Court held that

findings of disproportionality with respect to sen-

tence length should be “exceedingly rare.”

5

Three

years later, in Solem v. Helm,

6

the Court reached a

different result. Finding a sentence of life without

parole disproportionate, the Court in Solem square-

ly rejected the State’s argument that proportionality

analysis does not apply to terms of imprisonment.

The Court identified three objective factors for

courts to consider when analyzing proportionality:

●

The gravity of the offense and the harshness of

the penalty.

●

Sentences imposed on other criminals (for

more and less serious offenses) in the same

jurisdiction.

●

Sentences imposed (for the same offense) in

other jurisdictions.

7

Unlike Rummel, the three-part test announced in

Solem revealed the Court’s willingness to undertake a

detailed analysis of the proportionality of a sentence’s

length.

The Supreme Court’s consideration of the constitu-

tionality of life without parole 8 years later (in

Harmelin v. Michigan

8

) provided little clarification of

the applicable standards. A majority of the sharply

divided Court rejected the petitioner’s claim that

life without parole was an unconstitutional sentence

for the offense committed. Two members of the

majority, however, held that proportionality analysis

did not even apply outside the context of death

penalty cases. Three justices (concurring separately)

disagreed with this conclusion. Applying the first

prong of Solem, these justices held that life without

parole was not grossly disproportionate to the seri-

ous crimes the petitioner had committed. The other

two factors (intrajurisdictional and interjurisdictional

comparisons), they held, applied only in “the rare

case in which a threshold comparison of the crime

committed and the sentence imposed leads to an

inference of gross disproportionality.”

9

The four dis-

senting justices agreed that the eighth amendment

November 2000

11

contains a proportionality requirement and found

that it had been violated by the petitioner’s life

sentence.

10

Despite disagreement among the justices, the deci-

sion in Harmelin includes two important holdings:

(1) the eighth amendment’s proportionality analysis

applies to capital and noncapital cases, and (2) in

cases involving statutorily mandated minimum sen-

tences (even life without parole), courts or other

sentencing authorities need not consider mitigating

factors such as age (Logan, 1998).

Cases Involving Juveniles

Challenges of sentences of life without parole have

met with limited success in State courts and almost

no success in Federal court in cases involving juve-

nile offenders

11

(Logan, 1998). Most Federal courts

have adopted a restrictive view when comparing the

crime committed and the sentence imposed (the

first factor of the Solem test), focusing almost exclu-

sively on the seriousness of the offense committed

without considering offender culpability and individ-

ual mitigating circumstances (Logan, 1998).

12

The

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Harris v. Wright,

13

for example, upheld a mandatory life sentence for

a 15-year-old convicted of murder, finding that

“youth has no obvious bearing” on proportionality

analysis.

14

It also held that although capital punish-

ment must be treated specially,“mandatory life

imprisonment without parole is, for young and old

alike, only an outlying point on the continuum of

prison sentences.”

15

Like any other prison sentence,

the court held,“it raises no inference of dispropor-

tionality when imposed on a murderer.”

16

Following

the Supreme Court’s ruling in Harmelin, the Harris

court held that a detailed analysis of proportionality

was necessary only in the rare case in which “‘a

threshold comparison of the crime committed and

the sentence imposed leads to an inference of gross

disproportionality.’”

17

State courts have been somewhat more flexible

and willing to consider individual factors affecting

an offender’s culpability than Federal courts. In

California, for example, a court reviewing life with-

out parole must consider circumstances of the

offense (e.g., motive, consequences, and extent of

the defendant’s involvement) and characteristics of

the defendant (e.g., age, prior offenses, and mental

capacity).

18

California courts also must compare the

challenged punishment with sentences imposed

within and outside the State, as required by the sec-

ond and third prongs of the Solem test.

19

Courts in

Kansas similarly consider the nature of the offense,

the “character of the offender,” and the Solem com-

parative factors.

20

Invalidating a mandatory life sentence imposed on

two 14-year-olds convicted of rape, the Kentucky

Supreme Court in Workman v. Kentucky

21

held that

courts retain the power to determine whether “an

act of the legislature violates the provisions of the

Constitution.” Although the court upheld the

Kentucky law mandating life without parole for

those convicted of rape as applied to adults, it held

that a “different situation prevails when punishment

of this stringent a nature is applied to a juvenile.”

22

Under all the circumstances of the case, the court

held that life without parole for two 14-year-olds

“shocks the general conscience of society today

and is intolerable to fundamental fairness.”

23

In Naovarath v. State,

24

a case involving the constitu-

tionality of a life sentence imposed on a 13-year-old

convicted of murder, the Supreme Court of Nevada

undertook a similarly close examination of offender

characteristics. Proportionality analysis, the court in

Naovarath held, required consideration of the con-

vict’s age and his likely mental state at the time of

the crime.

25

Finding the sentence cruel and unusual,

the court held that “children are and should be

judged by different standards from those imposed

upon mature adults.”

26

Other State courts have been less willing to consider

a juvenile’s age when assessing the constitutionality

of life sentences. The Washington State Court of

Appeals in State v. Massey,

27

for instance, affirmed a

life sentence for a 13-year-old convicted of murder,

holding that proportionality analysis should not

include consideration of the defendant’s age,“only a

balance between the crime and the sentence

imposed.”

continued on next page

serious and chronic juvenile of-

fenders have had positive effects

on subsequent reoffense rates.

23

Graduated sanctions systems,

designed to place sentenced

juveniles—especially serious, vio-

lent, and chronic offenders—into

appropriate treatment programs

while protecting the public safety,

are being implemented in jurisdic-

tions across the country. These

programs and services recognize

that children are malleable and

that research-based interventions

are able to affect the lives of juve-

nile offenders positively and con-

structively while helping to reduce

the number of young people who

commit crimes that can put them

on death row or subject them to

life in prison without possibility of

release.

Conclusion

I

ndividuals who were juveniles

at the time they committed a

capital offense continue to be

sentenced to the death penalty in

the United States.Although the

number of juvenile offenders

affected by the death penalty is

small, these offenders serve as a

focal point for often highly politi-

cized debates about the constitu-

tionality of the death penalty,

public safety, alternatives available

to judges and juries in determin-

ing the fates of these youth, and,

most crucial, the effectiveness of

the juvenile justice system in safe-

guarding the due process rights

of youth.

12

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Endnotes

1

These States are Alabama,Arizona,

Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia,

Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana,

Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New

Hampshire, North Carolina,

Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South

Carolina, South Dakota,Texas, Utah,

Virginia, and Wyoming.

2

The data in this Bulletin are current

as of June 2000 and, with the excep-

tion of the sidebar on pages 10–12, are

taken from The Juvenile Death Penalty

Today, a report that first appeared in

1984 and has been issued 57 times by

Dean and Professor of Law Victor L.

Streib at the Claude W. Pettit College

of Law at Ohio Northern University in

Ada, OH (Streib, 2000). Streib states

that the reports “almost invariably

under-report the number of death-

sentenced juvenile offenders due to

State law in Illinois requires a mandatory life sen-

tence for any defendant convicted of killing

more than one person (even if convicted as an

accomplice).

28

The Illinois Supreme Court has not,

as yet, addressed the constitutionality of the

sentencing law as applied to juveniles convicted as

accomplices in murder trials (Hanna, 2000).

Endnotes

1

State v. Furman, 853 P.2d 1092, 1102 (Wash. 1993).

2

VT.STAT

.ANN. tit. 13, § 2303 (Supp. 1997) and VT.STAT.ANN. tit. 33, §

5506 (1991).

3

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 367 (1910) (“It is a precept of

justice that a punishment for crime should be graduated and propor-

tioned to the offense”).

4

445 U.S. 263 (1980).

5

Rummel, 445 U.S. at 272.

6

463 U.S. 277 (1983).

7

Solem, 463 U.S. at 291–292.

8

501 U.S. 957 (1991).

9

Harmelin, 501 U.S. at 1005 (Kennedy, J., concurring).

10

Harmelin, 501 U.S. at 1013 (White, J., dissenting).

11

Data on life without parole cases involving juveniles currently are not

being collected.

12

See, e.g., United States v. Simpson, 8 F.3d 546, 550 (7th Cir. 1993) (“‘[A]

particular offense that falls within legislatively prescribed limits will not

be considered disproportionate unless the sentencing judge has abused

his discretion’”), quoting United States v. Vasquez, 966 F.2d 254, 261 (7th

Cir. 1992).

13

93 F.3d 581 (9th Cir. 1996).

14

Harris, 93 F.3d at 585. See also Rodriguez v. Peters, 63 F.3d 546, 568

(7th Cir. 1995) (refused to consider age of 15-year-old offender in chal-

lenge of life sentence’s constitutionality).

15

Harris, 93 F.3d at 585.

16

Harris, 93 F.3d at 585.

17

Harris, 93 F.3d at 583, quoting Harmelin, 501 U.S. at 1005 (Kennedy, J.,

concurring).

18

People v. Hines, 938 P.2d 833, 443 (Cal. 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct.

855 (1998).

19

People v. Thongvilay, 72 Cal. Rptr. 2d 738, 749 (Cal. App. 1998).

20

State v. Scott, 947 P.2d 466, 470 (Kan. Ct. App.), aff’d in part, rev’d in

part. No. 75,684, 1998 WL 272730 (Kan. May 29, 1998).

21

429 S.W.2d 374, 377 (Ky. Ct. App. 1968).

22

Workman, 429 S.W.2d at 377.

23

Workman, 429 S.W.2d 374, 378 (Ky. 1968).

24

779 P.2d 944 (Nev. 1989).

25

Naovarath, 779 P.2d at 946.

26

Naovarath, 779 P.2d at 946–47. See also People v. Dillon, 668 P.2d 697,

726–27 (Cal. 1983) (reversing life sentence imposed on 17-year-old,

noting youth’s “unusual” immaturity).

27

803 P.2d 340, 348 (Wash. Ct. App. 1990).

28

In all 50 States, juveniles charged with acting as accomplices to

murder may be transferred to criminal court. Unlike Illinois, however,

34 States provide judges discretion when deciding on an appropriate

sentence for such offenders.

November 2000

13

Prevention and Early Intervention Programs

OJJDP is committed to interrupting the cycle of vio-

lence through prevention and early intervention

programs such as nurse home visitation, mentoring,

and family support services.

Prenatal and Early Childhood Nurse

Home Visitation

OJJDP is supporting implementation of the Prenatal

and Early Childhood Nurse Home Visitation

Program in six high-crime, urban areas. The program

sends nurses to visit low-income, first-time mothers

during their pregnancies. The nurses help women

improve their health, making it more likely that their

children will be born free of neurological problems.

Several rigorous studies indicate that the nurse

home visitation program reduces the risks for early

antisocial behavior and prevents problems that lead

to youth crime and delinquency, such as child abuse,

maternal substance abuse, and maternal criminal

involvement. Recent evidence shows that nurse

home visitation even reduces juvenile offending.

Adolescents whose mothers received nurse home

visitation services more than a decade earlier were

60 percent less likely than adolescents whose moth-

ers had not received a nurse home visitor to have

run away, 55 percent less likely to have been arrest-

ed, and 80 percent less likely to have been convicted

of a crime. When the program focuses on low-

income women, the public costs to fund the pro-

gram are recovered by the time the first child

reaches age 4, primarily because of the reduced

number of subsequent pregnancies and related

reductions in use of government welfare programs.

By the time children from high-risk families reach

age 15, the cost savings are four times the original

investment because of reductions in crime, welfare

expenditures, and healthcare costs and because of

taxes paid by working parents.

Youth Mentoring

Another effective intervention is to enlist caring,

responsible adults to work with at-risk youth in

need of positive role models. Big Brothers/Big

Sisters (BB/BS) mentoring programs, for example,

have been matching volunteer adults with youth to

help youth avoid the risky behaviors that compro-

mise their health and safety. A 1995 study of BB/BS

programs, conducted by Public/Private Ventures of

Philadelphia, PA, revealed positive results. Mentored

youth reported being 46 percent less likely to begin

using drugs, 27 percent less likely to begin drinking,

and approximately 33 percent less likely to hit

someone than were their nonmentored counter-

parts. In addition, BB/BS programs had a positive

effect on mentored youth’s success at school.

OJJDP’s Juvenile Mentoring Program (JUMP) pro-

vides one-to-one mentoring for youth at risk of

delinquency, gang involvement, educational failure, or

dropping out of school. Among its many objectives,

JUMP seeks to discourage use of illegal drugs and

firearms, involvement in violence and gangs, and

other delinquent activity and encourage participa-

tion in service and community activity. The JUMP

national evaluation will play an important role in

expanding the body of information about mentoring.

Preliminary evaluation findings reveal that both

youth and mentors view the experience as positive.

difficulty in obtaining accurate data”

(p. 2). However, the juvenile execution

data are complete, the annual juvenile

death sentencing data are almost (95

percent) complete, and the data for

juvenile offenders currently on death

row are fairly (90 percent) complete.

The report is available online at

www.law.onu.edu/faculty/streib/

juvdeath.htm.

3

Although 10 States classify all individ-

uals age 17 or older as adults and 3

other States classify all individuals age

16 or older as adults for purposes of

criminal responsibility (Snyder and

Sickmund, 1999), this Bulletin refers to

all individuals under age 18 at the time

that a criminal offense was committed

as “juveniles.”

4

408 U.S. 238 (1972).

5

428 U.S. 153 (1976).

6

383 U.S. 541 (1966).

7

455 U.S. 104 (1982).

8

455 U.S. 104, 116.

9

487 U.S. 815 (1988).

14

Coordinating Council on Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

10

492 U.S. 361 (1989).

11

492 U.S. 361 (the Stanford v. Kentucky

and Wilkins v. Missouri cases were

consolidated).

12

These diagnostic evaluations involved

psychiatric, neurological, psychological,

neuropsychological, educational, and

electroencephalographic (EEG) exami-

nations. Dr. Dorothy Lewis and

colleagues conducted psychiatric inter-

views with the offenders; obtained

detailed neurological histories; corrob-

orated those histories when possible

through physical examinations, record

reviews, and specialized tests such as

the EEG; performed neurological and

mental status examinations; deter-

mined whether offenders had been

physically and/or sexually abused as

youth through lengthy interviews;

performed neurometric quantitative

EEG’s; and conducted neuropsychol-

ogical and educational testing using

tests such as the WAIS, Bender-Gestalt

test, Rorschach Test, Halstead-Reitan

Battery of Neuropsychological Tests,

and Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-

Educational Battery.

13

For more information on inadequate

legal representation, see A Broken

System: Error Rates in Capital Cases

1973–1995, which states that the

most common errors found in capital

cases are “(1) egregiously incompetent

defense lawyering (accounting for 37%

of the state post-conviction reversals)

and (2) prosecutorial suppression of

evidence that the defendant is

innocent or does not deserve the

death penalty (accounting for another

16–19 percent, when all forms of law

enforcement misconduct are consid-

ered” (Liebman, Fagan, and West,

2000:5).

14

See Wright v. Angelone, No. 97–32

(4th Cir. July 16, 1998).

15

535 So. 2d 362 (La. 1988).

16

615 So. 2d 1333 (La. 1993).

17

586 So. 2d 978 (Ala. Ct. Crim. Ap.

1991).

18

636 So. 2d 494 (1994).

19

540 N.E.2d 1216 (Ind. 1989).

20

754 So. 2d 1 (Fla. 1999).

21

A report issued by the American Bar

Association in January 2000 details

recent legislative, judicial, and executive

branch activity relating to the death

penalty (American Bar Association,

2000).

22

G.A. Res. 44/25, annex, 44 U.N.

GAOR, Supp. No. 49, at 167, U.N. Doc.

A/44/49 (1989).

23

Lipsey and Wilson (1998:338) report

that in a meta-analysis of 200 studies

of intervention with serious offenders,

the best programs “were capable of

reducing recidivism rates by as much

as 40%” and that the “average” inter-

vention reduced recidivism rates by

approximately 12 percent. See also

Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention, 1998.

References

American Bar Association. 2000. A

Gathering Momentum: Continuing

Impacts of the American Bar Association

Call for a Moratorium on Executions.

Washington, DC: American Bar

Association.

Amnesty International. 1991. USA: The

Death Penalty and Juvenile Offenders.

New York, NY: Amnesty International

USA Publications.

Amnesty International. 1998. On the

Wrong Side of History: Children and

the Death Penalty in the USA. New

York, NY: Amnesty International USA

Publications.

Bassham, G. 1991. Rethinking the

emerging jurisprudence of juvenile

death. Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics,

and Public Policy 5(2):467–501.

Evans, K.L. 1992.Trying juveniles as

adults: Is the short-term gain of retri-

bution outweighed by the long-term

effects on society? Mississippi Law

Journal 62(1):95–131.

Hale, R.L. 1997. A Review of Juvenile

Executions in America. Criminology

Series, vol 3. Lewiston, NY: Edwin

Mellen Press.

Hanna, J. 2000. Mandatory life term for

teen rejected. Chicago Tribune (June 22).

Jackson, S. 1996.Too young to die—

juveniles and the death penalty—

a better alternative to killing our

children:Youth empowerment. New

England Journal on Criminal and Civil

Confinement 22(2):391–437.

Lewis, D.O., Pincus, J.H., Bard, B.,

Richardson, E., Prichep, L.S., Feldman, M.,

and Yeager, L. 1988. Neuropsychiatric,

psychoeducational, and family charac-

teristics of 14 juveniles condemned to

death in the United States. American

Journal of Psychiatry 145(5):585–589.

Liebman, J.S., Fagan, J., and West,V. 2000.

A Broken System: Error Rates in Capital

Cases 1973–1995. New York, NY:

Columbia Law School.

Lipsey, M.W., and Wilson, D.B. 1998.

Effective intervention for serious juve-

nile offenders:A synthesis of research.

In Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders:

Risk Factors and Successful Interventions,

edited by R. Loeber and D.P. Farrington.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications,

Inc., pp. 313–345.

Logan,W.A. 1998. Proportionality and

punishment: Imposing life without

parole on juveniles. Wake Forest Law

Review 33:681–725.

Matthews, S. 1995. Juvenile capital

offenders on empathy. Reclaiming

Children and Youth (Summer):10–12.

Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention. 1998. Serious

and Violent Juvenile Offenders. Bulletin.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Justice, Office of Justice Programs,

Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention.

Robinson, D.A., and Stephens, O.H.

1992. Patterns of mitigating factors in

juvenile death penalty cases. Criminal

Law Bulletin 28(3):246–275.

November 2000

15

Snell,T.L. 1999. Capital Punishment 1998.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Justice, Office of Justice Programs,

Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Snyder, H.N., and Sickmund, M. 1999.

Juvenile Offenders and Victims: 1999

National Report. Report. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of

Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile

Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Streib,V.L. 1999. Juvenile Death Penalty

Today: Death Sentences and Executions for

Juvenile Crimes, January 1973–June 1999.

Ada, OH: Ohio Northern University

Claude W. Pettit College of Law.

Streib,V.L. 2000. The Juvenile Death

Penalty Today: Death Sentences and

Executions for Juvenile Crimes, January 1,

1973–June 30, 2000. Ada, OH: Ohio

Northern University Claude W. Pettit

College of Law.

Additional Resources

Amnesty International. 1998. Betraying

the Young: Human Rights Violations Against

Children in the U.S. Justice System. New

York, NY:Amnesty International USA

Publications.

DeMuro, P. 1999. Consider the

Alternatives: Planning and Implementing

Detention Alternatives. Pathways to

Juvenile Detention Reform Series, vol.

4. Baltimore, MD:The Annie E. Casey

Foundation.

McCuen, G.E., ed. 1997. Death Penalty

and the Disadvantaged. Hudson,WI:

Gary E. McCuen Publications.

Parent, D., Dunworth,T., McDonald, D.,

and Rhodes,W. 1997. Key legislative

issues in criminal justice:Transferring

serious juvenile offenders to adult

courts. Alternatives to Incarceration

3(4):28–30.

Sanborn, J.B. 1996. Policies regarding

the prosecution of juvenile murderers:

Which system and who should decide?

Law and Policy 19(1 and 2):151–178.

Points of view or opinions expressed in

this document are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the

official position or policies of OJJDP or

the U.S. Department of Justice.

Coordinating Council Members

As designated by legislation, the Coordinating Council’s primary functions are to coordinate all Federal

juvenile delinquency prevention programs, all Federal programs and activities that detain or care for

unaccompanied juveniles, and all Federal programs relating to missing and exploited children.The Council

comprises nine statutory members and nine practitioner members representing disciplines that focus on youth.

Statutory Members

The Honorable Janet Reno,

Chairperson

Attorney General

U.S. Department of Justice

John J.Wilson,Vice Chair

Acting Administrator

Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention

The Honorable Donna E. Shalala, Ph.D.

Secretary

U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services

The Honorable Alexis M. Herman

Secretary

U.S. Department of Labor

The Honorable Richard W. Riley

Secretary

U.S. Department of Education

The Honorable Andrew Cuomo

Secretary

U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development

The Honorable Barry R. McCaffrey

Director

Office of National Drug Control Policy

Doris Meissner

Commissioner

U.S. Immigration and Naturalization

Service

Harris Wofford

Chief Executive Officer

Corporation for National and

Community Service

Practitioner Members

Robert A. Babbage, Jr.

Senior Managing Partner

InterSouth, Inc.

Larry K. Brendtro, Ph.D.

President

Reclaiming Youth

The Honorable William R. Byars, Jr.

Judge

Family Court of Kershaw County,

South Carolina

John A. Calhoun

Executive Director

National Crime Prevention Council

Larry EchoHawk

Professor

Brigham Young University Law School

The Honorable Adele L. Grubbs

Judge

Juvenile Court of Cobb County, Georgia

The Honorable Gordon A. Martin, Jr.

Associate Justice

Massachusetts Trial Court

The Honorable Michael W. McPhail

Judge

Juvenile Court of Forrest County,

Mississippi

Charles Sims

Chief of Police

Mississippi Police Department,

Hattiesburg

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Washington, DC 20531

Official Business

Penalty for Private Use $300

PRESORTED STANDARD

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

DOJ/OJJDP

PERMIT NO. G–91

NCJ 184748

Coordinating Council Bulletin

Acknowledgments

Lynn Cothern, Ph.D., is Senior Writer/Editor for the Juvenile Justice

Resource Center (JJRC) in Rockville, MD. Lucy Hudson, Project

Manager for JJRC, and Ellen McLaughlin,Writer/Editor for the

Juvenile Justice Clearinghouse (JJC) in Rockville, MD, revised and

updated the Bulletin using source material provided by the author.

Nancy Walsh, Senior Writer/Editor for JJC, wrote the sidebar on

pages 10–12.