Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs to

Improve School Achievement: A Community

Guide Health Equity Systematic Review

John A. Knopf, MPH; Robert A. Hahn, PhD, MPH; Krista K. Proia, MPH; Benedict I. Truman, MD, MPH;

Robert L. Johnson, MD; Carles Muntaner, MD; Jonathan E. Fielding, MD, MA, MPH, MBA;

Camara Phyllis Jones, MD, PhD, MPH; Mindy T. Fullilove, MD, MS; Pete C. Hunt, MPH; Shuli Qu, MPH;

Sajal K. Chattopadhyay, PhD; Bobby Milstein, PhD, MPH; the Community Preventive Services Task Force

rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr

Context: Low-income and minority status in the United States

are associated with poor educational outcomes, which, in turn,

reduce the long-term health benefits of education. Objective:

This systematic review assessed the extent to which

out-of-school-time academic (OSTA) programs for at-risk

students, most of whom are from low-income and racial/ethnic

minority families, can improve academic achievement. Because

most OSTA programs serve low-income and ethnic/racial

minority students, programs may improve health equity. Design:

Methods of the Guide to Community Preventive Services were

used. An existing systematic review assessing the effects of

OSTA programs on academic outcomes (Lauer et al 2006;

search period 1985-2003) was supplemented with a Community

Guide update (search period 2003-2011). Main Outcome

Measure: Standardized mean difference. Results: Thirty-two

studies from the existing review and 25 studies from the update

were combined and stratified by program focus (ie,

reading-focused, math-focused, general academic programs,

and programs with minimal academic focus). Focused programs

were more effective than general or minimal academic

programs. Reading-focused programs were effective only for

students in grades K-3. There was insufficient evidence to

determine effectiveness on behavioral outcomes and longer-term

academic outcomes. Conclusions: OSTA programs, particularly

focused programs, are effective in increasing academic

achievement for at-risk students. Ongoing school and social

J Public Health Management Practice

, 2015, 21(6), 594–608

Copyright

C

2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

environments that support learning and development may be

essential to ensure the longer-term benefits of OSTA programs.

Author Affiliation: Community Guide Branch, Division of Epidemiology, Analysis

and Library Services, Office of Public Health Scientific Services (Mr Knopf, Drs

Hahn and Chattopadhyay, and Mss Proia and Qu), Office of the Associate

Director for Science, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD & TB

Prevention (Dr Truman), Division of Adolescent & School Health, National Center

for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (Mr Hunt), and

Epidemiology and Analysis Program Office, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia (Dr Jones); Hygeia Dynamics, Boston,

Massachusetts (Dr Milstein); Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New

Jersey (Dr Johnson); University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario (Dr Muntaner);

UCLA Fielding School of Public Health (Dr Fielding); and Columbia University,

New York, New York (Dr Fullilove).

Names and affiliations of the Community Preventive Services Task Force mem-

bers can be found at www.thecommunityguide.org/about/task-force-members.

html.

Author affiliations are shown at the time the research was conducted.

The work of John Knopf, Krista Proia, and Shuli Qu was supported with funds

from the Oak Ridge Institute for Scientific Education (ORISE). The authors are

grateful to the following for advice on out-of-school-time-academic programs:

Mark Dynarski, PhD (Pemberton Research), Doris Entwisle, PhD (Johns Hopkins

University), and Elizabeth Warner, PhD (US Department of Education). The authors

are also grateful to the health equity consultation team: Ann Abramowitz, PhD

(Emory University); Geoffrey Borman, PhD (University of Wisconsin); Jeannie

Brooks-Gunn, PhD (Columbia); Kristen Bub, PhD (Auburn University); Duncan

Chaplin, PhD (Mathematica); Dennis Condron, PhD (Oakland University); Greg

Duncan, PhD (University of California,Irvine); Rebecca Herman, PhD (What Works);

Gloria Ladson-Billings, PhD (University of Wisconsin); Robert Lerman, PhD (Urban

Institute); Raegen Miller, MS (American Progress); Pedro Noguera, PhD (Columbia

University); Charles M. Payne, PhD (University of Chicago); Annie Pennucci, MPA

(Washington State Institute for Public Policy); Catherine Ross, PhD (University of

Texas, Austin); Janelle Scott, PhD (University of California, Berkeley); and Emily

Wentzel, PhD (University of Maryland). They thank those who provided editorial

support: Kate W. Harris, BA, and Kristen D. Folsom, MPH, of CDC’s Community

Guide Branch.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention.

No author has any conflict of interest or financial disclosure.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

594

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 595

KEY WORDS: achievement gap, disparities, education, minority

health

● Context

In the United States, disparities in educational achieve-

ment between students from racial/ethnic minority

families and those from white families, as well as be-

tween students from low-income families and those

from more affluent families, are well documented.

1,2

Although reading and math scores generally have

improved for all race/ethnic groups since 1992 and

for all income levels since 2003, gaps in educational

achievement persist.

3

Disparities in student educa-

tional achievement have long-term consequences: ed-

ucation has been demonstrated to be one of the most

important determinants of health and longevity.

4-6

Gaps in math and reading achievement expand dur-

ing the summer months when regular school is not

in session.

7

The “faucet theory”

8,9

hypothesizes that

summer loss is caused by the relative scarcity of aca-

demic resources for low-income students during sum-

mer when resources available during the school year

are “turned off.” Higher-income students often have

access to enrichment activities. “Summer loss” effects

accumulate over a lifetime of schooling and are a source

of the persistent achievement gap between students

of lower and higher socioeconomic status (SES).

8,9

Summer out-of-school-time programs may be partic-

ularly effective in countering summer loss.

This review evaluated the effectiveness of out-of-

school-time academic (OSTA) programs as a means

of narrowing the academic achievement gap. A recent

synthesis of prior reviews on OSTA programs calls for

a new systematic review with attention to characteris-

tics that make programs more or less effective.

10

OSTA

programs are defined as programs provided outside of

regular school hours to students in grades K-12 who

are either low-achieving or at risk of low achievement.

These programs are offered during the school year—

usually after school hours—or during summer recess.

These programs must include an academic component,

Supplemental d igital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations

appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this

article on the journal’s Web site (http://www.JPHMP.com).

Correspondence: Robert A. Hahn, PhD, MPH, Community Guide Branch,

Division of Epidemiology, Analysis and Library Services, Office of Public Health

Scientific Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1600 Clifton Rd,

DOI: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000268

which can range from minimal academic content, such

as supervised time for students to complete their home-

work or receive homework assistance, to more inten-

sive tutoring or remedial classes focused on specific

subjects, such as reading or math. Programs may in-

clude sports and recreation, snacks, or counseling. At-

tendance is most often voluntary, although students

may be required to participate under certain circum-

stances (eg, to avoid retention in grade).

An extensive body of evidence links educational

achievement and attainment to lifelong health out-

comes through 3 interrelated pathways: (1) devel-

opment of psychological and interpersonal strength,

such as a sense of control and social support, which,

in turn, contribute to healthy social interactions; (2)

problem-solving abilities and the ability to pursue and

maintain productive work and adequate income, and

the health benefits they provide; and (3) adoption of

healthy behaviors.

4,11-13

While educational experiments

are few, a wide range of studies are supportive of

a causal effect of education on downstream health.

13

Standardized tests of academic achievement assess ac-

quired knowledge and the ability to interact effec-

tively in the classroom setting, reason, and solve prob-

lems. Because these abilities predict long-term health

outcomes,

4,12,14,15

they provide a reasonable basis for

use as outcomes in Community Guide health equity

reviews.

Because academic problems are often associated

with low family income or minority status, if effec-

tive, OSTA programs are likely to advance academic

achievement of poor or minority populations. Because

improved academic performance is linked to improved

health status, and because poor and minority popula-

tions as a whole have lower health status, the benefits

of OSTA programs may reach beyond improved aca-

demic performance to improved health equity.

In this review, focused programs were distinguished

from general academic programs and from minimal

academic programs. Focused programs concentrated

on a single subject, such as math or reading. General

academic programs focused on more than 1 subject.

Minimal academic programs did not have a strong aca-

demic focus, but some included time for homework

or homework assistance. Cooper’s hypothesis

10

of “the

congruence between program goals and program out-

comes” was evaluated.

Using methods developed for the Community

Guide (a program that conducts systematic reviews

of public health interventions),

16

this systematic re-

view assessed the effectiveness of OSTA programs as

a means to improve educational outcomes. For pur-

poses of this review, a student population is consid-

ered at risk for low academic achievement if charac-

terized by at least one of the following risk factors:

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

596 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

low SES, racial/ethnic minority, low academic per-

formance, single-parent family, low maternal educa-

tion, or limited English proficiency. The plurality of

poor children in the United States are low-income

non-Hispanic white children (42.1% in 2010-2011) and

are thus included in this review.

17

● Evidence Acquisition

For this review, a coordination team (the team) was

constituted, including qualified systematic reviewers

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s

(CDC’s) Community Guide Branch, Community Pre-

ventive Services Task Force (Task Force) representa-

tives, and subject matter experts from other CDC pro-

grams, external agencies, organizations, and academic

institutions. A team of consultants with expertise on

educational policies and programs was also consti-

tuted. The teams worked under the guidance of the

Task Force.

Conceptual approach and analytic framework

The team hypothesized that the increased out-of-school

instructional time, safe environment, enhanced social-

ization, and the possibility of improved nutrition pro-

vided by OSTA programs might contribute to im-

proved cognitive performance, academic achievement,

and social and emotional skills (Figure 1). Because

OSTA programs may reduce at-risk students’ free out-

of-school time during which juvenile crime and victim-

ization peak, these programs may reduce delinquent

behavior. However, if supervision during OSTA pro-

grams is lax, time spent in these out-of-school programs

could increase deviant behavior by providing concen-

trated unsupervised socialization of groups of students

at risk of such behavior.

18

By providing supervised time outside of school

hours, programs may increase parental work time and

decrease childcare costs. The pathways described ear-

lier and in Figure 1 illustrate how immediate outcomes

could contribute to long-term improvements in edu-

cational outcomes and ultimately decreased morbidity

and early mortality.

4-6,11

Research questions

The review focused on 8 research questions:

1. Are OSTA programs effective in improving aca-

demic achievement, in particular achievement in

math and reading?

2. Are OSTA programs focused on specific topics, such

as reading or math, more effective in improving aca-

demic achievement than programs with a more gen-

eral focus? Are general programs more effective than

programs with a minimal academic focus?

FIGURE 1 ● Analytic Framework: Out-of-School-Time-Academic Programs

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 597

3. Do after-school programs and summer programs

differ in effectiveness?

4. Are programs differentially effective at different

grade levels?

5. Are programs with greater attendance or longer du-

ration more effective?

6. Is OSTA tutoring more effective than group instruc-

tion?

7. Do OSTA programs have effects on nonacademic

outcomes, such as delinquency and substance

abuse?

8. Do OSTA effects differ for low-income or minority

children versus higher-income or white children?

● Methods

Search for evidence

Using Community Guide methods, the team identified

a meta-analysis on OSTA by Lauer et al,

19

which in-

cluded studies published between January 1985 and

May 2003. The meta-analysis met Community Guide

standards

16

and was accepted by the Task Force as the

basis for this review.

To determine whether studies published after the

cutoff date of the Lauer et al

19

meta-analysis were

consistent with the Lauer et al findings, the team

conducted an update systematic search using search

criteria similar to those of Lauer et al. Citations and

reports published from 2003 to 2011 were searched in

the following databases: ERIC, PubMed, Sociological

Abstracts/Social Services Abstracts, and PsycINFO.

The complete search strategy is available at www.

thecommunityguide.org/healthequity/education/

supportingmaterials/SS-outofschooltime.html.Ref-

erence lists of identified articles were also searched.

The analysis in this review combines studies from the

Lauer et al meta-analysis with more recent research.

A systematic review of summer school programs by

Cooper et al,

10

synthesizing studies published between

1967 and 1998, was also identified. It included 71 stud-

ies, only one of which was also included in the Lauer

et al

19

meta-analysis. Differences between included

studies in these reviews may be a consequence of dif-

ferent inclusion criteria; for this reason, Cooper et al

results were not included in this review.

Inclusion criteria for Community Guide update

(2003-2011)

To qualify as a candidate for inclusion in this review, a

study had to:

r

evaluate the effectiveness of OSTA programs in

improving academic achievement for students in

grades K-12;

r

evaluate a study population at risk of academic fail-

ure (as indicated by ≥1 of the characteristics noted

earlier);

r

include 1 or more outcomes: reading or math

achievement as assessed through standardized test

scores; high school graduation; enrollment in post–

secondary education; or delinquency or substance

abuse;

r

have a control population or condition (treated or

untreated);

r

be conducted in a high-income country

20

;

r

be published in indexed scientific literature or a gov-

ernment document; and

r

be written in English.

Studies were excluded from this review if the study

population consisted exclusively of special needs or

gifted students.

The Lauer et al review

19

and the present update re-

view differ in several ways: (1) the Lauer et al review in-

cluded unpublished theses and dissertations, whereas

this update review included only peer-reviewed pub-

lished articles or government evaluations; (2) the Lauer

et al review excluded studies that combined findings

from multiple sites, whereas this update review in-

cluded aggregated multisite studies; (3) the Lauer et al

review extracted information only on reading and math

outcomes; this update also assessed post–secondary

academic achievement, delinquency, and substance

use; and (4) whereas the Lauer et al review examined

only studies conducted in the United States, this update

review included studies from any high-income country.

Data abstraction and quality assessment

A full description of the process for data abstraction

and quality assessment is available in Supplemental

Digital Content Appendix A (available at http://links.

lww.com/JPHMP/A155).

Analytic approach

The analytic approach for this review is available in

Supplemental Digital Content Appendix B ( available

at http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/A156).

● Evidence Synthesis

Study characteristics

Lauer et al

19

reviewed the abstracts of 1808 citations

and retrieved and reviewed 371 full-length articles,

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

598 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

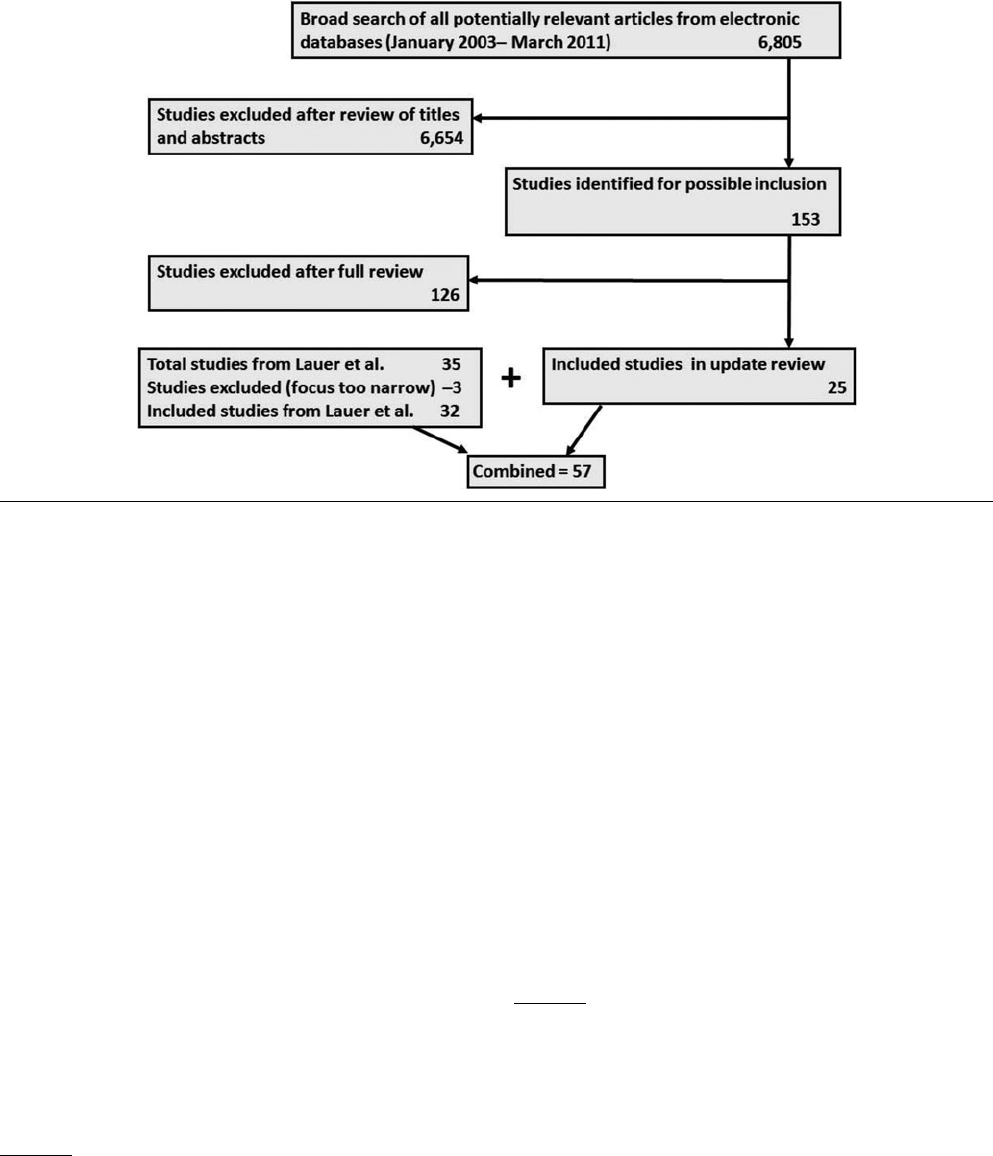

FIGURE 2 ●

Flowchart Showing Update Search, Number of Included Studies From That Search, and Number of Included

Studies From Previous Meta-analysis

a

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

a

From Lauer et al

19

of which 35 met their inclusion criteria. The update

review synthesis excluded 3 of those studies that re-

ported only school grades,

21-23

for a total of 32 studies

from Lauer et al.

24-55

The update search found 26 studies

(reported in 25 publications)

56-79

that met inclusion cri-

teria (Figure 2). By Community Guide standards,

16,80

all studies in the update were of greatest suitabil-

ity of design. One

78

was excluded from analysis be-

cause of limited quality of execution. Of the remain-

ing 25 studies, 6 (reported in 5 publications) were of

good quality of execution

56,70,75,76,79

and 19 were of fair

quality.

55,57-69,71-74,77

The combined analysis included 57

studies. Data necessary to calculate standardized mean

differences (SMDs) were not available in studies as-

sessing delinquency, drug abuse, or high school com-

pletion. Analyses were conducted in 2012-2013.

All included studies were conducted in the United

States, 63% in urban areas* and S. Ross, et al (unpub-

lished data, 1996) and the remainder in rural or mixed

settings or did not report urbanicity (Table). Summer

programs were evaluated in 49% of studies,

†

and S.

Ross, et al (unpublished data, 1996) and the remainder

evaluated after-school settings. Study populations

were predominantly from racial/ethnic minorities,

*References 24-28, 30-33, 35-37, 40, 44-46, 49, 50, 53-55, 58, 59, 63,

64, 66-69, 71-76.

†References 26-28, 34, 35-37, 39, 40, 42, 46-49, 50-52, 54, 58, 59, 61,

62, 69, 71, 73, 75, 76.

mostly black and low-SES families. Specifically, among

studies that reported race/ethnicity, 60% were major-

ity black

‡

and S. Ross, et al (unpublished data, 1996)

and among those reporting SES, 84% were majority

low SES.

§

The largest proportion of programs were

reading-focused

|

and general academics

¶

(40% each),

followed by math-focused

29,42,49,52,54,61,77

(12%) and

minimal academics

45,66,72,81

(7%); one program

77

had

separate math- and reading-focused arms. Of 51

programs for which didactic approach was reported,

most (47%) involved group instruction,** 33% in-

volved tutoring or individualized instruction,

††

and

the remainder (20%) used mixed approaches.

‡‡

Four

studies (in 3 articles) included controls involved

in OSTA programs

64,71,77

that were less intensive

or less academically rigorous than the intervention

‡References 25-27, 32, 40, 41, 46, 48-49, 51, 55, 58, 59, 62, 64, 65, 67,

69, 71-73, 75, 76, 79.

§References 24-30, 33-38, 40, 44-46, 48, 50, 53, 55, 58-67, 69-77, 79.

|References 12, 25, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 43, 44, 47, 50, 58, 59, 64,

69, 71, 73-77.

¶References 24, 27, 28, 32, 34, 36-38, 41, 46, 48, 51, 53, 55-57, 60, 62,

63, 65, 67, 70, 79.

**References 24, 26, 28, 30-35, 42, 43, 54, 58, 59, 65, 69-71, 73, 75-77,

79.

††References 12, 27, 29, 38, 41, 44-46, 48, 53, 55, 56, 60, 63, 66, 67,

72.

‡‡References 25, 36, 39, 40, 49, 50, 61, 62, 64, 74.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 599

TABLE ● Characteristics of Included Studies

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Characteristic Category

No. of Studies

Reporting

Characteristic

(%)

a

(N = 57)

Setting United States 57 (100%)

Urbanicity Urban 36 (63)

Rural 5 (9)

Mixed 8 (14)

NR 7 (12)

Study population

demographics

Grade levels served Elementary (K-5) 28 (49)

Elementary/middle 8 (14)

Middle (6-8) 7 (12)

Middle/high 3 (5)

High (9-12) 7 (12)

All 4 (7)

Race/ethnicity Majority black 25 (43)

Majority Hispanic 4 (7)

Majority nonwhite (unspecified) 7 (12)

Majority white 2 (4)

Mixed 4 (7)

NR 15 (26)

SES Majority low SES 42 (74)

<50% low SES 8 (14)

NR 7 (12)

Intervention characteristics Temporal location

b

Summer 28 (49)

After-school 29 (51)

Didactic method Tutoring or individualized instruction 17 (30)

Group instruction 24 (42)

Mixed 10 (18)

NR 6 (11)

Program focus Reading 23 (40)

Math 7 (12)

General academics 23 (40)

Minimal academics 4 (7)

Abbreviations: NR, not reported SES, socioeconomic status.

a

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

b

The temporal location for year-round programs is categorized by where the majority of academic instruction took place.

population. These studies assessed effects of programs

that contained additional components.

Intervention effects on academic achievement

Questions 1 and 2: Effectiveness of OSTA programs on

math, reading, and general focus.

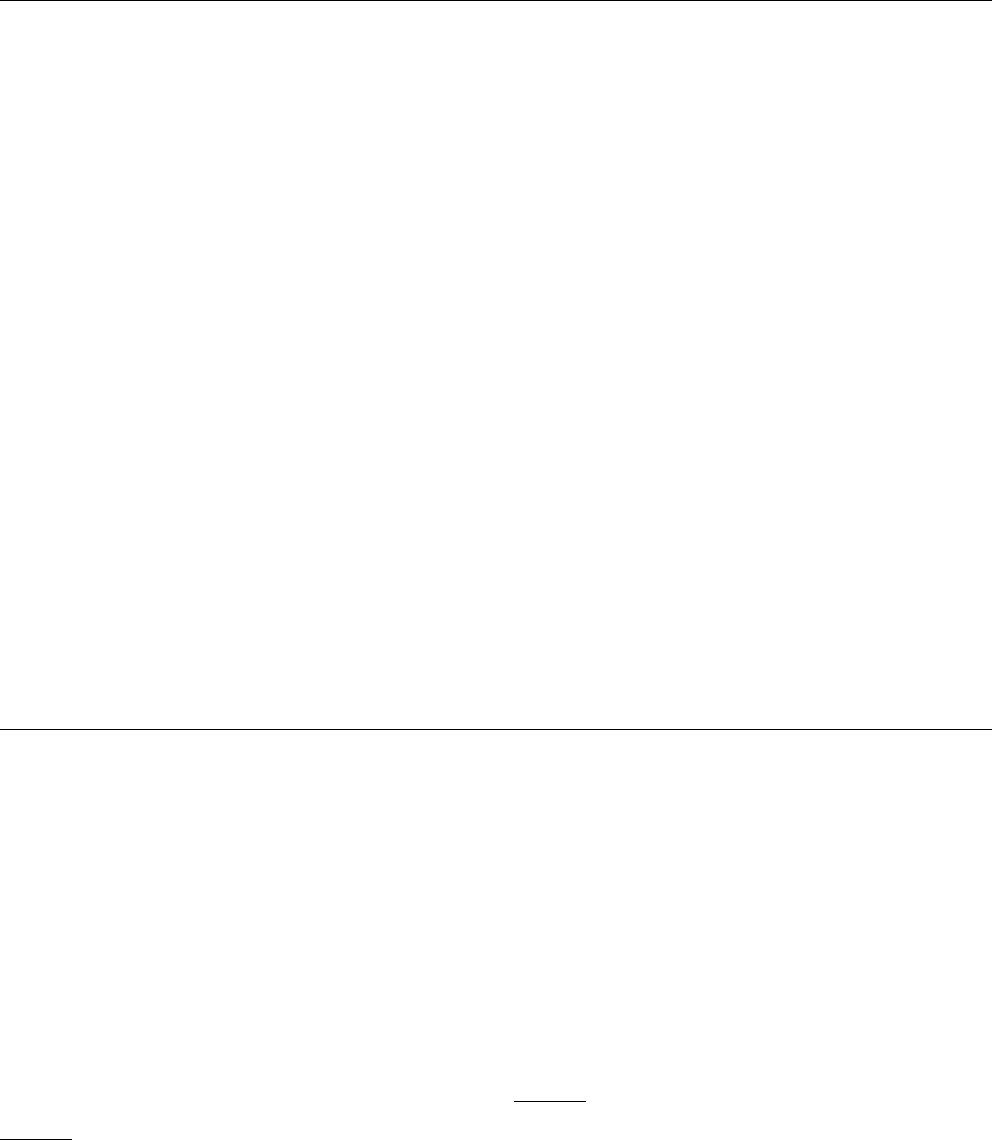

Reading achievement

The effects of OSTA programs on reading achieve-

ment were assessed in 45 studies* and S. Ross,

et al (unpublished data, 1996). The overall me-

*References 24-28, 30-41, 43-48, 50, 51, 53, 55-60, 63-64, 67, 69, 71,

73-77, 82.

dian SMD was 0.11 (interquartile interval [IQI]:

0.02-0.42). Substantial differences in effective-

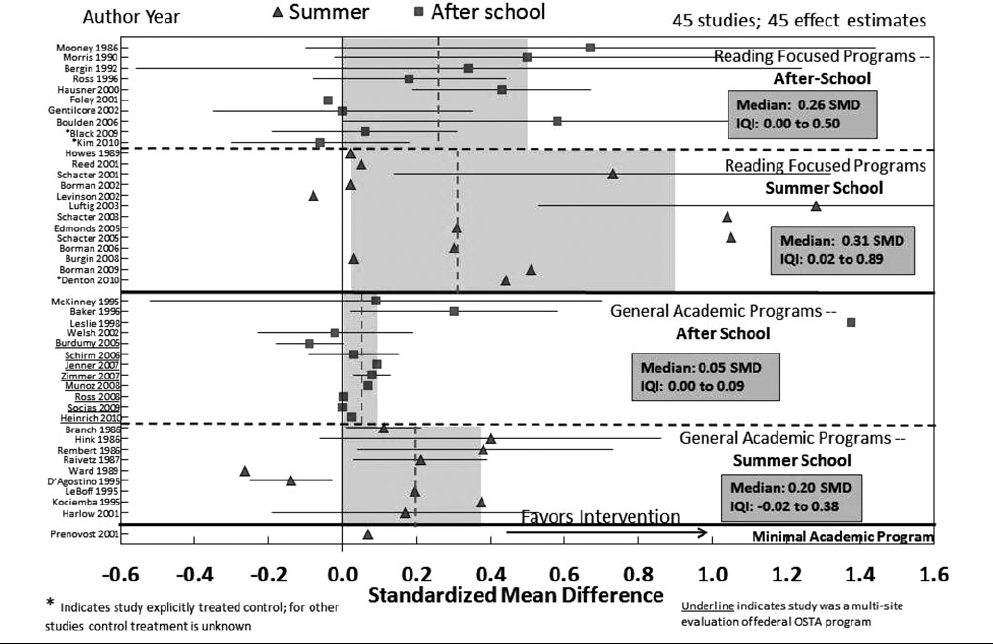

ness by program focus were found (Figure 3).

Twenty-three evaluations

†

and S. Ross, et al (unpub-

lished data, 1996) of reading-focused programs yielded

a median SMD of 0.31 (IQI: 0.02-0.58) compared with

a median SMD of 0.09 (IQI: 0.00-0.26) for the 21

evaluations of general academic programs.

‡

The only

minimal academic program

45

reported an SMD of 0.07

(Figure 3).

†References 25, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 43, 44, 47, 50, 58, 59, 64, 69,

71, 73-77.

‡References 24, 27, 28, 32, 34, 36-38, 41, 46, 48, 51, 53, 55-57, 60, 63,

65, 67, 82.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

600 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

FIGURE 3 ●

Effectiveness of OSTA Programs on Reading Achievement

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Abbreviations: IQI, interquartile interval; OSTA, Out-of-School-Time Academic; SMD, standardized mean difference.

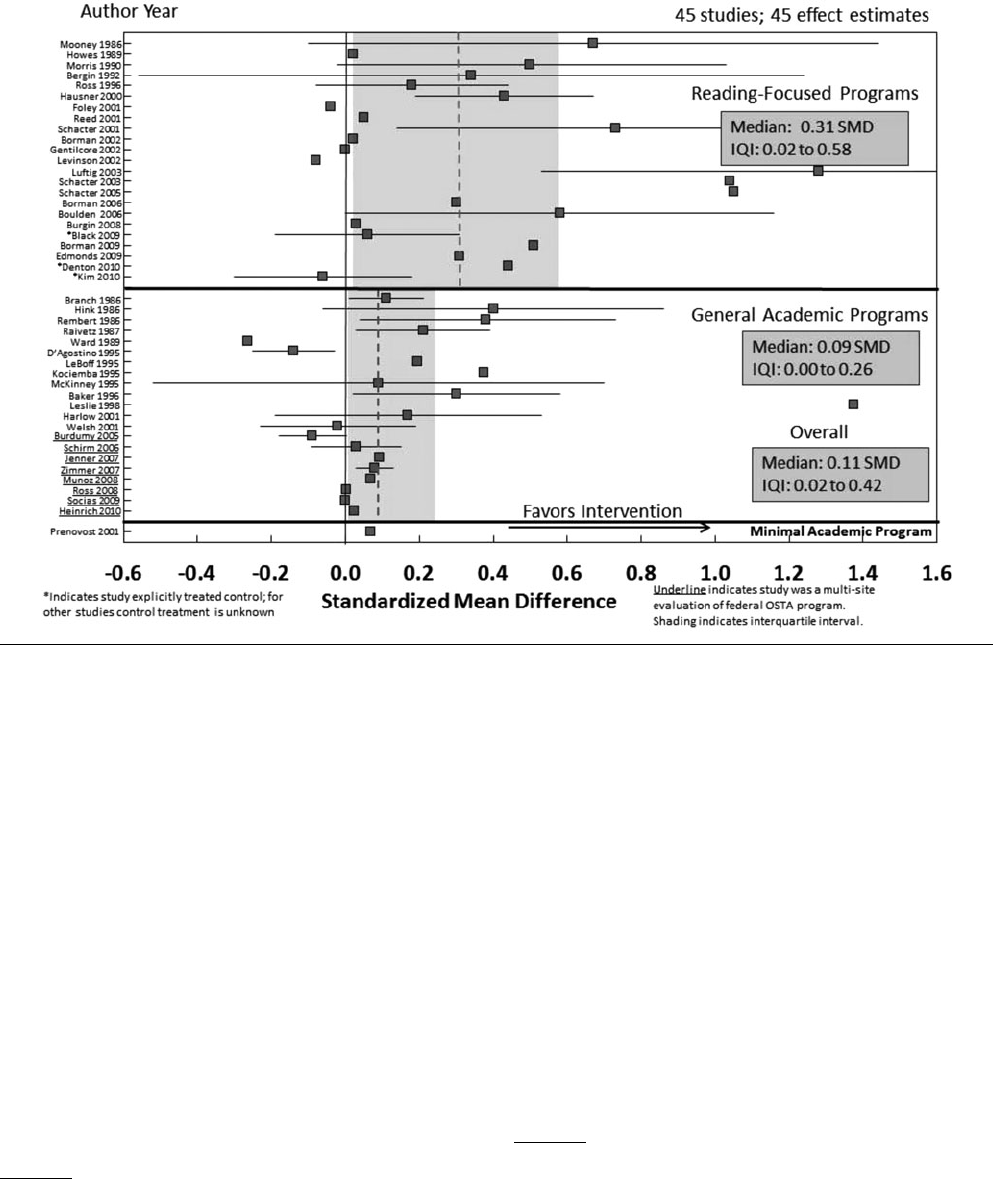

Math achievement

Twenty-seven studies

*

assessed the effects of OSTA pro-

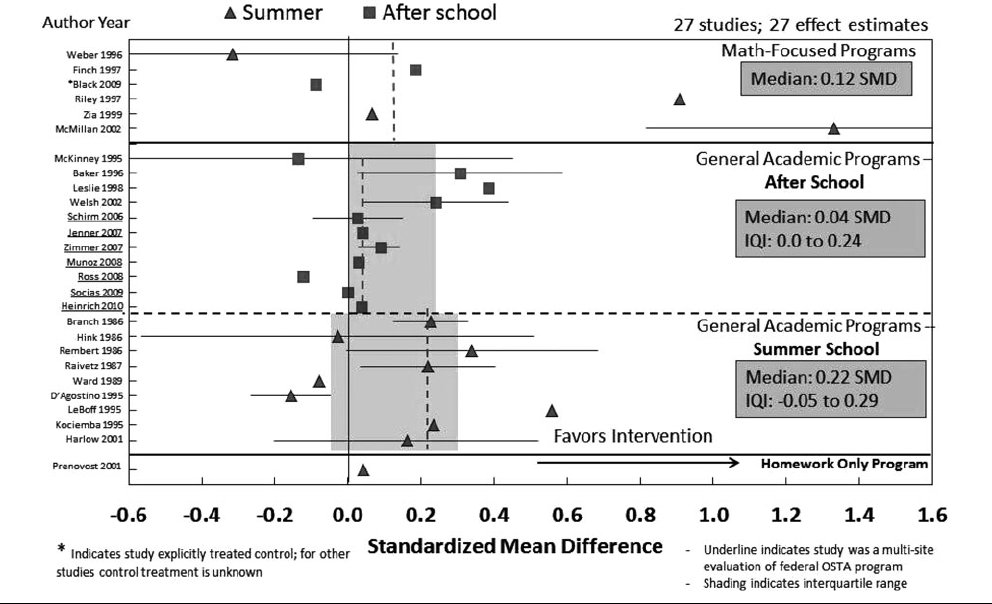

grams on math achievement. The overall median SMD

was 0.09 (IQI: −0.03 to 0.31). Six evaluations of math-

focused programs

29,42,49,52,54,77

yielded a median SMD of

0.12, compared with 20 evaluations of general academic

programs† with a median SMD of 0.065 (IQI: −0.01 to

0.24) (Figure 4). The only minimal academic program

45

reported an SMD of 0.043.

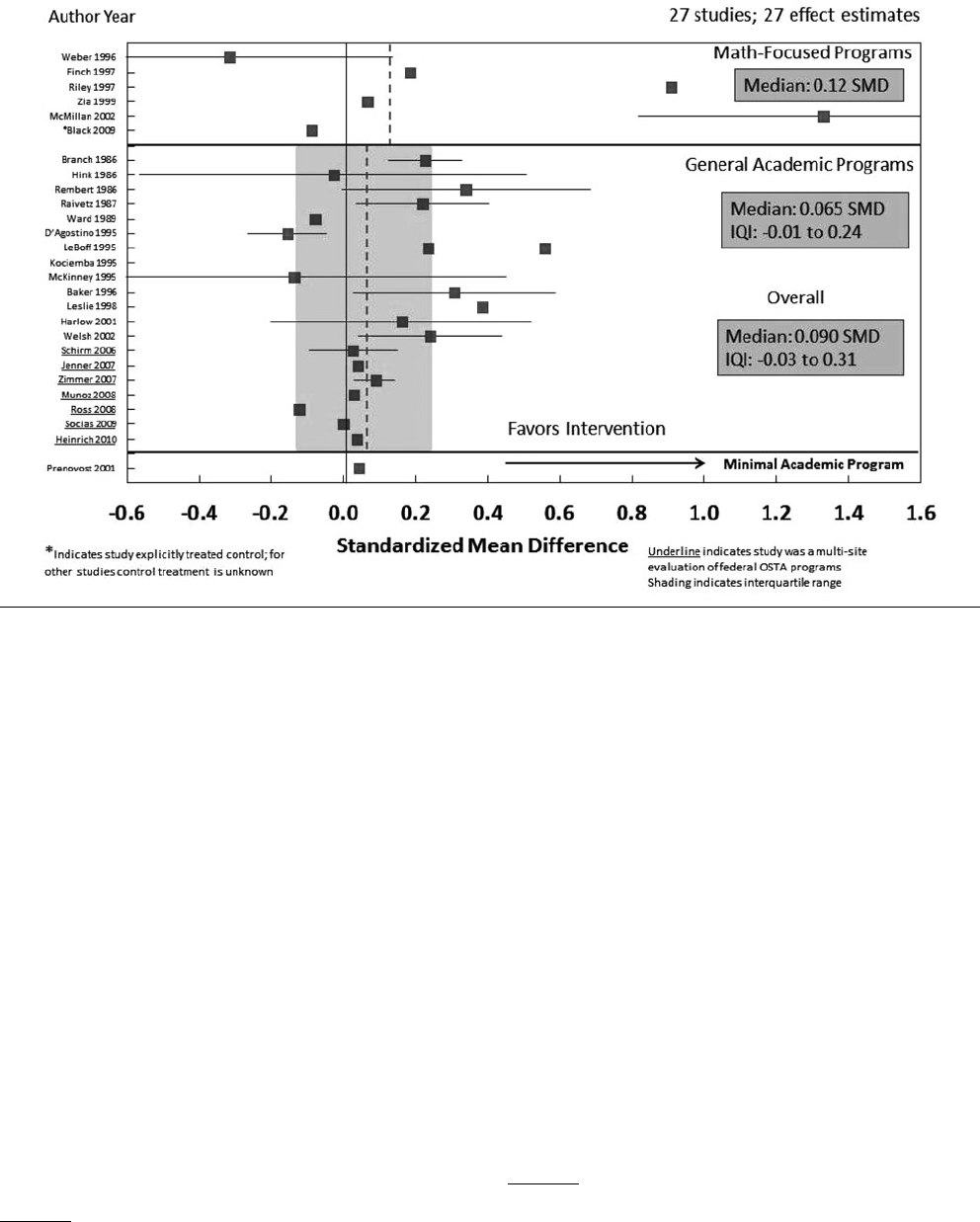

Additional stratified analyses for academic

achievement

Question 3: To assess differential effectiveness by tem-

poral setting (ie, after-school or summer programs),

each level of program focus (reading-focused, math-

focused, general academic, and minimal academic)

was further stratified. Differential effects on read-

ing achievement by temporal setting are small in the

*

References 24, 27-29, 32, 34, 36-38, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51-57, 60,

63, 65, 67, 77.

†References 24, 27, 28, 32, 34, 36-38, 41, 46, 48, 51, 53, 55-57, 60, 63,

65, 67.

reading-focused stratum, as indicated by median SMDs

of 0.26 (IQI: 0.0-0.50) and 0.31 (IQI: 0.02-0.89) for after-

school

‡

and S. Ross, et al (unpublished data, 1996) and

summer school programs,

§

respectively (Figure 5). Dif-

ferential effects on reading achievement by temporal

setting are larger for general academic programs, with

a median SMD of 0.06 (IQI: 0.00-0.091) for after-school

programs (Figure 5) compared with a median SMD of

0.20 (IQI: −0.02 to 0.38) for summer programs.

|

There were too few data points to draw a conclu-

sion about the differential effects on math achievement

of summer

29,52,77

versus after-school

42,49,54

math-focused

programs (Figure 6). General academic programs in the

summer¶ showed larger effects on math achievement

than after-school programs,** as evidenced by the me-

dian SMDs of 0.22 (IQI: −0.05 to 0.29) and 0.04 (IQI:

0.00-0.24), respectively (Figure 6).

‡References 25, 30, 31, 33, 43, 44, 64, 74, 77.

§References 26, 35, 39, 40, 47, 50, 58, 59, 69, 71, 73, 75, 76.

|References 24, 27, 28, 32, 34, 36-38, 41, 46, 48, 51, 53, 55-57, 60, 63,

65, 67, 82.

¶References 24, 38, 41, 53, 55-57, 60, 63, 65, 67.

**References 27, 28, 32, 34, 36, 37, 46, 48, 51.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 601

FIGURE 4 ●

Effectiveness of OSTA Programs on Math Achievement

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Abbreviations: IQI, interquartile interval; OSTA, Out-of-School-Time Academic; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Question 4: To assess differential effectiveness by

student-grade level, studies were ordered by grade

on the y-axis within program focus strata (Figure 7).

Among the reading-focused programs, those for el-

ementary grade students (average grade levels K-3)

were effective (median SMDs of 0.44 [IQI: 0.11-1.05])*

and S. Ross, et al (unpublished data, 1996), whereas

those for older elementary and middle school students

(average grade levels 4-8) were not (median 0.02 [IQI:

−0.06 to 0.06]).

30,31,39,43,64,77

This relationship did not hold

for general academic programs (Figure 7).

Math-focused programs may be associated with

achievement at higher-grade levels but not at lower-

grade levels; however, the small number of math-

focused programs limited inference ( see Supplemental

Digital Content Figure 8, available at: . . . ). For general

academic programs, there was no clear association be-

tween program effectiveness and student-grade level.

Question 5: Questions about program duration re-

sponse effects could not be answered, because no in-

cluded study reported the effects of both program du-

ration and attendance. Although Lauer et al

19

reported

both floor and ceiling effects for program duration—for

*References 25, 26, 33, 35, 40, 44, 47, 50, 58, 59, 69, 71, 73-76.

reading outcomes, benefit from programs with a min-

imum of 45 hours and no additional benefit beyond

200 hours—these findings were not corroborated in the

update studies.

Question 6: Programs described as “homework

assistance”

45,66,72

(some of which have minimal aca-

demic focus) and the federal Supplemental Educa-

tional Services

55,56,60,63,67

(required to have an academic

focus) were classified as tutorial programs. Programs

with reading or math tutoring/individualized instruc-

tion as their main mode of didactics

†

and S. Ross,

et al (unpublished data, 1996) were associated with

the lowest effects for both reading (median = 0.08

[IQI: 0.013-0.30] and math (median = 0.09 [IQI: 0.015-

0.23]); group instruction

‡

had greater effects for both

reading (median = 0.235 [IQI: 0.02-0.48]) and math

(median = 0.39 [IQI: −0.09 to 0.16]); and great-

est effects were associated with mixed-group and

tutoring approaches

25,36,39,40,49,50,64,74

in both reading (me-

dian = 0.375 [IQI: 0.06-0.73]) and math (effect = 0.86;

1study).

†References 27, 29, 38, 41, 44-46, 48, 53, 55, 56, 60, 63, 67.

‡References 24, 26, 28, 30-35, 42, 43, 54, 58, 59, 65, 69-71, 73, 75-77,

82.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

602 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

FIGURE 5 ●

Effectiveness of OSTA Programs on Reading Achievement, Stratified by Temporal Setting

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Abbreviations: IQI, interquartile interval; OSTA, Out-of-School-Time Academic; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Question 7: The small number of available studies

and inconsistency of findings yielded insufficient ev-

idence to draw conclusions on other outcomes. One

study

65

reported a relative improvement of 7.3% on

the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (www.riversidepublishing.

com/products/itbs/), a standardized test that assesses

reading, language arts, math, social studies, and science

knowledge combined. Favorable effects of OSTA pro-

grams were shown for high school completion across

4studies,

57,61,62,66

as evidenced by a median 6.8% rela-

tive change in intervention populations compared with

control populations (range, −1.1% to 15.0%). Similar

improvements were found for college enrollment in 3

studies,

57,61,62

with a median relative change of 7.0%

(range, 2.7%-24.0%). Two studies

61,62

reported the ef-

fects of OSTA programs on college completion, one

on completion of a bachelor’s degree and one on an

associate’s degree; results were inconsistent, with me-

dian relative percent changes of 17.3% and −17.5%,

respectively.

Mixed results were found for the effect of OSTA pro-

grams on delinquency, reported in 5 study arms from

4studies.

68,70,72,79

The results indicated a negligible ef-

fect in the unfavorable direction: the median relative

increase was 2.3% (range, −29.2% to 52.3%). The effect

of OSTA programs on substance abuse also yielded in-

consistent results from 4 study arms in 3 studies.

57,68,72

The median relative change of 8.8% was in the un-

favorable direction (range, −33.0%, 50.0%). Overall,

the small number of studies reporting these outcomes

yielded insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on

effectiveness.

Question 8: Few programs were reported to have

a majority of higher-SES students (6 for reading pro-

grams and 4 for math programs). Comparison of ef-

fects stratified by majority low versus high SES indi-

cated negligible differences for math programs (0.06

[IQI: −0.04 to 0.23] for low-SES students in math pro-

grams and 0.07 [IQI: −0.11 to 1.16] for higher-SES stu-

dents in math programs). However, reading programs

did appear to have differential effects on students

from different SES backgrounds, with greater improve-

ment among low-SES groups (0.195 [IQI: 0.02-0.43) than

among higher-SES groups (−0.07 [IQI: −0.08 to 0.18]).

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 603

FIGURE 6 ●

Effectiveness of OSTA Programs on Math Achievement, Stratified by Temporal Setting

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Abbreviations: IQI, interquartile interval; OSTA, Out-of-School-Time Academic; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Studies were not stratified by race/ethnicity because

this characteristic is likely to be confounded by SES.

Applicability of findings

Although included studies were conducted in the

United States, the team considered that the results may

be applicable to other high-income nations with sim-

ilar educational systems and achievement gaps. Most

evaluated programs were implemented in urban set-

tings and among low-income and racial/ethnic mi-

nority populations—predominantly black. The limited

number of studies evaluating the impact of OSTA pro-

grams on academic achievement of students from rural

or middle- and high-SES or predominantly white pop-

ulations limits knowledge of whether such students

would benefit equally from OSTA programs. The ef-

fects of OSTA programs on the academic achievement

of Hispanics and racial/ethnic minority populations

other than black are also unclear. The possibility of cul-

tural and language differences suggests the modifica-

tion of standard programs for Hispanics. Because most

studies were implemented in elementary school set-

tings, applicability of results to middle and high school

populations is also uncertain. The results are applica-

ble to both summer and after-school programs. Results

are applicable across levels of instructional individu-

ation, although the combination of group classes with

tutoring may have greater benefits than either approach

alone.

Potential harms, additional benefits, and

considerations for implementation

Included studies did not assess postulated potential

harms associated with OSTA programs, specifically

loss of recreational time and family time. Additional

benefits reported from the broader literature include

more time for parents to work

83

and the opportunity for

low-income students to receive an additional meal. Fi-

nally, participation in OSTA may reduce opportunities

for part-time student employment that may provide in-

come and promote self-confidence. However, part-time

work is also associated with increased risk behavior.

84-86

Multiple implementation challenges are reported.

For many federal programs, oversight is the re-

sponsibility of the state, and compliance with pro-

gram requirements and enforcement are commonly

incomplete.

60

School districts often do not notify par-

ents of available free programs, such as Supplemental

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

604 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

FIGURE 7 ●

Effectiveness of OSTA Programs on Reading Achievement, Stratified by Student Grade Level

qqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqq

Abbreviations: IQI, interquartile interval; OSTA, Out-of-School-Time Academic; SMD, standardized mean difference

Educational Services; thus, programs are often

underutilized.

55

In addition, participation in most

OSTA programs is voluntary, and attendance may be

especially low for students most in need.

72

Inadequate

staff training and high staff turnover are also reported.

77

Economic evidence

A separate systematic review assessing the economic

efficiency of OSTA programs was conducted by mem-

bers of the Community Guide economics team, using

the same search criteria as in the effectiveness review,

supplemented with economic terms and databases and

standardized methods.

87

Studies of cost, cost effec-

tiveness, and cost-benefit were assessed when avail-

able. Fourteen studies in 12 articles

76,79,81,83,88-95

were in-

cluded; all reported only program cost. All monetary

values in this review were converted to 2012 US dollars.

Annual costs of OSTA programs ranged from $623 to

$8705 per student and varied greatly by hours of oper-

ation. Eleven included studies in 9 articles

76,81,83,89,90,92-95

provided enough information to calculate hourly cost

per student, which ranged from $3.06 to $13.17. Ma-

jor cost drivers included salaries for teachers and staff,

costs for facilities and utilities, and transportation costs,

with salaries being the largest expense. The most expen-

sive programs were intensive, included case manage-

ment (to monitor and foster the progress of individual

program participants), or had more than 1 major cost

driver reported. Current research does not provide suf-

ficient data for cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit assess-

ments.

● Conclusion

Summary of findings

According to Community Guide criteria, there is strong

evidence that reading-focused OSTA programs are ef-

fective in improving the reading achievement of aca-

demically at-risk students in grades K-3. There is

sufficient evidence that math-focused programs are

effective in improving the math achievement of at-risk

students, with an indication of greater effects of math-

focused programs at higher-grade levels. There is suf-

ficient evidence of effectiveness of general academic

programs in improving the reading and math achieve-

ment of academically at-risk students, although the

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 605

magnitude of each effect is smaller than those from

reading- and math-focused programs.

There is evidence that OSTA programs offered dur-

ing the summer provide greater benefit than those of-

fered after school, particularly general academic pro-

grams. Evidence is insufficient to determine the effec-

tiveness of OSTA programs with minimal academic

content or the effect of OSTA programs on high school

completion, college enrollment, delinquency, or drug

abuse.

Evidence gaps

Additional research needed to help fill gaps in knowl-

edge about OSTA programs is detailed in see Sup-

plemental Digital Content Appendix C (available at:

http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/A157).

Discussion

This review indicated that OSTA programs overall have

beneficial effects on the math and reading achieve-

ment of at-risk students. OSTA programs are not all

equally effective. Academic focus (eg, on reading or

math) substantially improves academic achievement.

General academic programs have smaller effects, but

affect achievement in more than 1 subject. This Com-

munity Guide review synthesis confirms “the congru-

ence between program goals and program outcomes.”

10

The lack of clear findings of effects of OSTA on delin-

quency and substance abuse may be due to the small

number of studies, the harmful effects of social interac-

tion among at-risk youth when not well supervised,

18

or lack of effect.

The hypothesis that summer programs are more ef-

fective than after-school programs in improving read-

ing and math achievement was confirmed, particularly

for general academic programs. Summer programs can

include more hours; after-school programs must de-

liver a sufficient academic dosage between the end of

the regular school day and the time when students re-

turn home. Students may be tired after a full day of

school and thus less receptive to further instruction.

Summer programs may be particularly effective for

low-income students because the academic resources

available to other students during the summer are not

always available for these students.

7-9

In contrast, after-

school programs may be rapidly responsive to needs

that arise during the school year and may occur during

a greater span of the year.

Although the meta-analysis by Cooper et al

10

in-

cluded populations excluded in the present review,

their findings were nevertheless generally consistent

with this review. Cooper et al reported effects by cur-

riculum focus and academic subject outcome sepa-

rately: Comparing students exposed to a summer pro-

gram either to others not exposed or to the same stu-

dents prior to exposure, they found SMDs of 0.43 (95%

confidence interval [CI]: 0.32-0.54) for reading pro-

grams; 0.25 (95% CI: 0.12-0.38) for combined math and

reading programs (which this review classified as gen-

eral programs); and 0.24 (95% CI: 0.18-0.30) for a “mul-

tiple subjects” programs (also general programs).

The limitations of this review should be recognized.

Systematic reviews rely on the information provided

in included studies that may lack details desired for

review purposes. Descriptions of the programs them-

selves often lack detail so that it is difficult to deter-

mine what was done. Decisions about the classification

of studies as one type or another ideally are based on

available evidence, but in some cases are inferred.

Although the results of this review indicate favor-

able effects of OSTA programs on reading and math

achievement, these programs by themselves are un-

likely to bridge the achievement gap or overcome

the health disparities between minority and majority

children and between low-income and higher-income

populations. Even when well implemented, staffed,

and attended, OSTA programs are not likely to have

long-term effects in the absence of educational, com-

munity, and family environments that support these

benefits.

96-98

Despite the expansion of OSTA programs

in recent decades, the academic achievement gaps

between children from minority and majority popu-

lations, and between children from low-income and

higher-income populations, persist. Even with large

increases in federal No Child Left Behind funding for

OSTA programs, progress in closing these achievement

gaps has been slow. Nonetheless, because OSTA pro-

grams are commonly implemented in low-income com-

munities, they could be important components of com-

prehensive efforts to close the achievement gap and

reduce health inequities.

REFERENCES

1. Duncan GJ, Murnane RJ. Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequal-

ity, Schools, and Children’s life Chances. New York City, NY:

Russell Sage Foundation; 2011.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health dis-

parities and inequities report—United States, 2011. MMWR

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(suppl):1-114.

3. National Center for Education Statistics. The Nations Report

Card: Trends in Academic Progress 2012. Washington, DC: In-

stitute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education

Evaluation and Regional Assistance, US Department of Ed-

ucation; 2013.

4. Feinstein L, Sabates R, Anderson T, Sorhiando A, Hammond

C. What are the effects of education on health? Measuring

the effects of education on health and civic engagement. In:

Paper presented at: Copenhagen Symposium OECD; 2006.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

606 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

5. Montez JK, H ummer RA, Hayward MD. Educational attain-

ment and adult mortality in the United States: a system-

atic analysis of functional form. Demography. 2012;49(1):315-

336.

6. Hanushek EA. The economic value of education and cog-

nitive skills. In: Handbook of Education Policy Research.New

York, NY: Routledge; 2009:39-56.

7. Cooper H, Nye B, Charlton K, Lindsay J, Greathouse S. The

effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a nar-

rative and meta-analytic review. Rev Educ Res. 1996;66(3):227-

268.

8. Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. Children, Schools, & In-

equality. Social Inequality Series. Boulder, CO: Westview Press;

1997.

9. Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. Keep the faucet flow-

ing. Am Educ. 2001;25(3):10-15.

10. Cooper H, Charlton K, Valentine JC, Muhlenbruck L, Borman

GD. Making the most of summer school: a meta-analytic and

narrative review. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child

Development. Vol 65 (1, Serial No. 260). Hoboken, NJ: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000.

11. Egerter S, Braveman P, Sadegh-Nobari T, Grossman-Kahn R,

Dekker M. Education Matters for Health. Issue Brief 6: Education

and Health. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation;

2009. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/05/

education-matters-for-health.html. Accessed May 5, 2015.

12. Ross CE, Wu C. The links between education and health. Am

Sociol Rev. 1995;60:719-745.

13. Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education improves public health and

promotes health equity. Int J Health Ser. In press.

14. Bowers A. Reconsidering grades as data for decision making:

more than just academic knowledge. J Educ Adm. 2009;47:609-

629.

15. Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hilger N, Saez E, Schanzenbach DW,

Yagan D. How Does Your Kindergarten Classroom Affect Your

Earnings? Evidence From Project STAR. Cambridge, MA: Na-

tional Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. NBER Working

Paper No. 16381. www.nber.org/papers/w16381. Accessed

May 5, 2015.

16. Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an

evidence-based guide to community preventive services. Am

J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):35-43. Accessed M ay 5, 2015.

17. Kaiser Family Foundation. Poverty rate by race/ethnicity.

http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-

raceethnicity/. Accessed May 5, 2015.

18. Dishion T, Tipsord J. Peer contagion in child and adoles-

cent social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol.

2011;62:189-214.

19. Lauer PA, Akiba M, Wilkerson SB, Apthorp HS, Snow

D, Martin-Glenn ML. Out-of-school-time programs: a

meta-analysis of effects for at-risk students. Rev Educ Res.

2006;76(2):275-313.

20. The World Bank. High income countries. http://data.

worldbank.org/income-level/HIC. Accessed May 5, 2015.

21. Legro DL. An evaluation of an after-school partnership pro-

gram: the effects on young children’s performance [doctoral

dissertation, University of Houston, 1990]. Dissertation Abstr

Int. 1990;52:02A.

22. Smeallie JE. An evaluation of an after-school tutorial and

study skills program for middle school students at risk of

academic failure [doctoral dissertation, University of Mary-

land, College Park, 1997]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1997;58:06A.

23. Cosden M, Morrison G, Albanese AL, Macias S. When home-

work is not home work: after-school programs for homework

assistance. Educ Psychol. 2001;36(3):211-221.

24. Baker D, Witt PA. Evaluation of the impact of two after-school

programs. J Park Recreat Adm.

1996;14(3):60-81.

25. Bergin DA, Hudson LM, Chryst CF, Resetar M. An after-

school intervention program for educationally disadvan-

taged young children. Urban Rev. 1992;24(3):203-217.

26. Borman G, Rachuba L, Fairchild R, Kaplan J. Randomized Eval-

uation of a Multi-year Summer Program: Teach Baltimore. Year 3

Report [draft]. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, Madi-

son; 2002. http://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/

resources/3333. Accessed April 7, 2003.

27. Branch AY. Summer Training and Education Program (STEP).

Report on the 1985 Summer Experience. Philadel PA: Pub-

lic/Private Ventures; 1986.

28. D’Agostino J, Hiestand N. Advanced-skill instruction in

chapter 1 summer programs and student achievement. Pa-

per presented at: the annual meeting of the American Edu-

cational Research Association; 1995; San Francisco, CA.

29. Finch CE Jr. The effect of supplementary computer-assisted

instruction upon rural seventh-grade students to improve

math scores as measured by the Michigan educational assess-

ment program test [doctoral dissertation, Walden University,

1997]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1997;58:08A.

30. Foley EM, Eddins G. Preliminary Analysis of Virtual Y After-

School Program Participants’ Patterns of School Attendance and

Academic Performance. New York, NY: National Center for

Schools and Communities; 2001.

31. Gentilcore JC. The effect of an after-school academic inter-

vention service on a New York State eighth-grade English

language arts assessment: a case study [doctoral dissertation,

Hofstra University, 1997]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 2002;63:06A.

32. Harlow K, Baenen N. The Effectiveness of the Wake Summer-

bridge Summer Enrichment Program. Eye on Evaluation. E&R

Report. Raleigh, NC: Wake Country Public School System,

Department of Evaluation and Research; 2001.

33. Hausner MEI. The impact of kindergarten intervention

Project Accelerated Literacy on emerging literacy concepts

and second grade reading comprehension. Paper presented

at: the annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association; 2000; Seattle, WA.

34. Hink JJ. A systematic, time-extended study of a remedial

reading and math summer school program [doctoral disser-

tation, Wayne State University, 1986]. Dissertations Abstr Int.

1986;47:04A.

35. Howes M. Intervention procedures to enhance summer read-

ing achievement (summer school, library reading program)

[doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University, 1989].

Dissertations Abstr Int. 1989;51:01A.

36. Kociemba GD. The impact of compensatory summer school

on student achievement: grades 2 and 5 in the Minneapo-

lis public schools [doctoral dissertation, University of Min-

nesota, 1995]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1995;56:05A.

37. Leboff BA. The effectiveness of a six-week summer school

program on the achievement of urban, inner-city third-grade

children [doctoral dissertation, Texas Southern University,

1995]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1995;56:10A.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Out-of-School-Time Academic Programs for Health Equity ❘ 607

38. Leslie AVL. The effects of an after-school tutorial program on

the reading and mathematics achievement, failure rate, and

discipline referral rate of students in a rural middle school

[doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia, 1998]. Disserta-

tion Abstr Int. 1998;59:06A.

39. Levinson JL, Taira L. An investigation of summer school for

elementary students: outcomes and implications. Paper pre-

sented at: the annual meeting of the American Research As-

sociation; 2002; New Orleans, LA.

40. Luftig RL. When a little bit means a lot: the effects of a short-

term reading program on economically disadvantaged ele-

mentary schoolers. Literacy Res Instr. 2003;42(4):1-13.

41. McKinney AD. The effects of an after-school tutorial and

enrichment program on the academic achievement and self-

concept of below grade level first and second grade students

[doctoral dissertation, University of Mississippi, 1995]. Dis-

sertation Abstr Int. 1995;56:06A.

42. McMillan JH, Snyder AL. The effectiveness of summer re-

mediation for high-stakes testing. Paper presented at: the

annual meeting of the American Research Association; 2002;

New Orleans, LA.

43. Mooney C. The Effects of Peer Tutoring on Student Achievement.

Union, NJ: Kean College of New Jersey; 1986.

44. Morris D, Shaw B, Perney J. Helping low readers in grades 2

and 3: an after-school volunteer tutoring program. Elementary

Sch J. 1990;91(2):133-150.

45. Prenovost JK. A first-year evaluation of after school learning

programs in four urban middle schools in the Santa Ana

Unified School District [doctoral dissertation, University of

California, Irvine, 2001]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 2001;62:03A.

46. Raivetz MJ, Bousquet RJ. How they spent their summer va-

cation: Impact o f a tutorial program for students” at-risk” of

failing a state mandated high school proficiency test. Paper

presented at: the annual meeting of the American Educa-

tional Research Association; 1987; Washington, DC.

47. Reed GW. The relationship between participation in a de-

velopmental reading summer school program and reading

achievement among low-achieving first grade students [doc-

toral dissertation, St Louis University, 2001]. Dissertation Ab-

str Int. 2001;62:05A.

48. Rembert WI, Calvert SL, Watson JA. Effects of an academic

summer camp experience on black students’ high school

scholastic performance and subsequent college attendance

decisions. Coll Stud J. 1986;20(4):374-384.

49. Riley AHJ. Student achievement and attitudes in mathemat-

ics: An evaluation of the twenty-first century mathematics

center for urban high schools [doctoral dissertation, Temple

University, 1997]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1997;58:06A.

50. Schacter J. Reducing Social Inequality in Elementary School Read-

ing Achievement: Establishing Summer Literacy Day Camps for

Disadvantaged Children. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Family

Foundation; 2001:4.

51. Ward MS. North Carolina’s summer school program for

high-risk students: a two-year follow-up of student achieve-

ment. Paper presented at: the annual meeting of the Amer-

ican Educational Research Association; 1989; San Francisco,

CA.

52. Weber EL. An investigation of the long-term results of sum-

mer school [doctoral dissertation, University of Wyoming,

1996]. Dissertation Abstr Int. 1996;57:05A.

53. Welsh ME, Russell CA, Williams I, Reisner ER, White RN.

Promoting Learning and School Attendance Through After-School

Programs: Student-level Changes in Educational Performance

Across TASC’s First Three Years. Washington, DC: Policy Stud-

ies Associates; 2002.

54. Zia B, Larson JC, Mostow A. Instruction and student achieve-

ment in a summer school mathematics program. ERS Spec-

trum. 1999;17(2):39-47.

55. Zimmer R, Gill B, Razquin P, et al. State and Local Implemen-

tation of the No Child Left Behind Act, Volume I—Title I School

Choice, Supplemental Educational Services, and Student Achieve-

ment. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Evaluation and

Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service,

US Department of Education; 2007.

56. Socias M, deSousa J, Le Floch K. Supplemental Educational Ser-

vices and Student Achievement in Waiver Districts: Anchorage

and Hillsborough. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Evalu-

ation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies

Service, US Department of Education; 2009.

57. Schirm A, Stuart E, McKie A.

The Quantum Opportunities Pro-

gram Demonstration: Final Impacts. Washington, DC: Mathe-

matica Policy Research; 2008.

58. Schacter J, Jo B. Learning when school is not in session: a read-

ing summer day-camp intervention to improve the achieve-

ment of exiting first-grade students who are economically

disadvantaged. J Res Read. 2005;28(2):158-169.

59. Schacter J. Preventing summer reading declines in chil-

dren who are disadvantaged. J Early Interv. 2003;26(1):

47-58.

60. Ross S, Potter A, Paek J, McKay D, Sanders W, Ashton J.

Implementation and outcomes of Supplemental Educational

Services: the Tennessee state-wide evaluation study. JEduc

Stud Placed at Risk. 2008;2008(13):26-58.

61. Olsen R, Seftor N, Silva T, Myers D, DesRoches D, Young J.

Upward Bound Math-Science: Program Description and Interim

Impact Estimates. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Re-

search; 2007.

62. Myers D, Olsen R, Seftor N, Young J, Tuttle C. The Impact of

Regular Upward Bound: Results from the Third Follow-up Data

Collection. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research;

2007.

63. Munoz M, Potter A, Ross S. Supplemental Educational Ser-

vices as a consequence of the NCLB legislation: Evaluating

its impact on student achievement in a large urban district. J

Educ Stud Placed at Risk. 2008;13(1):1-25.

64. Kim J, Samson J, Fitzgerald R, Hartry A. A randomized ex-

periment of a mixed-methods literacy intervention for strug-

gling readers in grades 4-6: effects on word reading efficiency,

reading comprehension and vocabulary, and oral reading flu-

ency. Read Writ. 2010;23(9):1109-1129.

65. Jenner E, Jenner L. Results from a first-year evaluation of

academic impacts of an after-school program for at-risk stu-

dents. J Educ Stud Placed at Risk. 2007;12(2):213-237.

66. Huang D, Kim K, Cho J, Marshall A, Perez P. Keeping

kids in school: a study examining the long-term impact of

afterschool enrichment programs on students’ high school

dropout rates. J Contemp Issues Educ. 2011;6(1):4-23.

67. Heinrich C, Meyer R, Whitten G. Supplemental Education

Services under No Child Left Behind: who signs up, and

what do they gain? Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2010;32(2):273-298.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

608 ❘ Journal of Public Health Management and Practice

68. Gottfredson D, Gerstenblith S, Soule D, Womer S, Lu S.

Do after school programs reduce delinquency? Prev Sci.

2004;5(4):253-266.

69. Edmonds E, O’Donoghue C, Spano S, Algozzine R. Learning

when school is out. JEducRes. 2009;102(3):213-221.

70. Dynarski M, James-Burdumy S, Moore M, Rosenberg L, Deke

J, Mansfield W. When Schools Stay Open Late: The National

Evaluation of the 21st Century Community Learning Centers Pro-

gram: New Findings. Washington, DC: Institute of Education

Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Re-

gional Assistance, US Department of Education; 2004.

71. Denton C, Solari E, Ciancio D, Hecht S, Swank P. A pilot study

of a kindergarten summer school reading program in high-

poverty urban schools. Elementary Sch J. 2010;110(4):423-439.

72. Cross A, Gottfredson D, Wilson D, Rorie M, Connell N.

The impact of after-school programs on the routine activi-

ties of middle-school students: results from a randomized,

controlled trial. Criminol Public Policy. 2009;8(2):391-412.

73. Burgin J, Hughes G. Measuring the effectiveness of a sum-

mer literacy program for elementary students using writing

samples. Res Sch. 2008;15(2):55-64.

74. Boulden W. Evaluation of the Kansas City LULAC National

Education Service Center’s Young Reader’s Program. Child

Sch. 2006;28(2):107-114.

75. Borman G, Goetz M, Dowling M. Halting the sum-

mer achievement slide: a randomized field trial of the

KindergARTen summer camp. J Educ Stud Placed at Risk.

2009;14(2):133-147.

76. Borman G, Dowling M. Longitudinal achievement effects of

multiyear summer school: evidence from the Teach Baltimore

randomized field trial. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2006;28(1):25-48.

77. Black A, Somers M, Doolittle F, Unterman R, Grossman J.

The Evaluation of Enhanced Academic Instruction in After-School

Programs: Final Report. Washington, DC: Institute of Educa-

tion Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and

Regional Assistance, US Department of Education; 2009.

78. Hanlon T, Simons B, O’Grady K, Carswell S, Callaman J.

The effectiveness of an after-school program: targeting urban

African American youth. Educ Urban Soc. 2009;1(42):96-118.

79. James-Burdumy S, Dynarski M, Deke J. When elementary

schools stay open late: results from the national evaluation

of the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program.

Educ Eval Policy Anal. 2007;29(4):296-318.

80. Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero L, Briss P. Data collection in-

strument and procedure for systematic reviews in the

Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med.

2000;18(1S):44-74.

81. Gottfredson D, Cross A, Wilson D, Connell N, Rorie M. A

Randomized Trial of the Effects of an Enhanced After-School Pro-

gram for Middle-School Students. Washington, DC: Institute of

Educational Sciences, National Center for Education Evalua-

tion and Regional Assistance, US Department of Education;

2010.

82. James-Burdumy S, Dynarski M, Moore M, et al. When Schools

Stay Open Late: the National Evaluation of the 21st Century Com-

munity Learning Centers Program: Final Report. Washington,

DC: Institute of Educational Sciences, National Center for

Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, US Depart-

ment of Education; 2005.

83. Halpern R. A different kind of child development institution:

the history of after-school programs for low-income children.

Teach Coll Rec. 2002;104(2):178-211.

84. Cooper H, Valentine JC, Nye B, Lindsay JJ. Relationships be-

tween five after-school activities and academic achievement.

JEducPsychol. 1999;91(2):369-378.

85. Steinberg L, Fegley S, Dornbusch SM. Negative impact of

part-time work on adolescent adjustment: evidence from a

longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 1993;29(2):171-180.

86. Bachman JG, Schulenberg J. How part-time work inten-

sity relates to drug use, problem behavior, time use, and

satisfaction among high school seniors: are these conse-

quences or merely correlates? Dev Psychol. 1993;29(2):220-

235.

87. Carande-Kulis V, Maciosek M, Briss P, et al. Methods for sys-

tematic review of economic evaluations for the Guide to Com-

munity Preventative Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(IS):75-

91.

88. Brown W, Frates S, Rudge I, Tradewell R. The Costs and Ben-

efits of After School Programs: The Estimated Effects of the After

School Education and Safety Program Act of 2002 September.

Claremont, CA: The Rose Institute of Claremont-McKenna

College; 2002.

89. Grossman J, Price M, Fellerath V. Multiple Choices After School:

Findings From the Extended-Service Schools Initiative. Philadel-

phia, PA: Public/Private Ventures; 2002.

90. Grossman J, Lind C, Hayes C, McMaken J, Gersick A. The

Cost of Quality Out-of-School Time Programs. Philadelphia, PA:

Public/Private Ventures; 2009.

91. Herrera C, Arbreton A. A Report on the Experiences of Boys &

Girls Clubs in Boston and New York City: Increasing Opportuni-

ties for Older Youth in After-School Programs. Philadelphia, PA:

Public/Private Ventures; 2003.

92. Jacob B. Remedial education and student achievement: a re-

gression discontinuity analysis. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(1):226-

244.

93. Maxfield M, Castner L. The Quantum Opportunity Program

Demonstration: Implementation Findings. Washington, DC:

Mathematica Policy Research Inc; 2003.

94. Proscio T , Whiting B. After-School Grows Up: How four Large

American Cities Approach Scale and Quality in After-School Pro-

grams. After School Project of the Robert Wood Johnson Founda-

tion. New York, NY: The After School Project; 2004.

95. Walker K, Arbreton A. After-School Pursuits: An Examination

of Outcomes in the San Francisco Beacon Initiative. Philadelphia,

PA: Public/Private Ventures; 2004.

96. Henderson A, Mapp K. A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of

School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achieve-

ment. Annual Synthesis. Austin, TX: National Center for Fam-

ily and Community Connections with Schools; 2002.

97. Weiss H, Little P, Bouffard S, Deschenes S, Malone H. The

Federal Role in Out-of-School Learning: After-School, Summer

Learning, and Family Involvement as Critical Learning Sup-

ports. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project;

2009.

98. Priscilla L, Wimer C, Weiss H. After School Programs in the

21st Century: Their Potential and What It Takes to Achieve

It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Family Research Project;

2008:10.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.