Extremist Construction

of Identity:

How Escalating Demands for

Legitimacy Shape and Define In-

Group and Out-Group Dynamics

This Research Paper examines how the white supremacist movement

Christian Identity emerged from a non-extremist forerunner known as

British Israelism. By examining ideological shifts over the course of nearly a

century, the paper seeks to identify key pivot points in the movement’s shift

toward extremism and explain the process through which extremist

ideologues construct and define in-group and out-group identities. Based

on these findings, the paper proposes a new framework for analysing and

understanding the behaviour and emergence of extremist groups. The

proposed framework can be leveraged to design strategic counter-

terrorism communications programmes using a linkage-based approach

that deconstructs the process of extremist in-group and out-group

definition. Future publications will continue this study, seeking to refine the

framework and operationalise messaging recommendations.

DOI: 10.19165/2017.1.07

ISSN: 2468-0656

ICCT Research Paper

April 2017

Author:

J.M. Berger

About the Author

J.M. Berger

J.M. Berger is an Associate Fellow at ICCT. He is a researcher, analyst and consultant,

with a special focus on extremist activities in the U.S. and use of social media. Berger is

co-author of the critically acclaimed ISIS: The State of Terror with Jessica Stern and author

of Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam. Berger publishes the web

site Intelwire.com and has written for Politico, The Atlantic and Foreign Policy, among

others. He was previously a Fellow at George Washington University’s Program on

Extremism, a Non-resident Fellow with the Brookings Institution’s Project on U.S.

Relations with the Islamic World, and an Associate Fellow at the International Centre

for the Study of Radicalisation.

About ICCT

The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT) is an independent think and do tank

providing multidisciplinary policy advice and practical, solution-oriented implementation support on

prevention and the rule of law, two vital pillars of effective counter-terrorism. ICCT’s work focuses on themes

at the intersection of countering violent extremism and criminal justice sector responses, as well as human

rights-related aspects of counter-terrorism. The major project areas concern countering violent extremism,

rule of law, foreign fighters, country and regional analysis, rehabilitation, civil society engagement and victims’

voices. Functioning as a nucleus within the international counter-terrorism network, ICCT connects experts,

policymakers, civil society actors and practitioners from different fields by providing a platform for productive

collaboration, practical analysis, and exchange of experiences and expertise, with the ultimate aim of

identifying innovative and comprehensive approaches to preventing and countering terrorism.

1. Introduction and Overview

Political movements are not born extreme; they evolve that way over time.

This paper derives a theoretical framework for analysing extremist movements from a

text-based study of how an Anglophile movement known as British Israelism evolved

into the virulently racist Christian Identity over the course of a century.

Using a grounded theory approach

1

based on the analysis of ideological texts, this

framework aims to offer insights into how groups radicalise toward violence and how

to understand and counter these processes.

More broadly, this paper is a first step in developing and testing the hypothesis that

extremist group radicalisation represents an identifiable process that can be

understood as distinct from the contents of a movement’s ideology. That is not to say

that the content of an ideology is meaningless or unimportant. Rather, this research

seeks to explore whether universal processes of radicalisation provide a more useful

window into why identity-based extremist movements form in the first place and how

they evolve toward violence.

In future publications, the author intends to test this initial framework against a variety

of extremist movements, with the expectations that the findings will be further refined

based on analysis of additional texts.

The following hypotheses were developed as a result of this initial study:

Identity movements are oriented toward establishing the legitimacy of a

collective group (organised on the basis of geography, religion, ethnicity or other

prima facie commonalities).

Movements become extreme when the in-group’s demand for legitimacy

escalates to the point it can only be satisfied at the expense of an out-group.

Escalating demands for legitimacy can be measured in part by their expansion

from real, present-day conflicts between an in-group and an out-group (or

groups) to characterise the conflict as historical and set formal expectations for

the future of the conflict (such as through religious prophecy).

In texts, the process of escalation correlates to the increasing complexity of

linkages between concepts, and the bundling of multiple linkages into single

conceptual constructs. These mappings can inform efforts to counter extremist

messaging. However, it should be noted that this paper does not argue that

complexity is straightforwardly causative of extremist tendencies.

a) Definition of Legitimacy

Legitimacy is a word that encompasses many meanings in everyday use. In the context

of this paper, as derived from an analysis of the stipulated texts, it applies to the

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

4

conclusion that a particular collective identity group may rightfully be defined,

maintained and/or protected.

Any social collective has a normal, healthy need for legitimacy, which serves to protect

the community. When the rightful existence of an identity group is challenged,

members may respond by seeking out justifications for the in-group’s existence. These

justifications may be more elaborate for “imagined communities,” to borrow a phrase

from Dr. Benedict Anderson: communities that are defined by their conceptual nature

rather than bounded by physical limits and interpersonal relationships.

2

Since communities based on nation, race or religion are highly (or wholly) conceptual,

they are also prone to volatility. The healthy need for legitimacy can therefore spiral

out of control when an identity collective turns toward extremism. If unchecked by

internal or external pressures, in-groups can escalate their demands for legitimacy in

ways that distinguish them from healthy social collectives and identify them as

extremist.

The relevance of this definition for legitimacy is clearly demonstrated in the first

paragraph of the creedal statement of the Aryan Nations, a violent extremist group that

subscribes to the white supremacist ideology of Christian Identity:

WE BELIEVE in the preservation of our Race, individually and

collectively, as a people as demanded and directed by Yahweh. We

believe our Racial Nation has a right and is under obligation to

preserve itself and its members.

3

The development of Christian Identity’s ideology, starting with its non-violent roots in a

movement known as British Israelism, will be examined at greater length below.

Groups that are in the process of becoming more extreme typically escalate their

expectations and demands within the following ranges:

Recognition: In-group demands more and more recognition of its claimed

legitimacy and treats lack of adequate recognition as a threat.

Scope of Action: In-group requires increasing latitude to take an ever-widening

range of actions to advance its claim to legitimacy.

Attack on Out-Group: In-group enhances its legitimacy at the expense of out-

groups, using tactics that escalate from discrimination to segregation to

violence; if left unchecked, this culminates in extermination of the out-group.

Threat and Vulnerability Gap: In-groups see themselves as increasingly

vulnerable, and they see out-groups as increasingly threatening. Vulnerability

and threat are related, but not always identically premised.

Shifting Criteria for In-Group Membership: The definition of the in-group

becomes dramatically more expansive or restrictive. In the former instance, the

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

in-group is enlarged in order to maximise the marginalisation of the out-group.

In the latter, people who were defined as part of the in-group at earlier stages

are reclassified as out-group (for instance, as “race traitors” or “apostates”) if

they fail to keep pace with the in-group’s escalating demands for legitimacy.

For extremist in-groups, the insatiable need for legitimacy is an auto-immune disease

that will eventually deplete its host. If unchecked by internal or external pressures, the

process of escalation leads many extremist groups to expend resources faster than

they can be replenished. As a result, some extremist groups die out, but others adapt

by either reducing or further escalating their demands for legitimacy. In theory, the

former approach would be expected to slow the expenditure of resources; the latter

approach would be expected to be more effective at mobilising in-group members to

action.

The framework outlined in this paper is both related and indebted to social identity

theory. This framework follows a somewhat different structure and differentiates some

terms and concepts.

4

The substitution of legitimacy for the “status” sought by in-groups

as defined in Social Identity Theory is one meaningful distinction. Status must be

understood relative to in-group/out-group dynamics, whereas legitimacy offers a

starting point that primarily focuses on enhancing the in-group in the earlier stages of

identity construction, before expanding to address comparisons to out-groups.

b) Definitions of Extremism and Radicalisation

The words extremism and radicalisation (in the context of extremism) are poorly

defined in public discourse, and often not much clearer in the professional and

academic communities that study them. As Dr. Alex Schmid notes, “The popularity of

the concept of ‘radicalisation’ stands in no direct relationship to its actual explanatory

power regarding the root causes of terrorism.”

5

The same can be said for the term

extremism.

Many different definitions have been offered, none have been universally adopted. In

recent years, definitions have largely been framed in the context of violent extremism,

a term that is frequently used interchangeably with non-state terrorism (itself poorly

defined).

6

For various reasons, it is much more difficult and problematic to define extremism

outside of the context of violence, primarily because “extremist” is a politically freighted

term that is often used in a mainstream context to define opponents’ views.

Yet it should be clear that extremism is not always violent and it is not always associated

with non-state actors. For instance, movements based on discrimination, separatism

or voluntary social self-segregation do not necessarily advocate violence, although they

frequently evolve in that direction. And in-group/out-group dynamics have fueled

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

6

government policies throughout history, from segregation to genocide and a host of

intermediate options.

Not only is there no universally accepted definition, it is difficult to identify even a

consensus. Some definitions, particularly in policy circles, discuss only violent

extremism, especially in countries where nonviolent extremism may be protected

under the law.

7

Others are framed against the perceived mainstream of society, a

moving target.

8

Some academics and scholars define radicalisation in circular terms as

“acquisition of extreme ideas,”

9

or define extremists as people who have “radical or

extreme ideas.”

10

In the context of identity-based movements and derived from the study featured in this

paper, as well as the author’s previous study of identity extremist movements,

11

the

following definitions are proposed:

Extremism: A spectrum of beliefs in which an in-group’s success is inseparable from

negative acts against an out-group. Negative acts can include verbal attacks and

diminishment, discriminatory behaviour, or violence.

Competition is not inherently extremist, because it does not require harmful, out-of-

bounds acts against competitors (such as sabotage). The need for harmful activity must

be inseparable from the in-group’s understanding of success in order to qualify.

Similarly, not every harmful act is necessarily extremist.

Violent Extremism: The belief that an in-group’s success is inseparable from violence

against an out-group. A violent extremist ideology may subjectively characterise this

violence as defensive, offensive, or pre-emptive. Again, inseparability is the key element

here, reflecting that the need for violence against the out-group is not conditional or

situational. For instance, war is not automatically an extremist proposition. But endless,

apocalyptic or genocidal wars are usually seen as inseparable from the health of the in-

group.

Violent extremist groups may claim (sincerely or insincerely) to consider temporary

cessation of hostilities when certain conditions are met. For instance, al Qaeda

statements regarding the West sometimes outline conditions under which a truce or

treaty can occur.

12

But al Qaeda’s ideological texts stipulate in various ways that fighting

against out-groups must continue until the end of history.

13

The ability to entertain a

truce does not disqualify a movement from extremism, although the inability to

entertain a truce is likely a definitive indicator of such.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

From the two definitions above, a third follows:

Radicalisation into Extremism: The escalation of an in-group’s extremist orientation

through the endorsement of increasingly harmful actions against an out-group or out-

groups (usually correlating to the adoption of increasingly negative views of the same).

These definitions are applied within this paper, and the author believes they may be

useful in other contexts. However, additional grounded study may lead to revisions for

wider contexts.

c) Definition of Extremist Ideology

Dr. Haroro Ingram writes that “ideology is a tool that is used selectively by violent

extremists to construct their ‘system of meaning’ in response to psychosocial and

strategic factors.”

14

Derivative of this definition, and based on the study of the texts

discussed in this paper, extremist ideology is defined here as the set of justifications

that legitimises an in-group, which is primarily expressed through texts, including both

the written and spoken word.

Extremist ideologies can contain dramatically different content depending on the

identity group from which they derive meaning, but identity-based extremist ideologies

of various types may be covered by the following provisos:

Ideology is a description of the nature of an in-group, including its history,

practices and expectations for the future.

Extremist ideology describes the nature of an out-group, including its history,

practices and expectations about its future actions. Not all identity-based

movements need to describe an out-group, but extremist movements (by the

definitions above) must include this element.

In addition to defining general practices, ideology usually defines acceptable

tactics for maintaining or increasing the in-group’s legitimacy (such as isolation,

proselytisation, or violence against an out-group).

Ideology must be transmitted and marketed to members of an in-group in order to

become consequential; therefore it is inextricably linked to propaganda. Ideology has

no power if it cannot proliferate, and it cannot proliferate without the distribution of

texts (including the written word, video and audio). This paper will therefore frame

ideology as a textual and propagandistic process.

While the specific contents of an extremist ideology do matter, this research explores

the thesis that extremist ideologies emerge from a more clearly universal process.

Derived from the case study in this paper, a hypothesis is offered that the contents of

an ideology are retrofitted to meet a demand for greater legitimacy.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

8

Finally, this paper will argue that the process of ideological construction must be

understood at least as well as the contents of the ideology for purposes of countering

violent extremism, counter-terrorism messaging and deradicalisation programs.

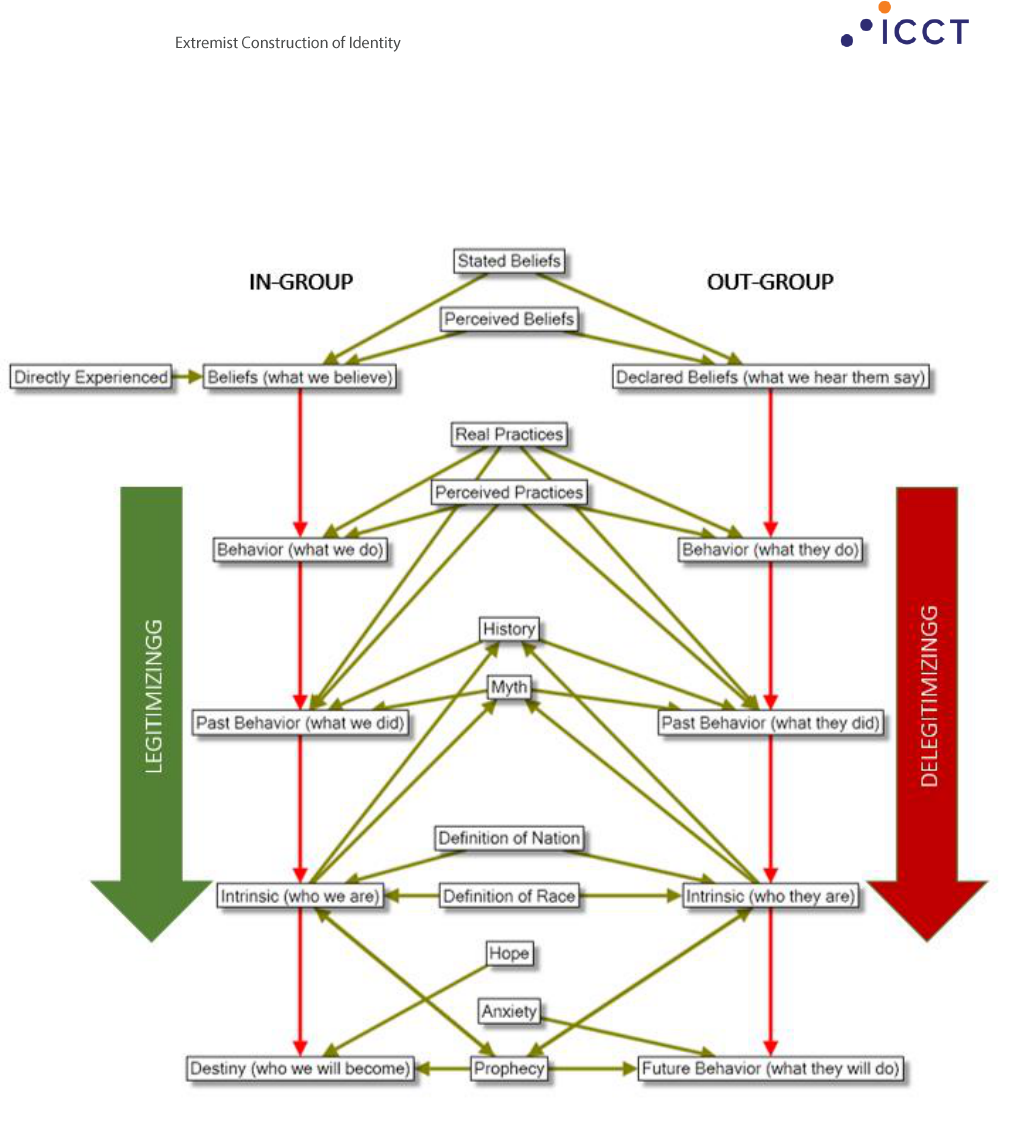

d) Linkages and Bundles

This paper builds on the framework presented by Ingram in “A ‘Linkage-Based’

Approach to Combating Militant Islamist Propaganda”.

15

Elements of group identity are

presented in texts by ideologues and propagandists by linking concepts, for instance

by linking an out-group to a crisis or threat, or by linking an in-group to a solution or

benefit.

In the ideological texts examined herein, these linkages were seen to be bundled into

high-level constructs, in which several concepts are connected to one another and then

conflated into a single idea. An example would be an ideological argument that draws

connections between a conspiracy theory, a scriptural reference, a folkloric tradition

and a real historical event, representing the bundled product simply as “history.”

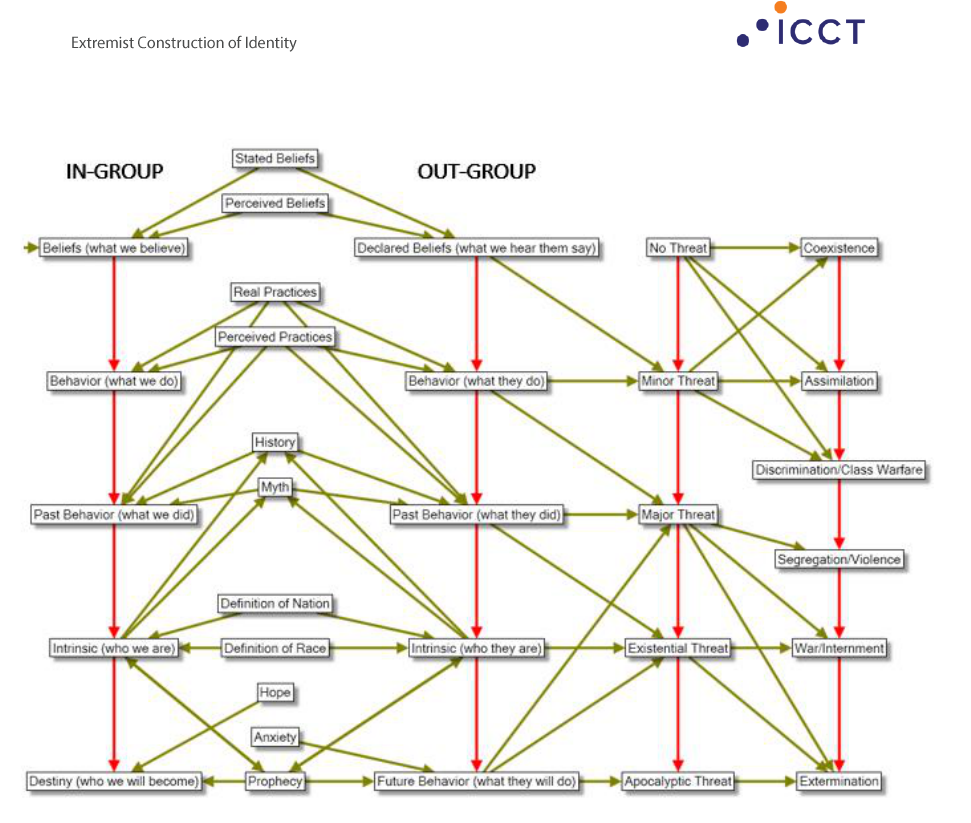

At the highest level, extremists tie an out-group to a crisis or crises, and connect the in-

group to solutions. But these high-level constructs can be unbundled into a series of

more complex links. For instance:

Elements of in-group and out-group identity (perceived beliefs, practices,

expectations, etc.) are linked to source knowledge (news, history, folklore,

scripture, myth, conspiracy theories, etc.).

Elements of in-group identity are linked to vulnerability assessment (mild,

major, existential, or apocalyptic).

Elements of out-group identity are linked to threat assessment (mild, major,

existential, or apocalyptic).

Vulnerability and threat assessment are bundled into a crisis construct,

which adds urgency to the in-group’s attempts to recruit and mobilise members.

The crisis construct is linked to prescribed solutions to the “out-group

problem” (such as assimilation, discrimination, segregation, or extermination).

Bundled concepts can themselves be bundled, resulting in very complex networks of

meaning. To fully dissect the construction of an identity group and associated

messaging, especially in the case of extremist movements, it is necessary to understand

how and when concepts are bundled and to unpack them into their component parts.

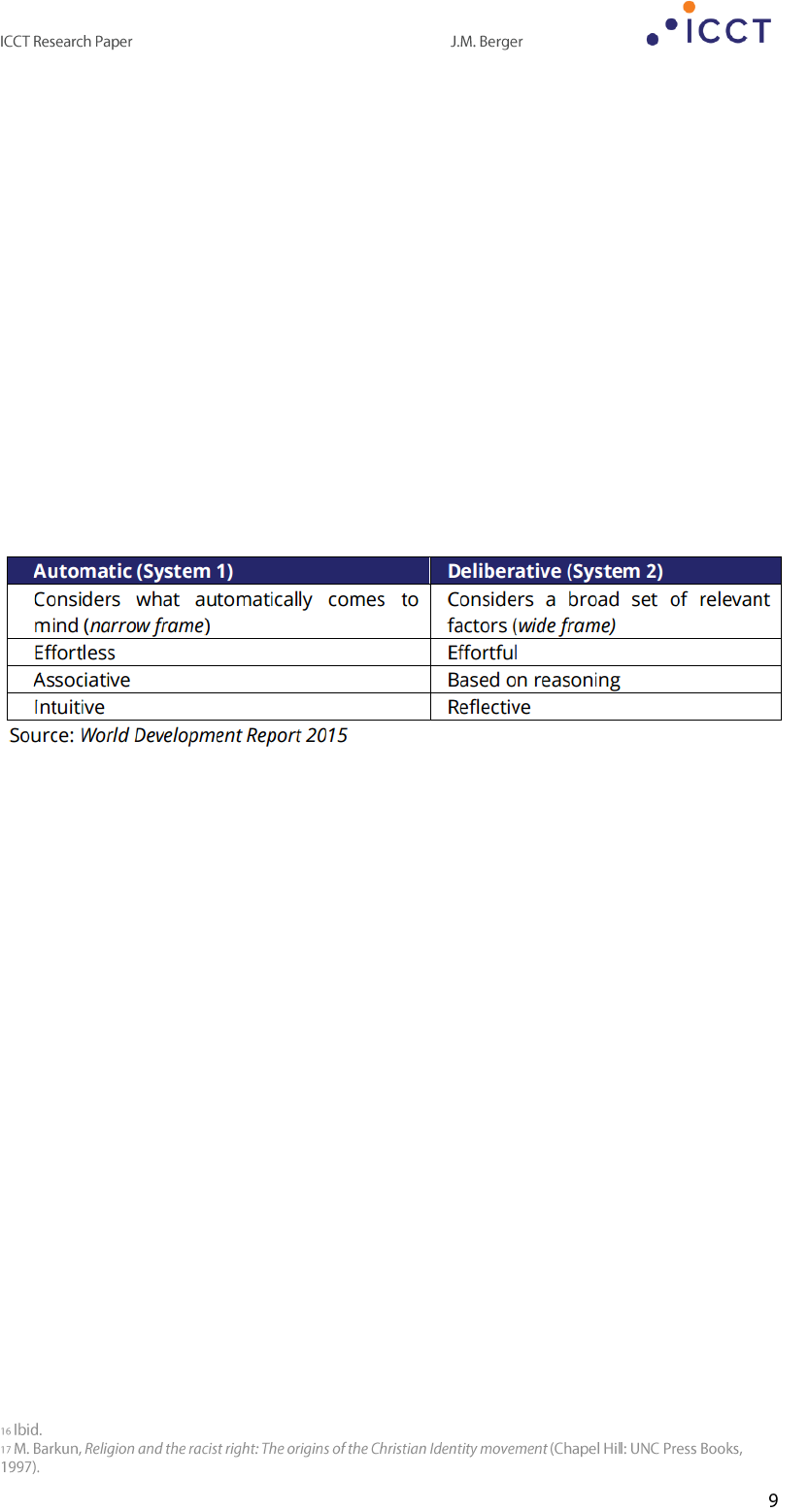

e) Automatic and Deliberative Thinking

In “Deciphering the Siren Call of Militant Islamist Propaganda,” Ingram argues that

extremist propaganda seeks to produce one of two reactions in target audiences:

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

[Daniel] Kahneman’s research … argues that the mind is characterised

by two systems of thinking: “System 1 operates automatically and

quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.” This

is also referred to as “thinking fast” or “automatic thinking”. In contrast,

“System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that

demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System

2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency,

choice, and concentration.” System 2 is also referred to as “thinking

slow” or “deliberative thinking”.

16

Ingram observes that deliberative thinking is invoked by extremist propagandists who

wish to trigger an assessment of automatic judgments in their audiences, often as a

response when automatic assertions are challenged. This paper will examine examples

of both types of thinking in the evolution of Christian Identity ideology. An expanded

explanation of these concepts can be found in “Deciphering the Siren Call of Militant

Islamist Propaganda.”

2. The Evolution of Christian Identity

a) Introduction

The violent racist movement Christian Identity provides a useful case study in the

evolution of extremist identity, because it went through a fairly clear and gradual

metamorphosis from a less extreme initial formulation into its full-blown violent

incarnation, and because its evolution is particularly well-documented in texts.

While there are many variations on the ideology, adherents of Christian Identity broadly

believe members of the “white race” are the Chosen People of God described in the

Christian Bible, and that other races are impure and part of a genetic lineage that can

be traced directly to Satan or to Satanic influences.

Dr. Michael Barkun provides an authoritative account of this movement’s origins and

evolution in his book, Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity

Movement, and this paper will not attempt to recreate that comprehensive narrative

history, however a brief chronology of the movement’s development and the situation

of the texts examined in this paper is presented in Appendix B.

17

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

10

This paper will instead examine a representative sample of the movement’s key texts,

from its earliest incarnations to its most-developed manifestations, to analyse the

movement’s evolution from the elevation of an in-group identity (by Christian Identity’s

direct precursor, British Israelism) into its later framing of a cosmic war against a

demonic out-group.

The texts are examined here in roughly chronological order, but the many competing

strains of thought and overlapping developments preclude a strictly linear evolution.

They were selected for their prominence and with an emphasis on texts that introduced

novel concepts which altered the movement’s trajectory. Some of these ideas

developed in parallel, while others are expressed more clearly or fully by texts taken

out of the chronological sequence.

b) Legitimacy of the In-Group

British Israelism was a historical theory originating in the late 19

th

century, which

stipulated with varying degrees of specificity that the “Chosen People” of the Old

Testament—known as the Israelites—were the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxon “race”.

18

In its very earliest iteration, the theory held that many Europeans were (unknowingly)

Jewish.

19

But this swiftly gave way to an argument that Europeans were the

descendants and heirs of the Chosen People of Israel, distinct from a Jewish identity.

British Israelism constructed an in-group identity with two primary and interrelated

components: nation and race. Adherents believed Anglo-Saxons were a distinct race

descended from the so-called “lost tribes” of the nation of Israel described in the Bible.

The fate of these tribes is unclear in canonical texts, although later apocryphal works

and religious and historical theories offer a variety of clues or explanations for their

disappearance.

20

British Israelists theorised that the lost tribes had migrated to Europe and seeded a

race of white Europeans, who were the rightful beneficiaries of covenants with God that

had been documented in the Christian Old Testament. British Israelism did not entirely

exclude modern Jews from the racial and religious line of God’s “chosen people”,

Rather, the theory initially sought to extend the biblical status of the “chosen” to the

race of Anglo-Saxons and the nation of the British Empire (and later to the United

States). As the movement solidified, the idea was fleshed out in a torrent of extremely

dense, pseudo-academic studies.

Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright

Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright, published in 1902 by J. H. Allen, represents a

mature explanation of the ideology.

21

The book also stands out as one of the more

accessible and influential works in a field overstuffed with elaborate scriptural citations,

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

biblical genealogies and the parsing of Hebrew names against other names and words

with similar sounds. In Barkun’s words, British Israelists “mimick[ed] techniques of

historical scholarship, so that conclusions might be advanced not merely as statements

of faith but as intersubjectively testable knowledge”.

22

In keeping with the general outline shared by most British Israelist theorists, Allen

argues that the nation of Israel described in the Bible has been misunderstood by

mainstream scholars as an exclusively Jewish state. He claims the lost tribes of Israel

migrated to the British Isles and survive today as Anglo-Saxons, constituting a separate

nation and a semi-distinct race from the tribe of Judah, whose descendants are

modern-day Jews.

In Allen’s iteration of British Israelist theory, scriptures are deployed to support a claim

that Anglo-Saxons and Jews descend from a single bloodline in antiquity that eventually

separated into somewhat distinct races, relying on the extensive genealogies

chronicled in the Old Testament.

23

The importance of these familial distinctions relate

to various Old Testament covenants that promised future greatness to the descendants

of Abraham.

Allen separates these covenants according to whom they were promised, resulting in a

“birthright” line, destined to be the “father of many nations”, and a distinct “sceptre”

line, which he interprets as the royal line of David, through the tribe of Judah, from

which Jesus Christ would be born.

24

A notable component of this genealogical history

involves junctures in the biblical narrative in which the birthright takes unexpected

turns. Allen relates several examples in which the birthright does not proceed to the

firstborn son, either due to God’s expressed preferences or due to actions taken by the

men involved (for instance, when God chooses Jacob, the younger son of Isaac, to

receive his birthright, instead of the older son, Esau).

25

In Allen’s view – which he defends with a mix of biblical citations, folklore and arcane

symbology – the lost tribes are heirs to the nation of Israel, distinct from the Jewish

people.

The biblical sources are a mix of what Allen presents as literal history and interpreted

prophecy. From folklore, Allen selects data points useful to his argument, such as

legends surrounding the “Stone of Scone,” an artifact used in the coronation of English

monarchs, said to have originally belonged to the biblical patriarch Jacob.

26

In the realm

of symbology, later in the text, Allen veers into increasingly fervid flights of imagination.

For example, he finds meaningful parallels between a biblical reference to a “scarlet

thread” linked to the “sceptre” bloodline and the British flag, which has literal scarlet

threads woven into its fabric.

27

Taken together, Allen argues, all of these data points prove that Anglo-Saxons are the

rightful heirs to God’s promises, specifically a promise that the descendants of the

biblical figure Ephraim would father “many nations” or “a company of nations”, which

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

12

Allen casts as a prefigurement of the British Empire. He further separates one of the

lost tribes – linked to the biblical figure Manasseh – as antecedent to the United States,

making Americans rightful heirs of a prophecy that Manasseh’s descendants would one

day form “a great nation” in the singular.

28

Allen does not stop with this elevation of

Anglo-Saxon destiny, however. He takes it a step further and argues that the “sceptre",

or royal line, has passed from the Jews to Israel, meaning the Anglo-Saxon tribes.

Race as Text versus Subtext

Judah’s Sceptre is heavily concerned with distinctions of race, but these are important

primarily as it concerns the proper inheritance of God’s prophesied blessings. In a

chapter titled “Race Versus Grace”, Allen mounts an argument that both race and grace

(meaning religiously correct belief and action) are necessary for Israel to fulfil prophecy

and establish the word of God on Earth.

29

This formulation frames British Israelism as an ethno-nationalist movement with some

significant loopholes and exceptions for those who are willing to assimilate.

One key exception applies to the Jews. Allen portrays the rift between the Israelites and

the Jews as religious and historical in nature, rather than intrinsically racial, and he

argues that Anglo-Saxon “Israel” will eventually be reunited with the Jews in accordance

with prophecy. As Allen explains, “The brotherhood is still broken, but it shall be mended”

(emphasis in original).

30

For Allen, the shared racial heritage of Jews and Anglo-Saxons

unites more than it divides.

Implicit but essential to this racial calculus is some manner of patronising superiority

and ultimate sovereignty over the world’s other races. But despite the centrality of race

to his argument, Allen neglects to mention – in the course of nearly 100,000 words –

how people of African or Asian descent might be impacted by the ascendance of

divinely ordained Anglo-Saxon hegemony, aside from a tangential note that the

abolition of slavery in the West was morally correct and in accordance with prophecy.

31

Earlier iterations of the British Israelite theory were slightly more forthcoming on this

point. The earliest formal statement of British Israelism as a distinct ideology was the

1876 tract, Lectures on Our Israelitish Origin. The book’s author, John Wilson, is described

by Barkun as a key figure in institutionalising the ideology as a movement.

32

In Lectures, Wilson presents a fairly typical theory of the time, describing three “major

races” that branch off from the sons of Noah – Shem (white), Ham (black), and Japheth

(Asian and indigenous people such as Native Americans) – accompanied by patronising

descriptions of non-white characteristics.

33

Few of these racial formulations were

original to Wilson; some had existed for centuries as part of theological justifications

for slavery. For instance, Wilson reiterates a well-known theological interpretation of

the day, used by others to justify the enslavement of Africans based on a biblical story

in which Ham’s son is cursed by God to be a slave.

34

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Wilson devotes more ink than Allen to a discussion of race and more visibly reflects the

prevalent racist attitudes of his day, but these elements are also clearly tangential to

his primary argument that Anglo-Saxons are the lineal inheritors of the nation of Israel.

While early adherents of British Israelism waxed on at great length to assert and justify

their elevated in-group status as the rightful heirs of prophecy and special status in the

eyes of God, their writings rarely ventured into out-group dynamics in any meaningful

way – even when discussing the most obvious potential challenge to their scriptural

claims of legitimacy, the Jews.

Out-Group Status Quo

British Israelism patently disenfranchises the Jews of their biblical covenants with God

and transfers the benefits of those covenants to Anglo-Saxons. But from the

perspective of Wilson, Allen and other British Israelists, this wasn’t larceny, it was simply

a lateral variation on the “normal” status quo.

British Israelists started from the assumption that the Jews had no covenants left to

lose. Most mainstream Christian theologians of the day endorsed some form of

“replacement theology” – a belief that Old Testament covenants were either

superseded or fulfilled by the coming of Christ.

35

We know the British Israelists

emerged from that tradition because they devoted many pages to detailed refutations

of replacement theology,

36

arguing that the old covenants had not been superseded or

fulfilled, but were still valid and subject to a legitimate claim by Anglo-Saxons.

In other words, British Israelists did not emerge to contest the legitimacy of a Jewish

claim to the benefits of the covenants. The very notion was so irrelevant to their

thinking that they never even dignified it with their attention. Instead, they emerged to

contest the contemporaneous Christian claim that the covenants had been replaced.

Thus, most early British Israelists did not frame Jews as an enemy out-group, treating

them instead as an alienated segment of the Israelite in-group. For Wilson, Jews and

Europeans alike are descendants of Shem and thus genetically superior to the other

two major races. Wilson often uses Caucasian and Semitic interchangeably, although

he specifies that Anglo-Saxons are the best exemplars of the race and further claims

that the Jewish line has been polluted by race-mixing—a point that would be recalled

by later writers and eventually take on much greater importance.

This miscegenation, along with the rejection and execution of Christ, contributed to

disqualifying modern Jews from participation in God’s covenants, Wilson argues, but he

stipulates that the Jews can be re-assimilated into the nation of Israel by converting to

Christianity.

37

While he criticises the Jews for “unceasing hatred [of] not only Christ, the

Head, but also His followers”, he is also very specific that they must not be excluded

from the fulfilment of prophecy, explaining:

Do we bring forward these historical truths to disparage the Jew? Far

from it. Only to illustrate the truth regarding Israel.

38

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

14

Allen, writing 27 years later, is far more careful to avoid disparaging Jews (or anyone

else) on racial grounds, arguing that in the future, Anglo-Israel and the tribe of Judah

“are again to be united, become one kingdom, and then remain so forever”.

39

Other

British Israelist authors generally followed the same template, expecting a future

reunification and embracing a patronising and often freighted philo-Semitism.

“Ephraim – the Anglo-Saxon – are reaching out the hand of love – of fraternal affection

– to Judah, the Jews, inviting them to terms of fellowship, such as in the days of old

when they came out of Egypt, and before the separation”, wrote E.P. Ingersoll in 1886’s

Lost Israel Found in the Anglo-Saxon Race.

40

“View the Jews, therefore, in any aspect you please, they at once arrest our attention,

inspire our thoughts and command our admiration”, wrote William H. Poole in 1889’s

Anglo

‐

Israel or the Saxon Race Proved to be the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel – before describing

a stereotypically unpleasant Jewish “countenance” as a byproduct of their rejection of

Christ.

41

Despite all the qualifications and stipulations, the fraternal impulses of the British

Israelists were fraught with underlying tensions, chiefly that their magnanimity toward

the Jews was predicated on a firm expectation of eventual assimilation. Jews must

eventually embrace Christianity in order for British Israelists’ prophetic expectations to

be fulfilled. This underlying tension would grow sharper as British Israelism evolved

into the mid-20

th

century, at the same time that a broader social strain of anti-Semitism

was evolving from a religious construct into a racial one.

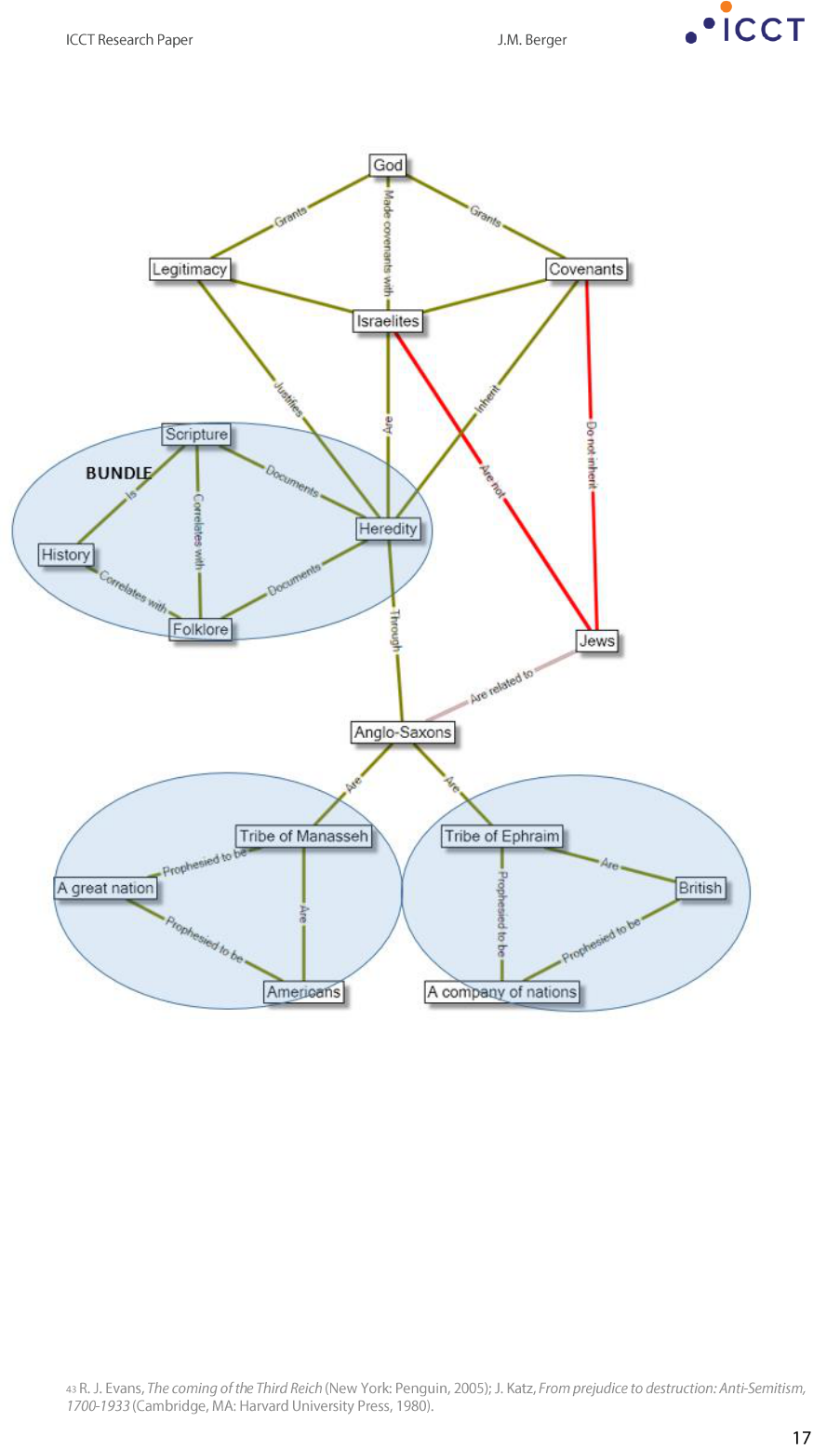

Judah’s Sceptre: Linkage Analysis

British Israelites sought to enhance in-group legitimacy by making Anglo-Saxons the

inheritors of biblical covenants and promises of greatness. This was accomplished in

texts through a pseudo-scholarly approach, designed to woo potential recruits through

deliberative arguments.

42

Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright creates its constructs of identity by establishing

elaborate conceptual linkages among a number of in-group concepts and knowledge

assets. These include but are not limited to:

In-Group Concept

Linkage

In-Group Concept

Heredity

Justifies

Legitimacy

Scripture

Documents

Heredity

Folklore

Correlates with

Scripture

History

Correlates with

Folklore

Scripture

Is

History

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Folklore

Documents

Heredity

God

Grants

Legitimacy

God

Made covenants with

Israelites

Anglo-Saxons

Descended from

Israelites

Anglo-Saxons

Inherit

Covenants

Anglo-Saxons

Are ignorant of

Heredity

Israelites

Are

Chosen People

Anglo-Saxons

Are

Israelites

Anglo-Saxons

Are

Chosen People

British

Are

Tribe of Ephraim

Americans

Are

Tribe of Manasseh

British

Prophesied to be

A company of nations

Americans

Prophesied to be

A great nation

Judah’s Sceptre is not a fully formed extremist interpretation of the world, in part

because it emerges from a discriminatory worldview in which it is not necessary to

disenfranchise Jews of what they do not possess. Furthermore, it does not critique

Jewish practices or historical behaviour (or rather, it does not single Jews out for more

criticism than Anglo-Saxons). Instead, its primary critique is intellectual in basis and

directed at mainstream Christian theologians whose conclusions differ from Allen’s.

Nevertheless, Allen provides seeds for the eventual development of an out-group

dynamic, setting the stage for the next generation of British Israelists. These are derived

from the in-group linkage that “God made covenants with the Israelites” and that

“Anglo-Saxons are Israelites”. The conclusions that follow from this premise are:

Out-Group Concept

Linkage

Out-Group Concept

Jews

Are not

Anglo-Saxons

Jews

Are not

Israelites

Jews

Do not inherit

Covenants

Allen could have marshaled the same sources to argue that Anglo-Saxons were simply

included or co-equal with the Jews in the inheritance of covenants. The fact that he, and

most other British Israelite authors, chose not to take this approach provided the

opening for an increasingly virulent strain of anti-Semitism that would eventually

subsume the original ideology’s particular and specific worldview.

At this stage in the movement’s evolution, however, Allen does not perceive a threat

from the out-group. Therefore, his prescription for a “solution” to the tension between

16

in-group and out-group franchises and preference divergence is relatively mild and

relegated to the vanishingly distant future:

In-Group Concept

Solves

Out-Group

Anglo-Saxons

Assimilate

Jews

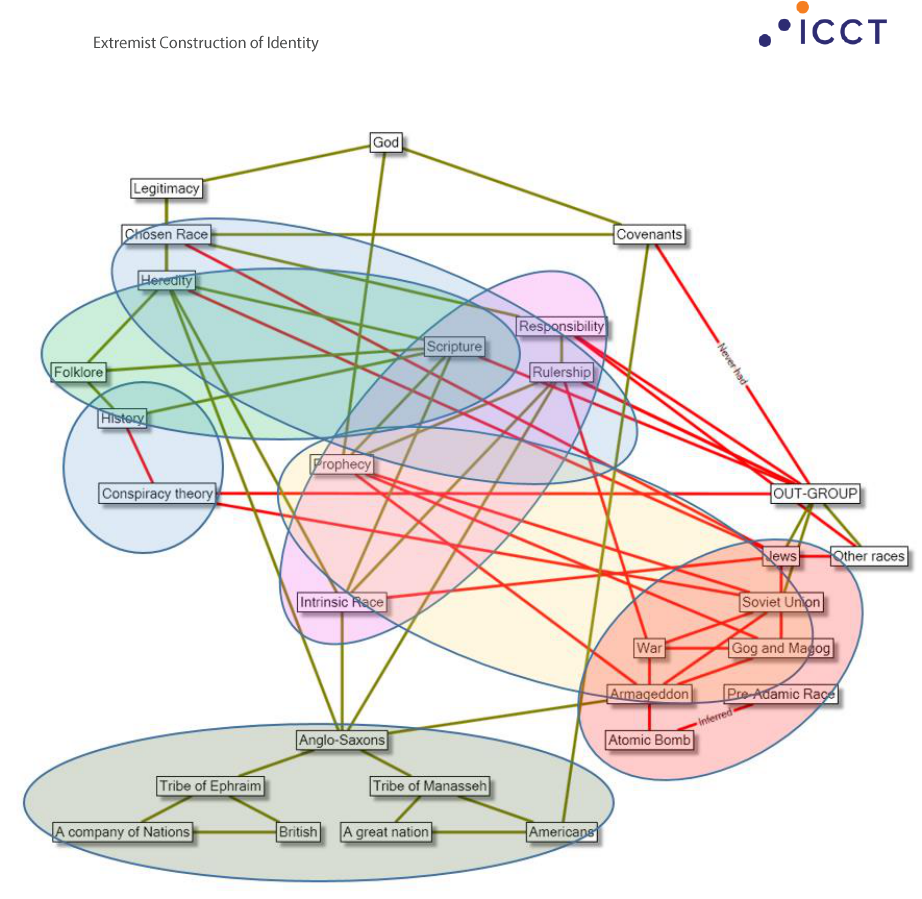

Many of the concepts in the text are bundled (see chart, next page), particularly the key

idea of heredity, which is a bundled collection of links between history, scripture,

folklore and analysis. The crucial argument that “Anglo-Saxons are Israelites” is built on

multiple bundles. Allen’s articulation of the ideology can be usefully diagrammed

according to these linkages and bundled concepts.

Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright uses these links and bundles to establish several

benchmarks of in-group identity, including:

Defining shared beliefs (religious)

Defining shared history (scripture, heredity)

Defining intrinsic, non-negotiable identity (heredity, Anglo-Israel nation)

For the early British Israelists, the heavy lifting is found in the work of constructing an

intrinsic identity (Anglo-Israel) through “historical” proofs, derived from the bundled

concepts of scripture, history and folklore. These are not treated as entirely

interchangeable. Scriptural genealogies and history are seen as identical constructs;

folklore is relegated to providing secondary and supporting proofs.

This bundle of concepts is the linchpin that keeps the wheels from flying off. Without

the genealogical argument, British Israelism falls apart. In contrast, the future fruits of

heredity are presented in relatively modest fashion – blessings due to a “great nation”

and a “company of nations”. When Allen invokes prophecy, he is most often pointing to

prophecies he believes have already been fulfilled, which in turn are bundled into the

historical and intrinsic constructs. Expectations for the future of the identity group

remain vague. The movement, in its early stages, seeks its legitimacy in the past.

Linkages in the text of Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright. Green lines represent links defining

the in-group; red lines pertain to out-groups.

c) Illegitimacy of the Out-Group

Racialisation of Jewish Identity

Around the time that British Israelism was evolving as a defined movement, a parallel

ideological shift regarding attitudes toward Jews was taking place in Germany and other

parts of Europe. It is not the intent of this paper to provide a thorough overview of this

transition outside of the British Israelism context. The brief summary here draws

primarily on Evans (2005) and Katz (1980).

43

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

18

Anti-Jewish sentiment was nothing new by the 19

th

century, but historically, its major

focus had been religious and based on a narrative that the Jews played a critical role in

the death of Christ. With the rise of nationalism in Europe, it became expedient to

define Jewish identity as racial rather than religious, in part because it meant that Jews

who intermarried or converted to Christianity (a significant 19

th

century demographic

in Germany) could not remove themselves from the out-group.

44

A series of French and German works promoted racialised concepts of anti-Semitism

throughout the late 19

th

century.

45

While the British Israelists were industriously

Semitising Anglo-Saxons with extensive biblical citations, influential German writers like

Theodor Fritsch instead Aryanised Christ, discarding biblical evidence to the contrary

as tainted by Jewish revisionism.

46

The new anti-Semitism did not win hearts and minds overnight, but its influence in

European society grew. In 1899, an English immigrant to Germany named Houston

Stewart Chamberlain published a book, Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, which

was widely read and helped spread racial anti-Semitism to a much wider audience.

47

There is considerably more to this story, of course, including the catastrophic

expansion of these themes in Nazi Germany, but the purpose here is simply to

introduce the strain of racialised anti-Semitism that would come to infect British

Israelism.

The shift from religious to racial anti-Semitism was extraordinarily consequential.

Although bigotry of any kind is problematic, racial prejudice is inherently more extreme

than religious prejudice in one key respect – members of a religious out-group can

usually convert to join the in-group through established procedures, but members of a

racial out-group cannot join the in-group, except through subterfuge (i.e., “passing”) or

through a lengthy, often generational, process of assimilation.

48

Simply put: you can elect to change your religion in order to escape persecution, but

you can almost never elect to change your race. This has serious ramifications for the

extremity of actions that an in-group will contemplate toward the out-group.

The shift to a racial out-group identity contributed to an ideological vision of a deeper

and more sinister conflict, one which by its very nature could never be mended or

reconciled, and one which required more extreme solutions. When a cultural dispute

between people of different races becomes grounded in beliefs about the intrinsic

qualities of race, it becomes profoundly radicalised.

British Israelism, Barkun writes, was often “philo-Semitic”, but it “operated in an

environment rife with anti-Semitism” and “racial theorizing”.

49

The movement also had

implicit elements of anti-Semitism in its elevation of the Anglo-Saxon line over the

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Judaic line, as well as reflecting general white racial attitudes of the day, which were not

especially enlightened and at times tended toward the conspiratorial.

50

For some early British Israelist writers, the movement actually allayed concerns about

perceived Jewish influence by offering a prophesied path toward purification and

reconciliation of the tribes of Israel.

51

The religious basis for the out-group formulation

offered an important escape clause, and one that could be safely postponed until

prophetic conditions were met at some unspecified point in the future.

William Cameron

British Israelist writer William J. Cameron was more notorious for his role in publishing

virulent racist and anti-Semitic material in the Dearborn Independent, a newspaper

owned by automobile magnate and infamous Nazi sympathiser Henry Ford.

Cameron was likely a British Israelite first, and an anti-Semite later.

52

In part thanks to

Cameron’s influence, British Israelism would shift from a patronising but inclusive

stance toward the Jews to the enemy out-group politics of extremism.

While it contained some British Israelist content, the Independent was heavily focused

on exposing so-called Jewish conspiracies emerging from the infamous anti-Semitic

tract The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. First published in English in 1919, the

book was popularised in the United States by Ford, Cameron and the Independent, and

its contents soon began to infect British Israelist thought.

The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion

While not part of the current of thought that produced British Israelism, the publication

of the infamous anti-Semitic conspiracy tract, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion,

would have a fateful impact on the movement. The book was a semi-plagiarised

concatenation of conspiracy theories about Jewish influence over society, first

published in Russia and later in English.

British Israelism’s shift toward anti-Semitism tracked with its rising popularity in

America. The Protocols were first published in book form for an American audience in

1920 by Small, Maynard & Co. of Boston, which is the reference work for this paper.

53

Protocols is essentially a litany of everything that can theoretically go wrong in a society

based on representative government, but it argues all these potential abuses are

happening or have already happened, and attributes them to a near-omnipotent Jewish

conspiracy by the titular “Learned Elders of Zion,” characterised in a very un-British

Israelite manner not just as the Jewish “race”

54

but also the nation of Israel.

55

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

20

Pushing a racial view of Jewish identity, Protocols has resonated throughout the years

for many reasons, particularly because of its astute critique of modernity and

representative government,

56

which was substantially lifted from Maurice Joly’s French

book Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu (1864). In that book, the

salient critique is attributed to a fictionalised version of Machiavelli in the context of

contemporaneous French Emperor Napoleon III.

57

In Protocols, the critique is recast as a description of international crises caused by a

race-based Jewish conspiracy. The crises are so diverse and wide-ranging that readers

could readily associate them with worrisome developments in the real world. The

prologue and appendix of the American edition clearly frames the October Revolution

of the Bolsheviks in Russia as a Jewish conspiracy, linking anti-Semitism to Communism,

a connection that would play out in British Israelist texts.

The conspiracy theories contained in Protocols were amplified and popularised by some

of the biggest megaphones of the day, including the propaganda machine of Hitler and

the Third Reich. In the United States, articles in Ford and Cameron’s Independent, were

subsequently collected in a book called The International Jew.

58

These ideas began to be echoed by British Israelists in the 1920s, but they did not

immediately subsume the movement.

59

Racialising British Israelism

Cameron availed himself of the implicit opening created by British Israelism’s

separation of the chosen nation of Israel and the Jewish tribe of Judah, which his

predecessors had studiously avoided. For example, one vituperative Independent

article, unattributed but believed to be authored by Cameron, seizes and expands on a

pillar of the British Israelite theory that previous authors had treated carefully – the

disenfranchisement of Jews from the covenants of God:

The pulpit has ... the mission of liberating the Church from the error

that Judah and Israel are synonymous. … The Jews are not ‘The Chosen

People,’ though practically the entire Church has succumbed to the

propaganda which declares them so.

60

The case for British Israel had always included this double-edged sword, although most

early authors declined to exploit it: if the British were the true heirs of Israel, was it

really necessary to allow any special consideration for the tribe of Judah, even

historically? British Israelism was slow to advance the argument, in part because of its

painstakingly constructed scriptural framework which relied heavily on the Old

Testament, a collection of Jewish holy books that did not easily lend itself to

disenfranchising its authors.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

In order to synchronise the new anti-Semitism with the old British Israelist theories, the

question of race would have to be addressed. Here, Cameron drew on John Wilson’s

pre-existing work. The racial theory presented in Wilson’s Lectures on Our Israelitish

Origin was tangential to the book’s primary argument and carefully hedged to avoid

“disparaging” the Jews, but crucially, he made reference to the Jews “mixing” with

Gentiles descended from the cursed lines of Cain and Esau (aka Edom), although he

still allowed for their eventual redemption and qualified return to the Anglo-Saxon line

through acceptance of Christ.

61

Cameron would adopt some of Wilson’s theories directly in his later writings, but by the

1930s, a wider racial theory was already becoming an important focus. In 1933, he

articulated his views in a series of lectures laying out a racialised version of British

Israelism. They were later collected and published as a book, The Covenant People.

62

After suffering significant professional blowback from his association with Ford,

Cameron was careful in his choice of words, but the lectures represent a clear

racialisation of British Israelist tradition. Cameron describes the Bible as being first and

foremost a racial history, the history of a racially delimited “chosen people,” forbidden

from mixing with other races.

63

He says:

Race is one of the most indelible natural facts and race is one of the

most insistent Biblical facts. The Bible is not a history of the human

race at large, but of one distinct strain of people amongst the family of

races. All the other races are considered with reference to it. … The

race to whose story our Bible is largely devoted is called "The Chosen

People."

64

Cameron then articulates an inherent contradiction in British Israelism, but one that

earlier influential writers had carefully avoided. If one race is “chosen”, or privileged,

then the stature of other races must be correspondingly diminished. Legitimacy can be

measured without direct reference to an out-group. In contrast, privilege cannot be

asserted in a vacuum; it is by definition predicated on relative status.

A man will rise and demand, "By what right does God choose one race

or people above another?" I like that form of the question. It is much

better than asking by what right God degrades one people beneath

another, although that is implied.

65

Despite his anti-Semitic track record, Cameron here rejects the premise that being the

chosen race means enjoying superiority over other races. He argues instead the

“chosen” status is a responsibility rather than a perquisite, charged with the sombre

responsibility lifting up the other people of the world—“it is a burden imposed,”

Cameron says—literally “the white man’s burden,” he says, citing Kipling.

66

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

22

To support his theory, Cameron frequently turns to Old Testament apocrypha, texts

which had been excluded from the canonical bible for various reasons, including

questions about their authenticity.

67

In justifying their citation, Cameron characterised

the apocrypha as akin to historical novels: “They are not history per se, but they are

historically accurate.”

68

Unlike his predecessors, Cameron brings a strong indictment against the current “race”

of Anglo-Saxon Israelites, particularly the United States, foreshadowing a critique that

would later flower in the Christian Identity paradigm. Cameron says the status of Anglo-

Saxons in America as the Chosen People is not intended as racial glorification. To the

contrary, he says:

When I turn to the United States of America and recall the hypocritical

character of much of our public life, of our intense engrossment with

material pursuits; when I think of the vast reaches of economic slavery,

of our antagonistic social classes, of our lawlessness, our violence, our

corruption in high places and low, our shameless surrender to sex, our

descent to dirt in drama and literature, our trampling of the Lord's

Sabbath, our supercilious sneer at religion, our dollar aristocracy and

our teeming millions of pauperized citizens - please don't tell me that

the truth that enables me to see these things is a truth invented to

glorify them!

69

Prefiguring later extremist currents, he characterises the founding documents of the

United States, excepting the Constitution, as a new covenant with God, particularly the

Declaration of Independence. “That declaration made us a People,” according to

Cameron. “It was the forerunner of our government. (What a descent we have made

since then!)”

70

Also foreshadowing extremist arguments to come, he claims unfair

taxation was at the heart of most biblical crises.

The Covenant People lectures moved the ball down the field, but Cameron remains

cautious in this text, likely due to the professional and social consequences of his earlier

and more overt anti-Semitism.

71

He discusses the importance of race extensively and

definitively states that the Bible is an intrinsically “racial” history. Cameron stipulates

that Biblical heroes like Moses are not Jewish, but despite his history with Ford, he does

not frame Jews as the out-group in these distinctly British Israelist ruminations.

In these lectures, the process of framing out-groups is instead seminal. While Cameron

likely held harsher views in private, here he simply plants seeds for more extreme

iterations of the ideology to come—specifically framing the spectre of an out-group

through a more exclusionary tone toward Jews.

In parallel, Cameron sets the stage for “purifying” the in-group with his criticisms of

America’s “corruption,” “shameless surrender to sex” and “descent into dirt.” The

nascent “othering” of insufficiently pure in-group members is concurrent with the

nascent process of defining the out-group.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

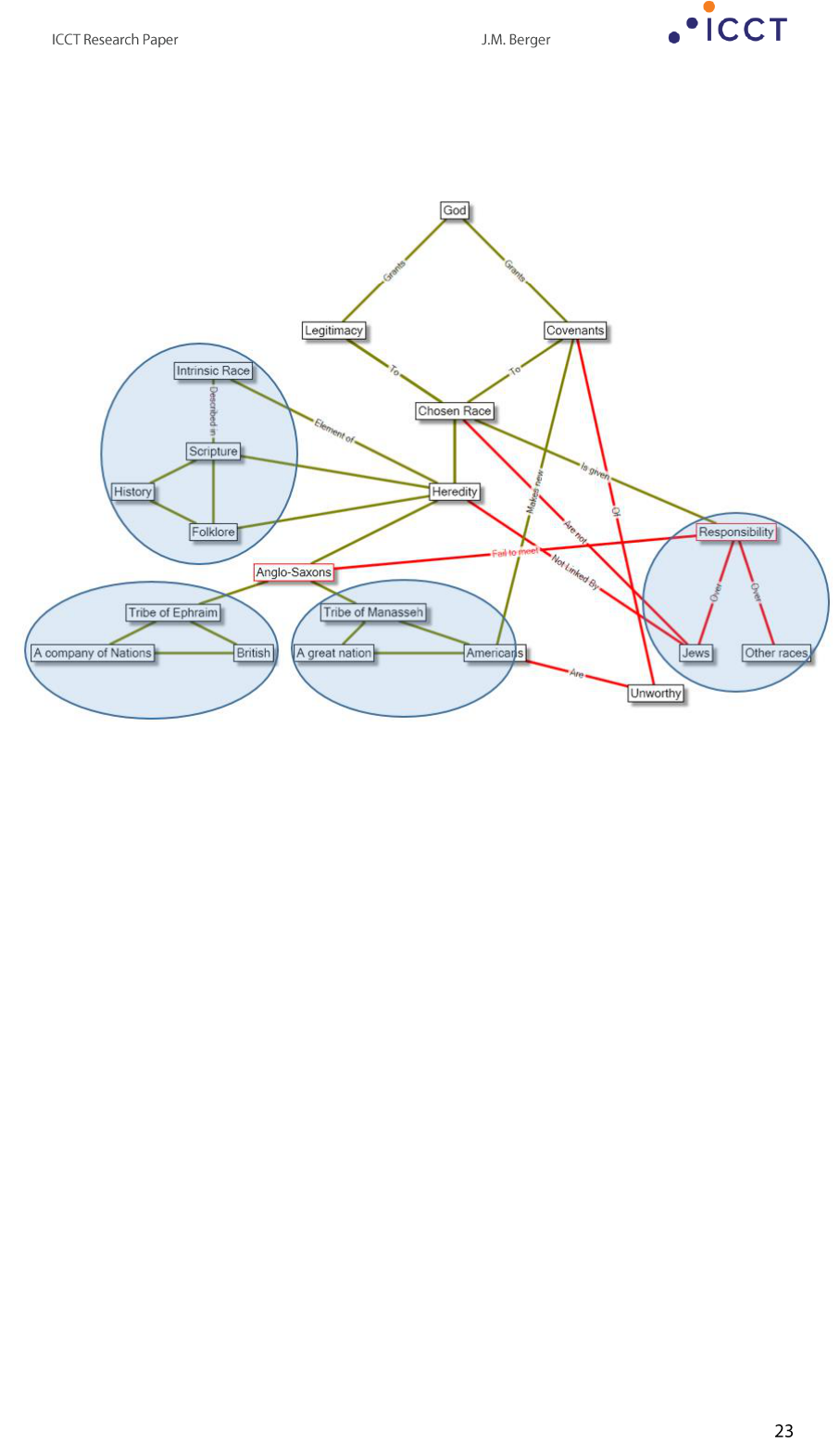

The Covenant People: Linkage Analysis

Linkages in the text of The Covenant People. Green lines represent links defining the in-group; red

pertains to out-groups.

Both implicitly and explicitly, The Covenant People radicalises and racialises British

Israelist ideas, although it still falls far short of a mature extremist outlook. Cameron

begins to define and justify the existence of racial out-groups, but he does not (in this

text) proscribe their existence or rights, except in the context of biblical covenants.

Notably missing (especially in light of Cameron’s previous ventures) is an external-

threat mentality. Cameron de-emphasises earlier British Israelist hereditary claims that

linked Jews to Anglo-Saxon Israel in antiquity, but he does not refute them. His

characterisation of the “white man’s burden” clearly subordinates other races to Anglo-

Saxons, but Cameron posits no threat from out-groups. And, sincerely or not, he

strongly criticises “racial vanity” and “racial egotism,” saying Anglo-Saxons should not

revel in a feeling of superiority.

Ultimately, The Covenant People is still recognisably British Israelist in form, but it shows

signs of mutation that would soon escalate in the work of Cameron’s close associate,

Howard Rand.

24

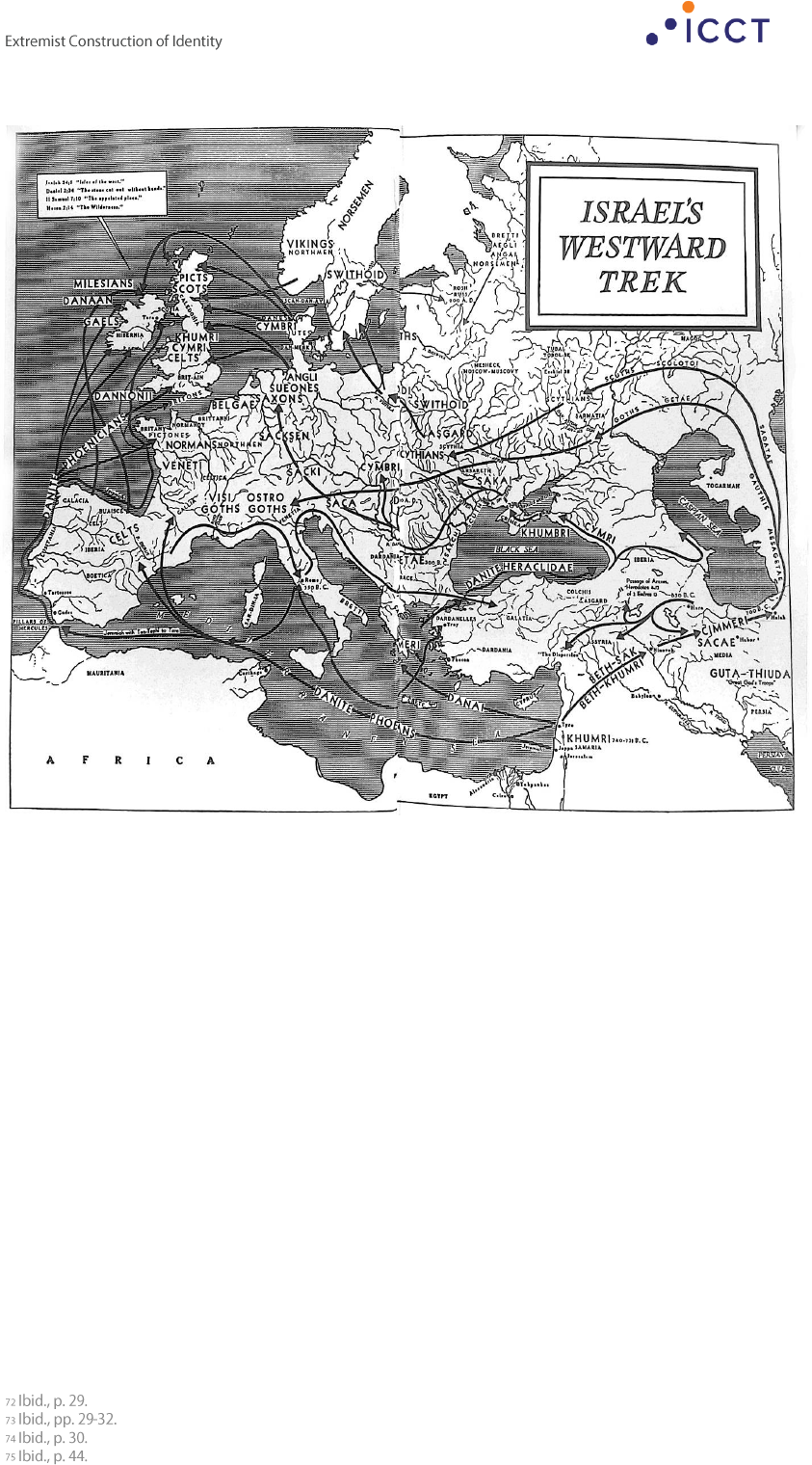

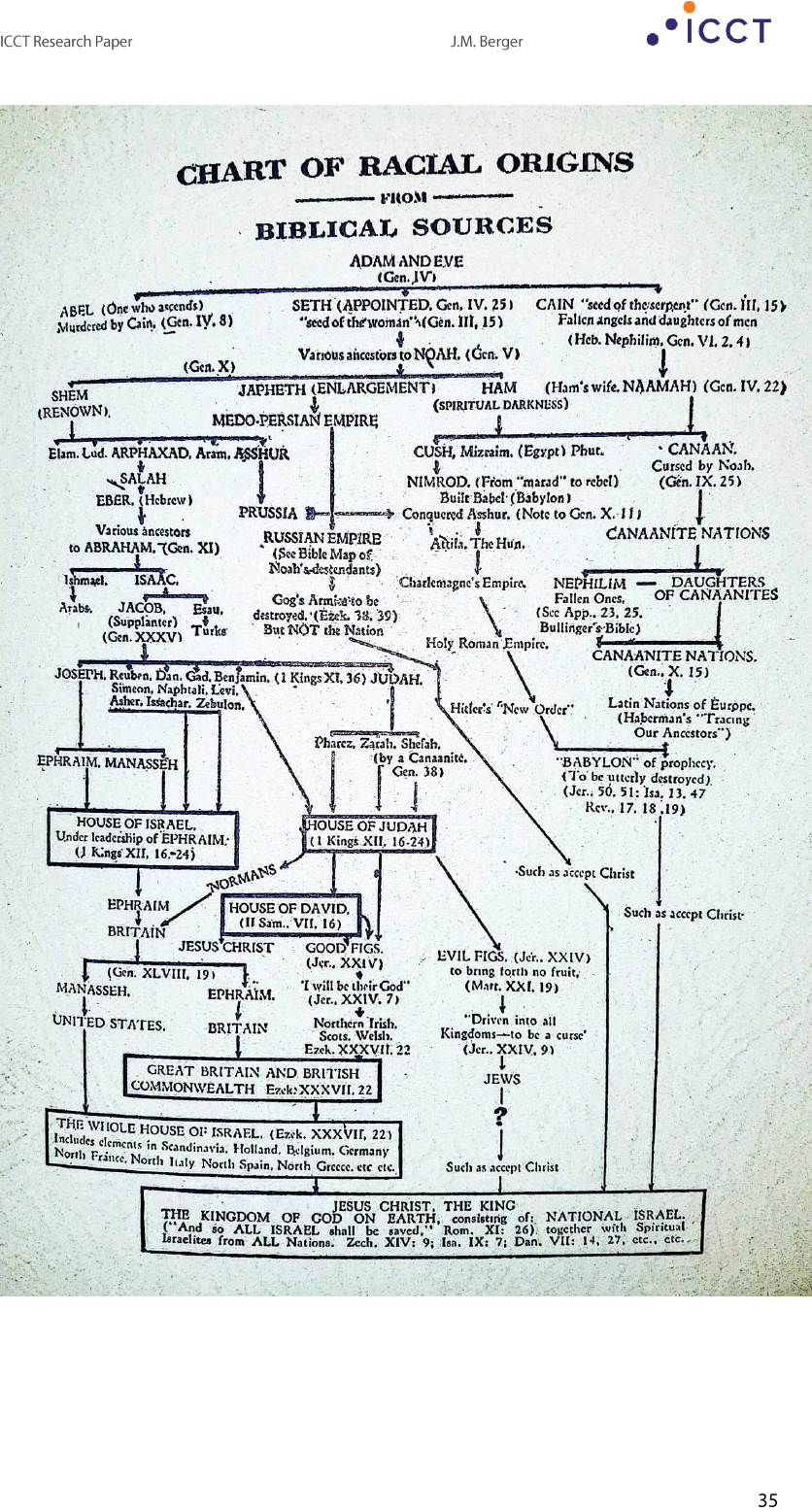

A two-page spread from the inside cover of Howard B. Rand’s Documentary Studies. Vol. 2

Howard B. Rand

Howard B. Rand was a tireless organiser and a “second-generation British Israelite,”

according to Barkun, having grown up reading Judah’s Sceptre at his father’s prodding.

He was involved in founding the Anglo-Saxon Federation of America in 1930, which

soon established branches around the United States.

72

His desire to expand the reach of British Israelism led him to William Cameron, who

helped extend the organisation’s reach by aligning with the American far right, where

Cameron was already well-known thanks to his work with Ford and the Independent. As

a result, elements of Communist paranoia and derivative anti-government rhetoric

began to infiltrate the ideology.

73

Under Rand, British Israelism also began to take on

apocalyptic and millenarian overtones, reflecting the mood of the late 1930s and the

outbreak of World War II.

74

Cameron and Rand parted ways around this time, due in part to Cameron’s alcoholism,

leaving Rand to continue to publish and largely author the British Israelist magazine

Destiny through 1970.

75

Highlights of Rand’s voluminous output were collected in three

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

volumes under the title “Documentary Studies,” consisting of more than 1,800 pages of

writings on British Israelism and related issues.

76

This paper will focus mostly on the first volume, covering 1939 to 1945, in order to

highlight elements that would morph into the earliest iteration of Christian Identity

toward the end of this period. It should be noted that the tremendous volume of Rand’s

output, and the equally vast and twisting corridors of his ideological constructs, cannot

be comprehensively captured in the extracts analysed here.

“No subject is more fascinating than prophecy”, Rand wrote, and he proved his

fascination with the topic at considerable length.

77

Although he continued to reiterate

past themes and biblical proofs of Anglo-Saxon descent, Rand forcefully brought

forward themes of prophecy and the destiny of Anglo-Saxons to play a fateful role in

the waning days of humanity, which he predicted were soon at hand.

In Rand’s conception, the historical puzzle-box of Anglo-Saxon descent, once the

primary fascination of British Israelists, increasingly took a back seat to the modern role

of the Anglo-Saxon race in a turbulent world. Correspondingly, Rand’s scriptural focus

turned from genealogies to prophecies, or passages that could be interpreted as such.

In prophecy, Rand found cause to escalate the legitimacy and importance of Anglo-

Saxon identity still further, building on Cameron’s conception of the “white man’s

burden”. With citations from the biblical book of Psalms and the prophetic book of

Micah, Rand built an argument that Anglo-Saxon Israelites were destined not only to

form a “great nation” and “a company of nations”, but to rule the entire world, with the

coming of a king of Israel in the not-too-distant future.

His vision was decidedly martial, and the pages of Destiny are consumed with imminent,

apocalyptic war, a new element in the British Israelist worldview. Citing the prophetic

Book of Daniel and the words of Christ in the New Testament, Rand claimed that Anglo-

Saxon Israel had to endure a time of punishment, which was concluding as part of

World Wars I and II, an era in which “Gentile” or “Babylonian” empires would stand in

opposition. The time for purification lay directly ahead and subsequently, Israel would

rise:

78

The people of this generation will not only be spectators but actors as

well in a titanic struggle involving all nations, the outcome of which will

decide for all time world rulership [emphasis in original].

79

The enemy, Rand wrote, was also discernible in biblical prophecy concerning the evil

ruler Gog and his land of Magog – cast here as Communist Russia, avowed enemies of

Christianity, destined to face off against an allied British and American Israel. War with

Russia, and Russia’s eventual destruction, would awaken Anglo-Saxons to the

realisation that they are the rightful heirs of Israel, Rand explained, tying the prophecy

to Armageddon, understood by many Christians as the final battle between good and

evil before the end of history.

80

The intermittent introduction of such apocalyptic

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

26

themes in Rand’s body of work tracked with parallel currents elsewhere in British

Israelism that will be discussed in the next section.

Racial awakening comes only after the situation becomes unimaginably desperate, with

the racial nations of the world aligned against the Anglo-Saxons.

81

Rand incorporates a

scriptural view of race throughout the pages of Destiny, following biblical genealogies

in the style of Wilson in Lectures on Our Israelitish Origins, but significantly different in

the details. Arabs are said to be descended from Jokshan, a son of Abraham. The

Chinese are said to be descendants of Moab, and the Japanese descendants of Ammon,

and Rand hypothesises both countries will be set against Israel in the final battle, with

other enemies including Afghanistan, Arabia, Armenia, Egypt, France, Germany,

Mongolia, Persia, Tibet, Turkey, and, of course, the Soviet Union.

82

Despite having been weaned on Allen’s Judah’s Sceptre, Rand is more emphatic than

many of his predecessors on the topic of distinguishing Jews from Israelites, employing

many familiar proofs of Anglo-Saxon heredity as disqualifying Jews from participation

in Israel.

83

He oscillates between religious and racial definitions, arguing that the

emergence of a distinct Jewish racial identity was a late historical development, the

result of race-mixing with outsiders after the Babylonian Captivity (around 540 BCE).

84

Because of these complications, Rand struggles at length to refute Christ’s Judaism,

declaring that the only Jew among the apostles was Judas.

85

Rand was openly anti-

Semitic,

86

but he still—grudgingly—allowed for the eventual reconciliation of Judah and

Israel on the condition that Jews accept Christ.

87

Rand referred to the Soviets and Communists and Bolsheviks interchangeably, the

latter term echoing the American edition of the Protocols, which laboriously

documented the supposed Jewish origins of Bolshevism and its link to the book’s titular

conspiracy.

88

Despite the clear intrusion of anti-Semitism on his worldview, Rand

repeatedly names Communism and the Soviet Union as the apocalyptic enemies

referred to in prophecy in the texts examined here, rather than Jews.

Rand escalated his linkage between Communism and Judaism as the years progressed,

accusing the Soviets of advocating for Zionism in Palestine at the expense of the British

Mandate.

89

Later, in 1948, the establishment of the modern state of Israel would drive

Rand deeper and deeper into anti-Semitism.

On its face, the declaration of a nation of Israel grounded in Jewish identity was the

most dramatic rebuke to British Israelism that could be imagined. Calling it an

“abomination” and an “incredible hoax,” he firmly tied these developments to a Jewish

conspiracy as outlined in the American edition of Protocols and amplified and expanded

in Ford and Cameron’s Independent articles.

90

Later, in the 1950s, Rand would build

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

more extensive bridges between the Protocols and British Israelism, but by then the

movement had largely left him behind, as Christian Identity came into its own.

91

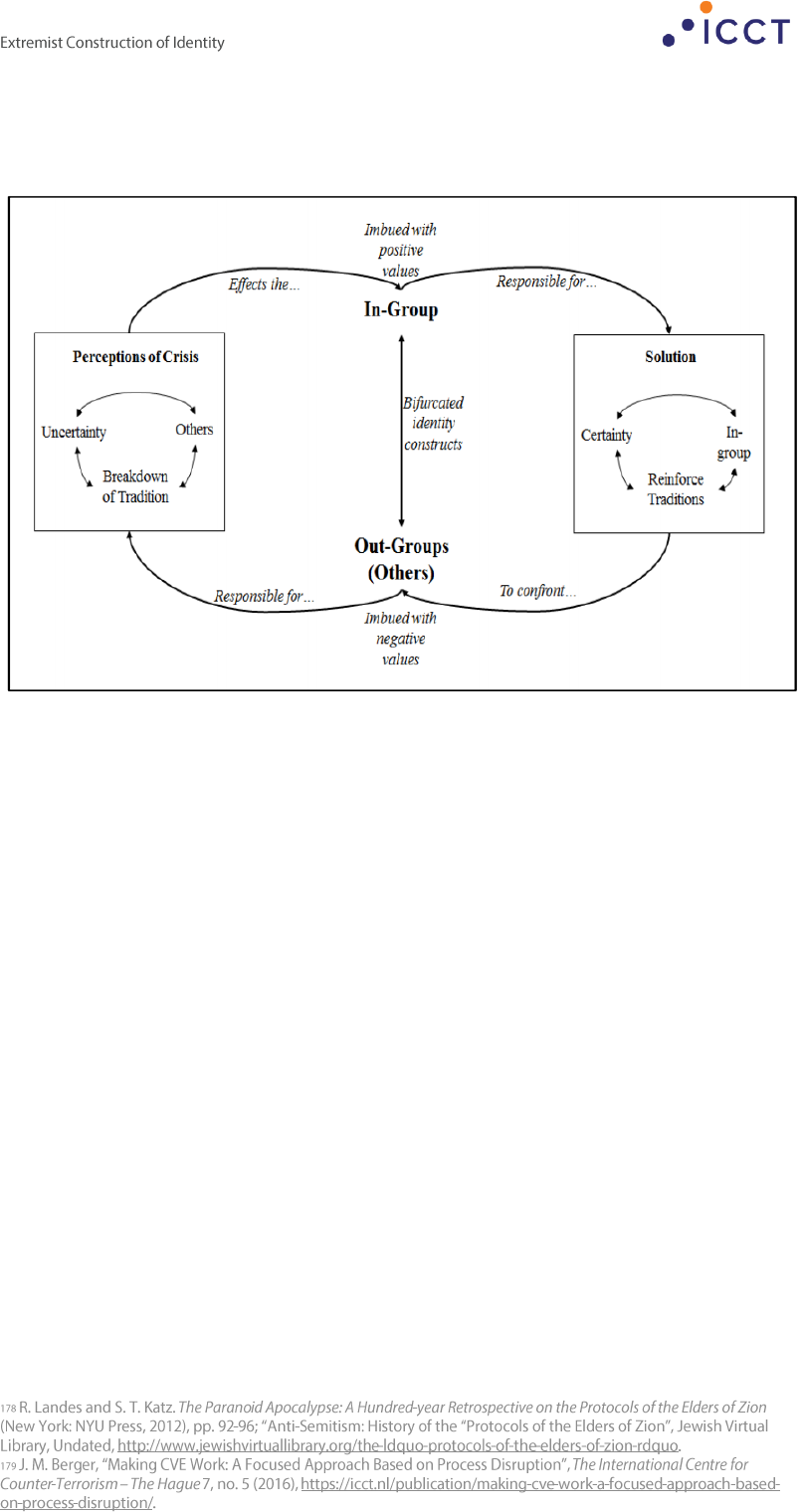

In all of the above, Rand is introducing something that had been absent in previous

iterations of British Israelism – a “crisis construct”. According to Ingram:

Perceptions of crisis may not only contribute to identity construction

processes but tend to act as an important push factor behind why

individuals support extremist groups and engage in politically

motivated violence (i.e. radicalise).

92

As described by Ingram, the crisis construct contains three interrelated factors: the

presence and influence of “Others”, uncertainty, and the breakdown of tradition. Rand

is a decidedly alarmist writer. His thesis incorporates all of these elements, including a

more extensive out-group description drawn from The Protocols, an alarmist

description of global chaos and uncertainty, and the failure of Anglo-Saxons to

acknowledge their traditional Israelite racial heritage.

In a full-blown extremist movement, following Ingram’s formulation, the crisis construct

is paired with a solution construct – a formulation of what the in-group can do to solve

the out-group crisis. Here, Rand falls short, lacking a vision or call to action beyond

racial awakening, after which apocalyptic events of an unclear nature take place with

the guidance of God. It would fall to the next generation to propose a violent solution

to the out-group problem, an evolution that is described in the following section.

93

Two final notes of interest pertain to Rand’s advancement of British Israelism toward

the realm of racialised extremism. First, Rand frequently responded directly in his texts

to inquiries from the readers of Destiny, and those readers were not necessarily inclined

to take his claims at face value.

94

Reader queries often led him to articulate more

complex justifications for his beliefs. This dynamic will be explored further in section

three of this paper, The Elements of Extremism.

Second, Rand hints in the pages of Destiny at his interest in or acceptance of a racial

theory that some form of sentient humanoid life existed prior to the creation events

described in the book of Genesis. Such “Pre-Adamite” theories existed long before

British Israelism, but by the 19

th

century, they had taken on racist dimensions,

specifying that prior to the events of Genesis, God created inferior races, who were the

progenitors of modern non-white races.

Rand posited the existence of a pre-Adamic race of evil men who were wiped out prior

to the events in Genesis by atomic weapons, or something very similar. This science-

fiction tint would merge with more elaborate and sinister pre-Adamic theories as

Christian Identity finally began to emerge as a distinct ideology.

95

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

28

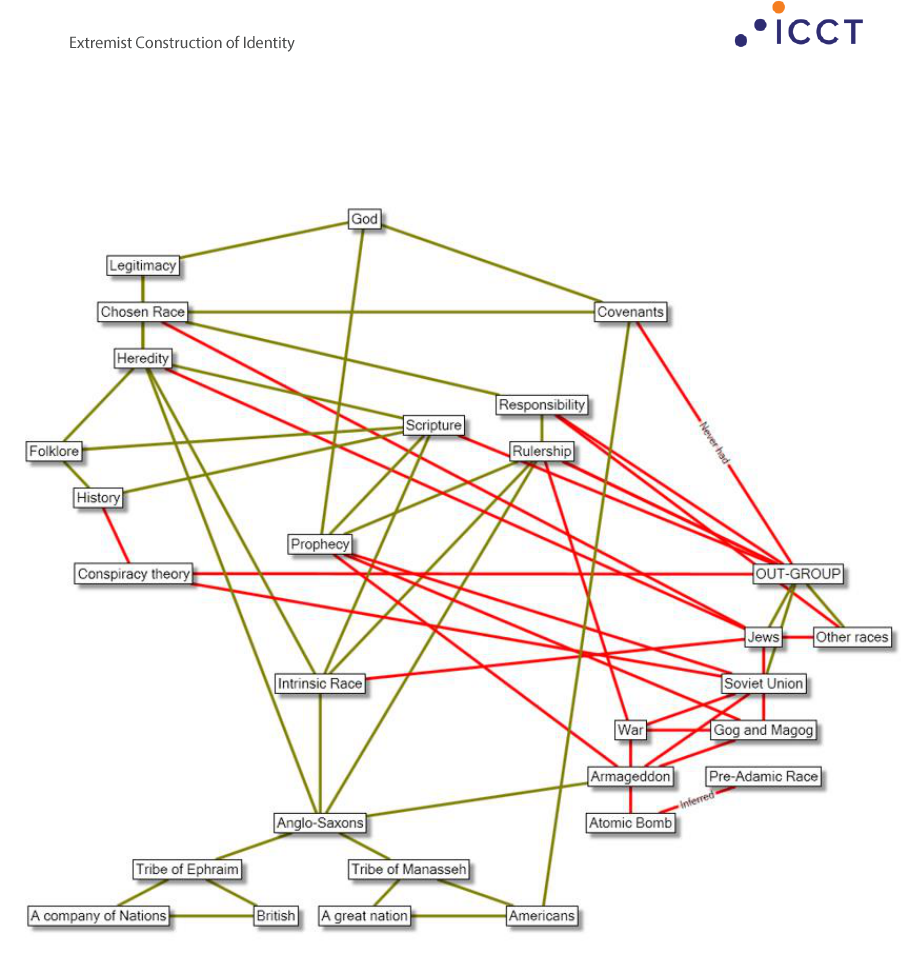

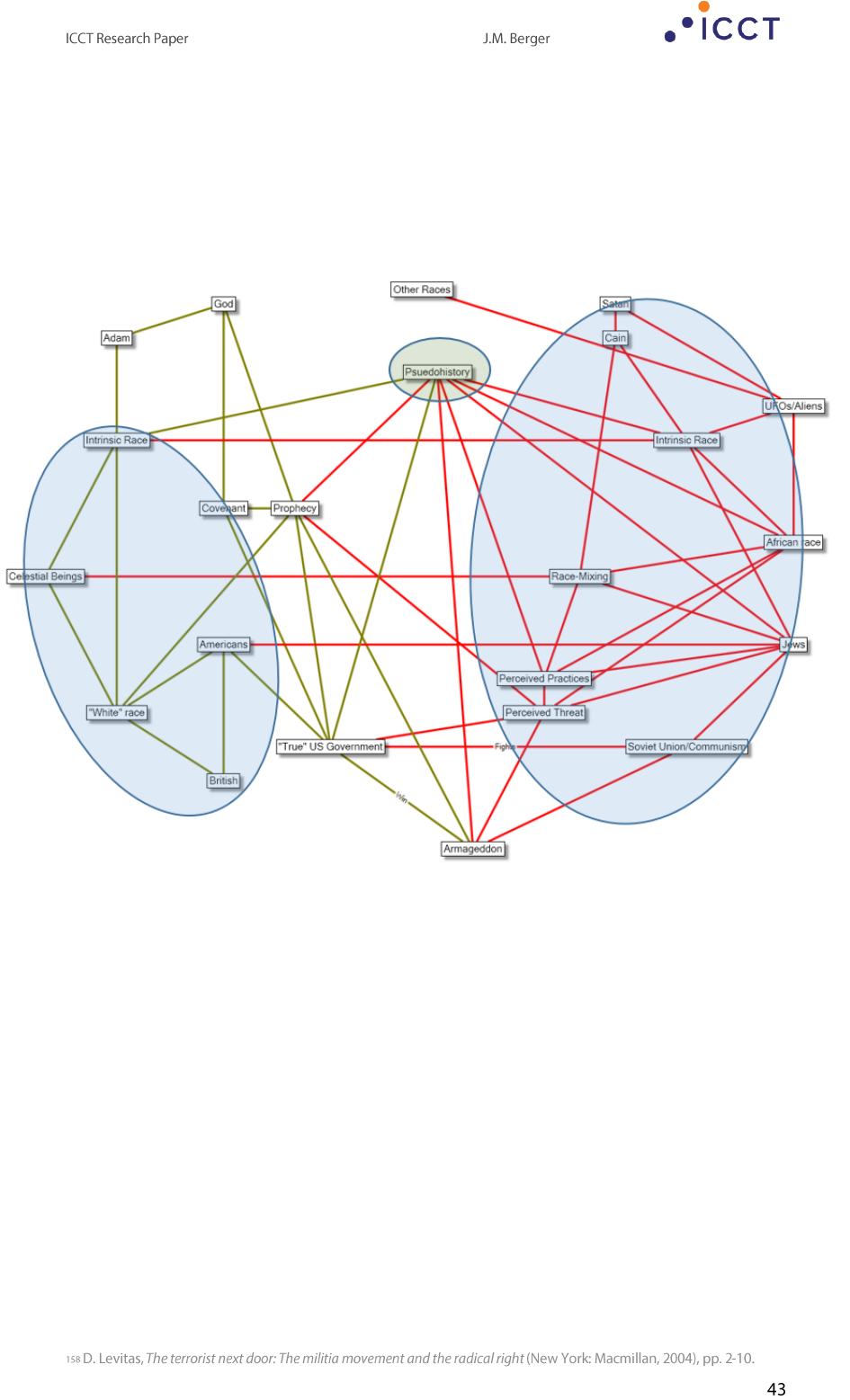

Destiny Magazine: Linkage Analysis

Linkages established in Destiny magazine. Green lines relate to in-group identity construction, red lines

relate to out-groups.

The era of the Anglo-Saxon Federation was in many ways the peak of British Israelism,

both in its popularity as a distinct ideology and the integrity of its original concepts. Yet

Cameron and then Rand, the custodians of the movement on an organisational basis,

the British Israelist worldview darkened considerably, introducing new and dangerous

concepts that set the stage for the progression from nascent anti-Semitism into full-

blown violent extremism.

A few things become apparent in the link chart above. First, Rand spends considerably

more effort than his predecessors on defining and marginalising out-groups. Second,

Rand has not fully and definitively named Jews as the out-group, but rather he has

bundled Jewish identity into a more clearly articulated enemy identity – the Soviet

Union – significantly advancing an anti-Semitic train of thought while still qualifying it in

various ways, most notably the expectation that Jews will eventually return to the fold

of Anglo-Saxon Israel by accepting Christ.

Rand’s racial out-group theory is underdeveloped and his religious out-group theory is

overdeveloped. Thus behavioural changes still offer an avenue to bring the out-group

in. His scenario has not yet escalated to the point that intrinsic and insurmountable

obstacles prevent unification.

Third, the conceptual connections in Rand’s work are far more complex than in the

earlier texts. This is the result of the escalating need for justifications of the in-group’s

legitimacy and the out-group’s illegitimacy, sparked in part by direct challenges from

Rand’s readers, but even more by complications on the global stage, most notably the

establishment of the modern nation of Israel, which presented an existential challenge

to the legitimacy of the British Israelist identity.

In addition to the increasingly complex network of linkages, Rand also creates a series

of overlapping bundles (see chart below), conflating the previous bundle of history-

folklore-scripture with conspiracy theory (primarily in the form of the Protocols), and

creating multiple overlapping bundles of out-group identity (Jews, Communists, Gog)

drawn from various sources (scripture, current events and the historical-conspiracy

bundle).

These complexities lead to a much wider range of solutions to the now fully articulated

threat presented by out-groups. Rand’s solutions ranged from assimilation to custodial

rulership to war, introducing the first spectre of potential violence to a movement that

had previously been dominated by quietists.

While the staggering scope of British Israelist textual output over the years is too large

to fully capture here, the dramatic shift toward the apocalyptic is notable. British

Israelist texts had at times flirted with out-group dynamics, but Rand’s formulation is a

marked change from the previous generation, albeit deflected somewhat from Jewish

identity in favour of Communism.

Finally, Rand’s work takes on an increasing sense of urgency amid predictions of

imminent war and the immediate onset of prophetic times. He is greatly concerned

with the calendar, building elaborate frameworks to argue that Armageddon and other

consequential events are near at hand. Although Rand’s tone and prescribed solutions

still fall short of the extremes that Christian Identity would soon embrace, all the

ingredients of looming disaster were finally in play.

30

Bundling of concepts in Destiny are more complex and overlapping than in previous British Israelist

writings.

All the landmarks of in-group identity-construction (detailed further in section three)

are found in the works of Cameron and especially Rand, including:

Defining shared beliefs (religious)

Defining shared practices (religious mores, although the authors also find their

peers lacking in this respect)

Defining shared history (heredity, Anglo-Israel)

Defining intrinsic, non-negotiable identity (based on racial elements elevated

from the preceding generation)

Defining shared expectations for the future (self-realisation, rulership)

In addition, Cameron and Rand have fully engaged with the process of defining an

out-group:

Defining perceived beliefs of out-group (Communist, atheist)

Defining perceived out-group practices (deception, manipulation, race-mixing)

Defining perceived out-group history (scriptural, Protocols conspiracy)

Defining intrinsic, non-negotiable out-group identity (racial and religious)

Defining expectations for out-group’s future disposition (oscillating between

assimilation on the low end, and Armageddon on the high end)

In Rand’s writings, anti-Semitism had forcefully entered the world of British Israelism,

but his more toxic contribution was, arguably, a well-developed apocalyptic and

millenarian narrative. Rand introduced a view of prophecy that foretold an imminent

and cataclysmic conflict between Anglo-Israel and the combined forces of Communism

and international Jewry.

This looming Armageddon dramatically escalated the perceived out-group threat. But

while Rand saw Jews as racially inferior, perhaps even subhuman, there were still lines

that he was not prepared to cross.

96

d) From Delegitimisation to Demonisation

Delegitimising Jewish Identity

The fallout of World War II, Nazi anti-Semitism and the rise of the Zionist state of Israel

created new and intense pressures on British Israelism. The emergence in Palestine of

a Jewish nation called “Israel” excited competing millenarian expectations among many

American evangelical Christians even as it posed a direct challenge to the legitimacy of

British Israelism’s claim that Anglo-Saxons were the heirs of biblical prophecy.

97

The fact that the Zionist movement sought to overthrow the British Mandate of

Palestine in order to establish its state of Israel rendered the conflict intractable to even

British Israelist thinkers’ formidable capacity for rationalisation.

This dynamic pushed British Israelists into a defensive mode, under existential threat

from the rival claim to Israel’s heritage and faced with a growing number of attacks

from both mainstream Christian theologians and serious historians. Dueling books and

pamphlets marked this new phase, with books such as Real Israel and Anglo-Israelism

seeking to “show the futility of British-Israelism”, and counter-punches such as Israel’s

Migrations: Or An Attack Answered.

98