Top Lang Disorders

Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 198–216

Copyright

c

2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Words Are Not Enough

Providing the Context for Social

Communication and Interaction

Pamela Rosenthal Rollins

This article elucidates the unfolding of 3 phases of cognitive development through which typical

children move during the first 2 years of life to illuminate the interrelationships among early cogni-

tion, communicative intention, and word-learning strategies. The resulting theoretical framework

makes clear the developmental prerequisites for social communication and sheds light on how

some children with autism spectrum disorder can learn words and phrases but fail to develop true

social language. This framework is then applied to a case example of a child called Henry, using

data from 10-min videos of clinician–child interaction that were collected each week to evaluate

the child’s progress in social communication while working with his graduate-student clinician.

Eye-tracking data also were collected as an indirect measure of eye contact. The data showed

that Henry made progress in social engagement, reciprocal verbal interactions, and diversity of

communicative intentions. In addition, eye-tracking data suggested an increase in eye contact

commensurate with a typical age mate. Implications for social communication intervention are

discussed. Key words: autism spectrum disorders, emerging language, eye tracking, social

cognition

A

UTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER (ASD) is a

heterogeneous neurodevelopmental dis-

order that severely compromises the develop-

ment of social relatedness, reciprocity, social

communication, joint attention, and learning.

The Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion (2014) estimated that 1 in 68 children

Author Affiliation: School of Behavioral and Brain

Sciences, The Callier Center for Communication

Disorders, University of Texas at Dallas.

The author thank the children and families who par-

ticipated in this study, the preschool program staff for

allowing her into their program, Dr Julia Evans for the

use of equipment, Megan Nauta, Mary Grace Shafer,

Allison Kroiss, and Shreya Krishnan for assistance with

training the student clinician and coding the data, and

Dr Sharon Lynn Bear for her editorial assistants.

The author has indicated that she has no financial dis-

closures to report. She has a nonfinancial relationship

with the owners of Pathways Early Autism Interven-

tion.

Corresponding Author: Pamela Rosenthal Rollins,

EdD, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, The

Callier Center for Communication Disorders, Univer-

sity of Texas at Dallas, 1966 Inwood Rd, Dallas, TX

75235 ([email protected]).

DOI: 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000095

are on the autism spectrum. Although there is

no cure for ASD, early identification and inter-

vention can make a significant difference in a

child’s cognitive, language, and adaptive func-

tioning (Dawson et al., 2010; Reichow, 2012;

Wallace & Rogers, 2010; Warren et al., 2011).

Deficits in social communication and interac-

tion, however, persist throughout life. This

makes understanding the early interrelation-

ship between social-cognitive challenges and

language development critical for supporting

the long-term success of these children.

IMPORTANCE OF SHARED ATTENTION

It is well recognized that children with ASD

have extraordinary challenges in develop-

ing shared attention and intention (Charman,

2003; Mundy, Sigman, & Kasari, 1990; Rollins,

1999; Rollins & Snow, 1998). Sharing at-

tention and intention is often demonstrated

when the child directs another’s attention

toward objects or events for the purpose

of sharing and when the child coordinates

attention between a social partner and ob-

jects or events of mutual interest. This

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

198

Words Are Not Enough 199

important social-cognitive milestone marks

the emergence of the intentional stance,

or the u nderstanding that other people have

attentions and intentions that are different

from their own, which can be shared verbally

or nonverbally with their communicative part-

ner (Rollins & Snow, 1998; Tomasello, 1999;

Tomasello & Carpenter, 2007). The emer-

gence of shared attention and intention sig-

nifies true social understanding and provides

the infrastructure for social communication

(Rollins, 2003; Tomasello, Carpenter, Call,

Behne, & Moll, 2005) and structural lan-

guage (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2013; Rollins

& Snow, 1998). Typical infants routinely en-

gage in shared attention with their caregivers

by 12 months (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984;

Carpenter, Nagel, & Tomasello, 1998), the age

at which first words often appear.

LINGUISTICALLY BASED

INTERVENTIONS AND SHARED

ATTENTION

Unlike typical children, children with ASD

often acquire words and phrases in the ab-

sence of shared attention (Rollins, 1999). This

apparent disassociation between language

and social cognition may make children with

ASD appear linguistically more sophisticated

than they actually are. Although there are

exceptions (see Kasari, Paparella, Freeman,

& Jahromi, 2008), language interventions

too often focus on language form without

considering the child’s underlying social-

cognitive skills, which are necessary for the

development of social communication. Many

language interventionists use evidence-based

practices, such as naturalistic interventions

that follow the child’s focus of attention, to

model language or expand on the language

forms produced by emerging-language chil-

dren with ASD. These linguistically based in-

terventions are rooted in language acquisition

and intervention research that is conducted

with participants who already are c apable

of shared attention and intention (Rollins,

2003, 2014). Such linguistically based inter-

ventions are developmentally too advanced

for children with ASD who use words even

though they have not yet established shared

attention for the intersubjective purpose

of sharing objects or events with another

person.

When exposed to linguistically based in-

terventions, children with ASD may develop

large vocabularies but fail to integrate their

word knowledge into generative language. In

addition, they may use isolated words and

phrases to request and label, which falls short

of the depth of true social communication.

True social communication would involve di-

recting another’s attention, such as by point-

ing and showing or commenting to share in-

formation. This requires the understanding

that others have attentions and intentions that

are different from one’s own (Camaioni, 1993;

Rollins & Snow, 1998). Intervention priorities

for children with ASD who are beginning to

use words should not focus solely on periph-

eral linguistic forms. Examples of linguistic

form goals include the acquisition of nouns

(e.g., body parts and object labels), increas-

ing the mean length of utterances by requiring

the child to use modifier-plus-noun sentence

constructions (e.g., labeling red ball vs. green

ball), or producing frozen phrases (e.g., I want

______, please). Rather, goals must be located

within a developmental framework appropri-

ate to the child’s social-cognitive abilities.

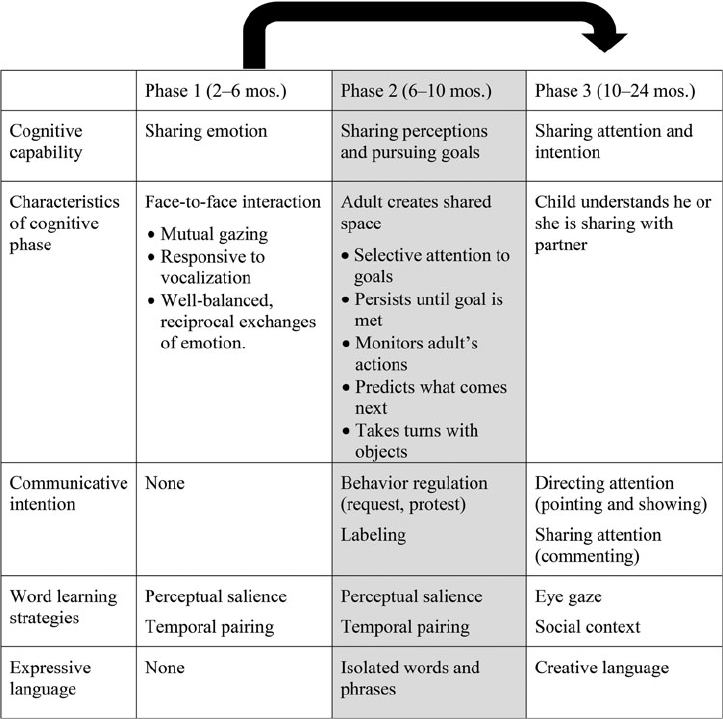

The purpose of this article was to eluci-

date the unfolding of the three phases of

cognitive development through which typi-

cal children move during the first 2 years of

life and to illuminate the interrelationships

among early cognition, communicative inten-

tion, and word-learning strategies (Figure 1).

The resulting theoretical framework makes

clear the developmental prerequisites for so-

cial communication and sheds light on how

some children with ASD can learn words and

phrases but fail to develop true social lan-

guage. These ideas are then translated into

clinical recommendations and illustrated with

a clinical case example.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

It is well accepted that infants are socially

motivated and prone to orient themselves

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

200 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

Figure 1. The interrelationships among early cognition, communication, word learning strategies, and

language (adapted from Rollins, 2014), of which only Phase 1 is the developmental precursor for social

cognition communication and interaction.

toward socially salient information from

very early in life. Newborns prefer lis-

tening to speech over nonspeech sounds

(Vouloumanos, Hauser, Werker, & Martin,

2010), and they are able to imitate adults of

their own volition (Meltzoff & Moore, 1983,

1989). They engage in vocal turn-taking in-

teractions (Trevarthen, 1979), respond differ-

entially to persons and objects (Legerstee,

1991; Trevarthen, 1979), and selectively at-

tend to human faces (Johnson & Morton,

1991; Maurer, 1985). Over the first years of

life, typical infants and young children un-

dergo several qualitative changes in how they

monitor, control, and predict the behavior

of others, culminating in the capacity for

mutual understanding and cooperation with

people around them. These gradual qualita-

tive changes have been quantified as move-

ment from “sharing emotions” to “sharing

perceptions and pursuing goals” to “sharing

attention and intention” (Tomasello et al.,

2005). As will be made clear, sharing emotions

and sharing attention and intention are so-

cially motivated whereas sharing perceptions

and pursuing goals are not. In fact, sharing

emotions is the developmental precursor to

sharing attention and intention (Adamson &

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 201

Russell, 1999; Rochat & Striano, 1999; Rollins

& Greenwald, 2013; Stern, 1985; Tomasello

et al., 2005) and, as such, constitutes the cog-

nitive underpinning for social communication

(Figure 1).

Phase 1: Sharing emotions

Around 2 months of age, infants across

cultures become increasingly alert and begin

to smile in response to social stimuli (Spitz,

1965; Wolff, 1987). The onset of social smil-

ing, coupled with an increase in gazing at

the caregiver’s face, is highly significant to

Western culture, as it launches dyads into a

new quality of shared experiences (Rochat

& Striano, 1999; Stern, 1985). These dyadic,

face-to-face interactions reflect well-balanced,

reciprocal, and rhythmic exchanges of af-

fect and emotions (Brazelton, Koslowski, &

Main, 1974; Stern, 1985; Trevarthen, 1979)

and are a precursor to later shared attention

(Adamson & Russell, 1999; Rochat & Striano,

1999; Rollins & Greenwald, 2013; Stern, 1985;

Tomasello et al., 2005). Within these inter-

actions, sensitive caregivers respond to the

infant as a communicative partner, and the

exchanges take on a conversational quality

(Snow, 1977), so much so that they have been

referred to as “protoconversations” (Bateson,

1975; Trevarthen, 1979).

Phase 2: Sharing perceptions and

pursuing goals

Around 6 months, typically developing

children become more interested in objects

and the interaction turns from dyadic to

triadic. Triadic refers to the child, the care-

giver, and a third entity, such as an object or

event. As illustrated in Figure 1, the cognitive

capabilities developed during this phase of

sharing perceptions and pursuing goals and

the emanating behavior and linguistic skills

are not inherently social (Tomasello et al.,

2005). What makes children appear to be

social during this phase is the caregiver’s

contribution to the interaction. For example,

caregivers, especially in Western cultures, fo-

cus on what the child is playing with and may

actively follow the child’s focus of attention

(e.g., by commenting on the child’s play with

objects). In so doing, the caregiver creates the

appearance of a shared interaction. Bakeman

and Adamson (1984) described these early

triadic interactions as “passive joint engage-

ment.” Children’s roles are passive in these

early interactions because they do not ac-

knowledge the caregiver’s contribution to the

interaction by attending to both the caregiver

and a shared referent. Rather, the caregiver

actively supports the child’s perceptions

by expanding the child’s solitary focus to

include the caregiver’s verbal and nonverbal

information about the attentional target.

Understanding another’s action and

predicting what comes next

The phase of sharing perceptions and pur-

suing goals can be challenging to understand.

The nuanced behaviors of which typical in-

fants are capable during this phase of cogni-

tion also may be assigned to children with

ASD. This contributes to misconceptions or

misunderstandings about the interactional ca-

pabilities of these children, whose cognitive

skills actually may have plateaued in this

phase. During this phase, both typical infants

and children with ASD engage in triadic in-

teractions that are not socially motivated, but

the interactions do help them acquire many

important cognitive abilities. Specifically, c hil-

dren in the phase of sharing perceptions and

pursuing goals are goal directed. They have

selective attention to their goals and often per-

sist until their goals are met.

In addition, they begin to understand that

their caregivers have intentional actions. They

monitor their caregiver’s actions and can

make predictions about what action comes

next in the interaction exchange, allowing

them to take turns with objects. For example,

the caregiver and the infant between 6 and

9 months of age may both be looking at

a block. The caregiver may start to build a

block tower. The infant learns to predict what

comes next and joins in an alternating se-

quence of placing blocks on the tower. After

the caregiver places a block on the tower, the

infant predicts that it is his or her turn and

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

202 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

does the same. Although they are both per-

ceiving the blocks and experiencing the same

activity of building the tower, the infant does

not yet look back at the caregiver and coor-

dinate his or her attention between the block

and the adult. The infant does not yet have

the understanding that they are sharing their

attention and intention to build the tower.

Regulating behavior

Toward the end of the phase for sharing

perceptions and pursuing goals (around 9–

10 months), typically developing infants

begin to use gestures and vocalizations

with communicative intent (Bates, Benigni,

Bretherton, Camaioni, & Volterra, 1979;

Bates, Camaioni, & Volterra, 1975). The

earliest preverbal intentions serve a pro-

toimperative function (i.e., nonverbal forms

of requesting and protesting). Typically

developing infants who have the cognitive

ability of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals are able to regulate or influence the

behavior of others but may not be able to in-

fluence their mental states (Camaioni, 1993).

Influencing another’s behavior requires little

more than the attribution of agency to the

interactive partner and the ability to share

perceptions of the intended goal (Camaioni,

1993; Tomasello et al., 2005). Children in this

phase have the will to affect the caregiver

by some purposeful behavior (Ninio & Snow,

1996), using instrumental communicative

acts such as requesting (actions, objects, or

assistance) and protesting.

Phase 3: Sharing attention and intention

As typical infants make the transition to

the phase of sharing attention and intentions

(between 10 and 12 months), they are ca-

pable not only of monitoring the caregiver’s

behavior but also of actively monitoring

the caregiver’s attentional focus (Bakeman &

Adamson, 1984; Carpenter et al., 1998). This

milestone is sometimes referred to as “re-

sponding to joint attention” (Mundy & Thorp,

2008). It marks the infant’s recognition that

the caregiver’s attention is different from his

or her own (Tomasello, 1995; Trevarthen &

Hubley, 1978). Soon, the infant begins to co-

ordinate his or her attention between the

caregiver and an object of mutual interest

and is actively looking back and forth be-

tween the caregiver and the object of atten-

tion (Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; Carpenter

et al., 1998).

This newly acquired social competency is a

form of cooperative intersubjectivity, as it in-

cludes the active sharing of thoughts and emo-

tions about an outside entity (Trevarthen &

Aitken, 2001). Tomasello et al. (2005) referred

to this development as “shared intention,” as it

reflects the understanding that other persons

have unique objects of attention and inten-

tions. This new level of social-cognitive skill

emerges around the first birthday in typical

children, but it is extraordinarily difficult for

children with ASD to attain (Camaioni, 1993;

Rollins & Snow, 1998; Rollins, Wambacq,

Dowell, Mathews, & Reese, 1998; Tomasello

et al., 2005).

The development of shared attention and

intention requires that both the adult and the

child have mutual knowledge that they are do-

ing something together in relationship, which

marks the emergence of mutual cooperation

(Tomasello et al., 2005). When the preverbal

child is capable of understanding that oth-

ers have attentions and intentions different

from his or her own, true social communica-

tion emerges (Camaioni, 1993). Children with

the social-cognitive understanding of shared

intention are capable of directing the care-

giver’s attention with gestures by showing an

object or pointing to an object for the pur-

pose of sharing interest (Bates et al., 1975;

Ninio & Snow, 1996; Tomasello, Carpenter,

& Liszkowski, 2007; Wetherby, Yonclas, &

Bryan, 1989).

As young children learn words, their e arly

communicative repertoire continues to re-

flect the unfolding of shared intentionality

and the mutual understanding that they are

communicating with another. Directing the

other’s attention (which has been referred to

as “initiating joint attention”; see Mundy &

Thorp, 2008) and a new skill of discussing

a joint focus of attention continue into the

second year of life. These early discussions

of the here and now often take the form of

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 203

commenting on objects or events in the imme-

diate environment while interacting around

toys or looking at picture books together.

TYPICAL WORD LEARNING

Children use a combination of perceptual,

cognitive, social, and linguistic inputs or cues

for word learning, and the child’s sensitiv-

ity to these cues changes over the course

of development (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, &

Hollich, 2000; Hollich et al., 2000; Rollins,

2003). Across the early word-learning period

(under 2 years), typically developing children

use both perceptual and social cues to iden-

tify words and meaning relations. Perceptual

cues, such as those that pair interesting things

they see with what they hear, dominate early

in development (i.e., before 10 months of

age). A progressive shift occurs toward the re-

liance on social factors around 12–18 months

(Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, Hennon, & Maguire,

2004; Hollich et al., 2000; Rollins, 2003). This

means that typical infants and children with

ASD who are functioning in the phase of shar-

ing perceptions and pursuing goals may be

learning words by using the earlier mecha-

nism of temporal pairing of what they hear

with perceptually salient objects and events

they see (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2000; Rollins,

2003; Rollins & Trautman, 2011). In contrast,

children with the ability to share attention

and intention begin to rely more heavily on

social cues and what appears to be intended.

These children learn new words in situations

in which the adult looks at and labels an ob-

ject that the child is not looking at. Here, for

word learning to occur, the child must use

eye contact and gaze shifts to determine the

adult’s intended focus (Baldwin, 1993). The

child also can learn the names of objects that

the adult intends (Tomasello & Barton, 1994).

HOW ASD IS DIFFERENT

Words in ASD

The apparent dissociation between lan-

guage and social cognition in children with

ASD may be explained through the lens of

the word learning and communicative func-

tions available to children in the second

phase of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals. Unlike typical infants who pass through

this phase before they begin to talk (∼6–

10 months), many children with ASD exhibit

sharing perceptions and pursuing goals capa-

bilities in early childhood (3–5 years) or even

later. These children with ASD may acquire

many words through the early word-learning

strategy of pairing perceptually salient objects

and events with the words and phrases that

they hear. Caregivers, teachers, and therapists

then support the child’s perceptions of ob-

jects and events through naming the object or

event. This, in turn, may facilitate the acquisi-

tion of many words (Rollins, 2003; Tomasello,

1999), but it does not lead to rule-governed

generative language (Tomasello, 1999). True

integration of vocabulary into grammar does

not happen until a child is able to share atten-

tion and intention (Bates & Goodman, 1997,

1999; Rollins, 2003; Rollins & Snow, 1998;

Tomasello, 1999).

Requesting and labeling in ASD

Consistent with the repertoire of commu-

nicative behaviors that can be acquired during

the phase of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals (as shown in Figure 1), many children

with ASD learn to use words and phrases for

the purpose of regulating or controlling an-

other person’s behavior (i.e., requesting and

protesting) but not for drawing their atten-

tion to objects or events of mutual interest

and sharing information. Some children with

ASD may begin to label objects and events in

their environment without any evidence that

they are sharing information with their social

partner.

Labeling is often elusive and misunder-

stood because the adult’s support of the

child’s attention gives the appearance of a

shared interaction. Labels appear more self-

directed and lack the intention to share in-

formation with another person. Labeling is

distinct from commenting, which denotes a

shared mutual understanding with another

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

204 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

person (Rollins, 2014). Some evidence-based

intervention practices require children with

ASD who are beginning to use words to la-

bel pictures and objects to use progressively

longer utterances for this function. These lin-

guistically based interventions, however, do

not provide the social environment necessary

for social communication to develop, as they

enable the child to continue to practice and

use forms that are not socially motivated. In

contrast, there is evidence to suggest that,

before a child with ASD develops shared at-

tention and intention, his or her interven-

tion should focus on critical foundational so-

cial communication skills, such as face-to-

face reciprocal social interactions (Ingersoll &

Gergans, 2007; Rollins, Campbell, Hoffman, &

Self, 2016; Schertz & Odom, 2007; Wallace &

Rogers, 2010), that are precursors to shared at-

tention (Adamson & Russell, 1999; Greenspan

& Shanker, 2004; Rollins et al., 2016; Rollins

& Greenwald, 2013).

Clinical recommendation

For social communication and creative lan-

guage to develop in a child, intervention prior-

ities must be located within a developmental

framework that pertains to the child’s social-

cognitive functioning. As described earlier

and illustrated in Figure 1, the first phase of

sharing emotions is the developmental pre-

cursor to the third phase of sharing attention

and intention. This three-phase framework

guides interventionists who work with chil-

dren on the spectrum who are functioning in

the second phase of sharing perceptions and

pursuing goals to focus their intervention ef-

forts instead on facilitating shared emotional

skills of face-to-face reciprocal social interac-

tions, mutual eye gazing, and contingent imi-

tation of vocalizations and gestures.

A handful of interventions are now available

that are mindful of the child’s social-cognitive

level and that address the early foundational

social communication skills necessary for

shared attention and creative language (see

Ingersoll & Gergans, 2007; Kasari et al., 2008;

Rollins et al., 2016; Schertz & Odom, 2007).

These interventions provide the social envi-

ronment necessary for social communication

by facilitating dyadic, face-to-face reciprocal

social interactions. In particular, our clinical

recommendation is for interventionists who

currently work with children in the second

phase of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals to facilitate Phase 1 sharing emotions

skills by including five key features essential

for this phase. The five key features include

the following: (a) position yourself face to

face with the child; (b) engage in social

sensory routines, limiting the use of toys

whenever possible; (c) establish eye contact

without verbal and physical prompts, making

sure to reinforce eye contact immediately;

(d) use animation; and (e) use contingent

imitation of the child’s gestures, vocalization,

and words. To support this recommendation,

I provide a clinical case example of Henry

and his graduate-student clinician, Alice.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE

Participants

Henry, a 29-month-old toddler with ASD

(see Table 1 for test scores and demographic

information), and Alice, his graduate-student

clinician, participated in this project. Henry

was functioning within the second cognitive

phase of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals. Consistent with a child in this phase,

Henry used verbal and nonverbal means to

request and label items in his environment.

Henry, however, rarely looked at his commu-

nicative partner; instead, he focused his gaze

on the objects around him.

Henry was enrolled in a linguistically based

program for toddlers aged 18 months to 3

1

/

2

years with ASD or other developmental disor-

ders. The program is a training site for grad-

uate students in speech–language pathology

and provides intensive communication inter-

ventions 4 days a week for 2

1

/

2

hr. Graduate

students provide the children with both

group and individual therapies. In this linguis-

tically based program, the goals for toddlers

with ASD who function in the second phase

of sharing perceptions and pursuing goals

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 205

Table 1. Henry’s test scores and family

demographics

Measure Result

Henry’s age at entry 29 months

Mother’s age 35 years

Mother’s education Bachelor’s degree

Language in the home English only

Day care Spanish-speaking

nanny

ADOS-1:

Communication

5

ADOS-1: Reciprocal

social interaction

9

ADOS-1 total score 14

CARS-2 rating 35

Range of concern Mild-moderate

PLS-5 2nd percentile

Note. ADOS-1 = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

Module 1 (Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, 2002) for chil-

dren with few to no words; CARS-2

= Childhood Autism

Rating Scale–2; PLS-5

= Preschool Language Scale, fifth

edition. A diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder was ver-

ified using a cutoff score of 12 on the ADOS and substan-

tiated with a score of above 30 on the CARS-2. All tests

were administered by trained clinicians.

include using words to request, increasing

utterance length, and engaging in reciprocal

turn-taking using objects.

The motivation for our engagement with

this case was to change Henry’s intervention

to be consistent with the developmental

framework described earlier. Specifically,

the goal was to move away from a linguistic

approach that focuses on the Phase 2 skills

to a social approach that focuses on the five

key features, described earlier, essential to

facilitating Phase 1 sharing emotions skills.

We used an informed consent procedure

approved by the Human Subjects Institutional

Review Board (IRB) from the University of

Texas at Dallas (IRB 13-10) to obtain Henry’s

parents’ permission for him to participate in

this research.

Procedures

Alice took Henry from his usual program to

a nearby therapy room for a 30-min individual

session each day. Once a week, the session

began with my digitally recording (on an iPad

2) 10 min of Alice and Henry’s interaction.

We used these tapes in both qualitative analy-

ses of clinician–child interaction and quantita-

tive analyses of Henry’s social interaction and

communication, as described in the following

text.

Baseline phase (Weeks 1–4)

The linguistic approach, which was used

initially with Henry, served as a baseline

against which the social approach could be

compared. During the baseline sessions, Alice

followed the linguistic approach and the rec-

ommendations for Henry’s program. Specifi-

cally, she actively followed Henry’s focus of

attention, stayed on Henry’s physical level,

chose simple, high-interest, slow-paced activ-

ities, used introductory alerters (e.g., gasps,

the child’s name, “Look!” and “Wow!”) to di-

rect Henry’s attention to objects and events.

She also used pause time, simplified her lan-

guage, and commented on Henry’s actions or

focus of attention.

Social intervention phases (Weeks 5–9)

To implement the social approach, we

needed an evidence-based practice that fit our

developmental framework and, specifically,

the five key features from the clinical rec-

ommendation. Although several toddler pro-

grams are available to facilitate the first phase

of sharing emotions (see Ingersoll & Gergans,

2007; Rollins et al., 2016; Schertz & Odom,

2007; Wallace & Rogers, 2010; Wetherby

& Woods, 2006), we chose the Pathways

to Early Autism Intervention (hereafter Path-

ways; Campbell & Thibodeau Hoffman, 2014)

to guide this intervention. This selection was

made for three reasons. First, evidence had

shown Pathways to be effective in increasing

the early foundational social communication

skills of eye contact, social engagement, and

verbal reciprocity in toddlers with ASD who

are enrolled in an IDEA Part C Early Childhood

Intervention program (Rollins et al., 2016).

Second, although other toddler programs use

key features similar to those of Pathways

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

206 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

(e.g., face-to-face reciprocal interactions, an-

imation, imitation), to our knowledge, they

do not work directly on eye contact. The im-

portance of facilitating eye contact as an inter-

vention target has been emphasized by Jones

and Klin (2013), who suggested that early in-

tervention focusing on eye contact may build

on the neural networks that subserve early re-

flexive gaze. Finally, key features of the Path-

ways program (i.e., face-to-face social sensory

routines, eye contact, animation, and imita-

tion) outlined in Table 2 could be used to

build on the bidirectional strategies that Alice

and Henry already were using, particularly be-

cause the Pathways features are added slowly.

This helps the clinician–child dyad develop

increasingly more sophisticated levels of in-

teraction before the clinician adds more diffi-

cult key features into the interaction. For ex-

ample, as we show in the q ualitative analysis

later, Henry learned to make and maintain eye

contact through reinforcement and without

physical prompts during social sensory rou-

tines before Alice required him to respond to

animation.

Behavioral measures

To evaluate Henry’s social interaction and

communication, we coded several behavioral

measures from the 10-min recordings of

Alice and Henry’s interaction. Specifically,

the digitized recordings were coded for

(a) social engagement (i.e., simultaneously

smiling and looking at Alice’s f ace), (b)

verbal reciprocity (i.e., taking at least one

vocal/verbal turn contingent on Alice’s

vocalization/verbalization); and (c) com-

municative intention (verbal and nonverbal

combined). Communicative intention was

coded using a coding scheme described

by Ninio, Snow, Pan, and Rollins (1994),

which emphasizes socially constructed

communicative interchanges. In Ninio

et al.’s (1994) scheme, communicative intent

is coded on the level of the social interchange

(e.g., engaging with a partner in routines,

regulating another’s behavior, engaging in

discussions), acknowledging the existence of

an organization of talk at a level higher than

the single utterance (see Dore & McDermott,

1982; Streeck, 1980). A social interchange

is defined as one or more rounds of talk, all

of which serve a unitary interactive function

implicitly agreed upon by the interlocutors.

Procedure for coding videos

Social engagement, verbal reciprocity, and

communicative intentions were coded from

the digitized videos using a continuous par-

tial interval coding system (Yoder & Symons,

2010). Specifically, each 10-min video was

segmented into 5-s intervals and linked to

a computer file for later coding, using the

digitized video functions of the CHILDES

Table 2. Pathways

a

interactional strategies to facilitate Phase 1 of sharing emotions by week

and recommended key features

Week Intervention Strategies Key Feature

Week 5 1. Engage in face-to-face positioning Face-to-face

2. Create dyadic social sensory games and routines (limit

toys)

Social sensory routines

3. Reinforce eye contact without verbal or physical

prompts

Eye contact

Week 6 4. Add animation, gestures, facial expressions, and vocal

quality

Animation

Weeks 7–9 5. Add imitation of action, gestures, and sounds Imitation

a

The Pathways strategies are explained by Pathways Early Autism Intervention, by M. Campbell and R. Thibodeau

Hoffman, 2014, Unpublished manuscript, Dallas, TX. They are shared here with permission of the authors.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 207

utilities (MacWhinney, 1991). In continuous

partial interval coding, a behavior of interest

is coded from the video only once per interval,

regardless of how many times the behavior oc-

curs during that interval. For a 10-min video,

there were a total of 120 codable intervals,

making the total possible frequency range

for each behavior between 0 and 120. Using

this system, each 5-s interval was coded for

each measure during separate passes through

the video. All coders were blind as to week

of intervention. Two coders independently

coded 20% of the videos from Weeks 1 to 4

(linguistically based intervention) and 20%

of the videos from Weeks 5 to 9 (socially

based intervention), chosen at random. In-

terrater reliability, expressed as Cohen’s κ ,

which takes into account chance agreement

between coders, ranged from 0.65 to 1.0 for

Weeks 1–4 and 0.76 to 1.0 for Weeks 5–9,

which is considered substantial to almost per-

fect agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Eye tracking

The naturalistic interactions captured on

video did not allow us to measure Henry’s

eye contact with Alice precisely, which was

a focus of the intervention. Therefore, Alice

brought Henry into the eye-tracking labora-

tory on two separate occasions. The first time

(Time 1) was during the baseline phase, and

the second (Time 2) was a few days after

the Week 9 session. The eye-tracking labo-

ratory was equipped with a SensoMotoric In-

struments (SMI) RED-m portable eye-tracking

laboratory, with a sampling rate of 60 and

120 Hz. The eye tracker was used to record

and quantify Henry’s eye movements as an

indirect measure of eye contact. To collect

the eye-tracking data, Henry sat on Alice’s lap

in front of a 15-in. LCD display. The video

stimulus was a female actor who was looking

directly into the camera and was engaged in

childhood songs (e.g., “Peek-a-boo,” “Wheels

on the Bus”) to simulate a dyadic interaction.

The scene was filmed in front of distractor

toys. The video was presented using a lap-

top that ran SMI’s Experiment Center soft-

ware. The eye tracker was first focused and

calibrated. During the calibration, Henry was

shown images of an animated and concen-

tric circle that appeared in one of five lo-

cations on the screen. Quality of calibration

was verified by the deviations on the x-and

y-axes. If any deviation was larger than 1

◦

,

the calibration procedure was repeated. The

SMI BeGaze video analysis package was used

to draw dynamic areas of interest (AOIs) on

each frame of the video to ensure continuous

motion within the AOIs. The BeGaze program

calculated the total fixation time and the per-

centage of visual fixation time to each set of

eyes, mouth + nose, body, all toys, and out-

side the region of AOIs.

In addition, we compared Henry’s eye-

tracking results with the results for Jena, a

typically developing child who matched on

age (29 months), mother’s age (34 years),

and language in the home (English). Jena

was enrolled in English-speaking day care and

scored in the 96th percentile on the Preschool

Language Scale (fifth edition). Jena’s mother

brought her to the eye-tracking laboratory one

time. All eye-tracking procedures used to col-

lect, record, and quantify Jens’s eye move-

ments were the same as those for Henry, ex-

cept that Jena sat on her mother’s lap.

Results

This section presents the results of three

analyses. The first is a qualitative analysis that

uses excerpts from the 10-min digitized videos

to elucidate Alice and Henry’s interaction

during the baseline and social intervention

phases. The qualitative analysis is followed by

two quantitative analyses of the results based

on the behavioral measures and eye-tracking

data.

Qualitative results

The qualitative results are presented in

terms of five excerpts. The excerpts begin

at baseline and span 8 weeks. Excerpts 2-5

illustrate key features from Table 2.

Excerpt 1: Baseline (linguistic intervention)

In this excerpt from Week 4, which il-

lustrates the linguistic intervention, Henry

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

208 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

and Alice are positioned next to each other,

building a block tower at a table. Alice has a

pile of blocks in front of her. Henry is stand-

ing, and Alice is kneeling.

Alice turns her head to the side to look at Henry

and says, “Henry!” while holding up a block.

Henry looks at the block in Alice’s hand and then

looks down at the floor.

Alice, still looking at Henry, says “Oh!”

Henry looks at the block in Alice’s hand, grabs it,

and says, “More block.”

Henry looks at the block tower and places the block

on top.

Alice looks at the pile blocks and says, “You want

another one?”

Alice looks at Henry and holds up a white block

and a pink block.

Henry continues to look at the block tower and

vocalizes to himself as he adjusts the pieces.

Henry looks at the pile of blocks in front of Alice.

Alice looks at Henry, holds up two blocks, and says,

“What color?”

Henry looks at the white block and tries to take it.

Alice, still looking at Henry, holds the blocks higher

and again says, “What color?”

Henry continues to look at the white block in

Alice’s hand, points to it and says, “White.”

Alice hands the block to Henry and says, “You want

the white block?”

Henry looks at the tower in front of him as he adds

the white block and says, “White.”

Alice looks at the tower and says, “I’ll put one on

top,” as she adds the block to the tower.

Henry, still looking at the tower, adjusts the block

that Alice added and vocalizes to himself.

Alice picks up a block from the table.

Henry, looking at the tower, jumps and smiles

while he vocalizes.

Alice slides the block to Henry and says, “Now

you.”

Henry looks at the tower as he adds the block to

the top.

In this excerpt, Alice chose simple, high-

interest, slow-paced activities, knelt to be on

Henry’s physical level, used alerters to di-

rect his attention to the block, simplified her

language, and used pause time to facilitate

Henry’s word use and turn-taking with an ob-

ject, which were the targets of the linguistic

approach. In response, Henry labeled and re-

quested as well as allowed Alice to take her

turn in building the tower. Although he ap-

peared happy, he never looked at Alice’s face,

as would be expected for a child with so-

cial understanding. Instead, he gazed at the

blocks and block tower for the entirety of the

interaction.

Excerpt 2: Social intervention, using

face-to-face, social sensory routines and eye

contact

In this excerpt from Week 5, Alice’s goals

are to position herself so that she is sitting

face to face with Henry while engaging him in

social sensory routines and reinforcing his eye

contactwithoutverbalorphysicalprompts.

Henry is sitting in an adult desk chair, and

Alice is sitting on the floor below him. He is

requesting that Alice spin him in the chair.

Alice spins the chair around one time and then

stops it in front of her.

Alice looks up at Henry and tries to look into his

eyes.

Henry looks at the arm of the chair as he touches

it.

Alice looks up at Henry’s face and tries again to

look into his eyes.

Alice moves Henry’s hand from the arm of the chair

and says, “Oh hand, comes off.” Henry continues

to look at and touch the arm of the chair and says,

“Go.”

Alice looks up at Henry until she is able to look

into his eyes. As soon as she looks into his eyes, she

spins the chair and says, “Spinning in the chair.”

Alice stops the chair in front of her, looks up at

Henry, and tries to look into his eyes.

Henry goes back to looking at the arm of the chair

and says, “Go.”

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 209

Alice continues trying to look into Henry’s eyes,

but Henry averts his gaze.

Henry says, “Go, go.”

Alice continues to look up at Henry and is now

able to look into his eyes; she immediately spins

the chair and says, “Spinning the chair.”

Alice stops the chair in front of her.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes, smiles, and says, “Go.”

Alice spins the chair and says, “Again.”

Alice stops the chair in front of herself.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes, smiles, and says, “Go.”

This excerpt illustrates the three key fea-

tures used in Week 5 (i.e., face-to-face social

sensory routines and eye contact) that Alice

had learned. Rather than sitting beside Henry,

as was seen in Excerpt 1, Alice sat face to face

with him, placing herself in his line of sight

whenever possible. Because Henry tended to

look down, averting his gaze, Alice sat below

him and looked up. She concentrated on find-

ing a motivating sensory routine without toys

(i.e., spinning in the chair). To reinforce eye

contactwithoutverbalorphysicalprompts,

Alice moved her face in line with Henry’s to

look into his eyes. She quickly reinforced the

brief eye contact by spinning him in the chair.

Henry soon understood that he needed to look

at Alice’s eyes to be spun and began to inte-

grate looking at Alice’s eyes with a smile (i.e.,

social engagement) and the word “go.”

Excerpt 3: Social intervention, using

face-to-face, social sensory routines, eye

contact, and animation

In this Week 6 excerpt, Alice adds anima-

tion to her repertoire of strategies. She con-

tinues to use face-to-face positioning when

engaging Henry in routines and quickly re-

inforces eye contact. By Week 6, however,

Henry is more socially engaged, as this ex-

cerpt illustrates. Alice and Henry are facing

each other about 4 ft apart; Henry sits in a

cube chair, and Alice kneels to be on his phys-

ical level. They are rolling a large therapy ball

back and forth. Henry has the ball.

Alice looks at Henry’s eyes and says, “Roll the ball

to....“

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes, gives a big smile, and

says, “Alice.”

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, opens her arms

wide and laughs with an exaggerated smile.

Henry, still looking at Alice eyes, rolls the ball with

a big smile.

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, smiles and

laughs while she catches the ball.

Henry and Alice look at each other, smiling and

laughing.

In Excerpt 3, Alice was more animated than

in earlier sessions when she was concentrat-

ing on reinforcing eye contact. Here, Henry

and Alice continuously looked at each other’s

eyes, which registered positive affect. They

laughed and smiled as they rolled the ball to

each other. Henry used words within the rou-

tine (e.g., “Alice”) and was socially engaged

(e.g., looked at Alice’s eyes and smiled).

Excerpt 4: Social intervention, using

face-to-face, social sensory routines, eye

contact, animation, and imitation

In Week 7, Alice adds imitation to her reper-

toire of strategies. She looks for opportunities

to imitate actions, gestures, and sounds. Be-

cause the interactional strategies are cumula-

tive, she is able to use all of the strategies to-

gether, as illustrated in this excerpt. Alice and

Henry are about 4 ft apart, facing each other;

Henry sits in a cube chair, and Alice kneels

to be on his physical level. They are rolling

a large therapy ball back and forth. Alice has

the ball.

Henry looks down briefly and laughs and smiles as

he puts his hand to his cheek.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes and vocalizes.

Alice looks at Henry and says, “Oh!” while imitating

his hand positioning.

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, says, “You’re

silly.”

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, says, “Roll the

ball,” and pats the ball.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

210 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, says, “Roll the

ball.”

Henry, still looking at Alice’s eyes, says, “To Alice.”

Alice looks at and points to Henry, and says, “To

....“

Henry continues looking at Alice’s eyes and says,

“Henry.”

Alice still looking at Henry’s eyes, says, “To Henry.”

Alice, still looking at Henry’s eyes, rolls the ball to

Henry, as she gasps and says, “Ahhh!”

Henry looks at Alice, smiles, and repeats, “Ahhh!”

while catching the ball.

Alice looks at Henry’s eyes and laughs.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes and makes vocaliza-

tions.

Alice continues looking at Henry and imitates his

vocalizations.

To summarize, in Excerpt 4, Alice imitated

Henry’s nonverbal actions (hand positioning)

and vocalizations. Henry continued to use

words within the routine and was socially en-

gaged (e.g., looked at Alice’s eyes and smiled).

He also started to imitate Alice’s vocalizations.

Excerpt 5: Social intervention, using

face-to-face, social sensory routines, eye

contact, animation, and imitation

In subsequent sessions, Alice continued to

use all of the interactional strategies from the

previous weeks. Henry appeared to be more

socially engaged, and their vocal play was

more reciprocal, as Excerpt 5 from Week 8

illustrates. Alice and Henry sat face to face. Al-

ice sat on the floor and Henry in a cube chair.

Henry looks away from Alice and vocalizes.

Alice looks at Henry’s eyes and imitates the vocal-

ization.

Henry gasps, looks at Alice’s eyes, and makes a

raspberry.

Alice looks into Henry’s eyes and gasps exaggerat-

edly.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes, gasps, and makes a

raspberry.

Alice looks into Henry’s eyes, gasps, makes a

raspberry, and then laughs.

Henry looks away from Alice’s eyes, smiling.

Henry looks at Alice’s eyes and makes a raspberry.

As Excerpt 5 illustrates, Henry continued to

be socially engaged with Alice. He appeared

to show progress in social communication

each week.

Quantitative results

The quantitative results are presented in

terms of the behavioral measures and eye-

tracking data.

Behavioral measures

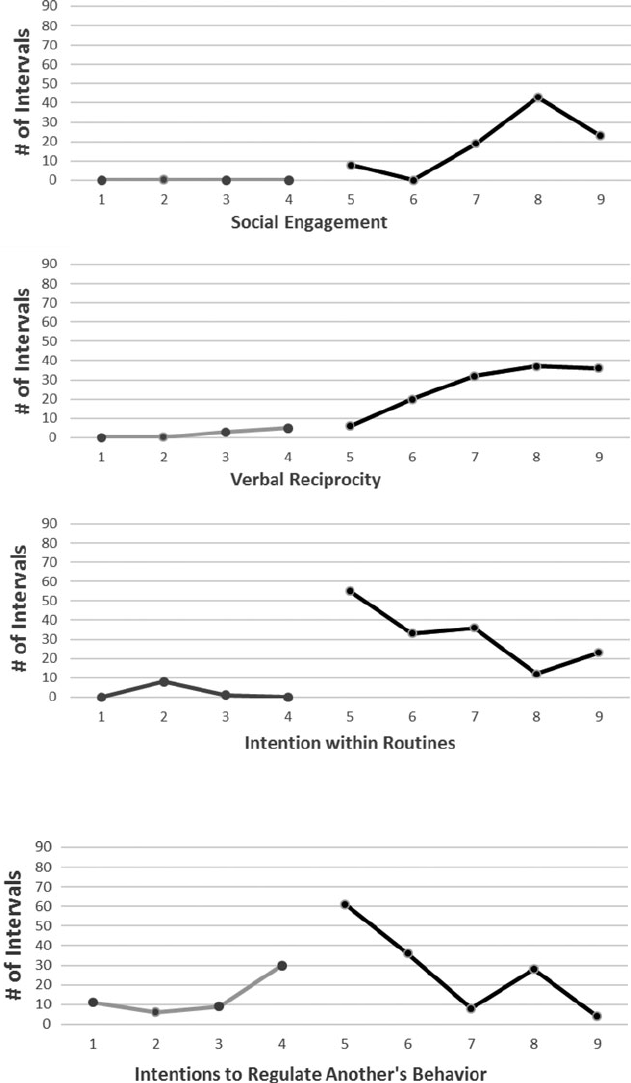

Henry’s progress in terms of changes in

behavioral measures is displayed in Figures

2 and 3. The number of 5-s intervals dur-

ing which a behavior was exhibited (y-axis)

was graphed by the week number (x-axis).

Thebaselinedataforthesecomparisonswere

gathered during the use of the linguistic ap-

proach (Weeks 1–4) before beginning the so-

cial approach. When Alice began using a so-

cial approach to intervention (Weeks 5–9),

Henry appeared to make progress on his use

of social engagement, verbal reciprocity, and

intentions within routines. Visual inspection

of the graphs in Figure 2 shows a clear pos-

itive slope for social engagement and verbal

reciprocity. It is noteworthy that intentions

within routines appeared to decline from the

first week to the last week of social inter-

vention (negative slope). Nonetheless, Henry

used more intentions within routines when

Alice used a social-cognitive approach to in-

tervention (Weeks 5–9) as compared with a

linguistic approach (Weeks 1–4). Henry made

progress in his use of intentions to regulate an-

other’s behavior when Alice used a linguistic

approach, which continued through Week 5,

when he was using eye contact to request ac-

tion in a sensory game. Regulating Alice’s be-

havior, however, declined as the intervention

became more social (Figure 3).

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 211

Figure 2. Henry’s performance on social engagement, verbal reciprocity, and engagement in social

routines across linguistic (Weeks 1–4) and social (Weeks 5–9) approaches to intervention.

Figure 3. Henry’s performance on intentions to regulate another’s behavior across linguistic (Weeks 1–4)

and social (Weeks 5–9) approaches to interventions.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

212 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

Eye tracking

We found that Henry’s percentage of fix-

ation time to eyes, mouth, body, and toys

changed from Time 1 to Time 2 (Table 3). The

percentage of time that Henry looked at the

eyes increased from 11.4% at Time 1 to 41.4%

at Time 2. The latter percentage is remark-

ably similar to the amount of time that Jena

looked at the eyes of the actor in the video.

The amount of time that Henry looked at the

mouth + nose area and the body decreased

with the intervention. In addition, he spent

more time looking outside the region of AIOs.

Although this is only an indirect measure, it

suggests that Henry’s eye contact improved.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

In this article, I elucidated the unfolding

of the three phases of cognitive development

through which typical children move during

the first 2 years of life and described the inter-

relationships between cognition, communica-

tive intention, word learning, and language (as

illustrated in Figure 1). In addition, I explained

that the social-cognitive trajectory necessary

for social communication and language con-

sists of sharing emotions and sharing atten-

tion and intention but that sharing percep-

tions and pursuing goals are not parts of the

social-cognitive trajectory (Tomasello et al.,

2005).

Historically, the second phase of sharing

perceptions and pursuing goals has not been

well understood or elaborated on, perhaps

because sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals are interwoven with sharing emotions

and sharing attention and intentions in

typically developing children (Tomasello

et al., 2005). Children with ASD, however,

often develop Phase 2 cognition, sharing

perceptions and pursuing goals, without the

neighboring social abilities. Cognitive skills

related to sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals allow children with ASD to do the

following: (a) be goal directed and persistent;

(b) understand that others have goals and

perceptually monitor their behavior; (c) pre-

dict what comes next; and (d) take turns in

an interaction that involves objects. Despite

the sophistication in understanding many

of these nonsocial-cognitive skills, these

children appear to lack the social cognition

necessary to understand mutual knowledge

and that they are in a relationship in which

their attention and intentions can be shared.

Interventions, therefore, need to be designed

to support these social developmental

advances.

Children with ASD who are in the phase of

sharing perceptions and pursuing goals can-

not yet use social cues or understand their

partner’s intentions to learn language. Rather,

these children use early perceptional word-

learning strategies, which limit them to iso-

lated words and phrases to label or regu-

late the behaviors of others. Unfortunately,

these peripheral language forms do not read-

ily progress to true social communication

and language (Rollins & Snow, 1998). Social

communication and creative language require

Table 3. Percentage of eye fixation on AOIs and outside the AOI for Henry at two time points

a

and for Jena, a typically developing child

Eye Mouth + Nose Body All Toys Outside AOI

Henry (Time 1) 11.7 46.0 11.7 8.4 22.2

Henry (Time 2) 41.4 3.8 0 0 54.8

Jena 41.0 18.3 14.2 0 26.5

Note.AOI= area of interest.

a

Henry was brought to the eye-tracking laboratory during baseline (Time 1) and, again, a few days after the Week 9

session (Time 2).

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 213

the foundational social-cognitive skill of

shared emotions and shared attention and in-

tention (Tomasello et al., 2005).

On the basis of this theoretical framework,

I made the clinical recommendation that in-

terventionists who work with children in the

second phase of sharing perceptions and pur-

suing goals focus their interventions efforts

on facilitating the sharing emotions skills of

Phase 1, as these are the critical precursors

of social communication. In particular, I rec-

ommended five key features essential to fa-

cilitate Phase 1 sharing emotions skills: (a)

position yourself face to face with the child;

(b) engage in social sensory routines, limiting

the use of toys whenever possible; (c) estab-

lish eye contact without verbal and physical

prompts, making sure to reinforce eye con-

tact immediately; (d) use animation; and (e)

use contingent imitation of the child gestures,

vocalization, and words. To support these rec-

ommendations, I presented a clinical case in

which we used Pathways, a social approach

to intervention, to slowly add and integrate all

five of the Phase 1 key features.

The child in the case example was Henry,

a 29-month-old toddler with ASD who was in

the phase of sharing perceptions and pursuing

goals. He used verbal and nonverbal means to

request and label items in his environment.

He rarely looked at his communicative part-

ner, focusing his gaze on the objects around

him. Because Henry was enrolled in a linguis-

tically based program, his initial goals focused

on peripheral language forms and engaging

in turn-taking with objects. The problem was

that Henry’s program created an environment

that perpetuated the nonsocial language skills

that he already was capable of producing.

After 4 weeks of linguistically based inter-

vention, Henry’s graduate-student clinician,

Alice, and I changed Henry’s intervention to

a social approach, using Pathways. This pro-

vided a naturalistic baseline of data against

which we could measure progress that cor-

responded with introduction of Pathways so-

cial approach. Alice learned to engage Henry

in eye contact and social engagement using

the five key features of face-to-face position-

ing, dyadic social sensory routines, reinforc-

ing eye contact without verbal or physical

prompts, and adding animation and imitation

(as summarized in Table 2). Once the social in-

tervention was initiated, Henry demonstrated

an increase in his sharing emotions capabili-

ties, as demonstrated by increased social en-

gagement and verbal reciprocity (illustrated

in Figure 2). I n addition, his communicative

intentions became more social when inten-

tion within social routines was added to his

repertoire (illustrated in Figure 3). This addi-

tion is commensurate with the developmental

trajectory of social communication in typical

children. That is, although requests emerge

early in typically developing children (as pro-

toimperatives; Bates et al., 1975), social par-

ticipation acts are more frequent (Snow, Pan,

Imbens-Bailey, & Herman, 1996). Social rou-

tines precede joint attention (Ninio & Snow,

1996; Rollins, in press) and provide the con-

texts for a shared mutual knowledge (Rollins,

2014).

Because we were unable to measure eye

contact objectively, we used eye-tracking

technology to obtain an indirect measure.

For this purpose, Henry was brought into an

eye-tracking laboratory once during baseline

(Time 1) and, again, a few days after the Week

9 intervention session (Time 2). The results of

the eye-tracking data suggest that, although

Henry spent more time looking outside the

AOIs (eyes, mouth + nose, body, and toys) at

Time 2, the percentage of time that he looked

at the eyes of the actor in the video increased

from 11.4% at Time 1 to 41.4% at Time 2.

The latter was commensurate with a typical

peer matched for chronological age and home

language.

The importance of facilitating eye contact

in interventions with children on the spec-

trum has been emphasized by Jones and Klin

(2013). They found that, despite the pres-

ence of early reflexive gaze to adult eyes,

infants with ASD exhibit a decline in eye

gaze between 2 and 6 months. Jones and

Klin suggested that infants with ASD who do

not engage in eye contact miss opportunities

to engage in social reciprocity and begin to

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

214 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

favor the object world. Jones and Klin sug-

gested that early intervention that focuses

on eye contact could build on the neural

networks that subserve early reflexive gaze,

which could have cascading effects on the de-

velopment of social communication, as well

as result in positive collateral changes in other

areas of development. This case example was

consistent this hypothesis.

It is noteworthy that this case example was

not a study with experimental control. There

are many threats to the internal validity of

this case example, including that Henry may

have shown improvement simply because he

had more time to develop, so that changes

could be due to simple maturation. The find-

ings of changes contingent on introducing the

socially based intervention, however, were

consistent with those of Rollins et al. (2016),

which differed in that the intervention was de-

livered by parents within an authentic home

setting. These two reports are consistent in

supporting the use of a social-cognitive ap-

proach over a linguistic approach for children

with ASD who seem to be stuck in the phase

of sharing perceptions and pursuing goals.

Early identification and intervention are

known to have positive implications for a

child’s level of functioning and school place-

ment (Dawson et al., 2010; Reichow, 2012;

Warren et al., 2011). It is imperative, however,

that interventionists providing early interven-

tion understand a child’s social-cognitive func-

tioning and not be deceived by peripheral

language forms. This case example provided

added support for the notion that evidence-

based practices used with young children

with ASD are most effective when grounded

in a comprehensive framework that is sensi-

tive to the child’s social-cognitive abilities.

REFERENCES

Adamson, L., & Russell, C. (1999). Emotion regulation

and the emergence of joint attention. In P. Rochat

(Ed.), Early social cognition: Understanding others

in the first months of life (pp. 281–295). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Bakeman, R., & Adamson, L. (1984). Coordinating at-

tention to people and objects in mother–infant

and peer–infant interaction. Child Development, 55,

1278–1289.

Baldwin, D. (1993). Early referential understanding: In-

fants’ ability to recognize referential acts for what they

are. Developmental Psychology, 29, 832–843.

Bates, E., Benigni, L., Bretherton, I., Camaioni, L., &

Volterra, V. (1979). The emergence of symbols: Cog-

nition and communication in infancy. New York:

Academic Press.

Bates, E., Camaioni, L., & Volterra, V. (1975). The acquisi-

tion of performatives prior to speech. Merrill-Palmer

Quarterly, 21, 205–224.

Bates, E., & Goodman, J. (1997). On the inseparability

of grammar and the lexicon: Evidence from acquisi-

tion, aphasia and real-time processing. Language and

Cognitive Processes, 12(5–6), 507–586.

Bates, E., & Goodman, J. (1999). On the emergence of

grammar from the lexicon. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.),

The emergence of language (pp. 29–79). Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Bateson, M. C. (1975). Mother–infant exchanges: The

epigenesis of conversation interaction. Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, 263, 101–113.

Brazelton, T. B., Koslowski, B., & Main, M. (1974). The

origins of reciprocity: The early mother-infant interac-

tion. In M. Lewis, & L. A. Rosenblum (Eds.), The effect

of the infant on its caregiver (pp. 49–76). New York:

Wiley.

Camaioni, L. (1993). The development of intentional

communication: A re-analysis. In J. Nadel, & L.

Camaioni (Eds.), New perspectives in early com-

munication development (pp. 82–96). New York:

Routledge.

Campbell, M., & Thibodeau Hoffman, R. (2014).

Pathways early autism intervention. Unpublished

manuscript, Dallas, TX: Pathways Early Intervention.

Carpenter, M., Nagel, K., & Tomasello, M. (1998). Social

cognition, joint attention, and communicative com-

petence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of

the Society for Research in Child Development, 63

(4, Serial No. 225).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Facts

about ASDs. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/

ncbddd/autism/data.html

Charman, T. (2003). Why is joint attention a pivotal

skill in autism? Philosophical Transactions of the

Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sci-

ences, 358(1430), 315–324.

Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Win-

ter, J., Greenson, J., et al. (2010). Randomized, con-

trolled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism:

The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125(1),

e17–e23.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Words Are Not Enough 215

Dore, J., & McDermott, R. P. (1982). Linguistic indeter-

minacy and social context in utterance interpretation.

Language, 58, 374–398.

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Khalulyan, A., del Rosario, M.,

McCarthy, B., Gomez, L., Sigman, M., et al. (2013). Is

early joint attention associated with school-age prag-

matic language? Autism, 19(2), 168–177.

Greenspan, S. I., & Shanker, S. (2004). The first idea:

How symbols, language and intelligence evolved

from our primate ancestors to modern human.Cam-

bridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Hennon, E. A., &

Maguire, M. J. (2004). Hybrid theories at the fron-

tier of developmental psychology: The emergentist

coalition model of word learning as a case in point.

In G. Hall, & S. Waxman (Eds.), Weaving a lexicon

(pp. 173–204). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hollich, G. (2000).

An emergentist coalition model for word learning:

Mapping words to objects is a product of the in-

teraction of multiple cues. In R. M. Golinkoff, K.

Hirsh-Pasek,L.Bloom,L.Smith,A.Woodward,N.

Akhtar, M. Tomasello,

... G. Hollich (Eds.), Becom-

ing a word learner: A debate on lexical acquisi-

tion (pp. 136–164). New York: Oxford University

Press.

Hollich, G., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Brand, R.

J., Brown, E., Chung, H. L., et al. (2000). Breaking

the language barrier: An emergentist coalition model

for the origins of word learning. Monographs of the

Society for Research in Child Development, 65(3),

1–135.

Ingersoll, B., & Gergans, S. (2007). The effect of a

parent-implemented imitation intervention on sponta-

neous imitation skills in young children with autism.

Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(2),

163–175.

Johnson, M. H., & Morton, J. (1991). Biology and cog-

nitive development: The case of face recognition.

Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Jones, W., & Klin, A. (2013). Attention to eyes is present

but in decline in 2–6-month-old infants later diag-

nosed with autism. Nature, 504(7480), 427–431.

doi:10.1038/nature12715

Kasari, C., Paparella, T., Freeman, S., & Jahromi, L.

(2008). Language outcome in autism: Randomized

comparison of joint attention and play interventions.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76,

125–137.

Landis, J., & Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of ob-

server agreement for categorical data. Biometrics,

33(1), 159–174.

Legerstee, M. (1991). The role of person and object in elic-

iting early imitation. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology, 51, 423–433.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., & Risi, S. (2002).

Autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS).Los

Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

MacWhinney, B. (1991). The CHILDES project: Computa-

tional tools for analyzing talk. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Maurer, D. (1985). Infants’ perception of faces. In T. Field,

& M. Fox (Eds.), Social perception in infants (pp. 73–

100). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Meltzoff, A. N., & Moore, M. K. (1983). Newborn in-

fants imitate adult facial gestures. Child Development,

54(3), 702–709.

Meltzoff, A. N., & Moore, M. K. (1989). Imitation in new-

born infants: Exploring the range o f gestures imitated

and the underlying mechanisms. Developmental Psy-

chology, 25(6), 954–962.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). A longitudi-

nal study of joint attention and language development

in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Develop-

mental Disorders, 20(1), 115–128.

Mundy, P., & Thorp, D. (2008). The neural basis of

early joint-attention behavior. In T. Charman, & W.

Stone (Eds.), Social & communication development

in autism spectrum disorders: Early identification,

diagnosis & intervention (pp. 296–336). New York:

The Guilford Press.

Ninio, A., & Snow, C. E. (1996). Pragmatic development.

Boulder, CO: Westview.

Ninio, A., Snow, C. E., Pan, B. A., & Rollins, P. R. (1994).

Classifying communicative acts in children’s interac-

tions. Journal of Communication Disorders, 27(2),

157–187.

Reichow, B. (2012). Overview of meta-analyses on early

intensive behavioral intervention for young children

with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 42(4), 512–520.

Rochat, P., & Striano, T. (1999). Social cognitive develop-

ment in the first year. In P. Rochat (Ed.), Early social

cognition (pp. 3–34). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rollins, P. R. (1999). Early pragmatic accomplishments

and vocabulary development in preschool children

with autism. American Journal of Speech-Language

Pathology, 8(2), 181–190.

Rollins, P. R. (2003). Caregiver contingent comments and

subsequent vocabulary comprehension. Applied Psy-

cholinguistics, 24, 221–234.

Rollins, P. R. (2014). Facilitating early social commu-

nication skills: From theory to practice. Shawnee

Mission, KS: AAPC Publishing.

Rollins, P. R. (in press). Developmental pragmatics. In

Y. Huang (Ed.), Handbook of pragmatics. Oxford,

England: Oxford University Press.

Rollins, P. R., Campbell, M., Hoffman, R. T., & Self, K.

(2016). A community-based early intervention pro-

gram for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders.

Autism: International Journal of Research and Prac-

tice, 20(2), 219–232.

Rollins, P. R., & Greenwald, L. C. (2013). Affect attune-

ment during mother–infant interaction: How specific

intensities predict the stability of infants’ joint atten-

tion. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 32(4),

339–366.

Copyright © 2016 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

216 TOPICS IN LANGUAGE DISORDERS/JULY–SEPTEMBER 2016

Rollins, P. R., & Snow, C. E. (1998). Shared attention and

grammatical development in typical children and chil-

dren with autism. Journal of Child Language, 25(3),

653–673.

Rollins, P. R., & Trautman, C. H. (2011). Caregiver input

before joint attention: The role of multimodal input.

Paper presented at the International Congress for the

Study of Child Language (IASCL), Baltimore, MD.

Rollins, P. R., Wambacq, I., Dowell, D., Mathews, L., &

Reese, P. B. (1998). An intervention technique for

children with autistic spectrum disorder: Joint atten-

tional routines. Journal of Communication Disor-

ders, 31(2), 181–193.

Schertz, H., & Odom, S. (2007). Promoting joint attention

in toddlers with autism: A parent-mediated develop-

mental model. Journal of Autism & Developmental

Disorders, 37(8), 1562–1575.

Snow, C. E. (1977). The development of conversation

between mothers and babies. Journal of Child Lan-

guage, 4, 1–22.

Snow, C. E., Pan, B. A., Imbens-Bailey, A., & Herman,

J. (1996). Learning how to say what one means: A

longitudinal study of children’s speech act use. Social

Development, 5, 56–84.

Spitz, R. A. (1965). The first year of life: A psychoanalytic

study of normal and deviant development of object

relations. New York: International Universities Press.

Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the in-

fant: View from psychoanalysis and development

psychology. New York: Basic Books.

Streeck, J. (1980). Speech acts in interaction: A critique

of Searle. Discourse Processes, 3, 133–154.

Tomasello, M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition.

In C. Moore, & P. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention:

Its origins and role in development (pp. 103–130).

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human

cognition. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M., & Barton, M. (1994). Learning words in

nonostensive contexts. Developmental Psychology,

30, 639–650.

Tomasello, M., & Carpenter, M. (2007). Shared intention-

ality. Developmental Science, 10(1), 121–125.

Tomasello, M., Carpenter, M., Call, J., Behne, T., & Moll,

H. (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: The

origins of cultural cognition. Behavioral and Brain