Libya

Dr. Simon Adams

and the

Responsibility

to Protect

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

Occasional Paper Series

No. 3, October 2012

e Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established

in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the

“Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes,

ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. rough its programs,

events and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility

to Protect is a resource and a forum for governments, international

institutions and non-governmental organizations on prevention and

early action to halt mass atrocities.

Cover Photo:

A family walks during a visit to Tripoli Street, the center of ghting between forces

loyal to Libyan leader Muammar Qadda and rebels in downtown Misrata, Libya.

Associated Press Images.

e views expressed in the Occasional Paper are those of the author andare not

necessarily held by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect.

© Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, 2012.

All Rights Reserved

CONTENTS

3 Executive Summary

5 The Arab Spring and Libya

6 The UN Security Council Responds

7 Qaddafi’s Libya

8 “No Fly Zone,” the AU “Road Map” and NATO

10 Mass Atrocity Crimes

11 Humanitarian Intervention versus R2P

12 R2P and Regime Change

14 Backlash

17 Conclusion

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

Executive Summary

For those concerned with the international community’s Responsibility

to Protect (R2P), the implementation of United Nations (UN) Security

Council Resolution 1973, which authorized a military intervention in

Libya, has caused much controversy and dissension.

From the start of Muammar al-Qadda’s violent crackdown against

protesters in February 2011, R2P informed the Security Council’s response.

Adopted at the UN World Summit in 2005 and intended as an antidote to

the inaction that had plagued the UN during the genocides in Cambodia,

Rwanda and Srebrenica, R2P represents a solemn commitment by the

international community to never again be passive spectators to genocide,

war crimes, ethnic cleansing or crimes against humanity. While R2P

played some role in preventing an escalation of deadly ethnic conict in

Kenya during 2007, it had never been utilized to mobilize the Security

Council to take coercive action against a UN member state before.

It is for this reason that Resolution 1970 of 26 February 2011, which

framed the Security Council’s response in terms of R2P, was hailed as a

groundbreaking diplomatic moment. Similarly, Resolution 1973, which

followed on 17 March, was initially seen as a timely and proportional

intervention to ensure the protection of civilians at grave risk of mass

atrocities. It was a regrettable, but necessary measure of last resort.

However, over the course of the following months the debate regarding the

meaning of the resolutions and their implementation became increasingly

bitter. Some argued that the Libyan intervention had been hijacked by

partisans of “regime change.” e alternative view was that “all necessary

measures” were being used by the NATO-led alliance to prevent atrocities

and protect civilians – nothing more and certainly nothing less. Questions

of proportionality and motivation began to undermine the unanimity

that initially existed.

e fall of Qadda’s government in August 2011, the internecine conicts

between rebel militias and the challenges of rebuilding from the ruins of

civil war mean that Libya continues to be a talisman for debates over R2P.

Moreover, the Security Council’s inability to take comprehensive action

with regard to mass atrocities in nearby Syria has widened the divide

between supporters and critics of the implementation of R2P in Libya.

is occasional paper from the Global Centre for the Responsibility

to Protect analyzes the debates that have shaped interpretations of the

intervention in Libya and argues that R2P played a crucial role in stopping

mass atrocities and saving lives.

3

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Madrusah

Tmassah

Al Fuqaha

Zillah

Birak

Umm al

Aranib

Tazirbu

Zighan

Rabyanah

Ghat

Toummo

Al' Uwaynat

Al Awaynat

Al Jawf

Awjilah

Jalu

Al

Jaghbub

,

Maradah

Dirj

Waddan

Sinawin

Al Qatrun

Tahrami

Waw al Kabir

Al Wigh

Al Qaryah

ash Sharqiyah

-

Ma'tan as Sarra

MURZŪQ

AL JUFRAH

NALUT

GHAT

SURT

SABHĀ

AL JABAL

AL GHARBI

MIŞRĀTAH

WADI ALHAYAT

AL WAHAT

AL BUTNAN

AL KUFRAH

ASH SHĀȚI

Marzuq

Al Kufrah

Sabha

Ghadāmis

T

a

r

h

ū

n

a

h

Hun

Adiri

Gharyan

Bani

Walid

-

Al' Aziziyah

Yafran

Nalut

Awbari

3

W

a

d

i

a

l

F

a

r

i

g

h

W

a

d

i

Z

a

m

z

a

m

-

-

Madrusah

Tmassah

Al Fuqaha

Zillah

Birak

Umm al

Aranib

Tazirbu

Zighan

Rabyanah

Ghat

Toummo

Al' Uwaynat

Al Awaynat

Al Jawf

Awjilah

Jalu

Al

Jaghbub

Al Adam

,

Maradah

Marsa al Brega

A

l

K

h

u

m

s

Dirj

Waddan

Sinawin

Al Qatrun

Tahrami

Waw al Kabir

Al Wigh

Al Qaryah

ash Sharqiyah

-

Ma'tan as Sarra

S

u

s

a

h

(

A

p

o

l

l

o

n

i

a

)

Marzuq

Al Kufrah

Ajdabiya

D

a

r

n

a

h

(

D

e

r

n

a

)

Al Marj (Barce)

Tubruq (Tobruk)

Sabha

Ghadāmis

A

z

Z

a

w

i

y

a

h

Z

u

w

a

r

a

h

T

a

r

h

ū

n

a

h

Hun

Adiri

Al Bayda

Banghazi

(Benghazi)

Misratah

Zlīten

Gharyan

Bani

Walid

-

Al' Aziziyah

Yafran

Nalut

Awbari

Surt (Sidra)

T

a

r

a

b

u

l

u

s

(

T

r

i

p

o

l

i

)

Valleta

Sahra'

Rabyanah

Sarīr

Kalanshiyū

L

i

b

y

a

n

D

e

s

e

r

t

L

i

b

y

a

n

P

l

a

t

e

a

u

H

a

m

a

d

a

t

d

e

T

i

n

r

h

e

r

t

M

e

s

a

c

h

M

e

l

l

e

t

Sahra'

Marzuq

Crete

S

a

r

i

r

T

i

b

a

s

t

i

R

a

'

s

a

t

T

i

n

-

S

a

h

r

a

'

A

w

b

a

r

i

R

a

'

s

a

l

H

i

l

a

l

M

E

D

I

T

E

R

R

A

N

E

A

N

S

E

A

Sabkhat

Shunayn

K

h

a

l

i

j

a

l

B

u

m

b

a

h

Gulf of Sidra

(Khalij Surt)

W

a

d

i

Z

a

m

z

a

m

-

-

W

a

d

i

T

i

l

a

l

W

a

d

i

a

l

F

a

r

i

g

h

W

a

d

i

a

l

H

a

m

i

m

MURZŪQ

AL JUFRAH

NALUT

GHAT

SURT

SABHĀ

AL JABAL

AL GHARBI

MIŞRĀTAH

WADI ALHAYAT

AL WAHAT

AL BUTNAN

AL KUFRAH

ASH SHĀȚI

SUDAN

GREECE

MALTA

A L G E R I A

E G Y P T

TUNISIA

NIGER

CHAD

The boundaries and names shown and the designations

used on this map do not imply official endorsement or

acceptance by the United Nations.

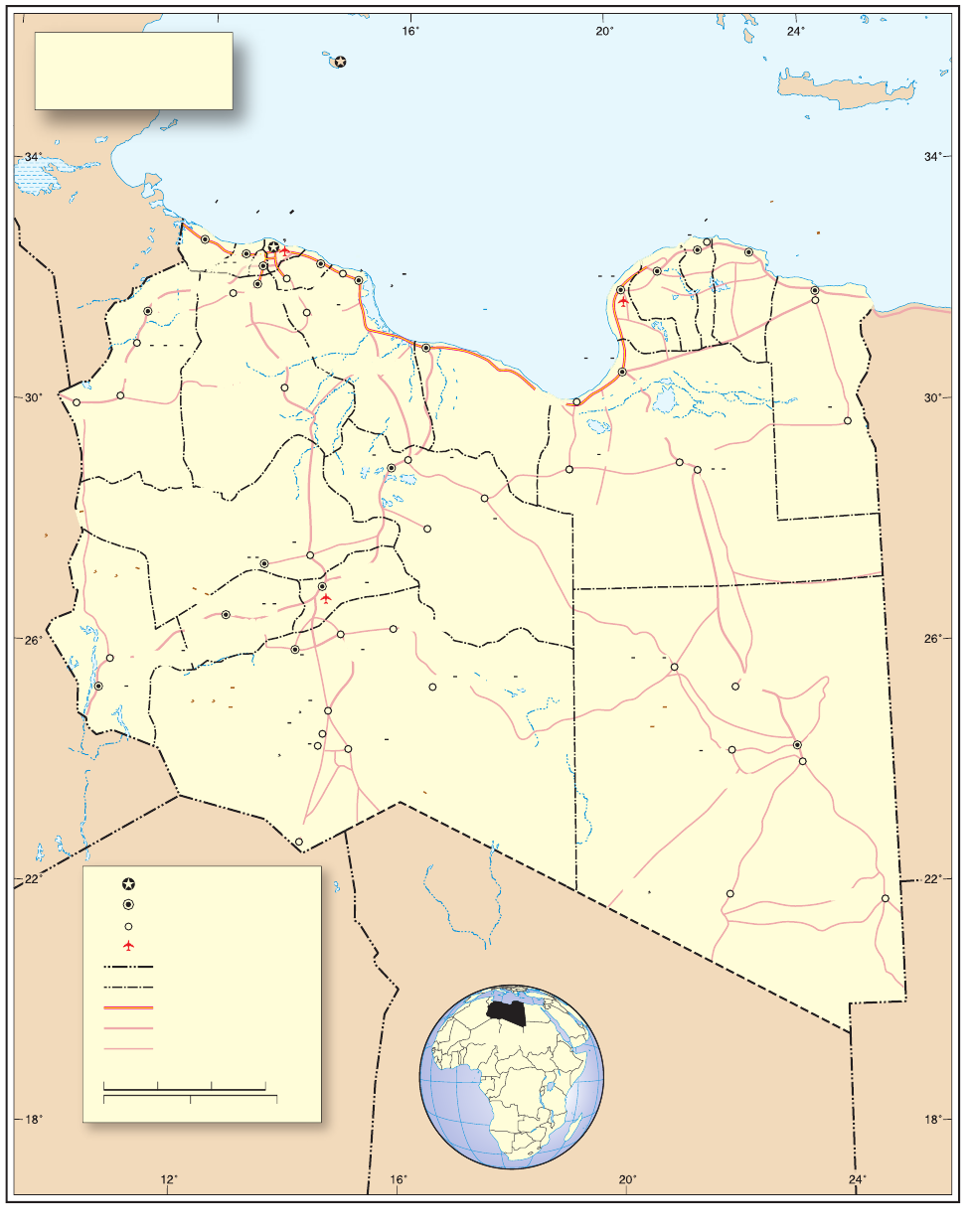

Map No. 3787 Rev. 7 UNITED NATIONS

February 2012

Department of Field Support

Cartographic Section

0 100 200 300 km

0

100 200 mi

LIBYA

6

7 8 9

National capital

Provincial capital

Town

Major airport

International boundary

Provincial boundary

Expressway

Main road

Secondary road

LIBYA

5

4

3

2

1

1 AN NUQĀT AL KHAMS

2 AZ ZĀWIYAH (AZZĀWIYA)

3 AL JIFARAH

4 TARĀBULUS (TRIPOLI)

5 AL MARQAB

6 BENGHAZI

7 AL MARJ

8 AL JABAL AL AKHDAR

9 DARNAH

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Madrusah

Tmassah

Al Fuqaha

Zillah

Birak

Umm al

Aranib

Tazirbu

Zighan

Rabyanah

Ghat

Toummo

Al' Uwaynat

Al Awaynat

Al Jawf

Awjilah

Jalu

Al

Jaghbub

,

Maradah

Dirj

Waddan

Sinawin

Al Qatrun

Tahrami

Waw al Kabir

Al Wigh

Al Qaryah

ash Sharqiyah

-

Ma'tan as Sarra

MURZŪQ

AL JUFRAH

NALUT

GHAT

SURT

SABHĀ

AL JABAL

AL GHARBI

MIŞRĀTAH

WADI ALHAYAT

AL WAHAT

AL BUTNAN

AL KUFRAH

ASH SHĀȚI

Marzuq

Al Kufrah

Sabha

Ghadāmis

T

a

r

h

ū

n

a

h

Hun

Adiri

Gharyan

Bani

Walid

-

Al' Aziziyah

Yafran

Nalut

Awbari

3

W

a

d

i

a

l

F

a

r

i

g

h

W

a

d

i

Z

a

m

z

a

m

-

-

Madrusah

Tmassah

Al Fuqaha

Zillah

Birak

Umm al

Aranib

Tazirbu

Zighan

Rabyanah

Ghat

Toummo

Al' Uwaynat

Al Awaynat

Al Jawf

Awjilah

Jalu

Al

Jaghbub

Al Adam

,

Maradah

Marsa al Brega

A

l

K

h

u

m

s

Dirj

Waddan

Sinawin

Al Qatrun

Tahrami

Waw al Kabir

Al Wigh

Al Qaryah

ash Sharqiyah

-

Ma'tan as Sarra

S

u

s

a

h

(

A

p

o

l

l

o

n

i

a

)

Marzuq

Al Kufrah

Ajdabiya

D

a

r

n

a

h

(

D

e

r

n

a

)

Al Marj (Barce)

Tubruq (Tobruk)

Sabha

Ghadāmis

A

z

Z

a

w

i

y

a

h

Z

u

w

a

r

a

h

T

a

r

h

ū

n

a

h

Hun

Adiri

Al Bayda

Banghazi

(Benghazi)

Misratah

Zlīten

Gharyan

Bani

Walid

-

Al' Aziziyah

Yafran

Nalut

Awbari

Surt (Sidra)

T

a

r

a

b

u

l

u

s

(

T

r

i

p

o

l

i

)

Valleta

Sahra'

Rabyanah

Sarīr

Kalanshiyū

L

i

b

y

a

n

D

e

s

e

r

t

L

i

b

y

a

n

P

l

a

t

e

a

u

H

a

m

a

d

a

t

d

e

T

i

n

r

h

e

r

t

M

e

s

a

c

h

M

e

l

l

e

t

Sahra'

Marzuq

Crete

S

a

r

i

r

T

i

b

a

s

t

i

R

a

'

s

a

t

T

i

n

-

S

a

h

r

a

'

A

w

b

a

r

i

R

a

'

s

a

l

H

i

l

a

l

M

E

D

I

T

E

R

R

A

N

E

A

N

S

E

A

Sabkhat

Shunayn

K

h

a

l

i

j

a

l

B

u

m

b

a

h

Gulf of Sidra

(Khalij Surt)

W

a

d

i

Z

a

m

z

a

m

-

-

W

a

d

i

T

i

l

a

l

W

a

d

i

a

l

F

a

r

i

g

h

W

a

d

i

a

l

H

a

m

i

m

MURZŪQ

AL JUFRAH

NALUT

GHAT

SURT

SABHĀ

AL JABAL

AL GHARBI

MIŞRĀTAH

WADI ALHAYAT

AL WAHAT

AL BUTNAN

AL KUFRAH

ASH SHĀȚI

SUDAN

GREECE

MALTA

A L G E R I A

E G Y P T

TUNISIA

NIGER

CHAD

The boundaries and names shown and the designations

used on this map do not imply official endorsement or

acceptance by the United Nations.

Map No. 3787 Rev. 7 UNITED NATIONS

February 2012

Department of Field Support

Cartographic Section

0 100 200 300 km

0

100 200 mi

LIBYA

6

7 8 9

National capital

Provincial capital

Town

Major airport

International boundary

Provincial boundary

Expressway

Main road

Secondary road

LIBYA

5

4

3

2

1

1 AN NUQĀT AL KHAMS

2 AZ ZĀWIYAH (AZZĀWIYA)

3 AL JIFARAH

4 TARĀBULUS (TRIPOLI)

5 AL MARQAB

6 BENGHAZI

7 AL MARJ

8 AL JABAL AL AKHDAR

9 DARNAH

4

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

The Arab Spring and Libya

1

On 17 December 2010 a young fruit and vegetable seller

named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on re in a desperate

protest against bureaucratic indifference and police

corruption in Tunisia. His gruesome death provoked a month

of erce anti-government protests, and on 14 January 2011

President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali ed into exile. Inspired

by the Tunisian experience, mass demonstrations against

the politically bankrupt regime of President Hosni Mubarak

began soon aer in Egypt. e civil revolt, focused around

Cairo’s Tahrir Square, succeeded in toppling his thirty-year

dictatorship within three weeks. Sensing that a seismic shi in

regional politics was now underway, similar protests erupted

in Bahrain, Yemen and elsewhere. As popular movements

for change radiated across the Middle East and North Africa

in the opening weeks of 2011, the question was not whether

this “Arab Spring” would continue, but which repressive

government would fall next.

Muammar al-Qadda, who had ruled Libya since seizing

power in a military coup in 1969, eyed these developments

suspiciously.

2

On 15 February, just four days aer Mubarak’s

resignation, protests began in Libya. An estimated two

hundred people gathered in front of police headquarters in

Benghazi demanding the release of a well-known human

rights lawyer. A number of people were injured as the

demonstration was broken up by the Libyan security forces.

When general protests against the government spread to other

towns the following day, the security forces employed lethal

force. Fourteen people were killed and Libyan supporters

of the Arab Spring, especially those overseas with better

access to social media, called for a “Day of Rage.” Despite

government warnings that live ammunition would be used to

disperse mobs, large demonstrations took place in at least four

major cities, including Benghazi and Tripoli, on 17 February.

Human Rights Watch estimated that twenty-four protesters

were killed by the security forces.

3

e demonstrations then

rapidly increased in scale and ferocity until they evolved into

a country-wide popular uprising against Qadda.

Protesters in Benghazi, Baida, Ajdabiya, Misrata and Zawiya

took to the streets. Some attacked symbols of the regime,

set re to police stations and damaged other government

buildings. Eyewitness accounts reported “dozens” killed

by security forces in Benghazi aer 17 February, including

een people shot at the funeral of a protestor who had been

killed earlier. While it was impossible to verify all of the

terrifying and sensational reports from inside Libya, it was

credibly claimed by Human Rights Watch and others that

by 20 February at least 173 people had been killed during

four days of protests.

4

About this time the rst shaky videos purportedly showing

armed men going door-to-door in Benghazi attacking

suspected opponents of the Qadda regime were broadcast

on the international news networks. ere were also stories of

military aircra ying low over demonstrations in a menacing

display of potential lethal violence. It was reported that three

people had been killed in Tajura, on the outskirts of Tripoli,

when a ghter plane opened re. Meanwhile, armed Qadda

loyalists reportedly patrolled Tripoli in pick-up trucks,

arresting or shooting at anyone suspected of public dissent.

5

As the uprising spread, the Libyan police were forced out of

Benghazi and then from Misrata by 24 February. A number of

towns in the east of the country began to slip from Qadda’s

control. Some protesters started arming themselves and

defending their neighborhoods from the security forces.

e situation shied inexorably from demonstration to

insurrection as volunteer militias were formed across the

east of the country.

e regime committed more desperate acts of violence and

issued blood-curdling threats. On the night of 20 February

Qadda’s heir apparent, his son Saif al-Islam, appeared on

Libyan television threatening that “thousands” would die and

“rivers of blood” would ow if the rebellion did not stop. e

next day, two Libyan ghter jets landed in Malta and their

pilots alleged that they had been ordered to bomb Benghazi.

6

Soon aer, Qadda, speaking in Tripoli, called upon loyalists

to “get out of your houses” and “attack” all opponents of the

regime. Invoking language that was reminiscent of the 1994

genocide in Rwanda, he described protesters as drug-crazed

“rats,” “cockroaches” and “cowards and traitors.” He le no

doubt about his intentions as he promised to “cleanse Libya

house by house.”

7

Estimates of the number of civilians killed between 15 and

22 February vary. Residents of Tajura described numerous

bodies littering the streets.

8

e UN Human Rights Council’s

International Commission of Inquiry received medical

records regarding protesters shot dead in Tripoli, with doctors

5

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

testifying that more than 200 bodies were brought into their

morgues over 20-21 February.

9

e International Criminal

Court (ICC) later estimated that 500 to 700 civilians were

killed in February prior to the outbreak of civil war.

10

Although some of the emerging stories were exaggerated,

by 22 February it was clear that the Qadda regime, in its

desperation to hold on to power, was willing to use extreme

violence to crush the popular uprising. Despite censorship,

confusion, rumors and misinformation, the threat of mass

atrocities was imminent and real.

11

The UN Security Council Responds

From New York, the UN Secretariat viewed developments

inLibya with grave concern. On 20 February the UN

Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, had spoken with Muammar

Qadda on the phone, telling him that the violence against

civilians “must stop immediately.”

12

Qadda did not heed

thecounsel, but a number of senior Libyan diplomats,

including the leadership of the Permanent Mission of Libya

to the UN, defected. One diplomat observed that, “the more

Qadda kills people, the more people go into the streets.”

Libya’s ambassadors to Indonesia, India and several other

countries resigned.

13

On 22 February the UN High Commissioner for Human

Rights, Navi Pillay, called for an immediate cessation

of the “grave human rights violations committed by the

Libyan authorities.” Pillay described the violence as possibly

constituting “crimes against humanity.”

14

ese sentiments

were echoed in a joint statement by the UN Secretary-

General’s Special Advisers on the Prevention of Genocide

and the Responsibility to Protect. e Special Advisers also

reminded Libya of its pledge at the 2005 UN World Summit

to protect populations “by preventing genocide, war crimes,

ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, as well as

their incitement.”

15

On the same day, the League of Arab States (Arab League)

banned Libya from attending its meetings. Ekmeleddin

Īhsanoğlu, Secretary-General of the Organization of the

Islamic Conference, condemned the Libyan government’s

use of excessive force against civilians. e UN Security

Council similarly “condemned the violence and use of force

against civilians, deplored the repression against peaceful

demonstrators, and expressed deep regret at the deaths of

hundreds of civilians.”

16

e African Union (AU) followed

with Jean Ping, Chair of the AU Commission, calling for an

immediate end to “repression and violence” in Libya.

17

On 25 February Ban Ki-moon voiced his growing concerns to

the UN Security Council. Meanwhile, in Geneva, Navi Pillay

reminded members of the Human Rights Council about their

individual responsibility to protect their populations and

their collective responsibility to act in a timely and decisive

manner when a state is manifestly failing to protect its

population.

18

Soon aer, coordinated action by the Human

Rights Council and the General Assembly paved the way for

Libya’s suspension from the council.

19

e Responsibility to Protect focused the international

response. Resolution 1970, unanimously adopted by the

Security Council on 26 February, explicitly invoked the

“Libyan authorities’ responsibility to protect its population.”

e resolution included a comprehensive package of coercive

measures – an arms embargo, asset freezes, travel bans and

referral of the situation to the ICC – aimed at persuading the

Qadda regime to stop killing its people.

During the weeks between Resolution 1970 and the adoption

of Resolution 1973 on 17 March, escalating violence prompted

regional and international organizations to again urge the

Qadda regime to stop the killing and resolve the crisis

through “peaceful means and serious dialogue.” On 10 March

the AU’s Peace and Security Council established an ad-hoc

High Level Committee on Libya, and on 12 March the Arab

League called for a “no-y zone” over Libya.

20

By 16 March pro-Qaddafi forces were approaching the

opposition stronghold of Benghazi and Saif al-Islam

al-Qadda was quoted on Western television as saying

the rebellion would “be over in forty-eight hours.” Libyan

television broadcast a message that the army was coming

to Benghazi “to cleanse your city from armed gangs.” Most

importantly, Qadda himself threatened the opposition in

Benghazi on national radio and television, saying that the

army was on its way “tonight” and that “we will show no

mercy and no pity.”

21

e unrelenting violence and political intransigence of

the Qadda regime, combined with the limited impact of

Resolution 1970 on its behavior, ruled out further mediation

and accommodation.

22

With Qadda’s forces on the outskirts

of Benghazi, the risk of civilian massacres seemed highly

probable if the city was allowed to fall. Urged on by the

6

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

Arab League, ten UN Security Council members supported

Resolution 1973 (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Colombia, France,

Gabon, Lebanon, Nigeria, Portugal, South Africa, United

Kingdom and United States) and ve abstained (Brazil, China,

Germany, India and Russia). Although the AU did not call for

a no-y zone, all three African members of the UN Security

Council voted for Resolution 1973. Such a vote was entirely

in keeping with Article 4(h) of the AU’s Constitutive Act,

which advocates a policy of “non-indierence,” rather than

non-interference, in the sovereign aairs of other states when

“grave circumstances,” including crimes against humanity,

are concerned.

In addition to reiterating the responsibility of the Libyan

authorities to protect its population, and deploring their

failure to comply with Resolution 1970, Resolution 1973

called for an immediate “cease-re and a complete end to

violence and all attacks against, and abuses of, civilians.” It

stressed the need “to intensify eorts to nd a solution to

the crisis which responds to the legitimate demands of the

Libyan people.” e text referred to “all necessary measures,”

including coercive military action but short of a “foreign

occupation force.” Two scenarios were specically identied:

the protection of “civilians and civilian populated areas under

threat of attack,” and the imposition of a “ban on all ights

in the airspace of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya in order to

help protect civilians.”

23

ose Security Council members who voted for Resolution

1973 understood that they were voting for air strikes to protect

civilians. For at least one of those who voted for Resolution

1973, Ambassador Ivan Barbalić of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the

inability of the UN to stop past atrocities weighed heavily.

He later commented that Benghazi could have potentially

developed into “a situation not unlike Srebrenica” if it were

allowed to be retaken by Qadda’s forces.

24

Moreover, the

decision to embark upon military intervention was only

takenaer other attempts at dissuasion had failed. e

nature and structure of the Qadda regime closed o other

diplomatic possibilities.

Qaddafi’s Libya

e ancient history of Libya is intimately connected with

the ebb and flow of empires across the Mediterranean,

Middle East and North Africa. Modern Libya, by contrast,

was a creation of the UN.

25

e defeat of fascist Italy in

World War II, during which Libya had been a signicant

battleground, enabled decolonization. In 1951 the United

Kingdom of Libya was created as a poor, weak, but nominally

independent,constitutional monarchy. Under King Idris

Libyawas the single largest per-capita recipient of United

States aid in the world by 1959.

26

e discovery of oil in 1959 changed everything. Within two

years Libya was an oil exporter, the revenues from which

generated considerable state wealth. Oil production increased

from 20,000 barrels per day in 1960, to nearly 3 million

barrels by the end of the decade. e economy, lubricated

by oil, grew by about 20 percent annually.

27

Libya was struggling to deal with the ramications of all

of this when an army coup in September 1969 brought to

power a small clique of young pan-Arabist ocers who

called themselves the Revolutionary Command Council

(RCC). Within the RCC was Muammar al-Qadda, then

a 27-year-old heavily inuenced by the politics of Colonel

Gamal Abdel Nasser in neighboring Egypt. As charismatic

as he was ruthless, Qadda emerged as the central military

gure of what he was now calling “the Libyan revolution.”

e political form of the new Libyan republic was increasingly

shaped by Qaddafi alone. In 1973 he suspended all

previous laws. Four years later he dramatically abolished

the government and declared Libya to be a “Jamahiriya”

(state of the masses). Qadda continued only as honorary

“guide of the revolution.” His motivations were not solely

ideological.Qadda was so suspicious of the possibility of a

military coup that he had abolished the Ministry of Defense

in 1969.

28

Over the following four decades he remained

Libya’skey military decision maker.

Despite Qadda’s pretensions with regard to creating a unique

system of self-governing socialist people’s committees, Libya

remained rmly under his eccentric direction. e ruling

circle was tight and repressive. Censorship was pervasive.

e formation of opposition political parties was outlawed

under Law 71 of 1972 and punishable by death.

29

e idea that opposition to Qadda was tantamount to

treason was one that Qadda himself returned to constantly.

For example, in a speech from 1993 he declared that “now

we should seek traitors” and “kill them.”

30

Dissidents were

detained, routinely tortured and sometimes publicly executed.

ose who made it into exile could be hunted down and

assassinated by Libyan intelligence agents. Libya was also

7

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

a major sponsor of international terrorism, including a

notorious connection to the blowing up of Pan Am Flight

103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988.

31

Qadda was able to use billions of petro-dollars to fund his

political ambitions and foreign entanglements, and also buy

o inchoate domestic opposition to his rule. Between 1969

and 1979 Libya received an estimated $95 billion in revenue

from oil.

32

Hard currency and hubris enabled a disastrous

military intervention in Chad, a call for jihad in the Congo,

an alliance with Uganda’s Idi Amin and support for armed

rebels in Mali. Qadda’s pan-Arab vision failed during the

1970s when it became clear that other rulers would not bow

to his leadership. Attempts from the late 1980s onwards to

re-fashion himself as a pan-African “king of kings” similarly

floundered, despite his willingness to bankroll various

African political allies.

33

Money from oil also enabled Qaddafi to construct an

impressive welfare apparatus during the 1970s.

34

Genuine

progress was made in advancing literacy and health care,

the residual eects of which are still apparent. e UN’s

2011 Human Development Index ranked Libya 64th out of

187 countries.

35

But receipt of economic handouts depended

upon political acquiescence, and by the late 1980s the

systemof distributive welfare was crumbling both literally

and guratively.

Completely dependent upon oil revenue and subject to

Qaddafi’s whims, Libyan economic development was

distorted. By 1970 oil was already providing 99 percent of

state revenue, but employing only 1 percent of the workforce.

36

Billions of dollars were wasted through mismanagement.

Endemic corruption meant that money that was not wasted

was oen siphoned into oshore bank accounts.

37

Confrontations with a range of foreign powers had made

Libya a pariah by the mid-1980s. Western sanctions,

especially on oil exports, started to have an impact on Libya’s

revenue, which fell from $21 billion annually to $5.4 billion

between 1982 and 1986.

38

e United States’ decision to

conduct airstrikes in Tripoli and Benghazi during April

1986, including on Qadda’s personal residences, represented

an obvious attempt to aect “regime change.”

39

Because of

Libya’s complicity in international terrorism, the UN applied

damaging sanctions from 1992 until 1999.

40

In an extraordinary reversal of political fortunes, aer giving

up hisweapons of mass destruction and the restoration of

relations with several Western powers from December 2003

onwards, Qadda was actually courted as a North African

buttress against al-Qaeda.

41

During 2004 British Prime

Minister Tony Blair and French President Jacques Chirac

both visited Libya. Between October 2004 and the end of

2009 the European Union granted €834.5 million worth

of arms export licenses to Libya, with Italy being Qadda’s

single largest supplier.

42

The overall effect of 40 years of Qaddafi’s misrule was

debilitating. Libya had a weak state and army, but possessed

a vigorously repressive internal security apparatus. ere was

no governmental accountability as Qadda had no formal

authority but possessed all real power.

Qadda also remained ercely resistant to the idea of reform.

For example, during a military mutiny in Misrata in 1993 and

an isolated Islamist uprising in Benghazi in 1995, extreme

violence was deployed with the air force being used to bomb

the mutinous soldiers into submission. In June 1996 the

security forces killed approximately 1,272 prisoners at Abu

Salim prison following protests there. During the following

month, when the crowd at a soccer game began to chant

anti-Qadda slogans a riot broke out and as many as y

people were shot dead by the security forces.

43

When protests began in Benghazi during February 2011,

Qadda relied upon the things he knew best – inammatory

rhetoric mixed with erce repression. When Libyans protested

or attacked symbols of his regime, he dismissed calls for

compromise or conciliation. Outside Libya, Qadda had no

signicant international allies who could pressure him to

moderate his behavior. Inside Libya, there were no restraints

upon his decision-making. Although Libya was a country of

more than six million people, one man made a negotiated

outcome to the rapidly escalating conictnext to impossible.

“No Fly Zone,” the AU “Road Map” and NATO

Implementation of Resolution 1973 began on 19 March with

a massive bombardment of Libyan air defenses and military

hardware, with a focus on Qadda’s forces outside Benghazi.

Although the United States, United Kingdom and France

initiated the operation, the NATO-led coalition assembled to

8

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

enforce Resolution 1973 would eventually encompass eighteen

states. Notably, three Arab countries – Qatar, Jordan, and

the United Arab Emirates – made military contributions.

44

In terms of the “no-y zone,” Qadda did not have much of

an air force to disable. He did, however, have tanks, heavy

artillery and ground troops. Although estimates vary, the

regular Libyan armed forces constituted approximately

100,000 personnel. Qaddafi, who had some personal

experience of coup plotting, deliberately kept his army weak.

e exception was four well-resourced brigades directly

linked to his tribe or to one of his sons, along with the

internalsecurity forces.

45

Although Qadda’s forces outside Benghazi were destroyed by

NATO bombers, his remaining troops displayed considerable

resilience. Aer falling back from Benghazi they were able

to maintain control of most of the west of the country, with

the notable exception of Misrata, and retake several towns

that had previously ousted the security forces. Despite being

targeted by NATO, Qadda’s forces continued to pose a threat

to civilians. For example, NATO claimed that on 20 April

alone it destroyed 25 tanks that were shelling civilian areas

in Ajdabiya and Misrata.

46

NATO’s military operations in Libya proceeded on the

assumption that air strikes would cause the Qadda regime

to abandon its “cleansing” campaign. e decision to resort to

air power emerged as the preferred option due to its perceived

low risk as compared to deploying foreign ground forces.

Although improvements in accuracy and discrimination

have signicantly lowered the risk of civilian casualties,

death and damage remain intrinsic to air warfare. is is

particularly the case in densely populated urban areas, with

the corresponding possibility of accidentally killing the very

population the mission is intended to protect.

Alternatives to coercive force were also still being explored. In

particular, the AU continued to argue in favor of a negotiated

settlement between Qadda and the rebels. On 10 April, aer

the airstrikes had begun, an AU delegation including the

presidents of South Africa, Uganda, Congo-Brazzaville, Mali

and Mauritania claimed to have secured Qadda’s support

for a “road map” to end the conict. e road map included

an immediate ceasere and negotiations on political reform.

e emerging political representatives of the rebellion in

Benghazi, who were now calling themselves the National

Transitional Council (NTC), rejected the initiative.

e NTC saw the AU, whose secretariat received substantial

funding from Libya, as protecting Qaddafi’s interests.

ey were especially skeptical given that two members of

the delegation, President Jacob Zuma of South Africa and

President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, had already publicly

criticized the NATO-led intervention. Indeed, Museveni had

written in March that while Qadda had made mistakes,

he was a “true nationalist” and that “I prefer nationalists

to puppets of foreign interests” – an inelegant stab at the

opposition. Another delegate, President Mohamed Ould

Abdel Aziz of Mauritania, who came to power in a military

coup in 2008, had close ties to Qadda, who had cancelled

Mauritania’s $100 million debt. It was therefore regrettable,

but not surprising, that the NTC rejected the AU road map

and repeated its demand that Qadda and his family leave

Libya as a precursor to peace talks.

47

Countries supporting the NATO-led intervention applied

little diplomatic pressure on the NTC to take the AU

initiativeseriously. Although Qadda’s gesture may have

been empty, it still should have been vigorously pursued.

However, the concerns of the NTC were also valid. e

fact that the AUdelegation publicly referred to Qadda

as “Brother Leader” rankled, as did the fact that the most

prominent member of the delegation, President Zuma, did

not visit Benghazi, returning to South Africa aer his time

with Qadda in Tripoli.

Most importantly, in Benghazi, the heart of the rebellion, the

AU’s criticism of “regime change” did not sit comfortably with

people whose lives were at grave risk if the regime survived.

Allegations that Qadda was recruiting mercenaries from

several AU member states, especially Chad and Niger, also

heightened suspicions. e AU delegation had been welcomed

at Qadda’s private compound in Tripoli, but in Benghazi

about a thousand protestors gathered outside their hotel. One

woman was photographed carrying a placard that read, in

English, “the people want to change the regime.”

48

A diplomatic opportunity was possibly missed, but this

was as much a mistake of the AU delegation as of those

enforcing the UN’s civilian protection mandate. While the

AU delegation had announced Qadda’s agreement to their

road map, Qadda made no such public statement. His

private commitment may have been genuine, but to the NTC

it appeared to be a cynical delaying tactic. Crucially, despite

the immediate ceasere promised in the road map, even as the

9

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

AU delegation checked into their hotel in Benghazi, Qadda’s

forces continued to shell the besieged city of Misrata.

49

As the opportunities for negotiation dissipated and the

NATO bombing campaign started to focus upon “command

and control” centers in Tripoli and other urban areas, the

possibility of civilian casualties grew. NATO Secretary-

General Anders Fogh Rasmussen later insisted that, “no

comparable air campaign in history has been so accurate

and so careful in avoiding harm to civilians.”

50

But, on 21

June, NATO held a press conference where it admitted to

a small number of civilian casualties caused by technical

malfunctions or targeting errors. A later investigation by

the UN Human Rights Council’s International Commission

of Inquiry found that sixty civilians were accidentally killed

in at least ve NATO strikes that went wrong. While the

commission declared that “we are quite sure that NATO

did not deliberately attack civilians,” this was little solace

for those who lost loved ones.

51

e Qadda regime purposefully misrepresented the issue

of NATO casualties. For example, a journalist writing for

e Economist from Tripoli reported at the start of July that:

e point, repeated relentlessly, is that civilians have been killed

by Western bombs and that the people remain loyal to the Brother

Leader. Crowds chanting his name greet reporters everywhere they

are taken on ocial tours. But nowhere else. e picture presented by

the regime oen falls apart, fast. Cons at funerals have sometimes

turned out to be empty. Bombing sites are recycled. An injured seven-

year-old in a hospital was the victim of a car crash, according to a

note passed on surreptitiously by a nurse. Journalists who point out

such blatant massaging of facts are harangued in the hotel corridors.

52

Over eight thousand sorties were eventually own over Libya

by the NATO-led alliance. Although the immediate objective

of stopping Qadda’s assault on Benghazi was successful,

theoperational directive confining the use of military

force solely to protecting civilians proved challenging. On

the one hand, such a mandate created expectations about

neutrality and impartiality.

53

On the other, limiting the

military operation to civilian protection was undermined

by developments on the ground.

While the east of the country was under the control of rebels

by the end of April, most of the west, including Tripoli, was

still controlled by Qadda’s forces. e Benghazi-based NTC

was busy transforming itself into an alternative government.

e various civilian militias had slowly consolidated into

a rebel army under the NTC’s loose overall command.

Increasingly, any attempt by Qadda’s forces to retake key

towns and villages in the east was met by fearsome NATO

airstrikes in coordination with the defending rebels. By any

measure, Libya was now in the midst of a full-blown civil war.

Mass Atrocity Crimes

Protecting civilians from mass atrocity crimes was the reason

the Security Council authorized a military intervention in

Libya. But crimes also continued throughout the civil war.

Aer being repulsed from Benghazi, the Qadda regime

continued to rely upon its weakened security forces and

also deployed suspected mercenaries, a number of whom

were allegedly recruited from neighboring African

countries or Eastern Europe.

54

A later investigation by the

UN Human Rights Council’s International Commission of

Inquiry concluded that “international crimes, specically

crimes against humanity and war crimes, were committed

by Qadda forces,” including “acts of murder, enforced

disappearance, and torture” that were “perpetrated within

the context of a widespread and systematic attack against a

civilian population.”

55

Among other war crimes, the rebel-

held western city of Misrata, home to half a million people,

was subjected to a vicious siege by loyalist forces from mid-

March until May.

Qaddafi’s troops indiscriminately shelled Misrata with

Grad rockets, mortars and artillery. A hospital in Misrata

was attacked and cluster munitions were fired into the

el-Shawahda residential district. Loyalist snipers preyed

upon civilians. In at least one case Qadda’s forces also

used civilians as a “human shield” to deter NATO attacks

on their positions. ere was a deliberate attempt to starve

the civilian population and block humanitarian aid from

reachingMisrata. ere were also widespread allegations that

loyalist forces were guilty of the “murder, rape and sexual

torture” of Misrata’s residents. Doctors testied to “military-

sanctioned rape” of women and girls as young as fourteen.

In all, more than 1,100 Misrata residents died as Qadda’s

forces besieged the city.

56

Given the extensive nature of war crimes perpetrated

in Misrata, it was clearly within the UN’s “all necessary

measures” mandate for NATO to attack Qadda’s forces

encircling the city. But as the duration of the Libya operation

10

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

lengthened beyond initial expectations, it became a battle

of nerves between Qadda and NATO as much as between

Qadda and the NTC rebels. Military stalemate and de facto

partition of Libya seemed a distinct possibility. Meanwhile

international public support for the intervention fell. In the

United States, for example, the percentage of “likely voters”

who supported the intervention in late March was 46 percent,

but by August it was down to 24 percent.

57

Far away from the frontlines of Misrata, the battle to hold

perpetrators of mass atrocity crimes legally responsible

for their actions also continued. On 27 June an ICC arrest

warrant was issued for Qadda, his son Saif al-Islam and

the head of intelligence services, Abdullah al-Senussi, for

responsibility for alleged crimes against humanity committed

since mid-February.

It was not until late May that the military momentum started

to shi decisively in favor of the rebels, with NATO air-

support proving crucial to their oensive. ey broke the

siege of Misrata and started to move towards Tripoli. Intense

ghting continued, but aer six months the nal collapse of

Qadda’s forces was rapid. On the night of 21 August rebel

forces were inside Tripoli.

Even as it became clear that all was lost, Qadda’s forces

continued to commit war crimes. On 23 August, as Tripoli

was falling to the rebels, soldiers from the 32nd Brigade,

following orders from a senior member of the military, carried

out a massacre of prisoners at a warehouse that had been

used earlier as a place of detention and torture. More than

y “civilians and combatants” were murdered by their

guards in addition to an unknown number who had been

tortured to death in earlier incidents. In the words of one

investigative report compiled aerwards, high-ranking

military commanders were at the warehouse, ordered the

massacre and conspired to “conceal and destroy evidence of

their crimes.”

58

Human Rights Watch documented similar

atrocities in al-Qawalish, al-Khoms and Bani Walid.

59

Such

massacres were part of an established pattern of conduct

rather than isolated incidents.

Humanitarian Intervention versus R2P

roughout the conict a number of media commentators

misleadingly labeled the international action in Libya as a

“humanitarian intervention.”

60

Some protagonists rushed to

defend the inviolability of Libya’s national sovereignty and

denounced Western malfeasance, while others proclaimed a

new dawn for the notion of just war. Almost all misrepresented

the Responsibility to Protect.

Even though the Responsibility to Protect features in just

three paragraphs of the 40-page outcome document of the

2005 UN World Summit, historian Martin Gilbert has

suggested that it constituted “the most signicant adjustment

to national sovereignty in 360 years.”

61

R2P’s core idea is

that all governments have an obligation to protect their

populations from four mass atrocity crimes: genocide, war

crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

It is primarily a preventive doctrine. However, R2P also

acknowledges that we live in an imperfect world and if a

state is “manifestly failing” to meet its responsibilities, the

international community is obliged to act. It is not a right to

intervene, but a responsibility to protect. e distinction is

not diplomatic artice. Aer the 1994 genocide in Rwanda

and the 1995 genocide in the Bosnian town of Srebrenica,

the international community resolved to never again be a

passive spectator to mass murder.

By contrast, the doctrine of humanitarian intervention may be

summed up as, “military intervention in a state, without the

approval of its authorities, and with the purpose of preventing

widespread suering or death among the inhabitants.”

62

is diers from the Responsibility to Protect on at least

three grounds.

First, the remit of humanitarian intervention, which aims at

preventing large scale suering, is far broader than that of R2P,

which focuses upon the prevention of the four mass atrocity

crimes. Second, humanitarian intervention automatically

focuses upon the use of military force, by a state or a group

of states, against another state without its consent. As such

it overlooks the broad range of preventive, negotiated and

other non-coercive measures that are central to R2P. ird,

to the extent that the doctrine of humanitarian intervention is

predicated on the basis of the “right to intervene,” it assumes

that it can proceed without the need to secure appropriate

authorization under international law.

e Security Council’s framing of the crisis in terms of

R2P and its authorization of Resolution 1973 made Libya

stand apart from cases of humanitarian intervention to

halt mass atrocities, such as NATO’s 1999 intervention in

Kosovo, which was conducted without UN authorization.

Although previous interventions to halt atrocities may have

11

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

been morally justiable, they lacked international legality.

63

Rather than compromising sovereignty, R2P harnesses the

notion of sovereignty as responsibility and seeks to respond

to extreme crises in a way that is both legitimate and legal.

64

Military action in Libya was preceded by a range of non-

military measures that sought to persuade the Qadda regime

to stop the killing. All the steps considered in Resolution 1970

—referral of the matter to the ICC, imposition of an arms

embargo, enforcement of a travel ban for certain individuals,

freezing the assets of senior regime gures — while coercive,

were peaceful. It was only when these measures failed that

the use of military force was nally considered.

It must also be remembered that since the 1990s there has

been a tendency to conate any military action in support

of humanitarian ends with military invasion for material

gain. Long considered the prime-motive for any foreign

intervention in the Middle East or North Africa, oil is only

one of many factors inuencing international interest in

this strategically important region. Libya was already fully

integrated into the world energy market and several Western

governments had extensive oil contracts with the Qadda

regime.

65

On 22 February, prior to Resolution 1970, it was

reported that the crisis in Libya had increased global oil

prices by 2.6 percent - reaching the highest point since before

the 2008 global nancial crisis. e price of oil increased

again following the rst airstrikes.

66

is volatility in the

oil market occurred at a time of growing uncertainty in

the global economy. If anything, oil was a disincentive for

intervention in Libya.

Unlike a “humanitarian intervention,” the decision to resort

to “all necessary measures” in Libya was not only legal under

international law, it also met a number of key political tests.

e Qadda regime was committing mass atrocities and its

public rhetoric was an open incitement to further crimes.

Qadda’s determination to hold onto power at all costs clearly

implied the risk of escalating violence, and senior Libyan

diplomats had defected in open disapproval of the regime’s

behavior. e fact that Resolution 1973 was adopted without

a single negative vote on the Security Council reected that

even those with serious reservations about a NATO-led

military intervention recognized that the world needed to

act. But in Libya there was also the vexed political question

of “regime change” to consider.

R2P and Regime Change

Airstrikes to halt the attacks of Qadda’s forces on civilians

in Benghazi, Misrata and elsewhere were clearly justiable

under “all necessary measures” in Resolution 1973. However,

as the civil war became a war of attrition between Qadda’s

forces and the rebel army, other forms of military intervention

became less clearly in keeping with the spirit, if not the letter,

of the UN mandate. For example, despite an arms embargo

under Resolution 1970, some countries provided sizeable

quantities of weapons to the rebels. In June France admitted

to supplying assault ries, rocket launchers and anti-tank

missiles, claiming that such actions were both morally

justiable and within the legal parameters of Resolution

1973. Dwarng the French contribution was that of Qatar,

which allegedly supplied militias connected to the NTC with

eighteen shipments amounting to 20,000 tons of weaponry.

67

Other forms of support from key members of the NATO-led

alliance included providing battleground leadership advice

during the nal rebel oensive on Tripoli and Sirte. During

August 2011 the New York Times reported that “Britain,

France and other nations deployed special forces on the

ground inside Libya to help train and arm the rebels.” Qatar

went much further, later admitting that it had “hundreds” of

troops “in every region” ghting against Qadda’s forces. is

was conrmed by a senior gure from the NTC.

68

Although

not a direct violation of Resolution 1973, which only expressly

forbid “a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of

Libyan territory,” this was not in keeping with the spirit of the

civilian protection mandate represented in Resolution 1973.

Although much of this support was only publicly admitted

in late October aer the Qadda regime had collapsed,

rumors and reports were circulating as early as June.

India’s Ambassador to the UN, Hardeep Singh Puri, started

disparagingly referring to NATO as the “armed wing” of the

UN Security Council precisely because he believed NATO’s

role in Libya had casually shied from protecting civilians in

Benghazi to overthrowing the government in Tripoli.

69

ere

was a growing view at the UN in New York that NATO was

no longer acting as a defensive shield for populations at risk,

but as the NTC’s air force.

Those who had most strenuously advocated in favor of

Resolutions 1970 and 1973 faced criticisms that R2P had been

12

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

co-opted by the “regime change” agenda of a few Western

powers. e contrary argument was that while Qadda’s

forces had been engaged, but not broken, they still constituted

a grave threat to civilians. Was there a strategic middle ground

between these positions?

e operational alternatives were far from desirable, but were

certainly more clearly in keeping with the original protective

mandate. Or, as “NATO Watch” argued:

e threat to Benghazi was the principal basis on which UN and

Arab League support was obtained for a no-y zone. at threat

was averted within days and no further resolution was gained for

NATO to support a rebel advance on Tripoli. Once [Qadda’s] heavy

weapons had been stopped the Libyan people could have been le to

struggle it out themselves (which might have prolonged the conict

and led to even more casualties). If no party had prevailed the option

of a negotiated political settlement brokered by the African Union

may have become more attractive.

70

Critiques of the ongoing intervention were especially strident

in the corridors of the UN, particularly regarding arms

being supplied to the NTC rebels despite the UN-authorized

embargo. Such activities le several countries enforcing

Resolution 1973 open to criticism regarding double standards

and clandestine agendas.

At the start of the intervention in Libya, President Barack

Obama of the United States had been careful to stay on

message, announcing on 21 March that, “when it comes to

our military action, we are doing so in support of United

Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 that specically

talks about humanitarian eorts, and we are going to make

sure that we stick to that mandate.”

71

But in a joint op-ed by

President Obama, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France and

Prime Minister David Cameron of the United Kingdom,

published around the world on 15 April, these leaders tried

to have it both ways. Aer referring to the “bloodbath” that

had been prevented in Benghazi, the three leaders argued that:

Our duty and mandate under UN Security Council Resolution 1973

is to protect civilians, and we are doing that. It is not to remove

Qadda by force. But it is impossible to imagine a future for Libya

with Qadda in power. It is unthinkable that someone who has

tried to massacre his own people can play a part in their future

government. e brave citizens of those towns that have held out

against forces that have been mercilessly targeting them would face

a fearful vengeance if the world accepted such an arrangement. It

would be an unconscionable betrayal.

72

As early as 10 March, before Resolution 1973 was passed,

France recognized the NTC as the legitimate representative

of the Libyan people. is conveyed the impression that,

beyond civilian protection, France had partisan interests in

Libya. Similarly, on 20 March, just a few days aer the NATO

bombing commenced, United Kingdom Defense Minister

Liam Fox said:

Mission accomplished would mean the Libyan people free to control

their own destiny. is is very clear – the international community

wants [Qadda’s] regime to end and wants the Libyan people to

control for themselves their own country.

73

ere is no doubt countries that were actively supporting

the Libyan intervention stretched their interpretation of

Resolution 1973 regarding “all necessary measures” to its

limit. But, on the other hand, questions regarding protection

of civilians cannot neglect political and military realities.

Given the well-founded fear that if Qadda were to regain

control of rebel-held territory he would perpetrate further

mass atrocities, assisting the rebels in preventing him from

doing so was, arguably, a legitimate part of the protection

mandate. Moreover, as has been argued by James Traub with

regard to Darfur:

Once the international community threatens to use coercive action

against a state committing atrocities, indigenous forces opposing the

state will see outside actors as their allies and act accordingly. e

discovery that the international community is on their side enhances

their sense of righteousness… ey will have little, if any, incentive

for diplomacy and compromise… Diplomats must make it clear

that they are intervening on behalf of a people, not an insurgency.

74

NATO’s prolonged campaign raised hopes among those

whose lives remained under threat and emboldened

the Benghazi-based NTC, while simultaneously raising

suspicion that the Libyan intervention was about more

thancivilian protection.

As the conict dragged on, these problems highlighted

the need to revisit the issue of establishing possible

guidelines for the use of military force in R2P situations.

In various high-level reports, books and speeches, Gareth

Evans, formerAustralian foreign minister and co-chair

13

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

of the international commission that developed R2P, has

consistently argued for ve criteria that could be used.

Without elaborating upon all of his supporting arguments,

the criteria are worth briey reviewing:

1.

Seriousness of harm. Is the threat clear and extreme

enough to justify military force?

2.

Proper purpose. Is the central purpose to halt or avert

the threat, despite “whatever other purposes or motives

may be involved?”

3.

Last resort. Has every reasonable non-military option

been explored?

4.

Proportional means. Are the scale, duration and intensity

of military action the minimum necessary?

5.

Balance of consequences. Is there a reasonable chance

of success in averting the threat without worsening the

situation? Is action preferable to inaction?

75

The Libya intervention initially met all five criteria.

However, it is arguable that as the civil war dragged on

the “proportional means” became less credible. But, it is

alsoimportant to remind ourselves of two essential facts.

e rst is that if Benghazi or Misrata had fallen to Qadda

there is every indication that widespread, indiscriminate

and deadly violence against civilians would have resulted.

Former British statesman Paddy Ashdown’s comment that

we should measure our success by “the horrors we prevent,

rather than the elegance of the outcome,” is perhaps relevant

in this regard.

76

Second, in some cases curtailing a government’s ability to

commit further mass atrocity crimes may not prove sucient

if such activities are integral to its survival. Few would quarrel

with the view that halting mass atrocities in Cambodia during

the genocidal rule of the Khmer Rouge, Uganda under Idi

Amin or Rwanda during the genocide became inseparable

from the goal of ending those regimes. Where a government

is the primary perpetrator of ongoing atrocities, changing

the leadership may sometimes be the only eective way to

end the crimes. In this context, permanently disabling the

capacity of the Qadda regime to harm its own people was

seen by some as essential to discharging the mandate of

civilian protection.

Backlash

Following the fall of Tripoli at the end of August, Libya’s

new leaders, having won a bitter civil war, faced enormous

challenges. Aer 42 years of dictatorship under Qadda,

the rule of law was almost non-existent. Infrastructure had

been damaged or destroyed throughout the country and

whatever limited governmental bureaucracy that existed

before February had collapsed. In addition, tribal divisions

and regional interests conicted with the NTC’s desire to

promote reconciliation and rebuilding.

According to the NTC an estimated 25,000 Libyans, including

soldiers from both the rebel and loyalist forces, died during

the civil war. One death, however, was especially notable. As

Tripoli fell to the rebels, Qadda and his entourage ed to

Sirte. Qadda continued to denounce the rebels in messages

broadcast via foreign media.

77

When rebels reached the center

of Sirte on 20 October, Qadda made the fateful decision to

ee the city in a convoy of vehicles.

Aer being detected from the air, the convoy was bombed,

apparently without NATO realizing Qadda was in one of

the cars. Qadda survived, but was wounded and disoriented.

He then walked with two aides towards the main road, before

hiding in a drainage pipe to avoid rebel soldiers. Upon

discovery he was infamously hauled from the pipe, beaten

and most likely tortured, before being executed by gunshots

to the belly and head. His corpse was then publicly displayed

in Misrata as a trophy of war.

Although the UN, the ICC and numerous international

human rights organizations would all call for an investigation

into the extra-judicial execution of Qadda, within Libya

there initially seemed to be little appetite for anything except

rejoicing over his demise. Nevertheless, his treatment at the

hands of his captors (recorded on smartphone and broadcast

around the world) was deeply disturbing and possibly

constituted a war crime.

78

While rebel forces had largely escaped critical scrutiny in the

international media during the struggle against Qadda’s

regime, organizations such as Human Rights Watch and

Amnesty International raised serious concerns about the

conduct of some rebel units. Human Rights Watch reported,

for example, on the situation in Tawergha, near Misrata,

where rebels had taken reprisals against a town mainly

comprised of black Africans who were collectively accused

14

OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES |

LIBYA AND THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

of siding with Qadda during the civil war. e town of

30,000 people was forcibly depopulated and much of it put

to ame. Human Rights Watch also documented another

incident where 53 pro-Qadda loyalists appeared to have

been summarily executed by rebel soldiers in Sirte.

79

e UN Human Rights Council’s International Commission

of Inquiry later concluded that anti-Qaddafi forces,

“committed serious violations, including war crimes and

breaches of international human rights law.” ese crimes

included “unlawful killing, arbitrary arrest, torture, enforced

disappearance, indiscriminate attacks and pillage.” e March

2012 report detailed ongoing attacks by anti-Qadda militias

against former residents of Tawergha, but also noted that

“the signicant dierence between the pastand the present

is that those responsible for abuses now are committing them

on an individual or unit level, and notas part of a system of

brutality sanctioned by the centralgovernment.”

80

Even before Qadda’s death the UN had recognized the NTC

as the legitimate representatives of the Libyan people. But the

end of the civil war led to broader reection regarding the

legitimacy of the intervention. Announcing the completion

of NATO’s operation at the end of October, the alliance’s

Secretary-General, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, claimed that

NATO-led forces had “prevented a massacre and saved

countless lives.”

81

But rather than focusing on the lives saved

in Benghazi and elsewhere, some critics continued to focus

upon the deaths resulting from six months of civil war.

82

For example, former President abo Mbeki echoed the South

African government’s criticisms of the Libyan intervention,

arguing that NATO members on the UN Security Council

had actively “blocked” the AU’s attempts to peacefully resolve

the Libyan conict.

83

A soer, but more widely reported,

critique came from former UN Secretary-General Kofi

Annan. Speaking at the University of Ottawa on 4 November,

at a meeting to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the

creation of the R2P concept, Annan expressed concern over

the fact that “regime change came up very quickly” in Libya.

84

Inuential voices in the mass media also chimed in, but the

real test would be inside the Security Council.

85

As Resolution 1973 passed in the Security Council, Syria

erupted in protest. Similarly inspired by the Arab Spring, an

opposition movement that had been developing since January

had become a popular uprising by mid-March. e reaction

of the Syrian security forces was bloody and unrelenting.

Over the following year more than 10,000 civilians would be

killed as the Syrian state used soldiers, tanks, artillery, attack

helicopters and even warships to crush popular opposition

to its rule. With the Security Council initially distracted by

Libya, and with permanent council member Russia a long-

standing ally, the government of President Bashar al-Assad

was able to prevaricate, break numerous promises to reform

and avoid UN action.

ere was a glaring disparity in the Security Council’s

response – timely and effective in Libya, tardy and

underwhelming in Syria. ere are ve factors that explain

the Security Council’s actions.

First, key actors in the region played a dierent role in both

crises. e Arab League’s rapid condemnation of Qadda’s

actions and calls for a no-y zone in Libya contrasted with its

initially cautious response to the situation in Syria. Lebanon,

the only Arab League member on the Security Council,

pushed the council to take action on Libya but initially

defended the Syrian government. e Arab League did not

start to play a leading role regarding the Syrian crisis until

the second half of 2011.

Second, whereas a sizable number of key Libyan ocials

defected from the regime (including the leadership of Libya’s

Permanent Mission to the UN, who made compelling

statements during Security Council discussions), in Syria

the regime maintained the formal allegiance of most senior

government ocials during the rst months of the crisis. e

Ambassador of Syria to the UN, Bashar Ja’afari, remained a

steadfast supporter of Assad.

ird, Libya’s status as a pariah state without powerful allies

contrasts with Syria, which maintains close relationships with

Russia and Iran. Fourth, public statements by Qadda that

he would “cleanse” the nation of “cockroaches” were viewed

as incitement to commit crimes against humanity, whereas

Assad made statements that were viewed as conciliatory

despite all evidence to the contrary. Finally, several council

members were nervous about the Security Council possibly

being drawn into another armed intervention.

Despite ongoing mass atrocity crimes, on 4 October 2011

Russia and China vetoed a Security Council resolution that

sought to impose sanctions, an arms embargo and travel bans

on the Syrian government. e ostensible justication was

that Russia and China were nervous that such UN-authorized

15

| GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT

measures might eventually lead to Syria becoming “the

next Libya.” e double veto was, therefore, also an explicit

challenge to the Responsibility to Protect.

The reality is that Russia would have vetoed the Syria

resolution even if the Libyan intervention had never happened

and R2P did not exist. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union

was Syria’s major military supplier and the government

allowed the Kremlin to establish a naval base at Tartus, the

Soviets’ only military outpost in the Mediterranean and

Middle East. Tartus remains a key component of Russia’s

plan to rebuild a global military presence befitting a

recovering superpower. Furthermore, in August 2011 the

Moscow Times had commented that Russia’s tepid support

for Security Council action in Libya had adversely aected

Russia’s arms industry and strategic interests. At the start

of the Syrian crisis, Assad’s government had $6 billion in

activearms contracts, making it one of the top ve importers

of Russianweaponry.

86

Traditionally nervous about any UN action that impinges

upon state sovereignty, China had only used its veto six times

since 1972. Lacking any direct interest in Libya and facing a

world outraged by Qadda’s crimes against his own people,

China abstained from the crucial Security Council resolution

that led to the Libyan intervention. However, Russia’s intense

lobbying convinced the Chinese to veto with regard to Syria.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Syria brought the issue of R2P and

selectivity into the center of the political debate. Although

some critics argued that selectivity posed a potentially fatal

risk to the norm, academic Michael Barnett argued that it

was necessary to not exaggerate the issue:

All international norms are selectively applied, especially norms that

include the use of force. If selectivity and inconsistent use doomed

international norms, then there would probably be no international

norms to speak of. e real measure of R2P’s success is whether it

helps those marked for death.

87

Libya and Syria also posed important questions regarding the

role of the IBSA countries – India, Brazil, South Africa – on

the Security Council. South Africa voted for Resolution 1973

while Brazil and India abstained. All three emerging powers

abstained on the Syria resolution in October. e position

of Ambassador Baso Sangqu of South Africa was that with

regard to Syria the “trajectory, the templates for the solution

were very clear, it was along similar lines to Libya.”

88

Such

a view became less sustainable the longer the crisis endured

and the more the coercive elements in the proposed resolution