Toward a More Collaborative Federal Response to Chronic Kidney

Disease

Andrew S. Narva, Michael Briggs, Regina Jordan, Meda E. Pavkov, Nilka Rios Burrows, and

Desmond E. Williams

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda MD, Centers for

Disease Control, Atlanta GA

Over the past twenty years, chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become recognized as a

significant public health problem in the United States. It is a common and costly disease: it is

estimated that CKD may affect 23.2 million Americans older than 20 years; (1) in 2006, costs

for Medicare patients with kidney disease exceeded $49 billion, or nearly one-quarter of all

Medicare spending. (2)

CKD is generally easy to diagnose, and effective treatments exist. (3–5) National objectives

reflecting quality of CKD care were included for the first time in Healthy People 2010. (6)

Despite this recognition, the publication of a number of clinical guidelines, and significant

effort on the part of voluntary health organizations and professional groups, data from the

United States Renal Data System (USRDS) and other sources suggest that much work remains

to be done to achieve acceptable levels of recommended care. In 2006, fewer than 35 percent

of people with diabetes and kidney disease received basic care (i.e., an eye exam, lipid

evaluation, and 2 measurements of hemoglobin A1c).(7) Seventy-three percent were treated

with renin-angiotensin system antagonists, a level little improved over the previous 5 years.

(8) Blood pressure control for CKD patients is poor; nearly half of the hypertensive patients

in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) had uncontrolled blood

pressure, and another quarter were unaware of their condition or left it untreated. (9) Fewer

than 40 percent of patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 30

mL/min/1.73

2

were coded with a CKD diagnosis. (10) One third of patients do not see a

nephrologist prior to initiation of renal replacement therapy and only 13 percent have seen a

dietitian prior to initiation. (11) Approximately half of patients with no pre-dialysis nephrology

care had pre-initiation hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL, compared with 35 percent of

patients with greater than 1 year of nephrologic care. (12) For more than 80 percent of patients

initiating hemodialysis, vascular access was provided by a catheter. (13)

As guardian of the nation’s health, the Federal government has developed the infrastructure to

promote population-based interventions which have proven effective in reducing the burden

of other chronic illnesses, such as stroke and cancer. In addition, the Federal government has

a unique role in addressing the morbidity associated with CKD through funding care for people

with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). An effective, coordinated response by Federal health

Corresponding author: Andrew S. Narva, MD Director, National Kidney Disease Education Program DKUH, NIDDK, NIH Two

Democracy Plaza, Room 644 6707 Democracy Blvd, MSC 5458 Bethesda, MD 20892-5458 Phone: 301-594-8864 Fax: 301-480-3510

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers

we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting

proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could

affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010 May ; 17(3): 282–288. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.006.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

agencies to the public health challenge of chronic kidney disease could have a significant effect

on the morbidity, mortality, and cost associated with CKD.

Current Federal efforts span a range of missions, including surveillance; professional and

patient education; outreach to high-risk populations; quality improvement; and delivery of, as

well as payment for, CKD treatment. Such activities are conducted by programs across several

Federal health agencies. Considered as a whole, the Federal government appears to have a

fairly comprehensive approach to CKD management.

However, Federal agencies do not function as a comprehensive system or, indeed, as a system

at all. Many programs operate independently of each other, which increases the risk of

contradictions, redundancies, and gaps. Even though agencies are doing excellent and needed

work on CKD issues—indeed, this paper highlights several notable examples—the collective

reach and impact of these programs fall short of their true potential. Improving communication

and coordination among Federal CKD programs would therefore be a key step in improving

the overall Federal response to CKD.

The barriers to achieving greater effectiveness begin with poor visibility. Federal program

managers experience difficulty in learning about, or staying abreast of, what other Federal

agencies do related to CKD.

Lack of coordination is among the sequelae of poor visibility: if program managers are unaware

of what is happening, it becomes difficult for them to work together. If duplicated efforts are

not visible, they cannot be avoided; if opportunities for collaboration are not identified, they

cannot be capitalized upon; if populations of focus are not clearly defined, communities in

need can fall through the cracks. What might otherwise be a well-coordinated group of Federal

programs, with aligned objectives and clear divisions of labor, has historically been a band

marching to the beats of different drummers.

In recent years, however, initiatives undertaken by 3 Federal agencies have made important

advances in coordinating efforts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has

begun to develop a surveillance system and public health analyses that require dialogue and

coordination among numerous agencies. The Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services

(CMS) has, through the successful Fistula First initiative and inclusion of chronic kidney

disease in the scope of work of Quality Improvement Organizations, helped build relationships

and infrastructure that support earlier diagnosis and treatment of CKD. The National Institute

of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, through its National Kidney Disease Education

Program, has reinvigorated and expanded the Kidney Interagency Coordinating Committee in

ways that make it a robust vehicle to share information about activities, identify and disseminate

promising practices and tools, and foster cross-agency collaboration.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In 2006, Congress appropriated funds to develop capacity and infrastructure at CDC for a

kidney disease surveillance, epidemiology, and health outcomes program. These funds seeded

what has now become the CDC CKD initiative. The CKD initiative is designed to develop and

implement public health strategies for promoting kidney health. These strategies seek to

prevent and reduce the progression of CKD, raise awareness about CKD and its risk factors,

promote early diagnosis, and improve outcomes and quality of life for those living with CKD.

CDC has developed collaborative relationships with research institutions, other Federal

agencies, and national organizations that are currently engaged in CKD action. CDC’s activities

are designed to provide fundamental and timely public health information for the CKD

professional and public audience.

Narva et al. Page 2

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

CDC—in collaboration with the University of Michigan, University of California at San

Francisco, and Johns Hopkins University—is attempting to establish a national surveillance

system for CKD in the United States. (14) The surveillance system currently uses existing local

and national sources of CKD data to quantify the CKD burden, identify gaps and deficiencies

in existing data sources, and propose creative solutions and remedies to fill gaps and

deficiencies. The surveillance project also is developing a plan to integrate all data sources into

a functional surveillance system. This surveillance system will be made available through an

interactive web-based interface that would provide current and trend data on the state of CKD.

CDC is collaborating with other Federal agencies, academia, national organizations, and the

public to develop a CKD fact sheet that will provide definitive information on the burden and

consequences of CKD in the United States that can be used by all partners. In collaboration

with the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the CKD

initiative supports the development, refinement, and collection of kidney measures in the

NHANES survey of American adults and children. (15)

CKD Health Evaluation Risk Information Sharing (CHERISH),a collaborative project of CDC

and the National Kidney Foundation, is a free health screening to identify individuals who have

CKD or are at increased risk for developing CKD. Screening participants can learn if they have

kidney disease or are at risk for kidney disease; they receive referrals if their results are outside

of normal ranges, as well as a follow-up survey to assess their care after the screening.

CHERISH has developed an algorithm using data from NHANES that maximizes the yield of

CKD detection and screening programs. CHERISH will assess the burden of kidney disease

in a high-risk targeted population, determine the individual’s subsequent access to care, and

address the likelihood of disease progression in those with evidence of CKD. This study is

currently being conducted in 8 sites in 4 states to test the feasibility of implementing such a

program. Preliminary data suggest strong participation rates from the public; preliminary

results were presented at October 2009 American Society of Nephrology meeting in San Diego.

(16)(17)

CDC also collaborates with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) - Puget Sound Health

Care System to examine the natural history of CKD and evaluate the rate of progression through

the stages of CKD and development of complications using national VA data sources. (18)

The CKD Cost-Effectiveness Study, conducted by CDC in collaboration with the Research

Triangle Institute, has developed and validated a lifetime simulation model to predict the

development and progression of CKD in the United States (19). The program is now using the

model to assess the cost-effectiveness of various public health interventions to prevent, delay,

and manage CKD and its complications. The first application of the model was to test the cost-

effectiveness of screening and early treatment of CKD. (20) CDC is also researching the direct

and indirect economic cost of CKD through its Cost of Illness Study. (21)

CDC continues to work in close collaboration with other Federal agencies. CDC activities

support CMS in its activities related to the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers

Act of 2008 (see below), and CDC is collaborating with NIDDK to lead the development of

new kidney objectives for Healthy People 2020.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

In 2004, each person with CKD annually cost Medicare $20,668, a 5.3 percent increase over

the previous year, and 41 percent more than in 1993. Medicare expenditures for ESRD in 2006

were an additional $22.7 billion; (22) they are projected to more than double, to $55.6 billion,

Narva et al. Page 3

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

by 2020. (23) Because the average cost of providing care for a dialysis patient is $72,000 per

year, (24) there are significant potential cost savings associated with implementation of

interventions that help slow the progression of CKD. According to the USRDS, Medicare saves

$250,000 for each patient who does not progress to dialysis (based on $65,000 annual cost of

Medicare ESRD services and a 4-year life expectancy). (24) Patients with CKD, diabetes, and

hypertension, either alone or in combination, represent the greatest disease burden to the

Medicare program. In 2007, patients with CKD made up 9.8 percent of the general Medicare

population, but expenditures associated with CKD amounted to 27.6 percent of costs. (25)

There is a clear need for medical interventions that help slow the progression of CKD and

reduce costs.

Quality Improvement Organizations

Created by Congress in 1982, Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs) work to improve

the quality of services provided to Medicare beneficiaries. CMS interprets this to include a

broad range of proactive initiatives that promote quality care. Included in its Scope of Work

for the program are tasks that direct QIOs to provide technical assistance, including information

exchanges, to Medicare providers to help them improve the quality of care they provide. (26)

The ninth Scope of Work, currently in effect, tasks QIOs with improving detection and care

of CKD with the aim of decreasing progression of chronic kidney disease among Medicare

beneficiaries. Specifically, CMS asks QIOs to focus on 3 areas: annual testing to determine

the rate of kidney failure due to diabetes; use of ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin receptor

blockers to slow progression of CKD in patients with diabetes and hypertension; and timely

placement of an arteriovenous fistula. (27)

Though these are important objectives in themselves, the strategies that QIOs employ to

achieve them help advance a more comprehensive and coordinated approach to CKD

management. CMS directs QIOs to increase provider use of tested and proven clinical practices;

disseminate to providers and patients tools and resources that are already available through

other Federal partners; and work in collaboration with others to achieve lasting system level

changes across a variety of care settings (e.g., hospitals, nursing homes, and community health

centers). (28)

Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative

The CMS-led Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative (FFBI) has achieved remarkable success

over the past 6 years—the percentage of prevalent hemodialysis patients in the United States

with an arteriovenous fistula as their primary vascular access rose from 32.4 percent at the

beginning of 2003 to 53.3 percent by August 2009. (29) The marked increase in fistula

placement may be an indicator of more comprehensive and better coordinated management of

CKD; additional progress will be difficult without improvements in early detection, patient

education, and early referral.

Further collaboration will be required to achieve the new CMS goal of a prevalent arteriovenous

fistula utilization rate of 66 percent. With leadership from CMS—and support from the ESRD

Networks, QIOs, and the more than 60 diverse groups in the FFBI Coalition—the FFBI works

to implement 7 strategies to achieve this new goal. (30) As with QIOs, these strategies

demonstrate how CMS can promote a more comprehensive response to CKD. The FFBI

Strategic Plan requires a high degree of partnership and coordination across specialties, practice

settings, and professional communities. Early referral to nephrologists is a key objective; late

referral has been shown to be a major determinant in the use of central venous catheters at

hemodialysis initiation. (31) The Strategic Plan seeks to engage a diverse group of referring

physicians and associated healthcare systems to increase awareness of the importance of AV

Narva et al. Page 4

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

fistulas, and especially the need for early referral to allow for placement and maturation prior

to initiation of hemodialysis.

The ESRD Networks and QIOs play a crucial role in this effort, disseminating information and

providing technical assistance to the numerous providers and partners with whom they are

already working. These partners are indeed a key component of the FFBI’s success. By sharing

information with and among a wide variety of stakeholders (e.g., renal and other professional

associations, dialysis providers, vascular access surgeons, hospital and primary care

associations, insurance providers, and community groups) the FFBI Coalition has helped reach

CKD patients and those in a position to influence practice patterns. The 6 CKD educational

sessions covered under the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008

provide a new opportunity to educate patients and caregivers on the importance of timely

placement of vascular access.

National Institutes of Health—The NIDDK and other institutes at NIH support a $523

million portfolio of kidney research. (32) The scope of this research is broad, examining basic,

clinical, and epidemiologic aspects of kidney disease. The USRDS, the annual NIDDK-funded

analysis of data on kidney disease in the United States, is used in quantifying public health

trends, guiding funding priorities, and designing targeted kidney research programs. Of

particular interest to other Federal agencies is the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study,

a longitudinal cohort study of 4,000 people with CKD, half of whom have diabetes. (33)

Longitudinal data is just becoming available, but the study will likely play a large role in

informing efforts to predict risk for progression of CKD and guide population management

interventions. The National Kidney Disease Education Program (NKDEP) was established by

NIDDK in 2000 to reduce the morbidity and mortality caused by CKD and its complications.

NKDEP aims to improve early detection of CKD, facilitate identification of patients at greatest

risk for progression to kidney failure, promote evidence-based interventions to slow

progression of CKD, and support the coordination of Federal responses to CKD. To achieve

its goals, NKDEP works in collaboration with a range of government, nonprofit, and health

care organizations to: raise awareness among people at risk for CKD about the need for testing;

provide information, training, and tools to help health care providers better detect and treat

CKD; and support changes in the laboratory community (e.g., standardizing the measurement

and reporting of serum creatinine and eGFR) that yield more accurate, reliable, and accessible

test results. Central to NKDEP’s approach is the concept that CKD should be identified and

addressed in the primary care setting, and that managing CKD prior to referral can improve

patient outcomes.

As a Federal program devoted to improving health outcomes associated with chronic kidney

disease, NKDEP is well suited to serve as a catalyst for a coordinated Federal response to CKD.

An appropriate vehicle has existed since 1987: the Kidney Interagency Coordinating

Committee, based at NIDDK and mandated by Congress to encourage cooperation,

communication, and collaboration among all Federal agencies involved in kidney research and

other activities.

Beginning in 2007, NKDEP took an active role in coordinating the Kidney Interagency

Coordinating Committee, expanding it from a brief pro forma annual meeting into an active,

multifaceted, year-round initiative. The committee has been revitalized by its member agencies

and now serves as a forum to raise awareness of the range of activities within the Federal

government around CKD detection and treatment. Improved interagency communication,

facilitated in part by a newsletter and Web-based tool (see below), has produced gratifying

efforts at collaboration, particularly among the NIH, CDC, and CMS.

Narva et al. Page 5

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

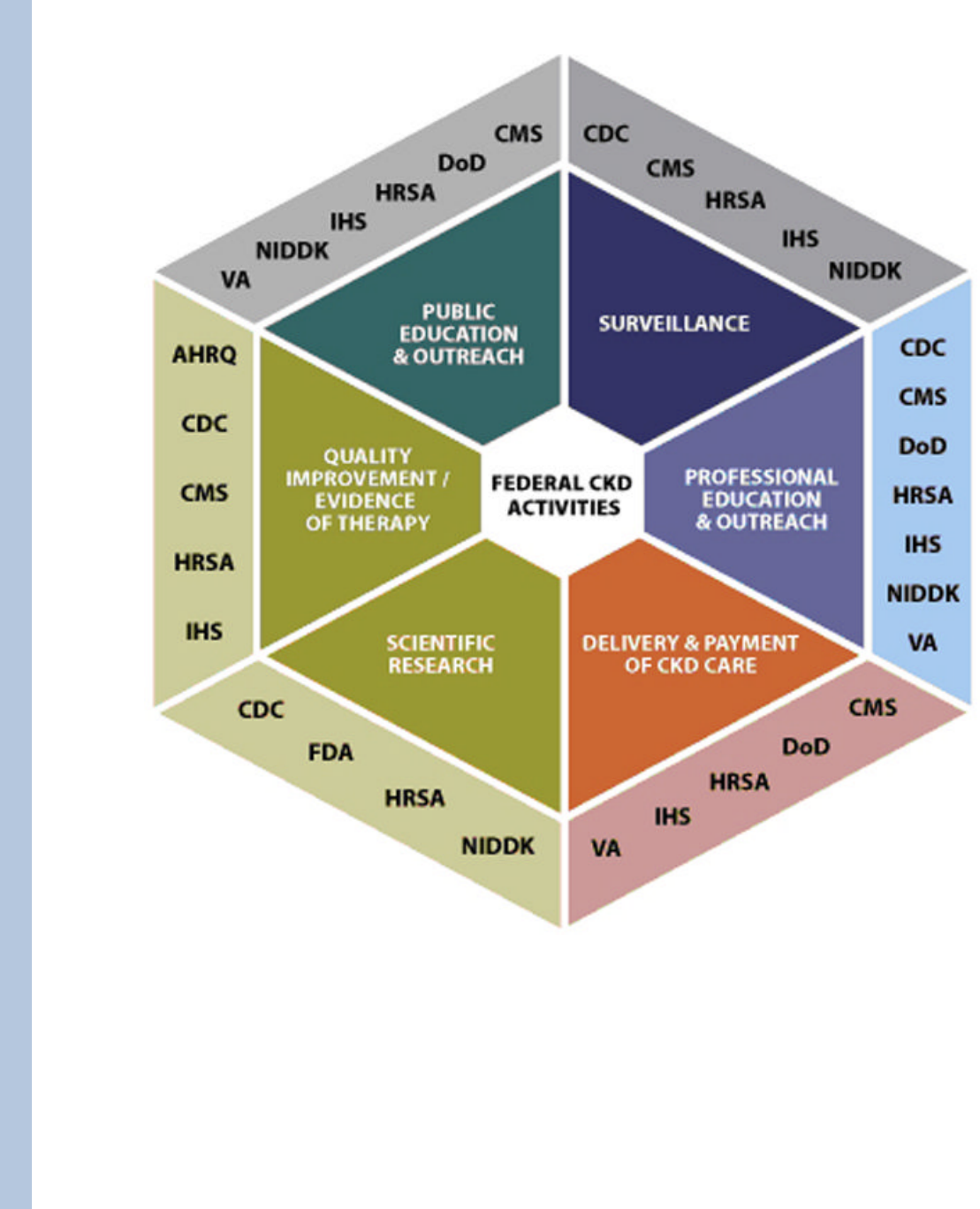

One novel product of the Kidney Interagency Coordinating Committee has been a matrix to

document the range of programs undertaken by each agency. The KICC Matrix, shown in its

concise reference form in Figure 1, is available on the NKDEP website as an interactive matrix

that enables Federal agencies and others to easily summarize all CKD-related activities across

9 Federal agencies. (34) Visitors can: click on a response category (e.g., Quality Improvement/

Evidence of Therapy, Scientific Research, Professional Education and Outreach) to learn about

agency activities in that area; click on an agency name to learn about its activities across

response categories; or click a Summary button to quickly learn what a particular agency is

doing in a particular response category. Contact information for each agency and initiative is

also provided to foster additional collaboration.

Other Efforts—In addition to the CDC, CMS, and NIH efforts described above, the Indian

Health Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Department of Defense all support direct

care systems which serve populations with a high prevalence of, or at high risk for, CKD.

Despite limited resources, each of these systems has demonstrated the ability to implement

systematic change to improve care in CKD, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. As Federally

funded direct-care systems, they are accountable to the public and have a strong incentive to

deliver care in the most cost-effective manner. The systems can be surprisingly innovative and

effective: the VA electronic health record is highly regarded, and American Indians with

diabetes appear to have reduced rates of ESRD despite growing prevalence of diabetes.

Recommendations for Further Collaboration

In addition to the improvements in communication and cooperation made possible by the

Kidney Interagency Coordinating Committee—as well as other opportunities for coordinated

planning, such as Healthy People 2020—there are several priority areas in which Federal

agencies can better align their efforts and amplify their collective impact. These include: a

cross-agency initiative to define quality improvement measures relevant to CKD; a systematic

assessment of existing clinical guidelines related to CKD, out of which may emerge a collective

effort to identify and close gaps in knowledge about primary and secondary CKD education;

joint development and distribution of prediction tools for progression to kidney failure; and

coordinated efforts to strengthen educational offerings and materials for primary care

providers.

It also will be important to look beyond those Federal agencies working directly on CKD toward

new models of collaboration and collective planning being adopted by others within the Federal

government. One example is the Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Collaboratory—a joint

initiative of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality, and the HHS Personalized Healthcare Initiative—which brings together

Federal agencies to share CDS-related information and support. Such a forum provides a

vehicle for Federal agencies to work together to improve clinical decision support on CKD-

related issues

Conclusion

The health agencies of the Federal government devote great resources to reducing the burden

of chronic kidney disease. Although these efforts, from surveillance of early CKD through

quality improvement of ESRD care, are comprehensive in scope, they are not perceived as

such. This may be due to the failure of the various agencies to coordinate their efforts. With

appropriate coordination, the effectiveness and coherence of each agency’s efforts could be

enhanced and implementation of system changes needed to improve CKD outcomes could be

promoted. Collaboration among Federal healthcare agencies is likely to enhance efforts to

reduce the burden of CKD in the United States.

Narva et al. Page 6

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

References

1. Levey AS, Stevens LA, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of Internal

Medicine 2009;150(9):604–613. [PubMed: 19414839]

2. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and

End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Vol. 1. National Institutes of Health, National Institute

of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2008. p. 84Fig

3. Giatras I, Lau J, Levey AS. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the progression of

nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme

Inhibition and Progressive Renal Disease Study Group. Annals of Internal Medicine 1997 Sep 1;127

(5):337–45. [PubMed: 9273824]

4. Jafar TH, Schmid CH, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic

renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001 Jul 17;135(2):

73–87. Erratum in: Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002 Aug 20;137(4):299. [PubMed: 11453706]

5. Sarnak MJ, Greene T, et al. The effect of a lower target blood pressure on the progression of kidney

disease: long-term follow-up of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study. Annals of Internal

Medicine 2005 Mr 1;142(5):342–51. [PubMed: 15738453]

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving

Health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov. 2000

7. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

8. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

9. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

10. Stevens LA, Fares G, et al. Low rates of testing and diagnostic codes usage in a commercial clinical

laboratory: Evidence for lack of physician awareness of chronic kidney disease. Journal of the

American Society of Nephrology 2005;16:2439–2448. [PubMed: 15930090]

11. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

12. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

13. U.S. Renal Data System, USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report

14. Saran R, Hedgeman E, et al. Establishing a National Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System

for the United States. Clinical Journal of American Society of Nephrology. 2010 In press.

15. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 [Assessed 11/23/2009]. Found at

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

16. Collins, A.; Vassalotti, J., et al. Prevalence and Control of CVD Risk Factors Among Initial CHERISH

Participants with CKD. American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Conference; 27 Oct -1 Nov 2009;

San Diego, CA. 2009. Poster Board number; F-PO1602

17. Chen, SC.; Li, S., et al. Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease: Initial Results from the CKD Health

Evaluation Risk Information Sharing (CHERISH) Program. American Society of Nephrology

Conference; 27 Oct -1 Nov 2009; San Diego, CA. 2009. Poster Board number; FPO1603

18. O’Hare, AM.; Pavkov, ME., et al. Prognostic Importance of Albuminuria Varies by eGFR. American

Society of Nephrology (ASN) Conference; 4–11 Nov 2008; Philadelphia, PA. 2008.

19. Hoerger T, Wittenborn J, et al. A Cost-Effectiveness Model of Chronic Kidney Disease: I. Model

Construction, Assumptions, and Validation. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2010 In press.

20. Hoerger, T.; Wittenborn, J., et al. The Cost-Effectiveness of Screening for Microalbuminuria: A

Simulation Model for Chronic Kidney Disease. National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Spring Clinical

Meetings; 25 29 Mar 2009; Nashville, TN. 2009.

21. Honeycutt, A.; Segel, J., et al. Medical Costs Attributable of Chronic Kidney Disease among Medicare

Beneficiaries. American Society of Nephrology Conference; 4–11 Nov 2008; Philadelphia, PA. 2008.

Poster Board number; SA-02908

22. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and

End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Vol. 2. National Institutes of Health, National Institute

of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2008. p. 177

Narva et al. Page 7

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

23. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the

United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney

Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2007. p. 92

24. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Volume Three: Reference Tables on

ESRD in the U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and

Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2009. p. 654Table H.31

25. U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Volume One: Atlas of CKD in the U.S.

National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases;

Bethesda, MD: 2009. p. 133Figure 1

26. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 9th Scope of Work for QIOs. [Accessed 10/19/09].

http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityImprovementOrgs/downloads/

9thSOWBaseContract_C_08-01-2008_2_.pdf

27. CMS, 9

th

Scope of Work for QIOs.

28. CMS, 9

th

Scope of Work for QIOs.

29. FFBI Press Release: –Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative Provides Road Map to Reach CMS Goal

of 66%.⍰ October 7, 2009. Found at

http://www.fistulafirst.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=wDp4IvjjXJ0%3d&tabid=144. Accessed

10/30/09. (Press release includes data through May 2009; August 2009 AVF figure found on the

FFBI homepage at www.fistulafirst.org. Accessed 10/30/09.)

30. Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative Strategic Plan. Aug 312009 [Accessed 10/30/09]. Found at

http://www.fistulafirst.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=wxrkvcyrokk%3d&tabid=39

31. Roderick P, Jones C, et al. Late referral for dialysis: improving the management of chronic renal

disease. QJM 2002;95:363–70. [PubMed: 12037244]

32. NIH Research Online Reporting Tool (RePORT). [Accessed 11/19/09]. Found at

http://report.nih.gov/rcdc/categories/Projectsearch.aspx?FY=2008&DCat=Kidney%20Disease

33. Feldman HI, Appel LJ, et al. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design and

Methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:S148–S153. [PubMed: 12819321]

34. NKDEP Website. [Accessed 11/4/09]. Found at

http://nkdep.nih.gov/about/kicc/federal-ckd-matrix.htm

Narva et al. Page 8

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Figure 1.

Narva et al. Page 9

Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 May 1.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript