U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Page 2 | Advancing American Kidney Health

CONTENTS

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................

I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................

II. Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................................................................................

III. HHS Initiatives ............................................................................................................................................................

Technical Appendix ........................................................................................................................................................

Page 3 | Advancing American Kidney Health

INTRODUCTION

One of the top healthcare priorities of the Trump Administration—and many other stakeholders in

American healthcare—has been the shift from paying for sickness and procedures to paying for health

and outcomes.

There is no better example of an area that needs this transformation than the way we prevent and treat

kidney disease. Approximately 37 million Americans have kidney disease, and, in 2017 kidney disease was

the ninth-leading cause of death in the United States. The primary form of treatment for kidney failure is

dialysis, which is one of the most burdensome, draining long-term treatments modern medicine has to

oer. I know this personally—as so many Americans do—because my father was on dialysis for years.

Dialysis is also far from sustainable: One hundred thousand Americans begin this treatment each

year, and approximately one in five of them are likely to die within a year. Further, the best option we

currently have to oer those with kidney failure is a kidney transplant, but there are almost 100,000

Americans currently on a waiting list for new kidneys. A kidney transplant saved my father’s life; we

want to make that same outcome possible for many more Americans, while also looking to the future to

develop new, better options.

Today’s status quo in kidney care also carries a tremendous financial cost. In 2016, Medicare fee-for-

service spent approximately $114 billion to cover people with kidney disease, representing more than

one in five dollars spent by the traditional Medicare program.

But there is hope. A system that pays for kidney health, rather than kidney sickness, would produce

much better outcomes, often at a lower cost, for millions of Americans. The Trump Administration

plans to eect this transformation through a new vision for treating kidney disease—Advancing

American Kidney Health—laid out in this document.

We have set three particular goals for delivering on this vision, with tangible metrics to measure

our success:

1. We need more eorts to prevent, detect, and slow the progression of kidney disease, in part by

addressing upstream risk factors like diabetes and hypertension. We aim to reduce the number

of Americans developing end-stage renal disease by 25 percent by 2030.

1. We need to provide patients who have kidney failure with more options for treatment, from

both today’s technologies and future technologies such as artificial kidneys, and make it easier

for patients to receive care at home or in other flexible ways. We aim to have 80 percent of new

American ESRD patients in 2025 receiving dialysis in the home or receiving a transplant.

2. We need to deliver more organs for transplants, so we can help more Americans escape the burdens

of dialysis altogether. We aim to double the number of kidneys available for transplant by 2030.

With the help of many stakeholders, inside and outside of government, HHS has diagnosed the prob-

lems with our system, detailed what success looks like, and laid out how to get there. Over the next

several years, we will execute on the strategies laid out in the following pages: pioneering new payment

models, updating regulations, educating and empowering patients, and supporting new paths for re-

search and development.

This eort will build on the work underway throughout many HHS agencies including ASPR, CDC, CMS,

FDA, HRSA, IHS, and NIH, and will engage outside kidney-care stakeholders and innovators in other fields.

By executing on this bold, comprehensive vision, we can achieve our goals, bring kidney care for all

Americans into the 21

st

century, and show that some of the most stubborn, costly problems in American

healthcare can be solved.

Alex M. Azar II

Secretary of Health and Human Services

Page 4 | Advancing American Kidney Health

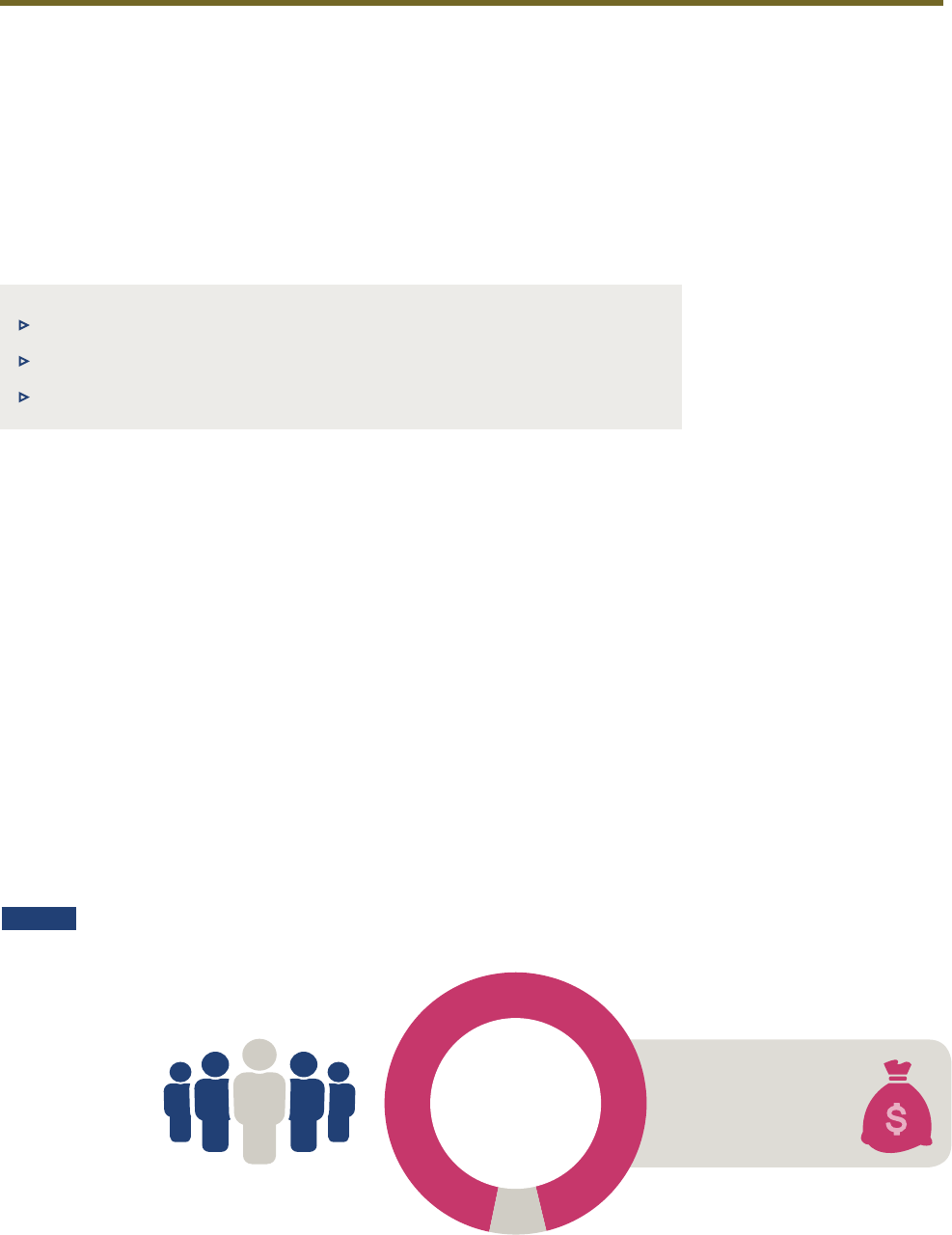

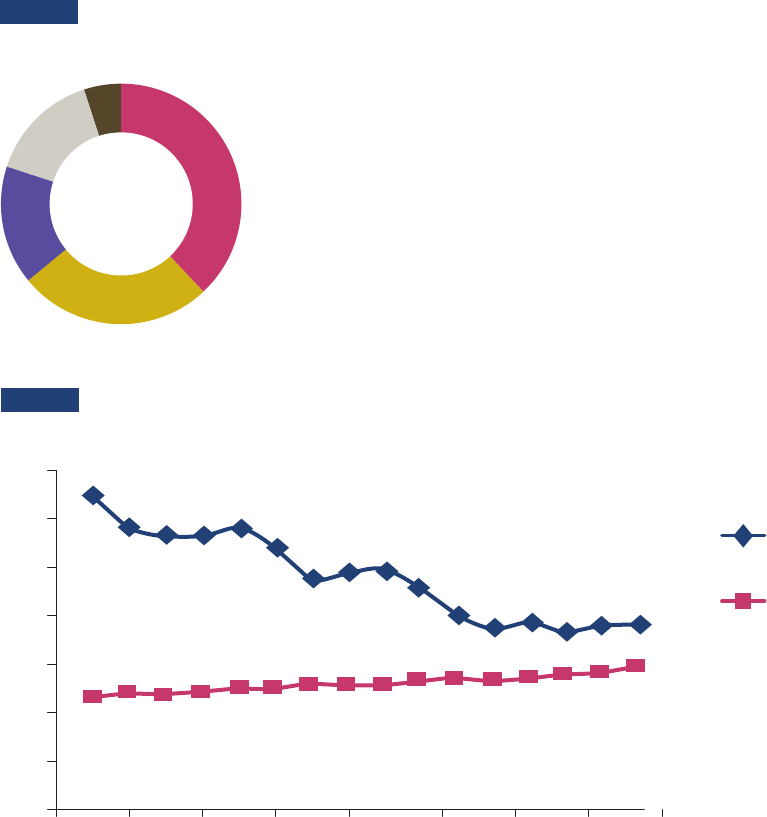

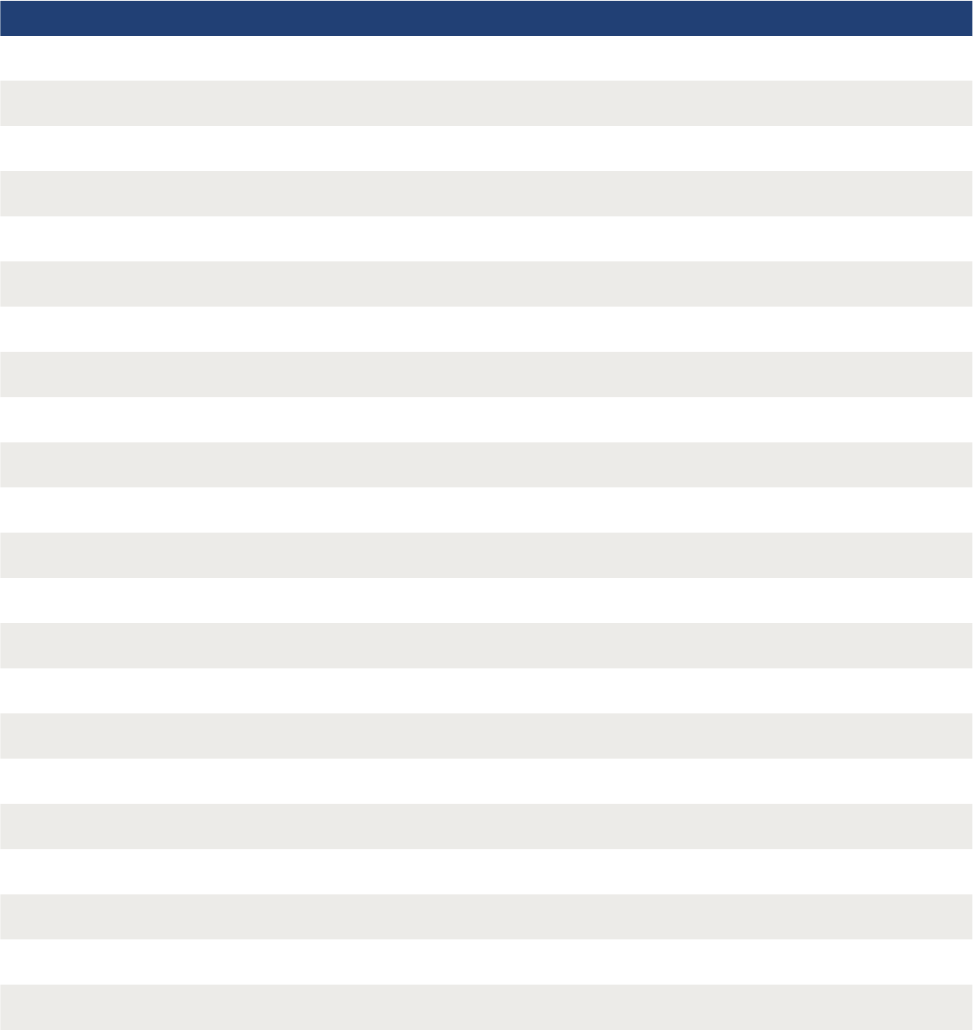

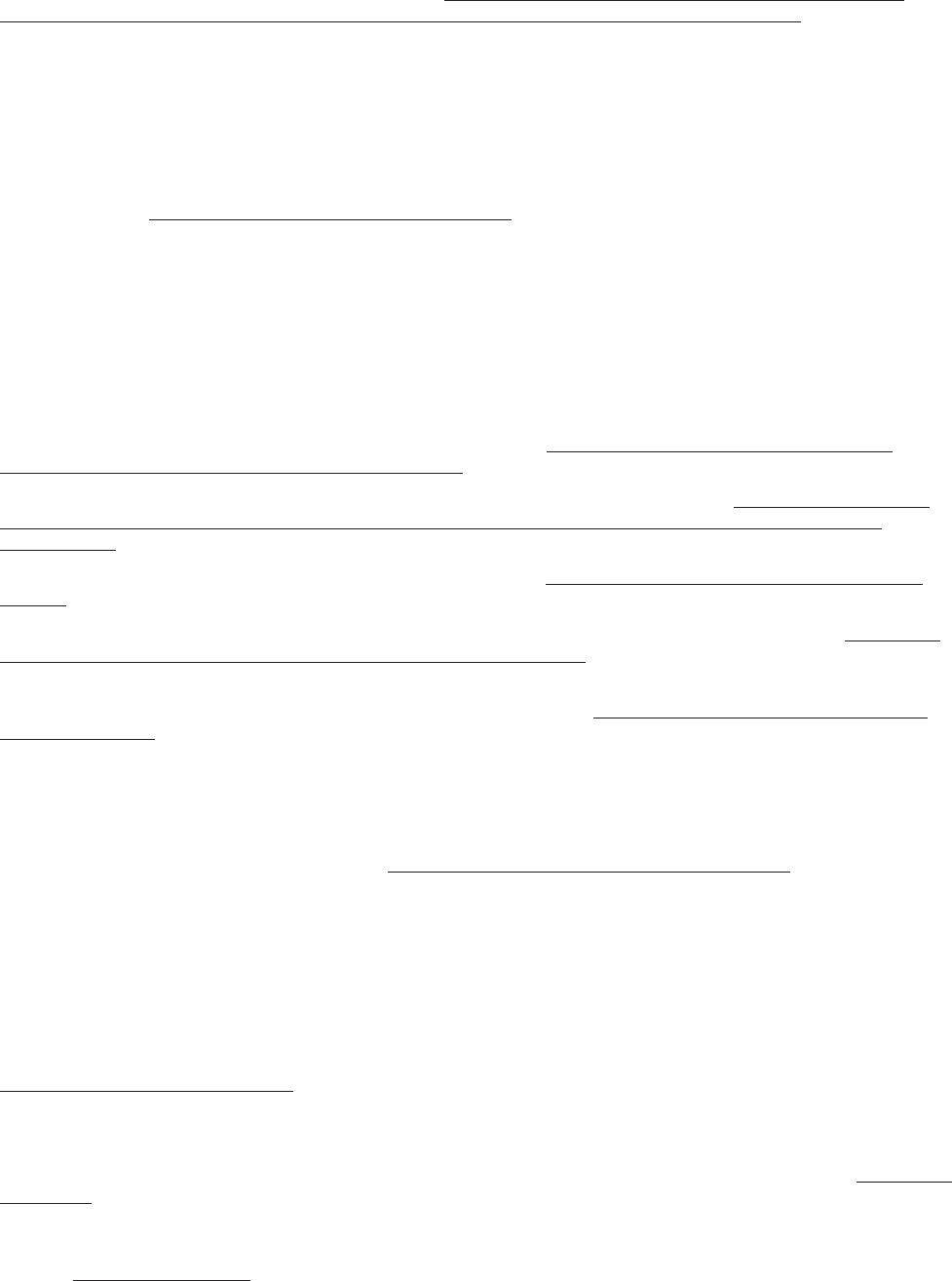

of the total Medicare population

1%

ESRD beneficiaries comprise less than

$35.4

BILLION IN 2016

7%

T

O

T

A

L

M

E

D

I

C

A

R

E

F

F

S

S

P

E

N

D

I

N

G

Medicare spending for ESRD beneficiaries

FIGURE 1

SOURCE: 2018 U.S. Renal Data System Annual Data Report.

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Goals for Advancing Kidney Health in America

As part of the Administration’s focus on improving person-centered care, the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS) is announcing its vision for advancing kidney health to revolution-

ize the way patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney failure are diagnosed, treated, and most

importantly, live. The initiatives discussed in this paper are designed to tackle the challenges people

living with kidney disease face throughout the stages of kidney disease, while also improving the lives

of patients, their caregivers, and family members. The overall goals of these eorts are to:

▶ GOAL 1: Reduce the Risk of Kidney Failure

▶ GOAL 2: Improve Access to and Quality of Person-Centered Treatment Options

▶ GOAL 3: Increase Access to Kidney Transplants

Brief Context on Kidney Disease

Approximately 37 million Americans, or 15 percent of the nation’s adults, have kidney disease.

1

Kidney

disease reduces the ability of a person’s kidneys to filter blood, causing wastes to build up in the body.

In 2017, the ninth leading cause of death in the United States was kidney disease.

2

Major risk factors for kidney disease include uncontrolled diabetes, high blood pressure, and a fam-

ily history of kidney failure. In some individuals, kidney disease progresses to kidney failure, often

referred to as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis or transplantation to survive.

3

ESRD is a life-threatening illness with a death rate (50 percent mortality in 5 years) worse than most

cancers that significantly aects quality of life. Even ESRD that is well managed with dialysis can

result in premature death or severe disability, heart disease, bone disease, arthritis, nerve damage, in-

fertility, and malnutrition.

4

Infections, including those related to the dialysis procedure, are frequent

causes of hospitalization and death among persons with ESRD. Dialysis treatments also pose a risk of

non-infectious complications. Currently, the only treatment alternative that can restore some or most

of normal kidney function is transplantation, which requires immunosuppressive therapy (to prevent

rejection of the kidney by the recipient’s body) and therefore places recipients at risk for infection and

malignancy due to immunosuppression.

Page 5 | Advancing American Kidney Health

Another indicator of the burden of kidney disease is the financial cost of treatment. Most individuals

with kidney failure are eligible for Medicare coverage, regardless of age.

5

Many Medicare beneficia-

ries with kidney failure suer from poor health status, often resulting from disease complications and

multiple co-morbidities that can lead to high rates of hospital admissions and readmissions.

6

Total

Medicare spending for beneficiaries with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and ESRD, including spending

on comorbidities and other health care services that may be unrelated to ESRD, was over $114 billion in

2016, representing 23 percent of total Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) spending, of which $35.4 billion

was spent on beneficiaries living with ESRD.

7

While less than 1 percent of the total Medicare popula-

tion has ESRD, spending on ESRD beneficiaries accounts for approximately 7 percent of total Medicare

FFS spending.

8

Figure 1 (previous page) shows the proportion of Medicare FFS spending attributable to

Medicare beneficiaries living with ESRD.

Over the past 70 years, there has not been the same level of innovation in treatments for people living

with kidney failure compared to treatments for other health conditions.

9

To improve quality of life

among people living with kidney failure, it is clear that new technological advances and alternatives to

dialysis for renal replacement therapy are urgently needed.

Additional information about kidney disease and its risk factors can be found in the Appendix.

Examples of Key Initiatives to Achieve Goals of the Kidney Care Vision

Eorts across HHS to advance kidney disease prevention and care in the United States include scaling

programs nationwide to optimize screening for kidney diseases, educating patients on care options with

coordinated care networks and other tools, supporting ground-breaking research to inform the next

generation of targeted therapies, creating new payment models and financial incentives to encourage

utilization of home dialysis and increase access to kidney transplants, encouraging accelerated develop-

ment of innovative products such as an artificial kidney, and undertaking a variety of eorts to increase

the number of kidneys available for transplant from both living and deceased donors.

Goal 1: Reduce the Risk of Kidney Failure

Examples of how HHS is addressing Goal 1 include the Indian Health Service’s (IHS’) eorts to adopt a

person-centered approach to care to improve outcomes for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/

ANs) at risk for diabetes complications such as kidney failure. The incidence of diabetes-related ESRD

(ESRD-D) among AI/AN populations decreased by over 40 percent between 2000 and 2015, resulting in

lower levels of disease burden for patients and lower spending on ESRD care.

10

The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) is updating its Hypertension Control Change Package for Clinicians to

improve CKD detection and care quality among persons at high risk for CKD progression. CDC is also

investing in state and local eorts to develop a public health response to CKD risk factors such as dia-

betes and heart disease.

11

Goal 2: Improve Access to and Quality of Person-Centered Treatment Options

HHS’ eorts to address Goal 2 include the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Kidney Precision

Medicine Project, which will use kidney biopsies to help redefine kidney disease into new molecu-

lar subgroups, paving the way for personalized treatments. The Oce of the Assistant Secretary for

Preparedness and Response’s (ASPR’s) programs are working to ensure individuals who need dialysis

treatment have ready access to treatment in the aftermath of disaster situations, through the availabil-

ity of portable dialysis technologies. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cleared devices

for home hemodialysis, and FDA actively supports innovative eorts to improve the quality of current

dialysis treatment and to develop new alternatives to dialysis for renal replacement therapy through its

Breakthrough programs and participation in KidneyX, the Kidney Innovation Accelerator. The Centers

for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has reviewed potential refinements to the ESRD-Prospective

Payment System to facilitate Medicare beneficiaries’ access to certain innovative treatment options

and, through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (Innovation Center), is providing

Page 6 | Advancing American Kidney Health

financial incentives to help clinicians better manage care aligned with beneficiaries’ preferences re-

garding home dialysis and kidney transplantation. CDC is working to translate evidence-based recom-

mendations into practical strategies to improve the quality and safety of care for patients undergoing

dialysis. CDC formed the Making Dialysis Safer for Patients Coalition, through which it collaborates

with partner organizations and patient representatives to implement core interventions proven to re-

duce dialysis bloodstream infections.

12

Goal 3: Increase Access to Kidney Transplants

To advance Goal 3, The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) is considering recom-

mendations from the Advisory Committee on Blood and Tissue Safety and Availability regarding

updating the U.S. Public Health Service Guideline for Reducing Human Immunodeficiency Virus,

Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Through Organ Transplantation, which may

increase available options for individuals who need kidney transplants. The Health Resources and

Services Administration (HRSA) is working to provide additional support for individuals who are

considering living donation by reducing financial barriers. In addition, new Innovation Center

models include financial incentives for health care providers to help Medicare beneficiaries move

through the kidney transplantation process.

Given the substantial burden kidney disease places on patients and their caregivers, it is imperative

that HHS continues to advance improvements and innovations in kidney disease prevention and care.

This paper outlines HHS’ goals for improving kidney care, finding alternatives to current dialysis

treatment, and increasing access to kidney transplants, and it describes agency initiatives designed to

address these goals.

Page 7 | Advancing American Kidney Health

II. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Goal 1: Reduce the Risk of Kidney Failure

The number of people with kidney failure has been growing in recent years, aicting more than

726,000 Americans in 2016.

13

Yet, 90 percent of adults with kidney disease and nearly half in advanced

stages of CKD are unaware they have the condition.

14

Associations have been found between diabetes,

hypertension, and CKD. For example, roughly 1 out of 5 adults with hypertension, and 1 out of 3 adults

with diabetes, may have kidney disease.

15

Moreover, among U.S. adults aged 18 years or older, diabetes

and high blood pressure are the primary reported causes of ESRD. Kidney disease usually progress-

es slowly in most individuals, and blood and urine tests can be used to monitor the progression of the

disease. Depending on the person and the stage of the disease, interventions can sometimes slow this

progression. Lifestyle and medication treatment for risk factors including diabetes and hypertension

are also important factors to address the progression of CKD. Two objectives for HHS’ eorts to reduce

the risk of kidney failure are:

OBJECTIVE 1. Advance public health surveillance capabilities and research to improve identification

of populations at risk and those in early stages of kidney disease

OBJECTIVE 2. Encourage adoption of evidence-based interventions to delay or stop progression

to kidney failure

Goal 2: Improve Access to and Quality of Person-Centered

Treatment Options

More than 100,000 Americans begin dialysis each year.

16

Approximately one in five will die with-

in one year, and half within five years.

17

Those with kidney failure typically must undergo dialysis

(often at a dialysis center) at least three times per week for three to four hours per session, or through

daily home peritoneal dialysis or home hemodialysis, and maintain an extremely restrictive diet.

Infections are a serious adverse outcome related to dialysis. Each year, approximately 29,500 blood-

stream infections occur in hemodialysis outpatients, and as many as one in two peritoneal dialysis

patients develops peritonitis.

18

These types of infections can lead to sepsis and can compromise the

patient’s treatment options, including ability to receive a kidney transplant. Eighty-seven percent

of Americans with kidney failure start treatment with hemodialysis. Of those on hemodialysis, the

majority (98 percent) receive in-center hemodialysis and only 2 percent use home dialysis.

19

Up to

85 percent of patients are eligible for home dialysis,

20

and in one study, 25 to 40 percent of patients

reported that they would select home dialysis if given the opportunity.

21

Higher survival has been

reported among individuals in the U.S. receiving home dialysis when compared to individuals receiv-

ing in-center hemodialysis treatment.

22

,

23

,

24

,

25

Supporting person-centered treatment options means

increasing the number of treatment modalities available for individuals living with kidney failure,

including home modalities, transplantation, and other alternatives to in-center hemodialysis still

under development.

Rapidly emerging technologies oer hope that new treatment options can improve patient outcomes

and lower the cost of care. HHS therefore supports eorts to develop and bring to market novel treat-

ments such as wearable, implantable, and/or biohybrid artificial kidneys as well as other biological and

drug-based alternatives to current dialysis treatments.

HHS aims to reduce morbidity and mortality among people living with advanced kidney disease and

increase the proportion of those with kidney failure receiving optimal treatment aligned with their

individual needs and preferences, based on informed patient choice.

OBJECTIVE 1. Improve care coordination and patient education for people living with kidney disease

Page 8 | Advancing American Kidney Health

and their caregivers, enabling more person-centric transitions to safe and eective treatments for

kidney failure

OBJECTIVE 2. Introduce new value-based kidney disease payment models that align health care pro-

vider incentives with patient preferences and improve quality of life

OBJECTIVE 3. Catalyze the development of innovative therapies including wearable or implant-

able artificial kidneys with funding from government, philanthropic and private entities through

KidneyX, and coordinating regulatory and payment policies to incentivize innovative product

development

Goal 3: Increase Access to Kidney Transplants

Nearly 95,000 patients are on the waiting list to receive a kidney transplant.

26

Kidney transplanta-

tion is generally associated with better outcomes compared to dialysis,

27

but only 30 percent of indi-

viduals who have experienced kidney failure are living with a functioning kidney transplant.

28

Many

Americans never have the chance to receive a kidney transplant due to shortages of available kidneys.

Objectives to improve access to kidney transplants are:

OBJECTIVE 1. Increase the utilization of available organs from deceased donors by increasing organ

recovery and reducing the organ discard rate

OBJECTIVE 2. Increase the number of living donors by removing disincentives to donation and ensur-

ing appropriate financial support

Page 9 | Advancing American Kidney Health

III. HHS INITIATIVES

By coordinating across HHS and partnering with people living with kidney disease, their caregivers,

organ donors, health care providers, and other stakeholders, HHS will enhance the ability of people

with kidney disease to improve their day-to-day well-being and quality of life. The specific activities

and initiatives HHS is undertaking to address the goals of this vision are described below.

Goal 1: Reduce the Risk of Kidney Failure

OBJECTIVE 1. Advance public health surveillance capabilities and research to improve identification

of populations at risk and those in early stages of kidney disease

In recent years, HHS has increasingly focused on developing better capabilities to identify kidney

disease early among high-risk patient populations and to support new research to uncover clinical-

ly-useful biomarkers that allow better prediction of the course of CKD and identify patients who could

be helped by particular therapies, or who should not be given specific drugs.

▶ CDC created and manages the national CKD Surveillance System, the only interactive and most

comprehensive collection of CKD-related data in the United States, helpful for monitoring prog-

ress toward achieving national Healthy People

29

objectives. Through its investments in the CKD

Surveillance System and innovative epidemiological research, CDC continues to strengthen

understanding of kidney disease prevalence, risk factors, and health consequences.

Find more information on the CKD Surveillance System at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/ckd/default.aspx

▶ The NIH-funded Chronic Renal Insuciency Cohort (CRIC) Study is examining risk factors

for progression of CKD and cardiovascular disease among patients with established CKD.

Additionally, the study is developing predictive models to identify high-risk subgroups,

informing future treatment trials, and examining the eect of ongoing clinical management

on outcomes. For example, CRIC researchers defined mortality risk subgroups in patients with

CKD based on whether levels of the hormone FGF23 in the blood change over time. FGF23 levels

in the blood were stable over time in most patients with CKD, but distinct subpopulations with

rising FGF23 levels over time were linked to higher risk of death.

Find more information about CRIC at: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/research-areas/

kidney-disease/eects-chronic-kidney-disease-adults-study-cric

▶ Hypertension is a leading cause of kidney disease and is the second leading cause of ESRD,

accounting for 26 percent of ESRD cases.

30

Heart disease can lead to and exacerbate CKD.

Hypertension can lead to kidney disease, which in turn can lead to worsened hypertension. It is

a dangerous cycle that, if not stopped, can lead to a heart attack, stroke, heart failure, or kidney

failure. The landmark NIH-funded Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) study

showed that lower blood pressure targets decrease the risk of death in high-risk patients with

cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CKD.

31

Find more information on the SPRINT trial at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/

systolic-blood-pressure-intervention-trial-sprint-study

▶ Diabetes is another major risk factor for kidney disease. Although testing for kidney disease

is recommended for people with diabetes, almost 60 percent of Medicare beneficiaries with a

diabetes diagnosis are not screened for kidney-damage (albuminuria), and approximately 93

Page 10 | Advancing American Kidney Health

percent of those with hypertension only (a risk factor for kidney disease) are not being tested

for this disease.

32

CDC is collaborating with NIH on the Longitudinal Study of Markers of

Kidney Disease, and with the National Centers for Health Statistics to investigate and validate

new markers for early kidney disease and identify new treatment options for diabetes-related

kidney disease.

Find more information on the Longitudinal Study of Markers of Kidney Disease at: https://www.cdc.

gov/kidneydisease/about-the-ckd-initiative.html

▶ The NIH-funded Kidney Precision Medicine Project seeks to uncover the biological root causes

of kidney disease through high throughput molecular, genetic, and cellular techniques from

research kidney biopsies. This will lead to new biomarkers, disease subgroups, molecular

targets, and most importantly the development of new drugs to treat and possibly forestall

kidney disease. Recruitment of patients for renal biopsy will start in Summer 2019.

Find more information on the NIH-funded Kidney Precision Medicine Project at: https://www.niddk.nih.

gov/research-funding/research-programs/kidney-precision-medicine-project-kpmp

▶ The NIH-funded Preventing Early Renal Loss in Diabetes (PERL) Study is a randomized, dou-

ble-blind trial to test whether the medication allopurinol can slow the progression of kidney

disease in people with type 1 diabetes and early diabetic kidney disease. Results from this study

are expected to be available at the end of 2019.

Find more information about PERL at: http://www.perl-study.org/

▶ Identification of patients with CKD for population health management, research and surveil-

lance using data available in electronic health records (EHRs) is challenged by poor recogni-

tion and resulting under-diagnosis of the disease, particularly in its early stages. As a result,

diagnosis codes cannot be used to accurately identify patients with CKD from the EHR. The

NIH convened researchers, clinicians, and informaticists to develop and validate an electronic

phenotype for CKD. An electronic phenotype is a defined set of data elements and rules that

help identify groups of patients using a computerized query. The resulting NIH CKD pheno-

type uses laboratory measures commonly available in the EHR to identify patients likely to

have CKD.

Find more information on the electronic phenotype at: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/

communication-programs/nkdep/working-groups/health-information-technology

Looking forward, HHS will further intensify its eorts to make kidney disease detection more accessi-

ble, including:

▶ As part of its CKD Initiative, CDC will continue to collaborate with other government agen-

cies, universities, and national organizations to support a robust portfolio of epidemiological

studies, including cost-eectiveness studies of the long-term ecacy of public health in-

terventions for CKD, and the Systematic Review on Barriers to CKD Screening Project, which

identifies and synthesizes current evidence on kidney disease screening and screening rates in

the United States. These activities support eorts to raise awareness of CKD and its complica-

tions, promote prevention and control of risk factors for CKD, and improve early diagnosis and

treatment among people living with kidney disease.

▶ The CKD Epidemiology in the Military Health System (MHS), a collaborative eort between

the CDC and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, aims to describe the

epidemiology of kidney disease among the active duty and non-active duty populations and

assess their risk factors for developing kidney disease. Specifically, this project examines 1)

Page 11 | Advancing American Kidney Health

the eects of maintaining good physical and psychological health on risk of CKD, and 2) the

long-term eects of non-sedentary lifestyle on risk of chronic conditions, including CKD.

Because the project includes non-active duty persons, i.e., family members of active duty

individuals and retirees from active duty, the findings will have implications beyond military

personnel.

Find more information on CKD Epidemiology in the MHS at: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/

about-the-ckd-initiative.html

OBJECTIVE 2. Encourage adoption of evidence-based interventions to delay or stop progression

to kidney failure

In the United States, 30 million individuals have diabetes, 84 million adults have prediabetes (are at

high risk for type 2 diabetes), and 75 million adults have high blood pressure.

33,34

HHS has supported

the development of several evidence-based national models for better managing kidney disease and

risk factors for its progression. These models aim to reduce the national rate of kidney failure.

▶ American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations have the highest prevalence of diabetes

of any U.S. racial/ethnic group.

35

The Special Diabetes Program for Indians (SDPI) represents

an important part of this broader approach to providing team-based care and care manage-

ment. The program has included a number of dierent components over time such as com-

munity directed grants that focus on locally developed solutions to improve diabetes preven-

tion and care, demonstrations and initiatives such as the SDPI Diabetes Prevention Initiative,

which built on the findings of an earlier clinical trial at NIH, the diabetes audit which collects

data on diabetic care provided by grantees to track outcomes, dissemination of diabetes

treatment algorithms and standards of care, and ongoing educational programs such as

webinars, periodic meetings and conferences, and consultations with health professionals

that have expertise in diabetes. Since its implementation, the incidence of diabetes-relat-

ed kidney failure among AI/AN populations decreased by over 40 percent between 2000 and

2015, resulting in lower spending for programs that cover the costs of AI/AN ESRD care.

36

The

SDPI and related eorts have also contributed to improvements in other diabetes-related

outcomes, including childhood obesity trends,

37

hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes,

38

and diabetic retinopathy.

39

Find more information on the SDPI at: https://www.ihs.gov/sdpi

▶ The CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) is a partnership of public and

private organizations working together to build a nationwide delivery system for a 12-month

lifestyle change program proven to prevent or delay onset of diabetes.

40

Congress specifically

authorized the National DPP in 2010 because of previous research—including the NIH-funded

Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and the DPP Outcomes Study —that demonstrated the

potential of the CDC-recognized lifestyle change program to prevent or delay the onset of type

2 diabetes. The National DPP is founded on four key pillars: 1) a trained workforce of lifestyle

coaches; 2) national quality standards supported by the CDC Diabetes Prevention Recognition

Program; 3) a network of program delivery organizations sustained through health benefit

coverage; and 4) participant engagement and referral. CDC also supports states’ eorts to

make the NDPP and other diabetes management interventions available to high-burden pop-

ulations and communities. These eorts include strengthening community-clinical linkages

to screen, test, and refer people with prediabetes to CDC-recognized organizations oering the

National DPP lifestyle change program; providing support to enroll and retain participants in

the program; and supporting pharmacist-patient care processes that help people with diabetes

better manage their medications.

Find more information on the CDC’s National DPP at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention

Page 12 | Advancing American Kidney Health

▶ The NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) promotes an

integrated health system model of team-based clinical care based on the pragmatic experience

of the IHS’ Kidney Disease Program. NIDDK has developed new clinical tools and educational

programs that improve the care of people with kidney disease in primary care settings. NIDDK

works in collaboration with government, nonprofit, and health care organizations to raise

awareness about screening for individuals at risk for kidney disease; educate individuals about

how to manage their disease; provide information, training, and tools that help health care

providers; and support important health systems changes.

Find more information on the NIH NIDDK at: http://www.niddk.nih.gov

▶ The Innovation Center’s Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (MDPP) expanded model is

a structured behavior change intervention that aims to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes

among Medicare beneficiaries with an indication of prediabetes. This model is an expansion of

the Diabetes Prevention Program model test under the authority of section 1115A of the Social

Security Act.

Find more information on the MDPP at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/medicare-diabetes-

prevention-program/

Looking forward, HHS will continue to support these programs and look for known and innovative

ways to scale their adoption, in partnership with communities.

▶ In late 2017, CDC announced a new five-year cooperative agreement to scale up the National

DPP in underserved areas and populations including Medicare beneficiaries, men, African

Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Pacific Islanders,

and noninstitutionalized people with visual impairments or physical disabilities.

▶ In late 2019, CDC will update its Hypertension Control Change Package for Clinicians (HCCP) to

include tools and resources to support CKD screening and early diagnosis among persons with

hypertension. This eort, part of CDC’s broader Million Hearts® initiative,

41

will better sup-

port clinician eorts to end the pernicious cycle between CKD and hypertension.

Find more information on the Hypertension Control Change Package for Clinicians at:

https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/files/HTN_Change_Package.pdf

Find more information on the Million Hearts initiative at: https://millionhearts.hhs.gov

▶ CDC has begun a collaboration with local health departments to develop innovative approaches

to increase the reach and eectiveness of public health strategies for diabetes, heart disease,

and stroke, including the use of clinical decision support tools within EHRs to promote early

detection of kidney disease.

▶ HHS supports continued funding for the SDPI, as reflected in the President’s Fiscal Year (FY)

2020 budget that proposes reauthorizing the SDPI at $150 million per year through FY 2021.

▶ NIH has recently funded the Improving Chronic Disease Management with Pieces (ICD-Pieces)

study, testing whether computer-generated reminders working in tandem with clinicians can

reduce hospitalizations in patients with coexisting CKD, diabetes, and hypertension, and im-

prove use of innovative and proven interventions.

Find more information on the ICD-Pieces study at: http://icd-pieces.com/

▶ ASPR is launching a new initiative called ExaHealth, to develop collaborative tools to acceler-

ate discovery of new therapies. The ExaHealth initiative will be one of many partnerships with

the Department of Energy to develop artificial intelligence tools and new methods for studying

Page 13 | Advancing American Kidney Health

complex biological functions in a concerted way, in order to develop new and more eective med-

ical interventions. These interventions will focus on acute onset of disease during pandemics and

man-made disasters, as well as and chronic diseases, whose onset can occur throughout a per-

son’s lifetime, including patients at risk for progression towards CKD and ESRD.

Goal 2: Improve Access to and Quality of Person-Centered

Treatment Options

OBJECTIVE 1. Improve care coordination and patient education for people living with kidney disease

and their caregivers, enabling more person-centric transitions to safe and eective treatments for

kidney failure

HHS supports the data and knowledge infrastructure necessary to inform more person-centric transi-

tions to safe and eective care for kidney failure.

▶ For example, the NIH supports production of the annual U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) Atlas,

which provides up-to-date statistics on incidence, morbidity, and mortality for patients transi-

tioning through kidney failure. These data have been used to inform clinical practice for kidney

disease patients and development of targeted interventions for specific populations. In 2018,

USRDS published a special transitions section that describes the transition from CKD to ESRD

in greater detail using linked data from the Veterans Health system. Key summary findings

include the finding that heart failure and acute kidney injury (AKI) are the most common cause

of hospitalizations in the six months before the start of hemodialysis, and infectious compli-

cations (vascular access infection, septicemia) are the most common causes of hospitalizations

after the start of hemodialysis.

42

Future eorts of the USRDS include a detailed investigation

of causes of early mortality among patients who start hemodialysis, as well as expanded ex-

ploration of data sets other than Medicare data to support additional analyses related to kidney

disease and kidney care.

Find more information on the USRDS at: https://www.usrds.org/

▶ Through its Making Dialysis Safer for Patients Coalition, CDC coordinates a wide array of orga-

nizations and individuals to promote implementation of evidence-based interventions to pre-

vent dialysis bloodstream infections. Best practices and strategies for implementation of these

interventions include provider training and feedback, patient engagement and empowerment,

and use of audit tools, checklists, and other resources. These interventions have been shown to

significantly reduce dialysis-related bloodstream infections (by 30 to 50 percent) and associat-

ed outcomes.

43

Find more information on the Making Dialysis Safer for Patients Coalition at: https://www.cdc.gov/

dialysis/coalition/index.html

▶ Through the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), CDC tracks bloodstream infections –

including those caused by antibiotic resistant organisms, vascular access infections, and other

outcomes among hemodialysis patients treated in clinics, and gives clinics immediate access

to the data reported. CDC produces standardized infection ratios that are posted publicly on

Medicare’s Dialysis Facility Compare website. National aggregate rates of infection are used for

benchmarking and in quality improvement initiatives.

Find more information on NHSN at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/dialysis/index.html

▶ ASPR and CMS have formed a collaboration to improve access to dialysis care during every di-

saster and have launched the emPOWER program. emPOWER provides data and mapping tools

Page 14 | Advancing American Kidney Health

to help communities protect the health of more than 4.1 million Medicare beneficiaries who rely

on electricity-dependent medical equipment and healthcare services, including nearly 400,000

dialysis patients. In the wakes of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the emPOWER Program helped

ASPR, CMS, and territorial public health ocials identify healthcare and resource gaps for dial-

ysis patients and immediately engage with End-Stage Renal Networks

44

and dialysis providers

to ensure continuity of their life-maintaining healthcare services.

Find more information on the emPOWER Program at: https://empowermap.hhs.gov/Fact Sheet_

emPOWER_FINALv5_508.pdf

Looking forward, HHS will continue to strengthen patient voices in policy development, address the

needs of vulnerable populations with portable dialysis technologies, and use payment incentives to

support patients making choices about their kidney care modalities.

▶ The Innovation Center has announced four new optional kidney care models: Kidney Care

First (KCF) for nephrology practices and Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC)

which oers three distinct payment options. These models will build on the existing

Comprehensive ESRD Care (CEC) Model, which began in 2015 and will end in 2020, and incor-

porate design elements from the recently announced Direct Contracting and Primary Care

First models. One of the key lessons learned from the CEC Model was the need to increase

coordinated care for beneficiaries with late-stage chronic kidney disease and beneficiaries

transitioning onto dialysis. These models will provide strong incentives to better manage

and coordinate care for beneficiaries with kidney disease. Model participants will be incen-

tivized through utilization measures and cost incentives to avoid unplanned dialysis starts in

the hospital, in an eort to avoid the cost and high mortality that occurs when beneficiaries

abruptly start dialysis. Additionally, CMS will also establish measures to demonstrate wheth-

er kidney disease is being delayed by the Model’s interventions and develop a quality measure

to incentivize better managing beneficiaries with late-stage CKD to avoid the more expensive

and burdensome dialysis process.

Find more information on the CKC Model at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/voluntary-

kidney-models/

▶ The FDA is developing a new survey to gain insight into patient preferences for new kidney

failure treatments. Information collected will be used by FDA and its partners including

device developers, patients, providers, payers, and other researchers to inform the develop-

ment of new treatments, including alternatives to dialysis. The patient preferences survey

will be an important example of how patient engagement can contribute to building infra-

structure for expanded patient-centered outcomes research and how patient input can be

used in FDA’s review processes. Results and methods will also be shared with those involved

in data collection efforts for other disease conditions to similarly inform the development of

new treatments.

▶ NIH is developing and testing an interoperable open-source electronic care plan tool for peo-

ple with multiple chronic conditions, including diabetes and kidney disease, to better coordi-

nate their care. In the context of kidney care, this tool will enable patients, physicians, nurses,

pharmacists, dieticians, and other health professionals, as well as community health workers,

to transfer critical, person-centered kidney care information across multiple settings of care

with diverse electronic health record systems using uniform data standards, supporting better

coordination of kidney care and research.

▶ Dialysis facilities are currently required to inform patients of their care options. To strengthen

patient education and support for patients’ selection of treatment modalities, CMS is consid-

ering options for new ways to improve quality of life for dialysis patients while also reducing

Medicare costs and minimizing regulatory burden.

Page 15 | Advancing American Kidney Health

▶ ASPR is working to ensure people living with kidney failure have access to readily available

portable dialysis technologies and access to treatments in any situation. Currently, treatment

options are limited following disaster events, and individuals on dialysis must be evacuated

and provided temporary housing to continue treatments. Beginning in 2019, ASPR will procure

and test portable dialysis units that can provide support to people living with kidney failure in

low-resource settings or within their homes, so that they can have access to dialysis with min-

imal power and from publicly-available water sources, allowing them to return home sooner

when a disaster occurs.

▶ CMS supports person-centered optimal starts for individuals living with ESRD. An “optimal

start” reflects adequate patient preparation resulting in pre-emptive transplant, initiation

of renal replacement with peritoneal dialysis or initiation of hemodialysis with a functioning

permanent vascular access. The Innovation Center is announcing the ESRD Treatment Choices

(ETC) Model, which will include financial incentives for ESRD facilities and Managing Clinicians

selected to participate in the model to better align with beneficiary choice on modalities such as

home dialysis or kidney transplants.

Find more information on the ETC Model at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/

esrd-treatment-choices-model/

OBJECTIVE 2. Introduce new value-based kidney disease payment models that align health care pro-

vider incentives with patient preferences and improve quality of life

As part of HHS’ commitment to transition to payment and delivery models that focus on patient out-

comes, preferences, and lowering costs, CMS is introducing a new payment model and has proposed

another payment model to encourage more coordinated care to delay kidney failure and ensure that

people living with kidney failure have access to the best available care options. Additionally, Medicare

will continue to support payment rule changes for the ESRD PPS that focus on patient care, support

innovation, reduce burdens, and lower costs.

▶ The Innovation Center’s ETC Model includes financial incentives for ESRD facilities and

Managing Clinicians selected to participate in the model to better align with patient choice

regarding home dialysis and kidney transplantation. The ETC Model will test the eective-

ness of outcomes-based payment adjustments to health care providers to increase utiliza-

tion of home dialysis and kidney/kidney-pancreas transplants. The Home Dialysis Payment

Adjustment (HDPA) would be in eect for the first three years of the Model, and would in-

crease payment for home dialysis and home dialysis-related services. The Performance

Payment Adjustment (PPA) would decrease or increase payment for dialysis and dialysis-re-

lated services based on a participating ESRD facility or Managing Clinician’s rate of home di-

alysis and transplants. The goal of the Model is to increase the transplant and home dialysis

rate across the country.

▶ The Innovation Center’s optional kidney care models (KCF and CKCC) include incentives for

health care providers to better manage the care for beneficiaries with kidney disease including

incentives for pre-emptive transplants, improving beneficiaries’ transition to dialysis, and en-

suring dialysis initiation is appropriately timed. The Model also includes incentives to manage

the total cost and quality of care for beneficiaries with kidney disease and kidney failure, and

strong financial incentives to move beneficiaries through the transplant process. Together

with the new ETC Model, the optional kidney care models demonstrate CMS’ commitment to

supporting high quality, coordinated care for people living with ESRD.

▶ CMS is considering ways to encourage ESRD facilities to furnish new and innovative drugs and bi-

ological products for the treatment of ESRD. The Transitional Drug Add-on Payment Adjustment

(TDAPA) is an add-on payment adjustment under the ESRD PPS intended to facilitate this goal for

Page 16 | Advancing American Kidney Health

Medicare beneficiaries. This is done by encouraging ESRD facilities to furnish certain qualifying

new renal dialysis drugs and biological products by allowing additional payment for them while

utilization data is collected.

▶ CMS recognizes that continual refinement of the ESRD PPS is necessary to benefit people living

with ESRD, and is therefore working with an analytical contractor to perform payment analysis

and develop potential refinements to the ESRD PPS. CMS plans to ask for stakeholder input on

data collection.

▶ Based on comments received during and after the CY 2019 ESRD PPS rulemaking, CMS is con-

sidering issues related to payment for new and innovative supplies and equipment that are renal

dialysis services furnished by ESRD facilities for ESRD beneficiaries.

OBJECTIVE 3. Catalyze the development of innovative therapies including wearable or implant-

able artificial kidneys with funding from government, philanthropic and private entities through

KidneyX, and coordinating regulatory and payment policies to incentivize innovative product

development

Ultimately, the best way to improve care for people living with kidney failure is to support the devel-

opment of novel therapies extending beyond the choices available today. Investing in foundational

research at the NIH, catalyzing rapid product development through public-private partnerships, and

creating clear and forward-looking guidelines for marketing approval for emerging technologies like

organ preservation may unleash innovation for years to come.

▶ KidneyX was ocially launched in 2018 as a public-private partnership with the American Society

of Nephrology to support the development of innovative therapies and diagnostics. KidneyX

is designed to leverage rapidly emerging technologies in areas such as regenerative medicine,

nanotechnology, and advanced materials to support early-stage development and lower the risk

of commercialization. KidneyX’s first prize, Redesign Dialysis, oers $2.6M for kidney failure

treatments beyond currently available options of dialysis and transplantation. Included among

the 15 winning teams announced in April 2019, were companies developing advanced nanofiltra-

tion for toxin removal, miniaturized wearable dialyzers, real-time infection and clotting sensors,

cell-based implantable dialyzers, and regenerative kidneys. The second phase currently under-

way will seek testable prototypes and announce winners in April 2020.

Find more information on KidneyX at: https://www.kidneyx.org

▶ In June 2019, the HHS Chief Technology Ocer signed an agreement with the heads of CMS,

NIH, FDA, and CDC to work closely together on KidneyX to ensure that unnecessary barriers to

patient access for innovative technologies are addressed. In July 2019, KidneyX is also launch-

ing a patient innovator prize focused on identifying and scaling new products and practices that

patients and caregivers have developed for their own care, recognizing that innovation often

happens at the frontlines of health. In 2020, KidneyX plans to launch Redesign Dialysis Phase

III to advance new products into human clinical trials, another prize focused on helping dialysis

patients manage fluids, a leading cause of ESRD hospitalizations, and a prize focused on spur-

ring development of therapies to slow progression of kidney disease.

▶ HHS and the Department of Veterans Aairs (VA) are exploring a partnership to streamline and

expedite clinical trials for kidney care-related treatments using the VA health system, similar

to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and VA Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment

(NAVIGATE), a partnership between the VA and the NCI to facilitate enrollment of veterans with

cancer into NCI-funded clinical trials.

Page 17 | Advancing American Kidney Health

▶ In May 2019, FDA issued final guidance that industry should consider when utilizing animal

studies to evaluate organ preservation devices. This guidance will help support the develop-

ment of next-generation organ preservation devices and systems, potentially capable of in-

creasing the supply of transplantable kidneys by salvaging and maintaining more kidneys. In

addition to recommendations that could be considered relevant for most animal studies such

as developing animal study protocols with consideration of the applicability of anatomical,

physiological, and immunological factors for humans, studies should include a control group

as a comparator. Specifically, for kidney preservation devices, animal studies should consid-

er three phases of the organ for transplantation: procurement, preservation, and reperfusion.

Following these recommendations will speed the review of kidney preservation devices, as well

as potentially improving the quality and functionality of these devices.

Find the FDA’s final guidance at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-

documents/utilizing-animal-studies-evaluate-organ-preservation-devices

Goal 3: Increase Access to Kidney Transplants

OBJECTIVE 1. Increase the utilization of available organs from deceased donors by increasing organ

recovery and reducing the organ discard rate

From 2007 through 2017, the annual rate of kidneys procured but not transplanted has ranged between

18-20 percent. In 2017, the discard rate of 18.9 percent reflected 3,534 kidneys that were procured but

not transplanted into waiting patients.

45

Some donor kidneys are not transplanted due to medically

justifiable reasons; however, it is estimated that thousands of discarded kidneys could provide benefit

to people on dialysis.

46

Education about the appropriate clinical use of kidneys would help maximize

the limited supply of donated organs used.

47

,

48

Addressing the availability and utilization of kidneys is

one of the ways HHS can help people living with ESRD through transplantation.

▶ HRSA supported a Collaborative Innovation and Improvement Network (COIIN) pilot project

through the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) with a limited number of

participating kidney transplant programs. The goal was to increase transplantation and reduce

the number of discarded kidneys, with a particular focus on increasing utilization of kidneys

deemed to be moderate-to higher-risk due to their clinical characteristics. In addition to sup-

porting education of transplant program sta, patients, and referring physicians on the eec-

tive use of these organs, the COIIN pilot also modified OPTN performance monitoring criteria

to reduce the risk-avoidance behaviors associated with the current monitoring system. Initial

results suggest that the COIIN pilot has resulted in increased utilization of kidneys among the

first cohort of participating transplant programs. It is possible that a recent decline in the dis-

card rate of moderate-risk kidneys may in part be related to the COIIN pilot.

Find more information on the HRSA COIIN at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/coiin/

▶ The OPTN implemented a policy change in June 2018 to expedite the process of allocating organs

and improve the eciency of organ placement. This change reduces the amount of time a trans-

plant program has to accept or refuse an organ oer, as well as reduces bottlenecks in the system

by limiting the number of organ oers a program can accept for any candidate at the same time.

▶ CMS added a transplant waitlist measure to the ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) for di-

alysis facilities via rulemaking in 2018 as a measure of dialysis center performance. The goal

of the ESRD QIP is to promote high-quality services in ESRD facilities treating patients with

ESRD. Under this value-based purchasing program, CMS pays for ESRD treatment by linking

a portion of payment directly to dialysis facilities’ performance on quality of care measures.

A list of CMS quality measures for ESRD care is included in the Appendix.

Page 18 | Advancing American Kidney Health

Looking forward, HHS plans to take a number of actions directly aimed at increasing the utilization

and availability of organs.

▶ HHS is updating the PHS Guideline for Reducing Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis

B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Through Organ Transplantation. The goal of the

existing 2013 Guideline was to reduce risk of unintended HIV, HBV, and HCV transmission, while

preserving availability of high quality organs: Since 2013, however, shifts in the composition of

the donor pool, as well as advances in testing and treatment technologies, have created oppor-

tunities to revise the Guideline. The current initiative will re-evaluate and, where warranted,

revise elements of the Guideline based on current risks to patients and improvements in tech-

nology. HHS is also considering the April 2019 recommendations of the Advisory Committee

on Blood and Tissue Safety and Availability concerning revising the Guideline. The revised

Guideline is intended to strengthen the overall process for assessing, communicating, and

managing donor risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV.

Find the current PHS Guideline at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3675207/pdf/

phr128000247.pdf

▶ HRSA has funded the OPTN to expand the COIIN pilot project in 2020, allowing more kidney

transplant programs to participate in this OPTN quality improvement activity focused on

changing program waitlist management and organ acceptance practices.

49

▶ The Innovation Center’s ETC Model includes a learning collaborative operated by the Center

for Clinical Standards and Quality (CCSQ), designed in collaboration with HRSA and informed

by the HRSA OPTN COIIN, to reduce the disparity in performance among Organ Procurement

Organizations (OPOs) and transplant centers with the goal of increasing recovery of kidneys

by OPOs and utilization of kidneys by transplant centers. This quality improvement learning

component will bring HRSA, CMS, transplant centers, OPOs, and the nation’s largest donor

hospitals together to generate increased quality and cost-savings to Medicare through the use

of systematic quality and process improvement. Additionally, this activity will directly engage

patients and families to motivate, activate and empower them to drive the requirement/demand

for utilization of viable kidneys.

▶ HHS is organizing a federal workshop to discuss considerations related to the use of Hepatitis

C virus positive (HCV+) donor organs in recipients who do not have HCV. Due to the recent

increase in the number of deaths from the opioid epidemic, more HCV+ potential organs are

available. HCV is now considered to be largely curable with the advent of direct acting anti-vi-

ral (DAA) therapy. Ten clinical trials are in process or have been completed to study whether

intentional use of HCV+ donor organs in HCV uninfected recipients is safe and eective when

recipients are proactively treated with DAA agents. The planned federal workshop is intended

to help facilitate a proactive and coordinated approach to developments in this area of study,

specifically with regards to potential changes in the standard of clinical care in transplantation.

▶ NIH research led to the seminal discovery of the APOL1 gene, which explains why kidney disease

progresses faster among African Americans compared to Caucasians. Building on the discovery

of the APOL1 gene in African Americans, NIH founded the APOLLO initiative, which will produce

information about the best use of donor kidneys with APOL1 gene variants and also improve do-

nor-recipient matching to decrease the rate of organ discard. OPOs nationwide are participating in

this study. Recruitment began in 2019 and will continue at least through 2021. More precise quan-

tification of risks of poor outcomes related to donor/recipient genetic architecture will enhance the

ecacy of the allocation of precious donor kidneys. Study results are anticipated in 2023.

Find out more information on the APOLLO initiative at: https://theapollonetwork.org/info.cfm

Page 19 | Advancing American Kidney Health

▶ HRSA, through the OPTN, is developing a new model to test accelerated placement of certain

kidneys that are at high risk for discard. Following recommendations from the National Kidney

Foundation Consensus Conference,

50

the OPTN Organ Center will develop and test a proof of

concept for expediting allocation of these organs with safety monitoring. The OPTN will evalu-

ate the concept for safety and improvements in allocation eciency.

▶ HHS is analyzing and improving transplantation metrics with a focus on increasing organ utili-

zation while maintaining good outcomes.

▶ HRSA, through the OPTN, convened an Ad Hoc System Performance Committee, which among

other issues, has discussed new potential performance metrics that monitor patient safety

while encouraging innovative practice.

▶ Per the 2019 OMB regulatory agenda, CMS is reviewing the OPO conditions for coverage and will

be proposing changes to the standards used to evaluate OPOs to ensure proper data collection

on the availability of transplantable organs and transplants.

▶ CMS has begun to develop and test new dialysis facility transplant referral measures, which, if

approved, could be added to Quality Incentive Program (QIP) through rulemaking in the future

and then via the Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web-enabled Network (CROWNWeb) sys-

tem and ultimately, Dialysis Facility Compare.

51

OBJECTIVE 2. Increase the number of living donors by removing disincentives to donation and en-

suring appropriate financial support

Living donors account for 30 percent of all kidney transplants in the U.S. However, many financial and

risk-based disincentives to donation persist, which may serve as barriers for individuals who would

otherwise be willing to donate a kidney.

▶ To further support living donors, HRSA is planning to expand the Reimbursement of Travel

and Subsistence Expenses toward Living Organ Donation program by increasing the eligibility

income threshold. HRSA is implementing a pilot to expand the qualifying expenses to include

coverage for lost wages and family expenses. The expansion of the current reimbursement pro-

gram will reduce financial barriers to organ donation and support the goal of increasing living

donor transplants.

Find more information on the Reimbursement of Travel and Subsistence Expenses toward Living

Organ Donation program at: https://grants.hrsa.gov/2010/Web2External/Interface/Common/

EHBDisplayAttachment.aspx?dm_rtc=16&dm_attid=49472bf1-7438-42-b406-d597fcf3b498

▶ In FY 2019, HRSA awarded a demonstration cooperative agreement to provide for reimburse-

ment of up to $5,000 in lost wages related to donor evaluation and surgical procedures regard-

less of the donor’s income. Findings from this three-year demonstration project will inform

whether expansion of the Reimbursement of Travel and Subsistence Expenses toward Living

Organ Donation program has a positive eect on kidney donation.

Page 20 | Advancing American Kidney Health

TECHNICAL APPENDIX

Background Information on Kidney Disease

Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

Kidney disease occurs when kidneys are damaged and become unable to filter blood optimally, causing

wastes to build up in the body. The condition is clinically categorized into five stages as the disease

progresses. The last stage of the disease occurs when the kidneys stop working altogether, which is of-

ten referred to as ESRD. Individuals in this stage of the disease require ongoing dialysis, if a transplant

is not available, in order to filter wastes out of the body.

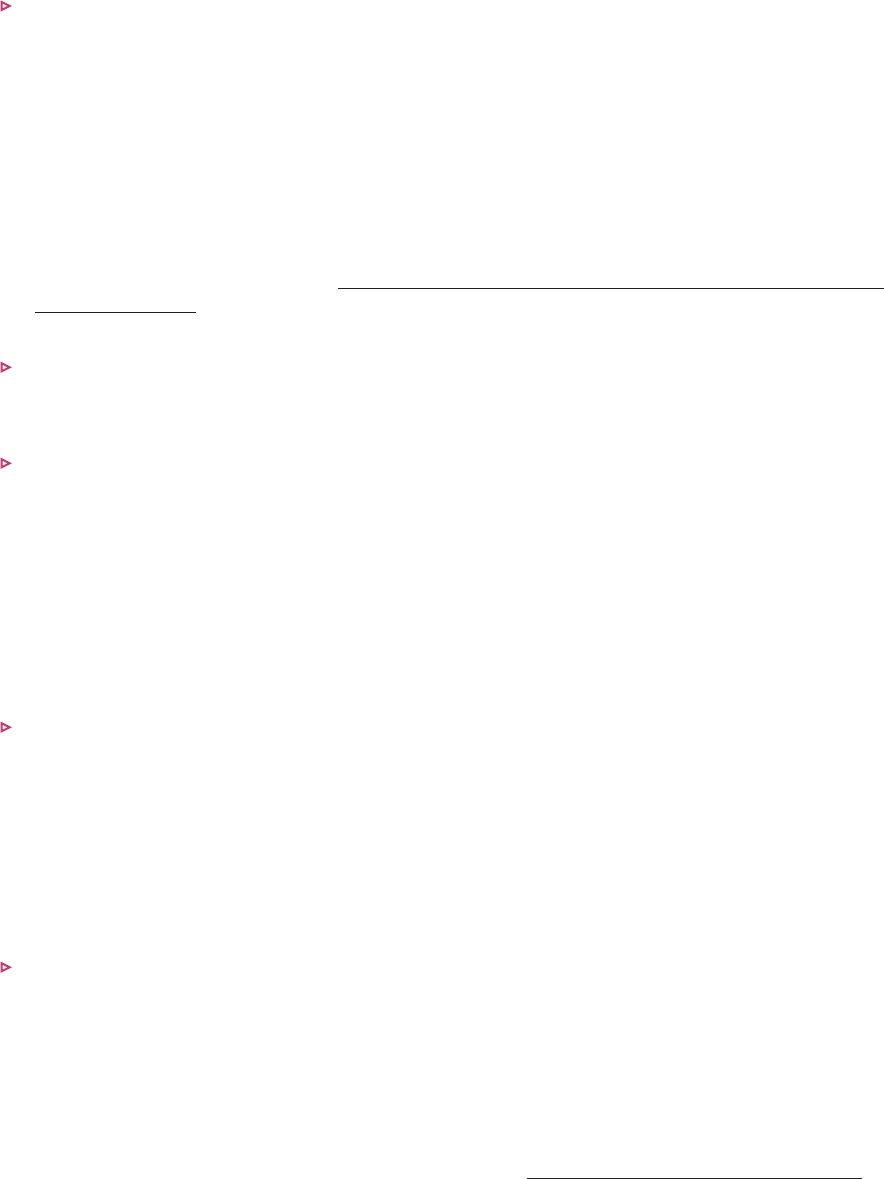

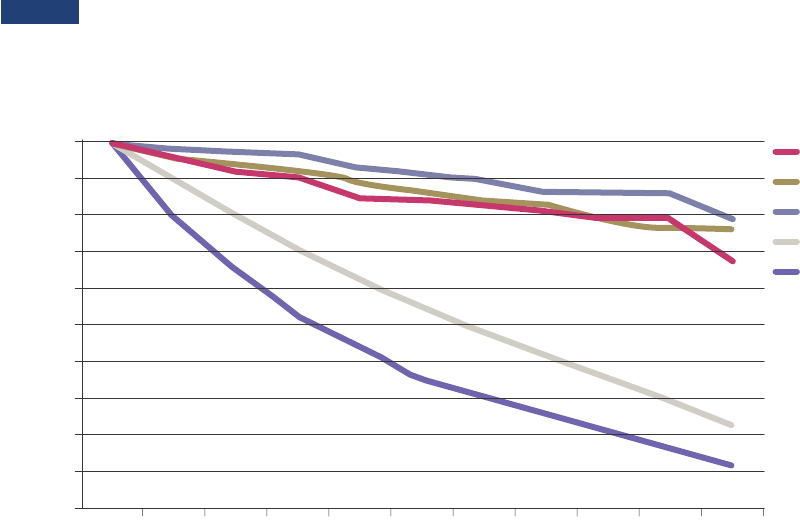

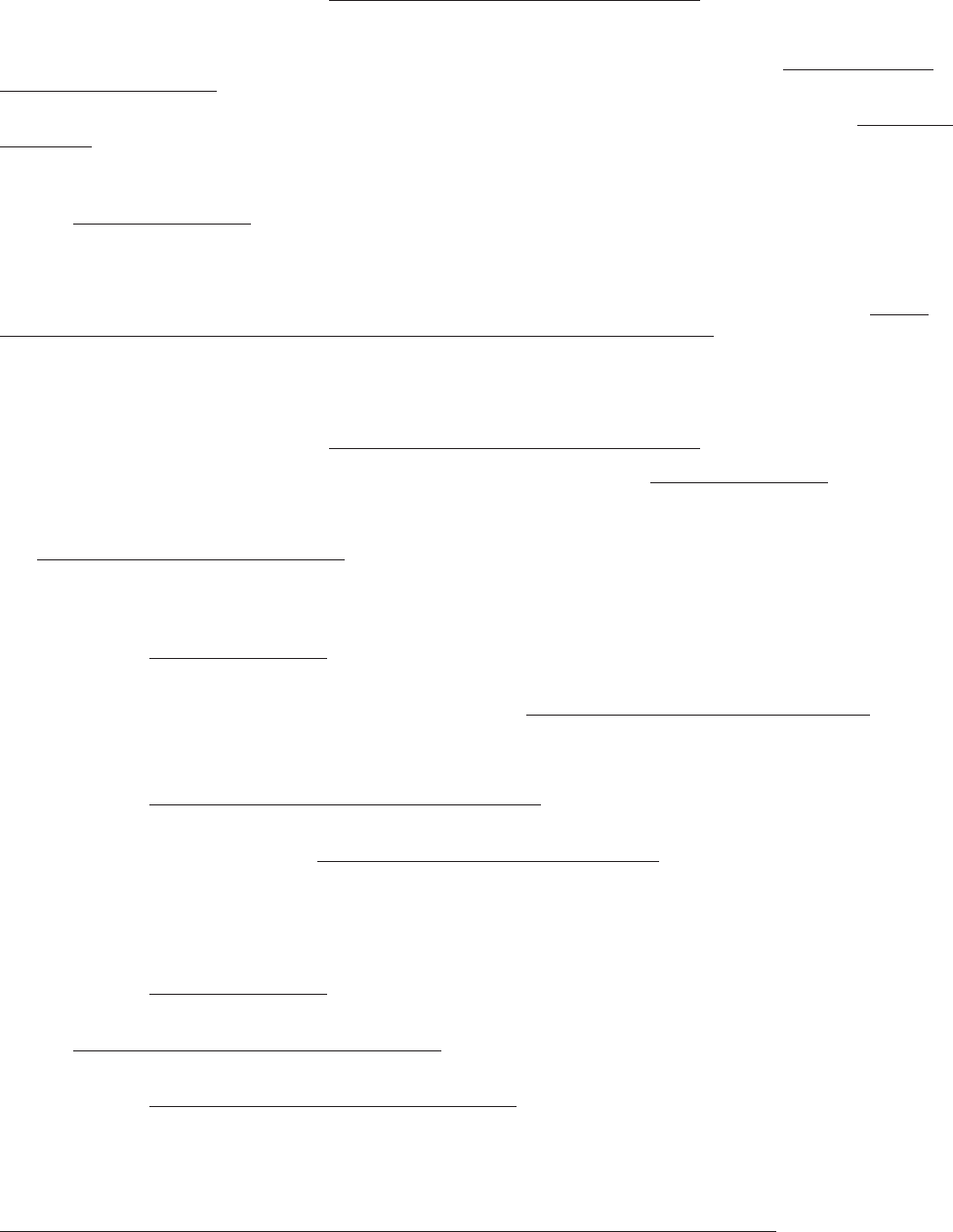

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of CKD in the U.S. population for stages 1 through 4 of the disease.

52

Figure 3 shows the disproportionate prevalence of the disease among older and minority individuals.

Prevalence of CKD by Stage, 1988-2016

FIGURE 2

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System—United States.

Website. https://nccd.cdc.gov/CKD.

YEAR

PERCENTAGE/PREVALENCE

1999-2000

2001-2002

2003-2004

2005-2006

2007-2008

2009-2010

2013-2014

2011-2012

2015-2016

1988-1994

CKD Stage 1

CKD Stage 2

CKD Stage 3

CKD Stage 4

Stages 1-4

Confidence Intervals

Page 21 | Advancing American Kidney Health

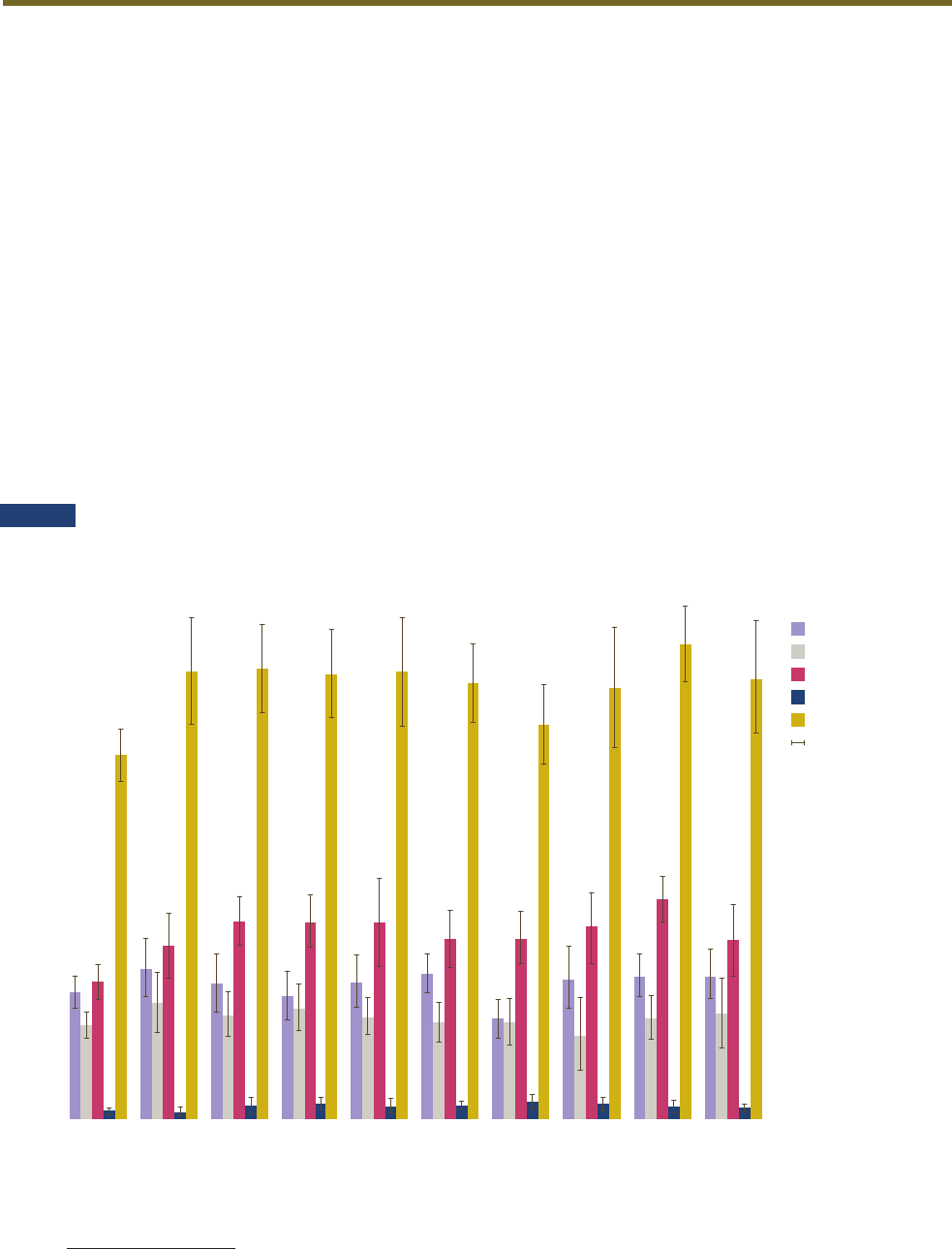

FIGURE 3

Percentage of CKD Among U.S. Adults Aged 18 Years and Older, by Sex and Race/Ethnicity

18-44

45–64

65+

Men

Women

Non-Hispanic whites

Non-Hispanic blacks

Non-Hispanic Asians

Hispanics

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

PERCENTAGE

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Percentage of CKD stages 1–4 among US adults aged 18 years or older using data

from the 2013–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.

NIH research led to the seminal discovery of the APOL1 gene, which explains why CKD progresses faster

among African Americans compared to Caucasians.

53

As of December 31, 2015, the prevalence of dialysis treatment was 1,470 per million U.S. population.

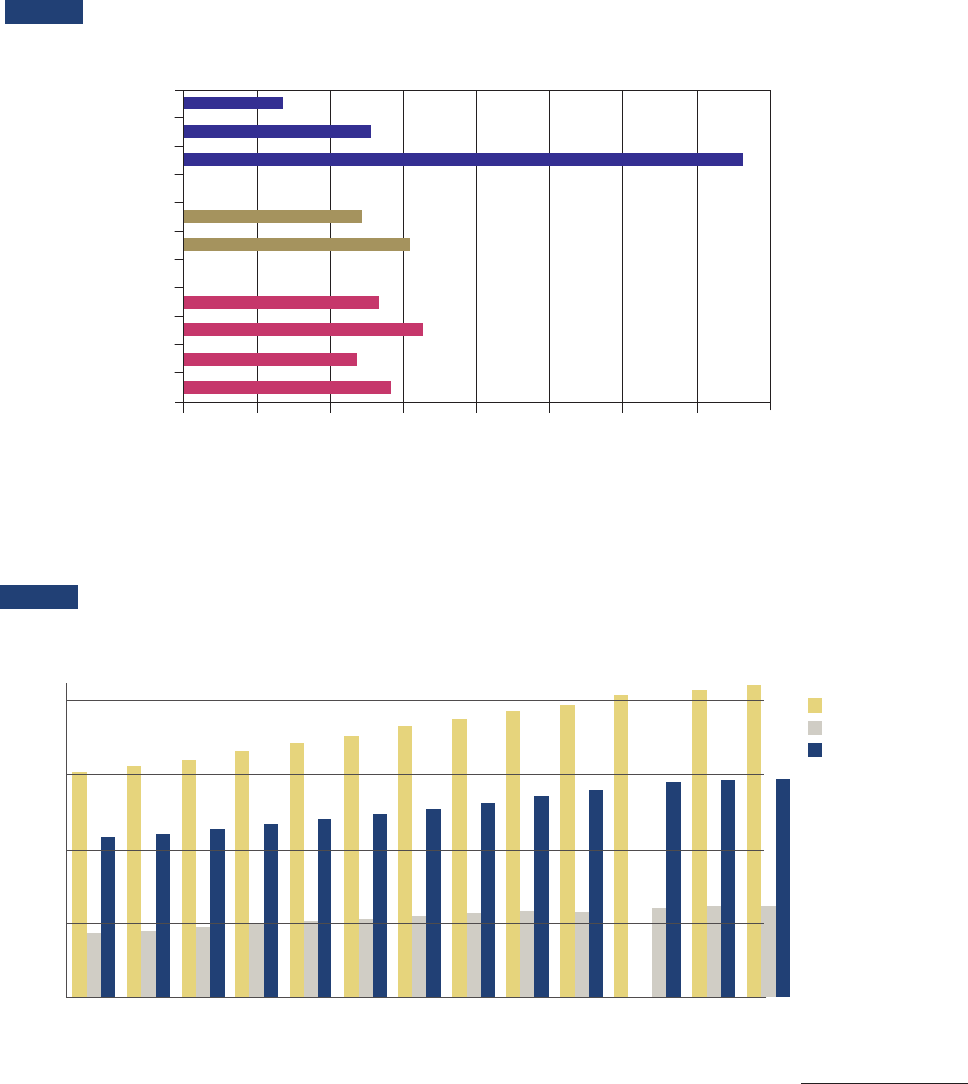

Figure 4 shows that the prevalence of ESRD has been increasing over time. The prevalence of ESRD

more than doubled between 1990 and 2015, and the number of prevalent ESRD cases has continued to

rise by approximately 20,000 cases per year, reaching 726,331 prevalent cases by 2016.

54

,

55

FIGURE 4

Prevalence of Treated ESRD, 2003-2015

POINT PREVALENCE PER MILLION RESIDENTS

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System—United States. Website.https://nccd.cdc.gov/CKD.

YEAR

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

2000

1500

1000

500

0

All treated ESRD

Functioning transplant

Receiving dialysis

Page 22 | Advancing American Kidney Health

Similar to trends for CKD, Figure 5 shows that the prevalence of ESRD is higher among racial minori-

ties.

56

Compared to Whites, ESRD prevalence in 2016 was approximately 9.5 times greater in Native

Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NH PI), 3.7 times greater in African Americans (Black Af/Am), 1.5 times

greater in American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN), and 1.3 times greater in Asians.

57

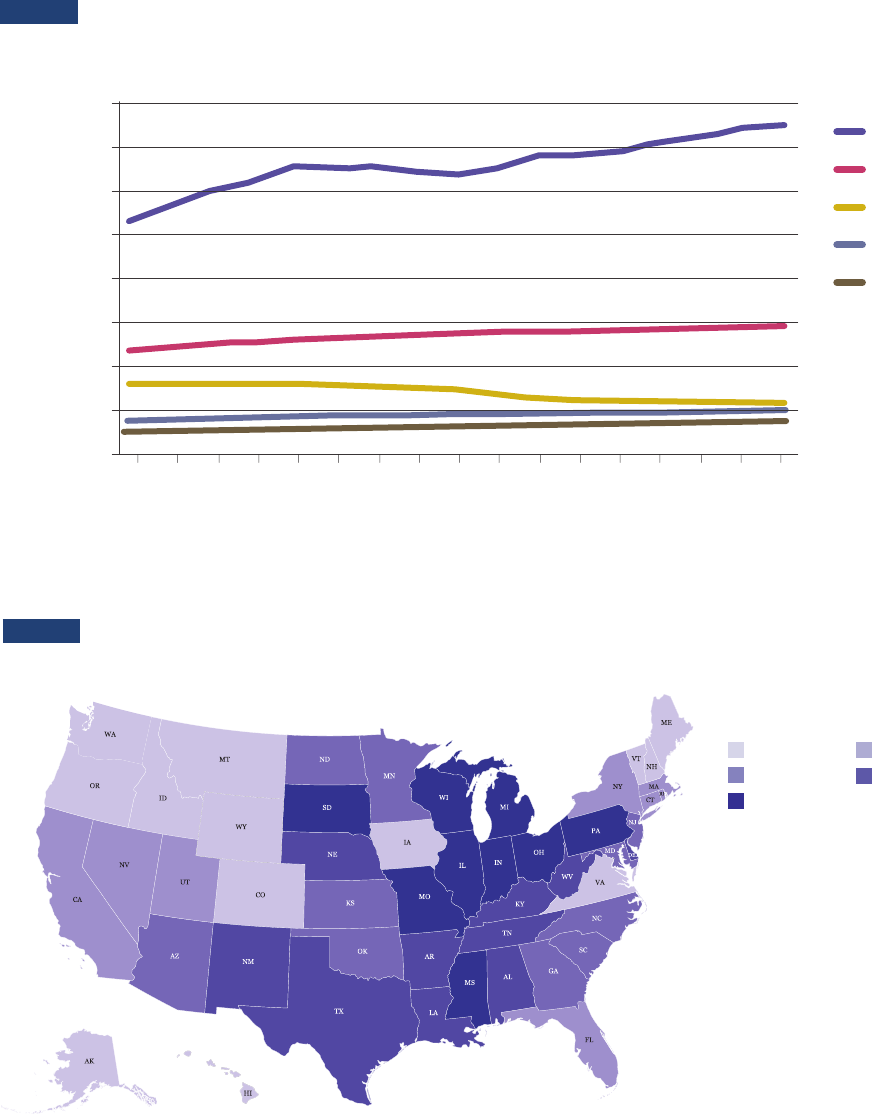

Figure 6 shows that the burden of ESRD varied significantly by state in 2015, ranging from highs of

2,428.8 per million residents in the District of Columbia, 2,212.6 in Illinois, and 2,203.6 in South Dakota

to lows of 1,185.8 per million residents in Vermont, 1,175.6 in Maine, and 1,155.7 in New Hampshire.

58

Trends in the Standardized Prevalence of ESRD, by Race, 2000-2016

White

Black/Af Am

AI/AN

Asian

NH/PI

SOURCE: USRDS Annual Data Report. Special analyses, USRDS ESRD Database. Point prevalence on December 31 of each year. Standardized

to the age-sex distribution of the 2011 U.S. population. Special analyses exclude unknown age, sex, and unknown/other race. Abbreviations

NH/PI: Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; AI/AN: American Indian/Alaska Native.

FIGURE 5

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

0

POINT PREVALENCE PER MILLION RESIDENTS

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Prevalence of ESRD by U.S. State for 2016

FIGURE 6

PREVALENCE PER MILLION

1,146 to 1,593 1,658 to 1, 90 9

1,921 to 2,016 2 ,019 to 2,107

2,163 to 2,563

Page 23 | Advancing American Kidney Health

Risk Factors

Major risk factors for ESRD include diabetes and high blood pressure (see Figure 7), in addition to hav-

ing a family history of kidney failure. Approximately 48 percent of individuals with severely reduced

kidney function who are not on dialysis, are not even aware they have CKD.

59

One positive trend is the decreasing rate of ESRD among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs).

The incidence of diabetes-related ESRD (ESRD-D) among AI/AN populations decreased by over 40 per-

cent between 2000 and 2015, resulting in lower levels of disease burden for patients and reduced spend-

ing for programs that cover the costs of AI/AN health care.

60

Measures related to the assessment and

treatment of ESRD-D risk factors showed more improvement during this period in AI/ANs than in the

general U.S. population.

61

This reduction in ESRD rates occurred after the Indian Health Service (IHS)

began implementing public health and population management approaches to diabetes and improve-

ments in clinical care in the mid-1980s. The approach taken by IHS to reduce diabetes may be a model

for reducing ESRD risk factors in other health care systems.

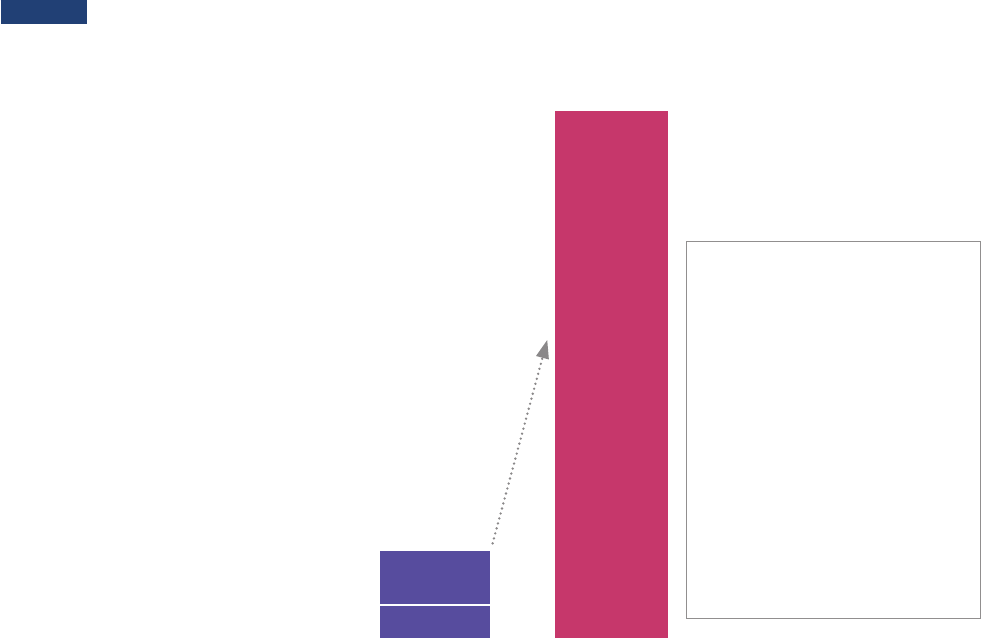

Figure 8 shows the significant decline in ESRD-D incidence in AI/ANs compared to Whites between

2001 and 2015.

Reported Causes of ESRD in the United States

Diabetes

High blood pressure

Glomerulonephritis

Other cause

Unknown cause

N=726,331 (all ages, 2016).

Includes polycystic kidney disease, among other causes.

SOURCE: US Renal Data System.

38%

16%

15%

26%

5%

FIGURE 7

Incidence per Million of Diabetes-Related ESRD in AI/AN and White Populations

FIGURE 8

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

1999

2003

2009

2001

2007

2005

2011

2013

2015

AI/AN

White

SOURCE: ASPE Analysis of USRDS 2017 Annual Data Report Reference Tables.

Page 24 | Advancing American Kidney Health

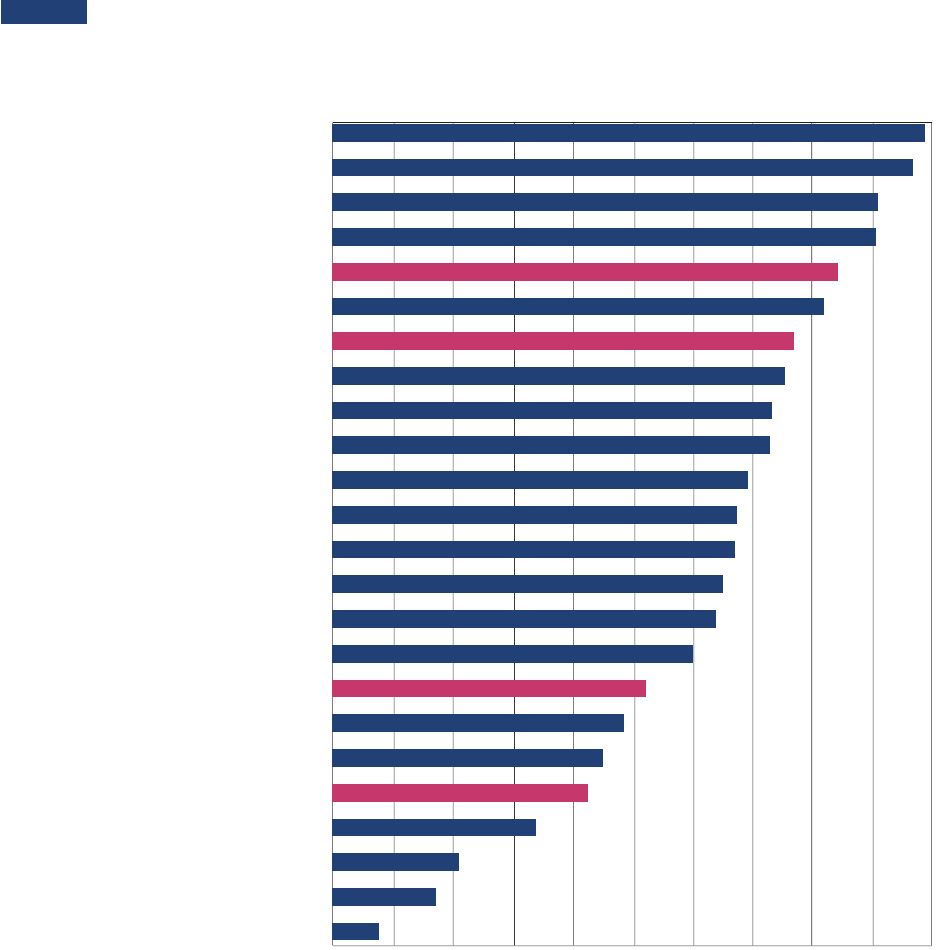

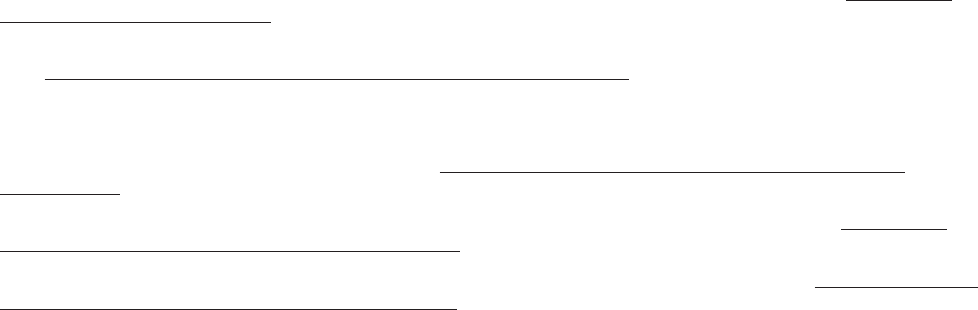

Treatment Options for ESRD

USRDS data indicate that at the end of 2016, approximately 63.1 percent of all prevalent ESRD patients

were receiving hemodialysis (HD) therapy, 7.0 percent were treated with peritoneal dialysis, and 29.6

percent had a functioning kidney transplant. Among HD cases, 98.0 percent used in-center HD, and 2.0

percent used home HD.

62

While home-based dialysis may not meet the needs of every patient, home di-

alysis has clear benefits for those who are suitable candidates. In addition to being more convenient for

many people living with ESRD, Figures 9 (below) and 10 (following page) show that survivability rates

for home dialysis are comparable to those of transplant recipients and hemodialysis.

63

,

64

A 2015 Government Accountability Oce (GAO) report found that facilities have financial incentives

in the short term to increase provision of hemodialysis in facilities rather than increasing home dial-

ysis.

65

For example, hemodialysis facilities may be able to increase the number of in-center patients

without adding a dialysis machine because each machine can be used by six to eight in-center patients.

However, for each new home patient, facilities may need to pay for the cost of an additional dialysis

machine. GAO also reported that facilities might be less inclined to provide home dialysis depending

on the adequacy of Medicare’s payments for home dialysis training and because Medicare’s monthly

payments to physicians for managing the care of home dialysis patients are often lower than for man-

aging in-center patients.

66

The CMS Innovation Center is announcing five new payment models, which include incentives to opti-

mize care for Medicare beneficiaries with kidney disease. These models represent important eorts by

HHS to improve care for patients with chronic kidney disease in the near future. Looking further into the

future, investments in research and new technology may be able to increase access to even better treat-

ment options. Innovations in kidney disease treatments include technology such as wearable, implant-

able, and biohybrid dialysis units, which could substantially improve quality of life for people living with

ESRD. NIH funding for biomedical research related to kidney disease totaled approximately $600 mil-

lion in fiscal year 2018.

67

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)

Survivability Rates for Nocturnal Home Hemodialysis (NHD)

vs. Other Treatment Modalities

SOURCE: USRDS 2018 Annual Data Report.

FIGURE 9

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

PATIENTS SURVIVING (%)

NHD: Avg age 46.4 years

Deceased donor transplant

Living donor transplant

Dialysis: 40-49 year (USRDS)

Dialysis: all ages (USRDS)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

YEARS

Page 25 | Advancing American Kidney Health

5-Year Survival of Cancers and ESRD by Treatment Type

FIGURE 10

Male Genital Cancer

Endocrine Cancer

Breast Cancer

Skin Cancer

ESKD–LD Txp*

Eye/Orbit Cancer

ESKD-DD Txp*

Urinary System Cancer

Kaposi Sarcoma

Lymphoma

Female Genital Cancer

Bones/Joint Cancer

All Cancer

So Tissue Cancer

Oral/Pharynx Cancer

Leukemia

ESKD–PD*

Myeloma

Digestive System Cancer

ESKD–HD*

Brain/CNS Cancer

Respiratory Cancer

Liver & Intrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer

Pancreatic Cancer

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

5-YEAR SURVIVAL RATE (PERCENTAGE)

*Reference population: incident ESKD patients, 2011. Adjusted for age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and primary

diagnosis

LEGEND

ESKD-LD Txp: end-stage kidney disease, received living donor transplant

ESKD-DD Txp: end-stage kidney disease, received deceased donor transplant

ESKD-PD: end-stage kidney disease, receiving peritoneal dialysis

ESKD-HD: end-stage kidney disease, receiving hemodialysis

SOURCES: United States Renal Data System, 2018 USRDS annual data report; SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015.

Page 26 | Advancing American Kidney Health

provides the majority of NIH’s funding for biomedical research on kidney disease, ESRD treatment, and

kidney donation.

68

HHS, in partnership with the American Society of Nephrology, also supports KidneyX,

which is designed to improve kidney care by investing in the development of new products and technolo-

gies like wearable and implantable dialyzers and regenerative kidneys.

Health Care Spending on CKD and ESRD

When Medicare entitlement was first extended to individuals with ESRD in 1972, approximately 10,000

individuals were receiving dialysis. By 2016, excluding transplant patients, there were 511,270 benefi-

ciaries being treated for ESRD. While ESRD patients comprise less than 1 percent of the total Medicare

population, they accounted for approximately 7 percent of Medicare FFS spending, totaling over $35.4

billion in 2016.

69

Medicare spending on CKD and ESRD was over $114 billion in 2018, representing 23

percent of total Medicare FFS spending.

70

Growth in total CKD spending has primarily been driven

by an increase in the number of identified cases, particularly those in the earlier disease stages (CKD

Stages 1-3).

71

In 2016, Medicare patient obligations – which may be paid by the patient, by a second-

ary insurer, or may be uncollected – represented 9.6 percent, or approximately $4 billion, of total FFS

Medicare Allowable Payments.

72

Between 2015 and 2016, average per person per year spending for hemodialysis (HD) care increased

from $88,782 to $90,971, or 2.5 percent, while total spending on HD care rose from $26.8 billion to $28.0

billion, or 4.5 percent (similar to the total growth in ESRD spending of 4.6 percent).

73

Total spending for

patients who have received kidney transplants increased from $3.3 billion to $3.4 billion, or 3 percent,

and per capita spending increased from $34,080 to $34,780, or 2.1 percent.

74

Kidney Transplantation

For some people living with ESRD, a transplant using a healthy kidney from a donor may be an option.

The Innovation Center’s ETC Model will support the goal of increasing access to kidney transplants

through financial incentives for ESRD facilities and Managing Clinicians. A functioning transplanted

kidney does a better job of filtering wastes than dialysis,

75

and transplant recipients have improved life

expectancy compared to individuals on dialysis.

76

Of the 36,529 organ transplants performed in the

U.S. in 2018, approximately 21,000 were kidney transplants.

77

Of these, approximately 30.4 percent were

from living donors and 69.6 percent from deceased donors.

78