RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER

OCTOBER 2017

I

nsecurity, crime, and state weakness are parts of

everyday life in much of Central America. Most

homicides and other crimes go unreported or unsolved

and law enforcement, judicial, and correctional systems

are overloaded, corrupt, and ineffective. Despite decades

of effort on remedies, the underlying security situation

remains largely the same, if not worse, in some countries.

Facing dangerous and daunting contexts, individuals

modify their behaviors in ways that have personal,

economic, societal, and even transnational consequences.

A focus on these dynamics can reveal opportunities for

strategic programming to curtail the damaging effects of

crime and violence to the region.

The problem is particularly severe in the three “Northern

Triangle” countries–El Salvador, Guatemala, and

Honduras–which regularly rank among the most violent

countries in Latin America and the world. (Note: This report

uses “Northern Triangle” to refer to these three countries

and “Central America” for those three plus Nicaragua,

Costa Rica, and Panama.) In 2016, El Salvador recorded

81.2 homicides per 100,000 people, the highest rate in the

Americas (with the possible exception of Venezuela, where

ofcial statistics are typically incomplete or unavailable).

Honduras and Guatemala reported rates of 59 and 27.3

By asking individuals not just about

crime victimization and perceptions

of crime, but also about their

behavior patterns in the face of

crime, the study delves deeper into

how and why insecurity aects the

social, political, and economic fabric

in Central America.

BENEATH THE VIOLENCE

HOW INSECURITY SHAPES DAILY LIFE AND

EMIGRATION IN CENTRAL AMERICA

A Report of the Latin American Public Opinion Project and the

Inter-American Dialogue

Ben Raderstorf, Carole J. Wilson, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, and Michael J.

Camilleri

per 100,000, respectively—lower than El Salvador but

still high enough to rank as third and fth most violent in

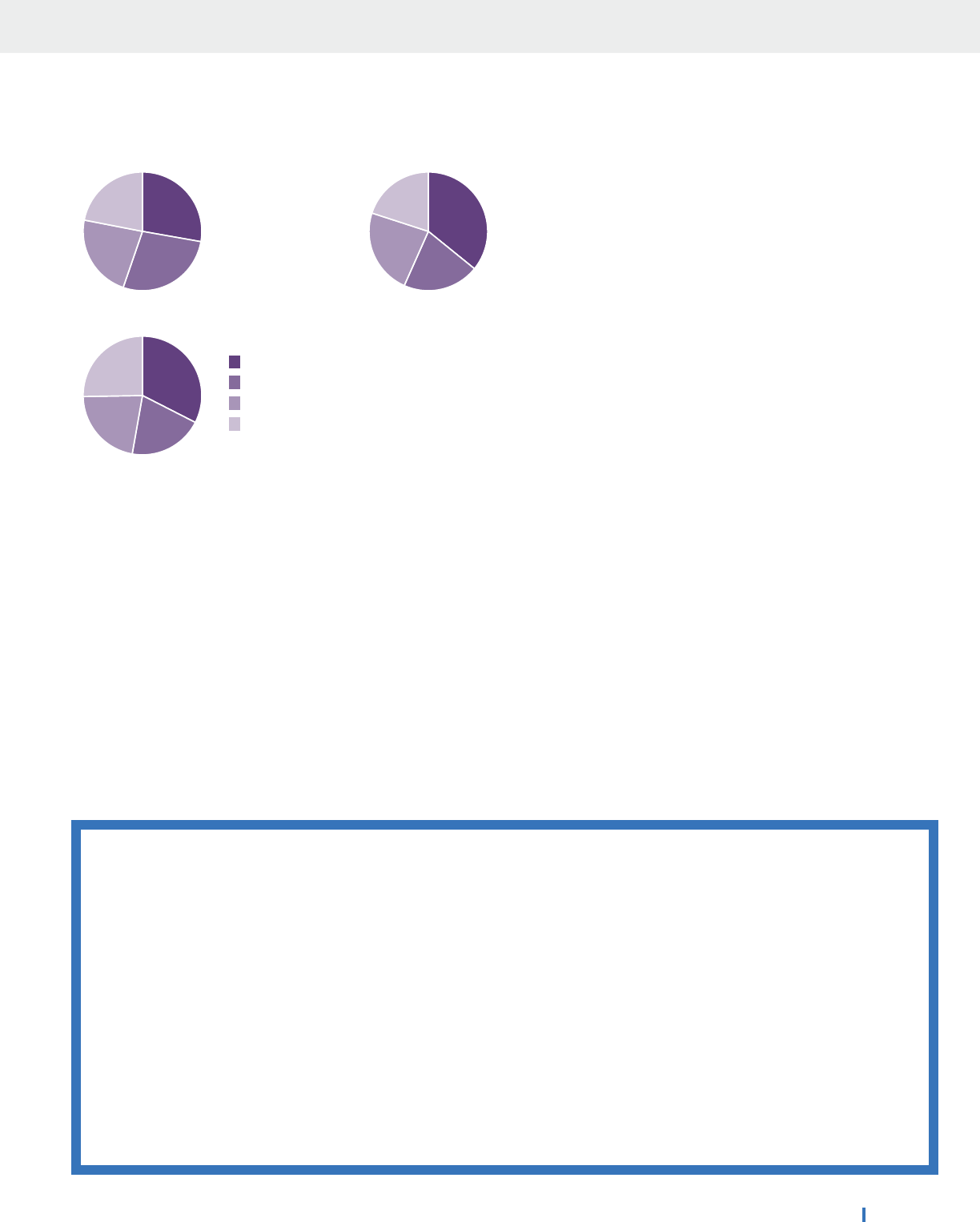

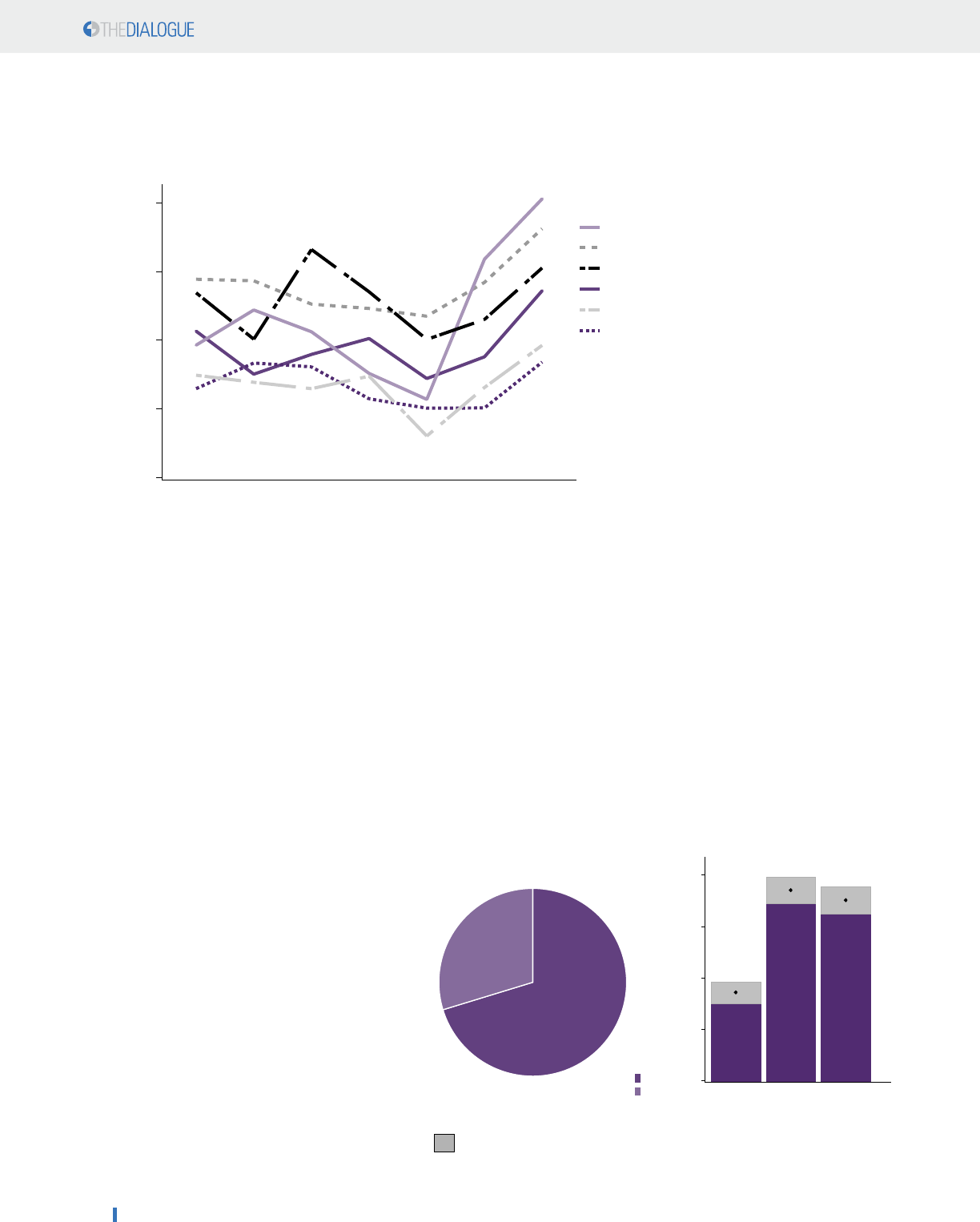

the Latin America and Caribbean region.

1

The reality of

high homicide rates registers among the population: in

the Northern Triangle, more than half the population has

“some” or “a lot of fear” of being a victim of homicide, with

El Salvador the most affected (see Figure 1).

2

The main drivers of violence—beyond a long history of civil

war, political instability, and weak judicial institutions—are

Beneath the Violence

2

Foreword

We are pleased to present “The Toll of Crime on Daily Life

and Intention to Emigrate in Central America,” a joint report

by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP)

at Vanderbilt University and the Peter D. Bell Rule of Law

Program at the Inter-American Dialogue.

This report, by Ben Raderstorf, Carole Wilson, Liz

Zechmeister, and Michael Camilleri, addresses critical

questions about how insecurity impacts everyday life in

Central America and how violence shapes behaviors from

economic activity to migration. Based on approximately

9,300 in-person interviews conducted across nationally

representative samples in Guatemala, Honduras, El

Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama as a part

of the 2016/17 AmericasBarometer, these ndings paint

a detailed portrait of the ongoing toll that crime takes

on countries in Central America. They also point the way

towards some potential solutions.

This report represents the culmination of a year-long

collaboration between LAPOP and the Inter-American

Dialogue that attempts to connect the dots between

opinion polling on security and actionable, concrete policy

recommendations. At the end of the report, the authors

provide a list of policy guidelines for decision makers in

Central America, the United States, and elsewhere.

LAPOP is a center for excellence in international survey

research. Its core project is the AmericasBarometer, a

regular study of how citizens experience and evaluate

democratic governance in 34 countries. LAPOP’s mission

is four-fold: produce high quality public opinion data;

develop cutting-edge methods in international survey

research; build local capacity in the eld of survey research

and analysis; and, disseminate timely results with rigor and

clarity.

Established in 2015 with support from the Ford Foundation

and named in honor of a founding Dialogue co-chair, the

Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program of the Inter-American

Dialogue strives to elevate policy discussions around

democratic institutions, government accountability, human

rights, and citizen engagement in Latin America.

The data used in this report are available free of

charge at LAPOP’s website: www.lapopsurveys.org.

Extensive information on LAPOP’s methods and the

AmericasBarometer survey can be found at the same

website. The AmericasBarometer survey has been made

possible because of support from the United States

Agency for International Development (USAID), Vanderbilt

University, the Inter-American Development Bank, the

United Nations Development Programme, the Open Society

Foundation, and a network of other partners across the

Americas. The opinions expressed in this study are those

of the authors and do not necessarily reect the point of

view of Vanderbilt University, the Inter-American Dialogue,

USAID, or any other sponsor or partner to the study.

We are grateful to Kevin Casas-Zamora, a non-resident

senior fellow at the Dialogue, for his instrumental role in

helping initiate and shape this collaborative project and

for his comments on drafts. We also thank USAID and the

Igarapé Institute, headquartered in Brazil, for input into

some of the questions that are used in this study.

MICHAEL SHIFTER MITCHELL A. SELIGSON

President Founder and Senior Advisor,

Inter-American Dialogue LAPOP

Centennial Professor of

Political Science,

Vanderbilt University

The 2016/17 AmericasBarometer shows that

fear of crime leads large percentages of the

population to alter their daily activities—

avoiding public transit or making purchases,

keeping children at home, changing jobs or

place of study, moving neighborhoods, and

even considering emigration.

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

3

gang activity and drug trafcking.

3

There are an estimated

54,000 gang members across the three countries,

4

divided

among groups that compete, often violently, for territory

and resources. These gangs, known as maras, often seek

to extract value directly from the communities. As a result,

criminal extortion is rampant. A 2015 estimate found

that Salvadorans alone pay an estimated $400 million in

extortion and protection fees to gangs and other criminal

groups.

5

Extortion, in turn, leads to country-wide networks

of fear and intimidation, tightly constraining economic

activity in many areas and sectors. According to an

estimate by the Inter-American Development Bank, crime-

related costs in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras are

equal to 3%, 6.2%, and 6.5% of GDP, respectively.

6

In recent years, violence in the region has received

signicant international attention as a major factor

in a wave of migration to the US

7

(see the 2014

AmericasBarometer Insights brief on “Violence and

Migration in Central America”

8

). In 2014, when the

crisis peaked, US Border Patrol agents apprehended

nearly a half million people at the US-Mexico border, in

large part families and unaccompanied children from

the Northern Triangle.

9

While migration rates have

since fallen somewhat—dropping sharply in 2015 but

bouncing back in 2016—much of that decline has come

from increased enforcement efforts on the part of the

Mexican government.

10

There are also anecdotal reports

that the Trump Administration’s policies and rhetoric

have discouraged migration, at least temporarily and

especially for unaccompanied minors.

11

In any case,

evidence suggests that the underlying desire to emigrate

remains strong. The 2016/17 AmericasBarometer nds

that intentions to move abroad have risen signicantly in

every country in Central America since 2014, especially in

Honduras.

12

At the same time, governments in the Northern Triangle

have been mostly unable to respond effectively to

problems of crime and security. Prison systems are

massively overcrowded, with one estimate placing El

Salvador’s current prison population at a staggering

348.2% of capacity.

13

Meanwhile, criminal justice systems

are widely seen as corrupt—and often with good reason:

11.6% of adults in the Northern Triangle report being asked

to pay a bribe to a police ofcer in a twelve-month period.

14

FIGURE 1: LEVEL OF FEAR OF BEING A VICTIM OF

HOMICIDE

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

27.9%

27.5%

22.7%

22.0%

Guatemala

35.7%

20.9%

23.4%

20.0%

El Salvador

32.6%

20.1%

21.9%

25.4%

Honduras

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

Level of Fear of Being a Victim of Homicide

A Lot of Fear

Some Fear

Little Fear

No Fear at All

This project asked questions in all six countries about “Out of fear

of crime, in the last 12 months…

Have you avoided leaving your home by yourself at night?”

Have you avoided public transportation?”

Have you prevented children from playing in the street?”

Have you felt the need to move to a different neighborhood?”

We also asked three questions in Guatemala, Honduras, and El

Salvador about “In the last 12 months…

Have you avoided buying things that you like because they may

get stolen?”

Have you changed your job or place of study out of fear of crime?”

Have you considered migrating from your country due to

insecurity?”

And one question in Guatemala only: “Out of fear of crime, in the

last 12 months…

Have you kept your minor children from going to school for fear of

their safety?”

Data collection for the Central American countries included in

the 2016/17 AmericasBarometer was conducted in late 2016

(Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua) and early

2017 (Guatemala and Panama). The samples are designed to be

nationally representative. In each country, approximately 1,550

adults were interviewed face-to-face.

Beneath the Violence

4

Together, all these factors paint a concerning picture of

the region. That is, the enormous burden of crime and

insecurity on the Northern Triangle—and how it generally

relates to migration, corruption, instability, and a lack of

economic opportunities—is well-documented.

However, understanding the more specic impact of

insecurity on individuals’ lives – who is more likely to

take precautions against crime and to what consequence

– is often hindered by a lack of granularity and clear,

consistent, and comparative data. National indicators,

especially crime trends beyond homicides, are often

inconsistent, of poor quality, and at times politicized.

There is also often a gap in understanding between those

statistics and the individual-level picture painted by the

many high-quality eld and ethnographic studies that have

been conducted over the years.

15

It is at times difcult to

elaborate clearly on how the security environment affects

the daily functions of a society as a whole and how it

drives economic activity, migration, and other trends.

By asking ordinary citizens to report on their own

circumstances, public opinion studies provide a window

into micro-level dynamics. However, a comprehensive

assessment requires sizeable modules on crime and

violence, in order to drill into the topic. For example,

the 2016/17 AmericasBarometer nds that nearly equal

proportions of the public in Uruguay and Honduras cite an

issue related to security as the most important problem

facing their country.

16

Yet across these diametrically

opposed countries – Uruguay among the safest in the

region and Honduras among the most violent in the world

– individuals’ specic experiences and concerns vary.

Via the inclusion of more detailed questions, surveys

provide a means to reveal exactly how problems of crime

and insecurity manifest in a particular context, and with

what consequences for individual behaviors and societal

outcomes.

This report, which presents ndings gathered as a part of

LAPOP’s 2016/17 AmericasBarometer surveys, begins to

ll in some of these gaps.

17

Analyses of the survey data,

which were collected in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras,

Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, more concretely

measure and diagnose the human and societal impact

of insecurity. By asking individuals not just about crime

victimization and perceptions of crime, but also about

their behavior patterns in the face of crime, the study

delves deeper into how and why insecurity affects the

social, political, and economic fabric in Central America.

In presenting key ndings from the project, we aim to shed

more light on the many complex and pressing security

concerns in the region—and inform discussions about how

to address them.

1. How Insecurity Shapes

Behavior in Central America

Measured by changes in behavior, the toll of insecurity

on daily life in Central America is widespread and

signicant. The 2016/17 AmericasBarometer shows that

fear of crime leads large percentages of the population

to alter their daily activities—avoiding public transit or

making purchases, keeping children at home, changing

jobs or place of study, moving neighborhoods, and even

considering emigration.

56.7%

67.6%

60.8%

69.2%

63.6%

65.9%

59.6%

36.9%

59.8%

46.8%

48.6%

56.6%

31.1%

42.2%

47.4%

25.5%

32.4%

50.2%

21.1%

15.0%

15.4%

19.4%

19.7%

19.5%

Panama

Costa Rica

Nicaragua

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

Panama

Costa Rica

Nicaragua

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

Panama

Costa Rica

Nicaragua

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

Panama

Costa Rica

Nicaragua

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

0 20 40 60 80

Prevented Children from Playing in the Street

Has Avoided Leaving House Alone at Night for Fear of Crime

Has Avoided Using Public Transportation for Fear of Crime

Has Felt Need to Move Neighborhoods for Fear of Crime

Percentage

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

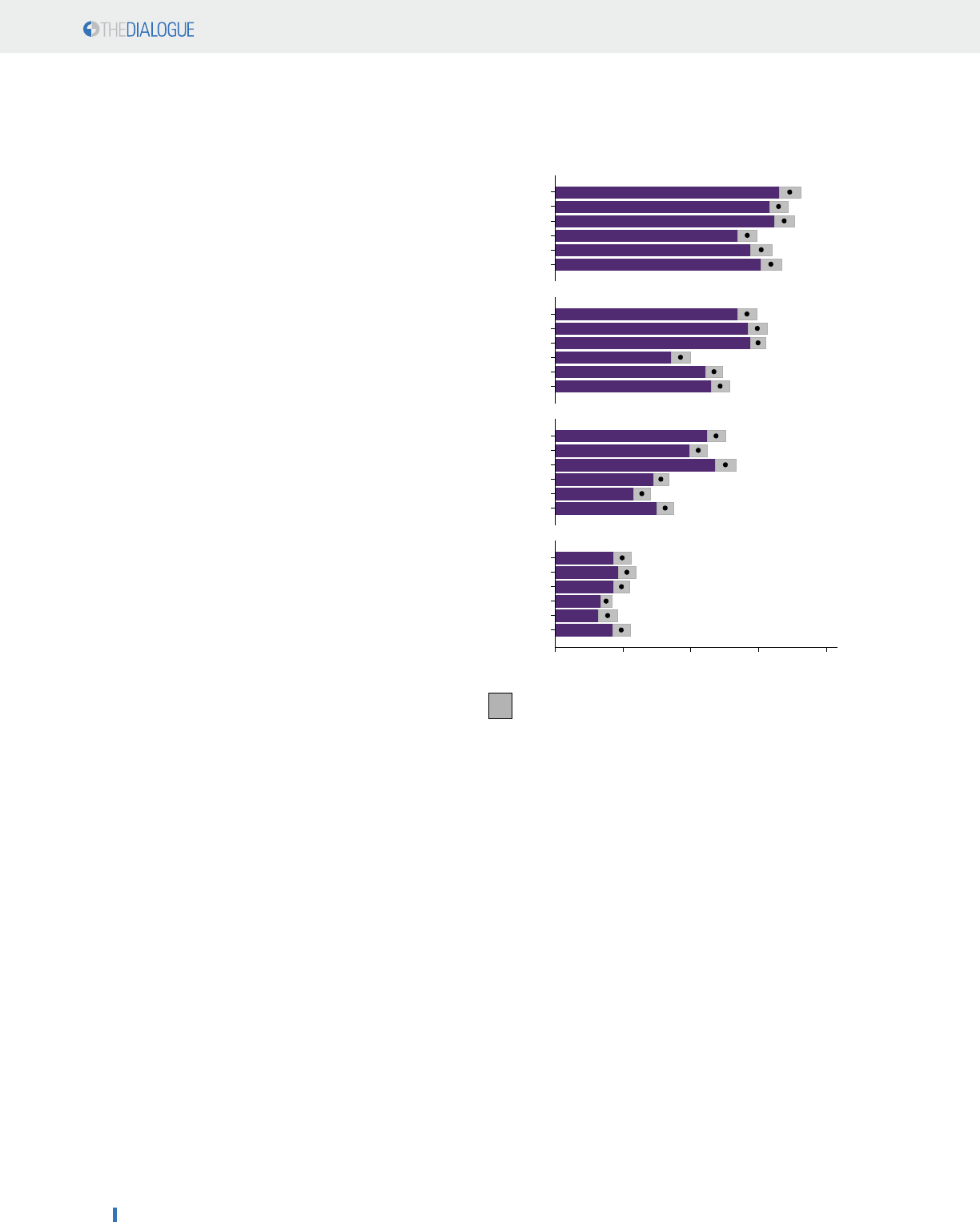

FIGURE 2: CRIME AVOIDANCE BEHAVIORS IN CENTRAL

AMERICA

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

5

As seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the distribution of impact

varies signicantly across behavior type and country

in Central America. Unsurprisingly, crime avoidance

behaviors are most common in Guatemala, Honduras,

and El Salvador. This is consistent with other statistics

on crime and security in the region, which generally nd

a sharp divide between the Northern Triangle and its

neighbors immediately to the south. Yet, surprisingly high

proportions of the population in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and

Panama report having changed their behavior, particularly

when it comes to preventing their children from playing on

the street or feeling the need to move neighborhoods. This

suggests that fears about family safety are more rigid—and

less connected to the underlying crime rates—than fears

about individual safety. That approximately two-thirds of

Central Americans (63.9%) report having prevented their

children from playing in the street may reect a widespread

state of panic, or it may simply reect a general tendency

toward caution in the care of others, even in the face of

comparatively smaller risk.

18

Digging deeper into the Northern Triangle specically—

measuring purchasing habits, changing jobs or place of

study, migration, and school attendance—we nd that the

behavioral impact of crime is particularly strong when

it comes to economic activity. In Guatemala, Honduras,

and El Salvador, just over half of the adult population

(50.5%) reports having avoided buying “things they like”

in the past year because they may be stolen.

19

These data

afrm the assumption that underlies assessments based

on aggregate economic data: crime and insecurity deter

individuals from spending, to the detriment of the country’s

FIGURE 3: CRIME AVOIDANCE, ECONOMIC ACTIVITY,

AND MIGRATION IN THE NORTHERN TRIANGLE

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

48.6%

51.2%

51.7%

35.1%

17.2%

37.1%

9.4%

12.4%

11.1%

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

El Salvador

Guatemala

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Has Avoided Buying Items for Fear of Robbery

Considered Migrating in Last 12 Months because of Insecurity

Has Changed Jobs or Study Locations for Fear of Crime

Percentage

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

68.6%

67.5%

69.2%

68.9%

64.3%

59.6%

61.3%

58.4%

62.6%

52.2%

46.3%

46.3%

53.1%

42.8%

45.5%

44.5%

51.8%

54.1%

52.2%

50.1%

29.8%

31.2%

27.4%

28.4%

32.9%

19.0%

20.3%

19.0%

22.0%

19.6%

9.4%

14.0%

12.2%

10.4%

8.0%

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

5

4

3

2

1

0 20 40 60 80

Prevented Children from Playing in the Street

Has Avoided Leaving House Alone at Night for Fear of Crime

Has Avoided Using Public Transportation for Fear of Crime

Has Avoided Buying Items for Fear of Robbery

Considered Migrating in Last 12 Months because of Insecurity

Has Felt Need to Move Neighborhoods for Fear of Crime

Has Changed Jobs or Study Locations for Fear of Crime

Percentage

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 4: CRIME AVOIDANCE BY QUINTILE OF WEALTH

IN CENTRAL AMERICA

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

Beneath the Violence

6

nancial situation. Additionally, 11% of those residing in

the Northern Triangle have changed their job or place of

study in the past year because of fear of crime.

20

This type

of outcome likely takes its own toll on the economy, and

also may be socially disruptive and destabilizing.

These crime avoidance behaviors are somewhat more

common in urban areas than in rural ones. For example,

23.3% of urban respondents in the Northern Triangle

report feeling the need to move neighborhoods due to

crime, while only 16.2% of rural respondents say the same.

There is only a small variation in responses by gender,

with female respondents slightly more likely to prevent

children from playing in the streets, avoid leaving the

house alone, and feel the need to move neighborhoods,

and male respondents slightly more likely to avoid public

transit. Variation in crime avoidance also exists across age

groups, with middle cohorts slightly more likely to engage

in crime avoidance—especially when it comes to pressure

to move neighborhoods: 25.7% of respondents between 36

and 45 years old report feeling a need to move, whereas

only 11.8% of those 66 years and older feel the same.

Interestingly, in most cases there is little variance in crime

avoidance behavior across wealth quintiles (see Figure

4). Among the exceptions are that those in the poorest

quintile are signicantly less likely to avoid leaving the

house alone at night and the wealthiest are signicantly

more likely to avoid public transit. We note that, while there

is not a statistical difference between the least wealthy

groups in their likelihood of avoiding public transportation,

the fact that 44.6% of the lowest two quintiles do so is

still a signicant and concerning nding.

21

Many of these

individuals are unlikely to have alternative forms of transit

(for example, 80 percent of adults in Honduras report

not owning a car

22

) and therefore exclusion from public

transport is a signicant blow to mobility and economic

opportunities.

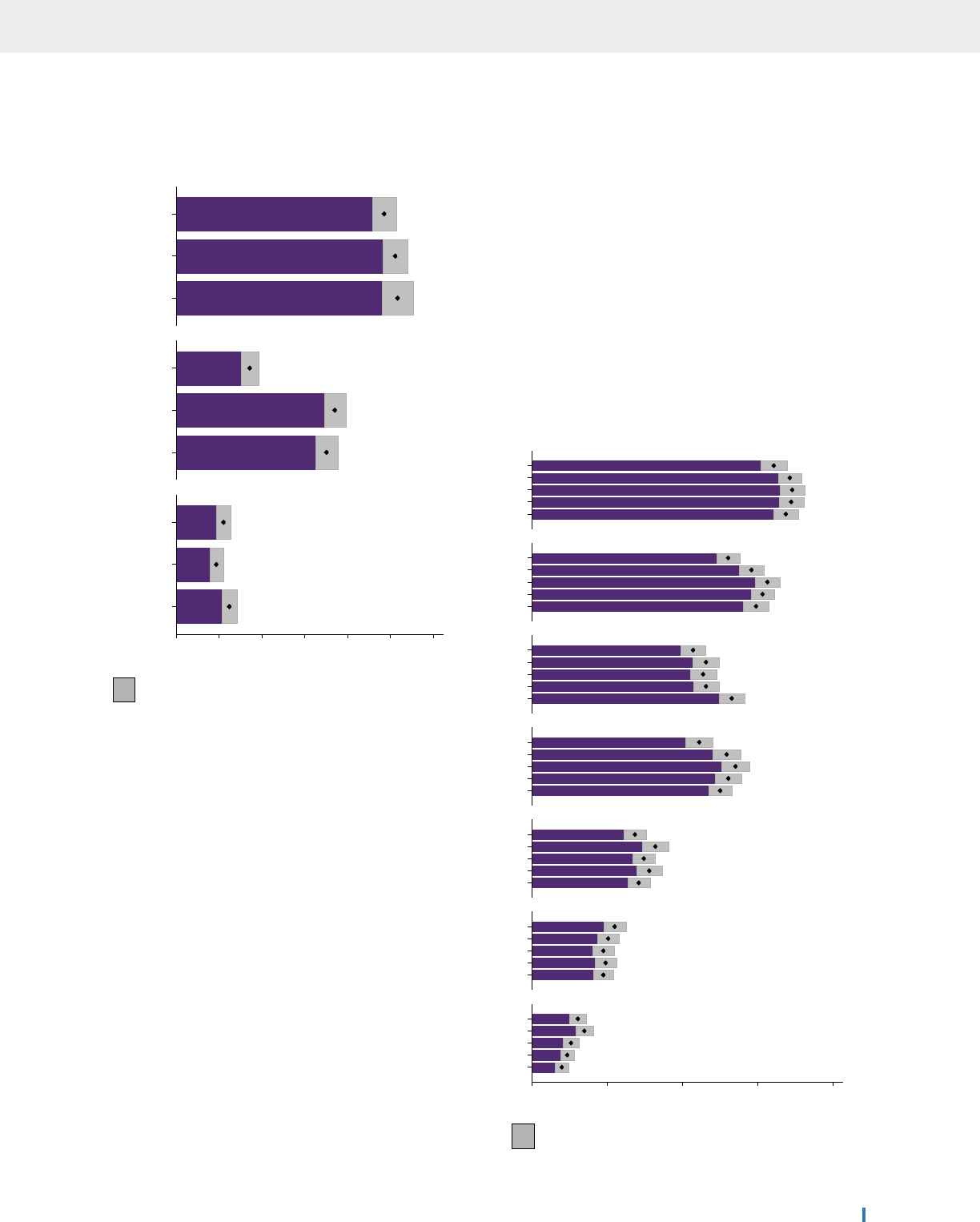

Finally, in Guatemala specically, approximately one in

three respondents (31.7%) report having kept children

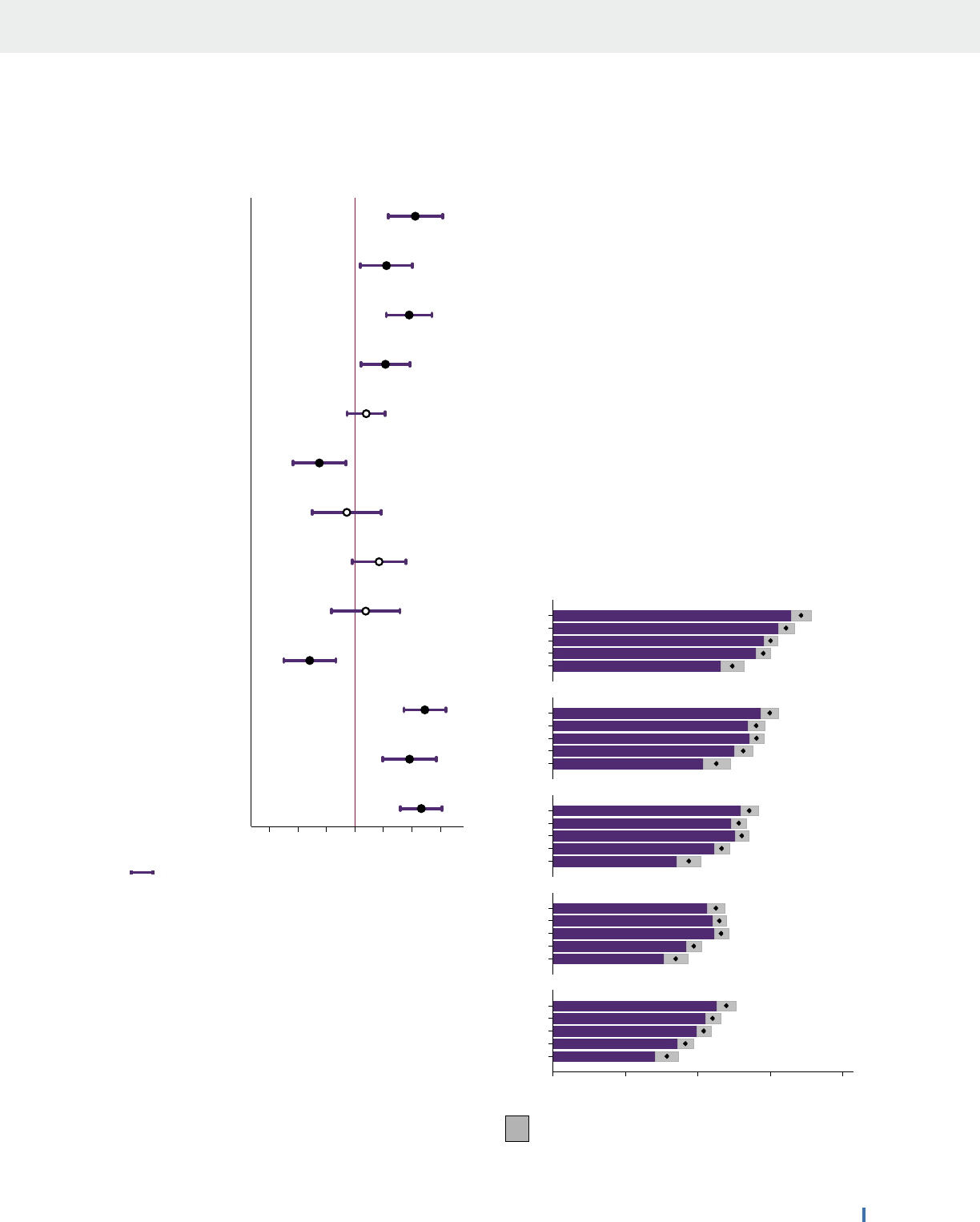

at home out of fear of crime (see Figure 5).

23

This is in

keeping with recent studies and reporting about a growing

number of children routinely missing school or college

because of fear of violence and criminal gangs. As

Francisco Benavides, a regional education adviser for Latin

America and the Caribbean at UNICEF described, “In some

areas of Latin America, we are talking about a second lost

generation.”

24

2. Creating and Validating a

Crime Avoidance Behavior

Index

With these ndings in mind, we create a crime avoidance

behavior index—a single score that reects how much

single individuals or specic populations change their daily

routines to seek security. This index, which is constructed

using the questions that were asked in all Central American

countries (VIC71, VIC72, VIC43, and VIC74; see earlier text

box for wording), can be used to measure the aggregate

impact of insecurity between countries (see Figure 6) as

well as compare crime avoidance behavior with other data

gathered as a part of the 2016/17 AmericasBarometer.

In short, the crime avoidance behavior index is a way of

measuring how much each individual goes out of his or

her way because of insecurity. It is essentially a numerical

shorthand for how “crime averse” any one person or group

is. With each individual assigned a score between 0 and

100, we can compare the aggregate impact of crime

avoidance across countries, as well as compare subgroups

based on various other traits and responses.

As expected, high index scores are associated with

increased perceptions of insecurity, crime victimization,

and gang presence. Those who have been a victim of any

type of crime in the last 12 months—including robbery,

burglary, assault, blackmail, fraud, and extortion—score

39.1% higher on the index than those who have not (60.1

versus 43.2). In other words, crime avoidance is higher

68.3%

31.7%

No

Yes

Kept Children Home from School Out of Fear of Crime

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 5: GUATEMALANS WHO REPORT KEEPING

CHILDREN HOME FROM SCHOOL BECAUSE OF CRIME

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

7

among those who are genuinely at risk for crime. Those

who report feeling “Very Unsafe” in their neighborhood

score almost twice as high on the crime avoidance index

as those who report feeling “Very Safe” (60.9 vs 33.7).

Respondents in neighborhoods without gang-related

grafti—as evaluated by the interviewer—engage in

measurably less crime avoidance behavior. Experiences

with police corruption and longer perceived police

response time also correlate with more crime avoidance

behavior (see Section 4).

In summary, the crime avoidance behavior index is a useful

and valid measure of the burden of crime in a population.

It correlates in the expected ways with indicators of crime,

gang presence, and weak rule of law and it is consistent

with observations made in macro-level studies and by

policymakers. Therefore, we can use the crime avoidance

behavior index to test how the daily impacts of security

are related to—and potentially the drivers of—various other

trends, above all the intention to emigrate.

3. Crime Avoidance and

Intentions to Migrate

Among the most important consequences of crime

avoidance, from a policy perspective, is migration. In

fact, crime avoidance behavior is one of the strongest

predictors of intention to migrate. This individual-

level dynamic helps explain why, in the past ve years,

intentions to “live or work in another country in the next

three years” have spiked in all countries in Central America,

especially in Honduras (see Figure 7).

4%15%28%28%24%

4%14%24%30%28%

7%17%28%26%22%

9%25%29%23%14%

9%23%28%25%16%

9%25%29%23%14%

Costa Rica

Nicaragua

Panama

Guatemala

El Salvador

Honduras

None 1 Item 2 Items 3 Items 4 Items

Crime Avoidance Behavior

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

34.1

36.5

40.0

45.8

47.4

48.0

Nicaragua

Costa Rica

Panama

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

0 10 20 30 40 50

Crime Avoidance Behavior

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 6: THE CRIME AVOIDANCE BEHAVIOR INDEX

ACROSS COUNTRIES

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

Crime avoidance behavior is one

of the strongest predictors of

intention to migrate and helps

explain why intentions to do so

have spiked in all countries in

Central America.

Beneath the Violence

8

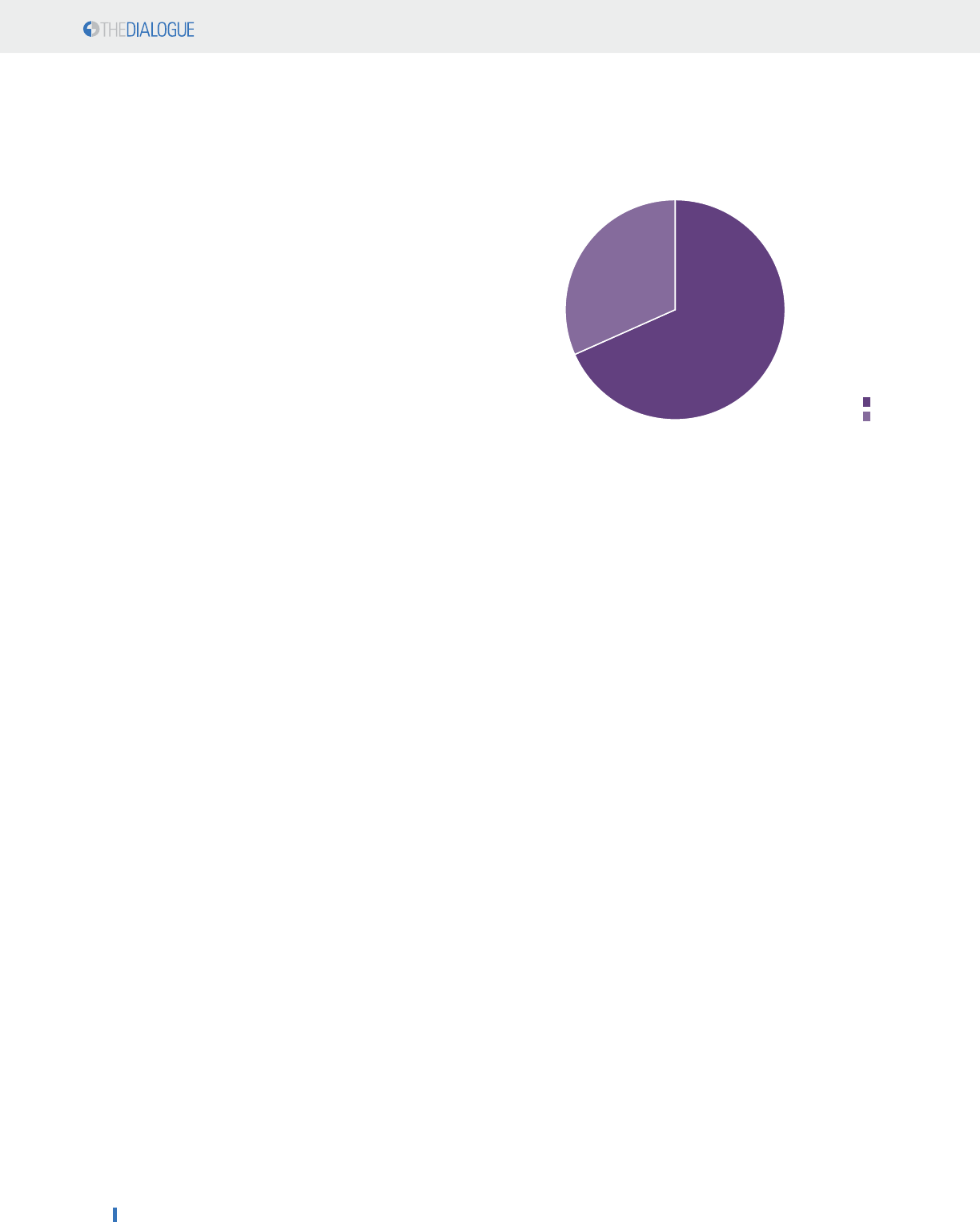

In the Northern Triangle specically, intentions to migrate—

as expected—are robustly linked to factors related to

insecurity. In fact, analyses of the survey data reveal

that security concerns play a central role in individual

motivation to migrate. 29.8% of adults in the Nortern

Triangle have considered migrating in the last 12 months

specically due to insecurity, as seen in Figure 8.

25

The

pressure to migrate due to insecurity is especially high in El

Salvador and Honduras when compared to Guatemala. This

rate is comparable to the 34.7% of adults in the Northern

Triangle that intend to live or work in another

country in the future regardless of motivation,

which suggests that many potential migrants

are driven by security, not just a search for

economic opportunities or other factors such as

family unication.

This is reinforced by comparing crime avoidance

behavior index scores in the Northern Triangle

to intentions to migrate for any reason. To

perform this analysis, we predict individuals’

intention to migrate out of the country with

measures of their individual characteristics,

security evaluations and behaviors, corruption

experiences, trust assessments, and economic

situation. Interestingly, crime avoidance

behavior is as strongly associated or more

strongly associated with migration than almost

all other factors measured, including gender,

age, wealth, perception of

neighborhood insecurity,

interpersonal trust, trust

in local and national

governments, experience of

bribery, crime victimization,

fear of being murdered,

gang activity, and change

in household income. Only

unemployment and receiving

remittances—which means

the respondent likely has

relatives abroad—have larger

regression coefcients than

the crime avoidance index.

These results are presented

in Figure 9, where the dots

and associated numbers

indicate the estimated effect

of a maximum unit change

in the independent variable

(y-axis) on individuals’

intentions (0-100 likelihood) to migrate out of the country.

The lines on either side of the dots represent the 95%

condence interval for the coefcient. Solid dots are

statistically different from zero, whereas hollow dots are

not.

These ndings provide strong empirical evidence for

the chorus of arguments that recent migration from the

Northern Triangle has been driven by “push” factors in

addition to “pull” factors. The most-discussed example of

70.2%

29.8%

No

Yes

Considered Migrating because of Insecurity

17.2%

37.1%

35.1%

0

10

20

30

40

Considered Migrating because of Insecurity

Guatemala El Salvador Honduras

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 8: PRESSURE TO MIGRATE REGIONALLY AND BY COUNTRY

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

0

10

20

30

40

Intends to Live or Work Abroad

2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016/17

Survey Wave

Honduras

El Salvador

Nicaragua

Guatemala

Panama

Costa Rica

Country

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 7: A DRAMATIC INCREASE IN INTENTIONS TO MIGRATE

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

9

this argument is the 2014 report “Children on the Run” by

the UNHCR, which interviewed 404 unaccompanied child

migrants and found “violence, insecurity and abuse” to be

the primary reasons they had risked the journey.

26

A 2014

Inter-American Dialogue survey of migrants from Central

America also found that “for Salvadorans and Hondurans,

violence in their country of origin was by far the leading

push factor, while for Guatemalans it was both violence

and the lack of opportunities” with family reunication

“secondary to the more immediate and pressing issues

of violence and poverty.”

27

The results in Figure 9 are

consistent with this pattern, showing that the toll of

insecurity on individuals’ daily lives – via their experiences

and their crime coping behaviors –is a key driver of

individual intentions to migrate, alongside factors that

indicate economic insecurity.

This suggests that US immigration control efforts that

focus exclusively on domestic policies and border security

are unlikely to be successful in deterring migration in the

long run. Even if changes in immigration policies or rhetoric

in the US result in a drop in border crossings—as many

have argued occurred in the initial months of the Trump

Administration

28

—the decline is likely to be temporary. As of

August 2017, there was already evidence that the number

of undocumented migrants apprehended at the US-Mexico

border was rising quickly back towards pre-Trump levels,

with a 22.5% month over month increase from July.

29

This is

especially true for families crossing the border, as opposed

to unaccompanied minors; apprehensions of family units

1.9

4.2

−1.4

2.0

11.7

9.6

12.3

−7.9

−6.2

5.4

9.5

5.5

10.6

Receives

Remittances

Loss in

Household

Income

Unemployed

Interpersonal

Trust

Police Response

Time

Police Officer

Asked for a

Bribe

Trust in

National Police

Trust in

Executive

Gang Signs or

Graffiti on the

Walls

Level of Fear

of Being a

Victim of

Homicide

Victim of Crime

in the Last 12

Months

Perception of

Neighborhood

Insecurity

Crime Avoidance

Behavior

−15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15

95% Confidence Interval

with Design−Effects

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 9: PREDICTORS OF INTENTIONS TO MIGRATE

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

68.5

60.1

49.6

58.1

64.4

45.1

56.2

59.9

56.2

52.6

51.3

37.5

54.2

46.6

52.2

46.5

38.9

46.0

45.0

33.9

31.5

41.7

36.6

44.1

47.9

4 Items

3 Items

2 Items

1 Item

None

4 Items

3 Items

2 Items

1 Item

None

4 Items

3 Items

2 Items

1 Item

None

4 Items

3 Items

2 Items

1 Item

None

4 Items

3 Items

2 Items

1 Item

None

0 20 40 60 80

Interpersonal Trust

Trust in Local Government

Trust in National Police

Trust in the National Legislature

Trust in Executive

Average

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 10: CRIME AVOIDANCE AND TRUST IN PUBLIC

INSTITUTIONS

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

Beneath the Violence

10

rose 30% relative to a similar 2016 period. This should not

be surprising, as these results show that the pressure to

migrate because of insecurity is high even for adults.

These ndings suggest that in order to reduce the number

of undocumented migrants risking the journey from the

Northern Triangle in the long term, the most effective

strategy is one that attempts to improve conditions in the

three countries, particularly in terms of security, violence,

and crime. We also suggest that tracking crime avoidance

behavior can be a useful tool to identify the populations

most at risk and likely to migrate.

4. Countering the Toll on

Governments and Societies

Crime avoidance behavior also provides an important lens

into how security situations negatively affect democracy

and the state—and how governments can counter the tide.

Crime avoidance is associated with diminished trust in

the executive, the legislature, the national police, and local

government (see Figure 10, where crime avoidance appears

on the y-axis as a count of how of the crime avoidance

items in the index that received a positive response).

There is also clear evidence that crime avoidance behavior

is associated with lower levels of interpersonal trust, as

measured by whether the respondent thinks “people from

around here” are trustworthy.

30

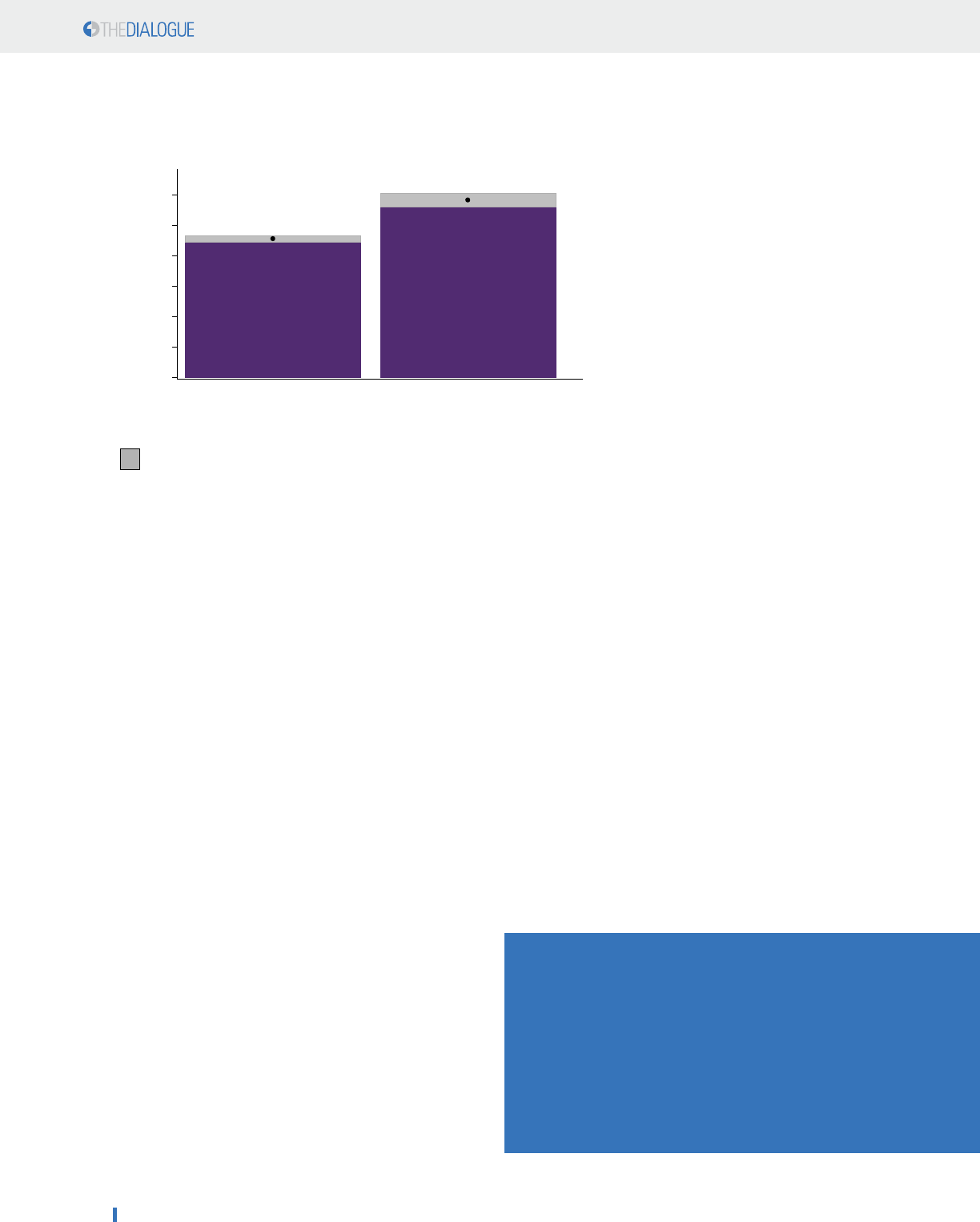

According to the AmericasBarometer, those who have

experienced police corruption in the past year in the

Northern Triangle engage in signicantly

more crime avoidance behavior than those

who have not, as shown in Figure 11. There

are several possible explanations for this

relationship. On one hand, those who are

more at risk of being targeted by violent

crime may also be targeted more often

by police corruption. This would suggest

that police corruption is of most concern

in the communities that are most plagued

by violence. On the other hand, it may also

be that those who have had a police ofcer

ask for a bribe are less likely to trust law

enforcement and attempt to take control

of their own security. In any case, the link

between corruption and crime avoidance

behavior supports the growing consensus

that ghting corruption is critical to solving

the Northern Triangle’s pressing challenges, including

violence and migration.

31

There is also evidence, detailed in Figure 12, that longer

perceived police response time is associated with more

crime avoidance behavior. This makes sense for obvious

reasons: if individuals anticipate that the police take hours

to arrive (or won’t come at all), they can be expected to

take measures to protect their own safety. The relationship,

however, is less strong than one might expect, and is less

dramatic than having experienced police bribery. This

suggests that the integrity of law enforcement is more

important than the proximity of the police. Therefore, police

reform—including controls against corruption and the

implementation of high quality community-based policing

approaches—may be more effective than simply bolstering

the size and presence of police forces.

Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, there is strong

evidence that crime avoidance behavior (along with being

45.6

58.3

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Crime Avoidance Behavior

No Yes

Police Officer Asked for a Bribe

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 11: POLICE CORRUPTION AND CRIME AVOIDANCE

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

There is strong evidence that crime

avoidance behavior (along with

being a victim of a crime) correlates

with increased engagement and

activity in the community.

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

11

41.0

43.9

47.2

49.9

50.3

50.6

0

10

20

30

40

50

Crime Avoidance Behavior

Less than 10

minutes

10 to 30

minutes

30 to 60

minutes

1 to 3 hours Less than 3

hours

There are no

police / They

won’t come

Police Response Time

95 % Confidence Interval

(with Design−Effects)

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 12: POLICE RESPONSE TIME AND CRIME AVOIDANCE

BEHAVIOR

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

a victim of a crime) correlates with increased engagement

and activity in the community. Higher crime avoidance

behavior scores are associated with attendance at

meetings of religious organizations, meetings of a parents’

association at a school, and meetings of a community

improvement committee or association (see Figure 13).

32

Likewise, intentions to migrate are also associated with

greater attendance in these community organizations. In

other words, instead of self-isolating, those individuals

most alert to crime are more engaged with their community

even if they hope to escape. This nding ts with previous

research on the “associativity of distrust” in Latin

America—a positive correlation between fear and the

tendency to participate in local organizations.

33

As Kevin

Casas-Zamora argues, this engagement can be “based

more on reasons of convenience—to ght crime—than

on solidarity.”

34

This is part of a broader

pattern of engagement: research has also

shown that crime victimization leads to

increased participation in politics around

the world.

35

At the same time, increased participation

may be the product of informal

community organizations, dispute settling

mechanisms, and local norms that emerge

in poor communities outside the reach of

the state. It is important for future studies

to delve into variations in the types of

local participation and efforts that are

emerging in response to crime, since some

may be more conducive to democratic

deepening than others. A good example

is how drug trafckers maintain order in poor

neighborhoods, as documented by Enrique

Desmond Arias and Corinne Davis Rodrigues

in Rio de Janeiro.

36

They argue that “trafckers

create a ‘myth of personal security’ in which

individual residents believe they can guarantee

their own safety through their actions and

political connections to trafckers.”

37

In that

sense, individuals most vulnerable to crime

may feel the need to participate in community

organizations and institutions for the sake of

self-protection through personal relationships,

yet the extent to which those organizations

operate outside the connes of the rule of law,

or within it, varies.

In either case, this suggests a critical new

piece in this puzzle in the Northern Triangle:

even though the people most affected by security issues are

less trustful of their neighbors and more likely to want to

move out of their community, they may also be more willing

to work to try to improve it. This nding may help point the

way forward when it comes to lessening the burden of crime

and violence—and by extension, stemming the pressure to

migrate. These vulnerable populations may be turning to

local groups as a last resort. This may also make them a

potential focal point for policy interventions, either by the

state or by development organizations. The ndings from

the AmericasBarometer study suggest that the Central

Americans who are most affected by crime and violence

are not passive actors. They are turning to their community

institutions, either to get help or to try to improve the

community themselves. Those looking to assist them

should follow.

−0.3

−1.6

−0.6

5.4

4.3

Gang Signs or

Graffiti on the

Walls

Crime Avoidance

Behavior

Level of Fear

of Being a

Victim of

Homicide

Victim of Crime

in the Last 12

Months

Perception of

Neighborhood

Insecurity

−4 −2 0 2 4 6 8

95% Confidence Interval

with Design−Effects

Source: Ó AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

FIGURE 13: COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION BY VARIOUS FACTORS

Source: © AmericasBarometer, LAPOP, 2016/17

Beneath the Violence

12

RECOMMENDATIONS

Focus on “push factors” instead of “pull factors”

behind migration. These ndings provide clear

evidence for the argument that migration from the

Northern Triangle is driven to a large degree by concern

about crime and fear of violence. Policymakers in

the United States looking to stem migration pressure

should continue to focus on improving security

and economic conditions in the Northern Triangle

countries, rather than focusing exclusively on domestic

immigration and border security policies.

Think of security as an economic investment. The high

incidence of crime avoidance behavior—particularly

in employment and purchasing decisions—suggests

a clear link between insecurity and missed economic

opportunities. Measures aimed at improving citizen

security situations should be framed as long-term

economic investments.

Invest in communities. Evidence suggests that

community organizations and local institutions can

be an important resource for those most vulnerable

to crime and violence. Investing in communities at

the micro level may be a critical juncture, both when it

comes to lessening the burden of insecurity and as a

potential way to stem pressure to migrate.

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

13

Protect access to transportation and education. The

sheer number of Central Americans that avoid public

transit or keep their children out of school because

of fear of crime translates to a signicant loss of

opportunity with signicant long-term impacts on

economic productivity and other outcomes. Improving

secure access to both these services is critical when it

comes to lessening the burden of crime and violence.

Fight petty corruption and improve police to bolster

community security. While the exact mechanisms still

need to be studied, the link between petty corruption by

police and crime avoidance behavior is clear. Improving

the quality and efcacy of local police will help ease

the impacts of crime. Fighting corruption more broadly

may also help improve overall trust in institutions and

improve the quality of public services, which can also

help lessen the burden of insecurity.

Stay focused on Honduras. Within Central America, the

highest burden of crime avoidance falls on individuals

in this country. Despite the recent progress in reducing

homicide rates, Honduras remains the most affected

in terms of crime avoidance behavior and it has the

highest (and most sharply increasing) rates of

intention

to migrate.

Beneath the Violence

14

ENDNOTES

1. Gagne, David (2017). “InSight Crime’s 2016 Homicide Round-up.” InSight Crime. http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/insight-

crime-2016-homicide-round-up

2. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. FEAR11. Thinking about your daily life, how much fear do you feel about being a direct victim

of homicide?

3. This assertion is supported by World Bank (2011). Crime and violence in Central America: A development challenge. Washington,

D.C., World Bank. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLAC/Resources/FINAL_VOLUME_I_ENGLISH_CrimeAndViolence.pdf

4. International Crisis Group (2017). Maa of the Poor: Gang Violence and Extortion in Central America. Latin America Report no. 62.

Brussels, International Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/central-america/62-maa-poor-gang-

violence-and-extortion-central-america

5. Dudley, Steven and Michael Lohmuller (2015). “Northern Triangle is the World’s Extortion Hotspot.” InSight Crime. http://www.

insightcrime.org/news-briefs/northern-triangle-world-extortion-hotspot

6. Jaitman, Laura et al. (2017) “The Costs of Crime and Violence: New Evidence and Insights in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Washington, DC, Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/8133#sthash.A20urGQ5.dpuf

7. International Crisis Group (2016). “Easy Prey: Criminal Violence and Central American Migration.” Brussels, International Crisis

Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/central-america/easy-prey-criminal-violence-and-central-american-

migration

8. Hiskey, Jonathan et al. (2014). “Violence and Migration in Central America.” AmericasBarometer Insights: 2014, no. 101. LAPOP.

https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/insights/IO901en.pdf

9. Bennett, Brian (2016). “Illegal border crossings by Central American families increase again.” Los Angeles Times. http://www.

latimes.com/nation/la-na-border-crossings-20161017-snap-story.html

10. International Crisis Group (2016). “Easy Prey: Criminal Violence and Central American Migration.” Brussels, International Crisis

Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/central-america/easy-prey-criminal-violence-and-central-american-

migration

11. Semple, Kirk (2017). “Central Americans, ‘Scared of What’s Happening’ in U.S., Stay Put.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.

com/2017/07/03/world/americas/honduras-migration-border-wall.html?mcubz=0

12. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. Q14. Note that the question asks about intentions to move abroad in general, and does not

reference a specic destination country.

13. World Prison Brief (2016). “El Salvador.” http://prisonstudies.org/country/el-salvador

14. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. EXC2.

15. See, for example, Nathan P. Jones (2013). “Understanding and addressing youth in ‘gangs’ in Mexico.” Woodrow Wilson International

Center for Scholars and the Justice in Mexico Project at the University of San Diego. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/

les/04_youth_gangs_jones.pdf

16. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP.

17. The analyses in this report are based on AmericasBarometer dataset version GM v07172017.

18. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. VIC74.

19. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. VIC40a.

20. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. VIC45N.

21. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP.

22. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. R5 (Honduras).

23. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. FEAR6FA.

24. Grifn, Jo (2016). “Too afraid for school: Latin America is losing new generation to gang violence.” The Guardian. https://www.

theguardian.com/teacher-network/2016/jan/27/risk-life-qualication-education-latin-america

25. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. Q14A.

26. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2014). “Children on the Run: Unaccompanied Children Leaving Central America

and Mexico and the Need for International Protection.” Washington, DC. http://www.unhcr.org/56fc266f4.html

27. Orozco, Manuel and Julia Yansura (2014). “Understanding Central American Migration: The crisis of Central American child migrants

in context.” Washington, DC, Inter-American Dialogue. http://www.thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/FinalDraft_

ChildMigrants_81314.pdf

28. Partlow, Joshua (2017). “The ‘Trump effect’ has slowed illegal U.S. border crossings. But for how long?” The Washington Post.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/the-trump-effect-has-slowed-illegal-us-border-crossings-but-for-how-

RULE OF LAW WORKING PAPER | OCTOBER 2017

How Insecurity Shapes Daily Life and Emigration in Central America

15

long/2017/05/21/dfa12a0a-39be-11e7-a59b-26e0451a96fd_story.html?utm_term=.d591388c5113

29. Isacson, Adam (2017). “After Post-Trump Slump, Cross-Border Migration is Increasing.” https://adamisacson.com/after-post-trump-

slump-cross-border-migration-is-increasing/

30. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. IT1.

31. Examples include Kevin Casas-Zamora and Miguel Carter (2017). “Beyond the Scandals: The Changing Context of Corruption in

Latin America.” Washington, DC, Inter-American Dialogue. http://www.thedialogue.org/resources/beyond-the-scandals-the-changing-

context-of-corruption-in-latin-america/; Cardenas, Jose (2015). “It’s Time for the U.S. to Tackle Corruption in Central America.”

Foreign Policy. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/11/09/its-time-for-the-u-s-to-tackle-corruption-in-central-america/; Raderstorf, Ben

and Michael Shifter (2017). “Can Central America Break the Cycle of Drugs, Corruption and Gang War?” The Cipher Brief. https://

www.thecipherbrief.com/can-central-america-break-the-cycle-of-drugs-corruption-and-gang-war; Maute, Arturo (2017). “Guatemala

Stumbles in Central America’s Anti-corruption Fight.” International Crisis Group. https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-

caribbean/central-america/guatemala/guatemala-stumbles-central-americas-anti-corruption-ght; Lapper, Richard. “Central America

Is As Violent As Ever. What Would it Take to Change?” Americas Quarterly. http://americasquarterly.org/content/central-america-

violent-ever-what-would-it-take-change

32. AmericasBarometer (2016/17). LAPOP. Dependent variable is an index of community participation based on CP6, CP7, and CP8.

Analysis includes Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador only. Country xed effects and controls for gender, urban/rural, age,

education, and wealth quintiles are included in the model but not shown in the gure.

33. Casas-Zamora, Kevin (2013). The Besieged Polis Citizen Insecurity and Democracy in Latin America. Washington, DC, Brookings

Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/citizen-insecurity-casas-zamora.pdf

34. Ibid. 8.

35. Bateson, Regina (2012). “Crime Victimization and Political Participation,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 106, No. 3, August.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/crime-victimization-and-political-participation/8

69FE42104FD02272845F47BA09886A4

36. Arias, Enrique Desmond and Corinne Davis Rodrigues (2006). “The Myth of Personal Security: Criminal Gangs, Dispute Resolution,

and Identity in Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas,” Latin American Politics and Society 48, no. 4: 53-81.

37. Ibid. 54.

Cover photo: Samantha Beddoes / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

www.thedialogue.org