Report on Indicators of

School Crime and Safety: 2022

NCES 2023-092

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

NCJ 307328

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

OFFICE OF JUSTICE PROGRAMS

A Publication of the National Center for Education Statistics at IES

Report on Indicators of

School Crime and Safety: 2022

Véronique Irwin

National Center for Education Statistics

Ke Wang

Jiashan Cui

American Institutes for Research

Alexandra Thompson

Bureau of Justice Statistics

NCES 2023092

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

September 2023

NCJ 307328

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, OFFICE OF JUSTICE PROGRAMS

U.S. Department of Education

Miguel A. Cardona

Secretary

Institute of Education Sciences

Mark Schneider

Director

National Center for Education Statistics

Pegy G. Carr

Commissioner

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, and reporting

data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fullls a congressional mandate to collect, collate,

analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condition of education in the United States; conduct and publish

reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and signicance of such statistics; assist state and local education

agencies in improving their statistical systems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing, publishing, and

disseminating statistical information about crime, its perpetrators and victims, and the operation of the justice system

at all levels of government. It fullls a congressional mandate to provide valid statistics on crime and justice systems,

support improvement to justice information systems, and participate with national and international organizations to

develop and recommend national standards for justice statistics.

We strive to make our products available in a variety of formats and in language that is appropriate to a variety of

audiences. You, as our customer, are the best judge of our success in communicating information eectively. If you

have any comments or suggestions about this product, we would like to hear from you. Please direct your comments to

NCES, IES, U.S. Department of Education

Potomac Center Plaza

550 12th Street SW

Washington, DC 20202

September 2023

This report was prepared for the National Center for Education Statistics under Contract No. EDIES12D0002 with

American Institutes for Research. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply

endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Suggested Citation

Irwin, V., Wang, K., Cui, J., and Thompson, A. (2023). Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 (NCES

2023092/NCJ 307328). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice

Statistics, Oce of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Washington, DC. Retrieved [date] from https://nces.

ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2023092.

This publication is only available online. To download, view, and print the entire report as a PDF le, go to https://nces.

ed.gov or https://bjs.ojp.gov.

Contact at NCES

Véronique Irwin

2022456108

Veronique.Irwin@ed.gov

Contact at BJS

Alexandra Thompson

2025325472

Alexandra.[email protected]v

U.S. Department of Justice

Merrick Garland

Attorney General

Oce of Justice Programs

Am

y L. Solomon

Assistant Attorney General

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Kevin M. Scott

Principal Deputy Director

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022

provides the most recent national indicators on school

crime and safety. The information presented in this report

serves as a reference for policymakers and practitioners

so that they can develop eective programs and policies

aimed at violence and school crime prevention. Accurate

information about the nature, extent, and scope of the

problem being addressed is essential for developing

eective programs and policies.

This is the 25th edition of Indicators of School Crime and

Safety, a joint eort of the Bureau of Justice Statistics

(BJS) and the National Center for Education Statistics

(NCES). This report provides summary statistics to

inform the nation about current aspects of crime and

safety in schools.

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety includes the

most recent available data at the time of its development,

compiled from a number of statistical data sources

supported by the federal government. Such sources

include results from the School-Associated Violent Death

Surveillance System, sponsored by the U.S. Department

of Education, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC); the

National Vital Statistics System, sponsored byCDC; the

School Shooting Safety Compendium, sponsored by

the U.S. Department of Defense; the Studies of Active

Shooter Incidents, sponsored by the Federal Bureau of

Investigation; the National Crime Victimization Survey

and School Crime Supplement to that survey, sponsored

by BJS and NCES, respectively; the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System, sponsored by CDC; the School Survey

on Crime and Safety, Fast Response Survey System,

EDFacts, and National Teacher and Principal Survey, all

sponsored by NCES; and the Campus Safety and Security

Survey, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education.

Some of these data are collected annually, while others are

collected less frequently.

T

his report is available as a PDF le at https://nces.ed.gov

or https://bjs.ojp.gov. BJS and NCES continue to work

together in order to provide timely and complete data on

the issues of school-related violence and safety.

Pegy G. Carr

Commissioner

National Center for Education Statistics

Kevin M. Scott

Principal Deputy Director

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Foreword

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | iii

The authors are grateful to the sponsoring agencies, the

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and the

Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), for supporting this report.

From BJS, we wish to thank Susannah Tapp, who veried

data from the National Crime Victimization Survey.

Outside of NCES and BJS, Nancy Brener and Tia Rogers

of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

generously provided data and performed a review of data

documentation. We also value the review of this report

and the continued support provided by the Oce of Safe

and Healthy Students.

The authors would like to thank the many individuals

who completed the survey instruments that make this

report possible.

Acknowledgments

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | iv

Contents

Page

Foreword .......................................................................... iii

Acknowledgments .................................................................. iv

List of Figures ...................................................................... vi

Introduction ....................................................................... 1

Highlights ......................................................................... 2

Violent Deaths, School Shootings, and Active Shooter Incidents ............................ 4

Nonfatal Student and Teacher Victimization ............................................ 6

Criminal Victimization Experienced by Students ....................................... 6

Student Reports of Bullying Victimization ............................................. 7

Teacher Victimization ............................................................. 9

School Environment ................................................................ 10

Criminal Incidents and Discipline Problems Reported by Public Schools .................... 10

Gangs and Hate-Related Speech ..................................................... 12

Student Fear and Avoidance ........................................................ 14

Teachers’ Reports of Student Behavior and Rule Enforcement ............................ 15

Fights, Weapons, and Illegal Substances ................................................ 16

Student Involvement in Physical Fights ............................................... 16

Students Carrying Weapons and Threats and Injuries With Weapons ....................... 18

Alcohol, Marijuana, and Illegal Drugs ................................................ 19

Safety, Discipline, and Mental Health Practices .......................................... 21

Safety and Security Measures ....................................................... 21

Disciplinary Actions .............................................................. 22

Mental Health Services ............................................................ 24

Postsecondary Campus Safety and Security ............................................. 26

Active Shooter Incidents ........................................................... 26

Criminal Incidents ............................................................... 26

Hate Crime Incidents ............................................................. 28

References ......................................................................... 30

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | v

List of Figures

Page

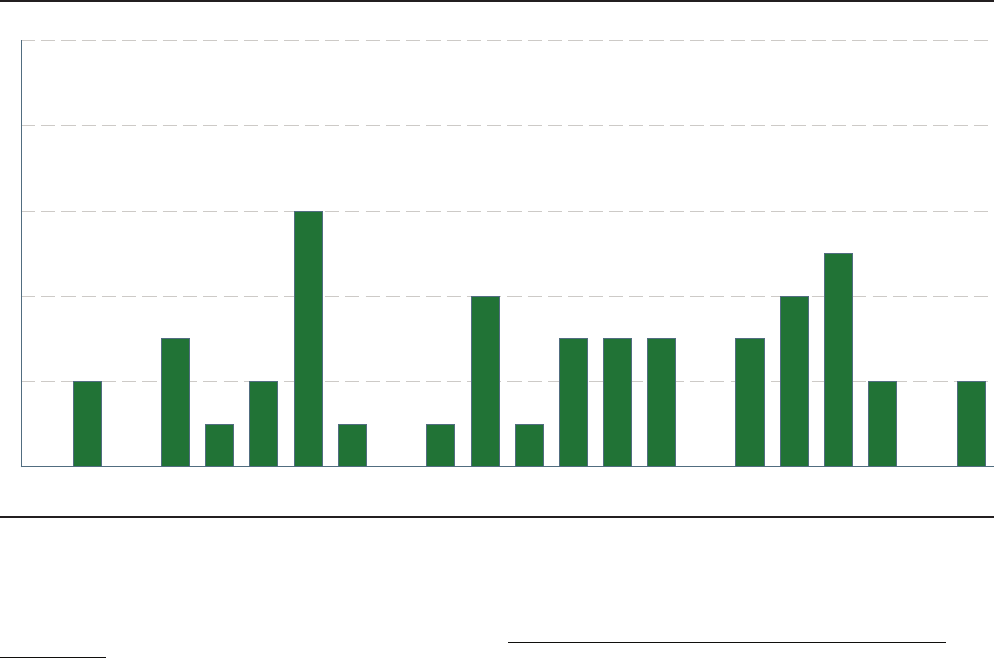

1. Number of active shooter incidents at elementary and secondary schools: 2000 through 2021 .......... 5

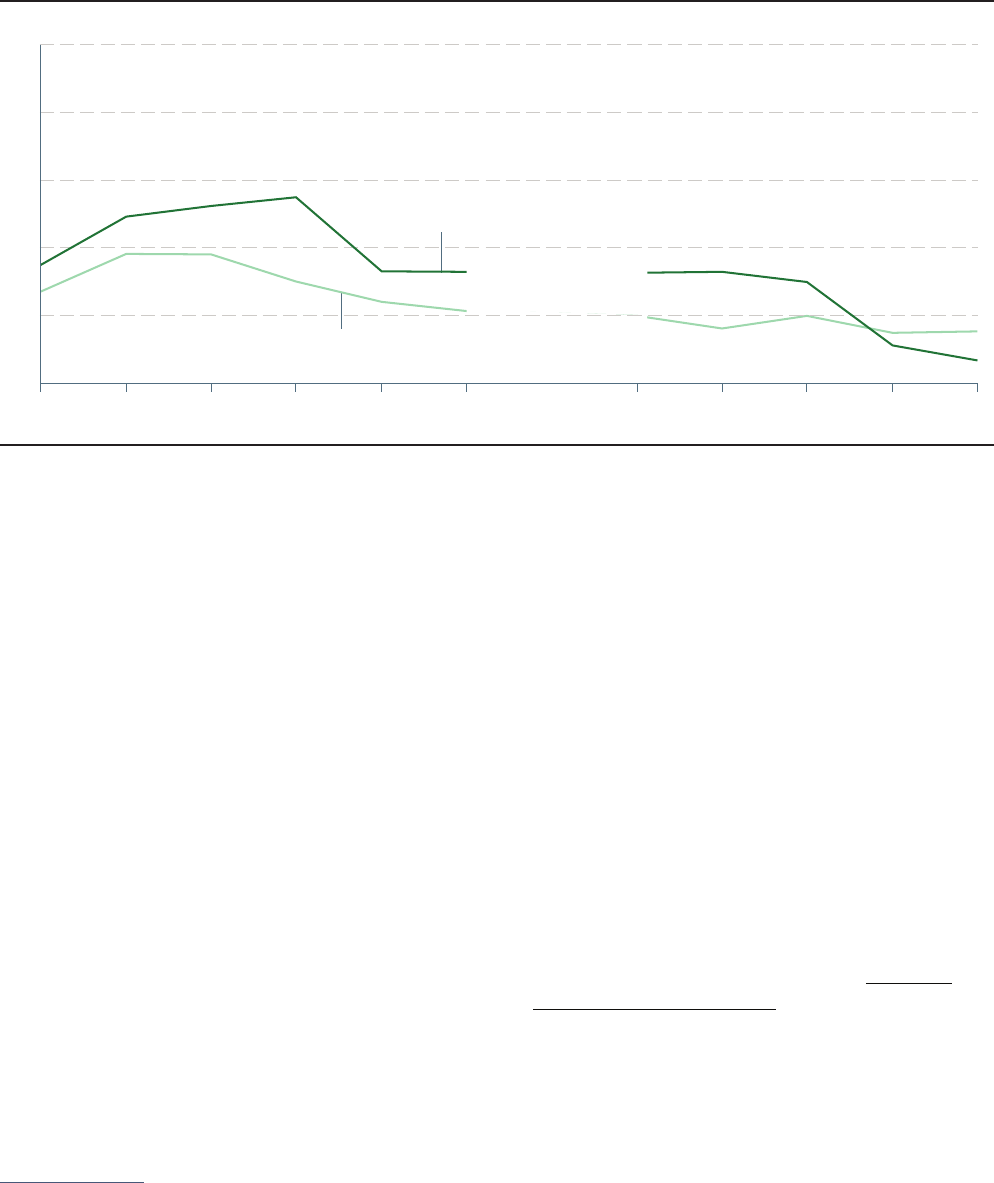

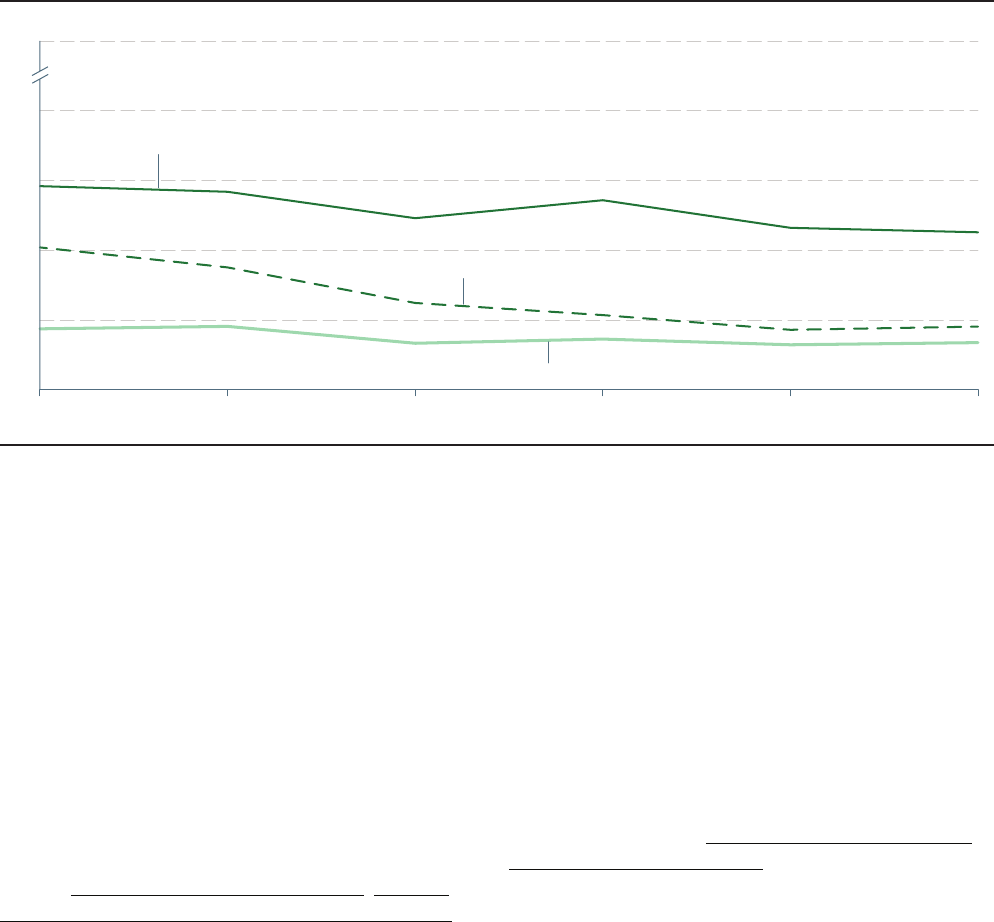

2. Rate of nonfatal victimization against students ages 1218 per 1,000 students, by location: 2010

through2021 ............................................................................ 7

3. Percentage of students ages 1218 who reported being bullied at school during the school year, by

selected student and school characteristics: 2019 ............................................... 8

4. Percentage of public school teachers who reported that they were threatened with injury or physically

attacked by a student from their school during the previous 12 months, by instructional level: School

year 202021 ............................................................................ 9

5. Percentage of public schools recording one or more incidents of crime at school and percentage

reporting incidents to sworn law enforcement: Selected years, 200910 through 201920 .............. 11

6. Percentage of public schools reporting selected discipline problems that occurred at least once a week:

School years 200910 and 201920 ........................................................... 12

7. Percentage of students ages 1218 who reported a gang presence, being called hate-related words, and

seeing hate-related grati at school during the school year: Selected years, 2009 through 2019 ......... 13

8. Percentage of students ages 1218 who reported being afraid of attack or harm during the school year

and percentage who reported avoiding one or more places in school because of fear of attack or harm

during the school year: 2019 ............................................................... 14

9. Percentage of public school teachers who agreed that student misbehavior and student tardiness and

class cutting interfered with their teaching and percentage who agreed that other teachers and the

principal enforced school rules: School years 201112 and 202021 ................................. 15

10. Percentage of students in grades 912 who reported having been in a physical ght at least one time

during the previous 12 months, by race/ethnicity and location: 2019 ............................... 17

11. Percentage of students in grades 912 who reported carrying a weapon at least 1 day anywhere or on

school property during the previous 30 days and percentage who reported being threatened or injured

with a weapon on school property at least one time during the previous 12 months: 2009, 2017, and 2019 .. 18

12. Percentage of students in grades 912 who reported using alcohol at least 1 day during the previous

30days, by selected student characteristics: 2019 .............................................. 19

13. Percentage of students in grades 912 who reported that illegal drugs were made available to them on

school property during the previous 12 months, by race/ethnicity and sexual identity: 2019 ............ 20

14. Percentage of public schools with a written plan for procedures to be performed in selected scenarios:

School year 201920 ...................................................................... 22

15. Percentage of public schools that took a serious disciplinary action in response to specic oenses,

bytype of oense: School years 200910 and 201920 ........................................... 23

16. Percentage of public schools providing diagnostic mental health assessments and treatment to students,

by selected school characteristics: 201920 .................................................... 25

17. Number of on-campus crimes reported and number per 10,000 full-time-equivalent (FTE) students in

degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by selected type of crime: 2010 through 2020 ............ 27

18. Number of on-campus hate crimes at degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by category of bias

motivating the crime and type of crime: 2020 ................................................. 29

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | vi

It is important to establish reliable indicators of the

current state of school crime and safety across the nation—

and to regularly update and monitor these indicators as

new data become available. These indicators can help

inform policymakers and practitioners of the nature,

extent, and scope of the problem being addressed as they

develop programs aimed at violence and school crime

prevention. This is the purpose of Indicators of School

Crime and Safety, a joint eort by the National Center

for Education Statistics (NCES) and the Bureau of Justice

Statistics (BJS).

The 2022 edition of the Report on Indicators of School Crime

and Safety is the 25th in a series of annual publications.

Beginning with the 2020 edition, this report has been

redesigned with the intention of increasing its usability

for a wider audience. This report does so by highlighting

selected ndings from 23 indicators on various school

crime and safety topics. By synthesizing ndings in this

way, the report allows readers to gauge the breadth

of the content more eciently and make connections

across indicators. As in previous editions, the full set

of 23 indicators—with each indicator presented as an

independent, more detailed analysis of a crime and safety

topic—can be accessed in the online Indicator System.

Each indicator can be found on the website, and readers

can download PDFs of the individual indicators. Indicators

online are hyperlinked to tables in the Digest of Education

Statistics, where readers can obtain the underlying

data. The PDF version of the report, however, has been

transformed into the Report on Indicators of School Crime

and Safety, which highlights and synthesizes key ndings

from the full set of 23 indicators online.

This report covers a variety of topics on school crime

and safety. It rst examines dierent types of student

victimization, including violent deaths and school

shootings, nonfatal criminal victimization, and bullying

victimization. Then, the report presents data on teacher

victimization. This report concludes the section on crime

and safety issues at the elementary and secondary level by

examining data on school conditions—such as discipline

problems, gangs, hate-related speech, possession of

weapons, and use and availability of illegal drugs—as

well as data that reect student perceptions about their

personal safety at school.

To address these issues that students and teachers

could experience, schools across the United States have

implemented preventive and responsive measures.

This report covers topics such as security practices,

disciplinary actions, and whether schools have plans for

scenarios such as active shooters, natural disasters, or a

pandemic disease.

In addition to practices and measures addressing specic

crime and safety concerns, many schools provide mental

health services to promote student well-being and improve

school climate. This report examines the prevalence

of mental health services in public schools, as well as

the limitations to providing mental health services that

schools may encounter.

Finally, at the postsecondary level, this report discusses

the number of reported on-campus criminal incidents

against persons and property, as well as on-campus

hate crime incidents, such as those motivated by biases

associated with race, sexual orientation, and religion.

In this report, where available, data on victimization

that occurred away from school are oered as a point of

comparison for data on victimization that occurred at

school. Indicators of crime and safety are compared across

dierent population subgroups and over time. Across

indicators, the year of the most recent data collection

varied by survey, generally ranging from 2019 to 2021.

In 2020—and to a lesser extent in 2021

1

—schools across

the country suspended or modied in-person classes in

accordance with federal, state, and local guidance related

to the risks associated with the coronavirus pandemic.

Students might have spent less time at school than in

previous years due to these modied procedures. Thus,

readers are encouraged to interpret data since 2020 in the

context of these pandemic-related modications.

A variety of data sources are used to present information

on these topics, including national surveys of students,

teachers, principals, and postsecondary institutions.

Readers should be cautious when comparing data from

dierent sources. Dierences across these sources in

aspects such as data collection procedures and timing,

the phrasing of questions used to collect information

from respondents, and interviewer training can aect the

comparability of results across data sources.

Findings described with comparative language (e.g.,

higher, lower, increase, and decrease) are statistically

signicant at the .05 level. Additional information about

methodoloy and the datasets analyzed in this report

may be found online in the Reader’s Guide and Guide to

Sources.

1

For data on student enrollment by type of instruction (remote, hybrid,

and in-person) in spring 2021, see https://ies.ed.gov/schoolsurvey/mss-

dashboard/.

Introduction

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 1

In recent years, reported incidents related to several

crime and safety issues have become less prevalent at

elementary and secondary schools when compared with

a decade earlier. Specically, incidents of nonfatal student

and teacher victimization, certain discipline problems,

and reports of some unfavorable conditions at school have

decreased over time:

2

• For students ages 1218, the rate of nonfatal

criminal victimization (including theft and violent

victimization) at school in 2019 was not signicantly

dierent than the rate in 2010. From 2019 to 2021, the

rate at school decreased from 30 to 7 victimizations

per 1,000 students.

• Lower percentages of public school teachers in 202021

than in 201112 reported being threatened with injury

by a student from their school (6 vs. 10 percent) and

being physically attacked by a student from their

school (4 vs. 6 percent).

3

• Lower percentages of public schools in 201920

than in 200910 reported that each of the following

discipline problems occurred at least once a week:

student bullying (15 vs. 23 percent), student sexual

harassment of other students (2 vs. 3 percent), and

student harassment of other students based on sexual

orientation or gender identity (2 vs. 3 percent).

• Lower percentages of students ages 1218 in 2019 than

in 2009 reported the following unfavorable conditions

at their school: gang presence (9 vs. 20 percent), being

called hate-related words (7 vs. 9 percent), and seeing

hate-related grati (23 vs. 29 percent).

• Lower percentages of students in grades 912 in

2019 than in 2009 reported the following issues:

having been in a physical ght on school property

in the previous 12months (8 vs. 11 percent); carrying

a weapon on school property during the previous

30days (3 vs. 6 percent); and using alcohol on at least

1day during the previous 30 days (29 vs. 42 percent).

2

In 2020—and to a lesser extent in 2021—schools across the country

suspended or modied in-person classes in accordance with federal, state,

and local guidance related to the risks associated with the coronavirus

pandemic. Students may have spent less time at school and had less in-

person interaction with their teachers and other students than in previous

years due to these modied procedures. Thus, readers are encouraged

to interpret data since 2020 in the context of these pandemic-related

modications.

3

Teachers who taught only prekindergarten students are excluded.

Includes teachers in both traditional public schools and public charter

schools.

In contrast, cyberbullying and some student discipline

problems related to teachers and classrooms have become

more common over time. Specically, higher percentages

of public schools in 201920 than in 200910 reported the

following problems at least once a week:

• student cyberbullying (16 vs. 8 percent);

• student verbal abuse of teachers (10 vs. 5 percent);

• student acts of disrespect for teachers other than

verbal abuse (15 vs. 9 percent); and

• widespread disorder in the classroom (4 vs. 3 percent).

Active shooter incidents

4

represent a subset of the

possible violent incidents that occur at school. From 2000

to 2021, at elementary and secondary schools, there were

46 active shooter incidents, with the annual number

ranging from 0 to 6 incidents. These 46 incidents resulted

in 276 casualties (108 killed and 168 wounded).

5

In 2021,

there were 2 active shooter incidents documented at

elementary and secondary schools.

Increasing percentages of public schools have

implemented certain safety and security practices and

have oered mental health services to students:

• In 201920, about 52 percent of public schools reported

having a written plan for procedures to be performed

in the event of a pandemic disease. This percentage

was higher than the percentage reported in 201718

(46percent).

• Between 200910 and 201920, the percentage of

public schools reporting the following safety and

security measures increased: controlling access to

school buildings (from 92 to 97 percent), using security

cameras (from 61 to 91 percent), and requiring faculty

and sta to wear badges or picture IDs (from 63 to

77percent).

• Between 200910 and 201920, the percentage of

public schools that reported having one or more

security sta present at school at least once a week

increased (from 43 to 65 percent).

• Higher percentages of public schools in 201920 than

in 201718 reported providing diagnostic mental health

assessment services to evaluate students for mental

health disorders (55 vs. 51 percent) and oering mental

health treatment services to students for mental health

disorders (42 vs. 38 percent).

4

An active shooter incident is an incident in which “one or more

individuals actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a

populated area.” Because the situation is active, law enforcement and

citizens involved in the incident have the potential to aect the outcome.

5

Number of casualties excludes the active shooters.

Highlights

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 2

Regarding safety issues on campuses of postsecondary

institutions, the rate of crime

• was 10 percent lower in 2019 than in 2010 (18.8vs.

20.9per 10,000 FTE students) but showed no

consistent trend during this period; and

• decreased by 20 percent between 2019 and 2020,

during the rst year of the pandemic (from 18.8 to

15.0per 10,000 FTE students).

Despite the overall rate of crime being lower in 2020

than in 2010, the rate of reported forcible sex oenses on

campus increased from 1.9 incidents per 10,000students

in 2010 to 6.6 incidents per 10,000 students in 2020.

6

Forcible sex oenses constituted 44 percent of all

criminal incidents reported on campus in 2020.

6

Reporting guidelines for forcible sex oenses changed in 2014. In years

prior to 2014, schools reported a total number of forcible sex oenses,

with no breakouts for specic types of oenses. Beginning in 2014, schools

were asked to report the numbers of two dierent types of forcible sex

oenses: rape and fondling. These two types were added together to

calculate the total number of reported forcible sex oenses. For instance,

5,200 rapes and 4,200 fondling incidents were reported in 2020, for a

total of 9,400 incidents of forcible sex oenses.

In 2020, a total of 571 hate crimes were reported on

the campuses of postsecondary institutions. This was

25percent lower than in 2019 (759 incidents) and

38percent lower than in 2010 (928 incidents). Race,

sexual orientation, and ethnicity were the three most

frequently reported categories of bias motivating on-

campus hate crimes at postsecondary institutions,

accounting for about 82 percent of reported hate crimes.

From 2000 to 2021, there were 18 active shooter incidents

documented at postsecondary institutions, with the

annual number ranging from 0 to 2. These incidents

resulted in 157 casualties (75 killed and 82 wounded).

7

There were 0 active shooter incidents documented at

postsecondary institutions in 2021.

7

Number of casualties excludes the active shooters.

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 3

Highlights

The most recent data released by the School-Associated

Violent Death Surveillance System (SAVDSS) cover the

period from July 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020, which

includes the rst spring of the coronavirus pandemic,

when many students were learning remotely.

8

During

this period, a total of 25 school-associated violent deaths

9

were documented in the United States. This included

23homicides, 1 suicide, and 1legal intervention death.

10,11

Of these 25 school-associated violent deaths, 11homicides

and 1 suicide were of school-age youth (ages 518). (Violent

Deaths at School and Away From School, School Shootings,

and Active Shooter Incidents)

The School Shooting Safety Compendium (SSSC) aims to

compile information on elementary/secondary school

shootings from publicly available sources into a single

comprehensive database. The SSSC denes “school

shootings” as incidents in which “a gun is brandished,

is red, or a bullet hits school property for any reason,

regardless of the number of victims, time of day, or day of

week.” During the coronavirus pandemic, this denition

includes shootings that happen on school property during

remote instruction.

Between 200001 and 202021, the number of school

shootings with casualties ranged from 11 to 93 per year.

8

Education Week. (2020, March 6). Map: Coronavirus and School Closures

in 20192020. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.edweek.org/

leadership/map-coronavirus-and-school-closures-in-20192020/2020/03.

9

The SAVDSS denes a school-associated violent death as “a homicide,

suicide, or legal intervention death (involving a law enforcement ocer),

in which the fatal injury occurred on the campus of a functioning

elementary or secondary school in the United States.” School-associated

violent deaths also include those that were documented to have occurred

while the victim was on the way to or from regular sessions at school or

while the victim was attending or traveling to or from an ocial school-

sponsored event. School-associated violent deaths include not only

students and sta members but also others at school, such as students’

parents and community members.

10

Data are subject to change until law enforcement reports have been

obtained and interviews with school and law enforcement ocials

have been completed. The details learned during the interviews can

occasionally change the classication of a case.

11

A legal intervention death is dened as a death caused by a law

enforcement agent in the course of arresting or attempting to arrest a

lawbreaker, suppressing a disturbance, maintaining order, or engaging in

another legal action.

On average, the number of shootings with casualties

in a given year diered from the prior year by about

47percent in either direction, with no consistent trend

throughout the period. In 202122, the number of school

shootings with casualties (188) was more than twice as

high as the next highest number of documented shootings

(93), which was documented the year before.

12

Because

the number of school shootings in 202122 is an outlier

compared to prior years, readers should interpret data

with caution. (Violent Deaths at School and Away From

School, School Shootings, and Active Shooter Incidents)

Active shooter incidents represent a subset of the possible

gun violence or serious violent incidents that occur at

schools. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) denes

an active shooter incident as an incident in which “one or

more individuals actively engaged in killing or attempting

to kill people in a populated area.” Because the situation

is active, law enforcement and citizens involved in the

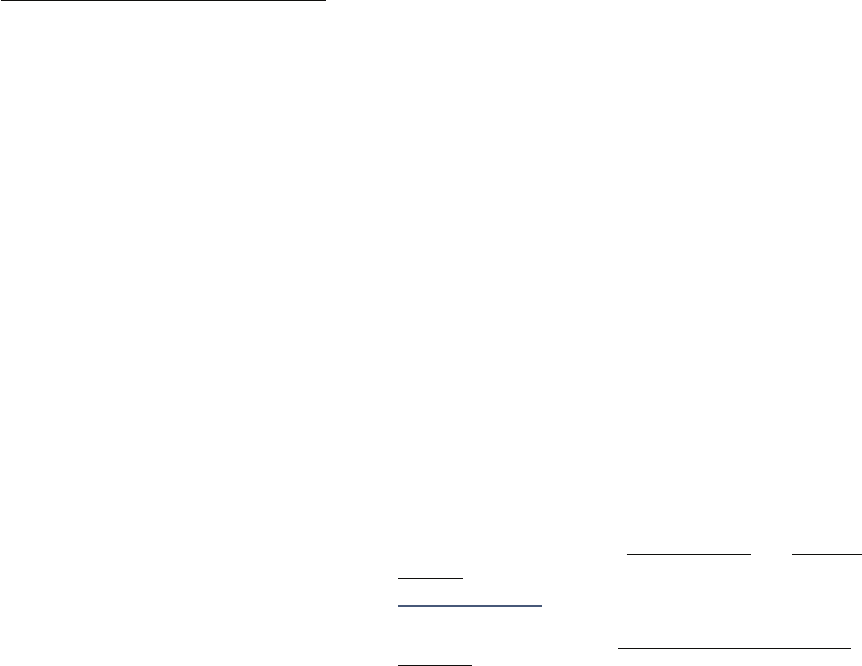

incident have the potential to aect the outcome. From

2000 to 2021, at elementary and secondary schools, there

were

• 46 active shooter incidents (gure 1);

• 0 to 6 active shooter incidents per year;

• 276 casualties (108 killed and 168 wounded) as a result

of active shooter incidents;

13

and

• 0 to 81 casualties per year from active shooter

incidents.

From 2000 to 2021, there were 47 active shooters

responsible for the 46 incidents at elementary and

secondary schools. Of the 47 active shooters,

• 46 were male and 1 was female;

• 34 were 12 to 18 years old;

• 5 were 19 to 24 years old; and

• 8 were 25 years old and above. (Violent Deaths at School

and Away From School, School Shootings, and Active

Shooter Incidents)

12

Due to school closures caused by the coronavirus pandemic, caution

should be used when comparing 201920 and 202021 data with data from

other years.

13

Number of casualties excludes the active shooters.

Violent Deaths, School Shootings, and Active Shooter

Incidents

From 2000 to 2021, there were 46 active shooter incidents at elementary and secondary schools, with the

number ranging from 0 to 6 per year during this period. There were 47 active shooters responsible for

these 46 incidents, more than two-thirds of whom were 12 to 18 years old.

In 2021–22, the number of school shootings with casualties (188) was more than twice as high as the next

highest number of documented shootings (93), which was documented the year before.

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 4

1

Includes one active shooter incident at a county board of education meeting.

2

Includes one active shooter incident at a city school board meeting.

NOTE: The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) denes an active shooter incident as an incident in which “one or more individuals actively engaged in killing or

attempting to kill people in a populated area.” Some data have been revised from previously published gures.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, A Study of Active Shooter Incidents in the United States Between 2000 and 2013, Active Shooter

Incidents in the United States in 2014 and 2015, Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2016 and 2017, Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2018,

Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2019, Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review 2000–2019, Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2020, and

Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2021, retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.fbi.gov/about/partnerships/ofce-of-partner-engagement/active-

shooter-resources. See Digest of Education Statistics 2022, table 228.15

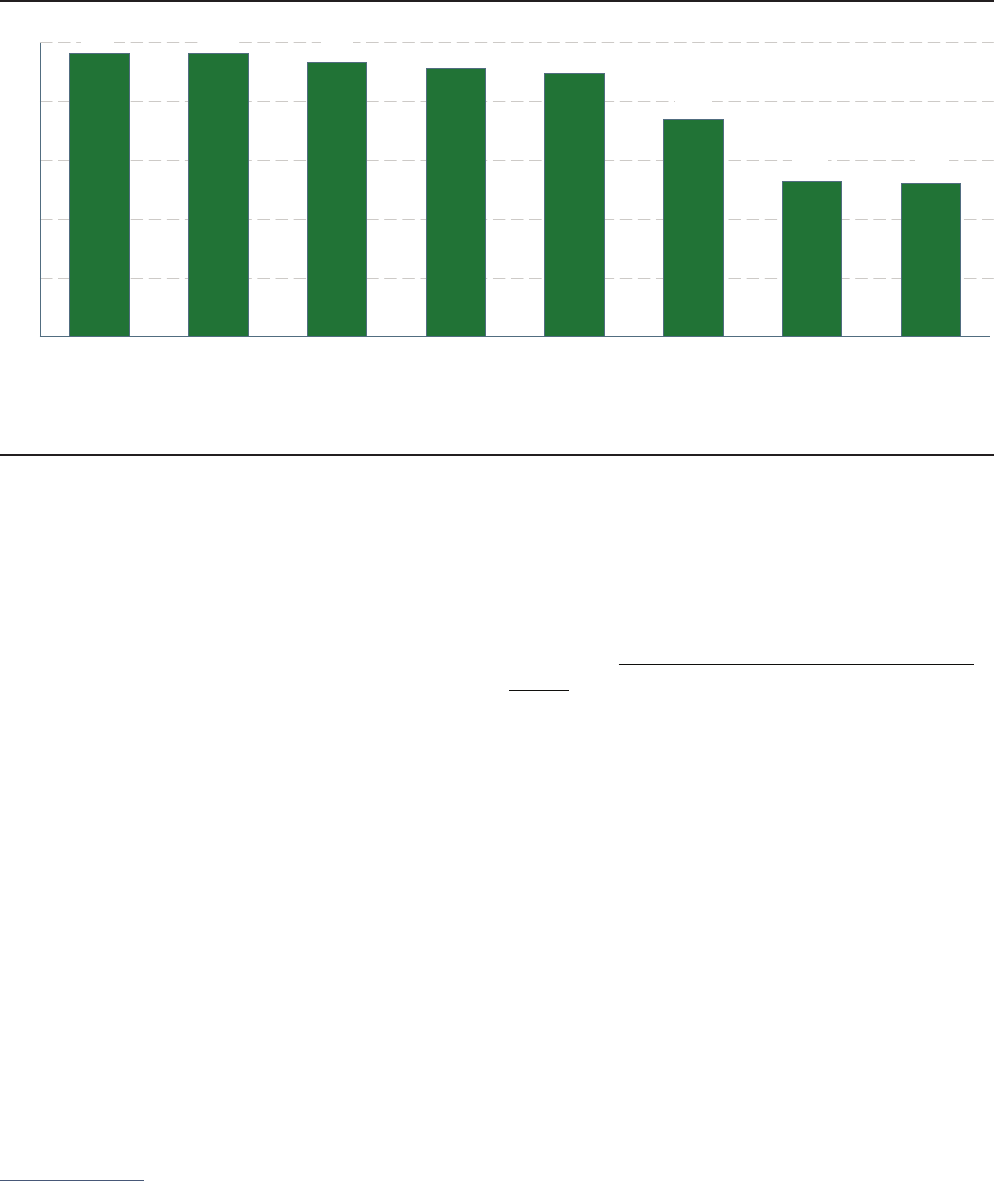

Figure 1. Number of active shooter incidents at elementary and secondary schools: 2000 through 2021

2000 2001 2002 2003

1

2004 2005 2006

Year

2007 2008 2009 2010

2

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

0

2

4

6

8

10

Number of incidents

2

3

00 0

11

2

6

1

0

4

1

333

0

3

4

5

22

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 5

Violent Deaths, School Shootings, and Active Shooter Incidents

Criminal Victimization Experienced by

Students

Data from the National Crime Victimization Survey

(NCVS) provide insights on nonfatal criminal victimization

experienced by students ages 1218, according to students’

own reports.

14

Nonfatal criminal victimization includes

theft

15

and violent victimization, the latter of which

includes rape, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated

assault, and simple assault. In 2021, students ages 1218

experienced 170,600 victimizations at school

16

and

384,300victimizations away from school. This translates

to a rate of 7 victimizations per 1,000 students at school

17

and a rate of 15 victimizations per 1,000 students away

from school (gure 2). (Incidence of Nonfatal Victimization

at School and Away From School)

14

“Students” refers to those ages 1218 whose educational attainment did

not exceed grade 12 at the time of the survey. An uncertain percentage of

these persons may not have attended school during the survey reference

period. These data do not take into account the number of hours that

students spend at school or away from school.

15

“Theft” includes attempted and completed purse-snatching, completed

pickpocketing, and all attempted and completed thefts, with the exception

of motor vehicle thefts. Theft does not include robbery, which involves the

threat or use of force and is classied as a violent crime.

16

“At school” is dened to include in the school building, on school

property, on a school bus, and going to and from school.

17

Data on the percentage of students ages 1218 who reported being

victimized at school during the previous 6 months are available from

the School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the NCVS. At the time of the

development of this report, the latest year for which SCS data are available

is 2019. See Prevalence of Criminal Victimization at School for changes

over time in the percentage of students reporting victimization at school,

as well as how the percentage varied by selected student and school

characteristics.

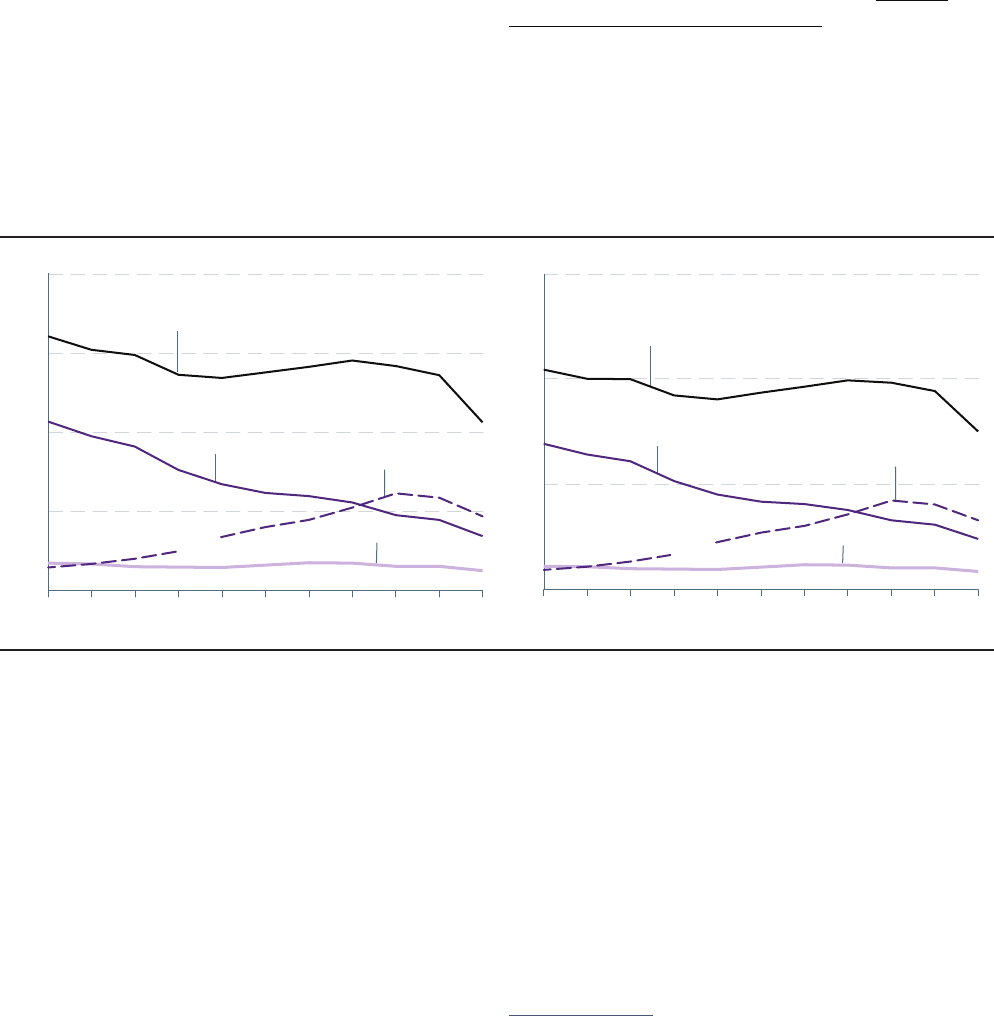

For students ages 1218, the total victimization rate in

2019 was not signicantly dierent than the rate in 2010,

both at school and away from school (gure 2). From 2019

to 2021, the total victimization rate at school decreased

from 30 to 7 victimizations per 1,000 students. During the

same period, from 2019 to 2021, the total victimization

rate away from school did not change signicantly

(15victimizations per 1,000students in 2021).

18

(Incidence

of Nonfatal Victimization at School and Away From School)

18

In 2020 and 2021, schools across the country suspended or modied in-

person classes in accordance with federal, state, and local guidance related

to the risks associated with the coronavirus pandemic. Students may have

spent less time at school than in previous years due to these modied

procedures.

Nonfatal Student and Teacher Victimization

In recent years, nonfatal student and teacher victimization was generally less prevalent than about a

decade ago:

• The nonfatal criminal victimization rate for students ages 1218 at school in 2019 was not signicantly

dierent than the rate in 2010. From 2019 to 2021, the rate at school decreased from 30 to 7victimizations

per 1,000 students.

• A lower percentage of students ages 1218 in 2019 than in 2009 reported being bullied at school (22 vs.

28percent).

• Lower percentages of public school teachers in 202021 than in 201112 reported being threatened with injury

by a student from their school (6 vs. 10 percent) and being physically attacked by a student from their school

(4 vs. 6 percent).

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 6

Student Reports of Bullying Victimization

Another type of student victimization that is important to

understand is bullying. Previous research has found that

students who are bullied are more likely to experience

depression and anxiety, have more health complaints,

and skip or drop out of school (Swearer and Hymel

2015; Hornor 2018). The involvement of young bullying

victims in recent suicides and school shootings has

also heightened concerns regarding the public health

implications of bullying (Hornor 2018).

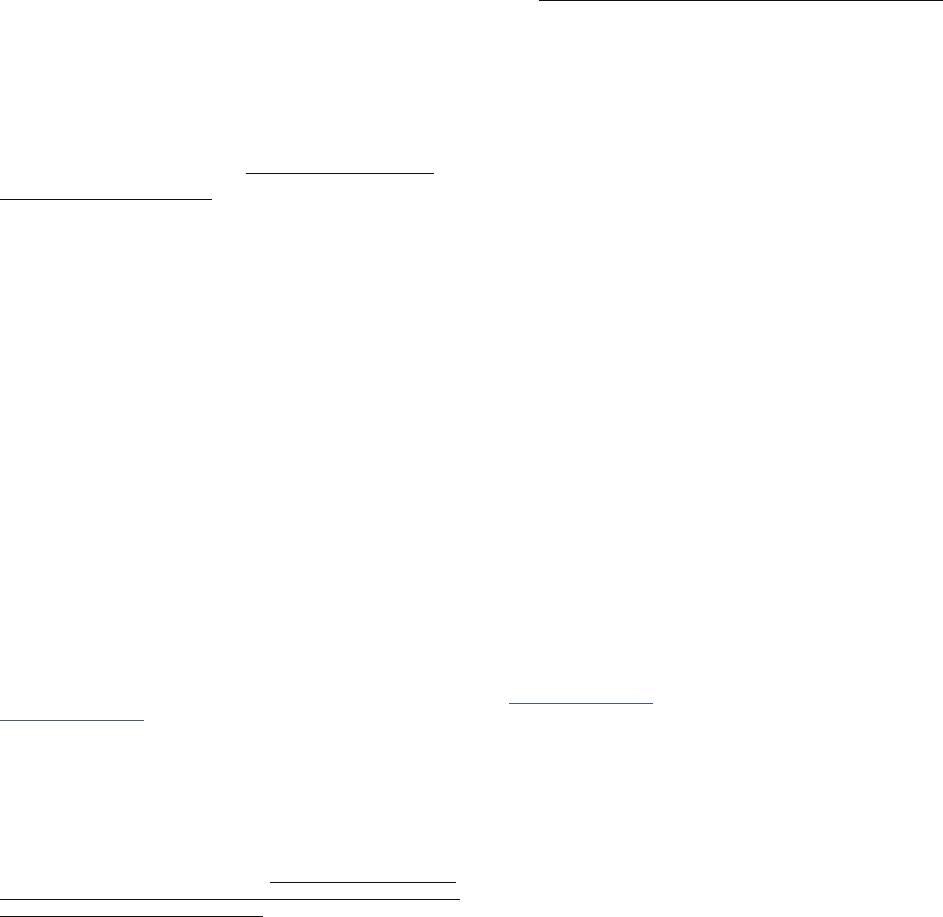

According to data from the School Crime Supplement

(SCS), during the school year in 2019, about 22 percent

of students ages 1218 reported being bullied

19

at school.

This was lower than the percentage who reported being

bullied in 2009 (28 percent). Students’ reports of being

bullied varied based on student and school characteristics

19

“Bullying” includes students who reported that another student had

made fun of them, called them names, or insulted them; spread rumors

about them; threatened them with harm; tried to make them do something

they did not want to do; excluded them from activities on purpose;

destroyed their property on purpose; or pushed, shoved, tripped, or spit

on them. In the total for students bullied at school, students who reported

more than one type of bullying were counted only once.

NOTE: Every 10 years, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) sample is redesigned to reect changes in the population. Due to a sample increase and redesign

in 2016, victimization estimates among students ages 12–18 in 2016 were not comparable to estimates for other years. Nonfatal victimization includes theft, rape, sexual

assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault. “At school” includes in the school building, on school property, on a school bus, and going to or from school. The

NCVS data in this report are reported in accordance with Bureau of Justice Statistics standards. The population size for students ages 12–18 was 25,132,500 in 2021. In

2020 and 2021, schools across the country suspended or modied in-person classes to mitigate the risks associated with the coronavirus pandemic. Students may have

spent less time at school than in previous years due to these modied procedures. Estimates may vary from previously published reports.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), 2010 through 2021. See Digest of Education Statistics

2022, table 228.20.

Figure 2. Rate of nonfatal victimization against students ages 12–18 per 1,000 students, by location: 2010 through 2021

2010 2015 20212020

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

Rate per 1,000 students

Away from school

At school

Year

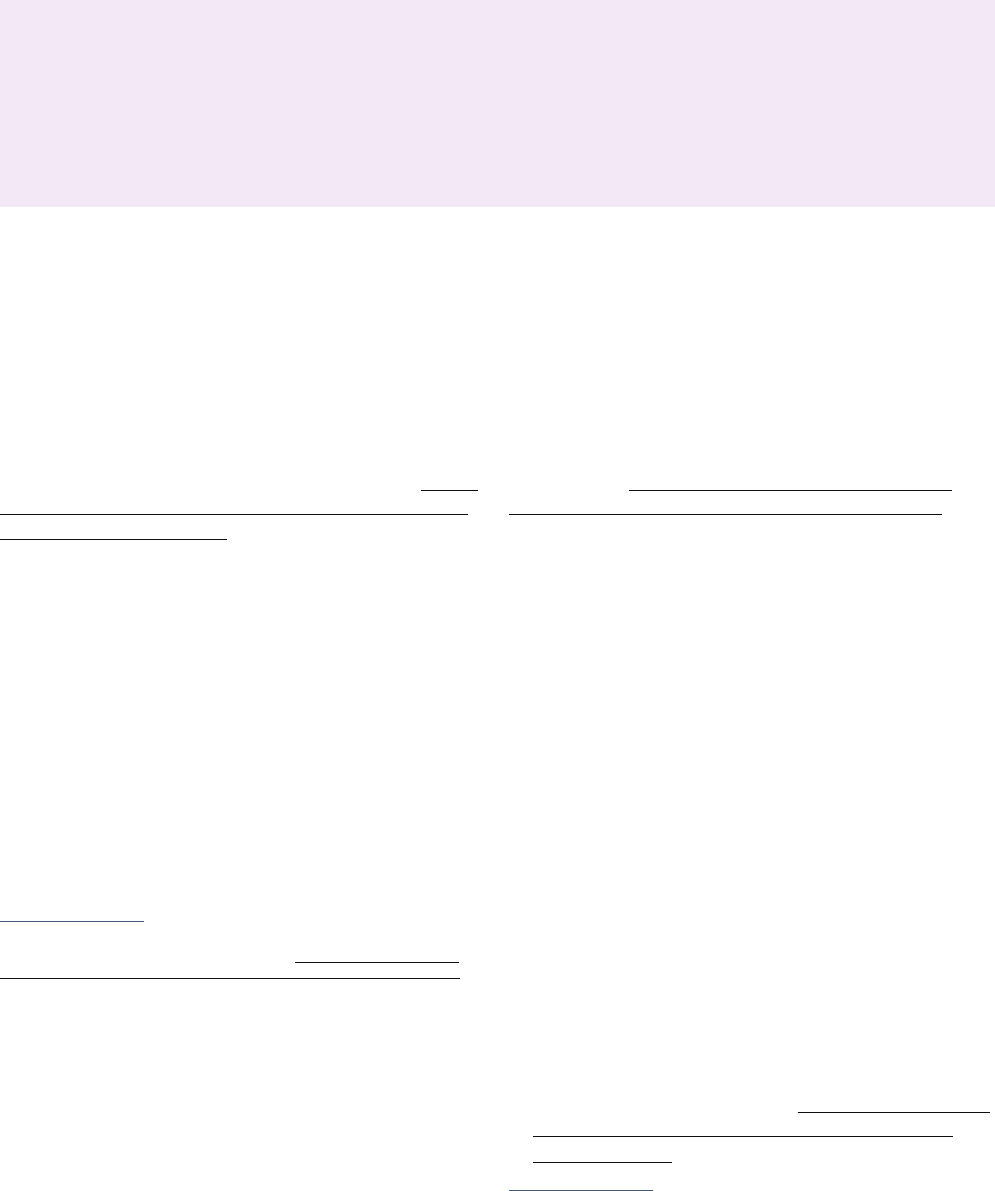

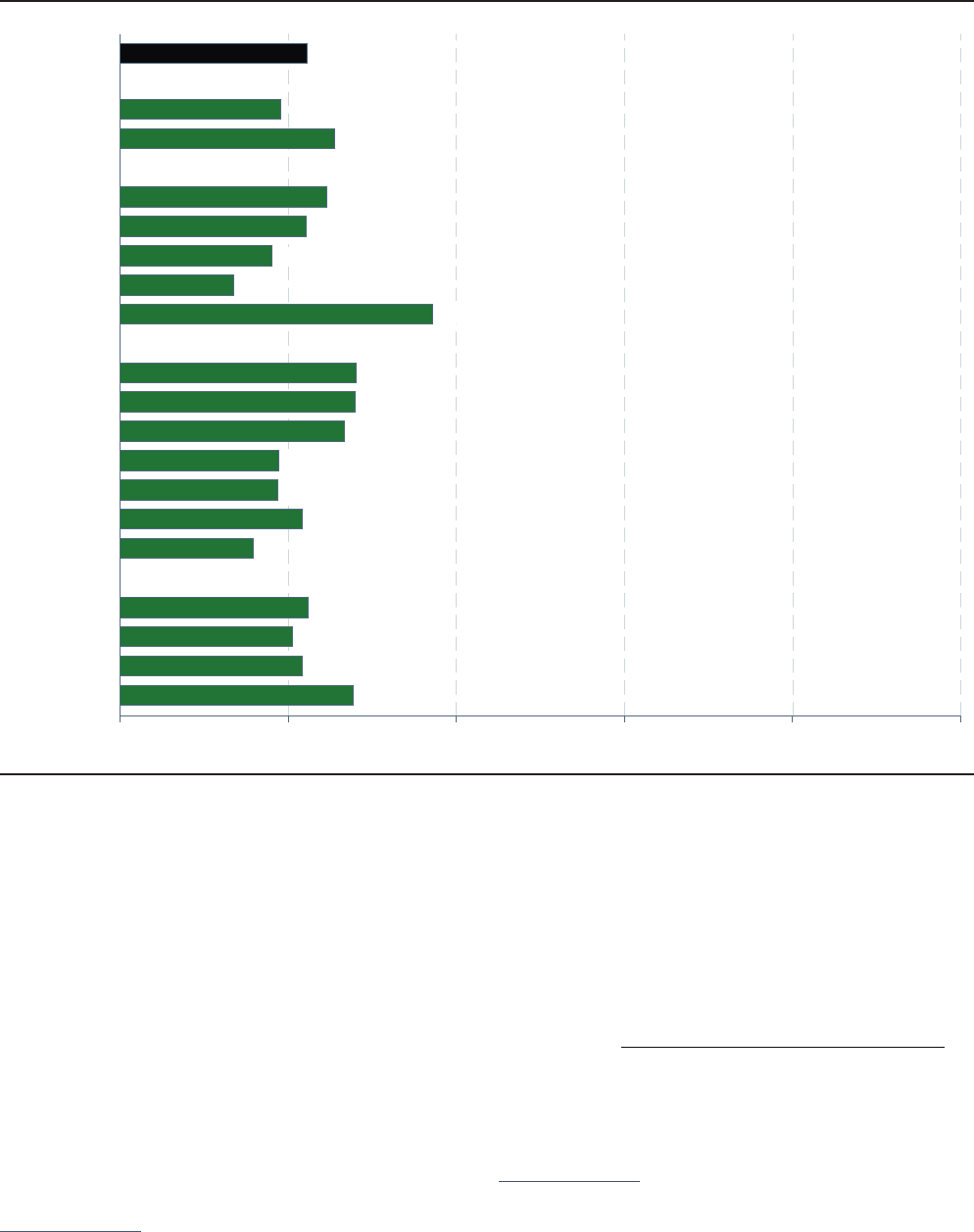

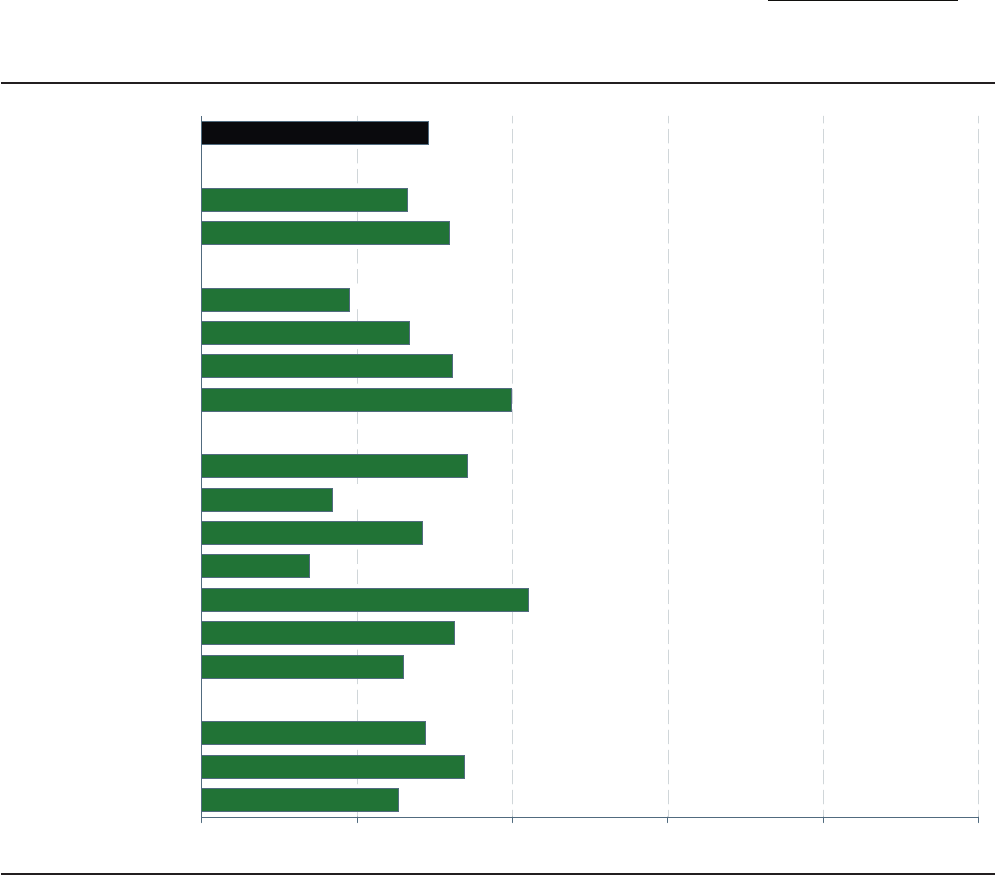

in 2019 (gure 3). For instance, the percentage of students

who reported being bullied at school during the school

year was

• higher for female students than for male students

(25vs. 19 percent);

• higher for students of Two or more races (37 percent)

than for White students (25 percent) and Black

students (22 percent), all of which were higher than for

Asian students (13 percent);

• higher for 6th-, 7th-, and 8th-graders (ranging from

27to 28 percent) than for 9th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders

(ranging from 16 to 19 percent); and

• higher for students enrolled in schools in rural areas

(28 percent) than for those enrolled in schools in other

locales (ranging from 21 to 22 percent). (Bullying at

School and Electronic Bullying)

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 7

Nonfatal Student and Teacher Victimization

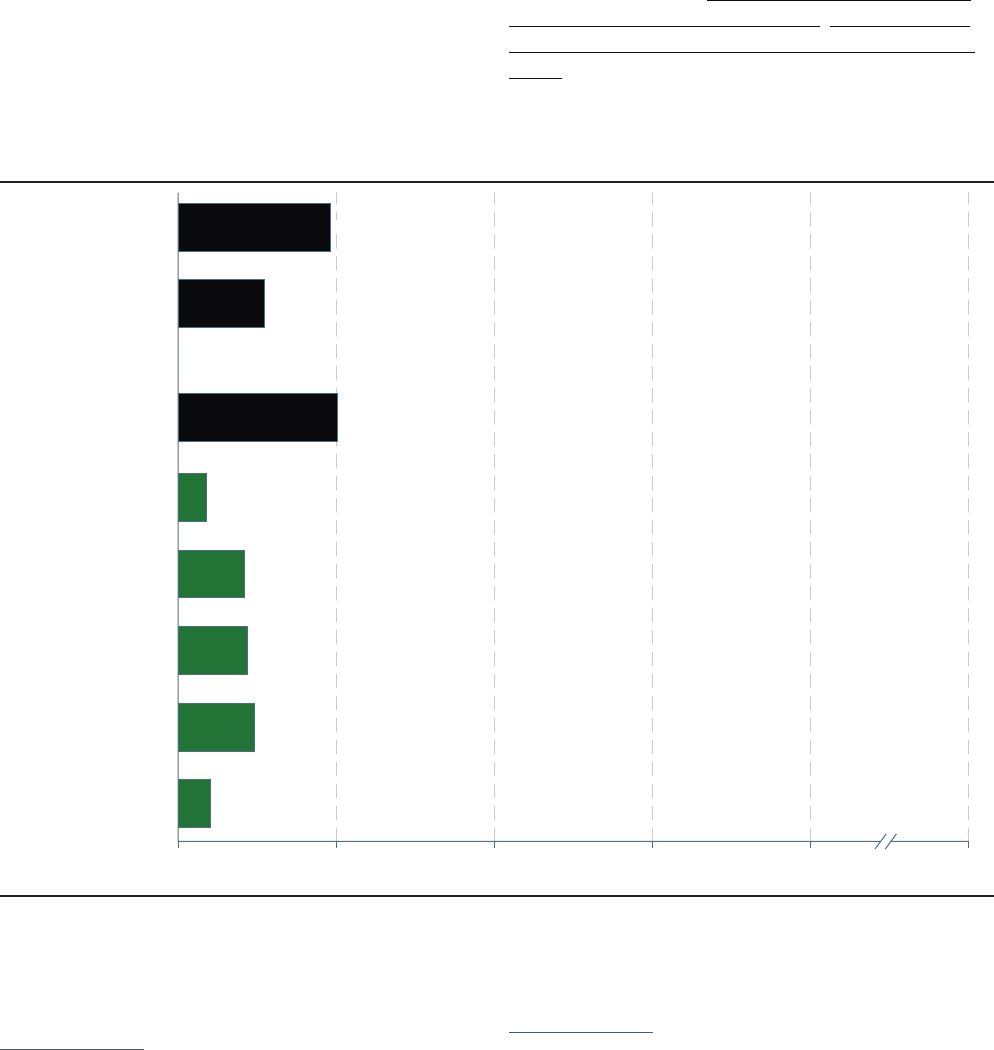

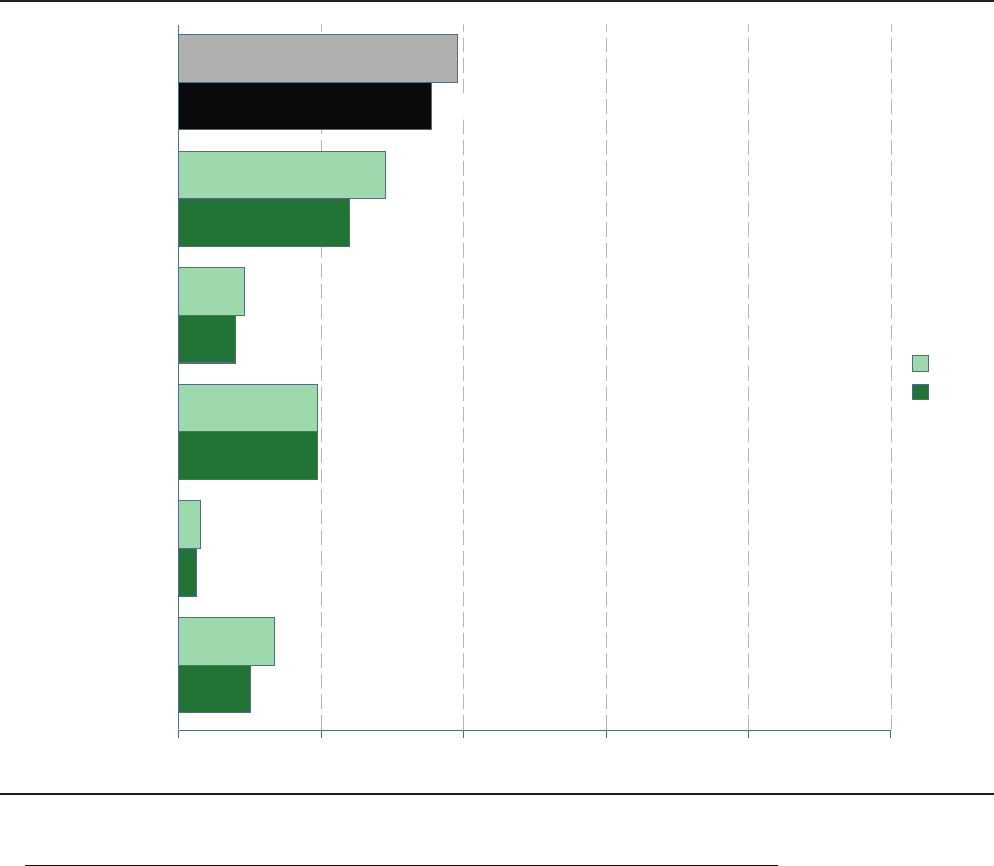

Figure 3. Percentage of students ages 12–18 who reported being bullied at school during the school year, by selected student

and school characteristics: 2019

Rural

Town

Suburban

City

12th

11th

10th

9th

8th

7th

6th

Two or more races

Asian

Hispanic

Black

White

Female

Male

Sex

Race/ethnicity

2

Grade

School locale

3

Total

1

0.0 20.0 40.0 60.0 80.0 100.0

19.1

22.2

25.5

24.6

22.2

18.0

13.5

37.1

28.1

28.0

26.7

18.9

18.7

21.7

15.8

22.4

20.5

21.7

27.7

Percent

Student or school characteristics

1

Total includes race categories not separately shown.

2

Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Data for Pacic Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native students did not meet reporting standards in 2019;

therefore, data for these two groups are not shown.

3

Excludes students with missing information about the school characteristic.

NOTE: “At school” includes in the school building, on school property, on a school bus, and going to and from school. Although rounded numbers are displayed, the gures

are based on unrounded data.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2019. See Digest of

Education Statistics 2020, table 230.40.

According to data from the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System (YRBSS), about 16 percent of students

in grades 912 reported being electronically

20

bullied

during the previous 12 months in 2019. The percentage of

students who reported being electronically bullied was

20

Being electronically bullied includes “being bullied through e-mail, chat

rooms, instant messaging, websites, or texting” for 2011 through 2015

and “being bullied through texting, Instagram, Facebook, or other social

media” for 2017 and 2019.

higher for gay, lesbian, or bisexual students (27 percent)

than for students who were not sure about their sexual

identity (19 percent), and both percentages were

higher than the percentage for heterosexual students

(14percent).

21

(Bullying at School and Electronic Bullying)

21

Since 2015, the YRBSS has included a question on students’ sexual

identity by asking students in grades 912 which of the following best

described them—“heterosexual (straight),” “gay or lesbian,” “bisexual,” or

“not sure.” In this report, students who identied as “gay or lesbian” or

“bisexual” are discussed together as the “gay, lesbian, or bisexual” group.

Students were not asked their gender identity on the YRBSS, for example,

whether they identied as transgender.

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 8

Nonfatal Student and Teacher Victimization

Teacher Victimization

In addition to students, teachers are also subject to

intimidation and violence, and students from their

schools sometimes commit these oenses. According to

data on public school teachers

22

from the 202021 National

Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), threats of injury

were more commonly reported than actual physical

attacks. Additionally, both types of teacher victimization

were less prevalent in 202021

23

than in 201112:

• The percentage of public school teachers who reported

being threatened with injury by a student from their

school was 6 percent in 202021, compared with

10percent in 201112.

• The percentage who reported being physically

attacked by a student from their school was 4 percent

in 202021, compared with 6 percent in 201112.

24

22

Includes teachers in both traditional public schools and public charter

schools. Excludes teachers who taught only prekindergarten students.

23

The 2020 calendar year was the rst year of the coronavirus pandemic,

so many schools shifted instruction from in-person classes to online-only

or hybrid education. Thus, in-person interactions between students and

teachers may have been limited.

24

The 201112 data were collected in the Schools and Stang Survey

(SASS). The NTPS was designed to allow comparisons with SASS data.

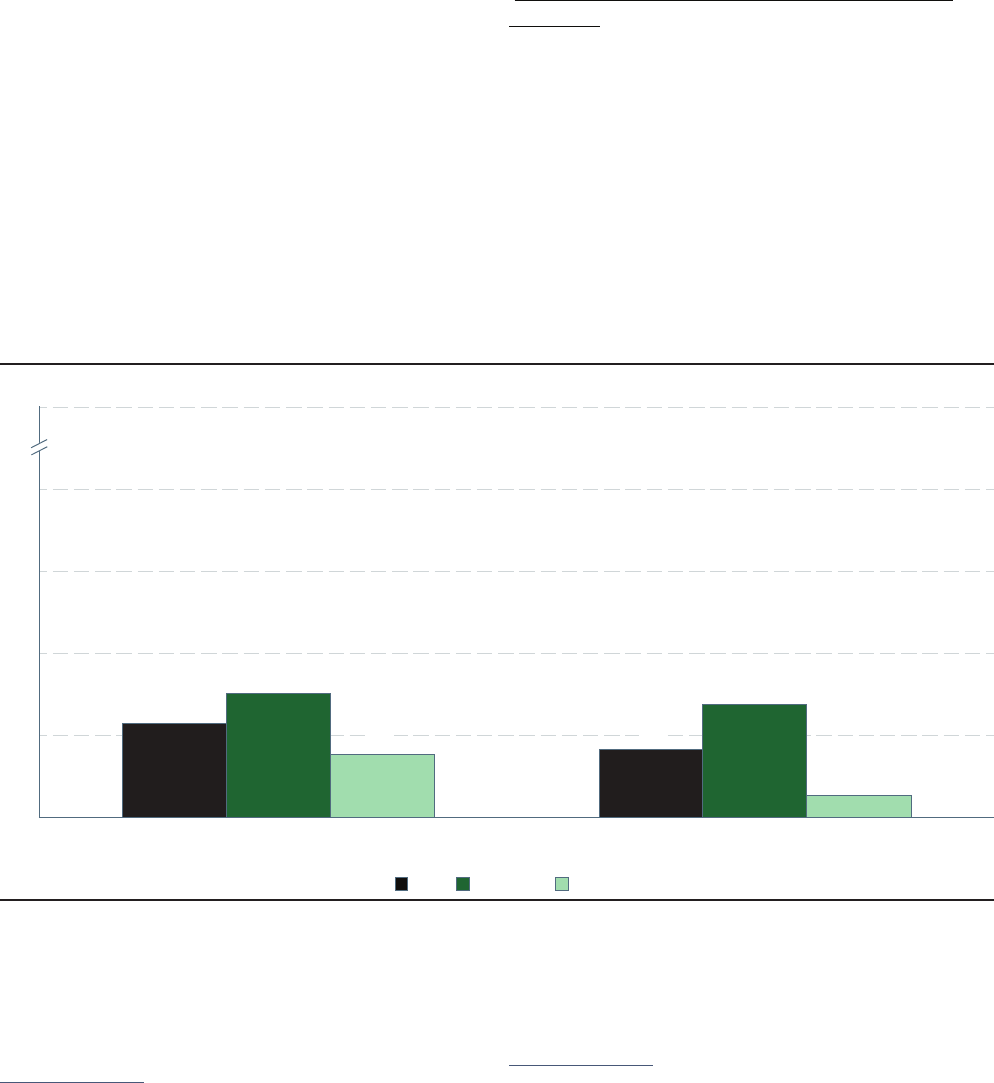

During the 202021 school year, higher percentages of

elementary public school teachers than of secondary

public school teachers reported being threatened with

injury (8 vs. 4 percent) and being physically attacked

(7vs. 1 percent) by a student from their school (gure 4).

25

(Teachers Threatened With Injury or Physically Attacked

byStudents)

25

Teachers were classied as elementary or secondary on the basis of

the grades they taught, rather than on the level of the school in which

they taught. In general, elementary teachers include those teaching any

of grades prekindergarten through grade 6 and those teaching multiple

grades, with a preponderance of grades taught being kindergarten

through grade 6. In general, secondary teachers include those teaching

any of grades 7 through 12 and those teaching multiple grades, with a

preponderance of grades taught being grades 7 through 12 and usually with

no grade taught being lower than grade 5.

NOTE: Includes teachers in both traditional public schools and public charter schools. Excludes teachers who taught only prekindergarten students. Teachers were

classied as elementary or secondary on the basis of the grades they taught, rather than on the level of the school in which they taught. In general, elementary teachers

include those teaching prekindergarten through grade 6 and those teaching multiple grades, with a preponderance of grades taught being kindergarten through grade 6. In

general, secondary teachers include those teaching any of grades 7 through 12 and those teaching multiple grades, with a preponderance of grades taught being grades 7

through 12 and usually with no grade taught being lower than grade 5.

SOURCE: National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), “Public School Teacher Data File,” 2020–21. See Digest of Education Statistics 2022, table 228.70.

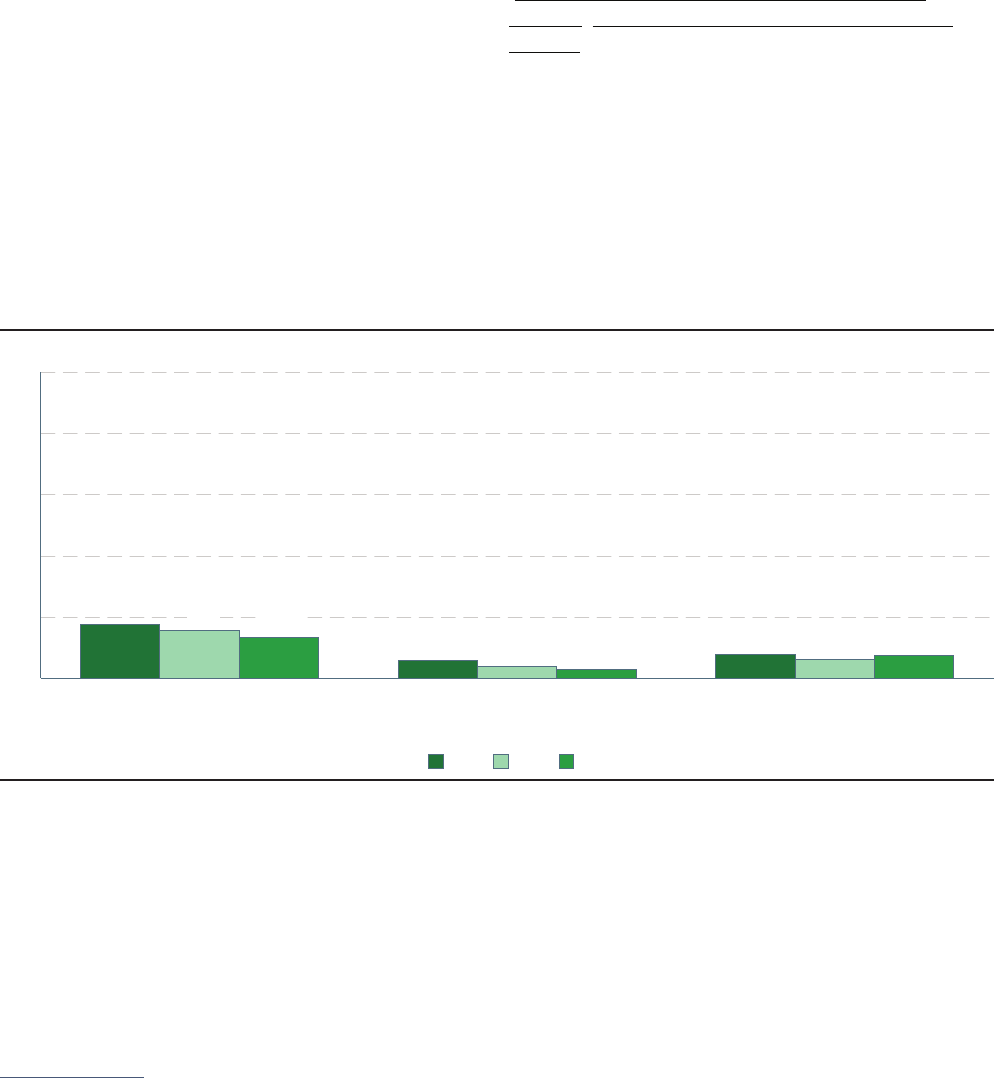

Figure 4. Percentage of public school teachers who reported that they were threatened with injury or physically attacked by a

student from their school during the previous 12 months, by instructional level: School year 2020–21

TotalElementarySecondary

Threatened with injury Physically attacked

5.7

7.6

6.9

Percent

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

100.0

Type of reported incident

4.1

1.4

3.9

0.0

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 9

Nonfatal Student and Teacher Victimization

Criminal Incidents and Discipline Problems

Reported by Public Schools

Criminal incidents and discipline problems at school

are aspects of the school safety environment for which

national data are available. The School Survey on Crime

and Safety (SSOCS) asked public school principals to

report the numbers of various types of criminal incidents

that occurred at their school

26

and to indicate how often

certain disciplinary problems happened in their school.

27

Such school-reported data can complement those data

covering similar issues based on students’ experience and

observation, such as those collected through the School

Crime Supplement (SCS) and the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System (YRBSS).

26

In SSOCS, “at school” was dened for respondents as including activities

that happen in school buildings, on school grounds, on school buses, and

at places that hold school-sponsored events or activities. In the survey

questions about criminal incidents, respondents were instructed to include

incidents that occurred before, during, or after normal school hours or

when school activities or events were in session.

27

Respondents were instructed to include discipline problems only

for those times that were during normal school hours or when school

activities or events were in session.

School Environment

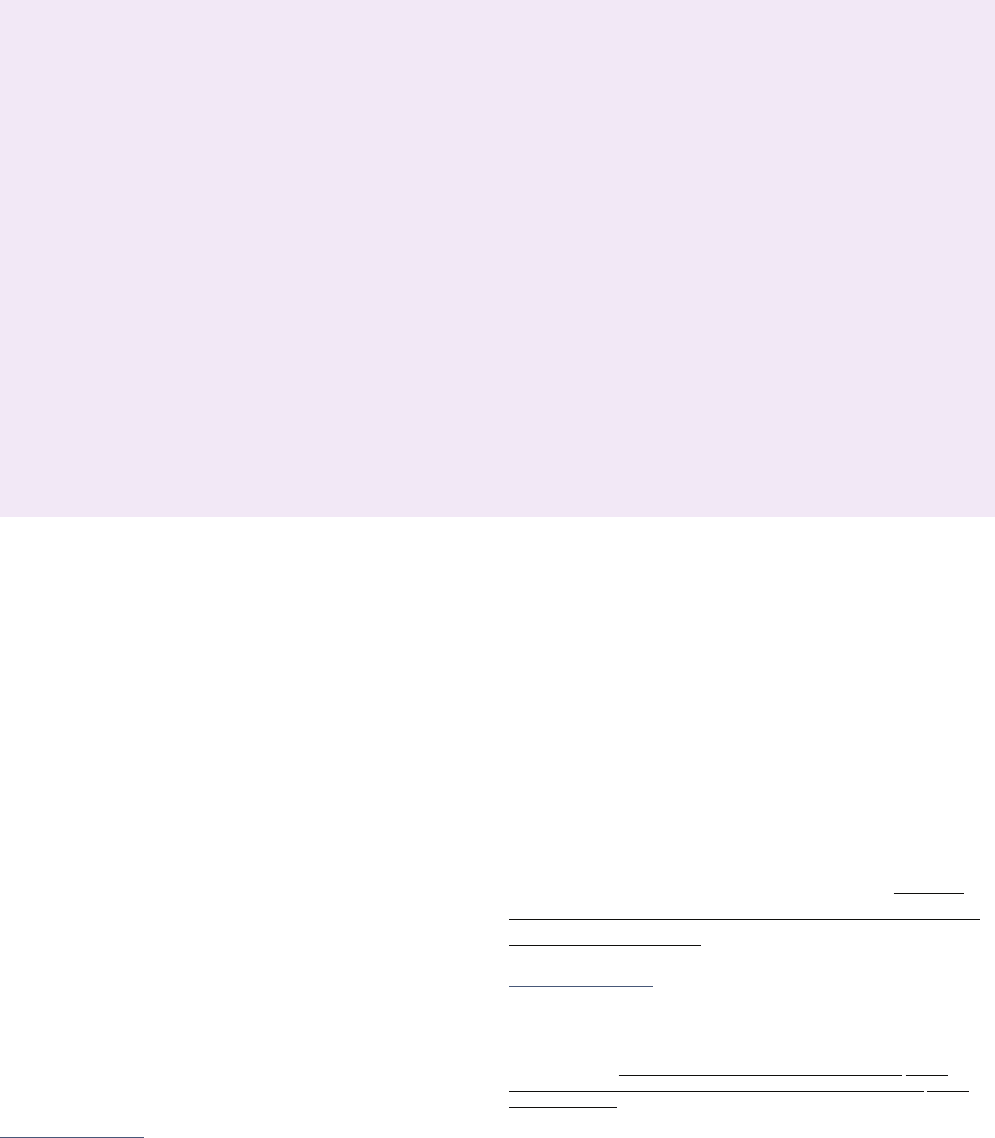

During the 201920 school year,

28

77 percent of public

schools recorded that one or more incidents of crime

29

had

taken place, amounting to 1.4 million incidents, or a rate of

29 incidents per 1,000 students enrolled (gure 5). During

the same school year, 47 percent of schools reported one

or more incidents of crime to sworn law enforcement,

amounting to 482,400 incidents, or a rate of 10 incidents

per 1,000 students enrolled. The percentage of public

schools that recorded one or more incidents of crime was

lower in 201920 than in 200910 (77 vs. 85 percent); the

same pattern can be observed for the percentage of public

schools that reported one or more criminal incidents

to sworn law enforcement (47 vs. 60 percent). (Criminal

Incidents Recorded by Public Schools and Those Reported to

Sworn Law Enforcement)

28

The coronavirus pandemic aected the 201920 data collection activities.

The change to virtual schooling and the adjusted school year may have

impacted the data collected by SSOCS. Readers should use caution when

comparing 201920 estimates with those from earlier years. For more

information, see Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public

Schools in 201920: Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety

(NCES 2022029).

29

In SSOCS, incidents of crime include violent incidents, thefts of items

valued at $10 or greater without personal confrontation, and other

criminal incidents. “Violent incidents” include rape or attempted rape;

sexual assault other than rape; physical attacks or ghts with or without

a weapon; threat of physical attacks with or without a weapon; and

robbery with or without a weapon. “Other incidents” include possession

of a rearm or explosive device; possession of a knife or sharp object;

distribution, possession, or use of illegal drugs or alcohol; inappropriate

distribution, possession, or use of prescription drugs; and vandalism. Note

that when referring to criminal incidents, the word “recorded” refers to all

incidents that were documented by the school, while “reported” is used to

identify incidents that were reported to sworn law enforcement.

Some aspects of the school environment showed improvements over time. For instance:

• A lower percentage of public schools in 201920 than in 200910 recorded one or more incidents of crime

(77vs. 85 percent).

• Lower percentages of public schools in 201920 than in 200910 reported student behaviors at school that

targeted fellow students, including student bullying at least once a week (15 vs. 23 percent) and sexual

harassment of other students at least once a week (2 vs. 3 percent).

• Lower percentages of students ages 1218 in 2019 than in 2009 reported the following unfavorable conditions

at their school: gang presence (9 vs. 20 percent), being called hate-related words (7 vs. 9 percent), and seeing

hate-related grati (23 vs. 29 percent).

• A lower percentage of public school teachers in 202021 than in 201112 agreed that student misbehavior

interfered with their teaching (32 vs. 41 percent).

However, other aspects did not improve:

• A higher percentage of public schools in 201920 than in 200910 reported cyberbullying among students at

least once a week (16 vs. 8 percent).

• A higher percentage of students in 2019 than in 2009 reported avoiding one or more places in school during

the school year because they thought someone might attack or harm them (5 vs. 4 percent).

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 10

In 201920, lower percentages of elementary schools and

combined/other schools recorded incidents of violent

crime

30

(58 and 60 percent, respectively) compared with

middle schools (91 percent) and secondary/high schools

(90 percent).

31

Similarly, lower percentages of elementary

schools and combined/other schools than of middle

schools and secondary/high schools reported incidents

of violent crime to sworn law enforcement. (Criminal

Incidents Recorded by Public Schools and Those Reported to

Sworn Law Enforcement)

Within the category of noncriminal incidents, student

bullying

32

and cyberbullying

33, 34

were among the most

prevalent discipline problems reported by public schools

to have occurred at least once a week in 201920 (reported

by 15 and 16 percent of public schools, respectively;

gure6). Student verbal abuse of teachers and acts

30

See previous footnote for the denition of “violent incidents.”

31

Elementary schools are dened as schools that enroll students in more

of grades K through 4 than in higher grades. Middle schools are dened as

schools that enroll students in more of grades 5 through 8 than in higher

or lower grades. Secondary/high schools are dened as schools that enroll

students in more of grades 9 through 12 than in lower grades. Combined/other

schools include all other combinations of grades, including K12 schools.

32

The SSOCS questionnaire denes bullying as “any unwanted aggressive

behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths that involves an observed

or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly

likely to be repeated. Bullying occurs among youth who are not siblings or

current dating partners.”

33

“Cyberbullying” was dened for respondents as “occurring when willful

and repeated harm is inicted through the use of computers, cell phones,

or other electronic devices.”

34

For all discipline problems except “student cyberbullying,” respondents

were instructed to include problems that occur at school.

of disrespect for teachers other than verbal abuse

were reported by 10and 15 percent of public schools,

respectively. (Discipline Problems Reported by Public

Schools)

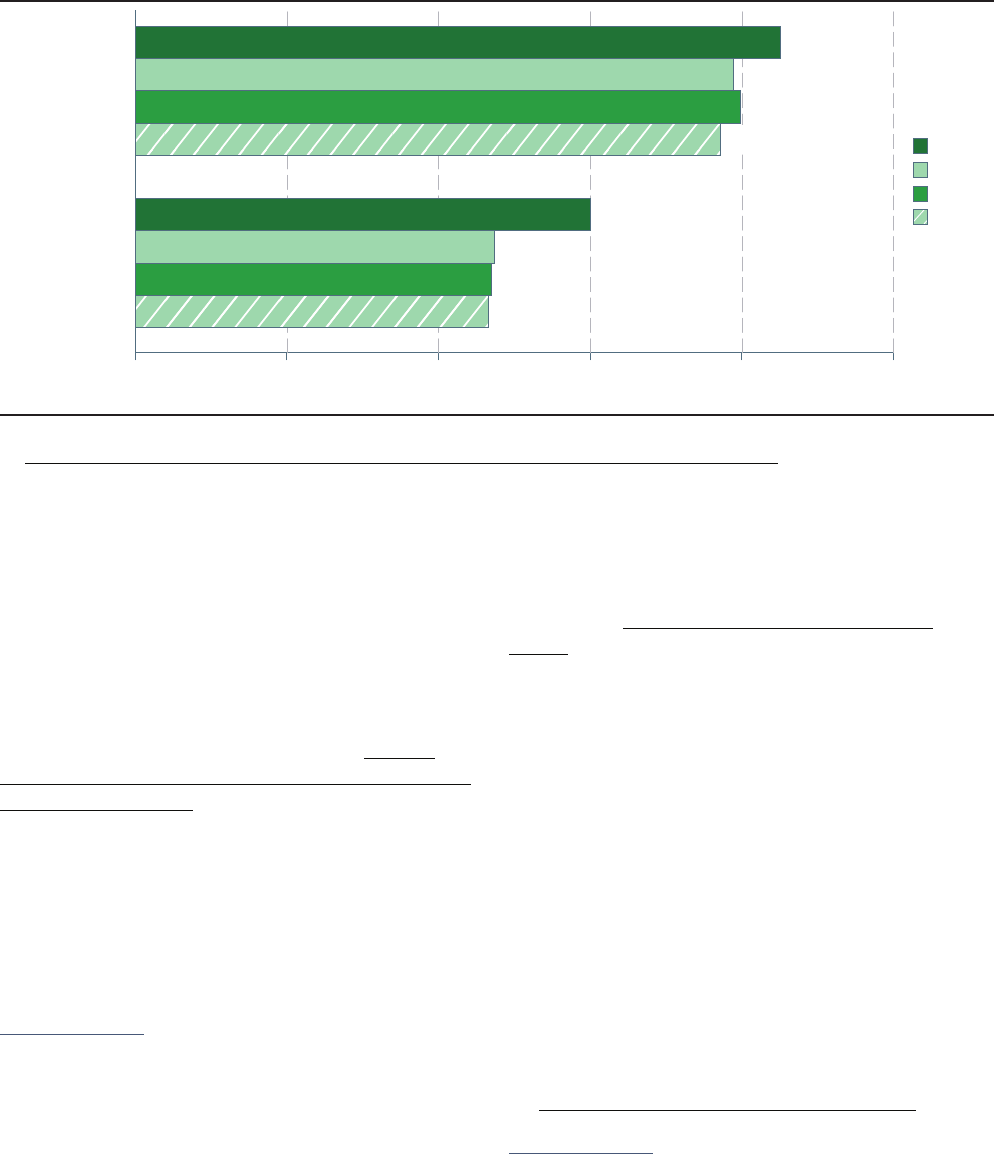

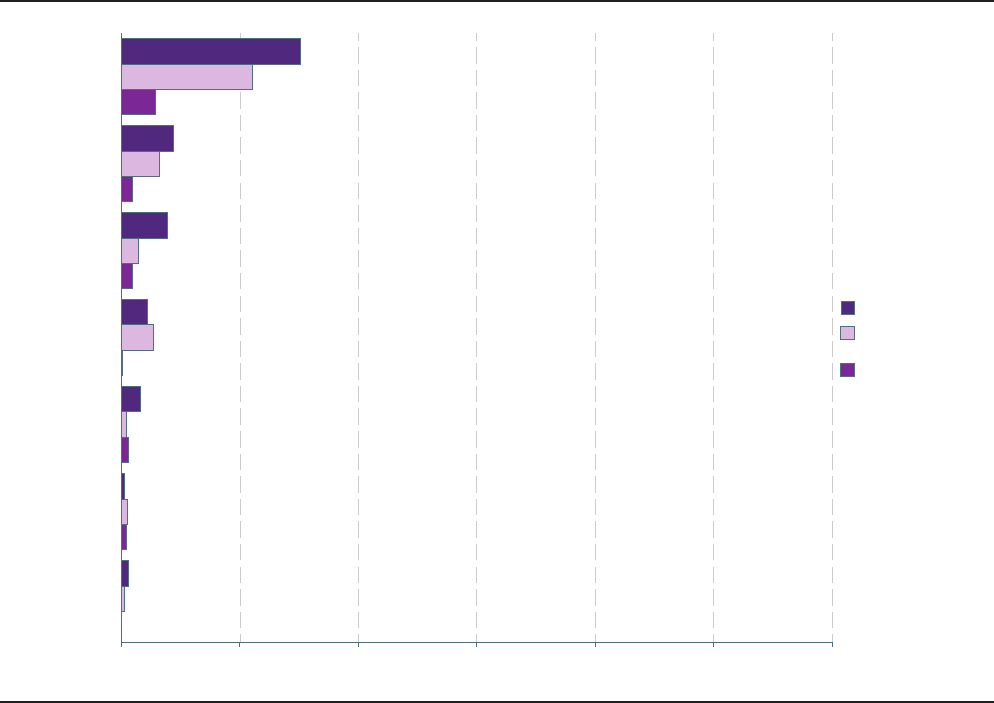

Higher percentages of public schools in 201920 than in

200910 reported

• cyberbullying (16 vs. 8 percent; gure 6);

• student acts of disrespect for teachers other than

verbal abuse (15 vs. 9 percent);

• student verbal abuse of teachers (10 vs. 5 percent); and

• widespread disorder in the classroom (4 vs. 3 percent).

In contrast, behaviors at school that targeted fellow

students were generally less prevalent. Lower percentages

of public schools in 201920 than in 200910 reported

• student bullying (15 vs. 23 percent);

• student sexual harassment of other students (2 vs.

3percent); and

• student harassment of other students based on sexual

orientation or gender identity

35, 36

(2 vs. 3 percent).

(Discipline Problems Reported by Public Schools)

35

Sexual orientation means one’s “emotional or physical attraction to the

same and/or opposite sex.” Gender identity means one’s “inner sense of

one’s own gender, which may or may not match the sex assigned at birth.”

36

Prior to 201516, the questionnaire asked about “student harassment of

other students based on sexual orientation or gender identity (i.e., lesbian,

gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning)” in one single item. The 201516,

201718, and 201920 questionnaires had one item asking about “student

harassment of other students based on sexual orientation,” followed by a

separate item asking about “student harassment of other students based

on gender identity.”

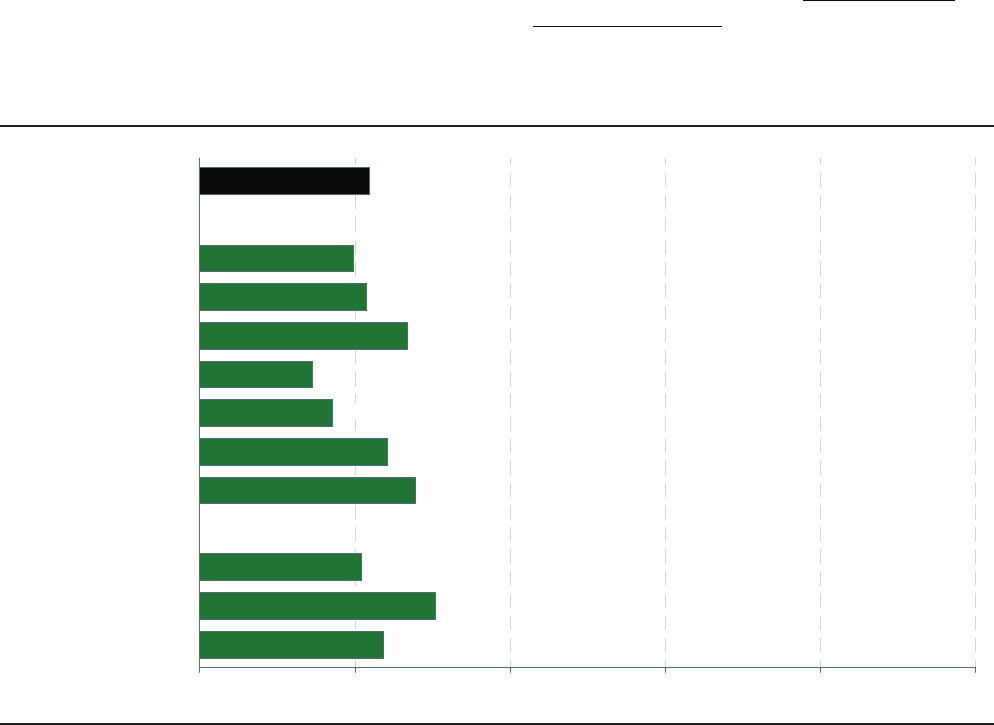

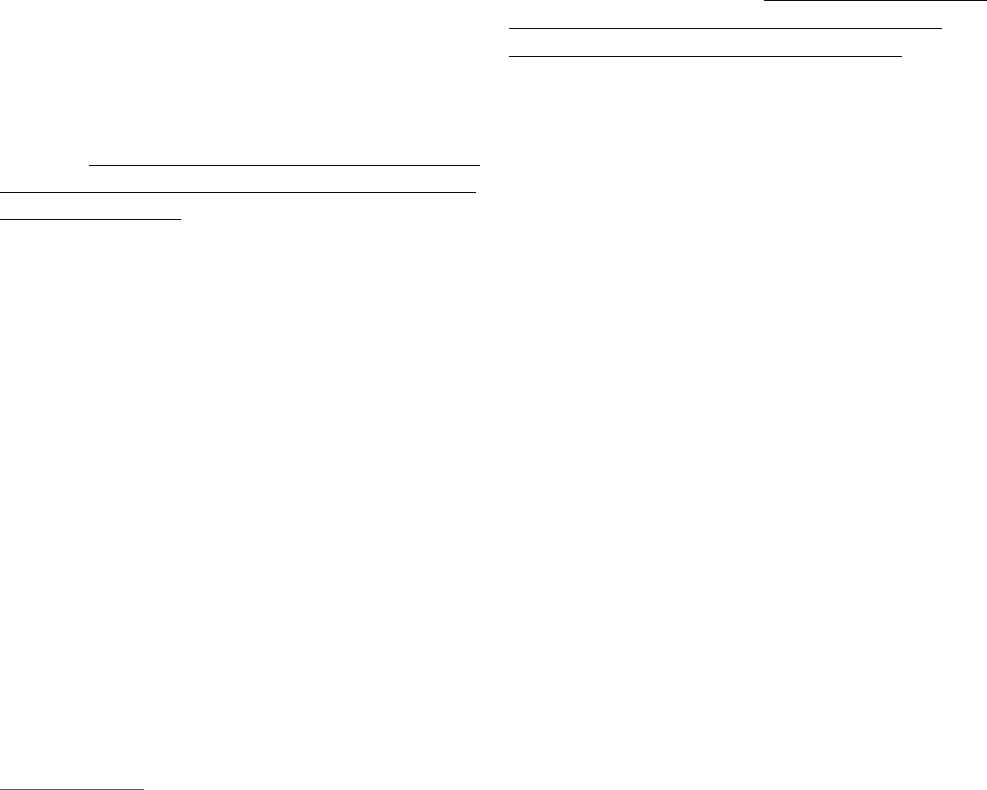

Figure 5. Percentage of public schools recording one or more incidents of crime at school and percentage reporting incidents to

sworn law enforcement: Selected years, 2009–10 through 2019–20

2009–10

2015–16

2017–18

2019–20

1

46.6

46.9

47.4

77.2

85.0

79.8

78.9

0.0 20.0 40.0 60.0 80.0 100.0

Percent

Recorded

Reported to sworn

law enforcement

60.0

1

The coronavirus pandemic affected the 2019–20 data collection activities. The change to virtual schooling and the adjusted school year may have impacted the data

collected by the School Survey on Crime and Safety. Readers should use caution when comparing 2019–20 estimates with those from earlier years. For more information,

see Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public Schools in 2019–20: Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety (NCES 2022-029).

NOTE: Responses were provided by the principal or the person most knowledgeable about crime and safety issues at the school. “At school” was dened as including

activities that happen in school buildings, on school grounds, on school buses, and at places that hold school-sponsored events or activities. Respondents were instructed

to include incidents that occurred before, during, and after normal school hours or when school activities or events were in session.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2019–20 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), 2020. See Digest of Education

Statistics 2021, table 229.10.

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 11

School Environment

Gangs and Hate-Related Speech

Another aspect of the school environment for which

national data are available is unfavorable conditions

related to crime and safety, such as the presence of

gangs and hate-related

37

words and grati. These data

are captured in the SCS based on student reports of

conditions at school during the school year. Lower

37

“Hate-related” refers to derogatory terms used by others in reference to

students’ personal characteristics.

percentages of students ages 1218 in 2019 than in 2009

reported these unfavorable conditions:

• gang presence (9 vs. 20 percent; gure 7);

• being called hate-related words (7 vs. 9 percent); and

• seeing hate-related grati (23 vs. 29 percent).

(Students’ Reports of Gangs at School; Students’ Reports

of Hate-Related Words and Hate-Related Grati)

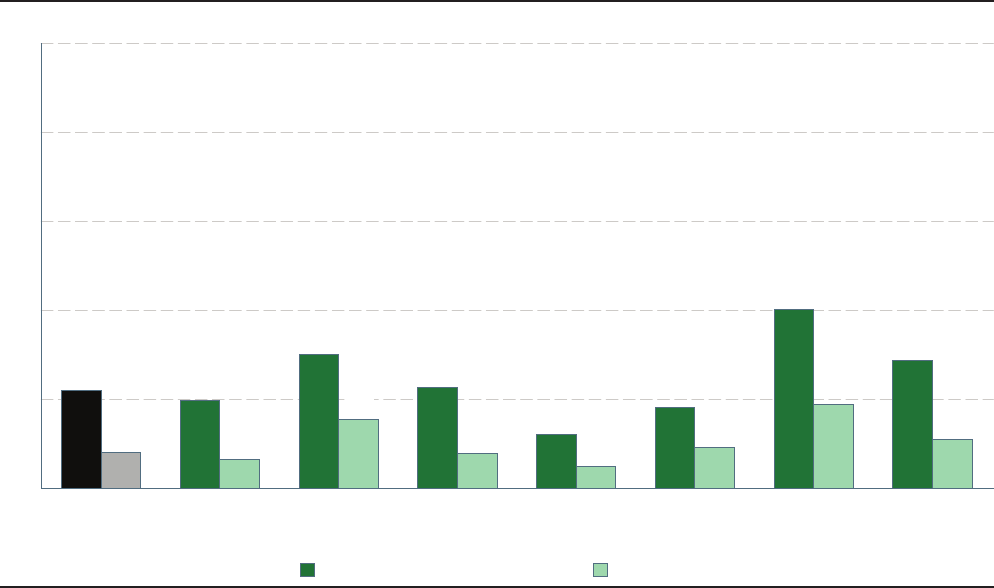

Figure 6. Percentage of public schools reporting selected discipline problems that occurred at least once a week: School years

2009–10 and 2019–20

1

The coronavirus pandemic affected the 2019–20 data collection activities. The change to virtual schooling and the adjusted school year may have impacted the data

collected by the School Survey on Crime and Safety. Readers should use caution when comparing 2019–20 estimates with those from earlier years. For more information,

see Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public Schools in 2019–20: Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety (NCES 2022-029).

NOTE: Responses were provided by the principal or the person most knowledgeable about crime and safety issues at the school. Respondents were instructed to include

discipline problems only for those times that were during normal school hours or when school activities or events were in session, unless the survey specied otherwise.

For all items except “student cyberbullying,” respondents were instructed to include problems that occur at school. “At school” was dened to include activities that happen

in school buildings, on school grounds, on school buses, and at places that hold school-sponsored events or activities. For the “student cyberbullying” item, respondents

were instructed to include cyberbullying “problems that can occur anywhere (both at your school and away from school).” Although rounded numbers are displayed, the

gures are based on unrounded data.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2009–10 and 2019–20 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), 2010 and 2020.

See Digest of Education Statistics 2021, table 230.10.

15.3

8.6

4.1

2.5

9.8

4.8

1.5

2.5

1.6

3.2

7.9

14.6

23.1

3.8

2.8

0.0 20.0 40.0 60.0 80.0 100.0

2009–10

2019–20

1

Percent

Discipline problem

Student racial/

ethnic tensions

Student bullying

Student sexual

harrassment of

other students

Student harrassment of

other students based

on sexual orientation

or gender identity

Student verbal

abuse of teachers

Widespread disorder

in classrooms

Student acts of

disrespect for

teachers other

than verbal abuse

Student cyberbullying

15.9

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 12

School Environment

In 2019, there were dierences in the reports of

these unfavorable conditions by student and school

characteristics. For instance, higher percentages of

9th-through 12th-graders (ranging from 10 to 12 percent)

than of 6th- through 8th-graders (ranging from 5 to

6percent) reported observing a gang presence at their

school. In contrast, the percentages of students who

reported being called a hate-related word at school

were lower for 10th- and 12th-graders (5 and 4 percent,

respectively) than for 7th- and 8th-graders (8 and

9percent, respectively), and there were no measurable

dierences by students’ grade level in the percentage

of students who reported seeing hate-related grati at

school. (Students’ Reports of Gangs at School; Students’

Reports of Hate-Related Words and Hate-Related Grati)

Students who reported being called hate-related words

at school during the school year were asked to indicate

whether the derogatory word they were called referred

to their race, ethnicity, religion, disability, gender, or

sexual orientation. In 2019, race was the most frequently

reported characteristic referred to by hate-related words.

The percentage of students who reported being called

a hate-related word referring to their race was lower for

White students (2 percent) than for students of any other

race/ethnicity for which data were available (ranging from

4 percent of Hispanic students to 9 percent of students

of Two or more races). (Students’ Reports of Hate-Related

Words and Hate-Related Grati)

NOTE: “At school” includes in the school building, on school property, on a school bus, and going to and from school. “Hate-related” refers to derogatory terms used by

others in reference to students’ personal characteristics.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2009 through 2019. See

Digest of Education Statistics 2020, tables 230.20 and 230.30.

2009 2011 2013 2015

Year

Percent

2017 2019

0.0

10.0

20.0

30.0

40.0

100.0

Seeing hate-related graffiti

Gang presence

Being called hate-related words

Figure 7. Percentage of students ages 12–18 who reported a gang presence, being called hate-related words, and seeing hate-

related grafti at school during the school year: Selected years, 2009 through 2019

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 13

School Environment

Student Fear and Avoidance

Another aspect of the school environment to consider is

students’ perceptions of personal safety at school. The

SCS collected such data by asking students ages 1218

about their fear of attack or harm at and away from

school. In 2019, about 5 percent of students ages 1218

reported that they had been afraid of attack or harm

38

at

school during the school year, which was higher than the

percentage of students who reported that they had been

afraid of attack or harm away from school (3 percent;

gure 8). The percentages of students who reported being

afraid of attack or harm at school and away from school

38

Students were asked if they were “never,” “almost never,” “sometimes,”

or “most of the time” afraid that someone would attack or harm them at

school or away from school. Students responding “sometimes” or “most of

the time” were considered afraid.

in 2019 were not measurably dierent from those in

2009. The SCS also asked students whether they avoided

one or more places in school

39

because they were fearful

that someone might attack or harm them. In 2019, the

percentage of students who reported avoiding one or

more places in school during the school year because

they thought someone might attack or harm them was

5percent, which was higher than the percentage who did

so in 2009 (4percent). (Students’ Perceptions of Personal

Safety at School and Away From School; Students’ Reports

of Avoiding School Activities or Classes or Specic Places in

School)

39

“Avoided one or more places in school” includes avoiding entrance to

the school, hallways or stairs in school, parts of the school cafeteria, any

school restrooms, and other places inside the school building. Students

who reported avoiding multiple places in school were counted only once

in the total for students avoiding one or more places.

1

“At school” includes in the school building, on school property, on a school bus, and going to and from school.

2

Students were asked if they were “never,” “almost never,” “sometimes,” or “most of the time” afraid that someone would attack or harm them at school or away from

school. Students responding “sometimes” or “most of the time” were considered afraid.

3

Students who reported avoiding multiple places in school were counted only once in the total for students avoiding one or more places.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2019. See Digest of

Education Statistics 2020, tables 230.70 and 230.80.

Figure 8. Percentage of students ages 12–18 who reported being afraid of attack or harm during the school year and percentage

who reported avoiding one or more places in school because of fear of attack or harm during the school year: 2019

Other places inside

the school building

Any school restrooms

Parts of the school cafeteria

Hallways or stairs in school

Entrance to the school

Avoided one or more

places in school

3

Were afraid of attack or

harm away from school

2

Were afraid of attack or

harm at school

1, 2

0.0 5.0 10.0

Percent

15.0 20.0 100.0

4.8

2.7

5.0

0.9

2.1

2.2

2.4

1.0

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 14

School Environment

In 2019, there were some measurable dierences by

student and school characteristics in the percentages

of students ages 1218 who reported fear and avoidance.

For example, the percentage of students who reported

avoiding one or more places in school because of fear of

attack or harm was

• higher for students of Two or more races (11 percent)

than for Hispanic (5 percent), Asian (4 percent), and

White (4 percent) students;

• higher for Black students (7 percent) than for White

students (4 percent);

• higher for 7th-, 8th-, and 9th-graders (5, 6, and

7percent, respectively) than for 12th-graders

(3percent);

• higher for those enrolled in schools in cities than

for those enrolled in schools in rural areas (6 vs.

4percent); and

• higher for public school students than for private

school students (5 vs. 2 percent). (Students’ Reports of

Avoiding School Activities or Classes or Specic Places in

School)

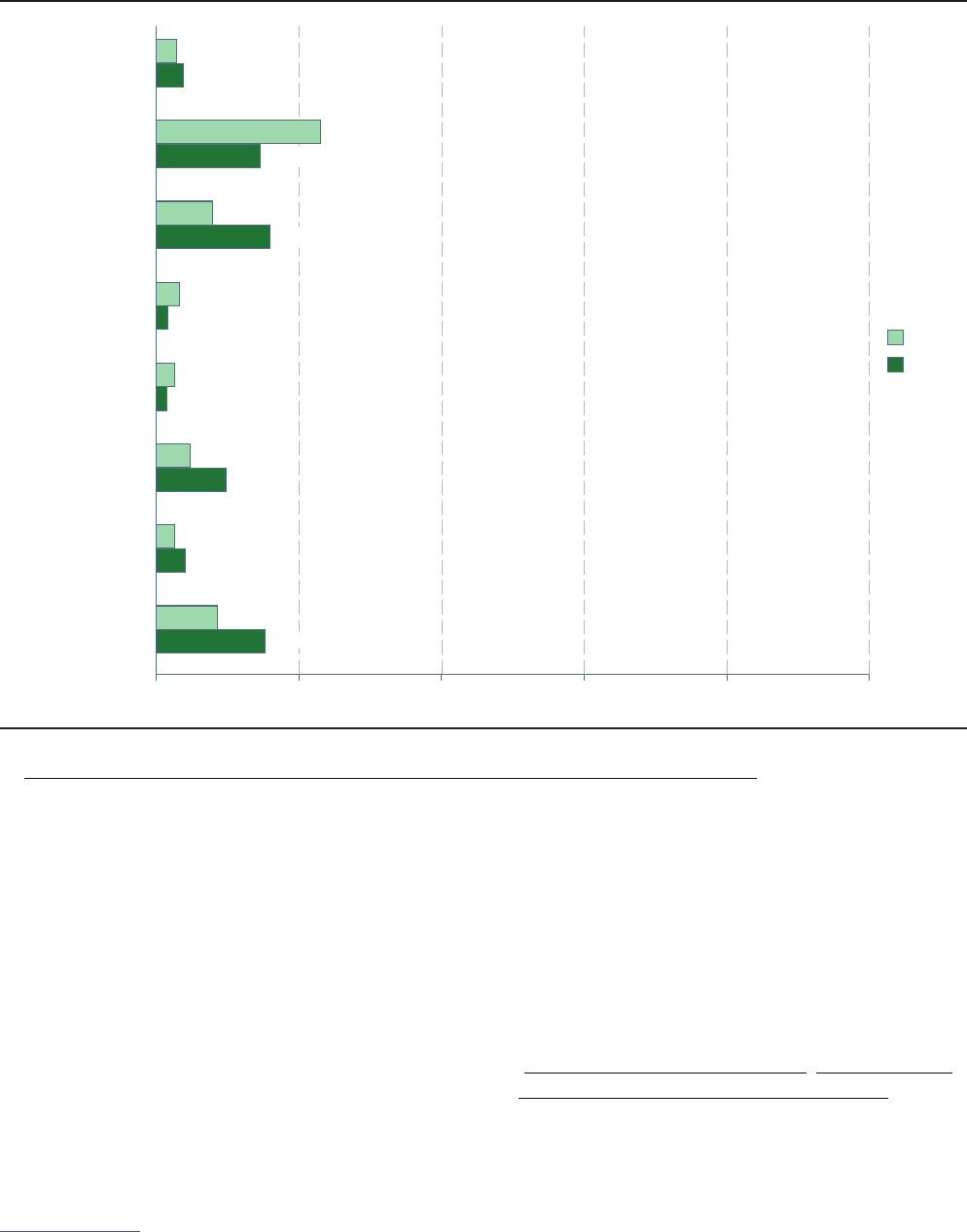

Teachers’ Reports of Student Behavior and

Rule Enforcement

Finally, teachers also reported on school order and

conditions in the 202021 National Teacher and Principal

Survey (NTPS). In 202021,

40

of all public school

teachers,

41

• 32 percent agreed that student misbehavior interfered

with their teaching;

• 37 percent agreed that student tardiness and class

cutting interfered with their teaching;

• 67 percent agreed that other teachers at their school

enforced the school rules for student behavior; and

• 83 percent agreed that the principal enforced the

school rules for student behavior (gure 9).

A lower percentage of public school teachers in 202021

than in 201112 reported that student misbehavior

interfered with their teaching (32 vs. 41 percent), while

the other percentages were not measurably dierent

between the 2 years. (Teachers’ Reports of Disruptive

Student Behaviors and Sta Rule Enforcement)

40

The 2020 calendar year was the rst year of the coronavirus pandemic,

and many schools shifted instruction from in-person classes to online-only

or hybrid education. Thus, in-person interactions between students and

teachers may have been limited.

41

Percentages represent both teachers who “strongly” agreed and those

who “somewhat” agreed with the statement.

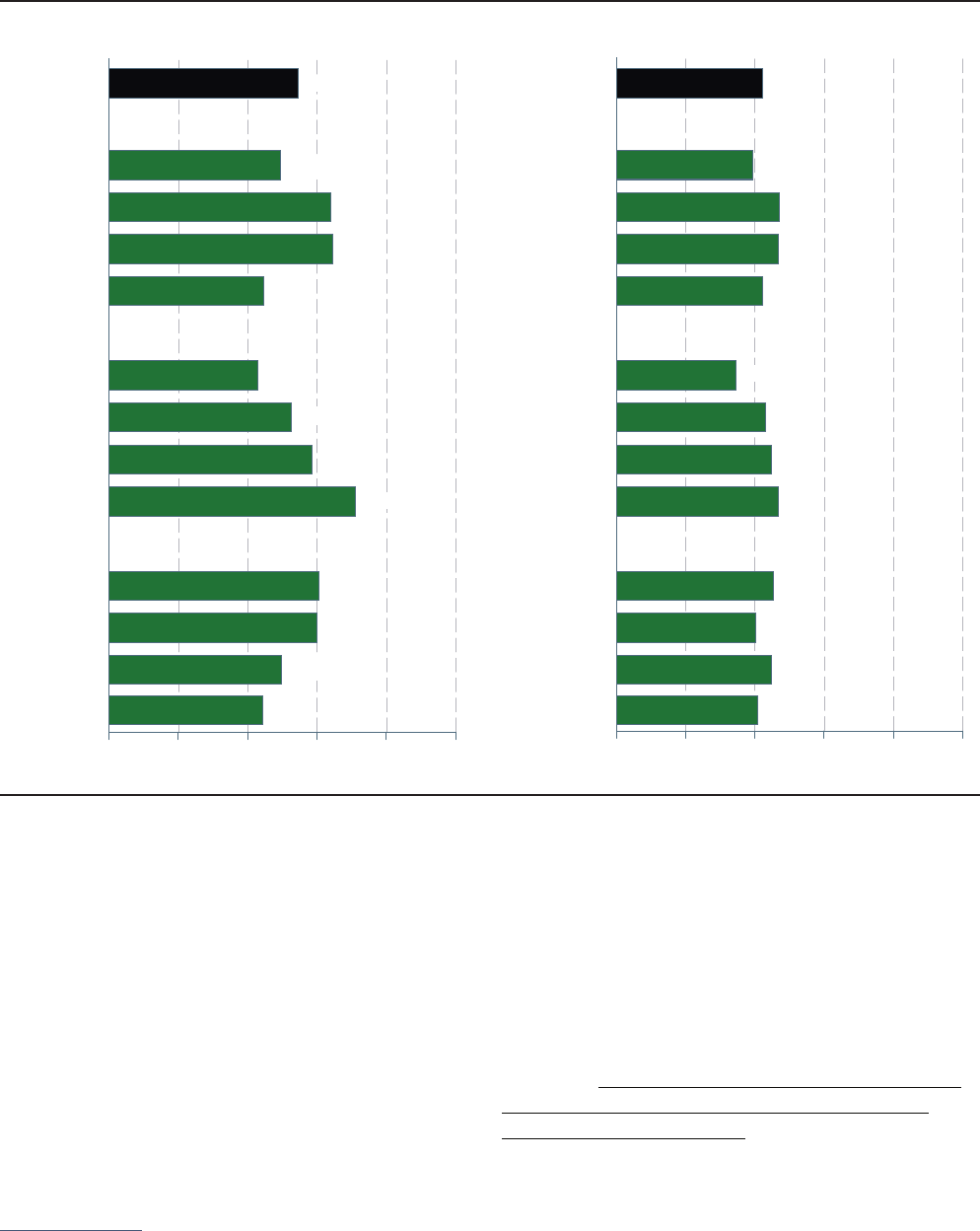

Figure 9. Percentage of public school teachers who agreed that student misbehavior and student tardiness and class cutting

interfered with their teaching and percentage who agreed that other teachers and the principal enforced school rules:

School years 2011–12 and 2020–21

1

The questionnaire provided the following examples of student misbehavior: noise, horseplay, or ghting in the halls, cafeteria, or student lounge.

2

Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement “rules for student behavior are consistently enforced by teachers in this school,

even for students who are not in their classes.”

3

Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement “my principal enforces school rules for student conduct and backs me up when I

need it.”

NOTE: Teachers who taught only prekindergarten students are excluded. Includes teachers in both traditional public schools and public charter schools. Percentages

represent both teachers who “strongly” agreed and those who “somewhat” agreed that student misbehavior and student tardiness and class cutting interfered with their

teaching, as well as teachers who “strongly” agreed and those who “somewhat” agreed that school rules were enforced by other teachers and the principal.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Stafng Survey (SASS), “Public School Teacher Data File,” 2011–12; and

National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), “Public School Teacher Data File,” 2020–21. See Digest of Education Statistics 2022, tables 230.90 and 230.92.

2020–212011–12

Student misbehavior

interfered with teaching

1

Student tardiness and class

cutting interfered with teaching

Other teachers

enforced school rules

2

Principal enforced

school rules

3

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

Percent

40.7

32.0

37.6

37.4

67.6

67.0

83.7

83.2

Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 | 15

School Environment

Student Involvement in Physical Fights

Guns, ghts, alcohol, and drugs are indicators of

disorder and incivility at school. The Youth Risk

Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) asked students in

grades 912 about their involvement in physical ghts,

anywhere

42

or on school property, during the previous

12months. Involvement in physical ghts includes both

as an aggressor and as an unwilling participant or victim.

The percentage of students in grades 912 who reported

having been in a physical ght anywhere during the

previous 12 months was lower in 2019 than in 2009 (22vs.

31 percent), and the percentage who reported having

been in a physical ght on school property in the previous

12 months was also lower in 2019 than in 2009 (8vs.

11percent). The percentage of students who reported

42

“Anywhere” includes occurrences on school property. The term

“anywhere” is not used in the YRBSS, and the survey did not dene “on

school property” for respondents.

having been in a physical ght on school property during

the previous 12 months in 2019 was

• higher for male students than for female students

(11vs. 4 percent);

• higher for students who were American Indian/Alaska

Native (19 percent), Black (15 percent), and of Two or

more races (11 percent) than for students who were

White (6 percent) and Asian (5 percent; gure 10);

• higher for Black students (15 percent) than for students

of Two or more races (11 percent) and Hispanic

students (8 percent); and

• higher for 9th-graders (11 percent) and 10th-graders

(8 percent) than for 11th-graders and 12th-graders

(6percent each).

There were no measurable dierences by sexual identity

in the percentages of students who reported having been

involved in a physical ght on school property in 2019.

(Physical Fights on School Property and Anywhere)

Fights, Weapons, and Illegal Substances

Lower percentages of students in grades 9–12 in 2019 than in 2009 reported the following issues:

• having been in a physical ght on school property in the previous 12 months (8 vs. 11 percent);

• carrying a weapon on school property during the previous 30 days (3 vs. 6 percent); and

• using alcohol on at least 1 day during the previous 30 days (29 vs. 42 percent).

However, the percentages of students in grades 9–12 who reported the following issues in 2019 were not

measurably dierent from 2009:

• being threatened or injured with a weapon on school property during the previous 12 months (7 percent in 2019);