Chapman University Digital Chapman University Digital

Commons Commons

Pharmacy Faculty Articles and Research School of Pharmacy

10-15-2022

The U.S. Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19 The U.S. Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19

Pandemic Era Pandemic Era

Keri Hurley-Kim

University of California, Irvine

Karina Babish

Rosary Academy

Eva Chen

Canyon High School

Alexis Diaz

Chaminade College Preparatory

Nathan Hahn

Portola High School

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/pharmacy_articles

Part of the Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, Other Pharmacy and

Pharmaceutical Sciences Commons, Other Public Health Commons, Pharmacy Administration, Policy and

Regulation Commons, and the Telemedicine Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hurley-Kim, K.; Babish, K.; Chen, E.; Diaz, A.; Hahn, N.; Evans, D.; Seed, S.M.; Hess, K.M. The U.S. Travel

Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Era.

Pharmacy

20222022,

10

, 134. https://doi.org/

10.3390/pharmacy10050134

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Pharmacy at Chapman University Digital

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pharmacy Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized

administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact

The U.S. Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Era The U.S. Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Era

Comments Comments

This article was originally published in

Pharmacy

, volume 10, in 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/

pharmacy10050134

This scholarship is part of the This scholarship is part of the Chapman University COVID-19 ArchivesChapman University COVID-19 Archives. .

Creative Commons License Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Copyright

The authors

Authors Authors

Keri Hurley-Kim, Karina Babish, Eva Chen, Alexis Diaz, Nathan Hahn, Derek Evans, Sheila M. Seed, and Karl

Hess

This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/

pharmacy_articles/941

Citation: Hurley-Kim, K.; Babish, K.;

Chen, E.; Diaz, A.; Hahn, N.; Evans,

D.; Seed, S.M.; Hess, K.M. The U.S.

Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a

Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Era.

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134. https://

doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10050134

Academic Editors: Natalie

DiPietro Mager, David Bright and

Jon Schommer

Received: 14 September 2022

Accepted: 12 October 2022

Published: 15 October 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2022 by the authors.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

pharmacy

Review

The U.S. Travel Health Pharmacists’ Role in a Post-COVID-19

Pandemic Era

Keri Hurley-Kim

1

, Karina Babish

2

, Eva Chen

3

, Alexis Diaz

4

, Nathan Hahn

5

, Derek Evans

6

, Sheila M. Seed

7

and Karl M. Hess

8,

*

1

University of California at Irvine School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Irvine, CA 92627, USA

2

Rosary Academy, Fullerton, CA 92831, USA

3

Canyon High School, Anaheim, CA 92807, USA

4

Chaminade College Preparatory, West Hills, CA 91304, USA

5

Portola High School, Irvine, CA 92618, USA

6

Evans Travel Health, Newport NP18 2NT, UK

7

Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Worcester, MA 01608, USA

8

Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, CA 92618, USA

* Correspondence: [email protected]

Abstract: Background:

Many countries have enforced strict regulations on travel since the emergence

of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in December 2019. However, with the development of

several vaccines and tests to help identify it, international travel has mostly resumed in the United

States (US). Community pharmacists have long been highly accessible to the public and are capable

of providing travel health services and are in an optimal position to provide COVID-19 patient

care services to those who are now starting to travel again.

Objectives:

(1) To discuss how the

COVID-19 pandemic has changed the practice of travel health and pharmacist provided travel health

services in the US and (2) to discuss the incorporation COVID-19 prevention measures, as well as

telehealth and other technologies, into travel health care services.

Methods:

A literature review was

undertaken utilizing the following search engines and internet websites: PubMed, Google Scholar,

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and the United

States Department of Health and Human Services to identify published articles on pharmacist and

pharmacy-based travel health services and patient care in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results:

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed many country’s entry requirements which may now

include COVID-19 vaccination, testing, and/or masking requirements in country. Telehealth and other

technological advancements may further aid the practice of travel health by increasing patient access

to care.

Conclusions:

Community pharmacists should consider incorporating COVID-19 vaccination

and testing services in their travel health practices in order to meet country-specific COVID-19 entry

requirements. Further, pharmacists should consider utilizing telehealth and other technologies to

increase access to care while further limiting the potential spread and impact of COVID-19.

Keywords:

COVID-19; community pharmacy; travel clinic; vaccines; point-of-care testing; telehealth

1. Background

The practice of travel health includes providing preventive and self-treatment mea-

sures to patients traveling internationally including travel-related immunizations (e.g., yel-

low fever, Japanese encephalitis, typhoid fever); medications for malaria, traveler’s diarrhea,

motion sickness, jet lag, and other diseases; as well as ordering and interpreting labora-

tory tests for confirmation of vaccine-associated antibodies [

1

,

2

]. This is done through

a comprehensive review of one’s travel plans such as their destination(s), arrival dates,

planned activities, length of stay, and personal health and medical information in order to

identify specific travel-related disease risks. Additionally, travel health providers adminis-

ter appropriate travel-related vaccines and furnish appropriate travel-related prescription

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10050134 https://www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmacy

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 2 of 11

and nonprescription medications based off of their patient risk assessment [

1

]. Organiza-

tions such as the CDC and WHO recommend that individuals traveling internationally

receive a pre-travel health consultation and any necessary vaccines and medications from a

healthcare provider four to eight weeks in advance of their departure [

3

,

4

]. It is therefore

important that individuals are able to access and receive care in a timely manner so that

they can receive all necessary vaccinations and medications prior to their departure.

While pharmacists have traditionally provided travel health services under protocol or

through a collaborative practice agreement with a physician, various states and territories

in the US now allow for more independent practice [

2

]. In a review of state laws and

regulations, pharmacists in 15 jurisdictions (i.e., a US state or territory) were able to

administer all routine vaccines independently and in eight jurisdictions, pharmacists were

able to administer all travel-related vaccines independently. Furthermore, in 27 jurisdictions,

pharmacists were authorized to furnish travel-related medications to patients and in at

least 23 jurisdictions, pharmacists were authorized to order travel health related laboratory

tests [

1

]. Pharmacists intending to practice in travel health should ensure that they have

the proper education and training as well as ensure that their clinic area is set up properly

with all necessary supplies and is conducive to providing patient care in a separate and

private environment but is still adjacent to the rest of workflow [5,6].

The American Pharmacists Association (APhA) has developed the Advanced Compe-

tency Pharmacy-Based Travel Health Services Training Program to prepare pharmacists to

offer travel health services (https://www.pharmacist.com/Education/Certificate-Traini

ng-Programs/Travel-Health (accessed on 13 October 2022)). The successful completion

of the APhA Pharmacy-Based Immunization Delivery Certificate Training Program and

being an authorized provider of immunizations in one’s state of practice are prerequisites

for enrollment in this course which offers 10 h of continuing education through self-study

and live seminar components. The certificate program helps prepare pharmacists to eval-

uate travel itineraries, assess health and safety risks based on destinations, and create

and communicate a plan for patients for the necessary prescription and nonprescription

medications, immunizations, supplies, and counseling for their trip. This program is based

off of the gold standard in travel health knowledge, the Body of Knowledge, which was

developed by the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM). Furthermore, this Body

of Knowledge serves as the basis for ISTM’s Certificate of Knowledge examination for

all travel health professionals. Those who successfully complete the exam are awarded

the Certificate in Travel Health (CTH

®

) by the ISTM. The CTH

®

is one of few credentials

offered across health disciplines and recognized internationally by health care providers

(https://www.istm.org/bodyofknowledge2 (accessed on 13 October 2022)) [5].

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of international travel increased annually from

28.5 million outbound international departures (excluding North American destinations) in

2010 to 44.8 million international departures in 2019. In 2020, as COVID-19 began rapidly

spreading throughout the world, public health protocols such as limiting international

travel began to be enacted to help contain the spread of infection in numerous countries.

As a result, international travel dropped to 9.8 million outbound departures in 2020 [

4

,

7

].

However, as rates of COVID-19 began to decline and as the pandemic began to evolve into

endemicity, international travel has begun to pick back up once again with 26.9 million

outbound departures from 2021 to April 2022 [8].

Identifying health risks associated with travel prior to departure has grown in im-

portance as a result of increasing international travel, the dynamic COVID-19 situation,

and presence of other infectious diseases more traditionally associated with international

travel (e.g., yellow fever, malaria, rabies, etc.). Pharmacists are in an optimal position to

provide travel health services given their ability to successfully implement such public

health services in community and ambulatory care settings [

9

,

10

]. Furthermore, it has

been estimated that approximately 90% of the US population lives within five miles of a

community pharmacy, thus making community pharmacists arguably the most accessible

healthcare provider in the US, allowing more individuals access to care [

11

]. The extended

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 3 of 11

hours that community pharmacies are open, particularly when other healthcare settings

are closed, further improves the public’s access to important public health services such as

immunizations and travel health care [

12

]. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic,

many states also implemented waivers or legislation that allowed pharmacy technicians

to administer COVID-19 vaccines to further increase patient access to care. As COVID-19

now transitions to an endemic phase in its epidemiology and many individuals resume

pre-pandemic travel schedules, considerations related to COVID-19 will remain a pertinent

and dynamic aspect of US travel health care services into the future.

2. Objectives and Methods

The aim of this paper is to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the practice

of travel health, specifically pharmacist provided travel health services in the US, and to

discuss the incorporation of COVID-19 prevention practices, telehealth, and use of other

technologies into the ongoing practice of travel health care. A literature review from 2018

to the present was undertaken utilizing PubMed and Google Scholar using the following

search terms: COVID-19, community pharmacy, community pharmacist, travel health, travel

medicine, travel clinic, vaccines, point-of-care testing, and telehealth. In addition, internet

websites including, but not limited to, the CDC, WHO, and the US Department of Health and

Human Services were identified as other sources of information on pharmacist-managed and

pharmacy-based travel health services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Results

Thirty-one original research peer-reviewed articles were identified along with informa-

tion from agency websites listed above that illustrate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

on travel and healthcare in general. In summary, our literature review shows changes to

travel health practices in response to the COVID-19 pandemic including changes in desti-

nation country’s entry requirements and regulations, inclusion of COVID-19 counseling

and vaccination as part of a travel health services, and the incorporation of telehealth and

other technological advancements to the practice of travel health in order to safely (and

efficiently) access care. Detailed findings from our literature review are discussed below in

the discussion section and grouped according to theme.

4. Discussion

4.1. Practices and Regulations

As discussed above, individuals who are traveling internationally should contact a

travel healthcare provider four to eight weeks before departure to ensure that all necessary

vaccines and medications can be provided and administered prior to their trip and that

their response to these measures can be monitored [

3

,

4

]. This is important since it is

also now essential to ensure that travelers are aware of any COVID-19 entry restrictions

at their destination while the pharmacist also confirms that they meet that country’s

COVID-19 vaccine requirements and perform any necessary COVID-19 testing within the

required timeframe. Masking guidelines for public transportation and elsewhere may

be specific to destination countries and are also pertinent to patient counseling during

travel health visits [

13

]. Pharmacists that practice in travel health should inform the

patient of any restrictions and communicate the required steps for the given destination(s).

These procedures are crucial given the ever-evolving and variable nature of COVID-19

waves and public health responses. Various countries often have significantly different

requirements and recommendations even where level of risk may be considered similar.

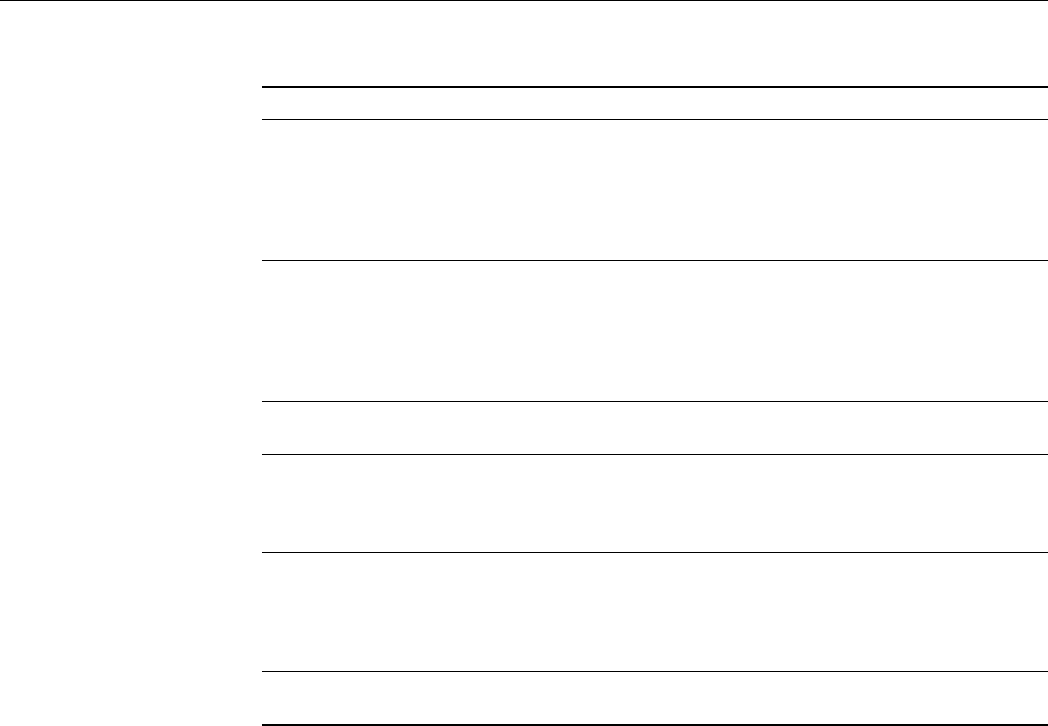

Table 1 is included as an example of variation in entry requirements related to COVID-19

in developing countries. It is up to date as of September 2022 but is not intended to serve

as a reference for specific travelers or itineraries. Pharmacists who wish to view updated

COVID-19 entry information can access this database at the U.S. Department of State’s

Bureau of Consular Affairs website at https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/travela

dvisories/COVID-19-Country-Specific-Information.html [14].

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 4 of 11

Table 1. Entry requirements for selected popular destinations [14].

Country COVID-19 Level Entry Requirements

Tanzania Level 1: Low Risk

Negative COVID-19 laboratory test 24–72 h before

departure, completed Traveler’s Health Surveillance Form,

and airport health screening which may include on-site

rapid antigen testing are all required. COVID-19

vaccination not required. Fully vaccinated travelers are

exempt from testing requirements.

Kenya

Level 2:

Moderate Risk

Negative COVID-19 laboratory test 24–72 h before

departure, on-site rapid antigen test on arrival, and

completed Traveler’s Health Surveillance Form are all

required. COVID-19, vaccination is not required. Fully

vaccinated travelers and those under age 5 years are exempt

from testing requirements. Masks are required indoors.

Thailand Level 3: High Risk

Full vaccination or negative COVID-19 laboratory test

within 72 h before departure is required.

Brazil Level 3: High Risk

COVID-19 vaccination required with limited exception.

Negative COVID-19 laboratory test within 24 h before

departure is required for unvaccinated travelers. Masks

required in certain jurisdictions.

Argentina Level 3: High Risk

Negative COVID-19 test not required, electronic sworn

statement required confirming absence of COVID-19

symptoms and vaccination status within 48 h before

departure. Medical travel insurance with coverage for

COVID-19 related events is required.

Vietnam

Level unknown:

Risk unknown

Negative COVID-19 test not required, but health screening

procedures upon arrival are required.

Note: database last accessed September 2022. Country specific information is subject to change.

4.2. Vaccinations, Testing, and Counseling for COVID-19

4.2.1. Administering COVID-19 Vaccines and Tests as Part of Travel Services

Pharmacists’ administration of COVID-19 vaccines and tests as part of travel clinic

services are crucial in protecting the health and welfare of travelers as well as the local

communities they visit. The CDC recommends that travelers receive routine vaccinations,

including COVID-19 vaccines, to lessen the chance of contracting and spreading infectious

diseases [

15

]. Table 2 provides COVID-19 vaccine resources, as the recommendations

and schedules for each vaccine differs depending on age, immunocompetent status, and

booster recommendations. Vaccination requirements and recommendations differ based

on itinerary, medical history and risk tolerance. Pharmacists providing travel health care

services can ensure that vaccines specific to certain countries, including the COVID-19

vaccine, are received in advance [

16

]. For travel, the CDC has yet to specifically recommend

the use of mix-and-match COVID-19 vaccination strategies wherein the formulation of

booster dose(s) is different from the primary series. However, this form of vaccination is

becoming more common in countries including the U.S. Emerging research has shown that

mixed inoculation is beneficial in boosting the effectiveness of vaccinations [

17

,

18

]. CDC

currently continues to recognize any combinations of accepted COVID-19 vaccines [19].

As of 12 June 2022, COVID-19 tests are no longer required for return entry into the US,

but some destination countries may still require testing depending on vaccination status for

entry [

14

]. Providing COVID-19 testing can be a vital service for patients at both pre- and

post-travel health appointments. Each country has their own specific testing requirements

regarding which test is acceptable and the timing of the test prior to entry. It is best to

review the entry requirements of each country during the pre-travel health visit.

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 5 of 11

Table 2. Recommended COVID-19 vaccine information resources for travel health clinicians.

COVID-19 Vaccine Resources Description

World Health Organization

(WHO)—Status of COVID-19

Vaccine within WHO EUL

https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites

/default/files/documents/Status_COVI

D_VAX_07July2022.pdf

Guidance document summarizing status of WHO

Emergency Use Listing for COVID-19 vaccines,

comprehensive of recognized and candidate

vaccines worldwide

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC)—COVID-19

Vaccines

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/20

19-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.htm

l#about-vaccines.

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-1

9/index.html

Information for the general public regarding

COVID-19 vaccine recommendations in the U.S.

COVID-19 vaccine resources for clinicians and

public health professionals

Immunization Action Coalition

(IAC)—Vaccines COVID-19

https://www.immunize.org/covid-19/

Comprehensive information and numerous

communication tools for professionals and

patients/general public for U.S. FDA approved

COVID-19 vaccines.

Johns Hopkins University

Coronavirus Resource

Center

https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines

COVID-19 vaccine information and public health

data visualization tools. Includes worldwide

country-level data.

American Pharmacists

Association

(APhA)—COVID-19

Vaccine schedules

https:

//s3.amazonaws.com/filehost.pharmaci

st.com/CDN/PDFS/APhA%20Guide

%20to%20Vaccination%20Schedules%20

Resource%207_27_22_web%20rev.pdf?A

WSAccessKeyId=AKIAYICBVAN2V7IW

VG4T&Expires=1661624398&Signature=

DrhUSbz4t8wTJ2CNGXv3of4inzs%3D.

https://www.pharmacist.com/Practice/

COVID-19/COVID-19-Vaccines

COVID-19 vaccine resources curated for

pharmacists and other clinicians in the U.S.

Includes visual COVID-19 vaccination schedules

for all ages.

American Health Systems

Pharmacist (ASHP)—COVID-19

Vaccines

https://www.ashp.org/covid-19/vaccin

es?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly

Clinical, policy, and logistical COVID-19 vaccine

information for U.S. health systems providers

Government of

Canada—Vaccines for

COVID-19

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-heal

th/services/diseases/coronavirus-disea

se-covid-19/vaccines.html

Information and resources for the general public

and professionals regarding COVID-19 vaccines

in Canada

National Health System

(NHS)—UK

Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Vaccines

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coro

navirus-covid-19/coronavirus-vaccinati

on/coronavirus-vaccine/#:~:text=Every

one%20aged%205%20and%20over,dose

%20before%20any%20booster%20doses

Information and resources for the general public

and professionals regarding COVID-19 vaccines in

the U.K., including for international travel.

European

Commission—COVID-19

Vaccines

https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-tr

avel-eu/coronavirus-response/safe-covi

d-19-vaccines-europeans_en

Public health, policy, and vaccination strategy

information for the European Union.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) or Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests

(NAAT) have a high degree of sensitivity (i.e., correctly identifies disease, produces fewer

false negative results) and specificity (i.e., correctly identifies those without disease, pro-

duces fewer false positives), detect the RNA of the virus, and are considered the gold

standard for COVID-19 identification. Most PCR/NAAT tests are processed in a laboratory

setting but some NAAT tests can be performed as a point of care test (POCT) [

20

]. It is

important to note that a false negative result may occur if someone tests too early after an

exposure to COVID-19 or if the sample is mishandled or improperly collected.

Antigen-based tests have similar specificity to PCR tests but have less sensitivity,

particularly if asymptomatic, they detect a specific viral protein of the virus. Antigen-

based tests can be processed in a variety of settings; laboratory, POCT or home self-

testing. Antigen tests may need to be performed several times for a definitive diagnosis,

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 6 of 11

a single negative test result is considered a preliminary result and does not rule out

illness [

20

]. Rapid antigen tests were found by other countries to be more inaccurate and

less sensitive to detecting COVID-19 than PCR tests [

21

]. One study concluded that antigen

tests misidentified asymptomatic individuals as COVID-19 negative when, in fact, they

were carrying the virus [22]. Another study found that the accuracy of rapid antigen tests

significantly higher in symptomatic patients rather than in asymptomatic patients, which is

most likely due to the higher viral load that could be more easily detected when at the early

phases of the disease [

23

]. However, frequent testing has shown to be useful in detecting the

Omicron variant, especially when identifying those with a high enough viral load [

24

,

25

].

Rapid antigen tests for this purpose have also been improving in accuracy and sensitivity,

but may still produce inaccurate results if the sample is mishandled or improperly collected.

In a 2021 study, the Abbott ID NOW test demonstrated a high degree of accuracy and a

strong agreement with RT-PCR results, which is similar to the high sensitivity of other tests,

such as AQ-TOP and GeneChecker [

26

]. The current Omicron variant mutations, though,

have a portion of the Spike protein (S protein) that cannot be detected by antibodies or

targeted by COVID-19 vaccines [

27

]. These mutations have led to reduced sensitivity in

an N-gene or S-gene genetic target with tests, suggesting that a higher viral load would

be necessary for rapid tests, which are able to detect multiple genetic targets, to detect the

sub-variants [

28

]. Table 3 includes the similarities and differences between the common

types of COVID-19 tests currently available, antibody testing is not used to diagnose a

current infection [29,30].

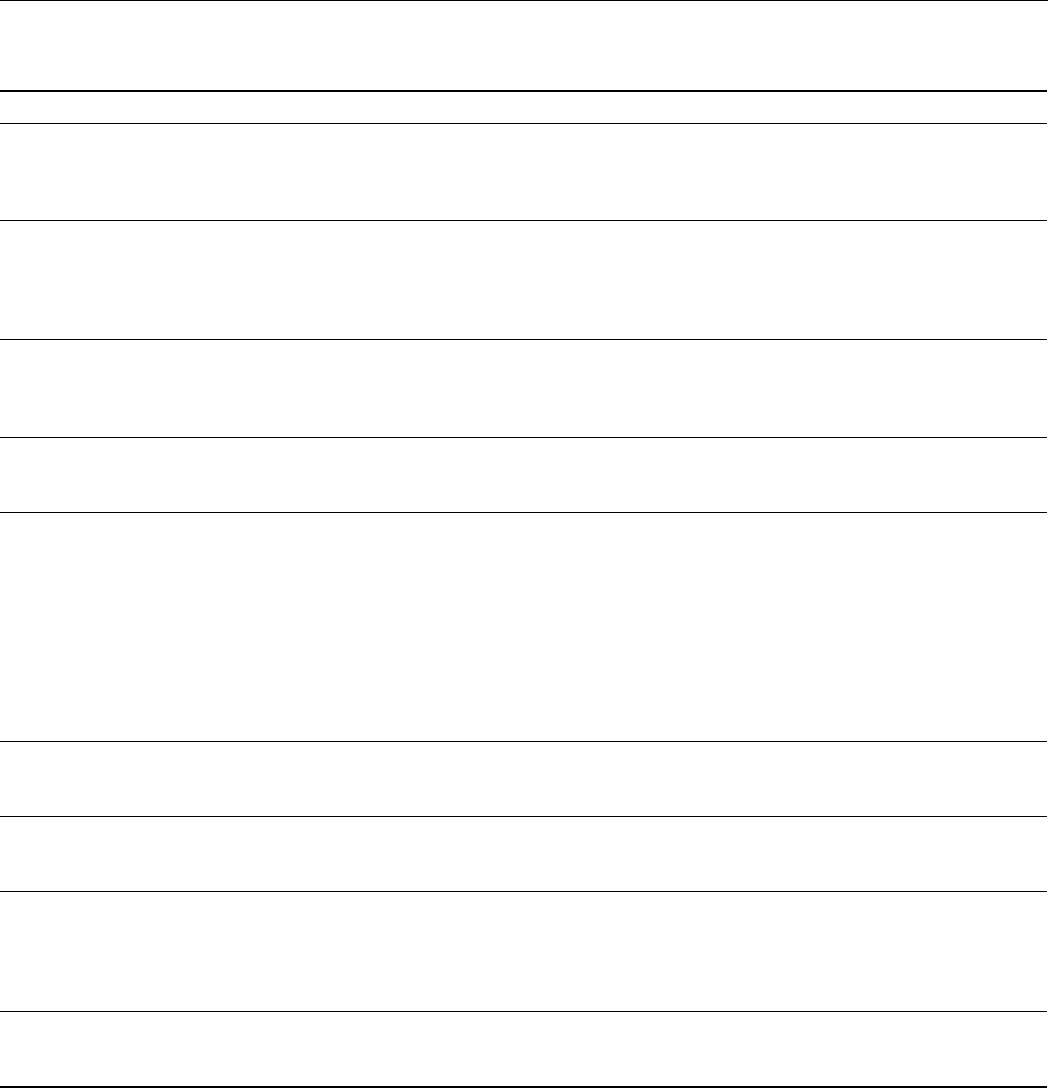

Table 3.

NAAT and Antigen Test Differences to Consider When Planning for Diagnostic or Screening

Use [20,30].

Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAATs) Antigen Tests

Analyte Detected Diagnose current infection Diagnose current infection

Specimen Type(s)

Nasal, Nasopharyngeal, Oropharyngeal,

Sputum, Saliva

Nasal, Nasopharyngeal, Breath

Sensitivity (for accuracy)

Laboratory tests: generally high

Point-of-Care tests: moderate-to-high

Generally moderate-to-high at peak viral load.

More accurate if symptomatic

Specificity High High

Authorized for Use at the Point-of-Care Most are not Most are

Turnaround Time

Most are 1–3 days

Some rapid tests in 15 min

Most are 15–30 min

Cost per Test Moderate (~$75–$100/test) Low (~$5–$50/test)

Advantages

Most sensitive test available

Short turnaround time for NAAT

Point-of-Care tests (rare)

Usually does not need to be repeated to

confirm results

Short turnaround time (~15 min)

Allows for rapid identification of infected

people, thus preventing further virus

transmission in the community, workplace, etc.

Comparable performance to NAATs for

diagnosis in symptomatic persons and

whether a culturable virus is present or not

Disadvantages

Longer turnaround time for lab-based tests

(1–3 days)

Higher cost per test

A positive NAAT diagnostic test should not be

repeated within 90 days in case detectable

RNA is still present after risk of transmission

has passed

Less sensitive (more false negative results)

compared to NAATs, especially among

asymptomatic people and with some variants

May need to be repeated to confirm results

(any negative test on a symptomatic person

should be confirmed with a PCR or NAAT test

(CDC, 2022)

Most community pharmacies in the U.S. administer COVID-19 PCR tests; however,

this may pose a significant barrier for travel patients due to the time required for results

to be reported since samples are mailed to an outside laboratory for processing. POCT

tests such a NAAT test or the Abbott ID NOW test could be utilized in a travel clinic or

community pharmacy setting to provide accurate and more timely results for patients.

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 7 of 11

4.2.2. Incorporating Counseling Regarding COVID-19 into Practice

Providing patient education on COVID-19 rates of transmissibility and preventative

measures required by the destination country (masking, quarantine, etc.) is important for

pharmacists to consider and implement. Many studies report a lack of general knowledge

and/or acceptance regarding the information surrounding the virus and its related vaccina-

tions. A survey carried out among international travelers to non-European destinations

in 2021 revealed that approximately 52.4% sourced their information from the internet,

while 42.4% sought a doctor or health professional [

31

]. Another survey of COVID-19

testing offered at US airports led to the conclusion that some travelers might not be able to

grasp the meaning of testing “positive” at the airport before taking off, largely because the

testing sites are private companies who may be less familiar with advising the public of

testing results [

32

]. In another study, where questionnaires were administered to evaluate

participant knowledge on COVID-19 and their perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine, it

was apparent that those without sufficient knowledge about vaccines are more likely to

be doubtful towards immunizations for viruses such as COVID-19 [

33

]. As proven in the

data collected from questionnaires and surveys, pharmacist involvement would be vital in

preserving post-COVID-19 travel health in a variety of ways, such as through providing

advice on safety measures and prevention protocols for travelers [34,35].

Carmosino et al. observed that patient education in promoting increased knowledge

and trust in vaccine approval allowed travelers to gain more awareness and have more

positive attitudes towards immunizations [

36

]. Another study found that people with

adequate knowledge of COVID-19 were more willing to receive immunizations for vaccine-

preventable diseases. Furthermore, 76% of the respondents were willing to receive COVID-

19 immunization later on, suggesting that with further guidance and counseling on the

pandemic, more people would be open to vaccination [27].

In general, a more informative service regarding infectious disease outbreaks, such as

COVID-19, would be helpful to offer at travel clinics. Current trends show that patients are

more willing to receive this service from pharmacists. In part with counseling, pharmacists

must also work with health care team members to reject misinformation related to COVID-

19, vaccinations, and other similar concerns [36].

4.3. Telehealth and Other Technologies

4.3.1. Movement towards and Rationale for Distance Consultations

Trends during the COVID-19 pandemic forecast the heavy reliance of pharmacists

and patients on technology in the future [

37

]. Telehealth, or telemedicine, is defined by the

US Department of Health and Human Services as “online care provided by a healthcare

provider without an in-person office visit” [

38

]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth

was already being used for patients with inflexible schedules who were unable to attend

in-person appointments with their healthcare provider. However, there has been a surge in

telehealth implementation during the past two years during the pandemic [37,39–42].

Healthcare providers offered telehealth as an alternative to in-person scheduled ap-

pointments, which allowed continual access to healthcare services which increased as

COVID-19 lockdowns prevented individuals from visiting their providers [

43

]. Some

participants in a pharmacy practice workforce survey noted that they faced challenges in

adjusting to remote practices at first; also mentioning that in-person contact was still much

more valuable [

37

]. There may also be technical and logistical challenges in implementing

telehealth; however, pharmacists should continue working towards expanding telehealth

services since information has become highly digitalized in the 21st century and since

telehealth can provide added flexibility and is expected to see an increase in its utility in the

near future [

37

]. Table 4 lists various resources and references for pharmacists to consider

for implementing telehealth into their practices.

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 8 of 11

Table 4. Telehealth/telemedicine resources and guidance.

Reference Web Link Summary

World Health Organization

WHO—Digital Health

https://www.who.int/health-topics/digita

l-health#tab=tab_1

Discusses the strategy and resources for

use in Digital Health

Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/

topic/hipaa.html

Federal law creation of standards to

protect sensitive healthcare information

being disclosed without the patient’s

consent or knowledge

ITIT Travel Health https://www.itit-travelhealth.org App for illness tracking in travelers

Best Telemedicine Companies in 2022

https://www.healthline.com/health/best-t

elemedicine-companies#how-we-chose

Options are based upon ratings types of

service, pricing accessibility and vetting

Chetu Software Solutions

https://www.chetu.com/healthcare/teleh

ealth.php

Example of a IT company that purpose

builds telehealth apps- HIPAA compliant

Itransition—telehealth solutions

https://www.itransition.com/healthcare/t

elemedicine

Builders of mobile App and web

portals—HIPAA compliant

Cogsworth https://get.cogsworth.com/telemedicine

Advertises they support allied healthcare,

clinics and practices- HIPAA compliant

There are various benefits of telehealth to both the patients and providers such as

increased access to care, flexible scheduling, decreased transportation costs, and lower

cancellation rates [

39

]. Education and training programs that incorporate resources on

telemedicine and remote patient care would be helpful in improving confidence for phar-

macists during their assessments [

37

,

43

]. Despite these benefits, one of the main concerns

with telehealth is that it may limit pharmacists to provide consult-only based services [

44

].

Overall, telehealth should become a useful addition to a pharmacist’s practice as it allows

for ongoing interactions between pharmacists and patients, regardless of hesitancy, for

in-person consultations in a post-COVID-19 pandemic world.

4.3.2. Other Technologies/Technological Innovations

Due to telehealth becoming more prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, other

technological advancements need to be made in order to adapt to a changing world.

The recent development of smartphone applications has aided in these services with

their capability to monitor travel health behavior and warn patients of possible risks

at destinations; however, there are some ethical issues such as maintaining up to date

information [

40

]. One such smartphone application is called the Illness Tracking in Travelers

(ITIT). ITIT has also been collaborating with the WHO to provide people with prompt public

health responses [

40

,

45

]. Travel medicine apps can benefit both providers and patients

as they can access different types of relevant travel-related data including geolocations,

contract tracing, and travel advisories, which would be beneficial in overseeing diseases

such as COVID-19.

5. Best Practices and Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the strain on existing healthcare systems

around the world, necessitating an increased scope of practice for pharmacists. Therefore,

in an effort to contain and prevent the further spread of COVID-19 while balancing the

increased demand for international travel, various COVID-19 preventative practices should

be incorporated into pharmacist provided travel health services. These include COVID-19

patient education and counseling (including methods to reduce one’s risk for COVID-19

and dispelling inaccurate information and myths surrounding COVID-19) as well as incor-

porating COVID-19 vaccines and testing into practice to help aid the traveler in meeting

country entry requirements. Routine immunizations such as influenza and pneumococcal

should also be administered for patients regardless of their travel plans in order to ensure

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 9 of 11

that patients are up-to-date with all of their routine vaccines. The advancement of tech-

nology and increasing use of remote communications, particularly the use of telehealth

during the pandemic, appears to be a lasting trend and its use may continue well beyond

the current pandemic. Pharmacists should therefore look to incorporate telehealth practices

in their travel health services to increase patient access to care while also minimizing the

amount of time that patients would need to be in a health care setting. Limitations to this

paper include that it was not undertaken as a systematic review and therefore relevant

work may have been excluded which could have strengthened our findings. Furthermore,

the COVID-19 situation is rapidly changing, thus potentially rendering certain research or

findings out of date. This illustrates the importance that pharmacists need to stay up to

date in order to provide the most effective and relevant care to their patients. However,

by incorporating COVID-19 prevention measures and adopting telehealth practices, phar-

macist provided travel health services can help meet the once again growing demand for

international travel while providing their patients with evidence-based recommendations

and counseling from the comfort of their own homes.

Author Contributions:

K.H.-K. served as primary author and helped revise and edit sections of the

manuscript; K.B., E.C., A.D. and N.H. initially developed the manuscript as part of a summer research

program for high school students at Chapman University School of Pharmacy and contributed to

final edits; D.E. and S.M.S. helped revise and edit sections of the manuscript; K.M.H. served as senior

author and finalized all edits and also served as research mentor to K.B., E.C., A.D. and N.H. All

authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding:

The authors report that no funding was requested or utilized to prepare this manuscript or

honorarium received.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1.

Hurley-Kim, K.; Sneed, R.; Hess, K.M. Pharmacists’ Scope of Practice in Travel Health: A Review of State Laws and Regulations.

J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 163–167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2.

Hurley-Kim, K.; Goad, J.; Seed, S.; Hess, K.M. Pharmacy Based Travel Health Services in the United States. Pharmacy

2019

, 7, 5.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers Health. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/contact-us

(accessed on 28 August 2022).

4.

World Health Organization. International Travel and Health. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-sourc

e/documents/emergencies/travel-advice/ith-travel-chapter-6-vaccines_cc218697-75d2-4032-b5b7-92e0fa171474.pdf?sfvrsn=

285473b4_4 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

5.

Gregorian, T.; Bach, A.; Hess, K.; Hurley, K.; Mirzaian, E.; Goad, J. Implementing Pharmacy-Based Travel Health Services: Insight

and Guidance from Frontline Practitioners. Calif. Pharm. J. 2017, 64, 23–29. [CrossRef]

6. Goodyer, L. Pharmacy and Travel Medicine: A Global Movement. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 39. [CrossRef]

7.

World Health Organization. Updated WHO Recommendations for International Traffic in Relation to COVID-19 Outbreak.

Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/updated-who-recommendations-for-international-traffic

-in-relation-to-covid-19-outbreak#:~{}:text=WHO%20continues%20to%20advise%20against,divert%20resources%20from%20o

ther%20interventions (accessed on 28 August 2022).

8.

United Stated Department of Commerce. International Air Travel Statistics Program (I-92). Available online: https://www.trade.

gov/us-international-air-travel-statistics-i-92-data (accessed on 28 August 2022).

9.

Hess, K.M.; Dai, C.; Garner, B.; Law, A.V. Measuring Outcomes Associated with a Pharmacist-Run Travel Health Clinic Located

in an Independent Community Pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2010, 50, 174–180. [CrossRef]

10.

Durham, M.J.; Goad, J.A.; Neinstein, L.S.; Lou, M. A Comparison of Pharmacist Travel-Health Specialists’ Versus Primary Care

Providers’ Recommendations for Travel-Related Medications, Vaccinations, and Patient Compliance in a College Health Setting.

J. Travel Med. 2011, 18, 20–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

11.

Berenbrok, L.A.; Tang, S.; Gabriel, N.; Guo, J.; Sharareh, N.; Patel, N.; Dickson, S.; Hernandez, I. Access to Community Pharmacies:

A Nationwide Geographic Information Systems Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022. [CrossRef]

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 10 of 11

12.

Goad, J.A.; Taitel, M.S.; Fensterheim, L.E.; Cannon, A.E. Vaccinations Administered During Off-Clinic Hours at a National

Community Pharmacy: Implications for Increasing Patient Access and Convenience. Ann. Fam. Med.

2013

, 11, 429–436. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

13.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Travel Recommendations. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/tr

avel/noticescovid19 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

14.

United States Department of State: Bureau of Consular Affairs. COVID-19 Country Specific Information. Available on-

line: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/traveladvisories/COVID-19-Country-Specific-Information.html (accessed on

28 August 2022).

15.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Routine Vaccines. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/routine-

vaccines (accessed on 28 August 2022).

16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Need Travel Vaccines? Plan Ahead. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/trav

el/page/travel-vaccines (accessed on 28 August 2022).

17.

Park, J.S.; Minn, D.; Hong, S.; Jeong, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, B. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients with

End-Stage Renal Disease Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis: The Efficacy of a Mix-and-Match Strategy. J. Korean Med. Sci.

2022, 37, 180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

18. Callaway, E. Mixing COVID vaccines triggers potent immune response. Nature 2021, 593, 10–38. [CrossRef]

19.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Requirement for Proof of COVID-19 Vaccination for Air Passengers. Available online:

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/proof-of-vaccination.html (accessed on 28 August 2022).

20.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Testing: What you Need to Know. Available online: https://www.cdc.go

v/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/testing.html (accessed on 28 August 2022).

21. Guglielmi, G. Fast coronavirus tests: What they can and can’t do. Nature 2020, 585, 496–498. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

22.

Indelicato, A.M.; Mohamed, Z.H.; Dewan, M.J.; Morley, C.P. Rapid Antigen Test Sensitivity for Asymptomatic COVID-19

Screening. PRiMER 2022, 6, 18. [CrossRef]

23.

Brümmer, L.E.; Katzenschlager, S.; Gaeddert, M.; Erdmann, C.; Schmitz, S.; Bota, M.; Grilli, M.; Larmann, J.; Weigand, M.A.;

Pollock, N.R.; et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: A living systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003735. [CrossRef]

24.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Variants of the Virus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-n

cov/variants/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fvariants%2Fo

micron-variant.html (accessed on 28 August 2022).

25.

Kahn, R.; Holmdahl, I.; Reddy, S.; Jernigan, J.; Mina, M.J.; Slayton, R.B. Mathematical Modeling to Inform Vaccination Strategies

and Testing Approaches for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Nursing Homes. Clin. Infect. Dis.

2022

, 74, 597–603.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

26.

Mahmoud, S.A.; Ganesan, S.; Ibrahim, E.; Thakre, B.; Teddy, J.G.; Rahejam, P.; Zaher, W.A. Evaluation of six different rapid

methods for nucleic acid detection of SARS-COV-2 virus. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5538–5543. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

27.

Chen, P.Y.; Chuang, P.N.; Chiang, C.H.; Chang, H.H.; Lu, C.W.; Huang, K.C. Impact of Coronavirus Infectious Disease (COVID-19)

pandemic on willingness of immunization-A community-based questionnaire study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262660. [CrossRef]

28.

Food and Drug Administration. SARS-CoV-A Viral Mutations: Impact on COVID-19 Tests. Available online: https://www.fda.go

v/medical-devices/coronavirus-covid-19-and-medical-devices/sars-cov-2-viral-mutations-impact-covid-19-tests#resolved (ac-

cessed on 28 August 2022).

29.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibody Testing Guidelines. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/

2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.htm (accessed on 28 August 2022).

30.

Pharmacist’s Letter. COVID-19 Testing FAQ’s. Available online: https://pharmacist.therapeuticresearch.com/Content/Segment

s/PRL/2020/Jun/COVID-19-Testing-FAQs-S2006001 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

31.

Bechini, A.; Zanobini, P.; Zanella, B.; Ancillotti, L.; Moscadelli, A.; Bonanni, P.; Boccalini, S. Travelers’ Attitudes, Behaviors, and

Practices on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases: A Study for Non-European Destinations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health

2021, 18, 3110. [CrossRef]

32.

Shaum, A.; Figueroa, A.; Lee, D.; Ertl, A.; Rothney, E.; Borntrager, D.; Davenport, E.; Gulati, R.K.; Brown, C.M. Cross-sectional

survey of SARS-CoV-2 testing at US airports and one health department’s proactive management of travelers. Trop. Dis. Travel

Med. Vaccines 2022, 8, 8. [CrossRef]

33.

Carmosino, E.; Ruisinger, J.F.; Kinsey, J.D.; Melton, B.L. Vaccination approval literacy and its effects on intention to receive future

COVID-19 immunization. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1374–1378.e2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

34.

O’Malley, M. Coping with COVID-19 in an Airport Pharmacy. Available online: https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/

(accessed on 13 December 2020).

35.

Bhuvan, K.C.; Alrasheedy, A.A.; Leggat, P.A.; Molugulu, N.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Khatiwada, A.P.; Shrestha, S. Pharmacies in the

Airport Ecosystem and How They Serve Travelers’ Health and Medicines Need: Findings and Implications for the Future. Integr.

Pharm. Res. Pract. 2022, 11, 9–19.

36.

Marwitz, K.K. The pharmacist’s active role in combating COVID-19 medication misinformation. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc.

2021

, 61,

71–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Pharmacy 2022, 10, 134 11 of 11

37.

Sasser, C.W.; Wolcott, M.D.; Morbitzer, K.A.; Eckel, S.F. Lessons learned from pharmacy learner and educator experiences during

early stages of COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 872–878. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

38.

US Department of Health and Human Services. What is Telehealth? Available online: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/patients/unde

rstanding-telehealth/#:~{}:text=Benefits%20of%20telehealth-,What%20does%20telehealth%20mean%3F,computer%2C%20tabl

et%2C%20or%20smartphone (accessed on 28 August 2022).

39.

Liu, C.; Patel, K.; Cernero, B.; Baratt, Y.; Dandan, N.; Marshall, O.; Li, H.; Efird, L. Expansion of Pharmacy Services During

COVID-19: Pharmacists and Pharmacy Extenders Filling the Gaps Through Telehealth Services. Hosp. Pharm.

2022

, 57, 349–354.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

40.

Ferretti, A.; Hedrich, N.; Lovey, T.; Vayena, E.; Schlagenhauf, P. Mobile apps for travel medicine and ethical considerations:

A systematic review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 43, 102143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

41.

Margolis, S.A.; Ypinazar, V.A. Tele-pharmacy in remote medical practice: The Royal Flying Doctor Service Medical Chest Program.

Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 937. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

42.

Cherry, J.; Rich, W.; McLennan, P. Telemedicine in remote Australia: The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) Medical Chest

Program. Rural Remote Health 2018, 18, 4502. [CrossRef]

43.

Ng, B.P.; Park, C. Accessibility of Telehealth Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medicare

Beneficiaries. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

44.

Jordan, D.; Guiu-Segura, J.M.; Sousa-Pinto, G.; Wang, L.N. How COVID-19 has impacted the role of pharmacists around the

world. Farm Hosp. 2021, 45, 89–95. [PubMed]

45.

Illness Tracking in Travelers. About ITIT. Available online: https://www.itit-travelhealth.org/beispiel-seite/ (accessed on

28 August 2022).