The Unprecedented

Federal Fiscal Policy

Response to the COVID-19

Pandemic and Its Impact

on State Budgets

Phil Dean

Chief Economist and Public Finance

Senior Research Fellow

Massive scal stimulus supported the economy during

the pandemic, but also contributed to goods shortages,

ination, and long-term debt.

May 2022

411 East South Temple Street

Salt Lake City, Utah 84111

801-585-5618

I

gardner.utah.edu

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

1

Analysis in Brief

The COVID-19 pandemic created enormous challenges

throughout the world. In addition to deaths, hospitalizations,

and various long-term health impacts, signicant economic

damage also occurred in COVID’s aftermath. This economic

damage included over 23 million unemployed U.S. workers. In

the midst of these enormous economic challenges, the federal

government began its scal response to the pandemic.

Within a year of the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in the

U.S., the federal government enacted unprecedented scal

stimulus amounting to nearly 25% of 2020 GDP (over $5 trillion).

This massive response far exceeded the federal scal response

to previous recessions. Similar to previous recessions,

expansionary monetary policy also played an important role.

The federal scal stimulus came in three waves, including a

$2.4 trillion (11.5% of GDP) Wave 1 in March and April 2020, a

$0.9 trillion (4.2% of GDP) Wave 2 in December 2020, and a $1.9

trillion (8.9% of GDP) Wave 3 in March 2021.

This federal funding supported state and local government

budgets both directly and indirectly. State and local governments

directly received federal funds to respond to the public health

emergency and support economic activity. Federal scal stimulus

also provided considerable funding to rms and households,

which indirectly supported state and local government budgets

by supporting income and consumption. As incomes and

spending grew, so did tax revenue.

The Unprecedented Federal Fiscal Policy Response to the

COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on State Budgets

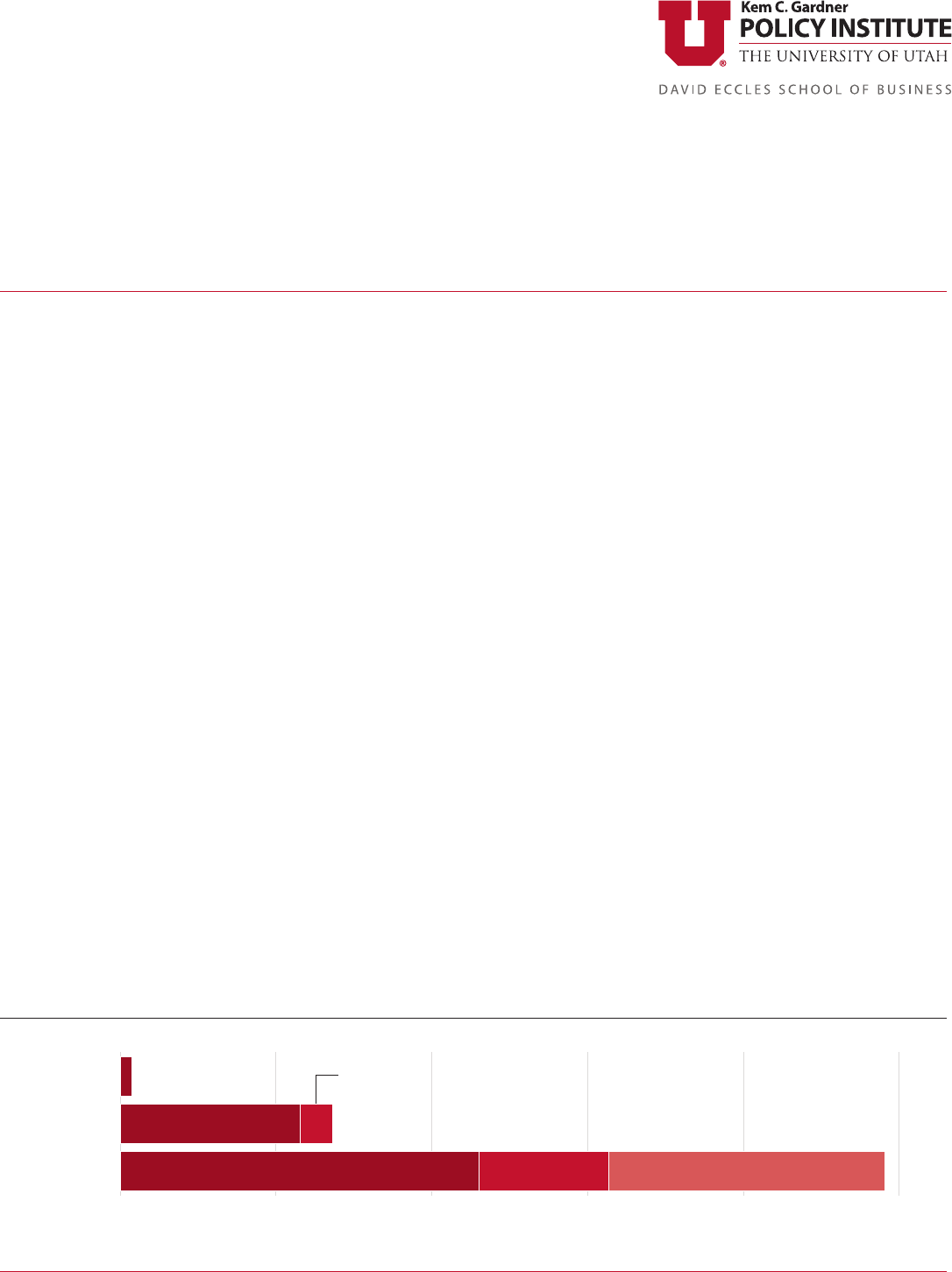

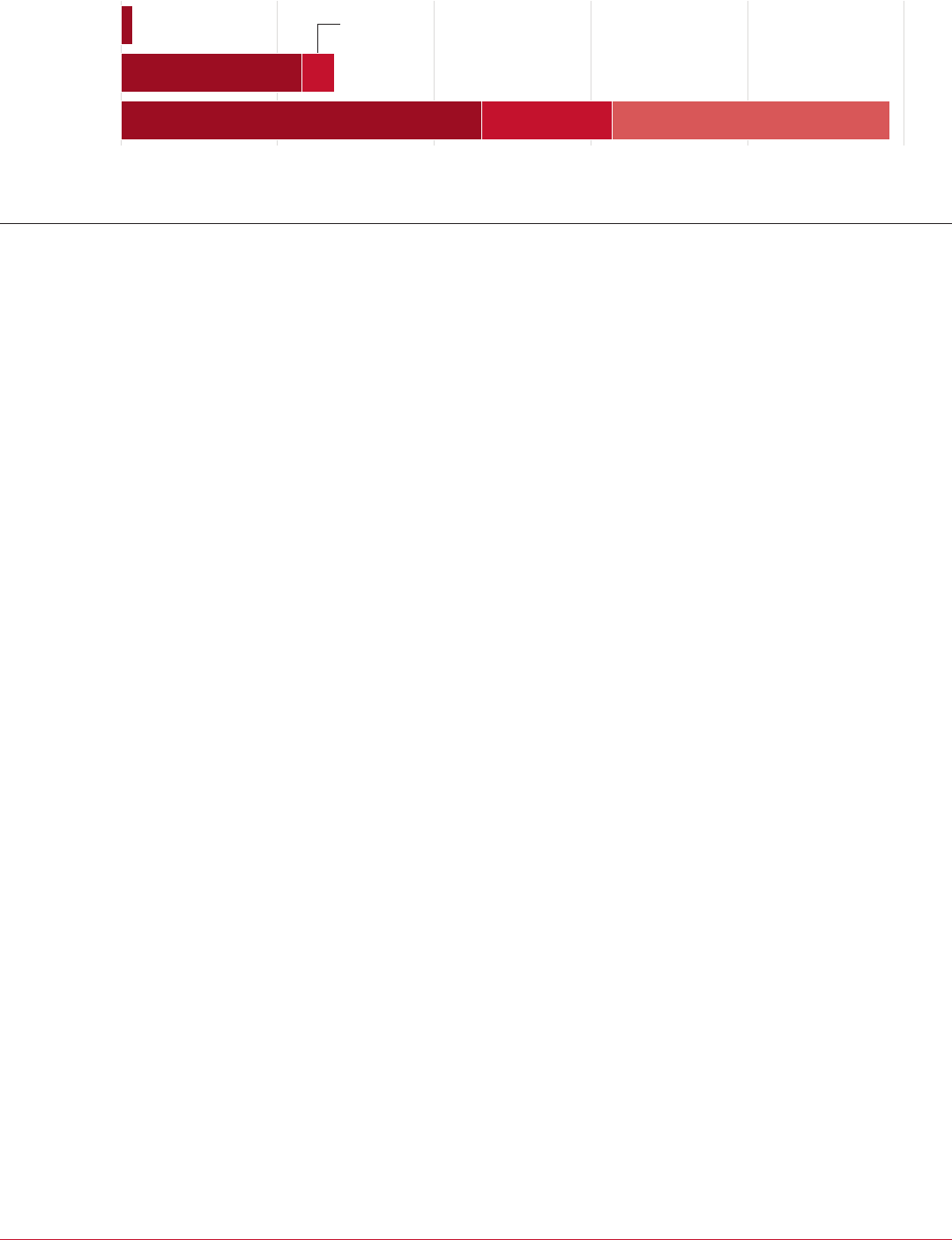

Federal Fiscal Response to Recent Recessions as % of U.S. GDP

Source: Congressional Budget Oce and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25%

Wave 1: 11.5% Wave 2: 4.2% Wave 3: 8.9%

(CARES, PPPHCEA, FFCRA) (Response and Relief) (ARPA)

Pandemic

(2020 & 2021)

0.4%

7.0%

24.6%

Dot-com Bust

(2001)

Federal Fiscal Response as % of GDP

ARRA: 5.7%

The Great Recession

(2008 & 2009)

Economic Stimulus

Act and TARP (net):1.3%

In short, scal stimulus propped up the ailing U.S. economy in

March and April 2020, when layos spiked due to shutdowns.

However, the scal stimulus also contributed to economic chal-

lenges such as goods shortages, ination, and long-term debt.

Key Findings

• Massive Pandemic Fiscal Stimulus – Within a year of the

COVID-19 pandemic beginning in the U.S., the federal govern-

ment enacted three waves of unprecedented scal stimulus

amounting to nearly 25% of 2020 GDP (over $5 trillion).

• Direct and Indirect State Budget Impacts – This federal

funding supported state and local government budgets both

(a) directly through state and local government grants and (b)

indirectly through economic support to rms and households.

• Fiscal Stimulus Benets and Costs – While helping the U.S.

economy overcome early pandemic challenges, the scal

stimulus also contributed to goods shortages, ination, and

long-term debt.

• Pandemic aid signicantly exceeded that of recent reces-

sions – Pandemic federal scal support exceeded a full year’s

worth of regular federal spending and more than tripled the

amount of aid as a percent of GDP provided for the Great

Recession. Federal scal support provided during the Dot-com

recession was even smaller tallying 0.4% of GDP, compared

with 7.0% for the Great Recession, and 24.6% for the pandemic.

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

2

Table of Contents

Introduction ..........................................3

Dealing with an Unknown Virus ..........................3

Pandemic Declared and Massive Economic

Disruption Begins ......................................3

Massive Federal Fiscal Response ..........................4

Comparison with Recent Recessions ......................5

Major Federal Funding Waves ............................5

Wave 1 – $2.4 Trillion Early Pandemic Response. . . . . . . . . .6

Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Act .............6

Families First Coronavirus Response Act ..................6

IRS Income Tax Filing Deadline Shift ......................6

CARES Act ...............................................6

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care

Enhancement Act ....................................10

Wave 2 – $0.9 Trillion Response and Relief Act ......... 11

Wave 3 – $1.9 Trillion American Rescue Plan Act ....... 11

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery

Funds (SLFRF) ........................................12

Economic Recovery .................................. 13

Incomes Increased During Pandemic ....................13

Households Using Stimulus Funds for Saving, Debt

Reduction, and Spending .............................13

Economic Challenges from Federal Fiscal Response ......14

Conclusion .......................................... 15

References .......................................... 16

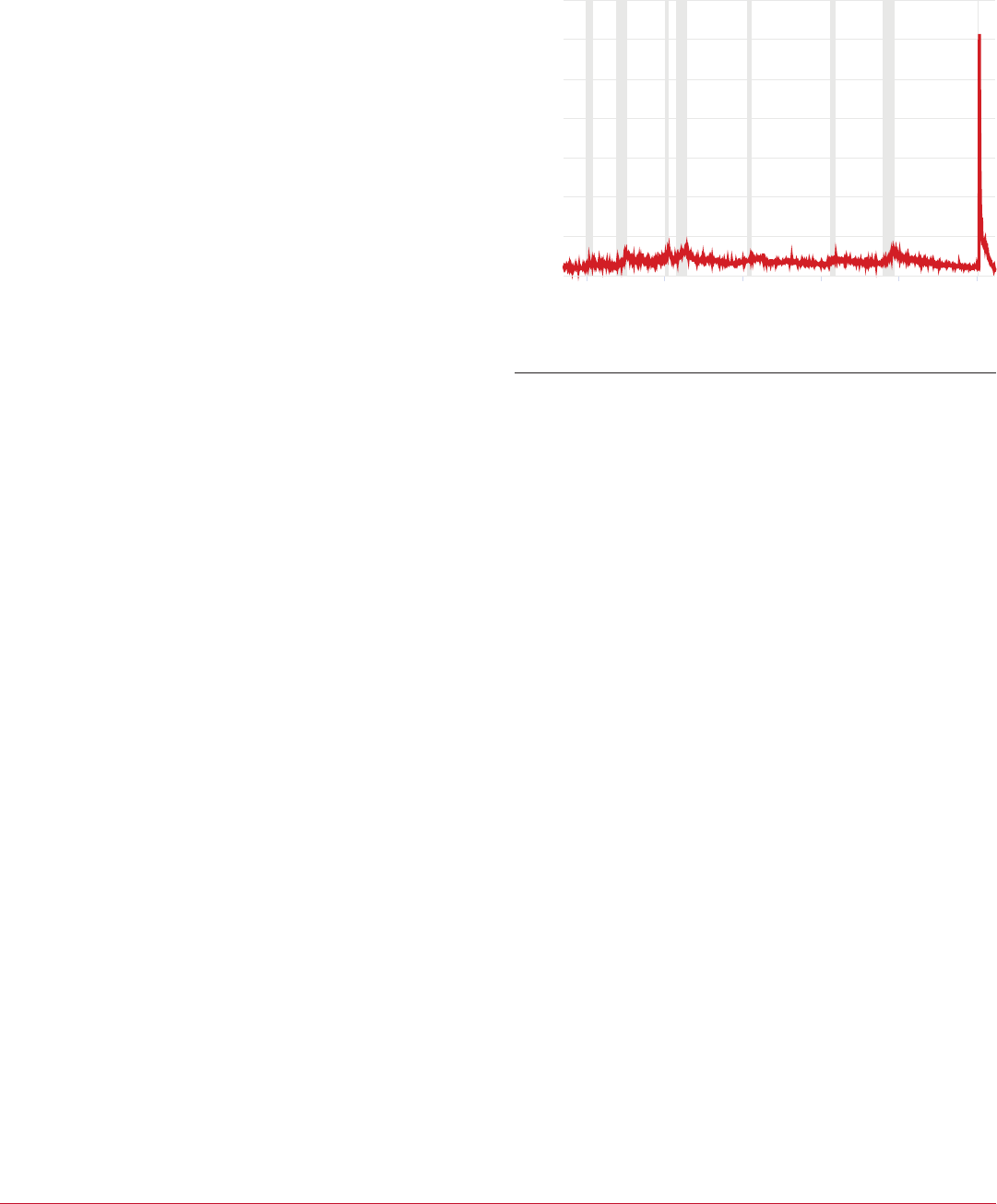

Figures

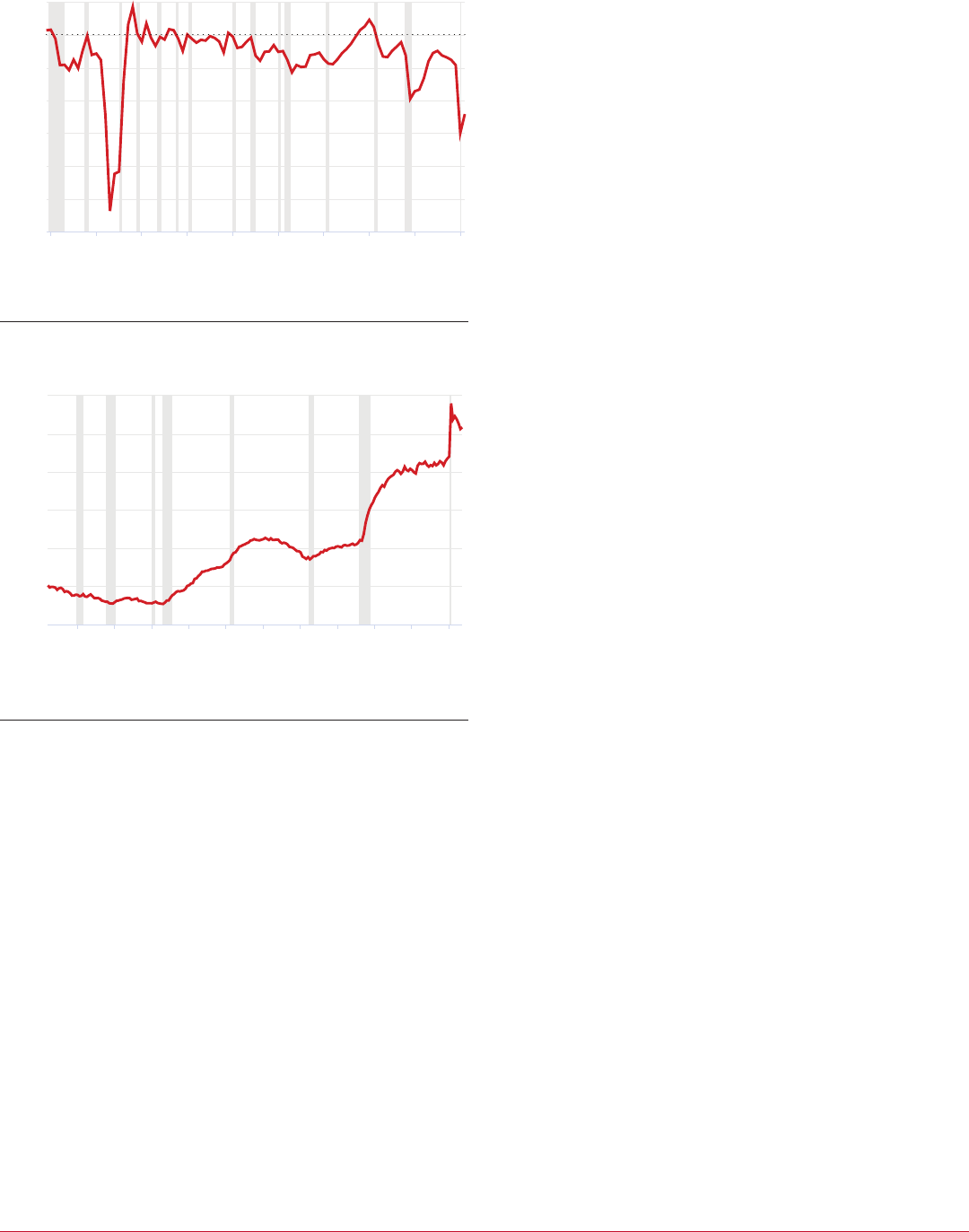

Figure 1: U.S. Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims,

1970-2022 .............................................3

Figure 2: U.S. Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims and

Major Fiscal Response Bills, 2020–2022 .................4

Figure 3 – Federal Fiscal Response to Recent

Recessions as % of U.S. GDP ............................5

Figure 4: U.S. Real GDP Per Capita, 1970–2021 ............13

Figure 5: U.S. Personal Income, 2000–2022 ...............13

Figure 6: U.S. Personal Saving Rate, 1960-2022 ...........13

Figure 7: Nominal Checkable Deposits and Currency for

Households and Nonprots, 1960–2021 ...............14

Figure 8: U.S. Household Debt Service Payments as

Percent of Disposable Personal Income, 1980–2021 ....14

Figure 9: Nominal U.S. Retail Sales, 1992-2021 ............14

Figure 10: Year-Over Change U.S. Consumer Price

Index (CPI), 1947-2022 ................................14

Figure 11: Federal Surplus or Decit as a Percent of GD,

1929–2021 ...........................................15

Figure 12: National Debt as a Percent of GDP,

1966-2021 ............................................14

Tables

Table 1: Major Federal Fiscal Response Bills During

COVID-19 Pandemic ...................................4

Table 2: Combined State, County, and City CARES Act

Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) Allocations in

Western States .........................................7

Table 3: Education Pandemic Allocations to

Western States .........................................8

Table 4: Paycheck Protection Program and Economic

Injury Disaster Loans in Western States .................9

Table 5: Unemployment Insurance Increases Above

Traditional Unemployment Insurance in

Western States .........................................9

Table 6: IRS Economic Impact Payments to

Households in Western States .........................12

Table 7: American Rescue Plan Act Coronavirus State

and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF) Allocations to

Western States and Local Governments ...............11

A version of this document was originally published in the California Journal of Politics and Policy

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

3

The COVID-19 pandemic created enormous challenges

throughout the world, including deaths, hospitalizations,

and various long-term health impacts. Signicant economic

damage also occurred in COVID’s aftermath. This damage

included widespread layos, including 6 million U.S. workers

ling for unemployment benets in a single week and a total of

over 23 million U.S. workers receiving unemployment benets

within several months of the pandemic declaration. In the

midst of these enormous economic challenges, the federal

government began its scal response to the pandemic.

This paper focuses on (a) the federal government’s 2020 and

2021 scal policy (i.e., spending and taxing) responses to the

COVID-19 pandemic and (b) the initial impacts of these scal

responses, particularly on western states. While the Federal

Reserve’s expansionary monetary policy (i.e., money supply

increase and corresponding interest rate reduction) also played a

signicant role in stabilizing the U.S. economy through the early

pandemic, the massive scale of the federal government’s scal

response to the COVID-19 pandemic (about 25% of 2020 GDP)

far exceeded its scal response to other economic downturns.

This massive and rapid federal scal response stabilized

household and company budgets, which in turn indirectly

rmed up state budgets as income taxes and sales taxes

stabilized and grew. In addition, the federal government

provided direct aid to states and their local governments to

help navigate the pandemic. At the same time, the massive

scal stimulus contributed to current economic and budget

challenges, such as goods shortages and ination.

Dealing with an Unknown Virus

COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 vi-

rus, a new (or novel) coronavirus strain not previously seen in hu-

mans. The rapid spread of this contagious new virus throughout

the world from the end of 2019 through early 2022 caused mas-

sive economic disruption, as people and organizations grappled

with an initially-unpredictable virus that threatened to overrun

health systems. Heated debates about the appropriate role of

public policy and private decisions in response to the pandemic

continue today, including scal policy’s role.

The pandemic’s economic consequences diered from

previous recessions in recent history because U.S. federal, state,

and local governments required certain businesses to either

suspend or dramatically alter operations, such as by mandating

physical distancing requirements or prohibiting or limiting facility

use or capacity. Unlike other recessions where a market-driven

shock drove economic declines, the government’s direct actions

contributed to and even mandated a portion of the precipitous

drop in economic activity. That is, people voluntarily determining

economic engagement levels did not account for all of the

economic activity decline. Although beyond this paper’s scope,

signicant questions remain about how much economic activity

would have dropped absent these government mandates to

suspend or dramatically alter basic societal operations. However,

it seems clear that some sizable level of market-driven economic

shock would have occurred in response to the pandemic absent

government mandates, but that government responses also

restricted voluntary activity that would have otherwise occurred

even with the virus’ prevalence.

Pandemic Declared and Massive Economic Disruption Begins

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a

global pandemic. That night, Utah found itself at the epicenter

of the U.S. pandemic when the National Basketball Association,

which held games that evening, suspended all future games

after two Utah Jazz players tested positive for the virus.

Beginning the following day, in quick succession, collegiate and

professional sports leagues, arts organizations, and educational

institutions suspended games, shows, and classes involving

large gatherings of people. In the following weeks, states issued

stay-at-home orders or advisory guidance,

and travel bans and

other restrictions were enacted (Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention 2020, and Moreland, Herlihy, and Tynan 2020).

Suddenly, what had for many been a noteworthy but somewhat

obscure world news item took center stage in U.S. daily life.

Business revenues quickly plummeted when rms and

governments could not conduct normal operations and,

in some cases, had to completely close. In response, rms

immediately began laying o employees at a massive scale,

Introduction

Figure 1: U.S. Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims,

1970-2022

Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration

n

U.S. Recessions

7

6

5

Initial Claims (Millions)

4

3

2

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

2020 2021 2022

1

1

2

0

7

6

5

Initial Claims (Millions)

4

3

2

1

0

CPRSAA ($0.01T)

CARES ($1.7T)

Wave 1 ($2.4T)

PPPHCEA

($0.5T)

Response and Relief ($0.9T)

Families First ($0.2T)

M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J A S O N D J F MJ F M A

ARPA ($1.9T)

Wave 2 ($0.9T)

Wave 3 ($1.9T)

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

4

dramatically increasing weekly unemployment insurance claims

to unprecedented levels. As Figure 1 shows, the staggering

immediate layo levels dwarfed previous unemployment

insurance initial claim activity, including claims during the

devastating Great Recession (2007-2009).

Seeing this massive unemployment increase, states antici-

pated revenue drops closely tied to declining household

and rm income (reducing income taxes) and private sector

spending declines (reducing sales and fuel taxes), coupled

with anticipated state spending increases for social support

programs, such as Medicaid.

In the following weeks and months, states and local

governments identied and began closing anticipated budget

gaps.

1

According to the National Association of State Budget

Ocers (NASBO), state executive budget recommendations

released in December 2019 and January 2020 initially projected

average FY 2021 General Fund increases of nearly 3.5%.

Actual enacted FY 2021 budget averages in the following

months dropped by about 5.5% from these initial budget

recommendations. However, because budget timelines vary

(including some states that budget biennially), states enacted

budgets at dierent time points during the pandemic. Some

states enacting budgets in May and June 2020 projected severe

year-over revenue declines of 20% or more (NASBO 2020).

Massive Federal Fiscal Response

In the chaotic early pandemic environment, when many

predicted a Great-Depression-like economic calamity,

2

the

federal government initiated its major scal response. Congress

acted remarkably quickly, enacting a massive initial federal scal

response in March and April 2020, followed by additional massive

supports in late 2020 and early 2021 (see Figure 2 and Table 1).

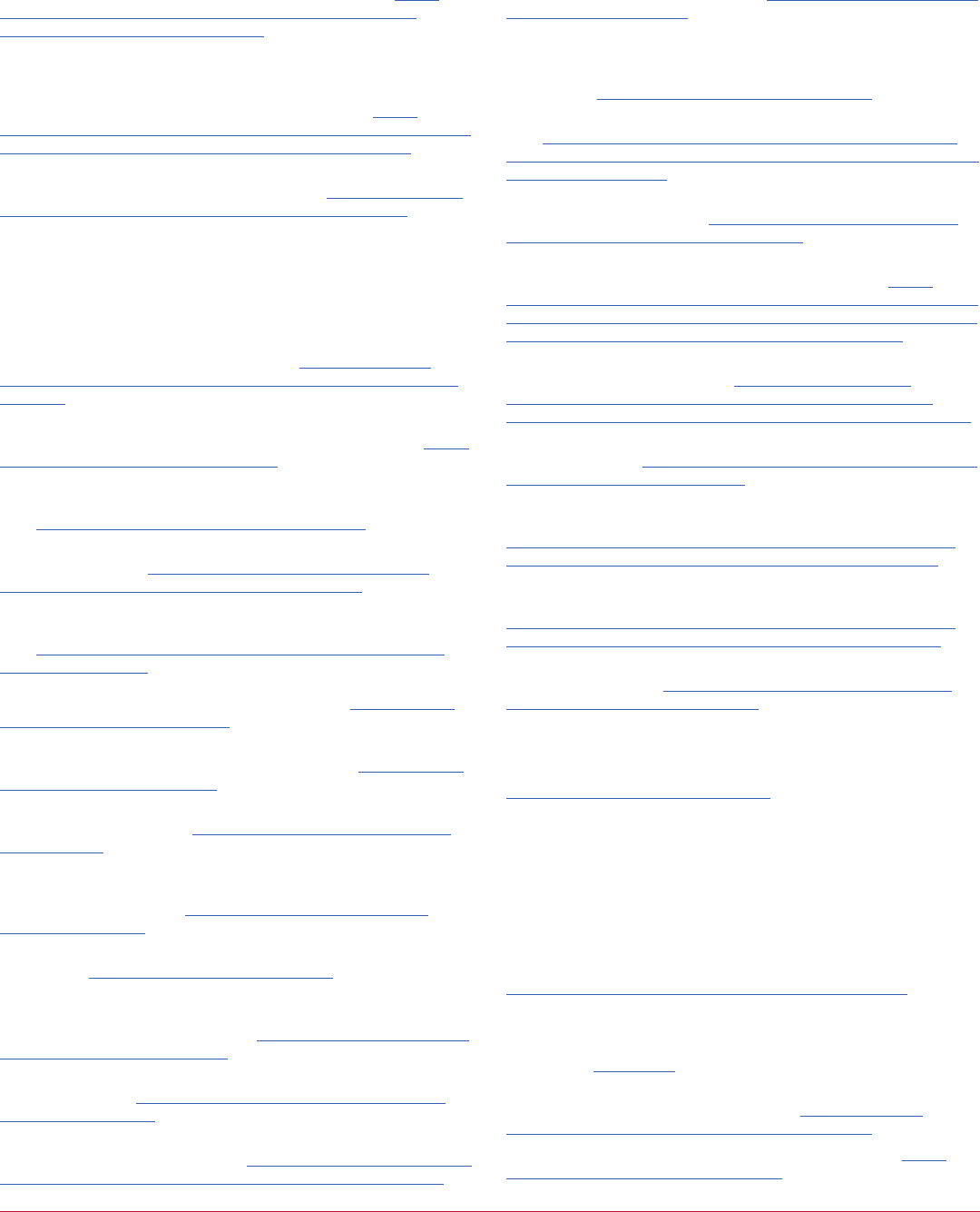

Figure 2: U.S. Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims and

Major Fiscal Response Bills, 2020–2022

Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration

n

U.S. Recession

This massive federal scal response can be thought of as

coming in three distinct funding waves totaling $5.1 trillion,

including (1) an initial Wave 1 in March and April 2020 in the

very early stages the U.S. pandemic, (2) a year-end Wave 2 in

December 2020 under the Trump administration, and (3) a 2021

Wave 3 response under the Biden administration. Later sections

highlight major provisions of each funding wave that directly

and indirectly supported state budgets.

As context for the over $5 trillion in federal scal supports

enacted within a one-year period but owing over several years,

this total amount equates to nearly 25% of 2020 U.S. Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) of about $21 trillion (U.S. Bureau of

Economic Analysis). This increased federal spending from about

20% of GDP between 2014–2019, to 30% in 2020 and 2021. As

additional context, 2019 federal spending (the scal year prior to

the pandemic) totaled $4.4 trillion (Congressional Budget Oce

2020). That is, the $5.1 trillion in pandemic federal scal responses

exceeded a full year’s worth of regular federal spending.

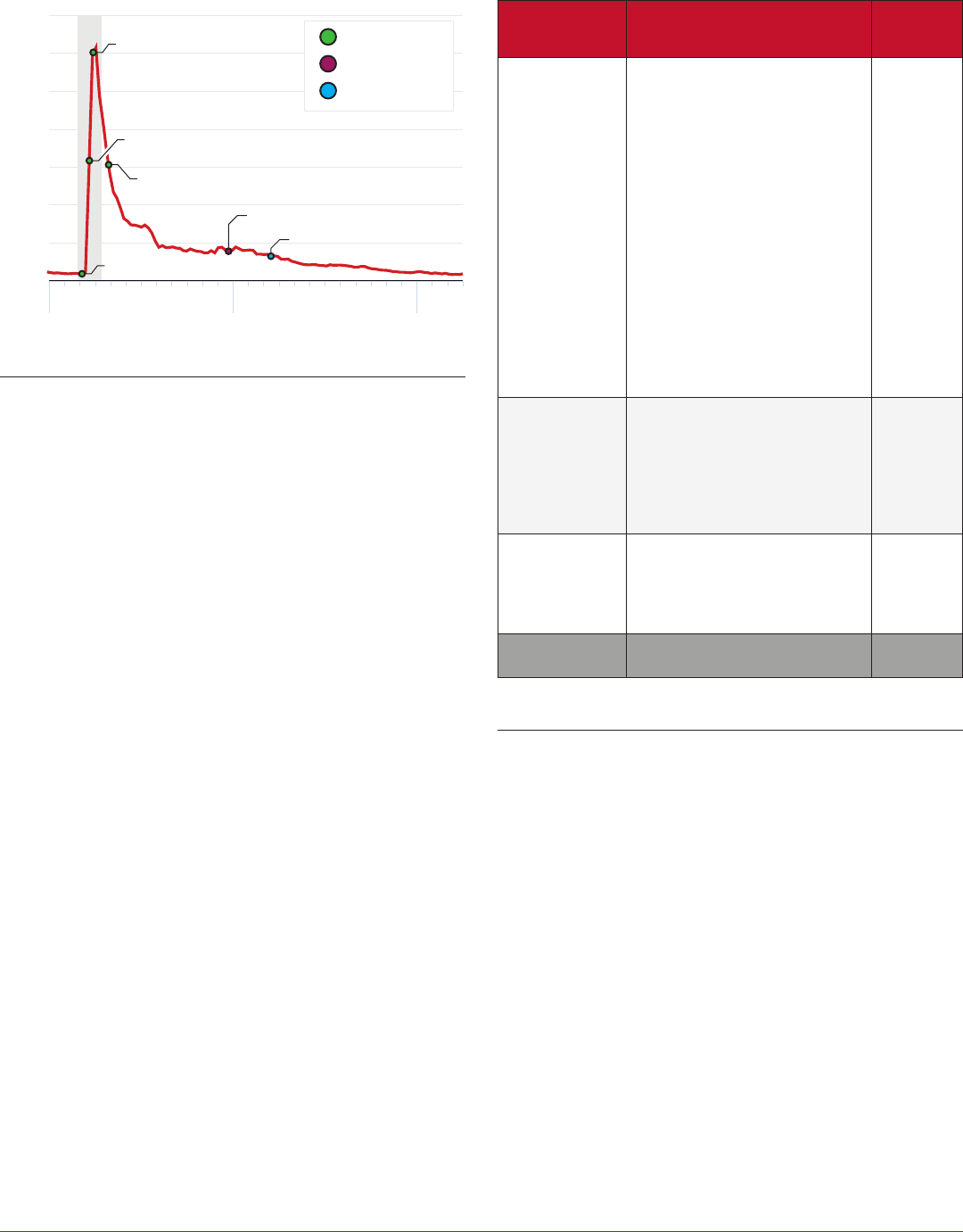

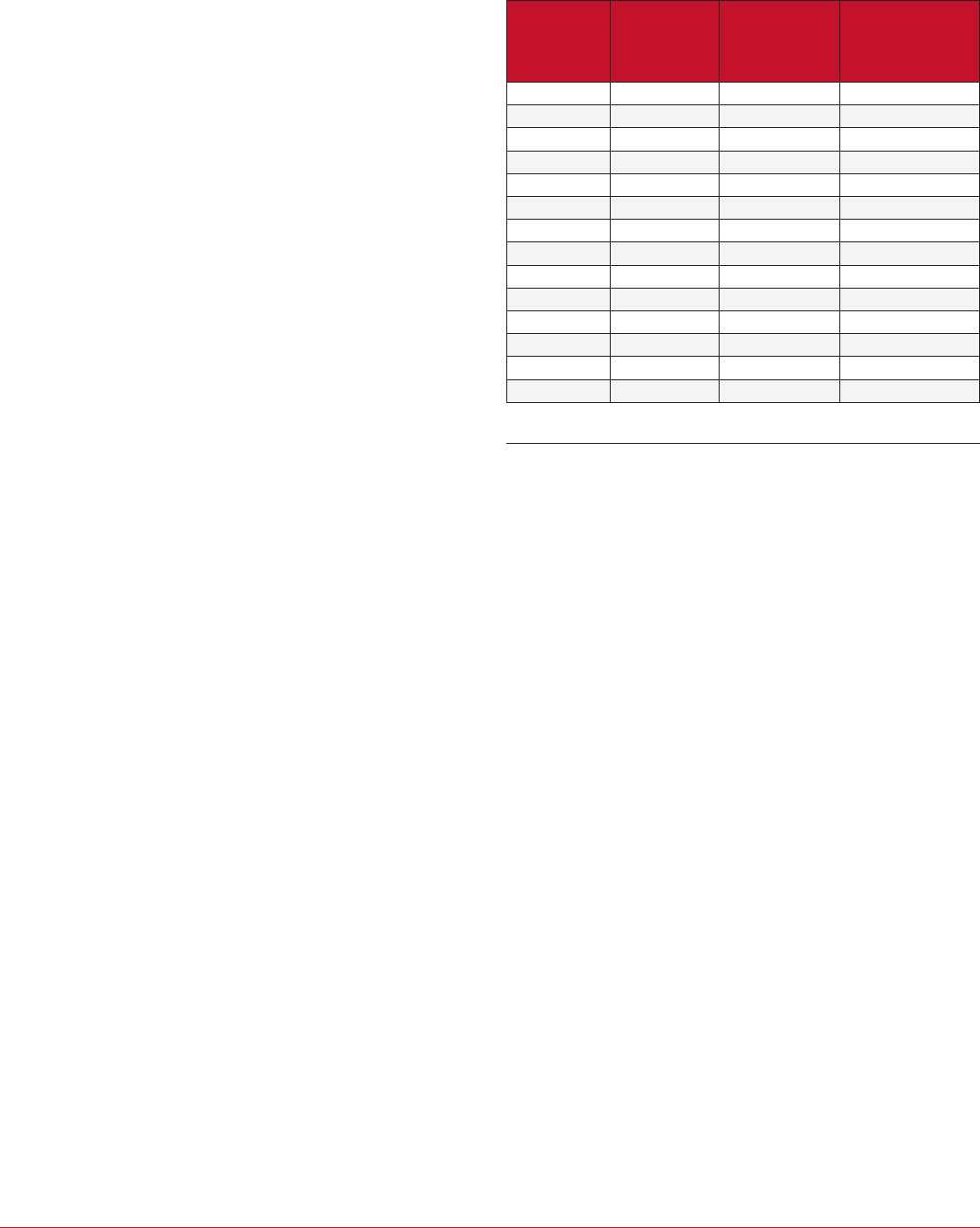

Table 1: Major Federal Fiscal Response Bills During

COVID-19 Pandemic

Timing Bill – Enactment Date

Amount

(% of 2020

GDP)

Wave 1

Early Pandemic

Response

(March–April 2020)

Trump

Administration

Coronavirus Preparedness

and Response Supplemental

Appropriations Act (CPRSAA) –

March 6, 2020 ($0.01 trillion)

Vote– House: 415-2, Senate: 96-1

Families First Coronavirus Response

Act (Families First, or FFCRA) –

March 18, 2020 ($0.2 trillion)

Vote– House: 363-40, Senate: 90-8

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security Act (CARES) –

March 27, 2020 ($1.7 trillion)

7

Vote– House: Voice vote, Senate: 96-0

Paycheck Protection Program and

Health Care Enhancement Act

(PPPHCEA) – April 24, 2020 ($0.5 trillion)

Vote– House: 388-5, Senate: Voice vote

$2.4 trillion

(11.5%)

Wave 2

2020 Year-

End Response

(December 2020)

Trump

Administration

Coronavirus Response and Relief

Supplemental Appropriations Act

(Response and Relief, or CRRSAA),

a component of the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021 –

December 27, 2020

Vote– House: 359-53 Senate: 92-6

$0.9 trillion

(4.2%)

Wave 3

2021 Response

(March 2021)

Biden

Administration

American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) –

March 11, 2021

Vote– House: 220-211, Senate: 50-49

$1.9 trillion

(8.9%)

TOTAL

$5.1 trillion

(24.5%)

*numbers may not sum precisely due to rounding

Source: Congressional Budget Oce, Congress.gov and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

7

6

5

Initial Claims (Millions)

4

3

2

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

2020 2021 2022

1

1

2

0

7

6

5

Initial Claims (Millions)

4

3

2

1

0

CPRSAA ($0.01T)

CARES ($1.7T)

Wave 1 ($2.4T)

PPPHCEA ($0.5T)

Response and Relief ($0.9T)

Families First ($0.2T)

M J J A S O N D J F M A M J J A S O N D J F MJ F M A

ARPA ($1.9T)

Wave 2 ($0.9T)

Wave 3 ($1.9T)

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

5

Figure 3: Federal Fiscal Response to Recent Recessions as % of U.S. GDP

Source: Congressional Budget Oce and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25%

Wave 1: 11.5% Wave 2: 4.2% Wave 3: 8.9%

(CARES, PPPHCEA, FFCRA) (Response and Relief) (ARPA)

Pandemic

(2020 & 2021)

0.4%

7.0%

24.6%

Dot-com Bust

(2001)

Federal Fiscal Response as % of GDP

ARRA: 5.7%

The Great Recession

(2008 & 2009)

Economic Stimulus

Act and TARP (net):1.3%

Comparison with Recent Recessions

While the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy served as the

most-used economic stabilization tool in prior recent recessions,

expansionary federal scal policy, along with expansionary

monetary policy, served as a major contributor to the United

States’ stabilization and recovery from major economic

disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. As explained later, this

massive scal and monetary response also contributed to the

current elevated U.S. ination level.

Figure 3 compares federal scal responses to recent recessions,

showing response amounts as a percentage of U.S. GDP.

Although pandemic funding amounts, particularly from the

Wave 3 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), will be spent over the

span of several years, Congress enacted all the largest funding

bills within a single year of each other, between March 2020 and

March 2021.

By way of comparison, in response to the nancial collapse

leading to the Great Recession, the Economic Stimulus Act

enacted in February 2008, the net scal impact of the Troubled

Asset Relief Program (TARP)

3

enacted in October 2008, and the

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) enacted in

February 2009 altogether provided federal economic stimulus

amounts totaling about $1 trillion (Congressional Budget Oce

2008, 2015, 2021). While ARRA’s nearly $840 billion price tag

in particular was considered very large compared to previous

scal stimulus amounts, that amount relative to GDP pales in

comparison to the pandemic scal response. For example,

just the pandemic-specic unemployment insurance benet

increases over and above traditional benet amounts alone

total over $670 billion (U.S. Department of Labor 2022).

Similarly, the scal policy response to the 2001 dot-com

recession included nearly $40 billion in taxpayer rebate checks

sent as a short-term economic stimulus eort that was part of

a broader long-term tax cut package in the Economic Growth

and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (Shapiro and Slemrod 2003). As

shown, these stimulus rebates also appear miniscule compared

to the pandemic response.

Major Federal Funding Waves

The following sections address the three major federal

scal response waves for the COVID-19 pandemic. The large

expansionary federal scal policy response included direct

aid to households and rms, which supported state and local

government revenue streams, as well as providing funds that

directly owed to states and local governments.

While the largest Wave 1 bills (CARES and PPPHCEA) had

broad bipartisan support in Congress, support for major scal

stimulus waned with each successive wave. The Wave 1 CARES

ACT passed with no dissenting votes and PPPHCEA passed with

only ve dissenting votes in the House. The Wave 2 Response

and Relief Act passed with 53 “no” votes in the House and six

“no” votes in the Senate. The Wave 3 American Rescue Plan

Act passed over a major partisan divide (211 “no” votes in the

House and 49 “no” votes in the Senate), with the sole vote

across party lines cast against the bill.

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

6

Wave 1 – $2.4 Trillion Early Pandemic Response (March and April 2020)

The $2.4 trillion Wave 1 of the federal scal response consisted

of four bills passed in the early pandemic months when the

most severe negative economic impacts occurred. The rst two

smaller bills focused much more on federal agencies and direct

pandemic responses, while the third and fourth Wave 1 bills,

including the enormous $1.7 trillion CARES Act, had a much

broader scope that included major economic responses.

Unlike many previous federal actions passed well into

economic downturns, these bills passed within days and weeks

of the March 11, 2020 pandemic declaration. While that funding

did not all necessarily hit the economy instantaneously, much

of it did arrive within the rst weeks and months. This early

response gave households, rms, and governments better

ability to plan their way through the pandemic, and helped to

avert some of the initially-anticipated disastrous state and local

government budget impacts.

Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Act ($0.01 trillion)

The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental

Appropriations Act, enacted several days prior to the

ocial pandemic declaration on March 6, 2020, provided a

comparatively small $8 billion amount (Congressional Budget

Oce 2020). This bill funded federal agencies for direct public

health responses, such as research, review, and purchase of

tests, vaccines, medical devices, and therapeutics; telehealth

funding for Medicaid providers; Small Business Association

(SBA) economic disaster loans; and various international eorts.

Notably, as the pandemic’s enormous scope became clearer

in the following weeks, the two following major bills grew by

orders of magnitude, with the CARES Act passed several weeks

later measuring in the trillions rather than single-digit billions.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act ($0.2 trillion)

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), enacted

on March 18, 2020, was a much larger bill, costing an estimated

$192 billion, split roughly evenly between spending increases

and tax reductions (Congressional Budget Oce 2020).

Major provisions include additional public health funding

for testing and other public health response items; extended

unemployment insurance benets for laid-o workers; enhanced

Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), Women,

Infants, and Children

(WIC), and other food and nutritional

benets; and tax credits to oset a new mandatory paid sick

leave policy applicable to most employers when an employee

or close family member required quarantine. This bill largely

targeted allocations to oset anticipated direct pandemic

impacts, but went beyond the CPRSAA enacted 12 days earlier

by allocating funds to not only federal agencies, but also to

households, rms, and governments.

Importantly for states, the bill also increased states’ traditional

Medicaid federal medical assistance percentages (FMAP) by

6.2 percentage points, along with other Medicaid changes.

Medicaid carries enormous scal impacts for states, averaging

nearly 20% of state General Fund spending (NASBO 2020). This

6.2 percentage point FMAP increase eectively boosted federal

Medicaid funding by 8% to 12%, freeing up state funds. By

reducing states’ share of Medicaid costs and temporarily shifting

that cost to the federal government, this provision provided

immediate budget relief to states expecting a pending increase

in Medicaid costs for new enrollees along with state revenue

declines corresponding to economic activity declines. However,

this provision did limit states’ ability to disenroll Medicaid

recipients through the end of the declared pandemic, which

increased future costs.

IRS Income Tax Filing Deadline Shift

Although done administratively rather than by an act of

Congress, on March 20, 2020 U.S. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin

also shifted the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) income tax ling

deadline from April 15, 2020 to July 15, 2020 (IRS 2020). While

providing cash ow assistance to the households and rms

remitting taxes, this action created scal challenges for states

that impose income taxes because as a practical administrative

matter, states conformed to this timing shift. For many states,

this timing shift moved a sizable amount of income tax revenue

from Fiscal Year 2020 into Fiscal Year 2021. Given the short time

period remaining in Fiscal Year 2020, the timing shift left states

scrambling to cut budgets or reallocate funds temporarily

between scal years. Notably, the impacts of this income

tax timing shift make year-over comparisons challenging for

annual budget states with income taxes.

CARES Act ($1.7 trillion)

The $1.7 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security

Act (CARES Act), by far the largest and most impactful Wave 1

bill, both provided massive scal stimulus through a wide array

of programs and began to help panicked businesses in freefall

survive the pandemic without continued massive layos.

Enacted on March 27, 2020 (just 16 days after the pandemic

declaration), the CARES Act includes too many provisions to

cover in depth here, so only the largest and most impactful will

be addressed.

CARES Act allocations beneted state budgets both directly

and indirectly.

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

7

Direct state and local government aid came through a wide

array of existing and new programs. In particular, state and

local governments beneted from the exible new Coronavirus

Relief Fund, allocable by state and local policymakers, but

subject to some limitations (Congressional Budget Oce 2020).

Probably more importantly, providing large funding amounts

to rms and households broadly supported economic activity,

leading state and local revenues to detach, to some extent,

from certain economic indicators such as the unemployment

rate. In other words, state and local revenues did not decline

as dramatically as unemployment increased. This is because

federal aid indirectly beneted state budgets through secondary

impacts from major economic programs such as the Paycheck

Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loans for

businesses, direct household economic impact payments to

most households from the IRS, and increased benets for the

unemployed through enhanced unemployment insurance

benets. As these programs broadly supported economic

activity, state revenues quickly recovered.

State and Local Government Coronavirus Relief Funds

Flexible state and local government aid generated signicant

controversy. In fact, it became a sticking point in bill negotiations.

Those supporting exible funding highlighted signicant

state and local government direct pandemic responses and

other growing costs such as Medicaid, as well as anticipated

revenue losses stemming from declining economic activity

and avoiding employee layos that would slow economic

recovery. Those opposed voiced concerns about inappropriately

taking advantage of the pandemic crisis to bail out spending

mismanagement by some state and local governments over

decades, including not fully funding promised pension benets.

4

CRF Allocations

In addition to broad-based rm and household allocations

detailed later that supported state General Fund revenues,

the CARES Act allocated $150 billion to the U.S. Treasury for

Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) direct exible allocations to states,

local, tribal, and territorial governments based on population,

subject to a $1.25 billion combined state and local minimum

allocation per state. Of the $139 billion allocated to states, cities,

and counties after $11 billion in tribal and territorial allocations

(see Table 2), 55% of the CRF funds were intended for states and

45% for cities and counties (U.S. Treasury 2022).

However, the U.S. Treasury only directly allocated funds to

cities and counties with a population size over 500,000, with

the remaining “local” funds allocated to states. The CARES Act

did not explicitly require states to allocate to cities and counties

the remaining “local” 45% funding share sent directly to states.

However, many states did so (National Conference of State

Legislatures 2022 and Paul G. Peterson Foundation 2022). CARES

Act local government funding allocations eased signicant

pressure on state budgets that would have otherwise occurred.

CRF Challenges

While states and local governments welcomed exible

CRF funds in the chaotic and uncertain environment of the

early pandemic, funding requirements also created some

challenges. One challenge related to fund use restrictions.

Per specic statutory language, funds explicitly could not be

used to oset government revenue declines and had to tie to

a “necessary” response to the pandemic. Unclear and evolving

U.S. Treasury guidance on “necessary” expenditures left states

to make allocations in a highly uncertain environment, with

the nal formal guidance promulgated after the original due

date for spending funds (U.S. Treasury 2021). Given the ongoing

pandemic’s enormous public health uncertainty, it was also

unclear how much funding should be reserved specically for

direct public health response, such as disease treatment, testing,

and contact tracing, and what portion should be allocated to

economic or other responses, such as osetting business impacts

or providing housing assistance.

The originally-enacted December 30 spending deadline also

created challenges. By the time CRF funds arrived beginning

in April 2020, governments had about eight months to actual-

ly spend funds by constructively receiving goods and services.

Although some government procurement provisions worked

through expedited processes, this was a very short time frame

to (a) decide how to allocate funds to dierent purposes, (b)

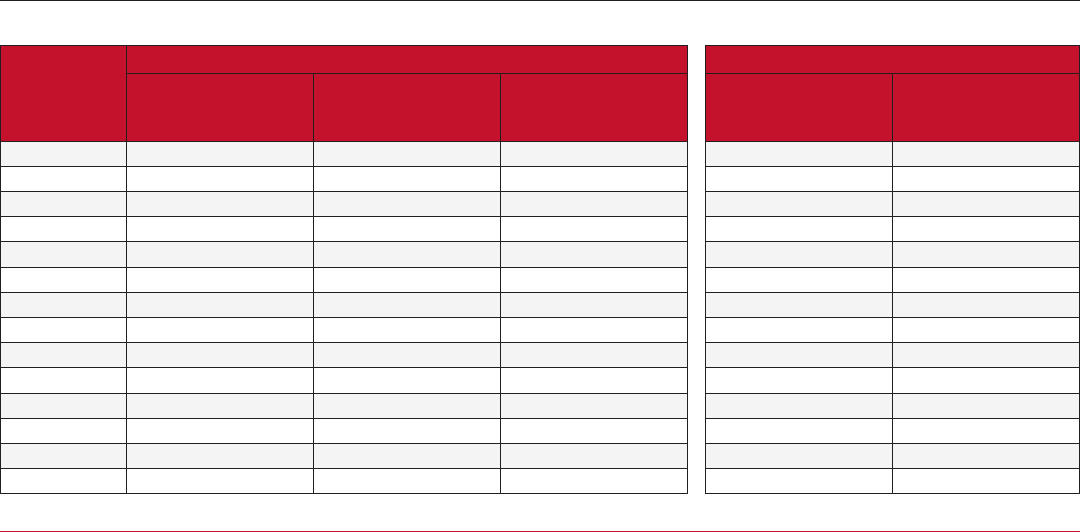

Table 2: Combined State, County, and City CARES

Act Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) Allocations in

Western States

State and

Local CRF

Allocations,

by State

Total

Amount

(in $ billions)

CRF Total

Amount

Per Capita

(whole dollars)

CRF State 55%

Allocation as % of

State General Fund

2019 Spending

Alaska $1.25 $1,709 12%

Arizona $2.82 $388 14%

California $15.32 $388 7%

Colorado $2.23 $388 9%

Hawaii $1.25 $883 9%

Idaho $1.25 $699 19%

Montana $1.25 $1,170 30%

Nevada $1.25 $406 15%

New Mexico $1.25 $596 11%

Oregon $1.64 $388 9%

Utah $1.25 $390 9%

Washington $2.95 $388 7%

Wyoming $1.25 $2,160 46%

U.S. Total $139 $423

Source: U.S. Treasury, U.S. Census Bureau, NASBO

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

8

procure goods and services in an environment of supply chain

disruptions and constrained labor availability, and (c) receive de-

livery of those goods and services prior to the statutory deadline.

Yet another challenge for CARES Act CRF and other one-time

state and local funding streams relates to limitations the non-re-

curring nature of the funds put on potential fund uses. Many pro-

posed uses would establish permanent programs with ongoing

costs, such as funding permanent employees, whereas the feder-

al revenues were only one-time. That is, because this funding was

not expected to be permanently available, states and local gov-

ernments that set up permanent programs using this one-time

funding would face future structural budget decits. This limited

the scope of the types of budget items the funds could cover

(such as pilot programs, equipment, buildings, and technology

acquisition) for those intent on avoiding future budget problems.

Education Funding

Beyond the mostly-exible state and local CRF allocations,

the CARES Act specically allocated funds to K-12 and higher

education agencies. Because education makes up about 45%

of state General Fund spending, including K-12 education (36%)

and higher education (9%) (NASBO 2020), federal scal relief for

education relieved pressure on state budgets that would have

otherwise occurred. Major programs included the Governor’s

Emergency Education Relief Fund (GEER), Elementary and

Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), and Higher

Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF). Table 3 shows K-12

and higher education pandemic allocations for western states,

including later bills (U.S. Department of Education 2022). For K-12

education, these allocations amounted to 2–3 times standard

annual federal funding.

Table 3: Education Pandemic Allocations to Western States

State

Public K -12 Higher Education

GEER and ESSER

Pandemic Funding

Increase ($ in billions)

Regular Pre-Pandemic

FY 2019 Funding

($ in billions)

Pandemic Funding

Per Enrolled Pupil

(whole dollars)

Pandemic Funding

Increase

($ in billions)

Pandemic Funding

Per Enrolled Student

(whole dollars)

Alaska $0.57 $0.40 $4,289 $0.08 $1,975

Arizona $4.11 $1.40 $3,567 $1.44 $1,637

California $23.95 $8.06 $3,885 $10.05 $2,649

Colorado $1.86 $0.72 $2,033 $0.98 $1,940

Hawaii $0.65 $0.30 $3,611 $0.27 $3,428

Idaho $0.71 $0.28 $2,272 $0.26 $1,361

Montana $0.61 $0.27 $4,079 $0.23 $3,747

Nevada $1.71 $0.49 $3,433 $0.41 $2,546

New Mexico $1.56 $0.54 $4,709 $0.45 $2,665

Oregon $1.79 $0.58 $3,070 $0.78 $2,353

Utah $1.00 $0.46 $1,461 $0.76 $1,540

Washington $2.98 $1.07 $2,607 $1.29 $2,561

Wyoming $0.48 $0.13 $5,055 $0.08 $1,933

U.S. Total $193.70 $60.34 $3,210 $74.90 $3,112

Source: U.S. Department of Education

Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and Economic Injury

Disaster Loans (EIDL)

The Paycheck Protection Program provided a lifeline to

businesses by making forgivable loans to rms that retained

employees through the early pandemic. Spending funds

on specic eligible expenses, particularly employee payroll,

allowed the loan to become a grant. While operating more

like a typical loan to be repaid, Economic Injury Disaster Loans

provided low-interest working capital loans to pay business

operating expenses and debt.

Including later allocations in other bills, these two business-

oriented programs ultimately totaled $1.1 trillion, including

about $800 billion in PPP loans (about $700 billion of which

has been forgiven), and over $300 billion in EIDL loans. Table 2

shows PPP and EIDL loan amounts for western states allocated

from the major scal response bills. These two programs allowed

employers to retain employees, supporting state individual and

corporate income tax revenue streams (U.S. Small Business

Administration 2020, 2021, and 2022).

Unemployment Insurance Benet Expansions

Most employers are required to pay unemployment insurance

taxes, which fund unemployment insurance benets that are

distributed to laid o employees who meet certain conditions.

During the pandemic, the federal government, through the

CARES Act and other scal response bills, augmented traditional

unemployment insurance benets.

These augmented benets included an extended time period

to claim benets, allowing previously-ineligible gig workers to

receive benets, and providing a $600 (and later $300) weekly

benet increase–all above the traditional benet, which on

average replaces roughly half of wages. The over $670 billion in

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

9

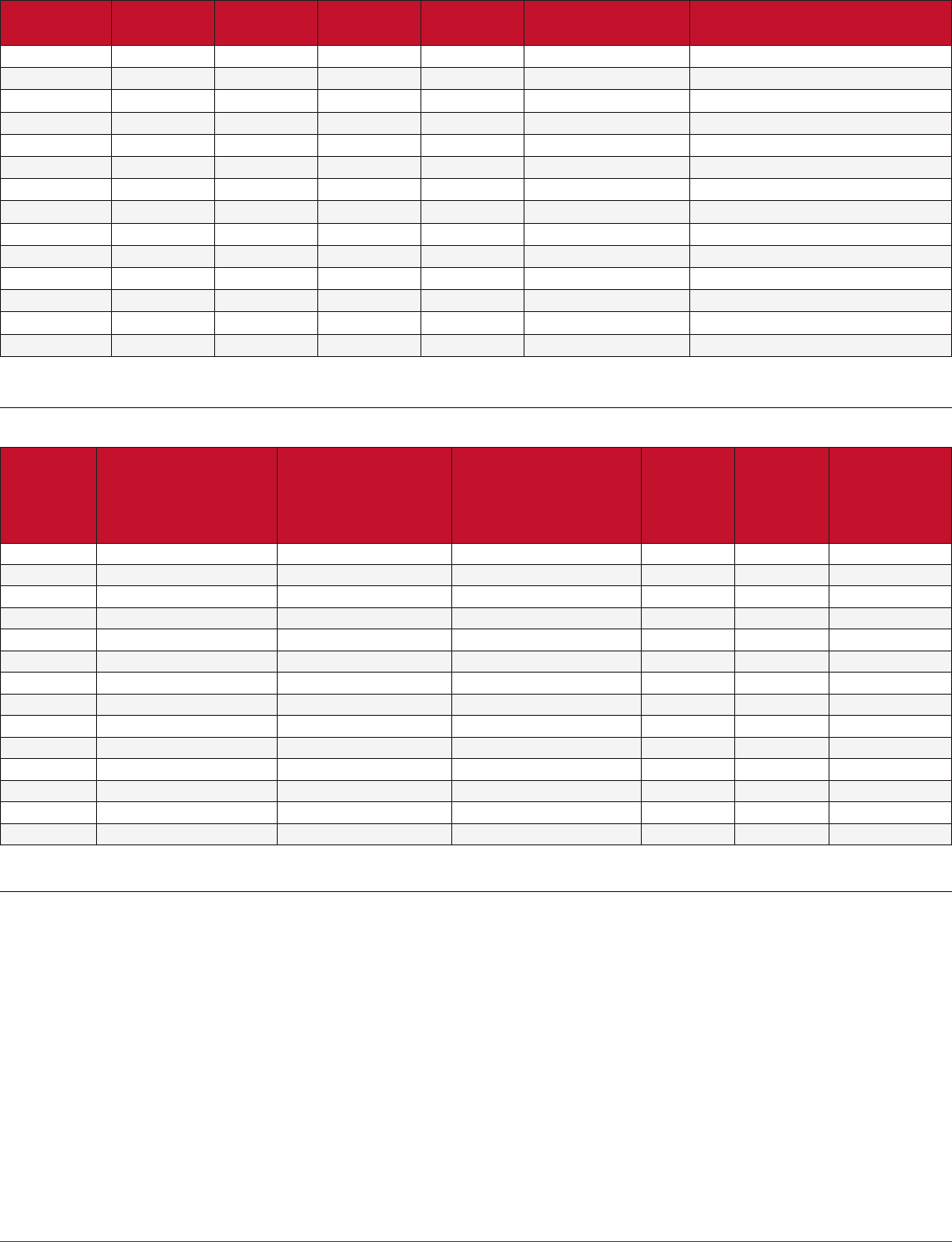

Table 4: Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loans in Western States

State

2020 PPP

($ in billions)

2021 PPP

($ in billions)

EIDL

($ in billions)

TOTAL

($ in billions)

Total PPP and EIDL Per

Capita (whole dollars)

Total PPP and EIDL Per Labor Force

Participant (whole dollars)

Alaska $1.3 $0.7 $0.7 $2.7 $3,649 $7,651

Arizona $8.7 $3.9 $4.8 $17.4 $2,430 $5,069

California $68.6 $35.9 $54.6 $159.1 $4,020 $8,196

Colorado $10.4 $4.7 $4.8 $19.9 $3,443 $6,418

Hawaii $2.5 $1.4 $1.5 $5.4 $3,699 $7,886

Idaho $2.6 $0.9 $1.0 $4.5 $2,446 $5,060

Montana $1.8 $0.8 $0.8 $3.4 $3,119 $6,270

Nevada $4.2 $2.8 $3.3 $10.3 $3,312 $6,683

New Mexico $2.3 $1.1 $1.2 $4.6 $2,170 $4,773

Oregon $7.1 $3.1 $3.2 $13.4 $3,160 $6,397

Utah $5.2 $1.8 $2.1 $9.1 $2,774 $5,765

Washington $12.5 $5.9 $5.8 $24.2 $3,135 $6,152

Wyoming $1.1 $0.6 $0.5 $2.2 $3,793 $7,604

U.S. Total $525 $278 $305 $1,108 $3,347 $6,776

*numbers may not sum precisely due to rounding

Source: U.S. Small Business Administration

increased allocations (see Table 5) stabilized household income

streams and increased consumer purchasing power for those

who lost their jobs or gig work, all of which improved state tax

collections (U.S. Department of Labor 2022).

The initial $600 weekly enhancement (which equates to a

$15 hourly increase on top of the traditional benet for a forty-

hour work week) in particular received widespread attention

because of concerns about economic disincentives to work. For

example, in the early months of the pandemic, Ganong, Noel,

and Vavra (2020) estimated that 76% of workers were eligible

for income replacement rates at or above 100% (meaning

full income replacement or greater), with a median income

replacement rate of 145% and those in the bottom two deciles

Table 5: Unemployment Insurance Increases Above Traditional Unemployment Insurance in Western States

State

$600 / $300 weekly

add-on benet

($ in billions)

Federal Pandemic

Unemp. Assistance (FPUC)

Self-employed

independent contractors

($ in billions)

Pandemic Unemp.

Assistance (PUA)

Extended benet

time period

($ in billions)

Pandemic Emergency Unemp.

Compensation (PEUC)

Other

($ in billions)

Total

($ in billions)

Total Unemp.

Augmentations

Per Capita

(whole dollars)

Alaska $0.7 $0.1 $0.1 $0.02 $1.0 $1,351

Arizona $8.6 $2.7 $0.8 $0.1 $12.2 $1,704

California $87.3 $32.1 $12.1 $3.0 $134.5 $3,398

Colorado $4.6 $2.6 $1.5 $0.4 $9.1 $1,574

Hawaii $2.6 $0.7 $1.0 $0.1 $4.4 $3,014

Idaho $0.7 $0.1 $0.1 $0.02 $1.0 $543

Montana $0.8 $0.2 $0.1 $0.03 $1.1 $1,009

Nevada $6.1 $1.3 $1.4 $0.3 $9.2 $2,958

New Mexico $2.2 $0.5 $0.5 $0.1 $3.3 $1,557

Oregon $5.2 $1.1 $1.4 $0.2 $7.9 $1,863

Utah $1.4 $0.1 $0.2 $0.05 $1.4 $427

Washington $9.5 $2.5 $2.7 $0.6 $15.3 $1,969

Wyoming $0.2 $0.03 $0.05 $0.01 $0.3 $517

U.S. Total $442 $131 $84 $15 $672 $2,030

*numbers may not sum precisely due to rounding

Source: U.S. Department of Labor

of the income distribution eligible for an income replacement

rate of over 200%.

In other words, rather than layos substantially decreasing

incomes, layos actually increased incomes, particularly for

those with lower pre-pandemic wages. After expiration of the

initial $600 weekly enhancement at the end of July 2020, the

Trump administration supported a continued $300 weekly

benet using workaround authority through the Federal

Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The Response and

Relief Act and ARPA bills later statutorily renewed the $300

weekly benet. However, over half of the states opted to end

the benet toward the middle of 2021 prior to ocial program

expiration, due to labor shortage concerns.

5

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

10

Household Economic Impact Payments. Another major

CARES Act economic stabilization program administered by the

IRS provided economic impact payments up to $1,200 per adult

and $500 per child, for households below certain income levels.

To exclude the highest income households, the bill reduced

payments for individuals with adjusted gross income (AGI)

greater than $75,000 ($150,000 for married couples ling a joint

return). While not included in income tax taxable income, the

economic impacts of these payments supported state revenues

as they facilitated increased sales taxable spending.

This CARES Act provision, which provided over $270 billion

directly to most U.S. households, represents the rst of three

rounds of direct broad-based pandemic economic impact

payments to most U.S. households. Each round included

dierent amounts for lers and their children, and dierent

phaseout ranges for those with higher incomes. Although

average payments varied slightly based on income and age mix

in dierent states, on average, the three rounds of IRS economic

impact payments provided about $2,400 per person (or about

$6,300 per household). Table 6 shows the combined amounts

of all three rounds of household economic impact payments

in western states, totaling over $800 billion nationally. As

explained later, these amounts supported, and continue to

support, consumer spending, saving, and debt reduction.

Other Programs. The CARES Act made other signicant

allocations through a large number of new and existing programs,

including $150 billion set aside for health care providers, $25

billion for transit agencies, and $160 billion for tax changes

related to income loss limitations, among many other provisions.

In addition to the $1.7 trillion in spending and tax changes,

the CARES Act authorized over $450 billion in U.S. Treasury

nancial support for various Federal Reserve lending facilities

to ensure liquidity for various large companies, smaller

companies, nonprots, and state and local governments.

Ultimately, the vast majority of these lending authorizations

went unused because normal lending channels remained

functional. This includes the Municipal Liquidity Facility for

state and local governments that only transacted two loans

with a value of $1.7 billion, compared to the $500 billion

authorized by the Federal Reserve using both the CARES Act

$450 billion authorization and the Federal Reserve’s own

discretionary authority. Among all of the CARES-authorized

lending facilities, only about 1% of capacity was utilized (U.S.

Government Accountabilty Oce 2022).

Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care

Enhancement Act (PPPHCEA) ($0.5 trillion)

Following enactment of the CARES ACT, the Paycheck

Protection Program quickly became oversubscribed, with

some business applicants shut out of funds. About a month

after passing the CARES Act, Congress passed the PPPHCEA,

which increased business PPP funding allocations by about

$320 billion. In addition to other provisions, the bill also funded

continued public health response eorts, providing $75 billion

in additional hospital funding and $25 billion for COVID-19

testing (Congressional Budget Oce 2020).

Table 6: IRS Economic Impact Payments to Households in Western States

State

2020 Census

Population

(millions)

Round 1 (CARES)

$1,200 per ler,

$500 per child

($ in billions)

Round 2 (Response &

Relief) $600 per ler,

$600 per child

($ in billions)

Round 3 (ARPA)

$1,400 per ler

and dependent

($ in billions)

TOTAL -

Economic Impact

Payments

($ in billions)

Total Economic Impact

Payments Per Capita

(whole dollars)

Alaska 0.74 $0.6 $0.3 $0.9 $1.8 $2,432

Arizona 7.16 $5.9 $3.1 $8.7 $17.7 $2,472

California 39.58 $29.6 $15.4 $43.5 $88.5 $2,236

Colorado 5.78 $4.6 $2.4 $6.4 $13.4 $2,318

Hawaii 1.46 $1.2 $0.6 $1.7 $3.5 $2,397

Idaho 1.84 $1.6 $0.9 $2.3 $4.8 $2,609

Montana 1.09 $1.0 $0.5 $1.4 $2.9 $2,661

Nevada 3.11 $2.6 $1.4 $3.9 $7.9 $2,540

New Mexico 2.12 $1.8 $0.9 $2.6 $5.3 $2,500

Oregon 4.24 $3.6 $1.8 $5.0 $10.4 $2,453

Utah 3.28 $2.6 $1.4 $3.9 $7.9 $2,409

Washington 7.72 $6.1 $3.2 $8.6 $17.9 $2,319

Wyoming 0.58 $0.5 $0.3 $0.7 $1.5 $2,586

U.S. Total 331 $271 $141 $390 $802 $2,423

Note: Additional amounts may be claimed through income tax credits if qualifying individuals did not receive direct payments

Source: Internal Revenue Service

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

11

Wave 2 – $0.9 Trillion Response and Relief Act (December 2020)

Wave 3 – $1.9 Trillion American Rescue Plan Act (March 2021)

Building on the funding structure created in the CARES Act and

other previous funding bills, the Coronavirus Response and Relief

Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) enacted on December

27, 2020 as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021

allocated more scal support funds, largely through previously-

created funding channels. By this time, signicant economic

recovery had occurred, including the U.S. unemployment rate

dropping from 14.7% to 6.7% and GDP recovering to near the

pre-pandemic peak. But a COVID-19 surge created uncertainty at

the time, dampening the economic outlook.

This bill allocated nearly $870 billion (Congressional Budget

Oce 2021), including for the following programs:

• Over $300 billion for additional business supports through

PPP, EIDL, and similar programs (see Table 4 for major

allocation amounts)

• Nearly $120 billion to extend enhanced unemployment

insurance benets, at a weekly $300 increase above the

traditional benet (see Table 5 for overall unemployment

insurance summary)

• Nearly $165 billion for additional direct IRS economic

impact payments to households, including $600 payments

per ler and dependent child, with allocation amounts

phasing out at incomes similar to those in the CARES Act

(see Table 6 for allocation payment amounts)

The American Rescue Plan Act allocated an estimated $1.9

trillion in spending and tax changes, making it the single

largest scal response bill in history (Congressional Budget

Oce 2021). The bill passed on a nearly party line vote in both

Houses of Congress, with the only member breaking ranks (Rep.

Golden - D, Maine) voting against the bill (U.S. Congress 2021).

As detailed later, by March 2021, signicant economic recovery

had occurred, prompting many to raise concerns about the

magnitude of the bill and its various broad-based elements that

were not focused specically on those still in need. As discussed

later, this included not only Republicans who opposed the bill,

but some fellow Democrats.

Major allocations include the following:

• Over $410 billion in economic impact payments to individ-

uals ($1,400 per ler and dependent), with steeper income

phaseouts (see Table 6 for allocation payment amounts)

• $350 billion in aid to state, local, territorial, and tribal

governments (see Table 7)

• Over $80 billion for K-12 and higher education (see Table 3)

• Nearly $80 billion for further public health responses,

including funds for vaccine purchase and mitigation,

testing, contact tracing, and mitigation measures

• Over $120 billion for other measures, including

transportation, SNAP benets, child care, rental assistance,

and other programs.

Although passed very close to the CARES Act’s previous

December 30, 2020 deadline, the bill also extended the

deadline for state and local governments to spend CARES Act

Coronavirus Relief Fund allocations.

Notably, the bill excluded new exible aid for states and

local governments. Over the previous months as the economy

recovered, a partisan divide emerged regarding state and

local government assistance levels actually needed given

strengthening state revenues. As early as April 2020, the

National Governors Association had requested $500 billion in

addition to the CARES Act’s $150 billion allocation for state and

local government aid (National Governors Association 2020).

But many questioned the request level, particularly as state

revenues recovered strongly, assisted in large part by massive

federal scal stimulus.

• Over $200 billion to further extend unemployment insur-

ance benets, at the weekly $300 increase level in addition

to traditional unemployment insurance benets (see Table 5)

• Over $175 billion for tax provisions (U.S. Treasury 2021),

including:

o Expansions of the child tax credit, including temporarily

increasing the credit amount from $2,000 to $3,000 per

qualifying child, adding an additional $600 for children

under age 6 (for a total credit of $3,600), allowing the

credit for 17-year-old children, making the credit fully

refundable, and providing advance payments on the

credit from July to December 2021;

o Expanding the child and dependent care tax credit; and

o Expanding the earned income tax credit.

• Nearly $175 billion for health-specic measures

• About $170 billion in educational support (see Table 3)

• Funding for a wide array of other programs, including

targeted small business, rental, and mortgage assistance.

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

12

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF)

As mentioned above, the American Rescue Plan Act

includes $350 billion in aid to state, local, territorial, and tribal

governments, which includes $195 billion to states and the

District of Columbia and $130 billion to local governments.

Table 7 shows SLFRF allocations to the western states.

Unlike the much shorter spending time period for CARES Act

allocations, these funds are available for obligation through

2024 (nal spending by 2026), with half of the funds distributed

to state and local governments in May 2021 and the remainder

to be sent in May 2022 (U.S. Treasury 2022).

Eligible funding uses include public health expenditures,

addressing negative economic impacts from COVID-19 (such

as impacts to households and businesses), replacing lost

public sector revenue, providing premium pay to essential

Table 7 – American Rescue Plan Act Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF) Allocations to Western

States and Local Governments

State

State

($ in billions)

County

($ in billions)

Metropolitan

Cities

($ in billions)

Other

($ in billions)

Total State and

Local SLFRF Amount

($ in billions)

Total SLFRF

Per Capita

(whole dollars)

SLFRF State Allocation

as % of State General

Fund 2019 Spending

Alaska $1.0 $0.1 $0.05 $0.04 $1.2 $1,622 20%

Arizona $4.2 $1.4 $1.0 $0.2 $6.8 $950 9%

California $27.0 $7.7 $7.0 $1.2 $42.9 $1,084 1%

Colorado $3.8 $1.1 $0.6 $0.3 $5.8 $1,003 8%

Hawaii $1.6 $0.3 $0.2 $0.05 $2.2 $1,473 13%

Idaho $1.1 $0.3 $0.1 $0.1 $1.6 $870 27%

Montana $0.9 $0.2 $0.05 $0.1 $1.3 $1,147 43%

Nevada $2.7 $0.6 $0.3 $0.2 $3.8 $1,222 22%

New Mexico $1.8 $0.4 $0.2 $0.2 $2.6 $1,226 16%

Oregon $2.6 $0.8 $0.4 $0.2 $4.0 $943 10%

Utah $1.4 $0.6 $0.3 $0.2 $2.5 $762 13%

Washington $4.4 $1.5 $0.8 $0.4 $7.1 $920 4%

Wyoming $1.1 $0.1 $0.02 $0.05 $1.2 $2,103 66%

U.S. Total $195 $65 $46 $20 $326 $985

Source: U.S. Treasury

workers in critical infrastructure sectors, and investing in water,

sewer, and broadband infrastructure. NASBO (2021) indicates

that of the roughly 40% of funds initially allocated by states

as of the fall 2021 study date, intended uses are as follows:

revenue replacement (32%), negative economic impacts (27%),

infrastructure (16%), services to disproportionately impacted

communities (15%), public health (9%), and other uses (1%).

Of the estimated $5.1 billion total federal scal response,

discretionary aid to states, local, tribal, and territorial

governments totals $500 billion (about 10% of total federal scal

response), including ARPA’s $350 billion for the Coronavirus

State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund and the CARES Act’s $150

billion for the Coronavirus Relief Fund. The federal government

also provided additional program-specic grants to states and

their local governments.

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

13

Figure 4: U.S. Real GDP Per Capita, 1970–2021

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Figure 6: U.S. Personal Saving Rate, 1960–2022

Figure 5: U.S. Personal Income, 2000–2022

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

n

U.S. Recessions

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

Percent

Billions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Economic Recovery

As Figure 4 shows, the combined eect of people returning

to more normal economic activity as vaccines became broadly

available, governments easing restrictions, and expansionary

scal and monetary policy helped the United States return to and

now exceed pre-pandemic GDP per capita levels. However, these

benets are not evenly spread throughout society and have

contributed to other economic challenges. This rapid economic

recovery stabilized state budgets, leading to sizable revenue

increases, even though revenue drops were initially anticipated

given widespread layos.

For example, driven by indirect state budget scal stimulus

impacts in the form of increased tax collections as economic

activity quickly recovered, NASBO (2021) indicates that 47 states

saw General Fund revenue collections exceed projections in FY

2021. By spurring additional demand for goods while supply

chains remained constrained, the federal scal response also

contributed to goods shortages and ination.

Incomes Increased During Pandemic

As businesses, particularly many goods-producing rms,

received scal stabilization funds such as the Paycheck

Protection Program, the rms not only received support to

keep existing employees on the job, but began searching

for additional employees as demand dramatically increased,

spurred by consumers ush with cash. This economic activity

initially stabilized, then increased, state income tax revenues.

As households received unemployment insurance compen-

sation and economic stimulus payments, this increased

personal income in the second quarter of 2020 by 8% over the

prior quarter and by nearly 11% over the prior year as shown in

Figure 5 (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2022).

Households Using Stimulus Funds for Saving, Debt

Reduction, and Spending

With these sizable income increases, households saved

sizable amounts, paid down debt, and increased spending.

Belsie (2020) and Armantier et al. (2020) initially estimate

that for Wave 1 direct stimulus allocations, households spent

about 30-40%, saved about 30-35%, and paid down debt

with about 30-35%. Armantier et al. (2021) further indicate

that households planned to spend even less of their Wave 2

and Wave 3 scal stimulus payments, instead focusing even

more on saving and debt reduction. Although personal saving

rates from current income have returned to more normal

levels (see Figure 6), sizable amounts of accumulated savings

remain available to consumers (see Figure 7). The timing of

households spending these sizable savings remains uncertain,

increasing uncertainty about the economic outlook and

May 2022

I

gardner.utah.edu INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

14

Figure 8: U.S. Household Debt Service Payments as Percent

of Disposable Personal Income, 1980–2021

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

n

U.S. Recessions

Figure 9: Nominal U.S. Retail Sales, 1992–2021 ($ millions)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Figure 7: Nominal Checkable Deposits and Currency for

Households and Nonprots, 1960–2021 ($ billions)

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Figure 10: Year-Over Change U.S. Consumer Price Index

(CPI), 1947–2022

Source: U.S. Board of Labor Statistics

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year Ago

Percent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year AgoPercent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

potentially contributing to inationary pressures if funds are

spent at once.

Household debt service levels as a percentage of GDP

dropped to multi-generational lows (see Figure 8), due in part

to households using stimulus payments to pay down debt and

to monetary policy allowing households to renance into lower

interest rate loans, particularly for mortgages. While savings are

a one-time funding source, these debt reductions create future

ongoing spending capacity likely to prop up future sales tax

collections.

Household spending re-focused on goods because many

services remained heavily restricted. This renewed goods

focus, including on remote sales on which many states began

collecting sales and use tax in the aftermath of a landmark

2018 Supreme Court decision, increased sales tax revenues in

many states.

As shown in Figure 9, this goods re-focusing caused a large

retail sales increase, which supported strong sales tax revenue

collections.

Economic Challenges from Federal Fiscal Response

However, along with the benets of a strong economic

recovery, the federal scal response also sowed seeds of future

economic and state budget challenges, including ination and

increased debt.

Ination. The most prominent short-term impact is that

the scal stimulus has contributed to current inationary

challenges, with U.S. consumer ination spiking to levels not

seen in over forty years (see Figure 10). While many factors

likely contribute to the price spike, including pandemic-specic

impacts (such as supply chain disruptions and labor shortages),

large-scale scal stimulus is a major contributing factor. Initially

projected to be transitory and closely related to pandemic-

specic factors, sustained and accelerating consumer price

ination has raised signicant concerns about long-term

inationary pressures if a wage-price spiral occurs, in which

workers demand higher wages, which rms then pass on to

consumers through higher prices.

gardner.utah.edu

I

May 2022

INFORMED DECISIONS

TM

15

Figure 12: National Debt as a Percent of GDP, 1966-2021

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

n

U.S. Recessions

Percent

Chained 2012 Dollars

Millions of Dollars

PercentBillions of Dollars

Percent Change from Year Ago

Percent of GDP

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

4,400

4,000

3,600

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

0

60,000

56,000

52,000

48,000

44,000

40,000

36,000

32,000

28,000

24,000

20,000

7 4

5

6

New 5

8

9

10

19851980 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

600,000

500,000

400,000

300,000

200,000

100,000

15.0

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

0.0

-2.5

-5.0

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

1970 2000199019801950 1960 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

1970 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

19701960 200019901980 2010 2020

$26,000

$24,000

$22,000

$20,000

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

2000

Billions of Dollars

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Wave 1

Wave 2

Wave 3

Figure 11: Federal Surplus or Decit as a Percent of GDP,

1929–2021

Source: U.S. Oce of Management and Budget

n

U.S. Recessions

5

0

-5

-10

-15

Percent of GDP

-20

-25

-30

1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Especially notable because a prominent critic belonged to the

same political party as the new president, in early 2021, while

debates occurred on the Wave 3 American Rescue Plan Act,

Larry Summers, former U.S. Treasury Secretary in the Clinton

administration and director of the National Economic Council

under the Obama administration, very publicly raised concerns

that the bill was over three times as large as the pandemic’s

economic output shortfall and could “set o inationary

pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation.”

6

Federal Reserve economists Jordà, Liu, Nechio, and Rivera-

Reyes (2022) recently indicated that “since the rst half of

2021, U.S. ination has increasingly outpaced ination in other

developed countries. Estimates suggest that scal support

measures designed to counteract the severity of the pandemic’s

economic eect may have contributed to this divergence by

raising ination about 3 percentage points by the end of 2021.”

In other words, federal scal stimulus is a major contributing

factor to current ination, although not the only factor.

States have not had to manage budgets in a high ination

environment for many decades, so ongoing future ination

could create future budget challenges. Nominally-increasing

revenue growth may at rst seem like a revenue windfall. But

ination creates higher costs on the spending side just to keep

pace. Said dierently, in such a rapidly changing environment

it is not entirely clear what portion of current state revenue

increases are primarily driven by overall ination, as opposed

to real net ongoing revenue increases that will not need to be

oset with higher spending just to pace with price increases.

Federal Government Debt. As Figure 11 shows, even prior to

the pandemic, the federal scal house was tremendously out of

order. Decits had been growing relative to GDP over the past

two decades, even during good economic times. Increased

federal borrowing nanced the federal pandemic scal

response’s additional decit spending. Figure 12 shows that

the federal scal response’s immediate societal benets came

at the expense of increasing federal government debt, which