1

Virginia Is for Teachers?

An Analysis of the State’s

Teacher Demand and Supply

November 19, 2018

Lucy Sorensen

Jamie Frank

Thomas Gais

Hao Sun

2

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Lucy Sorensen is a faculty fellow at the

Rockefeller Institute of Government

Jamie Frank is a visiting fellow at the

Rockefeller Institute of Government

Thomas Gais is a senior fellow at the

Rockefeller Institute of Government

Hao Sun is a student research assistant at the

Rockefeller Institute of Government

3

Introduction

States and school districts across the United States have reported grappling with

teacher shortages.

1

Teacher preparation program enrollments and graduates have

dropped at the national level, while the number of public school students has steadily

risen.

2

Teacher labor markets, however, differ greatly from state to state as well

as between communities.

3

Even within localities, certain subject areas or types of

schools face starker challenges in training, hiring, and retaining teachers.

4

For these reasons, the Rockefeller Institute of Government,

the public policy research think tank for the State University

of New York, is examining trends and patterns in teacher

supply and demand in a series of state reports to inform

state as well as national policies aimed at ensuring an

adequate supply of qualified teachers for all communities

and Pre-K-12 students. This report, which focuses on

Virginia, is the third in the series; the first two examined

teacher labor markets in New York and South Dakota.

5

Virginia’s teacher workforce faces real challenges.

Prekindergarten through twelfth grade student enrollment

has increased at twice the national rate of enrollment

growth since 2000. The proportion of students requiring

supplemental services and instruction, especially

economically disadvantaged students and English language

learners, has grown even faster. Also, different regions

of the state have experienced very different changes in

enrollment, a dynamic that could require large and rapid

shifts in the geographical distribution of teachers.

Running counter to the

national trend, in which

the number of graduates

from teacher education

programs in the US fell

by 28 percent between

2009 and 2016, the

number of graduates from

the Commonwealth’s

teacher preparation

programs increased by

11.0 percent over the same

seven years.

4

At the same time, Virginia’s teacher pipeline has grown. Running counter to the

national trend, in which the number of graduates from teacher education programs

in the US fell by 28 percent between 2009 and 2016, the number of graduates from

the Commonwealth’s teacher preparation programs increased by 11.0 percent over

the same seven years. Student-to-teacher ratios actually declined in recent years,

from nearly 12.6 students per teacher in 2002 to about 12.0 in 2016.

6

This decline

reflects the fact that growth in the number of teachers statewide outpaced the growth

in Virginia students since 2002.

However, despite the increase in teacher candidates,

the state has reported a high proportion of vacancies in

teacher positions; and although the number of students

with special education needs has not grown appreciably

in recent years, Virginia has repeatedly reported to the

federal government that its schools are experiencing

shortages in teachers with appropriate preparation in

special education.

In addition, Virginia exhibits large differences within the state regarding access to

well-qualified teachers. Teacher vacancies, turnover in teaching positions, and teacher

qualifications vary substantially across regions and school districts (called “divisions”

in the state) within Virginia, resulting in pockets of shortage, particularly in regions

of the state with higher rates of poverty. As we found in our prior analyses of New

York and South Dakota, the local-level distribution of qualified teachers appears to

be a less tractable problem than the overall, statewide balance between teachers and

enrollments.

To address these issues, the Virginia Department of Education has implemented

several policies to encourage more people to pursue teaching careers, to ease the

transition to certification for in-state and out-of-state educators, and to reward those

who are willing to teach in subjects with serious shortages.

Demand

The demand for K-12 teachers is comparatively strong in Virginia, especially for

teachers prepared for and willing to teach high school, English Language Learners

(ELLs), and economically disadvantaged students (EDSs). Four factors may affect the

demand for K-12 teachers in Virginia:

1. Student enrollment;

2. High-need student subgroup populations;

3. Age distribution of teachers; and

4. Teacher turnover and attrition.

Analyses of these factors suggest that the demand for public school teachers in

Virginia will continue to grow in coming years.

However, despite the

increase in teacher

candidates, the state has

reported a high proportion

of vacancies in teacher

positions.

5

Student Enrollment

The number of K-12 students in Virginia’s schools has increased steadily over the

past two decades, and at a rate greater than that for the entire US. Between 2000 to

2015, Virginia’s total public elementary and secondary school enrollment grew by 12.1

percent, compared to 6.9 percent growth nationwide, with forecasted regular growth

projected through 2027.

7

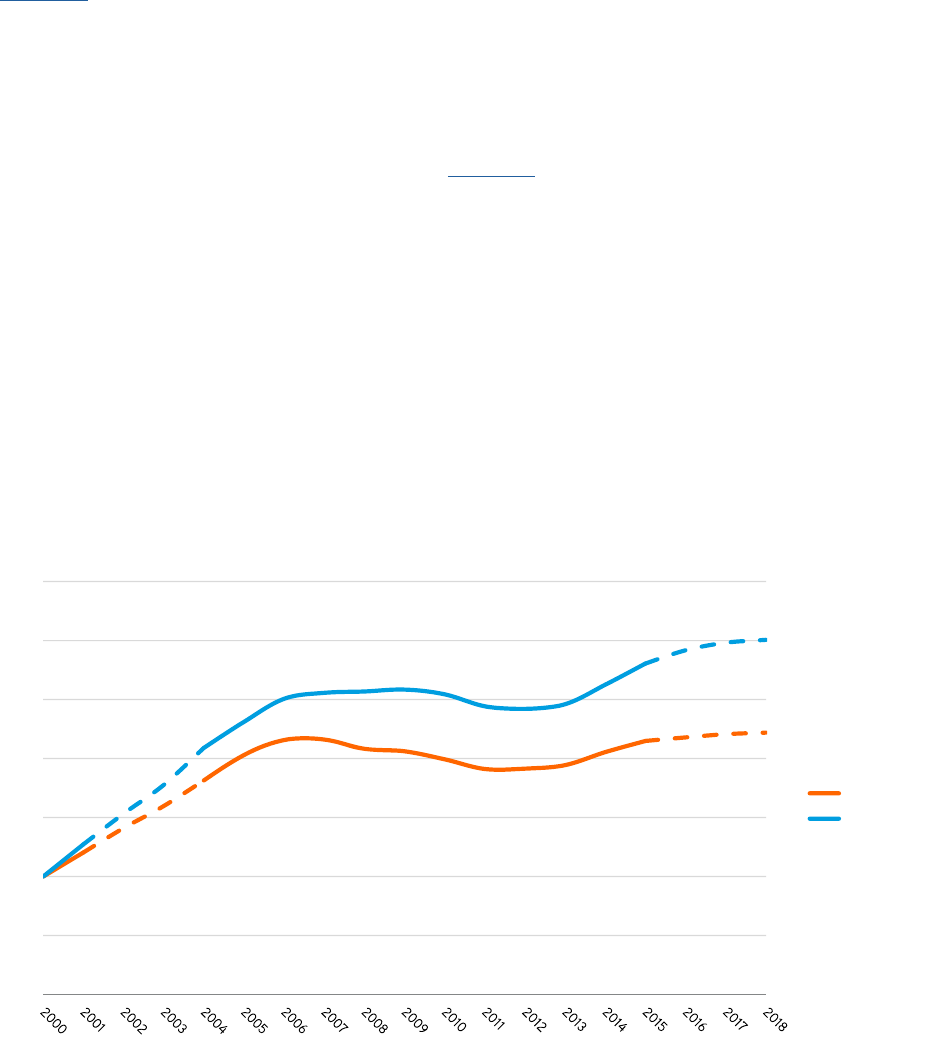

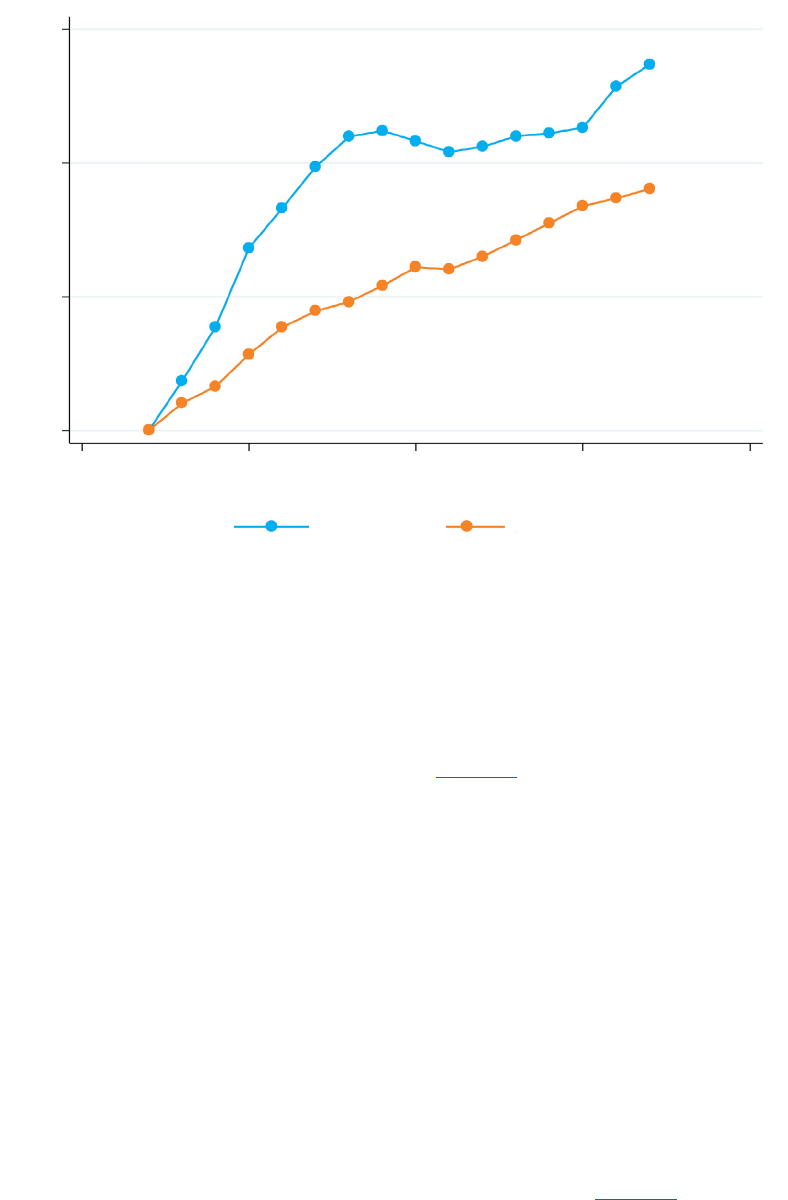

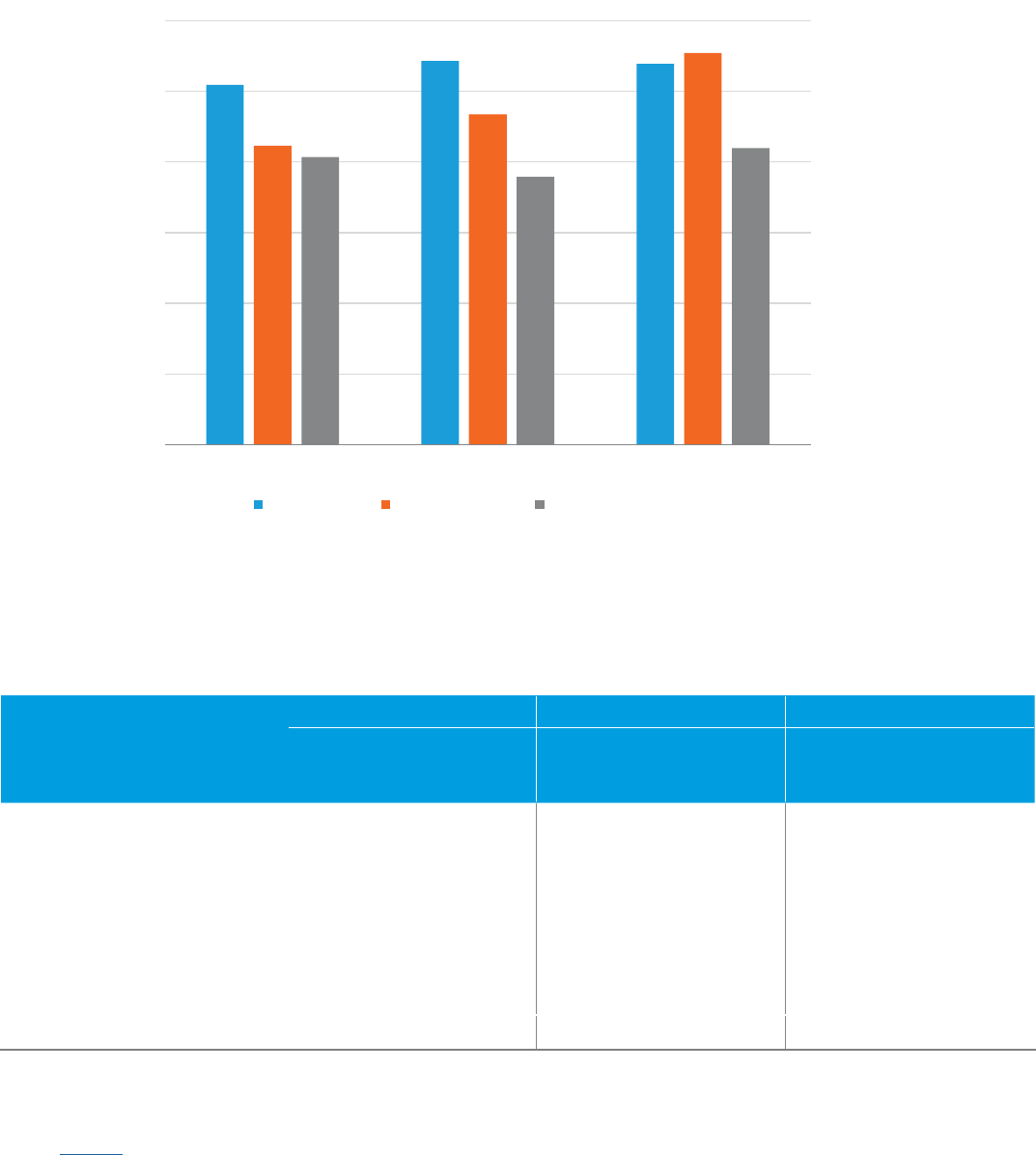

Virginia’s expansion in student enrollment was most striking in its high schools. As

Figure 1A shows, enrollment in grades 9 through 12 increased by 20 percent between

2000 and 2018 (estimated), much greater than the nationwide growth rate of 12

percent. Virginia’s enrollment also increased faster than the nation’s for younger

students — from prekindergarten through eighth grade — but the growth rates were

substantially lower. The Commonwealth’s increase in pre-K through eighth grade

enrollment was about 11 percent between 2000 and 2018 (again, estimated), while for

the US the increase was slightly over 5 percent (Figure 1B). The strong growth in high

school enrollment may reflect not only population changes but also improvements in

Virginia’s high school retention and completion rates. The four-year cohort graduation

rate in the state grew from 82.1 percent in 2008 to 91.2 percent in 2017.

8

The state’s public elementary and secondary school enrollment is expected to continue

to increase, though at a slower rate. The National Center for Education Statistics

projects that enrollment in Virginia will grow 3.3 percent between the fall of 2016 and

the fall of 2027, similar to the US growth rate of 3.2 percent over the same period.

9

FIGURE 1A. Public School Student Enrollment Trends Grades Nine through Twelve:

Percent Compared to Enrollment in 2000

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

125

United States

Virginia

6

DATA SOURCE: Digest of Education Statistics, National Center for Education Statistics, 2016.

NOTE. Enrollment values imputed for 2001-03, forecasted for 2015-18; enrollment numbers scaled as comparisons to

baseline state/national enrollment in 2000.

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

125

United States

Virginia

FIGURE 1B. Public School Student Enrollment Trends Pre-K through Eighth Grade:

Percent Compared to Enrollment in 2000

Falls Church and Arlington Counties

GREW BY OVER

15 percent

between 2010 and 2017

Loudoun County

INCREASED BY

26.8 percent

Central

Eastern

Ham

p

ton Roads

Northern

Southside

Southwest

Valle

y

West Central

Virginia's Eight Regions

Arlington

Falls Church

Loudoun

61 out of 133 counties

saw population

DECLINE

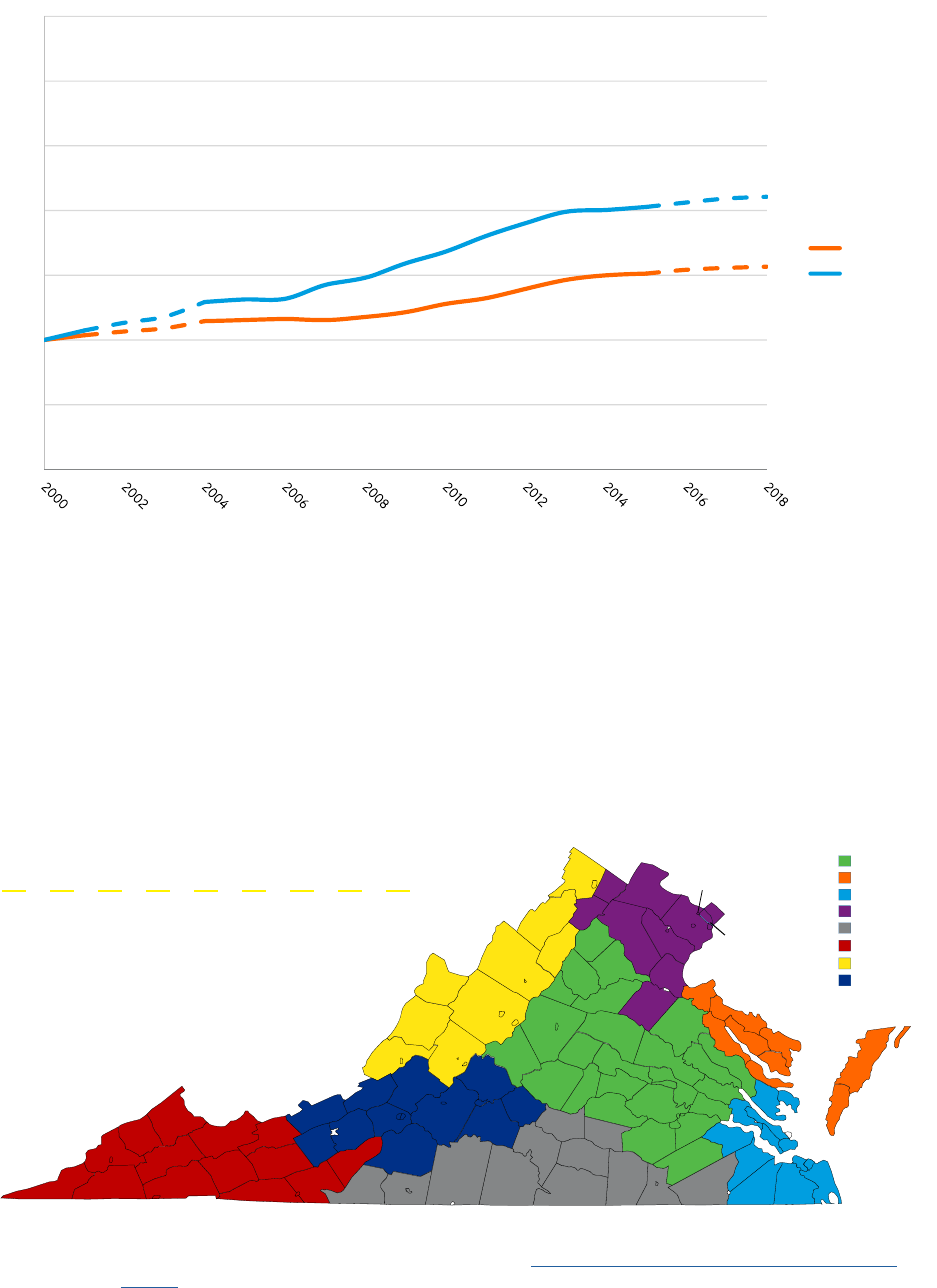

FIGURE 2. Virginia’s Uneven Population Growth

DATA SOURCE: University of Virginia, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Demographic Research Group, “Virginia’s

Demographic Regions,” accessed November 16, 2018, https://demographics.coopercenter.org/virginia-

regions.

7

Population growth, however, has been quite uneven

across the Commonwealth. It has been vigorous in the

Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads regions — where the

population counts of Falls Church and Arlington counties

all grew by over 15 percent between 2010 and 2017 — and

Loudoun County, which increased its population by 26.8

percent.

10

In contrast, most Virginia counties experienced

population changes of a much smaller magnitude, and

many (61 counties out of 133) saw population declines.

Special Education and ELL Students

The demand for teachers is also affected by the

characteristics of students. Of particular interest are the

changing numbers of special education, English Language

Learner (ELL), and economically disadvantaged students.

These pupils may require supplemental educational

resources and, in the case of special education and ELL

students, also require specially trained instructors.

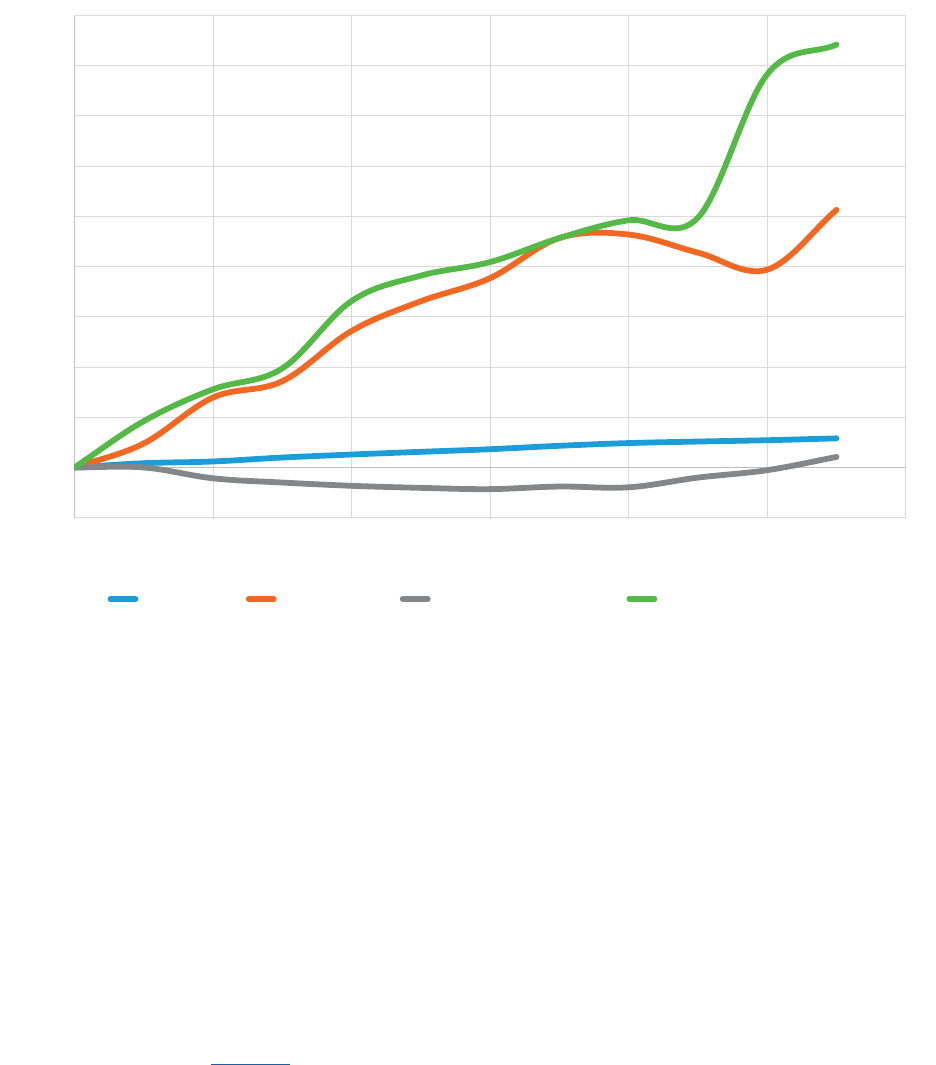

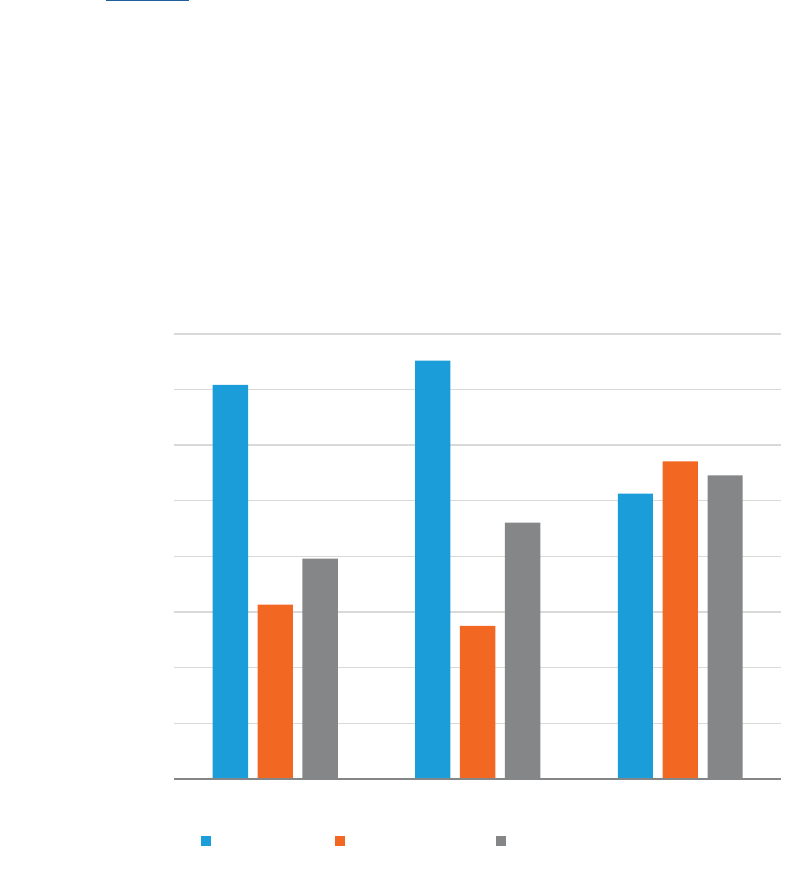

By comparison to the moderately strong upward trend in total student enrollment

increases in Virginia, the number of students who are economically disadvantaged

or English Language Learners have increased astronomically. As Figure 3 shows,

economically disadvantaged students increased in enrollment from 350,095 to 529,684

between 2007 and 2018 — or from 28.7 to 40.0 percent of the total student population.

The number of ELL students increased from 86,390 to 159,126 — or from 7.1 percent to

12.3 percent of the total student population. This rapid growth in student populations

requiring specialized instruction or greater resources may place additional demands

on the teacher workforce in the state.

For the last thirteen years, the Virginia Department of Education has identified special

education as the subject area with the most critical shortage for teachers.

11

However,

as Figure 3 indicates, the number of students with disabilities decreased over the

period 2007 to 2015 and only rose modestly after 2015. The shortage of special

education teachers becomes even more puzzling as we note below (in Table 1) that

there has been an increase in recent years in the number of graduates from Virginia

teacher education programs with preparation in special education. We return to this

puzzle later in this report.

By comparison to the

moderately strong upward

trend in total student

enrollment increases

in Virginia, the number

of students who are

economically disadvantaged

or English Language

Learners have increased

astronomically.

8

Teacher Turnover and Attrition

Heightened rates of teacher turnover or attrition can also boost demand for new

teachers and generate shortages. A 2017 report by Virginia’s Advisory Committee

on Teacher Shortages found that average teacher turnover among the state’s public

schools was 10.2 percent between the 2015-16 and 2016-17 school years — a rate

significantly higher than the national average of 8 percent.

12

The gap between Virginia and US turnover rates suggests the possibility of state-

specific factors pushing up attrition. If that is the case, one contributing factor may

be Virginia’s currently older teaching workforce. The 2011-12 Schools and Staffing

Survey determined the median age of Virginia’s teachers as 43.2 years, compared to

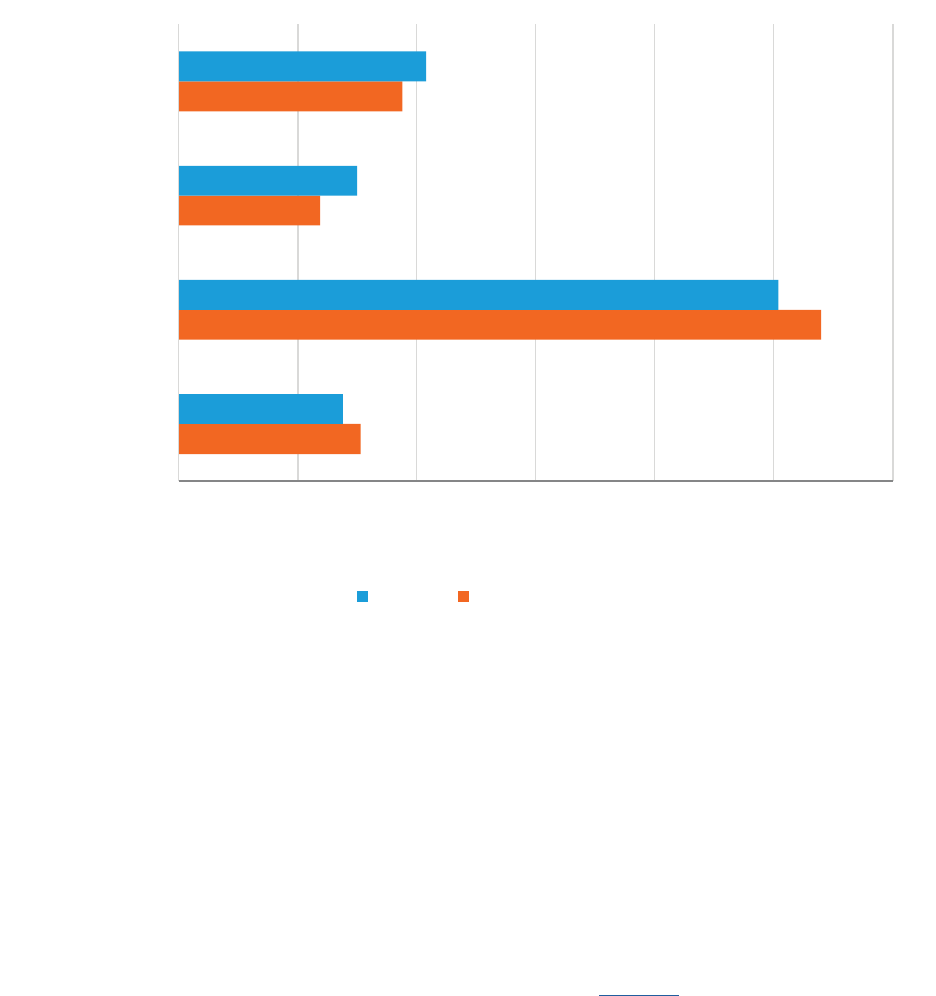

41.0 years in the US.

13

Figure 4, based on the survey data, shows that the percentage

of teachers over fifty years of age is relatively high in Virginia, suggesting that a larger

proportion of Virginia teachers are nearing retirement. Nonetheless, the magnitude of

the “graying” of the workforce as part of overall attrition is unclear. Retirement is one

of the three most frequently cited reasons for teacher attrition, comprising about 31

percent, but it is no greater than changing careers (31 percent) and less common than

“personal or life” reasons (43 percent).

14

School staffing problems, which, as we note

below, may be concentrated in certain parts of the state, are much more likely to be

related to turnover than to teacher retirements.

15

FIGURE 3. Percent Change in Enrollment since 2007 for Student Population Subgroups

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Percent Change in Total Enrollment of Group

Academic Year

All Students Disadvantaged Students with Disabilities English Language Learner

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “Fall Membership Reports, 2007-2018” and “VDOE Special

Education Child Count Reports 2007-2018.”

9

Supply

Some evidence suggests that Virginia has an ample supply of teachers, at least in

comparison to other states. We consider three factors related to the supply of Pre-K-12

teachers in Virginia public schools: (1) the number of full-time teachers; (2) teacher

preparation program graduates; and (3) out-of-state teachers.

Number of Teachers

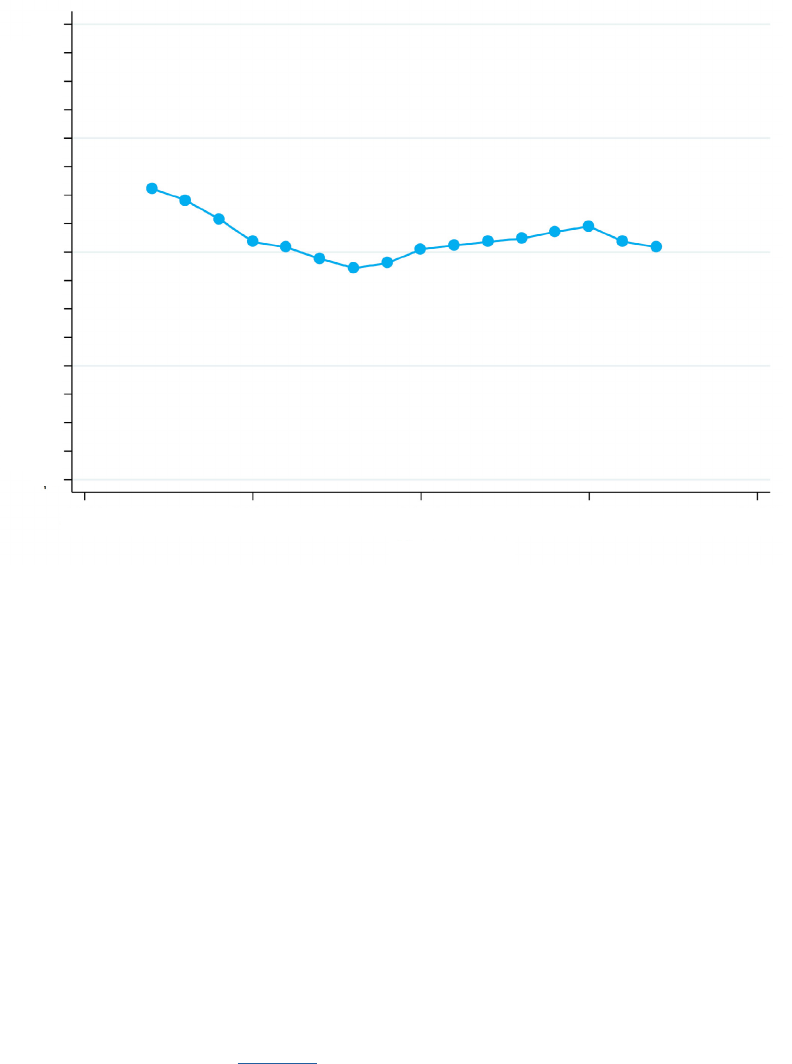

The number of teachers has grown statewide in recent years. Figure 5 shows that

while the number of teachers stalled between 2008 and 2015, the aggregate workforce

grew before the recession as well as after 2015. Following the economic recession,

Virginia lawmakers changed the state’s Standard of Quality (SOQ) state aid formula in

a way that made it difficult for local districts to maintain prerecession-level education

funding.

16

Despite the seven-year pause in growth, however, the statewide increase

in the number of teachers since 2002 has been greater than the increase in student

enrollment.

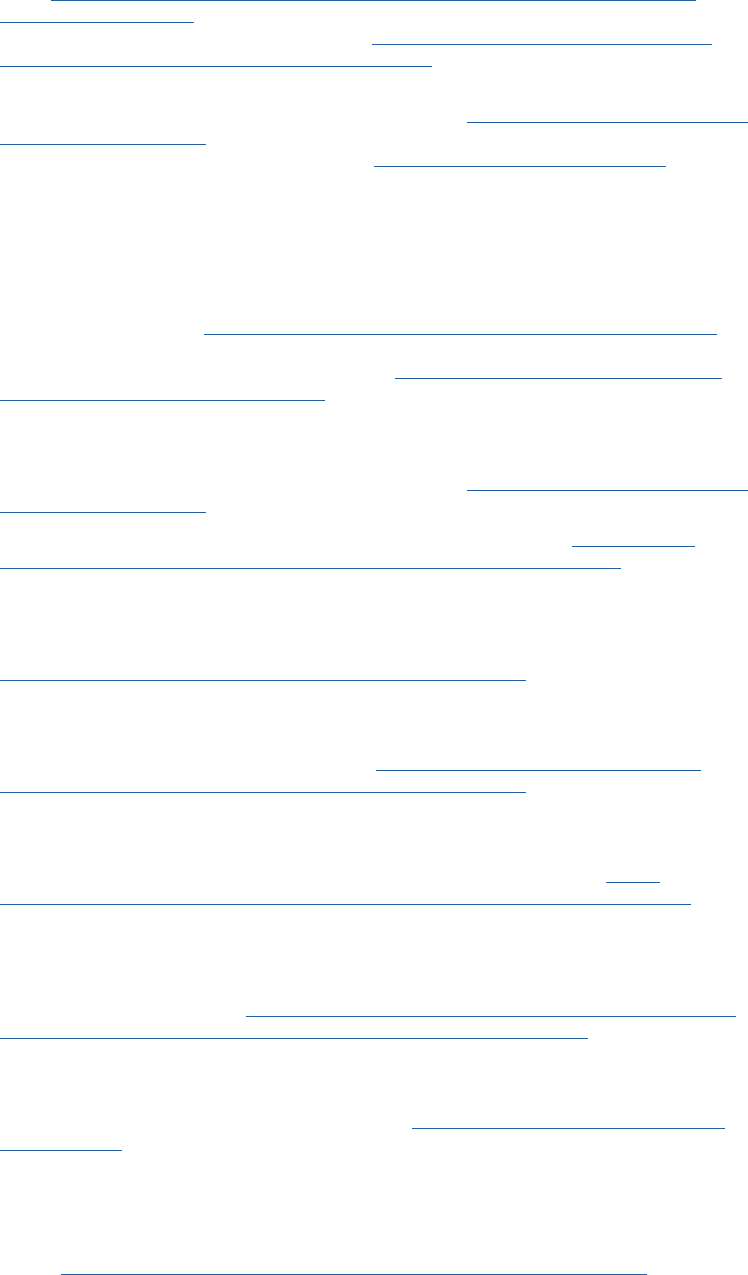

FIGURE 4. Percent of Teacher Workforce by Age Group, Virginia Compared to US

0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0 40.0 50.0 60.0

Less than

30 years

30–49 years

50–54 years

55 years or more

Percent of Teachers

Virginia United States

DATA SOURCE: Public School Teacher File, 2012, from the Schools and Staffing Survey, NCES.

10

One result of the growth in the total number of teachers in Virginia is a decline in the

average student-teacher ratio in the state. As Figure 6 shows, the student-teacher

ratio has varied little in recent years — from a high of 12.6 in 2002 to just over 11.8

in 2008. Except for the postrecession increases between 2008 and 2015, the overall

trend has been a reduction, down to just over 12.0 in 2016.

One noteworthy countervailing trend over this time period

has been the large reduction in the number of support

positions in schools. Since the budgetary cuts associated

with the economic recession (between the 2008-09

and 2016-17 school years), the state has lost a total of

2,524 support staff in schools.

17

This loss stems primarily

from a change in the Virginia Standards of Quality (SOQ)

funding formula in 2009, which capped the number

of state-funded support positions to one for each 4.03

instructional positions (where instructional positions

included guidance counselors and librarians, as described in Figure 6).

18

Support

positions are defined broadly to include positions in areas such as technology; pupil

transportation; operation and maintenance; professional development; attendance and

health; administration; and superintendent, school board, and school nurse positions.

19

One noteworthy

countervailing trend over

this time period has been

the large reduction in the

number of support positions

in schools.

Year

FIGURE 5. Growth in Teacher Counts and Student Enrollment from 2002 to 2016

DATA SOURCE: “Superintendent’s Annual Reports: 2002-17,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), Tables 2 and 17.

NOTE: For the values in this figure, the number of teachers is calculated as the sum of elementary teachers, secondary

teachers, guidance counselors, and librarians in order to be consistent across the entire time period.

2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

0 5 10 15

Percent Change Since 2002

Year

Teachers

Students

11

Teacher Preparation Pipeline

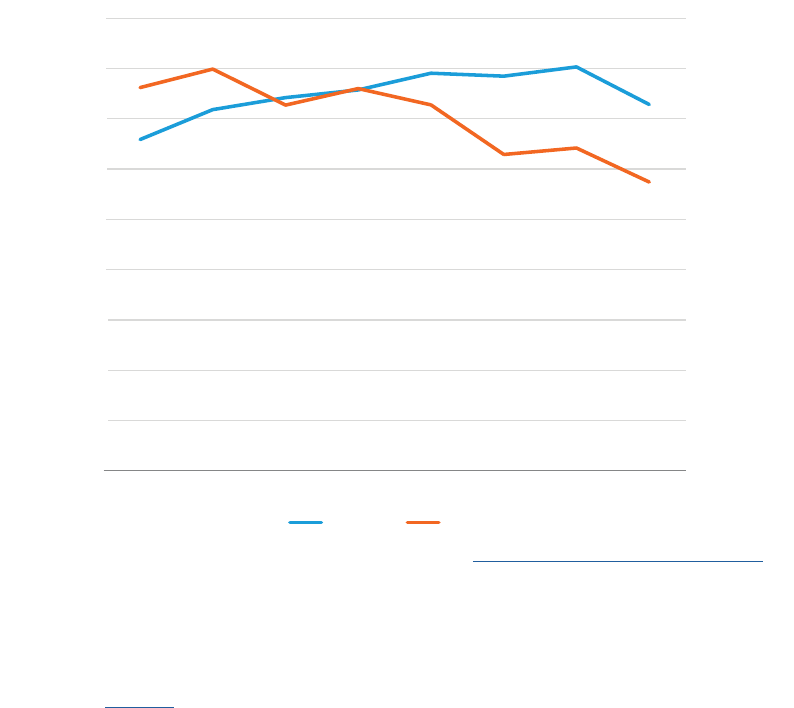

Another indicator of the supply of teachers to schools

in Virginia is the number of graduates from the state’s

teacher education programs. The state has forty

providers, including thirty-six traditional programs

in higher education institutions, plus four alternative

programs.

20

Unlike forty-five other states, which have

experienced declines in the number of graduates from

teacher education programs, Virginia has seen growth

between 2009 and 2016 (Figure 7). The growth has not

been consistent; most of the increase occurred before

2013, and a significant decline occurred between the

2015 and 2016 school years. Also, enrollment in teacher

preparation programs in Virginia declined over the same

period, perhaps auguring future declines in graduates.

Nonetheless, Virginia’s teacher education programs have, for the most part, provided

a steady supply of potential teachers — a distinctive strength in comparison to other

states in recent years.

Unlike forty-five other states,

which have experienced

declines in the number of

graduates from teacher

education programs, Virginia

has seen growth between

2009 and 2016

FIGURE 6. Adjusted Pupil-Teacher Ratio from 2002 to 2016

DATA SOURCE: “Superintendent’s Annual Reports: 2002-17,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE),

Tables 2 and 17.

NOTE: In this figure, the number of teachers underlying the ratio is calculated as the sum of elementary

teachers, secondary teachers, guidance counselors, and librarians to be consistent across the

entire time period. This pupil-to-teacher ratio is therefore lower in each year than it would be if

guidance counselors and librarians were not included.

2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Year

10 11 12 13 14

Pupil-to-Teacher Ratio

12

Although growth in the number of graduates has been widespread among different

subject area specializations, there are some large differences among specialization

areas. As Table 1 demonstrates, the greatest increases in the subject areas of

graduates between 2011 and 2015 occurred in the areas of special education, social

studies/history/social science, physical education/health, and secondary education.

The number of graduates prepared to teach ELL, Bilingual, and Multilingual subjects,

as well as middle school or junior high grades, also grew vigorously during this period.

In contrast, graduates prepared to teach science, elementary education, music and the

arts, and career and technical education increased only slightly between 2011 and

2015, and the number ready to teach foreign languages, mathematics, and English saw

declines.

Out-of-State Teachers

Virginia’s supply of teachers may benefit from the fact that the Commonwealth offers

an open system for teachers and graduates of teacher education programs from other

states. An individual coming into Virginia from any state may qualify for a Virginia

teaching license with comparable endorsement areas if the individual has completed

a teacher preparation program through a regionally accredited four-year college

or university approved by the sending state. Based on data collected by the U.S.

Department of Education, 60 percent of persons receiving an initial teaching credential

in Virginia in 2012-13 were prepared by an out-of-state teacher education program.

21

FIGURE 7. Trends in the Numbers of Graduates and Enrollment in Teacher Preparation

Programs in Viriginia, 2008 to 2016

-

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

-

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

4,500

2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16

Enrollment

Graduates

Graduates Enrollment

DATA SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, Title II Reports, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/Home.aspx.

Graduates

Enrollment

Graduates

Enrollment

4,500

4,000

3,500

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16

13

Also, licensure “by reciprocity” is provided for individuals who have obtained a valid

out-of-state license. Individuals who hold a valid out-of-state licenses, and who have

completed a minimum of three years of full-time, successful teaching experience in

a state other than Virginia, are exempted from the professional teacher’s assessment

requirements.

22

TABLE 1. Subject of Graduates of Teacher Education Programs in Virginia, 2011-15

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

%

Change

Elementary Education 1,474 1,481 1,445 1,572 1,505 2.1%

Special Education 465 537 621 587 669 43.9%

English, Language Arts, Reading, Speech 448 370 444 412 412 -8.0%

Other 367 188 159 380 477 30.0%

Social Studies, Social Sciences, History 305 378 477 495 480 57.4%

Music, Art, Drama, Dance 244 229 237 230 257 5.3%

Physical Education, Coaching, Health 222 292 280 288 345 55.4%

Mathematics 179 200 216 213 166 -7.3%

Junior High, Middle School Education 163 153 147 136 215 31.9%

Secondary Education 155 352 450 330 437 181.9%

Science 135 147 174 179 160 18.5%

ESL, Bilingual, Multilingual 105 64 127 111 137 30.5%

Foreign Languages 91 88 96 107 79 -13.2%

Technical, Occupational, Business 91 75 61 90 97 6.6%

Early Childhood Education 75 91 179 84 199 165.3%

General 59 0 17 0 201 240.7%

Total 4,578 4,645 5,130 5,214 5,836 27.5%

DATA SOURCE: “Title II Teacher Preparation Reports, 2012-16, U.S. Department of Education.

NOTE: Each cell refers to the number of graduates prepared in each of the listed subjects. However, a graduate may be

prepared to teach in more than one subject. Therefore, the total row may be larger than the total number of teacher

graduates. The “other” category is reported when teacher preparation program subject areas do not fit neatly into any

other subject categories. Some frequently reported “other” programs include: library, media, marketing, journalism,

and gifted education.

14

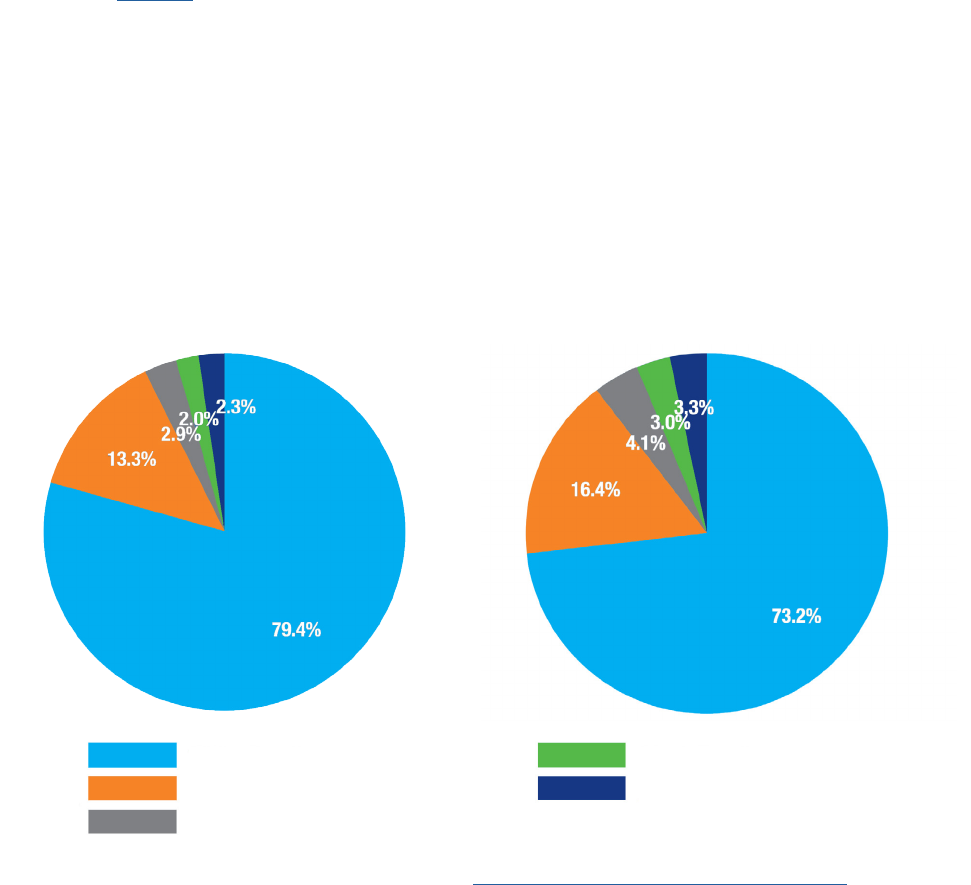

Diversity of Teachers

Virginia, like most other states (including the Rockefeller Institute’s analysis in South

Dakota and New York), faces the challenge of lacking a teacher workforce that fully

represents the racial diversity of students enrolled in public schools. In fact, as of

the 2015-16 school year, only 50.5 percent of students are non-Hispanic white; 22.9

percent are non-Hispanic black; 14.4 percent are of Hispanic origin; and the remaining

12.2 percent are of other race or multiple races.

23

Although Virginia does not provide publicly available data on the racial, ethnic, or

gender composition of its teachers, data from federal Title II reports on the enrollment

in teacher preparation programs offers a clue to such information. The breakdown is

presented in Figure 8. Hispanic enrollees increased from 13.3 percent of all enrollees in

2012 to 16.4 percent in 2016; black students increased their share in teacher preparation

programs from 2.9 to 4.1 percent; and white, non-Hispanic students declined over this

four-year period from 79.4 percent of all enrollees to 73.2 percent. These are hardly

large changes, though they do show that teacher preparation programs in Virginia

are serving a somewhat more diverse population — a change that, if sustained, may

eventually lead to a more diverse teacher workforce in the state.

FIGURE 8. Racial Diversity of Teacher Preparation Program Enrolled Students in 2012 and 2016

2012

2016

DATA SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, Title II Reports, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/DataTools/Tables.aspx.

White Enrollment

Hispanic Enrollment

Other Race/Ethnicity Enrollment

Black Enrollment

Asian Enrollment

15

Intrastate Differences: Poverty and Rural

Communities

Despite Virginia’s growth in its statewide teacher

workforce and the increase in graduates from the state’s

teacher education programs, there are signs of teacher

shortages in parts of the state. Challenges in balancing

teacher demand and supply may be revealed in several

ways: by vacancies in teaching positions, rates of

teacher turnover, indicators of teacher quality or fit with

their positions, and student-teacher ratios. All of these

measures show considerable variation across different

communities.

One indicator of shortage is the percentage of schools

with unfilled teaching positions. Vacancies are relatively

uncommon; only 1.1 percent of positions were unfilled

one month into the 2016-17 school year in Virginia. But a

report by the Virginia Department of Education revealed enormous differences across

divisions, with the highest rates of unfilled positions found among divisions with high

concentrations of poverty.

24

The most recent federal survey data, conducted for the

2011-12 school year, measured vacancies in another way — the percentage of schools

with any vacancies — and also found large local differences. The highest proportion

of schools with vacancies occurred among rural schools: 85.6 percent of Virginia’s

rural schools reported vacancies, compared to 72.4 in urban schools and 64.7 percent

in suburban areas.

Teacher turnover rates, which can affect demand, also

varied enormously across localities. Ten of Virginia’s

divisions had turnover rates between 23.7 and 31.1 percent,

between two and three times the average statewide rate

of 10.2 percent in 2016-17.

25

Like vacancies, the high

rates were typically found in rural divisions, largely in

the Southside, Central, and Eastern regions of the state.

However, turnover was also high in Falls Church City, a

wealthy and fast-growing division in the Northern region.

An imbalance between the supply and demand for

teachers may also be revealed by indicators of teacher

quality. One such indicator is whether a teacher has a provisional license. Provisional

licenses generally indicate less experienced and educationally qualified teachers.

26

A

high rate of teachers with provisional licenses may indicate challenges for a school or

district in recruiting and retaining strong teachers. Figure 9 shows differences in the

percentage of teachers with provisional licenses in the 2015-16 school year, averaged

across divisions, by characteristics of the communities served. The divisions are

classified into nine categories, distinguished by student poverty rates and community

type (urban, rural, and suburban/town).

27

The highest proportion of

schools with vacancies

occurred among rural

schools: 85.6 percent of

Virginia’s rural schools

reported vacancies,

compared to 72.4 in urban

schools and 64.7 percent in

suburban areas.

Ten of Virginia’s divisions

had turnover rates between

23.7 and 31.1 percent,

between two and three

times the average statewide

rate of 10.2 percent in

2016-17.

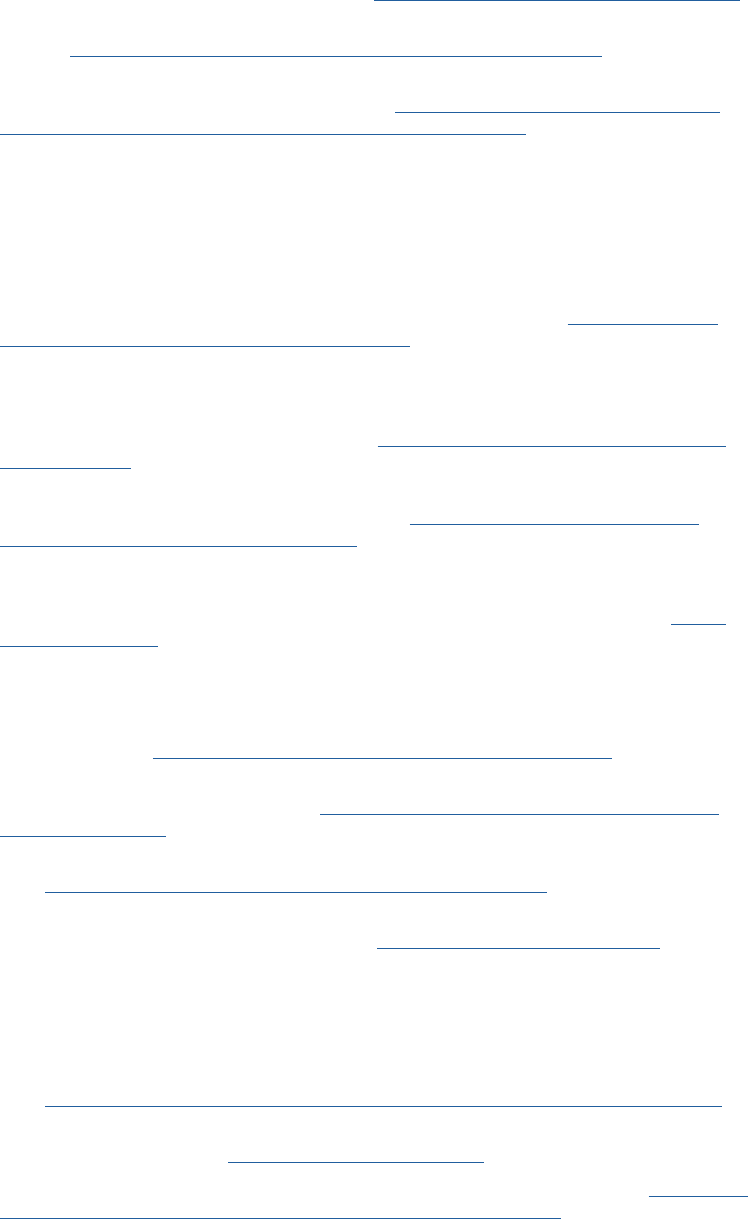

16

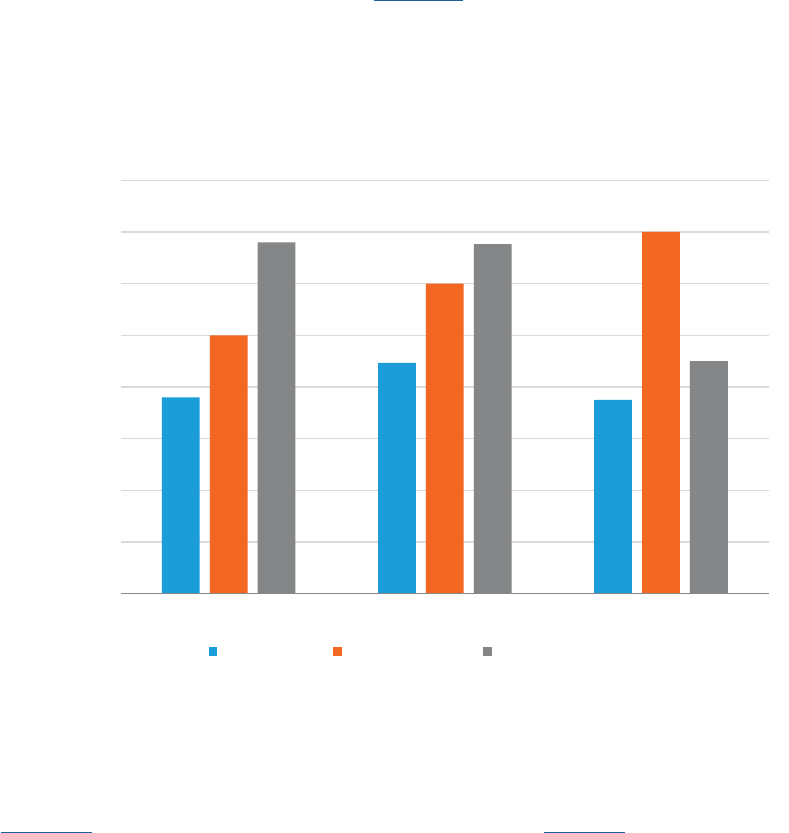

The highest average percentages of teachers without

full licenses are found among high-poverty divisions

in Virginia’s rural and suburban/town areas; nearly 7

percent of teachers, on average, had provisional licenses.

Teachers with provisional licenses were also relatively

common among divisions with medium-poverty rates,

while low-poverty divisions had the fewest teachers with

such licenses. Poverty rates among students thus showed

the strongest and most consistent association with high

rates of teachers with provisional licenses.

Another signal of difficulties in hiring and retaining strong

teachers is the percentage of core academic courses

taught by teachers who are not “highly qualified.” Highly qualified teachers must have

a bachelor’s degree and full state certification or licensure, and they must demonstrate

that they know each subject they teach.

28

Figure 10 shows the percent of core academic

classes (English, math, science, and social studies) taught by teachers who were not

highly qualified, compared again across districts in different communities and with

different student poverty rates.

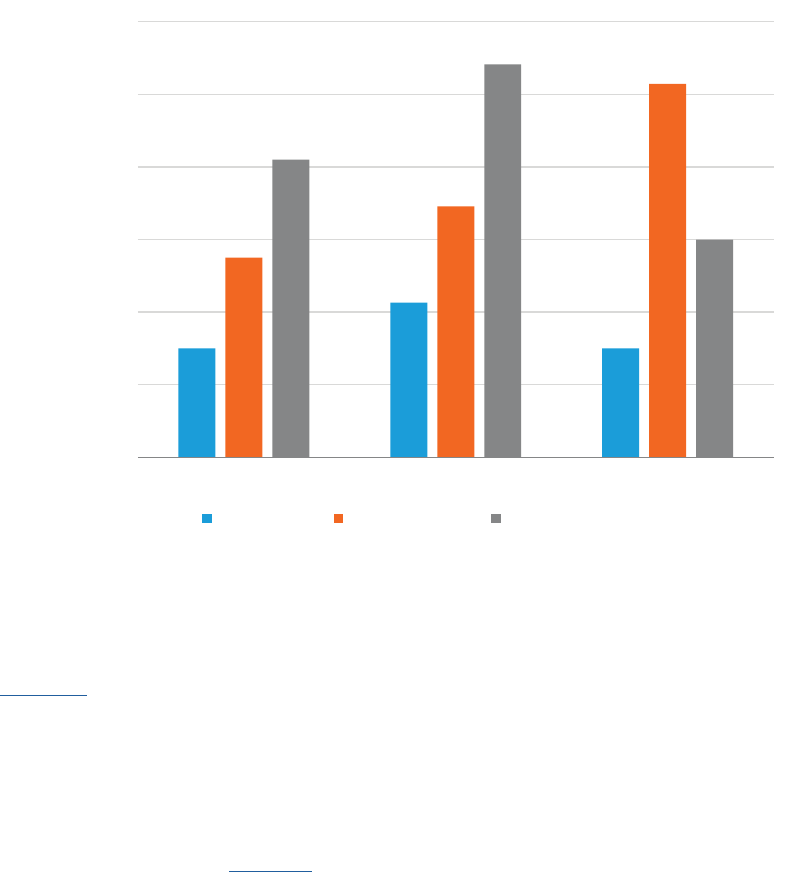

Figure 10 shows a pattern similar to that displayed in Figure 9. Again, divisions

with higher rates of lower-income students had relatively high percentages of core

academic courses taught by teachers who were not “highly qualified.” Divisions with

The highest average

percentages of teachers

without full licenses

are found among high-

poverty divisions in

Virginia’s rural and

suburban/town areas ...

FIGURE 9. Percent of Teachers with Provisional Licenses by Division Type, 2015-16

0.00

1.00

2.00

3.00

4.00

5.00

6.00

7.00

8.00

Rural Suburb/Town Urban

Average Percent of Teachers with Provisional

Licenses (%)

Low Poverty Medium Poverty High Poverty

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “School Quality Profile data, 2015-16”;

National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD)

district survey.”

17

the lowest poverty rates — whether in rural, suburban, or urban areas — all had low

percentages of courses taught by less qualified teachers, typically less than 1 percent.

The one exception to the pattern is found among the urban divisions. Medium-poverty

divisions showed higher rates of courses taught by less qualified teachers than high-

poverty divisions, but both indicated workforce difficulties greater than low-poverty

divisions.

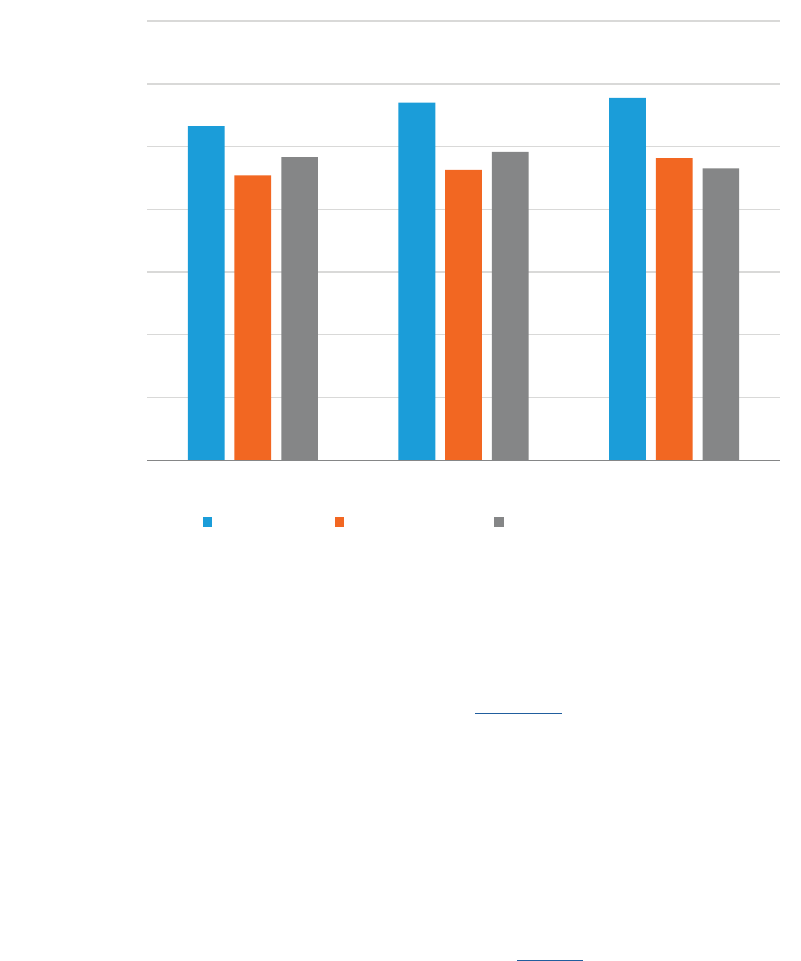

Figure 11 shows one more possible indicator of teacher quality across different

communities — the average percentage of teachers with masters or doctoral degrees.

Although the research does not consistently indicate that teachers that have masters

or doctoral degrees are more likely to be effective in terms of student learning, high

rates of advanced degrees may indicate that a district or school can select teachers

from a stronger pool of candidates. The averages across districts serving different

types of communities in Figure 11 show that, in Virginia, the differences across types

of divisions are, on average, small. Nonetheless, the low-poverty divisions consistently

report slightly higher percentages of teachers with advanced degrees, while there are

no consistent differences across rural, suburban, and urban divisions.

FIGURE 10. Percent of Core Academic Classes Taught by Teachers Not Highly Qualified by

Division Type, 2015-16

-

0.50

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

3.00

Rural Suburb/Town Urban

Average Percent of Core Academic Classes

Taught by Teachers Not Highly Qualified

Low Poverty Medium Poverty High Poverty

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “School Quality Profile data, 2015-2016”;

National Center of Education Statistics (NCES), “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD)

district survey.”

18

In one respect, poverty and ruralness are not negatively associated with a measure of

the local-level adequacy of the teacher workforce. Figure 12 shows the relationships

between the types of communities that districts serve and the average student-

teacher ratios for grades K-7. Urban divisions have somewhat higher student-teacher

ratios, as do low-poverty divisions in rural, suburban, and urban areas. However,

the differences are not great, generally about one student per teacher or less. The

weaknesses in high-poverty divisions in recruiting teachers are thus found not in the

numbers of teachers on staff, but rather in their qualifications.

The differences across these categories of divisions are also associated with other

student characteristics, including race and ethnicity. As Table 2 shows, rural divisions

have the highest proportions of white and the fewest Hispanic students. Urban divisions

generally have greater percentages of black and Hispanic students, while suburban/

town divisions have a racial and ethnic composition that lies between urban and rural

areas. Student poverty rates in Virginia are not consistently correlated with race or

ethnicity. In urban areas, greater percentages of black and Hispanic students are

found in the low-poverty divisions, while the opposite pattern for minority students is

evident in rural areas. The proportion of students who are English Language Learners

tends to follow the distribution of Hispanic students, while the percentage of students

with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) is somewhat lower in low-poverty districts.

FIGURE 11. Average Percent of Teachers with Masters or Doctoral Degrees by Division Type,

2015-16

-

10.00

20.00

30.00

40.00

50.00

60.00

70.00

Rural Suburb/Town Urban

Average Percent of teachers with either advanced

degrees (masters or doctoral) (%)

Low Poverty Medium Poverty High Poverty

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “School Quality Profile data, 2015-2016”;

National Center of Education Statistics (NCES), “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD)

district survey.”

19

Table 2 also shows the distribution of students across these nine categories and recent

changes in enrollment. These patterns have implications for where teachers may be

most needed in Virginia. It is clear that rural enrollment is declining, while most of

the current students (as well as recent enrollment growth) are found in suburban/

FIGURE 12. Average Student-to-Teacher Ratio (Grade K-7) by Division Type

8.00

9.00

10.00

11.00

12.00

13.00

14.00

Rural Suburb/Town Urban

Average Student-teacher ratio (K-7) (%)

Low Poverty Medium Poverty High Poverty

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “School Quality Profile data, 2015-2016”;

National Center of Education Statistics (NCES), “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD)

district survey.”

TABLE 2. Average Student Characteristics by Division Type

Rural Suburban/Town Urban

Student Characteristic

Low

Poverty

Medium

Poverty

High

Poverty

Low

Poverty

Medium

Poverty

High

Poverty

Low

Poverty

Medium

Poverty

High

Poverty

% White 76.5 74.2 72.5 64.8 62.0 72.0 42.5 47.7 64.6

% Black 17.8 20.4 23.1 27.5 19.4 19.3 44.1 33.8 25.4

% Hispanic 5.7 5.4 4.4 7.6 18.6 8.7 13.4 18.5 10.0

% ELL 2.3 2.2 1.6 3.9 9.5 4.2 8.9 13.8 4.8

% With IEP 13.3 13.4 13.9 12.4 14.1 13.1 13.8 13.2 12.3

Enrollment, thousands (2015) 70.1 96.8 93.7 359.8 145.5 230.3 91.8 150.3 45.2

% Change in enrollment, 2010-15 -2.8 -2.1 -2.3 3.6 6.9 5.8 2.1 1.4 0.9

DATA SOURCE: National Center of Education Statistics (NCES), “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD) district-level survey data.”

20

town divisions. In particular, suburban/town school

divisions with medium- and high-poverty rates have seen

the largest increases in K-12 enrollment. Assuming these

trends continue, and holding everything else constant, it

is possible that a disproportionate number of teachers

will be needed in economically struggling suburban/town

regions within the state.

In sum, divisions with greater poverty rates, indicated by

the proportion of students eligible for free lunch within a

division, are more likely to have teachers with provisional

licenses, are more likely to have core academic classes

taught by teachers not highly qualified for those subjects,

and are somewhat less likely to have teachers with

masters or doctoral degrees. The student-teacher ratios

in high-poverty divisions tend to be lower, though there

is not much variation among divisions on this measure

within Virginia. Unlike the patterns in many other states,

these differences are not clearly associated with the

distribution of black and Hispanic students. In Virginia,

gaps in teacher quality thus seem most consistently

associated with economic disadvantage rather than race

or ethnicity.

Subject Area Differences

In addition to differences across localities in teacher demand and supply patterns,

differences also exist in the labor market for teachers in their areas of specialization.

Based on school data from 2015, the Virginia Department of Education identified

the top ten critical shortage teaching endorsement areas in the state.

29

These areas

were identified based on: (a) total number of teaching positions that were unfilled; (b)

teaching positions that were filled by provisionally licensed teachers; and (c) teaching

positions that were filled by teachers who are licensed, but who are teaching in

academic subject areas other than their area of preparation.

The ten top subject areas of teacher shortage in 2015, ranked from the most to the less

severe areas, were:

1. Special education;

2. Childhood and elementary education, Pre-K-6;

3. Middle education, grades 6-8;

4. Career and technical education;

5. Mathematics, grades 6-12 (including Algebra 1);

6. School counselor, Pre-K-12;

7. English (secondary);

Divisions with greater

poverty rates, indicated by

the proportion of students

eligible for free lunch within

a division, are more likely

to have teachers with

provisional licenses, are

more likely to have core

academic classes taught by

teachers not highly qualified

for those subjects, and are

somewhat less likely to have

teachers with masters or

doctoral degrees.

21

8. Foreign languages, Pre-K-12;

9. Health and physical education, Pre-K-12

10. History and social science (secondary)

30

When these rankings are compared to the teacher preparation pipeline (Table 1) and

changes in student characteristics (Figure 3), some puzzles arise. One involves

special education. There has been a large increase in the number of graduates from

teacher preparation programs with endorsements in special education; the total

number of special educators in Virginia has remained relatively steady since 2011; and

the percentage of “qualified” special educators has increased. At the same time, there

has been little growth in the number of students with disabilities. Why then has it been

so difficult to fill special education positions?

Although we do not have the data to fully explain these discrepancies, one hypothesis

is that the shortage is due to a lack of teachers with specializations appropriate to the

specific needs of disabled students. For example, at the national level, the student-

teacher ratio of special education teachers has swelled, while the number of students

with learning disabilities, one of the milder forms of disability, has declined.

31

It is

possible that special education teachers are now expected to serve not only more

students but also those with comparatively severe disabilities, such as autism spectrum

disorder. Whether the graduates with some special education preparation are in fact

ready to teach a changing profile of students is a critical question, perhaps partly

answered by the fact that fully one-third of the teachers with provisional licenses in

Virginia are teaching special education.

32

Most of the other comparisons between trends in teacher preparation programs and

the state’s estimates of shortages by subject area are less puzzling. Elementary

education teachers are in short supply according to the state’s measures, and it is true

that graduates with such certifications have barely increased in recent years (Figure

7). Also, mathematics positions are not easy to fill — findings consistent with the 7.3

percent decline in graduates with that specialization between 2011 and 2015. Some

comparisons, however, are not readily reconciled. Middle education, grades 6 to 8, is

an area where shortages exist, yet graduates from teacher education programs with

that preparation have grown by nearly a third between 2011 and 2015. Of course, it can

be a slow process for yearly increases in teacher preparation program graduates to

translate into increases in teacher supply in a particular subject.

22

Combinations of Local and Subject Area Shortages

Evidence of other local-level differences in the teacher labor market and how they may

correlate with specific subject areas comes from Virginia Department of Education’s

2015 Plan to Ensure Excellent Educators for All Students, which identified five major

teacher equity gaps of concern:

33

1. School divisions with a large proportion of minority students have more first-

year teachers than low-minority school divisions.

2. School divisions with a large proportion of minority students have a greater

proportion of out-of-field mathematics teachers than low-minority school

divisions.

3. School divisions with a large proportion of low-income students have a greater

proportion of out-of-field foreign language teachers than high-income school

divisions.

4. School divisions with a large proportion of low-income students have a greater

proportion of out-of-field ELL teachers than high-income school divisions.

5. School divisions with a large proportion of low-income or minority students

have a greater proportion of out-of-field special education teachers than low-

minority, high-income school divisions.

The 2015 report suggested several possible root causes of these teacher equity

gaps: teacher preparation programs, recruitment challenges, working conditions, and

professional development.

Salaries

Teacher salaries may also contribute to teacher shortages and teacher equity gaps.

In general, Virginia’s teacher salaries are neither high nor growing, a challenge for a

state that seeks to recruit and retain teachers for a growing population of students

across a very diverse set of communities. Some facts:

• Twenty-four out of ninety-four counties experienced declines in teacher

salary, and five out of thirty-six cities experienced teacher salary declines

between 2015 and 2017.

34

• Virginia is currently ranked thirtieth out of fifty states in average teacher

salary ($50,620, compared to the national average of $57,420).

• In real dollar terms, teachers in Virginia have had their pay cut by 9 percent

since 2009 and 10 percent since 2003 (compared to a 3 percent decline

nationally).

35

• Virginia is a Right to Work state, and teachers are prohibited from collective

bargaining.

• Virginia only earned 63 percent of what similarly educated professionals

earned in nonteaching occupations.

36

23

• Compared to the six states that border Virginia, its statewide average salary

is middling: higher than the average salaries in West Virginia, Tennessee,

and North Carolina; similar to Kentucky’s; and substantially lower than those

offered in Maryland and the District of Columbia.

37

Teacher salaries are not equally distributed across divisions, though the pattern is

complex. As Figure 13 demonstrates, the average starting salaries of Virginia’s teachers

are higher in low-poverty divisions, at least in rural and suburban/town areas. In

urban areas, poverty rates of divisions are not associated with significant differences

in student poverty rates. Virginia schools receive 51 percent of their funding from local

revenues, a high percentage that limit the state’s ability to ensure equitable funding

between poor and wealthy divisions; it appears that equity is particularly challenging

outside Virginia’s cities.

38

FIGURE 13. Average Starting Salary for Teacher with Bachelor’s Degree by Division Type,

2015-16

35,000.00

36,000.00

37,000.00

38,000.00

39,000.00

40,000.00

41,000.00

42,000.00

43,000.00

Rural Suburb/Town Urban

Average Percent of Core Academic Classes

Taught by Teachers Not Highly Qualified

Low Poverty Medium Poverty High Poverty

DATA SOURCE: Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), “2015-2016 Teacher Salary Report”; National

Center of Education Statistics (NCES), “2016 Common Core of Data (CCD) district

survey.”

24

Policies/Responses to Teacher Shortages

Virginia has been working to address teacher shortage problems for nearly two

decades. In 2000, the state legislature asked the Virginia Board of Education to create

a Career Switcher program to help end the teacher shortage.

39

In this program, career

switchers can earn a one-year provisional license after completing coursework while

working full-time in their other career, and then receive ongoing support during their

first year of teaching.

The 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey by NCES reported that Virginia used a variety

of recruitment incentives for teachers.

40

The state was notable in comparison to other

states in its use of free training for district staff to prepare them to teach in current

or anticipated shortages, and for its pay incentives to recruit or retain teachers to

teach in less desirable locations and teach in fields where teacher shortages exist.

For example:

• 4.9 percent of Virginia districts used relocation assistance to recruit new

teachers (compared to 2.5 percent in the US).

• 38.2 percent of the state’s districts offered free training for district staff to

prepare them to teach in current or anticipated shortages (compared 27.1

percent in the US).

• 13.0 percent of districts used pay incentives to recruit or retain teachers to

teach in a less desirable location (compared to 5.6 percent in the US).

• 38.1 percent of districts relied on pay incentives to recruit or retain teachers to

teach in fields of shortage (compared to 13.5 percent in the US).

In addition, Virginia has allowed teachers who have retired to return to teaching

full-time while earning their retirement benefits if the teacher teaches in a critical

shortage area.

41

25

While these efforts may help address immediate shortage issues, several programs

in Virginia are designed to support the teacher pipeline. To incentivize students to

enter the teaching workforce, or to seek endorsement in a critical need area, the state

offers the Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program (VTSLP), which provides a

scholarship of up to $10,000 for education students at a public or private school who

are seeking endorsement in a critical shortage area or career and technical education.

The scholarship is also available to students seeking endorsement in any subject

but qualify as members of underrepresented minorities, including males seeking

endorsement in elementary or middle subjects.

42

The appropriation for this award in

2017-18 was $708,000.

43

In December 2017, Governor Terry McAuliffe introduced his

proposal to amend the VTSLP to better target critical shortage areas by increasing the

maximum award to $20,000 if the graduates teach for two years in a top five critical

shortage area, or in a district where more than half of the students participate in a free

and reduced price lunch program.

44

Virginia also operates a Virginia Teachers for Tomorrow program (VTfT), which offers

high school students an introduction to teaching as a career, where they earn college

credit and have an internship as a teacher.

45

VTfT is taken as a high school course for

credit; an estimated 2,000 students are currently enrolled in the program in fifty-two

different districts.

46

These “Grow Your Own” programs have been recognized in other

states.

Former Governor Terry McAuliffe proposed an additional $500 to be added to the

Tuition Assistance Grant (TAG) to seniors pursuing degrees in education.

47

He also

proposed $50,000 a year to help cover the cost of teaching exams and exam materials

for underrepresented students in the teaching profession in order to increase teacher

diversity across the state.

48

Finally, in December 2017, Governor McAuliffe signed Executive Order 14, which

authorized Virginia’s public colleges to offer an undergraduate program with a major

in education.

49

Currently in Virginia, teachers must complete a five-year program.

According to information provided by the Governor’s Office, this emergency regulation

will help expedite students’ entry into the workforce.

50

Still, many policy challenges remain. In addition to the local-level inequities and

subject area shortages described in this report, a 2017 report from the Virginia Board

of Education indicated that:

51

• Throughout the recession, the Standards of Quality (SOQ) formula underwent

changes that resulted in a reduction of support for public schools — around

$800 million per year.

• Nearly 40 percent of Virginia’s public school students are free or reduced

price lunch eligible, and the number is growing every year.

52

• According to survey results, Virginia has some of the lowest reports of

classroom autonomy, the highest percent of teachers saying they plan to

leave teaching immediately or when a better job comes along, and the lowest

percent of teachers who plan to remain in teaching as long as they are able to

do so, or until they are eligible for retirement benefits.

53

26

Virginia’s policymakers have taken several steps to address problems of teacher

recruitment, including well-targeted preservice efforts to address underserved

localities and endorsements as well as to recruit a more diverse teacher workforce.

Less emphasis to date has been placed on the in-service experience of teachers,

on retaining highly qualified teachers, for example, through changes in salaries and

professional autonomy sufficient to maintain a strong teacher workforce across all

divisions. Whether this focus on recruitment suffices by itself to alleviate the problems

of equity and subject area shortages is a question worth further investigation.

Conclusion

Virginia is a growing state, with increasing student enrollment. The number of teachers

in the state, though fluctuating, has grown even faster than enrollment; student-

teacher ratios have changed little over time; and the pipeline for teacher candidates

has been one of the strongest in the nation, a pipeline augmented by the relative ease

with which teachers from other states can qualify for Virginia positions.

There are, nonetheless, indications of imbalances between demand and supply.

Vacancies in teaching positions and teacher turnover are high in Virginia, compared to

other states. Also, even though there has been little overall growth in special education

pupils in the state, and despite the fact that special-education-prepared graduates

have increased in numbers in recent years, Virginia has indicated repeatedly that

schools have struggled to hire qualified special education teachers.

Similar to our findings in New York and South Dakota, our analyses found significant

gaps between school districts serving different communities and students with

different backgrounds. High-poverty districts in Virginia were less likely to have

teachers with full (rather than provisional) certification, they were less likely to have

“highly qualified” teachers responsible for core academic subjects, and they were

somewhat less likely to have teachers with advanced degrees. Although we do not

analyze the reasons behind these differences, we note that starting salaries for

teachers in low-poverty divisions are higher than in divisions with higher rates of

student poverty, at least within rural and suburban/town communities.

These equity gaps have been recognized by Virginia’s state government, and the state

has been addressing teacher recruitment issues in several ways, including scholarships

and other financial assistance for students in teacher education programs, and special

incentives to students preparing to teach in specialized areas with shortages or to

students who are members of underrepresented minorities in the teaching profession.

Although the range of Virginia’s efforts to address both overall and specific teacher

shortages is impressive, whether these and other policies and initiatives are making

a dent in the significant gaps in the teacher workforce between the state’s high- and

low-poverty areas, however, is a question still to be answered.

27

ENDNOTES

28

1 Leib Sutcher, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Desiree Carver-Thomas, A Coming Crisis in Teaching?

Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. (Palo Alto: Learning Policy Institute, September

2016), https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/A_Coming_Crisis_

in_Teaching_REPORT.pdf; Tawnell D. Hobbs, “In More High School Classes, the Teacher Is on

a Screen,” Wall Street Journal, October 25, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-more-high-

school-classes-the-teacher-is-on-a-screen-1540459802.

2 Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for

Education Statistics, 2017 Tables and Figures), Table 203.20, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/

d17/tables/dt17_203.20.asp; “2017 Title II Reports, National Teacher Education Data,” Academic

Year 2015-16 Data, accessed November 14, 2018, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/Home.aspx.

3 Donald Boyd et al., “The Draw of Home: How Teachers’ Preferences for Proximity Disadvantage

Urban Schools,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24, 1 (2005): 113-32.

4 James Cowan et al., “Missing Elements in the Discussion of Teacher Shortages,” Educational

Researcher 45, 8 (2016): 460-2.

5 Thomas Gais et al., The State of the New York Teacher Workforce (Albany: Rockefeller Institute of

Government, March 2018), https://rockinst.org/issue-area/state-new-york-teacher-workforce/;

Thomas Gais et al., Phase One Analysis of the Teacher Workforce in South Dakota (Albany:

Rockefeller Institute of Government, October 2017), https://rockinst.org/issue-area/phase-one-

analysis-teacher-workforce-south-dakota/.

6 This student-to-teacher ratio includes guidance counselors and librarians.

7 Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for

Education Statistics, 2017 Tables and Figures), Table 203.20, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/

d17/tables/dt17_203.20.asp.

8 “Virginia Cohort Reports,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), 2018, http://www.doe.

virginia.gov/statistics_reports/graduation_completion/cohort_reports/index.shtml.

9 Digest of Education Statistics, Table 203.20.

10 “Intercensal Estimates for Virginia, Counties, and Cities: 2010-2017,” University of Virginia Weldon

Cooper Center for Public Service, Demographics Research Group, accessed November 14, 2018,

https://demographics.coopercenter.org/virginia-population-estimates.

11 Virginia Department of Education (VDOE). (2007-2018). Critical Teaching Shortage Areas.

12 Preliminary Report from the Advisory Committee on Teacher Shortages (Richmond: Virginia

Department of Education (VDOE), October 2017), https://www.education.virginia.gov/media/

governorvirginiagov/secretary-of-education/pdf/final-acts-report.pdf.

13 Public School Teacher File, 2012, from the Schools and Staffing Survey, NCES.

14 Desiree Carver-Thomas and Linda Darling Hammond, Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters

and What We Can Do About It (Palo Alto: Learning Policy Institute, August 2017), https://

learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT.pdf.

15 Richard Ingersoll and David Perda, “Is the Supply of Mathematics and Science Teachers

Sufficient?,” American Educational Research Journal 43, 3 (2010): 563-94.

16 Funding Virginia’s Schools in a Global Economy and a Digital World (Richmond: Senate Finance

Committee, November 18, 2011), http://sfc.virginia.gov/pdf/retreat/2011%20Retreat/Presentation_

Final%20PDF%20for%20Website/6.%20Public%20Ed%202011%20FINAL.pdf.

17 Superintendent’s Annual Reports, 2009-2017.

18 Kent C. Dickey, “Overview of Standards of Quality Funding Process,” Presentation to the Standing

Committee of the Standards of Quality, April 29, 2009, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/boe/quality/

soq_funding.ppt.

19 Ibid.

20 “2017 Title II Reports, National Teacher Education Data.”

21 Data to calculate percentage from Digest of Education Statistics, 2017 Tables and Figures, Table

209.05, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_209.05.asp?current=yes. The

29

percentage of persons receiving an initial teaching credential in a state, but prepared elsewhere in

the US, as a whole was only 21 percent.

22 “Conditions for Licensure for Out-of-State Candidates by Reciprocity,” Virginia Department of

Education (VDOE), accessed November 14, 2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/licensure/.

23 “Fall Membership Report 2015-16,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), accessed November

14, 2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/statistics_reports/enrollment/index.shtml.

24 Preliminary Report from the Advisory Committee on Teacher Shortages (Richmond: Virginia

Department of Education (VDOE), October 2017): 5, https://www.education.virginia.gov/media/

governorvirginiagov/secretary-of-education/pdf/final-acts-report.pdf.

25 Ibid.

26 Charles T. Clotfelter, Helen F. Ladd, and Jacob L. Vigdor, “Teacher credentials and student

achievement: Longitudinal analysis with student fixed effects,” Economics of Education Review 26,

6 (2007): 673-82.

27 The ULOCAL code of the National Center for Education Statistics was used to distinguish urban,

suburban, town, and rural divisions. Divisions were considered urban when ULOCAL was 11-13;

suburban/town, 21-33; and rural, 41-43. For descriptions of the codes, see https://nces.ed.gov/

programs/edge/docs/LOCALE_CLASSIFICATIONS.pdf. Poverty was based on percentage of

students eligible for free lunch in 2015. The divisions were ranked on this measure and divided

into three categories — low, medium, and high — based on the 33.3 and 66.7 percentiles.

28 “New No Child Left Behind Flexibility: Highly Qualified Teacher,” Fact Sheet, U.S. Department of

Education, NCLB / Proven Methods, March 2004, https://www2.ed.gov/nclb/methods/teachers/

hqtflexibility.html.

29 “Commonwealth of Virginia Critical Shortage Teaching Endorsement Areas for 2017-2018 School

Year,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), n.d., http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/

workforce_data/shortage_areas/2017-2018.pdf.

30 With the exception of Social Studies/History, all of these subjects have consistently been listed

as areas of shortage in Virginia’s reports. For historical data on teacher shortages by state, see

“Teacher Shortage Areas,” U.S. Department of Education, accessed November 14, 2018, https://

tsa.ed.gov/#/reports.

31 Jim Dewey et al., “Explaining the Decline in Special Education Teacher Employment From 2005 to

2012,” Exceptional Children 83, 3 (2017): 315-29.

32 “Virginia State Quality Profile,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), 2017, accessed

November 14, 2018, http://schoolquality.virginia.gov/virginia-state-quality-profile.

33 Virginia’s Plan to Ensure Excellent Educators for All Students (Richmond: Virginia Department of

Education (VDOE), Revised August 2015), https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/equitable/

vaequityplan83115.pdf.

34 “Teacher Salaries in Virginia,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), accessed November 14,

2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/workforce_data/index.shtml.

35 “Rankings of States and Estimates of School Statistics, 2005-2018,” National Education

Association (NEA), accessed November 14, 2018, http://www.nea.org/home/44479.htm.

36 Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, and Carver-Thomas, A Coming Crisis in Teaching?

37 “Rankings of States and Estimates of School Statistics, 2005-2018.”

38 “Superintendent’s Annual Report, 2016-17.”

39 “Career Switcher Program,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), accessed November 14,

2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/educator_preparation/career_switcher/index.shtml.

40 “Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) 2011-12, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES),

accessed November 14, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/.

41 “Teaching While Retired,” Virginia Retirement System, last modified August 28, 2017, https://www.

varetire.org/retirees/working-after-retirement/teaching-while-retired.asp.

30

42 “Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program (VTSLP),” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE),

accessed November 14, 2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/financial_support/virginia-

teaching-scholarship-loan-program/.

43 Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program Application 2018-2019 (Richmond: Division of Teacher

Education and Licensure, Virginia Department of Education, n.d.), https://education.wm.edu/

documents/financialaid/vtslpapplication.pdf.

44 Office of the Governor, “Governor McAuliffe Signs Executive Directive 14 and Announces Budget

Actions to Address Virginia’s Teacher Shortage.” press release December 2017, http://www.doe.

virginia.gov/news/news_releases/2017/12_dec11_gov.shtml.

45 “Virginia Teachers for Tomorrow (VTFT),” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), accessed

November 14, 2018, http://www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching/educator_preparation/teachers_for_

tomorrow/index.shtml.

46 Margaret Carmel, “Appomattox ‘growing its own’ future teachers with Teachers for Tomorrow

program,” News & Advance, December 17, 2017, http://www.newsadvance.com/news/local/

appomattox-growing-its-own-future-teachers-with-teachers-for-tomorrow/article_05ce8c49-

e10a-5903-b398-e494c5f4396f.html.

47 Office of the Governor, “Governor McAuliffe Signs Executive Directive 14.”

48 “Office of Education,” from Commonwealth of Virginia 2018-2020 Biennial Budget, Part B:

Executive Budget Document, Office of Education (Richmond: Virginia Department of Planning

and Budgeting, December 18, 2017): B-90-B-162, http://dpb.virginia.gov/budget/buddoc18/partb/

OfficeOfEducation.pdf.

49 Office of the Governor, “Governor McAuliffe Signs Executive Directive 14.”

50 Ibid.

51 Virginia Board of Education’s 2016 Annual Report on the Condition and Needs of Public Schools

in Virginia (Richmond: Virginia Board of Education, November 2016), http://www.doe.virginia.gov/

boe/reports/annual_reports/2016.pdf.

52 “School Quality Profile,” Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), 2016.

53 “Schools and Staffing Survey 2011-12,” National Center for Education Statistics.

31

ABOUT THE ROCKEFELLER INSTITUTE

Created in 1981, the Rockefeller Institute of Government is a public policy think tank

providing cutting-edge, evidence-based policy. Our mission is to improve the capac-

ities of communities, state and local governments, and the federal system to work

toward genuine solutions to the nation’s problems. Through rigorous, objective, and

accessible analysis and outreach, the Institute gives citizens and governments facts

and tools relevant to public decisions.

Learn more at www.rockinst.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Rockefeller Institute of Government is undertaking a comprehensive study

of teacher supply and demand in states across the nation. This study is the

third in a series of reports to come. Special thanks to the staffs of the Council

of Chief State School Officers and the College Football Playoff Foundation’s

Extra Yard for Teachers program for their continued help and assistance on the

nationwide project with the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

32

LEARN MORE

www.rockinst.org

@rockefellerinst