The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship

& the Law & the Law

Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 2

5-15-2019

Copyrighting Experiences: How Copyright Law Applies to Virtual Copyrighting Experiences: How Copyright Law Applies to Virtual

Reality Programs Reality Programs

Alexis Dunne

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel

Part of the Computer Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gaming Law

Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Alexis Dunne,

Copyrighting Experiences: How Copyright Law Applies to Virtual Reality Programs

, 12 J.

Bus. Entrepreneurship & L. 329 (2019)

Available at:

https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/jbel/vol12/iss2/2

This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons.

It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Business, Entrepreneurship & the Law by an authorized editor

of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact bailey[email protected].

COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES: HOW

COPYRIGHT LAW APPLIES TO VIRTUAL

REALITY PROGRAMS

Alexis Dunne*

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 330

I. WHAT IS VR? ..................................................................... 334

A. The Reality-Virtuality Continuum ...................... 335

B. The Key Elements of Virtual Reality .................. 336

i. The Virtual World ................................. 336

ii. Sensory Feedback and Interaction .......... 336

iii. Immersion ............................................. 337

C. The Hardware & Software of VR ....................... 338

II. COPYRIGHT LAW & THE COPYRIGHTABILITY OF COMPUTER

PROGRAMS ......................................................................... 339

A. Copyright Law Can Change .............................. 340

B. Subject Matter Evolution ................................... 341

C. History of the Copyrightability of Computer

Programs .......................................................... 341

III. PROTECTING COMPUTER PROGRAMS AND

VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCES AS A LITERARY WORKS .... 342

A. Protecting the Literal Code ............................... 343

i. Basic Computer Program Concepts........ 343

ii. Protection for Both Source Code & Object

Code ...................................................... 344

iii. Applicability to VR ............................... 345

B. Protecting the Non-Literal Elements ................. 345

i. Early & Broad Protection of Non-Literal

Elements ................................................ 346

ii. Limiting the Protection of Non-Literal

Elements ................................................ 346

iii. Applicability to VR ............................... 349

IV. PROTECTING COMPUTER PROGRAMS AND VIRTUAL REALITY

EXPERIENCES AS AUDIO-VISUAL WORKS ............................ 350

A. VR Video Games ............................................... 351

i. Stern Electronics v. Kaufman ................ 351

ii. VR Application ..................................... 352

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

330

B. VR User Interfaces ............................................ 353

i. Apple v. Microsoft................................. 353

ii. VR Application ..................................... 355

iii. Useful Articles....................................... 357

CONCLUSION ............................................................................. 359

INTRODUCTION

“The future is exciting, but uncertain.”

1

Some predict that virtual

reality will fundamentally change the future of the entertainment industry,

2

while others believe it will remain “stuck in neutral.”

3

Some say virtual

reality will isolate us from each other.

4

Others say virtual reality will bring

us together.

5

Some say virtual reality will make us inactive.

6

Others say

virtual reality will inspire activity.

7

Critics and champions of virtual reality (VR) may disagree on

what impact it will have on humanity, but one thing for sure: it is

*J.D. Pepperdine University School of Law 2019

1

Steven Ornes, Everything Worth Knowing About... Virtual Reality,

DISCOVER MAGAZINE (June 12, 2017), http://discovermagazine.com/2017/jul-

aug/virtual-reality.

2

Simon Erickson, Is There a Future for Virtual Reality?, THE MOTLEY

FOOL (Nov. 25, 2017, 10:34 AM),

https://www.fool.com/investing/2017/11/25/is-there-a-future-for-virtual-

reality.aspx.

3

Id.

4

Ornes, supra note 1.

5

Id.

6

Id.

7

“VR has seen use in training surgeons, fighter pilots, and construction

workers. Today, it is also used to push our professional athletes to the furthest

heights of excellence. Virtual reality firm EON Sports specializes in creating

virtual training environments for athletes. Using both commercially available and

custom-designed head-mounted displays, Eon places athletes on the field

virtually.” How Reality Technology is Used in Business, REALITY TECHNOLOGIES,

http://www.realitytechnologies.com/sports (last visited Feb. 17, 2018).

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

331

coming.

8

And while it may only change the way we catch Pokémon,

9

it

could also change the entire way we communicate with each other,

10

watch

8

Ian Sherr, VR promised us the future. Too bad we’re stuck in the

present, CNET (Oct. 10, 2017, 12:14 PM), https://www.cnet.com/news/vr-

virtual-reality-future-depends-on-you-buying-a-dorky-headset-oculus-

zuckerberg-playstation-vive/ (quoting Mark Zuckerburg saying “[t]he future is

coming”).

9

See THE POKEMON COMPANY INTERNATIONAL, INC.,

https://www.pokemongo.com (last visited Jan. 17, 2018)

10

“As we continue to make big breakthroughs in the technology behind

VR, we’re also investing in efforts to explore immersive new VR experiences that

will help people connect and share.” “In the future, VR will enable even more

types of connection — like the ability for friends who live in different parts of the

world to spend time together and feel like they’re really there with each other.”

New Steps Toward the Future of Virtual Reality, FACEBOOK NEWSROOM (Feb. 21,

2016), https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/02/new-steps-toward-the-future-of-

virtual-reality/.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

332

movies,

11

learn,

12

train,

13

work,

14

play,

15

create,

16

exercise,

17

behave,

18

experience.

19

11

See THE VR CINEMA, https://thevrcinema.com (last visited Feb. 27,

2018).

12

“Educators and students alike are seeking an ever-

expanding immersive landscape, where students engage with teachers and each

other in transformative experiences through a wide spectrum of interactive

resources.” Elizabeth Reede, When Virtual Reality Meets Education,

TECHCRUNCH (Jan. 23, 2016), https://techcrunch.com/2016/01/23/when-virtual-

reality-meets-education/; See also Learn and Train with Virtual Reality,

UNIMERSIV, https://unimersiv.com.

13

Learn and Train with Virtual Reality, UNIMERSIV,

https://unimersiv.com.

14

“[M[any of the world's largest multinational corporations are already

integrating virtual reality technologies into their businesses.” How Reality

Technology is Used in Business, REALITY TECHNOLOGIES,

http://www.realitytechnologies.com/business (last visited Feb. 27, 2017).

15

See OCULUS, https://www.oculus.com/rift/#oui-csl-rift-games=robo-

recall (last visited January 17, 2018); VIVE, https://www.vive.com/us/ (last visited

January 17, 2018); PLAY STATION, https://www.playstation.com/en-

us/explore/playstation-vr/ (last visited Jan. 17, 2018).

16

“From architecture to interior home design, VR and related

technologies are changing the way we create the places we work, live, and play.”

How Reality technology is Being Used in Design, REALTY TECHNOLOGIES,

http://www.realitytechnologies.com/design (last visited Feb. 26, 2018); See also

TILT Brush, https://www.tiltbrush.com (last visited Jan. 17, 2018).

17

Kyle Melnick, Mayweather Boxing & Fitness VR Program Debuts At

First Gym This Month, VR SCOUT (Jan. 11, 2018),

https://vrscout.com/news/mayweather-boxing-fitness-vr-program-gym/#.

18

“Virtual reality therapy isn’t a new idea, and the concept far predates

the modern easy availability of head-mounted displays. The concept was

pioneered in 1992 in the doctoral dissertation of Dr. Max North, a computer

scientist. His thesis was that virtual reality was an ideal, safe place to administer

psychotherapy through exposure to various phobias and triggers.” How Reality

Technology is Used in Therapy, REALITY TECHNOLOGIES,

http://www.realitytechnologies.com/therapy (last visited Feb. 26, 2018).

19

“Whatever the industry, VR is largely about providing

understanding—whether that is understanding an entertaining story, learning an

abstract concept, or practicing a real skill. Actively using more of the human

sensory capability and motor skills has been known to increase sensory bandwidth

between human and information, but there is much more to understanding.

Actively participating in an action, making concepts intuitive, encouraging

motivation through engaging experiences, and the thoughts inside one’s head all

contribute to understanding.” Jason Jerald, THE VR BOOK 9 (M. Tamer Özsu et

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

333

The enormous potential of VR has attracted developers, investors,

and users.

20

On the investor side, Digi-Capital reported in July 2017 that

in the prior twelve months, investment in Augmented Reality (AR) and

VR sectors reached over $2 billion.

21

On the user side, [c]onsumers will spend $5.1 billion on virtual

reality gaming hardware, accessories and software in 2016. That’s up from

the $660 million spent in 2015, says the marketing leader. Meanwhile, the

global market is expected to grow to $8.9 billion in 2017 and $12.3 billion

in 2018,

22

and Brendan Iribe, CEO of Oculus, and Mark Zuckerburg, CEO

of Facebook, claim there will someday be a billion or more VR users.

23

So, there is money, passion, and optimism surrounding VR, but is

there protection for the VR software? With new kinds of intellectual

property comes questions of intellectual property protection, and it is

unclear exactly how VR’s various aspects will be protected. Patents will

presumably protect the hardware, the physical computer components, of

VR,

24

but it is less clear which kind regime of intellectual property will

protect the underlying software or the experiences themselves. Because

VR is a computer-generated environment,

25

and copyright law is the

al. eds., 2016).

20

“The recent surge in media coverage about VR has inspired the public

to become quite excited about its potential.” Id.

21

AR/VR Dealmakers invested over $800M in Q2 2017, DIGI-CAPITAL

(July 2017), http://www.digi-capital.com/news/2017/07/arvr-dealmakers-

invested-over-800m-in-q2-2017/#.Wl_K-CPMzOS.

22

John Gaudiosi, Virtual Reality Video Game Industry to Generate $5.1

Billion in 2016, FORTUNE, http://fortune.com/2016/01/05/virtual-reality-game-

industry-to-generate-billions/ (last visited Mar. 5, 2018).

23

Jerald, supra note 19, at 474.

24

“Oculus VR has been assigned at least one utility patent from the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office to protect its headset-based virtual reality

technologies. A problem in video playback where the display sometimes pans

further right or left than a wearer’s head is turning is addressed by the invention

protected by U.S. Patent No. 9063330, entitled Perception Based Predictive

Tracking for Head Mounted Displays.” William Cory Spence, Oculus Rift Patents

that chance the Virtual Reality Landscape, IP WATCHDOG (May 31, 2016),

http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/05/31/oculus-rift-patents-virtual-

reality/id=69483/.

25

“[Merriam-Webster 2015] has more recently defined the full term

virtual reality to be ‘an artificial environment which is experienced through

sensory stimuli (as sights and sounds) provided by a computer and in which one’s

actions partially determine what happens in the environment.’ In this book, virtual

reality is defined to be a computer-generated digital environment that can be

experienced and interacted with as if that environment were real.” Jerald, supra

note 19, at 9.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

334

typical avenue of protection for computer programs, developers of VR

software will likely look to Copyright Law for protection. Not only is it an

open question whether or not the protection of VR software will differ

from that of traditional software, it remains an open question exactly what

scope of protection copyright law affords traditional computer programs.

This note will attempt to shed light on the question of what kind

of protection copyright law affords VR experiences. Part II discusses the

nature of VR experiences and their implementation through specifically

tailored VR technology. Part III provides an overview of copyright

protection, its limitations, and specifically the history of the

copyrightability of computer programs. Parts IV and V outline case law

relevant to the discussion of the copyrightability of different types of VR

experiences and how that case law similarly or dissimilarly apply to the

protection of VR experiences. Part IV focuses on protecting VR

experiences as a literary work, through its underlying code and Part V will

focus on protecting VR experiences as audiovisual works, through its

visual outputs. Part VI discusses a potential avenue for obtaining copyright

protection through the useful article doctrine, while avoiding some of the

major roadblocks to copyright protection that discussed in the previous

sections. Finally, Part VII provides a summary and conclusion of the

current state of protection for the elements which make up VR experiences

as well as suggestions for how VR developers may want to proceed in

order to obtain the largest scope of protection for their works.

I. WHAT IS VR?

Merriam-Webster 2015 defines virtual reality as “an artificial

environment which is experienced through sensory stimuli (such as sights

and sounds) provided by a computer and in which one’s actions partially

determine what happens in the environment.”

26

More generally, VR is

“computer-generated digital environment that can be experienced and

interacted with as if that environment were real.”

27

26

Id.

27

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

335

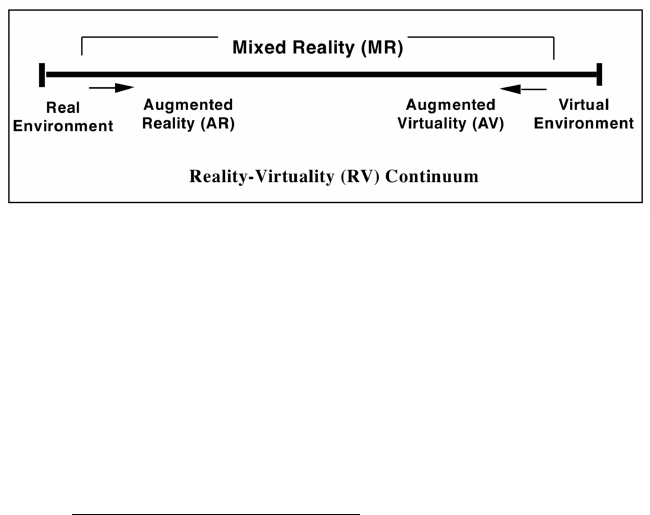

A. The Reality-Virtuality Continuum

VR is technically one of many phenomena that exist on the

spectrum of mixed reality (MR).

28

Paul Milgram, Haruo Takemura, Akira

Utsumi, and Fumio Kishino introduced the concept of this “mixed reality

spectrum,” referred to as the “Reality-Virtuality (RV) Continuum,” in

their often-cited paper, Augmented Reality: A class of displays on the

reality-virtuality continuum, where they dissected and classified the

various MR technologies.

29

Figure 2: Simplified Representation of a VR Continuum

30

The RV Continuum consists of realities which incorporate both

real world and virtual elements in varying degrees and ranges from the real

world (with zero virtual components) at one end to a fully immersive

virtual environment at the other end.

31

Between these ends lies the

“substratum” consisting of Augmented Reality (AR) and Augmented

Virtuality (AV), where an AR environment is “principally real, with added

computer[-]generated enhancements” and an AV environment is

“principally virtual, but augmented through the use of real (i.e.

28

“Reality takes many forms and can be considered to range on a

virtuality continuum from the real environment to virtual environments . . . . These

forms, which are somewhere between virtual and augmented reality, are broadly

defined as ‘mixed reality,’ which can be further broken down into ‘augmented

reality’ and ‘augmented virtuality.’” Jerald, supra note 19, at 9.

29

Fumio Kishino, Paul Milgram, Haruo Takemura, & Akira Utsumi,

Augmented Reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum, Proc.

SPIE 2351 TELEMANIPULATOR AND TELEPRESENCE TECHNOLOGIES 282 (Dec. 21,

1995),

http://etclab.mie.utoronto.ca/publication/1994/Milgram_Takemura_SPIE1994.p

df

30

Id. at 283.

31

Id.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

336

unmodelled) imaging data.”

32

Simply put, the RV Continuum ranges from

actual reality to virtual reality.

33

Because of the colloquial use of the term and the lack of necessity

in distinguishing the different realities for the purposes of this note, this

note will use the term “VR” to refer generally to any reality on the RV

Continuum (excluding actual reality without any virtual components),

unless explicitly noted.

B. The Key Elements of Virtual Reality

VR experiences differ from traditional computer-generated

experiences in a variety of ways. Key elements that define and shape a

given VR experience include its virtual world, sensory feedback and

interactivity, and immersion.

i. The Virtual World

The virtual world is the computer-generated, three-dimensional

environment that the user perceives around her in that VR experience.

34

The virtual world is similar to a computer screen display, except that

traditional computer screen displays are two-dimensional and spatially

confined, whereas virtual worlds are three-dimensional and spatially

unrestricted (in the sense that the user perceives it in every direction,

everywhere around her). Within the virtual world, there may exist virtual

objects, which the user can interact with.

ii. Sensory Feedback and Interaction

Sensory feedback involves the stimulation of senses, such as

vision and hearing.

35

The software and hardware of a VR experience will

aim to properly stimulate these senses, in a way that mimics how the user’s

senses are stimulated in a real-world environment.

36

This process of

32

Id. at 285.

33

The Ultimate Guide to Mixed Reality (MR) Technology, REALITY

TECHNOLOGIES, http://www.realitytechnologies.com/mixed-reality (last visited

Feb. 27, 2018).

34

Id.

35

Id.

36

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

337

providing feedback based on the user’s actions accomplishes the important

element of interactivity.

Hardware and software must track the user’s movements, such as

head movements or motion tracking, so that it can provide the proper

visual, aural, or other output. Tracking this correctly and providing the

properly calibrated outputs is integral for purposes of increasing

immersion and avoiding motion sickness. Beyond the visual and auditory

sensations, VR can incorporate other senses, such as taste, smell, and

tactile sensations, further immersing the user in the virtual experience.

37

For example, creating the sensation of “touching” a virtual object

is made possible through the use of “haptics.” “Haptics are artificial forces

between virtual objects and the user’s body.”

38

Tactile haptics, for

example, “provide a sense of touch through the skin”: one example of this

is Reactive Grip technology, which “utilizes sliding skin-contact plates

that can be added to any hand-held controller,” to imitate real world forces.

39

iii. Immersion

Each of these elements together provide the user with the

experience of immersion, the perception of being physically present in a

non-physical world.

40

An ideal VR experience is nearly indistinguishable from the real

world. In the 1960s, Ivan Sutherland, one of first VR creators, described

the ideal VR as “a room within which the computer can control the

existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good

enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining,

and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal.”

41

This is a standard

that is not currently possible,

42

but it is important to keep in mind when

considering the types of programs that may be developed in the future, and

what challenges with protection developers may eventually run into.

37

Jerald, supra note 19, at 42.

38

Id. at 37.

39

Id. at 37–38

40

The Ultimate Guide to Virtual Reality (VR) Technology, supra note

33.

41

“Perhaps the most graphic, well-known, and advanced example of this

is the 'holodeck' in Star Trek: The Next Generation, in which the user is immersed

in an environment which, for all intents and purposes, is real . . . it represents a

future ideal of virtual reality's potential.” Jack Russo & Michael Risch, The Law

of Virtual Reality, COMPUTERLAW GROUP LLP,

http://www.computerlaw.com/Articles/The-Law-of-Virtual-Reality.shtml.

42

Jerald, supra note 19, at 9.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

338

C. The Hardware & Software of VR

The previous section discussed the experience of VR. The other

side to VR is the hardware and software that actually generate the user

experience.

On the hardware side, a VR experience will generally require a

high-performance computer

43

and hardware that generates the visual

display, which typically takes the form of a head set. These headsets

provide what are referred to as “head-mounted displays” (HMDs).

44

These

HMDs are “more or less rigidly attached to the head.”

45

In a fully

immersive VR experience, the HMDs will block off the user’s vision to

the real world around her, and in its place, the HMD will project the

computer-generated reality.

The software component of VR is the program that instructs the

HMD. The software is “the computer code that creates virtual

environments, the audiovisual presentation to the user, the interactive

media including tactile components of the environment which are

experienced by the user, as well as video recordings of audiovisual

components to be played on a standard television or movie screen.”

46

This

computer software is the expression that copyright law would potentially

protect.

47

43

Russo & Risch, supra note 41. “Virtual reality environments, such as

rooms, cities, or entire worlds are created by computer software executing on

high-performance computer hardware.” Id.

44

Jerald, supra note 19, at 32.

45

Id.

46

Russo & Risch, supra note 41.

47

“Generally, existing statutory and case law will readily extend

protection to virtual worlds and even to particular original virtual objects, but the

very nature of virtual reality requires that subsequent participants be allowed

greater freedom to adapt, modify and extend existing virtual worlds and existing

virtual objects without liability for infringement except in the cases where (1)

strikingly similar or nearly identical copying occurs for virtual worlds and virtual

objects that simulate the real world and real objects or (2) substantial similarity

exists for unique virtual worlds and unique virtual objects.” Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

339

II. COPYRIGHT LAW & THE COPYRIGHTABILITY OF COMPUTER

PROGRAMS

The source of Congress’s ability to grant copyrights to authors of

copyrightable works through the Copyright Act is found in Article 1,

Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution.

48

It grants Congress

the power “[t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts, by

securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to

their respective writings and discoveries.”

49

This clause articulates the

purpose and method of granting copyrights.

50

The purpose is to “promote

the progress of . . . the useful arts,” which, in other words, is to incentivize

authors to create works of art.

51

Congress can incentivize authors by

“securing for limited times to authors . . . the exclusive right to their

respective writings,” which grants the author with a temporary monopoly

over his or her work of authorship.

52

A balance must be struck, however, between the breadth of these

monopolies and the public’s ability to use and enjoy those things which

should remain in the public domain for all to use; “[a]ny legislature has

only two basic considerations in designing a copyright law to provide

incentives: the breadth or scope of protection, and its length. Increasing

either one increases the opportunity for profit but also imposes a greater

cost on the public. There exists a tradeoff between these two dimensions:

the more there is of one, the less there needs to be of the other.”

53

Thus,

the Copyright Act articulates limitations on the proper subject matter of

copyrightable works.

54

The Copyright Act notes in the first Chapter that:

“In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship

extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation,

concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is

described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.”

55

This

limitation, which is referred to as the idea-expression dichotomy, stands

48

U.S. Const. art 1, § 8, cl. 8.

49

Id.

50

Id.

51

Id.

52

Id.

53

FINAL REPORT 126, 292–93 (National Commission on New

Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works ed., 1978), http://digital-law-

online.info/CONTU/PDF/AppendixH.pdf.

54

Id.

55

17 U.S.C. § 102 (2016).

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

340

for the rule that ideas cannot be copyrighted, but the expression of those

ideas can.

56

A closely related concept to the exclusions outlined in §102(b) is

the merger doctrine. While expression of an idea is copyrightable, it is

possible that in a particular circumstance the expression will “merge” with

the idea into an uncopyrightable whole.

57

This occurs when “only one of

a limited number of ways exist to express an idea.”

58

In such a

circumstance, the idea and the expression become indistinguishable from

each other, and the expression, like the idea, becomes uncopyrightable.

59

Also related is the doctrine of scenes á faire.

60

Under this doctrine,

when features in a given work are “indispensable, or at least standard, in

the treatment of a given idea, they are treated like ideas and are therefore

not protected by copyright.”

61

Each of these limitations to copyrightability, including the

exclusions outlined in §102(b), the merger doctrine, and the doctrine of

scenes á faire, play large roles in the case law concerning the scope of

copyright protection of computer software, and will be discussed in more

detail in Part IV and V.

A. Copyright Law Can Change

Technological advances often provide authors with novel avenues

of expression and unprecedented mediums in which they can manifest

art.

62

“Furthermore, the House Report suggests that the subject matter of

copyright may be expanded to include ‘those in which “scientific

discoveries and technological developments have made possible new

forms of creative expression that never existed before,” and those “in

existence for generation or centuries [but that] have only gradually come

to be recognized as creative and worthy of protection.”’’

63

The presence

56

Stephen M. McJohn, COPYRIGHT: EXAMPLES AND EXPLANATION 103

(2006).

57

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 35 F.3d 1435, 1444 (9th Cir.

1994).

58

Id.

59

Id.

60

Id.

61

Id.

62

Ellii Cho, Copyright of Trade Dress? Toward IP Protection of

Multisensory Effect Designs for Immersive Virtual Environments, 33 CARDOZO

ARTS & ENT. L.J. 801, 816 (2015).

63

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

341

of one of these technological advances coupled with the limitations on

copyrightable subject matter begs the question: is the new medium of

expression created by this new technology “a natural extension of works

now protected by the [Copyright] Act or is it completely outside

congressional intent?”

64

VR presents an example of one of these technologies. Through

VR and its corresponding computer software, authors can create virtual

worlds, experiences, objects, and interfaces, which represent a new kind

of artistic expression, and it is unclear exactly what scope of protection

Congress will afford to these virtual realities.

65

B. Subject Matter Evolution

The Copyright Act protects “original works of authorship fixed in

any tangible medium of expression now known or later developed, from

which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated,

either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.”

66

Following this

general statement of copyrightable subject matter, Congress lists eight

broad categories which serve as examples of copyrightable works.

67

This

list, however, is not exhaustive

68

and “the Copyright Act and its legislative

history reflect foresight and intent to expand the scope of copyrightable

subject matter to accommodate future technological advances as well as to

avoid absolute preclusion of materials that previously considered

unsuitable for copyright.”

69

For example, Congress added “designs, prints,

etchings and engraving in 1802, ‘musical composition’ in 1831, ‘dramatic

composition’ in 1856, ‘photographs and the negatives thereof’ in 1865,

and ‘statuary’ and ‘models or designs intended to be perfected as works of

fine arts’ in 1870.”

70

C. History of the Copyrightability of Computer Programs

Another example of this kind of accommodation occurred in 1980,

when Congress added the definition of a computer program to the

Copyright Act, after the Commission On New Technological Uses of

64

Greg S. Weber, The New Medium of Expression: Introducing Virtual

Reality and Anticipating Copyright Issues, 12 COMPUTER/L.J. 175, 187 (1993).

65

Russo & Risch, supra note 41.

66

17 U.S.C. § 102.

67

Id.

68

Cho, supra note 62.

69

Id. at 815–16.

70

Lotus Dev. Corp. v. Paperback Software Intern., 740 F. Supp. 37, 47

(D. Mass. 1990).

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

342

Copyrighted Works (CONTU) issued its final report.

71

In 1974, the 93rd

Congress recognized that certain problems raised by computer and other

new technologies were not adequately addressed in the pending bill (which

would become the Copyright Act of 1976).

72

To deal with these problems,

they established the CONTU to study the nature of computer programs, as

they related to copyright law, and to make recommendations as to changes

in the law.

73

CONTU’s findings emphasized a need for copyright protection of

the creative expression embodied in computer programs.

74

Accordingly,

in 1980, Congress added the definition for computer programs: “a set of

statements or instructions to be used directly or indirectly in a computer in

order to bring about a certain result.”

75

Since this addition, “computer

programs have been considered ‘literary works’ under the Copyright

Act.”

76

III. PROTECTING COMPUTER PROGRAMS AND

VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCES AS A LITERARY WORKS

“Literary Works” are the first example listed in the Copyright

Act’s list of works of authorship, and thus are undoubtedly eligible for

copyright protection.

77

The Copyright Act defines a literary work as

“works, other than audiovisual works, expressed in words, numbers, or

other verbal or numerical symbols or indicia, regardless of the nature of

the material objects, such as books, periodicals, manuscripts,

phonorecords, film, tapes, disks, or cards, in which they are embodied.”

78

Computer programs “fall squarely within the statutory definition of

literary works”

79

because they are “written in some form of computer

programming ‘language’” consisting of words or numbers.

80

71

Weber, supra note 64, at 187–88.

72

Paperback Software Intern, 740 F. Supp. at 49.

73

FINAL REPORT, supra note 53, at 1.

74

Paperback Software Intern, 740 F. Supp. at 50.

75

17 U.S.C. § 101 (2016).

76

Weber, supra note 64, at 188.

77

17 U.S.C § 102.

78

17 U.S.C § 101.

79

Paperback Software Intern, 740 F. Supp. at 49.

80

Id. at 43–44.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

343

A. Protecting the Literal Code

So, the written code that underlies computer programs is

copyrightable as a literary work and protected against exact copying.

However, there exist more than one type of computer program.

81

Specifically, there are operating system programs and application

programs that are written in difference types of code.

82

In Apple v.

Franklin, Franklin called into question the copyrightability of operating

system programs, while conceding the copyrightability of application

programs.

83

The Third Circuit, in its ruling of the case, decided the

copyrightability of operating system programs and whether or not

operating system programs and application programs deserved dissimilar

treatment under copyright law.

84

i. Basic Computer Program Concepts

Two different categories of programming language exist: source

code and object code.

85

Program developers write application programs,

programs which “perform specific tasks for the computer user, such as

word processing, checkbook balancing, or playing a game,”

86

in source

code, which consists of “high level readable language”.

87

A compiler, “a

separate program that reads the source code,” translates the source code

into object code.

88

Object code is “written in machine language that can be

executed directly by the computer's CPU without need for translation.”

89

Object code, at its lowest level, typically consists of binary language: i.e.,

ones and zeros.

90

A computer interprets these ones and zeros as

81

Ronald S. Laurie, Daniel S. Lin, & Matthew Sag, Source Code versus

Object Code: Patent Implications for the Open Source Community, 18 SANTA

CLARA HIGH TECH. L.J. 235 (2001),

https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1300&context=

chtlj.

82

Id.

83

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp., 714 F.2d 1240,

1243 (3d Cir. 1983). Arguably, Franklin conceded the copyrightability of

application programs because it had already been established in precedent and

also because they likely wanted protection for their own application program.

84

Id.

85

Laurie, Lin & Sag, supra note 81.

86

Franklin Computer Corp., 714 F.2d at 1243.

87

Laurie, Lim & Sag, supra note 81, at 238.

88

Id.

89

Paperback Software Intern, 740 F. Supp. at 40.

90

Id.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

344

instructions to operate in a particular way, creating the visual displays and

interactions typically associated with what users experience the program

to be.

91

ii. Protection for Both Source Code & Object Code

In 1984, the Third Circuit established that both source code and

object code are proper subjects of copyright protection as literary works.

92

In Apple v. Franklin, Franklin admitted to copying Apple’s programs, but

argued that Apple’s programs were not protected by copyright law.

93

Franklin argued that Apple’s programs were operating systems written in

object code, and thus constituted either (1) processes, systems, or methods

of operation,

94

or (2) ideas.

95

The court decided that “Franklin’s attack on operating system

programs as ‘methods’ or ‘processes’ seems inconsistent with its

concession that application programs are an appropriate subject of

copyright.”

96

Franklin conceded that application programs written in

source code were an appropriate subject of copyright, and the court found

no relevant distinction between the operating system and application

programs that would justify denying copyright protection for one and

affording copyright protection for the other.

97

So, without explicitly ruling

that Apple’s operating system programs were or were not processes,

systems, or methods of operation, the court concluded that so long as

application programs written in source code are not categorically excluded

from copyright protection, neither are operating system programs written

in object code.

98

The court did not necessarily reject Franklin’s argument that the

operating system program constituted an idea, but it decided that the

record lacked sufficient evidence for the court to make the determination

at the appellate level.

99

When analyzing whether or not Apple’s operating

91

Id.

92

Franklin Computer Corp., 714 F.2d at 1249. “Thus[,] a computer

program, whether in object code or source code, is a ‘literary work’ and is

protected from unauthorized copying, whether from its object code or source code

version.” Id.

93

Id. at 1245.

94

Id. at 1250.

95

Id. at 1252.

96

Id. at 1251.

97

Id.

98

Id.

99

Id. at 1253.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

345

system programs constituted unprotectable ideas instead of protectable

expressions, the court employed the merger doctrine: “If other programs

can be written or created which perform the same function as an Apple’s

operating system program, then that program is an expression of the idea

and hence copyrightable.”

100

In this particular context, the court

considered the idea of one of Apple’s programs to be “how to translate

source code into object code” and decided that if, as a practical matter,

there exist other ways of expressing that idea, then the expression does not

merge with the idea into an unprotectable whole.

101

iii. Applicability to VR

Developers of VR technology will likely develop both application

and operating system programs, because the user experiences will come

from application programs and those programs will interact with the

hardware of VR technology through operating system programs. In this

sense, protection for VR experiences should not different from that for

traditional computer programs, and both VR application and operating

system programs should, in the very least, not be categorically barred from

copyright protection.

B. Protecting the Non-Literal Elements

Beyond the discussion of the protectability of literal source or

object code, a special nature of computer programs creates a “vexatious

issue in Intellectual Property law” as programs can copy the functions and

operations of another computer program without copying the underlying

code

102

because there exists more than one way to write object code for

any given program operation.

103

This nature of computer programs raises

the question of whether or not the functions and operations, the “non-

literal elements” of a computer program, are protectable under Copyright

law.

104

100

Id.

101

Id.

102

Daniel A. D. Hunter, Protecting the Look and Feel of Computer

Software in the United States and Australia, 7 SANTA CLARA HIGH TECH. L.J. 95,

96 (1991).

103

Stephen M. McJohn, COPYRIGHT: EXAMPLES AND EXPLANATION 102

(2006).

104

Hunter, supra note 102, at 96.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

346

i. Early & Broad Protection of Non-Literal Elements

In an early case, in 1986, the Third Circuit extended copyright

protection beyond the literal object code to the “structure, sequence, and

organization” of the code of a computer program.

105

Whelan concerns

alleged infringement of the structure of a program used by dental

laboratories.

106

There, the court considered “whether the structure (or

sequence and organization) of a computer program is protectable by

copyright, or whether the protection of the copyright law extends only as

far as the literal computer code.”

107

In its analysis, the court focused on the distinction between an

uncopyrightable idea and a copyrightable expression of an idea, and it

determined that “[w]here there are various means of achieving the desired

purpose, then the particular means chosen is not necessary to the purpose;

hence, there is expression, not idea.”

108

The court in Whelan created a rule for determining when an aspect

of a computer program is an idea and when it is an expression of that idea,

and the court limited the expression to “everything that is not necessary to

[the program’s] purpose or function.”

109

Everything else is protectable as

expression.

110

This decision extends copyright protection far beyond the

literal object code, and for this reason, it has attracted criticism from other

courts and commentators.

111

Where the court in Whelan analogized computer programs to

other literary works, such as novels, critics contend that this analogy is

faulty because computer programs are largely factual, and thus deserve a

much thinner layer of protection.

112

ii. Limiting the Protection of Non-Literal Elements

Oracle v. Google represents the most recent decision on the

subject of the copyrightability of the structure, sequences, and

105

Whelan Assoc. v. Jaslow Dental Laboratory, Inc., 797 F.2d 1222 (3d

Cir. 1986).

106

Id. at 1224.

107

Id.

108

Id. at 1236.

109

Id. (italics omitted).

110

Id.

111

See generally McJohn, supra note 103.

112

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

347

organization of a computer program.

113

Initially, the district court found

that the structure, sequence, and organization of Oracle’s computer

program “were not subject to copyright protection,” and dismissed

Oracle’s claims based on Google’s copying of the structure, sequence, and

organization of its computer programs.

114

While acknowledging that “the

structure, sequence, and organization of a computer program may (or may

not) qualify as a protectable element,” the court decided that the specific

elements under scrutiny in this case were not eligible for protection,

because, in the court’s opinion, Oracle claimed “that it owns, by copyright,

the exclusive right to any and all possible implementations of the

taxonomy-like command structure” for the particular packages of code,

“even though it copyrighted only one implementation.”

115

Further, it

decided that even though the structure, sequence, and organization of the

program was “creative and original, it nevertheless held that it is a ‘system

or method of operation . . . and, therefore, cannot be copyrighted.’”

116

The Federal Circuit, in 2014, reversed and remanded the district

court’s decision, finding that the structure, sequence, and organization of

the packages of code were entitled to copyright protection.

117

In its

analysis, the court rejected Goggle’s contention that “there is a two-step

copyrightability analysis, wherein Section 102(a) grants copyright

protection to original works, while Section 102(b) takes it away if the work

has a functional component.”

118

The functional bar suggested by Google

is a reference to Section 102(b)’s exclusion of “methods of operation” to

copyrightable subject matter.

119

Instead, the court contended that

Congress’s intention with Section 102(b) is not to take away any rights

otherwise afforded, but is to “restate . . . that the basic dichotomy between

expression and idea.”

120

Further, the court noted that if it “were to accept

the district court’s suggestion that a computer program is uncopyrightable

simply because it carr[ies] out pre-assigned function, no computer

program is protectable.”

121

While the court acknowledged that “[c]icuit courts have struggled

with, and disagree over, the tests to be employed when attempting to draw

the line between what is protectable expression and what is not,” it decided

to use the test followed by the Ninth Circuit and Second Circuit, called the

113

Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google Inc., 872 F. Supp. 2d 974 (N.D. Cal. 2012).

114

Id.

115

Id. at 1001–02.

116

Id. at 997.

117

Oracle v. Google, Inc., 750 F.3d. 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

118

Id. at 1356.

119

Id. at 1357.

120

Id. at 1356.

121

Id. at 1367 (internal quotations omitted).

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

348

“abstraction-filtration-comparison test.”

122

This test represents a medium

approach between the broad protection offered in Wheelan and the narrow

protection offered in Lotus.

123

The first step of the test, the abstraction step, “break[s] down the

allegedly infringing program into its constituent structural parts.”

124

All

circuits agree this step contributes to the copyrightability analysis.

125

The

second stop, the filtration step, “sift[s] out all non-protectable material,

including ideas and expression that is necessarily incidental to those

ideas.”

126

The circuits have a less uniform opinion on this step, in terms of

whether it contributes to the analysis of copyrightability or to the analysis

of infringement, however the Ninth Circuit treats it as a defense to

infringement.

127

The third step, which is considered by all circuits to be part of the

infringement analysis,

128

“compares the remaining creative expression

with the allegedly infringing program.”

129

Ultimately, the court decided that a “an original work—even one

that serves a function—is entitled to copyright protection as long as the

author had multiple ways to express the underlying idea.”

130

This analysis

of the dichotomy between idea and expression resembles the merger

doctrine and declares that so long as there exists multiple ways to express

a particular idea, the expressions do not merge with the idea and they

constitute copyrightable subject matter.

Oracle suggests that there is protection for the non-literal

components of computer programs, so long as there exist multiple ways to

accomplish the functionality of the program. While this is a promising step

towards protection for computer programs, the Supreme Court denied

certiorari, there has been anything but consistency throughout the district

and circuit courts on the topic.

122

Id. at 1357.

123

Id.

124

Id.

125

Id. at 1358.

126

Id. at 1357 (internal quotations omitted).

127

Id. at 1358.

128

Id.

129

Id. at 1357.

130

Id. at 1367.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

349

iii. Applicability to VR

Because of the lack of clarity amongst the courts, programmers of

VR software wanting to protect the structure, sequences, and or operations

of their programs, should be wary of the scope of the protection that

copyright law will afford them.

131

Regarding copyrightability, the nuances

of VR programs, as compared to traditional computer programs, arguably

lie in their audiovisual outputs, as opposed to their underlying code. This

is because, while acknowledging the intricacies and challenges involved

in developing new kind of software, there is no obvious additional

component involved in the object code of VR software, as opposed to

traditional software, that would be anymore copyrightable than those

components discussed in the aforementioned cases.

132

For this reason, the

copyrightability of a VR program’s structure, sequence, and operations

will likely be interpreted the same way it would be for a traditional

program.

133

How, then, do VR developers protect their programs from

nonliteral infringement? The answer to this question is also unclear,

because, as articulated in CONTU’s final report, the other avenues of

protection are just as unreliable.

134

While patent protection offers a more

robust monopoly, “the acquisition of a patent . . . is time consuming and

expensive, . . . and the legal hurdles an applicant must overcome are

high.”

135

Further, it remains unclear if computer programs are even eligible

for patent protection because the Supreme Court has never explicitly

addressed the matter.

136

Trade secrecy is arguably further inadequate

because “it is inappropriate for protecting works that contain the secret and

are designed to be widely distributed.”

137

Not only are many computer

programs widely distributed, but also many of the non-literal elements are

readily observable from interaction with the program. These features make

trade secret protection inadequate for many aspects of computer programs.

Through interpreting the Copyright Act, courts may find that

copyright protection does not extend to the nonliteral components of

computer programs, but if those Congress decides those elements are

worthy of some form of protection, they may have to consider either

revising the Copyright Act or exploring new avenues of protection. With

VR being such a long-anticipated, promising, and coveted technology, it

131

Russo & Risch, supra note 41.

132

Jerald, supra note 19, at 9.

133

Id.

134

FINAL REPORT, supra note 53, at 16.

135

FINAL REPORT, supra note 53, at 17.

136

Id.

137

Id.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

350

may incentivize the Supreme Court to take more cases on the subject,

solidifying the rules governing its protection, which may, in turn,

incentivize Congress to expand the scope of protection for computer

software, whether it be through Copyright Law or some new form of

Intellectual Property devoted to computer software.

IV. PROTECTING COMPUTER PROGRAMS AND VIRTUAL REALITY

EXPERIENCES AS AUDIO-VISUAL WORKS

Also, relevant to the discussion of the copyrightability of VR

software is the line of cases concerning the copyrightability of the visual

display of programs registered as audiovisual works.

138

Originally, the

Copyright Office allowed separate registrations for the visual displays of

programs (on Form PA for audiovisual works) and for the underlying code

(on Form TX for literary works),

139

but in 1987, it held hearings “to obtain

comments and recommendations on how it should proceed in this area.”

140

One of the views suggested at these hearings advocated for a

“single registration to cover the entire work including visual displays.”

141

Under a single registration regime, one registration, whether it be as a

literary work or an audiovisual work, would “cover the entire work

including visual displays.”

142

A similar and related view advocates for a

single registration, where the registration form would not be a Form PA or

Form TX, but an entirely new form designed specifically for computer

programs.

143

Another view argues for separate registrations: one for the

underlying program code and one for the visual displays.

144

Under this

regime, advocates argued, “it would be clearer that an infringement of

visual displays can occur independent of any infringement of the

underlying program code.”

145

The last view contends that “the Copyright Office should not

allow any registration of visual displays of computer software” because

138

Hunter, supra note 102.

139

Russo & Risch, supra note 41.

140

Id.

141

Id.

142

Id.

143

Id.

144

Id.

145

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

351

“such displays are generally functional” and therefore not

copyrightable.

146

This view will be discussed in more detail below.

In June 1988, the Copyright Office settled on a single registration

regime, where the choice between registering a program on a Form PA or

Form TX depended on “which aspect of the work ‘predominates.’”

147

A. VR Video Games

Gaming is one of the most common and anticipated applications

of VR technology.

148

There is precedent in case law, specifically in Stern

Electronics v. Kaufman,

149

concerning the copyrightability of videogames

as audiovisual works, however the interactivity of VR experiences may

differentiate it from the video game discussed in Stern.

i. Stern Electronics v. Kaufman

The Second Circuit decided an early case which established the

copyrightability of video games as audiovisual works.

150

The case

concerned a coin-operated video game entitled “Scramble” and its alleged

infringement by another game, which replicated its visual display and

accompanying sounds.

151

Because the “knock-off” game did not copy the

underlying code, the Defendant argued that only the underlying code

deserved copyright protection and that the “visual images and

accompanying sounds of the video games fail[ed] to satisfy the fixation

and originality requirements of the Copyright Act.”

152

The Defendant’s claim rested on the fact that user interaction

dictated which images and sounds the program displayed.

153

Specifically

with “Scramble,” which displayed a spaceship moving through different

scenes and obstacles, the user “control[led] the altitude and speed of the

spaceship” and controlled when the spaceship would release bombs and

fire lasers.

154

So, the Defendant argued that because the visual displays

were different every time anyone user played the game, there was no one

146

Id.

147

Id.

148

“[B]oth of the current major players in the consumer VR space,

Oculus and HTC, have their roots in the video games industry.” How Reality

Technology is Used in Gaming, REALITY TECHNOLOGIES,

http://www.realitytechnologies.com/sports (last visited Feb. 17, 2018).

149

Stern Electronics, Inc. v. Kaufman, 669 F.2d 852 (2d Cir. 1982).

150

Id.

151

Id.

152

Id. at 853.

153

Id.

154

Id.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

352

audiovisual copyright applicable to each play of the game.

155

The court

disagreed, deciding that “the repetitive sequence of a substantial portion

of the sights and sounds of the game qualifies for copyright protection as

an audiovisual work.”

156

ii. VR Application

One of the most widely known and anticipated applications of VR

is video games.

157

A similar, and more general, application is a general

virtual “experience,” where the focus is not necessarily on an objective the

user must accomplish, but instead the focus is on the user having an

entertaining experience, such as participating in a storyline resembling a

theatrical work or experiencing a particular setting, like sitting in a park.

158

In any of these applications, the user’s experience will comprise

audiovisual displays in a perceived three-dimensional environment.

159

Courts will likely analyze the copyrightability of these displays in a similar

way they analyze audiovisual displays in video games because while each

user’s experience will be different, there exists the same sort of repetitive

sequences in both.

160

However, there may be additional challenges brought by

defendants concerning the special nature of virtual works.

161

First, virtual

experiences will be highly interactive on a scale unprecedented by

previous audiovisual works. Defendants could potentially argue that the

extreme level of interaction in VR differs so much from that employed in

the coin-operated “Scramble” so it destroys the presence of consistency

between the audiovisual displays; the different experiences of the different

users may be so different that there is no one consistent audiovisual

display.

162

Secondly, arguments against protecting a VR experience as an

audiovisual work may arise from the fact that VR may “exploit additional

senses, including, but not limited to, tactile and olfactory stimuli.”

163

This

could pose a problem because the Copyright Act defines an audiovisual

155

Id.

156

Id. at 856.

157

Russo & Risch, supra note 41.

158

Id.

159

Id.

160

See id.

161

Id.

162

Id.

163

Cho, supra note 62, at 811.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

353

work as “works that consist of a series of related images which are

intrinsically intended to be shown by the use of machines, or devices such

as projectors, viewers, or electronic equipment, together with

accompanying sounds,”

164

limiting the scope of an audiovisual work to the

visual and audio components.

165

So, while developers may intend to

protect the holistic experience of a VR environment, they may be limited

to protecting only certain components of the environment.

Instead of copyrighting a VR experience as an audiovisual work,

developers may attempt to protect the experience as a “compilation.” The

Copyright Act defines a “compilation” as “a work formed by the collection

and assembling of preexisting materials or of data that are selected,

coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole

constitutes an original work of authorship.”

166

A VR experience may fit

this definition as a collection of sensory effects, where originality is found

in the selection, coordination, and arrangement of the effects.

167

It is possible that Trademark law could provide an avenue of

protection. “Scent marks in particular are becoming increasingly popular,

as the imitation (or exploitation) of the senses or certain aesthetics is

revealed to play a significant role in consumer psychology.”

168

Further, in

Two Pesos v. Taco Cabana, the Supreme Court decided that the design of

a restaurant warranted trade dress protection.

169

Since this holding, trade

dress has protected user interfaces and website designs.

170

This suggests

that a virtual environment could be eligible for trade dress protection if

sufficiently distinctive.

B. VR User Interfaces

i. Apple v. Microsoft

In Apple v. Microsoft, which is one of the more recent cases

concerning the copyrightability of user interfaces, Apple sued Microsoft,

claiming that Microsoft infringed on its Lisa Desktop and Macintosh

Finder.

171

Specifically, Apple claimed Microsoft infringes on its “desktop

164

17 U.S.C. § 101.

165

Cho, supra note 62, at 811.

166

17 U.S.C. § 101.

167

Cho, supra note 62, at 819.

168

Cho, supra note 62, at 812.

169

Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763 (1992).

170

Cho, supra note 62, at 825.

171

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 35 F.3d 1435, 1438 (9th Cir.

1994).

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

354

metaphor with windows, icons and pull-down menus which can be

manipulated on the screen with a hand-held device called a mouse.”

172

The district court case represented the first “claim of copying a

computer program’s artistic look as an audiovisual work instead of

program codes registered as a literary work.”

173

This fact impacted

Apple’s contention that there was an ambiguity between the audiovisual

components and the literal program.

174

When looking at the line between copyrightable expression and

unprotected ideas, the court took into consideration the merger

doctrine.

175

In its analysis of a desktop icon representing a document, the

court considered an iconic image shaped like a page to be an obvious

choice.

176

The court also noted that this idea closely relates to the doctrine

of scenes à faire.

177

This doctrine posits that when particular features “are

as a practical matter indispensable, or at least standard, in the treatment of

a given [idea], they are treated like ideas and are therefore not protected

by copyright.”

178

The court relied on this doctrine in deciding that nothing

protects the mere use of Apple’s system of overlapping windows.

179

While not explicitly addressing the idea of functionality, the

merger doctrine and the scenes à faire doctrine inevitably incorporated

functionality.

180

For example, when applying the merger doctrine, the

court considered the expression of the icons to merge with the “idea” or

the icon, i.e. representing a document.

181

This “representation” is

functional in nature because the icon functions as an indication that when

you click on it, a document will come up.

182

Similarly, in its analysis of

the scenes à faire doctrine, the court decided that the system of overlapping

windows was indispensable to the “idea” of having multiple windows.

183

172

Id.

173

Id. at 1439.

174

Id. at 1441.

175

“Well-recognized precepts guide the process of analytic dissection.

First, when an idea and its expression are indistinguishable, or ‘merged,’ the

expression will only be protected against nearly identical copying.” Id. at 1444.

176

Id.

177

Id.

178

Id. (quoting Frybarger v. Int’l Bus. Machs. Corp., 812 F.2d 525, 530

(9th Cir. 1987)).

179

Id.

180

Id.

181

Id.

182

Id.

183

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

355

However, it is only indispensable if ease of functionality on the program

is essential.

184

The fact that functionality is inevitably part of the analysis of the

copyrightability of computer programs should come as no surprise

because the Copyright Act defines a computer program as “a set of

statements or instructions to be used directly or indirectly in a computer in

order to bring about a certain result.”

185

One can define functionality as the

ability to bring about a certain result.

186

Accordingly, it seems impossible

to separate a computer program’s copyrightability from its functionality.

However, the courts have viewed programs’ functionality as an obstacle

to the programs’ copyrightability.

187

In many cases, Section 102(b)

justifies this hurdle, by stating that “[i]n no case does copyright protection

for an original work of authorship extend to any . . . method of operation .

. . .”

188

However, in Oracle America, Inc. v. Google Inc., the court noted

that this is not supposed to be a second step to copyrightability that deters

from already copyrightable subject matter, but rather it is supposed to

emphasize the distinction between idea and expression.

189

ii. VR Application

Apple poses many problems for protecting VR experiences

through copyright, particularly because VR experiences, in a way, are the

ultimate user interface.

190

Instead of a user interface having an icon shaped

like a blank document, representing a document, a virtual environment

could have the actual document (represented virtually).

191

Instead of a user

clicking on an icon with a cursor controlled by a mouse, the user may

simply interact with the virtual document just as he or she would interact

with a real-world document.

192

This could implicate the merger doctrine

because there would be an extremely finite amount of ways to express the

“idea” of any given interaction.

193

184

Id.

185

17 U.S.C. § 101 (emphasis added).

186

Functionality, MERRIAM-WEBSTER (2019), https://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/functionality.

187

Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google Inc., 750 F.3d 1339, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

188

17 U.S.C. § 102.

189

Oracle Am., Inc., 750 F.3d at 1356.

190

“Software designers continually strive to produce increasingly user-

friendly interfaces. Virtual Reality is the utmost fulfillment of that end.” Weber,

supra note 64, at 189.

191

Id.

192

Id.

193

See generally Oracle Am., Inc., 750 F.3d at 1339.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

356

For example, in Manufacturers Technologies Inc., v. Cams, Inc.,

the district court decided that “the placement of common screen

components in certain specific locations is limited by several constraints,”

and that the narrow range of possibilities for the placement of headings

and other formatted displays rendered the screen display

uncopyrightable.

194

Similarly, the court decided that the method of

navigation of screen displays was not protected because the navigation

was highly dependent on the hardware and the possibility of internal

navigation was limited.

195

The court also considered its limitations in the

number of ways to appeal to the user’s comfort,

196

and decided that “to

give the plaintiff . . . protection for this aspect of its screen displays, would

come dangerously close to allowing it to monopolize a significant portion

of the easy-to-use internal navigational conventions for computers.”

197

Applying this analysis to VR, hardware limitations and limitations

created by facilitating user comfort would severely limit protection. Issues

with motion sickness, headaches, and general discomfort arise in many

VR experiences when the experiences do not align with the user’s

expectation of reality, particularly when a visual display lags behind the

user’s motion.

198

This is an extreme case of user discomfort, unparalleled

to the discomfort users could experience with a traditional computer

program.

199

In a less extreme, but also very relevant example, users would

expect an experience that attempts to imitate the real world to resemble

the real world. For example, objects would fall to the ground if not held

up, and if a user “grabbed” a virtual document, it would move with the

user’s hand. Generally speaking, user’s expectations of real-world

interactions may significantly limit user’s expectations in a VR

experience, and this could inhibit the range of possibilities for VR user

interfaces and methods of interactions with virtual objects.

This aspect of VR may incline courts to decide that the visual

displays in VR experiences merge very often with the courts’ idea. Thus,

protection will likely be more probable for interfaces and interactions that

are dissimilar from the real-world experience.

194

Mfs. Tech. Inc. v. Cams, Inc., 706 F. Supp. 984, 995 (D. Conn. 1989).

195

Id.

196

Id.

197

Id.

198

Anastasiia Ku, Motion Sickness in VR, UX PLANET (Nov. 29, 2018),

https://uxplanet.org/motion-sickness-in-vr-3fa8a78216e2).

199

Id.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

357

iii. Useful Articles

Many cases deciding the copyright eligibility of computer

programs hinge on determining whether particular aspects of computer

programs are functional in nature, which would bar protection either

through the “method of operation” limitation in the Copyright Act, or

through the merger or scenes à faire doctrine.

200

If any of these three

limitations apply to part of a computer program, courts will consider the

aspect more an idea than a protectable expression and will not afford the

aspect protection under Copyright Law.

201

While computer programs have

been registered and protected as literary and audiovisual works

historically, an additional category of copyright protection arguably exists:

sculptural, pictorial, or graphical works.

202

If one were to consider a

program (or the visual output of a program) a sculptural, pictorial, or

graphical work, then a protection exception to the functionality limitations

would exist. This exception is the useful article doctrine. The Copyright

Act defines a “useful article” as “an article having an intrinsic utilitarian

function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to

convey information”.

203

While the Copyright Act defines “useful article” in its general

definitions section, every other reference to “useful articles” appears either

in the definition of “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works” or in Section

113: “Scope of exclusive rights in pictorial, graphic, and sculptural

works.”

204

These references comprise the rules for the treatment of “useful

articles” in Copyright law, and are arguably only applicable to pictorial,

graphic, and sculptural works.

205

The Copyright Act’s definition of pictorial, graphical, and

sculptural works states the rule regarding the copyrightability of useful

articles:

“[T]he design of a useful article, as defined in this section, shall

be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to

the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural

200

See generally Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google Inc., 750 F.3d 1339, 1348

(Fed. Cir. 2014); Mfs. Tech. Inc. v. Cams, Inc., 706 F. Supp. 984, 995 (D. Conn.

1989).

201

Id.

202

See 17 U.S.C. § 101.

203

See 17 U.S.C. § 101.

204

17 U.S.C. § 113.

205

See generally 17 U.S.C. § 101, 113.

BUSINESS, ENTREPRENEURSHIP & THE LAW VOL. XII:II

358

features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing

independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.”

206

In 2017, the Supreme Court interpreted this section of the

Copyright Act.

207

The Court determined that to meet the first requirement

in the statute, the “separate identification,” “[t]he decisionmaker need only

be able to look at the useful article and spot some two- or three-

dimensional element that appears to have pictorial, graphic, or sculptural

qualities.”

208

The second requirement, the “independent-existence

requirement,” is “more difficult to satisfy,” and “[t]he decisionmaker must

determine that the separately identified feature has the capacity to exist

apart from the utilitarian aspects of the article,” meaning that “the feature

must be able to exist as its own pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work as

defined in § 101 once it is imagined apart from the useful article.”

209

There is arguably potential for the rules of pictorial, graphic, and

sculptural works to apply to virtual objects. The Copyright Act defines

pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works to “include two-dimensional and

three-dimensional works of fine, graphic, and applied art, [and]

photographs . . . ” among other examples.

210

While not an obvious or

immediate conclusion, a potential plaintiff could argue that one should

consider a virtual object as pictorial, graphic, or sculptural, and thus the

virtual object is immune to any arguments that it should not receive

protection because of the virtual object’s utilitarian nature. This would

require an analysis of the ontological status of virtual objects and whether

to consider them as two-dimensional or three-dimensional. One may more

likely consider virtual objects two- or three-dimensional than considering

components in a traditional computer program two- or three-dimensional

because of the level of interactivity between the virtual objects and the

user, and because they behave in a way very similar to real world two- or

three-dimensional objects. This is especially true because virtual objects

appear to exist in the world around the user.

211

This argument could potentially carry more weight when the

display of the virtual object maps itself onto a real-world physical object

in the real-world space surrounding the user. For example, a display of a

baseball bat could appear on a real-world rod, and when the user looks in

206

17 U.S.C. § 101.

207

Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1002 (2017).

208

Id. at 1010.

209

Id.

210

17 U.S.C. § 101.

211

See generally Weber, supra note 64.

2019 COPYRIGHTING EXPERIENCES

359

the direction of the real-world rod, he or she sees the display of the bat in

the rod’s place. This could strengthen the argument that one should

consider the virtual display of the object sculptural.