WIDENING THE TRAINING

PIPELINE:

Are Warrant Officer Instructor Pilots

the Best Solution to Increase Pilot

Production?

Aaron R. Ewing, Major, USAF

Air Command and Sta College

Evan L. Pettus, Brigadier General, Commandant

James Forsyth, PhD, Dean of Resident Programs

Bart R. Kessler, PhD, Dean of Distance Learning

Paul Springer, PhD, Director of Research

Please send inquiries or comments to

Editor

e Wright Flyer Papers

Department of Research and Publications (ACSC/DER)

Air Command and Sta College

225 Chennault Circle, Bldg. 1402

Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6426

Tel: (334) 953-3558

Fax: (334) 953-2269

E-mail: acsc.der.researchorgmailbox@us.af.mil

AIR UNIVERSITY

AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE

Widening the Training Pipeline:

Are Warrant Ocer Instructor Pilots the

Best Solution to Increase Pilot Production?

A R. E, ,

Wright Flyer Paper No. 77

Air University Press

Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center

Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

Commandant, Air Command and Sta

College

Brig Gen Evan L. Pettus

Director, Air University Press

Maj Richard T. Harrison

Project Editor

Catherine Parker

Illustrator

Daniel Armstrong

Print Specialist

Megan N. Hoehn

Air University Press

600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405

Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010

https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress

and

Twitter: https://twitter.com/aupress

Air University Press

Accepted by Air University Press August 2019 and published September 2020.

Disclaimer

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied

within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily repre-

sent the views of the Department of Defense, the Department of

the Air Force, the Air Education and Training Command, the Air

University, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public

release: distribution unlimited.

is Wright Flyer Paper and others in the series are available elec-

tronically at the AU Press website: https://www.airuniversity.af

.edu/AUPress/Wright-Flyers/

iii

Contents

List of Illustrations iv

Foreword v

Abstract vi

Introduction 1

Overview of the Study 1

Nature of the Problem 1

Purpose of the Study and Research Question 2

Research Structure and Methodology 2

Literature Review 3

Factors Driving the Pilot Shortage 3

Pilot Shortages by Fixed Wing Mission Set 5

History of the Warrant Ocer in the USAF 6

Warrant Ocer Utilization in Sister Services 7

Warrant Ocer Accession Timelines 11

Alternative Options to Increase Pilot Production 13

Comparison of Warrant Ocers and Alternatives 16

Analysis 24

Conclusion 25

Recommendation 26

Abbreviations 30

Bibliography 31

iv

List of Illustrations

Figures

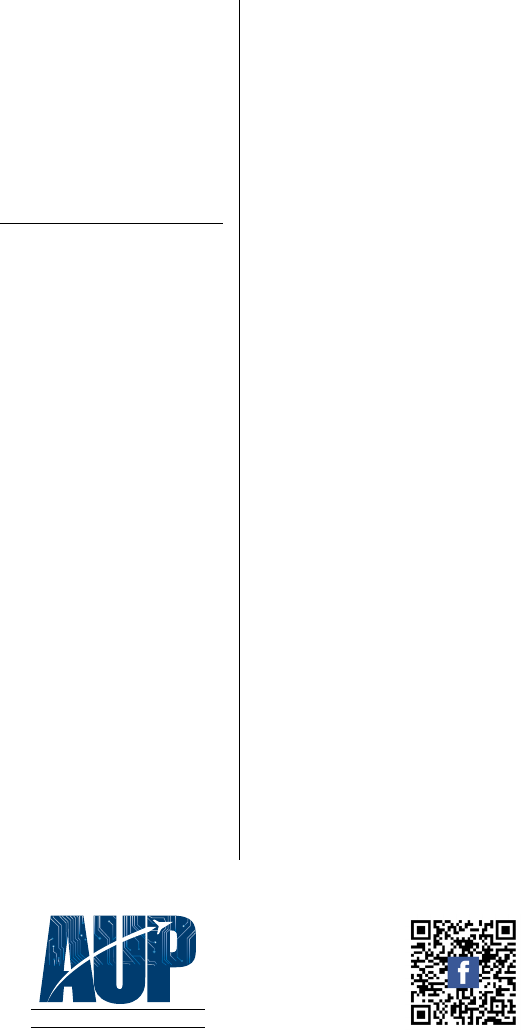

1. Airline hiring versus Air Force pilot attrition 4

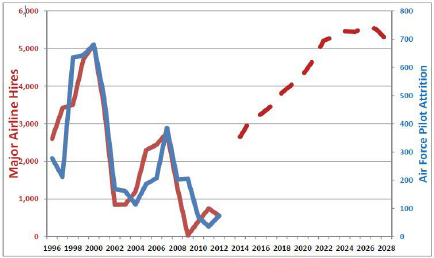

2. Distribution of warrant ocer accessions by

years of service 12

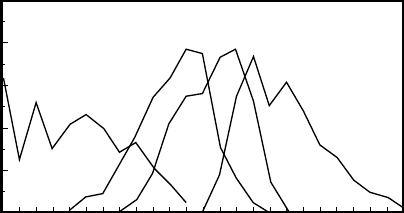

3. Distribution of Army Aviator promotions by

years of service 19

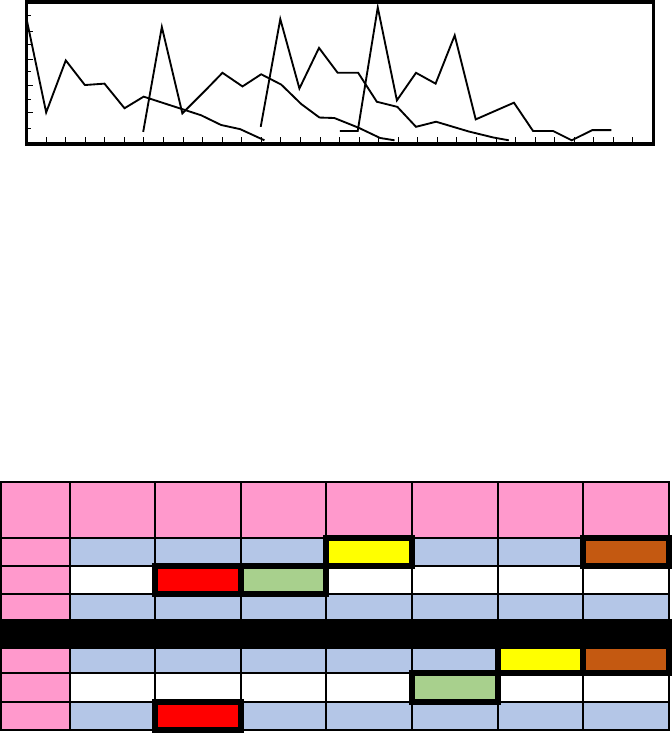

Tables

1. 2018 Military Pay Chart- monthly basic pay 19

2. Summary of the comparison between

methods and criteria 24

v

Foreword

It is my great pleasure to present another issue of e Wright Flyer Papers.

rough this series, Air Command and Sta College presents a sampling of

exemplary research produced by our resident and distance- learning stu-

dents. is series has long showcased the kind of visionary thinking that

drove the aspirations and activities of the earliest aviation pioneers. is

year’s selection of essays admirably extends that tradition. As the series title

indicates, these papers aim to present cutting- edge, actionable knowledge—

research that addresses some of the most complex security and defense chal-

lenges facing us today.

Recently, e Wright Flyer Papers transitioned to an exclusively electronic

publication format. It is our hope that our migration from print editions to an

electronic- only format will foster even greater intellectual debate among Air-

men and fellow members of the profession of arms as the series reaches a

growing global audience. By publishing these papers via the Air University

Press website, ACSC hopes not only to reach more readers, but also to sup-

port Air Force–wide eorts to conserve resources. In this spirit, we invite you

to peruse past and current issues of e Wright Flyer Papers at https://www

.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/Wright- Flyers/.

ank you for supporting e Wright Flyer Papers and our eorts to dis-

seminate outstanding ACSC student research for the benet of our Air Force

and war ghters everywhere. We trust that what follows will stimulate think-

ing, invite debate, and further encourage today’s air, space, and cyber war

ghters in their continuing search for innovative and improved ways to de-

fend our nation and way of life.

EVAN L. PETTUS

Brigadier General, USAF

Commandant

vi

Abstract

e United States Air Force is struggling to cope with a worldwide pilot

shortage that has le the service over 2,000 pilots short of what is needed to

fully man its squadrons. With pilot retention declining in a time of unprece-

dented airline hiring, the service is desperately trying to nd ways to increase

pilot production. To recover from the current shortage, the Air Force has de-

termined it needs to increase annual production from 1,200 to 1,600 pilots

per year. Despite identifying a need for increased production, the service has

yet to identify a clear method to accomplish this task. A 33 percent increase

of students will necessitate an increase of undergraduate pilot training (UPT)

instructors; where the Air Force intends to nd additional instructors given

the current pilot shortage is unclear.

is research paper seeks to ll this gap in knowledge by answering the

question, are warrant ocers the best solution to increase UPT instructor

manning to achieve the overarching goal of producing 1,600 pilots per year?

To answer the question, this study used a problem/solution framework to

compare four methods of increasing pilot production: warrant ocer UPT

instructors, contracted civilian UPT instructors, increasing the number of

rst assignment instructor pilots, and timeline reductions via the Pilot Train-

ing Next program. e four methods were assessed against ve criteria: time-

liness of implementation, personnel cost savings, training squadron manning

stability, impact on operational squadron manning, and quality of training.

Ultimately, this study concluded that warrant ocers are not the best option,

however, neither are any of the other methods. e problem of increasing

pilot production is too complex to be solved with a single, silver-bullet solu-

tion. While no single method could suciently satisfy all ve criteria, apply-

ing all four methods in parallel does have the potential to meet the Air Force’s

goal of producing 1,600 pilots per year.

1

Introduction

Overview of the Study

e United States Air Force (USAF) is contending with the most severe pi-

lot manning crisis in its 71-year history. e former Secretary of the Air Force,

Heather Wilson, has stated that active duty, guard, and reserve total force is

currently over 2,000 pilots short of what it needs to ll its billets.

1

While many

factors are at play, years of declining retention in a time of unprecedented air-

line hiring and a signicant decrease in authorized end strength despite sub-

stantial mission growth for the Air Force, have contributed signicantly to the

current pilot shortage. To address the shortage, Air Force is focusing eorts on

improving pilot retention and increasing pilot production. is research proj-

ect will focus on the latter eort by investigating how the Air Force can best

achieve its goal of increasing pilot production at a time when the current in-

ventory of available instructor pilots is at a premium.

One of the potential solutions the paper will investigate is utilizing warrant

ocers to serve as undergraduate pilot training (UPT) instructors. While the

Air Force eliminated warrant ocers from its rank structure long ago, all

three sister services currently and successfully employ warrant ocer pilots

in daily operations. Over the next several years the Air Force intends to in-

crease its overall end strength, presenting an opportunity for the service to

reconsider if it now has a need for warrant ocers in the force. is paper

hypothesizes that warrant ocers are the best long- term solution to the UPT

instructor manning problem and will compare this course of action to several

alternatives to determine the best way forward.

Nature of the Problem

In February 2017, the chief of sta of the Air Force (CSAF) established an

aircrew crisis task force with the purpose of identifying factors that drive de-

clining retention and recommend initiatives to reverse the trend. e task

force identied that problems in work/life balance, quality of service, and pay

discrepancies between military and airline pilots were the primary factors

causing pilots to leave military service. To address these problems the task

force presented 44 initiatives to the CSAF for approval and at the time of this

writing 37 of the task force’s recommendations had been implemented.

2

Hopefully these initiatives serve their intended purpose and retention rises;

however, retaining current pilots will only help short- term manning stability

2

in ying squadrons. In order to achieve long- term pilot manning stasis, the

Air Force must increase pilot production.

To alleviate the shortage, Air Force has determined that it is necessary to

increase the pilot production rate from 1,200 to 1,600 pilots per year.

3

If the

Air Force intends to increase the number of yearly students by 33 percent a

corresponding increase in required instructor pilots should be expected.

erein lies the problem, as the Air Force has yet to reveal where it is going to

nd additional instructors in times of a pilot shortage. Furthermore, given the

ceaseless pace of combat operations, the Air Force must nd a way to increase

instructor manning without negatively impacting combat capability.

Purpose of the Study and Research Question

Reassigning pilots from combat squadrons to serve as UPT instructors is

the only method the service currently implements to increase instructor man-

ning at ying training squadrons. Continuing to do so will have negative im-

plications to combat capability as operational squadrons already suer from

manning shortages. Any additional reduction in personnel will only further

degrade the unit’s ability to project combat airpower. us, it is imperative that

the Air Force nd alternative solutions to increase its pool of UPT instructor

pilots. is paper will investigate and compare various potential sources of

instructor pilots in order to answer the following research question: are war-

rant ocers the best solution to increase UPT instructor manning in order to

achieve the overarching goal of producing 1,600 pilots per year?

Research Structure and Methodology

is research paper will utilize the problem and/or solution framework to

identify the best method to increase instructor pilot manning at UPT squad-

rons and will compare the warrant ocer option against three alternative

methods that could feasibly increase pilot production: bolstering the number

of rst assignment instructor pilots, implementing contracted civilian in-

structors, and reducing the timeline to produce a pilot via the Pilot Training

Next program. Each option will be weighed against ve criteria: timeliness of

implementation, personnel cost savings, stability in training squadron man-

ning, impact on operational squadron manning, and quality of training. is

analysis will be essential in determining if warrant ocers are the best solu-

tion to increase instructor pilot manning at UPT squadrons to meet the Air

Force’s target of producing 1,600 pilots per year.

Examining the factors that lead to the current pilot shortage and under-

standing how the Air Force arrived at this unfortunate state of aairs will be

3

essential to provide a context in determining if warrant ocer instructor pi-

lots have advantages over the current practice of using traditional ocers as

UPT instructors. Additionally, statistical data on pilot manning shortages by

mission area will be analyzed to demonstrate that the Air Force will be unable

to increase instructor manning utilizing the current pool of pilots without

causing unacceptable harm to combat squadron manning.

Next, the paper will outline the history of the warrant ocer in the USAF,

as well as the reasoning behind the decision to eliminate the rank. Under-

standing this history is necessary to comprehend why Air Force senior lead-

ers are so resistant to the notion of reinstating the rank structure. While serv-

ing as the 17th chief master sergeant (CMSgt) of the Air Force, James Cody

conducted a video all call in which he provided insight into the Air Force’s

position on warrant ocers, “When we really have a conversation about war-

rant ocers, we’re talking about money, you don’t get dierent people; they

don’t get any better at their job. You just pay people dierent.”

4

If this paper is

to succeed in its goal of demonstrating how warrant ocers could provide

exceptional value in the realm of pilot training, it will be necessary to address

counter opinions held by senior Air Force leaders such as CMSgt Cody. Un-

derstanding the logic behind why the Air Force determined warrant ocers

were unnecessary is a necessary step in producing a counterargument.

Unlike the USAF, the US Army, Navy, and Marine Corps have employed

warrant ocers during the entirety of their existence. Research on sister ser-

vice viewpoints on the roles, responsibilities, and employment of warrant of-

cers will be presented to show that the Air Force may have missed the mark

in its original decision to eliminate the rank structure. In order to set the

foundation for the primary analysis of this paper, it must rst be established

that warrant ocers have a place in the modern Air Force.

Literature Review

Factors Driving the Pilot Shortage

e Air Force’s capacity to train new pilots is wholly dependent on having

a cadre of experienced pilots available to instruct new students. Years of de-

clining pilot retention combined with congressionally mandated force reduc-

tions have produced a climate where increasing pilot production will be dif-

cult. While many intangible factors contribute to a pilot’s decision to leave

military service, such as quality of life and increased stress from persistent

combat operations, the Air Force pilot attrition rate has a denitive direct cor-

relation to airline hiring. Figure 1 includes data from a study on Air Force

4

pilot attrition that not only conrms this correlation but also predicts that the

airline hiring rate will continue to increase until 2027.

Figure 1. Airline hiring versus Air Force pilot attrition

5

With airline hires expected to increase over the next decade, it is logical to

assume Air Force attrition will continue to rise and the service is scrambling

to nd ways to inuence pilots to stay. In addition to nonmonetary initiatives

designed to reduce additional duties and improve quality of life, the Air Force

recently increased the maximum aviation bonus to $455,000 in return for an

additional thirteen- year service commitment by pilots eligible to leave in s-

cal year (FY) 2018. At the time of this writing, only 34.6 percent of eligible

pilots had accepted the bonus, falling well short of the 64 percent target the

Air Force is hoping for.

6

It is clear that the pilot shortage is going to get worse

before it gets better; however, declining retention is only partially responsible

for the current shortage.

In addition to declining retention, the USAF pilot shortage is impacted by

signicant reductions in end strength compounded by an increase in mission

responsibilities. e end of the Cold War precipitated a massive military force

reduction that resulted in decreasing USAF authorized end strength from

over 500,000 in 1991 to only 311,000 in 2016.

7

Despite the 38 percent decrease

in manpower, the USAF has experienced signicant growth in responsibili-

ties over the past 27 years as mission sets that did not previously exist began

to materialize. During the Cold War, remotely piloted aircra (RPA) existed

only in the minds of innovators. Today, the war on violent extremism em-

ploys over 60 RPA combat orbits with 24-hour coverage, necessitating over

1,100 pilots to meet the demand.

8

Although space and cyber operations ex-

isted at the end of the cold war, the scope of responsibility in each domain has

magnied as the increasing threat from state and nonstate actors challenge

the United States’ ability to maintain information dominance. In 2016 alone,

over 4,000 oensive cyber operations were conducted against more than

5

100,000 adversarial targets.

9

While space and cyber do not require pilots to

conduct operations, signicant growth in cyber and space personnel limit the

Air Force’s ability to increase pilot authorizations due to congressional restric-

tions on authorized end strength. To put it simply, the USAF is too small to

meet its worldwide commitments.

Senior Department of Defense (DOD) leadership has recognized this fact

and is asking for congressional approval to grow. e Air Force’s current au-

thorized end strength sits at 325,100 for FY 2018. FY 2019 budget request

seeks an increase to 338,800 by 2023.

10

If approved, the USAF should be judi-

cious with the application of additional manpower. Clearly, some of the ad-

ditional personnel will be used to bolster the pilot corps. However, Air Force

must consider if the current practice of solely using commissioned ocers as

pilots remains the best course of action.

Given that sister services successfully employ warrant ocers as pilots, the

opportunity for end strength growth opens the door for the Air Force to recon-

sider its pilot rank structure. CMSgt Cody’s argument that changing a pilot’s

rank from commissioned to warrant ocer does not add capability is valid if

pilot authorizations remain constant. However, if an increase in end strength

is approved, the Air Force could gain signicant capability by reinstating war-

rant ocers to serve as UPT instructors. Doing so would allow hundreds of

ocers currently assigned to pilot training squadrons to return to their pri-

mary airframe, thereby restoring signicant combat capability to the force.

Pilot Shortages by Fixed Wing Mission Set

In April 2018, the Government Accountability Oce (GAO) was directed

by the US Senate to research the DOD’s management of the pilot workforce.

e goal was to identify the extent of the dierence between actual manning

and pilot authorizations for each branch of the military. During FY 2017, the

GAO found that the USAF had the following xed wing pilot shortages or

overages by mission area: -27 percent ghter, -8 percent bomber, 3 percent

mobility, 24 percent surveillance, and -13 percent special operations.

11

Ignor-

ing the dierences in mission set, the Air Force was 8 percent short of the

pilots needed to ll its authorizations across the force in FY 2017.

With shortages in three of the ve primary mission areas, the Air Force is

struggling to nd pilots to serve as undergraduate pilot training instructors.

In order to sustain combat operations, the Air Force has already begun to shi

the excess mobility and surveillance pilots to man positions in basic pilot

training that would traditionally be staed by ghter, bomber, and special

operations pilots; however, this course of action is unsustainable.

12

With air-

6

line hiring rates expected to increase until 2027, the trend of declining reten-

tion is going to linger. If the Air Force continues to cash in overages of mobil-

ity and surveillance pilots, then shortages will inevitably occur in those

communities as well. If the Air Force is going to achieve manning stability for

all operational units, then it is essential that it rapidly develops a cadre of pi-

lots dedicated to training. e Air Force needs a pilot that focuses on basic

pilot training for their entire career, and as this paper will investigate, warrant

ocers may ll that niche requirement.

History of the Warrant Ocer in the USAF

Birth of the USAF Warrant Ocer. e origins of the USAF warrant of-

cer can be traced to the rank structure created by the Army Air Forces (AAF)

during World War II. e explosive growth of personnel during the war re-

sulted in the AAF end strength increasing from 21,000 to over two million

soldiers.

13

To keep the service from becoming too top heavy in commissioned

ocers, the Army appointed warrant ocers in over 40 dierent specialties

and created entirely new categories of rank, including the new position of

ight warrant ocer. As a result, thousands of aviation cadets who tradition-

ally would hold commissioned ocer ranks instead entered service as ight

ocers.

Prior to the war, it was not abnormal for enlisted men to serve as pilots.

However, as aircra became more complex, the aircrew positions required for

safe operation increased. is created a discontinuity in the chain of com-

mand as enlisted pilots would technically be the aircra commander of ocer

crewmembers serving in other crew positions. To resolve this dilemma, the

Pentagon held the position that ight ocers were to be treated as “third lieu-

tenants” and were due all the same customs and courtesies as commissioned

ocers.

14

e chaos of war tended to drown out any objections by commis-

sioned ocers about the rank authority of this so- called third lieutenant.

However, as the hostilities ended, confusion on how the rank truly t into the

chain of command grew since ight ocers were technically not enlisted

men, nor were they commissioned ocers.

Post- WWII confusion on warrant ocers. e signicant drawdown af-

ter the war and the establishment of Air Force as a separate military branch

resulted in the service inheriting over 1,200 warrant ocers from the former

AAF rank structure.

15

ough the appointment of ight ocers ceased, the

Air Force continued to appoint warrant ocers without any clear career path

for them. roughout the 1950s the Air Force struggled to nd an identity for

its small warrant ocer corps. In 1953, Air Force Regulation 36–72 dened a

7

warrant ocer as “a technical specialist with supervisory ability, who is ap-

pointed for duty in one superintendent Air Force specialty.”

16

However, this

denition did not suciently encapsulate how the role of a warrant ocer

was distinct from an enlisted noncommissioned ocer. Similarly, at a time

when numerous warrant ocers lled commissioned ocer positions, this

denition did not identify how the responsibilities of a superintendent were

signicantly dierent from those of junior commissioned ocers.

17

Addition-

ally, the Air Force and Congress were at odds on warrant ocer appoint-

ments. e Air Force clearly believed warrant ocers were distinct from

commissioned ocers; however, the Ocer Grade Limitation Act of 1954

mandated that warrant ocers be counted against the cap on ocer authori-

zations.

18

As confusion on the appropriate roles and responsibilities of war-

rant ocers continued, the debate began on whether or not the USAF should

divest itself of the rank.

Death of the USAF warrant ocer. To resolve the confusion, the Air Force

directed the ocers of Air Command and Sta School to investigate whether

or not the service truly required warrant ocers to accomplish the mission. In

1954 they published the results of their study in a report entitled Should We

Eliminate the Grade of Warrant Ocer in the Air Force. e investigating o-

cers found that the majority of warrant ocer appointments were being used

as a reward for outstanding master sergeants who had reached a ceiling in

promotability aer achieving the maximum grade of E-7. ey also identied

that the Air Force needed to enhance the prestige of the senior noncommis-

sioned ocer corps in order to restore their authority to hold supervisory po-

sitions; however, they concluded that maintaining the warrant ocer ranks at

the top of the enlisted career ladder was not the best method to do so.

19

e Air Force needed to provide upward career mobility for its senior en-

listed members in order to satisfy a need for enlisted supervision at the group,

wing and major command level. To provide this upward mobility they recom-

mended that warrant ocers be eliminated and realigned to a “Warrant Air-

men” or “Superintendent” construct which focused more on supervisory and

management responsibilities, rather than on technical expertise.

20

is con-

cept eventually morphed into the E–8 and E–9 ranks in use today and the

subsequent death of the warrant ocer grades.

Warrant Ocer Utilization in Sister Services

During the 1950s, the edgling Air Force underwent a period of self-

reection as it attempted to carve out a unique service identity. In this pro-

cess, a need for senior enlisted supervision was identied and concluded that

8

a warrant ocer’s focus on technical expertise was incompatible for this role.

However, during this time, the Air Force failed also to consider whether it had

a need for some members to remain technical experts in their cra. e force

reductions following WWII also challenged sister services to codify the roles

and responsibilities of warrant ocers. However, the Army, Navy, and Marine

Corps reached dierent conclusions than the air service as evidenced by their

successful utilization of warrant ocers across numerous occupations today.

United States Navy. e US Navy (USN) has employed warrant ocers

longer than any other branch of the armed forces. In 1775 with the outbreak

of the Revolutionary War, Continental Congress established warrant ocer

grades to serve in eight unique positions upon newly commissioned frigates

to combat the British.

21

ese men were initially selected based upon their

expertise in civilian trades such as surgery, carpentry and gunnery. As the

naval technology matured, the Navy continued to add warrant ocers to its

force to meet its demand for specic technical knowledge. By WWII, the ini-

tial eight career elds had expanded to twelve and vast numbers of warrant

ocers had been added to meet wartime demands.

22

ough the warrant ocer has been a near constant position throughout

the history of the Navy, the necessity of the rank has not always been without

question. Similar to the experiences of the USAF, the personnel drawdown

following WWII challenged the Navy to consider whether or not warrant of-

cers were still necessary. From 1951 to 1959 three investigative boards were

convened to determine how warrant ocers t into the rank structure of the

Navy. ese boards ultimately decided to follow the same path as the Air

Force and eliminated warrant ocers in favor of adding the senior enlisted

E-8 and E-9 ranks.

23

As a result, this decision would not last for long. Drastic

cuts in the warrant ocer corps between 1959 and 1962 le the Navy strug-

gling to nd a replacement for the loss in technical expertise aboard its ships.

In 1963 the warrant ocer issue was reopened by another investigative board

which determined that warrant ocers should not only be reinstated but

their use should be expanded because of the rapidly growing technological

capabilities of modern warships.

24

While the Air Force held true to its initial decision, the Navy reversed

course and today there are twenty- six occupational designations where war-

rant ocers dutifully serve, including for a period of time, as pilots.

25

In 2006,

the Navy faced challenges with producing enough commissioned ocers to

meet its demand for pilots during a period of high accession. In response, the

Navy began an experimental program that generated warrant ocer pilots to

replace a portion of commissioned ocers in squadrons with extensive junior

ocer aviator populations. e goal was to create ying specialists that would

9

not be required to follow the traditional career path of a commissioned ocer

but would be able to remain ying without negative career repercussions.

26

Although the program was terminated in 2013 when the Navy reevaluated its

personnel requirements and no longer had a need to supplement its pilot bil-

lets with warrant ocers, it eectively proved that warrant ocers could reli-

ably serve as aviators.

27

e demise of the warrant ocer in the Air Force was largely due to its in-

ability to nd a dierence in responsibilities between senior noncommis-

sioned ocers and warrant ocers. However, the Navy was able to resolve

this confusion. e Navy denes an E–9 as a “senior enlisted leader respon-

sible for matters pertaining to leadership, administrative, and managerial

functions involving enlisted ratings.” In contrast, a warrant ocer is “a techni-

cal leader and specialist who directs technical operations in a given occupa-

tional specialty and serves successive tours in that specialty, yet remains the

technical expert.”

28

As will be discussed later in the analysis section of this

paper, it is this focus on technical leadership over successive tours that make

warrant ocers an appropriate t for the Air Force as UPT instructors.

United States Marine Corps. e origin of warrant ocers in the Marine

Corps can be traced back to WWI when Congress passed the National De-

fense Act of 1916, authorizing the military to expand quickly in response to

the great European war. Driven by technological advancements and in de-

mands resulting from rapid personnel growth, the Marine Corps instituted

warrant ocers for a specic purpose, “to maintain a selected body of person-

nel with special knowledge, training, and experience along particular lines...

beyond those required of noncommissioned ocers.”

29

Initially, 84 warrant

ocers were appointed as quartermaster clerks and marine gunners. Once

the United States ocially entered WWI, the demand for commissioned of-

cers in the Marine Corps increased and all but three of the initial 84 warrant

ocers were granted temporary commissions as second lieutenants.

30

At the

war’s conclusion, the need for ocers decreased and the temporary lieuten-

ants reverted back to the grade of warrant ocer. Similarly, growth of the

Marine Corps occurred during WWII. On a greater scale, Congress autho-

rized the appointment of 576 warrant ocers as well as granting the Secretary

of the Navy the responsibility for career management of warrant ocers, in-

cluding temporary commissions up to the rank of captain.

31

Following WWII, the lines of responsibility between warrant and commis-

sioned ocers became blurry. e Marine Corps trod a similar path as the

Air Force and Navy as it fought to alleviate the confusion. In 1959, the Marine

Corps headquarters directed a study on the warrant ocer force structure

which claried the role of the rank. First, warrant ocers jobs would be tech-

10

nical in nature and require long on- the- job or specialist training. Second,

their level of supervision would not require formal education such as a bach-

elor’s degree. ird, the rapid turnover of warrant ocers was undesirable.

Finally, warrant ocers should only be employed in technical positions that

were not suitable to prepare a commissioned ocer for broad, general, or

command duties.

32

is concept of employment for warrant ocers has sus-

tained eectiveness in the Marine Corps to the present day.

Current Marine Corps regulations dene a warrant ocer as “a technical

ocer specialist who performs duties that require extensive knowledge, train-

ing, and experience with the employment of particular capabilities which are

beyond the duties and responsibilities of senior noncommissioned ocers.”

33

Under this guidance, Marine Corps warrant ocers are divided into two func-

tional based categories: marine gunner and technical warrant ocer. Marine

gunners are experts in all aspects of infantry weapons and experts as unit lead

instructors for tactical training programs. In contrast, technical warrant o-

cers specialize in technical noncombat arms specialties such as intelligence

and electronics maintenance.

34

Although, the Marine Corps does not utilize

warrant ocers as pilots, the demonstrated experience and stability that they

provide to technically oriented career elds helps one to conceptualize how

warrant ocers could be benecial to USAF pilot training squadrons.

United States Army. e US Army (USA) warrant ocer corps recently

passed a 100-year milestone in dutiful service to the nation. In July 1918, the

US Congress rst introduced Army warrant ocers to serve in the Coast

Artillery Corps as mine planters charged with the defense of major ports

during WWI.

35

Aer the war, the Army warrant ocer corps followed a sim-

ilar path as its Navy and Marine counterparts. e force was initially reduced

and subsequently expanded in preparation for WWII. By the end of WWII,

the Army warrant ocer corps had grown to over 57,000 soldiers serving in

40 occupations.

36

During the 1950s the Army began to diverge from its sister services regard-

ing warrant ocers. While other branches questioned if warrant ocers were

needed, the Army greatly expanded its use of the grade. e establishment of

the Air Force as a separate branch of service in 1947 resulted in the Army los-

ing a substantial portion of its aviators and warrant ocers. ese ocers

were chosen as the answer to the pilot shortage problem. e Army graduated

its rst class of warrant ocer helicopter pilots in 1951. Among its regular

ocers, warrant ocers provided valuable continuity within the Army’s avia-

tion program which oen suered from rapid assignment rotation.

37

ough the Army did not question the need for warrant ocers aer

WWII, it did adjust the lens through which the rank was viewed. Prior to the

11

war, warrant ocer grades were utilized as a tool to reward long- serving en-

listed men, as well as former commissioned ocers of WWI who lacked the

educational requirements necessary for continued commissioned service.

38

Because the service lacked a clear policy on warrant ocers entering WWII,

appointment, assignment, promotion, and training were decentralized to ma-

jor commanders, which resulted in a disorganized force upon the war’s con-

clusion.

39

To establish centralized personnel management, the Army con-

ducted several studies during the 1950s in order to formalize the purpose and

form of the warrant ocer program. ese studies culminated in 1957 with

the Army publishing a denition of a warrant ocer as “a highly skilled tech-

nician who is provided to ll positions above the enlisted level which are too

specialized in scope to permit the eective development and continued utili-

zation of broadly- trained, branch- qualied commissioned ocers.”

40

Over the following six decades the Army warrant ocer corps continued

to evolve. ough the specic occupations have changed to match the de-

mands of emerging technology, the focus on technical and tactical employ-

ment of weapon systems has remained constant. Current Army regulations

highlight this unique aspect of warrant ocer grades: “warrant ocers re-

main single- specialty ocers whose career track is oriented towards pro-

gressing within their career eld rather than focusing on increased levels of

command and sta duty positions.”

41

is perspective, discussed later in this

paper, suggests that proper utilization of warrant ocers could signicantly

enhance unit manning stability. Furthermore, given the successful track re-

cord of warrant ocer pilots in the Army, and the specic technical nature of

instructing basic ight training, warrant ocers could provide exceptional

value to USAF pilot training squadrons.

Warrant Ocer Accession Timelines

e Army, Navy, and Marine Corps all recognize that the value of a warrant

ocer lies in their technical expertise at the tactical level of warfare. However,

the three services dier on determining when a person has the experience level

necessary to validate appointment into the warrant ocer corps. e three

personnel management models in use by the DOD for warrant ocer acces-

sions are early select, mid- career select, and late- career select.

e early select model is the least applied method as it is utilized only by the

Army and specically to acquire warrant ocer pilots. Under this model, the

Army selects approximately seventy- ve percent of its pilots from soldiers in

their rst or second term of enlistment with two to eight years of military expe-

rience in any occupation. e remaining quarter of Army aviators are recruited

12

directly from civilian life.

42

e ability to select pilots from outside its ranks

provides signicant advantages to the Army by expanding the applicant pool.

Many civilian applicants have prior ight experience which increases the likeli-

hood that the trainee will successfully graduate from military ight school.

e mid- career select model is used to select warrant ocers in technical

career elds for both the Army and the Marine Corps. For both services, an

applicant must have achieved a minimum grade of sergeant (E-5) and the

member must have typically completed 10 to 15 years of military service upon

selection.

43

e jobs of technical warrant ocers in the Army and Marine

Corps are closely related to the same occupational area that they worked as an

enlisted members.

44

Many of these technical warrant ocer billets have com-

parable responsibilities to jobs found in the civilian sector, such as equipment

maintenance. However, because the services do not recruit civilians for direct

accession into technical warrant ocer positions, the applicant pool in the

mid- career select model is considerably smaller than the early select model.

45

e Navy stands alone in using the late- career select model to appoint war-

rant ocers. Prior to applying for warrant ocer, Navy candidates must have

reached the rank of chief petty ocer (E-7). Almost all newly appointed naval

warrant ocers have at least 14 years of service. Occasionally, the applicants

have over 20 years of military experience and were eligible to retire.

46

Similar

to the Army and Marine Corps, the Navy values the technical expertise of its

warrant ocer corps and assigns them to supervisory and training positions

that align with their previous enlisted specialties. However, unlike the other

services, the Navy does not consider warrants to be “junior ocers” in these

positions due to their extensive experience in military service.

47

25

20

15

10

5

0

<0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24

Percentages of Accessions

Army Aviator

Army Technician

Marine Corps Technician

Navy

Years of Service

Figure 2. Distribution of warrant officer accessions by years of service

48

Figure 2 provides a graphical presentation of the diering patterns of war-

rant ocer accessions among the three services. From this gure, it becomes

13

clear that each military branch has a dierent viewpoint on the requisite ex-

perience level to serve as a warrant ocer. Note that Army aviators are the

warrant ocer corps with the least time in military service at accession. In

order to qualify for Air Force pilot training, a candidate must begin ight

training before age 30.

49

For this reason, if the Air Force was inclined to rein-

state its warrant ocer corps to serve as pilots, it would need to adopt an ac-

cession strategy that is similar to the one in use by the Army. For the purposes

of analysis later in this paper, an assumption is made that Air Force warrant

ocer pilots would be obtained via the early select method described above.

Alternative Options to Increase Pilot Production

Additional rst assignment instructor pilots. One option that may allow

the Air Force to bolster instructor manning at UPT squadrons is to increase

the allocation of rst assignment instructor pilots (FAIPs) per graduating

class. e current assignment process for graduating pilots is described in Air

Education and Training Command Instruction (AETCI) 36–2504. Prior to

receiving a follow- on assignment in a major weapon system (MWS), a stu-

dent’s training performance is evaluated to determine their potential to com-

plete the training successfully.

50

A student’s academic test scores, daily ight

performance, check ride grades, and ight commander rankings are com-

piled to produce a merit- based score.

51

ese standardized scores are used to

generate a class rank for each student which partially determines the follow-

on aircra they will y.

Before receiving an assignment, each student indicates their follow- on air-

cra preference from rst to last. ese preferences are combined with the

class ranking to determine the student’s next assignment. In general, the top

student in the class should get the rst assignment choice, assuming a training

slot is available

52

. If one is not available, the second, third, or fourth preference

would be assigned and so on. is process continues by class ranking until all

assignments have been fullled.

e only exception to the process is a student receiving a ight command-

er’s recommendation to become a FAIP. Typically, students receiving a FAIP

recommendation are in the top third of the class. Pilots with instructor duties

are required to have high maturity, ying, and interpersonal skills. When a

quota for a FAIP is le unlled aer the process described above, a high per-

forming student that otherwise may have received a preferred assignment is

instead selected to remain on station to become a UPT instructor. e new

pilot serves as a FAIP for three to four years, aer which an assignment in

another MWS is given. e leadership and supervisory responsibilities ac-

14

companying FAIP duties are limited; therefore, captains are prohibited from

FAIP selection because of the negative career progression that would occur.

53

Current regulations clearly indicate that FAIP assignments need to be

lled, even if it means not giving a high performing student a preferred fol-

low- on assignment. If the Air Force adjusted regulations to permit captains to

serve as FAIPs, the pool of potential instructor pilots could be immediately

increased. Furthermore, there are typically only one or two FAIP assignments

per graduating class. e Air Force could quickly improve its UPT instructor

manning by increasing the number of FAIP assignments given to each class.

However, such an action would temporarily decrease manning in operational

squadrons until an increase in yearly student production is obtained from the

additional instructor capacity. Given the current manning shortages in opera-

tional squadrons combined with ongoing combat operations, it is unclear if

this is an acceptable premise.

Contracted civilian instructors. e second option the Air Force may use

to increase instructor manning at UPT squadrons is to expand the resource

pool by looking outside its own ranks to the civilian market. e Air Force has

a recent history of utilizing contracted civilian pilots to ll manning shortages

in noncombat specialties across the force. Congressionally mandated force re-

ductions in 2014 forced the Air Force to close the 65th Aggressor Squadron,

resulting in a y percent reduction in organic red air support capacity at Nel-

lis Air Force Base.

54

To resolve this problem, the Air Force awarded Draken

International a contract to provide adversary training support sorties for

weapons school, operational test, and Red Flag exercises. e company owns a

eet of A-4 and L-139 decommissioned military aircra that are own by con-

tracted civilian pilots. e demonstrated success of this contract has led the

Air Force to expand its use of contracted red air. In August 2018, the Air Force

released a request for proposals, annually soliciting bids to support 30,000 ad-

versary air sorties in the continental US, Alaska, and Hawaii.

55

At rst glance, contract pilots seem like a logical solution to supplement

Air Force pilot shortages; however, the civilian option is not without potential

pitfalls of its own. First, the pilot shortage is not limited to the Air Force but is

a worldwide problem. e rapid growth of air travel in Asia is increasing

worldwide demand for pilots. Current estimates project a need for over 23,000

new pilots per year until 2029.

56

e Air Force is only one of many players in

competition for experienced pilots, and will undoubtedly face signicant

challenges recruiting them. Second, while the civilian market could expand

the pool of potential instructor pilots, the expansion would be limited by the

fact that not every civilian pilot is a suitable candidate to become a military

ight instructor. e performance characteristics of Air Force training air-

15

cra far exceed anything an average civilian pilot would have experienced. As

such, former military pilots are the most likely candidates to easily make the

transition to UPT instructor without requiring extensive training.

Timeline reductions via the pilot training next program. e nal

method this paper will analyze to determine the best way to increase pilot

production involves reducing the timeline to produce a pilot via syllabus re-

ductions and simulation. If the Air Force intends to increase the number of

students yearly, reducing the syllabus requirements for live ights is probably

a necessity, since the availability of daily sorties is limited by the fact that the

training aircra eet is a xed asset. Increasing the number of students

would only increase the demand for ight time, so training opportunities

must be found elsewhere.

e Air Force is already experimenting with this process in a program

known as pilot training next (PTN). e PTN program is designed to reduce

the overall cost and time it takes to produce a pilot by replacing ight hours

with modern virtual reality simulators.

57

Currently, each UPT base uses ve

or six high delity simulators to train 300–400 students per year.

58

Because

the simulators are such a low- density, high- demand asset, the students’ simu-

lator time is closely regulated, leaving little capacity for additional practice

outside of designated syllabus events. As a result, the vast majority of instruc-

tion under the current pilot training syllabus occurs in the aircra with stu-

dents receiving approximately 200 ight hours before graduation.

59

e PTN program is revamping ight simulation by investing in modern

virtual reality technology. Instead of purchasing traditional simulators at the

cost of two to three million dollars each, the Air Force has looked toward

commercial o- the- shelf technology to lower costs. For a cost of approxi-

mately $10,000, a virtual reality headset and personal computer are pro-

grammed with an ‘articially intelligent’ ight simulator program that oers

feedback on the student’s performance without a human instructor in the

loop.

60

e signicantly reduced cost allows the Air Force to provide each

student a simulator for personal use at their residence, and the Air Force is

hoping additional simulator time, and computer- based instruction will re-

place actual ight time.

In August 2018, the rst graduates of the PTN program received their

wings aer only six months of training, far faster than the year it takes tradi-

tional UPT students to graduate.

61

Under the new syllabus, these newly

minted pilots received only 60 hours of ight time before graduation, a sev-

enty percent reduction compared to traditional UPT students.

62

Additionally,

the PTN students did not y the T-38, or T-1 follow- on trainers that tradi-

tional UPT students y. Aer graduation, the students will proceed to train

16

for their assigned MWS having own only the T-6 trainer. With the inaugural

class being a test case and if the students fail to complete training for their

primary MWS, they will return to UPT to complete the second half of the

current syllabus in the T-38 or T-1.

63

While some portion of ight time needs to be replaced by simulators, the

Air Force must be careful in achieving the appropriate balance between the

two. Simulation cannot accurately replicate the physical forces of ight that

can create life- threatening cases of spatial disorientation and G induced loss of

consciousness. Additionally, no amount of preprogrammed simulations can

cover the nonstandard situations pilots experience in an actual air trac con-

trol environment. Simulators are useful to practice the basics of standard de-

partures, ight maneuvers, recoveries, instrument approaches, and pattern

operations. However, in real- world situations, air trac control will eventually

issue an instruction that causes a safety issue with conicting trac or terrain

that requires a pilot to rely on prior experience and judgement to diuse the

danger. e Federal Aviation Administration denes airmanship as “a sound

knowledge of and experience with the principles of ight, the knowledge, ex-

perience, and ability to operate an airplane with competence and precision

both on the ground and in the air, and the application of sound judgment that

results in optimal operational safety and eciency.”

64

e key word in this def-

inition is experience. While simulators help to build procedural knowledge,

true airmanship is best obtained through actual experience in the air.

Comparison of Warrant Ocers and Alternatives

To determine the best method for increasing instructor manning at UPT

squadrons and annual pilot production, warrant ocers, FAIPs, contractors,

and the PTN program will be compared against the following ve criteria:

timeliness of implementation, personnel cost savings, training squadron

manning stability, impact on operational squadron manning levels, and qual-

ity of training.

Timeliness of implementation. Of the four options outlined in this paper,

increasing FAIP assignments is by far the quickest method to increase in-

structor manning at UPT squadrons. Within a span of only a few months, the

Air Force could bolster instructor manning by giving additional FAIP assign-

ments to the next graduating class of pilots. e training apparatus for FAIPs

already exists, and the only delay in acquiring additional instructor pilots

would be a short break aer UPT graduation, while the newly winged aviator

waits for a training slot to open in the two- month pilot instructor training

(PIT) course.

17

Utilizing civilian contractors as UPT instructors is the second fastest

method that could be implemented. However, two assumptions need to be

made to validate this ranking. First, the time it takes for the Air Force to de-

velop contract requirements, release a request for proposals, nd contractors

to submit proposals, and select a contract winner varies widely depending

upon the scale of the contracted work. As such, an assumption is made that it

would take one to two years to award the contract. If the Air Force was willing

to issue contracts to individual pilots, rather than contracting a parent com-

pany to manage the workforce, this timeline could be reduced; however, re-

search for this project revealed no instances in which this method of contract

employment was utilized. e second assumption is that potential applicants

would be limited to civilians with former military ight experience. As de-

scribed earlier, a civilian that did not previously attend UPT would need ex-

tensive training to y high- performance aircra. is would only increase the

total training bill for the Air Force, negatively impacting its ability to produce

additional pilots. To become qualied instructors, former military pilots

would only need to attend the same two- month PIT course that FAIPs com-

plete. With these assumptions in mind, it would take approximately two to

three years to acquire a sizable Corps of contracted instructor pilots.

e PTN program ranks third in the speed of implementation. e rst

iteration of the program is already completed and has produced its rst round

of pilots. However, because the program is experimental, there is still a large

amount of uncertainty in the quality of pilots it produces. As described ear-

lier, if the pilots fail to graduate training for their assigned MWS, they will be

recycled to complete the second half of the traditional UPT syllabus. Depend-

ing upon the assigned MWS, it could take between four and twelve months

for these students to complete follow- on training, providing the rst chance

to assess the eectiveness of the PTN program. e second iteration of PTN

is already scheduled to begin in January 2019, and these students will follow

the same syllabus as the rst class.

65

In order to determine if the PTN syllabus

has achieved an appropriate balance of simulator and ight time, it will take

several years until enough students graduate to provide sucient data points

for statistical analysis. In the author’s estimate, the PTN program is a mini-

mum of ve years from being ready for full implementation. However, if the

rst several rounds of PTN pilots perform competitively with pilots from the

traditional UPT syllabus, this timeline could be reduced.

Warrant ocer instructor pilots would be the lengthiest method to in-

crease manning at UPT squadrons and for this reason, the Air Force would

rst need to develop a structure for training and career development of the

rank. e Army currently has a comprehensive education system for warrant

18

ocers that consists of preappointment, entry, advanced, senior, and master

level courses.

66

Air Force has none of this training apparatus and would need

to start from scratch. e Air Force could build these training programs in-

crementally by rst developing the preappointment and entry- level training

to get warrant ocer appointments going. As the initial appointees promote

up the warrant ocer rank ladder, advanced courses could be developed to

meet the need for further education. Incrementally developing training

courses could move the timeline for appointing warrant ocers earlier; how-

ever, it would still take several years to generate the initial courses. A second

problem that would delay the appointment of Air Force warrant ocers is the

need to nd applicability of the rank in multiple career elds. It would be

impractical to generate an entirely new rank structure solely for the UPT in-

structor career eld. However, the technical expertise that warrant ocers

provide could be a benecial addition across numerous disciplines in the Air

Force. Although, proving this case to senior Air Force leaders, as well as Con-

gress, would undoubtedly take a signicant amount of time. Due to these

issues, the rst Air Force warrant ocer appointment would most likely be

ve to ten years away.

Personnel cost savings. Warrant ocer instructor pilots have the highest

potential to reduce personnel costs at UPT squadrons if they were used to ll

billets currently occupied by company grade ocers (CGO). In addition to

instructor responsibilities, CGOs have additional duties within UPT squad-

rons that they perform when not in the cockpit. e duties assigned to lieu-

tenants consist primarily of administrative tasks, with very little supervisory

responsibilities. ese tasks are well within the capabilities of any warrant

ocer to perform. Captains at UPT squadrons are typically assigned as ight

commanders who supervise the lieutenants. While sister services primarily

utilize warrant ocers for their technical expertise, they are not restricted

from serving in supervisory positions as their experience grows. For the pur-

poses of analyzing potential cost savings, it will be assumed that warrant of-

cers in the grades of W-1 and W-2 are used to replace rst lieutenants (O-2),

and similarly W-3s are tting substitutions for captains (O-3).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of Army aviator warrant ocer promo-

tions by years of service. From this gure, it is important to note that in the

Army aviator population, W-2 promotions typically begin at four years of

service, and W-3 promotions begin aer nine years of service. In this analysis,

a similar promotion rate for the notional Air Force warrant ocer instructor

pilot will be used.

19

25

20

W-2 W-3

W-4 W-5

15

10

5

0

2

Percentages of Promotions

Years of Service

ARMY AVIATORS

4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34

Figure 3. Distribution of Army Aviator promotions by years of service

67

In the Air Force, ocer promotions to rst lieutenant occur automatically

aer two years of service, and promotions to captain happen aer four years.

Due to the time it currently takes to graduate UPT and subsequently com-

plete training to become an instructor, virtually all FAIPs at UPT squadrons

are rst lieutenants with two to four years in service. It will be similarly as-

sumed that warrant ocers would have a minimum of two years of time in

service before they are qualied instructor pilots. Furthermore, captains serv-

ing as ight commanders typically have anywhere between four and 10 years

of time in service.

Pay

Grade

2 or less Over 2 Over 3 Over 4 Over 6 Over 8 Over 10

O–3 4,143.90 4,697.10 5,069.70 5,527.80 5,793.00 6,083.40 6,271.20

O–2 3,580.50 4,077.90 4,696.20 4,854.10 4,955.10 4,955.10 4,955.10

O–1 3,107.70 3,234.90 3,910.20 3,910.20 3,910.20 3,910.20 3,910.20

W–3 3,910.80 4,073.70 4,240.80 4,296.00 4,470.60 4,815.30 5,174.10

W–2 3,460.50 3,787.80 3,888.60 3,957.60 4,182.30 4,530.90 4,703.70

W–1 3,037.50 3,364.50 3,452.40 3,638.10 3,857.70 4,181.70 4,332.60

Table 1. 2018 Military Pay Chart- monthly basic pay

Adapted From: Defense Finance and Accounting Service, “Basic Pay,” 2018 Military Pay Chart, (Washington, D.C:

Department of Defense Comptroller, 1 January 2018).

e outlined cells in Table 1 indicate the qualitative data that was used for

comparison in order to determine the potential cost savings by using the war-

rant ocer for CGO substitutions described above. For Example, a newly

promoted O-3 was compared to a newly promoted W-3. From this data, if an

O-2 is replaced by a W-1 or W-2, the annual personnel bill would be reduced

by an average of $7,362 per person. e W-3 for O-3 substitution results in

even greater annual savings at an average of $10,854 per person.

20

In addition to monetary savings from annual salaries, substituting warrant

ocers for CGOs could result in a signicantly reduced obligation to pay re-

tirement benets because many warrant ocers would likely separate before

completing the 20 years of service needed to retire. As discussed earlier, the

pay discrepancy between airline and military salaries is a signicant factor in

declining pilot retention. is discrepancy would only be higher for warrant

ocers and many would leave for higher paying civilian employment. In fact,

less than half of Army warrant ocer aviators complete 20 years of service.

68

Finally, while the Air Force would lose its training investment as warrant

ocers separated aer their 10-year service commitment, the loss would be

far less for a warrant ocer pilot than a commissioned ocer because war-

rant ocers would not have incurred additional expenses from training in

another MWS. e GAO estimates that it costs approximately $11,000,000 to

produce a ghter pilot. In contrast, the cost to produce a UPT instructor is

approximately $1,000,000.

69

e PTN program and increasing FAIP assignments tie for second in terms

of reducing personnel costs, since there would mainly be no change to the

current obligation. While the PTN program would save money in dierent

ways, such as replacing expensive ight hours for simulators, the impact on

personnel costs is negligible. It does not matter if a student is receiving in-

struction in an airplane or a simulator, the fact remains that an instructor

needs to be there to teach the student. If that instructor is a commissioned

ocer, the cost of employing them remains unchanged. Similarly, increasing

the use of FAIPs only adds more commissioned ocers to the payroll, and by

doing so, there are no unrealized savings in personnel costs.

Contract pilots rank fourth in personnel savings primarily because it is

impossible to say whether they would be cheaper than using commissioned

ocer instructor pilots. Conversely, contractors may actually increase costs to

the US taxpayer because their salaries need to be competitive with other op-

portunities in the civilian market. When military pilots are already leaving

service for higher salaries in the civilian sector, any contract the Air Force

proposes must provide an incentive that is more attractive than what the air-

lines provide. ere is serious international competition to acquire pilots. For

example, Air China is oering salaries beginning at $16,500 per month to

American pilots willing to y for a foreign airline.

70

If the Air Force does bring

competitive contract salaries to the table, it may inadvertently exacerbate its

retention problem and end up paying recently separated UPT instructors

more money to do the same job.

Some may argue that contractors would save money on healthcare costs

over military personnel; however, the relatively young age and good health of

21

the Air Force’s pilot community does not typically result in numerous expen-

sive hospital visits. Furthermore, a pilot with the necessary experience to be

hired by the airlines is unlikely to take a job as an Air Force contractor that

does not pay enough to cover health insurance. While healthcare costs may

not be directly absorbed by the Air Force, it would inevitably be incurred

through a higher contract salary.

Training squadron manning stability. Warrant ocers are the best op-

tion to bring instructor manning stability to UPT squadrons because they can

work in a single vocation for an entire career. In contrast, commissioned of-

cers require a wide breadth of knowledge because eventually they will lead

large and diverse groups of people. Wing commanders need to have a general

understanding of operations, maintenance, logistics, base support, and nu-

merous other functions. e scope of their command requires commanders

lead the people executing these tasks and functions. To acquire this wide body

of knowledge, commissioned ocers are expected to move to a dierent base

every three to four years.

is poses a problem, as every time a UPT instructor leaves for career

broadening opportunities, the Air Force incurs two additional training bills.

e departing instructor must attend training for a combat airframe, and the

replacement pilot must relearn how to y training aircra. ese additional

training bills could be signicantly reduced if warrants replaced commis-

sioned ocers as UPT instructors. e high degree of specialization, inherent

to the warrant ocer ranks would allow them to stay at the same location,

producing new pilots, for the entirety of their 10-year service commitment. A

warrant ocer instructor serving a 10-year assignment would eliminate six to

eight training requirements for commissioned ocers subject to a three- year

assignment cycle. While the initial two- year training investment to create a

UPT instructor is the same for commissioned and warrant ocers, the return

on that investment is signicantly higher for warrants.

Contracted instructor pilots rank slightly behind warrant ocers in the

competition to improve training squadron manning stability. eoretically,

so long as the Air Force maintained continuous funding, contract pilots could

remain employed as UPT instructors. However, the civilian status of contract

pilots carries a potential to produce hazardous problems in the UPT arena.

Because contractors are civilians, they have the option to quit if the condi-

tions of the contract become unfavorable. is exact situation occurred in

2009 at Vance Air Force Base when over 350 contracted aircra maintainers

went on strike over a dispute with the parent company that owned the con-

tract. With the aircra grounded, pilot training screeched to a halt. e re-

22

sulting pile up of students waiting to begin training caused a blockage in the

pipeline that took months to resolve.

71

To achieve a production rate of 1,600 pilots per year, the Air Force must

avoid situations that prevent a steady ow in the training pipeline. If the Air

Force issued contracts to individual pilots rather than selecting a parent com-

pany to provide the contracted workforce, the likelihood of a major work

stoppage could be reduced but not eliminated. An individual pilot that fails to

fulll the conditions of a contract would undoubtedly be subject to monetary

penalties. However, these penalties cannot guarantee that the pilot will not

quit. If the civilian marketplace presents an opportunity to achieve a higher

paying salary, the pilot may be enticed to accept the penalty and leave. e

threat of monetary penalties pales in comparison to punishment under the

Uniform Code of Military Justice for a warrant ocer that is absent without

leave. As such, contract pilots fall second to warrant ocers in enhancing

manning stability in UPT squadrons.

Finally, the PTN program and increasing FAIP assignments are the meth-

ods with the least impact toward improving instructor manning stability at

UPT squadrons. ough the PTN program should theoretically produce pi-

lots faster, and additional FAIPs would provide a self- sustained source of

manning by directly training their replacements, both programs would still

produce commissioned ocer pilots that are subject to a three- year assign-

ment cycle. If either of these programs were fully implemented, there would

be no appreciable change in manning stability from current operations.

Impact on operational squadron manning levels. Ignoring the amount of

time it takes to develop and award the contract itself, contract instructor pi-

lots could produce a near immediate positive impact on operational squadron

manning levels. Assuming the contractors are former military pilots, they

would not need to undertake the year- long UPT syllabus. In all likelihood,

these contractors would only need to complete the same PIT course that any

new instructor to UPT attends. Aer graduating, they could immediately be-

gin replacing military pilots, thereby freeing the military personnel to return

to operational squadrons. Additionally, because contractors do not count

against the Air Force’s total end strength authorization, they do not require a

one- for- one pilot swap between operational and training squadrons. Under

the current structure, the net personnel gain from a change of assignment for

either operational or training squadrons is zero. For each contracted UPT

instructor, operational squadrons could gain an additional body.

e PTN program is the second- best method to restore operational squad-

rons to full manning status. e experimental program should produce pilots

faster, thereby allowing them to attend follow- on training and get to opera-

23

tional squadrons well before a pilot is produced by the current syllabus. is

is evident in the case of the test class, as they reduced the UPT graduation

timeline by y percent in comparison with peers who followed the standard

syllabus. It remains to be seen if such a drastic reduction in the PTN students’

ight time will yield acceptable performance in follow- on training. If the stu-

dents have no problems progressing through the next phase of training, the

Air Force may decide to fully implement the program and operational squad-

rons may see improved manning relatively quickly. However, it is more likely

that the Air Force still needs a few years to adjust the balance of ight and

simulator time to guarantee consistency in the quality of pilots it produces.

Regardless of how long it takes to fully implement the PTN program, there

should eventually be a signicant reduction in the time it takes to make a pilot

and improve operational manning levels.

Warrant ocers rank third regarding their ability to improve operational

manning levels. Warrant ocer instructor pilots would have similar benets

as contract pilots by freeing commissioned ocers to return to operational

squadrons. However, because a warrant ocer would need to attend the full

pilot training course before PIT, the process of replacing commissioned o-

cer instructors would be delayed by an additional year in comparison with

contractors. Additionally, until a sizable warrant ocer instructor corps is

developed, warrant ocer UPT students would take training slots away from

commissioned ocers who otherwise would have reinforced operational

squadron manning.

Lastly, additional FAIPs is the worst option to provide immediate relief to

operational squadron manning shortages. First, assuming they follow the

standard UPT syllabus, the production timeline is unchanged, and it would

take approximately 16 months to make them useful UPT instructors. Second,

similar to the problem with warrant ocers as described above, the UPT

training slots used to create a FAIP prevent a newly minted pilot from going

to operational squadrons aer graduation. Finally, following graduation,

FAIPs serve a three to four- year assignment at their initial training squadron.

Hence, a FAIP will not directly improve operational squadron manning until

four to ve years aer beginning pilot training. Although, they do indirectly

contribute toward solving the manning shortage in operational squadrons by

training new pilots.

Quality of training. To determine which method presents the highest

quality of training, an assumption is made that warrant ocers, FAIPs, and

contract pilots would all be instructing under the current UPT syllabus. With

this in mind, since the current UPT syllabus is a time proven method of in-

structing aviators, all three methods have equally high potential to produce

24

quality pilots. ere is nothing to suggest that changing the instructor’s rank,

or adding civilians to the instructor corps, would negatively impact the qual-

ity of graduating pilots.

e worst option regarding quality of training is the PTN program. For

reasons already described, simulator time is not a perfect replicator of actual

ight conditions. Students graduating with reduced ight hours will be more

susceptible to airborne physiological incidents because they have less experi-

ence in the airplane. e ability to recognize, conrm, and recover from phys-

iological degradation is only gained through previous experience with the

phenomena that induced it. Before fully implementing the program, the Air

Force must acknowledge that PTN graduates will join operational squadrons

with less experience to counter the disorienting eects of ight. e service

must be willing to accept an increased risk of aviation accidents.

Analysis

e Air Force has established a goal of increasing production from 1,200 to

1,600 pilots per year, and additional students will necessitate a corresponding

increase of instructors to train them. e ceaseless pace of combat operations,

in concert with a widespread pilot shortage in operational squadrons, has

presented a situation where the Air Force may not be able to organically sup-

port increasing instructor manning at UPT squadrons. e objective of this

paper was to determine a solution to this problem and answer the question,

are warrant ocers the best solution to increase UPT instructor manning, in

order to achieve the overarching goal of producing 1,600 pilots per year?

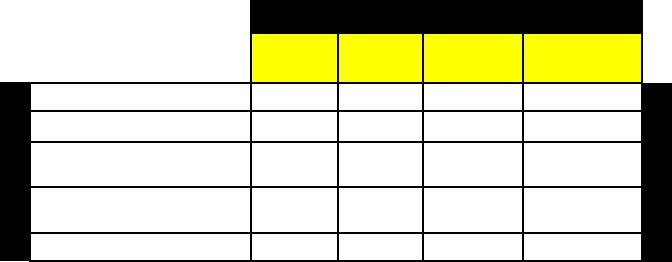

Criteria

Method to Increase Pilot Production

Rank

Warrant

Officers

Contract

Pilots

Additional

FAIPs

Pilot Training

Next

Timeliness of Implementation 4th 2nd 1st 3rd

Personnel Cost Savings 1st 4th 2nd (Tie) 2nd (Tie)

Training Squadron Manning

Stability

1st 2nd 3rd (Tie) 3rd (Tie)

Impact on Operational

Squadron Manning Levels

3rd 1st 4th 2nd

Quality of Training 1st (Tie) 1st (Tie) 1st (Tie) 4th

Table 2. Summary of the comparison between methods and criteria

Table 2 summarizes the results of the comparison between warrant ocers

and alternative methods to increase pilot production. Each method is given a

rank by how well it satises the previously identied criteria. A simple scan of

R

a

n

k

s

C

r

i

t

e

r

i

a

25

this table reveals that no single solution to the problem exists. While warrant

ocers are the best option regarding personnel cost savings and training

squadron manning stability, they cannot be implemented quickly and would

delay operational squadrons from returning to full manning status. To put it

simply, the answer to the question proposed in this paper is no. Warrant o-

cers are not the best option to increase instructor manning at UPT squadrons;

however, neither are any of the alternatives. e pilot shortage in the Air

Force is a complex problem that requires a multifaceted solution.

Conclusion

In order to provide a recommendation to solve the complex problem at